User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis

THE COMPARISON

A An 11-year-old Hispanic boy with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) on the abdomen. The geometric nature of the eruption and proximity to the belt buckle were highly suggestive of ACD to nickel; patch testing was not needed.

B A Black woman with ACD on the neck. A punch biopsy demonstrated spongiotic dermatitis that was typical of ACD. The diagnosis was supported by the patient’s history of dermatitis that developed after new products were applied to the hair. The patient declined patch testing.

C A Hispanic man with ACD on hair-bearing areas on the face where hair dye was used. The patient’s history of dermatitis following the application of hair dye was highly suggestive of ACD; patch testing confirmed the allergen was paraphenylenediamine (PPD).

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is an inflammatory condition of the skin caused by an immunologic response to one or more identifiable allergens. A delayed-type immune response (type IV hypersensitivity reaction) occurs after the skin is reexposed to an offending allergen.1 Severe pruritus is the main symptom of ACD in the early stages, accompanied by erythema, vesicles, and scaling in a distinct pattern corresponding to the allergen’s contact with the skin.2 Delayed widespread dermatitis after exposure to an allergen—a phenomenon known as autoeczematization (id reaction)—also may occur.3

The gold-standard diagnostic tool for ACD is patch testing, in which the patient is re-exposed to the suspected contact allergen(s) and observed for the development of dermatitis.4 However, ACD can be diagnosed with a detailed patient history including occupation, hobbies, personal care practices, and possible triggers with subsequent rashes. Thorough clinical examination of the skin is paramount. Indicators of possible ACD include dermatitis that persists despite use of appropriate treatment, an unexplained flare of previously quiescent dermatitis, and a diagnosis of dermatitis without a clear cause.1

Hairdressers, health care workers, and metal workers are at higher risk for ACD.5 Occupational ACD has notable socioeconomic implications, as it can result in frequent sick days, inability to perform tasks at work, and in some cases job loss.6

Patients with atopic dermatitis have impaired barrier function of the skin, permitting the entrance of allergens and subsequent sensitization.7 Allergic contact dermatitis is a challenge to manage, as complete avoidance of the allergen may not be possible.8

The underrepresentation of patients with skin of color (SOC) in educational materials as well as socioeconomic health disparities may contribute to the lower rates of diagnosis, patch testing, and treatment of ACD in this patient population.

Epidemiology

An ACD prevalence of 15.2% was reported in a study of 793 Danish patients who underwent skin prick and patch testing.9 Alinaghi et al10 conducted a meta-analysis of 20,107 patients across 28 studies who were patch tested to determine the prevalence of ACD in the general population. The researchers concluded that 20.1% (95% CI, 16.8%- 23.7%) of the general population experienced ACD. They analyzed 22 studies to determine the prevalence of ACD based on specific geographic area including 18,709 individuals from Europe with a prevalence of 19.5% (95% CI, 15.8%-23.4%), 1639 individuals from North America with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 9.2%-35.2%), and 2 studies from China (no other studies from Asia found) with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 17.4%-23.9%). Researchers did not find data from studies conducted in Africa or South America.10

The current available epidemiologic data on ACD are not representative of SOC populations. DeLeo et al11 looked at patch test reaction patterns in association with race and ethnicity in a large sample size (N=19,457); 17,803 (92.9%) of these patients were White and only 1360 (7.1%) were Black. Large-scale, inclusive studies are needed, which can only be achieved with increased suspicion for ACD and increased access to patch testing.

Allergic contact dermatitis is more common in women, with nickel being the most frequently identified allergen (Figure, A).10 Personal care products often are linked to ACD (Figure, B). An analysis of data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group revealed that the top 5 personal care product allergens were methylisothiazolinone (a preservative), fragrance mix I, balsam of Peru, quaternium-15 (a preservative), and paraphenylenediamine (PPD)(a common component of hair dye) (Figure, C).12

There is a paucity of epidemiologic data among various ethnic groups; however, a few studies have suggested that there is no difference in the frequency rates of positive patch test results in Black vs White populations.11,13,14 One study of patch test results from 114 Black patients and 877 White patients at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation in Ohio demonstrated a similar allergy frequency of 43.0% and 43.6%, respectively.13 However, there were differences in the types of allergen sensitization. Black patients had higher positive patch test rates for PPD than White patients (10.6% vs 4.5%). Black men had a higher frequency of sensitivity to PPD (21.2% vs 4.2%) and imidazolidinyl urea (a formaldehyde-releasing preservative) (9.1% vs 2.6%) compared to White men.13

Ethnicity and cultural practices influence epidemiologic patterns of ACD. Darker hair dyes used in Black patients14 and deeply pigmented PPD dye found in henna tattoos used in Indian and Black patients15 may lead to increased sensitization to PPD. Allergic contact dermatitis due to formaldehyde is more common in White patients, possibly due to more frequent use of formaldehyde-containing moisturizers, shampoos, and creams.15

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

In patients with SOC, the clinical features of ACD vary, posing a diagnostic challenge. Hyperpigmentation, lichenification, and induration are more likely to be seen than the papules, vesicles, and erythematous dermatitis often described in lighter skin tones or acute ACD. Erythema can be difficult to assess on darker skin and may appear violaceous or very faint pink.16

Worth noting

A high index of suspicion is necessary when interpreting patch tests in patients with SOC, as patch test kits use a reading plate with graduated intensities of erythema, papulation, and vesicular reactions to determine the likelihood of ACD. The potential contact allergens are placed on the skin on day 1 and covered. Then, on day 3 the allergens are removed. The skin is clinically evaluated using visual assessment and skin palpation. The reactions are graded as negative, irritant reaction, equivocal, weak positive, strong positive, or extreme reaction at around days 3 and 5 to capture both early and delayed reactions.17 A patch test may be positive even if obvious signs of erythema are not appreciated as expected.

Adjusting the lighting in the examination room, including side lighting, or using a blue background can be helpful in identifying erythema in darker skin tones.15,16,18 Palpation of the skin also is useful, as even slight texture changes and induration are indicators of a possible skin reaction to the test allergen.15

Health disparity highlight

Clinical photographs of ACD and patch test results in patients with SOC are not commonplace in the literature. Positive patch test results in patients with darker skin tones vary from those of patients with lighter skin tones, and if the clinician reading the patch test result is not familiar with the findings in darker skin tones, the diagnosis may be delayed or missed.15

Furthermore, Scott et al15 highlighted that many dermatology residency training programs have a paucity of SOC education in their curriculum. This lack of representation may contribute to the diagnostic challenges encountered by health care providers.

Timely access to health care and education as well as economic stability are essential for the successful management of patients with ACD. Some individuals with SOC have been disproportionately affected by social determinants of health. Rodriguez-Homs et al19 demonstrated that the distance needed to travel to a clinic and the poverty rate of the county the patient lives in play a role in referral to a clinician specializing in contact dermatitis.

A retrospective registry review of 2310 patients undergoing patch testing at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston revealed that 2.5% were Black, 5.5% were Latinx, 8.3% were Asian, and the remaining 83.7% were White.20 Qian et al21 also looked at patch testing patterns among various sociodemographic groups (N=1,107,530) and found that 69% of patients were White and 59% were female. Rates of patch testing among patients who were Black, lesser educated, male, lower income, and younger (children aged 0–12 years) were significantly lower than for other groups when ACD was suspected (P<.0001).21 The lower rates of patch testing in patients with SOC may be due to low suspicion of diagnosis, low referral rates due to limited medical insurance, and financial instability, as well as other socioeconomic factors.20

Tamazian et al16 reviewed pediatric populations at 13 US centers and found that Black children received patch testing less frequently than White and Hispanic children. Another review of pediatric patch testing in patients with SOC found that a less comprehensive panel of allergens was used in this population.22

The key to resolution of ACD is removal of the offending antigen, and if patients are not being tested, then they risk having a prolonged and complicated course of ACD with a poor prognosis. Patients with SOC also experience greater negative psychosocial impact due to ACD disease burden.21,23

The lower rates of patch testing in Black patients cannot solely be attributed to difficulty diagnosing ACD in darker skin tones; it is likely due to the impact of social determinants of health. Alleviating health disparities will improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

- Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74: 1029-1040. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1139

- Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

- Bertoli MJ, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Autoeczematization: a strange id reaction of the skin. Cutis. 2021;108:163-166. doi:10.12788/cutis.0342

- Johansen JD, Bonefeld CM, Schwensen JFB, et al. Novel insights into contact dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149:1162-1171. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2022.02.002

- Karagounis TK, Cohen DE. Occupational hand dermatitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2023;23:201-212. doi:10.1007/s11882-023-01070-5

- Cvetkovski RS, Rothman KJ, Olsen J, et al. Relation between diagnoses on severity, sick leave and loss of job among patients with occupational hand eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:93-98. doi:10.1111/j .1365-2133.2005.06415.x

- Owen JL, Vakharia PP, Silverberg JI. The role and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:293-302. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0340-7

- Brites GS, Ferreira I, Sebastião AI, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: from pathophysiology to development of new preventive strategies. Pharmacol Res. 2020;162:105282. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105282

- Nielsen NH, Menne T. The relationship between IgE‐mediated and cell‐mediated hypersensitivities in an unselected Danish population: the Glostrup Allergy Study, Denmark. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:669-672. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb06967.x

- Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:77-85. doi:10.1111/cod.13119

- DeLeo VA, Alexis A, Warshaw EM, et al. The association of race/ethnicity and patch test results: North American Contact Dermatitis Group, 1998- 2006. Dermatitis. 2016;27:288-292. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000220

- Warshaw EM, Schlarbaum JP, Silverberg JI, et al. Contact dermatitis to personal care products is increasing (but different!) in males and females: North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 1996-2016. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1446-1455. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.003

- Dickel H, Taylor JS, Evey P, et al. Comparison of patch test results with a standard series among white and black racial groups. Am J Contact Dermatol. 2001;12:77-82. doi:10.1053/ajcd.2001.20110

- DeLeo VA, Taylor SC, Belsito DV, et al. The effect of race and ethnicity on patch test results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl):S107-S112. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120792

- Scott I, Atwater AR, Reeder M. Update on contact dermatitis and patch testing in patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2021;108:10-12. doi:10.12788/cutis.0292

- Tamazian S, Oboite M, Treat JR. Patch testing in skin of color: a brief report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:952-953. doi:10.1111/pde.14578

- Litchman G, Nair PA, Atwater AR, et al. Contact dermatitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 9, 2023. Accessed September 25, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459230/

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.049

- Rodriguez-Homs LG, Liu B, Green CL, et al. Duration of dermatitis before patch test appointment is associated with distance to clinic and county poverty rate. Dermatitis. 2020;31:259-264. doi:10.1097 /DER.0000000000000581

- Foschi CM, Tam I, Schalock PC, et al. Patch testing results in skin of color: a retrospective review from the Massachusetts General Hospital contact dermatitis clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:452-454. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.09.022

- Qian MF, Li S, Honari G, et al. Sociodemographic disparities in patch testing for commercially insured patients with dermatitis: a retrospective analysis of administrative claims data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1411-1413. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.08.041

- Young K, Collis RW, Sheinbein D, et al. Retrospective review of pediatric patch testing results in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:953-954. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.031

- Kadyk DL, Hall S, Belsito DV. Quality of life of patients with allergic contact dermatitis: an exploratory analysis by gender, ethnicity, age, and occupation. Dermatitis. 2004;15:117-124.

THE COMPARISON

A An 11-year-old Hispanic boy with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) on the abdomen. The geometric nature of the eruption and proximity to the belt buckle were highly suggestive of ACD to nickel; patch testing was not needed.

B A Black woman with ACD on the neck. A punch biopsy demonstrated spongiotic dermatitis that was typical of ACD. The diagnosis was supported by the patient’s history of dermatitis that developed after new products were applied to the hair. The patient declined patch testing.

C A Hispanic man with ACD on hair-bearing areas on the face where hair dye was used. The patient’s history of dermatitis following the application of hair dye was highly suggestive of ACD; patch testing confirmed the allergen was paraphenylenediamine (PPD).

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is an inflammatory condition of the skin caused by an immunologic response to one or more identifiable allergens. A delayed-type immune response (type IV hypersensitivity reaction) occurs after the skin is reexposed to an offending allergen.1 Severe pruritus is the main symptom of ACD in the early stages, accompanied by erythema, vesicles, and scaling in a distinct pattern corresponding to the allergen’s contact with the skin.2 Delayed widespread dermatitis after exposure to an allergen—a phenomenon known as autoeczematization (id reaction)—also may occur.3

The gold-standard diagnostic tool for ACD is patch testing, in which the patient is re-exposed to the suspected contact allergen(s) and observed for the development of dermatitis.4 However, ACD can be diagnosed with a detailed patient history including occupation, hobbies, personal care practices, and possible triggers with subsequent rashes. Thorough clinical examination of the skin is paramount. Indicators of possible ACD include dermatitis that persists despite use of appropriate treatment, an unexplained flare of previously quiescent dermatitis, and a diagnosis of dermatitis without a clear cause.1

Hairdressers, health care workers, and metal workers are at higher risk for ACD.5 Occupational ACD has notable socioeconomic implications, as it can result in frequent sick days, inability to perform tasks at work, and in some cases job loss.6

Patients with atopic dermatitis have impaired barrier function of the skin, permitting the entrance of allergens and subsequent sensitization.7 Allergic contact dermatitis is a challenge to manage, as complete avoidance of the allergen may not be possible.8

The underrepresentation of patients with skin of color (SOC) in educational materials as well as socioeconomic health disparities may contribute to the lower rates of diagnosis, patch testing, and treatment of ACD in this patient population.

Epidemiology

An ACD prevalence of 15.2% was reported in a study of 793 Danish patients who underwent skin prick and patch testing.9 Alinaghi et al10 conducted a meta-analysis of 20,107 patients across 28 studies who were patch tested to determine the prevalence of ACD in the general population. The researchers concluded that 20.1% (95% CI, 16.8%- 23.7%) of the general population experienced ACD. They analyzed 22 studies to determine the prevalence of ACD based on specific geographic area including 18,709 individuals from Europe with a prevalence of 19.5% (95% CI, 15.8%-23.4%), 1639 individuals from North America with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 9.2%-35.2%), and 2 studies from China (no other studies from Asia found) with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 17.4%-23.9%). Researchers did not find data from studies conducted in Africa or South America.10

The current available epidemiologic data on ACD are not representative of SOC populations. DeLeo et al11 looked at patch test reaction patterns in association with race and ethnicity in a large sample size (N=19,457); 17,803 (92.9%) of these patients were White and only 1360 (7.1%) were Black. Large-scale, inclusive studies are needed, which can only be achieved with increased suspicion for ACD and increased access to patch testing.

Allergic contact dermatitis is more common in women, with nickel being the most frequently identified allergen (Figure, A).10 Personal care products often are linked to ACD (Figure, B). An analysis of data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group revealed that the top 5 personal care product allergens were methylisothiazolinone (a preservative), fragrance mix I, balsam of Peru, quaternium-15 (a preservative), and paraphenylenediamine (PPD)(a common component of hair dye) (Figure, C).12

There is a paucity of epidemiologic data among various ethnic groups; however, a few studies have suggested that there is no difference in the frequency rates of positive patch test results in Black vs White populations.11,13,14 One study of patch test results from 114 Black patients and 877 White patients at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation in Ohio demonstrated a similar allergy frequency of 43.0% and 43.6%, respectively.13 However, there were differences in the types of allergen sensitization. Black patients had higher positive patch test rates for PPD than White patients (10.6% vs 4.5%). Black men had a higher frequency of sensitivity to PPD (21.2% vs 4.2%) and imidazolidinyl urea (a formaldehyde-releasing preservative) (9.1% vs 2.6%) compared to White men.13

Ethnicity and cultural practices influence epidemiologic patterns of ACD. Darker hair dyes used in Black patients14 and deeply pigmented PPD dye found in henna tattoos used in Indian and Black patients15 may lead to increased sensitization to PPD. Allergic contact dermatitis due to formaldehyde is more common in White patients, possibly due to more frequent use of formaldehyde-containing moisturizers, shampoos, and creams.15

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

In patients with SOC, the clinical features of ACD vary, posing a diagnostic challenge. Hyperpigmentation, lichenification, and induration are more likely to be seen than the papules, vesicles, and erythematous dermatitis often described in lighter skin tones or acute ACD. Erythema can be difficult to assess on darker skin and may appear violaceous or very faint pink.16

Worth noting

A high index of suspicion is necessary when interpreting patch tests in patients with SOC, as patch test kits use a reading plate with graduated intensities of erythema, papulation, and vesicular reactions to determine the likelihood of ACD. The potential contact allergens are placed on the skin on day 1 and covered. Then, on day 3 the allergens are removed. The skin is clinically evaluated using visual assessment and skin palpation. The reactions are graded as negative, irritant reaction, equivocal, weak positive, strong positive, or extreme reaction at around days 3 and 5 to capture both early and delayed reactions.17 A patch test may be positive even if obvious signs of erythema are not appreciated as expected.

Adjusting the lighting in the examination room, including side lighting, or using a blue background can be helpful in identifying erythema in darker skin tones.15,16,18 Palpation of the skin also is useful, as even slight texture changes and induration are indicators of a possible skin reaction to the test allergen.15

Health disparity highlight

Clinical photographs of ACD and patch test results in patients with SOC are not commonplace in the literature. Positive patch test results in patients with darker skin tones vary from those of patients with lighter skin tones, and if the clinician reading the patch test result is not familiar with the findings in darker skin tones, the diagnosis may be delayed or missed.15

Furthermore, Scott et al15 highlighted that many dermatology residency training programs have a paucity of SOC education in their curriculum. This lack of representation may contribute to the diagnostic challenges encountered by health care providers.

Timely access to health care and education as well as economic stability are essential for the successful management of patients with ACD. Some individuals with SOC have been disproportionately affected by social determinants of health. Rodriguez-Homs et al19 demonstrated that the distance needed to travel to a clinic and the poverty rate of the county the patient lives in play a role in referral to a clinician specializing in contact dermatitis.

