User login

AVAHO

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

3D Printing for the Development of Palatal Defect Prosthetics

Three-dimensional (3D) printing has become a promising area of innovation in biomedical research.1,2 Previous research in orthopedic surgery has found that customized 3D printed implants, casts, orthoses, and prosthetics (eg, prosthetic hands) matched to an individual’s unique anatomy can result in more precise placement and better surgical outcomes.3-5 Customized prosthetics have also been found to lead to fewer complications.3,6

Recent advances in 3D printing technology has prompted investigation from surgeons to identify how this new tool may be incorporated into patient care.1,7 One of the most common applications of 3D printing is during preoperative planning in which surgeons gain better insight into patient-specific anatomy by using patient-specific printed models.8 Another promising application is the production of customized prosthetics suited to each patient’s unique anatomy.9 As a result, 3D printing has significantly impacted bone and cartilage restoration procedures and has the potential to completely transform the treatment of patients with debilitating musculoskeletal injuries.3,10

The potential surrounding 3D printed prosthetics has led to their adoption by several other specialties, including otolaryngology.11 The most widely used application of 3D printing among otolaryngologists is preoperative planning, and the incorporation of printed prosthetics intoreconstruction of the orbit, nasal septum, auricle, and palate has also been reported.2,12,13 Patient-specific implants might allow otolaryngologists to better rehabilitate, reconstruct, and/or regenerate craniofacial defects using more humane procedures.14

Patients with palatomaxillary cancers are treated by prosthodontists or otolaryngologists. An impression is made with a resin–which can be painful for postoperative patients–and a prosthetic is manufactured and implanted.15-17 Patients with cancer often see many specialists, though reconstructive care is a low priority. Many of these individuals also experience dynamic anatomic functional changes over time, leading to the need for multiple prothesis.

palatomaxillary prosthetics

This program aims to use patients’ previous computed tomography (CT) to tailor customized 3D printed palatomaxillary prosthetics to specifically fit their anatomy. Palatomaxillary defects are a source of profound disability for patients with head and neck cancers who are left with large anatomic defects as a direct result of treatment. Reconstruction of palatal defects poses unique challenges due to the complexity of patient anatomy.18,19

3D printed prosthetics for palatomaxillary defects have not been incorporated into patient care. We reviewed previous imaging research to determine if it could be used to assist patients who struggle with their function and appearance following treatment for head and neck cancers. The primary aim was to investigate whether 3D printing was a feasible strategy for creating patient-specific palatomaxillary prosthetics. The secondary aim is to determine whether these prosthetics should be tested in the future for use in reconstruction of maxillary defects.

Data Acquisition

This study was conducted at the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) and was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board (approval #28958, informed consent and patient contact excluded). A retrospective chart review was conducted on all patients with head and neck cancers who were treated at VAPAHCS from 2010 to 2022. Patients aged ≥ 18 years who had a palatomaxillary defect due to cancer treatment, had undergone a palatal resection, and who received treatment at any point from 2010 to 2022 were included in the review. CTs were not a specific inclusion criterion, though the quality of the scans was analyzed for eligible patients. Younger patients and those treated at VAPAHCS prior to 2010 were excluded.

There was no control group; all data was sourced from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) imaging system database. Among the 3595 patients reviewed, 5 met inclusion criteria and the quality of their craniofacial anatomy CTs were analyzed. To maintain accurate craniofacial 3D modeling, CTs require a maximum of 1 mm slice thickness. Of the 5 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 4 were found to have variability in the quality of their CTs and severe defects not suitable for prosthetic reconstruction, which led to their exclusion from the study. One patient was investigated to demonstrate if making these prostheses was feasible. This patient was diagnosed with a malignant neoplasm of the hard palate, underwent a partial maxillectomy, and a palatal obturator was placed to cover the defect.

The primary data collected was patient identifiers as well as the gross anatomy and dimensions of the patients’ craniofacial anatomy, as seen in previous imaging research.20 Before the imaging analysis, all personal health information was removed and the dataset was deidentified to ensure patient anonymity and noninvolvement.

CT Segmentation and 3D Printing

Using CTs of the patient’s craniofacial anatomy, we developed a model of the defects. This was achieved with deidentified CTs imported into the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved computerized aid design (CAD) software, Materialise Mimics. The hard palate was segmented and isolated based off the presented scan and any holes in the image were filled using the CAD software. The model was subsequently mirrored in Materialise 3-matic to replicate an original anatomical hard palate prosthesis. The final product was converted into a 3D model and imported into Formlabs preform software to generate 3D printing supports and orient it for printing. The prosthetic was printed using FDA-approved Biocompatible Denture Base Resin by a Formlabs 3B+ printer at the Palo Alto VA Simulation Center. The 3D printed prosthesis was washed using Formlabs Form Wash 80% ethyl alcohol to remove excess resin and subsequently cured to harden the malleable resin. Supports were later removed, and the prosthesis was sanded.

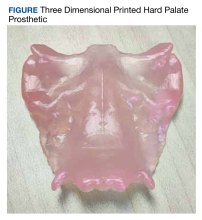

The primary aim of this study was to investigate whether using CTs to create patient-specific prosthetic renderings for patients with head and neck cancer could be a feasible strategy. The CTs from the patient were successfully used to generate a 3D printed prosthesis, and the prosthesis matched the original craniofacial anatomy seen in the patient's imaging (Figure). These results demonstrate that high quality CTs can be used as a template for 3D printed prostheses for mild to moderate palatomaxillary defects.

3D Printing Costs

One liter of Denture Base Resin costs $299; prostheses use about 5 mL of resin. The average annual salary of a 3D printing technician in the United States is $42,717, or $20.54 per hour.21 For an experienced 3D printing technician, the time required to segment the hard palate and prepare it for 3D printing is 1 to 2 hours. The process may exceed 2 hours if the technician is presented with a lower quality CT or if the patient has a complex craniofacial anatomy.

The average time it takes to print a palatal prosthetic is 5 hours. An additional hour is needed for postprocessing, which includes washing and sanding. Therefore, the cost of the materials and labor for an average 3D printed prosthetic is about $150. A Formlabs 3B+ printer is competitively priced around $10,000. The cost for Materialise Mimics software varies, but is estimated at $16,000 at VAPAHCS. The prices for these 2 items are not included in our price estimation but should be taken into consideration.

Prosthodontist Process and Cost

The typical process of creating a palatal prosthesis by a prosthodontist begins by examining the patient, creating a stone model, then creating a wax model. Biocompatible materials are selected and processed into a mold that is trimmed and polished to the desired shape. This is followed by another patient visit to ensure the prosthesis fits properly. Follow-up care is also necessary for maintenance and comfort.

The average cost of a palatal prosthesis varies depending on the type needed (ie, metal implant, teeth replacement), the materials used, the region in which the patient is receiving care, and the complexity of the case. For complex and customizable options like those required for patients with cancer, the prostheses typically cost several thousands of dollars. The Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code for a palatal lift prosthesis (D5955) lists prices ranging from $4000 to $8000 per prosthetic, not including the cost of the prosthodontist visits.22,23

Discussion

This program sought to determine whether imaging studies of maxillary defects are effective templates for developing 3D printed prosthetics and whether these prosthetics should be tested for future use in reconstruction of palatomaxillary defects. Our program illustrated that CTs served as feasible templates for developing hard palate prostheses for patients with palatomaxillary defects. It is important to note the CTs used were from a newer and more modern scanner and therefore yielded detailed palatal structures with higher accuracy more suitable for 3D modeling. Lower-quality CTs from the 4 patients excluded from the program were not suitable for 3D modeling. This suggests that with high-quality imaging, 3D printed prosthesis may be a viable strategy to help patients who struggle with their function following treatment for head and neck cancers.

