User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

If you’ve got 3 seconds, then you’ve got time to work out

Goffin’s cockatoo? More like golfin’ cockatoo

Can birds play golf? Of course not; it’s ridiculous. Humans can barely play golf, and we invented the sport. Anyway, moving on to “Brian retraction injury after elective aneurysm clipping.”

Hang on, we’re now hearing that a group of researchers, as part of a large international project comparing children’s innovation and problem-solving skills with those of cockatoos, have in fact taught a group of Goffin’s cockatoos how to play golf. Huh. What an oddly specific project. All right, fine, I guess we’ll go with the golf-playing birds.

Golf may seem very simple at its core. It is, essentially, whacking a ball with a stick. But the Scots who invented the game were undertaking a complex project involving combined usage of multiple tools, and until now, only primates were thought to be capable of utilizing compound tools to play games such as golf.

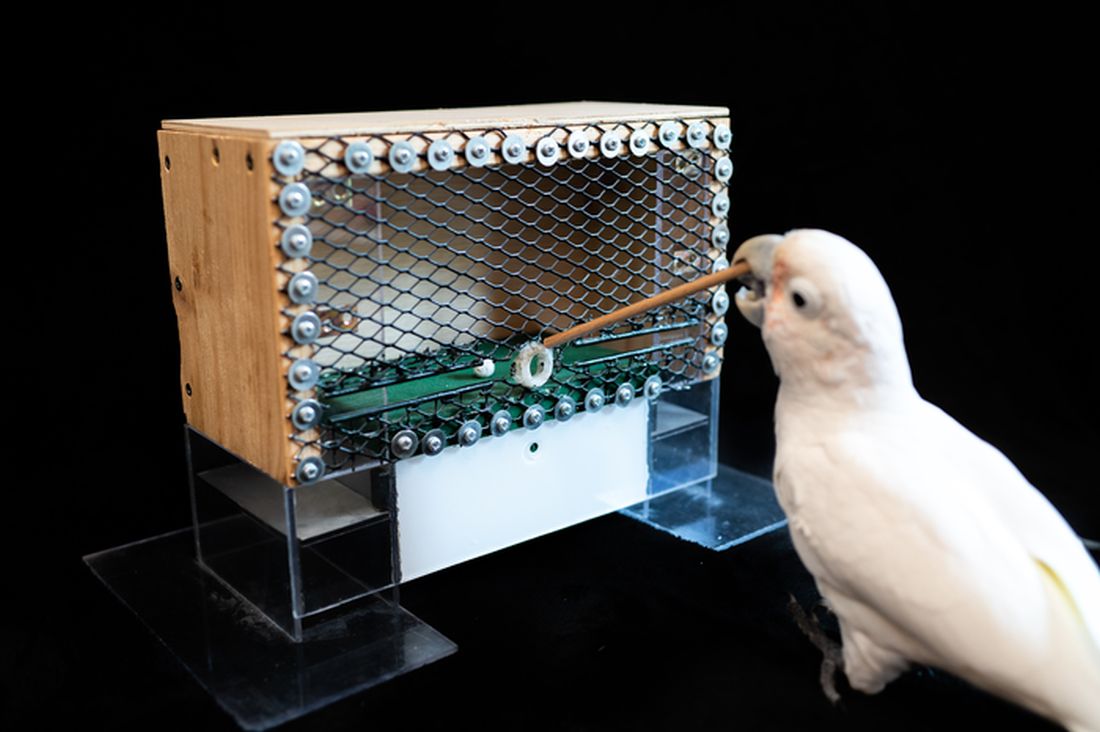

For this latest research, published in Scientific Reports, our intrepid birds were given a rudimentary form of golf to play (featuring a stick, a ball, and a closed box to get the ball through). Putting the ball through the hole gave the bird a reward. Not every cockatoo was able to hole out, but three did, with each inventing a unique way to manipulate the stick to hit the ball.

As entertaining as it would be to simply teach some birds how to play golf, we do loop back around to medical relevance. While children are perfectly capable of using tools, young children in particular are actually quite bad at using tools to solve novel solutions. Present a 5-year-old with a stick, a ball, and a hole, and that child might not figure out what the cockatoos did. The research really does give insight into the psychology behind the development of complex tools and technology by our ancient ancestors, according to the researchers.

We’re not entirely convinced this isn’t an elaborate ploy to get a bird out onto the PGA Tour. The LOTME staff can see the future headline already: “Painted bunting wins Valspar Championship in epic playoff.”

Work out now, sweat never

Okay, show of hands: Who’s familiar with “Name that tune?” The TV game show got a reboot last year, but some of us are old enough to remember the 1970s version hosted by national treasure Tom Kennedy.

The contestants try to identify a song as quickly as possible, claiming that they “can name that tune in five notes.” Or four notes, or three. Well, welcome to “Name that exercise study.”

Senior author Masatoshi Nakamura, PhD, and associates gathered together 39 students from Niigata (Japan) University of Health and Welfare and had them perform one isometric, concentric, or eccentric bicep curl with a dumbbell for 3 seconds a day at maximum effort for 5 days a week, over 4 weeks. And yes, we did say 3 seconds.

“Lifting the weight sees the bicep in concentric contraction, lowering the weight sees it in eccentric contraction, while holding the weight parallel to the ground is isometric,” they explained in a statement on Eurekalert.

The three exercise groups were compared with a group that did no exercise, and after 4 weeks of rigorous but brief science, the group doing eccentric contractions had the best results, as their overall muscle strength increased by 11.5%. After a total of just 60 seconds of exercise in 4 weeks. That’s 60 seconds. In 4 weeks.

Big news, but maybe we can do better. “Tom, we can do that exercise in 2 seconds.”

And one! And two! Whoa, feel the burn.

Tingling over anxiety

Apparently there are two kinds of people in this world. Those who love ASMR and those who just don’t get it.

ASMR, for those who don’t know, is the autonomous sensory meridian response. An online community has surfaced, with video creators making tapping sounds, whispering, or brushing mannequin hair to elicit “a pleasant tingling sensation originating from the scalp and neck which can spread to the rest of the body” from viewers, Charlotte M. Eid and associates said in PLOS One.

The people who are into these types of videos are more likely to have higher levels of neuroticism than those who aren’t, which gives ASMR the potential to be a nontraditional form of treatment for anxiety and/or neuroticism, they suggested.

The research involved a group of 64 volunteers who watched an ASMR video meant to trigger the tingles and then completed questionnaires to evaluate their levels of neuroticism, trait anxiety, and state anxiety, said Ms. Eid and associates of Northumbria University in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England.

The people who had a history of producing tingles from ASMR videos in the past had higher levels of anxiety, compared with those who didn’t. Those who responded to triggers also received some benefit from the video in the study, reporting lower levels of neuroticism and anxiety after watching, the investigators found.

Although people who didn’t have a history of tingles didn’t feel any reduction in anxiety after the video, that didn’t stop the people who weren’t familiar with the genre from catching tingles.

So if you find yourself a little high strung or anxious, or if you can’t sleep, consider watching a person pretending to give you a makeover or using fingernails to tap on books for some relaxation. Don’t knock it until you try it!

Living in the past? Not so far-fetched

It’s usually an insult when people tell us to stop living in the past, but the joke’s on them because we really do live in the past. By 15 seconds, to be exact, according to researchers from the University of California, Berkeley.

But wait, did you just read that last sentence 15 seconds ago, even though it feels like real time? Did we just type these words now, or 15 seconds ago?

Think of your brain as a web page you’re constantly refreshing. We are constantly seeing new pictures, images, and colors, and your brain is responsible for keeping everything in chronological order. This new research suggests that our brains show us images from 15 seconds prior. Is your mind blown yet?

“One could say our brain is procrastinating. It’s too much work to constantly update images, so it sticks to the past because the past is a good predictor of the present. We recycle information from the past because it’s faster, more efficient and less work,” senior author David Whitney explained in a statement from the university.

It seems like the 15-second rule helps us not lose our minds by keeping a steady flow of information, but it could be a bit dangerous if someone, such as a surgeon, needs to see things with extreme precision.

And now we are definitely feeling a bit anxious about our upcoming heart/spleen/gallbladder replacement. … Where’s that link to the ASMR video?

Goffin’s cockatoo? More like golfin’ cockatoo

Can birds play golf? Of course not; it’s ridiculous. Humans can barely play golf, and we invented the sport. Anyway, moving on to “Brian retraction injury after elective aneurysm clipping.”

Hang on, we’re now hearing that a group of researchers, as part of a large international project comparing children’s innovation and problem-solving skills with those of cockatoos, have in fact taught a group of Goffin’s cockatoos how to play golf. Huh. What an oddly specific project. All right, fine, I guess we’ll go with the golf-playing birds.

