User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Using the Blanch Sign to Differentiate Weathering Nodules From Auricular Tophaceous Gout

To the Editor:

We commend the recent report by Smith et al (Cutis. 2016;97:166, 175-176) that described multiple white nodules on the bilateral helical rims of the ears in a 40-year-old man, which was determined to be bilateral auricular tophaceous gout. Furthermore, we appreciate the inclusion of weathering nodules in the differential diagnosis and wish to share our experience with these lesions.

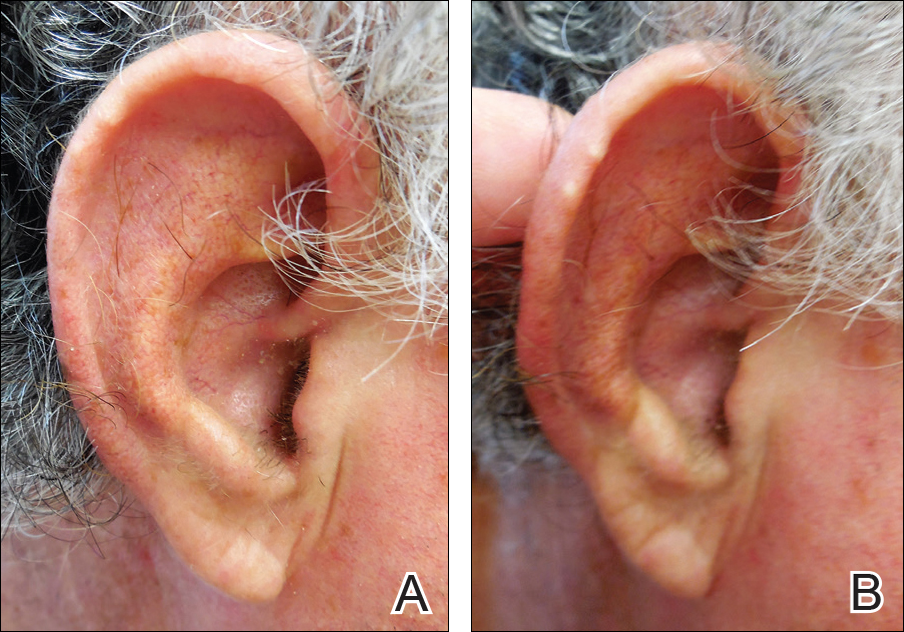

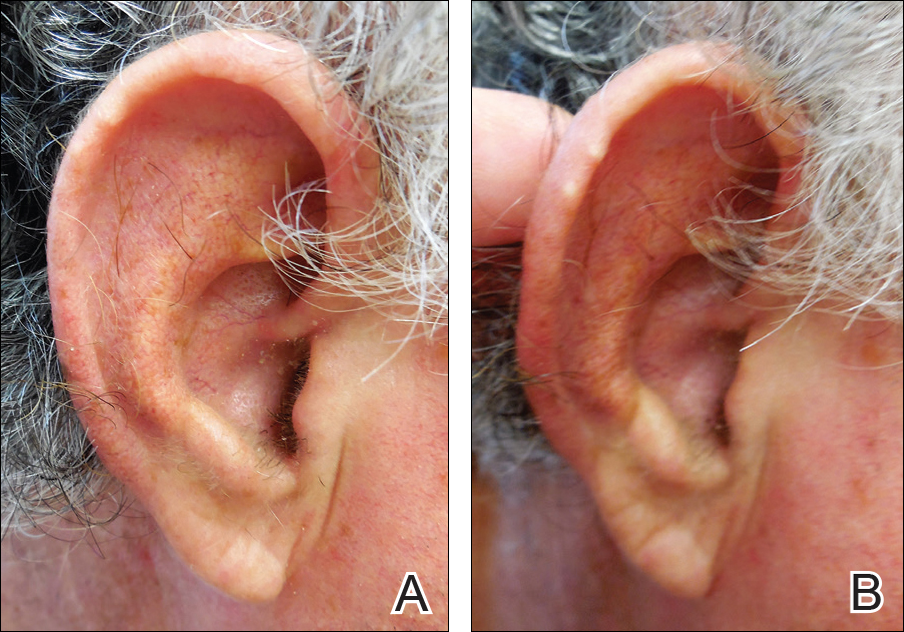

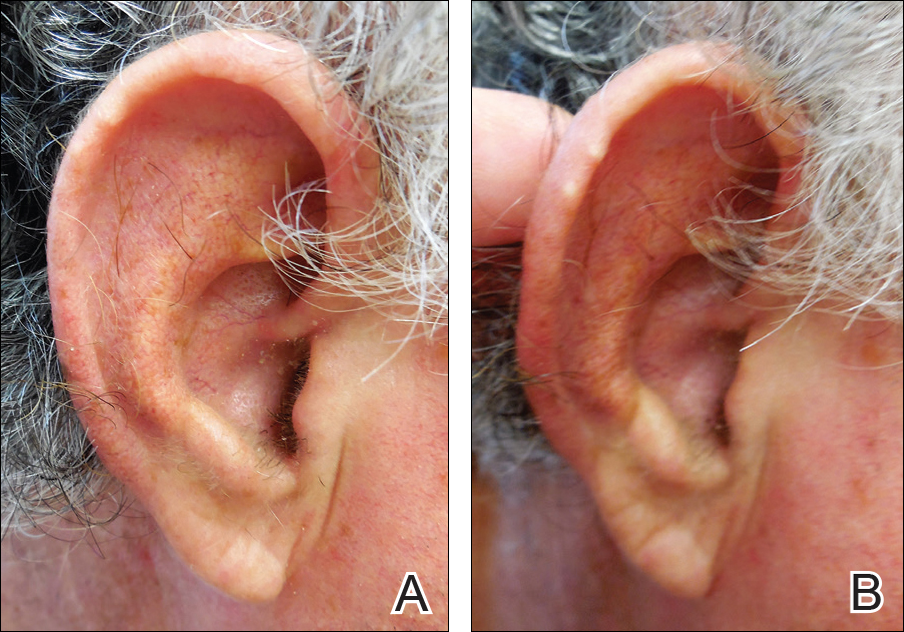

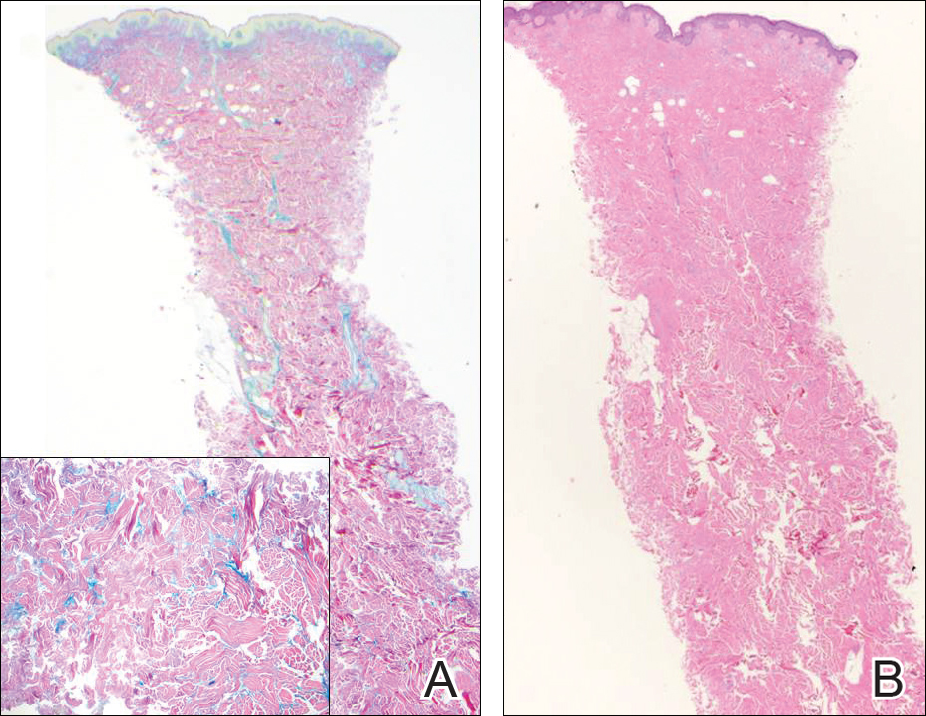

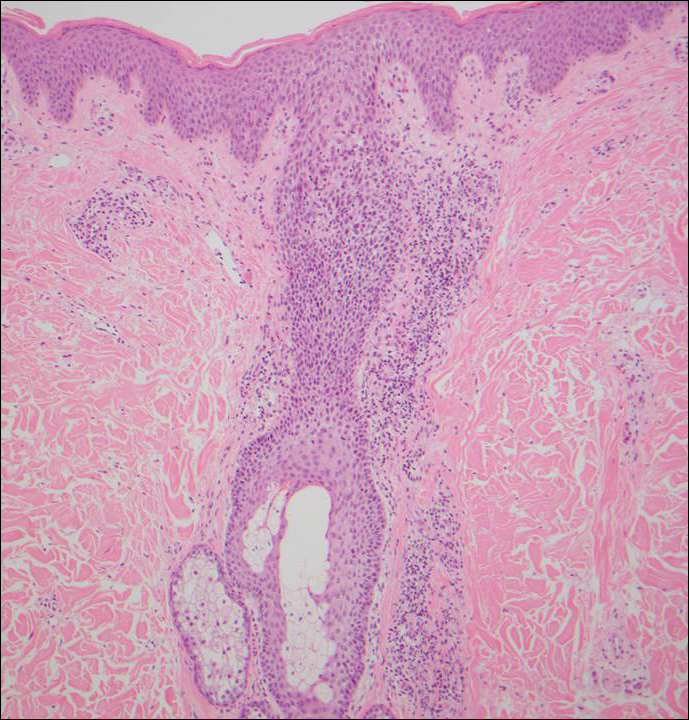

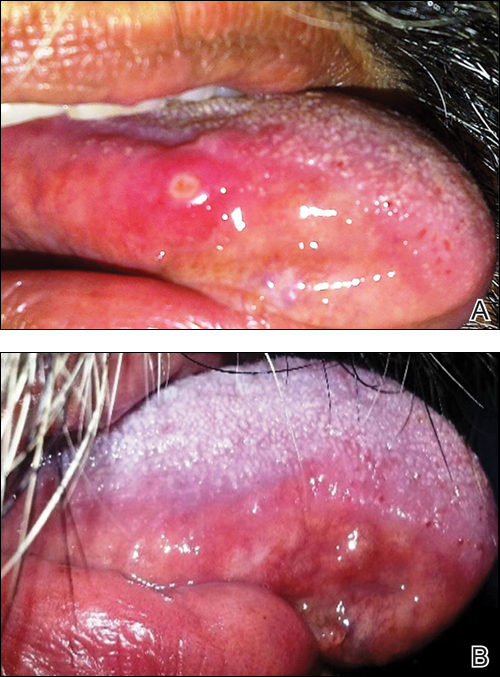

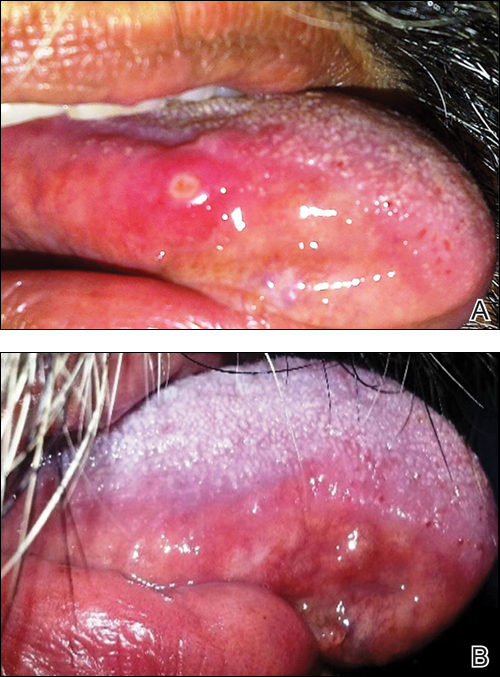

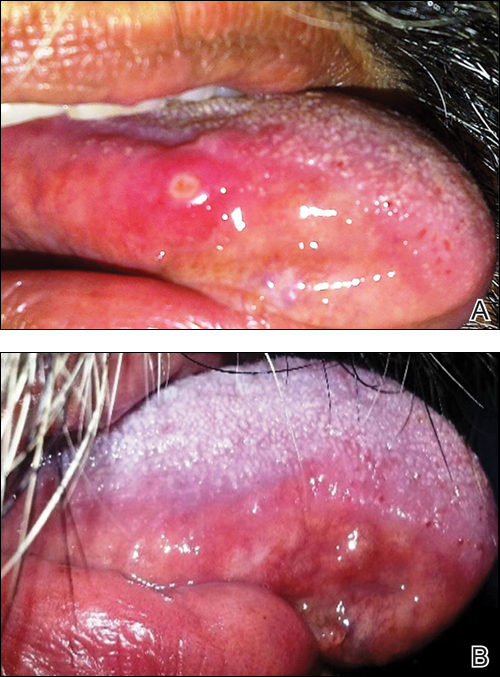

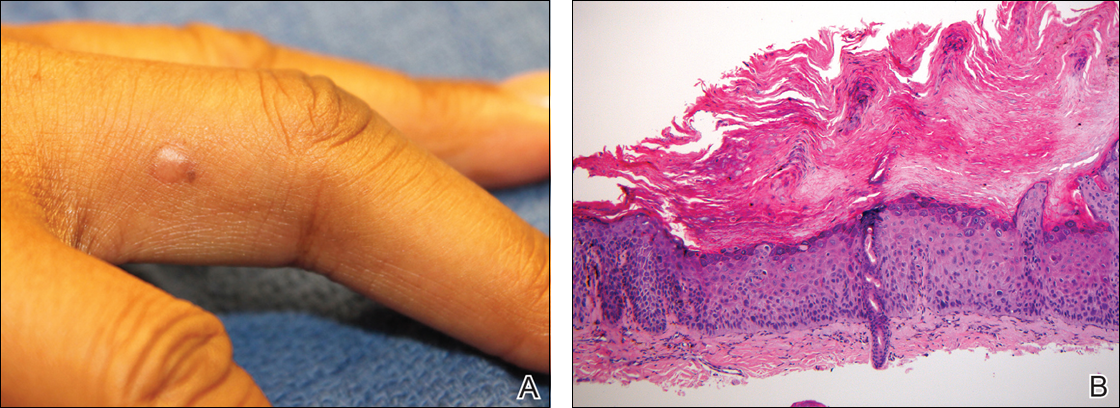

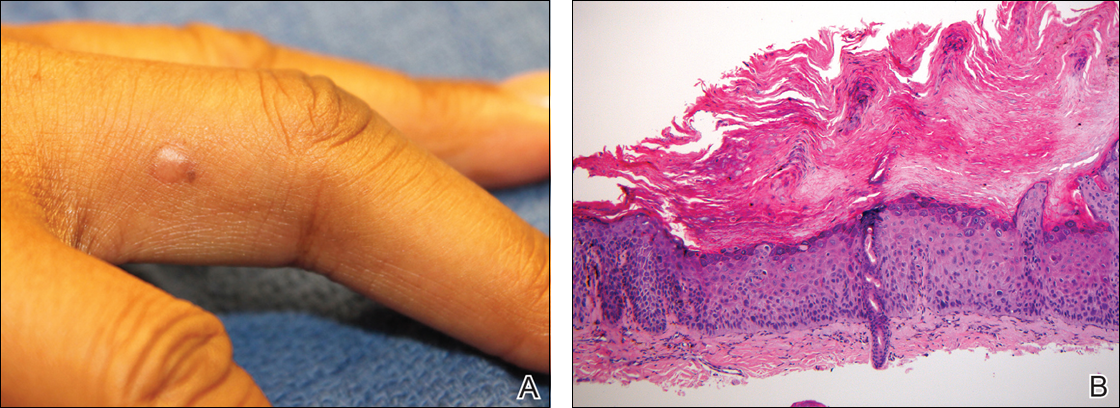

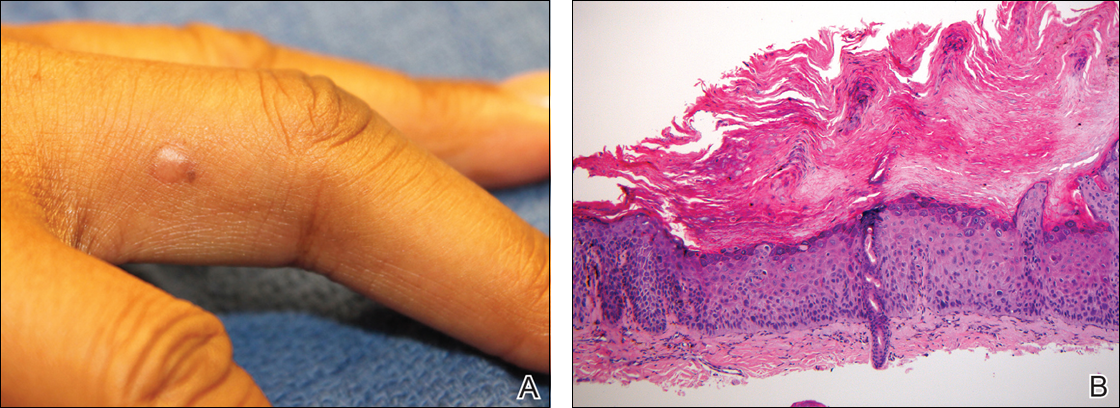

Auricular tophaceous gout and weathering nodules are clinically similar. Weathering nodules may appear as single or multiple, 2 to 3 mm in diameter and 1 to 2 mm in height, white to flesh-colored papules usually found on the helical rim of the ear (Figure 1).1 We recently described 10 patients with weathering nodules and their associated risk factors.2 We observed that the weathering nodules will blanch upon the application of pressure to the adjacent helical rim; a positive “blanch sign” may be used to differentiate weathering nodules from auricular tophaceous gout and other lesions of the ear (Figure 2). Furthermore, patients with weathering nodules typically exhibit a history of sun exposure and often have other cutaneous findings such as actinic keratoses. The pathogenesis of weathering nodules was previously thought to rely solely on actinic damage; however, we reported a pediatric case of weathering nodules that presented following radiotherapy to the ears.2

In summary, weathering nodules should be included in the differential diagnosis of auricular tophaceous gout. In addition, a positive blanch sign may be a useful clinical tool in differentiating weathering nodules from other ear lesions.

