User login

The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management® is an independent, peer-reviewed journal offering evidence-based, practical information for improving the quality, safety, and value of health care.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

2019-2020 flu season ends with ‘very high’ activity in New Jersey

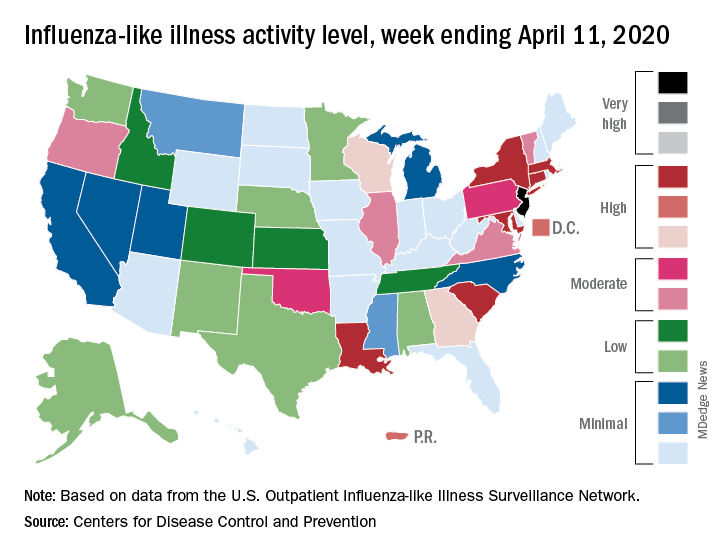

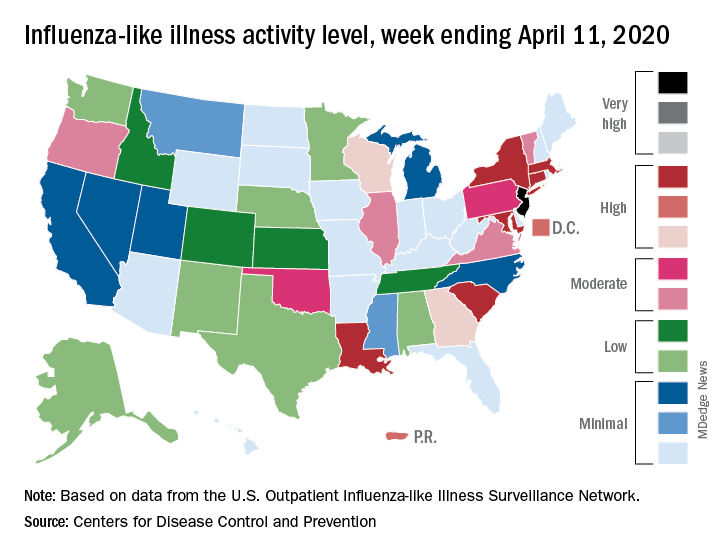

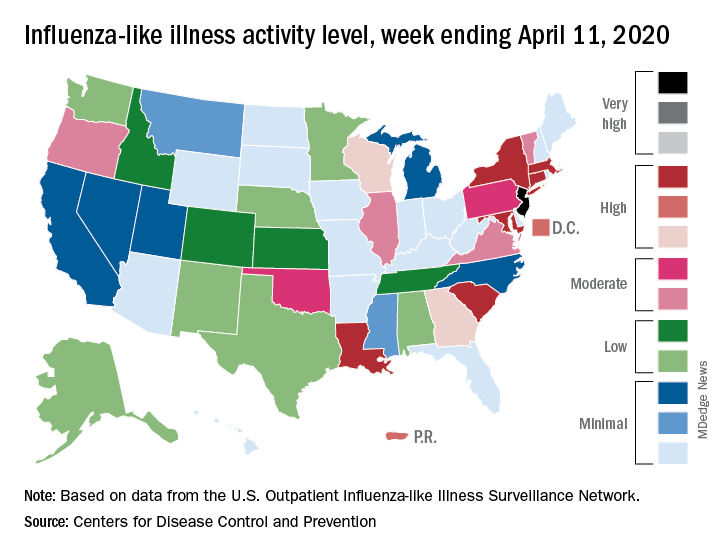

The 2019-2020 flu season is ending, but not without a revised map to reflect the COVID-induced new world order.

For the week ending April 11, those additions encompass only New Jersey at level 13 and New York City at level 12, the CDC reported April 17.

Eight states, plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, were in the “high” range of flu activity, which runs from level 8 to level 10, for the same week. Those eight states included Connecticut, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, South Carolina, and Wisconsin.

The CDC’s influenza division included this note with its latest FluView report: “The COVID-19 pandemic is affecting healthcare seeking behavior. The number of persons and their reasons for seeking care in the outpatient and ED settings is changing. These changes impact data from ILINet [Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network] in ways that are difficult to differentiate from changes in illness levels, therefore ILINet data should be interpreted with caution.”

Outpatient visits for influenza-like illness made up 2.9% of all visits to health care providers for the week ending April 11, which is the 23rd consecutive week that it’s been at or above the national baseline level of 2.4%. Twenty-three weeks is longer than this has occurred during any flu season since the CDC started setting a baseline in 2007, according to ILINet data.

Mortality from pneumonia and influenza, at 11.7%, was well above the epidemic threshold of 7.0%, although, again, pneumonia mortality “is being driven primarily by an increase in non-influenza pneumonia deaths due to COVID-19,” the CDC wrote.

The total number of influenza-related deaths in children, with reports of two more added this week, is 168 for the season – higher than two of the last three seasons: 144 in 2018-2019, 188 in 2017-2018, and 110 in 2016-2017, according to the CDC.

The 2019-2020 flu season is ending, but not without a revised map to reflect the COVID-induced new world order.

For the week ending April 11, those additions encompass only New Jersey at level 13 and New York City at level 12, the CDC reported April 17.

Eight states, plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, were in the “high” range of flu activity, which runs from level 8 to level 10, for the same week. Those eight states included Connecticut, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, South Carolina, and Wisconsin.

The CDC’s influenza division included this note with its latest FluView report: “The COVID-19 pandemic is affecting healthcare seeking behavior. The number of persons and their reasons for seeking care in the outpatient and ED settings is changing. These changes impact data from ILINet [Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network] in ways that are difficult to differentiate from changes in illness levels, therefore ILINet data should be interpreted with caution.”

Outpatient visits for influenza-like illness made up 2.9% of all visits to health care providers for the week ending April 11, which is the 23rd consecutive week that it’s been at or above the national baseline level of 2.4%. Twenty-three weeks is longer than this has occurred during any flu season since the CDC started setting a baseline in 2007, according to ILINet data.

Mortality from pneumonia and influenza, at 11.7%, was well above the epidemic threshold of 7.0%, although, again, pneumonia mortality “is being driven primarily by an increase in non-influenza pneumonia deaths due to COVID-19,” the CDC wrote.

The total number of influenza-related deaths in children, with reports of two more added this week, is 168 for the season – higher than two of the last three seasons: 144 in 2018-2019, 188 in 2017-2018, and 110 in 2016-2017, according to the CDC.

The 2019-2020 flu season is ending, but not without a revised map to reflect the COVID-induced new world order.

For the week ending April 11, those additions encompass only New Jersey at level 13 and New York City at level 12, the CDC reported April 17.

Eight states, plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, were in the “high” range of flu activity, which runs from level 8 to level 10, for the same week. Those eight states included Connecticut, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, South Carolina, and Wisconsin.

The CDC’s influenza division included this note with its latest FluView report: “The COVID-19 pandemic is affecting healthcare seeking behavior. The number of persons and their reasons for seeking care in the outpatient and ED settings is changing. These changes impact data from ILINet [Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network] in ways that are difficult to differentiate from changes in illness levels, therefore ILINet data should be interpreted with caution.”

Outpatient visits for influenza-like illness made up 2.9% of all visits to health care providers for the week ending April 11, which is the 23rd consecutive week that it’s been at or above the national baseline level of 2.4%. Twenty-three weeks is longer than this has occurred during any flu season since the CDC started setting a baseline in 2007, according to ILINet data.

