User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Inflammatory diet is linked to dementia

according to a new analysis of longitudinal data from the Framingham Heart Study Offspring Cohort.

The lack of an association with Alzheimer’s disease was a surprise because amyloid-beta prompts microglia and astrocytes to release markers of systemic inflammation, according to Debora Melo van Lent, PhD, who is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Texas Health San Antonio – Glenn Biggs Institute for Alzheimer’s and Neurodegenerative Diseases. “We expected to see a relationship between higher DII scores and an increased risk for incident Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Melo van Lent, who presented the findings at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Dr. Melo van Lent added that the most likely explanation is that the study was underpowered to produce a positive association, and the team is conducting further study in a larger population.

A modifiable risk factor

The study is the first to look at all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s disease dementia and their association with DII, Dr. Melo van Lent said.

“As diet is a modifiable risk factor, we can actually do something about it. If we take a closer look at five components of the DII which are most anti-inflammatory, these components are present in green leafy vegetables, vegetables, fruit, soy, whole grains, and green and black tea. Most of these components are included in the Mediterranean diet. When we look at the three most proinflammatory components, they are present in high caloric products; such as butter or margarine, pastries and sweets, fried snacks, and red or processed meat. These components are present in ‘Western diets,’ which are discouraged,” said Dr. Melo van Lent.

The researchers analyzed data from 1,486 participants who were free of dementia, stroke, or other neurologic diseases at baseline. They analyzed DII scores both in a continuous range and divided into quartiles, using the first quartile as a reference.

The mean age of participants was 69 years, and 53% were women. During follow-up, 11.3% developed AD dementia, and 14.8% developed non-AD dementia.

In the continuous model, DII was associated with increased risk of all-cause dementia after adjusting for age, sex, APOE E4 status, body mass index, smoking, physical activity index score, total energy intake, lipid-lowering medications, and total cholesterol to HDL cholesterol ratio (hazard ratio, 1.18; P =.001). In the quartile analysis, after adjustments, compared with quartile 1, there was an increased risk of all-cause dementia for those in quartile 3 (HR, 1.69; P =.020) and quartile 4 (HR, 1.84; P =.013).

In the continuous analysis, after adjustments, there was an association between DII score and Alzheimer’s dementia (HR, 1.15; P =.020). In the quartile analysis, no associations were significant, though there was a trend of quartile 4 versus quartile 1 (HR, 1.65; P =.077).

The researchers found no significant interactions between higher DII scores and sex, the APOE E4 allele, or physical activity with respect to all-cause dementia or Alzheimer’s dementia.

Intertwined variables

The results were interesting, but cause and effect relationships can be difficult to tease out from such a study, according to Claire Sexton, DPhil, director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, who was asked to comment on the study. Dr. Sexton noted that individuals who eat well are more likely to have energy to exercise, which could in turn help them to sleep better, and all of those factors could be involved in reducing dementia risk. “They’re all kind of intertwined. So in this study, they were taking into account physical activity, but they can’t take into account every single variable. It’s important for them to be followed up by randomized control trials.”

Dr. Sexton also referenced the U.S. Pointer study being conducted by the Alzheimer’s Association, which is examining various interventions related to diet, physical activity, and cognitive stimulation. “Whether intervening and improving people’s health behaviors then goes on to reduce their risk for dementia is a key question. We still need more results from studies to be reporting out before we get definitive answers,” she said.

The study was funded by the ASPEN Rhoads Research Foundation. Dr. Melo van Lent and Dr. Sexton have no relevant financial disclosures.

according to a new analysis of longitudinal data from the Framingham Heart Study Offspring Cohort.

The lack of an association with Alzheimer’s disease was a surprise because amyloid-beta prompts microglia and astrocytes to release markers of systemic inflammation, according to Debora Melo van Lent, PhD, who is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Texas Health San Antonio – Glenn Biggs Institute for Alzheimer’s and Neurodegenerative Diseases. “We expected to see a relationship between higher DII scores and an increased risk for incident Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Melo van Lent, who presented the findings at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Dr. Melo van Lent added that the most likely explanation is that the study was underpowered to produce a positive association, and the team is conducting further study in a larger population.

A modifiable risk factor

The study is the first to look at all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s disease dementia and their association with DII, Dr. Melo van Lent said.

“As diet is a modifiable risk factor, we can actually do something about it. If we take a closer look at five components of the DII which are most anti-inflammatory, these components are present in green leafy vegetables, vegetables, fruit, soy, whole grains, and green and black tea. Most of these components are included in the Mediterranean diet. When we look at the three most proinflammatory components, they are present in high caloric products; such as butter or margarine, pastries and sweets, fried snacks, and red or processed meat. These components are present in ‘Western diets,’ which are discouraged,” said Dr. Melo van Lent.

The researchers analyzed data from 1,486 participants who were free of dementia, stroke, or other neurologic diseases at baseline. They analyzed DII scores both in a continuous range and divided into quartiles, using the first quartile as a reference.

The mean age of participants was 69 years, and 53% were women. During follow-up, 11.3% developed AD dementia, and 14.8% developed non-AD dementia.

In the continuous model, DII was associated with increased risk of all-cause dementia after adjusting for age, sex, APOE E4 status, body mass index, smoking, physical activity index score, total energy intake, lipid-lowering medications, and total cholesterol to HDL cholesterol ratio (hazard ratio, 1.18; P =.001). In the quartile analysis, after adjustments, compared with quartile 1, there was an increased risk of all-cause dementia for those in quartile 3 (HR, 1.69; P =.020) and quartile 4 (HR, 1.84; P =.013).

In the continuous analysis, after adjustments, there was an association between DII score and Alzheimer’s dementia (HR, 1.15; P =.020). In the quartile analysis, no associations were significant, though there was a trend of quartile 4 versus quartile 1 (HR, 1.65; P =.077).

The researchers found no significant interactions between higher DII scores and sex, the APOE E4 allele, or physical activity with respect to all-cause dementia or Alzheimer’s dementia.

Intertwined variables

The results were interesting, but cause and effect relationships can be difficult to tease out from such a study, according to Claire Sexton, DPhil, director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, who was asked to comment on the study. Dr. Sexton noted that individuals who eat well are more likely to have energy to exercise, which could in turn help them to sleep better, and all of those factors could be involved in reducing dementia risk. “They’re all kind of intertwined. So in this study, they were taking into account physical activity, but they can’t take into account every single variable. It’s important for them to be followed up by randomized control trials.”

Dr. Sexton also referenced the U.S. Pointer study being conducted by the Alzheimer’s Association, which is examining various interventions related to diet, physical activity, and cognitive stimulation. “Whether intervening and improving people’s health behaviors then goes on to reduce their risk for dementia is a key question. We still need more results from studies to be reporting out before we get definitive answers,” she said.

The study was funded by the ASPEN Rhoads Research Foundation. Dr. Melo van Lent and Dr. Sexton have no relevant financial disclosures.

according to a new analysis of longitudinal data from the Framingham Heart Study Offspring Cohort.

The lack of an association with Alzheimer’s disease was a surprise because amyloid-beta prompts microglia and astrocytes to release markers of systemic inflammation, according to Debora Melo van Lent, PhD, who is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Texas Health San Antonio – Glenn Biggs Institute for Alzheimer’s and Neurodegenerative Diseases. “We expected to see a relationship between higher DII scores and an increased risk for incident Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Melo van Lent, who presented the findings at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Dr. Melo van Lent added that the most likely explanation is that the study was underpowered to produce a positive association, and the team is conducting further study in a larger population.

A modifiable risk factor

The study is the first to look at all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s disease dementia and their association with DII, Dr. Melo van Lent said.

“As diet is a modifiable risk factor, we can actually do something about it. If we take a closer look at five components of the DII which are most anti-inflammatory, these components are present in green leafy vegetables, vegetables, fruit, soy, whole grains, and green and black tea. Most of these components are included in the Mediterranean diet. When we look at the three most proinflammatory components, they are present in high caloric products; such as butter or margarine, pastries and sweets, fried snacks, and red or processed meat. These components are present in ‘Western diets,’ which are discouraged,” said Dr. Melo van Lent.

The researchers analyzed data from 1,486 participants who were free of dementia, stroke, or other neurologic diseases at baseline. They analyzed DII scores both in a continuous range and divided into quartiles, using the first quartile as a reference.

The mean age of participants was 69 years, and 53% were women. During follow-up, 11.3% developed AD dementia, and 14.8% developed non-AD dementia.

In the continuous model, DII was associated with increased risk of all-cause dementia after adjusting for age, sex, APOE E4 status, body mass index, smoking, physical activity index score, total energy intake, lipid-lowering medications, and total cholesterol to HDL cholesterol ratio (hazard ratio, 1.18; P =.001). In the quartile analysis, after adjustments, compared with quartile 1, there was an increased risk of all-cause dementia for those in quartile 3 (HR, 1.69; P =.020) and quartile 4 (HR, 1.84; P =.013).

