User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

A standardized approach to postop management of DOACs in AFib

Clinical question: Is it safe to adopt a standardized approach to direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) interruption for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) who are undergoing elective surgeries/procedures?

Background: At present, perioperative management of DOACs for patients with AFib has significant variation, and robust data are absent. Points of controversy include: The length of time to hold DOACs before and after the procedure, whether to bridge with heparin, and whether to measure coagulation function studies prior to the procedure.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Conducted in Canada, the United States, and Europe.

Synopsis: The PAUSE study included adults with atrial fibrillation who were long-term users of either apixaban, dabigatran, or rivaroxaban and were scheduled for an elective procedure (n = 3,007). Patients were placed on a standardized DOAC interruption schedule based on whether their procedure had high bleeding risk (held for 2 days prior; resumed 2-3 days after) or low bleeding risk (held for 1 day prior; resumed 1 day after).

The primary clinical outcomes were major bleeding and arterial thromboembolism. Authors determined safety by comparing to expected outcome rates derived from research on perioperative warfarin management.

They found that all three drugs were associated with acceptable rates of arterial thromboembolism (apixaban 0.2%, dabigatran 0.6%, rivaroxaban 0.4%). The rates of major bleeding observed with each drug (apixaban 0.6% low-risk procedures, 3% high-risk procedures; dabigatran 0.9% both low- and high-risk procedures; and rivaroxaban 1.3% low-risk procedures, 3% high-risk procedures) were similar to those in the BRIDGE trial (patients on warfarin who were not bridged perioperatively). However, it must still be noted that only dabigatran met the authors’ predetermined definition of safety for major bleeding.

Limitations include the lack of true control rates for major bleeding and stroke, the relatively low mean CHADS2-Va2Sc of 3.3-3.5, and that greater than 95% of patients were white.

Bottom line: For patients with moderate-risk atrial fibrillation, a standardized approach to DOAC interruption in the perioperative period that omits bridging along with coagulation function testing appears safe in this preliminary study.

Citation: Douketis JD et al. Perioperative management of patients with atrial fibrillation receiving a direct oral anticoagulant. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2431.

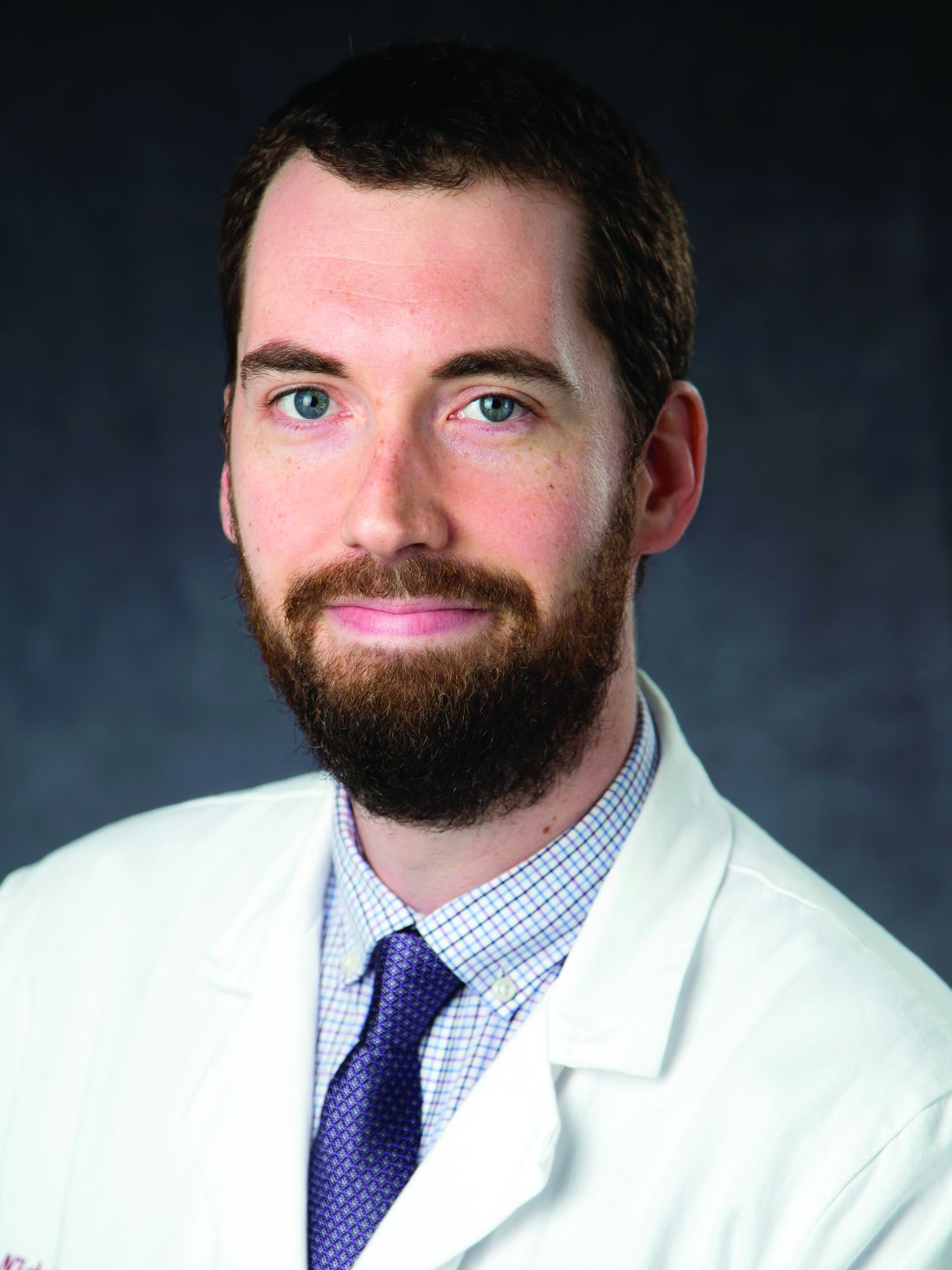

Dr. Gordon is a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland.

Clinical question: Is it safe to adopt a standardized approach to direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) interruption for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) who are undergoing elective surgeries/procedures?

Background: At present, perioperative management of DOACs for patients with AFib has significant variation, and robust data are absent. Points of controversy include: The length of time to hold DOACs before and after the procedure, whether to bridge with heparin, and whether to measure coagulation function studies prior to the procedure.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Conducted in Canada, the United States, and Europe.

Synopsis: The PAUSE study included adults with atrial fibrillation who were long-term users of either apixaban, dabigatran, or rivaroxaban and were scheduled for an elective procedure (n = 3,007). Patients were placed on a standardized DOAC interruption schedule based on whether their procedure had high bleeding risk (held for 2 days prior; resumed 2-3 days after) or low bleeding risk (held for 1 day prior; resumed 1 day after).

The primary clinical outcomes were major bleeding and arterial thromboembolism. Authors determined safety by comparing to expected outcome rates derived from research on perioperative warfarin management.

They found that all three drugs were associated with acceptable rates of arterial thromboembolism (apixaban 0.2%, dabigatran 0.6%, rivaroxaban 0.4%). The rates of major bleeding observed with each drug (apixaban 0.6% low-risk procedures, 3% high-risk procedures; dabigatran 0.9% both low- and high-risk procedures; and rivaroxaban 1.3% low-risk procedures, 3% high-risk procedures) were similar to those in the BRIDGE trial (patients on warfarin who were not bridged perioperatively). However, it must still be noted that only dabigatran met the authors’ predetermined definition of safety for major bleeding.

Limitations include the lack of true control rates for major bleeding and stroke, the relatively low mean CHADS2-Va2Sc of 3.3-3.5, and that greater than 95% of patients were white.

Bottom line: For patients with moderate-risk atrial fibrillation, a standardized approach to DOAC interruption in the perioperative period that omits bridging along with coagulation function testing appears safe in this preliminary study.

Citation: Douketis JD et al. Perioperative management of patients with atrial fibrillation receiving a direct oral anticoagulant. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2431.

