User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Hair Disorders in the Skin of Color Population: Report From the AAD Meeting

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Phacomatosis Cesioflammea in Association With von Recklinghausen Disease (Neurofibromatosis Type I)

To the Editor:

Vascular lesions associated with melanocytic nevi were first described by Ota et al1 in 1947 and given the name phacomatosis pigmentovascularis. In 2005, Happle2 reclassified phacomatosis pigmentovascularis into 3 well-defined types: (1) phacomatosis cesioflammea: blue spots (caesius means bluish gray in Latin) and nevus flammeus; (2) phacomatosis spilorosea: nevus spilus coexisting with a pale pink telangiectatic nevus; and (3) phacomatosis cesiomarmorata: blue spots and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. In 2011 Joshi et al3 described a case of a 31-year-old woman who had a port-wine stain in association with neurofibromatosis type I (NF-1). We present a case of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1.

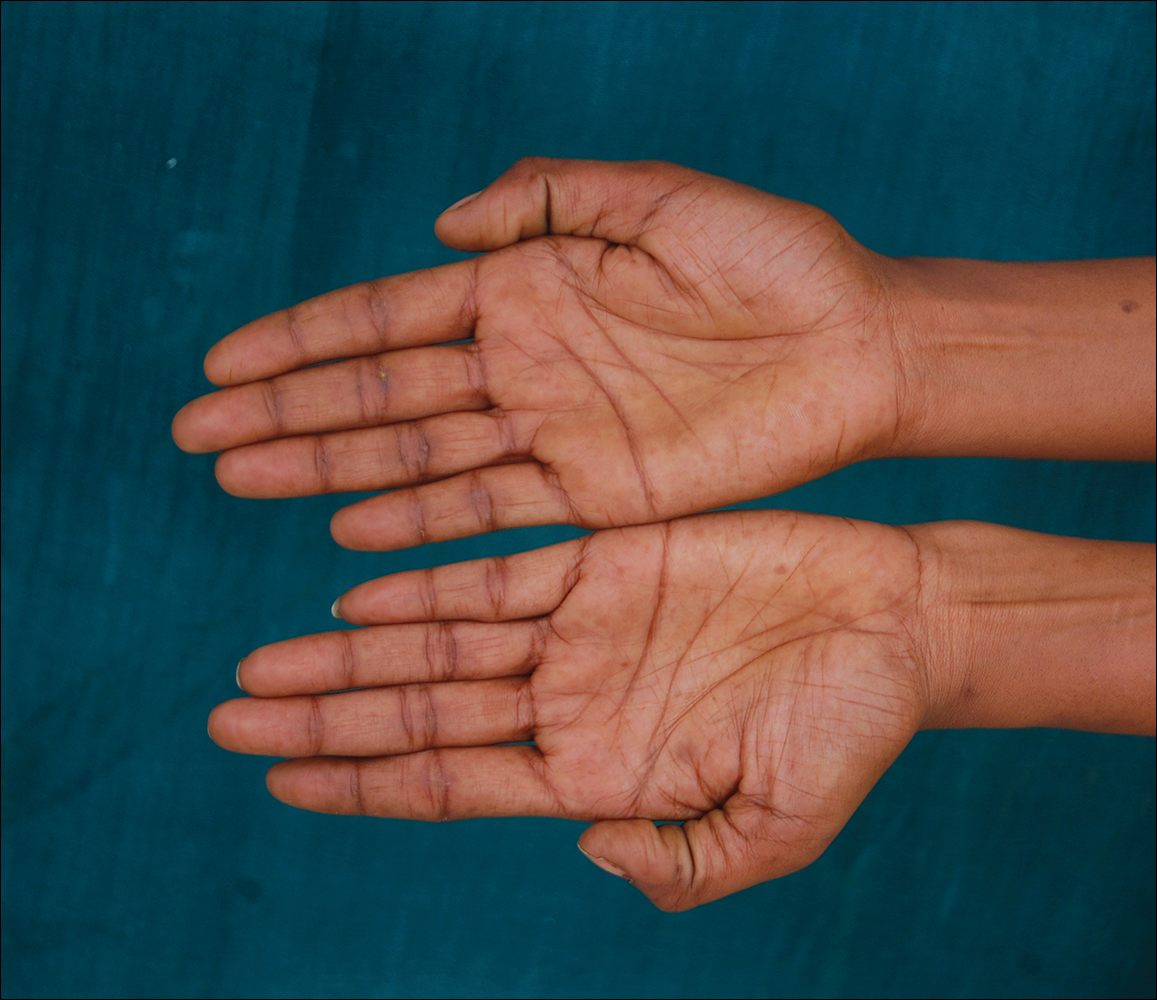

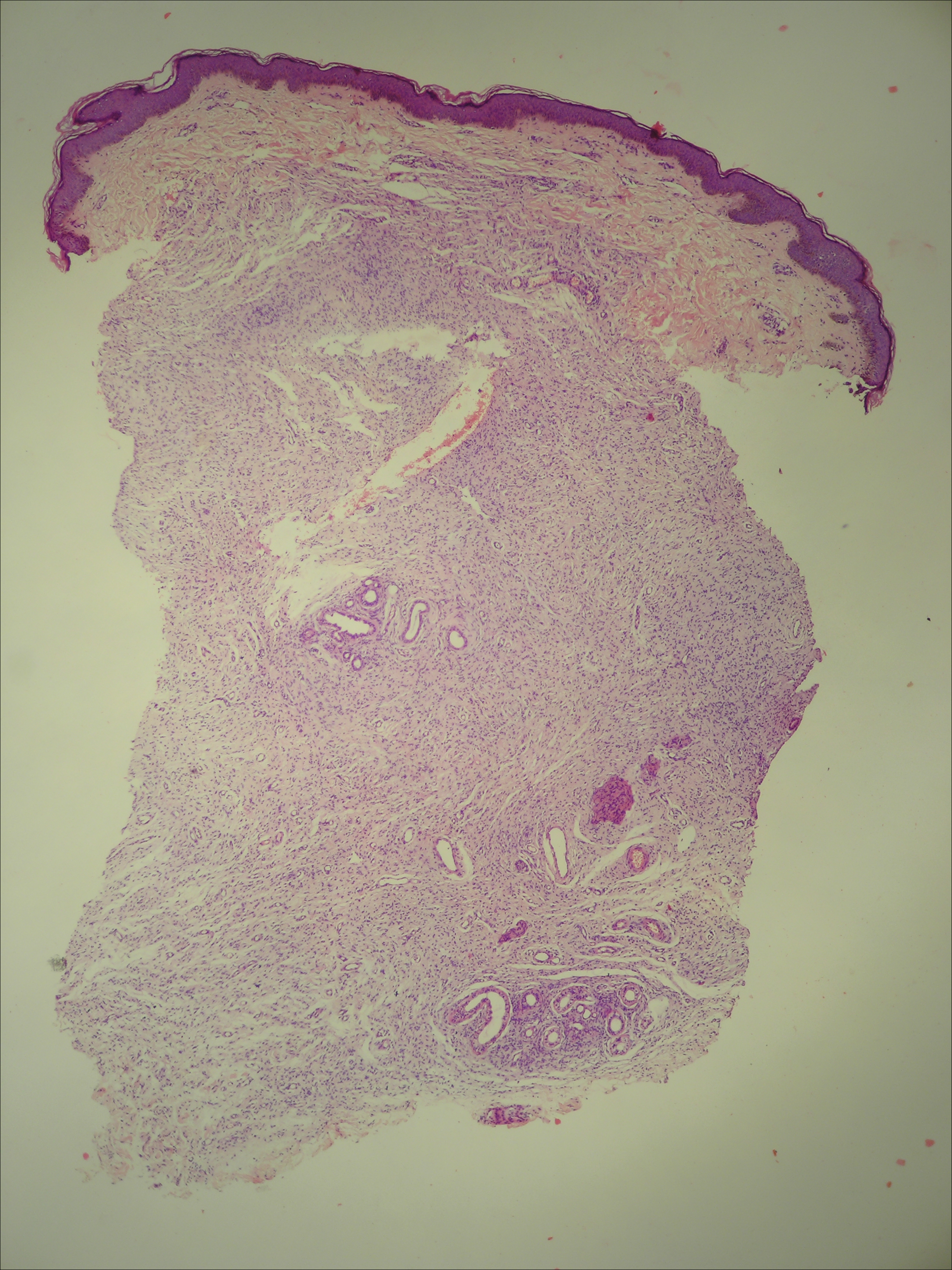

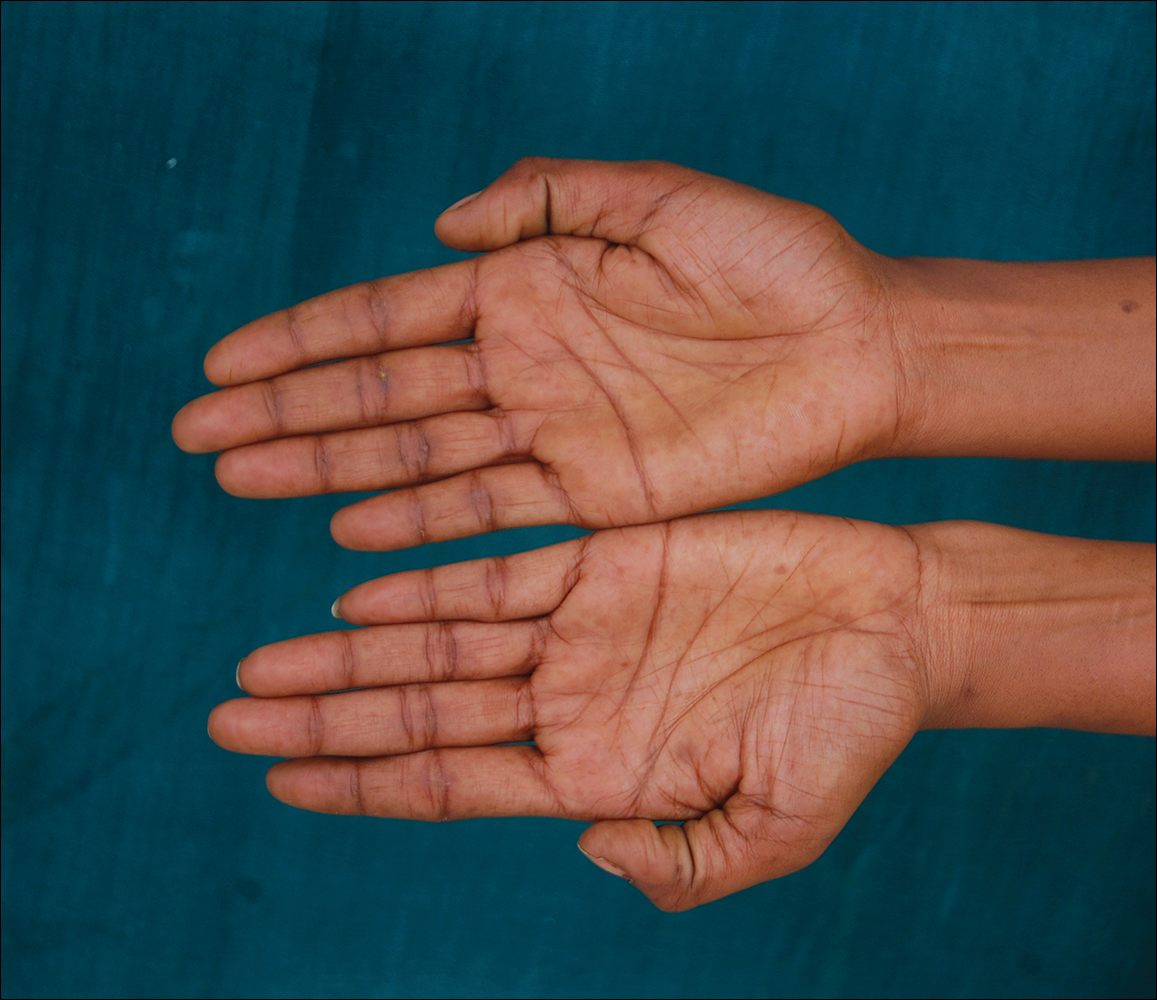

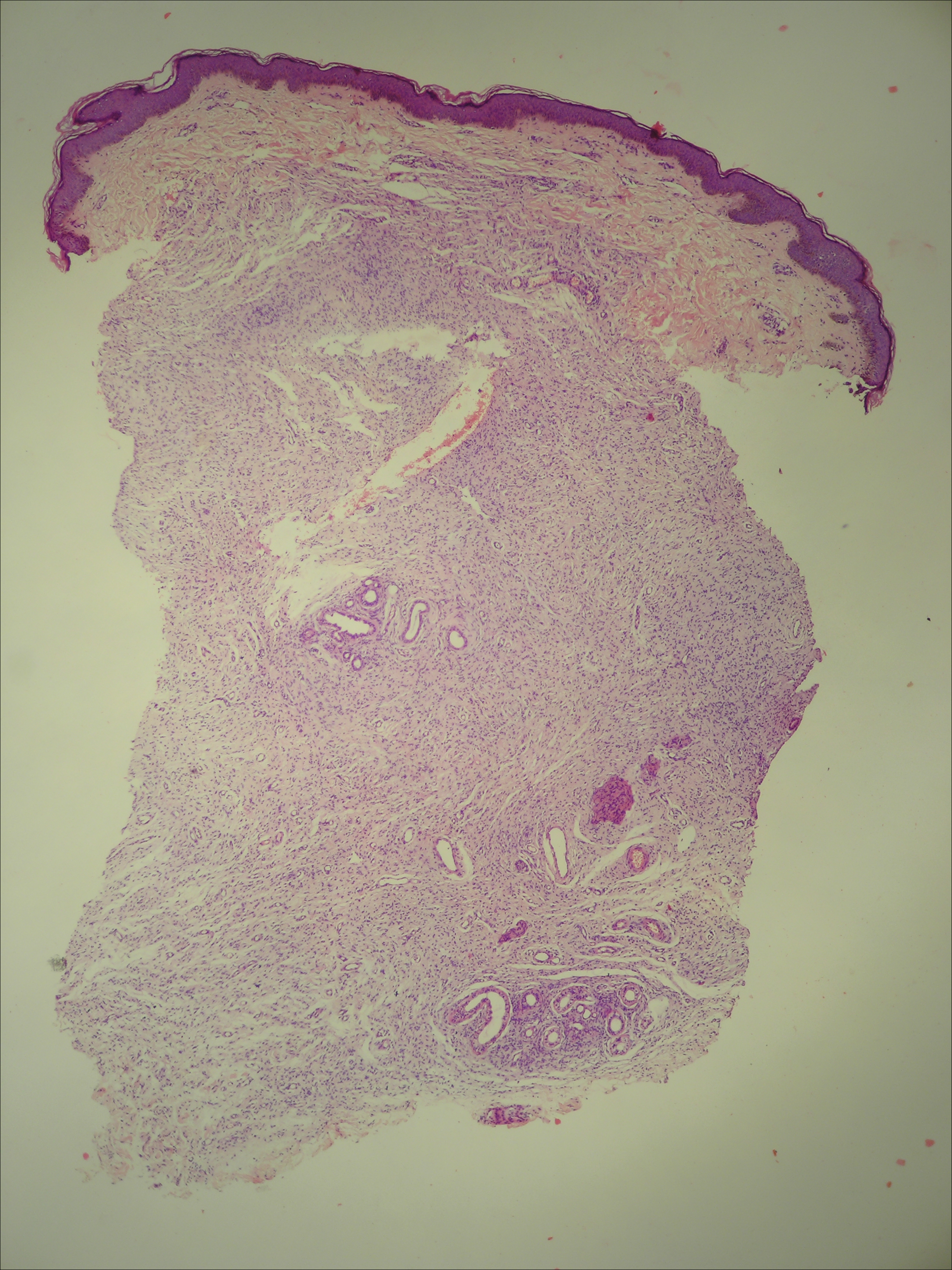

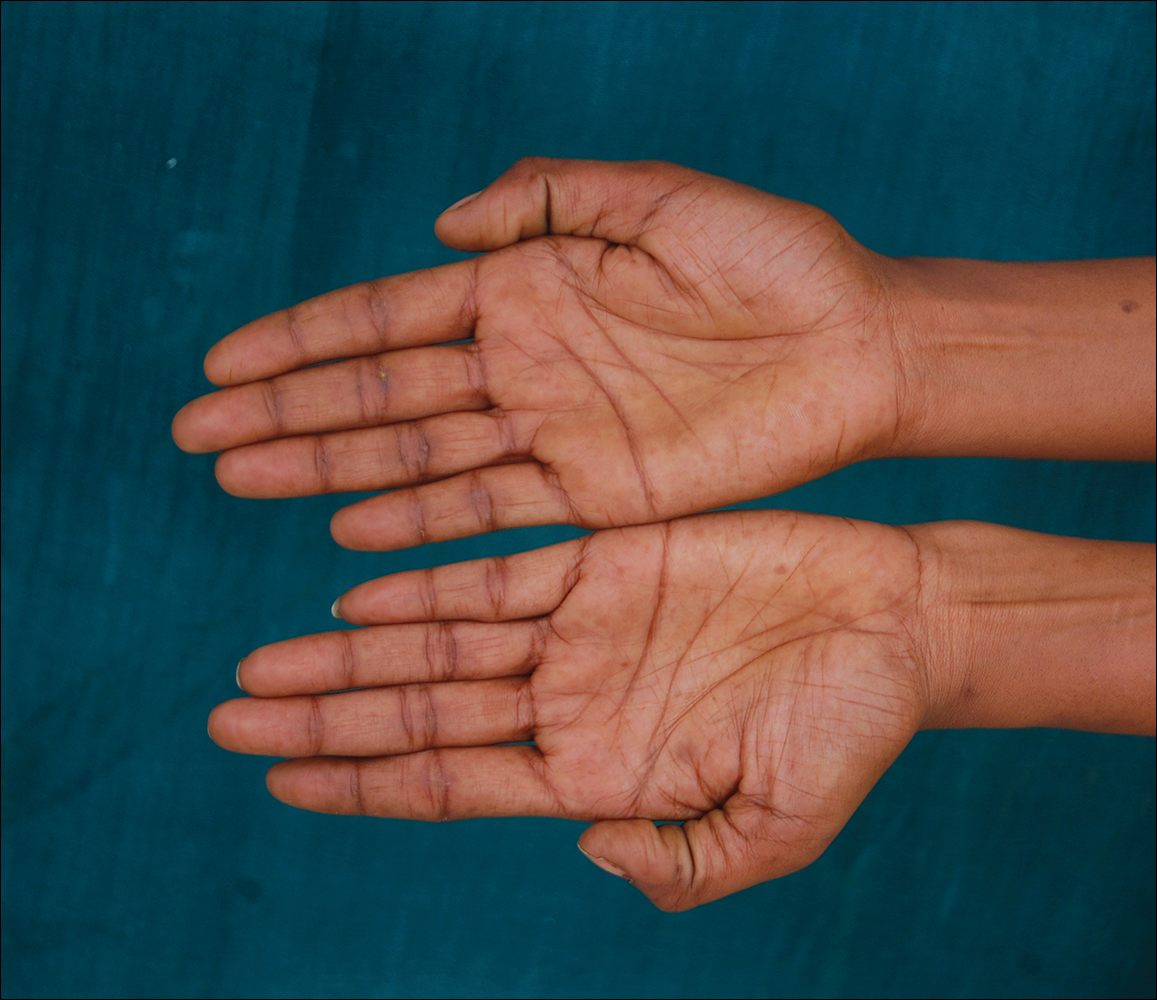

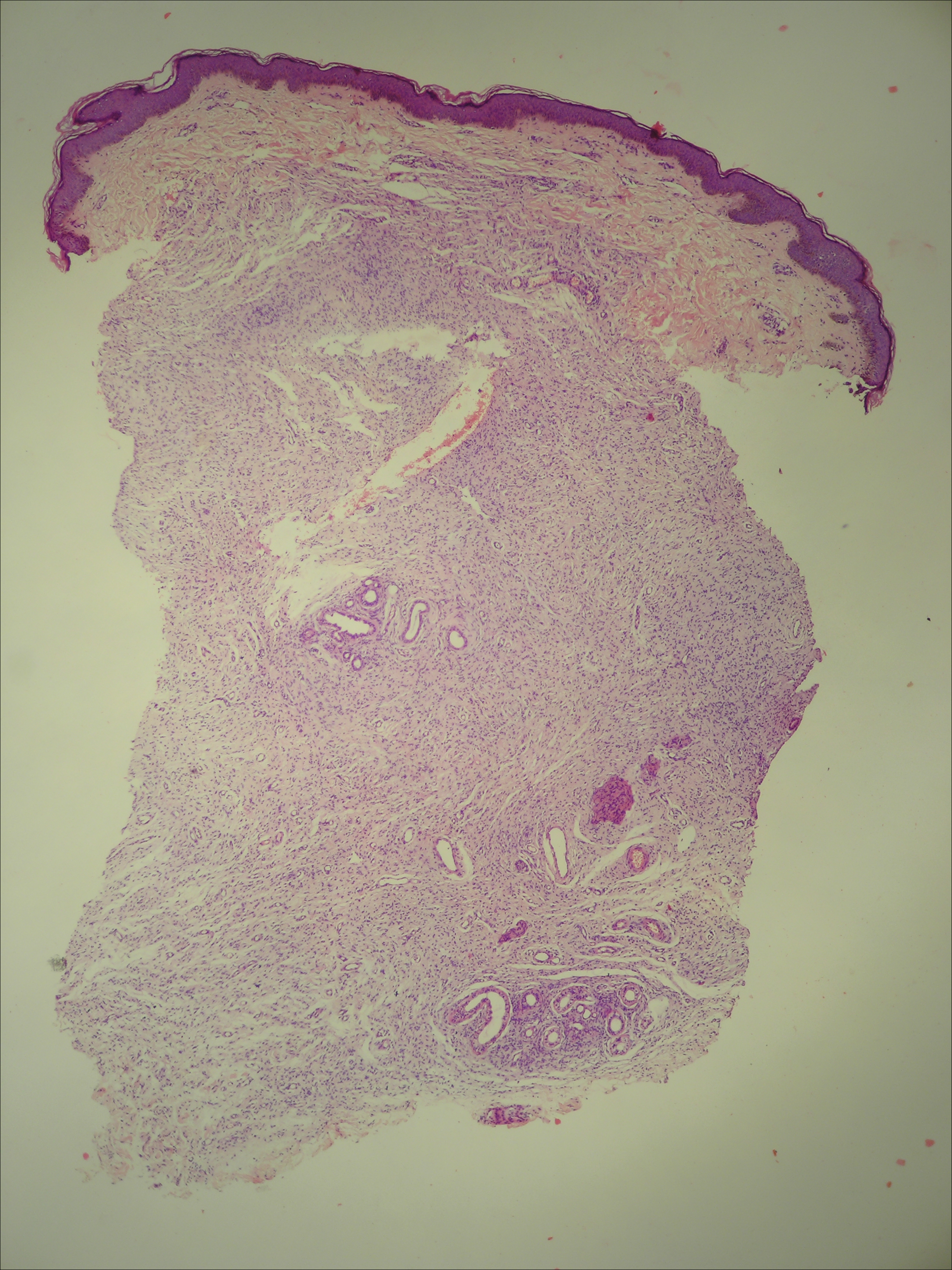

A 20-year-old woman presented to our outpatient section with a bluish black birthmark on the left side of the face since birth with the onset of multiple painless flesh-colored nodules on the trunk and arms of 1 year’s duration. She reported having occasional pruritus over the nodular lesions. Cutaneous examination showed multiple well-defined café au lait macules (0.5–3.0 cm) with regular margins. Multiple flesh-colored nodules were evident on the upper arms (Figure 1) and trunk. The nodules were firm in consistency and showed buttonholing phenomenon with some of the lesions demonstrating bag-of-worms consistency on palpation. Both palms showed multiple brownish frecklelike macules (Figure 2). A single bluish patch extended from the left ala of the nose to the sideburns. Adjoining the bluish patch was a subtle, ill-defined, nonblanchable red patch extending from the lower margin of the bluish patch to the mandibular ridge (Figure 3). Ocular examination showed melanosis bulbi of the left sclera and a few iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules) in both eyes. A biopsy of the skin nodule was obtained under local anesthesia after obtaining the patient’s informed consent; the specimen was fixed in 10% buffered formalin. A hematoxylin and eosin–stained section showed a well-circumscribed nonencapsulated tumor in the dermis composed of loosely spaced spindle cells and wavy collagenous strands (Figure 4). Routine hemogram and blood biochemistry including urinalysis were within reference range. Radiologic examination of the long bones was unremarkable. Our patient had 3 of 6 criteria defined by the National Institutes of Health for diagnosis of NF-1.4 On clinicopathological correlation we made a diagnosis of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1. We have reassured the patient about the benign nature of vascular nevus. She was informed that the skin nodules could increase in size during pregnancy and to regularly follow-up with an eye specialist if any visual abnormalities occur.