In the continuous analysis, after adjustments, there was an association between DII score and Alzheimer’s dementia (HR, 1.15; P =.020). In the quartile analysis, no associations were significant, though there was a trend of quartile 4 versus quartile 1 (HR, 1.65; P =.077).

The researchers found no significant interactions between higher DII scores and sex, the APOE E4 allele, or physical activity with respect to all-cause dementia or Alzheimer’s dementia.

Intertwined variables

The results were interesting, but cause and effect relationships can be difficult to tease out from such a study, according to Claire Sexton, DPhil, director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, who was asked to comment on the study. Dr. Sexton noted that individuals who eat well are more likely to have energy to exercise, which could in turn help them to sleep better, and all of those factors could be involved in reducing dementia risk. “They’re all kind of intertwined. So in this study, they were taking into account physical activity, but they can’t take into account every single variable. It’s important for them to be followed up by randomized control trials.”

Dr. Sexton also referenced the U.S. Pointer study being conducted by the Alzheimer’s Association, which is examining various interventions related to diet, physical activity, and cognitive stimulation. “Whether intervening and improving people’s health behaviors then goes on to reduce their risk for dementia is a key question. We still need more results from studies to be reporting out before we get definitive answers,” she said.

The study was funded by the ASPEN Rhoads Research Foundation. Dr. Melo van Lent and Dr. Sexton have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM AAIC 2021

‘Shocking’ early complications from teen-onset type 2 diabetes

Newly published data show alarmingly high rates and severity of early diabetes-specific complications in individuals who develop type 2 diabetes at a young age. This suggests intervention should be early and aggressive among these youngsters, said the researchers.

The results for the 500 young adult participants in the Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth 2 (TODAY 2) study were published online July 29 in the New England Journal of Medicine by the TODAY study group.

At follow-up – after originally participating in the TODAY trial when they were young teenagers – they had a mean age of 26.4 years.

At this time, more than two thirds had hypertension and half had dyslipidemia.

Overall, 60% had at least one diabetic microvascular complication (retinal disease, neuropathy, or diabetic kidney disease), and more than a quarter had two or more such complications.

“These data illustrate the serious personal and public health consequences of youth-onset type 2 diabetes in the transition to adulthood,” the researchers noted.

Don’t tread lightly just because they are young

“The fact that these youth are accumulating complications at a rapid rate and are broadly affected early in adulthood certainly suggests that aggressive therapy is needed, both for glycemic control and treatment of risk factors like hypertension and dyslipidemia,” study coauthor Philip S. Zeitler, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

“In the absence of studies specifically addressing this, we need to take a more aggressive approach than people might be inclined to, given that the age at diagnosis is young, around 14 years,” he added.

“Contrary to the inclination to be ‘gentle’ in treating them because they are kids, these data suggest that we can’t let these initial years go by without strong intervention, and we need to be prepared for polypharmacy.”

Unfortunately, as Dr. Zeitler and coauthors explained, youth-onset type 2 diabetes is characterized by a suboptimal response to currently approved diabetes medications.

New pediatric indications in the United States for drugs used to treat type 2 diabetes in adults, including the recent Food and Drug Administration approval of extended-release exenatide for children as young as 10 years of age, “helps, but only marginally,” said Dr. Zeitler, of the Clinical & Translational Research Center, Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora.

“In some cases, it will help get them covered by carriers, which is always good. But this is still a very limited set of medications. It doesn’t include more recently approved more potent glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists, like semaglutide, and doesn’t include the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. Pediatricians are used to using medications off label and that is necessary here while we await further approvals,” he said.

And he noted that most individuals with youth-onset type 2 diabetes in the United States are covered by public insurance or are uninsured, depending on which state they live in. While the two major Medicaid programs in Colorado allow full access to adult formularies, that’s not the case everywhere. Moreover, patients often face further access barriers in states without expanded Medicaid.

Follow-up shows all metrics worsening over time

In TODAY 2, patients participated in an observational follow-up in their usual care settings in 2011-2020. At the start, they were receiving metformin with or without insulin for diabetes, but whether this continued and whether they were treated for other risk factors was down to individual circumstances.

Participants’ median A1c increased over time, and the percentage with A1c < 6% (< 48 mmol/mol) declined from 75% at the time of TODAY entry to just 19% at the 15-year end of follow-up.

The proportion with an A1c ≤ 10% (≤ 86 mmol/mol) rose from 0% at baseline to 34% at 15 years.

At that time, nearly 50% were taking both metformin and insulin, while more than a quarter were taking no medications.

The prevalence of hypertension increased from 19.2% at baseline to 67.5% at 15 years, while dyslipidemia rose from 20.8% to 51.6%.

Kidney disease prevalence increased from 8.0% at baseline to 54.8% at 15 years. Nerve disease rose from 1.0% to 32.4%. Retinal disease jumped from 13.7% with milder nonproliferative retinopathy in 2010-2011 to 51.0% with any eye disease in 2017-2018, including 8.8% with moderate to severe retinal changes and 3.5% with macular edema.

Overall, at the time of the last visit, 39.9% had no diabetes complications, 31.8% had one, 21.3% had two, and 7.1% had three complications.

Serious cardiovascular events in mid-20s

There were 17 adjudicated serious cardiovascular events, including four myocardial infarctions, six heart failure events, three diagnoses of coronary artery disease, and four strokes.

Six participants died, one each from myocardial infarction, kidney failure, and drug overdose, and three from sepsis.

Dr. Zeitler called the macrovascular events “shocking,” noting that although the numbers are small, for people in their mid-20s “they should be zero ... While we don’t yet know if the rates are the same or faster than in adults, even if they are the same, these kids are only in their late 20s, as opposed to adults experiencing these problems in their 50s, 60s, and 70s.

“The fact that these complications are occurring when these individuals should be in the prime of their life for both family and work has huge implications,” he stressed.

Findings have multiple causes

The reasons for the findings are both biologic and socioeconomic, Dr. Zeitler said.

“We know already that many kids with type 2 have rapid [deterioration of] beta-cell [function], which is probably very biologic. It stands to reason that an individual who can get diabetes as an adolescent probably has more fragile beta cells in some way,” he noted.

“But we also know that many other things contribute: stress, social determinants, access to quality care and medications, access to healthy foods and physical activity, availability of family supervision given the realities of families’ economic status and jobs, etc.”

It’s also known that youth with type 2 diabetes have much more severe insulin resistance than that of adults with the condition, and that “once the kids left ... the [TODAY] study, risk factor treatment in the community was less than ideal, and a lot of kids who met criteria for treatment of their blood pressure or lipids were not being treated. This is likely at least partly sociologic and partly the general pediatric hesitancy to use medications.”

He said the TODAY team will soon have some new data to show that “glycemia during the early years makes a difference, again supporting intensive intervention early on.”

The TODAY study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Zeitler had no further disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Newly published data show alarmingly high rates and severity of early diabetes-specific complications in individuals who develop type 2 diabetes at a young age. This suggests intervention should be early and aggressive among these youngsters, said the researchers.

The results for the 500 young adult participants in the Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth 2 (TODAY 2) study were published online July 29 in the New England Journal of Medicine by the TODAY study group.

At follow-up – after originally participating in the TODAY trial when they were young teenagers – they had a mean age of 26.4 years.

At this time, more than two thirds had hypertension and half had dyslipidemia.

Overall, 60% had at least one diabetic microvascular complication (retinal disease, neuropathy, or diabetic kidney disease), and more than a quarter had two or more such complications.

“These data illustrate the serious personal and public health consequences of youth-onset type 2 diabetes in the transition to adulthood,” the researchers noted.

Don’t tread lightly just because they are young

“The fact that these youth are accumulating complications at a rapid rate and are broadly affected early in adulthood certainly suggests that aggressive therapy is needed, both for glycemic control and treatment of risk factors like hypertension and dyslipidemia,” study coauthor Philip S. Zeitler, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

“In the absence of studies specifically addressing this, we need to take a more aggressive approach than people might be inclined to, given that the age at diagnosis is young, around 14 years,” he added.

“Contrary to the inclination to be ‘gentle’ in treating them because they are kids, these data suggest that we can’t let these initial years go by without strong intervention, and we need to be prepared for polypharmacy.”

Unfortunately, as Dr. Zeitler and coauthors explained, youth-onset type 2 diabetes is characterized by a suboptimal response to currently approved diabetes medications.

New pediatric indications in the United States for drugs used to treat type 2 diabetes in adults, including the recent Food and Drug Administration approval of extended-release exenatide for children as young as 10 years of age, “helps, but only marginally,” said Dr. Zeitler, of the Clinical & Translational Research Center, Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora.

“In some cases, it will help get them covered by carriers, which is always good. But this is still a very limited set of medications. It doesn’t include more recently approved more potent glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists, like semaglutide, and doesn’t include the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. Pediatricians are used to using medications off label and that is necessary here while we await further approvals,” he said.

And he noted that most individuals with youth-onset type 2 diabetes in the United States are covered by public insurance or are uninsured, depending on which state they live in. While the two major Medicaid programs in Colorado allow full access to adult formularies, that’s not the case everywhere. Moreover, patients often face further access barriers in states without expanded Medicaid.

