User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

T2D plus heart failure packs a deadly punch

It’s bad news for patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes when they then develop heart failure during the next few years.

Patients with incident type 2 diabetes (T2D) who soon after also had heart failure appear faced a dramatically elevated mortality risk, higher than the incremental risk from any other cardiovascular or renal comorbidity that appeared following diabetes onset, in an analysis of more than 150,000 Danish patients with incident type 2 diabetes during 1998-2015.

The 5-year risk of death in patients who developed heart failure during the first 5 years following an initial diagnosis of T2D was about 48%, about threefold higher than in patients with newly diagnosed T2D who remained free of heart failure or any of the other studied comorbidities, Bochra Zareini, MD, and associates reported in a study published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. The studied patients had no known cardiovascular or renal disease at the time of their first T2D diagnosis.

“Our study reports not only on the absolute 5-year risk” of mortality, “but also takes into consideration when patients developed” a comorbidity. “What is surprising and worrying is the very high risk of death following heart failure and the potential life years lost when compared to T2D patients who do not develop heart failure,” said Dr. Zareini, a cardiologist at Herlev and Gentofte University Hospital in Copenhagen. “The implications of our study are to create awareness and highlight the importance of early detection of heart failure development in patients with T2D.” The results also showed that “heart failure is a common cardiovascular disease” in patients with newly diagnosed T2D, she added in an interview.

The data she and her associates reported came from a retrospective analysis of 153,403 Danish citizens in national health records who received a prescription for an antidiabetes drug for the first time during 1998-2015, excluding patients with a prior diagnosis of heart failure, ischemic heart disease (IHD), stroke, peripheral artery disease (PAD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), or gestational diabetes. They followed these patients for a median of just under 10 years, during which time 45% of the cohort had an incident diagnosis of at least one of these cardiovascular and renal conditions, based on medical-record entries from hospitalization discharges or ambulatory contacts.

Nearly two-thirds of the T2D patients with an incident comorbidity during follow-up had a single new diagnosis, a quarter had two new comorbidities appear during follow-up, and 13% developed at least three new comorbidities.

Heart failure, least common but deadliest comorbidity

The most common of the tracked comorbidities was IHD, which appeared in 8% of the T2D patients within 5 years and in 13% after 10 years. Next most common was stroke, affecting 3% of patients after 5 years and 5% after 10 years. CKD occurred in 2.2% after 5 years and in 4.0% after 10 years, PAD occurred in 2.1% after 5 years and in 3.0% at 10 years, and heart failure occurred in 1.6% at 5 years and in 2.2% after 10 years.

But despite being the least common of the studied comorbidities, heart failure was by far the most deadly, roughly tripling the 5-year mortality rate, compared with T2D patients with no comorbidities, regardless of exactly when it first appeared during the first 5 years after the initial T2D diagnosis. The next most deadly comorbidities were stroke and PAD, which each roughly doubled mortality, compared with the patients who remained free of any studied comorbidity. CKD boosted mortality by 70%-110%, depending on exactly when it appeared during the first 5 years of follow-up, and IHD, while the most frequent comorbidity was also the most benign, increasing mortality by about 30%.

The most deadly combinations of two comorbidities were when heart failure appeared with either CKD or with PAD; each of these combinations boosted mortality by 300%-400% when it occurred during the first few years after a T2D diagnosis.

The findings came from “a very big and unselected patient group of patients, making our results highly generalizable in terms of assessing the prognostic consequences of heart failure,” Dr. Zareini stressed.

Management implications

The dangerous combination of T2D and heart failure has been documented for several years, and prompted a focused statement in 2019 about best practices for managing these patients (Circulation. 2019 Aug 3;140[7]:e294-324). “Heart failure has been known for some time to predict poorer outcomes in patients with T2D. Not much surprising” in the new findings reported by Dr. Zareini and associates, commented Robert H. Eckel, MD, a cardiovascular endocrinologist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. Heart failure “rarely acts alone, but in combination with other forms of heart or renal disease,” he noted in an interview.

Earlier studies may have “overlooked” heart failure’s importance compared with other comorbidities because they often “only investigated one cardiovascular disease in patients with T2D,” Dr. Zareini noted. In recent years the importance of heart failure occurring in patients with T2D also gained heightened significance because of the growing role of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor drug class in treating patients with T2D and the documented ability of these drugs to significantly reduce hospitalizations for heart failure (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Apr 28;75[16]:1956-74). Dr. Zareini and associates put it this way in their report: “Heart failure has in recent years been recognized as an important clinical endpoint ... in patients with T2D, in particular, after the results from randomized, controlled trials of SGLT2 inhibitors showed benefit on cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalizations.”

Despite this, the new findings “do not address treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with T2D, nor can we use our data to address which patients should not be treated,” with this drug class, which instead should rely on “current evidence and expert consensus,” she said.

“Guidelines favor SGLT2 inhibitors or [glucagonlike peptide–1] receptor agonists in patients with a history of or high risk for major adverse coronary events,” and SGLT2 inhibitors are also “preferable in patients with renal disease,” Dr. Eckel noted.

Other avenues also exist for minimizing the onset of heart failure and other cardiovascular diseases in patients with T2D, Dr. Zareini said, citing modifiable risks that lead to heart failure that include hypertension, “diabetic cardiomyopathy,” and ISD. “Clinicians must treat all modifiable risk factors in patients with T2D in order to improve prognosis and limit development of cardiovascular and renal disease.”

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Zareini and Dr. Eckel had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Zareini B et al. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020 Jun 23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.006260.

It’s bad news for patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes when they then develop heart failure during the next few years.

Patients with incident type 2 diabetes (T2D) who soon after also had heart failure appear faced a dramatically elevated mortality risk, higher than the incremental risk from any other cardiovascular or renal comorbidity that appeared following diabetes onset, in an analysis of more than 150,000 Danish patients with incident type 2 diabetes during 1998-2015.

The 5-year risk of death in patients who developed heart failure during the first 5 years following an initial diagnosis of T2D was about 48%, about threefold higher than in patients with newly diagnosed T2D who remained free of heart failure or any of the other studied comorbidities, Bochra Zareini, MD, and associates reported in a study published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. The studied patients had no known cardiovascular or renal disease at the time of their first T2D diagnosis.

“Our study reports not only on the absolute 5-year risk” of mortality, “but also takes into consideration when patients developed” a comorbidity. “What is surprising and worrying is the very high risk of death following heart failure and the potential life years lost when compared to T2D patients who do not develop heart failure,” said Dr. Zareini, a cardiologist at Herlev and Gentofte University Hospital in Copenhagen. “The implications of our study are to create awareness and highlight the importance of early detection of heart failure development in patients with T2D.” The results also showed that “heart failure is a common cardiovascular disease” in patients with newly diagnosed T2D, she added in an interview.

The data she and her associates reported came from a retrospective analysis of 153,403 Danish citizens in national health records who received a prescription for an antidiabetes drug for the first time during 1998-2015, excluding patients with a prior diagnosis of heart failure, ischemic heart disease (IHD), stroke, peripheral artery disease (PAD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), or gestational diabetes. They followed these patients for a median of just under 10 years, during which time 45% of the cohort had an incident diagnosis of at least one of these cardiovascular and renal conditions, based on medical-record entries from hospitalization discharges or ambulatory contacts.

Nearly two-thirds of the T2D patients with an incident comorbidity during follow-up had a single new diagnosis, a quarter had two new comorbidities appear during follow-up, and 13% developed at least three new comorbidities.

Heart failure, least common but deadliest comorbidity

The most common of the tracked comorbidities was IHD, which appeared in 8% of the T2D patients within 5 years and in 13% after 10 years. Next most common was stroke, affecting 3% of patients after 5 years and 5% after 10 years. CKD occurred in 2.2% after 5 years and in 4.0% after 10 years, PAD occurred in 2.1% after 5 years and in 3.0% at 10 years, and heart failure occurred in 1.6% at 5 years and in 2.2% after 10 years.

