User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Metformin fails as early COVID-19 treatment but shows potential

Neither metformin, ivermectin, or fluvoxamine had any impact on reducing disease severity, hospitalization, or death from COVID-19, according to results from more than 1,000 overweight or obese adult patients in the COVID-OUT randomized trial.

However, metformin showed some potential in a secondary analysis.

Early treatment to prevent severe disease remains a goal in managing the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, and biophysical modeling suggested that metformin, ivermectin, and fluvoxamine may serve as antivirals to help reduce severe disease in COVID-19 patients, Carolyn T. Bramante, MD, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues wrote.

“We started enrolling patients at the end of December 2020,” Dr. Bramante said in an interview. “At that time, even though vaccine data were coming out, we thought it was important to test early outpatient treatment with widely available safe medications with no interactions, because the virus would evolve and vaccine availability may be limited.”

In a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers used a two-by-three factorial design to test the ability of metformin, ivermectin, and fluvoxamine to prevent severe COVID-19 infection in nonhospitalized adults aged 30-85 years. A total of 1,431 patients at six U.S. sites were enrolled within 3 days of a confirmed infection and less than 7 days after the start of symptoms, then randomized to one of six groups: metformin plus fluvoxamine; metformin plus ivermectin; metformin plus placebo; placebo plus fluvoxamine; placebo plus ivermectin; and placebo plus placebo.

A total of 1,323 patients were included in the primary analysis. The median age of the patients was 46 years, 56% were female (of whom 6% were pregnant), and all individuals met criteria for overweight or obesity. About half (52%) of the patients had been vaccinated against COVID-19.

The primary endpoint was a composite of hypoxemia, ED visit, hospitalization, or death. The analyses were adjusted for COVID-19 vaccination and other trial medications. Overall, the adjusted odds ratios of any primary event, compared with placebo, was 0.84 for metformin (P = .19), 1.05 for ivermectin (P = .78), and 0.94 for fluvoxamine (P = .75).

The researchers also conducted a prespecified secondary analysis of components of the primary endpoint. In this analysis, the aORs for an ED visit, hospitalization, or death was 0.58 for metformin, 1.39 for ivermectin, and 1.17 for fluvoxamine. The aORs for hospitalization or death were 0.47, 0.73, and 1.11 for metformin, ivermectin, and fluvoxamine, respectively. No medication-related serious adverse events were reported with any of the drugs during the study period.

The possible benefit for prevention of severe COVID-19 with metformin was a prespecified secondary endpoint, and therefore not definitive until more research has been completed, the researchers said. Metformin has demonstrated anti-inflammatory actions in previous studies, and has shown protective effects against COVID-19 lung injury in animal studies.

Previous observational studies also have shown an association between metformin use and less severe COVID-19 in patients already taking metformin. “The proposed mechanisms of action against COVID-19 for metformin include anti-inflammatory and antiviral activity and the prevention of hyperglycemia during acute illness,” they added.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the population age range and focus on overweight and obese patients, which may limit generalizability, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the disproportionately small percentage of Black and Latino patients and the potential lack of accuracy in identifying hypoxemia via home oxygen monitors.

However, the results demonstrate that none of the three repurposed drugs – metformin, ivermectin, and fluvoxamine – prevented primary events or reduced symptom severity in COVID-19, compared with placebos, the researchers concluded.

“Metformin had several streams of evidence supporting its use: in vitro, in silico [computer modeled], observational, and in tissue. We were not surprised to see that it reduced emergency department visits, hospitalization, and death,” Dr. Bramante said in an interview.

The take-home message for clinicians is to continue to look to guideline committees for direction on COVID-19 treatments, but to continue to consider metformin along with other treatments, she said.

“All research should be replicated, whether the primary outcome is positive or negative,” Dr. Bramante emphasized. “In this case, when our positive outcome was negative and secondary outcome was positive, a confirmatory trial for metformin is particularly important.”

Ineffective drugs are inefficient use of resources

“The results of the COVID-OUT trial provide persuasive additional data that increase the confidence and degree of certainty that fluvoxamine and ivermectin are not effective in preventing progression to severe disease,” wrote Salim S. Abdool Karim, MB, and Nikita Devnarain, PhD, of the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa, Durban, in an accompanying editorial.

At the start of the study, in 2020, data on the use of the three drugs to prevent severe COVID-19 were “either unavailable or equivocal,” they said. Since then, accumulating data support the current study findings of the nonefficacy of ivermectin and fluvoxamine, and the World Health Organization has advised against their use for COVID-19, although the WHO has not provided guidance for the use of metformin.

The authors called on clinicians to stop using ivermectin and fluvoxamine to treat COVID-19 patients.

“With respect to clinical decisions about COVID-19 treatment, some drug choices, especially those that have negative [World Health Organization] recommendations, are clearly wrong,” they wrote. “In keeping with evidence-based medical practice, patients with COVID-19 must be treated with efficacious medications; they deserve nothing less.”

The study was supported by the Parsemus Foundation, Rainwater Charitable Foundation, Fast Grants, and UnitedHealth Group Foundation. The fluvoxamine placebo tablets were donated by Apotex Pharmaceuticals. The ivermectin placebo and active tablets were donated by Edenbridge Pharmaceuticals. Lead author Dr. Bramante was supported the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Abdool Karim serves as a member of the World Health Organization Science Council. Dr. Devnarain had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Neither metformin, ivermectin, or fluvoxamine had any impact on reducing disease severity, hospitalization, or death from COVID-19, according to results from more than 1,000 overweight or obese adult patients in the COVID-OUT randomized trial.

However, metformin showed some potential in a secondary analysis.

Early treatment to prevent severe disease remains a goal in managing the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, and biophysical modeling suggested that metformin, ivermectin, and fluvoxamine may serve as antivirals to help reduce severe disease in COVID-19 patients, Carolyn T. Bramante, MD, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues wrote.

“We started enrolling patients at the end of December 2020,” Dr. Bramante said in an interview. “At that time, even though vaccine data were coming out, we thought it was important to test early outpatient treatment with widely available safe medications with no interactions, because the virus would evolve and vaccine availability may be limited.”

In a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers used a two-by-three factorial design to test the ability of metformin, ivermectin, and fluvoxamine to prevent severe COVID-19 infection in nonhospitalized adults aged 30-85 years. A total of 1,431 patients at six U.S. sites were enrolled within 3 days of a confirmed infection and less than 7 days after the start of symptoms, then randomized to one of six groups: metformin plus fluvoxamine; metformin plus ivermectin; metformin plus placebo; placebo plus fluvoxamine; placebo plus ivermectin; and placebo plus placebo.

A total of 1,323 patients were included in the primary analysis. The median age of the patients was 46 years, 56% were female (of whom 6% were pregnant), and all individuals met criteria for overweight or obesity. About half (52%) of the patients had been vaccinated against COVID-19.

The primary endpoint was a composite of hypoxemia, ED visit, hospitalization, or death. The analyses were adjusted for COVID-19 vaccination and other trial medications. Overall, the adjusted odds ratios of any primary event, compared with placebo, was 0.84 for metformin (P = .19), 1.05 for ivermectin (P = .78), and 0.94 for fluvoxamine (P = .75).

The researchers also conducted a prespecified secondary analysis of components of the primary endpoint. In this analysis, the aORs for an ED visit, hospitalization, or death was 0.58 for metformin, 1.39 for ivermectin, and 1.17 for fluvoxamine. The aORs for hospitalization or death were 0.47, 0.73, and 1.11 for metformin, ivermectin, and fluvoxamine, respectively. No medication-related serious adverse events were reported with any of the drugs during the study period.

The possible benefit for prevention of severe COVID-19 with metformin was a prespecified secondary endpoint, and therefore not definitive until more research has been completed, the researchers said. Metformin has demonstrated anti-inflammatory actions in previous studies, and has shown protective effects against COVID-19 lung injury in animal studies.

Previous observational studies also have shown an association between metformin use and less severe COVID-19 in patients already taking metformin. “The proposed mechanisms of action against COVID-19 for metformin include anti-inflammatory and antiviral activity and the prevention of hyperglycemia during acute illness,” they added.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the population age range and focus on overweight and obese patients, which may limit generalizability, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the disproportionately small percentage of Black and Latino patients and the potential lack of accuracy in identifying hypoxemia via home oxygen monitors.

However, the results demonstrate that none of the three repurposed drugs – metformin, ivermectin, and fluvoxamine – prevented primary events or reduced symptom severity in COVID-19, compared with placebos, the researchers concluded.