Dr. Gordon is a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland.

Clinical question: Is it safe to adopt a standardized approach to direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) interruption for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) who are undergoing elective surgeries/procedures?

Background: At present, perioperative management of DOACs for patients with AFib has significant variation, and robust data are absent. Points of controversy include: The length of time to hold DOACs before and after the procedure, whether to bridge with heparin, and whether to measure coagulation function studies prior to the procedure.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Conducted in Canada, the United States, and Europe.

Synopsis: The PAUSE study included adults with atrial fibrillation who were long-term users of either apixaban, dabigatran, or rivaroxaban and were scheduled for an elective procedure (n = 3,007). Patients were placed on a standardized DOAC interruption schedule based on whether their procedure had high bleeding risk (held for 2 days prior; resumed 2-3 days after) or low bleeding risk (held for 1 day prior; resumed 1 day after).

The primary clinical outcomes were major bleeding and arterial thromboembolism. Authors determined safety by comparing to expected outcome rates derived from research on perioperative warfarin management.

They found that all three drugs were associated with acceptable rates of arterial thromboembolism (apixaban 0.2%, dabigatran 0.6%, rivaroxaban 0.4%). The rates of major bleeding observed with each drug (apixaban 0.6% low-risk procedures, 3% high-risk procedures; dabigatran 0.9% both low- and high-risk procedures; and rivaroxaban 1.3% low-risk procedures, 3% high-risk procedures) were similar to those in the BRIDGE trial (patients on warfarin who were not bridged perioperatively). However, it must still be noted that only dabigatran met the authors’ predetermined definition of safety for major bleeding.

Limitations include the lack of true control rates for major bleeding and stroke, the relatively low mean CHADS2-Va2Sc of 3.3-3.5, and that greater than 95% of patients were white.

Bottom line: For patients with moderate-risk atrial fibrillation, a standardized approach to DOAC interruption in the perioperative period that omits bridging along with coagulation function testing appears safe in this preliminary study.

Citation: Douketis JD et al. Perioperative management of patients with atrial fibrillation receiving a direct oral anticoagulant. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2431.

Dr. Gordon is a hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland.

Calcium-induced autonomic denervation linked to lower post-op AF

Intraoperative injection of calcium chloride into the four major atrial ganglionated plexi (GPs) reduced the incidence of early postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) in patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery, in a proof-of-concept study.

“[We] hypothesized that injecting [calcium chloride] into the major atrial GPs during isolated CABG can reduce the incidence of POAF by calcium-induced autonomic neurotoxicity,” wrote Huishan Wang, MD, of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command in Shenyang, China, and colleagues. Their report was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The single-center, sham-controlled, proof-of-concept study included 200 patients without a history of AF undergoing isolated, off-pump CABG surgery. Participants were randomized (1:1) to receive an injection of either 5% calcium chloride or 0.9% sodium chloride into the four major GPs during CABG.

Post surgery, patients were monitored for the occurrence of POAF using routine 12-lead ECG and 7-day continuous telemetry and Holter monitoring. The primary endpoint was the incidence of POAF lasting 30 seconds or longer through 7 days. Various secondary outcomes, including POAF burden and length of hospitalization, were also measured.

After analysis, the researchers found that 15 patients in the calcium chloride arm and 36 patients in the sodium chloride arm developed POAF during the first 7 days post CABG, corresponding to a POAF hazard reduction of 63% (hazard ratio, 0.37; 95% confidence interval, 0.21-0.64; P = .001) with no significant adverse effects observed among study patients.

The calcium chloride injection also resulted in reduced AF burden and lower rates of amiodarone and esmolol use to treat POAF; however, there was no difference in the length of hospitalization between the two groups. The incidences of nonsustained atrial tachyarrhythmia (less than 30 seconds) and atrial couplets were also significantly reduced in the calcium chloride group.

“We selected the 4 major atrial GPs as our targets because [of] their role in the initiation and maintenance of AF is more established than other cardiac neural plexi,” the researchers explained. “Interruption of the atrial neural network by Ca-mediated GP neurotoxicity may underlie the therapeutic effects.”

Is ‘nuisance’ arrhythmia worth targeting?

In an editorial accompanying the report, John H. Alexander, MD, MHS, wrote that intraoperative calcium chloride atrial ganglionic ablation can now be considered as an effective intervention to prevent POAF in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. “These investigators should be congratulated for studying post-operative atrial fibrillation in cardiac surgery,” he stated.

“However, this trial has two significant limitations. Firstly, it was conducted in a single center in a very homogeneous population; secondly, POAF, in and of itself, is largely a nuisance arrhythmia and hardly worth preventing, but is associated with a higher risk of other adverse outcomes,” Dr. Alexander, professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said in an interview.

“The unanswered question is whether preventing perioperative AF will prevent stroke, heart failure, and death,” he further explained. “Answering these questions would require a larger trial (or trials) with longer term (months to years) follow-up.”

Dr. Wang and colleagues acknowledged that the current study was underpowered for some secondary outcomes, such as length of hospitalization. They explained that a large sample size is needed to detect a difference in length of hospitalization, as well as other outcomes.

“Further studies are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of calcium-induced atrial autonomic denervation in patients undergoing on-pump CABG and surgery for valvular heart disease,” they concluded.

The study was funded by the Provincial Key R & D Program in China. One author reported holding a U.S. patent related to the study. The remaining authors had no relevant relationships to disclose.

Intraoperative injection of calcium chloride into the four major atrial ganglionated plexi (GPs) reduced the incidence of early postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) in patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery, in a proof-of-concept study.

“[We] hypothesized that injecting [calcium chloride] into the major atrial GPs during isolated CABG can reduce the incidence of POAF by calcium-induced autonomic neurotoxicity,” wrote Huishan Wang, MD, of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command in Shenyang, China, and colleagues. Their report was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The single-center, sham-controlled, proof-of-concept study included 200 patients without a history of AF undergoing isolated, off-pump CABG surgery. Participants were randomized (1:1) to receive an injection of either 5% calcium chloride or 0.9% sodium chloride into the four major GPs during CABG.

Post surgery, patients were monitored for the occurrence of POAF using routine 12-lead ECG and 7-day continuous telemetry and Holter monitoring. The primary endpoint was the incidence of POAF lasting 30 seconds or longer through 7 days. Various secondary outcomes, including POAF burden and length of hospitalization, were also measured.

After analysis, the researchers found that 15 patients in the calcium chloride arm and 36 patients in the sodium chloride arm developed POAF during the first 7 days post CABG, corresponding to a POAF hazard reduction of 63% (hazard ratio, 0.37; 95% confidence interval, 0.21-0.64; P = .001) with no significant adverse effects observed among study patients.

The calcium chloride injection also resulted in reduced AF burden and lower rates of amiodarone and esmolol use to treat POAF; however, there was no difference in the length of hospitalization between the two groups. The incidences of nonsustained atrial tachyarrhythmia (less than 30 seconds) and atrial couplets were also significantly reduced in the calcium chloride group.

“We selected the 4 major atrial GPs as our targets because [of] their role in the initiation and maintenance of AF is more established than other cardiac neural plexi,” the researchers explained. “Interruption of the atrial neural network by Ca-mediated GP neurotoxicity may underlie the therapeutic effects.”

Is ‘nuisance’ arrhythmia worth targeting?

In an editorial accompanying the report, John H. Alexander, MD, MHS, wrote that intraoperative calcium chloride atrial ganglionic ablation can now be considered as an effective intervention to prevent POAF in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. “These investigators should be congratulated for studying post-operative atrial fibrillation in cardiac surgery,” he stated.

“However, this trial has two significant limitations. Firstly, it was conducted in a single center in a very homogeneous population; secondly, POAF, in and of itself, is largely a nuisance arrhythmia and hardly worth preventing, but is associated with a higher risk of other adverse outcomes,” Dr. Alexander, professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said in an interview.

“The unanswered question is whether preventing perioperative AF will prevent stroke, heart failure, and death,” he further explained. “Answering these questions would require a larger trial (or trials) with longer term (months to years) follow-up.”

