User login

The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management® is an independent, peer-reviewed journal offering evidence-based, practical information for improving the quality, safety, and value of health care.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Loneliness, social isolation in seniors need urgent attention

Health care systems need to take urgent action to address social isolation and loneliness among U.S. seniors, experts say.

A new report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) points out that social isolation in this population is a major public health concern that contributes to heart disease, depression, and premature death.

The report authors note that the health care system remains an underused partner in preventing, identifying, and intervening in social isolation and loneliness among adults over age 50.

For seniors who are homebound, have no family, or do not belong to community or faith groups, a medical appointment or home health visit may be one of the few social interactions they have, the report notes.

Health care providers and systems may be “first responders” in recognizing lonely or socially isolated patients, committee chair Dan Blazer, MD, from Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C., said during a press briefing.

As deadly as obesity, smoking

Committee member Julianne Holt-Lunstad, PhD, from Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, noted that social isolation and loneliness are “distinctly different.”

Social isolation is defined as an objective lack of (or limited) social connections, while loneliness is a subjective perception of social isolation or the subjective feeling of being lonely.

Not all older adults are isolated or lonely, but they are more likely to face predisposing factors such as living alone and the loss of loved ones, she explained.

The issue may be compounded for LGBT, minority, and immigrant older adults, who may already face barriers to care, stigma, and discrimination. Social isolation and loneliness may also directly stem from chronic illness, hearing or vision loss, or mobility issues. In these cases, health care providers might be able to help prevent or reduce social isolation and loneliness by directly addressing the underlying health-related causes.

Holt-Lunstad told the briefing. The report offers a vision for how the health care system can identify people at risk of social isolation and loneliness, intervene, and engage other community partners.

It recommends that providers use validated tools to periodically assess patients who may be at risk for social isolation and loneliness and connect them to community resources for help.

The report also calls for greater education and training among health providers. Schools of health professions and training programs for direct care workers (eg, home health aides, nurse aides, and personal care aides) should incorporate social isolation and loneliness in their curricula, the report says.

It also offers recommendations for leveraging digital health and health technology, improving community partnerships, increasing funding for research, and creation of a national resource center under the Department of Health and Human Services.

Blazer said there remains “much to be learned” about what approaches to mitigating social isolation and loneliness work best in which populations.

The report, from the Committee on the Health and Medical Dimensions of Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults, was sponsored by the AARP Foundation.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Health care systems need to take urgent action to address social isolation and loneliness among U.S. seniors, experts say.

A new report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) points out that social isolation in this population is a major public health concern that contributes to heart disease, depression, and premature death.

The report authors note that the health care system remains an underused partner in preventing, identifying, and intervening in social isolation and loneliness among adults over age 50.

For seniors who are homebound, have no family, or do not belong to community or faith groups, a medical appointment or home health visit may be one of the few social interactions they have, the report notes.

Health care providers and systems may be “first responders” in recognizing lonely or socially isolated patients, committee chair Dan Blazer, MD, from Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C., said during a press briefing.

As deadly as obesity, smoking

Committee member Julianne Holt-Lunstad, PhD, from Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, noted that social isolation and loneliness are “distinctly different.”

Social isolation is defined as an objective lack of (or limited) social connections, while loneliness is a subjective perception of social isolation or the subjective feeling of being lonely.

Not all older adults are isolated or lonely, but they are more likely to face predisposing factors such as living alone and the loss of loved ones, she explained.

The issue may be compounded for LGBT, minority, and immigrant older adults, who may already face barriers to care, stigma, and discrimination. Social isolation and loneliness may also directly stem from chronic illness, hearing or vision loss, or mobility issues. In these cases, health care providers might be able to help prevent or reduce social isolation and loneliness by directly addressing the underlying health-related causes.

Holt-Lunstad told the briefing. The report offers a vision for how the health care system can identify people at risk of social isolation and loneliness, intervene, and engage other community partners.

It recommends that providers use validated tools to periodically assess patients who may be at risk for social isolation and loneliness and connect them to community resources for help.

The report also calls for greater education and training among health providers. Schools of health professions and training programs for direct care workers (eg, home health aides, nurse aides, and personal care aides) should incorporate social isolation and loneliness in their curricula, the report says.

It also offers recommendations for leveraging digital health and health technology, improving community partnerships, increasing funding for research, and creation of a national resource center under the Department of Health and Human Services.

Blazer said there remains “much to be learned” about what approaches to mitigating social isolation and loneliness work best in which populations.

The report, from the Committee on the Health and Medical Dimensions of Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults, was sponsored by the AARP Foundation.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Health care systems need to take urgent action to address social isolation and loneliness among U.S. seniors, experts say.

A new report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) points out that social isolation in this population is a major public health concern that contributes to heart disease, depression, and premature death.

The report authors note that the health care system remains an underused partner in preventing, identifying, and intervening in social isolation and loneliness among adults over age 50.

For seniors who are homebound, have no family, or do not belong to community or faith groups, a medical appointment or home health visit may be one of the few social interactions they have, the report notes.

Health care providers and systems may be “first responders” in recognizing lonely or socially isolated patients, committee chair Dan Blazer, MD, from Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C., said during a press briefing.

As deadly as obesity, smoking

Committee member Julianne Holt-Lunstad, PhD, from Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, noted that social isolation and loneliness are “distinctly different.”

Social isolation is defined as an objective lack of (or limited) social connections, while loneliness is a subjective perception of social isolation or the subjective feeling of being lonely.

Not all older adults are isolated or lonely, but they are more likely to face predisposing factors such as living alone and the loss of loved ones, she explained.

The issue may be compounded for LGBT, minority, and immigrant older adults, who may already face barriers to care, stigma, and discrimination. Social isolation and loneliness may also directly stem from chronic illness, hearing or vision loss, or mobility issues. In these cases, health care providers might be able to help prevent or reduce social isolation and loneliness by directly addressing the underlying health-related causes.

Holt-Lunstad told the briefing. The report offers a vision for how the health care system can identify people at risk of social isolation and loneliness, intervene, and engage other community partners.

It recommends that providers use validated tools to periodically assess patients who may be at risk for social isolation and loneliness and connect them to community resources for help.

The report also calls for greater education and training among health providers. Schools of health professions and training programs for direct care workers (eg, home health aides, nurse aides, and personal care aides) should incorporate social isolation and loneliness in their curricula, the report says.

It also offers recommendations for leveraging digital health and health technology, improving community partnerships, increasing funding for research, and creation of a national resource center under the Department of Health and Human Services.

Blazer said there remains “much to be learned” about what approaches to mitigating social isolation and loneliness work best in which populations.

The report, from the Committee on the Health and Medical Dimensions of Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults, was sponsored by the AARP Foundation.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