“Metformin had several streams of evidence supporting its use: in vitro, in silico [computer modeled], observational, and in tissue. We were not surprised to see that it reduced emergency department visits, hospitalization, and death,” Dr. Bramante said in an interview.

The take-home message for clinicians is to continue to look to guideline committees for direction on COVID-19 treatments, but to continue to consider metformin along with other treatments, she said.

“All research should be replicated, whether the primary outcome is positive or negative,” Dr. Bramante emphasized. “In this case, when our positive outcome was negative and secondary outcome was positive, a confirmatory trial for metformin is particularly important.”

Ineffective drugs are inefficient use of resources

“The results of the COVID-OUT trial provide persuasive additional data that increase the confidence and degree of certainty that fluvoxamine and ivermectin are not effective in preventing progression to severe disease,” wrote Salim S. Abdool Karim, MB, and Nikita Devnarain, PhD, of the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa, Durban, in an accompanying editorial.

At the start of the study, in 2020, data on the use of the three drugs to prevent severe COVID-19 were “either unavailable or equivocal,” they said. Since then, accumulating data support the current study findings of the nonefficacy of ivermectin and fluvoxamine, and the World Health Organization has advised against their use for COVID-19, although the WHO has not provided guidance for the use of metformin.

The authors called on clinicians to stop using ivermectin and fluvoxamine to treat COVID-19 patients.

“With respect to clinical decisions about COVID-19 treatment, some drug choices, especially those that have negative [World Health Organization] recommendations, are clearly wrong,” they wrote. “In keeping with evidence-based medical practice, patients with COVID-19 must be treated with efficacious medications; they deserve nothing less.”

The study was supported by the Parsemus Foundation, Rainwater Charitable Foundation, Fast Grants, and UnitedHealth Group Foundation. The fluvoxamine placebo tablets were donated by Apotex Pharmaceuticals. The ivermectin placebo and active tablets were donated by Edenbridge Pharmaceuticals. Lead author Dr. Bramante was supported the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Abdool Karim serves as a member of the World Health Organization Science Council. Dr. Devnarain had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Neither metformin, ivermectin, or fluvoxamine had any impact on reducing disease severity, hospitalization, or death from COVID-19, according to results from more than 1,000 overweight or obese adult patients in the COVID-OUT randomized trial.

However, metformin showed some potential in a secondary analysis.

Early treatment to prevent severe disease remains a goal in managing the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, and biophysical modeling suggested that metformin, ivermectin, and fluvoxamine may serve as antivirals to help reduce severe disease in COVID-19 patients, Carolyn T. Bramante, MD, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues wrote.

“We started enrolling patients at the end of December 2020,” Dr. Bramante said in an interview. “At that time, even though vaccine data were coming out, we thought it was important to test early outpatient treatment with widely available safe medications with no interactions, because the virus would evolve and vaccine availability may be limited.”

In a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers used a two-by-three factorial design to test the ability of metformin, ivermectin, and fluvoxamine to prevent severe COVID-19 infection in nonhospitalized adults aged 30-85 years. A total of 1,431 patients at six U.S. sites were enrolled within 3 days of a confirmed infection and less than 7 days after the start of symptoms, then randomized to one of six groups: metformin plus fluvoxamine; metformin plus ivermectin; metformin plus placebo; placebo plus fluvoxamine; placebo plus ivermectin; and placebo plus placebo.

A total of 1,323 patients were included in the primary analysis. The median age of the patients was 46 years, 56% were female (of whom 6% were pregnant), and all individuals met criteria for overweight or obesity. About half (52%) of the patients had been vaccinated against COVID-19.

The primary endpoint was a composite of hypoxemia, ED visit, hospitalization, or death. The analyses were adjusted for COVID-19 vaccination and other trial medications. Overall, the adjusted odds ratios of any primary event, compared with placebo, was 0.84 for metformin (P = .19), 1.05 for ivermectin (P = .78), and 0.94 for fluvoxamine (P = .75).

The researchers also conducted a prespecified secondary analysis of components of the primary endpoint. In this analysis, the aORs for an ED visit, hospitalization, or death was 0.58 for metformin, 1.39 for ivermectin, and 1.17 for fluvoxamine. The aORs for hospitalization or death were 0.47, 0.73, and 1.11 for metformin, ivermectin, and fluvoxamine, respectively. No medication-related serious adverse events were reported with any of the drugs during the study period.

The possible benefit for prevention of severe COVID-19 with metformin was a prespecified secondary endpoint, and therefore not definitive until more research has been completed, the researchers said. Metformin has demonstrated anti-inflammatory actions in previous studies, and has shown protective effects against COVID-19 lung injury in animal studies.

Previous observational studies also have shown an association between metformin use and less severe COVID-19 in patients already taking metformin. “The proposed mechanisms of action against COVID-19 for metformin include anti-inflammatory and antiviral activity and the prevention of hyperglycemia during acute illness,” they added.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the population age range and focus on overweight and obese patients, which may limit generalizability, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the disproportionately small percentage of Black and Latino patients and the potential lack of accuracy in identifying hypoxemia via home oxygen monitors.

However, the results demonstrate that none of the three repurposed drugs – metformin, ivermectin, and fluvoxamine – prevented primary events or reduced symptom severity in COVID-19, compared with placebos, the researchers concluded.

“Metformin had several streams of evidence supporting its use: in vitro, in silico [computer modeled], observational, and in tissue. We were not surprised to see that it reduced emergency department visits, hospitalization, and death,” Dr. Bramante said in an interview.

The take-home message for clinicians is to continue to look to guideline committees for direction on COVID-19 treatments, but to continue to consider metformin along with other treatments, she said.

“All research should be replicated, whether the primary outcome is positive or negative,” Dr. Bramante emphasized. “In this case, when our positive outcome was negative and secondary outcome was positive, a confirmatory trial for metformin is particularly important.”

Ineffective drugs are inefficient use of resources

“The results of the COVID-OUT trial provide persuasive additional data that increase the confidence and degree of certainty that fluvoxamine and ivermectin are not effective in preventing progression to severe disease,” wrote Salim S. Abdool Karim, MB, and Nikita Devnarain, PhD, of the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa, Durban, in an accompanying editorial.

At the start of the study, in 2020, data on the use of the three drugs to prevent severe COVID-19 were “either unavailable or equivocal,” they said. Since then, accumulating data support the current study findings of the nonefficacy of ivermectin and fluvoxamine, and the World Health Organization has advised against their use for COVID-19, although the WHO has not provided guidance for the use of metformin.

The authors called on clinicians to stop using ivermectin and fluvoxamine to treat COVID-19 patients.

“With respect to clinical decisions about COVID-19 treatment, some drug choices, especially those that have negative [World Health Organization] recommendations, are clearly wrong,” they wrote. “In keeping with evidence-based medical practice, patients with COVID-19 must be treated with efficacious medications; they deserve nothing less.”

The study was supported by the Parsemus Foundation, Rainwater Charitable Foundation, Fast Grants, and UnitedHealth Group Foundation. The fluvoxamine placebo tablets were donated by Apotex Pharmaceuticals. The ivermectin placebo and active tablets were donated by Edenbridge Pharmaceuticals. Lead author Dr. Bramante was supported the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Abdool Karim serves as a member of the World Health Organization Science Council. Dr. Devnarain had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

No fish can escape this net ... of COVID testing

Something about this COVID testing smells fishy

The Chinese have been challenging America’s political and economic hegemony (yes, we did have to look that one up – you’re rude to ask) for some time, but now they’ve gone too far. Are we going to just sit here and let China do something more ridiculous than us in response to COVID? No way!

Here’s the deal: The government of the Chinese coastal city of Xiamen has decided that it’s not just the workers on returning fishing boats who have the potential to introduce COVID to the rest of the population. The fish also present a problem. So when the authorities say that everyone needs to be tested before they can enter the city, they mean everyone.

An employee of the municipal ocean development bureau told local media that “all people in Xiamen City need nucleic acid testing, and the fish catches must be tested as well,” according to the Guardian, which also said that “TV news reports showed officials swabbing the mouths of fish and the underside of crabs.”

In the words of George Takei: “Oh my.”

Hold on there a second, George Takei, because we here in the good old US of A have still got Los Angeles, where COVID testing also has taken a nonhuman turn. The LA County public health department recently announced that pets are now eligible for a free SARS-CoV-2 test through veterinarians and other animal care facilities.

“Our goal is to test many different species of animals including wildlife (deer, bats, raccoons), pets (dogs, cats, hamsters, pocket pets), marine mammals (seals), and more,” Veterinary Public Health announced.