- Kavanagh GM, Bradfield JW, Collins CM, et al. Weathering nodules of the ear: a clinicopathological study. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:550-554.

- Udkoff J, Cohen PR. Weathering nodules: a report of ten individuals with weathering nodules and review of the literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:433-436.

To the Editor:

We commend the recent report by Smith et al (Cutis. 2016;97:166, 175-176) that described multiple white nodules on the bilateral helical rims of the ears in a 40-year-old man, which was determined to be bilateral auricular tophaceous gout. Furthermore, we appreciate the inclusion of weathering nodules in the differential diagnosis and wish to share our experience with these lesions.

Auricular tophaceous gout and weathering nodules are clinically similar. Weathering nodules may appear as single or multiple, 2 to 3 mm in diameter and 1 to 2 mm in height, white to flesh-colored papules usually found on the helical rim of the ear (Figure 1).1 We recently described 10 patients with weathering nodules and their associated risk factors.2 We observed that the weathering nodules will blanch upon the application of pressure to the adjacent helical rim; a positive “blanch sign” may be used to differentiate weathering nodules from auricular tophaceous gout and other lesions of the ear (Figure 2). Furthermore, patients with weathering nodules typically exhibit a history of sun exposure and often have other cutaneous findings such as actinic keratoses. The pathogenesis of weathering nodules was previously thought to rely solely on actinic damage; however, we reported a pediatric case of weathering nodules that presented following radiotherapy to the ears.2

In summary, weathering nodules should be included in the differential diagnosis of auricular tophaceous gout. In addition, a positive blanch sign may be a useful clinical tool in differentiating weathering nodules from other ear lesions.

To the Editor:

We commend the recent report by Smith et al (Cutis. 2016;97:166, 175-176) that described multiple white nodules on the bilateral helical rims of the ears in a 40-year-old man, which was determined to be bilateral auricular tophaceous gout. Furthermore, we appreciate the inclusion of weathering nodules in the differential diagnosis and wish to share our experience with these lesions.

Auricular tophaceous gout and weathering nodules are clinically similar. Weathering nodules may appear as single or multiple, 2 to 3 mm in diameter and 1 to 2 mm in height, white to flesh-colored papules usually found on the helical rim of the ear (Figure 1).1 We recently described 10 patients with weathering nodules and their associated risk factors.2 We observed that the weathering nodules will blanch upon the application of pressure to the adjacent helical rim; a positive “blanch sign” may be used to differentiate weathering nodules from auricular tophaceous gout and other lesions of the ear (Figure 2). Furthermore, patients with weathering nodules typically exhibit a history of sun exposure and often have other cutaneous findings such as actinic keratoses. The pathogenesis of weathering nodules was previously thought to rely solely on actinic damage; however, we reported a pediatric case of weathering nodules that presented following radiotherapy to the ears.2

In summary, weathering nodules should be included in the differential diagnosis of auricular tophaceous gout. In addition, a positive blanch sign may be a useful clinical tool in differentiating weathering nodules from other ear lesions.

- Kavanagh GM, Bradfield JW, Collins CM, et al. Weathering nodules of the ear: a clinicopathological study. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:550-554.

- Udkoff J, Cohen PR. Weathering nodules: a report of ten individuals with weathering nodules and review of the literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:433-436.

- Kavanagh GM, Bradfield JW, Collins CM, et al. Weathering nodules of the ear: a clinicopathological study. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:550-554.

- Udkoff J, Cohen PR. Weathering nodules: a report of ten individuals with weathering nodules and review of the literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:433-436.

