User login

-

Isa-Kd improves PFS in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma

The risk of progression or death for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma was nearly halved with the addition of isatuximab to carfilzomib and dexamethasone, according to an interim analysis of the phase 3 IKEMA trial (NCT03275285).

After a median follow-up of 20.7 months, the median progression-free survival had not been reached for 179 patients treated with isatuximab (Sarclisa), carfilzomib (Kyprolis), and dexamethasone (together, known as Isa-Kd), compared with 19.5 months for 123 patients treated with carfilzomib and dexamethasone alone (Kd). The hazard ratio for progression free survival with the triple combination was 0.531 (P = .0007), reported coprincipal investigator Phillipe Moreau, MD, from the University Hospital Hôtel-Dieu in Nantes, France.

“The benefit of the triplet combination was observed across subgroups, including patients difficult to treat, such as [those with] high-risk cytogenetics or elderly patients,” he said in a late-breaking abstract presentation during the virtual annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

Isatuximab is an immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody targeting a CD38 transmembrane glycoprotein on multiple myeloma cells, with a mechanism of action similar to that of another anti-CD38 antibody, daratumumab (Darzalex). Isatuximab is approved in the United States and Europe in combination with pomalidomide and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma after at least two prior lines of therapy.

A ‘me too’ agent?

It’s unclear, however, whether isatuximab offers any additional benefit over daratumumab, an agent approved for use both in front line therapy combinations and for patients with relapsed/refractory disease, said Brea C. Lipe, MD, a multiple myeloma specialist at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Wilmot Cancer Institute, who was not involved in the study.

“Every time we get a new drug it’s nice to have another option, but it doesn’t really add anything different from daratumumab at this point,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Lipe noted the IKEMA results are similar to those seen in the phase 3 CANDOR trial, comparing carfilzomib, dexamethasone, and daratumumab to carfilzomib/dexamethasone alone in patients with relapsed/refractory myeloma. In addition, it’s unknown whether patients with disease that is refractory to daratumumab could benefit from isatuximab, she said.

Although isatuximab has been touted as offering more rapid and more convenient dosing than daratumumab, the introduction of rapid infusion and subcutaneous administration of daratumumab has negated any theoretical advantage of the newcomer, Dr. Lipe added.

Study details

In the IKEMA trial, 302 patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma who’d received one to three prior lines of therapy were stratified by the number of prior lines and by revised Multiple Myeloma International Staging System (R-ISS) and were then randomized on a 3:2 basis to treatment with carfilzomib 20 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, and 16 of cycle 1 and 56 mg/m2 on the corresponding days of each subsequent cycle plus dexamethasone 20 mg on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, 16, 22, and 23 of each cycle, with or without isatuximab. The antibody was dosed 10 mg/kg on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 in cycle 1 then every 2 weeks thereafter.

Treatments were continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or patient choice intervened.

At a prespecified interim analysis, the trial met its primary endpoint of a minimum 41% risk reduction in the hazard rate for progression free survival (PFS), with an actual risk reduction of 47%.

An analysis of PFS by subgroup showed significant benefits with the triple combination for patients aged 65 years and older, those with baseline estimated glomerular filtration rates below 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, those with more than one prior line of therapy, those who had not previously received a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., bortezomib) or immunomodulatory agent (e.g., lenalidomide), those with high-risk cytogenetic status, and those with R-ISS stage II at study entry.

Overall response rates were similar between the study arms, at 86.6% with Isa-Kd and 82.9% with Kd, but the rate of very good partial responses or better was significantly higher with the triplet, at 72.6% versus 56.1% (P = .0011). The rate of minimal residual disease negativity was also significantly lower with Isa-Kd in the intent-to-treat population, at 29.6% versus 13%, respectively (P = .0004).

Overall survival data were not mature at the time of data cutoff and will be reported later, Dr. Moreau said.

Grade 3 or greater treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) occurred in 76.8% of patients on the triplet and 67.2% of those on Kd. The incidences of death, serious TEAEs, or adverse events leading to discontinuation of therapy did not differ markedly between the treatment arms, however. Grade 3 or greater cardiac failure occurred in seven patients treated with the triplet (4%) and five treated with Kd (4.1%); respective rates of grade 3 or greater hematologic abnormalities included anemia in 22% and 19.7%, neutropenia in 19.2% and 7.4%, and thrombocytopenia in 29.9% and 23.8%.

The primary completion date for the trial is estimated to occur in November 2020, with final results in November 2023.

The study was sponsored by Sanofi. Dr. Moreau disclosed honoraria and a consulting or advisory role with several companies, not including Sanofi. Dr. Lipe disclosed impending advisory board activity for Janssen.

SOURCE: Moreau P et al. EHA Congress, Abstract LB2603.

The risk of progression or death for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma was nearly halved with the addition of isatuximab to carfilzomib and dexamethasone, according to an interim analysis of the phase 3 IKEMA trial (NCT03275285).

After a median follow-up of 20.7 months, the median progression-free survival had not been reached for 179 patients treated with isatuximab (Sarclisa), carfilzomib (Kyprolis), and dexamethasone (together, known as Isa-Kd), compared with 19.5 months for 123 patients treated with carfilzomib and dexamethasone alone (Kd). The hazard ratio for progression free survival with the triple combination was 0.531 (P = .0007), reported coprincipal investigator Phillipe Moreau, MD, from the University Hospital Hôtel-Dieu in Nantes, France.

“The benefit of the triplet combination was observed across subgroups, including patients difficult to treat, such as [those with] high-risk cytogenetics or elderly patients,” he said in a late-breaking abstract presentation during the virtual annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

Isatuximab is an immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody targeting a CD38 transmembrane glycoprotein on multiple myeloma cells, with a mechanism of action similar to that of another anti-CD38 antibody, daratumumab (Darzalex). Isatuximab is approved in the United States and Europe in combination with pomalidomide and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma after at least two prior lines of therapy.

A ‘me too’ agent?

It’s unclear, however, whether isatuximab offers any additional benefit over daratumumab, an agent approved for use both in front line therapy combinations and for patients with relapsed/refractory disease, said Brea C. Lipe, MD, a multiple myeloma specialist at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Wilmot Cancer Institute, who was not involved in the study.

“Every time we get a new drug it’s nice to have another option, but it doesn’t really add anything different from daratumumab at this point,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Lipe noted the IKEMA results are similar to those seen in the phase 3 CANDOR trial, comparing carfilzomib, dexamethasone, and daratumumab to carfilzomib/dexamethasone alone in patients with relapsed/refractory myeloma. In addition, it’s unknown whether patients with disease that is refractory to daratumumab could benefit from isatuximab, she said.

Although isatuximab has been touted as offering more rapid and more convenient dosing than daratumumab, the introduction of rapid infusion and subcutaneous administration of daratumumab has negated any theoretical advantage of the newcomer, Dr. Lipe added.

Study details

In the IKEMA trial, 302 patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma who’d received one to three prior lines of therapy were stratified by the number of prior lines and by revised Multiple Myeloma International Staging System (R-ISS) and were then randomized on a 3:2 basis to treatment with carfilzomib 20 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, and 16 of cycle 1 and 56 mg/m2 on the corresponding days of each subsequent cycle plus dexamethasone 20 mg on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, 16, 22, and 23 of each cycle, with or without isatuximab. The antibody was dosed 10 mg/kg on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 in cycle 1 then every 2 weeks thereafter.

Treatments were continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or patient choice intervened.

At a prespecified interim analysis, the trial met its primary endpoint of a minimum 41% risk reduction in the hazard rate for progression free survival (PFS), with an actual risk reduction of 47%.

An analysis of PFS by subgroup showed significant benefits with the triple combination for patients aged 65 years and older, those with baseline estimated glomerular filtration rates below 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, those with more than one prior line of therapy, those who had not previously received a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., bortezomib) or immunomodulatory agent (e.g., lenalidomide), those with high-risk cytogenetic status, and those with R-ISS stage II at study entry.

