User login

AVAHO

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Analysis of early onset cancers suggests need for genetic testing

according to a presentation at the AACR virtual meeting II.

Investigators analyzed blood samples from 1,201 patients who were aged 18-39 years when diagnosed with a solid tumor malignancy.

In this group, there were 877 patients with early onset cancers, defined as cancers for which 39 years of age is greater than 1 standard deviation below the mean age of diagnosis for the cancer type.

The remaining 324 patients had young adult cancers, defined as cancers for which 39 years of age is less than 1 standard deviation below the mean age of diagnosis.

The most common early onset cancers were breast, colorectal, kidney, pancreas, and ovarian cancer.

The most common young adult cancers were sarcoma, brain cancer, and testicular cancer, as expected, said investigator Zsofia K. Stadler, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Dr. Stadler and colleagues performed next-generation sequencing of the patient samples using a panel of up to 88 genes previously implicated in cancer predisposition. This revealed a significantly higher prevalence of germline mutations in patients with early onset cancers than in those with young adult cancers – 21% and 13%, respectively (P = .002).

In patients with only high- and moderate-risk cancer susceptibility genes, the prevalence was 15% in the early onset group and 10% in the young adult group (P = .01). “Among the early onset cancer group, pancreas, breast, and kidney cancer patients harbored the highest rates of germline mutations,” Dr. Stadler said, noting that the spectrum of mutated genes differed in early onset and young adult cancer patients.

“In early onset patients, the most commonly mutated genes were BRCA1 and BRCA2 [4.9%], Lynch syndrome genes [2.2%], ATM [1.6%], and CHECK2 [1.7%],” Dr. Stadler said. “On the other hand, in young adults, TP53 mutations [2.2%], and SDHA and SDHB mutations dominated [1.9%], with the majority of mutations occurring in sarcoma patients.”

These findings suggest the prevalence of inherited cancer susceptibility syndromes in young adults with cancer is not uniform.

“We found a very high prevalence of germline mutations in young patients with cancer types that typically present at later ages,” Dr. Stadler said, referring to the early onset patients.

Conversely, the young adult cancer patients had a prevalence and spectrum of mutations more similar to what is seen in pediatric cancer populations, she noted.

The findings are surprising, according to AACR past president Elaine R. Mardis, PhD, of The Ohio State University in Columbus.

Dr. Mardis said the results show that, in young adults with early onset cancers, “the germline prevalence of these mutations is significantly higher than we had previously thought.”

“Although representing only about 4% of all cancers, young adults with cancer ... face unique challenges,” Dr. Stadler said. “Identifying whether a young patient’s cancer occurred in the setting of an inherited cancer predisposition syndrome is especially important in this patient population.”

Such knowledge “can significantly impact the risk of second primary cancers and the need for increased surveillance measures or even risk-reducing surgeries,” Dr. Stadler explained. She added that it can also have implications for identifying at-risk family members, such as younger siblings or children who should pursue genetic testing and appropriate prevention measures.

“Our results suggest that, among patients with early onset cancer, the increased prevalence of germline mutations supports a role for genetic testing, irrespective of tumor type,” Dr. Stadler said.

This study was partially funded by the Precision, Interception and Prevention Program, the Robert and Katie Niehaus Center for Inherited Cancer Genomics, the Marie-Josee and Henry R. Kravis Center for Molecular Oncology, and a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Core Grant. Dr. Stadler reported that an immediate family member serves as a consultant in ophthalmology for Allergan, Adverum Biotechnologies, Alimera Sciences, BioMarin, Fortress Biotech, Genentech/Roche, Novartis, Optos, Regeneron, Regenxbio, and Spark Therapeutics. Dr. Mardis disclosed relationships with Qiagen NV, Pact Pharma LLC, Moderna Inc., and Interpreta LLC.

SOURCE: Stadler Z et al. AACR 2020, Abstract 1122.

according to a presentation at the AACR virtual meeting II.

Investigators analyzed blood samples from 1,201 patients who were aged 18-39 years when diagnosed with a solid tumor malignancy.

In this group, there were 877 patients with early onset cancers, defined as cancers for which 39 years of age is greater than 1 standard deviation below the mean age of diagnosis for the cancer type.

The remaining 324 patients had young adult cancers, defined as cancers for which 39 years of age is less than 1 standard deviation below the mean age of diagnosis.

The most common early onset cancers were breast, colorectal, kidney, pancreas, and ovarian cancer.

The most common young adult cancers were sarcoma, brain cancer, and testicular cancer, as expected, said investigator Zsofia K. Stadler, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Dr. Stadler and colleagues performed next-generation sequencing of the patient samples using a panel of up to 88 genes previously implicated in cancer predisposition. This revealed a significantly higher prevalence of germline mutations in patients with early onset cancers than in those with young adult cancers – 21% and 13%, respectively (P = .002).

In patients with only high- and moderate-risk cancer susceptibility genes, the prevalence was 15% in the early onset group and 10% in the young adult group (P = .01). “Among the early onset cancer group, pancreas, breast, and kidney cancer patients harbored the highest rates of germline mutations,” Dr. Stadler said, noting that the spectrum of mutated genes differed in early onset and young adult cancer patients.

“In early onset patients, the most commonly mutated genes were BRCA1 and BRCA2 [4.9%], Lynch syndrome genes [2.2%], ATM [1.6%], and CHECK2 [1.7%],” Dr. Stadler said. “On the other hand, in young adults, TP53 mutations [2.2%], and SDHA and SDHB mutations dominated [1.9%], with the majority of mutations occurring in sarcoma patients.”

These findings suggest the prevalence of inherited cancer susceptibility syndromes in young adults with cancer is not uniform.

“We found a very high prevalence of germline mutations in young patients with cancer types that typically present at later ages,” Dr. Stadler said, referring to the early onset patients.

Conversely, the young adult cancer patients had a prevalence and spectrum of mutations more similar to what is seen in pediatric cancer populations, she noted.

The findings are surprising, according to AACR past president Elaine R. Mardis, PhD, of The Ohio State University in Columbus.

Dr. Mardis said the results show that, in young adults with early onset cancers, “the germline prevalence of these mutations is significantly higher than we had previously thought.”

“Although representing only about 4% of all cancers, young adults with cancer ... face unique challenges,” Dr. Stadler said. “Identifying whether a young patient’s cancer occurred in the setting of an inherited cancer predisposition syndrome is especially important in this patient population.”

Such knowledge “can significantly impact the risk of second primary cancers and the need for increased surveillance measures or even risk-reducing surgeries,” Dr. Stadler explained. She added that it can also have implications for identifying at-risk family members, such as younger siblings or children who should pursue genetic testing and appropriate prevention measures.

“Our results suggest that, among patients with early onset cancer, the increased prevalence of germline mutations supports a role for genetic testing, irrespective of tumor type,” Dr. Stadler said.

This study was partially funded by the Precision, Interception and Prevention Program, the Robert and Katie Niehaus Center for Inherited Cancer Genomics, the Marie-Josee and Henry R. Kravis Center for Molecular Oncology, and a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Core Grant. Dr. Stadler reported that an immediate family member serves as a consultant in ophthalmology for Allergan, Adverum Biotechnologies, Alimera Sciences, BioMarin, Fortress Biotech, Genentech/Roche, Novartis, Optos, Regeneron, Regenxbio, and Spark Therapeutics. Dr. Mardis disclosed relationships with Qiagen NV, Pact Pharma LLC, Moderna Inc., and Interpreta LLC.

SOURCE: Stadler Z et al. AACR 2020, Abstract 1122.

according to a presentation at the AACR virtual meeting II.

Investigators analyzed blood samples from 1,201 patients who were aged 18-39 years when diagnosed with a solid tumor malignancy.

In this group, there were 877 patients with early onset cancers, defined as cancers for which 39 years of age is greater than 1 standard deviation below the mean age of diagnosis for the cancer type.

The remaining 324 patients had young adult cancers, defined as cancers for which 39 years of age is less than 1 standard deviation below the mean age of diagnosis.

The most common early onset cancers were breast, colorectal, kidney, pancreas, and ovarian cancer.

The most common young adult cancers were sarcoma, brain cancer, and testicular cancer, as expected, said investigator Zsofia K. Stadler, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Dr. Stadler and colleagues performed next-generation sequencing of the patient samples using a panel of up to 88 genes previously implicated in cancer predisposition. This revealed a significantly higher prevalence of germline mutations in patients with early onset cancers than in those with young adult cancers – 21% and 13%, respectively (P = .002).

