User login

The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management® is an independent, peer-reviewed journal offering evidence-based, practical information for improving the quality, safety, and value of health care.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Eliminating hepatitis by 2030: HHS releases new strategic plan

In an effort to counteract alarming trends in rising hepatitis infections, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has developed and released its Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan 2021-2025, which aims to eliminate viral hepatitis infection in the United States by 2030.

An estimated 3.3 million people in the United States were chronically infected with hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) as of 2016. In addition, the country “is currently facing unprecedented hepatitis A (HAV) outbreaks, while progress in preventing hepatitis B has stalled, and hepatitis C rates nearly tripled from 2011 to 2018,” according to the HHS.

The new plan, “A Roadmap to Elimination for the United States,” builds upon previous initiatives the HHS has made to tackle the diseases and was coordinated by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health through the Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy.

The plan focuses on HAV, HBV, and HCV, which have the largest impact on the health of the nation, according to the HHS. The plan addresses populations with the highest burden of viral hepatitis based on nationwide data so that resources can be focused there to achieve the greatest impact. Persons who inject drugs are a priority population for all three hepatitis viruses. HAV efforts will also include a focus on the homeless population. HBV efforts will also focus on Asian and Pacific Islander and the Black, non-Hispanic populations, while HCV efforts will include a focus on Black, non-Hispanic people, people born during 1945-1965, people with HIV, and the American Indian/Alaska Native population.

Goal-setting

There are five main goals outlined in the plan, according to the HHS:

- Prevent new hepatitis infections.

- Improve hepatitis-related health outcomes of people with viral hepatitis.

- Reduce hepatitis-related disparities and health inequities.

- Improve hepatitis surveillance and data use.

- Achieve integrated, coordinated efforts that address the viral hepatitis epidemics among all partners and stakeholders.

“The United States will be a place where new viral hepatitis infections are prevented, every person knows their status, and every person with viral hepatitis has high-quality health care and treatment and lives free from stigma and discrimination. This vision includes all people, regardless of age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, geographic location, or socioeconomic circumstance,” according to the HHS vision statement.

In an effort to counteract alarming trends in rising hepatitis infections, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has developed and released its Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan 2021-2025, which aims to eliminate viral hepatitis infection in the United States by 2030.

An estimated 3.3 million people in the United States were chronically infected with hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) as of 2016. In addition, the country “is currently facing unprecedented hepatitis A (HAV) outbreaks, while progress in preventing hepatitis B has stalled, and hepatitis C rates nearly tripled from 2011 to 2018,” according to the HHS.

The new plan, “A Roadmap to Elimination for the United States,” builds upon previous initiatives the HHS has made to tackle the diseases and was coordinated by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health through the Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy.

The plan focuses on HAV, HBV, and HCV, which have the largest impact on the health of the nation, according to the HHS. The plan addresses populations with the highest burden of viral hepatitis based on nationwide data so that resources can be focused there to achieve the greatest impact. Persons who inject drugs are a priority population for all three hepatitis viruses. HAV efforts will also include a focus on the homeless population. HBV efforts will also focus on Asian and Pacific Islander and the Black, non-Hispanic populations, while HCV efforts will include a focus on Black, non-Hispanic people, people born during 1945-1965, people with HIV, and the American Indian/Alaska Native population.

Goal-setting

There are five main goals outlined in the plan, according to the HHS:

- Prevent new hepatitis infections.

- Improve hepatitis-related health outcomes of people with viral hepatitis.

- Reduce hepatitis-related disparities and health inequities.

- Improve hepatitis surveillance and data use.

- Achieve integrated, coordinated efforts that address the viral hepatitis epidemics among all partners and stakeholders.

“The United States will be a place where new viral hepatitis infections are prevented, every person knows their status, and every person with viral hepatitis has high-quality health care and treatment and lives free from stigma and discrimination. This vision includes all people, regardless of age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, geographic location, or socioeconomic circumstance,” according to the HHS vision statement.

In an effort to counteract alarming trends in rising hepatitis infections, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has developed and released its Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan 2021-2025, which aims to eliminate viral hepatitis infection in the United States by 2030.

An estimated 3.3 million people in the United States were chronically infected with hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) as of 2016. In addition, the country “is currently facing unprecedented hepatitis A (HAV) outbreaks, while progress in preventing hepatitis B has stalled, and hepatitis C rates nearly tripled from 2011 to 2018,” according to the HHS.

The new plan, “A Roadmap to Elimination for the United States,” builds upon previous initiatives the HHS has made to tackle the diseases and was coordinated by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health through the Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy.

The plan focuses on HAV, HBV, and HCV, which have the largest impact on the health of the nation, according to the HHS. The plan addresses populations with the highest burden of viral hepatitis based on nationwide data so that resources can be focused there to achieve the greatest impact. Persons who inject drugs are a priority population for all three hepatitis viruses. HAV efforts will also include a focus on the homeless population. HBV efforts will also focus on Asian and Pacific Islander and the Black, non-Hispanic populations, while HCV efforts will include a focus on Black, non-Hispanic people, people born during 1945-1965, people with HIV, and the American Indian/Alaska Native population.

Goal-setting

There are five main goals outlined in the plan, according to the HHS:

- Prevent new hepatitis infections.

- Improve hepatitis-related health outcomes of people with viral hepatitis.

- Reduce hepatitis-related disparities and health inequities.

- Improve hepatitis surveillance and data use.

- Achieve integrated, coordinated efforts that address the viral hepatitis epidemics among all partners and stakeholders.

“The United States will be a place where new viral hepatitis infections are prevented, every person knows their status, and every person with viral hepatitis has high-quality health care and treatment and lives free from stigma and discrimination. This vision includes all people, regardless of age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, geographic location, or socioeconomic circumstance,” according to the HHS vision statement.

NEWS FROM HHS

Childhood smoking and depression contribute to young adult opioid use

Depression and tobacco use in childhood significantly increased the risk for opioid use in young adults, according to data from a prospective study of approximately 1,000 individuals.

Previous research, including the annual Monitoring the Future study, documents opioid use among adolescents in the United States, but childhood risk factors for opioid use in young adults have not been well studied, wrote Lilly Shanahan, PhD, of the University of Zürich, and colleagues.

In a prospective cohort study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers identified 1,252 non-Hispanic White and American Indian opioid-naive individuals aged 9-16 years in rural North Carolina. They interviewed participants and parents up to 7 times between January 1993 and December 2000, and interviewed participants only at ages 19, 21, 25, and 30 years between January 1999 and December 2015.

Overall, 24.2% of study participants had used a nonheroin opioid by age 30 years, and both chronic depression and dysthymia were significantly associated with this use (odds ratios 5.43 and 7.13, respectively).

In addition, 155 participants (8.8%) reported weekly use of a nonheroin opioid, and 95 (6.6%) reported weekly heroin use by age 30 years. Chronic depression and dysthymia also were strongly associated with weekly nonheroin opioid use (OR 8.89 and 11.51, respectively).

In a multivariate analysis, depression, tobacco use, and cannabis use at ages 9-16 years were strongly associated with overall opioid use at ages 19-30 years.

“One possible reason childhood chronic depression increases the risk of later opioid use is self-medication, including the use of psychoactive substances, to alleviate depression,” the researchers noted. In addition, the mood-altering properties of opioids may increase their appeal to depressed youth as a way to relieve impaired reward system function, they said.

Potential mechanisms for the association between early tobacco use and later opioid use include the alterations to neurodevelopment caused by nicotine exposure in adolescence, as well as increased risk for depression, reduced pain thresholds, and use of nicotine as a gateway to harder drugs, the researchers added.