Mortality from pneumonia and influenza, at 11.7%, was well above the epidemic threshold of 7.0%, although, again, pneumonia mortality “is being driven primarily by an increase in non-influenza pneumonia deaths due to COVID-19,” the CDC wrote.

The total number of influenza-related deaths in children, with reports of two more added this week, is 168 for the season – higher than two of the last three seasons: 144 in 2018-2019, 188 in 2017-2018, and 110 in 2016-2017, according to the CDC.

N.Y. universal testing: Many COVID-19+ pregnant women are asymptomatic

based on data from 215 pregnant women in New York City.

“The obstetrical population presents a unique challenge during this pandemic, since these patients have multiple interactions with the health care system and eventually most are admitted to the hospital for delivery,” wrote Desmond Sutton, MD, and colleagues at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York

In a letter published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers reviewed their experiences with 215 pregnant women who delivered infants during March 22–April 4, 2020, at the New York–Presbyterian Allen Hospital and Columbia University Irving Medical Center. All the women were screened for symptoms of the COVID-19 infection on admission.

Overall, four women (1.9%) had fevers or other symptoms on admission, and all of these women tested positive for the virus that causes COVID-19. The other 211 women were afebrile and asymptomatic at admission, and 210 of them were tested via nasopharyngeal swabs. A total of 29 asymptomatic women (13.7%) tested positive for COVID-19 infection.

“Thus, 29 of the 33 patients who were positive for SARS-CoV-2 at admission (87.9%) had no symptoms of COVID-19 at presentation,” Dr. Sutton and colleagues wrote.

Three of the 29 COVID-19-positive women who were asymptomatic on admission developed fevers before they were discharged from the hospital after a median stay of 2 days. Of these, two received antibiotics for presumed endomyometritis and one patient with presumed COVID-19 infection received supportive care. In addition, one patient who was initially negative developed COVID-19 symptoms after delivery and tested positive 3 days after her initial negative test.

“Our use of universal SARS-CoV-2 testing in all pregnant patients presenting for delivery revealed that at this point in the pandemic in New York City, most of the patients who were positive for SARS-CoV-2 at delivery were asymptomatic,” Dr. Sutton and colleagues said.

Although their numbers may not be generalizable to areas with lower infection rates, they highlight the risk of COVID-19 infection in asymptomatic pregnant women, they noted.

“The potential benefits of a universal testing approach include the ability to use COVID-19 status to determine hospital isolation practices and bed assignments, inform neonatal care, and guide the use of personal protective equipment,” they concluded.

Continuing challenges

“What I have seen in our institute is the debate about rapid testing and the inherent problems with false negatives and false positives,” Catherine Cansino, MD, of the University of California, Davis, said in an interview. “I think there is definitely a role for universal testing, especially in areas with high prevalence,” and the New York clinicians have made a strong case.

However, the challenge remains of obtaining quick test results that would still be reliable, as many rapid tests have a false-negative rate of as much as 20%, noted Dr. Cansino, who was not involved in the New York study.

Her institution is using a test with a higher level of accuracy, “but it can take several hours or a day to get the results,” at which point the women may have gone through labor and delivery and been in contact with multiple health care workers who have used personal protective equipment accordingly if they don’t know a patient’s status.

To help guide policies, Dr. Cansino said that outcome data would be useful. “It’s hard to know how outcomes are different, and it would be good to know how transmission rates differ between symptomatic carriers and those who are asymptomatic.”

“As SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, continues to spread, pregnant women remain a unique population with required frequent health system contacts and ultimate need for delivery,” Iris Krishna, MD, of the Emory Healthcare Network in Atlanta, said in an interview. “This report in a high prevalence area demonstrated 1 out of 8 asymptomatic pregnant patients presenting for delivery were SARS-CoV-2 positive, illustrating a need for universal screening.

“As this pandemic evolves, we are learning more and more, and it is important to expand our understanding of asymptomatic transmission and the risk this may pose,” said Dr. Krishna, who was not part of the New York study.

“Key benefits to universal screening are the capability for labor and delivery units to implement best hospital practices in their care of mothers and babies, such as admitting positive patients to cohort units,” she noted. Such units would “allow for closer monitoring of mothers and babies, as well as ensuring proper use of personal protective equipment by health care teams” and also would help preserve supplies of personal protective equipment.

Dr. Krishna cited hospital testing capacity as an obvious barrier to universal screening of pregnant women, as well as factors including the need for additional protective equipment to be used during swab collection. Also, “If you get a negative result and there is a strong suspicion for COVID-19 infection, when do you retest?” she asked. “These are key questions or areas of assessment that should be considered before embarking on universal screening for pregnant women.” In addition, some patients may refuse testing out of fear of stigma or separation from their newborn.

“Implementing an ‘opt out’ approach to screening is encouraged, whereby a patient is informed that a test will be included in standard preventive screening, and they may decline the test,” Dr. Krishna said. “Routine, opt-out screening approaches have proven to be highly effective as it removes the stigma associated with testing, fosters earlier diagnosis and treatment, reduces risk of transmission, and has proven to be cost effective. Pregnant women should be reassured that universal screening is beneficial for their care and the care of their newborn baby,” she emphasized.

“Institutions should consider implementing universal screening on labor and delivery as several geographic areas are predicted to reach their peak time of COVID-19 transmission, and it is clear that asymptomatic individuals continue to play a role in its transmission,” Dr. Krishna concluded.

Dr. Sutton and associates had no financial conflicts to disclose. Neither Dr. Cansino nor Dr. Krishna had any financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Cansino and Dr. Krishna are members of the Ob.Gyn. News Editorial Advisory Board.

SOURCE: Sutton D et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009316.

based on data from 215 pregnant women in New York City.

“The obstetrical population presents a unique challenge during this pandemic, since these patients have multiple interactions with the health care system and eventually most are admitted to the hospital for delivery,” wrote Desmond Sutton, MD, and colleagues at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York

In a letter published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers reviewed their experiences with 215 pregnant women who delivered infants during March 22–April 4, 2020, at the New York–Presbyterian Allen Hospital and Columbia University Irving Medical Center. All the women were screened for symptoms of the COVID-19 infection on admission.

Overall, four women (1.9%) had fevers or other symptoms on admission, and all of these women tested positive for the virus that causes COVID-19. The other 211 women were afebrile and asymptomatic at admission, and 210 of them were tested via nasopharyngeal swabs. A total of 29 asymptomatic women (13.7%) tested positive for COVID-19 infection.

“Thus, 29 of the 33 patients who were positive for SARS-CoV-2 at admission (87.9%) had no symptoms of COVID-19 at presentation,” Dr. Sutton and colleagues wrote.

Three of the 29 COVID-19-positive women who were asymptomatic on admission developed fevers before they were discharged from the hospital after a median stay of 2 days. Of these, two received antibiotics for presumed endomyometritis and one patient with presumed COVID-19 infection received supportive care. In addition, one patient who was initially negative developed COVID-19 symptoms after delivery and tested positive 3 days after her initial negative test.

“Our use of universal SARS-CoV-2 testing in all pregnant patients presenting for delivery revealed that at this point in the pandemic in New York City, most of the patients who were positive for SARS-CoV-2 at delivery were asymptomatic,” Dr. Sutton and colleagues said.

Although their numbers may not be generalizable to areas with lower infection rates, they highlight the risk of COVID-19 infection in asymptomatic pregnant women, they noted.

“The potential benefits of a universal testing approach include the ability to use COVID-19 status to determine hospital isolation practices and bed assignments, inform neonatal care, and guide the use of personal protective equipment,” they concluded.

Continuing challenges

“What I have seen in our institute is the debate about rapid testing and the inherent problems with false negatives and false positives,” Catherine Cansino, MD, of the University of California, Davis, said in an interview. “I think there is definitely a role for universal testing, especially in areas with high prevalence,” and the New York clinicians have made a strong case.