Dr. Wang and colleagues acknowledged that the current study was underpowered for some secondary outcomes, such as length of hospitalization. They explained that a large sample size is needed to detect a difference in length of hospitalization, as well as other outcomes.

“Further studies are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of calcium-induced atrial autonomic denervation in patients undergoing on-pump CABG and surgery for valvular heart disease,” they concluded.

The study was funded by the Provincial Key R & D Program in China. One author reported holding a U.S. patent related to the study. The remaining authors had no relevant relationships to disclose.

Intraoperative injection of calcium chloride into the four major atrial ganglionated plexi (GPs) reduced the incidence of early postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) in patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery, in a proof-of-concept study.

“[We] hypothesized that injecting [calcium chloride] into the major atrial GPs during isolated CABG can reduce the incidence of POAF by calcium-induced autonomic neurotoxicity,” wrote Huishan Wang, MD, of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command in Shenyang, China, and colleagues. Their report was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The single-center, sham-controlled, proof-of-concept study included 200 patients without a history of AF undergoing isolated, off-pump CABG surgery. Participants were randomized (1:1) to receive an injection of either 5% calcium chloride or 0.9% sodium chloride into the four major GPs during CABG.

Post surgery, patients were monitored for the occurrence of POAF using routine 12-lead ECG and 7-day continuous telemetry and Holter monitoring. The primary endpoint was the incidence of POAF lasting 30 seconds or longer through 7 days. Various secondary outcomes, including POAF burden and length of hospitalization, were also measured.

After analysis, the researchers found that 15 patients in the calcium chloride arm and 36 patients in the sodium chloride arm developed POAF during the first 7 days post CABG, corresponding to a POAF hazard reduction of 63% (hazard ratio, 0.37; 95% confidence interval, 0.21-0.64; P = .001) with no significant adverse effects observed among study patients.

The calcium chloride injection also resulted in reduced AF burden and lower rates of amiodarone and esmolol use to treat POAF; however, there was no difference in the length of hospitalization between the two groups. The incidences of nonsustained atrial tachyarrhythmia (less than 30 seconds) and atrial couplets were also significantly reduced in the calcium chloride group.

“We selected the 4 major atrial GPs as our targets because [of] their role in the initiation and maintenance of AF is more established than other cardiac neural plexi,” the researchers explained. “Interruption of the atrial neural network by Ca-mediated GP neurotoxicity may underlie the therapeutic effects.”

Is ‘nuisance’ arrhythmia worth targeting?

In an editorial accompanying the report, John H. Alexander, MD, MHS, wrote that intraoperative calcium chloride atrial ganglionic ablation can now be considered as an effective intervention to prevent POAF in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. “These investigators should be congratulated for studying post-operative atrial fibrillation in cardiac surgery,” he stated.

“However, this trial has two significant limitations. Firstly, it was conducted in a single center in a very homogeneous population; secondly, POAF, in and of itself, is largely a nuisance arrhythmia and hardly worth preventing, but is associated with a higher risk of other adverse outcomes,” Dr. Alexander, professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said in an interview.

“The unanswered question is whether preventing perioperative AF will prevent stroke, heart failure, and death,” he further explained. “Answering these questions would require a larger trial (or trials) with longer term (months to years) follow-up.”

Dr. Wang and colleagues acknowledged that the current study was underpowered for some secondary outcomes, such as length of hospitalization. They explained that a large sample size is needed to detect a difference in length of hospitalization, as well as other outcomes.

“Further studies are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of calcium-induced atrial autonomic denervation in patients undergoing on-pump CABG and surgery for valvular heart disease,” they concluded.

The study was funded by the Provincial Key R & D Program in China. One author reported holding a U.S. patent related to the study. The remaining authors had no relevant relationships to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

How can hospitalists change the status quo?

Lean framework for efficiency and empathy of care

“My census is too high.”

“I don’t have enough time to talk to patients.”

“These are outside our scope of practice.”

These are statements that I have heard from colleagues over the last fourteen years as a hospitalist. Back in 1996, when Dr. Bob Wachter coined the term ‘hospitalist,’ we were still in our infancy – the scope of what we could do had yet to be fully realized. Our focus was on providing care for hospitalized patients and improving quality of clinical care and patient safety. As health care organizations began to see the potential for our field, the demands on our services grew. We grew to comanage patients with our surgical colleagues, worked on patient satisfaction, facilitated transitions of care, and attempted to reduce readmissions – all of which improved patient care and the bottom line for our organizations.

Somewhere along the way, we were expected to staff high patient volumes to add more value, but this always seemed to come with compromise in another aspect of care or our own well-being. After all, there are only so many hours in the day and a limit on what one individual can accomplish in that time.

One of the reasons I love hospital medicine is the novelty of what we do – we are creative thinkers. We have the capacity to innovate solutions to hospital problems based on our expertise as frontline providers for our patients. Hospitalists of every discipline staff a large majority of inpatients, which makes our collective experience significant to the management of inpatient health care. We are often the ones tasked with executing improvement projects, but how often are we involved in their design? I know that we collectively have an enormous opportunity to improve our health care practice, both for ourselves, our patients, and the institutions we work for. But more than just being a voice of advocacy, we need to understand how to positively influence the health care structures that allow us to deliver quality patient care.

It is no surprise that the inefficiencies we deal with in our hospitals are many – daily workflow interruptions, delays in results, scheduling issues, communication difficulties. These are not unique to any one institution. The pandemic added more to that plate – PPE deficiencies, patient volume triage, and resource management are examples. Hospitals often contract consultants to help solve these problems, and many utilize a variety of frameworks to improve these system processes. The Lean framework is one of these, and it originated in the manufacturing industry to eliminate waste in systems in the pursuit of efficiency.

In my business training and prior hospital medicine leadership roles, I was educated in Lean thinking and methodologies for improving quality and applied its principles to projects for improving workflow. Last year I attended a virtual conference on ‘Lean Innovation during the pandemic’ for New York region hospitals, and it again highlighted how the Lean management methodology can help improve patient care but importantly, our workflow as clinicians. This got me thinking. Why is Lean well accepted in business and manufacturing circles, but less so in health care?

I think the answer is twofold – knowledge and people.

What is Lean and how can it help us?

The ‘Toyota Production System’-based philosophy has 14 core principles that help eliminate waste in systems in pursuit of efficiency. These principles are the “Toyota Way.” They center around two pillars: continuous improvement and respect for people. The cornerstone of this management methodology is based on efficient processes, developing employees to add value to the organization and continuous improvement through problem-solving and organizational learning.

Lean is often implemented with Six Sigma methodology. Six Sigma has its origins in Motorola. While Lean cuts waste in our systems to provide value, Six Sigma uses DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) to reduce variation in our processes. When done in its entirety, Lean Six Sigma methodology adds value by increasing efficiency, reducing cost, and improving our everyday work.

Statistical principles suggest that 80% of consequences comes from 20% of causes. Lean methodology and tools allow us to systematically identify root causes for the problems we face and help narrow it down to the ‘vital few.’ In other words, fixing these would give us the most bang for our buck. As hospitalists, we are able to do this better than most because we work in these hospital processes everyday – we truly know the strengths and weaknesses of our systems.

As a hospitalist, I would love for the process of seeing patients in hospitals to be more efficient, less variable, and be more cost-effective for my institution. By eliminating the time wasted performing unnecessary and redundant tasks in my everyday work, I can reallocate that time to patient care – the very reason I chose a career in medicine.

We, the people

There are two common rebuttals I hear for adopting Lean Six Sigma methodology in health care. A frequent misconception is that Lean is all about reducing staff or time with patients. The second is that manufacturing methodologies do not work for a service profession. For instance, an article published on Reuters Events (www.reutersevents.com/supplychain/supply-chain/end-just-time) talks about Lean JIT (Just In Time) inventory as a culprit for creating a supply chain deficit during COVID-19. It is not entirely without merit. However, if done the correct way, Lean is all about involving the frontline worker to create a workflow that would work best for them.

