User login

-

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

At the front lines of long COVID, local clinics prove vital

Big-name hospital chains across the United States are opening dedicated centers to help patients dealing with long COVID. But so are the lower-profile clinics and hospitals run by cities, counties and states – including Harborview Medical Center in Seattle.

They serve areas ranging from Campbell County, Wyo., with 47,000 residents, to New York City, with its 8.4 million people. Many providers working there are searching for innovative ways to approach this lingering illness with its variety of symptoms, from brain fog to shortness of breath to depression and more.

Their efforts often fall below the radar, with still-scant serious media attention to long COVID or the public health employees working to treat ailing patients.

Why are state and local health agencies taking on these duties?

They’re leading the way in part because the federal government has made only limited efforts, said Lisa McCorkell, a cofounder of the Patient-Led Research Collaborative. The international group was founded in spring 2020 by researchers who are also long COVID patients.

“It’s a big reason why long COVID isn’t talked about as much,” Ms. McCorkell said. “It’s definitely a national issue. But it trickles down to state and local health departments, and there’s not enough resources.”

The government clinics may be accessible to people without insurance and often are cheaper than clinics at private hospitals.

Harborview has treated more than 1,000 patients with long COVID, and another 200 patients are awaiting treatment, said Jessica Bender, MD, a codirector of the University of Washington Post-COVID Rehabilitation and Recovery Clinic in Seattle’s First Hill neighborhood.

The group Survivor Corps offers lists by states of clinics. While the publicly run clinics may be less expensive or even free for some patients, methods of payment vary from clinic to clinic. Federally qualified health clinics offer treatment on a sliding scale. For instance, the Riverside University Health System in California has federally qualified centers. And other providers who are not federally qualified also offer care paid for on a sliding scale. They include Campbell County Health, where some residents are eligible for discounts of 25%-100%, said spokesperson Norberto Orellana.

At Harborview, Dr. Bender said the public hospital’s post-COVID clinic initially began with a staff of rehabilitation doctors but expanded in 2021 to include family and internal medicine doctors. And it offers mental health programs with rehabilitation psychologists who instruct on how to deal with doctors or loved ones who don’t believe that long COVID exists.

“I have patients who really have been devastated by the lack of support from coworkers [and] family,” Dr. Bender said.

In Campbell County, Wyo., the pandemic surge did not arrive in earnest until late 2021. Physical therapists at Campbell County’s Health Rehabilitation Services organized a rehabilitation program for residents with long COVID after recognizing the need, said Shannon Sorensen, rehabilitation director at Campbell County Health.

“We had patients coming in showing chest pain, or heart palpitations. There were people trying to get back to work. They were frustrated,” Ms. Sorensen said.

Myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome activists have embraced the fight to recognize and help long COVID patients, noting the similarities between the conditions, and hope to help kickstart more organized research, treatment and benefits for long COVID sufferers and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients alike.

In Ft. Collins, Colo., disability activist Alison Sbrana has long had myalgic encephalomyelitis. She and other members of the local chapter of ME Action have met with state officials for several years and are finally seeing the results of those efforts.

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis has created the full-time position of policy adviser for long COVID and post–viral infection planning.

“This is one way forward of how state governments are (finally) paying attention to infection-triggered chronic illnesses and starting to think ahead on them,” Ms. Sbrana said.

New York City’s Health + Hospitals launched what may be the most expansive long COVID treatment program in the nation in April 2021. Called AfterCare, it provides physical and mental health services as well as community support systems and financial assistance.

A persistent issue for patients is that there isn’t yet a test for long COVID, like there is for COVID-19, said Amanda Johnson, MD, assistant vice president for ambulatory care and population health at New York Health + Hospitals. “It’s in many ways a diagnosis of exclusion. You have to make sure their shortness of breath isn’t caused by something else. The same with anemia,” she said.

California’s Department of Public Health has a detailed website devoted to the topic, including videos of “long haulers” describing their experiences.

Vermont is one of several states studying long COVID, said Mark Levine, MD, the state health commissioner. The state, in collaboration with the University of Vermont, has established a surveillance project to determine how many people have long COVID, as well as how severe it is, how long it lasts, and potential predispositions.

The University of Utah, Salt Lake City, established a comprehensive COVID-19 clinic more than a year ago that also handles long COVID patients, said Jeannette Brown, MD, PhD, an associate professor at the school and director of the COVID-19 clinic.

Jennifer Chevinsky, MD, MPH, already had a deep understanding of long COVID when she landed in Riverside County, Calif., in the summer of 2021. She came from Atlanta, where as part of her job as an epidemic intelligence service officer at the CDC, she heard stories of COVID-19 patients who were not getting better.

