User login

AVAHO

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Skull Base Regeneration During Treatment With Chemoradiation for Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Case Report

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) differs from other head and neck (H&N) cancers in its epidemiology and treatment. Unlike other H&N cancers, NPC has a distinct geographical distribution with a much higher incidence in endemic areas, such as southern China, than in areas where it is relatively uncommon, such as the United States.1 The etiology of NPC varies based on the geographical distribution, with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) thought to be the primary etiologic agent in endemic areas. On the other hand, in North America 2 additional subsets of NPC have been identified: human papillomavirus (HPV)–positive/EBV-negative and HPV-negative/EBV-negative.2,3 NPC arises from the epithelial lining of the nasopharynx, often in the fossa of Rosenmuller, and is the most seen tumor in the nasopharynx.4 NPC is less surgically accessible than other H&N cancers, and surgery to the nasopharynx poses more risks given the proximity of critical surrounding structures. NPC is radiosensitive, and therefore radiotherapy (RT), in combination with chemotherapy for locally advanced tumors, has become the mainstay of treatment for nonmetastatic NPC.4

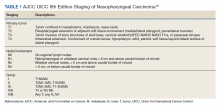

NPC often presents with an asymptomatic neck mass or with symptoms of epistaxis, nasal obstruction, and otitis media.5 Advanced cases of NPC can present with direct extension into the skull base, paranasal sinuses, and orbit, as well as involvement of cranial nerves. Radiation planning for tumors of the nasopharynx is complicated by the need to deliver an adequate dose to the tumor while limiting dose and toxicity to nearby critical structures such as the brainstem, optic chiasm, eyes, spinal cord (SC), temporal lobes, and cochleae. Achieving an adequate dose to nasopharyngeal primary tumors is especially complicated for T4 tumors invading the skull base with intracranial extension, in direct contact with these critical structures (Table 1).

Skull base invasion is a poor prognostic factor, predicting for an increased risk of locoregional recurrence and worse overall survival. Furthermore, the extent of skull base invasion in NPC affects overall prognosis, with cranial nerve involvement and intracranial extension predictive for worse outcomes.5 Depending on the extent of destruction, a bony defect along the skull base could develop with tumor shrinkage during RT, resulting in complications such as cerebrospinal fluid leaks, herniation, and atlantoaxial instability.6

There is a paucity of literature on the ability of bone to regenerate during or after RT for cases of NPC with skull base destruction. To our knowledge, nothing has been published detailing the extent of bony regeneration that can occur during treatment itself, as the tumor regresses and poses a threat of a skull base defect. Here we present a case of T4 HPV-positive/EBV-negative NPC with intracranial extension and describe the RT planning methods leading to prolonged local control, limited toxicities, and bony regeneration of the skull base during treatment.

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old male patient with no previous medical history presented to the emergency department with worsening diplopia, nasal obstruction, facial pain, and neck stiffness. The patient reported a 3 pack-year smoking history with recent smoking cessation. His physical examination was notable for a right abducens nerve palsy and an ulcerated nasopharyngeal mass on endoscopy.

Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 7-cm mass in the nasopharynx, eroding through the skull base with destruction and replacement of the clivus by tumor. Also noted was erosion of the petrous apices, carotid canals, sella turcica, dens, and the bilateral occipital condyles. There was intracranial extension with replacement of portions of the cavernous sinuses as well as mass effect on the prepontine cistern. Additional brain imaging studies, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans, were obtained for completion of the staging workup. The MRI correlated with the findings noted on CT and demonstrated involvement of Meckel cave, foramen ovale, foramen rotundum, Dorello canal, and the hypoglossal canals. No cervical lymphadenopathy or distant metastases were noted on imaging. Pathology from biopsy revealed poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, EBV-negative, strongly p16-positive, HPV-16 positive, and P53-negative.

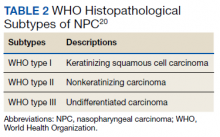

The H&N multidisciplinary tumor board recommended concurrent chemoradiation for this stage IVA (T4N0M0) EBV-negative, HPV-positive, Word Health Organization type I NPC (Table 2). The patient underwent CT simulation for RT planning, and both tumor volumes and critical normal structures were contoured. The goal was to deliver 70 Gy to the gross tumor. However, given the inability to deliver this dose while meeting the SC dose tolerance of < 45 Gy, a 2-Gy fraction was removed. Therefore, 34 fractions of 2 Gy were delivered to the tumor volume for a total dose of 68 Gy. Weekly cisplatin, at a dose of 40 mg/m2, was administered concurrently with RT.

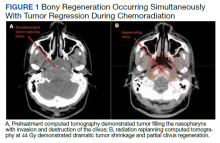

RT planning was complicated by the tumor’s contact with the brainstem and upper cervical SC, as well as proximity of the tumor to the optic apparatus. The patient underwent 2 replanning CT scans at 26 Gy and 44 Gy to evaluate for tumor shrinkage. These CT scans demonstrated shrinkage of the tumor away from critical neural structures, allowing the treatment volume to be reduced away from these structures in order to achieve required dose tolerances (brainstem < 54 Gy, optic nerves and chiasm < 50 Gy, SC < 45 Gy for this case). The replanning CT scan at 44 Gy, 5 weeks after treatment initiation, demonstrated that dramatic tumor shrinkage had occurred early in treatment, with separation of the remaining tumor from the area of the SC and brainstem with which it was initially in contact (Figure 1). This improvement allowed for shrinkage of the high-dose radiation field away from these critical neural structures.

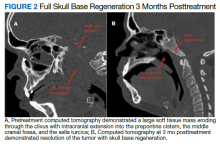

Baseline destruction of the skull base by tumor raised concern for craniospinal instability with tumor response. The patient was evaluated by neurosurgery before the start of RT, and the recommendation was for reimaging during treatment and close follow-up of the patient’s symptoms to determine whether surgical fixation would be indicated during or after treatment. The patient underwent a replanning CT scan at 44 Gy, 5 weeks after treatment initiation, that demonstrated impressive bony regeneration occurring during chemoradiation. New bone formation was noted in the region of the clivus and bilateral occipital condyles, which had been absent on CT prior to treatment initiation. Another CT at 54 Gy demonstrated further ossification of the clivus and bilateral occipital condyles, and bony regeneration occurring rapidly during chemoradiation. The posttreatment CT 3 months after completion of chemoradiation demonstrated complete skull base regeneration, maintaining stability of this area and precluding the need for neurosurgical intervention (Figure 2).

During RT,

The patient had no evidence of disease at 5 years posttreatment. After completing treatment, the patient experienced ongoing intermittent nasal congestion and occasional aural fullness. He experienced an early decay of several teeth starting 1 year after completion of RT, and he continues to visit his dentist for management. He experienced no other treatment-related toxicities. In particular, he has exhibited no signs of neurologic toxicity to date.

Discussion

RT for NPC is complicated by the proximity of these tumors to critical surrounding neural structures. It is challenging to achieve the required dose constraints to surrounding neural tissues while delivering the usual 70-Gy dose to the gross tumor, especially when the tumor comes into direct contact with these structures.

This case provides an example of response-adapted RT using imaging during treatment to shrink the high-dose target as the tumor shrinks away from critical surrounding structures.7 This strategy permits delivery of the maximum dose to the tumor while minimizing radiation dose, and therefore risk of toxicity, to normal surrounding structures. While it is typical to deliver 70 Gy to the full extent of tumor involvement for H&N tumors, this was not possible in this case as the tumor was in contact with the brainstem and upper cervical SC. Delivering the full 70 Gy to these areas of tumor would have placed this patient at substantial risk of brainstem and/or SC toxicity. This report demonstrates that response-adapted RT with shrinking fields can allow for tumor control while avoiding toxicity to critical neural structures for cases of locally advanced NPC in which tumor is abutting these structures.