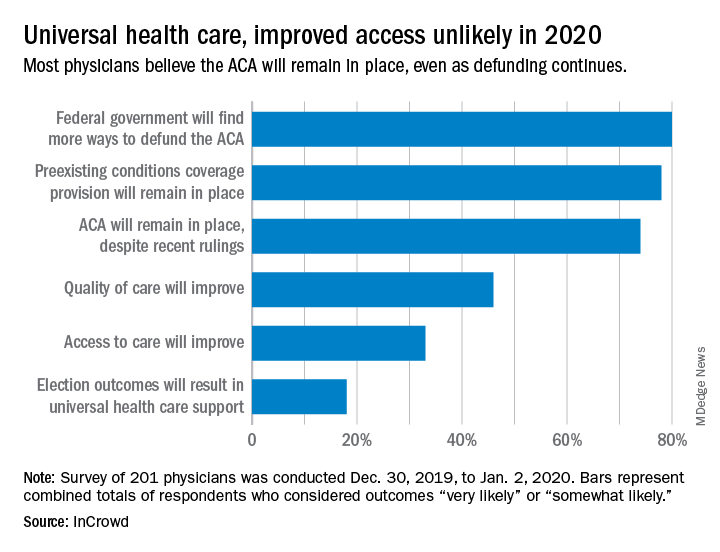

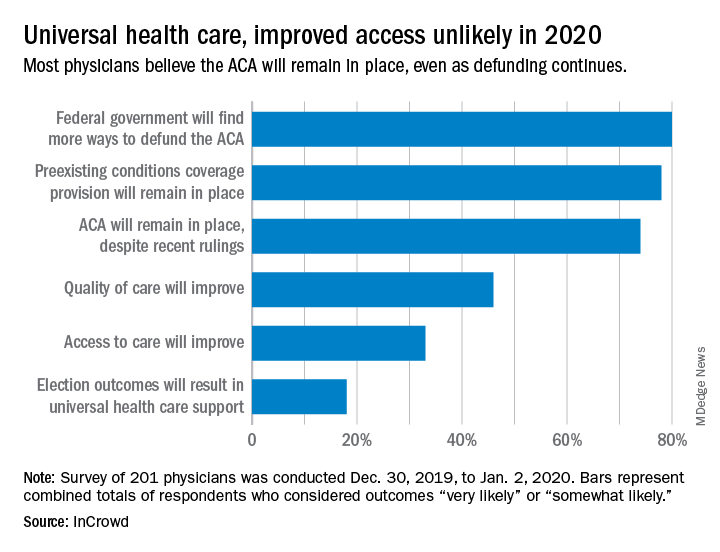

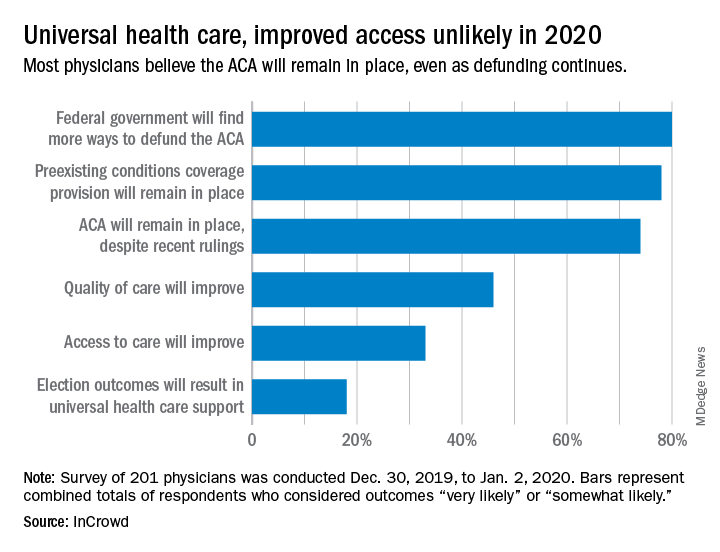

Survey: 2020 will see more attacks on ACA

When physicians gaze into their crystal balls to predict what’s coming in 2020, they see continued efforts to defund the Affordable Care Act – meaning the ACA will still be around to be defunded – but they don’t see a lot of support for universal health care, according to health care market research company InCrowd.

Expectations for universal health care came in at 18% of the 100 generalists and 101 specialists who responded to InCrowd’s fifth annual health care predictions survey, which left 82% who thought that “election outcomes will result in universal healthcare support” was somewhat or very unlikely in 2020.

One respondent, a specialist from California, commented that “the global data on universal healthcare for all shows that it results in overall improved population health. Unfortunately, we are so polarized in the US against universal healthcare driven by bias from health insurance companies and decision makers that are quick to ignore scientific data.”

This was the first time InCrowd asked physicians about universal health care, but ACA-related predictions have been included before, and all three scenarios presented were deemed to be increasingly likely, compared with 2019.

Respondents thought that federal government defunding was more likely to occur in 2020 (80%) than in 2019 (73%), but increased majorities also said that preexisting conditions coverage would continue (78% in 2020 vs. 70% in 2019) and that the ACA would remain in place (74% in 2020 vs. 60% in 2019), InCrowd reported after the survey, which was conducted from Dec. 30, 2019, to Jan. 2, 2020.

A respondent who thought the ACA will be eliminated said, “I have as many uninsured today as before the ACA. They are just different. Mainly younger patients who spend less in a year on healthcare than one month’s premium.” Another suggested that eliminateing it “will limit access to care and overload [emergency departments]. More people will die.”

Cost was addressed in a separate survey question that asked how physicians could help to reduce health care spending in 2020.

The leading answer, given by 37% of respondents, was for physicians to “inform themselves of costs and adapt cost-saving prescription practices.” Next came “limit use of expensive tests and scans” with 21%, followed by “prescribe generics when possible” at 20%, which was a substantial drop from the 38% it garnered in 2019, InCrowd noted.

“Participation in [shared savings] programs and risk-based incentive programs and pay-for-performance programs” would provide “better stewardship of resources,” a primary care physician from Michigan wrote.

When the survey turned to pharmaceutical industry predictions for 2020, cost was the major issue.

“What’s interesting about this year’s data is that we’re seeing less emphasis on the importance of bringing innovative, new therapies to market faster … versus expanding affordability, which was nearly a unanimous top priority for respondents,” Daniel S. Fitzgerald, InCrowd’s CEO and president, said in a separate statement.

When physicians gaze into their crystal balls to predict what’s coming in 2020, they see continued efforts to defund the Affordable Care Act – meaning the ACA will still be around to be defunded – but they don’t see a lot of support for universal health care, according to health care market research company InCrowd.

Expectations for universal health care came in at 18% of the 100 generalists and 101 specialists who responded to InCrowd’s fifth annual health care predictions survey, which left 82% who thought that “election outcomes will result in universal healthcare support” was somewhat or very unlikely in 2020.

One respondent, a specialist from California, commented that “the global data on universal healthcare for all shows that it results in overall improved population health. Unfortunately, we are so polarized in the US against universal healthcare driven by bias from health insurance companies and decision makers that are quick to ignore scientific data.”

This was the first time InCrowd asked physicians about universal health care, but ACA-related predictions have been included before, and all three scenarios presented were deemed to be increasingly likely, compared with 2019.

Respondents thought that federal government defunding was more likely to occur in 2020 (80%) than in 2019 (73%), but increased majorities also said that preexisting conditions coverage would continue (78% in 2020 vs. 70% in 2019) and that the ACA would remain in place (74% in 2020 vs. 60% in 2019), InCrowd reported after the survey, which was conducted from Dec. 30, 2019, to Jan. 2, 2020.

A respondent who thought the ACA will be eliminated said, “I have as many uninsured today as before the ACA. They are just different. Mainly younger patients who spend less in a year on healthcare than one month’s premium.” Another suggested that eliminateing it “will limit access to care and overload [emergency departments]. More people will die.”

Cost was addressed in a separate survey question that asked how physicians could help to reduce health care spending in 2020.

The leading answer, given by 37% of respondents, was for physicians to “inform themselves of costs and adapt cost-saving prescription practices.” Next came “limit use of expensive tests and scans” with 21%, followed by “prescribe generics when possible” at 20%, which was a substantial drop from the 38% it garnered in 2019, InCrowd noted.

“Participation in [shared savings] programs and risk-based incentive programs and pay-for-performance programs” would provide “better stewardship of resources,” a primary care physician from Michigan wrote.

When the survey turned to pharmaceutical industry predictions for 2020, cost was the major issue.

“What’s interesting about this year’s data is that we’re seeing less emphasis on the importance of bringing innovative, new therapies to market faster … versus expanding affordability, which was nearly a unanimous top priority for respondents,” Daniel S. Fitzgerald, InCrowd’s CEO and president, said in a separate statement.

When physicians gaze into their crystal balls to predict what’s coming in 2020, they see continued efforts to defund the Affordable Care Act – meaning the ACA will still be around to be defunded – but they don’t see a lot of support for universal health care, according to health care market research company InCrowd.

Expectations for universal health care came in at 18% of the 100 generalists and 101 specialists who responded to InCrowd’s fifth annual health care predictions survey, which left 82% who thought that “election outcomes will result in universal healthcare support” was somewhat or very unlikely in 2020.

One respondent, a specialist from California, commented that “the global data on universal healthcare for all shows that it results in overall improved population health. Unfortunately, we are so polarized in the US against universal healthcare driven by bias from health insurance companies and decision makers that are quick to ignore scientific data.”

This was the first time InCrowd asked physicians about universal health care, but ACA-related predictions have been included before, and all three scenarios presented were deemed to be increasingly likely, compared with 2019.

Respondents thought that federal government defunding was more likely to occur in 2020 (80%) than in 2019 (73%), but increased majorities also said that preexisting conditions coverage would continue (78% in 2020 vs. 70% in 2019) and that the ACA would remain in place (74% in 2020 vs. 60% in 2019), InCrowd reported after the survey, which was conducted from Dec. 30, 2019, to Jan. 2, 2020.

A respondent who thought the ACA will be eliminated said, “I have as many uninsured today as before the ACA. They are just different. Mainly younger patients who spend less in a year on healthcare than one month’s premium.” Another suggested that eliminateing it “will limit access to care and overload [emergency departments]. More people will die.”

Cost was addressed in a separate survey question that asked how physicians could help to reduce health care spending in 2020.

The leading answer, given by 37% of respondents, was for physicians to “inform themselves of costs and adapt cost-saving prescription practices.” Next came “limit use of expensive tests and scans” with 21%, followed by “prescribe generics when possible” at 20%, which was a substantial drop from the 38% it garnered in 2019, InCrowd noted.

“Participation in [shared savings] programs and risk-based incentive programs and pay-for-performance programs” would provide “better stewardship of resources,” a primary care physician from Michigan wrote.