Golf may seem very simple at its core. It is, essentially, whacking a ball with a stick. But the Scots who invented the game were undertaking a complex project involving combined usage of multiple tools, and until now, only primates were thought to be capable of utilizing compound tools to play games such as golf.

For this latest research, published in Scientific Reports, our intrepid birds were given a rudimentary form of golf to play (featuring a stick, a ball, and a closed box to get the ball through). Putting the ball through the hole gave the bird a reward. Not every cockatoo was able to hole out, but three did, with each inventing a unique way to manipulate the stick to hit the ball.

As entertaining as it would be to simply teach some birds how to play golf, we do loop back around to medical relevance. While children are perfectly capable of using tools, young children in particular are actually quite bad at using tools to solve novel solutions. Present a 5-year-old with a stick, a ball, and a hole, and that child might not figure out what the cockatoos did. The research really does give insight into the psychology behind the development of complex tools and technology by our ancient ancestors, according to the researchers.

We’re not entirely convinced this isn’t an elaborate ploy to get a bird out onto the PGA Tour. The LOTME staff can see the future headline already: “Painted bunting wins Valspar Championship in epic playoff.”

Work out now, sweat never

Okay, show of hands: Who’s familiar with “Name that tune?” The TV game show got a reboot last year, but some of us are old enough to remember the 1970s version hosted by national treasure Tom Kennedy.

The contestants try to identify a song as quickly as possible, claiming that they “can name that tune in five notes.” Or four notes, or three. Well, welcome to “Name that exercise study.”

Senior author Masatoshi Nakamura, PhD, and associates gathered together 39 students from Niigata (Japan) University of Health and Welfare and had them perform one isometric, concentric, or eccentric bicep curl with a dumbbell for 3 seconds a day at maximum effort for 5 days a week, over 4 weeks. And yes, we did say 3 seconds.

“Lifting the weight sees the bicep in concentric contraction, lowering the weight sees it in eccentric contraction, while holding the weight parallel to the ground is isometric,” they explained in a statement on Eurekalert.

The three exercise groups were compared with a group that did no exercise, and after 4 weeks of rigorous but brief science, the group doing eccentric contractions had the best results, as their overall muscle strength increased by 11.5%. After a total of just 60 seconds of exercise in 4 weeks. That’s 60 seconds. In 4 weeks.

Big news, but maybe we can do better. “Tom, we can do that exercise in 2 seconds.”

And one! And two! Whoa, feel the burn.

Tingling over anxiety

Apparently there are two kinds of people in this world. Those who love ASMR and those who just don’t get it.

ASMR, for those who don’t know, is the autonomous sensory meridian response. An online community has surfaced, with video creators making tapping sounds, whispering, or brushing mannequin hair to elicit “a pleasant tingling sensation originating from the scalp and neck which can spread to the rest of the body” from viewers, Charlotte M. Eid and associates said in PLOS One.

The people who are into these types of videos are more likely to have higher levels of neuroticism than those who aren’t, which gives ASMR the potential to be a nontraditional form of treatment for anxiety and/or neuroticism, they suggested.

The research involved a group of 64 volunteers who watched an ASMR video meant to trigger the tingles and then completed questionnaires to evaluate their levels of neuroticism, trait anxiety, and state anxiety, said Ms. Eid and associates of Northumbria University in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England.

The people who had a history of producing tingles from ASMR videos in the past had higher levels of anxiety, compared with those who didn’t. Those who responded to triggers also received some benefit from the video in the study, reporting lower levels of neuroticism and anxiety after watching, the investigators found.

Although people who didn’t have a history of tingles didn’t feel any reduction in anxiety after the video, that didn’t stop the people who weren’t familiar with the genre from catching tingles.

So if you find yourself a little high strung or anxious, or if you can’t sleep, consider watching a person pretending to give you a makeover or using fingernails to tap on books for some relaxation. Don’t knock it until you try it!

Living in the past? Not so far-fetched

It’s usually an insult when people tell us to stop living in the past, but the joke’s on them because we really do live in the past. By 15 seconds, to be exact, according to researchers from the University of California, Berkeley.

But wait, did you just read that last sentence 15 seconds ago, even though it feels like real time? Did we just type these words now, or 15 seconds ago?

Think of your brain as a web page you’re constantly refreshing. We are constantly seeing new pictures, images, and colors, and your brain is responsible for keeping everything in chronological order. This new research suggests that our brains show us images from 15 seconds prior. Is your mind blown yet?

“One could say our brain is procrastinating. It’s too much work to constantly update images, so it sticks to the past because the past is a good predictor of the present. We recycle information from the past because it’s faster, more efficient and less work,” senior author David Whitney explained in a statement from the university.

It seems like the 15-second rule helps us not lose our minds by keeping a steady flow of information, but it could be a bit dangerous if someone, such as a surgeon, needs to see things with extreme precision.

And now we are definitely feeling a bit anxious about our upcoming heart/spleen/gallbladder replacement. … Where’s that link to the ASMR video?

Goffin’s cockatoo? More like golfin’ cockatoo

Can birds play golf? Of course not; it’s ridiculous. Humans can barely play golf, and we invented the sport. Anyway, moving on to “Brian retraction injury after elective aneurysm clipping.”

Hang on, we’re now hearing that a group of researchers, as part of a large international project comparing children’s innovation and problem-solving skills with those of cockatoos, have in fact taught a group of Goffin’s cockatoos how to play golf. Huh. What an oddly specific project. All right, fine, I guess we’ll go with the golf-playing birds.

Golf may seem very simple at its core. It is, essentially, whacking a ball with a stick. But the Scots who invented the game were undertaking a complex project involving combined usage of multiple tools, and until now, only primates were thought to be capable of utilizing compound tools to play games such as golf.

For this latest research, published in Scientific Reports, our intrepid birds were given a rudimentary form of golf to play (featuring a stick, a ball, and a closed box to get the ball through). Putting the ball through the hole gave the bird a reward. Not every cockatoo was able to hole out, but three did, with each inventing a unique way to manipulate the stick to hit the ball.

As entertaining as it would be to simply teach some birds how to play golf, we do loop back around to medical relevance. While children are perfectly capable of using tools, young children in particular are actually quite bad at using tools to solve novel solutions. Present a 5-year-old with a stick, a ball, and a hole, and that child might not figure out what the cockatoos did. The research really does give insight into the psychology behind the development of complex tools and technology by our ancient ancestors, according to the researchers.

We’re not entirely convinced this isn’t an elaborate ploy to get a bird out onto the PGA Tour. The LOTME staff can see the future headline already: “Painted bunting wins Valspar Championship in epic playoff.”

Work out now, sweat never

Okay, show of hands: Who’s familiar with “Name that tune?” The TV game show got a reboot last year, but some of us are old enough to remember the 1970s version hosted by national treasure Tom Kennedy.

The contestants try to identify a song as quickly as possible, claiming that they “can name that tune in five notes.” Or four notes, or three. Well, welcome to “Name that exercise study.”

Senior author Masatoshi Nakamura, PhD, and associates gathered together 39 students from Niigata (Japan) University of Health and Welfare and had them perform one isometric, concentric, or eccentric bicep curl with a dumbbell for 3 seconds a day at maximum effort for 5 days a week, over 4 weeks. And yes, we did say 3 seconds.

“Lifting the weight sees the bicep in concentric contraction, lowering the weight sees it in eccentric contraction, while holding the weight parallel to the ground is isometric,” they explained in a statement on Eurekalert.

The three exercise groups were compared with a group that did no exercise, and after 4 weeks of rigorous but brief science, the group doing eccentric contractions had the best results, as their overall muscle strength increased by 11.5%. After a total of just 60 seconds of exercise in 4 weeks. That’s 60 seconds. In 4 weeks.

Big news, but maybe we can do better. “Tom, we can do that exercise in 2 seconds.”

And one! And two! Whoa, feel the burn.

Tingling over anxiety

Apparently there are two kinds of people in this world. Those who love ASMR and those who just don’t get it.

ASMR, for those who don’t know, is the autonomous sensory meridian response. An online community has surfaced, with video creators making tapping sounds, whispering, or brushing mannequin hair to elicit “a pleasant tingling sensation originating from the scalp and neck which can spread to the rest of the body” from viewers, Charlotte M. Eid and associates said in PLOS One.

The people who are into these types of videos are more likely to have higher levels of neuroticism than those who aren’t, which gives ASMR the potential to be a nontraditional form of treatment for anxiety and/or neuroticism, they suggested.

The research involved a group of 64 volunteers who watched an ASMR video meant to trigger the tingles and then completed questionnaires to evaluate their levels of neuroticism, trait anxiety, and state anxiety, said Ms. Eid and associates of Northumbria University in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England.

