User login

Aggressive up-front combination therapy, more lofty treatment goals, and earlier and more frequent reassessments to guide treatment are improving care of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) while at the same time making it more complex.

A larger number of oral and generic treatment options have in some respects ushered in more management ease. But overall, “I don’t know if management of these patients has ever been more complicated, given the treatment options and strategies,” said Murali M. Chakinala, MD, professor of medicine at Washington University, St. Louis. “We’re always thinking through approaches.”

Diagnosis continues to be challenging given the rarity of PAH and its nonspecific presentation – and in some cases it’s now harder. Experts such as Dr. Chakinala are seeing increasing number of aging patients with left heart disease, chronic kidney disease, and other comorbidities who have significant precapillary pulmonary hypertension and who exhibit hemodynamics consistent with PAH, or group 1 PH.

The question experts face is, do such patients have “true PAH,” as do a reported 25-50 people per million, or do they have another type of PH in the classification schema – or a mixture?

Deciding which patients “really fit into group 1 and should be managed like group 1,” Dr. Chakinala said, requires clinical acumen and has important implications, as patients with PAH are the main beneficiaries of vasodilator therapy. Most other patients with PH will not respond to or tolerate such treatment.

“These older patients may be getting PAH through different mechanisms than our younger patients, but because we define PAH through hemodynamic criteria and by ruling out other obvious explanations, they all get lumped together,” said Dr. Chakinala. “We need to parse these patients out better in the future, much like our oncology colleagues are doing.”

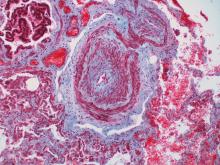

Personalized medicine hopefully is the next horizon for this condition, characterized by severe remodeling of the distal pulmonary arteries. Researchers are pushing to achieve deep phenotyping, identify biomarkers and improve risk assessment tools.

And with 80 or so centers now accredited by the Pulmonary Hypertension Association as Pulmonary Hypertension Care Centers, referred patients are accessing clinical trials of new nonvasodilatory drugs. Currently available therapies improve hemodynamics and symptoms, and can slow disease progression, but are not truly disease modifying, sources say.

“The endothelin, nitric oxide, and prostacyclin pathways have been exhaustively studied and we now have great drugs for those pathways,” said Dr. Chakinala, who leads the PHA’s scientific leadership council. But “we’re not going to put a greater dent into this disease until we have new drugs that work on different biologic pathways.”

Diagnostic challenges

The diagnosis of PAH – a remarkably heterogeneous condition that encompasses heritable forms and idiopathic forms, and that comprises a broad mix of predisposing conditions and exposures, from scleroderma to methamphetamine use – is still too often missed or delayed. Delayed diagnoses and misdiagnoses of PAH and other types of PH have been reported in up to 85% of at-risk patients, according to a 2016 literature review.

Being able to pivot from thinking about common pulmonary ailments or heart failure to considering PAH is a key part of earlier diagnosis and better treatment outcomes. “If someone has unexplained dyspnea or if they’re treated for other lung diseases and are not improving, think about a screening echocardiogram,” said Timothy L. Williamson, MD, vice president of quality and safety and a pulmonary and critical care physician at the University of Kansas Health Center, Kansas City.

One of the most common reasons Dr. Chakinala sees for missed diagnoses are right heart catheterizations that are incomplete or misinterpreted. (Right heart catheterizations are required to confirm the diagnosis.) “One can’t simply measure pressures and stop,” he said. “We need the full hemodynamic profile to know that it’s truly precapillary PAH ... and we need proper interpretation of [elements like] the waveforms.”

The 2019 World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension shifted the definition of PH from an arbitrarily defined mean pulmonary arterial pressure of at least 25 mm Hg at rest (as measured by right heart catheterization) to a more scientifically determined mPAP of at least 20 mm Hg.

The classification document also requires pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) of at least 3 Wood units in the definition of all forms of precapillary PH. PAH specifically is defined as the presence of mPAP of at least 20 mm Hg, PVR of at least 3 Wood units, and pulmonary arterial wedge pressure 15 mm Hg or less.