When the survey turned to pharmaceutical industry predictions for 2020, cost was the major issue.

“What’s interesting about this year’s data is that we’re seeing less emphasis on the importance of bringing innovative, new therapies to market faster … versus expanding affordability, which was nearly a unanimous top priority for respondents,” Daniel S. Fitzgerald, InCrowd’s CEO and president, said in a separate statement.

Does screening by primary care providers effectively detect melanoma and other skin cancers?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

No trials have directly assessed skin cancer morbidity associated with physician visual skin screening. A 2018 ecologic cohort study found no difference in melanoma mortality in a population undergoing a national screening program, although screening was associated with 41% more diagnoses of skin cancer.1 A 2012 cohort study found a reduction in melanoma mortality over 7 years associated with a population-based visual skin cancer screening program compared with similar populations that didn’t undergo specific screening.2 At 12-year follow-up, however, there was no longer a difference in mortality.

Primary care visual screening doesn’t decrease melanoma mortality

German researchers trained 1673 non-dermatologists (64% of general practitioners, obstetrician-gynecologists, and urologists in that region of Germany) and 116 dermatologists (98% in the region) to recognize skin cancer through whole-body visual inspection.1 They recruited and screened 360,000 adults (19% of the population older than 20 years; 74% women) and followed age- and sex-adjusted melanoma mortality over the next 10 years. Non-dermatologists performed most screening exams (77%); 37% of screened positive patients were lost to follow-up.

Melanoma mortality ultimately didn’t change in the screened region, compared with populations in other European countries without national screening programs. Screening detected approximately half of melanoma cases (585/1169) in the region and was associated with 41% greater detection of skin cancers compared with other countries.

Researchers recorded age-adjusted increases in incidence per 100,000 of melanoma from 14.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.3-15.1) to 18 (95% CI, 16.6-19.4), melanoma in situ from 5.8 (95% CI, 5.2-6.4) to 8.5 (95% CI, 7.5-9.5), squamous cell carcinoma from 11.2 (95% CI, 10.6-11.8) to 12.9 (95% CI, 12.0-13.8), and basal cell carcinoma from 60.5 (95% CI, 59.0-62.1) to 78.4 (95% CI, 75.9-80.8).

Visual screening by primary care providers vs screening by dermatologists

A cohort study of 16,383 Australian adults found that visual screening by primary care physicians detected melanoma over 3 years with a sensitivity of 40.2% (95% CIs not supplied) and specificity of 86.1% (95% CI, 85.6-86.6%; positive predictive value = 1.4%).3

A second cohort study, enrolling 7436 adults, that evaluated visual screening by dermatologists and plastic surgeons over 2 years found a sensitivity for melanoma of 49% (95% CI, 34.4-63.7%) and a specificity of 97.6% (95% CI, 97.2-97.9%) with a positive predictive value of 11.9% (95% CI, 7.8-17.2%).4

Visual screening more often detects thinner melanomas

A 3-year case-control study (3762 cases, 3824 controls) that examined the association between visual skin screening by a physician (type of physician not specified) and thickness of melanomas detected found that thin melanomas (≤ 0.75 mm) were more common among screened patients compared with unscreened patients (odds ratio [OR] = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.22-1.56) and thicker melanomas (≥ 0.75 mm) were less common (OR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98).5

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review of 8 observational cohort studies with a total of 200,000 patients found a consistent linear increase in melanoma mortality with increasing tumor thickness.6 The largest study (68,495 patients), which compared melanoma mortality for thinner (< 1 mm) and thicker lesions, reported risk ratios of 2.89 for lesion thicknesses of 1.01 to 2 mm (95% CI, 2.62-3.18); 4.69 for thicknesses of 2.01 to 4 mm (95% CI, 4.24-5.02); and 5.71 for thicknesses > 4 mm (95% CI, 5.10-6.39).

The downside of visual screening: False-positives

The 2012 cohort study, which reported outcomes from 16,000 biopsies performed following visual screening exams, found that 28 biopsies were performed for each diagnosis of melanoma and 9 to 10 biopsies for each basal cell carcinoma.2 Diagnosis rates (number of skin biopsies performed for each case of cancer diagnosed) were equal in men and women for both types of cancer. However, researchers observed more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in women than men (56 vs 28 biopsies per case).

Younger patients underwent more biopsies than older patients for each diagnosis of skin cancer. Women 20 to 34 years of age underwent more biopsies than women 65 years or older for each diagnosis of melanoma (19 additional excisions) and basal cell carcinoma (134 additional excisions). Women 35 to 49 years of age underwent 565 more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma than women 65 years or older. Similar patterns applied to men 20 to 34 years of age compared with men 65 years or older (24 additional biopsies per melanoma, 109 per basal cell carcinoma, and 898 per squamous cell carcinoma).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations, based on a systematic review of mostly cohort studies, state that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of clinician visual skin cancer screening.7,8

The American Academy of Dermatology states that skin cancer screening can save lives and supports research on the benefits and harms of screening in the primary care setting.9

Continue to: Editor's Takeaway

Editor’s Takeaway

Skin cancer screening by primary care physicians is associated with increased detection of skin cancers, including melanomas—even though we have no confirmation that it changes melanoma mortality. It is unclear what the appropriate rate of false-positive screening tests should be, but wider adoption of noninvasive diagnostic techniques such as dermoscopy might reduce unwarranted biopsies.

1. Kaiser M, Schiller J, Schreckenberger C. The effectiveness of a population-based skin cancer screening program: evidence from Germany. Eur J Health Econ. 2018:19:355-367.

2. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Weinstock MA, et al. Skin cancer screening participation and impact on melanoma incidence in Germany—an observational study on incidence trends in regions with and without population-based screening. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:970-974.

3. Aitken JF, Janda M, Elwood M, et al. Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006:54:105-114.

4. Fritschi L, Dye SA, Katris P. Validity of melanoma diagnosis in a community-based screening program. Am J Epidemiol. 2006:164:385-390.

5. Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, et al. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010:126:450-458.

6. Wernli KJ, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, et al. Screening for Skin Cancer in Adults: An Updated Systematic Evidence Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016. Evidence Synthesis 137.

7. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Geller AC, et al. Frequency of excisions and yields of malignant skin tumors in a population-based screening intervention of 360,288 whole-body examinations. Arch Dermatol. 2012:148:903-910.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Skin Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

9. Torres A. AAD statement on USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer screening. July 2016. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-statement-on-uspstf 26. Accessed May 2018.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

No trials have directly assessed skin cancer morbidity associated with physician visual skin screening. A 2018 ecologic cohort study found no difference in melanoma mortality in a population undergoing a national screening program, although screening was associated with 41% more diagnoses of skin cancer.1 A 2012 cohort study found a reduction in melanoma mortality over 7 years associated with a population-based visual skin cancer screening program compared with similar populations that didn’t undergo specific screening.2 At 12-year follow-up, however, there was no longer a difference in mortality.

Primary care visual screening doesn’t decrease melanoma mortality

German researchers trained 1673 non-dermatologists (64% of general practitioners, obstetrician-gynecologists, and urologists in that region of Germany) and 116 dermatologists (98% in the region) to recognize skin cancer through whole-body visual inspection.1 They recruited and screened 360,000 adults (19% of the population older than 20 years; 74% women) and followed age- and sex-adjusted melanoma mortality over the next 10 years. Non-dermatologists performed most screening exams (77%); 37% of screened positive patients were lost to follow-up.

Melanoma mortality ultimately didn’t change in the screened region, compared with populations in other European countries without national screening programs. Screening detected approximately half of melanoma cases (585/1169) in the region and was associated with 41% greater detection of skin cancers compared with other countries.

Researchers recorded age-adjusted increases in incidence per 100,000 of melanoma from 14.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.3-15.1) to 18 (95% CI, 16.6-19.4), melanoma in situ from 5.8 (95% CI, 5.2-6.4) to 8.5 (95% CI, 7.5-9.5), squamous cell carcinoma from 11.2 (95% CI, 10.6-11.8) to 12.9 (95% CI, 12.0-13.8), and basal cell carcinoma from 60.5 (95% CI, 59.0-62.1) to 78.4 (95% CI, 75.9-80.8).

