User login

Cardiology News is an independent news source that provides cardiologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on cardiology and the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is the online destination and multimedia properties of Cardiology News, the independent news publication for cardiologists. Cardiology news is the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in cardiology as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

Persistent asthma linked to higher carotid plaque burden

Persistent asthma is associated with increased carotid plaque burden and higher levels of inflammation, putting these patients at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events, new research suggests.

Using data from the MESA study, investigators analyzed more than 5,000 individuals, comparing carotid plaque and inflammatory markers in those with and without asthma.

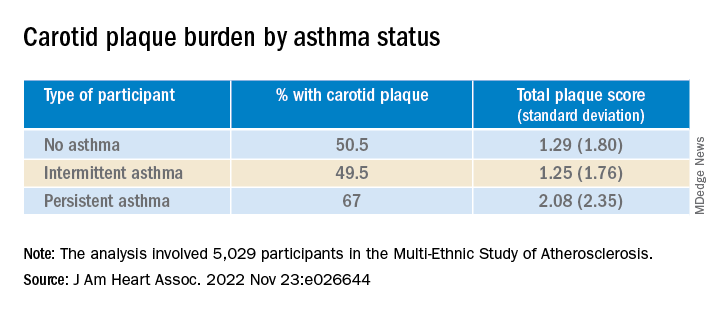

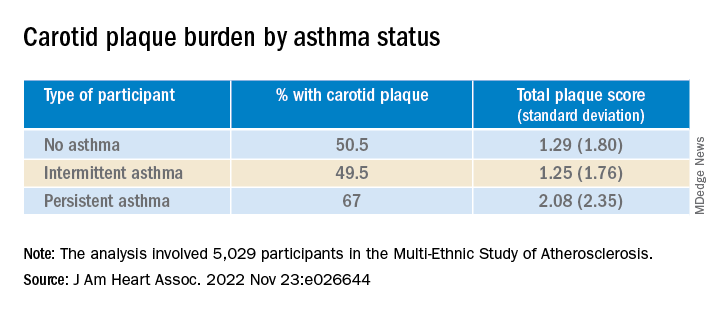

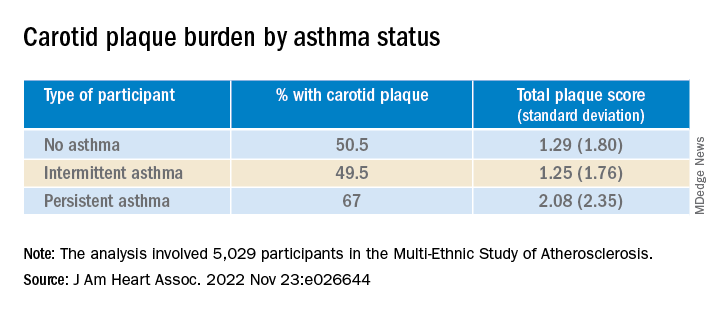

They found that carotid plaque was present in half of participants without asthma and half of those with intermittent asthma but in close to 70% of participants with persistent asthma.

.

“The take-home message is that the current study, paired with prior studies, highlights that individuals with more significant forms of asthma may be at higher cardiovascular risk and makes it imperative to address modifiable risk factors among patients with asthma,” lead author Matthew Tattersall, DO, MS, assistant professor of cardiovascular medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, told this news organization.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Limited data

Asthma and ASCVD are “highly prevalent inflammatory diseases,” the authors write. Carotid artery plaque detected by B-mode ultrasound “represents advanced, typically subclinical atherosclerosis that is a strong independent predictor of incident ASCVD events,” with inflammation playing a “key role” in precipitating these events, they note.

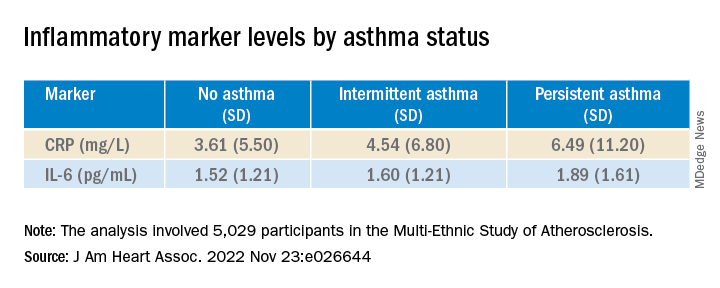

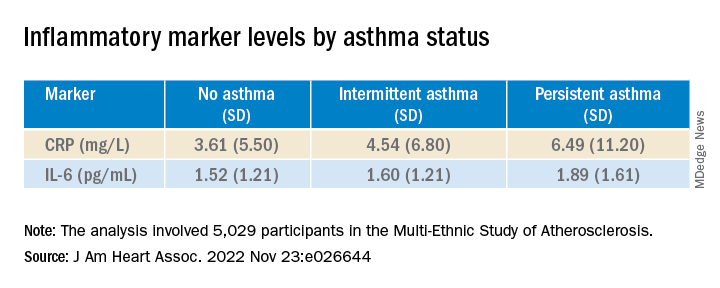

Serum inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and IL-6 are associated with increased ASCVD events, and in asthma, CRP and other inflammatory biomarkers are elevated and tend to further increase during exacerbations.

Currently, there are limited data looking at the associations of asthma, asthma severity, and atherosclerotic plaque burden, they note, so the researchers turned to the MESA study – a multiethnic population of individuals free of prevalent ASCVD at baseline. They hypothesized that persistent asthma would be associated with higher carotid plaque presence and burden.

They also wanted to explore “whether these associations would be attenuated after adjustment for baseline inflammatory biomarkers.”

Dr. Tattersall said the current study “links our previous work studying the manifestations of asthma,” in which he and his colleagues demonstrated increased cardiovascular events among MESA participants with persistent asthma, as well as late-onset asthma participants in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. His group also showed that early arterial injury occurs in adolescents with asthma.

However, there are also few data looking at the association with carotid plaque, “a late manifestation of arterial injury and a strong predictor of future cardiovascular events and asthma,” Dr. Tattersall added.

He and his group therefore “wanted to explore the entire spectrum of arterial injury, from the initial increase in the carotid media thickness to plaque formation to cardiovascular events.”

To do so, they studied participants in MESA, a study of close to 7,000 adults that began in the year 2000 and continues to follow participants today. At the time of enrollment, all were free from CVD.

The current analysis looked at 5,029 MESA participants (mean age 61.6 years, 53% female, 26% Black, 23% Hispanic, 12% Asian), comparing those with persistent asthma, defined as “asthma requiring use of controller medications,” intermittent asthma, defined as “asthma without controller medications,” and no asthma.

Participants underwent B-mode carotid ultrasound to detect carotid plaques, with a total plaque score (TPS) ranging from 0-12. The researchers used multivariable regression modeling to evaluate the association of asthma subtype and carotid plaque burden.

Interpret cautiously

Participants with persistent asthma were more likely to be female, have higher body mass index (BMI), and higher high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, compared with those without asthma.

Participants with persistent asthma had the highest burden of carotid plaque (P ≤ .003 for comparison of proportions and .002 for comparison of means).

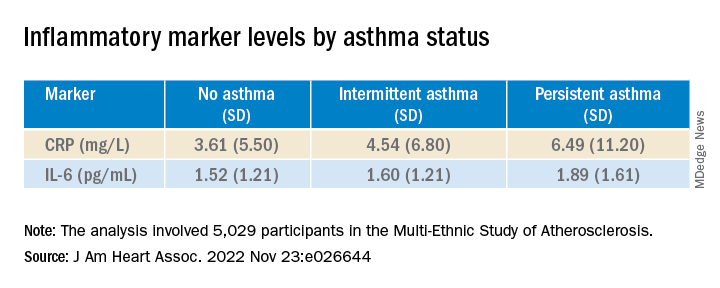

Moreover, participants with persistent asthma also had the highest systemic inflammatory marker levels – both CRP and IL-6 – compared with those without asthma. While participants with intermittent asthma also had higher average CRP, compared with those without asthma, their IL-6 levels were comparable.

In unadjusted models, persistent asthma was associated with higher odds of carotid plaque presence (odds ratio, 1.97; 95% confidence interval, 1.32-2.95) – an association that persisted even in models that adjusted for biologic confounders (both P < .01). There also was an association between persistent asthma and higher carotid TPS (P < .001).

