User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Updates in COPD Guidelines and Treatment

Al Wachami N, Guennouni M, Iderdar Y, et al. Estimating the global prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):297. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-17686-9

COPD trends brief. American Lung Association. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://www.lung.org/research/trends-in-lung-disease/copd-trends-brief

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). World Health Organization. March 16, 2023. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd)

Shalabi MS, Aqdi SW, Alfort OA, et al. Effectiveness and safety of bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Commun Med Public Health. 2023;10(8):2955-2959. doi:10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20232392

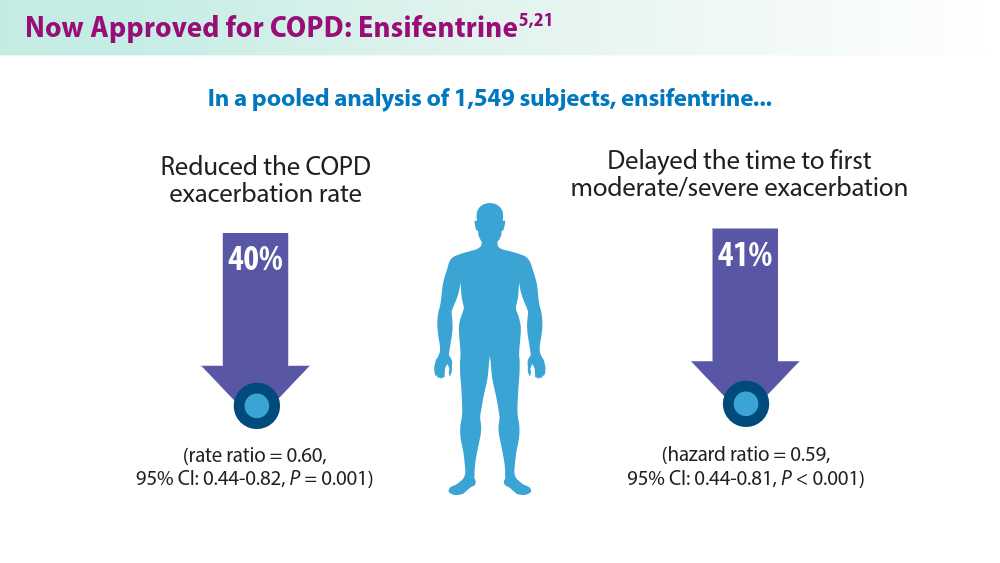

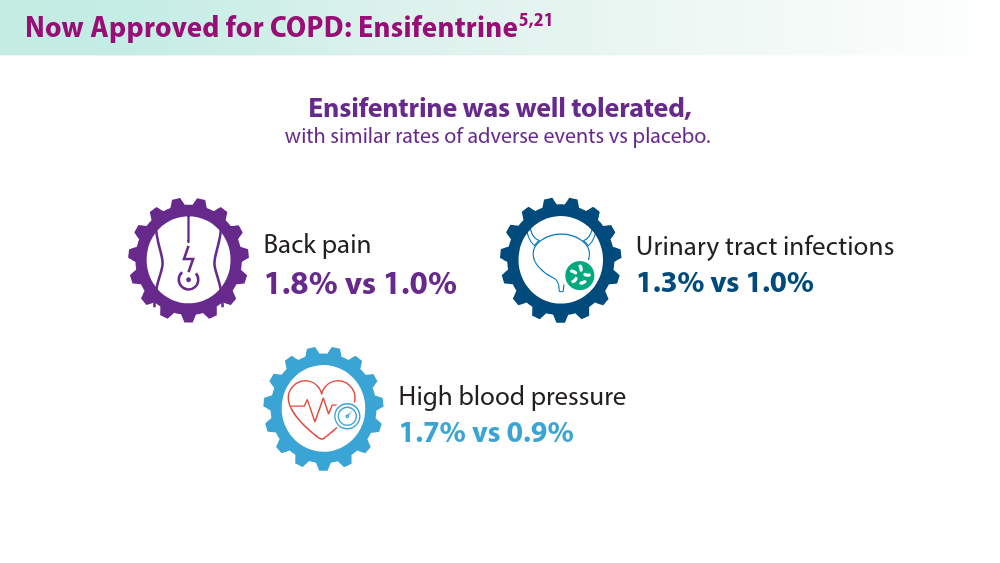

McCormick B. FDA approves ensifentrine for maintenance treatment of adult patients with COPD. AJMC. June 26, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://www.ajmc.com/view/fda-approves-ensifentrine-for-maintenance-treatment-of-adult-patients-with-copd

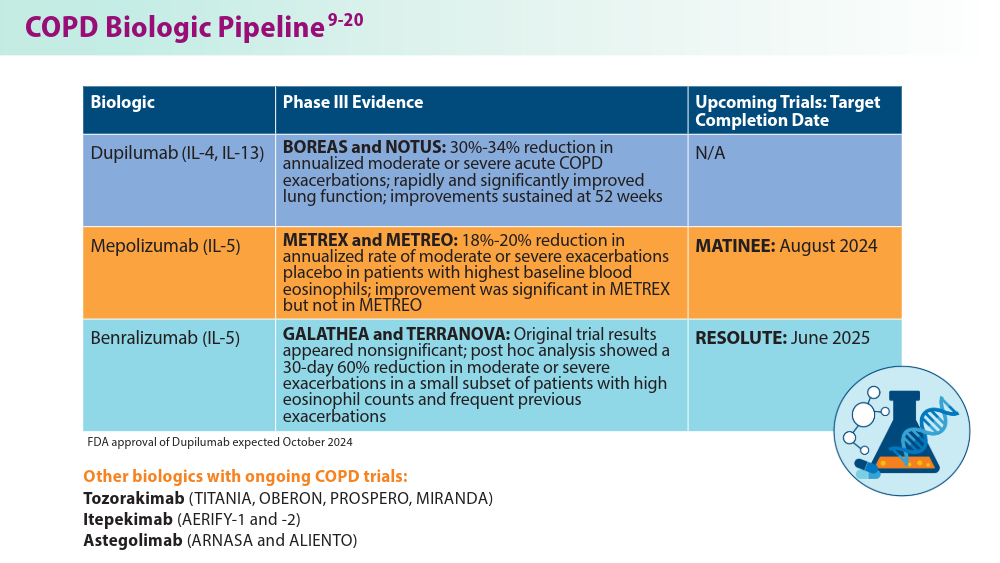

Kersul AL, Cosio BG. Biologics in COPD. Open Resp Arch. 2024;6(2):100306. doi:10.1016/j.opresp.2024.100306

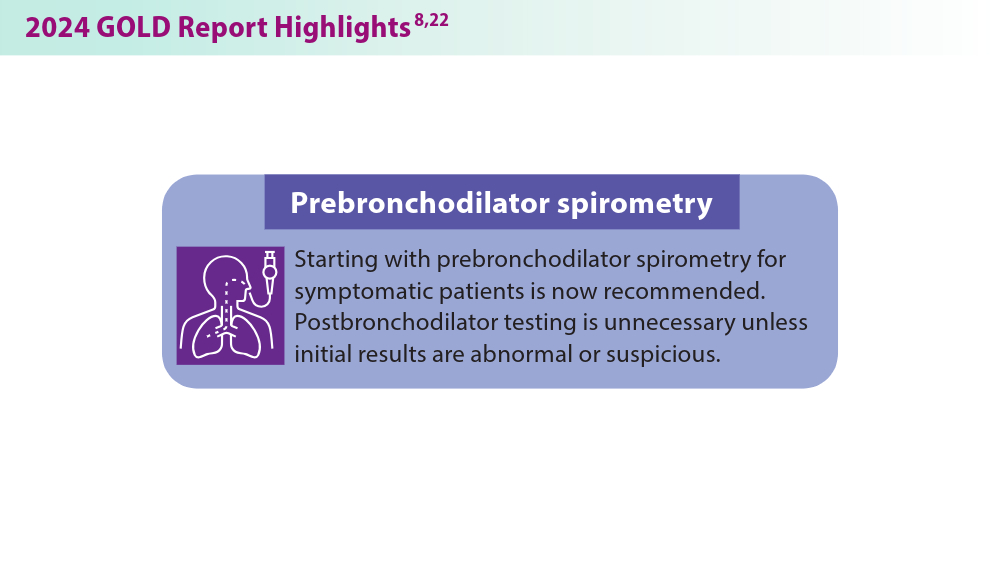

2023 GOLD Report. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2

2024 GOLD Report. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/

Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Dupixent® (dupilumab) late-breaking data from NOTUS confirmatory phase 3 COPD trial presented at ATS and published in the New England Journal of Medicine [press release]. May 20, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://investor.regeneron.com/news-releases/news-release-details/dupixentr-dupilumab-late-breaking-data-notus-confirmatory-phase

Pavord ID, Chapman KR, Bafadhel M, et al. Mepolizumab for eosinophil-associated COPD: analysis of METREX and METREO. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2021;16:1755-1770. doi:10.2147/COPD.S294333

Mepolizumab as add-on treatment in participants with COPD characterized by frequent exacerbations and eosinophil level (MATINEE). Clinicaltrials.gov. Updated August 28, 2023. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04133909

Singh D, Criner GJ, Agustí A, et al. Benralizumab prevents recurrent exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a post hoc analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2023;18:1595-1599. doi:10.2147/COPD.S418944

Efficacy and safety of benralizumab in moderate to very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with a history of frequent exacerbations (RESOLUTE). Clinicaltrials.gov. Updated May 8, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04053634

Efficacy and safety of tozorakimab in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with a history of exacerbations (TITANIA). Clinicaltrials.gov. Updated June 27, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05158387

Efficacy and safety of tozorakimab in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with a history of exacerbations (OBERON). Clinicaltrials.gov. Updated June 21, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05166889

Long-term efficacy and safety of tozorakimab in participants with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with a history of exacerbations (PROSPERO). Clinicaltrials.gov. Updated June 20, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05742802

Efficacy and safety of tozorakimab in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with a history of exacerbations (MIRANDA). Clinicaltrials.gov. Updated June 4, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06040086

Study to assess the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of SAR440340/REGN3500/itepekimab in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (AERIFY-1). ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated June 21, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04701983

Study to assess the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of SAR440340/REGN3500/itepekimab in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (AERIFY-2). ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated May 9, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04751487

ALIENTO and ARNASA: study designs of two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of astegolimab in patients with COPD. Medically. 2023. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://medically.gene.com/global/en/unrestricted/respiratory/ERS-2023/ers-2023-poster-brightling-aliento-and-arnasa-study-des.html

Anzueto A, Barjaktarevic IZ, Siler TM, et al. Ensifentrine, a novel phosphodiesterase 3 and 4 inhibitor for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase III trials (the ENHANCE trials). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;208(4):406-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.202306-0944OC