Firm Pink Nodule on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma

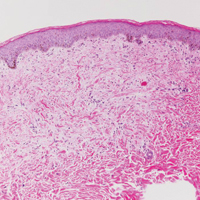

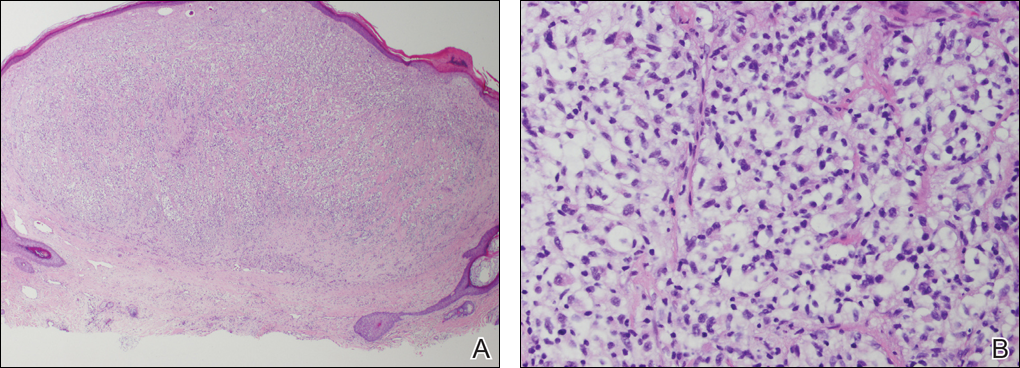

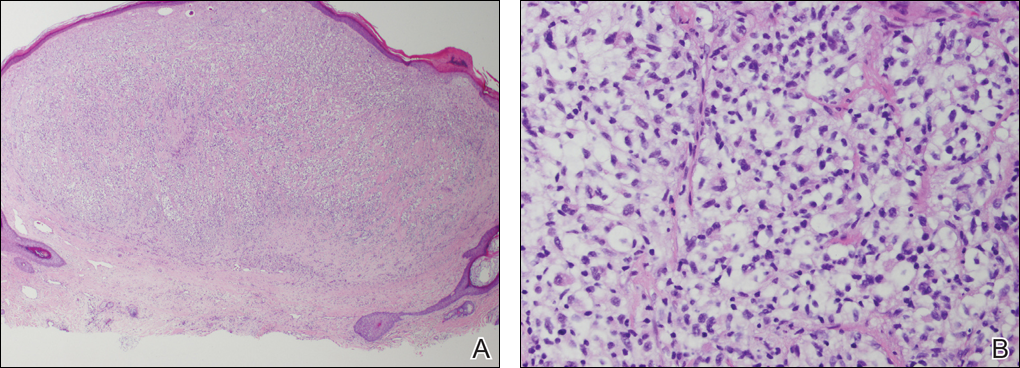

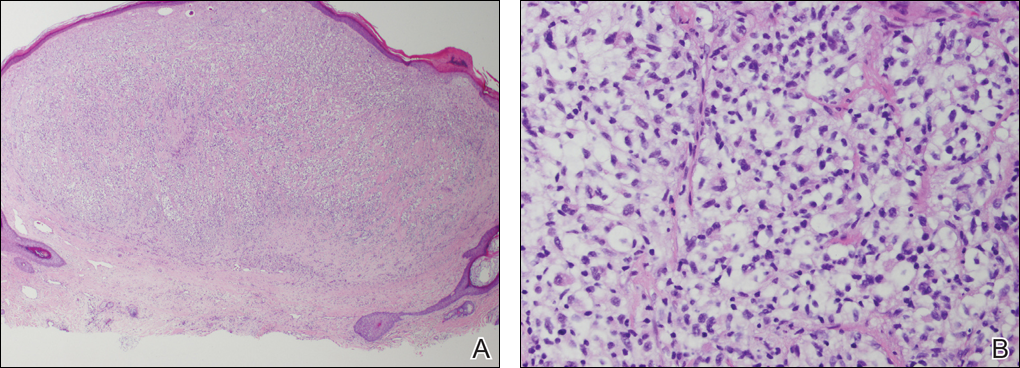

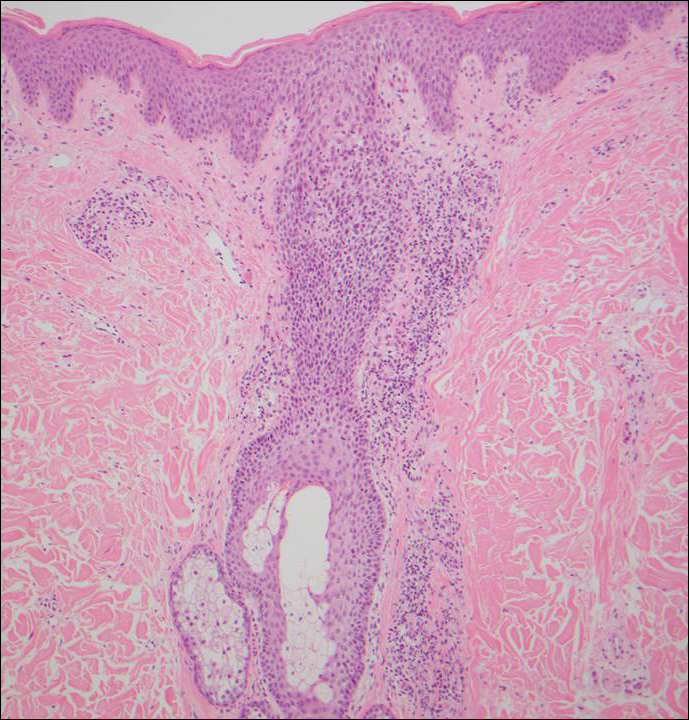

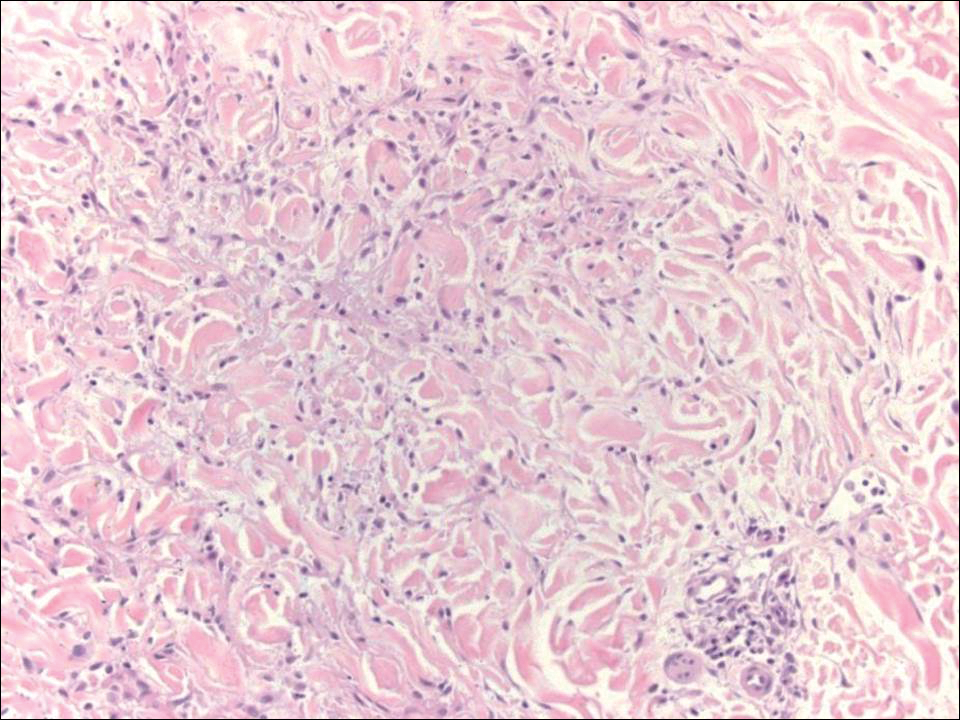

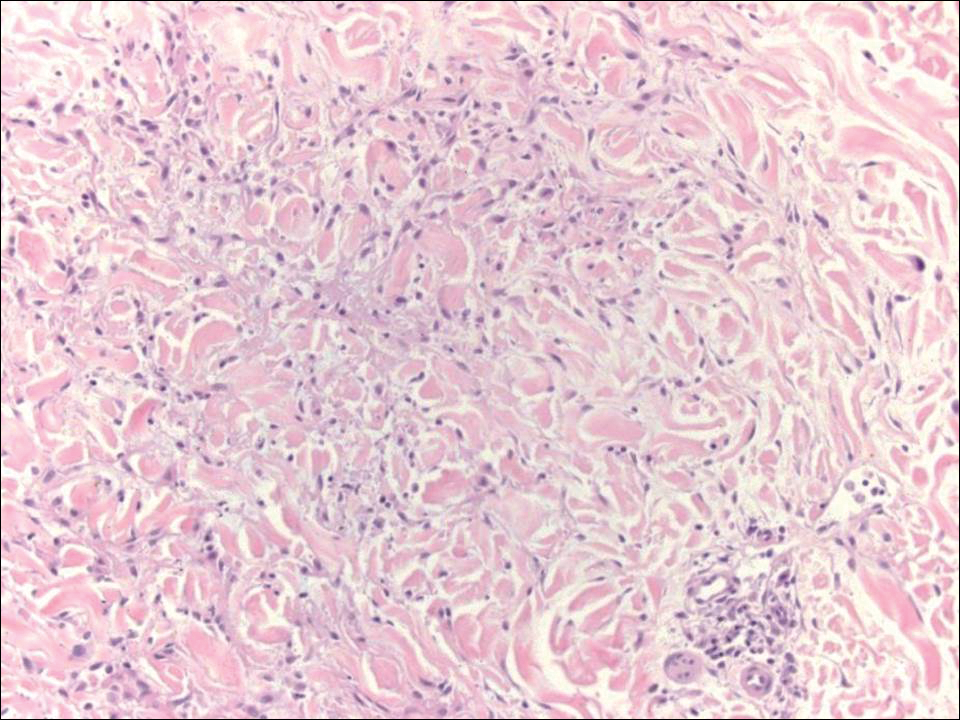

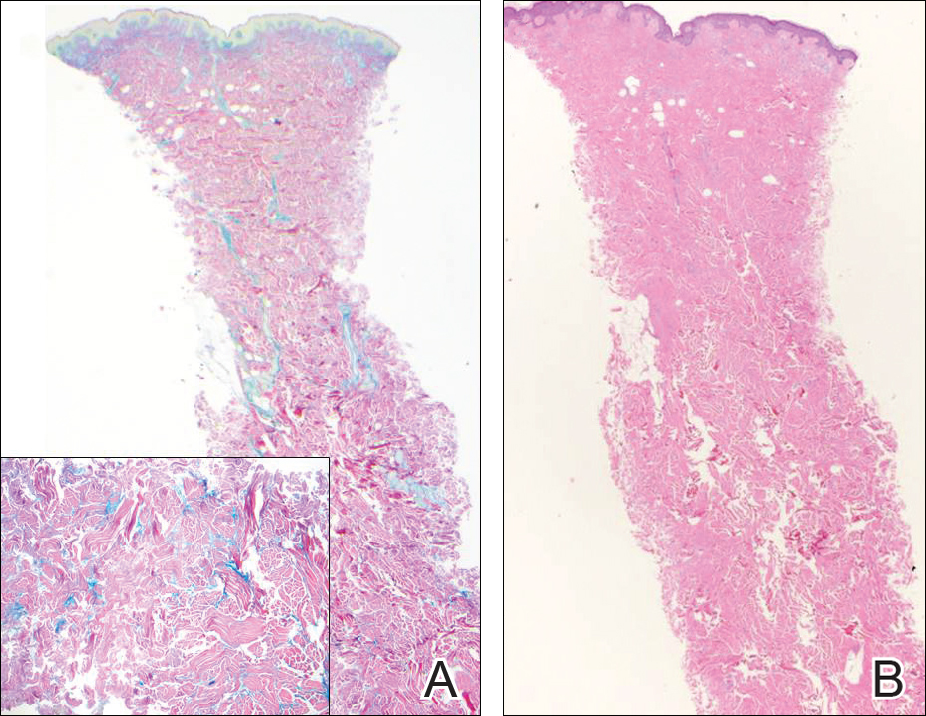

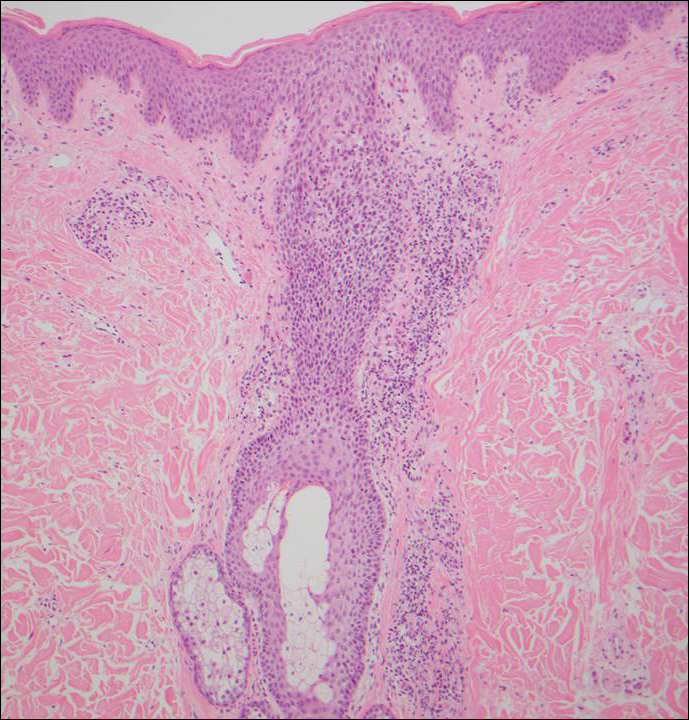

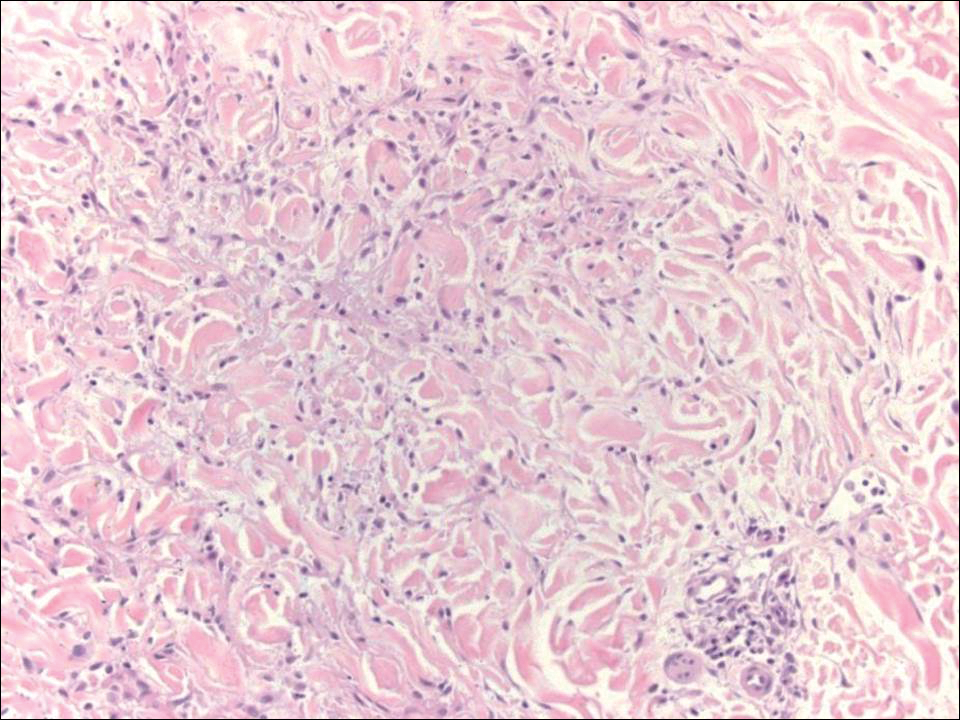

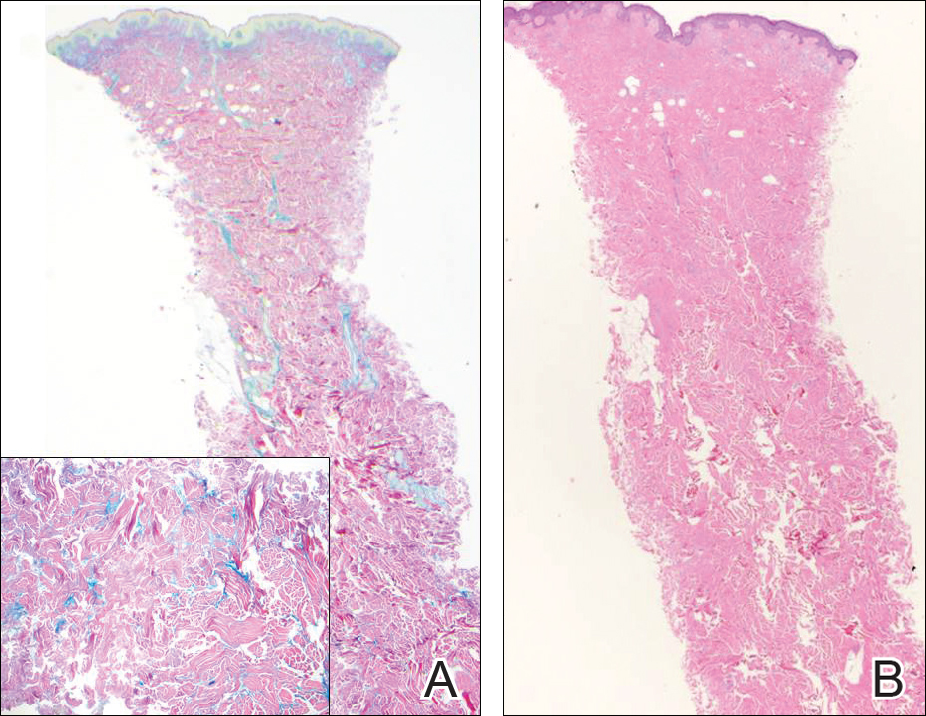

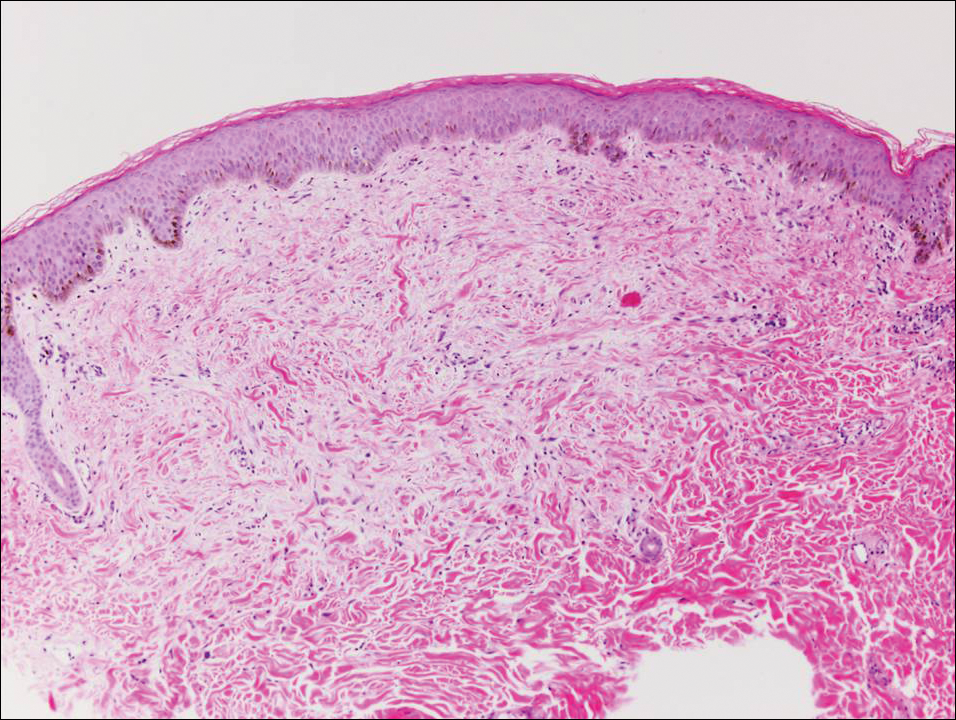

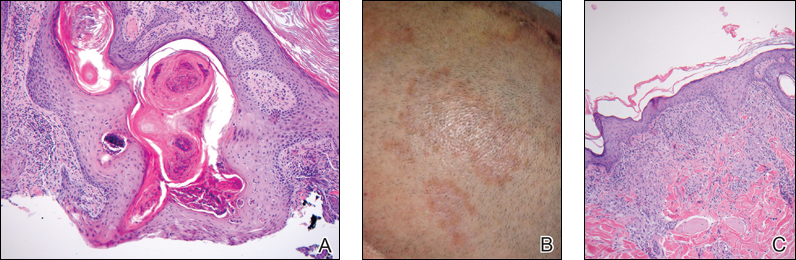

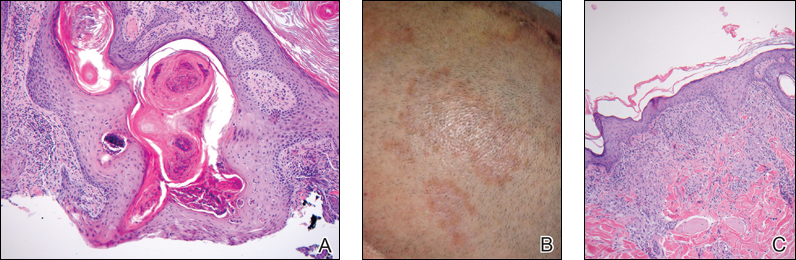

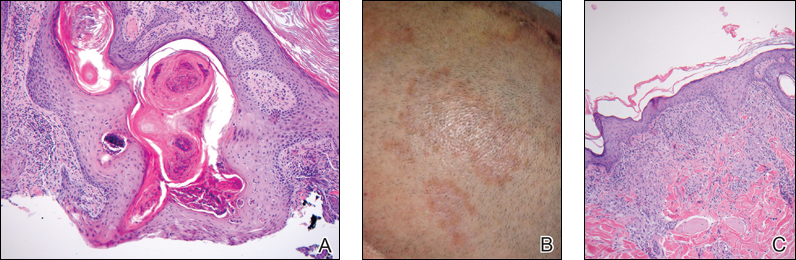

A shave biopsy of the right occipital scalp lesion demonstrated large clear cells arranged in oval nests with mildly atypical central nuclei (Figure). The findings were consistent with the clear cell type of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) with tumor involvement in the deep margin. PAX8 immunostain was positive in the tumor, further supporting the diagnosis of mRCC.

The most common patient demographic diagnosed with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is men in the sixth and seventh decades of life.1,2 The classic presentation of RCC includes the triad of flank pain, hematuria, and a palpable abdominal mass. Other symptoms may include fatigue, weight loss, and anemia; however, small localized tumors rarely are symptomatic, and less than 10% of patients with RCC present with this classic triad.3 Many RCCs are diagnosed from incidental findings on abdominal imaging or from the presentation of metastatic disease.1,2 The lungs, bones, and liver are the most common sites of metastases, while skin metastases are rare.2 One study found only 3.3% (10/306) of RCC cases had cutaneous metastases and the scalp was the most common location. In half of these patients, the skin metastases were present at initial RCC diagnosis.4

The most common presentation of a cutaneous metastasis of RCC entails the rapid development of a reddish blue nodule on the face or scalp.4,5 The differential diagnosis may include basal cell carcinoma, hemangioma, cutaneous angiosarcoma, pyogenic granuloma, and atypical fibroxanthoma. Careful elicitation of a medical history indicating any of the classic or systemic signs associated with RCC or a personal history of RCC should raise the suspicion for mRCC and prompt a biopsy.

Clear cell RCC is the most common type of primary RCC and 81% of mRCCs were found to be of the clear cell type. Clear cell RCC classically exhibits clear ballooned cytoplasm with distinct cell borders.6 Immunohistochemistry stains with PAX2 and PAX8 are helpful in diagnosing the renal origin of the metastatic tissue, with PAX8 being especially helpful (89% sensitivity).7

The von Hippel-Lindau gene, VHL, is involved in up to 60% of sporadic clear cell RCC cases, in addition to its involvement in VHL syndrome.1 von Hippel-Lindau syndrome is associated with clear cell RCC, retinal angiomas, hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system, and pheochromocytomas.1 The mutated VHL gene is associated with an increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which promotes angiogenesis, endothelial mutagenesis, and vascular permeability.8 These physiologic responses are likely responsible for the proliferation and dissemination of neoplastic cells in clear cell RCC.9 The understanding of this pathogenic mechanism has led to the development of targeted effective treatments in RCC.

Systemic treatments for mRCC are rapidly evolving and improving.9 Vascular endothelial growth factor tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as sorafenib, sunitinib, and pazopanib, as well as the VEGF monoclonal antibody bevacizumab, have all demonstrated notable efficacy in the treatment of RCC. Phase 3 clinical trials for the treatment of mRCC have demonstrated that the new, more biochemically potent VEGF tyrosine kinase inhibitor axitinib has superior efficacy to sorafenib, the prior standard of care.9 Our patient noted that the cutaneous mRCC lesion seemed to be improving after starting treatment with axitinib 2 months prior to presentation. In addition to systemic chemotherapy, the surgical removal of lesions often is indicated for the treatment of cutaneous mRCC.5,10 Our patient has continued axitinib and is doing well.

- Cohen HT, McGovern FJ. Medical progress: renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2477-2490.

- Schlesinger-Raab A, Treiber U, Zaak D, et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a population-based study with 25 years follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2485-2495.

- Motzer RJ, Bander NH, Nanus DM. Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:865-875.

- Dorairajan LN, Hemal AK, Aron M, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int. 1999;63:164-167.

- Arrabal-Polo MA, Arias-Santiago SA, Aneiros-Fernandez J, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:7948.

- Mai KT, Alhalouly T, Lamba M, et al. Distribution of subtypes of metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: correlating findings of fine-needle aspiration biopsy and surgical pathology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;28:66-70.

- Ozcan A, Roza F, Ro JY, et al. PAX2 and PAX8 expression in primary and metastatic renal tumors: a comprehensive comparison. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:1541-1551.

- Albiges L, Salem M, Rini B, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapies in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2011;25:813-833.

- Mittal K, Wood LS, Rini BI. Axitinib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Biol Ther. 2012;2:5.

- Kassam K, Tiong E, Nigar E, et al. Exophytic parietal skin metastases of renal cell carcinoma [published online December 26, 2013]. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2013;2013:196016.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma

A shave biopsy of the right occipital scalp lesion demonstrated large clear cells arranged in oval nests with mildly atypical central nuclei (Figure). The findings were consistent with the clear cell type of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) with tumor involvement in the deep margin. PAX8 immunostain was positive in the tumor, further supporting the diagnosis of mRCC.

The most common patient demographic diagnosed with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is men in the sixth and seventh decades of life.1,2 The classic presentation of RCC includes the triad of flank pain, hematuria, and a palpable abdominal mass. Other symptoms may include fatigue, weight loss, and anemia; however, small localized tumors rarely are symptomatic, and less than 10% of patients with RCC present with this classic triad.3 Many RCCs are diagnosed from incidental findings on abdominal imaging or from the presentation of metastatic disease.1,2 The lungs, bones, and liver are the most common sites of metastases, while skin metastases are rare.2 One study found only 3.3% (10/306) of RCC cases had cutaneous metastases and the scalp was the most common location. In half of these patients, the skin metastases were present at initial RCC diagnosis.4

The most common presentation of a cutaneous metastasis of RCC entails the rapid development of a reddish blue nodule on the face or scalp.4,5 The differential diagnosis may include basal cell carcinoma, hemangioma, cutaneous angiosarcoma, pyogenic granuloma, and atypical fibroxanthoma. Careful elicitation of a medical history indicating any of the classic or systemic signs associated with RCC or a personal history of RCC should raise the suspicion for mRCC and prompt a biopsy.

Clear cell RCC is the most common type of primary RCC and 81% of mRCCs were found to be of the clear cell type. Clear cell RCC classically exhibits clear ballooned cytoplasm with distinct cell borders.6 Immunohistochemistry stains with PAX2 and PAX8 are helpful in diagnosing the renal origin of the metastatic tissue, with PAX8 being especially helpful (89% sensitivity).7

The von Hippel-Lindau gene, VHL, is involved in up to 60% of sporadic clear cell RCC cases, in addition to its involvement in VHL syndrome.1 von Hippel-Lindau syndrome is associated with clear cell RCC, retinal angiomas, hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system, and pheochromocytomas.1 The mutated VHL gene is associated with an increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which promotes angiogenesis, endothelial mutagenesis, and vascular permeability.8 These physiologic responses are likely responsible for the proliferation and dissemination of neoplastic cells in clear cell RCC.9 The understanding of this pathogenic mechanism has led to the development of targeted effective treatments in RCC.