But despite being the least common of the studied comorbidities, heart failure was by far the most deadly, roughly tripling the 5-year mortality rate, compared with T2D patients with no comorbidities, regardless of exactly when it first appeared during the first 5 years after the initial T2D diagnosis. The next most deadly comorbidities were stroke and PAD, which each roughly doubled mortality, compared with the patients who remained free of any studied comorbidity. CKD boosted mortality by 70%-110%, depending on exactly when it appeared during the first 5 years of follow-up, and IHD, while the most frequent comorbidity was also the most benign, increasing mortality by about 30%.

The most deadly combinations of two comorbidities were when heart failure appeared with either CKD or with PAD; each of these combinations boosted mortality by 300%-400% when it occurred during the first few years after a T2D diagnosis.

The findings came from “a very big and unselected patient group of patients, making our results highly generalizable in terms of assessing the prognostic consequences of heart failure,” Dr. Zareini stressed.

Management implications

The dangerous combination of T2D and heart failure has been documented for several years, and prompted a focused statement in 2019 about best practices for managing these patients (Circulation. 2019 Aug 3;140[7]:e294-324). “Heart failure has been known for some time to predict poorer outcomes in patients with T2D. Not much surprising” in the new findings reported by Dr. Zareini and associates, commented Robert H. Eckel, MD, a cardiovascular endocrinologist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. Heart failure “rarely acts alone, but in combination with other forms of heart or renal disease,” he noted in an interview.

Earlier studies may have “overlooked” heart failure’s importance compared with other comorbidities because they often “only investigated one cardiovascular disease in patients with T2D,” Dr. Zareini noted. In recent years the importance of heart failure occurring in patients with T2D also gained heightened significance because of the growing role of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor drug class in treating patients with T2D and the documented ability of these drugs to significantly reduce hospitalizations for heart failure (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Apr 28;75[16]:1956-74). Dr. Zareini and associates put it this way in their report: “Heart failure has in recent years been recognized as an important clinical endpoint ... in patients with T2D, in particular, after the results from randomized, controlled trials of SGLT2 inhibitors showed benefit on cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalizations.”

Despite this, the new findings “do not address treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with T2D, nor can we use our data to address which patients should not be treated,” with this drug class, which instead should rely on “current evidence and expert consensus,” she said.

“Guidelines favor SGLT2 inhibitors or [glucagonlike peptide–1] receptor agonists in patients with a history of or high risk for major adverse coronary events,” and SGLT2 inhibitors are also “preferable in patients with renal disease,” Dr. Eckel noted.

Other avenues also exist for minimizing the onset of heart failure and other cardiovascular diseases in patients with T2D, Dr. Zareini said, citing modifiable risks that lead to heart failure that include hypertension, “diabetic cardiomyopathy,” and ISD. “Clinicians must treat all modifiable risk factors in patients with T2D in order to improve prognosis and limit development of cardiovascular and renal disease.”

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Zareini and Dr. Eckel had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Zareini B et al. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020 Jun 23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.006260.

It’s bad news for patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes when they then develop heart failure during the next few years.

Patients with incident type 2 diabetes (T2D) who soon after also had heart failure appear faced a dramatically elevated mortality risk, higher than the incremental risk from any other cardiovascular or renal comorbidity that appeared following diabetes onset, in an analysis of more than 150,000 Danish patients with incident type 2 diabetes during 1998-2015.

The 5-year risk of death in patients who developed heart failure during the first 5 years following an initial diagnosis of T2D was about 48%, about threefold higher than in patients with newly diagnosed T2D who remained free of heart failure or any of the other studied comorbidities, Bochra Zareini, MD, and associates reported in a study published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. The studied patients had no known cardiovascular or renal disease at the time of their first T2D diagnosis.

“Our study reports not only on the absolute 5-year risk” of mortality, “but also takes into consideration when patients developed” a comorbidity. “What is surprising and worrying is the very high risk of death following heart failure and the potential life years lost when compared to T2D patients who do not develop heart failure,” said Dr. Zareini, a cardiologist at Herlev and Gentofte University Hospital in Copenhagen. “The implications of our study are to create awareness and highlight the importance of early detection of heart failure development in patients with T2D.” The results also showed that “heart failure is a common cardiovascular disease” in patients with newly diagnosed T2D, she added in an interview.

The data she and her associates reported came from a retrospective analysis of 153,403 Danish citizens in national health records who received a prescription for an antidiabetes drug for the first time during 1998-2015, excluding patients with a prior diagnosis of heart failure, ischemic heart disease (IHD), stroke, peripheral artery disease (PAD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), or gestational diabetes. They followed these patients for a median of just under 10 years, during which time 45% of the cohort had an incident diagnosis of at least one of these cardiovascular and renal conditions, based on medical-record entries from hospitalization discharges or ambulatory contacts.

Nearly two-thirds of the T2D patients with an incident comorbidity during follow-up had a single new diagnosis, a quarter had two new comorbidities appear during follow-up, and 13% developed at least three new comorbidities.

Heart failure, least common but deadliest comorbidity

The most common of the tracked comorbidities was IHD, which appeared in 8% of the T2D patients within 5 years and in 13% after 10 years. Next most common was stroke, affecting 3% of patients after 5 years and 5% after 10 years. CKD occurred in 2.2% after 5 years and in 4.0% after 10 years, PAD occurred in 2.1% after 5 years and in 3.0% at 10 years, and heart failure occurred in 1.6% at 5 years and in 2.2% after 10 years.

But despite being the least common of the studied comorbidities, heart failure was by far the most deadly, roughly tripling the 5-year mortality rate, compared with T2D patients with no comorbidities, regardless of exactly when it first appeared during the first 5 years after the initial T2D diagnosis. The next most deadly comorbidities were stroke and PAD, which each roughly doubled mortality, compared with the patients who remained free of any studied comorbidity. CKD boosted mortality by 70%-110%, depending on exactly when it appeared during the first 5 years of follow-up, and IHD, while the most frequent comorbidity was also the most benign, increasing mortality by about 30%.

The most deadly combinations of two comorbidities were when heart failure appeared with either CKD or with PAD; each of these combinations boosted mortality by 300%-400% when it occurred during the first few years after a T2D diagnosis.

The findings came from “a very big and unselected patient group of patients, making our results highly generalizable in terms of assessing the prognostic consequences of heart failure,” Dr. Zareini stressed.

Management implications

The dangerous combination of T2D and heart failure has been documented for several years, and prompted a focused statement in 2019 about best practices for managing these patients (Circulation. 2019 Aug 3;140[7]:e294-324). “Heart failure has been known for some time to predict poorer outcomes in patients with T2D. Not much surprising” in the new findings reported by Dr. Zareini and associates, commented Robert H. Eckel, MD, a cardiovascular endocrinologist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. Heart failure “rarely acts alone, but in combination with other forms of heart or renal disease,” he noted in an interview.

Earlier studies may have “overlooked” heart failure’s importance compared with other comorbidities because they often “only investigated one cardiovascular disease in patients with T2D,” Dr. Zareini noted. In recent years the importance of heart failure occurring in patients with T2D also gained heightened significance because of the growing role of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor drug class in treating patients with T2D and the documented ability of these drugs to significantly reduce hospitalizations for heart failure (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Apr 28;75[16]:1956-74). Dr. Zareini and associates put it this way in their report: “Heart failure has in recent years been recognized as an important clinical endpoint ... in patients with T2D, in particular, after the results from randomized, controlled trials of SGLT2 inhibitors showed benefit on cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalizations.”

Despite this, the new findings “do not address treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with T2D, nor can we use our data to address which patients should not be treated,” with this drug class, which instead should rely on “current evidence and expert consensus,” she said.

“Guidelines favor SGLT2 inhibitors or [glucagonlike peptide–1] receptor agonists in patients with a history of or high risk for major adverse coronary events,” and SGLT2 inhibitors are also “preferable in patients with renal disease,” Dr. Eckel noted.

