User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

A 4-point thrombocytopenia score was found able to rule out suspected HIT

The real strength of the 4T score for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is its negative predictive value, according to hematologist Adam Cuker, MD, of the department of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The score assigns patients points based on degree of thrombocytopenia, timing of platelet count fall in relation to heparin exposure, presence of thrombosis and other sequelae, and the likelihood of other causes of thrombocytopenia.

A low score – 3 points or less – has a negative predictive value of 99.8%, “so HIT is basically ruled out; you do not need to order lab testing for HIT or manage the patient empirically for HIT,” and should look for other causes of thrombocytopenia, said Dr. Cuker, lead author of the American Society of Hematology’s most recent HIT guidelines.

Intermediate scores of 4 or 5 points, and high scores of 6-8 points, are a different story. The positive predictive value of an intermediate score is only 14%, and of a high score, 64%, so although they don’t confirm the diagnosis, “you have to take the possibility of HIT seriously.” Discontinue heparin, start a nonheparin anticoagulant, and order a HIT immunoassay. If it’s positive, order a functional assay to confirm the diagnosis, he said.

Suspicion of HIT “is perhaps the most common consult that we get on the hematology service. These are tough consults because it is a high-stakes decision.” There is about a 6% risk of thromboembolism, amputation, and death for every day treatment is delayed. “On the other hand, the nonheparin anticoagulants are expensive, and they carry about a 1% daily risk of major bleeding,” Dr. Cuker explained during his presentation at the 2020 Update in Nonneoplastic Hematology virtual conference.

ELISA immunoassay detects antiplatelet factor 4 heparin antibodies but doesn’t tell whether or not they are able to activate platelets and cause HIT. Functional tests such as the serotonin-release assay detect only those antibodies able to do so, but the assays are difficult to perform, and often require samples to be sent out to a reference lab.

ASH did not specify a particular nonheparin anticoagulant in its 2018 guidelines because “the best choice for your patient” depends on which drugs you have available, your familiarity with them, and patient factors, Dr. Cuker said at the conference sponsored by MedscapeLive.

It makes sense, for instance, to use a short-acting agent such as argatroban or bivalirudin in patients who are critically ill, at high risk of bleeding, or likely to need an urgent unplanned procedure. Fondaparinux or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) make sense if patients are clinically stable with good organ function and no more than average bleeding risk, because they are easier to administer and facilitate transition to the outpatient setting.

DOACs are newcomers to ASH’s guidelines. Just 81 patients had been reported in the literature when they were being drafted, but only 2 patients had recurrence or progression of thromboembolic events, and there were no major bleeds. The results compared favorably with other options.

The studies were subject to selection and reporting biases, “but, nonetheless, the panel felt the results were positive enough that DOACs ought to be listed as an option,” Dr. Cuker said.

The guidelines note that parenteral options may be the best choice for life- or limb-threatening thrombosis “because few such patients have been treated with a DOAC.” Anticoagulation must continue until platelet counts recover.

Dr. Cuker is a consultant for Synergy and has institutional research support from Alexion, Bayer, Sanofi, and other companies. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

The real strength of the 4T score for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is its negative predictive value, according to hematologist Adam Cuker, MD, of the department of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The score assigns patients points based on degree of thrombocytopenia, timing of platelet count fall in relation to heparin exposure, presence of thrombosis and other sequelae, and the likelihood of other causes of thrombocytopenia.

A low score – 3 points or less – has a negative predictive value of 99.8%, “so HIT is basically ruled out; you do not need to order lab testing for HIT or manage the patient empirically for HIT,” and should look for other causes of thrombocytopenia, said Dr. Cuker, lead author of the American Society of Hematology’s most recent HIT guidelines.

Intermediate scores of 4 or 5 points, and high scores of 6-8 points, are a different story. The positive predictive value of an intermediate score is only 14%, and of a high score, 64%, so although they don’t confirm the diagnosis, “you have to take the possibility of HIT seriously.” Discontinue heparin, start a nonheparin anticoagulant, and order a HIT immunoassay. If it’s positive, order a functional assay to confirm the diagnosis, he said.

Suspicion of HIT “is perhaps the most common consult that we get on the hematology service. These are tough consults because it is a high-stakes decision.” There is about a 6% risk of thromboembolism, amputation, and death for every day treatment is delayed. “On the other hand, the nonheparin anticoagulants are expensive, and they carry about a 1% daily risk of major bleeding,” Dr. Cuker explained during his presentation at the 2020 Update in Nonneoplastic Hematology virtual conference.

ELISA immunoassay detects antiplatelet factor 4 heparin antibodies but doesn’t tell whether or not they are able to activate platelets and cause HIT. Functional tests such as the serotonin-release assay detect only those antibodies able to do so, but the assays are difficult to perform, and often require samples to be sent out to a reference lab.

ASH did not specify a particular nonheparin anticoagulant in its 2018 guidelines because “the best choice for your patient” depends on which drugs you have available, your familiarity with them, and patient factors, Dr. Cuker said at the conference sponsored by MedscapeLive.

It makes sense, for instance, to use a short-acting agent such as argatroban or bivalirudin in patients who are critically ill, at high risk of bleeding, or likely to need an urgent unplanned procedure. Fondaparinux or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) make sense if patients are clinically stable with good organ function and no more than average bleeding risk, because they are easier to administer and facilitate transition to the outpatient setting.

DOACs are newcomers to ASH’s guidelines. Just 81 patients had been reported in the literature when they were being drafted, but only 2 patients had recurrence or progression of thromboembolic events, and there were no major bleeds. The results compared favorably with other options.

The studies were subject to selection and reporting biases, “but, nonetheless, the panel felt the results were positive enough that DOACs ought to be listed as an option,” Dr. Cuker said.

The guidelines note that parenteral options may be the best choice for life- or limb-threatening thrombosis “because few such patients have been treated with a DOAC.” Anticoagulation must continue until platelet counts recover.

Dr. Cuker is a consultant for Synergy and has institutional research support from Alexion, Bayer, Sanofi, and other companies. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

The real strength of the 4T score for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is its negative predictive value, according to hematologist Adam Cuker, MD, of the department of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The score assigns patients points based on degree of thrombocytopenia, timing of platelet count fall in relation to heparin exposure, presence of thrombosis and other sequelae, and the likelihood of other causes of thrombocytopenia.

A low score – 3 points or less – has a negative predictive value of 99.8%, “so HIT is basically ruled out; you do not need to order lab testing for HIT or manage the patient empirically for HIT,” and should look for other causes of thrombocytopenia, said Dr. Cuker, lead author of the American Society of Hematology’s most recent HIT guidelines.

Intermediate scores of 4 or 5 points, and high scores of 6-8 points, are a different story. The positive predictive value of an intermediate score is only 14%, and of a high score, 64%, so although they don’t confirm the diagnosis, “you have to take the possibility of HIT seriously.” Discontinue heparin, start a nonheparin anticoagulant, and order a HIT immunoassay. If it’s positive, order a functional assay to confirm the diagnosis, he said.

Suspicion of HIT “is perhaps the most common consult that we get on the hematology service. These are tough consults because it is a high-stakes decision.” There is about a 6% risk of thromboembolism, amputation, and death for every day treatment is delayed. “On the other hand, the nonheparin anticoagulants are expensive, and they carry about a 1% daily risk of major bleeding,” Dr. Cuker explained during his presentation at the 2020 Update in Nonneoplastic Hematology virtual conference.

ELISA immunoassay detects antiplatelet factor 4 heparin antibodies but doesn’t tell whether or not they are able to activate platelets and cause HIT. Functional tests such as the serotonin-release assay detect only those antibodies able to do so, but the assays are difficult to perform, and often require samples to be sent out to a reference lab.

ASH did not specify a particular nonheparin anticoagulant in its 2018 guidelines because “the best choice for your patient” depends on which drugs you have available, your familiarity with them, and patient factors, Dr. Cuker said at the conference sponsored by MedscapeLive.