Trends in treatment

The value of initial combination therapy with an endothelin receptor antagonist (ERA) and a phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitor in treatment-naive PAH was cemented in 2015 by the AMBITION trial. The primary endpoint (death, PAH hospitalization, or unsatisfactory clinical response) occurred in 18%, 34%, and 28% of patients who were randomized, respectively, to combination therapy, monotherapy with the ERA ambrisentan, or monotherapy with the PDE-5 inhibitor tadalafil – and in 31% of the two monotherapy groups combined.

The trial reported a 50% reduction in the primary endpoint in the combination-therapy group versus the pooled monotherapy group, as well as greater reductions in N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide levels, more satisfactory clinical response and greater improvement in 6-minute walking distance.

In practice, a minority of patients – typically older patients with multiple comorbidities – still receive initial monotherapy with sequential add-on therapies based on tolerance, but “for the most part PAH patients will start on combination therapy, most commonly with a ERA and PDE5 inhibitor,” Dr. Chakinala said.

For patients who are not improving on the ERA-PDE5 inhibitor approach – typically those who remain in the intermediate-risk category for intermediate-term mortality – substitution of the PDE5 inhibitor with the soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator riociguat may be considered, he and Dr. Williamson said. Clinical improvement with this substitution was demonstrated in the REPLACE trial.

Experts at PH care centers are also utilizing triple therapy for patients who do not improve to low-risk status after 2-4 months of dual combination therapy. The availability of oral prostacyclin analogues (selexipag and treprostinil) makes it easier to consider adding these agents early on, Dr. Chakinala and Dr. Richardson said.

Patients who fall into the high-risk category, at any point, are still best managed with parenteral prostacyclin analogues, Dr. Chakinala said.

In general, said Dr. Williamson, who also directs the University of Kansas Pulmonary Hypertension Comprehensive Care Center, “the PH community tends to be fairly aggressive up front, and with a low threshold for using prostacyclin analogues.”

The agents are “always part of the picture for someone who is really ill, in functional class IV, or has really impaired right ventricular function,” he said. “And we’re finding increased roles in patients who are not as ill but still have decompensated right ventricular dysfunction. It’s something we now consider.”

Recently published research on up-front oral triple therapy suggests possible benefit for some patients – but it’s far from conclusive, said Dr. Chakinala. The TRITON study randomized treatment-naive patients to the traditional ERA-PDE5 combination and either oral selexipag (a selective prostacyclin receptor agonist) or placebo as a third agent. It found no significant difference in reduction in PVR, the primary outcome, at week 26. However, the authors reported a “possible signal” for improved long-term outcomes with triple therapy.

“Based on this best evidence from a randomized clinical trial, I think it’s unfair to say that all patients should be on triple combination therapy right out of the gate,” he said. “Having said that, more recent [European] data showed that two drugs fell short of the mark in some patients, with high rates of clinical progression. And even in AMBITION, there were a number of patients in the combination arm who didn’t have a robust response.”

A 2021 retrospective analysis from the French Pulmonary Hypertension Registry – one of the European studies – assessed survival with monotherapy, dual therapy, or triple-combination therapy (two orals with a parenteral prostacyclin), and found no difference between monotherapy and dual therapy in high-risk patients.

Experts have been upping the ante, therefore, on early assessment and frequent reassessment of treatment response. Not long ago, patients were typically reassessed 6-12 months after the initiation of treatment. Now, experts at the PH care centers want to assess patients at 3-4 months and adjust or intensify treatment regimens for those who don’t yet qualify as low risk using a multidimensional risk score calculator.

The REVEAL (Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term PAH Management) risk score calculator, for instance, predicts the probability of 1-year survival and assigns patients to a strata of risk level based on either 12 or 6 variables (for the full or “lite” versions).]

Even better monitoring and risk assessment is needed, however, to “help sift out which patients are not improving enough on initial therapy or who are starting to fall off after being on a regimen for a period of time,” Dr. Chakinala said.

Today, with a network of accredited centers of expertise and a desire and need for many patients to remain close to home, Dr. Chakinala encourages finding a balance. Well-resourced clinicians can strive for early diagnosis and management – potentially initiating ERA–PDE-5 inhibitor combination therapy – but still should collaborate with PH experts.