A retrospective registry review of 2310 patients undergoing patch testing at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston revealed that 2.5% were Black, 5.5% were Latinx, 8.3% were Asian, and the remaining 83.7% were White.20 Qian et al21 also looked at patch testing patterns among various sociodemographic groups (N=1,107,530) and found that 69% of patients were White and 59% were female. Rates of patch testing among patients who were Black, lesser educated, male, lower income, and younger (children aged 0–12 years) were significantly lower than for other groups when ACD was suspected (P<.0001).21 The lower rates of patch testing in patients with SOC may be due to low suspicion of diagnosis, low referral rates due to limited medical insurance, and financial instability, as well as other socioeconomic factors.20

Tamazian et al16 reviewed pediatric populations at 13 US centers and found that Black children received patch testing less frequently than White and Hispanic children. Another review of pediatric patch testing in patients with SOC found that a less comprehensive panel of allergens was used in this population.22

The key to resolution of ACD is removal of the offending antigen, and if patients are not being tested, then they risk having a prolonged and complicated course of ACD with a poor prognosis. Patients with SOC also experience greater negative psychosocial impact due to ACD disease burden.21,23

The lower rates of patch testing in Black patients cannot solely be attributed to difficulty diagnosing ACD in darker skin tones; it is likely due to the impact of social determinants of health. Alleviating health disparities will improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

THE COMPARISON

A An 11-year-old Hispanic boy with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) on the abdomen. The geometric nature of the eruption and proximity to the belt buckle were highly suggestive of ACD to nickel; patch testing was not needed.

B A Black woman with ACD on the neck. A punch biopsy demonstrated spongiotic dermatitis that was typical of ACD. The diagnosis was supported by the patient’s history of dermatitis that developed after new products were applied to the hair. The patient declined patch testing.

C A Hispanic man with ACD on hair-bearing areas on the face where hair dye was used. The patient’s history of dermatitis following the application of hair dye was highly suggestive of ACD; patch testing confirmed the allergen was paraphenylenediamine (PPD).

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is an inflammatory condition of the skin caused by an immunologic response to one or more identifiable allergens. A delayed-type immune response (type IV hypersensitivity reaction) occurs after the skin is reexposed to an offending allergen.1 Severe pruritus is the main symptom of ACD in the early stages, accompanied by erythema, vesicles, and scaling in a distinct pattern corresponding to the allergen’s contact with the skin.2 Delayed widespread dermatitis after exposure to an allergen—a phenomenon known as autoeczematization (id reaction)—also may occur.3

The gold-standard diagnostic tool for ACD is patch testing, in which the patient is re-exposed to the suspected contact allergen(s) and observed for the development of dermatitis.4 However, ACD can be diagnosed with a detailed patient history including occupation, hobbies, personal care practices, and possible triggers with subsequent rashes. Thorough clinical examination of the skin is paramount. Indicators of possible ACD include dermatitis that persists despite use of appropriate treatment, an unexplained flare of previously quiescent dermatitis, and a diagnosis of dermatitis without a clear cause.1

Hairdressers, health care workers, and metal workers are at higher risk for ACD.5 Occupational ACD has notable socioeconomic implications, as it can result in frequent sick days, inability to perform tasks at work, and in some cases job loss.6

Patients with atopic dermatitis have impaired barrier function of the skin, permitting the entrance of allergens and subsequent sensitization.7 Allergic contact dermatitis is a challenge to manage, as complete avoidance of the allergen may not be possible.8

The underrepresentation of patients with skin of color (SOC) in educational materials as well as socioeconomic health disparities may contribute to the lower rates of diagnosis, patch testing, and treatment of ACD in this patient population.

Epidemiology

An ACD prevalence of 15.2% was reported in a study of 793 Danish patients who underwent skin prick and patch testing.9 Alinaghi et al10 conducted a meta-analysis of 20,107 patients across 28 studies who were patch tested to determine the prevalence of ACD in the general population. The researchers concluded that 20.1% (95% CI, 16.8%- 23.7%) of the general population experienced ACD. They analyzed 22 studies to determine the prevalence of ACD based on specific geographic area including 18,709 individuals from Europe with a prevalence of 19.5% (95% CI, 15.8%-23.4%), 1639 individuals from North America with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 9.2%-35.2%), and 2 studies from China (no other studies from Asia found) with a prevalence of 20.6% (95% CI, 17.4%-23.9%). Researchers did not find data from studies conducted in Africa or South America.10

The current available epidemiologic data on ACD are not representative of SOC populations. DeLeo et al11 looked at patch test reaction patterns in association with race and ethnicity in a large sample size (N=19,457); 17,803 (92.9%) of these patients were White and only 1360 (7.1%) were Black. Large-scale, inclusive studies are needed, which can only be achieved with increased suspicion for ACD and increased access to patch testing.

Allergic contact dermatitis is more common in women, with nickel being the most frequently identified allergen (Figure, A).10 Personal care products often are linked to ACD (Figure, B). An analysis of data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group revealed that the top 5 personal care product allergens were methylisothiazolinone (a preservative), fragrance mix I, balsam of Peru, quaternium-15 (a preservative), and paraphenylenediamine (PPD)(a common component of hair dye) (Figure, C).12

There is a paucity of epidemiologic data among various ethnic groups; however, a few studies have suggested that there is no difference in the frequency rates of positive patch test results in Black vs White populations.11,13,14 One study of patch test results from 114 Black patients and 877 White patients at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation in Ohio demonstrated a similar allergy frequency of 43.0% and 43.6%, respectively.13 However, there were differences in the types of allergen sensitization. Black patients had higher positive patch test rates for PPD than White patients (10.6% vs 4.5%). Black men had a higher frequency of sensitivity to PPD (21.2% vs 4.2%) and imidazolidinyl urea (a formaldehyde-releasing preservative) (9.1% vs 2.6%) compared to White men.13

Ethnicity and cultural practices influence epidemiologic patterns of ACD. Darker hair dyes used in Black patients14 and deeply pigmented PPD dye found in henna tattoos used in Indian and Black patients15 may lead to increased sensitization to PPD. Allergic contact dermatitis due to formaldehyde is more common in White patients, possibly due to more frequent use of formaldehyde-containing moisturizers, shampoos, and creams.15

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

In patients with SOC, the clinical features of ACD vary, posing a diagnostic challenge. Hyperpigmentation, lichenification, and induration are more likely to be seen than the papules, vesicles, and erythematous dermatitis often described in lighter skin tones or acute ACD. Erythema can be difficult to assess on darker skin and may appear violaceous or very faint pink.16

Worth noting

A high index of suspicion is necessary when interpreting patch tests in patients with SOC, as patch test kits use a reading plate with graduated intensities of erythema, papulation, and vesicular reactions to determine the likelihood of ACD. The potential contact allergens are placed on the skin on day 1 and covered. Then, on day 3 the allergens are removed. The skin is clinically evaluated using visual assessment and skin palpation. The reactions are graded as negative, irritant reaction, equivocal, weak positive, strong positive, or extreme reaction at around days 3 and 5 to capture both early and delayed reactions.17 A patch test may be positive even if obvious signs of erythema are not appreciated as expected.

Adjusting the lighting in the examination room, including side lighting, or using a blue background can be helpful in identifying erythema in darker skin tones.15,16,18 Palpation of the skin also is useful, as even slight texture changes and induration are indicators of a possible skin reaction to the test allergen.15

Health disparity highlight

Clinical photographs of ACD and patch test results in patients with SOC are not commonplace in the literature. Positive patch test results in patients with darker skin tones vary from those of patients with lighter skin tones, and if the clinician reading the patch test result is not familiar with the findings in darker skin tones, the diagnosis may be delayed or missed.15

Furthermore, Scott et al15 highlighted that many dermatology residency training programs have a paucity of SOC education in their curriculum. This lack of representation may contribute to the diagnostic challenges encountered by health care providers.

Timely access to health care and education as well as economic stability are essential for the successful management of patients with ACD. Some individuals with SOC have been disproportionately affected by social determinants of health. Rodriguez-Homs et al19 demonstrated that the distance needed to travel to a clinic and the poverty rate of the county the patient lives in play a role in referral to a clinician specializing in contact dermatitis.

A retrospective registry review of 2310 patients undergoing patch testing at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston revealed that 2.5% were Black, 5.5% were Latinx, 8.3% were Asian, and the remaining 83.7% were White.20 Qian et al21 also looked at patch testing patterns among various sociodemographic groups (N=1,107,530) and found that 69% of patients were White and 59% were female. Rates of patch testing among patients who were Black, lesser educated, male, lower income, and younger (children aged 0–12 years) were significantly lower than for other groups when ACD was suspected (P<.0001).21 The lower rates of patch testing in patients with SOC may be due to low suspicion of diagnosis, low referral rates due to limited medical insurance, and financial instability, as well as other socioeconomic factors.20

Tamazian et al16 reviewed pediatric populations at 13 US centers and found that Black children received patch testing less frequently than White and Hispanic children. Another review of pediatric patch testing in patients with SOC found that a less comprehensive panel of allergens was used in this population.22

The key to resolution of ACD is removal of the offending antigen, and if patients are not being tested, then they risk having a prolonged and complicated course of ACD with a poor prognosis. Patients with SOC also experience greater negative psychosocial impact due to ACD disease burden.21,23

The lower rates of patch testing in Black patients cannot solely be attributed to difficulty diagnosing ACD in darker skin tones; it is likely due to the impact of social determinants of health. Alleviating health disparities will improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

- Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74: 1029-1040. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1139

- Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

- Bertoli MJ, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Autoeczematization: a strange id reaction of the skin. Cutis. 2021;108:163-166. doi:10.12788/cutis.0342

- Johansen JD, Bonefeld CM, Schwensen JFB, et al. Novel insights into contact dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149:1162-1171. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2022.02.002

- Karagounis TK, Cohen DE. Occupational hand dermatitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2023;23:201-212. doi:10.1007/s11882-023-01070-5

- Cvetkovski RS, Rothman KJ, Olsen J, et al. Relation between diagnoses on severity, sick leave and loss of job among patients with occupational hand eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:93-98. doi:10.1111/j .1365-2133.2005.06415.x

- Owen JL, Vakharia PP, Silverberg JI. The role and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:293-302. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0340-7

- Brites GS, Ferreira I, Sebastião AI, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: from pathophysiology to development of new preventive strategies. Pharmacol Res. 2020;162:105282. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105282

- Nielsen NH, Menne T. The relationship between IgE‐mediated and cell‐mediated hypersensitivities in an unselected Danish population: the Glostrup Allergy Study, Denmark. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:669-672. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb06967.x

- Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:77-85. doi:10.1111/cod.13119

- DeLeo VA, Alexis A, Warshaw EM, et al. The association of race/ethnicity and patch test results: North American Contact Dermatitis Group, 1998- 2006. Dermatitis. 2016;27:288-292. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000220

- Warshaw EM, Schlarbaum JP, Silverberg JI, et al. Contact dermatitis to personal care products is increasing (but different!) in males and females: North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 1996-2016. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1446-1455. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.003

- Dickel H, Taylor JS, Evey P, et al. Comparison of patch test results with a standard series among white and black racial groups. Am J Contact Dermatol. 2001;12:77-82. doi:10.1053/ajcd.2001.20110

- DeLeo VA, Taylor SC, Belsito DV, et al. The effect of race and ethnicity on patch test results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl):S107-S112. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120792

- Scott I, Atwater AR, Reeder M. Update on contact dermatitis and patch testing in patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2021;108:10-12. doi:10.12788/cutis.0292

- Tamazian S, Oboite M, Treat JR. Patch testing in skin of color: a brief report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:952-953. doi:10.1111/pde.14578

- Litchman G, Nair PA, Atwater AR, et al. Contact dermatitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 9, 2023. Accessed September 25, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459230/

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.049

- Rodriguez-Homs LG, Liu B, Green CL, et al. Duration of dermatitis before patch test appointment is associated with distance to clinic and county poverty rate. Dermatitis. 2020;31:259-264. doi:10.1097 /DER.0000000000000581

- Foschi CM, Tam I, Schalock PC, et al. Patch testing results in skin of color: a retrospective review from the Massachusetts General Hospital contact dermatitis clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:452-454. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.09.022

- Qian MF, Li S, Honari G, et al. Sociodemographic disparities in patch testing for commercially insured patients with dermatitis: a retrospective analysis of administrative claims data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1411-1413. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.08.041

- Young K, Collis RW, Sheinbein D, et al. Retrospective review of pediatric patch testing results in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:953-954. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.031

- Kadyk DL, Hall S, Belsito DV. Quality of life of patients with allergic contact dermatitis: an exploratory analysis by gender, ethnicity, age, and occupation. Dermatitis. 2004;15:117-124.

- Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient diagnosis and evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74: 1029-1040. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1139

- Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

- Bertoli MJ, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Autoeczematization: a strange id reaction of the skin. Cutis. 2021;108:163-166. doi:10.12788/cutis.0342

- Johansen JD, Bonefeld CM, Schwensen JFB, et al. Novel insights into contact dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149:1162-1171. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2022.02.002

- Karagounis TK, Cohen DE. Occupational hand dermatitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2023;23:201-212. doi:10.1007/s11882-023-01070-5

- Cvetkovski RS, Rothman KJ, Olsen J, et al. Relation between diagnoses on severity, sick leave and loss of job among patients with occupational hand eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:93-98. doi:10.1111/j .1365-2133.2005.06415.x

- Owen JL, Vakharia PP, Silverberg JI. The role and diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:293-302. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0340-7

- Brites GS, Ferreira I, Sebastião AI, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: from pathophysiology to development of new preventive strategies. Pharmacol Res. 2020;162:105282. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105282

- Nielsen NH, Menne T. The relationship between IgE‐mediated and cell‐mediated hypersensitivities in an unselected Danish population: the Glostrup Allergy Study, Denmark. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:669-672. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb06967.x

- Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:77-85. doi:10.1111/cod.13119

- DeLeo VA, Alexis A, Warshaw EM, et al. The association of race/ethnicity and patch test results: North American Contact Dermatitis Group, 1998- 2006. Dermatitis. 2016;27:288-292. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000220

- Warshaw EM, Schlarbaum JP, Silverberg JI, et al. Contact dermatitis to personal care products is increasing (but different!) in males and females: North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 1996-2016. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1446-1455. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.003

- Dickel H, Taylor JS, Evey P, et al. Comparison of patch test results with a standard series among white and black racial groups. Am J Contact Dermatol. 2001;12:77-82. doi:10.1053/ajcd.2001.20110

- DeLeo VA, Taylor SC, Belsito DV, et al. The effect of race and ethnicity on patch test results. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl):S107-S112. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120792

- Scott I, Atwater AR, Reeder M. Update on contact dermatitis and patch testing in patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2021;108:10-12. doi:10.12788/cutis.0292

- Tamazian S, Oboite M, Treat JR. Patch testing in skin of color: a brief report. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:952-953. doi:10.1111/pde.14578

- Litchman G, Nair PA, Atwater AR, et al. Contact dermatitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 9, 2023. Accessed September 25, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459230/

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.049

- Rodriguez-Homs LG, Liu B, Green CL, et al. Duration of dermatitis before patch test appointment is associated with distance to clinic and county poverty rate. Dermatitis. 2020;31:259-264. doi:10.1097 /DER.0000000000000581

- Foschi CM, Tam I, Schalock PC, et al. Patch testing results in skin of color: a retrospective review from the Massachusetts General Hospital contact dermatitis clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:452-454. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.09.022

- Qian MF, Li S, Honari G, et al. Sociodemographic disparities in patch testing for commercially insured patients with dermatitis: a retrospective analysis of administrative claims data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1411-1413. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.08.041

- Young K, Collis RW, Sheinbein D, et al. Retrospective review of pediatric patch testing results in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:953-954. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.031

- Kadyk DL, Hall S, Belsito DV. Quality of life of patients with allergic contact dermatitis: an exploratory analysis by gender, ethnicity, age, and occupation. Dermatitis. 2004;15:117-124.

Reticular Hyperpigmentation With Keratotic Papules in the Axillae and Groin

The Diagnosis: Galli-Galli Disease

Several cutaneous conditions can present as reticulated hyperpigmentation or keratotic papules. Although genetic testing can help identify some of these dermatoses, biopsy typically is sufficient for diagnosis, and genetic testing can be considered for more clinically challenging cases. In our case, the clinical evidence and histopathologic findings were diagnostic of Galli-Galli disease (GGD), an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis with incomplete penetrance. Our patient was unaware of any family members with a diagnosis of GGD; however, she reported a great uncle with similar clinical findings.

Galli-Galli disease is a rare allelic variant of Dowling- Degos disease (DDD), both caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the keratin 5 gene, KRT5. Both conditions present as reticulated papules distributed symmetrically in the flexural regions, most commonly the axillae and groin, but also as comedolike papules, typically in patients aged 30 to 50 years.1 Cutaneous lesions primarily are of cosmetic concern but can be extremely pruritic, especially for patients with GGD. Gene mutations in protein O-fucosyltransferase 1, POFUT1; protein O-glucosyltransferase 1, POGLUT1; and presenilin enhancer 2, PSENEN, also have been discovered in cases of DDD and GGD.2,3

Galli-Galli disease and DDD are distinguishable by their histologic appearance. Both diseases show elongated fingerlike rete ridges and a thin suprapapillary epidermis. The basal projections often are described as bulbous or resembling antler horns.4 Galli-Galli disease can be differentiated from DDD by focal suprabasal acantholysis with minimal dyskeratosis (quiz images).5 Due to the genetic and clinical similarities, many consider GGD an acantholytic variant of DDD rather than its own entity. Indeed, some patients have shown acantholysis in one area of biopsy but not others.6

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD)(also known as benign familial or benign chronic pemphigus) is an autosomaldominant disorder caused by mutation of the ATPase secretory pathway Ca2+ transporting 1 gene, ATP2C1. Clinically, patients tend to present at a wide age range with fragile flaccid vesicles that commonly develop on the neck, axillae, and groin. Histologically, the epidermis is acanthotic with a dilapidated brick wall– like appearance from a few persistent intercellular connections amid widespread acantholysis (Figure 1).7 Unlike in autoimmune pemphigus, direct immunofluorescence is negative, and acantholysis spares the adnexal structures. Hailey-Hailey disease does not involve reticulated hyperpigmentation or the elongated bulbous rete seen in GGD. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is a rare, typically asymptomatic, hyperpigmented dermatosis. It presents as a conglomeration of scaly hyperpigmented macules or papillomatous papules that coalesce centrally and are reticulated toward the periphery.