However, the challenge remains of obtaining quick test results that would still be reliable, as many rapid tests have a false-negative rate of as much as 20%, noted Dr. Cansino, who was not involved in the New York study.

Her institution is using a test with a higher level of accuracy, “but it can take several hours or a day to get the results,” at which point the women may have gone through labor and delivery and been in contact with multiple health care workers who have used personal protective equipment accordingly if they don’t know a patient’s status.

To help guide policies, Dr. Cansino said that outcome data would be useful. “It’s hard to know how outcomes are different, and it would be good to know how transmission rates differ between symptomatic carriers and those who are asymptomatic.”

“As SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, continues to spread, pregnant women remain a unique population with required frequent health system contacts and ultimate need for delivery,” Iris Krishna, MD, of the Emory Healthcare Network in Atlanta, said in an interview. “This report in a high prevalence area demonstrated 1 out of 8 asymptomatic pregnant patients presenting for delivery were SARS-CoV-2 positive, illustrating a need for universal screening.

“As this pandemic evolves, we are learning more and more, and it is important to expand our understanding of asymptomatic transmission and the risk this may pose,” said Dr. Krishna, who was not part of the New York study.

“Key benefits to universal screening are the capability for labor and delivery units to implement best hospital practices in their care of mothers and babies, such as admitting positive patients to cohort units,” she noted. Such units would “allow for closer monitoring of mothers and babies, as well as ensuring proper use of personal protective equipment by health care teams” and also would help preserve supplies of personal protective equipment.

Dr. Krishna cited hospital testing capacity as an obvious barrier to universal screening of pregnant women, as well as factors including the need for additional protective equipment to be used during swab collection. Also, “If you get a negative result and there is a strong suspicion for COVID-19 infection, when do you retest?” she asked. “These are key questions or areas of assessment that should be considered before embarking on universal screening for pregnant women.” In addition, some patients may refuse testing out of fear of stigma or separation from their newborn.

“Implementing an ‘opt out’ approach to screening is encouraged, whereby a patient is informed that a test will be included in standard preventive screening, and they may decline the test,” Dr. Krishna said. “Routine, opt-out screening approaches have proven to be highly effective as it removes the stigma associated with testing, fosters earlier diagnosis and treatment, reduces risk of transmission, and has proven to be cost effective. Pregnant women should be reassured that universal screening is beneficial for their care and the care of their newborn baby,” she emphasized.

“Institutions should consider implementing universal screening on labor and delivery as several geographic areas are predicted to reach their peak time of COVID-19 transmission, and it is clear that asymptomatic individuals continue to play a role in its transmission,” Dr. Krishna concluded.

Dr. Sutton and associates had no financial conflicts to disclose. Neither Dr. Cansino nor Dr. Krishna had any financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Cansino and Dr. Krishna are members of the Ob.Gyn. News Editorial Advisory Board.

SOURCE: Sutton D et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009316.

based on data from 215 pregnant women in New York City.

“The obstetrical population presents a unique challenge during this pandemic, since these patients have multiple interactions with the health care system and eventually most are admitted to the hospital for delivery,” wrote Desmond Sutton, MD, and colleagues at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York

In a letter published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers reviewed their experiences with 215 pregnant women who delivered infants during March 22–April 4, 2020, at the New York–Presbyterian Allen Hospital and Columbia University Irving Medical Center. All the women were screened for symptoms of the COVID-19 infection on admission.

Overall, four women (1.9%) had fevers or other symptoms on admission, and all of these women tested positive for the virus that causes COVID-19. The other 211 women were afebrile and asymptomatic at admission, and 210 of them were tested via nasopharyngeal swabs. A total of 29 asymptomatic women (13.7%) tested positive for COVID-19 infection.

“Thus, 29 of the 33 patients who were positive for SARS-CoV-2 at admission (87.9%) had no symptoms of COVID-19 at presentation,” Dr. Sutton and colleagues wrote.

Three of the 29 COVID-19-positive women who were asymptomatic on admission developed fevers before they were discharged from the hospital after a median stay of 2 days. Of these, two received antibiotics for presumed endomyometritis and one patient with presumed COVID-19 infection received supportive care. In addition, one patient who was initially negative developed COVID-19 symptoms after delivery and tested positive 3 days after her initial negative test.

“Our use of universal SARS-CoV-2 testing in all pregnant patients presenting for delivery revealed that at this point in the pandemic in New York City, most of the patients who were positive for SARS-CoV-2 at delivery were asymptomatic,” Dr. Sutton and colleagues said.

Although their numbers may not be generalizable to areas with lower infection rates, they highlight the risk of COVID-19 infection in asymptomatic pregnant women, they noted.

“The potential benefits of a universal testing approach include the ability to use COVID-19 status to determine hospital isolation practices and bed assignments, inform neonatal care, and guide the use of personal protective equipment,” they concluded.

Continuing challenges

“What I have seen in our institute is the debate about rapid testing and the inherent problems with false negatives and false positives,” Catherine Cansino, MD, of the University of California, Davis, said in an interview. “I think there is definitely a role for universal testing, especially in areas with high prevalence,” and the New York clinicians have made a strong case.

However, the challenge remains of obtaining quick test results that would still be reliable, as many rapid tests have a false-negative rate of as much as 20%, noted Dr. Cansino, who was not involved in the New York study.

Her institution is using a test with a higher level of accuracy, “but it can take several hours or a day to get the results,” at which point the women may have gone through labor and delivery and been in contact with multiple health care workers who have used personal protective equipment accordingly if they don’t know a patient’s status.

To help guide policies, Dr. Cansino said that outcome data would be useful. “It’s hard to know how outcomes are different, and it would be good to know how transmission rates differ between symptomatic carriers and those who are asymptomatic.”

“As SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, continues to spread, pregnant women remain a unique population with required frequent health system contacts and ultimate need for delivery,” Iris Krishna, MD, of the Emory Healthcare Network in Atlanta, said in an interview. “This report in a high prevalence area demonstrated 1 out of 8 asymptomatic pregnant patients presenting for delivery were SARS-CoV-2 positive, illustrating a need for universal screening.

“As this pandemic evolves, we are learning more and more, and it is important to expand our understanding of asymptomatic transmission and the risk this may pose,” said Dr. Krishna, who was not part of the New York study.

“Key benefits to universal screening are the capability for labor and delivery units to implement best hospital practices in their care of mothers and babies, such as admitting positive patients to cohort units,” she noted. Such units would “allow for closer monitoring of mothers and babies, as well as ensuring proper use of personal protective equipment by health care teams” and also would help preserve supplies of personal protective equipment.

Dr. Krishna cited hospital testing capacity as an obvious barrier to universal screening of pregnant women, as well as factors including the need for additional protective equipment to be used during swab collection. Also, “If you get a negative result and there is a strong suspicion for COVID-19 infection, when do you retest?” she asked. “These are key questions or areas of assessment that should be considered before embarking on universal screening for pregnant women.” In addition, some patients may refuse testing out of fear of stigma or separation from their newborn.

“Implementing an ‘opt out’ approach to screening is encouraged, whereby a patient is informed that a test will be included in standard preventive screening, and they may decline the test,” Dr. Krishna said. “Routine, opt-out screening approaches have proven to be highly effective as it removes the stigma associated with testing, fosters earlier diagnosis and treatment, reduces risk of transmission, and has proven to be cost effective. Pregnant women should be reassured that universal screening is beneficial for their care and the care of their newborn baby,” she emphasized.

“Institutions should consider implementing universal screening on labor and delivery as several geographic areas are predicted to reach their peak time of COVID-19 transmission, and it is clear that asymptomatic individuals continue to play a role in its transmission,” Dr. Krishna concluded.

Dr. Sutton and associates had no financial conflicts to disclose. Neither Dr. Cansino nor Dr. Krishna had any financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Cansino and Dr. Krishna are members of the Ob.Gyn. News Editorial Advisory Board.