In patients with only high- and moderate-risk cancer susceptibility genes, the prevalence was 15% in the early onset group and 10% in the young adult group (P = .01). “Among the early onset cancer group, pancreas, breast, and kidney cancer patients harbored the highest rates of germline mutations,” Dr. Stadler said, noting that the spectrum of mutated genes differed in early onset and young adult cancer patients.

“In early onset patients, the most commonly mutated genes were BRCA1 and BRCA2 [4.9%], Lynch syndrome genes [2.2%], ATM [1.6%], and CHECK2 [1.7%],” Dr. Stadler said. “On the other hand, in young adults, TP53 mutations [2.2%], and SDHA and SDHB mutations dominated [1.9%], with the majority of mutations occurring in sarcoma patients.”

These findings suggest the prevalence of inherited cancer susceptibility syndromes in young adults with cancer is not uniform.

“We found a very high prevalence of germline mutations in young patients with cancer types that typically present at later ages,” Dr. Stadler said, referring to the early onset patients.

Conversely, the young adult cancer patients had a prevalence and spectrum of mutations more similar to what is seen in pediatric cancer populations, she noted.

The findings are surprising, according to AACR past president Elaine R. Mardis, PhD, of The Ohio State University in Columbus.

Dr. Mardis said the results show that, in young adults with early onset cancers, “the germline prevalence of these mutations is significantly higher than we had previously thought.”

“Although representing only about 4% of all cancers, young adults with cancer ... face unique challenges,” Dr. Stadler said. “Identifying whether a young patient’s cancer occurred in the setting of an inherited cancer predisposition syndrome is especially important in this patient population.”

Such knowledge “can significantly impact the risk of second primary cancers and the need for increased surveillance measures or even risk-reducing surgeries,” Dr. Stadler explained. She added that it can also have implications for identifying at-risk family members, such as younger siblings or children who should pursue genetic testing and appropriate prevention measures.

“Our results suggest that, among patients with early onset cancer, the increased prevalence of germline mutations supports a role for genetic testing, irrespective of tumor type,” Dr. Stadler said.

This study was partially funded by the Precision, Interception and Prevention Program, the Robert and Katie Niehaus Center for Inherited Cancer Genomics, the Marie-Josee and Henry R. Kravis Center for Molecular Oncology, and a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Core Grant. Dr. Stadler reported that an immediate family member serves as a consultant in ophthalmology for Allergan, Adverum Biotechnologies, Alimera Sciences, BioMarin, Fortress Biotech, Genentech/Roche, Novartis, Optos, Regeneron, Regenxbio, and Spark Therapeutics. Dr. Mardis disclosed relationships with Qiagen NV, Pact Pharma LLC, Moderna Inc., and Interpreta LLC.

SOURCE: Stadler Z et al. AACR 2020, Abstract 1122.

FROM AACR 2020

ctDNA clearance tracks with PFS in NSCLC subtype

The median PFS was 9.1 months for patients with ctDNA clearance and 3.9 months for those without ctDNA clearance three to four cycles after starting treatment with osimertinib, an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), and savolitinib, a MET TKI (P = 0.0146).

“[O]ur findings indicate that EGFR-mutant ctDNA clearance may be predictive of longer PFS for patients with EGFR-mutant, MET-amplified non–small cell lung cancer and detectable ctDNA at baseline,” said investigator Ryan Hartmaier, PhD, of AstraZeneca in Boston, Mass.

Dr. Hartmaier presented these findings at the AACR virtual meeting II.

Prior results of TATTON

Interim results of the TATTON study were published earlier this year (Lancet Oncol. 2020 Mar;21[3]:373-386). The trial enrolled patients with locally advanced or metastatic EGFR-mutant, MET-amplified NSCLC who had progressed on a prior EGFR TKI. Results included patients enrolled in parts B and D.

Part B consisted of patients who had previously received a third-generation EGFR TKI and patients who had not received a third-generation EGFR TKI and were either Thr790Met negative or Thr790Met positive. There were 144 patients in part B. All received oral osimertinib at 80 mg, 138 received savolitinib at 600 mg, and 8 received savolitinib at 300 mg daily. Part D included 42 patients who had not received a third-generation EGFR TKI and were Thr790Met negative. In this cohort, patients received osimertinib at 80 mg and savolitinib at 300 mg daily.

The objective response rate (all partial responses) was 48% in part B and 64% in part D. The median PFS was 7.6 months and 9.1 months, respectively.

Alexander E. Drilon, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York said results of the TATTON study demonstrate that MET dependence is an actionable EGFR TKI resistance mechanism in EGFR-mutant lung cancers.

“We all would welcome the approval of an EGFR and MET TKI combination in the future,” Dr. Drilon said in a discussion of the study at the AACR meeting.

According to Dr. Hartmaier, MET-based resistance mechanisms are seen in up to 10% of patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC following progression on first- and second-generation EGFR TKIs, and up to 25% of those progressing on osimertinib, a third-generation EGFR TKI.

“Nonclinical and clinical evidence suggests that combined treatment of a MET inhibitor and an EGFR TKI could overcome acquired MET-mediated resistance,” he said.

ctDNA analysis

Patients in the TATTON study had ctDNA samples collected at various time points from baseline through cycle five of treatment and until disease progression or treatment discontinuation.

Dr. Hartmaier’s analysis focused on ctDNA changes from baseline to day 1 of the third or fourth treatment cycle, time points at which the bulk of ctDNA could be observed, he said.

Among 34 evaluable patients in part B who received savolitinib at 600 mg, 22 had ctDNA clearance, and 12 had not. Among 16 evaluable patients in part D who received savolitinib at 300 mg, 13 had ctDNA clearance, and 3 had not.

Rates of ctDNA clearance were “remarkably similar” among the dosing groups, Dr. Hartmaier said.

In part B, the median PFS was 9.1 months for patients with ctDNA clearance and 3.9 months for patients without clearance (hazard ratio, 0.34; 95% confidence interval, 0.14-0.81; P = 0.0146).

Dr. Hartmaier did not present PFS results according to ctDNA clearance for patients in part D.

Dr. Drilon said serial ctDNA analyses can provide information on mechanisms of primary or acquired resistance, intra- and inter-tumoral heterogeneity, and the potential durability of benefit that can be achieved with combination targeted therapy. He acknowledged, however, that more work needs to be done in the field of MET-targeted therapy development.

“We need to work on standardizing diagnostic definitions of MET dependence, recognizing that loose definitions and poly-assay use make data challenging to interpret,” he said.

The TATTON study was supported by AstraZeneca. Dr. Hartmaier is an AstraZeneca employee and shareholder. Dr. Drilon disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Helsinn, Beigene, and other companies.

SOURCE: Hartmaier R, et al. AACR 2020, Abstract CT303.

The median PFS was 9.1 months for patients with ctDNA clearance and 3.9 months for those without ctDNA clearance three to four cycles after starting treatment with osimertinib, an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), and savolitinib, a MET TKI (P = 0.0146).

“[O]ur findings indicate that EGFR-mutant ctDNA clearance may be predictive of longer PFS for patients with EGFR-mutant, MET-amplified non–small cell lung cancer and detectable ctDNA at baseline,” said investigator Ryan Hartmaier, PhD, of AstraZeneca in Boston, Mass.

Dr. Hartmaier presented these findings at the AACR virtual meeting II.

Prior results of TATTON

Interim results of the TATTON study were published earlier this year (Lancet Oncol. 2020 Mar;21[3]:373-386). The trial enrolled patients with locally advanced or metastatic EGFR-mutant, MET-amplified NSCLC who had progressed on a prior EGFR TKI. Results included patients enrolled in parts B and D.

Part B consisted of patients who had previously received a third-generation EGFR TKI and patients who had not received a third-generation EGFR TKI and were either Thr790Met negative or Thr790Met positive. There were 144 patients in part B. All received oral osimertinib at 80 mg, 138 received savolitinib at 600 mg, and 8 received savolitinib at 300 mg daily. Part D included 42 patients who had not received a third-generation EGFR TKI and were Thr790Met negative. In this cohort, patients received osimertinib at 80 mg and savolitinib at 300 mg daily.

The objective response rate (all partial responses) was 48% in part B and 64% in part D. The median PFS was 7.6 months and 9.1 months, respectively.

Alexander E. Drilon, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York said results of the TATTON study demonstrate that MET dependence is an actionable EGFR TKI resistance mechanism in EGFR-mutant lung cancers.

“We all would welcome the approval of an EGFR and MET TKI combination in the future,” Dr. Drilon said in a discussion of the study at the AACR meeting.

According to Dr. Hartmaier, MET-based resistance mechanisms are seen in up to 10% of patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC following progression on first- and second-generation EGFR TKIs, and up to 25% of those progressing on osimertinib, a third-generation EGFR TKI.