Reducing the waste in our processes and empowering our frontline doctors to be creative in finding solutions naturally leads to cost reduction. The cornerstone of Lean is creating a continuously learning organization and putting your employees at the forefront. I think it is important that Lean principles be utilized within health care – but we cannot push to fix every problem in our systems to perfection at a significant expense to the physician and other health care staff.

Why HM can benefit from Lean

There is no hard and fast rule about the way health care should adopt Lean thinking. It is a way of thinking that aims to balance purpose, people, and process – extremes of inventory management may not be necessary to be successful in health care. Lean tools alone would not create results. John Shook, chairman of Lean Global Network, has said that the social side of Lean needs to be in balance with the technical side. In other words, rigidity and efficiency is good, but so is encouraging creativity and flexibility in thinking within the workforce.

In the crisis created by the novel coronavirus, many hospitals in New York state, including my own, turned to Lean to respond quickly and effectively to the challenges. Lean principles helped them problem-solve and develop strategies to both recover from the pandemic surge and adapt to future problems that could occur. Geographic clustering of patients, PPE supply, OR shut down and ramp up, emergency management offices at the peak of the pandemic, telehealth streamlining, and post-COVID-19 care planning are some areas where the application of Lean resulted in successful responses to the challenges that 2020 brought to our work.

As Warren Bennis said, ‘The manager accepts the status quo; the leader challenges it.’ As hospitalists, we can lead the way our hospitals provide care. Lean is not just a way for hospitals to cut costs (although it helps quite a bit there). Its processes and philosophies could enable hospitalists to maximize potential, efficiency, quality of care, and allow for a balanced work environment. When applied in a manner that focuses on continuous improvement (and is cognizant of its limitations), it has the potential to increase the capability of our service lines and streamline our processes and workday for greater efficiency. As a specialty, we stand to benefit by taking the lead role in choosing how best to improve how we work. We should think outside the box. What better time to do this than now?

Dr. Kanikkannan is a practicing hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at Albany (N.Y) Medical College. She is a former hospitalist medical director and has served on SHM’s national committees, and is a certified Lean Six Sigma black belt and MBA candidate.

Lean framework for efficiency and empathy of care

Lean framework for efficiency and empathy of care

“My census is too high.”

“I don’t have enough time to talk to patients.”

“These are outside our scope of practice.”

These are statements that I have heard from colleagues over the last fourteen years as a hospitalist. Back in 1996, when Dr. Bob Wachter coined the term ‘hospitalist,’ we were still in our infancy – the scope of what we could do had yet to be fully realized. Our focus was on providing care for hospitalized patients and improving quality of clinical care and patient safety. As health care organizations began to see the potential for our field, the demands on our services grew. We grew to comanage patients with our surgical colleagues, worked on patient satisfaction, facilitated transitions of care, and attempted to reduce readmissions – all of which improved patient care and the bottom line for our organizations.

Somewhere along the way, we were expected to staff high patient volumes to add more value, but this always seemed to come with compromise in another aspect of care or our own well-being. After all, there are only so many hours in the day and a limit on what one individual can accomplish in that time.

One of the reasons I love hospital medicine is the novelty of what we do – we are creative thinkers. We have the capacity to innovate solutions to hospital problems based on our expertise as frontline providers for our patients. Hospitalists of every discipline staff a large majority of inpatients, which makes our collective experience significant to the management of inpatient health care. We are often the ones tasked with executing improvement projects, but how often are we involved in their design? I know that we collectively have an enormous opportunity to improve our health care practice, both for ourselves, our patients, and the institutions we work for. But more than just being a voice of advocacy, we need to understand how to positively influence the health care structures that allow us to deliver quality patient care.

It is no surprise that the inefficiencies we deal with in our hospitals are many – daily workflow interruptions, delays in results, scheduling issues, communication difficulties. These are not unique to any one institution. The pandemic added more to that plate – PPE deficiencies, patient volume triage, and resource management are examples. Hospitals often contract consultants to help solve these problems, and many utilize a variety of frameworks to improve these system processes. The Lean framework is one of these, and it originated in the manufacturing industry to eliminate waste in systems in the pursuit of efficiency.

In my business training and prior hospital medicine leadership roles, I was educated in Lean thinking and methodologies for improving quality and applied its principles to projects for improving workflow. Last year I attended a virtual conference on ‘Lean Innovation during the pandemic’ for New York region hospitals, and it again highlighted how the Lean management methodology can help improve patient care but importantly, our workflow as clinicians. This got me thinking. Why is Lean well accepted in business and manufacturing circles, but less so in health care?

I think the answer is twofold – knowledge and people.

What is Lean and how can it help us?

The ‘Toyota Production System’-based philosophy has 14 core principles that help eliminate waste in systems in pursuit of efficiency. These principles are the “Toyota Way.” They center around two pillars: continuous improvement and respect for people. The cornerstone of this management methodology is based on efficient processes, developing employees to add value to the organization and continuous improvement through problem-solving and organizational learning.

Lean is often implemented with Six Sigma methodology. Six Sigma has its origins in Motorola. While Lean cuts waste in our systems to provide value, Six Sigma uses DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) to reduce variation in our processes. When done in its entirety, Lean Six Sigma methodology adds value by increasing efficiency, reducing cost, and improving our everyday work.

Statistical principles suggest that 80% of consequences comes from 20% of causes. Lean methodology and tools allow us to systematically identify root causes for the problems we face and help narrow it down to the ‘vital few.’ In other words, fixing these would give us the most bang for our buck. As hospitalists, we are able to do this better than most because we work in these hospital processes everyday – we truly know the strengths and weaknesses of our systems.

As a hospitalist, I would love for the process of seeing patients in hospitals to be more efficient, less variable, and be more cost-effective for my institution. By eliminating the time wasted performing unnecessary and redundant tasks in my everyday work, I can reallocate that time to patient care – the very reason I chose a career in medicine.

We, the people

There are two common rebuttals I hear for adopting Lean Six Sigma methodology in health care. A frequent misconception is that Lean is all about reducing staff or time with patients. The second is that manufacturing methodologies do not work for a service profession. For instance, an article published on Reuters Events (www.reutersevents.com/supplychain/supply-chain/end-just-time) talks about Lean JIT (Just In Time) inventory as a culprit for creating a supply chain deficit during COVID-19. It is not entirely without merit. However, if done the correct way, Lean is all about involving the frontline worker to create a workflow that would work best for them.

Reducing the waste in our processes and empowering our frontline doctors to be creative in finding solutions naturally leads to cost reduction. The cornerstone of Lean is creating a continuously learning organization and putting your employees at the forefront. I think it is important that Lean principles be utilized within health care – but we cannot push to fix every problem in our systems to perfection at a significant expense to the physician and other health care staff.

Why HM can benefit from Lean

There is no hard and fast rule about the way health care should adopt Lean thinking. It is a way of thinking that aims to balance purpose, people, and process – extremes of inventory management may not be necessary to be successful in health care. Lean tools alone would not create results. John Shook, chairman of Lean Global Network, has said that the social side of Lean needs to be in balance with the technical side. In other words, rigidity and efficiency is good, but so is encouraging creativity and flexibility in thinking within the workforce.

In the crisis created by the novel coronavirus, many hospitals in New York state, including my own, turned to Lean to respond quickly and effectively to the challenges. Lean principles helped them problem-solve and develop strategies to both recover from the pandemic surge and adapt to future problems that could occur. Geographic clustering of patients, PPE supply, OR shut down and ramp up, emergency management offices at the peak of the pandemic, telehealth streamlining, and post-COVID-19 care planning are some areas where the application of Lean resulted in successful responses to the challenges that 2020 brought to our work.

As Warren Bennis said, ‘The manager accepts the status quo; the leader challenges it.’ As hospitalists, we can lead the way our hospitals provide care. Lean is not just a way for hospitals to cut costs (although it helps quite a bit there). Its processes and philosophies could enable hospitalists to maximize potential, efficiency, quality of care, and allow for a balanced work environment. When applied in a manner that focuses on continuous improvement (and is cognizant of its limitations), it has the potential to increase the capability of our service lines and streamline our processes and workday for greater efficiency. As a specialty, we stand to benefit by taking the lead role in choosing how best to improve how we work. We should think outside the box. What better time to do this than now?

