User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Seniors intend to receive variant-specific COVID booster in coming months

of 2022.

That finding comes from a new poll by researchers at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who also report that when it comes to the shots, people appear to be putting more trust in their health care professionals than in public health authorities.

“When you are a doctor, you are a trusted source of medical information,” said Preeti Malani, MD, MSJ, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Michigan. “Use the ongoing conversation with your patient as an opportunity to answer their questions and counter any confusion.”

The vaccination campaign appears to be having a rub-off effect, too. More people say they’re likely to receive vaccines and boosters for other infections, such as flu, if they have already been vaccinated and boosted against COVID-19.

Inside the poll

Dr. Malani and her colleagues, who published their findings on the National Poll on Healthy Aging’s website, asked 1,024 adults older than 50 about their attitudes on COVID-19 vaccinations and their history of receiving the injections. The questions covered topics including whether the individual had contracted COVID, COVID vaccine doses, and the prevalence of a health care clinician’s opinion on vaccines and boosters. The poll was conducted July 21-26.

The researchers chose the age range of 50-65 years because this group is an important population for new booster shots that target specific variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19.

Only 19% of people aged 50-64 and 44% of those older than 65 said they had received both their first and second COVID-19 booster shots. What’s more, 17% of people said they had not received any doses of a COVID-19 vaccine.

The vast majority (77%) of respondents said their clinician’s recommendations were “very important” or “somewhat important” in their decision to receive the vaccine.

Dr. Malani said that in her practice, patients have expressed hesitation about COVID-19 vaccines because of concerns about the potential side effects of the shots.

Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, noted that Americans now appear to trust their physicians more than public health authorities such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention when it comes to COVID-19.

“More people are trusting their providers’ opinions [more] than the CDC or other public health agencies. That speaks volumes to me,” Dr. Gandhi said.

Among the more surprising findings of the poll, according to the researchers, was the number of people who said they had yet to contract COVID-19: 50% of those aged 50-64, and 69% of those older than 65. (Another 12% of those aged 50-64 said they were unsure if they’d ever had the infection.)

Dr. Malani said she hoped future studies would explore in depth the people who remain uninfected with COVID-19.

“We focus a lot on the science of COVID,” she said. “But we need to turn our attention to the behavioral aspects and how to address them.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

of 2022.

That finding comes from a new poll by researchers at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who also report that when it comes to the shots, people appear to be putting more trust in their health care professionals than in public health authorities.

“When you are a doctor, you are a trusted source of medical information,” said Preeti Malani, MD, MSJ, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Michigan. “Use the ongoing conversation with your patient as an opportunity to answer their questions and counter any confusion.”

The vaccination campaign appears to be having a rub-off effect, too. More people say they’re likely to receive vaccines and boosters for other infections, such as flu, if they have already been vaccinated and boosted against COVID-19.

Inside the poll

Dr. Malani and her colleagues, who published their findings on the National Poll on Healthy Aging’s website, asked 1,024 adults older than 50 about their attitudes on COVID-19 vaccinations and their history of receiving the injections. The questions covered topics including whether the individual had contracted COVID, COVID vaccine doses, and the prevalence of a health care clinician’s opinion on vaccines and boosters. The poll was conducted July 21-26.

The researchers chose the age range of 50-65 years because this group is an important population for new booster shots that target specific variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19.

Only 19% of people aged 50-64 and 44% of those older than 65 said they had received both their first and second COVID-19 booster shots. What’s more, 17% of people said they had not received any doses of a COVID-19 vaccine.

The vast majority (77%) of respondents said their clinician’s recommendations were “very important” or “somewhat important” in their decision to receive the vaccine.

Dr. Malani said that in her practice, patients have expressed hesitation about COVID-19 vaccines because of concerns about the potential side effects of the shots.

Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, noted that Americans now appear to trust their physicians more than public health authorities such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention when it comes to COVID-19.

“More people are trusting their providers’ opinions [more] than the CDC or other public health agencies. That speaks volumes to me,” Dr. Gandhi said.

Among the more surprising findings of the poll, according to the researchers, was the number of people who said they had yet to contract COVID-19: 50% of those aged 50-64, and 69% of those older than 65. (Another 12% of those aged 50-64 said they were unsure if they’d ever had the infection.)

Dr. Malani said she hoped future studies would explore in depth the people who remain uninfected with COVID-19.

“We focus a lot on the science of COVID,” she said. “But we need to turn our attention to the behavioral aspects and how to address them.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

of 2022.

That finding comes from a new poll by researchers at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who also report that when it comes to the shots, people appear to be putting more trust in their health care professionals than in public health authorities.

“When you are a doctor, you are a trusted source of medical information,” said Preeti Malani, MD, MSJ, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Michigan. “Use the ongoing conversation with your patient as an opportunity to answer their questions and counter any confusion.”

The vaccination campaign appears to be having a rub-off effect, too. More people say they’re likely to receive vaccines and boosters for other infections, such as flu, if they have already been vaccinated and boosted against COVID-19.

Inside the poll

Dr. Malani and her colleagues, who published their findings on the National Poll on Healthy Aging’s website, asked 1,024 adults older than 50 about their attitudes on COVID-19 vaccinations and their history of receiving the injections. The questions covered topics including whether the individual had contracted COVID, COVID vaccine doses, and the prevalence of a health care clinician’s opinion on vaccines and boosters. The poll was conducted July 21-26.

The researchers chose the age range of 50-65 years because this group is an important population for new booster shots that target specific variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19.

Only 19% of people aged 50-64 and 44% of those older than 65 said they had received both their first and second COVID-19 booster shots. What’s more, 17% of people said they had not received any doses of a COVID-19 vaccine.

The vast majority (77%) of respondents said their clinician’s recommendations were “very important” or “somewhat important” in their decision to receive the vaccine.

Dr. Malani said that in her practice, patients have expressed hesitation about COVID-19 vaccines because of concerns about the potential side effects of the shots.

Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, noted that Americans now appear to trust their physicians more than public health authorities such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention when it comes to COVID-19.

“More people are trusting their providers’ opinions [more] than the CDC or other public health agencies. That speaks volumes to me,” Dr. Gandhi said.

Among the more surprising findings of the poll, according to the researchers, was the number of people who said they had yet to contract COVID-19: 50% of those aged 50-64, and 69% of those older than 65. (Another 12% of those aged 50-64 said they were unsure if they’d ever had the infection.)

Dr. Malani said she hoped future studies would explore in depth the people who remain uninfected with COVID-19.

“We focus a lot on the science of COVID,” she said. “But we need to turn our attention to the behavioral aspects and how to address them.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sexual dysfunction, hair loss linked with long COVID

according to findings of a large study.

Anuradhaa Subramanian, PhD, with the Institute of Applied Health Research at the University of Birmingham (England), led the research published online in Nature Medicine.

The team analyzed 486,149 electronic health records from adult patients with confirmed COVID in the United Kingdom, compared with 1.9 million people with no history of COVID, from January 2020 to April 2021. Researchers matched both groups closely in terms of demographic, social, and clinical traits.

New symptoms

The team identified 62 symptoms, including the well-known indicators of long COVID, such as fatigue, loss of sense of smell, shortness of breath, and brain fog, but also hair loss, sexual dysfunction, chest pain, fever, loss of control of bowel movements, and limb swelling.

“These differences in symptoms reported between the infected and uninfected groups remained even after we accounted for age, sex, ethnic group, socioeconomic status, body mass index, smoking status, the presence of more than 80 health conditions, and past reporting of the same symptom,” Dr. Subramanian and coresearcher Shamil Haroon, PhD, wrote in a summary of their research in The Conversation.

They pointed out that only 20 of the symptoms they found are included in the World Health Organization’s clinical case definition for long COVID.