Follow-up shows all metrics worsening over time

In TODAY 2, patients participated in an observational follow-up in their usual care settings in 2011-2020. At the start, they were receiving metformin with or without insulin for diabetes, but whether this continued and whether they were treated for other risk factors was down to individual circumstances.

Participants’ median A1c increased over time, and the percentage with A1c < 6% (< 48 mmol/mol) declined from 75% at the time of TODAY entry to just 19% at the 15-year end of follow-up.

The proportion with an A1c ≤ 10% (≤ 86 mmol/mol) rose from 0% at baseline to 34% at 15 years.

At that time, nearly 50% were taking both metformin and insulin, while more than a quarter were taking no medications.

The prevalence of hypertension increased from 19.2% at baseline to 67.5% at 15 years, while dyslipidemia rose from 20.8% to 51.6%.

Kidney disease prevalence increased from 8.0% at baseline to 54.8% at 15 years. Nerve disease rose from 1.0% to 32.4%. Retinal disease jumped from 13.7% with milder nonproliferative retinopathy in 2010-2011 to 51.0% with any eye disease in 2017-2018, including 8.8% with moderate to severe retinal changes and 3.5% with macular edema.

Overall, at the time of the last visit, 39.9% had no diabetes complications, 31.8% had one, 21.3% had two, and 7.1% had three complications.

Serious cardiovascular events in mid-20s

There were 17 adjudicated serious cardiovascular events, including four myocardial infarctions, six heart failure events, three diagnoses of coronary artery disease, and four strokes.

Six participants died, one each from myocardial infarction, kidney failure, and drug overdose, and three from sepsis.

Dr. Zeitler called the macrovascular events “shocking,” noting that although the numbers are small, for people in their mid-20s “they should be zero ... While we don’t yet know if the rates are the same or faster than in adults, even if they are the same, these kids are only in their late 20s, as opposed to adults experiencing these problems in their 50s, 60s, and 70s.

“The fact that these complications are occurring when these individuals should be in the prime of their life for both family and work has huge implications,” he stressed.

Findings have multiple causes

The reasons for the findings are both biologic and socioeconomic, Dr. Zeitler said.

“We know already that many kids with type 2 have rapid [deterioration of] beta-cell [function], which is probably very biologic. It stands to reason that an individual who can get diabetes as an adolescent probably has more fragile beta cells in some way,” he noted.

“But we also know that many other things contribute: stress, social determinants, access to quality care and medications, access to healthy foods and physical activity, availability of family supervision given the realities of families’ economic status and jobs, etc.”

It’s also known that youth with type 2 diabetes have much more severe insulin resistance than that of adults with the condition, and that “once the kids left ... the [TODAY] study, risk factor treatment in the community was less than ideal, and a lot of kids who met criteria for treatment of their blood pressure or lipids were not being treated. This is likely at least partly sociologic and partly the general pediatric hesitancy to use medications.”

He said the TODAY team will soon have some new data to show that “glycemia during the early years makes a difference, again supporting intensive intervention early on.”

The TODAY study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Zeitler had no further disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Newly published data show alarmingly high rates and severity of early diabetes-specific complications in individuals who develop type 2 diabetes at a young age. This suggests intervention should be early and aggressive among these youngsters, said the researchers.

The results for the 500 young adult participants in the Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth 2 (TODAY 2) study were published online July 29 in the New England Journal of Medicine by the TODAY study group.

At follow-up – after originally participating in the TODAY trial when they were young teenagers – they had a mean age of 26.4 years.

At this time, more than two thirds had hypertension and half had dyslipidemia.

Overall, 60% had at least one diabetic microvascular complication (retinal disease, neuropathy, or diabetic kidney disease), and more than a quarter had two or more such complications.

“These data illustrate the serious personal and public health consequences of youth-onset type 2 diabetes in the transition to adulthood,” the researchers noted.

Don’t tread lightly just because they are young

“The fact that these youth are accumulating complications at a rapid rate and are broadly affected early in adulthood certainly suggests that aggressive therapy is needed, both for glycemic control and treatment of risk factors like hypertension and dyslipidemia,” study coauthor Philip S. Zeitler, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

“In the absence of studies specifically addressing this, we need to take a more aggressive approach than people might be inclined to, given that the age at diagnosis is young, around 14 years,” he added.

“Contrary to the inclination to be ‘gentle’ in treating them because they are kids, these data suggest that we can’t let these initial years go by without strong intervention, and we need to be prepared for polypharmacy.”

Unfortunately, as Dr. Zeitler and coauthors explained, youth-onset type 2 diabetes is characterized by a suboptimal response to currently approved diabetes medications.

New pediatric indications in the United States for drugs used to treat type 2 diabetes in adults, including the recent Food and Drug Administration approval of extended-release exenatide for children as young as 10 years of age, “helps, but only marginally,” said Dr. Zeitler, of the Clinical & Translational Research Center, Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora.

“In some cases, it will help get them covered by carriers, which is always good. But this is still a very limited set of medications. It doesn’t include more recently approved more potent glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists, like semaglutide, and doesn’t include the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. Pediatricians are used to using medications off label and that is necessary here while we await further approvals,” he said.

And he noted that most individuals with youth-onset type 2 diabetes in the United States are covered by public insurance or are uninsured, depending on which state they live in. While the two major Medicaid programs in Colorado allow full access to adult formularies, that’s not the case everywhere. Moreover, patients often face further access barriers in states without expanded Medicaid.

Follow-up shows all metrics worsening over time

In TODAY 2, patients participated in an observational follow-up in their usual care settings in 2011-2020. At the start, they were receiving metformin with or without insulin for diabetes, but whether this continued and whether they were treated for other risk factors was down to individual circumstances.

Participants’ median A1c increased over time, and the percentage with A1c < 6% (< 48 mmol/mol) declined from 75% at the time of TODAY entry to just 19% at the 15-year end of follow-up.

The proportion with an A1c ≤ 10% (≤ 86 mmol/mol) rose from 0% at baseline to 34% at 15 years.

At that time, nearly 50% were taking both metformin and insulin, while more than a quarter were taking no medications.

The prevalence of hypertension increased from 19.2% at baseline to 67.5% at 15 years, while dyslipidemia rose from 20.8% to 51.6%.

Kidney disease prevalence increased from 8.0% at baseline to 54.8% at 15 years. Nerve disease rose from 1.0% to 32.4%. Retinal disease jumped from 13.7% with milder nonproliferative retinopathy in 2010-2011 to 51.0% with any eye disease in 2017-2018, including 8.8% with moderate to severe retinal changes and 3.5% with macular edema.

Overall, at the time of the last visit, 39.9% had no diabetes complications, 31.8% had one, 21.3% had two, and 7.1% had three complications.

Serious cardiovascular events in mid-20s

There were 17 adjudicated serious cardiovascular events, including four myocardial infarctions, six heart failure events, three diagnoses of coronary artery disease, and four strokes.

Six participants died, one each from myocardial infarction, kidney failure, and drug overdose, and three from sepsis.

Dr. Zeitler called the macrovascular events “shocking,” noting that although the numbers are small, for people in their mid-20s “they should be zero ... While we don’t yet know if the rates are the same or faster than in adults, even if they are the same, these kids are only in their late 20s, as opposed to adults experiencing these problems in their 50s, 60s, and 70s.

“The fact that these complications are occurring when these individuals should be in the prime of their life for both family and work has huge implications,” he stressed.

Findings have multiple causes

The reasons for the findings are both biologic and socioeconomic, Dr. Zeitler said.

“We know already that many kids with type 2 have rapid [deterioration of] beta-cell [function], which is probably very biologic. It stands to reason that an individual who can get diabetes as an adolescent probably has more fragile beta cells in some way,” he noted.

“But we also know that many other things contribute: stress, social determinants, access to quality care and medications, access to healthy foods and physical activity, availability of family supervision given the realities of families’ economic status and jobs, etc.”

It’s also known that youth with type 2 diabetes have much more severe insulin resistance than that of adults with the condition, and that “once the kids left ... the [TODAY] study, risk factor treatment in the community was less than ideal, and a lot of kids who met criteria for treatment of their blood pressure or lipids were not being treated. This is likely at least partly sociologic and partly the general pediatric hesitancy to use medications.”

He said the TODAY team will soon have some new data to show that “glycemia during the early years makes a difference, again supporting intensive intervention early on.”

The TODAY study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Zeitler had no further disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 leaves wake of medical debt among U.S. adults

Despite the passage of four major relief bills in 2020 and 2021 and federal efforts to offset pandemic- and job-related coverage loss, many people continued to face financial challenges, especially those with a low income and those who are Black or Latino.

The survey, which included responses from 5,450 adults, revealed that 10% of adults aged 19-64 were uninsured during the first half of 2021, a rate lower than what was recorded in 2020 and 2019 in both federal and private surveys. However, uninsured rates were highest among those with low income, those younger than 50 years old, and Black and Latino adults.