Bony regeneration of the skull base following RT has been reported in the literature, but in limited reviews. Early reports used plain radiography to follow changes. Unger and colleagues demonstrated the regeneration of bone using skull radiographs 4 to 6 months after completion of RT for NPC.8 More recent literature details the ability of bone to regenerate after RT based on CT findings. Fang and colleagues reported on 90 cases of NPC with skull base destruction, with 63% having bony regeneration on posttreatment CT.9 Most of the patients in Fang’s report had bony regeneration within 1 year of treatment, and in general, bony regeneration became more evident on imaging with longer follow-up. Of note, local control was significantly greater in patients with regeneration vs persistent destruction (77% vs 21%, P < .001). On multivariate analysis, complete tumor response was significantly associated with bony regeneration; other factors such as age, sex, radiation dose, and chemotherapy were not significantly associated with the likelihood of bony regeneration.

Our report details a nasopharyngeal tumor that destroyed the skull base with no intact bony barrier. In such cases, concern arises regarding craniospinal instability with tumor regression if there is not simultaneous bone regeneration. Tumor invasion of the skull base and C1-2 vertebral bodies and complications from treatment of such tumor extent can lead to symptoms of craniospinal instability, including pain, difficulty with neck range of motion, and loss of strength and sensation in the upper and lower extremities.10 A case report of a woman treated with chemoradiation for a plasmacytoma of the skull base detailed her posttreatment presentation with quadriparesis resulting from craniospinal instability after tumor regression.11 Such instability is generally treated surgically, and during this woman’s surgery, there was an injury to the right vertebral artery, although this did not cause any additional neurologic deficits.

RT leads to hypocellularity, hypovascularity, and hypoxia of treated tissues, resulting in a reduced ability for growth and healing. Studies demonstrate that irradiated bone contains fewer osteoblast cells and osteocytes than unirradiated bone, resulting in reduced regenerative capacity.12,13 Furthermore, the reconstruction of bony defects resulting after cancer treatment has been shown to be difficult and associated with a high risk of complications.14 Given the impaired ability of irradiated bone to regenerate, studies have evaluated the use of growth factors and gene therapy to promote bone formation after treatment.15 Bone marrow stem cells have been shown to reverse radiation-induced cellular depletion and to increase osteocyte counts in animal studies.12 Further, overexpression of miR-34a, a tumor suppressor involved in tissue development, has been shown to improve osteoblastic differentiation of irradiated bone marrow stem cells and promote bone regeneration in vitro and in animal studies.13 While several techniques are being studied in vitro and in animal studies to promote bony regeneration after RT, there is a lack of data on use of these techniques in humans with cancer.

With our case, there was great uncertainty related to the ability of bone to regenerate during treatment and concern regarding consequences of formation of a skull base defect during treatment. CT imaging revealed bony regeneration of the central skull base and clivus, as well as occipital condyles, that occurred throughout the RT course. There was clear evidence of bone regeneration on the replanning CT obtained 5 weeks after treatment initiation. To our knowledge, this is the first report to demonstrate rapid bony regeneration during RT, thereby maintaining the integrity of the skull base and precluding the need for neurosurgical intervention. Moving forward, imaging should be considered during treatment for patients with tumor-related destruction of the skull base and upper cervical spine to evaluate the extent of bony regeneration during treatment and estimate the potential risk of craniocervical instability. Further studies with imaging during treatment are needed for more information on the likelihood of bony regeneration and factors that correlate with bony regeneration during treatment. As in other reports, our case demonstrates that bony regeneration may predict complete response to RT.9

Our patient’s tumor was HPV-positive and EBV-negative. In the US, the rate of HPV-positive NPC is 35%.16 However, HPV-positive NPC is much less common in endemic areas. A recent study from China of 1,328 patients with NPC revealed a 6.4% rate of HPV-positive/EBV-negative cases.17 In that study, patients with HPV-positive/EBV-negative tumors had improved survival compared to patients whose tumors were HPV-negative/EBV-positive. Another study suggests that the impact of HPV in NPC varies according to race, with HPV-positivity predicting for improved outcomes in East Asian patients and worse outcomes in White patients.17 A study from the University of Michigan suggests that both HPV-positive/EBV-negative and HPV-negative/EBV-negative NPC are associated with worse overall survival and locoregional control than EBV-positive NPC.2 Overall, the prognostic role of HPV in NPC remains unclear given conflicting information in the literature and the lack of large population studies.18

Conclusions

There is a paucity of literature on bony regeneration in patients with skull base destruction from advanced NPC, and in particular, the ability of skull base regeneration to occur during treatment simultaneous with tumor regression. Our patient had HPV-positive/EBV-negative NPC, but it is unclear how this subtype affected his prognosis. Factors such as tumor histology, radiosensitivity with rapid tumor regression, and young age may have all contributed to the rapidity of bone regeneration in our patient. This case report demonstrates that an impressive tumor response to chemoradiation with simultaneous bony regeneration is possible among patients presenting with tumor destruction of the skull base, precluding the need for neurosurgical intervention.

1. Chang ET, Adami HO. The enigmatic epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(10):1765-1777. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0353

2. Stenmark MH, McHugh JB, Schipper M, et al. Nonendemic HPV-positive nasopharyngeal carcinoma: association with poor prognosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(3):580-588. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.11.246

3. Maxwell JH, Kumar B, Feng FY, et al. HPV-positive/p16-positive/EBV-negative nasopharyngeal carcinoma in white North Americans. Head Neck. 2010;32(5):562-567. doi:10.1002/hed.21216

4. Chen YP, Chan ATC, Le QT, Blanchard P, Sun Y, Ma J. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet. 2019;394(10192):64-80. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30956-0

5. Roh JL, Sung MW, Kim KH, et al.. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma with skull base invasion: a necessity of staging subdivision. Am J Otolaryngol. 2004;25(1):26-32. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2003.09.011

6. Orr RD, Salo PT. Atlantoaxial instability complicating radiation therapy for recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. A case report. Spine. 1998;23(11):1280-1282. doi:10.1097/00007632-199806010-00021

7. Morgan HE, Sher DJ. Adaptive radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Cancers Head Neck. 2020;5:1. doi:10.1186/s41199-019-0046-z

8. Unger JD, Chiang LC, Unger GF. Apparent reformation of the base of the skull following radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiology. 1978;126(3):779-782. doi:10.1148/126.3.779

9. Fang FM, Leung SW, Wang CJ, et al. Computed tomography findings of bony regeneration after radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma with skull base destruction: implications for local control. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44(2):305-309. doi:10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00004-8

10. Tiruchelvarayan R, Lee KA, Ng I. Surgery for atlanto-axial (C1-2) involvement or instability in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Singapore Med J. 2012;53(6):416-421.

11. Samprón N, Arrazola M, Urculo E. Skull-base plasmacytoma with craniocervical instability [in Spanish]. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2009;20(5):478-483.

12. Zheutlin AR, Deshpande SS, Nelson NS, et al. Bone marrow stem cells assuage radiation-induced damage in a murine model of distraction osteogenesis: a histomorphometric evaluation. Cytotherapy. 2016;18(5):664-672. doi:10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.01.013

13. Liu H, Dong Y, Feng X, et al. miR-34a promotes bone regeneration in irradiated bone defects by enhancing osteoblast differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells in rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):180. doi:10.1186/s13287-019-1285-y

14. Holzapfel BM, Wagner F, Martine LC, et al. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine in musculoskeletal oncology. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016;35(3):475-487. doi:10.1007/s10555-016-9635-z

15. Hu WW, Ward BB, Wang Z, Krebsbach PH. Bone regeneration in defects compromised by radiotherapy. J Dent Res. 2010;89(1):77-81. doi:10.1177/0022034509352151

16. Wotman M, Oh EJ, Ahn S, Kraus D, Constantino P, Tham T. HPV status in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the United States: a SEER database study. Am J Otolaryngol. 2019;40(5):705-710. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2019.06.00717. Huang WB, Chan JYW, Liu DL. Human papillomavirus and World Health Organization type III nasopharyngeal carcinoma: multicenter study from an endemic area in Southern China. Cancer. 2018;124(3):530-536. doi:10.1002/cncr.31031.

18. Verma V, Simone CB 2nd, Lin C. Human papillomavirus and nasopharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2018;40(4):696-706. doi:10.1002/hed.24978

19. Lee AWM, Lydiatt WM, Colevas AD, et al. Nasopharynx. In: Amin MB, ed. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017:103.

20. Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, eds. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumors. In: World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. IARC Press; 2005.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) differs from other head and neck (H&N) cancers in its epidemiology and treatment. Unlike other H&N cancers, NPC has a distinct geographical distribution with a much higher incidence in endemic areas, such as southern China, than in areas where it is relatively uncommon, such as the United States.1 The etiology of NPC varies based on the geographical distribution, with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) thought to be the primary etiologic agent in endemic areas. On the other hand, in North America 2 additional subsets of NPC have been identified: human papillomavirus (HPV)–positive/EBV-negative and HPV-negative/EBV-negative.2,3 NPC arises from the epithelial lining of the nasopharynx, often in the fossa of Rosenmuller, and is the most seen tumor in the nasopharynx.4 NPC is less surgically accessible than other H&N cancers, and surgery to the nasopharynx poses more risks given the proximity of critical surrounding structures. NPC is radiosensitive, and therefore radiotherapy (RT), in combination with chemotherapy for locally advanced tumors, has become the mainstay of treatment for nonmetastatic NPC.4

NPC often presents with an asymptomatic neck mass or with symptoms of epistaxis, nasal obstruction, and otitis media.5 Advanced cases of NPC can present with direct extension into the skull base, paranasal sinuses, and orbit, as well as involvement of cranial nerves. Radiation planning for tumors of the nasopharynx is complicated by the need to deliver an adequate dose to the tumor while limiting dose and toxicity to nearby critical structures such as the brainstem, optic chiasm, eyes, spinal cord (SC), temporal lobes, and cochleae. Achieving an adequate dose to nasopharyngeal primary tumors is especially complicated for T4 tumors invading the skull base with intracranial extension, in direct contact with these critical structures (Table 1).

Skull base invasion is a poor prognostic factor, predicting for an increased risk of locoregional recurrence and worse overall survival. Furthermore, the extent of skull base invasion in NPC affects overall prognosis, with cranial nerve involvement and intracranial extension predictive for worse outcomes.5 Depending on the extent of destruction, a bony defect along the skull base could develop with tumor shrinkage during RT, resulting in complications such as cerebrospinal fluid leaks, herniation, and atlantoaxial instability.6

There is a paucity of literature on the ability of bone to regenerate during or after RT for cases of NPC with skull base destruction. To our knowledge, nothing has been published detailing the extent of bony regeneration that can occur during treatment itself, as the tumor regresses and poses a threat of a skull base defect. Here we present a case of T4 HPV-positive/EBV-negative NPC with intracranial extension and describe the RT planning methods leading to prolonged local control, limited toxicities, and bony regeneration of the skull base during treatment.

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old male patient with no previous medical history presented to the emergency department with worsening diplopia, nasal obstruction, facial pain, and neck stiffness. The patient reported a 3 pack-year smoking history with recent smoking cessation. His physical examination was notable for a right abducens nerve palsy and an ulcerated nasopharyngeal mass on endoscopy.

Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 7-cm mass in the nasopharynx, eroding through the skull base with destruction and replacement of the clivus by tumor. Also noted was erosion of the petrous apices, carotid canals, sella turcica, dens, and the bilateral occipital condyles. There was intracranial extension with replacement of portions of the cavernous sinuses as well as mass effect on the prepontine cistern. Additional brain imaging studies, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans, were obtained for completion of the staging workup. The MRI correlated with the findings noted on CT and demonstrated involvement of Meckel cave, foramen ovale, foramen rotundum, Dorello canal, and the hypoglossal canals. No cervical lymphadenopathy or distant metastases were noted on imaging. Pathology from biopsy revealed poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, EBV-negative, strongly p16-positive, HPV-16 positive, and P53-negative.

The H&N multidisciplinary tumor board recommended concurrent chemoradiation for this stage IVA (T4N0M0) EBV-negative, HPV-positive, Word Health Organization type I NPC (Table 2). The patient underwent CT simulation for RT planning, and both tumor volumes and critical normal structures were contoured. The goal was to deliver 70 Gy to the gross tumor. However, given the inability to deliver this dose while meeting the SC dose tolerance of < 45 Gy, a 2-Gy fraction was removed. Therefore, 34 fractions of 2 Gy were delivered to the tumor volume for a total dose of 68 Gy. Weekly cisplatin, at a dose of 40 mg/m2, was administered concurrently with RT.

RT planning was complicated by the tumor’s contact with the brainstem and upper cervical SC, as well as proximity of the tumor to the optic apparatus. The patient underwent 2 replanning CT scans at 26 Gy and 44 Gy to evaluate for tumor shrinkage. These CT scans demonstrated shrinkage of the tumor away from critical neural structures, allowing the treatment volume to be reduced away from these structures in order to achieve required dose tolerances (brainstem < 54 Gy, optic nerves and chiasm < 50 Gy, SC < 45 Gy for this case). The replanning CT scan at 44 Gy, 5 weeks after treatment initiation, demonstrated that dramatic tumor shrinkage had occurred early in treatment, with separation of the remaining tumor from the area of the SC and brainstem with which it was initially in contact (Figure 1). This improvement allowed for shrinkage of the high-dose radiation field away from these critical neural structures.

Baseline destruction of the skull base by tumor raised concern for craniospinal instability with tumor response. The patient was evaluated by neurosurgery before the start of RT, and the recommendation was for reimaging during treatment and close follow-up of the patient’s symptoms to determine whether surgical fixation would be indicated during or after treatment. The patient underwent a replanning CT scan at 44 Gy, 5 weeks after treatment initiation, that demonstrated impressive bony regeneration occurring during chemoradiation. New bone formation was noted in the region of the clivus and bilateral occipital condyles, which had been absent on CT prior to treatment initiation. Another CT at 54 Gy demonstrated further ossification of the clivus and bilateral occipital condyles, and bony regeneration occurring rapidly during chemoradiation. The posttreatment CT 3 months after completion of chemoradiation demonstrated complete skull base regeneration, maintaining stability of this area and precluding the need for neurosurgical intervention (Figure 2).

During RT,

The patient had no evidence of disease at 5 years posttreatment. After completing treatment, the patient experienced ongoing intermittent nasal congestion and occasional aural fullness. He experienced an early decay of several teeth starting 1 year after completion of RT, and he continues to visit his dentist for management. He experienced no other treatment-related toxicities. In particular, he has exhibited no signs of neurologic toxicity to date.

Discussion

RT for NPC is complicated by the proximity of these tumors to critical surrounding neural structures. It is challenging to achieve the required dose constraints to surrounding neural tissues while delivering the usual 70-Gy dose to the gross tumor, especially when the tumor comes into direct contact with these structures.

This case provides an example of response-adapted RT using imaging during treatment to shrink the high-dose target as the tumor shrinks away from critical surrounding structures.7 This strategy permits delivery of the maximum dose to the tumor while minimizing radiation dose, and therefore risk of toxicity, to normal surrounding structures. While it is typical to deliver 70 Gy to the full extent of tumor involvement for H&N tumors, this was not possible in this case as the tumor was in contact with the brainstem and upper cervical SC. Delivering the full 70 Gy to these areas of tumor would have placed this patient at substantial risk of brainstem and/or SC toxicity. This report demonstrates that response-adapted RT with shrinking fields can allow for tumor control while avoiding toxicity to critical neural structures for cases of locally advanced NPC in which tumor is abutting these structures.

Bony regeneration of the skull base following RT has been reported in the literature, but in limited reviews. Early reports used plain radiography to follow changes. Unger and colleagues demonstrated the regeneration of bone using skull radiographs 4 to 6 months after completion of RT for NPC.8 More recent literature details the ability of bone to regenerate after RT based on CT findings. Fang and colleagues reported on 90 cases of NPC with skull base destruction, with 63% having bony regeneration on posttreatment CT.9 Most of the patients in Fang’s report had bony regeneration within 1 year of treatment, and in general, bony regeneration became more evident on imaging with longer follow-up. Of note, local control was significantly greater in patients with regeneration vs persistent destruction (77% vs 21%, P < .001). On multivariate analysis, complete tumor response was significantly associated with bony regeneration; other factors such as age, sex, radiation dose, and chemotherapy were not significantly associated with the likelihood of bony regeneration.

