User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Vitiligo Patients Experience Barriers in Accessing Care

Vitiligo is a disorder typified by loss of pigmentation. Worldwide estimates of disease demonstrate 0.4% to 2% prevalence.1 Vitiligo generally is felt to be an autoimmune disorder with a complex multifactorial inheritance.2 Therapeutic options for vitiligo are largely off label and include topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) light phototherapy, and excimer (308 nm) laser therapy.3,4 Therapies for vitiligo are time consuming, as most topical therapies require twice-daily application. Additionally, many patients require 2 or more topical therapies due to involvement of both the head and neck as well as other body sites.3,4 Generalized disease often is treated with NB-UVB therapy 3 times weekly in-office visits, while excimer laser therapy is used for limited disease resistant to topical agents.3,4

Many barriers to good outcomes and care exist for patients with vitiligo.5 Patients may experience reduced quality of life and/or sexual dysfunction because of vitiligo lesions. The purpose of this pilot study was to identify barriers to access of care in vitiligo patients.

Methods

A survey was designed and then reviewed for unclear wording by members of the local vitiligo support group at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital and Beth Israel Medical Centers (New York, New York). Linguistic revision and clarifications were added to the survey to correct identified communication problems. The survey was then posted using an Internet-based survey software. Links to the survey were sent via email to 107 individuals in a LISTSERV comprising Vitiligo Support International members who participated in a New York City support group (led by C.G. and N.B.S.). Only 1 email was used per household and only individuals 18 years or older could participate. These individuals were asked to complete a deidentified, 82-question, institutional review board–reviewed and exempted survey addressing issues affecting delivery and receipt of medical care for vitiligo.

Data were analyzed using the χ2 test, analysis of variance, or Student t test depending on the type of variable (categorical vs continuous). Fisher exact or Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests were used when distributional assumptions were not met. A type I error rate (α=.05) was used to determine statistical significance. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 software.

Results

Respondents

The survey was completed by 81% (n=87) of individuals. The mean (SD) age of the treated patients about whom the respondents communicated was 33 (16) years and 71% (n=62) were women. The majority of respondents (64 [74%]) reported their race as white, followed by African American/black (12 [14%]), Hispanic (7 [8%]), and Asian (4 [5%]). Twenty-nine percent (22/76) of respondents reported a family income of less than $50,000 per year, 34% (26/76) reported an income of $50,000 to $100,000, and 37% (28/76) reported an income greater than $100,000, while 11 respondents did not report income.

Number of Physicians Seen

Respondents had reportedly seen an average (SD) number of 2 (1) physicians in the past/present before being offered any therapy for vitiligo and only 37% (32/87) of respondents reported being offered therapy by the first physician they saw. The number of physicians seen did not have a statistical relationship with years with vitiligo (ie, disease duration), sex, race, age of onset, income level, or number of sites affected.

Number of Sites Affected

The survey identified the following 23 sites affected by vitiligo: scalp, forehead, eyelids, lips, nose, cheeks, chin, neck, chest, stomach, back, upper arms, forearms, hands, wrists, fingers, genitalia, buttocks, thighs, calves/shins, ankles, feet, and toes. The average (SD) number of sites affected was 12 (6). The number of sites affected was correlated to the recommendation for phototherapy, while the recommendation for excimer laser therapy was inversely associated with the number of sites affected. The median number of sites affected for those who were not prescribed phototherapy was 10 (interquartile range [IQR]=9; P=.05); the median number of sites affected for those who were prescribed phototherapy was 15 (IQR=11). The association between the number of sites affected and whether the patient proceeded with phototherapy was not statistically significant. The need for phototherapy was not related to years with vitiligo (ie, disease duration), sex, or race.

Excimer laser therapy was prescribed more often to patients with fewer sites affected (median of 9 [IQR=3] vs median of 15 [IQR=9]; P=.04). Respondents who had fewer sites affected were on average more likely to proceed with excimer laser therapy (median of 8 [IQR=4] vs median of 11 [IQR=5]). The association between the number of sites affected and whether the patient proceeded with excimer laser therapy was not statistically significant.

Access to Topical Medications

Forty-one percent (36/87) of respondents reported difficulty accessing 1 or more topical therapies. Of 52 respondents who were prescribed a topical corticosteroid, 12 (23%) reported difficulty accessing therapy. Of 67 respondents who were prescribed a topical calcineurin inhibitor, 27 (40%) reported difficulty accessing medication (tacrolimus, n=17; pimecrolimus, n=10). Calcipotriene prescription coverage was not specifically addressed in this survey, as it usually is a second-line or adjunctive medication. Difficulty getting topical tacrolimus but not topical corticosteroids was associated with female sex (P=.03) but was not associated with race, income level, or level of education. Difficulty obtaining medication was not related to race, sex, level of education, or income level.

Consequences of Phototherapy

Twenty-three of 34 respondents (68%) who were told they required phototherapy actually received phototherapy and reported paying $38 weekly (IQR=$75). The majority of patients who proceeded with phototherapy lived (17/23 [74%]) or worked (16/23 [70%]) within 20 minutes of the therapy center. Self-reported response to phototherapy was good to very good in 65% (15/23) of respondents and no response in 30% (7/23); only 1 respondent reported worsening vitiligo. Sixty percent (15/25) of respondents said they were not satisfied with phototherapy. Respondents who were satisfied with the outcome of phototherapy had on average fewer sites affected by vitiligo (mean [SD], 10 [8]; P=.05). The association with other demographic and economic parameters (eg, sex, race, level of education, income level) was not statistically significant. Proceeding with phototherapy was not related to race, sex, level of education, or income level.

When questioned how many aspects of daily life (eg, work, home, school) were affected by phototherapy, 40% (35/87) of respondents reported that more than one life parameter was disturbed. Thirty-five percent (8/23) of respondents who received phototherapy reported that it affected their daily life “quite a bit” or “severely.” More respondents were likely to report that the therapy interfered with their life “somewhat,” “quite a bit,” or “severely” (76% [19/25]; 95% confidence interval, 55%-92%; P=.01) rather than “not at all” or “a little.”

Excimer Laser

Nine of 17 respondents (53%) who were recommended to undergo excimer laser therapy actually received therapy and reported paying $100 weekly (IQR=$60).

There was a trend toward significance of excimer usage being associated with lower age quartile (0–20 years)(P=.0553) and income more than $100,000 (P=.0788), neither of which reached statistical significance.

Insurance Coverage

Respondents were offered 7 answer options regarding the reason for noncoverage of topical calcineurin inhibitors. They were allowed to pick more than one reason where appropriate. For individuals who were prescribed topical tacrolimus but did not receive drug (n=17), the following reasons were cited: “no insurance coverage for the medication” (59% [10/17]), “your deductible was too high” (24% [4/17]), “prior authorization failed to produce coverage of the medication” (24% [4/17]), “your copay was prohibitively expensive” (24% [4/17]), “you were uncomfortable with the medication’s side effects” (18% [3/17]), “the tube was too small to cover your skin affected areas” (12% [2/17]), and “other” (29% [5/17]). Three patients selected 3 or more reasons, 8 patients selected 2 reasons, and 5 patients selected one reason.

Comment

It has been reported that patients with vitiligo may have difficulty related to treatment compliance for a variety of reasons.5 We identified notable barriers that arise for some, if not all, patients with vitiligo in the United States at some point in their care, including interference with other aspects of daily life, lack of coverage by current health insurance provider, and high out-of-pocket expenses, in addition to the negative effects of vitiligo on quality of life that have already been reported.6,7 These barriers are not a function of race/ethnicity, income level, or age of onset, but they may be impacted, as in the case of tacrolimus, by female sex. It is clear that, based on this study’s numbers, many patients will be unable to receive and/or comply with recommended treatment plans.

A limitation of this analysis is the study population, a select group of patients who had not been prescribed all the therapies in question. The sample size may not be large enough to demonstrate differences between level of education, race, or income level; however, even with a sample size of 87 respondents, the barriers to access of care are prominent. Larger population-based surveys would potentially tease out patterns of barriers not apparent with a smaller sample. No data were generated specific to calcipotriene, and this medication was not specified as a write-in agent on open question by any respondents; therefore, access to topical calcipotriene cannot be projected from this study. Phototherapy was queried as a nonspecific term and the breakdown of NB-UVB versus psoralen plus UVA was not available for this survey. Data suggesting a burden of socioeconomic barriers have been reported for atopic dermatitis8 and psoriasis,9 which corroborate the need for greater research in the field of access to care in dermatology.

Despite some advancement in the care of vitiligo, patients often are unable to access preferred or recommended treatment modalities. Standard recommendations for care are initial usage of calcineurin inhibitors for facial involvement and topical high-potency corticosteroids for involvement of the body.3,4 Based on this survey, it would seem that many patients are not able to receive the standard of care. Similarly, NB-UVB phototherapy and excimer laser therapy are recommended for widespread vitiligo and lesions unresponsive to topical care. It would seem that almost half of our respondents did not have access to one or more of the recommended therapies. Barriers to care may have substantial clinical and psychological outcomes, which were not evaluated in this study but merit future research.

- Krüger C, Schallreuter KU. A review of the worldwide prevalence of vitiligo in children/adolescents and adults. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1206-1212.

- Jin Y, Birlea SA, Fain PR, et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 13 new susceptibility loci for generalized vitiligo. Nat Genet. 2012;44:676-680.

- Silverberg NB. Pediatric vitiligo. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014;61:347-366.

- Taieb A, Alomar A, Böhm M, et al, Vitiligo European Task Force (VETF); European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV); Union Europénne des Médecins Spécialistes (UEMS). Guidelines for the management of vitiligo: the European Dermatology Forum consensus. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:5-19.

- Abraham S, Raghavan P. Myths and facts about vitiligo: an epidemiological study. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2015;77:8-13.

- Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Quality of life impairment in children and adolescents with vitiligo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:309-318.

- Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Association between vitiligo extent and distribution and quality-of-life impairment. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:159-164.

- Silverberg JI, Hanifin JM. Adult eczema prevalence and associations with asthma and other health and demographic factors: a US population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:1132-1138.

- Hamilton MP, Ntais D, Griffiths CE, et al. Psoriasis treatment and management—a systematic review of full economic evaluations. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:574-583.

Vitiligo is a disorder typified by loss of pigmentation. Worldwide estimates of disease demonstrate 0.4% to 2% prevalence.1 Vitiligo generally is felt to be an autoimmune disorder with a complex multifactorial inheritance.2 Therapeutic options for vitiligo are largely off label and include topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) light phototherapy, and excimer (308 nm) laser therapy.3,4 Therapies for vitiligo are time consuming, as most topical therapies require twice-daily application. Additionally, many patients require 2 or more topical therapies due to involvement of both the head and neck as well as other body sites.3,4 Generalized disease often is treated with NB-UVB therapy 3 times weekly in-office visits, while excimer laser therapy is used for limited disease resistant to topical agents.3,4

Many barriers to good outcomes and care exist for patients with vitiligo.5 Patients may experience reduced quality of life and/or sexual dysfunction because of vitiligo lesions. The purpose of this pilot study was to identify barriers to access of care in vitiligo patients.

Methods

A survey was designed and then reviewed for unclear wording by members of the local vitiligo support group at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital and Beth Israel Medical Centers (New York, New York). Linguistic revision and clarifications were added to the survey to correct identified communication problems. The survey was then posted using an Internet-based survey software. Links to the survey were sent via email to 107 individuals in a LISTSERV comprising Vitiligo Support International members who participated in a New York City support group (led by C.G. and N.B.S.). Only 1 email was used per household and only individuals 18 years or older could participate. These individuals were asked to complete a deidentified, 82-question, institutional review board–reviewed and exempted survey addressing issues affecting delivery and receipt of medical care for vitiligo.

Data were analyzed using the χ2 test, analysis of variance, or Student t test depending on the type of variable (categorical vs continuous). Fisher exact or Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests were used when distributional assumptions were not met. A type I error rate (α=.05) was used to determine statistical significance. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 software.

Results

Respondents

The survey was completed by 81% (n=87) of individuals. The mean (SD) age of the treated patients about whom the respondents communicated was 33 (16) years and 71% (n=62) were women. The majority of respondents (64 [74%]) reported their race as white, followed by African American/black (12 [14%]), Hispanic (7 [8%]), and Asian (4 [5%]). Twenty-nine percent (22/76) of respondents reported a family income of less than $50,000 per year, 34% (26/76) reported an income of $50,000 to $100,000, and 37% (28/76) reported an income greater than $100,000, while 11 respondents did not report income.

Number of Physicians Seen

Respondents had reportedly seen an average (SD) number of 2 (1) physicians in the past/present before being offered any therapy for vitiligo and only 37% (32/87) of respondents reported being offered therapy by the first physician they saw. The number of physicians seen did not have a statistical relationship with years with vitiligo (ie, disease duration), sex, race, age of onset, income level, or number of sites affected.

Number of Sites Affected

The survey identified the following 23 sites affected by vitiligo: scalp, forehead, eyelids, lips, nose, cheeks, chin, neck, chest, stomach, back, upper arms, forearms, hands, wrists, fingers, genitalia, buttocks, thighs, calves/shins, ankles, feet, and toes. The average (SD) number of sites affected was 12 (6). The number of sites affected was correlated to the recommendation for phototherapy, while the recommendation for excimer laser therapy was inversely associated with the number of sites affected. The median number of sites affected for those who were not prescribed phototherapy was 10 (interquartile range [IQR]=9; P=.05); the median number of sites affected for those who were prescribed phototherapy was 15 (IQR=11). The association between the number of sites affected and whether the patient proceeded with phototherapy was not statistically significant. The need for phototherapy was not related to years with vitiligo (ie, disease duration), sex, or race.

Excimer laser therapy was prescribed more often to patients with fewer sites affected (median of 9 [IQR=3] vs median of 15 [IQR=9]; P=.04). Respondents who had fewer sites affected were on average more likely to proceed with excimer laser therapy (median of 8 [IQR=4] vs median of 11 [IQR=5]). The association between the number of sites affected and whether the patient proceeded with excimer laser therapy was not statistically significant.

