User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Hairless Scalp Lesion

The Diagnosis: Nevus Sebaceus of Jadassohn

The diagnosis of nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn was made clinically based on the lesion’s appearance and presence since birth as well as the absence of systemic symptoms. Clinically, nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn typically manifests as a well-demarcated, yellow- brown plaque often located on the scalp, as was seen in our patient. The lack of pruritus and pain further supported the diagnosis in our patient. No biopsy was performed, as the presentation was considered classic for this condition. Our patient opted to forgo surgery and will be routinely monitored for any changes, as nevus sebaceus has a potential risk, albeit low, for malignant transformation later in life. No changes have been observed since the initial presentation, and regular follow-ups are planned to monitor for future developments.

Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn is a hamartomatous lesion involving the pilosebaceous follicle and adjacent adnexal structures.1-3 It most commonly forms on the scalp (59.3%) and is accompanied by partial or total alopecia. 3,4 It is seen less often on the face, periauricular area, or neck1,4; thorax or limbs5; and oral or genital mucosae.6 Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn affects approximately 0.3% of newborns,1 usually as a solitary lesion that can form an extensive plaque. The male-to-female occurrence ratio has been reported as equal to slightly more predominant in females; all races and ethnicities are affected.1,5

Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn follows 3 stages of clinical development: infantile, adolescent, and adulthood. It manifests at birth or shortly afterward as a smooth hairless patch or plaque that is yellowish and can be hyperpigmented in Black patients.5 It may have an oval or linear configuration, typically is asymptomatic, and often arises along the Blaschko lines when it occurs as multiple lesions (a rare manifestation).1 During puberty, hormonal changes cause accelerated growth, sebaceous gland maturation, and epidermal hyperplasia. 7 Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn often is not identified until this stage, when its classic wartlike appearance has fully developed.1

Patients with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn have a 10% to 20% risk for tumor development in adulthood.2,7 Trichoblastoma and syringocystadenoma papilliferum are the most frequently described neoplasms.8 Basal cell carcinoma is the most common malignant secondary neoplasm with an occurrence rate of 0.8%.6,9 However, basal cell carcinoma and trichoblastoma may share histopathologic features, which may lead to misdiagnosis and a higher reported incidence of basal cell carcinoma in adults than is accurate.2

Early prophylactic surgical removal of nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn has been recommended; however, surgical management is controversial because the risk for a benign secondary neoplasm remains relatively high while the risk for malignancy is much lower.2,7 Surgical excision remains an acceptable option once the patient is mature enough to tolerate the procedure.1 However, patient education regarding watchful waiting vs a surgical approach— and the risks of each—is critical to ensure shared decision-making and a management plan tailored to the individual.

The differential diagnosis includes hypertrophic lichen planus, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (Letterer-Siwe disease type), epidermal nevus, and seborrheic keratosis. Hypertrophic lichen planus often occurs symmetrically on the dorsal feet and shins with thick, scaly, and extremely pruritic plaques. The lesions often persist for an average of 6 years and may lead to multiple keratoacanthomas or follicular base squamous cell carcinomas. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (Letterer-Siwe disease type) manifests with acute, disseminated, visceral, and cutaneous lesions before 2 years of age. These lesions appear as 1- to 2-mm, pink, seborrheic papules, pustules, or vesicles on the scalp, flexural neck, axilla, perineum, and trunk; they often are associated with petechiae, purpura, scale, crust, erosion, impetiginization, and tender fissures. Epidermal nevus occurs within the first year of life and is a hamartoma of the epidermis and papillary dermis. It manifests as papillomatous pigmented linear lines along the Blaschko lines. Seborrheic keratosis manifests as well-demarcated, waxy/verrucous, brown papules with a “stuck on” appearance on hair-bearing skin sparing the mucosae. They are common benign lesions associated with sun exposure and often manifest in the fourth decade of life.10

- Baigrie D, Troxell T, Cook C. Nevus sebaceus. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 16, 2023. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482493/

- Terenzi V, Indrizzi E, Buonaccorsi S, et al. Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. J Craniofac Surg. 2006;17:1234-1239. doi:10.1097/01 .scs.0000221531.56529.cc

- Kelati A, Baybay H, Gallouj S, et al. Dermoscopic analysis of nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 13 cases. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;3:83-91. doi:10.1159/000460258

- Ugras N, Ozgun G, Adim SB, et al. Nevus sebaceous at unusual location: a rare presentation. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2012;55:419-420. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.101768

- Serpas de Lopez RM, Hernandez-Perez E. Jadassohn’s sebaceous nevus. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1985;11:68-72. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725 .1985.tb02893.x

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2 pt 1):263-268. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(00)90136-1

- Santibanez-Gallerani A, Marshall D, Duarte AM, et al. Should nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn in children be excised? a study of 757 cases, and literature review. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:658-660. doi:10.1097/00001665-200309000-00010

- Chahboun F, Eljazouly M, Elomari M, et al. Trichoblastoma arising from the nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Cureus. 2021;13:E15325. doi:10.7759/cureus.15325

- Cazzato G, Cimmino A, Colagrande A, et al. The multiple faces of nodular trichoblastoma: review of the literature with case presentation. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2021;8:265-270. doi:10.3390 /dermatopathology8030032

- Dandekar MN, Gandhi RK. Neoplastic dermatology. In: Alikhan A, Hocker TLH (eds). Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2016: 321-366.

The Diagnosis: Nevus Sebaceus of Jadassohn

The diagnosis of nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn was made clinically based on the lesion’s appearance and presence since birth as well as the absence of systemic symptoms. Clinically, nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn typically manifests as a well-demarcated, yellow- brown plaque often located on the scalp, as was seen in our patient. The lack of pruritus and pain further supported the diagnosis in our patient. No biopsy was performed, as the presentation was considered classic for this condition. Our patient opted to forgo surgery and will be routinely monitored for any changes, as nevus sebaceus has a potential risk, albeit low, for malignant transformation later in life. No changes have been observed since the initial presentation, and regular follow-ups are planned to monitor for future developments.

Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn is a hamartomatous lesion involving the pilosebaceous follicle and adjacent adnexal structures.1-3 It most commonly forms on the scalp (59.3%) and is accompanied by partial or total alopecia. 3,4 It is seen less often on the face, periauricular area, or neck1,4; thorax or limbs5; and oral or genital mucosae.6 Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn affects approximately 0.3% of newborns,1 usually as a solitary lesion that can form an extensive plaque. The male-to-female occurrence ratio has been reported as equal to slightly more predominant in females; all races and ethnicities are affected.1,5

Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn follows 3 stages of clinical development: infantile, adolescent, and adulthood. It manifests at birth or shortly afterward as a smooth hairless patch or plaque that is yellowish and can be hyperpigmented in Black patients.5 It may have an oval or linear configuration, typically is asymptomatic, and often arises along the Blaschko lines when it occurs as multiple lesions (a rare manifestation).1 During puberty, hormonal changes cause accelerated growth, sebaceous gland maturation, and epidermal hyperplasia. 7 Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn often is not identified until this stage, when its classic wartlike appearance has fully developed.1

Patients with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn have a 10% to 20% risk for tumor development in adulthood.2,7 Trichoblastoma and syringocystadenoma papilliferum are the most frequently described neoplasms.8 Basal cell carcinoma is the most common malignant secondary neoplasm with an occurrence rate of 0.8%.6,9 However, basal cell carcinoma and trichoblastoma may share histopathologic features, which may lead to misdiagnosis and a higher reported incidence of basal cell carcinoma in adults than is accurate.2

Early prophylactic surgical removal of nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn has been recommended; however, surgical management is controversial because the risk for a benign secondary neoplasm remains relatively high while the risk for malignancy is much lower.2,7 Surgical excision remains an acceptable option once the patient is mature enough to tolerate the procedure.1 However, patient education regarding watchful waiting vs a surgical approach— and the risks of each—is critical to ensure shared decision-making and a management plan tailored to the individual.

The differential diagnosis includes hypertrophic lichen planus, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (Letterer-Siwe disease type), epidermal nevus, and seborrheic keratosis. Hypertrophic lichen planus often occurs symmetrically on the dorsal feet and shins with thick, scaly, and extremely pruritic plaques. The lesions often persist for an average of 6 years and may lead to multiple keratoacanthomas or follicular base squamous cell carcinomas. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (Letterer-Siwe disease type) manifests with acute, disseminated, visceral, and cutaneous lesions before 2 years of age. These lesions appear as 1- to 2-mm, pink, seborrheic papules, pustules, or vesicles on the scalp, flexural neck, axilla, perineum, and trunk; they often are associated with petechiae, purpura, scale, crust, erosion, impetiginization, and tender fissures. Epidermal nevus occurs within the first year of life and is a hamartoma of the epidermis and papillary dermis. It manifests as papillomatous pigmented linear lines along the Blaschko lines. Seborrheic keratosis manifests as well-demarcated, waxy/verrucous, brown papules with a “stuck on” appearance on hair-bearing skin sparing the mucosae. They are common benign lesions associated with sun exposure and often manifest in the fourth decade of life.10

The Diagnosis: Nevus Sebaceus of Jadassohn

The diagnosis of nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn was made clinically based on the lesion’s appearance and presence since birth as well as the absence of systemic symptoms. Clinically, nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn typically manifests as a well-demarcated, yellow- brown plaque often located on the scalp, as was seen in our patient. The lack of pruritus and pain further supported the diagnosis in our patient. No biopsy was performed, as the presentation was considered classic for this condition. Our patient opted to forgo surgery and will be routinely monitored for any changes, as nevus sebaceus has a potential risk, albeit low, for malignant transformation later in life. No changes have been observed since the initial presentation, and regular follow-ups are planned to monitor for future developments.

Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn is a hamartomatous lesion involving the pilosebaceous follicle and adjacent adnexal structures.1-3 It most commonly forms on the scalp (59.3%) and is accompanied by partial or total alopecia. 3,4 It is seen less often on the face, periauricular area, or neck1,4; thorax or limbs5; and oral or genital mucosae.6 Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn affects approximately 0.3% of newborns,1 usually as a solitary lesion that can form an extensive plaque. The male-to-female occurrence ratio has been reported as equal to slightly more predominant in females; all races and ethnicities are affected.1,5

Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn follows 3 stages of clinical development: infantile, adolescent, and adulthood. It manifests at birth or shortly afterward as a smooth hairless patch or plaque that is yellowish and can be hyperpigmented in Black patients.5 It may have an oval or linear configuration, typically is asymptomatic, and often arises along the Blaschko lines when it occurs as multiple lesions (a rare manifestation).1 During puberty, hormonal changes cause accelerated growth, sebaceous gland maturation, and epidermal hyperplasia. 7 Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn often is not identified until this stage, when its classic wartlike appearance has fully developed.1

Patients with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn have a 10% to 20% risk for tumor development in adulthood.2,7 Trichoblastoma and syringocystadenoma papilliferum are the most frequently described neoplasms.8 Basal cell carcinoma is the most common malignant secondary neoplasm with an occurrence rate of 0.8%.6,9 However, basal cell carcinoma and trichoblastoma may share histopathologic features, which may lead to misdiagnosis and a higher reported incidence of basal cell carcinoma in adults than is accurate.2

Early prophylactic surgical removal of nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn has been recommended; however, surgical management is controversial because the risk for a benign secondary neoplasm remains relatively high while the risk for malignancy is much lower.2,7 Surgical excision remains an acceptable option once the patient is mature enough to tolerate the procedure.1 However, patient education regarding watchful waiting vs a surgical approach— and the risks of each—is critical to ensure shared decision-making and a management plan tailored to the individual.

The differential diagnosis includes hypertrophic lichen planus, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (Letterer-Siwe disease type), epidermal nevus, and seborrheic keratosis. Hypertrophic lichen planus often occurs symmetrically on the dorsal feet and shins with thick, scaly, and extremely pruritic plaques. The lesions often persist for an average of 6 years and may lead to multiple keratoacanthomas or follicular base squamous cell carcinomas. Langerhans cell histiocytosis (Letterer-Siwe disease type) manifests with acute, disseminated, visceral, and cutaneous lesions before 2 years of age. These lesions appear as 1- to 2-mm, pink, seborrheic papules, pustules, or vesicles on the scalp, flexural neck, axilla, perineum, and trunk; they often are associated with petechiae, purpura, scale, crust, erosion, impetiginization, and tender fissures. Epidermal nevus occurs within the first year of life and is a hamartoma of the epidermis and papillary dermis. It manifests as papillomatous pigmented linear lines along the Blaschko lines. Seborrheic keratosis manifests as well-demarcated, waxy/verrucous, brown papules with a “stuck on” appearance on hair-bearing skin sparing the mucosae. They are common benign lesions associated with sun exposure and often manifest in the fourth decade of life.10

- Baigrie D, Troxell T, Cook C. Nevus sebaceus. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 16, 2023. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482493/

- Terenzi V, Indrizzi E, Buonaccorsi S, et al. Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. J Craniofac Surg. 2006;17:1234-1239. doi:10.1097/01 .scs.0000221531.56529.cc

- Kelati A, Baybay H, Gallouj S, et al. Dermoscopic analysis of nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 13 cases. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;3:83-91. doi:10.1159/000460258

- Ugras N, Ozgun G, Adim SB, et al. Nevus sebaceous at unusual location: a rare presentation. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2012;55:419-420. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.101768

- Serpas de Lopez RM, Hernandez-Perez E. Jadassohn’s sebaceous nevus. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1985;11:68-72. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725 .1985.tb02893.x

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2 pt 1):263-268. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(00)90136-1

- Santibanez-Gallerani A, Marshall D, Duarte AM, et al. Should nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn in children be excised? a study of 757 cases, and literature review. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:658-660. doi:10.1097/00001665-200309000-00010

- Chahboun F, Eljazouly M, Elomari M, et al. Trichoblastoma arising from the nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Cureus. 2021;13:E15325. doi:10.7759/cureus.15325

- Cazzato G, Cimmino A, Colagrande A, et al. The multiple faces of nodular trichoblastoma: review of the literature with case presentation. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2021;8:265-270. doi:10.3390 /dermatopathology8030032

- Dandekar MN, Gandhi RK. Neoplastic dermatology. In: Alikhan A, Hocker TLH (eds). Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2016: 321-366.

- Baigrie D, Troxell T, Cook C. Nevus sebaceus. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 16, 2023. Accessed September 12, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482493/

- Terenzi V, Indrizzi E, Buonaccorsi S, et al. Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. J Craniofac Surg. 2006;17:1234-1239. doi:10.1097/01 .scs.0000221531.56529.cc

- Kelati A, Baybay H, Gallouj S, et al. Dermoscopic analysis of nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 13 cases. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;3:83-91. doi:10.1159/000460258

- Ugras N, Ozgun G, Adim SB, et al. Nevus sebaceous at unusual location: a rare presentation. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2012;55:419-420. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.101768

- Serpas de Lopez RM, Hernandez-Perez E. Jadassohn’s sebaceous nevus. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1985;11:68-72. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725 .1985.tb02893.x

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2 pt 1):263-268. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(00)90136-1

- Santibanez-Gallerani A, Marshall D, Duarte AM, et al. Should nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn in children be excised? a study of 757 cases, and literature review. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:658-660. doi:10.1097/00001665-200309000-00010

- Chahboun F, Eljazouly M, Elomari M, et al. Trichoblastoma arising from the nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Cureus. 2021;13:E15325. doi:10.7759/cureus.15325

- Cazzato G, Cimmino A, Colagrande A, et al. The multiple faces of nodular trichoblastoma: review of the literature with case presentation. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2021;8:265-270. doi:10.3390 /dermatopathology8030032

- Dandekar MN, Gandhi RK. Neoplastic dermatology. In: Alikhan A, Hocker TLH (eds). Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2016: 321-366.

A 23-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with hair loss on the scalp of several years’ duration. The patient reported persistent pigmented bumps on the back of the scalp. He denied any pruritus or pain and had no systemic symptoms or comorbidities. Physical examination revealed a 1×1.5-cm, yellow-brown, hairless plaque on the left parietal scalp.

Western Pygmy Rattlesnake Envenomation and Bite Management

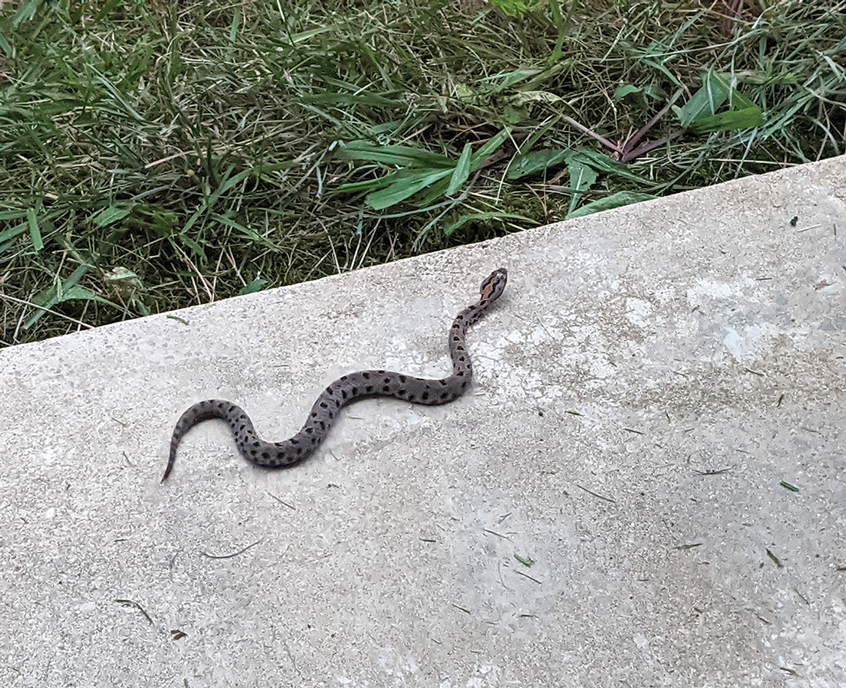

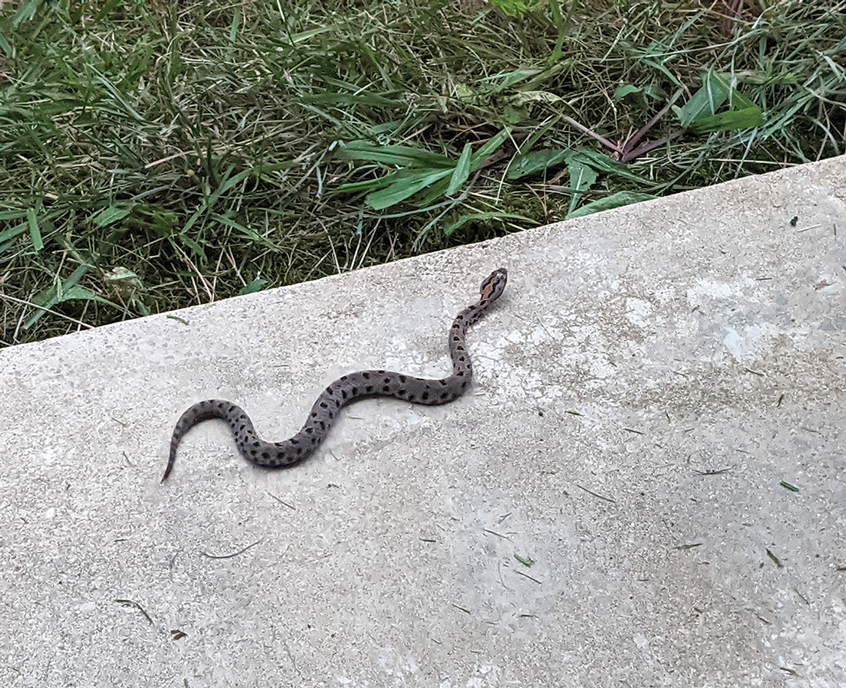

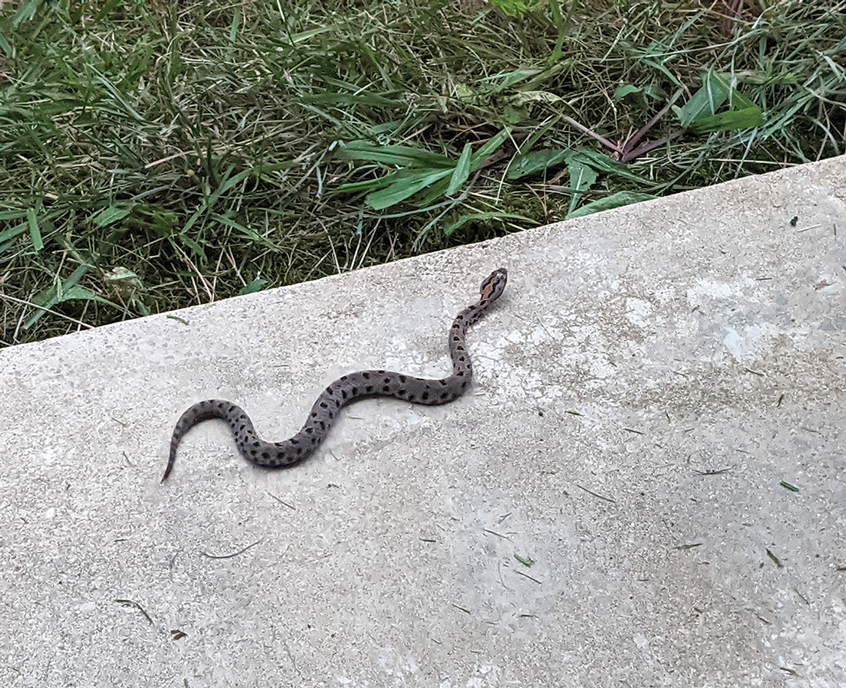

There are 375 species of poisonous snakes, with approximately 20,000 deaths worldwide each year due to snakebites, mostly in Asia and Africa.1 The death rate in the United States is 14 to 20 cases per year. In the United States, a variety of rattlesnakes are poisonous. There are 2 genera of rattlesnakes: Sistrurus (3 species) and Crotalus (23 species). The pygmy rattlesnake belongs to the Sistrurus miliarius species that is divided into 3 subspecies: the Carolina pigmy rattlesnake (S miliarius miliarius), the western pygmy rattlesnake (S miliarius streckeri), and the dusky pygmy rattlesnake (S miliarius barbouri).2