Visual screening by primary care providers vs screening by dermatologists

A cohort study of 16,383 Australian adults found that visual screening by primary care physicians detected melanoma over 3 years with a sensitivity of 40.2% (95% CIs not supplied) and specificity of 86.1% (95% CI, 85.6-86.6%; positive predictive value = 1.4%).3

A second cohort study, enrolling 7436 adults, that evaluated visual screening by dermatologists and plastic surgeons over 2 years found a sensitivity for melanoma of 49% (95% CI, 34.4-63.7%) and a specificity of 97.6% (95% CI, 97.2-97.9%) with a positive predictive value of 11.9% (95% CI, 7.8-17.2%).4

Visual screening more often detects thinner melanomas

A 3-year case-control study (3762 cases, 3824 controls) that examined the association between visual skin screening by a physician (type of physician not specified) and thickness of melanomas detected found that thin melanomas (≤ 0.75 mm) were more common among screened patients compared with unscreened patients (odds ratio [OR] = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.22-1.56) and thicker melanomas (≥ 0.75 mm) were less common (OR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98).5

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review of 8 observational cohort studies with a total of 200,000 patients found a consistent linear increase in melanoma mortality with increasing tumor thickness.6 The largest study (68,495 patients), which compared melanoma mortality for thinner (< 1 mm) and thicker lesions, reported risk ratios of 2.89 for lesion thicknesses of 1.01 to 2 mm (95% CI, 2.62-3.18); 4.69 for thicknesses of 2.01 to 4 mm (95% CI, 4.24-5.02); and 5.71 for thicknesses > 4 mm (95% CI, 5.10-6.39).

The downside of visual screening: False-positives

The 2012 cohort study, which reported outcomes from 16,000 biopsies performed following visual screening exams, found that 28 biopsies were performed for each diagnosis of melanoma and 9 to 10 biopsies for each basal cell carcinoma.2 Diagnosis rates (number of skin biopsies performed for each case of cancer diagnosed) were equal in men and women for both types of cancer. However, researchers observed more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in women than men (56 vs 28 biopsies per case).

Younger patients underwent more biopsies than older patients for each diagnosis of skin cancer. Women 20 to 34 years of age underwent more biopsies than women 65 years or older for each diagnosis of melanoma (19 additional excisions) and basal cell carcinoma (134 additional excisions). Women 35 to 49 years of age underwent 565 more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma than women 65 years or older. Similar patterns applied to men 20 to 34 years of age compared with men 65 years or older (24 additional biopsies per melanoma, 109 per basal cell carcinoma, and 898 per squamous cell carcinoma).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations, based on a systematic review of mostly cohort studies, state that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of clinician visual skin cancer screening.7,8

The American Academy of Dermatology states that skin cancer screening can save lives and supports research on the benefits and harms of screening in the primary care setting.9

Continue to: Editor's Takeaway

Editor’s Takeaway

Skin cancer screening by primary care physicians is associated with increased detection of skin cancers, including melanomas—even though we have no confirmation that it changes melanoma mortality. It is unclear what the appropriate rate of false-positive screening tests should be, but wider adoption of noninvasive diagnostic techniques such as dermoscopy might reduce unwarranted biopsies.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

No trials have directly assessed skin cancer morbidity associated with physician visual skin screening. A 2018 ecologic cohort study found no difference in melanoma mortality in a population undergoing a national screening program, although screening was associated with 41% more diagnoses of skin cancer.1 A 2012 cohort study found a reduction in melanoma mortality over 7 years associated with a population-based visual skin cancer screening program compared with similar populations that didn’t undergo specific screening.2 At 12-year follow-up, however, there was no longer a difference in mortality.

Primary care visual screening doesn’t decrease melanoma mortality

German researchers trained 1673 non-dermatologists (64% of general practitioners, obstetrician-gynecologists, and urologists in that region of Germany) and 116 dermatologists (98% in the region) to recognize skin cancer through whole-body visual inspection.1 They recruited and screened 360,000 adults (19% of the population older than 20 years; 74% women) and followed age- and sex-adjusted melanoma mortality over the next 10 years. Non-dermatologists performed most screening exams (77%); 37% of screened positive patients were lost to follow-up.

Melanoma mortality ultimately didn’t change in the screened region, compared with populations in other European countries without national screening programs. Screening detected approximately half of melanoma cases (585/1169) in the region and was associated with 41% greater detection of skin cancers compared with other countries.

Researchers recorded age-adjusted increases in incidence per 100,000 of melanoma from 14.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.3-15.1) to 18 (95% CI, 16.6-19.4), melanoma in situ from 5.8 (95% CI, 5.2-6.4) to 8.5 (95% CI, 7.5-9.5), squamous cell carcinoma from 11.2 (95% CI, 10.6-11.8) to 12.9 (95% CI, 12.0-13.8), and basal cell carcinoma from 60.5 (95% CI, 59.0-62.1) to 78.4 (95% CI, 75.9-80.8).

Visual screening by primary care providers vs screening by dermatologists

A cohort study of 16,383 Australian adults found that visual screening by primary care physicians detected melanoma over 3 years with a sensitivity of 40.2% (95% CIs not supplied) and specificity of 86.1% (95% CI, 85.6-86.6%; positive predictive value = 1.4%).3

A second cohort study, enrolling 7436 adults, that evaluated visual screening by dermatologists and plastic surgeons over 2 years found a sensitivity for melanoma of 49% (95% CI, 34.4-63.7%) and a specificity of 97.6% (95% CI, 97.2-97.9%) with a positive predictive value of 11.9% (95% CI, 7.8-17.2%).4

Visual screening more often detects thinner melanomas

A 3-year case-control study (3762 cases, 3824 controls) that examined the association between visual skin screening by a physician (type of physician not specified) and thickness of melanomas detected found that thin melanomas (≤ 0.75 mm) were more common among screened patients compared with unscreened patients (odds ratio [OR] = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.22-1.56) and thicker melanomas (≥ 0.75 mm) were less common (OR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98).5

Continue to: A systematic review...

A systematic review of 8 observational cohort studies with a total of 200,000 patients found a consistent linear increase in melanoma mortality with increasing tumor thickness.6 The largest study (68,495 patients), which compared melanoma mortality for thinner (< 1 mm) and thicker lesions, reported risk ratios of 2.89 for lesion thicknesses of 1.01 to 2 mm (95% CI, 2.62-3.18); 4.69 for thicknesses of 2.01 to 4 mm (95% CI, 4.24-5.02); and 5.71 for thicknesses > 4 mm (95% CI, 5.10-6.39).

The downside of visual screening: False-positives

The 2012 cohort study, which reported outcomes from 16,000 biopsies performed following visual screening exams, found that 28 biopsies were performed for each diagnosis of melanoma and 9 to 10 biopsies for each basal cell carcinoma.2 Diagnosis rates (number of skin biopsies performed for each case of cancer diagnosed) were equal in men and women for both types of cancer. However, researchers observed more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in women than men (56 vs 28 biopsies per case).

Younger patients underwent more biopsies than older patients for each diagnosis of skin cancer. Women 20 to 34 years of age underwent more biopsies than women 65 years or older for each diagnosis of melanoma (19 additional excisions) and basal cell carcinoma (134 additional excisions). Women 35 to 49 years of age underwent 565 more biopsies for each diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma than women 65 years or older. Similar patterns applied to men 20 to 34 years of age compared with men 65 years or older (24 additional biopsies per melanoma, 109 per basal cell carcinoma, and 898 per squamous cell carcinoma).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations, based on a systematic review of mostly cohort studies, state that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of clinician visual skin cancer screening.7,8

The American Academy of Dermatology states that skin cancer screening can save lives and supports research on the benefits and harms of screening in the primary care setting.9

Continue to: Editor's Takeaway

Editor’s Takeaway

Skin cancer screening by primary care physicians is associated with increased detection of skin cancers, including melanomas—even though we have no confirmation that it changes melanoma mortality. It is unclear what the appropriate rate of false-positive screening tests should be, but wider adoption of noninvasive diagnostic techniques such as dermoscopy might reduce unwarranted biopsies.

1. Kaiser M, Schiller J, Schreckenberger C. The effectiveness of a population-based skin cancer screening program: evidence from Germany. Eur J Health Econ. 2018:19:355-367.

2. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Weinstock MA, et al. Skin cancer screening participation and impact on melanoma incidence in Germany—an observational study on incidence trends in regions with and without population-based screening. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:970-974.

3. Aitken JF, Janda M, Elwood M, et al. Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006:54:105-114.

4. Fritschi L, Dye SA, Katris P. Validity of melanoma diagnosis in a community-based screening program. Am J Epidemiol. 2006:164:385-390.

5. Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, et al. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010:126:450-458.

6. Wernli KJ, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, et al. Screening for Skin Cancer in Adults: An Updated Systematic Evidence Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016. Evidence Synthesis 137.

7. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Geller AC, et al. Frequency of excisions and yields of malignant skin tumors in a population-based screening intervention of 360,288 whole-body examinations. Arch Dermatol. 2012:148:903-910.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Skin Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

9. Torres A. AAD statement on USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer screening. July 2016. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-statement-on-uspstf 26. Accessed May 2018.