Now she is a deputy public health officer for Riverside County, in a region known for its deserts, sizzling summer temperatures and diverse populations. She said her department has helped launch programs such as post–COVID-19 follow-up phone calls and long COVID training programs that reach out to the many Latino residents in this county of 2.4 million people. It also includes Black and Native American residents.

“We’re making sure information is circulated with community and faith-based organizations, and community health workers,” she said.

Ms. McCorkell said there is still much work to do to raise public awareness of the risks of long COVID and how to obtain care for patients. She would like to see a national public health campaign about long COVID, possibly spearheaded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in partnership with local health workers and community-based organizations.

“That,” she said, “could make a big difference.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Big-name hospital chains across the United States are opening dedicated centers to help patients dealing with long COVID. But so are the lower-profile clinics and hospitals run by cities, counties and states – including Harborview Medical Center in Seattle.

They serve areas ranging from Campbell County, Wyo., with 47,000 residents, to New York City, with its 8.4 million people. Many providers working there are searching for innovative ways to approach this lingering illness with its variety of symptoms, from brain fog to shortness of breath to depression and more.

Their efforts often fall below the radar, with still-scant serious media attention to long COVID or the public health employees working to treat ailing patients.

Why are state and local health agencies taking on these duties?

They’re leading the way in part because the federal government has made only limited efforts, said Lisa McCorkell, a cofounder of the Patient-Led Research Collaborative. The international group was founded in spring 2020 by researchers who are also long COVID patients.

“It’s a big reason why long COVID isn’t talked about as much,” Ms. McCorkell said. “It’s definitely a national issue. But it trickles down to state and local health departments, and there’s not enough resources.”

The government clinics may be accessible to people without insurance and often are cheaper than clinics at private hospitals.

Harborview has treated more than 1,000 patients with long COVID, and another 200 patients are awaiting treatment, said Jessica Bender, MD, a codirector of the University of Washington Post-COVID Rehabilitation and Recovery Clinic in Seattle’s First Hill neighborhood.

The group Survivor Corps offers lists by states of clinics. While the publicly run clinics may be less expensive or even free for some patients, methods of payment vary from clinic to clinic. Federally qualified health clinics offer treatment on a sliding scale. For instance, the Riverside University Health System in California has federally qualified centers. And other providers who are not federally qualified also offer care paid for on a sliding scale. They include Campbell County Health, where some residents are eligible for discounts of 25%-100%, said spokesperson Norberto Orellana.

At Harborview, Dr. Bender said the public hospital’s post-COVID clinic initially began with a staff of rehabilitation doctors but expanded in 2021 to include family and internal medicine doctors. And it offers mental health programs with rehabilitation psychologists who instruct on how to deal with doctors or loved ones who don’t believe that long COVID exists.

“I have patients who really have been devastated by the lack of support from coworkers [and] family,” Dr. Bender said.

In Campbell County, Wyo., the pandemic surge did not arrive in earnest until late 2021. Physical therapists at Campbell County’s Health Rehabilitation Services organized a rehabilitation program for residents with long COVID after recognizing the need, said Shannon Sorensen, rehabilitation director at Campbell County Health.

“We had patients coming in showing chest pain, or heart palpitations. There were people trying to get back to work. They were frustrated,” Ms. Sorensen said.

Myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome activists have embraced the fight to recognize and help long COVID patients, noting the similarities between the conditions, and hope to help kickstart more organized research, treatment and benefits for long COVID sufferers and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients alike.

In Ft. Collins, Colo., disability activist Alison Sbrana has long had myalgic encephalomyelitis. She and other members of the local chapter of ME Action have met with state officials for several years and are finally seeing the results of those efforts.

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis has created the full-time position of policy adviser for long COVID and post–viral infection planning.

“This is one way forward of how state governments are (finally) paying attention to infection-triggered chronic illnesses and starting to think ahead on them,” Ms. Sbrana said.

New York City’s Health + Hospitals launched what may be the most expansive long COVID treatment program in the nation in April 2021. Called AfterCare, it provides physical and mental health services as well as community support systems and financial assistance.

A persistent issue for patients is that there isn’t yet a test for long COVID, like there is for COVID-19, said Amanda Johnson, MD, assistant vice president for ambulatory care and population health at New York Health + Hospitals. “It’s in many ways a diagnosis of exclusion. You have to make sure their shortness of breath isn’t caused by something else. The same with anemia,” she said.

California’s Department of Public Health has a detailed website devoted to the topic, including videos of “long haulers” describing their experiences.

Vermont is one of several states studying long COVID, said Mark Levine, MD, the state health commissioner. The state, in collaboration with the University of Vermont, has established a surveillance project to determine how many people have long COVID, as well as how severe it is, how long it lasts, and potential predispositions.

The University of Utah, Salt Lake City, established a comprehensive COVID-19 clinic more than a year ago that also handles long COVID patients, said Jeannette Brown, MD, PhD, an associate professor at the school and director of the COVID-19 clinic.