For most adults who lost employee health insurance, the coverage gap was relatively brief, with 54% saying their coverage gap lasted 3-4 months. Only 16% of adults said coverage gaps lasted a year or longer.

“The good news is that this survey is suggesting that the coverage losses during the pandemic may have been offset by federal efforts to help people get and maintain health insurance coverage,” lead author Sara Collins, PhD, Commonwealth Fund vice president for health care coverage, access, and tracking, said in an interview.

“The bad news is that a third of Americans continue to struggle with medical bills and medical debt, even among those who have health insurance coverage,” Dr. Collins added.

Indeed, the survey found that about one-third of insured adults reported a medical bill problem or that they were paying off medical debt, as did approximately half of those who were uninsured. Medical debt caused 35% of respondents to use up most or all of their savings to pay it off.

Meanwhile, 27% of adults said medical bills left them unable to pay for necessities such as food, heat, or rent. What surprised Dr. Collins was that 43% of adults said they received a lower credit rating as a result of their medical debt, and 35% said they had taken on more credit card debt to pay off these bills.

“The fact that it’s bleeding over into people’s financial security in terms of their credit scores, I think is something that really needs to be looked at by policymakers,” Dr. Collins said.

When analyzed by race/ethnicity, the researchers found that 55% of Black adults and 44% of Latino/Hispanic adults reported medical bills and debt problems, compared with 32% of White adults. In addition, 47% of those living below the poverty line also reported problems with medical bills.

According to the survey, 45% of respondents were directly affected by the pandemic in at least one of three ways – testing positive or getting sick from COVID-19, losing income, or losing employer coverage – with Black and Latinx adults and those with lower incomes at greater risk.

George Abraham, MD, president of the American College of Physicians, said the Commonwealth Fund’s findings were not surprising because it has always been known that underrepresented populations struggle for access to care because of socioeconomic factors. He said these populations were more vulnerable in terms of more severe infections and disease burden during the pandemic.

“[This study] validates what primary care physicians have been saying all along in regard to our patients’ access to care and their ability to cover health care costs,” said Dr. Abraham, who was not involved with the study. “This will hopefully be an eye-opener and wake-up call that reiterates that we still do not have equitable access to care and vulnerable populations are disproportionately affected.”

He believes that, although people are insured, many of them may contend with medical debt when they fall ill because they can’t afford the premiums.

“Even though they may have been registered for health coverage, they may not have active coverage at the time of illness simply because they weren’t able to make their last premium payments because they’ve been down, because they lost their job, or whatever else,” Dr. Abraham explained. “On paper, they appear to have health care coverage. But in reality, clearly, that coverage does not match their needs or it’s not affordable.”

For Dr. Abraham, the study emphasizes the need to continue support for health care reform, including pricing it so that insurance is available for those with fewer socioeconomic resources.

Yalda Jabbarpour, MD, medical director of the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies, Washington, said high-deductible health plans need to be “reined in” because they can lead to greater debt, particularly among vulnerable populations.

“Hopefully this will encourage policymakers to look more closely at the problem of medical debt as a contributing factor to financial instability,” Dr. Jabbarpour said. “Federal relief is important, so is expanding access to comprehensive, affordable health care coverage.”

Dr. Collins said there should also be a way to raise awareness of the health care marketplace and coverage options so that people have an easier time getting insured.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite the passage of four major relief bills in 2020 and 2021 and federal efforts to offset pandemic- and job-related coverage loss, many people continued to face financial challenges, especially those with a low income and those who are Black or Latino.

The survey, which included responses from 5,450 adults, revealed that 10% of adults aged 19-64 were uninsured during the first half of 2021, a rate lower than what was recorded in 2020 and 2019 in both federal and private surveys. However, uninsured rates were highest among those with low income, those younger than 50 years old, and Black and Latino adults.

For most adults who lost employee health insurance, the coverage gap was relatively brief, with 54% saying their coverage gap lasted 3-4 months. Only 16% of adults said coverage gaps lasted a year or longer.

“The good news is that this survey is suggesting that the coverage losses during the pandemic may have been offset by federal efforts to help people get and maintain health insurance coverage,” lead author Sara Collins, PhD, Commonwealth Fund vice president for health care coverage, access, and tracking, said in an interview.

“The bad news is that a third of Americans continue to struggle with medical bills and medical debt, even among those who have health insurance coverage,” Dr. Collins added.

Indeed, the survey found that about one-third of insured adults reported a medical bill problem or that they were paying off medical debt, as did approximately half of those who were uninsured. Medical debt caused 35% of respondents to use up most or all of their savings to pay it off.

Meanwhile, 27% of adults said medical bills left them unable to pay for necessities such as food, heat, or rent. What surprised Dr. Collins was that 43% of adults said they received a lower credit rating as a result of their medical debt, and 35% said they had taken on more credit card debt to pay off these bills.

“The fact that it’s bleeding over into people’s financial security in terms of their credit scores, I think is something that really needs to be looked at by policymakers,” Dr. Collins said.

When analyzed by race/ethnicity, the researchers found that 55% of Black adults and 44% of Latino/Hispanic adults reported medical bills and debt problems, compared with 32% of White adults. In addition, 47% of those living below the poverty line also reported problems with medical bills.

According to the survey, 45% of respondents were directly affected by the pandemic in at least one of three ways – testing positive or getting sick from COVID-19, losing income, or losing employer coverage – with Black and Latinx adults and those with lower incomes at greater risk.

George Abraham, MD, president of the American College of Physicians, said the Commonwealth Fund’s findings were not surprising because it has always been known that underrepresented populations struggle for access to care because of socioeconomic factors. He said these populations were more vulnerable in terms of more severe infections and disease burden during the pandemic.

“[This study] validates what primary care physicians have been saying all along in regard to our patients’ access to care and their ability to cover health care costs,” said Dr. Abraham, who was not involved with the study. “This will hopefully be an eye-opener and wake-up call that reiterates that we still do not have equitable access to care and vulnerable populations are disproportionately affected.”

He believes that, although people are insured, many of them may contend with medical debt when they fall ill because they can’t afford the premiums.

“Even though they may have been registered for health coverage, they may not have active coverage at the time of illness simply because they weren’t able to make their last premium payments because they’ve been down, because they lost their job, or whatever else,” Dr. Abraham explained. “On paper, they appear to have health care coverage. But in reality, clearly, that coverage does not match their needs or it’s not affordable.”

For Dr. Abraham, the study emphasizes the need to continue support for health care reform, including pricing it so that insurance is available for those with fewer socioeconomic resources.

Yalda Jabbarpour, MD, medical director of the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies, Washington, said high-deductible health plans need to be “reined in” because they can lead to greater debt, particularly among vulnerable populations.

“Hopefully this will encourage policymakers to look more closely at the problem of medical debt as a contributing factor to financial instability,” Dr. Jabbarpour said. “Federal relief is important, so is expanding access to comprehensive, affordable health care coverage.”

Dr. Collins said there should also be a way to raise awareness of the health care marketplace and coverage options so that people have an easier time getting insured.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite the passage of four major relief bills in 2020 and 2021 and federal efforts to offset pandemic- and job-related coverage loss, many people continued to face financial challenges, especially those with a low income and those who are Black or Latino.

The survey, which included responses from 5,450 adults, revealed that 10% of adults aged 19-64 were uninsured during the first half of 2021, a rate lower than what was recorded in 2020 and 2019 in both federal and private surveys. However, uninsured rates were highest among those with low income, those younger than 50 years old, and Black and Latino adults.

For most adults who lost employee health insurance, the coverage gap was relatively brief, with 54% saying their coverage gap lasted 3-4 months. Only 16% of adults said coverage gaps lasted a year or longer.

“The good news is that this survey is suggesting that the coverage losses during the pandemic may have been offset by federal efforts to help people get and maintain health insurance coverage,” lead author Sara Collins, PhD, Commonwealth Fund vice president for health care coverage, access, and tracking, said in an interview.

“The bad news is that a third of Americans continue to struggle with medical bills and medical debt, even among those who have health insurance coverage,” Dr. Collins added.

Indeed, the survey found that about one-third of insured adults reported a medical bill problem or that they were paying off medical debt, as did approximately half of those who were uninsured. Medical debt caused 35% of respondents to use up most or all of their savings to pay it off.

Meanwhile, 27% of adults said medical bills left them unable to pay for necessities such as food, heat, or rent. What surprised Dr. Collins was that 43% of adults said they received a lower credit rating as a result of their medical debt, and 35% said they had taken on more credit card debt to pay off these bills.

“The fact that it’s bleeding over into people’s financial security in terms of their credit scores, I think is something that really needs to be looked at by policymakers,” Dr. Collins said.

When analyzed by race/ethnicity, the researchers found that 55% of Black adults and 44% of Latino/Hispanic adults reported medical bills and debt problems, compared with 32% of White adults. In addition, 47% of those living below the poverty line also reported problems with medical bills.