The people who had a history of producing tingles from ASMR videos in the past had higher levels of anxiety, compared with those who didn’t. Those who responded to triggers also received some benefit from the video in the study, reporting lower levels of neuroticism and anxiety after watching, the investigators found.

Although people who didn’t have a history of tingles didn’t feel any reduction in anxiety after the video, that didn’t stop the people who weren’t familiar with the genre from catching tingles.

So if you find yourself a little high strung or anxious, or if you can’t sleep, consider watching a person pretending to give you a makeover or using fingernails to tap on books for some relaxation. Don’t knock it until you try it!

Living in the past? Not so far-fetched

It’s usually an insult when people tell us to stop living in the past, but the joke’s on them because we really do live in the past. By 15 seconds, to be exact, according to researchers from the University of California, Berkeley.

But wait, did you just read that last sentence 15 seconds ago, even though it feels like real time? Did we just type these words now, or 15 seconds ago?

Think of your brain as a web page you’re constantly refreshing. We are constantly seeing new pictures, images, and colors, and your brain is responsible for keeping everything in chronological order. This new research suggests that our brains show us images from 15 seconds prior. Is your mind blown yet?

“One could say our brain is procrastinating. It’s too much work to constantly update images, so it sticks to the past because the past is a good predictor of the present. We recycle information from the past because it’s faster, more efficient and less work,” senior author David Whitney explained in a statement from the university.

It seems like the 15-second rule helps us not lose our minds by keeping a steady flow of information, but it could be a bit dangerous if someone, such as a surgeon, needs to see things with extreme precision.

And now we are definitely feeling a bit anxious about our upcoming heart/spleen/gallbladder replacement. … Where’s that link to the ASMR video?

Substantial numbers of U.S. youth report vaping cannabis

Adolescents and young adults who use e-cigarettes reported vaping cannabis, according to selected data from the national Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study.

Ruoyan Sun, PhD, an assistant professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and colleagues examined results of PATH’s wave5 survey conducted from December 2018 to November 2019. PATH is a National Institutes of Health–Food and Drug Administration collaboration begun in 2013.

Their analysis, published online Feb. 7, 2022, in JAMA Pediatrics, evaluated the frequency of cannabis vaping across several age groups: 164 respondents ages 12-14; 919 participants ages 15-17; and 3,038 participants ages 18-24. Respondents included for analysis reported electronic nicotine product consumption in the past 30 days. In response to the question “When you have used an electronic product, how often were you using it to smoke marijuana, marijuana concentrates, marijuana waxes, THC, or hash oils?” 35.0% (95% confidence interval, 29.3%-41.2%) of current e-smokers aged 12-14 years said they had done so, as did 51.3% (95% CI, 47.7%-54.9%) of those aged 15-17 years and 54.6% (95% CI, 52.5%-56.7%) of young adults aged 18-24.

The prevalence of those who reported vaping cannabis every time they vaped was 3.1% (95% CI, 1.3%-6.9%) of youths aged 12-14 years, 6.7% (95% CI, 5.3%-8.6%) of youths aged 15-17 years, and 10.3% (95% CI, 9.0%-11.6%) of young adults aged 18-24.

Among children ages 12-14, 65% said they never vaped cannabis, while 48.7% and 45.4%, respectively, in the two older groups said they did.

“This is a very important finding and it mirrors what some of us have already seen in practice,” said pediatric pulmonologist S. Christy Sadreameli, MD, MHS, an assistant professor of pediatrics at John Hopkins University, Baltimore. “It is important for pediatricians to realize that dual use of cannabis and nicotine vaping, and exclusive use of cannabis vaping, are not uncommon. It informs how we ask questions and how we counsel our patients.” Dr. Sadreameli was not involved in the PATH study.

Overall, the survey participants were 56% male, with 24% of respondents identifying as Hispanic, 8% as non-Hispanic Black, 58% as non-Hispanic White, and 10% as of other race/ethnicity. The weighted proportion of current e-cigarette use was 3.0% (95% CI, 2.6%-3.4%) in youths ages 12-14 years, 14.4% (95% CI, 13.5%-15.3%) in those 15-17 years, and 26.2% (95% CI, 25.3%-27.1%) in young adults.

Other recent national surveys such as the National Institute on Drug Abuses’s Monitoring the Future are reporting a growing prevalence of youth cannabis vaping, Dr. Sun said. For example, the prevalence of cannabis vaping in the past 12-month period among grade 12 students grew from 9.5% in 2017 to 22.1% in 2020. Vaping cannabis was more prevalent among Hispanic teens than other ethnicities.

Vaping devices such as e-cigarettes, vaping pens, e-cigars, and e-hookahs can be used to inhale multiple substances, including nicotine, cannabis, and opium, Dr. Sun noted in an interview. “So in addition to asking about the behavior of vaping itself, pediatricians could pay more attention to what is being vaped in these devices.”

According to Dr. Sadreameli, vaping more than one substance at a time could potentially work synergistically to cause more harm, compared with one product alone. “The other aspect to consider is that vaping multiple types of products may increase the chance of harm from other components of the mixture,” she said. For instance, a lot of the e-cigarette or vaping use-associated lung injury (EVALI) cases have been linked to vitamin E acetate, which was found in certain cannabis formulations. “Anecdotally, most EVALI patients I’ve met seemed to report use of multiple products, including cannabis-containing and nicotine-containing products.”

Dr. Sadreameli added that some cannabis vapers will have other issues. “For example, there is a severe vomiting syndrome I’ve seen, which is induced by cannabis and improved by cessation from cannabis,” she said. “It is important for pediatricians to ask the right questions of their patients in order to better understand what they may be experiencing, provide counseling, and to help them.”

A related issue is cessation, she said. “For those working to achieve cessation from nicotine-based products, sometimes nicotine replacement therapies are helpful. However, cessation from cannabis-containing products is going to look different.”

Although the study did not yield information on the prevalence simultaneous nicotine/cannabis vaping, the authors suggested that some vapers may be combining substances. Previous studies may have modestly overestimated the prevalence of nicotine vaping given their finding that some current e-cigarette users reported vaping cannabis every time they vaped and may be vaping cannabis exclusively. “However, if some current users vaped nicotine and cannabis simultaneously, then overestimation of nicotine vaping would be smaller,” they wrote.

Future surveys on this area should contain detailed questions on nicotine and cannabis vaping, including the substance being vaped and the frequency and intensity of use, Dr. Sun said. “In addition, these surveys could examine some other substances that are being vaped, such as opium and cocaine.”

The PATH study is supported by the NIH, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Department of Health & Human Services, and the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products. The authors and Dr. Sadreameli had no competing interests to disclose.

Adolescents and young adults who use e-cigarettes reported vaping cannabis, according to selected data from the national Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study.

Ruoyan Sun, PhD, an assistant professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and colleagues examined results of PATH’s wave5 survey conducted from December 2018 to November 2019. PATH is a National Institutes of Health–Food and Drug Administration collaboration begun in 2013.

Their analysis, published online Feb. 7, 2022, in JAMA Pediatrics, evaluated the frequency of cannabis vaping across several age groups: 164 respondents ages 12-14; 919 participants ages 15-17; and 3,038 participants ages 18-24. Respondents included for analysis reported electronic nicotine product consumption in the past 30 days. In response to the question “When you have used an electronic product, how often were you using it to smoke marijuana, marijuana concentrates, marijuana waxes, THC, or hash oils?” 35.0% (95% confidence interval, 29.3%-41.2%) of current e-smokers aged 12-14 years said they had done so, as did 51.3% (95% CI, 47.7%-54.9%) of those aged 15-17 years and 54.6% (95% CI, 52.5%-56.7%) of young adults aged 18-24.

The prevalence of those who reported vaping cannabis every time they vaped was 3.1% (95% CI, 1.3%-6.9%) of youths aged 12-14 years, 6.7% (95% CI, 5.3%-8.6%) of youths aged 15-17 years, and 10.3% (95% CI, 9.0%-11.6%) of young adults aged 18-24.

Among children ages 12-14, 65% said they never vaped cannabis, while 48.7% and 45.4%, respectively, in the two older groups said they did.

“This is a very important finding and it mirrors what some of us have already seen in practice,” said pediatric pulmonologist S. Christy Sadreameli, MD, MHS, an assistant professor of pediatrics at John Hopkins University, Baltimore. “It is important for pediatricians to realize that dual use of cannabis and nicotine vaping, and exclusive use of cannabis vaping, are not uncommon. It informs how we ask questions and how we counsel our patients.” Dr. Sadreameli was not involved in the PATH study.