Dr. Kanikkannan is a practicing hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at Albany (N.Y) Medical College. She is a former hospitalist medical director and has served on SHM’s national committees, and is a certified Lean Six Sigma black belt and MBA candidate.

“My census is too high.”

“I don’t have enough time to talk to patients.”

“These are outside our scope of practice.”

These are statements that I have heard from colleagues over the last fourteen years as a hospitalist. Back in 1996, when Dr. Bob Wachter coined the term ‘hospitalist,’ we were still in our infancy – the scope of what we could do had yet to be fully realized. Our focus was on providing care for hospitalized patients and improving quality of clinical care and patient safety. As health care organizations began to see the potential for our field, the demands on our services grew. We grew to comanage patients with our surgical colleagues, worked on patient satisfaction, facilitated transitions of care, and attempted to reduce readmissions – all of which improved patient care and the bottom line for our organizations.

Somewhere along the way, we were expected to staff high patient volumes to add more value, but this always seemed to come with compromise in another aspect of care or our own well-being. After all, there are only so many hours in the day and a limit on what one individual can accomplish in that time.

One of the reasons I love hospital medicine is the novelty of what we do – we are creative thinkers. We have the capacity to innovate solutions to hospital problems based on our expertise as frontline providers for our patients. Hospitalists of every discipline staff a large majority of inpatients, which makes our collective experience significant to the management of inpatient health care. We are often the ones tasked with executing improvement projects, but how often are we involved in their design? I know that we collectively have an enormous opportunity to improve our health care practice, both for ourselves, our patients, and the institutions we work for. But more than just being a voice of advocacy, we need to understand how to positively influence the health care structures that allow us to deliver quality patient care.

It is no surprise that the inefficiencies we deal with in our hospitals are many – daily workflow interruptions, delays in results, scheduling issues, communication difficulties. These are not unique to any one institution. The pandemic added more to that plate – PPE deficiencies, patient volume triage, and resource management are examples. Hospitals often contract consultants to help solve these problems, and many utilize a variety of frameworks to improve these system processes. The Lean framework is one of these, and it originated in the manufacturing industry to eliminate waste in systems in the pursuit of efficiency.

In my business training and prior hospital medicine leadership roles, I was educated in Lean thinking and methodologies for improving quality and applied its principles to projects for improving workflow. Last year I attended a virtual conference on ‘Lean Innovation during the pandemic’ for New York region hospitals, and it again highlighted how the Lean management methodology can help improve patient care but importantly, our workflow as clinicians. This got me thinking. Why is Lean well accepted in business and manufacturing circles, but less so in health care?

I think the answer is twofold – knowledge and people.

What is Lean and how can it help us?

The ‘Toyota Production System’-based philosophy has 14 core principles that help eliminate waste in systems in pursuit of efficiency. These principles are the “Toyota Way.” They center around two pillars: continuous improvement and respect for people. The cornerstone of this management methodology is based on efficient processes, developing employees to add value to the organization and continuous improvement through problem-solving and organizational learning.

Lean is often implemented with Six Sigma methodology. Six Sigma has its origins in Motorola. While Lean cuts waste in our systems to provide value, Six Sigma uses DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) to reduce variation in our processes. When done in its entirety, Lean Six Sigma methodology adds value by increasing efficiency, reducing cost, and improving our everyday work.

Statistical principles suggest that 80% of consequences comes from 20% of causes. Lean methodology and tools allow us to systematically identify root causes for the problems we face and help narrow it down to the ‘vital few.’ In other words, fixing these would give us the most bang for our buck. As hospitalists, we are able to do this better than most because we work in these hospital processes everyday – we truly know the strengths and weaknesses of our systems.

As a hospitalist, I would love for the process of seeing patients in hospitals to be more efficient, less variable, and be more cost-effective for my institution. By eliminating the time wasted performing unnecessary and redundant tasks in my everyday work, I can reallocate that time to patient care – the very reason I chose a career in medicine.

We, the people

There are two common rebuttals I hear for adopting Lean Six Sigma methodology in health care. A frequent misconception is that Lean is all about reducing staff or time with patients. The second is that manufacturing methodologies do not work for a service profession. For instance, an article published on Reuters Events (www.reutersevents.com/supplychain/supply-chain/end-just-time) talks about Lean JIT (Just In Time) inventory as a culprit for creating a supply chain deficit during COVID-19. It is not entirely without merit. However, if done the correct way, Lean is all about involving the frontline worker to create a workflow that would work best for them.

Reducing the waste in our processes and empowering our frontline doctors to be creative in finding solutions naturally leads to cost reduction. The cornerstone of Lean is creating a continuously learning organization and putting your employees at the forefront. I think it is important that Lean principles be utilized within health care – but we cannot push to fix every problem in our systems to perfection at a significant expense to the physician and other health care staff.

Why HM can benefit from Lean

There is no hard and fast rule about the way health care should adopt Lean thinking. It is a way of thinking that aims to balance purpose, people, and process – extremes of inventory management may not be necessary to be successful in health care. Lean tools alone would not create results. John Shook, chairman of Lean Global Network, has said that the social side of Lean needs to be in balance with the technical side. In other words, rigidity and efficiency is good, but so is encouraging creativity and flexibility in thinking within the workforce.

In the crisis created by the novel coronavirus, many hospitals in New York state, including my own, turned to Lean to respond quickly and effectively to the challenges. Lean principles helped them problem-solve and develop strategies to both recover from the pandemic surge and adapt to future problems that could occur. Geographic clustering of patients, PPE supply, OR shut down and ramp up, emergency management offices at the peak of the pandemic, telehealth streamlining, and post-COVID-19 care planning are some areas where the application of Lean resulted in successful responses to the challenges that 2020 brought to our work.

As Warren Bennis said, ‘The manager accepts the status quo; the leader challenges it.’ As hospitalists, we can lead the way our hospitals provide care. Lean is not just a way for hospitals to cut costs (although it helps quite a bit there). Its processes and philosophies could enable hospitalists to maximize potential, efficiency, quality of care, and allow for a balanced work environment. When applied in a manner that focuses on continuous improvement (and is cognizant of its limitations), it has the potential to increase the capability of our service lines and streamline our processes and workday for greater efficiency. As a specialty, we stand to benefit by taking the lead role in choosing how best to improve how we work. We should think outside the box. What better time to do this than now?

Dr. Kanikkannan is a practicing hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at Albany (N.Y) Medical College. She is a former hospitalist medical director and has served on SHM’s national committees, and is a certified Lean Six Sigma black belt and MBA candidate.

Feds to states: Give COVID-19 vaccine to 65+ and those with comorbidities

Federal health officials are urging states to vaccinate all Americans over age 65 and those aged 16-64 who have a documented underlying health condition that makes them more vulnerable to COVID-19.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Alex Azar and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Robert Redfield, MD, made the recommendation in a briefing with reporters on Jan. 12, saying that the current vaccine supply was sufficient to meet demand for the next phase of immunization as recommended by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

“We are ready for a transition that we outlined last September in the playbook we sent to states,” Mr. Azar said. Both he and U.S. Army General Gustave F. Perna, chief operations officer for Operation Warp Speed, said that confidence in the distribution system had led to the decision to urge wider access.

The federal government will also increase the number of sites eligible to receive vaccine – including some 13,000 federally qualified community health centers – and will not keep doses in reserve as insurance against issues that might prevent people from receiving a second dose on a timely basis.

“We don’t need to hold back reserve doses,” Mr. Azar said, noting that if there were any “glitches in production” the federal government would move to fulfill obligations for second doses first and delay initial doses.

Azar: Use it or lose it

In a move that is sure to generate pushback, Mr. Azar said that states that don’t quickly administer vaccines will receive fewer doses in the future. That policy will not go into effect until later in February, which leaves open the possibility that it could be reversed by the incoming Biden administration.