They also found that people more likely to have persistent symptoms 3 months after COVID infection were also more likely to be young, female, smokers, to belong to certain minority ethnic groups, and to have lower socioeconomic status. They were also more likely to be obese and have a wide range of health conditions.

Dr. Haroon, an associate clinical professor at the University of Birmingham, said that one reason it appeared that younger people were more likely to get symptoms of long COVID may be that older adults with COVID were more likely to be hospitalized and weren’t included in this study.

“Since we only considered nonhospitalized adults, the older adults we included in our study may have been relatively healthier and thus had a lower symptom burden,” he said.

Dr. Subramania noted that older patients were more likely to report lasting COVID-related symptoms in the study, but when researchers accounted for a wide range of other conditions that patients had before infection (which generally more commonly happen in older adults), they found younger age as a risk factor for long-term COVID-related symptoms.

In the study period, most patients were unvaccinated, and results came before the widespread Delta and Omicron variants.

More than half (56.6%) of the patients infected with the virus that causes COVID had been diagnosed in 2020, and 43.4% in 2021. Less than 5% (4.5%) of the patients infected with the virus and 4.7% of the patients with no recorded evidence of a COVID infection had received at least a single dose of a COVID vaccine before the study started.

Eric Topol, MD, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif., and editor-in-chief of Medscape, said more studies need to be done to see whether results would be different with vaccination status and evolving variants.

But he noted that this study has several strengths: “The hair loss, libido loss, and ejaculation difficulty are all new symptoms,” and the study – large and carefully controlled – shows these issues were among those more likely to occur.

A loss of sense of smell – which is not a new observation – was still the most likely risk shown in the study, followed by hair loss, sneezing, ejaculation difficulty, and reduced sex drive; followed by shortness of breath, fatigue, chest pain associated with breathing difficulties, hoarseness, and fever.

Three main clusters of symptoms

Given the wide range of symptoms, long COVID likely represents a group of conditions, the authors wrote.

They found three main clusters. The largest, with roughly 80% of people with long COVID in the study, faced a broad spectrum of symptoms, ranging from fatigue to headache and pain. The second-largest group, (15%) mostly had symptoms having to do with mental health and thinking skills, including depression, anxiety, brain fog, and insomnia. The smallest group (5%) had mainly respiratory symptoms such as shortness of breath, coughing, and wheezing.

Putting symptoms in clusters will be important to start understanding what leads to long COVID, said Farha Ikramuddin, MD, a rehabilitation specialist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

She added that, while the symptoms listed in this paper are new in published research, she has certainly been seeing them over time in her long COVID clinic. (The researchers also used only coded health care data, so they were limited in what symptoms they could discover, she notes.)

Dr. Ikramuddin said a strength of the paper is its large size, but she also cautioned that it’s difficult to determine whether members of the comparison group truly had no COVID infection when the information is taken from their medical records. Often, people test at home or assume they have COVID and don’t test; therefore the information wouldn’t be recorded.

Evaluating nonhospitalized patients is also important, she said, as much of the research on long COVID has come from hospitalized patients, so little has been known about the symptoms of those with milder infections.

“Patients who have been hospitalized and have long COVID look very different from the patients who were not hospitalized,” Dr. Ikramuddin said.

One clear message from the paper, she said, is that listening and asking extensive questions about symptoms are important with patients who have had COVID.

“Counseling has also become very important for our patients in the pandemic,” she said.

It will also be important to do studies on returning to work for patients with long COVID to see how many are able to return and at what capacity, Dr. Ikramuddin said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to findings of a large study.

Anuradhaa Subramanian, PhD, with the Institute of Applied Health Research at the University of Birmingham (England), led the research published online in Nature Medicine.

The team analyzed 486,149 electronic health records from adult patients with confirmed COVID in the United Kingdom, compared with 1.9 million people with no history of COVID, from January 2020 to April 2021. Researchers matched both groups closely in terms of demographic, social, and clinical traits.

New symptoms

The team identified 62 symptoms, including the well-known indicators of long COVID, such as fatigue, loss of sense of smell, shortness of breath, and brain fog, but also hair loss, sexual dysfunction, chest pain, fever, loss of control of bowel movements, and limb swelling.

“These differences in symptoms reported between the infected and uninfected groups remained even after we accounted for age, sex, ethnic group, socioeconomic status, body mass index, smoking status, the presence of more than 80 health conditions, and past reporting of the same symptom,” Dr. Subramanian and coresearcher Shamil Haroon, PhD, wrote in a summary of their research in The Conversation.

They pointed out that only 20 of the symptoms they found are included in the World Health Organization’s clinical case definition for long COVID.

They also found that people more likely to have persistent symptoms 3 months after COVID infection were also more likely to be young, female, smokers, to belong to certain minority ethnic groups, and to have lower socioeconomic status. They were also more likely to be obese and have a wide range of health conditions.

Dr. Haroon, an associate clinical professor at the University of Birmingham, said that one reason it appeared that younger people were more likely to get symptoms of long COVID may be that older adults with COVID were more likely to be hospitalized and weren’t included in this study.

“Since we only considered nonhospitalized adults, the older adults we included in our study may have been relatively healthier and thus had a lower symptom burden,” he said.

Dr. Subramania noted that older patients were more likely to report lasting COVID-related symptoms in the study, but when researchers accounted for a wide range of other conditions that patients had before infection (which generally more commonly happen in older adults), they found younger age as a risk factor for long-term COVID-related symptoms.

In the study period, most patients were unvaccinated, and results came before the widespread Delta and Omicron variants.

More than half (56.6%) of the patients infected with the virus that causes COVID had been diagnosed in 2020, and 43.4% in 2021. Less than 5% (4.5%) of the patients infected with the virus and 4.7% of the patients with no recorded evidence of a COVID infection had received at least a single dose of a COVID vaccine before the study started.

Eric Topol, MD, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif., and editor-in-chief of Medscape, said more studies need to be done to see whether results would be different with vaccination status and evolving variants.

But he noted that this study has several strengths: “The hair loss, libido loss, and ejaculation difficulty are all new symptoms,” and the study – large and carefully controlled – shows these issues were among those more likely to occur.

A loss of sense of smell – which is not a new observation – was still the most likely risk shown in the study, followed by hair loss, sneezing, ejaculation difficulty, and reduced sex drive; followed by shortness of breath, fatigue, chest pain associated with breathing difficulties, hoarseness, and fever.

Three main clusters of symptoms

Given the wide range of symptoms, long COVID likely represents a group of conditions, the authors wrote.

They found three main clusters. The largest, with roughly 80% of people with long COVID in the study, faced a broad spectrum of symptoms, ranging from fatigue to headache and pain. The second-largest group, (15%) mostly had symptoms having to do with mental health and thinking skills, including depression, anxiety, brain fog, and insomnia. The smallest group (5%) had mainly respiratory symptoms such as shortness of breath, coughing, and wheezing.

Putting symptoms in clusters will be important to start understanding what leads to long COVID, said Farha Ikramuddin, MD, a rehabilitation specialist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

She added that, while the symptoms listed in this paper are new in published research, she has certainly been seeing them over time in her long COVID clinic. (The researchers also used only coded health care data, so they were limited in what symptoms they could discover, she notes.)

Dr. Ikramuddin said a strength of the paper is its large size, but she also cautioned that it’s difficult to determine whether members of the comparison group truly had no COVID infection when the information is taken from their medical records. Often, people test at home or assume they have COVID and don’t test; therefore the information wouldn’t be recorded.

Evaluating nonhospitalized patients is also important, she said, as much of the research on long COVID has come from hospitalized patients, so little has been known about the symptoms of those with milder infections.

“Patients who have been hospitalized and have long COVID look very different from the patients who were not hospitalized,” Dr. Ikramuddin said.