US Preventive Services Taskforce. Lung cancer: screening. March 9, 2021. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/lung-cancer-screening

Al Wachami N, Guennouni M, Iderdar Y, et al. Estimating the global prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):297. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-17686-9

COPD trends brief. American Lung Association. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://www.lung.org/research/trends-in-lung-disease/copd-trends-brief

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). World Health Organization. March 16, 2023. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd)

Shalabi MS, Aqdi SW, Alfort OA, et al. Effectiveness and safety of bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Commun Med Public Health. 2023;10(8):2955-2959. doi:10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20232392

McCormick B. FDA approves ensifentrine for maintenance treatment of adult patients with COPD. AJMC. June 26, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://www.ajmc.com/view/fda-approves-ensifentrine-for-maintenance-treatment-of-adult-patients-with-copd

Kersul AL, Cosio BG. Biologics in COPD. Open Resp Arch. 2024;6(2):100306. doi:10.1016/j.opresp.2024.100306

2023 GOLD Report. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2

2024 GOLD Report. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/

Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Dupixent® (dupilumab) late-breaking data from NOTUS confirmatory phase 3 COPD trial presented at ATS and published in the New England Journal of Medicine [press release]. May 20, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://investor.regeneron.com/news-releases/news-release-details/dupixentr-dupilumab-late-breaking-data-notus-confirmatory-phase

Pavord ID, Chapman KR, Bafadhel M, et al. Mepolizumab for eosinophil-associated COPD: analysis of METREX and METREO. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2021;16:1755-1770. doi:10.2147/COPD.S294333

Mepolizumab as add-on treatment in participants with COPD characterized by frequent exacerbations and eosinophil level (MATINEE). Clinicaltrials.gov. Updated August 28, 2023. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04133909

Singh D, Criner GJ, Agustí A, et al. Benralizumab prevents recurrent exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a post hoc analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2023;18:1595-1599. doi:10.2147/COPD.S418944

Efficacy and safety of benralizumab in moderate to very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with a history of frequent exacerbations (RESOLUTE). Clinicaltrials.gov. Updated May 8, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04053634

Efficacy and safety of tozorakimab in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with a history of exacerbations (TITANIA). Clinicaltrials.gov. Updated June 27, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05158387

Efficacy and safety of tozorakimab in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with a history of exacerbations (OBERON). Clinicaltrials.gov. Updated June 21, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05166889

Long-term efficacy and safety of tozorakimab in participants with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with a history of exacerbations (PROSPERO). Clinicaltrials.gov. Updated June 20, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05742802

Efficacy and safety of tozorakimab in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with a history of exacerbations (MIRANDA). Clinicaltrials.gov. Updated June 4, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06040086

Study to assess the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of SAR440340/REGN3500/itepekimab in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (AERIFY-1). ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated June 21, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04701983

Study to assess the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of SAR440340/REGN3500/itepekimab in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (AERIFY-2). ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated May 9, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04751487

ALIENTO and ARNASA: study designs of two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of astegolimab in patients with COPD. Medically. 2023. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://medically.gene.com/global/en/unrestricted/respiratory/ERS-2023/ers-2023-poster-brightling-aliento-and-arnasa-study-des.html

Anzueto A, Barjaktarevic IZ, Siler TM, et al. Ensifentrine, a novel phosphodiesterase 3 and 4 inhibitor for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase III trials (the ENHANCE trials). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;208(4):406-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.202306-0944OC

US Preventive Services Taskforce. Lung cancer: screening. March 9, 2021. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/lung-cancer-screening

Al Wachami N, Guennouni M, Iderdar Y, et al. Estimating the global prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):297. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-17686-9

COPD trends brief. American Lung Association. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://www.lung.org/research/trends-in-lung-disease/copd-trends-brief

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). World Health Organization. March 16, 2023. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd)

Shalabi MS, Aqdi SW, Alfort OA, et al. Effectiveness and safety of bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Commun Med Public Health. 2023;10(8):2955-2959. doi:10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20232392

McCormick B. FDA approves ensifentrine for maintenance treatment of adult patients with COPD. AJMC. June 26, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://www.ajmc.com/view/fda-approves-ensifentrine-for-maintenance-treatment-of-adult-patients-with-copd

Kersul AL, Cosio BG. Biologics in COPD. Open Resp Arch. 2024;6(2):100306. doi:10.1016/j.opresp.2024.100306

2023 GOLD Report. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2

2024 GOLD Report. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/

Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Dupixent® (dupilumab) late-breaking data from NOTUS confirmatory phase 3 COPD trial presented at ATS and published in the New England Journal of Medicine [press release]. May 20, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://investor.regeneron.com/news-releases/news-release-details/dupixentr-dupilumab-late-breaking-data-notus-confirmatory-phase

Pavord ID, Chapman KR, Bafadhel M, et al. Mepolizumab for eosinophil-associated COPD: analysis of METREX and METREO. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2021;16:1755-1770. doi:10.2147/COPD.S294333

Mepolizumab as add-on treatment in participants with COPD characterized by frequent exacerbations and eosinophil level (MATINEE). Clinicaltrials.gov. Updated August 28, 2023. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04133909

Singh D, Criner GJ, Agustí A, et al. Benralizumab prevents recurrent exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a post hoc analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2023;18:1595-1599. doi:10.2147/COPD.S418944

Efficacy and safety of benralizumab in moderate to very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with a history of frequent exacerbations (RESOLUTE). Clinicaltrials.gov. Updated May 8, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04053634

Efficacy and safety of tozorakimab in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with a history of exacerbations (TITANIA). Clinicaltrials.gov. Updated June 27, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05158387

Efficacy and safety of tozorakimab in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with a history of exacerbations (OBERON). Clinicaltrials.gov. Updated June 21, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05166889

Long-term efficacy and safety of tozorakimab in participants with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with a history of exacerbations (PROSPERO). Clinicaltrials.gov. Updated June 20, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05742802

Efficacy and safety of tozorakimab in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with a history of exacerbations (MIRANDA). Clinicaltrials.gov. Updated June 4, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06040086

Study to assess the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of SAR440340/REGN3500/itepekimab in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (AERIFY-1). ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated June 21, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04701983

Study to assess the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of SAR440340/REGN3500/itepekimab in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (AERIFY-2). ClinicalTrials.gov. Updated May 9, 2024. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04751487

ALIENTO and ARNASA: study designs of two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of astegolimab in patients with COPD. Medically. 2023. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://medically.gene.com/global/en/unrestricted/respiratory/ERS-2023/ers-2023-poster-brightling-aliento-and-arnasa-study-des.html

Anzueto A, Barjaktarevic IZ, Siler TM, et al. Ensifentrine, a novel phosphodiesterase 3 and 4 inhibitor for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase III trials (the ENHANCE trials). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;208(4):406-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.202306-0944OC

US Preventive Services Taskforce. Lung cancer: screening. March 9, 2021. Accessed July 11, 2024. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/lung-cancer-screening

Noninvasive Ventilation in Neuromuscular Disease

- Gong Y, Sankari A. Noninvasive ventilation. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024.Updated December 11, 2022. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK578188/

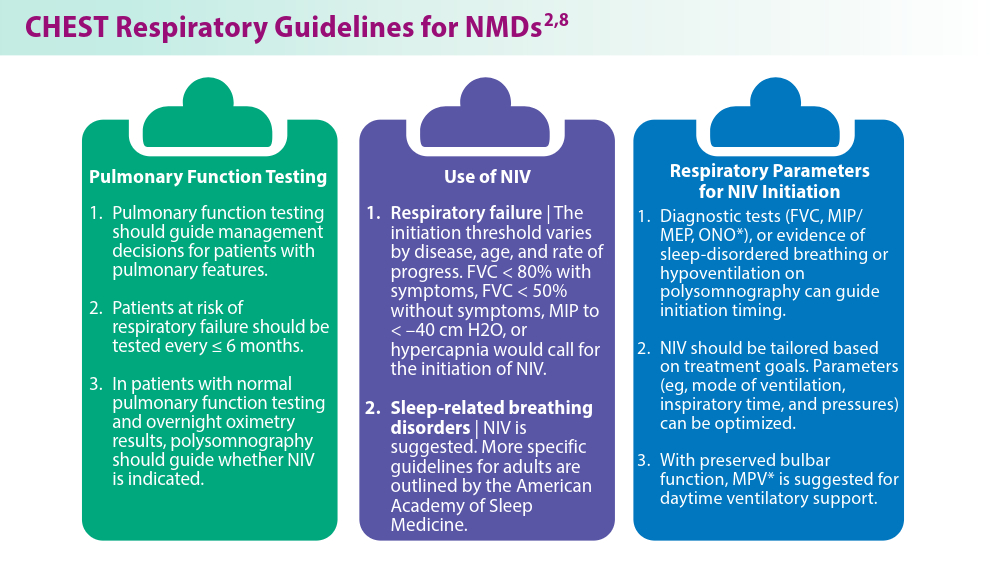

- Khan A, Frazer-Green L, Amin R, et al. Respiratory management of patients with neuromuscular weakness: an American College of Chest Physicians clinical practice guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2023;164(2):394-413. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2023.03.011

- Taran S, McCredie VA, Goligher EC. Noninvasive and invasive mechanical ventilation for neurologic disorders. Handb Clin Neurol. 2022;189:361-386. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-91532-8.00015-X

- Rao F, Garuti G, Vitacca M, et al; for the UILDM Respiratory Group. Management of respiratory complications and rehabilitation in individuals with muscular dystrophies: 1st Consensus Conference report from UILDM - Italian Muscular Dystrophy Association (Milan, January 25-26, 2019). Acta Myol. 2021;40(1):8-42. doi:10.36185/2532-1900-045

- Respiratory assist devices. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Revised January 1, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/ medicare-coverage-database/view/lcd.aspx?lcdid=33800

- What you need to know about the Philips PAP device recalls. American College of Chest Physicians. February 1, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.chestnet.org/Newsroom/CHEST-News/2021/07/What-YouNeed-to-Know-About-the-Philips-PAP-Device-Recall

- Orr JE, Chen K, Vaida F, et al. Effectiveness of long-term noninvasive ventilation measured by remote monitoring in neuromuscular disease. ERJ Open Res. 2023;9(5):00163-2023. doi:10.1183/23120541.00163-2023

- Kapur VK, Auckley DH, Chowdhuri S, et al. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(3):479-504. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6506