Systemic treatments for mRCC are rapidly evolving and improving.9 Vascular endothelial growth factor tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as sorafenib, sunitinib, and pazopanib, as well as the VEGF monoclonal antibody bevacizumab, have all demonstrated notable efficacy in the treatment of RCC. Phase 3 clinical trials for the treatment of mRCC have demonstrated that the new, more biochemically potent VEGF tyrosine kinase inhibitor axitinib has superior efficacy to sorafenib, the prior standard of care.9 Our patient noted that the cutaneous mRCC lesion seemed to be improving after starting treatment with axitinib 2 months prior to presentation. In addition to systemic chemotherapy, the surgical removal of lesions often is indicated for the treatment of cutaneous mRCC.5,10 Our patient has continued axitinib and is doing well.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma

A shave biopsy of the right occipital scalp lesion demonstrated large clear cells arranged in oval nests with mildly atypical central nuclei (Figure). The findings were consistent with the clear cell type of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) with tumor involvement in the deep margin. PAX8 immunostain was positive in the tumor, further supporting the diagnosis of mRCC.

The most common patient demographic diagnosed with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is men in the sixth and seventh decades of life.1,2 The classic presentation of RCC includes the triad of flank pain, hematuria, and a palpable abdominal mass. Other symptoms may include fatigue, weight loss, and anemia; however, small localized tumors rarely are symptomatic, and less than 10% of patients with RCC present with this classic triad.3 Many RCCs are diagnosed from incidental findings on abdominal imaging or from the presentation of metastatic disease.1,2 The lungs, bones, and liver are the most common sites of metastases, while skin metastases are rare.2 One study found only 3.3% (10/306) of RCC cases had cutaneous metastases and the scalp was the most common location. In half of these patients, the skin metastases were present at initial RCC diagnosis.4

The most common presentation of a cutaneous metastasis of RCC entails the rapid development of a reddish blue nodule on the face or scalp.4,5 The differential diagnosis may include basal cell carcinoma, hemangioma, cutaneous angiosarcoma, pyogenic granuloma, and atypical fibroxanthoma. Careful elicitation of a medical history indicating any of the classic or systemic signs associated with RCC or a personal history of RCC should raise the suspicion for mRCC and prompt a biopsy.

Clear cell RCC is the most common type of primary RCC and 81% of mRCCs were found to be of the clear cell type. Clear cell RCC classically exhibits clear ballooned cytoplasm with distinct cell borders.6 Immunohistochemistry stains with PAX2 and PAX8 are helpful in diagnosing the renal origin of the metastatic tissue, with PAX8 being especially helpful (89% sensitivity).7

The von Hippel-Lindau gene, VHL, is involved in up to 60% of sporadic clear cell RCC cases, in addition to its involvement in VHL syndrome.1 von Hippel-Lindau syndrome is associated with clear cell RCC, retinal angiomas, hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system, and pheochromocytomas.1 The mutated VHL gene is associated with an increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which promotes angiogenesis, endothelial mutagenesis, and vascular permeability.8 These physiologic responses are likely responsible for the proliferation and dissemination of neoplastic cells in clear cell RCC.9 The understanding of this pathogenic mechanism has led to the development of targeted effective treatments in RCC.

Systemic treatments for mRCC are rapidly evolving and improving.9 Vascular endothelial growth factor tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as sorafenib, sunitinib, and pazopanib, as well as the VEGF monoclonal antibody bevacizumab, have all demonstrated notable efficacy in the treatment of RCC. Phase 3 clinical trials for the treatment of mRCC have demonstrated that the new, more biochemically potent VEGF tyrosine kinase inhibitor axitinib has superior efficacy to sorafenib, the prior standard of care.9 Our patient noted that the cutaneous mRCC lesion seemed to be improving after starting treatment with axitinib 2 months prior to presentation. In addition to systemic chemotherapy, the surgical removal of lesions often is indicated for the treatment of cutaneous mRCC.5,10 Our patient has continued axitinib and is doing well.

- Cohen HT, McGovern FJ. Medical progress: renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2477-2490.

- Schlesinger-Raab A, Treiber U, Zaak D, et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a population-based study with 25 years follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2485-2495.

- Motzer RJ, Bander NH, Nanus DM. Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:865-875.

- Dorairajan LN, Hemal AK, Aron M, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int. 1999;63:164-167.

- Arrabal-Polo MA, Arias-Santiago SA, Aneiros-Fernandez J, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:7948.

- Mai KT, Alhalouly T, Lamba M, et al. Distribution of subtypes of metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: correlating findings of fine-needle aspiration biopsy and surgical pathology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;28:66-70.

- Ozcan A, Roza F, Ro JY, et al. PAX2 and PAX8 expression in primary and metastatic renal tumors: a comprehensive comparison. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:1541-1551.

- Albiges L, Salem M, Rini B, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapies in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2011;25:813-833.

- Mittal K, Wood LS, Rini BI. Axitinib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Biol Ther. 2012;2:5.

- Kassam K, Tiong E, Nigar E, et al. Exophytic parietal skin metastases of renal cell carcinoma [published online December 26, 2013]. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2013;2013:196016.

- Cohen HT, McGovern FJ. Medical progress: renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2477-2490.

- Schlesinger-Raab A, Treiber U, Zaak D, et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a population-based study with 25 years follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2485-2495.

- Motzer RJ, Bander NH, Nanus DM. Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:865-875.

- Dorairajan LN, Hemal AK, Aron M, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int. 1999;63:164-167.

- Arrabal-Polo MA, Arias-Santiago SA, Aneiros-Fernandez J, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:7948.

- Mai KT, Alhalouly T, Lamba M, et al. Distribution of subtypes of metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: correlating findings of fine-needle aspiration biopsy and surgical pathology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;28:66-70.

- Ozcan A, Roza F, Ro JY, et al. PAX2 and PAX8 expression in primary and metastatic renal tumors: a comprehensive comparison. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:1541-1551.

- Albiges L, Salem M, Rini B, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapies in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2011;25:813-833.

- Mittal K, Wood LS, Rini BI. Axitinib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Biol Ther. 2012;2:5.

- Kassam K, Tiong E, Nigar E, et al. Exophytic parietal skin metastases of renal cell carcinoma [published online December 26, 2013]. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2013;2013:196016.

A 69-year-old man with stage IV renal cell carcinoma (RCC) but no history of skin cancer presented with a nodule on the right side of the posterior scalp of 2 months' duration. He noted that the lesion bled intermittently and crusted over. Three years prior, the patient had a left-sided nephrectomy, which showed a 7-cm tumor consistent with clear cell RCC (Fuhrman nuclear grade 2). Over the last 6 months, RCC metastases to the right kidney, lungs, and right cervical lymph nodes were found. His current chemotherapy treatment was axitinib; he was previously on pazopanib and everolimus. Physical examination revealed a 10×10-mm, pink-yellow, firm nodule with overlying telangiectases on the right side of the posterior scalp.

Psoriasis Treatment Considerations in Military Patients: Unique Patients, Unique Drugs

Psoriasis is a common dermatologic problem with nearly 5% prevalence in the United States. There is a bimodal distribution with peak onset between 20 and 30 years of age and 50 and 60 years, which means that this condition can arise before, during, or after military service.1 Unfortunately, for many prospective recruits psoriasis is a medically disqualifying condition that can prevent entry into active duty unless a medical waiver is granted. For active-duty military, new-onset psoriasis and its treatment can impair affected service members’ ability to perform mission-critical work and can prevent them from deploying to remote or austere locations. In this way, psoriasis presents a unique challenge for active-duty service members.

Many therapies are available that can effectively treat psoriasis, but these treatments often carry a side-effect profile that limits their use during travel or in austere settings. Herein, we discuss the unique challenges of treating psoriasis patients who are in the military at a time when global mobility is critical to mission success. Although in some ways these challenges truly are unique to the military population, we strongly believe that similar but perhaps underappreciated challenges exist in the civilian sector. Close examination of these challenges may reveal that alternative treatment choices are sometimes indicated for reasons beyond just efficacy, side-effect profile, and cost.

Treatment Considerations

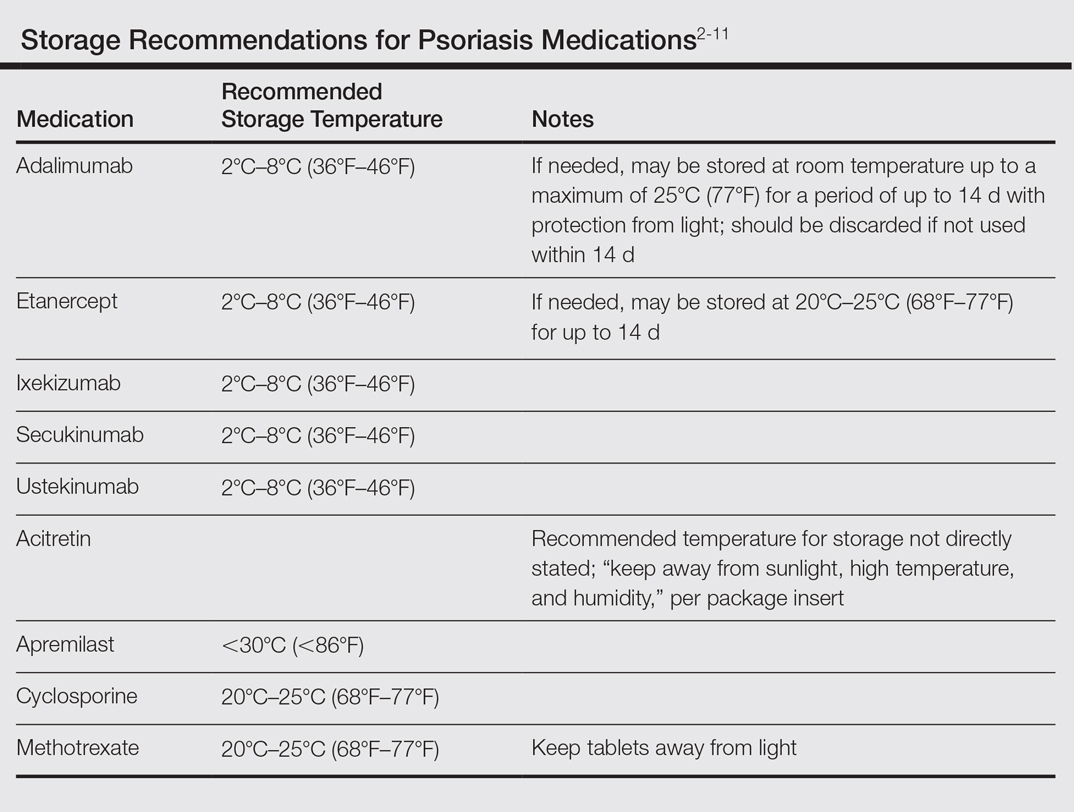

The medical treatment of psoriasis has undergone substantial change in recent decades. Before the turn of the century, the mainstays of medical treatment were steroids, methotrexate, and phototherapy. Today, a wide array of biologics and other systemic drugs are altering the impact of psoriasis in our society. With so many treatment options currently available, the question becomes, “Which one is best for my patient?” Immediate considerations are efficacy versus side effects as well as cost; however, in military dermatology, the ability to store, transport, and administer the treatment can be just as important.

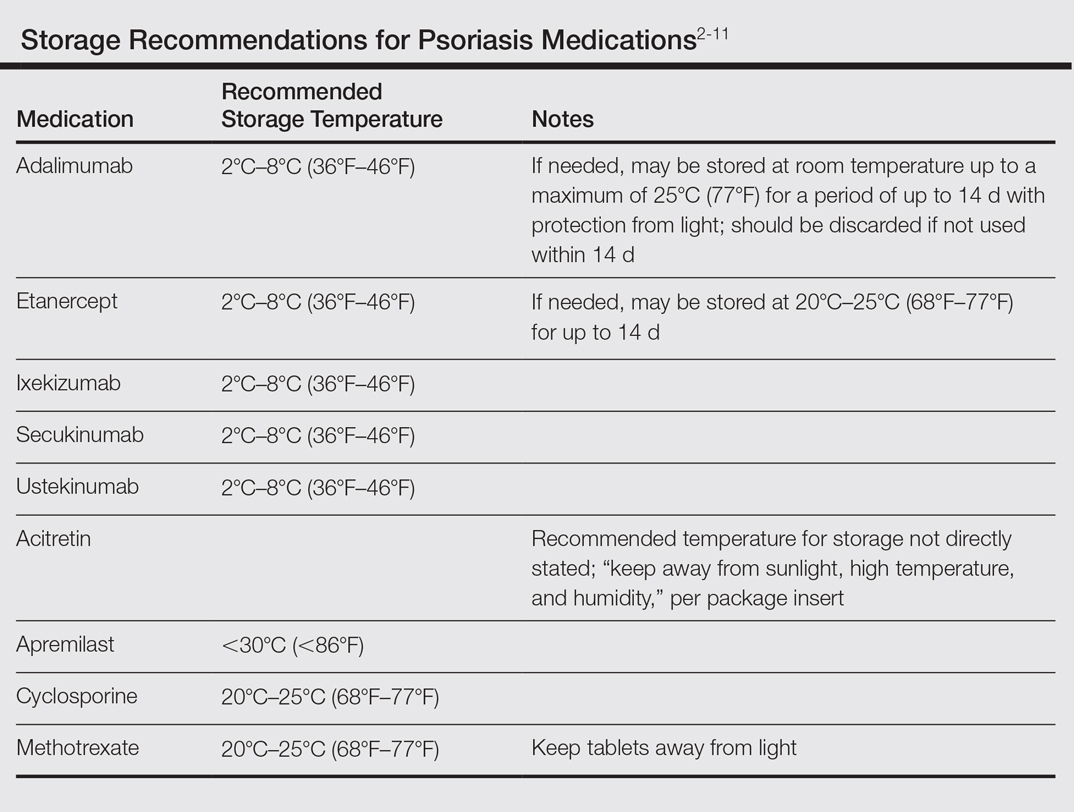

Although these problems may at first seem unique to active-duty military members, they also affect a substantial segment of the civilian sector. Take for instance the government contractor who deploys in support of military contingency actions, or the foreign aid workers, international businessmen, and diplomats around the world. In fact, any person who travels extensively might have difficulty carrying and storing their medications (Table) or encounter barriers that prevent routine access to care. Travel also may increase the risk of exposure to virulent pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which may further limit treatment options. This group of world travelers together comprises a minority of psoriasis patients who may be better treated with novel agents rather than with what might be considered the standard of care in a domestic setting.

Options for Care

Methotrexate

In many ways, methotrexate is the gold standard of psoriasis treatment. It is a first-line medication for many patients because it is typically well tolerated, has well-established efficacy, is easy to administer, and is relatively inexpensive.12 Although it is easy to store, transport, and administer, it requires regular laboratory monitoring at 3-month intervals or more frequently with dosage changes. It also is contraindicated in women of childbearing age who plan to become pregnant, which can be a considerable hindrance in the young active-duty population.

Cyclosporine

Cyclosporine is another inexpensive medication that can produce excellent results in the treatment of psoriasis.1,12 Although long-term use of cyclosporine in transplant patients has been well studied, its use for the treatment of dermatologic conditions is usually limited to 1 year. The need for monthly blood pressure checks and at least quarterly laboratory monitoring means it is not an optimal choice for a deployed service member.

Acitretin

Acitretin is another systemic medication with an established track record in psoriasis treatment. Although close follow-up and laboratory monitoring is required for both males and females, use of this medication can have a greater effect on women of childbearing age, as it is absolutely contraindicated in any female trying to conceive.13 In addition, acitretin is stored in fat cells, and traces of the drug can be found in the blood for up to 3 years. During this period, patients are advised to strictly avoid pregnancy and are even restricted from donating blood.13 Given these concerns, acitretin is not always a reasonable treatment option for the military service member.

Biologics

Biologics are the newest agents in the treatment of psoriasis. They require less laboratory monitoring and can provide excellent results. Adalimumab is a reasonable first-line biologic treatment for some patients. We find the laboratory monitoring is minimally obtrusive, side effects usually are limited, and the efficacy is great enough that most patients elect to continue treatment. Unfortunately, adalimumab has some major drawbacks in our specific use scenario in that it requires nearly continuous refrigeration and is never to exceed 25°C (77°F), it has a relatively close-interval dosing schedule, and it can cause immunosuppression. However, for short trips to nonaustere locations with an acceptable risk for pathogenic exposure, adalimumab may remain a viable option for many travelers, as it can be stored at room temperature for up to 14 days.2 Ustekinumab also is a reasonable choice for many travelers because dosing is every 12 weeks and it carries a lower risk of immunosuppression.2,3 Ustekinumab, however, has the major drawback of high cost.12 Newer IL-17A inhibitors such as secukinumab or ixekizumab also can offer excellent results, but long-term infection rates have not been reported. Overall, the infection rates are comparable to ustekinumab.14,15 After the loading phase, secukinumab is dosed monthly and logistically could still pose a problem due to the need for continued refrigeration.14

Apremilast

Although it is not the best first-line treatment for every patient, apremilast carries 3 distinct advantages in treating the military patient population: (1) laboratory monitoring is required only once per year, (2) it is easy to store, and (3) it is easy to administer. However, the major downside is that apremilast is less effective than other systemic agents in the treatment of psoriasis.16 As with other systemic drugs, adjunctive topical treatment can provide additional therapeutic effects, and for many patients, this combined approach is sufficient to reach their therapeutic goals.