One clear message from the paper, she said, is that listening and asking extensive questions about symptoms are important with patients who have had COVID.

“Counseling has also become very important for our patients in the pandemic,” she said.

It will also be important to do studies on returning to work for patients with long COVID to see how many are able to return and at what capacity, Dr. Ikramuddin said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to findings of a large study.

Anuradhaa Subramanian, PhD, with the Institute of Applied Health Research at the University of Birmingham (England), led the research published online in Nature Medicine.

The team analyzed 486,149 electronic health records from adult patients with confirmed COVID in the United Kingdom, compared with 1.9 million people with no history of COVID, from January 2020 to April 2021. Researchers matched both groups closely in terms of demographic, social, and clinical traits.

New symptoms

The team identified 62 symptoms, including the well-known indicators of long COVID, such as fatigue, loss of sense of smell, shortness of breath, and brain fog, but also hair loss, sexual dysfunction, chest pain, fever, loss of control of bowel movements, and limb swelling.

“These differences in symptoms reported between the infected and uninfected groups remained even after we accounted for age, sex, ethnic group, socioeconomic status, body mass index, smoking status, the presence of more than 80 health conditions, and past reporting of the same symptom,” Dr. Subramanian and coresearcher Shamil Haroon, PhD, wrote in a summary of their research in The Conversation.

They pointed out that only 20 of the symptoms they found are included in the World Health Organization’s clinical case definition for long COVID.

They also found that people more likely to have persistent symptoms 3 months after COVID infection were also more likely to be young, female, smokers, to belong to certain minority ethnic groups, and to have lower socioeconomic status. They were also more likely to be obese and have a wide range of health conditions.

Dr. Haroon, an associate clinical professor at the University of Birmingham, said that one reason it appeared that younger people were more likely to get symptoms of long COVID may be that older adults with COVID were more likely to be hospitalized and weren’t included in this study.

“Since we only considered nonhospitalized adults, the older adults we included in our study may have been relatively healthier and thus had a lower symptom burden,” he said.

Dr. Subramania noted that older patients were more likely to report lasting COVID-related symptoms in the study, but when researchers accounted for a wide range of other conditions that patients had before infection (which generally more commonly happen in older adults), they found younger age as a risk factor for long-term COVID-related symptoms.

In the study period, most patients were unvaccinated, and results came before the widespread Delta and Omicron variants.

More than half (56.6%) of the patients infected with the virus that causes COVID had been diagnosed in 2020, and 43.4% in 2021. Less than 5% (4.5%) of the patients infected with the virus and 4.7% of the patients with no recorded evidence of a COVID infection had received at least a single dose of a COVID vaccine before the study started.

Eric Topol, MD, founder and director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif., and editor-in-chief of Medscape, said more studies need to be done to see whether results would be different with vaccination status and evolving variants.

But he noted that this study has several strengths: “The hair loss, libido loss, and ejaculation difficulty are all new symptoms,” and the study – large and carefully controlled – shows these issues were among those more likely to occur.

A loss of sense of smell – which is not a new observation – was still the most likely risk shown in the study, followed by hair loss, sneezing, ejaculation difficulty, and reduced sex drive; followed by shortness of breath, fatigue, chest pain associated with breathing difficulties, hoarseness, and fever.

Three main clusters of symptoms

Given the wide range of symptoms, long COVID likely represents a group of conditions, the authors wrote.

They found three main clusters. The largest, with roughly 80% of people with long COVID in the study, faced a broad spectrum of symptoms, ranging from fatigue to headache and pain. The second-largest group, (15%) mostly had symptoms having to do with mental health and thinking skills, including depression, anxiety, brain fog, and insomnia. The smallest group (5%) had mainly respiratory symptoms such as shortness of breath, coughing, and wheezing.

Putting symptoms in clusters will be important to start understanding what leads to long COVID, said Farha Ikramuddin, MD, a rehabilitation specialist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

She added that, while the symptoms listed in this paper are new in published research, she has certainly been seeing them over time in her long COVID clinic. (The researchers also used only coded health care data, so they were limited in what symptoms they could discover, she notes.)

Dr. Ikramuddin said a strength of the paper is its large size, but she also cautioned that it’s difficult to determine whether members of the comparison group truly had no COVID infection when the information is taken from their medical records. Often, people test at home or assume they have COVID and don’t test; therefore the information wouldn’t be recorded.

Evaluating nonhospitalized patients is also important, she said, as much of the research on long COVID has come from hospitalized patients, so little has been known about the symptoms of those with milder infections.

“Patients who have been hospitalized and have long COVID look very different from the patients who were not hospitalized,” Dr. Ikramuddin said.

One clear message from the paper, she said, is that listening and asking extensive questions about symptoms are important with patients who have had COVID.

“Counseling has also become very important for our patients in the pandemic,” she said.

It will also be important to do studies on returning to work for patients with long COVID to see how many are able to return and at what capacity, Dr. Ikramuddin said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM NATURE MEDICINE

U.S. tops 10,000 confirmed monkeypox cases: CDC

The United States passed the 10,000 mark on Aug. 10, with the number climbing to 10,768 by the morning of Aug. 12, according to the latest CDC data. Monkeypox cases have been found in every state except Wyoming. New York (2,187), California (1,892), and Florida (1,053) have reported the most cases. So far, no monkeypox deaths have been reported in the United States.

The numbers are increasing, with 1,391 cases reported in the United States on Aug. 12 alone, by far the most in 1 day since the current outbreak began.

“We are still operating under a containment goal, although I know many states are starting to wonder if we’re shifting to more of a mitigation phase right now, given that our case counts are still rising rapidly,” Jennifer McQuiston, DVM, the CDC’s top monkeypox official, told a group of the agency’s advisers on Aug. 9, according to CBS News.

Since late July, the United States has reported more monkeypox cases than any other nation. After the United States, Spain has reported 5,162 cases, the United Kingdom 3,017, and France 2,423, according to the World Health Organization.

Globally, 31,655 cases have been recorded, with 5,108 of those cases coming in the last 7 days, according to the WHO. There have been 12 deaths attributed to monkeypox, with one coming in the last week.

The smallpox-like disease was first found in humans in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1970 and has become more common in West and Central Africa. It began spreading to European and other Western nations in May 2022.

The WHO declared it a global public health emergency in late July, and the Biden administration declared it a national health emergency Aug. 4.

To fight the spread of monkeypox, the Biden administration is buying $26 million worth of SIGA Technologies Inc.’s IV version of the antiviral drug TPOXX, the company announced on Aug. 9.

U.S. health officials also modified monkeypox vaccine dosing instructions to stretch the supply of vaccine. Instead of sticking with a standard shot that would enter deep into tissue, the FDA now encourages a new way: just under the skin at one-fifth the usual dose.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The United States passed the 10,000 mark on Aug. 10, with the number climbing to 10,768 by the morning of Aug. 12, according to the latest CDC data. Monkeypox cases have been found in every state except Wyoming. New York (2,187), California (1,892), and Florida (1,053) have reported the most cases. So far, no monkeypox deaths have been reported in the United States.

The numbers are increasing, with 1,391 cases reported in the United States on Aug. 12 alone, by far the most in 1 day since the current outbreak began.

“We are still operating under a containment goal, although I know many states are starting to wonder if we’re shifting to more of a mitigation phase right now, given that our case counts are still rising rapidly,” Jennifer McQuiston, DVM, the CDC’s top monkeypox official, told a group of the agency’s advisers on Aug. 9, according to CBS News.

Since late July, the United States has reported more monkeypox cases than any other nation. After the United States, Spain has reported 5,162 cases, the United Kingdom 3,017, and France 2,423, according to the World Health Organization.