3D printed prosthesis may also be a more patient centered and convenient option. In the traditional prosthesis creation workflow, the patient must physically bite down onto a resin (alginate or silicone) to make an impression, a very painful postoperative process that is irritating to the raw edges of the surgical bed.15,16 Prosthodontists then create a prosthetic minus the tumor and typically secure it with clips or glue.17 Many patients also experience changes in their anatomy over time requiring them to have a new protheses created. This is particularly important in veterans with palatomaxillary defects since many VA medical centers do not have a prosthodontist on staff, making accessibility to these specialists difficult. 3D printing provides a contactless prosthetic creation process. This convenience may reduce a patient’s pain and the number of visits for which they need a specialist.

Future Directions

Additional research is needed to determine the full potential of 3D printed prosthetics. 3D printed prostheses have been effectively used for patient education in areas of presurgical planning, prosthesis creation, and trainee education.24 This research represents an early step in the development of a new technology for use in otolaryngology. Specifically, many veterans with a history of head and neck cancers have sustained changes to their craniofacial anatomy following treatment. Using imaging to create 3D printed prosthetics could be very effective for these patients. Prosthetics could improve a patient’s quality of life by restoring/approximating their anatomy after cancer treatment.

Significant time and care must be taken by cancer and reconstructive surgeons to properly fit a prosthesis. Improperly fitting prosthetics leads to mucosal ulceration that then may lead to a need for fitting a new prosthetic. The advantage of 3D printed prosthetics is that they may more precisely fit the anatomy of each patient using CT results, thus potentially reducing the time needed to fit the prosthetic as well as the risk associated with an improperly fit prosthetic. 3D printed prosthesis could be used directly in the future, however, clinical trials are needed to verify its efficacy vs prosthodontic options.

Another consideration for potential future use of 3D printed prosthetics is cost. We estimated that the cost of the materials and labor of our 3D printed prosthetic to be about $150. Pricing of current molded prosthetics varies, but is often listed at several thousand dollars. Another consideration is the durability of 3D printed prosthetics vs standard prosthetics. Since we were unable to use the prosthetic in the patient, it was difficult to determine its durability. The significant cost of the 3D printer and software necessary for 3D printed prosthetics must also be considered and may be prohibitive. While many academic hospitals are considering the purchase of 3D printers and licenses, this may be challenging for resource-constrained institutions. 3D printing may also be difficult for groups without any prior experience in the field. Outsourcing to a third party is possible, though doing so adds more cost to the project. While we recognize there is a learning curve associated with adopting any new technology, it’s equally important to note that 3D printing is being rapidly integrated and has already made significant advancements in personalized medicine.8,25,26

Limitations

This program had several limitations. First, we only obtained CTs of sufficient quality from 1 patient to generate a 3D printed prosthesis. Further research with additional patients is necessary to validate this process. Second, we were unable to trial the prosthesis in the patient because we did not have FDA approval. Additionally, it is difficult to calculate a true cost estimate for this process as materials and software costs vary dramatically across institutions as well as over time.

Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to demonstrate the possibility to develop prosthetics for the hard palate for patients suffering from palatomaxillary defects. A 3D printed prosthetic was generated that matched the patient’s craniofacial anatomy. Future research should test the feasibility of these prosthetics in patient care against a traditional prosthodontic impression. Though this is a proof-of-concept study and no prosthetics were implanted as part of this investigation, we showcase the feasibility of printing prosthetics for palatomaxillary defects. The use of 3D printed prosthetics may be a more humane process, potentially lower cost, and be more accessible to veterans.

1. Crafts TD, Ellsperman SE, Wannemuehler TJ, Bellicchi TD, Shipchandler TZ, Mantravadi AV. Three-dimensional printing and its applications in otorhinolaryngology-head and neck surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(6):999-1010. doi:10.1177/0194599816678372

2. Virani FR, Chua EC, Timbang MR, Hsieh TY, Senders CW. Three-dimensional printing in cleft care: a systematic review. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2022;59(4):484-496. doi:10.1177/10556656211013175

3. Lal H, Patralekh MK. 3D printing and its applications in orthopaedic trauma: A technological marvel. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2018;9(3):260-268. doi:10.1016/j.jcot.2018.07.022

4. Vujaklija I, Farina D. 3D printed upper limb prosthetics. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2018;15(7):505-512. doi:10.1080/17434440.2018.1494568

5. Ten Kate J, Smit G, Breedveld P. 3D-printed upper limb prostheses: a review. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2017;12(3):300-314. doi:10.1080/17483107.2016.1253117

6. Thomas CN, Mavrommatis S, Schroder LK, Cole PA. An overview of 3D printing and the orthopaedic application of patient-specific models in malunion surgery. Injury. 2022;53(3):977-983. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2021.11.019

7. Colaco M, Igel DA, Atala A. The potential of 3D printing in urological research and patient care. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15(4):213-221. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2018.6

8. Meyer-Szary J, Luis MS, Mikulski S, et al. The role of 3D printing in planning complex medical procedures and training of medical professionals-cross-sectional multispecialty review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3331. Published 2022 Mar 11. doi:10.3390/ijerph19063331

9. Moya D, Gobbato B, Valente S, Roca R. Use of preoperative planning and 3D printing in orthopedics and traumatology: entering a new era. Acta Ortop Mex. 2022;36(1):39-47.

10. Wixted CM, Peterson JR, Kadakia RJ, Adams SB. Three-dimensional printing in orthopaedic surgery: current applications and future developments. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2021;5(4):e20.00230-11. Published 2021 Apr 20. doi:10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-20-00230

11. Hong CJ, Giannopoulos AA, Hong BY, et al. Clinical applications of three-dimensional printing in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(9):2045-2052. doi:10.1002/lary.2783112. Sigron GR, Barba M, Chammartin F, Msallem B, Berg BI, Thieringer FM. Functional and cosmetic outcome after reconstruction of isolated, unilateral orbital floor fractures (blow-out fractures) with and without the support of 3D-printed orbital anatomical models. J Clin Med. 2021;10(16):3509. Published 2021 Aug 9. doi:10.3390/jcm10163509

13. Kimura K, Davis S, Thomas E, et al. 3D Customization for microtia repair in hemifacial microsomia. Laryngoscope. 2022;132(3):545-549. doi:10.1002/lary.29823

14. Nyberg EL, Farris AL, Hung BP, et al. 3D-printing technologies for craniofacial rehabilitation, reconstruction, and regeneration. Ann Biomed Eng. 2017;45(1):45-57. doi:10.1007/s10439-016-1668-5

15. Flores-Ruiz R, Castellanos-Cosano L, Serrera-Figallo MA, et al. Evolution of oral cancer treatment in an andalusian population sample: rehabilitation with prosthetic obturation and removable partial prosthesis. J Clin Exp Dent. 2017;9(8):e1008-e1014. doi:10.4317/jced.54023

16. Rogers SN, Lowe D, McNally D, Brown JS, Vaughan ED. Health-related quality of life after maxillectomy: a comparison between prosthetic obturation and free flap. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(2):174-181. doi:10.1053/joms.2003.50044

17. Pool C, Shokri T, Vincent A, Wang W, Kadakia S, Ducic Y. Prosthetic reconstruction of the maxilla and palate. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(2):114-119. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709143

18. Badhey AK, Khan MN. Palatomaxillary reconstruction: fibula or scapula. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(2):86-91. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709431

19. Jategaonkar AA, Kaul VF, Lee E, Genden EM. Surgery of the palatomaxillary structure. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(2):71-76. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709430

20. Lobb DC, Cottler P, Dart D, Black JS. The use of patient-specific three-dimensional printed surgical models enhances plastic surgery resident education in craniofacial surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2019;30(2):339-341. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000005322

21. 3D printing technician salary in the United States. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.salary.com/research/salary/posting/3d-printing-technician-salary22. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System. Outpatient dental professional nationwide charges by HCPCS code. January-December 2020. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/docs/RO/Outpatient-DataTables/v3-27_Table-I.pdf23. Washington State Department of Labor and Industries. Professional services fee schedule HCPCS level II fees. October 1, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://lni.wa.gov/patient-care/billing-payments/marfsdocs/2020/2020FSHCPCS.pdf24. Low CM, Morris JM, Price DL, et al. Three-dimensional printing: current use in rhinology and endoscopic skull base surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2019;33(6):770-781. doi:10.1177/1945892419866319