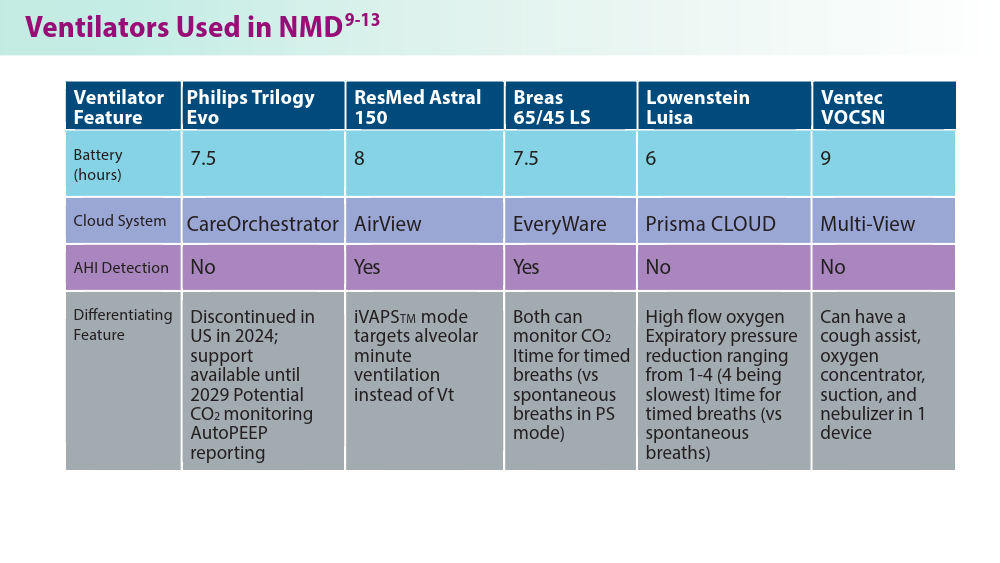

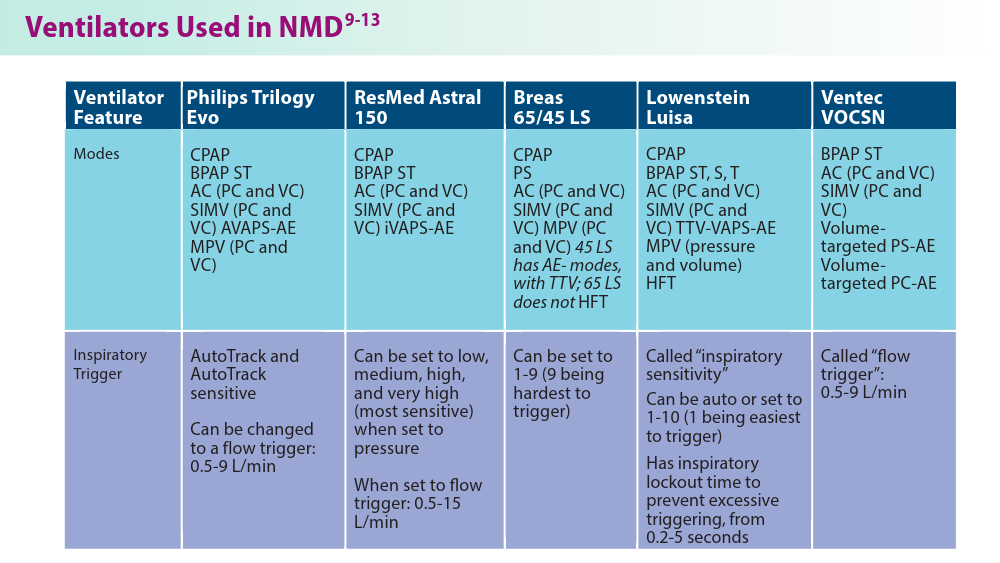

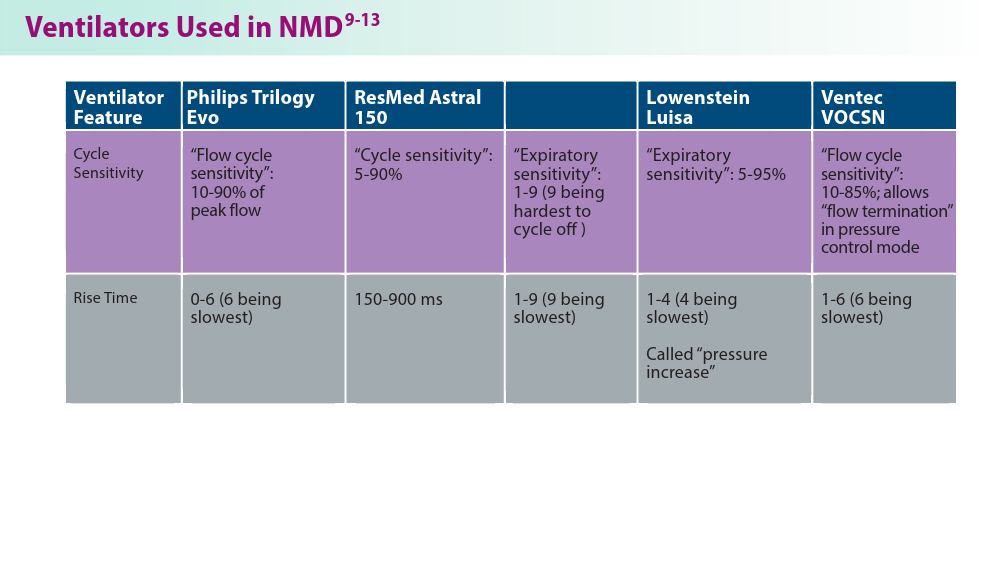

- Phillips Respironics. Trilogy Evo Clinical Manual. 2019

- ResMed. Astral Series Clinical Guide. 2018

- Breas. Vivo 45 LS User Manual. 2023

- Lowenstein Medical. Luisa Life Support Ventilation.

- Ventec Life Systems. VOCSN Clinical and Technical Manual. 2019

- Gong Y, Sankari A. Noninvasive ventilation. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024.Updated December 11, 2022. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK578188/

- Khan A, Frazer-Green L, Amin R, et al. Respiratory management of patients with neuromuscular weakness: an American College of Chest Physicians clinical practice guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2023;164(2):394-413. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2023.03.011

- Taran S, McCredie VA, Goligher EC. Noninvasive and invasive mechanical ventilation for neurologic disorders. Handb Clin Neurol. 2022;189:361-386. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-91532-8.00015-X

- Rao F, Garuti G, Vitacca M, et al; for the UILDM Respiratory Group. Management of respiratory complications and rehabilitation in individuals with muscular dystrophies: 1st Consensus Conference report from UILDM - Italian Muscular Dystrophy Association (Milan, January 25-26, 2019). Acta Myol. 2021;40(1):8-42. doi:10.36185/2532-1900-045

- Respiratory assist devices. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Revised January 1, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/ medicare-coverage-database/view/lcd.aspx?lcdid=33800

- What you need to know about the Philips PAP device recalls. American College of Chest Physicians. February 1, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.chestnet.org/Newsroom/CHEST-News/2021/07/What-YouNeed-to-Know-About-the-Philips-PAP-Device-Recall

- Orr JE, Chen K, Vaida F, et al. Effectiveness of long-term noninvasive ventilation measured by remote monitoring in neuromuscular disease. ERJ Open Res. 2023;9(5):00163-2023. doi:10.1183/23120541.00163-2023

- Kapur VK, Auckley DH, Chowdhuri S, et al. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(3):479-504. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6506

- Phillips Respironics. Trilogy Evo Clinical Manual. 2019

- ResMed. Astral Series Clinical Guide. 2018

- Breas. Vivo 45 LS User Manual. 2023

- Lowenstein Medical. Luisa Life Support Ventilation.

- Ventec Life Systems. VOCSN Clinical and Technical Manual. 2019

- Gong Y, Sankari A. Noninvasive ventilation. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024.Updated December 11, 2022. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK578188/

- Khan A, Frazer-Green L, Amin R, et al. Respiratory management of patients with neuromuscular weakness: an American College of Chest Physicians clinical practice guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2023;164(2):394-413. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2023.03.011

- Taran S, McCredie VA, Goligher EC. Noninvasive and invasive mechanical ventilation for neurologic disorders. Handb Clin Neurol. 2022;189:361-386. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-91532-8.00015-X

- Rao F, Garuti G, Vitacca M, et al; for the UILDM Respiratory Group. Management of respiratory complications and rehabilitation in individuals with muscular dystrophies: 1st Consensus Conference report from UILDM - Italian Muscular Dystrophy Association (Milan, January 25-26, 2019). Acta Myol. 2021;40(1):8-42. doi:10.36185/2532-1900-045

- Respiratory assist devices. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Revised January 1, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/ medicare-coverage-database/view/lcd.aspx?lcdid=33800

- What you need to know about the Philips PAP device recalls. American College of Chest Physicians. February 1, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://www.chestnet.org/Newsroom/CHEST-News/2021/07/What-YouNeed-to-Know-About-the-Philips-PAP-Device-Recall

- Orr JE, Chen K, Vaida F, et al. Effectiveness of long-term noninvasive ventilation measured by remote monitoring in neuromuscular disease. ERJ Open Res. 2023;9(5):00163-2023. doi:10.1183/23120541.00163-2023

- Kapur VK, Auckley DH, Chowdhuri S, et al. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(3):479-504. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6506

- Phillips Respironics. Trilogy Evo Clinical Manual. 2019

- ResMed. Astral Series Clinical Guide. 2018

- Breas. Vivo 45 LS User Manual. 2023

- Lowenstein Medical. Luisa Life Support Ventilation.

- Ventec Life Systems. VOCSN Clinical and Technical Manual. 2019

The Wellness Industry: Financially Toxic, Says Ethicist

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m at the Division of Medical Ethics at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine in New York City.

We have many debates and arguments that are swirling around about the out-of-control costs of Medicare. Many people are arguing we’ve got to trim it and cut back, and many people note that we can’t just go on and on with that kind of expenditure.

People look around for savings. Rightly, we can’t go on with the prices that we’re paying. No system could. We’ll bankrupt ourselves if we don’t drive prices down.

There’s another area that is driving up cost where, despite the fact that Medicare doesn’t pay for it, we could capture resources and hopefully shift them back to things like Medicare coverage or the insurance of other efficacious procedures. That area is the wellness industry.

That’s money coming out of people’s pockets that we could hopefully aim at the payment of things that we know work, not seeing the money drain out to cover bunk, nonsense, and charlatanism.

Does any or most of this stuff work? Do anything? Help anybody? No. We are spending money on charlatans and quacks. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which you might think is the agency that could step in and start to get rid of some of this nonsense, is just too overwhelmed trying to track drugs, devices, and vaccines to give much attention to the wellness industry.

What am I talking about specifically? I’m talking about everything from gut probiotics that are sold in sodas to probiotic facial creams and the Goop industry of Gwyneth Paltrow, where you have people buying things like wellness mats or vaginal eggs that are supposed to maintain gynecologic health.