It makes sense, for instance, to use a short-acting agent such as argatroban or bivalirudin in patients who are critically ill, at high risk of bleeding, or likely to need an urgent unplanned procedure. Fondaparinux or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) make sense if patients are clinically stable with good organ function and no more than average bleeding risk, because they are easier to administer and facilitate transition to the outpatient setting.

DOACs are newcomers to ASH’s guidelines. Just 81 patients had been reported in the literature when they were being drafted, but only 2 patients had recurrence or progression of thromboembolic events, and there were no major bleeds. The results compared favorably with other options.

The studies were subject to selection and reporting biases, “but, nonetheless, the panel felt the results were positive enough that DOACs ought to be listed as an option,” Dr. Cuker said.

The guidelines note that parenteral options may be the best choice for life- or limb-threatening thrombosis “because few such patients have been treated with a DOAC.” Anticoagulation must continue until platelet counts recover.

Dr. Cuker is a consultant for Synergy and has institutional research support from Alexion, Bayer, Sanofi, and other companies. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM 2020 UNNH

Physicians react: Doctors worry about patients reading their clinical notes

Patients will soon be able to read the notes that physicians make during an episode of care, as well as information about diagnostic testing and imaging results, tests for STDs, fetal ultrasounds, and cancer biopsies. This open access is raising concerns among physicians.

As part of the 21st Century Cures Act, patients have the right to see their medical notes. Known as Open Notes, the policy will go into effect on April 5, 2021. The Department of Health & Human Services recently changed the original start date, which was to be Nov. 2, 2020.

The mandate has some physicians worrying about potential legal risks and possible violation of doctor-patient confidentiality. When asked to share their views on the new Open Notes mandate, many physicians expressed their concerns but also cited some of the positive effects that could come from this.

Potentially more legal woes for physicians?

A key concern raised by one physician commenter is that patients could misunderstand legitimate medical terminology or even put a physician in legal crosshairs. For example, a medical term such as “spontaneous abortion” could be misconstrued by patients. A physician might write notes with the idea that a patient is reading them and thus might alter those notes in a way that creates legal trouble.

“This layers another level of censorship and legal liability onto physicians, who in attempting to be [politically correct], may omit critical information or have to use euphemisms in order to avoid conflict,” one physician said.

She also questioned whether notes might now have to be run through legal counsel before being posted to avoid potential liability.

Another doctor questioned how physicians would be able to document patients suspected of faking injuries for pain medication, for example. Could such documentation lead to lawsuits for the doctor?

As one physician noted, some patients “are drug seekers. Some refuse to aid in their own care. Some are malingerers. Not documenting that is bad medicine.”

The possibility of violating doctor-patient confidentiality laws, particularly for teenagers, could be another negative effect of Open Notes, said one physician.

“Won’t this violate the statutes that teenagers have the right to confidential evaluations?” the commenter mused. “If charts are to be immediately available, then STDs and pregnancies they weren’t ready to talk about will now be suddenly known by their parents.”

One doctor has already faced this issue. “I already ran into this problem once,” he noted. “Now I warn those on their parents’ insurance before I start the visit. I have literally had a patient state, ‘well then we are done,’ and leave without being seen due to it.”

Another physician questioned the possibility of having to write notes differently than they do now, especially if the patients have lower reading comprehension abilities.

One physician who uses Open Notes said he receives patient requests for changes that have little to do with the actual diagnosis and relate to ancillary issues. He highlighted patients who “don’t want psych diagnosis in their chart or are concerned a diagnosis will raise their insurance premium, so they ask me to delete it.”

Will Open Notes erode patient communication?

One physician questioned whether it would lead to patients being less open and forthcoming about their medical concerns with doctors.

“The main problem I see is the patient not telling me the whole story, or worse, telling me the story, and then asking me not to document it (as many have done in the past) because they don’t want their spouse, family, etc. to read the notes and they have already given their permission for them to do so, for a variety of reasons,” he commented. “This includes topics of STDs, infidelity, depression, suicidal thoughts, and other symptoms the patient doesn’t want their family to read about.”

Some physicians envision positive developments

Many physicians are unconcerned by the new mandate. “I see some potential good in this, such as improving doctor-patient communication and more scrupulous charting,” one physician said.

A doctor working in the U.S. federal health care system noted that open access has been a part of that system for decades.

“Since health care providers work in this unveiled setting for their entire career, they usually know how to write appropriate clinical notes and what information needs to be included in them,” he wrote. “Now it’s time for the rest of the medical community to catch up to a reality that we have worked within for decades now.

“The world did not end, malpractice complaints did not increase, and physician/patient relationships were not damaged. Living in the information age, archaic practices like private notes were surely going to end at some point.”

One doctor who has been using Open Notes has had experiences in which the patient noted an error in the medical chart that needed correcting. “I have had one patient correct me on a timeline in the HPI which was helpful and I made the requested correction in that instance,” he said.

Another physician agreed. “I’ve had patients add or correct valuable information I’ve missed. Good probably outweighs the bad if we set limits on behaviors expressed by the personality disordered group. The majority of people don’t seem to care and still ask me ‘what would you do’ or ‘tell me what to do.’ It’s all about patient/physician trust.”

Another talked about how Open Notes should have little or no impact. “Here’s a novel concept – talking to our patients,” he commented. “There is nothing in every one of my chart notes that has not already been discussed with my patients and I dictate (speech to text) my findings and plan in front of them. So, if they are reviewing my office notes, it will only serve to reinforce what we have already discussed.”

“I don’t intend to change anything,” he added. “Chances are if they were to see a test result before I have a chance to discuss it with them, they will have already ‘Googled’ its meaning and we can have more meaningful interaction if they have a basic understanding of the test.”

“I understand that this is anxiety provoking, but in general I think it is appropriate for patients to have access to their notes,” said another physician. “If physicians write lousy notes that say they did things they didn’t do, that fail to actually state a diagnosis and a plan (and they often do), that is the doc’s problem, not the patient’s.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients will soon be able to read the notes that physicians make during an episode of care, as well as information about diagnostic testing and imaging results, tests for STDs, fetal ultrasounds, and cancer biopsies. This open access is raising concerns among physicians.

As part of the 21st Century Cures Act, patients have the right to see their medical notes. Known as Open Notes, the policy will go into effect on April 5, 2021. The Department of Health & Human Services recently changed the original start date, which was to be Nov. 2, 2020.

The mandate has some physicians worrying about potential legal risks and possible violation of doctor-patient confidentiality. When asked to share their views on the new Open Notes mandate, many physicians expressed their concerns but also cited some of the positive effects that could come from this.

Potentially more legal woes for physicians?

A key concern raised by one physician commenter is that patients could misunderstand legitimate medical terminology or even put a physician in legal crosshairs. For example, a medical term such as “spontaneous abortion” could be misconstrued by patients. A physician might write notes with the idea that a patient is reading them and thus might alter those notes in a way that creates legal trouble.

“This layers another level of censorship and legal liability onto physicians, who in attempting to be [politically correct], may omit critical information or have to use euphemisms in order to avoid conflict,” one physician said.

She also questioned whether notes might now have to be run through legal counsel before being posted to avoid potential liability.

Another doctor questioned how physicians would be able to document patients suspected of faking injuries for pain medication, for example. Could such documentation lead to lawsuits for the doctor?

As one physician noted, some patients “are drug seekers. Some refuse to aid in their own care. Some are malingerers. Not documenting that is bad medicine.”

The possibility of violating doctor-patient confidentiality laws, particularly for teenagers, could be another negative effect of Open Notes, said one physician.

“Won’t this violate the statutes that teenagers have the right to confidential evaluations?” the commenter mused. “If charts are to be immediately available, then STDs and pregnancies they weren’t ready to talk about will now be suddenly known by their parents.”

One doctor has already faced this issue. “I already ran into this problem once,” he noted. “Now I warn those on their parents’ insurance before I start the visit. I have literally had a patient state, ‘well then we are done,’ and leave without being seen due to it.”

Another physician questioned the possibility of having to write notes differently than they do now, especially if the patients have lower reading comprehension abilities.