The term phacomatosis is applied to genetically determined disorders of tissue derived from ectodermal origin (eg, skin, central nervous system, eyes) and commonly includes NF-1, tuberous sclerosis, and von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Neurofibromatosis type I was first described by German pathologist Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen.5 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis has been defined as the association of vascular nevus with a pigmentary nevus. Its pathogenesis can be explained by the twin spotting phenomenon.6 Twin spots are paired patches of mutant tissue that differ from each other and from the surrounding normal background skin. They can occur as 2 clinical types: allelic and nonallelic twin spotting. Our patient had nonallelic twin spots for 2 nevoid conditions: vascular (nevus flammeus) and pigmentary (nevus of Ota). Nevus of Ota was distributed in the V2 segment (maxillary nerve) of the fifth cranial nerve along with classical melanosis bulbi, which is considered a characteristic clinical feature of nevus of Ota (nevus cesius).7 Nevus flammeus (port-wine stain) is a vascular malformation presenting with flat lesions that persists throughout a patient’s life. The phenomenon of twin spotting, or didymosis (didymos means twin in Greek), has been proposed for co-occurrence of vascular and pigmented nevi.8 The association of NF-1 along with phacomatosis cesioflammea (a twin spot) could be explained from mosaicism of tissues derived from neuroectodermal and mesenchymal elements. Neurofibromatosis type I can occur as a mosaic disorder due to either postzygotic germ line or somatic mutations in the NF1 gene located on the proximal long arm of chromosome 17.9 Irrespective of the mutational event, a mosaic patient has a mixture of cells, some have normal copies of a particular gene and others have an abnormal copy of the same gene. Somatic mutation can lead to segmental (localized), generalized, or gonadal mosaicism. Somatic mutations occurring early during embryonic development produce generalized mosaicism, and generalized mosaics clinically appear similar to nonmosaic NF-1 cases.10,11 However, due to a lack of adequate facilities for mutation analysis and financial constraints, we were unable to confirm our case as generalized somatic mosaic for NF1 gene.

Several morphologic abnormalities have been reported with phacomatosis cesioflammea. Wu et al12 reported a single case of phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum in a 9-month-old infant. Shields et al13 suggested that a thorough ocular examination on a periodic basis is essential to rule out melanoma of ocular tissues in patients with nevus flammeus and ocular melanosis.

Phacomatosis cesioflammea can occur in association with NF-1. The exact incidence of association is not known. The nevoid condition can be treated with appropriate lasers.

- Ota M, Kawamura T, Ito N. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (Ota). Jpn J Dermatol. 1947;52:1-3.

- Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385-388.

- Joshi A, Manchanda Y, Rijhwani M. Port-wine-stain with rare associations in two cases from Kuwait: phakomatosis pigmentovascularis redefined. Gulf J Dermatol Venereol. 2011;18:59-64.

- Neurofibromatosis. Conference Statement. National Institutes of Health Consensus. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:575-578.

- Gerber PA, Antal AS, Neumann NJ, et al. Neurofibromatosis. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14:102-105.

- Goyal T, Varshney A. Phacomatosis cesioflammea: first case report from India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:307.

- Happle R. Didymosis cesioanemica: an unusual counterpart of phakomatosis cesioflammea. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:471.

- Happle R, Steijlen PM. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis interpreted as a phenomenon of twin spots [in German]. Hautarzt. 1989;40:721-724.

- Adigun CG, Stein J. Segmental neurofibromatosis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:25.

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

- Boyd KP, Korf BR, Theos A. Neurofibromatosis type 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1-14.