Jennifer Chevinsky, MD, MPH, already had a deep understanding of long COVID when she landed in Riverside County, Calif., in the summer of 2021. She came from Atlanta, where as part of her job as an epidemic intelligence service officer at the CDC, she heard stories of COVID-19 patients who were not getting better.

Now she is a deputy public health officer for Riverside County, in a region known for its deserts, sizzling summer temperatures and diverse populations. She said her department has helped launch programs such as post–COVID-19 follow-up phone calls and long COVID training programs that reach out to the many Latino residents in this county of 2.4 million people. It also includes Black and Native American residents.

“We’re making sure information is circulated with community and faith-based organizations, and community health workers,” she said.

Ms. McCorkell said there is still much work to do to raise public awareness of the risks of long COVID and how to obtain care for patients. She would like to see a national public health campaign about long COVID, possibly spearheaded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in partnership with local health workers and community-based organizations.

“That,” she said, “could make a big difference.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Big-name hospital chains across the United States are opening dedicated centers to help patients dealing with long COVID. But so are the lower-profile clinics and hospitals run by cities, counties and states – including Harborview Medical Center in Seattle.

They serve areas ranging from Campbell County, Wyo., with 47,000 residents, to New York City, with its 8.4 million people. Many providers working there are searching for innovative ways to approach this lingering illness with its variety of symptoms, from brain fog to shortness of breath to depression and more.

Their efforts often fall below the radar, with still-scant serious media attention to long COVID or the public health employees working to treat ailing patients.

Why are state and local health agencies taking on these duties?

They’re leading the way in part because the federal government has made only limited efforts, said Lisa McCorkell, a cofounder of the Patient-Led Research Collaborative. The international group was founded in spring 2020 by researchers who are also long COVID patients.

“It’s a big reason why long COVID isn’t talked about as much,” Ms. McCorkell said. “It’s definitely a national issue. But it trickles down to state and local health departments, and there’s not enough resources.”

The government clinics may be accessible to people without insurance and often are cheaper than clinics at private hospitals.

Harborview has treated more than 1,000 patients with long COVID, and another 200 patients are awaiting treatment, said Jessica Bender, MD, a codirector of the University of Washington Post-COVID Rehabilitation and Recovery Clinic in Seattle’s First Hill neighborhood.

The group Survivor Corps offers lists by states of clinics. While the publicly run clinics may be less expensive or even free for some patients, methods of payment vary from clinic to clinic. Federally qualified health clinics offer treatment on a sliding scale. For instance, the Riverside University Health System in California has federally qualified centers. And other providers who are not federally qualified also offer care paid for on a sliding scale. They include Campbell County Health, where some residents are eligible for discounts of 25%-100%, said spokesperson Norberto Orellana.

At Harborview, Dr. Bender said the public hospital’s post-COVID clinic initially began with a staff of rehabilitation doctors but expanded in 2021 to include family and internal medicine doctors. And it offers mental health programs with rehabilitation psychologists who instruct on how to deal with doctors or loved ones who don’t believe that long COVID exists.

“I have patients who really have been devastated by the lack of support from coworkers [and] family,” Dr. Bender said.

In Campbell County, Wyo., the pandemic surge did not arrive in earnest until late 2021. Physical therapists at Campbell County’s Health Rehabilitation Services organized a rehabilitation program for residents with long COVID after recognizing the need, said Shannon Sorensen, rehabilitation director at Campbell County Health.

“We had patients coming in showing chest pain, or heart palpitations. There were people trying to get back to work. They were frustrated,” Ms. Sorensen said.

Myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome activists have embraced the fight to recognize and help long COVID patients, noting the similarities between the conditions, and hope to help kickstart more organized research, treatment and benefits for long COVID sufferers and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome patients alike.

In Ft. Collins, Colo., disability activist Alison Sbrana has long had myalgic encephalomyelitis. She and other members of the local chapter of ME Action have met with state officials for several years and are finally seeing the results of those efforts.

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis has created the full-time position of policy adviser for long COVID and post–viral infection planning.

“This is one way forward of how state governments are (finally) paying attention to infection-triggered chronic illnesses and starting to think ahead on them,” Ms. Sbrana said.

New York City’s Health + Hospitals launched what may be the most expansive long COVID treatment program in the nation in April 2021. Called AfterCare, it provides physical and mental health services as well as community support systems and financial assistance.

A persistent issue for patients is that there isn’t yet a test for long COVID, like there is for COVID-19, said Amanda Johnson, MD, assistant vice president for ambulatory care and population health at New York Health + Hospitals. “It’s in many ways a diagnosis of exclusion. You have to make sure their shortness of breath isn’t caused by something else. The same with anemia,” she said.