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis most commonly is seen on the trunk, initially presenting in adolescents and young adults. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is histologically similar to acanthosis nigricans. Histopathology will show hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and minimal to no inflammatory infiltrate, with no elongated rete ridges or acantholysis (Figure 2).8

Pemphigus vulgaris is a blistering disease resulting from the development of autoantibodies against desmogleins 1 and 3. Similar to GGD, there is suprabasal acantholysis, which often results in a tombstonelike appearance consisting of separation between the basal layer cells of the epidermis but with maintained attachment to the underlying basement membrane zone. Unlike HHD, the acantholysis tends to involve the follicular epithelium in pemphigus vulgaris (Figure 3). Clinically, the blisters are positive for Nikolsky sign and can be both cutaneous or mucosal, commonly arising initially in the mouth during the fourth or fifth decades of life. Ruptured blisters can result in painful and hemorrhagic erosions.9 Direct immunofluorescence exhibits a classic chicken wire–like deposition of IgG and C3 between keratinocytes of the epidermis. Although sometimes difficult to appreciate, the deposition can be more prominent in the lower epidermis, in contrast to pemphigus foliaceus, which can have more prominent deposition in the upper epidermis.

Darier disease (or dyskeratosis follicularis) is an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by mutation of the ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 gene, ATP2A2. Clinically, this disorder arises in adolescents as red-brown, greasy, crusted papules in seborrheic areas that may coalesce into papillomatous clusters. Palmar punctate keratoses and pits also are common. Histologically, Darier disease can appear similar to GGD, as both can show acantholysis and dyskeratosis. Darier disease will tend to show more prominent dyskeratosis with corps ronds and grains, as well as thicker villilike projections of keratinocytes into the papillary dermis, in contrast to the thinner, fingerlike or bulbous projections that hang down from the epidermis in GGD (Figure 4).10

- Hanneken S, Rütten A, Eigelshoven S, et al. Morbus Galli-Galli. Hautarzt. 2013;64:282.

- Wilson NJ, Cole C, Kroboth K, et al. Mutations in POGLUT1 in Galli- Galli/Dowling-Degos disease. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:270-274.

- Ralser DJ, Basmanav FB, Tafazzoli A, et al. Mutations in γ-secretase subunit–encoding PSENEN underlie Dowling-Degos disease associated with acne inversa. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:1485-1490.

- Desai CA, Virmani N, Sakhiya J, et al. An uncommon presentation of Galli-Galli disease. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016; 82:720-723.

- Joshi TP, Shaver S, Tschen J. Exacerbation of Galli-Galli disease following dialysis treatment: a case report and review of aggravating factors. Cureus. 2021;13:E15401.

- Muller CS, Pfohler C, Tilgen W. Changing a concept—controversy on the confusion spectrum of the reticulate pigmented disorders of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;36:44-48.

- Dai Y, Yu L, Wang Y, et al. Case report: a case of Hailey-Hailey disease mimicking condyloma acuminatum and a novel splice-site mutation of ATP2C1 gene. Front Genet. 2021;12:777630.

- Banjar TA, Abdulwahab RA, Al Hawsawi KA. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud: a case report and review of the literature. Cureus. 2022;14:E24557.

- Porro AM, Seque CA, Ferreira MCC, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:264-278.

- Bachar-Wikström E, Wikström JD. Darier disease—a multi-organ condition? Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00430.

The Diagnosis: Galli-Galli Disease

Several cutaneous conditions can present as reticulated hyperpigmentation or keratotic papules. Although genetic testing can help identify some of these dermatoses, biopsy typically is sufficient for diagnosis, and genetic testing can be considered for more clinically challenging cases. In our case, the clinical evidence and histopathologic findings were diagnostic of Galli-Galli disease (GGD), an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis with incomplete penetrance. Our patient was unaware of any family members with a diagnosis of GGD; however, she reported a great uncle with similar clinical findings.

Galli-Galli disease is a rare allelic variant of Dowling- Degos disease (DDD), both caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the keratin 5 gene, KRT5. Both conditions present as reticulated papules distributed symmetrically in the flexural regions, most commonly the axillae and groin, but also as comedolike papules, typically in patients aged 30 to 50 years.1 Cutaneous lesions primarily are of cosmetic concern but can be extremely pruritic, especially for patients with GGD. Gene mutations in protein O-fucosyltransferase 1, POFUT1; protein O-glucosyltransferase 1, POGLUT1; and presenilin enhancer 2, PSENEN, also have been discovered in cases of DDD and GGD.2,3

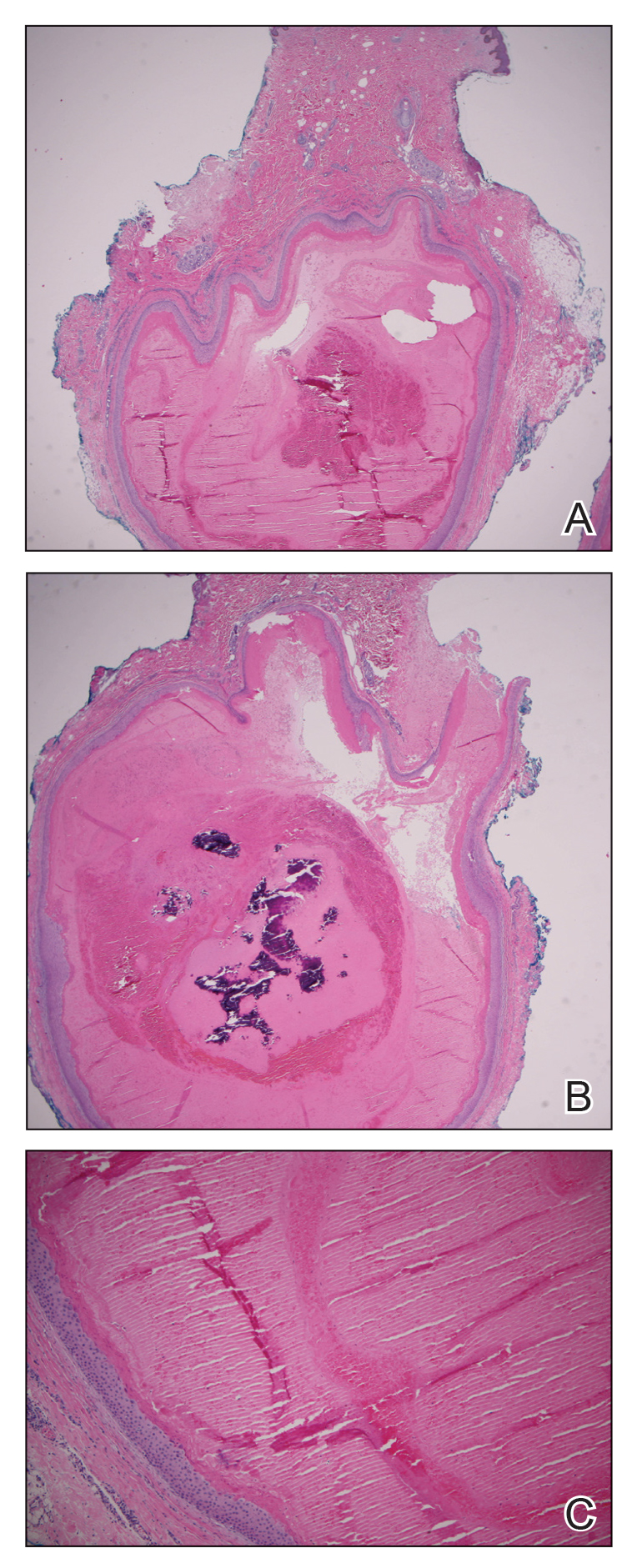

Galli-Galli disease and DDD are distinguishable by their histologic appearance. Both diseases show elongated fingerlike rete ridges and a thin suprapapillary epidermis. The basal projections often are described as bulbous or resembling antler horns.4 Galli-Galli disease can be differentiated from DDD by focal suprabasal acantholysis with minimal dyskeratosis (quiz images).5 Due to the genetic and clinical similarities, many consider GGD an acantholytic variant of DDD rather than its own entity. Indeed, some patients have shown acantholysis in one area of biopsy but not others.6

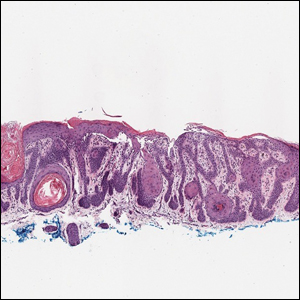

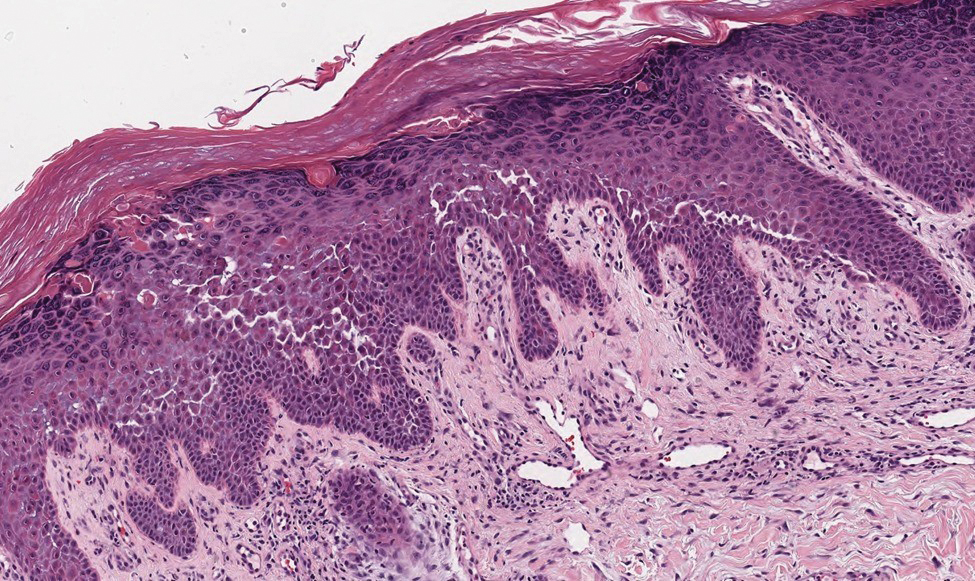

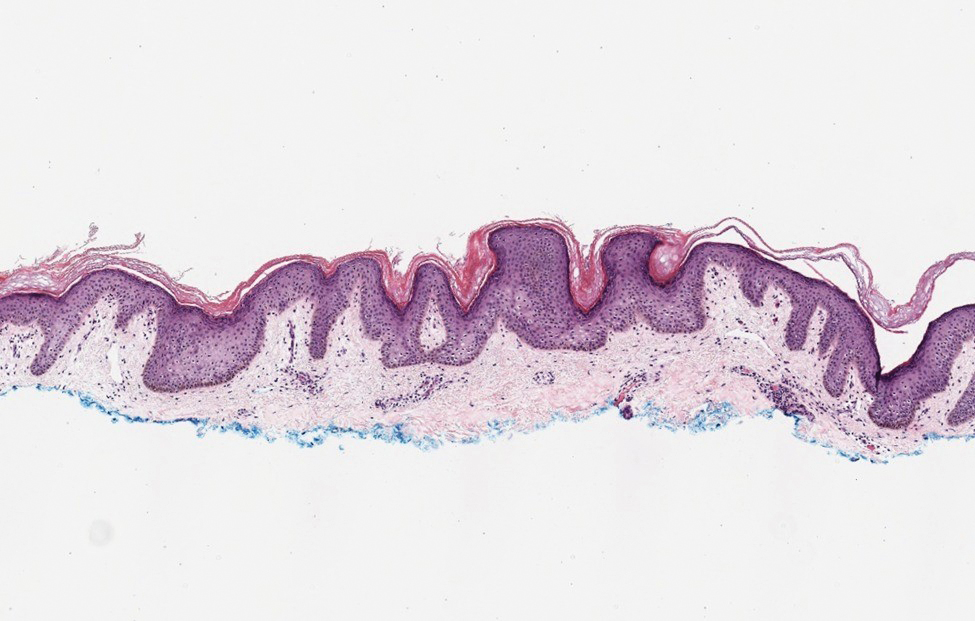

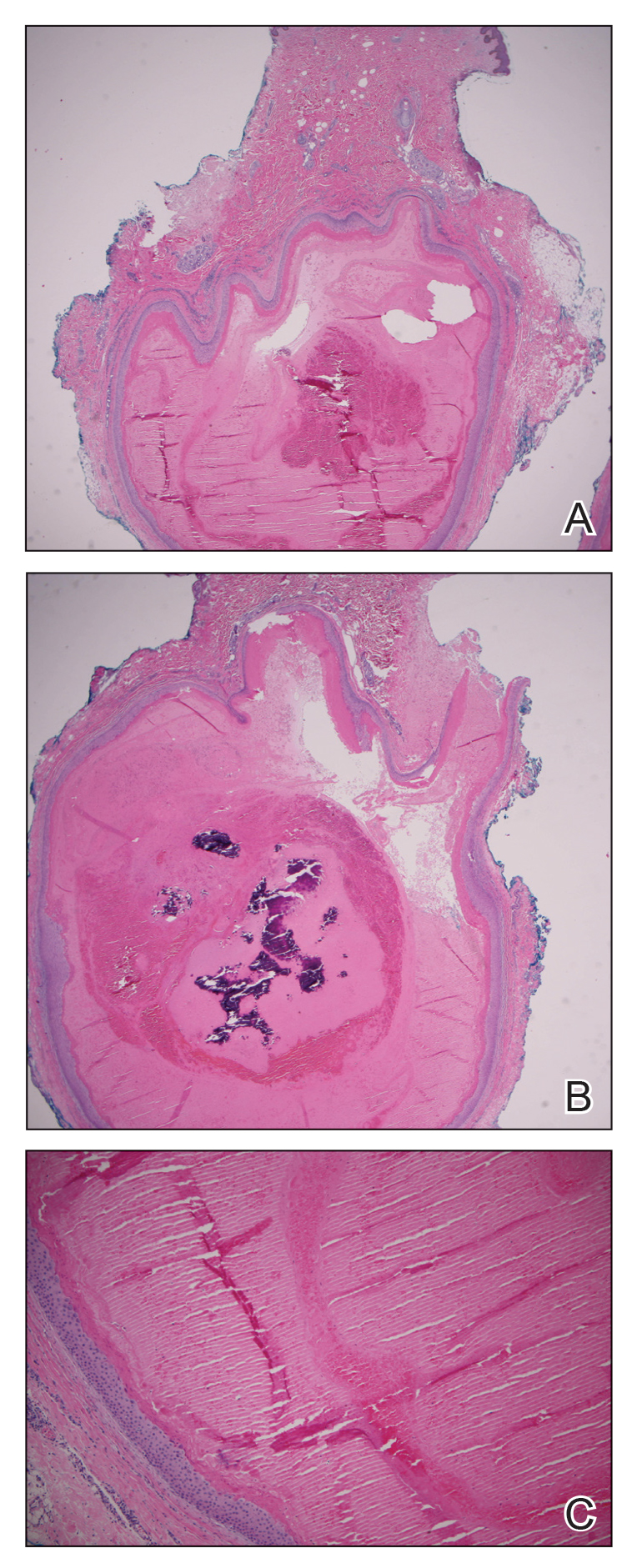

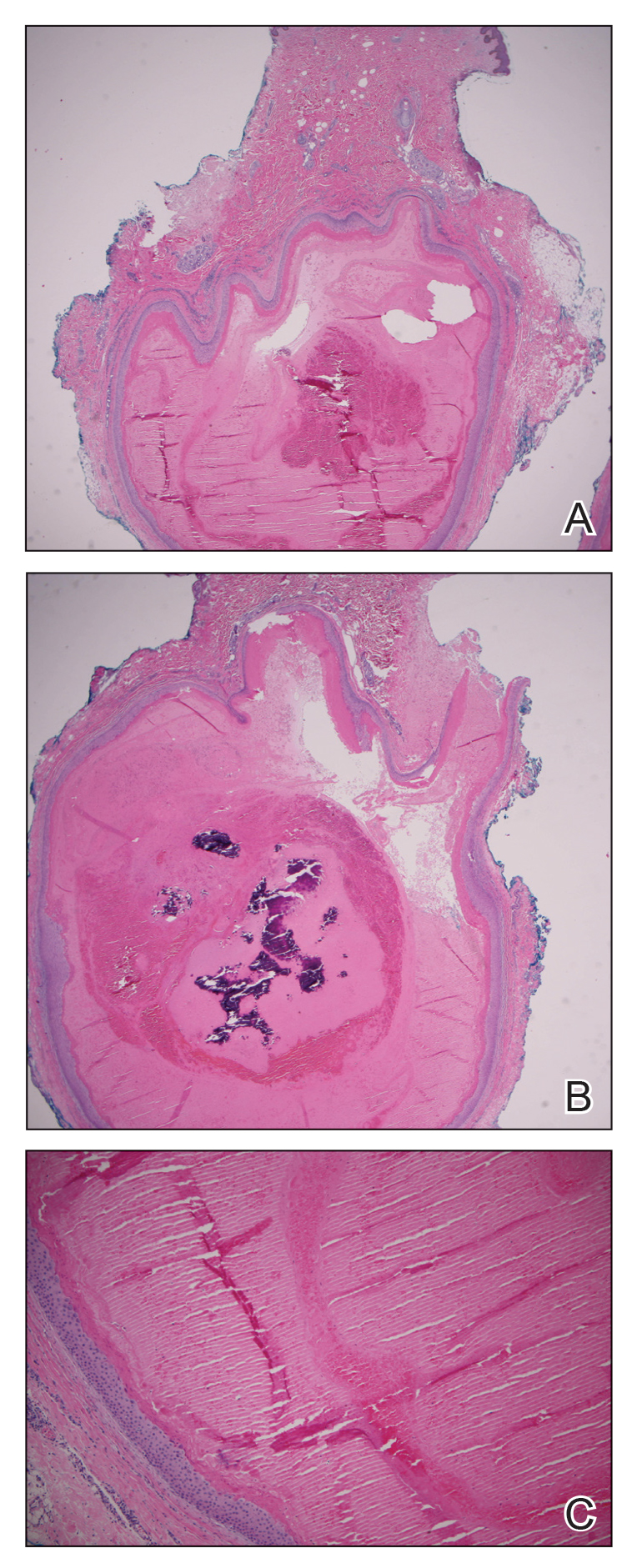

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD)(also known as benign familial or benign chronic pemphigus) is an autosomaldominant disorder caused by mutation of the ATPase secretory pathway Ca2+ transporting 1 gene, ATP2C1. Clinically, patients tend to present at a wide age range with fragile flaccid vesicles that commonly develop on the neck, axillae, and groin. Histologically, the epidermis is acanthotic with a dilapidated brick wall– like appearance from a few persistent intercellular connections amid widespread acantholysis (Figure 1).7 Unlike in autoimmune pemphigus, direct immunofluorescence is negative, and acantholysis spares the adnexal structures. Hailey-Hailey disease does not involve reticulated hyperpigmentation or the elongated bulbous rete seen in GGD. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is a rare, typically asymptomatic, hyperpigmented dermatosis. It presents as a conglomeration of scaly hyperpigmented macules or papillomatous papules that coalesce centrally and are reticulated toward the periphery.