“We have too much vaccine sitting in freezers at hospitals with hospitals not using it,” said Mr. Azar, who also blamed the slow administration process on a reporting lag and states being what he called “overly prescriptive” in who has been eligible to receive a shot.

“I would rather have people working to get appointments to get vaccinated than having vaccine going to waste sitting in freezers,” he told reporters.

Mr. Azar had already been pushing for broader vaccination, telling states to do so in an Operation Warp Speed briefing on Jan. 6. At that briefing, he also said that the federal government would be stepping up vaccination through an “early launch” of a federal partnership with 19 pharmacy chains, which will let states allocate vaccines directly to some 40,000 pharmacy sites.

Gen. Perna said during the Jan. 12 briefing that the aim is to further expand that to some 70,000 locations total.

The CDC reported that as of Jan. 11 some 25.4 million doses have been distributed, with 8.9 million administered. An additional 4.2 million doses were distributed to long-term care facilities, and 937,000 residents and staff have received a dose.

“Pace of administration”

Alaska, Connecticut, North Dakota, South Dakota, the District of Columbia, West Virginia, and the Northern Mariana Islands have administered the most vaccines per capita, according to the CDC. But even these locations have immunized only 4%-5% of their populations, the New York Times reports. At the bottom: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina.

The federal government can encourage but not require states to move on to new phases of vaccination.

“States ultimately determine how they will proceed with vaccination,” said Marcus Plescia, MD, MPH, chief medical officer for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. “Most will be cautious about assuring there are doses for those needing a second dose,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Plescia said that ensuring a second dose is available is especially important for health care workers “who need to be confident that they are protected and not inadvertently transmitting the disease themselves.”

He added that “once we reach a steady state of supply and administration, the rate-limiting factor will be supply of vaccine.”

That supply could now be threatened if states don’t comply with a just-announced federal action that will change how doses are allocated.

Beginning in late February, vaccine allocations to states will be based on “the pace of administration reported by states,” and the size of the 65-and-older population, said Mr. Azar, who has previously criticized New York Governor Andrew Cuomo for fining hospitals that didn’t use up vaccine supply within a week.

“This new system gives states a strong incentive to ensure that all vaccinations are being promptly reported, which they currently are not,” he said.

Currently, allocations are based on a state’s or territory’s population.

Prepandemic, states were required to report vaccinations within 30 days. Since COVID-19 vaccines became available, the CDC has required reporting of shots within 72 hours.

Dr. Redfield said the requirement has caused some difficulty, and that the CDC is investigating why some states have reported using only 15% of doses while others have used 80%.

States have been scrambling to ramp up vaccinations.

Just ahead of the federal briefing, Gov. Cuomo tweeted that New York would be opening up vaccinations to anyone older than 65.

The Associated Press is reporting that some states have started mass vaccination sites.

Arizona has begun operating a 24/7 appointment-only vaccination program at State Farm Stadium outside of Phoenix, with the aim of immunizing 6,000 people each day, according to local radio station KJZZ.

California and Florida have also taken steps to use stadiums, while Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Texas will use convention centers and fairgrounds, Axios has reported.

In Florida, Palm Beach County Health Director Alina Alonso, MD, told county commissioners on Jan. 12 that there isn’t enough vaccine to meet demand, WPTV reported. “We need to realize that there’s a shortage of vaccine. So it’s not the plan, it’s not our ability to do it. It’s simply supply and demand at this point,” Dr. Alonso said, according to the TV station report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Federal health officials are urging states to vaccinate all Americans over age 65 and those aged 16-64 who have a documented underlying health condition that makes them more vulnerable to COVID-19.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Alex Azar and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Robert Redfield, MD, made the recommendation in a briefing with reporters on Jan. 12, saying that the current vaccine supply was sufficient to meet demand for the next phase of immunization as recommended by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

“We are ready for a transition that we outlined last September in the playbook we sent to states,” Mr. Azar said. Both he and U.S. Army General Gustave F. Perna, chief operations officer for Operation Warp Speed, said that confidence in the distribution system had led to the decision to urge wider access.

The federal government will also increase the number of sites eligible to receive vaccine – including some 13,000 federally qualified community health centers – and will not keep doses in reserve as insurance against issues that might prevent people from receiving a second dose on a timely basis.

“We don’t need to hold back reserve doses,” Mr. Azar said, noting that if there were any “glitches in production” the federal government would move to fulfill obligations for second doses first and delay initial doses.

Azar: Use it or lose it

In a move that is sure to generate pushback, Mr. Azar said that states that don’t quickly administer vaccines will receive fewer doses in the future. That policy will not go into effect until later in February, which leaves open the possibility that it could be reversed by the incoming Biden administration.

“We have too much vaccine sitting in freezers at hospitals with hospitals not using it,” said Mr. Azar, who also blamed the slow administration process on a reporting lag and states being what he called “overly prescriptive” in who has been eligible to receive a shot.

“I would rather have people working to get appointments to get vaccinated than having vaccine going to waste sitting in freezers,” he told reporters.

Mr. Azar had already been pushing for broader vaccination, telling states to do so in an Operation Warp Speed briefing on Jan. 6. At that briefing, he also said that the federal government would be stepping up vaccination through an “early launch” of a federal partnership with 19 pharmacy chains, which will let states allocate vaccines directly to some 40,000 pharmacy sites.

Gen. Perna said during the Jan. 12 briefing that the aim is to further expand that to some 70,000 locations total.

The CDC reported that as of Jan. 11 some 25.4 million doses have been distributed, with 8.9 million administered. An additional 4.2 million doses were distributed to long-term care facilities, and 937,000 residents and staff have received a dose.

“Pace of administration”

Alaska, Connecticut, North Dakota, South Dakota, the District of Columbia, West Virginia, and the Northern Mariana Islands have administered the most vaccines per capita, according to the CDC. But even these locations have immunized only 4%-5% of their populations, the New York Times reports. At the bottom: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina.

The federal government can encourage but not require states to move on to new phases of vaccination.

“States ultimately determine how they will proceed with vaccination,” said Marcus Plescia, MD, MPH, chief medical officer for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. “Most will be cautious about assuring there are doses for those needing a second dose,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Plescia said that ensuring a second dose is available is especially important for health care workers “who need to be confident that they are protected and not inadvertently transmitting the disease themselves.”

He added that “once we reach a steady state of supply and administration, the rate-limiting factor will be supply of vaccine.”

That supply could now be threatened if states don’t comply with a just-announced federal action that will change how doses are allocated.

Beginning in late February, vaccine allocations to states will be based on “the pace of administration reported by states,” and the size of the 65-and-older population, said Mr. Azar, who has previously criticized New York Governor Andrew Cuomo for fining hospitals that didn’t use up vaccine supply within a week.

“This new system gives states a strong incentive to ensure that all vaccinations are being promptly reported, which they currently are not,” he said.

Currently, allocations are based on a state’s or territory’s population.

Prepandemic, states were required to report vaccinations within 30 days. Since COVID-19 vaccines became available, the CDC has required reporting of shots within 72 hours.

Dr. Redfield said the requirement has caused some difficulty, and that the CDC is investigating why some states have reported using only 15% of doses while others have used 80%.

States have been scrambling to ramp up vaccinations.

Just ahead of the federal briefing, Gov. Cuomo tweeted that New York would be opening up vaccinations to anyone older than 65.

The Associated Press is reporting that some states have started mass vaccination sites.

Arizona has begun operating a 24/7 appointment-only vaccination program at State Farm Stadium outside of Phoenix, with the aim of immunizing 6,000 people each day, according to local radio station KJZZ.

California and Florida have also taken steps to use stadiums, while Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Texas will use convention centers and fairgrounds, Axios has reported.