- Wu CY, Chen PH, Chen GS. Phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:309-310.

- Shields CL, Kligman BE, Suriano M, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type in 7 patients: combination of ocular pigmentation (melanocytosis or melanosis) and nevus flammeus with risk for melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:746-750.

To the Editor:

Vascular lesions associated with melanocytic nevi were first described by Ota et al1 in 1947 and given the name phacomatosis pigmentovascularis. In 2005, Happle2 reclassified phacomatosis pigmentovascularis into 3 well-defined types: (1) phacomatosis cesioflammea: blue spots (caesius means bluish gray in Latin) and nevus flammeus; (2) phacomatosis spilorosea: nevus spilus coexisting with a pale pink telangiectatic nevus; and (3) phacomatosis cesiomarmorata: blue spots and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. In 2011 Joshi et al3 described a case of a 31-year-old woman who had a port-wine stain in association with neurofibromatosis type I (NF-1). We present a case of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1.

A 20-year-old woman presented to our outpatient section with a bluish black birthmark on the left side of the face since birth with the onset of multiple painless flesh-colored nodules on the trunk and arms of 1 year’s duration. She reported having occasional pruritus over the nodular lesions. Cutaneous examination showed multiple well-defined café au lait macules (0.5–3.0 cm) with regular margins. Multiple flesh-colored nodules were evident on the upper arms (Figure 1) and trunk. The nodules were firm in consistency and showed buttonholing phenomenon with some of the lesions demonstrating bag-of-worms consistency on palpation. Both palms showed multiple brownish frecklelike macules (Figure 2). A single bluish patch extended from the left ala of the nose to the sideburns. Adjoining the bluish patch was a subtle, ill-defined, nonblanchable red patch extending from the lower margin of the bluish patch to the mandibular ridge (Figure 3). Ocular examination showed melanosis bulbi of the left sclera and a few iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules) in both eyes. A biopsy of the skin nodule was obtained under local anesthesia after obtaining the patient’s informed consent; the specimen was fixed in 10% buffered formalin. A hematoxylin and eosin–stained section showed a well-circumscribed nonencapsulated tumor in the dermis composed of loosely spaced spindle cells and wavy collagenous strands (Figure 4). Routine hemogram and blood biochemistry including urinalysis were within reference range. Radiologic examination of the long bones was unremarkable. Our patient had 3 of 6 criteria defined by the National Institutes of Health for diagnosis of NF-1.4 On clinicopathological correlation we made a diagnosis of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1. We have reassured the patient about the benign nature of vascular nevus. She was informed that the skin nodules could increase in size during pregnancy and to regularly follow-up with an eye specialist if any visual abnormalities occur.

The term phacomatosis is applied to genetically determined disorders of tissue derived from ectodermal origin (eg, skin, central nervous system, eyes) and commonly includes NF-1, tuberous sclerosis, and von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Neurofibromatosis type I was first described by German pathologist Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen.5 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis has been defined as the association of vascular nevus with a pigmentary nevus. Its pathogenesis can be explained by the twin spotting phenomenon.6 Twin spots are paired patches of mutant tissue that differ from each other and from the surrounding normal background skin. They can occur as 2 clinical types: allelic and nonallelic twin spotting. Our patient had nonallelic twin spots for 2 nevoid conditions: vascular (nevus flammeus) and pigmentary (nevus of Ota). Nevus of Ota was distributed in the V2 segment (maxillary nerve) of the fifth cranial nerve along with classical melanosis bulbi, which is considered a characteristic clinical feature of nevus of Ota (nevus cesius).7 Nevus flammeus (port-wine stain) is a vascular malformation presenting with flat lesions that persists throughout a patient’s life. The phenomenon of twin spotting, or didymosis (didymos means twin in Greek), has been proposed for co-occurrence of vascular and pigmented nevi.8 The association of NF-1 along with phacomatosis cesioflammea (a twin spot) could be explained from mosaicism of tissues derived from neuroectodermal and mesenchymal elements. Neurofibromatosis type I can occur as a mosaic disorder due to either postzygotic germ line or somatic mutations in the NF1 gene located on the proximal long arm of chromosome 17.9 Irrespective of the mutational event, a mosaic patient has a mixture of cells, some have normal copies of a particular gene and others have an abnormal copy of the same gene. Somatic mutation can lead to segmental (localized), generalized, or gonadal mosaicism. Somatic mutations occurring early during embryonic development produce generalized mosaicism, and generalized mosaics clinically appear similar to nonmosaic NF-1 cases.10,11 However, due to a lack of adequate facilities for mutation analysis and financial constraints, we were unable to confirm our case as generalized somatic mosaic for NF1 gene.

Several morphologic abnormalities have been reported with phacomatosis cesioflammea. Wu et al12 reported a single case of phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum in a 9-month-old infant. Shields et al13 suggested that a thorough ocular examination on a periodic basis is essential to rule out melanoma of ocular tissues in patients with nevus flammeus and ocular melanosis.

Phacomatosis cesioflammea can occur in association with NF-1. The exact incidence of association is not known. The nevoid condition can be treated with appropriate lasers.

To the Editor:

Vascular lesions associated with melanocytic nevi were first described by Ota et al1 in 1947 and given the name phacomatosis pigmentovascularis. In 2005, Happle2 reclassified phacomatosis pigmentovascularis into 3 well-defined types: (1) phacomatosis cesioflammea: blue spots (caesius means bluish gray in Latin) and nevus flammeus; (2) phacomatosis spilorosea: nevus spilus coexisting with a pale pink telangiectatic nevus; and (3) phacomatosis cesiomarmorata: blue spots and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. In 2011 Joshi et al3 described a case of a 31-year-old woman who had a port-wine stain in association with neurofibromatosis type I (NF-1). We present a case of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1.

A 20-year-old woman presented to our outpatient section with a bluish black birthmark on the left side of the face since birth with the onset of multiple painless flesh-colored nodules on the trunk and arms of 1 year’s duration. She reported having occasional pruritus over the nodular lesions. Cutaneous examination showed multiple well-defined café au lait macules (0.5–3.0 cm) with regular margins. Multiple flesh-colored nodules were evident on the upper arms (Figure 1) and trunk. The nodules were firm in consistency and showed buttonholing phenomenon with some of the lesions demonstrating bag-of-worms consistency on palpation. Both palms showed multiple brownish frecklelike macules (Figure 2). A single bluish patch extended from the left ala of the nose to the sideburns. Adjoining the bluish patch was a subtle, ill-defined, nonblanchable red patch extending from the lower margin of the bluish patch to the mandibular ridge (Figure 3). Ocular examination showed melanosis bulbi of the left sclera and a few iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules) in both eyes. A biopsy of the skin nodule was obtained under local anesthesia after obtaining the patient’s informed consent; the specimen was fixed in 10% buffered formalin. A hematoxylin and eosin–stained section showed a well-circumscribed nonencapsulated tumor in the dermis composed of loosely spaced spindle cells and wavy collagenous strands (Figure 4). Routine hemogram and blood biochemistry including urinalysis were within reference range. Radiologic examination of the long bones was unremarkable. Our patient had 3 of 6 criteria defined by the National Institutes of Health for diagnosis of NF-1.4 On clinicopathological correlation we made a diagnosis of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1. We have reassured the patient about the benign nature of vascular nevus. She was informed that the skin nodules could increase in size during pregnancy and to regularly follow-up with an eye specialist if any visual abnormalities occur.

The term phacomatosis is applied to genetically determined disorders of tissue derived from ectodermal origin (eg, skin, central nervous system, eyes) and commonly includes NF-1, tuberous sclerosis, and von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Neurofibromatosis type I was first described by German pathologist Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen.5 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis has been defined as the association of vascular nevus with a pigmentary nevus. Its pathogenesis can be explained by the twin spotting phenomenon.6 Twin spots are paired patches of mutant tissue that differ from each other and from the surrounding normal background skin. They can occur as 2 clinical types: allelic and nonallelic twin spotting. Our patient had nonallelic twin spots for 2 nevoid conditions: vascular (nevus flammeus) and pigmentary (nevus of Ota). Nevus of Ota was distributed in the V2 segment (maxillary nerve) of the fifth cranial nerve along with classical melanosis bulbi, which is considered a characteristic clinical feature of nevus of Ota (nevus cesius).7 Nevus flammeus (port-wine stain) is a vascular malformation presenting with flat lesions that persists throughout a patient’s life. The phenomenon of twin spotting, or didymosis (didymos means twin in Greek), has been proposed for co-occurrence of vascular and pigmented nevi.8 The association of NF-1 along with phacomatosis cesioflammea (a twin spot) could be explained from mosaicism of tissues derived from neuroectodermal and mesenchymal elements. Neurofibromatosis type I can occur as a mosaic disorder due to either postzygotic germ line or somatic mutations in the NF1 gene located on the proximal long arm of chromosome 17.9 Irrespective of the mutational event, a mosaic patient has a mixture of cells, some have normal copies of a particular gene and others have an abnormal copy of the same gene. Somatic mutation can lead to segmental (localized), generalized, or gonadal mosaicism. Somatic mutations occurring early during embryonic development produce generalized mosaicism, and generalized mosaics clinically appear similar to nonmosaic NF-1 cases.10,11 However, due to a lack of adequate facilities for mutation analysis and financial constraints, we were unable to confirm our case as generalized somatic mosaic for NF1 gene.

Several morphologic abnormalities have been reported with phacomatosis cesioflammea. Wu et al12 reported a single case of phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum in a 9-month-old infant. Shields et al13 suggested that a thorough ocular examination on a periodic basis is essential to rule out melanoma of ocular tissues in patients with nevus flammeus and ocular melanosis.

Phacomatosis cesioflammea can occur in association with NF-1. The exact incidence of association is not known. The nevoid condition can be treated with appropriate lasers.

- Ota M, Kawamura T, Ito N. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (Ota). Jpn J Dermatol. 1947;52:1-3.

- Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385-388.

- Joshi A, Manchanda Y, Rijhwani M. Port-wine-stain with rare associations in two cases from Kuwait: phakomatosis pigmentovascularis redefined. Gulf J Dermatol Venereol. 2011;18:59-64.

- Neurofibromatosis. Conference Statement. National Institutes of Health Consensus. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:575-578.

- Gerber PA, Antal AS, Neumann NJ, et al. Neurofibromatosis. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14:102-105.

- Goyal T, Varshney A. Phacomatosis cesioflammea: first case report from India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:307.

- Happle R. Didymosis cesioanemica: an unusual counterpart of phakomatosis cesioflammea. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:471.

- Happle R, Steijlen PM. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis interpreted as a phenomenon of twin spots [in German]. Hautarzt. 1989;40:721-724.

- Adigun CG, Stein J. Segmental neurofibromatosis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:25.

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

- Boyd KP, Korf BR, Theos A. Neurofibromatosis type 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1-14.

- Wu CY, Chen PH, Chen GS. Phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:309-310.

- Shields CL, Kligman BE, Suriano M, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type in 7 patients: combination of ocular pigmentation (melanocytosis or melanosis) and nevus flammeus with risk for melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:746-750.

- Ota M, Kawamura T, Ito N. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (Ota). Jpn J Dermatol. 1947;52:1-3.

- Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385-388.

- Joshi A, Manchanda Y, Rijhwani M. Port-wine-stain with rare associations in two cases from Kuwait: phakomatosis pigmentovascularis redefined. Gulf J Dermatol Venereol. 2011;18:59-64.

- Neurofibromatosis. Conference Statement. National Institutes of Health Consensus. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:575-578.

- Gerber PA, Antal AS, Neumann NJ, et al. Neurofibromatosis. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14:102-105.

- Goyal T, Varshney A. Phacomatosis cesioflammea: first case report from India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:307.

- Happle R. Didymosis cesioanemica: an unusual counterpart of phakomatosis cesioflammea. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:471.

- Happle R, Steijlen PM. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis interpreted as a phenomenon of twin spots [in German]. Hautarzt. 1989;40:721-724.

- Adigun CG, Stein J. Segmental neurofibromatosis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:25.

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

- Boyd KP, Korf BR, Theos A. Neurofibromatosis type 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1-14.

- Wu CY, Chen PH, Chen GS. Phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:309-310.

- Shields CL, Kligman BE, Suriano M, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type in 7 patients: combination of ocular pigmentation (melanocytosis or melanosis) and nevus flammeus with risk for melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:746-750.

Practice Points

- Phacomatosis cesioflammea can be associated with neurofibromatosis type I.

- The port-wine stain component of phacomatosis cesioflammea may develop nodularity in long-standing cases.

- The Nd:YAG laser is beneficial for treating blue spots of phacomatosis cesioflammea.