California’s Department of Public Health has a detailed website devoted to the topic, including videos of “long haulers” describing their experiences.

Vermont is one of several states studying long COVID, said Mark Levine, MD, the state health commissioner. The state, in collaboration with the University of Vermont, has established a surveillance project to determine how many people have long COVID, as well as how severe it is, how long it lasts, and potential predispositions.

The University of Utah, Salt Lake City, established a comprehensive COVID-19 clinic more than a year ago that also handles long COVID patients, said Jeannette Brown, MD, PhD, an associate professor at the school and director of the COVID-19 clinic.

Jennifer Chevinsky, MD, MPH, already had a deep understanding of long COVID when she landed in Riverside County, Calif., in the summer of 2021. She came from Atlanta, where as part of her job as an epidemic intelligence service officer at the CDC, she heard stories of COVID-19 patients who were not getting better.

Now she is a deputy public health officer for Riverside County, in a region known for its deserts, sizzling summer temperatures and diverse populations. She said her department has helped launch programs such as post–COVID-19 follow-up phone calls and long COVID training programs that reach out to the many Latino residents in this county of 2.4 million people. It also includes Black and Native American residents.

“We’re making sure information is circulated with community and faith-based organizations, and community health workers,” she said.

Ms. McCorkell said there is still much work to do to raise public awareness of the risks of long COVID and how to obtain care for patients. She would like to see a national public health campaign about long COVID, possibly spearheaded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in partnership with local health workers and community-based organizations.

“That,” she said, “could make a big difference.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