Access to Topical Medications

Forty-one percent (36/87) of respondents reported difficulty accessing 1 or more topical therapies. Of 52 respondents who were prescribed a topical corticosteroid, 12 (23%) reported difficulty accessing therapy. Of 67 respondents who were prescribed a topical calcineurin inhibitor, 27 (40%) reported difficulty accessing medication (tacrolimus, n=17; pimecrolimus, n=10). Calcipotriene prescription coverage was not specifically addressed in this survey, as it usually is a second-line or adjunctive medication. Difficulty getting topical tacrolimus but not topical corticosteroids was associated with female sex (P=.03) but was not associated with race, income level, or level of education. Difficulty obtaining medication was not related to race, sex, level of education, or income level.

Consequences of Phototherapy

Twenty-three of 34 respondents (68%) who were told they required phototherapy actually received phototherapy and reported paying $38 weekly (IQR=$75). The majority of patients who proceeded with phototherapy lived (17/23 [74%]) or worked (16/23 [70%]) within 20 minutes of the therapy center. Self-reported response to phototherapy was good to very good in 65% (15/23) of respondents and no response in 30% (7/23); only 1 respondent reported worsening vitiligo. Sixty percent (15/25) of respondents said they were not satisfied with phototherapy. Respondents who were satisfied with the outcome of phototherapy had on average fewer sites affected by vitiligo (mean [SD], 10 [8]; P=.05). The association with other demographic and economic parameters (eg, sex, race, level of education, income level) was not statistically significant. Proceeding with phototherapy was not related to race, sex, level of education, or income level.

When questioned how many aspects of daily life (eg, work, home, school) were affected by phototherapy, 40% (35/87) of respondents reported that more than one life parameter was disturbed. Thirty-five percent (8/23) of respondents who received phototherapy reported that it affected their daily life “quite a bit” or “severely.” More respondents were likely to report that the therapy interfered with their life “somewhat,” “quite a bit,” or “severely” (76% [19/25]; 95% confidence interval, 55%-92%; P=.01) rather than “not at all” or “a little.”

Excimer Laser

Nine of 17 respondents (53%) who were recommended to undergo excimer laser therapy actually received therapy and reported paying $100 weekly (IQR=$60).

There was a trend toward significance of excimer usage being associated with lower age quartile (0–20 years)(P=.0553) and income more than $100,000 (P=.0788), neither of which reached statistical significance.

Insurance Coverage

Respondents were offered 7 answer options regarding the reason for noncoverage of topical calcineurin inhibitors. They were allowed to pick more than one reason where appropriate. For individuals who were prescribed topical tacrolimus but did not receive drug (n=17), the following reasons were cited: “no insurance coverage for the medication” (59% [10/17]), “your deductible was too high” (24% [4/17]), “prior authorization failed to produce coverage of the medication” (24% [4/17]), “your copay was prohibitively expensive” (24% [4/17]), “you were uncomfortable with the medication’s side effects” (18% [3/17]), “the tube was too small to cover your skin affected areas” (12% [2/17]), and “other” (29% [5/17]). Three patients selected 3 or more reasons, 8 patients selected 2 reasons, and 5 patients selected one reason.

Comment

It has been reported that patients with vitiligo may have difficulty related to treatment compliance for a variety of reasons.5 We identified notable barriers that arise for some, if not all, patients with vitiligo in the United States at some point in their care, including interference with other aspects of daily life, lack of coverage by current health insurance provider, and high out-of-pocket expenses, in addition to the negative effects of vitiligo on quality of life that have already been reported.6,7 These barriers are not a function of race/ethnicity, income level, or age of onset, but they may be impacted, as in the case of tacrolimus, by female sex. It is clear that, based on this study’s numbers, many patients will be unable to receive and/or comply with recommended treatment plans.

A limitation of this analysis is the study population, a select group of patients who had not been prescribed all the therapies in question. The sample size may not be large enough to demonstrate differences between level of education, race, or income level; however, even with a sample size of 87 respondents, the barriers to access of care are prominent. Larger population-based surveys would potentially tease out patterns of barriers not apparent with a smaller sample. No data were generated specific to calcipotriene, and this medication was not specified as a write-in agent on open question by any respondents; therefore, access to topical calcipotriene cannot be projected from this study. Phototherapy was queried as a nonspecific term and the breakdown of NB-UVB versus psoralen plus UVA was not available for this survey. Data suggesting a burden of socioeconomic barriers have been reported for atopic dermatitis8 and psoriasis,9 which corroborate the need for greater research in the field of access to care in dermatology.

Despite some advancement in the care of vitiligo, patients often are unable to access preferred or recommended treatment modalities. Standard recommendations for care are initial usage of calcineurin inhibitors for facial involvement and topical high-potency corticosteroids for involvement of the body.3,4 Based on this survey, it would seem that many patients are not able to receive the standard of care. Similarly, NB-UVB phototherapy and excimer laser therapy are recommended for widespread vitiligo and lesions unresponsive to topical care. It would seem that almost half of our respondents did not have access to one or more of the recommended therapies. Barriers to care may have substantial clinical and psychological outcomes, which were not evaluated in this study but merit future research.

Vitiligo is a disorder typified by loss of pigmentation. Worldwide estimates of disease demonstrate 0.4% to 2% prevalence.1 Vitiligo generally is felt to be an autoimmune disorder with a complex multifactorial inheritance.2 Therapeutic options for vitiligo are largely off label and include topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) light phototherapy, and excimer (308 nm) laser therapy.3,4 Therapies for vitiligo are time consuming, as most topical therapies require twice-daily application. Additionally, many patients require 2 or more topical therapies due to involvement of both the head and neck as well as other body sites.3,4 Generalized disease often is treated with NB-UVB therapy 3 times weekly in-office visits, while excimer laser therapy is used for limited disease resistant to topical agents.3,4

Many barriers to good outcomes and care exist for patients with vitiligo.5 Patients may experience reduced quality of life and/or sexual dysfunction because of vitiligo lesions. The purpose of this pilot study was to identify barriers to access of care in vitiligo patients.

Methods

A survey was designed and then reviewed for unclear wording by members of the local vitiligo support group at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital and Beth Israel Medical Centers (New York, New York). Linguistic revision and clarifications were added to the survey to correct identified communication problems. The survey was then posted using an Internet-based survey software. Links to the survey were sent via email to 107 individuals in a LISTSERV comprising Vitiligo Support International members who participated in a New York City support group (led by C.G. and N.B.S.). Only 1 email was used per household and only individuals 18 years or older could participate. These individuals were asked to complete a deidentified, 82-question, institutional review board–reviewed and exempted survey addressing issues affecting delivery and receipt of medical care for vitiligo.

Data were analyzed using the χ2 test, analysis of variance, or Student t test depending on the type of variable (categorical vs continuous). Fisher exact or Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests were used when distributional assumptions were not met. A type I error rate (α=.05) was used to determine statistical significance. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 software.

Results

Respondents

The survey was completed by 81% (n=87) of individuals. The mean (SD) age of the treated patients about whom the respondents communicated was 33 (16) years and 71% (n=62) were women. The majority of respondents (64 [74%]) reported their race as white, followed by African American/black (12 [14%]), Hispanic (7 [8%]), and Asian (4 [5%]). Twenty-nine percent (22/76) of respondents reported a family income of less than $50,000 per year, 34% (26/76) reported an income of $50,000 to $100,000, and 37% (28/76) reported an income greater than $100,000, while 11 respondents did not report income.

Number of Physicians Seen

Respondents had reportedly seen an average (SD) number of 2 (1) physicians in the past/present before being offered any therapy for vitiligo and only 37% (32/87) of respondents reported being offered therapy by the first physician they saw. The number of physicians seen did not have a statistical relationship with years with vitiligo (ie, disease duration), sex, race, age of onset, income level, or number of sites affected.

Number of Sites Affected

The survey identified the following 23 sites affected by vitiligo: scalp, forehead, eyelids, lips, nose, cheeks, chin, neck, chest, stomach, back, upper arms, forearms, hands, wrists, fingers, genitalia, buttocks, thighs, calves/shins, ankles, feet, and toes. The average (SD) number of sites affected was 12 (6). The number of sites affected was correlated to the recommendation for phototherapy, while the recommendation for excimer laser therapy was inversely associated with the number of sites affected. The median number of sites affected for those who were not prescribed phototherapy was 10 (interquartile range [IQR]=9; P=.05); the median number of sites affected for those who were prescribed phototherapy was 15 (IQR=11). The association between the number of sites affected and whether the patient proceeded with phototherapy was not statistically significant. The need for phototherapy was not related to years with vitiligo (ie, disease duration), sex, or race.

Excimer laser therapy was prescribed more often to patients with fewer sites affected (median of 9 [IQR=3] vs median of 15 [IQR=9]; P=.04). Respondents who had fewer sites affected were on average more likely to proceed with excimer laser therapy (median of 8 [IQR=4] vs median of 11 [IQR=5]). The association between the number of sites affected and whether the patient proceeded with excimer laser therapy was not statistically significant.

Access to Topical Medications

Forty-one percent (36/87) of respondents reported difficulty accessing 1 or more topical therapies. Of 52 respondents who were prescribed a topical corticosteroid, 12 (23%) reported difficulty accessing therapy. Of 67 respondents who were prescribed a topical calcineurin inhibitor, 27 (40%) reported difficulty accessing medication (tacrolimus, n=17; pimecrolimus, n=10). Calcipotriene prescription coverage was not specifically addressed in this survey, as it usually is a second-line or adjunctive medication. Difficulty getting topical tacrolimus but not topical corticosteroids was associated with female sex (P=.03) but was not associated with race, income level, or level of education. Difficulty obtaining medication was not related to race, sex, level of education, or income level.

Consequences of Phototherapy

Twenty-three of 34 respondents (68%) who were told they required phototherapy actually received phototherapy and reported paying $38 weekly (IQR=$75). The majority of patients who proceeded with phototherapy lived (17/23 [74%]) or worked (16/23 [70%]) within 20 minutes of the therapy center. Self-reported response to phototherapy was good to very good in 65% (15/23) of respondents and no response in 30% (7/23); only 1 respondent reported worsening vitiligo. Sixty percent (15/25) of respondents said they were not satisfied with phototherapy. Respondents who were satisfied with the outcome of phototherapy had on average fewer sites affected by vitiligo (mean [SD], 10 [8]; P=.05). The association with other demographic and economic parameters (eg, sex, race, level of education, income level) was not statistically significant. Proceeding with phototherapy was not related to race, sex, level of education, or income level.

When questioned how many aspects of daily life (eg, work, home, school) were affected by phototherapy, 40% (35/87) of respondents reported that more than one life parameter was disturbed. Thirty-five percent (8/23) of respondents who received phototherapy reported that it affected their daily life “quite a bit” or “severely.” More respondents were likely to report that the therapy interfered with their life “somewhat,” “quite a bit,” or “severely” (76% [19/25]; 95% confidence interval, 55%-92%; P=.01) rather than “not at all” or “a little.”

Excimer Laser

Nine of 17 respondents (53%) who were recommended to undergo excimer laser therapy actually received therapy and reported paying $100 weekly (IQR=$60).

There was a trend toward significance of excimer usage being associated with lower age quartile (0–20 years)(P=.0553) and income more than $100,000 (P=.0788), neither of which reached statistical significance.

Insurance Coverage

Respondents were offered 7 answer options regarding the reason for noncoverage of topical calcineurin inhibitors. They were allowed to pick more than one reason where appropriate. For individuals who were prescribed topical tacrolimus but did not receive drug (n=17), the following reasons were cited: “no insurance coverage for the medication” (59% [10/17]), “your deductible was too high” (24% [4/17]), “prior authorization failed to produce coverage of the medication” (24% [4/17]), “your copay was prohibitively expensive” (24% [4/17]), “you were uncomfortable with the medication’s side effects” (18% [3/17]), “the tube was too small to cover your skin affected areas” (12% [2/17]), and “other” (29% [5/17]). Three patients selected 3 or more reasons, 8 patients selected 2 reasons, and 5 patients selected one reason.

Comment

It has been reported that patients with vitiligo may have difficulty related to treatment compliance for a variety of reasons.5 We identified notable barriers that arise for some, if not all, patients with vitiligo in the United States at some point in their care, including interference with other aspects of daily life, lack of coverage by current health insurance provider, and high out-of-pocket expenses, in addition to the negative effects of vitiligo on quality of life that have already been reported.6,7 These barriers are not a function of race/ethnicity, income level, or age of onset, but they may be impacted, as in the case of tacrolimus, by female sex. It is clear that, based on this study’s numbers, many patients will be unable to receive and/or comply with recommended treatment plans.

A limitation of this analysis is the study population, a select group of patients who had not been prescribed all the therapies in question. The sample size may not be large enough to demonstrate differences between level of education, race, or income level; however, even with a sample size of 87 respondents, the barriers to access of care are prominent. Larger population-based surveys would potentially tease out patterns of barriers not apparent with a smaller sample. No data were generated specific to calcipotriene, and this medication was not specified as a write-in agent on open question by any respondents; therefore, access to topical calcipotriene cannot be projected from this study. Phototherapy was queried as a nonspecific term and the breakdown of NB-UVB versus psoralen plus UVA was not available for this survey. Data suggesting a burden of socioeconomic barriers have been reported for atopic dermatitis8 and psoriasis,9 which corroborate the need for greater research in the field of access to care in dermatology.

Despite some advancement in the care of vitiligo, patients often are unable to access preferred or recommended treatment modalities. Standard recommendations for care are initial usage of calcineurin inhibitors for facial involvement and topical high-potency corticosteroids for involvement of the body.3,4 Based on this survey, it would seem that many patients are not able to receive the standard of care. Similarly, NB-UVB phototherapy and excimer laser therapy are recommended for widespread vitiligo and lesions unresponsive to topical care. It would seem that almost half of our respondents did not have access to one or more of the recommended therapies. Barriers to care may have substantial clinical and psychological outcomes, which were not evaluated in this study but merit future research.

- Krüger C, Schallreuter KU. A review of the worldwide prevalence of vitiligo in children/adolescents and adults. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1206-1212.

- Jin Y, Birlea SA, Fain PR, et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 13 new susceptibility loci for generalized vitiligo. Nat Genet. 2012;44:676-680.