One physician who uses Open Notes said he receives patient requests for changes that have little to do with the actual diagnosis and relate to ancillary issues. He highlighted patients who “don’t want psych diagnosis in their chart or are concerned a diagnosis will raise their insurance premium, so they ask me to delete it.”

Will Open Notes erode patient communication?

One physician questioned whether it would lead to patients being less open and forthcoming about their medical concerns with doctors.

“The main problem I see is the patient not telling me the whole story, or worse, telling me the story, and then asking me not to document it (as many have done in the past) because they don’t want their spouse, family, etc. to read the notes and they have already given their permission for them to do so, for a variety of reasons,” he commented. “This includes topics of STDs, infidelity, depression, suicidal thoughts, and other symptoms the patient doesn’t want their family to read about.”

Some physicians envision positive developments

Many physicians are unconcerned by the new mandate. “I see some potential good in this, such as improving doctor-patient communication and more scrupulous charting,” one physician said.

A doctor working in the U.S. federal health care system noted that open access has been a part of that system for decades.

“Since health care providers work in this unveiled setting for their entire career, they usually know how to write appropriate clinical notes and what information needs to be included in them,” he wrote. “Now it’s time for the rest of the medical community to catch up to a reality that we have worked within for decades now.

“The world did not end, malpractice complaints did not increase, and physician/patient relationships were not damaged. Living in the information age, archaic practices like private notes were surely going to end at some point.”

One doctor who has been using Open Notes has had experiences in which the patient noted an error in the medical chart that needed correcting. “I have had one patient correct me on a timeline in the HPI which was helpful and I made the requested correction in that instance,” he said.

Another physician agreed. “I’ve had patients add or correct valuable information I’ve missed. Good probably outweighs the bad if we set limits on behaviors expressed by the personality disordered group. The majority of people don’t seem to care and still ask me ‘what would you do’ or ‘tell me what to do.’ It’s all about patient/physician trust.”

Another talked about how Open Notes should have little or no impact. “Here’s a novel concept – talking to our patients,” he commented. “There is nothing in every one of my chart notes that has not already been discussed with my patients and I dictate (speech to text) my findings and plan in front of them. So, if they are reviewing my office notes, it will only serve to reinforce what we have already discussed.”

“I don’t intend to change anything,” he added. “Chances are if they were to see a test result before I have a chance to discuss it with them, they will have already ‘Googled’ its meaning and we can have more meaningful interaction if they have a basic understanding of the test.”

“I understand that this is anxiety provoking, but in general I think it is appropriate for patients to have access to their notes,” said another physician. “If physicians write lousy notes that say they did things they didn’t do, that fail to actually state a diagnosis and a plan (and they often do), that is the doc’s problem, not the patient’s.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients will soon be able to read the notes that physicians make during an episode of care, as well as information about diagnostic testing and imaging results, tests for STDs, fetal ultrasounds, and cancer biopsies. This open access is raising concerns among physicians.

As part of the 21st Century Cures Act, patients have the right to see their medical notes. Known as Open Notes, the policy will go into effect on April 5, 2021. The Department of Health & Human Services recently changed the original start date, which was to be Nov. 2, 2020.

The mandate has some physicians worrying about potential legal risks and possible violation of doctor-patient confidentiality. When asked to share their views on the new Open Notes mandate, many physicians expressed their concerns but also cited some of the positive effects that could come from this.

Potentially more legal woes for physicians?

A key concern raised by one physician commenter is that patients could misunderstand legitimate medical terminology or even put a physician in legal crosshairs. For example, a medical term such as “spontaneous abortion” could be misconstrued by patients. A physician might write notes with the idea that a patient is reading them and thus might alter those notes in a way that creates legal trouble.

“This layers another level of censorship and legal liability onto physicians, who in attempting to be [politically correct], may omit critical information or have to use euphemisms in order to avoid conflict,” one physician said.

She also questioned whether notes might now have to be run through legal counsel before being posted to avoid potential liability.

Another doctor questioned how physicians would be able to document patients suspected of faking injuries for pain medication, for example. Could such documentation lead to lawsuits for the doctor?

As one physician noted, some patients “are drug seekers. Some refuse to aid in their own care. Some are malingerers. Not documenting that is bad medicine.”

The possibility of violating doctor-patient confidentiality laws, particularly for teenagers, could be another negative effect of Open Notes, said one physician.

“Won’t this violate the statutes that teenagers have the right to confidential evaluations?” the commenter mused. “If charts are to be immediately available, then STDs and pregnancies they weren’t ready to talk about will now be suddenly known by their parents.”

One doctor has already faced this issue. “I already ran into this problem once,” he noted. “Now I warn those on their parents’ insurance before I start the visit. I have literally had a patient state, ‘well then we are done,’ and leave without being seen due to it.”

Another physician questioned the possibility of having to write notes differently than they do now, especially if the patients have lower reading comprehension abilities.

One physician who uses Open Notes said he receives patient requests for changes that have little to do with the actual diagnosis and relate to ancillary issues. He highlighted patients who “don’t want psych diagnosis in their chart or are concerned a diagnosis will raise their insurance premium, so they ask me to delete it.”

Will Open Notes erode patient communication?

One physician questioned whether it would lead to patients being less open and forthcoming about their medical concerns with doctors.

“The main problem I see is the patient not telling me the whole story, or worse, telling me the story, and then asking me not to document it (as many have done in the past) because they don’t want their spouse, family, etc. to read the notes and they have already given their permission for them to do so, for a variety of reasons,” he commented. “This includes topics of STDs, infidelity, depression, suicidal thoughts, and other symptoms the patient doesn’t want their family to read about.”

Some physicians envision positive developments

Many physicians are unconcerned by the new mandate. “I see some potential good in this, such as improving doctor-patient communication and more scrupulous charting,” one physician said.

A doctor working in the U.S. federal health care system noted that open access has been a part of that system for decades.

“Since health care providers work in this unveiled setting for their entire career, they usually know how to write appropriate clinical notes and what information needs to be included in them,” he wrote. “Now it’s time for the rest of the medical community to catch up to a reality that we have worked within for decades now.

“The world did not end, malpractice complaints did not increase, and physician/patient relationships were not damaged. Living in the information age, archaic practices like private notes were surely going to end at some point.”

One doctor who has been using Open Notes has had experiences in which the patient noted an error in the medical chart that needed correcting. “I have had one patient correct me on a timeline in the HPI which was helpful and I made the requested correction in that instance,” he said.

Another physician agreed. “I’ve had patients add or correct valuable information I’ve missed. Good probably outweighs the bad if we set limits on behaviors expressed by the personality disordered group. The majority of people don’t seem to care and still ask me ‘what would you do’ or ‘tell me what to do.’ It’s all about patient/physician trust.”

Another talked about how Open Notes should have little or no impact. “Here’s a novel concept – talking to our patients,” he commented. “There is nothing in every one of my chart notes that has not already been discussed with my patients and I dictate (speech to text) my findings and plan in front of them. So, if they are reviewing my office notes, it will only serve to reinforce what we have already discussed.”

“I don’t intend to change anything,” he added. “Chances are if they were to see a test result before I have a chance to discuss it with them, they will have already ‘Googled’ its meaning and we can have more meaningful interaction if they have a basic understanding of the test.”

“I understand that this is anxiety provoking, but in general I think it is appropriate for patients to have access to their notes,” said another physician. “If physicians write lousy notes that say they did things they didn’t do, that fail to actually state a diagnosis and a plan (and they often do), that is the doc’s problem, not the patient’s.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Updated ACC decision pathway embraces new heart failure treatment strategies

A newly updated expert consensus from the American College of Cardiology for management of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction includes several new guideline-directed medical therapies among other substantial changes relative to its 2017 predecessor.

The advances in treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) have resulted in a substantial increase in complexity in reaching treatment goals, according to the authors of the new guidance. Structured similarly to the 2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway, the update accommodates a series of practical tips to bring all patients on board with the newer as well as the established therapies with lifesaving potential.