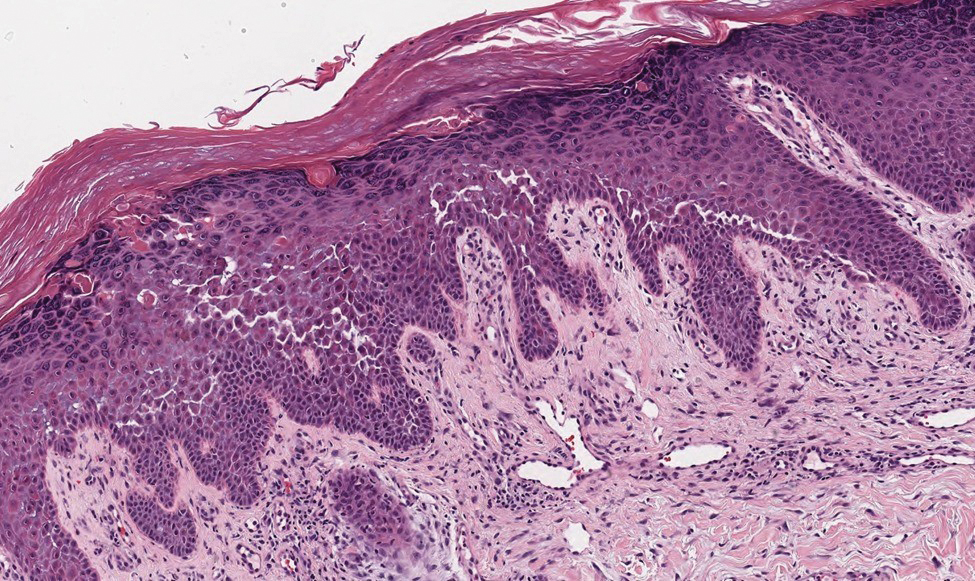

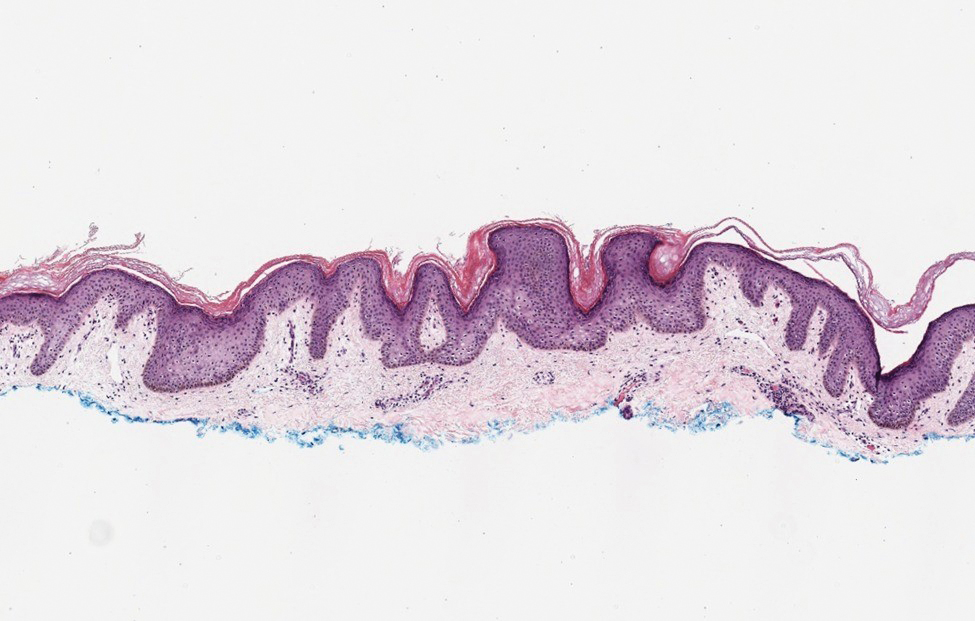

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis most commonly is seen on the trunk, initially presenting in adolescents and young adults. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is histologically similar to acanthosis nigricans. Histopathology will show hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and minimal to no inflammatory infiltrate, with no elongated rete ridges or acantholysis (Figure 2).8

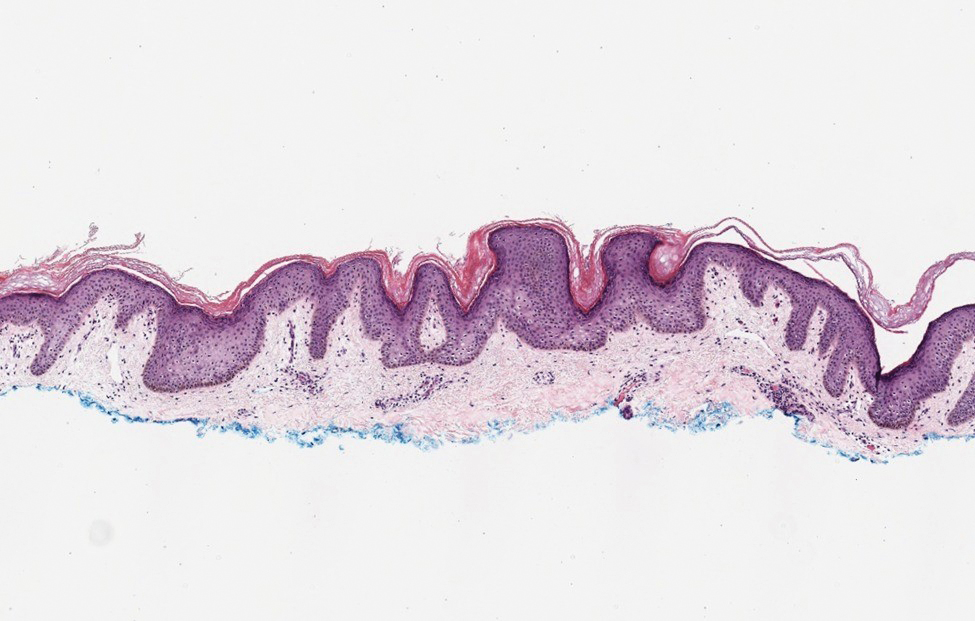

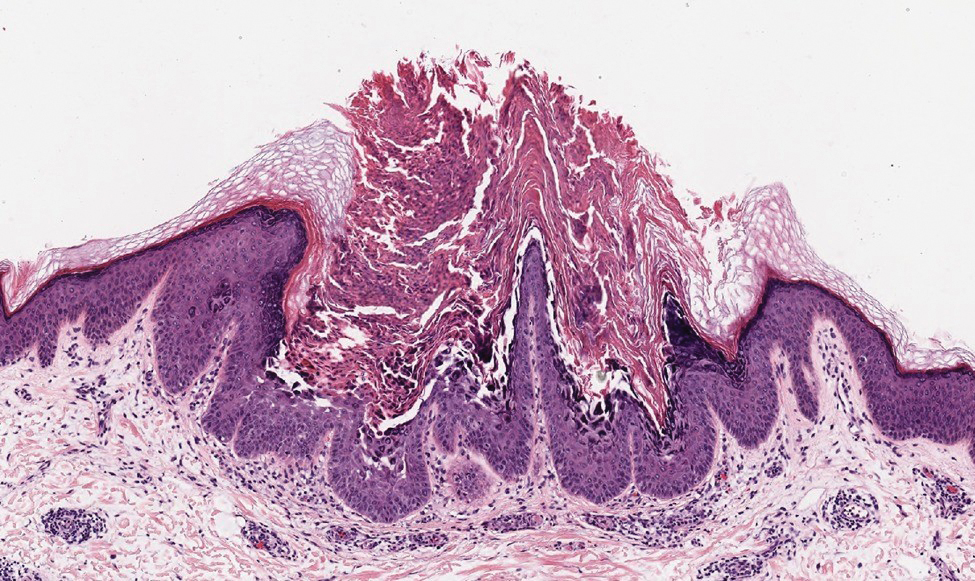

Pemphigus vulgaris is a blistering disease resulting from the development of autoantibodies against desmogleins 1 and 3. Similar to GGD, there is suprabasal acantholysis, which often results in a tombstonelike appearance consisting of separation between the basal layer cells of the epidermis but with maintained attachment to the underlying basement membrane zone. Unlike HHD, the acantholysis tends to involve the follicular epithelium in pemphigus vulgaris (Figure 3). Clinically, the blisters are positive for Nikolsky sign and can be both cutaneous or mucosal, commonly arising initially in the mouth during the fourth or fifth decades of life. Ruptured blisters can result in painful and hemorrhagic erosions.9 Direct immunofluorescence exhibits a classic chicken wire–like deposition of IgG and C3 between keratinocytes of the epidermis. Although sometimes difficult to appreciate, the deposition can be more prominent in the lower epidermis, in contrast to pemphigus foliaceus, which can have more prominent deposition in the upper epidermis.

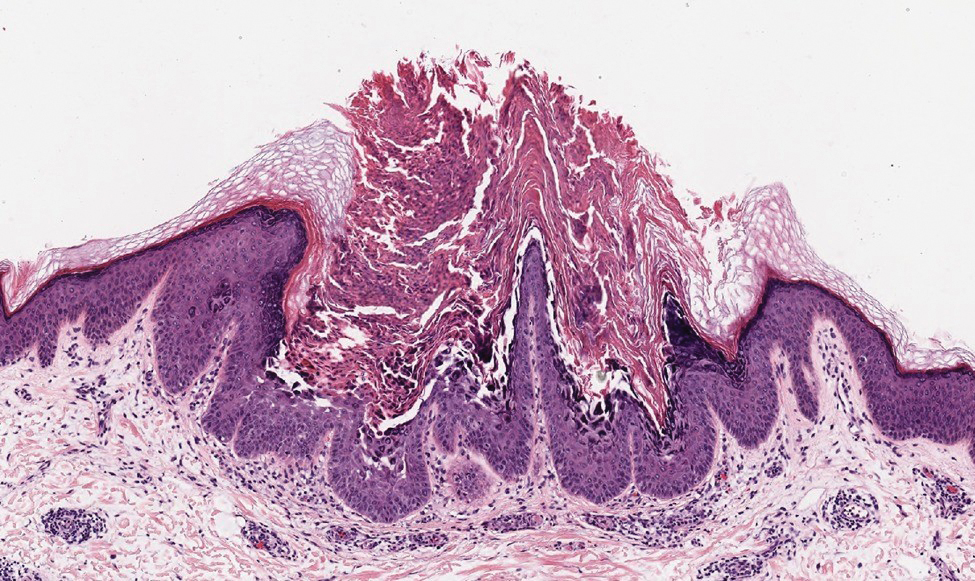

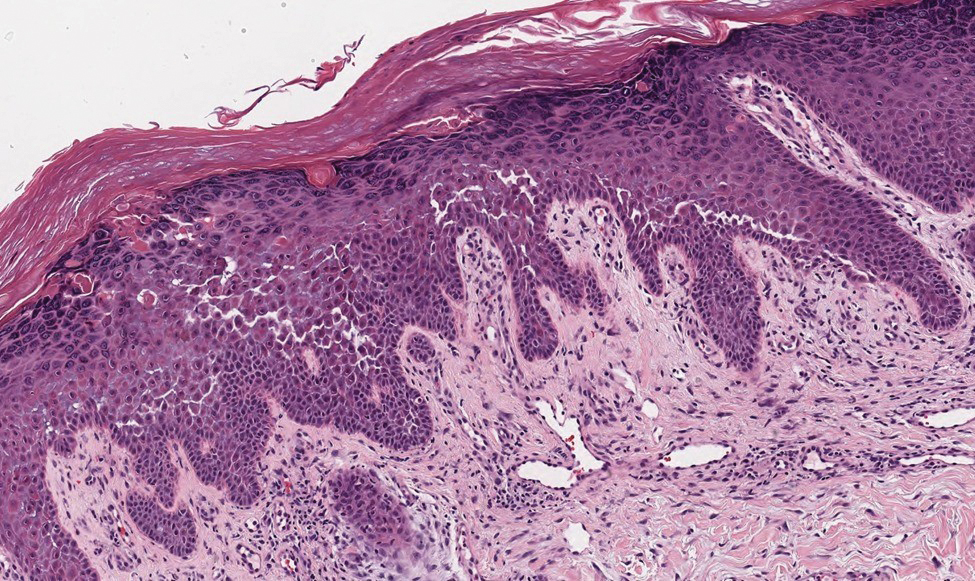

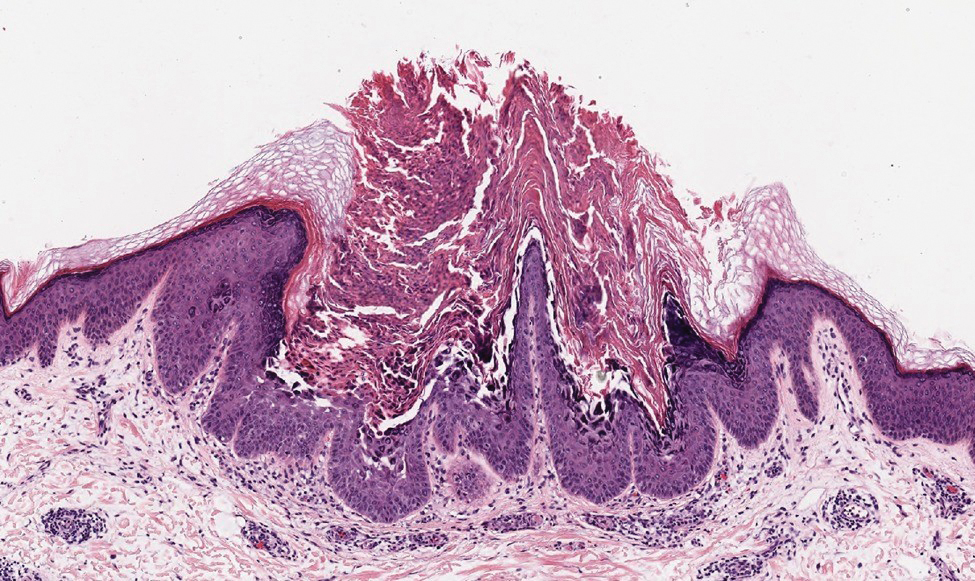

Darier disease (or dyskeratosis follicularis) is an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by mutation of the ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 gene, ATP2A2. Clinically, this disorder arises in adolescents as red-brown, greasy, crusted papules in seborrheic areas that may coalesce into papillomatous clusters. Palmar punctate keratoses and pits also are common. Histologically, Darier disease can appear similar to GGD, as both can show acantholysis and dyskeratosis. Darier disease will tend to show more prominent dyskeratosis with corps ronds and grains, as well as thicker villilike projections of keratinocytes into the papillary dermis, in contrast to the thinner, fingerlike or bulbous projections that hang down from the epidermis in GGD (Figure 4).10

The Diagnosis: Galli-Galli Disease

Several cutaneous conditions can present as reticulated hyperpigmentation or keratotic papules. Although genetic testing can help identify some of these dermatoses, biopsy typically is sufficient for diagnosis, and genetic testing can be considered for more clinically challenging cases. In our case, the clinical evidence and histopathologic findings were diagnostic of Galli-Galli disease (GGD), an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis with incomplete penetrance. Our patient was unaware of any family members with a diagnosis of GGD; however, she reported a great uncle with similar clinical findings.

Galli-Galli disease is a rare allelic variant of Dowling- Degos disease (DDD), both caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the keratin 5 gene, KRT5. Both conditions present as reticulated papules distributed symmetrically in the flexural regions, most commonly the axillae and groin, but also as comedolike papules, typically in patients aged 30 to 50 years.1 Cutaneous lesions primarily are of cosmetic concern but can be extremely pruritic, especially for patients with GGD. Gene mutations in protein O-fucosyltransferase 1, POFUT1; protein O-glucosyltransferase 1, POGLUT1; and presenilin enhancer 2, PSENEN, also have been discovered in cases of DDD and GGD.2,3

Galli-Galli disease and DDD are distinguishable by their histologic appearance. Both diseases show elongated fingerlike rete ridges and a thin suprapapillary epidermis. The basal projections often are described as bulbous or resembling antler horns.4 Galli-Galli disease can be differentiated from DDD by focal suprabasal acantholysis with minimal dyskeratosis (quiz images).5 Due to the genetic and clinical similarities, many consider GGD an acantholytic variant of DDD rather than its own entity. Indeed, some patients have shown acantholysis in one area of biopsy but not others.6

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD)(also known as benign familial or benign chronic pemphigus) is an autosomaldominant disorder caused by mutation of the ATPase secretory pathway Ca2+ transporting 1 gene, ATP2C1. Clinically, patients tend to present at a wide age range with fragile flaccid vesicles that commonly develop on the neck, axillae, and groin. Histologically, the epidermis is acanthotic with a dilapidated brick wall– like appearance from a few persistent intercellular connections amid widespread acantholysis (Figure 1).7 Unlike in autoimmune pemphigus, direct immunofluorescence is negative, and acantholysis spares the adnexal structures. Hailey-Hailey disease does not involve reticulated hyperpigmentation or the elongated bulbous rete seen in GGD. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is a rare, typically asymptomatic, hyperpigmented dermatosis. It presents as a conglomeration of scaly hyperpigmented macules or papillomatous papules that coalesce centrally and are reticulated toward the periphery.

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis most commonly is seen on the trunk, initially presenting in adolescents and young adults. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is histologically similar to acanthosis nigricans. Histopathology will show hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and minimal to no inflammatory infiltrate, with no elongated rete ridges or acantholysis (Figure 2).8

Pemphigus vulgaris is a blistering disease resulting from the development of autoantibodies against desmogleins 1 and 3. Similar to GGD, there is suprabasal acantholysis, which often results in a tombstonelike appearance consisting of separation between the basal layer cells of the epidermis but with maintained attachment to the underlying basement membrane zone. Unlike HHD, the acantholysis tends to involve the follicular epithelium in pemphigus vulgaris (Figure 3). Clinically, the blisters are positive for Nikolsky sign and can be both cutaneous or mucosal, commonly arising initially in the mouth during the fourth or fifth decades of life. Ruptured blisters can result in painful and hemorrhagic erosions.9 Direct immunofluorescence exhibits a classic chicken wire–like deposition of IgG and C3 between keratinocytes of the epidermis. Although sometimes difficult to appreciate, the deposition can be more prominent in the lower epidermis, in contrast to pemphigus foliaceus, which can have more prominent deposition in the upper epidermis.