Several childhood risk factors were not associated with young adult opioid use in multivariate analysis in this study, including alcohol use, sociodemographic status, maltreatment, family dysfunction, and anxiety, the researchers wrote. “Previous studies typically measured these risk factors retrospectively or in late adolescence and young adulthood, and most did not consider depressive disorders, which may mediate associations between select childhood risk factors and later opioid use,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the inability to distinguish between medical and nonmedical opioid use, the incomplete list of available opioids, and the exclusion of Black participants because of low sample size, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the longitudinal, community-representative design and the inclusion of up to 11 assessments of opioid use, they said.

“Our findings suggest strong opportunities for early prevention and intervention, including in primary care settings,” using known evidence-based strategies, they concluded.

More screening is needed

“Children in the United States are at high risk of serious adult health issues as a result of childhood factors such as ACEs (adverse childhood experiences),” said Suzanne C. Boulter, MD, of the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H. “This study looks prospectively at other factors in childhood over a long period of time leading to opioid usage, with its serious risks and health consequences including overdose death,” she said. “It is unclear what the effects of COVID-19 will be on the population of children growing up now and how opioid usage might change as a result,” she noted.

“Some of the links to adult usage are predictable, such as depression, tobacco use, and cannabis use in early adolescence,” said Dr. Boulter. “Surprising was the lack of correlation between anxiety, early alcohol use, child mistreatment, and sociodemographic factors with future opioid use,” she said.

The take-home message for clinicians is to screen children and adolescents for factors leading to opioid usage in young adults “with preventive strategies including avoidance of pain medication prescriptions and early referral and treatment for depression and use of cannabis and tobacco products using tools like SBIRT (Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment),” Dr. Boulter emphasized.

As for additional research, “It would be interesting to study e-cigarette usage and see if the correlation with future opioid usage is similar to older tobacco products,” she said. “Also helpful would be to delve deeper into connections between medical or dental diagnoses when opioids were first prescribed and later usage of those products,” Dr. Boulter noted.

The study was supported in part by the by the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Boulter had no disclosures but serves on the Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

Depression and tobacco use in childhood significantly increased the risk for opioid use in young adults, according to data from a prospective study of approximately 1,000 individuals.

Previous research, including the annual Monitoring the Future study, documents opioid use among adolescents in the United States, but childhood risk factors for opioid use in young adults have not been well studied, wrote Lilly Shanahan, PhD, of the University of Zürich, and colleagues.

In a prospective cohort study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers identified 1,252 non-Hispanic White and American Indian opioid-naive individuals aged 9-16 years in rural North Carolina. They interviewed participants and parents up to 7 times between January 1993 and December 2000, and interviewed participants only at ages 19, 21, 25, and 30 years between January 1999 and December 2015.

Overall, 24.2% of study participants had used a nonheroin opioid by age 30 years, and both chronic depression and dysthymia were significantly associated with this use (odds ratios 5.43 and 7.13, respectively).

In addition, 155 participants (8.8%) reported weekly use of a nonheroin opioid, and 95 (6.6%) reported weekly heroin use by age 30 years. Chronic depression and dysthymia also were strongly associated with weekly nonheroin opioid use (OR 8.89 and 11.51, respectively).

In a multivariate analysis, depression, tobacco use, and cannabis use at ages 9-16 years were strongly associated with overall opioid use at ages 19-30 years.

“One possible reason childhood chronic depression increases the risk of later opioid use is self-medication, including the use of psychoactive substances, to alleviate depression,” the researchers noted. In addition, the mood-altering properties of opioids may increase their appeal to depressed youth as a way to relieve impaired reward system function, they said.

Potential mechanisms for the association between early tobacco use and later opioid use include the alterations to neurodevelopment caused by nicotine exposure in adolescence, as well as increased risk for depression, reduced pain thresholds, and use of nicotine as a gateway to harder drugs, the researchers added.

Several childhood risk factors were not associated with young adult opioid use in multivariate analysis in this study, including alcohol use, sociodemographic status, maltreatment, family dysfunction, and anxiety, the researchers wrote. “Previous studies typically measured these risk factors retrospectively or in late adolescence and young adulthood, and most did not consider depressive disorders, which may mediate associations between select childhood risk factors and later opioid use,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the inability to distinguish between medical and nonmedical opioid use, the incomplete list of available opioids, and the exclusion of Black participants because of low sample size, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the longitudinal, community-representative design and the inclusion of up to 11 assessments of opioid use, they said.

“Our findings suggest strong opportunities for early prevention and intervention, including in primary care settings,” using known evidence-based strategies, they concluded.

More screening is needed

“Children in the United States are at high risk of serious adult health issues as a result of childhood factors such as ACEs (adverse childhood experiences),” said Suzanne C. Boulter, MD, of the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H. “This study looks prospectively at other factors in childhood over a long period of time leading to opioid usage, with its serious risks and health consequences including overdose death,” she said. “It is unclear what the effects of COVID-19 will be on the population of children growing up now and how opioid usage might change as a result,” she noted.

“Some of the links to adult usage are predictable, such as depression, tobacco use, and cannabis use in early adolescence,” said Dr. Boulter. “Surprising was the lack of correlation between anxiety, early alcohol use, child mistreatment, and sociodemographic factors with future opioid use,” she said.

The take-home message for clinicians is to screen children and adolescents for factors leading to opioid usage in young adults “with preventive strategies including avoidance of pain medication prescriptions and early referral and treatment for depression and use of cannabis and tobacco products using tools like SBIRT (Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment),” Dr. Boulter emphasized.

As for additional research, “It would be interesting to study e-cigarette usage and see if the correlation with future opioid usage is similar to older tobacco products,” she said. “Also helpful would be to delve deeper into connections between medical or dental diagnoses when opioids were first prescribed and later usage of those products,” Dr. Boulter noted.

The study was supported in part by the by the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Boulter had no disclosures but serves on the Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

Depression and tobacco use in childhood significantly increased the risk for opioid use in young adults, according to data from a prospective study of approximately 1,000 individuals.

Previous research, including the annual Monitoring the Future study, documents opioid use among adolescents in the United States, but childhood risk factors for opioid use in young adults have not been well studied, wrote Lilly Shanahan, PhD, of the University of Zürich, and colleagues.

In a prospective cohort study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers identified 1,252 non-Hispanic White and American Indian opioid-naive individuals aged 9-16 years in rural North Carolina. They interviewed participants and parents up to 7 times between January 1993 and December 2000, and interviewed participants only at ages 19, 21, 25, and 30 years between January 1999 and December 2015.

Overall, 24.2% of study participants had used a nonheroin opioid by age 30 years, and both chronic depression and dysthymia were significantly associated with this use (odds ratios 5.43 and 7.13, respectively).

In addition, 155 participants (8.8%) reported weekly use of a nonheroin opioid, and 95 (6.6%) reported weekly heroin use by age 30 years. Chronic depression and dysthymia also were strongly associated with weekly nonheroin opioid use (OR 8.89 and 11.51, respectively).

In a multivariate analysis, depression, tobacco use, and cannabis use at ages 9-16 years were strongly associated with overall opioid use at ages 19-30 years.

“One possible reason childhood chronic depression increases the risk of later opioid use is self-medication, including the use of psychoactive substances, to alleviate depression,” the researchers noted. In addition, the mood-altering properties of opioids may increase their appeal to depressed youth as a way to relieve impaired reward system function, they said.

Potential mechanisms for the association between early tobacco use and later opioid use include the alterations to neurodevelopment caused by nicotine exposure in adolescence, as well as increased risk for depression, reduced pain thresholds, and use of nicotine as a gateway to harder drugs, the researchers added.

Several childhood risk factors were not associated with young adult opioid use in multivariate analysis in this study, including alcohol use, sociodemographic status, maltreatment, family dysfunction, and anxiety, the researchers wrote. “Previous studies typically measured these risk factors retrospectively or in late adolescence and young adulthood, and most did not consider depressive disorders, which may mediate associations between select childhood risk factors and later opioid use,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the inability to distinguish between medical and nonmedical opioid use, the incomplete list of available opioids, and the exclusion of Black participants because of low sample size, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the longitudinal, community-representative design and the inclusion of up to 11 assessments of opioid use, they said.