The potential return from implementing these recommendations is not trivial. Relative to an ACE inhibitor and a beta-blocker alone, optimal implementation of the current guideline-directed medical therapies (GDMT) “can extend medical survival by more than 6 years,” according to Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, chief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

A member of the writing committee for the 2021 update, Dr. Fonarow explained that the consensus pathway is more than a list of therapies and recommended doses. The detailed advice on how to overcome the barriers to GDMT is meant to close the substantial gap between current practice and unmet opportunities for inhibiting HFrEF progression.

“Optimal GDMT among HFrEF patients is distressingly low, due in part to the number and complexity of medications that now constitute GDMT,” said the chair of the writing committee, Thomas M. Maddox, MD, executive director, Healthcare Innovation Lab, BJC HealthCare/Washington University, St. Louis. Like Dr. Fonarow, Dr. Maddox emphasized that the importance of the update for the practical strategies it offers to place patients on optimal care.

In the 2017 guidance, 10 pivotal issues were tackled, ranging from advice of how to put HFrEF patients on the multiple drugs that now constitute optimal therapy to when to transition patients to hospice care. The 2021 update covers the same ground but incorporates new information that has changed the definition of optimal care.

Perhaps most importantly, sacubitril/valsartan, an angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNi), and SGLT2 inhibitors represent major new additions in HFrEF GDMT. Dr. Maddox called the practical information about how these should be incorporated into HFrEF management represents one of the “major highlights” of the update.

Two algorithms outline the expert consensus recommendations of the order and the dose of the multiple drugs that now constitute the current GDMT. With the goal of explaining exactly how to place patients on all the HFrEF therapies associated with improved outcome, “I think these figures can really help us in guiding our patients to optimal medication regimens and dosages,” Dr. Maddox said. If successful, clinicians “can make a significant difference in these patients’ length and quality of life.”

Most cardiologists and others who treat HFrEF are likely aware of the major improvements in outcome documented in large trials when an ARNi and a SGLT2 inhibitor were added to previously established GDMT, but the update like the 2017 document is focused on the practical strategies of implementation, according to Larry A. Allen, MD, medical director of advanced heart failure at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

“The 2017 Expert Consensus Decision Pathway got a lot of attention because it takes a very practical approach to questions that clinicians and their patients have to tackle everyday but for which there was not always clean answers from the data,” said Dr. Allen, a member of the writing committee for both the 2017 expert consensus and the 2021 update. He noted that the earlier document was one of the most downloaded articles from the ACC’s journal in the year it appeared.

“There is excellent data on the benefits of beta-blockers, ARNi, mineralocorticoid antagonists, and SGLT2 inhibitors, but how does one decide what order to use them in?” Dr. Allen asked in outlining goals of the expert consensus.

While the new update “focuses on the newer drug classes, particularly SGLT2 inhibitors,” it traces care from first-line therapies to end-of-life management, according to Dr. Allen. This includes information on when to consider advanced therapies, such as left ventricular assist devices or transplant in order to get patients to these treatments before the opportunity for benefit is missed.

Both the 2017 version and the update offer a table to summarize triggers for referral. The complexity of individualizing care in a group of patients likely to have variable manifestations of disease and multiple comorbidities was a theme of the 2017 document that has been reprised in the 2021 update,

“Good communication and team-based care” is one of common management gaps that the update addresses, Dr. Allen said. He indicated that the checklists and algorithms in the update would help with complex decision-making and encourage the multidisciplinary care that ensures optimal management.

SOURCE: Maddox TM et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 Jan 11. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.022.

A newly updated expert consensus from the American College of Cardiology for management of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction includes several new guideline-directed medical therapies among other substantial changes relative to its 2017 predecessor.

The advances in treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) have resulted in a substantial increase in complexity in reaching treatment goals, according to the authors of the new guidance. Structured similarly to the 2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway, the update accommodates a series of practical tips to bring all patients on board with the newer as well as the established therapies with lifesaving potential.

The potential return from implementing these recommendations is not trivial. Relative to an ACE inhibitor and a beta-blocker alone, optimal implementation of the current guideline-directed medical therapies (GDMT) “can extend medical survival by more than 6 years,” according to Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, chief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

A member of the writing committee for the 2021 update, Dr. Fonarow explained that the consensus pathway is more than a list of therapies and recommended doses. The detailed advice on how to overcome the barriers to GDMT is meant to close the substantial gap between current practice and unmet opportunities for inhibiting HFrEF progression.

“Optimal GDMT among HFrEF patients is distressingly low, due in part to the number and complexity of medications that now constitute GDMT,” said the chair of the writing committee, Thomas M. Maddox, MD, executive director, Healthcare Innovation Lab, BJC HealthCare/Washington University, St. Louis. Like Dr. Fonarow, Dr. Maddox emphasized that the importance of the update for the practical strategies it offers to place patients on optimal care.

In the 2017 guidance, 10 pivotal issues were tackled, ranging from advice of how to put HFrEF patients on the multiple drugs that now constitute optimal therapy to when to transition patients to hospice care. The 2021 update covers the same ground but incorporates new information that has changed the definition of optimal care.

Perhaps most importantly, sacubitril/valsartan, an angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNi), and SGLT2 inhibitors represent major new additions in HFrEF GDMT. Dr. Maddox called the practical information about how these should be incorporated into HFrEF management represents one of the “major highlights” of the update.

Two algorithms outline the expert consensus recommendations of the order and the dose of the multiple drugs that now constitute the current GDMT. With the goal of explaining exactly how to place patients on all the HFrEF therapies associated with improved outcome, “I think these figures can really help us in guiding our patients to optimal medication regimens and dosages,” Dr. Maddox said. If successful, clinicians “can make a significant difference in these patients’ length and quality of life.”

Most cardiologists and others who treat HFrEF are likely aware of the major improvements in outcome documented in large trials when an ARNi and a SGLT2 inhibitor were added to previously established GDMT, but the update like the 2017 document is focused on the practical strategies of implementation, according to Larry A. Allen, MD, medical director of advanced heart failure at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

“The 2017 Expert Consensus Decision Pathway got a lot of attention because it takes a very practical approach to questions that clinicians and their patients have to tackle everyday but for which there was not always clean answers from the data,” said Dr. Allen, a member of the writing committee for both the 2017 expert consensus and the 2021 update. He noted that the earlier document was one of the most downloaded articles from the ACC’s journal in the year it appeared.

“There is excellent data on the benefits of beta-blockers, ARNi, mineralocorticoid antagonists, and SGLT2 inhibitors, but how does one decide what order to use them in?” Dr. Allen asked in outlining goals of the expert consensus.

While the new update “focuses on the newer drug classes, particularly SGLT2 inhibitors,” it traces care from first-line therapies to end-of-life management, according to Dr. Allen. This includes information on when to consider advanced therapies, such as left ventricular assist devices or transplant in order to get patients to these treatments before the opportunity for benefit is missed.

Both the 2017 version and the update offer a table to summarize triggers for referral. The complexity of individualizing care in a group of patients likely to have variable manifestations of disease and multiple comorbidities was a theme of the 2017 document that has been reprised in the 2021 update,

“Good communication and team-based care” is one of common management gaps that the update addresses, Dr. Allen said. He indicated that the checklists and algorithms in the update would help with complex decision-making and encourage the multidisciplinary care that ensures optimal management.

SOURCE: Maddox TM et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 Jan 11. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.022.

A newly updated expert consensus from the American College of Cardiology for management of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction includes several new guideline-directed medical therapies among other substantial changes relative to its 2017 predecessor.

The advances in treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) have resulted in a substantial increase in complexity in reaching treatment goals, according to the authors of the new guidance. Structured similarly to the 2017 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway, the update accommodates a series of practical tips to bring all patients on board with the newer as well as the established therapies with lifesaving potential.