Darier disease (or dyskeratosis follicularis) is an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by mutation of the ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 gene, ATP2A2. Clinically, this disorder arises in adolescents as red-brown, greasy, crusted papules in seborrheic areas that may coalesce into papillomatous clusters. Palmar punctate keratoses and pits also are common. Histologically, Darier disease can appear similar to GGD, as both can show acantholysis and dyskeratosis. Darier disease will tend to show more prominent dyskeratosis with corps ronds and grains, as well as thicker villilike projections of keratinocytes into the papillary dermis, in contrast to the thinner, fingerlike or bulbous projections that hang down from the epidermis in GGD (Figure 4).10

- Hanneken S, Rütten A, Eigelshoven S, et al. Morbus Galli-Galli. Hautarzt. 2013;64:282.

- Wilson NJ, Cole C, Kroboth K, et al. Mutations in POGLUT1 in Galli- Galli/Dowling-Degos disease. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:270-274.

- Ralser DJ, Basmanav FB, Tafazzoli A, et al. Mutations in γ-secretase subunit–encoding PSENEN underlie Dowling-Degos disease associated with acne inversa. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:1485-1490.

- Desai CA, Virmani N, Sakhiya J, et al. An uncommon presentation of Galli-Galli disease. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016; 82:720-723.

- Joshi TP, Shaver S, Tschen J. Exacerbation of Galli-Galli disease following dialysis treatment: a case report and review of aggravating factors. Cureus. 2021;13:E15401.

- Muller CS, Pfohler C, Tilgen W. Changing a concept—controversy on the confusion spectrum of the reticulate pigmented disorders of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;36:44-48.

- Dai Y, Yu L, Wang Y, et al. Case report: a case of Hailey-Hailey disease mimicking condyloma acuminatum and a novel splice-site mutation of ATP2C1 gene. Front Genet. 2021;12:777630.

- Banjar TA, Abdulwahab RA, Al Hawsawi KA. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud: a case report and review of the literature. Cureus. 2022;14:E24557.

- Porro AM, Seque CA, Ferreira MCC, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:264-278.

- Bachar-Wikström E, Wikström JD. Darier disease—a multi-organ condition? Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00430.

- Hanneken S, Rütten A, Eigelshoven S, et al. Morbus Galli-Galli. Hautarzt. 2013;64:282.

- Wilson NJ, Cole C, Kroboth K, et al. Mutations in POGLUT1 in Galli- Galli/Dowling-Degos disease. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:270-274.

- Ralser DJ, Basmanav FB, Tafazzoli A, et al. Mutations in γ-secretase subunit–encoding PSENEN underlie Dowling-Degos disease associated with acne inversa. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:1485-1490.

- Desai CA, Virmani N, Sakhiya J, et al. An uncommon presentation of Galli-Galli disease. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016; 82:720-723.

- Joshi TP, Shaver S, Tschen J. Exacerbation of Galli-Galli disease following dialysis treatment: a case report and review of aggravating factors. Cureus. 2021;13:E15401.

- Muller CS, Pfohler C, Tilgen W. Changing a concept—controversy on the confusion spectrum of the reticulate pigmented disorders of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;36:44-48.

- Dai Y, Yu L, Wang Y, et al. Case report: a case of Hailey-Hailey disease mimicking condyloma acuminatum and a novel splice-site mutation of ATP2C1 gene. Front Genet. 2021;12:777630.

- Banjar TA, Abdulwahab RA, Al Hawsawi KA. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud: a case report and review of the literature. Cureus. 2022;14:E24557.

- Porro AM, Seque CA, Ferreira MCC, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:264-278.

- Bachar-Wikström E, Wikström JD. Darier disease—a multi-organ condition? Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00430.

A 37-year-old woman presented with multiple hyperkeratotic small papules in the axillae and groin of 1 year’s duration. She reported pruritus and occasional sleep disruption. Subtle background reticulated hyperpigmentation was present. The patient reported that she had a great uncle with similar findings.

Video-Based Coaching for Dermatology Resident Surgical Education

To the Editor:

Video-based coaching (VBC) involves a surgeon recording a surgery and then reviewing the video with a surgical coach; it is a form of education that is gaining popularity among surgical specialties.1 Video-based education is underutilized in dermatology residency training.2 We conducted a pilot study at our dermatology residency program to evaluate the efficacy and feasibility of VBC.