Other avenues also exist for minimizing the onset of heart failure and other cardiovascular diseases in patients with T2D, Dr. Zareini said, citing modifiable risks that lead to heart failure that include hypertension, “diabetic cardiomyopathy,” and ISD. “Clinicians must treat all modifiable risk factors in patients with T2D in order to improve prognosis and limit development of cardiovascular and renal disease.”

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Zareini and Dr. Eckel had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Zareini B et al. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020 Jun 23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.006260.

FROM CIRCULATION: CARDIOVASCULAR QUALITY AND OUTCOMES

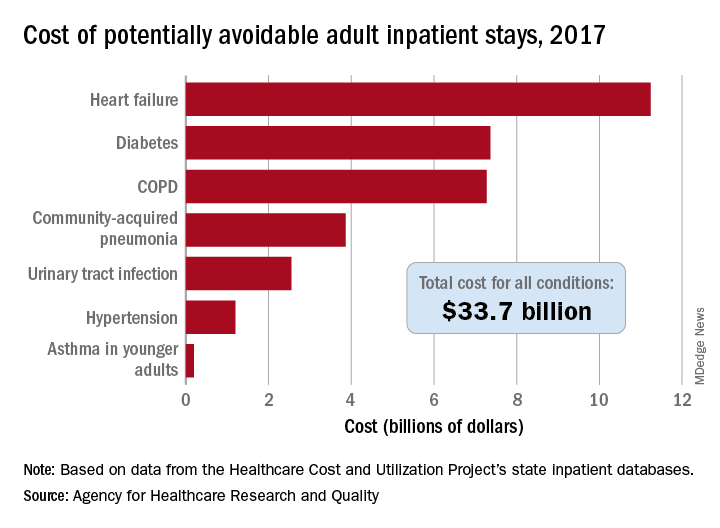

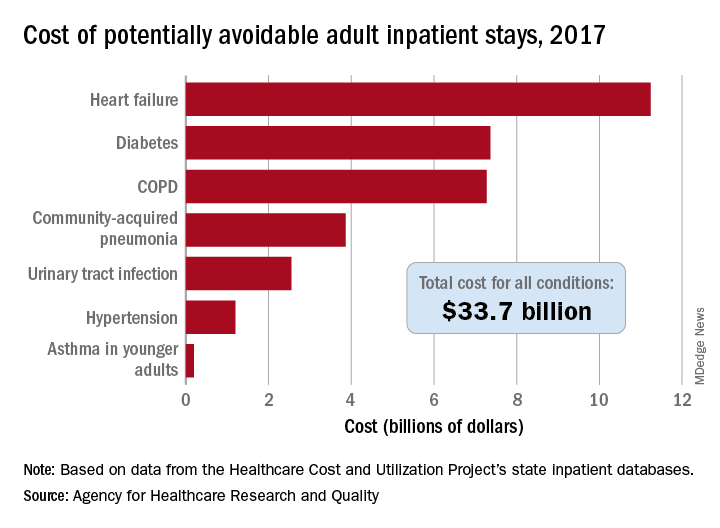

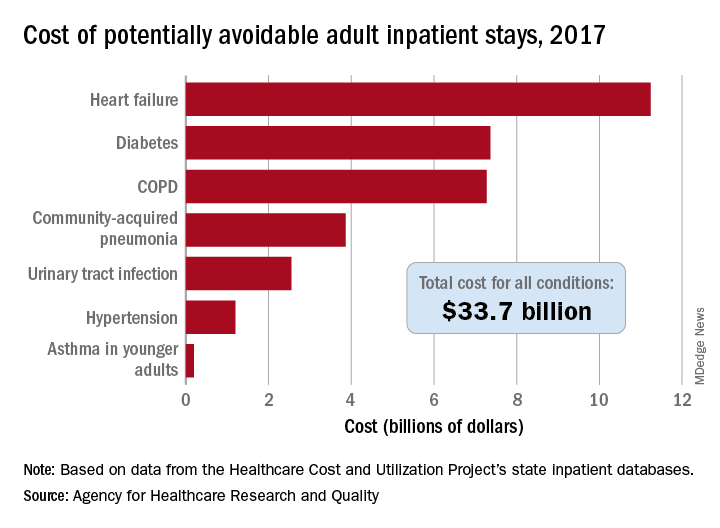

Cost of preventable adult hospital stays topped $33 billion in 2017

according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

That year, there were 27.4 million inpatient visits by adults with a total cost of $380.1 billion, although obstetric stays were not included in the analysis. Of those inpatient admissions, 3.5 million (12.9%) were deemed to be “avoidable, in part, through timely and quality primary and preventive care,” Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and H. Joanna Jiang, PhD, said in a recent AHRQ statistical brief.

The charges for those 3.5 million visits came to $33.7 billion, or 8.9% of aggregate hospital costs in 2017, based on data from the AHRQ Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s state inpatient databases.

“Determining the volume and costs of potentially preventable inpatient stays can identify where potential cost savings might be found associated with reducing these hospitalizations overall and among specific subpopulations,” the investigators pointed out.

Of the seven conditions that are potentially avoidable, heart failure was the most expensive, producing more than 1.1 million inpatient admissions at a cost of $11.2 billion. Diabetes was next with a cost of almost $7.4 billion, followed by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) at nearly $7.3 billion, they said.

Those three conditions, along with hypertension and asthma in younger adults, brought the total cost of the preventable-stay equation’s chronic side to $27.3 billion in 2017, versus $6.4 billion for the two acute conditions, community-acquired pneumonia and urinary tract infections, said Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Dr. Jiang of the AHRQ.

The rate of potentially avoidable stays for chronic conditions was higher for men (1,112/100,000 population) than for women (954/100,000), but women had a higher rate for acute conditions, 346 vs. 257, which made the overall rates similar (1,369 for men and 1,300 for women), they reported.

Differences by race/ethnicity were more striking. The rate of potentially avoidable stays for blacks was 2,573/100,000 in 2017, compared with 1,315 for Hispanics, 1,173 for whites, and 581 for Asians/Pacific Islanders. The considerable margins between those figures, however, were far eclipsed by the “other” category, which had 4,911 stays per 100,000, the researchers said.

Large disparities also can be seen when looking at community-level income. Communities with income in the lowest quartile had a preventable-hospitalization rate of 2,013/100,000, and the rate dropped with each successive quartile until it reached 878/100,000 for the highest-income communities, according to the report.

“High hospital admission rates for these conditions may indicate areas where changes to the healthcare delivery system could be implemented to improve patient outcomes and lower costs,” Dr. McDermott and Dr. Jiang wrote.

SOURCE: McDermott KW and Jiang HJ. HCUP Statistical Brief #259. June 2020.

according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

That year, there were 27.4 million inpatient visits by adults with a total cost of $380.1 billion, although obstetric stays were not included in the analysis. Of those inpatient admissions, 3.5 million (12.9%) were deemed to be “avoidable, in part, through timely and quality primary and preventive care,” Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and H. Joanna Jiang, PhD, said in a recent AHRQ statistical brief.

The charges for those 3.5 million visits came to $33.7 billion, or 8.9% of aggregate hospital costs in 2017, based on data from the AHRQ Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s state inpatient databases.

“Determining the volume and costs of potentially preventable inpatient stays can identify where potential cost savings might be found associated with reducing these hospitalizations overall and among specific subpopulations,” the investigators pointed out.

Of the seven conditions that are potentially avoidable, heart failure was the most expensive, producing more than 1.1 million inpatient admissions at a cost of $11.2 billion. Diabetes was next with a cost of almost $7.4 billion, followed by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) at nearly $7.3 billion, they said.

Those three conditions, along with hypertension and asthma in younger adults, brought the total cost of the preventable-stay equation’s chronic side to $27.3 billion in 2017, versus $6.4 billion for the two acute conditions, community-acquired pneumonia and urinary tract infections, said Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Dr. Jiang of the AHRQ.