Globally, 31,655 cases have been recorded, with 5,108 of those cases coming in the last 7 days, according to the WHO. There have been 12 deaths attributed to monkeypox, with one coming in the last week.

The smallpox-like disease was first found in humans in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1970 and has become more common in West and Central Africa. It began spreading to European and other Western nations in May 2022.

The WHO declared it a global public health emergency in late July, and the Biden administration declared it a national health emergency Aug. 4.

To fight the spread of monkeypox, the Biden administration is buying $26 million worth of SIGA Technologies Inc.’s IV version of the antiviral drug TPOXX, the company announced on Aug. 9.

U.S. health officials also modified monkeypox vaccine dosing instructions to stretch the supply of vaccine. Instead of sticking with a standard shot that would enter deep into tissue, the FDA now encourages a new way: just under the skin at one-fifth the usual dose.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The United States passed the 10,000 mark on Aug. 10, with the number climbing to 10,768 by the morning of Aug. 12, according to the latest CDC data. Monkeypox cases have been found in every state except Wyoming. New York (2,187), California (1,892), and Florida (1,053) have reported the most cases. So far, no monkeypox deaths have been reported in the United States.

The numbers are increasing, with 1,391 cases reported in the United States on Aug. 12 alone, by far the most in 1 day since the current outbreak began.

“We are still operating under a containment goal, although I know many states are starting to wonder if we’re shifting to more of a mitigation phase right now, given that our case counts are still rising rapidly,” Jennifer McQuiston, DVM, the CDC’s top monkeypox official, told a group of the agency’s advisers on Aug. 9, according to CBS News.

Since late July, the United States has reported more monkeypox cases than any other nation. After the United States, Spain has reported 5,162 cases, the United Kingdom 3,017, and France 2,423, according to the World Health Organization.

Globally, 31,655 cases have been recorded, with 5,108 of those cases coming in the last 7 days, according to the WHO. There have been 12 deaths attributed to monkeypox, with one coming in the last week.

The smallpox-like disease was first found in humans in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1970 and has become more common in West and Central Africa. It began spreading to European and other Western nations in May 2022.

The WHO declared it a global public health emergency in late July, and the Biden administration declared it a national health emergency Aug. 4.

To fight the spread of monkeypox, the Biden administration is buying $26 million worth of SIGA Technologies Inc.’s IV version of the antiviral drug TPOXX, the company announced on Aug. 9.

U.S. health officials also modified monkeypox vaccine dosing instructions to stretch the supply of vaccine. Instead of sticking with a standard shot that would enter deep into tissue, the FDA now encourages a new way: just under the skin at one-fifth the usual dose.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Saddled with med school debt, yet left out of loan forgiveness plans

In a recently obtained plan by Politico, the Biden administration is zeroing in on a broad student loan forgiveness plan to be released imminently. The plan would broadly forgive $10,000 in federal student loans, including graduate and PLUS loans. However, there’s a rub: The plan restricts the forgiveness to those with incomes below $150,000.

This would unfairly exclude many in health care from receiving this forgiveness, an egregious oversight given how much health care providers have sacrificed during the pandemic.

What was proposed?

Previously, it was reported that the Biden administration was considering this same amount of forgiveness, but with plans to exclude borrowers by either career or income. Student loan payments have been on an extended CARES Act forbearance since March 2020, with payment resumption planned for Aug. 31. The administration has said that they would deliver a plan for further extensions before this date and have repeatedly teased including forgiveness.

Forgiveness for some ...

Forgiving $10,000 of federal student loans would relieve some 15 million borrowers of student debt, roughly one-third of the 45 million borrowers with debt.

This would provide a massive boost to these borrowers (who disproportionately are female, low-income, and non-White), many of whom were targeted by predatory institutions whose education didn’t offer any actual tangible benefit to their earnings. While this is a group that absolutely ought to have their loans forgiven, drawing an income line inappropriately restricts those in health care from receiving any forgiveness.

... But not for others

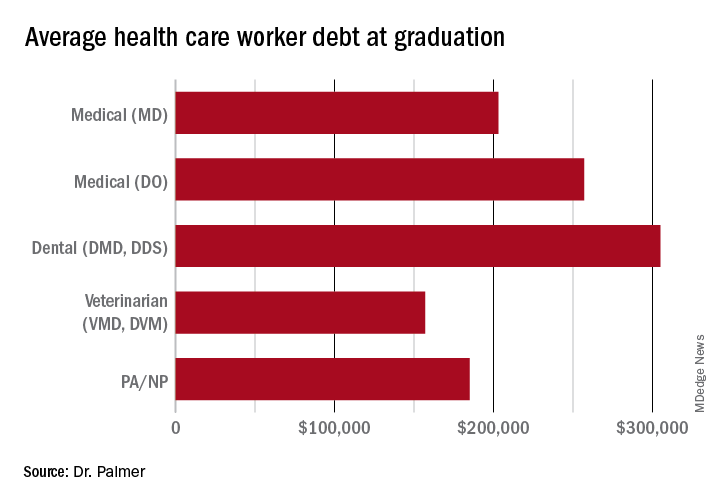

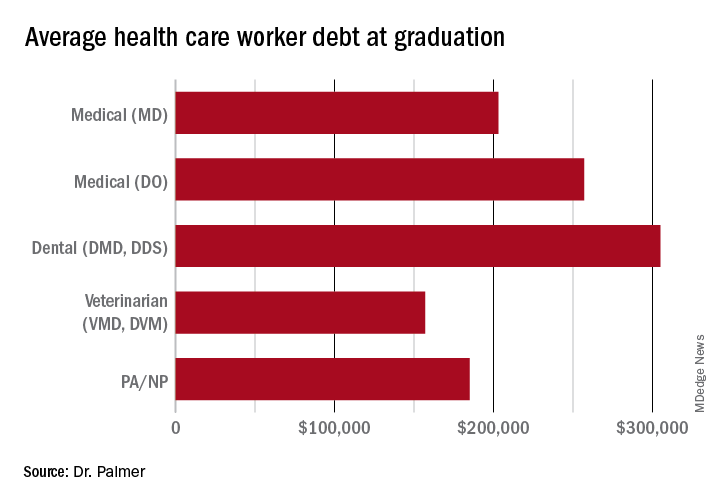

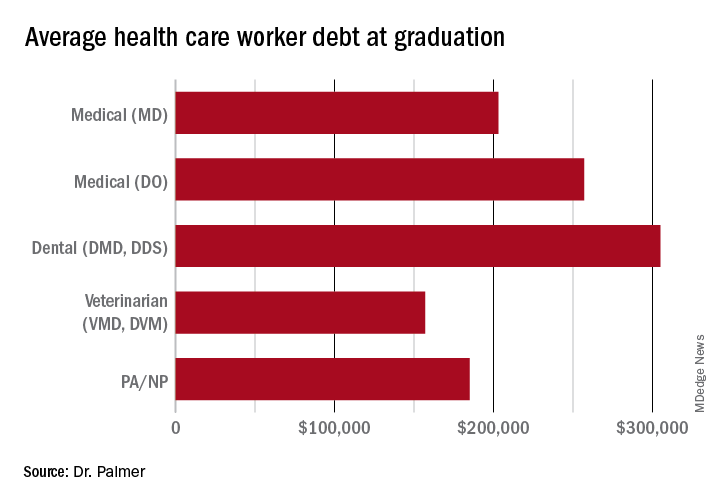

Someone making an annual gross income of $150,000 is in the 80th percentile of earners in the United States (for comparison, the top 1% took home more than $505,000 in 2021). What student loan borrowers make up the remaining 20%? Overwhelmingly, health care providers occupy that tier: physicians, dentists, veterinarians, and advanced-practice nurses.

These schools leave their graduates with some of the highest student loan burdens, with veterinarians, dentists, and physicians having the highest debt-to-income ratios of any professional careers.