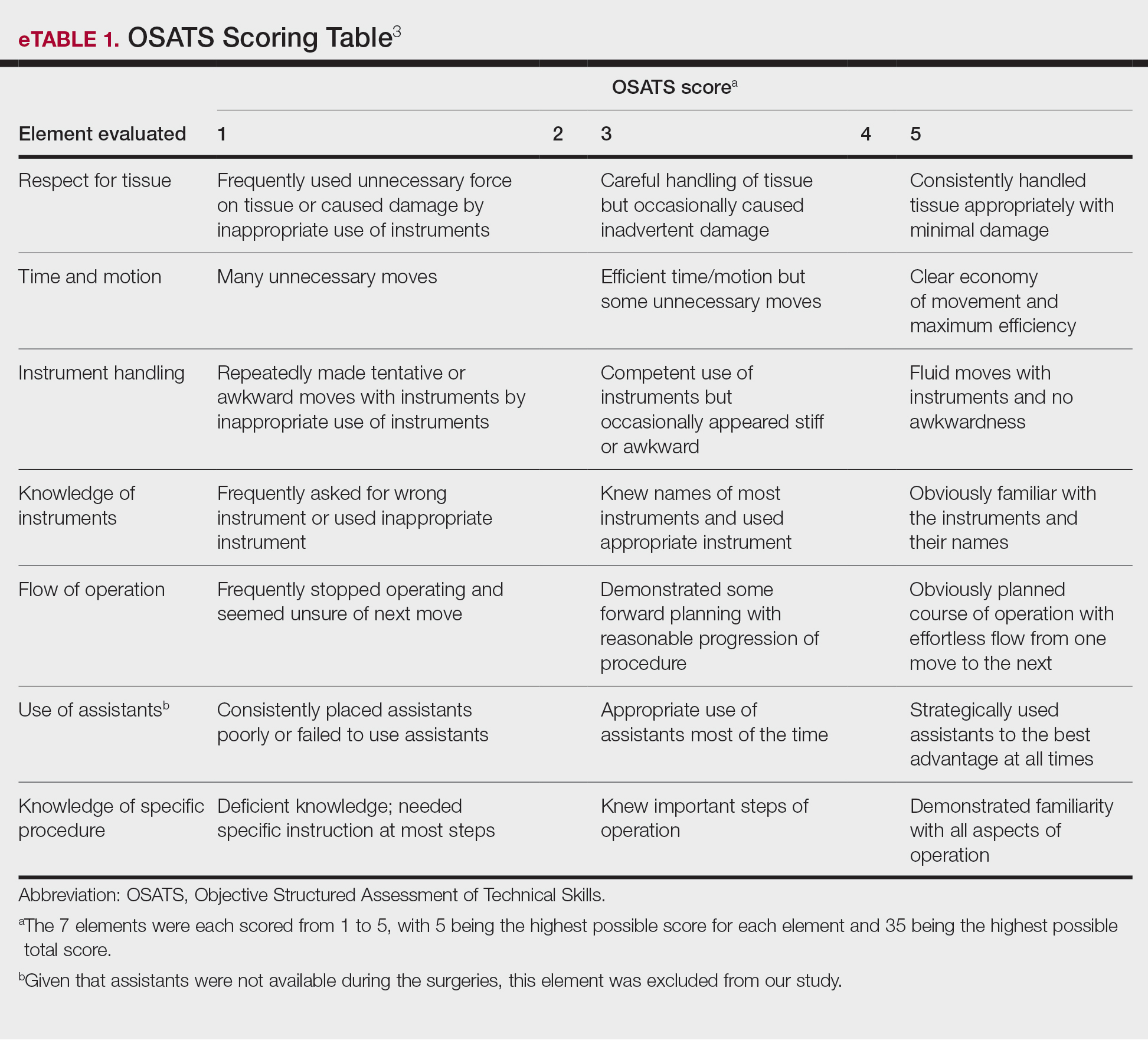

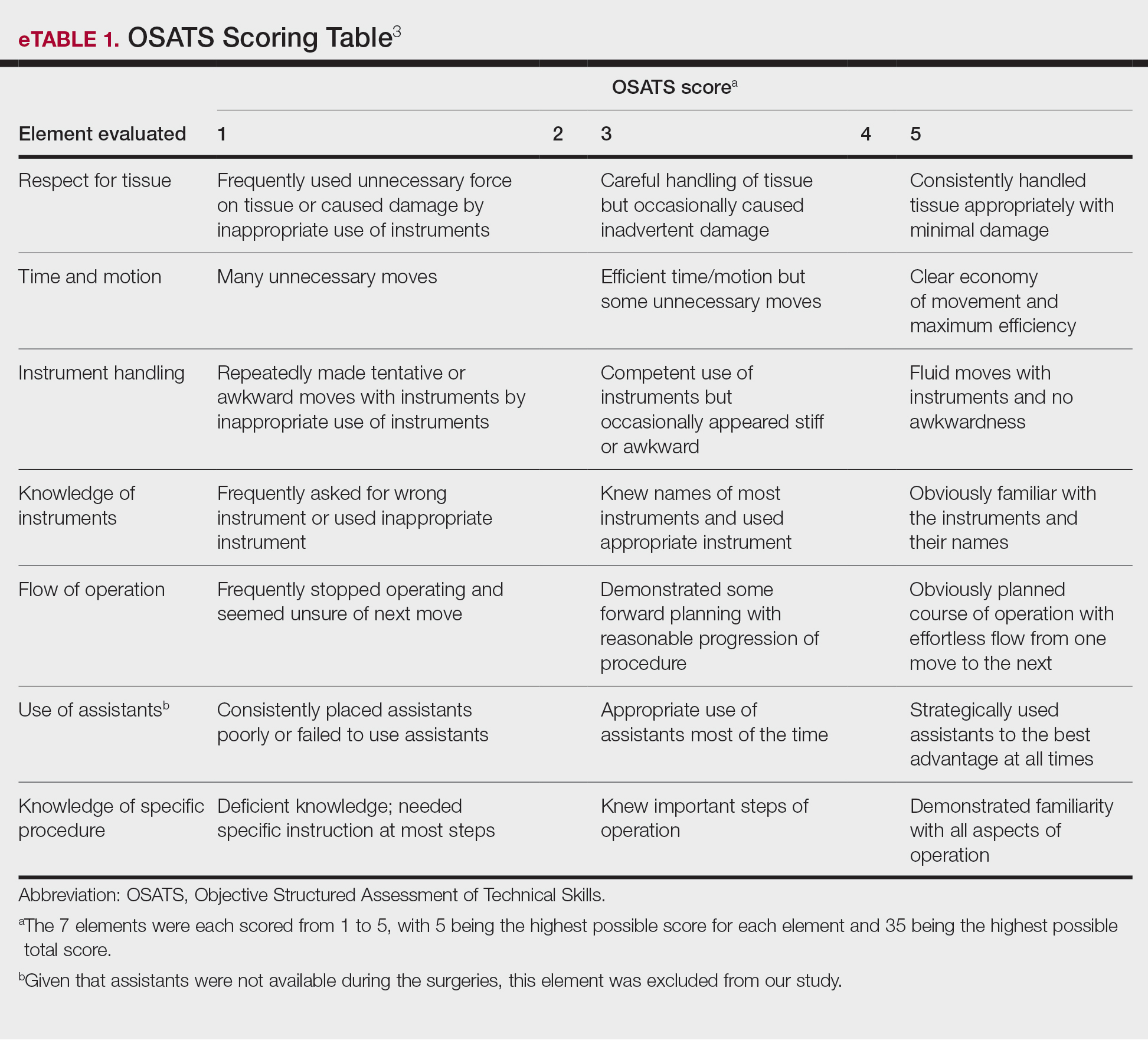

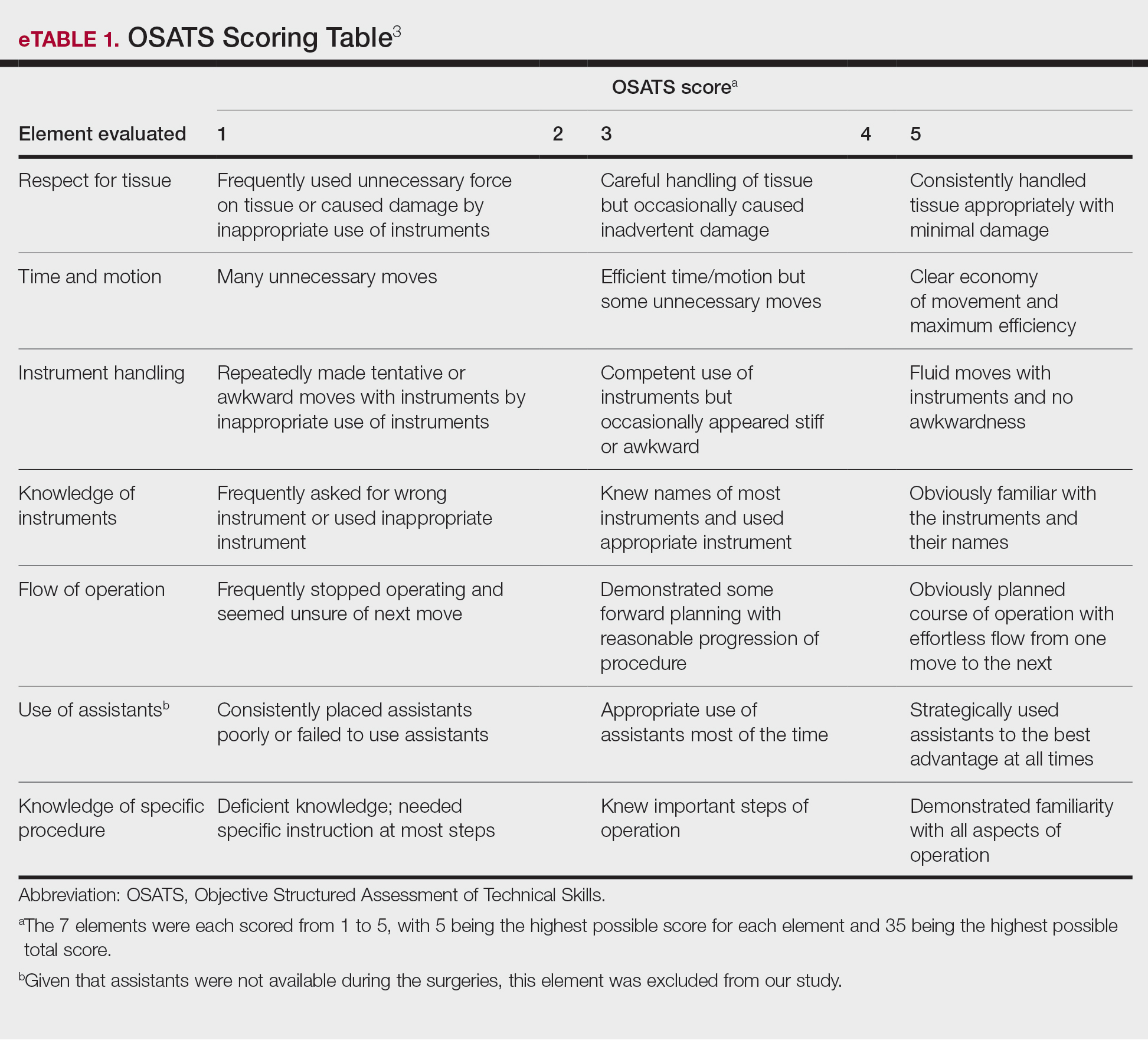

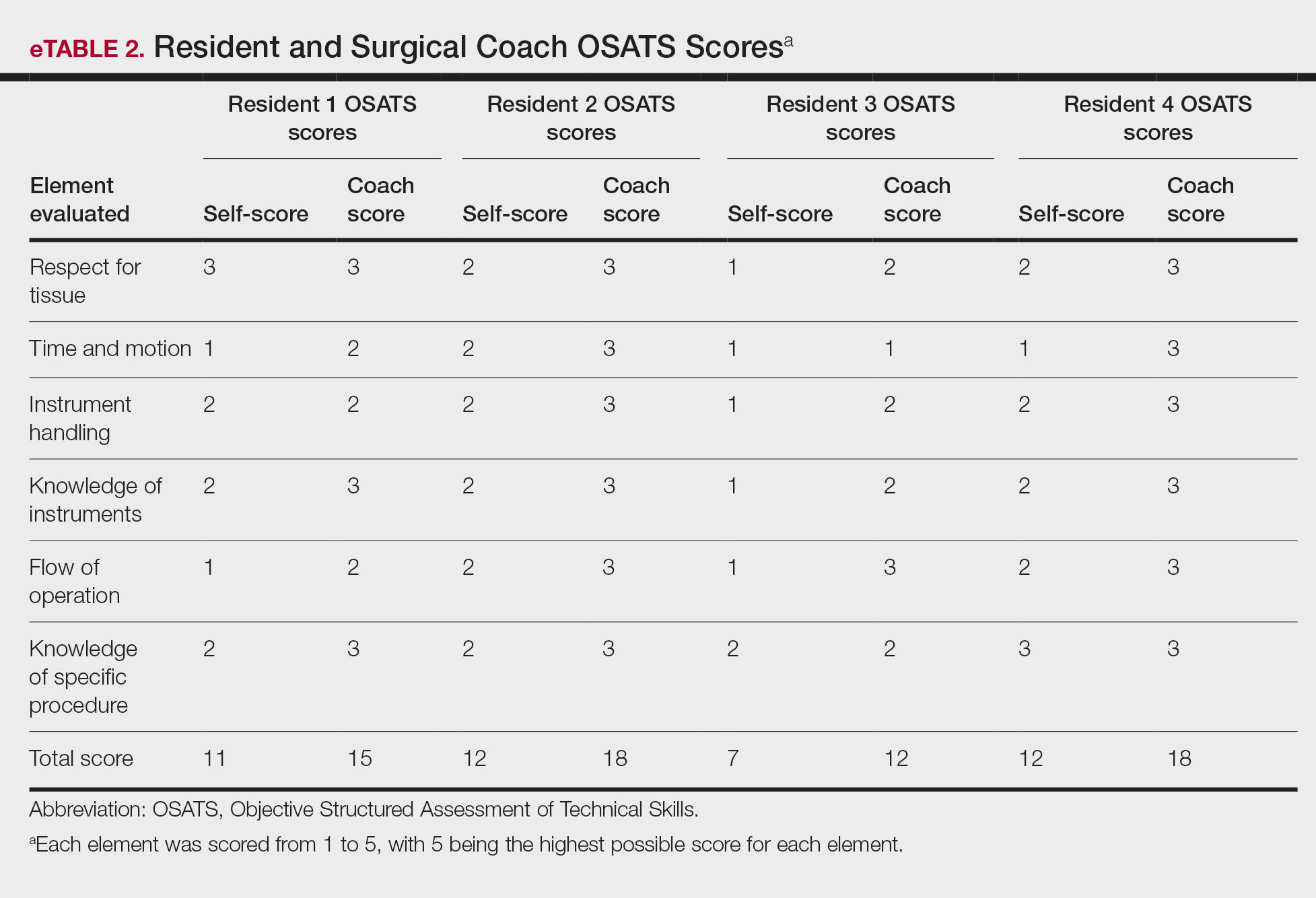

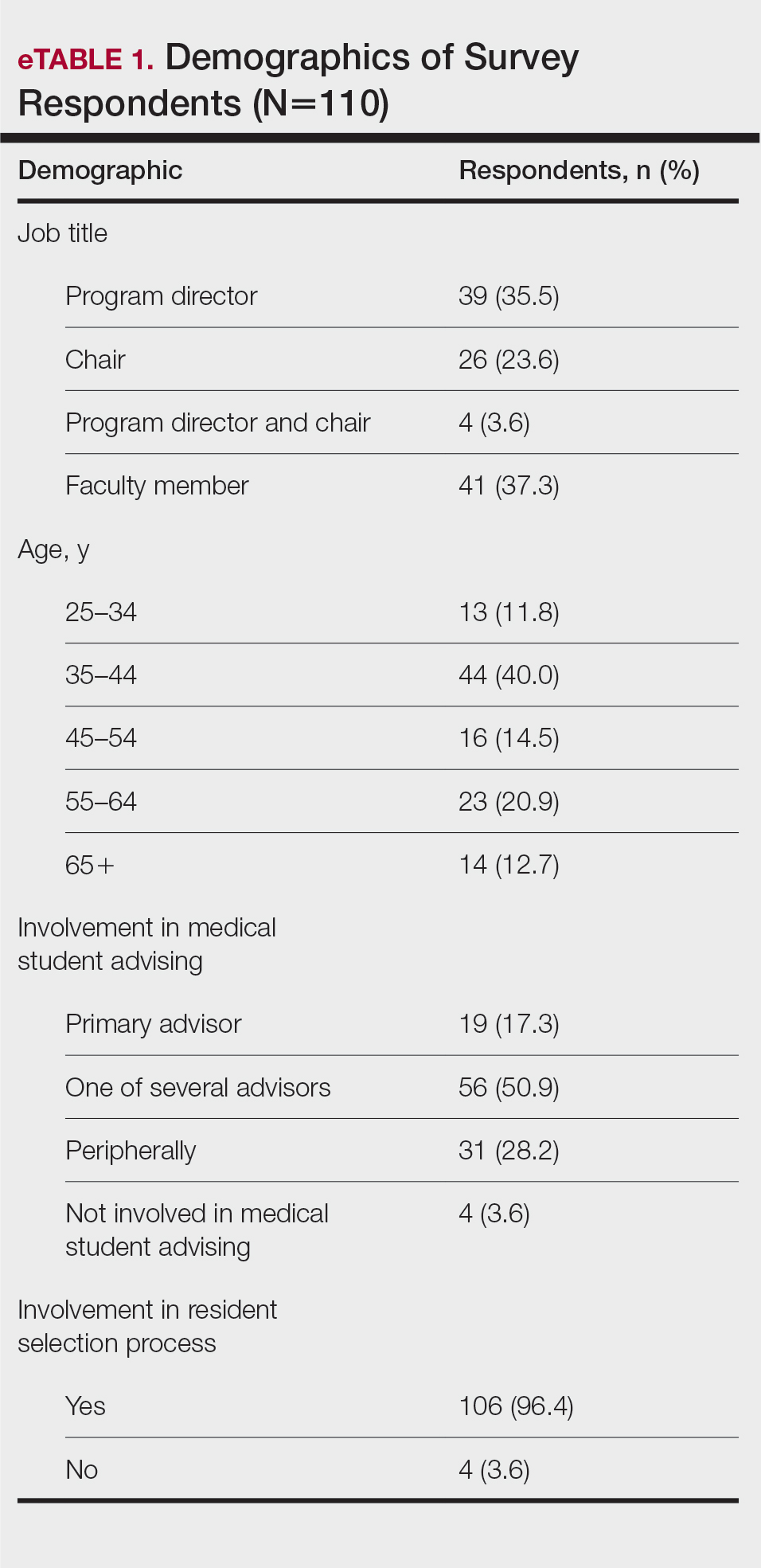

The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School institutional review board approved this study. All 4 first-year dermatology residents were recruited to participate in this study. Participants filled out a prestudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Participants used a head-mounted point-of-view camera to record themselves performing a wide local excision on the trunk or extremities of a live human patient. Participants then reviewed the recording on their own and scored themselves using the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) scoring table (scored from 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest possible score for each element), which is a validated tool for assessing surgical skills (eTable 1).3 Given that there were no assistants participating in the surgery, this element of the OSATS scoring table was excluded, making a maximum possible score of 30 and a minimum possible score of 6. After scoring themselves, participants then had a 1-on-1 coaching session with a fellowship-trained dermatologic surgeon (M.F. or T.H.) via online teleconferencing.

During the coaching session, participants and coaches reviewed the video. The surgical coaches also scored the residents using the OSATS, then residents and coaches discussed how the resident could improve using the OSATS scores as a guide. The residents then completed a poststudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Descriptive statistics were reported.

