User login

Cardiology News is an independent news source that provides cardiologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on cardiology and the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is the online destination and multimedia properties of Cardiology News, the independent news publication for cardiologists. Cardiology news is the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in cardiology as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

Seniors face higher risk of other medical conditions after COVID-19

The findings of the observational study, which were published in the BMJ, show the risk of a new condition being triggered by COVID is more than twice as high in seniors, compared with younger patients. Plus, the researchers observed an even higher risk among those who were hospitalized, with nearly half (46%) of patients having developed new conditions after the acute COVID-19 infection period.

Respiratory failure with shortness of breath was the most common postacute sequela, but a wide range of heart, kidney, lung, liver, cognitive, mental health, and other conditions were diagnosed at least 3 weeks after initial infection and persisted beyond 30 days.

This is one of the first studies to specifically describe the incidence and severity of new conditions triggered by COVID-19 infection in a general sample of older adults, said study author Ken Cohen MD, FACP, executive director of translational research at Optum Labs and national senior medical director at Optum Care.

“Much of what has been published on the postacute sequelae of COVID-19 has been predominantly from a younger population, and many of the patients had been hospitalized,” Dr. Cohen noted. “This was the first study to focus on a large population of seniors, most of whom did not require hospitalization.”

Dr. Cohen and colleagues reviewed the health insurance records of more than 133,000 Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 or older who were diagnosed with COVID-19 before April 2020. They also matched individuals by age, race, sex, hospitalization status, and other factors to comparison groups without COVID-19 (one from 2020 and one from 2019), and to a group diagnosed with other lower respiratory tract viral infections before the pandemic.

Risk of developing new conditions was higher in hospitalized

After acute COVID-19 infection, 32% of seniors sought medical care for at least one new medical condition in 2020, compared with 21% of uninfected people in the same year.

The most commonly observed conditions included:

- Respiratory failure (7.55% higher risk).

- Fatigue (5.66% higher risk).

- High blood pressure (4.43% higher risk).

- Memory problems (2.63% higher risk).

- Kidney injury (2.59% higher risk).

- Mental health diagnoses (2.5% higher risk).

- Blood-clotting disorders (1.47 % higher risk).

- Heart rhythm disorders (2.9% higher risk).

The risk of developing new conditions was even higher among those 23,486 who were hospitalized in 2020. Those individuals showed a 23.6% higher risk for developing at least one new condition, compared with uninfected seniors in the same year. Also, patients older than 75 had a higher risk for neurological disorders, including dementia, encephalopathy, and memory problems. The researchers also found that respiratory failure and kidney injury were significantly more likely to affect men and Black patients.

When those who had COVID were compared with the group with other lower respiratory viral infections before the pandemic, only the risks of respiratory failure (2.39% higher), dementia (0.71% higher), and fatigue (0.18% higher) were higher.

Primary care providers can learn from these data to better evaluate and manage their geriatric patients with COVID-19 infection, said Amit Shah, MD, a geriatrician with the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, in an interview.

“We must assess older patients who have had COVID-19 for more than just improvement from the respiratory symptoms of COVID-19 in post-COVID follow-up visits,” he said. “Older individuals with frailty have vulnerability to subsequent complications from severe illnesses and it is common to see post-illness diagnoses, such as new diagnosis of delirium; dementia; or renal, respiratory, or cardiac issues that is precipitated by the original illness. This study confirms that this is likely the case with COVID-19 as well.

“Primary care physicians should be vigilant for these complications, including attention to the rehabilitation needs of older patients with longer-term postviral fatigue from COVID-19,” Dr. Shah added.

Data predates ‘Omicron wave’

It remains uncertain whether sequelae will differ with the Omicron variant, but the findings remain applicable, Dr. Cohen said.

“We know that illness from the Omicron variant is on average less severe in those that have been vaccinated. However, throughout the Omicron wave, individuals who have not been vaccinated continue to have significant rates of serious illness and hospitalization,” he said.

“Our findings showed that serious illness with hospitalization was associated with a higher rate of sequelae. It can therefore be inferred that the rates of sequelae seen in our study would continue to occur in unvaccinated individuals who contract Omicron, but might occur less frequently in vaccinated individuals who contract Omicron and have less severe illness.”

Dr. Cohen serves as a consultant for Pfizer. Dr. Shah has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The findings of the observational study, which were published in the BMJ, show the risk of a new condition being triggered by COVID is more than twice as high in seniors, compared with younger patients. Plus, the researchers observed an even higher risk among those who were hospitalized, with nearly half (46%) of patients having developed new conditions after the acute COVID-19 infection period.

Respiratory failure with shortness of breath was the most common postacute sequela, but a wide range of heart, kidney, lung, liver, cognitive, mental health, and other conditions were diagnosed at least 3 weeks after initial infection and persisted beyond 30 days.

This is one of the first studies to specifically describe the incidence and severity of new conditions triggered by COVID-19 infection in a general sample of older adults, said study author Ken Cohen MD, FACP, executive director of translational research at Optum Labs and national senior medical director at Optum Care.

“Much of what has been published on the postacute sequelae of COVID-19 has been predominantly from a younger population, and many of the patients had been hospitalized,” Dr. Cohen noted. “This was the first study to focus on a large population of seniors, most of whom did not require hospitalization.”

Dr. Cohen and colleagues reviewed the health insurance records of more than 133,000 Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 or older who were diagnosed with COVID-19 before April 2020. They also matched individuals by age, race, sex, hospitalization status, and other factors to comparison groups without COVID-19 (one from 2020 and one from 2019), and to a group diagnosed with other lower respiratory tract viral infections before the pandemic.

Risk of developing new conditions was higher in hospitalized

After acute COVID-19 infection, 32% of seniors sought medical care for at least one new medical condition in 2020, compared with 21% of uninfected people in the same year.

The most commonly observed conditions included:

- Respiratory failure (7.55% higher risk).

- Fatigue (5.66% higher risk).

- High blood pressure (4.43% higher risk).

- Memory problems (2.63% higher risk).

- Kidney injury (2.59% higher risk).

- Mental health diagnoses (2.5% higher risk).

- Blood-clotting disorders (1.47 % higher risk).

- Heart rhythm disorders (2.9% higher risk).

The risk of developing new conditions was even higher among those 23,486 who were hospitalized in 2020. Those individuals showed a 23.6% higher risk for developing at least one new condition, compared with uninfected seniors in the same year. Also, patients older than 75 had a higher risk for neurological disorders, including dementia, encephalopathy, and memory problems. The researchers also found that respiratory failure and kidney injury were significantly more likely to affect men and Black patients.

When those who had COVID were compared with the group with other lower respiratory viral infections before the pandemic, only the risks of respiratory failure (2.39% higher), dementia (0.71% higher), and fatigue (0.18% higher) were higher.

Primary care providers can learn from these data to better evaluate and manage their geriatric patients with COVID-19 infection, said Amit Shah, MD, a geriatrician with the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, in an interview.

“We must assess older patients who have had COVID-19 for more than just improvement from the respiratory symptoms of COVID-19 in post-COVID follow-up visits,” he said. “Older individuals with frailty have vulnerability to subsequent complications from severe illnesses and it is common to see post-illness diagnoses, such as new diagnosis of delirium; dementia; or renal, respiratory, or cardiac issues that is precipitated by the original illness. This study confirms that this is likely the case with COVID-19 as well.

“Primary care physicians should be vigilant for these complications, including attention to the rehabilitation needs of older patients with longer-term postviral fatigue from COVID-19,” Dr. Shah added.

Data predates ‘Omicron wave’

It remains uncertain whether sequelae will differ with the Omicron variant, but the findings remain applicable, Dr. Cohen said.

“We know that illness from the Omicron variant is on average less severe in those that have been vaccinated. However, throughout the Omicron wave, individuals who have not been vaccinated continue to have significant rates of serious illness and hospitalization,” he said.

“Our findings showed that serious illness with hospitalization was associated with a higher rate of sequelae. It can therefore be inferred that the rates of sequelae seen in our study would continue to occur in unvaccinated individuals who contract Omicron, but might occur less frequently in vaccinated individuals who contract Omicron and have less severe illness.”