Recalcitrant Hyperkeratotic Plaques

The Diagnosis: Hypertrophic Lupus Erythematosus

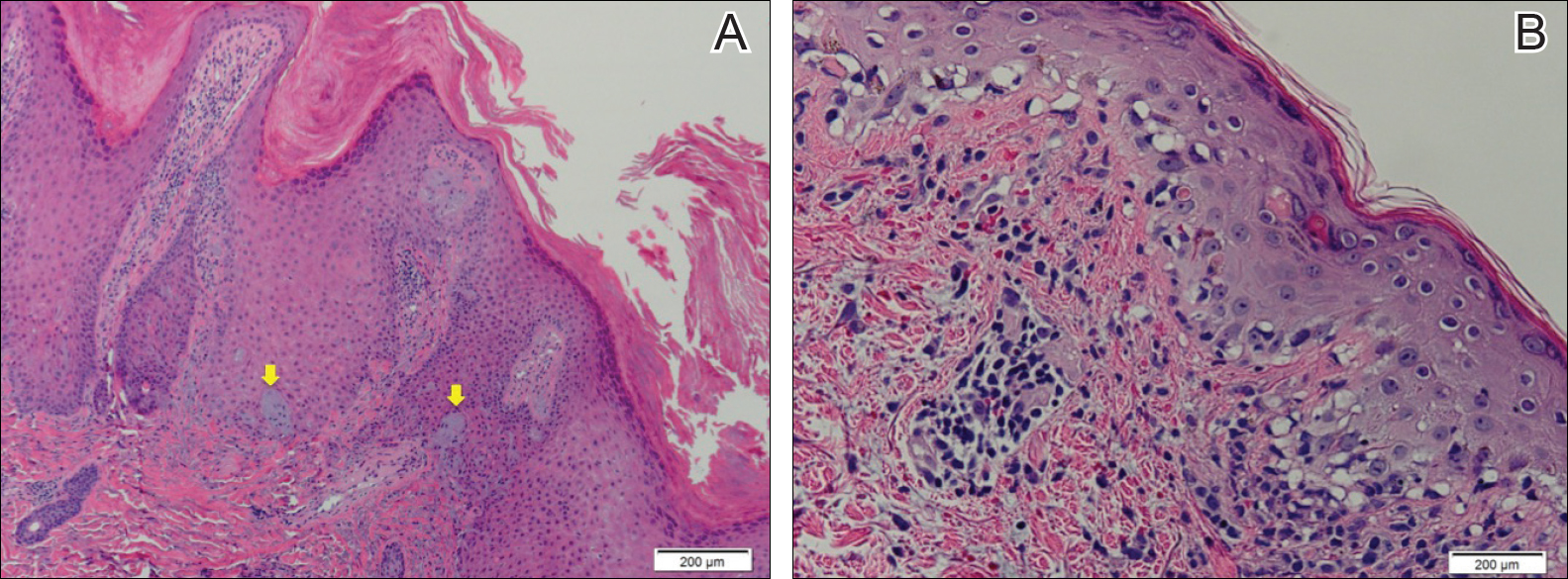

Physical examination at initial presentation revealed well-demarcated, 2- to 3-cm plaques with scale distributed most extensively on the elbows and shins with lesser involvement of the chest and abdomen. After treatment with topical steroids, adalimumab, methotrexate, and narrowband UVB phototherapy, new annular, erythematous, and edematous lesions began to appear on the chest and abdomen (Figure 1). These new lesions appeared less hyperkeratotic than the older ones.

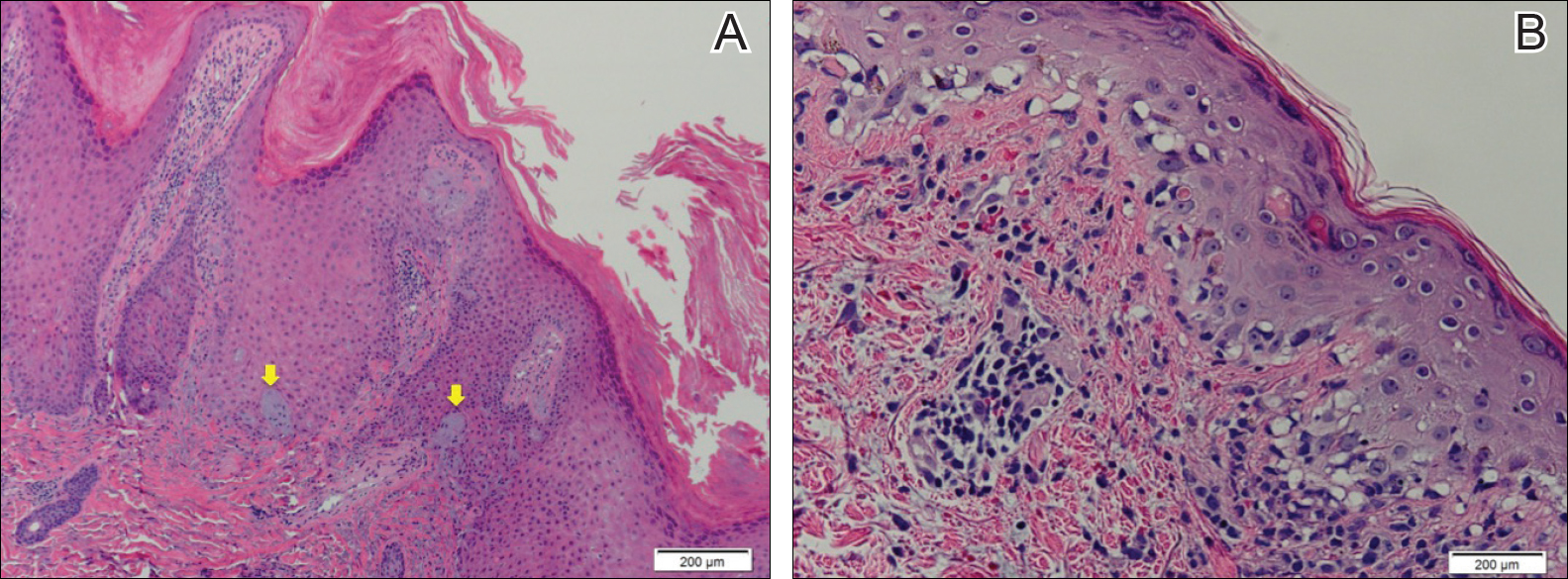

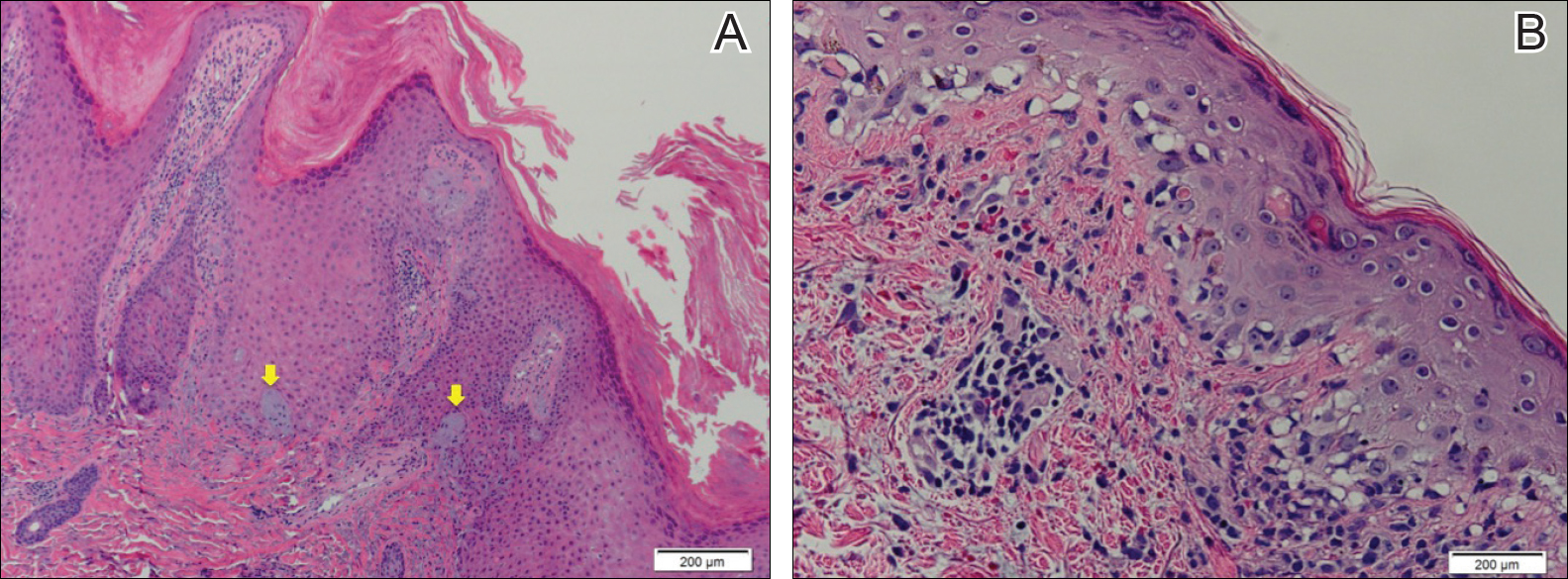

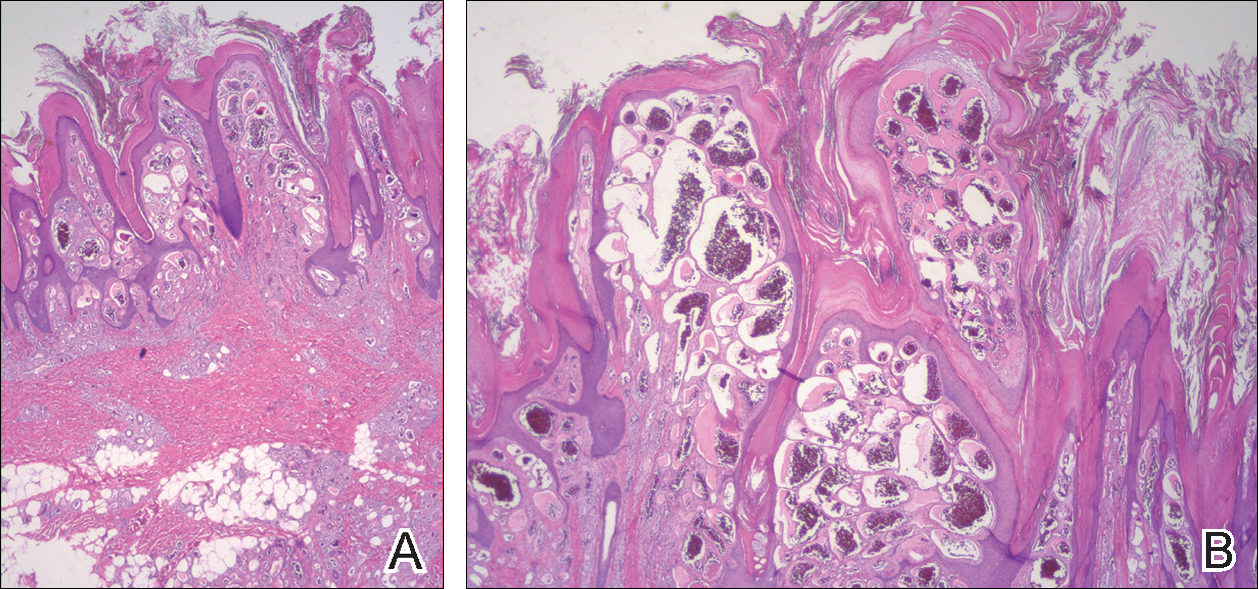

Biopsy of a hyperkeratotic lesion from the patient's arm revealed marked hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, epidermal hyperplasia, focal vacuolar change, solar elastosis, and transepidermal elastotic elimination (Figure 2A). A second biopsy performed on a newer chest lesion revealed interface changes, degeneration of the basal layer, follicular plugging, and dermal mucin (Figure 2B). Serology revealed an antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:1280 (reference range, <1:40 dilution) and hemoglobin of 11.5 g/dL (reference range, 14.0-17.5 g/dL). On the basis of clinical, histologic, and serologic findings, hypertrophic lupus erythematosus (LE) was diagnosed. The patient was treated with oral prednisone, which resulted in rapid improvement.

Hypertrophic LE is a rare subset of chronic cutaneous lupus first described by Behcet1 in 1942. Lesions are identified as verrucous keratotic plaques with a characteristic erythematous indurated border.2 Patients predominantly are middle-aged women with lesions distributed on sun-exposed areas. Most often, hypertrophic LE is seen in association with the classic lesions of discoid LE; however, patients may present exclusively with the cutaneous manifestations of hypertrophic LE. More rarely, as seen in this case, hypertrophic LE may present in conjunction with systemic features.3 The diagnosis of systemic LE requires 4 of the following criteria be fulfilled: malar rash; discoid rash; photosensitivity; oral ulcers; arthritis; cardiopulmonary serositis; renal involvement; positive ANA titer; and neurologic, hematologic, or immunologic disorders.4 Our patient qualified for discoid rash, photosensitivity, cardiopulmonary involvement with mitral valve defects and pulmonary pleuritis, hematologic disorder (anemia), and a positive ANA titer. Furthermore, in patients with only cutaneous discoid LE, serology generally reveals negative or low-titer ANA and negative anti-Ro antibodies.5

Hypertrophic LE is characterized histologically by irregular epidermal hyperplasia in association with features of classic cutaneous LE. Distinctive features of cutaneous LE include interface changes, follicular plugging, dermal mucin, and angiocentric lymphocytic inflammation.6 Notably, additional biopsies of the less hyperkeratotic lesions on our patient's chest and abdomen were performed, which revealed classic cutaneous LE features (Figure 2B).

Hypertrophic LE has 2 histological variants: lichen planus-like and keratoacanthoma (KA)-like patterns. Most cases are described as lichen planus-like, with a dense bandlike infiltrate in association with irregular epidermal hyperplasia, vacuolar interface changes, and reactive squamous atypia.5 In contrast, the less common KA-like lesions consist of a keratinous center with vigorous squamous epithelial proliferation.6

Clinically, hypertrophic LE may resemble hypertrophic psoriasis, lichen planus, KA, or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Due to the presence of pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia, the histopathologic differential includes hypertrophic lichen planus, SCC, KA, and deep fungal infections. However, these other diseases lack the classic features of cutaneous LE, which include interface changes, follicular plugging, dermal mucin, and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation. Additionally, transepidermal elastotic elimination (Figure 2A) helps distinguish hypertrophic LE from other diagnoses.7 One of the most important tasks is distinguishing hypertrophic LE from SCC. Hypertrophic LE does not typically display eosinophil infiltrates, which differentiates it from SCC and KA. Additionally, studies report that CD123 positivity can be useful.6 Positive plasmacytoid dendritic cells are abundant at the dermoepidermal junction in hypertrophic LE, while only single or rare clusters of CD123+ cells are seen in SCC.8 Also, SCC has been found to arise in long-standing cutaneous LE lesions including both discoid and hypertrophic LE. Therefore, clinical and sometimes histological follow-up is required.

Hypertrophic LE often is challenging to treat and frequently is resistant to antimalarial drugs. The primary goals of treatment involve reducing inflammatory infiltrate and minimizing hyperkeratinization. Topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors often are inadequate as monotherapy due to reduced penetrance through the thick lesions; however, intralesional corticosteroids may be beneficial in patients with localized disease.9 Unfortunately, topical or intralesional treatments are impractical in patients with extensive lesions, as seen in our patient, in which case systemic corticosteroids can be beneficial.

Topical retinoids also have been found to be highly effective.10 Specifically, retinoids such as acitretin and isotretinoin, in some cases combined with antimalarial drugs, are effective in reducing the keratinization of these lesions. Successful treatment also has been reported with ustekinumab, thalidomide, mycophenolate mofetil, and pulsed dye laser.11 As in other types of cutaneous LE, hyperkeratotic LE is photosensitive; avoidance of prolonged sun exposure should be advised.8

- Bechet PE. Lupus erythematosus hypertrophicus et profundus. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1942;45:33-39.