Our report details a nasopharyngeal tumor that destroyed the skull base with no intact bony barrier. In such cases, concern arises regarding craniospinal instability with tumor regression if there is not simultaneous bone regeneration. Tumor invasion of the skull base and C1-2 vertebral bodies and complications from treatment of such tumor extent can lead to symptoms of craniospinal instability, including pain, difficulty with neck range of motion, and loss of strength and sensation in the upper and lower extremities.10 A case report of a woman treated with chemoradiation for a plasmacytoma of the skull base detailed her posttreatment presentation with quadriparesis resulting from craniospinal instability after tumor regression.11 Such instability is generally treated surgically, and during this woman’s surgery, there was an injury to the right vertebral artery, although this did not cause any additional neurologic deficits.

RT leads to hypocellularity, hypovascularity, and hypoxia of treated tissues, resulting in a reduced ability for growth and healing. Studies demonstrate that irradiated bone contains fewer osteoblast cells and osteocytes than unirradiated bone, resulting in reduced regenerative capacity.12,13 Furthermore, the reconstruction of bony defects resulting after cancer treatment has been shown to be difficult and associated with a high risk of complications.14 Given the impaired ability of irradiated bone to regenerate, studies have evaluated the use of growth factors and gene therapy to promote bone formation after treatment.15 Bone marrow stem cells have been shown to reverse radiation-induced cellular depletion and to increase osteocyte counts in animal studies.12 Further, overexpression of miR-34a, a tumor suppressor involved in tissue development, has been shown to improve osteoblastic differentiation of irradiated bone marrow stem cells and promote bone regeneration in vitro and in animal studies.13 While several techniques are being studied in vitro and in animal studies to promote bony regeneration after RT, there is a lack of data on use of these techniques in humans with cancer.

With our case, there was great uncertainty related to the ability of bone to regenerate during treatment and concern regarding consequences of formation of a skull base defect during treatment. CT imaging revealed bony regeneration of the central skull base and clivus, as well as occipital condyles, that occurred throughout the RT course. There was clear evidence of bone regeneration on the replanning CT obtained 5 weeks after treatment initiation. To our knowledge, this is the first report to demonstrate rapid bony regeneration during RT, thereby maintaining the integrity of the skull base and precluding the need for neurosurgical intervention. Moving forward, imaging should be considered during treatment for patients with tumor-related destruction of the skull base and upper cervical spine to evaluate the extent of bony regeneration during treatment and estimate the potential risk of craniocervical instability. Further studies with imaging during treatment are needed for more information on the likelihood of bony regeneration and factors that correlate with bony regeneration during treatment. As in other reports, our case demonstrates that bony regeneration may predict complete response to RT.9

Our patient’s tumor was HPV-positive and EBV-negative. In the US, the rate of HPV-positive NPC is 35%.16 However, HPV-positive NPC is much less common in endemic areas. A recent study from China of 1,328 patients with NPC revealed a 6.4% rate of HPV-positive/EBV-negative cases.17 In that study, patients with HPV-positive/EBV-negative tumors had improved survival compared to patients whose tumors were HPV-negative/EBV-positive. Another study suggests that the impact of HPV in NPC varies according to race, with HPV-positivity predicting for improved outcomes in East Asian patients and worse outcomes in White patients.17 A study from the University of Michigan suggests that both HPV-positive/EBV-negative and HPV-negative/EBV-negative NPC are associated with worse overall survival and locoregional control than EBV-positive NPC.2 Overall, the prognostic role of HPV in NPC remains unclear given conflicting information in the literature and the lack of large population studies.18

Conclusions

There is a paucity of literature on bony regeneration in patients with skull base destruction from advanced NPC, and in particular, the ability of skull base regeneration to occur during treatment simultaneous with tumor regression. Our patient had HPV-positive/EBV-negative NPC, but it is unclear how this subtype affected his prognosis. Factors such as tumor histology, radiosensitivity with rapid tumor regression, and young age may have all contributed to the rapidity of bone regeneration in our patient. This case report demonstrates that an impressive tumor response to chemoradiation with simultaneous bony regeneration is possible among patients presenting with tumor destruction of the skull base, precluding the need for neurosurgical intervention.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) differs from other head and neck (H&N) cancers in its epidemiology and treatment. Unlike other H&N cancers, NPC has a distinct geographical distribution with a much higher incidence in endemic areas, such as southern China, than in areas where it is relatively uncommon, such as the United States.1 The etiology of NPC varies based on the geographical distribution, with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) thought to be the primary etiologic agent in endemic areas. On the other hand, in North America 2 additional subsets of NPC have been identified: human papillomavirus (HPV)–positive/EBV-negative and HPV-negative/EBV-negative.2,3 NPC arises from the epithelial lining of the nasopharynx, often in the fossa of Rosenmuller, and is the most seen tumor in the nasopharynx.4 NPC is less surgically accessible than other H&N cancers, and surgery to the nasopharynx poses more risks given the proximity of critical surrounding structures. NPC is radiosensitive, and therefore radiotherapy (RT), in combination with chemotherapy for locally advanced tumors, has become the mainstay of treatment for nonmetastatic NPC.4

NPC often presents with an asymptomatic neck mass or with symptoms of epistaxis, nasal obstruction, and otitis media.5 Advanced cases of NPC can present with direct extension into the skull base, paranasal sinuses, and orbit, as well as involvement of cranial nerves. Radiation planning for tumors of the nasopharynx is complicated by the need to deliver an adequate dose to the tumor while limiting dose and toxicity to nearby critical structures such as the brainstem, optic chiasm, eyes, spinal cord (SC), temporal lobes, and cochleae. Achieving an adequate dose to nasopharyngeal primary tumors is especially complicated for T4 tumors invading the skull base with intracranial extension, in direct contact with these critical structures (Table 1).

Skull base invasion is a poor prognostic factor, predicting for an increased risk of locoregional recurrence and worse overall survival. Furthermore, the extent of skull base invasion in NPC affects overall prognosis, with cranial nerve involvement and intracranial extension predictive for worse outcomes.5 Depending on the extent of destruction, a bony defect along the skull base could develop with tumor shrinkage during RT, resulting in complications such as cerebrospinal fluid leaks, herniation, and atlantoaxial instability.6

There is a paucity of literature on the ability of bone to regenerate during or after RT for cases of NPC with skull base destruction. To our knowledge, nothing has been published detailing the extent of bony regeneration that can occur during treatment itself, as the tumor regresses and poses a threat of a skull base defect. Here we present a case of T4 HPV-positive/EBV-negative NPC with intracranial extension and describe the RT planning methods leading to prolonged local control, limited toxicities, and bony regeneration of the skull base during treatment.

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old male patient with no previous medical history presented to the emergency department with worsening diplopia, nasal obstruction, facial pain, and neck stiffness. The patient reported a 3 pack-year smoking history with recent smoking cessation. His physical examination was notable for a right abducens nerve palsy and an ulcerated nasopharyngeal mass on endoscopy.

Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 7-cm mass in the nasopharynx, eroding through the skull base with destruction and replacement of the clivus by tumor. Also noted was erosion of the petrous apices, carotid canals, sella turcica, dens, and the bilateral occipital condyles. There was intracranial extension with replacement of portions of the cavernous sinuses as well as mass effect on the prepontine cistern. Additional brain imaging studies, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans, were obtained for completion of the staging workup. The MRI correlated with the findings noted on CT and demonstrated involvement of Meckel cave, foramen ovale, foramen rotundum, Dorello canal, and the hypoglossal canals. No cervical lymphadenopathy or distant metastases were noted on imaging. Pathology from biopsy revealed poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, EBV-negative, strongly p16-positive, HPV-16 positive, and P53-negative.

The H&N multidisciplinary tumor board recommended concurrent chemoradiation for this stage IVA (T4N0M0) EBV-negative, HPV-positive, Word Health Organization type I NPC (Table 2). The patient underwent CT simulation for RT planning, and both tumor volumes and critical normal structures were contoured. The goal was to deliver 70 Gy to the gross tumor. However, given the inability to deliver this dose while meeting the SC dose tolerance of < 45 Gy, a 2-Gy fraction was removed. Therefore, 34 fractions of 2 Gy were delivered to the tumor volume for a total dose of 68 Gy. Weekly cisplatin, at a dose of 40 mg/m2, was administered concurrently with RT.