In Florida, Palm Beach County Health Director Alina Alonso, MD, told county commissioners on Jan. 12 that there isn’t enough vaccine to meet demand, WPTV reported. “We need to realize that there’s a shortage of vaccine. So it’s not the plan, it’s not our ability to do it. It’s simply supply and demand at this point,” Dr. Alonso said, according to the TV station report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Federal health officials are urging states to vaccinate all Americans over age 65 and those aged 16-64 who have a documented underlying health condition that makes them more vulnerable to COVID-19.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Alex Azar and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Robert Redfield, MD, made the recommendation in a briefing with reporters on Jan. 12, saying that the current vaccine supply was sufficient to meet demand for the next phase of immunization as recommended by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

“We are ready for a transition that we outlined last September in the playbook we sent to states,” Mr. Azar said. Both he and U.S. Army General Gustave F. Perna, chief operations officer for Operation Warp Speed, said that confidence in the distribution system had led to the decision to urge wider access.

The federal government will also increase the number of sites eligible to receive vaccine – including some 13,000 federally qualified community health centers – and will not keep doses in reserve as insurance against issues that might prevent people from receiving a second dose on a timely basis.

“We don’t need to hold back reserve doses,” Mr. Azar said, noting that if there were any “glitches in production” the federal government would move to fulfill obligations for second doses first and delay initial doses.

Azar: Use it or lose it

In a move that is sure to generate pushback, Mr. Azar said that states that don’t quickly administer vaccines will receive fewer doses in the future. That policy will not go into effect until later in February, which leaves open the possibility that it could be reversed by the incoming Biden administration.

“We have too much vaccine sitting in freezers at hospitals with hospitals not using it,” said Mr. Azar, who also blamed the slow administration process on a reporting lag and states being what he called “overly prescriptive” in who has been eligible to receive a shot.

“I would rather have people working to get appointments to get vaccinated than having vaccine going to waste sitting in freezers,” he told reporters.

Mr. Azar had already been pushing for broader vaccination, telling states to do so in an Operation Warp Speed briefing on Jan. 6. At that briefing, he also said that the federal government would be stepping up vaccination through an “early launch” of a federal partnership with 19 pharmacy chains, which will let states allocate vaccines directly to some 40,000 pharmacy sites.

Gen. Perna said during the Jan. 12 briefing that the aim is to further expand that to some 70,000 locations total.

The CDC reported that as of Jan. 11 some 25.4 million doses have been distributed, with 8.9 million administered. An additional 4.2 million doses were distributed to long-term care facilities, and 937,000 residents and staff have received a dose.

“Pace of administration”

Alaska, Connecticut, North Dakota, South Dakota, the District of Columbia, West Virginia, and the Northern Mariana Islands have administered the most vaccines per capita, according to the CDC. But even these locations have immunized only 4%-5% of their populations, the New York Times reports. At the bottom: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina.

The federal government can encourage but not require states to move on to new phases of vaccination.

“States ultimately determine how they will proceed with vaccination,” said Marcus Plescia, MD, MPH, chief medical officer for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. “Most will be cautious about assuring there are doses for those needing a second dose,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Plescia said that ensuring a second dose is available is especially important for health care workers “who need to be confident that they are protected and not inadvertently transmitting the disease themselves.”

He added that “once we reach a steady state of supply and administration, the rate-limiting factor will be supply of vaccine.”

That supply could now be threatened if states don’t comply with a just-announced federal action that will change how doses are allocated.

Beginning in late February, vaccine allocations to states will be based on “the pace of administration reported by states,” and the size of the 65-and-older population, said Mr. Azar, who has previously criticized New York Governor Andrew Cuomo for fining hospitals that didn’t use up vaccine supply within a week.

“This new system gives states a strong incentive to ensure that all vaccinations are being promptly reported, which they currently are not,” he said.

Currently, allocations are based on a state’s or territory’s population.

Prepandemic, states were required to report vaccinations within 30 days. Since COVID-19 vaccines became available, the CDC has required reporting of shots within 72 hours.

Dr. Redfield said the requirement has caused some difficulty, and that the CDC is investigating why some states have reported using only 15% of doses while others have used 80%.

States have been scrambling to ramp up vaccinations.

Just ahead of the federal briefing, Gov. Cuomo tweeted that New York would be opening up vaccinations to anyone older than 65.

The Associated Press is reporting that some states have started mass vaccination sites.

Arizona has begun operating a 24/7 appointment-only vaccination program at State Farm Stadium outside of Phoenix, with the aim of immunizing 6,000 people each day, according to local radio station KJZZ.

California and Florida have also taken steps to use stadiums, while Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Texas will use convention centers and fairgrounds, Axios has reported.

In Florida, Palm Beach County Health Director Alina Alonso, MD, told county commissioners on Jan. 12 that there isn’t enough vaccine to meet demand, WPTV reported. “We need to realize that there’s a shortage of vaccine. So it’s not the plan, it’s not our ability to do it. It’s simply supply and demand at this point,” Dr. Alonso said, according to the TV station report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

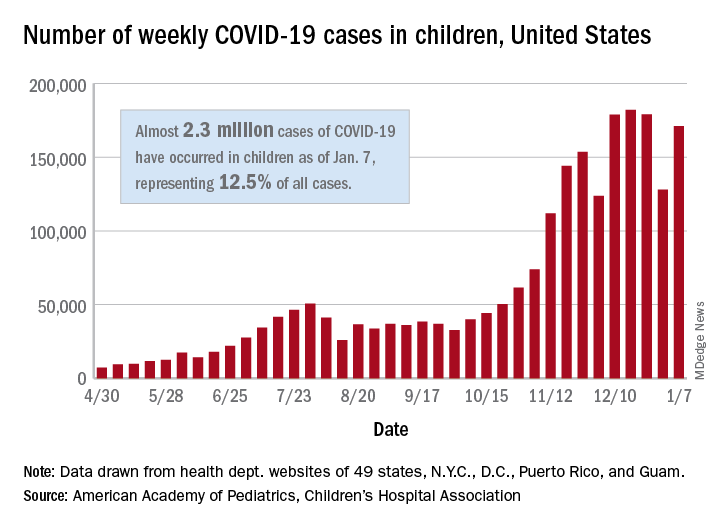

Averting COVID hospitalizations with monoclonal antibodies

The United States has allocated more than 641,000 monoclonal antibody treatments for outpatients to ease pressure on strained hospitals, but officials from Operation Warp Speed report that more than half of that reserve sits unused as clinicians grapple with best practices.

There are space and personnel limitations in hospitals right now, Janet Woodcock, MD, therapeutics lead on Operation Warp Speed, acknowledges in an interview with this news organization. “Special areas and procedures must be set up.” And the operation is in the process of broadening availability beyond hospitals, she points out.

But for frontline clinicians, questions about treatment efficacy and the logistics of administering intravenous drugs to infectious outpatients loom large.

More than 50 monoclonal antibody products that target SARS-CoV-2 are now in development. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has already issued Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for two such drugs on the basis of phase 2 trial data – bamlanivimab, made by Eli Lilly, and a cocktail of casirivimab plus imdevimab, made by Regeneron – and another two-antibody cocktail from AstraZeneca, AZD7442, has started phase 3 clinical trials. The Regeneron combination was used to treat President Donald Trump when he contracted COVID-19 in October.

Monoclonal antibody drugs are based on the natural antibodies that the body uses to fight infections. They work by binding to a specific target and then blocking its action or flagging it for destruction by other parts of the immune system. Both bamlanivimab and the casirivimab plus imdevimab combination target the spike protein of the virus and stop it from attaching to and entering human cells.

Targeting the spike protein out of the hospital

The antibody drugs covered by EUAs do not cure COVID-19, but they have been shown to reduce hospitalizations and visits to the emergency department for patients at high risk for disease progression. They are approved to treat patients older than 12 years with mild to moderate COVID-19 who are at high risk of progressing to severe disease or hospitalization. They are not authorized for use in patients who have been hospitalized or who are on ventilators. The hope is that antibody drugs will reduce the number of severe cases of COVID-19 and ease pressure on overstretched hospitals.

Most COVID-19 patients are outpatients, so we need something to keep them from getting worse.

This is important because it targets the greatest need in COVID-19 therapeutics, says Rajesh Gandhi, MD, an infectious disease physician at Harvard Medical School in Boston, who is a member of two panels evaluating COVID-19 treatments: one for the Infectious Disease Society of America and the other for the National Institutes of Health. “Up to now, most of the focus has been on hospitalized patients,” he says, but “most COVID-19 patients are outpatients, so we need something to keep them from getting worse.”