SOURCE: Sutton D et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009316.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Universal COVID-19 testing for pregnant women entering hospitals for delivery could better protect patients and staff.

Major finding: Approximately 88% of 33 pregnant women who tested positive for COVID-19 infection at hospital admission were asymptomatic; about 14% of the 215 women overall tested positive for the novel coronavirus.

Study details: The data come from a review of 215 pregnant women who delivered infants between March 22 and April 4, 2020, in New York City.

Disclosures: The authors had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Sutton D et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009316.

Infectious disease experts say testing is key to reopening

The key to opening up the American economy rests on the ability to conduct mass testing, according to the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).

As policymakers weigh how to safely reopen parts of the United States, the IDSA, along with its HIV Medicine Association, issued a set of recommendations outlining the steps that would be necessary in order to begin easing physical distancing measures.

“A stepwise approach to reopening should reflect early diagnosis and enhanced surveillance for COVID-19 cases, linkage of cases to appropriate levels of care, isolation and/or quarantine, contact tracing, and data processing capabilities for state and local public health departments,” according to the recommendation document.

Some of the recommended steps include the following:

- Widespread testing and surveillance, including use of validated nucleic acid amplification assays and anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibody detection.

- The ability to diagnose, treat, and isolate individuals with COVID-19.

- Scaling up of health care capacity and supplies to manage recurrent episodic outbreaks.

- Maintaining a degree of physical distancing to prevent recurrent outbreaks, including use of masks, limiting gatherings, and continued distancing for susceptible adults.

“The recommendations stress that physical distancing policy changes must be based on relevant data and adequate public health resources and capacities and calls for a rolling and incremental approach to lifting these restrictions, ” Thomas File Jr., MD, IDSA president and a professor at Northeastern Ohio Universities, Rootstown, said during an April 17 press briefing.

The rolling approach “must reflect state and regional capacities for diagnosing, isolating, and treating people with the virus, tracing their contacts, protecting health care workers, and addressing the needs of populations disproportionately affected by COVID-19,” he continued.

In order to fully lift physical distancing restrictions, there would need to be effective treatments for COVID-19 and a protective vaccine that can be deployed to key at-risk populations, according to the recommendations.

During the call, Tina Q. Tan, MD, professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago, and a member of the IDSA board of directors, said that easing social distancing requirements requires comprehensive data and that “one of the major missing data points” is the number of people who are currently infected or have been infected. She warned that easing restrictions too soon could have “disastrous consequences,” including an increase in spread of infection, hospitalization, and death rates, as well as overwhelming health care facilities.

“In order to reopen, we have to have the ability to safely, successfully, and rapidly diagnose and treat, as well as isolate, individuals with COVID-19, as well as track their contacts,” she said.

The implementation of more widespread, comprehensive testing would better enable targeting of resources, such as personal protective equipment, ICU beds, and ventilators, Dr. Tan said. “This is needed in order to ensure that, if there is an outbreak and it does occur again, the health care system and the first responders are ready for this,” she said.

The key to opening up the American economy rests on the ability to conduct mass testing, according to the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).

As policymakers weigh how to safely reopen parts of the United States, the IDSA, along with its HIV Medicine Association, issued a set of recommendations outlining the steps that would be necessary in order to begin easing physical distancing measures.

“A stepwise approach to reopening should reflect early diagnosis and enhanced surveillance for COVID-19 cases, linkage of cases to appropriate levels of care, isolation and/or quarantine, contact tracing, and data processing capabilities for state and local public health departments,” according to the recommendation document.

Some of the recommended steps include the following:

- Widespread testing and surveillance, including use of validated nucleic acid amplification assays and anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibody detection.

- The ability to diagnose, treat, and isolate individuals with COVID-19.

- Scaling up of health care capacity and supplies to manage recurrent episodic outbreaks.

- Maintaining a degree of physical distancing to prevent recurrent outbreaks, including use of masks, limiting gatherings, and continued distancing for susceptible adults.

“The recommendations stress that physical distancing policy changes must be based on relevant data and adequate public health resources and capacities and calls for a rolling and incremental approach to lifting these restrictions, ” Thomas File Jr., MD, IDSA president and a professor at Northeastern Ohio Universities, Rootstown, said during an April 17 press briefing.

The rolling approach “must reflect state and regional capacities for diagnosing, isolating, and treating people with the virus, tracing their contacts, protecting health care workers, and addressing the needs of populations disproportionately affected by COVID-19,” he continued.

In order to fully lift physical distancing restrictions, there would need to be effective treatments for COVID-19 and a protective vaccine that can be deployed to key at-risk populations, according to the recommendations.

During the call, Tina Q. Tan, MD, professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago, and a member of the IDSA board of directors, said that easing social distancing requirements requires comprehensive data and that “one of the major missing data points” is the number of people who are currently infected or have been infected. She warned that easing restrictions too soon could have “disastrous consequences,” including an increase in spread of infection, hospitalization, and death rates, as well as overwhelming health care facilities.

“In order to reopen, we have to have the ability to safely, successfully, and rapidly diagnose and treat, as well as isolate, individuals with COVID-19, as well as track their contacts,” she said.

The implementation of more widespread, comprehensive testing would better enable targeting of resources, such as personal protective equipment, ICU beds, and ventilators, Dr. Tan said. “This is needed in order to ensure that, if there is an outbreak and it does occur again, the health care system and the first responders are ready for this,” she said.

The key to opening up the American economy rests on the ability to conduct mass testing, according to the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).

As policymakers weigh how to safely reopen parts of the United States, the IDSA, along with its HIV Medicine Association, issued a set of recommendations outlining the steps that would be necessary in order to begin easing physical distancing measures.

“A stepwise approach to reopening should reflect early diagnosis and enhanced surveillance for COVID-19 cases, linkage of cases to appropriate levels of care, isolation and/or quarantine, contact tracing, and data processing capabilities for state and local public health departments,” according to the recommendation document.

Some of the recommended steps include the following:

- Widespread testing and surveillance, including use of validated nucleic acid amplification assays and anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibody detection.

- The ability to diagnose, treat, and isolate individuals with COVID-19.

- Scaling up of health care capacity and supplies to manage recurrent episodic outbreaks.

- Maintaining a degree of physical distancing to prevent recurrent outbreaks, including use of masks, limiting gatherings, and continued distancing for susceptible adults.

“The recommendations stress that physical distancing policy changes must be based on relevant data and adequate public health resources and capacities and calls for a rolling and incremental approach to lifting these restrictions, ” Thomas File Jr., MD, IDSA president and a professor at Northeastern Ohio Universities, Rootstown, said during an April 17 press briefing.

The rolling approach “must reflect state and regional capacities for diagnosing, isolating, and treating people with the virus, tracing their contacts, protecting health care workers, and addressing the needs of populations disproportionately affected by COVID-19,” he continued.

In order to fully lift physical distancing restrictions, there would need to be effective treatments for COVID-19 and a protective vaccine that can be deployed to key at-risk populations, according to the recommendations.

During the call, Tina Q. Tan, MD, professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago, and a member of the IDSA board of directors, said that easing social distancing requirements requires comprehensive data and that “one of the major missing data points” is the number of people who are currently infected or have been infected. She warned that easing restrictions too soon could have “disastrous consequences,” including an increase in spread of infection, hospitalization, and death rates, as well as overwhelming health care facilities.

“In order to reopen, we have to have the ability to safely, successfully, and rapidly diagnose and treat, as well as isolate, individuals with COVID-19, as well as track their contacts,” she said.

The implementation of more widespread, comprehensive testing would better enable targeting of resources, such as personal protective equipment, ICU beds, and ventilators, Dr. Tan said. “This is needed in order to ensure that, if there is an outbreak and it does occur again, the health care system and the first responders are ready for this,” she said.

How to sanitize N95 masks for reuse: NIH study

Exposing contaminated N95 respirators to vaporized hydrogen peroxide (VHP) or ultraviolet (UV) light appears to eliminate the SARS-CoV-2 virus from the material and preserve the integrity of the masks fit for up to three uses, a National Institutes of Health (NIH) study shows.