We’re talking about things like PEMF, or pulse electronic magnetic fields, where you buy a machine and expose yourself to mild magnetic pulses. I went online to look them up, and the machines cost $5000-$50,000. There’s no evidence that it works. By the way, the machines are not only out there as being sold for pain relief and many other things to humans, but also they’re being sold for your pets.

That industry is completely out of control. Wellness interventions, whether it’s transcranial magnetism or all manner of supplements that are sold in health food stores, over and over again, we see a world in which wellness is promoted but no data are introduced to show that any of it helps, works, or does anybody any good.

It may not be all that harmful, but it’s certainly financially toxic to many people who end up spending good amounts of money using these things. I think doctors need to ask patients if they are using any of these things, particularly if they have chronic conditions. They’re likely, many of them, to be seduced by online advertisement to get involved with this stuff because it’s preventive or it’ll help treat some condition that they have.

The industry is out of control. We’re trying to figure out how to spend money on things we know work in medicine, and yet we continue to tolerate bunk, nonsense, quackery, and charlatanism, just letting it grow and grow and grow in terms of cost.

That’s money that could go elsewhere. That is money that is being taken out of the pockets of patients. They’re doing things that may even delay medical treatment, which won’t really help them, and they are doing things that perhaps might even interfere with medical care that really is known to be beneficial.

I think it’s time to push for more money for the FDA to regulate the wellness side. I think it’s time for the Federal Trade Commission to go after ads that promise health benefits. I think it’s time to have some honest conversations with patients: What are you using? What are you doing? Tell me about it, and here’s why I think you could probably spend your money in a better way.

Dr. Caplan, director, Division of Medical Ethics, New York University Langone Medical Center, New York, disclosed ties with Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position). He serves as a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m at the Division of Medical Ethics at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine in New York City.

We have many debates and arguments that are swirling around about the out-of-control costs of Medicare. Many people are arguing we’ve got to trim it and cut back, and many people note that we can’t just go on and on with that kind of expenditure.

People look around for savings. Rightly, we can’t go on with the prices that we’re paying. No system could. We’ll bankrupt ourselves if we don’t drive prices down.

There’s another area that is driving up cost where, despite the fact that Medicare doesn’t pay for it, we could capture resources and hopefully shift them back to things like Medicare coverage or the insurance of other efficacious procedures. That area is the wellness industry.

That’s money coming out of people’s pockets that we could hopefully aim at the payment of things that we know work, not seeing the money drain out to cover bunk, nonsense, and charlatanism.

Does any or most of this stuff work? Do anything? Help anybody? No. We are spending money on charlatans and quacks. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which you might think is the agency that could step in and start to get rid of some of this nonsense, is just too overwhelmed trying to track drugs, devices, and vaccines to give much attention to the wellness industry.

What am I talking about specifically? I’m talking about everything from gut probiotics that are sold in sodas to probiotic facial creams and the Goop industry of Gwyneth Paltrow, where you have people buying things like wellness mats or vaginal eggs that are supposed to maintain gynecologic health.

We’re talking about things like PEMF, or pulse electronic magnetic fields, where you buy a machine and expose yourself to mild magnetic pulses. I went online to look them up, and the machines cost $5000-$50,000. There’s no evidence that it works. By the way, the machines are not only out there as being sold for pain relief and many other things to humans, but also they’re being sold for your pets.

That industry is completely out of control. Wellness interventions, whether it’s transcranial magnetism or all manner of supplements that are sold in health food stores, over and over again, we see a world in which wellness is promoted but no data are introduced to show that any of it helps, works, or does anybody any good.

It may not be all that harmful, but it’s certainly financially toxic to many people who end up spending good amounts of money using these things. I think doctors need to ask patients if they are using any of these things, particularly if they have chronic conditions. They’re likely, many of them, to be seduced by online advertisement to get involved with this stuff because it’s preventive or it’ll help treat some condition that they have.

The industry is out of control. We’re trying to figure out how to spend money on things we know work in medicine, and yet we continue to tolerate bunk, nonsense, quackery, and charlatanism, just letting it grow and grow and grow in terms of cost.

That’s money that could go elsewhere. That is money that is being taken out of the pockets of patients. They’re doing things that may even delay medical treatment, which won’t really help them, and they are doing things that perhaps might even interfere with medical care that really is known to be beneficial.

I think it’s time to push for more money for the FDA to regulate the wellness side. I think it’s time for the Federal Trade Commission to go after ads that promise health benefits. I think it’s time to have some honest conversations with patients: What are you using? What are you doing? Tell me about it, and here’s why I think you could probably spend your money in a better way.

Dr. Caplan, director, Division of Medical Ethics, New York University Langone Medical Center, New York, disclosed ties with Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position). He serves as a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m at the Division of Medical Ethics at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine in New York City.

We have many debates and arguments that are swirling around about the out-of-control costs of Medicare. Many people are arguing we’ve got to trim it and cut back, and many people note that we can’t just go on and on with that kind of expenditure.

People look around for savings. Rightly, we can’t go on with the prices that we’re paying. No system could. We’ll bankrupt ourselves if we don’t drive prices down.

There’s another area that is driving up cost where, despite the fact that Medicare doesn’t pay for it, we could capture resources and hopefully shift them back to things like Medicare coverage or the insurance of other efficacious procedures. That area is the wellness industry.

That’s money coming out of people’s pockets that we could hopefully aim at the payment of things that we know work, not seeing the money drain out to cover bunk, nonsense, and charlatanism.

Does any or most of this stuff work? Do anything? Help anybody? No. We are spending money on charlatans and quacks. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which you might think is the agency that could step in and start to get rid of some of this nonsense, is just too overwhelmed trying to track drugs, devices, and vaccines to give much attention to the wellness industry.

What am I talking about specifically? I’m talking about everything from gut probiotics that are sold in sodas to probiotic facial creams and the Goop industry of Gwyneth Paltrow, where you have people buying things like wellness mats or vaginal eggs that are supposed to maintain gynecologic health.

We’re talking about things like PEMF, or pulse electronic magnetic fields, where you buy a machine and expose yourself to mild magnetic pulses. I went online to look them up, and the machines cost $5000-$50,000. There’s no evidence that it works. By the way, the machines are not only out there as being sold for pain relief and many other things to humans, but also they’re being sold for your pets.

That industry is completely out of control. Wellness interventions, whether it’s transcranial magnetism or all manner of supplements that are sold in health food stores, over and over again, we see a world in which wellness is promoted but no data are introduced to show that any of it helps, works, or does anybody any good.

It may not be all that harmful, but it’s certainly financially toxic to many people who end up spending good amounts of money using these things. I think doctors need to ask patients if they are using any of these things, particularly if they have chronic conditions. They’re likely, many of them, to be seduced by online advertisement to get involved with this stuff because it’s preventive or it’ll help treat some condition that they have.

The industry is out of control. We’re trying to figure out how to spend money on things we know work in medicine, and yet we continue to tolerate bunk, nonsense, quackery, and charlatanism, just letting it grow and grow and grow in terms of cost.

That’s money that could go elsewhere. That is money that is being taken out of the pockets of patients. They’re doing things that may even delay medical treatment, which won’t really help them, and they are doing things that perhaps might even interfere with medical care that really is known to be beneficial.

I think it’s time to push for more money for the FDA to regulate the wellness side. I think it’s time for the Federal Trade Commission to go after ads that promise health benefits. I think it’s time to have some honest conversations with patients: What are you using? What are you doing? Tell me about it, and here’s why I think you could probably spend your money in a better way.

Dr. Caplan, director, Division of Medical Ethics, New York University Langone Medical Center, New York, disclosed ties with Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position). He serves as a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Hospital to home tracheostomy care

SLEEP MEDICINE NETWORK

Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation and Neuromuscular Section

Technological improvement has enhanced our ability to support these patients with complex conditions in their home settings. However, clinical practice guidelines are lacking, and current practice relies on a consensus of expert opinions.1-3

Once a patient who has had a tracheostomy begins transitioning care to home, identifying caregivers is vital.

Caregivers need to be educated on daily tracheostomy care, airway clearance, and ventilator management.

Protocols to standardize this transition, such as the “Trach Trail” protocol, help reduce ICU readmissions with new tracheostomies (P = .05), eliminate predischarge mortality (P = .05), and may decrease ICU length of stay (P = 0.72).4 Standardized protocols for aspects of tracheostomy care, such as the “Go-Bag” from Boston Children’s Hospital, ensure that a consistent approach keeps providers, families, and patients familiar with their equipment and safety procedures, improving outcomes and decreasing tracheostomy-related adverse events.4-6

Understanding the landscape surrounding which equipment companies have trained field respiratory therapists is crucial. Airway clearance is key to improving ventilation and oxygenation and maintaining tracheostomy patency. Knowing the types of airway clearance modalities used for each patient remains critical.

Trach care may look substantially different for some populations, like patients in the neonatal ICU. Trach changes may happen more frequently. Speaking valve times may be gradually increased while planning for possible decannulation. Skin care involving granulation tissue and stoma complications is particularly important for this population. Active infants need well-fitting trach ties to balance enough support to maintain their trach without causing skin breakdown or discomfort. Securing the trach to prevent pulling or dislodgement as infants become more active is crucial as developmental milestones are achieved.

We hope national societies prioritize standardizing care for this vulnerable population while promoting additional high-quality, patient-centered outcomes in research studies. Implementation strategies to promote interprofessional teams to enhance education, communication, and outcomes will reduce health care disparities.

References

1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med Vol 161. pp Sherman JM, Davis S, Albamonte-Petrick S, et al. Care of the child with a chronic tracheostomy. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(1):297-308. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.ats1-00 297-308, 2000

2. Mitchell RB, Hussey HM, Setzen G, et al. Clinical consensus statement: tracheostomy care. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(1):6-20. Preprint. Posted online September 18, 2012. PMID: 22990518. doi: 10.1177/0194599812460376

3. Sterni LM, Collaco JM, Baker CD, et al; ATS Pediatric Chronic Home Ventilation Workgroup. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: pediatric chronic home invasive ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(8):e16-35. PMID: 27082538; PMCID: PMC5439679. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0276ST

4. Cherney RL, Pandian V, Ninan A, et al. The Trach Trail: a systems-based pathway to improve quality of tracheostomy care and interdisciplinary collaboration. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(2):232-243. doi: 10.1177/0194599820917427

5. Brown J. Tracheostomy to noninvasive ventilation: from acute care to home. Sleep Med Clin. 2020;15(4):593-598. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2020.08.003

6. Kohn J, McKeon M, Munhall D, Blanchette S, Wells S, Watters K. Standardization of pediatric tracheostomy care with “Go-bags.” Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;121:154-156. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.03.022

SLEEP MEDICINE NETWORK

Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation and Neuromuscular Section

Technological improvement has enhanced our ability to support these patients with complex conditions in their home settings. However, clinical practice guidelines are lacking, and current practice relies on a consensus of expert opinions.1-3

Once a patient who has had a tracheostomy begins transitioning care to home, identifying caregivers is vital.