Both panels have said that, despite the EUAs, more evidence is needed to be sure of the efficacy of the drugs and to determine which patients will benefit the most from them.

These aren’t the mature data from drug development that guideline groups are accustomed to working with, Dr. Woodcock points out. “But this is an emergency and the data taken as a whole are pretty convincing,” she says. “As I look at the totality of the evidence, monoclonal antibodies will have a big effect in keeping people out of the hospital and helping them recover faster.”

High-risk patients are eligible for treatment, especially those older than 65 years and those with comorbidities who are younger. Access to the drugs is increasing for clinicians who are able to infuse safely or work with a site that will.

In the Boston area, several hospitals, including Massachusetts General where Dr. Gandhi works, have set up infusion centers where newly diagnosed patients can get the antibody treatment if their doctor thinks it will benefit them. And Coram, a provider of at-home infusion therapy owned by the CVS pharmacy chain, is running a pilot program offering the Eli Lilly drug to people in seven cities – including Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Tampa – and their surrounding communities with a physician referral.

Getting that referral could be tricky, however, for patients without a primary care physician or for those whose doctor isn’t already connected to one of the institutions providing the infusions. The hospitals are sending out communications on how patients and physicians can get the therapy, but Dr. Gandhi says that making information about access available should be a priority. The window for the effective treatment is small – the drugs appear to work best before patients begin to make their own antibodies, says Dr. Gandhi – so it’s vital that doctors act quickly if they have a patient who is eligible.

And rolling out the new therapies to patients around the world will be a major logistical undertaking.

The first hurdle will be making enough of them to go around. Case numbers are skyrocketing around the globe, and producing the drugs is a complex time- and labor-intensive process that requires specialized facilities. Antibodies are produced by cell lines in bioreactors, so a plant that churns out generic aspirin tablets can’t simply be converted into an antibody factory.

“These types of drugs are manufactured in a sterile injectables plant, which is different from a plant where oral solids are made,” says Kim Crabtree, senior director of pharma portfolio management for Henry Schein Medical, a medical supplies distributor. “Those are not as plentiful as a standard pill factory.”

The doses required are also relatively high – 1.2 g of each antibody in Regeneron’s cocktail – which will further strain production capacity. Leah Lipsich, PhD, vice president of strategic program direction at Regeneron, says the company is prepared for high demand and has been able to respond, thanks to its rapid development and manufacturing technology, known as VelociSuite, which allows it to rapidly scale-up from discovery to productions in weeks instead of months.

“We knew supply would be a huge problem for COVID-19, but because we had such confidence in our technology, we went immediately from research-scale to our largest-scale manufacturing,” she says. “We’ve been manufacturing our cocktail for months now.”

The company has also partnered with Roche, the biggest manufacturer and vendor of monoclonal antibodies in the world, to manufacture and supply the drugs. Once full manufacturing capacity is reached in 2021, the companies expect to produce at least 2 million doses a year.

Then there is the issue of getting the drugs from the factories to the places they will be used.

Antibodies are temperature sensitive and need to be refrigerated during transport and storage, so a cold-chain-compliant supply chain is required. Fortunately, they can be kept at standard refrigerator temperatures, ranging from 2° C to 8° C, rather than the ultra-low temperatures required by some COVID-19 vaccines.

Two million doses a year

Medical logistics companies have a lot of experience dealing with products like these and are well prepared to handle the new antibody drugs. “There are quite a few products like these on the market, and the supply chain is used to shipping them,” Ms. Crabtree says.

They will be shipped to distribution centers in refrigerated trucks, repacked into smaller lots that can sustain the correct temperature for 24 hours, and then sent to their final destination, often in something as simple as a Styrofoam cooler filled with dry ice.

The expected rise in demand shouldn’t be too much of an issue for distributors either, says Ms. Crabtree; they have built systems that can deal with short-term surges in volume. The annual flu vaccine, for example, involves shipping a lot of product in a very short time, usually from August to November. “The distribution system is used to seasonal variations and peaks in demand,” she says.

The next question is how the treatments will be administered. Although most patients who will receive monoclonal antibodies will be ambulatory and not hospitalized, the administration requires intravenous infusion. Hospitals, of course, have a lot of experience with intravenous drugs, but typically give them only to inpatients. Most other monoclonal antibody drugs – such as those for cancer and autoimmune disorders – are given in specialized suites in doctor’s offices or in stand-alone infusion clinics.

That means that the places best suited to treat COVID-19 patients with antibodies are those that regularly deal with people who are immunocompromised, and such patients should not be interacting with people who have an infectious disease. “How do we protect the staff and other patients?” Dr. Gandhi asks.

Protecting staff and other patients

This is not an insurmountable obstacle, he points out, but it is one that requires careful thought and planning to accommodate COVID-19 patients without unduly disrupting life-saving treatments for other patients. It might involve, for example, treating COVID-19 patients in sequestered parts of the clinic or at different times of day, with even greater attention paid to cleaning, he explains. “We now have many months of experience with infection control, so we know how to do this; it’s just a question of logistics.”

But even once all the details around manufacturing, transporting, and administering the drugs are sorted out, there is still the issue of how they will be distributed fairly and equitably.

Despite multiple companies working to produce an array of different antibody drugs, demand is still expected to exceed supply for many months. “With more than 200,000 new cases a day in the United States, there won’t be enough antibodies to treat all of the high-risk patients,” says Dr. Gandhi. “Most of us are worried that demand will far outstrip supply. People are talking about lotteries to determine who gets them.”

The Department of Health and Human Services will continue to distribute the drugs to states on the basis of their COVID-19 burdens, and the states will then decide how much to provide to each health care facility.

Although the HHS goal is to ensure that the drugs reach as many patients as possible, no matter where they live and regardless of their income, there are still concerns that larger facilities serving more affluent areas will end up being favored, if only because they are the ones best equipped to deal with the drugs right now.

“We are all aware that this has affected certain communities more, so we need to make sure that the drugs are used equitably and made available to the communities that were hardest hit,” says Dr. Gandhi. The ability to monitor drug distribution should be built into the rollout, so that institutions and governments will have some sense of whether they are being doled out evenly, he adds.

Equity in distribution will be an issue for the rest of the world as well. Currently, 80% of monoclonal antibodies are sold in Canada, Europe, and the United States; few, if any, are available in low- and middle-income countries. The treatments are expensive: the cost of producing one g of marketed monoclonal antibodies is between $95 and $200, which does not include the cost of R&D, packaging, shipping, or administration. The median price for antibody treatment not related to COVID-19 runs from $15,000 to $200,000 per year in the United States.

Regeneron’s Dr. Lipsich says that the company has not yet set a price for its antibody cocktail. The government paid $450 million for its 300,000 doses, but that price includes the costs of research, manufacturing, and distribution, so is not a useful indicator of the eventual per-dose price. “We’re not in a position to talk about how it will be priced yet, but we will do our best to make it affordable and accessible to all,” she says.

There are some projects underway to ensure that the drugs are made available in poorer countries. In April, the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator – an initiative launched by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome, and Mastercard to speed-up the response to the global pandemic – reserved manufacturing capacity with Fujifilm Diosynth Biotechnologies in Denmark for future monoclonal antibody therapies that will supply low- and middle-income countries. In October, the initiative announced that Eli Lilly would use that reserved capacity to produce its antibody drug starting in April 2021.

In the meantime, Lilly will make some of its product manufactured in other facilities available to lower-income countries. To help keep costs down, the company’s collaborators have agreed to waive their royalties on antibodies distributed in low- and middle-income countries.

“Everyone is looking carefully at how the drugs are distributed to ensure all will get access,” said Dr. Lipsich.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The United States has allocated more than 641,000 monoclonal antibody treatments for outpatients to ease pressure on strained hospitals, but officials from Operation Warp Speed report that more than half of that reserve sits unused as clinicians grapple with best practices.