According to the survey, 45% of respondents were directly affected by the pandemic in at least one of three ways – testing positive or getting sick from COVID-19, losing income, or losing employer coverage – with Black and Latinx adults and those with lower incomes at greater risk.

George Abraham, MD, president of the American College of Physicians, said the Commonwealth Fund’s findings were not surprising because it has always been known that underrepresented populations struggle for access to care because of socioeconomic factors. He said these populations were more vulnerable in terms of more severe infections and disease burden during the pandemic.

“[This study] validates what primary care physicians have been saying all along in regard to our patients’ access to care and their ability to cover health care costs,” said Dr. Abraham, who was not involved with the study. “This will hopefully be an eye-opener and wake-up call that reiterates that we still do not have equitable access to care and vulnerable populations are disproportionately affected.”

He believes that, although people are insured, many of them may contend with medical debt when they fall ill because they can’t afford the premiums.

“Even though they may have been registered for health coverage, they may not have active coverage at the time of illness simply because they weren’t able to make their last premium payments because they’ve been down, because they lost their job, or whatever else,” Dr. Abraham explained. “On paper, they appear to have health care coverage. But in reality, clearly, that coverage does not match their needs or it’s not affordable.”

For Dr. Abraham, the study emphasizes the need to continue support for health care reform, including pricing it so that insurance is available for those with fewer socioeconomic resources.

Yalda Jabbarpour, MD, medical director of the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies, Washington, said high-deductible health plans need to be “reined in” because they can lead to greater debt, particularly among vulnerable populations.

“Hopefully this will encourage policymakers to look more closely at the problem of medical debt as a contributing factor to financial instability,” Dr. Jabbarpour said. “Federal relief is important, so is expanding access to comprehensive, affordable health care coverage.”

Dr. Collins said there should also be a way to raise awareness of the health care marketplace and coverage options so that people have an easier time getting insured.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ESC heart failure guideline to integrate bounty of new meds

Today there are so many evidence-based drug therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) that physicians treating HF patients almost don’t know what to do them.

It’s an exciting new age that way, but to many vexingly unclear how best to merge the shiny new options with mainstay regimens based on time-honored renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors and beta-blockers.

To impart some clarity, the authors of a new HF guideline document recently took center stage at the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC-HFA) annual meeting to preview their updated recommendations, with novel twists based on recent major trials, for the new age of HF pharmacotherapeutics.

The guideline committee considered the evidence base that existed “up until the end of March of this year,” Theresa A. McDonagh, MD, King’s College London, said during the presentation. The document “is now finalized, it’s with the publishers, and it will be presented in full with simultaneous publication at the ESC meeting” that starts August 27.

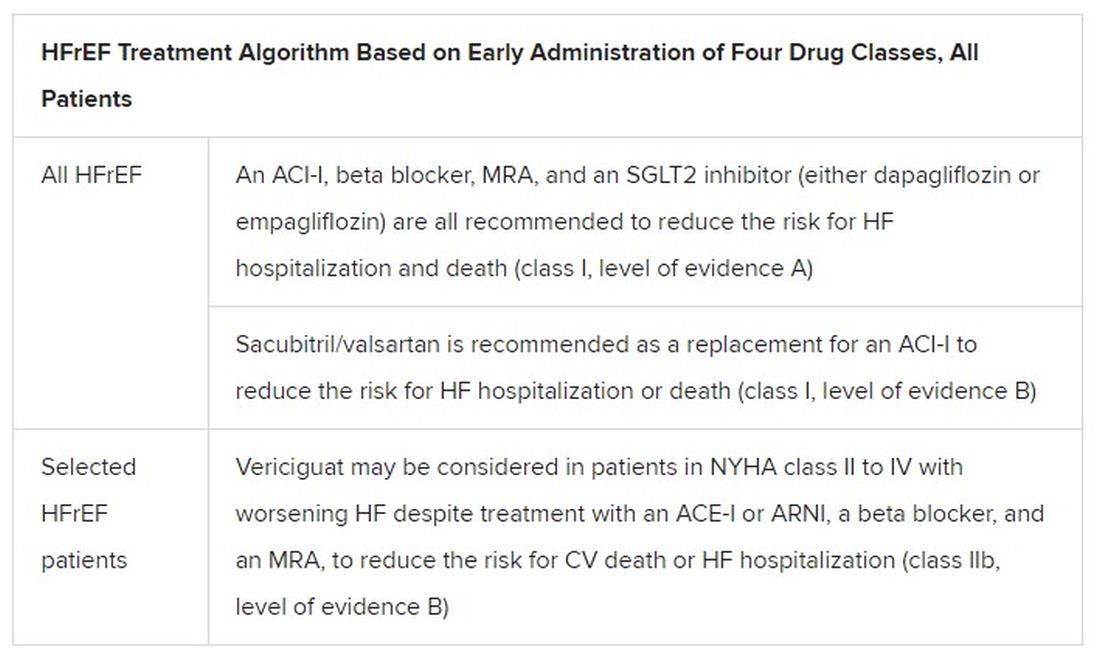

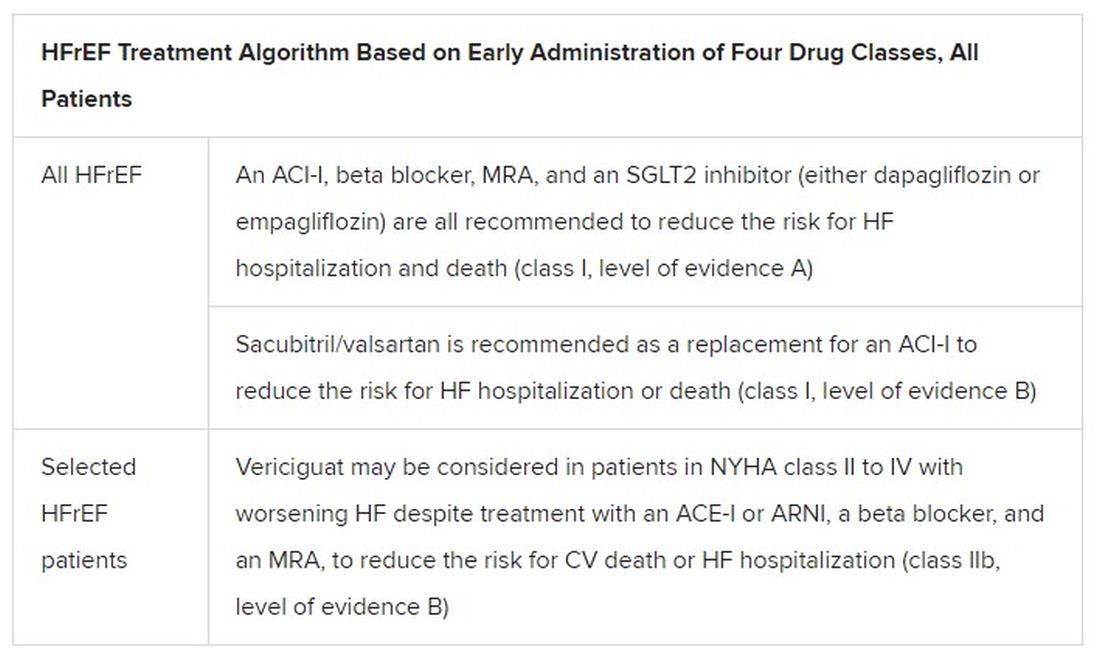

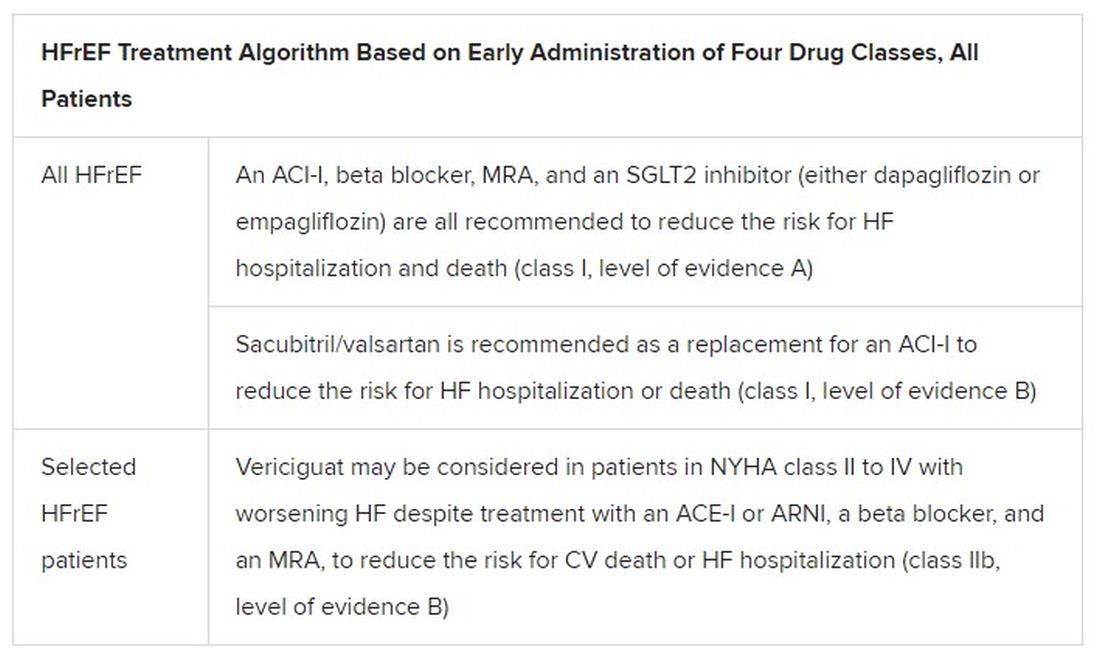

It describes a game plan, already followed by some clinicians in practice without official guidance, for initiating drugs from each of four classes in virtually all patients with HFrEF.

