User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Palifermin-Associated Cutaneous Papular Rash of the Head and Neck

To the Editor:

Palifermin is a recombinant keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to prevent oral mucositis following radiation therapy or chemotherapy. Cutaneous reactions associated with palifermin have been reported.1-5 One case described a distinctive polymorphous eruption in a patient treated with palifermin.6 On histologic analysis, papules demonstrated findings similar to verrucae, with evidence of papillomatosis, hypergranulosis, and hyperorthokeratosis. Given its mechanism of action as a KGF, it was concluded that these findings were likely the direct result of palifermin.6 We report a similar case of a patient who was given palifermin prior to an autologous stem cell transplant. Histopathologic analysis confirmed epidermal dysmaturation and marked hypergranulosis. We present this case to expand the paucity of data on palifermin-associated cutaneous reactions.

A 63-year-old man with a history of psoriasis, eczema, and relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma was admitted to the hospital for routine management of an autologous stem cell transplant with a conditioning regimen involving thiotepa, busulfan, and cyclophosphamide. The patient had completed a 3-day course of palifermin 1 day prior to the current presentation. On admission, he developed a pruritic erythematous rash over the face and axillae. Within 24 hours, the facial rash progressed with appreciable edema, and he reported difficulty opening his eyes. He denied any fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or increased fatigue. He also denied use of any other medications other than starting a course of prophylactic trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 3 times weekly 2 months prior to admission.

Diffuse blanching erythema with a well-demarcated linear border was noted along the lower anterior neck extending to the posterior hairline. There was notable edema but no evidence of pustules or overlying scale. Similar areas of blanchable erythema were present along the axillae and inguinal folds. There also were flesh-colored to pink papules within the axillary vaults and on the back that occasionally coalesced into plaques. There was no involvement of the mucous membranes or acral sites.

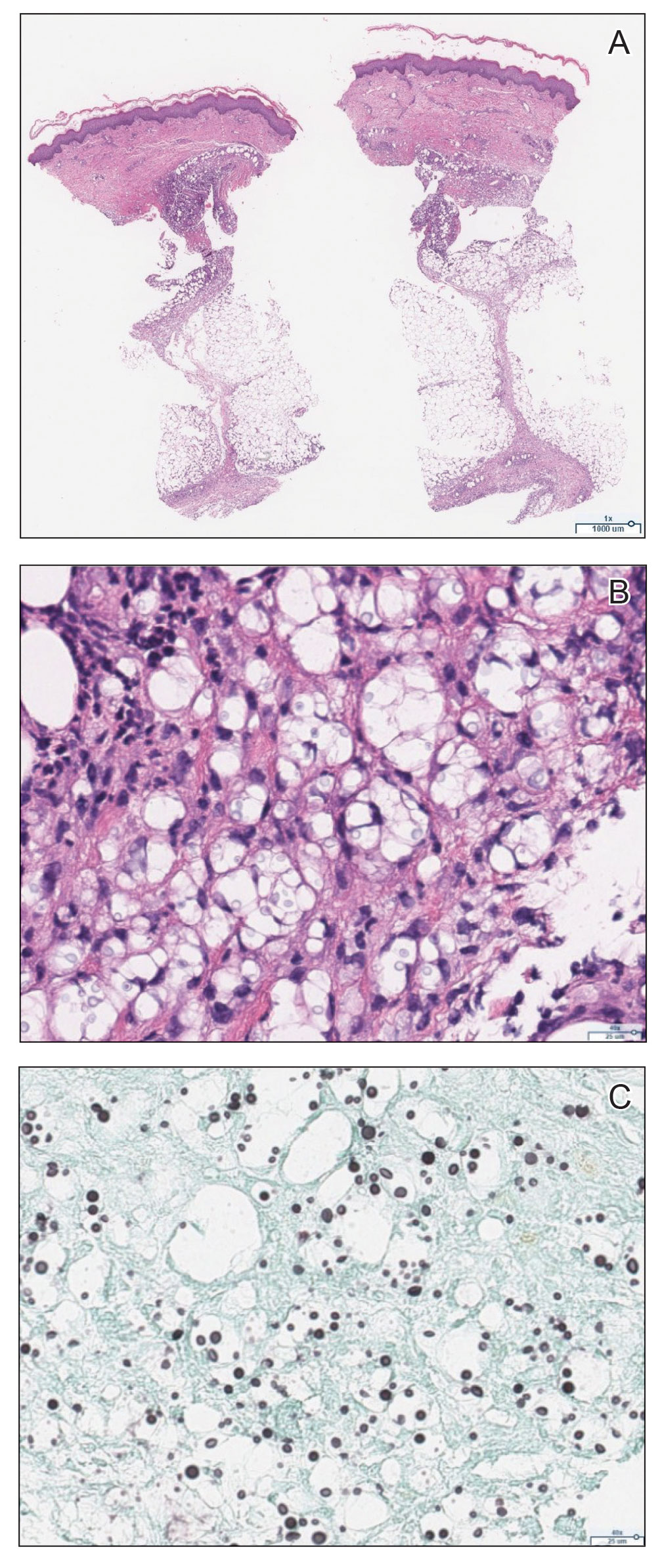

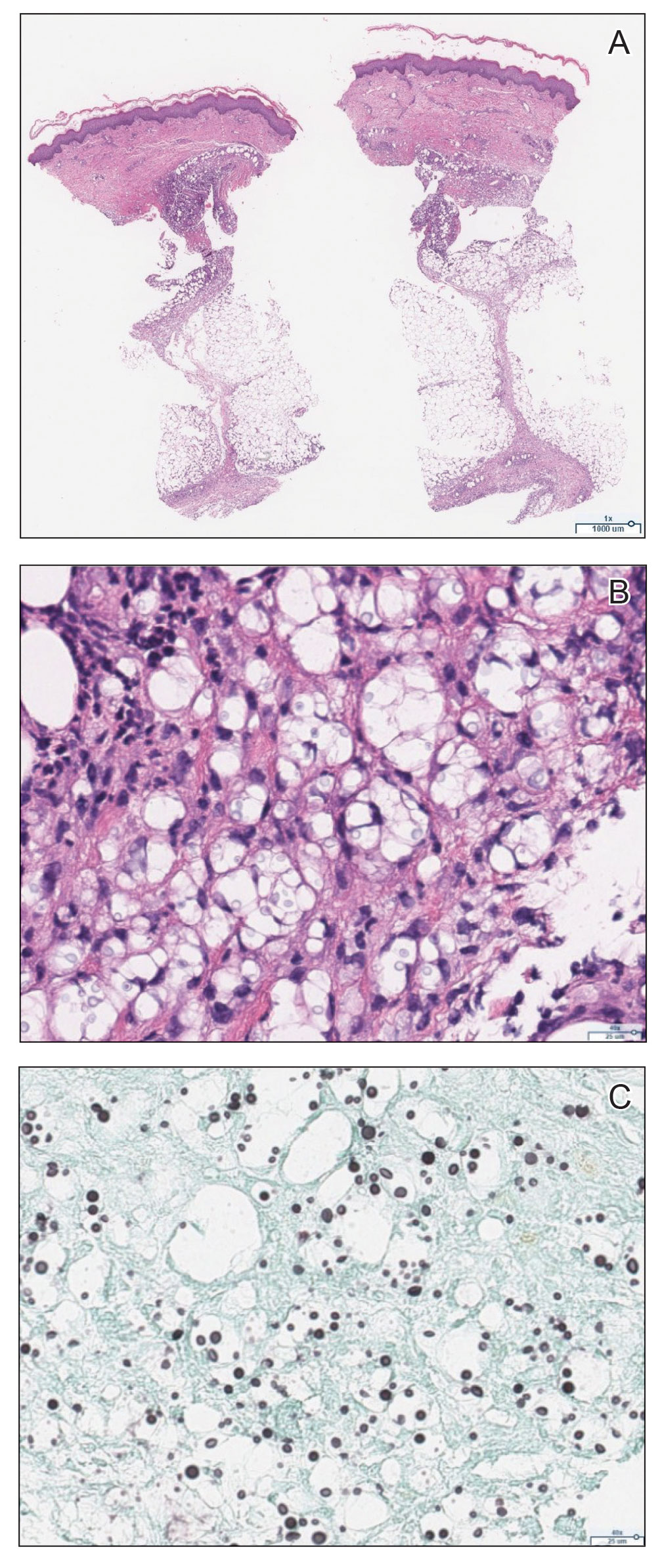

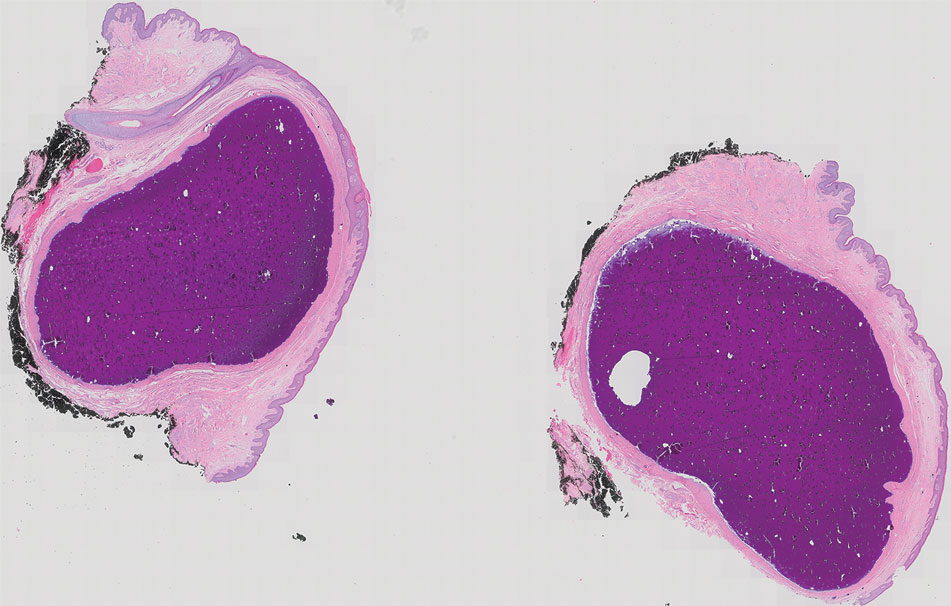

A complete blood cell count with differential and a comprehensive metabolic profile largely were unremarkable. A potassium hydroxide preparation of the face and groin was negative for hyphae and Demodex mites. Histopathologic analysis from a punch biopsy of a representative papule from the posterior neck demonstrated epidermal dysmaturation with marked thickening of the granular cell layer with notably large keratohyalin granules (Figure 1).