Hegemony restored.

Not even God could save them from worms

The Dark Ages may not have been as dark and violent as many people think, but there’s no denying that life in medieval Europe kind of sucked. The only real alternative to serfdom was a job with the Catholic Church. Medieval friars, for example, lived in stone buildings, had access to fresh fruits and vegetables, and even had latrines and running water. Luxuries compared with the life of the average peasant.

So why then, despite having access to more modern sanitation and amenities, did the friars have so many gut parasites? That’s the question raised by a group of researchers from the University of Cambridge, who conducted a study of 19 medieval friars buried at a local friary (Oh, doesn’t your town have one of those?) and 25 local people buried at a nonreligious cemetery during a similar time period. Of those 19 friars, 11 were infected with worms and parasites, compared with just 8 of 25 townspeople.

This doesn’t make a lot of sense. The friars had a good life by old-time standards: They had basic sanitation down and a solid diet. These things should lead to a healthier population. The problem, the researchers found, is two pronged and a vicious cycle. First off, the friars had plenty of fresh food, but they used human feces to fertilize their produce. There’s a reason modern practice for human waste fertilization is to let the waste compost for 6 months: The waiting period allows the parasites a chance to kindly die off, which prevents reinfection.

Secondly, the friars’ diet of fresh fruits and vegetables mixed together into a salad, while appealing to our modern-day sensibilities, was not a great choice. By comparison, laypeople tended to eat a boiled mishmash of whatever they could find, and while that’s kind of gross, the key here is that their food was cooked. And heat kills parasites. The uncooked salads did no such thing, so the monks ate infected food, expelled infected poop, and grew more infected food with their infected poop.

Once the worms arrived, they never left, making them the worst kind of house guest. Read the room, worms, take your dinner and move on. You don’t have to go home, but you can’t stay here.

What’s a shared genotype between friends?

Do you find it hard to tell the difference between Katy Perry and Zooey Deschanel? They look alike, but they’re not related. Or are they? According to new research, people who look and act very similar but are not related may share DNA.

“Our study provides a rare insight into human likeness by showing that people with extreme look-alike faces share common genotypes, whereas they are discordant at the epigenome and microbiome levels,” senior author Manel Esteller of the Josep Carreras Leukemia Research Institute in Barcelona said in a written statement. “Genomics clusters them together, and the rest sets them apart.”

The Internet has been a great source in being able to find look-alikes. The research team found photos of doppelgangers photographed by François Brunelle, a Canadian artist. Using facial recognition algorithms, the investigators were able to measure likeness between the each pair of look-alikes. The participants also completed a questionnaire about lifestyle and provided a saliva sample.

The results showed that the look-alikes had similar genotypes but different DNA methylation and microbiome landscapes. The look-alikes also seemed to have similarities in weight, height, and behaviors such as smoking, proving that doppelgangers not only look alike but also share common interests.

Next time someone tells you that you look like their best friend Steve, you won’t have to wonder much what Steve is like.

The secret to a good relationship? It’s a secret

Strong relationships are built on honesty and trust, right? Being open with your partner and/or friends is usually a good practice for keeping the relationship healthy, but the latest evidence suggests that maybe you shouldn’t share everything.

According to the first known study on the emotional, behavioral, and relational aspect of consumer behavior, not disclosing certain purchases to your partner can actually be a good thing for the relationship. How? Well, it all has to do with guilt.

In a series of studies, the researchers asked couples about their secret consumptions. The most commonly hidden thing by far was a product (65%).

“We found that 90% of people have recently kept everyday consumer behaviors a secret from a close other – like a friend or spouse – even though they also report that they don’t think their partner would care if they knew about it,” Kelley Gullo Wight, one of the study’s two lead authors, said in a written statement.

Keeping a hidden stash of chocolate produces guilt, which the researchers found to be the key factor, making the perpetrator want to do more in the relationship to ease that sense of betrayal or dishonesty. They called it a “greater relationship investment,” meaning the person is more likely to do a little extra for their partner, like shell out more money for the next anniversary gift or yield to watching their partner’s favorite program.

So don’t feel too bad about that secret Amazon purchase. As long as the other person doesn’t see the box, nobody has to know. Your relationship can only improve.

Something about this COVID testing smells fishy

The Chinese have been challenging America’s political and economic hegemony (yes, we did have to look that one up – you’re rude to ask) for some time, but now they’ve gone too far. Are we going to just sit here and let China do something more ridiculous than us in response to COVID? No way!

Here’s the deal: The government of the Chinese coastal city of Xiamen has decided that it’s not just the workers on returning fishing boats who have the potential to introduce COVID to the rest of the population. The fish also present a problem. So when the authorities say that everyone needs to be tested before they can enter the city, they mean everyone.

An employee of the municipal ocean development bureau told local media that “all people in Xiamen City need nucleic acid testing, and the fish catches must be tested as well,” according to the Guardian, which also said that “TV news reports showed officials swabbing the mouths of fish and the underside of crabs.”

In the words of George Takei: “Oh my.”

Hold on there a second, George Takei, because we here in the good old US of A have still got Los Angeles, where COVID testing also has taken a nonhuman turn. The LA County public health department recently announced that pets are now eligible for a free SARS-CoV-2 test through veterinarians and other animal care facilities.

“Our goal is to test many different species of animals including wildlife (deer, bats, raccoons), pets (dogs, cats, hamsters, pocket pets), marine mammals (seals), and more,” Veterinary Public Health announced.

Hegemony restored.

Not even God could save them from worms

The Dark Ages may not have been as dark and violent as many people think, but there’s no denying that life in medieval Europe kind of sucked. The only real alternative to serfdom was a job with the Catholic Church. Medieval friars, for example, lived in stone buildings, had access to fresh fruits and vegetables, and even had latrines and running water. Luxuries compared with the life of the average peasant.

So why then, despite having access to more modern sanitation and amenities, did the friars have so many gut parasites? That’s the question raised by a group of researchers from the University of Cambridge, who conducted a study of 19 medieval friars buried at a local friary (Oh, doesn’t your town have one of those?) and 25 local people buried at a nonreligious cemetery during a similar time period. Of those 19 friars, 11 were infected with worms and parasites, compared with just 8 of 25 townspeople.

This doesn’t make a lot of sense. The friars had a good life by old-time standards: They had basic sanitation down and a solid diet. These things should lead to a healthier population. The problem, the researchers found, is two pronged and a vicious cycle. First off, the friars had plenty of fresh food, but they used human feces to fertilize their produce. There’s a reason modern practice for human waste fertilization is to let the waste compost for 6 months: The waiting period allows the parasites a chance to kindly die off, which prevents reinfection.

Secondly, the friars’ diet of fresh fruits and vegetables mixed together into a salad, while appealing to our modern-day sensibilities, was not a great choice. By comparison, laypeople tended to eat a boiled mishmash of whatever they could find, and while that’s kind of gross, the key here is that their food was cooked. And heat kills parasites. The uncooked salads did no such thing, so the monks ate infected food, expelled infected poop, and grew more infected food with their infected poop.

Once the worms arrived, they never left, making them the worst kind of house guest. Read the room, worms, take your dinner and move on. You don’t have to go home, but you can’t stay here.

What’s a shared genotype between friends?

Do you find it hard to tell the difference between Katy Perry and Zooey Deschanel? They look alike, but they’re not related. Or are they? According to new research, people who look and act very similar but are not related may share DNA.

“Our study provides a rare insight into human likeness by showing that people with extreme look-alike faces share common genotypes, whereas they are discordant at the epigenome and microbiome levels,” senior author Manel Esteller of the Josep Carreras Leukemia Research Institute in Barcelona said in a written statement. “Genomics clusters them together, and the rest sets them apart.”

The Internet has been a great source in being able to find look-alikes. The research team found photos of doppelgangers photographed by François Brunelle, a Canadian artist. Using facial recognition algorithms, the investigators were able to measure likeness between the each pair of look-alikes. The participants also completed a questionnaire about lifestyle and provided a saliva sample.

The results showed that the look-alikes had similar genotypes but different DNA methylation and microbiome landscapes. The look-alikes also seemed to have similarities in weight, height, and behaviors such as smoking, proving that doppelgangers not only look alike but also share common interests.

Next time someone tells you that you look like their best friend Steve, you won’t have to wonder much what Steve is like.

The secret to a good relationship? It’s a secret

Strong relationships are built on honesty and trust, right? Being open with your partner and/or friends is usually a good practice for keeping the relationship healthy, but the latest evidence suggests that maybe you shouldn’t share everything.