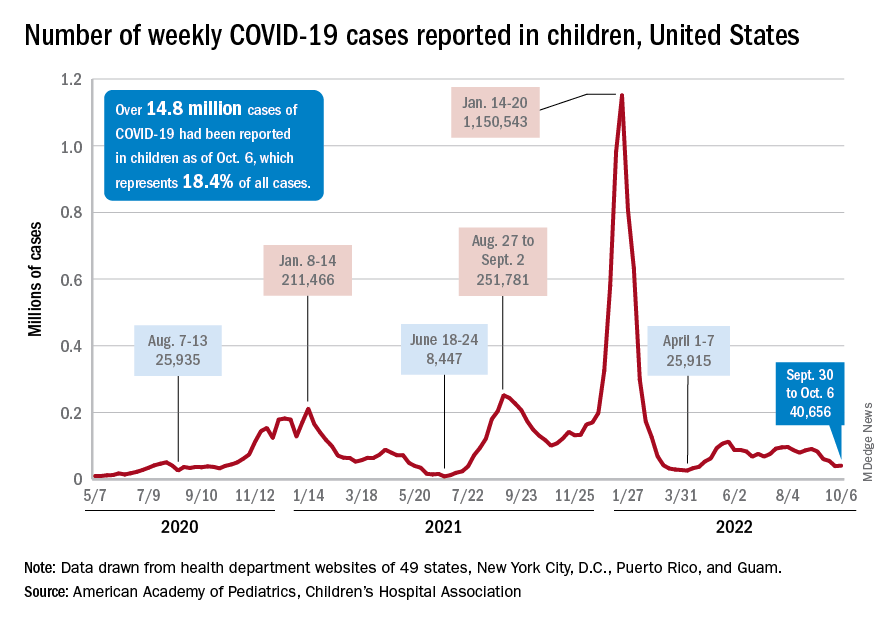

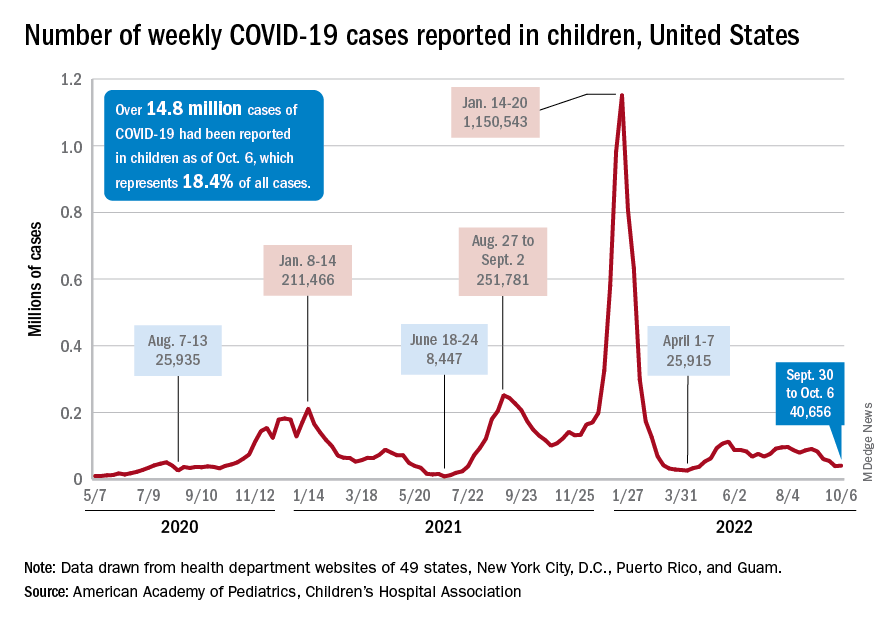

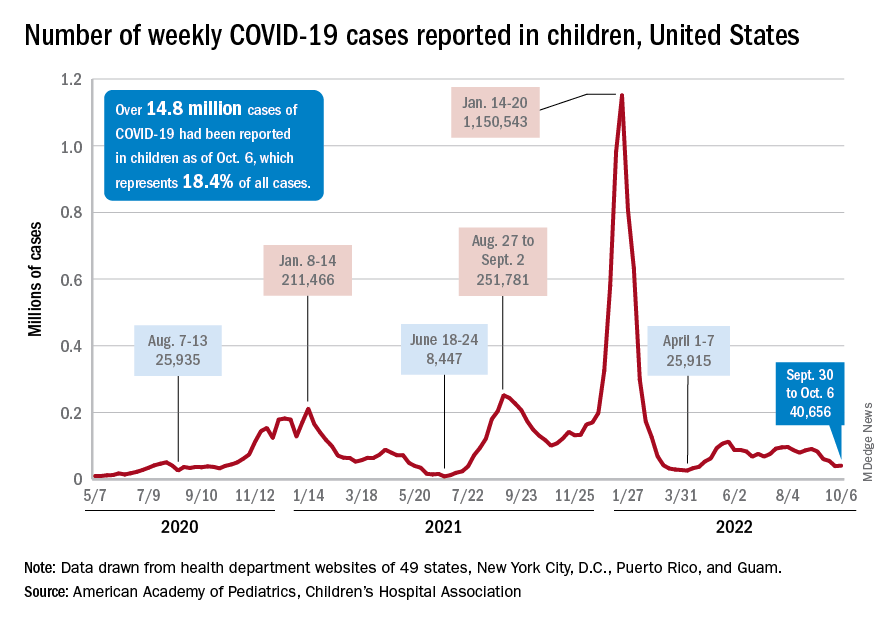

Children and COVID: Downward trend reverses with small increase in new cases

A small increase in new cases brought COVID-19’s latest losing streak to an end at 4 weeks, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The 40,656 new cases reported bring the U.S. cumulative count of child COVID-19 cases to over 14.8 million since the pandemic began, which represents 18.4% of all cases, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report based on state-level data.

The increase in new cases was not reflected in emergency department visits or hospital admissions, which both continued sustained declines that started in August. In the week from Sept. 27 to Oct. 4, the 7-day averages for ED visits with diagnosed COVID were down by 21.5% (age 0-11), 27.3% (12-15), and 18.2% (16-17), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said, while the most recent 7-day average for new admissions – 127 per day for Oct. 2-8 – among children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID was down from 161 per day the previous week, a drop of over 21%.

The state-level data that are currently available (several states are no longer reporting) show Alaska (25.5%) and Vermont (25.4%) have the highest proportions of cumulative cases in children, and Florida (12.3%) and Utah (13.5%) have the lowest. Rhode Island has the highest rate of COVID-19 per 100,000 children at 40,427, while Missouri has the lowest at 14,252. The national average is 19,687 per 100,000, the AAP and CHA reported.