Dry heat (70° C) was also found to eliminate the virus on masks but was effective for two uses instead of three.

Robert Fischer, PhD, with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Hamilton, Montana, and colleagues posted the findings on a preprint server on April 15. The paper has not yet been peer reviewed.

Four methods tested

Fischer and colleagues compared four methods for decontaminating the masks, which are designed for one-time use: UV radiation (260-285 nm); 70° C dry heat; 70% ethanol spray; and VHP.

For each method, the researchers compared the rate at which SARS-CoV-2 is inactivated on N95 filter fabric to that on stainless steel.

All four methods eliminated detectable SARS-CoV-2 virus from the fabric test samples, though the time needed for decontamination varied. VHP was the quickest, requiring 10 minutes. Dry heat and UV light each required approximately 60 minutes. Ethanol required an intermediate amount of time.

To test durability over three uses, the researchers treated intact, clean masks with the same decontamination method and assessed function via quantitative fit testing.

Volunteers from the Rocky Mountain laboratory wore the masks for 2 hours to test fit and seal.

The researchers found that masks that had been decontaminated with ethanol spray did not function effectively after decontamination, and they did not recommend use of that method.

By contrast, masks decontaminated with UV and VHP could be used up to three times and function properly. Masks decontaminated with dry heat could be used two times before function declined.

“Our results indicate that N95 respirators can be decontaminated and reused in times of shortage for up to three times for UV and HPV, and up to two times for dry heat,” the authors write. “However, utmost care should be given to ensure the proper functioning of the N95 respirator after each decontamination using readily available qualitative fit testing tools and to ensure that treatments are carried out for sufficient time to achieve desired risk-reduction.”

Reassurance for clinicians

The results will reassure clinicians, many of whom are already using these decontamination methods, Ravina Kullar, PharmD, MPH, an infectious disease expert with the Infectious Diseases Society of America, told Medscape Medical News.

Kullar, who is also an adjunct faculty member at the David Geffen School of Medicine of the University of California, Los Angeles, said the most widely used methods have been UV light and VPH.

UV light has been used for years to decontaminate rooms, she said. She also said that so far, supplies of hydrogen peroxide are adequate.

A shortcoming of the study, Kullar said, is that it tested the masks for only 2 hours, whereas in clinical practice, they are being worn for much longer periods.

After the study is peer reviewed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) may update its recommendations, she said.

So far, she noted, the CDC has not approved any method for decontaminating masks, “but it has said that it does not object to using these sterilizers, disinfectants, devices, and air purifiers for effectively killing this virus.”

Safe, multiple use of the masks is critical in the COVID-19 crisis, she said.

“We have to look at other mechanisms to keep these N95 respirators in use when there’s such a shortage,” she said.

Integrity of the fit was an important factor in the study.

“All health care workers have to go through a fitting to have that mask fitted appropriately. That’s why these N95s are only approved for health care professionals, not the lay public,” she said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health; the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency; the University of California, Los Angeles; the US National Science Foundation; and the US Department of Defense.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Exposing contaminated N95 respirators to vaporized hydrogen peroxide (VHP) or ultraviolet (UV) light appears to eliminate the SARS-CoV-2 virus from the material and preserve the integrity of the masks fit for up to three uses, a National Institutes of Health (NIH) study shows.

Dry heat (70° C) was also found to eliminate the virus on masks but was effective for two uses instead of three.

Robert Fischer, PhD, with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Hamilton, Montana, and colleagues posted the findings on a preprint server on April 15. The paper has not yet been peer reviewed.

Four methods tested

Fischer and colleagues compared four methods for decontaminating the masks, which are designed for one-time use: UV radiation (260-285 nm); 70° C dry heat; 70% ethanol spray; and VHP.

For each method, the researchers compared the rate at which SARS-CoV-2 is inactivated on N95 filter fabric to that on stainless steel.

All four methods eliminated detectable SARS-CoV-2 virus from the fabric test samples, though the time needed for decontamination varied. VHP was the quickest, requiring 10 minutes. Dry heat and UV light each required approximately 60 minutes. Ethanol required an intermediate amount of time.

To test durability over three uses, the researchers treated intact, clean masks with the same decontamination method and assessed function via quantitative fit testing.

Volunteers from the Rocky Mountain laboratory wore the masks for 2 hours to test fit and seal.

The researchers found that masks that had been decontaminated with ethanol spray did not function effectively after decontamination, and they did not recommend use of that method.

By contrast, masks decontaminated with UV and VHP could be used up to three times and function properly. Masks decontaminated with dry heat could be used two times before function declined.

“Our results indicate that N95 respirators can be decontaminated and reused in times of shortage for up to three times for UV and HPV, and up to two times for dry heat,” the authors write. “However, utmost care should be given to ensure the proper functioning of the N95 respirator after each decontamination using readily available qualitative fit testing tools and to ensure that treatments are carried out for sufficient time to achieve desired risk-reduction.”

Reassurance for clinicians

The results will reassure clinicians, many of whom are already using these decontamination methods, Ravina Kullar, PharmD, MPH, an infectious disease expert with the Infectious Diseases Society of America, told Medscape Medical News.

Kullar, who is also an adjunct faculty member at the David Geffen School of Medicine of the University of California, Los Angeles, said the most widely used methods have been UV light and VPH.

UV light has been used for years to decontaminate rooms, she said. She also said that so far, supplies of hydrogen peroxide are adequate.

A shortcoming of the study, Kullar said, is that it tested the masks for only 2 hours, whereas in clinical practice, they are being worn for much longer periods.

After the study is peer reviewed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) may update its recommendations, she said.

So far, she noted, the CDC has not approved any method for decontaminating masks, “but it has said that it does not object to using these sterilizers, disinfectants, devices, and air purifiers for effectively killing this virus.”

Safe, multiple use of the masks is critical in the COVID-19 crisis, she said.

“We have to look at other mechanisms to keep these N95 respirators in use when there’s such a shortage,” she said.

Integrity of the fit was an important factor in the study.

“All health care workers have to go through a fitting to have that mask fitted appropriately. That’s why these N95s are only approved for health care professionals, not the lay public,” she said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health; the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency; the University of California, Los Angeles; the US National Science Foundation; and the US Department of Defense.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Exposing contaminated N95 respirators to vaporized hydrogen peroxide (VHP) or ultraviolet (UV) light appears to eliminate the SARS-CoV-2 virus from the material and preserve the integrity of the masks fit for up to three uses, a National Institutes of Health (NIH) study shows.

Dry heat (70° C) was also found to eliminate the virus on masks but was effective for two uses instead of three.

Robert Fischer, PhD, with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Hamilton, Montana, and colleagues posted the findings on a preprint server on April 15. The paper has not yet been peer reviewed.

Four methods tested

Fischer and colleagues compared four methods for decontaminating the masks, which are designed for one-time use: UV radiation (260-285 nm); 70° C dry heat; 70% ethanol spray; and VHP.

For each method, the researchers compared the rate at which SARS-CoV-2 is inactivated on N95 filter fabric to that on stainless steel.

All four methods eliminated detectable SARS-CoV-2 virus from the fabric test samples, though the time needed for decontamination varied. VHP was the quickest, requiring 10 minutes. Dry heat and UV light each required approximately 60 minutes. Ethanol required an intermediate amount of time.

To test durability over three uses, the researchers treated intact, clean masks with the same decontamination method and assessed function via quantitative fit testing.

Volunteers from the Rocky Mountain laboratory wore the masks for 2 hours to test fit and seal.

The researchers found that masks that had been decontaminated with ethanol spray did not function effectively after decontamination, and they did not recommend use of that method.

By contrast, masks decontaminated with UV and VHP could be used up to three times and function properly. Masks decontaminated with dry heat could be used two times before function declined.