The potential return from implementing these recommendations is not trivial. Relative to an ACE inhibitor and a beta-blocker alone, optimal implementation of the current guideline-directed medical therapies (GDMT) “can extend medical survival by more than 6 years,” according to Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, chief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

A member of the writing committee for the 2021 update, Dr. Fonarow explained that the consensus pathway is more than a list of therapies and recommended doses. The detailed advice on how to overcome the barriers to GDMT is meant to close the substantial gap between current practice and unmet opportunities for inhibiting HFrEF progression.

“Optimal GDMT among HFrEF patients is distressingly low, due in part to the number and complexity of medications that now constitute GDMT,” said the chair of the writing committee, Thomas M. Maddox, MD, executive director, Healthcare Innovation Lab, BJC HealthCare/Washington University, St. Louis. Like Dr. Fonarow, Dr. Maddox emphasized that the importance of the update for the practical strategies it offers to place patients on optimal care.

In the 2017 guidance, 10 pivotal issues were tackled, ranging from advice of how to put HFrEF patients on the multiple drugs that now constitute optimal therapy to when to transition patients to hospice care. The 2021 update covers the same ground but incorporates new information that has changed the definition of optimal care.

Perhaps most importantly, sacubitril/valsartan, an angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNi), and SGLT2 inhibitors represent major new additions in HFrEF GDMT. Dr. Maddox called the practical information about how these should be incorporated into HFrEF management represents one of the “major highlights” of the update.

Two algorithms outline the expert consensus recommendations of the order and the dose of the multiple drugs that now constitute the current GDMT. With the goal of explaining exactly how to place patients on all the HFrEF therapies associated with improved outcome, “I think these figures can really help us in guiding our patients to optimal medication regimens and dosages,” Dr. Maddox said. If successful, clinicians “can make a significant difference in these patients’ length and quality of life.”

Most cardiologists and others who treat HFrEF are likely aware of the major improvements in outcome documented in large trials when an ARNi and a SGLT2 inhibitor were added to previously established GDMT, but the update like the 2017 document is focused on the practical strategies of implementation, according to Larry A. Allen, MD, medical director of advanced heart failure at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

“The 2017 Expert Consensus Decision Pathway got a lot of attention because it takes a very practical approach to questions that clinicians and their patients have to tackle everyday but for which there was not always clean answers from the data,” said Dr. Allen, a member of the writing committee for both the 2017 expert consensus and the 2021 update. He noted that the earlier document was one of the most downloaded articles from the ACC’s journal in the year it appeared.

“There is excellent data on the benefits of beta-blockers, ARNi, mineralocorticoid antagonists, and SGLT2 inhibitors, but how does one decide what order to use them in?” Dr. Allen asked in outlining goals of the expert consensus.

While the new update “focuses on the newer drug classes, particularly SGLT2 inhibitors,” it traces care from first-line therapies to end-of-life management, according to Dr. Allen. This includes information on when to consider advanced therapies, such as left ventricular assist devices or transplant in order to get patients to these treatments before the opportunity for benefit is missed.

Both the 2017 version and the update offer a table to summarize triggers for referral. The complexity of individualizing care in a group of patients likely to have variable manifestations of disease and multiple comorbidities was a theme of the 2017 document that has been reprised in the 2021 update,

“Good communication and team-based care” is one of common management gaps that the update addresses, Dr. Allen said. He indicated that the checklists and algorithms in the update would help with complex decision-making and encourage the multidisciplinary care that ensures optimal management.

SOURCE: Maddox TM et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 Jan 11. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.022.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Complications and death within 30 days after noncardiac surgery

Background: There have been advances in perioperative care and technology for adults, but at the same time the patient population is increasingly medically complex. We do not know the current mortality risk of noncardiac surgery in adults.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Twenty-eight academic centers in 14 countries in North America, South America, Asia, Europe, Africa, and Australia. At least four academic centers represented each of these continents, except Africa, with one center reporting there.

Synopsis: The VISION study included 40,004 inpatients, aged 45 years and older, followed for 30-day mortality after noncardiac surgery. One-third of surgeries were considered low risk. A startling 99.1% of patients completed the study. Mortality rate was 1.8%, with 71% of patients dying during the index admission and 29% dying after discharge.

Nine events were independently associated with postoperative death, but the top three – major bleeding, myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery (MINS), and sepsis – accounted for 45% of the attributable fraction. These, on average, occurred within 1-6 days after surgery. The other events (infection, kidney injury with dialysis, stroke, venous thromboembolism, new atrial fibrillation, and congestive heart failure) constituted less than 3% of the attributable fraction. Findings suggest that closer monitoring in the hospital and post discharge might improve survival after noncardiac surgery.

Limitations for hospitalists include that patients were younger and less medically complex than our typically comanaged patients: More than half of patients were aged 45-64, less than 10% had chronic kidney disease stage 3b or greater, and only 20% had diabetes mellitus.

Bottom line: Postoperative and postdischarge bleeding, myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery, and sepsis are major risk factors for 30-day mortality in adults undergoing noncardiac surgery. Closer postoperative monitoring for these conditions should be explored.

Citation: The Vision Study Investigators (Spence J et al.) Association between complications and death within 30 days after noncardiac surgery. CMAJ. 2019 Jul 29;191(30):E830-7.

Dr. Brouillette is a med-peds hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland.

Background: There have been advances in perioperative care and technology for adults, but at the same time the patient population is increasingly medically complex. We do not know the current mortality risk of noncardiac surgery in adults.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Twenty-eight academic centers in 14 countries in North America, South America, Asia, Europe, Africa, and Australia. At least four academic centers represented each of these continents, except Africa, with one center reporting there.

Synopsis: The VISION study included 40,004 inpatients, aged 45 years and older, followed for 30-day mortality after noncardiac surgery. One-third of surgeries were considered low risk. A startling 99.1% of patients completed the study. Mortality rate was 1.8%, with 71% of patients dying during the index admission and 29% dying after discharge.

Nine events were independently associated with postoperative death, but the top three – major bleeding, myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery (MINS), and sepsis – accounted for 45% of the attributable fraction. These, on average, occurred within 1-6 days after surgery. The other events (infection, kidney injury with dialysis, stroke, venous thromboembolism, new atrial fibrillation, and congestive heart failure) constituted less than 3% of the attributable fraction. Findings suggest that closer monitoring in the hospital and post discharge might improve survival after noncardiac surgery.

Limitations for hospitalists include that patients were younger and less medically complex than our typically comanaged patients: More than half of patients were aged 45-64, less than 10% had chronic kidney disease stage 3b or greater, and only 20% had diabetes mellitus.

Bottom line: Postoperative and postdischarge bleeding, myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery, and sepsis are major risk factors for 30-day mortality in adults undergoing noncardiac surgery. Closer postoperative monitoring for these conditions should be explored.

Citation: The Vision Study Investigators (Spence J et al.) Association between complications and death within 30 days after noncardiac surgery. CMAJ. 2019 Jul 29;191(30):E830-7.

Dr. Brouillette is a med-peds hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland.

Background: There have been advances in perioperative care and technology for adults, but at the same time the patient population is increasingly medically complex. We do not know the current mortality risk of noncardiac surgery in adults.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Twenty-eight academic centers in 14 countries in North America, South America, Asia, Europe, Africa, and Australia. At least four academic centers represented each of these continents, except Africa, with one center reporting there.

Synopsis: The VISION study included 40,004 inpatients, aged 45 years and older, followed for 30-day mortality after noncardiac surgery. One-third of surgeries were considered low risk. A startling 99.1% of patients completed the study. Mortality rate was 1.8%, with 71% of patients dying during the index admission and 29% dying after discharge.

Nine events were independently associated with postoperative death, but the top three – major bleeding, myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery (MINS), and sepsis – accounted for 45% of the attributable fraction. These, on average, occurred within 1-6 days after surgery. The other events (infection, kidney injury with dialysis, stroke, venous thromboembolism, new atrial fibrillation, and congestive heart failure) constituted less than 3% of the attributable fraction. Findings suggest that closer monitoring in the hospital and post discharge might improve survival after noncardiac surgery.