- Bernardi M, Bahrami S, Callen JP. Hypertrophic lupus erythematous complicating long-standing systemic lupus erythematous. Lupus. 2011;20:549-550.

- Spann CR, Callen JP, Klein JB, et al. Clinical, serologic and immunogenetic studies in patients with chronic cutaneous (discoid) lupus erythematosus who have verrucous and/or hypertrophic skin lesions. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:256-261.

- Yu C, Gershwin E, Chang C. Diagnostic criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus: a critical review [published online January 21, 2014]. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:10-13.

- Provost TT. The relationship between discoid and systemic lupus erythematous. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1308-1310.

- Arps DP, Patel RM. Cutaneous hypertrophic lupus erythematous: a challenging histopathologic diagnosis in the absence of clinical information. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:1205-1210.

- Daldon PE, De Souza EM, Cintra ML. Hypertrophic lupus erythematous: a clinicopathological study of 14 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:443-448.

- Ko CJ, Srivastava B, Braverman I, et al. Hypertrophiclupus erythematous: the diagnostic utility of CD123 staining. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:889-892.

- Walling HW, Sontheimer RD. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus. issues in diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:366-381.

- Al-Mutairi N, Rijhwani M, Nour-Eldin O. Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus treated successfully with acitretin as monotherapy. J Dermatol. 2005;32:482-486.

- Winchester D, Duffin KC, Hansen C. Response to ustekinumab in a patient with both severe psoriasis and hypertrophic cutaneous lupus. Lupus. 2012;12:1007-1010.

The Diagnosis: Hypertrophic Lupus Erythematosus

Physical examination at initial presentation revealed well-demarcated, 2- to 3-cm plaques with scale distributed most extensively on the elbows and shins with lesser involvement of the chest and abdomen. After treatment with topical steroids, adalimumab, methotrexate, and narrowband UVB phototherapy, new annular, erythematous, and edematous lesions began to appear on the chest and abdomen (Figure 1). These new lesions appeared less hyperkeratotic than the older ones.

Biopsy of a hyperkeratotic lesion from the patient's arm revealed marked hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, epidermal hyperplasia, focal vacuolar change, solar elastosis, and transepidermal elastotic elimination (Figure 2A). A second biopsy performed on a newer chest lesion revealed interface changes, degeneration of the basal layer, follicular plugging, and dermal mucin (Figure 2B). Serology revealed an antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:1280 (reference range, <1:40 dilution) and hemoglobin of 11.5 g/dL (reference range, 14.0-17.5 g/dL). On the basis of clinical, histologic, and serologic findings, hypertrophic lupus erythematosus (LE) was diagnosed. The patient was treated with oral prednisone, which resulted in rapid improvement.

Hypertrophic LE is a rare subset of chronic cutaneous lupus first described by Behcet1 in 1942. Lesions are identified as verrucous keratotic plaques with a characteristic erythematous indurated border.2 Patients predominantly are middle-aged women with lesions distributed on sun-exposed areas. Most often, hypertrophic LE is seen in association with the classic lesions of discoid LE; however, patients may present exclusively with the cutaneous manifestations of hypertrophic LE. More rarely, as seen in this case, hypertrophic LE may present in conjunction with systemic features.3 The diagnosis of systemic LE requires 4 of the following criteria be fulfilled: malar rash; discoid rash; photosensitivity; oral ulcers; arthritis; cardiopulmonary serositis; renal involvement; positive ANA titer; and neurologic, hematologic, or immunologic disorders.4 Our patient qualified for discoid rash, photosensitivity, cardiopulmonary involvement with mitral valve defects and pulmonary pleuritis, hematologic disorder (anemia), and a positive ANA titer. Furthermore, in patients with only cutaneous discoid LE, serology generally reveals negative or low-titer ANA and negative anti-Ro antibodies.5

Hypertrophic LE is characterized histologically by irregular epidermal hyperplasia in association with features of classic cutaneous LE. Distinctive features of cutaneous LE include interface changes, follicular plugging, dermal mucin, and angiocentric lymphocytic inflammation.6 Notably, additional biopsies of the less hyperkeratotic lesions on our patient's chest and abdomen were performed, which revealed classic cutaneous LE features (Figure 2B).

Hypertrophic LE has 2 histological variants: lichen planus-like and keratoacanthoma (KA)-like patterns. Most cases are described as lichen planus-like, with a dense bandlike infiltrate in association with irregular epidermal hyperplasia, vacuolar interface changes, and reactive squamous atypia.5 In contrast, the less common KA-like lesions consist of a keratinous center with vigorous squamous epithelial proliferation.6

Clinically, hypertrophic LE may resemble hypertrophic psoriasis, lichen planus, KA, or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Due to the presence of pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia, the histopathologic differential includes hypertrophic lichen planus, SCC, KA, and deep fungal infections. However, these other diseases lack the classic features of cutaneous LE, which include interface changes, follicular plugging, dermal mucin, and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation. Additionally, transepidermal elastotic elimination (Figure 2A) helps distinguish hypertrophic LE from other diagnoses.7 One of the most important tasks is distinguishing hypertrophic LE from SCC. Hypertrophic LE does not typically display eosinophil infiltrates, which differentiates it from SCC and KA. Additionally, studies report that CD123 positivity can be useful.6 Positive plasmacytoid dendritic cells are abundant at the dermoepidermal junction in hypertrophic LE, while only single or rare clusters of CD123+ cells are seen in SCC.8 Also, SCC has been found to arise in long-standing cutaneous LE lesions including both discoid and hypertrophic LE. Therefore, clinical and sometimes histological follow-up is required.

Hypertrophic LE often is challenging to treat and frequently is resistant to antimalarial drugs. The primary goals of treatment involve reducing inflammatory infiltrate and minimizing hyperkeratinization. Topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors often are inadequate as monotherapy due to reduced penetrance through the thick lesions; however, intralesional corticosteroids may be beneficial in patients with localized disease.9 Unfortunately, topical or intralesional treatments are impractical in patients with extensive lesions, as seen in our patient, in which case systemic corticosteroids can be beneficial.

Topical retinoids also have been found to be highly effective.10 Specifically, retinoids such as acitretin and isotretinoin, in some cases combined with antimalarial drugs, are effective in reducing the keratinization of these lesions. Successful treatment also has been reported with ustekinumab, thalidomide, mycophenolate mofetil, and pulsed dye laser.11 As in other types of cutaneous LE, hyperkeratotic LE is photosensitive; avoidance of prolonged sun exposure should be advised.8

The Diagnosis: Hypertrophic Lupus Erythematosus

Physical examination at initial presentation revealed well-demarcated, 2- to 3-cm plaques with scale distributed most extensively on the elbows and shins with lesser involvement of the chest and abdomen. After treatment with topical steroids, adalimumab, methotrexate, and narrowband UVB phototherapy, new annular, erythematous, and edematous lesions began to appear on the chest and abdomen (Figure 1). These new lesions appeared less hyperkeratotic than the older ones.

Biopsy of a hyperkeratotic lesion from the patient's arm revealed marked hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, epidermal hyperplasia, focal vacuolar change, solar elastosis, and transepidermal elastotic elimination (Figure 2A). A second biopsy performed on a newer chest lesion revealed interface changes, degeneration of the basal layer, follicular plugging, and dermal mucin (Figure 2B). Serology revealed an antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:1280 (reference range, <1:40 dilution) and hemoglobin of 11.5 g/dL (reference range, 14.0-17.5 g/dL). On the basis of clinical, histologic, and serologic findings, hypertrophic lupus erythematosus (LE) was diagnosed. The patient was treated with oral prednisone, which resulted in rapid improvement.

Hypertrophic LE is a rare subset of chronic cutaneous lupus first described by Behcet1 in 1942. Lesions are identified as verrucous keratotic plaques with a characteristic erythematous indurated border.2 Patients predominantly are middle-aged women with lesions distributed on sun-exposed areas. Most often, hypertrophic LE is seen in association with the classic lesions of discoid LE; however, patients may present exclusively with the cutaneous manifestations of hypertrophic LE. More rarely, as seen in this case, hypertrophic LE may present in conjunction with systemic features.3 The diagnosis of systemic LE requires 4 of the following criteria be fulfilled: malar rash; discoid rash; photosensitivity; oral ulcers; arthritis; cardiopulmonary serositis; renal involvement; positive ANA titer; and neurologic, hematologic, or immunologic disorders.4 Our patient qualified for discoid rash, photosensitivity, cardiopulmonary involvement with mitral valve defects and pulmonary pleuritis, hematologic disorder (anemia), and a positive ANA titer. Furthermore, in patients with only cutaneous discoid LE, serology generally reveals negative or low-titer ANA and negative anti-Ro antibodies.5

Hypertrophic LE is characterized histologically by irregular epidermal hyperplasia in association with features of classic cutaneous LE. Distinctive features of cutaneous LE include interface changes, follicular plugging, dermal mucin, and angiocentric lymphocytic inflammation.6 Notably, additional biopsies of the less hyperkeratotic lesions on our patient's chest and abdomen were performed, which revealed classic cutaneous LE features (Figure 2B).

Hypertrophic LE has 2 histological variants: lichen planus-like and keratoacanthoma (KA)-like patterns. Most cases are described as lichen planus-like, with a dense bandlike infiltrate in association with irregular epidermal hyperplasia, vacuolar interface changes, and reactive squamous atypia.5 In contrast, the less common KA-like lesions consist of a keratinous center with vigorous squamous epithelial proliferation.6

Clinically, hypertrophic LE may resemble hypertrophic psoriasis, lichen planus, KA, or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Due to the presence of pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia, the histopathologic differential includes hypertrophic lichen planus, SCC, KA, and deep fungal infections. However, these other diseases lack the classic features of cutaneous LE, which include interface changes, follicular plugging, dermal mucin, and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation. Additionally, transepidermal elastotic elimination (Figure 2A) helps distinguish hypertrophic LE from other diagnoses.7 One of the most important tasks is distinguishing hypertrophic LE from SCC. Hypertrophic LE does not typically display eosinophil infiltrates, which differentiates it from SCC and KA. Additionally, studies report that CD123 positivity can be useful.6 Positive plasmacytoid dendritic cells are abundant at the dermoepidermal junction in hypertrophic LE, while only single or rare clusters of CD123+ cells are seen in SCC.8 Also, SCC has been found to arise in long-standing cutaneous LE lesions including both discoid and hypertrophic LE. Therefore, clinical and sometimes histological follow-up is required.

Hypertrophic LE often is challenging to treat and frequently is resistant to antimalarial drugs. The primary goals of treatment involve reducing inflammatory infiltrate and minimizing hyperkeratinization. Topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors often are inadequate as monotherapy due to reduced penetrance through the thick lesions; however, intralesional corticosteroids may be beneficial in patients with localized disease.9 Unfortunately, topical or intralesional treatments are impractical in patients with extensive lesions, as seen in our patient, in which case systemic corticosteroids can be beneficial.

Topical retinoids also have been found to be highly effective.10 Specifically, retinoids such as acitretin and isotretinoin, in some cases combined with antimalarial drugs, are effective in reducing the keratinization of these lesions. Successful treatment also has been reported with ustekinumab, thalidomide, mycophenolate mofetil, and pulsed dye laser.11 As in other types of cutaneous LE, hyperkeratotic LE is photosensitive; avoidance of prolonged sun exposure should be advised.8

- Bechet PE. Lupus erythematosus hypertrophicus et profundus. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1942;45:33-39.

- Bernardi M, Bahrami S, Callen JP. Hypertrophic lupus erythematous complicating long-standing systemic lupus erythematous. Lupus. 2011;20:549-550.

- Spann CR, Callen JP, Klein JB, et al. Clinical, serologic and immunogenetic studies in patients with chronic cutaneous (discoid) lupus erythematosus who have verrucous and/or hypertrophic skin lesions. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:256-261.

- Yu C, Gershwin E, Chang C. Diagnostic criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus: a critical review [published online January 21, 2014]. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:10-13.

- Provost TT. The relationship between discoid and systemic lupus erythematous. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1308-1310.

- Arps DP, Patel RM. Cutaneous hypertrophic lupus erythematous: a challenging histopathologic diagnosis in the absence of clinical information. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:1205-1210.

- Daldon PE, De Souza EM, Cintra ML. Hypertrophic lupus erythematous: a clinicopathological study of 14 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:443-448.

- Ko CJ, Srivastava B, Braverman I, et al. Hypertrophiclupus erythematous: the diagnostic utility of CD123 staining. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:889-892.

- Walling HW, Sontheimer RD. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus. issues in diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:366-381.

- Al-Mutairi N, Rijhwani M, Nour-Eldin O. Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus treated successfully with acitretin as monotherapy. J Dermatol. 2005;32:482-486.

- Winchester D, Duffin KC, Hansen C. Response to ustekinumab in a patient with both severe psoriasis and hypertrophic cutaneous lupus. Lupus. 2012;12:1007-1010.

- Bechet PE. Lupus erythematosus hypertrophicus et profundus. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1942;45:33-39.

- Bernardi M, Bahrami S, Callen JP. Hypertrophic lupus erythematous complicating long-standing systemic lupus erythematous. Lupus. 2011;20:549-550.

- Spann CR, Callen JP, Klein JB, et al. Clinical, serologic and immunogenetic studies in patients with chronic cutaneous (discoid) lupus erythematosus who have verrucous and/or hypertrophic skin lesions. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:256-261.

- Yu C, Gershwin E, Chang C. Diagnostic criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus: a critical review [published online January 21, 2014]. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:10-13.

- Provost TT. The relationship between discoid and systemic lupus erythematous. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1308-1310.

- Arps DP, Patel RM. Cutaneous hypertrophic lupus erythematous: a challenging histopathologic diagnosis in the absence of clinical information. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:1205-1210.

- Daldon PE, De Souza EM, Cintra ML. Hypertrophic lupus erythematous: a clinicopathological study of 14 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:443-448.

- Ko CJ, Srivastava B, Braverman I, et al. Hypertrophiclupus erythematous: the diagnostic utility of CD123 staining. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:889-892.

- Walling HW, Sontheimer RD. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus. issues in diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:366-381.

