User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Diffuse Rash With Associated Ulceration

The Diagnosis: Epidermotropic CD8+ T-Cell Lymphoma

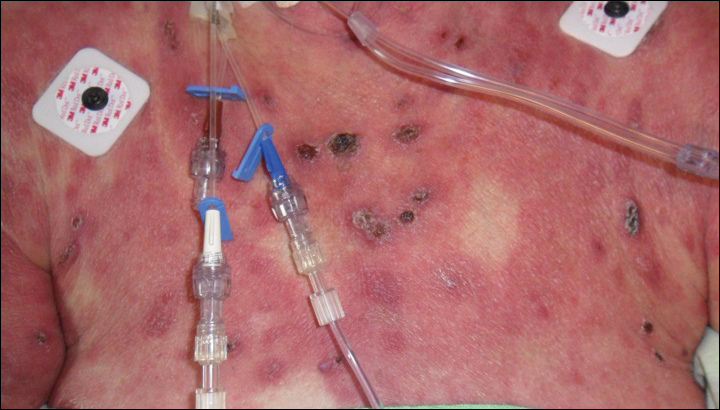

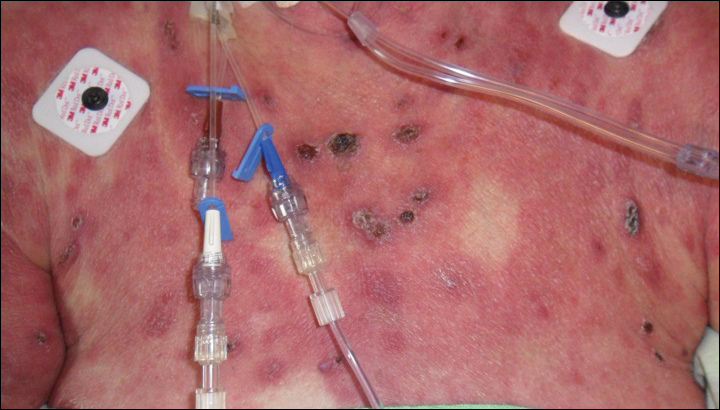

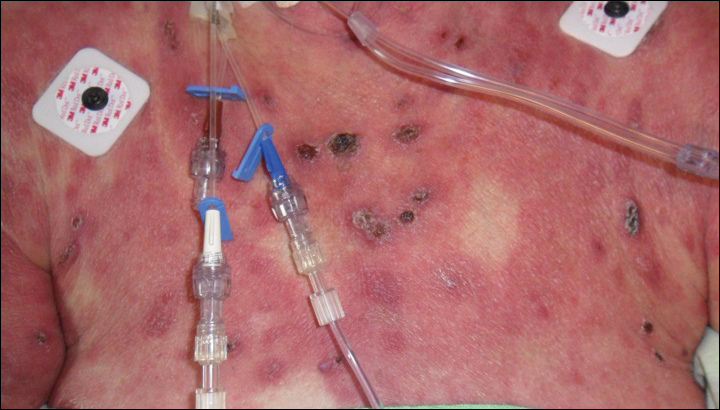

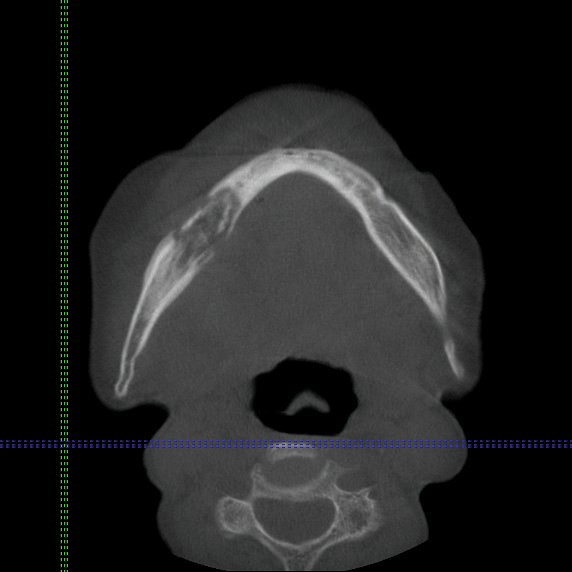

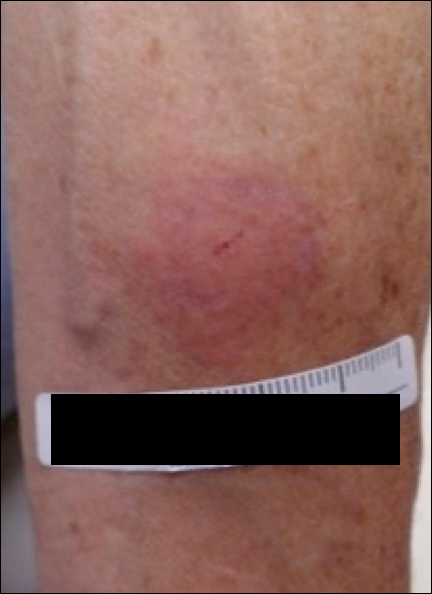

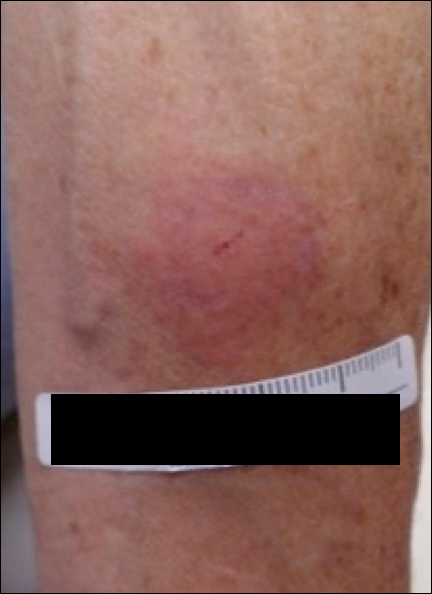

Epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma is a rare aggressive form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), accounting for less than 1% of all cases.1 Since this subtype of CTCL was first described in 1999 by Berti et al,2 approximately 45 cases have been reported in the literature.1 It typically is found in elderly men and presents as disseminated or localized papules, patches, plaques, nodules, and tumors, often with central necrosis, ulceration, crusting, and hemorrhage (Figure 1).1,3 These lesions rapidly progress and can affect any skin site, but acral accentuation and mucosal involvement are common.4 Due to the rapidly progressive nature of this disease, patients typically present with widespread plaque- and tumor-stage disease.3 Frequency of systemic spread is high, with metastasis to the central nervous system, lungs, and testes being most common. Lymph nodes typically are spared, helping to differentiate this form of CTCL from classic mycosis fungoides.