“Our findings suggest strong opportunities for early prevention and intervention, including in primary care settings,” using known evidence-based strategies, they concluded.

More screening is needed

“Children in the United States are at high risk of serious adult health issues as a result of childhood factors such as ACEs (adverse childhood experiences),” said Suzanne C. Boulter, MD, of the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H. “This study looks prospectively at other factors in childhood over a long period of time leading to opioid usage, with its serious risks and health consequences including overdose death,” she said. “It is unclear what the effects of COVID-19 will be on the population of children growing up now and how opioid usage might change as a result,” she noted.

“Some of the links to adult usage are predictable, such as depression, tobacco use, and cannabis use in early adolescence,” said Dr. Boulter. “Surprising was the lack of correlation between anxiety, early alcohol use, child mistreatment, and sociodemographic factors with future opioid use,” she said.

The take-home message for clinicians is to screen children and adolescents for factors leading to opioid usage in young adults “with preventive strategies including avoidance of pain medication prescriptions and early referral and treatment for depression and use of cannabis and tobacco products using tools like SBIRT (Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment),” Dr. Boulter emphasized.

As for additional research, “It would be interesting to study e-cigarette usage and see if the correlation with future opioid usage is similar to older tobacco products,” she said. “Also helpful would be to delve deeper into connections between medical or dental diagnoses when opioids were first prescribed and later usage of those products,” Dr. Boulter noted.

The study was supported in part by the by the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Boulter had no disclosures but serves on the Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Endocrine Society calls for action to reduce insulin costs

The Endocrine Society has issued a new position statement calling on all stakeholders, including clinicians, to play a role in reducing the cost of insulin for patients with diabetes in the United States.

“Addressing Insulin Access and Affordability: An Endocrine Society Position Statement,” was published online Jan. 12 in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

“The society believes all stakeholders across the supply chain have a role to play in addressing the high price of insulin,” said the 11 authors, who are all members of the society’s advocacy and public outreach core committee.

This is the first such statement from a major professional organization in 2021, which is the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin.

And the call for action was issued just a week prior to the inauguration of incoming U.S. President Joe Biden, who has pledged to “build on the Affordable Care Act by giving Americans more choice, reducing health care costs, and making our health care system less complex to navigate.”

The cost of insulin has nearly tripled in the past 15 years in the United States, and a lack of transparency in the drug supply chain has made it challenging to identify and address the causes of soaring costs.

The high cost of insulin has made access particularly difficult for people with diabetes with a low income, who have high-deductible health plans, are Medicare beneficiaries using Part B to cover insulin delivered via pump, or are in the Medicare Part D “donut hole,” as well as young adults once they reach their 26th birthday and can no longer be covered under their parents’ insurance.

“Inventors Frederick Banting and Charles Best sold the insulin patent for a mere $1 in the 1920s because they wanted their discovery to save lives and for insulin to be affordable and accessible to everyone who needed it,” said Endocrine Society President-elect Carol Wysham, MD, of the Rockwood/MultiCare Health Systems, Spokane, Wash.

“People with diabetes without full insurance are often paying increasing out-of-pocket costs for insulin resulting in many rationing their medication or skipping lifesaving doses altogether,” she said.

The society’s statement called for allowing government negotiation of drug prices and greater transparency across the supply chain to elucidate the reasons for rising insulin costs.

For physicians in particular, they advised training in use of lower-cost human NPH and regular insulin for appropriate patients with type 2 diabetes, and considering patients’ individual financial and coverage status when prescribing insulin.

Pharmacists are advised to learn about and share information with patients about lower-cost options offered by manufacturers.

Other policy recommendations for relevant stakeholders include:

- Limit future insulin list price increases to the rate of inflation.

- Limit out-of-pocket costs without increasing premiums or deductibles by limiting cost sharing to copays of no more than $35, providing first-dollar coverage, or capping costs at no more than $100 per month.

- Eliminate rebates or pass savings from rebates along to consumers without increasing premiums or deductibles.

- Expedite approval of insulin biosimilars to create market competition.

- Include real-time benefit information in electronic medical records.

- Develop a payment model for Medicare Part B beneficiaries, as well as Part D, to lower out-of-pocket copays.

For manufacturers, the society also recommended improving patient assistance programs to be less restrictive and more accountable. And employers, they said, should limit copays without increasing premiums or deductibles, and seek plan options that benefit people with diabetes and provide education about these options during open enrollment.

Of the 11 writing panel members, 4 have pharmaceutical industry disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Endocrine Society has issued a new position statement calling on all stakeholders, including clinicians, to play a role in reducing the cost of insulin for patients with diabetes in the United States.

“Addressing Insulin Access and Affordability: An Endocrine Society Position Statement,” was published online Jan. 12 in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

“The society believes all stakeholders across the supply chain have a role to play in addressing the high price of insulin,” said the 11 authors, who are all members of the society’s advocacy and public outreach core committee.

This is the first such statement from a major professional organization in 2021, which is the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin.

And the call for action was issued just a week prior to the inauguration of incoming U.S. President Joe Biden, who has pledged to “build on the Affordable Care Act by giving Americans more choice, reducing health care costs, and making our health care system less complex to navigate.”

The cost of insulin has nearly tripled in the past 15 years in the United States, and a lack of transparency in the drug supply chain has made it challenging to identify and address the causes of soaring costs.

The high cost of insulin has made access particularly difficult for people with diabetes with a low income, who have high-deductible health plans, are Medicare beneficiaries using Part B to cover insulin delivered via pump, or are in the Medicare Part D “donut hole,” as well as young adults once they reach their 26th birthday and can no longer be covered under their parents’ insurance.

“Inventors Frederick Banting and Charles Best sold the insulin patent for a mere $1 in the 1920s because they wanted their discovery to save lives and for insulin to be affordable and accessible to everyone who needed it,” said Endocrine Society President-elect Carol Wysham, MD, of the Rockwood/MultiCare Health Systems, Spokane, Wash.

“People with diabetes without full insurance are often paying increasing out-of-pocket costs for insulin resulting in many rationing their medication or skipping lifesaving doses altogether,” she said.

The society’s statement called for allowing government negotiation of drug prices and greater transparency across the supply chain to elucidate the reasons for rising insulin costs.

For physicians in particular, they advised training in use of lower-cost human NPH and regular insulin for appropriate patients with type 2 diabetes, and considering patients’ individual financial and coverage status when prescribing insulin.

Pharmacists are advised to learn about and share information with patients about lower-cost options offered by manufacturers.

Other policy recommendations for relevant stakeholders include:

- Limit future insulin list price increases to the rate of inflation.

- Limit out-of-pocket costs without increasing premiums or deductibles by limiting cost sharing to copays of no more than $35, providing first-dollar coverage, or capping costs at no more than $100 per month.

- Eliminate rebates or pass savings from rebates along to consumers without increasing premiums or deductibles.

- Expedite approval of insulin biosimilars to create market competition.

- Include real-time benefit information in electronic medical records.

- Develop a payment model for Medicare Part B beneficiaries, as well as Part D, to lower out-of-pocket copays.

For manufacturers, the society also recommended improving patient assistance programs to be less restrictive and more accountable. And employers, they said, should limit copays without increasing premiums or deductibles, and seek plan options that benefit people with diabetes and provide education about these options during open enrollment.

Of the 11 writing panel members, 4 have pharmaceutical industry disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Endocrine Society has issued a new position statement calling on all stakeholders, including clinicians, to play a role in reducing the cost of insulin for patients with diabetes in the United States.

“Addressing Insulin Access and Affordability: An Endocrine Society Position Statement,” was published online Jan. 12 in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

“The society believes all stakeholders across the supply chain have a role to play in addressing the high price of insulin,” said the 11 authors, who are all members of the society’s advocacy and public outreach core committee.