“Nonclinical and clinical evidence suggests that combined treatment of a MET inhibitor and an EGFR TKI could overcome acquired MET-mediated resistance,” he said.

ctDNA analysis

Patients in the TATTON study had ctDNA samples collected at various time points from baseline through cycle five of treatment and until disease progression or treatment discontinuation.

Dr. Hartmaier’s analysis focused on ctDNA changes from baseline to day 1 of the third or fourth treatment cycle, time points at which the bulk of ctDNA could be observed, he said.

Among 34 evaluable patients in part B who received savolitinib at 600 mg, 22 had ctDNA clearance, and 12 had not. Among 16 evaluable patients in part D who received savolitinib at 300 mg, 13 had ctDNA clearance, and 3 had not.

Rates of ctDNA clearance were “remarkably similar” among the dosing groups, Dr. Hartmaier said.

In part B, the median PFS was 9.1 months for patients with ctDNA clearance and 3.9 months for patients without clearance (hazard ratio, 0.34; 95% confidence interval, 0.14-0.81; P = 0.0146).

Dr. Hartmaier did not present PFS results according to ctDNA clearance for patients in part D.

Dr. Drilon said serial ctDNA analyses can provide information on mechanisms of primary or acquired resistance, intra- and inter-tumoral heterogeneity, and the potential durability of benefit that can be achieved with combination targeted therapy. He acknowledged, however, that more work needs to be done in the field of MET-targeted therapy development.

“We need to work on standardizing diagnostic definitions of MET dependence, recognizing that loose definitions and poly-assay use make data challenging to interpret,” he said.

The TATTON study was supported by AstraZeneca. Dr. Hartmaier is an AstraZeneca employee and shareholder. Dr. Drilon disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Helsinn, Beigene, and other companies.

SOURCE: Hartmaier R, et al. AACR 2020, Abstract CT303.

The median PFS was 9.1 months for patients with ctDNA clearance and 3.9 months for those without ctDNA clearance three to four cycles after starting treatment with osimertinib, an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), and savolitinib, a MET TKI (P = 0.0146).

“[O]ur findings indicate that EGFR-mutant ctDNA clearance may be predictive of longer PFS for patients with EGFR-mutant, MET-amplified non–small cell lung cancer and detectable ctDNA at baseline,” said investigator Ryan Hartmaier, PhD, of AstraZeneca in Boston, Mass.

Dr. Hartmaier presented these findings at the AACR virtual meeting II.

Prior results of TATTON

Interim results of the TATTON study were published earlier this year (Lancet Oncol. 2020 Mar;21[3]:373-386). The trial enrolled patients with locally advanced or metastatic EGFR-mutant, MET-amplified NSCLC who had progressed on a prior EGFR TKI. Results included patients enrolled in parts B and D.

Part B consisted of patients who had previously received a third-generation EGFR TKI and patients who had not received a third-generation EGFR TKI and were either Thr790Met negative or Thr790Met positive. There were 144 patients in part B. All received oral osimertinib at 80 mg, 138 received savolitinib at 600 mg, and 8 received savolitinib at 300 mg daily. Part D included 42 patients who had not received a third-generation EGFR TKI and were Thr790Met negative. In this cohort, patients received osimertinib at 80 mg and savolitinib at 300 mg daily.

The objective response rate (all partial responses) was 48% in part B and 64% in part D. The median PFS was 7.6 months and 9.1 months, respectively.

Alexander E. Drilon, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York said results of the TATTON study demonstrate that MET dependence is an actionable EGFR TKI resistance mechanism in EGFR-mutant lung cancers.

“We all would welcome the approval of an EGFR and MET TKI combination in the future,” Dr. Drilon said in a discussion of the study at the AACR meeting.

According to Dr. Hartmaier, MET-based resistance mechanisms are seen in up to 10% of patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC following progression on first- and second-generation EGFR TKIs, and up to 25% of those progressing on osimertinib, a third-generation EGFR TKI.

“Nonclinical and clinical evidence suggests that combined treatment of a MET inhibitor and an EGFR TKI could overcome acquired MET-mediated resistance,” he said.

ctDNA analysis

Patients in the TATTON study had ctDNA samples collected at various time points from baseline through cycle five of treatment and until disease progression or treatment discontinuation.

Dr. Hartmaier’s analysis focused on ctDNA changes from baseline to day 1 of the third or fourth treatment cycle, time points at which the bulk of ctDNA could be observed, he said.

Among 34 evaluable patients in part B who received savolitinib at 600 mg, 22 had ctDNA clearance, and 12 had not. Among 16 evaluable patients in part D who received savolitinib at 300 mg, 13 had ctDNA clearance, and 3 had not.

Rates of ctDNA clearance were “remarkably similar” among the dosing groups, Dr. Hartmaier said.

In part B, the median PFS was 9.1 months for patients with ctDNA clearance and 3.9 months for patients without clearance (hazard ratio, 0.34; 95% confidence interval, 0.14-0.81; P = 0.0146).

Dr. Hartmaier did not present PFS results according to ctDNA clearance for patients in part D.

Dr. Drilon said serial ctDNA analyses can provide information on mechanisms of primary or acquired resistance, intra- and inter-tumoral heterogeneity, and the potential durability of benefit that can be achieved with combination targeted therapy. He acknowledged, however, that more work needs to be done in the field of MET-targeted therapy development.

“We need to work on standardizing diagnostic definitions of MET dependence, recognizing that loose definitions and poly-assay use make data challenging to interpret,” he said.

The TATTON study was supported by AstraZeneca. Dr. Hartmaier is an AstraZeneca employee and shareholder. Dr. Drilon disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Helsinn, Beigene, and other companies.

SOURCE: Hartmaier R, et al. AACR 2020, Abstract CT303.

FROM AACR 2020

AGA releases BRCA risk guidance

BRCA carrier status alone should not influence screening recommendations for colorectal cancer or pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, according to an American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update.

Relationships between BRCA carrier status and risks of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and colorectal cancer (CRC) remain unclear, reported lead author Sonia S. Kupfer, MD, AGAF, of the University of Chicago, and colleagues.

“Pathogenic variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have ... been associated with variable risk of GI cancer, including CRC, PDAC, biliary, and gastric cancers,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology. “However, the magnitude of GI cancer risks is not well established and there is minimal evidence or guidance on screening for GI cancers among BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers.”

According to the investigators, personalized screening for CRC is well supported by evidence, as higher-risk individuals, such as those with a family history of CRC, have been shown to benefit from earlier and more frequent colonoscopies. Although the value of risk-based screening is less clear for other types of GI cancer, the investigators cited a growing body of evidence that supports screening individuals at high risk of PDAC.

Still, data illuminating the role of BRCA carrier status are relatively scarce, which has led to variability in clinical practice.

“Lack of accurate CRC and PDAC risk estimates in BRCA1 and BRCA2 leave physicians and patients without guidance, and result in a range of screening recommendations and practices in this population,” wrote Dr. Kupfer and colleagues.

To offer some clarity, they drafted the present clinical practice update on behalf of the AGA. The recommendations are framed within a discussion of relevant publications.

Data from multiple studies, for instance, suggest that BRCA pathogenic variants are found in 1.3% of patients with early-onset CRC, 0.2% of those with high-risk CRC, and 1.0% of those with any type of CRC, all of which are higher rates “than would be expected by chance.

“However,” the investigators added, “this association is not proof that the observed BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants play a causative role in CRC.”

The investigators went on to discuss a 2018 meta-analysis by Oho et al., which included 14 studies evaluating risk of CRC among BRCA carriers. The analysis found that BRCA carriers had a 24% increased risk of CRC, which Dr. Kupfer and colleagues described as “small but statistically significant.” Subgroup analysis suggested that BRCA1 carriers drove this association, with a 49% increased risk of CRC, whereas no significant link was found with BRCA2.

Dr. Kupfer and colleagues described the 49% increase as “very modest,” and therefore insufficient to warrant more intensive screening, particularly when considered in the context of other risk factors, such as Lynch syndrome, which may entail a 1,600% increased risk of CRC. For PDAC, no such meta-analysis has been conducted; however, multiple studies have pointed to associations between BRCA and risk of PDAC.

For example, a 2018 case-control study by Hu et al. showed that BRCA1 and BRCA2 had relative prevalence rates of 0.59% and 1.95% among patients with PDAC. These rates translated to a 158% increased risk of PDAC for BRCA1, and a 520% increase risk for BRCA2; but Dr. Kupfer and colleagues noted that the BRCA2 carriers were from high-risk families, so the findings may not extend to the general population.

In light of these findings, the update recommends PDAC screening for BRCA carriers only if they have a family history of PDAC, with the caveat that the association between risk and degree of family involvement remains unknown.