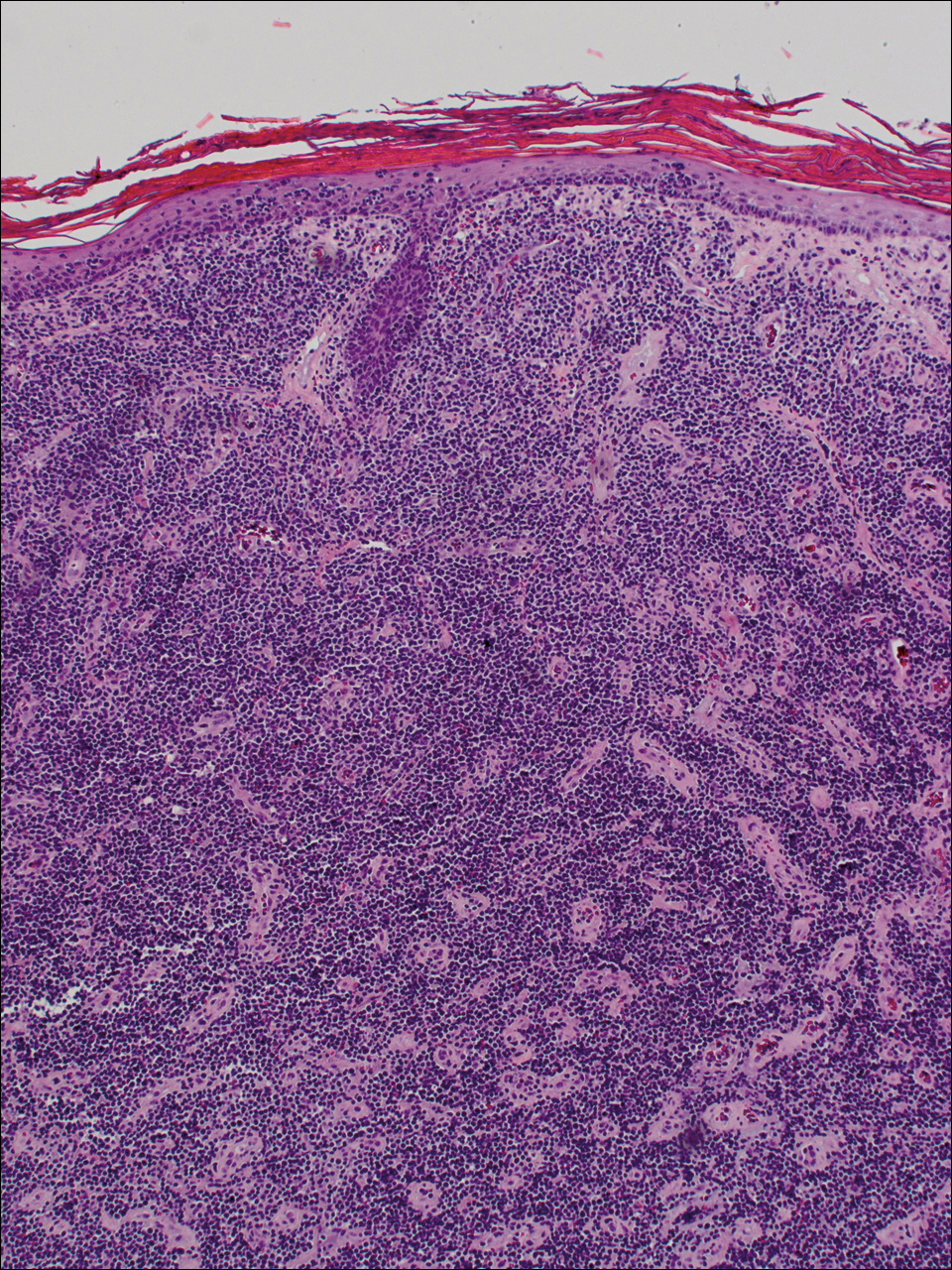

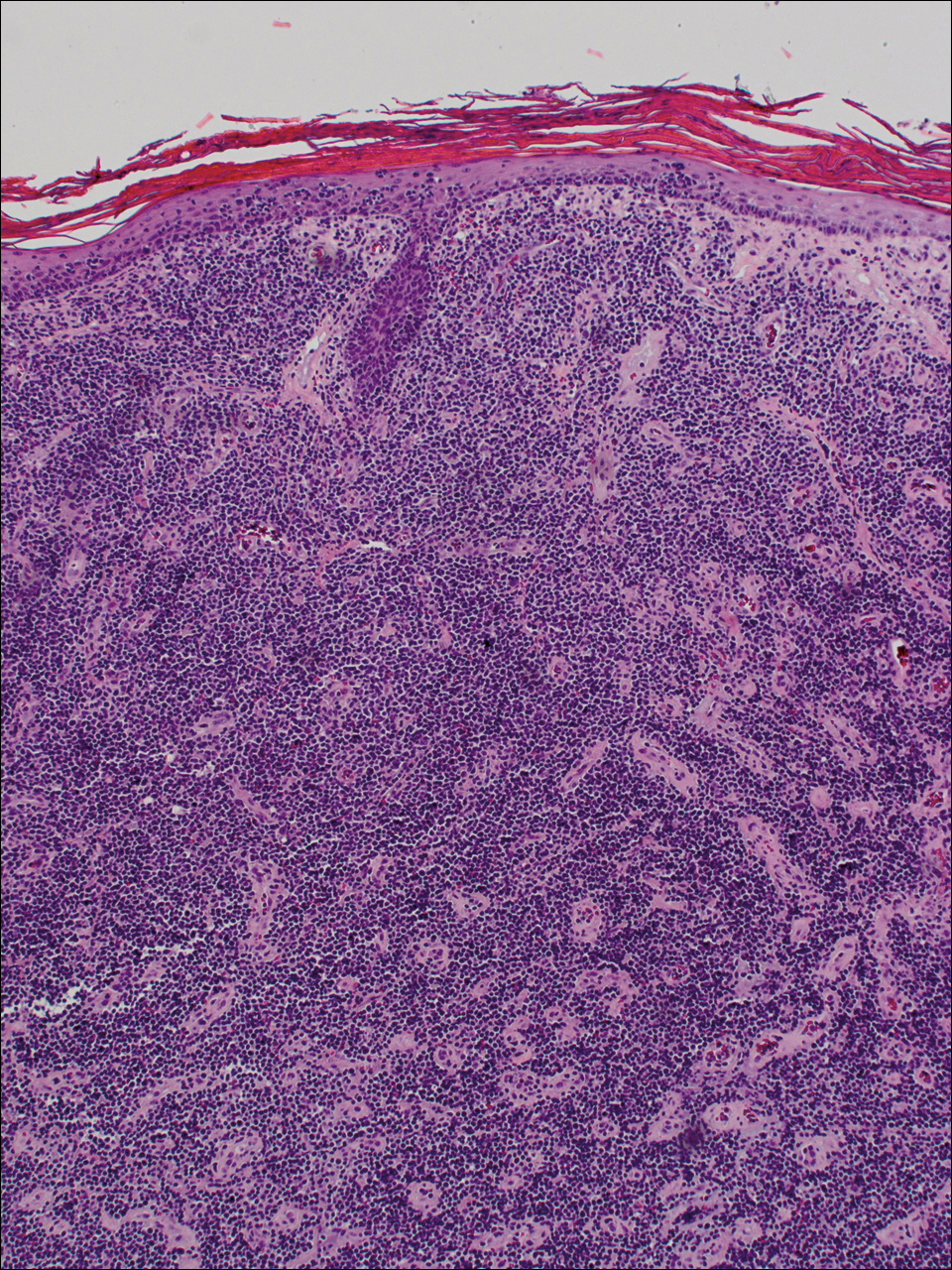

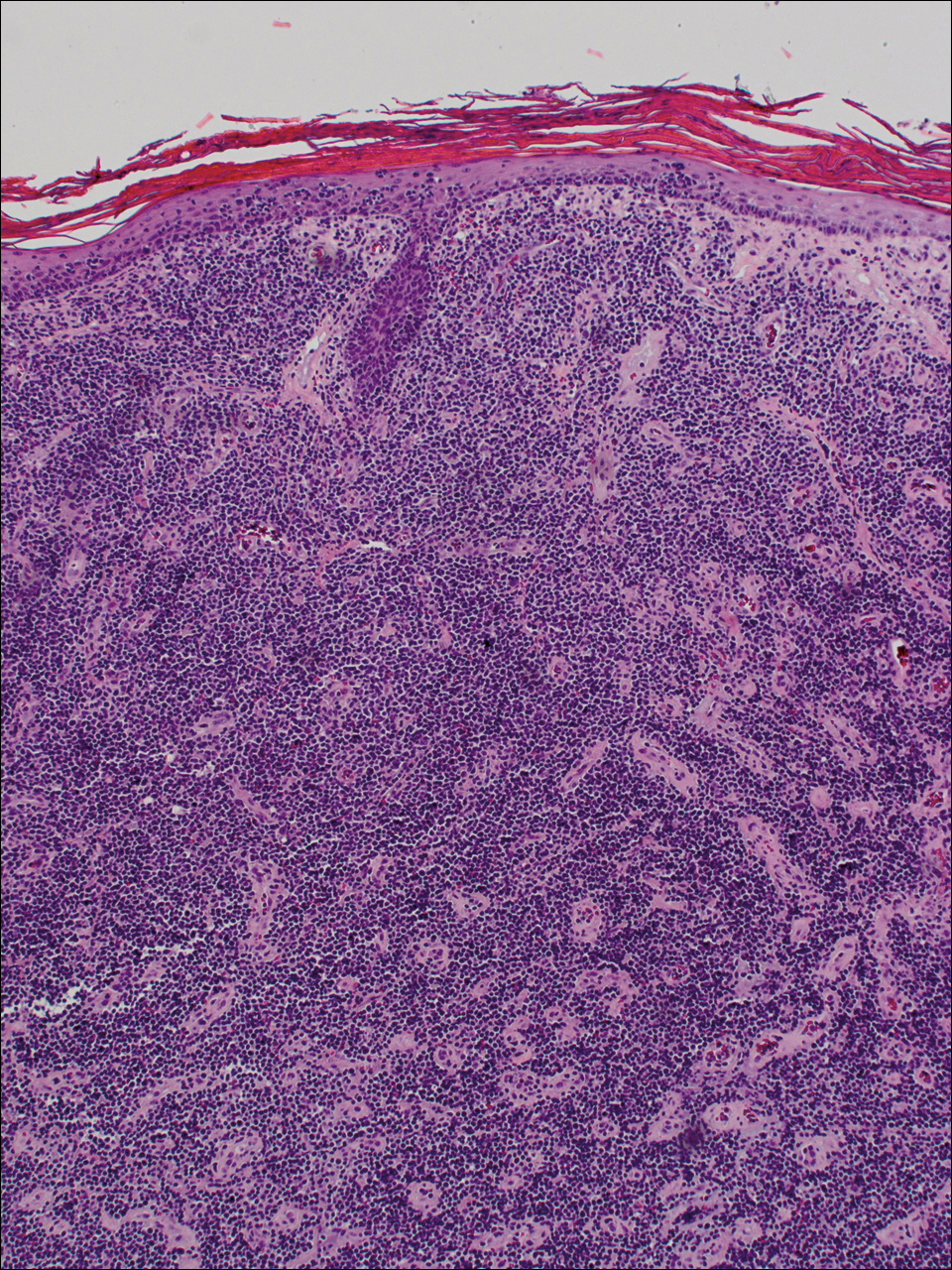

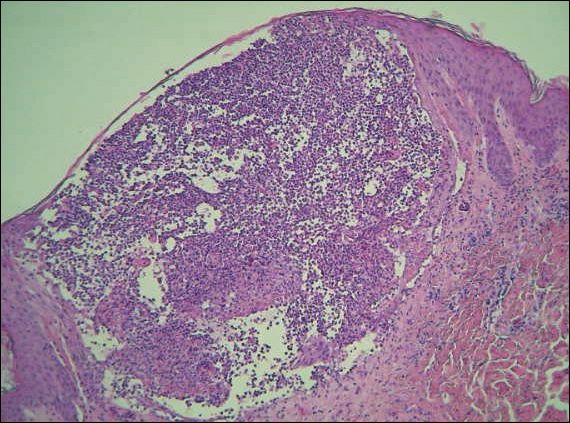

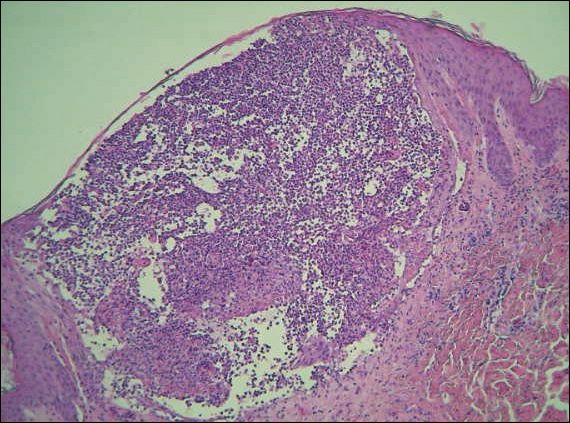

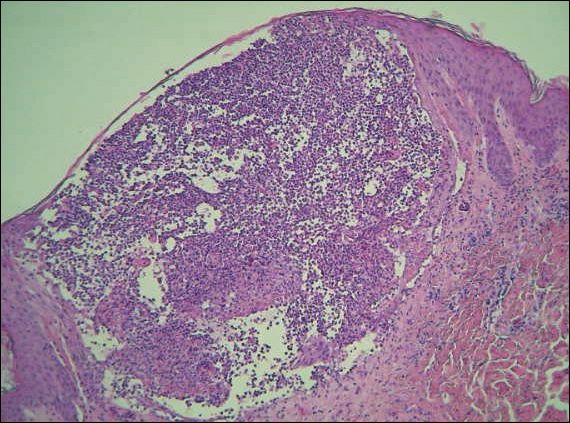

Diagnosis of epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma is based on a combination of clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical features. Histopathologic components include epidermotropism, particularly in the basal cell layer, in a pagetoid or linear pattern. A second feature is a dermal infiltrate consisting of a nodular or diffuse pattern of atypical lymphocytes that extend to the subcutaneous fat (Figure 2). All cases of epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma express the CD8+ phenotype and most have a high Ki-67 proliferation index and are CD3, CD45RA, and/or T-cell intracellular antigen 1 positive.1

Due to its aggressive nature, epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma has a poor prognosis, with an average 5-year survival rate of 18% and median survival of 22.5 months.3 Treatment proves difficult as conventional therapies for CD4+ CTCL have proven ineffective for epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma. Partial response has been seen with bexarotene alone and with total skin electron beam therapy combined with oral retinoids.1

- Nofal A, Abdel-Mawla MY, Assaf M, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma: proposed diagnostic criteria and therapeutic evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:748-759.

- Berti E, Tomasini D, Vermeer MH, et al. Primary cutaneous CD8-positive epidermotropic cytotoxic T cell lymphomas. a distinct clinicopathological entity with an aggressive clinical behavior. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:483-492.

- Gormley RH, Hess SD, Anand D, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:300-307.

- Nofal A, Abdel-Mawla MY, Assaf M, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T cell lymphoma: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:76-81.

The Diagnosis: Epidermotropic CD8+ T-Cell Lymphoma

Epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma is a rare aggressive form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), accounting for less than 1% of all cases.1 Since this subtype of CTCL was first described in 1999 by Berti et al,2 approximately 45 cases have been reported in the literature.1 It typically is found in elderly men and presents as disseminated or localized papules, patches, plaques, nodules, and tumors, often with central necrosis, ulceration, crusting, and hemorrhage (Figure 1).1,3 These lesions rapidly progress and can affect any skin site, but acral accentuation and mucosal involvement are common.4 Due to the rapidly progressive nature of this disease, patients typically present with widespread plaque- and tumor-stage disease.3 Frequency of systemic spread is high, with metastasis to the central nervous system, lungs, and testes being most common. Lymph nodes typically are spared, helping to differentiate this form of CTCL from classic mycosis fungoides.

Diagnosis of epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma is based on a combination of clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical features. Histopathologic components include epidermotropism, particularly in the basal cell layer, in a pagetoid or linear pattern. A second feature is a dermal infiltrate consisting of a nodular or diffuse pattern of atypical lymphocytes that extend to the subcutaneous fat (Figure 2). All cases of epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma express the CD8+ phenotype and most have a high Ki-67 proliferation index and are CD3, CD45RA, and/or T-cell intracellular antigen 1 positive.1

Due to its aggressive nature, epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma has a poor prognosis, with an average 5-year survival rate of 18% and median survival of 22.5 months.3 Treatment proves difficult as conventional therapies for CD4+ CTCL have proven ineffective for epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma. Partial response has been seen with bexarotene alone and with total skin electron beam therapy combined with oral retinoids.1

The Diagnosis: Epidermotropic CD8+ T-Cell Lymphoma

Epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma is a rare aggressive form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), accounting for less than 1% of all cases.1 Since this subtype of CTCL was first described in 1999 by Berti et al,2 approximately 45 cases have been reported in the literature.1 It typically is found in elderly men and presents as disseminated or localized papules, patches, plaques, nodules, and tumors, often with central necrosis, ulceration, crusting, and hemorrhage (Figure 1).1,3 These lesions rapidly progress and can affect any skin site, but acral accentuation and mucosal involvement are common.4 Due to the rapidly progressive nature of this disease, patients typically present with widespread plaque- and tumor-stage disease.3 Frequency of systemic spread is high, with metastasis to the central nervous system, lungs, and testes being most common. Lymph nodes typically are spared, helping to differentiate this form of CTCL from classic mycosis fungoides.

Diagnosis of epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma is based on a combination of clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical features. Histopathologic components include epidermotropism, particularly in the basal cell layer, in a pagetoid or linear pattern. A second feature is a dermal infiltrate consisting of a nodular or diffuse pattern of atypical lymphocytes that extend to the subcutaneous fat (Figure 2). All cases of epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma express the CD8+ phenotype and most have a high Ki-67 proliferation index and are CD3, CD45RA, and/or T-cell intracellular antigen 1 positive.1

Due to its aggressive nature, epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma has a poor prognosis, with an average 5-year survival rate of 18% and median survival of 22.5 months.3 Treatment proves difficult as conventional therapies for CD4+ CTCL have proven ineffective for epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma. Partial response has been seen with bexarotene alone and with total skin electron beam therapy combined with oral retinoids.1

- Nofal A, Abdel-Mawla MY, Assaf M, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma: proposed diagnostic criteria and therapeutic evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:748-759.

- Berti E, Tomasini D, Vermeer MH, et al. Primary cutaneous CD8-positive epidermotropic cytotoxic T cell lymphomas. a distinct clinicopathological entity with an aggressive clinical behavior. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:483-492.

- Gormley RH, Hess SD, Anand D, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:300-307.

- Nofal A, Abdel-Mawla MY, Assaf M, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T cell lymphoma: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:76-81.

- Nofal A, Abdel-Mawla MY, Assaf M, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma: proposed diagnostic criteria and therapeutic evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:748-759.

- Berti E, Tomasini D, Vermeer MH, et al. Primary cutaneous CD8-positive epidermotropic cytotoxic T cell lymphomas. a distinct clinicopathological entity with an aggressive clinical behavior. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:483-492.

- Gormley RH, Hess SD, Anand D, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:300-307.

- Nofal A, Abdel-Mawla MY, Assaf M, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T cell lymphoma: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:76-81.

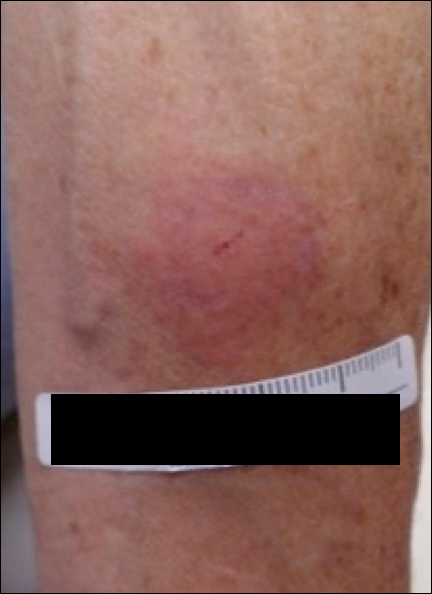

A 72-year-old woman who was admitted for pneumonia and acute hypoxic respiratory failure was seen for an inpatient consultation for a diffuse rash with associated ulceration. She reported a rash of 20 months' duration that began on the legs and then spread to the trunk, arms, head, and neck with minimal pruritus and no pain or photosensitivity. She had been treated with hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone without improvement. The patient noted recent ulceration on the rash. Physical examination revealed violaceous patches, plaques, nodules, and tumors with rare ulceration involving the face, trunk, and extremities. Biopsy showed a diffuse infiltration of the dermis with medium-sized atypical lymphocytes with scant cytoplasm and round to irregular hyperchromatic nuclei with clumped chromatin. Epidermotropism with small collections of atypical lymphocytes also was present within the epidermis.

Acne and Antiaging: Is There a Connection?