RT planning was complicated by the tumor’s contact with the brainstem and upper cervical SC, as well as proximity of the tumor to the optic apparatus. The patient underwent 2 replanning CT scans at 26 Gy and 44 Gy to evaluate for tumor shrinkage. These CT scans demonstrated shrinkage of the tumor away from critical neural structures, allowing the treatment volume to be reduced away from these structures in order to achieve required dose tolerances (brainstem < 54 Gy, optic nerves and chiasm < 50 Gy, SC < 45 Gy for this case). The replanning CT scan at 44 Gy, 5 weeks after treatment initiation, demonstrated that dramatic tumor shrinkage had occurred early in treatment, with separation of the remaining tumor from the area of the SC and brainstem with which it was initially in contact (Figure 1). This improvement allowed for shrinkage of the high-dose radiation field away from these critical neural structures.

Baseline destruction of the skull base by tumor raised concern for craniospinal instability with tumor response. The patient was evaluated by neurosurgery before the start of RT, and the recommendation was for reimaging during treatment and close follow-up of the patient’s symptoms to determine whether surgical fixation would be indicated during or after treatment. The patient underwent a replanning CT scan at 44 Gy, 5 weeks after treatment initiation, that demonstrated impressive bony regeneration occurring during chemoradiation. New bone formation was noted in the region of the clivus and bilateral occipital condyles, which had been absent on CT prior to treatment initiation. Another CT at 54 Gy demonstrated further ossification of the clivus and bilateral occipital condyles, and bony regeneration occurring rapidly during chemoradiation. The posttreatment CT 3 months after completion of chemoradiation demonstrated complete skull base regeneration, maintaining stability of this area and precluding the need for neurosurgical intervention (Figure 2).

During RT,

The patient had no evidence of disease at 5 years posttreatment. After completing treatment, the patient experienced ongoing intermittent nasal congestion and occasional aural fullness. He experienced an early decay of several teeth starting 1 year after completion of RT, and he continues to visit his dentist for management. He experienced no other treatment-related toxicities. In particular, he has exhibited no signs of neurologic toxicity to date.

Discussion

RT for NPC is complicated by the proximity of these tumors to critical surrounding neural structures. It is challenging to achieve the required dose constraints to surrounding neural tissues while delivering the usual 70-Gy dose to the gross tumor, especially when the tumor comes into direct contact with these structures.

This case provides an example of response-adapted RT using imaging during treatment to shrink the high-dose target as the tumor shrinks away from critical surrounding structures.7 This strategy permits delivery of the maximum dose to the tumor while minimizing radiation dose, and therefore risk of toxicity, to normal surrounding structures. While it is typical to deliver 70 Gy to the full extent of tumor involvement for H&N tumors, this was not possible in this case as the tumor was in contact with the brainstem and upper cervical SC. Delivering the full 70 Gy to these areas of tumor would have placed this patient at substantial risk of brainstem and/or SC toxicity. This report demonstrates that response-adapted RT with shrinking fields can allow for tumor control while avoiding toxicity to critical neural structures for cases of locally advanced NPC in which tumor is abutting these structures.

Bony regeneration of the skull base following RT has been reported in the literature, but in limited reviews. Early reports used plain radiography to follow changes. Unger and colleagues demonstrated the regeneration of bone using skull radiographs 4 to 6 months after completion of RT for NPC.8 More recent literature details the ability of bone to regenerate after RT based on CT findings. Fang and colleagues reported on 90 cases of NPC with skull base destruction, with 63% having bony regeneration on posttreatment CT.9 Most of the patients in Fang’s report had bony regeneration within 1 year of treatment, and in general, bony regeneration became more evident on imaging with longer follow-up. Of note, local control was significantly greater in patients with regeneration vs persistent destruction (77% vs 21%, P < .001). On multivariate analysis, complete tumor response was significantly associated with bony regeneration; other factors such as age, sex, radiation dose, and chemotherapy were not significantly associated with the likelihood of bony regeneration.

Our report details a nasopharyngeal tumor that destroyed the skull base with no intact bony barrier. In such cases, concern arises regarding craniospinal instability with tumor regression if there is not simultaneous bone regeneration. Tumor invasion of the skull base and C1-2 vertebral bodies and complications from treatment of such tumor extent can lead to symptoms of craniospinal instability, including pain, difficulty with neck range of motion, and loss of strength and sensation in the upper and lower extremities.10 A case report of a woman treated with chemoradiation for a plasmacytoma of the skull base detailed her posttreatment presentation with quadriparesis resulting from craniospinal instability after tumor regression.11 Such instability is generally treated surgically, and during this woman’s surgery, there was an injury to the right vertebral artery, although this did not cause any additional neurologic deficits.

RT leads to hypocellularity, hypovascularity, and hypoxia of treated tissues, resulting in a reduced ability for growth and healing. Studies demonstrate that irradiated bone contains fewer osteoblast cells and osteocytes than unirradiated bone, resulting in reduced regenerative capacity.12,13 Furthermore, the reconstruction of bony defects resulting after cancer treatment has been shown to be difficult and associated with a high risk of complications.14 Given the impaired ability of irradiated bone to regenerate, studies have evaluated the use of growth factors and gene therapy to promote bone formation after treatment.15 Bone marrow stem cells have been shown to reverse radiation-induced cellular depletion and to increase osteocyte counts in animal studies.12 Further, overexpression of miR-34a, a tumor suppressor involved in tissue development, has been shown to improve osteoblastic differentiation of irradiated bone marrow stem cells and promote bone regeneration in vitro and in animal studies.13 While several techniques are being studied in vitro and in animal studies to promote bony regeneration after RT, there is a lack of data on use of these techniques in humans with cancer.

With our case, there was great uncertainty related to the ability of bone to regenerate during treatment and concern regarding consequences of formation of a skull base defect during treatment. CT imaging revealed bony regeneration of the central skull base and clivus, as well as occipital condyles, that occurred throughout the RT course. There was clear evidence of bone regeneration on the replanning CT obtained 5 weeks after treatment initiation. To our knowledge, this is the first report to demonstrate rapid bony regeneration during RT, thereby maintaining the integrity of the skull base and precluding the need for neurosurgical intervention. Moving forward, imaging should be considered during treatment for patients with tumor-related destruction of the skull base and upper cervical spine to evaluate the extent of bony regeneration during treatment and estimate the potential risk of craniocervical instability. Further studies with imaging during treatment are needed for more information on the likelihood of bony regeneration and factors that correlate with bony regeneration during treatment. As in other reports, our case demonstrates that bony regeneration may predict complete response to RT.9

Our patient’s tumor was HPV-positive and EBV-negative. In the US, the rate of HPV-positive NPC is 35%.16 However, HPV-positive NPC is much less common in endemic areas. A recent study from China of 1,328 patients with NPC revealed a 6.4% rate of HPV-positive/EBV-negative cases.17 In that study, patients with HPV-positive/EBV-negative tumors had improved survival compared to patients whose tumors were HPV-negative/EBV-positive. Another study suggests that the impact of HPV in NPC varies according to race, with HPV-positivity predicting for improved outcomes in East Asian patients and worse outcomes in White patients.17 A study from the University of Michigan suggests that both HPV-positive/EBV-negative and HPV-negative/EBV-negative NPC are associated with worse overall survival and locoregional control than EBV-positive NPC.2 Overall, the prognostic role of HPV in NPC remains unclear given conflicting information in the literature and the lack of large population studies.18

Conclusions

There is a paucity of literature on bony regeneration in patients with skull base destruction from advanced NPC, and in particular, the ability of skull base regeneration to occur during treatment simultaneous with tumor regression. Our patient had HPV-positive/EBV-negative NPC, but it is unclear how this subtype affected his prognosis. Factors such as tumor histology, radiosensitivity with rapid tumor regression, and young age may have all contributed to the rapidity of bone regeneration in our patient. This case report demonstrates that an impressive tumor response to chemoradiation with simultaneous bony regeneration is possible among patients presenting with tumor destruction of the skull base, precluding the need for neurosurgical intervention.