Overall response rates were similar between the study arms, at 86.6% with Isa-Kd and 82.9% with Kd, but the rate of very good partial responses or better was significantly higher with the triplet, at 72.6% versus 56.1% (P = .0011). The rate of minimal residual disease negativity was also significantly lower with Isa-Kd in the intent-to-treat population, at 29.6% versus 13%, respectively (P = .0004).

Overall survival data were not mature at the time of data cutoff and will be reported later, Dr. Moreau said.

Grade 3 or greater treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) occurred in 76.8% of patients on the triplet and 67.2% of those on Kd. The incidences of death, serious TEAEs, or adverse events leading to discontinuation of therapy did not differ markedly between the treatment arms, however. Grade 3 or greater cardiac failure occurred in seven patients treated with the triplet (4%) and five treated with Kd (4.1%); respective rates of grade 3 or greater hematologic abnormalities included anemia in 22% and 19.7%, neutropenia in 19.2% and 7.4%, and thrombocytopenia in 29.9% and 23.8%.

The primary completion date for the trial is estimated to occur in November 2020, with final results in November 2023.

The study was sponsored by Sanofi. Dr. Moreau disclosed honoraria and a consulting or advisory role with several companies, not including Sanofi. Dr. Lipe disclosed impending advisory board activity for Janssen.

SOURCE: Moreau P et al. EHA Congress, Abstract LB2603.

The risk of progression or death for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma was nearly halved with the addition of isatuximab to carfilzomib and dexamethasone, according to an interim analysis of the phase 3 IKEMA trial (NCT03275285).

After a median follow-up of 20.7 months, the median progression-free survival had not been reached for 179 patients treated with isatuximab (Sarclisa), carfilzomib (Kyprolis), and dexamethasone (together, known as Isa-Kd), compared with 19.5 months for 123 patients treated with carfilzomib and dexamethasone alone (Kd). The hazard ratio for progression free survival with the triple combination was 0.531 (P = .0007), reported coprincipal investigator Phillipe Moreau, MD, from the University Hospital Hôtel-Dieu in Nantes, France.

“The benefit of the triplet combination was observed across subgroups, including patients difficult to treat, such as [those with] high-risk cytogenetics or elderly patients,” he said in a late-breaking abstract presentation during the virtual annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

Isatuximab is an immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody targeting a CD38 transmembrane glycoprotein on multiple myeloma cells, with a mechanism of action similar to that of another anti-CD38 antibody, daratumumab (Darzalex). Isatuximab is approved in the United States and Europe in combination with pomalidomide and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma after at least two prior lines of therapy.

A ‘me too’ agent?

It’s unclear, however, whether isatuximab offers any additional benefit over daratumumab, an agent approved for use both in front line therapy combinations and for patients with relapsed/refractory disease, said Brea C. Lipe, MD, a multiple myeloma specialist at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Wilmot Cancer Institute, who was not involved in the study.

“Every time we get a new drug it’s nice to have another option, but it doesn’t really add anything different from daratumumab at this point,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Lipe noted the IKEMA results are similar to those seen in the phase 3 CANDOR trial, comparing carfilzomib, dexamethasone, and daratumumab to carfilzomib/dexamethasone alone in patients with relapsed/refractory myeloma. In addition, it’s unknown whether patients with disease that is refractory to daratumumab could benefit from isatuximab, she said.

Although isatuximab has been touted as offering more rapid and more convenient dosing than daratumumab, the introduction of rapid infusion and subcutaneous administration of daratumumab has negated any theoretical advantage of the newcomer, Dr. Lipe added.

Study details

In the IKEMA trial, 302 patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma who’d received one to three prior lines of therapy were stratified by the number of prior lines and by revised Multiple Myeloma International Staging System (R-ISS) and were then randomized on a 3:2 basis to treatment with carfilzomib 20 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, and 16 of cycle 1 and 56 mg/m2 on the corresponding days of each subsequent cycle plus dexamethasone 20 mg on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, 16, 22, and 23 of each cycle, with or without isatuximab. The antibody was dosed 10 mg/kg on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 in cycle 1 then every 2 weeks thereafter.

Treatments were continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or patient choice intervened.

At a prespecified interim analysis, the trial met its primary endpoint of a minimum 41% risk reduction in the hazard rate for progression free survival (PFS), with an actual risk reduction of 47%.

An analysis of PFS by subgroup showed significant benefits with the triple combination for patients aged 65 years and older, those with baseline estimated glomerular filtration rates below 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, those with more than one prior line of therapy, those who had not previously received a proteasome inhibitor (e.g., bortezomib) or immunomodulatory agent (e.g., lenalidomide), those with high-risk cytogenetic status, and those with R-ISS stage II at study entry.

Overall response rates were similar between the study arms, at 86.6% with Isa-Kd and 82.9% with Kd, but the rate of very good partial responses or better was significantly higher with the triplet, at 72.6% versus 56.1% (P = .0011). The rate of minimal residual disease negativity was also significantly lower with Isa-Kd in the intent-to-treat population, at 29.6% versus 13%, respectively (P = .0004).

Overall survival data were not mature at the time of data cutoff and will be reported later, Dr. Moreau said.

Grade 3 or greater treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) occurred in 76.8% of patients on the triplet and 67.2% of those on Kd. The incidences of death, serious TEAEs, or adverse events leading to discontinuation of therapy did not differ markedly between the treatment arms, however. Grade 3 or greater cardiac failure occurred in seven patients treated with the triplet (4%) and five treated with Kd (4.1%); respective rates of grade 3 or greater hematologic abnormalities included anemia in 22% and 19.7%, neutropenia in 19.2% and 7.4%, and thrombocytopenia in 29.9% and 23.8%.

The primary completion date for the trial is estimated to occur in November 2020, with final results in November 2023.

The study was sponsored by Sanofi. Dr. Moreau disclosed honoraria and a consulting or advisory role with several companies, not including Sanofi. Dr. Lipe disclosed impending advisory board activity for Janssen.

SOURCE: Moreau P et al. EHA Congress, Abstract LB2603.

FROM EHA CONGRESS

Telehealth and medical liability

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to the rapid uptake of telehealth nationwide in primary care and specialty practices. Over the last few months many practices have actually performed more telehealth visits than traditional in-person visits. The use of telehealth, which had been increasing slowly for the last few years, accelerated rapidly during the pandemic. Long term, telehealth has the potential to increase access to primary care and specialists, and make follow-up easier for many patients, changing how health care is delivered to millions of patients throughout the world.

Since telehealth will be a regular part of our practices from now on, it is important for clinicians to recognize how telehealth visits are viewed in a legal arena.

As is often the case with technological advances, the law needs time to adapt. Will a health care provider treating a patient using telemedicine be held to the same standard of care applicable to an in-person encounter? Stated differently, will consideration be given to the obvious limitations imposed by a telemedicine exam?

Standard of care in medical malpractice cases

The central question in most medical malpractice cases is whether the provider complied with the generally accepted standard of care when evaluating, diagnosing, or treating a patient. This standard typically takes into consideration the provider’s particular specialty as well as all the circumstances surrounding the encounter.1 Medical providers, not state legislators, usually define the standard of care for medical professionals. In malpractice cases, medical experts explain the applicable standard of care to the jury and guide its determination of whether, in the particular case, the standard of care was met. In this way, the law has long recognized that the medical profession itself is best suited to establish the appropriate standards of care under any particular set of circumstances. This standard of care is often referred to as the “reasonable professional under the circumstances” standard of care.

Telemedicine standard of care

Despite the fact that the complex and often nebulous concept of standard of care has been traditionally left to the medical experts to define, state legislators and regulators throughout the nation have chosen to weigh in on this issue in the context of telemedicine. Most states with telemedicine regulations have followed the model policy adopted by the Federation of State Medical Boards in April 2014 which states that “[t]reatment and consultation recommendations made in an online setting … will be held to the same standards of appropriate practice as those in traditional (in-person) settings.”2 States that have adopted this model policy have effectively created a “legal fiction” requiring a jury to ignore the fact that the care was provided virtually by telemedicine technologies and instead assume that the physician treated the patient in person, i.e, applying an “in-person” standard of care. Hawaii appears to be the lone notable exception. Its telemedicine law recognizes that an in-person standard of care should not be applied if there was not a face-to-face visit.3

Proponents of the in-person telemedicine standard claim that it is necessary to ensure patient safety, thus justifying the “legal fiction.” Holding the provider to the in-person standard, it is argued, forces the physician to err on the side of caution and require an actual in-person encounter to ensure the advantages of sight, touch, and sense of things are fully available.4 This discourages the use of telemedicine and deprives the population of its many benefits.