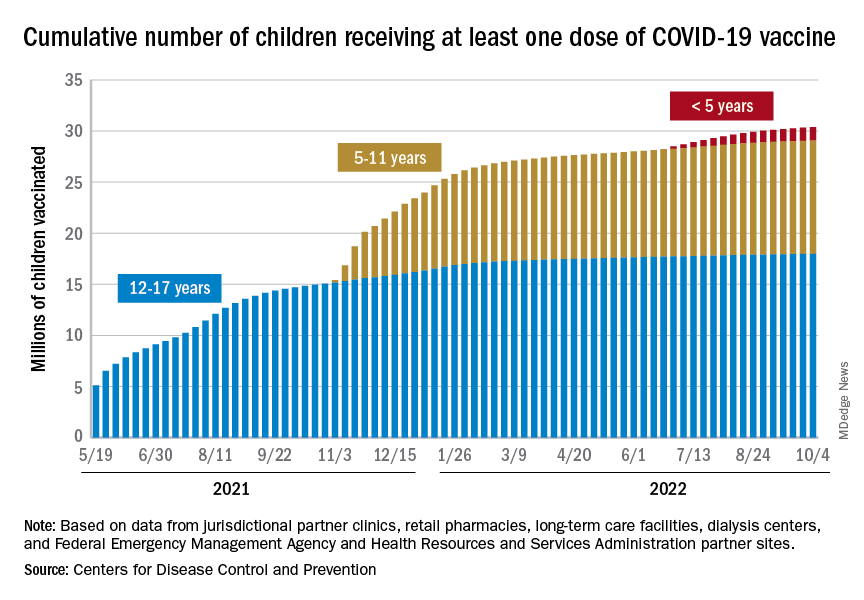

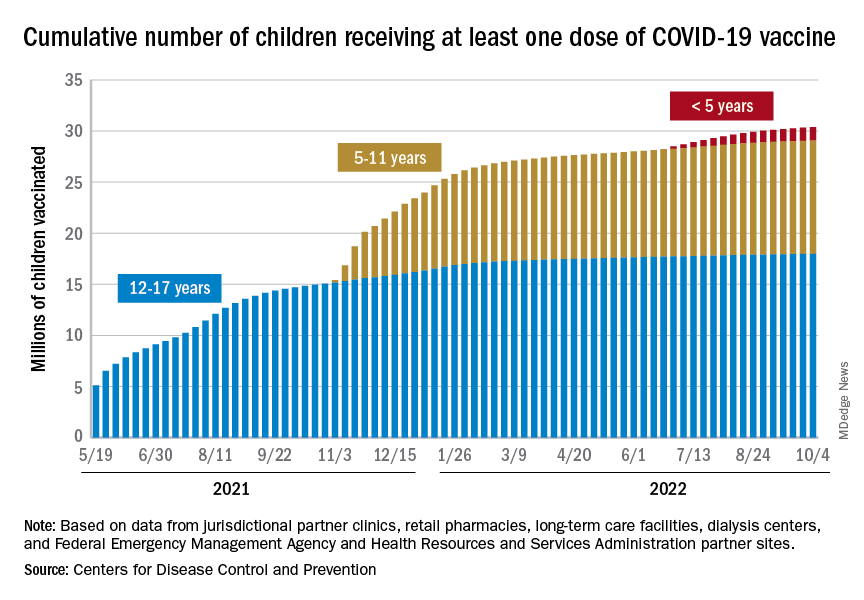

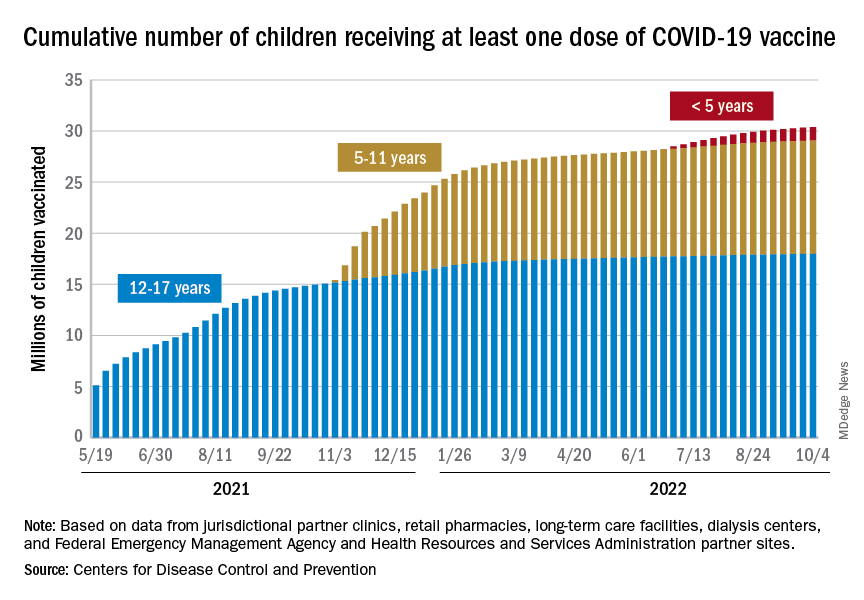

Taking a look at vaccination

Vaccinations were up slightly in children aged 12-17 years, as 20,000 initial doses were given during the week of Sept. 29 to Oct. 5, compared with 17,000 and 18,000 the previous 2 weeks. Initial vaccinations in younger children, however, continued declines dating back to August, the AAP said in its weekly vaccination trends report.

The District of Columbia and Massachusetts have the most highly vaccinated groups of 12- to 17-year-olds, as 100% and 95%, respectively, have received initial doses, while Wyoming (39%) and Idaho (42%) have the lowest. D.C. (73%) and Vermont (68%) have the highest proportions of vaccinated 5- to 11-year-olds, and Alabama (17%) and Mississippi (18%) have the lowest. For children under age 5 years, those in D.C. (33%) and Vermont (26%) are the most likely to have received an initial COVID vaccination, while Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi share national-low rates of 2%, the AAP said its report, which is based on CDC data.