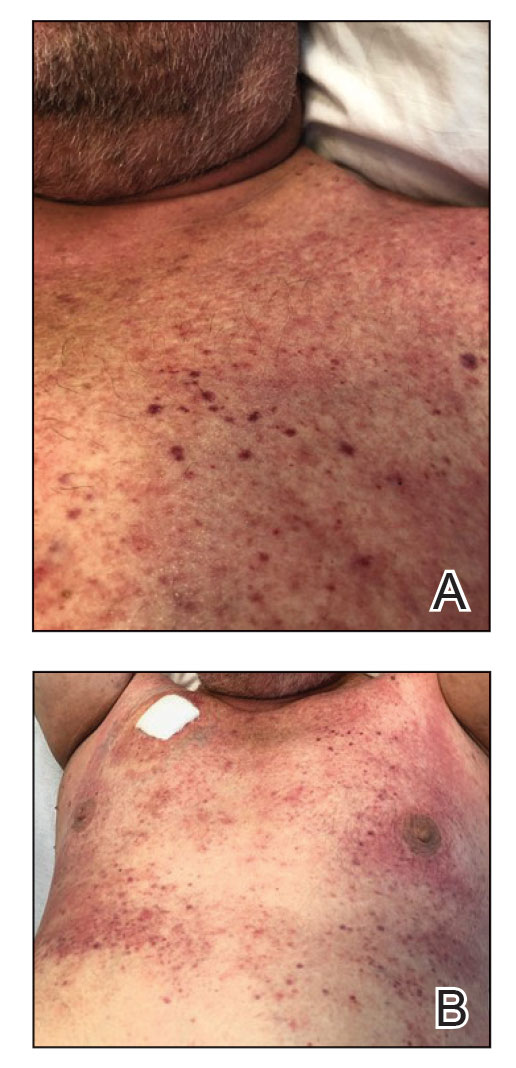

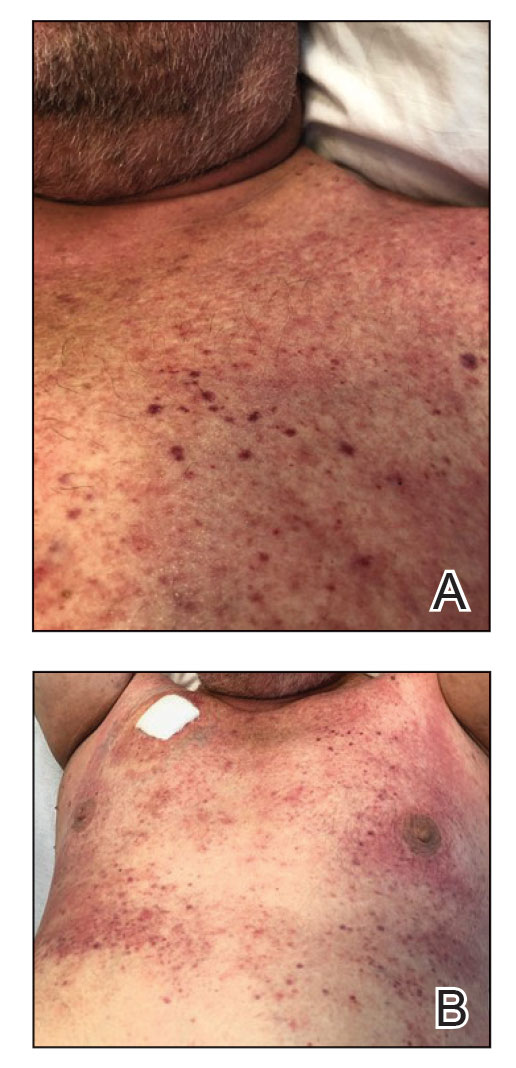

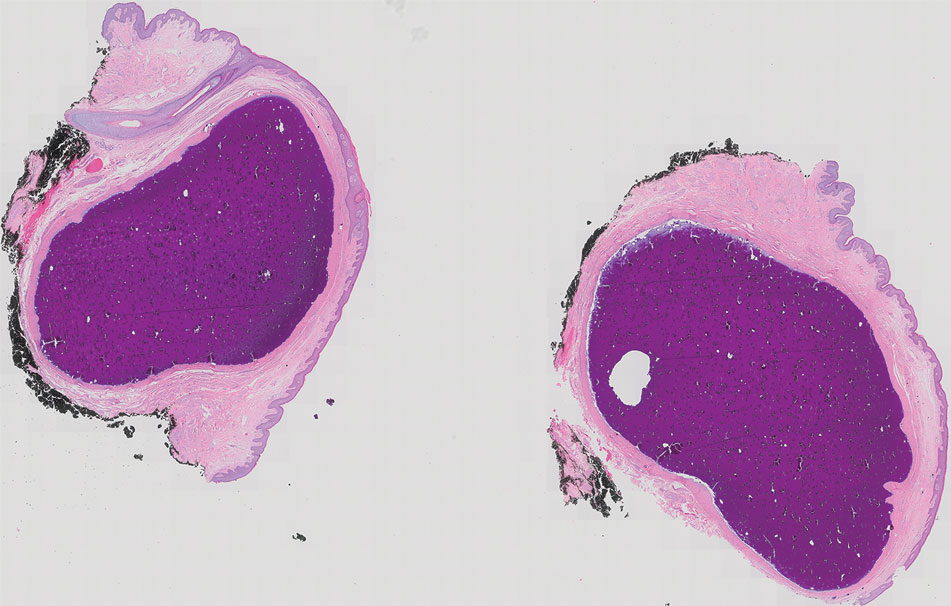

In the setting of treatment with thiotepa, we recommended supportive care with cool compresses rather than topical medication because he was neutropenic, and we wanted to avoid further immunosuppression or toxicity. By 24 hours after completing the course of palifermin, the patient experienced complete resolution of the rash. At his request, the trial of palifermin was restarted 10 days into conditioning therapy. A similar rash with less facial edema but more prominent involvement of the chest appeared 3 days into the retrial (Figure 2). The medication was discontinued, which resulted in resolution of the rash. Again, the patient remained afebrile without involvement of the mucous membranes. Liver enzyme and creatinine levels remained within reference range.Eosinophilia and the level of atypical lymphocytes could not be assessed because of leukopenia in the setting of recent chemotherapy. The rash self-resolved in 4 days.

Palifermin is a recombinant form of human KGF that is more stable than the endogenous form but retains all vital properties of the protein.5-7 Similar to other growth factors, KGF induces differentiation, proliferation, and migration of cells in vivo.8 However, it uniquely produces a targeted effect on epithelial cells in the skin, oral mucosa, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and genitourinary system.7-9

Palifermin was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2004 for the prevention and treatment of severe oral mucositis in patients receiving myelotoxic therapy prior to stem cell transplantation.7,9 Severe mucositis occurs in approximately 70% to 80% of patients receiving radiation or chemotherapy-based conditioning treatments.4,7 Compared to placebo, palifermin has been shown to greatly reduce the incidence of Grade 4 oral mucositis, defined as severe enough to prevent alimentation.10

The proliferative effect of palifermin on the oral mucosa is beneficial to patients but likely is the driving force behind its cutaneous adverse effects. A nonspecific rash is the most commonly cited treatment-related adverse event associated with palifermin, occurring in approximately 62% of patients.5,7,9

Our case is a rare report of a palifermin-associated cutaneous reaction. Previous cases have cited the occurrence of palmoplantar erythrodysesthesias, papulopustular eruptions involving the face and chest, and a papular rash involving the dorsal hands and intertriginous areas.1-4 Another report documented a “mild rash” but failed to further characterize the morphology or the body site involved.5

In 2009, King et al6 reported the occurrence of a lichen planus–like eruption involving the intertriginous regions and of white oral plaques in a patient treated with palifermin. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of a representative lesion in that patient demonstrated an appearance similar to that of verrucae, including papillomatosis, hypergranulosis, and hyperorthokeratosis.

King et al6 expanded analysis of the reaction to include immunohistochemical study, using targeted antibody stains for cytokeratin 5/6 and Ki-67 protein. Staining with Ki-67 showed dramatically increased activity within basilar and suprabasilar keratinocytes in a biopsy taken at the height of the reaction. Biopsy specimens obtained when the eruption was clinically resolving—2 days after the first biopsy—showed decreased Ki-67 staining. These findings taken together suggest a direct causal effect of palifermin inducing hyperkeratotic changes appreciated on examination of treated patients.6

We present this case to add to current data regarding palifermin-induced cutaneous changes. Unique to our patient was a strikingly well-demarcated rash confined to the head and neck. Although a photosensitive eruption due to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is conceivable, the fixed time course of the eruption—corresponding to (1) initiation and discontinuation of palifermin and (2) histologic findings—led us to conclude that this self-limited eruption likely was due to palifermin.

- Gorcey L, Lewin JM, Trufant J, et al. Papular eruption associated with palifermin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E101-E102. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.006

- Grzegorczyk-Jaz´win´ska A, Kozak I, Karakulska-Prystupiuk E, et al. Transient oral cavity and skin complications after mucositis preventing therapy (palifermin) in a patient after allogeneic PBSCT. case history. Adv Med Sci. 2006;51(suppl 1):66-68.

- Keijzer A, Huijgens PC, van de Loosdrecht AA. Palifermin and palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia. Br J Haematol. 2007;136:856-857. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06509.x

- Sibelt LAG, Aboosy N, van der Velden WJFM, et al. Palifermin-induced flexural hyperpigmentation: a clinical and histological study of five cases. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:1200-1203. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08816.x

- Keefe D, Lees J, Horvath N. Palifermin for oral mucositis in the high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplant setting: the Royal Adelaide Hospital Cancer Centre experience. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:580-582. doi:10.1007/s00520-006-0048-3

- King B, Knopp E, Galan A, et al. Palifermin-associated papular eruption. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:179-182. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2008.548

- Spielberger R, Stiff P, Bensinger W, et al. Palifermin for oral mucositis after intensive therapy for hematologic cancers. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2590-2598. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040125

- Rubin JS, Bottaro DP, Chedid M, et al. Keratinocyte growth factor. Cell Biol Int. 1995;19:399-411. doi:10.1006/cbir.1995.1085

- McDonnell AM, Lenz KL. Palifermin: role in the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiation-induced mucositis. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:86-94. doi:10.1345/aph.1G473

- Maria OM, Eliopoulos N, Muanza T. Radiation-induced oral mucositis. Front Oncol. 2017;7:89. doi:10.3389/fonc.2017.00089

To the Editor:

Palifermin is a recombinant keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to prevent oral mucositis following radiation therapy or chemotherapy. Cutaneous reactions associated with palifermin have been reported.1-5 One case described a distinctive polymorphous eruption in a patient treated with palifermin.6 On histologic analysis, papules demonstrated findings similar to verrucae, with evidence of papillomatosis, hypergranulosis, and hyperorthokeratosis. Given its mechanism of action as a KGF, it was concluded that these findings were likely the direct result of palifermin.6 We report a similar case of a patient who was given palifermin prior to an autologous stem cell transplant. Histopathologic analysis confirmed epidermal dysmaturation and marked hypergranulosis. We present this case to expand the paucity of data on palifermin-associated cutaneous reactions.

A 63-year-old man with a history of psoriasis, eczema, and relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma was admitted to the hospital for routine management of an autologous stem cell transplant with a conditioning regimen involving thiotepa, busulfan, and cyclophosphamide. The patient had completed a 3-day course of palifermin 1 day prior to the current presentation. On admission, he developed a pruritic erythematous rash over the face and axillae. Within 24 hours, the facial rash progressed with appreciable edema, and he reported difficulty opening his eyes. He denied any fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or increased fatigue. He also denied use of any other medications other than starting a course of prophylactic trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 3 times weekly 2 months prior to admission.