New indicated drugs, new perspective for HFrEF

Three of the drug categories are old acquaintances. Among them are the RAS inhibitors, which include angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitors, beta-blockers, and the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. The latter drugs are gaining new respect after having been underplayed in HF prescribing despite longstanding evidence of efficacy.

Completing the quartet of first-line HFrEF drug classes is a recent arrival to the HF arena, the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors.

“We now have new data and a simplified treatment algorithm for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction based on the early administration of the four major classes of drugs,” said Marco Metra, MD, University of Brescia (Italy), previewing the medical-therapy portions of the new guideline at the ESC-HFA sessions, which launched virtually and live in Florence, Italy, on July 29.

The new game plan offers a simple answer to a once-common but complex question: How and in what order are the different drug classes initiated in patients with HFrEF? In the new document, the stated goal is to get them all on board expeditiously and safely, by any means possible.

The guideline writers did not specify a sequence, preferring to leave that decision to physicians, said Dr. Metra, who stated only two guiding principles. The first is to consider the patient’s unique circumstances. The order in which the drugs are introduced might vary, depending on, for example, whether the patient has low or high blood pressure or renal dysfunction.

Second, “it is very important that we try to give all four classes of drugs to the patient in the shortest time possible, because this saves lives,” he said.

That there is no recommendation on sequencing the drugs has led some to the wrong interpretation that all should be started at once, observed coauthor Javed Butler, MD, MPH, University of Mississippi, Jackson, as a panelist during the presentation. Far from it, he said. “The doctor with the patient in front of you can make the best decision. The idea here is to get all the therapies on as soon as possible, as safely as possible.”

“The order in which they are introduced is not really important,” agreed Vijay Chopra, MD, Max Super Specialty Hospital Saket, New Delhi, another coauthor on the panel. “The important thing is that at least some dose of all the four drugs needs to be introduced in the first 4-6 weeks, and then up-titrated.”

Other medical therapy can be more tailored, Dr. Metra noted, such as loop diuretics for patients with congestion, iron for those with iron deficiency, and other drugs depending on whether there is, for example, atrial fibrillation or coronary disease.

Adoption of emerging definitions

The document adopts the emerging characterization of HFrEF by a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) up to 40%.

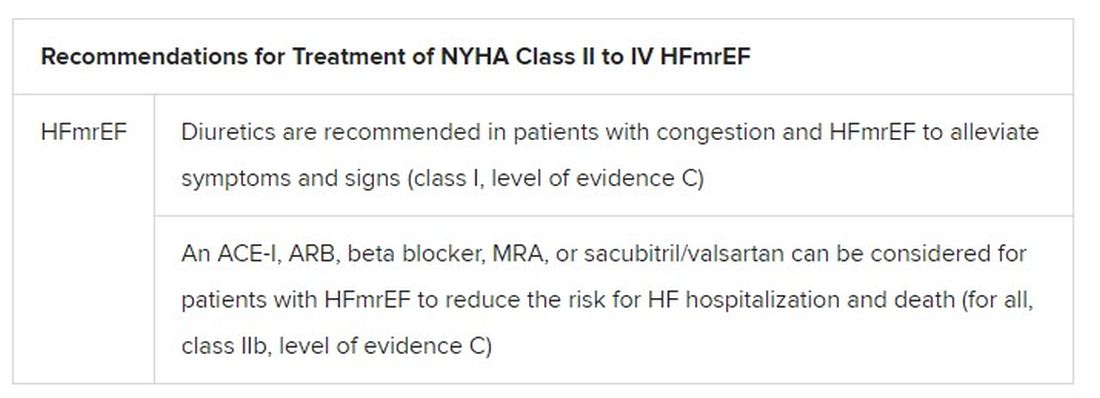

And it will leverage an expanding evidence base for medication in a segment of patients once said to have HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), who had therefore lacked specific, guideline-directed medical therapies. Now, patients with an LVEF of 41%-49% will be said to have HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), a tweak to the recently introduced HF with “mid-range” LVEF that is designed to assert its nature as something to treat. The new document’s HFmrEF recommendations come with various class and level-of-evidence ratings.

That leaves HFpEF to be characterized by an LVEF of 50% in combination with structural or functional abnormalities associated with LV diastolic dysfunction or raised LV filling pressures, including raised natriuretic peptide levels.

The definitions are consistent with those proposed internationally by the ESC-HFA, the Heart Failure Society of America, and other groups in a statement published in March.

Expanded HFrEF med landscape

Since the 2016 ESC guideline on HF therapy, Dr. McDonagh said, “there’s been no substantial change in the evidence for many of the classical drugs that we use in heart failure. However, we had a lot of new and exciting evidence to consider,” especially in support of the SGLT2 inhibitors as one of the core medications in HFrEF.

The new data came from two controlled trials in particular. In DAPA-HF, patients with HFrEF who were initially without diabetes and who went on dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) showed a 27% drop in cardiovascular (CV) death or worsening-HF events over a median of 18 months.

“That was followed up with very concordant results with empagliflozin [Jardiance, Boehringer Ingelheim/Eli Lilly] in HFrEF in the EMPEROR-Reduced trial,” Dr. McDonagh said. In that trial, comparable patients who took empagliflozin showed a 25% drop in a primary endpoint similar to that in DAPA-HF over the median 16-month follow-up.

Other HFrEF recommendations are for selected patients. They include ivabradine, already in the guidelines, for patients in sinus rhythm with an elevated resting heart rate who can’t take beta-blockers for whatever reason. But, Dr. McDonagh noted, “we had some new classes of drugs to consider as well.”

In particular, the oral soluble guanylate-cyclase receptor stimulator vericiguat (Verquvo) emerged about a year ago from the VICTORIA trial as a modest success for patients with HFrEF and a previous HF hospitalization. In the trial with more than 5,000 patients, treatment with vericiguat atop standard drug and device therapy was followed by a significant 10% drop in risk for CV death or HF hospitalization.

Available now or likely to be available in the United States, the European Union, Japan, and other countries, vericiguat is recommended in the new guideline for VICTORIA-like patients who don’t adequately respond to other indicated medications.

Little for HFpEF as newly defined

“Almost nothing is new” in the guidelines for HFpEF, Dr. Metra said. The document recommends screening for and treatment of any underlying disorder and comorbidities, plus diuretics for any congestion. “That’s what we have to date.”

But that evidence base might soon change. The new HFpEF recommendations could possibly be up-staged at the ESC sessions by the August 27 scheduled presentation of EMPEROR-Preserved, a randomized test of empagliflozin in HFpEF and – it could be said – HFmrEF. The trial entered patients with chronic HF and an LVEF greater than 40%.

Eli Lilly and Boehringer Ingelheim offered the world a peek at the results, which suggest the SGLT2 inhibitor had a positive impact on the primary endpoint of CV death or HF hospitalization. They announced the cursory top-line outcomes in early July as part of its regulatory obligations, noting that the trial had “met” its primary endpoint.

But many unknowns remain, including the degree of benefit and whether it varied among subgroups, and especially whether outcomes were different for HFmrEF than for HFpEF.

