User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Argyria From a Topical Home Remedy

To the Editor:

Argyria is a rare disease caused by chronic exposure to products with high silver content (eg, oral ingestion, inhalation, percutaneous absorption). With time, the blood levels of silver surpass the body’s renal and hepatic excretory capacities that lead to silver granules being deposited in the skin and internal organs, including the liver, spleen, adrenal glands, and bone marrow.1 The cutaneous deposition results in a blue or blue-gray pigmentation of the skin, mucous membranes, and nails. Intervals of exposure that span from 8 months to 5 years prior to symptom onset have been described in the literature.2 The discoloration that results often is permanent, with no established way of effectively removing silver deposits from the tissue.3

A 22-year-old autistic man, who was completely dependent on his mother’s care, presented to the emergency department with a primary concern of abdominal pain. The mother reported that he was indicating abdominal pain by motioning to his stomach for the last 5 days. The mother also reported he did not have a bowel movement during this time, and she noticed his hands were shaking. Prior to presentation, the mother had given him 2 enemas and had him on a 3-day strict liquid fast consisting of water, lemon juice, cayenne pepper, honey, and orange juice. Notably, the mother had a strong history of using naturopathic remedies for treatment of her son’s ailments.

On admission, the patient was stable. There was a 2-point decrease in the patient’s body mass index over the last month. Initial serum electrolytes were highly abnormal with a serum sodium level of 124 mEq/L (reference range, 135–145 mEq/L), blood urea nitrogen of 3 mg/dL (reference range, 7–20 mg/dL), creatinine of 0.77 mg/dL (reference range, 0.74–1.35 mg/dL), and lactic acid of 2.1 mEq/L (reference range, 0.5–1 mEq/L). Serum osmolality was 272 mOsm/kg (reference range, 275–295 mOsm/kg). Urine osmolality was 114 mOsm/kg (reference range, 500–850 mOsm/kg) with a low-normal urine sodium level of 41 mmol/24 hr (reference range, 40–220 mmol/24 hr). Abnormalities were felt to be secondary to malnutrition from the strict liquid diet (blood urea nitrogen and creatinine ratio of 3:1 suggestive of notable protein calorie malnutrition). The patient was given 1 L of normal saline in the emergency department, with further fluids held so as not to increase serum sodium level too rapidly. A regular diet was started.

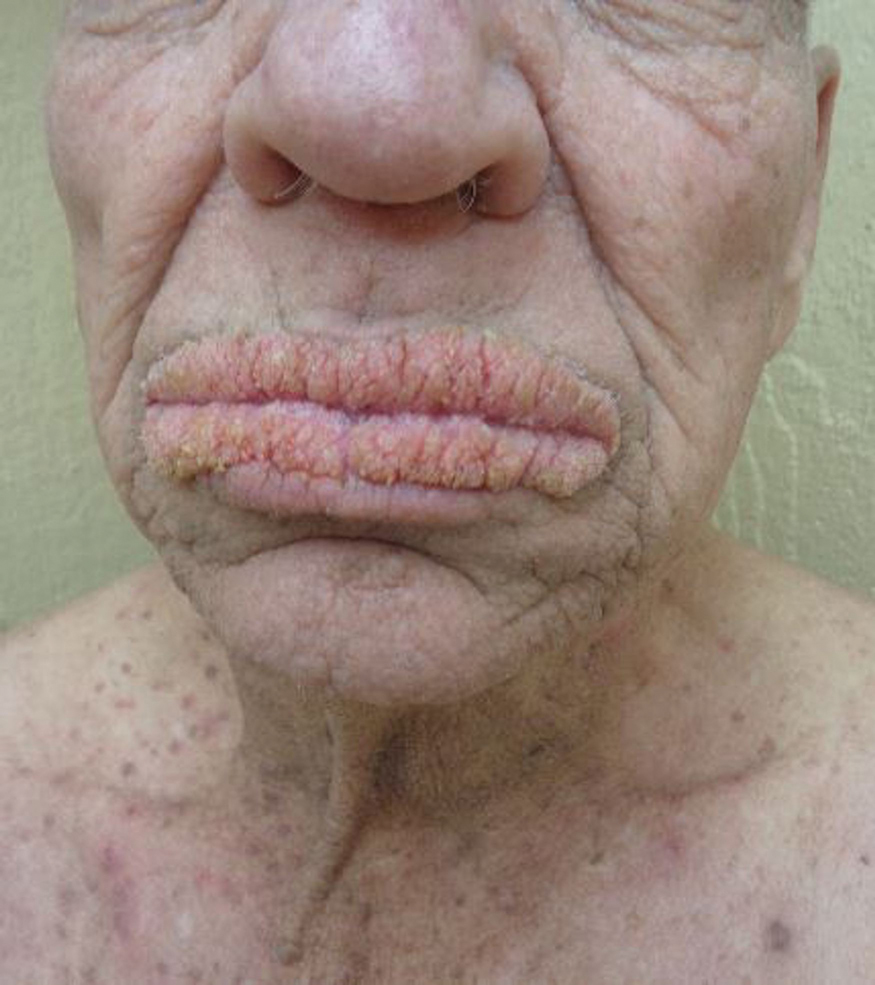

Physical examination revealed dry mucosal membranes but otherwise was unremarkable. Active bowel sounds were noted, as well as a soft, nontender, and nondistended abdomen; however, when examining the patient’s hands for reported shaking, a distinct abnormality of the nails was noticed. The patient had slate blue discoloration of the lunula, along with hyperpigmented violaceous discoloration of the proximal nail bed on all 10 fingernails (Figure 1). No abnormalities were seen on the toenails. The mother had a distinct bluish gray discoloration of the face as well as similar nail findings (Figure 2), strongly suggestive of colloidal silver use. An urgent serum silver level was ordered on the patient as well as a heavy metal panel. The mother was found applying numerous “natural remedies” to the patient’s skin while in the hospital, including a liquid spray and lotion, both in unmarked bottles. At that time, the mother was informed that no external supplements should be applied to her son. The serum silver level was elevated substantially at 94.3 ng/mL (reference range, <1.0 ng/mL). When the mother was confronted, she initially denied use of silver but later admitted to notable silver content in the cream she was applying to her son’s skin. The mother reported that she read online that colloidal silver had been historically used to cure numerous ailments and she was ordering products from an online company. She was counseled on the dangers of both topical application and ingestion of silver, and all supplements were removed from the home.

Argyria is a rare condition caused by chronic exposure to silver and is characterized by a blue-gray pigmentation in the skin and appendages, mucous membranes, and internal organs.4 Clinically, argyria is classified as generalized or localized. Generalized argyria results from ingestion or inhalation of silver compounds, where granules deposit preferentially in sun-exposed areas of skin as well as internal organs, with the highest concentration in the liver, spleen, and adrenal glands; discoloration often is permanent.5 On the contrary, localized argyria results from direct external contact with silver and granules deposited in the hands, eyes, and mucosa.5 Although the exact mechanism of penetration from topical silver remains unknown, it is thought to enter via the eccrine sweat ducts, as histopathology reveals silver granules found in highest concentration surrounding sweat glands in the dermis.6

Initial differential diagnoses for altered nail pigmentation include drug-induced causes, systemic diseases, cyanosis, and exposure to metals.7 The most commonly indicated medications resulting in blue nail pigment changes include antimalarials, minocycline, zidovudine, and phenothiazine. Systemic diseases that may cause blue nail color change include Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, Addison disease, methemoglobinemia, and alkaptonuria.7 Metals include gold, mercury, arsenic, bismuth, lead, and silver.4 After a thorough review of the patient’s medications and lack of support for any underlying disease process, contact with metals, particularly silver, was ranked highly on our differential list. In support of this theory, the mother’s bluish gray facial skin led to high clinical suspicion that she was ingesting colloidal silver and also was exposing her son to silver.

Treatment of argyria is challenging but first and foremost involves discontinuation of the source of chronic silver exposure. Unfortunately, the discoloration of generalized argyria often is permanent. Sunscreen can be used to help prevent any further darkening of pigment. The pigment in localized argyria has been reported to slowly fade with time, and there also have been reports of successful treatment using a low-fluence Q-switched 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.8

- Molina-Hernandez AI, Diaz-Gonzalez JM, Saeb-Lima M, et al. Argyria after silver nitrate intake: case report and brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:520.

- Lencastre A, Lobo M, João A. Argyria—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:413-416.

- Park S-W, Kim J-H, Shin H-T, et al. An effective modality for argyria treatment: Q-switched 1,064-nm Nd:YAG laser. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:511-512.

- Molina-Hernandez AI, Diaz-Gonzalez JM, Saeb-Lima M, et al. Argyria after silver nitrate intake: case report and brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:520.

- Garcias-Ladaria J, Hernandez-Bel P, Torregrosa-Calatayud JL, et al. Localized cutaneous argyria: a report of 2 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:253-254.

- Kapur N, Landon G, Yu RC. Localized argyria in an antique restorer. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:191-192.

- Kubba A, Kubba R, Batrani M, Pal T. Argyria an unrecognized cause of cutaneous pigmentation in Indian patients: a case series and review of the literature. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:805-811.

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee HK, et al. Successful treatment of argyria using a low-fluence Q-switched 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:751-753.

To the Editor:

Argyria is a rare disease caused by chronic exposure to products with high silver content (eg, oral ingestion, inhalation, percutaneous absorption). With time, the blood levels of silver surpass the body’s renal and hepatic excretory capacities that lead to silver granules being deposited in the skin and internal organs, including the liver, spleen, adrenal glands, and bone marrow.1 The cutaneous deposition results in a blue or blue-gray pigmentation of the skin, mucous membranes, and nails. Intervals of exposure that span from 8 months to 5 years prior to symptom onset have been described in the literature.2 The discoloration that results often is permanent, with no established way of effectively removing silver deposits from the tissue.3

A 22-year-old autistic man, who was completely dependent on his mother’s care, presented to the emergency department with a primary concern of abdominal pain. The mother reported that he was indicating abdominal pain by motioning to his stomach for the last 5 days. The mother also reported he did not have a bowel movement during this time, and she noticed his hands were shaking. Prior to presentation, the mother had given him 2 enemas and had him on a 3-day strict liquid fast consisting of water, lemon juice, cayenne pepper, honey, and orange juice. Notably, the mother had a strong history of using naturopathic remedies for treatment of her son’s ailments.

On admission, the patient was stable. There was a 2-point decrease in the patient’s body mass index over the last month. Initial serum electrolytes were highly abnormal with a serum sodium level of 124 mEq/L (reference range, 135–145 mEq/L), blood urea nitrogen of 3 mg/dL (reference range, 7–20 mg/dL), creatinine of 0.77 mg/dL (reference range, 0.74–1.35 mg/dL), and lactic acid of 2.1 mEq/L (reference range, 0.5–1 mEq/L). Serum osmolality was 272 mOsm/kg (reference range, 275–295 mOsm/kg). Urine osmolality was 114 mOsm/kg (reference range, 500–850 mOsm/kg) with a low-normal urine sodium level of 41 mmol/24 hr (reference range, 40–220 mmol/24 hr). Abnormalities were felt to be secondary to malnutrition from the strict liquid diet (blood urea nitrogen and creatinine ratio of 3:1 suggestive of notable protein calorie malnutrition). The patient was given 1 L of normal saline in the emergency department, with further fluids held so as not to increase serum sodium level too rapidly. A regular diet was started.

Physical examination revealed dry mucosal membranes but otherwise was unremarkable. Active bowel sounds were noted, as well as a soft, nontender, and nondistended abdomen; however, when examining the patient’s hands for reported shaking, a distinct abnormality of the nails was noticed. The patient had slate blue discoloration of the lunula, along with hyperpigmented violaceous discoloration of the proximal nail bed on all 10 fingernails (Figure 1). No abnormalities were seen on the toenails. The mother had a distinct bluish gray discoloration of the face as well as similar nail findings (Figure 2), strongly suggestive of colloidal silver use. An urgent serum silver level was ordered on the patient as well as a heavy metal panel. The mother was found applying numerous “natural remedies” to the patient’s skin while in the hospital, including a liquid spray and lotion, both in unmarked bottles. At that time, the mother was informed that no external supplements should be applied to her son. The serum silver level was elevated substantially at 94.3 ng/mL (reference range, <1.0 ng/mL). When the mother was confronted, she initially denied use of silver but later admitted to notable silver content in the cream she was applying to her son’s skin. The mother reported that she read online that colloidal silver had been historically used to cure numerous ailments and she was ordering products from an online company. She was counseled on the dangers of both topical application and ingestion of silver, and all supplements were removed from the home.

Argyria is a rare condition caused by chronic exposure to silver and is characterized by a blue-gray pigmentation in the skin and appendages, mucous membranes, and internal organs.4 Clinically, argyria is classified as generalized or localized. Generalized argyria results from ingestion or inhalation of silver compounds, where granules deposit preferentially in sun-exposed areas of skin as well as internal organs, with the highest concentration in the liver, spleen, and adrenal glands; discoloration often is permanent.5 On the contrary, localized argyria results from direct external contact with silver and granules deposited in the hands, eyes, and mucosa.5 Although the exact mechanism of penetration from topical silver remains unknown, it is thought to enter via the eccrine sweat ducts, as histopathology reveals silver granules found in highest concentration surrounding sweat glands in the dermis.6

Initial differential diagnoses for altered nail pigmentation include drug-induced causes, systemic diseases, cyanosis, and exposure to metals.7 The most commonly indicated medications resulting in blue nail pigment changes include antimalarials, minocycline, zidovudine, and phenothiazine. Systemic diseases that may cause blue nail color change include Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, Addison disease, methemoglobinemia, and alkaptonuria.7 Metals include gold, mercury, arsenic, bismuth, lead, and silver.4 After a thorough review of the patient’s medications and lack of support for any underlying disease process, contact with metals, particularly silver, was ranked highly on our differential list. In support of this theory, the mother’s bluish gray facial skin led to high clinical suspicion that she was ingesting colloidal silver and also was exposing her son to silver.

Treatment of argyria is challenging but first and foremost involves discontinuation of the source of chronic silver exposure. Unfortunately, the discoloration of generalized argyria often is permanent. Sunscreen can be used to help prevent any further darkening of pigment. The pigment in localized argyria has been reported to slowly fade with time, and there also have been reports of successful treatment using a low-fluence Q-switched 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.8

To the Editor:

Argyria is a rare disease caused by chronic exposure to products with high silver content (eg, oral ingestion, inhalation, percutaneous absorption). With time, the blood levels of silver surpass the body’s renal and hepatic excretory capacities that lead to silver granules being deposited in the skin and internal organs, including the liver, spleen, adrenal glands, and bone marrow.1 The cutaneous deposition results in a blue or blue-gray pigmentation of the skin, mucous membranes, and nails. Intervals of exposure that span from 8 months to 5 years prior to symptom onset have been described in the literature.2 The discoloration that results often is permanent, with no established way of effectively removing silver deposits from the tissue.3

A 22-year-old autistic man, who was completely dependent on his mother’s care, presented to the emergency department with a primary concern of abdominal pain. The mother reported that he was indicating abdominal pain by motioning to his stomach for the last 5 days. The mother also reported he did not have a bowel movement during this time, and she noticed his hands were shaking. Prior to presentation, the mother had given him 2 enemas and had him on a 3-day strict liquid fast consisting of water, lemon juice, cayenne pepper, honey, and orange juice. Notably, the mother had a strong history of using naturopathic remedies for treatment of her son’s ailments.

On admission, the patient was stable. There was a 2-point decrease in the patient’s body mass index over the last month. Initial serum electrolytes were highly abnormal with a serum sodium level of 124 mEq/L (reference range, 135–145 mEq/L), blood urea nitrogen of 3 mg/dL (reference range, 7–20 mg/dL), creatinine of 0.77 mg/dL (reference range, 0.74–1.35 mg/dL), and lactic acid of 2.1 mEq/L (reference range, 0.5–1 mEq/L). Serum osmolality was 272 mOsm/kg (reference range, 275–295 mOsm/kg). Urine osmolality was 114 mOsm/kg (reference range, 500–850 mOsm/kg) with a low-normal urine sodium level of 41 mmol/24 hr (reference range, 40–220 mmol/24 hr). Abnormalities were felt to be secondary to malnutrition from the strict liquid diet (blood urea nitrogen and creatinine ratio of 3:1 suggestive of notable protein calorie malnutrition). The patient was given 1 L of normal saline in the emergency department, with further fluids held so as not to increase serum sodium level too rapidly. A regular diet was started.

Physical examination revealed dry mucosal membranes but otherwise was unremarkable. Active bowel sounds were noted, as well as a soft, nontender, and nondistended abdomen; however, when examining the patient’s hands for reported shaking, a distinct abnormality of the nails was noticed. The patient had slate blue discoloration of the lunula, along with hyperpigmented violaceous discoloration of the proximal nail bed on all 10 fingernails (Figure 1). No abnormalities were seen on the toenails. The mother had a distinct bluish gray discoloration of the face as well as similar nail findings (Figure 2), strongly suggestive of colloidal silver use. An urgent serum silver level was ordered on the patient as well as a heavy metal panel. The mother was found applying numerous “natural remedies” to the patient’s skin while in the hospital, including a liquid spray and lotion, both in unmarked bottles. At that time, the mother was informed that no external supplements should be applied to her son. The serum silver level was elevated substantially at 94.3 ng/mL (reference range, <1.0 ng/mL). When the mother was confronted, she initially denied use of silver but later admitted to notable silver content in the cream she was applying to her son’s skin. The mother reported that she read online that colloidal silver had been historically used to cure numerous ailments and she was ordering products from an online company. She was counseled on the dangers of both topical application and ingestion of silver, and all supplements were removed from the home.

Argyria is a rare condition caused by chronic exposure to silver and is characterized by a blue-gray pigmentation in the skin and appendages, mucous membranes, and internal organs.4 Clinically, argyria is classified as generalized or localized. Generalized argyria results from ingestion or inhalation of silver compounds, where granules deposit preferentially in sun-exposed areas of skin as well as internal organs, with the highest concentration in the liver, spleen, and adrenal glands; discoloration often is permanent.5 On the contrary, localized argyria results from direct external contact with silver and granules deposited in the hands, eyes, and mucosa.5 Although the exact mechanism of penetration from topical silver remains unknown, it is thought to enter via the eccrine sweat ducts, as histopathology reveals silver granules found in highest concentration surrounding sweat glands in the dermis.6

Initial differential diagnoses for altered nail pigmentation include drug-induced causes, systemic diseases, cyanosis, and exposure to metals.7 The most commonly indicated medications resulting in blue nail pigment changes include antimalarials, minocycline, zidovudine, and phenothiazine. Systemic diseases that may cause blue nail color change include Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, Addison disease, methemoglobinemia, and alkaptonuria.7 Metals include gold, mercury, arsenic, bismuth, lead, and silver.4 After a thorough review of the patient’s medications and lack of support for any underlying disease process, contact with metals, particularly silver, was ranked highly on our differential list. In support of this theory, the mother’s bluish gray facial skin led to high clinical suspicion that she was ingesting colloidal silver and also was exposing her son to silver.

Treatment of argyria is challenging but first and foremost involves discontinuation of the source of chronic silver exposure. Unfortunately, the discoloration of generalized argyria often is permanent. Sunscreen can be used to help prevent any further darkening of pigment. The pigment in localized argyria has been reported to slowly fade with time, and there also have been reports of successful treatment using a low-fluence Q-switched 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.8

- Molina-Hernandez AI, Diaz-Gonzalez JM, Saeb-Lima M, et al. Argyria after silver nitrate intake: case report and brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:520.

- Lencastre A, Lobo M, João A. Argyria—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:413-416.

- Park S-W, Kim J-H, Shin H-T, et al. An effective modality for argyria treatment: Q-switched 1,064-nm Nd:YAG laser. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:511-512.

- Molina-Hernandez AI, Diaz-Gonzalez JM, Saeb-Lima M, et al. Argyria after silver nitrate intake: case report and brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:520.

- Garcias-Ladaria J, Hernandez-Bel P, Torregrosa-Calatayud JL, et al. Localized cutaneous argyria: a report of 2 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:253-254.

- Kapur N, Landon G, Yu RC. Localized argyria in an antique restorer. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:191-192.

- Kubba A, Kubba R, Batrani M, Pal T. Argyria an unrecognized cause of cutaneous pigmentation in Indian patients: a case series and review of the literature. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:805-811.

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee HK, et al. Successful treatment of argyria using a low-fluence Q-switched 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:751-753.

- Molina-Hernandez AI, Diaz-Gonzalez JM, Saeb-Lima M, et al. Argyria after silver nitrate intake: case report and brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:520.

- Lencastre A, Lobo M, João A. Argyria—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:413-416.

- Park S-W, Kim J-H, Shin H-T, et al. An effective modality for argyria treatment: Q-switched 1,064-nm Nd:YAG laser. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:511-512.

- Molina-Hernandez AI, Diaz-Gonzalez JM, Saeb-Lima M, et al. Argyria after silver nitrate intake: case report and brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:520.

- Garcias-Ladaria J, Hernandez-Bel P, Torregrosa-Calatayud JL, et al. Localized cutaneous argyria: a report of 2 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:253-254.

- Kapur N, Landon G, Yu RC. Localized argyria in an antique restorer. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:191-192.

- Kubba A, Kubba R, Batrani M, Pal T. Argyria an unrecognized cause of cutaneous pigmentation in Indian patients: a case series and review of the literature. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:805-811.

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee HK, et al. Successful treatment of argyria using a low-fluence Q-switched 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:751-753.

Practice Points

- Argyria results from chronic exposure to products with a high silver content and may result in abnormalities of the skin and internal organs.

- Examination of the fingernails can provide important clues to underlying systemic conditions or external exposures.

Squamoid Eccrine Ductal Carcinoma

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma (SEDC) is an aggressive underrecognized cutaneous malignancy of unknown etiology.1 It is most likely to occur in sun-exposed areas of the body, most commonly the head and neck. Risk factors include male sex, increased age, and chronic immunosuppression.1-4 Current reports suggest that SEDC is likely a high-grade subtype of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) with a high risk for local recurrence (25%) and metastasis (13%).1,3,5,6 There are as few as 56 cases of SEDC reported in the literature; however, the number of cases may be closer to 100 due to SEDC being classified as either adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin or ductal eccrine carcinoma with squamous differentiation.1

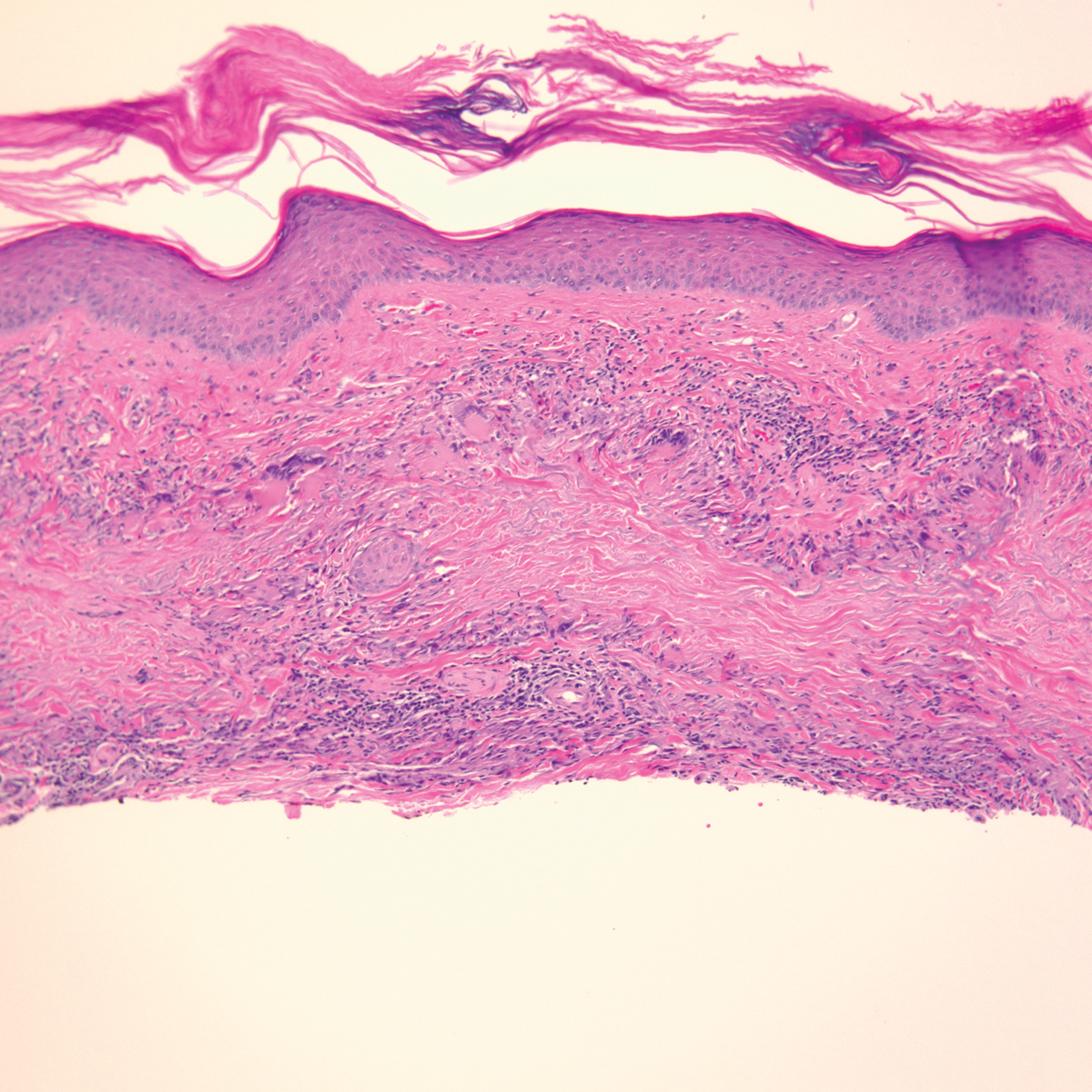

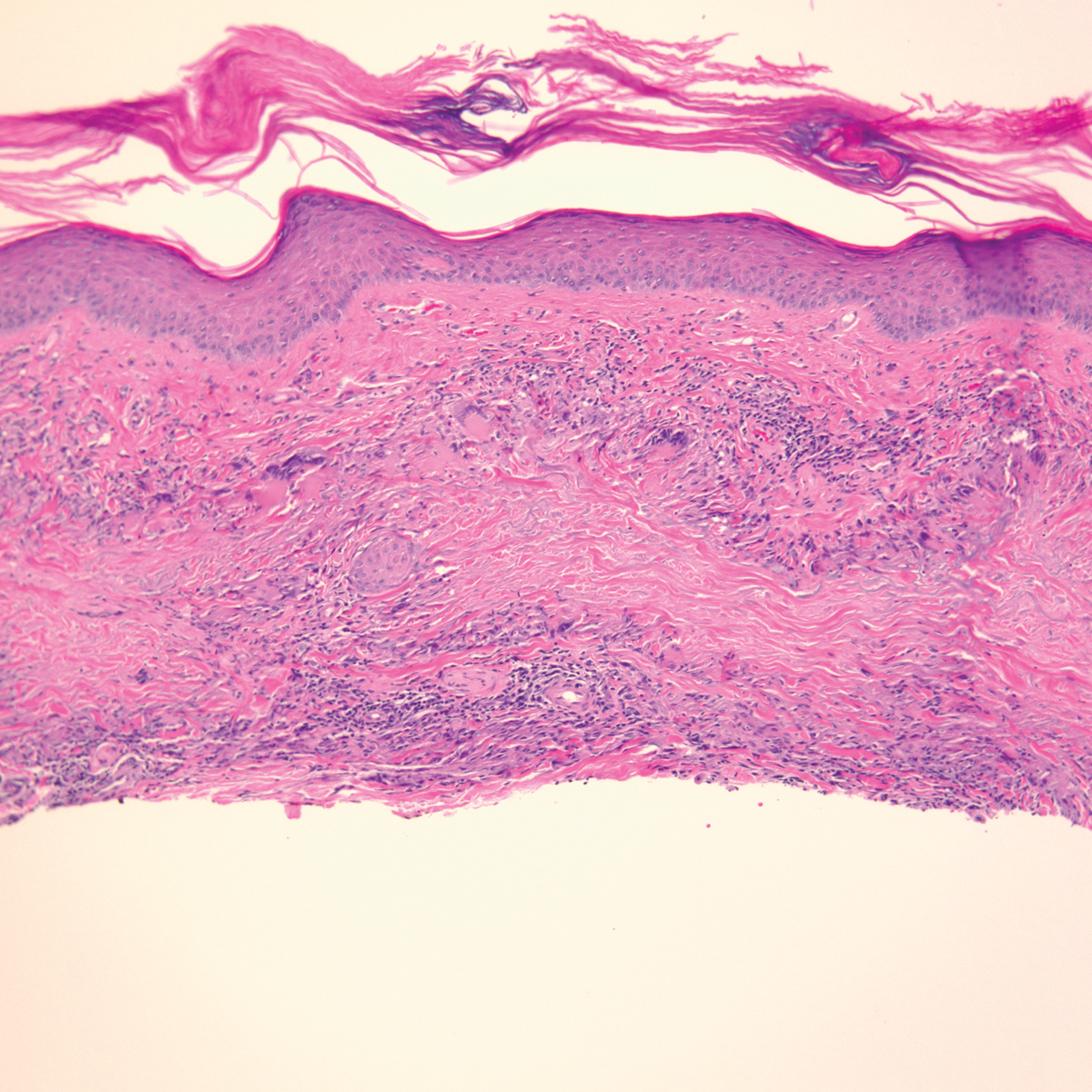

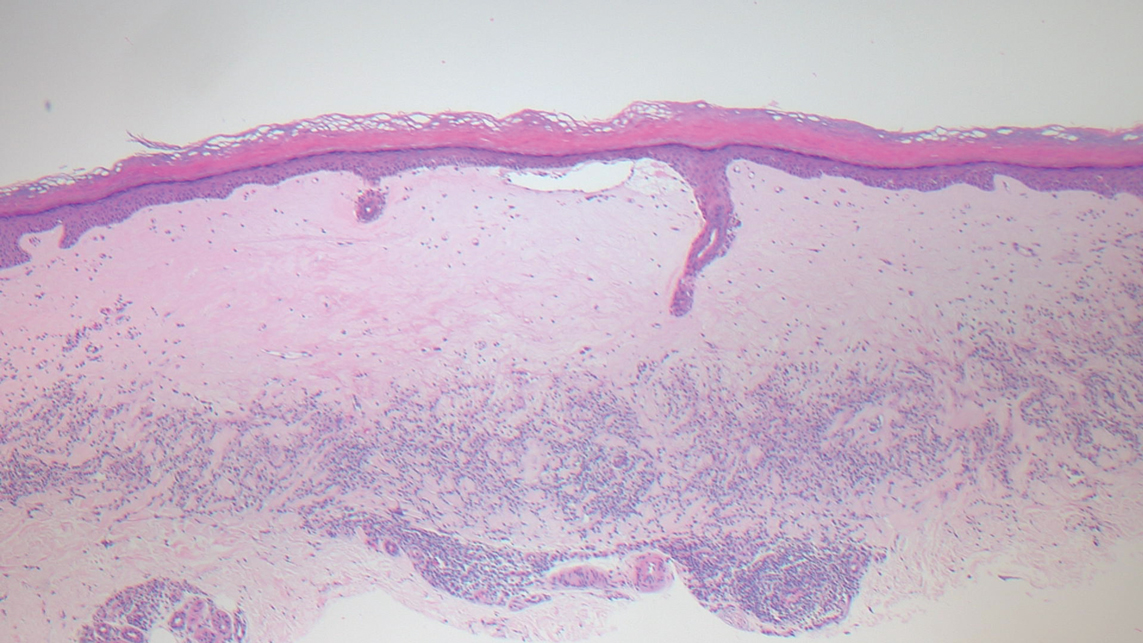

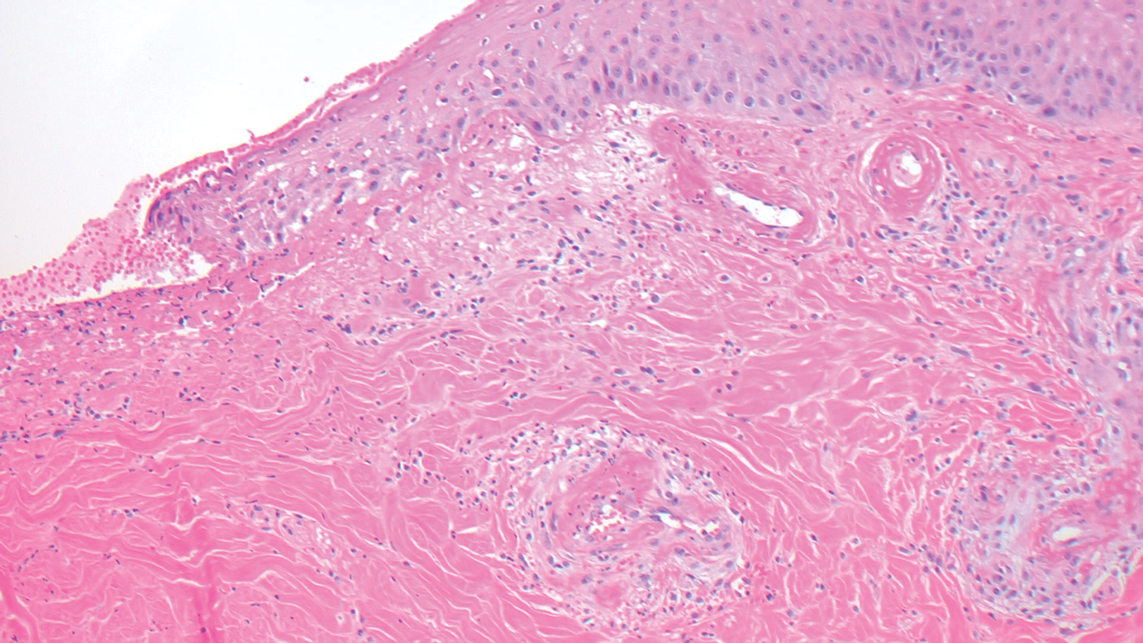

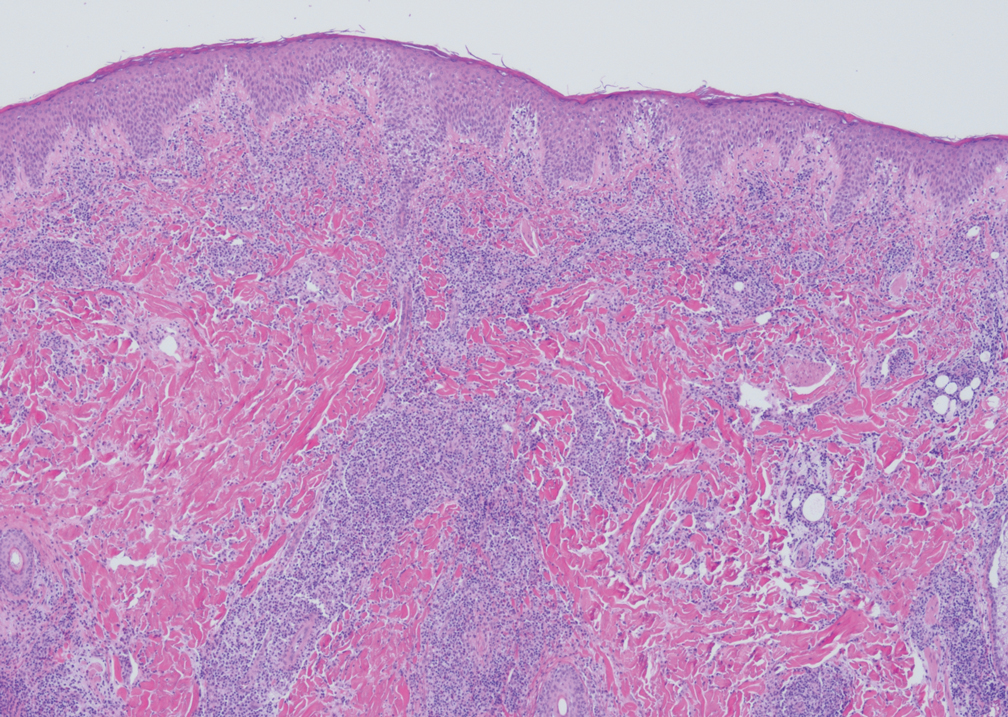

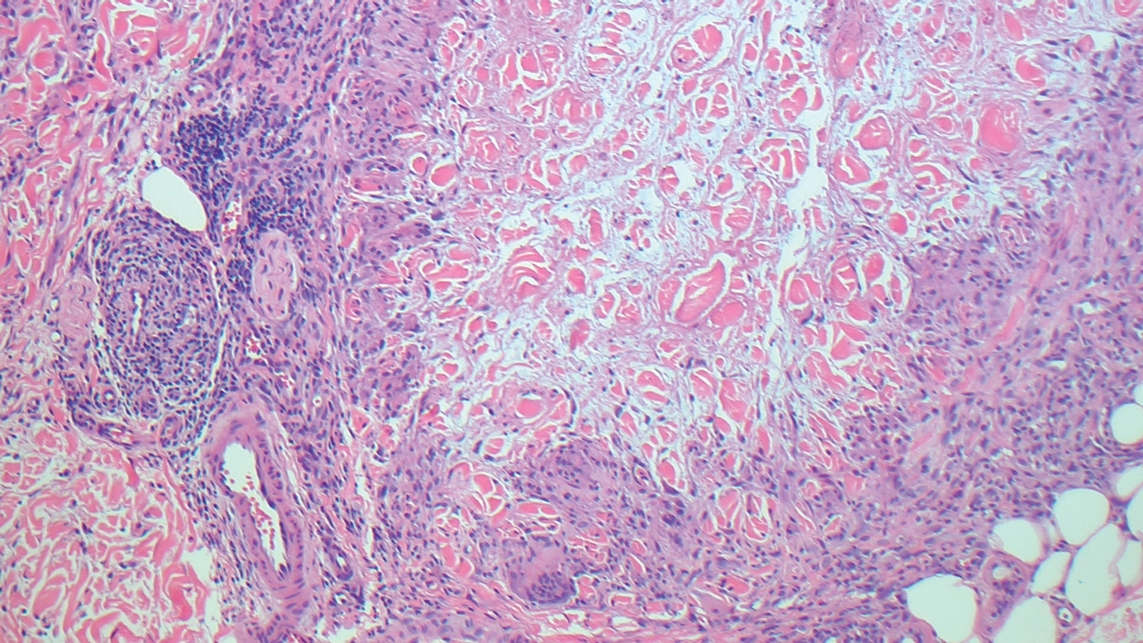

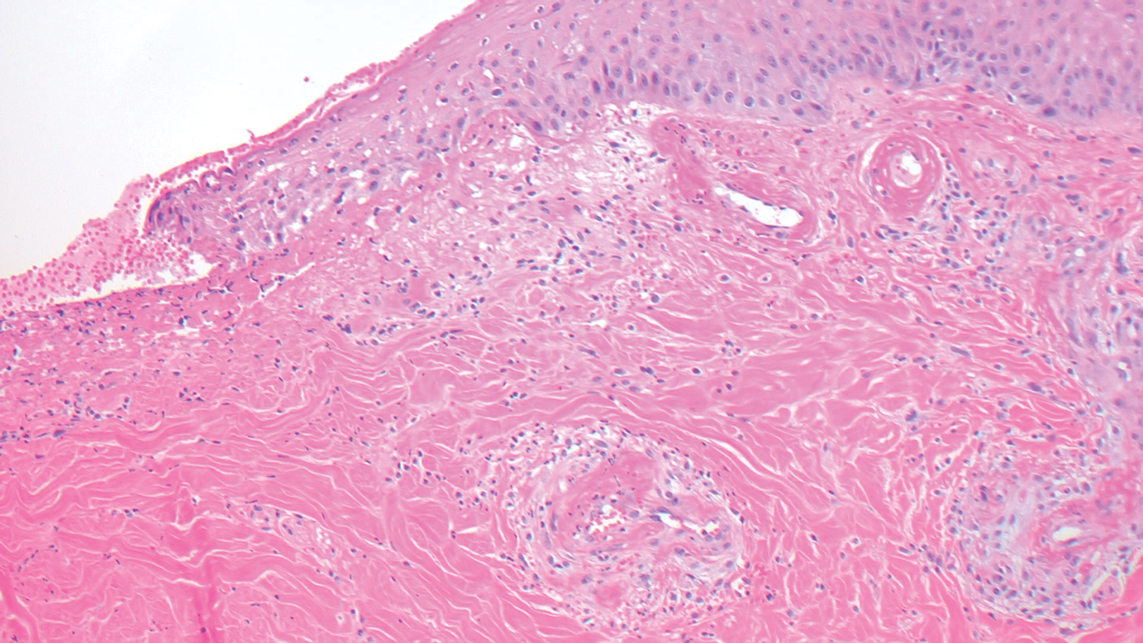

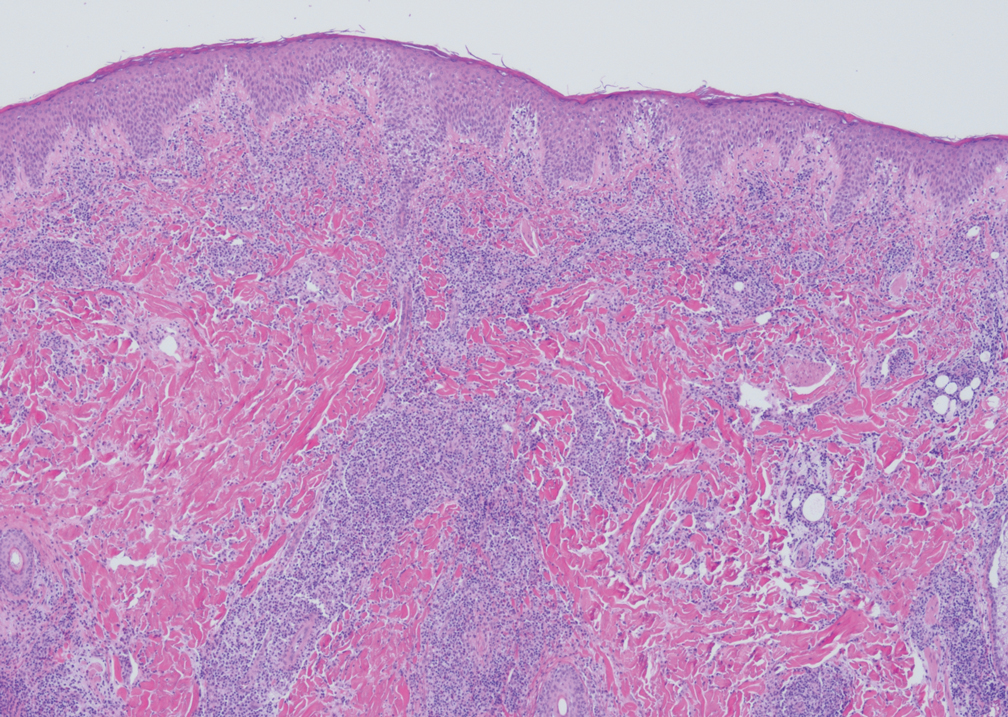

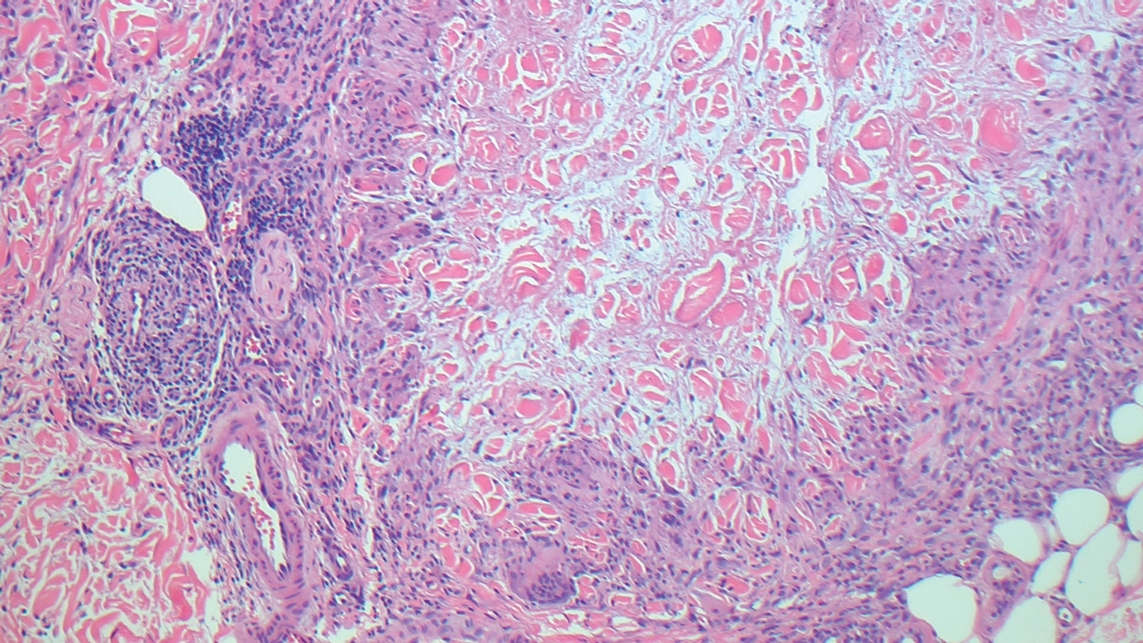

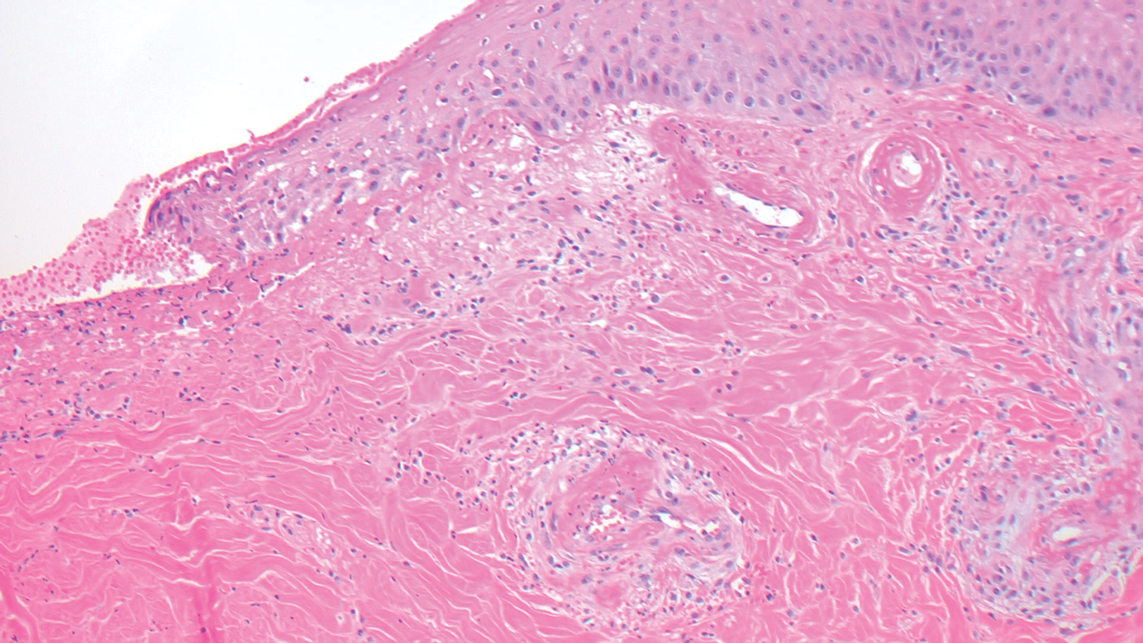

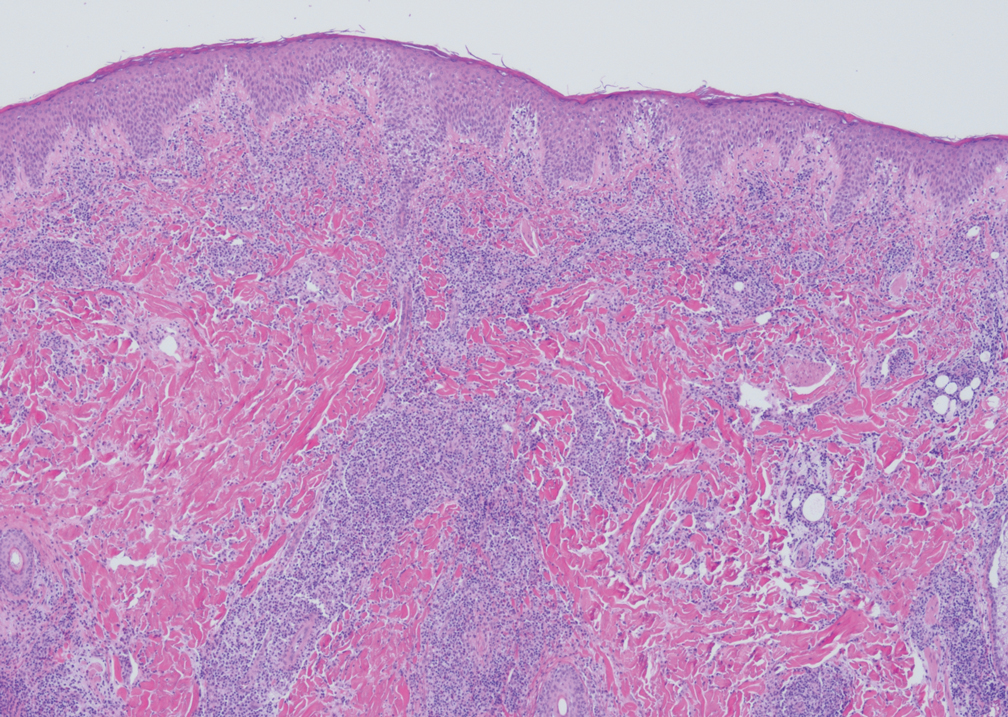

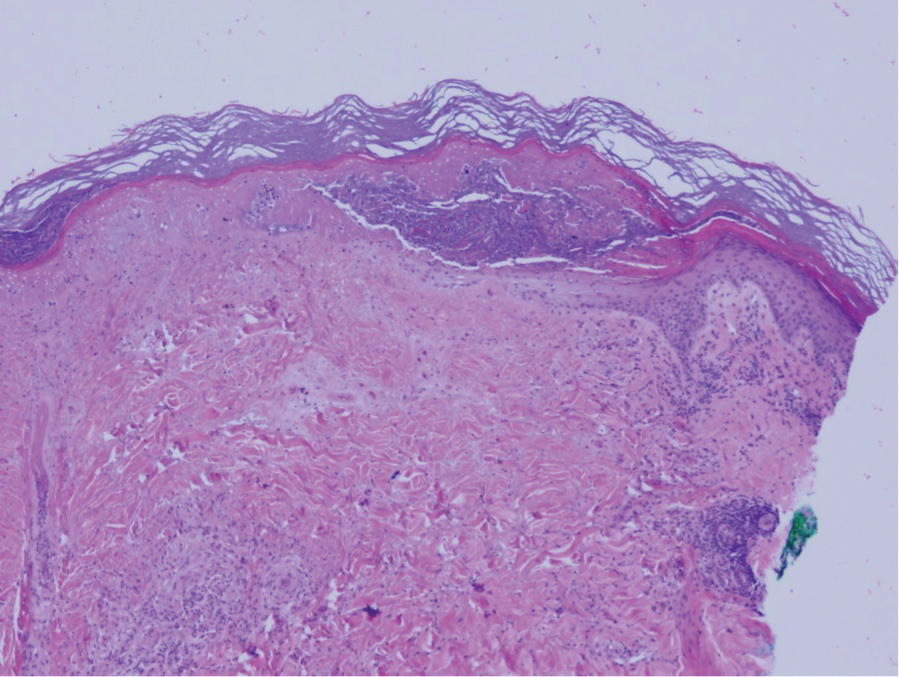

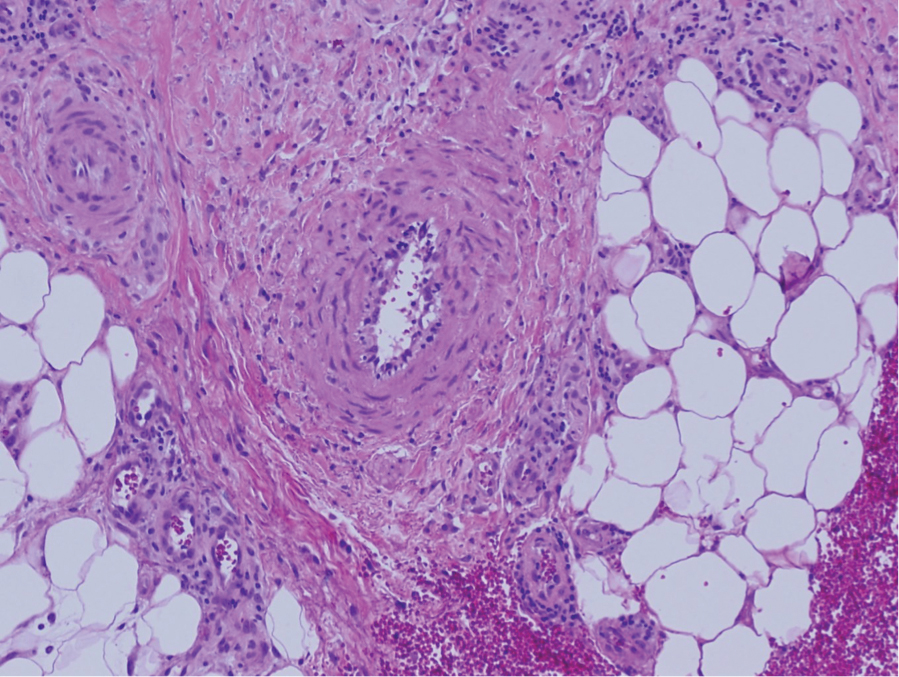

Clinically, SEDC mimics keratinocyte carcinomas. Histologically, SEDC is biphasic, with a superficial portion resembling well-differentiated SCC and a deeply invasive portion having infiltrative irregular cords with ductal differentiation. Perineural invasion (PNI) frequently is present. Multiple connections to the overlying epidermis also can be seen, serving as a subtle clue to the diagnosis on broad superficial specimens.1-3 Due to superficial sampling, approximately 50% of reported cases are misdiagnosed as SCC during the initial biopsy.4 The diagnosis of SEDC often is made during complete excision when deeper tissue is sampled. Establishing an accurate diagnosis is important given the more aggressive nature of SEDC compared with SCC and its proclivity for PNI.1,3,6 The purpose of this review is to increase awareness of this underrecognized entity and describe the histologic findings that help distinguish SEDC from SCC.

Patient Chart Review

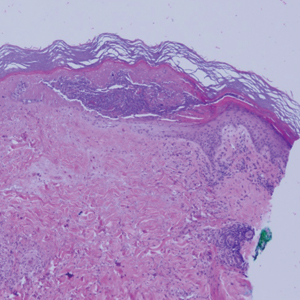

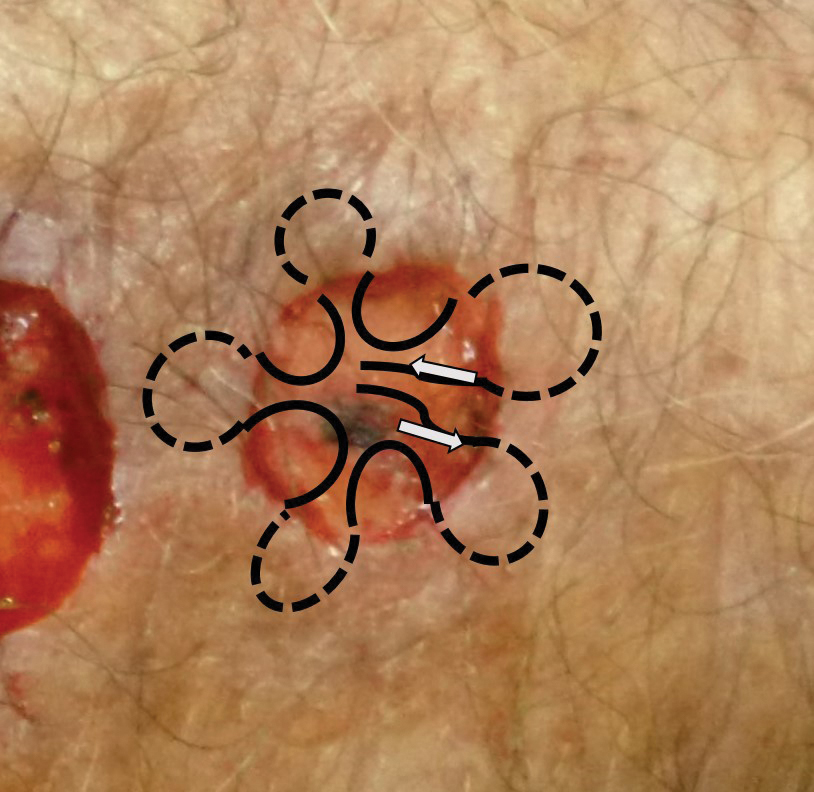

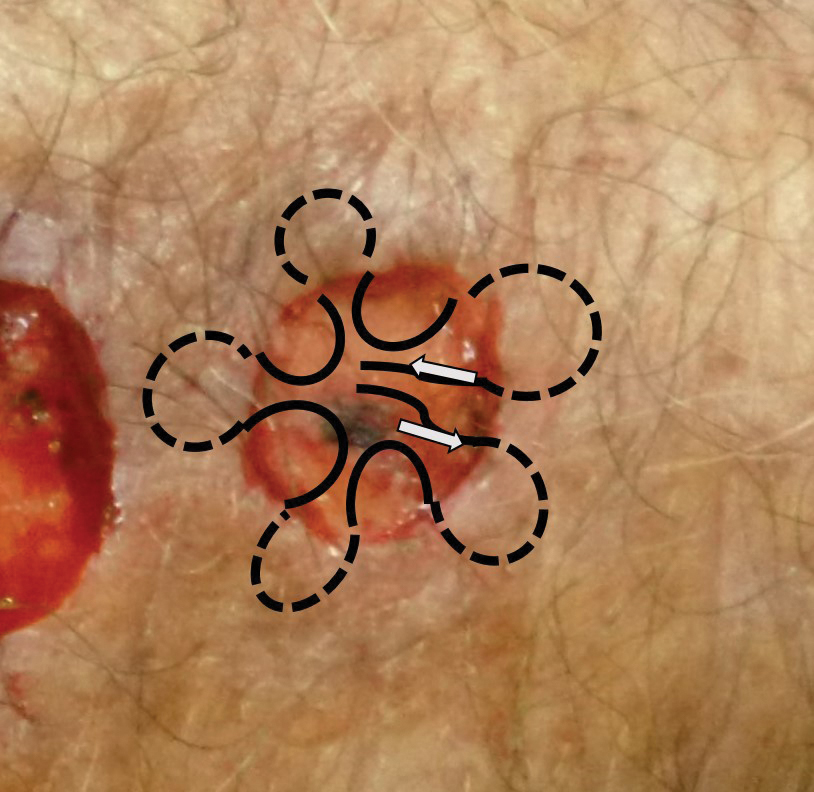

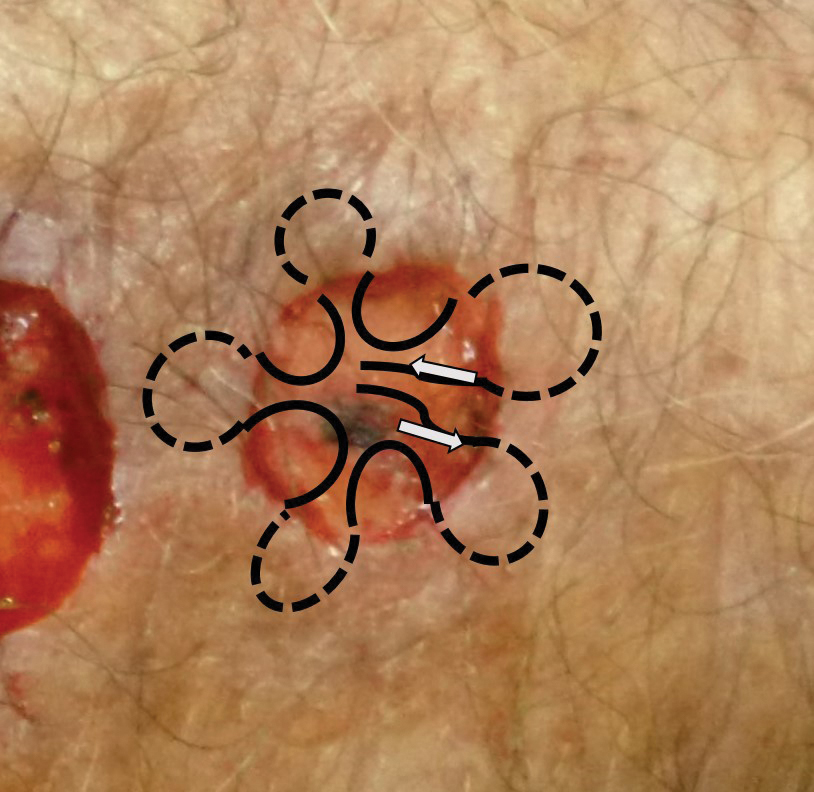

We reviewed chart notes as well as frozen and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections from all 5 patients diagnosed with SEDC at a single institution between November 2018 and May 2020. The mean age of patients was 81 years, and 4 were male. Four of the patients presented for MMS with a preoperative diagnosis of SCC per the original biopsy results. Only 1 patient had a preoperative diagnosis of SEDC. The details of each case are recorded in the Table. All tumors were greater than 2 cm in diameter on initial presentation, were located on the head, and clinically resembled keratinocyte carcinoma with either a nodular or plaquelike appearance (Figure 1).

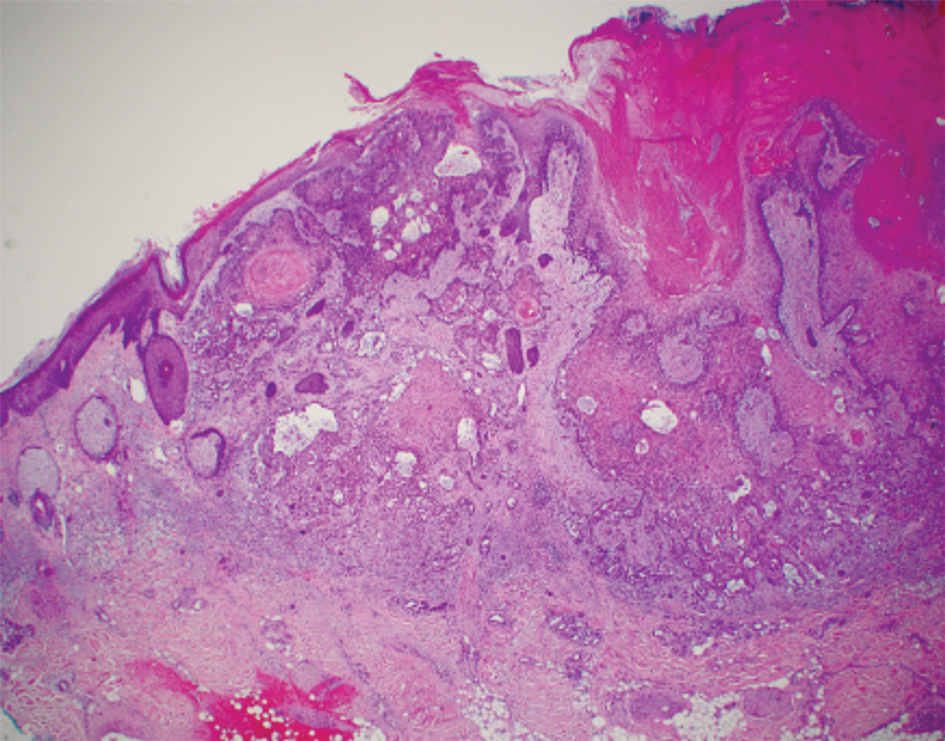

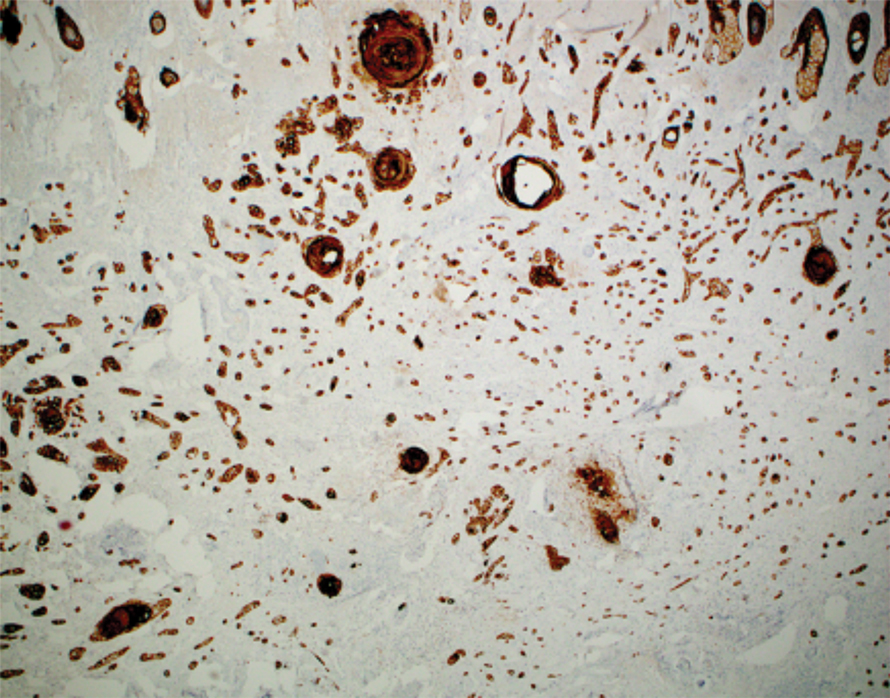

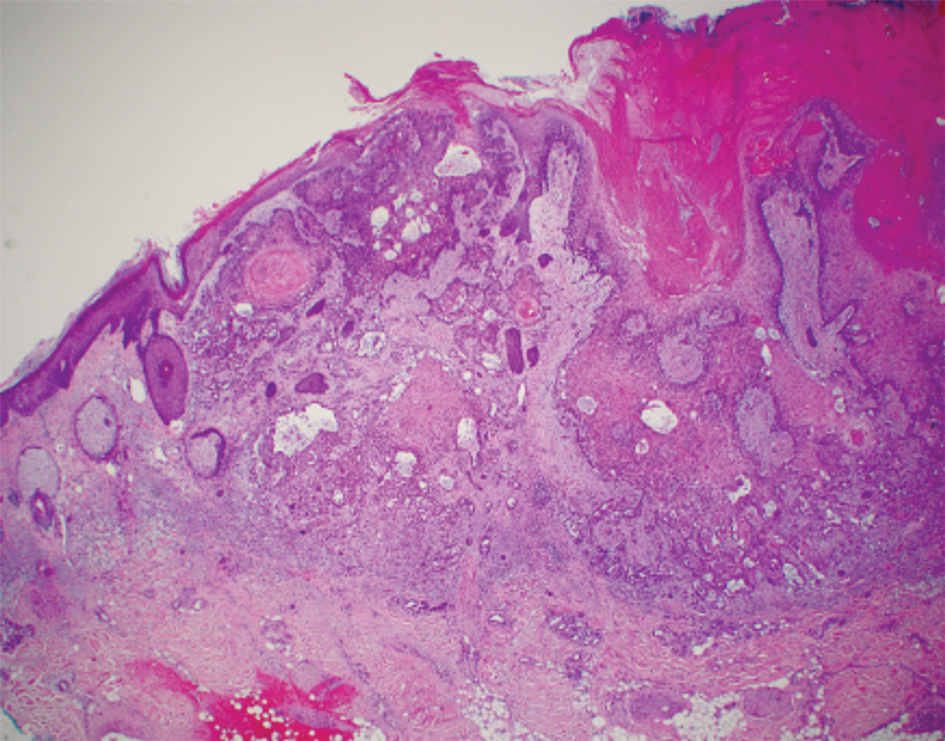

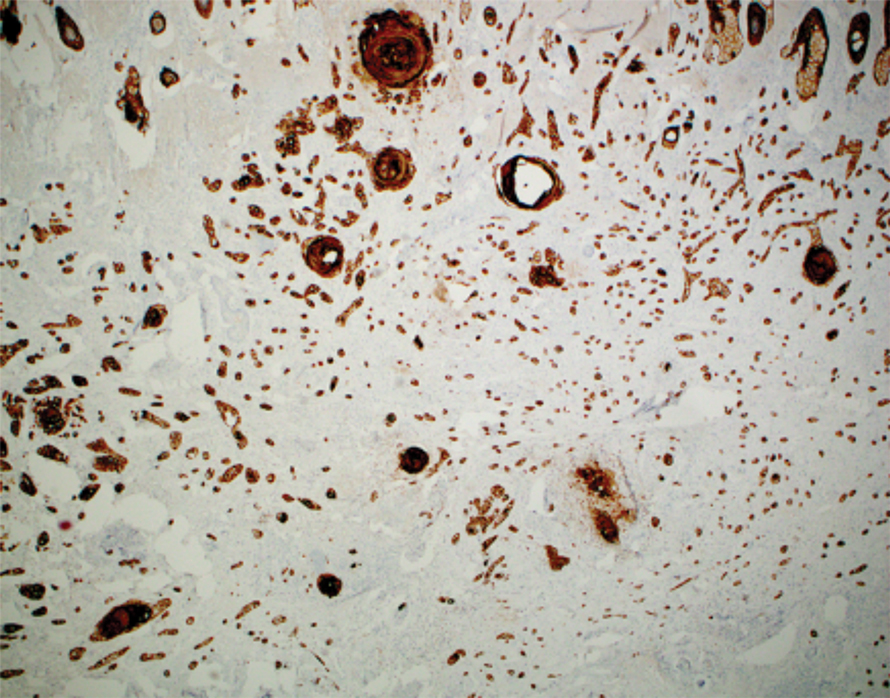

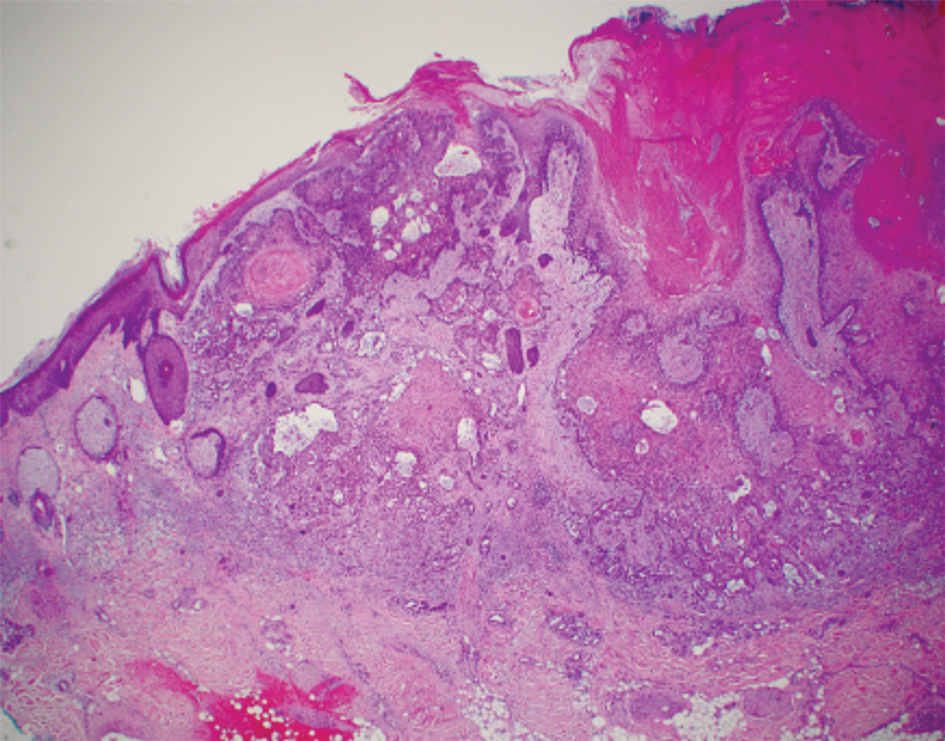

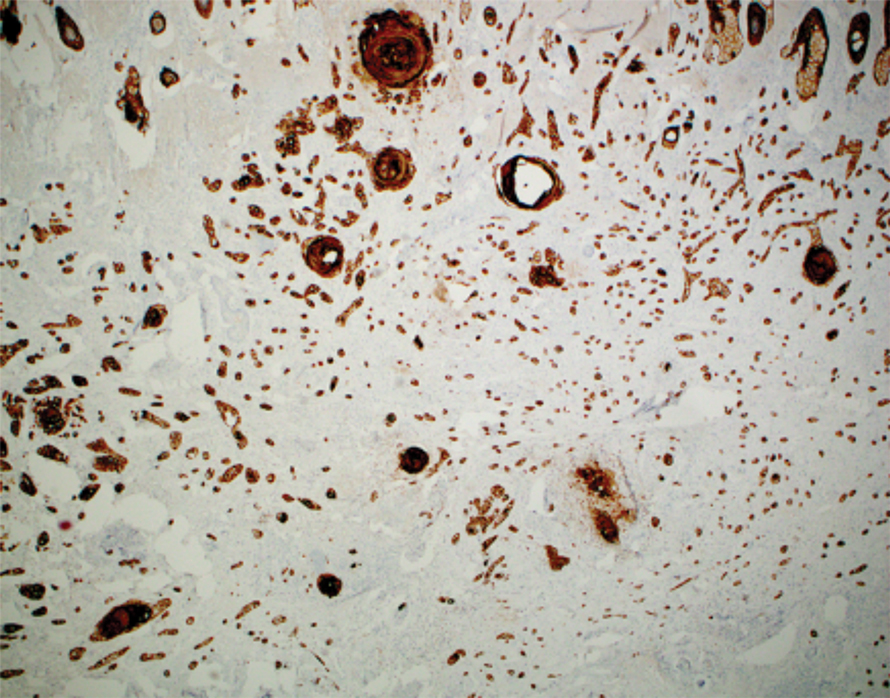

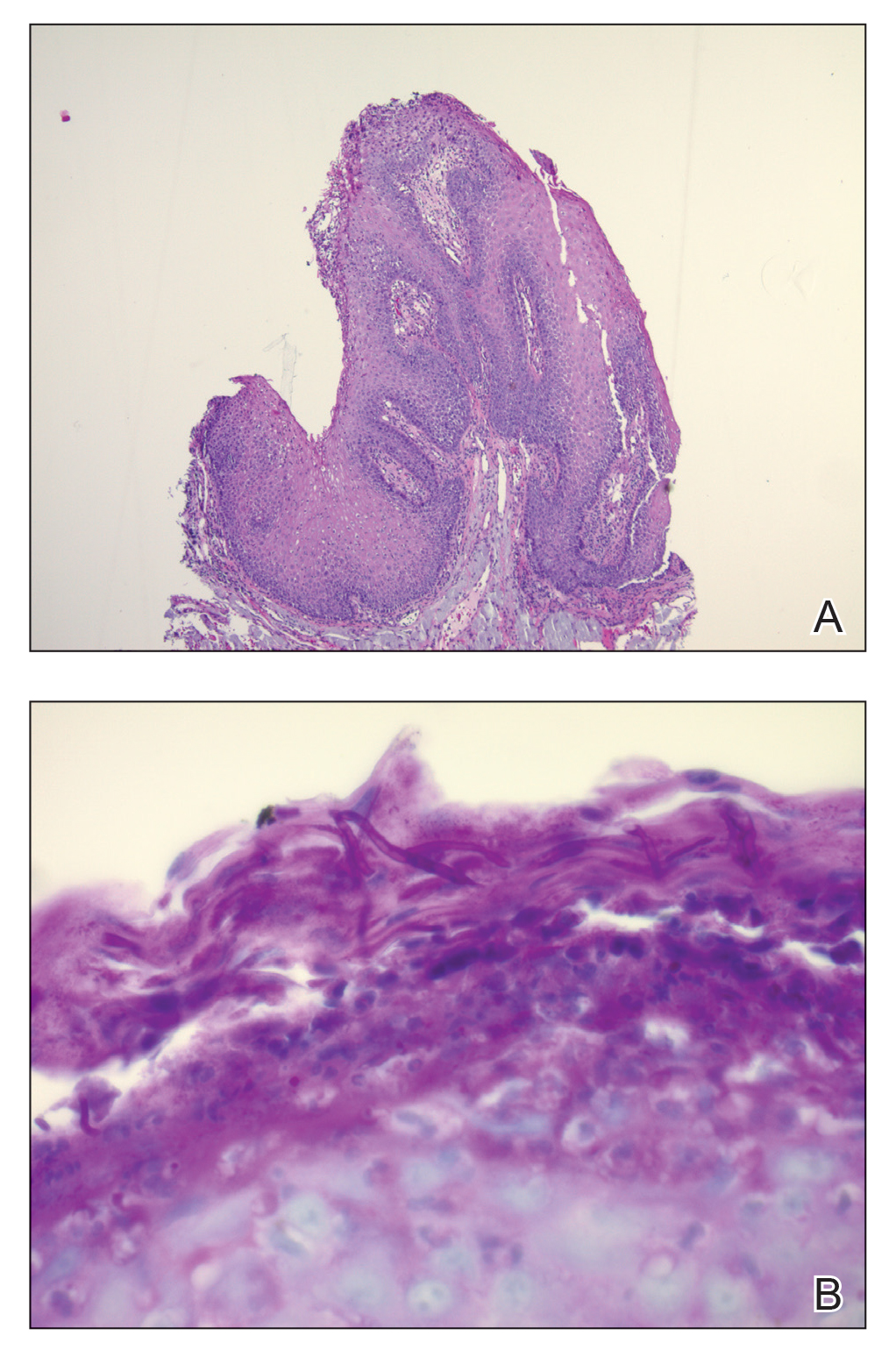

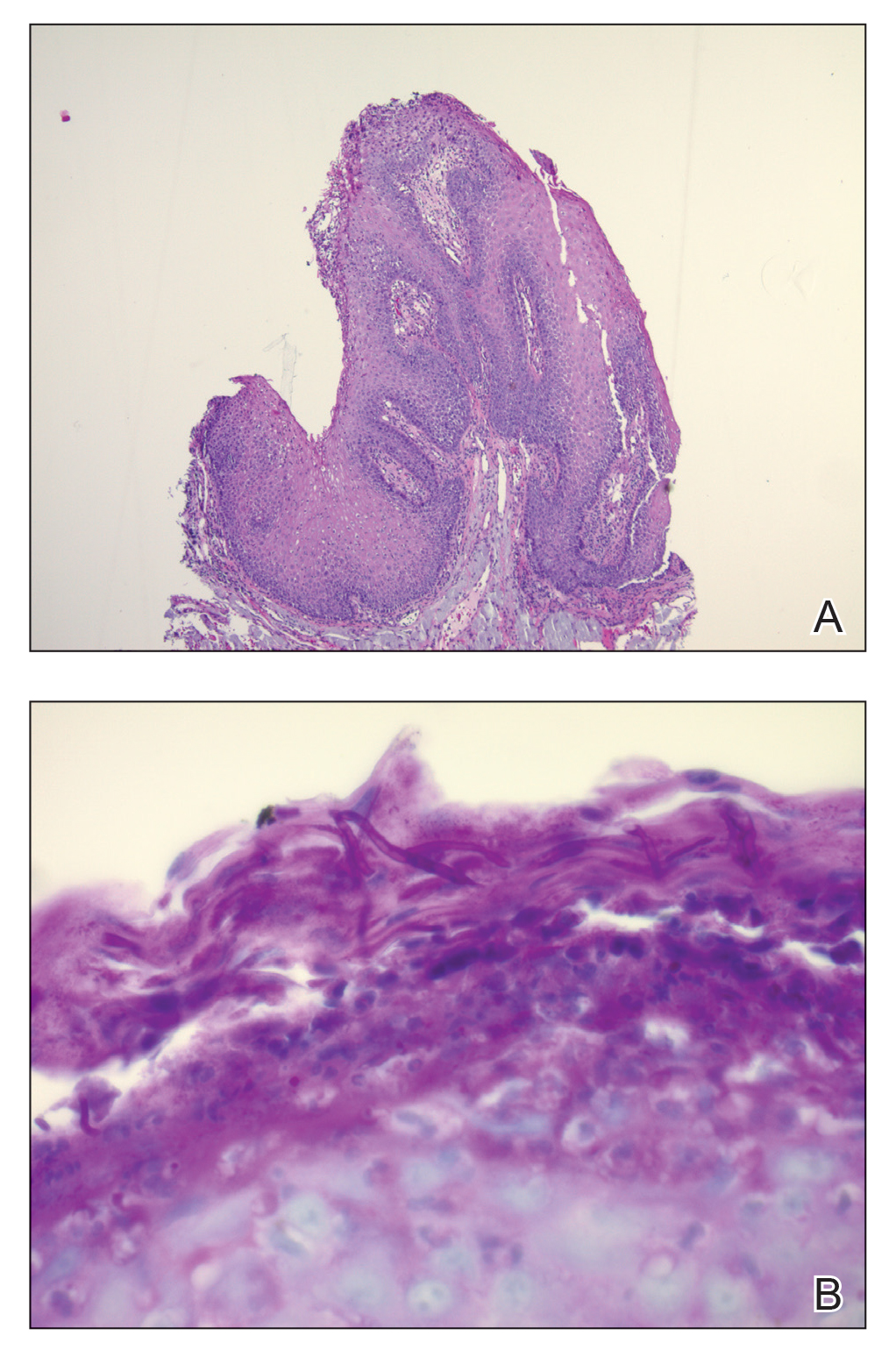

Intraoperative histologic examination of the excised tissue revealed a biphasic pattern consisting of superficial SCC features overlying deeper dermal and subcutaneous infiltrative malignant ductal elements with gland formation in all 5 patients (Figures 2–4). Immunohistochemical staining with cytokeratin AE1/AE3 revealed thin strands of carcinoma in the mid to deeper dermis with squamous differentiation and eccrine ductal differentiation (Figure 5), thus confirming the diagnosis in all 5 patients.

The median depth of tumor invasion was 4.1 mm (range, 2.2–5.45 mm). Ulceration was seen in 3 of the patients, and PNI of large-caliber nerves was observed in all 5 patients. A connection with the overlying epidermis was present in all 5 patients. All 5 patients required more than 1 Mohs stage for complete tumor clearance (Table).

In 4 of the patients, nodal imaging performed at the time of diagnosis revealed no evidence of metastasis. Two patients received adjuvant radiation therapy, and none demonstrated evidence of recurrence. The mean follow-up time was 11 months (range, 6.5–18 months) for the 4 cases with available follow-up data (Table).

Literature Review

A PubMed review of the literature using the search term squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma resulted in 28 articles, 19 of which were included in the review based on inclusion criteria (original articles available in English, in full text, and pertained to SEDC). Our review yielded 56 cases of SEDC.1-19 The mean age of patients with SEDC was 72 years. The number of male and female cases was 52% (29/56) and 48% (27/56), respectively. The most common location of SEDC was on the head or neck (71% [40/56]), followed by the extremities (19% [11/56]). Immunosuppression was noted in 9% (5/56) of cases. Wide local excision was the most commonly employed treatment modality (91% [51/56]), with MMS being used in 4 patients (7%). Adjuvant radiation was reported in 5% (3/56) of cases. Perineural invasion was reported in 34% (19/56) of cases. Recurrence was seen in 23% (13/56) of cases, with a mean time to recurrence of 10.4 months. Metastasis to regional lymph nodes was observed in 13% (7/56) of cases, with 7% (4/56) of those cases having distant metastases.

Comment

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma was successfully treated with MMS in all 5 of the patients we reviewed. Recognition of a distinct biphasic pattern consisting of squamous differentiation superficially with epidermal connection overlying deeper dermal and subcutaneous infiltrative malignant ductal elements with gland formation should lead to consideration of this diagnosis. A thorough inspection for PNI also should be performed, as this finding was present in all of 5 cases and in 34% of reported cases in our literature review.

The differential diagnosis for SEDC includes SCC, metastatic adenocarcinoma with squamoid features, and eccrine tumors, including eccrine poroma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), and porocarcinoma with squamous differentiation. The combination of histologic features with the immunoexpression profile of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), cytokeratin (CK) 5/6, and p63 can effectively exclude the other entities in the differential and confirm the diagnosis of SEDC.1,3,4 While the diagnosis of SEDC relies on the specific histologic features of multiple surface attachments and superficial squamoid changes with deep ductular elements, immunohistochemistry can nonetheless be adjunctive in difficult cases. Positive immunohistochemical staining for CEA and EMA can help to highlight and delineate true glandular elements, whereas CK5/6 highlights the overall contour of the tumor, displaying more clearly the multiple epidermal attachments and the subtle infiltrative nature of the deeper components of invasive cords and ducts. In addition, the combination of CK5/6 and p63 positivity supports the primary cutaneous nature of the lesion rather than metastatic adenocarcinoma.13,20 Other markers of eccrine secretory coils, such as CK7, CAM5.2, and S100, also are sometimes used for confirmation, some of which can aid in distinction from noneccrine sweat gland differentiation, as CK7 and CAM5.2 are negative in both luminal and basal cells of the dermal duct while being positive within the secretory coil, and S100 protein is expressed within eccrine secretory coil but negative within the apocrine sweat glands.2,4,21

The clinical findings from our chart review corroborated those reported in the literature. The mean age of SEDC in the 5 patients we reviewed was 81 years, and all cases presented on the head, consistent with the findings observed in the literature. Although 4 of our cases were male, there may not be a difference in risk based on sex as previously thought.1 Our literature review revealed an almost equivalent percentage of male and female cases, with 52% being male.

Immunosuppression has been associated with an increased risk for SEDC. Our literature review revealed that approximately 9% (5/56) of cases occurred in immunosuppressed individuals. Two of these reported cases were in the setting of underlying chronic lymphocytic leukemia, 2 in individuals with a history of organ transplant, and 1 treated with azathioprine for myasthenia gravis.2,4,10,12,13 Our chart review supported this correlation, as all 5 patients had a medical history potentially consistent with being in an immunocompromised state (Table). Notably, patient 5 represents a unique case of SEDC occurring in the setting of HIV. The patient had HIV for 33 years, with his most recent CD4+ count of 794 mm3 and HIV-1 RNA load of 35 copies/mL. Given that HIV-positive individuals may have more than a 2-fold increased risk of SCC, a greater degree of suspicion for SEDC should be maintained for these patients.22,23

The etiology of SEDC is controversial but is thought to be either an SCC arising from eccrine glands or a variant of eccrine carcinoma with extensive squamoid differentiation.4,6,13,14,17,24 While SEDC certainly appears to share the proclivity for PNI with the malignant eccrine tumor MAC, it is simultaneously quite distinct, demonstrating nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic activity, both of which are lacking in the bland nature of MACs.12,25

The exact prevalence of SEDC is difficult to ascertain because of its frequent misdiagnosis and variable nomenclature used within the literature. Most reported cases of SEDC are mistakenly diagnosed as SCC on the initial shave or punch biopsy because of superficial sampling. This also was the case in 4 of the patients we reviewed. In addition, there are reported cases of SEDC that were referred to by the investigators as cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma (cASC), among other descriptors, such as ductal eccrine carcinoma with squamous differentiation, adnexal carcinoma with squamous and ductal differentiation, and syringoid eccrine carcinoma.26-32 While the World Health Organization classifies SEDC as a distinct variant of cASC, which is a rare variant of SCC in itself, the 2 can be differentiated. Despite the similar clinical and histologic features shared between cASC and SEDC, the neoplastic aggregates in SEDC exhibit ductal differentiation containing lumina positive for CEA and EMA.4 Overall, we favor the term squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma, as there has recently been more uniformity for the designation of this disease entity as such.

It is unclear whether the high incidence of local recurrence (23% [13/56]) of SEDC reported in the literature is related to the treatment modality employed (ie, wide local excision) or due to the innate aggressiveness of SEDC.1,3,5 The literature has shown that MMS has lower recurrence rates than other treatments at 5-year follow-up for SCC (3.1%–5%) and eccrine carcinomas (0%–5%).33,34 Although studies assessing tumor behavior or comparing treatment modalities are limited because of the rarity and underrecognition of SEDC, MMS has been used several times for SEDC with only 1 recurrence reported.4,13,17,24 Given that all 5 of the patients we reviewed required more than 1 Mohs stage for complete tumor clearance and none demonstrated evidence of recurrence or metastasis (Table), we recommend MMS as the treatment of choice for SEDC.

Conclusion

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma is a rare but likely underdiagnosed cutaneous tumor of uncertain etiology. Because of its propensity for recurrence and metastasis, excision of SEDC with complete circumferential peripheral and deep margin assessment with close follow-up is recommended.

- van der Horst MP, Garcia-Herrera A, Markiewicz D, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:755-760.

- Jacob J, Kugelman L. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Cutis. 2018;101:378-380, 385.

- Yim S, Lee YH, Chae SW, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma of the ear helix. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7:1409-1411.

- Terushkin E, Leffell DJ, Futoryan T, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:287-292.

- Jung YH, Jo HJ, Kang MS. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma of the scalp. Korean J Pathol. 2012;46:278-281.

- Saraiva MI, Vieira MA, Portocarrero LK, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:799-802.

- Phan K, Kim L, Lim P, et al. A case report of temple squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a diagnostic challenge beneath the tip of the iceberg. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13213.

- McKissack SS, Wohltmann W, Dalton SR, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: an aggressive mimicker of squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:140-143.

- Lobo-Jardim MM, Souza BdCE, Kakizaki P, et al. Dermoscopy of squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: an aid for early diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:893-895.

- Chan H, Howard V, Moir D, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma of the scalp. Aust J Dermatol. 2016;57:E117-E119.

- Wang B, Jarell AD, Bingham JL, et al. PET/CT imaging of squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40:322-324.

- Frouin E, Vignon-Pennamen MD, Balme B, et al. Anatomoclinical study of 30 cases of sclerosing sweat duct carcinomas (microcystic adnexal carcinoma, syringomatous carcinoma and squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1978-1994.

- Clark S, Young A, Piatigorsky E, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery in the setting of squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: addressing a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:33-36.

- Pusiol T, Morichetti D, Zorzi MG, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: inappropriate diagnosis. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1819-1820.

- Kavand S, Cassarino DS. “Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma”: an unusual low-grade case with follicular differentiation. are these tumors squamoid variants of microcystic adnexal carcinoma? Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:849-852.

- Wasserman DI, Sack J, Gonzalez-Serva A, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for a squamoid eccrine carcinoma with lymphatic invasion. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1126-1129.

- Kim YJ, Kim AR, Yu DS. Mohs micrographic surgery for squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1462-1464.

- Herrero J, Monteagudo C, Jorda E, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Histopathology. 1998;32:478-480.

- Wong TY, Suster S, Mihm MC. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Histopathology. 1997;30:288-293.

- Qureshi HS, Ormsby AH, Lee MW, et al. The diagnostic utility of p63, CK5/6, CK 7, and CK 20 in distinguishing primary cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic carcinomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:145-152.

- Dabbs DJ. Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry: Theranostic and Genomic Applications. 4th ed. Elsevier/Saunders; 2014.

- Silverberg MJ, Leyden W, Warton EM, et al. HIV infection status, immunodeficiency, and the incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:350-360.

- Asgari MM, Ray GT, Quesenberry CP Jr, et al. Association of multiple primary skin cancers with human immunodeficiency virus infection, CD4 count, and viral load. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:892-896.

- Tolkachjov SN. Adnexal carcinomas treated with Mohs micrographic surgery: a comprehensive review. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1199-1207.

- Kazakov DV. Cutaneous Adnexal Tumors. Wolters Kluwer Health/ Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- Weidner N, Foucar E. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin. an aggressive mucin- and gland-forming squamous carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:775-779.

- Banks ER, Cooper PH. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a report of 10 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:227-234.

- Ko CJ, Leffell DJ, McNiff JM. Adenosquamous carcinoma: a report of nine cases with p63 and cytokeratin 5/6 staining. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:448-452.

- Patel V, Squires SM, Liu DY, et al. Cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma: a rare neoplasm with biphasic differentiation. Cutis. 2014;94:231-233.

- Chhibber V, Lyle S, Mahalingam M. Ductal eccrine carcinoma with squamous differentiation: apropos a case. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:503-507.

- Sidiropoulos M, Sade S, Al-Habeeb A, et al. Syringoid eccrine carcinoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of four cases. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:788-792.

- Azorín D, López-Ríos F, Ballestín C, et al. Primary cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:542-545.

- Wildemore JK, Lee JB, Humphreys TR. Mohs surgery for malignant eccrine neoplasms. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(12 pt 2):1574-1579.

- Garcia-Zuazaga J, Olbricht SM. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Adv Dermatol. 2008;24:33-57.

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma (SEDC) is an aggressive underrecognized cutaneous malignancy of unknown etiology.1 It is most likely to occur in sun-exposed areas of the body, most commonly the head and neck. Risk factors include male sex, increased age, and chronic immunosuppression.1-4 Current reports suggest that SEDC is likely a high-grade subtype of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) with a high risk for local recurrence (25%) and metastasis (13%).1,3,5,6 There are as few as 56 cases of SEDC reported in the literature; however, the number of cases may be closer to 100 due to SEDC being classified as either adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin or ductal eccrine carcinoma with squamous differentiation.1

Clinically, SEDC mimics keratinocyte carcinomas. Histologically, SEDC is biphasic, with a superficial portion resembling well-differentiated SCC and a deeply invasive portion having infiltrative irregular cords with ductal differentiation. Perineural invasion (PNI) frequently is present. Multiple connections to the overlying epidermis also can be seen, serving as a subtle clue to the diagnosis on broad superficial specimens.1-3 Due to superficial sampling, approximately 50% of reported cases are misdiagnosed as SCC during the initial biopsy.4 The diagnosis of SEDC often is made during complete excision when deeper tissue is sampled. Establishing an accurate diagnosis is important given the more aggressive nature of SEDC compared with SCC and its proclivity for PNI.1,3,6 The purpose of this review is to increase awareness of this underrecognized entity and describe the histologic findings that help distinguish SEDC from SCC.

Patient Chart Review

We reviewed chart notes as well as frozen and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections from all 5 patients diagnosed with SEDC at a single institution between November 2018 and May 2020. The mean age of patients was 81 years, and 4 were male. Four of the patients presented for MMS with a preoperative diagnosis of SCC per the original biopsy results. Only 1 patient had a preoperative diagnosis of SEDC. The details of each case are recorded in the Table. All tumors were greater than 2 cm in diameter on initial presentation, were located on the head, and clinically resembled keratinocyte carcinoma with either a nodular or plaquelike appearance (Figure 1).

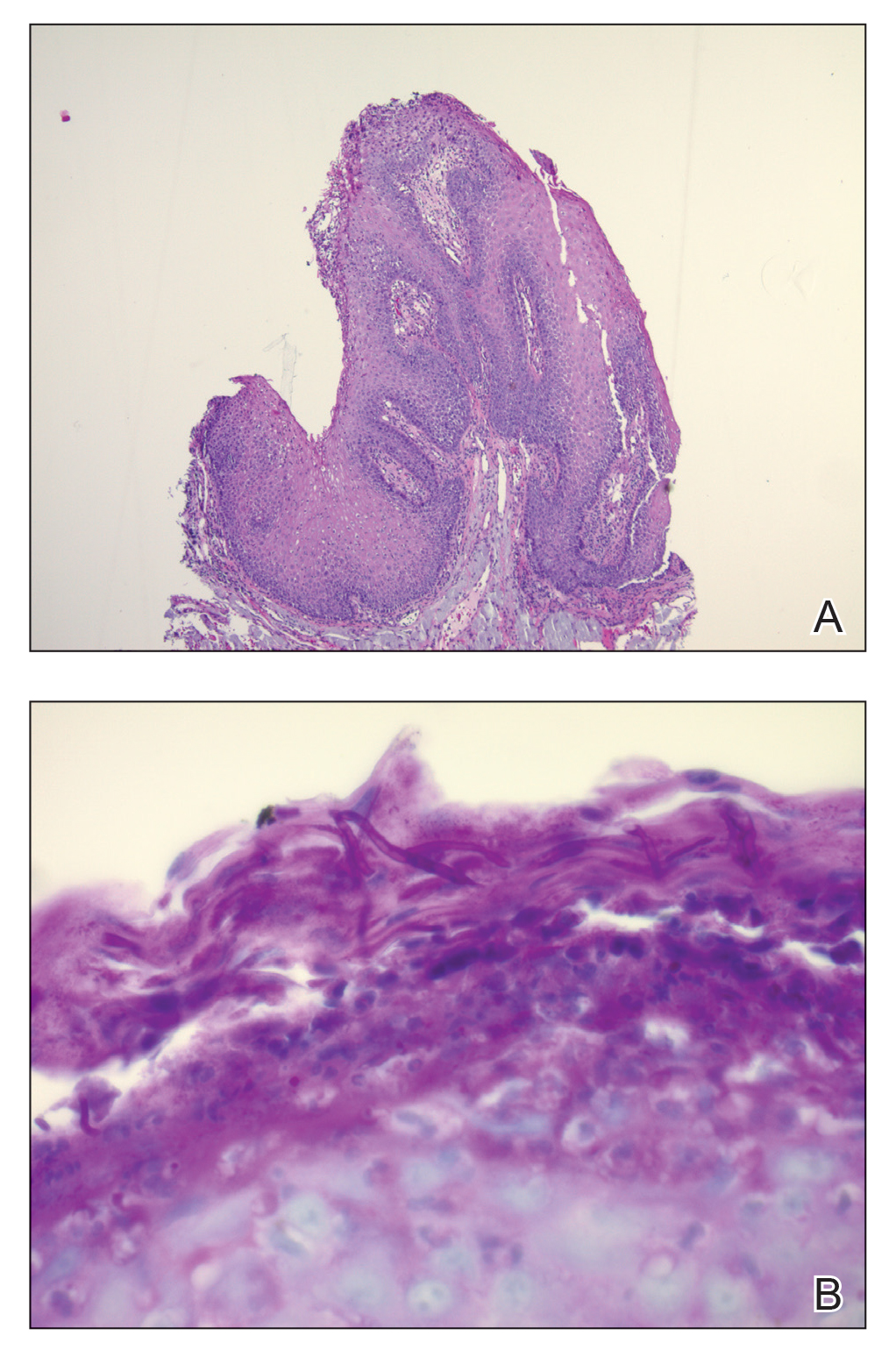

Intraoperative histologic examination of the excised tissue revealed a biphasic pattern consisting of superficial SCC features overlying deeper dermal and subcutaneous infiltrative malignant ductal elements with gland formation in all 5 patients (Figures 2–4). Immunohistochemical staining with cytokeratin AE1/AE3 revealed thin strands of carcinoma in the mid to deeper dermis with squamous differentiation and eccrine ductal differentiation (Figure 5), thus confirming the diagnosis in all 5 patients.

The median depth of tumor invasion was 4.1 mm (range, 2.2–5.45 mm). Ulceration was seen in 3 of the patients, and PNI of large-caliber nerves was observed in all 5 patients. A connection with the overlying epidermis was present in all 5 patients. All 5 patients required more than 1 Mohs stage for complete tumor clearance (Table).

In 4 of the patients, nodal imaging performed at the time of diagnosis revealed no evidence of metastasis. Two patients received adjuvant radiation therapy, and none demonstrated evidence of recurrence. The mean follow-up time was 11 months (range, 6.5–18 months) for the 4 cases with available follow-up data (Table).

Literature Review

A PubMed review of the literature using the search term squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma resulted in 28 articles, 19 of which were included in the review based on inclusion criteria (original articles available in English, in full text, and pertained to SEDC). Our review yielded 56 cases of SEDC.1-19 The mean age of patients with SEDC was 72 years. The number of male and female cases was 52% (29/56) and 48% (27/56), respectively. The most common location of SEDC was on the head or neck (71% [40/56]), followed by the extremities (19% [11/56]). Immunosuppression was noted in 9% (5/56) of cases. Wide local excision was the most commonly employed treatment modality (91% [51/56]), with MMS being used in 4 patients (7%). Adjuvant radiation was reported in 5% (3/56) of cases. Perineural invasion was reported in 34% (19/56) of cases. Recurrence was seen in 23% (13/56) of cases, with a mean time to recurrence of 10.4 months. Metastasis to regional lymph nodes was observed in 13% (7/56) of cases, with 7% (4/56) of those cases having distant metastases.

Comment

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma was successfully treated with MMS in all 5 of the patients we reviewed. Recognition of a distinct biphasic pattern consisting of squamous differentiation superficially with epidermal connection overlying deeper dermal and subcutaneous infiltrative malignant ductal elements with gland formation should lead to consideration of this diagnosis. A thorough inspection for PNI also should be performed, as this finding was present in all of 5 cases and in 34% of reported cases in our literature review.

The differential diagnosis for SEDC includes SCC, metastatic adenocarcinoma with squamoid features, and eccrine tumors, including eccrine poroma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), and porocarcinoma with squamous differentiation. The combination of histologic features with the immunoexpression profile of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), cytokeratin (CK) 5/6, and p63 can effectively exclude the other entities in the differential and confirm the diagnosis of SEDC.1,3,4 While the diagnosis of SEDC relies on the specific histologic features of multiple surface attachments and superficial squamoid changes with deep ductular elements, immunohistochemistry can nonetheless be adjunctive in difficult cases. Positive immunohistochemical staining for CEA and EMA can help to highlight and delineate true glandular elements, whereas CK5/6 highlights the overall contour of the tumor, displaying more clearly the multiple epidermal attachments and the subtle infiltrative nature of the deeper components of invasive cords and ducts. In addition, the combination of CK5/6 and p63 positivity supports the primary cutaneous nature of the lesion rather than metastatic adenocarcinoma.13,20 Other markers of eccrine secretory coils, such as CK7, CAM5.2, and S100, also are sometimes used for confirmation, some of which can aid in distinction from noneccrine sweat gland differentiation, as CK7 and CAM5.2 are negative in both luminal and basal cells of the dermal duct while being positive within the secretory coil, and S100 protein is expressed within eccrine secretory coil but negative within the apocrine sweat glands.2,4,21

The clinical findings from our chart review corroborated those reported in the literature. The mean age of SEDC in the 5 patients we reviewed was 81 years, and all cases presented on the head, consistent with the findings observed in the literature. Although 4 of our cases were male, there may not be a difference in risk based on sex as previously thought.1 Our literature review revealed an almost equivalent percentage of male and female cases, with 52% being male.

Immunosuppression has been associated with an increased risk for SEDC. Our literature review revealed that approximately 9% (5/56) of cases occurred in immunosuppressed individuals. Two of these reported cases were in the setting of underlying chronic lymphocytic leukemia, 2 in individuals with a history of organ transplant, and 1 treated with azathioprine for myasthenia gravis.2,4,10,12,13 Our chart review supported this correlation, as all 5 patients had a medical history potentially consistent with being in an immunocompromised state (Table). Notably, patient 5 represents a unique case of SEDC occurring in the setting of HIV. The patient had HIV for 33 years, with his most recent CD4+ count of 794 mm3 and HIV-1 RNA load of 35 copies/mL. Given that HIV-positive individuals may have more than a 2-fold increased risk of SCC, a greater degree of suspicion for SEDC should be maintained for these patients.22,23

The etiology of SEDC is controversial but is thought to be either an SCC arising from eccrine glands or a variant of eccrine carcinoma with extensive squamoid differentiation.4,6,13,14,17,24 While SEDC certainly appears to share the proclivity for PNI with the malignant eccrine tumor MAC, it is simultaneously quite distinct, demonstrating nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic activity, both of which are lacking in the bland nature of MACs.12,25

The exact prevalence of SEDC is difficult to ascertain because of its frequent misdiagnosis and variable nomenclature used within the literature. Most reported cases of SEDC are mistakenly diagnosed as SCC on the initial shave or punch biopsy because of superficial sampling. This also was the case in 4 of the patients we reviewed. In addition, there are reported cases of SEDC that were referred to by the investigators as cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma (cASC), among other descriptors, such as ductal eccrine carcinoma with squamous differentiation, adnexal carcinoma with squamous and ductal differentiation, and syringoid eccrine carcinoma.26-32 While the World Health Organization classifies SEDC as a distinct variant of cASC, which is a rare variant of SCC in itself, the 2 can be differentiated. Despite the similar clinical and histologic features shared between cASC and SEDC, the neoplastic aggregates in SEDC exhibit ductal differentiation containing lumina positive for CEA and EMA.4 Overall, we favor the term squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma, as there has recently been more uniformity for the designation of this disease entity as such.

It is unclear whether the high incidence of local recurrence (23% [13/56]) of SEDC reported in the literature is related to the treatment modality employed (ie, wide local excision) or due to the innate aggressiveness of SEDC.1,3,5 The literature has shown that MMS has lower recurrence rates than other treatments at 5-year follow-up for SCC (3.1%–5%) and eccrine carcinomas (0%–5%).33,34 Although studies assessing tumor behavior or comparing treatment modalities are limited because of the rarity and underrecognition of SEDC, MMS has been used several times for SEDC with only 1 recurrence reported.4,13,17,24 Given that all 5 of the patients we reviewed required more than 1 Mohs stage for complete tumor clearance and none demonstrated evidence of recurrence or metastasis (Table), we recommend MMS as the treatment of choice for SEDC.

Conclusion

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma is a rare but likely underdiagnosed cutaneous tumor of uncertain etiology. Because of its propensity for recurrence and metastasis, excision of SEDC with complete circumferential peripheral and deep margin assessment with close follow-up is recommended.

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma (SEDC) is an aggressive underrecognized cutaneous malignancy of unknown etiology.1 It is most likely to occur in sun-exposed areas of the body, most commonly the head and neck. Risk factors include male sex, increased age, and chronic immunosuppression.1-4 Current reports suggest that SEDC is likely a high-grade subtype of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) with a high risk for local recurrence (25%) and metastasis (13%).1,3,5,6 There are as few as 56 cases of SEDC reported in the literature; however, the number of cases may be closer to 100 due to SEDC being classified as either adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin or ductal eccrine carcinoma with squamous differentiation.1

Clinically, SEDC mimics keratinocyte carcinomas. Histologically, SEDC is biphasic, with a superficial portion resembling well-differentiated SCC and a deeply invasive portion having infiltrative irregular cords with ductal differentiation. Perineural invasion (PNI) frequently is present. Multiple connections to the overlying epidermis also can be seen, serving as a subtle clue to the diagnosis on broad superficial specimens.1-3 Due to superficial sampling, approximately 50% of reported cases are misdiagnosed as SCC during the initial biopsy.4 The diagnosis of SEDC often is made during complete excision when deeper tissue is sampled. Establishing an accurate diagnosis is important given the more aggressive nature of SEDC compared with SCC and its proclivity for PNI.1,3,6 The purpose of this review is to increase awareness of this underrecognized entity and describe the histologic findings that help distinguish SEDC from SCC.

Patient Chart Review

We reviewed chart notes as well as frozen and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections from all 5 patients diagnosed with SEDC at a single institution between November 2018 and May 2020. The mean age of patients was 81 years, and 4 were male. Four of the patients presented for MMS with a preoperative diagnosis of SCC per the original biopsy results. Only 1 patient had a preoperative diagnosis of SEDC. The details of each case are recorded in the Table. All tumors were greater than 2 cm in diameter on initial presentation, were located on the head, and clinically resembled keratinocyte carcinoma with either a nodular or plaquelike appearance (Figure 1).

Intraoperative histologic examination of the excised tissue revealed a biphasic pattern consisting of superficial SCC features overlying deeper dermal and subcutaneous infiltrative malignant ductal elements with gland formation in all 5 patients (Figures 2–4). Immunohistochemical staining with cytokeratin AE1/AE3 revealed thin strands of carcinoma in the mid to deeper dermis with squamous differentiation and eccrine ductal differentiation (Figure 5), thus confirming the diagnosis in all 5 patients.

The median depth of tumor invasion was 4.1 mm (range, 2.2–5.45 mm). Ulceration was seen in 3 of the patients, and PNI of large-caliber nerves was observed in all 5 patients. A connection with the overlying epidermis was present in all 5 patients. All 5 patients required more than 1 Mohs stage for complete tumor clearance (Table).

In 4 of the patients, nodal imaging performed at the time of diagnosis revealed no evidence of metastasis. Two patients received adjuvant radiation therapy, and none demonstrated evidence of recurrence. The mean follow-up time was 11 months (range, 6.5–18 months) for the 4 cases with available follow-up data (Table).

Literature Review

A PubMed review of the literature using the search term squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma resulted in 28 articles, 19 of which were included in the review based on inclusion criteria (original articles available in English, in full text, and pertained to SEDC). Our review yielded 56 cases of SEDC.1-19 The mean age of patients with SEDC was 72 years. The number of male and female cases was 52% (29/56) and 48% (27/56), respectively. The most common location of SEDC was on the head or neck (71% [40/56]), followed by the extremities (19% [11/56]). Immunosuppression was noted in 9% (5/56) of cases. Wide local excision was the most commonly employed treatment modality (91% [51/56]), with MMS being used in 4 patients (7%). Adjuvant radiation was reported in 5% (3/56) of cases. Perineural invasion was reported in 34% (19/56) of cases. Recurrence was seen in 23% (13/56) of cases, with a mean time to recurrence of 10.4 months. Metastasis to regional lymph nodes was observed in 13% (7/56) of cases, with 7% (4/56) of those cases having distant metastases.

Comment

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma was successfully treated with MMS in all 5 of the patients we reviewed. Recognition of a distinct biphasic pattern consisting of squamous differentiation superficially with epidermal connection overlying deeper dermal and subcutaneous infiltrative malignant ductal elements with gland formation should lead to consideration of this diagnosis. A thorough inspection for PNI also should be performed, as this finding was present in all of 5 cases and in 34% of reported cases in our literature review.

The differential diagnosis for SEDC includes SCC, metastatic adenocarcinoma with squamoid features, and eccrine tumors, including eccrine poroma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC), and porocarcinoma with squamous differentiation. The combination of histologic features with the immunoexpression profile of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), cytokeratin (CK) 5/6, and p63 can effectively exclude the other entities in the differential and confirm the diagnosis of SEDC.1,3,4 While the diagnosis of SEDC relies on the specific histologic features of multiple surface attachments and superficial squamoid changes with deep ductular elements, immunohistochemistry can nonetheless be adjunctive in difficult cases. Positive immunohistochemical staining for CEA and EMA can help to highlight and delineate true glandular elements, whereas CK5/6 highlights the overall contour of the tumor, displaying more clearly the multiple epidermal attachments and the subtle infiltrative nature of the deeper components of invasive cords and ducts. In addition, the combination of CK5/6 and p63 positivity supports the primary cutaneous nature of the lesion rather than metastatic adenocarcinoma.13,20 Other markers of eccrine secretory coils, such as CK7, CAM5.2, and S100, also are sometimes used for confirmation, some of which can aid in distinction from noneccrine sweat gland differentiation, as CK7 and CAM5.2 are negative in both luminal and basal cells of the dermal duct while being positive within the secretory coil, and S100 protein is expressed within eccrine secretory coil but negative within the apocrine sweat glands.2,4,21

The clinical findings from our chart review corroborated those reported in the literature. The mean age of SEDC in the 5 patients we reviewed was 81 years, and all cases presented on the head, consistent with the findings observed in the literature. Although 4 of our cases were male, there may not be a difference in risk based on sex as previously thought.1 Our literature review revealed an almost equivalent percentage of male and female cases, with 52% being male.

Immunosuppression has been associated with an increased risk for SEDC. Our literature review revealed that approximately 9% (5/56) of cases occurred in immunosuppressed individuals. Two of these reported cases were in the setting of underlying chronic lymphocytic leukemia, 2 in individuals with a history of organ transplant, and 1 treated with azathioprine for myasthenia gravis.2,4,10,12,13 Our chart review supported this correlation, as all 5 patients had a medical history potentially consistent with being in an immunocompromised state (Table). Notably, patient 5 represents a unique case of SEDC occurring in the setting of HIV. The patient had HIV for 33 years, with his most recent CD4+ count of 794 mm3 and HIV-1 RNA load of 35 copies/mL. Given that HIV-positive individuals may have more than a 2-fold increased risk of SCC, a greater degree of suspicion for SEDC should be maintained for these patients.22,23

The etiology of SEDC is controversial but is thought to be either an SCC arising from eccrine glands or a variant of eccrine carcinoma with extensive squamoid differentiation.4,6,13,14,17,24 While SEDC certainly appears to share the proclivity for PNI with the malignant eccrine tumor MAC, it is simultaneously quite distinct, demonstrating nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic activity, both of which are lacking in the bland nature of MACs.12,25

The exact prevalence of SEDC is difficult to ascertain because of its frequent misdiagnosis and variable nomenclature used within the literature. Most reported cases of SEDC are mistakenly diagnosed as SCC on the initial shave or punch biopsy because of superficial sampling. This also was the case in 4 of the patients we reviewed. In addition, there are reported cases of SEDC that were referred to by the investigators as cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma (cASC), among other descriptors, such as ductal eccrine carcinoma with squamous differentiation, adnexal carcinoma with squamous and ductal differentiation, and syringoid eccrine carcinoma.26-32 While the World Health Organization classifies SEDC as a distinct variant of cASC, which is a rare variant of SCC in itself, the 2 can be differentiated. Despite the similar clinical and histologic features shared between cASC and SEDC, the neoplastic aggregates in SEDC exhibit ductal differentiation containing lumina positive for CEA and EMA.4 Overall, we favor the term squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma, as there has recently been more uniformity for the designation of this disease entity as such.

It is unclear whether the high incidence of local recurrence (23% [13/56]) of SEDC reported in the literature is related to the treatment modality employed (ie, wide local excision) or due to the innate aggressiveness of SEDC.1,3,5 The literature has shown that MMS has lower recurrence rates than other treatments at 5-year follow-up for SCC (3.1%–5%) and eccrine carcinomas (0%–5%).33,34 Although studies assessing tumor behavior or comparing treatment modalities are limited because of the rarity and underrecognition of SEDC, MMS has been used several times for SEDC with only 1 recurrence reported.4,13,17,24 Given that all 5 of the patients we reviewed required more than 1 Mohs stage for complete tumor clearance and none demonstrated evidence of recurrence or metastasis (Table), we recommend MMS as the treatment of choice for SEDC.

Conclusion

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma is a rare but likely underdiagnosed cutaneous tumor of uncertain etiology. Because of its propensity for recurrence and metastasis, excision of SEDC with complete circumferential peripheral and deep margin assessment with close follow-up is recommended.

- van der Horst MP, Garcia-Herrera A, Markiewicz D, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:755-760.

- Jacob J, Kugelman L. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Cutis. 2018;101:378-380, 385.

- Yim S, Lee YH, Chae SW, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma of the ear helix. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7:1409-1411.

- Terushkin E, Leffell DJ, Futoryan T, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:287-292.

- Jung YH, Jo HJ, Kang MS. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma of the scalp. Korean J Pathol. 2012;46:278-281.

- Saraiva MI, Vieira MA, Portocarrero LK, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:799-802.

- Phan K, Kim L, Lim P, et al. A case report of temple squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a diagnostic challenge beneath the tip of the iceberg. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13213.

- McKissack SS, Wohltmann W, Dalton SR, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: an aggressive mimicker of squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:140-143.

- Lobo-Jardim MM, Souza BdCE, Kakizaki P, et al. Dermoscopy of squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: an aid for early diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:893-895.

- Chan H, Howard V, Moir D, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma of the scalp. Aust J Dermatol. 2016;57:E117-E119.

- Wang B, Jarell AD, Bingham JL, et al. PET/CT imaging of squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40:322-324.

- Frouin E, Vignon-Pennamen MD, Balme B, et al. Anatomoclinical study of 30 cases of sclerosing sweat duct carcinomas (microcystic adnexal carcinoma, syringomatous carcinoma and squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1978-1994.

- Clark S, Young A, Piatigorsky E, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery in the setting of squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: addressing a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:33-36.

- Pusiol T, Morichetti D, Zorzi MG, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: inappropriate diagnosis. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1819-1820.

- Kavand S, Cassarino DS. “Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma”: an unusual low-grade case with follicular differentiation. are these tumors squamoid variants of microcystic adnexal carcinoma? Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:849-852.

- Wasserman DI, Sack J, Gonzalez-Serva A, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for a squamoid eccrine carcinoma with lymphatic invasion. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1126-1129.

- Kim YJ, Kim AR, Yu DS. Mohs micrographic surgery for squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1462-1464.

- Herrero J, Monteagudo C, Jorda E, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Histopathology. 1998;32:478-480.

- Wong TY, Suster S, Mihm MC. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Histopathology. 1997;30:288-293.

- Qureshi HS, Ormsby AH, Lee MW, et al. The diagnostic utility of p63, CK5/6, CK 7, and CK 20 in distinguishing primary cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic carcinomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:145-152.

- Dabbs DJ. Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry: Theranostic and Genomic Applications. 4th ed. Elsevier/Saunders; 2014.

- Silverberg MJ, Leyden W, Warton EM, et al. HIV infection status, immunodeficiency, and the incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:350-360.

- Asgari MM, Ray GT, Quesenberry CP Jr, et al. Association of multiple primary skin cancers with human immunodeficiency virus infection, CD4 count, and viral load. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:892-896.

- Tolkachjov SN. Adnexal carcinomas treated with Mohs micrographic surgery: a comprehensive review. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1199-1207.

- Kazakov DV. Cutaneous Adnexal Tumors. Wolters Kluwer Health/ Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- Weidner N, Foucar E. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin. an aggressive mucin- and gland-forming squamous carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:775-779.

- Banks ER, Cooper PH. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a report of 10 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:227-234.

- Ko CJ, Leffell DJ, McNiff JM. Adenosquamous carcinoma: a report of nine cases with p63 and cytokeratin 5/6 staining. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:448-452.

- Patel V, Squires SM, Liu DY, et al. Cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma: a rare neoplasm with biphasic differentiation. Cutis. 2014;94:231-233.

- Chhibber V, Lyle S, Mahalingam M. Ductal eccrine carcinoma with squamous differentiation: apropos a case. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:503-507.

- Sidiropoulos M, Sade S, Al-Habeeb A, et al. Syringoid eccrine carcinoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of four cases. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:788-792.

- Azorín D, López-Ríos F, Ballestín C, et al. Primary cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:542-545.

- Wildemore JK, Lee JB, Humphreys TR. Mohs surgery for malignant eccrine neoplasms. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(12 pt 2):1574-1579.

- Garcia-Zuazaga J, Olbricht SM. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Adv Dermatol. 2008;24:33-57.

- van der Horst MP, Garcia-Herrera A, Markiewicz D, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:755-760.

- Jacob J, Kugelman L. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Cutis. 2018;101:378-380, 385.

- Yim S, Lee YH, Chae SW, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma of the ear helix. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7:1409-1411.

- Terushkin E, Leffell DJ, Futoryan T, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:287-292.

- Jung YH, Jo HJ, Kang MS. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma of the scalp. Korean J Pathol. 2012;46:278-281.

- Saraiva MI, Vieira MA, Portocarrero LK, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:799-802.

- Phan K, Kim L, Lim P, et al. A case report of temple squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a diagnostic challenge beneath the tip of the iceberg. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13213.

- McKissack SS, Wohltmann W, Dalton SR, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: an aggressive mimicker of squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:140-143.

- Lobo-Jardim MM, Souza BdCE, Kakizaki P, et al. Dermoscopy of squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: an aid for early diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:893-895.

- Chan H, Howard V, Moir D, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma of the scalp. Aust J Dermatol. 2016;57:E117-E119.

- Wang B, Jarell AD, Bingham JL, et al. PET/CT imaging of squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40:322-324.

- Frouin E, Vignon-Pennamen MD, Balme B, et al. Anatomoclinical study of 30 cases of sclerosing sweat duct carcinomas (microcystic adnexal carcinoma, syringomatous carcinoma and squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1978-1994.

- Clark S, Young A, Piatigorsky E, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery in the setting of squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: addressing a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:33-36.

- Pusiol T, Morichetti D, Zorzi MG, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: inappropriate diagnosis. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1819-1820.

- Kavand S, Cassarino DS. “Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma”: an unusual low-grade case with follicular differentiation. are these tumors squamoid variants of microcystic adnexal carcinoma? Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:849-852.

- Wasserman DI, Sack J, Gonzalez-Serva A, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for a squamoid eccrine carcinoma with lymphatic invasion. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1126-1129.

- Kim YJ, Kim AR, Yu DS. Mohs micrographic surgery for squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1462-1464.

- Herrero J, Monteagudo C, Jorda E, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Histopathology. 1998;32:478-480.

- Wong TY, Suster S, Mihm MC. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Histopathology. 1997;30:288-293.