This is the first such statement from a major professional organization in 2021, which is the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin.

And the call for action was issued just a week prior to the inauguration of incoming U.S. President Joe Biden, who has pledged to “build on the Affordable Care Act by giving Americans more choice, reducing health care costs, and making our health care system less complex to navigate.”

The cost of insulin has nearly tripled in the past 15 years in the United States, and a lack of transparency in the drug supply chain has made it challenging to identify and address the causes of soaring costs.

The high cost of insulin has made access particularly difficult for people with diabetes with a low income, who have high-deductible health plans, are Medicare beneficiaries using Part B to cover insulin delivered via pump, or are in the Medicare Part D “donut hole,” as well as young adults once they reach their 26th birthday and can no longer be covered under their parents’ insurance.

“Inventors Frederick Banting and Charles Best sold the insulin patent for a mere $1 in the 1920s because they wanted their discovery to save lives and for insulin to be affordable and accessible to everyone who needed it,” said Endocrine Society President-elect Carol Wysham, MD, of the Rockwood/MultiCare Health Systems, Spokane, Wash.

“People with diabetes without full insurance are often paying increasing out-of-pocket costs for insulin resulting in many rationing their medication or skipping lifesaving doses altogether,” she said.

The society’s statement called for allowing government negotiation of drug prices and greater transparency across the supply chain to elucidate the reasons for rising insulin costs.

For physicians in particular, they advised training in use of lower-cost human NPH and regular insulin for appropriate patients with type 2 diabetes, and considering patients’ individual financial and coverage status when prescribing insulin.

Pharmacists are advised to learn about and share information with patients about lower-cost options offered by manufacturers.

Other policy recommendations for relevant stakeholders include:

- Limit future insulin list price increases to the rate of inflation.

- Limit out-of-pocket costs without increasing premiums or deductibles by limiting cost sharing to copays of no more than $35, providing first-dollar coverage, or capping costs at no more than $100 per month.

- Eliminate rebates or pass savings from rebates along to consumers without increasing premiums or deductibles.

- Expedite approval of insulin biosimilars to create market competition.

- Include real-time benefit information in electronic medical records.

- Develop a payment model for Medicare Part B beneficiaries, as well as Part D, to lower out-of-pocket copays.

For manufacturers, the society also recommended improving patient assistance programs to be less restrictive and more accountable. And employers, they said, should limit copays without increasing premiums or deductibles, and seek plan options that benefit people with diabetes and provide education about these options during open enrollment.

Of the 11 writing panel members, 4 have pharmaceutical industry disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

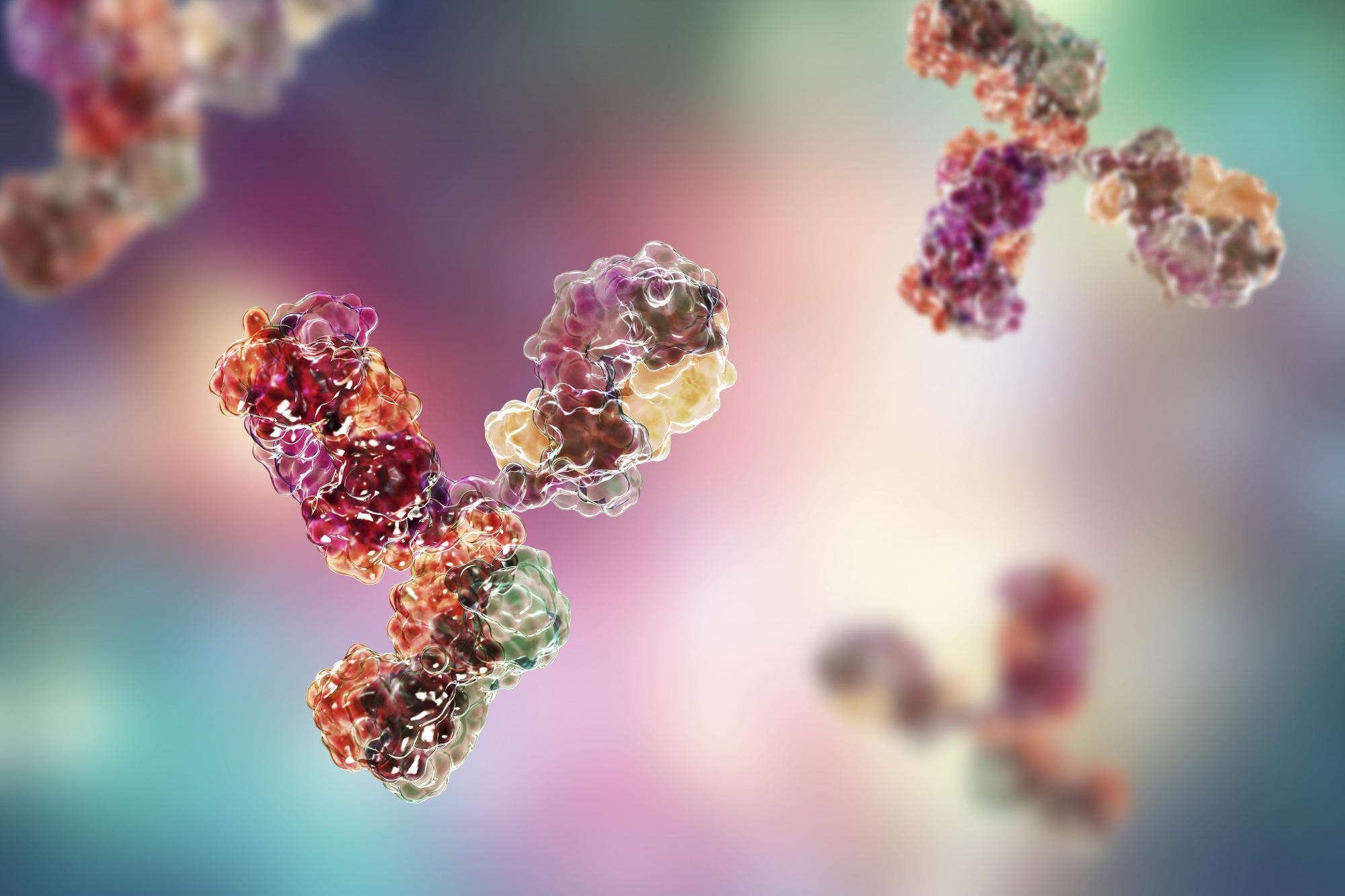

Averting COVID hospitalizations with monoclonal antibodies

The United States has allocated more than 641,000 monoclonal antibody treatments for outpatients to ease pressure on strained hospitals, but officials from Operation Warp Speed report that more than half of that reserve sits unused as clinicians grapple with best practices.

There are space and personnel limitations in hospitals right now, Janet Woodcock, MD, therapeutics lead on Operation Warp Speed, acknowledges in an interview with this news organization. “Special areas and procedures must be set up.” And the operation is in the process of broadening availability beyond hospitals, she points out.

But for frontline clinicians, questions about treatment efficacy and the logistics of administering intravenous drugs to infectious outpatients loom large.

More than 50 monoclonal antibody products that target SARS-CoV-2 are now in development. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has already issued Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for two such drugs on the basis of phase 2 trial data – bamlanivimab, made by Eli Lilly, and a cocktail of casirivimab plus imdevimab, made by Regeneron – and another two-antibody cocktail from AstraZeneca, AZD7442, has started phase 3 clinical trials. The Regeneron combination was used to treat President Donald Trump when he contracted COVID-19 in October.

Monoclonal antibody drugs are based on the natural antibodies that the body uses to fight infections. They work by binding to a specific target and then blocking its action or flagging it for destruction by other parts of the immune system. Both bamlanivimab and the casirivimab plus imdevimab combination target the spike protein of the virus and stop it from attaching to and entering human cells.