In further adjusted models, IL-6 was independently associated with presence of carotid plaque (P = .0001 per 1-SD increment of 1.53), as well as TPS (P < .001). CRP was “slightly associated” with carotid TPS (P = .04) but not carotid plaque presence (P = .07).

There was no attenuation after the researchers evaluated the associations of asthma subtype and carotid plaque presence or TPS and fully adjusted for baseline IL-6 or CRP (P = .02 and P = .01, respectively).

“Since this study is observational, we cannot confirm causation, but the study adds to the growing literature exploring the systemic effects of asthma,” Dr. Tattersall commented.

“Our initial hypothesis was that it was driven by inflammation, as both asthma and CVD are inflammatory conditions,” he continued. “We did adjust for inflammatory biomarkers in this analysis, but there was no change in the association.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Tattersall and colleagues are “cautious in the interpretation,” since the inflammatory biomarkers “were only collected at one point, and these measures can be dynamic, thus adjustment may not tell the whole story.”

Heightened awareness

Robert Brook, MD, professor and director of cardiovascular disease prevention, Wayne State University, Detroit, said the “main contribution of this study is the novel demonstration of a significant association between persistent (but not intermittent) asthma with carotid atherosclerosis in the MESA cohort, a large multi-ethnic population.”

These findings “support the biological plausibility of the growing epidemiological evidence that asthma independently increases the risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” added Dr. Brook, who was not involved with the study.

“The main take-home message for clinicians is that, just like in COPD (which is well-established), asthma is often a systemic condition in that the inflammation and disease process can impact the whole body,” he said.

“Health care providers should have a heightened awareness of the potentially increased cardiovascular risk of their patients with asthma and pay special attention to controlling their heart disease risk factors (for example, hyperlipidemia, hypertension),” Dr. Brook stated.

Dr. Tattersall was supported by an American Heart Association Career Development Award. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Center for Research Resources. Dr. Tattersall and co-authors and Dr. Brook declare no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Persistent asthma is associated with increased carotid plaque burden and higher levels of inflammation, putting these patients at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events, new research suggests.

Using data from the MESA study, investigators analyzed more than 5,000 individuals, comparing carotid plaque and inflammatory markers in those with and without asthma.

They found that carotid plaque was present in half of participants without asthma and half of those with intermittent asthma but in close to 70% of participants with persistent asthma.

.

“The take-home message is that the current study, paired with prior studies, highlights that individuals with more significant forms of asthma may be at higher cardiovascular risk and makes it imperative to address modifiable risk factors among patients with asthma,” lead author Matthew Tattersall, DO, MS, assistant professor of cardiovascular medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, told this news organization.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Limited data

Asthma and ASCVD are “highly prevalent inflammatory diseases,” the authors write. Carotid artery plaque detected by B-mode ultrasound “represents advanced, typically subclinical atherosclerosis that is a strong independent predictor of incident ASCVD events,” with inflammation playing a “key role” in precipitating these events, they note.

Serum inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and IL-6 are associated with increased ASCVD events, and in asthma, CRP and other inflammatory biomarkers are elevated and tend to further increase during exacerbations.

Currently, there are limited data looking at the associations of asthma, asthma severity, and atherosclerotic plaque burden, they note, so the researchers turned to the MESA study – a multiethnic population of individuals free of prevalent ASCVD at baseline. They hypothesized that persistent asthma would be associated with higher carotid plaque presence and burden.

They also wanted to explore “whether these associations would be attenuated after adjustment for baseline inflammatory biomarkers.”

Dr. Tattersall said the current study “links our previous work studying the manifestations of asthma,” in which he and his colleagues demonstrated increased cardiovascular events among MESA participants with persistent asthma, as well as late-onset asthma participants in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. His group also showed that early arterial injury occurs in adolescents with asthma.

However, there are also few data looking at the association with carotid plaque, “a late manifestation of arterial injury and a strong predictor of future cardiovascular events and asthma,” Dr. Tattersall added.

He and his group therefore “wanted to explore the entire spectrum of arterial injury, from the initial increase in the carotid media thickness to plaque formation to cardiovascular events.”

To do so, they studied participants in MESA, a study of close to 7,000 adults that began in the year 2000 and continues to follow participants today. At the time of enrollment, all were free from CVD.

The current analysis looked at 5,029 MESA participants (mean age 61.6 years, 53% female, 26% Black, 23% Hispanic, 12% Asian), comparing those with persistent asthma, defined as “asthma requiring use of controller medications,” intermittent asthma, defined as “asthma without controller medications,” and no asthma.

Participants underwent B-mode carotid ultrasound to detect carotid plaques, with a total plaque score (TPS) ranging from 0-12. The researchers used multivariable regression modeling to evaluate the association of asthma subtype and carotid plaque burden.

Interpret cautiously

Participants with persistent asthma were more likely to be female, have higher body mass index (BMI), and higher high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, compared with those without asthma.

Participants with persistent asthma had the highest burden of carotid plaque (P ≤ .003 for comparison of proportions and .002 for comparison of means).

Moreover, participants with persistent asthma also had the highest systemic inflammatory marker levels – both CRP and IL-6 – compared with those without asthma. While participants with intermittent asthma also had higher average CRP, compared with those without asthma, their IL-6 levels were comparable.

In unadjusted models, persistent asthma was associated with higher odds of carotid plaque presence (odds ratio, 1.97; 95% confidence interval, 1.32-2.95) – an association that persisted even in models that adjusted for biologic confounders (both P < .01). There also was an association between persistent asthma and higher carotid TPS (P < .001).

In further adjusted models, IL-6 was independently associated with presence of carotid plaque (P = .0001 per 1-SD increment of 1.53), as well as TPS (P < .001). CRP was “slightly associated” with carotid TPS (P = .04) but not carotid plaque presence (P = .07).

There was no attenuation after the researchers evaluated the associations of asthma subtype and carotid plaque presence or TPS and fully adjusted for baseline IL-6 or CRP (P = .02 and P = .01, respectively).

“Since this study is observational, we cannot confirm causation, but the study adds to the growing literature exploring the systemic effects of asthma,” Dr. Tattersall commented.

“Our initial hypothesis was that it was driven by inflammation, as both asthma and CVD are inflammatory conditions,” he continued. “We did adjust for inflammatory biomarkers in this analysis, but there was no change in the association.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Tattersall and colleagues are “cautious in the interpretation,” since the inflammatory biomarkers “were only collected at one point, and these measures can be dynamic, thus adjustment may not tell the whole story.”

Heightened awareness

Robert Brook, MD, professor and director of cardiovascular disease prevention, Wayne State University, Detroit, said the “main contribution of this study is the novel demonstration of a significant association between persistent (but not intermittent) asthma with carotid atherosclerosis in the MESA cohort, a large multi-ethnic population.”

These findings “support the biological plausibility of the growing epidemiological evidence that asthma independently increases the risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” added Dr. Brook, who was not involved with the study.

“The main take-home message for clinicians is that, just like in COPD (which is well-established), asthma is often a systemic condition in that the inflammation and disease process can impact the whole body,” he said.

“Health care providers should have a heightened awareness of the potentially increased cardiovascular risk of their patients with asthma and pay special attention to controlling their heart disease risk factors (for example, hyperlipidemia, hypertension),” Dr. Brook stated.

Dr. Tattersall was supported by an American Heart Association Career Development Award. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Center for Research Resources. Dr. Tattersall and co-authors and Dr. Brook declare no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Persistent asthma is associated with increased carotid plaque burden and higher levels of inflammation, putting these patients at risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events, new research suggests.

Using data from the MESA study, investigators analyzed more than 5,000 individuals, comparing carotid plaque and inflammatory markers in those with and without asthma.

They found that carotid plaque was present in half of participants without asthma and half of those with intermittent asthma but in close to 70% of participants with persistent asthma.

.

“The take-home message is that the current study, paired with prior studies, highlights that individuals with more significant forms of asthma may be at higher cardiovascular risk and makes it imperative to address modifiable risk factors among patients with asthma,” lead author Matthew Tattersall, DO, MS, assistant professor of cardiovascular medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, told this news organization.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Limited data

Asthma and ASCVD are “highly prevalent inflammatory diseases,” the authors write. Carotid artery plaque detected by B-mode ultrasound “represents advanced, typically subclinical atherosclerosis that is a strong independent predictor of incident ASCVD events,” with inflammation playing a “key role” in precipitating these events, they note.