- Silverberg NB. Pediatric vitiligo. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014;61:347-366.

- Taieb A, Alomar A, Böhm M, et al, Vitiligo European Task Force (VETF); European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV); Union Europénne des Médecins Spécialistes (UEMS). Guidelines for the management of vitiligo: the European Dermatology Forum consensus. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:5-19.

- Abraham S, Raghavan P. Myths and facts about vitiligo: an epidemiological study. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2015;77:8-13.

- Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Quality of life impairment in children and adolescents with vitiligo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:309-318.

- Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Association between vitiligo extent and distribution and quality-of-life impairment. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:159-164.

- Silverberg JI, Hanifin JM. Adult eczema prevalence and associations with asthma and other health and demographic factors: a US population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:1132-1138.

- Hamilton MP, Ntais D, Griffiths CE, et al. Psoriasis treatment and management—a systematic review of full economic evaluations. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:574-583.

- Krüger C, Schallreuter KU. A review of the worldwide prevalence of vitiligo in children/adolescents and adults. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1206-1212.

- Jin Y, Birlea SA, Fain PR, et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 13 new susceptibility loci for generalized vitiligo. Nat Genet. 2012;44:676-680.

- Silverberg NB. Pediatric vitiligo. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014;61:347-366.

- Taieb A, Alomar A, Böhm M, et al, Vitiligo European Task Force (VETF); European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV); Union Europénne des Médecins Spécialistes (UEMS). Guidelines for the management of vitiligo: the European Dermatology Forum consensus. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:5-19.

- Abraham S, Raghavan P. Myths and facts about vitiligo: an epidemiological study. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2015;77:8-13.

- Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Quality of life impairment in children and adolescents with vitiligo. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:309-318.

- Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Association between vitiligo extent and distribution and quality-of-life impairment. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:159-164.

- Silverberg JI, Hanifin JM. Adult eczema prevalence and associations with asthma and other health and demographic factors: a US population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:1132-1138.

- Hamilton MP, Ntais D, Griffiths CE, et al. Psoriasis treatment and management—a systematic review of full economic evaluations. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:574-583.

Practice Points

- Patients with vitiligo may experience difficulty receiving the care prescribed to them.

- It is best to identify barriers such as work schedule or distance before recommending a treatment plan.

Tinea Capitis Caused by Trichophyton rubrum Mimicking Favus

In 1909, Sabouraud1 published a report delineating the clinical subsets of a chronic fungal infection of the scalp known as favus. The rarest subset was termed favus papyroide and consisted of a thin, dry, gray, parchmentlike crust up to 5 cm in diameter. Hair shafts were described as piercing the crust, with the underlying skin exhibiting erythema, moisture, and erosions. Children were reported to be affected more often than adults.1 Subsequent descriptions of patients with similar presentations have not appeared in the medical literature. In this case, an elderly woman with tinea capitis (TC) due to Trichophyton rubrum exhibited features of favus papyroide.