According to the first known study on the emotional, behavioral, and relational aspect of consumer behavior, not disclosing certain purchases to your partner can actually be a good thing for the relationship. How? Well, it all has to do with guilt.

In a series of studies, the researchers asked couples about their secret consumptions. The most commonly hidden thing by far was a product (65%).

“We found that 90% of people have recently kept everyday consumer behaviors a secret from a close other – like a friend or spouse – even though they also report that they don’t think their partner would care if they knew about it,” Kelley Gullo Wight, one of the study’s two lead authors, said in a written statement.

Keeping a hidden stash of chocolate produces guilt, which the researchers found to be the key factor, making the perpetrator want to do more in the relationship to ease that sense of betrayal or dishonesty. They called it a “greater relationship investment,” meaning the person is more likely to do a little extra for their partner, like shell out more money for the next anniversary gift or yield to watching their partner’s favorite program.

So don’t feel too bad about that secret Amazon purchase. As long as the other person doesn’t see the box, nobody has to know. Your relationship can only improve.

Something about this COVID testing smells fishy

The Chinese have been challenging America’s political and economic hegemony (yes, we did have to look that one up – you’re rude to ask) for some time, but now they’ve gone too far. Are we going to just sit here and let China do something more ridiculous than us in response to COVID? No way!

Here’s the deal: The government of the Chinese coastal city of Xiamen has decided that it’s not just the workers on returning fishing boats who have the potential to introduce COVID to the rest of the population. The fish also present a problem. So when the authorities say that everyone needs to be tested before they can enter the city, they mean everyone.

An employee of the municipal ocean development bureau told local media that “all people in Xiamen City need nucleic acid testing, and the fish catches must be tested as well,” according to the Guardian, which also said that “TV news reports showed officials swabbing the mouths of fish and the underside of crabs.”

In the words of George Takei: “Oh my.”

Hold on there a second, George Takei, because we here in the good old US of A have still got Los Angeles, where COVID testing also has taken a nonhuman turn. The LA County public health department recently announced that pets are now eligible for a free SARS-CoV-2 test through veterinarians and other animal care facilities.

“Our goal is to test many different species of animals including wildlife (deer, bats, raccoons), pets (dogs, cats, hamsters, pocket pets), marine mammals (seals), and more,” Veterinary Public Health announced.

Hegemony restored.

Not even God could save them from worms

The Dark Ages may not have been as dark and violent as many people think, but there’s no denying that life in medieval Europe kind of sucked. The only real alternative to serfdom was a job with the Catholic Church. Medieval friars, for example, lived in stone buildings, had access to fresh fruits and vegetables, and even had latrines and running water. Luxuries compared with the life of the average peasant.

So why then, despite having access to more modern sanitation and amenities, did the friars have so many gut parasites? That’s the question raised by a group of researchers from the University of Cambridge, who conducted a study of 19 medieval friars buried at a local friary (Oh, doesn’t your town have one of those?) and 25 local people buried at a nonreligious cemetery during a similar time period. Of those 19 friars, 11 were infected with worms and parasites, compared with just 8 of 25 townspeople.

This doesn’t make a lot of sense. The friars had a good life by old-time standards: They had basic sanitation down and a solid diet. These things should lead to a healthier population. The problem, the researchers found, is two pronged and a vicious cycle. First off, the friars had plenty of fresh food, but they used human feces to fertilize their produce. There’s a reason modern practice for human waste fertilization is to let the waste compost for 6 months: The waiting period allows the parasites a chance to kindly die off, which prevents reinfection.

Secondly, the friars’ diet of fresh fruits and vegetables mixed together into a salad, while appealing to our modern-day sensibilities, was not a great choice. By comparison, laypeople tended to eat a boiled mishmash of whatever they could find, and while that’s kind of gross, the key here is that their food was cooked. And heat kills parasites. The uncooked salads did no such thing, so the monks ate infected food, expelled infected poop, and grew more infected food with their infected poop.

Once the worms arrived, they never left, making them the worst kind of house guest. Read the room, worms, take your dinner and move on. You don’t have to go home, but you can’t stay here.

What’s a shared genotype between friends?

Do you find it hard to tell the difference between Katy Perry and Zooey Deschanel? They look alike, but they’re not related. Or are they? According to new research, people who look and act very similar but are not related may share DNA.

“Our study provides a rare insight into human likeness by showing that people with extreme look-alike faces share common genotypes, whereas they are discordant at the epigenome and microbiome levels,” senior author Manel Esteller of the Josep Carreras Leukemia Research Institute in Barcelona said in a written statement. “Genomics clusters them together, and the rest sets them apart.”

The Internet has been a great source in being able to find look-alikes. The research team found photos of doppelgangers photographed by François Brunelle, a Canadian artist. Using facial recognition algorithms, the investigators were able to measure likeness between the each pair of look-alikes. The participants also completed a questionnaire about lifestyle and provided a saliva sample.

The results showed that the look-alikes had similar genotypes but different DNA methylation and microbiome landscapes. The look-alikes also seemed to have similarities in weight, height, and behaviors such as smoking, proving that doppelgangers not only look alike but also share common interests.

Next time someone tells you that you look like their best friend Steve, you won’t have to wonder much what Steve is like.

The secret to a good relationship? It’s a secret

Strong relationships are built on honesty and trust, right? Being open with your partner and/or friends is usually a good practice for keeping the relationship healthy, but the latest evidence suggests that maybe you shouldn’t share everything.

According to the first known study on the emotional, behavioral, and relational aspect of consumer behavior, not disclosing certain purchases to your partner can actually be a good thing for the relationship. How? Well, it all has to do with guilt.

In a series of studies, the researchers asked couples about their secret consumptions. The most commonly hidden thing by far was a product (65%).

“We found that 90% of people have recently kept everyday consumer behaviors a secret from a close other – like a friend or spouse – even though they also report that they don’t think their partner would care if they knew about it,” Kelley Gullo Wight, one of the study’s two lead authors, said in a written statement.

Keeping a hidden stash of chocolate produces guilt, which the researchers found to be the key factor, making the perpetrator want to do more in the relationship to ease that sense of betrayal or dishonesty. They called it a “greater relationship investment,” meaning the person is more likely to do a little extra for their partner, like shell out more money for the next anniversary gift or yield to watching their partner’s favorite program.

So don’t feel too bad about that secret Amazon purchase. As long as the other person doesn’t see the box, nobody has to know. Your relationship can only improve.

Are we up the creek without a paddle? What COVID, monkeypox, and nature are trying to tell us

Monkeypox. Polio. Covid. A quick glance at the news on any given day seems to indicate that outbreaks, epidemics, and perhaps even pandemics are increasing in frequency.

Granted, these types of events are hardly new; from the plagues of the 5th and 13th centuries to the Spanish flu in the 20th century and SARS-CoV-2 today, they’ve been with us from time immemorial.

What appears to be different, however, is not their frequency, but their intensity, with research reinforcing that we may be facing unique challenges and smaller windows to intervene as we move forward.

Findings from a modeling study, published in 2021 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, underscore that without effective intervention, the probability of extreme events like COVID-19 will likely increase threefold in the coming decades.

Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, told this news organization.

“It’s all been based on some unusual cluster of cases that were causing severe disease and overwhelming local authorities. So often, like Indiana Jones, somebody got dispatched to deal with an outbreak,” Dr. Adalja said.

In a perfect post-COVID world, government bodies, scientists, clinicians, and others would cross silos to coordinate pandemic prevention, not just preparedness. The public would trust those who carry the title “public health” in their daily responsibilities, and in turn, public health experts would get back to their core responsibility – infectious disease preparedness – the role they were initially assigned following Europe’s Black Death during the 14th century. Instead, the world finds itself at a crossroads, with emerging and reemerging infectious disease outbreaks that on the surface appear to arise haphazardly but in reality are the result of decades of reaction and containment policies aimed at putting out fires, not addressing their cause.

Dr. Adalja noted that only when the threat of biological weapons became a reality in the mid-2000s was there a realization that economies of scale could be exploited by merging interests and efforts to develop health security medical countermeasures. For example, it encouraged governments to more closely integrate agencies like the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority and infectious disease research organizations and individuals.

Still, while significant strides have been made in certain areas, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has revealed substantial weaknesses remaining in public and private health systems, as well as major gaps in infectious disease preparedness.

The role of spillover events

No matter whom you ask, scientists, public health and conservation experts, and infectious disease clinicians all point to one of the most important threats to human health. As Walt Kelly’s Pogo famously put it, “We have met the enemy, and he is us.”