25. Aimar A, Palermo A, Innocenti B. The role of 3D printing in medical applications: a state of the art. J Healthc Eng. 2019;2019:5340616. Published 2019 Mar 21. doi:10.1155/2019/5340616

26. Garcia J, Yang Z, Mongrain R, Leask RL, Lachapelle K. 3D printing materials and their use in medical education: a review of current technology and trends for the future. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn. 2018;4(1):27-40. doi:10.1136/bmjstel-2017-000234

Three-dimensional (3D) printing has become a promising area of innovation in biomedical research.1,2 Previous research in orthopedic surgery has found that customized 3D printed implants, casts, orthoses, and prosthetics (eg, prosthetic hands) matched to an individual’s unique anatomy can result in more precise placement and better surgical outcomes.3-5 Customized prosthetics have also been found to lead to fewer complications.3,6

Recent advances in 3D printing technology has prompted investigation from surgeons to identify how this new tool may be incorporated into patient care.1,7 One of the most common applications of 3D printing is during preoperative planning in which surgeons gain better insight into patient-specific anatomy by using patient-specific printed models.8 Another promising application is the production of customized prosthetics suited to each patient’s unique anatomy.9 As a result, 3D printing has significantly impacted bone and cartilage restoration procedures and has the potential to completely transform the treatment of patients with debilitating musculoskeletal injuries.3,10

The potential surrounding 3D printed prosthetics has led to their adoption by several other specialties, including otolaryngology.11 The most widely used application of 3D printing among otolaryngologists is preoperative planning, and the incorporation of printed prosthetics intoreconstruction of the orbit, nasal septum, auricle, and palate has also been reported.2,12,13 Patient-specific implants might allow otolaryngologists to better rehabilitate, reconstruct, and/or regenerate craniofacial defects using more humane procedures.14

Patients with palatomaxillary cancers are treated by prosthodontists or otolaryngologists. An impression is made with a resin–which can be painful for postoperative patients–and a prosthetic is manufactured and implanted.15-17 Patients with cancer often see many specialists, though reconstructive care is a low priority. Many of these individuals also experience dynamic anatomic functional changes over time, leading to the need for multiple prothesis.

palatomaxillary prosthetics

This program aims to use patients’ previous computed tomography (CT) to tailor customized 3D printed palatomaxillary prosthetics to specifically fit their anatomy. Palatomaxillary defects are a source of profound disability for patients with head and neck cancers who are left with large anatomic defects as a direct result of treatment. Reconstruction of palatal defects poses unique challenges due to the complexity of patient anatomy.18,19

3D printed prosthetics for palatomaxillary defects have not been incorporated into patient care. We reviewed previous imaging research to determine if it could be used to assist patients who struggle with their function and appearance following treatment for head and neck cancers. The primary aim was to investigate whether 3D printing was a feasible strategy for creating patient-specific palatomaxillary prosthetics. The secondary aim is to determine whether these prosthetics should be tested in the future for use in reconstruction of maxillary defects.

Data Acquisition

This study was conducted at the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) and was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board (approval #28958, informed consent and patient contact excluded). A retrospective chart review was conducted on all patients with head and neck cancers who were treated at VAPAHCS from 2010 to 2022. Patients aged ≥ 18 years who had a palatomaxillary defect due to cancer treatment, had undergone a palatal resection, and who received treatment at any point from 2010 to 2022 were included in the review. CTs were not a specific inclusion criterion, though the quality of the scans was analyzed for eligible patients. Younger patients and those treated at VAPAHCS prior to 2010 were excluded.

There was no control group; all data was sourced from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) imaging system database. Among the 3595 patients reviewed, 5 met inclusion criteria and the quality of their craniofacial anatomy CTs were analyzed. To maintain accurate craniofacial 3D modeling, CTs require a maximum of 1 mm slice thickness. Of the 5 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 4 were found to have variability in the quality of their CTs and severe defects not suitable for prosthetic reconstruction, which led to their exclusion from the study. One patient was investigated to demonstrate if making these prostheses was feasible. This patient was diagnosed with a malignant neoplasm of the hard palate, underwent a partial maxillectomy, and a palatal obturator was placed to cover the defect.

The primary data collected was patient identifiers as well as the gross anatomy and dimensions of the patients’ craniofacial anatomy, as seen in previous imaging research.20 Before the imaging analysis, all personal health information was removed and the dataset was deidentified to ensure patient anonymity and noninvolvement.

CT Segmentation and 3D Printing

Using CTs of the patient’s craniofacial anatomy, we developed a model of the defects. This was achieved with deidentified CTs imported into the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved computerized aid design (CAD) software, Materialise Mimics. The hard palate was segmented and isolated based off the presented scan and any holes in the image were filled using the CAD software. The model was subsequently mirrored in Materialise 3-matic to replicate an original anatomical hard palate prosthesis. The final product was converted into a 3D model and imported into Formlabs preform software to generate 3D printing supports and orient it for printing. The prosthetic was printed using FDA-approved Biocompatible Denture Base Resin by a Formlabs 3B+ printer at the Palo Alto VA Simulation Center. The 3D printed prosthesis was washed using Formlabs Form Wash 80% ethyl alcohol to remove excess resin and subsequently cured to harden the malleable resin. Supports were later removed, and the prosthesis was sanded.

The primary aim of this study was to investigate whether using CTs to create patient-specific prosthetic renderings for patients with head and neck cancer could be a feasible strategy. The CTs from the patient were successfully used to generate a 3D printed prosthesis, and the prosthesis matched the original craniofacial anatomy seen in the patient's imaging (Figure). These results demonstrate that high quality CTs can be used as a template for 3D printed prostheses for mild to moderate palatomaxillary defects.

3D Printing Costs

One liter of Denture Base Resin costs $299; prostheses use about 5 mL of resin. The average annual salary of a 3D printing technician in the United States is $42,717, or $20.54 per hour.21 For an experienced 3D printing technician, the time required to segment the hard palate and prepare it for 3D printing is 1 to 2 hours. The process may exceed 2 hours if the technician is presented with a lower quality CT or if the patient has a complex craniofacial anatomy.

The average time it takes to print a palatal prosthetic is 5 hours. An additional hour is needed for postprocessing, which includes washing and sanding. Therefore, the cost of the materials and labor for an average 3D printed prosthetic is about $150. A Formlabs 3B+ printer is competitively priced around $10,000. The cost for Materialise Mimics software varies, but is estimated at $16,000 at VAPAHCS. The prices for these 2 items are not included in our price estimation but should be taken into consideration.

Prosthodontist Process and Cost

The typical process of creating a palatal prosthesis by a prosthodontist begins by examining the patient, creating a stone model, then creating a wax model. Biocompatible materials are selected and processed into a mold that is trimmed and polished to the desired shape. This is followed by another patient visit to ensure the prosthesis fits properly. Follow-up care is also necessary for maintenance and comfort.

The average cost of a palatal prosthesis varies depending on the type needed (ie, metal implant, teeth replacement), the materials used, the region in which the patient is receiving care, and the complexity of the case. For complex and customizable options like those required for patients with cancer, the prostheses typically cost several thousands of dollars. The Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code for a palatal lift prosthesis (D5955) lists prices ranging from $4000 to $8000 per prosthetic, not including the cost of the prosthodontist visits.22,23

Discussion

This program sought to determine whether imaging studies of maxillary defects are effective templates for developing 3D printed prosthetics and whether these prosthetics should be tested for future use in reconstruction of palatomaxillary defects. Our program illustrated that CTs served as feasible templates for developing hard palate prostheses for patients with palatomaxillary defects. It is important to note the CTs used were from a newer and more modern scanner and therefore yielded detailed palatal structures with higher accuracy more suitable for 3D modeling. Lower-quality CTs from the 4 patients excluded from the program were not suitable for 3D modeling. This suggests that with high-quality imaging, 3D printed prosthesis may be a viable strategy to help patients who struggle with their function following treatment for head and neck cancers.