The western pygmy rattlesnake belongs to the Crotalidae family. The rattlesnakes in this family also are known as pit vipers. All pit vipers have common characteristics for identification: triangular head, fangs, elliptical pupils, and a heat-sensing pit between the eyes. The western pygmy rattlesnake is found in Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Tennessee.1 It is small bodied (15–20 inches)3 and grayish-brown, with a brown dorsal stripe with black blotches on its back. It is found in glades, second-growth forests near rock ledges, and areas where powerlines cut through dense forest.3 Its venom is hemorrhagic, causing tissue damage, but does not contain neurotoxins.4 Bites from the western pygmy rattlesnake often do not lead to death, but the venom, which contains numerous proteins and enzymes, does cause necrotic hemorrhagic ulceration at the site of envenomation and possible loss of digit.5,6

We present a case of a man who was bitten on the right third digit by a western pygmy rattlesnake. We describe the clinical course and treatment.

Case Report

A 56-year-old right-handed man presented to the emergency department with a rapidly swelling, painful hand following a snakebite to the dorsal aspect of the right third digit (Figure 1). He was able to capture a photograph of the snake at the time of injury, which helped identify it as a western pygmy rattlesnake (Figure 2). He also photographed the hand immediately after the bite occurred (Figure 3). Vitals on presentation included an elevated blood pressure of 161/100 mm Hg; no fever (temperature, 36.4 °C); and normal pulse oximetry of 98%, pulse of 86 beats per minute, and respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute.

After the snakebite, the patient’s family called the Missouri Poison Center immediately. The family identified the snake species and shared this information with the poison center. Poison control recommended calling the nearest hospitals to determine if antivenom was available and make notification of arrival.

The patient’s tetanus toxoid immunization was updated immediately upon arrival. The hand was marked to monitor swelling. Initial laboratory test results revealed the following values: sodium, 133 mmol/L (reference range, 136–145 mmol/L); potassium, 3.4 mmol/L (3.6–5.2 mmol/L); lactic acid, 2.4 mmol/L (0.5–2.2 mmol/L); creatine kinase, 425 U/L (55–170 U/L); platelet count, 68/µL (150,000–450,000/µL); fibrinogen, 169 mg/dL (185–410 mg/dL); and glucose, 121 mg/dL (74–106 mg/dL). The remainder of the complete blood cell count and metabolic panel was unremarkable. Radiographs of the hand did not show any fractures, dislocations, or foreign bodies. Missouri Poison Center was consulted. Given the patient’s severe pain, edema beyond 40 cm, and developing ecchymosis on the inner arm, the bite was graded as a 3 on the traditional snakebite severity scale. Poison control recommended 4 to 6 vials of antivenom over 60 minutes. Six vials of Crotalidae polyvalent immune fab antivenom were given.

The patient’s complete blood cell count remained unremarkable throughout his admission. His metabolic panel returned to normal at 6 hours postadmission: sodium, 139 mmol/L; potassium, 4.0 mmol/L. His lactate and creatinine kinase were not rechecked. His fibrinogen was trending upward. Serial laboratory test results revealed fibrinogen levels of 153, 158, 161, 159, 173, and 216 mg/dL at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 hours, respectively. Other laboratory test results including prothrombin time (11.0 s) and international normalized ratio (0.98) remained within reference range (11–13 s and 0.80–1.39, respectively) during serial monitoring.

The patient was hospitalized for 40 hours while waiting for his fibrinogen level to normalize. The local skin necrosis worsened acutely in this 40-hour window (Figure 4). Intravenous antibiotics were not administered during the hospital stay. Before discharge, the patient was evaluated by the surgery service, who did not recommend debridement.

Following discharge, the patient consulted a wound care expert. The area of necrosis was unroofed and debrided in the outpatient setting (Figure 5). The patient was started on oral cefalexin 500 mg twice daily for 10 days and instructed to perform twice-daily dressing changes with silver sulfadiazine cream 1%. A hand surgeon was consulted for consideration of a reverse cross-finger flap, which was not recommended. Twice-daily dressing changes for the wound—consisting of application of silver sulfadiazine cream 1% directly to the wound followed by gauze, self-adhesive soft-rolled gauze, and elastic bandages—were performed for 2 weeks.

After 2 weeks, the wound was left open to the air and cleaned with soap and water as needed. At 6 weeks, the wound was completely healed via secondary intention, except for some minor remaining ulceration at the location of the fang entry point (Figure 6). The patient had no loss of finger function or sensation.

Surgical Management of Snakebites

The surgeon’s role in managing snakebites is controversial. Snakebites were once perceived as a surgical emergency due to symptoms mimicking compartment syndrome; however, snakebites rarely cause a true compartment syndrome.7 Prophylactic bite excision and fasciotomies are not recommended. Incision and suction of the fang marks may be beneficial if performed within 15 to 30 minutes from the time of the bite.8 With access to a surgeon in this short time period being nearly impossible, incision and suctioning of fang marks generally is not recommended.9 Retained snake fangs are a possibility, and the infection could spread to a nearby joint, causing septic arthritis,10 which would be an indication for surgical intervention. Bites to the finger often cause major swelling, and the benefits of dermotomy are documented.11 Generally, early administration of antivenom will decrease local tissue reaction and prevent additional tissue loss.12 In our patient, the decision to perform dermotomy was made when the area of necrosis had declared itself and the skin reached its elastic limit. Bozkurt et al13 described the neurovascular bundles within the digit as functioning as small compartments. When the skin of the digit reaches its elastic limit, pressure within the compartment may exceed the capillary closing pressure, and the integrity of small vessels and nerves may be compromised. Our case highlights the benefit of dermotomy as well as the functional and cosmetic results that can be achieved.

Wound Care for Snakebites

There is little published on the treatment of snakebites after patients are stabilized medically for hospital discharge. Venomous snakes inject toxins that predominantly consist of enzymes (eg, phospholipase A2, phosphodiesterase, hyaluronidase, peptidase, metalloproteinase) that cause tissue destruction through diverse mechanisms.14 The venom of western pygmy rattlesnakes is hemotoxic and can cause necrotic hemorrhagic ulceration,4 as was the case in our patient.

Silver sulfadiazine commonly is used to prevent infection in burn patients. Given the large surface area of exposed dermis after debridement and concern for infection, silver sulfadiazine was chosen in our patient for local wound care treatment. Silver sulfadiazine is a widely available and low-cost drug.15 Its antibacterial effects are due to the silver ions, which only act superficially and therefore limit systemic absorption.16 Application should be performed in a clean manner with minimal trauma to the tissue. This technique is best achieved by using sterile gloves and applying the medication manually. A 0.0625-inch layer should be applied to entirely cover the cleaned debrided area.17 When performing application with tongue blades or cotton swabs, it is important to never “double dip.” Patient education on proper administration is imperative to a successful outcome.

Final Thoughts

Our case demonstrates the safe use of Crotalidae polyvalent immune fab antivenom for the treatment of western pygmy rattlesnake (S miliarius streckeri) envenomation. Early administration of antivenom following pit viper rattlesnake envenomations is important to mitigate systemic effects and the extent of soft tissue damage. There are few studies on local wound care treatment after rattlesnake envenomation. This case highlights the role of dermotomy and wound care with silver sulfadiazine cream 1%.

- Biggers B. Management of Missouri snake bites. Mo Med. 2017;114:254-257.

- Stamm R. Sistrurus miliarius pigmy rattlesnake. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Sistrurus_miliarius/

- Missouri Department of Conservation. Western pygmy rattlesnake. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/western-pygmy-rattlesnake

- AnimalSake. Facts about the pigmy rattlesnake that are sure to surprise you. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://animalsake.com/pygmy-rattlesnake

- King AM, Crim WS, Menke NB, et al. Pygmy rattlesnake envenomation treated with crotalidae polyvalent immune fab antivenom. Toxicon. 2012;60:1287-1289.

- Juckett G, Hancox JG. Venomous snakebites in the United States: management review and update. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:1367-1375.

- Toschlog EA, Bauer CR, Hall EL, et al. Surgical considerations in the management of pit viper snake envenomation. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:726-735.

- Cribari C. Management of poisonous snakebite. American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma; 2004. https://www.hartcountyga.gov/documents/PoisonousSnakebiteTreatment.pdf

- Walker JP, Morrison RL. Current management of copperhead snakebite. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:470-474.

- Gelman D, Bates T, Nuelle JAV. Septic arthritis of the proximal interphalangeal joint after rattlesnake bite. J Hand Surg Am. 2022;47:484.e1-484.e4.

- Watt CH Jr. Treatment of poisonous snakebite with emphasis on digit dermotomy. South Med J. 1985;78:694-699.

- Corneille MG, Larson S, Stewart RM, et al. A large single-center experience with treatment of patients with crotalid envenomations: outcomes with and evolution of antivenin therapy. Am J Surg. 2006;192:848-852.

- Bozkurt M, Kulahci Y, Zor F, et al. The management of pit viper envenomation of the hand. Hand (NY). 2008;3:324-331.

- Aziz H, Rhee P, Pandit V, et al. The current concepts in management of animal (dog, cat, snake, scorpion) and human bite wounds. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:641-648.

- Hummel RP, MacMillan BG, Altemeier WA. Topical and systemic antibacterial agents in the treatment of burns. Ann Surg. 1970;172:370-384.

- Modak SM, Sampath L, Fox CL. Combined topical use of silver sulfadiazine and antibiotics as a possible solution to bacterial resistance in burn wounds. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1988;9:359-363.

- Oaks RJ, Cindass R. Silver sulfadiazine. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated January 22, 2023. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556054/

There are 375 species of poisonous snakes, with approximately 20,000 deaths worldwide each year due to snakebites, mostly in Asia and Africa.1 The death rate in the United States is 14 to 20 cases per year. In the United States, a variety of rattlesnakes are poisonous. There are 2 genera of rattlesnakes: Sistrurus (3 species) and Crotalus (23 species). The pygmy rattlesnake belongs to the Sistrurus miliarius species that is divided into 3 subspecies: the Carolina pigmy rattlesnake (S miliarius miliarius), the western pygmy rattlesnake (S miliarius streckeri), and the dusky pygmy rattlesnake (S miliarius barbouri).2

The western pygmy rattlesnake belongs to the Crotalidae family. The rattlesnakes in this family also are known as pit vipers. All pit vipers have common characteristics for identification: triangular head, fangs, elliptical pupils, and a heat-sensing pit between the eyes. The western pygmy rattlesnake is found in Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Tennessee.1 It is small bodied (15–20 inches)3 and grayish-brown, with a brown dorsal stripe with black blotches on its back. It is found in glades, second-growth forests near rock ledges, and areas where powerlines cut through dense forest.3 Its venom is hemorrhagic, causing tissue damage, but does not contain neurotoxins.4 Bites from the western pygmy rattlesnake often do not lead to death, but the venom, which contains numerous proteins and enzymes, does cause necrotic hemorrhagic ulceration at the site of envenomation and possible loss of digit.5,6

We present a case of a man who was bitten on the right third digit by a western pygmy rattlesnake. We describe the clinical course and treatment.

Case Report

A 56-year-old right-handed man presented to the emergency department with a rapidly swelling, painful hand following a snakebite to the dorsal aspect of the right third digit (Figure 1). He was able to capture a photograph of the snake at the time of injury, which helped identify it as a western pygmy rattlesnake (Figure 2). He also photographed the hand immediately after the bite occurred (Figure 3). Vitals on presentation included an elevated blood pressure of 161/100 mm Hg; no fever (temperature, 36.4 °C); and normal pulse oximetry of 98%, pulse of 86 beats per minute, and respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute.

After the snakebite, the patient’s family called the Missouri Poison Center immediately. The family identified the snake species and shared this information with the poison center. Poison control recommended calling the nearest hospitals to determine if antivenom was available and make notification of arrival.

The patient’s tetanus toxoid immunization was updated immediately upon arrival. The hand was marked to monitor swelling. Initial laboratory test results revealed the following values: sodium, 133 mmol/L (reference range, 136–145 mmol/L); potassium, 3.4 mmol/L (3.6–5.2 mmol/L); lactic acid, 2.4 mmol/L (0.5–2.2 mmol/L); creatine kinase, 425 U/L (55–170 U/L); platelet count, 68/µL (150,000–450,000/µL); fibrinogen, 169 mg/dL (185–410 mg/dL); and glucose, 121 mg/dL (74–106 mg/dL). The remainder of the complete blood cell count and metabolic panel was unremarkable. Radiographs of the hand did not show any fractures, dislocations, or foreign bodies. Missouri Poison Center was consulted. Given the patient’s severe pain, edema beyond 40 cm, and developing ecchymosis on the inner arm, the bite was graded as a 3 on the traditional snakebite severity scale. Poison control recommended 4 to 6 vials of antivenom over 60 minutes. Six vials of Crotalidae polyvalent immune fab antivenom were given.

The patient’s complete blood cell count remained unremarkable throughout his admission. His metabolic panel returned to normal at 6 hours postadmission: sodium, 139 mmol/L; potassium, 4.0 mmol/L. His lactate and creatinine kinase were not rechecked. His fibrinogen was trending upward. Serial laboratory test results revealed fibrinogen levels of 153, 158, 161, 159, 173, and 216 mg/dL at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 hours, respectively. Other laboratory test results including prothrombin time (11.0 s) and international normalized ratio (0.98) remained within reference range (11–13 s and 0.80–1.39, respectively) during serial monitoring.

The patient was hospitalized for 40 hours while waiting for his fibrinogen level to normalize. The local skin necrosis worsened acutely in this 40-hour window (Figure 4). Intravenous antibiotics were not administered during the hospital stay. Before discharge, the patient was evaluated by the surgery service, who did not recommend debridement.

Following discharge, the patient consulted a wound care expert. The area of necrosis was unroofed and debrided in the outpatient setting (Figure 5). The patient was started on oral cefalexin 500 mg twice daily for 10 days and instructed to perform twice-daily dressing changes with silver sulfadiazine cream 1%. A hand surgeon was consulted for consideration of a reverse cross-finger flap, which was not recommended. Twice-daily dressing changes for the wound—consisting of application of silver sulfadiazine cream 1% directly to the wound followed by gauze, self-adhesive soft-rolled gauze, and elastic bandages—were performed for 2 weeks.

After 2 weeks, the wound was left open to the air and cleaned with soap and water as needed. At 6 weeks, the wound was completely healed via secondary intention, except for some minor remaining ulceration at the location of the fang entry point (Figure 6). The patient had no loss of finger function or sensation.

Surgical Management of Snakebites

The surgeon’s role in managing snakebites is controversial. Snakebites were once perceived as a surgical emergency due to symptoms mimicking compartment syndrome; however, snakebites rarely cause a true compartment syndrome.7 Prophylactic bite excision and fasciotomies are not recommended. Incision and suction of the fang marks may be beneficial if performed within 15 to 30 minutes from the time of the bite.8 With access to a surgeon in this short time period being nearly impossible, incision and suctioning of fang marks generally is not recommended.9 Retained snake fangs are a possibility, and the infection could spread to a nearby joint, causing septic arthritis,10 which would be an indication for surgical intervention. Bites to the finger often cause major swelling, and the benefits of dermotomy are documented.11 Generally, early administration of antivenom will decrease local tissue reaction and prevent additional tissue loss.12 In our patient, the decision to perform dermotomy was made when the area of necrosis had declared itself and the skin reached its elastic limit. Bozkurt et al13 described the neurovascular bundles within the digit as functioning as small compartments. When the skin of the digit reaches its elastic limit, pressure within the compartment may exceed the capillary closing pressure, and the integrity of small vessels and nerves may be compromised. Our case highlights the benefit of dermotomy as well as the functional and cosmetic results that can be achieved.

Wound Care for Snakebites

There is little published on the treatment of snakebites after patients are stabilized medically for hospital discharge. Venomous snakes inject toxins that predominantly consist of enzymes (eg, phospholipase A2, phosphodiesterase, hyaluronidase, peptidase, metalloproteinase) that cause tissue destruction through diverse mechanisms.14 The venom of western pygmy rattlesnakes is hemotoxic and can cause necrotic hemorrhagic ulceration,4 as was the case in our patient.

Silver sulfadiazine commonly is used to prevent infection in burn patients. Given the large surface area of exposed dermis after debridement and concern for infection, silver sulfadiazine was chosen in our patient for local wound care treatment. Silver sulfadiazine is a widely available and low-cost drug.15 Its antibacterial effects are due to the silver ions, which only act superficially and therefore limit systemic absorption.16 Application should be performed in a clean manner with minimal trauma to the tissue. This technique is best achieved by using sterile gloves and applying the medication manually. A 0.0625-inch layer should be applied to entirely cover the cleaned debrided area.17 When performing application with tongue blades or cotton swabs, it is important to never “double dip.” Patient education on proper administration is imperative to a successful outcome.

Final Thoughts

Our case demonstrates the safe use of Crotalidae polyvalent immune fab antivenom for the treatment of western pygmy rattlesnake (S miliarius streckeri) envenomation. Early administration of antivenom following pit viper rattlesnake envenomations is important to mitigate systemic effects and the extent of soft tissue damage. There are few studies on local wound care treatment after rattlesnake envenomation. This case highlights the role of dermotomy and wound care with silver sulfadiazine cream 1%.