As a chronic inflammatory skin disease well known for its poor cosmesis including scarring, residual macular erythema, and postinflammatory pigment alteration, acne vulgaris may, according to recent research, confer some antiaging benefits to affected patients. In a research letter published online on September 27 in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, Ribero et al analyzed white blood cells and found that women who said they had acne had longer telomeres (the "caps" at the end of chromosomes that protect them from deteriorating following repeated cell replication). Telomere length, or rather shortening, has been correlated with age-related degenerative change, according to Saum et al (Exp Gerontol. 2014;58:250-255), and therefore the thinking is that in women with acne, something is going on that maintains the length of the cellular guardians. Let's clarify a couple things to help us all understand the why and what.

The impetus of this study, according to Ribero et al, was the observation that women with acne show signs of aging later than those who have never had acne. I personally have not witnessed this finding in my patients, and given that acne in its essence is a disease of chronic inflammation resulting from, for example, persistent activation of toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) pattern recognition receptors, one would think the skin damage accrued would make these individuals look older, right? Last I checked, pitted scarring does not make one immediately think of the fountain of youth.

The results from the study show that there is a link between acne and longer telomeres, but the study did not show that telomere length is a cause of acne, that women with longer telomeres had fewer signs of skin aging, or that women with acne lived longer.

Given these points, Ribero et al concluded that "delayed skin aging may be due to reduced senescence," which means that skin aging may be delayed because the longer telomeres in the cells protect them from deterioration. They did find that the expression of one gene in particular was reduced in women with acne--the regulatory gene zinc finger protein 420, ZNF420--suggesting that those without acne may produce more of a particular protein linked to that gene, though the significance is unclear.

What's the issue?

This study is interesting, but it is important not to make any broad conclusions, such as those who get acne will live longer or look younger longer regardless of other factors such as acne treatment, comorbidities, or even environmental factors. This study may give more support for the genetic contribution of acne, but much more work is needed to determine the clinical relevance. For starters, what about men?

Would you assure your acne patients that their disease may be for their own cosmetic good?

As a chronic inflammatory skin disease well known for its poor cosmesis including scarring, residual macular erythema, and postinflammatory pigment alteration, acne vulgaris may, according to recent research, confer some antiaging benefits to affected patients. In a research letter published online on September 27 in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, Ribero et al analyzed white blood cells and found that women who said they had acne had longer telomeres (the "caps" at the end of chromosomes that protect them from deteriorating following repeated cell replication). Telomere length, or rather shortening, has been correlated with age-related degenerative change, according to Saum et al (Exp Gerontol. 2014;58:250-255), and therefore the thinking is that in women with acne, something is going on that maintains the length of the cellular guardians. Let's clarify a couple things to help us all understand the why and what.

The impetus of this study, according to Ribero et al, was the observation that women with acne show signs of aging later than those who have never had acne. I personally have not witnessed this finding in my patients, and given that acne in its essence is a disease of chronic inflammation resulting from, for example, persistent activation of toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) pattern recognition receptors, one would think the skin damage accrued would make these individuals look older, right? Last I checked, pitted scarring does not make one immediately think of the fountain of youth.

The results from the study show that there is a link between acne and longer telomeres, but the study did not show that telomere length is a cause of acne, that women with longer telomeres had fewer signs of skin aging, or that women with acne lived longer.

Given these points, Ribero et al concluded that "delayed skin aging may be due to reduced senescence," which means that skin aging may be delayed because the longer telomeres in the cells protect them from deterioration. They did find that the expression of one gene in particular was reduced in women with acne--the regulatory gene zinc finger protein 420, ZNF420--suggesting that those without acne may produce more of a particular protein linked to that gene, though the significance is unclear.

What's the issue?

This study is interesting, but it is important not to make any broad conclusions, such as those who get acne will live longer or look younger longer regardless of other factors such as acne treatment, comorbidities, or even environmental factors. This study may give more support for the genetic contribution of acne, but much more work is needed to determine the clinical relevance. For starters, what about men?

Would you assure your acne patients that their disease may be for their own cosmetic good?

As a chronic inflammatory skin disease well known for its poor cosmesis including scarring, residual macular erythema, and postinflammatory pigment alteration, acne vulgaris may, according to recent research, confer some antiaging benefits to affected patients. In a research letter published online on September 27 in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, Ribero et al analyzed white blood cells and found that women who said they had acne had longer telomeres (the "caps" at the end of chromosomes that protect them from deteriorating following repeated cell replication). Telomere length, or rather shortening, has been correlated with age-related degenerative change, according to Saum et al (Exp Gerontol. 2014;58:250-255), and therefore the thinking is that in women with acne, something is going on that maintains the length of the cellular guardians. Let's clarify a couple things to help us all understand the why and what.

The impetus of this study, according to Ribero et al, was the observation that women with acne show signs of aging later than those who have never had acne. I personally have not witnessed this finding in my patients, and given that acne in its essence is a disease of chronic inflammation resulting from, for example, persistent activation of toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) pattern recognition receptors, one would think the skin damage accrued would make these individuals look older, right? Last I checked, pitted scarring does not make one immediately think of the fountain of youth.

The results from the study show that there is a link between acne and longer telomeres, but the study did not show that telomere length is a cause of acne, that women with longer telomeres had fewer signs of skin aging, or that women with acne lived longer.

Given these points, Ribero et al concluded that "delayed skin aging may be due to reduced senescence," which means that skin aging may be delayed because the longer telomeres in the cells protect them from deterioration. They did find that the expression of one gene in particular was reduced in women with acne--the regulatory gene zinc finger protein 420, ZNF420--suggesting that those without acne may produce more of a particular protein linked to that gene, though the significance is unclear.

What's the issue?

This study is interesting, but it is important not to make any broad conclusions, such as those who get acne will live longer or look younger longer regardless of other factors such as acne treatment, comorbidities, or even environmental factors. This study may give more support for the genetic contribution of acne, but much more work is needed to determine the clinical relevance. For starters, what about men?

Would you assure your acne patients that their disease may be for their own cosmetic good?

Autoimmune Progesterone Dermatitis Presenting With Purpura

To the Editor:

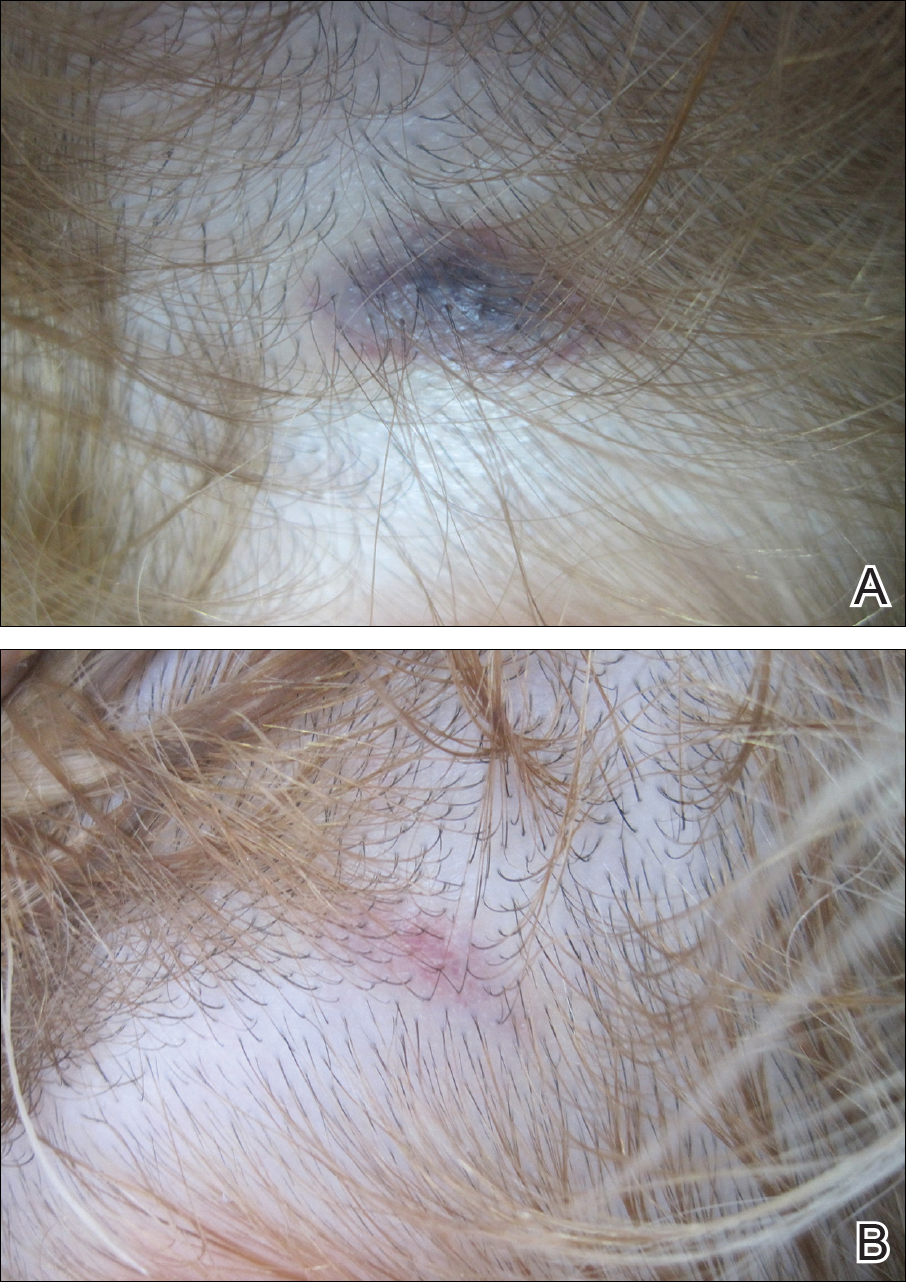

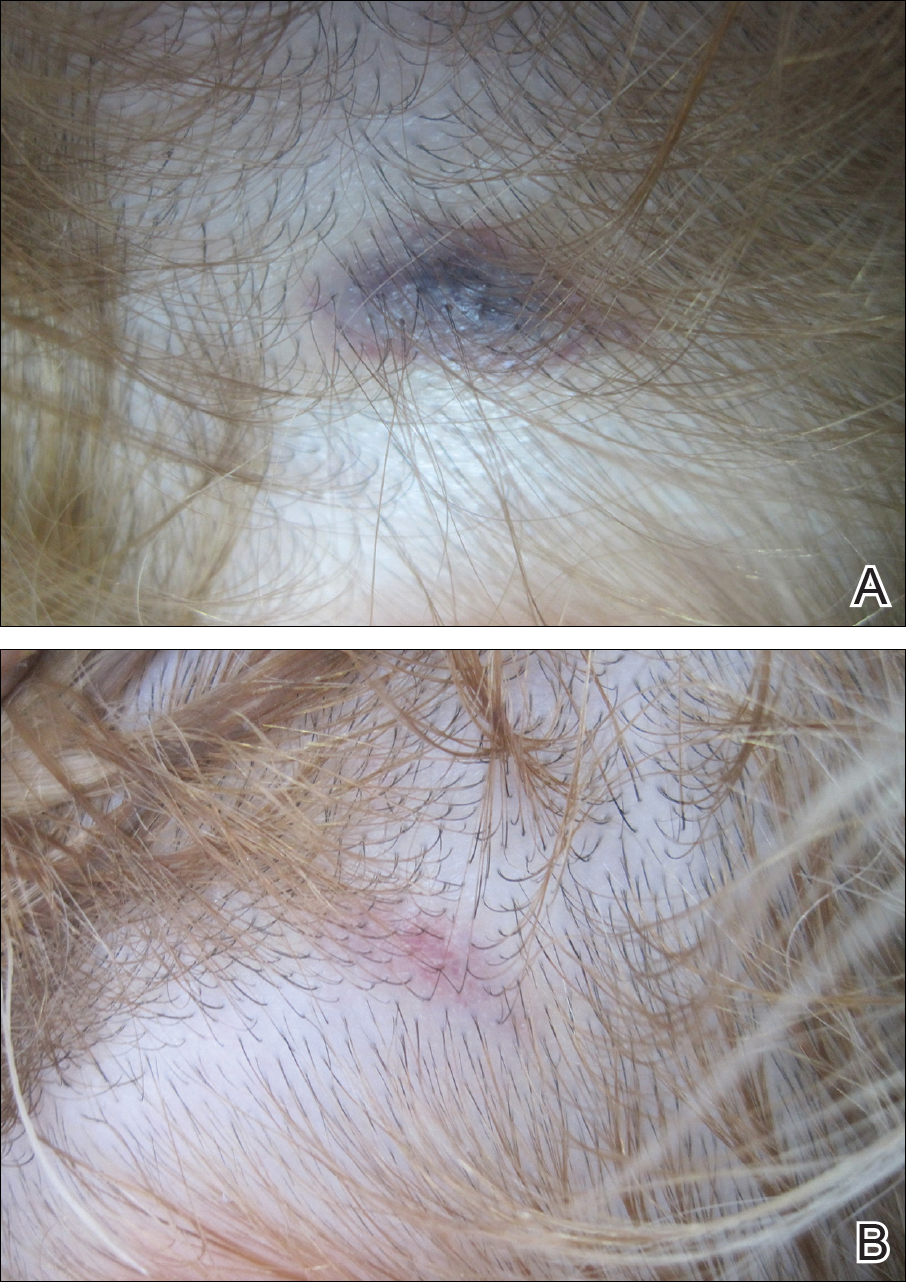

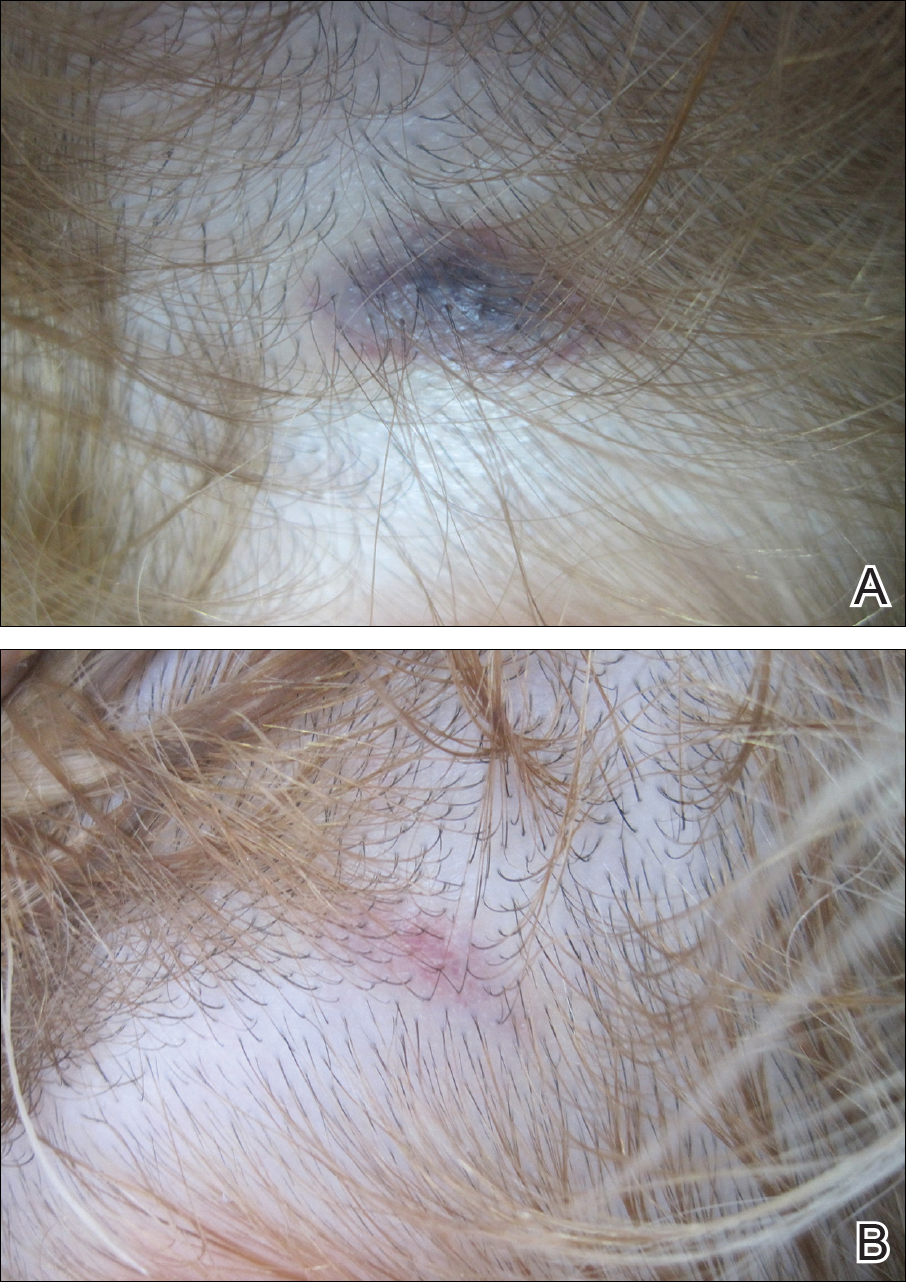

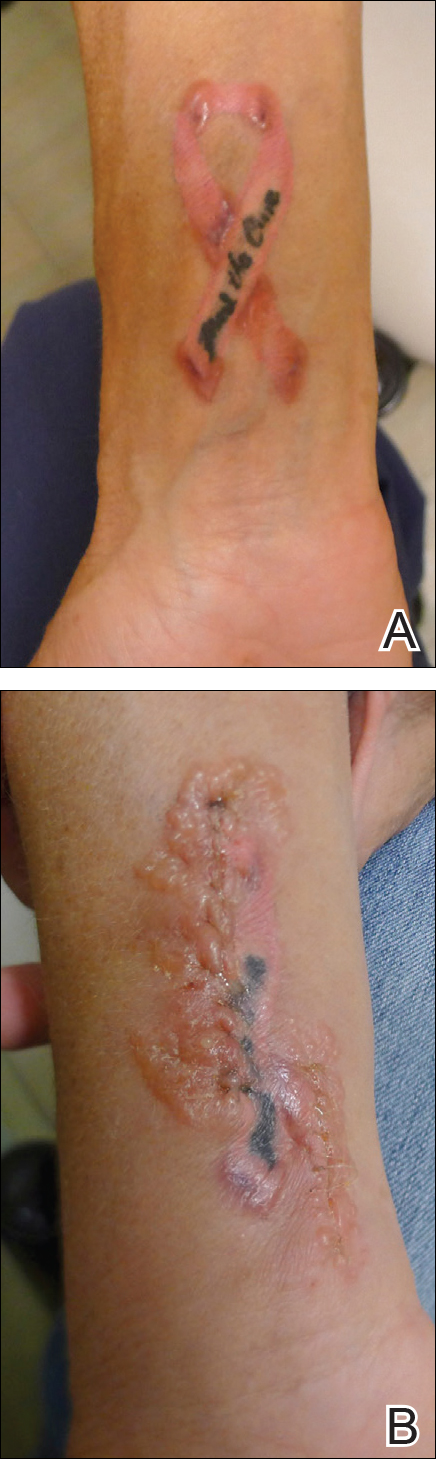

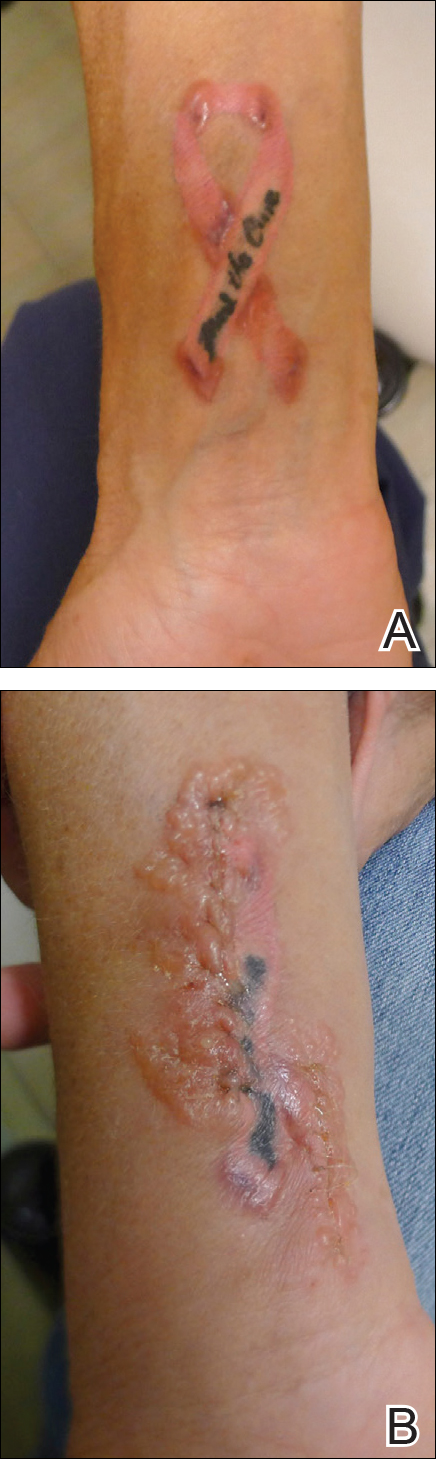

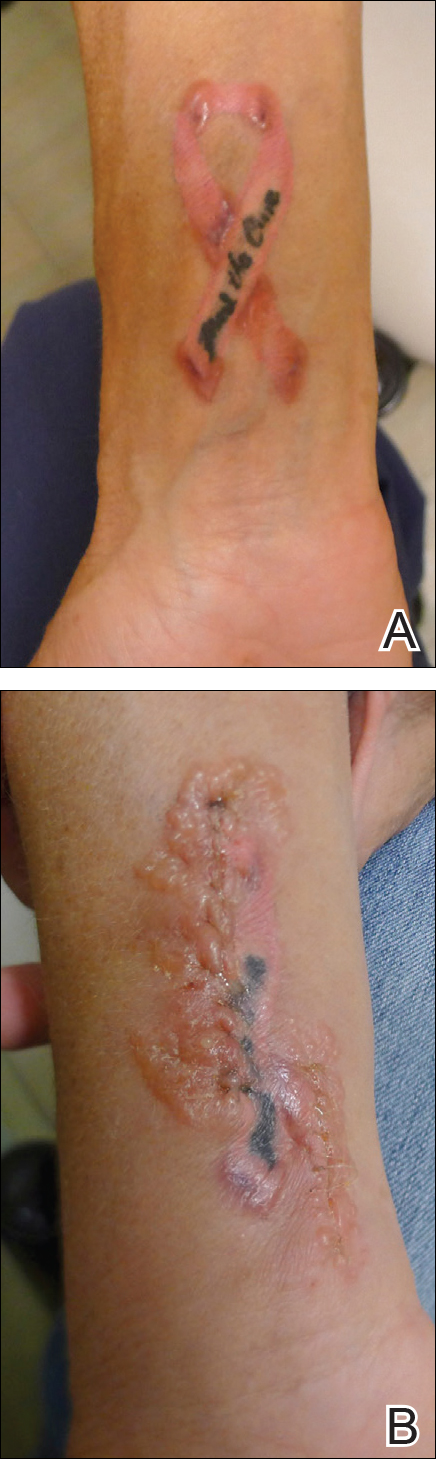

A 32-year-old woman presented with a recurrent painful eruption on the scalp of 1 year's duration. The lesion occurred on the left temporal region 1 week prior to menstruation and spontaneously resolved following menses; it recurred every month for 1 year. She had no notable medical history. She had taken oral contraceptive pills for 4 years and stopped 2 years prior to the development of the lesions. Dermatologic examination revealed a purple-colored, violaceous, centrally elevated, painful plaque that measured 2 cm in diameter in the left temporal region of the scalp (Figure, A). Laboratory test results were within reference range. The lesion spontaneously resolved with mild residual erythema at a follow-up visit after menstruation (Figure, B).

Because the eruption occurred and relapsed with the patient's menstrual cycle, we suspected progesterone hypersensitivity. An intradermal skin test was performed on the forearm with 0.05 mL of medroxyprogesterone acetate, and saline was used as a negative control. An indurated erythematous nodule occurred on the progesterone-treated side within 6 hours. Based on these findings and the patient's history, she was diagnosed with autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (APD). We recommended her to use gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists as treatment, but the patient refused. At 6-month follow-up she had recurrent lesions but did not report any concerns.

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is a rare condition that is characterized by cyclical skin eruptions, typically occurring in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle with spontaneous resolution after menses.1,2 It was first described by Geber3 in a patient with cyclical urticarial lesions. In 1964, Shelley et al4 characterized APD in a 27-year-old woman with a pruritic vesicular eruption with cyclical premenstrual exacerbations. Although it is believed there is no genetic predisposition to APD, a case series involving 3 sisters demonstrated that genetic susceptibility might play a role in the etiology.5 The etiology of APD is still unknown. It is thought to represent an autoimmune reaction to endogenous or exogenous progesterone.1 Our patient also had used oral contraceptives for 4 years and this exogenous progesterone might have played a role in the sensitization of the patient and the development of this autoimmune reaction.

The clinical features of APD usually begin 3 to 10 days prior to menstruation and end 1 to 2 days after menses. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis can present in a variety of forms including eczema, erythema multiforme, erythema annulare centrifugum, fixed drug eruption, stomatitis, folliculitis, urticaria, and angioedema.6 A case of APD presenting with petechiae and purpura has been reported.7 There are no specific histologic findings for APD.8 Demonstration of progesterone sensitivity with a progesterone challenge test is the mainstay of diagnosis. Immediate urticaria may occur in some patients, with others experiencing a delayed reaction peaking at 24 to 96 hours.9 The main criteria of APD include the following: recurrent cyclic lesions related to the menstrual cycle; positive intradermal progesterone skin test; and prevention of lesions by inhibiting ovulation.1 Two of these criteria were positive in our patient, but we did not use any medications to prevent ovulation at the patient's request.

Current treatment modalities often attempt to inhibit the secretion of endogenous progesterone by suppressing ovulation. Oral contraceptives and conjugated estrogens have limited efficacy rates.8 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (ie, buserelin, triptorelin) have been used with success.1,6 Tamoxifen and danazol are other treatment options. For cases refractory to medical treatments, bilateral oophorectomy can be considered a definitive treatment.6

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis may present in many different clinical forms. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients with recurrent skin lesions related to menstrual cycle both in women of childbearing age and in men taking synthetic progesterone.

- Lee MK, Lee WY, Yong SJ, et al. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis misdiagnosed as allergic contact dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:141-144.

- García-Ortega P, Scorza E. Progesterone autoimmune dermatitis with positive autologous serum skin test result. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:495-498.

- Geber J. Desensitization in the treatment of menstrual intoxication and other allergic symptoms. Br J Dermatol. 1930;51:265-268.

- Shelley WB, Preucel RW, Spoont SS. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: cure by oophorectomy. JAMA. 1964;190:35-38.

- Chawla SV, Quirk C, Sondheimer SJ, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:341-342.

- Medeiros S, Rodrigues-Alves R, Costa M, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: treatment with oophorectomy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:e12-e13.

- Wintzen M, Goor-van Egmond MB, Noz KC. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting with purpura and petechiae. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:316.

- Baptist AP, Baldwin JL. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis in a patient with endometriosis: case report and review of the literature. Clin Mol Allergy. 2004;2:10.

- Le K, Wood G. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis diagnosed by progesterone pessary. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:139-141.

To the Editor:

A 32-year-old woman presented with a recurrent painful eruption on the scalp of 1 year's duration. The lesion occurred on the left temporal region 1 week prior to menstruation and spontaneously resolved following menses; it recurred every month for 1 year. She had no notable medical history. She had taken oral contraceptive pills for 4 years and stopped 2 years prior to the development of the lesions. Dermatologic examination revealed a purple-colored, violaceous, centrally elevated, painful plaque that measured 2 cm in diameter in the left temporal region of the scalp (Figure, A). Laboratory test results were within reference range. The lesion spontaneously resolved with mild residual erythema at a follow-up visit after menstruation (Figure, B).

Because the eruption occurred and relapsed with the patient's menstrual cycle, we suspected progesterone hypersensitivity. An intradermal skin test was performed on the forearm with 0.05 mL of medroxyprogesterone acetate, and saline was used as a negative control. An indurated erythematous nodule occurred on the progesterone-treated side within 6 hours. Based on these findings and the patient's history, she was diagnosed with autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (APD). We recommended her to use gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists as treatment, but the patient refused. At 6-month follow-up she had recurrent lesions but did not report any concerns.