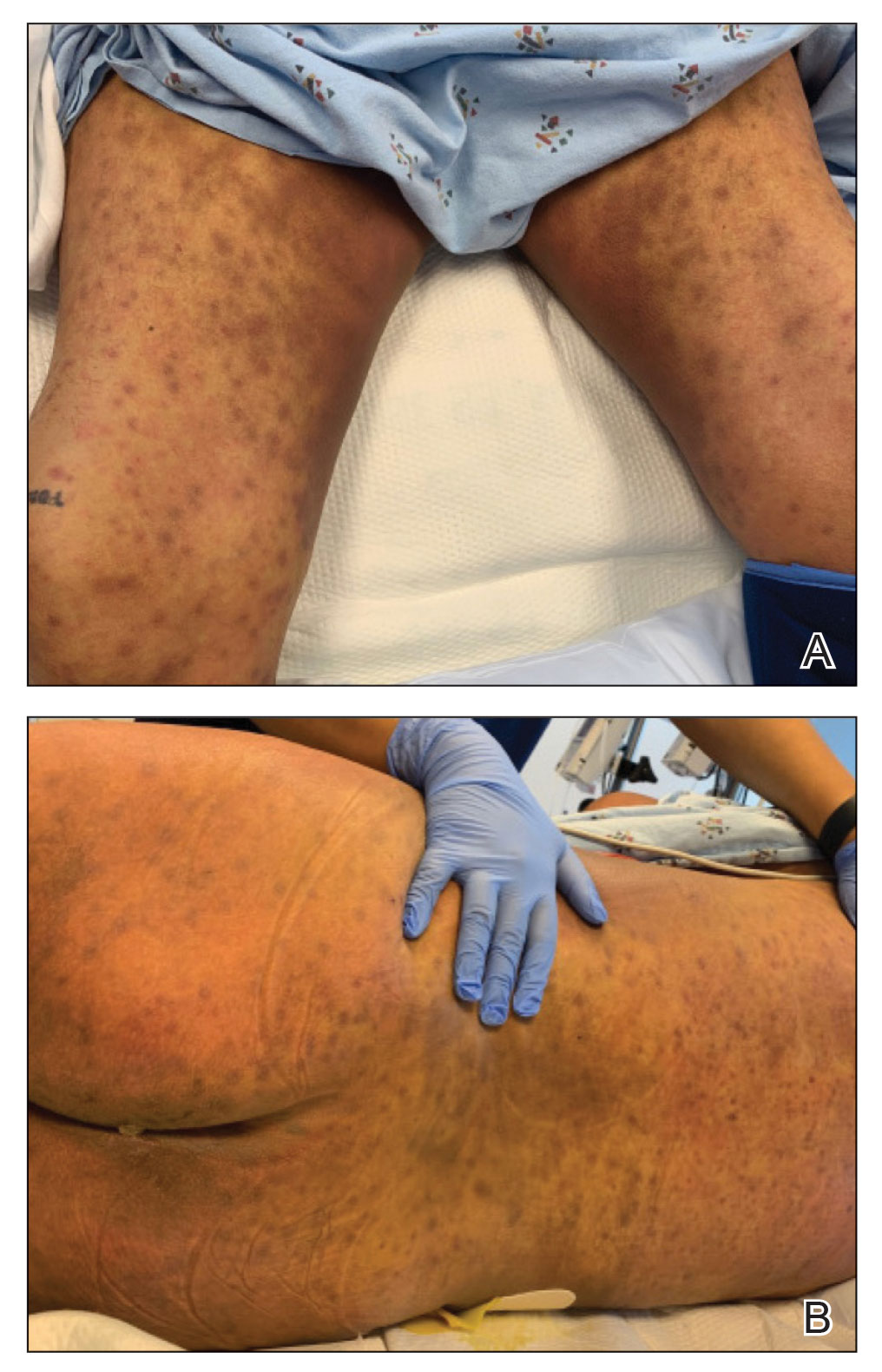

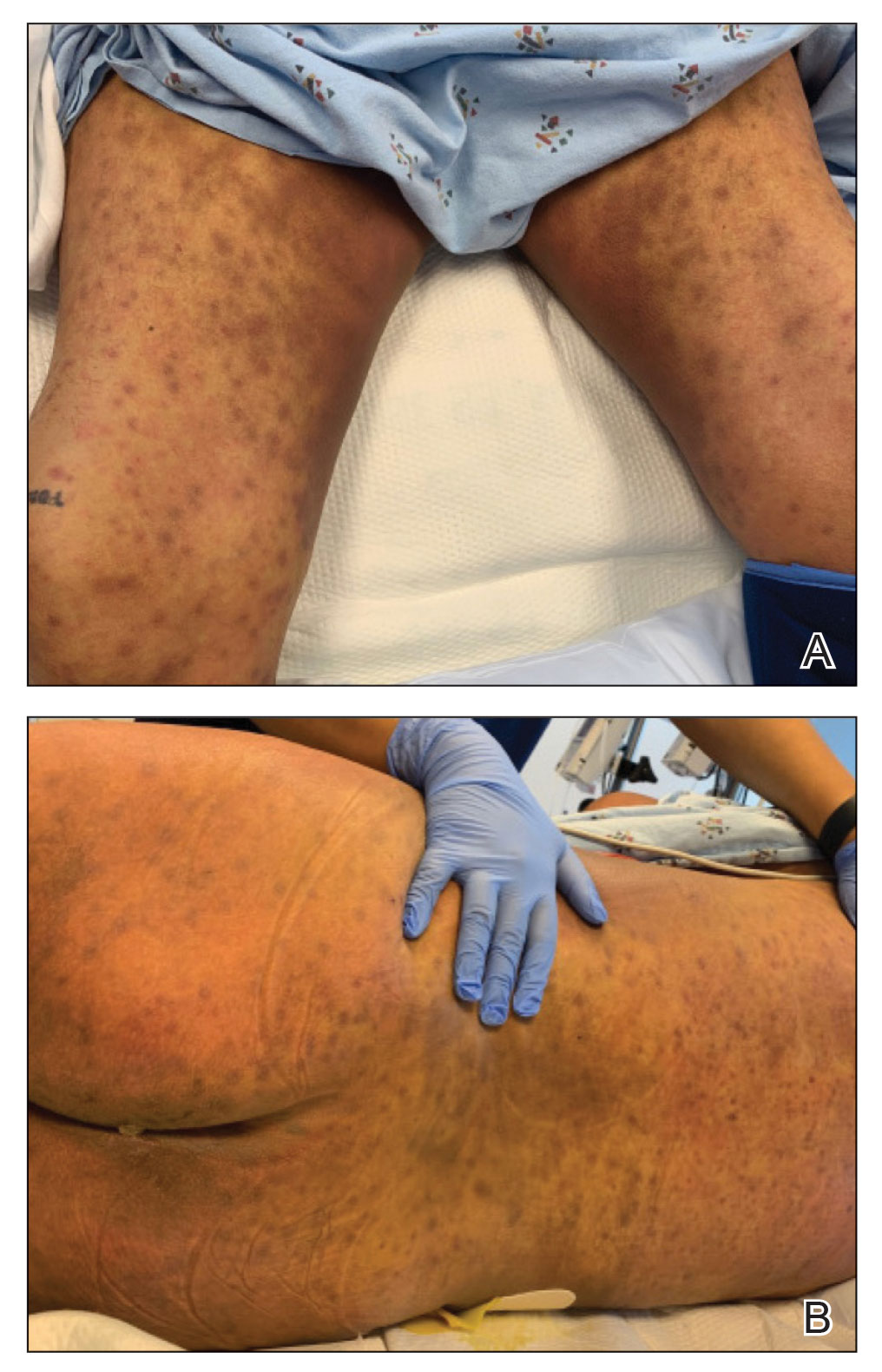

Diffuse blanching erythema with a well-demarcated linear border was noted along the lower anterior neck extending to the posterior hairline. There was notable edema but no evidence of pustules or overlying scale. Similar areas of blanchable erythema were present along the axillae and inguinal folds. There also were flesh-colored to pink papules within the axillary vaults and on the back that occasionally coalesced into plaques. There was no involvement of the mucous membranes or acral sites.

A complete blood cell count with differential and a comprehensive metabolic profile largely were unremarkable. A potassium hydroxide preparation of the face and groin was negative for hyphae and Demodex mites. Histopathologic analysis from a punch biopsy of a representative papule from the posterior neck demonstrated epidermal dysmaturation with marked thickening of the granular cell layer with notably large keratohyalin granules (Figure 1).

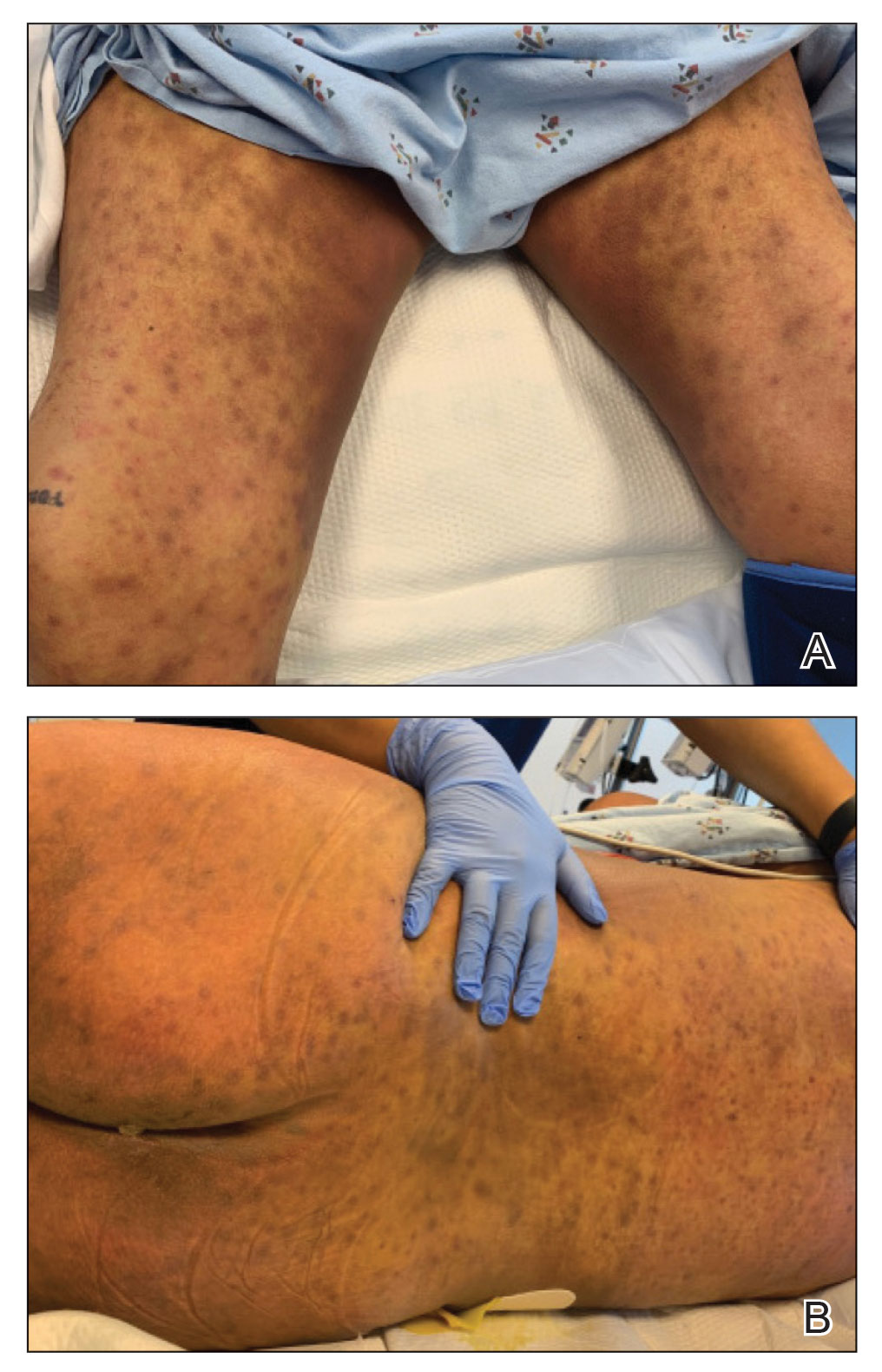

In the setting of treatment with thiotepa, we recommended supportive care with cool compresses rather than topical medication because he was neutropenic, and we wanted to avoid further immunosuppression or toxicity. By 24 hours after completing the course of palifermin, the patient experienced complete resolution of the rash. At his request, the trial of palifermin was restarted 10 days into conditioning therapy. A similar rash with less facial edema but more prominent involvement of the chest appeared 3 days into the retrial (Figure 2). The medication was discontinued, which resulted in resolution of the rash. Again, the patient remained afebrile without involvement of the mucous membranes. Liver enzyme and creatinine levels remained within reference range.Eosinophilia and the level of atypical lymphocytes could not be assessed because of leukopenia in the setting of recent chemotherapy. The rash self-resolved in 4 days.

Palifermin is a recombinant form of human KGF that is more stable than the endogenous form but retains all vital properties of the protein.5-7 Similar to other growth factors, KGF induces differentiation, proliferation, and migration of cells in vivo.8 However, it uniquely produces a targeted effect on epithelial cells in the skin, oral mucosa, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and genitourinary system.7-9

Palifermin was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2004 for the prevention and treatment of severe oral mucositis in patients receiving myelotoxic therapy prior to stem cell transplantation.7,9 Severe mucositis occurs in approximately 70% to 80% of patients receiving radiation or chemotherapy-based conditioning treatments.4,7 Compared to placebo, palifermin has been shown to greatly reduce the incidence of Grade 4 oral mucositis, defined as severe enough to prevent alimentation.10

The proliferative effect of palifermin on the oral mucosa is beneficial to patients but likely is the driving force behind its cutaneous adverse effects. A nonspecific rash is the most commonly cited treatment-related adverse event associated with palifermin, occurring in approximately 62% of patients.5,7,9

Our case is a rare report of a palifermin-associated cutaneous reaction. Previous cases have cited the occurrence of palmoplantar erythrodysesthesias, papulopustular eruptions involving the face and chest, and a papular rash involving the dorsal hands and intertriginous areas.1-4 Another report documented a “mild rash” but failed to further characterize the morphology or the body site involved.5

In 2009, King et al6 reported the occurrence of a lichen planus–like eruption involving the intertriginous regions and of white oral plaques in a patient treated with palifermin. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of a representative lesion in that patient demonstrated an appearance similar to that of verrucae, including papillomatosis, hypergranulosis, and hyperorthokeratosis.

King et al6 expanded analysis of the reaction to include immunohistochemical study, using targeted antibody stains for cytokeratin 5/6 and Ki-67 protein. Staining with Ki-67 showed dramatically increased activity within basilar and suprabasilar keratinocytes in a biopsy taken at the height of the reaction. Biopsy specimens obtained when the eruption was clinically resolving—2 days after the first biopsy—showed decreased Ki-67 staining. These findings taken together suggest a direct causal effect of palifermin inducing hyperkeratotic changes appreciated on examination of treated patients.6

We present this case to add to current data regarding palifermin-induced cutaneous changes. Unique to our patient was a strikingly well-demarcated rash confined to the head and neck. Although a photosensitive eruption due to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is conceivable, the fixed time course of the eruption—corresponding to (1) initiation and discontinuation of palifermin and (2) histologic findings—led us to conclude that this self-limited eruption likely was due to palifermin.

To the Editor:

Palifermin is a recombinant keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to prevent oral mucositis following radiation therapy or chemotherapy. Cutaneous reactions associated with palifermin have been reported.1-5 One case described a distinctive polymorphous eruption in a patient treated with palifermin.6 On histologic analysis, papules demonstrated findings similar to verrucae, with evidence of papillomatosis, hypergranulosis, and hyperorthokeratosis. Given its mechanism of action as a KGF, it was concluded that these findings were likely the direct result of palifermin.6 We report a similar case of a patient who was given palifermin prior to an autologous stem cell transplant. Histopathologic analysis confirmed epidermal dysmaturation and marked hypergranulosis. We present this case to expand the paucity of data on palifermin-associated cutaneous reactions.