There are 375 species of poisonous snakes, with approximately 20,000 deaths worldwide each year due to snakebites, mostly in Asia and Africa.1 The death rate in the United States is 14 to 20 cases per year. In the United States, a variety of rattlesnakes are poisonous. There are 2 genera of rattlesnakes: Sistrurus (3 species) and Crotalus (23 species). The pygmy rattlesnake belongs to the Sistrurus miliarius species that is divided into 3 subspecies: the Carolina pigmy rattlesnake (S miliarius miliarius), the western pygmy rattlesnake (S miliarius streckeri), and the dusky pygmy rattlesnake (S miliarius barbouri).2

The western pygmy rattlesnake belongs to the Crotalidae family. The rattlesnakes in this family also are known as pit vipers. All pit vipers have common characteristics for identification: triangular head, fangs, elliptical pupils, and a heat-sensing pit between the eyes. The western pygmy rattlesnake is found in Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Tennessee.1 It is small bodied (15–20 inches)3 and grayish-brown, with a brown dorsal stripe with black blotches on its back. It is found in glades, second-growth forests near rock ledges, and areas where powerlines cut through dense forest.3 Its venom is hemorrhagic, causing tissue damage, but does not contain neurotoxins.4 Bites from the western pygmy rattlesnake often do not lead to death, but the venom, which contains numerous proteins and enzymes, does cause necrotic hemorrhagic ulceration at the site of envenomation and possible loss of digit.5,6

We present a case of a man who was bitten on the right third digit by a western pygmy rattlesnake. We describe the clinical course and treatment.

Case Report

A 56-year-old right-handed man presented to the emergency department with a rapidly swelling, painful hand following a snakebite to the dorsal aspect of the right third digit (Figure 1). He was able to capture a photograph of the snake at the time of injury, which helped identify it as a western pygmy rattlesnake (Figure 2). He also photographed the hand immediately after the bite occurred (Figure 3). Vitals on presentation included an elevated blood pressure of 161/100 mm Hg; no fever (temperature, 36.4 °C); and normal pulse oximetry of 98%, pulse of 86 beats per minute, and respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute.

After the snakebite, the patient’s family called the Missouri Poison Center immediately. The family identified the snake species and shared this information with the poison center. Poison control recommended calling the nearest hospitals to determine if antivenom was available and make notification of arrival.

The patient’s tetanus toxoid immunization was updated immediately upon arrival. The hand was marked to monitor swelling. Initial laboratory test results revealed the following values: sodium, 133 mmol/L (reference range, 136–145 mmol/L); potassium, 3.4 mmol/L (3.6–5.2 mmol/L); lactic acid, 2.4 mmol/L (0.5–2.2 mmol/L); creatine kinase, 425 U/L (55–170 U/L); platelet count, 68/µL (150,000–450,000/µL); fibrinogen, 169 mg/dL (185–410 mg/dL); and glucose, 121 mg/dL (74–106 mg/dL). The remainder of the complete blood cell count and metabolic panel was unremarkable. Radiographs of the hand did not show any fractures, dislocations, or foreign bodies. Missouri Poison Center was consulted. Given the patient’s severe pain, edema beyond 40 cm, and developing ecchymosis on the inner arm, the bite was graded as a 3 on the traditional snakebite severity scale. Poison control recommended 4 to 6 vials of antivenom over 60 minutes. Six vials of Crotalidae polyvalent immune fab antivenom were given.

The patient’s complete blood cell count remained unremarkable throughout his admission. His metabolic panel returned to normal at 6 hours postadmission: sodium, 139 mmol/L; potassium, 4.0 mmol/L. His lactate and creatinine kinase were not rechecked. His fibrinogen was trending upward. Serial laboratory test results revealed fibrinogen levels of 153, 158, 161, 159, 173, and 216 mg/dL at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 hours, respectively. Other laboratory test results including prothrombin time (11.0 s) and international normalized ratio (0.98) remained within reference range (11–13 s and 0.80–1.39, respectively) during serial monitoring.

The patient was hospitalized for 40 hours while waiting for his fibrinogen level to normalize. The local skin necrosis worsened acutely in this 40-hour window (Figure 4). Intravenous antibiotics were not administered during the hospital stay. Before discharge, the patient was evaluated by the surgery service, who did not recommend debridement.

Following discharge, the patient consulted a wound care expert. The area of necrosis was unroofed and debrided in the outpatient setting (Figure 5). The patient was started on oral cefalexin 500 mg twice daily for 10 days and instructed to perform twice-daily dressing changes with silver sulfadiazine cream 1%. A hand surgeon was consulted for consideration of a reverse cross-finger flap, which was not recommended. Twice-daily dressing changes for the wound—consisting of application of silver sulfadiazine cream 1% directly to the wound followed by gauze, self-adhesive soft-rolled gauze, and elastic bandages—were performed for 2 weeks.

After 2 weeks, the wound was left open to the air and cleaned with soap and water as needed. At 6 weeks, the wound was completely healed via secondary intention, except for some minor remaining ulceration at the location of the fang entry point (Figure 6). The patient had no loss of finger function or sensation.

Surgical Management of Snakebites

The surgeon’s role in managing snakebites is controversial. Snakebites were once perceived as a surgical emergency due to symptoms mimicking compartment syndrome; however, snakebites rarely cause a true compartment syndrome.7 Prophylactic bite excision and fasciotomies are not recommended. Incision and suction of the fang marks may be beneficial if performed within 15 to 30 minutes from the time of the bite.8 With access to a surgeon in this short time period being nearly impossible, incision and suctioning of fang marks generally is not recommended.9 Retained snake fangs are a possibility, and the infection could spread to a nearby joint, causing septic arthritis,10 which would be an indication for surgical intervention. Bites to the finger often cause major swelling, and the benefits of dermotomy are documented.11 Generally, early administration of antivenom will decrease local tissue reaction and prevent additional tissue loss.12 In our patient, the decision to perform dermotomy was made when the area of necrosis had declared itself and the skin reached its elastic limit. Bozkurt et al13 described the neurovascular bundles within the digit as functioning as small compartments. When the skin of the digit reaches its elastic limit, pressure within the compartment may exceed the capillary closing pressure, and the integrity of small vessels and nerves may be compromised. Our case highlights the benefit of dermotomy as well as the functional and cosmetic results that can be achieved.

Wound Care for Snakebites

There is little published on the treatment of snakebites after patients are stabilized medically for hospital discharge. Venomous snakes inject toxins that predominantly consist of enzymes (eg, phospholipase A2, phosphodiesterase, hyaluronidase, peptidase, metalloproteinase) that cause tissue destruction through diverse mechanisms.14 The venom of western pygmy rattlesnakes is hemotoxic and can cause necrotic hemorrhagic ulceration,4 as was the case in our patient.

Silver sulfadiazine commonly is used to prevent infection in burn patients. Given the large surface area of exposed dermis after debridement and concern for infection, silver sulfadiazine was chosen in our patient for local wound care treatment. Silver sulfadiazine is a widely available and low-cost drug.15 Its antibacterial effects are due to the silver ions, which only act superficially and therefore limit systemic absorption.16 Application should be performed in a clean manner with minimal trauma to the tissue. This technique is best achieved by using sterile gloves and applying the medication manually. A 0.0625-inch layer should be applied to entirely cover the cleaned debrided area.17 When performing application with tongue blades or cotton swabs, it is important to never “double dip.” Patient education on proper administration is imperative to a successful outcome.

Final Thoughts

Our case demonstrates the safe use of Crotalidae polyvalent immune fab antivenom for the treatment of western pygmy rattlesnake (S miliarius streckeri) envenomation. Early administration of antivenom following pit viper rattlesnake envenomations is important to mitigate systemic effects and the extent of soft tissue damage. There are few studies on local wound care treatment after rattlesnake envenomation. This case highlights the role of dermotomy and wound care with silver sulfadiazine cream 1%.

- Biggers B. Management of Missouri snake bites. Mo Med. 2017;114:254-257.

- Stamm R. Sistrurus miliarius pigmy rattlesnake. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Sistrurus_miliarius/

- Missouri Department of Conservation. Western pygmy rattlesnake. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/western-pygmy-rattlesnake

- AnimalSake. Facts about the pigmy rattlesnake that are sure to surprise you. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://animalsake.com/pygmy-rattlesnake

- King AM, Crim WS, Menke NB, et al. Pygmy rattlesnake envenomation treated with crotalidae polyvalent immune fab antivenom. Toxicon. 2012;60:1287-1289.

- Juckett G, Hancox JG. Venomous snakebites in the United States: management review and update. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:1367-1375.

- Toschlog EA, Bauer CR, Hall EL, et al. Surgical considerations in the management of pit viper snake envenomation. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:726-735.

- Cribari C. Management of poisonous snakebite. American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma; 2004. https://www.hartcountyga.gov/documents/PoisonousSnakebiteTreatment.pdf

- Walker JP, Morrison RL. Current management of copperhead snakebite. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:470-474.

- Gelman D, Bates T, Nuelle JAV. Septic arthritis of the proximal interphalangeal joint after rattlesnake bite. J Hand Surg Am. 2022;47:484.e1-484.e4.

- Watt CH Jr. Treatment of poisonous snakebite with emphasis on digit dermotomy. South Med J. 1985;78:694-699.

- Corneille MG, Larson S, Stewart RM, et al. A large single-center experience with treatment of patients with crotalid envenomations: outcomes with and evolution of antivenin therapy. Am J Surg. 2006;192:848-852.

- Bozkurt M, Kulahci Y, Zor F, et al. The management of pit viper envenomation of the hand. Hand (NY). 2008;3:324-331.

- Aziz H, Rhee P, Pandit V, et al. The current concepts in management of animal (dog, cat, snake, scorpion) and human bite wounds. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:641-648.

- Hummel RP, MacMillan BG, Altemeier WA. Topical and systemic antibacterial agents in the treatment of burns. Ann Surg. 1970;172:370-384.

- Modak SM, Sampath L, Fox CL. Combined topical use of silver sulfadiazine and antibiotics as a possible solution to bacterial resistance in burn wounds. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1988;9:359-363.

- Oaks RJ, Cindass R. Silver sulfadiazine. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated January 22, 2023. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556054/

- Biggers B. Management of Missouri snake bites. Mo Med. 2017;114:254-257.

- Stamm R. Sistrurus miliarius pigmy rattlesnake. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Sistrurus_miliarius/

- Missouri Department of Conservation. Western pygmy rattlesnake. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/western-pygmy-rattlesnake

- AnimalSake. Facts about the pigmy rattlesnake that are sure to surprise you. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://animalsake.com/pygmy-rattlesnake

- King AM, Crim WS, Menke NB, et al. Pygmy rattlesnake envenomation treated with crotalidae polyvalent immune fab antivenom. Toxicon. 2012;60:1287-1289.

- Juckett G, Hancox JG. Venomous snakebites in the United States: management review and update. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:1367-1375.

- Toschlog EA, Bauer CR, Hall EL, et al. Surgical considerations in the management of pit viper snake envenomation. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:726-735.

- Cribari C. Management of poisonous snakebite. American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma; 2004. https://www.hartcountyga.gov/documents/PoisonousSnakebiteTreatment.pdf

- Walker JP, Morrison RL. Current management of copperhead snakebite. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:470-474.

- Gelman D, Bates T, Nuelle JAV. Septic arthritis of the proximal interphalangeal joint after rattlesnake bite. J Hand Surg Am. 2022;47:484.e1-484.e4.

- Watt CH Jr. Treatment of poisonous snakebite with emphasis on digit dermotomy. South Med J. 1985;78:694-699.

- Corneille MG, Larson S, Stewart RM, et al. A large single-center experience with treatment of patients with crotalid envenomations: outcomes with and evolution of antivenin therapy. Am J Surg. 2006;192:848-852.

- Bozkurt M, Kulahci Y, Zor F, et al. The management of pit viper envenomation of the hand. Hand (NY). 2008;3:324-331.

- Aziz H, Rhee P, Pandit V, et al. The current concepts in management of animal (dog, cat, snake, scorpion) and human bite wounds. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:641-648.

- Hummel RP, MacMillan BG, Altemeier WA. Topical and systemic antibacterial agents in the treatment of burns. Ann Surg. 1970;172:370-384.

- Modak SM, Sampath L, Fox CL. Combined topical use of silver sulfadiazine and antibiotics as a possible solution to bacterial resistance in burn wounds. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1988;9:359-363.

- Oaks RJ, Cindass R. Silver sulfadiazine. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated January 22, 2023. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556054/

Practice Points

- Patients should seek medical attention immediately for western pygmy rattlesnake bites for early initiation of antivenom treatment.

- Contact the closest emergency department to confirm they are equipped to treat rattlesnake bites and notify them of a pending arrival.

- Consider dermotomy or local debridement of bites involving the digits.

- Monitor the wound in the days and weeks following the bite to ensure adequate healing.

Multiple Painless Whitish Papules on the Vulva and Perianal Region

THE DIAGNOSIS: Papular Acantholytic Dyskeratosis

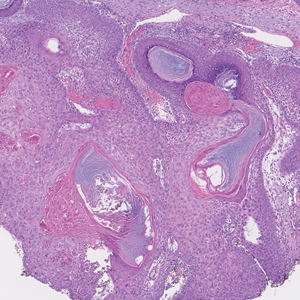

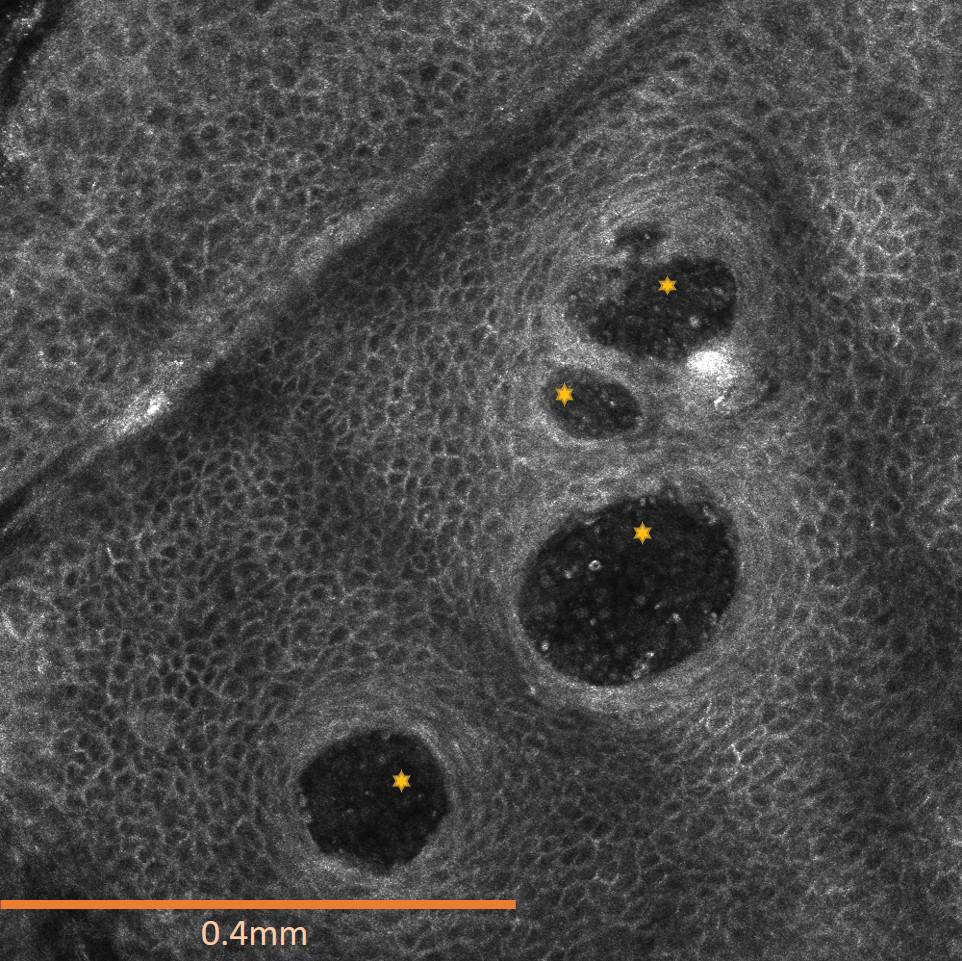

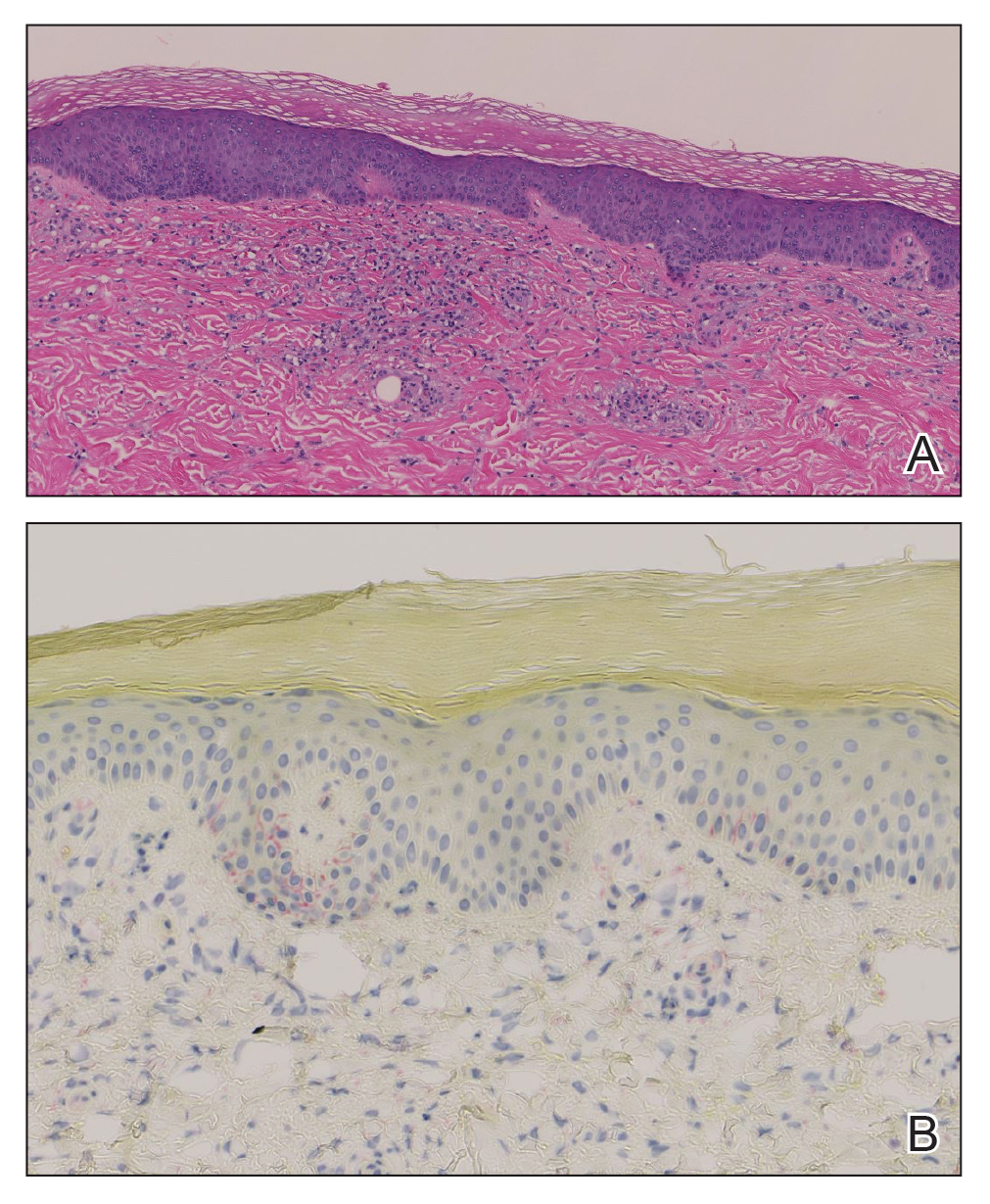

Histopathology of the lesion in our patient revealed hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, dyskeratosis, and acantholysis of keratinocytes. The dermis showed variable chronic inflammatory cells. Corps ronds and grains in the acantholytic layer of the epidermis were identified. Hair follicles were not affected by acantholysis. Anti–desmoglein 1 and anti–desmoglein 3 serum antibodies were negative. Based on the combined clinical and histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with papular acantholytic dyskeratosis (PAD) of the genitocrural area.