Serum inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and IL-6 are associated with increased ASCVD events, and in asthma, CRP and other inflammatory biomarkers are elevated and tend to further increase during exacerbations.

Currently, there are limited data looking at the associations of asthma, asthma severity, and atherosclerotic plaque burden, they note, so the researchers turned to the MESA study – a multiethnic population of individuals free of prevalent ASCVD at baseline. They hypothesized that persistent asthma would be associated with higher carotid plaque presence and burden.

They also wanted to explore “whether these associations would be attenuated after adjustment for baseline inflammatory biomarkers.”

Dr. Tattersall said the current study “links our previous work studying the manifestations of asthma,” in which he and his colleagues demonstrated increased cardiovascular events among MESA participants with persistent asthma, as well as late-onset asthma participants in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. His group also showed that early arterial injury occurs in adolescents with asthma.

However, there are also few data looking at the association with carotid plaque, “a late manifestation of arterial injury and a strong predictor of future cardiovascular events and asthma,” Dr. Tattersall added.

He and his group therefore “wanted to explore the entire spectrum of arterial injury, from the initial increase in the carotid media thickness to plaque formation to cardiovascular events.”

To do so, they studied participants in MESA, a study of close to 7,000 adults that began in the year 2000 and continues to follow participants today. At the time of enrollment, all were free from CVD.

The current analysis looked at 5,029 MESA participants (mean age 61.6 years, 53% female, 26% Black, 23% Hispanic, 12% Asian), comparing those with persistent asthma, defined as “asthma requiring use of controller medications,” intermittent asthma, defined as “asthma without controller medications,” and no asthma.

Participants underwent B-mode carotid ultrasound to detect carotid plaques, with a total plaque score (TPS) ranging from 0-12. The researchers used multivariable regression modeling to evaluate the association of asthma subtype and carotid plaque burden.

Interpret cautiously

Participants with persistent asthma were more likely to be female, have higher body mass index (BMI), and higher high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, compared with those without asthma.

Participants with persistent asthma had the highest burden of carotid plaque (P ≤ .003 for comparison of proportions and .002 for comparison of means).

Moreover, participants with persistent asthma also had the highest systemic inflammatory marker levels – both CRP and IL-6 – compared with those without asthma. While participants with intermittent asthma also had higher average CRP, compared with those without asthma, their IL-6 levels were comparable.

In unadjusted models, persistent asthma was associated with higher odds of carotid plaque presence (odds ratio, 1.97; 95% confidence interval, 1.32-2.95) – an association that persisted even in models that adjusted for biologic confounders (both P < .01). There also was an association between persistent asthma and higher carotid TPS (P < .001).

In further adjusted models, IL-6 was independently associated with presence of carotid plaque (P = .0001 per 1-SD increment of 1.53), as well as TPS (P < .001). CRP was “slightly associated” with carotid TPS (P = .04) but not carotid plaque presence (P = .07).

There was no attenuation after the researchers evaluated the associations of asthma subtype and carotid plaque presence or TPS and fully adjusted for baseline IL-6 or CRP (P = .02 and P = .01, respectively).

“Since this study is observational, we cannot confirm causation, but the study adds to the growing literature exploring the systemic effects of asthma,” Dr. Tattersall commented.

“Our initial hypothesis was that it was driven by inflammation, as both asthma and CVD are inflammatory conditions,” he continued. “We did adjust for inflammatory biomarkers in this analysis, but there was no change in the association.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Tattersall and colleagues are “cautious in the interpretation,” since the inflammatory biomarkers “were only collected at one point, and these measures can be dynamic, thus adjustment may not tell the whole story.”

Heightened awareness

Robert Brook, MD, professor and director of cardiovascular disease prevention, Wayne State University, Detroit, said the “main contribution of this study is the novel demonstration of a significant association between persistent (but not intermittent) asthma with carotid atherosclerosis in the MESA cohort, a large multi-ethnic population.”

These findings “support the biological plausibility of the growing epidemiological evidence that asthma independently increases the risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” added Dr. Brook, who was not involved with the study.

“The main take-home message for clinicians is that, just like in COPD (which is well-established), asthma is often a systemic condition in that the inflammation and disease process can impact the whole body,” he said.

“Health care providers should have a heightened awareness of the potentially increased cardiovascular risk of their patients with asthma and pay special attention to controlling their heart disease risk factors (for example, hyperlipidemia, hypertension),” Dr. Brook stated.

Dr. Tattersall was supported by an American Heart Association Career Development Award. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Center for Research Resources. Dr. Tattersall and co-authors and Dr. Brook declare no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Just 8 minutes of exercise a day is all you need

according to a new study in the European Heart Journal.

Just 54 minutes of vigorous exercise per week provides the most bang for your buck, researchers found, lowering the risk of early death from any cause by 36%, and your chances of getting heart disease by 35%.

Scientists examined data from fitness trackers worn by more than 71,000 people studied in the United Kingdom, then analyzed their health over the next several years.

While more time spent exercising unsurprisingly led to better health, the protective effects of exercise start to plateau after a certain point, according to the study.

A tough, short workout improves blood pressure, shrinks artery-clogging plaques, and boosts your overall fitness.

Vigorous exercise helps your body adapt better than moderate exercise does, leading to more notable benefits, says study author Matthew Ahmadi, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Sydney.

“Collectively, these will lower a person’s risk of cardiovascular disease. Exercise can also lower body inflammation, which will in turn lower the risk for certain cancers,” he says.

The CDC recommends at least 150 minutes of “moderate intensity” exercise each week, such as walking at a brisk pace. Or you could spend 75 minutes each week doing vigorous exercise, like running, it says. The CDC also recommends muscle strengthening activities, like lifting weights, at least 2 days per week.

But only 54% of Americans actually manage to get their 150 minutes of aerobic activity in each week, according to the most recent data from the National Center for Health Statistics. Even fewer – just 24% – also squeeze in the two recommended strength workouts.

So 8 minutes a day instead of 30 minutes could persuade busy people to get the exercise they need.

“Lack of time is one of the main reasons people have reported for not engaging in exercise,” says Dr. Ahmadi.

Vigorous exercise doesn’t mean you have to run, bike, or lift weights. Scientists consider a physical activity “vigorous” if it’s greater than 6 times your resting metabolic rate, or MET. That includes all kinds of strenuous movement, including dancing in a nightclub or carrying groceries upstairs.

“All of these activities are equally beneficial,” says Dr. Ahmadi.

He recommends aiming for 2-minute bouts of a heart-pumping activity, spread throughout the day for the most benefit in the least amount of time. If you wear a smartwatch or other device that tracks your heart rate, you’ll be above the threshold if your heart is pumping at 77% or more of your max heart rate (which most fitness trackers help you calculate).

No smartwatch? “The easiest way a person can infer if they are doing vigorous activity is if they are breathing hard enough that it’s difficult to have a conversation or speak in a full sentence while doing the activity,” Dr. Ahmadi says. In other words, if you’re huffing and puffing, then you’re in the zone.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to a new study in the European Heart Journal.

Just 54 minutes of vigorous exercise per week provides the most bang for your buck, researchers found, lowering the risk of early death from any cause by 36%, and your chances of getting heart disease by 35%.

Scientists examined data from fitness trackers worn by more than 71,000 people studied in the United Kingdom, then analyzed their health over the next several years.

While more time spent exercising unsurprisingly led to better health, the protective effects of exercise start to plateau after a certain point, according to the study.

A tough, short workout improves blood pressure, shrinks artery-clogging plaques, and boosts your overall fitness.

Vigorous exercise helps your body adapt better than moderate exercise does, leading to more notable benefits, says study author Matthew Ahmadi, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Sydney.

“Collectively, these will lower a person’s risk of cardiovascular disease. Exercise can also lower body inflammation, which will in turn lower the risk for certain cancers,” he says.

The CDC recommends at least 150 minutes of “moderate intensity” exercise each week, such as walking at a brisk pace. Or you could spend 75 minutes each week doing vigorous exercise, like running, it says. The CDC also recommends muscle strengthening activities, like lifting weights, at least 2 days per week.