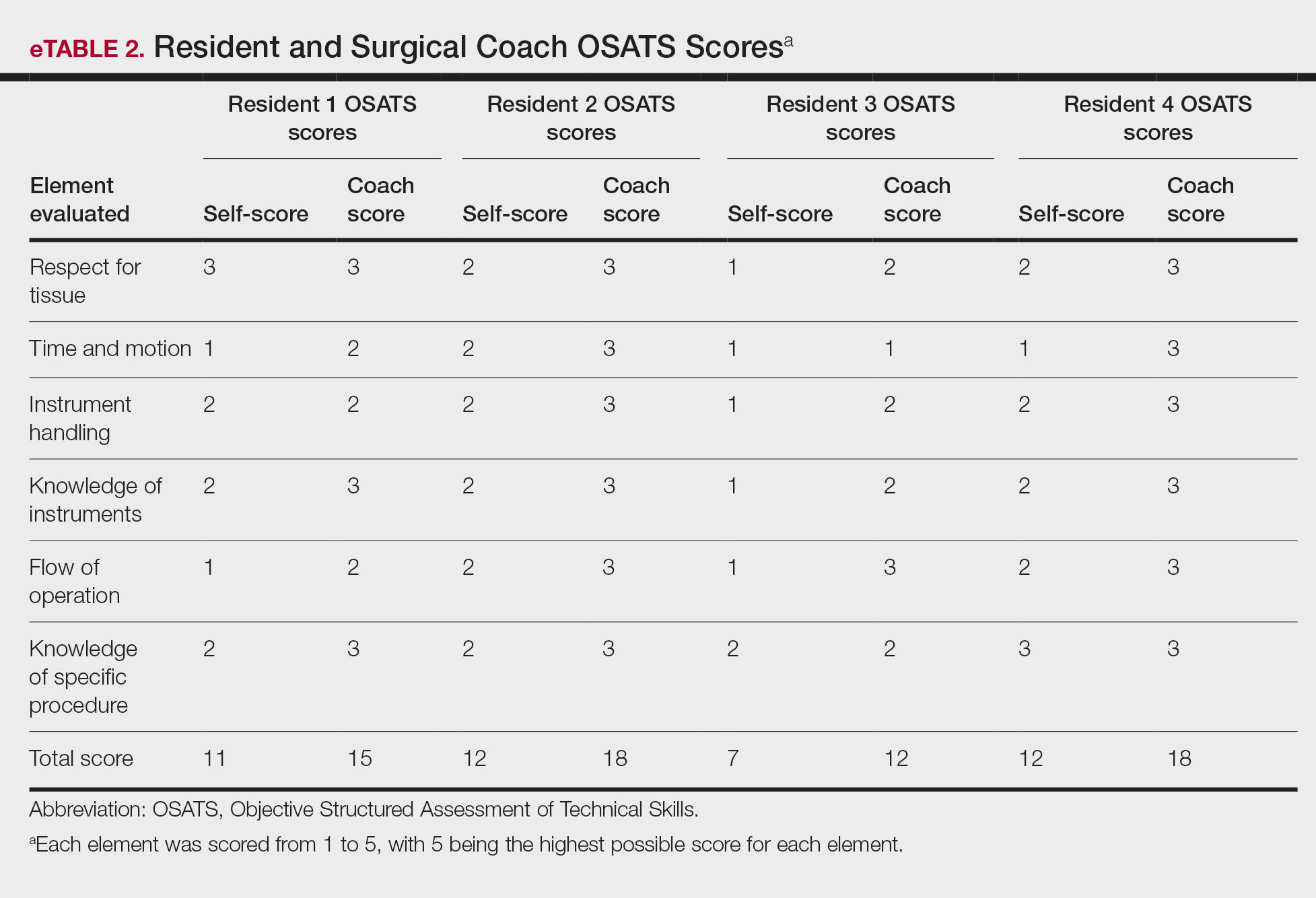

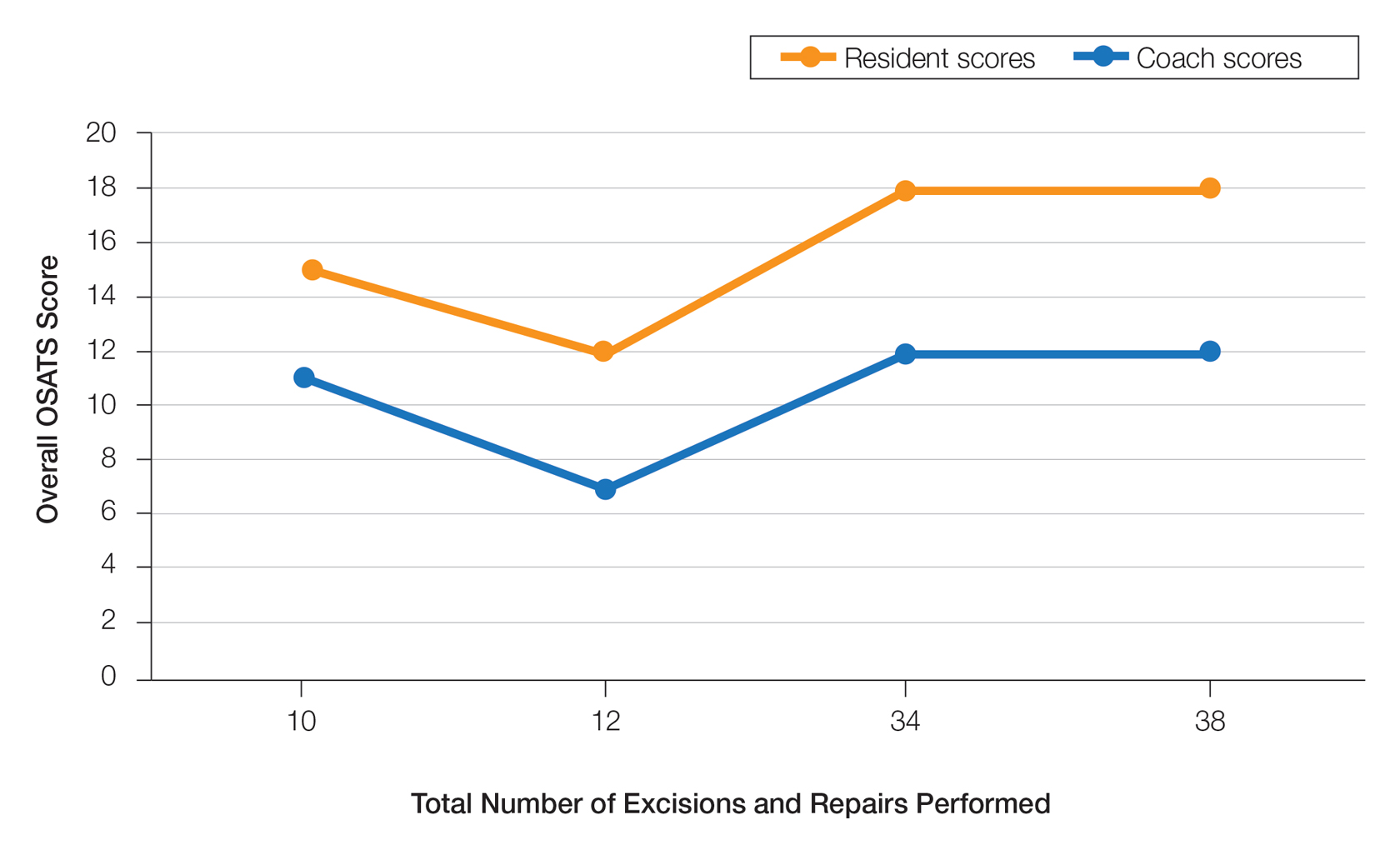

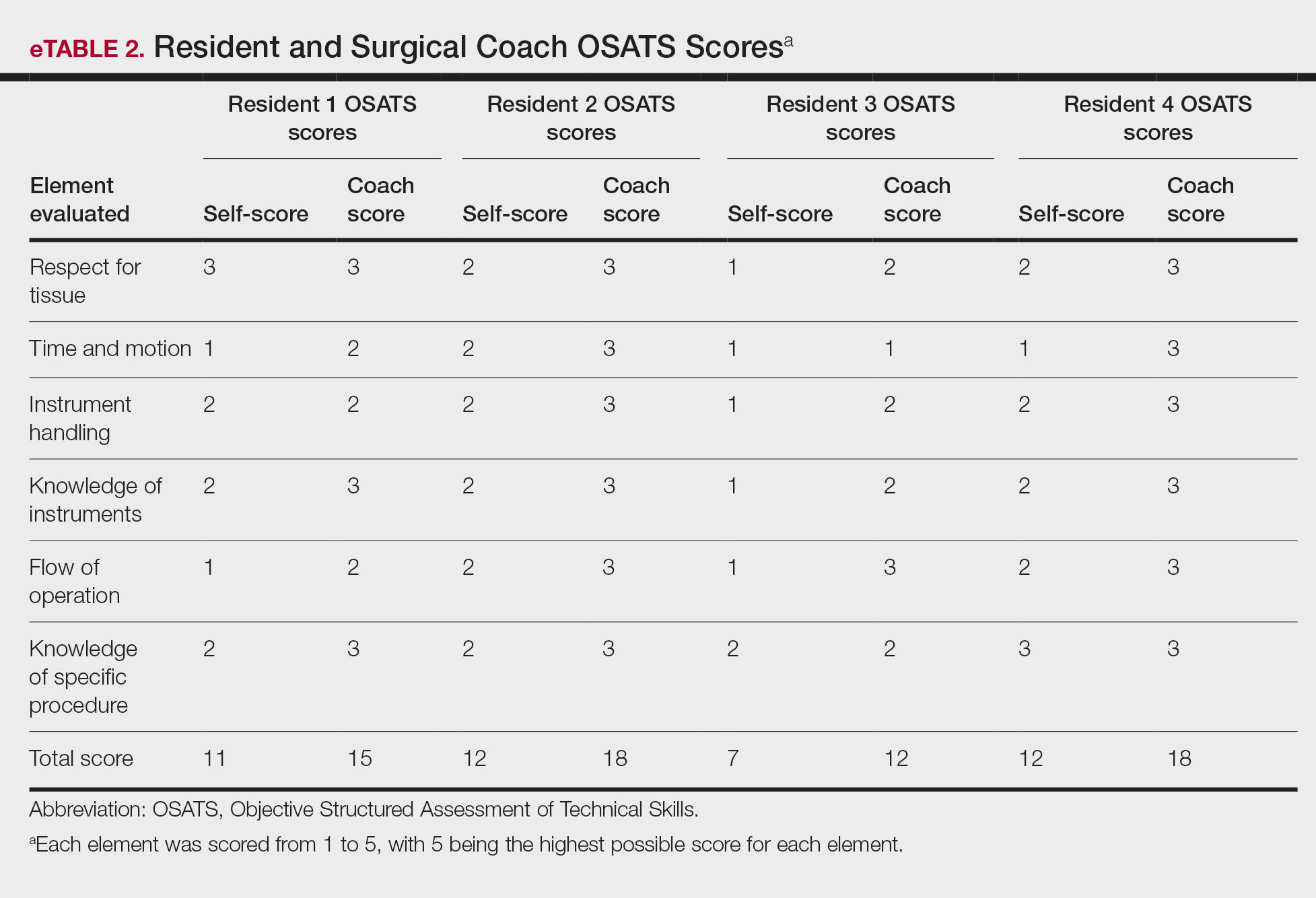

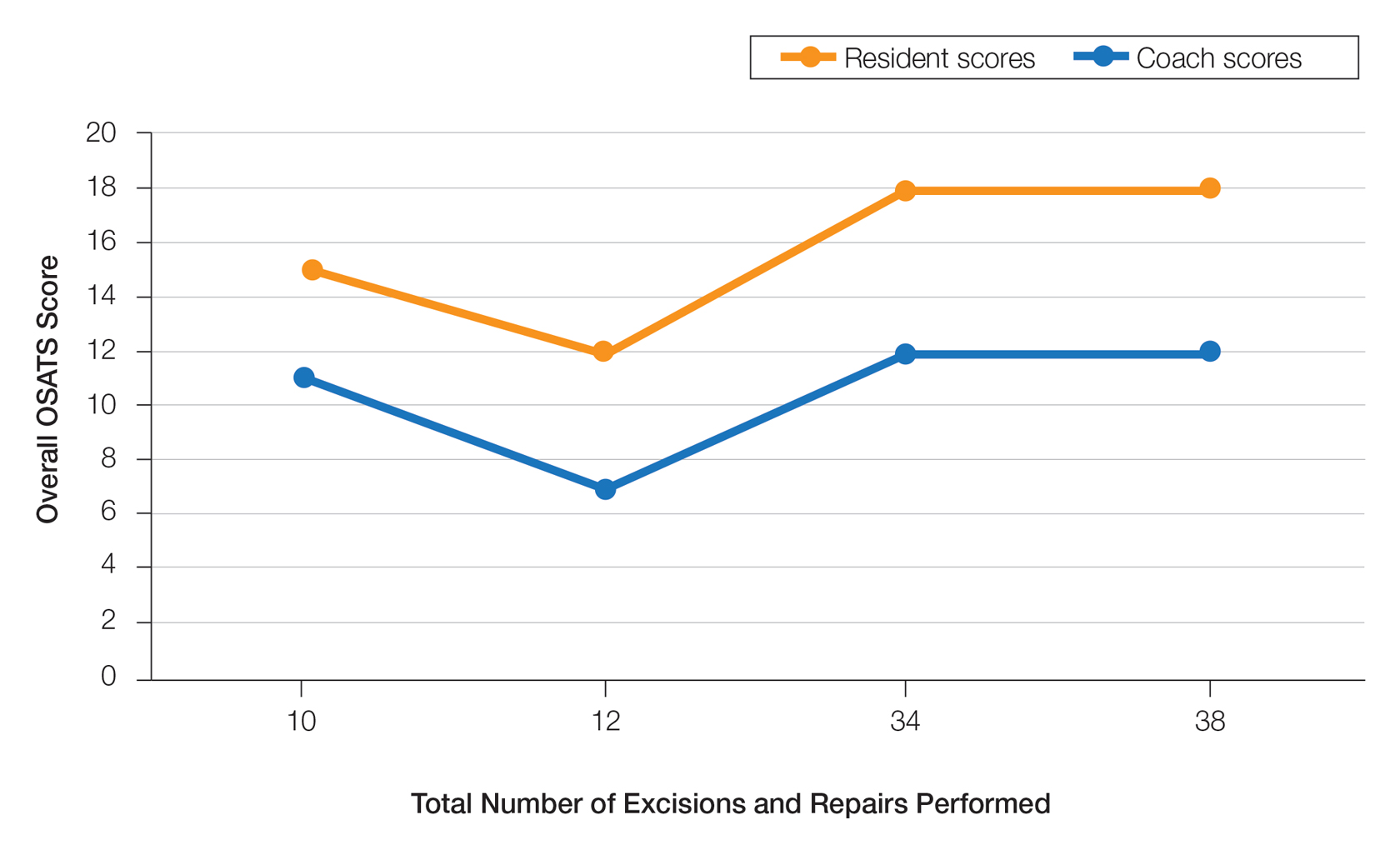

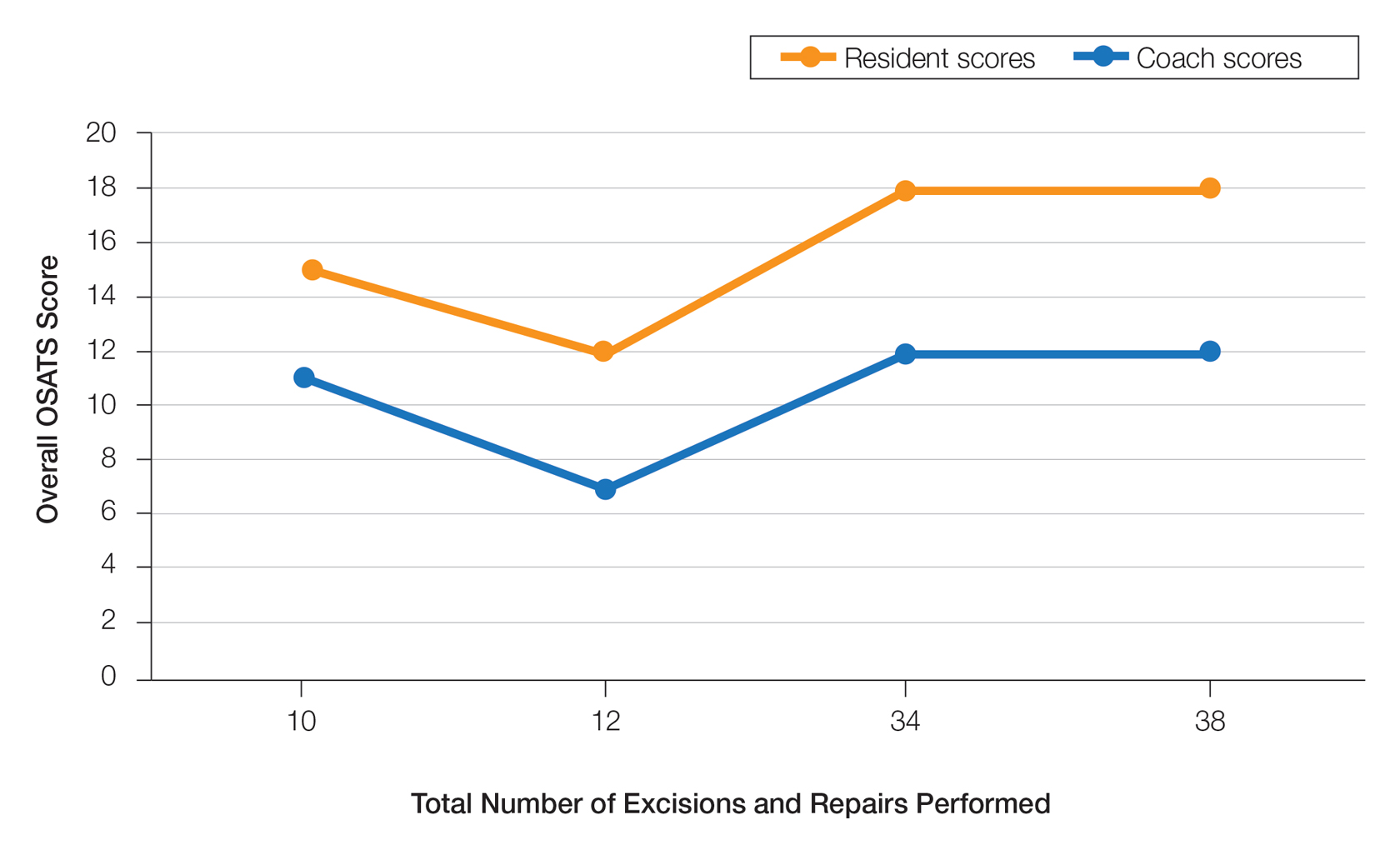

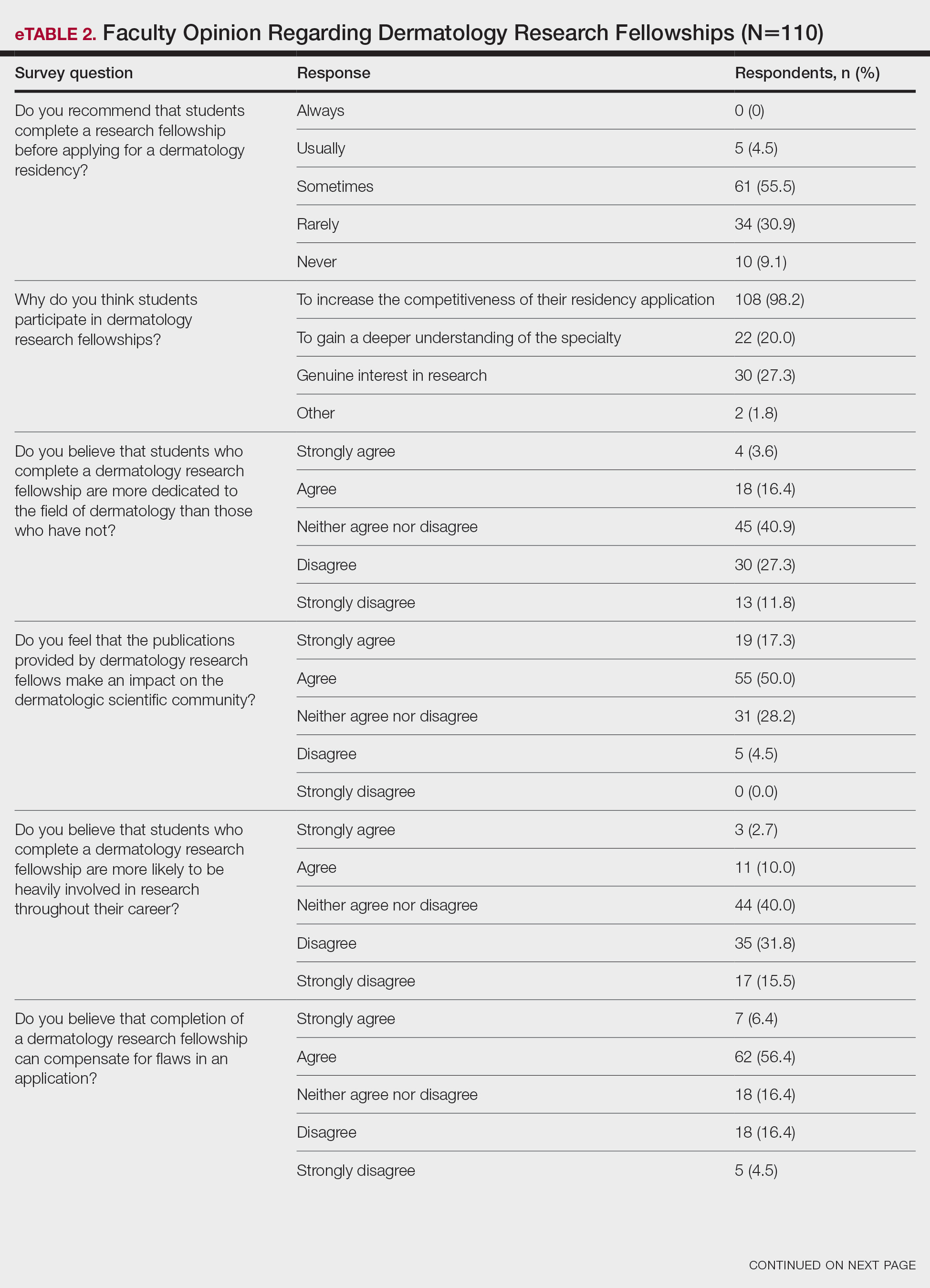

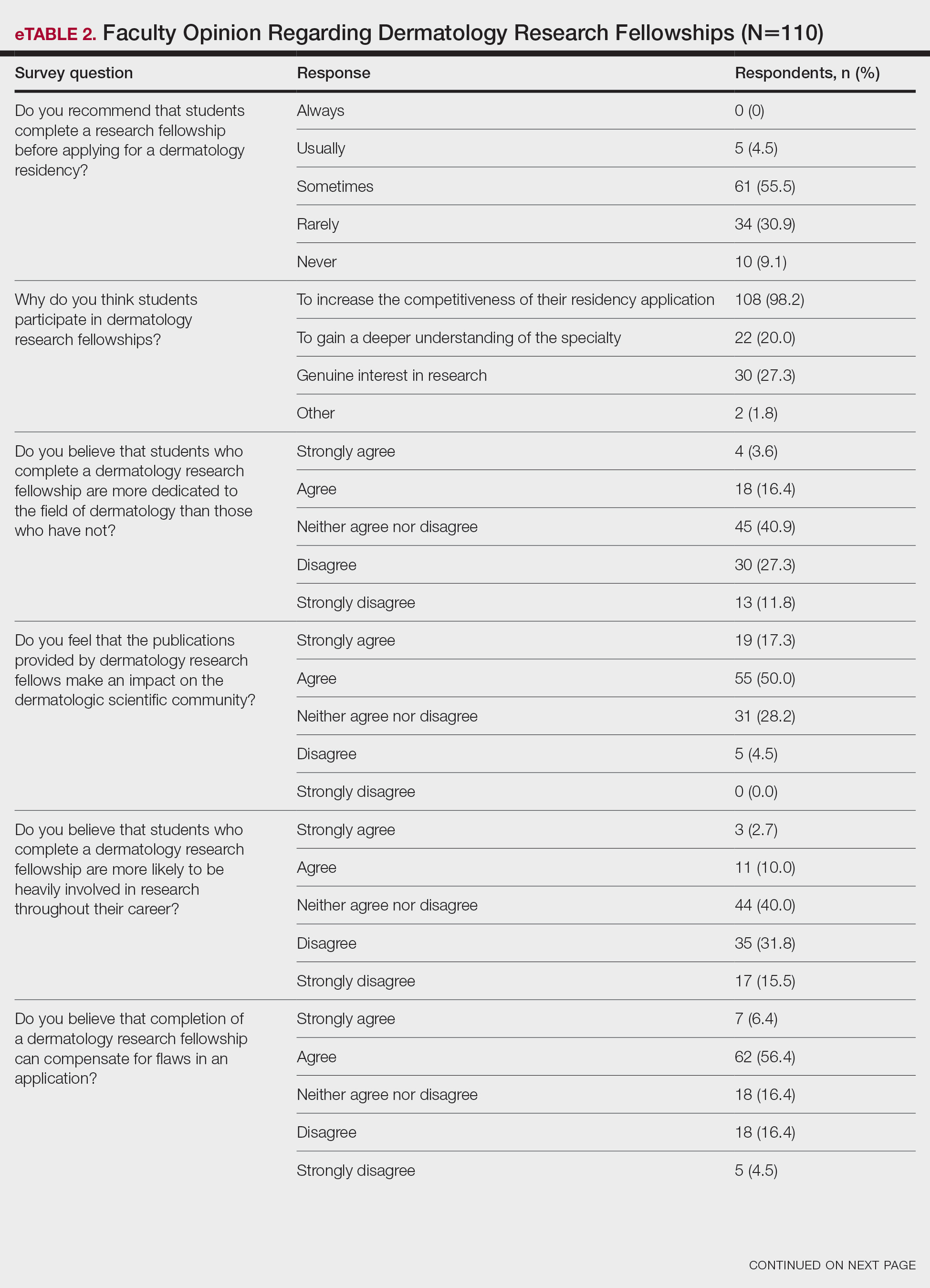

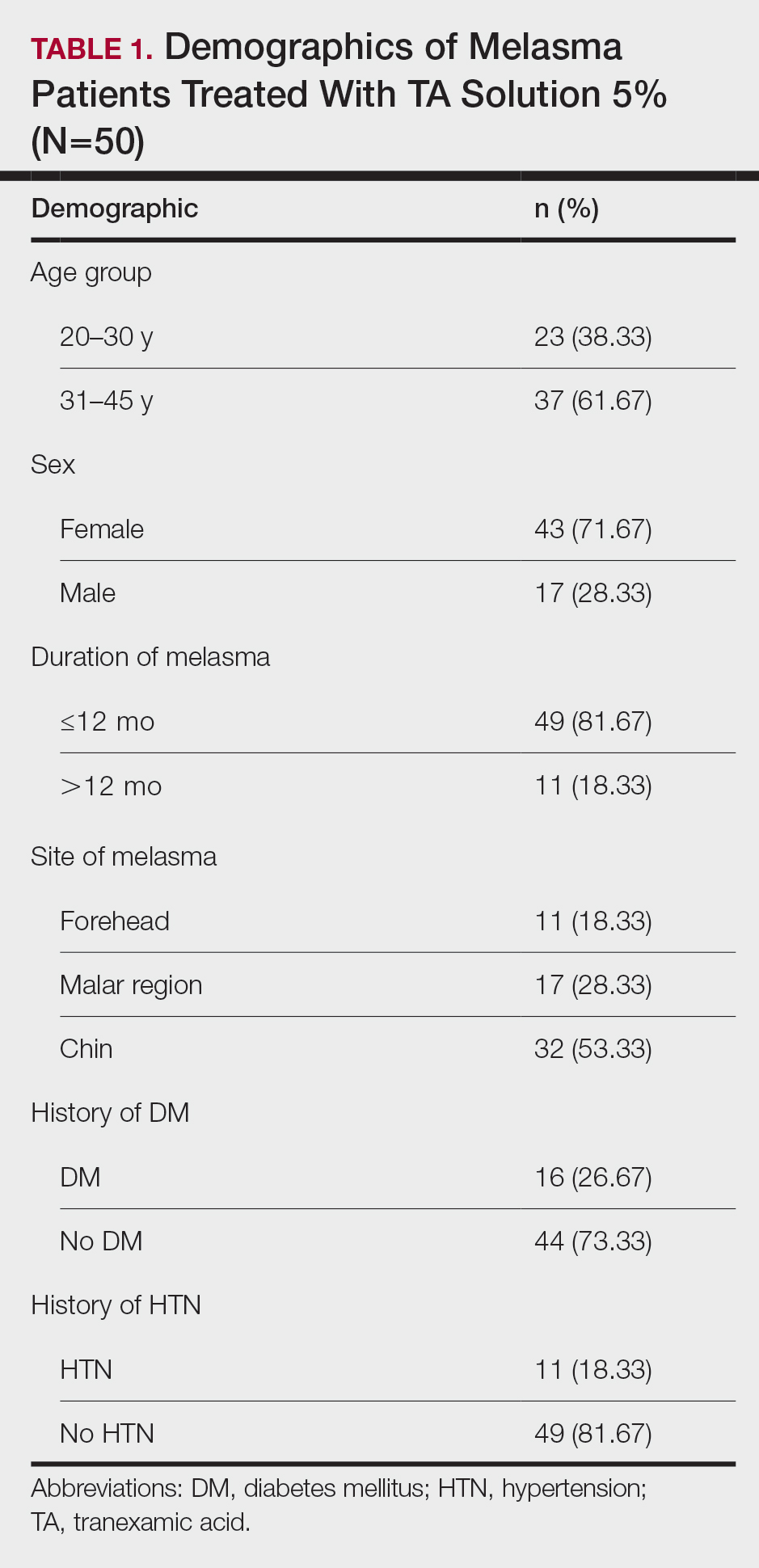

On average, residents spent 31.3 minutes reviewing their own surgeries and scoring themselves. The average time for a coaching session, which included time spent scoring, was 13.8 minutes. Residents scored themselves lower than the surgical coaches did by an average of 5.25 points (eTable 2). Residents gave themselves an average total score of 10.5, while their respective surgical coaches gave the residents an average score of 15.75. There was a trend of residents with greater surgical experience having higher OSATS scores (Figure). After the coaching session, 3 of 4 residents reported that they felt more confident in their surgical skills. All residents felt more confident in assessing their surgical skills and felt that VBC was an effective teaching measure. All residents agreed that VBC should be continued as part of their residency training.