A 63-year-old man with a history of psoriasis, eczema, and relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma was admitted to the hospital for routine management of an autologous stem cell transplant with a conditioning regimen involving thiotepa, busulfan, and cyclophosphamide. The patient had completed a 3-day course of palifermin 1 day prior to the current presentation. On admission, he developed a pruritic erythematous rash over the face and axillae. Within 24 hours, the facial rash progressed with appreciable edema, and he reported difficulty opening his eyes. He denied any fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or increased fatigue. He also denied use of any other medications other than starting a course of prophylactic trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 3 times weekly 2 months prior to admission.

Diffuse blanching erythema with a well-demarcated linear border was noted along the lower anterior neck extending to the posterior hairline. There was notable edema but no evidence of pustules or overlying scale. Similar areas of blanchable erythema were present along the axillae and inguinal folds. There also were flesh-colored to pink papules within the axillary vaults and on the back that occasionally coalesced into plaques. There was no involvement of the mucous membranes or acral sites.

A complete blood cell count with differential and a comprehensive metabolic profile largely were unremarkable. A potassium hydroxide preparation of the face and groin was negative for hyphae and Demodex mites. Histopathologic analysis from a punch biopsy of a representative papule from the posterior neck demonstrated epidermal dysmaturation with marked thickening of the granular cell layer with notably large keratohyalin granules (Figure 1).

In the setting of treatment with thiotepa, we recommended supportive care with cool compresses rather than topical medication because he was neutropenic, and we wanted to avoid further immunosuppression or toxicity. By 24 hours after completing the course of palifermin, the patient experienced complete resolution of the rash. At his request, the trial of palifermin was restarted 10 days into conditioning therapy. A similar rash with less facial edema but more prominent involvement of the chest appeared 3 days into the retrial (Figure 2). The medication was discontinued, which resulted in resolution of the rash. Again, the patient remained afebrile without involvement of the mucous membranes. Liver enzyme and creatinine levels remained within reference range.Eosinophilia and the level of atypical lymphocytes could not be assessed because of leukopenia in the setting of recent chemotherapy. The rash self-resolved in 4 days.

Palifermin is a recombinant form of human KGF that is more stable than the endogenous form but retains all vital properties of the protein.5-7 Similar to other growth factors, KGF induces differentiation, proliferation, and migration of cells in vivo.8 However, it uniquely produces a targeted effect on epithelial cells in the skin, oral mucosa, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and genitourinary system.7-9

Palifermin was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2004 for the prevention and treatment of severe oral mucositis in patients receiving myelotoxic therapy prior to stem cell transplantation.7,9 Severe mucositis occurs in approximately 70% to 80% of patients receiving radiation or chemotherapy-based conditioning treatments.4,7 Compared to placebo, palifermin has been shown to greatly reduce the incidence of Grade 4 oral mucositis, defined as severe enough to prevent alimentation.10

The proliferative effect of palifermin on the oral mucosa is beneficial to patients but likely is the driving force behind its cutaneous adverse effects. A nonspecific rash is the most commonly cited treatment-related adverse event associated with palifermin, occurring in approximately 62% of patients.5,7,9

Our case is a rare report of a palifermin-associated cutaneous reaction. Previous cases have cited the occurrence of palmoplantar erythrodysesthesias, papulopustular eruptions involving the face and chest, and a papular rash involving the dorsal hands and intertriginous areas.1-4 Another report documented a “mild rash” but failed to further characterize the morphology or the body site involved.5

In 2009, King et al6 reported the occurrence of a lichen planus–like eruption involving the intertriginous regions and of white oral plaques in a patient treated with palifermin. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of a representative lesion in that patient demonstrated an appearance similar to that of verrucae, including papillomatosis, hypergranulosis, and hyperorthokeratosis.

King et al6 expanded analysis of the reaction to include immunohistochemical study, using targeted antibody stains for cytokeratin 5/6 and Ki-67 protein. Staining with Ki-67 showed dramatically increased activity within basilar and suprabasilar keratinocytes in a biopsy taken at the height of the reaction. Biopsy specimens obtained when the eruption was clinically resolving—2 days after the first biopsy—showed decreased Ki-67 staining. These findings taken together suggest a direct causal effect of palifermin inducing hyperkeratotic changes appreciated on examination of treated patients.6

We present this case to add to current data regarding palifermin-induced cutaneous changes. Unique to our patient was a strikingly well-demarcated rash confined to the head and neck. Although a photosensitive eruption due to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is conceivable, the fixed time course of the eruption—corresponding to (1) initiation and discontinuation of palifermin and (2) histologic findings—led us to conclude that this self-limited eruption likely was due to palifermin.

- Gorcey L, Lewin JM, Trufant J, et al. Papular eruption associated with palifermin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E101-E102. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.006

- Grzegorczyk-Jaz´win´ska A, Kozak I, Karakulska-Prystupiuk E, et al. Transient oral cavity and skin complications after mucositis preventing therapy (palifermin) in a patient after allogeneic PBSCT. case history. Adv Med Sci. 2006;51(suppl 1):66-68.

- Keijzer A, Huijgens PC, van de Loosdrecht AA. Palifermin and palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia. Br J Haematol. 2007;136:856-857. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06509.x

- Sibelt LAG, Aboosy N, van der Velden WJFM, et al. Palifermin-induced flexural hyperpigmentation: a clinical and histological study of five cases. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:1200-1203. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08816.x

- Keefe D, Lees J, Horvath N. Palifermin for oral mucositis in the high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplant setting: the Royal Adelaide Hospital Cancer Centre experience. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:580-582. doi:10.1007/s00520-006-0048-3

- King B, Knopp E, Galan A, et al. Palifermin-associated papular eruption. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:179-182. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2008.548

- Spielberger R, Stiff P, Bensinger W, et al. Palifermin for oral mucositis after intensive therapy for hematologic cancers. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2590-2598. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040125

- Rubin JS, Bottaro DP, Chedid M, et al. Keratinocyte growth factor. Cell Biol Int. 1995;19:399-411. doi:10.1006/cbir.1995.1085

- McDonnell AM, Lenz KL. Palifermin: role in the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiation-induced mucositis. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:86-94. doi:10.1345/aph.1G473

- Maria OM, Eliopoulos N, Muanza T. Radiation-induced oral mucositis. Front Oncol. 2017;7:89. doi:10.3389/fonc.2017.00089

- Gorcey L, Lewin JM, Trufant J, et al. Papular eruption associated with palifermin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E101-E102. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.006

- Grzegorczyk-Jaz´win´ska A, Kozak I, Karakulska-Prystupiuk E, et al. Transient oral cavity and skin complications after mucositis preventing therapy (palifermin) in a patient after allogeneic PBSCT. case history. Adv Med Sci. 2006;51(suppl 1):66-68.

- Keijzer A, Huijgens PC, van de Loosdrecht AA. Palifermin and palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia. Br J Haematol. 2007;136:856-857. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06509.x

- Sibelt LAG, Aboosy N, van der Velden WJFM, et al. Palifermin-induced flexural hyperpigmentation: a clinical and histological study of five cases. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:1200-1203. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08816.x

- Keefe D, Lees J, Horvath N. Palifermin for oral mucositis in the high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplant setting: the Royal Adelaide Hospital Cancer Centre experience. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:580-582. doi:10.1007/s00520-006-0048-3

- King B, Knopp E, Galan A, et al. Palifermin-associated papular eruption. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:179-182. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2008.548

- Spielberger R, Stiff P, Bensinger W, et al. Palifermin for oral mucositis after intensive therapy for hematologic cancers. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2590-2598. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040125

- Rubin JS, Bottaro DP, Chedid M, et al. Keratinocyte growth factor. Cell Biol Int. 1995;19:399-411. doi:10.1006/cbir.1995.1085

- McDonnell AM, Lenz KL. Palifermin: role in the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiation-induced mucositis. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:86-94. doi:10.1345/aph.1G473

- Maria OM, Eliopoulos N, Muanza T. Radiation-induced oral mucositis. Front Oncol. 2017;7:89. doi:10.3389/fonc.2017.00089

Practice Points

- Palifermin is a recombinant keratinocyte growth factor that is US Food and Drug Administration approved to prevent oral mucositis in patients undergoing chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

- Histologically, the rash can resemble verrucae with evidence of hypergranulosis, hyperorthokeratosis, and papillomatosis.

- Cutaneous reactions have been reported with use of palifermin and generally are benign and self-limited with removal of the offending agent.

Erythematous Plaques on the Dorsal Aspect of the Hand

The Diagnosis: Majocchi Granuloma

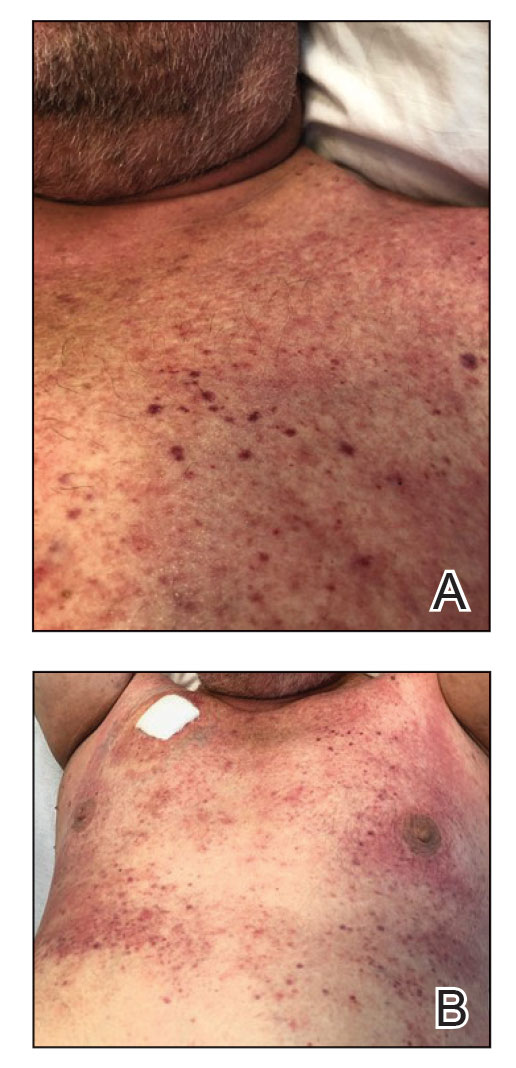

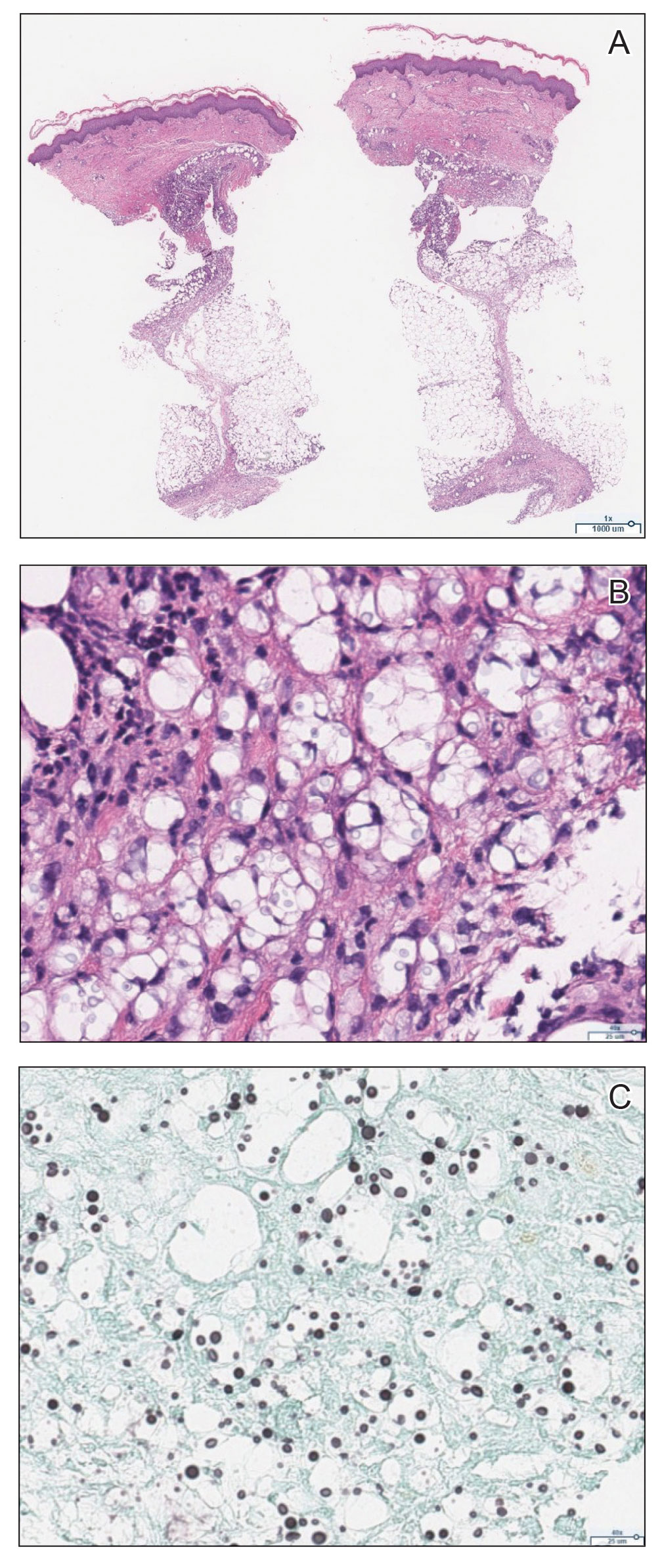

Histopathology showed rare follicular-based organisms highlighted by periodic acid–Schiff staining. This finding along with her use of clobetasol ointment on the hands led to a diagnosis of Majocchi granuloma in our patient. Clobetasol and crisaborole ointments were discontinued, and she was started on oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 4 weeks, which resulted in resolution of the rash.