Flat forgiveness is regressive

Forgiving any student debt is the right direction. Too may have fallen victim to an industry without quality control, appropriate regulation, or price control. Quite the opposite, the blank-check model of student loan financing has led to an arms race as it comes to capital improvements in university spending.

The price of medical schools has risen more than four times as fast as inflation over the past 30 years, with dental and veterinary schools and nursing education showing similarly exaggerated price increases. Trainees in these fields are more likely to have taken on six-figure debt, with average debt loads at graduation in the table below. While $10,000 will move the proverbial needle less for these borrowers, does that mean they should be excluded?

Health care workers’ income declines during the pandemic

Now, over 2½ years since the start of the COVID pandemic, multiple reports have demonstrated that health care workers have suffered a loss in income. This loss in income was never compensated for, as the Paycheck Protection Program and the individual economic stimuli typically excluded doctors and high earners.

COVID and the hazard tax

As a provider during the COVID-19 pandemic, I didn’t ask for hazard pay. I supported those who did but recognized their requests were more ceremonial than they were likely to be successful.

However, I flatly reject the idea that my fellow health care practitioners are not deserving of student loan forgiveness simply based on an arbitrary income threshold. Health care providers are saddled with high debt burden, have suffered lost income, and have given of themselves during a devastating pandemic, where more than 1 million perished in the United States.

Bottom line

Health care workers should not be excluded from student loan forgiveness. Sadly, the Biden administration has signaled that they are dropping career-based exclusions in favor of more broadly harmful income-based forgiveness restrictions. This will disproportionately harm physicians and other health care workers.

These practitioners have suffered financially as a result of working through the COVID pandemic; should they also be forced to shoulder another financial injury by being excluded from student loan forgiveness?

Dr. Palmer is the chief operating officer and cofounder of Panacea Financial. He is also a practicing pediatric hospitalist at Boston Children’s Hospital and is on faculty at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a recently obtained plan by Politico, the Biden administration is zeroing in on a broad student loan forgiveness plan to be released imminently. The plan would broadly forgive $10,000 in federal student loans, including graduate and PLUS loans. However, there’s a rub: The plan restricts the forgiveness to those with incomes below $150,000.

This would unfairly exclude many in health care from receiving this forgiveness, an egregious oversight given how much health care providers have sacrificed during the pandemic.

What was proposed?

Previously, it was reported that the Biden administration was considering this same amount of forgiveness, but with plans to exclude borrowers by either career or income. Student loan payments have been on an extended CARES Act forbearance since March 2020, with payment resumption planned for Aug. 31. The administration has said that they would deliver a plan for further extensions before this date and have repeatedly teased including forgiveness.

Forgiveness for some ...

Forgiving $10,000 of federal student loans would relieve some 15 million borrowers of student debt, roughly one-third of the 45 million borrowers with debt.

This would provide a massive boost to these borrowers (who disproportionately are female, low-income, and non-White), many of whom were targeted by predatory institutions whose education didn’t offer any actual tangible benefit to their earnings. While this is a group that absolutely ought to have their loans forgiven, drawing an income line inappropriately restricts those in health care from receiving any forgiveness.

... But not for others

Someone making an annual gross income of $150,000 is in the 80th percentile of earners in the United States (for comparison, the top 1% took home more than $505,000 in 2021). What student loan borrowers make up the remaining 20%? Overwhelmingly, health care providers occupy that tier: physicians, dentists, veterinarians, and advanced-practice nurses.

These schools leave their graduates with some of the highest student loan burdens, with veterinarians, dentists, and physicians having the highest debt-to-income ratios of any professional careers.

Flat forgiveness is regressive

Forgiving any student debt is the right direction. Too may have fallen victim to an industry without quality control, appropriate regulation, or price control. Quite the opposite, the blank-check model of student loan financing has led to an arms race as it comes to capital improvements in university spending.

The price of medical schools has risen more than four times as fast as inflation over the past 30 years, with dental and veterinary schools and nursing education showing similarly exaggerated price increases. Trainees in these fields are more likely to have taken on six-figure debt, with average debt loads at graduation in the table below. While $10,000 will move the proverbial needle less for these borrowers, does that mean they should be excluded?

Health care workers’ income declines during the pandemic

Now, over 2½ years since the start of the COVID pandemic, multiple reports have demonstrated that health care workers have suffered a loss in income. This loss in income was never compensated for, as the Paycheck Protection Program and the individual economic stimuli typically excluded doctors and high earners.

COVID and the hazard tax

As a provider during the COVID-19 pandemic, I didn’t ask for hazard pay. I supported those who did but recognized their requests were more ceremonial than they were likely to be successful.

However, I flatly reject the idea that my fellow health care practitioners are not deserving of student loan forgiveness simply based on an arbitrary income threshold. Health care providers are saddled with high debt burden, have suffered lost income, and have given of themselves during a devastating pandemic, where more than 1 million perished in the United States.

Bottom line

Health care workers should not be excluded from student loan forgiveness. Sadly, the Biden administration has signaled that they are dropping career-based exclusions in favor of more broadly harmful income-based forgiveness restrictions. This will disproportionately harm physicians and other health care workers.

These practitioners have suffered financially as a result of working through the COVID pandemic; should they also be forced to shoulder another financial injury by being excluded from student loan forgiveness?

Dr. Palmer is the chief operating officer and cofounder of Panacea Financial. He is also a practicing pediatric hospitalist at Boston Children’s Hospital and is on faculty at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a recently obtained plan by Politico, the Biden administration is zeroing in on a broad student loan forgiveness plan to be released imminently. The plan would broadly forgive $10,000 in federal student loans, including graduate and PLUS loans. However, there’s a rub: The plan restricts the forgiveness to those with incomes below $150,000.

This would unfairly exclude many in health care from receiving this forgiveness, an egregious oversight given how much health care providers have sacrificed during the pandemic.

What was proposed?

Previously, it was reported that the Biden administration was considering this same amount of forgiveness, but with plans to exclude borrowers by either career or income. Student loan payments have been on an extended CARES Act forbearance since March 2020, with payment resumption planned for Aug. 31. The administration has said that they would deliver a plan for further extensions before this date and have repeatedly teased including forgiveness.

Forgiveness for some ...

Forgiving $10,000 of federal student loans would relieve some 15 million borrowers of student debt, roughly one-third of the 45 million borrowers with debt.

This would provide a massive boost to these borrowers (who disproportionately are female, low-income, and non-White), many of whom were targeted by predatory institutions whose education didn’t offer any actual tangible benefit to their earnings. While this is a group that absolutely ought to have their loans forgiven, drawing an income line inappropriately restricts those in health care from receiving any forgiveness.

... But not for others

Someone making an annual gross income of $150,000 is in the 80th percentile of earners in the United States (for comparison, the top 1% took home more than $505,000 in 2021). What student loan borrowers make up the remaining 20%? Overwhelmingly, health care providers occupy that tier: physicians, dentists, veterinarians, and advanced-practice nurses.

These schools leave their graduates with some of the highest student loan burdens, with veterinarians, dentists, and physicians having the highest debt-to-income ratios of any professional careers.

Flat forgiveness is regressive

Forgiving any student debt is the right direction. Too may have fallen victim to an industry without quality control, appropriate regulation, or price control. Quite the opposite, the blank-check model of student loan financing has led to an arms race as it comes to capital improvements in university spending.

The price of medical schools has risen more than four times as fast as inflation over the past 30 years, with dental and veterinary schools and nursing education showing similarly exaggerated price increases. Trainees in these fields are more likely to have taken on six-figure debt, with average debt loads at graduation in the table below. While $10,000 will move the proverbial needle less for these borrowers, does that mean they should be excluded?