But only 54% of Americans actually manage to get their 150 minutes of aerobic activity in each week, according to the most recent data from the National Center for Health Statistics. Even fewer – just 24% – also squeeze in the two recommended strength workouts.

So 8 minutes a day instead of 30 minutes could persuade busy people to get the exercise they need.

“Lack of time is one of the main reasons people have reported for not engaging in exercise,” says Dr. Ahmadi.

Vigorous exercise doesn’t mean you have to run, bike, or lift weights. Scientists consider a physical activity “vigorous” if it’s greater than 6 times your resting metabolic rate, or MET. That includes all kinds of strenuous movement, including dancing in a nightclub or carrying groceries upstairs.

“All of these activities are equally beneficial,” says Dr. Ahmadi.

He recommends aiming for 2-minute bouts of a heart-pumping activity, spread throughout the day for the most benefit in the least amount of time. If you wear a smartwatch or other device that tracks your heart rate, you’ll be above the threshold if your heart is pumping at 77% or more of your max heart rate (which most fitness trackers help you calculate).

No smartwatch? “The easiest way a person can infer if they are doing vigorous activity is if they are breathing hard enough that it’s difficult to have a conversation or speak in a full sentence while doing the activity,” Dr. Ahmadi says. In other words, if you’re huffing and puffing, then you’re in the zone.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to a new study in the European Heart Journal.

Just 54 minutes of vigorous exercise per week provides the most bang for your buck, researchers found, lowering the risk of early death from any cause by 36%, and your chances of getting heart disease by 35%.

Scientists examined data from fitness trackers worn by more than 71,000 people studied in the United Kingdom, then analyzed their health over the next several years.

While more time spent exercising unsurprisingly led to better health, the protective effects of exercise start to plateau after a certain point, according to the study.

A tough, short workout improves blood pressure, shrinks artery-clogging plaques, and boosts your overall fitness.

Vigorous exercise helps your body adapt better than moderate exercise does, leading to more notable benefits, says study author Matthew Ahmadi, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Sydney.

“Collectively, these will lower a person’s risk of cardiovascular disease. Exercise can also lower body inflammation, which will in turn lower the risk for certain cancers,” he says.

The CDC recommends at least 150 minutes of “moderate intensity” exercise each week, such as walking at a brisk pace. Or you could spend 75 minutes each week doing vigorous exercise, like running, it says. The CDC also recommends muscle strengthening activities, like lifting weights, at least 2 days per week.

But only 54% of Americans actually manage to get their 150 minutes of aerobic activity in each week, according to the most recent data from the National Center for Health Statistics. Even fewer – just 24% – also squeeze in the two recommended strength workouts.

So 8 minutes a day instead of 30 minutes could persuade busy people to get the exercise they need.

“Lack of time is one of the main reasons people have reported for not engaging in exercise,” says Dr. Ahmadi.

Vigorous exercise doesn’t mean you have to run, bike, or lift weights. Scientists consider a physical activity “vigorous” if it’s greater than 6 times your resting metabolic rate, or MET. That includes all kinds of strenuous movement, including dancing in a nightclub or carrying groceries upstairs.

“All of these activities are equally beneficial,” says Dr. Ahmadi.

He recommends aiming for 2-minute bouts of a heart-pumping activity, spread throughout the day for the most benefit in the least amount of time. If you wear a smartwatch or other device that tracks your heart rate, you’ll be above the threshold if your heart is pumping at 77% or more of your max heart rate (which most fitness trackers help you calculate).

No smartwatch? “The easiest way a person can infer if they are doing vigorous activity is if they are breathing hard enough that it’s difficult to have a conversation or speak in a full sentence while doing the activity,” Dr. Ahmadi says. In other words, if you’re huffing and puffing, then you’re in the zone.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM EUROPEAN HEART JOURNAL

Vitamin D fails to stave off statin-related muscle symptoms

Vitamin D supplements do not prevent muscle symptoms in new statin users or affect the likelihood of discontinuing a statin due to muscle pain and discomfort, a substudy of the VITAL trial indicates.

Among more than 2,000 randomized participants, statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS) were reported by 31% assigned to vitamin D and 31% assigned to placebo.

The two groups were equally likely to stop taking a statin due to muscle symptoms, at 13%.

No significant difference was observed in SAMS (odds ratio [OR], 0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.80-1.18) or statin discontinuations (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.80-1.35) after adjustment for baseline variables and other characteristics, namely age, sex, and African-American race, previously found to be associated with SAMS in VITAL.

“We actually thought when we started out that maybe we were going to show something, that maybe it was going to be that the people who got the vitamin D were least likely to have a problem with a statin than all those who didn’t get vitamin D, but that is not what we showed,” senior author Neil J. Stone, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, told this news organization.

He noted that patients in the clinic with low levels of vitamin D often have muscle pain and discomfort and that previous unblinded studies suggested vitamin D might benefit patients with SAMS and reduce statin intolerance.

As previously reported, the double-blind VITAL trial showed no difference in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease or cancer at 5 years among 25,871 middle-aged adults randomized to vitamin D3 at 2000 IU/d or placebo, regardless of their baseline vitamin D level.

Unlike previous studies showing a benefit with vitamin D on SAMS, importantly, VITAL participants were unaware of whether they were taking vitamin D or placebo and were not expecting any help with their muscle symptoms, first author Mark A. Hlatky, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University, pointed out in an interview.

As to how many statin users turn to the popular supplement for SAMS, he said that number couldn’t be pinned down, despite a lengthy search. “But I think it’s very common, because up to half of people stop taking their statins within a year and many of these do so because of statin-associated muscle symptoms, and we found it in about 30% of people who have them. I have them myself and was motivated to study it because I thought this was an interesting question.”

The results were published online in JAMA Cardiology.

SAMS by baseline 25-OHD

The substudy included 2,083 patients who initiated statin therapy after randomization and were surveyed in early 2016 about their statin use and muscle symptoms.

Two-thirds, or 1,397 patients, had 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25-OHD) measured at baseline, with 47% having levels < 30 ng/mL and 13% levels < 20 ng/mL.

Serum 25-OHD levels were virtually identical in the two treatment groups (mean, 30.4 ng/mL; median, 30.0 ng/mL). The frequency of SAMS did not differ between those assigned to vitamin D or placebo (28% vs. 31%).

The odds ratios for the association with vitamin D on SAMS were:

- 0.86 in all respondents with 25-OHD measured (95% CI, 0.69-1.09).

- 0.87 in those with levels ≥ 30 ng/mL (95% CI, 0.64-1.19).

- 0.85 with levels of 20-30 ng/mL (95% CI, 0.56-1.28).

- 0.93 with levels < 20 ng/mL (95% CI, 0.50-1.74).

The test for treatment effect modification by baseline serum 25-OHD level was not significant (P for interaction = .83).

In addition, the rate of muscle symptoms was similar between participants randomized to vitamin D and placebo when researchers used a cutpoint to define low 25-OHD of < 30 ng/mL (27% vs. 30%) or < 20 ng/mL (33% vs. 35%).

“We didn’t find any evidence at all that the people who came into the study with low levels of vitamin D did better with the supplement in this case,” Dr. Hlatky said. “So that wasn’t the reason we didn’t see anything.”

Critics may suggest the trial didn’t use a high enough dose of vitamin D, but both Dr. Hlatky and Dr. Stone say that’s unlikely to be a factor in the results because 2,000 IU/d is a substantial dose and well above the recommended adult daily dose of 600-800 IU.

They caution that the substudy wasn’t prespecified, was smaller than the parent trial, and did not have a protocol in place to detail SAMS. They also can’t rule out the possibility that vitamin D may have an effect in patients who have confirmed intolerance to multiple statins, especially after adjustment for the statin type and dose.

“If you’re taking vitamin D to keep from having statin-associated muscle symptoms, this very carefully done substudy with the various caveats doesn’t support that and that’s not something I would give my patients,” Dr. Stone said.

“The most important thing from a negative study is that it allows you to focus your attention on things that may be much more productive rather than assuming that just giving everybody vitamin D will take care of the statin issue,” he added. “Maybe the answer is going to be somewhere else, and there’ll be a lot of people I’m sure who will offer their advice as what the answer is but, I would argue, we want to see more studies to pin it down. So people can get some science behind what they do to try to reduce statin-associated muscle symptoms.”