For these reasons, in the special case of deployable, active-duty military members we often consider starting treatment with apremilast versus other systemic agents. As with all systemic psoriasis treatments, we generally advise patients to return 16 weeks after initiating treatment to assess efficacy and evaluate their deployment status. Although apremilast may take longer to reach full efficacy than many other systemic agents, one clinical trial suggested this time frame is sufficient to evaluate response to treatment.16 After this initial assessment, we revert to yearly monitoring, and the patient is usually cleared to deploy with minimal restrictions.

Final Considerations

The manifestation of psoriasis is different in every patient, and military service poses additional treatment challenges. For all of our military patients, we recommend an initial period of close follow-up after starting any new systemic agent, which is necessary to ensure the treatment is effective and well tolerated and also that we are good stewards of our resources. Once efficacy is established and side effects remain tolerable, we generally endorse continued treatment without specific travel or work restrictions.

We are cognizant of the unique nature of military service, and all too often we find ourselves trying to practice good medicine in bad places. As military physicians, we serve a population that is eager to do their job and willing to make incredible sacrifices to do so. After considering the wide range of circumstances unique to the military, our responsibility as providers is to do our best to improve service members’ quality of life as they carry out their missions.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Kalb RE, Fiorentino DF, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of serious infection with biologic and systemic treatment of psoriasis: results from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:961-969.

- Stelara [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc; 2009.

- Humira [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; 2007.

- Cosentyx [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2016.

- Otezla [package insert]. Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2014.

- Enbrel [package insert]. Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen; 2015.

- Taltz [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2016.

- Methotrexate [package insert]. Morgantown, WV: Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2016.

- Gengraf [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: Abbvie Inc; 2015.

- Acitretin [package insert]. Mason, OH: Prasco Laboratories; 2015.

- Beyer V, Wolverton SE. Recent trends in systemic psoriasis treatment costs. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:46-54.

- Wolverton SE. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

- Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis—results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:326-338.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, et al. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [published online June 8, 2016]. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:345-356.

- Papp K, Reich K, Leonardi CL, et al. Apremilast, anoral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results of a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (Efficacy and Safety Trial Evaluating the Effects of Apremilast in Psoriasis [ESTEEM] 1). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:37-49.

Psoriasis is a common dermatologic problem with nearly 5% prevalence in the United States. There is a bimodal distribution with peak onset between 20 and 30 years of age and 50 and 60 years, which means that this condition can arise before, during, or after military service.1 Unfortunately, for many prospective recruits psoriasis is a medically disqualifying condition that can prevent entry into active duty unless a medical waiver is granted. For active-duty military, new-onset psoriasis and its treatment can impair affected service members’ ability to perform mission-critical work and can prevent them from deploying to remote or austere locations. In this way, psoriasis presents a unique challenge for active-duty service members.

Many therapies are available that can effectively treat psoriasis, but these treatments often carry a side-effect profile that limits their use during travel or in austere settings. Herein, we discuss the unique challenges of treating psoriasis patients who are in the military at a time when global mobility is critical to mission success. Although in some ways these challenges truly are unique to the military population, we strongly believe that similar but perhaps underappreciated challenges exist in the civilian sector. Close examination of these challenges may reveal that alternative treatment choices are sometimes indicated for reasons beyond just efficacy, side-effect profile, and cost.

Treatment Considerations

The medical treatment of psoriasis has undergone substantial change in recent decades. Before the turn of the century, the mainstays of medical treatment were steroids, methotrexate, and phototherapy. Today, a wide array of biologics and other systemic drugs are altering the impact of psoriasis in our society. With so many treatment options currently available, the question becomes, “Which one is best for my patient?” Immediate considerations are efficacy versus side effects as well as cost; however, in military dermatology, the ability to store, transport, and administer the treatment can be just as important.

Although these problems may at first seem unique to active-duty military members, they also affect a substantial segment of the civilian sector. Take for instance the government contractor who deploys in support of military contingency actions, or the foreign aid workers, international businessmen, and diplomats around the world. In fact, any person who travels extensively might have difficulty carrying and storing their medications (Table) or encounter barriers that prevent routine access to care. Travel also may increase the risk of exposure to virulent pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which may further limit treatment options. This group of world travelers together comprises a minority of psoriasis patients who may be better treated with novel agents rather than with what might be considered the standard of care in a domestic setting.

Options for Care

Methotrexate

In many ways, methotrexate is the gold standard of psoriasis treatment. It is a first-line medication for many patients because it is typically well tolerated, has well-established efficacy, is easy to administer, and is relatively inexpensive.12 Although it is easy to store, transport, and administer, it requires regular laboratory monitoring at 3-month intervals or more frequently with dosage changes. It also is contraindicated in women of childbearing age who plan to become pregnant, which can be a considerable hindrance in the young active-duty population.

Cyclosporine

Cyclosporine is another inexpensive medication that can produce excellent results in the treatment of psoriasis.1,12 Although long-term use of cyclosporine in transplant patients has been well studied, its use for the treatment of dermatologic conditions is usually limited to 1 year. The need for monthly blood pressure checks and at least quarterly laboratory monitoring means it is not an optimal choice for a deployed service member.

Acitretin

Acitretin is another systemic medication with an established track record in psoriasis treatment. Although close follow-up and laboratory monitoring is required for both males and females, use of this medication can have a greater effect on women of childbearing age, as it is absolutely contraindicated in any female trying to conceive.13 In addition, acitretin is stored in fat cells, and traces of the drug can be found in the blood for up to 3 years. During this period, patients are advised to strictly avoid pregnancy and are even restricted from donating blood.13 Given these concerns, acitretin is not always a reasonable treatment option for the military service member.

Biologics

Biologics are the newest agents in the treatment of psoriasis. They require less laboratory monitoring and can provide excellent results. Adalimumab is a reasonable first-line biologic treatment for some patients. We find the laboratory monitoring is minimally obtrusive, side effects usually are limited, and the efficacy is great enough that most patients elect to continue treatment. Unfortunately, adalimumab has some major drawbacks in our specific use scenario in that it requires nearly continuous refrigeration and is never to exceed 25°C (77°F), it has a relatively close-interval dosing schedule, and it can cause immunosuppression. However, for short trips to nonaustere locations with an acceptable risk for pathogenic exposure, adalimumab may remain a viable option for many travelers, as it can be stored at room temperature for up to 14 days.2 Ustekinumab also is a reasonable choice for many travelers because dosing is every 12 weeks and it carries a lower risk of immunosuppression.2,3 Ustekinumab, however, has the major drawback of high cost.12 Newer IL-17A inhibitors such as secukinumab or ixekizumab also can offer excellent results, but long-term infection rates have not been reported. Overall, the infection rates are comparable to ustekinumab.14,15 After the loading phase, secukinumab is dosed monthly and logistically could still pose a problem due to the need for continued refrigeration.14

Apremilast

Although it is not the best first-line treatment for every patient, apremilast carries 3 distinct advantages in treating the military patient population: (1) laboratory monitoring is required only once per year, (2) it is easy to store, and (3) it is easy to administer. However, the major downside is that apremilast is less effective than other systemic agents in the treatment of psoriasis.16 As with other systemic drugs, adjunctive topical treatment can provide additional therapeutic effects, and for many patients, this combined approach is sufficient to reach their therapeutic goals.

For these reasons, in the special case of deployable, active-duty military members we often consider starting treatment with apremilast versus other systemic agents. As with all systemic psoriasis treatments, we generally advise patients to return 16 weeks after initiating treatment to assess efficacy and evaluate their deployment status. Although apremilast may take longer to reach full efficacy than many other systemic agents, one clinical trial suggested this time frame is sufficient to evaluate response to treatment.16 After this initial assessment, we revert to yearly monitoring, and the patient is usually cleared to deploy with minimal restrictions.

Final Considerations

The manifestation of psoriasis is different in every patient, and military service poses additional treatment challenges. For all of our military patients, we recommend an initial period of close follow-up after starting any new systemic agent, which is necessary to ensure the treatment is effective and well tolerated and also that we are good stewards of our resources. Once efficacy is established and side effects remain tolerable, we generally endorse continued treatment without specific travel or work restrictions.

We are cognizant of the unique nature of military service, and all too often we find ourselves trying to practice good medicine in bad places. As military physicians, we serve a population that is eager to do their job and willing to make incredible sacrifices to do so. After considering the wide range of circumstances unique to the military, our responsibility as providers is to do our best to improve service members’ quality of life as they carry out their missions.

Psoriasis is a common dermatologic problem with nearly 5% prevalence in the United States. There is a bimodal distribution with peak onset between 20 and 30 years of age and 50 and 60 years, which means that this condition can arise before, during, or after military service.1 Unfortunately, for many prospective recruits psoriasis is a medically disqualifying condition that can prevent entry into active duty unless a medical waiver is granted. For active-duty military, new-onset psoriasis and its treatment can impair affected service members’ ability to perform mission-critical work and can prevent them from deploying to remote or austere locations. In this way, psoriasis presents a unique challenge for active-duty service members.

Many therapies are available that can effectively treat psoriasis, but these treatments often carry a side-effect profile that limits their use during travel or in austere settings. Herein, we discuss the unique challenges of treating psoriasis patients who are in the military at a time when global mobility is critical to mission success. Although in some ways these challenges truly are unique to the military population, we strongly believe that similar but perhaps underappreciated challenges exist in the civilian sector. Close examination of these challenges may reveal that alternative treatment choices are sometimes indicated for reasons beyond just efficacy, side-effect profile, and cost.

Treatment Considerations

The medical treatment of psoriasis has undergone substantial change in recent decades. Before the turn of the century, the mainstays of medical treatment were steroids, methotrexate, and phototherapy. Today, a wide array of biologics and other systemic drugs are altering the impact of psoriasis in our society. With so many treatment options currently available, the question becomes, “Which one is best for my patient?” Immediate considerations are efficacy versus side effects as well as cost; however, in military dermatology, the ability to store, transport, and administer the treatment can be just as important.

Although these problems may at first seem unique to active-duty military members, they also affect a substantial segment of the civilian sector. Take for instance the government contractor who deploys in support of military contingency actions, or the foreign aid workers, international businessmen, and diplomats around the world. In fact, any person who travels extensively might have difficulty carrying and storing their medications (Table) or encounter barriers that prevent routine access to care. Travel also may increase the risk of exposure to virulent pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which may further limit treatment options. This group of world travelers together comprises a minority of psoriasis patients who may be better treated with novel agents rather than with what might be considered the standard of care in a domestic setting.

Options for Care

Methotrexate

In many ways, methotrexate is the gold standard of psoriasis treatment. It is a first-line medication for many patients because it is typically well tolerated, has well-established efficacy, is easy to administer, and is relatively inexpensive.12 Although it is easy to store, transport, and administer, it requires regular laboratory monitoring at 3-month intervals or more frequently with dosage changes. It also is contraindicated in women of childbearing age who plan to become pregnant, which can be a considerable hindrance in the young active-duty population.

Cyclosporine

Cyclosporine is another inexpensive medication that can produce excellent results in the treatment of psoriasis.1,12 Although long-term use of cyclosporine in transplant patients has been well studied, its use for the treatment of dermatologic conditions is usually limited to 1 year. The need for monthly blood pressure checks and at least quarterly laboratory monitoring means it is not an optimal choice for a deployed service member.

Acitretin

Acitretin is another systemic medication with an established track record in psoriasis treatment. Although close follow-up and laboratory monitoring is required for both males and females, use of this medication can have a greater effect on women of childbearing age, as it is absolutely contraindicated in any female trying to conceive.13 In addition, acitretin is stored in fat cells, and traces of the drug can be found in the blood for up to 3 years. During this period, patients are advised to strictly avoid pregnancy and are even restricted from donating blood.13 Given these concerns, acitretin is not always a reasonable treatment option for the military service member.

Biologics

Biologics are the newest agents in the treatment of psoriasis. They require less laboratory monitoring and can provide excellent results. Adalimumab is a reasonable first-line biologic treatment for some patients. We find the laboratory monitoring is minimally obtrusive, side effects usually are limited, and the efficacy is great enough that most patients elect to continue treatment. Unfortunately, adalimumab has some major drawbacks in our specific use scenario in that it requires nearly continuous refrigeration and is never to exceed 25°C (77°F), it has a relatively close-interval dosing schedule, and it can cause immunosuppression. However, for short trips to nonaustere locations with an acceptable risk for pathogenic exposure, adalimumab may remain a viable option for many travelers, as it can be stored at room temperature for up to 14 days.2 Ustekinumab also is a reasonable choice for many travelers because dosing is every 12 weeks and it carries a lower risk of immunosuppression.2,3 Ustekinumab, however, has the major drawback of high cost.12 Newer IL-17A inhibitors such as secukinumab or ixekizumab also can offer excellent results, but long-term infection rates have not been reported. Overall, the infection rates are comparable to ustekinumab.14,15 After the loading phase, secukinumab is dosed monthly and logistically could still pose a problem due to the need for continued refrigeration.14

Apremilast

Although it is not the best first-line treatment for every patient, apremilast carries 3 distinct advantages in treating the military patient population: (1) laboratory monitoring is required only once per year, (2) it is easy to store, and (3) it is easy to administer. However, the major downside is that apremilast is less effective than other systemic agents in the treatment of psoriasis.16 As with other systemic drugs, adjunctive topical treatment can provide additional therapeutic effects, and for many patients, this combined approach is sufficient to reach their therapeutic goals.

For these reasons, in the special case of deployable, active-duty military members we often consider starting treatment with apremilast versus other systemic agents. As with all systemic psoriasis treatments, we generally advise patients to return 16 weeks after initiating treatment to assess efficacy and evaluate their deployment status. Although apremilast may take longer to reach full efficacy than many other systemic agents, one clinical trial suggested this time frame is sufficient to evaluate response to treatment.16 After this initial assessment, we revert to yearly monitoring, and the patient is usually cleared to deploy with minimal restrictions.

Final Considerations

The manifestation of psoriasis is different in every patient, and military service poses additional treatment challenges. For all of our military patients, we recommend an initial period of close follow-up after starting any new systemic agent, which is necessary to ensure the treatment is effective and well tolerated and also that we are good stewards of our resources. Once efficacy is established and side effects remain tolerable, we generally endorse continued treatment without specific travel or work restrictions.

We are cognizant of the unique nature of military service, and all too often we find ourselves trying to practice good medicine in bad places. As military physicians, we serve a population that is eager to do their job and willing to make incredible sacrifices to do so. After considering the wide range of circumstances unique to the military, our responsibility as providers is to do our best to improve service members’ quality of life as they carry out their missions.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Kalb RE, Fiorentino DF, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of serious infection with biologic and systemic treatment of psoriasis: results from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:961-969.

- Stelara [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc; 2009.

- Humira [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; 2007.

- Cosentyx [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2016.

- Otezla [package insert]. Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2014.

- Enbrel [package insert]. Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen; 2015.

- Taltz [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2016.

- Methotrexate [package insert]. Morgantown, WV: Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2016.

- Gengraf [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: Abbvie Inc; 2015.

- Acitretin [package insert]. Mason, OH: Prasco Laboratories; 2015.

- Beyer V, Wolverton SE. Recent trends in systemic psoriasis treatment costs. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:46-54.

- Wolverton SE. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

- Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis—results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:326-338.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, et al. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [published online June 8, 2016]. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:345-356.

- Papp K, Reich K, Leonardi CL, et al. Apremilast, anoral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results of a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (Efficacy and Safety Trial Evaluating the Effects of Apremilast in Psoriasis [ESTEEM] 1). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:37-49.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Kalb RE, Fiorentino DF, Lebwohl MG, et al. Risk of serious infection with biologic and systemic treatment of psoriasis: results from the Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:961-969.

- Stelara [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc; 2009.

- Humira [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; 2007.

- Cosentyx [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2016.

- Otezla [package insert]. Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2014.

- Enbrel [package insert]. Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen; 2015.

- Taltz [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2016.

- Methotrexate [package insert]. Morgantown, WV: Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2016.

- Gengraf [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: Abbvie Inc; 2015.

- Acitretin [package insert]. Mason, OH: Prasco Laboratories; 2015.

- Beyer V, Wolverton SE. Recent trends in systemic psoriasis treatment costs. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:46-54.

- Wolverton SE. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

- Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis—results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:326-338.

- Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA, et al. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [published online June 8, 2016]. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:345-356.

- Papp K, Reich K, Leonardi CL, et al. Apremilast, anoral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results of a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (Efficacy and Safety Trial Evaluating the Effects of Apremilast in Psoriasis [ESTEEM] 1). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:37-49.

Practice Points

- Establishing goals of treatment with each patient is a critical step in treating the patient rather than the diagnosis.