1. Chang ET, Adami HO. The enigmatic epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(10):1765-1777. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0353

2. Stenmark MH, McHugh JB, Schipper M, et al. Nonendemic HPV-positive nasopharyngeal carcinoma: association with poor prognosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(3):580-588. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.11.246

3. Maxwell JH, Kumar B, Feng FY, et al. HPV-positive/p16-positive/EBV-negative nasopharyngeal carcinoma in white North Americans. Head Neck. 2010;32(5):562-567. doi:10.1002/hed.21216

4. Chen YP, Chan ATC, Le QT, Blanchard P, Sun Y, Ma J. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet. 2019;394(10192):64-80. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30956-0

5. Roh JL, Sung MW, Kim KH, et al.. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma with skull base invasion: a necessity of staging subdivision. Am J Otolaryngol. 2004;25(1):26-32. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2003.09.011

6. Orr RD, Salo PT. Atlantoaxial instability complicating radiation therapy for recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. A case report. Spine. 1998;23(11):1280-1282. doi:10.1097/00007632-199806010-00021

7. Morgan HE, Sher DJ. Adaptive radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Cancers Head Neck. 2020;5:1. doi:10.1186/s41199-019-0046-z

8. Unger JD, Chiang LC, Unger GF. Apparent reformation of the base of the skull following radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiology. 1978;126(3):779-782. doi:10.1148/126.3.779

9. Fang FM, Leung SW, Wang CJ, et al. Computed tomography findings of bony regeneration after radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma with skull base destruction: implications for local control. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44(2):305-309. doi:10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00004-8

10. Tiruchelvarayan R, Lee KA, Ng I. Surgery for atlanto-axial (C1-2) involvement or instability in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Singapore Med J. 2012;53(6):416-421.

11. Samprón N, Arrazola M, Urculo E. Skull-base plasmacytoma with craniocervical instability [in Spanish]. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2009;20(5):478-483.

12. Zheutlin AR, Deshpande SS, Nelson NS, et al. Bone marrow stem cells assuage radiation-induced damage in a murine model of distraction osteogenesis: a histomorphometric evaluation. Cytotherapy. 2016;18(5):664-672. doi:10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.01.013

13. Liu H, Dong Y, Feng X, et al. miR-34a promotes bone regeneration in irradiated bone defects by enhancing osteoblast differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells in rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):180. doi:10.1186/s13287-019-1285-y

14. Holzapfel BM, Wagner F, Martine LC, et al. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine in musculoskeletal oncology. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016;35(3):475-487. doi:10.1007/s10555-016-9635-z

15. Hu WW, Ward BB, Wang Z, Krebsbach PH. Bone regeneration in defects compromised by radiotherapy. J Dent Res. 2010;89(1):77-81. doi:10.1177/0022034509352151

16. Wotman M, Oh EJ, Ahn S, Kraus D, Constantino P, Tham T. HPV status in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the United States: a SEER database study. Am J Otolaryngol. 2019;40(5):705-710. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2019.06.00717. Huang WB, Chan JYW, Liu DL. Human papillomavirus and World Health Organization type III nasopharyngeal carcinoma: multicenter study from an endemic area in Southern China. Cancer. 2018;124(3):530-536. doi:10.1002/cncr.31031.

18. Verma V, Simone CB 2nd, Lin C. Human papillomavirus and nasopharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2018;40(4):696-706. doi:10.1002/hed.24978

19. Lee AWM, Lydiatt WM, Colevas AD, et al. Nasopharynx. In: Amin MB, ed. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017:103.

20. Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, eds. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumors. In: World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. IARC Press; 2005.

1. Chang ET, Adami HO. The enigmatic epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(10):1765-1777. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0353

2. Stenmark MH, McHugh JB, Schipper M, et al. Nonendemic HPV-positive nasopharyngeal carcinoma: association with poor prognosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(3):580-588. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.11.246

3. Maxwell JH, Kumar B, Feng FY, et al. HPV-positive/p16-positive/EBV-negative nasopharyngeal carcinoma in white North Americans. Head Neck. 2010;32(5):562-567. doi:10.1002/hed.21216

4. Chen YP, Chan ATC, Le QT, Blanchard P, Sun Y, Ma J. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet. 2019;394(10192):64-80. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30956-0

5. Roh JL, Sung MW, Kim KH, et al.. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma with skull base invasion: a necessity of staging subdivision. Am J Otolaryngol. 2004;25(1):26-32. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2003.09.011

6. Orr RD, Salo PT. Atlantoaxial instability complicating radiation therapy for recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. A case report. Spine. 1998;23(11):1280-1282. doi:10.1097/00007632-199806010-00021

7. Morgan HE, Sher DJ. Adaptive radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Cancers Head Neck. 2020;5:1. doi:10.1186/s41199-019-0046-z

8. Unger JD, Chiang LC, Unger GF. Apparent reformation of the base of the skull following radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiology. 1978;126(3):779-782. doi:10.1148/126.3.779

9. Fang FM, Leung SW, Wang CJ, et al. Computed tomography findings of bony regeneration after radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma with skull base destruction: implications for local control. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44(2):305-309. doi:10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00004-8

10. Tiruchelvarayan R, Lee KA, Ng I. Surgery for atlanto-axial (C1-2) involvement or instability in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Singapore Med J. 2012;53(6):416-421.

11. Samprón N, Arrazola M, Urculo E. Skull-base plasmacytoma with craniocervical instability [in Spanish]. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2009;20(5):478-483.

12. Zheutlin AR, Deshpande SS, Nelson NS, et al. Bone marrow stem cells assuage radiation-induced damage in a murine model of distraction osteogenesis: a histomorphometric evaluation. Cytotherapy. 2016;18(5):664-672. doi:10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.01.013

13. Liu H, Dong Y, Feng X, et al. miR-34a promotes bone regeneration in irradiated bone defects by enhancing osteoblast differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells in rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):180. doi:10.1186/s13287-019-1285-y

14. Holzapfel BM, Wagner F, Martine LC, et al. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine in musculoskeletal oncology. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016;35(3):475-487. doi:10.1007/s10555-016-9635-z

15. Hu WW, Ward BB, Wang Z, Krebsbach PH. Bone regeneration in defects compromised by radiotherapy. J Dent Res. 2010;89(1):77-81. doi:10.1177/0022034509352151

16. Wotman M, Oh EJ, Ahn S, Kraus D, Constantino P, Tham T. HPV status in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the United States: a SEER database study. Am J Otolaryngol. 2019;40(5):705-710. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2019.06.00717. Huang WB, Chan JYW, Liu DL. Human papillomavirus and World Health Organization type III nasopharyngeal carcinoma: multicenter study from an endemic area in Southern China. Cancer. 2018;124(3):530-536. doi:10.1002/cncr.31031.

18. Verma V, Simone CB 2nd, Lin C. Human papillomavirus and nasopharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2018;40(4):696-706. doi:10.1002/hed.24978

19. Lee AWM, Lydiatt WM, Colevas AD, et al. Nasopharynx. In: Amin MB, ed. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017:103.

20. Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, eds. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumors. In: World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. IARC Press; 2005.

Early-onset colon cancer projected to double by 2030

from 7.9 to 12.9 cases in 2015 per 100,000 people. The reason for the increase isn’t well understood.

The findings were highlighted in a recent review article published online in the New England Journal of Medicine. “It’s a national phenomenon and it’s also occurring in other parts of the developed world. We’re used to seeing mostly older people who have this diagnosis. Now we’re seeing a lot of younger people with this disease. It’s rather alarming,” said author Frank Sinicrope, MD, a medical oncologist with Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

The trend contrasts with a decline in later-onset CRC likely attributable to increases in screening. As a result of the two trends, but especially the increased number of early-onset cases, the median age of diagnosis dropped from 72 in the early 2000s to 66 today.