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is a rare condition that is characterized by cyclical skin eruptions, typically occurring in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle with spontaneous resolution after menses.1,2 It was first described by Geber3 in a patient with cyclical urticarial lesions. In 1964, Shelley et al4 characterized APD in a 27-year-old woman with a pruritic vesicular eruption with cyclical premenstrual exacerbations. Although it is believed there is no genetic predisposition to APD, a case series involving 3 sisters demonstrated that genetic susceptibility might play a role in the etiology.5 The etiology of APD is still unknown. It is thought to represent an autoimmune reaction to endogenous or exogenous progesterone.1 Our patient also had used oral contraceptives for 4 years and this exogenous progesterone might have played a role in the sensitization of the patient and the development of this autoimmune reaction.

The clinical features of APD usually begin 3 to 10 days prior to menstruation and end 1 to 2 days after menses. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis can present in a variety of forms including eczema, erythema multiforme, erythema annulare centrifugum, fixed drug eruption, stomatitis, folliculitis, urticaria, and angioedema.6 A case of APD presenting with petechiae and purpura has been reported.7 There are no specific histologic findings for APD.8 Demonstration of progesterone sensitivity with a progesterone challenge test is the mainstay of diagnosis. Immediate urticaria may occur in some patients, with others experiencing a delayed reaction peaking at 24 to 96 hours.9 The main criteria of APD include the following: recurrent cyclic lesions related to the menstrual cycle; positive intradermal progesterone skin test; and prevention of lesions by inhibiting ovulation.1 Two of these criteria were positive in our patient, but we did not use any medications to prevent ovulation at the patient's request.

Current treatment modalities often attempt to inhibit the secretion of endogenous progesterone by suppressing ovulation. Oral contraceptives and conjugated estrogens have limited efficacy rates.8 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (ie, buserelin, triptorelin) have been used with success.1,6 Tamoxifen and danazol are other treatment options. For cases refractory to medical treatments, bilateral oophorectomy can be considered a definitive treatment.6

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis may present in many different clinical forms. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients with recurrent skin lesions related to menstrual cycle both in women of childbearing age and in men taking synthetic progesterone.

To the Editor:

A 32-year-old woman presented with a recurrent painful eruption on the scalp of 1 year's duration. The lesion occurred on the left temporal region 1 week prior to menstruation and spontaneously resolved following menses; it recurred every month for 1 year. She had no notable medical history. She had taken oral contraceptive pills for 4 years and stopped 2 years prior to the development of the lesions. Dermatologic examination revealed a purple-colored, violaceous, centrally elevated, painful plaque that measured 2 cm in diameter in the left temporal region of the scalp (Figure, A). Laboratory test results were within reference range. The lesion spontaneously resolved with mild residual erythema at a follow-up visit after menstruation (Figure, B).

Because the eruption occurred and relapsed with the patient's menstrual cycle, we suspected progesterone hypersensitivity. An intradermal skin test was performed on the forearm with 0.05 mL of medroxyprogesterone acetate, and saline was used as a negative control. An indurated erythematous nodule occurred on the progesterone-treated side within 6 hours. Based on these findings and the patient's history, she was diagnosed with autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (APD). We recommended her to use gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists as treatment, but the patient refused. At 6-month follow-up she had recurrent lesions but did not report any concerns.

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is a rare condition that is characterized by cyclical skin eruptions, typically occurring in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle with spontaneous resolution after menses.1,2 It was first described by Geber3 in a patient with cyclical urticarial lesions. In 1964, Shelley et al4 characterized APD in a 27-year-old woman with a pruritic vesicular eruption with cyclical premenstrual exacerbations. Although it is believed there is no genetic predisposition to APD, a case series involving 3 sisters demonstrated that genetic susceptibility might play a role in the etiology.5 The etiology of APD is still unknown. It is thought to represent an autoimmune reaction to endogenous or exogenous progesterone.1 Our patient also had used oral contraceptives for 4 years and this exogenous progesterone might have played a role in the sensitization of the patient and the development of this autoimmune reaction.

The clinical features of APD usually begin 3 to 10 days prior to menstruation and end 1 to 2 days after menses. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis can present in a variety of forms including eczema, erythema multiforme, erythema annulare centrifugum, fixed drug eruption, stomatitis, folliculitis, urticaria, and angioedema.6 A case of APD presenting with petechiae and purpura has been reported.7 There are no specific histologic findings for APD.8 Demonstration of progesterone sensitivity with a progesterone challenge test is the mainstay of diagnosis. Immediate urticaria may occur in some patients, with others experiencing a delayed reaction peaking at 24 to 96 hours.9 The main criteria of APD include the following: recurrent cyclic lesions related to the menstrual cycle; positive intradermal progesterone skin test; and prevention of lesions by inhibiting ovulation.1 Two of these criteria were positive in our patient, but we did not use any medications to prevent ovulation at the patient's request.

Current treatment modalities often attempt to inhibit the secretion of endogenous progesterone by suppressing ovulation. Oral contraceptives and conjugated estrogens have limited efficacy rates.8 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (ie, buserelin, triptorelin) have been used with success.1,6 Tamoxifen and danazol are other treatment options. For cases refractory to medical treatments, bilateral oophorectomy can be considered a definitive treatment.6

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis may present in many different clinical forms. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients with recurrent skin lesions related to menstrual cycle both in women of childbearing age and in men taking synthetic progesterone.

- Lee MK, Lee WY, Yong SJ, et al. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis misdiagnosed as allergic contact dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:141-144.

- García-Ortega P, Scorza E. Progesterone autoimmune dermatitis with positive autologous serum skin test result. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:495-498.

- Geber J. Desensitization in the treatment of menstrual intoxication and other allergic symptoms. Br J Dermatol. 1930;51:265-268.

- Shelley WB, Preucel RW, Spoont SS. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: cure by oophorectomy. JAMA. 1964;190:35-38.

- Chawla SV, Quirk C, Sondheimer SJ, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:341-342.

- Medeiros S, Rodrigues-Alves R, Costa M, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: treatment with oophorectomy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:e12-e13.

- Wintzen M, Goor-van Egmond MB, Noz KC. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting with purpura and petechiae. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:316.

- Baptist AP, Baldwin JL. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis in a patient with endometriosis: case report and review of the literature. Clin Mol Allergy. 2004;2:10.

- Le K, Wood G. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis diagnosed by progesterone pessary. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:139-141.

- Lee MK, Lee WY, Yong SJ, et al. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis misdiagnosed as allergic contact dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:141-144.

- García-Ortega P, Scorza E. Progesterone autoimmune dermatitis with positive autologous serum skin test result. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:495-498.

- Geber J. Desensitization in the treatment of menstrual intoxication and other allergic symptoms. Br J Dermatol. 1930;51:265-268.

- Shelley WB, Preucel RW, Spoont SS. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: cure by oophorectomy. JAMA. 1964;190:35-38.

- Chawla SV, Quirk C, Sondheimer SJ, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:341-342.

- Medeiros S, Rodrigues-Alves R, Costa M, et al. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: treatment with oophorectomy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:e12-e13.

- Wintzen M, Goor-van Egmond MB, Noz KC. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting with purpura and petechiae. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:316.

- Baptist AP, Baldwin JL. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis in a patient with endometriosis: case report and review of the literature. Clin Mol Allergy. 2004;2:10.

- Le K, Wood G. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis diagnosed by progesterone pessary. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:139-141.

Practice Points

- Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is characterized by cyclical skin eruptions, typically occurring in the second half of the menstrual cycle.

- Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is thought to be an autoimmune reaction to endogenous or exogenous progesterone.

- This condition should be considered in female patients with recurrent skin lesions related to their menstrual cycle.

Sunscreen and Sperm: Can Chemical UV Filters Alter Sperm Function?

In an article published online on September 1 in Endocrinology, Rehfeld et al discussed their results after testing 29 UV filters. They found that 13 of 29 filters tested had in vitro effects on Ca2+: 4-methylbenzylidene camphor, 3-benzylidene camphor, menthyl anthranilate, isoamyl p-methoxycinnamate, ethylhexyl salicylate, benzylidene camphor sulfonic acid, homosalate, ethylhexyl methoxycinnamate, octcrylene, butyl methoxydibenzoylmethane, and diethylamino hydroxybenzoyl hexyl benzoate.

This study was prompted by a prior study by Schiffer et al (EMBO Rep. 2014;15:758-765) on multiple endocrine disrupting chemicals of which 33 of 96 tested chemicals induced Ca2+ signals in human sperm cells in vitro. Of these previously tested chemicals, some of the chemical sunscreen filters were the most potent, leading to the current study.

Rehfeld et al sought to determine how the UV filters affected calcium signaling, which is a pathway that is essential for sperm cells to be able to swim healthily. These calcium-signaling pathways usually are triggered by progesterone, but the authors showed that 13 of 29 UV filters (45%) also commenced calcium signaling. This effect began at low doses of the chemicals, below the levels of some UV filters found in people after whole-body application of sunscreens.

What’s the issue?

Are these chemical UV filters mimicking progesterone in vivo and could it be interfering with sperm motility? A suboptimal progesterone-induced Ca2+ influx has been associated with reduced male fertility and CatSper (cation channel of sperm) is essential for male fertility (Hum Reprod. 1995;10:120-124).

The UV filters tested are widely available in Europe and the United States. Although this study was in vitro, the in vivo effects will need to be explored. It has been reported by Chivsvert et al (Anal Chim Acta. 2012;752:11-29) that some UV filters can be transcutaneously absorbed into bodily tissues, which could be potentially important for men trying to conceive or for reproductively challenged couples.

What do you discuss with your patients regarding sunscreen safety?

In an article published online on September 1 in Endocrinology, Rehfeld et al discussed their results after testing 29 UV filters. They found that 13 of 29 filters tested had in vitro effects on Ca2+: 4-methylbenzylidene camphor, 3-benzylidene camphor, menthyl anthranilate, isoamyl p-methoxycinnamate, ethylhexyl salicylate, benzylidene camphor sulfonic acid, homosalate, ethylhexyl methoxycinnamate, octcrylene, butyl methoxydibenzoylmethane, and diethylamino hydroxybenzoyl hexyl benzoate.

This study was prompted by a prior study by Schiffer et al (EMBO Rep. 2014;15:758-765) on multiple endocrine disrupting chemicals of which 33 of 96 tested chemicals induced Ca2+ signals in human sperm cells in vitro. Of these previously tested chemicals, some of the chemical sunscreen filters were the most potent, leading to the current study.

Rehfeld et al sought to determine how the UV filters affected calcium signaling, which is a pathway that is essential for sperm cells to be able to swim healthily. These calcium-signaling pathways usually are triggered by progesterone, but the authors showed that 13 of 29 UV filters (45%) also commenced calcium signaling. This effect began at low doses of the chemicals, below the levels of some UV filters found in people after whole-body application of sunscreens.

What’s the issue?

Are these chemical UV filters mimicking progesterone in vivo and could it be interfering with sperm motility? A suboptimal progesterone-induced Ca2+ influx has been associated with reduced male fertility and CatSper (cation channel of sperm) is essential for male fertility (Hum Reprod. 1995;10:120-124).

The UV filters tested are widely available in Europe and the United States. Although this study was in vitro, the in vivo effects will need to be explored. It has been reported by Chivsvert et al (Anal Chim Acta. 2012;752:11-29) that some UV filters can be transcutaneously absorbed into bodily tissues, which could be potentially important for men trying to conceive or for reproductively challenged couples.

What do you discuss with your patients regarding sunscreen safety?

In an article published online on September 1 in Endocrinology, Rehfeld et al discussed their results after testing 29 UV filters. They found that 13 of 29 filters tested had in vitro effects on Ca2+: 4-methylbenzylidene camphor, 3-benzylidene camphor, menthyl anthranilate, isoamyl p-methoxycinnamate, ethylhexyl salicylate, benzylidene camphor sulfonic acid, homosalate, ethylhexyl methoxycinnamate, octcrylene, butyl methoxydibenzoylmethane, and diethylamino hydroxybenzoyl hexyl benzoate.

This study was prompted by a prior study by Schiffer et al (EMBO Rep. 2014;15:758-765) on multiple endocrine disrupting chemicals of which 33 of 96 tested chemicals induced Ca2+ signals in human sperm cells in vitro. Of these previously tested chemicals, some of the chemical sunscreen filters were the most potent, leading to the current study.

Rehfeld et al sought to determine how the UV filters affected calcium signaling, which is a pathway that is essential for sperm cells to be able to swim healthily. These calcium-signaling pathways usually are triggered by progesterone, but the authors showed that 13 of 29 UV filters (45%) also commenced calcium signaling. This effect began at low doses of the chemicals, below the levels of some UV filters found in people after whole-body application of sunscreens.

What’s the issue?

Are these chemical UV filters mimicking progesterone in vivo and could it be interfering with sperm motility? A suboptimal progesterone-induced Ca2+ influx has been associated with reduced male fertility and CatSper (cation channel of sperm) is essential for male fertility (Hum Reprod. 1995;10:120-124).

The UV filters tested are widely available in Europe and the United States. Although this study was in vitro, the in vivo effects will need to be explored. It has been reported by Chivsvert et al (Anal Chim Acta. 2012;752:11-29) that some UV filters can be transcutaneously absorbed into bodily tissues, which could be potentially important for men trying to conceive or for reproductively challenged couples.

What do you discuss with your patients regarding sunscreen safety?

NORD Urges Congress to Pass 21st Century Cures Act

The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) is urging Congress to pass the 21st Century Cures Act, which includes provisions important to the rare disease community such as additional funding for NIH and continuation of the FDA Patient-Focused Drug Development Initiative.

This legislation also would reauthorize the Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Review Voucher Program, which incentivizes development of treatments for rare pediatric diseases. Through this program, priority review vouchers are awarded to companies that develop new treatments for children with rare diseases. The program will expire at the end of this year, and NORD is advocating its long-term reauthorization.

Watch the NORD website for opportunities to join NORD and its policy partners in supporting this legislation and reauthorization of the voucher program.