1. Kaiser M, Schiller J, Schreckenberger C. The effectiveness of a population-based skin cancer screening program: evidence from Germany. Eur J Health Econ. 2018:19:355-367.

2. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Weinstock MA, et al. Skin cancer screening participation and impact on melanoma incidence in Germany—an observational study on incidence trends in regions with and without population-based screening. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:970-974.

3. Aitken JF, Janda M, Elwood M, et al. Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006:54:105-114.

4. Fritschi L, Dye SA, Katris P. Validity of melanoma diagnosis in a community-based screening program. Am J Epidemiol. 2006:164:385-390.

5. Aitken JF, Elwood M, Baade PD, et al. Clinical whole-body skin examination reduces the incidence of thick melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2010:126:450-458.

6. Wernli KJ, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, et al. Screening for Skin Cancer in Adults: An Updated Systematic Evidence Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016. Evidence Synthesis 137.

7. Waldmann A, Nolte S, Geller AC, et al. Frequency of excisions and yields of malignant skin tumors in a population-based screening intervention of 360,288 whole-body examinations. Arch Dermatol. 2012:148:903-910.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Skin Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

9. Torres A. AAD statement on USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer screening. July 2016. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-statement-on-uspstf 26. Accessed May 2018.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Possibly. No trials have directly assessed detection of melanoma and other skin cancers by primary care providers.

Training a group comprised largely of primary care physicians to perform skin cancer screening was associated with a 41% increase in skin cancer diagnoses but no change in melanoma mortality.

Visual screening for melanoma by primary care physicians is 40% sensitive and 86% specific (compared with 49% and 98%, respectively, for dermatologists and plastic surgeons).

Melanomas found by visual screening are 38% more likely to be thin (≤ 0.75 mm) than melanomas discovered without screening, which correlates with improved outcomes.

Visual skin cancer screening overall is associated with false-positive rates as follows: 28 biopsies for each melanoma detected, 9 to 10 biopsies for each basal cell carcinoma, and 28 to 56 biopsies for squamous cell carcinoma. False-positive rates are higher for women—as much as double the rate for men—and younger patients—as much as 20-fold the rate for older patients (strength of recommendations for all foregoing statements: B, cohort studies).

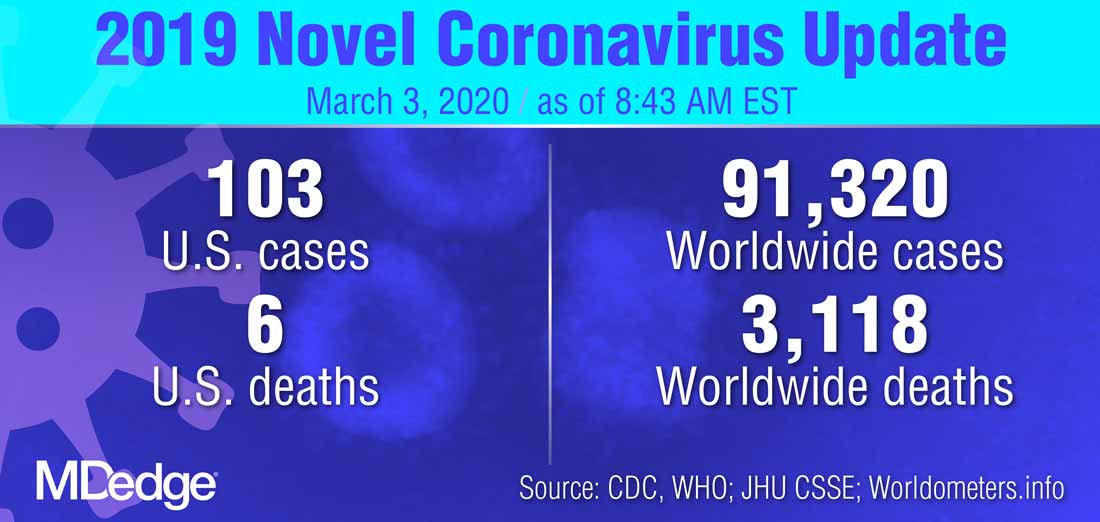

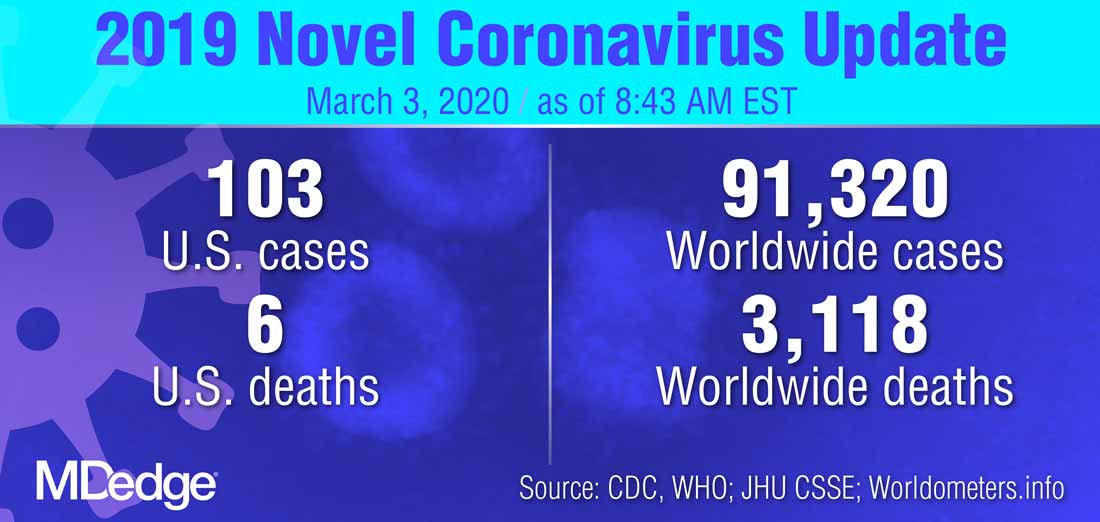

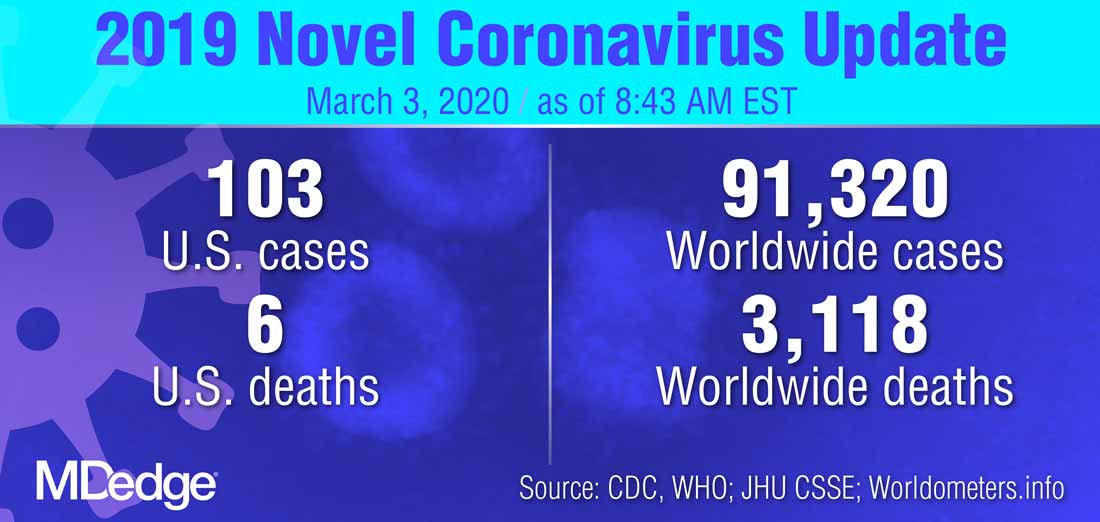

FDA moves to expand coronavirus testing capacity; CDC clarifies testing criteria

The White House Coronavirus Task Force appeared at a press briefing March 2 to provide updates about testing strategies and public health coordination to address the current outbreak of the coronavirus COVID-19. Speaking at the briefing, led by Vice President Mike Pence, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) director Robert Redfield, MD, said, “Working with our public health partners we continue to be able to identify new community cases and use our public health efforts to aggressively confirm, isolate, and do contact tracking.” Calling state, local, tribal, and territorial public health departments “the backbone of the public health system in our country,” Dr. Redfield noted that he expected many more confirmed COVID-19 cases to emerge.

At least some of the expected increase in confirmed cases of COVID-19 will occur because of expanded testing capacity, noted several of the task force members. On Feb. 29, the Food and Drug Administration issued a the virus that is causing the current outbreak of COVID-19.