Overall, the survey participants were 56% male, with 24% of respondents identifying as Hispanic, 8% as non-Hispanic Black, 58% as non-Hispanic White, and 10% as of other race/ethnicity. The weighted proportion of current e-cigarette use was 3.0% (95% CI, 2.6%-3.4%) in youths ages 12-14 years, 14.4% (95% CI, 13.5%-15.3%) in those 15-17 years, and 26.2% (95% CI, 25.3%-27.1%) in young adults.

Other recent national surveys such as the National Institute on Drug Abuses’s Monitoring the Future are reporting a growing prevalence of youth cannabis vaping, Dr. Sun said. For example, the prevalence of cannabis vaping in the past 12-month period among grade 12 students grew from 9.5% in 2017 to 22.1% in 2020. Vaping cannabis was more prevalent among Hispanic teens than other ethnicities.

Vaping devices such as e-cigarettes, vaping pens, e-cigars, and e-hookahs can be used to inhale multiple substances, including nicotine, cannabis, and opium, Dr. Sun noted in an interview. “So in addition to asking about the behavior of vaping itself, pediatricians could pay more attention to what is being vaped in these devices.”

According to Dr. Sadreameli, vaping more than one substance at a time could potentially work synergistically to cause more harm, compared with one product alone. “The other aspect to consider is that vaping multiple types of products may increase the chance of harm from other components of the mixture,” she said. For instance, a lot of the e-cigarette or vaping use-associated lung injury (EVALI) cases have been linked to vitamin E acetate, which was found in certain cannabis formulations. “Anecdotally, most EVALI patients I’ve met seemed to report use of multiple products, including cannabis-containing and nicotine-containing products.”

Dr. Sadreameli added that some cannabis vapers will have other issues. “For example, there is a severe vomiting syndrome I’ve seen, which is induced by cannabis and improved by cessation from cannabis,” she said. “It is important for pediatricians to ask the right questions of their patients in order to better understand what they may be experiencing, provide counseling, and to help them.”

A related issue is cessation, she said. “For those working to achieve cessation from nicotine-based products, sometimes nicotine replacement therapies are helpful. However, cessation from cannabis-containing products is going to look different.”

Although the study did not yield information on the prevalence simultaneous nicotine/cannabis vaping, the authors suggested that some vapers may be combining substances. Previous studies may have modestly overestimated the prevalence of nicotine vaping given their finding that some current e-cigarette users reported vaping cannabis every time they vaped and may be vaping cannabis exclusively. “However, if some current users vaped nicotine and cannabis simultaneously, then overestimation of nicotine vaping would be smaller,” they wrote.

Future surveys on this area should contain detailed questions on nicotine and cannabis vaping, including the substance being vaped and the frequency and intensity of use, Dr. Sun said. “In addition, these surveys could examine some other substances that are being vaped, such as opium and cocaine.”

The PATH study is supported by the NIH, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Department of Health & Human Services, and the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products. The authors and Dr. Sadreameli had no competing interests to disclose.

Adolescents and young adults who use e-cigarettes reported vaping cannabis, according to selected data from the national Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study.

Ruoyan Sun, PhD, an assistant professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and colleagues examined results of PATH’s wave5 survey conducted from December 2018 to November 2019. PATH is a National Institutes of Health–Food and Drug Administration collaboration begun in 2013.

Their analysis, published online Feb. 7, 2022, in JAMA Pediatrics, evaluated the frequency of cannabis vaping across several age groups: 164 respondents ages 12-14; 919 participants ages 15-17; and 3,038 participants ages 18-24. Respondents included for analysis reported electronic nicotine product consumption in the past 30 days. In response to the question “When you have used an electronic product, how often were you using it to smoke marijuana, marijuana concentrates, marijuana waxes, THC, or hash oils?” 35.0% (95% confidence interval, 29.3%-41.2%) of current e-smokers aged 12-14 years said they had done so, as did 51.3% (95% CI, 47.7%-54.9%) of those aged 15-17 years and 54.6% (95% CI, 52.5%-56.7%) of young adults aged 18-24.

The prevalence of those who reported vaping cannabis every time they vaped was 3.1% (95% CI, 1.3%-6.9%) of youths aged 12-14 years, 6.7% (95% CI, 5.3%-8.6%) of youths aged 15-17 years, and 10.3% (95% CI, 9.0%-11.6%) of young adults aged 18-24.

Among children ages 12-14, 65% said they never vaped cannabis, while 48.7% and 45.4%, respectively, in the two older groups said they did.

“This is a very important finding and it mirrors what some of us have already seen in practice,” said pediatric pulmonologist S. Christy Sadreameli, MD, MHS, an assistant professor of pediatrics at John Hopkins University, Baltimore. “It is important for pediatricians to realize that dual use of cannabis and nicotine vaping, and exclusive use of cannabis vaping, are not uncommon. It informs how we ask questions and how we counsel our patients.” Dr. Sadreameli was not involved in the PATH study.

Overall, the survey participants were 56% male, with 24% of respondents identifying as Hispanic, 8% as non-Hispanic Black, 58% as non-Hispanic White, and 10% as of other race/ethnicity. The weighted proportion of current e-cigarette use was 3.0% (95% CI, 2.6%-3.4%) in youths ages 12-14 years, 14.4% (95% CI, 13.5%-15.3%) in those 15-17 years, and 26.2% (95% CI, 25.3%-27.1%) in young adults.

Other recent national surveys such as the National Institute on Drug Abuses’s Monitoring the Future are reporting a growing prevalence of youth cannabis vaping, Dr. Sun said. For example, the prevalence of cannabis vaping in the past 12-month period among grade 12 students grew from 9.5% in 2017 to 22.1% in 2020. Vaping cannabis was more prevalent among Hispanic teens than other ethnicities.

Vaping devices such as e-cigarettes, vaping pens, e-cigars, and e-hookahs can be used to inhale multiple substances, including nicotine, cannabis, and opium, Dr. Sun noted in an interview. “So in addition to asking about the behavior of vaping itself, pediatricians could pay more attention to what is being vaped in these devices.”

According to Dr. Sadreameli, vaping more than one substance at a time could potentially work synergistically to cause more harm, compared with one product alone. “The other aspect to consider is that vaping multiple types of products may increase the chance of harm from other components of the mixture,” she said. For instance, a lot of the e-cigarette or vaping use-associated lung injury (EVALI) cases have been linked to vitamin E acetate, which was found in certain cannabis formulations. “Anecdotally, most EVALI patients I’ve met seemed to report use of multiple products, including cannabis-containing and nicotine-containing products.”

Dr. Sadreameli added that some cannabis vapers will have other issues. “For example, there is a severe vomiting syndrome I’ve seen, which is induced by cannabis and improved by cessation from cannabis,” she said. “It is important for pediatricians to ask the right questions of their patients in order to better understand what they may be experiencing, provide counseling, and to help them.”

A related issue is cessation, she said. “For those working to achieve cessation from nicotine-based products, sometimes nicotine replacement therapies are helpful. However, cessation from cannabis-containing products is going to look different.”

Although the study did not yield information on the prevalence simultaneous nicotine/cannabis vaping, the authors suggested that some vapers may be combining substances. Previous studies may have modestly overestimated the prevalence of nicotine vaping given their finding that some current e-cigarette users reported vaping cannabis every time they vaped and may be vaping cannabis exclusively. “However, if some current users vaped nicotine and cannabis simultaneously, then overestimation of nicotine vaping would be smaller,” they wrote.

Future surveys on this area should contain detailed questions on nicotine and cannabis vaping, including the substance being vaped and the frequency and intensity of use, Dr. Sun said. “In addition, these surveys could examine some other substances that are being vaped, such as opium and cocaine.”

The PATH study is supported by the NIH, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Department of Health & Human Services, and the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products. The authors and Dr. Sadreameli had no competing interests to disclose.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Promising leads to crack long COVID discovered

It’s a story of promise at a time of urgent need.

They proposed many theories on what might be driving long COVID. A role for a virus “cryptic reservoir” that could reactivate at any time, “viral remnants” that trigger chronic inflammation, and action by “autoimmune antibodies” that cause ongoing symptoms are possibilities.

In fact, it’s likely that research will show long COVID is a condition with more than one cause, the experts said during a recent webinar.

People might experience post-infection problems, including organ damage that takes time to heal after initial COVID-19 illness. Or they may be living with post-immune factors, including ongoing immune system responses triggered by autoantibodies.

Determining the cause or causes of long COVID is essential for treatment. For example, if one person’s symptoms persist because of an overactive immune system, “we need to provide immunosuppressant therapies,” Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, said. “But we don’t want to give that to someone who has a persistent virus reservoir,” meaning remnants of the virus remain in their bodies.