Case Report

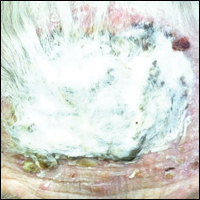

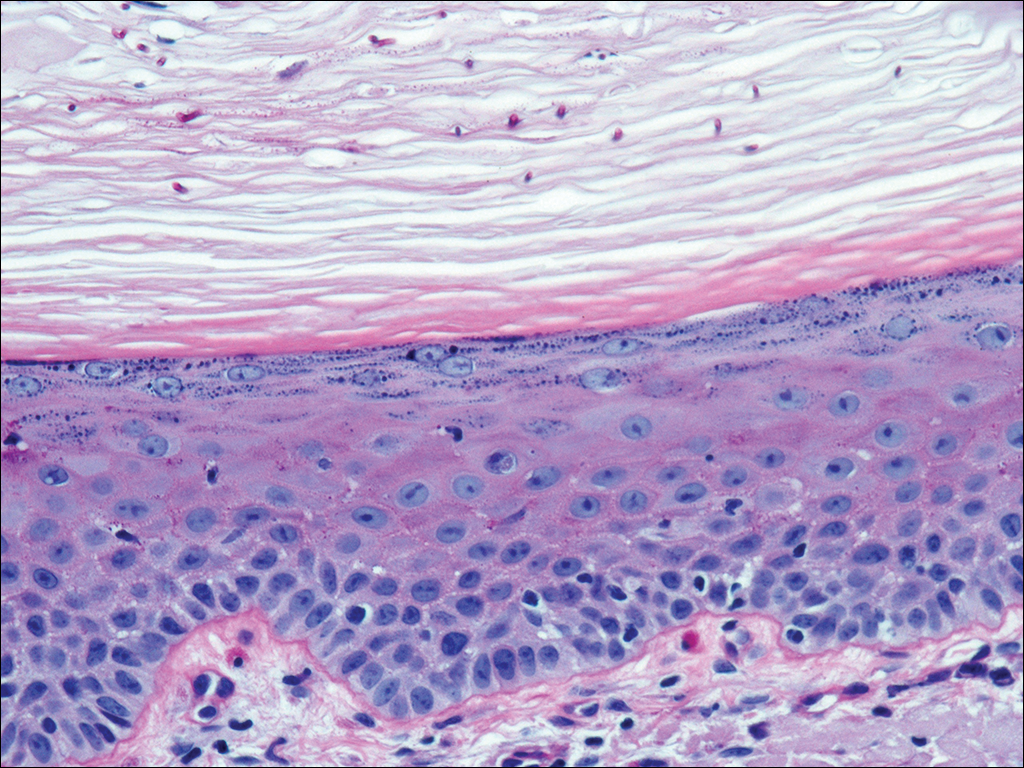

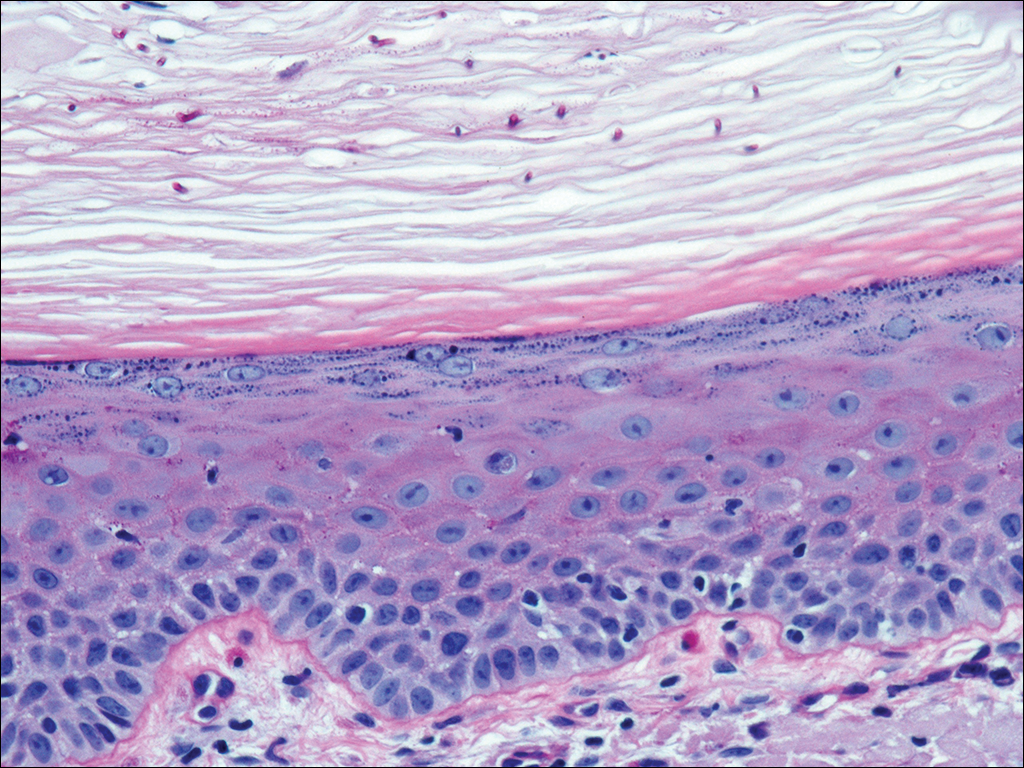

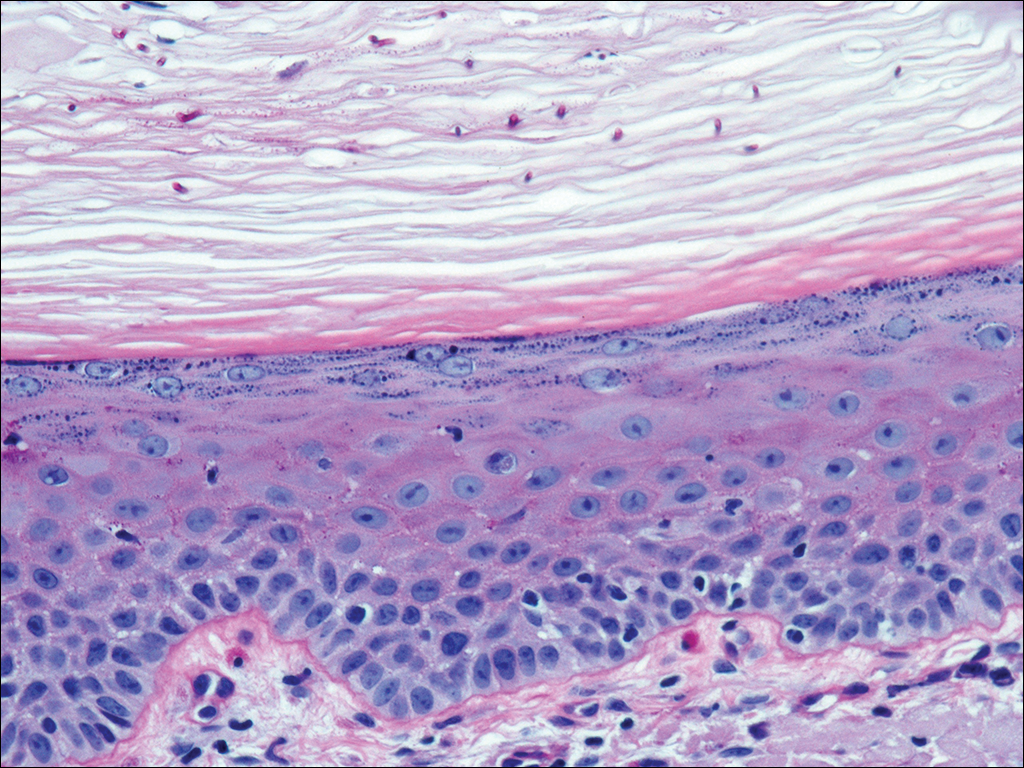

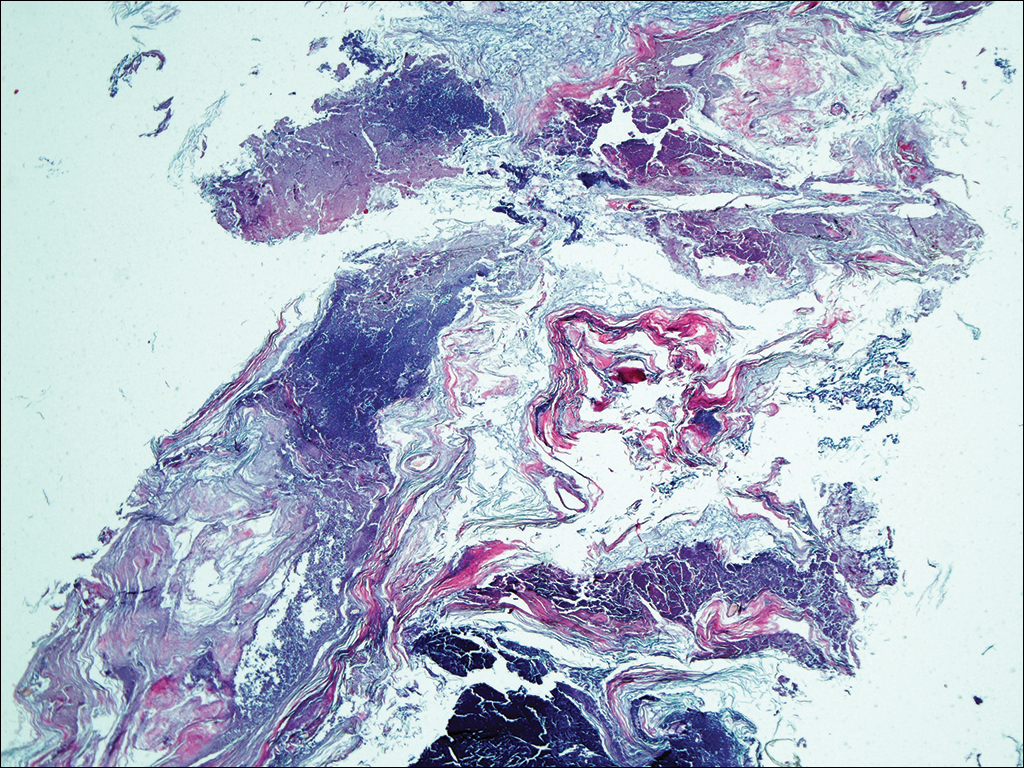

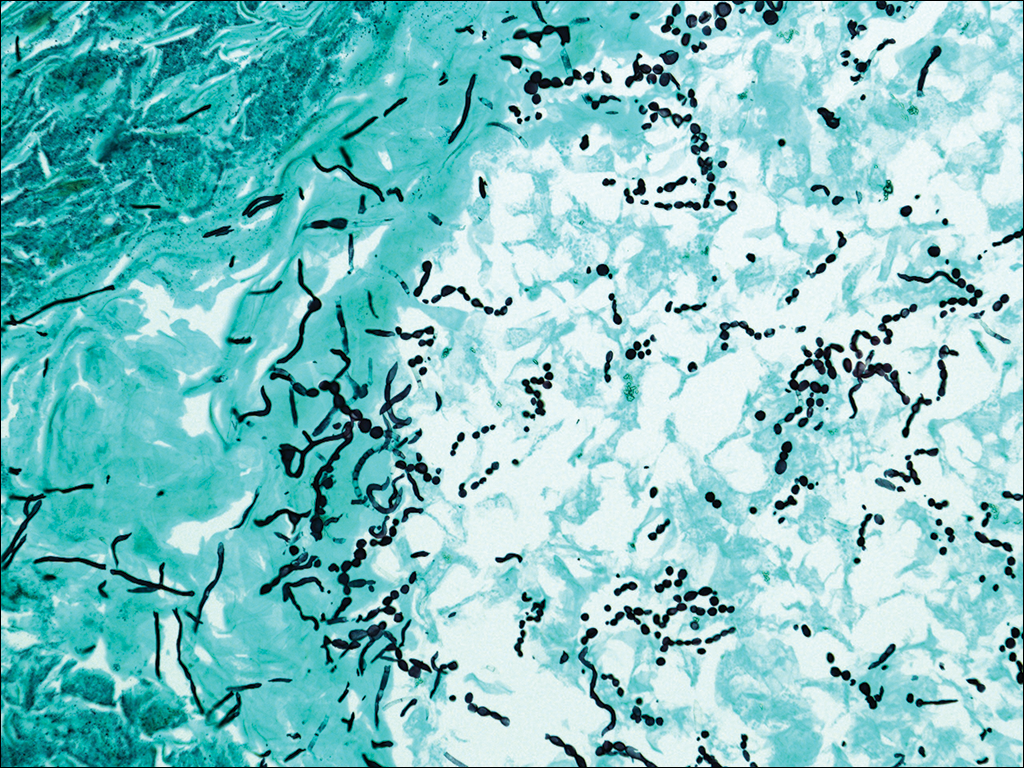

An 87-year-old woman with a long history of actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancers presented to our dermatology clinic with numerous growths on the head, neck, and arms. The patient resided in a nursing home and had a history of hypertension, osteoarthritis, and mild to moderate dementia. Physical examination revealed a frail elderly woman in a wheelchair. Numerous actinic keratoses were noted on the arms and face. Examination of the scalp revealed a large, white-gray, palm-sized plaque on the crown (Figure 1) with 2 yellow, quarter-sized, hyperkeratotic nodules on the left temple and left parietal scalp. The differential diagnosis for the nodules on the temple and scalp included squamous cell carcinoma and hyperkeratotic actinic keratosis, and both lesions were biopsied. Histologically, they demonstrated pronounced hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis with numerous infiltrating neutrophils. The stratum malpighii exhibited focal atypia consistent with an actinic keratosis with areas of spongiosis and pustular folliculitis but no evidence of an invasive cutaneous malignancy. Periodic acid–Schiff stains were performed on both specimens and revealed numerous fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum (Figure 2) as well as evidence of a fungal folliculitis.

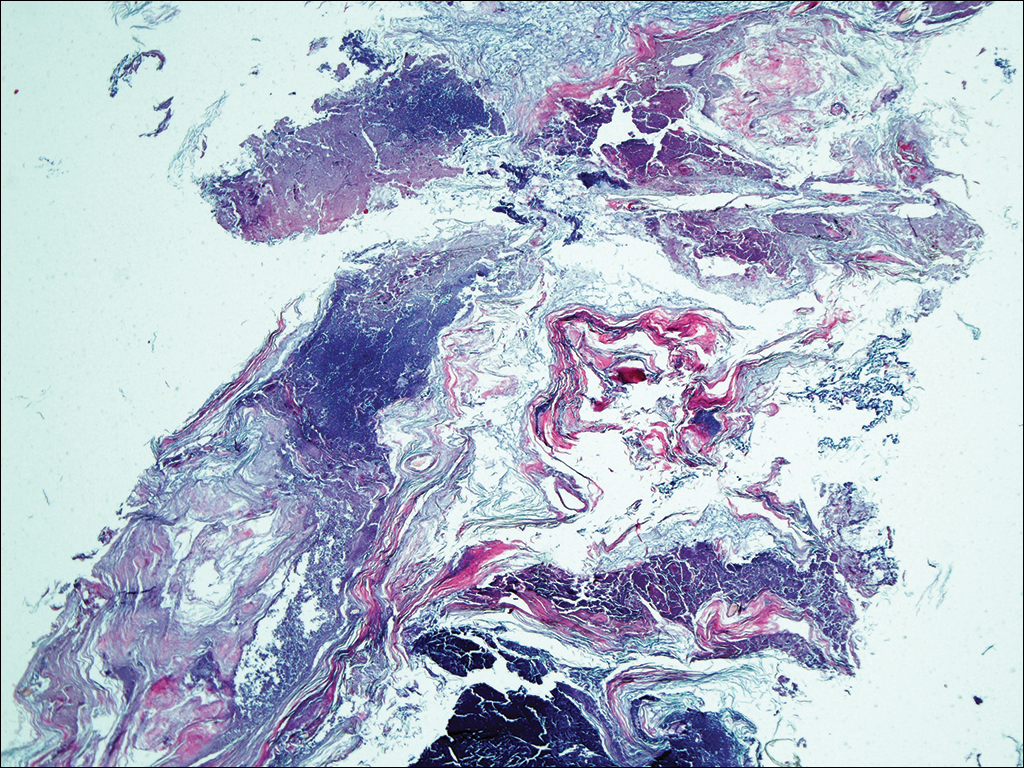

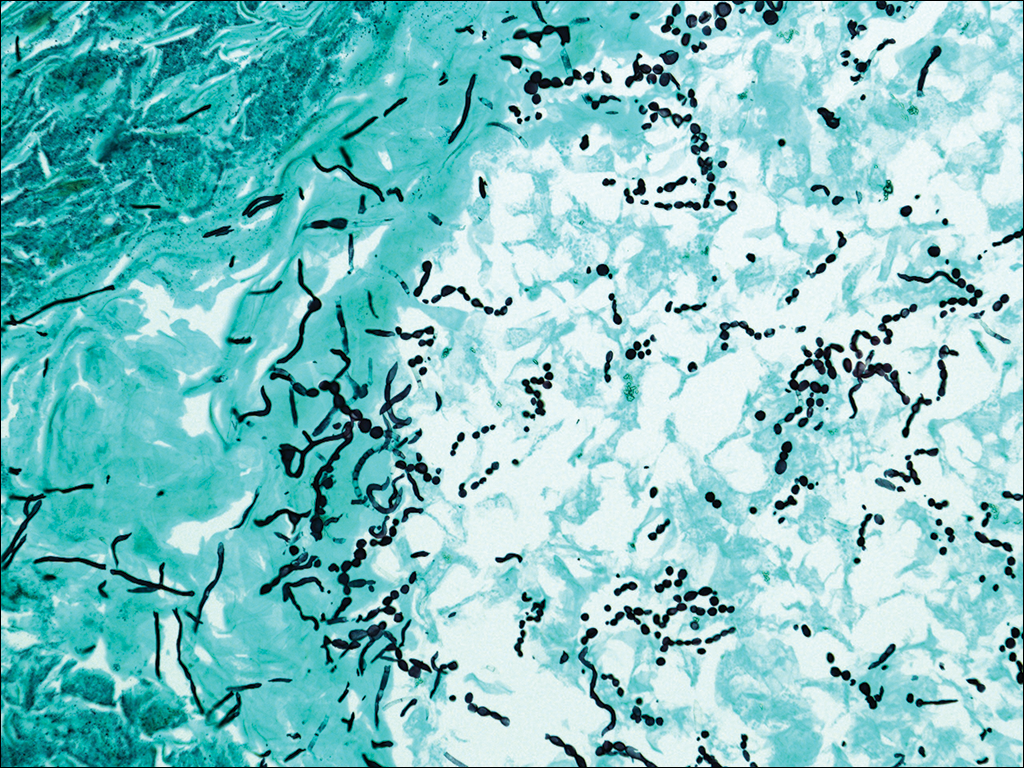

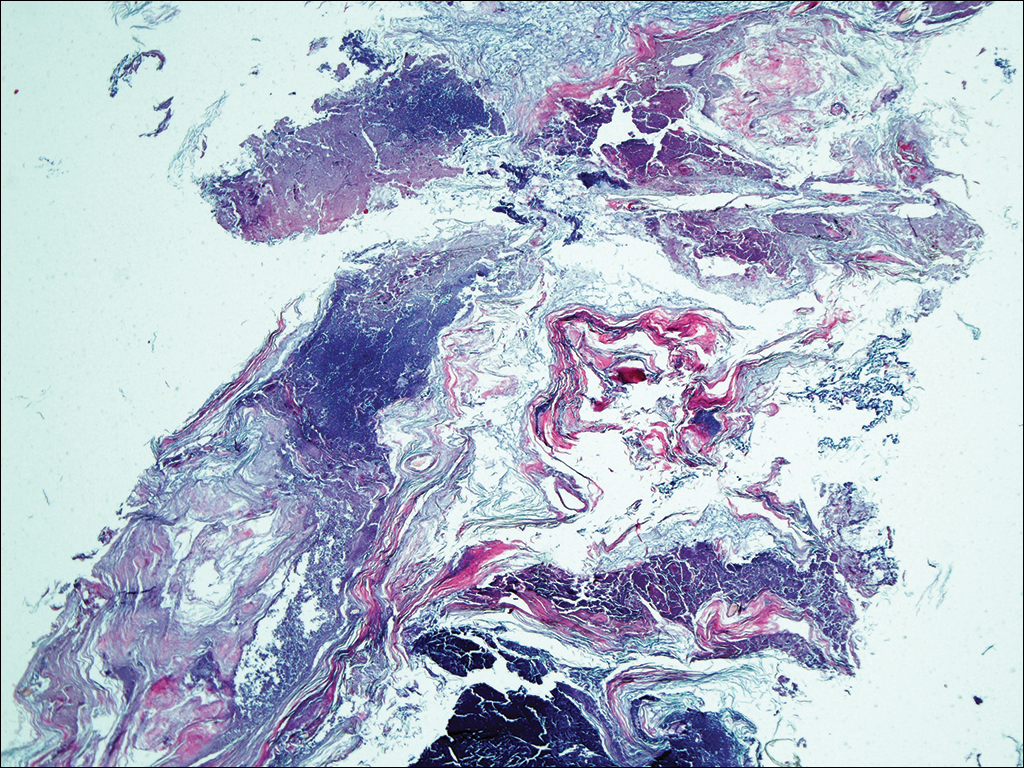

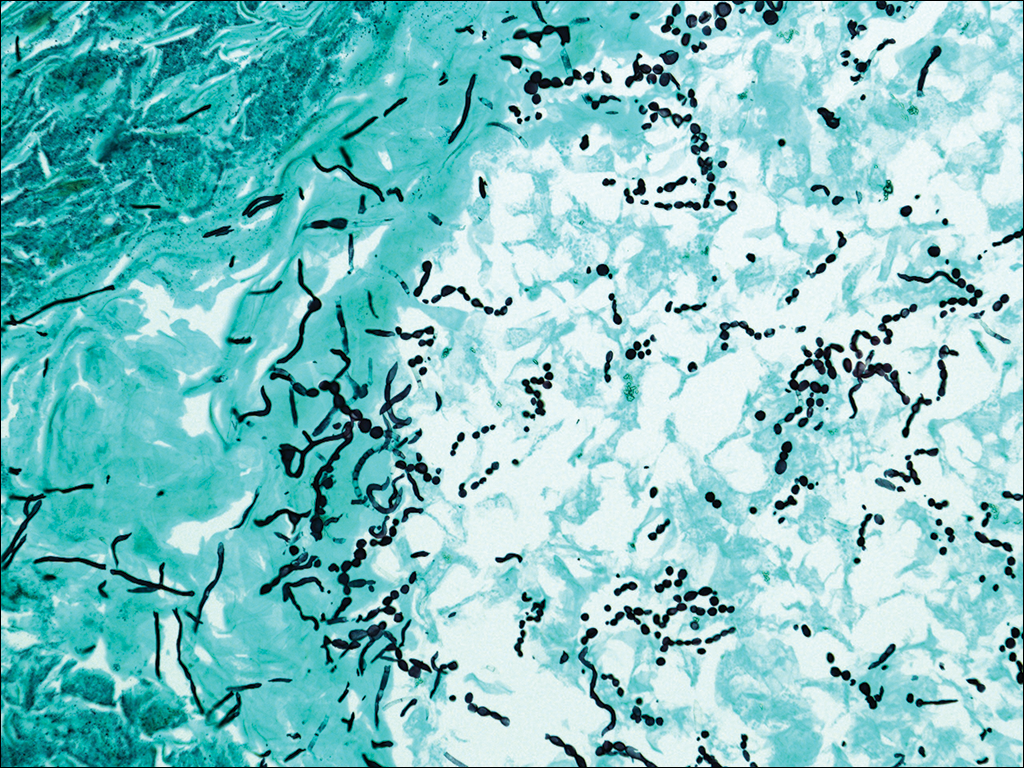

At a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, a portion of the hyperkeratotic material on the crown of the scalp was lifted free from the skin surface, removed with scissors, and submitted for histologic analysis and culture. The underlying skin exhibited substantial erythema and diffuse alopecia. The specimen consisted entirely of masses of hyperkeratotic and parakeratotic stratum corneum with numerous infiltrating neutrophils, cellular debris, and focal secondary bacterial colonization (Figure 3). Fungal hyphae and spores were readily demonstrated on Gomori methenamine-silver stain (Figure 4). A fungal culture from this material failed to demonstrate growth at 28 days. The organism was molecularly identified as T rubrum using the Sanger sequencing assay. The patient was treated with fluconazole 150 mg once daily for 3 weeks with eventual resolution of the plaque. The patient died approximately 3 months later (unrelated to her scalp infection).

Comment

Favus, or tinea favosa, is a chronic inflammatory dermatophyte infection of the scalp, less commonly involving the skin and nails.2 The classic lesion is termed a scutulum or godet consisting of concave, cup-shaped, yellow crusts typically pierced by a single hair shaft.1 With an increase in size, the scutula may become confluent. Alopecia commonly results and infected patients may exude a “cheesy” or “mousy” odor from the lesions.3 Sabouraud1 delineated 3 clinical presentations of favus: (1) favus pityroide, the most common type consisting of a seborrheic dermatitis–like picture and scutula; (2) favus impetigoide, exhibiting honey-colored crusts reminiscent of impetigo but without appreciable scutula; and (3) favus papyroide, the rarest variant, demonstrating a dry, gray, parchmentlike crust pierced by hair shafts overlying an eroded erythematous scalp.

Favus usually is acquired in childhood or adolescence and often persists into adulthood.3 It is transmitted directly by hairs, infected keratinocytes, and fomites. Child-to-child transmission is much less common than other forms of TC.4 The responsible organism is almost always Trichophyton schoenleinii, with rare cases of Trichophyton violaceum, Trichophyton verrucosum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes var quinckeanum, Microsporum canis, and Microsporum gypseum having been reported.2,5,6 This anthropophilic dermatophyte infects only humans, is capable of surviving in the same dwelling space for generations, and is believed to require prolonged exposure for transmission. Trichophyton schoenleinii was the predominant infectious cause of TC in eastern Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but its incidence has dramatically declined in the last 50 years.7 A survey conducted in 1997 and published in 2001 of TC that was culture-positive for T schoenleinii in 19 European countries found only 3 cases among 3671 isolates (0.08%).8 Between 1980 and 2005, no cases were reported in the British Isles.9 Currently, favus generally is found in impoverished geographic regions with poor hygiene, malnutrition, and limited access to health care; however, endemic foci in Kentucky, Quebec, and Montreal have been reported in North America.10 Although favus rarely resolves spontaneously, T schoenleinii was eradicated in most of the world with the introduction of griseofulvin in 1958.7 Terbinafine and itraconazole are currently the drugs of choice for therapy.10

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection in children, with 1 in 20 US children displaying evidence of overt infection.11 Infection in adults is rare and most affected patients typically display serious illnesses with concomitant immune compromise.12 Only 3% to 5% of cases arise in patients older than 20 years.13 Adult hair appears to be relatively resistant to dermatophyte infection, probably from the fungistatic properties of long-chain fatty acids found in sebum.13 Tinea capitis in adults usually occurs in postmenopausal women, presumably from involution of sebaceous glands associated with declining estrogen levels. Patients typically exhibit erythematous scaly patches with central clearing, alopecia, varying degrees of inflammation, and few pustules, though exudative and heavily inflammatory lesions also have been described.14

In the current case, TC was not raised in the differential diagnosis. Regardless, given that scaly red patches and papules of the scalp may represent a dermatophyte infection in this patient population, clinicians are encouraged to consider this possibility. Transmission is by direct human-to-human contact and contact with objects containing fomites including brushes, combs, bedding, clothing, toys, furniture, and telephones.15 It is frequently spread among family members and classmates.16

Prior to World War II, most cases of TC in the United States were due to M canis, with Microsporum audouinii becoming more prevalent until the 1960s and 1970s when Trichophyton tonsurans began surging in incidence.12,17 Currently, the latter organism is responsible for more than 95% of TC cases in the United States.18Microsporum canis is the main causative species in Europe but varies widely by country. In the Middle East and Africa, T violaceum is responsible for many infections.

Trichophyton rubrum–associated TC appears to be a rare occurrence. A global study in 1995 noted that less than 1% of TC cases were due to T rubrum infection, most having been described in emerging nations.12 A meta-analysis of 9 studies from developed countries found only 9 of 10,145 cases of TC with a culture positive for T rubrum.14 In adults, infected patients typically exhibit either evidence of a concomitant fungal infection of the skin and/or nails or health conditions with impaired immunity, whereas in children, interfamilial spread appears more common.11

- Sabouraud R. Les favus atypiques, clinique. Paris. 1909;4:296-299.

- Olkit M. Favus of the scalp: an overview and update. Mycopathologia. 2010;170:143-154.

- Elewski BE. Tinea capitis: a current perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:1-20.

- Aly R, Hay RJ, del Palacio A, et al. Epidemiology of tinea capitis. Med Mycol. 2000;38(suppl 1):183-188.

- Joly J, Delage G, Auger P, et al. Favus: twenty indigenous cases in the province of Quebec. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1647-1648.

- Garcia-Sanchez MS, Pereira M, Pereira MM, et al. Favus due to Trichophyton mentagrophytes var. quinckeanum. Dermatology. 1997;194:177-179.

- Seebacher C, Bouchara JP, Mignon B. Updates on the epidemiology of dermatophyte infections. Mycopathologia. 2008;166:335-352.

- Hay RJ, Robles W, Midgley MK, et al. Tinea capitis in Europe: new perspective on an old problem. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:229-233.

- Borman AM, Campbell CK, Fraser M, et al. Analysis of the dermatophyte species isolated in the British Isles between 1980 and 2005 and review of worldwide dermatophyte trends over the last three decades. Med Mycol. 2007;45:131-141.

- Rippon JW. Dermatophytosis and dermatomycosis. In: Rippon JW. Medical Mycology: The Pathogenic Fungi and the Pathogenic Actinomycetes. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1988:197-199.

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Penny J, Alander SW. Trichophyton rubrum tinea capitis in a young child. Ped Dermatol. 2004;21:63-65.

- Schwinn A, Ebert J, Brocker EB. Frequency of Trichophyton rubrum in tinea capitis. Mycoses. 1995;38:1-7.

- Ziemer A, Kohl K, Schroder G. Trichophyton rubrum induced inflammatory tinea capitis in a 63-year-old man. Mycoses. 2005;48:76-79.

- Anstey A, Lucke TW, Philpot C. Tinea capitis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:113-115.

- Schwinn A, Ebert J, Muller I, et al. Trichophyton rubrum as the causative agent of tinea capitis in three children. Mycoses. 1995;38:9-11.

- Chang SE, Kang SK, Choi JH, et al. Tinea capitis due to Trichophyton rubrum in a neonate. Ped Dermatol. 2002;19:356-358.

- Stiller MJ, Rosenthal SA, Weinstein AS. Tinea capitis caused by Trichophyton rubrum in a 67-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:257-258.

- Foster KW, Ghannoum MA, Elewski BE. Epidemiologic surveillance of cutaneous fungal infection in the United States from 1999 to 2002. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:748-752.

In 1909, Sabouraud1 published a report delineating the clinical subsets of a chronic fungal infection of the scalp known as favus. The rarest subset was termed favus papyroide and consisted of a thin, dry, gray, parchmentlike crust up to 5 cm in diameter. Hair shafts were described as piercing the crust, with the underlying skin exhibiting erythema, moisture, and erosions. Children were reported to be affected more often than adults.1 Subsequent descriptions of patients with similar presentations have not appeared in the medical literature. In this case, an elderly woman with tinea capitis (TC) due to Trichophyton rubrum exhibited features of favus papyroide.

Case Report

An 87-year-old woman with a long history of actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancers presented to our dermatology clinic with numerous growths on the head, neck, and arms. The patient resided in a nursing home and had a history of hypertension, osteoarthritis, and mild to moderate dementia. Physical examination revealed a frail elderly woman in a wheelchair. Numerous actinic keratoses were noted on the arms and face. Examination of the scalp revealed a large, white-gray, palm-sized plaque on the crown (Figure 1) with 2 yellow, quarter-sized, hyperkeratotic nodules on the left temple and left parietal scalp. The differential diagnosis for the nodules on the temple and scalp included squamous cell carcinoma and hyperkeratotic actinic keratosis, and both lesions were biopsied. Histologically, they demonstrated pronounced hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis with numerous infiltrating neutrophils. The stratum malpighii exhibited focal atypia consistent with an actinic keratosis with areas of spongiosis and pustular folliculitis but no evidence of an invasive cutaneous malignancy. Periodic acid–Schiff stains were performed on both specimens and revealed numerous fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum (Figure 2) as well as evidence of a fungal folliculitis.

At a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, a portion of the hyperkeratotic material on the crown of the scalp was lifted free from the skin surface, removed with scissors, and submitted for histologic analysis and culture. The underlying skin exhibited substantial erythema and diffuse alopecia. The specimen consisted entirely of masses of hyperkeratotic and parakeratotic stratum corneum with numerous infiltrating neutrophils, cellular debris, and focal secondary bacterial colonization (Figure 3). Fungal hyphae and spores were readily demonstrated on Gomori methenamine-silver stain (Figure 4). A fungal culture from this material failed to demonstrate growth at 28 days. The organism was molecularly identified as T rubrum using the Sanger sequencing assay. The patient was treated with fluconazole 150 mg once daily for 3 weeks with eventual resolution of the plaque. The patient died approximately 3 months later (unrelated to her scalp infection).

Comment

Favus, or tinea favosa, is a chronic inflammatory dermatophyte infection of the scalp, less commonly involving the skin and nails.2 The classic lesion is termed a scutulum or godet consisting of concave, cup-shaped, yellow crusts typically pierced by a single hair shaft.1 With an increase in size, the scutula may become confluent. Alopecia commonly results and infected patients may exude a “cheesy” or “mousy” odor from the lesions.3 Sabouraud1 delineated 3 clinical presentations of favus: (1) favus pityroide, the most common type consisting of a seborrheic dermatitis–like picture and scutula; (2) favus impetigoide, exhibiting honey-colored crusts reminiscent of impetigo but without appreciable scutula; and (3) favus papyroide, the rarest variant, demonstrating a dry, gray, parchmentlike crust pierced by hair shafts overlying an eroded erythematous scalp.

Favus usually is acquired in childhood or adolescence and often persists into adulthood.3 It is transmitted directly by hairs, infected keratinocytes, and fomites. Child-to-child transmission is much less common than other forms of TC.4 The responsible organism is almost always Trichophyton schoenleinii, with rare cases of Trichophyton violaceum, Trichophyton verrucosum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes var quinckeanum, Microsporum canis, and Microsporum gypseum having been reported.2,5,6 This anthropophilic dermatophyte infects only humans, is capable of surviving in the same dwelling space for generations, and is believed to require prolonged exposure for transmission. Trichophyton schoenleinii was the predominant infectious cause of TC in eastern Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but its incidence has dramatically declined in the last 50 years.7 A survey conducted in 1997 and published in 2001 of TC that was culture-positive for T schoenleinii in 19 European countries found only 3 cases among 3671 isolates (0.08%).8 Between 1980 and 2005, no cases were reported in the British Isles.9 Currently, favus generally is found in impoverished geographic regions with poor hygiene, malnutrition, and limited access to health care; however, endemic foci in Kentucky, Quebec, and Montreal have been reported in North America.10 Although favus rarely resolves spontaneously, T schoenleinii was eradicated in most of the world with the introduction of griseofulvin in 1958.7 Terbinafine and itraconazole are currently the drugs of choice for therapy.10

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection in children, with 1 in 20 US children displaying evidence of overt infection.11 Infection in adults is rare and most affected patients typically display serious illnesses with concomitant immune compromise.12 Only 3% to 5% of cases arise in patients older than 20 years.13 Adult hair appears to be relatively resistant to dermatophyte infection, probably from the fungistatic properties of long-chain fatty acids found in sebum.13 Tinea capitis in adults usually occurs in postmenopausal women, presumably from involution of sebaceous glands associated with declining estrogen levels. Patients typically exhibit erythematous scaly patches with central clearing, alopecia, varying degrees of inflammation, and few pustules, though exudative and heavily inflammatory lesions also have been described.14

In the current case, TC was not raised in the differential diagnosis. Regardless, given that scaly red patches and papules of the scalp may represent a dermatophyte infection in this patient population, clinicians are encouraged to consider this possibility. Transmission is by direct human-to-human contact and contact with objects containing fomites including brushes, combs, bedding, clothing, toys, furniture, and telephones.15 It is frequently spread among family members and classmates.16

Prior to World War II, most cases of TC in the United States were due to M canis, with Microsporum audouinii becoming more prevalent until the 1960s and 1970s when Trichophyton tonsurans began surging in incidence.12,17 Currently, the latter organism is responsible for more than 95% of TC cases in the United States.18Microsporum canis is the main causative species in Europe but varies widely by country. In the Middle East and Africa, T violaceum is responsible for many infections.

Trichophyton rubrum–associated TC appears to be a rare occurrence. A global study in 1995 noted that less than 1% of TC cases were due to T rubrum infection, most having been described in emerging nations.12 A meta-analysis of 9 studies from developed countries found only 9 of 10,145 cases of TC with a culture positive for T rubrum.14 In adults, infected patients typically exhibit either evidence of a concomitant fungal infection of the skin and/or nails or health conditions with impaired immunity, whereas in children, interfamilial spread appears more common.11

In 1909, Sabouraud1 published a report delineating the clinical subsets of a chronic fungal infection of the scalp known as favus. The rarest subset was termed favus papyroide and consisted of a thin, dry, gray, parchmentlike crust up to 5 cm in diameter. Hair shafts were described as piercing the crust, with the underlying skin exhibiting erythema, moisture, and erosions. Children were reported to be affected more often than adults.1 Subsequent descriptions of patients with similar presentations have not appeared in the medical literature. In this case, an elderly woman with tinea capitis (TC) due to Trichophyton rubrum exhibited features of favus papyroide.

Case Report

An 87-year-old woman with a long history of actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancers presented to our dermatology clinic with numerous growths on the head, neck, and arms. The patient resided in a nursing home and had a history of hypertension, osteoarthritis, and mild to moderate dementia. Physical examination revealed a frail elderly woman in a wheelchair. Numerous actinic keratoses were noted on the arms and face. Examination of the scalp revealed a large, white-gray, palm-sized plaque on the crown (Figure 1) with 2 yellow, quarter-sized, hyperkeratotic nodules on the left temple and left parietal scalp. The differential diagnosis for the nodules on the temple and scalp included squamous cell carcinoma and hyperkeratotic actinic keratosis, and both lesions were biopsied. Histologically, they demonstrated pronounced hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis with numerous infiltrating neutrophils. The stratum malpighii exhibited focal atypia consistent with an actinic keratosis with areas of spongiosis and pustular folliculitis but no evidence of an invasive cutaneous malignancy. Periodic acid–Schiff stains were performed on both specimens and revealed numerous fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum (Figure 2) as well as evidence of a fungal folliculitis.

At a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, a portion of the hyperkeratotic material on the crown of the scalp was lifted free from the skin surface, removed with scissors, and submitted for histologic analysis and culture. The underlying skin exhibited substantial erythema and diffuse alopecia. The specimen consisted entirely of masses of hyperkeratotic and parakeratotic stratum corneum with numerous infiltrating neutrophils, cellular debris, and focal secondary bacterial colonization (Figure 3). Fungal hyphae and spores were readily demonstrated on Gomori methenamine-silver stain (Figure 4). A fungal culture from this material failed to demonstrate growth at 28 days. The organism was molecularly identified as T rubrum using the Sanger sequencing assay. The patient was treated with fluconazole 150 mg once daily for 3 weeks with eventual resolution of the plaque. The patient died approximately 3 months later (unrelated to her scalp infection).

Comment

Favus, or tinea favosa, is a chronic inflammatory dermatophyte infection of the scalp, less commonly involving the skin and nails.2 The classic lesion is termed a scutulum or godet consisting of concave, cup-shaped, yellow crusts typically pierced by a single hair shaft.1 With an increase in size, the scutula may become confluent. Alopecia commonly results and infected patients may exude a “cheesy” or “mousy” odor from the lesions.3 Sabouraud1 delineated 3 clinical presentations of favus: (1) favus pityroide, the most common type consisting of a seborrheic dermatitis–like picture and scutula; (2) favus impetigoide, exhibiting honey-colored crusts reminiscent of impetigo but without appreciable scutula; and (3) favus papyroide, the rarest variant, demonstrating a dry, gray, parchmentlike crust pierced by hair shafts overlying an eroded erythematous scalp.

Favus usually is acquired in childhood or adolescence and often persists into adulthood.3 It is transmitted directly by hairs, infected keratinocytes, and fomites. Child-to-child transmission is much less common than other forms of TC.4 The responsible organism is almost always Trichophyton schoenleinii, with rare cases of Trichophyton violaceum, Trichophyton verrucosum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes var quinckeanum, Microsporum canis, and Microsporum gypseum having been reported.2,5,6 This anthropophilic dermatophyte infects only humans, is capable of surviving in the same dwelling space for generations, and is believed to require prolonged exposure for transmission. Trichophyton schoenleinii was the predominant infectious cause of TC in eastern Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but its incidence has dramatically declined in the last 50 years.7 A survey conducted in 1997 and published in 2001 of TC that was culture-positive for T schoenleinii in 19 European countries found only 3 cases among 3671 isolates (0.08%).8 Between 1980 and 2005, no cases were reported in the British Isles.9 Currently, favus generally is found in impoverished geographic regions with poor hygiene, malnutrition, and limited access to health care; however, endemic foci in Kentucky, Quebec, and Montreal have been reported in North America.10 Although favus rarely resolves spontaneously, T schoenleinii was eradicated in most of the world with the introduction of griseofulvin in 1958.7 Terbinafine and itraconazole are currently the drugs of choice for therapy.10

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection in children, with 1 in 20 US children displaying evidence of overt infection.11 Infection in adults is rare and most affected patients typically display serious illnesses with concomitant immune compromise.12 Only 3% to 5% of cases arise in patients older than 20 years.13 Adult hair appears to be relatively resistant to dermatophyte infection, probably from the fungistatic properties of long-chain fatty acids found in sebum.13 Tinea capitis in adults usually occurs in postmenopausal women, presumably from involution of sebaceous glands associated with declining estrogen levels. Patients typically exhibit erythematous scaly patches with central clearing, alopecia, varying degrees of inflammation, and few pustules, though exudative and heavily inflammatory lesions also have been described.14

In the current case, TC was not raised in the differential diagnosis. Regardless, given that scaly red patches and papules of the scalp may represent a dermatophyte infection in this patient population, clinicians are encouraged to consider this possibility. Transmission is by direct human-to-human contact and contact with objects containing fomites including brushes, combs, bedding, clothing, toys, furniture, and telephones.15 It is frequently spread among family members and classmates.16

Prior to World War II, most cases of TC in the United States were due to M canis, with Microsporum audouinii becoming more prevalent until the 1960s and 1970s when Trichophyton tonsurans began surging in incidence.12,17 Currently, the latter organism is responsible for more than 95% of TC cases in the United States.18Microsporum canis is the main causative species in Europe but varies widely by country. In the Middle East and Africa, T violaceum is responsible for many infections.

Trichophyton rubrum–associated TC appears to be a rare occurrence. A global study in 1995 noted that less than 1% of TC cases were due to T rubrum infection, most having been described in emerging nations.12 A meta-analysis of 9 studies from developed countries found only 9 of 10,145 cases of TC with a culture positive for T rubrum.14 In adults, infected patients typically exhibit either evidence of a concomitant fungal infection of the skin and/or nails or health conditions with impaired immunity, whereas in children, interfamilial spread appears more common.11

- Sabouraud R. Les favus atypiques, clinique. Paris. 1909;4:296-299.

- Olkit M. Favus of the scalp: an overview and update. Mycopathologia. 2010;170:143-154.

- Elewski BE. Tinea capitis: a current perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:1-20.

- Aly R, Hay RJ, del Palacio A, et al. Epidemiology of tinea capitis. Med Mycol. 2000;38(suppl 1):183-188.

- Joly J, Delage G, Auger P, et al. Favus: twenty indigenous cases in the province of Quebec. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1647-1648.

- Garcia-Sanchez MS, Pereira M, Pereira MM, et al. Favus due to Trichophyton mentagrophytes var. quinckeanum. Dermatology. 1997;194:177-179.

- Seebacher C, Bouchara JP, Mignon B. Updates on the epidemiology of dermatophyte infections. Mycopathologia. 2008;166:335-352.

- Hay RJ, Robles W, Midgley MK, et al. Tinea capitis in Europe: new perspective on an old problem. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:229-233.

- Borman AM, Campbell CK, Fraser M, et al. Analysis of the dermatophyte species isolated in the British Isles between 1980 and 2005 and review of worldwide dermatophyte trends over the last three decades. Med Mycol. 2007;45:131-141.

- Rippon JW. Dermatophytosis and dermatomycosis. In: Rippon JW. Medical Mycology: The Pathogenic Fungi and the Pathogenic Actinomycetes. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1988:197-199.

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Penny J, Alander SW. Trichophyton rubrum tinea capitis in a young child. Ped Dermatol. 2004;21:63-65.

- Schwinn A, Ebert J, Brocker EB. Frequency of Trichophyton rubrum in tinea capitis. Mycoses. 1995;38:1-7.

- Ziemer A, Kohl K, Schroder G. Trichophyton rubrum induced inflammatory tinea capitis in a 63-year-old man. Mycoses. 2005;48:76-79.

- Anstey A, Lucke TW, Philpot C. Tinea capitis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:113-115.

- Schwinn A, Ebert J, Muller I, et al. Trichophyton rubrum as the causative agent of tinea capitis in three children. Mycoses. 1995;38:9-11.

- Chang SE, Kang SK, Choi JH, et al. Tinea capitis due to Trichophyton rubrum in a neonate. Ped Dermatol. 2002;19:356-358.

- Stiller MJ, Rosenthal SA, Weinstein AS. Tinea capitis caused by Trichophyton rubrum in a 67-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:257-258.

- Foster KW, Ghannoum MA, Elewski BE. Epidemiologic surveillance of cutaneous fungal infection in the United States from 1999 to 2002. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:748-752.

- Sabouraud R. Les favus atypiques, clinique. Paris. 1909;4:296-299.

- Olkit M. Favus of the scalp: an overview and update. Mycopathologia. 2010;170:143-154.

- Elewski BE. Tinea capitis: a current perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:1-20.

- Aly R, Hay RJ, del Palacio A, et al. Epidemiology of tinea capitis. Med Mycol. 2000;38(suppl 1):183-188.

- Joly J, Delage G, Auger P, et al. Favus: twenty indigenous cases in the province of Quebec. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1647-1648.

- Garcia-Sanchez MS, Pereira M, Pereira MM, et al. Favus due to Trichophyton mentagrophytes var. quinckeanum. Dermatology. 1997;194:177-179.

- Seebacher C, Bouchara JP, Mignon B. Updates on the epidemiology of dermatophyte infections. Mycopathologia. 2008;166:335-352.

- Hay RJ, Robles W, Midgley MK, et al. Tinea capitis in Europe: new perspective on an old problem. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:229-233.

- Borman AM, Campbell CK, Fraser M, et al. Analysis of the dermatophyte species isolated in the British Isles between 1980 and 2005 and review of worldwide dermatophyte trends over the last three decades. Med Mycol. 2007;45:131-141.

- Rippon JW. Dermatophytosis and dermatomycosis. In: Rippon JW. Medical Mycology: The Pathogenic Fungi and the Pathogenic Actinomycetes. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1988:197-199.

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Penny J, Alander SW. Trichophyton rubrum tinea capitis in a young child. Ped Dermatol. 2004;21:63-65.

- Schwinn A, Ebert J, Brocker EB. Frequency of Trichophyton rubrum in tinea capitis. Mycoses. 1995;38:1-7.

- Ziemer A, Kohl K, Schroder G. Trichophyton rubrum induced inflammatory tinea capitis in a 63-year-old man. Mycoses. 2005;48:76-79.

- Anstey A, Lucke TW, Philpot C. Tinea capitis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:113-115.

- Schwinn A, Ebert J, Muller I, et al. Trichophyton rubrum as the causative agent of tinea capitis in three children. Mycoses. 1995;38:9-11.

- Chang SE, Kang SK, Choi JH, et al. Tinea capitis due to Trichophyton rubrum in a neonate. Ped Dermatol. 2002;19:356-358.

- Stiller MJ, Rosenthal SA, Weinstein AS. Tinea capitis caused by Trichophyton rubrum in a 67-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:257-258.

- Foster KW, Ghannoum MA, Elewski BE. Epidemiologic surveillance of cutaneous fungal infection in the United States from 1999 to 2002. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:748-752.

Practice Points

- Although favus is uncommonly seen in developed countries, it still exists and can mimick other conditions, notably cutaneous malignancies.

- Favus may affect the skin and nails in addition to the hair.

- The lesions of favus may persist for many years.

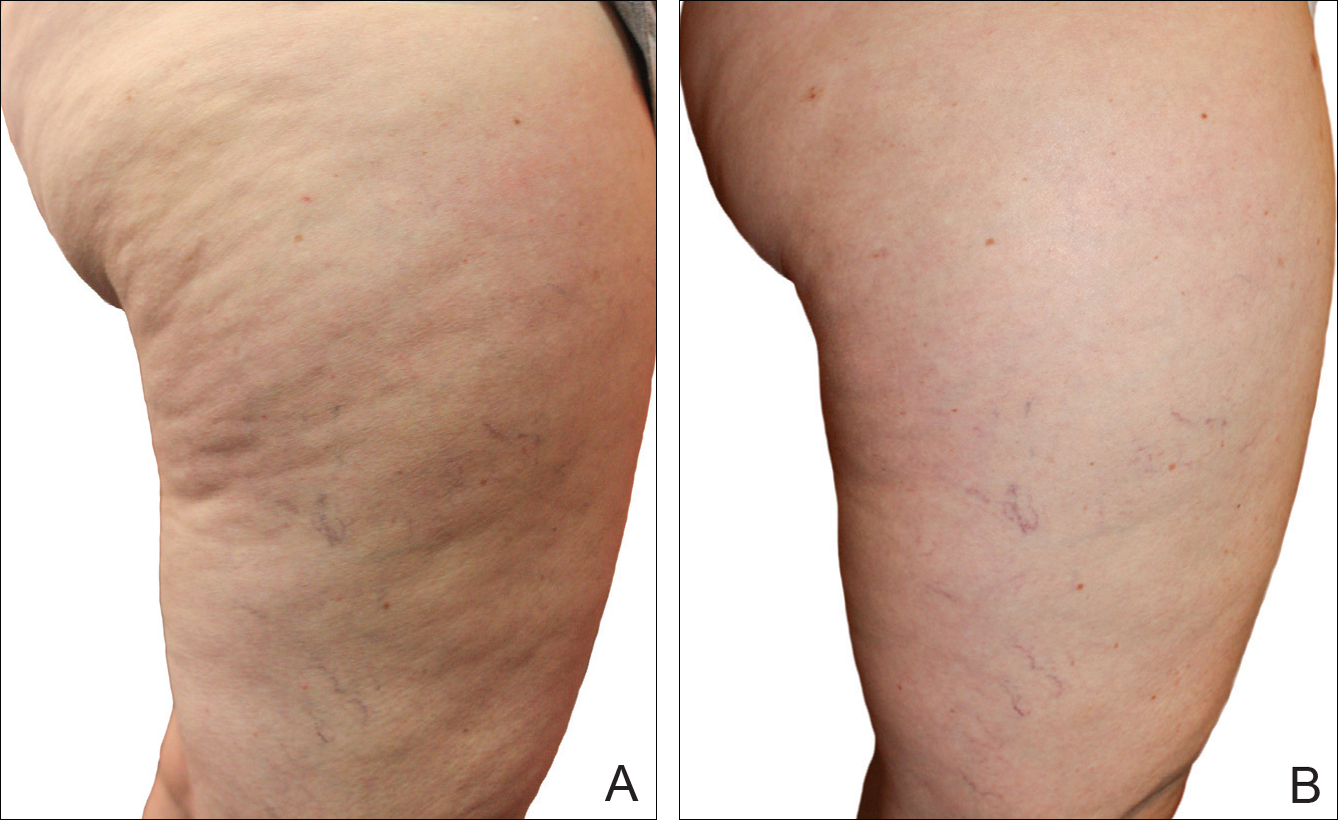

A Noninvasive Mechanical Treatment to Reduce the Visible Appearance of Cellulite

Cellulite is a cosmetic problem, not a disease process. It affects 85% to 90% of all women worldwide and was described nearly 100 years ago.1 Causes may be genetic, hormonal, or vascular in nature and may be related to the septa configuration in the subdermal tissue. Fibrosis at the dermal-subcutaneous junction as well as decreased vascular and lymphatic circulation also may be causative factors.