Upgrades for familiar agents

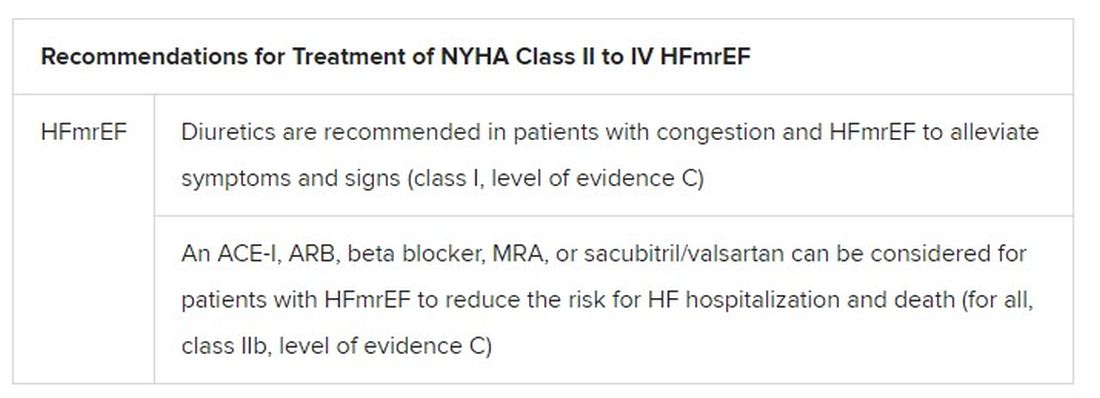

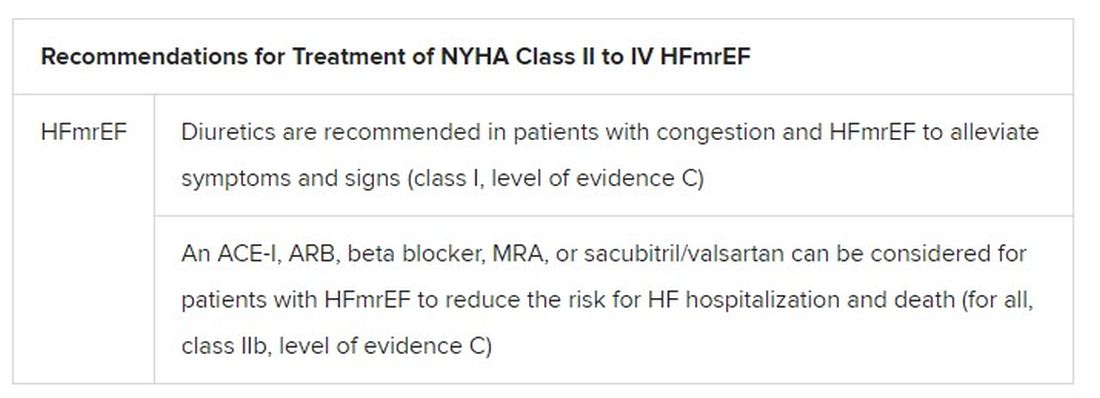

Still, HFmrEF gets noteworthy attention in the document. “For the first time, we have recommendations for these patients,” Dr. Metra said. “We already knew that diuretics are indicated for the treatment of congestion. But now, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid antagonists, as well as sacubitril/valsartan, may be considered to improve outcomes in these patients.” Their upgrades in the new guidelines were based on review of trials in the CHARM program and of TOPCAT and PARAGON-HF, among others, he said.

The new document also includes “treatment algorithms based on phenotypes”; that is, comorbidities and less common HF precipitants. For example, “assessment of iron status is now mandated in all patients with heart failure,” Dr. Metra said.

AFFIRM-HF is the key trial in this arena, with its more than 1,100 iron-deficient patients with LVEF less than 50% who had been recently hospitalized for HF. A year of treatment with ferric carboxymaltose (Ferinject/Injectafer, Vifor) led to a 26% drop in risk for HF hospitalization, but without affecting mortality.

For those who are iron deficient, Dr. Metra said, “ferric carboxymaltose intravenously should be considered not only in patients with low ejection fraction and outpatients, but also in patients recently hospitalized for acute heart failure.”

The SGLT2 inhibitors are recommended in HFrEF patients with type 2 diabetes. And treatment with tafamidis (Vyndaqel, Pfizer) in patients with genetic or wild-type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis gets a class I recommendation based on survival gains seen in the ATTR-ACT trial.

Also recommended is a full CV assessment for patients with cancer who are on cardiotoxic agents or otherwise might be at risk for chemotherapy cardiotoxicity. “Beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors should be considered in those who develop left ventricular systolic dysfunction after anticancer therapy,” Dr. Metra said.

The ongoing pandemic made its mark on the document’s genesis, as it has with most everything else. “For better or worse, we were a ‘COVID guideline,’ ” Dr. McDonagh said. The writing committee consisted of “a large task force of 31 individuals, including two patients,” and there were “only two face-to-face meetings prior to the first wave of COVID hitting Europe.”

The committee voted on each of the recommendations, “and we had to have agreement of more than 75% of the task force to assign a class of recommendation or level of evidence,” she said. “I think we did the best we could in the circumstances. We had the benefit of many discussions over Zoom, and I think at the end of the day we have achieved a consensus.”

With such a large body of participants and the 75% threshold for agreement, “you end up with perhaps a conservative guideline. But that’s not a bad thing for clinical practice, for guidelines to be conservative,” Dr. McDonagh said. “They’re mainly concerned with looking at evidence and safety.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Today there are so many evidence-based drug therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) that physicians treating HF patients almost don’t know what to do them.

It’s an exciting new age that way, but to many vexingly unclear how best to merge the shiny new options with mainstay regimens based on time-honored renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors and beta-blockers.

To impart some clarity, the authors of a new HF guideline document recently took center stage at the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC-HFA) annual meeting to preview their updated recommendations, with novel twists based on recent major trials, for the new age of HF pharmacotherapeutics.

The guideline committee considered the evidence base that existed “up until the end of March of this year,” Theresa A. McDonagh, MD, King’s College London, said during the presentation. The document “is now finalized, it’s with the publishers, and it will be presented in full with simultaneous publication at the ESC meeting” that starts August 27.

It describes a game plan, already followed by some clinicians in practice without official guidance, for initiating drugs from each of four classes in virtually all patients with HFrEF.

New indicated drugs, new perspective for HFrEF

Three of the drug categories are old acquaintances. Among them are the RAS inhibitors, which include angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitors, beta-blockers, and the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. The latter drugs are gaining new respect after having been underplayed in HF prescribing despite longstanding evidence of efficacy.

Completing the quartet of first-line HFrEF drug classes is a recent arrival to the HF arena, the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors.

“We now have new data and a simplified treatment algorithm for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction based on the early administration of the four major classes of drugs,” said Marco Metra, MD, University of Brescia (Italy), previewing the medical-therapy portions of the new guideline at the ESC-HFA sessions, which launched virtually and live in Florence, Italy, on July 29.

The new game plan offers a simple answer to a once-common but complex question: How and in what order are the different drug classes initiated in patients with HFrEF? In the new document, the stated goal is to get them all on board expeditiously and safely, by any means possible.

The guideline writers did not specify a sequence, preferring to leave that decision to physicians, said Dr. Metra, who stated only two guiding principles. The first is to consider the patient’s unique circumstances. The order in which the drugs are introduced might vary, depending on, for example, whether the patient has low or high blood pressure or renal dysfunction.

Second, “it is very important that we try to give all four classes of drugs to the patient in the shortest time possible, because this saves lives,” he said.

That there is no recommendation on sequencing the drugs has led some to the wrong interpretation that all should be started at once, observed coauthor Javed Butler, MD, MPH, University of Mississippi, Jackson, as a panelist during the presentation. Far from it, he said. “The doctor with the patient in front of you can make the best decision. The idea here is to get all the therapies on as soon as possible, as safely as possible.”

“The order in which they are introduced is not really important,” agreed Vijay Chopra, MD, Max Super Specialty Hospital Saket, New Delhi, another coauthor on the panel. “The important thing is that at least some dose of all the four drugs needs to be introduced in the first 4-6 weeks, and then up-titrated.”

Other medical therapy can be more tailored, Dr. Metra noted, such as loop diuretics for patients with congestion, iron for those with iron deficiency, and other drugs depending on whether there is, for example, atrial fibrillation or coronary disease.

Adoption of emerging definitions

The document adopts the emerging characterization of HFrEF by a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) up to 40%.

And it will leverage an expanding evidence base for medication in a segment of patients once said to have HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), who had therefore lacked specific, guideline-directed medical therapies. Now, patients with an LVEF of 41%-49% will be said to have HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), a tweak to the recently introduced HF with “mid-range” LVEF that is designed to assert its nature as something to treat. The new document’s HFmrEF recommendations come with various class and level-of-evidence ratings.

That leaves HFpEF to be characterized by an LVEF of 50% in combination with structural or functional abnormalities associated with LV diastolic dysfunction or raised LV filling pressures, including raised natriuretic peptide levels.

The definitions are consistent with those proposed internationally by the ESC-HFA, the Heart Failure Society of America, and other groups in a statement published in March.

Expanded HFrEF med landscape

Since the 2016 ESC guideline on HF therapy, Dr. McDonagh said, “there’s been no substantial change in the evidence for many of the classical drugs that we use in heart failure. However, we had a lot of new and exciting evidence to consider,” especially in support of the SGLT2 inhibitors as one of the core medications in HFrEF.

The new data came from two controlled trials in particular. In DAPA-HF, patients with HFrEF who were initially without diabetes and who went on dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) showed a 27% drop in cardiovascular (CV) death or worsening-HF events over a median of 18 months.

“That was followed up with very concordant results with empagliflozin [Jardiance, Boehringer Ingelheim/Eli Lilly] in HFrEF in the EMPEROR-Reduced trial,” Dr. McDonagh said. In that trial, comparable patients who took empagliflozin showed a 25% drop in a primary endpoint similar to that in DAPA-HF over the median 16-month follow-up.