- A good social history can reveal job-related impact of disease and potential logistical roadblocks to treatment.

- Efficacy must be weighed against the burden of logistical constraints for each patient; potential issues include difficulty complying with follow-up visits, access to laboratory monitoring, exposure to pathogens, and adequacy of medication transport and storage.

Over-the-counter and Natural Remedies for Onychomycosis: Do They Really Work?

Onychomycosis is a fungal infection of the nail unit by dermatophytes, yeasts, and nondermatophyte molds. It is characterized by a white or yellow discoloration of the nail plate; hyperkeratosis of the nail bed; distal detachment of the nail plate from its bed (onycholysis); and nail plate dystrophy, including thickening, crumbling, and ridging. Onychomycosis is an important problem, representing 30% of all superficial fungal infections and an estimated 50% of all nail diseases.1 Reported prevalence rates of onychomycosis in the United States and worldwide are varied, but the mean prevalence based on population-based studies in Europe and North America is estimated to be 4.3%.2 It is more common in older individuals, with an incidence rate of 20% in those older than 60 years and 50% in those older than 70 years.3 Onychomycosis is more common in patients with diabetes and 1.9 to 2.8 times higher than the general population.4 Dermatophytes are responsible for the majority of cases of onychomycosis, particularly Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton mentagrophytes.5

Onychomycosis is divided into different subtypes based on clinical presentation, which in turn are characterized by varying infecting organisms and prognoses. The subtypes of onychomycosis are distal and lateral subungual (DLSO), proximal subungual, superficial, endonyx, mixed pattern, total dystrophic, and secondary. Distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis are by far the most common presentation and begins when the infecting organism invades the hyponychium and distal or lateral nail bed. Trichophyton rubrum is the most common organism and T mentagrophytes is second, but Candida parapsilosis and Candida albicans also are possibilities. Proximal subungual onychomycosis is far less frequent than DLSO and is usually caused by T rubrum. The fungus invades the proximal nail folds and penetrates the newly growing nail plate.6 This pattern is more common in immunosuppressed patients and should prompt testing for human immunodeficiency virus.7 Total dystrophic onychomycosis is the end stage of fungal nail plate invasion, may follow DLSO or proximal subungual onychomycosis, and is difficult to treat.6

Onychomycosis causes pain, paresthesia, and difficulty with ambulation.8 In patients with peripheral neuropathy and vascular problems, including diabetes, onychomycosis can increase the risk for foot ulcers, with amputation in severe cases.9 Patients also may present with aesthetic concerns that may impact their quality of life.10

Given the effect on quality of life along with medical risks associated with onychomycosis, a safe and successful treatment modality with a low risk of recurrence is desirable. Unfortunately, treatment of nail fungus is quite challenging for a number of reasons. First, the thickness of the nail and/or the fungal mass may be a barrier to the delivery of topical and systemic drugs at the source of the infection. In addition, the nail plate does not have intrinsic immunity. Also, recurrence after treatment is common due to residual hyphae or spores that were not previously eliminated.11 Finally, many topical medications require long treatment courses, which may limit patient compliance, especially in patients who want to use nail polish for cosmesis or camouflage.

Currently Approved Therapies for Onychomycosis

Several definitions are needed to better interpret the results of onychomycosis clinical trials. Complete cure is defined as a negative potassium hydroxide preparation and negative fungal culture with a completely normal appearance of the nail. Mycological cure is defined as potassium hydroxide microscopy and fungal culture negative. Clinical cure is stated as 0% nail plate involvement but at times is reported as less than 5% and less than 10% involvement.

Terbinafine and itraconazole are the only US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved systemic therapies, and ciclopirox, efinaconazole, and tavaborole are the only FDA-approved topicals. Advantages of systemic agents generally are higher cure rates and shorter treatment courses, thus better compliance. Disadvantages include greater incidence of systemic side effects and drug-drug interactions as well as the need for laboratory monitoring. Pros of topical therapies are low potential for adverse effects, no drug-drug interactions, and no monitoring of blood work. Cons include lower efficacy, long treatment courses, and poor patient compliance.

Terbinafine, an allylamine, taken orally once daily (250 mg) for 12 weeks for toenails and 6 weeks for fingernails currently is the preferred systemic treatment of onychomycosis, with complete cure rates of 38% and 59% and mycological cure rates of 70% and 79% for toenails and fingernails, respectively.12 Itraconazole, an azole, is dosed orally at 200 mg daily for 3 months for toenails, with a complete cure rate of 14% and mycological cure rate of 54%.13 For fingernail onychomycosis only, itraconazole is dosed at 200 mg twice daily for 1 week, followed by a treatment-free period of 3 weeks, and then another 1-week course at thesame dose. The complete cure rate is 47% and the mycological cure is 61% for this pulse regimen.13

Ciclopirox is a hydroxypyridone and the 8% nail lacquer formulation was approved in 1999, making it the first topical medication to gain FDA approval for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis. Based on 2 clinical trials, complete cure rates for toenails are 5.5% and 8.5% and mycological cure rates are 29% and 36% at 48 weeks with removal of residual lacquer and debridement.14 Efinaconazole is an azole and the 10% solution was FDA approved for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in 2014.15 In 2 clinical trials, complete cure rates were 17.8% and 15.2% and mycological cure rates were 55.2% and 53.4% with once daily toenail application for 48 weeks.16 Tavaborole is a benzoxaborole and the 5% solution also was approved for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in 2014.17 Two clinical trials reported complete cure rates of 6.5% and 9.1% and mycological cure rates of 31.1% and 35.9% with once daily toenail application for 48 weeks.18

Given the poor efficacy, systemic side effects, potential for drug-drug interactions, long-term treatment courses, and cost associated with current systemic and/or topical treatments, there has been a renewed interest in natural remedies and over-the-counter (OTC) therapies for onychomycosis. This review summarizes the in vitro and in vivo data, mechanisms of action, and clinical efficacy of various natural and OTC agents for the treatment of onychomycosis. Specifically, we summarize the data on tea tree oil (TTO), a popular topical cough suppressant (TCS), natural coniferous resin (NCR) lacquer, Ageratina pichinchensis (AP) extract, and ozonized sunflower oil.

Tea Tree Oil

Background

Tea tree oil is a volatile oil whose medicinal use dates back to the early 20th century when the Bundjabung aborigines of North and New South Wales extracted TTO from the dried leaves of the Melaleuca alternifolia plant and used it to treat superficial wounds.19 Tea tree oil has been shown to be an effective treatment of tinea pedis,20 and it is widely used in Australia as well as in Europe and North America.21 Tea tree oil also has been investigated as an antifungal agent for the treatment of onychomycosis, both in vitro22-28 and in clinical trials.29,30

In Vitro Data

Because TTO is composed of more than 100 active components,23 the antifungal activity of these individual components was investigated against 14 fungal isolates, including C albicans, T mentagrophytes, and Aspergillus species. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for α-pinene was less than 0.004% for T mentagrophytes and the components with the greatest MIC and minimum fungicidal concentration for the fungi tested were terpinen-4-ol and α-terpineol, respectively.22 The antifungal activity of TTO also was tested using disk diffusion assay experiments with 58 clinical isolates of fungi including C albicans, T rubrum, T mentagrophytes, and Aspergillus niger.24 Tea tree oil was most effective at inhibiting T rubrum followed by T mentagrophytes,24 which are the 2 most common etiologies of onychomycosis.5 In another report, the authors determined the MIC of TTO utilizing 4 different experiments with T rubrum as the infecting organism. Because TTO inhibited the growth of T rubrum at all concentrations greater than 0.1%, they found that the MIC was 0.1%.25 Given the lack of adequate nail penetration of most topical therapies, TTO in nanocapsules (TTO-NC), TTO nanoemulsions, and normal emulsions were tested in vitro for their ability to inhibit the growth of T rubrum inoculated into nail shavings. Colony growth decreased significantly within the first week of treatment, with TTO-NC showing maximum efficacy (P<.001). This study showed that TTO, particularly TTO-NC, was effective in inhibiting the growth of T rubrum in vitro and that using nanocapsule technology may increase nail penetration and bioavailability.31

Much of what we know about TTO’s antifungal mechanism of action comes from experiments involving C albicans. To date, it has not been studied in T rubrum or T mentagrophytes, the 2 most common etiologies of onychomycosis.5 In C albicans, TTO causes altered permeability of plasma membranes,32 dose-dependent alteration of respiration,33 decreased glucose-induced acidification of media surrounding fungi,32 and reversible inhibition of germ tube formation.19,34

Clinical Trials

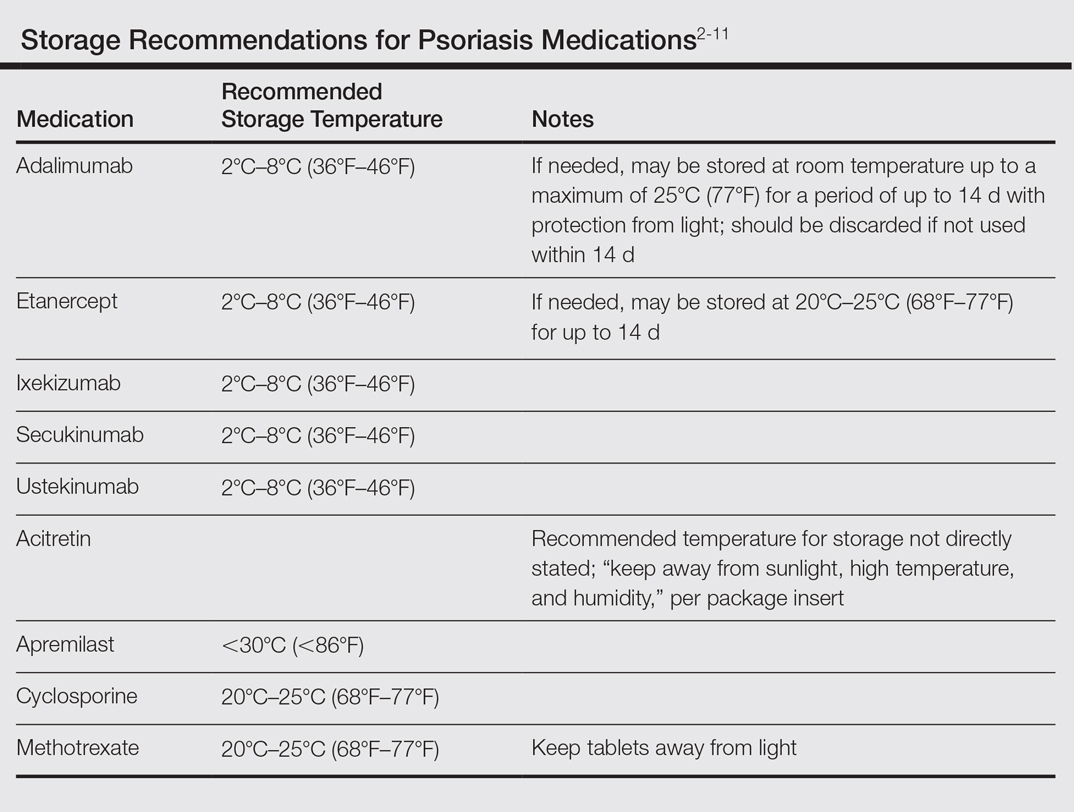

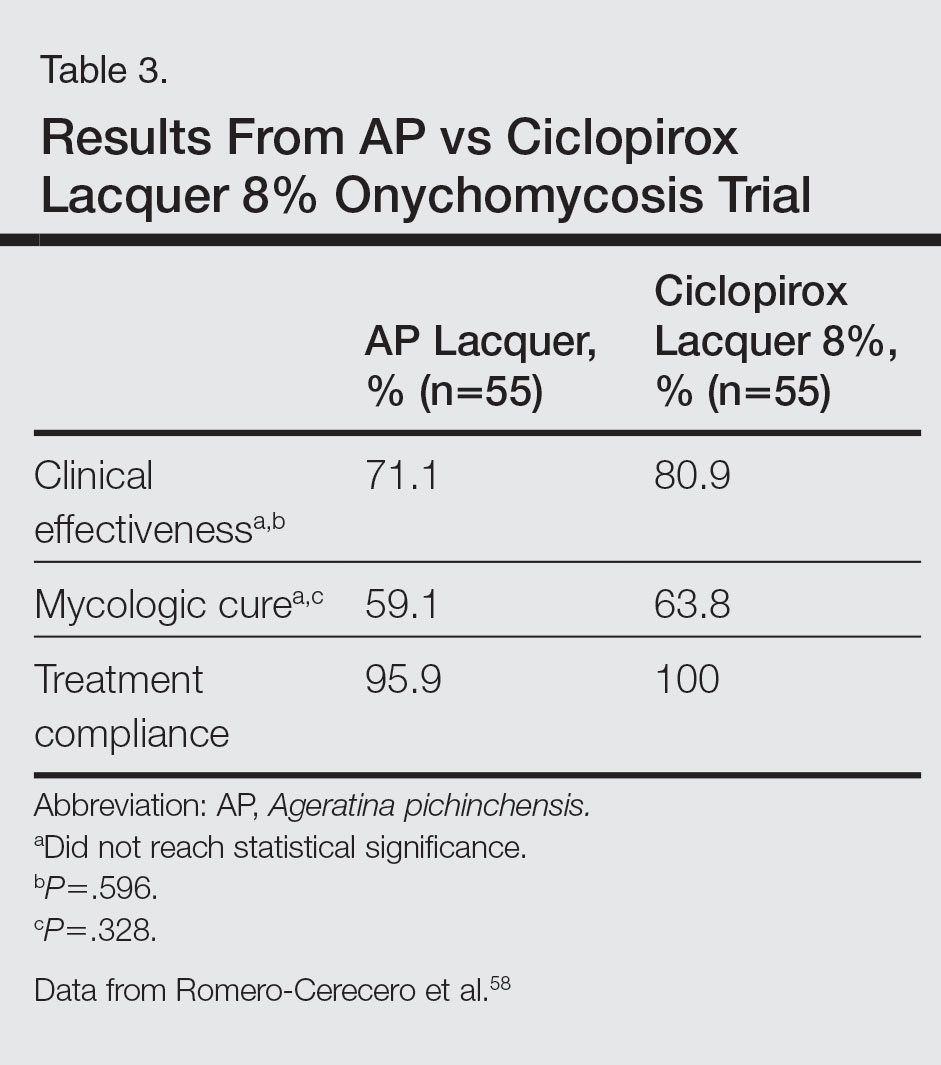

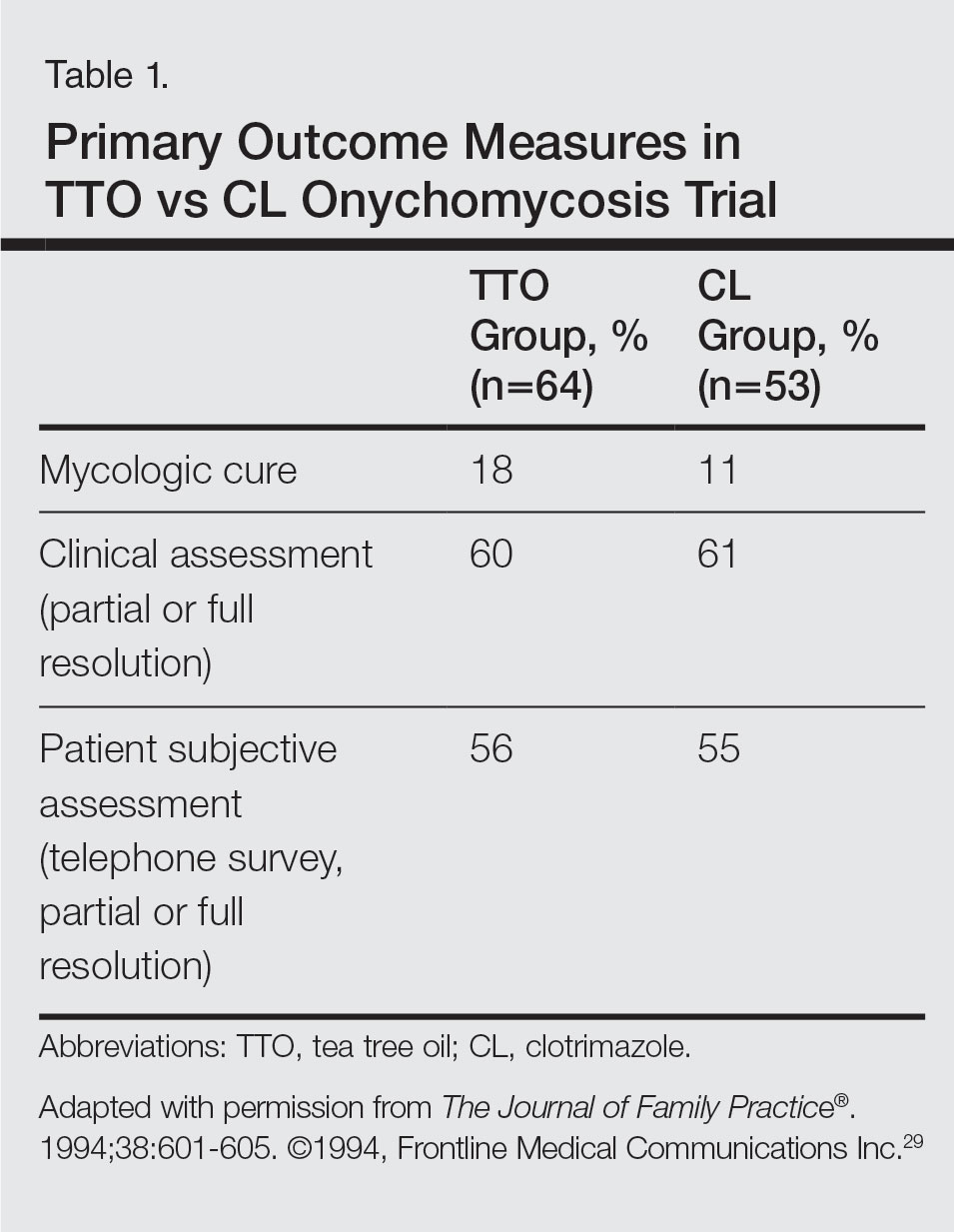

A randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial was performed on 117 patients with culture-proven DLSO who were randomized to receive TTO 100% or clotrimazole solution 1% applied twice daily to affected toenails for 6 months.29 Primary outcome measures were mycologic cure, clinical assessment, and patient subjective assessment (Table 1). There were no statistical differences between the 2 treatment groups. Erythema and irritation were the most common adverse reactions occurring in 7.8% (5/64) of the TTO group.29