Caregivers need to be educated on daily tracheostomy care, airway clearance, and ventilator management.

Protocols to standardize this transition, such as the “Trach Trail” protocol, help reduce ICU readmissions with new tracheostomies (P = .05), eliminate predischarge mortality (P = .05), and may decrease ICU length of stay (P = 0.72).4 Standardized protocols for aspects of tracheostomy care, such as the “Go-Bag” from Boston Children’s Hospital, ensure that a consistent approach keeps providers, families, and patients familiar with their equipment and safety procedures, improving outcomes and decreasing tracheostomy-related adverse events.4-6

Understanding the landscape surrounding which equipment companies have trained field respiratory therapists is crucial. Airway clearance is key to improving ventilation and oxygenation and maintaining tracheostomy patency. Knowing the types of airway clearance modalities used for each patient remains critical.

Trach care may look substantially different for some populations, like patients in the neonatal ICU. Trach changes may happen more frequently. Speaking valve times may be gradually increased while planning for possible decannulation. Skin care involving granulation tissue and stoma complications is particularly important for this population. Active infants need well-fitting trach ties to balance enough support to maintain their trach without causing skin breakdown or discomfort. Securing the trach to prevent pulling or dislodgement as infants become more active is crucial as developmental milestones are achieved.

We hope national societies prioritize standardizing care for this vulnerable population while promoting additional high-quality, patient-centered outcomes in research studies. Implementation strategies to promote interprofessional teams to enhance education, communication, and outcomes will reduce health care disparities.

References

1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med Vol 161. pp Sherman JM, Davis S, Albamonte-Petrick S, et al. Care of the child with a chronic tracheostomy. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(1):297-308. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.ats1-00 297-308, 2000

2. Mitchell RB, Hussey HM, Setzen G, et al. Clinical consensus statement: tracheostomy care. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(1):6-20. Preprint. Posted online September 18, 2012. PMID: 22990518. doi: 10.1177/0194599812460376

3. Sterni LM, Collaco JM, Baker CD, et al; ATS Pediatric Chronic Home Ventilation Workgroup. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: pediatric chronic home invasive ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(8):e16-35. PMID: 27082538; PMCID: PMC5439679. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0276ST

4. Cherney RL, Pandian V, Ninan A, et al. The Trach Trail: a systems-based pathway to improve quality of tracheostomy care and interdisciplinary collaboration. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(2):232-243. doi: 10.1177/0194599820917427

5. Brown J. Tracheostomy to noninvasive ventilation: from acute care to home. Sleep Med Clin. 2020;15(4):593-598. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2020.08.003

6. Kohn J, McKeon M, Munhall D, Blanchette S, Wells S, Watters K. Standardization of pediatric tracheostomy care with “Go-bags.” Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;121:154-156. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.03.022

SLEEP MEDICINE NETWORK

Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation and Neuromuscular Section

Technological improvement has enhanced our ability to support these patients with complex conditions in their home settings. However, clinical practice guidelines are lacking, and current practice relies on a consensus of expert opinions.1-3

Once a patient who has had a tracheostomy begins transitioning care to home, identifying caregivers is vital.

Caregivers need to be educated on daily tracheostomy care, airway clearance, and ventilator management.

Protocols to standardize this transition, such as the “Trach Trail” protocol, help reduce ICU readmissions with new tracheostomies (P = .05), eliminate predischarge mortality (P = .05), and may decrease ICU length of stay (P = 0.72).4 Standardized protocols for aspects of tracheostomy care, such as the “Go-Bag” from Boston Children’s Hospital, ensure that a consistent approach keeps providers, families, and patients familiar with their equipment and safety procedures, improving outcomes and decreasing tracheostomy-related adverse events.4-6

Understanding the landscape surrounding which equipment companies have trained field respiratory therapists is crucial. Airway clearance is key to improving ventilation and oxygenation and maintaining tracheostomy patency. Knowing the types of airway clearance modalities used for each patient remains critical.

Trach care may look substantially different for some populations, like patients in the neonatal ICU. Trach changes may happen more frequently. Speaking valve times may be gradually increased while planning for possible decannulation. Skin care involving granulation tissue and stoma complications is particularly important for this population. Active infants need well-fitting trach ties to balance enough support to maintain their trach without causing skin breakdown or discomfort. Securing the trach to prevent pulling or dislodgement as infants become more active is crucial as developmental milestones are achieved.

We hope national societies prioritize standardizing care for this vulnerable population while promoting additional high-quality, patient-centered outcomes in research studies. Implementation strategies to promote interprofessional teams to enhance education, communication, and outcomes will reduce health care disparities.

References

1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med Vol 161. pp Sherman JM, Davis S, Albamonte-Petrick S, et al. Care of the child with a chronic tracheostomy. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(1):297-308. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.ats1-00 297-308, 2000

2. Mitchell RB, Hussey HM, Setzen G, et al. Clinical consensus statement: tracheostomy care. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(1):6-20. Preprint. Posted online September 18, 2012. PMID: 22990518. doi: 10.1177/0194599812460376

3. Sterni LM, Collaco JM, Baker CD, et al; ATS Pediatric Chronic Home Ventilation Workgroup. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: pediatric chronic home invasive ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(8):e16-35. PMID: 27082538; PMCID: PMC5439679. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0276ST

4. Cherney RL, Pandian V, Ninan A, et al. The Trach Trail: a systems-based pathway to improve quality of tracheostomy care and interdisciplinary collaboration. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(2):232-243. doi: 10.1177/0194599820917427

5. Brown J. Tracheostomy to noninvasive ventilation: from acute care to home. Sleep Med Clin. 2020;15(4):593-598. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2020.08.003

6. Kohn J, McKeon M, Munhall D, Blanchette S, Wells S, Watters K. Standardization of pediatric tracheostomy care with “Go-bags.” Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;121:154-156. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.03.022

HALT early recognition is key

DIFFUSE LUNG DISEASE AND LUNG TRANSPLANT NETWORK

Lung Transplant Section

Hyperammonemia after lung transplantation (HALT) is a rare but serious complication occurring in 1% to 4% of patients with high morbidity and mortality. Early recognition is crucial, as mortality rates can reach 75%.1

HALT arises from excess ammonia production or decreased clearance and is often linked to infections by urea-splitting organisms, including mycoplasma and ureaplasma. Prompt, aggressive treatment is essential and typically includes dietary protein restriction, renal replacement therapy (ideally intermittent hemodialysis), bowel decontamination (lactulose, rifaximin, metronidazole, or neomycin), amino acids (arginine and levocarnitine), nitrogen scavengers (sodium phenylbutyrate or glycerol phenylbutyrate), and empiric antimicrobial coverage for urea-splitting organisms.2 Given concerns for calcineurin inhibitor-induced hyperammonemia, transition to an alternative agent may be considered.

Given the severe risks associated with HALT, vigilance is vital, particularly in intubated and sedated patients where monitoring of neurologic status is more challenging. Protocols may involve routine serum ammonia monitoring, polymerase chain reaction testing for mycoplasma and ureaplasma at the time of transplant or with postoperative bronchoscopy, and empiric antimicrobial treatment. No definitive ammonia threshold exists, but altered sensorium with elevated levels warrants immediate and more aggressive treatment with levels >75 μmol/L. Early testing and symptom recognition can significantly improve survival rates in this potentially devastating condition.

References

1. Leger RF, Silverman MS, Hauck ES, Guvakova KD. Hyperammonemia post lung transplantation: a review. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med. 2020;14:1179548420966234. doi:10.1177/1179548420966234

2. Chen C, Bain KB, Luppa JA. Hyperammonemia syndrome after lung transplantation: a single center experience. Transplantation. 2016;100(3):678-684. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000000868

DIFFUSE LUNG DISEASE AND LUNG TRANSPLANT NETWORK

Lung Transplant Section

Hyperammonemia after lung transplantation (HALT) is a rare but serious complication occurring in 1% to 4% of patients with high morbidity and mortality. Early recognition is crucial, as mortality rates can reach 75%.1

HALT arises from excess ammonia production or decreased clearance and is often linked to infections by urea-splitting organisms, including mycoplasma and ureaplasma. Prompt, aggressive treatment is essential and typically includes dietary protein restriction, renal replacement therapy (ideally intermittent hemodialysis), bowel decontamination (lactulose, rifaximin, metronidazole, or neomycin), amino acids (arginine and levocarnitine), nitrogen scavengers (sodium phenylbutyrate or glycerol phenylbutyrate), and empiric antimicrobial coverage for urea-splitting organisms.2 Given concerns for calcineurin inhibitor-induced hyperammonemia, transition to an alternative agent may be considered.

Given the severe risks associated with HALT, vigilance is vital, particularly in intubated and sedated patients where monitoring of neurologic status is more challenging. Protocols may involve routine serum ammonia monitoring, polymerase chain reaction testing for mycoplasma and ureaplasma at the time of transplant or with postoperative bronchoscopy, and empiric antimicrobial treatment. No definitive ammonia threshold exists, but altered sensorium with elevated levels warrants immediate and more aggressive treatment with levels >75 μmol/L. Early testing and symptom recognition can significantly improve survival rates in this potentially devastating condition.

References

1. Leger RF, Silverman MS, Hauck ES, Guvakova KD. Hyperammonemia post lung transplantation: a review. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med. 2020;14:1179548420966234. doi:10.1177/1179548420966234

2. Chen C, Bain KB, Luppa JA. Hyperammonemia syndrome after lung transplantation: a single center experience. Transplantation. 2016;100(3):678-684. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000000868

DIFFUSE LUNG DISEASE AND LUNG TRANSPLANT NETWORK

Lung Transplant Section

Hyperammonemia after lung transplantation (HALT) is a rare but serious complication occurring in 1% to 4% of patients with high morbidity and mortality. Early recognition is crucial, as mortality rates can reach 75%.1

HALT arises from excess ammonia production or decreased clearance and is often linked to infections by urea-splitting organisms, including mycoplasma and ureaplasma. Prompt, aggressive treatment is essential and typically includes dietary protein restriction, renal replacement therapy (ideally intermittent hemodialysis), bowel decontamination (lactulose, rifaximin, metronidazole, or neomycin), amino acids (arginine and levocarnitine), nitrogen scavengers (sodium phenylbutyrate or glycerol phenylbutyrate), and empiric antimicrobial coverage for urea-splitting organisms.2 Given concerns for calcineurin inhibitor-induced hyperammonemia, transition to an alternative agent may be considered.