Limitations for hospitalists include that patients were younger and less medically complex than our typically comanaged patients: More than half of patients were aged 45-64, less than 10% had chronic kidney disease stage 3b or greater, and only 20% had diabetes mellitus.

Bottom line: Postoperative and postdischarge bleeding, myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery, and sepsis are major risk factors for 30-day mortality in adults undergoing noncardiac surgery. Closer postoperative monitoring for these conditions should be explored.

Citation: The Vision Study Investigators (Spence J et al.) Association between complications and death within 30 days after noncardiac surgery. CMAJ. 2019 Jul 29;191(30):E830-7.

Dr. Brouillette is a med-peds hospitalist at Maine Medical Center in Portland.

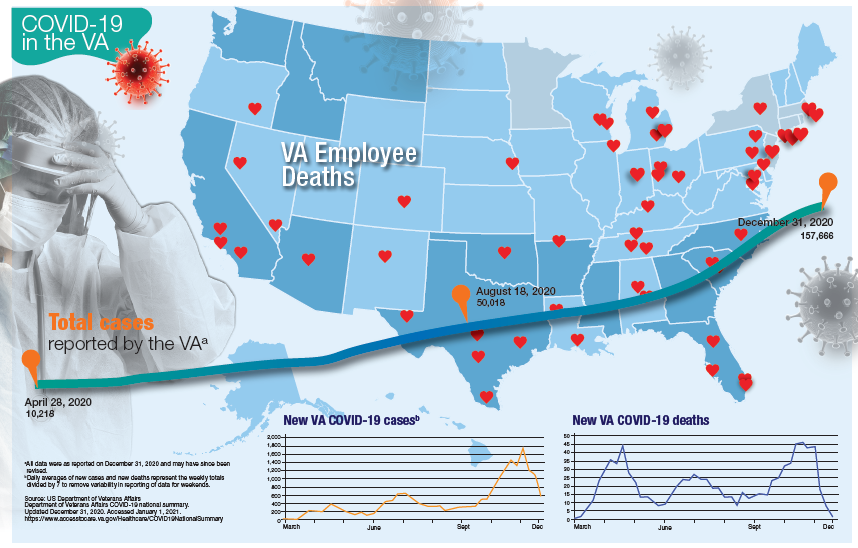

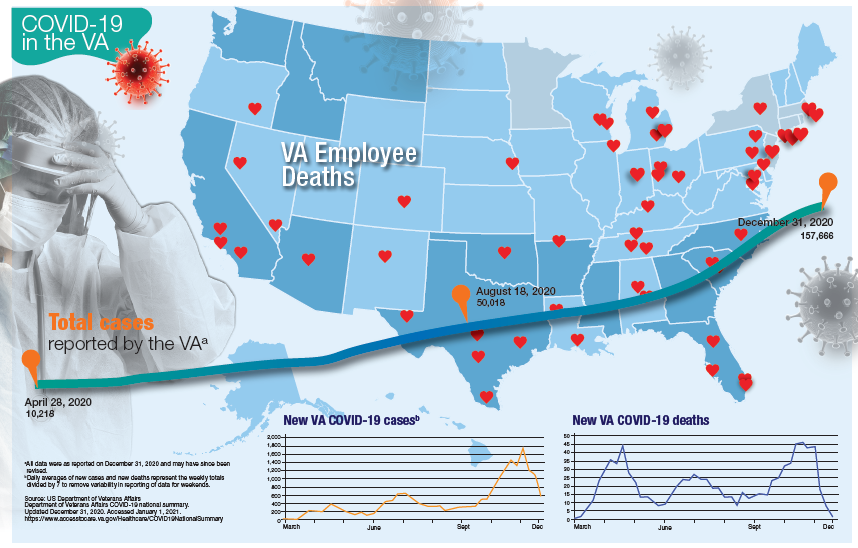

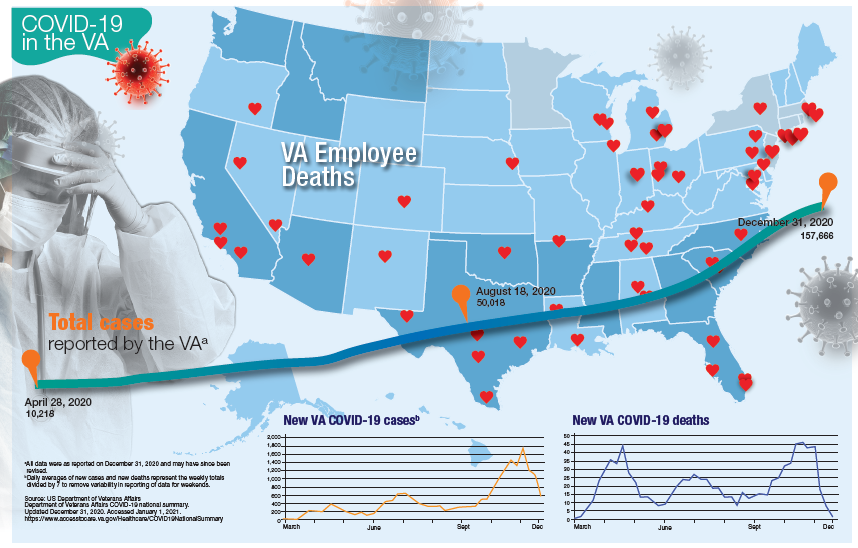

VA Ramps up Vaccinations as COVID-19 Cases Continue to Rise

Updated January 12, 2020

More than 181,000 veterans have contracted the COVID-19 virus and 7,385 have died, according to data released by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) on January 12, 2020. The number of cases and deaths have increased sharply since November 2020. The VA also reports that it has administered at least 1 dose of the 2 approved vaccines to 33,875 veterans and 174,724 employees as of January 6.

Currently, the VA reports nearly 19,000 active cases of COVID-19, including 1,270 among VA employees. One hundred five VA employees have died from COVID-19.

Although facilities across the country are facing increased pressure as the number of cases rise, those in Southern California and Texas are reporting significant infection rates. Thirteen facilities have at least 300 active cases, including facilities in Loma Linda (418), Long Beach (381), Greater Los Angeles (361), and San Diego (274), all in California. In Texas, San Antonio (394), Dallas (370), Temple (338), and Houston (328) have all seen large numbers of active cases. Facilities in Columbia, South Carolina (420); Phoenix (407); Atlanta, Georgia (359); Cleveland, Ohio (352); and Orlando, (341) and Gainesville, Florida (340) also have reported significant numbers of cases.

While early on in the pandemic facilities in New York and New Jersey had reported the largest number of deaths, now nearly every facility has reported at least 1 death. Fourteen facilities have reported at least 100 deaths and 53 have reported between 50 and 99 deaths. The 7,385 VA COVID-19 deaths represent 2.0% of the 375,300 deaths reported in the US by Johns Hopkins University. VA has reported 0.8% of the total number of COVID-19 cases.

The VA also reports the demographic breakdown of its COVID-19 cases. Among the active cases, 56.9% are White, 18.3% Black, 9.4% Hispanic, and 1.4% Native American, Alaska Native, or Pacific Islander.

Updated January 12, 2020

More than 181,000 veterans have contracted the COVID-19 virus and 7,385 have died, according to data released by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) on January 12, 2020. The number of cases and deaths have increased sharply since November 2020. The VA also reports that it has administered at least 1 dose of the 2 approved vaccines to 33,875 veterans and 174,724 employees as of January 6.

Currently, the VA reports nearly 19,000 active cases of COVID-19, including 1,270 among VA employees. One hundred five VA employees have died from COVID-19.

Although facilities across the country are facing increased pressure as the number of cases rise, those in Southern California and Texas are reporting significant infection rates. Thirteen facilities have at least 300 active cases, including facilities in Loma Linda (418), Long Beach (381), Greater Los Angeles (361), and San Diego (274), all in California. In Texas, San Antonio (394), Dallas (370), Temple (338), and Houston (328) have all seen large numbers of active cases. Facilities in Columbia, South Carolina (420); Phoenix (407); Atlanta, Georgia (359); Cleveland, Ohio (352); and Orlando, (341) and Gainesville, Florida (340) also have reported significant numbers of cases.