Targeting the spike protein out of the hospital

The antibody drugs covered by EUAs do not cure COVID-19, but they have been shown to reduce hospitalizations and visits to the emergency department for patients at high risk for disease progression. They are approved to treat patients older than 12 years with mild to moderate COVID-19 who are at high risk of progressing to severe disease or hospitalization. They are not authorized for use in patients who have been hospitalized or who are on ventilators. The hope is that antibody drugs will reduce the number of severe cases of COVID-19 and ease pressure on overstretched hospitals.

Most COVID-19 patients are outpatients, so we need something to keep them from getting worse.

This is important because it targets the greatest need in COVID-19 therapeutics, says Rajesh Gandhi, MD, an infectious disease physician at Harvard Medical School in Boston, who is a member of two panels evaluating COVID-19 treatments: one for the Infectious Disease Society of America and the other for the National Institutes of Health. “Up to now, most of the focus has been on hospitalized patients,” he says, but “most COVID-19 patients are outpatients, so we need something to keep them from getting worse.”

Both panels have said that, despite the EUAs, more evidence is needed to be sure of the efficacy of the drugs and to determine which patients will benefit the most from them.

These aren’t the mature data from drug development that guideline groups are accustomed to working with, Dr. Woodcock points out. “But this is an emergency and the data taken as a whole are pretty convincing,” she says. “As I look at the totality of the evidence, monoclonal antibodies will have a big effect in keeping people out of the hospital and helping them recover faster.”

High-risk patients are eligible for treatment, especially those older than 65 years and those with comorbidities who are younger. Access to the drugs is increasing for clinicians who are able to infuse safely or work with a site that will.

In the Boston area, several hospitals, including Massachusetts General where Dr. Gandhi works, have set up infusion centers where newly diagnosed patients can get the antibody treatment if their doctor thinks it will benefit them. And Coram, a provider of at-home infusion therapy owned by the CVS pharmacy chain, is running a pilot program offering the Eli Lilly drug to people in seven cities – including Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Tampa – and their surrounding communities with a physician referral.

Getting that referral could be tricky, however, for patients without a primary care physician or for those whose doctor isn’t already connected to one of the institutions providing the infusions. The hospitals are sending out communications on how patients and physicians can get the therapy, but Dr. Gandhi says that making information about access available should be a priority. The window for the effective treatment is small – the drugs appear to work best before patients begin to make their own antibodies, says Dr. Gandhi – so it’s vital that doctors act quickly if they have a patient who is eligible.

And rolling out the new therapies to patients around the world will be a major logistical undertaking.

The first hurdle will be making enough of them to go around. Case numbers are skyrocketing around the globe, and producing the drugs is a complex time- and labor-intensive process that requires specialized facilities. Antibodies are produced by cell lines in bioreactors, so a plant that churns out generic aspirin tablets can’t simply be converted into an antibody factory.

“These types of drugs are manufactured in a sterile injectables plant, which is different from a plant where oral solids are made,” says Kim Crabtree, senior director of pharma portfolio management for Henry Schein Medical, a medical supplies distributor. “Those are not as plentiful as a standard pill factory.”

The doses required are also relatively high – 1.2 g of each antibody in Regeneron’s cocktail – which will further strain production capacity. Leah Lipsich, PhD, vice president of strategic program direction at Regeneron, says the company is prepared for high demand and has been able to respond, thanks to its rapid development and manufacturing technology, known as VelociSuite, which allows it to rapidly scale-up from discovery to productions in weeks instead of months.

“We knew supply would be a huge problem for COVID-19, but because we had such confidence in our technology, we went immediately from research-scale to our largest-scale manufacturing,” she says. “We’ve been manufacturing our cocktail for months now.”

The company has also partnered with Roche, the biggest manufacturer and vendor of monoclonal antibodies in the world, to manufacture and supply the drugs. Once full manufacturing capacity is reached in 2021, the companies expect to produce at least 2 million doses a year.

Then there is the issue of getting the drugs from the factories to the places they will be used.

Antibodies are temperature sensitive and need to be refrigerated during transport and storage, so a cold-chain-compliant supply chain is required. Fortunately, they can be kept at standard refrigerator temperatures, ranging from 2° C to 8° C, rather than the ultra-low temperatures required by some COVID-19 vaccines.

Two million doses a year

Medical logistics companies have a lot of experience dealing with products like these and are well prepared to handle the new antibody drugs. “There are quite a few products like these on the market, and the supply chain is used to shipping them,” Ms. Crabtree says.

They will be shipped to distribution centers in refrigerated trucks, repacked into smaller lots that can sustain the correct temperature for 24 hours, and then sent to their final destination, often in something as simple as a Styrofoam cooler filled with dry ice.

The expected rise in demand shouldn’t be too much of an issue for distributors either, says Ms. Crabtree; they have built systems that can deal with short-term surges in volume. The annual flu vaccine, for example, involves shipping a lot of product in a very short time, usually from August to November. “The distribution system is used to seasonal variations and peaks in demand,” she says.

The next question is how the treatments will be administered. Although most patients who will receive monoclonal antibodies will be ambulatory and not hospitalized, the administration requires intravenous infusion. Hospitals, of course, have a lot of experience with intravenous drugs, but typically give them only to inpatients. Most other monoclonal antibody drugs – such as those for cancer and autoimmune disorders – are given in specialized suites in doctor’s offices or in stand-alone infusion clinics.

That means that the places best suited to treat COVID-19 patients with antibodies are those that regularly deal with people who are immunocompromised, and such patients should not be interacting with people who have an infectious disease. “How do we protect the staff and other patients?” Dr. Gandhi asks.

Protecting staff and other patients

This is not an insurmountable obstacle, he points out, but it is one that requires careful thought and planning to accommodate COVID-19 patients without unduly disrupting life-saving treatments for other patients. It might involve, for example, treating COVID-19 patients in sequestered parts of the clinic or at different times of day, with even greater attention paid to cleaning, he explains. “We now have many months of experience with infection control, so we know how to do this; it’s just a question of logistics.”

But even once all the details around manufacturing, transporting, and administering the drugs are sorted out, there is still the issue of how they will be distributed fairly and equitably.

Despite multiple companies working to produce an array of different antibody drugs, demand is still expected to exceed supply for many months. “With more than 200,000 new cases a day in the United States, there won’t be enough antibodies to treat all of the high-risk patients,” says Dr. Gandhi. “Most of us are worried that demand will far outstrip supply. People are talking about lotteries to determine who gets them.”

The Department of Health and Human Services will continue to distribute the drugs to states on the basis of their COVID-19 burdens, and the states will then decide how much to provide to each health care facility.

Although the HHS goal is to ensure that the drugs reach as many patients as possible, no matter where they live and regardless of their income, there are still concerns that larger facilities serving more affluent areas will end up being favored, if only because they are the ones best equipped to deal with the drugs right now.

“We are all aware that this has affected certain communities more, so we need to make sure that the drugs are used equitably and made available to the communities that were hardest hit,” says Dr. Gandhi. The ability to monitor drug distribution should be built into the rollout, so that institutions and governments will have some sense of whether they are being doled out evenly, he adds.

Equity in distribution will be an issue for the rest of the world as well. Currently, 80% of monoclonal antibodies are sold in Canada, Europe, and the United States; few, if any, are available in low- and middle-income countries. The treatments are expensive: the cost of producing one g of marketed monoclonal antibodies is between $95 and $200, which does not include the cost of R&D, packaging, shipping, or administration. The median price for antibody treatment not related to COVID-19 runs from $15,000 to $200,000 per year in the United States.