“Although patients with early-onset colorectal cancer are more likely to have a hereditary syndrome than those who have later-onset disease, most cases are sporadic, with no identifiable cause. Furthermore, somatic mutational profiling of early-onset colorectal cancers has not revealed previously unidentified or actionable alterations to inform our understanding of the pathogenesis of these cancers or to guide treatment,” he wrote in the review.

“Early-onset colorectal cancers are most commonly detected in the rectum, followed by the distal colon; more than 70% of early-onset colorectal cancers are in the left colon at presentation,” he wrote in the review. Younger patients tend to be unfamiliar with CRC symptoms, which are often mistaken for benign conditions.

“We’ve moved the screening age down to 45, but that still is not going to capture a lot of these patients,” Dr. Sinicrope said. He estimates that 25% of rectal cancers and 10%-12% of colon cancers diagnosed in the next 10 years will be early onset.

Although the direct cause of the increased incidence isn’t clear, Dr. Sinicrope suggested it may reflect changing dietary habits and rising obesity among adolescents. “The sugar-containing beverages, the processed sugar and a lot of red meat in the diet and refined grains … reflect changes in the diet over the last 50 years. We may now be seeing the end result of many of these dietary changes that have occurred,” he said, calling for a greater emphasis on plant-based diets, which promote a healthier gut microbiome that may reduce CRC risk. Western-style diets can change the gut microbiome leading to inflammation which increases the risk of CRC.

Most patients with early CRC present with advanced disease in the left colon. And, pathogenic germline variants are present in one in six patients – half of which are associated with Lynch syndrome which increases the risk for CRC.

Dr. Sinicrope highlighted the need for more risk-based intervention, which in turn requires a better knowledge of family history.

“We need to do better job to risk stratify, and that will help us figure out who’s best to target our screening efforts toward,” Dr. Sinicrope said. He pointed out guidelines from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer and the American Cancer Society that can help physicians identify patients who might benefit from earlier screening. The American Cancer Society recommends that CRC screening be conducted at 45 years for average-risk individuals.

“The best screening test is the one that the patient will do,” Dr. Sinicrope said.

from 7.9 to 12.9 cases in 2015 per 100,000 people. The reason for the increase isn’t well understood.

The findings were highlighted in a recent review article published online in the New England Journal of Medicine. “It’s a national phenomenon and it’s also occurring in other parts of the developed world. We’re used to seeing mostly older people who have this diagnosis. Now we’re seeing a lot of younger people with this disease. It’s rather alarming,” said author Frank Sinicrope, MD, a medical oncologist with Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

The trend contrasts with a decline in later-onset CRC likely attributable to increases in screening. As a result of the two trends, but especially the increased number of early-onset cases, the median age of diagnosis dropped from 72 in the early 2000s to 66 today.

“Although patients with early-onset colorectal cancer are more likely to have a hereditary syndrome than those who have later-onset disease, most cases are sporadic, with no identifiable cause. Furthermore, somatic mutational profiling of early-onset colorectal cancers has not revealed previously unidentified or actionable alterations to inform our understanding of the pathogenesis of these cancers or to guide treatment,” he wrote in the review.

“Early-onset colorectal cancers are most commonly detected in the rectum, followed by the distal colon; more than 70% of early-onset colorectal cancers are in the left colon at presentation,” he wrote in the review. Younger patients tend to be unfamiliar with CRC symptoms, which are often mistaken for benign conditions.

“We’ve moved the screening age down to 45, but that still is not going to capture a lot of these patients,” Dr. Sinicrope said. He estimates that 25% of rectal cancers and 10%-12% of colon cancers diagnosed in the next 10 years will be early onset.

Although the direct cause of the increased incidence isn’t clear, Dr. Sinicrope suggested it may reflect changing dietary habits and rising obesity among adolescents. “The sugar-containing beverages, the processed sugar and a lot of red meat in the diet and refined grains … reflect changes in the diet over the last 50 years. We may now be seeing the end result of many of these dietary changes that have occurred,” he said, calling for a greater emphasis on plant-based diets, which promote a healthier gut microbiome that may reduce CRC risk. Western-style diets can change the gut microbiome leading to inflammation which increases the risk of CRC.

Most patients with early CRC present with advanced disease in the left colon. And, pathogenic germline variants are present in one in six patients – half of which are associated with Lynch syndrome which increases the risk for CRC.

Dr. Sinicrope highlighted the need for more risk-based intervention, which in turn requires a better knowledge of family history.

“We need to do better job to risk stratify, and that will help us figure out who’s best to target our screening efforts toward,” Dr. Sinicrope said. He pointed out guidelines from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer and the American Cancer Society that can help physicians identify patients who might benefit from earlier screening. The American Cancer Society recommends that CRC screening be conducted at 45 years for average-risk individuals.

“The best screening test is the one that the patient will do,” Dr. Sinicrope said.

from 7.9 to 12.9 cases in 2015 per 100,000 people. The reason for the increase isn’t well understood.

The findings were highlighted in a recent review article published online in the New England Journal of Medicine. “It’s a national phenomenon and it’s also occurring in other parts of the developed world. We’re used to seeing mostly older people who have this diagnosis. Now we’re seeing a lot of younger people with this disease. It’s rather alarming,” said author Frank Sinicrope, MD, a medical oncologist with Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

The trend contrasts with a decline in later-onset CRC likely attributable to increases in screening. As a result of the two trends, but especially the increased number of early-onset cases, the median age of diagnosis dropped from 72 in the early 2000s to 66 today.

“Although patients with early-onset colorectal cancer are more likely to have a hereditary syndrome than those who have later-onset disease, most cases are sporadic, with no identifiable cause. Furthermore, somatic mutational profiling of early-onset colorectal cancers has not revealed previously unidentified or actionable alterations to inform our understanding of the pathogenesis of these cancers or to guide treatment,” he wrote in the review.

“Early-onset colorectal cancers are most commonly detected in the rectum, followed by the distal colon; more than 70% of early-onset colorectal cancers are in the left colon at presentation,” he wrote in the review. Younger patients tend to be unfamiliar with CRC symptoms, which are often mistaken for benign conditions.

“We’ve moved the screening age down to 45, but that still is not going to capture a lot of these patients,” Dr. Sinicrope said. He estimates that 25% of rectal cancers and 10%-12% of colon cancers diagnosed in the next 10 years will be early onset.

Although the direct cause of the increased incidence isn’t clear, Dr. Sinicrope suggested it may reflect changing dietary habits and rising obesity among adolescents. “The sugar-containing beverages, the processed sugar and a lot of red meat in the diet and refined grains … reflect changes in the diet over the last 50 years. We may now be seeing the end result of many of these dietary changes that have occurred,” he said, calling for a greater emphasis on plant-based diets, which promote a healthier gut microbiome that may reduce CRC risk. Western-style diets can change the gut microbiome leading to inflammation which increases the risk of CRC.

Most patients with early CRC present with advanced disease in the left colon. And, pathogenic germline variants are present in one in six patients – half of which are associated with Lynch syndrome which increases the risk for CRC.

Dr. Sinicrope highlighted the need for more risk-based intervention, which in turn requires a better knowledge of family history.

“We need to do better job to risk stratify, and that will help us figure out who’s best to target our screening efforts toward,” Dr. Sinicrope said. He pointed out guidelines from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer and the American Cancer Society that can help physicians identify patients who might benefit from earlier screening. The American Cancer Society recommends that CRC screening be conducted at 45 years for average-risk individuals.

“The best screening test is the one that the patient will do,” Dr. Sinicrope said.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Head and neck cancer patients recommend 11 needed improvements in health care

HNC has a high burden of treatment-related adverse events, along with frequent trouble with speech, swallowing, facial disfigurement, and psychological distress.

Among cancer patients, “they have the highest rates of emergency department use and hospitalization during treatment. They also have the highest rates of psychological distress. We have some Ontario data that shows they’ve got the highest rates of suicide and self-harm. So I think this is a really special population that we need to support,” Christopher Noel, MD, PhD, said in an interview. Dr. Noel was the lead author of the study, which was published in JAMA Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery.