Given the severe risks associated with HALT, vigilance is vital, particularly in intubated and sedated patients where monitoring of neurologic status is more challenging. Protocols may involve routine serum ammonia monitoring, polymerase chain reaction testing for mycoplasma and ureaplasma at the time of transplant or with postoperative bronchoscopy, and empiric antimicrobial treatment. No definitive ammonia threshold exists, but altered sensorium with elevated levels warrants immediate and more aggressive treatment with levels >75 μmol/L. Early testing and symptom recognition can significantly improve survival rates in this potentially devastating condition.

References

1. Leger RF, Silverman MS, Hauck ES, Guvakova KD. Hyperammonemia post lung transplantation: a review. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med. 2020;14:1179548420966234. doi:10.1177/1179548420966234

2. Chen C, Bain KB, Luppa JA. Hyperammonemia syndrome after lung transplantation: a single center experience. Transplantation. 2016;100(3):678-684. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000000868

SURMOUNT-OSA Results: ‘Impressive’ in Improving Sleep Apnea

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Akshay B. Jain, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr. Akshay Jain, an endocrinologist in Vancouver, Canada, and with me is a very special guest. Today we have Dr. James Kim, a primary care physician working in Calgary, Canada. Both Dr. Kim and I were fortunate to attend the recently concluded American Diabetes Association annual conference in Orlando in June.

We thought we could share with you some of the key learnings that we found very insightful and clinically quite relevant. We were hoping to bring our own conclusion regarding what these findings were, both from a primary care perspective and an endocrinology perspective.

There were so many different studies that, frankly, it was difficult to pick them, but we handpicked a few studies we felt we could do a bit of a deeper dive on, and we’ll talk about each of these studies.

Welcome, Dr. Kim, and thanks for joining us.

James W. Kim, MBBCh, PgDip, MScCH: Thank you so much, Dr Jain. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Dr. Jain: Probably the best place to start would be with the SURMOUNT-OSA study. This was highlighted at the American Diabetes Association conference. Essentially, it looked at people who are living with obesity who also had obstructive sleep apnea.

This was a randomized controlled trial where individuals tested either got tirzepatide (trade name, Mounjaro) or placebo treatment. They looked at the change in their apnea-hypopnea index at the end of the study.

This included both people who were using CPAP machines and those who were not using CPAP machines at baseline. We do know that many individuals with sleep apnea may not use these machines.

That was a big reduction.

Dr. Kim, what’s the relevance of this study in primary care?

Dr. Kim: Oh, it’s massive. Obstructive sleep apnea is probably one of the most underdiagnosed yet huge cardiac risk factors that we tend to overlook in primary care. We sometimes say, oh, it’s just sleep apnea; what’s the big deal? We know it’s a big problem. We know that more than 50% of people with type 2 diabetes have obstructive sleep apnea, and some studies have even quoted that 90% of their population cohorts had sleep apnea. This is a big deal.

What do we know so far? We know that obstructive sleep apnea, which I’m just going to call OSA, increases the risk for hypertension, bad cholesterol, and worsening blood glucose in terms of A1c and fasting glucose, which eventually leads to myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, stroke, and eventually cardiovascular death.

We also know that people with type 2 diabetes have an increased risk for OSA. There seems to be a bidirectional relationship between diabetes and OSA. It seems like weight plays the biggest role in terms of developing OSA, and numerous studies have shown this.

Also, thankfully, some of the studies showed that weight loss improves not just OSA but also blood pressure, cholesterol, blood glucose, and insulin sensitivities. These have been fascinating. We see these patients every single day. If you think about it in your population, for 50%-90% of the patients to have OSA is a large number. If you haven’t seen a person with OSA this week, you probably missed them, very likely.

Therefore, the SURMOUNT-OSA trial was quite fascinating with, as you mentioned, 50%-60% reduction in the severity of OSA, which is very impressive. Even more impressive, I think, is that for about 50% of the patients on tirzepatide, the OSA improves so much that they may not even need to be on CPAP machines.

Those who were on CPAP may not need to be on CPAP any longer. These are huge data, especially for primary care, because as you mentioned, we see these people every single day.

Dr. Jain: Thanks for pointing that out. Clearly, it’s very clinically relevant. I think the most important takeaway for me from this study was the correlation between weight loss and AHI improvement.

Clearly, it showed that placebo had about a 6% drop in AHI, whereas there was a 60% drop in the tirzepatide group, so you can see that it’s significantly different. The placebo group did not have any significant degree of weight loss, whereas the tirzepatide group had nearly 20% weight loss. This again goes to show that there is a very close correlation between weight loss and improvement in OSA.

What’s very important to note is that we’ve seen this in the past as well. We had seen some of these data with other GLP-1 agents, but the extent of improvement that we have seen in the SURMOUNT-OSA trial is significantly more than what we’ve seen in previous studies. There is a ray of hope now where we have medical management to offer people who are living with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea.

Dr. Kim: I want to add that, from a primary care perspective, this study also showed the improvement of the sleep apnea–related symptoms as well. The biggest problem with sleep apnea — or at least what patients’ spouses complain of, is the person snoring too much; it’s a symptom.

It’s the next-day symptoms that really do disturb people, like chronic fatigue. I have numerous patients who say that, once they’ve been treated for sleep apnea, they feel like a brand-new person. They have sudden bursts of energy that they never felt before, and over 50% of these people have huge improvements in the symptoms as well.

This is a huge trial. The only thing that I wish this study included were people with mild obstructive sleep apnea who were symptomatic. I do understand that, with other studies in this population, the data have been conflicting, but it would have been really awesome if they had those patients included. However, it is still a significant study for primary care.

Dr. Jain: That’s a really good point. Fatigue improves and overall quality of life improves. That’s very important from a primary care perspective.

From an endocrinology perspective, we know that management of sleep apnea can often lead to improvement in male hypogonadism, polycystic ovary syndrome, and insulin resistance. The amount of insulin required, or the number of medications needed for managing diabetes, can improve. Hypertension can improve as well. There are multiple benefits that you can get from appropriate management of sleep apnea.

Thanks, Dr. Kim. We really appreciate your insights on SURMOUNT-OSA.

Dr. Jain is a clinical instructor, Department of Endocrinology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Dr. Kim is a clinical assistant professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Calgary in Alberta. Both disclosed conflicts of interest with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Akshay B. Jain, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr. Akshay Jain, an endocrinologist in Vancouver, Canada, and with me is a very special guest. Today we have Dr. James Kim, a primary care physician working in Calgary, Canada. Both Dr. Kim and I were fortunate to attend the recently concluded American Diabetes Association annual conference in Orlando in June.

We thought we could share with you some of the key learnings that we found very insightful and clinically quite relevant. We were hoping to bring our own conclusion regarding what these findings were, both from a primary care perspective and an endocrinology perspective.

There were so many different studies that, frankly, it was difficult to pick them, but we handpicked a few studies we felt we could do a bit of a deeper dive on, and we’ll talk about each of these studies.

Welcome, Dr. Kim, and thanks for joining us.

James W. Kim, MBBCh, PgDip, MScCH: Thank you so much, Dr Jain. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Dr. Jain: Probably the best place to start would be with the SURMOUNT-OSA study. This was highlighted at the American Diabetes Association conference. Essentially, it looked at people who are living with obesity who also had obstructive sleep apnea.

This was a randomized controlled trial where individuals tested either got tirzepatide (trade name, Mounjaro) or placebo treatment. They looked at the change in their apnea-hypopnea index at the end of the study.

This included both people who were using CPAP machines and those who were not using CPAP machines at baseline. We do know that many individuals with sleep apnea may not use these machines.

That was a big reduction.

Dr. Kim, what’s the relevance of this study in primary care?

Dr. Kim: Oh, it’s massive. Obstructive sleep apnea is probably one of the most underdiagnosed yet huge cardiac risk factors that we tend to overlook in primary care. We sometimes say, oh, it’s just sleep apnea; what’s the big deal? We know it’s a big problem. We know that more than 50% of people with type 2 diabetes have obstructive sleep apnea, and some studies have even quoted that 90% of their population cohorts had sleep apnea. This is a big deal.

What do we know so far? We know that obstructive sleep apnea, which I’m just going to call OSA, increases the risk for hypertension, bad cholesterol, and worsening blood glucose in terms of A1c and fasting glucose, which eventually leads to myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, stroke, and eventually cardiovascular death.

We also know that people with type 2 diabetes have an increased risk for OSA. There seems to be a bidirectional relationship between diabetes and OSA. It seems like weight plays the biggest role in terms of developing OSA, and numerous studies have shown this.

Also, thankfully, some of the studies showed that weight loss improves not just OSA but also blood pressure, cholesterol, blood glucose, and insulin sensitivities. These have been fascinating. We see these patients every single day. If you think about it in your population, for 50%-90% of the patients to have OSA is a large number. If you haven’t seen a person with OSA this week, you probably missed them, very likely.

Therefore, the SURMOUNT-OSA trial was quite fascinating with, as you mentioned, 50%-60% reduction in the severity of OSA, which is very impressive. Even more impressive, I think, is that for about 50% of the patients on tirzepatide, the OSA improves so much that they may not even need to be on CPAP machines.

Those who were on CPAP may not need to be on CPAP any longer. These are huge data, especially for primary care, because as you mentioned, we see these people every single day.

Dr. Jain: Thanks for pointing that out. Clearly, it’s very clinically relevant. I think the most important takeaway for me from this study was the correlation between weight loss and AHI improvement.

Clearly, it showed that placebo had about a 6% drop in AHI, whereas there was a 60% drop in the tirzepatide group, so you can see that it’s significantly different. The placebo group did not have any significant degree of weight loss, whereas the tirzepatide group had nearly 20% weight loss. This again goes to show that there is a very close correlation between weight loss and improvement in OSA.

What’s very important to note is that we’ve seen this in the past as well. We had seen some of these data with other GLP-1 agents, but the extent of improvement that we have seen in the SURMOUNT-OSA trial is significantly more than what we’ve seen in previous studies. There is a ray of hope now where we have medical management to offer people who are living with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea.

Dr. Kim: I want to add that, from a primary care perspective, this study also showed the improvement of the sleep apnea–related symptoms as well. The biggest problem with sleep apnea — or at least what patients’ spouses complain of, is the person snoring too much; it’s a symptom.

It’s the next-day symptoms that really do disturb people, like chronic fatigue. I have numerous patients who say that, once they’ve been treated for sleep apnea, they feel like a brand-new person. They have sudden bursts of energy that they never felt before, and over 50% of these people have huge improvements in the symptoms as well.

This is a huge trial. The only thing that I wish this study included were people with mild obstructive sleep apnea who were symptomatic. I do understand that, with other studies in this population, the data have been conflicting, but it would have been really awesome if they had those patients included. However, it is still a significant study for primary care.

Dr. Jain: That’s a really good point. Fatigue improves and overall quality of life improves. That’s very important from a primary care perspective.