Paul D. Thompson, MD, chief of cardiology emeritus at Hartford (Conn.) Hospital, and a SAMS expert who was not involved with the research, said, “This is a useful publication, and it’s smart in that it took advantage of a study that was already done.”

He acknowledged being skeptical of a beneficial effect of vitamin D supplementation on SAMS, because some previous data have been retracted, but said that potential treatments are best tested in patients with confirmed statin myalgia, as was the case in his team’s negative trial of CoQ10 supplementation.

That said, the present “study was able to at least give some of the best evidence so far that vitamin D doesn’t do anything to improve symptoms,” Dr. Thompson said. “So maybe it will cut down on so many vitamin D levels [being measured] and use of vitamin D when you don’t really need it.”

The study was sponsored by the Hyperlipidemia Research Fund at Northwestern University. The VITAL trial was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, and Quest Diagnostics performed the laboratory measurements at no additional costs. Dr. Hlatky reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Stone reports a grant from the Hyperlipidemia Research Fund at Northwestern and honorarium for educational activity for Knowledge to Practice. Dr. Thompson is on the executive committee for a study examining bempedoic acid in patients with statin-associated muscle symptoms.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Vitamin D supplements do not prevent muscle symptoms in new statin users or affect the likelihood of discontinuing a statin due to muscle pain and discomfort, a substudy of the VITAL trial indicates.

Among more than 2,000 randomized participants, statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS) were reported by 31% assigned to vitamin D and 31% assigned to placebo.

The two groups were equally likely to stop taking a statin due to muscle symptoms, at 13%.

No significant difference was observed in SAMS (odds ratio [OR], 0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.80-1.18) or statin discontinuations (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.80-1.35) after adjustment for baseline variables and other characteristics, namely age, sex, and African-American race, previously found to be associated with SAMS in VITAL.

“We actually thought when we started out that maybe we were going to show something, that maybe it was going to be that the people who got the vitamin D were least likely to have a problem with a statin than all those who didn’t get vitamin D, but that is not what we showed,” senior author Neil J. Stone, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, told this news organization.

He noted that patients in the clinic with low levels of vitamin D often have muscle pain and discomfort and that previous unblinded studies suggested vitamin D might benefit patients with SAMS and reduce statin intolerance.

As previously reported, the double-blind VITAL trial showed no difference in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease or cancer at 5 years among 25,871 middle-aged adults randomized to vitamin D3 at 2000 IU/d or placebo, regardless of their baseline vitamin D level.

Unlike previous studies showing a benefit with vitamin D on SAMS, importantly, VITAL participants were unaware of whether they were taking vitamin D or placebo and were not expecting any help with their muscle symptoms, first author Mark A. Hlatky, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University, pointed out in an interview.

As to how many statin users turn to the popular supplement for SAMS, he said that number couldn’t be pinned down, despite a lengthy search. “But I think it’s very common, because up to half of people stop taking their statins within a year and many of these do so because of statin-associated muscle symptoms, and we found it in about 30% of people who have them. I have them myself and was motivated to study it because I thought this was an interesting question.”

The results were published online in JAMA Cardiology.

SAMS by baseline 25-OHD

The substudy included 2,083 patients who initiated statin therapy after randomization and were surveyed in early 2016 about their statin use and muscle symptoms.

Two-thirds, or 1,397 patients, had 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25-OHD) measured at baseline, with 47% having levels < 30 ng/mL and 13% levels < 20 ng/mL.

Serum 25-OHD levels were virtually identical in the two treatment groups (mean, 30.4 ng/mL; median, 30.0 ng/mL). The frequency of SAMS did not differ between those assigned to vitamin D or placebo (28% vs. 31%).

The odds ratios for the association with vitamin D on SAMS were:

- 0.86 in all respondents with 25-OHD measured (95% CI, 0.69-1.09).

- 0.87 in those with levels ≥ 30 ng/mL (95% CI, 0.64-1.19).

- 0.85 with levels of 20-30 ng/mL (95% CI, 0.56-1.28).

- 0.93 with levels < 20 ng/mL (95% CI, 0.50-1.74).

The test for treatment effect modification by baseline serum 25-OHD level was not significant (P for interaction = .83).

In addition, the rate of muscle symptoms was similar between participants randomized to vitamin D and placebo when researchers used a cutpoint to define low 25-OHD of < 30 ng/mL (27% vs. 30%) or < 20 ng/mL (33% vs. 35%).

“We didn’t find any evidence at all that the people who came into the study with low levels of vitamin D did better with the supplement in this case,” Dr. Hlatky said. “So that wasn’t the reason we didn’t see anything.”

Critics may suggest the trial didn’t use a high enough dose of vitamin D, but both Dr. Hlatky and Dr. Stone say that’s unlikely to be a factor in the results because 2,000 IU/d is a substantial dose and well above the recommended adult daily dose of 600-800 IU.

They caution that the substudy wasn’t prespecified, was smaller than the parent trial, and did not have a protocol in place to detail SAMS. They also can’t rule out the possibility that vitamin D may have an effect in patients who have confirmed intolerance to multiple statins, especially after adjustment for the statin type and dose.

“If you’re taking vitamin D to keep from having statin-associated muscle symptoms, this very carefully done substudy with the various caveats doesn’t support that and that’s not something I would give my patients,” Dr. Stone said.

“The most important thing from a negative study is that it allows you to focus your attention on things that may be much more productive rather than assuming that just giving everybody vitamin D will take care of the statin issue,” he added. “Maybe the answer is going to be somewhere else, and there’ll be a lot of people I’m sure who will offer their advice as what the answer is but, I would argue, we want to see more studies to pin it down. So people can get some science behind what they do to try to reduce statin-associated muscle symptoms.”

Paul D. Thompson, MD, chief of cardiology emeritus at Hartford (Conn.) Hospital, and a SAMS expert who was not involved with the research, said, “This is a useful publication, and it’s smart in that it took advantage of a study that was already done.”

He acknowledged being skeptical of a beneficial effect of vitamin D supplementation on SAMS, because some previous data have been retracted, but said that potential treatments are best tested in patients with confirmed statin myalgia, as was the case in his team’s negative trial of CoQ10 supplementation.

That said, the present “study was able to at least give some of the best evidence so far that vitamin D doesn’t do anything to improve symptoms,” Dr. Thompson said. “So maybe it will cut down on so many vitamin D levels [being measured] and use of vitamin D when you don’t really need it.”

The study was sponsored by the Hyperlipidemia Research Fund at Northwestern University. The VITAL trial was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, and Quest Diagnostics performed the laboratory measurements at no additional costs. Dr. Hlatky reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Stone reports a grant from the Hyperlipidemia Research Fund at Northwestern and honorarium for educational activity for Knowledge to Practice. Dr. Thompson is on the executive committee for a study examining bempedoic acid in patients with statin-associated muscle symptoms.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Vitamin D supplements do not prevent muscle symptoms in new statin users or affect the likelihood of discontinuing a statin due to muscle pain and discomfort, a substudy of the VITAL trial indicates.

Among more than 2,000 randomized participants, statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS) were reported by 31% assigned to vitamin D and 31% assigned to placebo.

The two groups were equally likely to stop taking a statin due to muscle symptoms, at 13%.

No significant difference was observed in SAMS (odds ratio [OR], 0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.80-1.18) or statin discontinuations (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.80-1.35) after adjustment for baseline variables and other characteristics, namely age, sex, and African-American race, previously found to be associated with SAMS in VITAL.

“We actually thought when we started out that maybe we were going to show something, that maybe it was going to be that the people who got the vitamin D were least likely to have a problem with a statin than all those who didn’t get vitamin D, but that is not what we showed,” senior author Neil J. Stone, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, told this news organization.

He noted that patients in the clinic with low levels of vitamin D often have muscle pain and discomfort and that previous unblinded studies suggested vitamin D might benefit patients with SAMS and reduce statin intolerance.

As previously reported, the double-blind VITAL trial showed no difference in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease or cancer at 5 years among 25,871 middle-aged adults randomized to vitamin D3 at 2000 IU/d or placebo, regardless of their baseline vitamin D level.

Unlike previous studies showing a benefit with vitamin D on SAMS, importantly, VITAL participants were unaware of whether they were taking vitamin D or placebo and were not expecting any help with their muscle symptoms, first author Mark A. Hlatky, MD, Stanford (Calif.) University, pointed out in an interview.