While early on in the pandemic facilities in New York and New Jersey had reported the largest number of deaths, now nearly every facility has reported at least 1 death. Fourteen facilities have reported at least 100 deaths and 53 have reported between 50 and 99 deaths. The 7,385 VA COVID-19 deaths represent 2.0% of the 375,300 deaths reported in the US by Johns Hopkins University. VA has reported 0.8% of the total number of COVID-19 cases.

The VA also reports the demographic breakdown of its COVID-19 cases. Among the active cases, 56.9% are White, 18.3% Black, 9.4% Hispanic, and 1.4% Native American, Alaska Native, or Pacific Islander.

Updated January 12, 2020

More than 181,000 veterans have contracted the COVID-19 virus and 7,385 have died, according to data released by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) on January 12, 2020. The number of cases and deaths have increased sharply since November 2020. The VA also reports that it has administered at least 1 dose of the 2 approved vaccines to 33,875 veterans and 174,724 employees as of January 6.

Currently, the VA reports nearly 19,000 active cases of COVID-19, including 1,270 among VA employees. One hundred five VA employees have died from COVID-19.

Although facilities across the country are facing increased pressure as the number of cases rise, those in Southern California and Texas are reporting significant infection rates. Thirteen facilities have at least 300 active cases, including facilities in Loma Linda (418), Long Beach (381), Greater Los Angeles (361), and San Diego (274), all in California. In Texas, San Antonio (394), Dallas (370), Temple (338), and Houston (328) have all seen large numbers of active cases. Facilities in Columbia, South Carolina (420); Phoenix (407); Atlanta, Georgia (359); Cleveland, Ohio (352); and Orlando, (341) and Gainesville, Florida (340) also have reported significant numbers of cases.

While early on in the pandemic facilities in New York and New Jersey had reported the largest number of deaths, now nearly every facility has reported at least 1 death. Fourteen facilities have reported at least 100 deaths and 53 have reported between 50 and 99 deaths. The 7,385 VA COVID-19 deaths represent 2.0% of the 375,300 deaths reported in the US by Johns Hopkins University. VA has reported 0.8% of the total number of COVID-19 cases.

The VA also reports the demographic breakdown of its COVID-19 cases. Among the active cases, 56.9% are White, 18.3% Black, 9.4% Hispanic, and 1.4% Native American, Alaska Native, or Pacific Islander.

Over half of COVID-19 transmission may occur via asymptomatic people

As COVID-19 cases surge and vaccinations lag, health authorities continue to seek additional ways to mitigate the spread of the novel coronavirus.

Now, a modeling study estimates that more than half of transmissions come from pre-, never-, and asymptomatic individuals, indicating that symptom-based screening will have little effect on spread.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study, published online Jan. 7 in JAMA Network Open, concludes that for optimal control, protective measures such as masking and social distancing should be supplemented with strategic testing of potentially exposed but asymptomatic individuals .

“In the absence of effective and widespread use of therapeutics or vaccines that can shorten or eliminate infectivity, successful control of SARS-CoV-2 cannot rely solely on identifying and isolating symptomatic cases; even if implemented effectively, this strategy would be insufficient,” CDC biologist Michael J. Johansson, PhD, and colleagues warn. “Multiple measures that effectively address transmission risk in the absence of symptoms are imperative to control SARS-CoV-2.”

According to the authors, the effectiveness of some current transmission prevention efforts has been disputed and subject to mixed messaging. Therefore, they decided to model the proportion of COVID-19 infections that are likely the result of individuals who show no symptoms and may be unknowingly infecting others.

“Unfortunately, there continues to be some skepticism about the value of community-wide mitigation efforts for preventing transmission such as masking, distancing, and hand hygiene, particularly for people without symptoms,” corresponding author Jay C. Butler, MD, said in an interview. “So we wanted to have a base assumption about how much transmission occurs from asymptomatic people to underscore the importance of mitigation measures and of creating immunity through vaccine delivery.”

Such a yardstick is especially germane in the context of the new, more transmissible variant. “It really puts [things] in a bigger box and underscores, boldfaces, and italicizes the need to change people’s behaviors and the importance of mitigation,” Dr. Butler said. It also highlights the advisability of targeted strategic testing in congregate settings, schools, and universities, which is already underway.

The analysis

Based on data from several COVID-19 studies from last year, the CDC’s analytical model assumes at baseline that infectiousness peaks at the median point of symptom onset, and that 30% of infected individuals never develop symptoms but are nevertheless 75% as infectious as those who develop overt symptoms.

The investigators then model multiple scenarios of transmission based pre- and never-symptomatic individuals, assuming different incubation and infectious periods, and varying numbers of days from point of infection to symptom onset.

When combined, the models predicts that 59% of all transmission would come from asymptomatic transmission – 35% from presymptomatic individuals and 24% from never-symptomatic individuals.

The findings complement those of an earlier CDC analysis, according to the authors.

The overall proportion of transmission from presymptomatic and never-symptomatic individuals is key to identifying mitigation measures that may be able to control SARS-CoV-2, the authors stated.

For example, they explain, if the infection reproduction number (R) in a particular setting is 2.0, a reduction in transmission of at least 50% is needed in order to reduce R to below 1.0. “Given that in some settings R is likely much greater than 2 and more than half of transmissions may come from individuals who are asymptomatic at the time of transmission, effective control must mitigate transmission risk from people without symptoms,” they wrote.

The authors acknowledge that the study applies a simplistic model to a complex and evolving phenomenon, and that the exact proportions of presymptomatic and never-symptomatic transmission and the incubation periods are not known. They also note symptoms and transmissions appear to vary across different population groups, with older individuals more likely than younger persons to experience symptoms, according to previous studies.

“Assume that everyone is potentially infected”

Other experts agree that expanded testing of asymptomatic individuals is important. “Screening for fever and isolation of symptomatic individuals is a common-sense approach to help prevent spread, but these measures are by no means adequate since it’s been clearly documented that individuals who are either asymptomatic or presymptomatic can still spread the virus,” said Brett Williams, MD, an infectious disease specialist and assistant professor of medicine at Rush University in Chicago.

“As we saw with the White House Rose Garden superspreader outbreak, testing does not reliably exclude infection either because the tested individual has not yet become positive or the test is falsely negative,” Dr. Williams, who was not involved in the CDC study, said in an interview. He further noted that when prevalence is as high as it currently is in the United States, the rate of false negatives will be high because a large proportion of those screened will be unknowingly infected.

At his center, all visitors and staff are screened with a temperature probe on entry, and since the earliest days of the pandemic, universal masking has been required. “Nationally there have been many instances of hospital break room outbreaks because of staff eating lunch together, and these outbreaks also demonstrate the incompleteness of symptomatic isolation,” Dr. Williams said.

For his part, virologist Frank Esper, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the Cleveland Clinic, said that while it’s been understood for some time that many infected people will not exhibit symptoms, “the question that remains is just how infectious are they?”

Dr. Esper’s takeaway from the modeling study is not so much that we need more screening of possibly exposed but asymptomatic people, but rather testing symptomatic people and tracing their contacts is not enough.

“We need to continue to assume that everyone is potentially infected whether they know it or not. And even though we have ramped up our testing to a much greater capacity than in the first wave, we need to continue to wear masks and socially distance because just identifying people who are sick and isolating or quarantining them is not going to be enough to contain the pandemic.”

And although assumption-based modeling is helpful, it cannot tell us “how many asymptomatic people are actually infected,” said Dr. Esper, who was not involved in the CDC study.

Dr. Esper also pointed out that the study estimates are based on data from early Chinese studies, but the virus has since changed. The new, more transmissible strain in the United States and elsewhere may involve not only more infections but also a longer presymptomatic stage. “So the CDC study may actually undershoot asymptomatic infections,” he said.