3D printed prosthesis may also be a more patient centered and convenient option. In the traditional prosthesis creation workflow, the patient must physically bite down onto a resin (alginate or silicone) to make an impression, a very painful postoperative process that is irritating to the raw edges of the surgical bed.15,16 Prosthodontists then create a prosthetic minus the tumor and typically secure it with clips or glue.17 Many patients also experience changes in their anatomy over time requiring them to have a new protheses created. This is particularly important in veterans with palatomaxillary defects since many VA medical centers do not have a prosthodontist on staff, making accessibility to these specialists difficult. 3D printing provides a contactless prosthetic creation process. This convenience may reduce a patient’s pain and the number of visits for which they need a specialist.

Future Directions

Additional research is needed to determine the full potential of 3D printed prosthetics. 3D printed prostheses have been effectively used for patient education in areas of presurgical planning, prosthesis creation, and trainee education.24 This research represents an early step in the development of a new technology for use in otolaryngology. Specifically, many veterans with a history of head and neck cancers have sustained changes to their craniofacial anatomy following treatment. Using imaging to create 3D printed prosthetics could be very effective for these patients. Prosthetics could improve a patient’s quality of life by restoring/approximating their anatomy after cancer treatment.

Significant time and care must be taken by cancer and reconstructive surgeons to properly fit a prosthesis. Improperly fitting prosthetics leads to mucosal ulceration that then may lead to a need for fitting a new prosthetic. The advantage of 3D printed prosthetics is that they may more precisely fit the anatomy of each patient using CT results, thus potentially reducing the time needed to fit the prosthetic as well as the risk associated with an improperly fit prosthetic. 3D printed prosthesis could be used directly in the future, however, clinical trials are needed to verify its efficacy vs prosthodontic options.

Another consideration for potential future use of 3D printed prosthetics is cost. We estimated that the cost of the materials and labor of our 3D printed prosthetic to be about $150. Pricing of current molded prosthetics varies, but is often listed at several thousand dollars. Another consideration is the durability of 3D printed prosthetics vs standard prosthetics. Since we were unable to use the prosthetic in the patient, it was difficult to determine its durability. The significant cost of the 3D printer and software necessary for 3D printed prosthetics must also be considered and may be prohibitive. While many academic hospitals are considering the purchase of 3D printers and licenses, this may be challenging for resource-constrained institutions. 3D printing may also be difficult for groups without any prior experience in the field. Outsourcing to a third party is possible, though doing so adds more cost to the project. While we recognize there is a learning curve associated with adopting any new technology, it’s equally important to note that 3D printing is being rapidly integrated and has already made significant advancements in personalized medicine.8,25,26

Limitations

This program had several limitations. First, we only obtained CTs of sufficient quality from 1 patient to generate a 3D printed prosthesis. Further research with additional patients is necessary to validate this process. Second, we were unable to trial the prosthesis in the patient because we did not have FDA approval. Additionally, it is difficult to calculate a true cost estimate for this process as materials and software costs vary dramatically across institutions as well as over time.

Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to demonstrate the possibility to develop prosthetics for the hard palate for patients suffering from palatomaxillary defects. A 3D printed prosthetic was generated that matched the patient’s craniofacial anatomy. Future research should test the feasibility of these prosthetics in patient care against a traditional prosthodontic impression. Though this is a proof-of-concept study and no prosthetics were implanted as part of this investigation, we showcase the feasibility of printing prosthetics for palatomaxillary defects. The use of 3D printed prosthetics may be a more humane process, potentially lower cost, and be more accessible to veterans.

Three-dimensional (3D) printing has become a promising area of innovation in biomedical research.1,2 Previous research in orthopedic surgery has found that customized 3D printed implants, casts, orthoses, and prosthetics (eg, prosthetic hands) matched to an individual’s unique anatomy can result in more precise placement and better surgical outcomes.3-5 Customized prosthetics have also been found to lead to fewer complications.3,6

Recent advances in 3D printing technology has prompted investigation from surgeons to identify how this new tool may be incorporated into patient care.1,7 One of the most common applications of 3D printing is during preoperative planning in which surgeons gain better insight into patient-specific anatomy by using patient-specific printed models.8 Another promising application is the production of customized prosthetics suited to each patient’s unique anatomy.9 As a result, 3D printing has significantly impacted bone and cartilage restoration procedures and has the potential to completely transform the treatment of patients with debilitating musculoskeletal injuries.3,10

The potential surrounding 3D printed prosthetics has led to their adoption by several other specialties, including otolaryngology.11 The most widely used application of 3D printing among otolaryngologists is preoperative planning, and the incorporation of printed prosthetics intoreconstruction of the orbit, nasal septum, auricle, and palate has also been reported.2,12,13 Patient-specific implants might allow otolaryngologists to better rehabilitate, reconstruct, and/or regenerate craniofacial defects using more humane procedures.14

Patients with palatomaxillary cancers are treated by prosthodontists or otolaryngologists. An impression is made with a resin–which can be painful for postoperative patients–and a prosthetic is manufactured and implanted.15-17 Patients with cancer often see many specialists, though reconstructive care is a low priority. Many of these individuals also experience dynamic anatomic functional changes over time, leading to the need for multiple prothesis.

palatomaxillary prosthetics

This program aims to use patients’ previous computed tomography (CT) to tailor customized 3D printed palatomaxillary prosthetics to specifically fit their anatomy. Palatomaxillary defects are a source of profound disability for patients with head and neck cancers who are left with large anatomic defects as a direct result of treatment. Reconstruction of palatal defects poses unique challenges due to the complexity of patient anatomy.18,19

3D printed prosthetics for palatomaxillary defects have not been incorporated into patient care. We reviewed previous imaging research to determine if it could be used to assist patients who struggle with their function and appearance following treatment for head and neck cancers. The primary aim was to investigate whether 3D printing was a feasible strategy for creating patient-specific palatomaxillary prosthetics. The secondary aim is to determine whether these prosthetics should be tested in the future for use in reconstruction of maxillary defects.

Data Acquisition

This study was conducted at the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) and was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board (approval #28958, informed consent and patient contact excluded). A retrospective chart review was conducted on all patients with head and neck cancers who were treated at VAPAHCS from 2010 to 2022. Patients aged ≥ 18 years who had a palatomaxillary defect due to cancer treatment, had undergone a palatal resection, and who received treatment at any point from 2010 to 2022 were included in the review. CTs were not a specific inclusion criterion, though the quality of the scans was analyzed for eligible patients. Younger patients and those treated at VAPAHCS prior to 2010 were excluded.

There was no control group; all data was sourced from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) imaging system database. Among the 3595 patients reviewed, 5 met inclusion criteria and the quality of their craniofacial anatomy CTs were analyzed. To maintain accurate craniofacial 3D modeling, CTs require a maximum of 1 mm slice thickness. Of the 5 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 4 were found to have variability in the quality of their CTs and severe defects not suitable for prosthetic reconstruction, which led to their exclusion from the study. One patient was investigated to demonstrate if making these prostheses was feasible. This patient was diagnosed with a malignant neoplasm of the hard palate, underwent a partial maxillectomy, and a palatal obturator was placed to cover the defect.

The primary data collected was patient identifiers as well as the gross anatomy and dimensions of the patients’ craniofacial anatomy, as seen in previous imaging research.20 Before the imaging analysis, all personal health information was removed and the dataset was deidentified to ensure patient anonymity and noninvolvement.

CT Segmentation and 3D Printing

Using CTs of the patient’s craniofacial anatomy, we developed a model of the defects. This was achieved with deidentified CTs imported into the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved computerized aid design (CAD) software, Materialise Mimics. The hard palate was segmented and isolated based off the presented scan and any holes in the image were filled using the CAD software. The model was subsequently mirrored in Materialise 3-matic to replicate an original anatomical hard palate prosthesis. The final product was converted into a 3D model and imported into Formlabs preform software to generate 3D printing supports and orient it for printing. The prosthetic was printed using FDA-approved Biocompatible Denture Base Resin by a Formlabs 3B+ printer at the Palo Alto VA Simulation Center. The 3D printed prosthesis was washed using Formlabs Form Wash 80% ethyl alcohol to remove excess resin and subsequently cured to harden the malleable resin. Supports were later removed, and the prosthesis was sanded.