As to how many statin users turn to the popular supplement for SAMS, he said that number couldn’t be pinned down, despite a lengthy search. “But I think it’s very common, because up to half of people stop taking their statins within a year and many of these do so because of statin-associated muscle symptoms, and we found it in about 30% of people who have them. I have them myself and was motivated to study it because I thought this was an interesting question.”

The results were published online in JAMA Cardiology.

SAMS by baseline 25-OHD

The substudy included 2,083 patients who initiated statin therapy after randomization and were surveyed in early 2016 about their statin use and muscle symptoms.

Two-thirds, or 1,397 patients, had 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25-OHD) measured at baseline, with 47% having levels < 30 ng/mL and 13% levels < 20 ng/mL.

Serum 25-OHD levels were virtually identical in the two treatment groups (mean, 30.4 ng/mL; median, 30.0 ng/mL). The frequency of SAMS did not differ between those assigned to vitamin D or placebo (28% vs. 31%).

The odds ratios for the association with vitamin D on SAMS were:

- 0.86 in all respondents with 25-OHD measured (95% CI, 0.69-1.09).

- 0.87 in those with levels ≥ 30 ng/mL (95% CI, 0.64-1.19).

- 0.85 with levels of 20-30 ng/mL (95% CI, 0.56-1.28).

- 0.93 with levels < 20 ng/mL (95% CI, 0.50-1.74).

The test for treatment effect modification by baseline serum 25-OHD level was not significant (P for interaction = .83).

In addition, the rate of muscle symptoms was similar between participants randomized to vitamin D and placebo when researchers used a cutpoint to define low 25-OHD of < 30 ng/mL (27% vs. 30%) or < 20 ng/mL (33% vs. 35%).

“We didn’t find any evidence at all that the people who came into the study with low levels of vitamin D did better with the supplement in this case,” Dr. Hlatky said. “So that wasn’t the reason we didn’t see anything.”

Critics may suggest the trial didn’t use a high enough dose of vitamin D, but both Dr. Hlatky and Dr. Stone say that’s unlikely to be a factor in the results because 2,000 IU/d is a substantial dose and well above the recommended adult daily dose of 600-800 IU.

They caution that the substudy wasn’t prespecified, was smaller than the parent trial, and did not have a protocol in place to detail SAMS. They also can’t rule out the possibility that vitamin D may have an effect in patients who have confirmed intolerance to multiple statins, especially after adjustment for the statin type and dose.

“If you’re taking vitamin D to keep from having statin-associated muscle symptoms, this very carefully done substudy with the various caveats doesn’t support that and that’s not something I would give my patients,” Dr. Stone said.

“The most important thing from a negative study is that it allows you to focus your attention on things that may be much more productive rather than assuming that just giving everybody vitamin D will take care of the statin issue,” he added. “Maybe the answer is going to be somewhere else, and there’ll be a lot of people I’m sure who will offer their advice as what the answer is but, I would argue, we want to see more studies to pin it down. So people can get some science behind what they do to try to reduce statin-associated muscle symptoms.”

Paul D. Thompson, MD, chief of cardiology emeritus at Hartford (Conn.) Hospital, and a SAMS expert who was not involved with the research, said, “This is a useful publication, and it’s smart in that it took advantage of a study that was already done.”

He acknowledged being skeptical of a beneficial effect of vitamin D supplementation on SAMS, because some previous data have been retracted, but said that potential treatments are best tested in patients with confirmed statin myalgia, as was the case in his team’s negative trial of CoQ10 supplementation.

That said, the present “study was able to at least give some of the best evidence so far that vitamin D doesn’t do anything to improve symptoms,” Dr. Thompson said. “So maybe it will cut down on so many vitamin D levels [being measured] and use of vitamin D when you don’t really need it.”

The study was sponsored by the Hyperlipidemia Research Fund at Northwestern University. The VITAL trial was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, and Quest Diagnostics performed the laboratory measurements at no additional costs. Dr. Hlatky reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Stone reports a grant from the Hyperlipidemia Research Fund at Northwestern and honorarium for educational activity for Knowledge to Practice. Dr. Thompson is on the executive committee for a study examining bempedoic acid in patients with statin-associated muscle symptoms.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiovascular societies less apt to recognize women, minorities

Major cardiovascular societies are more apt to give out awards to men and White individuals than to women and minorities, according to a look at 2 decades’ worth of data.

“Women received significantly fewer awards than men in all societies, countries, and award categories,” author Martha Gulati, MD, director of preventive cardiology at Smidt Heart Institute at Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles, said in a news release. “This bias may be responsible for preventing underrepresented groups from ascending the academic ladder and receiving senior awards like lifetime achievement awards.”

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

A slow climb

The findings are based on a review of honors given from 2000 to 2021 by the ACC, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, the Heart Rhythm Society, the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Cardiovascular Society.

Among the 173 unique awards, 94 were given by the AHA, 27 by the HRS, 17 by the ACC, 16 by the CCS, 8 by the ASE, 7 by the ESC, and 4 by the SCAI. There were 3,044 recipients of these awards, including 2,830 unique awardees.

The vast majority of the awardees were White (75.2%), with Asian, Hispanic/Latino, and Black awardees representing just 18.9%, 4.5%, and 1.4% of the total awardees, respectively.

In a gender analysis, the researchers looked at 169 awards after excluding female-specific awards. These 169 awards were distributed to 2,995 recipients. More than three-quarters of these awardees (76.2%) were men, with women making up less than one-quarter (23.8%).

Encouragingly, there was an increasing trend in recognition of women over time, with 7.7% of female awardees in 2000 and climbing to 31.2% in 2021 (average annual percentage change, 6.6%; P < .05).

The distribution of awards also became more racially/ethnically diverse over time; in 2000, 92.3% of awardees were White versus 62.8% in 2021 (AAPC, –1.4%; P < .001).

There was also a significant increase in Asian (AAPC, 5.7%; P < .001), Hispanic/Latino (AAPC, 4.8%; P = .040), and Black (AAPC, 7.8%; P < .05) honorees.

Core influencers

By award type, women received fewer leadership awards than men, “which can be attributed to fewer leadership opportunities for women and a lack of acknowledgment of leadership responsibilities fulfilled by women,” the researchers said.

Award recipients with a PhD degree were nearly gender balanced (48.2% women), whereas men formed an overwhelming majority of awardees with an MD (84.7%).

Awards with male eponyms had fewer women recipients than did noneponymous awards (20.9% vs. 23.2%; P < .01).

“Male-eponymous awards can deter women applicants and give a subtle hint to selection committees to favor men as winners, creating an implicit bias,” the researchers said.

“Given the increased emphasis on redesigning cardiovascular health care delivery by incorporating the tenets of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), cardiovascular societies have a significant role as core influencers,” Dr. Gulati and colleagues wrote.

They said that equitable award distribution can be a “key strategy to celebrate women and diverse members of the cardiovascular workforce and promulgate DEI.”

“Recognition of their contributions is pivotal to enhancing their self-perception. In addition to boosting confidence, receiving an award can also catalyze their career trajectory,” the authors added.

The study had no specific funding. The authors have declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Major cardiovascular societies are more apt to give out awards to men and White individuals than to women and minorities, according to a look at 2 decades’ worth of data.

“Women received significantly fewer awards than men in all societies, countries, and award categories,” author Martha Gulati, MD, director of preventive cardiology at Smidt Heart Institute at Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles, said in a news release. “This bias may be responsible for preventing underrepresented groups from ascending the academic ladder and receiving senior awards like lifetime achievement awards.”

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

A slow climb

The findings are based on a review of honors given from 2000 to 2021 by the ACC, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, the Heart Rhythm Society, the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Cardiovascular Society.

Among the 173 unique awards, 94 were given by the AHA, 27 by the HRS, 17 by the ACC, 16 by the CCS, 8 by the ASE, 7 by the ESC, and 4 by the SCAI. There were 3,044 recipients of these awards, including 2,830 unique awardees.

The vast majority of the awardees were White (75.2%), with Asian, Hispanic/Latino, and Black awardees representing just 18.9%, 4.5%, and 1.4% of the total awardees, respectively.

In a gender analysis, the researchers looked at 169 awards after excluding female-specific awards. These 169 awards were distributed to 2,995 recipients. More than three-quarters of these awardees (76.2%) were men, with women making up less than one-quarter (23.8%).