Video-based coaching has the potential to provide several benefits for dermatology trainees. Because receiving feedback intraoperatively often can be distracting and incomplete, video review can instead allow the surgeon to focus on performing the surgery and then later focus on learning while reviewing the video.1,4 Feedback also can be more comprehensive and delivered without concern for time constraints or disturbing clinic flow as well as without the additional concern of the patient overhearing comments and feedback.3 Although independent video review in the absence of coaching can lead to improvement in surgical skills, the addition of VBC provides even greater potential educational benefit.4 During the COVID-19 pandemic, VBC allowed coaches to provide feedback without additional exposures. We utilized dermatologic surgery faculty as coaches, but this format of training also would apply to general dermatology faculty.

Another goal of VBC is to enhance a trainee’s ability to perform self-directed learning, which requires accurate self-assessment.4 Accurately assessing one’s own strengths empowers a trainee to act with appropriate confidence, while understanding one’s own weaknesses allows a trainee to effectively balance confidence and caution in daily practice.5 Interestingly, in our study all residents scored themselves lower than surgical coaches, but with 1 coaching session, the residents subsequently reported greater surgical confidence.

Time constraints can be a potential barrier to surgical coaching.4 Our study demonstrates that VBC requires minimal time investment. Increasing the speed of video playback allowed for efficient evaluation of resident surgeries without compromising the coach’s ability to provide comprehensive feedback. Our feedback sessions were performed virtually, which allowed for ease of scheduling between trainees and coaches.

Our pilot study demonstrated that VBC is relatively easy to implement in a dermatology residency training setting, leveraging relatively low-cost technologies and allowing for a means of learning that residents felt was effective. Video-based coaching requires minimal time investment from both trainees and coaches and has the potential to enhance surgical confidence. Our current study is limited by its small sample size. Future studies should include follow-up recordings and assess the efficacy of VBC in enhancing surgical skills.

- Greenberg CC, Dombrowski J, Dimick JB. Video-based surgical coaching: an emerging approach to performance improvement. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:282-283.

- Dai J, Bordeaux JS, Miller CJ, et al. Assessing surgical training and deliberate practice methods in dermatology residency: a survey of dermatology program directors. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:977-984.

- Chitgopeker P, Sidey K, Aronson A, et al. Surgical skills video-based assessment tool for dermatology residents: a prospective pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:614-616.

- Bull NB, Silverman CD, Bonrath EM. Targeted surgical coaching can improve operative self-assessment ability: a single-blinded nonrandomized trial. Surgery. 2020;167:308-313.

- Eva KW, Regehr G. Self-assessment in the health professions: a reformulation and research agenda. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 suppl):S46-S54.

To the Editor:

Video-based coaching (VBC) involves a surgeon recording a surgery and then reviewing the video with a surgical coach; it is a form of education that is gaining popularity among surgical specialties.1 Video-based education is underutilized in dermatology residency training.2 We conducted a pilot study at our dermatology residency program to evaluate the efficacy and feasibility of VBC.

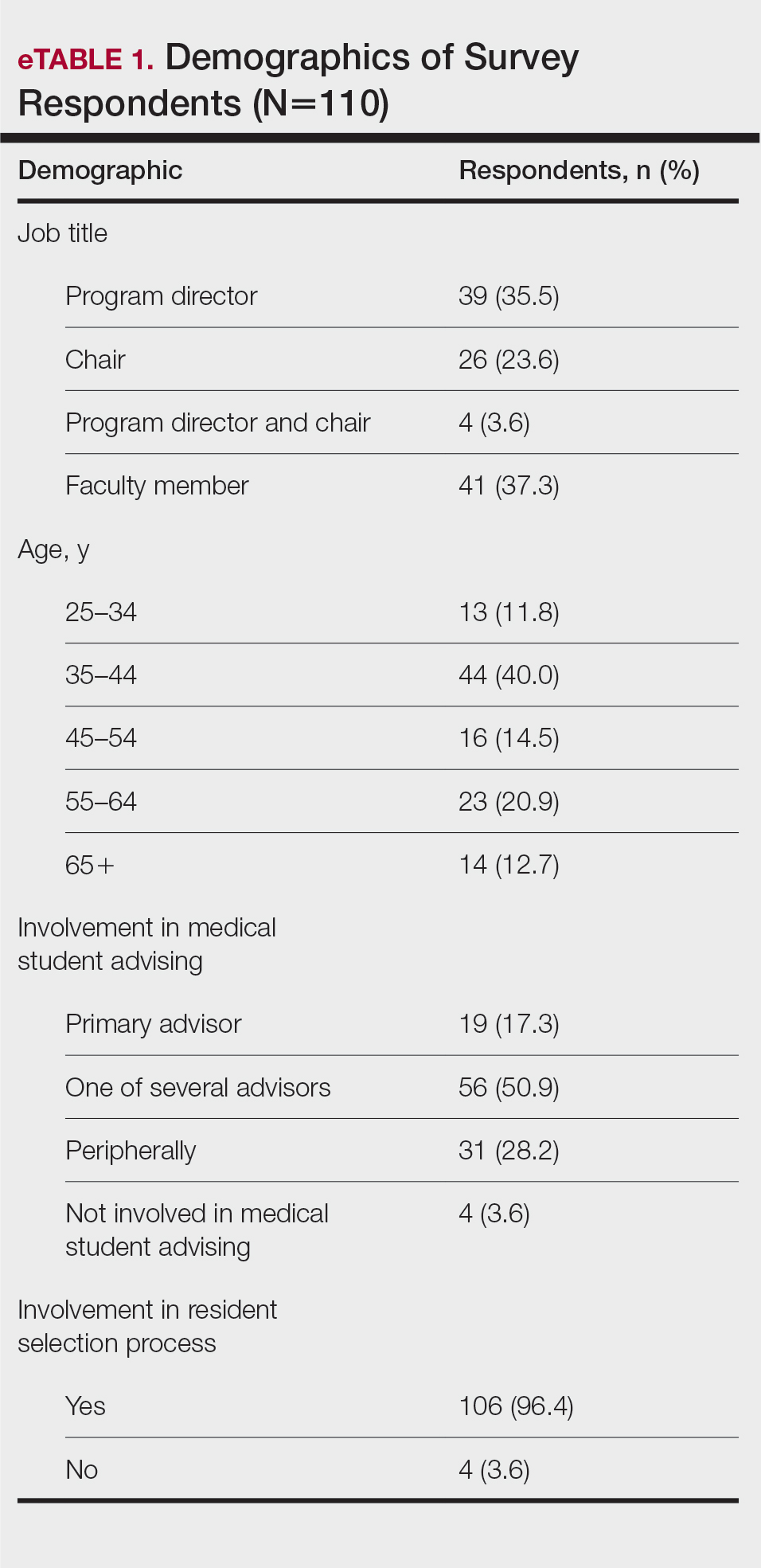

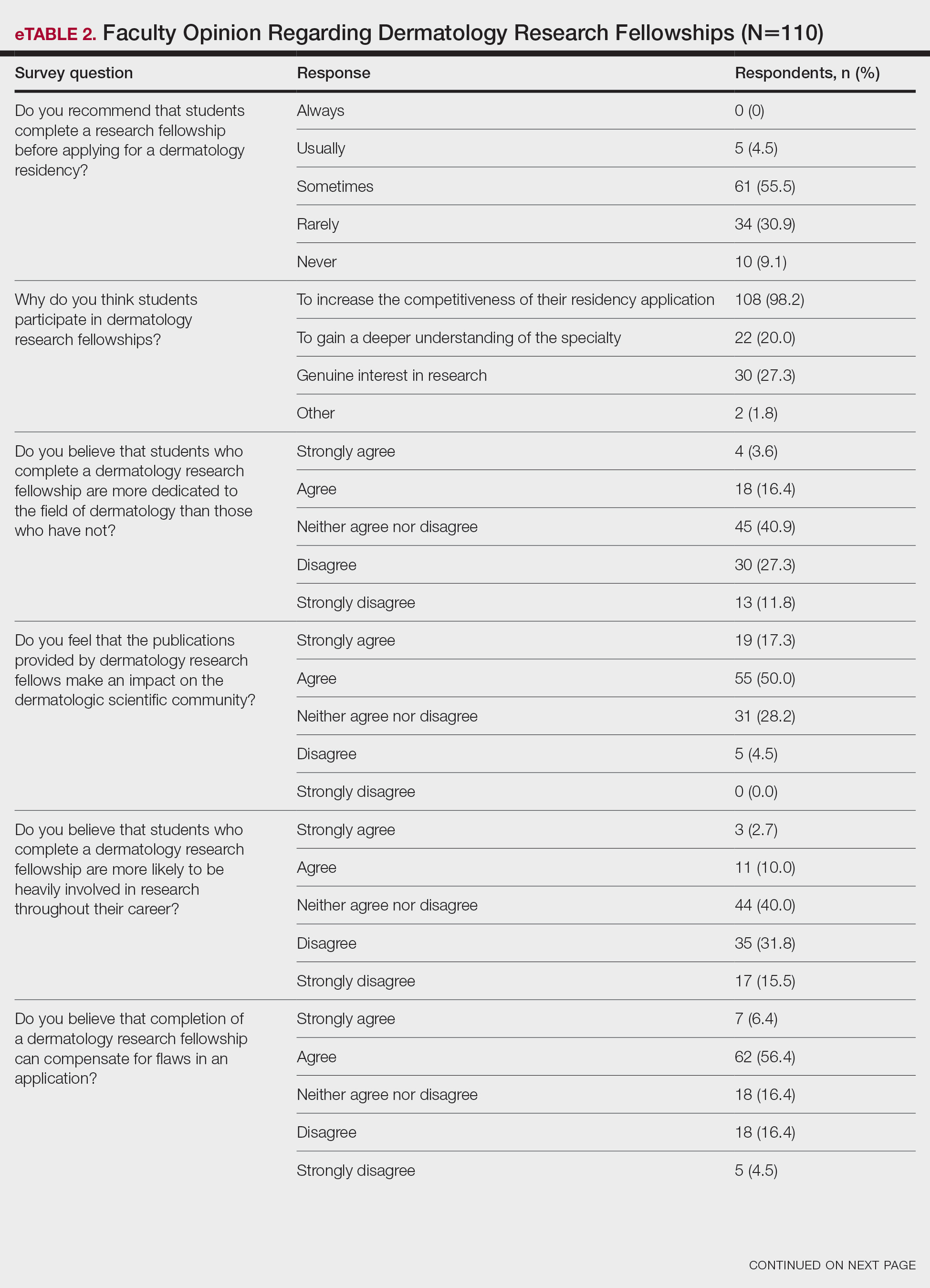

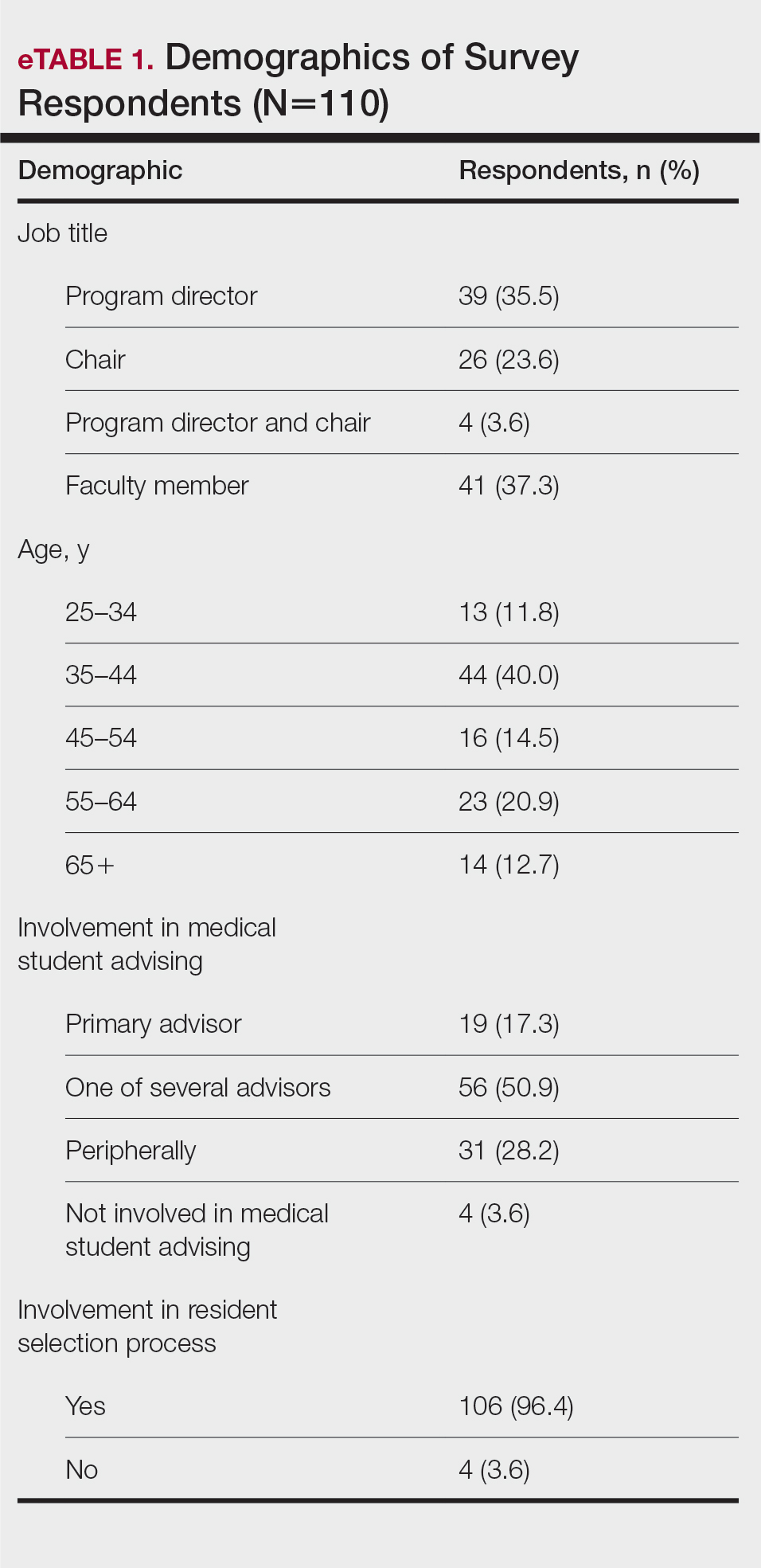

The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School institutional review board approved this study. All 4 first-year dermatology residents were recruited to participate in this study. Participants filled out a prestudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Participants used a head-mounted point-of-view camera to record themselves performing a wide local excision on the trunk or extremities of a live human patient. Participants then reviewed the recording on their own and scored themselves using the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) scoring table (scored from 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest possible score for each element), which is a validated tool for assessing surgical skills (eTable 1).3 Given that there were no assistants participating in the surgery, this element of the OSATS scoring table was excluded, making a maximum possible score of 30 and a minimum possible score of 6. After scoring themselves, participants then had a 1-on-1 coaching session with a fellowship-trained dermatologic surgeon (M.F. or T.H.) via online teleconferencing.

During the coaching session, participants and coaches reviewed the video. The surgical coaches also scored the residents using the OSATS, then residents and coaches discussed how the resident could improve using the OSATS scores as a guide. The residents then completed a poststudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Descriptive statistics were reported.

On average, residents spent 31.3 minutes reviewing their own surgeries and scoring themselves. The average time for a coaching session, which included time spent scoring, was 13.8 minutes. Residents scored themselves lower than the surgical coaches did by an average of 5.25 points (eTable 2). Residents gave themselves an average total score of 10.5, while their respective surgical coaches gave the residents an average score of 15.75. There was a trend of residents with greater surgical experience having higher OSATS scores (Figure). After the coaching session, 3 of 4 residents reported that they felt more confident in their surgical skills. All residents felt more confident in assessing their surgical skills and felt that VBC was an effective teaching measure. All residents agreed that VBC should be continued as part of their residency training.

Video-based coaching has the potential to provide several benefits for dermatology trainees. Because receiving feedback intraoperatively often can be distracting and incomplete, video review can instead allow the surgeon to focus on performing the surgery and then later focus on learning while reviewing the video.1,4 Feedback also can be more comprehensive and delivered without concern for time constraints or disturbing clinic flow as well as without the additional concern of the patient overhearing comments and feedback.3 Although independent video review in the absence of coaching can lead to improvement in surgical skills, the addition of VBC provides even greater potential educational benefit.4 During the COVID-19 pandemic, VBC allowed coaches to provide feedback without additional exposures. We utilized dermatologic surgery faculty as coaches, but this format of training also would apply to general dermatology faculty.

Another goal of VBC is to enhance a trainee’s ability to perform self-directed learning, which requires accurate self-assessment.4 Accurately assessing one’s own strengths empowers a trainee to act with appropriate confidence, while understanding one’s own weaknesses allows a trainee to effectively balance confidence and caution in daily practice.5 Interestingly, in our study all residents scored themselves lower than surgical coaches, but with 1 coaching session, the residents subsequently reported greater surgical confidence.

Time constraints can be a potential barrier to surgical coaching.4 Our study demonstrates that VBC requires minimal time investment. Increasing the speed of video playback allowed for efficient evaluation of resident surgeries without compromising the coach’s ability to provide comprehensive feedback. Our feedback sessions were performed virtually, which allowed for ease of scheduling between trainees and coaches.

Our pilot study demonstrated that VBC is relatively easy to implement in a dermatology residency training setting, leveraging relatively low-cost technologies and allowing for a means of learning that residents felt was effective. Video-based coaching requires minimal time investment from both trainees and coaches and has the potential to enhance surgical confidence. Our current study is limited by its small sample size. Future studies should include follow-up recordings and assess the efficacy of VBC in enhancing surgical skills.

To the Editor:

Video-based coaching (VBC) involves a surgeon recording a surgery and then reviewing the video with a surgical coach; it is a form of education that is gaining popularity among surgical specialties.1 Video-based education is underutilized in dermatology residency training.2 We conducted a pilot study at our dermatology residency program to evaluate the efficacy and feasibility of VBC.

The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School institutional review board approved this study. All 4 first-year dermatology residents were recruited to participate in this study. Participants filled out a prestudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Participants used a head-mounted point-of-view camera to record themselves performing a wide local excision on the trunk or extremities of a live human patient. Participants then reviewed the recording on their own and scored themselves using the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) scoring table (scored from 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest possible score for each element), which is a validated tool for assessing surgical skills (eTable 1).3 Given that there were no assistants participating in the surgery, this element of the OSATS scoring table was excluded, making a maximum possible score of 30 and a minimum possible score of 6. After scoring themselves, participants then had a 1-on-1 coaching session with a fellowship-trained dermatologic surgeon (M.F. or T.H.) via online teleconferencing.