From an endocrinology perspective, we know that management of sleep apnea can often lead to improvement in male hypogonadism, polycystic ovary syndrome, and insulin resistance. The amount of insulin required, or the number of medications needed for managing diabetes, can improve. Hypertension can improve as well. There are multiple benefits that you can get from appropriate management of sleep apnea.

Thanks, Dr. Kim. We really appreciate your insights on SURMOUNT-OSA.

Dr. Jain is a clinical instructor, Department of Endocrinology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Dr. Kim is a clinical assistant professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Calgary in Alberta. Both disclosed conflicts of interest with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Akshay B. Jain, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr. Akshay Jain, an endocrinologist in Vancouver, Canada, and with me is a very special guest. Today we have Dr. James Kim, a primary care physician working in Calgary, Canada. Both Dr. Kim and I were fortunate to attend the recently concluded American Diabetes Association annual conference in Orlando in June.

We thought we could share with you some of the key learnings that we found very insightful and clinically quite relevant. We were hoping to bring our own conclusion regarding what these findings were, both from a primary care perspective and an endocrinology perspective.

There were so many different studies that, frankly, it was difficult to pick them, but we handpicked a few studies we felt we could do a bit of a deeper dive on, and we’ll talk about each of these studies.

Welcome, Dr. Kim, and thanks for joining us.

James W. Kim, MBBCh, PgDip, MScCH: Thank you so much, Dr Jain. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Dr. Jain: Probably the best place to start would be with the SURMOUNT-OSA study. This was highlighted at the American Diabetes Association conference. Essentially, it looked at people who are living with obesity who also had obstructive sleep apnea.

This was a randomized controlled trial where individuals tested either got tirzepatide (trade name, Mounjaro) or placebo treatment. They looked at the change in their apnea-hypopnea index at the end of the study.

This included both people who were using CPAP machines and those who were not using CPAP machines at baseline. We do know that many individuals with sleep apnea may not use these machines.

That was a big reduction.

Dr. Kim, what’s the relevance of this study in primary care?

Dr. Kim: Oh, it’s massive. Obstructive sleep apnea is probably one of the most underdiagnosed yet huge cardiac risk factors that we tend to overlook in primary care. We sometimes say, oh, it’s just sleep apnea; what’s the big deal? We know it’s a big problem. We know that more than 50% of people with type 2 diabetes have obstructive sleep apnea, and some studies have even quoted that 90% of their population cohorts had sleep apnea. This is a big deal.

What do we know so far? We know that obstructive sleep apnea, which I’m just going to call OSA, increases the risk for hypertension, bad cholesterol, and worsening blood glucose in terms of A1c and fasting glucose, which eventually leads to myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, stroke, and eventually cardiovascular death.

We also know that people with type 2 diabetes have an increased risk for OSA. There seems to be a bidirectional relationship between diabetes and OSA. It seems like weight plays the biggest role in terms of developing OSA, and numerous studies have shown this.

Also, thankfully, some of the studies showed that weight loss improves not just OSA but also blood pressure, cholesterol, blood glucose, and insulin sensitivities. These have been fascinating. We see these patients every single day. If you think about it in your population, for 50%-90% of the patients to have OSA is a large number. If you haven’t seen a person with OSA this week, you probably missed them, very likely.

Therefore, the SURMOUNT-OSA trial was quite fascinating with, as you mentioned, 50%-60% reduction in the severity of OSA, which is very impressive. Even more impressive, I think, is that for about 50% of the patients on tirzepatide, the OSA improves so much that they may not even need to be on CPAP machines.

Those who were on CPAP may not need to be on CPAP any longer. These are huge data, especially for primary care, because as you mentioned, we see these people every single day.

Dr. Jain: Thanks for pointing that out. Clearly, it’s very clinically relevant. I think the most important takeaway for me from this study was the correlation between weight loss and AHI improvement.

Clearly, it showed that placebo had about a 6% drop in AHI, whereas there was a 60% drop in the tirzepatide group, so you can see that it’s significantly different. The placebo group did not have any significant degree of weight loss, whereas the tirzepatide group had nearly 20% weight loss. This again goes to show that there is a very close correlation between weight loss and improvement in OSA.

What’s very important to note is that we’ve seen this in the past as well. We had seen some of these data with other GLP-1 agents, but the extent of improvement that we have seen in the SURMOUNT-OSA trial is significantly more than what we’ve seen in previous studies. There is a ray of hope now where we have medical management to offer people who are living with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea.

Dr. Kim: I want to add that, from a primary care perspective, this study also showed the improvement of the sleep apnea–related symptoms as well. The biggest problem with sleep apnea — or at least what patients’ spouses complain of, is the person snoring too much; it’s a symptom.

It’s the next-day symptoms that really do disturb people, like chronic fatigue. I have numerous patients who say that, once they’ve been treated for sleep apnea, they feel like a brand-new person. They have sudden bursts of energy that they never felt before, and over 50% of these people have huge improvements in the symptoms as well.

This is a huge trial. The only thing that I wish this study included were people with mild obstructive sleep apnea who were symptomatic. I do understand that, with other studies in this population, the data have been conflicting, but it would have been really awesome if they had those patients included. However, it is still a significant study for primary care.

Dr. Jain: That’s a really good point. Fatigue improves and overall quality of life improves. That’s very important from a primary care perspective.

From an endocrinology perspective, we know that management of sleep apnea can often lead to improvement in male hypogonadism, polycystic ovary syndrome, and insulin resistance. The amount of insulin required, or the number of medications needed for managing diabetes, can improve. Hypertension can improve as well. There are multiple benefits that you can get from appropriate management of sleep apnea.

Thanks, Dr. Kim. We really appreciate your insights on SURMOUNT-OSA.

Dr. Jain is a clinical instructor, Department of Endocrinology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Dr. Kim is a clinical assistant professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Calgary in Alberta. Both disclosed conflicts of interest with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Pulmonary Hypertension: Comorbidities and Novel Therapeutics

- Cullivan S, Gaine S, Sitbon O. New trends in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. 2023;32(167):220211. doi:10.1183/16000617.0211-2022

- Mocumbi A, Humbert M, Saxena A, et al. Pulmonary hypertension [published correction appears in Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10(1):5]. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10(1):1. doi:10.1038/s41572-023-00486-7

- Lang IM, Palazzini M. The burden of comorbidities in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2019;21(suppl K):K21-K28. doi:10.1093/ eurheartj/suz205

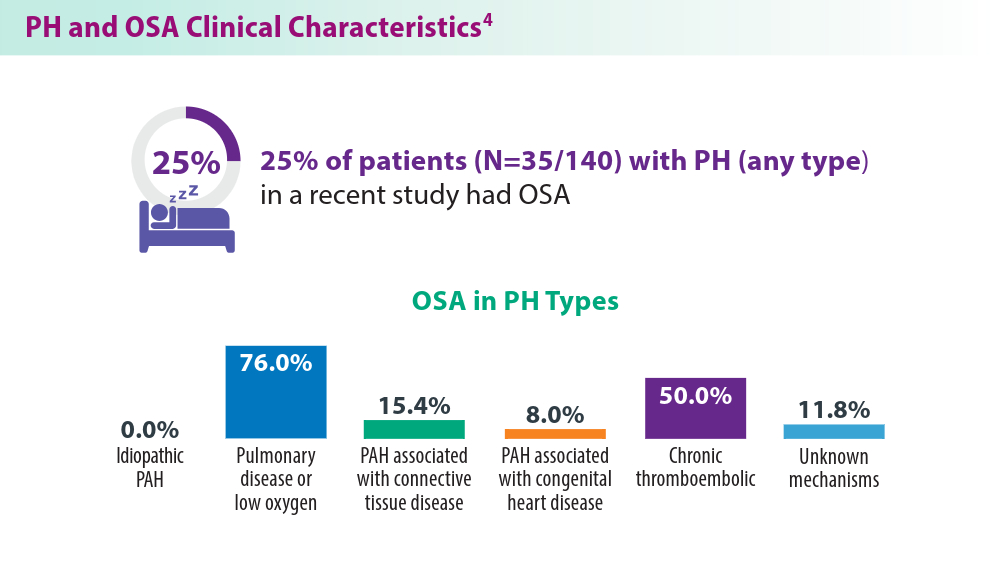

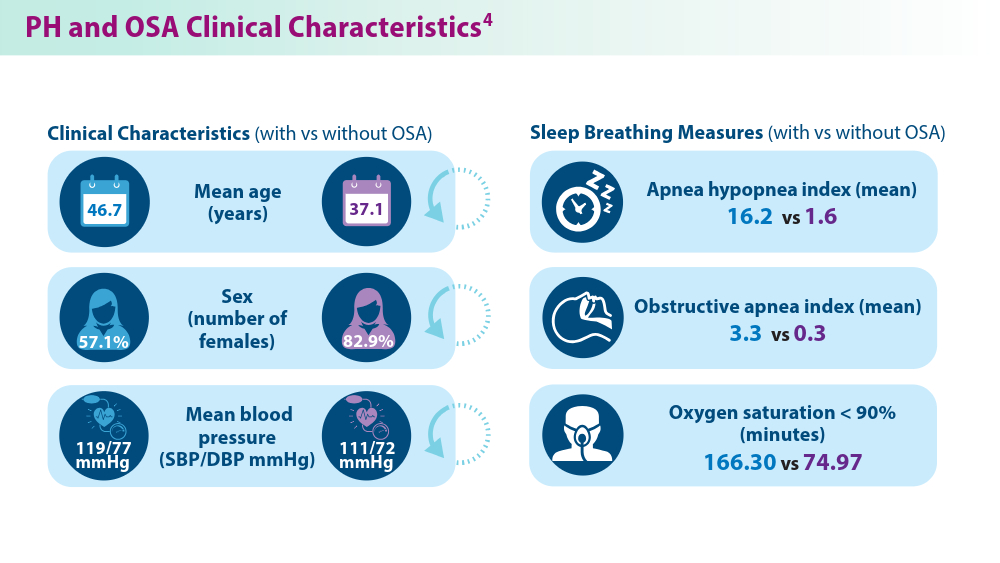

- Yan L, Zhao Z, Zhao Q, et al. The clinical characteristics of patients with pulmonary hypertension combined with obstructive sleep apnoea. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21(1):378. doi:10.1186/s12890-021-01755-5