When all states and territories are combined, 71% of children aged 12-17 have received at least one dose of vaccine, as have 38.6% of all children 5-11 years old and 6.7% of those under age 5. Almost 61% of the nation’s 16- to 17-year-olds have been fully vaccinated, along with 31.5% of those aged 5-11 and 2.4% of children younger than 5 years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

About 42 million children – 58% of the population under the age of 18 years – have not received any vaccine yet, the AAP noted. Meanwhile, CDC data indicate that 36 children died of COVID in the last week, with pediatric deaths now totaling 1,781 over the course of the pandemic.

A small increase in new cases brought COVID-19’s latest losing streak to an end at 4 weeks, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The 40,656 new cases reported bring the U.S. cumulative count of child COVID-19 cases to over 14.8 million since the pandemic began, which represents 18.4% of all cases, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report based on state-level data.

The increase in new cases was not reflected in emergency department visits or hospital admissions, which both continued sustained declines that started in August. In the week from Sept. 27 to Oct. 4, the 7-day averages for ED visits with diagnosed COVID were down by 21.5% (age 0-11), 27.3% (12-15), and 18.2% (16-17), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said, while the most recent 7-day average for new admissions – 127 per day for Oct. 2-8 – among children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID was down from 161 per day the previous week, a drop of over 21%.

The state-level data that are currently available (several states are no longer reporting) show Alaska (25.5%) and Vermont (25.4%) have the highest proportions of cumulative cases in children, and Florida (12.3%) and Utah (13.5%) have the lowest. Rhode Island has the highest rate of COVID-19 per 100,000 children at 40,427, while Missouri has the lowest at 14,252. The national average is 19,687 per 100,000, the AAP and CHA reported.

Taking a look at vaccination

Vaccinations were up slightly in children aged 12-17 years, as 20,000 initial doses were given during the week of Sept. 29 to Oct. 5, compared with 17,000 and 18,000 the previous 2 weeks. Initial vaccinations in younger children, however, continued declines dating back to August, the AAP said in its weekly vaccination trends report.

The District of Columbia and Massachusetts have the most highly vaccinated groups of 12- to 17-year-olds, as 100% and 95%, respectively, have received initial doses, while Wyoming (39%) and Idaho (42%) have the lowest. D.C. (73%) and Vermont (68%) have the highest proportions of vaccinated 5- to 11-year-olds, and Alabama (17%) and Mississippi (18%) have the lowest. For children under age 5 years, those in D.C. (33%) and Vermont (26%) are the most likely to have received an initial COVID vaccination, while Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi share national-low rates of 2%, the AAP said its report, which is based on CDC data.

When all states and territories are combined, 71% of children aged 12-17 have received at least one dose of vaccine, as have 38.6% of all children 5-11 years old and 6.7% of those under age 5. Almost 61% of the nation’s 16- to 17-year-olds have been fully vaccinated, along with 31.5% of those aged 5-11 and 2.4% of children younger than 5 years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

About 42 million children – 58% of the population under the age of 18 years – have not received any vaccine yet, the AAP noted. Meanwhile, CDC data indicate that 36 children died of COVID in the last week, with pediatric deaths now totaling 1,781 over the course of the pandemic.

A small increase in new cases brought COVID-19’s latest losing streak to an end at 4 weeks, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The 40,656 new cases reported bring the U.S. cumulative count of child COVID-19 cases to over 14.8 million since the pandemic began, which represents 18.4% of all cases, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report based on state-level data.

The increase in new cases was not reflected in emergency department visits or hospital admissions, which both continued sustained declines that started in August. In the week from Sept. 27 to Oct. 4, the 7-day averages for ED visits with diagnosed COVID were down by 21.5% (age 0-11), 27.3% (12-15), and 18.2% (16-17), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said, while the most recent 7-day average for new admissions – 127 per day for Oct. 2-8 – among children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID was down from 161 per day the previous week, a drop of over 21%.

The state-level data that are currently available (several states are no longer reporting) show Alaska (25.5%) and Vermont (25.4%) have the highest proportions of cumulative cases in children, and Florida (12.3%) and Utah (13.5%) have the lowest. Rhode Island has the highest rate of COVID-19 per 100,000 children at 40,427, while Missouri has the lowest at 14,252. The national average is 19,687 per 100,000, the AAP and CHA reported.

Taking a look at vaccination

Vaccinations were up slightly in children aged 12-17 years, as 20,000 initial doses were given during the week of Sept. 29 to Oct. 5, compared with 17,000 and 18,000 the previous 2 weeks. Initial vaccinations in younger children, however, continued declines dating back to August, the AAP said in its weekly vaccination trends report.