Majocchi granuloma (also known as nodular granulomatous perifolliculitis) is a perifollicular granulomatous process caused by a dermatophyte infection of the hair follicles. Trichophyton rubrum is the most commonly implicated organism, followed by Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Epidermophyton floccosum, which also cause tinea corporis and tinea pedis.1 This condition most commonly occurs in women aged 20 to 35 years. Risk factors include trauma, occlusion of the hair follicles, immunosuppression, and use of potent topical corticosteroids in patients with tinea.2,3 Immunocompetent patients present with perifollicular papules or pustules with erythematous scaly plaques on the extremities, while immunocompromised patients may have subcutaneous nodules or abscesses on any hair-bearing parts of the body.3

Majocchi granuloma is considered a dermal fungal infection in which the disruption of hair follicles from occlusion or trauma allows fungal organisms and keratinaceous material substrates to be introduced into the dermis. The differential diagnosis is based on the types of presenting lesions. The papules of Majocchi granuloma can resemble folliculitis, acne, or insect bites, while nodules can resemble erythema nodosum or furunculosis.4 Plaques, such as those seen in our patient, can mimic cellulitis and allergic or irritant contact dermatitis.4 Additionally, the plaques may appear annular or figurate, which may resemble erythema gyratum repens or erythema annulare centrifugum.

The diagnosis of Majocchi granuloma often requires fungal culture and biopsy because a potassium hydroxide preparation is unable to distinguish between superficial and invasive dermatophytes.3 Histopathology will show perifollicular granulomatous inflammation. Fungal elements can be detected with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining of the hairs and hair follicles as well as dermal infiltrates.4

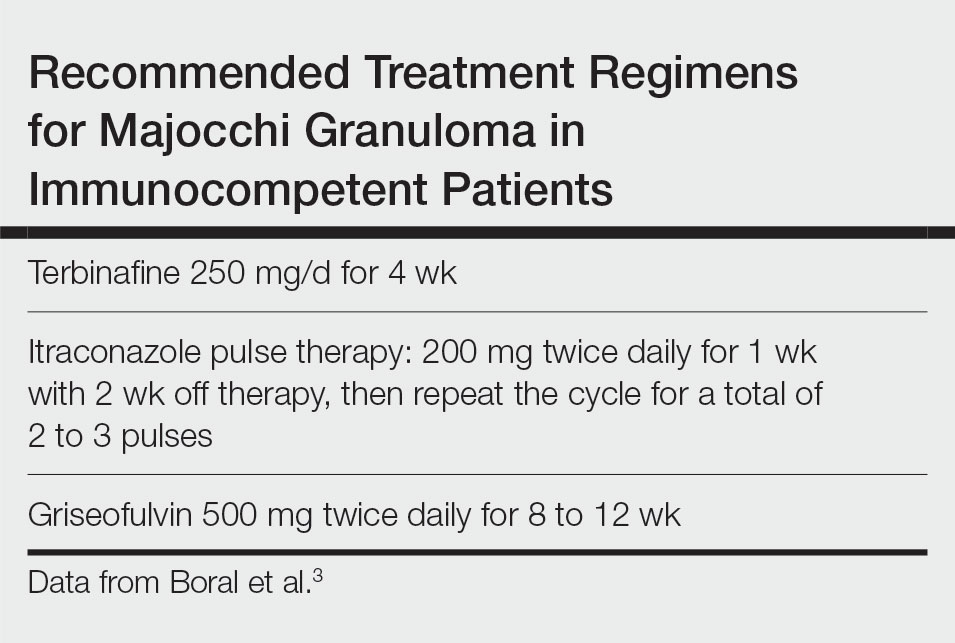

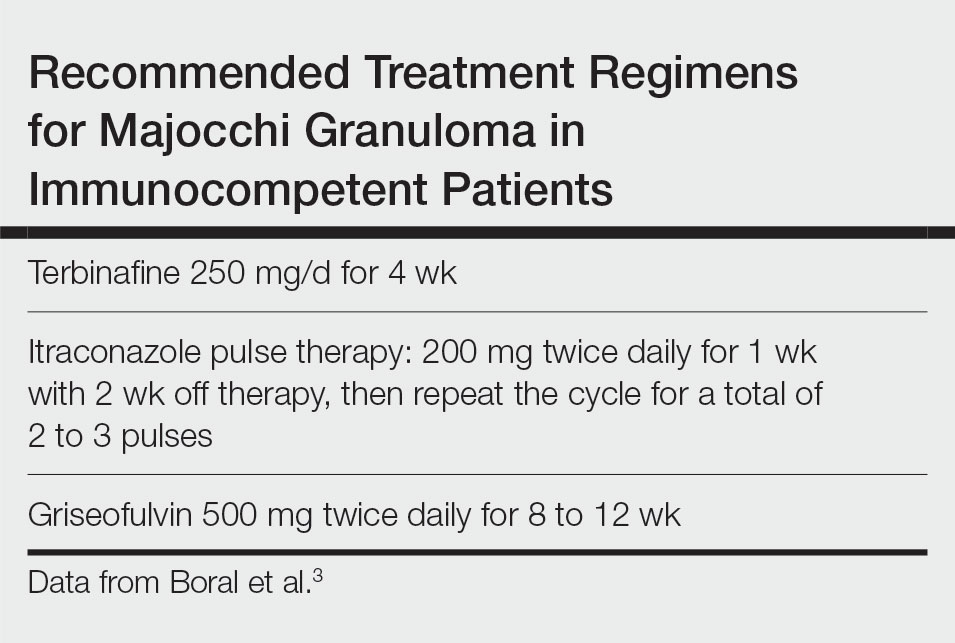

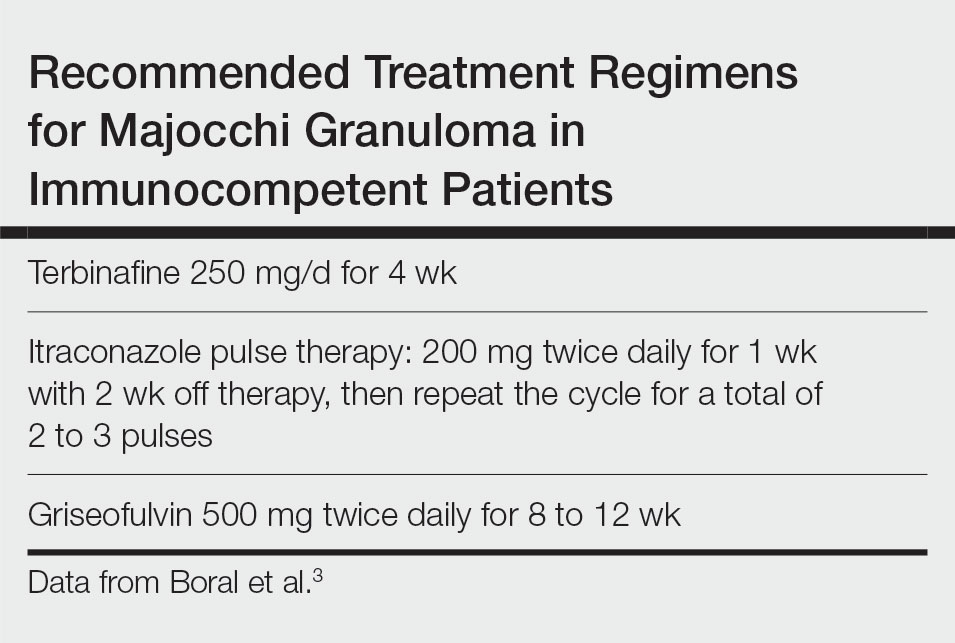

Topical corticosteroids should be discontinued. Systemic antifungals are the treatment of choice for Majocchi granuloma, as topical antifungals are not effective against deep fungal infections. Although there are no standard guidelines on duration or dosage, recommended regimens in immunocompetent patients include terbinafine 250 mg/d for 4 weeks; itraconazole pulse therapy consisting of 200 mg twice daily for 1 week with 2 weeks off therapy, then repeat the cycle for a total of 2 to 3 pulses; and griseofulvin 500 mg twice daily for 8 to 12 weeks (Table).3 For immunocompromised patients, combination therapy with more than one antifungal may be necessary.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston DM. Diseases resulting from fungi and yeasts. In: James WD, Berger T, Elston D, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2016:285-318.

- Li FQ, Lv S, Xia JX. Majocchi’s granuloma after topical corticosteroids therapy. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2014;2014:507176.

- Boral H, Durdu M, Ilkit M. Majocchi’s granuloma: current perspectives. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:751-760.

- I˙lkit M, Durdu M, Karakas¸ M. Majocchi’s granuloma: a symptom complex caused by fungal pathogens. Med Mycol. 2012;50:449-457.

The Diagnosis: Majocchi Granuloma

Histopathology showed rare follicular-based organisms highlighted by periodic acid–Schiff staining. This finding along with her use of clobetasol ointment on the hands led to a diagnosis of Majocchi granuloma in our patient. Clobetasol and crisaborole ointments were discontinued, and she was started on oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 4 weeks, which resulted in resolution of the rash.

Majocchi granuloma (also known as nodular granulomatous perifolliculitis) is a perifollicular granulomatous process caused by a dermatophyte infection of the hair follicles. Trichophyton rubrum is the most commonly implicated organism, followed by Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Epidermophyton floccosum, which also cause tinea corporis and tinea pedis.1 This condition most commonly occurs in women aged 20 to 35 years. Risk factors include trauma, occlusion of the hair follicles, immunosuppression, and use of potent topical corticosteroids in patients with tinea.2,3 Immunocompetent patients present with perifollicular papules or pustules with erythematous scaly plaques on the extremities, while immunocompromised patients may have subcutaneous nodules or abscesses on any hair-bearing parts of the body.3

Majocchi granuloma is considered a dermal fungal infection in which the disruption of hair follicles from occlusion or trauma allows fungal organisms and keratinaceous material substrates to be introduced into the dermis. The differential diagnosis is based on the types of presenting lesions. The papules of Majocchi granuloma can resemble folliculitis, acne, or insect bites, while nodules can resemble erythema nodosum or furunculosis.4 Plaques, such as those seen in our patient, can mimic cellulitis and allergic or irritant contact dermatitis.4 Additionally, the plaques may appear annular or figurate, which may resemble erythema gyratum repens or erythema annulare centrifugum.

The diagnosis of Majocchi granuloma often requires fungal culture and biopsy because a potassium hydroxide preparation is unable to distinguish between superficial and invasive dermatophytes.3 Histopathology will show perifollicular granulomatous inflammation. Fungal elements can be detected with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining of the hairs and hair follicles as well as dermal infiltrates.4

Topical corticosteroids should be discontinued. Systemic antifungals are the treatment of choice for Majocchi granuloma, as topical antifungals are not effective against deep fungal infections. Although there are no standard guidelines on duration or dosage, recommended regimens in immunocompetent patients include terbinafine 250 mg/d for 4 weeks; itraconazole pulse therapy consisting of 200 mg twice daily for 1 week with 2 weeks off therapy, then repeat the cycle for a total of 2 to 3 pulses; and griseofulvin 500 mg twice daily for 8 to 12 weeks (Table).3 For immunocompromised patients, combination therapy with more than one antifungal may be necessary.

The Diagnosis: Majocchi Granuloma

Histopathology showed rare follicular-based organisms highlighted by periodic acid–Schiff staining. This finding along with her use of clobetasol ointment on the hands led to a diagnosis of Majocchi granuloma in our patient. Clobetasol and crisaborole ointments were discontinued, and she was started on oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 4 weeks, which resulted in resolution of the rash.