“Our results indicate that N95 respirators can be decontaminated and reused in times of shortage for up to three times for UV and HPV, and up to two times for dry heat,” the authors write. “However, utmost care should be given to ensure the proper functioning of the N95 respirator after each decontamination using readily available qualitative fit testing tools and to ensure that treatments are carried out for sufficient time to achieve desired risk-reduction.”

Reassurance for clinicians

The results will reassure clinicians, many of whom are already using these decontamination methods, Ravina Kullar, PharmD, MPH, an infectious disease expert with the Infectious Diseases Society of America, told Medscape Medical News.

Kullar, who is also an adjunct faculty member at the David Geffen School of Medicine of the University of California, Los Angeles, said the most widely used methods have been UV light and VPH.

UV light has been used for years to decontaminate rooms, she said. She also said that so far, supplies of hydrogen peroxide are adequate.

A shortcoming of the study, Kullar said, is that it tested the masks for only 2 hours, whereas in clinical practice, they are being worn for much longer periods.

After the study is peer reviewed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) may update its recommendations, she said.

So far, she noted, the CDC has not approved any method for decontaminating masks, “but it has said that it does not object to using these sterilizers, disinfectants, devices, and air purifiers for effectively killing this virus.”

Safe, multiple use of the masks is critical in the COVID-19 crisis, she said.

“We have to look at other mechanisms to keep these N95 respirators in use when there’s such a shortage,” she said.

Integrity of the fit was an important factor in the study.

“All health care workers have to go through a fitting to have that mask fitted appropriately. That’s why these N95s are only approved for health care professionals, not the lay public,” she said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health; the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency; the University of California, Los Angeles; the US National Science Foundation; and the US Department of Defense.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19: How intensive care cardiology can inform the response

Because of their place at the interface between critical care and cardiovascular medicine, critical care cardiologists are in a good position to come up with novel approaches to adapting critical care systems to the current crisis. Health care and clinical resources have been severely strained in some places, and increasing evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 can cause injury to most organ systems. More than a quarter of hospitalized patients have cardiac injury, which can be a key reason for clinical deterioration.

An international group of critical care cardiologists led by Jason Katz, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., offered suggestions for scalable models for critical care delivery in the context of COVID-19 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Critical care cardiology developed in response to changes in patient populations and their clinical needs. Respiratory insufficiency, heart failure, structural heart disease, and multisystem organ dysfunction became more common than patients with complicated acute MI, leading cardiologists in critical care cardiology to become more proficient in general critical care medicine, and to become leaders in forming collaborative multidisciplinary teams. The authors argued that COVID-19 is precipitating a similar need to adapt to the changing needs of patients.

“This pandemic should serve as a clarion call to our health care systems that we should continue to develop a nimble workforce that can adapt to change quickly during a crisis. We believe critical care cardiologists are well positioned to help serve society in this capacity,” the authors wrote.

Surge staging

They proposed four surge stages based in part on an American College of Chest Physicians–endorsed model (Chest 2014 Oct;146:e61S-74S), which regards a 25% capacity surge as minor. At the other end of the spectrum, a 200% surge is defined as a “disaster.” In minor surges (less than 25% increase), the traditional cardiac ICU (CICU) model can continue to be applied. During moderate (25%-100% increases) or major (100%-200%) surges, the critical care cardiologist should collaborate or consult within multiple health care teams. Physicians not trained in critical care can assist with care of intubated and critically ill patients under the supervision of a critical care cardiologist or under the supervision of a partnership between a non–cardiac critical care medicine provider and a cardiologist. The number of patients cared for by each team should increase in step with the size of the surge.

In disaster situations (more than 200% surge), there should be adaptive and dynamic staffing reorganization. The report included an illustration of a range of steps that can be taken, including alterations to staffing, regional care systems, resource management, and triage practices. Scoring systems such as Sequential Organ Failure Assessment may be useful for triaging, but the authors also suggest employment of validated cardiac disease–specific scores, because traditional ICU measures don’t always apply well to CICU populations.

At the hospital level, deferrals should be made for elective cardiac procedures that require CICU or postanesthesia care unit recovery periods. Semielective procedures should be considered after risk-benefit considerations when delays could lead to morbidity or mortality. Even some traditional emergency procedures may need to be reevaluated in the COVID-19 context: For example, some low-risk ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) patients don’t require ICU care but are manageable in cardiac intermediate care beds instead. Historical triage practices should be reexamined to predict which STEMI patients will require ICU care.

Resource allocation

The CICU work flow will be affected as some of its beds are opened up to COVID-19 patients. Standard philosophies of concentrating intense resources will have to give way to a utilitarian approach that evaluates operations based on efficiency, equity, and justice. Physician-patient contact should be minimized using technological links when possible, and rounds might be reorganized to first examine patients without COVID-19, in order to minimize between-patient spread.

Military medicine, which is used to ramping up operations during times of crisis, has potential lessons for the current pandemic. In the face of mass casualties, military physicians often turn to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization triage system, which separates patients into four categories: immediate, requiring lifesaving intervention; delayed, requiring intervention within hours to days; minimal, where the patient is injured but ambulatory; and expectant patients who are deceased or too injured to save. Impersonal though this system may be, it may be required in the most severe scenarios when resources are scarce or absent.

The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Katz J et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Apr 15. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.02.01.

Because of their place at the interface between critical care and cardiovascular medicine, critical care cardiologists are in a good position to come up with novel approaches to adapting critical care systems to the current crisis. Health care and clinical resources have been severely strained in some places, and increasing evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 can cause injury to most organ systems. More than a quarter of hospitalized patients have cardiac injury, which can be a key reason for clinical deterioration.

An international group of critical care cardiologists led by Jason Katz, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., offered suggestions for scalable models for critical care delivery in the context of COVID-19 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Critical care cardiology developed in response to changes in patient populations and their clinical needs. Respiratory insufficiency, heart failure, structural heart disease, and multisystem organ dysfunction became more common than patients with complicated acute MI, leading cardiologists in critical care cardiology to become more proficient in general critical care medicine, and to become leaders in forming collaborative multidisciplinary teams. The authors argued that COVID-19 is precipitating a similar need to adapt to the changing needs of patients.

“This pandemic should serve as a clarion call to our health care systems that we should continue to develop a nimble workforce that can adapt to change quickly during a crisis. We believe critical care cardiologists are well positioned to help serve society in this capacity,” the authors wrote.

Surge staging

They proposed four surge stages based in part on an American College of Chest Physicians–endorsed model (Chest 2014 Oct;146:e61S-74S), which regards a 25% capacity surge as minor. At the other end of the spectrum, a 200% surge is defined as a “disaster.” In minor surges (less than 25% increase), the traditional cardiac ICU (CICU) model can continue to be applied. During moderate (25%-100% increases) or major (100%-200%) surges, the critical care cardiologist should collaborate or consult within multiple health care teams. Physicians not trained in critical care can assist with care of intubated and critically ill patients under the supervision of a critical care cardiologist or under the supervision of a partnership between a non–cardiac critical care medicine provider and a cardiologist. The number of patients cared for by each team should increase in step with the size of the surge.

In disaster situations (more than 200% surge), there should be adaptive and dynamic staffing reorganization. The report included an illustration of a range of steps that can be taken, including alterations to staffing, regional care systems, resource management, and triage practices. Scoring systems such as Sequential Organ Failure Assessment may be useful for triaging, but the authors also suggest employment of validated cardiac disease–specific scores, because traditional ICU measures don’t always apply well to CICU populations.

At the hospital level, deferrals should be made for elective cardiac procedures that require CICU or postanesthesia care unit recovery periods. Semielective procedures should be considered after risk-benefit considerations when delays could lead to morbidity or mortality. Even some traditional emergency procedures may need to be reevaluated in the COVID-19 context: For example, some low-risk ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) patients don’t require ICU care but are manageable in cardiac intermediate care beds instead. Historical triage practices should be reexamined to predict which STEMI patients will require ICU care.