The rate of potentially avoidable stays for chronic conditions was higher for men (1,112/100,000 population) than for women (954/100,000), but women had a higher rate for acute conditions, 346 vs. 257, which made the overall rates similar (1,369 for men and 1,300 for women), they reported.

Differences by race/ethnicity were more striking. The rate of potentially avoidable stays for blacks was 2,573/100,000 in 2017, compared with 1,315 for Hispanics, 1,173 for whites, and 581 for Asians/Pacific Islanders. The considerable margins between those figures, however, were far eclipsed by the “other” category, which had 4,911 stays per 100,000, the researchers said.

Large disparities also can be seen when looking at community-level income. Communities with income in the lowest quartile had a preventable-hospitalization rate of 2,013/100,000, and the rate dropped with each successive quartile until it reached 878/100,000 for the highest-income communities, according to the report.

“High hospital admission rates for these conditions may indicate areas where changes to the healthcare delivery system could be implemented to improve patient outcomes and lower costs,” Dr. McDermott and Dr. Jiang wrote.

SOURCE: McDermott KW and Jiang HJ. HCUP Statistical Brief #259. June 2020.

according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

That year, there were 27.4 million inpatient visits by adults with a total cost of $380.1 billion, although obstetric stays were not included in the analysis. Of those inpatient admissions, 3.5 million (12.9%) were deemed to be “avoidable, in part, through timely and quality primary and preventive care,” Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and H. Joanna Jiang, PhD, said in a recent AHRQ statistical brief.

The charges for those 3.5 million visits came to $33.7 billion, or 8.9% of aggregate hospital costs in 2017, based on data from the AHRQ Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s state inpatient databases.

“Determining the volume and costs of potentially preventable inpatient stays can identify where potential cost savings might be found associated with reducing these hospitalizations overall and among specific subpopulations,” the investigators pointed out.

Of the seven conditions that are potentially avoidable, heart failure was the most expensive, producing more than 1.1 million inpatient admissions at a cost of $11.2 billion. Diabetes was next with a cost of almost $7.4 billion, followed by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) at nearly $7.3 billion, they said.

Those three conditions, along with hypertension and asthma in younger adults, brought the total cost of the preventable-stay equation’s chronic side to $27.3 billion in 2017, versus $6.4 billion for the two acute conditions, community-acquired pneumonia and urinary tract infections, said Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Dr. Jiang of the AHRQ.

The rate of potentially avoidable stays for chronic conditions was higher for men (1,112/100,000 population) than for women (954/100,000), but women had a higher rate for acute conditions, 346 vs. 257, which made the overall rates similar (1,369 for men and 1,300 for women), they reported.

Differences by race/ethnicity were more striking. The rate of potentially avoidable stays for blacks was 2,573/100,000 in 2017, compared with 1,315 for Hispanics, 1,173 for whites, and 581 for Asians/Pacific Islanders. The considerable margins between those figures, however, were far eclipsed by the “other” category, which had 4,911 stays per 100,000, the researchers said.

Large disparities also can be seen when looking at community-level income. Communities with income in the lowest quartile had a preventable-hospitalization rate of 2,013/100,000, and the rate dropped with each successive quartile until it reached 878/100,000 for the highest-income communities, according to the report.

“High hospital admission rates for these conditions may indicate areas where changes to the healthcare delivery system could be implemented to improve patient outcomes and lower costs,” Dr. McDermott and Dr. Jiang wrote.

SOURCE: McDermott KW and Jiang HJ. HCUP Statistical Brief #259. June 2020.

Hashtag medicine: #ShareTheMicNowMed highlights Black female physicians on social media

Prominent female physicians are handing over their social media platforms today to black female physicians as part of a campaign called #ShareTheMicNowMed.

The social media event, which will play out on both Twitter and Instagram, is an offshoot of #ShareTheMicNow, held earlier this month. For that event, more than 90 women, including A-list celebrities like Ellen DeGeneres, Julia Roberts, and Senator Elizabeth Warren, swapped accounts with women of color, such as “I’m Still Here” author Austin Channing Brown, Olympic fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad, and #MeToo founder Tarana Burke.

The physician event will feature 10 teams of two, with one physician handing over her account to her black female counterpart for the day. The takeover will allow the black physician to share her thoughts about the successes and challenges she faces as a woman of color in medicine.

“It was such an honor to be contacted by Arghavan Salles, MD, PhD, to participate in an event that has a goal of connecting like-minded women from various backgrounds to share a diverse perspective with a different audience,” Minnesota family medicine physician Jay-Sheree Allen, MD, told Medscape Medical News. “This event is not only incredibly important but timely.”

Only about 5% of all active physicians in 2018 identified as Black or African American, according to a report by the Association of American Medical Colleges. And of those, just over a third are female, the report found.

“I think that as we hear those small numbers we often celebrate the success of those people without looking back and understanding where all of the barriers are that are limiting talented black women from entering medicine at every stage,” another campaign participant, Chicago pediatrician Rebekah Fenton, MD, told Medscape Medical News.

Allen says that, amid continuing worldwide protests over racial injustice, prompted by the death of George Floyd while in Minneapolis police custody last month, the online event is very timely and an important way to advocate for black lives and engage in a productive conversation.

“I believe that with the #ShareTheMicNowMed movement we will start to show people how they can become allies. I always say that a candle loses nothing by lighting another candle, and sharing that stage is one of the many ways you can support the Black Lives Matters movement by amplifying black voices,” she said.

Allen went on to add that women in medicine have many of the same experiences as any other doctor but do face some unique challenges. This is especially true for female physicians of color, she noted.

To join the conversation follow the hashtag #ShareTheMicNowMed all day on Monday, June 22, 2020.

This article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Prominent female physicians are handing over their social media platforms today to black female physicians as part of a campaign called #ShareTheMicNowMed.

The social media event, which will play out on both Twitter and Instagram, is an offshoot of #ShareTheMicNow, held earlier this month. For that event, more than 90 women, including A-list celebrities like Ellen DeGeneres, Julia Roberts, and Senator Elizabeth Warren, swapped accounts with women of color, such as “I’m Still Here” author Austin Channing Brown, Olympic fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad, and #MeToo founder Tarana Burke.

The physician event will feature 10 teams of two, with one physician handing over her account to her black female counterpart for the day. The takeover will allow the black physician to share her thoughts about the successes and challenges she faces as a woman of color in medicine.

“It was such an honor to be contacted by Arghavan Salles, MD, PhD, to participate in an event that has a goal of connecting like-minded women from various backgrounds to share a diverse perspective with a different audience,” Minnesota family medicine physician Jay-Sheree Allen, MD, told Medscape Medical News. “This event is not only incredibly important but timely.”

Only about 5% of all active physicians in 2018 identified as Black or African American, according to a report by the Association of American Medical Colleges. And of those, just over a third are female, the report found.

“I think that as we hear those small numbers we often celebrate the success of those people without looking back and understanding where all of the barriers are that are limiting talented black women from entering medicine at every stage,” another campaign participant, Chicago pediatrician Rebekah Fenton, MD, told Medscape Medical News.

Allen says that, amid continuing worldwide protests over racial injustice, prompted by the death of George Floyd while in Minneapolis police custody last month, the online event is very timely and an important way to advocate for black lives and engage in a productive conversation.

“I believe that with the #ShareTheMicNowMed movement we will start to show people how they can become allies. I always say that a candle loses nothing by lighting another candle, and sharing that stage is one of the many ways you can support the Black Lives Matters movement by amplifying black voices,” she said.

Allen went on to add that women in medicine have many of the same experiences as any other doctor but do face some unique challenges. This is especially true for female physicians of color, she noted.

To join the conversation follow the hashtag #ShareTheMicNowMed all day on Monday, June 22, 2020.

This article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Prominent female physicians are handing over their social media platforms today to black female physicians as part of a campaign called #ShareTheMicNowMed.

The social media event, which will play out on both Twitter and Instagram, is an offshoot of #ShareTheMicNow, held earlier this month. For that event, more than 90 women, including A-list celebrities like Ellen DeGeneres, Julia Roberts, and Senator Elizabeth Warren, swapped accounts with women of color, such as “I’m Still Here” author Austin Channing Brown, Olympic fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad, and #MeToo founder Tarana Burke.

The physician event will feature 10 teams of two, with one physician handing over her account to her black female counterpart for the day. The takeover will allow the black physician to share her thoughts about the successes and challenges she faces as a woman of color in medicine.

“It was such an honor to be contacted by Arghavan Salles, MD, PhD, to participate in an event that has a goal of connecting like-minded women from various backgrounds to share a diverse perspective with a different audience,” Minnesota family medicine physician Jay-Sheree Allen, MD, told Medscape Medical News. “This event is not only incredibly important but timely.”

Only about 5% of all active physicians in 2018 identified as Black or African American, according to a report by the Association of American Medical Colleges. And of those, just over a third are female, the report found.

“I think that as we hear those small numbers we often celebrate the success of those people without looking back and understanding where all of the barriers are that are limiting talented black women from entering medicine at every stage,” another campaign participant, Chicago pediatrician Rebekah Fenton, MD, told Medscape Medical News.

Allen says that, amid continuing worldwide protests over racial injustice, prompted by the death of George Floyd while in Minneapolis police custody last month, the online event is very timely and an important way to advocate for black lives and engage in a productive conversation.

“I believe that with the #ShareTheMicNowMed movement we will start to show people how they can become allies. I always say that a candle loses nothing by lighting another candle, and sharing that stage is one of the many ways you can support the Black Lives Matters movement by amplifying black voices,” she said.

Allen went on to add that women in medicine have many of the same experiences as any other doctor but do face some unique challenges. This is especially true for female physicians of color, she noted.

To join the conversation follow the hashtag #ShareTheMicNowMed all day on Monday, June 22, 2020.

This article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Daily Recap: Headache as COVID evolution predictor; psoriasis drug treats canker sores

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Headache may predict clinical evolution of COVID-19

Headache may be a key symptom of COVID-19 that predicts the disease’s clinical evolution, new research suggests. An observational study of more than 100 patients showed that headache onset could occur during the presymptomatic or symptomatic phase of COVID-19.

Headache itself was associated with a shorter symptomatic period, while headache and anosmia were associated with a shorter hospitalization period.

It seems that those patients who start early on, during the asymptomatic or early symptomatic period of COVID-19, with headache have a more localized inflammatory response that may reflect the ability of the body to better control and respond to the infection,” lead investigator Patricia Pozo-Rosich, MD, PhD, said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society. Read more.

More tops news from the AHS meeting is available on our website.

Pilot study shows apremilast effective for severe recurrent canker sores

Apremilast was highly effective in treating patients with severe recurrent aphthous stomatitis, with rapid response and an excellent safety profile, results from a small pilot study showed.

Apremilast is approved by the FDA for psoriasis and was shown in a recent phase 2 trial to be effective for Behçet’s disease aphthosis.

Dr. Alison Bruce and colleagues found that, within 4 weeks of therapy, complete clearance of RAS lesions occurred in all patients except one in whom ulcers were reported to be less severe. Remission in all patients was sustained during 16 weeks of treatment, Dr. Bruce noted at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. Read more.

For more top news from the AAD virtual conference, visit our website.

Where does dexamethasone fit in with diabetic ketoacidosis in COVID-19?

A new article in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (JCEM) addresses unique concerns and considerations regarding diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) in the setting of COVID-19.

“Hospitals and clinicians need to be able to quickly identify and manage DKA in COVID patients to save lives. This involves determining the options for management, including when less intensive subcutaneous insulin is indicated, and understanding how to guide patients on avoiding this serious complication,” corresponding author Marie E. McDonnell, MD, said in an Endocrine Society statement.

The new article briefly touches on the fact that upward adjustments to intensive intravenous insulin therapy for DKA may be necessary in patients with COVID-19 who are receiving concomitant corticosteroids or vasopressors. But it was written prior to the June 16 announcement of the “RECOVERY” trial results with dexamethasone. The UK National Health Service immediately approved the drug’s use in the COVID-19 setting, despite the fact that there has been no published article on the findings yet.

“The peer review will be critical. It looks as if it only benefits people who need respiratory support, but I want to understand that in much more detail,” said Dr. McDonnell. Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Headache may predict clinical evolution of COVID-19

Headache may be a key symptom of COVID-19 that predicts the disease’s clinical evolution, new research suggests. An observational study of more than 100 patients showed that headache onset could occur during the presymptomatic or symptomatic phase of COVID-19.

Headache itself was associated with a shorter symptomatic period, while headache and anosmia were associated with a shorter hospitalization period.

It seems that those patients who start early on, during the asymptomatic or early symptomatic period of COVID-19, with headache have a more localized inflammatory response that may reflect the ability of the body to better control and respond to the infection,” lead investigator Patricia Pozo-Rosich, MD, PhD, said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society. Read more.

More tops news from the AHS meeting is available on our website.

Pilot study shows apremilast effective for severe recurrent canker sores

Apremilast was highly effective in treating patients with severe recurrent aphthous stomatitis, with rapid response and an excellent safety profile, results from a small pilot study showed.

Apremilast is approved by the FDA for psoriasis and was shown in a recent phase 2 trial to be effective for Behçet’s disease aphthosis.

Dr. Alison Bruce and colleagues found that, within 4 weeks of therapy, complete clearance of RAS lesions occurred in all patients except one in whom ulcers were reported to be less severe. Remission in all patients was sustained during 16 weeks of treatment, Dr. Bruce noted at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. Read more.

For more top news from the AAD virtual conference, visit our website.

Where does dexamethasone fit in with diabetic ketoacidosis in COVID-19?

A new article in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (JCEM) addresses unique concerns and considerations regarding diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) in the setting of COVID-19.

“Hospitals and clinicians need to be able to quickly identify and manage DKA in COVID patients to save lives. This involves determining the options for management, including when less intensive subcutaneous insulin is indicated, and understanding how to guide patients on avoiding this serious complication,” corresponding author Marie E. McDonnell, MD, said in an Endocrine Society statement.

The new article briefly touches on the fact that upward adjustments to intensive intravenous insulin therapy for DKA may be necessary in patients with COVID-19 who are receiving concomitant corticosteroids or vasopressors. But it was written prior to the June 16 announcement of the “RECOVERY” trial results with dexamethasone. The UK National Health Service immediately approved the drug’s use in the COVID-19 setting, despite the fact that there has been no published article on the findings yet.

“The peer review will be critical. It looks as if it only benefits people who need respiratory support, but I want to understand that in much more detail,” said Dr. McDonnell. Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Headache may predict clinical evolution of COVID-19

Headache may be a key symptom of COVID-19 that predicts the disease’s clinical evolution, new research suggests. An observational study of more than 100 patients showed that headache onset could occur during the presymptomatic or symptomatic phase of COVID-19.

Headache itself was associated with a shorter symptomatic period, while headache and anosmia were associated with a shorter hospitalization period.

It seems that those patients who start early on, during the asymptomatic or early symptomatic period of COVID-19, with headache have a more localized inflammatory response that may reflect the ability of the body to better control and respond to the infection,” lead investigator Patricia Pozo-Rosich, MD, PhD, said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society. Read more.

More tops news from the AHS meeting is available on our website.

Pilot study shows apremilast effective for severe recurrent canker sores

Apremilast was highly effective in treating patients with severe recurrent aphthous stomatitis, with rapid response and an excellent safety profile, results from a small pilot study showed.

Apremilast is approved by the FDA for psoriasis and was shown in a recent phase 2 trial to be effective for Behçet’s disease aphthosis.

Dr. Alison Bruce and colleagues found that, within 4 weeks of therapy, complete clearance of RAS lesions occurred in all patients except one in whom ulcers were reported to be less severe. Remission in all patients was sustained during 16 weeks of treatment, Dr. Bruce noted at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. Read more.

For more top news from the AAD virtual conference, visit our website.

Where does dexamethasone fit in with diabetic ketoacidosis in COVID-19?

A new article in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (JCEM) addresses unique concerns and considerations regarding diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) in the setting of COVID-19.

“Hospitals and clinicians need to be able to quickly identify and manage DKA in COVID patients to save lives. This involves determining the options for management, including when less intensive subcutaneous insulin is indicated, and understanding how to guide patients on avoiding this serious complication,” corresponding author Marie E. McDonnell, MD, said in an Endocrine Society statement.

The new article briefly touches on the fact that upward adjustments to intensive intravenous insulin therapy for DKA may be necessary in patients with COVID-19 who are receiving concomitant corticosteroids or vasopressors. But it was written prior to the June 16 announcement of the “RECOVERY” trial results with dexamethasone. The UK National Health Service immediately approved the drug’s use in the COVID-19 setting, despite the fact that there has been no published article on the findings yet.

“The peer review will be critical. It looks as if it only benefits people who need respiratory support, but I want to understand that in much more detail,” said Dr. McDonnell. Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

‘Collateral damage’: COVID-19 threatens patients with COPD

according to a commentary published in CHEST (2020 May 28. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.549) by a group of physicians who study COPD.

Not only is COPD among the most prevalent underlying diseases among hospitalized COVID-19 patients (Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020 Jun 8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.05.041), but other unanticipated factors of treatment put these patients at extra risk. Valerie Press, MD, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of Chicago, and colleagues aimed to alert physicians to be aware of potential negative effects, or collateral damage, that the pandemic can have on their patients with COPD, even those without a COVID-19 diagnosis.

These concerns include that patients may delay presenting to the ED with acute exacerbations of COPD and once they present they may be at later stages of the exacerbation. Further, evaluation for COVID-19 as a possible trigger of acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) is essential; however, implementing proven AECOPD therapies remains challenging. For instance, routine therapy with corticosteroids for AECOPD may be delayed due to diagnostic uncertainty and hesitation to treat COVID-19 with steroids while COVID-19 testing is pending,” Dr. Press and her colleagues stated.

Shortages and scarcity of medications such as albuterol inhalers to treat COPD have been reported. In addition, patients with COPD are currently less likely to access their health care providers because of fear of COVID-19 infection. This barrier to care and the current higher threshold for presenting to the hospital may to lead to more cases of AECOPD and worsening health in these patients, according to the authors.

Dr. Press said in an interview: “Access to medications delivered through inhalers is challenging even without the pandemic due to high cost of medications. Generic medications are key to improving access for patients with chronic lung disease, so once the generic albuterol becomes available, this should help with access. In the meantime, some companies help provide medications at reduced cost, but usually only on a short time basis. In addition, some pharmacies have lower-cost albuterol inhalers, but these are often not supplied with a full month of dosing.”

In addition to all these concerns is the economic toll this pandemic is taking on patients. The association between COPD and socioeconomic status has been studied in depth (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019; 199[8]:961-69) and would indicate that low-income patients with COPD would face an increased burden during an economic downturn. The authors noted, “Historic rapid job loss and unemployment in the U.S., coupled with a health system of employment-integrated health insurance coverage, makes it more likely that people with COPD will not be able to afford their medication.”

Dr. Press stressed that the COVID pandemic has highlighted critically important disparities in access to health care and disparities in health. “Many of the recommendations regarding stay-at-home and other safety mechanisms to prevent contracting and spreading COVID-19 have not been feasible for all sub-populations in the United States. Those that were essential workers did not have the ability to stay home. Further, those that rely on public transportation had less opportunities to social distance. Finally, while telemedicine opportunities have advanced for clinical care, not all patients have equal access to these capabilities and health disparities could widen in this regard as well. Clinicians have a responsibility to identify social determinants of health that increase risks to our patients’ health and limit their safety.”*

The authors offer some concrete suggestions of how physicians can address some of these concerns, including the following:

- Be alert to potential barriers to accessing medication and be aware of generic albuterol inhaler recently approved by the FDA in response to COVID-19–related shortages.

- Use telemedicine to monitor patients and improvement of home self-management. Clinicians should help patients “seek care with worsening symptoms and have clear management guidelines regarding seeking phone/video visits; implementing therapy with corticosteroids, antibiotics, or inhalers and nebulizers; COVID-19 testing recommendations; and thresholds for seeking emergent, urgent, or outpatient care in person,” Dr. Press added, “Building on the work of nurse advice lines and case management and other support services for high-risk patients with COPD may continue via telehealth and telephone visits.”

- Ensure that untried therapy for COVID-19 “does not displace proven and necessary treatments for patients with COPD, hence placing them at increased risk for poor outcomes.”

Dr. Press is also concerned about the post–COVID-19 period for patients with COPD. “It is too early to know if there are specific after effects of the COVID infection on patients with COPD, but given the damage the virus does to even healthy lungs, there is reason to have concern that COVID could cause worsening damage to the lungs of individuals with COPD.”

She noted, “Post-ICU [PICU] syndrome has been recognized in patients with ARDS generally, and patients who recover from critical illness may have long-lasting (and permanent) effects on strength, cognition, disability, and pulmonary function. Whether the PICU syndrome in patients with ARDS due to COVID-19 specifically is different from the PICU syndrome due to other causes remains unknown. But clinicians whose patients with COPD survive COVID-19 may expect long-lasting effects and slow recovery in cases where COVID-19 led to severe ARDS and a prolonged ICU stay. Assessment of overall patient recovery and functional capacity (beyond lung function and dyspnea symptoms) including deconditioning, anxiety, PTSD, weakness, and malnutrition will need to be addressed. Additionally, clinicians may help patients and their families understand the expected recovery and help facilitate family conversations about residual effects of COVID-19.”

The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Press V et al. Chest. 2020 May 28. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.549.

CORRECTION: *This story was updated with further comments and clarifications from Dr. Press. 6/23/2020

according to a commentary published in CHEST (2020 May 28. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.549) by a group of physicians who study COPD.

Not only is COPD among the most prevalent underlying diseases among hospitalized COVID-19 patients (Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020 Jun 8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.05.041), but other unanticipated factors of treatment put these patients at extra risk. Valerie Press, MD, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of Chicago, and colleagues aimed to alert physicians to be aware of potential negative effects, or collateral damage, that the pandemic can have on their patients with COPD, even those without a COVID-19 diagnosis.

These concerns include that patients may delay presenting to the ED with acute exacerbations of COPD and once they present they may be at later stages of the exacerbation. Further, evaluation for COVID-19 as a possible trigger of acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) is essential; however, implementing proven AECOPD therapies remains challenging. For instance, routine therapy with corticosteroids for AECOPD may be delayed due to diagnostic uncertainty and hesitation to treat COVID-19 with steroids while COVID-19 testing is pending,” Dr. Press and her colleagues stated.

Shortages and scarcity of medications such as albuterol inhalers to treat COPD have been reported. In addition, patients with COPD are currently less likely to access their health care providers because of fear of COVID-19 infection. This barrier to care and the current higher threshold for presenting to the hospital may to lead to more cases of AECOPD and worsening health in these patients, according to the authors.

Dr. Press said in an interview: “Access to medications delivered through inhalers is challenging even without the pandemic due to high cost of medications. Generic medications are key to improving access for patients with chronic lung disease, so once the generic albuterol becomes available, this should help with access. In the meantime, some companies help provide medications at reduced cost, but usually only on a short time basis. In addition, some pharmacies have lower-cost albuterol inhalers, but these are often not supplied with a full month of dosing.”

In addition to all these concerns is the economic toll this pandemic is taking on patients. The association between COPD and socioeconomic status has been studied in depth (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019; 199[8]:961-69) and would indicate that low-income patients with COPD would face an increased burden during an economic downturn. The authors noted, “Historic rapid job loss and unemployment in the U.S., coupled with a health system of employment-integrated health insurance coverage, makes it more likely that people with COPD will not be able to afford their medication.”

Dr. Press stressed that the COVID pandemic has highlighted critically important disparities in access to health care and disparities in health. “Many of the recommendations regarding stay-at-home and other safety mechanisms to prevent contracting and spreading COVID-19 have not been feasible for all sub-populations in the United States. Those that were essential workers did not have the ability to stay home. Further, those that rely on public transportation had less opportunities to social distance. Finally, while telemedicine opportunities have advanced for clinical care, not all patients have equal access to these capabilities and health disparities could widen in this regard as well. Clinicians have a responsibility to identify social determinants of health that increase risks to our patients’ health and limit their safety.”*

The authors offer some concrete suggestions of how physicians can address some of these concerns, including the following:

- Be alert to potential barriers to accessing medication and be aware of generic albuterol inhaler recently approved by the FDA in response to COVID-19–related shortages.

- Use telemedicine to monitor patients and improvement of home self-management. Clinicians should help patients “seek care with worsening symptoms and have clear management guidelines regarding seeking phone/video visits; implementing therapy with corticosteroids, antibiotics, or inhalers and nebulizers; COVID-19 testing recommendations; and thresholds for seeking emergent, urgent, or outpatient care in person,” Dr. Press added, “Building on the work of nurse advice lines and case management and other support services for high-risk patients with COPD may continue via telehealth and telephone visits.”

- Ensure that untried therapy for COVID-19 “does not displace proven and necessary treatments for patients with COPD, hence placing them at increased risk for poor outcomes.”

Dr. Press is also concerned about the post–COVID-19 period for patients with COPD. “It is too early to know if there are specific after effects of the COVID infection on patients with COPD, but given the damage the virus does to even healthy lungs, there is reason to have concern that COVID could cause worsening damage to the lungs of individuals with COPD.”

She noted, “Post-ICU [PICU] syndrome has been recognized in patients with ARDS generally, and patients who recover from critical illness may have long-lasting (and permanent) effects on strength, cognition, disability, and pulmonary function. Whether the PICU syndrome in patients with ARDS due to COVID-19 specifically is different from the PICU syndrome due to other causes remains unknown. But clinicians whose patients with COPD survive COVID-19 may expect long-lasting effects and slow recovery in cases where COVID-19 led to severe ARDS and a prolonged ICU stay. Assessment of overall patient recovery and functional capacity (beyond lung function and dyspnea symptoms) including deconditioning, anxiety, PTSD, weakness, and malnutrition will need to be addressed. Additionally, clinicians may help patients and their families understand the expected recovery and help facilitate family conversations about residual effects of COVID-19.”

The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Press V et al. Chest. 2020 May 28. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.549.

CORRECTION: *This story was updated with further comments and clarifications from Dr. Press. 6/23/2020

according to a commentary published in CHEST (2020 May 28. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.549) by a group of physicians who study COPD.

Not only is COPD among the most prevalent underlying diseases among hospitalized COVID-19 patients (Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020 Jun 8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.05.041), but other unanticipated factors of treatment put these patients at extra risk. Valerie Press, MD, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of Chicago, and colleagues aimed to alert physicians to be aware of potential negative effects, or collateral damage, that the pandemic can have on their patients with COPD, even those without a COVID-19 diagnosis.

These concerns include that patients may delay presenting to the ED with acute exacerbations of COPD and once they present they may be at later stages of the exacerbation. Further, evaluation for COVID-19 as a possible trigger of acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) is essential; however, implementing proven AECOPD therapies remains challenging. For instance, routine therapy with corticosteroids for AECOPD may be delayed due to diagnostic uncertainty and hesitation to treat COVID-19 with steroids while COVID-19 testing is pending,” Dr. Press and her colleagues stated.

Shortages and scarcity of medications such as albuterol inhalers to treat COPD have been reported. In addition, patients with COPD are currently less likely to access their health care providers because of fear of COVID-19 infection. This barrier to care and the current higher threshold for presenting to the hospital may to lead to more cases of AECOPD and worsening health in these patients, according to the authors.

Dr. Press said in an interview: “Access to medications delivered through inhalers is challenging even without the pandemic due to high cost of medications. Generic medications are key to improving access for patients with chronic lung disease, so once the generic albuterol becomes available, this should help with access. In the meantime, some companies help provide medications at reduced cost, but usually only on a short time basis. In addition, some pharmacies have lower-cost albuterol inhalers, but these are often not supplied with a full month of dosing.”

In addition to all these concerns is the economic toll this pandemic is taking on patients. The association between COPD and socioeconomic status has been studied in depth (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019; 199[8]:961-69) and would indicate that low-income patients with COPD would face an increased burden during an economic downturn. The authors noted, “Historic rapid job loss and unemployment in the U.S., coupled with a health system of employment-integrated health insurance coverage, makes it more likely that people with COPD will not be able to afford their medication.”

Dr. Press stressed that the COVID pandemic has highlighted critically important disparities in access to health care and disparities in health. “Many of the recommendations regarding stay-at-home and other safety mechanisms to prevent contracting and spreading COVID-19 have not been feasible for all sub-populations in the United States. Those that were essential workers did not have the ability to stay home. Further, those that rely on public transportation had less opportunities to social distance. Finally, while telemedicine opportunities have advanced for clinical care, not all patients have equal access to these capabilities and health disparities could widen in this regard as well. Clinicians have a responsibility to identify social determinants of health that increase risks to our patients’ health and limit their safety.”*

The authors offer some concrete suggestions of how physicians can address some of these concerns, including the following:

- Be alert to potential barriers to accessing medication and be aware of generic albuterol inhaler recently approved by the FDA in response to COVID-19–related shortages.

- Use telemedicine to monitor patients and improvement of home self-management. Clinicians should help patients “seek care with worsening symptoms and have clear management guidelines regarding seeking phone/video visits; implementing therapy with corticosteroids, antibiotics, or inhalers and nebulizers; COVID-19 testing recommendations; and thresholds for seeking emergent, urgent, or outpatient care in person,” Dr. Press added, “Building on the work of nurse advice lines and case management and other support services for high-risk patients with COPD may continue via telehealth and telephone visits.”

- Ensure that untried therapy for COVID-19 “does not displace proven and necessary treatments for patients with COPD, hence placing them at increased risk for poor outcomes.”

Dr. Press is also concerned about the post–COVID-19 period for patients with COPD. “It is too early to know if there are specific after effects of the COVID infection on patients with COPD, but given the damage the virus does to even healthy lungs, there is reason to have concern that COVID could cause worsening damage to the lungs of individuals with COPD.”

She noted, “Post-ICU [PICU] syndrome has been recognized in patients with ARDS generally, and patients who recover from critical illness may have long-lasting (and permanent) effects on strength, cognition, disability, and pulmonary function. Whether the PICU syndrome in patients with ARDS due to COVID-19 specifically is different from the PICU syndrome due to other causes remains unknown. But clinicians whose patients with COPD survive COVID-19 may expect long-lasting effects and slow recovery in cases where COVID-19 led to severe ARDS and a prolonged ICU stay. Assessment of overall patient recovery and functional capacity (beyond lung function and dyspnea symptoms) including deconditioning, anxiety, PTSD, weakness, and malnutrition will need to be addressed. Additionally, clinicians may help patients and their families understand the expected recovery and help facilitate family conversations about residual effects of COVID-19.”

The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Press V et al. Chest. 2020 May 28. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.549.

CORRECTION: *This story was updated with further comments and clarifications from Dr. Press. 6/23/2020

FROM CHEST

Where does dexamethasone fit in with diabetic ketoacidosis in COVID-19?

A new article in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (JCEM) addresses unique concerns and considerations regarding diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) in the setting of COVID-19.

Corresponding author Marie E. McDonnell, MD, director of the diabetes program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, discussed the recommendations with Medscape Medical News and also spoke about the news this week that the corticosteroid dexamethasone reduced death rates in severely ill patients with COVID-19.

The full JCEM article, by lead author Nadine E. Palermo, DO, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Hypertension, also at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, covers DKA diagnosis and triage, and emphasizes that usual hospital protocols for DKA management may need to be adjusted during COVID-19 to help preserve personal protective equipment and ICU beds.

“Hospitals and clinicians need to be able to quickly identify and manage DKA in COVID patients to save lives. This involves determining the options for management, including when less intensive subcutaneous insulin is indicated, and understanding how to guide patients on avoiding this serious complication,” McDonnell said in an Endocrine Society statement.

What about dexamethasone for severe COVID-19 in diabetes?

The new article briefly touches on the fact that upward adjustments to intensive intravenous insulin therapy for DKA may be necessary in patients with COVID-19 who are receiving concomitant corticosteroids or vasopressors.

But it was written prior to the June 16 announcement of the “RECOVERY” trial results with dexamethasone. The UK National Health Service immediately approved the drug’s use in the COVID-19 setting, despite the fact that there has been no published article on the findings yet.

McDonnell told Medscape Medical News that she would need to see formal results to better understand exactly which patients were studied and which ones benefited.

“The peer review will be critical. It looks as if it only benefits people who need respiratory support, but I want to understand that in much more detail,” she said. “If they all had acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS],” that’s different.

“There are already some data supporting steroid use in ARDS,” she noted, but added that not all of it suggests benefit.

She pointed to one of several studies now showing that diabetes, and hyperglycemia among people without a prior diabetes diagnosis, are both strong predictors of mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

“There was a very clear relationship between hyperglycemia and outcomes. We really shouldn’t put people at risk until we have clear data,” she said.

If, once the data are reviewed and appropriate dexamethasone becomes an established treatment for severe COVID-19, hyperglycemia would be a concern among all patients, not just those with previously diagnosed diabetes, she noted.

“We know a good number of people with prediabetes develop hyperglycemia when put on steroids. They can push people over the edge. We’re not going to miss anybody, but treating steroid-induced hyperglycemia is really hard,” McDonnell explained.

She also recommended 2014 guidance from Diabetes UK and the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists, which addresses management of inpatient steroid-induced DKA in patients with and without pre-existing diabetes.

Another major concern, she said, is “patients trying to get dexamethasone when they start to get sick” because this is not the right population to use this agent.

“We worry about people who do not need this drug. If they have diabetes, they put themselves at risk of hyperglycemia, which then increases the risk of severe COVID-19. And then they’re also putting themselves at risk of DKA. It would just be bad medicine,” she said.

Managing DKA in the face of COVID-19: Flexibility is key

In the JCEM article, Palermo and colleagues emphasize that the usual hospital protocols for DKA management may need to be adjusted during COVID-19 in the interest of reducing transmission risk and preserving scare resources.

They provide evidence for alternative treatment strategies, such as the use of subcutaneous rather than intravenous insulin when appropriate.

“We wanted to outline when exactly you should consider nonintensive management strategies for DKA,” McDonnell further explained to Medscape Medical News.

“That would include those with mild or some with moderate DKA. ... The idea is to remind our colleagues about that because hospitals tend to operate on a protocol-driven algorithmic methodology, they can forget to step off the usual care pathway even if evidence supports that,” she said.

But on the other hand, she also said that, in some very complex or severely ill patients with COVID-19, classical intravenous insulin therapy makes the most sense even if their DKA is mild.

The outpatient setting: Prevention and preparation

The new article also addresses several concerns regarding DKA prevention in the outpatient setting.

As with other guidelines, it includes a reminder that patients with diabetes should be advised to discontinue sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors if they become ill with COVID-19, especially if they’re not eating or drinking normally, because they raise the risk for DKA.

Also, for patients with type 1 diabetes, particularly those with a history of repeated DKA, “this is the time to make sure we reach out to patients to refill their insulin prescriptions and address issues related to cost and other access difficulties,” McDonnell said.

The authors also emphasize that insulin starts and education should not be postponed during the pandemic. “Patients identified as meeting criteria to start insulin should be referred for urgent education, either in person or, whenever possible and practical, via video teleconferencing,” they urge.

McDonnell has reported receiving research funding from Novo Nordisk. The other two authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new article in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (JCEM) addresses unique concerns and considerations regarding diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) in the setting of COVID-19.

Corresponding author Marie E. McDonnell, MD, director of the diabetes program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, discussed the recommendations with Medscape Medical News and also spoke about the news this week that the corticosteroid dexamethasone reduced death rates in severely ill patients with COVID-19.

The full JCEM article, by lead author Nadine E. Palermo, DO, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Hypertension, also at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, covers DKA diagnosis and triage, and emphasizes that usual hospital protocols for DKA management may need to be adjusted during COVID-19 to help preserve personal protective equipment and ICU beds.

“Hospitals and clinicians need to be able to quickly identify and manage DKA in COVID patients to save lives. This involves determining the options for management, including when less intensive subcutaneous insulin is indicated, and understanding how to guide patients on avoiding this serious complication,” McDonnell said in an Endocrine Society statement.

What about dexamethasone for severe COVID-19 in diabetes?

The new article briefly touches on the fact that upward adjustments to intensive intravenous insulin therapy for DKA may be necessary in patients with COVID-19 who are receiving concomitant corticosteroids or vasopressors.

But it was written prior to the June 16 announcement of the “RECOVERY” trial results with dexamethasone. The UK National Health Service immediately approved the drug’s use in the COVID-19 setting, despite the fact that there has been no published article on the findings yet.

McDonnell told Medscape Medical News that she would need to see formal results to better understand exactly which patients were studied and which ones benefited.

“The peer review will be critical. It looks as if it only benefits people who need respiratory support, but I want to understand that in much more detail,” she said. “If they all had acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS],” that’s different.

“There are already some data supporting steroid use in ARDS,” she noted, but added that not all of it suggests benefit.

She pointed to one of several studies now showing that diabetes, and hyperglycemia among people without a prior diabetes diagnosis, are both strong predictors of mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

“There was a very clear relationship between hyperglycemia and outcomes. We really shouldn’t put people at risk until we have clear data,” she said.

If, once the data are reviewed and appropriate dexamethasone becomes an established treatment for severe COVID-19, hyperglycemia would be a concern among all patients, not just those with previously diagnosed diabetes, she noted.

“We know a good number of people with prediabetes develop hyperglycemia when put on steroids. They can push people over the edge. We’re not going to miss anybody, but treating steroid-induced hyperglycemia is really hard,” McDonnell explained.

She also recommended 2014 guidance from Diabetes UK and the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists, which addresses management of inpatient steroid-induced DKA in patients with and without pre-existing diabetes.

Another major concern, she said, is “patients trying to get dexamethasone when they start to get sick” because this is not the right population to use this agent.

“We worry about people who do not need this drug. If they have diabetes, they put themselves at risk of hyperglycemia, which then increases the risk of severe COVID-19. And then they’re also putting themselves at risk of DKA. It would just be bad medicine,” she said.

Managing DKA in the face of COVID-19: Flexibility is key

In the JCEM article, Palermo and colleagues emphasize that the usual hospital protocols for DKA management may need to be adjusted during COVID-19 in the interest of reducing transmission risk and preserving scare resources.

They provide evidence for alternative treatment strategies, such as the use of subcutaneous rather than intravenous insulin when appropriate.

“We wanted to outline when exactly you should consider nonintensive management strategies for DKA,” McDonnell further explained to Medscape Medical News.

“That would include those with mild or some with moderate DKA. ... The idea is to remind our colleagues about that because hospitals tend to operate on a protocol-driven algorithmic methodology, they can forget to step off the usual care pathway even if evidence supports that,” she said.

But on the other hand, she also said that, in some very complex or severely ill patients with COVID-19, classical intravenous insulin therapy makes the most sense even if their DKA is mild.

The outpatient setting: Prevention and preparation