Majocchi granuloma (also known as nodular granulomatous perifolliculitis) is a perifollicular granulomatous process caused by a dermatophyte infection of the hair follicles. Trichophyton rubrum is the most commonly implicated organism, followed by Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Epidermophyton floccosum, which also cause tinea corporis and tinea pedis.1 This condition most commonly occurs in women aged 20 to 35 years. Risk factors include trauma, occlusion of the hair follicles, immunosuppression, and use of potent topical corticosteroids in patients with tinea.2,3 Immunocompetent patients present with perifollicular papules or pustules with erythematous scaly plaques on the extremities, while immunocompromised patients may have subcutaneous nodules or abscesses on any hair-bearing parts of the body.3

Majocchi granuloma is considered a dermal fungal infection in which the disruption of hair follicles from occlusion or trauma allows fungal organisms and keratinaceous material substrates to be introduced into the dermis. The differential diagnosis is based on the types of presenting lesions. The papules of Majocchi granuloma can resemble folliculitis, acne, or insect bites, while nodules can resemble erythema nodosum or furunculosis.4 Plaques, such as those seen in our patient, can mimic cellulitis and allergic or irritant contact dermatitis.4 Additionally, the plaques may appear annular or figurate, which may resemble erythema gyratum repens or erythema annulare centrifugum.

The diagnosis of Majocchi granuloma often requires fungal culture and biopsy because a potassium hydroxide preparation is unable to distinguish between superficial and invasive dermatophytes.3 Histopathology will show perifollicular granulomatous inflammation. Fungal elements can be detected with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining of the hairs and hair follicles as well as dermal infiltrates.4

Topical corticosteroids should be discontinued. Systemic antifungals are the treatment of choice for Majocchi granuloma, as topical antifungals are not effective against deep fungal infections. Although there are no standard guidelines on duration or dosage, recommended regimens in immunocompetent patients include terbinafine 250 mg/d for 4 weeks; itraconazole pulse therapy consisting of 200 mg twice daily for 1 week with 2 weeks off therapy, then repeat the cycle for a total of 2 to 3 pulses; and griseofulvin 500 mg twice daily for 8 to 12 weeks (Table).3 For immunocompromised patients, combination therapy with more than one antifungal may be necessary.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston DM. Diseases resulting from fungi and yeasts. In: James WD, Berger T, Elston D, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2016:285-318.

- Li FQ, Lv S, Xia JX. Majocchi’s granuloma after topical corticosteroids therapy. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2014;2014:507176.

- Boral H, Durdu M, Ilkit M. Majocchi’s granuloma: current perspectives. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:751-760.

- I˙lkit M, Durdu M, Karakas¸ M. Majocchi’s granuloma: a symptom complex caused by fungal pathogens. Med Mycol. 2012;50:449-457.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston DM. Diseases resulting from fungi and yeasts. In: James WD, Berger T, Elston D, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2016:285-318.

- Li FQ, Lv S, Xia JX. Majocchi’s granuloma after topical corticosteroids therapy. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2014;2014:507176.

- Boral H, Durdu M, Ilkit M. Majocchi’s granuloma: current perspectives. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:751-760.

- I˙lkit M, Durdu M, Karakas¸ M. Majocchi’s granuloma: a symptom complex caused by fungal pathogens. Med Mycol. 2012;50:449-457.

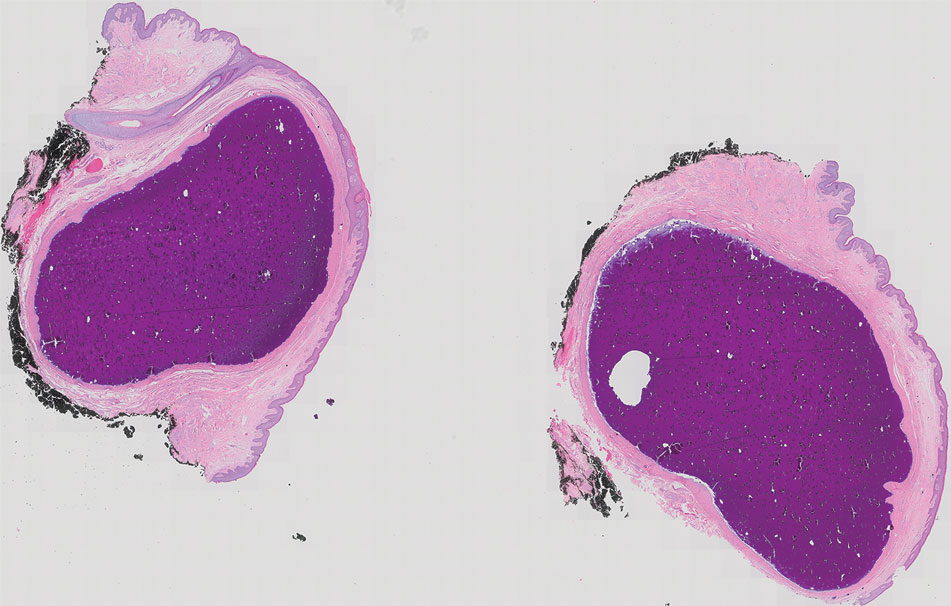

A 33-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic rash on the left hand that was suspected by her primary care physician to be a flare of hand dermatitis. The patient had a history of irritant hand dermatitis diagnosed 2 years prior that was suspected to be secondary to frequent handwashing and was well controlled with clobetasol and crisaborole ointments for 1 year. Four months prior to the current presentation, she developed a flare that was refractory to these topical therapies; treatment with biweekly dupilumab 300 mg was initiated by dermatology, but the rash continued to evolve. A punch biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Analysis of a Pilot Curriculum for Business Education in Dermatology Residency

To the Editor:

With health care constituting one of the larger segments of the US economy, medical practice is increasingly subject to business considerations.1 Patients, providers, and organizations are all required to make decisions that reflect choices beyond clinical needs alone. Given the impact of market forces, clinicians often are asked to navigate operational and business decisions. Accordingly, education about the policy and systems that shape care delivery can improve quality and help patients.2

The ability to understand the ecosystem of health care is of utmost importance for medical providers and can be achieved through resident education. Teaching fundamental business concepts enables residents to deliver care that is responsive to the constraints and opportunities encountered by patients and organizations, which ultimately will better prepare them to serve as advocates in alignment with their principal duties as physicians.

Despite the recognizable relationship between business and medicine, training has not yet been standardized to include topics in business education, and clinicians in dermatology are remarkably positioned to benefit because of the variety of practice settings and services they can provide. In dermatology, the diversity of services provided gives rise to complex coding and use of modifiers. Proper utilization of coding and billing is critical to create accurate documentation and receive appropriate reimbursement.3 Furthermore, clinicians in dermatology have to contend with the influence of insurance at many points of care, such as with coverage of pharmaceuticals. Formularies often have wide variability in coverage and are changing as new drugs come to market in the dermatologic space.4

The landscape of practice structure also has undergone change with increasing consolidation and mergers. The acquisition of practices by private equity firms has induced changes in practice infrastructure. The impact of changing organizational and managerial influences continues to be a topic of debate, with disparate opinions on how these developments shape standards of physician satisfaction and patient care.5

The convergence of these factors points to an important question that is gaining popularity: How will young dermatologists work within the context of all these parameters to best advocate and care for their patients? These questions are garnering more attention and were recently investigated through a survey of participants in a pilot program to evaluate the importance of business education in dermatology residency.

A survey of residency program directors was created by Patrinley and Dewan,6 which found that business education during residency was important and additional training should be implemented. Despite the perceived importance of business education, only half of the programs represented by survey respondents offered any structured educational opportunities, revealing a discrepancy between believed importance and practical implementation of business training, which suggests the need to develop a standardized, dermatology-specific curriculum that could be accessed by all residents in training.6

We performed a search of the medical literature to identify models of business education in residency programs. Only a few programs were identified, in which courses were predominantly instructed to trainees in primary care–based fields. According to course graduates, the programs were beneficial.7,8 Programs that had descriptive information about curriculum structure and content were chosen for further investigation and included internal medicine programs at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) and Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons (New York, New York). UCSF implemented a Program in Residency Investigation Methods and Epidemiology (PRIME program) to deliver seven 90-minute sessions dedicated to introducing residents to medical economics. Sessions were constructed with the intent of being interactive seminars that took on a variety of forms, including reading-based discussions, case-based analysis, and simulation-based learning.7 Columbia University developed a pilot program of week-long didactic sessions that were delivered to third-year internal medicine residents. These seminars featured discussions on health policy and economics, health insurance, technology and cost assessment, legal medicine, public health, community-oriented primary care, and local health department initiatives.8 We drew on both courses to build a lecture series focused on the business of dermatology that was delivered to dermatology residents at UMass Chan Medical School (Worcester, Massachusetts). Topic selection also was informed by qualitative input collected via email from recent graduates of the UMass dermatology residency program, focusing on the following areas: the US medical economy and health care costs; billing, coding, and claims processing; quality, relative value units (RVUs), reimbursement, and the merit-based incentive payment system; coverage of pharmaceuticals and teledermatology; and management. Residents were not required to prepare for any of the sessions; they were provided with handouts and slideshow presentations for reference to review at their convenience if desired. Five seminars were virtually conducted by an MD/MBA candidate at the institution (E.H.). They were recorded over the course of an academic year at 1- to 2-month intervals. Each 45-minute session was conducted in a lecture-discussion format and included case examples to help illustrate key principles and stimulate conversation. For example, the lecture on reimbursement incorporated a fee schedule calculation for a shave biopsy, using RVU and geographic pricing cost index (GCPI) multipliers. This demonstrated the variation in Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reimbursement in relation to (1) constituents of the RVU calculation (ie, work, practice expense, and malpractice) and (2) practice in a particular location (ie, the GCPI). Following this example, a conversation ensued among participants regarding the factors that drive valuation, with particular interest in variation based on urban vs suburban locations across the United States. Participants also found it of interest to examine the percentage of the valuation dedicated to each constituent and how features such as lesion size informed the final assessment of the charge. Another stylistic choice in developing the model was to include prompts for further consideration prior to transitioning topics in the lectures. For example: when examining the burden of skin disease, the audience was prompted to consider: “What is driving cost escalations, and how will services of the clinical domain meet these evolving needs?” At another point in the introductory lecture, residents were asked: “How do different types of insurance plans impact the management of patients with dermatologic concerns?” These questions were intended to transition residents to the next topic of discussion and highlight take-home points of consideration for medical practice. The project was reviewed by the UMass institutional review board and met criteria for exemption.