Resource allocation

The CICU work flow will be affected as some of its beds are opened up to COVID-19 patients. Standard philosophies of concentrating intense resources will have to give way to a utilitarian approach that evaluates operations based on efficiency, equity, and justice. Physician-patient contact should be minimized using technological links when possible, and rounds might be reorganized to first examine patients without COVID-19, in order to minimize between-patient spread.

Military medicine, which is used to ramping up operations during times of crisis, has potential lessons for the current pandemic. In the face of mass casualties, military physicians often turn to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization triage system, which separates patients into four categories: immediate, requiring lifesaving intervention; delayed, requiring intervention within hours to days; minimal, where the patient is injured but ambulatory; and expectant patients who are deceased or too injured to save. Impersonal though this system may be, it may be required in the most severe scenarios when resources are scarce or absent.

The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Katz J et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Apr 15. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.02.01.

Because of their place at the interface between critical care and cardiovascular medicine, critical care cardiologists are in a good position to come up with novel approaches to adapting critical care systems to the current crisis. Health care and clinical resources have been severely strained in some places, and increasing evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 can cause injury to most organ systems. More than a quarter of hospitalized patients have cardiac injury, which can be a key reason for clinical deterioration.

An international group of critical care cardiologists led by Jason Katz, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., offered suggestions for scalable models for critical care delivery in the context of COVID-19 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Critical care cardiology developed in response to changes in patient populations and their clinical needs. Respiratory insufficiency, heart failure, structural heart disease, and multisystem organ dysfunction became more common than patients with complicated acute MI, leading cardiologists in critical care cardiology to become more proficient in general critical care medicine, and to become leaders in forming collaborative multidisciplinary teams. The authors argued that COVID-19 is precipitating a similar need to adapt to the changing needs of patients.

“This pandemic should serve as a clarion call to our health care systems that we should continue to develop a nimble workforce that can adapt to change quickly during a crisis. We believe critical care cardiologists are well positioned to help serve society in this capacity,” the authors wrote.

Surge staging

They proposed four surge stages based in part on an American College of Chest Physicians–endorsed model (Chest 2014 Oct;146:e61S-74S), which regards a 25% capacity surge as minor. At the other end of the spectrum, a 200% surge is defined as a “disaster.” In minor surges (less than 25% increase), the traditional cardiac ICU (CICU) model can continue to be applied. During moderate (25%-100% increases) or major (100%-200%) surges, the critical care cardiologist should collaborate or consult within multiple health care teams. Physicians not trained in critical care can assist with care of intubated and critically ill patients under the supervision of a critical care cardiologist or under the supervision of a partnership between a non–cardiac critical care medicine provider and a cardiologist. The number of patients cared for by each team should increase in step with the size of the surge.

In disaster situations (more than 200% surge), there should be adaptive and dynamic staffing reorganization. The report included an illustration of a range of steps that can be taken, including alterations to staffing, regional care systems, resource management, and triage practices. Scoring systems such as Sequential Organ Failure Assessment may be useful for triaging, but the authors also suggest employment of validated cardiac disease–specific scores, because traditional ICU measures don’t always apply well to CICU populations.

At the hospital level, deferrals should be made for elective cardiac procedures that require CICU or postanesthesia care unit recovery periods. Semielective procedures should be considered after risk-benefit considerations when delays could lead to morbidity or mortality. Even some traditional emergency procedures may need to be reevaluated in the COVID-19 context: For example, some low-risk ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) patients don’t require ICU care but are manageable in cardiac intermediate care beds instead. Historical triage practices should be reexamined to predict which STEMI patients will require ICU care.

Resource allocation

The CICU work flow will be affected as some of its beds are opened up to COVID-19 patients. Standard philosophies of concentrating intense resources will have to give way to a utilitarian approach that evaluates operations based on efficiency, equity, and justice. Physician-patient contact should be minimized using technological links when possible, and rounds might be reorganized to first examine patients without COVID-19, in order to minimize between-patient spread.

Military medicine, which is used to ramping up operations during times of crisis, has potential lessons for the current pandemic. In the face of mass casualties, military physicians often turn to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization triage system, which separates patients into four categories: immediate, requiring lifesaving intervention; delayed, requiring intervention within hours to days; minimal, where the patient is injured but ambulatory; and expectant patients who are deceased or too injured to save. Impersonal though this system may be, it may be required in the most severe scenarios when resources are scarce or absent.

The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Katz J et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Apr 15. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.02.01.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Obesity link to severe COVID-19, especially in patients aged under 60

It is becoming increasingly clear that obesity is one of the biggest risk factors for severe COVID-19 disease, particularly among younger patients.

Newly published data from New York show that, among those aged under 60 years, obesity was twice as likely to result in hospitalization for COVID-19 and also significantly increased the likelihood that a person would end up in intensive care.

“Obesity [in people younger than 60] appears to be a previously unrecognized risk factor for hospital admission and need for critical care. This has important and practical implications when nearly 40% of adults in the U.S. are obese with a body mass index [BMI] of [at least] 30,” wrote Jennifer Lighter, MD, of New York University Langone Health, and colleagues in their research letter published in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Similar findings in a preprint publication, yet to be peer reviewed, from another New York hospital show that, with the exception of older age, obesity (BMI greater than 40 kg/m2) had the strongest association with hospitalization for COVID-19, increasing the risk more than 500%.

Meanwhile, a new French study shows a high frequency of obesity among patients admitted to one ICU for COVID-19; furthermore, disease severity increased with increasing BMI. One of the authors said in an interview that many of the presenting patients were younger, with their only risk factor being obesity.

“Patients with obesity should avoid any COVID-19 contamination by enforcing all prevention measures during the current pandemic,” wrote the authors, led by Arthur Simonnet, MD, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Lille (France).

They also stressed that COVID-19 patients “with severe obesity should be monitored more closely.”

Those with obesity are young and become very sick, very quickly

François Pattou, MD, PhD, coauthor of the French article published in Obesity said in an interview that, when patients with COVID-19 began to arrive at their ICU in Lille, there were young patients who did not have any other comorbidities.

“They were just obese,” he observed, adding that they seemed “to have a very specific disease, something different” from that seen before, with patients becoming very sick, very quickly.

In their study, they examined 124 consecutive patients admitted to intensive care with COVID-19 between Feb. 25 and April 5, 2020, and compared them with a historical control group of 306 patients admitted to the ICU at the same hospital for non–COVID-19-related severe acute respiratory disease in 2019.

By April 6, 60 patients with COVID-19 had been discharged from intensive care, 18 had died, and 46 remained in the unit. The majority (73%) were male, and their median age was 60 years. Obesity and severe obesity were significantly more prevalent among the patients with COVID-19, at 47.6% and 28.2% versus 25.2% and 10.8% among historical controls (P < .001 for trend).

A key finding was that those with a BMI greater than 35 had a more than 600% increased risk of requiring mechanical ventilation (odds ratio, 7.36; P = .021), compared with those with a BMI less than 25, even after adjusting for age, diabetes, and hypertension.

Obesity in under 60s at least doubles risk of admission in U.S.

The studies out of New York, one of which was stratified by age, paint a similar picture.

Dr. Lighter and colleagues found that, of the 3,615 individuals who tested positive for COVID-19 in their series, 775 (21%) had a BMI of 30-34 and 595 (16%) had a BMI of at least 35. Obesity wasn’t a predictor of admission to hospital or the ICU in those over the age of 60 years, but in those younger than 60 years, it was.

Those under age 60 with a BMI of 30-34 were twice as likely to be admitted to hospital (hazard ratio, 2.0; P < .0001) and critical care (HR, 1.8; P = .006), compared with those under age 60 with a BMI less than 30. Likewise, those under age 60 with a BMI of at least 35 were 2.2 (P < .0001) and 3.6 (P < .0001) times more likely to be admitted to acute and critical care.

“Unfortunately, obesity in people [less than] 60 years is a newly identified epidemiologic risk factor which may contribute to increased morbidity rates [with COVID-19] experienced in the U.S.,” they concluded.