Regeneron’s Dr. Lipsich says that the company has not yet set a price for its antibody cocktail. The government paid $450 million for its 300,000 doses, but that price includes the costs of research, manufacturing, and distribution, so is not a useful indicator of the eventual per-dose price. “We’re not in a position to talk about how it will be priced yet, but we will do our best to make it affordable and accessible to all,” she says.

There are some projects underway to ensure that the drugs are made available in poorer countries. In April, the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator – an initiative launched by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome, and Mastercard to speed-up the response to the global pandemic – reserved manufacturing capacity with Fujifilm Diosynth Biotechnologies in Denmark for future monoclonal antibody therapies that will supply low- and middle-income countries. In October, the initiative announced that Eli Lilly would use that reserved capacity to produce its antibody drug starting in April 2021.

In the meantime, Lilly will make some of its product manufactured in other facilities available to lower-income countries. To help keep costs down, the company’s collaborators have agreed to waive their royalties on antibodies distributed in low- and middle-income countries.

“Everyone is looking carefully at how the drugs are distributed to ensure all will get access,” said Dr. Lipsich.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The United States has allocated more than 641,000 monoclonal antibody treatments for outpatients to ease pressure on strained hospitals, but officials from Operation Warp Speed report that more than half of that reserve sits unused as clinicians grapple with best practices.

There are space and personnel limitations in hospitals right now, Janet Woodcock, MD, therapeutics lead on Operation Warp Speed, acknowledges in an interview with this news organization. “Special areas and procedures must be set up.” And the operation is in the process of broadening availability beyond hospitals, she points out.

But for frontline clinicians, questions about treatment efficacy and the logistics of administering intravenous drugs to infectious outpatients loom large.

More than 50 monoclonal antibody products that target SARS-CoV-2 are now in development. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has already issued Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for two such drugs on the basis of phase 2 trial data – bamlanivimab, made by Eli Lilly, and a cocktail of casirivimab plus imdevimab, made by Regeneron – and another two-antibody cocktail from AstraZeneca, AZD7442, has started phase 3 clinical trials. The Regeneron combination was used to treat President Donald Trump when he contracted COVID-19 in October.

Monoclonal antibody drugs are based on the natural antibodies that the body uses to fight infections. They work by binding to a specific target and then blocking its action or flagging it for destruction by other parts of the immune system. Both bamlanivimab and the casirivimab plus imdevimab combination target the spike protein of the virus and stop it from attaching to and entering human cells.

Targeting the spike protein out of the hospital

The antibody drugs covered by EUAs do not cure COVID-19, but they have been shown to reduce hospitalizations and visits to the emergency department for patients at high risk for disease progression. They are approved to treat patients older than 12 years with mild to moderate COVID-19 who are at high risk of progressing to severe disease or hospitalization. They are not authorized for use in patients who have been hospitalized or who are on ventilators. The hope is that antibody drugs will reduce the number of severe cases of COVID-19 and ease pressure on overstretched hospitals.

Most COVID-19 patients are outpatients, so we need something to keep them from getting worse.

This is important because it targets the greatest need in COVID-19 therapeutics, says Rajesh Gandhi, MD, an infectious disease physician at Harvard Medical School in Boston, who is a member of two panels evaluating COVID-19 treatments: one for the Infectious Disease Society of America and the other for the National Institutes of Health. “Up to now, most of the focus has been on hospitalized patients,” he says, but “most COVID-19 patients are outpatients, so we need something to keep them from getting worse.”

Both panels have said that, despite the EUAs, more evidence is needed to be sure of the efficacy of the drugs and to determine which patients will benefit the most from them.

These aren’t the mature data from drug development that guideline groups are accustomed to working with, Dr. Woodcock points out. “But this is an emergency and the data taken as a whole are pretty convincing,” she says. “As I look at the totality of the evidence, monoclonal antibodies will have a big effect in keeping people out of the hospital and helping them recover faster.”

High-risk patients are eligible for treatment, especially those older than 65 years and those with comorbidities who are younger. Access to the drugs is increasing for clinicians who are able to infuse safely or work with a site that will.

In the Boston area, several hospitals, including Massachusetts General where Dr. Gandhi works, have set up infusion centers where newly diagnosed patients can get the antibody treatment if their doctor thinks it will benefit them. And Coram, a provider of at-home infusion therapy owned by the CVS pharmacy chain, is running a pilot program offering the Eli Lilly drug to people in seven cities – including Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Tampa – and their surrounding communities with a physician referral.

Getting that referral could be tricky, however, for patients without a primary care physician or for those whose doctor isn’t already connected to one of the institutions providing the infusions. The hospitals are sending out communications on how patients and physicians can get the therapy, but Dr. Gandhi says that making information about access available should be a priority. The window for the effective treatment is small – the drugs appear to work best before patients begin to make their own antibodies, says Dr. Gandhi – so it’s vital that doctors act quickly if they have a patient who is eligible.

And rolling out the new therapies to patients around the world will be a major logistical undertaking.

The first hurdle will be making enough of them to go around. Case numbers are skyrocketing around the globe, and producing the drugs is a complex time- and labor-intensive process that requires specialized facilities. Antibodies are produced by cell lines in bioreactors, so a plant that churns out generic aspirin tablets can’t simply be converted into an antibody factory.

“These types of drugs are manufactured in a sterile injectables plant, which is different from a plant where oral solids are made,” says Kim Crabtree, senior director of pharma portfolio management for Henry Schein Medical, a medical supplies distributor. “Those are not as plentiful as a standard pill factory.”

The doses required are also relatively high – 1.2 g of each antibody in Regeneron’s cocktail – which will further strain production capacity. Leah Lipsich, PhD, vice president of strategic program direction at Regeneron, says the company is prepared for high demand and has been able to respond, thanks to its rapid development and manufacturing technology, known as VelociSuite, which allows it to rapidly scale-up from discovery to productions in weeks instead of months.

“We knew supply would be a huge problem for COVID-19, but because we had such confidence in our technology, we went immediately from research-scale to our largest-scale manufacturing,” she says. “We’ve been manufacturing our cocktail for months now.”

The company has also partnered with Roche, the biggest manufacturer and vendor of monoclonal antibodies in the world, to manufacture and supply the drugs. Once full manufacturing capacity is reached in 2021, the companies expect to produce at least 2 million doses a year.

Then there is the issue of getting the drugs from the factories to the places they will be used.

Antibodies are temperature sensitive and need to be refrigerated during transport and storage, so a cold-chain-compliant supply chain is required. Fortunately, they can be kept at standard refrigerator temperatures, ranging from 2° C to 8° C, rather than the ultra-low temperatures required by some COVID-19 vaccines.

Two million doses a year

Medical logistics companies have a lot of experience dealing with products like these and are well prepared to handle the new antibody drugs. “There are quite a few products like these on the market, and the supply chain is used to shipping them,” Ms. Crabtree says.

They will be shipped to distribution centers in refrigerated trucks, repacked into smaller lots that can sustain the correct temperature for 24 hours, and then sent to their final destination, often in something as simple as a Styrofoam cooler filled with dry ice.

The expected rise in demand shouldn’t be too much of an issue for distributors either, says Ms. Crabtree; they have built systems that can deal with short-term surges in volume. The annual flu vaccine, for example, involves shipping a lot of product in a very short time, usually from August to November. “The distribution system is used to seasonal variations and peaks in demand,” she says.

The next question is how the treatments will be administered. Although most patients who will receive monoclonal antibodies will be ambulatory and not hospitalized, the administration requires intravenous infusion. Hospitals, of course, have a lot of experience with intravenous drugs, but typically give them only to inpatients. Most other monoclonal antibody drugs – such as those for cancer and autoimmune disorders – are given in specialized suites in doctor’s offices or in stand-alone infusion clinics.

That means that the places best suited to treat COVID-19 patients with antibodies are those that regularly deal with people who are immunocompromised, and such patients should not be interacting with people who have an infectious disease. “How do we protect the staff and other patients?” Dr. Gandhi asks.