“It’s a good idea to comanage these patients and let the experts see them periodically to help you determine when your patient may be declining,” he said. “The timetable for reassessment, the complexity of the reassessment, and the need to escalate to more advanced therapies has never been more important.”

Research highlights

Therapies that target inflammation and altered metabolism – including metformin – are among those being investigated for PAH. So are therapies targeting dysfunctional bone morphogenetic protein pathway signaling, which has been shown to be associated with hereditary, idiopathic, and likely other forms of PAH; one such drug, called sotatercept, is currently at the phase 3 trial stage.

Most promising for PAH may be the research efforts involving deep phenotyping, said Andrew J. Sweatt, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and the Vera Moulton Wall Center for Pulmonary Vascular Disease.

“It’s where a lot of research is headed – deep phenotyping to deconstruct the molecular and clinical heterogeneity that exists within PAH ... to detect distinct subphenotypes of patients who would respond to particular therapies,” said Dr. Sweatt, who led a review of PH clinical research presented at the 2020 American Thoracic Society International Conference

“Right now, we largely treat all patients the same ... [while] we know that patients have a wide response to therapies and there’s a lot of clinical heterogeneity in how their disease evolves over time,” he said.

Data from a large National Institutes of Health–funded multicenter phenotyping study of PH is being analyzed and should yield findings and publications starting this year, said Anna R. Hemnes, MD, associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and an investigator with the initiative, coined “Redefining Pulmonary Hypertension through Pulmonary Disease Phenomics (PVDOMICS).”

Patients have undergone advanced imaging (for example, echocardiography, cardiac MRI, chest CT, ventilation/perfusion scans), advanced testing through right heart catheterization, body composition testing, quality of life questionnaires, and blood draws that have been analyzed for DNA and RNA expression, proteomics, and metabolomics, said Dr. Hemnes, assistant director of Vanderbilt’s Pulmonary Vascular Center.

The initiative aims to refine the classification of all kinds of PH and “to bring precision medicine to the field so we’re no longer characterizing somebody [based on imaging] and right heart catheterization, but we also incorporating molecular pieces and biomarkers into the diagnostic evaluation,” she said.

In the short term, the results of deep phenotyping should “allow us to be more effective with our therapy recommendations,” Dr. Hemnes said. “Then hopefully in the longer term, [identified biomarkers] will help us to develop new, more effective therapies.”

Dr. Sweatt and Dr. Williamson reported that they have no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Hemnes reported that she holds stock in Tenax (which is studying a tyrosine kinase inhibitor for PAH) and serves as a consultant for Acceleron, Bayer, GossamerBio, United Therapeutics, and Janssen. She also receives research funding from Imara. Dr. Chakinala reported that he is an investigator on clinical trials for a number of pharmaceutical companies. He also serves on advisory boards for Phase Bio, Liquidia/Rare Gen, Bayer, Janssen, Trio Health Analytics, and Aerovate.

Aggressive up-front combination therapy, more lofty treatment goals, and earlier and more frequent reassessments to guide treatment are improving care of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) while at the same time making it more complex.

A larger number of oral and generic treatment options have in some respects ushered in more management ease. But overall, “I don’t know if management of these patients has ever been more complicated, given the treatment options and strategies,” said Murali M. Chakinala, MD, professor of medicine at Washington University, St. Louis. “We’re always thinking through approaches.”

Diagnosis continues to be challenging given the rarity of PAH and its nonspecific presentation – and in some cases it’s now harder. Experts such as Dr. Chakinala are seeing increasing number of aging patients with left heart disease, chronic kidney disease, and other comorbidities who have significant precapillary pulmonary hypertension and who exhibit hemodynamics consistent with PAH, or group 1 PH.

The question experts face is, do such patients have “true PAH,” as do a reported 25-50 people per million, or do they have another type of PH in the classification schema – or a mixture?

Deciding which patients “really fit into group 1 and should be managed like group 1,” Dr. Chakinala said, requires clinical acumen and has important implications, as patients with PAH are the main beneficiaries of vasodilator therapy. Most other patients with PH will not respond to or tolerate such treatment.