Ultimately, for both CRC and PDAC, the investigators called for further BRCA research, based on the conclusion that “results from published studies provide inconsistent levels of evidence.”

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kupfer SS et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Apr 23. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.086.

BRCA carrier status alone should not influence screening recommendations for colorectal cancer or pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, according to an American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update.

Relationships between BRCA carrier status and risks of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and colorectal cancer (CRC) remain unclear, reported lead author Sonia S. Kupfer, MD, AGAF, of the University of Chicago, and colleagues.

“Pathogenic variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have ... been associated with variable risk of GI cancer, including CRC, PDAC, biliary, and gastric cancers,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology. “However, the magnitude of GI cancer risks is not well established and there is minimal evidence or guidance on screening for GI cancers among BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers.”

According to the investigators, personalized screening for CRC is well supported by evidence, as higher-risk individuals, such as those with a family history of CRC, have been shown to benefit from earlier and more frequent colonoscopies. Although the value of risk-based screening is less clear for other types of GI cancer, the investigators cited a growing body of evidence that supports screening individuals at high risk of PDAC.

Still, data illuminating the role of BRCA carrier status are relatively scarce, which has led to variability in clinical practice.

“Lack of accurate CRC and PDAC risk estimates in BRCA1 and BRCA2 leave physicians and patients without guidance, and result in a range of screening recommendations and practices in this population,” wrote Dr. Kupfer and colleagues.

To offer some clarity, they drafted the present clinical practice update on behalf of the AGA. The recommendations are framed within a discussion of relevant publications.

Data from multiple studies, for instance, suggest that BRCA pathogenic variants are found in 1.3% of patients with early-onset CRC, 0.2% of those with high-risk CRC, and 1.0% of those with any type of CRC, all of which are higher rates “than would be expected by chance.

“However,” the investigators added, “this association is not proof that the observed BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants play a causative role in CRC.”

The investigators went on to discuss a 2018 meta-analysis by Oho et al., which included 14 studies evaluating risk of CRC among BRCA carriers. The analysis found that BRCA carriers had a 24% increased risk of CRC, which Dr. Kupfer and colleagues described as “small but statistically significant.” Subgroup analysis suggested that BRCA1 carriers drove this association, with a 49% increased risk of CRC, whereas no significant link was found with BRCA2.

Dr. Kupfer and colleagues described the 49% increase as “very modest,” and therefore insufficient to warrant more intensive screening, particularly when considered in the context of other risk factors, such as Lynch syndrome, which may entail a 1,600% increased risk of CRC. For PDAC, no such meta-analysis has been conducted; however, multiple studies have pointed to associations between BRCA and risk of PDAC.

For example, a 2018 case-control study by Hu et al. showed that BRCA1 and BRCA2 had relative prevalence rates of 0.59% and 1.95% among patients with PDAC. These rates translated to a 158% increased risk of PDAC for BRCA1, and a 520% increase risk for BRCA2; but Dr. Kupfer and colleagues noted that the BRCA2 carriers were from high-risk families, so the findings may not extend to the general population.

In light of these findings, the update recommends PDAC screening for BRCA carriers only if they have a family history of PDAC, with the caveat that the association between risk and degree of family involvement remains unknown.

Ultimately, for both CRC and PDAC, the investigators called for further BRCA research, based on the conclusion that “results from published studies provide inconsistent levels of evidence.”

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kupfer SS et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Apr 23. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.086.

BRCA carrier status alone should not influence screening recommendations for colorectal cancer or pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, according to an American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update.

Relationships between BRCA carrier status and risks of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and colorectal cancer (CRC) remain unclear, reported lead author Sonia S. Kupfer, MD, AGAF, of the University of Chicago, and colleagues.

“Pathogenic variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have ... been associated with variable risk of GI cancer, including CRC, PDAC, biliary, and gastric cancers,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology. “However, the magnitude of GI cancer risks is not well established and there is minimal evidence or guidance on screening for GI cancers among BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers.”

According to the investigators, personalized screening for CRC is well supported by evidence, as higher-risk individuals, such as those with a family history of CRC, have been shown to benefit from earlier and more frequent colonoscopies. Although the value of risk-based screening is less clear for other types of GI cancer, the investigators cited a growing body of evidence that supports screening individuals at high risk of PDAC.

Still, data illuminating the role of BRCA carrier status are relatively scarce, which has led to variability in clinical practice.

“Lack of accurate CRC and PDAC risk estimates in BRCA1 and BRCA2 leave physicians and patients without guidance, and result in a range of screening recommendations and practices in this population,” wrote Dr. Kupfer and colleagues.

To offer some clarity, they drafted the present clinical practice update on behalf of the AGA. The recommendations are framed within a discussion of relevant publications.

Data from multiple studies, for instance, suggest that BRCA pathogenic variants are found in 1.3% of patients with early-onset CRC, 0.2% of those with high-risk CRC, and 1.0% of those with any type of CRC, all of which are higher rates “than would be expected by chance.

“However,” the investigators added, “this association is not proof that the observed BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants play a causative role in CRC.”

The investigators went on to discuss a 2018 meta-analysis by Oho et al., which included 14 studies evaluating risk of CRC among BRCA carriers. The analysis found that BRCA carriers had a 24% increased risk of CRC, which Dr. Kupfer and colleagues described as “small but statistically significant.” Subgroup analysis suggested that BRCA1 carriers drove this association, with a 49% increased risk of CRC, whereas no significant link was found with BRCA2.

Dr. Kupfer and colleagues described the 49% increase as “very modest,” and therefore insufficient to warrant more intensive screening, particularly when considered in the context of other risk factors, such as Lynch syndrome, which may entail a 1,600% increased risk of CRC. For PDAC, no such meta-analysis has been conducted; however, multiple studies have pointed to associations between BRCA and risk of PDAC.

For example, a 2018 case-control study by Hu et al. showed that BRCA1 and BRCA2 had relative prevalence rates of 0.59% and 1.95% among patients with PDAC. These rates translated to a 158% increased risk of PDAC for BRCA1, and a 520% increase risk for BRCA2; but Dr. Kupfer and colleagues noted that the BRCA2 carriers were from high-risk families, so the findings may not extend to the general population.

In light of these findings, the update recommends PDAC screening for BRCA carriers only if they have a family history of PDAC, with the caveat that the association between risk and degree of family involvement remains unknown.

Ultimately, for both CRC and PDAC, the investigators called for further BRCA research, based on the conclusion that “results from published studies provide inconsistent levels of evidence.”

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kupfer SS et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Apr 23. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.086.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Hypercalcemia Is of Uncertain Significance in Patients With Advanced Adenocarcinoma of the Prostate

Hypercalcemia is found when the corrected serum calcium level is > 10.5 mg/dL.1 Its symptoms are not specific and may include polyuria, dehydration, polydipsia, anorexia, nausea and/or vomiting, constipation, and other central nervous system manifestations, including confusion, delirium, cognitive impairment, muscle weakness, psychotic symptoms, and even coma.1,2

Hypercalcemia has varied etiologies; however, malignancy-induced hypercalcemia is one of the most common causes. In the US, the most common causes of malignancy-induced hypercalcemia are primary tumors of the lung or breast, multiple myeloma (MM), squamous cell carcinoma of the head or neck, renal cancer, and ovarian cancer.1

Men with prostate cancer and bone metastasis have relatively worse prognosis than do patient with no metastasis.3 In a recent meta-analysis of patients with bone-involved castration-resistant prostate cancer, the median survival was 21 months.3

Hypercalcemia is a rare manifestation of prostate cancer. In a retrospective study conducted between 2009 and 2013 using the Oncology Services Comprehensive Electronic Records (OSCER) warehouse of electronic health records (EHR), the rates of malignancy-induced hypercalcemia were the lowest among patients with prostate cancer, ranging from 1.4 to 2.1%.1

We present this case to discuss different pathophysiologic mechanisms leading to hypercalcemia in a patient with prostate cancer with bone metastasis and to study the role of humoral and growth factors in the pathogenesis of the disease.

Case Presentation

An African American man aged 69 years presented to the emergency department (ED) with generalized weakness, fatigue, and lower extremities muscle weakness. He reported a 40-lb weight loss over the past 3 months, intermittent lower back pain, and a 50 pack-year smoking history. A physical examination suggested clinical signs of dehydration.