Health care workers’ income declines during the pandemic

Now, over 2½ years since the start of the COVID pandemic, multiple reports have demonstrated that health care workers have suffered a loss in income. This loss in income was never compensated for, as the Paycheck Protection Program and the individual economic stimuli typically excluded doctors and high earners.

COVID and the hazard tax

As a provider during the COVID-19 pandemic, I didn’t ask for hazard pay. I supported those who did but recognized their requests were more ceremonial than they were likely to be successful.

However, I flatly reject the idea that my fellow health care practitioners are not deserving of student loan forgiveness simply based on an arbitrary income threshold. Health care providers are saddled with high debt burden, have suffered lost income, and have given of themselves during a devastating pandemic, where more than 1 million perished in the United States.

Bottom line

Health care workers should not be excluded from student loan forgiveness. Sadly, the Biden administration has signaled that they are dropping career-based exclusions in favor of more broadly harmful income-based forgiveness restrictions. This will disproportionately harm physicians and other health care workers.

These practitioners have suffered financially as a result of working through the COVID pandemic; should they also be forced to shoulder another financial injury by being excluded from student loan forgiveness?

Dr. Palmer is the chief operating officer and cofounder of Panacea Financial. He is also a practicing pediatric hospitalist at Boston Children’s Hospital and is on faculty at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Regular fasting linked to less severe COVID: Study

, according to the findings of a new study.

The study was done on men and women in Utah who were, on average, in their 60s and got COVID before vaccines were available.

Roughly one in three people in Utah fast from time to time – higher than in other states. This is partly because more than 60% of people in Utah belong to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and roughly 40% of them fast – typically skipping two meals in a row.

Those who fasted, on average, for a day a month over the past 40 years were not less likely to get COVID, but they were less likely to be hospitalized or die from the virus.

“Intermittent fasting has already shown to lower inflammation and improve cardiovascular health,” lead study author Benjamin Horne, PhD, of Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute in Salt Lake City, said in a statement.

“In this study, we’re finding additional benefits when it comes to battling an infection of COVID-19 in patients who have been fasting for decades,” he said.

The study was published in BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health.

Intermittent fasting not a substitute for a COVID-19 vaccine

Importantly, intermittent fasting shouldn’t be seen as a substitute for getting a COVID vaccine, the researchers stressed. Rather, periodic fasting might be a health habit to consider, since it is also linked to a lower risk of diabetes and heart disease, for example.

But anyone who wants to consider intermittent fasting should consult their doctor first, Dr. Horne stressed, especially if they are elderly, pregnant, or have diabetes, heart disease, or kidney disease.

Fasting didn’t prevent COVID-19 but made it less severe

In their study, the team looked at data from 1,524 adults who were seen in the cardiac catheterization lab at Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute, completed a survey, and had a test for the virus that causes COVID-19 from March 16, 2020, to Feb. 25, 2021.

Of these patients, 205 tested positive for COVID, and of these, 73 reported that they had fasted regularly at least once a month.

Similar numbers of patients got COVID-19 whether they had, or had not, fasted regularly (14%, versus 13%).

But among those who tested positive for the virus, fewer patients were hospitalized for COVID or died during the study follow-up if they had fasted regularly (11%) than if they had not fasted regularly (29%).

Even when the analyses were adjusted for age, smoking, alcohol use, ethnicity, history of heart disease, and other factors, periodic fasting was still an independent predictor of a lower risk of hospitalization or death.

Several things may explain the findings, the researchers suggested.

A loss of appetite is a typical response to infection, they noted.

Fasting reduces inflammation, and after 12-14 hours of fasting, the body switches from using glucose in the blood to using ketones, including linoleic acid.

“There’s a pocket on the surface of SARS-CoV-2 that linoleic acid fits into – and can make the virus less able to attach to other cells,” Dr. Horne said.

Intermittent fasting also promotes autophagy, he noted, which is “the body’s recycling system that helps your body destroy and recycle damaged and infected cells.”

The researchers concluded that intermittent fasting plans should be investigated in further research “as a complementary therapy to vaccines to reduce COVID-19 severity, both during the pandemic and post pandemic, since repeat vaccinations cannot be performed every few months indefinitely for the entire world and vaccine access is limited in many nations.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to the findings of a new study.

The study was done on men and women in Utah who were, on average, in their 60s and got COVID before vaccines were available.

Roughly one in three people in Utah fast from time to time – higher than in other states. This is partly because more than 60% of people in Utah belong to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and roughly 40% of them fast – typically skipping two meals in a row.

Those who fasted, on average, for a day a month over the past 40 years were not less likely to get COVID, but they were less likely to be hospitalized or die from the virus.

“Intermittent fasting has already shown to lower inflammation and improve cardiovascular health,” lead study author Benjamin Horne, PhD, of Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute in Salt Lake City, said in a statement.

“In this study, we’re finding additional benefits when it comes to battling an infection of COVID-19 in patients who have been fasting for decades,” he said.

The study was published in BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health.

Intermittent fasting not a substitute for a COVID-19 vaccine

Importantly, intermittent fasting shouldn’t be seen as a substitute for getting a COVID vaccine, the researchers stressed. Rather, periodic fasting might be a health habit to consider, since it is also linked to a lower risk of diabetes and heart disease, for example.

But anyone who wants to consider intermittent fasting should consult their doctor first, Dr. Horne stressed, especially if they are elderly, pregnant, or have diabetes, heart disease, or kidney disease.

Fasting didn’t prevent COVID-19 but made it less severe

In their study, the team looked at data from 1,524 adults who were seen in the cardiac catheterization lab at Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute, completed a survey, and had a test for the virus that causes COVID-19 from March 16, 2020, to Feb. 25, 2021.

Of these patients, 205 tested positive for COVID, and of these, 73 reported that they had fasted regularly at least once a month.

Similar numbers of patients got COVID-19 whether they had, or had not, fasted regularly (14%, versus 13%).

But among those who tested positive for the virus, fewer patients were hospitalized for COVID or died during the study follow-up if they had fasted regularly (11%) than if they had not fasted regularly (29%).

Even when the analyses were adjusted for age, smoking, alcohol use, ethnicity, history of heart disease, and other factors, periodic fasting was still an independent predictor of a lower risk of hospitalization or death.

Several things may explain the findings, the researchers suggested.

A loss of appetite is a typical response to infection, they noted.

Fasting reduces inflammation, and after 12-14 hours of fasting, the body switches from using glucose in the blood to using ketones, including linoleic acid.

“There’s a pocket on the surface of SARS-CoV-2 that linoleic acid fits into – and can make the virus less able to attach to other cells,” Dr. Horne said.

Intermittent fasting also promotes autophagy, he noted, which is “the body’s recycling system that helps your body destroy and recycle damaged and infected cells.”

The researchers concluded that intermittent fasting plans should be investigated in further research “as a complementary therapy to vaccines to reduce COVID-19 severity, both during the pandemic and post pandemic, since repeat vaccinations cannot be performed every few months indefinitely for the entire world and vaccine access is limited in many nations.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to the findings of a new study.

The study was done on men and women in Utah who were, on average, in their 60s and got COVID before vaccines were available.

Roughly one in three people in Utah fast from time to time – higher than in other states. This is partly because more than 60% of people in Utah belong to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and roughly 40% of them fast – typically skipping two meals in a row.

Those who fasted, on average, for a day a month over the past 40 years were not less likely to get COVID, but they were less likely to be hospitalized or die from the virus.

“Intermittent fasting has already shown to lower inflammation and improve cardiovascular health,” lead study author Benjamin Horne, PhD, of Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute in Salt Lake City, said in a statement.

“In this study, we’re finding additional benefits when it comes to battling an infection of COVID-19 in patients who have been fasting for decades,” he said.

The study was published in BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health.