- Al-Mutairi N, Rijhwani M, Nour-Eldin O. Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus treated successfully with acitretin as monotherapy. J Dermatol. 2005;32:482-486.

- Winchester D, Duffin KC, Hansen C. Response to ustekinumab in a patient with both severe psoriasis and hypertrophic cutaneous lupus. Lupus. 2012;12:1007-1010.

A 53-year-old man presented with a persistent, hyperkeratotic, pruritic rash on the arms, chest, and abdomen. The patient was treated for presumed psoriasis for 9 months by a primary care physician. However, despite an extensive treatment history, which included topical steroids, adalimumab, methotrexate, and narrowband UVB phototherapy, his condition worsened, and new erythematous and edematous lesions with no scale appeared on the back and chest. The patient's history also was notable for splenic rupture and mitral valve defects for which he was maintained on warfarin. In addition, he was evaluated by an allergist for new-onset dyspnea and treated with prednisone, which subsequently resulted in partial resolution of the skin lesions.

Cosmetic Treatments for Skin of Color: Report From the AAD Meeting

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Update on Confocal Microscopy and Skin Cancer Imaging: Report from the AAD Meeting

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Cutaneous Manifestations of Tick-Borne Diseases

Infection Risk With Biologic Therapy for Psoriasis: Report From the AAD Meeting

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Friable Warty Plaque on the Heel

The Diagnosis: Verrucous Hemangioma

Verrucous hemangioma (VH) is a rare vascular anomaly that has not been definitively delineated as a malformation or a tumor, as it has features of both. Verrucous hemangioma presents at birth as a compressible soft mass with a red violaceous hue favoring the legs.1,2 Over time VH will develop a warty, friable, and keratotic surface that can begin to evolve as early as 6 months or as late as 34 years of age.3 Verrucous hemangioma does not involute and tends to grow proportionally with the patient. Thus, VH classically has been considered a vascular malformation.

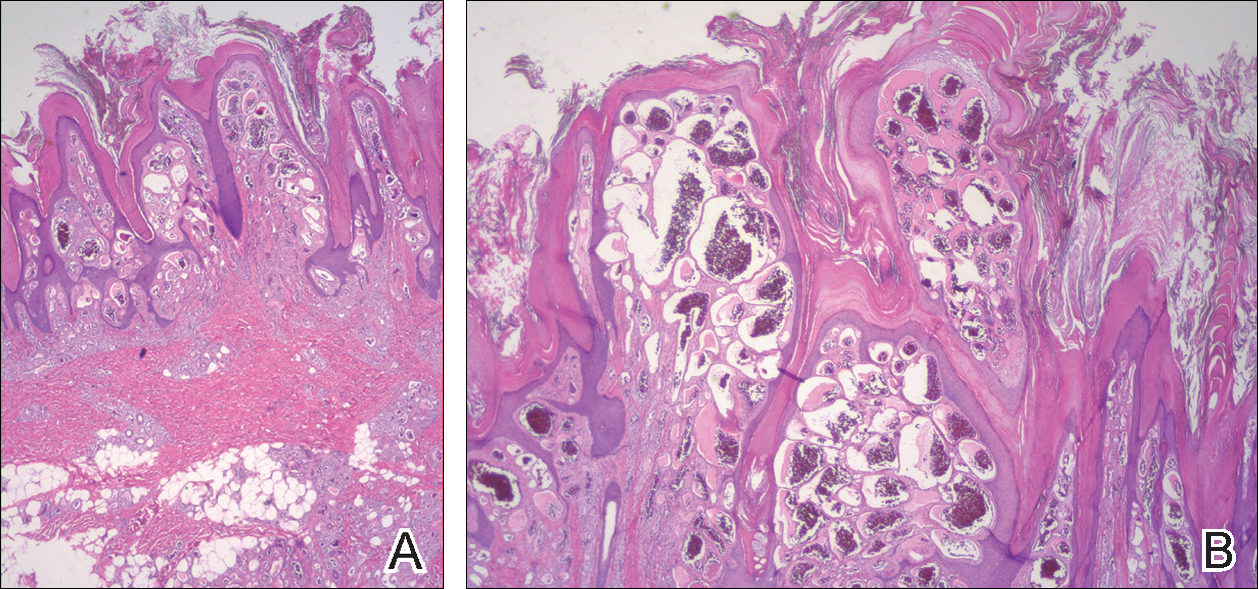

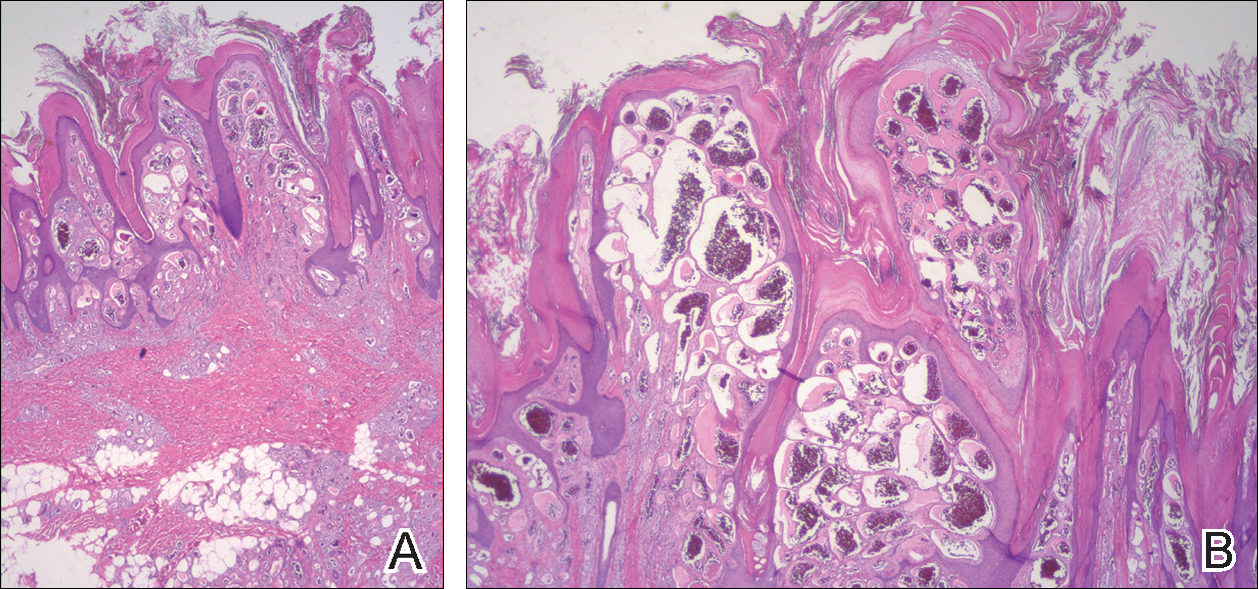

On histopathology VH shows collections of uniform, thin-walled vessels with a multilamellated basement membrane throughout the dermis, similar to an infantile hemangioma (IH). These lesions extend deep into the subcutaneous tissue and often involve the underlying fascia. The papillary dermis has large ectatic vessels, while the epidermis displays verrucous hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and irregular acanthosis without viral change (Figure).4,5 The superficial component can resemble an angiokeratoma; however, VH is differentiated by a deeper component that is often larger in size and has a more protracted clinical course.

Similar to IH, immunohistochemical studies have shown that VH expresses Wilms tumor 1 and glucose transporter 1 but is negative for D2-40.4 These findings suggest that VH is a vascular tumor rather than a vascular malformation, as was previously reported.6 Additional research has shown that the immunohistochemical staining profile of VH is nearly identical to IH, which has led to postulation that VH may be of placental mesodermal origin, as has been hypothesized for IH.5

Due to its deep infiltration and tendency for recurrence, VH is most effectively treated with wide local excision.3,6-8 Preoperative planning with magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated. Although laser monotherapy and other local destructive therapies have been largely unsuccessful, postsurgical laser therapy with CO2 lasers as well as dual pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser have shown promise in preventing recurrence.3

- Tennant LB, Mulliken JB, Perez-Atayde AR, et al. Verrucous hemangioma revisited. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:208-215.

- Koc M, Kavala M, Kocatür E, et al. An unusual vascular tumor: verrucous hemangioma. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:7.

- Yang CH, Ohara K. Successful surgical treatment of verrucous hemangioma: a combined approach. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:913-919; discussion 920.

- Trindade F, Torrelo A, Requena L, et al. An immunohistochemical study of verrucous hemangiomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:472-476.

- Laing EL, Brasch HD, Steel R, et al. Verrucous hemangioma expresses primitive markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:391-396.

- Mankani MH, Dufresne CR. Verrucous malformations: their presentation and management. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;45:31-36.

- Clairwood MQ, Bruckner AL, Dadras SS. Verrucous hemangioma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:740-746.

- Segura Palacios JM, Boixeda P, Rocha J, et al. Laser treatment for verrucous hemangioma. Laser Med Sci. 2012;27:681-684.

The Diagnosis: Verrucous Hemangioma

Verrucous hemangioma (VH) is a rare vascular anomaly that has not been definitively delineated as a malformation or a tumor, as it has features of both. Verrucous hemangioma presents at birth as a compressible soft mass with a red violaceous hue favoring the legs.1,2 Over time VH will develop a warty, friable, and keratotic surface that can begin to evolve as early as 6 months or as late as 34 years of age.3 Verrucous hemangioma does not involute and tends to grow proportionally with the patient. Thus, VH classically has been considered a vascular malformation.

On histopathology VH shows collections of uniform, thin-walled vessels with a multilamellated basement membrane throughout the dermis, similar to an infantile hemangioma (IH). These lesions extend deep into the subcutaneous tissue and often involve the underlying fascia. The papillary dermis has large ectatic vessels, while the epidermis displays verrucous hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and irregular acanthosis without viral change (Figure).4,5 The superficial component can resemble an angiokeratoma; however, VH is differentiated by a deeper component that is often larger in size and has a more protracted clinical course.

Similar to IH, immunohistochemical studies have shown that VH expresses Wilms tumor 1 and glucose transporter 1 but is negative for D2-40.4 These findings suggest that VH is a vascular tumor rather than a vascular malformation, as was previously reported.6 Additional research has shown that the immunohistochemical staining profile of VH is nearly identical to IH, which has led to postulation that VH may be of placental mesodermal origin, as has been hypothesized for IH.5

Due to its deep infiltration and tendency for recurrence, VH is most effectively treated with wide local excision.3,6-8 Preoperative planning with magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated. Although laser monotherapy and other local destructive therapies have been largely unsuccessful, postsurgical laser therapy with CO2 lasers as well as dual pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser have shown promise in preventing recurrence.3

The Diagnosis: Verrucous Hemangioma

Verrucous hemangioma (VH) is a rare vascular anomaly that has not been definitively delineated as a malformation or a tumor, as it has features of both. Verrucous hemangioma presents at birth as a compressible soft mass with a red violaceous hue favoring the legs.1,2 Over time VH will develop a warty, friable, and keratotic surface that can begin to evolve as early as 6 months or as late as 34 years of age.3 Verrucous hemangioma does not involute and tends to grow proportionally with the patient. Thus, VH classically has been considered a vascular malformation.

On histopathology VH shows collections of uniform, thin-walled vessels with a multilamellated basement membrane throughout the dermis, similar to an infantile hemangioma (IH). These lesions extend deep into the subcutaneous tissue and often involve the underlying fascia. The papillary dermis has large ectatic vessels, while the epidermis displays verrucous hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and irregular acanthosis without viral change (Figure).4,5 The superficial component can resemble an angiokeratoma; however, VH is differentiated by a deeper component that is often larger in size and has a more protracted clinical course.

Similar to IH, immunohistochemical studies have shown that VH expresses Wilms tumor 1 and glucose transporter 1 but is negative for D2-40.4 These findings suggest that VH is a vascular tumor rather than a vascular malformation, as was previously reported.6 Additional research has shown that the immunohistochemical staining profile of VH is nearly identical to IH, which has led to postulation that VH may be of placental mesodermal origin, as has been hypothesized for IH.5

Due to its deep infiltration and tendency for recurrence, VH is most effectively treated with wide local excision.3,6-8 Preoperative planning with magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated. Although laser monotherapy and other local destructive therapies have been largely unsuccessful, postsurgical laser therapy with CO2 lasers as well as dual pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser have shown promise in preventing recurrence.3

- Tennant LB, Mulliken JB, Perez-Atayde AR, et al. Verrucous hemangioma revisited. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:208-215.

- Koc M, Kavala M, Kocatür E, et al. An unusual vascular tumor: verrucous hemangioma. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:7.

- Yang CH, Ohara K. Successful surgical treatment of verrucous hemangioma: a combined approach. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:913-919; discussion 920.

- Trindade F, Torrelo A, Requena L, et al. An immunohistochemical study of verrucous hemangiomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:472-476.

- Laing EL, Brasch HD, Steel R, et al. Verrucous hemangioma expresses primitive markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:391-396.

- Mankani MH, Dufresne CR. Verrucous malformations: their presentation and management. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;45:31-36.

- Clairwood MQ, Bruckner AL, Dadras SS. Verrucous hemangioma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:740-746.

- Segura Palacios JM, Boixeda P, Rocha J, et al. Laser treatment for verrucous hemangioma. Laser Med Sci. 2012;27:681-684.

- Tennant LB, Mulliken JB, Perez-Atayde AR, et al. Verrucous hemangioma revisited. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:208-215.

- Koc M, Kavala M, Kocatür E, et al. An unusual vascular tumor: verrucous hemangioma. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:7.

- Yang CH, Ohara K. Successful surgical treatment of verrucous hemangioma: a combined approach. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:913-919; discussion 920.

- Trindade F, Torrelo A, Requena L, et al. An immunohistochemical study of verrucous hemangiomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:472-476.

- Laing EL, Brasch HD, Steel R, et al. Verrucous hemangioma expresses primitive markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:391-396.

- Mankani MH, Dufresne CR. Verrucous malformations: their presentation and management. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;45:31-36.

- Clairwood MQ, Bruckner AL, Dadras SS. Verrucous hemangioma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:740-746.

- Segura Palacios JM, Boixeda P, Rocha J, et al. Laser treatment for verrucous hemangioma. Laser Med Sci. 2012;27:681-684.

A 31-year-old man presented with a large friable and warty plaque on the left heel. He recalled that the lesion had been present since birth as a flat red birthmark that grew proportionally with him. Throughout his adolescence its surface became increasingly rough and bumpy. The patient described receiving laser treatment twice in his early 20s without notable improvement. He wanted the lesion removed because it was easily traumatized, resulting in bleeding, pain, and infection. The patient reported being otherwise healthy.

Herpes Zoster Following Varicella Vaccination in Children

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) causes varicella as a primary infection. It is a highly contagious disease characterized by a widespread papulovesicular eruption with fever and malaise.1,2 After the primary infection, the virus remains latent within the sensory dorsal root ganglia and can reactivate as herpes zoster (HZ).1-5 Herpes zoster is characterized by unilateral radicular pain and a vesicular rash in a dermatomal pattern.1,2 It is most common in adults, especially elderly and immunocompromised patients, but rarely occurs in children. Herpes zoster is most often seen in individuals previously infected with VZV, but it also has occurred in individuals without known varicella infection,1-17 possibly because these individuals had a prior subclinical VZV infection.

A live attenuated VZV vaccine was created after isolation of the virus from a child in Japan.2 Since the introduction of the vaccine in 1995 in the United States, the incidence of VZV and HZ has declined.5 Herpes zoster rates after vaccination vary from 14 to 19 per 100,000 individuals.3,5 Breakthrough disease with the wild-type strain does occur in vaccinated children, but vaccine-strain HZ also has been reported.1-5 The risk for HZ caused by reactivated VZV vaccine in healthy children is unknown. We present a case of HZ in an otherwise healthy 19-month-old boy with no known varicella exposure who received the VZV vaccine at 13 months of age.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 19-month-old boy presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash that began 2 days prior on the right groin and spread to the right leg. The patient’s mother denied that the child had been febrile and noted that the rash did not appear to bother him in any way. The patient was up-to-date on his vaccinations and received the first dose of the varicella series 6 months prior to presentation. He had no personal history of varicella, no exposure to sick contacts with varicella, and no known exposure to the virus. He was otherwise completely healthy with no signs or symptoms of immunocompromise.

Physical examination revealed grouped vesicles on an erythematous base on the right thigh, right sacrum, and lower abdomen that did not cross the midline (Figure). There were no other pertinent physical examination findings. The eruption was most consistent with HZ but concern remained for herpes simplex virus (HSV) or impetigo. A bacterial culture and polymerase chain reaction assay for VZV and HSV from skin swabs was ordered. The patient was prescribed acyclovir 20 mg/kg every 6 hours for 5 days. Laboratory testing revealed a positive result for VZV on polymerase chain reaction and a negative result for HSV. The majority of the patient’s lesions had crusted after 2 days of treatment with acyclovir, and the rash had nearly resolved 1 week after presentation. Subsequent evaluation with a complete blood cell count with differential and basic metabolic profile was normal. Levels of IgG, IgA, and IgM also were normal; IgE was slightly elevated.

Comment

Herpes zoster in children is an uncommon clinical entity. Most children with HZ are immunocompromised, have a history of varicella, or were exposed to varicella during gestation.8 With the introduction of the live VZV vaccine, the incidence of HZ has declined, but reactivation of the live vaccine leading to HZ infection is possible. The vaccine is 90% effective, and breakthrough varicella has been reported in 15% to 20% of vaccinated patients.1-17 The cause of HZ in vaccinated children is unclear due to the potential for either wild-type or vaccine-strain VZV to induce HZ.

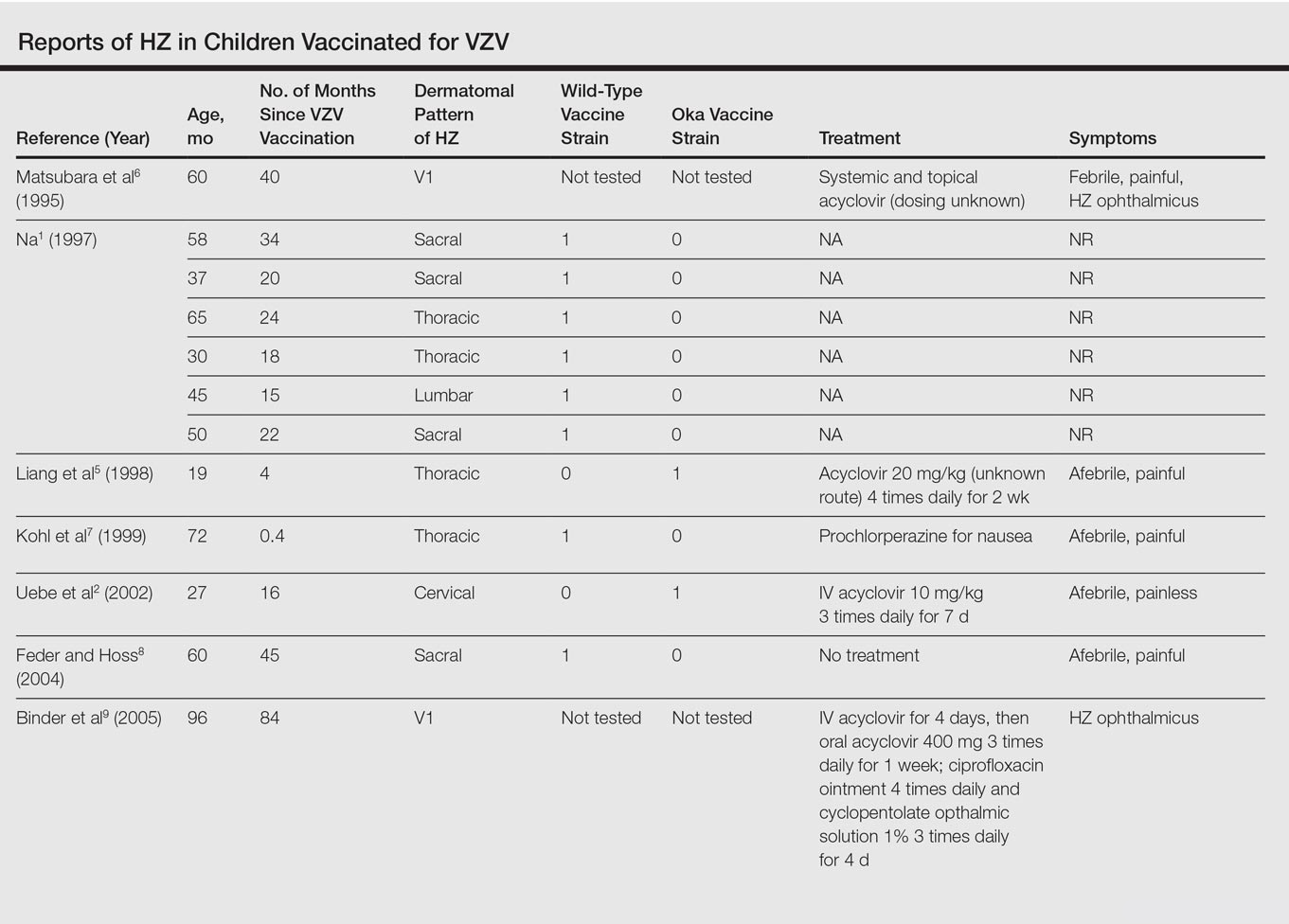

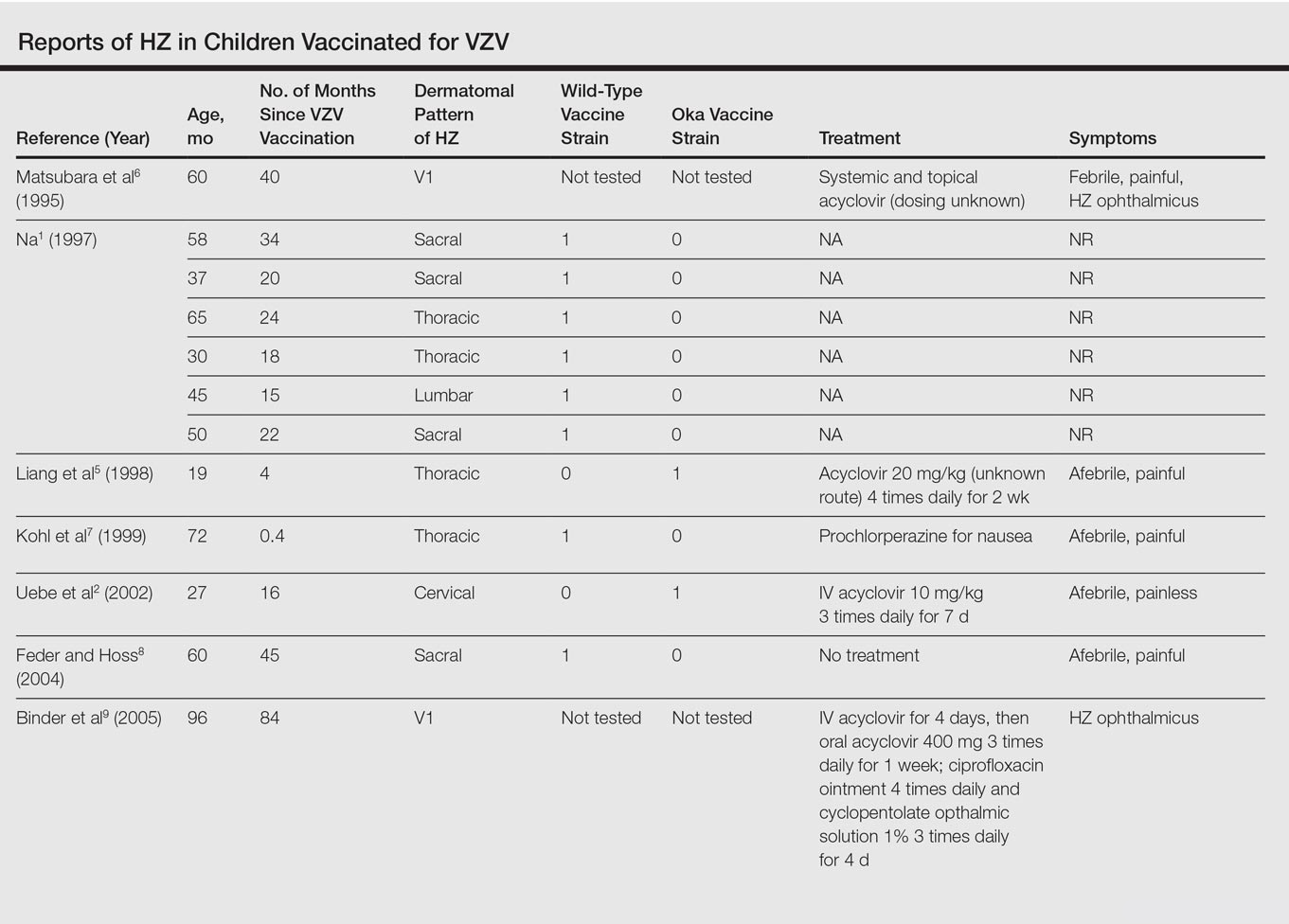

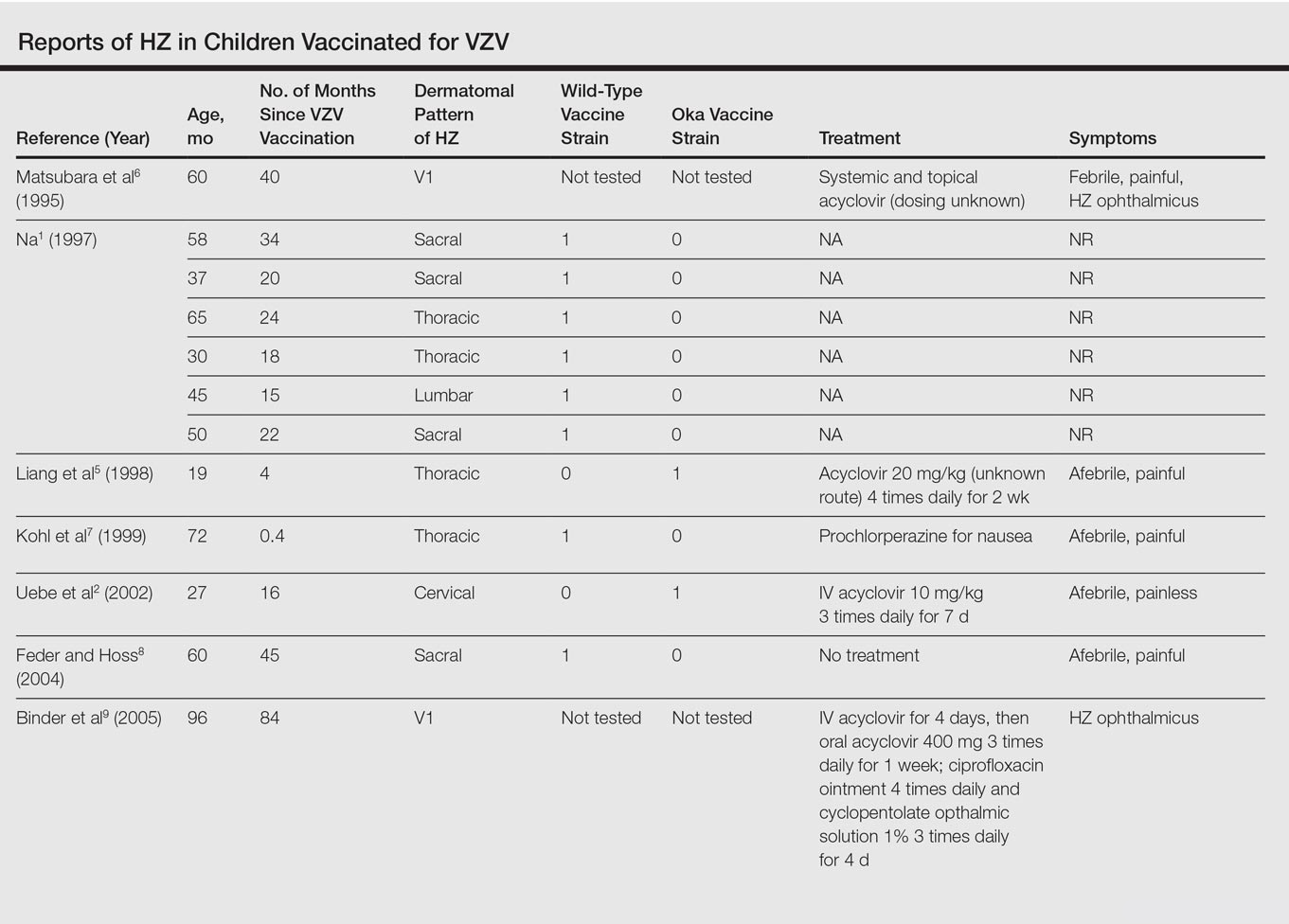

Twenty-two cases of HZ in healthy children after vaccination were identified with a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms herpes zoster infection after vaccination and herpes zoster infection AND immunocompetent AND vaccination in separate searches for all English-language studies (Table). The search was limited to immunocompetent children and adolescents who were 18 years or younger with no history of varicella or exposure to varicella during gestation.