Laboratory test results indicated hypercalcemia, macrocytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia: calcium 15.8 mg/dL, serum albumin 4.1 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 139 μ/L, blood urea nitrogen 55 mg/dL, creatinine 3.4 mg/dL (baseline 1.4-1.5 mg/dL), hemoglobin 8 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume 99.6 fL, and platelets 100,000/μL. The patient was admitted for hypercalcemia. His intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) was suppressed at 16 pg/mL, phosphorous was 3.8 mg/dL, parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) was < 0.74 pmol/L, vitamin D (25 hydroxy cholecalciferol) was mildly decreased at 17.2 ng/mL, and 1,25 dihydroxy cholecalciferol (calcitriol) was < 5.0 (normal range 20-79.3 pg/mL).

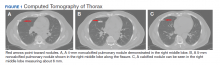

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen was taken due to the patient’s heavy smoking history, an incidentally detected right lung base nodule on chest X-ray, and hypercalcemia. The CT scan showed multiple right middle lobe lung nodules with and without calcifications and calcified right hilar lymph nodes (Figure 1).

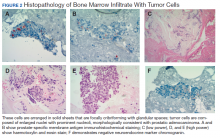

To evaluate the pancytopenia, a bone marrow biopsy was done, which showed that 80 to 90% of the marrow space was replaced by fibrosis and metastatic malignancy. Trilinear hematopoiesis was not seen (Figure 2). The tumor cells were positive for prostate- specific membrane antigen (PSMA) and negative for cytokeratin 7 and 20 (CK7 and CK20).4 The former is a membrane protein expressed on prostate tissues, including cancer; the latter is a form of protein used to identify adenocarcinoma of unknown primary origin (CK7 usually found in primary/ metastatic lung adenocarcinoma and CK20 usually in primary and some metastatic diseases of colon adenocarcinoma).5 A prostatic specific antigen (PSA) test was markedly elevated: 335.94 ng/mL (1.46 ng/mL on a previous 2011 test).

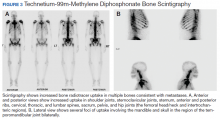

Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate was diagnosed without a prostate biopsy. To determine the extent of bone metastases, a technetium-99m-methylene diphosphonate (MDP) bone scintigraphy demonstrated a superscan with intense foci of increased radiotracer uptake involving the bilateral shoulders, sternoclavicular joints, and sternum with heterogeneous uptake involving bilateral anterior and posterior ribs; cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spines; sacrum, pelvis, and bilateral hips, including the femoral head/neck and intertrochanteric regions. Also noted were several foci of radiotracer uptake involving the mandible and bilateral skull in the region of the temporomandibular joints (Figure 3).

The patient was initially treated with IV isotonic saline, followed by calcitonin and then pamidronate after kidney function improved. His calcium level responded to the therapy, and a plan was made by medical oncology to start androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) prior to discharge.

He was initially treated with bicalutamide, while a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist (leuprolide) was added 1 week later. Bicalutamide was then discontinued and a combined androgen blockade consisting of leuprolide, ketoconazole, and hydrocortisone was started. This therapy resulted in remission, and PSA declined to 1.73 ng/ mL 3 months later. At that time the patient enrolled in a clinical trial with leuprolide and bicalutamide combined therapy. About 6 months after his diagnosis, patient’s cancer progressed and became hormone refractory disease. At that time, bicalutamide was discontinued, and his therapy was switched to combined leuprolide and enzalutamide. After 6 months of therapy with enzalutamide, the patient’s cancer progressed again. He was later treated with docetaxel chemotherapy but died 16 months after diagnosis.

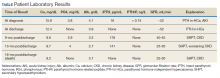

showed improvement of hypercalcemia at the time of discharge, but 9 months later and toward the time of expiration, our patient developed secondary hyperparathyroidism, with calcium maintained in the normal range, while iPTH was significantly elevated, a finding likely explained by a decline in kidney function and a fall in glomerular filtration rate (Table).

Discussion

Hypercalcemia in the setting of prostate cancer is a rare complication with an uncertain pathophysiology.6 Several mechanisms have been proposed for hypercalcemia of malignancy, these comprise humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy mediated by increased PTHrP; local osteolytic hypercalcemia with secretion of other humoral factors; excess extrarenal activation of vitamin D (1,25[OH]2D); PTH secretion, ectopic or primary; and multiple concurrent etiologies.7

PTHrP is the predominant mediator for hypercalcemia of malignancy and is estimated to account for 80% of hypercalcemia in patients with cancer. This protein shares a substantial sequence homology with PTH; in fact, 8 of the first 13 amino acids at the N-terminal portion of PTH were identical.8 PTHrP has multiple isoforms (PTHrP 141, PTHrP 139, and PTHrP 173). Like PTH, it enhances renal tubular reabsorption of calcium while increasing urinary phosphorus excretion.7 The result is both hypercalcemia and hypophosphatemia. However, unlike PTH, PTHrP does not increase 1,25(OH)2D and thus does not increase intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphorus. PTHrP acts on osteoblasts, leading to enhanced synthesis of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL).7

In one study, PTHrP was detected immunohistochemically in prostate cancer cells. Iwamura and colleagues used 33 radical prostatectomy specimens from patients with clinically localized carcinoma of the prostate.9 None of these patients demonstrated hypercalcemia prior to the surgery. Using a mouse monoclonal antibody to an amino acid fragment, all cases demonstrated some degree of immunoreactivity throughout the cytoplasm of the tumor cells, but immunostaining was absent from inflammatory and stromal cells.9Furthermore, the intensity of the staining appeared to directly correlate with increasing tumor grade.9

Another study by Iwamura and colleagues suggested that PTHrP may play a significant role in the growth of prostate cancer by acting locally in an autocrine fashion.10 In this study, all prostate cancer cell lines from different sources expressed PTHrP immunoreactivity as well as evidence of DNA synthesis, the latter being measured by thymidine incorporation assay. Moreover, when these cells were incubated with various concentrations of mouse monoclonal antibody directed to PTHrP fragment, PTHrP-induced DNA synthesis was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner and almost completely neutralized at a specific concentration. Interestingly, the study demonstrated that cancer cell line derived from bone metastatic lesions secreted significantly greater amounts of PTHrP than did the cell line derived from the metastasis in the brain or in the lymph node. These findings suggest that PTHrP production may confer some advantage on the ability of prostate cancer cells to grow in bone.10

Ando and colleagues reported that neuroendocrine dedifferentiated prostate cancer can develop as a result of long-term ADT even after several years of therapy and has the potential to worsen and develop severe hypercalcemia.8 Neuron-specific enolase was used as the specific marker for the neuroendocrine cell, which suggested that the prostate cancer cell derived from the neuroendocrine cell might synthesize PTHrP and be responsible for the observed hypercalcemia.8

Other mechanisms cited for hypercalcemia of malignancy include other humoral factors associated with increased remodeling and comprise interleukin 1, 3, 6 (IL-1, IL-3, IL-6); tumor necrosis factor α; transforming growth factor A and B observed in metastatic bone lesions in breast cancer; lymphotoxin; E series prostaglandins; and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α seen in MM.

Local osteolytic hypercalcemia accounts for about 20% of cases and is usually associated with extensive bone metastases. It is most commonly seen in MM and metastatic breast cancer and less commonly in leukemia. The proposed mechanism is thought to be because of the release of local cytokines from the tumor, resulting in excess osteoclast activation and enhanced bone resorption often through RANK/RANKL interaction.

Extrarenal production of 1,25(OH)2D by the tumor accounts for about 1% of cases of hypercalcemia in malignancy. 1,25(OH)2D causes increased intestinal absorption of calcium and enhances osteolytic bone resorption, resulting in increased serum calcium. This mechanism is most commonly seen with Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma and had been reported in ovarian dysgerminoma.7

In our patient, bone imaging showed osteoblastic lesions, a finding that likely contrasts the local osteolytic bone destruction theory. PTHrP was not significantly elevated in the serum, and PTH levels ruled out any form of primary hyperparathyroidism. In addition, histopathology showed no evidence of mosaicism or neuroendocrine dedifferentiation.

Findings in aggregate tell us that an exact pathophysiologic mechanism leading to hypercalcemia in prostate cancer is still unclear and may involve an interplay between growth factors and possible osteolytic materials, yet it must be studied thoroughly.

Conclusions

Hypercalcemia in pure metastatic adenocarcinoma of prostate is a rare finding and is of uncertain significance. Some studies suggested a search for unusual histopathologies, including neuroendocrine cancer and neuroendocrine dedifferentiation.8,11 However, in adenocarcinoma alone, it has an uncertain pathophysiology that needs to be further studied. Studies needed to investigate the role of PTHrP as a growth factor for both prostate cancer cells and development of hypercalcemia and possibly target-directed monoclonal antibody therapies may need to be extensively researched.