“These older patients may be getting PAH through different mechanisms than our younger patients, but because we define PAH through hemodynamic criteria and by ruling out other obvious explanations, they all get lumped together,” said Dr. Chakinala. “We need to parse these patients out better in the future, much like our oncology colleagues are doing.”

Personalized medicine hopefully is the next horizon for this condition, characterized by severe remodeling of the distal pulmonary arteries. Researchers are pushing to achieve deep phenotyping, identify biomarkers and improve risk assessment tools.

And with 80 or so centers now accredited by the Pulmonary Hypertension Association as Pulmonary Hypertension Care Centers, referred patients are accessing clinical trials of new nonvasodilatory drugs. Currently available therapies improve hemodynamics and symptoms, and can slow disease progression, but are not truly disease modifying, sources say.

“The endothelin, nitric oxide, and prostacyclin pathways have been exhaustively studied and we now have great drugs for those pathways,” said Dr. Chakinala, who leads the PHA’s scientific leadership council. But “we’re not going to put a greater dent into this disease until we have new drugs that work on different biologic pathways.”

Diagnostic challenges

The diagnosis of PAH – a remarkably heterogeneous condition that encompasses heritable forms and idiopathic forms, and that comprises a broad mix of predisposing conditions and exposures, from scleroderma to methamphetamine use – is still too often missed or delayed. Delayed diagnoses and misdiagnoses of PAH and other types of PH have been reported in up to 85% of at-risk patients, according to a 2016 literature review.

Being able to pivot from thinking about common pulmonary ailments or heart failure to considering PAH is a key part of earlier diagnosis and better treatment outcomes. “If someone has unexplained dyspnea or if they’re treated for other lung diseases and are not improving, think about a screening echocardiogram,” said Timothy L. Williamson, MD, vice president of quality and safety and a pulmonary and critical care physician at the University of Kansas Health Center, Kansas City.

One of the most common reasons Dr. Chakinala sees for missed diagnoses are right heart catheterizations that are incomplete or misinterpreted. (Right heart catheterizations are required to confirm the diagnosis.) “One can’t simply measure pressures and stop,” he said. “We need the full hemodynamic profile to know that it’s truly precapillary PAH ... and we need proper interpretation of [elements like] the waveforms.”

The 2019 World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension shifted the definition of PH from an arbitrarily defined mean pulmonary arterial pressure of at least 25 mm Hg at rest (as measured by right heart catheterization) to a more scientifically determined mPAP of at least 20 mm Hg.

The classification document also requires pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) of at least 3 Wood units in the definition of all forms of precapillary PH. PAH specifically is defined as the presence of mPAP of at least 20 mm Hg, PVR of at least 3 Wood units, and pulmonary arterial wedge pressure 15 mm Hg or less.

Trends in treatment

The value of initial combination therapy with an endothelin receptor antagonist (ERA) and a phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitor in treatment-naive PAH was cemented in 2015 by the AMBITION trial. The primary endpoint (death, PAH hospitalization, or unsatisfactory clinical response) occurred in 18%, 34%, and 28% of patients who were randomized, respectively, to combination therapy, monotherapy with the ERA ambrisentan, or monotherapy with the PDE-5 inhibitor tadalafil – and in 31% of the two monotherapy groups combined.

The trial reported a 50% reduction in the primary endpoint in the combination-therapy group versus the pooled monotherapy group, as well as greater reductions in N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide levels, more satisfactory clinical response and greater improvement in 6-minute walking distance.

In practice, a minority of patients – typically older patients with multiple comorbidities – still receive initial monotherapy with sequential add-on therapies based on tolerance, but “for the most part PAH patients will start on combination therapy, most commonly with a ERA and PDE5 inhibitor,” Dr. Chakinala said.

For patients who are not improving on the ERA-PDE5 inhibitor approach – typically those who remain in the intermediate-risk category for intermediate-term mortality – substitution of the PDE5 inhibitor with the soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator riociguat may be considered, he and Dr. Williamson said. Clinical improvement with this substitution was demonstrated in the REPLACE trial.

Experts at PH care centers are also utilizing triple therapy for patients who do not improve to low-risk status after 2-4 months of dual combination therapy. The availability of oral prostacyclin analogues (selexipag and treprostinil) makes it easier to consider adding these agents early on, Dr. Chakinala and Dr. Richardson said.