The primary aim of this study was to investigate whether using CTs to create patient-specific prosthetic renderings for patients with head and neck cancer could be a feasible strategy. The CTs from the patient were successfully used to generate a 3D printed prosthesis, and the prosthesis matched the original craniofacial anatomy seen in the patient's imaging (Figure). These results demonstrate that high quality CTs can be used as a template for 3D printed prostheses for mild to moderate palatomaxillary defects.

3D Printing Costs

One liter of Denture Base Resin costs $299; prostheses use about 5 mL of resin. The average annual salary of a 3D printing technician in the United States is $42,717, or $20.54 per hour.21 For an experienced 3D printing technician, the time required to segment the hard palate and prepare it for 3D printing is 1 to 2 hours. The process may exceed 2 hours if the technician is presented with a lower quality CT or if the patient has a complex craniofacial anatomy.

The average time it takes to print a palatal prosthetic is 5 hours. An additional hour is needed for postprocessing, which includes washing and sanding. Therefore, the cost of the materials and labor for an average 3D printed prosthetic is about $150. A Formlabs 3B+ printer is competitively priced around $10,000. The cost for Materialise Mimics software varies, but is estimated at $16,000 at VAPAHCS. The prices for these 2 items are not included in our price estimation but should be taken into consideration.

Prosthodontist Process and Cost

The typical process of creating a palatal prosthesis by a prosthodontist begins by examining the patient, creating a stone model, then creating a wax model. Biocompatible materials are selected and processed into a mold that is trimmed and polished to the desired shape. This is followed by another patient visit to ensure the prosthesis fits properly. Follow-up care is also necessary for maintenance and comfort.

The average cost of a palatal prosthesis varies depending on the type needed (ie, metal implant, teeth replacement), the materials used, the region in which the patient is receiving care, and the complexity of the case. For complex and customizable options like those required for patients with cancer, the prostheses typically cost several thousands of dollars. The Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code for a palatal lift prosthesis (D5955) lists prices ranging from $4000 to $8000 per prosthetic, not including the cost of the prosthodontist visits.22,23

Discussion

This program sought to determine whether imaging studies of maxillary defects are effective templates for developing 3D printed prosthetics and whether these prosthetics should be tested for future use in reconstruction of palatomaxillary defects. Our program illustrated that CTs served as feasible templates for developing hard palate prostheses for patients with palatomaxillary defects. It is important to note the CTs used were from a newer and more modern scanner and therefore yielded detailed palatal structures with higher accuracy more suitable for 3D modeling. Lower-quality CTs from the 4 patients excluded from the program were not suitable for 3D modeling. This suggests that with high-quality imaging, 3D printed prosthesis may be a viable strategy to help patients who struggle with their function following treatment for head and neck cancers.

3D printed prosthesis may also be a more patient centered and convenient option. In the traditional prosthesis creation workflow, the patient must physically bite down onto a resin (alginate or silicone) to make an impression, a very painful postoperative process that is irritating to the raw edges of the surgical bed.15,16 Prosthodontists then create a prosthetic minus the tumor and typically secure it with clips or glue.17 Many patients also experience changes in their anatomy over time requiring them to have a new protheses created. This is particularly important in veterans with palatomaxillary defects since many VA medical centers do not have a prosthodontist on staff, making accessibility to these specialists difficult. 3D printing provides a contactless prosthetic creation process. This convenience may reduce a patient’s pain and the number of visits for which they need a specialist.

Future Directions

Additional research is needed to determine the full potential of 3D printed prosthetics. 3D printed prostheses have been effectively used for patient education in areas of presurgical planning, prosthesis creation, and trainee education.24 This research represents an early step in the development of a new technology for use in otolaryngology. Specifically, many veterans with a history of head and neck cancers have sustained changes to their craniofacial anatomy following treatment. Using imaging to create 3D printed prosthetics could be very effective for these patients. Prosthetics could improve a patient’s quality of life by restoring/approximating their anatomy after cancer treatment.

Significant time and care must be taken by cancer and reconstructive surgeons to properly fit a prosthesis. Improperly fitting prosthetics leads to mucosal ulceration that then may lead to a need for fitting a new prosthetic. The advantage of 3D printed prosthetics is that they may more precisely fit the anatomy of each patient using CT results, thus potentially reducing the time needed to fit the prosthetic as well as the risk associated with an improperly fit prosthetic. 3D printed prosthesis could be used directly in the future, however, clinical trials are needed to verify its efficacy vs prosthodontic options.

Another consideration for potential future use of 3D printed prosthetics is cost. We estimated that the cost of the materials and labor of our 3D printed prosthetic to be about $150. Pricing of current molded prosthetics varies, but is often listed at several thousand dollars. Another consideration is the durability of 3D printed prosthetics vs standard prosthetics. Since we were unable to use the prosthetic in the patient, it was difficult to determine its durability. The significant cost of the 3D printer and software necessary for 3D printed prosthetics must also be considered and may be prohibitive. While many academic hospitals are considering the purchase of 3D printers and licenses, this may be challenging for resource-constrained institutions. 3D printing may also be difficult for groups without any prior experience in the field. Outsourcing to a third party is possible, though doing so adds more cost to the project. While we recognize there is a learning curve associated with adopting any new technology, it’s equally important to note that 3D printing is being rapidly integrated and has already made significant advancements in personalized medicine.8,25,26

Limitations

This program had several limitations. First, we only obtained CTs of sufficient quality from 1 patient to generate a 3D printed prosthesis. Further research with additional patients is necessary to validate this process. Second, we were unable to trial the prosthesis in the patient because we did not have FDA approval. Additionally, it is difficult to calculate a true cost estimate for this process as materials and software costs vary dramatically across institutions as well as over time.

Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to demonstrate the possibility to develop prosthetics for the hard palate for patients suffering from palatomaxillary defects. A 3D printed prosthetic was generated that matched the patient’s craniofacial anatomy. Future research should test the feasibility of these prosthetics in patient care against a traditional prosthodontic impression. Though this is a proof-of-concept study and no prosthetics were implanted as part of this investigation, we showcase the feasibility of printing prosthetics for palatomaxillary defects. The use of 3D printed prosthetics may be a more humane process, potentially lower cost, and be more accessible to veterans.

1. Crafts TD, Ellsperman SE, Wannemuehler TJ, Bellicchi TD, Shipchandler TZ, Mantravadi AV. Three-dimensional printing and its applications in otorhinolaryngology-head and neck surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(6):999-1010. doi:10.1177/0194599816678372

2. Virani FR, Chua EC, Timbang MR, Hsieh TY, Senders CW. Three-dimensional printing in cleft care: a systematic review. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2022;59(4):484-496. doi:10.1177/10556656211013175

3. Lal H, Patralekh MK. 3D printing and its applications in orthopaedic trauma: A technological marvel. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2018;9(3):260-268. doi:10.1016/j.jcot.2018.07.022

4. Vujaklija I, Farina D. 3D printed upper limb prosthetics. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2018;15(7):505-512. doi:10.1080/17434440.2018.1494568

5. Ten Kate J, Smit G, Breedveld P. 3D-printed upper limb prostheses: a review. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2017;12(3):300-314. doi:10.1080/17483107.2016.1253117

6. Thomas CN, Mavrommatis S, Schroder LK, Cole PA. An overview of 3D printing and the orthopaedic application of patient-specific models in malunion surgery. Injury. 2022;53(3):977-983. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2021.11.019

7. Colaco M, Igel DA, Atala A. The potential of 3D printing in urological research and patient care. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15(4):213-221. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2018.6

8. Meyer-Szary J, Luis MS, Mikulski S, et al. The role of 3D printing in planning complex medical procedures and training of medical professionals-cross-sectional multispecialty review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3331. Published 2022 Mar 11. doi:10.3390/ijerph19063331

9. Moya D, Gobbato B, Valente S, Roca R. Use of preoperative planning and 3D printing in orthopedics and traumatology: entering a new era. Acta Ortop Mex. 2022;36(1):39-47.