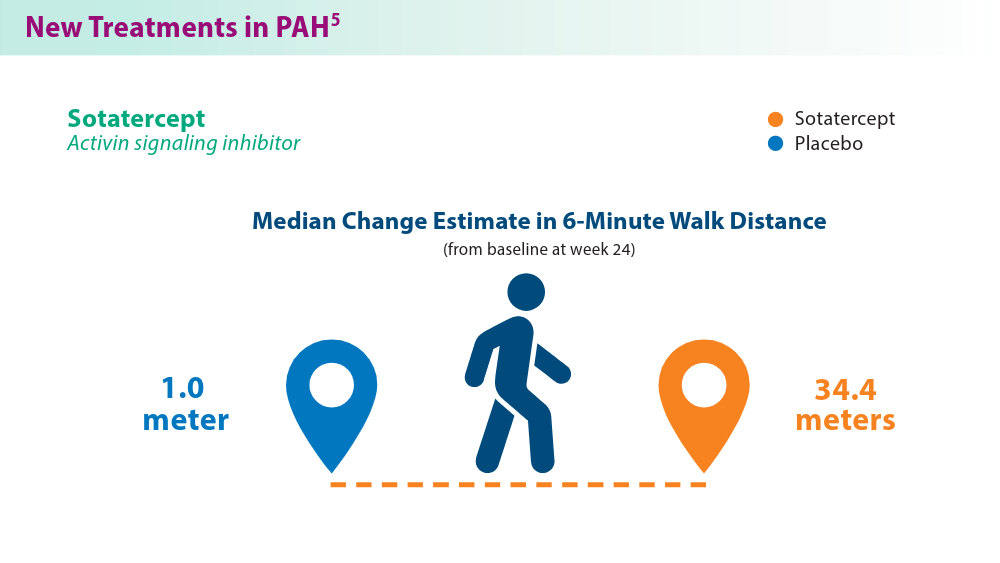

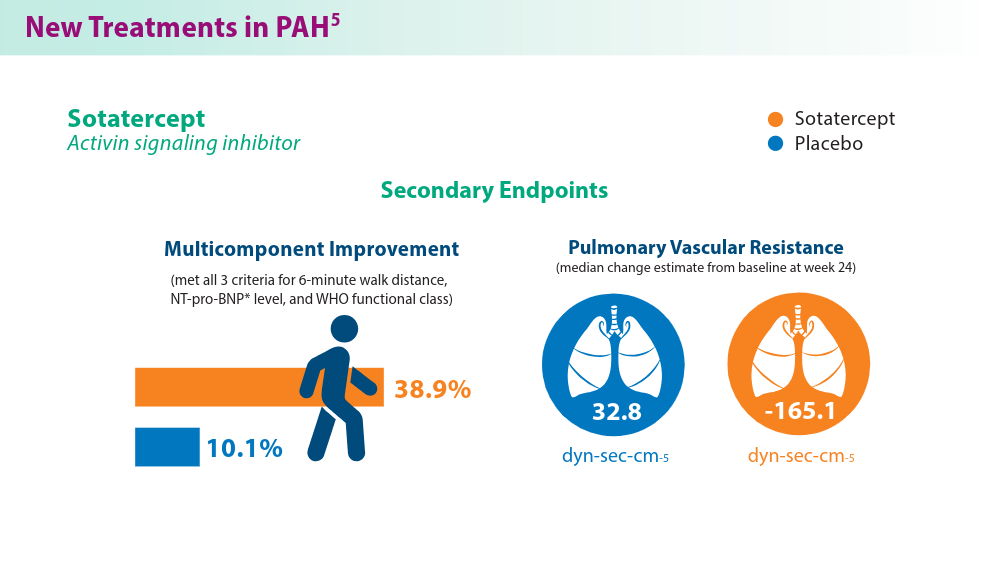

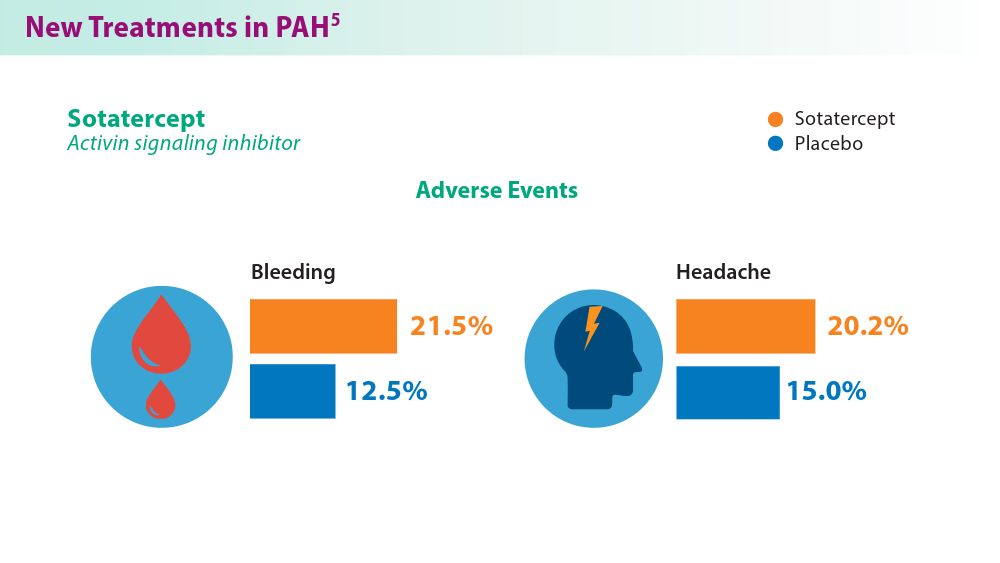

- Hoeper MM, Badesch DB, Ghofrani HA, et al; for the STELLAR Trial Investigators. Phase 3 trial of sotatercept for treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(16):1478-1490. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2213558

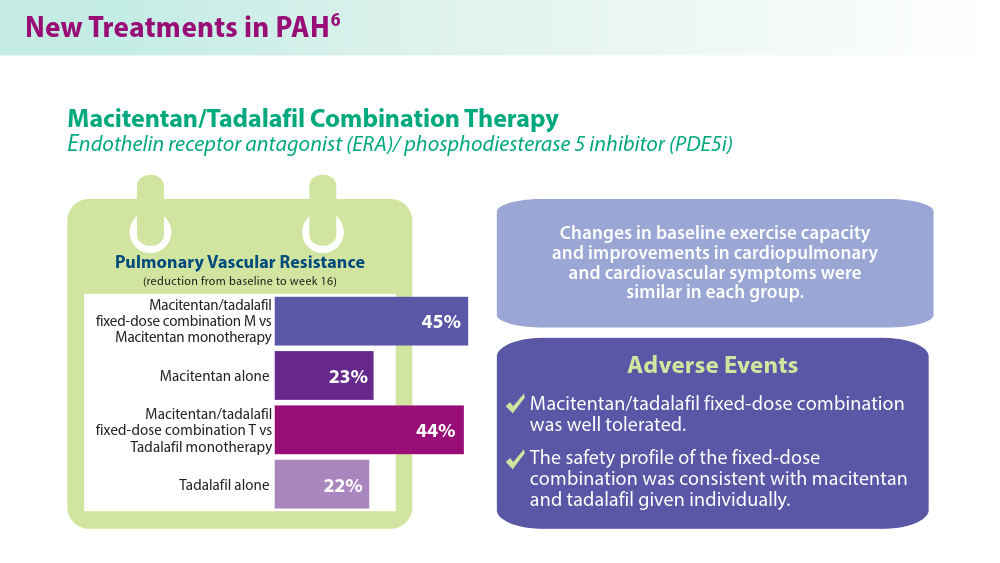

- Grünig E, Jansa P, Fan F, et al. Randomized trial of macitentan/tadalafil single-tablet combination therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83(4):473-484. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.10.045

- Higuchi S, Horinouchi H, Aoki T, et al. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty in the management of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Radiographics. 2022;42(6):1881-1896. doi:10.1148/rg.210102

- Cullivan S, Gaine S, Sitbon O. New trends in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. 2023;32(167):220211. doi:10.1183/16000617.0211-2022

- Mocumbi A, Humbert M, Saxena A, et al. Pulmonary hypertension [published correction appears in Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10(1):5]. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10(1):1. doi:10.1038/s41572-023-00486-7

- Lang IM, Palazzini M. The burden of comorbidities in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2019;21(suppl K):K21-K28. doi:10.1093/ eurheartj/suz205

- Yan L, Zhao Z, Zhao Q, et al. The clinical characteristics of patients with pulmonary hypertension combined with obstructive sleep apnoea. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21(1):378. doi:10.1186/s12890-021-01755-5

- Hoeper MM, Badesch DB, Ghofrani HA, et al; for the STELLAR Trial Investigators. Phase 3 trial of sotatercept for treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(16):1478-1490. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2213558

- Grünig E, Jansa P, Fan F, et al. Randomized trial of macitentan/tadalafil single-tablet combination therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83(4):473-484. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.10.045

- Higuchi S, Horinouchi H, Aoki T, et al. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty in the management of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Radiographics. 2022;42(6):1881-1896. doi:10.1148/rg.210102

- Cullivan S, Gaine S, Sitbon O. New trends in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. 2023;32(167):220211. doi:10.1183/16000617.0211-2022

- Mocumbi A, Humbert M, Saxena A, et al. Pulmonary hypertension [published correction appears in Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10(1):5]. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10(1):1. doi:10.1038/s41572-023-00486-7

- Lang IM, Palazzini M. The burden of comorbidities in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2019;21(suppl K):K21-K28. doi:10.1093/ eurheartj/suz205

- Yan L, Zhao Z, Zhao Q, et al. The clinical characteristics of patients with pulmonary hypertension combined with obstructive sleep apnoea. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21(1):378. doi:10.1186/s12890-021-01755-5

- Hoeper MM, Badesch DB, Ghofrani HA, et al; for the STELLAR Trial Investigators. Phase 3 trial of sotatercept for treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(16):1478-1490. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2213558

- Grünig E, Jansa P, Fan F, et al. Randomized trial of macitentan/tadalafil single-tablet combination therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83(4):473-484. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.10.045

- Higuchi S, Horinouchi H, Aoki T, et al. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty in the management of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Radiographics. 2022;42(6):1881-1896. doi:10.1148/rg.210102

Advancements in nutritional management for critically ill patients

CRITICAL CARE NETWORK

Nonrespiratory Critical Care Section

Nutrition plays an important role in the management and recovery of critically ill patients admitted to the ICU. Major guidelines recommend that critically ill patients should receive 1.2 to 2.0 g/kg/day of protein, with an emphasis on early (within 48 hours of ICU admission) enteral nutrition.1-3

In a randomized controlled trial involving 173 critically ill patients who stayed in the ICU in Zhejiang, China, Wang and colleagues studied the impact of early high protein intake (1.5 g/kg/day vs 0.8 g/kg/day).4 The primary outcome of 28-day mortality was lower among the high protein intake group (8.14% vs 19.54%). Still, this intention-to-treat analysis did not reach a statistical significance (P = .051). However, a time-to-event analysis using the Cox proportional hazard model showed that the high protein intake group had a significantly lower 28-day mortality rate, shorter ICU stays, and improved nutritional status, particularly in patients with sepsis (P = .045).