Although its typical histopathologic pattern mimics both Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier disease, PAD is a rare unique clinicopathologic entity recognized by dermatopathologists. It usually occurs in middle-aged women with no family history of similar conditions. The multiple localized, flesh-colored to whitish papules of PAD tend to coalesce into plaques in the anogenital and genitocrural regions. Plaques usually are asymptomatic but may be pruritic. Histopathologically, PAD will demonstrate hyperkeratosis, dyskeratosis, and acantholysis. Corps ronds and grains will be present in the acantholytic layer of the epidermis.1,2

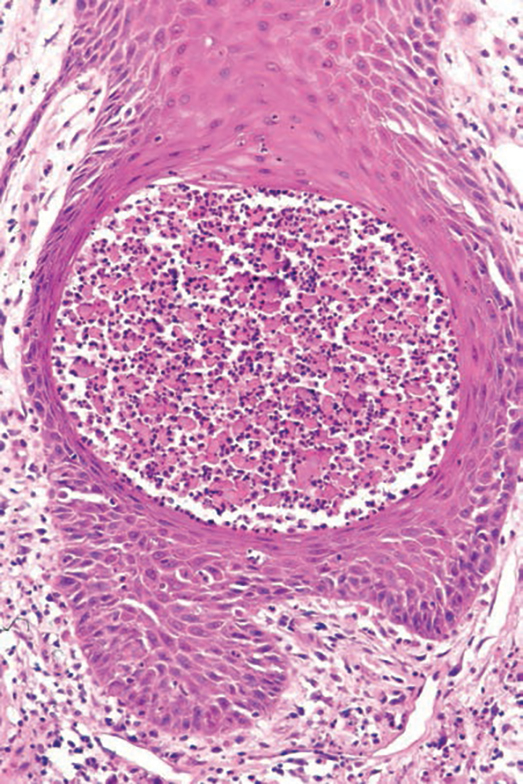

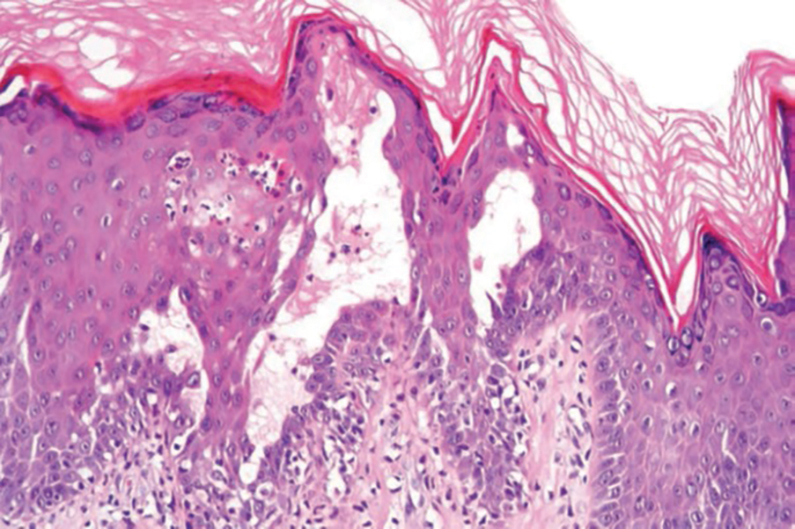

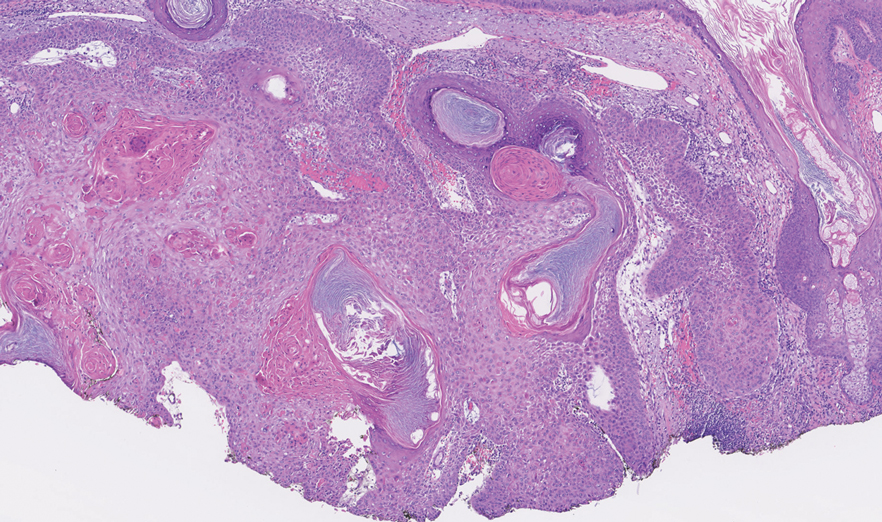

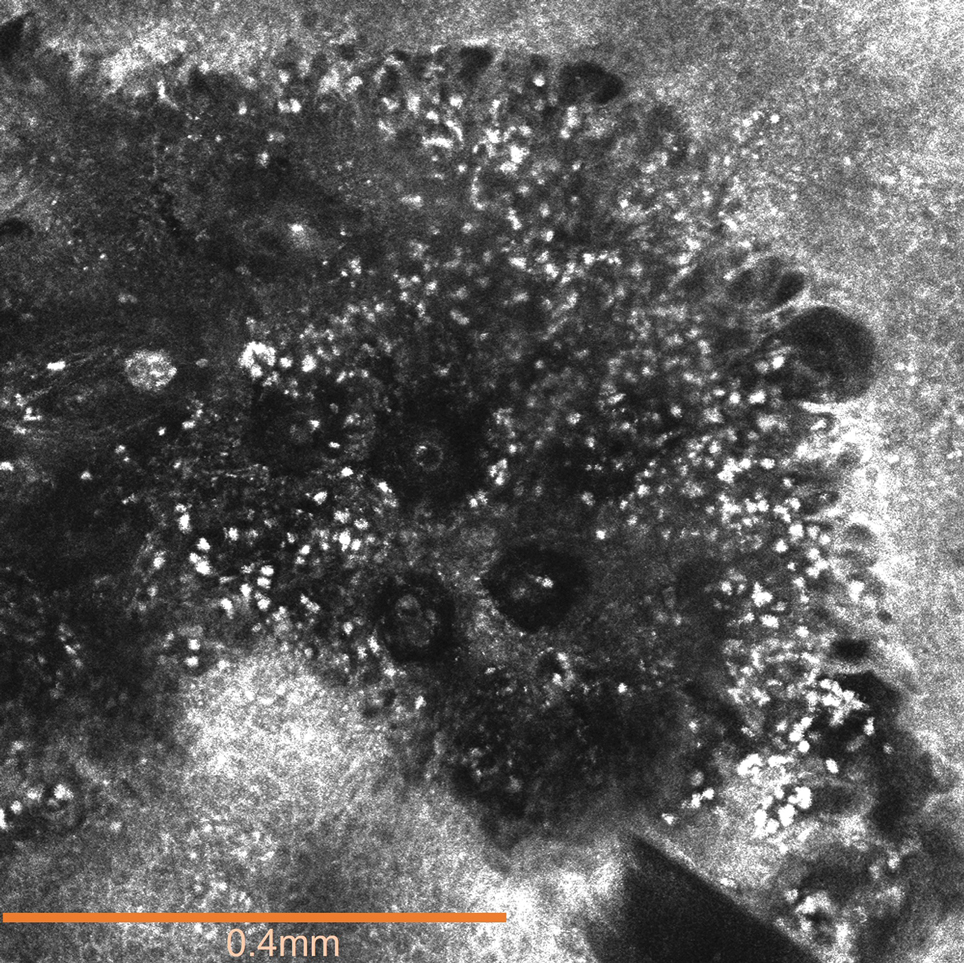

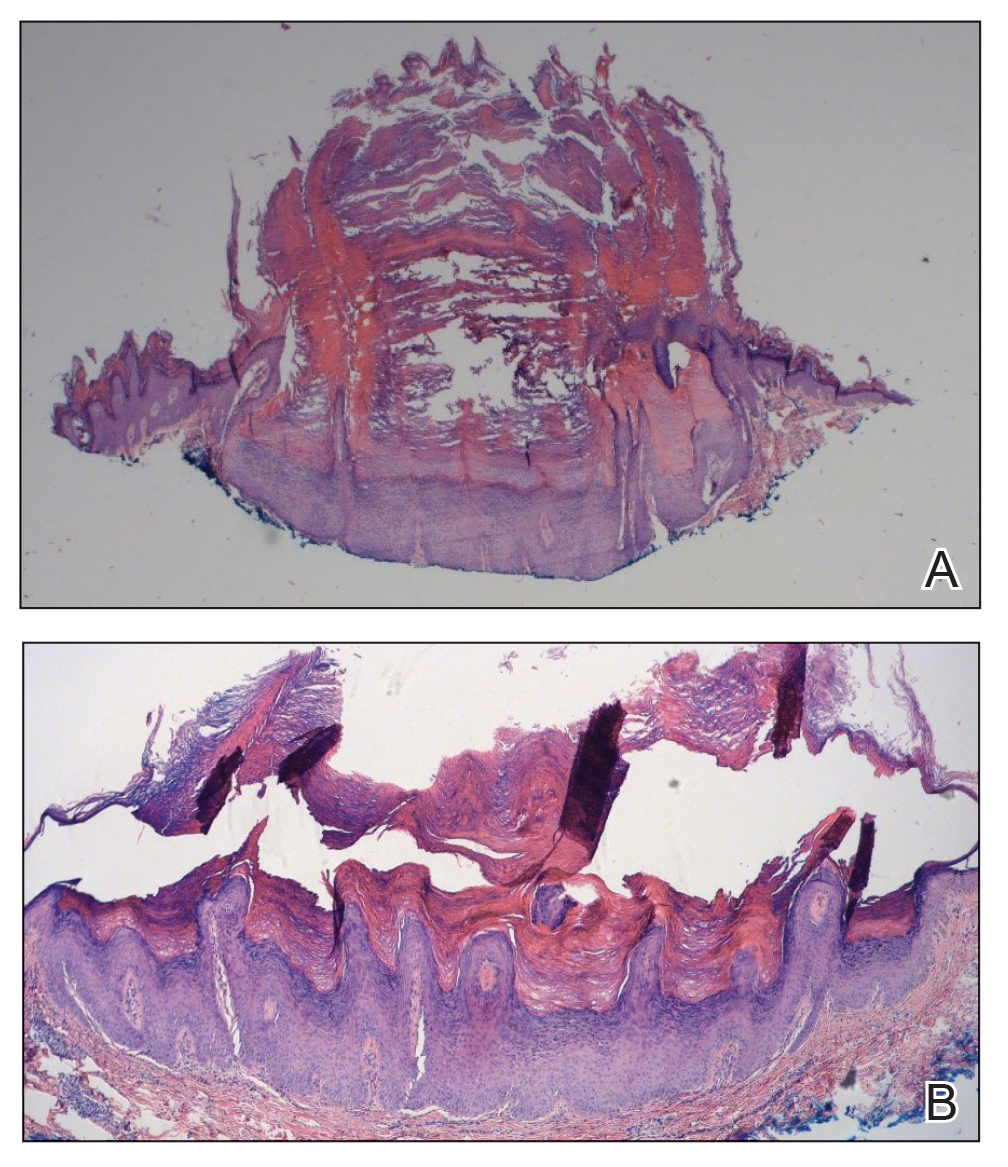

The differential diagnosis for PAD includes pemphigus vegetans, Hailey-Hailey disease, Darier disease, and Grover disease. Patients usually develop pemphigus vegetans at an older age (typically 50–70 years).3 Histopathologically, it is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with an eosinophilic microabscess as well as acantholysis that involves the follicular epithelium (Figure 1),4 which were not seen in our patient. Direct immunofluorescence will show the intercellular pattern of the pemphigus group, and antidesmoglein antibodies can be detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.4,5