Interestingly, a study preprint, which has not been peer reviewed, found dogs were accurate more than half the time in sniffing out long COVID, said Dr. Iwasaki, professor of immunobiology and developmental biology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The dogs were tasked with identifying 45 people with long COVID versus 188 people without it. The findings suggest the presence of a unique chemical in the sweat of people with long COVID that could someday lead to a diagnostic test.

Viral persistence possible

If one of the main theories holds, it could be that the coronavirus somehow remains in the body in some form for some people after COVID-19.

Mady Hornig, MD, agreed this is a possibility that needs to be investigated further.

“A weakened immune response to an infection may mean that you have cryptic reservoirs of virus that are continuing to cause symptoms,” she said during the briefing. Dr. Hornig is a doctor-scientist specializing in epidemiology at Columbia University, New York.

“That may explain why some patients with long COVID feel better after vaccination,” because the vaccine creates a strong antibody response to fight COVID-19, Dr. Iwasaki said.

Researchers are unearthing additional potential factors contributing to long COVID.

Viral persistence could also reactivate other dormant viruses in the body, such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), said Lawrence Purpura, MD, MPH, an infectious disease specialist at New York Presbyterian/Columbia University. Reactivation of Epstein-Barr is one of four identifying signs of long COVID revealed in a Jan. 25 study published in the journal Cell.

Immune overactivation also possible?

For other people with long COVID, it’s not the virus sticking around but the body’s reaction that’s the issue.

Investigators suggest autoimmunity plays a role, and they point to the presence of autoantibodies, for example.

When these autoantibodies persist, they can cause tissue and organ damage over time.

Other investigators are proposing “immune exhaustion” in long COVID because of similarities to chronic fatigue syndrome, Dr. Hornig said.

“It should be ‘all hands on deck’ for research into long COVID,” she said. “The number of disabled individuals who will likely qualify for a diagnosis of [chronic fatigue syndrome] is growing by the second.”

Forging ahead on future research

It’s clear there is more work to do. There are investigators working on banking tissue samples from people with long COVID to learn more, for example.

Also, finding a biomarker unique to long COVID could vastly improve the precision of diagnosing long COVID, especially if the dog sniffing option does not pan out.

Of the thousands of biomarker possibilities, Dr. Hornig said, “maybe that’s one or two that ultimately make a real impact on patient care. So it’s going to be critical to find those quickly, translate them, and make them available.”

In the meantime, some answers might come from a large study sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. The NIH is funding the “Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery” project using $470 million from the American Rescue Plan. Investigators at NYU Langone Health are leading the effort and plan to share the wealth by funding more than 100 researchers at more than 30 institutions to create a “metacohort” to study long COVID. More information is available at recovercovid.org.

“Fortunately, through the global research effort, we are now really starting to expand our understanding of how long COVID manifests, how common it is, and what the underlying mechanisms may be,” Dr. Purpura said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

It’s a story of promise at a time of urgent need.

They proposed many theories on what might be driving long COVID. A role for a virus “cryptic reservoir” that could reactivate at any time, “viral remnants” that trigger chronic inflammation, and action by “autoimmune antibodies” that cause ongoing symptoms are possibilities.

In fact, it’s likely that research will show long COVID is a condition with more than one cause, the experts said during a recent webinar.

People might experience post-infection problems, including organ damage that takes time to heal after initial COVID-19 illness. Or they may be living with post-immune factors, including ongoing immune system responses triggered by autoantibodies.

Determining the cause or causes of long COVID is essential for treatment. For example, if one person’s symptoms persist because of an overactive immune system, “we need to provide immunosuppressant therapies,” Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, said. “But we don’t want to give that to someone who has a persistent virus reservoir,” meaning remnants of the virus remain in their bodies.

Interestingly, a study preprint, which has not been peer reviewed, found dogs were accurate more than half the time in sniffing out long COVID, said Dr. Iwasaki, professor of immunobiology and developmental biology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The dogs were tasked with identifying 45 people with long COVID versus 188 people without it. The findings suggest the presence of a unique chemical in the sweat of people with long COVID that could someday lead to a diagnostic test.

Viral persistence possible

If one of the main theories holds, it could be that the coronavirus somehow remains in the body in some form for some people after COVID-19.

Mady Hornig, MD, agreed this is a possibility that needs to be investigated further.

“A weakened immune response to an infection may mean that you have cryptic reservoirs of virus that are continuing to cause symptoms,” she said during the briefing. Dr. Hornig is a doctor-scientist specializing in epidemiology at Columbia University, New York.

“That may explain why some patients with long COVID feel better after vaccination,” because the vaccine creates a strong antibody response to fight COVID-19, Dr. Iwasaki said.

Researchers are unearthing additional potential factors contributing to long COVID.

Viral persistence could also reactivate other dormant viruses in the body, such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), said Lawrence Purpura, MD, MPH, an infectious disease specialist at New York Presbyterian/Columbia University. Reactivation of Epstein-Barr is one of four identifying signs of long COVID revealed in a Jan. 25 study published in the journal Cell.

Immune overactivation also possible?

For other people with long COVID, it’s not the virus sticking around but the body’s reaction that’s the issue.

Investigators suggest autoimmunity plays a role, and they point to the presence of autoantibodies, for example.

When these autoantibodies persist, they can cause tissue and organ damage over time.

Other investigators are proposing “immune exhaustion” in long COVID because of similarities to chronic fatigue syndrome, Dr. Hornig said.

“It should be ‘all hands on deck’ for research into long COVID,” she said. “The number of disabled individuals who will likely qualify for a diagnosis of [chronic fatigue syndrome] is growing by the second.”

Forging ahead on future research

It’s clear there is more work to do. There are investigators working on banking tissue samples from people with long COVID to learn more, for example.

Also, finding a biomarker unique to long COVID could vastly improve the precision of diagnosing long COVID, especially if the dog sniffing option does not pan out.

Of the thousands of biomarker possibilities, Dr. Hornig said, “maybe that’s one or two that ultimately make a real impact on patient care. So it’s going to be critical to find those quickly, translate them, and make them available.”

In the meantime, some answers might come from a large study sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. The NIH is funding the “Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery” project using $470 million from the American Rescue Plan. Investigators at NYU Langone Health are leading the effort and plan to share the wealth by funding more than 100 researchers at more than 30 institutions to create a “metacohort” to study long COVID. More information is available at recovercovid.org.

“Fortunately, through the global research effort, we are now really starting to expand our understanding of how long COVID manifests, how common it is, and what the underlying mechanisms may be,” Dr. Purpura said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

It’s a story of promise at a time of urgent need.

They proposed many theories on what might be driving long COVID. A role for a virus “cryptic reservoir” that could reactivate at any time, “viral remnants” that trigger chronic inflammation, and action by “autoimmune antibodies” that cause ongoing symptoms are possibilities.

In fact, it’s likely that research will show long COVID is a condition with more than one cause, the experts said during a recent webinar.

People might experience post-infection problems, including organ damage that takes time to heal after initial COVID-19 illness. Or they may be living with post-immune factors, including ongoing immune system responses triggered by autoantibodies.

Determining the cause or causes of long COVID is essential for treatment. For example, if one person’s symptoms persist because of an overactive immune system, “we need to provide immunosuppressant therapies,” Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, said. “But we don’t want to give that to someone who has a persistent virus reservoir,” meaning remnants of the virus remain in their bodies.

Interestingly, a study preprint, which has not been peer reviewed, found dogs were accurate more than half the time in sniffing out long COVID, said Dr. Iwasaki, professor of immunobiology and developmental biology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The dogs were tasked with identifying 45 people with long COVID versus 188 people without it. The findings suggest the presence of a unique chemical in the sweat of people with long COVID that could someday lead to a diagnostic test.

Viral persistence possible

If one of the main theories holds, it could be that the coronavirus somehow remains in the body in some form for some people after COVID-19.

Mady Hornig, MD, agreed this is a possibility that needs to be investigated further.

“A weakened immune response to an infection may mean that you have cryptic reservoirs of virus that are continuing to cause symptoms,” she said during the briefing. Dr. Hornig is a doctor-scientist specializing in epidemiology at Columbia University, New York.

“That may explain why some patients with long COVID feel better after vaccination,” because the vaccine creates a strong antibody response to fight COVID-19, Dr. Iwasaki said.

Researchers are unearthing additional potential factors contributing to long COVID.

Viral persistence could also reactivate other dormant viruses in the body, such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), said Lawrence Purpura, MD, MPH, an infectious disease specialist at New York Presbyterian/Columbia University. Reactivation of Epstein-Barr is one of four identifying signs of long COVID revealed in a Jan. 25 study published in the journal Cell.