10. Wixted CM, Peterson JR, Kadakia RJ, Adams SB. Three-dimensional printing in orthopaedic surgery: current applications and future developments. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2021;5(4):e20.00230-11. Published 2021 Apr 20. doi:10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-20-00230

11. Hong CJ, Giannopoulos AA, Hong BY, et al. Clinical applications of three-dimensional printing in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(9):2045-2052. doi:10.1002/lary.2783112. Sigron GR, Barba M, Chammartin F, Msallem B, Berg BI, Thieringer FM. Functional and cosmetic outcome after reconstruction of isolated, unilateral orbital floor fractures (blow-out fractures) with and without the support of 3D-printed orbital anatomical models. J Clin Med. 2021;10(16):3509. Published 2021 Aug 9. doi:10.3390/jcm10163509

13. Kimura K, Davis S, Thomas E, et al. 3D Customization for microtia repair in hemifacial microsomia. Laryngoscope. 2022;132(3):545-549. doi:10.1002/lary.29823

14. Nyberg EL, Farris AL, Hung BP, et al. 3D-printing technologies for craniofacial rehabilitation, reconstruction, and regeneration. Ann Biomed Eng. 2017;45(1):45-57. doi:10.1007/s10439-016-1668-5

15. Flores-Ruiz R, Castellanos-Cosano L, Serrera-Figallo MA, et al. Evolution of oral cancer treatment in an andalusian population sample: rehabilitation with prosthetic obturation and removable partial prosthesis. J Clin Exp Dent. 2017;9(8):e1008-e1014. doi:10.4317/jced.54023

16. Rogers SN, Lowe D, McNally D, Brown JS, Vaughan ED. Health-related quality of life after maxillectomy: a comparison between prosthetic obturation and free flap. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(2):174-181. doi:10.1053/joms.2003.50044

17. Pool C, Shokri T, Vincent A, Wang W, Kadakia S, Ducic Y. Prosthetic reconstruction of the maxilla and palate. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(2):114-119. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709143

18. Badhey AK, Khan MN. Palatomaxillary reconstruction: fibula or scapula. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(2):86-91. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709431

19. Jategaonkar AA, Kaul VF, Lee E, Genden EM. Surgery of the palatomaxillary structure. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(2):71-76. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709430

20. Lobb DC, Cottler P, Dart D, Black JS. The use of patient-specific three-dimensional printed surgical models enhances plastic surgery resident education in craniofacial surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2019;30(2):339-341. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000005322

21. 3D printing technician salary in the United States. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.salary.com/research/salary/posting/3d-printing-technician-salary22. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System. Outpatient dental professional nationwide charges by HCPCS code. January-December 2020. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/docs/RO/Outpatient-DataTables/v3-27_Table-I.pdf23. Washington State Department of Labor and Industries. Professional services fee schedule HCPCS level II fees. October 1, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://lni.wa.gov/patient-care/billing-payments/marfsdocs/2020/2020FSHCPCS.pdf24. Low CM, Morris JM, Price DL, et al. Three-dimensional printing: current use in rhinology and endoscopic skull base surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2019;33(6):770-781. doi:10.1177/1945892419866319

25. Aimar A, Palermo A, Innocenti B. The role of 3D printing in medical applications: a state of the art. J Healthc Eng. 2019;2019:5340616. Published 2019 Mar 21. doi:10.1155/2019/5340616

26. Garcia J, Yang Z, Mongrain R, Leask RL, Lachapelle K. 3D printing materials and their use in medical education: a review of current technology and trends for the future. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn. 2018;4(1):27-40. doi:10.1136/bmjstel-2017-000234

1. Crafts TD, Ellsperman SE, Wannemuehler TJ, Bellicchi TD, Shipchandler TZ, Mantravadi AV. Three-dimensional printing and its applications in otorhinolaryngology-head and neck surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(6):999-1010. doi:10.1177/0194599816678372

2. Virani FR, Chua EC, Timbang MR, Hsieh TY, Senders CW. Three-dimensional printing in cleft care: a systematic review. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2022;59(4):484-496. doi:10.1177/10556656211013175

3. Lal H, Patralekh MK. 3D printing and its applications in orthopaedic trauma: A technological marvel. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2018;9(3):260-268. doi:10.1016/j.jcot.2018.07.022

4. Vujaklija I, Farina D. 3D printed upper limb prosthetics. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2018;15(7):505-512. doi:10.1080/17434440.2018.1494568

5. Ten Kate J, Smit G, Breedveld P. 3D-printed upper limb prostheses: a review. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2017;12(3):300-314. doi:10.1080/17483107.2016.1253117

6. Thomas CN, Mavrommatis S, Schroder LK, Cole PA. An overview of 3D printing and the orthopaedic application of patient-specific models in malunion surgery. Injury. 2022;53(3):977-983. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2021.11.019

7. Colaco M, Igel DA, Atala A. The potential of 3D printing in urological research and patient care. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15(4):213-221. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2018.6

8. Meyer-Szary J, Luis MS, Mikulski S, et al. The role of 3D printing in planning complex medical procedures and training of medical professionals-cross-sectional multispecialty review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3331. Published 2022 Mar 11. doi:10.3390/ijerph19063331

9. Moya D, Gobbato B, Valente S, Roca R. Use of preoperative planning and 3D printing in orthopedics and traumatology: entering a new era. Acta Ortop Mex. 2022;36(1):39-47.

10. Wixted CM, Peterson JR, Kadakia RJ, Adams SB. Three-dimensional printing in orthopaedic surgery: current applications and future developments. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2021;5(4):e20.00230-11. Published 2021 Apr 20. doi:10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-20-00230

11. Hong CJ, Giannopoulos AA, Hong BY, et al. Clinical applications of three-dimensional printing in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(9):2045-2052. doi:10.1002/lary.2783112. Sigron GR, Barba M, Chammartin F, Msallem B, Berg BI, Thieringer FM. Functional and cosmetic outcome after reconstruction of isolated, unilateral orbital floor fractures (blow-out fractures) with and without the support of 3D-printed orbital anatomical models. J Clin Med. 2021;10(16):3509. Published 2021 Aug 9. doi:10.3390/jcm10163509

13. Kimura K, Davis S, Thomas E, et al. 3D Customization for microtia repair in hemifacial microsomia. Laryngoscope. 2022;132(3):545-549. doi:10.1002/lary.29823

14. Nyberg EL, Farris AL, Hung BP, et al. 3D-printing technologies for craniofacial rehabilitation, reconstruction, and regeneration. Ann Biomed Eng. 2017;45(1):45-57. doi:10.1007/s10439-016-1668-5

15. Flores-Ruiz R, Castellanos-Cosano L, Serrera-Figallo MA, et al. Evolution of oral cancer treatment in an andalusian population sample: rehabilitation with prosthetic obturation and removable partial prosthesis. J Clin Exp Dent. 2017;9(8):e1008-e1014. doi:10.4317/jced.54023

16. Rogers SN, Lowe D, McNally D, Brown JS, Vaughan ED. Health-related quality of life after maxillectomy: a comparison between prosthetic obturation and free flap. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(2):174-181. doi:10.1053/joms.2003.50044

17. Pool C, Shokri T, Vincent A, Wang W, Kadakia S, Ducic Y. Prosthetic reconstruction of the maxilla and palate. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(2):114-119. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709143

18. Badhey AK, Khan MN. Palatomaxillary reconstruction: fibula or scapula. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(2):86-91. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709431

19. Jategaonkar AA, Kaul VF, Lee E, Genden EM. Surgery of the palatomaxillary structure. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(2):71-76. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1709430

20. Lobb DC, Cottler P, Dart D, Black JS. The use of patient-specific three-dimensional printed surgical models enhances plastic surgery resident education in craniofacial surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2019;30(2):339-341. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000005322

