User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Nearly 10% of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 later readmitted

About 1 in 11 patients discharged after COVID-19 treatment is readmitted to the same hospital, according to researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Older age and chronic diseases are associated with increased risk, said senior author Adi V. Gundlapalli, MD, PhD, chief public health informatics officer of the CDC’s Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services.

Gundlapalli and colleagues published the finding November 9 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

To get a picture of readmission after COVID-19 hospitalization, the researchers analyzed records of 126,137 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 between March and July and included in the Premier Healthcare Database, which covers discharge records from 865 nongovernmental, community, and teaching hospitals.

Overall, 15% of the patients died during hospitalization. Of those who survived to discharge, 9% were readmitted to the same hospital within 2 months of discharge; 1.6% of patients were readmitted more than once. The median interval from discharge to first readmission was 8 days (interquartile range, 3-20 days). This short interval suggests that patients are probably not suffering a relapse, Gundlapalli said in an interview. More likely they experienced some adverse event, such as difficulty breathing, that led their caretakers to send them back to the hospital.

Forty-five percent of the primary discharge diagnoses after readmission were infectious and parasitic diseases, primarily COVID-19. The next most common were circulatory system symptoms (11%) and digestive symptoms (7%).

After controlling for covariates, the researchers found that patients were more likely to be readmitted if they had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (odds ratio [OR], 1.4), heart failure (OR, 1.6), diabetes (OR, 1.2), or chronic kidney disease (OR, 1.6).

They also found increased odds among patients discharged from the index hospitalization to a skilled nursing facility (OR, 1.4) or with home health organization support (OR, 1.3), compared with being discharged to home or self-care. Looked at another way, the rate of readmission was 15% among those discharged to a skilled nursing facility, 12% among those needing home health care and 7% of those discharged to home or self-care.

The researchers also found that people who had been hospitalized within 3 months prior to the index hospitalization were 2.6 times more likely to be readmitted than were those without prior inpatient care.

Further, the odds of readmission increased significantly among people over 65 years of age, compared with people aged 18 to 39 years.

“The results are not surprising,” Gundlapalli said. “We have known from before that elderly patients, especially with chronic conditions, certain clinical conditions, and those who have been hospitalized before, are at risk for readmission.”

But admitting COVID-19 patients requires special planning because they must be isolated and because more personal protective equipment (PPE) is required, he pointed out.

One unexpected finding from the report is that non-Hispanic White people were more likely to be readmitted than were people of other racial or ethnic groups. This contrasts with other research showing Hispanic and Black individuals are more severely affected by COVID-19 than White people. More research is needed to explain this result, Gundlapalli said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About 1 in 11 patients discharged after COVID-19 treatment is readmitted to the same hospital, according to researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Older age and chronic diseases are associated with increased risk, said senior author Adi V. Gundlapalli, MD, PhD, chief public health informatics officer of the CDC’s Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services.

Gundlapalli and colleagues published the finding November 9 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

To get a picture of readmission after COVID-19 hospitalization, the researchers analyzed records of 126,137 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 between March and July and included in the Premier Healthcare Database, which covers discharge records from 865 nongovernmental, community, and teaching hospitals.

Overall, 15% of the patients died during hospitalization. Of those who survived to discharge, 9% were readmitted to the same hospital within 2 months of discharge; 1.6% of patients were readmitted more than once. The median interval from discharge to first readmission was 8 days (interquartile range, 3-20 days). This short interval suggests that patients are probably not suffering a relapse, Gundlapalli said in an interview. More likely they experienced some adverse event, such as difficulty breathing, that led their caretakers to send them back to the hospital.

Forty-five percent of the primary discharge diagnoses after readmission were infectious and parasitic diseases, primarily COVID-19. The next most common were circulatory system symptoms (11%) and digestive symptoms (7%).

After controlling for covariates, the researchers found that patients were more likely to be readmitted if they had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (odds ratio [OR], 1.4), heart failure (OR, 1.6), diabetes (OR, 1.2), or chronic kidney disease (OR, 1.6).

They also found increased odds among patients discharged from the index hospitalization to a skilled nursing facility (OR, 1.4) or with home health organization support (OR, 1.3), compared with being discharged to home or self-care. Looked at another way, the rate of readmission was 15% among those discharged to a skilled nursing facility, 12% among those needing home health care and 7% of those discharged to home or self-care.

The researchers also found that people who had been hospitalized within 3 months prior to the index hospitalization were 2.6 times more likely to be readmitted than were those without prior inpatient care.

Further, the odds of readmission increased significantly among people over 65 years of age, compared with people aged 18 to 39 years.

“The results are not surprising,” Gundlapalli said. “We have known from before that elderly patients, especially with chronic conditions, certain clinical conditions, and those who have been hospitalized before, are at risk for readmission.”

But admitting COVID-19 patients requires special planning because they must be isolated and because more personal protective equipment (PPE) is required, he pointed out.

One unexpected finding from the report is that non-Hispanic White people were more likely to be readmitted than were people of other racial or ethnic groups. This contrasts with other research showing Hispanic and Black individuals are more severely affected by COVID-19 than White people. More research is needed to explain this result, Gundlapalli said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About 1 in 11 patients discharged after COVID-19 treatment is readmitted to the same hospital, according to researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Older age and chronic diseases are associated with increased risk, said senior author Adi V. Gundlapalli, MD, PhD, chief public health informatics officer of the CDC’s Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services.

Gundlapalli and colleagues published the finding November 9 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

To get a picture of readmission after COVID-19 hospitalization, the researchers analyzed records of 126,137 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 between March and July and included in the Premier Healthcare Database, which covers discharge records from 865 nongovernmental, community, and teaching hospitals.

Overall, 15% of the patients died during hospitalization. Of those who survived to discharge, 9% were readmitted to the same hospital within 2 months of discharge; 1.6% of patients were readmitted more than once. The median interval from discharge to first readmission was 8 days (interquartile range, 3-20 days). This short interval suggests that patients are probably not suffering a relapse, Gundlapalli said in an interview. More likely they experienced some adverse event, such as difficulty breathing, that led their caretakers to send them back to the hospital.

Forty-five percent of the primary discharge diagnoses after readmission were infectious and parasitic diseases, primarily COVID-19. The next most common were circulatory system symptoms (11%) and digestive symptoms (7%).

After controlling for covariates, the researchers found that patients were more likely to be readmitted if they had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (odds ratio [OR], 1.4), heart failure (OR, 1.6), diabetes (OR, 1.2), or chronic kidney disease (OR, 1.6).

They also found increased odds among patients discharged from the index hospitalization to a skilled nursing facility (OR, 1.4) or with home health organization support (OR, 1.3), compared with being discharged to home or self-care. Looked at another way, the rate of readmission was 15% among those discharged to a skilled nursing facility, 12% among those needing home health care and 7% of those discharged to home or self-care.

The researchers also found that people who had been hospitalized within 3 months prior to the index hospitalization were 2.6 times more likely to be readmitted than were those without prior inpatient care.

Further, the odds of readmission increased significantly among people over 65 years of age, compared with people aged 18 to 39 years.

“The results are not surprising,” Gundlapalli said. “We have known from before that elderly patients, especially with chronic conditions, certain clinical conditions, and those who have been hospitalized before, are at risk for readmission.”

But admitting COVID-19 patients requires special planning because they must be isolated and because more personal protective equipment (PPE) is required, he pointed out.

One unexpected finding from the report is that non-Hispanic White people were more likely to be readmitted than were people of other racial or ethnic groups. This contrasts with other research showing Hispanic and Black individuals are more severely affected by COVID-19 than White people. More research is needed to explain this result, Gundlapalli said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Should our patients really go home for the holidays?

As an East Coast transplant residing in Texas, I look forward to the annual sojourn home to celebrate the holidays with family and friends – as do many of our patients and their families. But this is 2020. SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, is still circulating. To make matters worse, cases are rising in 45 states and internationally. The day of this writing 102,831 new cases were reported in the United States.

Social distancing, wearing masks, and hand washing have been strategies recommended to help mitigate the spread of the virus. We know adherence is not always 100%. The reality is that several families will consider traveling and gathering with others over the holidays. Their actions may lead to increased infections, hospitalizations, and even deaths. It behooves us to at least remind them of the potential consequences of the activity, and if travel and/or holiday gatherings are inevitable, to provide some guidance to help them look at both the risks and benefits and offer strategies to minimize infection and spread.

What should be considered prior to travel?

Here is a list of points to ponder:

- Is your patient is in a high-risk group for developing severe disease or visiting someone who is in a high-risk group?

- What is their mode of transportation?

- What is their destination?

- How prevalent is the disease at their destination, compared with their community?

- What will be their accommodations?

- How will attendees prepare for the gathering, if at all?

- Will multiple families congregate after quarantining for 2 weeks or simply arrive?

- At the destination, will people wear masks and socially distance?

- Is an outdoor venue an option?

All of these questions should be considered by patients.

Review high-risk groups

In terms of high-risk groups, we usually focus on underlying medical conditions or extremes of age, but Black and LatinX children and their families have been diagnosed with COVID-19 and hospitalized more frequently than other racial/ ethnic groups in the United States. Of 277,285 school-aged children infected between March 1 and Sept. 19, 2020, 42% were LatinX, 32% White, and 17% Black, yet they comprise 18%, 60%, and 11% of the U.S. population, respectively. Of those hospitalized, 45% were LatinX, 22% White, and 24% Black. LatinX and Black children also have disproportionately higher mortality rates.

Think about transmission and how to mitigate it

Many patients erroneously think combining multiple households for small group gatherings is inconsequential. These types of gatherings serve as a continued source of SARS-CoV-2 spread. For example, a person in Illinois with mild upper respiratory infection symptoms attended a funeral; he reported embracing the family members after the funeral. He dined with two people the evening prior to the funeral, sharing the meal using common serving dishes. Four days later, he attended a birthday party with nine family members. Some of the family members with symptoms subsequently attended church, infecting another church attendee. A cluster of 16 cases of COVID-19 was subsequently identified, including three deaths likely resulting from this one introduction of COVID-19 at these two family gatherings.

In Tennessee and Wisconsin, household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was studied prospectively. A total of 101 index cases and 191 asymptomatic household contacts were enrolled between April and Sept. 2020; 102 of 191 (53%) had SARS-CoV-2 detected during the 14-day follow-up. Most infections (75%) were identified within 5 days and occurred whether the index case was an adult or child.

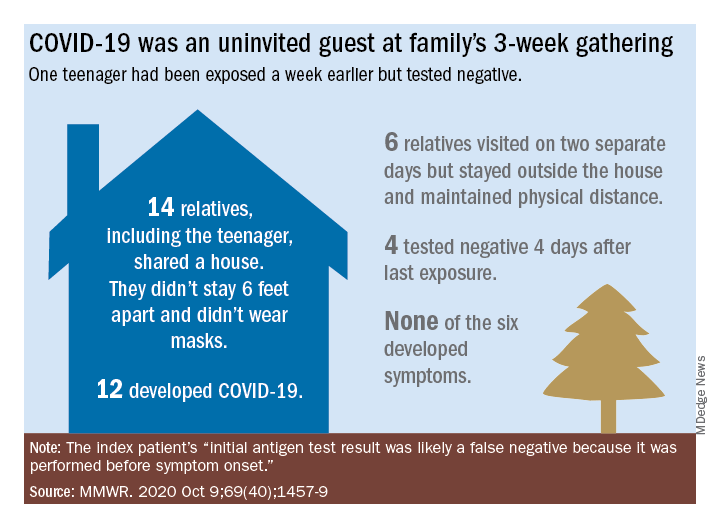

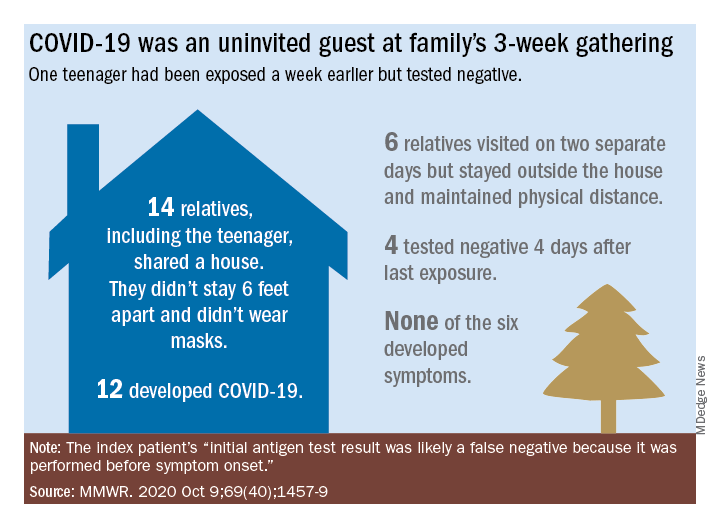

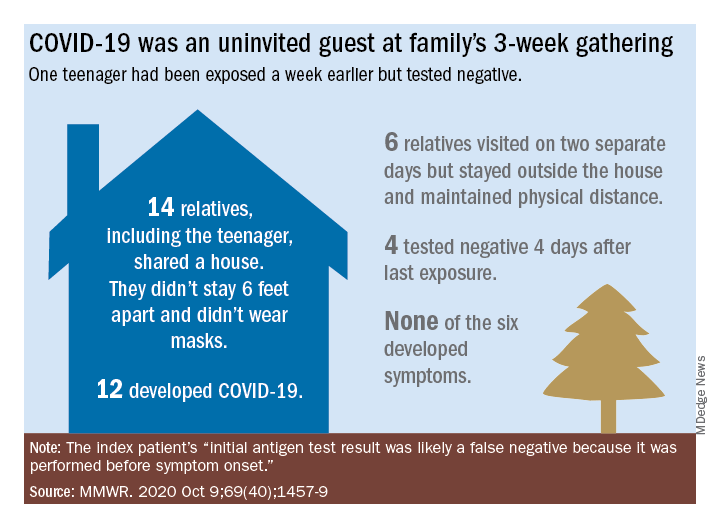

Lastly, one adolescent was identified as the source for an outbreak at a family gathering where 15 persons from five households and four states shared a house between 8 and 25 days in July 2020. Six additional members visited the house. The index case had an exposure to COVID-19 and had a negative antigen test 4 days after exposure. She was asymptomatic when tested. She developed nasal congestion 2 days later, the same day she and her family departed for the gathering. A total of 11 household contacts developed confirmed, suspected, or probable COVID-19, and the teen developed symptoms. This report illustrates how easily SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted, and how when implemented, mitigation strategies work because none of the six who only visited the house was infected. It also serves as a reminder that antigen testing is indicated only for use within the first 5-12 days of onset of symptoms. In this case, the adolescent was asymptomatic when tested and had a false-negative test result.

Ponder modes of transportation

How will your patient arrive to their holiday destination? Nonstop travel by car with household members is probably the safest way. However, for many families, buses and trains are the only options, and social distancing may be challenging. Air travel is a must for others. Acquisition of COVID-19 during air travel appears to be low, but not absent based on how air enters and leaves the cabin. The challenge is socially distancing throughout the check in and boarding processes, as well as minimizing contact with common surfaces. There also is loss of social distancing once on board. Ideally, masks should be worn during the flight. Additionally, for those with international destinations, most countries now require a negative polymerase chain reaction COVID-19 test within a specified time frame for entry.

Essentially the safest place for your patients during the holidays is celebrating at home with their household contacts. The risk for disease acquisition increases with travel. You will not have the opportunity to discuss holiday plans with most parents. However, you can encourage them to consider the pros and cons of travel with reminders via telephone, e-mail, and /or social messaging directly from your practices similar to those sent for other medically necessary interventions. As for me, I will be celebrating virtually this year. There is a first time for everything.

For additional information that also is patient friendly, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers information about travel within the United States and international travel.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

As an East Coast transplant residing in Texas, I look forward to the annual sojourn home to celebrate the holidays with family and friends – as do many of our patients and their families. But this is 2020. SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, is still circulating. To make matters worse, cases are rising in 45 states and internationally. The day of this writing 102,831 new cases were reported in the United States.

Social distancing, wearing masks, and hand washing have been strategies recommended to help mitigate the spread of the virus. We know adherence is not always 100%. The reality is that several families will consider traveling and gathering with others over the holidays. Their actions may lead to increased infections, hospitalizations, and even deaths. It behooves us to at least remind them of the potential consequences of the activity, and if travel and/or holiday gatherings are inevitable, to provide some guidance to help them look at both the risks and benefits and offer strategies to minimize infection and spread.

What should be considered prior to travel?

Here is a list of points to ponder:

- Is your patient is in a high-risk group for developing severe disease or visiting someone who is in a high-risk group?

- What is their mode of transportation?

- What is their destination?

- How prevalent is the disease at their destination, compared with their community?

- What will be their accommodations?

- How will attendees prepare for the gathering, if at all?

- Will multiple families congregate after quarantining for 2 weeks or simply arrive?

- At the destination, will people wear masks and socially distance?

- Is an outdoor venue an option?

All of these questions should be considered by patients.

Review high-risk groups

In terms of high-risk groups, we usually focus on underlying medical conditions or extremes of age, but Black and LatinX children and their families have been diagnosed with COVID-19 and hospitalized more frequently than other racial/ ethnic groups in the United States. Of 277,285 school-aged children infected between March 1 and Sept. 19, 2020, 42% were LatinX, 32% White, and 17% Black, yet they comprise 18%, 60%, and 11% of the U.S. population, respectively. Of those hospitalized, 45% were LatinX, 22% White, and 24% Black. LatinX and Black children also have disproportionately higher mortality rates.

Think about transmission and how to mitigate it

Many patients erroneously think combining multiple households for small group gatherings is inconsequential. These types of gatherings serve as a continued source of SARS-CoV-2 spread. For example, a person in Illinois with mild upper respiratory infection symptoms attended a funeral; he reported embracing the family members after the funeral. He dined with two people the evening prior to the funeral, sharing the meal using common serving dishes. Four days later, he attended a birthday party with nine family members. Some of the family members with symptoms subsequently attended church, infecting another church attendee. A cluster of 16 cases of COVID-19 was subsequently identified, including three deaths likely resulting from this one introduction of COVID-19 at these two family gatherings.

In Tennessee and Wisconsin, household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was studied prospectively. A total of 101 index cases and 191 asymptomatic household contacts were enrolled between April and Sept. 2020; 102 of 191 (53%) had SARS-CoV-2 detected during the 14-day follow-up. Most infections (75%) were identified within 5 days and occurred whether the index case was an adult or child.

Lastly, one adolescent was identified as the source for an outbreak at a family gathering where 15 persons from five households and four states shared a house between 8 and 25 days in July 2020. Six additional members visited the house. The index case had an exposure to COVID-19 and had a negative antigen test 4 days after exposure. She was asymptomatic when tested. She developed nasal congestion 2 days later, the same day she and her family departed for the gathering. A total of 11 household contacts developed confirmed, suspected, or probable COVID-19, and the teen developed symptoms. This report illustrates how easily SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted, and how when implemented, mitigation strategies work because none of the six who only visited the house was infected. It also serves as a reminder that antigen testing is indicated only for use within the first 5-12 days of onset of symptoms. In this case, the adolescent was asymptomatic when tested and had a false-negative test result.

Ponder modes of transportation

How will your patient arrive to their holiday destination? Nonstop travel by car with household members is probably the safest way. However, for many families, buses and trains are the only options, and social distancing may be challenging. Air travel is a must for others. Acquisition of COVID-19 during air travel appears to be low, but not absent based on how air enters and leaves the cabin. The challenge is socially distancing throughout the check in and boarding processes, as well as minimizing contact with common surfaces. There also is loss of social distancing once on board. Ideally, masks should be worn during the flight. Additionally, for those with international destinations, most countries now require a negative polymerase chain reaction COVID-19 test within a specified time frame for entry.

Essentially the safest place for your patients during the holidays is celebrating at home with their household contacts. The risk for disease acquisition increases with travel. You will not have the opportunity to discuss holiday plans with most parents. However, you can encourage them to consider the pros and cons of travel with reminders via telephone, e-mail, and /or social messaging directly from your practices similar to those sent for other medically necessary interventions. As for me, I will be celebrating virtually this year. There is a first time for everything.

For additional information that also is patient friendly, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers information about travel within the United States and international travel.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

As an East Coast transplant residing in Texas, I look forward to the annual sojourn home to celebrate the holidays with family and friends – as do many of our patients and their families. But this is 2020. SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, is still circulating. To make matters worse, cases are rising in 45 states and internationally. The day of this writing 102,831 new cases were reported in the United States.

Social distancing, wearing masks, and hand washing have been strategies recommended to help mitigate the spread of the virus. We know adherence is not always 100%. The reality is that several families will consider traveling and gathering with others over the holidays. Their actions may lead to increased infections, hospitalizations, and even deaths. It behooves us to at least remind them of the potential consequences of the activity, and if travel and/or holiday gatherings are inevitable, to provide some guidance to help them look at both the risks and benefits and offer strategies to minimize infection and spread.

What should be considered prior to travel?

Here is a list of points to ponder:

- Is your patient is in a high-risk group for developing severe disease or visiting someone who is in a high-risk group?

- What is their mode of transportation?

- What is their destination?

- How prevalent is the disease at their destination, compared with their community?

- What will be their accommodations?

- How will attendees prepare for the gathering, if at all?

- Will multiple families congregate after quarantining for 2 weeks or simply arrive?

- At the destination, will people wear masks and socially distance?

- Is an outdoor venue an option?

All of these questions should be considered by patients.

Review high-risk groups

In terms of high-risk groups, we usually focus on underlying medical conditions or extremes of age, but Black and LatinX children and their families have been diagnosed with COVID-19 and hospitalized more frequently than other racial/ ethnic groups in the United States. Of 277,285 school-aged children infected between March 1 and Sept. 19, 2020, 42% were LatinX, 32% White, and 17% Black, yet they comprise 18%, 60%, and 11% of the U.S. population, respectively. Of those hospitalized, 45% were LatinX, 22% White, and 24% Black. LatinX and Black children also have disproportionately higher mortality rates.

Think about transmission and how to mitigate it

Many patients erroneously think combining multiple households for small group gatherings is inconsequential. These types of gatherings serve as a continued source of SARS-CoV-2 spread. For example, a person in Illinois with mild upper respiratory infection symptoms attended a funeral; he reported embracing the family members after the funeral. He dined with two people the evening prior to the funeral, sharing the meal using common serving dishes. Four days later, he attended a birthday party with nine family members. Some of the family members with symptoms subsequently attended church, infecting another church attendee. A cluster of 16 cases of COVID-19 was subsequently identified, including three deaths likely resulting from this one introduction of COVID-19 at these two family gatherings.

In Tennessee and Wisconsin, household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was studied prospectively. A total of 101 index cases and 191 asymptomatic household contacts were enrolled between April and Sept. 2020; 102 of 191 (53%) had SARS-CoV-2 detected during the 14-day follow-up. Most infections (75%) were identified within 5 days and occurred whether the index case was an adult or child.

Lastly, one adolescent was identified as the source for an outbreak at a family gathering where 15 persons from five households and four states shared a house between 8 and 25 days in July 2020. Six additional members visited the house. The index case had an exposure to COVID-19 and had a negative antigen test 4 days after exposure. She was asymptomatic when tested. She developed nasal congestion 2 days later, the same day she and her family departed for the gathering. A total of 11 household contacts developed confirmed, suspected, or probable COVID-19, and the teen developed symptoms. This report illustrates how easily SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted, and how when implemented, mitigation strategies work because none of the six who only visited the house was infected. It also serves as a reminder that antigen testing is indicated only for use within the first 5-12 days of onset of symptoms. In this case, the adolescent was asymptomatic when tested and had a false-negative test result.

Ponder modes of transportation

How will your patient arrive to their holiday destination? Nonstop travel by car with household members is probably the safest way. However, for many families, buses and trains are the only options, and social distancing may be challenging. Air travel is a must for others. Acquisition of COVID-19 during air travel appears to be low, but not absent based on how air enters and leaves the cabin. The challenge is socially distancing throughout the check in and boarding processes, as well as minimizing contact with common surfaces. There also is loss of social distancing once on board. Ideally, masks should be worn during the flight. Additionally, for those with international destinations, most countries now require a negative polymerase chain reaction COVID-19 test within a specified time frame for entry.

Essentially the safest place for your patients during the holidays is celebrating at home with their household contacts. The risk for disease acquisition increases with travel. You will not have the opportunity to discuss holiday plans with most parents. However, you can encourage them to consider the pros and cons of travel with reminders via telephone, e-mail, and /or social messaging directly from your practices similar to those sent for other medically necessary interventions. As for me, I will be celebrating virtually this year. There is a first time for everything.

For additional information that also is patient friendly, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers information about travel within the United States and international travel.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Patients with mental illness a priority for COVID vaccine, experts say

With this week’s announcement that Pfizer’s vaccine candidate against SARS-CoV-2 was 90% effective in preventing COVID-19, the world is one step closer to an effective vaccine.

Nevertheless, with a limited supply of initial doses, the question becomes, who should get it first? Individuals with severe mental illness should be a priority group to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, assert the authors of a perspective article published Nov. 1 in World Psychiatry.

Patients with underlying physical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, obesity, immunodeficiency, and cancer, are particularly vulnerable to developing more severe illness and dying from COVID-19.

In these populations, the risk of a more severe course of infection or early death is significant enough for the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to make these patients priority recipients of a vaccine against COVID-19.

Marc De Hert, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at KU Leuven (Belgium), and coauthors argued that those with severe mental illness also fit into this group.

Even without factoring COVID-19 into the calculation, those with severe mental illness have a two- to threefold higher mortality rate than the general population, resulting in reduction in life expectancy of 10-20 years, they noted. This is largely because of physical diseases including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and respiratory ailments.

Individuals with severe mental illness also have higher rates of obesity than the general population and obesity is a risk factor for dying from COVID-19.

High-risk population

Like their peers with physical illnesses, recent studies suggest that those with severe mental illness are also at increased risk of morbidity and mortality from COVID-19.

For example, a recent U.S. case-control study with over 61 million adults showed that those recently diagnosed with a mental health disorder had a significantly increased risk for COVID-19 infection, an effect strongest for depression and schizophrenia.

Other recent studies have confirmed these data, including one linking a psychiatric diagnosis in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 to a significantly increased risk for death, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

Dr. De Hert and colleagues put these findings into perspective with this example: In 2017, there were an estimated 11.2 million adults in the United States with severe mental illness. Taking into account the 8.5% death rate in COVID-19 patients recently diagnosed with a severe mental illness, this means that about 1 million patients with severe mental illness in the United States would die if all were infected with the virus.

In light of this knowledge, and taking into account published ethical principles that should guide vaccine allocation, Dr. De Hert and colleagues said it is “paramount” that persons with severe mental illness be prioritized to guarantee that they receive a COVID-19 vaccine during the first phase of its distribution.

“It is our responsibility as psychiatrists in this global health crisis to advocate for the needs of our patients with governments and public health policy bodies,” they wrote.

The authors also encourage public health agencies to develop and implement targeted programs to ensure that patients with severe mental illness and their health care providers “are made aware of these increased risks as well as the benefits of vaccination.”

An argument for fairness

Paul S. Appelbaum, MD, professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law at Columbia University, New York, also believes those with severe mental illness should be a priority group for a COVID vaccine.

“When we’re prioritizing groups for a COVID-19 vaccine, let’s not forget that people with serious mental illness have much lower life expectancies, more obesity, and more undiagnosed chronic conditions. They should be a priority group,” Dr. Appelbaum said in an interview.

“The argument for including people with severe mental illnesses among the vulnerable populations who should be prioritized for receipt of a COVID-19 vaccine is an argument for fairness in constructing that group,” he added.

“Like people with other chronic conditions associated with poor outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 infection, people with severe mental illnesses are more likely to be hospitalized and more likely to die. Although they are often systematically ignored when decisions are made about allocation of resources, there is some hope that, with enough public attention to this issue, they can be included this time,” Dr. Appelbaum said.

Dr. De Hert and Dr. Applebaum disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With this week’s announcement that Pfizer’s vaccine candidate against SARS-CoV-2 was 90% effective in preventing COVID-19, the world is one step closer to an effective vaccine.

Nevertheless, with a limited supply of initial doses, the question becomes, who should get it first? Individuals with severe mental illness should be a priority group to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, assert the authors of a perspective article published Nov. 1 in World Psychiatry.

Patients with underlying physical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, obesity, immunodeficiency, and cancer, are particularly vulnerable to developing more severe illness and dying from COVID-19.

In these populations, the risk of a more severe course of infection or early death is significant enough for the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to make these patients priority recipients of a vaccine against COVID-19.

Marc De Hert, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at KU Leuven (Belgium), and coauthors argued that those with severe mental illness also fit into this group.

Even without factoring COVID-19 into the calculation, those with severe mental illness have a two- to threefold higher mortality rate than the general population, resulting in reduction in life expectancy of 10-20 years, they noted. This is largely because of physical diseases including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and respiratory ailments.

Individuals with severe mental illness also have higher rates of obesity than the general population and obesity is a risk factor for dying from COVID-19.

High-risk population

Like their peers with physical illnesses, recent studies suggest that those with severe mental illness are also at increased risk of morbidity and mortality from COVID-19.

For example, a recent U.S. case-control study with over 61 million adults showed that those recently diagnosed with a mental health disorder had a significantly increased risk for COVID-19 infection, an effect strongest for depression and schizophrenia.

Other recent studies have confirmed these data, including one linking a psychiatric diagnosis in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 to a significantly increased risk for death, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

Dr. De Hert and colleagues put these findings into perspective with this example: In 2017, there were an estimated 11.2 million adults in the United States with severe mental illness. Taking into account the 8.5% death rate in COVID-19 patients recently diagnosed with a severe mental illness, this means that about 1 million patients with severe mental illness in the United States would die if all were infected with the virus.

In light of this knowledge, and taking into account published ethical principles that should guide vaccine allocation, Dr. De Hert and colleagues said it is “paramount” that persons with severe mental illness be prioritized to guarantee that they receive a COVID-19 vaccine during the first phase of its distribution.

“It is our responsibility as psychiatrists in this global health crisis to advocate for the needs of our patients with governments and public health policy bodies,” they wrote.

The authors also encourage public health agencies to develop and implement targeted programs to ensure that patients with severe mental illness and their health care providers “are made aware of these increased risks as well as the benefits of vaccination.”

An argument for fairness

Paul S. Appelbaum, MD, professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law at Columbia University, New York, also believes those with severe mental illness should be a priority group for a COVID vaccine.

“When we’re prioritizing groups for a COVID-19 vaccine, let’s not forget that people with serious mental illness have much lower life expectancies, more obesity, and more undiagnosed chronic conditions. They should be a priority group,” Dr. Appelbaum said in an interview.

“The argument for including people with severe mental illnesses among the vulnerable populations who should be prioritized for receipt of a COVID-19 vaccine is an argument for fairness in constructing that group,” he added.

“Like people with other chronic conditions associated with poor outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 infection, people with severe mental illnesses are more likely to be hospitalized and more likely to die. Although they are often systematically ignored when decisions are made about allocation of resources, there is some hope that, with enough public attention to this issue, they can be included this time,” Dr. Appelbaum said.

Dr. De Hert and Dr. Applebaum disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With this week’s announcement that Pfizer’s vaccine candidate against SARS-CoV-2 was 90% effective in preventing COVID-19, the world is one step closer to an effective vaccine.

Nevertheless, with a limited supply of initial doses, the question becomes, who should get it first? Individuals with severe mental illness should be a priority group to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, assert the authors of a perspective article published Nov. 1 in World Psychiatry.

Patients with underlying physical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, obesity, immunodeficiency, and cancer, are particularly vulnerable to developing more severe illness and dying from COVID-19.

In these populations, the risk of a more severe course of infection or early death is significant enough for the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to make these patients priority recipients of a vaccine against COVID-19.

Marc De Hert, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at KU Leuven (Belgium), and coauthors argued that those with severe mental illness also fit into this group.

Even without factoring COVID-19 into the calculation, those with severe mental illness have a two- to threefold higher mortality rate than the general population, resulting in reduction in life expectancy of 10-20 years, they noted. This is largely because of physical diseases including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and respiratory ailments.

Individuals with severe mental illness also have higher rates of obesity than the general population and obesity is a risk factor for dying from COVID-19.

High-risk population

Like their peers with physical illnesses, recent studies suggest that those with severe mental illness are also at increased risk of morbidity and mortality from COVID-19.

For example, a recent U.S. case-control study with over 61 million adults showed that those recently diagnosed with a mental health disorder had a significantly increased risk for COVID-19 infection, an effect strongest for depression and schizophrenia.

Other recent studies have confirmed these data, including one linking a psychiatric diagnosis in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 to a significantly increased risk for death, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

Dr. De Hert and colleagues put these findings into perspective with this example: In 2017, there were an estimated 11.2 million adults in the United States with severe mental illness. Taking into account the 8.5% death rate in COVID-19 patients recently diagnosed with a severe mental illness, this means that about 1 million patients with severe mental illness in the United States would die if all were infected with the virus.

In light of this knowledge, and taking into account published ethical principles that should guide vaccine allocation, Dr. De Hert and colleagues said it is “paramount” that persons with severe mental illness be prioritized to guarantee that they receive a COVID-19 vaccine during the first phase of its distribution.

“It is our responsibility as psychiatrists in this global health crisis to advocate for the needs of our patients with governments and public health policy bodies,” they wrote.

The authors also encourage public health agencies to develop and implement targeted programs to ensure that patients with severe mental illness and their health care providers “are made aware of these increased risks as well as the benefits of vaccination.”

An argument for fairness

Paul S. Appelbaum, MD, professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law at Columbia University, New York, also believes those with severe mental illness should be a priority group for a COVID vaccine.

“When we’re prioritizing groups for a COVID-19 vaccine, let’s not forget that people with serious mental illness have much lower life expectancies, more obesity, and more undiagnosed chronic conditions. They should be a priority group,” Dr. Appelbaum said in an interview.

“The argument for including people with severe mental illnesses among the vulnerable populations who should be prioritized for receipt of a COVID-19 vaccine is an argument for fairness in constructing that group,” he added.

“Like people with other chronic conditions associated with poor outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 infection, people with severe mental illnesses are more likely to be hospitalized and more likely to die. Although they are often systematically ignored when decisions are made about allocation of resources, there is some hope that, with enough public attention to this issue, they can be included this time,” Dr. Appelbaum said.

Dr. De Hert and Dr. Applebaum disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

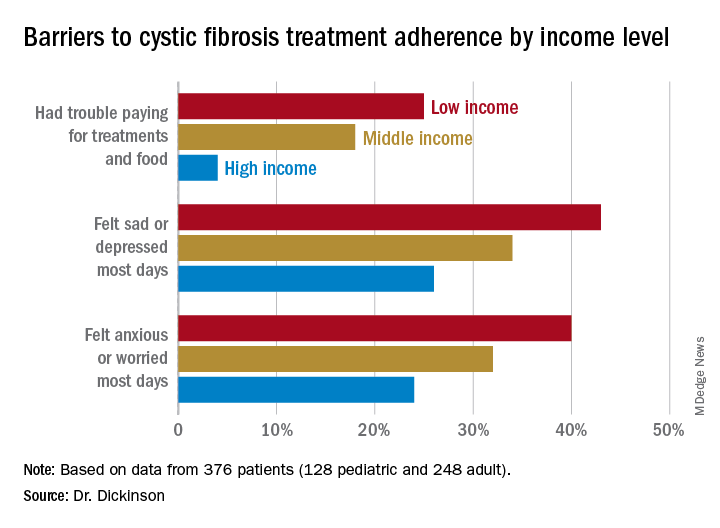

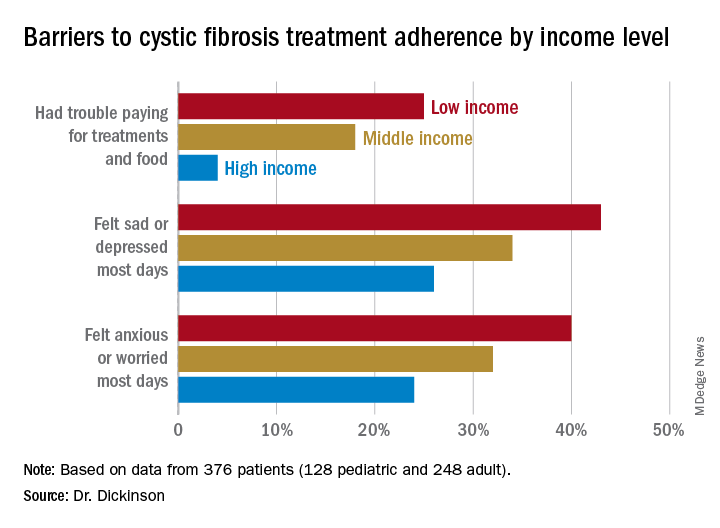

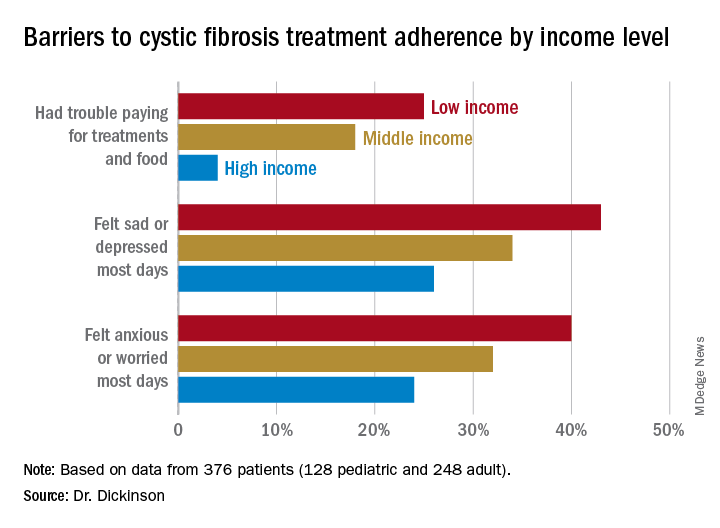

Poverty raises depression risk in patients with cystic fibrosis

Poor people with chronic illness have greater difficulty managing their disease than do their better-off counterparts, and a new study confirms this reality for patients with cystic fibrosis.

and anxiety symptoms, according to a new cross-sectional study. The data were drawn from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s Success with Therapies Research Consortium.

“Assessing the special challenges that individuals with lower SES face, including financial barriers, is essential to understand how we can address the unique combinations of adherence barriers. In other chronic disorders, financial barriers or lower socioeconomic status is associated with nonadherence, but this relationship has not been well established in cystic fibrosis,” said Kimberly Dickinson, MD, MPH, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, during her presentation of the results at the virtual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference.

“I’ve always thought that my patients in the poorer population were doing worse, and I think this demonstrates that that’s true,” said Robert Giusti, MD, in an interview. Dr. Giusti is a clinical professor of pediatrics at the New York University and director of the Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis Center in New York. He was not involved in the study.

“These are very pertinent issues, especially if you think about the pandemic, and some of the issues related to mental health. It just highlights the importance of socioeconomic status and screening for some of the known risk factors so that we can develop interventions or programs to provide equitable care to all of our cystic fibrosis patients,” said Ryan Perkins, MD, who moderated the session where the study was presented. He is a pediatric and adult pulmonary fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, also in Boston.

The researchers looked retrospectively at 1 year’s worth of pharmacy refill receipts and number of times prescriptions were refilled versus the number of times prescribed, then calculated medicinal possession ratios. This was cross-referenced with annual household income and insurance status of patients with CF at 12 pediatric and 9 adult CF care centers, for a total of 376 patients (128 pediatric and 248 adult).

In this population, 32% of participants had public or no insurance, 68% had private or military insurance. The public/no insurance group was more likely than the private/military insurance group to report having trouble paying for treatments, food, or critical expenses related to CF care (23.3% vs. 12.1%, respectively); feeling symptoms on most days of depression (42.5% vs. 31.3%) or anxiety (40.0% vs. 28.5%); and experiencing conflict or stress with loved ones over treatments (30.0% vs. 20.3%) (P < .05 for all).

In all, 35% had a household income less than $40,000 per year, 33% between $44,000 and $100,000, and 32% higher than $100,000. The low-income group had a lower composite medication possession ratio (0.41) than the middle- (0.44) or high-income (0.52) groups, were more likely to have trouble paying for treatments, food, or treatment-related expenses (25%, 18%, 4%, respectively); were more likely most days to report symptoms of depression (43%, 34%, 26%) or anxiety (40%, 32%, 24%), and to have concerns about whether treatments were effective (42%, 27%, 29%). They were more likely to not be able to maintain a daily schedule or routine for treatments (28%, 22%, 14%).

The study showed that adherence barriers and suboptimal adherence are issues that cross all socioeconomic categories, though they were more problematic in the lowest bracket. Greater anxiety and depression among lower income individuals and those with private or no insurance was a key finding, according to Dr. Dickinson. “It highlights the importance of screening for mental health comorbidities that may impact non-adherence,” she said.

The study received funding from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Dr. Dickinson, Dr. Giusti, and Dr. Perkins have no relevant financial disclosures.

Poor people with chronic illness have greater difficulty managing their disease than do their better-off counterparts, and a new study confirms this reality for patients with cystic fibrosis.

and anxiety symptoms, according to a new cross-sectional study. The data were drawn from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s Success with Therapies Research Consortium.

“Assessing the special challenges that individuals with lower SES face, including financial barriers, is essential to understand how we can address the unique combinations of adherence barriers. In other chronic disorders, financial barriers or lower socioeconomic status is associated with nonadherence, but this relationship has not been well established in cystic fibrosis,” said Kimberly Dickinson, MD, MPH, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, during her presentation of the results at the virtual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference.

“I’ve always thought that my patients in the poorer population were doing worse, and I think this demonstrates that that’s true,” said Robert Giusti, MD, in an interview. Dr. Giusti is a clinical professor of pediatrics at the New York University and director of the Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis Center in New York. He was not involved in the study.

“These are very pertinent issues, especially if you think about the pandemic, and some of the issues related to mental health. It just highlights the importance of socioeconomic status and screening for some of the known risk factors so that we can develop interventions or programs to provide equitable care to all of our cystic fibrosis patients,” said Ryan Perkins, MD, who moderated the session where the study was presented. He is a pediatric and adult pulmonary fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, also in Boston.

The researchers looked retrospectively at 1 year’s worth of pharmacy refill receipts and number of times prescriptions were refilled versus the number of times prescribed, then calculated medicinal possession ratios. This was cross-referenced with annual household income and insurance status of patients with CF at 12 pediatric and 9 adult CF care centers, for a total of 376 patients (128 pediatric and 248 adult).

In this population, 32% of participants had public or no insurance, 68% had private or military insurance. The public/no insurance group was more likely than the private/military insurance group to report having trouble paying for treatments, food, or critical expenses related to CF care (23.3% vs. 12.1%, respectively); feeling symptoms on most days of depression (42.5% vs. 31.3%) or anxiety (40.0% vs. 28.5%); and experiencing conflict or stress with loved ones over treatments (30.0% vs. 20.3%) (P < .05 for all).

In all, 35% had a household income less than $40,000 per year, 33% between $44,000 and $100,000, and 32% higher than $100,000. The low-income group had a lower composite medication possession ratio (0.41) than the middle- (0.44) or high-income (0.52) groups, were more likely to have trouble paying for treatments, food, or treatment-related expenses (25%, 18%, 4%, respectively); were more likely most days to report symptoms of depression (43%, 34%, 26%) or anxiety (40%, 32%, 24%), and to have concerns about whether treatments were effective (42%, 27%, 29%). They were more likely to not be able to maintain a daily schedule or routine for treatments (28%, 22%, 14%).

The study showed that adherence barriers and suboptimal adherence are issues that cross all socioeconomic categories, though they were more problematic in the lowest bracket. Greater anxiety and depression among lower income individuals and those with private or no insurance was a key finding, according to Dr. Dickinson. “It highlights the importance of screening for mental health comorbidities that may impact non-adherence,” she said.

The study received funding from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Dr. Dickinson, Dr. Giusti, and Dr. Perkins have no relevant financial disclosures.

Poor people with chronic illness have greater difficulty managing their disease than do their better-off counterparts, and a new study confirms this reality for patients with cystic fibrosis.

and anxiety symptoms, according to a new cross-sectional study. The data were drawn from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s Success with Therapies Research Consortium.

“Assessing the special challenges that individuals with lower SES face, including financial barriers, is essential to understand how we can address the unique combinations of adherence barriers. In other chronic disorders, financial barriers or lower socioeconomic status is associated with nonadherence, but this relationship has not been well established in cystic fibrosis,” said Kimberly Dickinson, MD, MPH, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, during her presentation of the results at the virtual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference.

“I’ve always thought that my patients in the poorer population were doing worse, and I think this demonstrates that that’s true,” said Robert Giusti, MD, in an interview. Dr. Giusti is a clinical professor of pediatrics at the New York University and director of the Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis Center in New York. He was not involved in the study.

“These are very pertinent issues, especially if you think about the pandemic, and some of the issues related to mental health. It just highlights the importance of socioeconomic status and screening for some of the known risk factors so that we can develop interventions or programs to provide equitable care to all of our cystic fibrosis patients,” said Ryan Perkins, MD, who moderated the session where the study was presented. He is a pediatric and adult pulmonary fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, also in Boston.

The researchers looked retrospectively at 1 year’s worth of pharmacy refill receipts and number of times prescriptions were refilled versus the number of times prescribed, then calculated medicinal possession ratios. This was cross-referenced with annual household income and insurance status of patients with CF at 12 pediatric and 9 adult CF care centers, for a total of 376 patients (128 pediatric and 248 adult).

In this population, 32% of participants had public or no insurance, 68% had private or military insurance. The public/no insurance group was more likely than the private/military insurance group to report having trouble paying for treatments, food, or critical expenses related to CF care (23.3% vs. 12.1%, respectively); feeling symptoms on most days of depression (42.5% vs. 31.3%) or anxiety (40.0% vs. 28.5%); and experiencing conflict or stress with loved ones over treatments (30.0% vs. 20.3%) (P < .05 for all).

In all, 35% had a household income less than $40,000 per year, 33% between $44,000 and $100,000, and 32% higher than $100,000. The low-income group had a lower composite medication possession ratio (0.41) than the middle- (0.44) or high-income (0.52) groups, were more likely to have trouble paying for treatments, food, or treatment-related expenses (25%, 18%, 4%, respectively); were more likely most days to report symptoms of depression (43%, 34%, 26%) or anxiety (40%, 32%, 24%), and to have concerns about whether treatments were effective (42%, 27%, 29%). They were more likely to not be able to maintain a daily schedule or routine for treatments (28%, 22%, 14%).

The study showed that adherence barriers and suboptimal adherence are issues that cross all socioeconomic categories, though they were more problematic in the lowest bracket. Greater anxiety and depression among lower income individuals and those with private or no insurance was a key finding, according to Dr. Dickinson. “It highlights the importance of screening for mental health comorbidities that may impact non-adherence,” she said.

The study received funding from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Dr. Dickinson, Dr. Giusti, and Dr. Perkins have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM NACFC 2020

.

Biden plan to lower Medicare eligibility age to 60 faces hostility from hospitals

Of his many plans to expand insurance coverage, President-elect Joe Biden’s simplest strategy is lowering the eligibility age for Medicare from 65 to 60.

But the plan is sure to face long odds, even if the Democrats can snag control of the Senate in January by winning two runoff elections in Georgia.

Republicans, who fought the creation of Medicare in the 1960s and typically oppose expanding government entitlement programs, are not the biggest obstacle. Instead, the nation’s hospitals, a powerful political force, are poised to derail any effort.

“Hospitals certainly are not going to be happy with it,” said Jonathan Oberlander, professor of health policy and management at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Medicare reimbursement rates for patients admitted to hospitals average half what commercial or employer-sponsored insurance plans pay.

“It will be a huge lift [in Congress] as the realities of lower Medicare reimbursement rates will activate some powerful interests against this,” said Josh Archambault, a senior fellow with the conservative Foundation for Government Accountability.

Biden, who turns 78 this month, said his plan will help Americans who retire early and those who are unemployed or can’t find jobs with health benefits.

“It reflects the reality that, even after the current crisis ends, older Americans are likely to find it difficult to secure jobs,” Biden wrote in April.

Lowering the Medicare eligibility age is popular. About 85% of Democrats and 69% of Republicans favor allowing those as young as 50 to buy into Medicare, according to a KFF tracking poll from January 2019. (KHN is an editorially independent program of KFF.)

Although opposition from the hospital industry is expected to be fierce, that is not the only obstacle to Biden’s plan.

Critics, especially Republicans on Capitol Hill, will point to the nation’s $3 trillion budget deficit as well as the dim outlook for the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund. That fund is on track to reach insolvency in 2024. That means there won’t be enough money to fully pay hospitals and nursing homes for inpatient care for Medicare beneficiaries.

Moreover, it’s unclear whether expanding Medicare will fit on the Democrats’ crowded health agenda, which also includes dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, possibly rescuing the Affordable Care Act if the Supreme Court strikes down part or all of the law in a current case, expanding Obamacare subsidies and lowering drug costs.

Biden’s proposal is a nod to the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, which has advocated for Sen. Bernie Sanders’ (I-Vt.) government-run “Medicare for All” health system that would provide universal coverage. Biden opposed that effort, saying the nation could not afford it. He wanted to retain the private health insurance system, which covers 180 million people.

To expand coverage, Biden has proposed two major initiatives. In addition to the Medicare eligibility change, he wants Congress to approve a government-run health plan that people could buy into instead of purchasing coverage from insurance companies on their own or through the Obamacare marketplaces. Insurers helped beat back this “public option” initiative in 2009 during the congressional debate over the ACA.

The appeal of lowering Medicare eligibility to help those without insurance lies with leveraging a popular government program that has low administrative costs.

“It is hard to find a reform idea that is more popular than opening up Medicare” to people as young as 60, Oberlander said. He said early retirees would like the concept, as would employers, who could save on their health costs as workers gravitate to Medicare.

The eligibility age has been set at 65 since Medicare was created in 1965 as part of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society reform package. It was designed to coincide with the age when people at that time qualified for Social Security. Today, people generally qualify for early, reduced Social Security benefits at age 62, though they have to wait until age 66 for full benefits.

While people can qualify on the basis of other criteria, such as having a disability or end-stage renal disease, 85% of the 57 million Medicare enrollees are in the program simply because they’re old enough.

Lowering the age to 60 could add as many as 23 million people to Medicare, according to an analysis by the consulting firm Avalere Health. It’s unclear, however, if everyone who would be eligible would sign up or if Biden would limit the expansion to the 1.7 million people in that age range who are uninsured and the 3.2 million who buy coverage on their own.

Avalere says 3.2 million people in that age group buy coverage on the individual market.

While the 60-to-65 group has the lowest uninsured rate (8%) among adults, it has the highest health costs and pays the highest rates for individual coverage, said Cristina Boccuti, director of health policy at West Health, a nonpartisan research group.

About 13 million of those between 60 and 65 have coverage through their employer, according to Avalere. While they would not have to drop coverage to join Medicare, they could possibly opt to also pay to join the federal program and use it as a wraparound for their existing coverage. Medicare might then pick up costs for some services that the consumers would have to shoulder out-of-pocket.

Some 4 million people between 60 and 65 are enrolled in Medicaid, the state-federal health insurance program for low-income people. Shifting them to Medicare would make that their primary health insurer, a move that would save states money since they split Medicaid costs with the federal government.

Chris Pope, a senior fellow with the conservative Manhattan Institute, said getting health industry support, particularly from hospitals, will be vital for any health coverage expansion. “Hospitals are very aware about generous commercial rates being replaced by lower Medicare rates,” he said.

“Members of Congress, a lot of them are close to their hospitals and do not want to see them with a revenue hole,” he said.

President Barack Obama made a deal with the industry on the way to passing the ACA. In exchange for gaining millions of paying customers and lowering their uncompensated care by billions of dollars, the hospital industry agreed to give up future Medicare funds designed to help them cope with the uninsured. Showing the industry’s prowess on Capitol Hill, Congress has delayed those funding cuts for more than six years.

Jacob Hacker, a Yale University political scientist, noted that expanding Medicare would reduce the number of Americans who rely on employer-sponsored coverage. The pitfalls of the employer system were highlighted in 2020 as millions lost their jobs and workplace health coverage.

Even if they can win the two Georgia seats and take control of the Senate with the vice president breaking any ties, Democrats would be unlikely to pass major legislation without GOP support — unless they are willing to jettison the long-standing filibuster rule so they can pass most legislation with a simple 51-vote majority instead of 60 votes.

Hacker said that slim margin would make it difficult for Democrats to deal with many health issues all at once.

“Congress is not good at parallel processing,” Hacker said, referring to handling multiple priorities at the same time. “And the window is relatively short.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Of his many plans to expand insurance coverage, President-elect Joe Biden’s simplest strategy is lowering the eligibility age for Medicare from 65 to 60.

But the plan is sure to face long odds, even if the Democrats can snag control of the Senate in January by winning two runoff elections in Georgia.

Republicans, who fought the creation of Medicare in the 1960s and typically oppose expanding government entitlement programs, are not the biggest obstacle. Instead, the nation’s hospitals, a powerful political force, are poised to derail any effort.

“Hospitals certainly are not going to be happy with it,” said Jonathan Oberlander, professor of health policy and management at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Medicare reimbursement rates for patients admitted to hospitals average half what commercial or employer-sponsored insurance plans pay.

“It will be a huge lift [in Congress] as the realities of lower Medicare reimbursement rates will activate some powerful interests against this,” said Josh Archambault, a senior fellow with the conservative Foundation for Government Accountability.

Biden, who turns 78 this month, said his plan will help Americans who retire early and those who are unemployed or can’t find jobs with health benefits.

“It reflects the reality that, even after the current crisis ends, older Americans are likely to find it difficult to secure jobs,” Biden wrote in April.

Lowering the Medicare eligibility age is popular. About 85% of Democrats and 69% of Republicans favor allowing those as young as 50 to buy into Medicare, according to a KFF tracking poll from January 2019. (KHN is an editorially independent program of KFF.)

Although opposition from the hospital industry is expected to be fierce, that is not the only obstacle to Biden’s plan.

Critics, especially Republicans on Capitol Hill, will point to the nation’s $3 trillion budget deficit as well as the dim outlook for the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund. That fund is on track to reach insolvency in 2024. That means there won’t be enough money to fully pay hospitals and nursing homes for inpatient care for Medicare beneficiaries.

Moreover, it’s unclear whether expanding Medicare will fit on the Democrats’ crowded health agenda, which also includes dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, possibly rescuing the Affordable Care Act if the Supreme Court strikes down part or all of the law in a current case, expanding Obamacare subsidies and lowering drug costs.

Biden’s proposal is a nod to the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, which has advocated for Sen. Bernie Sanders’ (I-Vt.) government-run “Medicare for All” health system that would provide universal coverage. Biden opposed that effort, saying the nation could not afford it. He wanted to retain the private health insurance system, which covers 180 million people.

To expand coverage, Biden has proposed two major initiatives. In addition to the Medicare eligibility change, he wants Congress to approve a government-run health plan that people could buy into instead of purchasing coverage from insurance companies on their own or through the Obamacare marketplaces. Insurers helped beat back this “public option” initiative in 2009 during the congressional debate over the ACA.

The appeal of lowering Medicare eligibility to help those without insurance lies with leveraging a popular government program that has low administrative costs.

“It is hard to find a reform idea that is more popular than opening up Medicare” to people as young as 60, Oberlander said. He said early retirees would like the concept, as would employers, who could save on their health costs as workers gravitate to Medicare.

The eligibility age has been set at 65 since Medicare was created in 1965 as part of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society reform package. It was designed to coincide with the age when people at that time qualified for Social Security. Today, people generally qualify for early, reduced Social Security benefits at age 62, though they have to wait until age 66 for full benefits.

While people can qualify on the basis of other criteria, such as having a disability or end-stage renal disease, 85% of the 57 million Medicare enrollees are in the program simply because they’re old enough.

Lowering the age to 60 could add as many as 23 million people to Medicare, according to an analysis by the consulting firm Avalere Health. It’s unclear, however, if everyone who would be eligible would sign up or if Biden would limit the expansion to the 1.7 million people in that age range who are uninsured and the 3.2 million who buy coverage on their own.

Avalere says 3.2 million people in that age group buy coverage on the individual market.

While the 60-to-65 group has the lowest uninsured rate (8%) among adults, it has the highest health costs and pays the highest rates for individual coverage, said Cristina Boccuti, director of health policy at West Health, a nonpartisan research group.

About 13 million of those between 60 and 65 have coverage through their employer, according to Avalere. While they would not have to drop coverage to join Medicare, they could possibly opt to also pay to join the federal program and use it as a wraparound for their existing coverage. Medicare might then pick up costs for some services that the consumers would have to shoulder out-of-pocket.

Some 4 million people between 60 and 65 are enrolled in Medicaid, the state-federal health insurance program for low-income people. Shifting them to Medicare would make that their primary health insurer, a move that would save states money since they split Medicaid costs with the federal government.

Chris Pope, a senior fellow with the conservative Manhattan Institute, said getting health industry support, particularly from hospitals, will be vital for any health coverage expansion. “Hospitals are very aware about generous commercial rates being replaced by lower Medicare rates,” he said.

“Members of Congress, a lot of them are close to their hospitals and do not want to see them with a revenue hole,” he said.

President Barack Obama made a deal with the industry on the way to passing the ACA. In exchange for gaining millions of paying customers and lowering their uncompensated care by billions of dollars, the hospital industry agreed to give up future Medicare funds designed to help them cope with the uninsured. Showing the industry’s prowess on Capitol Hill, Congress has delayed those funding cuts for more than six years.

Jacob Hacker, a Yale University political scientist, noted that expanding Medicare would reduce the number of Americans who rely on employer-sponsored coverage. The pitfalls of the employer system were highlighted in 2020 as millions lost their jobs and workplace health coverage.

Even if they can win the two Georgia seats and take control of the Senate with the vice president breaking any ties, Democrats would be unlikely to pass major legislation without GOP support — unless they are willing to jettison the long-standing filibuster rule so they can pass most legislation with a simple 51-vote majority instead of 60 votes.

Hacker said that slim margin would make it difficult for Democrats to deal with many health issues all at once.

“Congress is not good at parallel processing,” Hacker said, referring to handling multiple priorities at the same time. “And the window is relatively short.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Of his many plans to expand insurance coverage, President-elect Joe Biden’s simplest strategy is lowering the eligibility age for Medicare from 65 to 60.

But the plan is sure to face long odds, even if the Democrats can snag control of the Senate in January by winning two runoff elections in Georgia.

Republicans, who fought the creation of Medicare in the 1960s and typically oppose expanding government entitlement programs, are not the biggest obstacle. Instead, the nation’s hospitals, a powerful political force, are poised to derail any effort.

“Hospitals certainly are not going to be happy with it,” said Jonathan Oberlander, professor of health policy and management at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Medicare reimbursement rates for patients admitted to hospitals average half what commercial or employer-sponsored insurance plans pay.

“It will be a huge lift [in Congress] as the realities of lower Medicare reimbursement rates will activate some powerful interests against this,” said Josh Archambault, a senior fellow with the conservative Foundation for Government Accountability.

Biden, who turns 78 this month, said his plan will help Americans who retire early and those who are unemployed or can’t find jobs with health benefits.

“It reflects the reality that, even after the current crisis ends, older Americans are likely to find it difficult to secure jobs,” Biden wrote in April.

Lowering the Medicare eligibility age is popular. About 85% of Democrats and 69% of Republicans favor allowing those as young as 50 to buy into Medicare, according to a KFF tracking poll from January 2019. (KHN is an editorially independent program of KFF.)

Although opposition from the hospital industry is expected to be fierce, that is not the only obstacle to Biden’s plan.

Critics, especially Republicans on Capitol Hill, will point to the nation’s $3 trillion budget deficit as well as the dim outlook for the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund. That fund is on track to reach insolvency in 2024. That means there won’t be enough money to fully pay hospitals and nursing homes for inpatient care for Medicare beneficiaries.

Moreover, it’s unclear whether expanding Medicare will fit on the Democrats’ crowded health agenda, which also includes dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, possibly rescuing the Affordable Care Act if the Supreme Court strikes down part or all of the law in a current case, expanding Obamacare subsidies and lowering drug costs.

Biden’s proposal is a nod to the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, which has advocated for Sen. Bernie Sanders’ (I-Vt.) government-run “Medicare for All” health system that would provide universal coverage. Biden opposed that effort, saying the nation could not afford it. He wanted to retain the private health insurance system, which covers 180 million people.

To expand coverage, Biden has proposed two major initiatives. In addition to the Medicare eligibility change, he wants Congress to approve a government-run health plan that people could buy into instead of purchasing coverage from insurance companies on their own or through the Obamacare marketplaces. Insurers helped beat back this “public option” initiative in 2009 during the congressional debate over the ACA.

The appeal of lowering Medicare eligibility to help those without insurance lies with leveraging a popular government program that has low administrative costs.

“It is hard to find a reform idea that is more popular than opening up Medicare” to people as young as 60, Oberlander said. He said early retirees would like the concept, as would employers, who could save on their health costs as workers gravitate to Medicare.

The eligibility age has been set at 65 since Medicare was created in 1965 as part of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society reform package. It was designed to coincide with the age when people at that time qualified for Social Security. Today, people generally qualify for early, reduced Social Security benefits at age 62, though they have to wait until age 66 for full benefits.

While people can qualify on the basis of other criteria, such as having a disability or end-stage renal disease, 85% of the 57 million Medicare enrollees are in the program simply because they’re old enough.

Lowering the age to 60 could add as many as 23 million people to Medicare, according to an analysis by the consulting firm Avalere Health. It’s unclear, however, if everyone who would be eligible would sign up or if Biden would limit the expansion to the 1.7 million people in that age range who are uninsured and the 3.2 million who buy coverage on their own.

Avalere says 3.2 million people in that age group buy coverage on the individual market.

While the 60-to-65 group has the lowest uninsured rate (8%) among adults, it has the highest health costs and pays the highest rates for individual coverage, said Cristina Boccuti, director of health policy at West Health, a nonpartisan research group.

About 13 million of those between 60 and 65 have coverage through their employer, according to Avalere. While they would not have to drop coverage to join Medicare, they could possibly opt to also pay to join the federal program and use it as a wraparound for their existing coverage. Medicare might then pick up costs for some services that the consumers would have to shoulder out-of-pocket.

Some 4 million people between 60 and 65 are enrolled in Medicaid, the state-federal health insurance program for low-income people. Shifting them to Medicare would make that their primary health insurer, a move that would save states money since they split Medicaid costs with the federal government.

Chris Pope, a senior fellow with the conservative Manhattan Institute, said getting health industry support, particularly from hospitals, will be vital for any health coverage expansion. “Hospitals are very aware about generous commercial rates being replaced by lower Medicare rates,” he said.