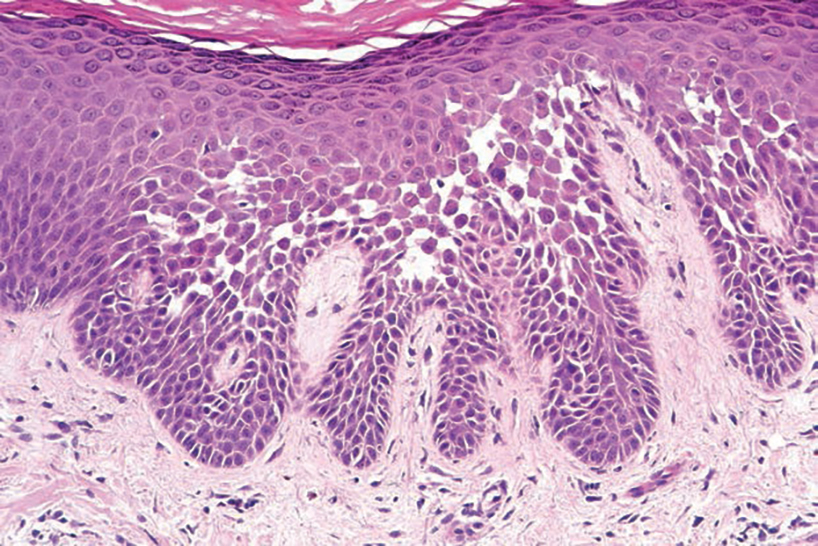

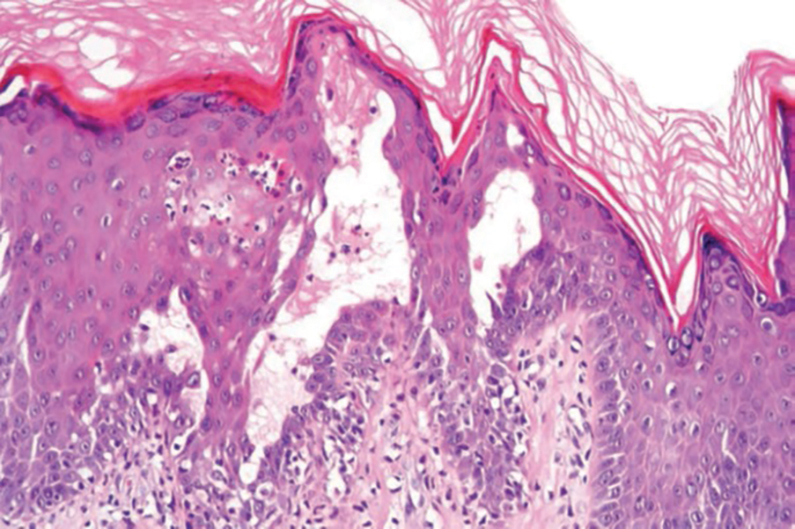

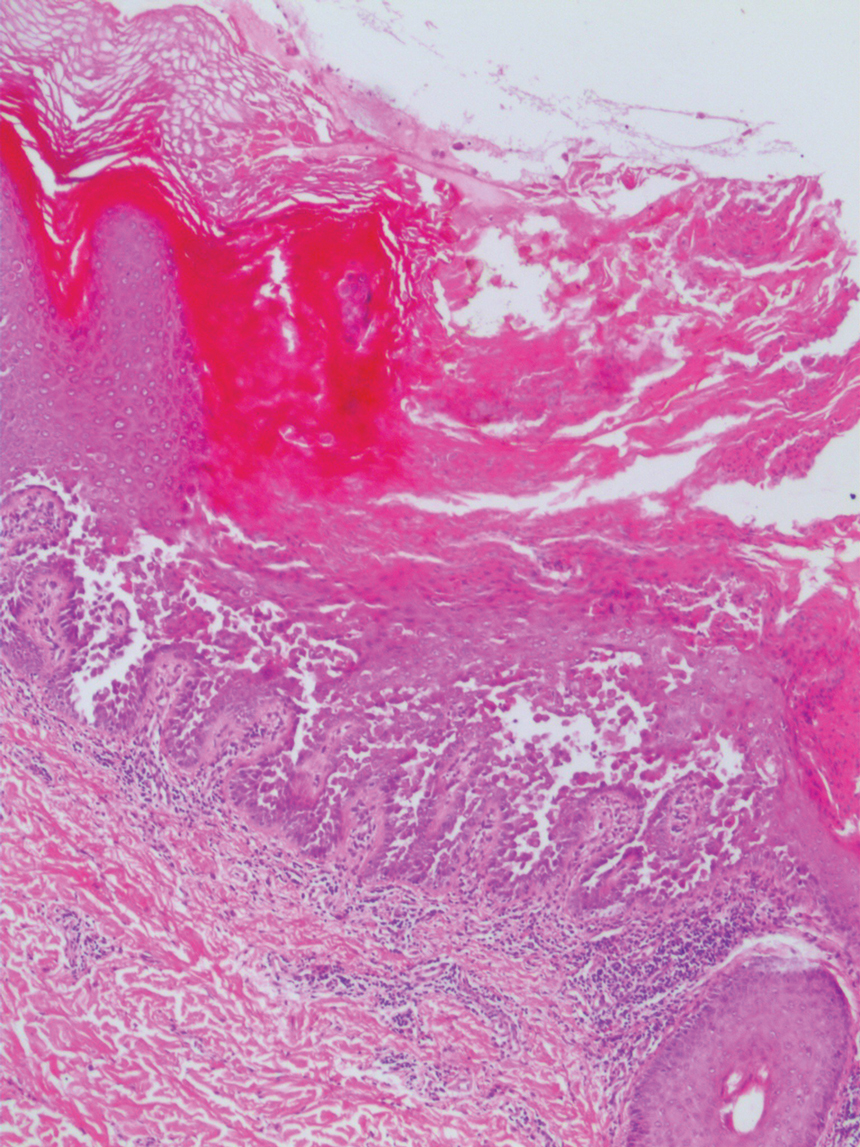

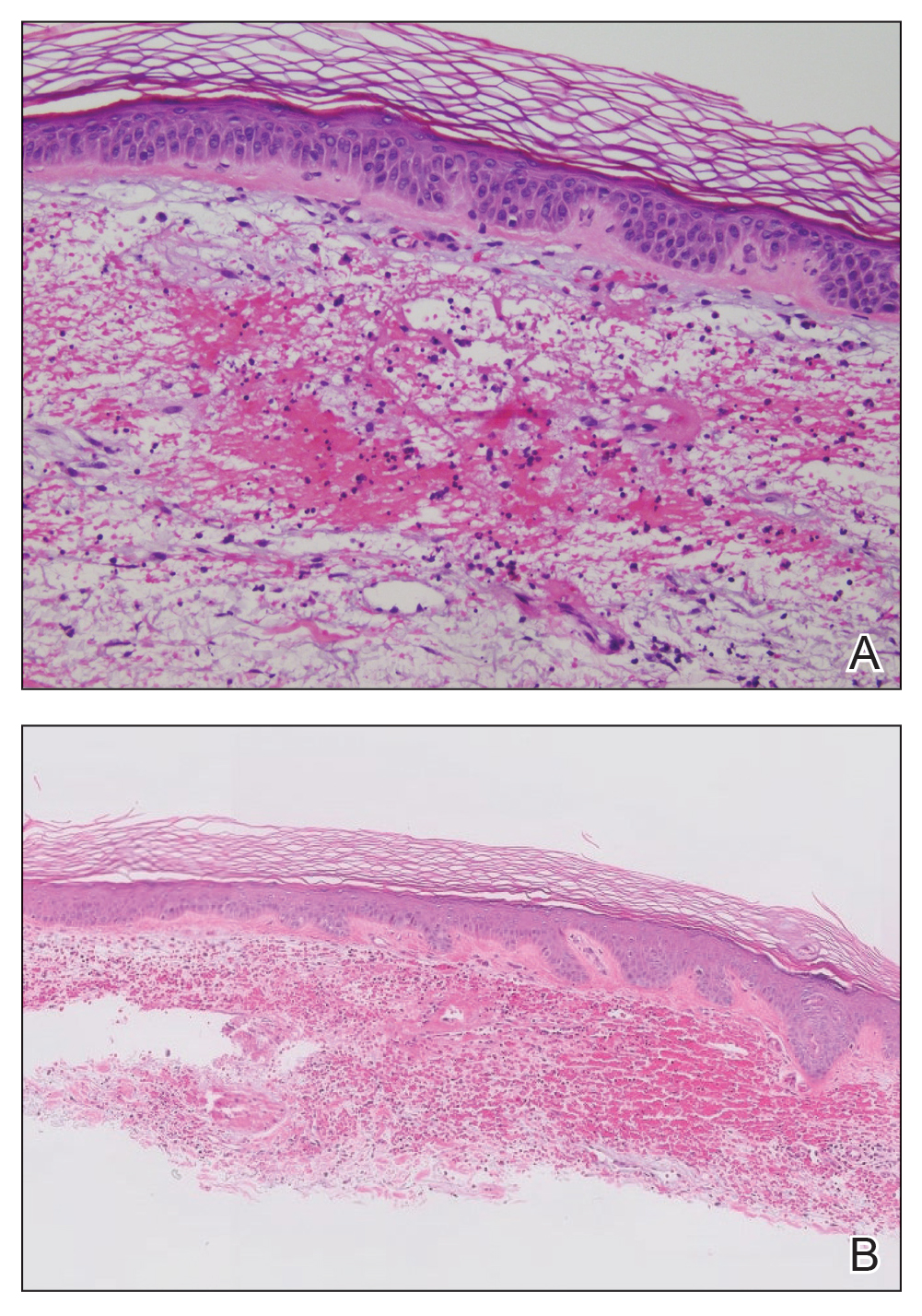

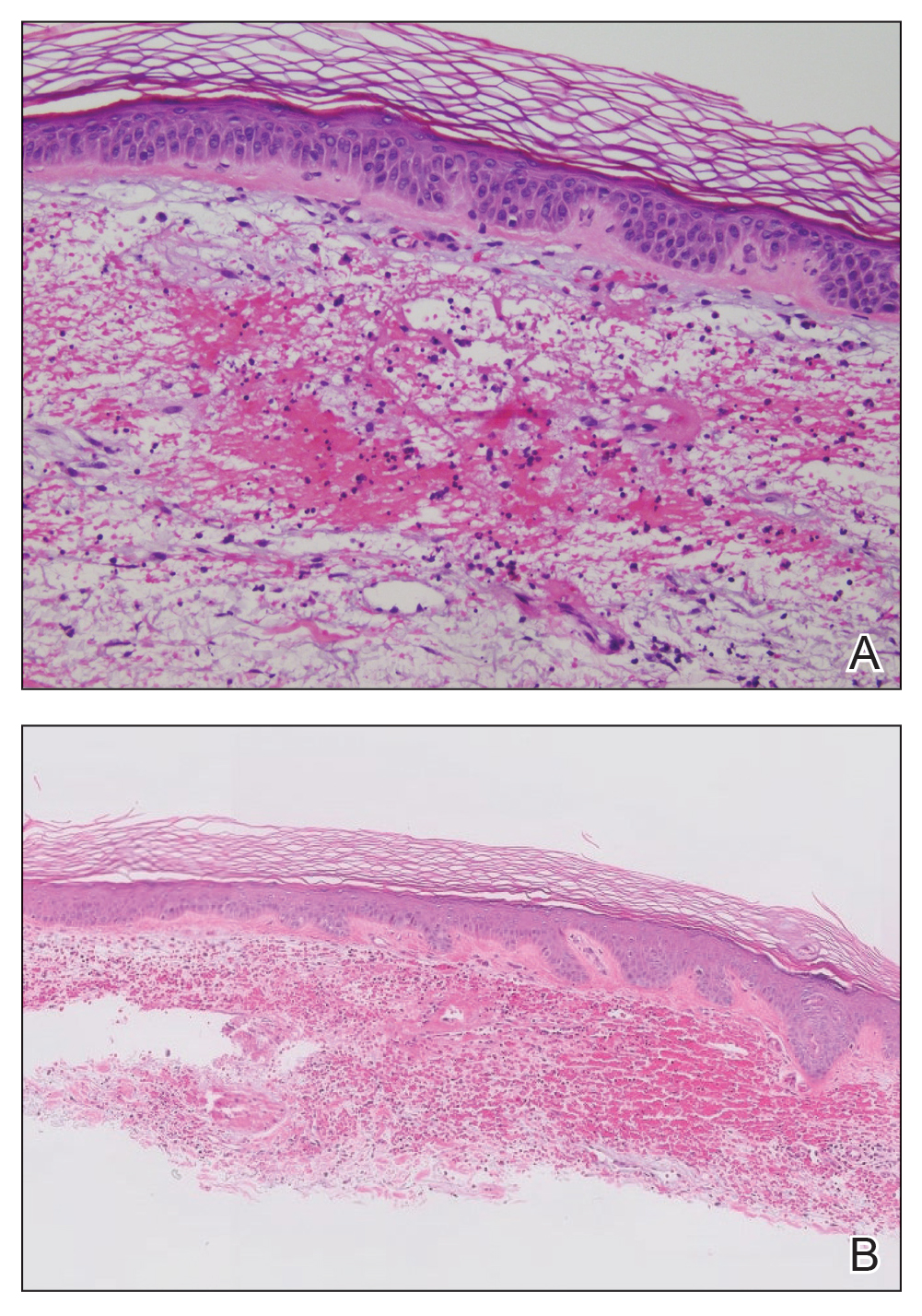

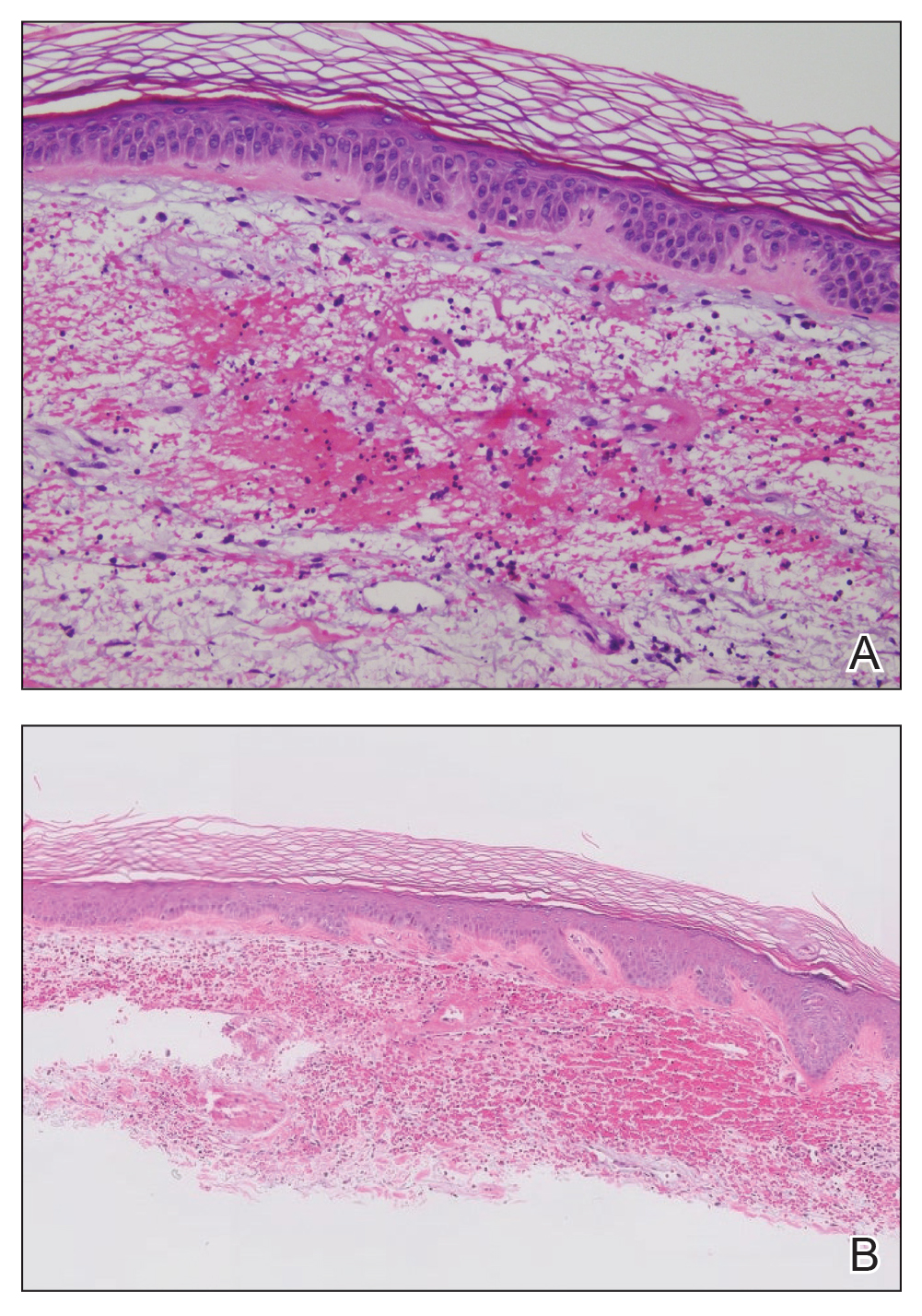

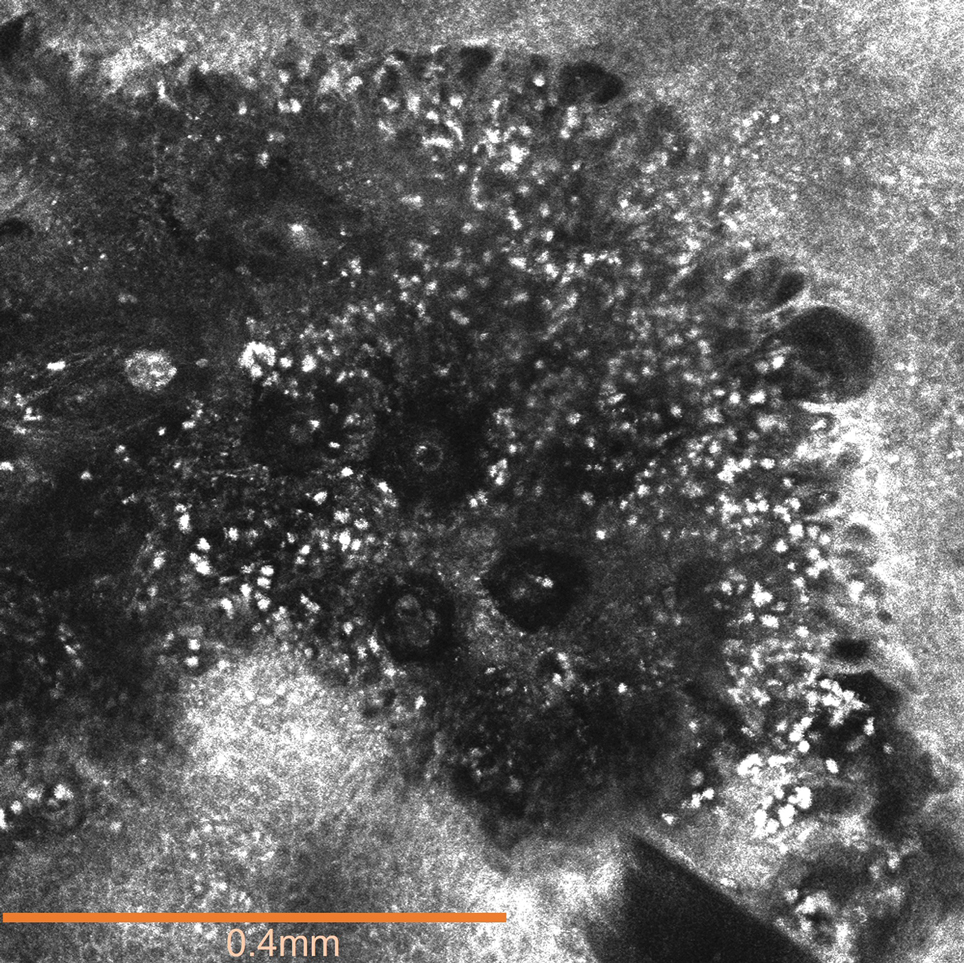

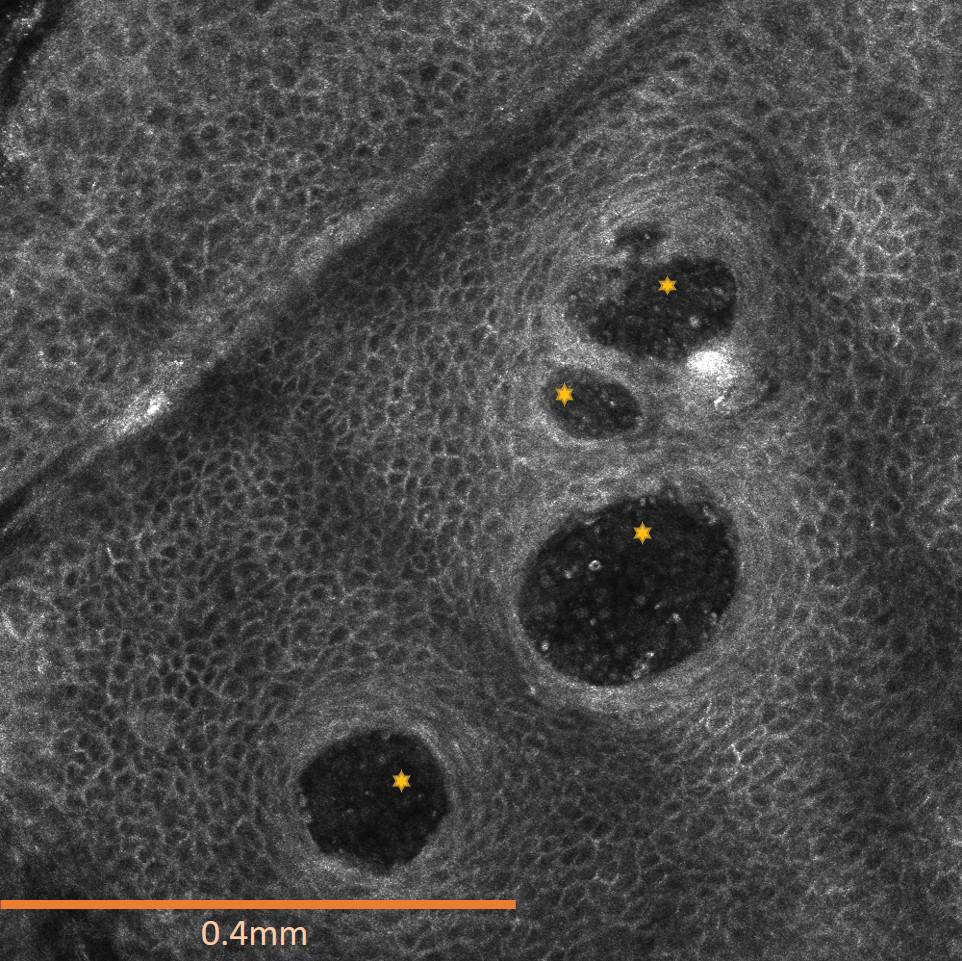

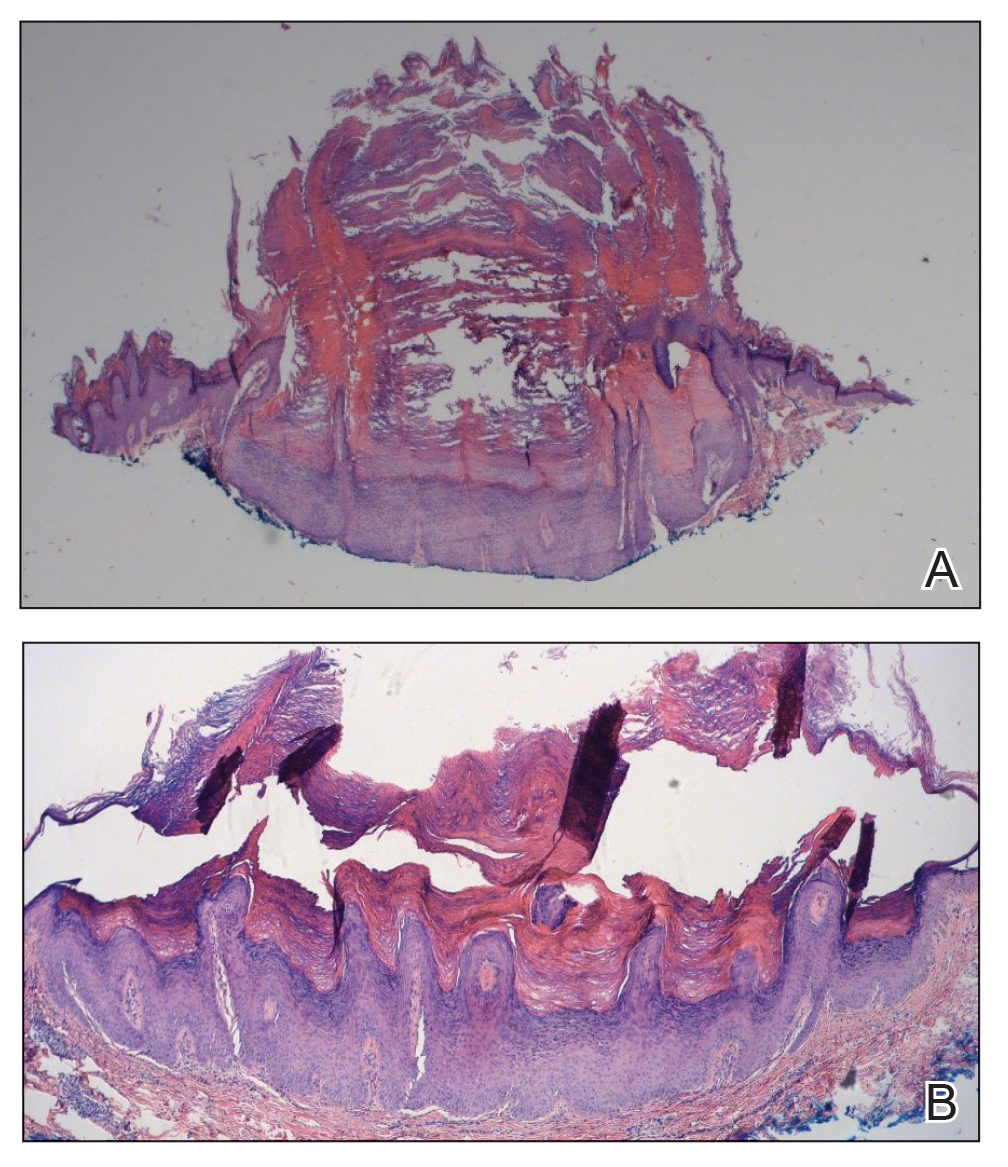

Hailey-Hailey disease (also known as benign familial pemphigus) typically manifests as itchy malodorous vesicles and erosions, especially in intertriginous areas. The most commonly affected sites are the groin, neck, under the breasts, and between the buttocks. In one study, two-thirds of affected patients reported a relevant family history.4 Histopathology will show minimal dyskeratosis and suprabasilar acantholysis with loss of intercellular bridges, classically described as resembling a dilapidated brick wall (Figure 2).4,5 There is no notable follicular involvement with acantholysis.4

characteristic dilapidated brick wall appearance (H&E, original

magnification ×40).