Highly qualified laboratories, including both those run by public agencies and private labs, are now authorized to begin using their own validated test for the virus as long as they submit an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to the Food and Drug Administration within 15 days of notifying the agency of validation.

“To effectively respond to the COVID-19 outbreak, rapid detection of cases and contacts, appropriate clinical management and infection control, and implementation of community mitigation efforts are critical. This can best be achieved with wide availability of testing capabilities in health care settings, reference and commercial laboratories, and at the point of care,” the agency wrote in a press announcement of the expedited test expansion.

On Feb. 4, the Secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services declared a coronavirus public health emergency. The FDA was then authorized to allow individual laboratories with validated coronavirus tests to begin testing samples immediately. The goal is a more rapid and expanded testing capacity in the United States.

“The global emergence of COVID-19 is concerning, and we appreciate the efforts of the FDA to help bring more testing capability to the U.S.,” Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), said in the press release.

The new guidance that permits the immediate use of clinical tests after individual development and validation, said the FDA, only applies to labs already certified to perform high complexity testing under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments. Many governmental, academic, and private laboratories fall into this category, however.

“Under this policy, we expect certain laboratories who develop validated tests for coronavirus would begin using them right away prior to FDA review,” said Jeffrey Shuren, MD, JD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health. “We believe this action will support laboratories across the country working on this urgent public health situation,” he added in the press release.

“By the end of this week, close to a million tests will be available,” FDA Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, said during the March 2 briefing.*

Updated criteria

The CDC is maintaining updated criteria for the virus testing on its website. Testing criteria are based both on clinical features and epidemiologic risk.

Individuals with less severe clinical features – those who have either fever or signs and symptoms of lower respiratory disease such as cough or shortness of breath, but who don’t require hospitalization – should be tested if they have high epidemiologic risk. “High risk” is defined by the CDC as any individual, including health care workers, who has had close contact with a person with confirmed COVID-19 within the past 2 weeks. For health care workers, testing can be considered even if they have relatively mild respiratory symptoms or have had contact with a person who is suspected, but not yet confirmed, to have coronavirus.

In its testing guidance, the CDC recognizes that defining close contact is difficult. General guidelines are that individuals are considered to have been in close contact with a person who has COVID-19 if they were within about six feet of the person for a prolonged period, or cared for or have spent a prolonged amount of time in the same room or house as a person with confirmed COVID-19.

Individuals who have both fever and signs or symptoms of lower respiratory illness who require hospitalization should be tested if they have a history of travel from any affected geographic area within 14 days of the onset of their symptoms. The CDC now defines “affected geographic area” as any country or region that has at least a CDC Level 2 Travel Health Notice for COVID-19, so that the testing criteria themselves don’t need to be updated when new geographic areas are included in these alerts. As of March 3, China, Iran, Italy, Japan, and South Korea all have Level 2 or 3 travel alerts.

The CDC now recommends that any patient who has severe acute lower respiratory illness that requires hospitalization and doesn’t have an alternative diagnosis should be tested, even without any identified source of exposure.

“Despite seeing these new cases, the risk to the American people is low,” said the CDC’s Dr. Redfield. In response to a question from the press about how fast the coronavirus will spread across the United States, Dr. Redfield said, “From the beginning we’ve anticipated seeing community cases pop up.” He added that as these cases arise, testing and public health strategies will focus on unearthing linkages and contacts to learn how the virus is spreading. “We’ll use the public health strategies that we can to limit that transmission,” he said.

*An earlier version of this article misattributed this quote.

The White House Coronavirus Task Force appeared at a press briefing March 2 to provide updates about testing strategies and public health coordination to address the current outbreak of the coronavirus COVID-19. Speaking at the briefing, led by Vice President Mike Pence, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) director Robert Redfield, MD, said, “Working with our public health partners we continue to be able to identify new community cases and use our public health efforts to aggressively confirm, isolate, and do contact tracking.” Calling state, local, tribal, and territorial public health departments “the backbone of the public health system in our country,” Dr. Redfield noted that he expected many more confirmed COVID-19 cases to emerge.

At least some of the expected increase in confirmed cases of COVID-19 will occur because of expanded testing capacity, noted several of the task force members. On Feb. 29, the Food and Drug Administration issued a the virus that is causing the current outbreak of COVID-19.

Highly qualified laboratories, including both those run by public agencies and private labs, are now authorized to begin using their own validated test for the virus as long as they submit an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to the Food and Drug Administration within 15 days of notifying the agency of validation.

“To effectively respond to the COVID-19 outbreak, rapid detection of cases and contacts, appropriate clinical management and infection control, and implementation of community mitigation efforts are critical. This can best be achieved with wide availability of testing capabilities in health care settings, reference and commercial laboratories, and at the point of care,” the agency wrote in a press announcement of the expedited test expansion.

On Feb. 4, the Secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services declared a coronavirus public health emergency. The FDA was then authorized to allow individual laboratories with validated coronavirus tests to begin testing samples immediately. The goal is a more rapid and expanded testing capacity in the United States.

“The global emergence of COVID-19 is concerning, and we appreciate the efforts of the FDA to help bring more testing capability to the U.S.,” Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), said in the press release.

The new guidance that permits the immediate use of clinical tests after individual development and validation, said the FDA, only applies to labs already certified to perform high complexity testing under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments. Many governmental, academic, and private laboratories fall into this category, however.

“Under this policy, we expect certain laboratories who develop validated tests for coronavirus would begin using them right away prior to FDA review,” said Jeffrey Shuren, MD, JD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health. “We believe this action will support laboratories across the country working on this urgent public health situation,” he added in the press release.

“By the end of this week, close to a million tests will be available,” FDA Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, said during the March 2 briefing.*

Updated criteria

The CDC is maintaining updated criteria for the virus testing on its website. Testing criteria are based both on clinical features and epidemiologic risk.

Individuals with less severe clinical features – those who have either fever or signs and symptoms of lower respiratory disease such as cough or shortness of breath, but who don’t require hospitalization – should be tested if they have high epidemiologic risk. “High risk” is defined by the CDC as any individual, including health care workers, who has had close contact with a person with confirmed COVID-19 within the past 2 weeks. For health care workers, testing can be considered even if they have relatively mild respiratory symptoms or have had contact with a person who is suspected, but not yet confirmed, to have coronavirus.

In its testing guidance, the CDC recognizes that defining close contact is difficult. General guidelines are that individuals are considered to have been in close contact with a person who has COVID-19 if they were within about six feet of the person for a prolonged period, or cared for or have spent a prolonged amount of time in the same room or house as a person with confirmed COVID-19.

Individuals who have both fever and signs or symptoms of lower respiratory illness who require hospitalization should be tested if they have a history of travel from any affected geographic area within 14 days of the onset of their symptoms. The CDC now defines “affected geographic area” as any country or region that has at least a CDC Level 2 Travel Health Notice for COVID-19, so that the testing criteria themselves don’t need to be updated when new geographic areas are included in these alerts. As of March 3, China, Iran, Italy, Japan, and South Korea all have Level 2 or 3 travel alerts.

The CDC now recommends that any patient who has severe acute lower respiratory illness that requires hospitalization and doesn’t have an alternative diagnosis should be tested, even without any identified source of exposure.

“Despite seeing these new cases, the risk to the American people is low,” said the CDC’s Dr. Redfield. In response to a question from the press about how fast the coronavirus will spread across the United States, Dr. Redfield said, “From the beginning we’ve anticipated seeing community cases pop up.” He added that as these cases arise, testing and public health strategies will focus on unearthing linkages and contacts to learn how the virus is spreading. “We’ll use the public health strategies that we can to limit that transmission,” he said.

*An earlier version of this article misattributed this quote.

The White House Coronavirus Task Force appeared at a press briefing March 2 to provide updates about testing strategies and public health coordination to address the current outbreak of the coronavirus COVID-19. Speaking at the briefing, led by Vice President Mike Pence, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) director Robert Redfield, MD, said, “Working with our public health partners we continue to be able to identify new community cases and use our public health efforts to aggressively confirm, isolate, and do contact tracking.” Calling state, local, tribal, and territorial public health departments “the backbone of the public health system in our country,” Dr. Redfield noted that he expected many more confirmed COVID-19 cases to emerge.

At least some of the expected increase in confirmed cases of COVID-19 will occur because of expanded testing capacity, noted several of the task force members. On Feb. 29, the Food and Drug Administration issued a the virus that is causing the current outbreak of COVID-19.

Highly qualified laboratories, including both those run by public agencies and private labs, are now authorized to begin using their own validated test for the virus as long as they submit an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to the Food and Drug Administration within 15 days of notifying the agency of validation.