Intermittent fasting not a substitute for a COVID-19 vaccine

Importantly, intermittent fasting shouldn’t be seen as a substitute for getting a COVID vaccine, the researchers stressed. Rather, periodic fasting might be a health habit to consider, since it is also linked to a lower risk of diabetes and heart disease, for example.

But anyone who wants to consider intermittent fasting should consult their doctor first, Dr. Horne stressed, especially if they are elderly, pregnant, or have diabetes, heart disease, or kidney disease.

Fasting didn’t prevent COVID-19 but made it less severe

In their study, the team looked at data from 1,524 adults who were seen in the cardiac catheterization lab at Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute, completed a survey, and had a test for the virus that causes COVID-19 from March 16, 2020, to Feb. 25, 2021.

Of these patients, 205 tested positive for COVID, and of these, 73 reported that they had fasted regularly at least once a month.

Similar numbers of patients got COVID-19 whether they had, or had not, fasted regularly (14%, versus 13%).

But among those who tested positive for the virus, fewer patients were hospitalized for COVID or died during the study follow-up if they had fasted regularly (11%) than if they had not fasted regularly (29%).

Even when the analyses were adjusted for age, smoking, alcohol use, ethnicity, history of heart disease, and other factors, periodic fasting was still an independent predictor of a lower risk of hospitalization or death.

Several things may explain the findings, the researchers suggested.

A loss of appetite is a typical response to infection, they noted.

Fasting reduces inflammation, and after 12-14 hours of fasting, the body switches from using glucose in the blood to using ketones, including linoleic acid.

“There’s a pocket on the surface of SARS-CoV-2 that linoleic acid fits into – and can make the virus less able to attach to other cells,” Dr. Horne said.

Intermittent fasting also promotes autophagy, he noted, which is “the body’s recycling system that helps your body destroy and recycle damaged and infected cells.”

The researchers concluded that intermittent fasting plans should be investigated in further research “as a complementary therapy to vaccines to reduce COVID-19 severity, both during the pandemic and post pandemic, since repeat vaccinations cannot be performed every few months indefinitely for the entire world and vaccine access is limited in many nations.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM BMJ NUTRITION, PREVENTION & HEALTH

Long COVID’s grip will likely tighten as infections continue

COVID-19 is far from done in the United States, with more than 111,000 new cases being recorded a day in the second week of August, according to Johns Hopkins University, and 625 deaths being reported every day. , a condition that already has affected between 7.7 million and 23 million Americans, according to U.S. government estimates.

“It is evident that long COVID is real, that it already impacts a substantial number of people, and that this number may continue to grow as new infections occur,” the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) said in a research action plan released Aug. 4.

“We are heading towards a big problem on our hands,” says Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research and development at the Veterans Affairs Hospital in St. Louis. “It’s like if we are falling in a plane, hurtling towards the ground. It doesn’t matter at what speed we are falling; what matters is that we are all falling, and falling fast. It’s a real problem. We needed to bring attention to this, yesterday,” he said.

Bryan Lau, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and co-lead of a long COVID study there, says whether it’s 5% of the 92 million officially recorded U.S. COVID-19 cases, or 30% – on the higher end of estimates – that means anywhere between 4.5 million and 27 million Americans will have the effects of long COVID.

Other experts put the estimates even higher.

“If we conservatively assume 100 million working-age adults have been infected, that implies 10 to 33 million may have long COVID,” Alice Burns, PhD, associate director for the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, wrote in an analysis.

And even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says only a fraction of cases have been recorded.

That, in turn, means tens of millions of people who struggle to work, to get to school, and to take care of their families – and who will be making demands on an already stressed U.S. health care system.

The HHS said in its Aug. 4 report that long COVID could keep 1 million people a day out of work, with a loss of $50 billion in annual pay.

Dr. Lau said health workers and policymakers are woefully unprepared.

“If you have a family unit, and the mom or dad can’t work, or has trouble taking their child to activities, where does the question of support come into play? Where is there potential for food issues, or housing issues?” he asked. “I see the potential for the burden to be extremely large in that capacity.”

Dr. Lau said he has yet to see any strong estimates of how many cases of long COVID might develop. Because a person has to get COVID-19 to ultimately get long COVID, the two are linked. In other words, as COVID-19 cases rise, so will cases of long COVID, and vice versa.

Evidence from the Kaiser Family Foundation analysis suggests a significant impact on employment: Surveys showed more than half of adults with long COVID who worked before becoming infected are either out of work or working fewer hours. Conditions associated with long COVID – such as fatigue, malaise, or problems concentrating – limit people’s ability to work, even if they have jobs that allow for accommodations.

Two surveys of people with long COVID who had worked before becoming infected showed that between 22% and 27% of them were out of work after getting long COVID. In comparison, among all working-age adults in 2019, only 7% were out of work. Given the sheer number of working-age adults with long COVID, the effects on employment may be profound and are likely to involve more people over time. One study estimates that long COVID already accounts for 15% of unfilled jobs.

The most severe symptoms of long COVID include brain fog and heart complications, known to persist for weeks for months after a COVID-19 infection.

A study from the University of Norway published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases found 53% of people tested had at least one symptom of thinking problems 13 months after infection with COVID-19. According to the HHS’ latest report on long COVID, people with thinking problems, heart conditions, mobility issues, and other symptoms are going to need a considerable amount of care. Many will need lengthy periods of rehabilitation.

Dr. Al-Aly worries that long COVID has already severely affected the labor force and the job market, all while burdening the country’s health care system.

“While there are variations in how individuals respond and cope with long COVID, the unifying thread is that with the level of disability it causes, more people will be struggling to keep up with the demands of the workforce and more people will be out on disability than ever before,” he said.

Studies from Johns Hopkins and the University of Washington estimate that 5%-30% of people could get long COVID in the future. Projections beyond that are hazy.

“So far, all the studies we have done on long COVID have been reactionary. Much of the activism around long COVID has been patient led. We are seeing more and more people with lasting symptoms. We need our research to catch up,” Dr. Lau said.

Theo Vos, MD, PhD, professor of health sciences at University of Washington, Seattle, said the main reasons for the huge range of predictions are the variety of methods used, as well as differences in sample size. Also, much long COVID data is self-reported, making it difficult for epidemiologists to track.

“With self-reported data, you can’t plug people into a machine and say this is what they have or this is what they don’t have. At the population level, the only thing you can do is ask questions. There is no systematic way to define long COVID,” he said.

Dr. Vos’s most recent study, which is being peer-reviewed and revised, found that most people with long COVID have symptoms similar to those seen in other autoimmune diseases. But sometimes the immune system can overreact, causing the more severe symptoms, such as brain fog and heart problems, associated with long COVID.

One reason that researchers struggle to come up with numbers, said Dr. Al-Aly, is the rapid rise of new variants. These variants appear to sometimes cause less severe disease than previous ones, but it’s not clear whether that means different risks for long COVID.

“There’s a wide diversity in severity. Someone can have long COVID and be fully functional, while others are not functional at all. We still have a long way to go before we figure out why,” Dr. Lau said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

COVID-19 is far from done in the United States, with more than 111,000 new cases being recorded a day in the second week of August, according to Johns Hopkins University, and 625 deaths being reported every day. , a condition that already has affected between 7.7 million and 23 million Americans, according to U.S. government estimates.

“It is evident that long COVID is real, that it already impacts a substantial number of people, and that this number may continue to grow as new infections occur,” the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) said in a research action plan released Aug. 4.

“We are heading towards a big problem on our hands,” says Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research and development at the Veterans Affairs Hospital in St. Louis. “It’s like if we are falling in a plane, hurtling towards the ground. It doesn’t matter at what speed we are falling; what matters is that we are all falling, and falling fast. It’s a real problem. We needed to bring attention to this, yesterday,” he said.