Cellulite has a multifactorial etiology. Khan et al2 noted that there are specific classic patterns of cellulite that affect women exclusively. White women tend to have somewhat higher rates of cellulite than Asian women. The authors also stated that lifestyle factors such as high carbohydrate diets may lead to an increase in total body fat content, which enhances the appearance of cellulite.2

The subdermal anatomy affects the appearance of cellulite. Utilizing in vivo magnetic resonance imaging, Querleux et al3 showed that women with visible cellulite have dermal septa that are thinner and generally more perpendicular to the skin’s surface than women without cellulite. In women without cellulite, the orientation of the septa is more angled into a crisscross pattern. In women with a high percentage of perpendicular septa, the perpendicular septa allow for fat herniation with dimpling of the skin compared to the crisscross septa pattern.2 Other investigators have discussed the reduction of blood flow in specific areas of the body in women, particularly in cellulite-prone areas such as the buttocks and thighs, as another causative factor.2,4,5 Rossi and Vergnanini6 showed that the blood flow was 35% lower in affected cellulite regions than in nonaffected regions without cellulite, which can cause congestion of blood and lymphatic flow and increased subdermal pressure, thus increasing the appearance of cellulite.

Although there is some controversy regarding the effects of weight loss on the appearance of cellulite,2,7 it appears that the subdermal septa and morphology have more of an effect on the appearance of cellulite.2,3,8

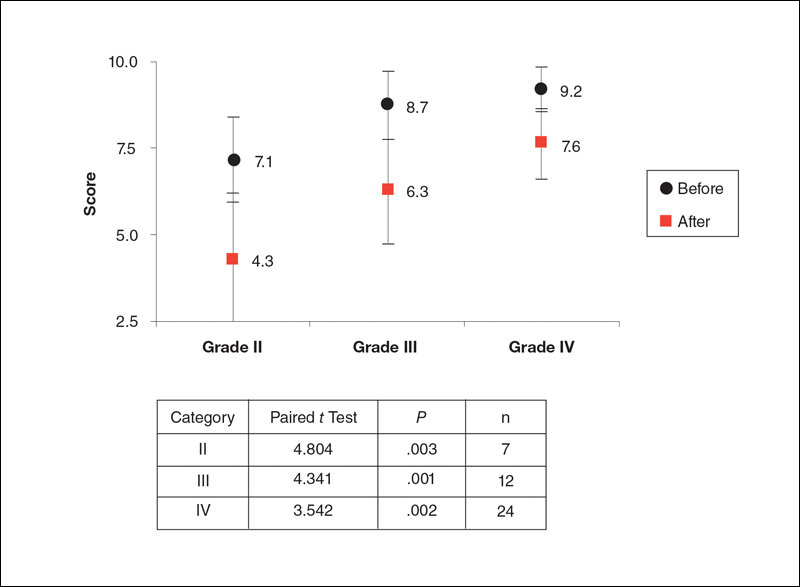

Rossi and Vergnanini6 proposed a 4-grade system for evaluating the appearance of cellulite (grade I, no cellulite; grade II, skin that is smooth and without any pronounced dimpling upon standing or lying down but may show some dimpling upon pinching and strong muscle contraction; grade III, cellulite is present in upright positions but not when the patient is in a supine position; grade IV, cellulite can be seen when the patient is standing and in a supine position). Both grades III and IV can be exacerbated by maximal voluntary contraction and strong pinching of the skin because these actions cause the subcutaneous fat to move toward the surface of the skin between the septa. This grading system aligns with categories I through III described by Mirrashed et al.9

There are many cellulite treatments available but few actually create a reduction in the visible appearance of cellulite. A number of these treatments were reviewed by Khan et al,10 including massage; a noninvasive suction-assisted massage technique; and topical agents such as xanthine, retinols, and other botanicals.4,11-14 Liposuction has not been shown to be effective in the treatment of cellulite and in fact may increase the appearance of cellulite.9,15 Mesotherapy, a modality that entails injecting substances into the subcutaneous fat layer, is another treatment of cellulite. Two of the most common agents purported to dissolve fat include phosphatidylcholine and sodium deoxycholate. The efficacy and safety of mesotherapy remains controversial and unproven. A July 2008 position statement from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons stated that “low levels of validity and quality of the literature does not allow [American Society of Plastic Surgeons] to support a recommendation for the use of mesotherapy/injection lipolysis for fat reduction.”16 Other modalities such as noninvasive dual-wavelength laser/suction devices; low-energy diode laser, contact cooling, suction, and massage devices; and infrared, bipolar radiofrequency, and suction with mechanical massage devices are available and show some small improvements in the visible appearance of cellulite, but no rating scales were used in any of these studies.17,18 DiBernardo19 utilized a 1440-nm pulsed laser to treat cellulite. It is an invasive treatment that works by breaking down some of the connective tissue septa responsible for the majority and greater severity of the dermal dimpling seen in cellulite, increasing the thickness of the dermis as well as its elasticity, reducing subcutaneous fat, and improving circulation and reducing general lymphatic congestion.19 The system showed promise but was an invasive treatment, and one session could cost $5000 to $7000 for bilateral areas and another $2500 for each additional area.20 Burns21 expressed that the short-term results showed promise in reducing the appearance of cellulite. Noninvasive ultrasound22,23 as well as extracorporeal shock wave therapy24,25 also has shown some improvement in the firmness of collagen but generally not in the appearance of cellulite.

We sought to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a noninvasive mechanical treatment of cellulite.

Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Policy for Protection of Human Research Subjects and the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were recruited through local area medical facilities in southeastern Michigan. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to beginning the study.

Patients with grades II to IV cellulite, according to the Rossi and Vergnanini6 grading system, were allowed to participate. All participants in the study were asked not to make lifestyle changes (eg, exercise habits, diet) or use any other treatments for cellulite that might be available to them during the study period. Exclusion criteria included history of deep vein thrombosis, cancer diagnosed within the last year, pregnancy, hemophilia, severe lymphedema, presence of a pacemaker, epilepsy, seizure disorder, or current use of anticoagulants. History of partial or total joint replacements, acute hernia, nonunited fractures, advanced arthritis, or detached retina also excluded participation in the study.

Participants completed an 8-week, twice-weekly treatment protocol with a noninvasive mechanical device performed in clinic. The device consisted of a 10.16-cm belt with a layer of nonslip material wrapped around the belt. The belt was attached to a mechanical oscillator. We adjusted the stroke length to approximately 2 cm and moved the dermis at that length at approximately 1000 strokes per minute.

Each participant was treated for a total treatment time of 18 to 24 minutes. The total treatment area included the top of the iliac crest to just above the top of the popliteal space. The width of the belt (10.16 cm) was equal to 1 individual treatment area. Each individual treatment area was treated for 2 minutes. First the buttocks and bilateral thighs were treated, followed by the right lateral thigh and the left lateral thigh. The belt was moved progressively down the total treatment area until all individual treatment areas were addressed. The average participant had 3 to 4 bilateral thigh and buttocks treatment areas and 3 to 4 lateral treatment areas on both the left and right sides of the body.