Immune overactivation also possible?

For other people with long COVID, it’s not the virus sticking around but the body’s reaction that’s the issue.

Investigators suggest autoimmunity plays a role, and they point to the presence of autoantibodies, for example.

When these autoantibodies persist, they can cause tissue and organ damage over time.

Other investigators are proposing “immune exhaustion” in long COVID because of similarities to chronic fatigue syndrome, Dr. Hornig said.

“It should be ‘all hands on deck’ for research into long COVID,” she said. “The number of disabled individuals who will likely qualify for a diagnosis of [chronic fatigue syndrome] is growing by the second.”

Forging ahead on future research

It’s clear there is more work to do. There are investigators working on banking tissue samples from people with long COVID to learn more, for example.

Also, finding a biomarker unique to long COVID could vastly improve the precision of diagnosing long COVID, especially if the dog sniffing option does not pan out.

Of the thousands of biomarker possibilities, Dr. Hornig said, “maybe that’s one or two that ultimately make a real impact on patient care. So it’s going to be critical to find those quickly, translate them, and make them available.”

In the meantime, some answers might come from a large study sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. The NIH is funding the “Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery” project using $470 million from the American Rescue Plan. Investigators at NYU Langone Health are leading the effort and plan to share the wealth by funding more than 100 researchers at more than 30 institutions to create a “metacohort” to study long COVID. More information is available at recovercovid.org.

“Fortunately, through the global research effort, we are now really starting to expand our understanding of how long COVID manifests, how common it is, and what the underlying mechanisms may be,” Dr. Purpura said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Cystic fibrosis in retreat, but still unbeaten

In 1938, the year that cystic fibrosis (CF) was first described clinically, four of five children born with the disease did not live past their first birthdays.

In 2019, the median age at death for patients enrolled in the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) registry was 32 years, and the predicted life expectancy for patients with CF who were born from 2015 through 2019 was 46 years.

Those numbers reflect the remarkable progress made in the past 4 decades in the care of patients with CF, but also highlight the obstacles ahead, given that the predicted life expectancy for the overall U.S. population in 2019 (pre–COVID-19) was 78.9 years.

Julie Desch, MD, is a CF survivor who has beaten the odds and then some. At age 61, the retired surgical pathologist is a CF patient advocate, speaker, and a board member of the Cystic Fibrosis Research Institute, a not-for-profit organization that funds CF research and offers education, advocacy, and psychosocial support for persons with CF and their families and caregivers.

In an interview, Dr. Desch said that while there has been remarkable progress in her lifetime in the field of CF research and treatment, particularly in the development of drugs that modulate function of the underlying cause of approximately 90% of CF cases, there are still many CF patients who cannot benefit from these therapies.

“There are still 10% of people who don’t make a protein to be modified, so that’s a huge unmet need,” she said.

Genetic disorder

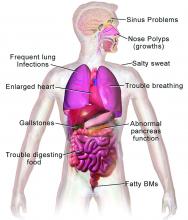

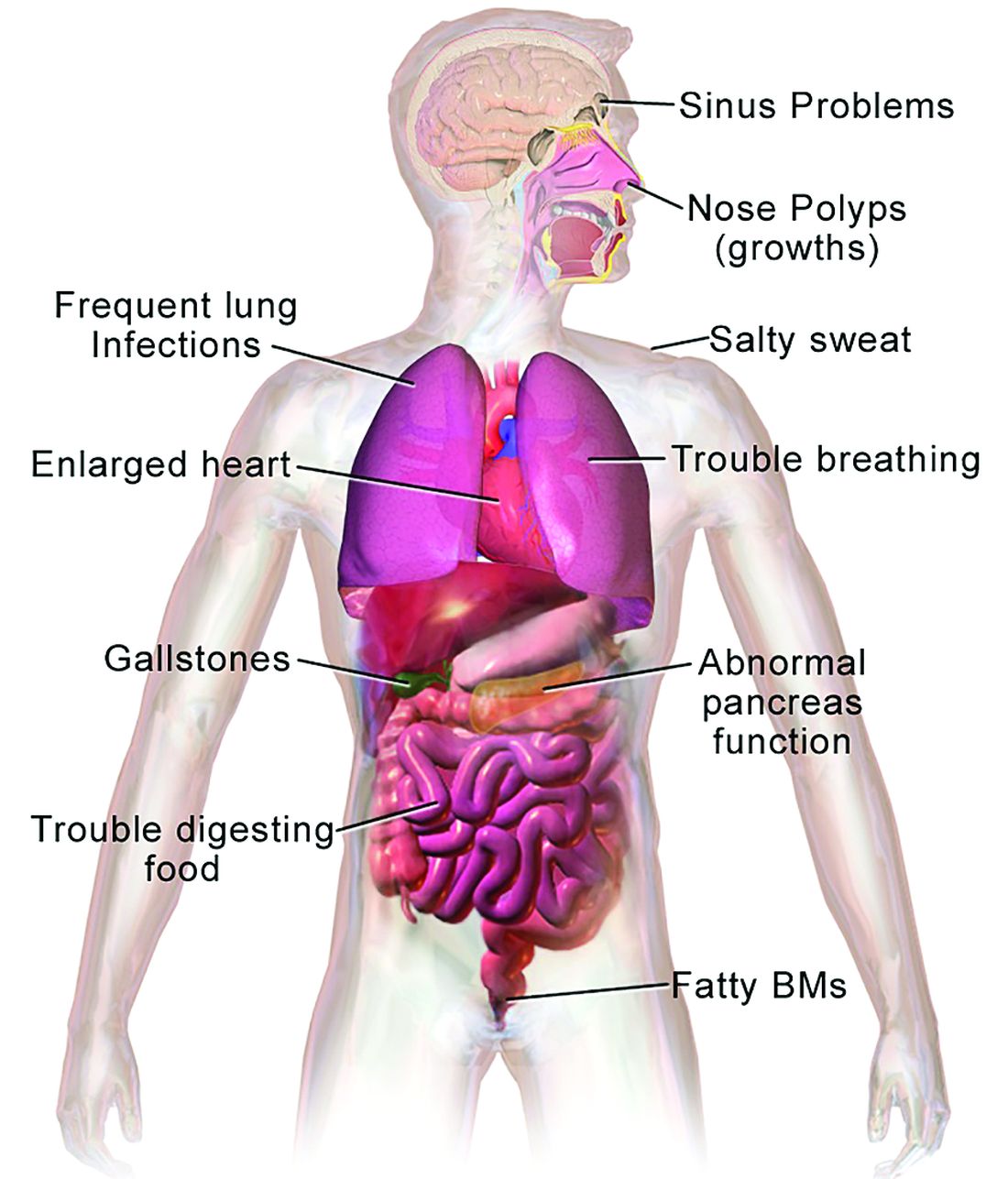

CF is a chronic autosomal recessive disorder with multiorgan and multisystem manifestations. It is caused by mutations in the CFTR gene, which codes for the protein CF transmembrane conductance regulator. CFTR controls transport of chloride ions across cell membranes, specifically the apical membrane of epithelial cells in tissues of the airways, intestinal tract, pancreas, kidneys, sweat glands, and the reproductive system, notably the vas deferens in males.

The F508 deletion (F508del) mutation is the most common, occurring in approximately 70% of persons with CF. It is a class 2-type protein processing mutation, leading to defects in cellular processing, protein stability, and chloride channel gating defects.

The CFTR protein also secretes bicarbonate to regulate the pH of airway surface liquid, and inhibits the epithelial sodium channel, which mediates passive sodium transport across apical membranes of sodium-absorbing epithelial cells in the kidneys, intestine, and airways.

CF typically presents with the buildup in the lungs of abnormally viscous and sticky mucus leading to frequent, severe infections, particularly with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, progressive lung damage and, prior to the development of effective disease management, to premature death. The phenotype often includes malnutrition due to malabsorption, and failure to thrive.

Diagnosis

In all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia, newborns are screened for CF with an assay for immunoreactive trypsinogen (IRT) an indirect marker for pancreatic injury that is elevated in serum in most newborns with CF, but also detected in premature infants or those delivered under stressful circumstances. In some states newborns are tested only for IRT, with a diagnosis confirmed with a sweat chloride test and/or a CFTR mutation panel.

Treatment

There is no cure for CF, but the discovery of the gene in 1989 by Canadian and U.S. investigators has led to life-prolonging therapeutic interventions, specifically the development of CFTR modulators.

CFTR modulators include potentiators such as ivacaftor (Kalydeco), and correctors such as lumacaftor and tezacaftor (available in the combination Orkambi), and most recently in the triple combination of elexacaftor, tezacaftor, and ivacaftor (Trikafta; ETI).