Dr. Cohen serves as a consultant for Pfizer. Dr. Shah has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The findings of the observational study, which were published in the BMJ, show the risk of a new condition being triggered by COVID is more than twice as high in seniors, compared with younger patients. Plus, the researchers observed an even higher risk among those who were hospitalized, with nearly half (46%) of patients having developed new conditions after the acute COVID-19 infection period.

Respiratory failure with shortness of breath was the most common postacute sequela, but a wide range of heart, kidney, lung, liver, cognitive, mental health, and other conditions were diagnosed at least 3 weeks after initial infection and persisted beyond 30 days.

This is one of the first studies to specifically describe the incidence and severity of new conditions triggered by COVID-19 infection in a general sample of older adults, said study author Ken Cohen MD, FACP, executive director of translational research at Optum Labs and national senior medical director at Optum Care.

“Much of what has been published on the postacute sequelae of COVID-19 has been predominantly from a younger population, and many of the patients had been hospitalized,” Dr. Cohen noted. “This was the first study to focus on a large population of seniors, most of whom did not require hospitalization.”

Dr. Cohen and colleagues reviewed the health insurance records of more than 133,000 Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 or older who were diagnosed with COVID-19 before April 2020. They also matched individuals by age, race, sex, hospitalization status, and other factors to comparison groups without COVID-19 (one from 2020 and one from 2019), and to a group diagnosed with other lower respiratory tract viral infections before the pandemic.

Risk of developing new conditions was higher in hospitalized

After acute COVID-19 infection, 32% of seniors sought medical care for at least one new medical condition in 2020, compared with 21% of uninfected people in the same year.

The most commonly observed conditions included:

- Respiratory failure (7.55% higher risk).

- Fatigue (5.66% higher risk).

- High blood pressure (4.43% higher risk).

- Memory problems (2.63% higher risk).

- Kidney injury (2.59% higher risk).

- Mental health diagnoses (2.5% higher risk).

- Blood-clotting disorders (1.47 % higher risk).

- Heart rhythm disorders (2.9% higher risk).

The risk of developing new conditions was even higher among those 23,486 who were hospitalized in 2020. Those individuals showed a 23.6% higher risk for developing at least one new condition, compared with uninfected seniors in the same year. Also, patients older than 75 had a higher risk for neurological disorders, including dementia, encephalopathy, and memory problems. The researchers also found that respiratory failure and kidney injury were significantly more likely to affect men and Black patients.

When those who had COVID were compared with the group with other lower respiratory viral infections before the pandemic, only the risks of respiratory failure (2.39% higher), dementia (0.71% higher), and fatigue (0.18% higher) were higher.

Primary care providers can learn from these data to better evaluate and manage their geriatric patients with COVID-19 infection, said Amit Shah, MD, a geriatrician with the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, in an interview.

“We must assess older patients who have had COVID-19 for more than just improvement from the respiratory symptoms of COVID-19 in post-COVID follow-up visits,” he said. “Older individuals with frailty have vulnerability to subsequent complications from severe illnesses and it is common to see post-illness diagnoses, such as new diagnosis of delirium; dementia; or renal, respiratory, or cardiac issues that is precipitated by the original illness. This study confirms that this is likely the case with COVID-19 as well.

“Primary care physicians should be vigilant for these complications, including attention to the rehabilitation needs of older patients with longer-term postviral fatigue from COVID-19,” Dr. Shah added.

Data predates ‘Omicron wave’

It remains uncertain whether sequelae will differ with the Omicron variant, but the findings remain applicable, Dr. Cohen said.

“We know that illness from the Omicron variant is on average less severe in those that have been vaccinated. However, throughout the Omicron wave, individuals who have not been vaccinated continue to have significant rates of serious illness and hospitalization,” he said.

“Our findings showed that serious illness with hospitalization was associated with a higher rate of sequelae. It can therefore be inferred that the rates of sequelae seen in our study would continue to occur in unvaccinated individuals who contract Omicron, but might occur less frequently in vaccinated individuals who contract Omicron and have less severe illness.”

Dr. Cohen serves as a consultant for Pfizer. Dr. Shah has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

FROM BMJ

Heavy cannabis use tied to less diabetes in women

Women who used marijuana (cannabis) at least four times in the previous month (heavy users) were less likely to have type 2 diabetes than women who were light users or nonusers, in a nationally representative U.S. observational study.

In contrast, there were no differences in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in men who were light or heavy cannabis users versus nonusers.

These findings are based on data from the 2013-2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), whereby participants self-reported their cannabis use.

The study by Ayobami S. Ogunsola, MD, MPH, a graduate student at Texas A&M University, College Station, and colleagues was recently published in Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research.

What do the findings mean?

Although overall findings linking cannabis use and diabetes have been inconsistent, the gender differences in the current study are consistent with animal studies and some clinical studies, senior author Ibraheem M. Karaye, MD, MPH, said in an interview.

However, these gender differences need to be confirmed, and “we strongly recommend that more biological or biochemical studies be conducted that could actually tell us the mechanisms,” said Dr. Karaye, an assistant professor in the department of population health, Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y.

“It’s indisputable that medical marijuana has some medical benefits,” he added. “Women [who use cannabis] have been shown to lose more weight than men, for example.”

“If women [cannabis users] are less likely to develop diabetes or more likely to express improvement of symptoms of diabetes,” he noted, “this means that hyperglycemic medications that are being prescribed should be watched scrupulously. Otherwise, there is a risk that [women] may overrespond.”

That is, Dr. Karaye continued, women “may be at risk of developing hypoglycemia because the cannabis is acting synergistically with the regular drug that is being used to treat the diabetes.”

U.S. clinicians, especially in states with legalized medical marijuana, need to be aware of the potential synergy.

“One would have to consider the patient as a whole,” he stressed. “For example, a woman that uses medical marijuana may actually respond differently to hyperglycemic medication.”

Conflicting reports explained by sex differences?

Evidence on whether cannabis use is linked with type 2 diabetes is limited and conflicting, the researchers wrote. They hypothesized that these conflicting findings might be explained by sex differences.

To “help inform current diabetes prevention and mitigation efforts,” they investigated sex differences in cannabis use and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in 15,602 men and women in the 2013-2014, 2015-2016, and 2017-2018 NHANES surveys.

Participants were classified as having type 2 diabetes if they had a physician’s diagnosis; a 2-hour plasma glucose of at least 200 mg/dL (in a glucose tolerance test); fasting blood glucose of at least 126 mg/dL; or A1c of at least 6.5%.

About half of respondents were women (52%) and close to half (44%) were age 18-39.

More than a third (38%) had a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2, indicating obesity.

Roughly 1 in 10 had a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes (13.5%) or A1c of at least 6.5% (9.8%).

Close to a fifth smoked cigarettes (16%). Similarly, 14.5% used cannabis at least four times a week, 3.3% used it less often, and the rest did not use it. Half of participants were not physically active (49%).

Just over half had at least a college education (55%).

Heavy cannabis users were more likely to be younger than age 40 (57% of men, 57% of women), college graduates (54% of men, 63% of women), cigarette smokers (79% of men, 83% of women), and physically inactive (39% of men, 49% of women).

Among women, heavy cannabis users were 49% less likely to have type 2 diabetes than nonusers, after adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, physical activity, tobacco use, alcohol use, marital status, difficulty walking, employment status, income, and BMI (adjusted odds ratio, 0.51; 95% confidence interval, 0.31-0.84).

There were no significant differences between light cannabis users versus nonusers and diabetes prevalence in women, or between light or heavy cannabis users versus nonusers and diabetes prevalence in men.

Limitations, yet biologically plausible

The researchers acknowledged several study limitations.

They do not know how long participants had used marijuana. The men and women may have underreported their cannabis use, especially in states where medical marijuana was not legal, and the NHANES data did not specify whether the cannabis was recreational or medicinal.

The study may have been underpowered to detect a smaller difference in men who used versus did not use marijuana.