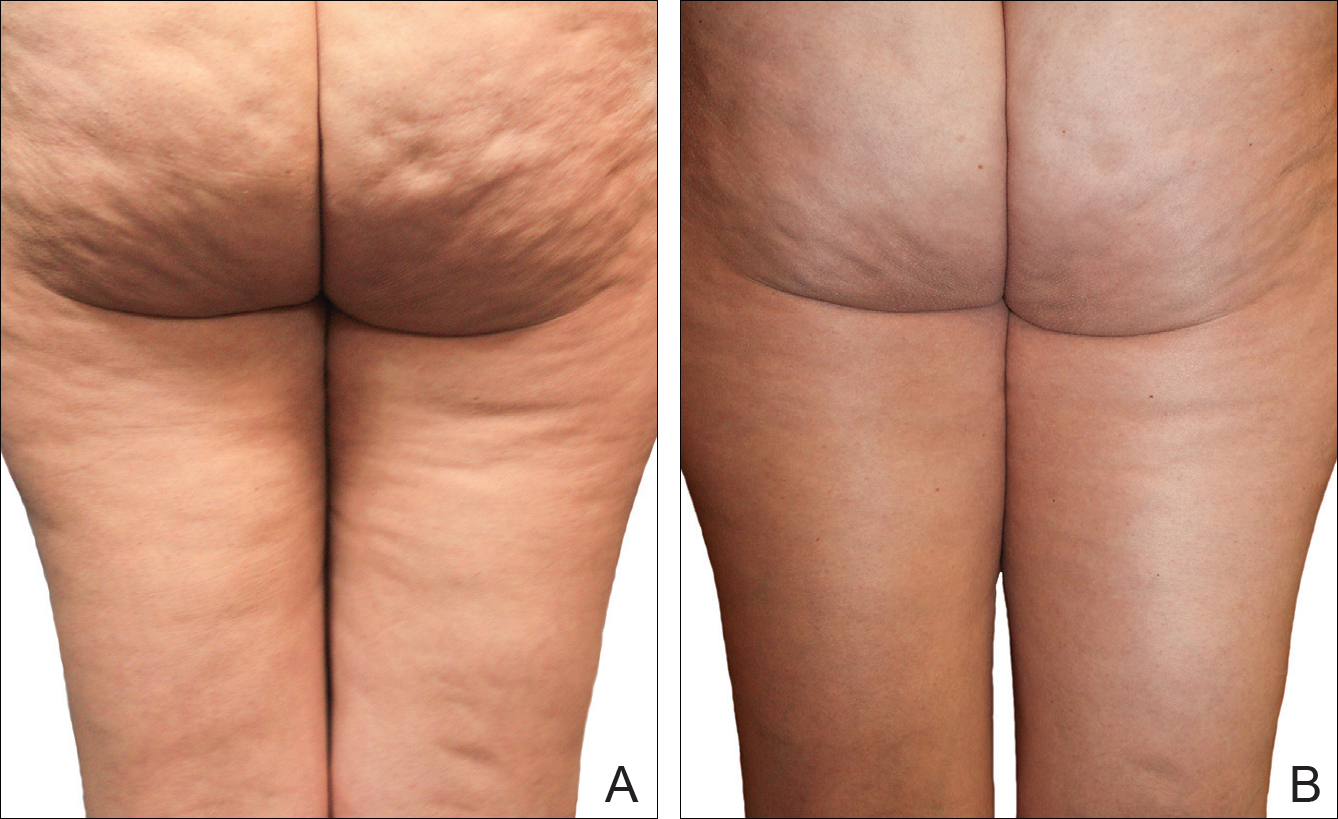

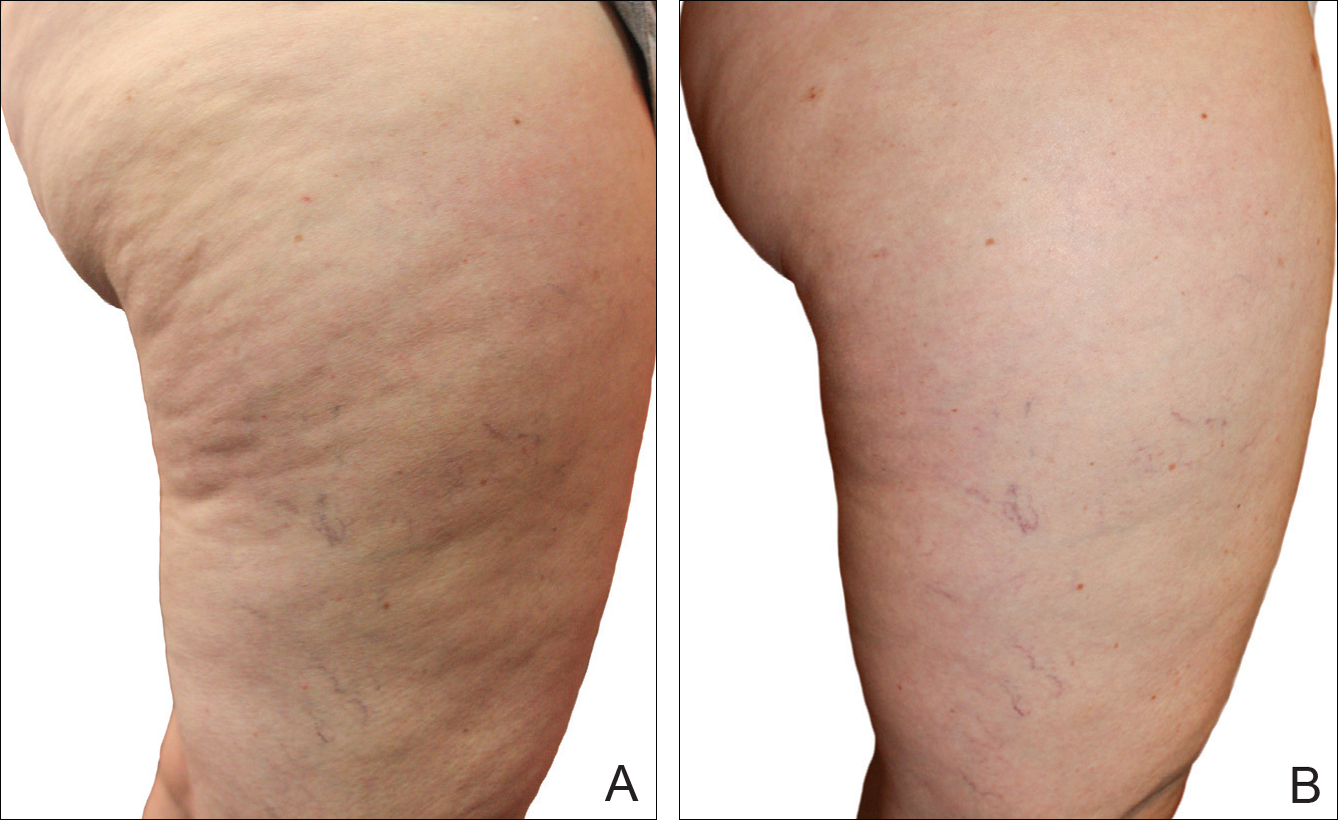

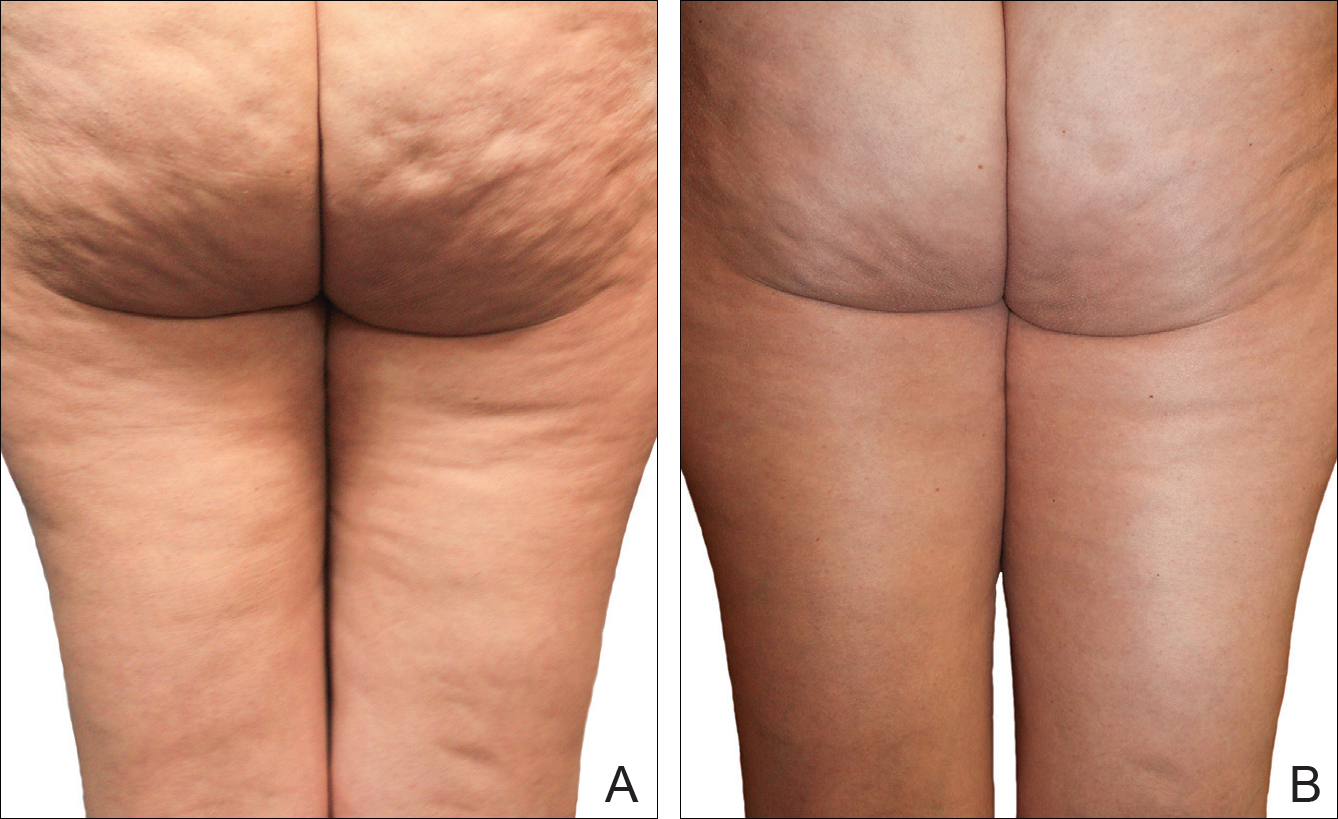

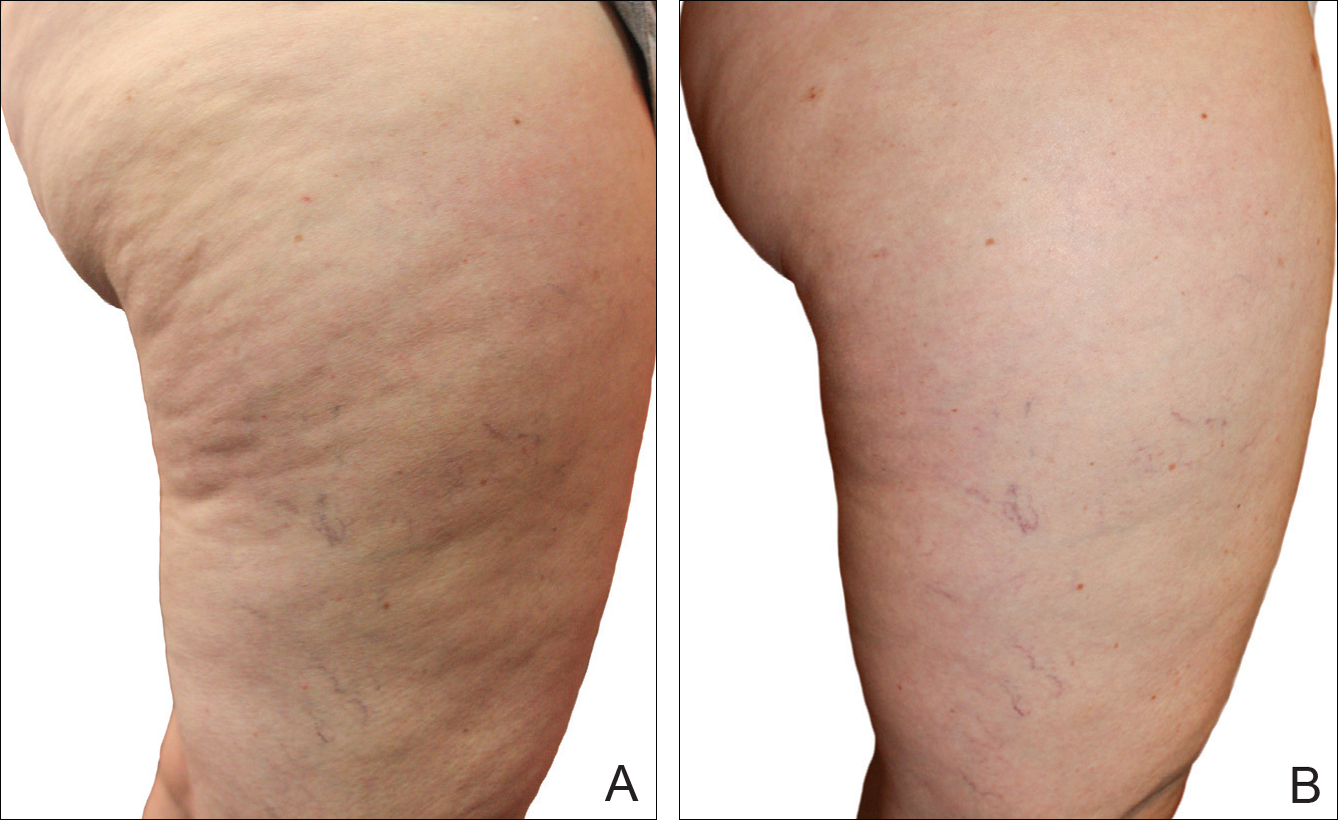

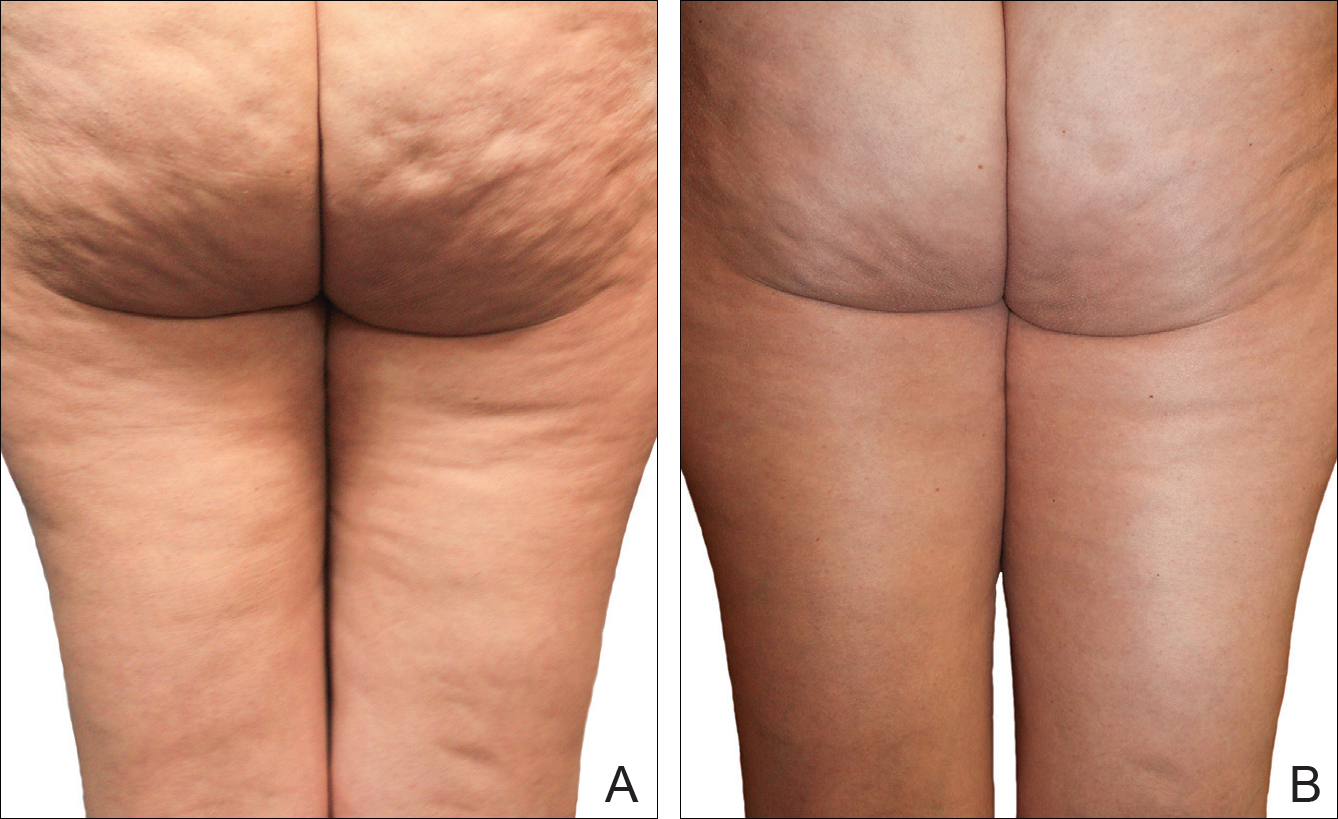

Digital photographs were taken with standardized lighting for all participants. Photographs were taken before the first treatment on the lateral and posterior aspects of the participant and were taken again at the end of the treatment program immediately before the last treatment. Participants were asked to contract the gluteal musculature for all photographs.

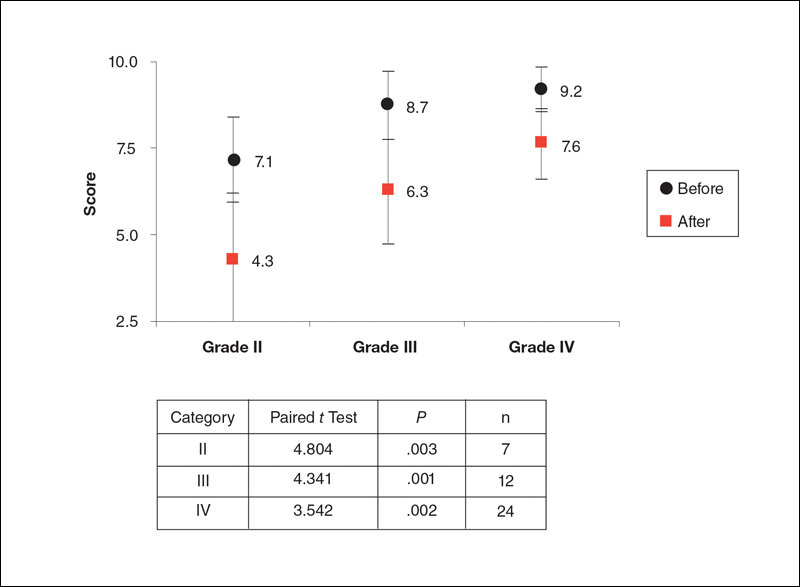

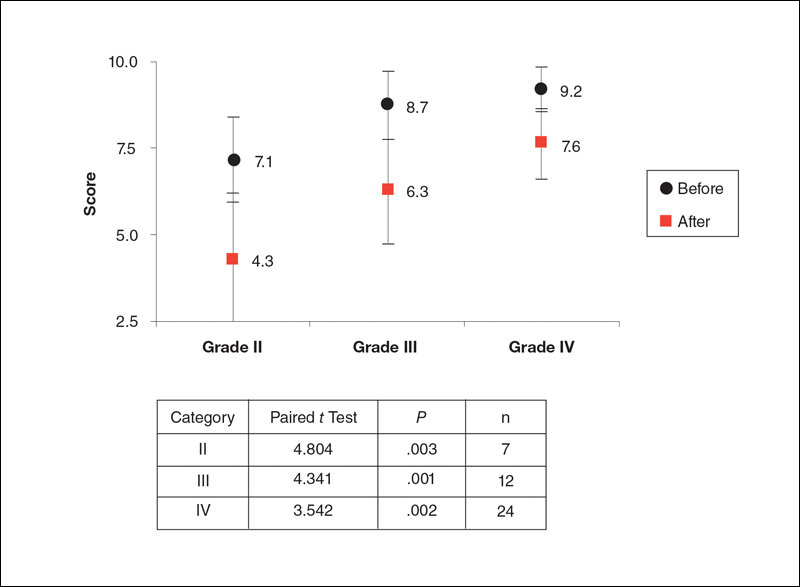

Two board-certified plastic surgeons were asked to rate the before/after photographs in a blinded manner. They graded each photograph on a rating scale of 0 to 10 (0=no cellulite; 10=worst possible cellulite). These data were analyzed using a Wilcoxon signed rank test. These data were compared to the participants self-evaluation of the appearance of cellulite in the photographs from the initial and final treatments using a rating scale of 0 to 10 (0=no cellulite; 10=worst possible cellulite).