“The reason why these outbreaks of novel infectious diseases are increasingly occurring is because of human-driven environmental change, particularly land use, unsafe practices when raising farmed animals, and commercial wildlife markets,” Neil M. Vora, MD, a physician specializing in pandemic prevention at Conservation International and a former Centers for Disease Control and Prevention epidemic intelligence officer, said in an interview.

In fact, more than 60% of emerging infections and diseases are due to these “spillover events” (zoonotic spillover) that occur when pathogens that commonly circulate in wildlife jump over to new, human hosts.

Several examples come to mind.

COVID-19 may have begun as an enzootic virus from two undetermined animals, using the Huanan Seafood Market as a possible intermediate reservoir, according to a July 26 preprint in the journal Science.

Likewise, while the Ebola virus was originally attributed to deforestation efforts to create palm oil (which allowed fruit bat carriers to transfer the virus to humans), recent research suggests that bats dwelling in the walls of human dwellings and hospitals are responsible for the 2018 outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

(Incidentally, just this week, a new Ebola case was confirmed in Eastern Congo, and it has been genetically linked to the previous outbreak, despite that outbreak having been declared over in early July.)

“When we clear forests, we create opportunities for humans to live alongside the forest edge and displace wildlife. There’s evidence that shows when [these] biodiverse areas are cleared, specialist species that evolved to live in the forests first start to disappear, whereas generalist species – rodents and bats – continue to survive and are able to carry pathogens that can be passed on to humans,” Dr. Vora explained.

So far, China’s outbreak of the novel Langya henipavirus is believed to have spread (either directly or indirectly) by rodents and shrews, according to reports from public health authorities like the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, which is currently monitoring the situation.

Yet, an overreliance on surveillance and containment only perpetuates what Dr. Vora says are cycles of panic and neglect.

“We saw it with Ebola in 2015, in 2016 to 2017 with Zika, you see it with tuberculosis, with sexually transmitted infections, and with COVID. You have policymakers working on solutions, and once they think that they’ve fixed the problem, they’re going to move on to the next crisis.”

It’s also a question of equity.

Reports detailing the reemergence of monkeypox in Nigeria in 2017 were largely ignored, despite the fact that the United States assisted in diagnosing an early case in an 11-year-old boy. At the time, it was clear that the virus was spreading by human-to-human transmission versus animal-to-human transmission, something that had not been seen previously.

“The current model [is] waiting for pathogens to spill over and then [continuing] to spread signals that rich countries are tolerant of these outbreaks so long as they don’t grow into epidemics or pandemics,” Dr. Vora said.

This model is clearly broken; roughly 5 years after Nigeria reported the resurgence of monkeypox, the United States has more than 14,000 confirmed cases, which represents more than a quarter of the total number of cases reported worldwide.

Public health on the brink

I’s difficult to imagine a future without outbreaks and more pandemics, and if experts are to be believed, we are ill-prepared.

“I think that we are in a situation where this is a major threat, and people have become complacent about it,” said Dr. Adalja, who noted that we should be asking ourselves if the “government is actually in a position to be able to respond in a way that we need them to or is [that response] tied up in bureaucracy and inefficiency?”

COVID-19 should have been seen as a wake-up call, and many of those deaths were preventable. “With monkeypox, they’re faltering; it should have been a layup, not a disaster,” he emphasized.

Ellen Eaton, MD, associate professor of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, also pointed to the reality that by the time COVID-19 reached North America, the United States had already moved away from the model of the public health department as the epicenter of knowledge, education, awareness, and, ironically, public health.

“Thinking about my community, very few people knew the face and name of our local and state health officers,” she told this news organization.

“There was just this inherent mistrust of these people. If you add in a lot of talking heads, a lot of politicians and messaging from non-experts that countered what was coming out of our public health agencies early, you had this huge disconnect; in the South, it was the perfect storm for vaccine hesitancy.”

At last count, this perfect storm has led to 1.46 million COVID cases and just over 20,000 deaths – many of which were preventable – in Alabama alone.

“In certain parts of America, we were starting with a broken system with limited resources and few providers,” Dr. Eaton explained.

Dr. Eaton said that a lot of fields, not just medicine and public health, have finite resources that have been stretched to capacity by COVID, and now monkeypox, and wondered what was next as we’re headed into autumn and influenza season. But she also mentioned the tremendous implications of climate change on infectious diseases and community health and wellness.

“There’s a tremendous need to have the ability to survey not just humans but also how the disease burden in our environment that is fluctuating with climate change is going to impact communities in really important ways,” Dr. Eaton said.

Upstream prevention

Dr. Vora said he could not agree more and believes that upstream prevention holds the key.

“We have to make sure while there’s tension on this issue that the right solutions are implemented,” he said.

In coming years, postspillover containment strategies – vaccine research and development and strengthening health care surveillance, for example – are likely to become inadequate.

“We saw it with COVID and we are seeing it again with monkeypox,” Dr. Vora said. “We also have to invest further upstream to prevent spillovers in the first place, for example, by addressing deforestation, commercial wildlife markets and trade, [and] infection control when raising farm animals.”

“The thing is, when you invest in those upstream solutions, you are also mitigating climate change and loss of biodiversity. I’m not saying that we should not invest in postspillover containment efforts; we’re never going to contain every spillover. But we also have to invest in prevention,” he added.

In a piece published in Nature, Dr. Vora and his coauthors acknowledge that several international bodies such as the World Health Organization and G7 have invested in initiatives to facilitate coordinated, global responses to climate change, pandemic preparedness, and response. But they point out that these efforts fail to “explicitly address the negative feedback cycle between environmental degradation, wildlife exploitation, and the emergence of pathogens.”

“Environmental conservation is no longer a left-wing fringe issue, it’s moving into public consciousness, and ... it is public health,” Dr. Vora said. “When we destroy nature, we’re destroying our own ability to survive.”

Dr. Adalja, Dr. Vora, and Dr. Eaton report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Monkeypox. Polio. Covid. A quick glance at the news on any given day seems to indicate that outbreaks, epidemics, and perhaps even pandemics are increasing in frequency.

Granted, these types of events are hardly new; from the plagues of the 5th and 13th centuries to the Spanish flu in the 20th century and SARS-CoV-2 today, they’ve been with us from time immemorial.

What appears to be different, however, is not their frequency, but their intensity, with research reinforcing that we may be facing unique challenges and smaller windows to intervene as we move forward.

Findings from a modeling study, published in 2021 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, underscore that without effective intervention, the probability of extreme events like COVID-19 will likely increase threefold in the coming decades.

Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, told this news organization.

“It’s all been based on some unusual cluster of cases that were causing severe disease and overwhelming local authorities. So often, like Indiana Jones, somebody got dispatched to deal with an outbreak,” Dr. Adalja said.

In a perfect post-COVID world, government bodies, scientists, clinicians, and others would cross silos to coordinate pandemic prevention, not just preparedness. The public would trust those who carry the title “public health” in their daily responsibilities, and in turn, public health experts would get back to their core responsibility – infectious disease preparedness – the role they were initially assigned following Europe’s Black Death during the 14th century. Instead, the world finds itself at a crossroads, with emerging and reemerging infectious disease outbreaks that on the surface appear to arise haphazardly but in reality are the result of decades of reaction and containment policies aimed at putting out fires, not addressing their cause.

Dr. Adalja noted that only when the threat of biological weapons became a reality in the mid-2000s was there a realization that economies of scale could be exploited by merging interests and efforts to develop health security medical countermeasures. For example, it encouraged governments to more closely integrate agencies like the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority and infectious disease research organizations and individuals.

Still, while significant strides have been made in certain areas, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has revealed substantial weaknesses remaining in public and private health systems, as well as major gaps in infectious disease preparedness.

The role of spillover events

No matter whom you ask, scientists, public health and conservation experts, and infectious disease clinicians all point to one of the most important threats to human health. As Walt Kelly’s Pogo famously put it, “We have met the enemy, and he is us.”

“The reason why these outbreaks of novel infectious diseases are increasingly occurring is because of human-driven environmental change, particularly land use, unsafe practices when raising farmed animals, and commercial wildlife markets,” Neil M. Vora, MD, a physician specializing in pandemic prevention at Conservation International and a former Centers for Disease Control and Prevention epidemic intelligence officer, said in an interview.

In fact, more than 60% of emerging infections and diseases are due to these “spillover events” (zoonotic spillover) that occur when pathogens that commonly circulate in wildlife jump over to new, human hosts.

Several examples come to mind.