Another study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 60 patients with clinical and mycologic evidence of DLSO who were randomized to treatment with a cream containing butenafine hydrochloride 2% and TTO 5% (n=40) or a control cream containing only TTO (n=20), with active treatment for 8 weeks and final follow-up at 36 weeks.30 Patients were instructed to apply the cream 3 times daily under occlusion for 8 weeks and the nail was debrided between weeks 4 and 6 if feasible. If the nail could not be debrided after 8 weeks, it was considered resistant to treatment. At the end of the study, the complete cure rate was 80% in the active group compared to 0% in the placebo group (P<.0001), and the mean time to complete healing with progressive nail growth was 29 weeks. There were no adverse effects in the placebo group, but 4 patients in the active group had mild skin inflammation.30

Topical Cough Suppressant

Background

Topical cough suppressants, which are made up of several natural ingredients, are OTC ointments for adults and children 2 years and older that are indicated as cough suppressants when applied to the chest and throat and as relief of mild muscle and joint pains.35 The active ingredients are camphor 4.8%, eucalyptus oil 1.2%, and menthol 2.6%, while the inactive ingredients are cedarleaf oil, nutmeg oil, petrolatum, thymol, and turpentine oil.35 Some of the active and inactive ingredients in TCSs have shown efficacy against dermatophytes in vitro,36-38 and although they are not specifically indicated for onychomycosis, they have been popularized as home remedies for fungal nail infections.36,39 A TCS has been evaluated for its efficacy for the treatment of onychomycosis in one clinical trial.40

In Vitro Data

An in vitro study was performed to evaluate the antifungal activity of the individual and combined components of TCS on 16 different dermatophytes, nondermatophytes, and molds. The zones of inhibition against these organisms were greatest for camphor, menthol, thymol, and eucalyptus oil. Interestingly, there were large zones of inhibition and a synergistic effect when a mixture of components was used against T rubrum and T mentagrophytes.36 The in vitro activity of thymol, a component of TCS, was tested against Candida species.37 The essential oil subtypes Thymus vulgaris and Thymus zygis (subspecies zygis) showed similar antifungal activity, which was superior to Thymus mastichina, and all 3 compounds had similar MIC and minimal lethal concentration values. The authors showed that the antifungal mechanism was due to cell membrane damage and inhibition of germ tube formation.37 It should be noted that Candida species are less common causes of onychomycosis, and it is not known whether this data is applicable to T rubrum. In another study, the authors investigated the antifungal activity of Thymus pulegioides and found that MIC ranged from 0.16 to 0.32 μL/mL for dermatophytes and Aspergillus strains and 0.32 to 0.64 μL/mL for Candida species. When an essential oil concentration of 0.08 μL/mL was used against T rubrum, ergosterol content decreased by 70 %, indicating that T pulegioides inhibits ergosterol biosynthesis in T rubrum.38

Clinical Observations and Clinical Trial

There is one report documenting the clinical observations on a group of patients with a clinical diagnosis of onychomycosis who were instructed to apply TCS to affected nail(s) once daily.36 Eighty-five charts were reviewed (mean age, 77 years), and although follow-up was not complete or standardized, the following data were reported: 32 (38%) cleared their fungal infection, 21 (25%) had no record of change but also no record of compliance, 19 (22%) had only 1 documented follow-up visit, 9 (11%) reported they did not use the treatment, and 4 (5%) did not return for a follow-up visit. Of the 32 patients whose nails were cured, 3 (9%) had clearance within 5 months, 8 (25%) within 7 months, 11 (34%) within 9 months, 4 (13%) within 11 months, and 6 (19%) within 16 months.36

A small pilot study was performed to evaluate the efficacy of daily application of TCS in the treatment of onychomycosis in patients 18 years and older with at least 1 great toenail affected.40 The primary end points were mycologic cure at 48 weeks and clinical cure at the end of the study graded as complete, partial, or no change. The secondary end point was patient satisfaction with the appearance of the affected nail at 48 weeks. Eighteen participants completed the study; 55% (10/18) were male, with an average age of 51 years (age range, 30–85 years). The mean initial amount of affected nail was 62% (range, 16%–100%), and cultures included dermatophytes, nondermatophytes, and molds. With TCS treatment, 27.8% (5/18) showed mycologic cure of which 4 (22.2%) had a complete clinical cure. Ten participants (55.6%) had partial clinical cure and 3 (16.7%) had no clinical improvement. Interestingly, the 4 participants who had complete clinical cure had baseline cultures positive for either T mentagrophytes or C parapsilosis. Most patients were content with the treatment, as 9 participants stated that they were very satisfied and 9 stated that they were satisfied. The average ratio of affected to total nail area declined from 63% at screening to 41% at the end of the study (P<.001). No adverse effects were reported with study drug.40

NCR Lacquer

Background

Resins are natural products derived from coniferous trees and are believed to protect trees against insects and microbial pathogens.41 Natural coniferous resin derived from the Norway spruce tree (Picea abies) mixed with boiled animal fat or butter has been used topically for centuries in Finland and Sweden to treat infections and wounds.42-44 The activity of NCR has been studied against a wide range of microbes, demonstrating broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against both gram-positive bacteria and fungi.45-48 There are 2 published clinical trials evaluating NCR in the treatment of onychomycosis.49,50

In Vitro Data

Natural coniferous resin has shown antifungal activity against T mentagrophytes, Trichophyton tonsurans, and T rubrum in vitro, which was demonstrated using medicated disks of resin on petri dishes inoculated with these organisms.46 In another study, the authors evaluated the antifungal activity of NCR against human pathogenic fungi and yeasts using agar plate diffusion tests and showed that the resin had antifungal activity against Trichophyton species but not against Fusarium and most Candida species. Electron microscopy of T mentagrophytes exposed to NCR showed that all cells were dead inside the inhibition zone, with striking changes seen in the hyphal cell walls, while fungal cells outside the inhibition zone were morphologically normal.47 In another report, utilizing the European Pharmacopoeia challenge test, NCR was highly effective against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria as well as C albicans.42

Clinical Trials

In one preliminary observational and prospective clinical trial, 15 participants with clinical and mycologic evidence of onychomycosis were instructed to apply NCR lacquer once daily for 9 months with a 4-week washout period, with the primary outcome measures being clinical and mycologic cure.49 Thirteen (87%) enrolled participants were male and the average age was 65 years (age range, 37–80 years). The DLSO subtype was present in 9 (60%) participants. The mycologic cure rate at the end of the study was 65% (95% CI, 42%-87%), and none achieved clinical cure, but 6 participants showed some improvement in the appearance of the nail.49

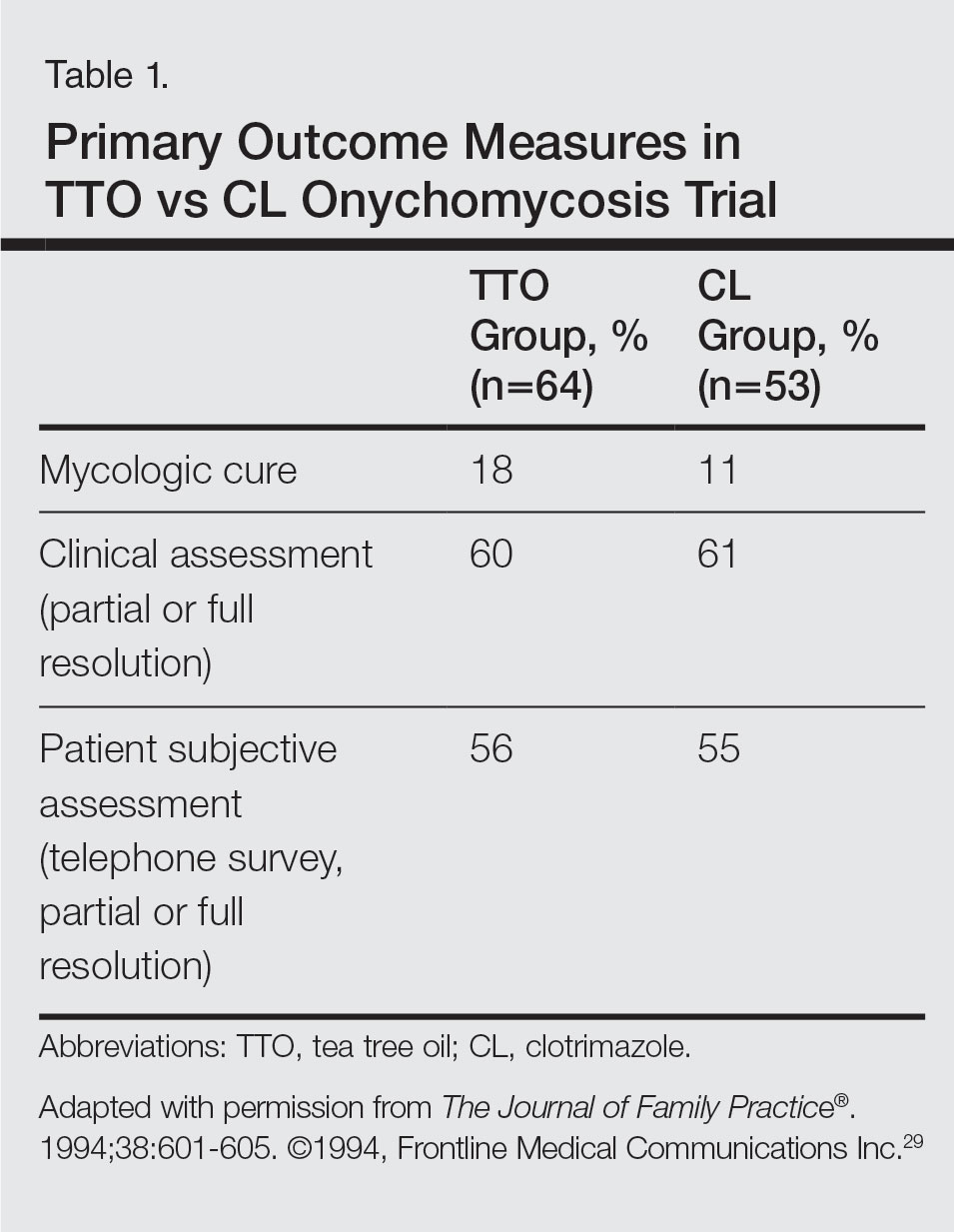

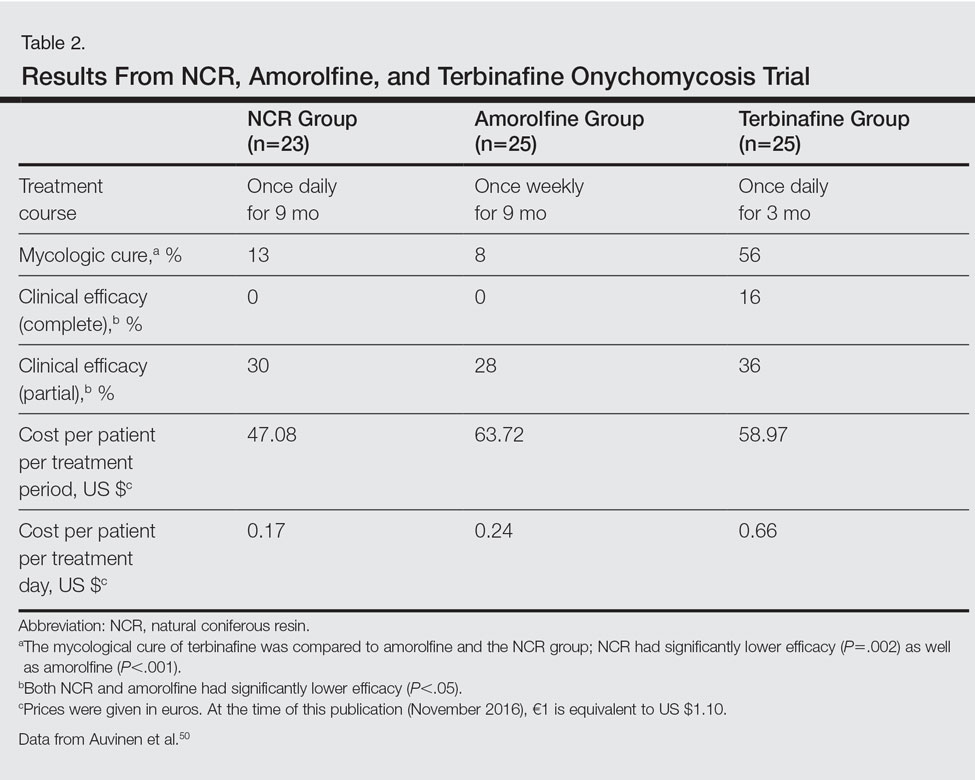

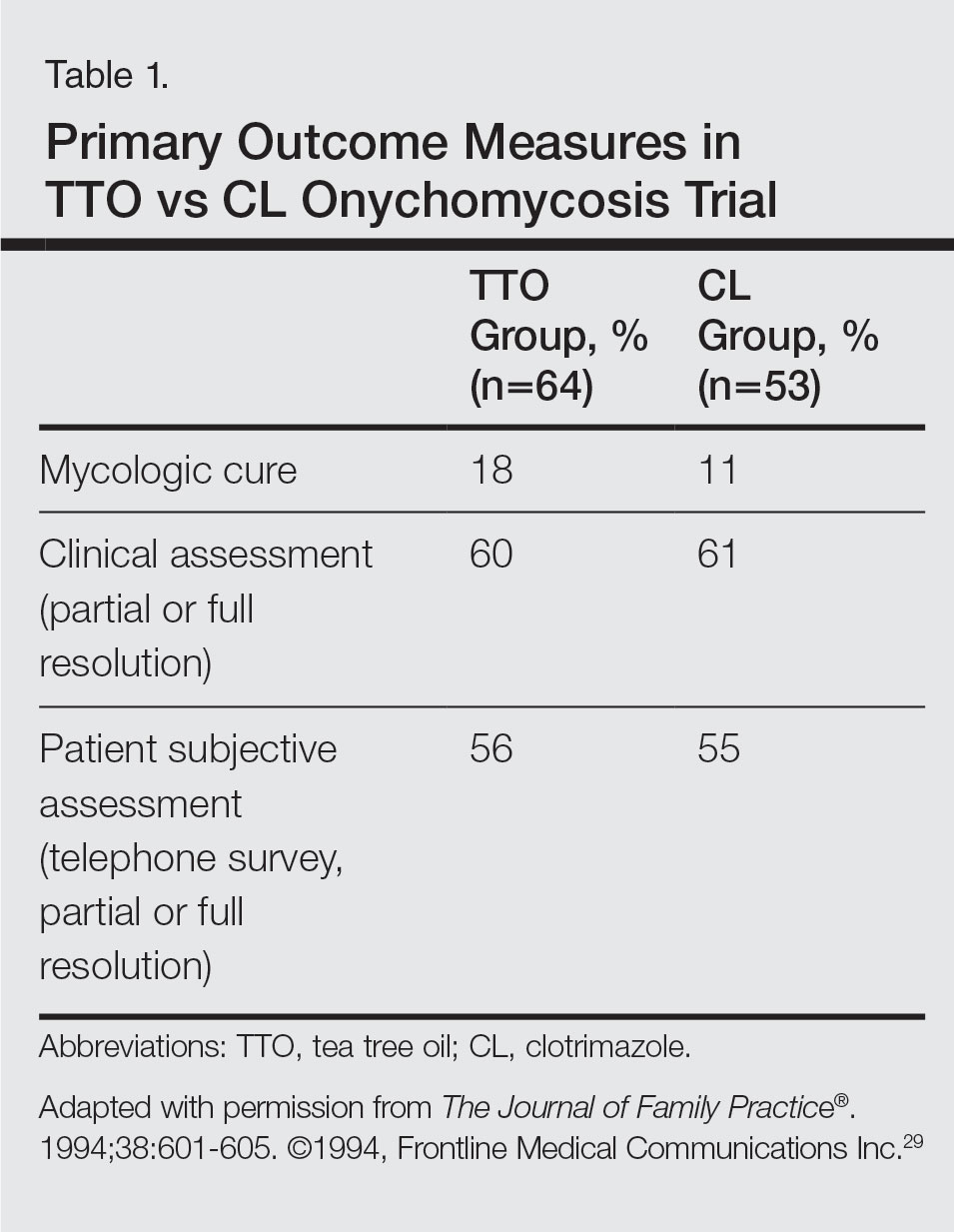

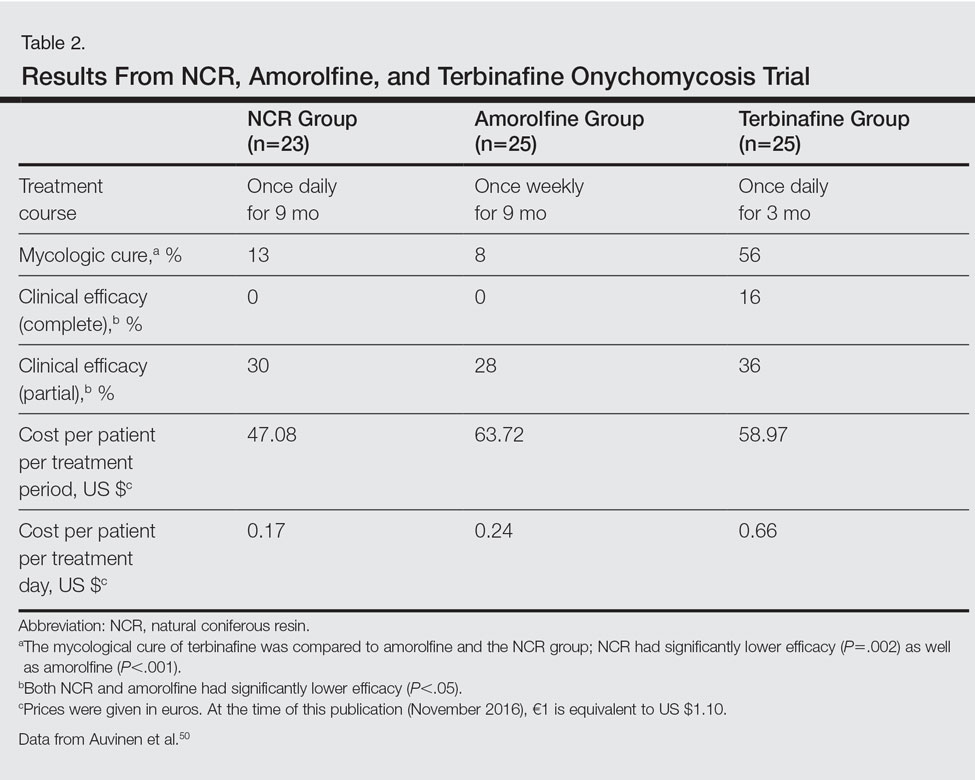

The second trial was a prospective, controlled, investigator-blinded study of 73 patients with clinical and mycologic evidence of toenail onychomycosis who were randomized to receive NCR 30%, amorolfine lacquer 5%, or 250 mg oral terbinafine.50 The primary end point was mycologic cure at 10 months, and secondary end points were clinical efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and patient compliance. Clinical efficacy was based on the proximal linear growth of healthy nail and was classified as unchanged, partial, or complete. Partial responses were described as substantial decreases in onycholysis, subungual hyperkeratosis, and streaks. A complete response was defined as a fully normal appearance of the toenail. Most patients were male in the NCR (91% [21/23]), amorolfine (80% [20/25]), and terbinafine (68% [17/25]) groups; the average ages were 64, 63, and 64 years, respectively. Trichophyton rubrum was cultured most often in all 3 groups: NCR, 87% (20/23); amorolfine, 96% (24/25); and terbinafine, 84% (21/25). The remaining cases were from T mentagrophytes. A summary of the results is shown in Table 2. Patient compliance was 100% in all except 1 patient in the amorolfine treatment group with moderate compliance. There were no adverse events, except for 2 in the terbinafine group: diarrhea and rash.50

AP Extract

Background

Ageratina pichinchensis, a member of the Asteraceae family, has been used historically in Mexico for fungal infections of the skin.51,52 Fresh or dried leaves were extracted with alcohol and the product was administered topically onto damaged skin without considerable skin irritation.53 Multiple studies have demonstrated that AP extract has in vitro antifungal activity along with other members of the Asteraceae family.54-56 There also is evidence from clinical trials that AP extract is effective against superficial dermatophyte infections such as tinea pedis.57 Given the positive antifungal in vitro data, the potential use of this agent was investigated for onychomycosis treatment.53,58

In Vitro Data

The antifungal properties of the Asteraceae family have been tested in several in vitro experiments. Eupatorium aschenbornianum, described as synonymous with A pichinchensis,59 was found to be most active against the dermatophytes T rubrum and T mentagrophytes with MICs of 0.3 and 0.03 mg/mL, respectively.54 It is thought that the primary antimycotic activity is due to encecalin, an acetylchromene compound that was identified in other plants from the Asteraceae family and has activity against dermatophytes.55 In another study, Ageratum houstanianum Mill, a comparable member of the Asteraceae family, had fungitoxic activity against T rubrum and C albicans isolated from nail infections.56

Clinical Trials

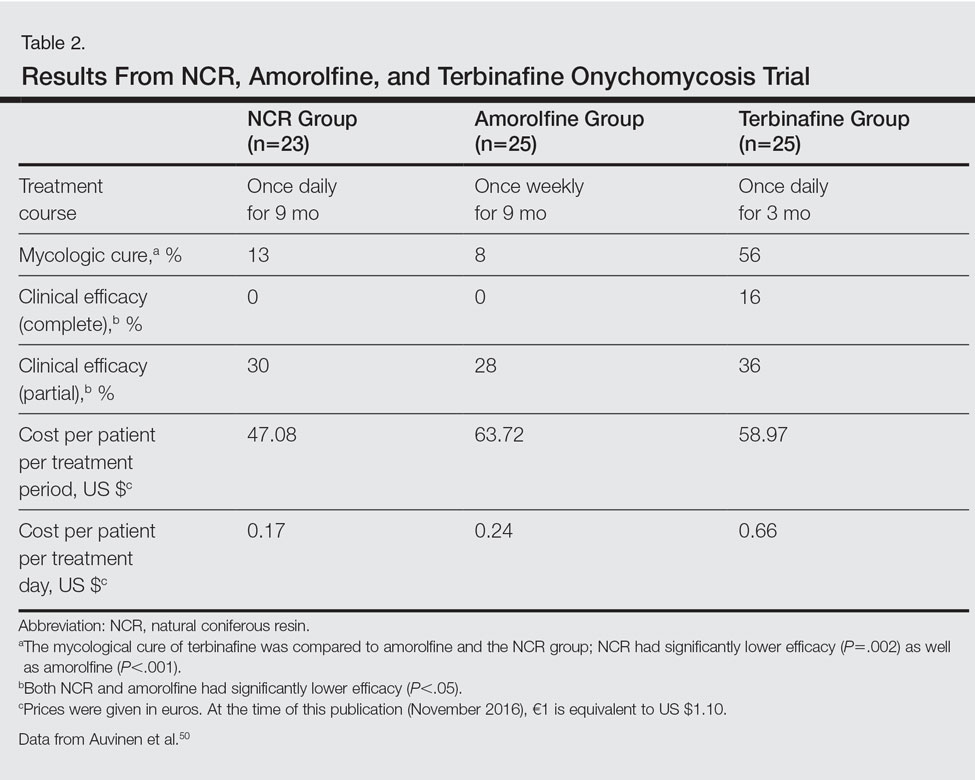

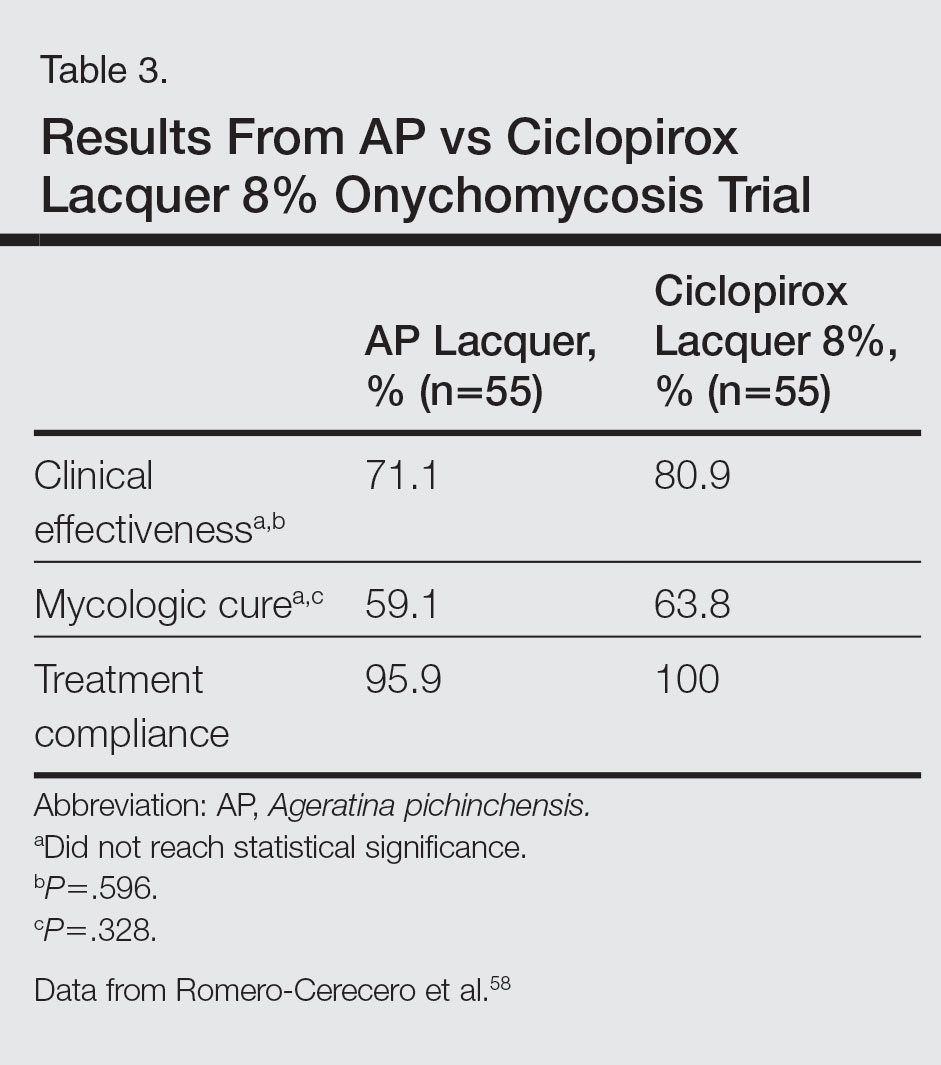

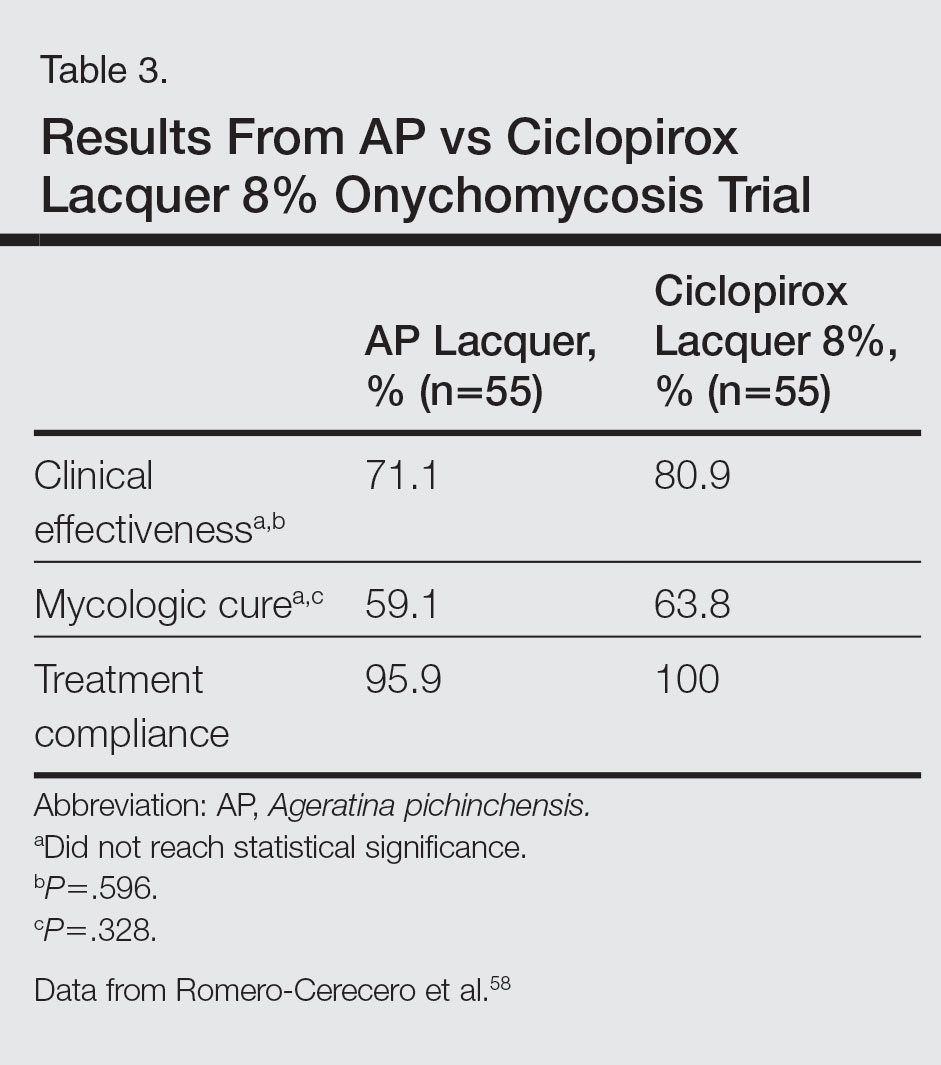

A double-blind controlled trial was performed on 110 patients with clinical and mycologic evidence of mild to moderate toenail onychomycosis randomized to treatment with AP lacquer or ciclopirox lacquer 8% (control).58 Primary end points were clinical effectiveness (completely normal nails) and mycologic cure. Patients were instructed to apply the lacquer once every third day during the first month, twice a week for the second month, and once a week for 16 weeks, with removal of the lacquer weekly. Demographics were similar between the AP lacquer and control groups, with mean ages of 44.6 and 46.5 years, respectively; women made up 74.5% and 67.2%, respectively, of each treatment group, with most patients having a 2- to 5-year history of disease (41.8% and 40.1%, respectively).58 A summary of the data is shown in Table 3. No severe side effects were documented, but minimal nail fold skin pain was reported in 3 patients in the control group in the first week, resolving later in the trial.58

A follow-up study was performed to determine the optimal concentration of AP lacquer for the treatment of onychomycosis.53 One hundred twenty-two patients aged 19 to 65 years with clinical and mycologic evidence of mild to moderate DLSO were randomized to receive 12.6% or 16.8% AP lacquer applied once daily to the affected nails for 6 months. The nails were graded as healthy, mild, or moderately affected before and after treatment. There were no significant differences in demographics between the 2 treatment groups, and 77% of patients were women with a median age of 47 years. There were no significant side effects from either concentration of AP lacquer.53

Ozonized Sunflower Oil

Background

Ozonized sunflower oil is derived by reacting ozone (O3) with sunflower plant (Helianthus annuus) oil to form a petroleum jelly–like material.60 It was originally shown to have antibacterial properties in vitro,61 and further studies have confirmed these findings and demonstrated anti-inflammatory, wound healing, and antifungal properties.62-64 A formulation of ozonized sunflower oil used in Cuba is clinically indicated for the treatment of tinea pedis and impetigo.65 The clinical efficacy of this product has been evaluated in a clinical trial for the treatment of onychomycosis.65

In Vitro Data

A compound made up of 30% ozonized sunflower oil with 0.5% of α-lipoic acid was found to have antifungal activity against C albicans using the disk diffusion method, in addition to other bacterial organisms. The MIC values ranged from 2.0 to 3.5 mg/mL.62 Another study was designed to evaluate the in vitro antifungal activity of this formulation on samples cultured from patients with onychomycosis using the disk diffusion method. They found inhibition of growth of C albicans, C parapsilosis, and Candida tropicalis, which was inferior to amphotericin B, ketoconazole, fluconazole, and itraconazole.64

Clinical Trial