1. Gastanaga VM, Schwartzberg LS, Jain RK, et al. Prevalence of hypercalcemia among cancer patients in the United States. Cancer Med. 2016;5(8):2091‐2100. doi:10.1002/cam4.749

2. Grill V, Martin TJ. Hypercalcemia of malignancy. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2000;1(4):253‐263. doi:10.1023/a:1026597816193

3. Halabi S, Kelly WK, Ma H, et al. Meta-analysis evaluating the impact of site of metastasis on overall survival in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(14):1652‐1659. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.65.7270

4. Chang SS. Overview of prostate-specific membrane antigen. Rev Urol. 2004;6(suppl 10):S13‐S18.

5. Kummar S, Fogarasi M, Canova A, Mota A, Ciesielski T. Cytokeratin 7 and 20 staining for the diagnosis of lung and colorectal adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(12):1884‐1887. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600326

6. Avashia JH, Walsh TD, Thomas AJ Jr, Kaye M, Licata A. Metastatic carcinoma of the prostate with hypercalcemia [published correction appears in Cleve Clin J Med. 1991;58(3):284]. Cleve Clin J Med. 1990;57(7):636‐638. doi:10.3949/ccjm.57.7.636.

7. Goldner W. Cancer-related hypercalcemia. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(5):426‐432. doi:10.1200/JOP.2016.011155.

8. Ando T, Watanabe K, Mizusawa T, Katagiri A. Hypercalcemia due to parathyroid hormone-related peptide secreted by neuroendocrine dedifferentiated prostate cancer. Urol Case Rep. 2018;22:67‐69. doi:10.1016/j.eucr.2018.11.001

9. Iwamura M, di Sant’Agnese PA, Wu G, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of parathyroid hormonerelated protein in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1993;53(8):1724‐1726.

10. Iwamura M, Abrahamsson PA, Foss KA, Wu G, Cockett AT, Deftos LJ. Parathyroid hormone-related protein: a potential autocrine growth regulator in human prostate cancer cell lines. Urology. 1994;43(5):675‐679. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(94)90183-x

11. Smith DC, Tucker JA, Trump DL. Hypercalcemia and neuroendocrine carcinoma of the prostate: a report of three cases and a review of the literature. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(3):499‐505. doi:10.1200/JCO.1992.10.3.499.

Hypercalcemia is found when the corrected serum calcium level is > 10.5 mg/dL.1 Its symptoms are not specific and may include polyuria, dehydration, polydipsia, anorexia, nausea and/or vomiting, constipation, and other central nervous system manifestations, including confusion, delirium, cognitive impairment, muscle weakness, psychotic symptoms, and even coma.1,2

Hypercalcemia has varied etiologies; however, malignancy-induced hypercalcemia is one of the most common causes. In the US, the most common causes of malignancy-induced hypercalcemia are primary tumors of the lung or breast, multiple myeloma (MM), squamous cell carcinoma of the head or neck, renal cancer, and ovarian cancer.1

Men with prostate cancer and bone metastasis have relatively worse prognosis than do patient with no metastasis.3 In a recent meta-analysis of patients with bone-involved castration-resistant prostate cancer, the median survival was 21 months.3

Hypercalcemia is a rare manifestation of prostate cancer. In a retrospective study conducted between 2009 and 2013 using the Oncology Services Comprehensive Electronic Records (OSCER) warehouse of electronic health records (EHR), the rates of malignancy-induced hypercalcemia were the lowest among patients with prostate cancer, ranging from 1.4 to 2.1%.1

We present this case to discuss different pathophysiologic mechanisms leading to hypercalcemia in a patient with prostate cancer with bone metastasis and to study the role of humoral and growth factors in the pathogenesis of the disease.

Case Presentation

An African American man aged 69 years presented to the emergency department (ED) with generalized weakness, fatigue, and lower extremities muscle weakness. He reported a 40-lb weight loss over the past 3 months, intermittent lower back pain, and a 50 pack-year smoking history. A physical examination suggested clinical signs of dehydration.

Laboratory test results indicated hypercalcemia, macrocytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia: calcium 15.8 mg/dL, serum albumin 4.1 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 139 μ/L, blood urea nitrogen 55 mg/dL, creatinine 3.4 mg/dL (baseline 1.4-1.5 mg/dL), hemoglobin 8 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume 99.6 fL, and platelets 100,000/μL. The patient was admitted for hypercalcemia. His intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) was suppressed at 16 pg/mL, phosphorous was 3.8 mg/dL, parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) was < 0.74 pmol/L, vitamin D (25 hydroxy cholecalciferol) was mildly decreased at 17.2 ng/mL, and 1,25 dihydroxy cholecalciferol (calcitriol) was < 5.0 (normal range 20-79.3 pg/mL).

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen was taken due to the patient’s heavy smoking history, an incidentally detected right lung base nodule on chest X-ray, and hypercalcemia. The CT scan showed multiple right middle lobe lung nodules with and without calcifications and calcified right hilar lymph nodes (Figure 1).

To evaluate the pancytopenia, a bone marrow biopsy was done, which showed that 80 to 90% of the marrow space was replaced by fibrosis and metastatic malignancy. Trilinear hematopoiesis was not seen (Figure 2). The tumor cells were positive for prostate- specific membrane antigen (PSMA) and negative for cytokeratin 7 and 20 (CK7 and CK20).4 The former is a membrane protein expressed on prostate tissues, including cancer; the latter is a form of protein used to identify adenocarcinoma of unknown primary origin (CK7 usually found in primary/ metastatic lung adenocarcinoma and CK20 usually in primary and some metastatic diseases of colon adenocarcinoma).5 A prostatic specific antigen (PSA) test was markedly elevated: 335.94 ng/mL (1.46 ng/mL on a previous 2011 test).

Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate was diagnosed without a prostate biopsy. To determine the extent of bone metastases, a technetium-99m-methylene diphosphonate (MDP) bone scintigraphy demonstrated a superscan with intense foci of increased radiotracer uptake involving the bilateral shoulders, sternoclavicular joints, and sternum with heterogeneous uptake involving bilateral anterior and posterior ribs; cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spines; sacrum, pelvis, and bilateral hips, including the femoral head/neck and intertrochanteric regions. Also noted were several foci of radiotracer uptake involving the mandible and bilateral skull in the region of the temporomandibular joints (Figure 3).

The patient was initially treated with IV isotonic saline, followed by calcitonin and then pamidronate after kidney function improved. His calcium level responded to the therapy, and a plan was made by medical oncology to start androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) prior to discharge.

He was initially treated with bicalutamide, while a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist (leuprolide) was added 1 week later. Bicalutamide was then discontinued and a combined androgen blockade consisting of leuprolide, ketoconazole, and hydrocortisone was started. This therapy resulted in remission, and PSA declined to 1.73 ng/ mL 3 months later. At that time the patient enrolled in a clinical trial with leuprolide and bicalutamide combined therapy. About 6 months after his diagnosis, patient’s cancer progressed and became hormone refractory disease. At that time, bicalutamide was discontinued, and his therapy was switched to combined leuprolide and enzalutamide. After 6 months of therapy with enzalutamide, the patient’s cancer progressed again. He was later treated with docetaxel chemotherapy but died 16 months after diagnosis.

showed improvement of hypercalcemia at the time of discharge, but 9 months later and toward the time of expiration, our patient developed secondary hyperparathyroidism, with calcium maintained in the normal range, while iPTH was significantly elevated, a finding likely explained by a decline in kidney function and a fall in glomerular filtration rate (Table).