The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) is urging Congress to pass the 21st Century Cures Act, which includes provisions important to the rare disease community such as additional funding for NIH and continuation of the FDA Patient-Focused Drug Development Initiative.

This legislation also would reauthorize the Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Review Voucher Program, which incentivizes development of treatments for rare pediatric diseases. Through this program, priority review vouchers are awarded to companies that develop new treatments for children with rare diseases. The program will expire at the end of this year, and NORD is advocating its long-term reauthorization.

Watch the NORD website for opportunities to join NORD and its policy partners in supporting this legislation and reauthorization of the voucher program.

The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) is urging Congress to pass the 21st Century Cures Act, which includes provisions important to the rare disease community such as additional funding for NIH and continuation of the FDA Patient-Focused Drug Development Initiative.

This legislation also would reauthorize the Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Review Voucher Program, which incentivizes development of treatments for rare pediatric diseases. Through this program, priority review vouchers are awarded to companies that develop new treatments for children with rare diseases. The program will expire at the end of this year, and NORD is advocating its long-term reauthorization.

Watch the NORD website for opportunities to join NORD and its policy partners in supporting this legislation and reauthorization of the voucher program.

Acute Localized Exanthematous Pustulosis Caused by Flurbiprofen

To the Editor:

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is an acute skin reaction that is characterized by generalized, nonfollicular, pinhead-sized, sterile pustules on an erythematous and edematous background. The eruption can be accompanied by fever and neutrophilic leukocytosis. Skin symptoms arise quickly (within a few hours), most commonly following drug administration. The medications most frequently responsible are beta-lactam antibiotics, macrolides, calcium channel blockers, and antimalarials. Pustules spontaneously resolve in 15 days and generalized desquamation occurs approximately 2 weeks later. The estimated incidence rate of AGEP is approximately 1 to 5 cases per million per year. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP) is a less common form of AGEP. We report a case of ALEP localized on the face that was caused by flurbiprofen, a propionic acid derivative from the family of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

A 40-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department due to the sudden onset of multiple pustules on the face. One week earlier she started oral flurbiprofen (8.75 mg daily) for a sore throat. After 3 days of therapy, multiple pruritic, erythematous and edematous lesions appeared abruptly on the face with associated multiple small nonfollicular pustules. At presentation the patient was febrile (temperature, 38.2°C) and presented with bilateral ocular edema and superficial small nonfollicular pustules on an erythematous background over the face, scalp, and oral mucosa (Figure 1). The rest of the body was not involved. The patient denied prior adverse reactions to other drugs. The white blood cell count was 15,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), with an increased neutrophil count (12,000/μL [reference range, 1800–7800/μL]). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level was elevated (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 53 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; C-reactive protein, 98 mg/dL [reference range, 0–5 mg/dL]). Bacterial and fungal cultures of skin lesions were negative. The results of a viral polymerase chain reaction analysis proved the absence of varicella-zoster virus or herpes simplex virus. Histopathology of a skin biopsy specimen showed subcorneal pustules composed of neutrophils and eosinophils, epidermal spongiosis, some necrotic keratinocytes, vacuolization of the basal layer, papillary edema, and a perivascular neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltrate (Figure 2). A leukocytoclastic infiltrate within and around the walls of blood vessels at the superficial level of the dermis and red cell extravasation in the epidermis was present. She discontinued use of flurbiprofen and was treated with a systemic corticosteroid (methylprednisolone 0.5 mg/kg daily). The pustules rapidly resolved within 7 days after discontinuation of flurbiprofen and were followed by transient scaling and discrete residual hyperpigmentation.

Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis is a less common form of a pustular drug eruption in which lesions are consistent with AGEP but typically are localized to the face, neck, or chest. The definition of ALEP was introduced by Prange et al1 to describe a woman who was diagnosed with a localized pustular eruption on the face without a generalized distribution as in AGEP. In the past, this localized eruption was described under different names (eg, localized pustular eruption, localized toxin follicular pustuloderma, nongeneralized acute exanthematic pustulosis).2-5 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms localized pustulosis, localized pustular eruption, and localized pustuloderma, only 16 separate cases of ALEP have been documented since the report by Prange et al.1 The medications most frequently responsible are antibiotics. Three cases developed following administration of amoxicillin2,5,6; 2 cases of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid7,8; 1 of penicillin1; 1 of azithromycin9; 1 of levofloxacin10; and 1 of combination of cephalosporin, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and vancomycin.11 Other nonantibiotic causative drugs include sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim,12 infliximab,13 sorafenib,14 docetaxel,15 finasteride,16 ibuprofen,17 and paracetamol.18 In reported cases, the lesions are consistent with the characteristics of AGEP both clinically and histopathologically but are localized typically to the face, neck, or chest. In the majority of patients with ALEP, the absence of fever has been observed, but it does not appear distinctive for diagnosis. Our patient represents another case of ALEP with flurbiprofen as the causative drug. The close relationship between the administration of the drug and the development of the pustules, the rapid acute resolution as soon as treatment was interrupted, and the histologic findings all supported the diagnosis of ALEP following administration of flurbiprofen. This NSAID—2-fluoro-α-methyl-(1,1'-biphenyl)-4-acetic acid—is a prostaglandin synthetase inhibitor with anti-inflammatory activity. It is a propionic acid derivative that is similar to ibuprofen, which was once involved in the occurrence of ALEP.17 In 2009, Rastogi et al17 reported a case of a 64-year-old woman with an acute outbreak of multiple pustular lesions and underlying erythema affecting the cheeks and chin without fever who had been taking ibuprofen for a toothache. The case is similar to ours and confirms that NSAIDs can induce ALEP. Compared with other NSAIDs, propionic acid derivatives are usually well tolerated and serious adverse reactions rarely have been documented.19

The physiopathologic mechanisms of ALEP are unknown but likely are similar to AGEP. The demonstration of drug-specific positive patch test responses and in vitro lymphocyte proliferative responses in patients with a history of AGEP strongly suggests that this adverse cutaneous reaction occurs via a drug-specific T cell–mediated process.20

Further study is needed to understand the etiopathogenesis of the localized form of the disease and to facilitate a correct diagnosis of this rare disorder.

- Prange B, Marini A, Kalke A, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP). J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:210-212.

- Shuttleworth D. A localized, recurrent pustular eruption following amoxycillin administration. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14:367-368.

- De Argila D, Ortiz-Frutos J, Rodriguez-Peralto JL, et al. An atypical case of non-generalized acute exanthematic pustulosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 1996;87:475-478.

- Corbalan-Velez R, Peon G, Ara M, et al. Localized toxic follicular pustuloderma. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:209-211.

- Prieto A, de Barrio M, López-Sáez P, et al. Recurrent localized pustular eruption induced by amoxicillin. Allergy. 1997;52:777-778.

- Vickers JL, Matherne RJ, Mainous EG, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis: a cutaneous drug reaction in a dental setting. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1200-1203.

- Betto P, Germi L, Bonoldi E, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP) caused by amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:295-296.

- Ozkaya-Parlakay A, Azkur D, Kara A, et al. Localized acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid. Turk J Pediatr. 2011;53:229-232.

- Zweegers J, Bovenschen HJ. A woman with skin abnormalities around the mouth [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2012;156:A4613.

- Corral de la Calle M, Martín Díaz MA, Flores CR, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis secondary to levofloxacin. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1076-1077.

- Sim HS, Seol JE, Chun JS, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis on the face. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S3368-S3370.

- Lee I, Turner M, Lee CC. Acute patchy exanthematous pustulosis caused by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e41-e43.

- Lee HY, Pelivani N, Beltraminelli H, et al. Amicrobial pustulosis-like rash in a patient with Crohn’s disease under anti-TNF-alpha blocker. Dermatology. 2011;222:304-310.

- Liang CP, Yang CS, Shen JL, et al. Sorafenib-induced acute localized exanthematous pustulosis in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:443-445.

- Kim SW, Lee UH, Jang SJ, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis induced by docetaxel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e44-e46.

- Tresch S, Cozzio A, Kamarashev J, et al. T cell-mediated acute localized exanthematous pustulosis caused by finasteride. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:589-594.

- Rastogi S, Modi M, Dhawan V. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP) caused by Ibuprofen. a case report. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;47:132-134.

- Wohl Y, Goldberg I, Sharazi I, et al. A case of paracetamol-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis in a pregnant woman localized in the neck region. Skinmed. 2004;3:47-49.

- Mehra KK, Rupawala AH, Gogtay NJ. Immediate hypersensitivity reaction to a single oral dose of flurbiprofen. J Postgrad Med. 2010;56:36-37.

- Girardi M, Duncan KO, Tigelaar RE, et al. Cross comparison of patch-test and lymphocyte proliferation responses in patients with a history of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:343-346.

To the Editor:

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is an acute skin reaction that is characterized by generalized, nonfollicular, pinhead-sized, sterile pustules on an erythematous and edematous background. The eruption can be accompanied by fever and neutrophilic leukocytosis. Skin symptoms arise quickly (within a few hours), most commonly following drug administration. The medications most frequently responsible are beta-lactam antibiotics, macrolides, calcium channel blockers, and antimalarials. Pustules spontaneously resolve in 15 days and generalized desquamation occurs approximately 2 weeks later. The estimated incidence rate of AGEP is approximately 1 to 5 cases per million per year. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP) is a less common form of AGEP. We report a case of ALEP localized on the face that was caused by flurbiprofen, a propionic acid derivative from the family of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

A 40-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department due to the sudden onset of multiple pustules on the face. One week earlier she started oral flurbiprofen (8.75 mg daily) for a sore throat. After 3 days of therapy, multiple pruritic, erythematous and edematous lesions appeared abruptly on the face with associated multiple small nonfollicular pustules. At presentation the patient was febrile (temperature, 38.2°C) and presented with bilateral ocular edema and superficial small nonfollicular pustules on an erythematous background over the face, scalp, and oral mucosa (Figure 1). The rest of the body was not involved. The patient denied prior adverse reactions to other drugs. The white blood cell count was 15,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), with an increased neutrophil count (12,000/μL [reference range, 1800–7800/μL]). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level was elevated (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 53 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; C-reactive protein, 98 mg/dL [reference range, 0–5 mg/dL]). Bacterial and fungal cultures of skin lesions were negative. The results of a viral polymerase chain reaction analysis proved the absence of varicella-zoster virus or herpes simplex virus. Histopathology of a skin biopsy specimen showed subcorneal pustules composed of neutrophils and eosinophils, epidermal spongiosis, some necrotic keratinocytes, vacuolization of the basal layer, papillary edema, and a perivascular neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltrate (Figure 2). A leukocytoclastic infiltrate within and around the walls of blood vessels at the superficial level of the dermis and red cell extravasation in the epidermis was present. She discontinued use of flurbiprofen and was treated with a systemic corticosteroid (methylprednisolone 0.5 mg/kg daily). The pustules rapidly resolved within 7 days after discontinuation of flurbiprofen and were followed by transient scaling and discrete residual hyperpigmentation.

Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis is a less common form of a pustular drug eruption in which lesions are consistent with AGEP but typically are localized to the face, neck, or chest. The definition of ALEP was introduced by Prange et al1 to describe a woman who was diagnosed with a localized pustular eruption on the face without a generalized distribution as in AGEP. In the past, this localized eruption was described under different names (eg, localized pustular eruption, localized toxin follicular pustuloderma, nongeneralized acute exanthematic pustulosis).2-5 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms localized pustulosis, localized pustular eruption, and localized pustuloderma, only 16 separate cases of ALEP have been documented since the report by Prange et al.1 The medications most frequently responsible are antibiotics. Three cases developed following administration of amoxicillin2,5,6; 2 cases of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid7,8; 1 of penicillin1; 1 of azithromycin9; 1 of levofloxacin10; and 1 of combination of cephalosporin, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and vancomycin.11 Other nonantibiotic causative drugs include sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim,12 infliximab,13 sorafenib,14 docetaxel,15 finasteride,16 ibuprofen,17 and paracetamol.18 In reported cases, the lesions are consistent with the characteristics of AGEP both clinically and histopathologically but are localized typically to the face, neck, or chest. In the majority of patients with ALEP, the absence of fever has been observed, but it does not appear distinctive for diagnosis. Our patient represents another case of ALEP with flurbiprofen as the causative drug. The close relationship between the administration of the drug and the development of the pustules, the rapid acute resolution as soon as treatment was interrupted, and the histologic findings all supported the diagnosis of ALEP following administration of flurbiprofen. This NSAID—2-fluoro-α-methyl-(1,1'-biphenyl)-4-acetic acid—is a prostaglandin synthetase inhibitor with anti-inflammatory activity. It is a propionic acid derivative that is similar to ibuprofen, which was once involved in the occurrence of ALEP.17 In 2009, Rastogi et al17 reported a case of a 64-year-old woman with an acute outbreak of multiple pustular lesions and underlying erythema affecting the cheeks and chin without fever who had been taking ibuprofen for a toothache. The case is similar to ours and confirms that NSAIDs can induce ALEP. Compared with other NSAIDs, propionic acid derivatives are usually well tolerated and serious adverse reactions rarely have been documented.19

The physiopathologic mechanisms of ALEP are unknown but likely are similar to AGEP. The demonstration of drug-specific positive patch test responses and in vitro lymphocyte proliferative responses in patients with a history of AGEP strongly suggests that this adverse cutaneous reaction occurs via a drug-specific T cell–mediated process.20

Further study is needed to understand the etiopathogenesis of the localized form of the disease and to facilitate a correct diagnosis of this rare disorder.