Patients who fall into the high-risk category, at any point, are still best managed with parenteral prostacyclin analogues, Dr. Chakinala said.

In general, said Dr. Williamson, who also directs the University of Kansas Pulmonary Hypertension Comprehensive Care Center, “the PH community tends to be fairly aggressive up front, and with a low threshold for using prostacyclin analogues.”

The agents are “always part of the picture for someone who is really ill, in functional class IV, or has really impaired right ventricular function,” he said. “And we’re finding increased roles in patients who are not as ill but still have decompensated right ventricular dysfunction. It’s something we now consider.”

Recently published research on up-front oral triple therapy suggests possible benefit for some patients – but it’s far from conclusive, said Dr. Chakinala. The TRITON study randomized treatment-naive patients to the traditional ERA-PDE5 combination and either oral selexipag (a selective prostacyclin receptor agonist) or placebo as a third agent. It found no significant difference in reduction in PVR, the primary outcome, at week 26. However, the authors reported a “possible signal” for improved long-term outcomes with triple therapy.

“Based on this best evidence from a randomized clinical trial, I think it’s unfair to say that all patients should be on triple combination therapy right out of the gate,” he said. “Having said that, more recent [European] data showed that two drugs fell short of the mark in some patients, with high rates of clinical progression. And even in AMBITION, there were a number of patients in the combination arm who didn’t have a robust response.”

A 2021 retrospective analysis from the French Pulmonary Hypertension Registry – one of the European studies – assessed survival with monotherapy, dual therapy, or triple-combination therapy (two orals with a parenteral prostacyclin), and found no difference between monotherapy and dual therapy in high-risk patients.

Experts have been upping the ante, therefore, on early assessment and frequent reassessment of treatment response. Not long ago, patients were typically reassessed 6-12 months after the initiation of treatment. Now, experts at the PH care centers want to assess patients at 3-4 months and adjust or intensify treatment regimens for those who don’t yet qualify as low risk using a multidimensional risk score calculator.

The REVEAL (Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term PAH Management) risk score calculator, for instance, predicts the probability of 1-year survival and assigns patients to a strata of risk level based on either 12 or 6 variables (for the full or “lite” versions).]

Even better monitoring and risk assessment is needed, however, to “help sift out which patients are not improving enough on initial therapy or who are starting to fall off after being on a regimen for a period of time,” Dr. Chakinala said.

Today, with a network of accredited centers of expertise and a desire and need for many patients to remain close to home, Dr. Chakinala encourages finding a balance. Well-resourced clinicians can strive for early diagnosis and management – potentially initiating ERA–PDE-5 inhibitor combination therapy – but still should collaborate with PH experts.

“It’s a good idea to comanage these patients and let the experts see them periodically to help you determine when your patient may be declining,” he said. “The timetable for reassessment, the complexity of the reassessment, and the need to escalate to more advanced therapies has never been more important.”

Research highlights

Therapies that target inflammation and altered metabolism – including metformin – are among those being investigated for PAH. So are therapies targeting dysfunctional bone morphogenetic protein pathway signaling, which has been shown to be associated with hereditary, idiopathic, and likely other forms of PAH; one such drug, called sotatercept, is currently at the phase 3 trial stage.

Most promising for PAH may be the research efforts involving deep phenotyping, said Andrew J. Sweatt, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and the Vera Moulton Wall Center for Pulmonary Vascular Disease.

“It’s where a lot of research is headed – deep phenotyping to deconstruct the molecular and clinical heterogeneity that exists within PAH ... to detect distinct subphenotypes of patients who would respond to particular therapies,” said Dr. Sweatt, who led a review of PH clinical research presented at the 2020 American Thoracic Society International Conference

“Right now, we largely treat all patients the same ... [while] we know that patients have a wide response to therapies and there’s a lot of clinical heterogeneity in how their disease evolves over time,” he said.

Data from a large National Institutes of Health–funded multicenter phenotyping study of PH is being analyzed and should yield findings and publications starting this year, said Anna R. Hemnes, MD, associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and an investigator with the initiative, coined “Redefining Pulmonary Hypertension through Pulmonary Disease Phenomics (PVDOMICS).”