Encouragingly, there was an increasing trend in recognition of women over time, with 7.7% of female awardees in 2000 and climbing to 31.2% in 2021 (average annual percentage change, 6.6%; P < .05).

The distribution of awards also became more racially/ethnically diverse over time; in 2000, 92.3% of awardees were White versus 62.8% in 2021 (AAPC, –1.4%; P < .001).

There was also a significant increase in Asian (AAPC, 5.7%; P < .001), Hispanic/Latino (AAPC, 4.8%; P = .040), and Black (AAPC, 7.8%; P < .05) honorees.

Core influencers

By award type, women received fewer leadership awards than men, “which can be attributed to fewer leadership opportunities for women and a lack of acknowledgment of leadership responsibilities fulfilled by women,” the researchers said.

Award recipients with a PhD degree were nearly gender balanced (48.2% women), whereas men formed an overwhelming majority of awardees with an MD (84.7%).

Awards with male eponyms had fewer women recipients than did noneponymous awards (20.9% vs. 23.2%; P < .01).

“Male-eponymous awards can deter women applicants and give a subtle hint to selection committees to favor men as winners, creating an implicit bias,” the researchers said.

“Given the increased emphasis on redesigning cardiovascular health care delivery by incorporating the tenets of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), cardiovascular societies have a significant role as core influencers,” Dr. Gulati and colleagues wrote.

They said that equitable award distribution can be a “key strategy to celebrate women and diverse members of the cardiovascular workforce and promulgate DEI.”

“Recognition of their contributions is pivotal to enhancing their self-perception. In addition to boosting confidence, receiving an award can also catalyze their career trajectory,” the authors added.

The study had no specific funding. The authors have declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Major cardiovascular societies are more apt to give out awards to men and White individuals than to women and minorities, according to a look at 2 decades’ worth of data.

“Women received significantly fewer awards than men in all societies, countries, and award categories,” author Martha Gulati, MD, director of preventive cardiology at Smidt Heart Institute at Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles, said in a news release. “This bias may be responsible for preventing underrepresented groups from ascending the academic ladder and receiving senior awards like lifetime achievement awards.”

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

A slow climb

The findings are based on a review of honors given from 2000 to 2021 by the ACC, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, the Heart Rhythm Society, the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Cardiovascular Society.

Among the 173 unique awards, 94 were given by the AHA, 27 by the HRS, 17 by the ACC, 16 by the CCS, 8 by the ASE, 7 by the ESC, and 4 by the SCAI. There were 3,044 recipients of these awards, including 2,830 unique awardees.

The vast majority of the awardees were White (75.2%), with Asian, Hispanic/Latino, and Black awardees representing just 18.9%, 4.5%, and 1.4% of the total awardees, respectively.

In a gender analysis, the researchers looked at 169 awards after excluding female-specific awards. These 169 awards were distributed to 2,995 recipients. More than three-quarters of these awardees (76.2%) were men, with women making up less than one-quarter (23.8%).

Encouragingly, there was an increasing trend in recognition of women over time, with 7.7% of female awardees in 2000 and climbing to 31.2% in 2021 (average annual percentage change, 6.6%; P < .05).

The distribution of awards also became more racially/ethnically diverse over time; in 2000, 92.3% of awardees were White versus 62.8% in 2021 (AAPC, –1.4%; P < .001).

There was also a significant increase in Asian (AAPC, 5.7%; P < .001), Hispanic/Latino (AAPC, 4.8%; P = .040), and Black (AAPC, 7.8%; P < .05) honorees.

Core influencers

By award type, women received fewer leadership awards than men, “which can be attributed to fewer leadership opportunities for women and a lack of acknowledgment of leadership responsibilities fulfilled by women,” the researchers said.

Award recipients with a PhD degree were nearly gender balanced (48.2% women), whereas men formed an overwhelming majority of awardees with an MD (84.7%).

Awards with male eponyms had fewer women recipients than did noneponymous awards (20.9% vs. 23.2%; P < .01).

“Male-eponymous awards can deter women applicants and give a subtle hint to selection committees to favor men as winners, creating an implicit bias,” the researchers said.

“Given the increased emphasis on redesigning cardiovascular health care delivery by incorporating the tenets of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), cardiovascular societies have a significant role as core influencers,” Dr. Gulati and colleagues wrote.

They said that equitable award distribution can be a “key strategy to celebrate women and diverse members of the cardiovascular workforce and promulgate DEI.”

“Recognition of their contributions is pivotal to enhancing their self-perception. In addition to boosting confidence, receiving an award can also catalyze their career trajectory,” the authors added.

The study had no specific funding. The authors have declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

New genetic variant linked to maturity-onset diabetes of the young

A newly discovered genetic variant that is associated with type 2 diabetes (T2D) is responsible for almost 7% of all diabetes cases in Greenland, according to a whole-genome sequencing analysis of 448 Greenlandic Inuit individuals.

The variant, identified as c.1108G>T, “has the largest population impact of any previously reported variant” within the HNF1A gene – a gene that can cause maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY), reported senior author Torben Hansen, MD, PhD, of the University of Copenhagen, and colleagues in The Lancet Regional Health–Europe. The c.1108G>T variant does not cause MODY, but other variants within the HNF1A gene do. However, carriers of this variant, which is present in 1.9% of the Greenlandic Inuit population and has not been found elsewhere, have normal insulin sensitivity, but decreased beta-cell function and a more than fourfold risk of developing type 2 diabetes. “This adds to a previous discovery that about 11% of all diabetes in Greenlandic Inuit is explained by a mutation in the TBC1D4 variant,” Dr. Hansen told this publication. “Thus 1 in 5 patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes in Greenland have a specific mutation explaining their diabetes. In European populations only about 1%-2% of patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes have a known genetic etiology.”

The finding “provides new avenues to subgroup patients, detect diabetes in family members, and pursue precision treatment trials,” noted the authors, although they acknowledged that treatment choices for individuals with this variant still need to be explored. “We know from HNF1A-mutation carriers with European ancestry that they benefit from sulfonylurea treatment,” said Dr. Hansen. “However, we have not yet done treatment studies in Inuit.” The investigators noted that “it is not always the case that variants in HNF1A result in an increased insulin secretory response to sulfonylurea. ... Whether carriers of the c.1108G>T variant could benefit from treatment with sulfonylurea should be pursued within the context of a randomized clinical trial establishing both short- and long-term efficacy of sulfonylurea in these patients.”

A total of 4,497 study participants were randomly sampled from two cross-sectional cohorts in an adult Greenlandic population health survey. Among 448 participants who had whole genome sequencing, 14 known MODY genes were screened for both previously identified as well as novel variants. This identified the c.1108G>T variant, which was then genotyped in the full cohort in order to estimate an allele frequency of 1.3% in the general Greenlandic population, and 1.9% in the Inuit component. The variant was not found in genome sequences of other populations.

The researchers then tested the association of the variant with T2D and showed strong association with T2D (odds ratio, 4.35) and higher hemoglobin A1c levels.

“This is very well-conducted and exciting research that highlights the importance of studying the genetics of diverse populations,” said Miriam Udler, MD, PhD, director of the Massachusetts General Diabetes Genetics Clinic, and assistant professor at Harvard University, both in Boston. “This manuscript builds on prior work from the researchers identifying another genetic variant specific to the Greenlandic Inuit population in the gene TBC1D4,” she added. “About 3.8% of people in this population carry two copies of the TBC1D4 variant and have about a 10-fold increased risk of diabetes. Together the two variants affect 18% of Greenlanders with diabetes.”

With its fourfold increased risk of diabetes, the new variant falls into “an ever-growing category” of “intermediate risk” genetic variants, explained Dr. Udler – “meaning that they have a large impact on diabetes risk, but cannot fully predict whether someone will get diabetes. The contribution of additional risk factors is particularly important for ‘intermediate risk’ genetic variants,” she added. “Thus, clinically, we can tell patients who have variants such as HNF1A c.1108>T that they are at substantial increased risk of diabetes, but that many will not develop diabetes. And for those who do develop diabetes, we are not yet able to advise on particular therapeutic strategies.”