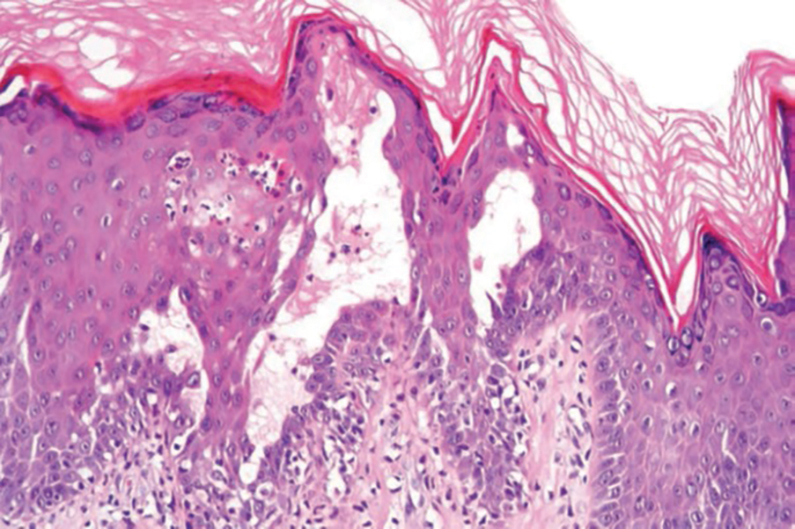

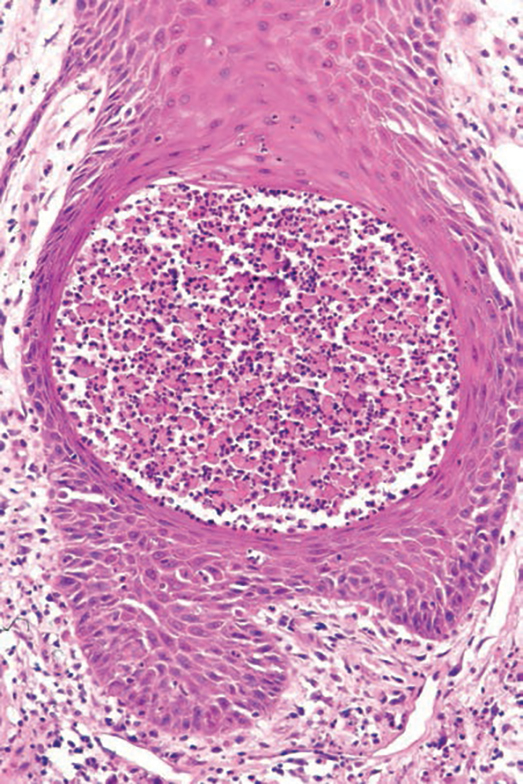

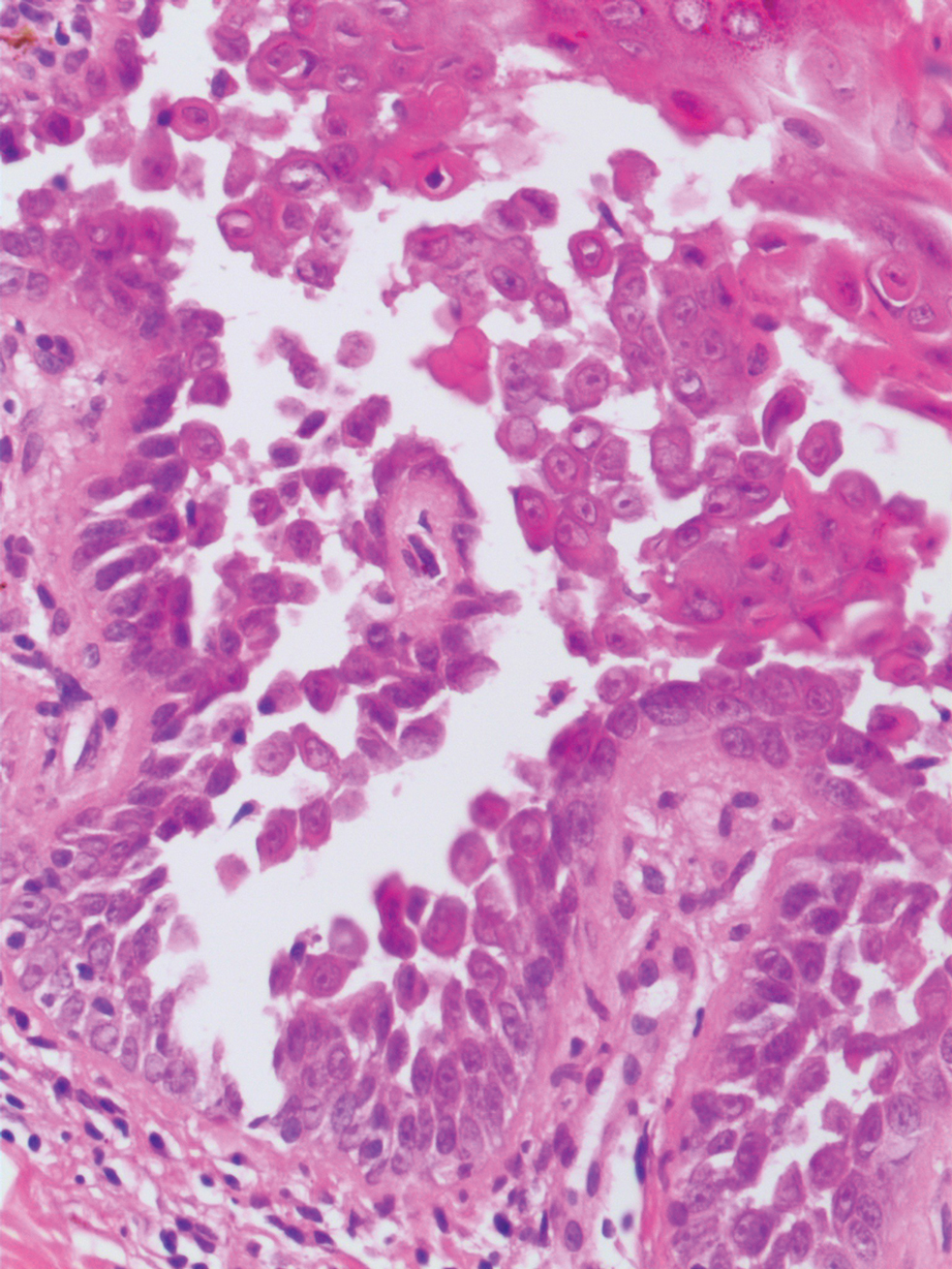

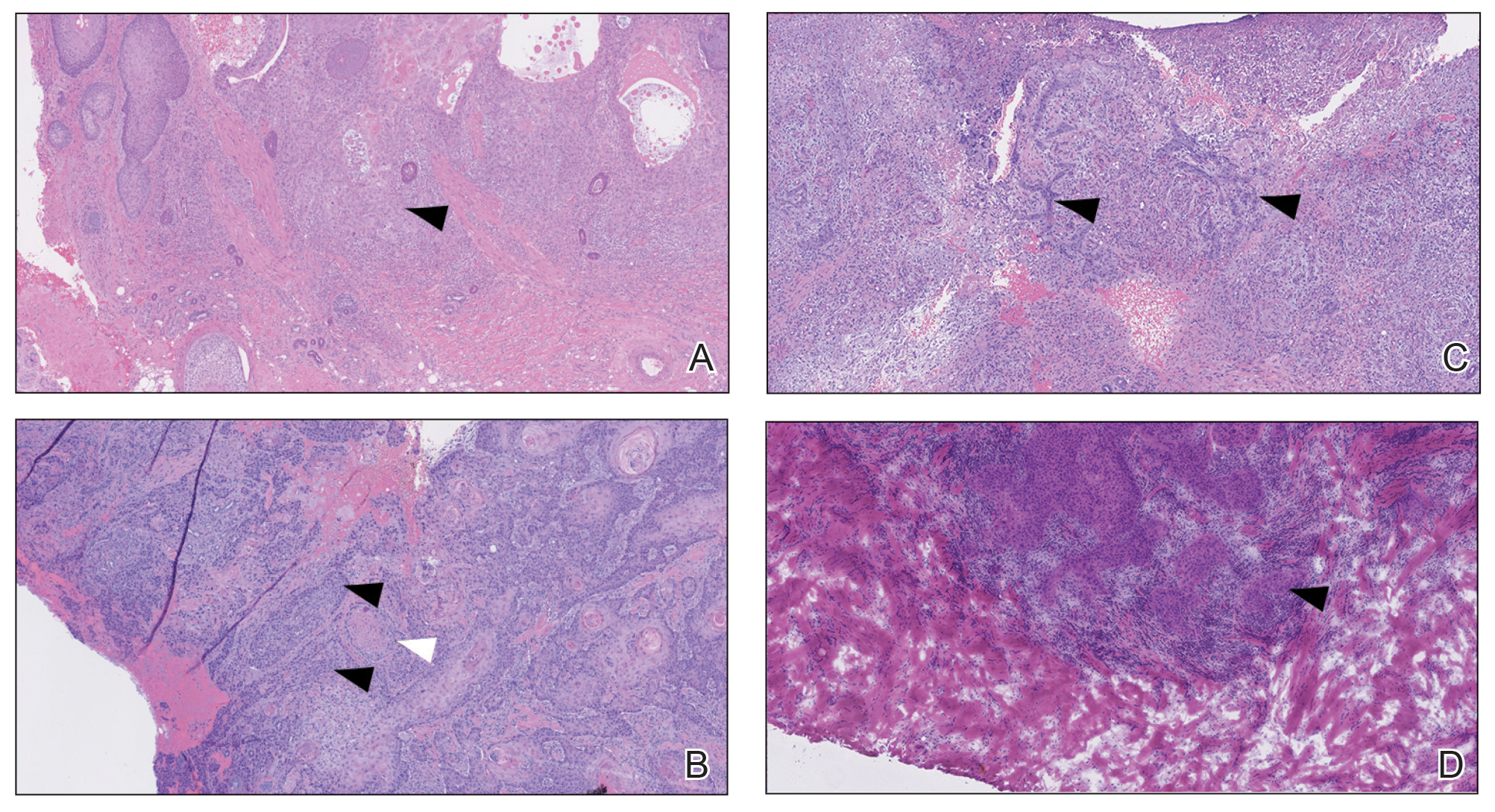

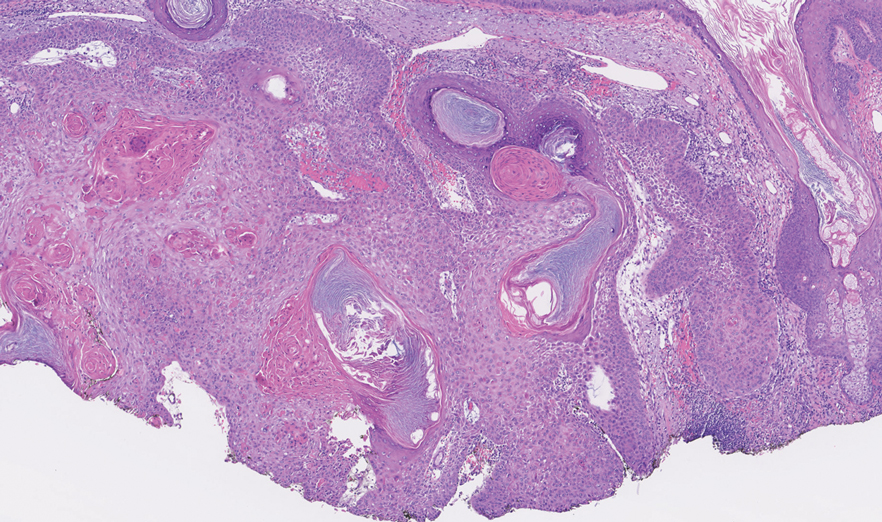

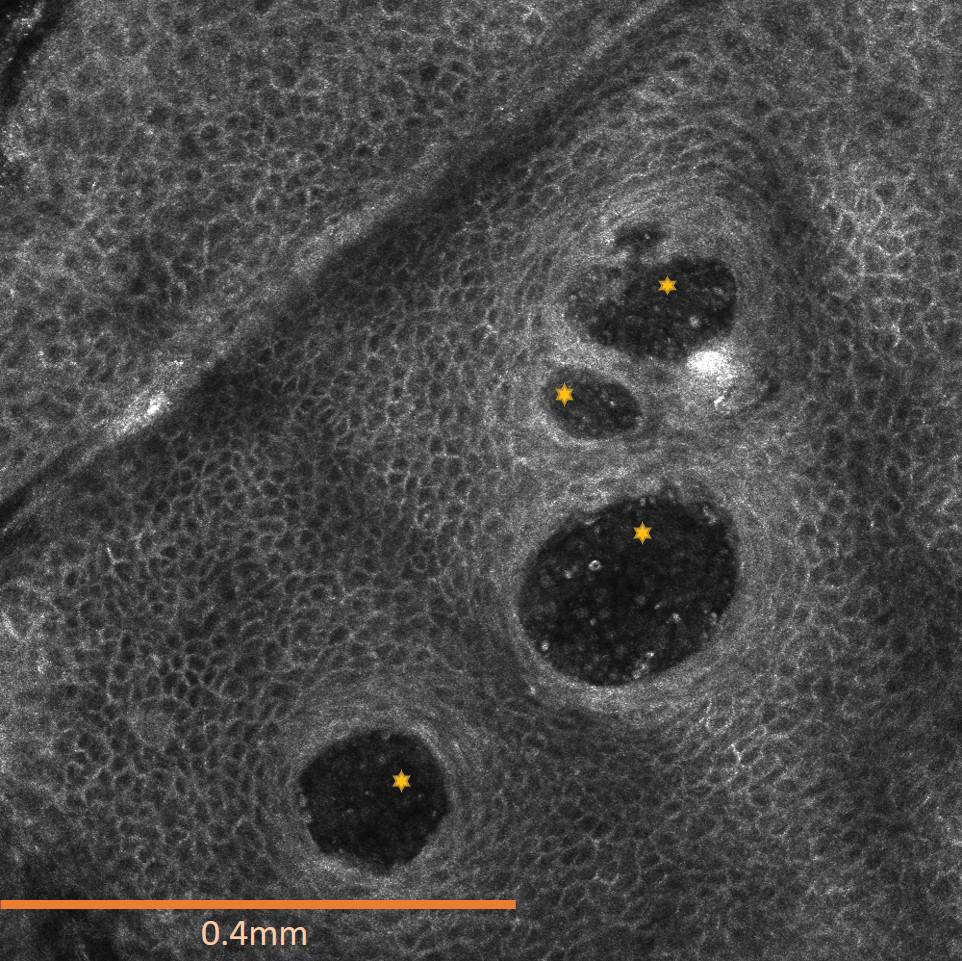

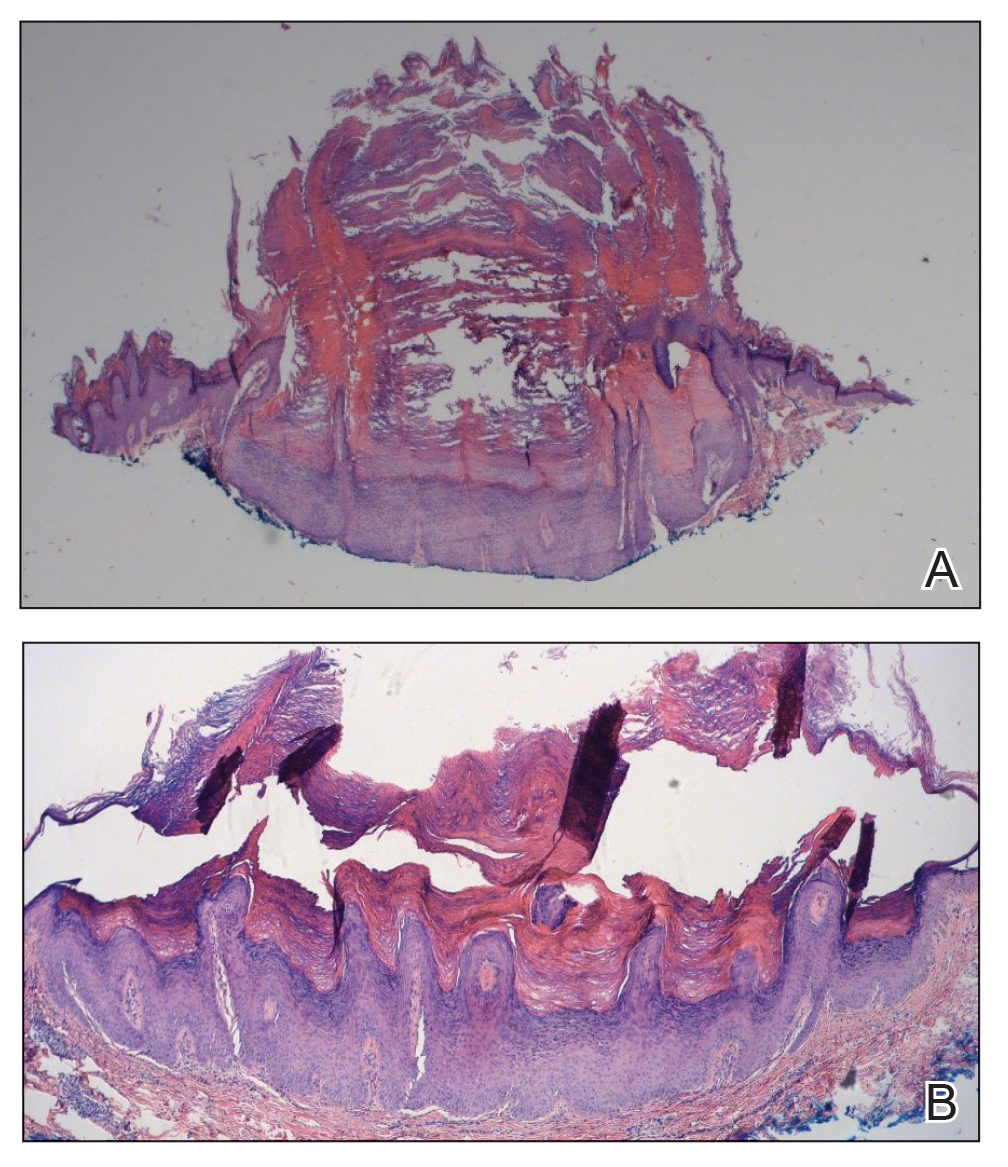

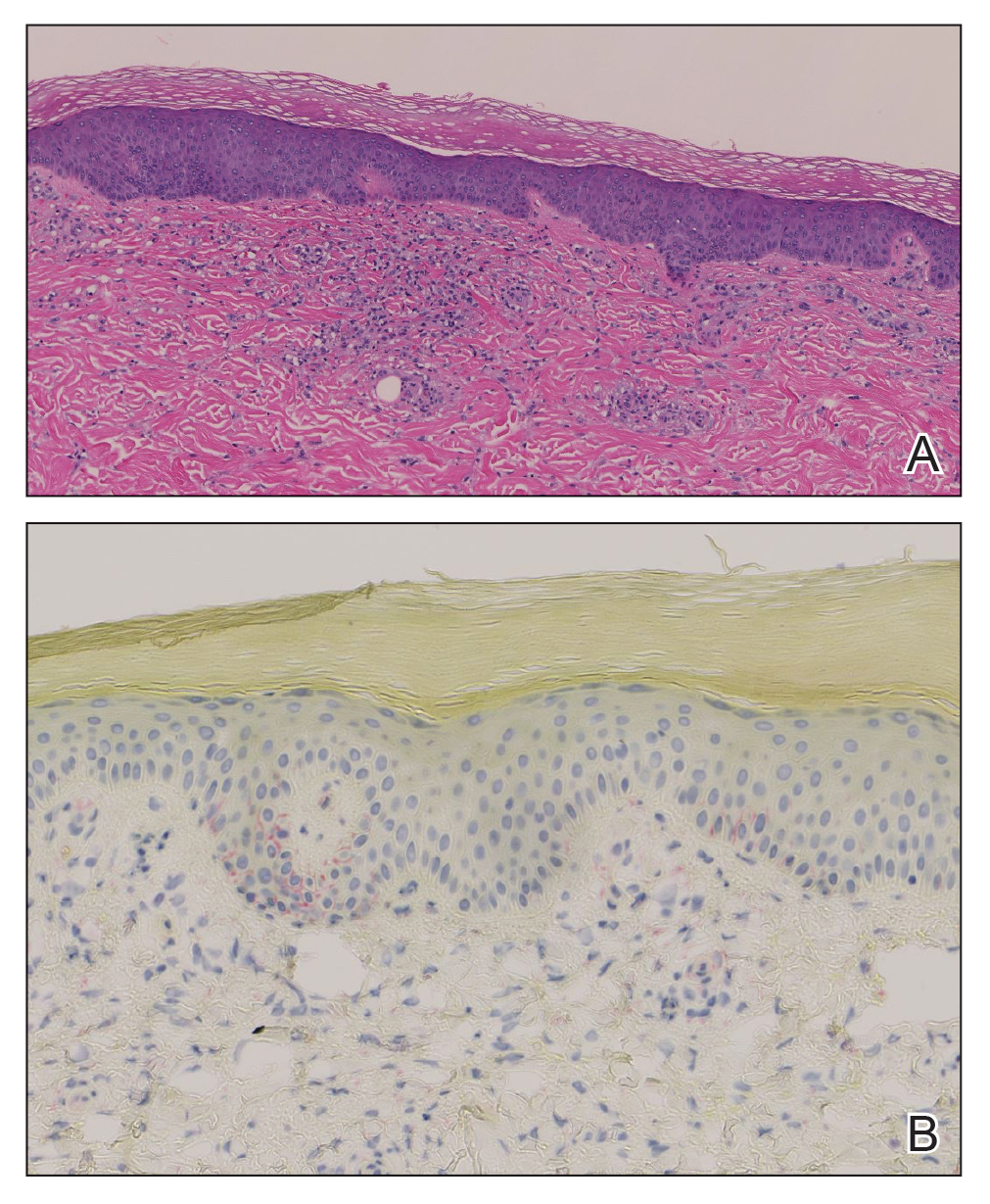

Darier disease (also known as keratosis follicularis) typically is inherited in an autosomal-dominant pattern.4 It is found on the seborrheic areas such as the scalp, forehead, nasolabial folds, and upper chest. Characteristic features include distal notching of the nails, mucosal lesions, and palmoplantar papules. Histopathology will reveal acantholysis, dyskeratosis, suprabasilar acantholysis, and corps ronds and grains.4 Acantholysis in Darier disease can be in discrete foci and/or widespread (Figure 3).4 Darier disease demonstrates more dyskeratosis than Hailey-Hailey disease.4,5

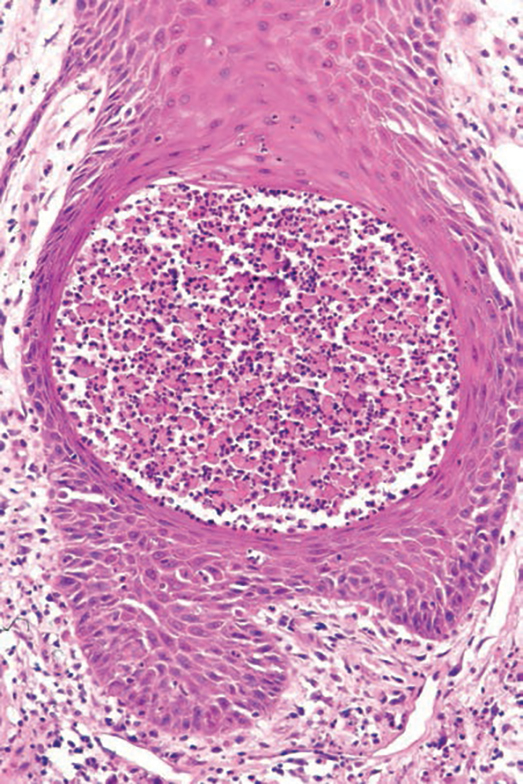

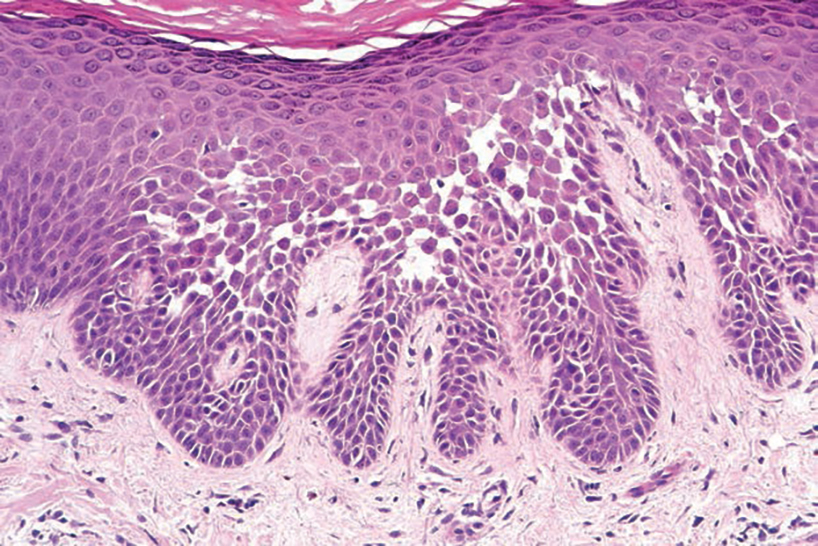

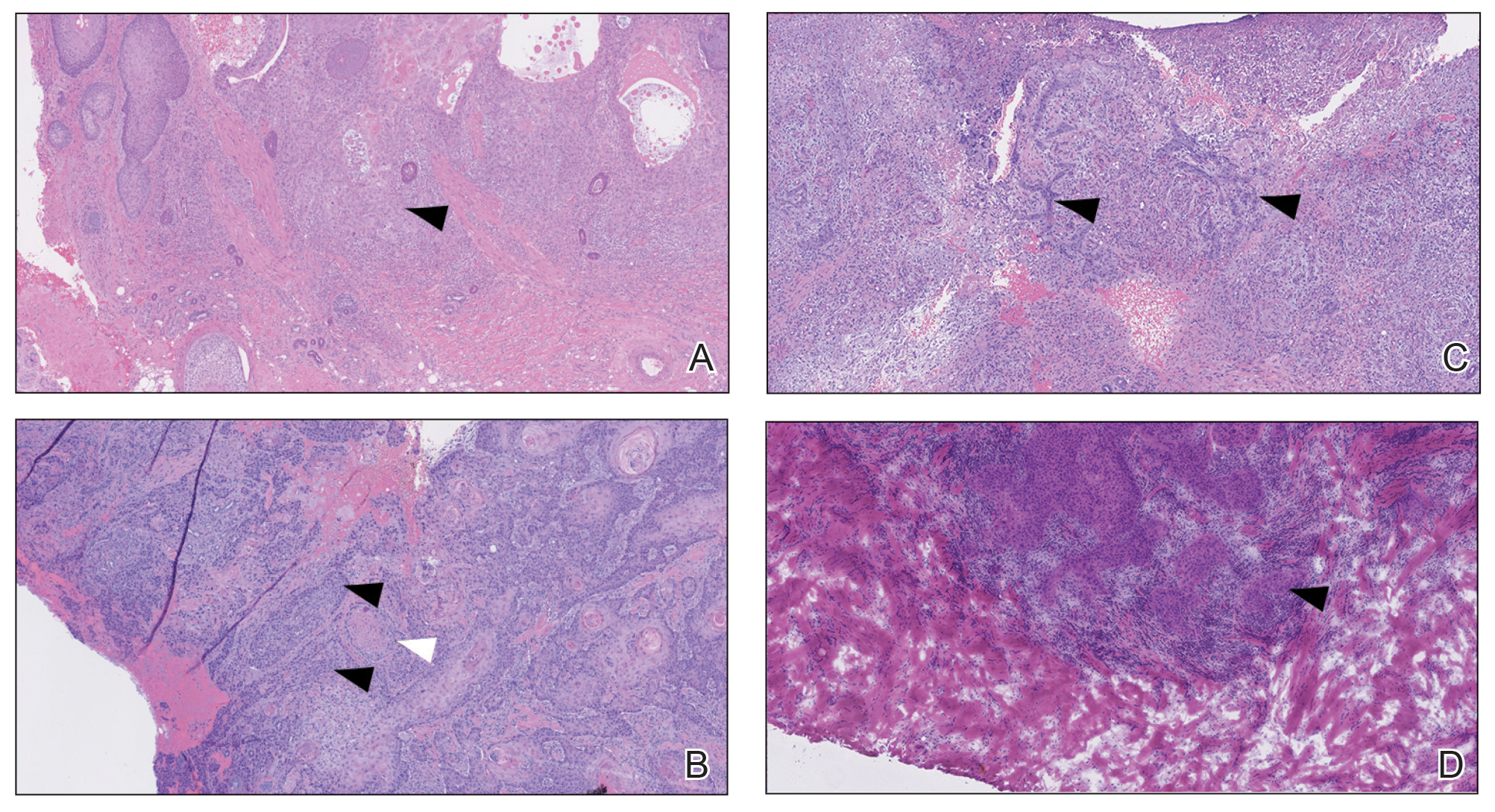

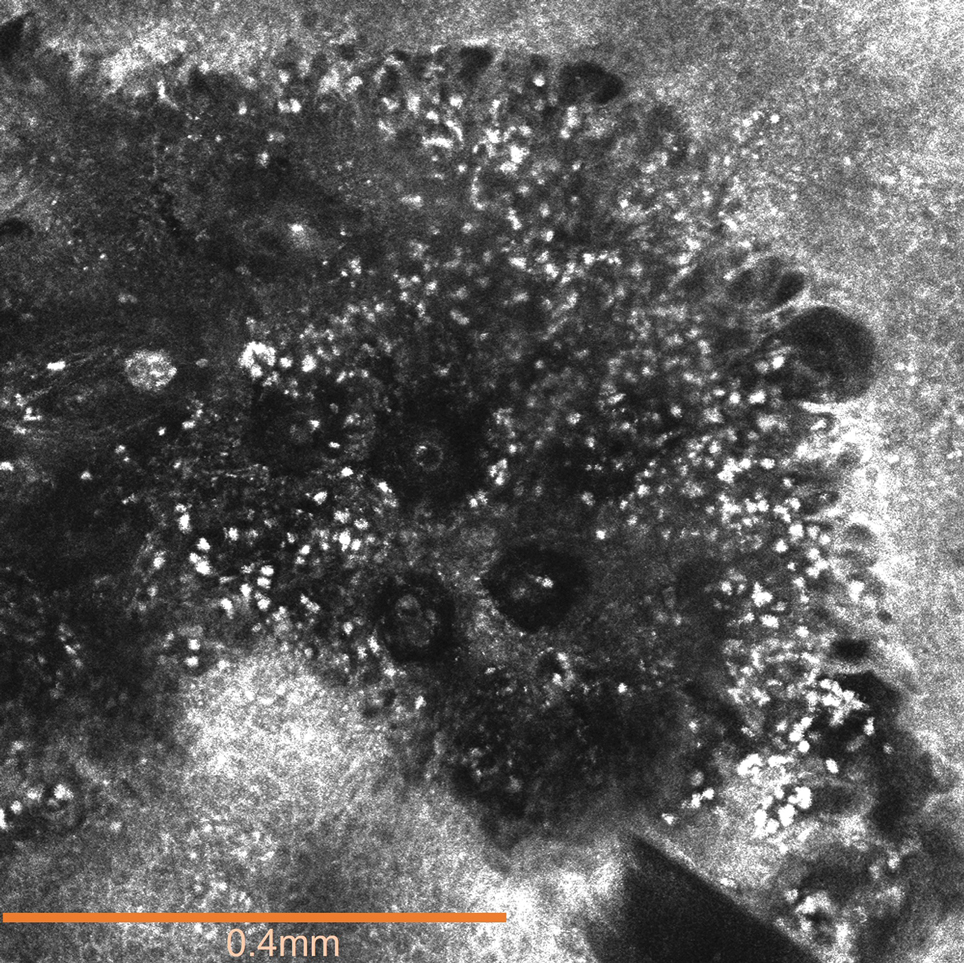

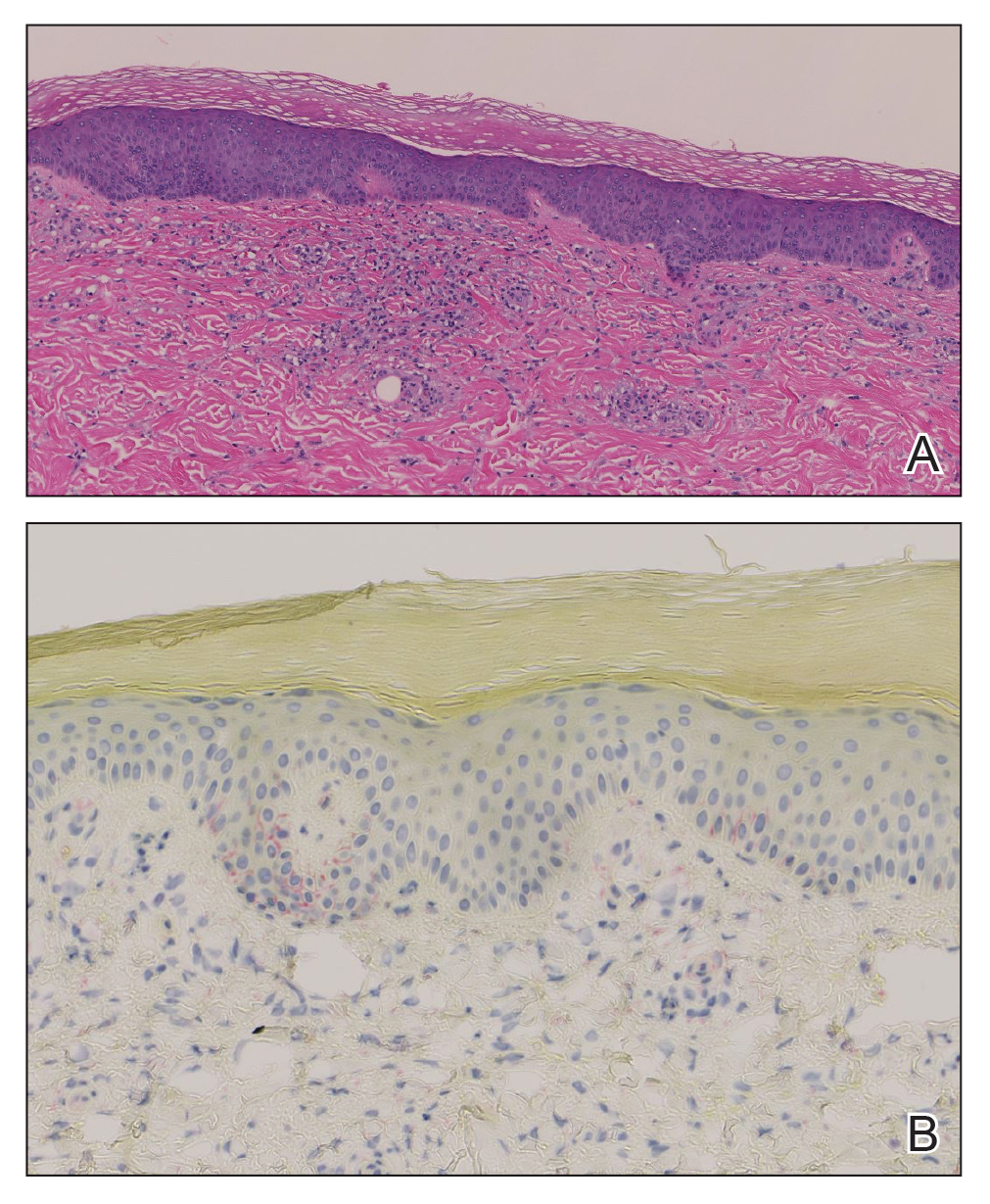

Grover disease (also referred to as transient acantholytic dermatosis) is observed predominantly in individuals who are middle-aged or older, though occurrence in children has been rarely reported.4 It affects the trunk, neck, and proximal limbs but spares the genital area. Histopathology may reveal acantholysis (similar to Hailey-Hailey disease or pemphigus vulgaris), dyskeratosis (resembling Darier disease), spongiosis, parakeratosis, and a superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with eosinophils.4 A histologic clue to the diagnosis is small lesion size (1–3 mm). Usually, only 1 or 2 small discrete lesions that span a few rete ridges are noted (Figure 4).4 Grover disease can cause follicular or acrosyringeal involvement.4

- Al-Muriesh M, Abdul-Fattah B, Wang X, et al. Papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the anogenital and genitocrural area: case series and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:749-758. doi:10.1111/cup.12736

- Harrell J, Nielson C, Beers P, et al. Eruption on the vulva and groin. JAAD Case Reports. 2019;6:6-8. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.11.003

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 26, 2023. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545229

- Acantholytic disorders. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin: With Clinical Correlations. Elsevier/ Saunders; 2012:171-200.

- Mohr MR, Erdag G, Shada AL, et al. Two patients with Hailey- Hailey disease, multiple primary melanomas, and other cancers. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:211215. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.445

THE DIAGNOSIS: Papular Acantholytic Dyskeratosis

Histopathology of the lesion in our patient revealed hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, dyskeratosis, and acantholysis of keratinocytes. The dermis showed variable chronic inflammatory cells. Corps ronds and grains in the acantholytic layer of the epidermis were identified. Hair follicles were not affected by acantholysis. Anti–desmoglein 1 and anti–desmoglein 3 serum antibodies were negative. Based on the combined clinical and histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with papular acantholytic dyskeratosis (PAD) of the genitocrural area.