And importantly, this was an observational study (a snapshot at one point in time), so it cannot say whether the heavy cannabis use in women caused a decreased likelihood of diabetes.

Nevertheless, the inverse association between cannabis use and presence of type 2 diabetes is biologically plausible, Dr. Ogunsola and colleagues wrote.

The two major cannabis compounds, cannabidiol and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, stimulate CBD1 and CBD2 receptors in the central and peripheral nervous systems, respectively. And “activation of the CBD1 receptor increases insulin secretion, glucagon, and somatostatin, and activates metabolic processes in fat and skeletal muscles – mechanisms that improve glucose disposal,” they explained.

The researchers speculated that the sex differences they found for this association may be caused by differences in sex hormones, or the endocannabinoid system, or fat deposits.

Therefore, “additional studies are needed to investigate the sex-based heterogeneity reported in this study and to elucidate potential mechanisms for the observation,” they concluded.

The study did not receive any funding and the researchers have no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women who used marijuana (cannabis) at least four times in the previous month (heavy users) were less likely to have type 2 diabetes than women who were light users or nonusers, in a nationally representative U.S. observational study.

In contrast, there were no differences in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in men who were light or heavy cannabis users versus nonusers.

These findings are based on data from the 2013-2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), whereby participants self-reported their cannabis use.

The study by Ayobami S. Ogunsola, MD, MPH, a graduate student at Texas A&M University, College Station, and colleagues was recently published in Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research.

What do the findings mean?

Although overall findings linking cannabis use and diabetes have been inconsistent, the gender differences in the current study are consistent with animal studies and some clinical studies, senior author Ibraheem M. Karaye, MD, MPH, said in an interview.

However, these gender differences need to be confirmed, and “we strongly recommend that more biological or biochemical studies be conducted that could actually tell us the mechanisms,” said Dr. Karaye, an assistant professor in the department of population health, Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y.

“It’s indisputable that medical marijuana has some medical benefits,” he added. “Women [who use cannabis] have been shown to lose more weight than men, for example.”

“If women [cannabis users] are less likely to develop diabetes or more likely to express improvement of symptoms of diabetes,” he noted, “this means that hyperglycemic medications that are being prescribed should be watched scrupulously. Otherwise, there is a risk that [women] may overrespond.”

That is, Dr. Karaye continued, women “may be at risk of developing hypoglycemia because the cannabis is acting synergistically with the regular drug that is being used to treat the diabetes.”

U.S. clinicians, especially in states with legalized medical marijuana, need to be aware of the potential synergy.

“One would have to consider the patient as a whole,” he stressed. “For example, a woman that uses medical marijuana may actually respond differently to hyperglycemic medication.”

Conflicting reports explained by sex differences?

Evidence on whether cannabis use is linked with type 2 diabetes is limited and conflicting, the researchers wrote. They hypothesized that these conflicting findings might be explained by sex differences.

To “help inform current diabetes prevention and mitigation efforts,” they investigated sex differences in cannabis use and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in 15,602 men and women in the 2013-2014, 2015-2016, and 2017-2018 NHANES surveys.

Participants were classified as having type 2 diabetes if they had a physician’s diagnosis; a 2-hour plasma glucose of at least 200 mg/dL (in a glucose tolerance test); fasting blood glucose of at least 126 mg/dL; or A1c of at least 6.5%.

About half of respondents were women (52%) and close to half (44%) were age 18-39.

More than a third (38%) had a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2, indicating obesity.

Roughly 1 in 10 had a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes (13.5%) or A1c of at least 6.5% (9.8%).

Close to a fifth smoked cigarettes (16%). Similarly, 14.5% used cannabis at least four times a week, 3.3% used it less often, and the rest did not use it. Half of participants were not physically active (49%).

Just over half had at least a college education (55%).

Heavy cannabis users were more likely to be younger than age 40 (57% of men, 57% of women), college graduates (54% of men, 63% of women), cigarette smokers (79% of men, 83% of women), and physically inactive (39% of men, 49% of women).

Among women, heavy cannabis users were 49% less likely to have type 2 diabetes than nonusers, after adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, physical activity, tobacco use, alcohol use, marital status, difficulty walking, employment status, income, and BMI (adjusted odds ratio, 0.51; 95% confidence interval, 0.31-0.84).

There were no significant differences between light cannabis users versus nonusers and diabetes prevalence in women, or between light or heavy cannabis users versus nonusers and diabetes prevalence in men.

Limitations, yet biologically plausible

The researchers acknowledged several study limitations.

They do not know how long participants had used marijuana. The men and women may have underreported their cannabis use, especially in states where medical marijuana was not legal, and the NHANES data did not specify whether the cannabis was recreational or medicinal.

The study may have been underpowered to detect a smaller difference in men who used versus did not use marijuana.

And importantly, this was an observational study (a snapshot at one point in time), so it cannot say whether the heavy cannabis use in women caused a decreased likelihood of diabetes.

Nevertheless, the inverse association between cannabis use and presence of type 2 diabetes is biologically plausible, Dr. Ogunsola and colleagues wrote.

The two major cannabis compounds, cannabidiol and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, stimulate CBD1 and CBD2 receptors in the central and peripheral nervous systems, respectively. And “activation of the CBD1 receptor increases insulin secretion, glucagon, and somatostatin, and activates metabolic processes in fat and skeletal muscles – mechanisms that improve glucose disposal,” they explained.

The researchers speculated that the sex differences they found for this association may be caused by differences in sex hormones, or the endocannabinoid system, or fat deposits.

Therefore, “additional studies are needed to investigate the sex-based heterogeneity reported in this study and to elucidate potential mechanisms for the observation,” they concluded.

The study did not receive any funding and the researchers have no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women who used marijuana (cannabis) at least four times in the previous month (heavy users) were less likely to have type 2 diabetes than women who were light users or nonusers, in a nationally representative U.S. observational study.

In contrast, there were no differences in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in men who were light or heavy cannabis users versus nonusers.

These findings are based on data from the 2013-2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), whereby participants self-reported their cannabis use.

The study by Ayobami S. Ogunsola, MD, MPH, a graduate student at Texas A&M University, College Station, and colleagues was recently published in Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research.

What do the findings mean?

Although overall findings linking cannabis use and diabetes have been inconsistent, the gender differences in the current study are consistent with animal studies and some clinical studies, senior author Ibraheem M. Karaye, MD, MPH, said in an interview.

However, these gender differences need to be confirmed, and “we strongly recommend that more biological or biochemical studies be conducted that could actually tell us the mechanisms,” said Dr. Karaye, an assistant professor in the department of population health, Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y.

“It’s indisputable that medical marijuana has some medical benefits,” he added. “Women [who use cannabis] have been shown to lose more weight than men, for example.”

“If women [cannabis users] are less likely to develop diabetes or more likely to express improvement of symptoms of diabetes,” he noted, “this means that hyperglycemic medications that are being prescribed should be watched scrupulously. Otherwise, there is a risk that [women] may overrespond.”

That is, Dr. Karaye continued, women “may be at risk of developing hypoglycemia because the cannabis is acting synergistically with the regular drug that is being used to treat the diabetes.”

U.S. clinicians, especially in states with legalized medical marijuana, need to be aware of the potential synergy.

“One would have to consider the patient as a whole,” he stressed. “For example, a woman that uses medical marijuana may actually respond differently to hyperglycemic medication.”

Conflicting reports explained by sex differences?

Evidence on whether cannabis use is linked with type 2 diabetes is limited and conflicting, the researchers wrote. They hypothesized that these conflicting findings might be explained by sex differences.

To “help inform current diabetes prevention and mitigation efforts,” they investigated sex differences in cannabis use and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in 15,602 men and women in the 2013-2014, 2015-2016, and 2017-2018 NHANES surveys.

Participants were classified as having type 2 diabetes if they had a physician’s diagnosis; a 2-hour plasma glucose of at least 200 mg/dL (in a glucose tolerance test); fasting blood glucose of at least 126 mg/dL; or A1c of at least 6.5%.

About half of respondents were women (52%) and close to half (44%) were age 18-39.

More than a third (38%) had a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2, indicating obesity.

Roughly 1 in 10 had a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes (13.5%) or A1c of at least 6.5% (9.8%).

Close to a fifth smoked cigarettes (16%). Similarly, 14.5% used cannabis at least four times a week, 3.3% used it less often, and the rest did not use it. Half of participants were not physically active (49%).

Just over half had at least a college education (55%).

Heavy cannabis users were more likely to be younger than age 40 (57% of men, 57% of women), college graduates (54% of men, 63% of women), cigarette smokers (79% of men, 83% of women), and physically inactive (39% of men, 49% of women).

Among women, heavy cannabis users were 49% less likely to have type 2 diabetes than nonusers, after adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, physical activity, tobacco use, alcohol use, marital status, difficulty walking, employment status, income, and BMI (adjusted odds ratio, 0.51; 95% confidence interval, 0.31-0.84).

There were no significant differences between light cannabis users versus nonusers and diabetes prevalence in women, or between light or heavy cannabis users versus nonusers and diabetes prevalence in men.

Limitations, yet biologically plausible

The researchers acknowledged several study limitations.

They do not know how long participants had used marijuana. The men and women may have underreported their cannabis use, especially in states where medical marijuana was not legal, and the NHANES data did not specify whether the cannabis was recreational or medicinal.

The study may have been underpowered to detect a smaller difference in men who used versus did not use marijuana.

And importantly, this was an observational study (a snapshot at one point in time), so it cannot say whether the heavy cannabis use in women caused a decreased likelihood of diabetes.

Nevertheless, the inverse association between cannabis use and presence of type 2 diabetes is biologically plausible, Dr. Ogunsola and colleagues wrote.

The two major cannabis compounds, cannabidiol and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, stimulate CBD1 and CBD2 receptors in the central and peripheral nervous systems, respectively. And “activation of the CBD1 receptor increases insulin secretion, glucagon, and somatostatin, and activates metabolic processes in fat and skeletal muscles – mechanisms that improve glucose disposal,” they explained.

The researchers speculated that the sex differences they found for this association may be caused by differences in sex hormones, or the endocannabinoid system, or fat deposits.

Therefore, “additional studies are needed to investigate the sex-based heterogeneity reported in this study and to elucidate potential mechanisms for the observation,” they concluded.

The study did not receive any funding and the researchers have no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CANNABIS AND CANNABINOID RESEARCH

If you’ve got 3 seconds, then you’ve got time to work out

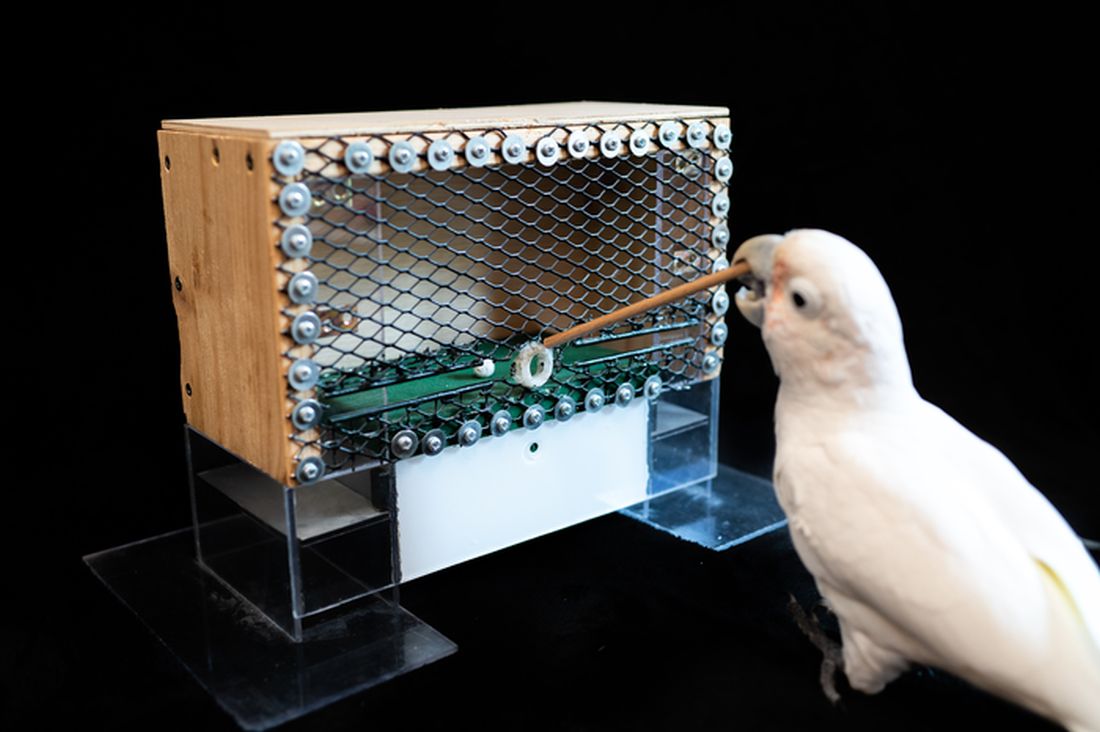

Goffin’s cockatoo? More like golfin’ cockatoo

Can birds play golf? Of course not; it’s ridiculous. Humans can barely play golf, and we invented the sport. Anyway, moving on to “Brian retraction injury after elective aneurysm clipping.”

Hang on, we’re now hearing that a group of researchers, as part of a large international project comparing children’s innovation and problem-solving skills with those of cockatoos, have in fact taught a group of Goffin’s cockatoos how to play golf. Huh. What an oddly specific project. All right, fine, I guess we’ll go with the golf-playing birds.

Golf may seem very simple at its core. It is, essentially, whacking a ball with a stick. But the Scots who invented the game were undertaking a complex project involving combined usage of multiple tools, and until now, only primates were thought to be capable of utilizing compound tools to play games such as golf.

For this latest research, published in Scientific Reports, our intrepid birds were given a rudimentary form of golf to play (featuring a stick, a ball, and a closed box to get the ball through). Putting the ball through the hole gave the bird a reward. Not every cockatoo was able to hole out, but three did, with each inventing a unique way to manipulate the stick to hit the ball.

As entertaining as it would be to simply teach some birds how to play golf, we do loop back around to medical relevance. While children are perfectly capable of using tools, young children in particular are actually quite bad at using tools to solve novel solutions. Present a 5-year-old with a stick, a ball, and a hole, and that child might not figure out what the cockatoos did. The research really does give insight into the psychology behind the development of complex tools and technology by our ancient ancestors, according to the researchers.

We’re not entirely convinced this isn’t an elaborate ploy to get a bird out onto the PGA Tour. The LOTME staff can see the future headline already: “Painted bunting wins Valspar Championship in epic playoff.”

Work out now, sweat never

Okay, show of hands: Who’s familiar with “Name that tune?” The TV game show got a reboot last year, but some of us are old enough to remember the 1970s version hosted by national treasure Tom Kennedy.

The contestants try to identify a song as quickly as possible, claiming that they “can name that tune in five notes.” Or four notes, or three. Well, welcome to “Name that exercise study.”

Senior author Masatoshi Nakamura, PhD, and associates gathered together 39 students from Niigata (Japan) University of Health and Welfare and had them perform one isometric, concentric, or eccentric bicep curl with a dumbbell for 3 seconds a day at maximum effort for 5 days a week, over 4 weeks. And yes, we did say 3 seconds.

“Lifting the weight sees the bicep in concentric contraction, lowering the weight sees it in eccentric contraction, while holding the weight parallel to the ground is isometric,” they explained in a statement on Eurekalert.

The three exercise groups were compared with a group that did no exercise, and after 4 weeks of rigorous but brief science, the group doing eccentric contractions had the best results, as their overall muscle strength increased by 11.5%. After a total of just 60 seconds of exercise in 4 weeks. That’s 60 seconds. In 4 weeks.

Big news, but maybe we can do better. “Tom, we can do that exercise in 2 seconds.”

And one! And two! Whoa, feel the burn.

Tingling over anxiety

Apparently there are two kinds of people in this world. Those who love ASMR and those who just don’t get it.

ASMR, for those who don’t know, is the autonomous sensory meridian response. An online community has surfaced, with video creators making tapping sounds, whispering, or brushing mannequin hair to elicit “a pleasant tingling sensation originating from the scalp and neck which can spread to the rest of the body” from viewers, Charlotte M. Eid and associates said in PLOS One.

The people who are into these types of videos are more likely to have higher levels of neuroticism than those who aren’t, which gives ASMR the potential to be a nontraditional form of treatment for anxiety and/or neuroticism, they suggested.

The research involved a group of 64 volunteers who watched an ASMR video meant to trigger the tingles and then completed questionnaires to evaluate their levels of neuroticism, trait anxiety, and state anxiety, said Ms. Eid and associates of Northumbria University in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England.

The people who had a history of producing tingles from ASMR videos in the past had higher levels of anxiety, compared with those who didn’t. Those who responded to triggers also received some benefit from the video in the study, reporting lower levels of neuroticism and anxiety after watching, the investigators found.

Although people who didn’t have a history of tingles didn’t feel any reduction in anxiety after the video, that didn’t stop the people who weren’t familiar with the genre from catching tingles.

So if you find yourself a little high strung or anxious, or if you can’t sleep, consider watching a person pretending to give you a makeover or using fingernails to tap on books for some relaxation. Don’t knock it until you try it!

Living in the past? Not so far-fetched

It’s usually an insult when people tell us to stop living in the past, but the joke’s on them because we really do live in the past. By 15 seconds, to be exact, according to researchers from the University of California, Berkeley.

But wait, did you just read that last sentence 15 seconds ago, even though it feels like real time? Did we just type these words now, or 15 seconds ago?

Think of your brain as a web page you’re constantly refreshing. We are constantly seeing new pictures, images, and colors, and your brain is responsible for keeping everything in chronological order. This new research suggests that our brains show us images from 15 seconds prior. Is your mind blown yet?

“One could say our brain is procrastinating. It’s too much work to constantly update images, so it sticks to the past because the past is a good predictor of the present. We recycle information from the past because it’s faster, more efficient and less work,” senior author David Whitney explained in a statement from the university.

It seems like the 15-second rule helps us not lose our minds by keeping a steady flow of information, but it could be a bit dangerous if someone, such as a surgeon, needs to see things with extreme precision.

And now we are definitely feeling a bit anxious about our upcoming heart/spleen/gallbladder replacement. … Where’s that link to the ASMR video?

Goffin’s cockatoo? More like golfin’ cockatoo

Can birds play golf? Of course not; it’s ridiculous. Humans can barely play golf, and we invented the sport. Anyway, moving on to “Brian retraction injury after elective aneurysm clipping.”

Hang on, we’re now hearing that a group of researchers, as part of a large international project comparing children’s innovation and problem-solving skills with those of cockatoos, have in fact taught a group of Goffin’s cockatoos how to play golf. Huh. What an oddly specific project. All right, fine, I guess we’ll go with the golf-playing birds.

Golf may seem very simple at its core. It is, essentially, whacking a ball with a stick. But the Scots who invented the game were undertaking a complex project involving combined usage of multiple tools, and until now, only primates were thought to be capable of utilizing compound tools to play games such as golf.

For this latest research, published in Scientific Reports, our intrepid birds were given a rudimentary form of golf to play (featuring a stick, a ball, and a closed box to get the ball through). Putting the ball through the hole gave the bird a reward. Not every cockatoo was able to hole out, but three did, with each inventing a unique way to manipulate the stick to hit the ball.

As entertaining as it would be to simply teach some birds how to play golf, we do loop back around to medical relevance. While children are perfectly capable of using tools, young children in particular are actually quite bad at using tools to solve novel solutions. Present a 5-year-old with a stick, a ball, and a hole, and that child might not figure out what the cockatoos did. The research really does give insight into the psychology behind the development of complex tools and technology by our ancient ancestors, according to the researchers.

We’re not entirely convinced this isn’t an elaborate ploy to get a bird out onto the PGA Tour. The LOTME staff can see the future headline already: “Painted bunting wins Valspar Championship in epic playoff.”

Work out now, sweat never

Okay, show of hands: Who’s familiar with “Name that tune?” The TV game show got a reboot last year, but some of us are old enough to remember the 1970s version hosted by national treasure Tom Kennedy.

The contestants try to identify a song as quickly as possible, claiming that they “can name that tune in five notes.” Or four notes, or three. Well, welcome to “Name that exercise study.”

Senior author Masatoshi Nakamura, PhD, and associates gathered together 39 students from Niigata (Japan) University of Health and Welfare and had them perform one isometric, concentric, or eccentric bicep curl with a dumbbell for 3 seconds a day at maximum effort for 5 days a week, over 4 weeks. And yes, we did say 3 seconds.

“Lifting the weight sees the bicep in concentric contraction, lowering the weight sees it in eccentric contraction, while holding the weight parallel to the ground is isometric,” they explained in a statement on Eurekalert.

The three exercise groups were compared with a group that did no exercise, and after 4 weeks of rigorous but brief science, the group doing eccentric contractions had the best results, as their overall muscle strength increased by 11.5%. After a total of just 60 seconds of exercise in 4 weeks. That’s 60 seconds. In 4 weeks.

Big news, but maybe we can do better. “Tom, we can do that exercise in 2 seconds.”

And one! And two! Whoa, feel the burn.

Tingling over anxiety

Apparently there are two kinds of people in this world. Those who love ASMR and those who just don’t get it.

ASMR, for those who don’t know, is the autonomous sensory meridian response. An online community has surfaced, with video creators making tapping sounds, whispering, or brushing mannequin hair to elicit “a pleasant tingling sensation originating from the scalp and neck which can spread to the rest of the body” from viewers, Charlotte M. Eid and associates said in PLOS One.

The people who are into these types of videos are more likely to have higher levels of neuroticism than those who aren’t, which gives ASMR the potential to be a nontraditional form of treatment for anxiety and/or neuroticism, they suggested.

The research involved a group of 64 volunteers who watched an ASMR video meant to trigger the tingles and then completed questionnaires to evaluate their levels of neuroticism, trait anxiety, and state anxiety, said Ms. Eid and associates of Northumbria University in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England.

The people who had a history of producing tingles from ASMR videos in the past had higher levels of anxiety, compared with those who didn’t. Those who responded to triggers also received some benefit from the video in the study, reporting lower levels of neuroticism and anxiety after watching, the investigators found.

Although people who didn’t have a history of tingles didn’t feel any reduction in anxiety after the video, that didn’t stop the people who weren’t familiar with the genre from catching tingles.

So if you find yourself a little high strung or anxious, or if you can’t sleep, consider watching a person pretending to give you a makeover or using fingernails to tap on books for some relaxation. Don’t knock it until you try it!

Living in the past? Not so far-fetched

It’s usually an insult when people tell us to stop living in the past, but the joke’s on them because we really do live in the past. By 15 seconds, to be exact, according to researchers from the University of California, Berkeley.

But wait, did you just read that last sentence 15 seconds ago, even though it feels like real time? Did we just type these words now, or 15 seconds ago?

Think of your brain as a web page you’re constantly refreshing. We are constantly seeing new pictures, images, and colors, and your brain is responsible for keeping everything in chronological order. This new research suggests that our brains show us images from 15 seconds prior. Is your mind blown yet?

“One could say our brain is procrastinating. It’s too much work to constantly update images, so it sticks to the past because the past is a good predictor of the present. We recycle information from the past because it’s faster, more efficient and less work,” senior author David Whitney explained in a statement from the university.

It seems like the 15-second rule helps us not lose our minds by keeping a steady flow of information, but it could be a bit dangerous if someone, such as a surgeon, needs to see things with extreme precision.

And now we are definitely feeling a bit anxious about our upcoming heart/spleen/gallbladder replacement. … Where’s that link to the ASMR video?

Goffin’s cockatoo? More like golfin’ cockatoo

Can birds play golf? Of course not; it’s ridiculous. Humans can barely play golf, and we invented the sport. Anyway, moving on to “Brian retraction injury after elective aneurysm clipping.”

Hang on, we’re now hearing that a group of researchers, as part of a large international project comparing children’s innovation and problem-solving skills with those of cockatoos, have in fact taught a group of Goffin’s cockatoos how to play golf. Huh. What an oddly specific project. All right, fine, I guess we’ll go with the golf-playing birds.

Golf may seem very simple at its core. It is, essentially, whacking a ball with a stick. But the Scots who invented the game were undertaking a complex project involving combined usage of multiple tools, and until now, only primates were thought to be capable of utilizing compound tools to play games such as golf.

For this latest research, published in Scientific Reports, our intrepid birds were given a rudimentary form of golf to play (featuring a stick, a ball, and a closed box to get the ball through). Putting the ball through the hole gave the bird a reward. Not every cockatoo was able to hole out, but three did, with each inventing a unique way to manipulate the stick to hit the ball.

As entertaining as it would be to simply teach some birds how to play golf, we do loop back around to medical relevance. While children are perfectly capable of using tools, young children in particular are actually quite bad at using tools to solve novel solutions. Present a 5-year-old with a stick, a ball, and a hole, and that child might not figure out what the cockatoos did. The research really does give insight into the psychology behind the development of complex tools and technology by our ancient ancestors, according to the researchers.

We’re not entirely convinced this isn’t an elaborate ploy to get a bird out onto the PGA Tour. The LOTME staff can see the future headline already: “Painted bunting wins Valspar Championship in epic playoff.”

Work out now, sweat never

Okay, show of hands: Who’s familiar with “Name that tune?” The TV game show got a reboot last year, but some of us are old enough to remember the 1970s version hosted by national treasure Tom Kennedy.

The contestants try to identify a song as quickly as possible, claiming that they “can name that tune in five notes.” Or four notes, or three. Well, welcome to “Name that exercise study.”

Senior author Masatoshi Nakamura, PhD, and associates gathered together 39 students from Niigata (Japan) University of Health and Welfare and had them perform one isometric, concentric, or eccentric bicep curl with a dumbbell for 3 seconds a day at maximum effort for 5 days a week, over 4 weeks. And yes, we did say 3 seconds.

“Lifting the weight sees the bicep in concentric contraction, lowering the weight sees it in eccentric contraction, while holding the weight parallel to the ground is isometric,” they explained in a statement on Eurekalert.

The three exercise groups were compared with a group that did no exercise, and after 4 weeks of rigorous but brief science, the group doing eccentric contractions had the best results, as their overall muscle strength increased by 11.5%. After a total of just 60 seconds of exercise in 4 weeks. That’s 60 seconds. In 4 weeks.

Big news, but maybe we can do better. “Tom, we can do that exercise in 2 seconds.”

And one! And two! Whoa, feel the burn.

Tingling over anxiety

Apparently there are two kinds of people in this world. Those who love ASMR and those who just don’t get it.

ASMR, for those who don’t know, is the autonomous sensory meridian response. An online community has surfaced, with video creators making tapping sounds, whispering, or brushing mannequin hair to elicit “a pleasant tingling sensation originating from the scalp and neck which can spread to the rest of the body” from viewers, Charlotte M. Eid and associates said in PLOS One.

The people who are into these types of videos are more likely to have higher levels of neuroticism than those who aren’t, which gives ASMR the potential to be a nontraditional form of treatment for anxiety and/or neuroticism, they suggested.

The research involved a group of 64 volunteers who watched an ASMR video meant to trigger the tingles and then completed questionnaires to evaluate their levels of neuroticism, trait anxiety, and state anxiety, said Ms. Eid and associates of Northumbria University in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England.

The people who had a history of producing tingles from ASMR videos in the past had higher levels of anxiety, compared with those who didn’t. Those who responded to triggers also received some benefit from the video in the study, reporting lower levels of neuroticism and anxiety after watching, the investigators found.

Although people who didn’t have a history of tingles didn’t feel any reduction in anxiety after the video, that didn’t stop the people who weren’t familiar with the genre from catching tingles.

So if you find yourself a little high strung or anxious, or if you can’t sleep, consider watching a person pretending to give you a makeover or using fingernails to tap on books for some relaxation. Don’t knock it until you try it!

Living in the past? Not so far-fetched

It’s usually an insult when people tell us to stop living in the past, but the joke’s on them because we really do live in the past. By 15 seconds, to be exact, according to researchers from the University of California, Berkeley.

But wait, did you just read that last sentence 15 seconds ago, even though it feels like real time? Did we just type these words now, or 15 seconds ago?

Think of your brain as a web page you’re constantly refreshing. We are constantly seeing new pictures, images, and colors, and your brain is responsible for keeping everything in chronological order. This new research suggests that our brains show us images from 15 seconds prior. Is your mind blown yet?

“One could say our brain is procrastinating. It’s too much work to constantly update images, so it sticks to the past because the past is a good predictor of the present. We recycle information from the past because it’s faster, more efficient and less work,” senior author David Whitney explained in a statement from the university.

It seems like the 15-second rule helps us not lose our minds by keeping a steady flow of information, but it could be a bit dangerous if someone, such as a surgeon, needs to see things with extreme precision.

And now we are definitely feeling a bit anxious about our upcoming heart/spleen/gallbladder replacement. … Where’s that link to the ASMR video?

Chronic marijuana use linked to recurrent stroke

, new observational research suggests. “Our analysis shows young marijuana users with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack remain at significantly high risk for future strokes,” said lead study author Akhil Jain, MD, a resident physician at Mercy Fitzgerald Hospital in Darby, Pennsylvania.

“It’s essential to raise awareness among young adults about the impact of chronic habitual use of marijuana, especially if they have established cardiovascular risk factors or previous stroke.”

The study will be presented during the International Stroke Conference, presented by the American Stroke Association, a division of the American Heart Association.

An increasing number of jurisdictions are allowing marijuana use. To date, 18 states and the District of Columbia have legalized recreational cannabis use, the investigators noted.

Research suggests cannabis use disorder – defined as the chronic habitual use of cannabis – is more prevalent in the young adult population. But Dr. Jain said the population of marijuana users is “a changing dynamic.”

Cannabis use has been linked to an increased risk for first-time stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA). Traditional stroke risk factors include hypertension, diabetes, and diseases related to blood vessels or blood circulation, including atherosclerosis.

Young adults might have additional stroke risk factors, such as behavioral habits like substance abuse, low physical activity, and smoking, oral contraceptives use among females, and brain infections, especially in the immunocompromised, said Dr. Jain.

Research from the American Heart Association shows stroke rates are increasing among adults 18 to 45 years of age. Each year, young adults account for up to 15% of strokes in the United States.

Prevalence and risk for recurrent stroke in patients with previous stroke or TIA in cannabis users have not been clearly established, the researchers pointed out.

A higher rate of recurrent stroke

For this new study, Dr. Jain and colleagues used data from the National Inpatient Sample from October 2015 to December 2017. They identified hospitalizations among young adults 18 to 45 years of age with a previous history of stroke or TIA.

They then grouped these patients into those with cannabis use disorder (4,690) and those without cannabis use disorder (156,700). The median age in both cohorts was 37 years.

The analysis did not include those who were considered in remission from cannabis use disorder.

Results showed that 6.9% of those with cannabis use disorder were hospitalized for a recurrent stroke, compared with 5.4% of those without cannabis use disorder (P < .001).

After adjustment for demographic factors (age, sex, race, household income), and pre-existing conditions, patients with cannabis use disorder were 48% more likely to be hospitalized for recurrent stroke than those without cannabis use disorder (odds ratio, 1.48; 95% confidence interval, 1.28-1.71; P < .001).

Compared with the group without cannabis use disorder, the cannabis use disorder group had more men (55.2% vs. 40.2%), more African American people (44.6% vs. 37.2%), and more use of tobacco (73.9% vs. 39.6%) and alcohol (16.5% vs. 3.6%). They also had a greater percentage of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, and psychoses.

But a smaller percentage of those with cannabis use disorder had hypertension (51.3% vs. 55.6%; P = .001) and diabetes (16.3% vs. 22.7%; P < .001), which is an “interesting” finding, said Dr. Jain.

“We observed that even with a lower rate of cardiovascular risk factors, after controlling for all the risk factors, we still found the cannabis users had a higher rate of recurrent stroke.”

He noted this was a retrospective study without a control group. “If both groups had comparable hypertension, then this risk might actually be more evident,” said Dr. Jain. “We need a prospective study with comparable groups.”

Living in low-income neighborhoods and in northeast and southern regions of the United States was also more common in the cannabis use disorder group.

Hypothesis-generating research

The study did not investigate the possible mechanisms by which marijuana use might increase stroke risk, but Dr. Jain speculated that these could include factors such as impaired blood vessel function, changes in blood supply, an increased tendency of blood clotting, impaired energy production in brain cells, and an imbalance between molecules that harm healthy tissue and the antioxidant defenses that neutralize them.

As cannabis use may pose a different risk for a new stroke, as opposed a previous stroke, Dr. Jain said it would be interesting to study the amount of “residual function deficit” experienced with the first stroke.

The new study represents “foundational research” upon which other research teams can build, said Dr. Jain. “Our study is hypothesis-generating research for a future prospective randomized controlled trial.”

A limitation of the study is that it did not consider the effect of various doses, duration, and forms of cannabis abuse, or use of medicinal cannabis or other drugs.

Robert L. Page II, PharmD, professor, departments of clinical pharmacy and physical medicine/rehabilitation, University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Aurora, provided a comment on this new research.

A cannabis use disorder diagnosis provides “specific criteria” with regard to chronicity of use and reflects “more of a physical and psychological dependence upon cannabis,” said Dr. Page, who chaired the writing group for the AHA 2020 cannabis and cardiovascular disease scientific statement.

He explained what sets people with cannabis use disorder apart from “run-of-the-mill” recreational cannabis users is that “these are individuals who use a cannabis product, whether it’s smoking it, vaping it, or consuming it via an edible, and are using it on a regular basis, in a chronic fashion.”

The study received no outside funding. The authors report no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new observational research suggests. “Our analysis shows young marijuana users with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack remain at significantly high risk for future strokes,” said lead study author Akhil Jain, MD, a resident physician at Mercy Fitzgerald Hospital in Darby, Pennsylvania.

“It’s essential to raise awareness among young adults about the impact of chronic habitual use of marijuana, especially if they have established cardiovascular risk factors or previous stroke.”

The study will be presented during the International Stroke Conference, presented by the American Stroke Association, a division of the American Heart Association.

An increasing number of jurisdictions are allowing marijuana use. To date, 18 states and the District of Columbia have legalized recreational cannabis use, the investigators noted.

Research suggests cannabis use disorder – defined as the chronic habitual use of cannabis – is more prevalent in the young adult population. But Dr. Jain said the population of marijuana users is “a changing dynamic.”

Cannabis use has been linked to an increased risk for first-time stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA). Traditional stroke risk factors include hypertension, diabetes, and diseases related to blood vessels or blood circulation, including atherosclerosis.

Young adults might have additional stroke risk factors, such as behavioral habits like substance abuse, low physical activity, and smoking, oral contraceptives use among females, and brain infections, especially in the immunocompromised, said Dr. Jain.

Research from the American Heart Association shows stroke rates are increasing among adults 18 to 45 years of age. Each year, young adults account for up to 15% of strokes in the United States.

Prevalence and risk for recurrent stroke in patients with previous stroke or TIA in cannabis users have not been clearly established, the researchers pointed out.

A higher rate of recurrent stroke

For this new study, Dr. Jain and colleagues used data from the National Inpatient Sample from October 2015 to December 2017. They identified hospitalizations among young adults 18 to 45 years of age with a previous history of stroke or TIA.

They then grouped these patients into those with cannabis use disorder (4,690) and those without cannabis use disorder (156,700). The median age in both cohorts was 37 years.

The analysis did not include those who were considered in remission from cannabis use disorder.

Results showed that 6.9% of those with cannabis use disorder were hospitalized for a recurrent stroke, compared with 5.4% of those without cannabis use disorder (P < .001).

After adjustment for demographic factors (age, sex, race, household income), and pre-existing conditions, patients with cannabis use disorder were 48% more likely to be hospitalized for recurrent stroke than those without cannabis use disorder (odds ratio, 1.48; 95% confidence interval, 1.28-1.71; P < .001).

Compared with the group without cannabis use disorder, the cannabis use disorder group had more men (55.2% vs. 40.2%), more African American people (44.6% vs. 37.2%), and more use of tobacco (73.9% vs. 39.6%) and alcohol (16.5% vs. 3.6%). They also had a greater percentage of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, and psychoses.

But a smaller percentage of those with cannabis use disorder had hypertension (51.3% vs. 55.6%; P = .001) and diabetes (16.3% vs. 22.7%; P < .001), which is an “interesting” finding, said Dr. Jain.

“We observed that even with a lower rate of cardiovascular risk factors, after controlling for all the risk factors, we still found the cannabis users had a higher rate of recurrent stroke.”

He noted this was a retrospective study without a control group. “If both groups had comparable hypertension, then this risk might actually be more evident,” said Dr. Jain. “We need a prospective study with comparable groups.”

Living in low-income neighborhoods and in northeast and southern regions of the United States was also more common in the cannabis use disorder group.

Hypothesis-generating research

The study did not investigate the possible mechanisms by which marijuana use might increase stroke risk, but Dr. Jain speculated that these could include factors such as impaired blood vessel function, changes in blood supply, an increased tendency of blood clotting, impaired energy production in brain cells, and an imbalance between molecules that harm healthy tissue and the antioxidant defenses that neutralize them.

As cannabis use may pose a different risk for a new stroke, as opposed a previous stroke, Dr. Jain said it would be interesting to study the amount of “residual function deficit” experienced with the first stroke.

The new study represents “foundational research” upon which other research teams can build, said Dr. Jain. “Our study is hypothesis-generating research for a future prospective randomized controlled trial.”

A limitation of the study is that it did not consider the effect of various doses, duration, and forms of cannabis abuse, or use of medicinal cannabis or other drugs.

Robert L. Page II, PharmD, professor, departments of clinical pharmacy and physical medicine/rehabilitation, University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Aurora, provided a comment on this new research.

A cannabis use disorder diagnosis provides “specific criteria” with regard to chronicity of use and reflects “more of a physical and psychological dependence upon cannabis,” said Dr. Page, who chaired the writing group for the AHA 2020 cannabis and cardiovascular disease scientific statement.

He explained what sets people with cannabis use disorder apart from “run-of-the-mill” recreational cannabis users is that “these are individuals who use a cannabis product, whether it’s smoking it, vaping it, or consuming it via an edible, and are using it on a regular basis, in a chronic fashion.”

The study received no outside funding. The authors report no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new observational research suggests. “Our analysis shows young marijuana users with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack remain at significantly high risk for future strokes,” said lead study author Akhil Jain, MD, a resident physician at Mercy Fitzgerald Hospital in Darby, Pennsylvania.

“It’s essential to raise awareness among young adults about the impact of chronic habitual use of marijuana, especially if they have established cardiovascular risk factors or previous stroke.”

The study will be presented during the International Stroke Conference, presented by the American Stroke Association, a division of the American Heart Association.

An increasing number of jurisdictions are allowing marijuana use. To date, 18 states and the District of Columbia have legalized recreational cannabis use, the investigators noted.

Research suggests cannabis use disorder – defined as the chronic habitual use of cannabis – is more prevalent in the young adult population. But Dr. Jain said the population of marijuana users is “a changing dynamic.”

Cannabis use has been linked to an increased risk for first-time stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA). Traditional stroke risk factors include hypertension, diabetes, and diseases related to blood vessels or blood circulation, including atherosclerosis.

Young adults might have additional stroke risk factors, such as behavioral habits like substance abuse, low physical activity, and smoking, oral contraceptives use among females, and brain infections, especially in the immunocompromised, said Dr. Jain.

Research from the American Heart Association shows stroke rates are increasing among adults 18 to 45 years of age. Each year, young adults account for up to 15% of strokes in the United States.

Prevalence and risk for recurrent stroke in patients with previous stroke or TIA in cannabis users have not been clearly established, the researchers pointed out.

A higher rate of recurrent stroke

For this new study, Dr. Jain and colleagues used data from the National Inpatient Sample from October 2015 to December 2017. They identified hospitalizations among young adults 18 to 45 years of age with a previous history of stroke or TIA.

They then grouped these patients into those with cannabis use disorder (4,690) and those without cannabis use disorder (156,700). The median age in both cohorts was 37 years.

The analysis did not include those who were considered in remission from cannabis use disorder.

Results showed that 6.9% of those with cannabis use disorder were hospitalized for a recurrent stroke, compared with 5.4% of those without cannabis use disorder (P < .001).

After adjustment for demographic factors (age, sex, race, household income), and pre-existing conditions, patients with cannabis use disorder were 48% more likely to be hospitalized for recurrent stroke than those without cannabis use disorder (odds ratio, 1.48; 95% confidence interval, 1.28-1.71; P < .001).

Compared with the group without cannabis use disorder, the cannabis use disorder group had more men (55.2% vs. 40.2%), more African American people (44.6% vs. 37.2%), and more use of tobacco (73.9% vs. 39.6%) and alcohol (16.5% vs. 3.6%). They also had a greater percentage of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, and psychoses.

But a smaller percentage of those with cannabis use disorder had hypertension (51.3% vs. 55.6%; P = .001) and diabetes (16.3% vs. 22.7%; P < .001), which is an “interesting” finding, said Dr. Jain.

“We observed that even with a lower rate of cardiovascular risk factors, after controlling for all the risk factors, we still found the cannabis users had a higher rate of recurrent stroke.”

He noted this was a retrospective study without a control group. “If both groups had comparable hypertension, then this risk might actually be more evident,” said Dr. Jain. “We need a prospective study with comparable groups.”

Living in low-income neighborhoods and in northeast and southern regions of the United States was also more common in the cannabis use disorder group.

Hypothesis-generating research

The study did not investigate the possible mechanisms by which marijuana use might increase stroke risk, but Dr. Jain speculated that these could include factors such as impaired blood vessel function, changes in blood supply, an increased tendency of blood clotting, impaired energy production in brain cells, and an imbalance between molecules that harm healthy tissue and the antioxidant defenses that neutralize them.

As cannabis use may pose a different risk for a new stroke, as opposed a previous stroke, Dr. Jain said it would be interesting to study the amount of “residual function deficit” experienced with the first stroke.

The new study represents “foundational research” upon which other research teams can build, said Dr. Jain. “Our study is hypothesis-generating research for a future prospective randomized controlled trial.”

A limitation of the study is that it did not consider the effect of various doses, duration, and forms of cannabis abuse, or use of medicinal cannabis or other drugs.

Robert L. Page II, PharmD, professor, departments of clinical pharmacy and physical medicine/rehabilitation, University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Aurora, provided a comment on this new research.

A cannabis use disorder diagnosis provides “specific criteria” with regard to chronicity of use and reflects “more of a physical and psychological dependence upon cannabis,” said Dr. Page, who chaired the writing group for the AHA 2020 cannabis and cardiovascular disease scientific statement.

He explained what sets people with cannabis use disorder apart from “run-of-the-mill” recreational cannabis users is that “these are individuals who use a cannabis product, whether it’s smoking it, vaping it, or consuming it via an edible, and are using it on a regular basis, in a chronic fashion.”

The study received no outside funding. The authors report no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ISC 2022

Switching to a healthy diet can add 10 years to life

Just a few changes to your diet could add years to your life, but the sooner you start the better.

Maintaining a healthy diet is important, but most people find this difficult to do daily. In a new study, researchers examined the effects of individual healthful and nonhealthful types of foods and estimated the impact by age and sex of swapping some for others.

say the Norwegian scientists who conducted the study, published in PLOS Medicine on Feb. 8.

They developed an online tool that anyone can use to get an idea of how individual food choices can affect life expectancy.

The biggest overall impact comes from eating more plant-based foods (legumes), whole grains and nuts, and less red and processed meat. Fruits and vegetables also have a positive health impact, but on average people who eat a typical Western diet are already consuming those in relatively high amounts. Fish is included on the healthful list, whereas sugar-sweetened beverages (sodas) and foods based on refined [white] grains, such as white bread, are among those to be avoided.

The study found that although it’s never too late to start, young adults can expect to see more years gained by adopting healthful eating than would older adults.

“Our results indicate that for individuals with a typical Western diet, sustained dietary changes at any age may give substantial health benefits, although the gains are the largest if changes start early in life,” said the researchers.

Depending on how many healthy dietary “switches” are made and maintained and the amounts consumed, a 20-year-old man in the United States could extend his life up to 13 years, and a 20-year old woman by 11 years.

That number drops with age but changing from a typical diet to the optimized diet at age 60 years could still increase life expectancy by 8 years for women and 9 years for men, and even an 80-year-old female could gain more than 3 years with healthier food choices.

Until now, research in this area has shown health benefits associated with separate food groups or specific diet patterns, while focusing less on the health impact of other dietary changes. The statistical ‘modeling’ approach used in this study bridges that gap, the researchers said.

“Understanding the relative health potential of different food groups could enable people to make feasible and significant health gains,” they concluded.

A version of this article was first published on WebMD.com.

Just a few changes to your diet could add years to your life, but the sooner you start the better.

Maintaining a healthy diet is important, but most people find this difficult to do daily. In a new study, researchers examined the effects of individual healthful and nonhealthful types of foods and estimated the impact by age and sex of swapping some for others.

say the Norwegian scientists who conducted the study, published in PLOS Medicine on Feb. 8.

They developed an online tool that anyone can use to get an idea of how individual food choices can affect life expectancy.

The biggest overall impact comes from eating more plant-based foods (legumes), whole grains and nuts, and less red and processed meat. Fruits and vegetables also have a positive health impact, but on average people who eat a typical Western diet are already consuming those in relatively high amounts. Fish is included on the healthful list, whereas sugar-sweetened beverages (sodas) and foods based on refined [white] grains, such as white bread, are among those to be avoided.

The study found that although it’s never too late to start, young adults can expect to see more years gained by adopting healthful eating than would older adults.

“Our results indicate that for individuals with a typical Western diet, sustained dietary changes at any age may give substantial health benefits, although the gains are the largest if changes start early in life,” said the researchers.

Depending on how many healthy dietary “switches” are made and maintained and the amounts consumed, a 20-year-old man in the United States could extend his life up to 13 years, and a 20-year old woman by 11 years.

That number drops with age but changing from a typical diet to the optimized diet at age 60 years could still increase life expectancy by 8 years for women and 9 years for men, and even an 80-year-old female could gain more than 3 years with healthier food choices.

Until now, research in this area has shown health benefits associated with separate food groups or specific diet patterns, while focusing less on the health impact of other dietary changes. The statistical ‘modeling’ approach used in this study bridges that gap, the researchers said.

“Understanding the relative health potential of different food groups could enable people to make feasible and significant health gains,” they concluded.

A version of this article was first published on WebMD.com.

Just a few changes to your diet could add years to your life, but the sooner you start the better.

Maintaining a healthy diet is important, but most people find this difficult to do daily. In a new study, researchers examined the effects of individual healthful and nonhealthful types of foods and estimated the impact by age and sex of swapping some for others.

say the Norwegian scientists who conducted the study, published in PLOS Medicine on Feb. 8.

They developed an online tool that anyone can use to get an idea of how individual food choices can affect life expectancy.