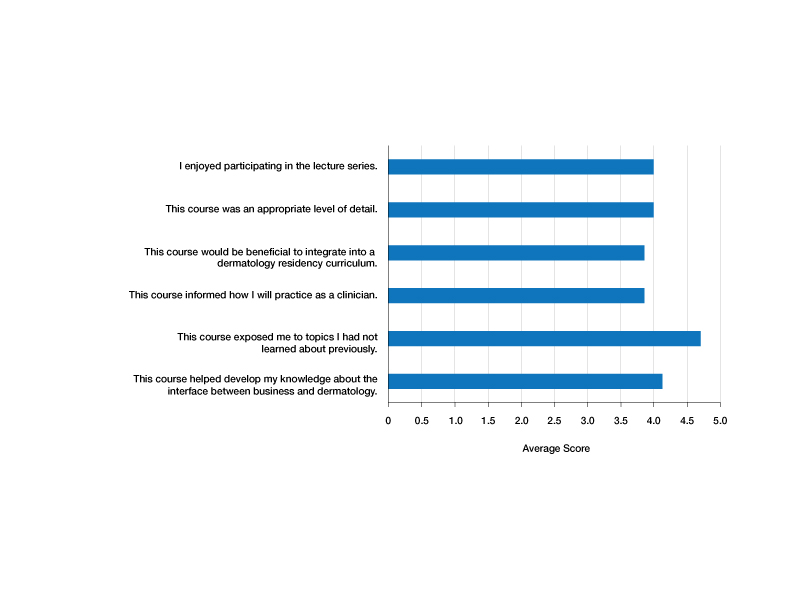

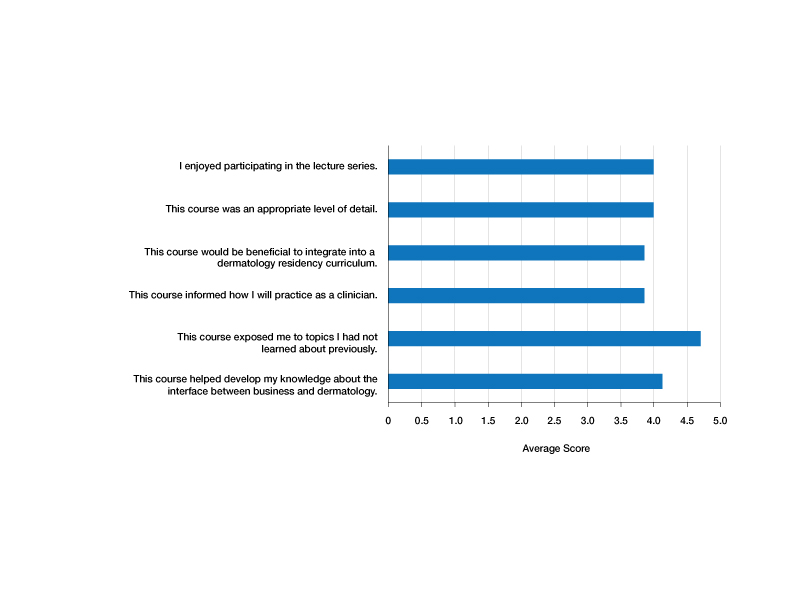

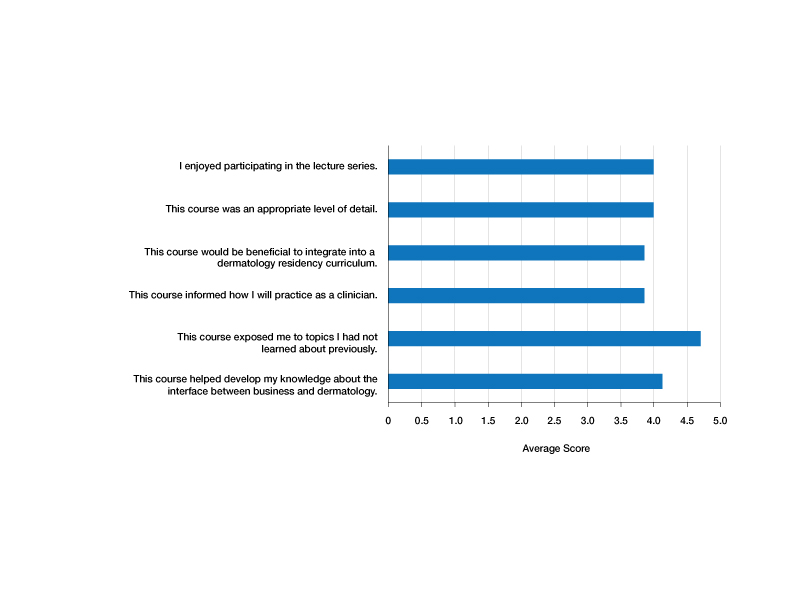

Residents who participated in at least 1 lecture (N=10) were surveyed after attendance; there were 7 responses (70% response rate). Residents were asked to rate a series of statements on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) and to provide commentary via an online form. Respondents indicated that the course was enjoyable (average score, 4.00), provided an appropriate level of detail (average score, 4.00), would be beneficial to integrate into a dermatology residency curriculum (average score, 3.86), and informed how they would practice as a clinician (average score, 3.86)(Figure). The respondents agreed that the course met the main goals of this initiative: it helped them develop knowledge about the interface between business and dermatology (4.14) and exposed residents to topics they had not learned about previously (4.71).

Although the course generally was well received, areas for improvement were identified from respondents’ comments, relating to audience engagement and refining the level of detail in the lectures. Recommendations included “less technical jargon and more focus on ‘big picture’ concepts, given audience’s low baseline knowledge”; “more case examples in each module”; and “more diagrams or interactive activities (polls, quizzes, break-out rooms) because the lectures were a bit dense.” This input was taken into consideration when revising the lectures for future use; they were reconstructed to have more case-based examples and prompts to encourage participation.

Resident commentary also demonstrated appreciation for education in this subject material. Statements such as “this is an important topic for future dermatologists” and “thank you so much for taking the time to implement this course” reflected the perceived value of this material during critical academic time. Another resident remarked: “This was great, thanks for putting it together.”

Given the positive experience of the residents and successful implementation of the series, this course was made available to all dermatology trainees on a network server with accompanying written documents. It is planned to be offered on a 3-year cycle in the future and will be updated to reflect inevitable changes in health care.

Although the relationship between business and medicine is increasingly important, teaching business principles has not become standardized or required in medical training. Despite the perception that this content is of value, implementation of programming has lagged behind that recognition, likely due to challenges in designing the curriculum and diffusing content into an already-saturated schedule. A model course that can be replicated in other residency programs would be valuable. We introduced a dermatology-specific lecture series to help prepare trainees for dermatology practice in a variety of clinical settings and train them with the language of business and operations that will equip them to respond to the needs of their patients, their practice, and the medical environment. Findings of this pilot study may not be generalizable to all dermatology residency programs because the sample size was small; the study was conducted at a single institution; and the content was delivered entirely online.

1. Tan S, Seiger K, Renehan P, et al. Trends in private equity acquisition of dermatology practices in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1013-1021. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1634

2. The business of health care in the United States. Harvard Online [Internet]. June 27, 2022. Accessed July 24, 2023. https://www.harvardonline.harvard.edu/blog/business-health-care-united-states

3. Ranpariya V, Cull D, Feldman SR, et al. Evaluation and management 2021 coding guidelines: key changes and implications. The Dermatologist. December 2020. Accessed July 24, 2023. https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/thederm/article/evaluation-and-management-2021-coding-guidelines-key-changes-and-implications?key=Ranpariya&elastic%5B0%5D=brand%3A73468

4. Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS Jr, et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:958-972.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.043

5. Resneck JS Jr. Dermatology practice consolidation fueled by private equity investment: potential consequences for the specialty and patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:13-14. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5558

6. Patrinely JR Jr, Dewan AK. Business education in dermatology residency: a survey of program directors. Cutis. 2021;108:E7-E19. doi:10.12788/cutis.0331

7. Kohlwes RJ, Chou CL. A curriculum in medical economics for residents. Acad Med. 2002;77:465-466. doi:10.1097/00001888-200205000-00040

8. Fiebach NH, Rao D, Hamm ME. A curriculum in health systems and public health for internal medicine residents. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4 suppl 3):S264-S269. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.025

To the Editor:

With health care constituting one of the larger segments of the US economy, medical practice is increasingly subject to business considerations.1 Patients, providers, and organizations are all required to make decisions that reflect choices beyond clinical needs alone. Given the impact of market forces, clinicians often are asked to navigate operational and business decisions. Accordingly, education about the policy and systems that shape care delivery can improve quality and help patients.2

The ability to understand the ecosystem of health care is of utmost importance for medical providers and can be achieved through resident education. Teaching fundamental business concepts enables residents to deliver care that is responsive to the constraints and opportunities encountered by patients and organizations, which ultimately will better prepare them to serve as advocates in alignment with their principal duties as physicians.

Despite the recognizable relationship between business and medicine, training has not yet been standardized to include topics in business education, and clinicians in dermatology are remarkably positioned to benefit because of the variety of practice settings and services they can provide. In dermatology, the diversity of services provided gives rise to complex coding and use of modifiers. Proper utilization of coding and billing is critical to create accurate documentation and receive appropriate reimbursement.3 Furthermore, clinicians in dermatology have to contend with the influence of insurance at many points of care, such as with coverage of pharmaceuticals. Formularies often have wide variability in coverage and are changing as new drugs come to market in the dermatologic space.4

The landscape of practice structure also has undergone change with increasing consolidation and mergers. The acquisition of practices by private equity firms has induced changes in practice infrastructure. The impact of changing organizational and managerial influences continues to be a topic of debate, with disparate opinions on how these developments shape standards of physician satisfaction and patient care.5

The convergence of these factors points to an important question that is gaining popularity: How will young dermatologists work within the context of all these parameters to best advocate and care for their patients? These questions are garnering more attention and were recently investigated through a survey of participants in a pilot program to evaluate the importance of business education in dermatology residency.

A survey of residency program directors was created by Patrinley and Dewan,6 which found that business education during residency was important and additional training should be implemented. Despite the perceived importance of business education, only half of the programs represented by survey respondents offered any structured educational opportunities, revealing a discrepancy between believed importance and practical implementation of business training, which suggests the need to develop a standardized, dermatology-specific curriculum that could be accessed by all residents in training.6

We performed a search of the medical literature to identify models of business education in residency programs. Only a few programs were identified, in which courses were predominantly instructed to trainees in primary care–based fields. According to course graduates, the programs were beneficial.7,8 Programs that had descriptive information about curriculum structure and content were chosen for further investigation and included internal medicine programs at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) and Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons (New York, New York). UCSF implemented a Program in Residency Investigation Methods and Epidemiology (PRIME program) to deliver seven 90-minute sessions dedicated to introducing residents to medical economics. Sessions were constructed with the intent of being interactive seminars that took on a variety of forms, including reading-based discussions, case-based analysis, and simulation-based learning.7 Columbia University developed a pilot program of week-long didactic sessions that were delivered to third-year internal medicine residents. These seminars featured discussions on health policy and economics, health insurance, technology and cost assessment, legal medicine, public health, community-oriented primary care, and local health department initiatives.8 We drew on both courses to build a lecture series focused on the business of dermatology that was delivered to dermatology residents at UMass Chan Medical School (Worcester, Massachusetts). Topic selection also was informed by qualitative input collected via email from recent graduates of the UMass dermatology residency program, focusing on the following areas: the US medical economy and health care costs; billing, coding, and claims processing; quality, relative value units (RVUs), reimbursement, and the merit-based incentive payment system; coverage of pharmaceuticals and teledermatology; and management. Residents were not required to prepare for any of the sessions; they were provided with handouts and slideshow presentations for reference to review at their convenience if desired. Five seminars were virtually conducted by an MD/MBA candidate at the institution (E.H.). They were recorded over the course of an academic year at 1- to 2-month intervals. Each 45-minute session was conducted in a lecture-discussion format and included case examples to help illustrate key principles and stimulate conversation. For example, the lecture on reimbursement incorporated a fee schedule calculation for a shave biopsy, using RVU and geographic pricing cost index (GCPI) multipliers. This demonstrated the variation in Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reimbursement in relation to (1) constituents of the RVU calculation (ie, work, practice expense, and malpractice) and (2) practice in a particular location (ie, the GCPI). Following this example, a conversation ensued among participants regarding the factors that drive valuation, with particular interest in variation based on urban vs suburban locations across the United States. Participants also found it of interest to examine the percentage of the valuation dedicated to each constituent and how features such as lesion size informed the final assessment of the charge. Another stylistic choice in developing the model was to include prompts for further consideration prior to transitioning topics in the lectures. For example: when examining the burden of skin disease, the audience was prompted to consider: “What is driving cost escalations, and how will services of the clinical domain meet these evolving needs?” At another point in the introductory lecture, residents were asked: “How do different types of insurance plans impact the management of patients with dermatologic concerns?” These questions were intended to transition residents to the next topic of discussion and highlight take-home points of consideration for medical practice. The project was reviewed by the UMass institutional review board and met criteria for exemption.

Residents who participated in at least 1 lecture (N=10) were surveyed after attendance; there were 7 responses (70% response rate). Residents were asked to rate a series of statements on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) and to provide commentary via an online form. Respondents indicated that the course was enjoyable (average score, 4.00), provided an appropriate level of detail (average score, 4.00), would be beneficial to integrate into a dermatology residency curriculum (average score, 3.86), and informed how they would practice as a clinician (average score, 3.86)(Figure). The respondents agreed that the course met the main goals of this initiative: it helped them develop knowledge about the interface between business and dermatology (4.14) and exposed residents to topics they had not learned about previously (4.71).

Although the course generally was well received, areas for improvement were identified from respondents’ comments, relating to audience engagement and refining the level of detail in the lectures. Recommendations included “less technical jargon and more focus on ‘big picture’ concepts, given audience’s low baseline knowledge”; “more case examples in each module”; and “more diagrams or interactive activities (polls, quizzes, break-out rooms) because the lectures were a bit dense.” This input was taken into consideration when revising the lectures for future use; they were reconstructed to have more case-based examples and prompts to encourage participation.

Resident commentary also demonstrated appreciation for education in this subject material. Statements such as “this is an important topic for future dermatologists” and “thank you so much for taking the time to implement this course” reflected the perceived value of this material during critical academic time. Another resident remarked: “This was great, thanks for putting it together.”

Given the positive experience of the residents and successful implementation of the series, this course was made available to all dermatology trainees on a network server with accompanying written documents. It is planned to be offered on a 3-year cycle in the future and will be updated to reflect inevitable changes in health care.

Although the relationship between business and medicine is increasingly important, teaching business principles has not become standardized or required in medical training. Despite the perception that this content is of value, implementation of programming has lagged behind that recognition, likely due to challenges in designing the curriculum and diffusing content into an already-saturated schedule. A model course that can be replicated in other residency programs would be valuable. We introduced a dermatology-specific lecture series to help prepare trainees for dermatology practice in a variety of clinical settings and train them with the language of business and operations that will equip them to respond to the needs of their patients, their practice, and the medical environment. Findings of this pilot study may not be generalizable to all dermatology residency programs because the sample size was small; the study was conducted at a single institution; and the content was delivered entirely online.