Protecting staff and other patients

This is not an insurmountable obstacle, he points out, but it is one that requires careful thought and planning to accommodate COVID-19 patients without unduly disrupting life-saving treatments for other patients. It might involve, for example, treating COVID-19 patients in sequestered parts of the clinic or at different times of day, with even greater attention paid to cleaning, he explains. “We now have many months of experience with infection control, so we know how to do this; it’s just a question of logistics.”

But even once all the details around manufacturing, transporting, and administering the drugs are sorted out, there is still the issue of how they will be distributed fairly and equitably.

Despite multiple companies working to produce an array of different antibody drugs, demand is still expected to exceed supply for many months. “With more than 200,000 new cases a day in the United States, there won’t be enough antibodies to treat all of the high-risk patients,” says Dr. Gandhi. “Most of us are worried that demand will far outstrip supply. People are talking about lotteries to determine who gets them.”

The Department of Health and Human Services will continue to distribute the drugs to states on the basis of their COVID-19 burdens, and the states will then decide how much to provide to each health care facility.

Although the HHS goal is to ensure that the drugs reach as many patients as possible, no matter where they live and regardless of their income, there are still concerns that larger facilities serving more affluent areas will end up being favored, if only because they are the ones best equipped to deal with the drugs right now.

“We are all aware that this has affected certain communities more, so we need to make sure that the drugs are used equitably and made available to the communities that were hardest hit,” says Dr. Gandhi. The ability to monitor drug distribution should be built into the rollout, so that institutions and governments will have some sense of whether they are being doled out evenly, he adds.

Equity in distribution will be an issue for the rest of the world as well. Currently, 80% of monoclonal antibodies are sold in Canada, Europe, and the United States; few, if any, are available in low- and middle-income countries. The treatments are expensive: the cost of producing one g of marketed monoclonal antibodies is between $95 and $200, which does not include the cost of R&D, packaging, shipping, or administration. The median price for antibody treatment not related to COVID-19 runs from $15,000 to $200,000 per year in the United States.

Regeneron’s Dr. Lipsich says that the company has not yet set a price for its antibody cocktail. The government paid $450 million for its 300,000 doses, but that price includes the costs of research, manufacturing, and distribution, so is not a useful indicator of the eventual per-dose price. “We’re not in a position to talk about how it will be priced yet, but we will do our best to make it affordable and accessible to all,” she says.

There are some projects underway to ensure that the drugs are made available in poorer countries. In April, the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator – an initiative launched by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome, and Mastercard to speed-up the response to the global pandemic – reserved manufacturing capacity with Fujifilm Diosynth Biotechnologies in Denmark for future monoclonal antibody therapies that will supply low- and middle-income countries. In October, the initiative announced that Eli Lilly would use that reserved capacity to produce its antibody drug starting in April 2021.

In the meantime, Lilly will make some of its product manufactured in other facilities available to lower-income countries. To help keep costs down, the company’s collaborators have agreed to waive their royalties on antibodies distributed in low- and middle-income countries.

“Everyone is looking carefully at how the drugs are distributed to ensure all will get access,” said Dr. Lipsich.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The United States has allocated more than 641,000 monoclonal antibody treatments for outpatients to ease pressure on strained hospitals, but officials from Operation Warp Speed report that more than half of that reserve sits unused as clinicians grapple with best practices.

There are space and personnel limitations in hospitals right now, Janet Woodcock, MD, therapeutics lead on Operation Warp Speed, acknowledges in an interview with this news organization. “Special areas and procedures must be set up.” And the operation is in the process of broadening availability beyond hospitals, she points out.

But for frontline clinicians, questions about treatment efficacy and the logistics of administering intravenous drugs to infectious outpatients loom large.

More than 50 monoclonal antibody products that target SARS-CoV-2 are now in development. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has already issued Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for two such drugs on the basis of phase 2 trial data – bamlanivimab, made by Eli Lilly, and a cocktail of casirivimab plus imdevimab, made by Regeneron – and another two-antibody cocktail from AstraZeneca, AZD7442, has started phase 3 clinical trials. The Regeneron combination was used to treat President Donald Trump when he contracted COVID-19 in October.

Monoclonal antibody drugs are based on the natural antibodies that the body uses to fight infections. They work by binding to a specific target and then blocking its action or flagging it for destruction by other parts of the immune system. Both bamlanivimab and the casirivimab plus imdevimab combination target the spike protein of the virus and stop it from attaching to and entering human cells.

Targeting the spike protein out of the hospital

The antibody drugs covered by EUAs do not cure COVID-19, but they have been shown to reduce hospitalizations and visits to the emergency department for patients at high risk for disease progression. They are approved to treat patients older than 12 years with mild to moderate COVID-19 who are at high risk of progressing to severe disease or hospitalization. They are not authorized for use in patients who have been hospitalized or who are on ventilators. The hope is that antibody drugs will reduce the number of severe cases of COVID-19 and ease pressure on overstretched hospitals.

Most COVID-19 patients are outpatients, so we need something to keep them from getting worse.

This is important because it targets the greatest need in COVID-19 therapeutics, says Rajesh Gandhi, MD, an infectious disease physician at Harvard Medical School in Boston, who is a member of two panels evaluating COVID-19 treatments: one for the Infectious Disease Society of America and the other for the National Institutes of Health. “Up to now, most of the focus has been on hospitalized patients,” he says, but “most COVID-19 patients are outpatients, so we need something to keep them from getting worse.”

Both panels have said that, despite the EUAs, more evidence is needed to be sure of the efficacy of the drugs and to determine which patients will benefit the most from them.

These aren’t the mature data from drug development that guideline groups are accustomed to working with, Dr. Woodcock points out. “But this is an emergency and the data taken as a whole are pretty convincing,” she says. “As I look at the totality of the evidence, monoclonal antibodies will have a big effect in keeping people out of the hospital and helping them recover faster.”

High-risk patients are eligible for treatment, especially those older than 65 years and those with comorbidities who are younger. Access to the drugs is increasing for clinicians who are able to infuse safely or work with a site that will.

In the Boston area, several hospitals, including Massachusetts General where Dr. Gandhi works, have set up infusion centers where newly diagnosed patients can get the antibody treatment if their doctor thinks it will benefit them. And Coram, a provider of at-home infusion therapy owned by the CVS pharmacy chain, is running a pilot program offering the Eli Lilly drug to people in seven cities – including Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Tampa – and their surrounding communities with a physician referral.

Getting that referral could be tricky, however, for patients without a primary care physician or for those whose doctor isn’t already connected to one of the institutions providing the infusions. The hospitals are sending out communications on how patients and physicians can get the therapy, but Dr. Gandhi says that making information about access available should be a priority. The window for the effective treatment is small – the drugs appear to work best before patients begin to make their own antibodies, says Dr. Gandhi – so it’s vital that doctors act quickly if they have a patient who is eligible.

And rolling out the new therapies to patients around the world will be a major logistical undertaking.

The first hurdle will be making enough of them to go around. Case numbers are skyrocketing around the globe, and producing the drugs is a complex time- and labor-intensive process that requires specialized facilities. Antibodies are produced by cell lines in bioreactors, so a plant that churns out generic aspirin tablets can’t simply be converted into an antibody factory.

“These types of drugs are manufactured in a sterile injectables plant, which is different from a plant where oral solids are made,” says Kim Crabtree, senior director of pharma portfolio management for Henry Schein Medical, a medical supplies distributor. “Those are not as plentiful as a standard pill factory.”

The doses required are also relatively high – 1.2 g of each antibody in Regeneron’s cocktail – which will further strain production capacity. Leah Lipsich, PhD, vice president of strategic program direction at Regeneron, says the company is prepared for high demand and has been able to respond, thanks to its rapid development and manufacturing technology, known as VelociSuite, which allows it to rapidly scale-up from discovery to productions in weeks instead of months.