Discussion

Hypercalcemia in the setting of prostate cancer is a rare complication with an uncertain pathophysiology.6 Several mechanisms have been proposed for hypercalcemia of malignancy, these comprise humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy mediated by increased PTHrP; local osteolytic hypercalcemia with secretion of other humoral factors; excess extrarenal activation of vitamin D (1,25[OH]2D); PTH secretion, ectopic or primary; and multiple concurrent etiologies.7

PTHrP is the predominant mediator for hypercalcemia of malignancy and is estimated to account for 80% of hypercalcemia in patients with cancer. This protein shares a substantial sequence homology with PTH; in fact, 8 of the first 13 amino acids at the N-terminal portion of PTH were identical.8 PTHrP has multiple isoforms (PTHrP 141, PTHrP 139, and PTHrP 173). Like PTH, it enhances renal tubular reabsorption of calcium while increasing urinary phosphorus excretion.7 The result is both hypercalcemia and hypophosphatemia. However, unlike PTH, PTHrP does not increase 1,25(OH)2D and thus does not increase intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphorus. PTHrP acts on osteoblasts, leading to enhanced synthesis of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL).7

In one study, PTHrP was detected immunohistochemically in prostate cancer cells. Iwamura and colleagues used 33 radical prostatectomy specimens from patients with clinically localized carcinoma of the prostate.9 None of these patients demonstrated hypercalcemia prior to the surgery. Using a mouse monoclonal antibody to an amino acid fragment, all cases demonstrated some degree of immunoreactivity throughout the cytoplasm of the tumor cells, but immunostaining was absent from inflammatory and stromal cells.9Furthermore, the intensity of the staining appeared to directly correlate with increasing tumor grade.9

Another study by Iwamura and colleagues suggested that PTHrP may play a significant role in the growth of prostate cancer by acting locally in an autocrine fashion.10 In this study, all prostate cancer cell lines from different sources expressed PTHrP immunoreactivity as well as evidence of DNA synthesis, the latter being measured by thymidine incorporation assay. Moreover, when these cells were incubated with various concentrations of mouse monoclonal antibody directed to PTHrP fragment, PTHrP-induced DNA synthesis was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner and almost completely neutralized at a specific concentration. Interestingly, the study demonstrated that cancer cell line derived from bone metastatic lesions secreted significantly greater amounts of PTHrP than did the cell line derived from the metastasis in the brain or in the lymph node. These findings suggest that PTHrP production may confer some advantage on the ability of prostate cancer cells to grow in bone.10

Ando and colleagues reported that neuroendocrine dedifferentiated prostate cancer can develop as a result of long-term ADT even after several years of therapy and has the potential to worsen and develop severe hypercalcemia.8 Neuron-specific enolase was used as the specific marker for the neuroendocrine cell, which suggested that the prostate cancer cell derived from the neuroendocrine cell might synthesize PTHrP and be responsible for the observed hypercalcemia.8

Other mechanisms cited for hypercalcemia of malignancy include other humoral factors associated with increased remodeling and comprise interleukin 1, 3, 6 (IL-1, IL-3, IL-6); tumor necrosis factor α; transforming growth factor A and B observed in metastatic bone lesions in breast cancer; lymphotoxin; E series prostaglandins; and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α seen in MM.

Local osteolytic hypercalcemia accounts for about 20% of cases and is usually associated with extensive bone metastases. It is most commonly seen in MM and metastatic breast cancer and less commonly in leukemia. The proposed mechanism is thought to be because of the release of local cytokines from the tumor, resulting in excess osteoclast activation and enhanced bone resorption often through RANK/RANKL interaction.

Extrarenal production of 1,25(OH)2D by the tumor accounts for about 1% of cases of hypercalcemia in malignancy. 1,25(OH)2D causes increased intestinal absorption of calcium and enhances osteolytic bone resorption, resulting in increased serum calcium. This mechanism is most commonly seen with Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma and had been reported in ovarian dysgerminoma.7

In our patient, bone imaging showed osteoblastic lesions, a finding that likely contrasts the local osteolytic bone destruction theory. PTHrP was not significantly elevated in the serum, and PTH levels ruled out any form of primary hyperparathyroidism. In addition, histopathology showed no evidence of mosaicism or neuroendocrine dedifferentiation.

Findings in aggregate tell us that an exact pathophysiologic mechanism leading to hypercalcemia in prostate cancer is still unclear and may involve an interplay between growth factors and possible osteolytic materials, yet it must be studied thoroughly.

Conclusions

Hypercalcemia in pure metastatic adenocarcinoma of prostate is a rare finding and is of uncertain significance. Some studies suggested a search for unusual histopathologies, including neuroendocrine cancer and neuroendocrine dedifferentiation.8,11 However, in adenocarcinoma alone, it has an uncertain pathophysiology that needs to be further studied. Studies needed to investigate the role of PTHrP as a growth factor for both prostate cancer cells and development of hypercalcemia and possibly target-directed monoclonal antibody therapies may need to be extensively researched.

Hypercalcemia is found when the corrected serum calcium level is > 10.5 mg/dL.1 Its symptoms are not specific and may include polyuria, dehydration, polydipsia, anorexia, nausea and/or vomiting, constipation, and other central nervous system manifestations, including confusion, delirium, cognitive impairment, muscle weakness, psychotic symptoms, and even coma.1,2

Hypercalcemia has varied etiologies; however, malignancy-induced hypercalcemia is one of the most common causes. In the US, the most common causes of malignancy-induced hypercalcemia are primary tumors of the lung or breast, multiple myeloma (MM), squamous cell carcinoma of the head or neck, renal cancer, and ovarian cancer.1

Men with prostate cancer and bone metastasis have relatively worse prognosis than do patient with no metastasis.3 In a recent meta-analysis of patients with bone-involved castration-resistant prostate cancer, the median survival was 21 months.3

Hypercalcemia is a rare manifestation of prostate cancer. In a retrospective study conducted between 2009 and 2013 using the Oncology Services Comprehensive Electronic Records (OSCER) warehouse of electronic health records (EHR), the rates of malignancy-induced hypercalcemia were the lowest among patients with prostate cancer, ranging from 1.4 to 2.1%.1

We present this case to discuss different pathophysiologic mechanisms leading to hypercalcemia in a patient with prostate cancer with bone metastasis and to study the role of humoral and growth factors in the pathogenesis of the disease.

Case Presentation

An African American man aged 69 years presented to the emergency department (ED) with generalized weakness, fatigue, and lower extremities muscle weakness. He reported a 40-lb weight loss over the past 3 months, intermittent lower back pain, and a 50 pack-year smoking history. A physical examination suggested clinical signs of dehydration.

Laboratory test results indicated hypercalcemia, macrocytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia: calcium 15.8 mg/dL, serum albumin 4.1 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 139 μ/L, blood urea nitrogen 55 mg/dL, creatinine 3.4 mg/dL (baseline 1.4-1.5 mg/dL), hemoglobin 8 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume 99.6 fL, and platelets 100,000/μL. The patient was admitted for hypercalcemia. His intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) was suppressed at 16 pg/mL, phosphorous was 3.8 mg/dL, parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) was < 0.74 pmol/L, vitamin D (25 hydroxy cholecalciferol) was mildly decreased at 17.2 ng/mL, and 1,25 dihydroxy cholecalciferol (calcitriol) was < 5.0 (normal range 20-79.3 pg/mL).

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen was taken due to the patient’s heavy smoking history, an incidentally detected right lung base nodule on chest X-ray, and hypercalcemia. The CT scan showed multiple right middle lobe lung nodules with and without calcifications and calcified right hilar lymph nodes (Figure 1).

To evaluate the pancytopenia, a bone marrow biopsy was done, which showed that 80 to 90% of the marrow space was replaced by fibrosis and metastatic malignancy. Trilinear hematopoiesis was not seen (Figure 2). The tumor cells were positive for prostate- specific membrane antigen (PSMA) and negative for cytokeratin 7 and 20 (CK7 and CK20).4 The former is a membrane protein expressed on prostate tissues, including cancer; the latter is a form of protein used to identify adenocarcinoma of unknown primary origin (CK7 usually found in primary/ metastatic lung adenocarcinoma and CK20 usually in primary and some metastatic diseases of colon adenocarcinoma).5 A prostatic specific antigen (PSA) test was markedly elevated: 335.94 ng/mL (1.46 ng/mL on a previous 2011 test).

Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate was diagnosed without a prostate biopsy. To determine the extent of bone metastases, a technetium-99m-methylene diphosphonate (MDP) bone scintigraphy demonstrated a superscan with intense foci of increased radiotracer uptake involving the bilateral shoulders, sternoclavicular joints, and sternum with heterogeneous uptake involving bilateral anterior and posterior ribs; cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spines; sacrum, pelvis, and bilateral hips, including the femoral head/neck and intertrochanteric regions. Also noted were several foci of radiotracer uptake involving the mandible and bilateral skull in the region of the temporomandibular joints (Figure 3).

The patient was initially treated with IV isotonic saline, followed by calcitonin and then pamidronate after kidney function improved. His calcium level responded to the therapy, and a plan was made by medical oncology to start androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) prior to discharge.

He was initially treated with bicalutamide, while a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist (leuprolide) was added 1 week later. Bicalutamide was then discontinued and a combined androgen blockade consisting of leuprolide, ketoconazole, and hydrocortisone was started. This therapy resulted in remission, and PSA declined to 1.73 ng/ mL 3 months later. At that time the patient enrolled in a clinical trial with leuprolide and bicalutamide combined therapy. About 6 months after his diagnosis, patient’s cancer progressed and became hormone refractory disease. At that time, bicalutamide was discontinued, and his therapy was switched to combined leuprolide and enzalutamide. After 6 months of therapy with enzalutamide, the patient’s cancer progressed again. He was later treated with docetaxel chemotherapy but died 16 months after diagnosis.

showed improvement of hypercalcemia at the time of discharge, but 9 months later and toward the time of expiration, our patient developed secondary hyperparathyroidism, with calcium maintained in the normal range, while iPTH was significantly elevated, a finding likely explained by a decline in kidney function and a fall in glomerular filtration rate (Table).