Although its typical histopathologic pattern mimics both Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier disease, PAD is a rare unique clinicopathologic entity recognized by dermatopathologists. It usually occurs in middle-aged women with no family history of similar conditions. The multiple localized, flesh-colored to whitish papules of PAD tend to coalesce into plaques in the anogenital and genitocrural regions. Plaques usually are asymptomatic but may be pruritic. Histopathologically, PAD will demonstrate hyperkeratosis, dyskeratosis, and acantholysis. Corps ronds and grains will be present in the acantholytic layer of the epidermis.1,2

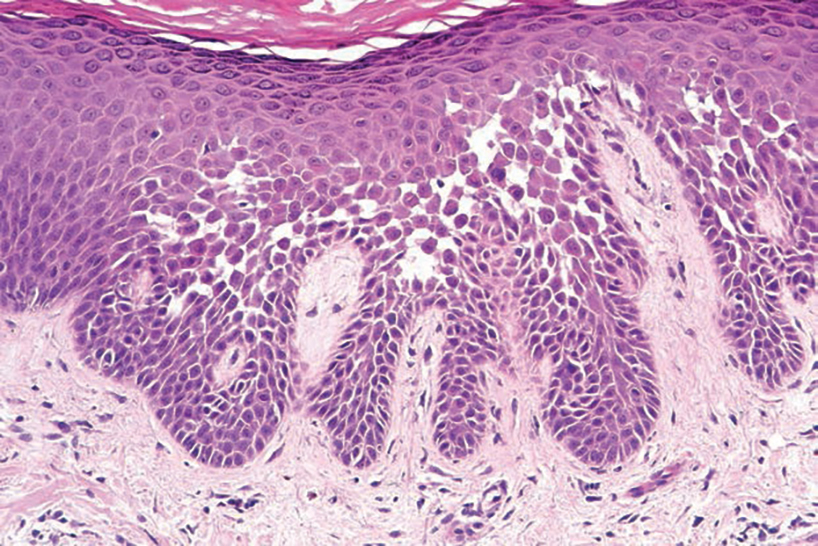

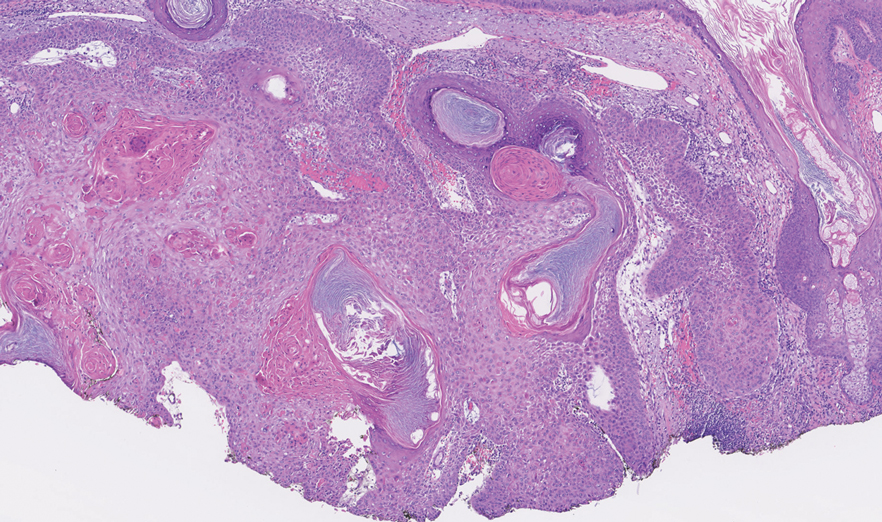

The differential diagnosis for PAD includes pemphigus vegetans, Hailey-Hailey disease, Darier disease, and Grover disease. Patients usually develop pemphigus vegetans at an older age (typically 50–70 years).3 Histopathologically, it is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with an eosinophilic microabscess as well as acantholysis that involves the follicular epithelium (Figure 1),4 which were not seen in our patient. Direct immunofluorescence will show the intercellular pattern of the pemphigus group, and antidesmoglein antibodies can be detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.4,5

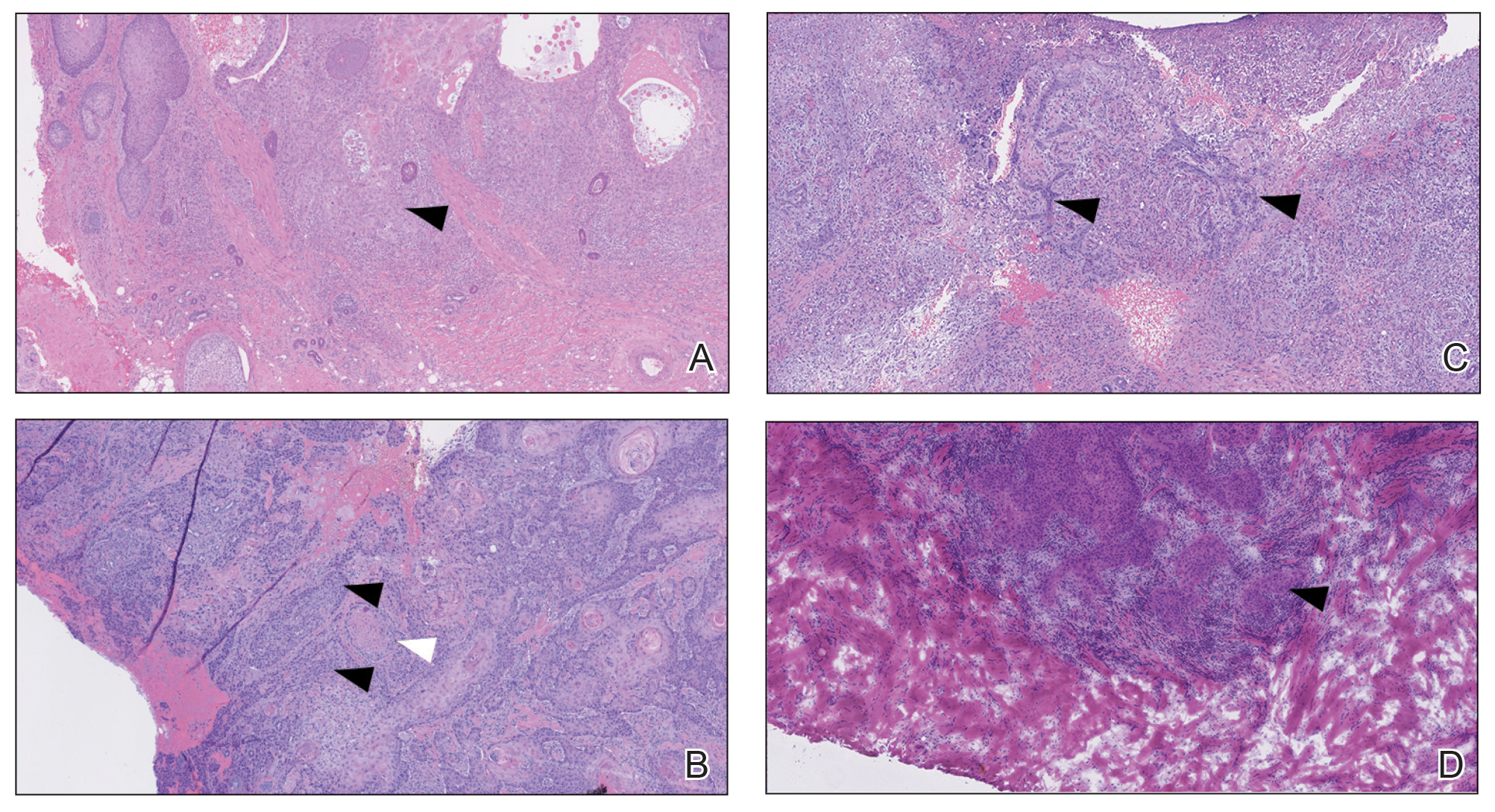

Hailey-Hailey disease (also known as benign familial pemphigus) typically manifests as itchy malodorous vesicles and erosions, especially in intertriginous areas. The most commonly affected sites are the groin, neck, under the breasts, and between the buttocks. In one study, two-thirds of affected patients reported a relevant family history.4 Histopathology will show minimal dyskeratosis and suprabasilar acantholysis with loss of intercellular bridges, classically described as resembling a dilapidated brick wall (Figure 2).4,5 There is no notable follicular involvement with acantholysis.4

characteristic dilapidated brick wall appearance (H&E, original

magnification ×40).

Darier disease (also known as keratosis follicularis) typically is inherited in an autosomal-dominant pattern.4 It is found on the seborrheic areas such as the scalp, forehead, nasolabial folds, and upper chest. Characteristic features include distal notching of the nails, mucosal lesions, and palmoplantar papules. Histopathology will reveal acantholysis, dyskeratosis, suprabasilar acantholysis, and corps ronds and grains.4 Acantholysis in Darier disease can be in discrete foci and/or widespread (Figure 3).4 Darier disease demonstrates more dyskeratosis than Hailey-Hailey disease.4,5

Grover disease (also referred to as transient acantholytic dermatosis) is observed predominantly in individuals who are middle-aged or older, though occurrence in children has been rarely reported.4 It affects the trunk, neck, and proximal limbs but spares the genital area. Histopathology may reveal acantholysis (similar to Hailey-Hailey disease or pemphigus vulgaris), dyskeratosis (resembling Darier disease), spongiosis, parakeratosis, and a superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with eosinophils.4 A histologic clue to the diagnosis is small lesion size (1–3 mm). Usually, only 1 or 2 small discrete lesions that span a few rete ridges are noted (Figure 4).4 Grover disease can cause follicular or acrosyringeal involvement.4

THE DIAGNOSIS: Papular Acantholytic Dyskeratosis

Histopathology of the lesion in our patient revealed hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, dyskeratosis, and acantholysis of keratinocytes. The dermis showed variable chronic inflammatory cells. Corps ronds and grains in the acantholytic layer of the epidermis were identified. Hair follicles were not affected by acantholysis. Anti–desmoglein 1 and anti–desmoglein 3 serum antibodies were negative. Based on the combined clinical and histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with papular acantholytic dyskeratosis (PAD) of the genitocrural area.

Although its typical histopathologic pattern mimics both Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier disease, PAD is a rare unique clinicopathologic entity recognized by dermatopathologists. It usually occurs in middle-aged women with no family history of similar conditions. The multiple localized, flesh-colored to whitish papules of PAD tend to coalesce into plaques in the anogenital and genitocrural regions. Plaques usually are asymptomatic but may be pruritic. Histopathologically, PAD will demonstrate hyperkeratosis, dyskeratosis, and acantholysis. Corps ronds and grains will be present in the acantholytic layer of the epidermis.1,2

The differential diagnosis for PAD includes pemphigus vegetans, Hailey-Hailey disease, Darier disease, and Grover disease. Patients usually develop pemphigus vegetans at an older age (typically 50–70 years).3 Histopathologically, it is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with an eosinophilic microabscess as well as acantholysis that involves the follicular epithelium (Figure 1),4 which were not seen in our patient. Direct immunofluorescence will show the intercellular pattern of the pemphigus group, and antidesmoglein antibodies can be detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.4,5

Hailey-Hailey disease (also known as benign familial pemphigus) typically manifests as itchy malodorous vesicles and erosions, especially in intertriginous areas. The most commonly affected sites are the groin, neck, under the breasts, and between the buttocks. In one study, two-thirds of affected patients reported a relevant family history.4 Histopathology will show minimal dyskeratosis and suprabasilar acantholysis with loss of intercellular bridges, classically described as resembling a dilapidated brick wall (Figure 2).4,5 There is no notable follicular involvement with acantholysis.4

characteristic dilapidated brick wall appearance (H&E, original

magnification ×40).

Darier disease (also known as keratosis follicularis) typically is inherited in an autosomal-dominant pattern.4 It is found on the seborrheic areas such as the scalp, forehead, nasolabial folds, and upper chest. Characteristic features include distal notching of the nails, mucosal lesions, and palmoplantar papules. Histopathology will reveal acantholysis, dyskeratosis, suprabasilar acantholysis, and corps ronds and grains.4 Acantholysis in Darier disease can be in discrete foci and/or widespread (Figure 3).4 Darier disease demonstrates more dyskeratosis than Hailey-Hailey disease.4,5

Grover disease (also referred to as transient acantholytic dermatosis) is observed predominantly in individuals who are middle-aged or older, though occurrence in children has been rarely reported.4 It affects the trunk, neck, and proximal limbs but spares the genital area. Histopathology may reveal acantholysis (similar to Hailey-Hailey disease or pemphigus vulgaris), dyskeratosis (resembling Darier disease), spongiosis, parakeratosis, and a superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with eosinophils.4 A histologic clue to the diagnosis is small lesion size (1–3 mm). Usually, only 1 or 2 small discrete lesions that span a few rete ridges are noted (Figure 4).4 Grover disease can cause follicular or acrosyringeal involvement.4

- Al-Muriesh M, Abdul-Fattah B, Wang X, et al. Papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the anogenital and genitocrural area: case series and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:749-758. doi:10.1111/cup.12736

- Harrell J, Nielson C, Beers P, et al. Eruption on the vulva and groin. JAAD Case Reports. 2019;6:6-8. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.11.003

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 26, 2023. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545229

- Acantholytic disorders. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin: With Clinical Correlations. Elsevier/ Saunders; 2012:171-200.

- Mohr MR, Erdag G, Shada AL, et al. Two patients with Hailey- Hailey disease, multiple primary melanomas, and other cancers. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:211215. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.445

- Al-Muriesh M, Abdul-Fattah B, Wang X, et al. Papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the anogenital and genitocrural area: case series and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:749-758. doi:10.1111/cup.12736

- Harrell J, Nielson C, Beers P, et al. Eruption on the vulva and groin. JAAD Case Reports. 2019;6:6-8. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.11.003

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 26, 2023. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545229

- Acantholytic disorders. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin: With Clinical Correlations. Elsevier/ Saunders; 2012:171-200.

- Mohr MR, Erdag G, Shada AL, et al. Two patients with Hailey- Hailey disease, multiple primary melanomas, and other cancers. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:211215. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.445

A 21-year-old woman presented with a chronic eruption in the anogenital region of 4 years’ duration. Clinical examination revealed numerous painless, mildly itchy, malodorous, whitish papules on an erythematous base that were distributed on the vulva and perianal region. There were no erosions, and no other areas were involved. Routine laboratory tests were within reference range. The patient had no sexual partner and no family history of similar lesions. A skin biopsy was performed.

Pediatric Melanoma Outcomes by Race and Socioeconomic Factors

To the Editor:

Skin cancers are extremely common worldwide. Malignant melanomas comprise approximately 1 in 5 of these cancers. Exposure to UV radiation is postulated to be responsible for a global rise in melanoma cases over the past 50 years.1 Pediatric melanoma is a particularly rare condition that affects approximately 6 in every 1 million children.2 Melanoma incidence in children ranges by age, increasing by approximately 10-fold from age 1 to 4 years to age 15 to 19 years. Tumor ulceration is a feature more commonly seen among children younger than 10 years and is associated with worse outcomes. Tumor thickness and ulceration strongly predict sentinel lymph node metastases among children, which also is associated with a poor prognosis.3

A recent study evaluating stage IV melanoma survival rates in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) vs older adults found that survival is much worse among AYAs. Thicker tumors and public health insurance also were associated with worse survival rates for AYAs, while early detection was associated with better survival rates.4

Health disparities and their role in the prognosis of pediatric melanoma is another important factor. One study analyzed this relationship at the state level using Texas Cancer Registry data (1995-2009).5 Patients’ socioeconomic status (SES) and driving distance to the nearest pediatric cancer care center were included in the analysis. Hispanic children were found to be 3 times more likely to present with advanced disease than non-Hispanic White children. Although SES and distance to the nearest treatment center were not found to affect the melanoma stage at presentation, Hispanic ethnicity or being in the lowest SES quartile were correlated with a higher mortality risk.5

When considering specific subtypes of melanoma, acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM) is known to develop in patients with skin of color. A 2023 study by Holman et al6 reported that the percentage of melanomas that were ALMs ranged from 0.8% in non-Hispanic White individuals to 19.1% in Hispanic Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Asian/Pacific Islander individuals. However, ALM is rare in children. In a pooled cohort study with patient information retrieved from the nationwide Dutch Pathology Registry, only 1 child and 1 adolescent were found to have ALM across a total of 514 patients.7 We sought to analyze pediatric melanoma outcomes based on race and other barriers to appropriate care.

We conducted a search of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database from January 1995 to December 2016 for patients aged 21 years and younger with a primary melanoma diagnosis. The primary outcome was the 5-year survival rate. County-level SES variables were used to calculate a prosperity index. Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazards model were used to compare 5-year survival rates among the different racial/ethnic groups.

A sample of 2742 patients was identified during the study period and followed for 5 years. Eighty-two percent were White, 6% Hispanic, 2% Asian, 1% Black, and 5% classified as other/unknown race (data were missing for 4%). The cohort was predominantly female (61%). White patients were more likely to present with localized disease than any other race/ethnicity (83% vs 65% in Hispanic, 60% in Asian/Pacific Islander, and 45% in Black patients [P<.05]).

Black and Hispanic patients had the worst 5-year survival rates on bivariate analysis. On multivariate analysis, this finding remained significant for Hispanic patients when compared with White patients (hazard ratio, 2.37 [P<.05]). Increasing age, male sex, advanced stage at diagnosis, and failure to receive surgery were associated with increased odds of mortality.

Patients with regionalized and disseminated disease had increased odds of mortality (6.16 and 64.45, respectively; P<.05) compared with patients with localized disease. Socioeconomic status and urbanization were not found to influence 5-year survival rates.

Pediatric melanoma often presents a clinical challenge with special considerations. Pediatric-specific predisposing risk factors for melanoma and an atypical clinical presentation are some of the major concerns that necessitate a tailored approach to this malignancy, especially among different age groups, skin types, and racial and socioeconomic groups.5

Standard ABCDE criteria often are inadequate for accurate detection of pediatric melanomas. Initial lesions often manifest as raised, red, amelanotic lesions mimicking pyogenic granulomas. Lesions tend to be very small (<6 mm in diameter) and can be uniform in color, thereby making the melanoma more difficult to detect compared to the characteristic findings in adults.5 Bleeding or ulceration often can be a warning sign during physical examination.

With regard to incidence, pediatric melanoma is relatively rare. Since the 1970s, the incidence of pediatric melanoma has been increasing; however, a recent analysis of the SEER database showed a decreasing trend from 2000 to 2010.4

Our analysis of the SEER data showed an increased risk for pediatric melanoma in older adolescents. In addition, the incidence of pediatric melanoma was higher in females of all racial groups except Asian/Pacific Islander individuals. However, SES was not found to significantly influence the 5-year survival rate in pediatric melanoma.

White pediatric patients were more likely to present with localized disease compared with other races. Pediatric melanoma patients with regional disease had a 6-fold increase in mortality rate vs those with localized disease; those with disseminated disease had a 65-fold higher risk. Consistent with this, Black and Hispanic patients had the worst 5-year survival rates on bivariate analysis.

These findings suggest a relationship between race, melanoma spread, and disease severity. Patient education programs need to be directed specifically to minority groups to improve their knowledge on evolving skin lesions and sun protection practices. Physicians also need to have heightened suspicion and better knowledge of the unique traits of pediatric melanoma.5

Given the considerable influence these disparities can have on melanoma outcomes, further research is needed to characterize outcomes based on race and determine obstacles to appropriate care. Improved public outreach initiatives that accommodate specific cultural barriers (eg, language, traditional patterns of behavior) also are required to improve current circumstances.

- Arnold M, Singh D, Laversanne M, et al. Global burden of cutaneous melanoma in 2020 and projections to 2040. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:495-503.

- McCormack L, Hawryluk EB. Pediatric melanoma update. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:707-715.

- Saiyed FK, Hamilton EC, Austin MT. Pediatric melanoma: incidence, treatment, and prognosis. Pediatric Health Med Ther. 2017;8:39-45.

- Wojcik KY, Hawkins M, Anderson-Mellies A, et al. Melanoma survival by age group: population-based disparities for adolescent and young adult patients by stage, tumor thickness, and insurance type. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:831-840.

- Hamilton EC, Nguyen HT, Chang YC, et al. Health disparities influence childhood melanoma stage at diagnosis and outcome. J Pediatr. 2016;175:182-187.

- Holman DM, King JB, White A, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma incidence by sex, race, ethnicity, and stage in the United States, 2010-2019. Prev Med. 2023;175:107692. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2023.107692

- El Sharouni MA, Rawson RV, Potter AJ, et al. Melanomas in children and adolescents: clinicopathologic features and survival outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:609-616. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.08.067

To the Editor: