User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

What is the real risk of smart phones in medicine?

Over the 10 years we’ve been writing this column, we have often found inspiration for topics while traveling – especially while flying. This is not just because of the idle time spent in the air, but instead because of the many ways that air travel and health care experiences are similar. Both industries focus heavily on safety, are tightly regulated, and employ highly trained individuals.

Consumers may recognize the similarities as well – health care and air travel are both well-known for long waits, uncertainty, and implicit risk. Both sectors are also notorious drivers of innovation, constantly leveraging new technologies in pursuit of better outcomes and experiences. Occasionally, however, advancements in technology can present unforeseen challenges and even compromise safety, with the potential to produce unexpected consequences.

A familiar reminder of this potential was provided to us at the commencement of a recent flight, when we were instructed to turn off our personal electronic devices or flip them into “airplane mode.” This same admonishment is often given to patients and visitors in health care settings – everywhere from clinic waiting rooms to intensive care units – though the reason for this is typically left vague. This got us thinking. More importantly, what other emerging technologies have the potential to create issues we may not have anticipated?

Mayo Clinic findings on radio communication used by mobile phones

Once our flight landed, we did some research to answer our initial question about personal communication technology and its ability to interfere with sensitive electronic devices. Specifically, we wanted to know whether radio communication used by mobile phones could affect the operation of medical equipment, potentially leading to dire consequences for patients. Spoiler alert: There is very little evidence that this can occur. In fact, a well-documented study performed by the Mayo Clinic in 2007 found interference in 0 out of 300 tests performed. To quote the authors, “the incidence of clinically important interference was 0%.”

We could find no other studies since 2007 that strongly contradict Mayo’s findings, except for several anecdotal reports and articles that postulate the theoretical possibility.

This is confirmed by the American Heart Association, who maintains a list of devices that may interfere with ICDs and pacemakers on their website. According to the AHA, “wireless transmissions from the antennae of phones available in the United States are a very small risk to ICDs and even less of a risk for pacemakers.” And in case you’re wondering, the story is quite similar for airplanes as well.

The latest publication from NASA’s Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) documents incidents related to personal electronic devices during air travel. Most involve smoke production – or even small fires – caused by malfunctioning phone batteries during charging. Only a few entries reference wireless interference, and these were all minor and unconfirmed events. As with health care environments, airplanes don’t appear to face significant risks from radio interference. But that doesn’t mean personal electronics are completely harmless to patients.

Smartphones’ risks to patient with cardiac devices

On May 13 of 2021, the FDA issued a warning to cardiac patients about their smart phones and smart watches. Many current personal electronic devices and accessories are equipped with strong magnets, such as those contained in the “MagSafe” connector on the iPhone 12, that can deactivate pacemakers and implanted cardiac defibrillators. These medical devices are designed to be manipulated by magnets for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, but strong magnetic fields can disable them unintentionally, leading to catastrophic results.

Apple and other manufacturers have acknowledged this risk and recommend that smartphones and other devices be kept at least 6 inches from cardiac devices. Given the ubiquity of offending products, it is also imperative that we warn our patients about this risk to their physical wellbeing.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and chief medical officer of Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

Over the 10 years we’ve been writing this column, we have often found inspiration for topics while traveling – especially while flying. This is not just because of the idle time spent in the air, but instead because of the many ways that air travel and health care experiences are similar. Both industries focus heavily on safety, are tightly regulated, and employ highly trained individuals.

Consumers may recognize the similarities as well – health care and air travel are both well-known for long waits, uncertainty, and implicit risk. Both sectors are also notorious drivers of innovation, constantly leveraging new technologies in pursuit of better outcomes and experiences. Occasionally, however, advancements in technology can present unforeseen challenges and even compromise safety, with the potential to produce unexpected consequences.

A familiar reminder of this potential was provided to us at the commencement of a recent flight, when we were instructed to turn off our personal electronic devices or flip them into “airplane mode.” This same admonishment is often given to patients and visitors in health care settings – everywhere from clinic waiting rooms to intensive care units – though the reason for this is typically left vague. This got us thinking. More importantly, what other emerging technologies have the potential to create issues we may not have anticipated?

Mayo Clinic findings on radio communication used by mobile phones

Once our flight landed, we did some research to answer our initial question about personal communication technology and its ability to interfere with sensitive electronic devices. Specifically, we wanted to know whether radio communication used by mobile phones could affect the operation of medical equipment, potentially leading to dire consequences for patients. Spoiler alert: There is very little evidence that this can occur. In fact, a well-documented study performed by the Mayo Clinic in 2007 found interference in 0 out of 300 tests performed. To quote the authors, “the incidence of clinically important interference was 0%.”

We could find no other studies since 2007 that strongly contradict Mayo’s findings, except for several anecdotal reports and articles that postulate the theoretical possibility.

This is confirmed by the American Heart Association, who maintains a list of devices that may interfere with ICDs and pacemakers on their website. According to the AHA, “wireless transmissions from the antennae of phones available in the United States are a very small risk to ICDs and even less of a risk for pacemakers.” And in case you’re wondering, the story is quite similar for airplanes as well.

The latest publication from NASA’s Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) documents incidents related to personal electronic devices during air travel. Most involve smoke production – or even small fires – caused by malfunctioning phone batteries during charging. Only a few entries reference wireless interference, and these were all minor and unconfirmed events. As with health care environments, airplanes don’t appear to face significant risks from radio interference. But that doesn’t mean personal electronics are completely harmless to patients.

Smartphones’ risks to patient with cardiac devices

On May 13 of 2021, the FDA issued a warning to cardiac patients about their smart phones and smart watches. Many current personal electronic devices and accessories are equipped with strong magnets, such as those contained in the “MagSafe” connector on the iPhone 12, that can deactivate pacemakers and implanted cardiac defibrillators. These medical devices are designed to be manipulated by magnets for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, but strong magnetic fields can disable them unintentionally, leading to catastrophic results.

Apple and other manufacturers have acknowledged this risk and recommend that smartphones and other devices be kept at least 6 inches from cardiac devices. Given the ubiquity of offending products, it is also imperative that we warn our patients about this risk to their physical wellbeing.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and chief medical officer of Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

Over the 10 years we’ve been writing this column, we have often found inspiration for topics while traveling – especially while flying. This is not just because of the idle time spent in the air, but instead because of the many ways that air travel and health care experiences are similar. Both industries focus heavily on safety, are tightly regulated, and employ highly trained individuals.

Consumers may recognize the similarities as well – health care and air travel are both well-known for long waits, uncertainty, and implicit risk. Both sectors are also notorious drivers of innovation, constantly leveraging new technologies in pursuit of better outcomes and experiences. Occasionally, however, advancements in technology can present unforeseen challenges and even compromise safety, with the potential to produce unexpected consequences.

A familiar reminder of this potential was provided to us at the commencement of a recent flight, when we were instructed to turn off our personal electronic devices or flip them into “airplane mode.” This same admonishment is often given to patients and visitors in health care settings – everywhere from clinic waiting rooms to intensive care units – though the reason for this is typically left vague. This got us thinking. More importantly, what other emerging technologies have the potential to create issues we may not have anticipated?

Mayo Clinic findings on radio communication used by mobile phones

Once our flight landed, we did some research to answer our initial question about personal communication technology and its ability to interfere with sensitive electronic devices. Specifically, we wanted to know whether radio communication used by mobile phones could affect the operation of medical equipment, potentially leading to dire consequences for patients. Spoiler alert: There is very little evidence that this can occur. In fact, a well-documented study performed by the Mayo Clinic in 2007 found interference in 0 out of 300 tests performed. To quote the authors, “the incidence of clinically important interference was 0%.”

We could find no other studies since 2007 that strongly contradict Mayo’s findings, except for several anecdotal reports and articles that postulate the theoretical possibility.

This is confirmed by the American Heart Association, who maintains a list of devices that may interfere with ICDs and pacemakers on their website. According to the AHA, “wireless transmissions from the antennae of phones available in the United States are a very small risk to ICDs and even less of a risk for pacemakers.” And in case you’re wondering, the story is quite similar for airplanes as well.

The latest publication from NASA’s Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) documents incidents related to personal electronic devices during air travel. Most involve smoke production – or even small fires – caused by malfunctioning phone batteries during charging. Only a few entries reference wireless interference, and these were all minor and unconfirmed events. As with health care environments, airplanes don’t appear to face significant risks from radio interference. But that doesn’t mean personal electronics are completely harmless to patients.

Smartphones’ risks to patient with cardiac devices

On May 13 of 2021, the FDA issued a warning to cardiac patients about their smart phones and smart watches. Many current personal electronic devices and accessories are equipped with strong magnets, such as those contained in the “MagSafe” connector on the iPhone 12, that can deactivate pacemakers and implanted cardiac defibrillators. These medical devices are designed to be manipulated by magnets for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, but strong magnetic fields can disable them unintentionally, leading to catastrophic results.

Apple and other manufacturers have acknowledged this risk and recommend that smartphones and other devices be kept at least 6 inches from cardiac devices. Given the ubiquity of offending products, it is also imperative that we warn our patients about this risk to their physical wellbeing.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and chief medical officer of Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

Injectable monoclonal antibodies prevent COVID-19 in trial

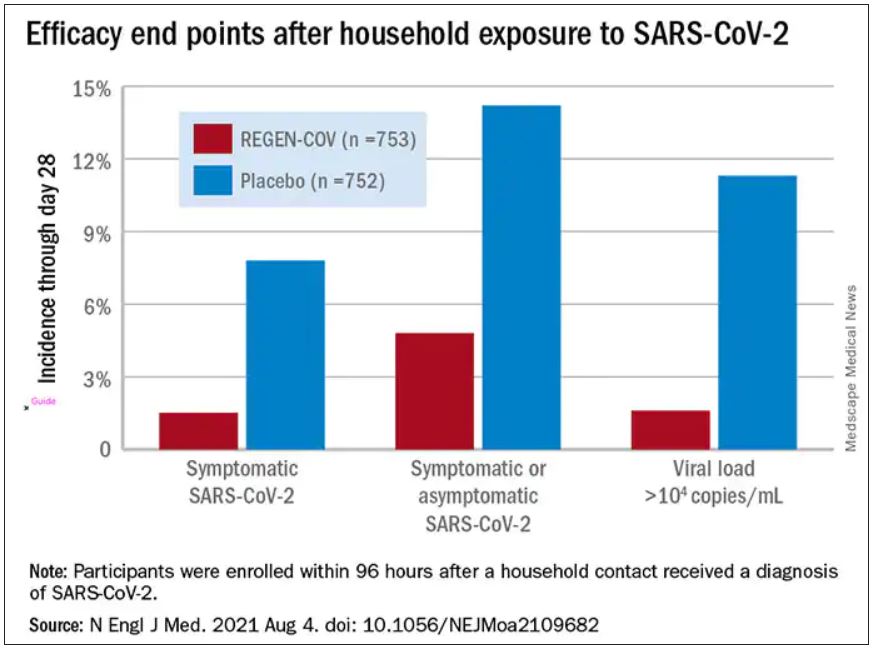

according to results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial published online August 4, 2021, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The cocktail of the monoclonal antibodies casirivimab and imdevimab (REGEN-COV, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) reduced participants’ relative risk of infection by 72%, compared with placebo within the first week. After the first week, risk reduction increased to 93%.

“Long after you would be exposed by your household, there is an enduring effect that prevents you from community spread,” said David Wohl, MD, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was a site investigator for the trial but not a study author.

Participants were enrolled within 96 hours after someone in their household tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Participants were randomly assigned to receive 1,200 mg of REGEN-COV subcutaneously or a placebo. Based on serologic testing, study participants showed no evidence of current or previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. The median age of participants was 42.9, but 45% were male teenagers (ages 12-17).

In the group that received REGEN-COV, 11 out of 753 participants developed symptomatic COVID-19, compared with 59 out of 752 participants who received placebo. The relative risk reduction for the study’s 4-week period was 81.4% (P < .001). Of the participants that did develop a SARS-CoV-2 infection, those that received REGEN-COV were less likely to be symptomatic. Asymptomatic infections developed in 25 participants who received REGEN-COV versus 48 in the placebo group. The relative risk of developing any SARS-CoV-2 infection, symptomatic or asymptomatic, was reduced by 66.4% with REGEN-COV (P < .001).

Among the patients who were symptomatic, symptoms subsided within a median of 1.2 weeks for the group that received REGEN-COV, 2 weeks earlier than the placebo group. These patients also had a shorter duration of a high viral load (>104 copies/mL). Few adverse events were reported in the treatment or placebo groups. Monoclonal antibodies “seem to be incredibly safe,” Dr. Wohl said.

“These monoclonal antibodies have proven they can reduce the viral replication in the nose,” said study author Myron Cohen, MD, an infectious disease specialist and professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina.

The Food and Drug Administration first granted REGEN-COV emergency use authorization (EUA) in November 2020 for use in patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 who were also at high risk for progressing to severe COVID-19. At that time, the cocktail of monoclonal antibodies was delivered by a single intravenous infusion.

In January, Regeneron first announced the success of this trial of the subcutaneous injection for exposed household contacts based on early results, and in June of 2021, the FDA expanded the EUA to include a subcutaneous delivery when IV is not feasible. On July 30, the EUA was expanded again to include prophylactic use in exposed patients based on these trial results.

The U.S. government has purchased approximately 1.5 million doses of REGEN-COV from Regeneron and has agreed to make the treatments free of charge to patients.

But despite being free, available, and backed by promising data, monoclonal antibodies as a therapeutic answer to COVID-19 still hasn’t really taken off. “The problem is, it first requires knowledge and awareness,” Dr. Wohl said. “A lot [of people] don’t know this exists. To be honest, vaccination has taken up all the oxygen in the room.”

Dr. Cohen agreed. One reason for the slow uptake may be because the drug supply is owned by the government and not a pharmaceutical company. There hasn’t been a typical marketing push to make physicians and consumers aware. Additionally, “the logistics are daunting,” Dr. Cohen said. The office spaces where many physicians care for patients “often aren’t appropriate for patients who think they have SARS-CoV-2.”

“Right now, there’s not a mechanism” to administer the drug to people who could benefit from it, Dr. Wohl said. Eligible patients are either immunocompromised and unlikely to mount a sufficient immune response with vaccination, or not fully vaccinated. They should have been exposed to an infected individual or have a high likelihood of exposure due to where they live, such as in a prison or nursing home. Local doctors are unlikely to be the primary administrators of the drug, Dr. Wohl added. “How do we operationalize this for people who fit the criteria?”

There’s also an issue of timing. REGEN-COV is most effective when given early, Dr. Cohen said. “[Monoclonal antibodies] really only work well in the replication phase.” Many patients who would be eligible delay care until they’ve had symptoms for several days, when REGEN-COV would no longer have the desired effect.

Eventually, Dr. Wohl suspects demand will increase when people realize REGEN-COV can help those with COVID-19 and those who have been exposed. But before then, “we do have to think about how to integrate this into a workflow people can access without being confused.”

The trial was done before there was widespread vaccination, so it’s unclear what the results mean for people who have been vaccinated. Dr. Cohen and Dr. Wohl said there are ongoing conversations about whether monoclonal antibodies could be complementary to vaccination and if there’s potential for continued monthly use of these therapies.

Cohen and Wohl reported no relevant financial relationships. The trial was supported by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, F. Hoffmann–La Roche, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, and the COVID-19 Prevention Network.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial published online August 4, 2021, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The cocktail of the monoclonal antibodies casirivimab and imdevimab (REGEN-COV, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) reduced participants’ relative risk of infection by 72%, compared with placebo within the first week. After the first week, risk reduction increased to 93%.

“Long after you would be exposed by your household, there is an enduring effect that prevents you from community spread,” said David Wohl, MD, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was a site investigator for the trial but not a study author.

Participants were enrolled within 96 hours after someone in their household tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Participants were randomly assigned to receive 1,200 mg of REGEN-COV subcutaneously or a placebo. Based on serologic testing, study participants showed no evidence of current or previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. The median age of participants was 42.9, but 45% were male teenagers (ages 12-17).

In the group that received REGEN-COV, 11 out of 753 participants developed symptomatic COVID-19, compared with 59 out of 752 participants who received placebo. The relative risk reduction for the study’s 4-week period was 81.4% (P < .001). Of the participants that did develop a SARS-CoV-2 infection, those that received REGEN-COV were less likely to be symptomatic. Asymptomatic infections developed in 25 participants who received REGEN-COV versus 48 in the placebo group. The relative risk of developing any SARS-CoV-2 infection, symptomatic or asymptomatic, was reduced by 66.4% with REGEN-COV (P < .001).

Among the patients who were symptomatic, symptoms subsided within a median of 1.2 weeks for the group that received REGEN-COV, 2 weeks earlier than the placebo group. These patients also had a shorter duration of a high viral load (>104 copies/mL). Few adverse events were reported in the treatment or placebo groups. Monoclonal antibodies “seem to be incredibly safe,” Dr. Wohl said.

“These monoclonal antibodies have proven they can reduce the viral replication in the nose,” said study author Myron Cohen, MD, an infectious disease specialist and professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina.

The Food and Drug Administration first granted REGEN-COV emergency use authorization (EUA) in November 2020 for use in patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 who were also at high risk for progressing to severe COVID-19. At that time, the cocktail of monoclonal antibodies was delivered by a single intravenous infusion.

In January, Regeneron first announced the success of this trial of the subcutaneous injection for exposed household contacts based on early results, and in June of 2021, the FDA expanded the EUA to include a subcutaneous delivery when IV is not feasible. On July 30, the EUA was expanded again to include prophylactic use in exposed patients based on these trial results.

The U.S. government has purchased approximately 1.5 million doses of REGEN-COV from Regeneron and has agreed to make the treatments free of charge to patients.

But despite being free, available, and backed by promising data, monoclonal antibodies as a therapeutic answer to COVID-19 still hasn’t really taken off. “The problem is, it first requires knowledge and awareness,” Dr. Wohl said. “A lot [of people] don’t know this exists. To be honest, vaccination has taken up all the oxygen in the room.”

Dr. Cohen agreed. One reason for the slow uptake may be because the drug supply is owned by the government and not a pharmaceutical company. There hasn’t been a typical marketing push to make physicians and consumers aware. Additionally, “the logistics are daunting,” Dr. Cohen said. The office spaces where many physicians care for patients “often aren’t appropriate for patients who think they have SARS-CoV-2.”

“Right now, there’s not a mechanism” to administer the drug to people who could benefit from it, Dr. Wohl said. Eligible patients are either immunocompromised and unlikely to mount a sufficient immune response with vaccination, or not fully vaccinated. They should have been exposed to an infected individual or have a high likelihood of exposure due to where they live, such as in a prison or nursing home. Local doctors are unlikely to be the primary administrators of the drug, Dr. Wohl added. “How do we operationalize this for people who fit the criteria?”

There’s also an issue of timing. REGEN-COV is most effective when given early, Dr. Cohen said. “[Monoclonal antibodies] really only work well in the replication phase.” Many patients who would be eligible delay care until they’ve had symptoms for several days, when REGEN-COV would no longer have the desired effect.

Eventually, Dr. Wohl suspects demand will increase when people realize REGEN-COV can help those with COVID-19 and those who have been exposed. But before then, “we do have to think about how to integrate this into a workflow people can access without being confused.”

The trial was done before there was widespread vaccination, so it’s unclear what the results mean for people who have been vaccinated. Dr. Cohen and Dr. Wohl said there are ongoing conversations about whether monoclonal antibodies could be complementary to vaccination and if there’s potential for continued monthly use of these therapies.

Cohen and Wohl reported no relevant financial relationships. The trial was supported by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, F. Hoffmann–La Roche, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, and the COVID-19 Prevention Network.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial published online August 4, 2021, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The cocktail of the monoclonal antibodies casirivimab and imdevimab (REGEN-COV, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) reduced participants’ relative risk of infection by 72%, compared with placebo within the first week. After the first week, risk reduction increased to 93%.

“Long after you would be exposed by your household, there is an enduring effect that prevents you from community spread,” said David Wohl, MD, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was a site investigator for the trial but not a study author.

Participants were enrolled within 96 hours after someone in their household tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Participants were randomly assigned to receive 1,200 mg of REGEN-COV subcutaneously or a placebo. Based on serologic testing, study participants showed no evidence of current or previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. The median age of participants was 42.9, but 45% were male teenagers (ages 12-17).

In the group that received REGEN-COV, 11 out of 753 participants developed symptomatic COVID-19, compared with 59 out of 752 participants who received placebo. The relative risk reduction for the study’s 4-week period was 81.4% (P < .001). Of the participants that did develop a SARS-CoV-2 infection, those that received REGEN-COV were less likely to be symptomatic. Asymptomatic infections developed in 25 participants who received REGEN-COV versus 48 in the placebo group. The relative risk of developing any SARS-CoV-2 infection, symptomatic or asymptomatic, was reduced by 66.4% with REGEN-COV (P < .001).

Among the patients who were symptomatic, symptoms subsided within a median of 1.2 weeks for the group that received REGEN-COV, 2 weeks earlier than the placebo group. These patients also had a shorter duration of a high viral load (>104 copies/mL). Few adverse events were reported in the treatment or placebo groups. Monoclonal antibodies “seem to be incredibly safe,” Dr. Wohl said.

“These monoclonal antibodies have proven they can reduce the viral replication in the nose,” said study author Myron Cohen, MD, an infectious disease specialist and professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina.

The Food and Drug Administration first granted REGEN-COV emergency use authorization (EUA) in November 2020 for use in patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 who were also at high risk for progressing to severe COVID-19. At that time, the cocktail of monoclonal antibodies was delivered by a single intravenous infusion.

In January, Regeneron first announced the success of this trial of the subcutaneous injection for exposed household contacts based on early results, and in June of 2021, the FDA expanded the EUA to include a subcutaneous delivery when IV is not feasible. On July 30, the EUA was expanded again to include prophylactic use in exposed patients based on these trial results.

The U.S. government has purchased approximately 1.5 million doses of REGEN-COV from Regeneron and has agreed to make the treatments free of charge to patients.

But despite being free, available, and backed by promising data, monoclonal antibodies as a therapeutic answer to COVID-19 still hasn’t really taken off. “The problem is, it first requires knowledge and awareness,” Dr. Wohl said. “A lot [of people] don’t know this exists. To be honest, vaccination has taken up all the oxygen in the room.”

Dr. Cohen agreed. One reason for the slow uptake may be because the drug supply is owned by the government and not a pharmaceutical company. There hasn’t been a typical marketing push to make physicians and consumers aware. Additionally, “the logistics are daunting,” Dr. Cohen said. The office spaces where many physicians care for patients “often aren’t appropriate for patients who think they have SARS-CoV-2.”

“Right now, there’s not a mechanism” to administer the drug to people who could benefit from it, Dr. Wohl said. Eligible patients are either immunocompromised and unlikely to mount a sufficient immune response with vaccination, or not fully vaccinated. They should have been exposed to an infected individual or have a high likelihood of exposure due to where they live, such as in a prison or nursing home. Local doctors are unlikely to be the primary administrators of the drug, Dr. Wohl added. “How do we operationalize this for people who fit the criteria?”

There’s also an issue of timing. REGEN-COV is most effective when given early, Dr. Cohen said. “[Monoclonal antibodies] really only work well in the replication phase.” Many patients who would be eligible delay care until they’ve had symptoms for several days, when REGEN-COV would no longer have the desired effect.

Eventually, Dr. Wohl suspects demand will increase when people realize REGEN-COV can help those with COVID-19 and those who have been exposed. But before then, “we do have to think about how to integrate this into a workflow people can access without being confused.”

The trial was done before there was widespread vaccination, so it’s unclear what the results mean for people who have been vaccinated. Dr. Cohen and Dr. Wohl said there are ongoing conversations about whether monoclonal antibodies could be complementary to vaccination and if there’s potential for continued monthly use of these therapies.

Cohen and Wohl reported no relevant financial relationships. The trial was supported by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, F. Hoffmann–La Roche, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, and the COVID-19 Prevention Network.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Moderna says boosters may be needed after 6 months

Moderna says neutralizing antibodies generated by its COVID-19 vaccine against three variants of the virus that causes the disease waned substantially 6 months after the second dose.

Because of this, the company expects an increase in breakthrough infections with a need for boosters before winter.

In an experiment, a 50-mg dose of the vaccine, given as a third shot, boosted levels of antibodies in 20 previously vaccinated people by 32 times against the Beta variant, by 44 times against the Gamma variant, and by 42 times against Delta.

The new data was presented in an earnings call to investors and is based on a small study that hasn’t yet been published in medical literature.

The company also said its vaccine remained highly effective at preventing severe COVID outcomes through 6 months.

Last week, Pfizer released early data suggesting a similar drop in protection from its vaccine. The company also showed a third dose substantially boosted protection, including against the Delta variant.

The new results come just 1 day after the World Health Organization implored wealthy nations to hold off on third doses until more of the world’s population could get a first dose.

More than 80% of the 4 billion vaccine doses given around the world have been distributed to high-income countries.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Moderna says neutralizing antibodies generated by its COVID-19 vaccine against three variants of the virus that causes the disease waned substantially 6 months after the second dose.

Because of this, the company expects an increase in breakthrough infections with a need for boosters before winter.

In an experiment, a 50-mg dose of the vaccine, given as a third shot, boosted levels of antibodies in 20 previously vaccinated people by 32 times against the Beta variant, by 44 times against the Gamma variant, and by 42 times against Delta.

The new data was presented in an earnings call to investors and is based on a small study that hasn’t yet been published in medical literature.

The company also said its vaccine remained highly effective at preventing severe COVID outcomes through 6 months.

Last week, Pfizer released early data suggesting a similar drop in protection from its vaccine. The company also showed a third dose substantially boosted protection, including against the Delta variant.

The new results come just 1 day after the World Health Organization implored wealthy nations to hold off on third doses until more of the world’s population could get a first dose.

More than 80% of the 4 billion vaccine doses given around the world have been distributed to high-income countries.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Moderna says neutralizing antibodies generated by its COVID-19 vaccine against three variants of the virus that causes the disease waned substantially 6 months after the second dose.

Because of this, the company expects an increase in breakthrough infections with a need for boosters before winter.

In an experiment, a 50-mg dose of the vaccine, given as a third shot, boosted levels of antibodies in 20 previously vaccinated people by 32 times against the Beta variant, by 44 times against the Gamma variant, and by 42 times against Delta.

The new data was presented in an earnings call to investors and is based on a small study that hasn’t yet been published in medical literature.

The company also said its vaccine remained highly effective at preventing severe COVID outcomes through 6 months.

Last week, Pfizer released early data suggesting a similar drop in protection from its vaccine. The company also showed a third dose substantially boosted protection, including against the Delta variant.

The new results come just 1 day after the World Health Organization implored wealthy nations to hold off on third doses until more of the world’s population could get a first dose.

More than 80% of the 4 billion vaccine doses given around the world have been distributed to high-income countries.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Despite retraction, study using fraudulent Surgisphere data still cited

A retracted study on the safety of blood pressure medications in patients with COVID-19 continues to be cited nearly a year later, new research shows.

The study in question, published on May 1, 2020, in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed no increased risk for in-hospital death with the use of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Concerns about the veracity of the Surgisphere database used for the study, however, led to a June 4 retraction and to the June 13 retraction of a second study, published in the Lancet, that focused on hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 treatment.

Although the Surgisphere scandal caused a global reckoning of COVID-19 scientific studies, the new analysis identified 652 citations of the NEJM article as of May 31.

More than a third of the citations occurred in the first 2 months after the retraction, 54% were at least 3 months later, and 2.8% at least 6 months later. In May, 11 months after the article was retracted, it was cited 21 times, senior author Emily G. McDonald, MD, MSc, McGill University, Montreal, and colleagues reported in a research letter in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“In early May and June there were already more than 200 citations in one of the world’s leading scientific journals, so I do believe it was a highly influential article early on and had an impact on different types of studies or research taking place,” she said in an interview.

Dr. McDonald said she’s also “certain that it impacted patient care,” observing that when there are no guidelines available on how to manage patients, physicians will turn to the most recent evidence in the most reputable journals.

“In the case of ACE [inhibitors] and ARBs, although the study was based on fraudulent data, we were lucky that the overall message was in the end probably correct, but that might not have been the case for another study or dataset,” she said.

Early in the pandemic, concerns existed that ACE inhibitors and ARBs could be harmful, increasing the expression of ACE2 receptors, which the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to gain entry into cells. The first randomized trial to examine the issue, BRACE CORONA, showed no clinical benefit to interrupting use of the agents in hospitalized patients. An observational study suggested ACE inhibitors may even be protective.

Of two high-profile retractions, McDonald said they chose to bypass the hydroxychloroquine study, which had an eye-popping Altmetric attention score of 23,084, compared with 3,727 for the NEJM paper, because it may have been cited for “other” reasons. “We wanted to focus less on the politics and more on the problem of retracted work.”

The team found that researchers across the globe were citing the retracted ACE/ARB paper (18.7% in the United States, 8.1% in Italy, and 44% other countries). Most citations were used to support a statement in the main text of a study, but in nearly 3% of cases, the data were incorporated into new analyses.

Just 17.6% of the studies cited or noted the retraction. “For sure, that was surprising to us. We suspected it, but our study confirmed it,” Dr. McDonald said.

Although retracted articles can be identified by a watermark or line of text, in some cases that can be easily missed, she noted. What’s more, not all citation software points out when a study has been retracted, a fate shared by the copyediting process.

“There are a lot of mechanisms in place and, in general, what’s happening is rare but there isn’t a perfect automated system solution to absolutely prevent this from happening,” she said. “It’s still subject to human error.”

The findings also have to be taken in the context of a rapidly emerging pandemic and the unprecedented torrent of scientific papers released over the past year.

“That might have contributed to why this happened, but the takeaway message is that this can happen despite our best efforts, and we need to challenge ourselves to come up with a system solution to prevent this from happening in the future,” Dr. McDonald said. “Current mechanisms are probably capturing 95% of it, but we need to do better.”

Limitations of the present analysis are that it was limited to the single retracted study; used only a single search engine, Google Scholar, to identify the citing works; and that additional citations may have been missed, the authors noted.

McDonald and coauthor Todd C. Lee, MD, report being signatories on a public letter calling for the retraction of the Surgisphere papers. Dr. Lee also reported receiving research support from Fonds De Recherche du Quebec-Sante during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A retracted study on the safety of blood pressure medications in patients with COVID-19 continues to be cited nearly a year later, new research shows.

The study in question, published on May 1, 2020, in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed no increased risk for in-hospital death with the use of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Concerns about the veracity of the Surgisphere database used for the study, however, led to a June 4 retraction and to the June 13 retraction of a second study, published in the Lancet, that focused on hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 treatment.

Although the Surgisphere scandal caused a global reckoning of COVID-19 scientific studies, the new analysis identified 652 citations of the NEJM article as of May 31.

More than a third of the citations occurred in the first 2 months after the retraction, 54% were at least 3 months later, and 2.8% at least 6 months later. In May, 11 months after the article was retracted, it was cited 21 times, senior author Emily G. McDonald, MD, MSc, McGill University, Montreal, and colleagues reported in a research letter in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“In early May and June there were already more than 200 citations in one of the world’s leading scientific journals, so I do believe it was a highly influential article early on and had an impact on different types of studies or research taking place,” she said in an interview.

Dr. McDonald said she’s also “certain that it impacted patient care,” observing that when there are no guidelines available on how to manage patients, physicians will turn to the most recent evidence in the most reputable journals.

“In the case of ACE [inhibitors] and ARBs, although the study was based on fraudulent data, we were lucky that the overall message was in the end probably correct, but that might not have been the case for another study or dataset,” she said.

Early in the pandemic, concerns existed that ACE inhibitors and ARBs could be harmful, increasing the expression of ACE2 receptors, which the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to gain entry into cells. The first randomized trial to examine the issue, BRACE CORONA, showed no clinical benefit to interrupting use of the agents in hospitalized patients. An observational study suggested ACE inhibitors may even be protective.

Of two high-profile retractions, McDonald said they chose to bypass the hydroxychloroquine study, which had an eye-popping Altmetric attention score of 23,084, compared with 3,727 for the NEJM paper, because it may have been cited for “other” reasons. “We wanted to focus less on the politics and more on the problem of retracted work.”

The team found that researchers across the globe were citing the retracted ACE/ARB paper (18.7% in the United States, 8.1% in Italy, and 44% other countries). Most citations were used to support a statement in the main text of a study, but in nearly 3% of cases, the data were incorporated into new analyses.

Just 17.6% of the studies cited or noted the retraction. “For sure, that was surprising to us. We suspected it, but our study confirmed it,” Dr. McDonald said.

Although retracted articles can be identified by a watermark or line of text, in some cases that can be easily missed, she noted. What’s more, not all citation software points out when a study has been retracted, a fate shared by the copyediting process.

“There are a lot of mechanisms in place and, in general, what’s happening is rare but there isn’t a perfect automated system solution to absolutely prevent this from happening,” she said. “It’s still subject to human error.”

The findings also have to be taken in the context of a rapidly emerging pandemic and the unprecedented torrent of scientific papers released over the past year.

“That might have contributed to why this happened, but the takeaway message is that this can happen despite our best efforts, and we need to challenge ourselves to come up with a system solution to prevent this from happening in the future,” Dr. McDonald said. “Current mechanisms are probably capturing 95% of it, but we need to do better.”

Limitations of the present analysis are that it was limited to the single retracted study; used only a single search engine, Google Scholar, to identify the citing works; and that additional citations may have been missed, the authors noted.

McDonald and coauthor Todd C. Lee, MD, report being signatories on a public letter calling for the retraction of the Surgisphere papers. Dr. Lee also reported receiving research support from Fonds De Recherche du Quebec-Sante during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A retracted study on the safety of blood pressure medications in patients with COVID-19 continues to be cited nearly a year later, new research shows.

The study in question, published on May 1, 2020, in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed no increased risk for in-hospital death with the use of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

Concerns about the veracity of the Surgisphere database used for the study, however, led to a June 4 retraction and to the June 13 retraction of a second study, published in the Lancet, that focused on hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 treatment.

Although the Surgisphere scandal caused a global reckoning of COVID-19 scientific studies, the new analysis identified 652 citations of the NEJM article as of May 31.

More than a third of the citations occurred in the first 2 months after the retraction, 54% were at least 3 months later, and 2.8% at least 6 months later. In May, 11 months after the article was retracted, it was cited 21 times, senior author Emily G. McDonald, MD, MSc, McGill University, Montreal, and colleagues reported in a research letter in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“In early May and June there were already more than 200 citations in one of the world’s leading scientific journals, so I do believe it was a highly influential article early on and had an impact on different types of studies or research taking place,” she said in an interview.

Dr. McDonald said she’s also “certain that it impacted patient care,” observing that when there are no guidelines available on how to manage patients, physicians will turn to the most recent evidence in the most reputable journals.

“In the case of ACE [inhibitors] and ARBs, although the study was based on fraudulent data, we were lucky that the overall message was in the end probably correct, but that might not have been the case for another study or dataset,” she said.

Early in the pandemic, concerns existed that ACE inhibitors and ARBs could be harmful, increasing the expression of ACE2 receptors, which the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to gain entry into cells. The first randomized trial to examine the issue, BRACE CORONA, showed no clinical benefit to interrupting use of the agents in hospitalized patients. An observational study suggested ACE inhibitors may even be protective.

Of two high-profile retractions, McDonald said they chose to bypass the hydroxychloroquine study, which had an eye-popping Altmetric attention score of 23,084, compared with 3,727 for the NEJM paper, because it may have been cited for “other” reasons. “We wanted to focus less on the politics and more on the problem of retracted work.”

The team found that researchers across the globe were citing the retracted ACE/ARB paper (18.7% in the United States, 8.1% in Italy, and 44% other countries). Most citations were used to support a statement in the main text of a study, but in nearly 3% of cases, the data were incorporated into new analyses.

Just 17.6% of the studies cited or noted the retraction. “For sure, that was surprising to us. We suspected it, but our study confirmed it,” Dr. McDonald said.

Although retracted articles can be identified by a watermark or line of text, in some cases that can be easily missed, she noted. What’s more, not all citation software points out when a study has been retracted, a fate shared by the copyediting process.

“There are a lot of mechanisms in place and, in general, what’s happening is rare but there isn’t a perfect automated system solution to absolutely prevent this from happening,” she said. “It’s still subject to human error.”

The findings also have to be taken in the context of a rapidly emerging pandemic and the unprecedented torrent of scientific papers released over the past year.

“That might have contributed to why this happened, but the takeaway message is that this can happen despite our best efforts, and we need to challenge ourselves to come up with a system solution to prevent this from happening in the future,” Dr. McDonald said. “Current mechanisms are probably capturing 95% of it, but we need to do better.”

Limitations of the present analysis are that it was limited to the single retracted study; used only a single search engine, Google Scholar, to identify the citing works; and that additional citations may have been missed, the authors noted.

McDonald and coauthor Todd C. Lee, MD, report being signatories on a public letter calling for the retraction of the Surgisphere papers. Dr. Lee also reported receiving research support from Fonds De Recherche du Quebec-Sante during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Myocarditis tied to COVID-19 shots more common than reported?

While cases of pericarditis or myocarditis temporally linked to COVID-19 vaccination remain rare, they may happen more often than reported, according to a large review of electronic medical records (EMRs).

They also appear to represent two “distinct syndromes,” George Diaz, MD, Providence Regional Medical Center Everett (Washington), said in an interview.

Myocarditis typically occurs soon after vaccination in younger patients and mostly after the second dose, while pericarditis occurs later in older patients, after the first or second dose.

Dr. Diaz and colleagues reported their analysis in a research letter published online August 4 in JAMA.

They reviewed the records of 2,000,287 people who received at least one COVID-19 vaccination at 40 hospitals in Washington, Oregon, Montana, and California that are part of the Providence health care system and use the same EMRs.

The median age of the cohort was 57 years and 59% were women.

A little more than three quarters (77%) received more than one dose; most received the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer (53%) and Moderna (44%); 3% received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

The records showed that 20 people had vaccine-related myocarditis (1.0 per 100,000) and 37 had pericarditis (1.8 per 100,000).

A recent report, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System, suggested an incidence of myocarditis of about 4.8 cases per 1 million following receipt of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine.

The new study shows a “similar pattern, although at higher incidence, suggesting vaccine adverse event underreporting. In addition, pericarditis may be more common than myocarditis among older patients,” the study team wrote.

“Our study resulted in higher numbers of cases probably because we searched the EMR, and VAERS requires doctors to report suspected cases voluntarily,” Dr. Diaz said in an interview.

Also, in the governments’ statistics, pericarditis and myocarditis were “lumped together,” he noted.

Myocarditis cases

The 20 myocarditis cases occurred a median of 3.5 days after vaccination (11 after the Moderna vaccine and 9 after the Pfizer vaccine), 15 of the patients (75%) were men, and the median age was 36 years.

Four individuals (20%) developed myocarditis symptoms after the first vaccination and 16 (80%) after the second dose. Nineteen of the patients (95%) were admitted to the hospital and all were discharged after a median of 2 days.

None of the 20 patients were readmitted or died. Two received a second vaccination after onset of myocarditis; neither had worsening of symptoms. At last available follow-up (median, 23.5 days after symptom onset), 13 patients (65%) had a resolution of their myocarditis symptoms and seven (35%) were improving.

Pericarditis cases

The 37 pericarditis cases occurred a median of 20 days after the most recent COVID-19 vaccination: 23 (62%) with Pfizer, 12 (32%) with Moderna, and 2 (5%) with the J&J vaccine. Fifteen developed pericarditis after the first vaccine dose (41%) and 22 (59%) after the second.

Twenty-seven (73%) of the cases occurred in men; the median age was 59 years.

Thirteen patients (35%) were admitted to the hospital, none to intensive care. The median hospital stay was 1 day. Seven patients with pericarditis received a second vaccination. No patient died.

At last available follow-up (median, 28 days), 7 patients (19%) had resolved symptoms and 23 (62%) were improving.

The researchers also calculate that the average monthly number of cases of myocarditis or myopericarditis during the prevaccine period of January 2019 through January 2021 was 16.9 (95% confidence interval, 15.3-18.6) compared with 27.3 (95% CI, 22.4-32.9) during the vaccine period of February through May 2021 (P < .001).

The mean numbers of pericarditis cases during the same periods were 49.1 (95% CI, 46.4-51.9) and 78.8 (95% CI, 70.3-87.9), respectively (P < .001).

The authors say limitations of their analysis include potential missed cases outside care settings and missed diagnoses of myocarditis or pericarditis, which would underestimate the incidence, as well as inaccurate EMR vaccination information.

“Temporal association does not prove causation, although the short span between vaccination and myocarditis onset and the elevated incidence of myocarditis and pericarditis in the study hospitals lend support to a possible relationship,” they wrote.

In late June, the Food and Drug Administration added a warning to the fact sheets accompanying the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, flagging the rare risk of heart inflammation after their use.

Dr. Diaz cautioned that myocarditis and pericarditis events remain “a rare occurrence” after COVID-19 vaccination.

“When discussing vaccination with patients, [health care providers] can advise them that patients generally recover in the rare event they get pericarditis or myocarditis and no deaths were found, and that the vaccines are safe and effective,” Dr. Diaz said.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Diaz reported receipt of clinical trial research support from Gilead Sciences, Regeneron, Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Edesa Biotech and scientific advisory board membership for Safeology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While cases of pericarditis or myocarditis temporally linked to COVID-19 vaccination remain rare, they may happen more often than reported, according to a large review of electronic medical records (EMRs).

They also appear to represent two “distinct syndromes,” George Diaz, MD, Providence Regional Medical Center Everett (Washington), said in an interview.

Myocarditis typically occurs soon after vaccination in younger patients and mostly after the second dose, while pericarditis occurs later in older patients, after the first or second dose.

Dr. Diaz and colleagues reported their analysis in a research letter published online August 4 in JAMA.

They reviewed the records of 2,000,287 people who received at least one COVID-19 vaccination at 40 hospitals in Washington, Oregon, Montana, and California that are part of the Providence health care system and use the same EMRs.

The median age of the cohort was 57 years and 59% were women.

A little more than three quarters (77%) received more than one dose; most received the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer (53%) and Moderna (44%); 3% received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

The records showed that 20 people had vaccine-related myocarditis (1.0 per 100,000) and 37 had pericarditis (1.8 per 100,000).

A recent report, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System, suggested an incidence of myocarditis of about 4.8 cases per 1 million following receipt of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine.

The new study shows a “similar pattern, although at higher incidence, suggesting vaccine adverse event underreporting. In addition, pericarditis may be more common than myocarditis among older patients,” the study team wrote.

“Our study resulted in higher numbers of cases probably because we searched the EMR, and VAERS requires doctors to report suspected cases voluntarily,” Dr. Diaz said in an interview.

Also, in the governments’ statistics, pericarditis and myocarditis were “lumped together,” he noted.

Myocarditis cases

The 20 myocarditis cases occurred a median of 3.5 days after vaccination (11 after the Moderna vaccine and 9 after the Pfizer vaccine), 15 of the patients (75%) were men, and the median age was 36 years.

Four individuals (20%) developed myocarditis symptoms after the first vaccination and 16 (80%) after the second dose. Nineteen of the patients (95%) were admitted to the hospital and all were discharged after a median of 2 days.

None of the 20 patients were readmitted or died. Two received a second vaccination after onset of myocarditis; neither had worsening of symptoms. At last available follow-up (median, 23.5 days after symptom onset), 13 patients (65%) had a resolution of their myocarditis symptoms and seven (35%) were improving.

Pericarditis cases

The 37 pericarditis cases occurred a median of 20 days after the most recent COVID-19 vaccination: 23 (62%) with Pfizer, 12 (32%) with Moderna, and 2 (5%) with the J&J vaccine. Fifteen developed pericarditis after the first vaccine dose (41%) and 22 (59%) after the second.

Twenty-seven (73%) of the cases occurred in men; the median age was 59 years.

Thirteen patients (35%) were admitted to the hospital, none to intensive care. The median hospital stay was 1 day. Seven patients with pericarditis received a second vaccination. No patient died.

At last available follow-up (median, 28 days), 7 patients (19%) had resolved symptoms and 23 (62%) were improving.

The researchers also calculate that the average monthly number of cases of myocarditis or myopericarditis during the prevaccine period of January 2019 through January 2021 was 16.9 (95% confidence interval, 15.3-18.6) compared with 27.3 (95% CI, 22.4-32.9) during the vaccine period of February through May 2021 (P < .001).

The mean numbers of pericarditis cases during the same periods were 49.1 (95% CI, 46.4-51.9) and 78.8 (95% CI, 70.3-87.9), respectively (P < .001).

The authors say limitations of their analysis include potential missed cases outside care settings and missed diagnoses of myocarditis or pericarditis, which would underestimate the incidence, as well as inaccurate EMR vaccination information.

“Temporal association does not prove causation, although the short span between vaccination and myocarditis onset and the elevated incidence of myocarditis and pericarditis in the study hospitals lend support to a possible relationship,” they wrote.

In late June, the Food and Drug Administration added a warning to the fact sheets accompanying the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, flagging the rare risk of heart inflammation after their use.

Dr. Diaz cautioned that myocarditis and pericarditis events remain “a rare occurrence” after COVID-19 vaccination.

“When discussing vaccination with patients, [health care providers] can advise them that patients generally recover in the rare event they get pericarditis or myocarditis and no deaths were found, and that the vaccines are safe and effective,” Dr. Diaz said.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Diaz reported receipt of clinical trial research support from Gilead Sciences, Regeneron, Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Edesa Biotech and scientific advisory board membership for Safeology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While cases of pericarditis or myocarditis temporally linked to COVID-19 vaccination remain rare, they may happen more often than reported, according to a large review of electronic medical records (EMRs).

They also appear to represent two “distinct syndromes,” George Diaz, MD, Providence Regional Medical Center Everett (Washington), said in an interview.

Myocarditis typically occurs soon after vaccination in younger patients and mostly after the second dose, while pericarditis occurs later in older patients, after the first or second dose.

Dr. Diaz and colleagues reported their analysis in a research letter published online August 4 in JAMA.

They reviewed the records of 2,000,287 people who received at least one COVID-19 vaccination at 40 hospitals in Washington, Oregon, Montana, and California that are part of the Providence health care system and use the same EMRs.

The median age of the cohort was 57 years and 59% were women.

A little more than three quarters (77%) received more than one dose; most received the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer (53%) and Moderna (44%); 3% received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

The records showed that 20 people had vaccine-related myocarditis (1.0 per 100,000) and 37 had pericarditis (1.8 per 100,000).

A recent report, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System, suggested an incidence of myocarditis of about 4.8 cases per 1 million following receipt of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine.

The new study shows a “similar pattern, although at higher incidence, suggesting vaccine adverse event underreporting. In addition, pericarditis may be more common than myocarditis among older patients,” the study team wrote.

“Our study resulted in higher numbers of cases probably because we searched the EMR, and VAERS requires doctors to report suspected cases voluntarily,” Dr. Diaz said in an interview.

Also, in the governments’ statistics, pericarditis and myocarditis were “lumped together,” he noted.

Myocarditis cases

The 20 myocarditis cases occurred a median of 3.5 days after vaccination (11 after the Moderna vaccine and 9 after the Pfizer vaccine), 15 of the patients (75%) were men, and the median age was 36 years.

Four individuals (20%) developed myocarditis symptoms after the first vaccination and 16 (80%) after the second dose. Nineteen of the patients (95%) were admitted to the hospital and all were discharged after a median of 2 days.

None of the 20 patients were readmitted or died. Two received a second vaccination after onset of myocarditis; neither had worsening of symptoms. At last available follow-up (median, 23.5 days after symptom onset), 13 patients (65%) had a resolution of their myocarditis symptoms and seven (35%) were improving.

Pericarditis cases

The 37 pericarditis cases occurred a median of 20 days after the most recent COVID-19 vaccination: 23 (62%) with Pfizer, 12 (32%) with Moderna, and 2 (5%) with the J&J vaccine. Fifteen developed pericarditis after the first vaccine dose (41%) and 22 (59%) after the second.

Twenty-seven (73%) of the cases occurred in men; the median age was 59 years.

Thirteen patients (35%) were admitted to the hospital, none to intensive care. The median hospital stay was 1 day. Seven patients with pericarditis received a second vaccination. No patient died.

At last available follow-up (median, 28 days), 7 patients (19%) had resolved symptoms and 23 (62%) were improving.

The researchers also calculate that the average monthly number of cases of myocarditis or myopericarditis during the prevaccine period of January 2019 through January 2021 was 16.9 (95% confidence interval, 15.3-18.6) compared with 27.3 (95% CI, 22.4-32.9) during the vaccine period of February through May 2021 (P < .001).

The mean numbers of pericarditis cases during the same periods were 49.1 (95% CI, 46.4-51.9) and 78.8 (95% CI, 70.3-87.9), respectively (P < .001).

The authors say limitations of their analysis include potential missed cases outside care settings and missed diagnoses of myocarditis or pericarditis, which would underestimate the incidence, as well as inaccurate EMR vaccination information.

“Temporal association does not prove causation, although the short span between vaccination and myocarditis onset and the elevated incidence of myocarditis and pericarditis in the study hospitals lend support to a possible relationship,” they wrote.

In late June, the Food and Drug Administration added a warning to the fact sheets accompanying the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, flagging the rare risk of heart inflammation after their use.

Dr. Diaz cautioned that myocarditis and pericarditis events remain “a rare occurrence” after COVID-19 vaccination.

“When discussing vaccination with patients, [health care providers] can advise them that patients generally recover in the rare event they get pericarditis or myocarditis and no deaths were found, and that the vaccines are safe and effective,” Dr. Diaz said.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Diaz reported receipt of clinical trial research support from Gilead Sciences, Regeneron, Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Edesa Biotech and scientific advisory board membership for Safeology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

U.S. health system ranks last among 11 high-income countries

The U.S. health care system ranked last overall among 11 high-income countries in an analysis by the nonprofit Commonwealth Fund, according to a report released on Aug. 4.

The report is the seventh international comparison of countries’ health systems by the Commonwealth Fund since 2004, and the United States has ranked last in every edition, David Blumenthal, MD, president of the Commonwealth Fund, told reporters during a press briefing.

Researchers analyzed survey answers from tens of thousands of patients and physicians in 11 countries. They analyzed performance on 71 measures across five categories – access to care, care process, administrative efficiency, equity, and health care outcomes. Administrative data were gathered from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and the World Health Organization.

Among contributors to the poor showing by the United States is that half (50%) of lower-income U.S. adults and 27% of higher-income U.S. adults say costs keep them from getting needed health care.

“In no other country does income inequality so profoundly limit access to care,” Dr. Blumenthal said.

In the United Kingdom, only 12% with lower incomes and 7% with higher incomes said costs kept them from care.

In a stark comparison, the researchers found that “a high-income person in the U.S. was more likely to report financial barriers than a low-income person in nearly all the other countries surveyed: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the U.K.”

Norway, the Netherlands, and Australia were ranked at the top overall in that order. Rounding out the 11 in overall ranking were the U.K., Germany, New Zealand, Sweden, France, Switzerland, Canada, and the United States.

“What this report tells us is that our health care system is not working for Americans, particularly those with lower incomes, who are at a severe disadvantage compared to citizens of other countries. And they are paying the price with their health and their lives,” Dr. Blumenthal said in a press release.

“To catch up with other high-income countries, the administration and Congress would have to expand access to health care, equitably, to all Americans, act aggressively to control costs, and invest in the social services we know can lead to a healthier population.”

High infant mortality, low life expectancy in U.S.

Several factors contributed to the U.S. ranking at the bottom of the outcomes category. Among them are that the United States has the highest infant mortality rate (5.7 deaths per 1,000 live births) and lowest life expectancy at age 60 (living on average 23.1 years after age 60), compared with the other countries surveyed. The U.S. rate of preventable mortality (177 deaths per 100,000 population) is more than double that of the best-performing country, Switzerland.

Lead author Eric Schneider, MD, senior vice president for policy and research at the Commonwealth Fund, pointed out that, in terms of the change in avoidable mortality over a decade, not only did the United States have the highest rate, compared with the other countries surveyed, “it also experienced the smallest decline in avoidable mortality over that 10-year period.”

The U.S. maternal mortality rate of 17.4 deaths per 100,000 live births is twice that of France, the country with the next-highest rate (7.6 deaths per 100,000 live births).

U.S. excelled in only one category

The only category in which the United States did not rank last was in “care process,” where it ranked second behind only New Zealand.

The care process category combines preventive care, safe care, coordinated care, and patient engagement and preferences. The category includes indicators such as mammography screening and influenza vaccination for older adults as well as the percentage of adults counseled by a health care provider about nutrition, smoking, or alcohol use.

The United States and Germany performed best on engagement and patient preferences, although U.S. adults have the lowest rates of continuity with the same doctor.

New Zealand and the United States ranked highest in the safe care category, with higher reported use of computerized alerts and routine review of medications.

‘Too little, too late’: Key recommendations for U.S. to improve

Reginald Williams, vice president of International Health Policy and Practice Innovations at the Commonwealth Fund, pointed out that the U.S. shortcomings in health care come despite spending more than twice as much of its GDP (17% in 2019) as the average OECD country.

“It appears that the US delivers too little of the care that is most needed and often delivers that care too late, especially for people with chronic illnesses,” he said.

He then summarized the team’s recommendations on how the United States can change course.

First is expanding insurance coverage, he said, noting that the United States is the only one of the 11 countries that lacks universal coverage and nearly 30 million people remain uninsured.

Top-performing countries in the survey have universal coverage, annual out-of-pocket caps on covered benefits, and full coverage for primary care and treatment for chronic conditions, he said.

The United States must also improve access to care, he said.

“Top-ranking countries like the Netherlands and Norway ensure timely availability to care by telephone on nights and weekends, and in-person follow-up at home, if needed,” he said.

Mr. Williams said reducing administrative burdens is also critical to free up resources for improving health. He gave an example: “Norway determines patient copayments or physician fees on a regional basis, applying standardized copayments to all physicians within a specialty in a geographic area.”

Reducing income-related barriers is important as well, he said.

The fear of unpredictably high bills and other issues prevent people in the United States from getting the care they ultimately need, he said, adding that top-performing countries invest more in social services to reduce health risks.

That could have implications for the COVID-19 response.

Responding effectively to COVID-19 requires that patients can access affordable health care services, Mr. Williams noted.

“We know from our research that more than two-thirds of U.S. adults say their potential out-of-pocket costs would figure prominently in their decisions to get care if they had coronavirus symptoms,” he said.

Dr. Schneider summed up in the press release: “This study makes clear that higher U.S. spending on health care is not producing better health especially as the U.S. continues on a path of deepening inequality. A country that spends as much as we do should have the best health system in the world. We should adapt what works in other high-income countries to build a better health care system that provides affordable, high-quality health care for everyone.”

Dr. Blumenthal, Dr. Schneider, and Mr. Williams reported no relevant financial relationships outside their employment with the Commonwealth Fund.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. health care system ranked last overall among 11 high-income countries in an analysis by the nonprofit Commonwealth Fund, according to a report released on Aug. 4.

The report is the seventh international comparison of countries’ health systems by the Commonwealth Fund since 2004, and the United States has ranked last in every edition, David Blumenthal, MD, president of the Commonwealth Fund, told reporters during a press briefing.

Researchers analyzed survey answers from tens of thousands of patients and physicians in 11 countries. They analyzed performance on 71 measures across five categories – access to care, care process, administrative efficiency, equity, and health care outcomes. Administrative data were gathered from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and the World Health Organization.

Among contributors to the poor showing by the United States is that half (50%) of lower-income U.S. adults and 27% of higher-income U.S. adults say costs keep them from getting needed health care.

“In no other country does income inequality so profoundly limit access to care,” Dr. Blumenthal said.

In the United Kingdom, only 12% with lower incomes and 7% with higher incomes said costs kept them from care.

In a stark comparison, the researchers found that “a high-income person in the U.S. was more likely to report financial barriers than a low-income person in nearly all the other countries surveyed: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the U.K.”

Norway, the Netherlands, and Australia were ranked at the top overall in that order. Rounding out the 11 in overall ranking were the U.K., Germany, New Zealand, Sweden, France, Switzerland, Canada, and the United States.

“What this report tells us is that our health care system is not working for Americans, particularly those with lower incomes, who are at a severe disadvantage compared to citizens of other countries. And they are paying the price with their health and their lives,” Dr. Blumenthal said in a press release.

“To catch up with other high-income countries, the administration and Congress would have to expand access to health care, equitably, to all Americans, act aggressively to control costs, and invest in the social services we know can lead to a healthier population.”

High infant mortality, low life expectancy in U.S.

Several factors contributed to the U.S. ranking at the bottom of the outcomes category. Among them are that the United States has the highest infant mortality rate (5.7 deaths per 1,000 live births) and lowest life expectancy at age 60 (living on average 23.1 years after age 60), compared with the other countries surveyed. The U.S. rate of preventable mortality (177 deaths per 100,000 population) is more than double that of the best-performing country, Switzerland.

Lead author Eric Schneider, MD, senior vice president for policy and research at the Commonwealth Fund, pointed out that, in terms of the change in avoidable mortality over a decade, not only did the United States have the highest rate, compared with the other countries surveyed, “it also experienced the smallest decline in avoidable mortality over that 10-year period.”

The U.S. maternal mortality rate of 17.4 deaths per 100,000 live births is twice that of France, the country with the next-highest rate (7.6 deaths per 100,000 live births).

U.S. excelled in only one category

The only category in which the United States did not rank last was in “care process,” where it ranked second behind only New Zealand.

The care process category combines preventive care, safe care, coordinated care, and patient engagement and preferences. The category includes indicators such as mammography screening and influenza vaccination for older adults as well as the percentage of adults counseled by a health care provider about nutrition, smoking, or alcohol use.

The United States and Germany performed best on engagement and patient preferences, although U.S. adults have the lowest rates of continuity with the same doctor.

New Zealand and the United States ranked highest in the safe care category, with higher reported use of computerized alerts and routine review of medications.

‘Too little, too late’: Key recommendations for U.S. to improve

Reginald Williams, vice president of International Health Policy and Practice Innovations at the Commonwealth Fund, pointed out that the U.S. shortcomings in health care come despite spending more than twice as much of its GDP (17% in 2019) as the average OECD country.

“It appears that the US delivers too little of the care that is most needed and often delivers that care too late, especially for people with chronic illnesses,” he said.

He then summarized the team’s recommendations on how the United States can change course.

First is expanding insurance coverage, he said, noting that the United States is the only one of the 11 countries that lacks universal coverage and nearly 30 million people remain uninsured.

Top-performing countries in the survey have universal coverage, annual out-of-pocket caps on covered benefits, and full coverage for primary care and treatment for chronic conditions, he said.

The United States must also improve access to care, he said.