To the Editor:

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is an acute skin reaction that is characterized by generalized, nonfollicular, pinhead-sized, sterile pustules on an erythematous and edematous background. The eruption can be accompanied by fever and neutrophilic leukocytosis. Skin symptoms arise quickly (within a few hours), most commonly following drug administration. The medications most frequently responsible are beta-lactam antibiotics, macrolides, calcium channel blockers, and antimalarials. Pustules spontaneously resolve in 15 days and generalized desquamation occurs approximately 2 weeks later. The estimated incidence rate of AGEP is approximately 1 to 5 cases per million per year. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP) is a less common form of AGEP. We report a case of ALEP localized on the face that was caused by flurbiprofen, a propionic acid derivative from the family of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

A 40-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department due to the sudden onset of multiple pustules on the face. One week earlier she started oral flurbiprofen (8.75 mg daily) for a sore throat. After 3 days of therapy, multiple pruritic, erythematous and edematous lesions appeared abruptly on the face with associated multiple small nonfollicular pustules. At presentation the patient was febrile (temperature, 38.2°C) and presented with bilateral ocular edema and superficial small nonfollicular pustules on an erythematous background over the face, scalp, and oral mucosa (Figure 1). The rest of the body was not involved. The patient denied prior adverse reactions to other drugs. The white blood cell count was 15,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), with an increased neutrophil count (12,000/μL [reference range, 1800–7800/μL]). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level was elevated (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 53 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; C-reactive protein, 98 mg/dL [reference range, 0–5 mg/dL]). Bacterial and fungal cultures of skin lesions were negative. The results of a viral polymerase chain reaction analysis proved the absence of varicella-zoster virus or herpes simplex virus. Histopathology of a skin biopsy specimen showed subcorneal pustules composed of neutrophils and eosinophils, epidermal spongiosis, some necrotic keratinocytes, vacuolization of the basal layer, papillary edema, and a perivascular neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltrate (Figure 2). A leukocytoclastic infiltrate within and around the walls of blood vessels at the superficial level of the dermis and red cell extravasation in the epidermis was present. She discontinued use of flurbiprofen and was treated with a systemic corticosteroid (methylprednisolone 0.5 mg/kg daily). The pustules rapidly resolved within 7 days after discontinuation of flurbiprofen and were followed by transient scaling and discrete residual hyperpigmentation.

Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis is a less common form of a pustular drug eruption in which lesions are consistent with AGEP but typically are localized to the face, neck, or chest. The definition of ALEP was introduced by Prange et al1 to describe a woman who was diagnosed with a localized pustular eruption on the face without a generalized distribution as in AGEP. In the past, this localized eruption was described under different names (eg, localized pustular eruption, localized toxin follicular pustuloderma, nongeneralized acute exanthematic pustulosis).2-5 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms localized pustulosis, localized pustular eruption, and localized pustuloderma, only 16 separate cases of ALEP have been documented since the report by Prange et al.1 The medications most frequently responsible are antibiotics. Three cases developed following administration of amoxicillin2,5,6; 2 cases of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid7,8; 1 of penicillin1; 1 of azithromycin9; 1 of levofloxacin10; and 1 of combination of cephalosporin, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and vancomycin.11 Other nonantibiotic causative drugs include sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim,12 infliximab,13 sorafenib,14 docetaxel,15 finasteride,16 ibuprofen,17 and paracetamol.18 In reported cases, the lesions are consistent with the characteristics of AGEP both clinically and histopathologically but are localized typically to the face, neck, or chest. In the majority of patients with ALEP, the absence of fever has been observed, but it does not appear distinctive for diagnosis. Our patient represents another case of ALEP with flurbiprofen as the causative drug. The close relationship between the administration of the drug and the development of the pustules, the rapid acute resolution as soon as treatment was interrupted, and the histologic findings all supported the diagnosis of ALEP following administration of flurbiprofen. This NSAID—2-fluoro-α-methyl-(1,1'-biphenyl)-4-acetic acid—is a prostaglandin synthetase inhibitor with anti-inflammatory activity. It is a propionic acid derivative that is similar to ibuprofen, which was once involved in the occurrence of ALEP.17 In 2009, Rastogi et al17 reported a case of a 64-year-old woman with an acute outbreak of multiple pustular lesions and underlying erythema affecting the cheeks and chin without fever who had been taking ibuprofen for a toothache. The case is similar to ours and confirms that NSAIDs can induce ALEP. Compared with other NSAIDs, propionic acid derivatives are usually well tolerated and serious adverse reactions rarely have been documented.19

The physiopathologic mechanisms of ALEP are unknown but likely are similar to AGEP. The demonstration of drug-specific positive patch test responses and in vitro lymphocyte proliferative responses in patients with a history of AGEP strongly suggests that this adverse cutaneous reaction occurs via a drug-specific T cell–mediated process.20

Further study is needed to understand the etiopathogenesis of the localized form of the disease and to facilitate a correct diagnosis of this rare disorder.

- Prange B, Marini A, Kalke A, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP). J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:210-212.

- Shuttleworth D. A localized, recurrent pustular eruption following amoxycillin administration. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14:367-368.

- De Argila D, Ortiz-Frutos J, Rodriguez-Peralto JL, et al. An atypical case of non-generalized acute exanthematic pustulosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 1996;87:475-478.

- Corbalan-Velez R, Peon G, Ara M, et al. Localized toxic follicular pustuloderma. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:209-211.

- Prieto A, de Barrio M, López-Sáez P, et al. Recurrent localized pustular eruption induced by amoxicillin. Allergy. 1997;52:777-778.

- Vickers JL, Matherne RJ, Mainous EG, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis: a cutaneous drug reaction in a dental setting. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1200-1203.

- Betto P, Germi L, Bonoldi E, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP) caused by amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:295-296.

- Ozkaya-Parlakay A, Azkur D, Kara A, et al. Localized acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid. Turk J Pediatr. 2011;53:229-232.

- Zweegers J, Bovenschen HJ. A woman with skin abnormalities around the mouth [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2012;156:A4613.

- Corral de la Calle M, Martín Díaz MA, Flores CR, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis secondary to levofloxacin. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1076-1077.

- Sim HS, Seol JE, Chun JS, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis on the face. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S3368-S3370.

- Lee I, Turner M, Lee CC. Acute patchy exanthematous pustulosis caused by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e41-e43.

- Lee HY, Pelivani N, Beltraminelli H, et al. Amicrobial pustulosis-like rash in a patient with Crohn’s disease under anti-TNF-alpha blocker. Dermatology. 2011;222:304-310.

- Liang CP, Yang CS, Shen JL, et al. Sorafenib-induced acute localized exanthematous pustulosis in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:443-445.

- Kim SW, Lee UH, Jang SJ, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis induced by docetaxel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e44-e46.

- Tresch S, Cozzio A, Kamarashev J, et al. T cell-mediated acute localized exanthematous pustulosis caused by finasteride. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:589-594.

- Rastogi S, Modi M, Dhawan V. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP) caused by Ibuprofen. a case report. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;47:132-134.

- Wohl Y, Goldberg I, Sharazi I, et al. A case of paracetamol-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis in a pregnant woman localized in the neck region. Skinmed. 2004;3:47-49.

- Mehra KK, Rupawala AH, Gogtay NJ. Immediate hypersensitivity reaction to a single oral dose of flurbiprofen. J Postgrad Med. 2010;56:36-37.

- Girardi M, Duncan KO, Tigelaar RE, et al. Cross comparison of patch-test and lymphocyte proliferation responses in patients with a history of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:343-346.

- Prange B, Marini A, Kalke A, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP). J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:210-212.

- Shuttleworth D. A localized, recurrent pustular eruption following amoxycillin administration. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14:367-368.

- De Argila D, Ortiz-Frutos J, Rodriguez-Peralto JL, et al. An atypical case of non-generalized acute exanthematic pustulosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 1996;87:475-478.

- Corbalan-Velez R, Peon G, Ara M, et al. Localized toxic follicular pustuloderma. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:209-211.

- Prieto A, de Barrio M, López-Sáez P, et al. Recurrent localized pustular eruption induced by amoxicillin. Allergy. 1997;52:777-778.

- Vickers JL, Matherne RJ, Mainous EG, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis: a cutaneous drug reaction in a dental setting. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1200-1203.

- Betto P, Germi L, Bonoldi E, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP) caused by amoxicillin-clavulanic acid. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:295-296.

- Ozkaya-Parlakay A, Azkur D, Kara A, et al. Localized acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid. Turk J Pediatr. 2011;53:229-232.

- Zweegers J, Bovenschen HJ. A woman with skin abnormalities around the mouth [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2012;156:A4613.

- Corral de la Calle M, Martín Díaz MA, Flores CR, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis secondary to levofloxacin. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1076-1077.

- Sim HS, Seol JE, Chun JS, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis on the face. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S3368-S3370.

- Lee I, Turner M, Lee CC. Acute patchy exanthematous pustulosis caused by sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e41-e43.

- Lee HY, Pelivani N, Beltraminelli H, et al. Amicrobial pustulosis-like rash in a patient with Crohn’s disease under anti-TNF-alpha blocker. Dermatology. 2011;222:304-310.

- Liang CP, Yang CS, Shen JL, et al. Sorafenib-induced acute localized exanthematous pustulosis in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:443-445.

- Kim SW, Lee UH, Jang SJ, et al. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis induced by docetaxel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e44-e46.

- Tresch S, Cozzio A, Kamarashev J, et al. T cell-mediated acute localized exanthematous pustulosis caused by finasteride. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:589-594.

- Rastogi S, Modi M, Dhawan V. Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis (ALEP) caused by Ibuprofen. a case report. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;47:132-134.

- Wohl Y, Goldberg I, Sharazi I, et al. A case of paracetamol-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis in a pregnant woman localized in the neck region. Skinmed. 2004;3:47-49.

- Mehra KK, Rupawala AH, Gogtay NJ. Immediate hypersensitivity reaction to a single oral dose of flurbiprofen. J Postgrad Med. 2010;56:36-37.

- Girardi M, Duncan KO, Tigelaar RE, et al. Cross comparison of patch-test and lymphocyte proliferation responses in patients with a history of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:343-346.

Practice Points

- Acute localized exanthematous pustulosis is a form of a pustular drug eruption in which lesions are consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis but typically localized in a single area.

- The medications most frequently responsible are antibiotics. Flurbiprofen, a propionic acid derivative, could be a rare causative agent of this disease.

Accuracy and Sources of Images From Direct Google Image Searches for Common Dermatology Terms

To the Editor:

Prior studies have assessed the quality of text-based dermatology information on the Internet using traditional search engine queries.1 However, little is understood about the sources, accuracy, and quality of online dermatology images derived from direct image searches. Previous work has shown that direct search engine image queries were largely accurate for 3 pediatric dermatology diagnosis searches: atopic dermatitis, lichen striatus, and subcutaneous fat necrosis.2 We assessed images obtained for common dermatologic conditions from a Google image search (GIS) compared to a traditional text-based Google web search (GWS).