COVID-19 may have begun as an enzootic virus from two undetermined animals, using the Huanan Seafood Market as a possible intermediate reservoir, according to a July 26 preprint in the journal Science.

Likewise, while the Ebola virus was originally attributed to deforestation efforts to create palm oil (which allowed fruit bat carriers to transfer the virus to humans), recent research suggests that bats dwelling in the walls of human dwellings and hospitals are responsible for the 2018 outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

(Incidentally, just this week, a new Ebola case was confirmed in Eastern Congo, and it has been genetically linked to the previous outbreak, despite that outbreak having been declared over in early July.)

“When we clear forests, we create opportunities for humans to live alongside the forest edge and displace wildlife. There’s evidence that shows when [these] biodiverse areas are cleared, specialist species that evolved to live in the forests first start to disappear, whereas generalist species – rodents and bats – continue to survive and are able to carry pathogens that can be passed on to humans,” Dr. Vora explained.

So far, China’s outbreak of the novel Langya henipavirus is believed to have spread (either directly or indirectly) by rodents and shrews, according to reports from public health authorities like the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, which is currently monitoring the situation.

Yet, an overreliance on surveillance and containment only perpetuates what Dr. Vora says are cycles of panic and neglect.

“We saw it with Ebola in 2015, in 2016 to 2017 with Zika, you see it with tuberculosis, with sexually transmitted infections, and with COVID. You have policymakers working on solutions, and once they think that they’ve fixed the problem, they’re going to move on to the next crisis.”

It’s also a question of equity.

Reports detailing the reemergence of monkeypox in Nigeria in 2017 were largely ignored, despite the fact that the United States assisted in diagnosing an early case in an 11-year-old boy. At the time, it was clear that the virus was spreading by human-to-human transmission versus animal-to-human transmission, something that had not been seen previously.

“The current model [is] waiting for pathogens to spill over and then [continuing] to spread signals that rich countries are tolerant of these outbreaks so long as they don’t grow into epidemics or pandemics,” Dr. Vora said.

This model is clearly broken; roughly 5 years after Nigeria reported the resurgence of monkeypox, the United States has more than 14,000 confirmed cases, which represents more than a quarter of the total number of cases reported worldwide.

Public health on the brink

I’s difficult to imagine a future without outbreaks and more pandemics, and if experts are to be believed, we are ill-prepared.

“I think that we are in a situation where this is a major threat, and people have become complacent about it,” said Dr. Adalja, who noted that we should be asking ourselves if the “government is actually in a position to be able to respond in a way that we need them to or is [that response] tied up in bureaucracy and inefficiency?”

COVID-19 should have been seen as a wake-up call, and many of those deaths were preventable. “With monkeypox, they’re faltering; it should have been a layup, not a disaster,” he emphasized.

Ellen Eaton, MD, associate professor of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, also pointed to the reality that by the time COVID-19 reached North America, the United States had already moved away from the model of the public health department as the epicenter of knowledge, education, awareness, and, ironically, public health.

“Thinking about my community, very few people knew the face and name of our local and state health officers,” she told this news organization.

“There was just this inherent mistrust of these people. If you add in a lot of talking heads, a lot of politicians and messaging from non-experts that countered what was coming out of our public health agencies early, you had this huge disconnect; in the South, it was the perfect storm for vaccine hesitancy.”

At last count, this perfect storm has led to 1.46 million COVID cases and just over 20,000 deaths – many of which were preventable – in Alabama alone.

“In certain parts of America, we were starting with a broken system with limited resources and few providers,” Dr. Eaton explained.

Dr. Eaton said that a lot of fields, not just medicine and public health, have finite resources that have been stretched to capacity by COVID, and now monkeypox, and wondered what was next as we’re headed into autumn and influenza season. But she also mentioned the tremendous implications of climate change on infectious diseases and community health and wellness.

“There’s a tremendous need to have the ability to survey not just humans but also how the disease burden in our environment that is fluctuating with climate change is going to impact communities in really important ways,” Dr. Eaton said.

Upstream prevention

Dr. Vora said he could not agree more and believes that upstream prevention holds the key.

“We have to make sure while there’s tension on this issue that the right solutions are implemented,” he said.

In coming years, postspillover containment strategies – vaccine research and development and strengthening health care surveillance, for example – are likely to become inadequate.

“We saw it with COVID and we are seeing it again with monkeypox,” Dr. Vora said. “We also have to invest further upstream to prevent spillovers in the first place, for example, by addressing deforestation, commercial wildlife markets and trade, [and] infection control when raising farm animals.”

“The thing is, when you invest in those upstream solutions, you are also mitigating climate change and loss of biodiversity. I’m not saying that we should not invest in postspillover containment efforts; we’re never going to contain every spillover. But we also have to invest in prevention,” he added.

In a piece published in Nature, Dr. Vora and his coauthors acknowledge that several international bodies such as the World Health Organization and G7 have invested in initiatives to facilitate coordinated, global responses to climate change, pandemic preparedness, and response. But they point out that these efforts fail to “explicitly address the negative feedback cycle between environmental degradation, wildlife exploitation, and the emergence of pathogens.”

“Environmental conservation is no longer a left-wing fringe issue, it’s moving into public consciousness, and ... it is public health,” Dr. Vora said. “When we destroy nature, we’re destroying our own ability to survive.”

Dr. Adalja, Dr. Vora, and Dr. Eaton report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Monkeypox. Polio. Covid. A quick glance at the news on any given day seems to indicate that outbreaks, epidemics, and perhaps even pandemics are increasing in frequency.

Granted, these types of events are hardly new; from the plagues of the 5th and 13th centuries to the Spanish flu in the 20th century and SARS-CoV-2 today, they’ve been with us from time immemorial.

What appears to be different, however, is not their frequency, but their intensity, with research reinforcing that we may be facing unique challenges and smaller windows to intervene as we move forward.

Findings from a modeling study, published in 2021 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, underscore that without effective intervention, the probability of extreme events like COVID-19 will likely increase threefold in the coming decades.

Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, told this news organization.

“It’s all been based on some unusual cluster of cases that were causing severe disease and overwhelming local authorities. So often, like Indiana Jones, somebody got dispatched to deal with an outbreak,” Dr. Adalja said.

In a perfect post-COVID world, government bodies, scientists, clinicians, and others would cross silos to coordinate pandemic prevention, not just preparedness. The public would trust those who carry the title “public health” in their daily responsibilities, and in turn, public health experts would get back to their core responsibility – infectious disease preparedness – the role they were initially assigned following Europe’s Black Death during the 14th century. Instead, the world finds itself at a crossroads, with emerging and reemerging infectious disease outbreaks that on the surface appear to arise haphazardly but in reality are the result of decades of reaction and containment policies aimed at putting out fires, not addressing their cause.

Dr. Adalja noted that only when the threat of biological weapons became a reality in the mid-2000s was there a realization that economies of scale could be exploited by merging interests and efforts to develop health security medical countermeasures. For example, it encouraged governments to more closely integrate agencies like the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority and infectious disease research organizations and individuals.

Still, while significant strides have been made in certain areas, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has revealed substantial weaknesses remaining in public and private health systems, as well as major gaps in infectious disease preparedness.

The role of spillover events

No matter whom you ask, scientists, public health and conservation experts, and infectious disease clinicians all point to one of the most important threats to human health. As Walt Kelly’s Pogo famously put it, “We have met the enemy, and he is us.”

“The reason why these outbreaks of novel infectious diseases are increasingly occurring is because of human-driven environmental change, particularly land use, unsafe practices when raising farmed animals, and commercial wildlife markets,” Neil M. Vora, MD, a physician specializing in pandemic prevention at Conservation International and a former Centers for Disease Control and Prevention epidemic intelligence officer, said in an interview.

In fact, more than 60% of emerging infections and diseases are due to these “spillover events” (zoonotic spillover) that occur when pathogens that commonly circulate in wildlife jump over to new, human hosts.

Several examples come to mind.

COVID-19 may have begun as an enzootic virus from two undetermined animals, using the Huanan Seafood Market as a possible intermediate reservoir, according to a July 26 preprint in the journal Science.

Likewise, while the Ebola virus was originally attributed to deforestation efforts to create palm oil (which allowed fruit bat carriers to transfer the virus to humans), recent research suggests that bats dwelling in the walls of human dwellings and hospitals are responsible for the 2018 outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

(Incidentally, just this week, a new Ebola case was confirmed in Eastern Congo, and it has been genetically linked to the previous outbreak, despite that outbreak having been declared over in early July.)