Still, she emphasized, the importance of studying diverse populations with specific genetic risk factors is the end-goal of precision medicine. “An active area of research is determining whether and how to return such information about ‘intermediate risk’ variants to patients who get clinical genetic testing for diabetes, since typically only variants that are very high risk ... are returned in clinical testing reports.” Dr. Udler added that “many more such “intermediate risk’ variants likely exist in all populations, but have yet to be characterized because they are less common than HNF1A c.1108>T; however, ongoing worldwide efforts to increase the sample sizes of human genetic studies will facilitate such discovery.”

The study was funded by Novo Nordisk Foundation, Independent Research Fund Denmark, and Karen Elise Jensen’s Foundation. Dr. Hansen and Dr. Udler had no disclosures.

A newly discovered genetic variant that is associated with type 2 diabetes (T2D) is responsible for almost 7% of all diabetes cases in Greenland, according to a whole-genome sequencing analysis of 448 Greenlandic Inuit individuals.

The variant, identified as c.1108G>T, “has the largest population impact of any previously reported variant” within the HNF1A gene – a gene that can cause maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY), reported senior author Torben Hansen, MD, PhD, of the University of Copenhagen, and colleagues in The Lancet Regional Health–Europe. The c.1108G>T variant does not cause MODY, but other variants within the HNF1A gene do. However, carriers of this variant, which is present in 1.9% of the Greenlandic Inuit population and has not been found elsewhere, have normal insulin sensitivity, but decreased beta-cell function and a more than fourfold risk of developing type 2 diabetes. “This adds to a previous discovery that about 11% of all diabetes in Greenlandic Inuit is explained by a mutation in the TBC1D4 variant,” Dr. Hansen told this publication. “Thus 1 in 5 patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes in Greenland have a specific mutation explaining their diabetes. In European populations only about 1%-2% of patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes have a known genetic etiology.”

The finding “provides new avenues to subgroup patients, detect diabetes in family members, and pursue precision treatment trials,” noted the authors, although they acknowledged that treatment choices for individuals with this variant still need to be explored. “We know from HNF1A-mutation carriers with European ancestry that they benefit from sulfonylurea treatment,” said Dr. Hansen. “However, we have not yet done treatment studies in Inuit.” The investigators noted that “it is not always the case that variants in HNF1A result in an increased insulin secretory response to sulfonylurea. ... Whether carriers of the c.1108G>T variant could benefit from treatment with sulfonylurea should be pursued within the context of a randomized clinical trial establishing both short- and long-term efficacy of sulfonylurea in these patients.”

A total of 4,497 study participants were randomly sampled from two cross-sectional cohorts in an adult Greenlandic population health survey. Among 448 participants who had whole genome sequencing, 14 known MODY genes were screened for both previously identified as well as novel variants. This identified the c.1108G>T variant, which was then genotyped in the full cohort in order to estimate an allele frequency of 1.3% in the general Greenlandic population, and 1.9% in the Inuit component. The variant was not found in genome sequences of other populations.

The researchers then tested the association of the variant with T2D and showed strong association with T2D (odds ratio, 4.35) and higher hemoglobin A1c levels.

“This is very well-conducted and exciting research that highlights the importance of studying the genetics of diverse populations,” said Miriam Udler, MD, PhD, director of the Massachusetts General Diabetes Genetics Clinic, and assistant professor at Harvard University, both in Boston. “This manuscript builds on prior work from the researchers identifying another genetic variant specific to the Greenlandic Inuit population in the gene TBC1D4,” she added. “About 3.8% of people in this population carry two copies of the TBC1D4 variant and have about a 10-fold increased risk of diabetes. Together the two variants affect 18% of Greenlanders with diabetes.”

With its fourfold increased risk of diabetes, the new variant falls into “an ever-growing category” of “intermediate risk” genetic variants, explained Dr. Udler – “meaning that they have a large impact on diabetes risk, but cannot fully predict whether someone will get diabetes. The contribution of additional risk factors is particularly important for ‘intermediate risk’ genetic variants,” she added. “Thus, clinically, we can tell patients who have variants such as HNF1A c.1108>T that they are at substantial increased risk of diabetes, but that many will not develop diabetes. And for those who do develop diabetes, we are not yet able to advise on particular therapeutic strategies.”

Still, she emphasized, the importance of studying diverse populations with specific genetic risk factors is the end-goal of precision medicine. “An active area of research is determining whether and how to return such information about ‘intermediate risk’ variants to patients who get clinical genetic testing for diabetes, since typically only variants that are very high risk ... are returned in clinical testing reports.” Dr. Udler added that “many more such “intermediate risk’ variants likely exist in all populations, but have yet to be characterized because they are less common than HNF1A c.1108>T; however, ongoing worldwide efforts to increase the sample sizes of human genetic studies will facilitate such discovery.”

The study was funded by Novo Nordisk Foundation, Independent Research Fund Denmark, and Karen Elise Jensen’s Foundation. Dr. Hansen and Dr. Udler had no disclosures.

A newly discovered genetic variant that is associated with type 2 diabetes (T2D) is responsible for almost 7% of all diabetes cases in Greenland, according to a whole-genome sequencing analysis of 448 Greenlandic Inuit individuals.

The variant, identified as c.1108G>T, “has the largest population impact of any previously reported variant” within the HNF1A gene – a gene that can cause maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY), reported senior author Torben Hansen, MD, PhD, of the University of Copenhagen, and colleagues in The Lancet Regional Health–Europe. The c.1108G>T variant does not cause MODY, but other variants within the HNF1A gene do. However, carriers of this variant, which is present in 1.9% of the Greenlandic Inuit population and has not been found elsewhere, have normal insulin sensitivity, but decreased beta-cell function and a more than fourfold risk of developing type 2 diabetes. “This adds to a previous discovery that about 11% of all diabetes in Greenlandic Inuit is explained by a mutation in the TBC1D4 variant,” Dr. Hansen told this publication. “Thus 1 in 5 patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes in Greenland have a specific mutation explaining their diabetes. In European populations only about 1%-2% of patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes have a known genetic etiology.”

The finding “provides new avenues to subgroup patients, detect diabetes in family members, and pursue precision treatment trials,” noted the authors, although they acknowledged that treatment choices for individuals with this variant still need to be explored. “We know from HNF1A-mutation carriers with European ancestry that they benefit from sulfonylurea treatment,” said Dr. Hansen. “However, we have not yet done treatment studies in Inuit.” The investigators noted that “it is not always the case that variants in HNF1A result in an increased insulin secretory response to sulfonylurea. ... Whether carriers of the c.1108G>T variant could benefit from treatment with sulfonylurea should be pursued within the context of a randomized clinical trial establishing both short- and long-term efficacy of sulfonylurea in these patients.”

A total of 4,497 study participants were randomly sampled from two cross-sectional cohorts in an adult Greenlandic population health survey. Among 448 participants who had whole genome sequencing, 14 known MODY genes were screened for both previously identified as well as novel variants. This identified the c.1108G>T variant, which was then genotyped in the full cohort in order to estimate an allele frequency of 1.3% in the general Greenlandic population, and 1.9% in the Inuit component. The variant was not found in genome sequences of other populations.

The researchers then tested the association of the variant with T2D and showed strong association with T2D (odds ratio, 4.35) and higher hemoglobin A1c levels.

“This is very well-conducted and exciting research that highlights the importance of studying the genetics of diverse populations,” said Miriam Udler, MD, PhD, director of the Massachusetts General Diabetes Genetics Clinic, and assistant professor at Harvard University, both in Boston. “This manuscript builds on prior work from the researchers identifying another genetic variant specific to the Greenlandic Inuit population in the gene TBC1D4,” she added. “About 3.8% of people in this population carry two copies of the TBC1D4 variant and have about a 10-fold increased risk of diabetes. Together the two variants affect 18% of Greenlanders with diabetes.”

With its fourfold increased risk of diabetes, the new variant falls into “an ever-growing category” of “intermediate risk” genetic variants, explained Dr. Udler – “meaning that they have a large impact on diabetes risk, but cannot fully predict whether someone will get diabetes. The contribution of additional risk factors is particularly important for ‘intermediate risk’ genetic variants,” she added. “Thus, clinically, we can tell patients who have variants such as HNF1A c.1108>T that they are at substantial increased risk of diabetes, but that many will not develop diabetes. And for those who do develop diabetes, we are not yet able to advise on particular therapeutic strategies.”