He also agreed with the authors that when it comes to infection, not all humans are equal. “Older people tend to be more symptomatic and become symptomatic more quickly so the asymptomatic rate is not the same across board from young people age 20 to older people.”

The bottom line, said David. A. Hirschwerk, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Northwell Health in Manhasset, N.Y., is that these data support the maintenance of protective measures we’ve been taking over the past months. “They support the concept that asymptomatic people are a significant source of transmission and that we need to adhere to mask wearing and social distancing, particularly indoors,” Dr. Hirschwerk, who was not involved in the analysis, said in an interview. “More testing would be better but it has to be fast and it has to be efficient, and there are a lot of challenges to overcome.”

The study was done as part of the CDC’s coronavirus disease 2019 response and was supported solely by federal base and response funding. The authors and commentators have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As COVID-19 cases surge and vaccinations lag, health authorities continue to seek additional ways to mitigate the spread of the novel coronavirus.

Now, a modeling study estimates that more than half of transmissions come from pre-, never-, and asymptomatic individuals, indicating that symptom-based screening will have little effect on spread.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study, published online Jan. 7 in JAMA Network Open, concludes that for optimal control, protective measures such as masking and social distancing should be supplemented with strategic testing of potentially exposed but asymptomatic individuals .

“In the absence of effective and widespread use of therapeutics or vaccines that can shorten or eliminate infectivity, successful control of SARS-CoV-2 cannot rely solely on identifying and isolating symptomatic cases; even if implemented effectively, this strategy would be insufficient,” CDC biologist Michael J. Johansson, PhD, and colleagues warn. “Multiple measures that effectively address transmission risk in the absence of symptoms are imperative to control SARS-CoV-2.”

According to the authors, the effectiveness of some current transmission prevention efforts has been disputed and subject to mixed messaging. Therefore, they decided to model the proportion of COVID-19 infections that are likely the result of individuals who show no symptoms and may be unknowingly infecting others.

“Unfortunately, there continues to be some skepticism about the value of community-wide mitigation efforts for preventing transmission such as masking, distancing, and hand hygiene, particularly for people without symptoms,” corresponding author Jay C. Butler, MD, said in an interview. “So we wanted to have a base assumption about how much transmission occurs from asymptomatic people to underscore the importance of mitigation measures and of creating immunity through vaccine delivery.”

Such a yardstick is especially germane in the context of the new, more transmissible variant. “It really puts [things] in a bigger box and underscores, boldfaces, and italicizes the need to change people’s behaviors and the importance of mitigation,” Dr. Butler said. It also highlights the advisability of targeted strategic testing in congregate settings, schools, and universities, which is already underway.

The analysis

Based on data from several COVID-19 studies from last year, the CDC’s analytical model assumes at baseline that infectiousness peaks at the median point of symptom onset, and that 30% of infected individuals never develop symptoms but are nevertheless 75% as infectious as those who develop overt symptoms.

The investigators then model multiple scenarios of transmission based pre- and never-symptomatic individuals, assuming different incubation and infectious periods, and varying numbers of days from point of infection to symptom onset.

When combined, the models predicts that 59% of all transmission would come from asymptomatic transmission – 35% from presymptomatic individuals and 24% from never-symptomatic individuals.

The findings complement those of an earlier CDC analysis, according to the authors.

The overall proportion of transmission from presymptomatic and never-symptomatic individuals is key to identifying mitigation measures that may be able to control SARS-CoV-2, the authors stated.

For example, they explain, if the infection reproduction number (R) in a particular setting is 2.0, a reduction in transmission of at least 50% is needed in order to reduce R to below 1.0. “Given that in some settings R is likely much greater than 2 and more than half of transmissions may come from individuals who are asymptomatic at the time of transmission, effective control must mitigate transmission risk from people without symptoms,” they wrote.

The authors acknowledge that the study applies a simplistic model to a complex and evolving phenomenon, and that the exact proportions of presymptomatic and never-symptomatic transmission and the incubation periods are not known. They also note symptoms and transmissions appear to vary across different population groups, with older individuals more likely than younger persons to experience symptoms, according to previous studies.

“Assume that everyone is potentially infected”

Other experts agree that expanded testing of asymptomatic individuals is important. “Screening for fever and isolation of symptomatic individuals is a common-sense approach to help prevent spread, but these measures are by no means adequate since it’s been clearly documented that individuals who are either asymptomatic or presymptomatic can still spread the virus,” said Brett Williams, MD, an infectious disease specialist and assistant professor of medicine at Rush University in Chicago.

“As we saw with the White House Rose Garden superspreader outbreak, testing does not reliably exclude infection either because the tested individual has not yet become positive or the test is falsely negative,” Dr. Williams, who was not involved in the CDC study, said in an interview. He further noted that when prevalence is as high as it currently is in the United States, the rate of false negatives will be high because a large proportion of those screened will be unknowingly infected.

At his center, all visitors and staff are screened with a temperature probe on entry, and since the earliest days of the pandemic, universal masking has been required. “Nationally there have been many instances of hospital break room outbreaks because of staff eating lunch together, and these outbreaks also demonstrate the incompleteness of symptomatic isolation,” Dr. Williams said.

For his part, virologist Frank Esper, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the Cleveland Clinic, said that while it’s been understood for some time that many infected people will not exhibit symptoms, “the question that remains is just how infectious are they?”

Dr. Esper’s takeaway from the modeling study is not so much that we need more screening of possibly exposed but asymptomatic people, but rather testing symptomatic people and tracing their contacts is not enough.

“We need to continue to assume that everyone is potentially infected whether they know it or not. And even though we have ramped up our testing to a much greater capacity than in the first wave, we need to continue to wear masks and socially distance because just identifying people who are sick and isolating or quarantining them is not going to be enough to contain the pandemic.”

And although assumption-based modeling is helpful, it cannot tell us “how many asymptomatic people are actually infected,” said Dr. Esper, who was not involved in the CDC study.

Dr. Esper also pointed out that the study estimates are based on data from early Chinese studies, but the virus has since changed. The new, more transmissible strain in the United States and elsewhere may involve not only more infections but also a longer presymptomatic stage. “So the CDC study may actually undershoot asymptomatic infections,” he said.

He also agreed with the authors that when it comes to infection, not all humans are equal. “Older people tend to be more symptomatic and become symptomatic more quickly so the asymptomatic rate is not the same across board from young people age 20 to older people.”

The bottom line, said David. A. Hirschwerk, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Northwell Health in Manhasset, N.Y., is that these data support the maintenance of protective measures we’ve been taking over the past months. “They support the concept that asymptomatic people are a significant source of transmission and that we need to adhere to mask wearing and social distancing, particularly indoors,” Dr. Hirschwerk, who was not involved in the analysis, said in an interview. “More testing would be better but it has to be fast and it has to be efficient, and there are a lot of challenges to overcome.”

The study was done as part of the CDC’s coronavirus disease 2019 response and was supported solely by federal base and response funding. The authors and commentators have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As COVID-19 cases surge and vaccinations lag, health authorities continue to seek additional ways to mitigate the spread of the novel coronavirus.

Now, a modeling study estimates that more than half of transmissions come from pre-, never-, and asymptomatic individuals, indicating that symptom-based screening will have little effect on spread.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study, published online Jan. 7 in JAMA Network Open, concludes that for optimal control, protective measures such as masking and social distancing should be supplemented with strategic testing of potentially exposed but asymptomatic individuals .

“In the absence of effective and widespread use of therapeutics or vaccines that can shorten or eliminate infectivity, successful control of SARS-CoV-2 cannot rely solely on identifying and isolating symptomatic cases; even if implemented effectively, this strategy would be insufficient,” CDC biologist Michael J. Johansson, PhD, and colleagues warn. “Multiple measures that effectively address transmission risk in the absence of symptoms are imperative to control SARS-CoV-2.”

According to the authors, the effectiveness of some current transmission prevention efforts has been disputed and subject to mixed messaging. Therefore, they decided to model the proportion of COVID-19 infections that are likely the result of individuals who show no symptoms and may be unknowingly infecting others.