Discussion

Hypercalcemia in the setting of prostate cancer is a rare complication with an uncertain pathophysiology.6 Several mechanisms have been proposed for hypercalcemia of malignancy, these comprise humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy mediated by increased PTHrP; local osteolytic hypercalcemia with secretion of other humoral factors; excess extrarenal activation of vitamin D (1,25[OH]2D); PTH secretion, ectopic or primary; and multiple concurrent etiologies.7

PTHrP is the predominant mediator for hypercalcemia of malignancy and is estimated to account for 80% of hypercalcemia in patients with cancer. This protein shares a substantial sequence homology with PTH; in fact, 8 of the first 13 amino acids at the N-terminal portion of PTH were identical.8 PTHrP has multiple isoforms (PTHrP 141, PTHrP 139, and PTHrP 173). Like PTH, it enhances renal tubular reabsorption of calcium while increasing urinary phosphorus excretion.7 The result is both hypercalcemia and hypophosphatemia. However, unlike PTH, PTHrP does not increase 1,25(OH)2D and thus does not increase intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphorus. PTHrP acts on osteoblasts, leading to enhanced synthesis of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL).7

In one study, PTHrP was detected immunohistochemically in prostate cancer cells. Iwamura and colleagues used 33 radical prostatectomy specimens from patients with clinically localized carcinoma of the prostate.9 None of these patients demonstrated hypercalcemia prior to the surgery. Using a mouse monoclonal antibody to an amino acid fragment, all cases demonstrated some degree of immunoreactivity throughout the cytoplasm of the tumor cells, but immunostaining was absent from inflammatory and stromal cells.9Furthermore, the intensity of the staining appeared to directly correlate with increasing tumor grade.9

Another study by Iwamura and colleagues suggested that PTHrP may play a significant role in the growth of prostate cancer by acting locally in an autocrine fashion.10 In this study, all prostate cancer cell lines from different sources expressed PTHrP immunoreactivity as well as evidence of DNA synthesis, the latter being measured by thymidine incorporation assay. Moreover, when these cells were incubated with various concentrations of mouse monoclonal antibody directed to PTHrP fragment, PTHrP-induced DNA synthesis was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner and almost completely neutralized at a specific concentration. Interestingly, the study demonstrated that cancer cell line derived from bone metastatic lesions secreted significantly greater amounts of PTHrP than did the cell line derived from the metastasis in the brain or in the lymph node. These findings suggest that PTHrP production may confer some advantage on the ability of prostate cancer cells to grow in bone.10

Ando and colleagues reported that neuroendocrine dedifferentiated prostate cancer can develop as a result of long-term ADT even after several years of therapy and has the potential to worsen and develop severe hypercalcemia.8 Neuron-specific enolase was used as the specific marker for the neuroendocrine cell, which suggested that the prostate cancer cell derived from the neuroendocrine cell might synthesize PTHrP and be responsible for the observed hypercalcemia.8

Other mechanisms cited for hypercalcemia of malignancy include other humoral factors associated with increased remodeling and comprise interleukin 1, 3, 6 (IL-1, IL-3, IL-6); tumor necrosis factor α; transforming growth factor A and B observed in metastatic bone lesions in breast cancer; lymphotoxin; E series prostaglandins; and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α seen in MM.

Local osteolytic hypercalcemia accounts for about 20% of cases and is usually associated with extensive bone metastases. It is most commonly seen in MM and metastatic breast cancer and less commonly in leukemia. The proposed mechanism is thought to be because of the release of local cytokines from the tumor, resulting in excess osteoclast activation and enhanced bone resorption often through RANK/RANKL interaction.

Extrarenal production of 1,25(OH)2D by the tumor accounts for about 1% of cases of hypercalcemia in malignancy. 1,25(OH)2D causes increased intestinal absorption of calcium and enhances osteolytic bone resorption, resulting in increased serum calcium. This mechanism is most commonly seen with Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma and had been reported in ovarian dysgerminoma.7

In our patient, bone imaging showed osteoblastic lesions, a finding that likely contrasts the local osteolytic bone destruction theory. PTHrP was not significantly elevated in the serum, and PTH levels ruled out any form of primary hyperparathyroidism. In addition, histopathology showed no evidence of mosaicism or neuroendocrine dedifferentiation.

Findings in aggregate tell us that an exact pathophysiologic mechanism leading to hypercalcemia in prostate cancer is still unclear and may involve an interplay between growth factors and possible osteolytic materials, yet it must be studied thoroughly.

Conclusions

Hypercalcemia in pure metastatic adenocarcinoma of prostate is a rare finding and is of uncertain significance. Some studies suggested a search for unusual histopathologies, including neuroendocrine cancer and neuroendocrine dedifferentiation.8,11 However, in adenocarcinoma alone, it has an uncertain pathophysiology that needs to be further studied. Studies needed to investigate the role of PTHrP as a growth factor for both prostate cancer cells and development of hypercalcemia and possibly target-directed monoclonal antibody therapies may need to be extensively researched.

1. Gastanaga VM, Schwartzberg LS, Jain RK, et al. Prevalence of hypercalcemia among cancer patients in the United States. Cancer Med. 2016;5(8):2091‐2100. doi:10.1002/cam4.749

2. Grill V, Martin TJ. Hypercalcemia of malignancy. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2000;1(4):253‐263. doi:10.1023/a:1026597816193

3. Halabi S, Kelly WK, Ma H, et al. Meta-analysis evaluating the impact of site of metastasis on overall survival in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(14):1652‐1659. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.65.7270

4. Chang SS. Overview of prostate-specific membrane antigen. Rev Urol. 2004;6(suppl 10):S13‐S18.

5. Kummar S, Fogarasi M, Canova A, Mota A, Ciesielski T. Cytokeratin 7 and 20 staining for the diagnosis of lung and colorectal adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(12):1884‐1887. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600326

6. Avashia JH, Walsh TD, Thomas AJ Jr, Kaye M, Licata A. Metastatic carcinoma of the prostate with hypercalcemia [published correction appears in Cleve Clin J Med. 1991;58(3):284]. Cleve Clin J Med. 1990;57(7):636‐638. doi:10.3949/ccjm.57.7.636.

7. Goldner W. Cancer-related hypercalcemia. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(5):426‐432. doi:10.1200/JOP.2016.011155.

8. Ando T, Watanabe K, Mizusawa T, Katagiri A. Hypercalcemia due to parathyroid hormone-related peptide secreted by neuroendocrine dedifferentiated prostate cancer. Urol Case Rep. 2018;22:67‐69. doi:10.1016/j.eucr.2018.11.001

9. Iwamura M, di Sant’Agnese PA, Wu G, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of parathyroid hormonerelated protein in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1993;53(8):1724‐1726.

10. Iwamura M, Abrahamsson PA, Foss KA, Wu G, Cockett AT, Deftos LJ. Parathyroid hormone-related protein: a potential autocrine growth regulator in human prostate cancer cell lines. Urology. 1994;43(5):675‐679. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(94)90183-x

11. Smith DC, Tucker JA, Trump DL. Hypercalcemia and neuroendocrine carcinoma of the prostate: a report of three cases and a review of the literature. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(3):499‐505. doi:10.1200/JCO.1992.10.3.499.

1. Gastanaga VM, Schwartzberg LS, Jain RK, et al. Prevalence of hypercalcemia among cancer patients in the United States. Cancer Med. 2016;5(8):2091‐2100. doi:10.1002/cam4.749

2. Grill V, Martin TJ. Hypercalcemia of malignancy. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2000;1(4):253‐263. doi:10.1023/a:1026597816193

3. Halabi S, Kelly WK, Ma H, et al. Meta-analysis evaluating the impact of site of metastasis on overall survival in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(14):1652‐1659. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.65.7270

4. Chang SS. Overview of prostate-specific membrane antigen. Rev Urol. 2004;6(suppl 10):S13‐S18.

5. Kummar S, Fogarasi M, Canova A, Mota A, Ciesielski T. Cytokeratin 7 and 20 staining for the diagnosis of lung and colorectal adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(12):1884‐1887. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600326

6. Avashia JH, Walsh TD, Thomas AJ Jr, Kaye M, Licata A. Metastatic carcinoma of the prostate with hypercalcemia [published correction appears in Cleve Clin J Med. 1991;58(3):284]. Cleve Clin J Med. 1990;57(7):636‐638. doi:10.3949/ccjm.57.7.636.