21. 3D printing technician salary in the United States. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.salary.com/research/salary/posting/3d-printing-technician-salary22. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System. Outpatient dental professional nationwide charges by HCPCS code. January-December 2020. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/docs/RO/Outpatient-DataTables/v3-27_Table-I.pdf23. Washington State Department of Labor and Industries. Professional services fee schedule HCPCS level II fees. October 1, 2020. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://lni.wa.gov/patient-care/billing-payments/marfsdocs/2020/2020FSHCPCS.pdf24. Low CM, Morris JM, Price DL, et al. Three-dimensional printing: current use in rhinology and endoscopic skull base surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2019;33(6):770-781. doi:10.1177/1945892419866319

25. Aimar A, Palermo A, Innocenti B. The role of 3D printing in medical applications: a state of the art. J Healthc Eng. 2019;2019:5340616. Published 2019 Mar 21. doi:10.1155/2019/5340616

26. Garcia J, Yang Z, Mongrain R, Leask RL, Lachapelle K. 3D printing materials and their use in medical education: a review of current technology and trends for the future. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn. 2018;4(1):27-40. doi:10.1136/bmjstel-2017-000234

Improving Fecal Immunochemical Test Collection for Colorectal Cancer Screening During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third-most common cancer worldwide and accounts for almost 11% of all cancer diagnoses, with > 1.9 million cases reported globally.1,2 CRC is the second-most deadly cancer, responsible for about 935,000 deaths.1 Over the past several decades, a steady decline in CRC incidence and mortality has been reported in developed countries, including the US.3,4 From 2008 through 2017, an annual reduction of 3% in CRC death rates was reported in individuals aged ≥ 65 years.5 This decline can mainly be attributed to improvements made in health systems and advancements in CRC screening programs.3,5

US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends CRC screening in individuals aged 45 to 75 years. USPSTF recommends direct visualization tests, such as colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy for CRC screening.6 Although colonoscopy is commonly used for CRC screening, it is an invasive procedure that requires bowel preparation and sedation, and has the potential risk of colonic perforation, bleeding, and infection. Additionally, social determinants—such as health care costs, missed work, and geographic location (eg, rural communities)—may limit colonoscopy utilization.7 As a result, other cost-effective, noninvasive tests such as high-sensitivity guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) and fecal immunochemical test (FIT) are also used for CRC screening. These tests detect occult blood in the stool of individuals who may be at risk for CRC, helping direct them to colonoscopy if they screen positive.8

The gFOBT relies on simple oxidation and requires a stool sample to detect the presence of the heme component of blood.9 If heme is present in the stool sample, it will enable the oxidation of guaiac to form a blue-colored dye when added to hydrogen peroxide. It is important to note that the oxidation component of this test may lead to false-positive results, as it may detect dietary hemoglobin present in red meat. Medications or foods that have peroxidase properties may also result in a false-positive gFOBT result. Additionally, false-negative results may be caused by antioxidants, which may interfere with the oxidation of guaiac.

FIT uses antibodies, which bind to the intact globin component of human hemoglobin.9 The quantity of bound antibody-hemoglobin complex is detected and measured by a variety of automated quantitative techniques. This testing strategy eliminates the need for food or medication restrictions and the subjective visual assessment of change in color, as required for the gFOBT.9 A 2016 meta-analysis found that FIT performed better compared with gFOBT in terms of specificity, positivity rate, number needed to scope, and number needed to screen.8 The FIT screening method has also been found to have greater adherence rates, which is likely due to fewer stool sampling requirements and the lack of medication or dietary restrictions, compared with gFOBT.7,8

The COVID-19 pandemic had a drastic impact on CRC preventive care services. In March 2020, elective colonoscopies were temporarily ceased across the country and the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) deferred all elective surgeries and medical procedures, including screening and surveillance colonoscopies. In line with these recommendations, elective colonoscopies were temporarily ceased across the country.10 The National Cancer Institute’s Population-Based Research to Optimize the Screening Process consortium reported that CRC screening rates decreased by 82% across the US in 2020.11 Public health measures are likely the main reason for this decline, but other factors may include a lack of resource availability in outpatient settings and public fear of the pandemic.10

The James A. Haley Veterans Affairs Hospital (JAHVAH) in Tampa, Florida, encouraged the use of FIT in place of colonoscopies to avoid delaying preventive services. The initiative to continue CRC screening methods via FIT was scrutinized when laboratory personnel reported that in fiscal year (FY) 2020, 62% of the FIT kits that patients returned to the laboratory were missing information or had other errors (Figure 1). These improperly returned FIT kits led to delayed processing, canceled orders, increased staff workload, and more costs for FIT repetition.

Research shows many patients often fail to adhere to the instructions for proper FIT sample collection and return. Wang and colleagues reported that of 4916 FIT samples returned to the laboratory, 971 (20%) had collection errors, and 910 (94%) of those samples were missing a sample collection date.12 The sample collection date is important because hemoglobin degradation occurs over time, which may create false-negative FIT results. Although studies have found that sample return times of ≤ 10 days are not associated with a decrease in FIT positive rates, it is recommended to mail completed FITs within 24 hours of sample collection.13

Because remote screening methods like FIT were preferred during the COVID-19 pandemic, we conducted a quality improvement (QI) project to address FIT inefficiency. The aim of this initiative was to determine the root cause behind incorrectly returned FIT kits and to increase correctly collected and testable FIT kits upon initial laboratory arrival by at least 20% by the second quarter of FY 2021.

Quality Improvement Project

This QI project was conducted from July 2020 to June 2021 at the JAHVAH, which provides primary care and specialty health services to veterans in central and south Florida. The QI was designed based on the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) model of health care improvement. The QI team consisted of physicians, nurses, administrative staff, and laboratory personnel. A SIPOC (Suppliers, Input, Process, Output, Customers) map was initially designed to help clarify the different groups involved in the process of FIT kit distribution and return. This map helped the team decide who should be involved in the solution process.

The QI team performed a root cause analysis using a fishbone diagram and identified the reasons FIT kits were returned to the laboratory with errors that prevented processing. The team brainstormed potential change ideas and created an impact vs effort chart to increase the number of correctly returned and testable FIT kits upon initial arrival at the laboratory by at least 20% by the second quarter of FY 2021. We identified strengths and prioritized change ideas to improve the number of testable and correctly returned FIT kits to the hospital laboratory. These ideas included centralizing FIT kit dispersal to a new administrative group, building redundant patient reminders on kit completion and giving patients more accessible places for kit return.

Patients included in the study were adults aged 50 to 75 years seen at the JAHVAH outpatient clinic who were asked to undergo FIT CRC screening. FIT orders for other facilities were excluded. The primary endpoint of this project was to improve the number of correctly returned FITs. The number of correct and incorrect returned FITs were measured from July 2020 to June 2021. FITs returned with errors were categorized by the type of error, including: no order on file in the electronic health record (EHR), canceled test, expired test, unable to identify test, missing information, and missing collection date.

We attempted to calculate costs of FITs that were returned to the laboratory but could not be analyzed and were discarded. In FY 2020, 1568 FITs were discarded. Each FIT cost about $7.80 to process for an annualized expense of $12,230 for discarded FITs.

Root Cause Analysis

Root causes were obtained by making a fishbone diagram. From this diagram, an impact vs effort chart was created to form and prioritize ideas for our PDSA cycles. Data about correctly and incorrectly returned kits were collected monthly from laboratory personnel, then analyzed by the QI team using run charts to look for change in frequency and patterns.

To improve this process, a swim lane chart for FIT processing was assembled and later used to make a comprehensive fishbone diagram to establish the 6 main root cause errors: missing FIT EHR order, cancelled FIT EHR order, expired stool specimen, partial patient identifiers, no patient identifiers, and no stool collection date. Pareto and run charts were superimposed with the laboratory data. The most common cause of incorrectly returned FITs was no collection date.