Bryan Lau, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and co-lead of a long COVID study there, says whether it’s 5% of the 92 million officially recorded U.S. COVID-19 cases, or 30% – on the higher end of estimates – that means anywhere between 4.5 million and 27 million Americans will have the effects of long COVID.

Other experts put the estimates even higher.

“If we conservatively assume 100 million working-age adults have been infected, that implies 10 to 33 million may have long COVID,” Alice Burns, PhD, associate director for the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, wrote in an analysis.

And even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says only a fraction of cases have been recorded.

That, in turn, means tens of millions of people who struggle to work, to get to school, and to take care of their families – and who will be making demands on an already stressed U.S. health care system.

The HHS said in its Aug. 4 report that long COVID could keep 1 million people a day out of work, with a loss of $50 billion in annual pay.

Dr. Lau said health workers and policymakers are woefully unprepared.

“If you have a family unit, and the mom or dad can’t work, or has trouble taking their child to activities, where does the question of support come into play? Where is there potential for food issues, or housing issues?” he asked. “I see the potential for the burden to be extremely large in that capacity.”

Dr. Lau said he has yet to see any strong estimates of how many cases of long COVID might develop. Because a person has to get COVID-19 to ultimately get long COVID, the two are linked. In other words, as COVID-19 cases rise, so will cases of long COVID, and vice versa.

Evidence from the Kaiser Family Foundation analysis suggests a significant impact on employment: Surveys showed more than half of adults with long COVID who worked before becoming infected are either out of work or working fewer hours. Conditions associated with long COVID – such as fatigue, malaise, or problems concentrating – limit people’s ability to work, even if they have jobs that allow for accommodations.

Two surveys of people with long COVID who had worked before becoming infected showed that between 22% and 27% of them were out of work after getting long COVID. In comparison, among all working-age adults in 2019, only 7% were out of work. Given the sheer number of working-age adults with long COVID, the effects on employment may be profound and are likely to involve more people over time. One study estimates that long COVID already accounts for 15% of unfilled jobs.

The most severe symptoms of long COVID include brain fog and heart complications, known to persist for weeks for months after a COVID-19 infection.

A study from the University of Norway published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases found 53% of people tested had at least one symptom of thinking problems 13 months after infection with COVID-19. According to the HHS’ latest report on long COVID, people with thinking problems, heart conditions, mobility issues, and other symptoms are going to need a considerable amount of care. Many will need lengthy periods of rehabilitation.

Dr. Al-Aly worries that long COVID has already severely affected the labor force and the job market, all while burdening the country’s health care system.

“While there are variations in how individuals respond and cope with long COVID, the unifying thread is that with the level of disability it causes, more people will be struggling to keep up with the demands of the workforce and more people will be out on disability than ever before,” he said.

Studies from Johns Hopkins and the University of Washington estimate that 5%-30% of people could get long COVID in the future. Projections beyond that are hazy.

“So far, all the studies we have done on long COVID have been reactionary. Much of the activism around long COVID has been patient led. We are seeing more and more people with lasting symptoms. We need our research to catch up,” Dr. Lau said.

Theo Vos, MD, PhD, professor of health sciences at University of Washington, Seattle, said the main reasons for the huge range of predictions are the variety of methods used, as well as differences in sample size. Also, much long COVID data is self-reported, making it difficult for epidemiologists to track.

“With self-reported data, you can’t plug people into a machine and say this is what they have or this is what they don’t have. At the population level, the only thing you can do is ask questions. There is no systematic way to define long COVID,” he said.

Dr. Vos’s most recent study, which is being peer-reviewed and revised, found that most people with long COVID have symptoms similar to those seen in other autoimmune diseases. But sometimes the immune system can overreact, causing the more severe symptoms, such as brain fog and heart problems, associated with long COVID.

One reason that researchers struggle to come up with numbers, said Dr. Al-Aly, is the rapid rise of new variants. These variants appear to sometimes cause less severe disease than previous ones, but it’s not clear whether that means different risks for long COVID.

“There’s a wide diversity in severity. Someone can have long COVID and be fully functional, while others are not functional at all. We still have a long way to go before we figure out why,” Dr. Lau said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

COVID-19 is far from done in the United States, with more than 111,000 new cases being recorded a day in the second week of August, according to Johns Hopkins University, and 625 deaths being reported every day. , a condition that already has affected between 7.7 million and 23 million Americans, according to U.S. government estimates.

“It is evident that long COVID is real, that it already impacts a substantial number of people, and that this number may continue to grow as new infections occur,” the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) said in a research action plan released Aug. 4.

“We are heading towards a big problem on our hands,” says Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research and development at the Veterans Affairs Hospital in St. Louis. “It’s like if we are falling in a plane, hurtling towards the ground. It doesn’t matter at what speed we are falling; what matters is that we are all falling, and falling fast. It’s a real problem. We needed to bring attention to this, yesterday,” he said.

Bryan Lau, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and co-lead of a long COVID study there, says whether it’s 5% of the 92 million officially recorded U.S. COVID-19 cases, or 30% – on the higher end of estimates – that means anywhere between 4.5 million and 27 million Americans will have the effects of long COVID.

Other experts put the estimates even higher.

“If we conservatively assume 100 million working-age adults have been infected, that implies 10 to 33 million may have long COVID,” Alice Burns, PhD, associate director for the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, wrote in an analysis.

And even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says only a fraction of cases have been recorded.

That, in turn, means tens of millions of people who struggle to work, to get to school, and to take care of their families – and who will be making demands on an already stressed U.S. health care system.

The HHS said in its Aug. 4 report that long COVID could keep 1 million people a day out of work, with a loss of $50 billion in annual pay.

Dr. Lau said health workers and policymakers are woefully unprepared.

“If you have a family unit, and the mom or dad can’t work, or has trouble taking their child to activities, where does the question of support come into play? Where is there potential for food issues, or housing issues?” he asked. “I see the potential for the burden to be extremely large in that capacity.”

Dr. Lau said he has yet to see any strong estimates of how many cases of long COVID might develop. Because a person has to get COVID-19 to ultimately get long COVID, the two are linked. In other words, as COVID-19 cases rise, so will cases of long COVID, and vice versa.

Evidence from the Kaiser Family Foundation analysis suggests a significant impact on employment: Surveys showed more than half of adults with long COVID who worked before becoming infected are either out of work or working fewer hours. Conditions associated with long COVID – such as fatigue, malaise, or problems concentrating – limit people’s ability to work, even if they have jobs that allow for accommodations.

Two surveys of people with long COVID who had worked before becoming infected showed that between 22% and 27% of them were out of work after getting long COVID. In comparison, among all working-age adults in 2019, only 7% were out of work. Given the sheer number of working-age adults with long COVID, the effects on employment may be profound and are likely to involve more people over time. One study estimates that long COVID already accounts for 15% of unfilled jobs.

The most severe symptoms of long COVID include brain fog and heart complications, known to persist for weeks for months after a COVID-19 infection.

A study from the University of Norway published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases found 53% of people tested had at least one symptom of thinking problems 13 months after infection with COVID-19. According to the HHS’ latest report on long COVID, people with thinking problems, heart conditions, mobility issues, and other symptoms are going to need a considerable amount of care. Many will need lengthy periods of rehabilitation.

Dr. Al-Aly worries that long COVID has already severely affected the labor force and the job market, all while burdening the country’s health care system.

“While there are variations in how individuals respond and cope with long COVID, the unifying thread is that with the level of disability it causes, more people will be struggling to keep up with the demands of the workforce and more people will be out on disability than ever before,” he said.

Studies from Johns Hopkins and the University of Washington estimate that 5%-30% of people could get long COVID in the future. Projections beyond that are hazy.