“When we clear forests, we create opportunities for humans to live alongside the forest edge and displace wildlife. There’s evidence that shows when [these] biodiverse areas are cleared, specialist species that evolved to live in the forests first start to disappear, whereas generalist species – rodents and bats – continue to survive and are able to carry pathogens that can be passed on to humans,” Dr. Vora explained.

So far, China’s outbreak of the novel Langya henipavirus is believed to have spread (either directly or indirectly) by rodents and shrews, according to reports from public health authorities like the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, which is currently monitoring the situation.

Yet, an overreliance on surveillance and containment only perpetuates what Dr. Vora says are cycles of panic and neglect.

“We saw it with Ebola in 2015, in 2016 to 2017 with Zika, you see it with tuberculosis, with sexually transmitted infections, and with COVID. You have policymakers working on solutions, and once they think that they’ve fixed the problem, they’re going to move on to the next crisis.”

It’s also a question of equity.

Reports detailing the reemergence of monkeypox in Nigeria in 2017 were largely ignored, despite the fact that the United States assisted in diagnosing an early case in an 11-year-old boy. At the time, it was clear that the virus was spreading by human-to-human transmission versus animal-to-human transmission, something that had not been seen previously.

“The current model [is] waiting for pathogens to spill over and then [continuing] to spread signals that rich countries are tolerant of these outbreaks so long as they don’t grow into epidemics or pandemics,” Dr. Vora said.

This model is clearly broken; roughly 5 years after Nigeria reported the resurgence of monkeypox, the United States has more than 14,000 confirmed cases, which represents more than a quarter of the total number of cases reported worldwide.

Public health on the brink

I’s difficult to imagine a future without outbreaks and more pandemics, and if experts are to be believed, we are ill-prepared.

“I think that we are in a situation where this is a major threat, and people have become complacent about it,” said Dr. Adalja, who noted that we should be asking ourselves if the “government is actually in a position to be able to respond in a way that we need them to or is [that response] tied up in bureaucracy and inefficiency?”

COVID-19 should have been seen as a wake-up call, and many of those deaths were preventable. “With monkeypox, they’re faltering; it should have been a layup, not a disaster,” he emphasized.

Ellen Eaton, MD, associate professor of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, also pointed to the reality that by the time COVID-19 reached North America, the United States had already moved away from the model of the public health department as the epicenter of knowledge, education, awareness, and, ironically, public health.

“Thinking about my community, very few people knew the face and name of our local and state health officers,” she told this news organization.

“There was just this inherent mistrust of these people. If you add in a lot of talking heads, a lot of politicians and messaging from non-experts that countered what was coming out of our public health agencies early, you had this huge disconnect; in the South, it was the perfect storm for vaccine hesitancy.”

At last count, this perfect storm has led to 1.46 million COVID cases and just over 20,000 deaths – many of which were preventable – in Alabama alone.

“In certain parts of America, we were starting with a broken system with limited resources and few providers,” Dr. Eaton explained.

Dr. Eaton said that a lot of fields, not just medicine and public health, have finite resources that have been stretched to capacity by COVID, and now monkeypox, and wondered what was next as we’re headed into autumn and influenza season. But she also mentioned the tremendous implications of climate change on infectious diseases and community health and wellness.

“There’s a tremendous need to have the ability to survey not just humans but also how the disease burden in our environment that is fluctuating with climate change is going to impact communities in really important ways,” Dr. Eaton said.

Upstream prevention

Dr. Vora said he could not agree more and believes that upstream prevention holds the key.

“We have to make sure while there’s tension on this issue that the right solutions are implemented,” he said.

In coming years, postspillover containment strategies – vaccine research and development and strengthening health care surveillance, for example – are likely to become inadequate.

“We saw it with COVID and we are seeing it again with monkeypox,” Dr. Vora said. “We also have to invest further upstream to prevent spillovers in the first place, for example, by addressing deforestation, commercial wildlife markets and trade, [and] infection control when raising farm animals.”

“The thing is, when you invest in those upstream solutions, you are also mitigating climate change and loss of biodiversity. I’m not saying that we should not invest in postspillover containment efforts; we’re never going to contain every spillover. But we also have to invest in prevention,” he added.

In a piece published in Nature, Dr. Vora and his coauthors acknowledge that several international bodies such as the World Health Organization and G7 have invested in initiatives to facilitate coordinated, global responses to climate change, pandemic preparedness, and response. But they point out that these efforts fail to “explicitly address the negative feedback cycle between environmental degradation, wildlife exploitation, and the emergence of pathogens.”

“Environmental conservation is no longer a left-wing fringe issue, it’s moving into public consciousness, and ... it is public health,” Dr. Vora said. “When we destroy nature, we’re destroying our own ability to survive.”

Dr. Adalja, Dr. Vora, and Dr. Eaton report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

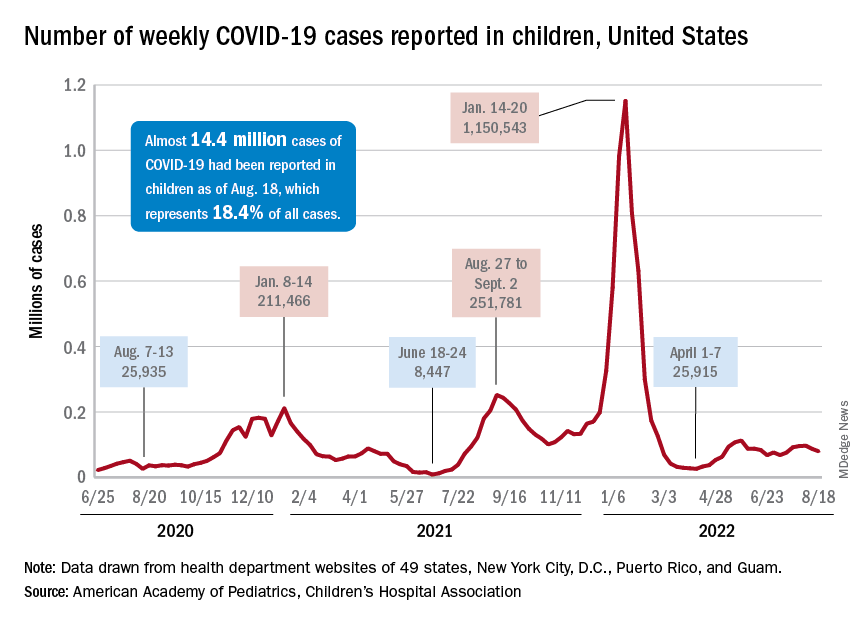

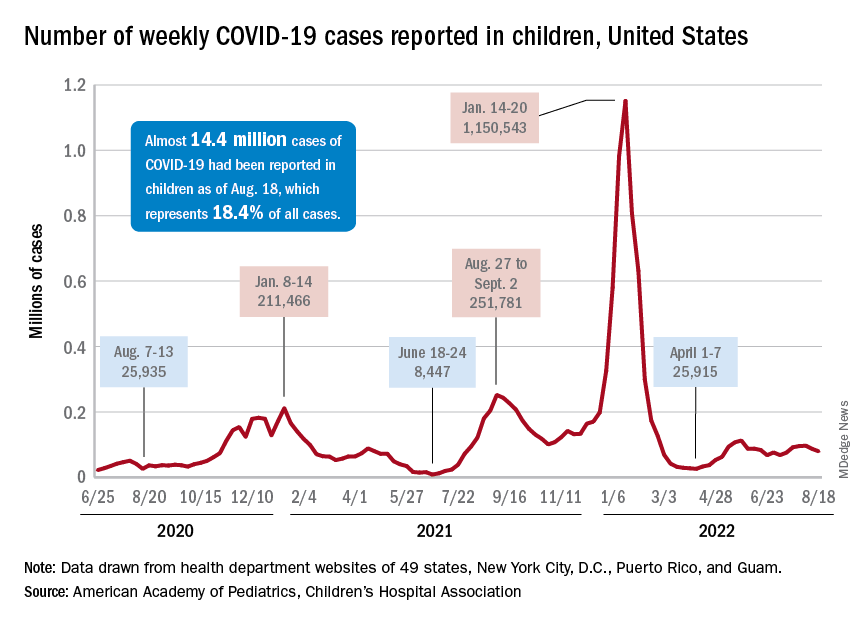

Children and COVID: New cases fall again, ED rates rebound for some

The 7-day average percentage of ED visits with diagnosed COVID, which had reached a post-Omicron high of 3.5% in late July for those aged 12-15, began to fall and was down to 3.0% on Aug. 12. That trend reversed, however, and the rate was up to 3.6% on Aug. 19, the last date for which data are available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That change of COVID fortunes cannot yet be seen for all children. The 7-day average ED visit rate for those aged 0-11 years peaked at 6.8% during the last week of July and has continued to fall, dropping from 5.7% on Aug. 12 to 5.1% on Aug. 19. Children aged 16-17 years seem to be taking a middle path: Their ED-visit rate declined from late July into mid-August but held steady over the last week, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

There is a hint of the same trend regarding new admissions among children aged 0-17 years. The national rate, which had declined in recent weeks, ticked up from 0.42 to 0.43 new admissions per 100,000 population over the last week of available data, the CDC said.