Other HFrEF recommendations are for selected patients. They include ivabradine, already in the guidelines, for patients in sinus rhythm with an elevated resting heart rate who can’t take beta-blockers for whatever reason. But, Dr. McDonagh noted, “we had some new classes of drugs to consider as well.”

In particular, the oral soluble guanylate-cyclase receptor stimulator vericiguat (Verquvo) emerged about a year ago from the VICTORIA trial as a modest success for patients with HFrEF and a previous HF hospitalization. In the trial with more than 5,000 patients, treatment with vericiguat atop standard drug and device therapy was followed by a significant 10% drop in risk for CV death or HF hospitalization.

Available now or likely to be available in the United States, the European Union, Japan, and other countries, vericiguat is recommended in the new guideline for VICTORIA-like patients who don’t adequately respond to other indicated medications.

Little for HFpEF as newly defined

“Almost nothing is new” in the guidelines for HFpEF, Dr. Metra said. The document recommends screening for and treatment of any underlying disorder and comorbidities, plus diuretics for any congestion. “That’s what we have to date.”

But that evidence base might soon change. The new HFpEF recommendations could possibly be up-staged at the ESC sessions by the August 27 scheduled presentation of EMPEROR-Preserved, a randomized test of empagliflozin in HFpEF and – it could be said – HFmrEF. The trial entered patients with chronic HF and an LVEF greater than 40%.

Eli Lilly and Boehringer Ingelheim offered the world a peek at the results, which suggest the SGLT2 inhibitor had a positive impact on the primary endpoint of CV death or HF hospitalization. They announced the cursory top-line outcomes in early July as part of its regulatory obligations, noting that the trial had “met” its primary endpoint.

But many unknowns remain, including the degree of benefit and whether it varied among subgroups, and especially whether outcomes were different for HFmrEF than for HFpEF.

Upgrades for familiar agents

Still, HFmrEF gets noteworthy attention in the document. “For the first time, we have recommendations for these patients,” Dr. Metra said. “We already knew that diuretics are indicated for the treatment of congestion. But now, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta-blockers, mineralocorticoid antagonists, as well as sacubitril/valsartan, may be considered to improve outcomes in these patients.” Their upgrades in the new guidelines were based on review of trials in the CHARM program and of TOPCAT and PARAGON-HF, among others, he said.

The new document also includes “treatment algorithms based on phenotypes”; that is, comorbidities and less common HF precipitants. For example, “assessment of iron status is now mandated in all patients with heart failure,” Dr. Metra said.

AFFIRM-HF is the key trial in this arena, with its more than 1,100 iron-deficient patients with LVEF less than 50% who had been recently hospitalized for HF. A year of treatment with ferric carboxymaltose (Ferinject/Injectafer, Vifor) led to a 26% drop in risk for HF hospitalization, but without affecting mortality.

For those who are iron deficient, Dr. Metra said, “ferric carboxymaltose intravenously should be considered not only in patients with low ejection fraction and outpatients, but also in patients recently hospitalized for acute heart failure.”

The SGLT2 inhibitors are recommended in HFrEF patients with type 2 diabetes. And treatment with tafamidis (Vyndaqel, Pfizer) in patients with genetic or wild-type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis gets a class I recommendation based on survival gains seen in the ATTR-ACT trial.

Also recommended is a full CV assessment for patients with cancer who are on cardiotoxic agents or otherwise might be at risk for chemotherapy cardiotoxicity. “Beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors should be considered in those who develop left ventricular systolic dysfunction after anticancer therapy,” Dr. Metra said.

The ongoing pandemic made its mark on the document’s genesis, as it has with most everything else. “For better or worse, we were a ‘COVID guideline,’ ” Dr. McDonagh said. The writing committee consisted of “a large task force of 31 individuals, including two patients,” and there were “only two face-to-face meetings prior to the first wave of COVID hitting Europe.”

The committee voted on each of the recommendations, “and we had to have agreement of more than 75% of the task force to assign a class of recommendation or level of evidence,” she said. “I think we did the best we could in the circumstances. We had the benefit of many discussions over Zoom, and I think at the end of the day we have achieved a consensus.”

With such a large body of participants and the 75% threshold for agreement, “you end up with perhaps a conservative guideline. But that’s not a bad thing for clinical practice, for guidelines to be conservative,” Dr. McDonagh said. “They’re mainly concerned with looking at evidence and safety.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Today there are so many evidence-based drug therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) that physicians treating HF patients almost don’t know what to do them.

It’s an exciting new age that way, but to many vexingly unclear how best to merge the shiny new options with mainstay regimens based on time-honored renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors and beta-blockers.

To impart some clarity, the authors of a new HF guideline document recently took center stage at the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC-HFA) annual meeting to preview their updated recommendations, with novel twists based on recent major trials, for the new age of HF pharmacotherapeutics.

The guideline committee considered the evidence base that existed “up until the end of March of this year,” Theresa A. McDonagh, MD, King’s College London, said during the presentation. The document “is now finalized, it’s with the publishers, and it will be presented in full with simultaneous publication at the ESC meeting” that starts August 27.

It describes a game plan, already followed by some clinicians in practice without official guidance, for initiating drugs from each of four classes in virtually all patients with HFrEF.

New indicated drugs, new perspective for HFrEF

Three of the drug categories are old acquaintances. Among them are the RAS inhibitors, which include angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitors, beta-blockers, and the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. The latter drugs are gaining new respect after having been underplayed in HF prescribing despite longstanding evidence of efficacy.

Completing the quartet of first-line HFrEF drug classes is a recent arrival to the HF arena, the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors.

“We now have new data and a simplified treatment algorithm for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction based on the early administration of the four major classes of drugs,” said Marco Metra, MD, University of Brescia (Italy), previewing the medical-therapy portions of the new guideline at the ESC-HFA sessions, which launched virtually and live in Florence, Italy, on July 29.

The new game plan offers a simple answer to a once-common but complex question: How and in what order are the different drug classes initiated in patients with HFrEF? In the new document, the stated goal is to get them all on board expeditiously and safely, by any means possible.

The guideline writers did not specify a sequence, preferring to leave that decision to physicians, said Dr. Metra, who stated only two guiding principles. The first is to consider the patient’s unique circumstances. The order in which the drugs are introduced might vary, depending on, for example, whether the patient has low or high blood pressure or renal dysfunction.

Second, “it is very important that we try to give all four classes of drugs to the patient in the shortest time possible, because this saves lives,” he said.

That there is no recommendation on sequencing the drugs has led some to the wrong interpretation that all should be started at once, observed coauthor Javed Butler, MD, MPH, University of Mississippi, Jackson, as a panelist during the presentation. Far from it, he said. “The doctor with the patient in front of you can make the best decision. The idea here is to get all the therapies on as soon as possible, as safely as possible.”

“The order in which they are introduced is not really important,” agreed Vijay Chopra, MD, Max Super Specialty Hospital Saket, New Delhi, another coauthor on the panel. “The important thing is that at least some dose of all the four drugs needs to be introduced in the first 4-6 weeks, and then up-titrated.”

Other medical therapy can be more tailored, Dr. Metra noted, such as loop diuretics for patients with congestion, iron for those with iron deficiency, and other drugs depending on whether there is, for example, atrial fibrillation or coronary disease.

Adoption of emerging definitions

The document adopts the emerging characterization of HFrEF by a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) up to 40%.

And it will leverage an expanding evidence base for medication in a segment of patients once said to have HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), who had therefore lacked specific, guideline-directed medical therapies. Now, patients with an LVEF of 41%-49% will be said to have HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), a tweak to the recently introduced HF with “mid-range” LVEF that is designed to assert its nature as something to treat. The new document’s HFmrEF recommendations come with various class and level-of-evidence ratings.

That leaves HFpEF to be characterized by an LVEF of 50% in combination with structural or functional abnormalities associated with LV diastolic dysfunction or raised LV filling pressures, including raised natriuretic peptide levels.

The definitions are consistent with those proposed internationally by the ESC-HFA, the Heart Failure Society of America, and other groups in a statement published in March.

Expanded HFrEF med landscape

Since the 2016 ESC guideline on HF therapy, Dr. McDonagh said, “there’s been no substantial change in the evidence for many of the classical drugs that we use in heart failure. However, we had a lot of new and exciting evidence to consider,” especially in support of the SGLT2 inhibitors as one of the core medications in HFrEF.

The new data came from two controlled trials in particular. In DAPA-HF, patients with HFrEF who were initially without diabetes and who went on dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) showed a 27% drop in cardiovascular (CV) death or worsening-HF events over a median of 18 months.

“That was followed up with very concordant results with empagliflozin [Jardiance, Boehringer Ingelheim/Eli Lilly] in HFrEF in the EMPEROR-Reduced trial,” Dr. McDonagh said. In that trial, comparable patients who took empagliflozin showed a 25% drop in a primary endpoint similar to that in DAPA-HF over the median 16-month follow-up.