Telemedicine can overcome geographical barriers, increase clinical support, improve health outcomes, reduce health care costs, encourage patient input, reduce travel, and foster continuity of care. The pandemic, which has significantly limited the ability of providers to see patients in person, only underscores the benefits of telemedicine.

The legislatively imposed in-person telemedicine standard of care should be replaced with the “reasonable professional under the circumstances” standard in order to fairly judge physicians’ care and promote overall population health. The “reasonable professional under the circumstances” standard has applied to physicians and other health care professionals outside of telemedicine for decades, and it has served the medical community and public well. It is unfortunate that legislators felt the need to weigh in and define a distinctly different standard of care for telemedicine than for the rest of medicine, as this may present unforeseen obstacles to the use of telemedicine.

The in-person telemedicine standard of care remains a significant barrier for long-term telemedicine. Eliminating this legal fiction has the potential to further expand physicians’ use of telemedicine and fulfill its promise of improving access to care and improving population health.

Mr. Horner (partner), Mr. Milewski (partner), and Mr. Gajer (associate) are attorneys with White and Williams. They specialize in defending health care providers in medical malpractice lawsuits and other health care–related matters. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community Medicine at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow Dr. Skolnik, and feel free to submit questions to him on Twitter: @neilskolnik. The authors have no financial conflicts related to the content of this piece.

References

1. Cowan v. Doering, 111 N.J. 451-62,.1988.

2. Model Policy For The Appropriate Use Of Telemedicine Technologies In The Practice Of Medicine. State Medical Boards Appropriate Regulation of Telemedicine. April 2014..

3. Haw. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 453-1.3(c).

4. Kaspar BJ. Iowa Law Review. 2014 Jan;99:839-59.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to the rapid uptake of telehealth nationwide in primary care and specialty practices. Over the last few months many practices have actually performed more telehealth visits than traditional in-person visits. The use of telehealth, which had been increasing slowly for the last few years, accelerated rapidly during the pandemic. Long term, telehealth has the potential to increase access to primary care and specialists, and make follow-up easier for many patients, changing how health care is delivered to millions of patients throughout the world.

Since telehealth will be a regular part of our practices from now on, it is important for clinicians to recognize how telehealth visits are viewed in a legal arena.

As is often the case with technological advances, the law needs time to adapt. Will a health care provider treating a patient using telemedicine be held to the same standard of care applicable to an in-person encounter? Stated differently, will consideration be given to the obvious limitations imposed by a telemedicine exam?

Standard of care in medical malpractice cases

The central question in most medical malpractice cases is whether the provider complied with the generally accepted standard of care when evaluating, diagnosing, or treating a patient. This standard typically takes into consideration the provider’s particular specialty as well as all the circumstances surrounding the encounter.1 Medical providers, not state legislators, usually define the standard of care for medical professionals. In malpractice cases, medical experts explain the applicable standard of care to the jury and guide its determination of whether, in the particular case, the standard of care was met. In this way, the law has long recognized that the medical profession itself is best suited to establish the appropriate standards of care under any particular set of circumstances. This standard of care is often referred to as the “reasonable professional under the circumstances” standard of care.

Telemedicine standard of care

Despite the fact that the complex and often nebulous concept of standard of care has been traditionally left to the medical experts to define, state legislators and regulators throughout the nation have chosen to weigh in on this issue in the context of telemedicine. Most states with telemedicine regulations have followed the model policy adopted by the Federation of State Medical Boards in April 2014 which states that “[t]reatment and consultation recommendations made in an online setting … will be held to the same standards of appropriate practice as those in traditional (in-person) settings.”2 States that have adopted this model policy have effectively created a “legal fiction” requiring a jury to ignore the fact that the care was provided virtually by telemedicine technologies and instead assume that the physician treated the patient in person, i.e, applying an “in-person” standard of care. Hawaii appears to be the lone notable exception. Its telemedicine law recognizes that an in-person standard of care should not be applied if there was not a face-to-face visit.3

Proponents of the in-person telemedicine standard claim that it is necessary to ensure patient safety, thus justifying the “legal fiction.” Holding the provider to the in-person standard, it is argued, forces the physician to err on the side of caution and require an actual in-person encounter to ensure the advantages of sight, touch, and sense of things are fully available.4 This discourages the use of telemedicine and deprives the population of its many benefits.

Telemedicine can overcome geographical barriers, increase clinical support, improve health outcomes, reduce health care costs, encourage patient input, reduce travel, and foster continuity of care. The pandemic, which has significantly limited the ability of providers to see patients in person, only underscores the benefits of telemedicine.

The legislatively imposed in-person telemedicine standard of care should be replaced with the “reasonable professional under the circumstances” standard in order to fairly judge physicians’ care and promote overall population health. The “reasonable professional under the circumstances” standard has applied to physicians and other health care professionals outside of telemedicine for decades, and it has served the medical community and public well. It is unfortunate that legislators felt the need to weigh in and define a distinctly different standard of care for telemedicine than for the rest of medicine, as this may present unforeseen obstacles to the use of telemedicine.

The in-person telemedicine standard of care remains a significant barrier for long-term telemedicine. Eliminating this legal fiction has the potential to further expand physicians’ use of telemedicine and fulfill its promise of improving access to care and improving population health.

Mr. Horner (partner), Mr. Milewski (partner), and Mr. Gajer (associate) are attorneys with White and Williams. They specialize in defending health care providers in medical malpractice lawsuits and other health care–related matters. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community Medicine at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow Dr. Skolnik, and feel free to submit questions to him on Twitter: @neilskolnik. The authors have no financial conflicts related to the content of this piece.

References

1. Cowan v. Doering, 111 N.J. 451-62,.1988.

2. Model Policy For The Appropriate Use Of Telemedicine Technologies In The Practice Of Medicine. State Medical Boards Appropriate Regulation of Telemedicine. April 2014..

3. Haw. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 453-1.3(c).

4. Kaspar BJ. Iowa Law Review. 2014 Jan;99:839-59.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to the rapid uptake of telehealth nationwide in primary care and specialty practices. Over the last few months many practices have actually performed more telehealth visits than traditional in-person visits. The use of telehealth, which had been increasing slowly for the last few years, accelerated rapidly during the pandemic. Long term, telehealth has the potential to increase access to primary care and specialists, and make follow-up easier for many patients, changing how health care is delivered to millions of patients throughout the world.

Since telehealth will be a regular part of our practices from now on, it is important for clinicians to recognize how telehealth visits are viewed in a legal arena.

As is often the case with technological advances, the law needs time to adapt. Will a health care provider treating a patient using telemedicine be held to the same standard of care applicable to an in-person encounter? Stated differently, will consideration be given to the obvious limitations imposed by a telemedicine exam?

Standard of care in medical malpractice cases

The central question in most medical malpractice cases is whether the provider complied with the generally accepted standard of care when evaluating, diagnosing, or treating a patient. This standard typically takes into consideration the provider’s particular specialty as well as all the circumstances surrounding the encounter.1 Medical providers, not state legislators, usually define the standard of care for medical professionals. In malpractice cases, medical experts explain the applicable standard of care to the jury and guide its determination of whether, in the particular case, the standard of care was met. In this way, the law has long recognized that the medical profession itself is best suited to establish the appropriate standards of care under any particular set of circumstances. This standard of care is often referred to as the “reasonable professional under the circumstances” standard of care.