Neil Sweezey, MD, FRCPC, a CF expert at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto, told this news organization that the ideal therapy for CF, genetic correction of the underlying mutations, is still not feasible, but that CFTR modulators are a close second.

“For 90% of patients, the three-drug combination Trikafta has been shown to be quite safe, quite tolerable, and quite remarkably beneficial,” he said.

In a study reported at CHEST 2021 by investigators from Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, 32 adults who were started on the triple combination had significantly improved in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), gain in body mass index, decreased sweat chloride and decreased colonization by Pseudomonas species. In addition, patients had significant improvements in blood inflammatory markers.

Christopher H. Goss, MD, FCCP, professor of pulmonary critical care and sleep medicine and professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington in Seattle, agreed that with the availability of the triple combination, “these are extraordinary times. An astounding fact is that most patients have complete resolution of cough, and the exacerbation rates have just plummeted,” he said in an interview.

Some of the reductions in exacerbations may be attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic, he noted, because patients in isolation have less exposure to circulating respiratory viruses.

“But it has been miraculous, and the clinical effect is certainly still more astounding than the effects of ivacaftor, which was the first truly breakthrough drug. Weight goes up, well-being increases, and the population lung function has shifted up to better grade lung function, in the entire population,” he said.

In addition, the need for lung and heart transplantation has sharply declined.

“I had a patient who had decided to forgo transplantation, despite absolutely horrible lung function, and he’s now bowling and leading a very productive life, when before he had been preparing for end of life,” Dr. Goss said.

Dr. Sweezey emphasized that as with all medications, patients being started on the triple combination require close monitoring for potential adverse events that might require dose modification or, for a small number of patients, withdrawal.

Burden of care

CFTR modulators have reduced but not eliminated the need for some patients to have mucolytic therapy, which may include dornase alfa, a recombinant human deoxyribonuclease (DNase) that reduces the viscosity of lung secretions, hypertonic saline inhaled twice daily (for patients 12 and older), mannitol, and physical manipulations to help patients clear mucus. This can include both manual percussion and the use of devices for high-frequency chest wall oscillation.

The complex nature of CF often requires a combination of other therapies to address comorbidities. These therapies may include infection prophylaxis and treatment with antibiotics and antifungals, nutrition support, and therapy for CF-related complications, including gastrointestinal issues, liver diseases, diabetes, and osteopenia that may be related to poor nutrient absorption, chronic inflammation, or other sequelae of CF.

In addition, patients often require frequent CF care center visits – ideally a minimum of every 3 months – which can result in significant loss of work or school time.

“Outcomes for patients in the long run have been absolutely proven to be best if they’re followed in big, established, multidisciplinary well-organized CF centers,” Dr. Sweezey said. “In the United States and Canada if you’re looked after on a regular basis, which means quarterly, every 3 months – whether you need it or not, you really do need it – and if the patients are seen and assessed and checked every 3 months all of their lives, they have small changes caught early, whether it’s an infection you can slap down with medication or a nutrition problem that may be affecting a child’s growth and development.”

“We’re really kind of at a pivotal moment in CF, where we realize things are changing,” said A. Whitney Brown, MD, senior director for clinical affairs at the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, and an adult CF and lung transplant physician in the Inova Advanced Lung Disease Program in Falls Church, Va.

“Patient needs and interest have evolved, because of the pandemic and because of the highly effective modulator therapy, but we want to take great effort to study it in a rigorous way, to make sure that as we are agile and adapt the care model, that we can maintain the same quality outcomes that we have traditionally done,” she said in an interview.

The Lancet Respiratory Medicine Commission on the future of CF care states that models of care “need to consider management approaches (including disease monitoring) to maintain health and delay lung transplantation, while minimizing the burden of care for patients and their families.”

‘A great problem to have’

One of the most significant changes in CF care has been the growing population of CF patients like Dr. Desch who are living well into adulthood, with some approaching Medicare eligibility.

With the advent of triple therapy and CFTR modulators being started earlier in life, lung function can be preserved, damage to other organs can be minimized, and life expectancy for patients with CF will continue to improve.

“We’re anticipating that there may be some needs in the aging CF population that are different than what we have historically had,” Dr. Brown said. “Will there be geriatric providers that need to become experts in CF care? That’s a great problem to have,” she said.

Dr. Goss agreed, noting that CF is steadily shifting from a near uniformly fatal disease to a chronic disorder that in many cases can be managed “with a complex regimen of novel drugs, much like HIV.”

He noted that there are multiple drug interactions with the triple combination, “so it’s really important that people don’t start a CF patient on a drug without consulting a pharmacist, because you can totally inactivate ETI, or augment it dramatically, and we’ve seen both happen.”

Cost and access

All experts interviewed for this article agreed that while the care of patients with CF has improved exponentially over the last few decades, there are still troubling inequities in care.

One of the largest impediments is the cost of care, with the triple combination costing more than $300,000 per year.

“Clearly patients aren’t paying that, but insurance companies are, and that’s causing all kinds of trickle-down effects that definitely affect patients. The patients like myself who are able to have insurance that covers it benefit, but there are so many people that don’t,” Dr. Desch said.

Dr. Sweezey noted that prior to the advent of ETI, patients with CF in Canada had better outcomes and longer life expectancy than did similar patients in the United States because of universal access to care and coordinated services under Canada’s health care system, compared with the highly fragmented and inefficient U.S. system. He added that the wider availability of ETI in the United States vs. Canada may begin to narrow that gap, however.

As noted before, there is a substantial proportion of patients – an estimated 10% – who have CFTR mutations that are not correctable by currently available CFTR modulators, and these patients are at significant risk for irreversible airway complications and lung damage.

In addition, although CF occurs most frequently among people of White ancestry, the disease does not respect distinctions of race or ethnicity.

“It’s not just [Whites] – a lot of people from different racial backgrounds, ethnic backgrounds, are not being diagnosed or are not being diagnosed soon enough to have effective care early enough,” Dr. Desch said.

That statement is supported by the Lancet Respiratory Medicine Commission on the future of cystic fibrosis care, whose members noted in 2019 that “epidemiological studies in the past 2 decades have shown that cystic fibrosis occurs and is more frequent than was previously thought in populations of non-European descent, and the disease is now recognized in many regions of the world.”

The commission members noted that the costs of adequate CF care may be beyond the reach of many patients in developing nations.

Still, if the substantial barriers of cost and access can be overcome, the future will continue to look brighter for patients with CF. As Dr. Sweezey put it: “There are studies that are pushing lower age limits for using these modulators, and as the evidence builds for the efficacy and safety at younger ages, I think all of us are hoping that we’ll end up being able to use either the current or future modulators to actually prevent trouble in CF, rather than trying to come along and fix it after it’s been there.”

Dr. Brown disclosed advisory board activity for Vertex that ended prior to her joining the CF Foundation. Dr. Desch, Dr. Goss, and Dr. Sweezey reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

In 1938, the year that cystic fibrosis (CF) was first described clinically, four of five children born with the disease did not live past their first birthdays.

In 2019, the median age at death for patients enrolled in the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) registry was 32 years, and the predicted life expectancy for patients with CF who were born from 2015 through 2019 was 46 years.

Those numbers reflect the remarkable progress made in the past 4 decades in the care of patients with CF, but also highlight the obstacles ahead, given that the predicted life expectancy for the overall U.S. population in 2019 (pre–COVID-19) was 78.9 years.

Julie Desch, MD, is a CF survivor who has beaten the odds and then some. At age 61, the retired surgical pathologist is a CF patient advocate, speaker, and a board member of the Cystic Fibrosis Research Institute, a not-for-profit organization that funds CF research and offers education, advocacy, and psychosocial support for persons with CF and their families and caregivers.

In an interview, Dr. Desch said that while there has been remarkable progress in her lifetime in the field of CF research and treatment, particularly in the development of drugs that modulate function of the underlying cause of approximately 90% of CF cases, there are still many CF patients who cannot benefit from these therapies.

“There are still 10% of people who don’t make a protein to be modified, so that’s a huge unmet need,” she said.

Genetic disorder

CF is a chronic autosomal recessive disorder with multiorgan and multisystem manifestations. It is caused by mutations in the CFTR gene, which codes for the protein CF transmembrane conductance regulator. CFTR controls transport of chloride ions across cell membranes, specifically the apical membrane of epithelial cells in tissues of the airways, intestinal tract, pancreas, kidneys, sweat glands, and the reproductive system, notably the vas deferens in males.

The F508 deletion (F508del) mutation is the most common, occurring in approximately 70% of persons with CF. It is a class 2-type protein processing mutation, leading to defects in cellular processing, protein stability, and chloride channel gating defects.