- Qureshi HS, Ormsby AH, Lee MW, et al. The diagnostic utility of p63, CK5/6, CK 7, and CK 20 in distinguishing primary cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic carcinomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:145-152.

- Dabbs DJ. Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry: Theranostic and Genomic Applications. 4th ed. Elsevier/Saunders; 2014.

- Silverberg MJ, Leyden W, Warton EM, et al. HIV infection status, immunodeficiency, and the incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:350-360.

- Asgari MM, Ray GT, Quesenberry CP Jr, et al. Association of multiple primary skin cancers with human immunodeficiency virus infection, CD4 count, and viral load. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:892-896.

- Tolkachjov SN. Adnexal carcinomas treated with Mohs micrographic surgery: a comprehensive review. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1199-1207.

- Kazakov DV. Cutaneous Adnexal Tumors. Wolters Kluwer Health/ Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- Weidner N, Foucar E. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin. an aggressive mucin- and gland-forming squamous carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:775-779.

- Banks ER, Cooper PH. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a report of 10 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:227-234.

- Ko CJ, Leffell DJ, McNiff JM. Adenosquamous carcinoma: a report of nine cases with p63 and cytokeratin 5/6 staining. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:448-452.

- Patel V, Squires SM, Liu DY, et al. Cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma: a rare neoplasm with biphasic differentiation. Cutis. 2014;94:231-233.

- Chhibber V, Lyle S, Mahalingam M. Ductal eccrine carcinoma with squamous differentiation: apropos a case. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:503-507.

- Sidiropoulos M, Sade S, Al-Habeeb A, et al. Syringoid eccrine carcinoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of four cases. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:788-792.

- Azorín D, López-Ríos F, Ballestín C, et al. Primary cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:542-545.

- Wildemore JK, Lee JB, Humphreys TR. Mohs surgery for malignant eccrine neoplasms. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(12 pt 2):1574-1579.

- Garcia-Zuazaga J, Olbricht SM. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Adv Dermatol. 2008;24:33-57.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma is an aggressive underrecognized cutaneous malignancy that often is misdiagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) during initial biopsy.

- Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma has a biphasic histologic appearance with a superficial portion resembling well-differentiated SCC and a deeply invasive portion comprised of infiltrative irregular cords with ductal differentiation.

- Excision with complete circumferential peripheral and deep margin assessment with close follow-up is recommended for these patients because of the high risk for recurrence and metastasis.

Nivolumab-Induced Granuloma Annulare

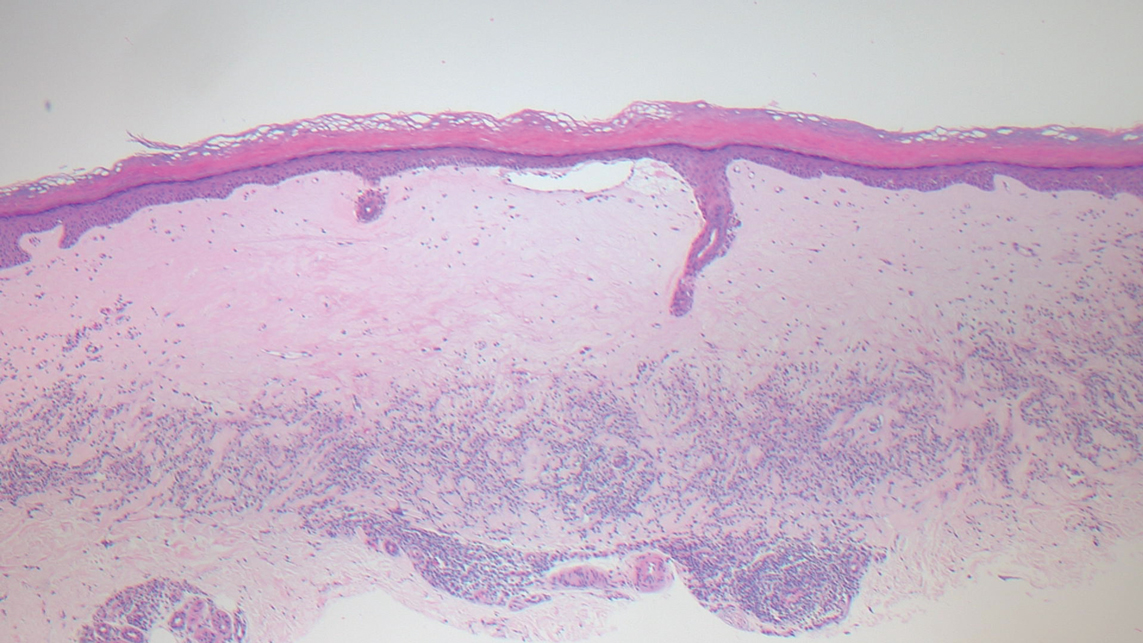

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a benign, cutaneous, granulomatous disease of unclear etiology. Typically, GA presents in young adults as asymptomatic, annular, flesh-colored to pink papules and plaques, commonly on the upper and lower extremities. Histologically, GA is characterized by mucin deposition, palisading or an interstitial granulomatous pattern, and collagen and elastic fiber degeneration.1

Granuloma annulare has been associated with various medications and medical conditions, including diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, thyroid disease, and HIV.1 More recently, immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been reported to trigger GA.2 We report a case of nivolumab-induced GA in a 54-year-old woman.

Case Report

A 54-year-old woman presented with an itchy rash on the upper extremities, face, and chest of 4 months’ duration. The patient noted that the rash started on the hands and progressed to include the arms, face, and chest. She also reported associated mild tenderness. She had a history of stage IV non–small-cell lung carcinoma with metastases to the ribs and adrenal glands. She had been started on biweekly intravenous infusions of the ICI nivolumab by her oncologist approximately 1 year prior to the current presentation after failing a course of conventional chemotherapy. The most recent positron emission tomography–computed tomography scan 1 month prior to presentation showed a stable lung mass with radiologic disappearance of metastases, indicating a favorable response to nivolumab. The patient also had a history of hypothyroidism and depression, which were treated with oral levothyroxine 75 μg once daily and oral sertraline 50 mg once daily, respectively, both for longer than 5 years.

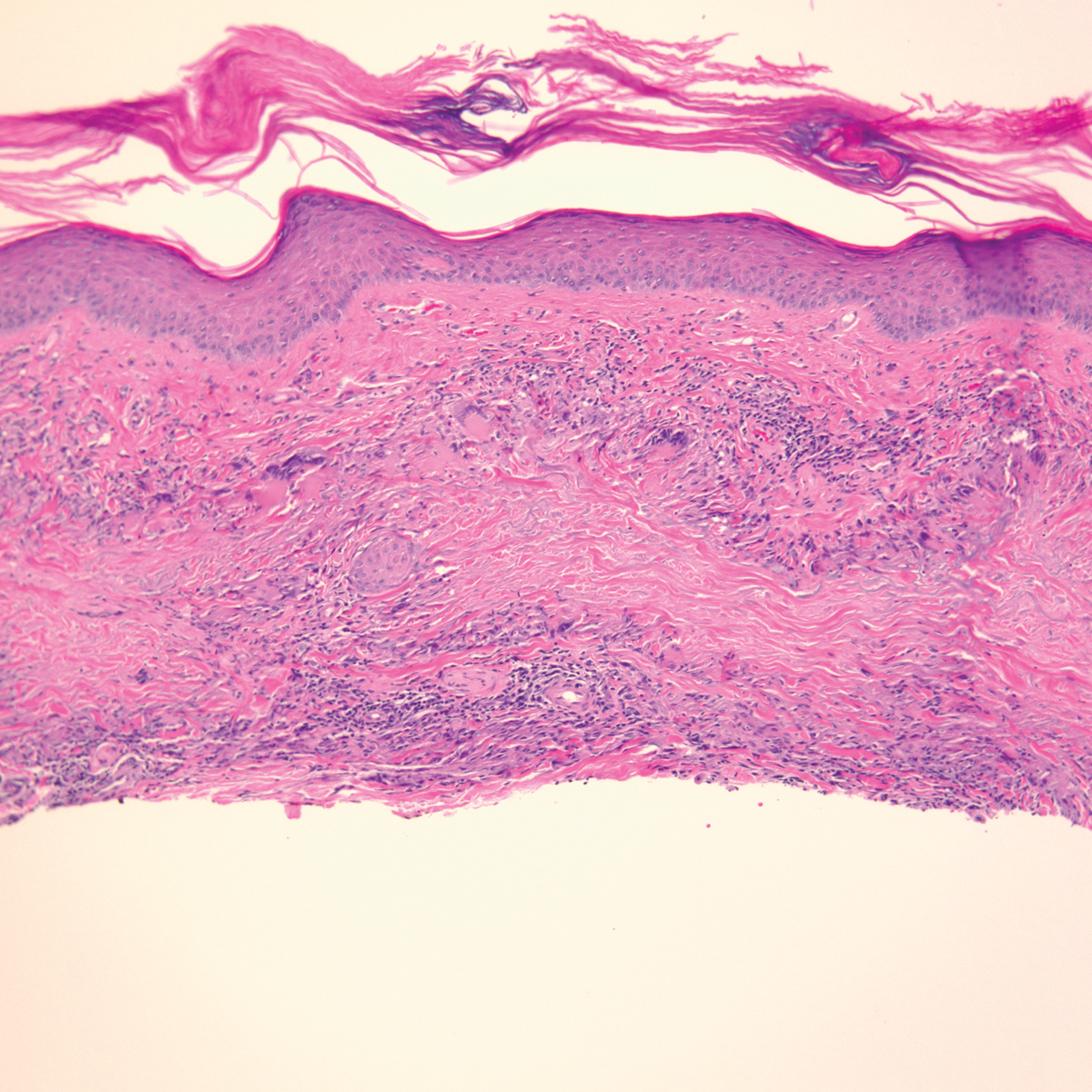

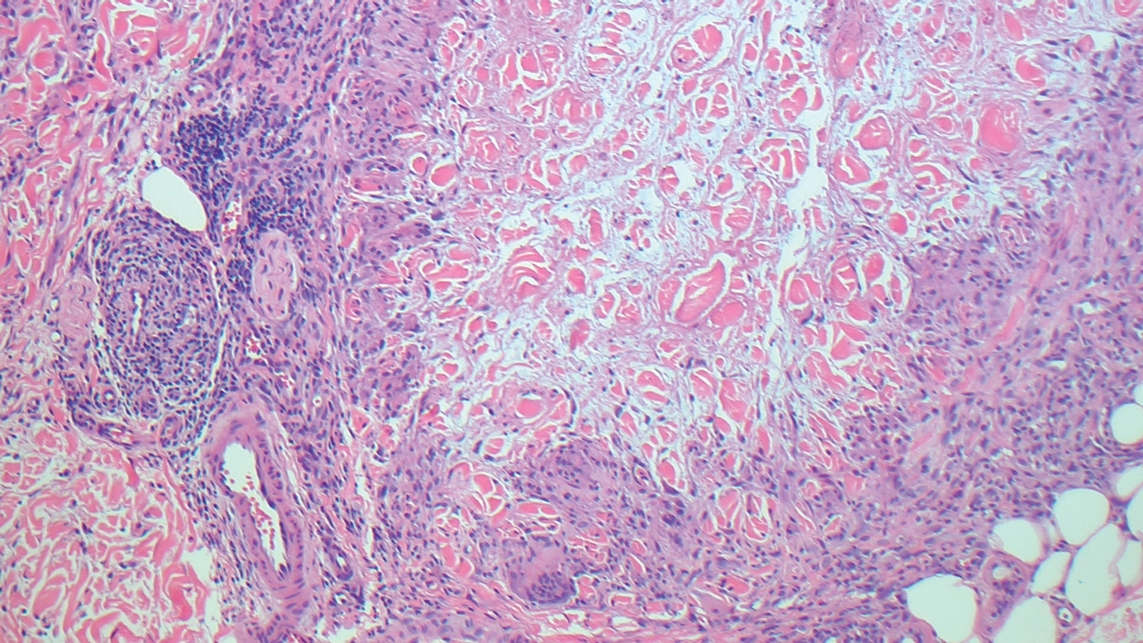

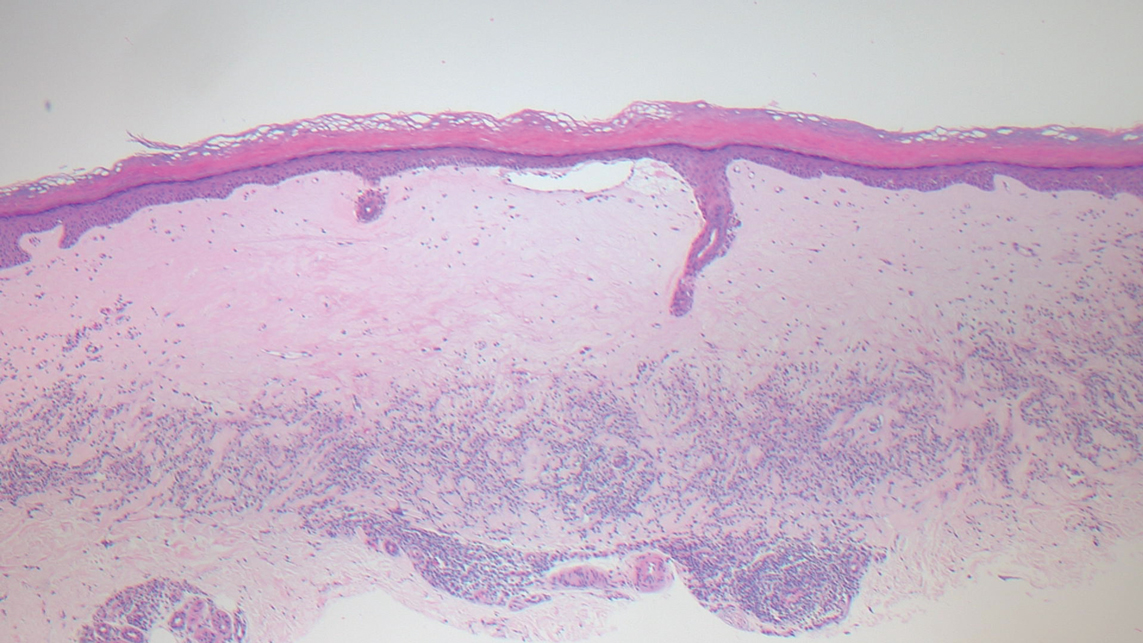

Physical examination revealed annular, erythematous, flat-topped papules, some with surmounting fine scale, coalescing into larger plaques along the dorsal surface of the hands and arms (Figure 1) as well as the forehead and chest. A biopsy of a papule on the dorsal aspect of the left hand revealed nodules of histiocytes admixed with Langerhans giant cells within the dermis; mucin was noted centrally within some nodules (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal elements compared to control. Polarization of the specimen was negative for foreign bodies. The biopsy findings therefore were consistent with a diagnosis of GA.

A 3-month treatment course of betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% cream twice daily failed. Narrowband UVB phototherapy was then initiated at 3 sessions weekly. The eruption of GA improved after 3 months of phototherapy. Subsequently, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Comment

Discovery of specific immune checkpoints in tumor-induced immunosuppression revolutionized oncologic therapy. An example is the programmed cell-death protein 1 (PD-1) receptor that is expressed on activated immune cells, including T cells and macrophages.3,4 Upon binding to the PD-1 ligand (PD-L1), T-cell proliferation is inhibited, resulting in downregulation of the immune response. As a result, tumor cells have evolved to overexpress PD-L1 to evade immunologic detection.3 Nivolumab, a fully human IgG4 antibody to PD-1, has emerged along with other ICIs as effective treatments for numerous cancers, including melanoma and non–small-cell lung cancer. By disrupting downregulation of T cells, ICIs improve immune-mediated antitumor activity.3

However, the resulting immunologic disturbance by ICIs has been reported to induce various cutaneous and systemic immune-mediated adverse reactions, including granulomatous reactions such as sarcoidosis, GA, and a cutaneous sarcoidlike granulomatous reaction.1,2,5,6 Our patient represents a rare case of nivolumab-induced GA.

Recent evidence suggests that GA might be caused in part by a cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction that is regulated by a helper T cell subset 1 inflammatory reaction. Through release of cytokines by activated CD4+ T cells, macrophages are recruited, forming the granulomatous pattern and secreting enzymes that can degrade connective tissue. Nivolumab and other ICIs can thus trigger this reaction because their blockade of PD-1 enhances T cell–mediated immune reactions.2 In addition, because macrophages themselves also express PD-1, ICIs can directly enhance macrophage recruitment and proliferation, further increasing the risk of a granulomatous reaction.4

Interestingly, cutaneous adverse reactions to nivolumab have been associated with improved survival in melanoma patients.7 The nature of this association with granulomatous reactions in general and with GA specifically remains to be determined.

Conclusion

Since the approval of the first PD-1 inhibitors, pembrolizumab and nivolumab, in 2014, other ICIs targeting the immune checkpoint pathway have been developed. Newer agents targeting PD-L1 (avelumab, atezolizumab, and durvalumab) were recently approved. Additionally, cemiplimab, another PD-1 inhibitor, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2018 for the treatment of advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.8 Indications for all ICIs also have expanded considerably.3 Therefore, the incidence of immune-mediated adverse reactions, including GA, is bound to increase. Physicians should be cognizant of this association to accurately diagnose and effectively treat adverse reactions in patients who are taking ICIs.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.055

- Wu J, Kwong BY, Martires KJ, et al. Granuloma annulare associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 2018;32:E124-E126. doi:10.1111/jdv.14617