Telemedicine standard of care

Despite the fact that the complex and often nebulous concept of standard of care has been traditionally left to the medical experts to define, state legislators and regulators throughout the nation have chosen to weigh in on this issue in the context of telemedicine. Most states with telemedicine regulations have followed the model policy adopted by the Federation of State Medical Boards in April 2014 which states that “[t]reatment and consultation recommendations made in an online setting … will be held to the same standards of appropriate practice as those in traditional (in-person) settings.”2 States that have adopted this model policy have effectively created a “legal fiction” requiring a jury to ignore the fact that the care was provided virtually by telemedicine technologies and instead assume that the physician treated the patient in person, i.e, applying an “in-person” standard of care. Hawaii appears to be the lone notable exception. Its telemedicine law recognizes that an in-person standard of care should not be applied if there was not a face-to-face visit.3

Proponents of the in-person telemedicine standard claim that it is necessary to ensure patient safety, thus justifying the “legal fiction.” Holding the provider to the in-person standard, it is argued, forces the physician to err on the side of caution and require an actual in-person encounter to ensure the advantages of sight, touch, and sense of things are fully available.4 This discourages the use of telemedicine and deprives the population of its many benefits.

Telemedicine can overcome geographical barriers, increase clinical support, improve health outcomes, reduce health care costs, encourage patient input, reduce travel, and foster continuity of care. The pandemic, which has significantly limited the ability of providers to see patients in person, only underscores the benefits of telemedicine.

The legislatively imposed in-person telemedicine standard of care should be replaced with the “reasonable professional under the circumstances” standard in order to fairly judge physicians’ care and promote overall population health. The “reasonable professional under the circumstances” standard has applied to physicians and other health care professionals outside of telemedicine for decades, and it has served the medical community and public well. It is unfortunate that legislators felt the need to weigh in and define a distinctly different standard of care for telemedicine than for the rest of medicine, as this may present unforeseen obstacles to the use of telemedicine.

The in-person telemedicine standard of care remains a significant barrier for long-term telemedicine. Eliminating this legal fiction has the potential to further expand physicians’ use of telemedicine and fulfill its promise of improving access to care and improving population health.

Mr. Horner (partner), Mr. Milewski (partner), and Mr. Gajer (associate) are attorneys with White and Williams. They specialize in defending health care providers in medical malpractice lawsuits and other health care–related matters. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community Medicine at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Follow Dr. Skolnik, and feel free to submit questions to him on Twitter: @neilskolnik. The authors have no financial conflicts related to the content of this piece.

References

1. Cowan v. Doering, 111 N.J. 451-62,.1988.

2. Model Policy For The Appropriate Use Of Telemedicine Technologies In The Practice Of Medicine. State Medical Boards Appropriate Regulation of Telemedicine. April 2014..

3. Haw. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 453-1.3(c).

4. Kaspar BJ. Iowa Law Review. 2014 Jan;99:839-59.

COVID-19: Medicare data show long hospital stays, disparities

according to a new analysis by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

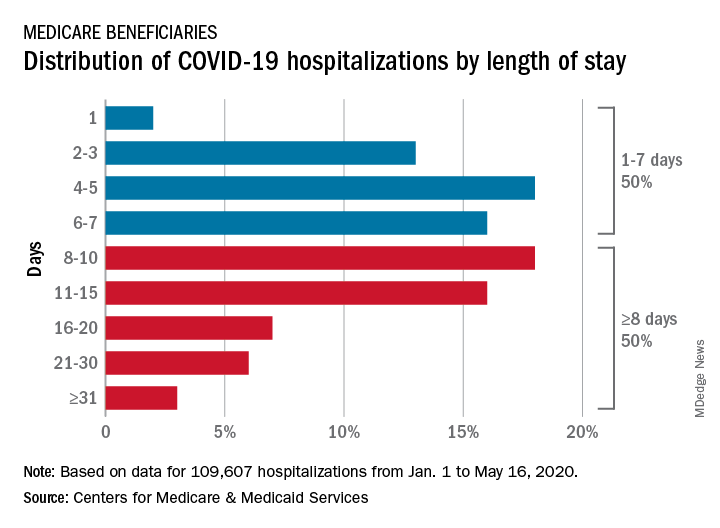

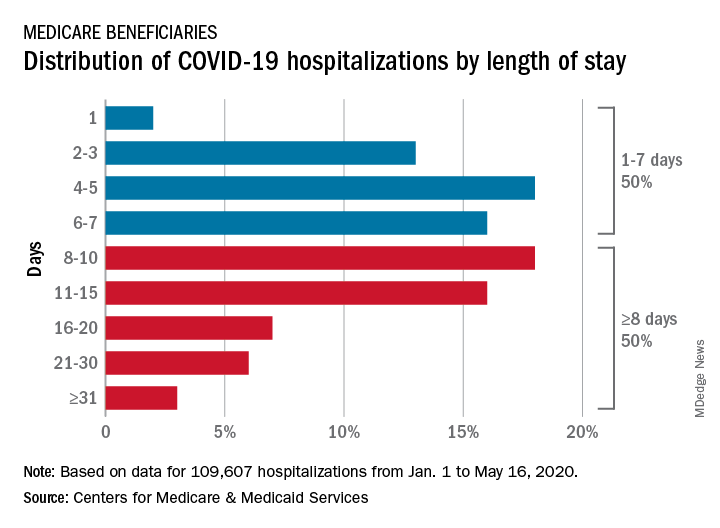

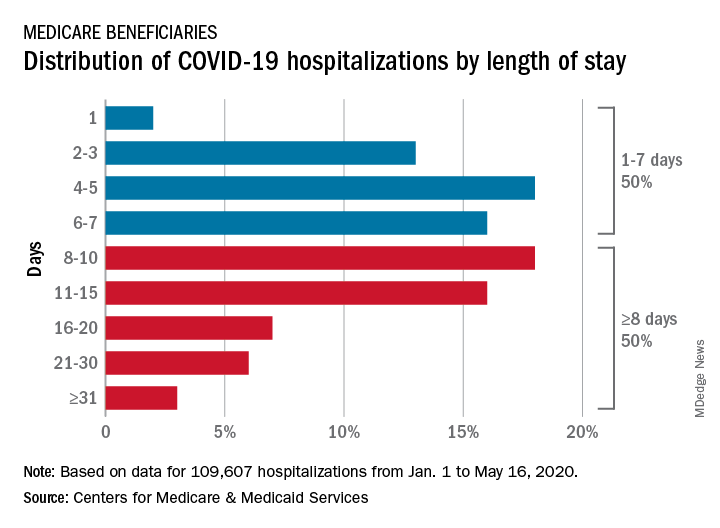

CMS encounter and claims data show almost 110,000 hospital stays for COVID-19 from Jan. 1 to May 16, 2020. Of the longer admissions, 18% were 8-10 days, 16% were 11-15 days, and another 16% were 16 days or longer, the CMS reported in a preliminary data snapshot released June 22.

The hospitalization rate for the Medicare population was 175 per 100,000 as of May 16, but the CMS data show a number of disparities involving race/ethnicity and other demographic characteristics were uncovered, such as the following:

- Black patients were hospitalized for COVID-19 at a much higher rate, at 465 per 100,000 beneficiaries, than were Hispanics (258), Asians (187), and whites (123).

- Residents of urban/suburban areas had a much higher hospitalization rate than did those living in rural areas: 205 versus 57 per 100,000.

- Beneficiaries enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid had 473 hospitalizations per 100,000, but the rate for those with Medicare only was 112.

“The disparities in the data reflect longstanding challenges facing minority communities and low-income older adults, many of whom face structural challenges to their health that go far beyond what is traditionally considered ‘medical,’ ” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a separate statement.

according to a new analysis by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

CMS encounter and claims data show almost 110,000 hospital stays for COVID-19 from Jan. 1 to May 16, 2020. Of the longer admissions, 18% were 8-10 days, 16% were 11-15 days, and another 16% were 16 days or longer, the CMS reported in a preliminary data snapshot released June 22.

The hospitalization rate for the Medicare population was 175 per 100,000 as of May 16, but the CMS data show a number of disparities involving race/ethnicity and other demographic characteristics were uncovered, such as the following:

- Black patients were hospitalized for COVID-19 at a much higher rate, at 465 per 100,000 beneficiaries, than were Hispanics (258), Asians (187), and whites (123).

- Residents of urban/suburban areas had a much higher hospitalization rate than did those living in rural areas: 205 versus 57 per 100,000.

- Beneficiaries enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid had 473 hospitalizations per 100,000, but the rate for those with Medicare only was 112.

“The disparities in the data reflect longstanding challenges facing minority communities and low-income older adults, many of whom face structural challenges to their health that go far beyond what is traditionally considered ‘medical,’ ” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a separate statement.

according to a new analysis by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

CMS encounter and claims data show almost 110,000 hospital stays for COVID-19 from Jan. 1 to May 16, 2020. Of the longer admissions, 18% were 8-10 days, 16% were 11-15 days, and another 16% were 16 days or longer, the CMS reported in a preliminary data snapshot released June 22.

The hospitalization rate for the Medicare population was 175 per 100,000 as of May 16, but the CMS data show a number of disparities involving race/ethnicity and other demographic characteristics were uncovered, such as the following:

- Black patients were hospitalized for COVID-19 at a much higher rate, at 465 per 100,000 beneficiaries, than were Hispanics (258), Asians (187), and whites (123).

- Residents of urban/suburban areas had a much higher hospitalization rate than did those living in rural areas: 205 versus 57 per 100,000.

- Beneficiaries enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid had 473 hospitalizations per 100,000, but the rate for those with Medicare only was 112.

“The disparities in the data reflect longstanding challenges facing minority communities and low-income older adults, many of whom face structural challenges to their health that go far beyond what is traditionally considered ‘medical,’ ” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a separate statement.

Guidance on infection prevention for health care personnel

As we reopen our offices we are faced with the challenge of determining the best way to do it safely – protecting ourselves, our staff, and our patients.

In this column we will focus on selected details of the recommendations from IDSA and the CDC that may be helpful in primary care offices.

Face masks

Many clinicians have asked whether a physician should use a mask while seeing patients without COVID-19 in the office, and if yes, which type. The IDSA guideline states that mask usage is imperative for reducing the risk of health care workers contracting COVID-19.1 The evidence is derived from a number of sources, including a retrospective study from Wuhan (China) University that examined two groups of health care workers during the outbreak. The first group wore N95 masks and washed their hands frequently, while the second group did not wear masks and washed their hands less frequently. In the group that took greater actions to protect themselves, none of the 493 staff members contracted COVID-19, compared with 10 of 213 staff members in the other group. The decrease in infection rate occurred in the group that wore masks despite the fact that this group had 733% more exposure to COVID-19 patients.2 Further evidence came from a case-control study done in hospitals in Hong Kong during the 2003 SARS-CoV outbreak.3 This study showed that mask wearing was the most significant intervention for reducing infection, followed by gowning, and then handwashing. These findings make it clear that mask usage is a must for all health care providers who may be caring for patients who could have COVID-19.

The guideline also reviews evidence about the use of surgical masks versus N95 masks. On reviewing indirect evidence from the SARS-CoV epidemic, IDSA found that wearing any mask – surgical or N95 – led to a large reduction in the risk of developing an infection. In this systematic review of five observational studies in health care personnel, for those wearing surgical masks, the odds ratio for developing an infection was 0.13 (95% CI, 0.03-0.62), and for those wearing N95 masks, the odds ratio was 0.12 (95% CI, 0.06-0.26). There was not a significant difference between risk reductions for those who wore surgical masks and N95 masks, respectively.1,4 The IDSA guideline panel recommended “that health care personnel caring for patients with suspected or known COVID-19 use either a surgical mask or N95 respirator ... as part of appropriate PPE.” Since there is not a significant difference in outcomes between those who use surgical masks and those who use N95 respirators, and the IDSA guideline states either type of mask is considered appropriate when taking care of patients with suspected or known COVID-19, in our opinion, use of surgical masks rather than N95s is sufficient when performing low-risk activities. Such activities include seeing patients who do not have a high likelihood of COVID-19 in the office setting.

The IDSA recommendation also discusses universal masking, defined as both patients and clinicians wearing masks. The recommendation is supported by the findings of a study in which universal mask usage was used to prevent the spread of H1N 1 during the 2009 outbreak. In this study of staff members and patients exposed to H1N1 who all wore masks, only 0.48% of 836 acquired infection. In the same study, not wearing a mask by either the provider or patient increased the risk of infection.5 Also, in a prospective study of hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients, universal masking caused infection rates to drop from 10.3% to 4.4%.6

The IDSA guideline states the following: “There may be some, albeit uncertain, benefit to universal masking in the absence of resource constraints. However, the benefits of universal masking with surgical masks should be weighed against the risk of increasing the PPE burn rate and contextualized to the background COVID-19 prevalence rate for asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic HCPs [health care providers] and visitors.”1

The CDC’s guidance statement says the following: “Continued community transmission has increased the number of individuals potentially exposed to and infectious with SARS-CoV-2. Fever and symptom screening have proven to be relatively ineffective in identifying all infected individuals, including HCPs. Symptom screening also will not identify individuals who are infected but otherwise asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic; additional interventions are needed to limit the unrecognized introduction of SARS-CoV-2 into healthcare settings by these individuals. As part of aggressive source control measures, healthcare facilities should consider implementing policies requiring everyone entering the facility to wear a cloth face covering (if tolerated) while in the building, regardless of symptoms.”7

It is our opinion, based on the CDC and IDSA recommendations, that both clinicians and patients should be required to wear masks when patients are seen in the office if possible. Many offices have instituted a policy that says, if a patient refuses to wear a mask during an office visit, then the patient will not be seen.

Eye protection

Many clinicians are uncertain about whether eye protection needs to be used when seeing asymptomatic patients. The IDSA acknowledges that there are not studies that have looked critically at eye protection, but the society also acknowledges “appropriate personal protective equipment includes, in addition to a mask or respirator, eye protection, gown and gloves.”1 In addition, the CDC recommends that, for healthcare workers located in areas with moderate or higher prevalence of COVID-19, HCPs should wear eye protection in addition to facemasks since they may encounter asymptomatic individuals with COVID-19.

Gowns and gloves

Gowns and gloves are recommended as a part of personal protective gear when caring for patients who have COVID-19. The IDSA guideline is clear in its recommendations, but does not cite evidence for having no gloves versus having gloves. Furthermore, they state that the evidence is insufficient to recommend double gloves, with the top glove used to take off a personal protective gown, and the inner glove discarded after the gown is removed. The CDC do not make recommendations for routine use of gloves in the care of patients who do not have COVID-19, even in areas where there may be asymptomatic COVID-19, and recommends standard precautions, specifically practicing hand hygiene before and after patient contact.8

The Bottom Line

When seeing patients with COVID-19, N-95 masks, goggles or face shields, gowns, and gloves should be used, with hand hygiene routinely practiced before and after seeing patients. For offices seeing patients not suspected of having COVID-19, the IDSA guideline clarifies that there is not a statistical difference in acquisition of infection with the use of surgical face masks vs N95 respirators. According to the CDC recommendations, eye protection in addition to facemasks should be used by the health care provider, and masks should be worn by patients. Hand hygiene should be used routinely before and after all patient contact. With use of these approaches, it should be safe for offices to reopen and see patients.

Neil Skolnik, MD, is professor of family and community medicine at the Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director of the Family Medicine Residency Program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Jeffrey Matthews, DO, is a second-year resident in the Family Medicine Residency at Abington Jefferson Health. For questions or comments, feel free to contact Dr. Skolnik on Twitter @NeilSkolnik.

References

1. Lynch JB, Davitkov P, Anderson DJ, et al. COVID-19 Guideline, Part 2: Infection Prevention. IDSA Home. https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-infection-prevention/. April 27, 2020. Accessed June 10, 2020.

2. J Hosp Infect. 2020 May;105(1):104-5.

3. Lancet. 2003;361(9368):1519-20.

4. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2020 Apr 4. doi: 2020;10.1111/irv.12745.

5. J Hosp Infect. 2010;74(3):271-7.

6. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(8):999-1006.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Suspected or Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Healthcare Settings. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-recommendations.html. Accessed Jun 16, 2020.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare Infection Prevention and Control FAQs for COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-faq.html. Accessed June 15, 2020.

As we reopen our offices we are faced with the challenge of determining the best way to do it safely – protecting ourselves, our staff, and our patients.

In this column we will focus on selected details of the recommendations from IDSA and the CDC that may be helpful in primary care offices.

Face masks

Many clinicians have asked whether a physician should use a mask while seeing patients without COVID-19 in the office, and if yes, which type. The IDSA guideline states that mask usage is imperative for reducing the risk of health care workers contracting COVID-19.1 The evidence is derived from a number of sources, including a retrospective study from Wuhan (China) University that examined two groups of health care workers during the outbreak. The first group wore N95 masks and washed their hands frequently, while the second group did not wear masks and washed their hands less frequently. In the group that took greater actions to protect themselves, none of the 493 staff members contracted COVID-19, compared with 10 of 213 staff members in the other group. The decrease in infection rate occurred in the group that wore masks despite the fact that this group had 733% more exposure to COVID-19 patients.2 Further evidence came from a case-control study done in hospitals in Hong Kong during the 2003 SARS-CoV outbreak.3 This study showed that mask wearing was the most significant intervention for reducing infection, followed by gowning, and then handwashing. These findings make it clear that mask usage is a must for all health care providers who may be caring for patients who could have COVID-19.

The guideline also reviews evidence about the use of surgical masks versus N95 masks. On reviewing indirect evidence from the SARS-CoV epidemic, IDSA found that wearing any mask – surgical or N95 – led to a large reduction in the risk of developing an infection. In this systematic review of five observational studies in health care personnel, for those wearing surgical masks, the odds ratio for developing an infection was 0.13 (95% CI, 0.03-0.62), and for those wearing N95 masks, the odds ratio was 0.12 (95% CI, 0.06-0.26). There was not a significant difference between risk reductions for those who wore surgical masks and N95 masks, respectively.1,4 The IDSA guideline panel recommended “that health care personnel caring for patients with suspected or known COVID-19 use either a surgical mask or N95 respirator ... as part of appropriate PPE.” Since there is not a significant difference in outcomes between those who use surgical masks and those who use N95 respirators, and the IDSA guideline states either type of mask is considered appropriate when taking care of patients with suspected or known COVID-19, in our opinion, use of surgical masks rather than N95s is sufficient when performing low-risk activities. Such activities include seeing patients who do not have a high likelihood of COVID-19 in the office setting.

The IDSA recommendation also discusses universal masking, defined as both patients and clinicians wearing masks. The recommendation is supported by the findings of a study in which universal mask usage was used to prevent the spread of H1N 1 during the 2009 outbreak. In this study of staff members and patients exposed to H1N1 who all wore masks, only 0.48% of 836 acquired infection. In the same study, not wearing a mask by either the provider or patient increased the risk of infection.5 Also, in a prospective study of hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients, universal masking caused infection rates to drop from 10.3% to 4.4%.6

The IDSA guideline states the following: “There may be some, albeit uncertain, benefit to universal masking in the absence of resource constraints. However, the benefits of universal masking with surgical masks should be weighed against the risk of increasing the PPE burn rate and contextualized to the background COVID-19 prevalence rate for asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic HCPs [health care providers] and visitors.”1

The CDC’s guidance statement says the following: “Continued community transmission has increased the number of individuals potentially exposed to and infectious with SARS-CoV-2. Fever and symptom screening have proven to be relatively ineffective in identifying all infected individuals, including HCPs. Symptom screening also will not identify individuals who are infected but otherwise asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic; additional interventions are needed to limit the unrecognized introduction of SARS-CoV-2 into healthcare settings by these individuals. As part of aggressive source control measures, healthcare facilities should consider implementing policies requiring everyone entering the facility to wear a cloth face covering (if tolerated) while in the building, regardless of symptoms.”7

It is our opinion, based on the CDC and IDSA recommendations, that both clinicians and patients should be required to wear masks when patients are seen in the office if possible. Many offices have instituted a policy that says, if a patient refuses to wear a mask during an office visit, then the patient will not be seen.

Eye protection

Many clinicians are uncertain about whether eye protection needs to be used when seeing asymptomatic patients. The IDSA acknowledges that there are not studies that have looked critically at eye protection, but the society also acknowledges “appropriate personal protective equipment includes, in addition to a mask or respirator, eye protection, gown and gloves.”1 In addition, the CDC recommends that, for healthcare workers located in areas with moderate or higher prevalence of COVID-19, HCPs should wear eye protection in addition to facemasks since they may encounter asymptomatic individuals with COVID-19.

Gowns and gloves

Gowns and gloves are recommended as a part of personal protective gear when caring for patients who have COVID-19. The IDSA guideline is clear in its recommendations, but does not cite evidence for having no gloves versus having gloves. Furthermore, they state that the evidence is insufficient to recommend double gloves, with the top glove used to take off a personal protective gown, and the inner glove discarded after the gown is removed. The CDC do not make recommendations for routine use of gloves in the care of patients who do not have COVID-19, even in areas where there may be asymptomatic COVID-19, and recommends standard precautions, specifically practicing hand hygiene before and after patient contact.8

The Bottom Line

When seeing patients with COVID-19, N-95 masks, goggles or face shields, gowns, and gloves should be used, with hand hygiene routinely practiced before and after seeing patients. For offices seeing patients not suspected of having COVID-19, the IDSA guideline clarifies that there is not a statistical difference in acquisition of infection with the use of surgical face masks vs N95 respirators. According to the CDC recommendations, eye protection in addition to facemasks should be used by the health care provider, and masks should be worn by patients. Hand hygiene should be used routinely before and after all patient contact. With use of these approaches, it should be safe for offices to reopen and see patients.

Neil Skolnik, MD, is professor of family and community medicine at the Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director of the Family Medicine Residency Program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Jeffrey Matthews, DO, is a second-year resident in the Family Medicine Residency at Abington Jefferson Health. For questions or comments, feel free to contact Dr. Skolnik on Twitter @NeilSkolnik.

References

1. Lynch JB, Davitkov P, Anderson DJ, et al. COVID-19 Guideline, Part 2: Infection Prevention. IDSA Home. https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-infection-prevention/. April 27, 2020. Accessed June 10, 2020.

2. J Hosp Infect. 2020 May;105(1):104-5.

3. Lancet. 2003;361(9368):1519-20.

4. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2020 Apr 4. doi: 2020;10.1111/irv.12745.

5. J Hosp Infect. 2010;74(3):271-7.

6. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(8):999-1006.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Suspected or Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Healthcare Settings. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-recommendations.html. Accessed Jun 16, 2020.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare Infection Prevention and Control FAQs for COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-faq.html. Accessed June 15, 2020.

As we reopen our offices we are faced with the challenge of determining the best way to do it safely – protecting ourselves, our staff, and our patients.

In this column we will focus on selected details of the recommendations from IDSA and the CDC that may be helpful in primary care offices.

Face masks

Many clinicians have asked whether a physician should use a mask while seeing patients without COVID-19 in the office, and if yes, which type. The IDSA guideline states that mask usage is imperative for reducing the risk of health care workers contracting COVID-19.1 The evidence is derived from a number of sources, including a retrospective study from Wuhan (China) University that examined two groups of health care workers during the outbreak. The first group wore N95 masks and washed their hands frequently, while the second group did not wear masks and washed their hands less frequently. In the group that took greater actions to protect themselves, none of the 493 staff members contracted COVID-19, compared with 10 of 213 staff members in the other group. The decrease in infection rate occurred in the group that wore masks despite the fact that this group had 733% more exposure to COVID-19 patients.2 Further evidence came from a case-control study done in hospitals in Hong Kong during the 2003 SARS-CoV outbreak.3 This study showed that mask wearing was the most significant intervention for reducing infection, followed by gowning, and then handwashing. These findings make it clear that mask usage is a must for all health care providers who may be caring for patients who could have COVID-19.

The guideline also reviews evidence about the use of surgical masks versus N95 masks. On reviewing indirect evidence from the SARS-CoV epidemic, IDSA found that wearing any mask – surgical or N95 – led to a large reduction in the risk of developing an infection. In this systematic review of five observational studies in health care personnel, for those wearing surgical masks, the odds ratio for developing an infection was 0.13 (95% CI, 0.03-0.62), and for those wearing N95 masks, the odds ratio was 0.12 (95% CI, 0.06-0.26). There was not a significant difference between risk reductions for those who wore surgical masks and N95 masks, respectively.1,4 The IDSA guideline panel recommended “that health care personnel caring for patients with suspected or known COVID-19 use either a surgical mask or N95 respirator ... as part of appropriate PPE.” Since there is not a significant difference in outcomes between those who use surgical masks and those who use N95 respirators, and the IDSA guideline states either type of mask is considered appropriate when taking care of patients with suspected or known COVID-19, in our opinion, use of surgical masks rather than N95s is sufficient when performing low-risk activities. Such activities include seeing patients who do not have a high likelihood of COVID-19 in the office setting.

The IDSA recommendation also discusses universal masking, defined as both patients and clinicians wearing masks. The recommendation is supported by the findings of a study in which universal mask usage was used to prevent the spread of H1N 1 during the 2009 outbreak. In this study of staff members and patients exposed to H1N1 who all wore masks, only 0.48% of 836 acquired infection. In the same study, not wearing a mask by either the provider or patient increased the risk of infection.5 Also, in a prospective study of hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients, universal masking caused infection rates to drop from 10.3% to 4.4%.6

The IDSA guideline states the following: “There may be some, albeit uncertain, benefit to universal masking in the absence of resource constraints. However, the benefits of universal masking with surgical masks should be weighed against the risk of increasing the PPE burn rate and contextualized to the background COVID-19 prevalence rate for asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic HCPs [health care providers] and visitors.”1

The CDC’s guidance statement says the following: “Continued community transmission has increased the number of individuals potentially exposed to and infectious with SARS-CoV-2. Fever and symptom screening have proven to be relatively ineffective in identifying all infected individuals, including HCPs. Symptom screening also will not identify individuals who are infected but otherwise asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic; additional interventions are needed to limit the unrecognized introduction of SARS-CoV-2 into healthcare settings by these individuals. As part of aggressive source control measures, healthcare facilities should consider implementing policies requiring everyone entering the facility to wear a cloth face covering (if tolerated) while in the building, regardless of symptoms.”7

It is our opinion, based on the CDC and IDSA recommendations, that both clinicians and patients should be required to wear masks when patients are seen in the office if possible. Many offices have instituted a policy that says, if a patient refuses to wear a mask during an office visit, then the patient will not be seen.

Eye protection

Many clinicians are uncertain about whether eye protection needs to be used when seeing asymptomatic patients. The IDSA acknowledges that there are not studies that have looked critically at eye protection, but the society also acknowledges “appropriate personal protective equipment includes, in addition to a mask or respirator, eye protection, gown and gloves.”1 In addition, the CDC recommends that, for healthcare workers located in areas with moderate or higher prevalence of COVID-19, HCPs should wear eye protection in addition to facemasks since they may encounter asymptomatic individuals with COVID-19.

Gowns and gloves

Gowns and gloves are recommended as a part of personal protective gear when caring for patients who have COVID-19. The IDSA guideline is clear in its recommendations, but does not cite evidence for having no gloves versus having gloves. Furthermore, they state that the evidence is insufficient to recommend double gloves, with the top glove used to take off a personal protective gown, and the inner glove discarded after the gown is removed. The CDC do not make recommendations for routine use of gloves in the care of patients who do not have COVID-19, even in areas where there may be asymptomatic COVID-19, and recommends standard precautions, specifically practicing hand hygiene before and after patient contact.8

The Bottom Line

When seeing patients with COVID-19, N-95 masks, goggles or face shields, gowns, and gloves should be used, with hand hygiene routinely practiced before and after seeing patients. For offices seeing patients not suspected of having COVID-19, the IDSA guideline clarifies that there is not a statistical difference in acquisition of infection with the use of surgical face masks vs N95 respirators. According to the CDC recommendations, eye protection in addition to facemasks should be used by the health care provider, and masks should be worn by patients. Hand hygiene should be used routinely before and after all patient contact. With use of these approaches, it should be safe for offices to reopen and see patients.

Neil Skolnik, MD, is professor of family and community medicine at the Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director of the Family Medicine Residency Program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. Jeffrey Matthews, DO, is a second-year resident in the Family Medicine Residency at Abington Jefferson Health. For questions or comments, feel free to contact Dr. Skolnik on Twitter @NeilSkolnik.

References

1. Lynch JB, Davitkov P, Anderson DJ, et al. COVID-19 Guideline, Part 2: Infection Prevention. IDSA Home. https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-infection-prevention/. April 27, 2020. Accessed June 10, 2020.

2. J Hosp Infect. 2020 May;105(1):104-5.

3. Lancet. 2003;361(9368):1519-20.

4. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2020 Apr 4. doi: 2020;10.1111/irv.12745.

5. J Hosp Infect. 2010;74(3):271-7.

6. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(8):999-1006.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Suspected or Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Healthcare Settings. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-recommendations.html. Accessed Jun 16, 2020.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare Infection Prevention and Control FAQs for COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-faq.html. Accessed June 15, 2020.

ACR issues guidances for MIS-C and pediatric rheumatic disease during pandemic

Two new clinical guidance documents from the American College of Rheumatology provide evidence-based recommendations for managing pediatric rheumatic disease during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as diagnostic and treatment recommendations for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) associated with COVID-19 infection.

Although several children’s hospitals have published their treatment protocols for MIS-C since the condition’s initial discovery, the ACR appears to be the first medical organization to review all the most current evidence to issue interim guidance with the expectations that it will change as more data become available.

“It is challenging having to make recommendations not having a lot of scientific evidence, but we still felt we had to use whatever’s out there to the best of our ability and use our experience to put together these recommendations,” Dawn M. Wahezi, MD, chief of pediatric rheumatology at Children’s Hospital at Montefiore and an associate professor of pediatrics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, said in an interview.

“We wanted to be mindful of the fact that there are things we know and things we don’t know, and we have to be careful about what we’re recommending,” said Dr. Wahezi, a member of the ACR working group that assembled the recommendations for pediatric rheumatic disease management during the pandemic. “We’re recommending the best we can at this moment, but if there are new studies that come out and suggest otherwise, we will definitely have to go back and amend the document.”

The foremost priority of the pediatric rheumatic disease guidance focuses on maintaining control of the disease and avoiding flares that may put children at greater risk of infection. Dr. Wahezi said the ACR has received many calls from patients and clinicians asking whether patients should continue their immunosuppressant medications. Fear of the coronavirus infection, medication shortages, difficulty getting to the pharmacy, uneasiness about going to the clinic or hospital for infusions, and other barriers may have led to gaps in medication.

“We didn’t want people to be too quick to hold patients’ medications just because they were scared of COVID,” Dr. Wahezi said. “If they did have medication stopped for one reason or another and their disease flared, having active disease, regardless of which disease it is, actually puts you at higher risk for infection. By controlling their disease, that would be the way to protect them the most.”

A key takeaway in the guidance on MIS-C, meanwhile, is an emphasis on its rarity lest physicians be too quick to diagnose it and miss another serious condition with overlapping symptoms, explained Lauren Henderson, MD, an attending rheumatologist at Boston Children’s Hospital and assistant professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Henderson participated in the ACR group that wrote the MIS-C guidance.

“The first thing we want to be thoughtful about clinically is to recognize that children in general with the acute infectious phase of SARS-CoV-2 have mild symptoms and generally do well,” Dr. Henderson said. “From what we can tell from all the data, MIS-C is rare. That really needs to be considered when clinicians on the ground are doing the diagnostic evaluation” because of concerns that clinicians “could rush to diagnose and treat patients with MIS-C and miss important diagnoses like malignancies and infections.”

Management of pediatric rheumatic disease during the pandemic

The COVID-19 clinical guidance for managing pediatric rheumatic disease grew from the work of the North American Pediatric Rheumatology Clinical Guidance Task Force, which included seven pediatric rheumatologists, two pediatric infectious disease physicians, one adult rheumatologist, and one pediatric nurse practitioner. The general guidance covers usual preventive measures for reducing risk for COVID-19 infection, the recommendation that children continue to receive recommended vaccines unless contraindicated by medication, and routine in-person visits for ophthalmologic surveillance of those with a history of uveitis or at high risk for chronic uveitis. The guidance also notes the risk of mental health concerns, such as depression and anxiety, related to quarantine and the pandemic.

The top recommendation is initiation or continuation of all medications necessary to control underlying disease, including NSAIDs, hydroxychloroquine, ACE inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers, colchicine, conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (cDMARDs), biologic DMARDs, and targeted synthetic DMARDs. Even patients who may have had exposure to COVID-19 or who have an asymptomatic COVID-19 infection should continue to take these medications with the exception of ACEi/ARBs.

In those with pediatric rheumatic disease who have a symptomatic COVID-19 infection, “NSAIDs, HCQ, and colchicine may be continued, if necessary, to control underlying disease,” as can interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6 inhibitors, but “cDMARDs, bDMARDs [except IL-1 and IL-6 inhibitors] and tsDMARDs should be temporarily delayed or withheld,” according to the guidance. Glucocorticoids can be continued at the lowest possible dose to control disease.

“There’s nothing in the literature that suggests people who have rheumatic disease, especially children, and people who are on these medications, really are at increased risk for COVID-19,” Dr. Wahezi said. “That’s why we didn’t want people to be overcautious in stopping medications when the main priority is to control their disease.”

She noted some experts’ speculations that these medications may actually benefit patients with rheumatic disease who develop a COVID-19 infection because the medications keep the immune response in check. “If you allow them to have this dysregulated immune response and have active disease, you’re potentially putting them at greater risk,” Dr. Wahezi said, although she stressed that inadequate evidence exists to support these speculations right now.

Lack of evidence has been the biggest challenge all around with developing this guidance, she said.

“Because this is such an unprecedented situation and because people are so desperate to find treatments both for the illness and to protect those at risk for it, there are lots of people trying to put evidence out there, but it may not be the best-quality evidence,” Dr. Wahezi said.

Insufficient evidence also drove the group’s determination that “SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing is not useful in informing on the history of infection or risk of reinfection,” as the guidance states. Too much variability in the assays exist, Dr. Wahezi said, and, further, it’s unclear what the clinical significance of a positive test would be.

“We didn’t want anyone to feel they had to make clinical decisions based on the results of that antibody testing,” she said. “Even if the test is accurate, we don’t know how to interpret it because it’s so new.”

The guidance also notes that patients with stable disease and previously stable lab markers on stable doses of their medication may be able to extend the interval for medication toxicity lab testing a few months if there is concern about exposure to COVID-19 to get the blood work.

“If you’re just starting a medicine or there’s someone who’s had abnormalities with the medicine in the past or you’re making medication adjustments, you wouldn’t do it in those scenarios, but if there’s someone who’s been on the drug for a long time and are nervous to get [blood] drawn, it’s probably okay to delay it,” Dr. Wahezi said. Lab work for disease activity measures, on the other hand, remain particularly important, especially since telemedicine visits may require clinicians to rely on lab results more than previously.

Management of MIS-C associated with COVID-19

The task force that developed guidance for the new inflammatory condition recently linked to SARS-CoV-2 infections in children included nine pediatric rheumatologists, two adult rheumatologists, two pediatric cardiologists, two pediatric infectious disease specialists, and one pediatric critical care physician.

The guidance includes a figure for the diagnostic pathway in evaluating children suspected of having MIS-C and extensive detail on diagnostic work-up, but the task force intentionally avoided providing a case definition for the condition. Existing case definitions from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, World Health Organization, and the United Kingdom’s Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health differ from one another and are based on unclear evidence, Dr. Henderson noted. “We really don’t have enough data to know the sensitivity and specificity of each parameter, and until that’s available, we didn’t want to add to the confusion,” she said.

The guidance also stresses that MIS-C is a rare complication, so patients suspected of having the condition who do not have “life-threatening manifestations should undergo diagnostic evaluation for MIS-C as well as other possible infectious and noninfectious etiologies before immunomodulatory treatment is initiated,” the guidance states.

Unless a child is in shock or otherwise requires urgent care, physicians should take the time to complete the diagnostic work-up while monitoring the child, Dr. Henderson said. If the child does have MIS-C, the guidance currently recommends intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and/or glucocorticoids to prevent coronary artery aneurysms, the same treatment other institutions have been recommending.

“We don’t have rigorous comparative studies looking at different types of treatments,” Dr. Henderson said, noting that the vast majority of children in the literature received IVIG and/or glucocorticoid treatment. “Often children really responded quite forcefully to those treatments, but we don’t have high-quality data yet to know that this treatment is better than supportive care or another medication.”

Dr. Henderson also stressed the importance of children receiving care at a facility with the necessary expertise to manage MIS-C and receiving long-term follow-up care from a multidisciplinary clinical team that includes a rheumatologist, an infectious disease doctor, a cardiologist, and possibly a hematologist.

“Making sure children are admitted to a hospital that has the resources and are followed by physicians with expertise or understanding of the intricacies of MIS-C is really important,” she said, particularly for children with cardiac involvement. “We don’t know if all the kids presenting with left ventricular dysfunction and shock are at risk for having myocardial fibrosis down the line,” she noted. “There is so much we do not understand and very little data to guide us on what to do, so these children really need to be under the care of a cardiologist and rheumatologist to make sure that their care is tailored to them.”

Although MIS-C shares overlapping symptoms with Kawasaki disease, it’s still unclear how similar or different the two conditions are, Dr. Henderson said.

“We can definitely say that when we look at MIS-C and compare it to historical groups of Kawasaki disease before the pandemic, there are definitely different features in the MIS-C group,” she said. Kawasaki disease generally only affects children under age 5, whereas MIS-C patients run the gamut from age 1-17. Racial demographics are also different, with a higher proportion of black children affected by MIS-C.

It’s possible that the pathophysiology of both conditions will turn out to be similar, particularly given the hypothesis that Kawasaki disease is triggered by infections in genetically predisposed people. However, the severity of symptoms and risk of aneurysms appear greater with MIS-C so far.

“The degree to which these patients are presenting with left ventricular dysfunction and shock is much higher than what we’ve seen previously,” Dr. Henderson said. “Children can have aneurysms even if they don’t meet all the Kawasaki disease features, which makes it feel that this is somehow clinically different from what we’ve seen before. It’s not just the kids who have the rash and the conjunctivitis and the extremity changes and oral changes who have the aneurysms.”

The reason for including both IVIG and glucocorticoids as possible first-line drugs to prevent aneurysms is that some evidence suggests children with MIS-C may have higher levels of IVIG resistance, she said.

Like Dr. Wahezi, Dr. Henderson emphasized the necessarily transient nature of these recommendations.

“These recommendations will almost certainly change based on evolving understanding of MIS-C and the data,” Dr. Henderson said, adding that this new, unique condition highlights the importance of including children in allocating funding for research and in clinical trials.

“Children are not always identical to adults, and it’s really important that we have high-quality data to inform our decisions about how to care for them,” she said.

Dr. Wahezi had no disclosures. Dr. Henderson has consulted for Sobi and Adaptive Technologies. The guidelines did not note other disclosures for members of the ACR groups.

SOURCES: COVID-19 Clinical Guidance for Pediatric Patients with Rheumatic Disease and Clinical Guidance for Pediatric Patients with Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) Associated with SARS-CoV-2 and Hyperinflammation in COVID-19

Two new clinical guidance documents from the American College of Rheumatology provide evidence-based recommendations for managing pediatric rheumatic disease during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as diagnostic and treatment recommendations for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) associated with COVID-19 infection.