The mean age for HZ infection was 5.3 years. The average time between vaccination and HZ infection was 3.3 years. There was a spread of dermatomal patterns with cases in the first division of the trigeminal nerve, cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral distributions. Of the 22 cases of HZ we reviewed, 16 underwent genotype testing to determine the source of the infection. The Oka vaccine strain virus was identified in 8 (50%) cases, while wild-type virus was found in 8 (50%) cases.1,2,4,5,7,8,10,11,13,14,16 Twelve cases were treated with acyclovir.2,3,5,6,9-12,14-17 The method of delivery, either oral or intravenous, and the length of treatment depended on the severity of the disease. Patients with meningoencephalitis and HZ ophthalmicus received intravenous acyclovir more often and also had a longer course of acyclovir compared to those individuals with involvement limited to the skin.

This review found HZ occurs from reactivation of wild-type or Oka vaccine-strain VZV in immunocompetent children.1-17 It shows that subclinical varicella infection is not the only explanation for HZ in a healthy vaccinated child. It is currently not clear why some healthy children experience HZ from vaccine-strain VZV. When HZ presents in a vaccinated immunocompetent child without a history of varicella infection or exposure, the possibility for vaccine strain–induced HZ should be considered.

- . Herpes zoster in three healthy children immunized with varicella vaccine (Oka/Biken); the causative virus differed from vaccine strain on PCR analysis of the IV variable region (R5) and of a PstI-site region. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:255-258.

- Uebe B, Sauerbrei A, Burdach S, et al. Herpes zoster by reactivated vaccine varicella zoster virus in a healthy child [published online June 25, 2002]. Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161:442-444.

- Obieta MP, Jacinto SS. Herpes zoster after varicella vaccination in a healthy young child. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:640-641.

- Ota K, Kim V, Lavi S, et al. Vaccine-strain varicella zoster virus causing recurrent herpes zoster in an immunocompetent 2-year-old. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:847-848.

- Liang GL, Heidelberg KA, Jacobson RM, et al. Herpes zoster after varicella vaccination. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:761-763.

- Matsubara K, Nigami H, Harigaya H, et al. Herpes zoster in a normal child after varicella vaccination. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1995;37:648-650.

- Kohl S, Rapp J, Larussa P, et al. Natural varicella-zoster virus reactivation shortly after varicella immunization in a child. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:1112-1113.

- Feder HM Jr, Hoss DM. Herpes zoster in otherwise healthy children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:451-457; quiz 458-460.

- Binder NR, Holland GN, Hosea S, et al. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus in an otherwise-healthy child. J AAPOS. 2005;9:597-598.

- Levin MJ, DeBiasi RL, Bostik V, et al. Herpes zoster with skin lesions and meningitis caused by 2 different genotypes of the Oka varicella-zoster virus vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1444-1447.

- Iyer S, Mittal MK, Hodinka RL. Herpes zoster and meningitis resulting from reactivation of varicella vaccine virus in an immunocompetent child. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:792-795.

- Lin P, Yoon MK, Chiu CS. Herpes zoster keratouveitis and inflammatory ocular hypertension 8 years after varicella vaccination. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:33-35.

- Chouliaras G, Spoulou V, Quinlivan M, et al. Vaccine-associated herpes zoster ophthalmicus [correction of opthalmicus] and encephalitis in an immunocompetent child [published online March 1, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;125:E969-E972.

- Han JY, Hanson DC, Way SS. Herpes zoster and meningitis due to reactivation of varicella vaccine virus in an immunocompetent child. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:266-268.

- Ryu WY, Kim NY, Kwon YH, et al. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus with isolated trochlear nerve palsy in an otherwise healthy 13-year-old girl. J AAPOS. 2014;18:193-195.

- Iwasaki S, Motokura K, Honda Y, et al. Vaccine-strain herpes zoster found in the trigeminal nerve area in a healthy child: a case report [published online November 3, 2016]. J Clin Virol. 2016;85:44-47.

- Peterson N, Goodman S, Peterson M, et al. Herpes zoster in children. Cutis. 2016;98:94-95.

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) causes varicella as a primary infection. It is a highly contagious disease characterized by a widespread papulovesicular eruption with fever and malaise.1,2 After the primary infection, the virus remains latent within the sensory dorsal root ganglia and can reactivate as herpes zoster (HZ).1-5 Herpes zoster is characterized by unilateral radicular pain and a vesicular rash in a dermatomal pattern.1,2 It is most common in adults, especially elderly and immunocompromised patients, but rarely occurs in children. Herpes zoster is most often seen in individuals previously infected with VZV, but it also has occurred in individuals without known varicella infection,1-17 possibly because these individuals had a prior subclinical VZV infection.

A live attenuated VZV vaccine was created after isolation of the virus from a child in Japan.2 Since the introduction of the vaccine in 1995 in the United States, the incidence of VZV and HZ has declined.5 Herpes zoster rates after vaccination vary from 14 to 19 per 100,000 individuals.3,5 Breakthrough disease with the wild-type strain does occur in vaccinated children, but vaccine-strain HZ also has been reported.1-5 The risk for HZ caused by reactivated VZV vaccine in healthy children is unknown. We present a case of HZ in an otherwise healthy 19-month-old boy with no known varicella exposure who received the VZV vaccine at 13 months of age.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 19-month-old boy presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash that began 2 days prior on the right groin and spread to the right leg. The patient’s mother denied that the child had been febrile and noted that the rash did not appear to bother him in any way. The patient was up-to-date on his vaccinations and received the first dose of the varicella series 6 months prior to presentation. He had no personal history of varicella, no exposure to sick contacts with varicella, and no known exposure to the virus. He was otherwise completely healthy with no signs or symptoms of immunocompromise.

Physical examination revealed grouped vesicles on an erythematous base on the right thigh, right sacrum, and lower abdomen that did not cross the midline (Figure). There were no other pertinent physical examination findings. The eruption was most consistent with HZ but concern remained for herpes simplex virus (HSV) or impetigo. A bacterial culture and polymerase chain reaction assay for VZV and HSV from skin swabs was ordered. The patient was prescribed acyclovir 20 mg/kg every 6 hours for 5 days. Laboratory testing revealed a positive result for VZV on polymerase chain reaction and a negative result for HSV. The majority of the patient’s lesions had crusted after 2 days of treatment with acyclovir, and the rash had nearly resolved 1 week after presentation. Subsequent evaluation with a complete blood cell count with differential and basic metabolic profile was normal. Levels of IgG, IgA, and IgM also were normal; IgE was slightly elevated.

Comment

Herpes zoster in children is an uncommon clinical entity. Most children with HZ are immunocompromised, have a history of varicella, or were exposed to varicella during gestation.8 With the introduction of the live VZV vaccine, the incidence of HZ has declined, but reactivation of the live vaccine leading to HZ infection is possible. The vaccine is 90% effective, and breakthrough varicella has been reported in 15% to 20% of vaccinated patients.1-17 The cause of HZ in vaccinated children is unclear due to the potential for either wild-type or vaccine-strain VZV to induce HZ.

Twenty-two cases of HZ in healthy children after vaccination were identified with a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms herpes zoster infection after vaccination and herpes zoster infection AND immunocompetent AND vaccination in separate searches for all English-language studies (Table). The search was limited to immunocompetent children and adolescents who were 18 years or younger with no history of varicella or exposure to varicella during gestation.

The mean age for HZ infection was 5.3 years. The average time between vaccination and HZ infection was 3.3 years. There was a spread of dermatomal patterns with cases in the first division of the trigeminal nerve, cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral distributions. Of the 22 cases of HZ we reviewed, 16 underwent genotype testing to determine the source of the infection. The Oka vaccine strain virus was identified in 8 (50%) cases, while wild-type virus was found in 8 (50%) cases.1,2,4,5,7,8,10,11,13,14,16 Twelve cases were treated with acyclovir.2,3,5,6,9-12,14-17 The method of delivery, either oral or intravenous, and the length of treatment depended on the severity of the disease. Patients with meningoencephalitis and HZ ophthalmicus received intravenous acyclovir more often and also had a longer course of acyclovir compared to those individuals with involvement limited to the skin.

This review found HZ occurs from reactivation of wild-type or Oka vaccine-strain VZV in immunocompetent children.1-17 It shows that subclinical varicella infection is not the only explanation for HZ in a healthy vaccinated child. It is currently not clear why some healthy children experience HZ from vaccine-strain VZV. When HZ presents in a vaccinated immunocompetent child without a history of varicella infection or exposure, the possibility for vaccine strain–induced HZ should be considered.

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) causes varicella as a primary infection. It is a highly contagious disease characterized by a widespread papulovesicular eruption with fever and malaise.1,2 After the primary infection, the virus remains latent within the sensory dorsal root ganglia and can reactivate as herpes zoster (HZ).1-5 Herpes zoster is characterized by unilateral radicular pain and a vesicular rash in a dermatomal pattern.1,2 It is most common in adults, especially elderly and immunocompromised patients, but rarely occurs in children. Herpes zoster is most often seen in individuals previously infected with VZV, but it also has occurred in individuals without known varicella infection,1-17 possibly because these individuals had a prior subclinical VZV infection.

A live attenuated VZV vaccine was created after isolation of the virus from a child in Japan.2 Since the introduction of the vaccine in 1995 in the United States, the incidence of VZV and HZ has declined.5 Herpes zoster rates after vaccination vary from 14 to 19 per 100,000 individuals.3,5 Breakthrough disease with the wild-type strain does occur in vaccinated children, but vaccine-strain HZ also has been reported.1-5 The risk for HZ caused by reactivated VZV vaccine in healthy children is unknown. We present a case of HZ in an otherwise healthy 19-month-old boy with no known varicella exposure who received the VZV vaccine at 13 months of age.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 19-month-old boy presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash that began 2 days prior on the right groin and spread to the right leg. The patient’s mother denied that the child had been febrile and noted that the rash did not appear to bother him in any way. The patient was up-to-date on his vaccinations and received the first dose of the varicella series 6 months prior to presentation. He had no personal history of varicella, no exposure to sick contacts with varicella, and no known exposure to the virus. He was otherwise completely healthy with no signs or symptoms of immunocompromise.

Physical examination revealed grouped vesicles on an erythematous base on the right thigh, right sacrum, and lower abdomen that did not cross the midline (Figure). There were no other pertinent physical examination findings. The eruption was most consistent with HZ but concern remained for herpes simplex virus (HSV) or impetigo. A bacterial culture and polymerase chain reaction assay for VZV and HSV from skin swabs was ordered. The patient was prescribed acyclovir 20 mg/kg every 6 hours for 5 days. Laboratory testing revealed a positive result for VZV on polymerase chain reaction and a negative result for HSV. The majority of the patient’s lesions had crusted after 2 days of treatment with acyclovir, and the rash had nearly resolved 1 week after presentation. Subsequent evaluation with a complete blood cell count with differential and basic metabolic profile was normal. Levels of IgG, IgA, and IgM also were normal; IgE was slightly elevated.

Comment

Herpes zoster in children is an uncommon clinical entity. Most children with HZ are immunocompromised, have a history of varicella, or were exposed to varicella during gestation.8 With the introduction of the live VZV vaccine, the incidence of HZ has declined, but reactivation of the live vaccine leading to HZ infection is possible. The vaccine is 90% effective, and breakthrough varicella has been reported in 15% to 20% of vaccinated patients.1-17 The cause of HZ in vaccinated children is unclear due to the potential for either wild-type or vaccine-strain VZV to induce HZ.

Twenty-two cases of HZ in healthy children after vaccination were identified with a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms herpes zoster infection after vaccination and herpes zoster infection AND immunocompetent AND vaccination in separate searches for all English-language studies (Table). The search was limited to immunocompetent children and adolescents who were 18 years or younger with no history of varicella or exposure to varicella during gestation.

The mean age for HZ infection was 5.3 years. The average time between vaccination and HZ infection was 3.3 years. There was a spread of dermatomal patterns with cases in the first division of the trigeminal nerve, cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral distributions. Of the 22 cases of HZ we reviewed, 16 underwent genotype testing to determine the source of the infection. The Oka vaccine strain virus was identified in 8 (50%) cases, while wild-type virus was found in 8 (50%) cases.1,2,4,5,7,8,10,11,13,14,16 Twelve cases were treated with acyclovir.2,3,5,6,9-12,14-17 The method of delivery, either oral or intravenous, and the length of treatment depended on the severity of the disease. Patients with meningoencephalitis and HZ ophthalmicus received intravenous acyclovir more often and also had a longer course of acyclovir compared to those individuals with involvement limited to the skin.

This review found HZ occurs from reactivation of wild-type or Oka vaccine-strain VZV in immunocompetent children.1-17 It shows that subclinical varicella infection is not the only explanation for HZ in a healthy vaccinated child. It is currently not clear why some healthy children experience HZ from vaccine-strain VZV. When HZ presents in a vaccinated immunocompetent child without a history of varicella infection or exposure, the possibility for vaccine strain–induced HZ should be considered.

- . Herpes zoster in three healthy children immunized with varicella vaccine (Oka/Biken); the causative virus differed from vaccine strain on PCR analysis of the IV variable region (R5) and of a PstI-site region. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:255-258.

- Uebe B, Sauerbrei A, Burdach S, et al. Herpes zoster by reactivated vaccine varicella zoster virus in a healthy child [published online June 25, 2002]. Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161:442-444.

- Obieta MP, Jacinto SS. Herpes zoster after varicella vaccination in a healthy young child. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:640-641.