PDSA Cycles

Beginning in January 2021, PDSA cycles from the ideas in the impact vs effort chart were used. Organization and implementation of the project occurred from July 2020 to April 2021. The team reassessed the data in April 2021 to evaluate progress after PDSA initiation. The mean rate of missing collection date dropped from 24% in FY 2020 prior to PDSA cycles to 14% in April 2021; however, the number of incorrectly returned kits was similar to the baseline level. When reviewing this discrepancy, the QI team found that although the missing collection date rate had improved, the rate of FITs with not enough information had increased from 5% in FY 2020 to 67% in April 2021 (Figure 2). After discussing with laboratory personnel, it was determined that the EHR order was missing when the process pathway changed. Our PDSA initiative changed the process pathway and different individuals were responsible for FIT dispersal. The error was quickly addressed with the help of clinical and administrative staff; a 30-day follow-up on June 21, 2021, revealed that only 9% of the patients had sent back kits with not enough information.

After troubleshooting, the team achieved a sustainable increase in the number of correctly returned FIT kits from an average of 38% before the project to 72% after 30-day follow-up.

Discussion

Proper collection and return of FIT samples are vital for process efficiency for both physicians and patients. This initiative aimed to improve the rate of correctly returned FIT kits by 20%, but its final numbers showed an improvement of 33.6%. Operational benefits from this project included early detection of CRC, improved laboratory workflow, decreased FIT kit waste, and increased patient satisfaction.

The multipronged PDSA cycle attempted to increase the rate of correctly returned FIT kits. We improved kit comprehension and laboratory accessibility, and instituted redundant return reminders for patients. We also centralized a new process pathway for FIT distribution and educated physicians and support staff. Sampling and FIT return may seem like a simple procedure, but the FIT can be cumbersome for patients and directions can be confusing. Therefore, to maximize screening participation, it is essential to minimize confusion in the collection and return of a FIT sample.14,15

This QI initiative was presented at Grand Rounds at the University of South Florida in June 2021 and has since been shared with other VA hospitals. It was also presented at the American College of Gastroenterology Conference in 2021.

Limitations

This study was a single-center QI project and focused mostly on FIT kit return rates. To fully address CRC screening, it is important to ensure that individuals with a positive screen are appropriately followed up with a colonoscopy. Although follow-up was not in the scope of this project, it is key to CRC screening in general and should be the subject of future research.

Conclusions

FIT is a useful method for CRC screening that can be particularly helpful when in-person visits are limited, as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. This increase in demand for FITs during the pandemic revealed process deficiencies and gave JAHVAH an opportunity to improve workflow. Through the aid of a multidisciplinary team, the process to complete and return FITs improved and surpassed the goal of 20% improvement. Our goal is to continue to fine-tune the workflow and troubleshoot the system as needed.

1. Sawicki T, Ruszkowska M, Danielewicz A, Niedz′wiedzka E, Arłukowicz T, Przybyłowicz KE. A review of colorectal cancer in terms of epidemiology, risk factors, development, symptoms and diagnosis. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(9):2025. Published 2021 Apr 22. doi:10.3390/cancers13092025

2. Rawla P, Sunkara T, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Prz Gastroenterol. 2019;14(2):89-103. doi:10.5114/pg.2018.81072

3. Yang DX, Gross CP, Soulos PR, Yu JB. Estimating the magnitude of colorectal cancers prevented during the era of screening: 1976 to 2009. Cancer. 2014;120(18):2893-2901. doi:10.1002/cncr.28794

4. Naishadham D, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Siegel R, Cokkinides V, Jemal A. State disparities in colorectal cancer mortality patterns in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(7):1296-1302. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0250

5. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(3):145-164. doi:10.3322/caac.21601

6. US Preventive Services Task Force, Davidson KW, Barry MJ, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third-most common cancer worldwide and accounts for almost 11% of all cancer diagnoses, with > 1.9 million cases reported globally.1,2 CRC is the second-most deadly cancer, responsible for about 935,000 deaths.1 Over the past several decades, a steady decline in CRC incidence and mortality has been reported in developed countries, including the US.3,4 From 2008 through 2017, an annual reduction of 3% in CRC death rates was reported in individuals aged ≥ 65 years.5 This decline can mainly be attributed to improvements made in health systems and advancements in CRC screening programs.3,5

US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends CRC screening in individuals aged 45 to 75 years. USPSTF recommends direct visualization tests, such as colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy for CRC screening.6 Although colonoscopy is commonly used for CRC screening, it is an invasive procedure that requires bowel preparation and sedation, and has the potential risk of colonic perforation, bleeding, and infection. Additionally, social determinants—such as health care costs, missed work, and geographic location (eg, rural communities)—may limit colonoscopy utilization.7 As a result, other cost-effective, noninvasive tests such as high-sensitivity guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) and fecal immunochemical test (FIT) are also used for CRC screening. These tests detect occult blood in the stool of individuals who may be at risk for CRC, helping direct them to colonoscopy if they screen positive.8

The gFOBT relies on simple oxidation and requires a stool sample to detect the presence of the heme component of blood.9 If heme is present in the stool sample, it will enable the oxidation of guaiac to form a blue-colored dye when added to hydrogen peroxide. It is important to note that the oxidation component of this test may lead to false-positive results, as it may detect dietary hemoglobin present in red meat. Medications or foods that have peroxidase properties may also result in a false-positive gFOBT result. Additionally, false-negative results may be caused by antioxidants, which may interfere with the oxidation of guaiac.

FIT uses antibodies, which bind to the intact globin component of human hemoglobin.9 The quantity of bound antibody-hemoglobin complex is detected and measured by a variety of automated quantitative techniques. This testing strategy eliminates the need for food or medication restrictions and the subjective visual assessment of change in color, as required for the gFOBT.9 A 2016 meta-analysis found that FIT performed better compared with gFOBT in terms of specificity, positivity rate, number needed to scope, and number needed to screen.8 The FIT screening method has also been found to have greater adherence rates, which is likely due to fewer stool sampling requirements and the lack of medication or dietary restrictions, compared with gFOBT.7,8

The COVID-19 pandemic had a drastic impact on CRC preventive care services. In March 2020, elective colonoscopies were temporarily ceased across the country and the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) deferred all elective surgeries and medical procedures, including screening and surveillance colonoscopies. In line with these recommendations, elective colonoscopies were temporarily ceased across the country.10 The National Cancer Institute’s Population-Based Research to Optimize the Screening Process consortium reported that CRC screening rates decreased by 82% across the US in 2020.11 Public health measures are likely the main reason for this decline, but other factors may include a lack of resource availability in outpatient settings and public fear of the pandemic.10

The James A. Haley Veterans Affairs Hospital (JAHVAH) in Tampa, Florida, encouraged the use of FIT in place of colonoscopies to avoid delaying preventive services. The initiative to continue CRC screening methods via FIT was scrutinized when laboratory personnel reported that in fiscal year (FY) 2020, 62% of the FIT kits that patients returned to the laboratory were missing information or had other errors (Figure 1). These improperly returned FIT kits led to delayed processing, canceled orders, increased staff workload, and more costs for FIT repetition.

Research shows many patients often fail to adhere to the instructions for proper FIT sample collection and return. Wang and colleagues reported that of 4916 FIT samples returned to the laboratory, 971 (20%) had collection errors, and 910 (94%) of those samples were missing a sample collection date.12 The sample collection date is important because hemoglobin degradation occurs over time, which may create false-negative FIT results. Although studies have found that sample return times of ≤ 10 days are not associated with a decrease in FIT positive rates, it is recommended to mail completed FITs within 24 hours of sample collection.13

Because remote screening methods like FIT were preferred during the COVID-19 pandemic, we conducted a quality improvement (QI) project to address FIT inefficiency. The aim of this initiative was to determine the root cause behind incorrectly returned FIT kits and to increase correctly collected and testable FIT kits upon initial laboratory arrival by at least 20% by the second quarter of FY 2021.

Quality Improvement Project

This QI project was conducted from July 2020 to June 2021 at the JAHVAH, which provides primary care and specialty health services to veterans in central and south Florida. The QI was designed based on the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) model of health care improvement. The QI team consisted of physicians, nurses, administrative staff, and laboratory personnel. A SIPOC (Suppliers, Input, Process, Output, Customers) map was initially designed to help clarify the different groups involved in the process of FIT kit distribution and return. This map helped the team decide who should be involved in the solution process.