“We knew supply would be a huge problem for COVID-19, but because we had such confidence in our technology, we went immediately from research-scale to our largest-scale manufacturing,” she says. “We’ve been manufacturing our cocktail for months now.”

The company has also partnered with Roche, the biggest manufacturer and vendor of monoclonal antibodies in the world, to manufacture and supply the drugs. Once full manufacturing capacity is reached in 2021, the companies expect to produce at least 2 million doses a year.

Then there is the issue of getting the drugs from the factories to the places they will be used.

Antibodies are temperature sensitive and need to be refrigerated during transport and storage, so a cold-chain-compliant supply chain is required. Fortunately, they can be kept at standard refrigerator temperatures, ranging from 2° C to 8° C, rather than the ultra-low temperatures required by some COVID-19 vaccines.

Two million doses a year

Medical logistics companies have a lot of experience dealing with products like these and are well prepared to handle the new antibody drugs. “There are quite a few products like these on the market, and the supply chain is used to shipping them,” Ms. Crabtree says.

They will be shipped to distribution centers in refrigerated trucks, repacked into smaller lots that can sustain the correct temperature for 24 hours, and then sent to their final destination, often in something as simple as a Styrofoam cooler filled with dry ice.

The expected rise in demand shouldn’t be too much of an issue for distributors either, says Ms. Crabtree; they have built systems that can deal with short-term surges in volume. The annual flu vaccine, for example, involves shipping a lot of product in a very short time, usually from August to November. “The distribution system is used to seasonal variations and peaks in demand,” she says.

The next question is how the treatments will be administered. Although most patients who will receive monoclonal antibodies will be ambulatory and not hospitalized, the administration requires intravenous infusion. Hospitals, of course, have a lot of experience with intravenous drugs, but typically give them only to inpatients. Most other monoclonal antibody drugs – such as those for cancer and autoimmune disorders – are given in specialized suites in doctor’s offices or in stand-alone infusion clinics.

That means that the places best suited to treat COVID-19 patients with antibodies are those that regularly deal with people who are immunocompromised, and such patients should not be interacting with people who have an infectious disease. “How do we protect the staff and other patients?” Dr. Gandhi asks.

Protecting staff and other patients

This is not an insurmountable obstacle, he points out, but it is one that requires careful thought and planning to accommodate COVID-19 patients without unduly disrupting life-saving treatments for other patients. It might involve, for example, treating COVID-19 patients in sequestered parts of the clinic or at different times of day, with even greater attention paid to cleaning, he explains. “We now have many months of experience with infection control, so we know how to do this; it’s just a question of logistics.”

But even once all the details around manufacturing, transporting, and administering the drugs are sorted out, there is still the issue of how they will be distributed fairly and equitably.

Despite multiple companies working to produce an array of different antibody drugs, demand is still expected to exceed supply for many months. “With more than 200,000 new cases a day in the United States, there won’t be enough antibodies to treat all of the high-risk patients,” says Dr. Gandhi. “Most of us are worried that demand will far outstrip supply. People are talking about lotteries to determine who gets them.”

The Department of Health and Human Services will continue to distribute the drugs to states on the basis of their COVID-19 burdens, and the states will then decide how much to provide to each health care facility.

Although the HHS goal is to ensure that the drugs reach as many patients as possible, no matter where they live and regardless of their income, there are still concerns that larger facilities serving more affluent areas will end up being favored, if only because they are the ones best equipped to deal with the drugs right now.

“We are all aware that this has affected certain communities more, so we need to make sure that the drugs are used equitably and made available to the communities that were hardest hit,” says Dr. Gandhi. The ability to monitor drug distribution should be built into the rollout, so that institutions and governments will have some sense of whether they are being doled out evenly, he adds.

Equity in distribution will be an issue for the rest of the world as well. Currently, 80% of monoclonal antibodies are sold in Canada, Europe, and the United States; few, if any, are available in low- and middle-income countries. The treatments are expensive: the cost of producing one g of marketed monoclonal antibodies is between $95 and $200, which does not include the cost of R&D, packaging, shipping, or administration. The median price for antibody treatment not related to COVID-19 runs from $15,000 to $200,000 per year in the United States.

Regeneron’s Dr. Lipsich says that the company has not yet set a price for its antibody cocktail. The government paid $450 million for its 300,000 doses, but that price includes the costs of research, manufacturing, and distribution, so is not a useful indicator of the eventual per-dose price. “We’re not in a position to talk about how it will be priced yet, but we will do our best to make it affordable and accessible to all,” she says.

There are some projects underway to ensure that the drugs are made available in poorer countries. In April, the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator – an initiative launched by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome, and Mastercard to speed-up the response to the global pandemic – reserved manufacturing capacity with Fujifilm Diosynth Biotechnologies in Denmark for future monoclonal antibody therapies that will supply low- and middle-income countries. In October, the initiative announced that Eli Lilly would use that reserved capacity to produce its antibody drug starting in April 2021.

In the meantime, Lilly will make some of its product manufactured in other facilities available to lower-income countries. To help keep costs down, the company’s collaborators have agreed to waive their royalties on antibodies distributed in low- and middle-income countries.

“Everyone is looking carefully at how the drugs are distributed to ensure all will get access,” said Dr. Lipsich.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In COVID-19 patients, risk of bleeding rivals risk of thromboembolism

There is no question that COVID-19 infection increases the risks of serious thromboembolic events, including pulmonary embolism (PE), but it also increases the risk of bleeding, complicating the benefit-to-risk calculations for anticoagulation, according to a review of data at the virtual Going Back to the Heart of Cardiology meeting.

“Bleeding is a significant cause of morbidity in patients with COVID-19, and this is an important concept to appreciate,” reported Rachel P. Rosovsky, MD, director of thrombosis research, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

At least five guidelines, including those issued by the American College of Cardiology, International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH), and the American College of Chest Physicians, have recently addressed anticoagulation in patients infected with COVID-19, but there are “substantive differences” between them, according to Dr. Rosovsky. The reason is that they are essentially no high quality trials to guide practice. Rather, the recommendations are based primarily on retrospective studies and expert opinion.

The single most common theme from the guidelines is that anticoagulation must be individualized to balance patient-specific risks of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and bleeding, said Dr. Rosovsky, whose group published a recent comparison of these guidelines (Flaczyk A et al. Crit Care 2020;24:559).

Although there is general consensus that all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 should receive anticoagulation unless there are contraindications, there are differences in the recommended intensity of the anticoagulation for different risk groups and there is even less is less consensus on the need to anticoagulate outpatients or patients after discharge, according to Dr. Rosovsky

In her own center, the standard is a prophylactic dose of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) in an algorithm that calls for dose adjustments for some groups such as those with renal impairment or obesity. Alternative forms of anticoagulation are recommended for patients with a history of thrombocytopenia or are at high risk for hemorrhage. Full dose LMWH is recommended in patients already on an oral anticoagulant at time of hospitalization.

“The biggest question right now is when to consider increasing from a prophylactic dose to intermediate or full dose anticoagulation in high risk patients, especially those in the ICU patients,” Dr. Rosovsky said.

Current practices are diverse, according to a recently published survey led by Dr. Rosovsky (Rosovsky RP et al. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4:969-83). According to the survey, which had responses from more than 500 physicians in 41 countries, 30% of centers escalate from a prophylactic dose of anticoagulation to an intermediate dose when patients move to the ICU. Although not all answered this question, 25% reported that they do not escalate at ICU transfer. For 15% of respondents, dose escalation is being offered to patients with a D-dimer exceeding six-times the upper limit of normal.

These practices have developed in the absence of prospective clinical trials, which are urgently needed, according to Dr. Rosovsky. The reason that trials specific to COVID-19 are particularly important is that this infection also engenders a high risk of major bleeding.