“To effectively respond to the COVID-19 outbreak, rapid detection of cases and contacts, appropriate clinical management and infection control, and implementation of community mitigation efforts are critical. This can best be achieved with wide availability of testing capabilities in health care settings, reference and commercial laboratories, and at the point of care,” the agency wrote in a press announcement of the expedited test expansion.

On Feb. 4, the Secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services declared a coronavirus public health emergency. The FDA was then authorized to allow individual laboratories with validated coronavirus tests to begin testing samples immediately. The goal is a more rapid and expanded testing capacity in the United States.

“The global emergence of COVID-19 is concerning, and we appreciate the efforts of the FDA to help bring more testing capability to the U.S.,” Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), said in the press release.

The new guidance that permits the immediate use of clinical tests after individual development and validation, said the FDA, only applies to labs already certified to perform high complexity testing under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments. Many governmental, academic, and private laboratories fall into this category, however.

“Under this policy, we expect certain laboratories who develop validated tests for coronavirus would begin using them right away prior to FDA review,” said Jeffrey Shuren, MD, JD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health. “We believe this action will support laboratories across the country working on this urgent public health situation,” he added in the press release.

“By the end of this week, close to a million tests will be available,” FDA Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, said during the March 2 briefing.*

Updated criteria

The CDC is maintaining updated criteria for the virus testing on its website. Testing criteria are based both on clinical features and epidemiologic risk.

Individuals with less severe clinical features – those who have either fever or signs and symptoms of lower respiratory disease such as cough or shortness of breath, but who don’t require hospitalization – should be tested if they have high epidemiologic risk. “High risk” is defined by the CDC as any individual, including health care workers, who has had close contact with a person with confirmed COVID-19 within the past 2 weeks. For health care workers, testing can be considered even if they have relatively mild respiratory symptoms or have had contact with a person who is suspected, but not yet confirmed, to have coronavirus.

In its testing guidance, the CDC recognizes that defining close contact is difficult. General guidelines are that individuals are considered to have been in close contact with a person who has COVID-19 if they were within about six feet of the person for a prolonged period, or cared for or have spent a prolonged amount of time in the same room or house as a person with confirmed COVID-19.

Individuals who have both fever and signs or symptoms of lower respiratory illness who require hospitalization should be tested if they have a history of travel from any affected geographic area within 14 days of the onset of their symptoms. The CDC now defines “affected geographic area” as any country or region that has at least a CDC Level 2 Travel Health Notice for COVID-19, so that the testing criteria themselves don’t need to be updated when new geographic areas are included in these alerts. As of March 3, China, Iran, Italy, Japan, and South Korea all have Level 2 or 3 travel alerts.

The CDC now recommends that any patient who has severe acute lower respiratory illness that requires hospitalization and doesn’t have an alternative diagnosis should be tested, even without any identified source of exposure.

“Despite seeing these new cases, the risk to the American people is low,” said the CDC’s Dr. Redfield. In response to a question from the press about how fast the coronavirus will spread across the United States, Dr. Redfield said, “From the beginning we’ve anticipated seeing community cases pop up.” He added that as these cases arise, testing and public health strategies will focus on unearthing linkages and contacts to learn how the virus is spreading. “We’ll use the public health strategies that we can to limit that transmission,” he said.

*An earlier version of this article misattributed this quote.

FROM A PRESS BRIEFING BY THE WHITE HOUSE CORONAVIRUS TASK FORCE

Pembro ups survival in NSCLC: ‘Really extraordinary’ results

More than a third (35%) of patients with relapsed non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck) were still alive at 3 years, according to long-term results from a pivotal clinical trial.

The results also showed that, among the 10% of patients who completed all 35 cycles of pembrolizumab, the 3-year overall survival was approximately 99%, with progression-free survival (PFS) at around 70%.

“It is too soon to say that pembrolizumab is a potential cure...and we know that it doesn’t work for all patients, but the agent remains very, very promising,” said lead investigator Roy Herbst, MD, PhD, Department of Medical Oncology, Yale Comprehensive Cancer Center, New Haven, Connecticut.

These new results come from the KEYNOTE-010 trial, conducted in more than 1000 patients with NSCLC who had progressed on chemotherapy, randomized to receive immunotherapy with pembrolizumab or chemotherapy with docetaxel.

The results were published online on February 20 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology and were previously presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the European Society of Medical Oncology.

Overall survival at 3 years was 35% in patients with PD-L1 expression ≥ 50% in the tumor, and 23% in those with PD-L1 ≥ 1%.

This compares with 3-year overall survival of 11-13% with docetaxel.

These results are “really extraordinary,” Herbst commented to Medscape Medical News.

The 3-year overall survival rate of 35% in patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% “is huge,” he said. “It really shows the durability of the response.”

Herbst commented that the “almost 100%” survival at 3 years among patients who completed 35 cycles of pembrolizumab shows that this treatment period (of about 2 years) is “probably about the right time to treat.”

“Currently, the agent is being used in all potential settings, before any other treatment, after other treatment, and with other treatments,” he said.

“Our hope is to find the very best way to use pembrolizumab to treat individual lung cancer patients, assessing how much PD-L1 a tumor expresses, what stage the patient is in, as well as other variables and biomarkers we are working on. This is the story of tailored therapy,” Herbst said.

Approached for comment, Solange Peters, MD, PhD, Oncology Department, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne, Switzerland, said that the results are “very good” and “confirm the paradigms we have been seeing in melanoma,” with good long-term control, which is “very reassuring.”

However, she told Medscape Medical News that the trial raises an important question: «How long do you need to expose your patient with lung cancer to immunotherapy in order to get this long-term control?»

She said the “good news” is that, for the 10% of patients who completed 2 years of treatment per protocol, almost all of them are still alive at 3 years, “which is not observed with chemotherapy.”

The question for Peters is “more about the definition of long-term control,” as it was seen that almost one in three patients nevertheless had some form of progression.

This suggests that you have a group of people “who are nicely controlled, you stop the drug, and 1 year later a third of them have progressed.”

Peters said: “So how long do you need to treat these patients? I would say I still don’t know.”

“If I were one of these patients probably I would still want to continue [on the drug]. Of course, some might have progressed even while remaining on the drug, but the proportion who would have progressed is probably smaller than this one.”

Responses on Re-introduction of Therapy

The study also allowed patients who had completed 35 cycles of pembrolizumab to be restarted on the drug if they experienced progression.

The team found that, among 14 patients, 43% had a partial response and 36% had stable disease.

Herbst highlighted this finding and told Medscape Medical News that this «could be very important to physicians because they might want to think about using the drug again» in patients who have progressed on it.

He believes that the progression was not because of any resistance per se but rather a slowing down of the adaptive immune response.

“It’s just that it needs a boost,” he said, while noting that tissue specimens will nevertheless be required to demonstrate the theory.

Peters agreed that these results are “very promising,” but questioned their overall significance, as it is “a very small number of patients” from a subset whose disease was controlled while on treatment and then progressed after stopping.

She also pointed out that, in another study in patients with lung cancer (CheckMate-153), some patients were rechallenged with immunotherapy after having stopped treatment at 1 year “with very poor results.”

Peters said studies in melanoma have shown “rechallenge can be useful in a significant proportion of patients, but still you have not demonstrated that stopping and rechallenging is the same as not stopping.”

Study Details

KEYNOTE-010 involved patients with NSCLC from 202 centers in 24 countries with stage IIIB/IV disease expressing PD-L1 who had experienced disease progression after at least two cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy.

They were randomized 1:1:1 to open-label pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg, pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg, or docetaxel 75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks.

Pembrolizumab was continued for 35 treatment cycles over 2 years and docetaxel was continued for the maximum duration allowed by local regulators.

Patients who stopped pembrolizumab after a complete response or completing all 35 cycles, and who subsequently experienced disease progression, could receive up to 17 additional cycles over 1 year if they had not received another anticancer therapy in the meantime.

Among the 1,034 patients originally recruited between August 2013 and February 2015, 691 were assigned to pembrolizumab at 3 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg and 343 to docetaxel.

For the intention-to-treat analysis in 1033 patients, the mean duration of follow-up was 42.6 months, with a median treatment duration of 3.5 months in the pembrolizumab group and 2.0 months in the docetaxel group.

Compared with docetaxel, pembrolizumab was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of death, at a hazard ratio of 0.53 in patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% and 0.69 in those with PD-L1 ≥ 1% (both P < .0001).

In patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50%, median overall survival was 16.9 months in those given pembrolizumab and 8.2 months with docetaxel. Among those with PD-L1 ≥ 1%, median overall survival was 11.8 months with pembrolizumab versus 8.4 months with docetaxel.

Overall survival on Kaplan-Meier analysis was 34.5% with pembrolizumab and 12.7% with docetaxel in the PD-L1 ≥ 50% group, and 22.9% versus 11.0% in the PD-L1 ≥ 1% group.