To the Editor:

With health care constituting one of the larger segments of the US economy, medical practice is increasingly subject to business considerations.1 Patients, providers, and organizations are all required to make decisions that reflect choices beyond clinical needs alone. Given the impact of market forces, clinicians often are asked to navigate operational and business decisions. Accordingly, education about the policy and systems that shape care delivery can improve quality and help patients.2

The ability to understand the ecosystem of health care is of utmost importance for medical providers and can be achieved through resident education. Teaching fundamental business concepts enables residents to deliver care that is responsive to the constraints and opportunities encountered by patients and organizations, which ultimately will better prepare them to serve as advocates in alignment with their principal duties as physicians.

Despite the recognizable relationship between business and medicine, training has not yet been standardized to include topics in business education, and clinicians in dermatology are remarkably positioned to benefit because of the variety of practice settings and services they can provide. In dermatology, the diversity of services provided gives rise to complex coding and use of modifiers. Proper utilization of coding and billing is critical to create accurate documentation and receive appropriate reimbursement.3 Furthermore, clinicians in dermatology have to contend with the influence of insurance at many points of care, such as with coverage of pharmaceuticals. Formularies often have wide variability in coverage and are changing as new drugs come to market in the dermatologic space.4

The landscape of practice structure also has undergone change with increasing consolidation and mergers. The acquisition of practices by private equity firms has induced changes in practice infrastructure. The impact of changing organizational and managerial influences continues to be a topic of debate, with disparate opinions on how these developments shape standards of physician satisfaction and patient care.5

The convergence of these factors points to an important question that is gaining popularity: How will young dermatologists work within the context of all these parameters to best advocate and care for their patients? These questions are garnering more attention and were recently investigated through a survey of participants in a pilot program to evaluate the importance of business education in dermatology residency.

A survey of residency program directors was created by Patrinley and Dewan,6 which found that business education during residency was important and additional training should be implemented. Despite the perceived importance of business education, only half of the programs represented by survey respondents offered any structured educational opportunities, revealing a discrepancy between believed importance and practical implementation of business training, which suggests the need to develop a standardized, dermatology-specific curriculum that could be accessed by all residents in training.6

We performed a search of the medical literature to identify models of business education in residency programs. Only a few programs were identified, in which courses were predominantly instructed to trainees in primary care–based fields. According to course graduates, the programs were beneficial.7,8 Programs that had descriptive information about curriculum structure and content were chosen for further investigation and included internal medicine programs at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) and Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons (New York, New York). UCSF implemented a Program in Residency Investigation Methods and Epidemiology (PRIME program) to deliver seven 90-minute sessions dedicated to introducing residents to medical economics. Sessions were constructed with the intent of being interactive seminars that took on a variety of forms, including reading-based discussions, case-based analysis, and simulation-based learning.7 Columbia University developed a pilot program of week-long didactic sessions that were delivered to third-year internal medicine residents. These seminars featured discussions on health policy and economics, health insurance, technology and cost assessment, legal medicine, public health, community-oriented primary care, and local health department initiatives.8 We drew on both courses to build a lecture series focused on the business of dermatology that was delivered to dermatology residents at UMass Chan Medical School (Worcester, Massachusetts). Topic selection also was informed by qualitative input collected via email from recent graduates of the UMass dermatology residency program, focusing on the following areas: the US medical economy and health care costs; billing, coding, and claims processing; quality, relative value units (RVUs), reimbursement, and the merit-based incentive payment system; coverage of pharmaceuticals and teledermatology; and management. Residents were not required to prepare for any of the sessions; they were provided with handouts and slideshow presentations for reference to review at their convenience if desired. Five seminars were virtually conducted by an MD/MBA candidate at the institution (E.H.). They were recorded over the course of an academic year at 1- to 2-month intervals. Each 45-minute session was conducted in a lecture-discussion format and included case examples to help illustrate key principles and stimulate conversation. For example, the lecture on reimbursement incorporated a fee schedule calculation for a shave biopsy, using RVU and geographic pricing cost index (GCPI) multipliers. This demonstrated the variation in Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reimbursement in relation to (1) constituents of the RVU calculation (ie, work, practice expense, and malpractice) and (2) practice in a particular location (ie, the GCPI). Following this example, a conversation ensued among participants regarding the factors that drive valuation, with particular interest in variation based on urban vs suburban locations across the United States. Participants also found it of interest to examine the percentage of the valuation dedicated to each constituent and how features such as lesion size informed the final assessment of the charge. Another stylistic choice in developing the model was to include prompts for further consideration prior to transitioning topics in the lectures. For example: when examining the burden of skin disease, the audience was prompted to consider: “What is driving cost escalations, and how will services of the clinical domain meet these evolving needs?” At another point in the introductory lecture, residents were asked: “How do different types of insurance plans impact the management of patients with dermatologic concerns?” These questions were intended to transition residents to the next topic of discussion and highlight take-home points of consideration for medical practice. The project was reviewed by the UMass institutional review board and met criteria for exemption.

Residents who participated in at least 1 lecture (N=10) were surveyed after attendance; there were 7 responses (70% response rate). Residents were asked to rate a series of statements on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) and to provide commentary via an online form. Respondents indicated that the course was enjoyable (average score, 4.00), provided an appropriate level of detail (average score, 4.00), would be beneficial to integrate into a dermatology residency curriculum (average score, 3.86), and informed how they would practice as a clinician (average score, 3.86)(Figure). The respondents agreed that the course met the main goals of this initiative: it helped them develop knowledge about the interface between business and dermatology (4.14) and exposed residents to topics they had not learned about previously (4.71).

Although the course generally was well received, areas for improvement were identified from respondents’ comments, relating to audience engagement and refining the level of detail in the lectures. Recommendations included “less technical jargon and more focus on ‘big picture’ concepts, given audience’s low baseline knowledge”; “more case examples in each module”; and “more diagrams or interactive activities (polls, quizzes, break-out rooms) because the lectures were a bit dense.” This input was taken into consideration when revising the lectures for future use; they were reconstructed to have more case-based examples and prompts to encourage participation.

Resident commentary also demonstrated appreciation for education in this subject material. Statements such as “this is an important topic for future dermatologists” and “thank you so much for taking the time to implement this course” reflected the perceived value of this material during critical academic time. Another resident remarked: “This was great, thanks for putting it together.”

Given the positive experience of the residents and successful implementation of the series, this course was made available to all dermatology trainees on a network server with accompanying written documents. It is planned to be offered on a 3-year cycle in the future and will be updated to reflect inevitable changes in health care.

Although the relationship between business and medicine is increasingly important, teaching business principles has not become standardized or required in medical training. Despite the perception that this content is of value, implementation of programming has lagged behind that recognition, likely due to challenges in designing the curriculum and diffusing content into an already-saturated schedule. A model course that can be replicated in other residency programs would be valuable. We introduced a dermatology-specific lecture series to help prepare trainees for dermatology practice in a variety of clinical settings and train them with the language of business and operations that will equip them to respond to the needs of their patients, their practice, and the medical environment. Findings of this pilot study may not be generalizable to all dermatology residency programs because the sample size was small; the study was conducted at a single institution; and the content was delivered entirely online.

1. Tan S, Seiger K, Renehan P, et al. Trends in private equity acquisition of dermatology practices in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1013-1021. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1634

2. The business of health care in the United States. Harvard Online [Internet]. June 27, 2022. Accessed July 24, 2023. https://www.harvardonline.harvard.edu/blog/business-health-care-united-states

3. Ranpariya V, Cull D, Feldman SR, et al. Evaluation and management 2021 coding guidelines: key changes and implications. The Dermatologist. December 2020. Accessed July 24, 2023. https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/thederm/article/evaluation-and-management-2021-coding-guidelines-key-changes-and-implications?key=Ranpariya&elastic%5B0%5D=brand%3A73468

4. Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS Jr, et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:958-972.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.043

5. Resneck JS Jr. Dermatology practice consolidation fueled by private equity investment: potential consequences for the specialty and patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:13-14. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5558

6. Patrinely JR Jr, Dewan AK. Business education in dermatology residency: a survey of program directors. Cutis. 2021;108:E7-E19. doi:10.12788/cutis.0331

7. Kohlwes RJ, Chou CL. A curriculum in medical economics for residents. Acad Med. 2002;77:465-466. doi:10.1097/00001888-200205000-00040

8. Fiebach NH, Rao D, Hamm ME. A curriculum in health systems and public health for internal medicine residents. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4 suppl 3):S264-S269. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.025

1. Tan S, Seiger K, Renehan P, et al. Trends in private equity acquisition of dermatology practices in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1013-1021. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1634

2. The business of health care in the United States. Harvard Online [Internet]. June 27, 2022. Accessed July 24, 2023. https://www.harvardonline.harvard.edu/blog/business-health-care-united-states

3. Ranpariya V, Cull D, Feldman SR, et al. Evaluation and management 2021 coding guidelines: key changes and implications. The Dermatologist. December 2020. Accessed July 24, 2023. https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/thederm/article/evaluation-and-management-2021-coding-guidelines-key-changes-and-implications?key=Ranpariya&elastic%5B0%5D=brand%3A73468

4. Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS Jr, et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:958-972.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.043

5. Resneck JS Jr. Dermatology practice consolidation fueled by private equity investment: potential consequences for the specialty and patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:13-14. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5558

6. Patrinely JR Jr, Dewan AK. Business education in dermatology residency: a survey of program directors. Cutis. 2021;108:E7-E19. doi:10.12788/cutis.0331

7. Kohlwes RJ, Chou CL. A curriculum in medical economics for residents. Acad Med. 2002;77:465-466. doi:10.1097/00001888-200205000-00040

8. Fiebach NH, Rao D, Hamm ME. A curriculum in health systems and public health for internal medicine residents. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4 suppl 3):S264-S269. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.025

Practice Points

- Business education in dermatology residency promotes understanding of the health care ecosystem and can enable residents to more effectively deliver care that is responsive to the needs of their patients.

- Teaching fundamental business principles to residents can inform decision-making on patient, provider, and systems levels.

- A pilot curriculum supports implementation of business education teaching and will be particularly helpful in dermatology.

Adjuvant Scalp Rolling for Patients With Refractory Alopecia Areata

To the Editor:

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune nonscarring hair loss disorder that can present at any age. Patients with AA have a disproportionately high comorbidity burden and low quality of life, often grappling with anxiety, depression, and psychosocial sequelae involving identity, such as reduced self-esteem.1,2 Although conventional therapies aim to reduce hair loss, none are curative.3 Response to treatment is highly unpredictable, with current data suggesting that up to 50% of patients recover within 1 year while 14% to 25% progress to either alopecia totalis (total scalp hair loss) or alopecia universalis (total body hair loss).4 Options for therapeutic intervention remain limited and vary in safety and effectiveness, warranting further research to identify optimal modalities and minimize side effects. Interestingly, scalp rolling has been used as an adjuvant to topical triamcinolone acetonide.3,5 However, the extent of its effect in combination with other therapies remains unclear. We report 3 pediatric patients with confirmed AA refractory to conventional topical treatment who experienced remarkable scalp hair regrowth after adding biweekly scalp rolling as an adjuvant therapy.

A 7-year-old boy with AA presented with 95% scalp hair loss of 7 months’ duration (Figure 1A)(patient 1). Prior treatments included mometasone solution and clobetasol solution 0.05%. After 3 months of conventional topical therapy, twice-weekly scalp rolling with a 0.25-mm scalp roller of their choosing was added to the regimen, with clobetasol solution 0.05% and minoxidil foam 5% applied immediately after each scalp rolling session. The patient experienced 95% scalp hair regrowth after 13 months of treatment (Figure 1B). No pain, bleeding, or other side effects were reported.

An 11-year-old girl with AA presented with 100% hair loss of 7 months’ duration (Figure 2A)(patient 2). Prior treatments included fluocinonide solution and intralesional Kenalog injections. After 4 months of conventional topical therapy, twice-weekly scalp rolling with a 0.25-mm scalp roller of their choosing was added to the regimen, with clobetasol solution 0.05% and minoxidil foam 5% applied immediately after each scalp rolling session. The patient experienced 95% scalp hair regrowth after 13 months of treatment (Figure 2B). No pain, bleeding, or other side effects were reported.

A 16-year-old boy with AA presented with 30% hair loss of 4 years’ duration (Figure 3A)(patient 3). Prior treatments included squaric acid and intralesional Kenalog injections. After 2 years of conventional topical therapy, twice-weekly scalp rolling with a 0.25-mm scalp roller of their choosing was added to the regimen, with clobetasol solution 0.05% and minoxidil foam 5% applied immediately after each scalp rolling session. The patient experienced 95% scalp hair regrowth at 17 months (Figure 3B). No pain, bleeding, or other side effects were reported.