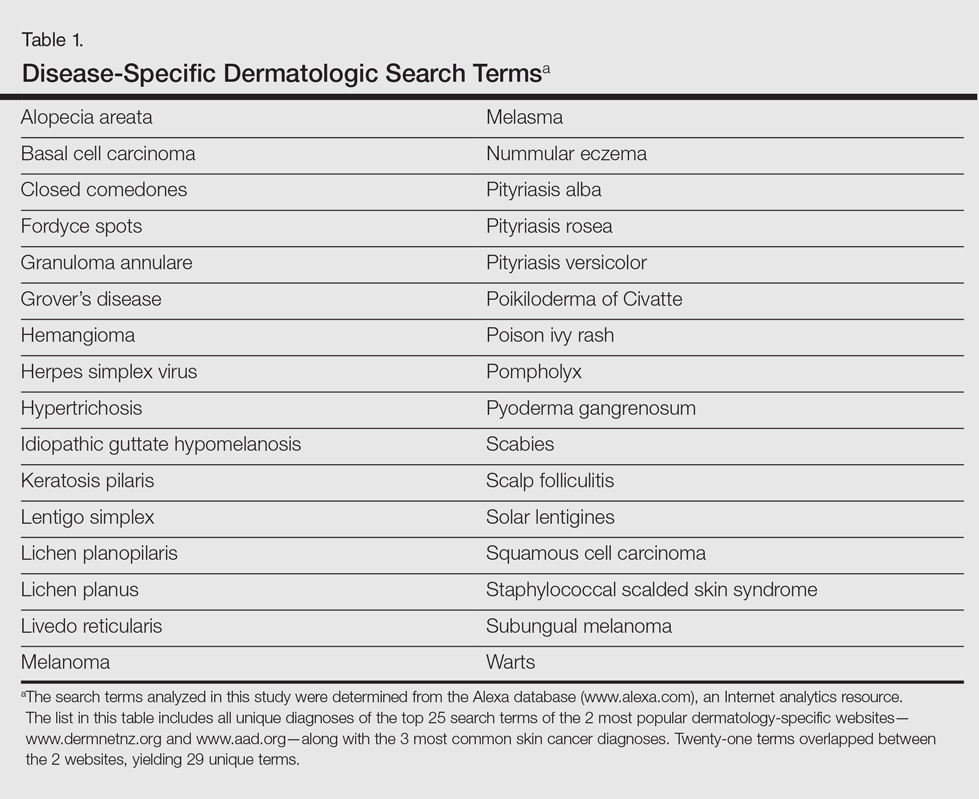

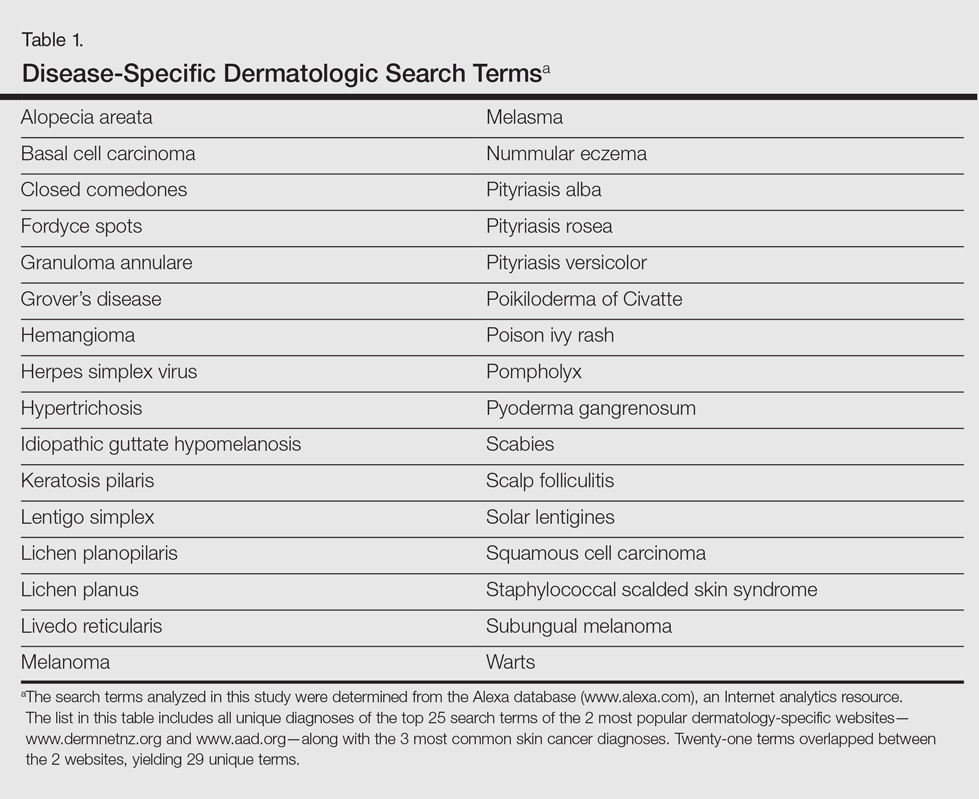

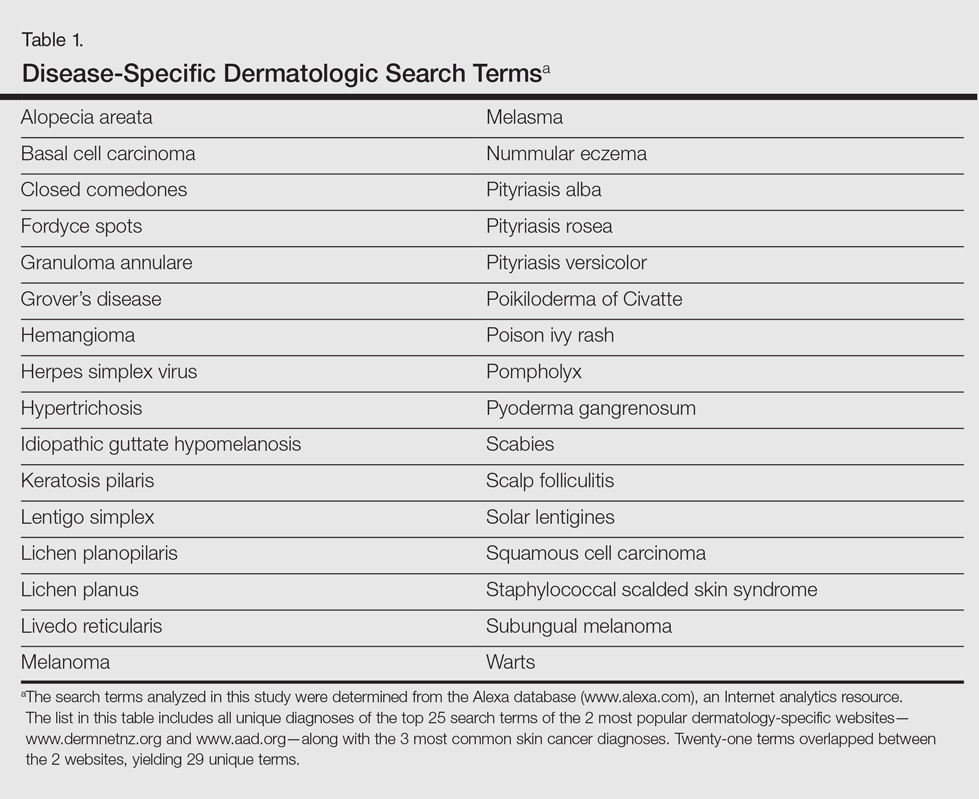

Image results for 32 unique dermatologic search terms were analyzed (Table 1). These search terms were selected using the results of a prior study that identified the most common dermatologic diagnoses that led users to the 2 most popular dermatology-specific websites worldwide: the American Academy of Dermatology (www.aad.org) and DermNet New Zealand (www.dermnetnz.org).3 The Alexa directory (www.alexa.com), a large publicly available Internet analytics resource, was used to determine the most common dermatology search terms that led a user to either www.dermnetnz.org or www.aad.org. In addition, searches for the 3 most common types of skin cancer—melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma—were included. Each term was entered into a GIS and a GWS. The first 10 results, which represent 92% of the websites ultimately visited by users,4 were analyzed. The source, diagnostic accuracy, and Fitzpatrick skin type of the images was determined. Website sources were organized into 11 categories. All data collection occurred within a 1-week period in August 2015.

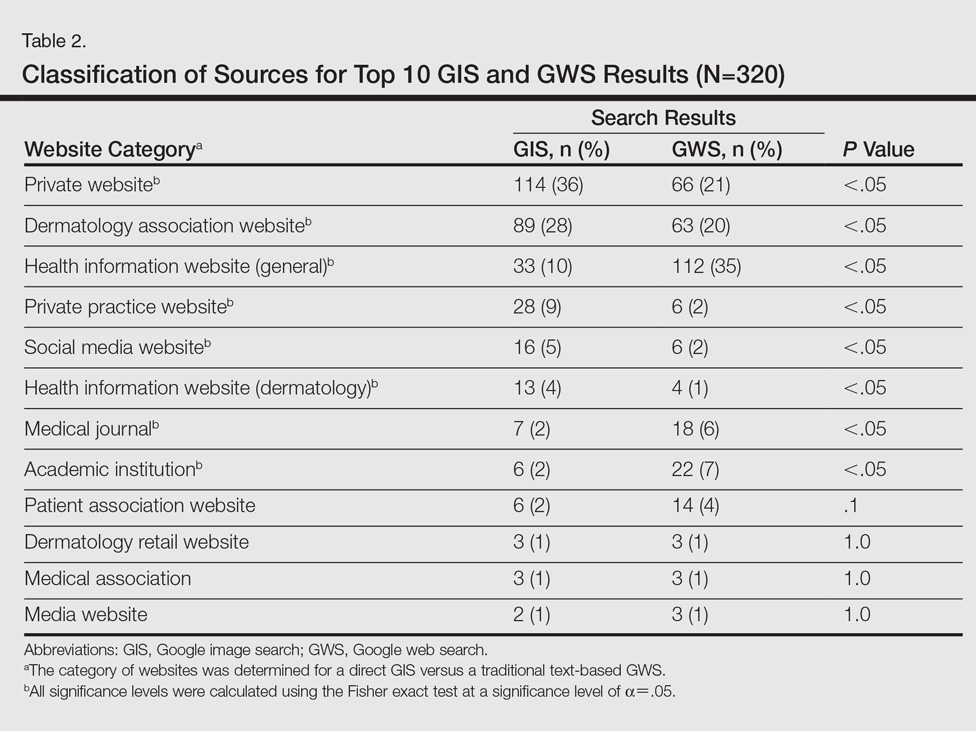

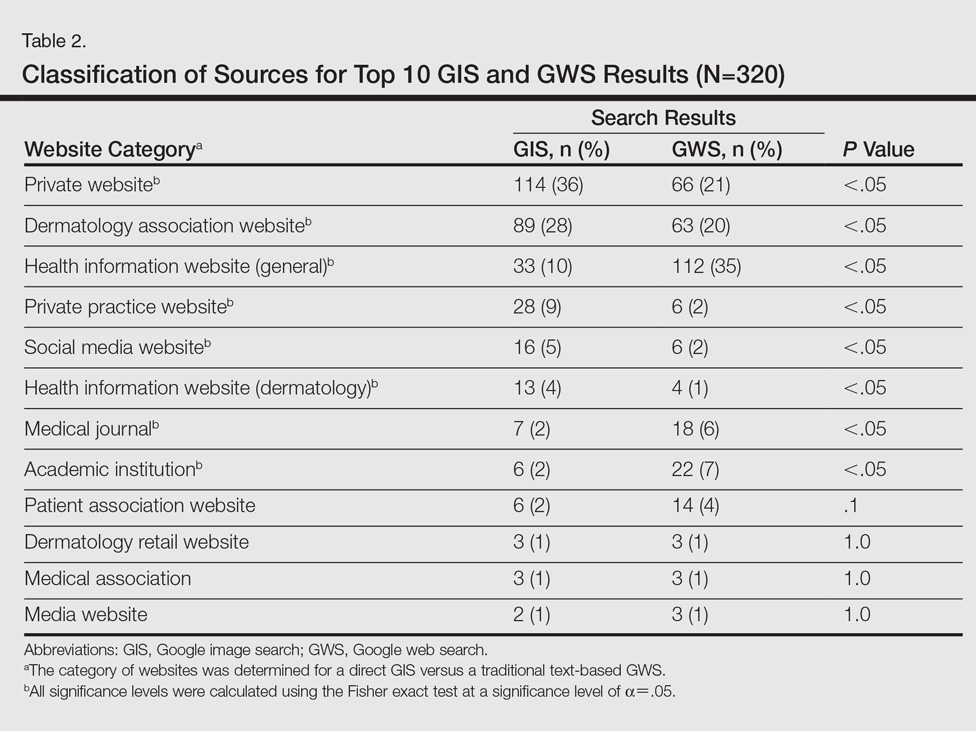

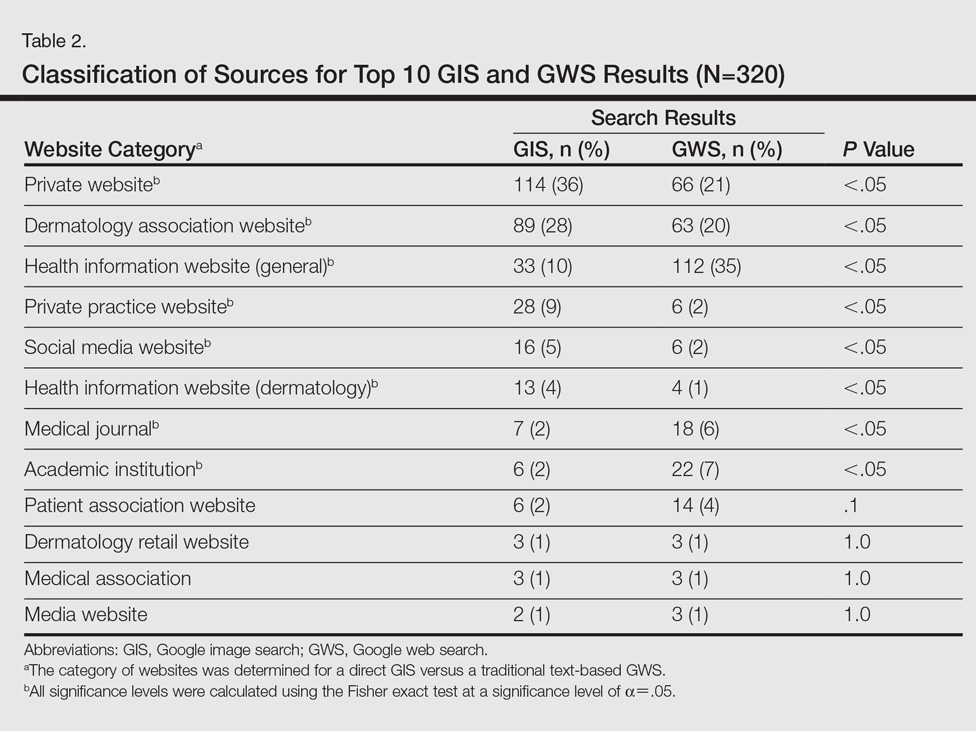

A total of 320 images were analyzed. In the GIS, private websites (36%), dermatology association websites (28%), and general health information websites (10%) were the 3 most common sources. In the GWS, health information websites (35%), private websites (21%), and dermatology association websites (20%) accounted for the most common sources (Table 2). The majority of images were of Fitzpatrick skin types I and II (89%) and nearly all images were diagnostically accurate (98%). There was no statistically significant difference in accuracy of diagnosis between physician-associated websites (100% accuracy) versus nonphysician-associated sites (98% accuracy, P=.25).

Our results showed high diagnostic accuracy among the top GIS results for common dermatology search terms. Diagnostic accuracy did not vary between websites that were physician associated versus those that were not. Our results are comparable to the reported accuracy of online dermatologic health information.1 In GIS results, the majority of images were provided by private websites, whereas the top websites in GWS results were health information websites.

Only 1% of images were of Fitzpatrick skin types VI and VII. Presentation of skin diseases is remarkably different based on the patient’s skin type.5 The shortage of readily accessible images of skin of color is in line with the lack of familiarity physicians and trainees have with dermatologic conditions in ethnic skin.6

Based on the results from this analysis, providers and patients searching for dermatologic conditions via a direct GIS should be cognizant of several considerations. Although our results showed that GIS was accurate, the searcher should note that image-based searches are not accompanied by relevant text that can help confirm relevancy and accuracy. Image searches depend on textual tags added by the source website. Websites that represent dermatological associations and academic centers can add an additional layer of confidence for users. Patients and clinicians also should be aware that the consideration of a patient’s Fitzpatrick skin type is critical when assessing the relevancy of a GIS result. In conclusion, search results via GIS queries are accurate for the dermatological diagnoses tested but may be lacking in skin of color variations, suggesting a potential unmet need based on our growing ethnic skin population.

- Jensen JD, Dunnick CA, Arbuckle HA, et al. Dermatology information on the Internet: an appraisal by dermatologists and dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:1101-1103.

- Cutrone M, Grimalt R. Dermatological image search engines on the Internet: do they work? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:175-177.

- Xu S, Nault A, Bhatia A. Search and engagement analysis of association websites representing dermatologists—implications and opportunities for web visibility and patient education: website rankings of dermatology associations. Pract Dermatol. In press.

- comScore releases July 2015 U.S. desktop search engine rankings [press release]. Reston, VA: comScore, Inc; August 14, 2015. http://www.comscore.com/Insights/Market-Rankings/comScore-Releases-July-2015-U.S.-Desktop-Search-Engine-Rankings. Accessed October 18, 2016.

- Kundu RV, Patterson S. Dermatologic conditions in skin of color: part I. special considerations for common skin disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:850-856.

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-618.