Weekly cases fall below 80,000

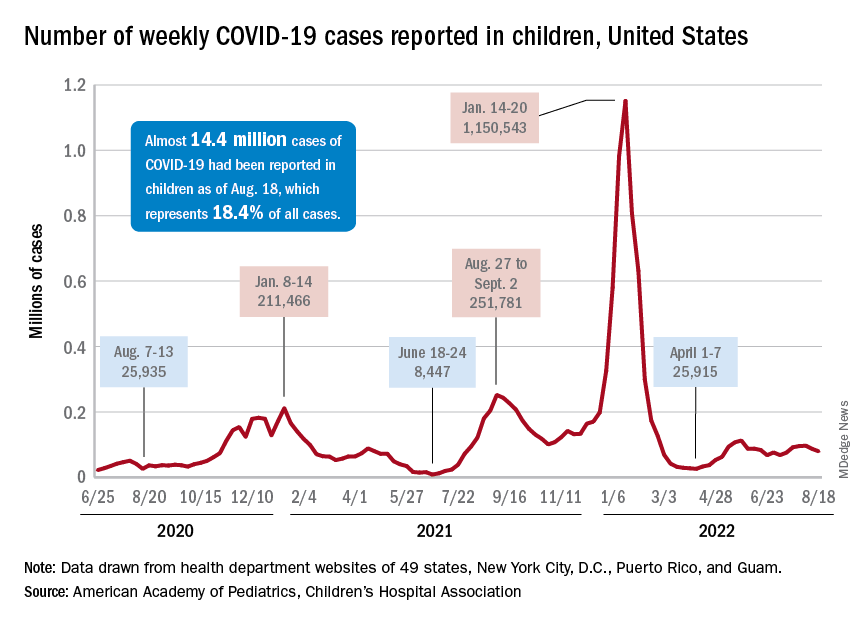

New cases in general were down by 8.5% from the previous week, dropping from 87,902 for the week of Aug. 5-11 to 79,525 for Aug. 12-18. That marked the second straight week with fewer cases after a 4-week period that saw weekly totals increase from almost 68,000 to nearly 97,000, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The AAP and CHA put the cumulative number of child COVID-19 cases at just under 14.4 million since the pandemic began, which represents 18.4% of cases among all ages. The CDC estimates that there have been almost 14.7 million cases in children aged 0-17 years, as well as 1,750 deaths, of which 14 were reported in the last week (Aug. 16-22).

The CDC age subgroups indicate that children aged 0-4 years have experienced fewer cases (2.9 million) than children aged 5-11 years (5.6 million cases) and 12-15 (3.0 million cases) but more deaths: 548 so far, versus 432 for 5- to 11-year-olds and 437 for 12- to 15-year-olds, the COVID Data Tracker shows. Those aged 0-4 make up 6% of the total U.S. population, compared with 8.7% and 5.1%, respectively, for the older children.

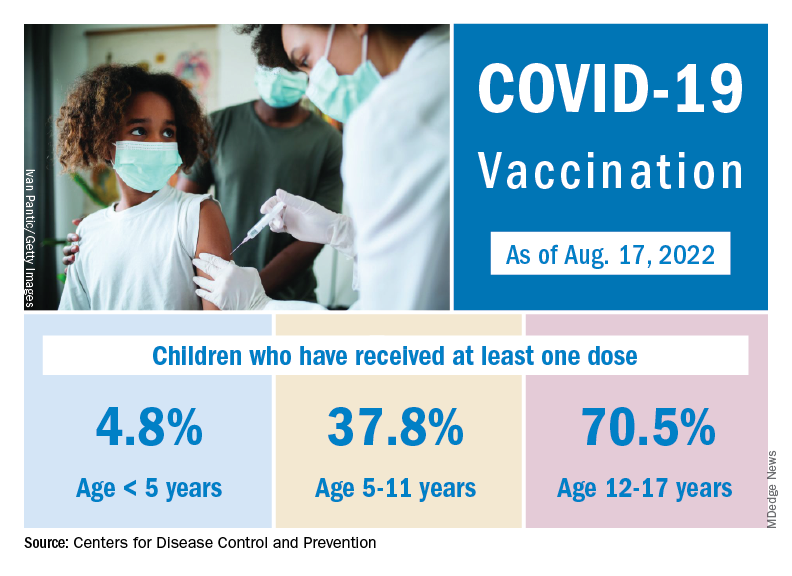

Most younger children still not vaccinated

Although it may not qualify as a big push to vaccinate children before the start of the new school year, first-time vaccinations did rise somewhat in late July and August for children aged 5-17 years. Among children younger than 5 years, though, initial doses of the vaccine fell during the second full week of August, especially in 2- to 4-year-olds, based on the CDC data.

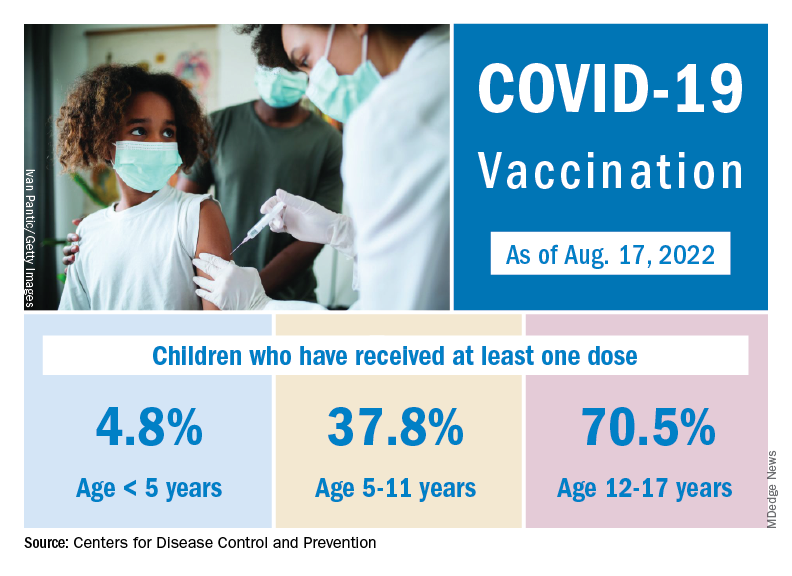

Through almost 2 months of vaccine eligibility, 4.8% of children under age 5 have received at least one dose and 0.9% are fully vaccinated as of Aug. 17. The current rates are 37.8% (one dose) and 30.4% (completed) for those aged 5-11 and 70.5% and 60.3% for 12- to 17-year-olds.

The 7-day average percentage of ED visits with diagnosed COVID, which had reached a post-Omicron high of 3.5% in late July for those aged 12-15, began to fall and was down to 3.0% on Aug. 12. That trend reversed, however, and the rate was up to 3.6% on Aug. 19, the last date for which data are available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That change of COVID fortunes cannot yet be seen for all children. The 7-day average ED visit rate for those aged 0-11 years peaked at 6.8% during the last week of July and has continued to fall, dropping from 5.7% on Aug. 12 to 5.1% on Aug. 19. Children aged 16-17 years seem to be taking a middle path: Their ED-visit rate declined from late July into mid-August but held steady over the last week, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

There is a hint of the same trend regarding new admissions among children aged 0-17 years. The national rate, which had declined in recent weeks, ticked up from 0.42 to 0.43 new admissions per 100,000 population over the last week of available data, the CDC said.

Weekly cases fall below 80,000

New cases in general were down by 8.5% from the previous week, dropping from 87,902 for the week of Aug. 5-11 to 79,525 for Aug. 12-18. That marked the second straight week with fewer cases after a 4-week period that saw weekly totals increase from almost 68,000 to nearly 97,000, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The AAP and CHA put the cumulative number of child COVID-19 cases at just under 14.4 million since the pandemic began, which represents 18.4% of cases among all ages. The CDC estimates that there have been almost 14.7 million cases in children aged 0-17 years, as well as 1,750 deaths, of which 14 were reported in the last week (Aug. 16-22).