The CFTR protein also secretes bicarbonate to regulate the pH of airway surface liquid, and inhibits the epithelial sodium channel, which mediates passive sodium transport across apical membranes of sodium-absorbing epithelial cells in the kidneys, intestine, and airways.

CF typically presents with the buildup in the lungs of abnormally viscous and sticky mucus leading to frequent, severe infections, particularly with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, progressive lung damage and, prior to the development of effective disease management, to premature death. The phenotype often includes malnutrition due to malabsorption, and failure to thrive.

Diagnosis

In all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia, newborns are screened for CF with an assay for immunoreactive trypsinogen (IRT) an indirect marker for pancreatic injury that is elevated in serum in most newborns with CF, but also detected in premature infants or those delivered under stressful circumstances. In some states newborns are tested only for IRT, with a diagnosis confirmed with a sweat chloride test and/or a CFTR mutation panel.

Treatment

There is no cure for CF, but the discovery of the gene in 1989 by Canadian and U.S. investigators has led to life-prolonging therapeutic interventions, specifically the development of CFTR modulators.

CFTR modulators include potentiators such as ivacaftor (Kalydeco), and correctors such as lumacaftor and tezacaftor (available in the combination Orkambi), and most recently in the triple combination of elexacaftor, tezacaftor, and ivacaftor (Trikafta; ETI).

Neil Sweezey, MD, FRCPC, a CF expert at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto, told this news organization that the ideal therapy for CF, genetic correction of the underlying mutations, is still not feasible, but that CFTR modulators are a close second.

“For 90% of patients, the three-drug combination Trikafta has been shown to be quite safe, quite tolerable, and quite remarkably beneficial,” he said.

In a study reported at CHEST 2021 by investigators from Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, 32 adults who were started on the triple combination had significantly improved in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), gain in body mass index, decreased sweat chloride and decreased colonization by Pseudomonas species. In addition, patients had significant improvements in blood inflammatory markers.

Christopher H. Goss, MD, FCCP, professor of pulmonary critical care and sleep medicine and professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington in Seattle, agreed that with the availability of the triple combination, “these are extraordinary times. An astounding fact is that most patients have complete resolution of cough, and the exacerbation rates have just plummeted,” he said in an interview.

Some of the reductions in exacerbations may be attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic, he noted, because patients in isolation have less exposure to circulating respiratory viruses.

“But it has been miraculous, and the clinical effect is certainly still more astounding than the effects of ivacaftor, which was the first truly breakthrough drug. Weight goes up, well-being increases, and the population lung function has shifted up to better grade lung function, in the entire population,” he said.

In addition, the need for lung and heart transplantation has sharply declined.

“I had a patient who had decided to forgo transplantation, despite absolutely horrible lung function, and he’s now bowling and leading a very productive life, when before he had been preparing for end of life,” Dr. Goss said.

Dr. Sweezey emphasized that as with all medications, patients being started on the triple combination require close monitoring for potential adverse events that might require dose modification or, for a small number of patients, withdrawal.

Burden of care

CFTR modulators have reduced but not eliminated the need for some patients to have mucolytic therapy, which may include dornase alfa, a recombinant human deoxyribonuclease (DNase) that reduces the viscosity of lung secretions, hypertonic saline inhaled twice daily (for patients 12 and older), mannitol, and physical manipulations to help patients clear mucus. This can include both manual percussion and the use of devices for high-frequency chest wall oscillation.

The complex nature of CF often requires a combination of other therapies to address comorbidities. These therapies may include infection prophylaxis and treatment with antibiotics and antifungals, nutrition support, and therapy for CF-related complications, including gastrointestinal issues, liver diseases, diabetes, and osteopenia that may be related to poor nutrient absorption, chronic inflammation, or other sequelae of CF.

In addition, patients often require frequent CF care center visits – ideally a minimum of every 3 months – which can result in significant loss of work or school time.

“Outcomes for patients in the long run have been absolutely proven to be best if they’re followed in big, established, multidisciplinary well-organized CF centers,” Dr. Sweezey said. “In the United States and Canada if you’re looked after on a regular basis, which means quarterly, every 3 months – whether you need it or not, you really do need it – and if the patients are seen and assessed and checked every 3 months all of their lives, they have small changes caught early, whether it’s an infection you can slap down with medication or a nutrition problem that may be affecting a child’s growth and development.”

“We’re really kind of at a pivotal moment in CF, where we realize things are changing,” said A. Whitney Brown, MD, senior director for clinical affairs at the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, and an adult CF and lung transplant physician in the Inova Advanced Lung Disease Program in Falls Church, Va.

“Patient needs and interest have evolved, because of the pandemic and because of the highly effective modulator therapy, but we want to take great effort to study it in a rigorous way, to make sure that as we are agile and adapt the care model, that we can maintain the same quality outcomes that we have traditionally done,” she said in an interview.

The Lancet Respiratory Medicine Commission on the future of CF care states that models of care “need to consider management approaches (including disease monitoring) to maintain health and delay lung transplantation, while minimizing the burden of care for patients and their families.”

‘A great problem to have’

One of the most significant changes in CF care has been the growing population of CF patients like Dr. Desch who are living well into adulthood, with some approaching Medicare eligibility.

With the advent of triple therapy and CFTR modulators being started earlier in life, lung function can be preserved, damage to other organs can be minimized, and life expectancy for patients with CF will continue to improve.

“We’re anticipating that there may be some needs in the aging CF population that are different than what we have historically had,” Dr. Brown said. “Will there be geriatric providers that need to become experts in CF care? That’s a great problem to have,” she said.

Dr. Goss agreed, noting that CF is steadily shifting from a near uniformly fatal disease to a chronic disorder that in many cases can be managed “with a complex regimen of novel drugs, much like HIV.”

He noted that there are multiple drug interactions with the triple combination, “so it’s really important that people don’t start a CF patient on a drug without consulting a pharmacist, because you can totally inactivate ETI, or augment it dramatically, and we’ve seen both happen.”

Cost and access

All experts interviewed for this article agreed that while the care of patients with CF has improved exponentially over the last few decades, there are still troubling inequities in care.

One of the largest impediments is the cost of care, with the triple combination costing more than $300,000 per year.

“Clearly patients aren’t paying that, but insurance companies are, and that’s causing all kinds of trickle-down effects that definitely affect patients. The patients like myself who are able to have insurance that covers it benefit, but there are so many people that don’t,” Dr. Desch said.

Dr. Sweezey noted that prior to the advent of ETI, patients with CF in Canada had better outcomes and longer life expectancy than did similar patients in the United States because of universal access to care and coordinated services under Canada’s health care system, compared with the highly fragmented and inefficient U.S. system. He added that the wider availability of ETI in the United States vs. Canada may begin to narrow that gap, however.

As noted before, there is a substantial proportion of patients – an estimated 10% – who have CFTR mutations that are not correctable by currently available CFTR modulators, and these patients are at significant risk for irreversible airway complications and lung damage.

In addition, although CF occurs most frequently among people of White ancestry, the disease does not respect distinctions of race or ethnicity.

“It’s not just [Whites] – a lot of people from different racial backgrounds, ethnic backgrounds, are not being diagnosed or are not being diagnosed soon enough to have effective care early enough,” Dr. Desch said.

That statement is supported by the Lancet Respiratory Medicine Commission on the future of cystic fibrosis care, whose members noted in 2019 that “epidemiological studies in the past 2 decades have shown that cystic fibrosis occurs and is more frequent than was previously thought in populations of non-European descent, and the disease is now recognized in many regions of the world.”

The commission members noted that the costs of adequate CF care may be beyond the reach of many patients in developing nations.

Still, if the substantial barriers of cost and access can be overcome, the future will continue to look brighter for patients with CF. As Dr. Sweezey put it: “There are studies that are pushing lower age limits for using these modulators, and as the evidence builds for the efficacy and safety at younger ages, I think all of us are hoping that we’ll end up being able to use either the current or future modulators to actually prevent trouble in CF, rather than trying to come along and fix it after it’s been there.”

Dr. Brown disclosed advisory board activity for Vertex that ended prior to her joining the CF Foundation. Dr. Desch, Dr. Goss, and Dr. Sweezey reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

In 1938, the year that cystic fibrosis (CF) was first described clinically, four of five children born with the disease did not live past their first birthdays.

In 2019, the median age at death for patients enrolled in the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) registry was 32 years, and the predicted life expectancy for patients with CF who were born from 2015 through 2019 was 46 years.

Those numbers reflect the remarkable progress made in the past 4 decades in the care of patients with CF, but also highlight the obstacles ahead, given that the predicted life expectancy for the overall U.S. population in 2019 (pre–COVID-19) was 78.9 years.