Patients have undergone advanced imaging (for example, echocardiography, cardiac MRI, chest CT, ventilation/perfusion scans), advanced testing through right heart catheterization, body composition testing, quality of life questionnaires, and blood draws that have been analyzed for DNA and RNA expression, proteomics, and metabolomics, said Dr. Hemnes, assistant director of Vanderbilt’s Pulmonary Vascular Center.

The initiative aims to refine the classification of all kinds of PH and “to bring precision medicine to the field so we’re no longer characterizing somebody [based on imaging] and right heart catheterization, but we also incorporating molecular pieces and biomarkers into the diagnostic evaluation,” she said.

In the short term, the results of deep phenotyping should “allow us to be more effective with our therapy recommendations,” Dr. Hemnes said. “Then hopefully in the longer term, [identified biomarkers] will help us to develop new, more effective therapies.”

Dr. Sweatt and Dr. Williamson reported that they have no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Hemnes reported that she holds stock in Tenax (which is studying a tyrosine kinase inhibitor for PAH) and serves as a consultant for Acceleron, Bayer, GossamerBio, United Therapeutics, and Janssen. She also receives research funding from Imara. Dr. Chakinala reported that he is an investigator on clinical trials for a number of pharmaceutical companies. He also serves on advisory boards for Phase Bio, Liquidia/Rare Gen, Bayer, Janssen, Trio Health Analytics, and Aerovate.

Aggressive up-front combination therapy, more lofty treatment goals, and earlier and more frequent reassessments to guide treatment are improving care of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) while at the same time making it more complex.

A larger number of oral and generic treatment options have in some respects ushered in more management ease. But overall, “I don’t know if management of these patients has ever been more complicated, given the treatment options and strategies,” said Murali M. Chakinala, MD, professor of medicine at Washington University, St. Louis. “We’re always thinking through approaches.”

Diagnosis continues to be challenging given the rarity of PAH and its nonspecific presentation – and in some cases it’s now harder. Experts such as Dr. Chakinala are seeing increasing number of aging patients with left heart disease, chronic kidney disease, and other comorbidities who have significant precapillary pulmonary hypertension and who exhibit hemodynamics consistent with PAH, or group 1 PH.

The question experts face is, do such patients have “true PAH,” as do a reported 25-50 people per million, or do they have another type of PH in the classification schema – or a mixture?

Deciding which patients “really fit into group 1 and should be managed like group 1,” Dr. Chakinala said, requires clinical acumen and has important implications, as patients with PAH are the main beneficiaries of vasodilator therapy. Most other patients with PH will not respond to or tolerate such treatment.

“These older patients may be getting PAH through different mechanisms than our younger patients, but because we define PAH through hemodynamic criteria and by ruling out other obvious explanations, they all get lumped together,” said Dr. Chakinala. “We need to parse these patients out better in the future, much like our oncology colleagues are doing.”

Personalized medicine hopefully is the next horizon for this condition, characterized by severe remodeling of the distal pulmonary arteries. Researchers are pushing to achieve deep phenotyping, identify biomarkers and improve risk assessment tools.

And with 80 or so centers now accredited by the Pulmonary Hypertension Association as Pulmonary Hypertension Care Centers, referred patients are accessing clinical trials of new nonvasodilatory drugs. Currently available therapies improve hemodynamics and symptoms, and can slow disease progression, but are not truly disease modifying, sources say.

“The endothelin, nitric oxide, and prostacyclin pathways have been exhaustively studied and we now have great drugs for those pathways,” said Dr. Chakinala, who leads the PHA’s scientific leadership council. But “we’re not going to put a greater dent into this disease until we have new drugs that work on different biologic pathways.”

Diagnostic challenges

The diagnosis of PAH – a remarkably heterogeneous condition that encompasses heritable forms and idiopathic forms, and that comprises a broad mix of predisposing conditions and exposures, from scleroderma to methamphetamine use – is still too often missed or delayed. Delayed diagnoses and misdiagnoses of PAH and other types of PH have been reported in up to 85% of at-risk patients, according to a 2016 literature review.

Being able to pivot from thinking about common pulmonary ailments or heart failure to considering PAH is a key part of earlier diagnosis and better treatment outcomes. “If someone has unexplained dyspnea or if they’re treated for other lung diseases and are not improving, think about a screening echocardiogram,” said Timothy L. Williamson, MD, vice president of quality and safety and a pulmonary and critical care physician at the University of Kansas Health Center, Kansas City.

One of the most common reasons Dr. Chakinala sees for missed diagnoses are right heart catheterizations that are incomplete or misinterpreted. (Right heart catheterizations are required to confirm the diagnosis.) “One can’t simply measure pressures and stop,” he said. “We need the full hemodynamic profile to know that it’s truly precapillary PAH ... and we need proper interpretation of [elements like] the waveforms.”

The 2019 World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension shifted the definition of PH from an arbitrarily defined mean pulmonary arterial pressure of at least 25 mm Hg at rest (as measured by right heart catheterization) to a more scientifically determined mPAP of at least 20 mm Hg.

The classification document also requires pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) of at least 3 Wood units in the definition of all forms of precapillary PH. PAH specifically is defined as the presence of mPAP of at least 20 mm Hg, PVR of at least 3 Wood units, and pulmonary arterial wedge pressure 15 mm Hg or less.

Trends in treatment

The value of initial combination therapy with an endothelin receptor antagonist (ERA) and a phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitor in treatment-naive PAH was cemented in 2015 by the AMBITION trial. The primary endpoint (death, PAH hospitalization, or unsatisfactory clinical response) occurred in 18%, 34%, and 28% of patients who were randomized, respectively, to combination therapy, monotherapy with the ERA ambrisentan, or monotherapy with the PDE-5 inhibitor tadalafil – and in 31% of the two monotherapy groups combined.

The trial reported a 50% reduction in the primary endpoint in the combination-therapy group versus the pooled monotherapy group, as well as greater reductions in N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide levels, more satisfactory clinical response and greater improvement in 6-minute walking distance.

In practice, a minority of patients – typically older patients with multiple comorbidities – still receive initial monotherapy with sequential add-on therapies based on tolerance, but “for the most part PAH patients will start on combination therapy, most commonly with a ERA and PDE5 inhibitor,” Dr. Chakinala said.

For patients who are not improving on the ERA-PDE5 inhibitor approach – typically those who remain in the intermediate-risk category for intermediate-term mortality – substitution of the PDE5 inhibitor with the soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator riociguat may be considered, he and Dr. Williamson said. Clinical improvement with this substitution was demonstrated in the REPLACE trial.

Experts at PH care centers are also utilizing triple therapy for patients who do not improve to low-risk status after 2-4 months of dual combination therapy. The availability of oral prostacyclin analogues (selexipag and treprostinil) makes it easier to consider adding these agents early on, Dr. Chakinala and Dr. Richardson said.

Patients who fall into the high-risk category, at any point, are still best managed with parenteral prostacyclin analogues, Dr. Chakinala said.

In general, said Dr. Williamson, who also directs the University of Kansas Pulmonary Hypertension Comprehensive Care Center, “the PH community tends to be fairly aggressive up front, and with a low threshold for using prostacyclin analogues.”

The agents are “always part of the picture for someone who is really ill, in functional class IV, or has really impaired right ventricular function,” he said. “And we’re finding increased roles in patients who are not as ill but still have decompensated right ventricular dysfunction. It’s something we now consider.”

Recently published research on up-front oral triple therapy suggests possible benefit for some patients – but it’s far from conclusive, said Dr. Chakinala. The TRITON study randomized treatment-naive patients to the traditional ERA-PDE5 combination and either oral selexipag (a selective prostacyclin receptor agonist) or placebo as a third agent. It found no significant difference in reduction in PVR, the primary outcome, at week 26. However, the authors reported a “possible signal” for improved long-term outcomes with triple therapy.

“Based on this best evidence from a randomized clinical trial, I think it’s unfair to say that all patients should be on triple combination therapy right out of the gate,” he said. “Having said that, more recent [European] data showed that two drugs fell short of the mark in some patients, with high rates of clinical progression. And even in AMBITION, there were a number of patients in the combination arm who didn’t have a robust response.”

A 2021 retrospective analysis from the French Pulmonary Hypertension Registry – one of the European studies – assessed survival with monotherapy, dual therapy, or triple-combination therapy (two orals with a parenteral prostacyclin), and found no difference between monotherapy and dual therapy in high-risk patients.

Experts have been upping the ante, therefore, on early assessment and frequent reassessment of treatment response. Not long ago, patients were typically reassessed 6-12 months after the initiation of treatment. Now, experts at the PH care centers want to assess patients at 3-4 months and adjust or intensify treatment regimens for those who don’t yet qualify as low risk using a multidimensional risk score calculator.

The REVEAL (Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term PAH Management) risk score calculator, for instance, predicts the probability of 1-year survival and assigns patients to a strata of risk level based on either 12 or 6 variables (for the full or “lite” versions).]

Even better monitoring and risk assessment is needed, however, to “help sift out which patients are not improving enough on initial therapy or who are starting to fall off after being on a regimen for a period of time,” Dr. Chakinala said.

Today, with a network of accredited centers of expertise and a desire and need for many patients to remain close to home, Dr. Chakinala encourages finding a balance. Well-resourced clinicians can strive for early diagnosis and management – potentially initiating ERA–PDE-5 inhibitor combination therapy – but still should collaborate with PH experts.

“It’s a good idea to comanage these patients and let the experts see them periodically to help you determine when your patient may be declining,” he said. “The timetable for reassessment, the complexity of the reassessment, and the need to escalate to more advanced therapies has never been more important.”

Research highlights

Therapies that target inflammation and altered metabolism – including metformin – are among those being investigated for PAH. So are therapies targeting dysfunctional bone morphogenetic protein pathway signaling, which has been shown to be associated with hereditary, idiopathic, and likely other forms of PAH; one such drug, called sotatercept, is currently at the phase 3 trial stage.

Most promising for PAH may be the research efforts involving deep phenotyping, said Andrew J. Sweatt, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and the Vera Moulton Wall Center for Pulmonary Vascular Disease.

“It’s where a lot of research is headed – deep phenotyping to deconstruct the molecular and clinical heterogeneity that exists within PAH ... to detect distinct subphenotypes of patients who would respond to particular therapies,” said Dr. Sweatt, who led a review of PH clinical research presented at the 2020 American Thoracic Society International Conference

“Right now, we largely treat all patients the same ... [while] we know that patients have a wide response to therapies and there’s a lot of clinical heterogeneity in how their disease evolves over time,” he said.

Data from a large National Institutes of Health–funded multicenter phenotyping study of PH is being analyzed and should yield findings and publications starting this year, said Anna R. Hemnes, MD, associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and an investigator with the initiative, coined “Redefining Pulmonary Hypertension through Pulmonary Disease Phenomics (PVDOMICS).”

Patients have undergone advanced imaging (for example, echocardiography, cardiac MRI, chest CT, ventilation/perfusion scans), advanced testing through right heart catheterization, body composition testing, quality of life questionnaires, and blood draws that have been analyzed for DNA and RNA expression, proteomics, and metabolomics, said Dr. Hemnes, assistant director of Vanderbilt’s Pulmonary Vascular Center.

The initiative aims to refine the classification of all kinds of PH and “to bring precision medicine to the field so we’re no longer characterizing somebody [based on imaging] and right heart catheterization, but we also incorporating molecular pieces and biomarkers into the diagnostic evaluation,” she said.

In the short term, the results of deep phenotyping should “allow us to be more effective with our therapy recommendations,” Dr. Hemnes said. “Then hopefully in the longer term, [identified biomarkers] will help us to develop new, more effective therapies.”

Dr. Sweatt and Dr. Williamson reported that they have no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Hemnes reported that she holds stock in Tenax (which is studying a tyrosine kinase inhibitor for PAH) and serves as a consultant for Acceleron, Bayer, GossamerBio, United Therapeutics, and Janssen. She also receives research funding from Imara. Dr. Chakinala reported that he is an investigator on clinical trials for a number of pharmaceutical companies. He also serves on advisory boards for Phase Bio, Liquidia/Rare Gen, Bayer, Janssen, Trio Health Analytics, and Aerovate.