And in the other U.S. study, Christopher M. Petrilli, MD, of New York University, and colleagues looked at 4,103 patients with COVID-19 treated between March 1 and April 2, 2020, and followed to April 7.

Just under half of patients (48.7%) were hospitalized, of whom 22.3% required mechanical ventilation and 14.6% died or were discharged to hospice. The research was published on medRxiv, showing that, apart from age, the strongest predictors of hospitalization were BMI greater than 40 (OR, 6.2) and heart failure (OR, 4.3).

“It is notable that the chronic condition with the strongest association with critical illness was obesity, with a substantially higher odds ratio than any cardiovascular or pulmonary disease,” they noted.

Inflammation is a possible culprit

Dr. Pattou believes that the culprit behind the increased risk of disease severity seen with obesity in COVID-19 is inflammation, mediated by fibrin deposits in the circulation, which his colleagues have seen on autopsy, and which “block oxygen passage through the blood.”

This may help explain why mechanical ventilation can be less successful in these patients. “The answer is to get rid of this inflammation,” Dr. Pattou observed.

Dr. Petrilli and colleagues also observed that obesity “is well-recognized to be a proinflammatory condition.”

And their findings showed “the importance of inflammatory markers in distinguishing future critical from noncritical illness,” they said, noting that, among these markers, early elevations in C-reactive protein and D-dimer “had the strongest association with mechanical ventilation or mortality.”

Livio Luzi, MD, of IRCCS MultiMedica, Milan, Italy, has previously written on the relationship between influenza and obesity, and discussed in an interview the potential lessons for the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Obesity is characterized by an impairment of immune response and by a low-grade chronic inflammation. Furthermore, obese subjects have an altered dynamic of pulmonary ventilation, with reduced diaphragmatic excursion,” Dr. Luzi said. These factors, alongside others, “may help to explain” the current results, and stress the importance of close monitoring of those with obesity and COVID-19.

No relevant financial relationships were declared.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It is becoming increasingly clear that obesity is one of the biggest risk factors for severe COVID-19 disease, particularly among younger patients.

Newly published data from New York show that, among those aged under 60 years, obesity was twice as likely to result in hospitalization for COVID-19 and also significantly increased the likelihood that a person would end up in intensive care.

“Obesity [in people younger than 60] appears to be a previously unrecognized risk factor for hospital admission and need for critical care. This has important and practical implications when nearly 40% of adults in the U.S. are obese with a body mass index [BMI] of [at least] 30,” wrote Jennifer Lighter, MD, of New York University Langone Health, and colleagues in their research letter published in Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Similar findings in a preprint publication, yet to be peer reviewed, from another New York hospital show that, with the exception of older age, obesity (BMI greater than 40 kg/m2) had the strongest association with hospitalization for COVID-19, increasing the risk more than 500%.

Meanwhile, a new French study shows a high frequency of obesity among patients admitted to one ICU for COVID-19; furthermore, disease severity increased with increasing BMI. One of the authors said in an interview that many of the presenting patients were younger, with their only risk factor being obesity.

“Patients with obesity should avoid any COVID-19 contamination by enforcing all prevention measures during the current pandemic,” wrote the authors, led by Arthur Simonnet, MD, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Lille (France).

They also stressed that COVID-19 patients “with severe obesity should be monitored more closely.”

Those with obesity are young and become very sick, very quickly

François Pattou, MD, PhD, coauthor of the French article published in Obesity said in an interview that, when patients with COVID-19 began to arrive at their ICU in Lille, there were young patients who did not have any other comorbidities.

“They were just obese,” he observed, adding that they seemed “to have a very specific disease, something different” from that seen before, with patients becoming very sick, very quickly.

In their study, they examined 124 consecutive patients admitted to intensive care with COVID-19 between Feb. 25 and April 5, 2020, and compared them with a historical control group of 306 patients admitted to the ICU at the same hospital for non–COVID-19-related severe acute respiratory disease in 2019.

By April 6, 60 patients with COVID-19 had been discharged from intensive care, 18 had died, and 46 remained in the unit. The majority (73%) were male, and their median age was 60 years. Obesity and severe obesity were significantly more prevalent among the patients with COVID-19, at 47.6% and 28.2% versus 25.2% and 10.8% among historical controls (P < .001 for trend).

A key finding was that those with a BMI greater than 35 had a more than 600% increased risk of requiring mechanical ventilation (odds ratio, 7.36; P = .021), compared with those with a BMI less than 25, even after adjusting for age, diabetes, and hypertension.

Obesity in under 60s at least doubles risk of admission in U.S.

The studies out of New York, one of which was stratified by age, paint a similar picture.

Dr. Lighter and colleagues found that, of the 3,615 individuals who tested positive for COVID-19 in their series, 775 (21%) had a BMI of 30-34 and 595 (16%) had a BMI of at least 35. Obesity wasn’t a predictor of admission to hospital or the ICU in those over the age of 60 years, but in those younger than 60 years, it was.

Those under age 60 with a BMI of 30-34 were twice as likely to be admitted to hospital (hazard ratio, 2.0; P < .0001) and critical care (HR, 1.8; P = .006), compared with those under age 60 with a BMI less than 30. Likewise, those under age 60 with a BMI of at least 35 were 2.2 (P < .0001) and 3.6 (P < .0001) times more likely to be admitted to acute and critical care.

“Unfortunately, obesity in people [less than] 60 years is a newly identified epidemiologic risk factor which may contribute to increased morbidity rates [with COVID-19] experienced in the U.S.,” they concluded.

And in the other U.S. study, Christopher M. Petrilli, MD, of New York University, and colleagues looked at 4,103 patients with COVID-19 treated between March 1 and April 2, 2020, and followed to April 7.

Just under half of patients (48.7%) were hospitalized, of whom 22.3% required mechanical ventilation and 14.6% died or were discharged to hospice. The research was published on medRxiv, showing that, apart from age, the strongest predictors of hospitalization were BMI greater than 40 (OR, 6.2) and heart failure (OR, 4.3).

“It is notable that the chronic condition with the strongest association with critical illness was obesity, with a substantially higher odds ratio than any cardiovascular or pulmonary disease,” they noted.

Inflammation is a possible culprit

Dr. Pattou believes that the culprit behind the increased risk of disease severity seen with obesity in COVID-19 is inflammation, mediated by fibrin deposits in the circulation, which his colleagues have seen on autopsy, and which “block oxygen passage through the blood.”

This may help explain why mechanical ventilation can be less successful in these patients. “The answer is to get rid of this inflammation,” Dr. Pattou observed.

Dr. Petrilli and colleagues also observed that obesity “is well-recognized to be a proinflammatory condition.”

And their findings showed “the importance of inflammatory markers in distinguishing future critical from noncritical illness,” they said, noting that, among these markers, early elevations in C-reactive protein and D-dimer “had the strongest association with mechanical ventilation or mortality.”

Livio Luzi, MD, of IRCCS MultiMedica, Milan, Italy, has previously written on the relationship between influenza and obesity, and discussed in an interview the potential lessons for the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Obesity is characterized by an impairment of immune response and by a low-grade chronic inflammation. Furthermore, obese subjects have an altered dynamic of pulmonary ventilation, with reduced diaphragmatic excursion,” Dr. Luzi said. These factors, alongside others, “may help to explain” the current results, and stress the importance of close monitoring of those with obesity and COVID-19.

No relevant financial relationships were declared.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It is becoming increasingly clear that obesity is one of the biggest risk factors for severe COVID-19 disease, particularly among younger patients.

Newly published data from New York show that, among those aged under 60 years, obesity was twice as likely to result in hospitalization for COVID-19 and also significantly increased the likelihood that a person would end up in intensive care.

“Obesity [in people younger than 60] appears to be a previously unrecognized risk factor for hospital admission and need for critical care. This has important and practical implications when nearly 40% of adults in the U.S. are obese with a body mass index [BMI] of [at least] 30,” wrote Jennifer Lighter, MD, of New York University Langone Health, and colleagues in their research letter published in Clinical Infectious Diseases.