These issues can strongly affect quality of life, and even patient outcomes. “Even a 1-day interruption in treatment has been shown to impact oncologic outcomes. This is a very big issue whether you’re a surgeon, a medical oncologist, or a radiation oncologist,” said Dr. Noel, who is a resident physician at the University of Toronto.

He advocates that physicians interview patients and review the results in a structured way and then act on it. “If we just rely on patient [provided] communication, we’re going to miss about 50% of patient symptoms,” he said.

The researchers aimed for the patient’s perspective on treatment. “What is the patient’s perception of going through head neck cancer and their treatment, and managing their symptoms at home? And where do they think that we could do better?” Dr. Noel asked.

The most pressing issue was that patients felt their emotional and informational needs often were not met. That challenge is even harder for patients who have trouble communicating, which in turn makes them more prone to isolation and loneliness. Many felt that they had to get the information on their own. “They wanted it to be a more effortless process,” said Dr. Noel.

He described one patient with oropharynx cancer who was able to talk to people about her grief over her diagnosis, but treatment led to her throat becoming swollen and she lost the ability to communicate. “She felt very isolated and lonely. She really highlighted the emotional and psychosocial barriers in cancer care. Her treatment inherently leaves her feeling very isolated and lonely, and she had such a hard time connecting with a psychotherapist,” Dr. Noel said.

Another common issue revolved around efforts to communicate about symptoms and adverse effects of treatment. Resources often aren’t available on evenings or weekends, and it can take time for a nurse to call them back. Patients wanted to see more modern approaches, such as use of email or apps.

The patients in the study recommended 11 health care improvements.

- 1. Nurse navigator teams should have hours extended to evenings and weekends.

- 2. Patient communication methods should be expanded, using methods like email or apps.

- 3. HNC resources should be more broadly disseminated.

- 4. Education and information approaches should be individualized to the patient.

- 5. All HNC patients should be offered psychological resources.

- 6. Mental health needs should be assessed repeatedly throughout treatment and extended care.

- 7. Physicians should recognize the added symptom burden often faced by patients who travel extensively for treatment.

- 8. Partners and caregivers should be included as part of the treatment team.

- 9. Share symptom data with patients, which can improve engagement.

- 10. Review symptom scores and act on them regularly.

- 11. A member of the care team should be identified to oversee symptom management.

Dr. Noel had no relevant financial disclosures.

HNC has a high burden of treatment-related adverse events, along with frequent trouble with speech, swallowing, facial disfigurement, and psychological distress.

Among cancer patients, “they have the highest rates of emergency department use and hospitalization during treatment. They also have the highest rates of psychological distress. We have some Ontario data that shows they’ve got the highest rates of suicide and self-harm. So I think this is a really special population that we need to support,” Christopher Noel, MD, PhD, said in an interview. Dr. Noel was the lead author of the study, which was published in JAMA Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery.

These issues can strongly affect quality of life, and even patient outcomes. “Even a 1-day interruption in treatment has been shown to impact oncologic outcomes. This is a very big issue whether you’re a surgeon, a medical oncologist, or a radiation oncologist,” said Dr. Noel, who is a resident physician at the University of Toronto.

He advocates that physicians interview patients and review the results in a structured way and then act on it. “If we just rely on patient [provided] communication, we’re going to miss about 50% of patient symptoms,” he said.

The researchers aimed for the patient’s perspective on treatment. “What is the patient’s perception of going through head neck cancer and their treatment, and managing their symptoms at home? And where do they think that we could do better?” Dr. Noel asked.

The most pressing issue was that patients felt their emotional and informational needs often were not met. That challenge is even harder for patients who have trouble communicating, which in turn makes them more prone to isolation and loneliness. Many felt that they had to get the information on their own. “They wanted it to be a more effortless process,” said Dr. Noel.

He described one patient with oropharynx cancer who was able to talk to people about her grief over her diagnosis, but treatment led to her throat becoming swollen and she lost the ability to communicate. “She felt very isolated and lonely. She really highlighted the emotional and psychosocial barriers in cancer care. Her treatment inherently leaves her feeling very isolated and lonely, and she had such a hard time connecting with a psychotherapist,” Dr. Noel said.

Another common issue revolved around efforts to communicate about symptoms and adverse effects of treatment. Resources often aren’t available on evenings or weekends, and it can take time for a nurse to call them back. Patients wanted to see more modern approaches, such as use of email or apps.

The patients in the study recommended 11 health care improvements.

- 1. Nurse navigator teams should have hours extended to evenings and weekends.

- 2. Patient communication methods should be expanded, using methods like email or apps.

- 3. HNC resources should be more broadly disseminated.

- 4. Education and information approaches should be individualized to the patient.

- 5. All HNC patients should be offered psychological resources.

- 6. Mental health needs should be assessed repeatedly throughout treatment and extended care.

- 7. Physicians should recognize the added symptom burden often faced by patients who travel extensively for treatment.

- 8. Partners and caregivers should be included as part of the treatment team.

- 9. Share symptom data with patients, which can improve engagement.

- 10. Review symptom scores and act on them regularly.

- 11. A member of the care team should be identified to oversee symptom management.

Dr. Noel had no relevant financial disclosures.

HNC has a high burden of treatment-related adverse events, along with frequent trouble with speech, swallowing, facial disfigurement, and psychological distress.

Among cancer patients, “they have the highest rates of emergency department use and hospitalization during treatment. They also have the highest rates of psychological distress. We have some Ontario data that shows they’ve got the highest rates of suicide and self-harm. So I think this is a really special population that we need to support,” Christopher Noel, MD, PhD, said in an interview. Dr. Noel was the lead author of the study, which was published in JAMA Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery.

These issues can strongly affect quality of life, and even patient outcomes. “Even a 1-day interruption in treatment has been shown to impact oncologic outcomes. This is a very big issue whether you’re a surgeon, a medical oncologist, or a radiation oncologist,” said Dr. Noel, who is a resident physician at the University of Toronto.

He advocates that physicians interview patients and review the results in a structured way and then act on it. “If we just rely on patient [provided] communication, we’re going to miss about 50% of patient symptoms,” he said.

The researchers aimed for the patient’s perspective on treatment. “What is the patient’s perception of going through head neck cancer and their treatment, and managing their symptoms at home? And where do they think that we could do better?” Dr. Noel asked.

The most pressing issue was that patients felt their emotional and informational needs often were not met. That challenge is even harder for patients who have trouble communicating, which in turn makes them more prone to isolation and loneliness. Many felt that they had to get the information on their own. “They wanted it to be a more effortless process,” said Dr. Noel.

He described one patient with oropharynx cancer who was able to talk to people about her grief over her diagnosis, but treatment led to her throat becoming swollen and she lost the ability to communicate. “She felt very isolated and lonely. She really highlighted the emotional and psychosocial barriers in cancer care. Her treatment inherently leaves her feeling very isolated and lonely, and she had such a hard time connecting with a psychotherapist,” Dr. Noel said.

Another common issue revolved around efforts to communicate about symptoms and adverse effects of treatment. Resources often aren’t available on evenings or weekends, and it can take time for a nurse to call them back. Patients wanted to see more modern approaches, such as use of email or apps.

The patients in the study recommended 11 health care improvements.

- 1. Nurse navigator teams should have hours extended to evenings and weekends.

- 2. Patient communication methods should be expanded, using methods like email or apps.

- 3. HNC resources should be more broadly disseminated.

- 4. Education and information approaches should be individualized to the patient.

- 5. All HNC patients should be offered psychological resources.

- 6. Mental health needs should be assessed repeatedly throughout treatment and extended care.

- 7. Physicians should recognize the added symptom burden often faced by patients who travel extensively for treatment.

- 8. Partners and caregivers should be included as part of the treatment team.

- 9. Share symptom data with patients, which can improve engagement.

- 10. Review symptom scores and act on them regularly.

- 11. A member of the care team should be identified to oversee symptom management.

Dr. Noel had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA OTOLARYNGOLOGY – HEAD & NECK SURGERY

Dodging potholes from cancer care to hospice transitions

I’m often in the position of caring for patients after they’ve stopped active cancer treatments, but before they’ve made the decision to enroll in hospice. They remain under my care until they feel emotionally ready, or until their care needs have escalated to the point in which hospice is unavoidable.