PFS significantly improved with pembrolizumab versus docetaxel, at a hazard ratio of 0.57 (P < .00001) among patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% and 0.83 (P < .005) in those with PD-L1 ≥ 1%.

In terms of safety, 17.7% of patients who completed 2 years of pembrolizumab had grade 3-5 treatment-related adverse events, compared with 16.6% among all pembrolizumab-treated patients and 36.6% of those given docetaxel.

The team reports that 79 patients completed 35 cycles of pembrolizumab, with a median follow-up of 43.4 months.

Compared with the overall patient group, these patients were less likely to be aged ≥ 65 years and to have received two or more prior treatment lines, although they were more likely to be current or former smokers and to have squamous tumor histology.

Patients who completed 35 cycles had an objective response rate of 94.9%, and 91.0% were still alive at the data cutoff. Overall survival rates were 98.7% at 12 months and 86.3% at 24 months.

Of 71 patients eligible for analysis, 23 experienced progression after completing pembrolizumab, at PFS rates at 12 and 24 months of 72.5% and 57.7%, respectively.

A total of 14 patients were given a second course of pembrolizumab, of whom six had a partial response and five had stable disease. At the data cutoff, five patients had completed 17 additional cycles and 11 were alive.

Pembro Approved at Fixed Dose

One notable aspect of the study is that patients in the pembrolizumab arm were given two different doses of the drug based on body weight, whereas the drug is approved in the United States at a fixed dose of 200 mg.

Herbst told Medscape Medical News he considers the 200-mg dose to be appropriate.

“I didn’t think that the 3-mg versus 10-mg dose per kg that we used in our study made much difference in an average-sized person,” he said, adding that the 200-mg dose “is something a little bit more than 3 mg/kg.”

“So I think that this is clearly the right dos, and I don’t think more would make any difference,” he said.

The study was funded by Merck, the manufacturer of pembrolizumab. Herbst has reported having a consulting or advisory role for many pharmaceutical companies. Other coauthors have also reported relationships with industry, and some of the authors are Merck employees. Peters has reported receiving education grants, providing consultation, attending advisory boards, and/or providing lectures for many pharmaceutical companies.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More than a third (35%) of patients with relapsed non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck) were still alive at 3 years, according to long-term results from a pivotal clinical trial.

The results also showed that, among the 10% of patients who completed all 35 cycles of pembrolizumab, the 3-year overall survival was approximately 99%, with progression-free survival (PFS) at around 70%.

“It is too soon to say that pembrolizumab is a potential cure...and we know that it doesn’t work for all patients, but the agent remains very, very promising,” said lead investigator Roy Herbst, MD, PhD, Department of Medical Oncology, Yale Comprehensive Cancer Center, New Haven, Connecticut.

These new results come from the KEYNOTE-010 trial, conducted in more than 1000 patients with NSCLC who had progressed on chemotherapy, randomized to receive immunotherapy with pembrolizumab or chemotherapy with docetaxel.

The results were published online on February 20 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology and were previously presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the European Society of Medical Oncology.

Overall survival at 3 years was 35% in patients with PD-L1 expression ≥ 50% in the tumor, and 23% in those with PD-L1 ≥ 1%.

This compares with 3-year overall survival of 11-13% with docetaxel.

These results are “really extraordinary,” Herbst commented to Medscape Medical News.

The 3-year overall survival rate of 35% in patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% “is huge,” he said. “It really shows the durability of the response.”

Herbst commented that the “almost 100%” survival at 3 years among patients who completed 35 cycles of pembrolizumab shows that this treatment period (of about 2 years) is “probably about the right time to treat.”

“Currently, the agent is being used in all potential settings, before any other treatment, after other treatment, and with other treatments,” he said.

“Our hope is to find the very best way to use pembrolizumab to treat individual lung cancer patients, assessing how much PD-L1 a tumor expresses, what stage the patient is in, as well as other variables and biomarkers we are working on. This is the story of tailored therapy,” Herbst said.

Approached for comment, Solange Peters, MD, PhD, Oncology Department, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne, Switzerland, said that the results are “very good” and “confirm the paradigms we have been seeing in melanoma,” with good long-term control, which is “very reassuring.”

However, she told Medscape Medical News that the trial raises an important question: «How long do you need to expose your patient with lung cancer to immunotherapy in order to get this long-term control?»

She said the “good news” is that, for the 10% of patients who completed 2 years of treatment per protocol, almost all of them are still alive at 3 years, “which is not observed with chemotherapy.”

The question for Peters is “more about the definition of long-term control,” as it was seen that almost one in three patients nevertheless had some form of progression.

This suggests that you have a group of people “who are nicely controlled, you stop the drug, and 1 year later a third of them have progressed.”

Peters said: “So how long do you need to treat these patients? I would say I still don’t know.”

“If I were one of these patients probably I would still want to continue [on the drug]. Of course, some might have progressed even while remaining on the drug, but the proportion who would have progressed is probably smaller than this one.”

Responses on Re-introduction of Therapy

The study also allowed patients who had completed 35 cycles of pembrolizumab to be restarted on the drug if they experienced progression.

The team found that, among 14 patients, 43% had a partial response and 36% had stable disease.

Herbst highlighted this finding and told Medscape Medical News that this «could be very important to physicians because they might want to think about using the drug again» in patients who have progressed on it.

He believes that the progression was not because of any resistance per se but rather a slowing down of the adaptive immune response.

“It’s just that it needs a boost,” he said, while noting that tissue specimens will nevertheless be required to demonstrate the theory.

Peters agreed that these results are “very promising,” but questioned their overall significance, as it is “a very small number of patients” from a subset whose disease was controlled while on treatment and then progressed after stopping.

She also pointed out that, in another study in patients with lung cancer (CheckMate-153), some patients were rechallenged with immunotherapy after having stopped treatment at 1 year “with very poor results.”

Peters said studies in melanoma have shown “rechallenge can be useful in a significant proportion of patients, but still you have not demonstrated that stopping and rechallenging is the same as not stopping.”

Study Details

KEYNOTE-010 involved patients with NSCLC from 202 centers in 24 countries with stage IIIB/IV disease expressing PD-L1 who had experienced disease progression after at least two cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy.

They were randomized 1:1:1 to open-label pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg, pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg, or docetaxel 75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks.

Pembrolizumab was continued for 35 treatment cycles over 2 years and docetaxel was continued for the maximum duration allowed by local regulators.

Patients who stopped pembrolizumab after a complete response or completing all 35 cycles, and who subsequently experienced disease progression, could receive up to 17 additional cycles over 1 year if they had not received another anticancer therapy in the meantime.

Among the 1,034 patients originally recruited between August 2013 and February 2015, 691 were assigned to pembrolizumab at 3 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg and 343 to docetaxel.

For the intention-to-treat analysis in 1033 patients, the mean duration of follow-up was 42.6 months, with a median treatment duration of 3.5 months in the pembrolizumab group and 2.0 months in the docetaxel group.

Compared with docetaxel, pembrolizumab was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of death, at a hazard ratio of 0.53 in patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% and 0.69 in those with PD-L1 ≥ 1% (both P < .0001).

In patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50%, median overall survival was 16.9 months in those given pembrolizumab and 8.2 months with docetaxel. Among those with PD-L1 ≥ 1%, median overall survival was 11.8 months with pembrolizumab versus 8.4 months with docetaxel.

Overall survival on Kaplan-Meier analysis was 34.5% with pembrolizumab and 12.7% with docetaxel in the PD-L1 ≥ 50% group, and 22.9% versus 11.0% in the PD-L1 ≥ 1% group.

PFS significantly improved with pembrolizumab versus docetaxel, at a hazard ratio of 0.57 (P < .00001) among patients with PD-L1 ≥ 50% and 0.83 (P < .005) in those with PD-L1 ≥ 1%.

In terms of safety, 17.7% of patients who completed 2 years of pembrolizumab had grade 3-5 treatment-related adverse events, compared with 16.6% among all pembrolizumab-treated patients and 36.6% of those given docetaxel.

The team reports that 79 patients completed 35 cycles of pembrolizumab, with a median follow-up of 43.4 months.

Compared with the overall patient group, these patients were less likely to be aged ≥ 65 years and to have received two or more prior treatment lines, although they were more likely to be current or former smokers and to have squamous tumor histology.

Patients who completed 35 cycles had an objective response rate of 94.9%, and 91.0% were still alive at the data cutoff. Overall survival rates were 98.7% at 12 months and 86.3% at 24 months.

Of 71 patients eligible for analysis, 23 experienced progression after completing pembrolizumab, at PFS rates at 12 and 24 months of 72.5% and 57.7%, respectively.