The District of Columbia and Massachusetts have the most highly vaccinated groups of 12- to 17-year-olds, as 100% and 95%, respectively, have received initial doses, while Wyoming (39%) and Idaho (42%) have the lowest. D.C. (73%) and Vermont (68%) have the highest proportions of vaccinated 5- to 11-year-olds, and Alabama (17%) and Mississippi (18%) have the lowest. For children under age 5 years, those in D.C. (33%) and Vermont (26%) are the most likely to have received an initial COVID vaccination, while Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi share national-low rates of 2%, the AAP said its report, which is based on CDC data.

When all states and territories are combined, 71% of children aged 12-17 have received at least one dose of vaccine, as have 38.6% of all children 5-11 years old and 6.7% of those under age 5. Almost 61% of the nation’s 16- to 17-year-olds have been fully vaccinated, along with 31.5% of those aged 5-11 and 2.4% of children younger than 5 years, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

About 42 million children – 58% of the population under the age of 18 years – have not received any vaccine yet, the AAP noted. Meanwhile, CDC data indicate that 36 children died of COVID in the last week, with pediatric deaths now totaling 1,781 over the course of the pandemic.

Like texting and driving: The human cost of AI

A recent medical meeting I attended included multiple sessions on the use of artificial intelligence (AI), a mere preview, I suspect, of what is to come for both patients and physicians.

I vow not to be a contrarian, but I have concerns. If we’d known how cell phones would permeate nearly every waking moment of our lives, would we have built in more protections from the onset?

Although anyone can see the enormous potential of AI in medicine, harnessing the wonders of it without guarding against the dangers could be paramount to texting and driving.

A palpable disruption in the common work-a-day human interaction is a given. CEOs who mind the bottom line will seek every opportunity to cut personnel whenever machine learning can deliver. As our dependence on algorithms increases, our need to understand electrocardiogram interpretation and echocardiographic calculations will wane. Subtle case information will go undetected. Nuanced subconscious alerts regarding the patient condition will go unnoticed.

These realities are never reflected in the pronouncements of companies who promote and develop AI.

The 2-minute echo

In September 2020, Carolyn Lam, MBBS, PhD, and James Hare, MBA, founders of the AI tech company US2.AI, told Healthcare Transformers that AI advances in echocardiology will turn “a manual process of 30 minutes, 250 clicks, with up to 21% variability among fully trained sonographers analyzing the same exam, into an AI-automated process taking 2 minutes, 1 click, with 0% variability.”

Let’s contrast this 2-minute human-machine interaction with the standard 20- to 30-minute human-to-human echocardiography procedure.

Take Mrs. Smith, for instance. She is referred for echocardiography for shortness of breath. She’s shown to a room and instructed to lie down on a table, where she undergoes a brief AI-directed acquisition of images and then a cheery dismissal from the imaging lab. Medical corporate chief financial officers will salivate at the efficiency, the decrease in cost for personnel, and the sharp increase in put-through for the echo lab schedule.

But what if Mrs. Smith gets a standard 30-minute sonographer-directed exam and the astute echocardiographer notes a left ventricular ejection fraction of 38%. A conversation with the patient reveals that she lost her son a few weeks ago. Upon completion of the study, the patient stands up and then adds, “I hope I can sleep in my bed tonight.” Thinking there may be more to the patient’s insomnia than grief-driven anxiety, the sonographer asks her to explain. “I had to sleep in a chair last night because I couldn’t breathe,” Mrs. Smith replies.

The sonographer reasons correctly that Mrs. Smith is likely a few weeks past an acute coronary syndrome for which she didn’t seek attention and is now in heart failure. The consulting cardiologist is alerted. Mrs. Smith is worked into the office schedule a week earlier than planned, and a costly in-patient stay for acute heart failure or worse is avoided.

Here’s a true-life example (some details have been changed to protect the patient’s identity): Mr. Rodriquez was referred for echocardiography because of dizziness. The sonographer notes significant mitral regurgitation and a decline in left ventricular ejection fraction from moderately impaired to severely reduced. When the sonographer inquires about a fresh bruise over Mr. Rodriguez’s left eye, he replies that he “must have fallen, but can’t remember.” The sonographer also notes runs of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia on the echo telemetry, and after a phone call from the echo lab to the ordering physician, Mr. Rodriquez is admitted. Instead of chancing a sudden death at home while awaiting follow-up, he undergoes catheterization and gets an implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

These scenarios illustrate that a 2-minute visit for AI-directed acquisition of echocardiogram images will never garner the protections of a conversation with a human. Any attempts at downplaying the importance of these human interactions are misguided.

Sometimes we embrace the latest advances in medicine while failing to tend to the most rudimentary necessities of data analysis and reporting. Catherine M. Otto, MD, director of the heart valve clinic and a professor of cardiology at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, is a fan of the basics.

At the recent annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, she commented on the AI-ENHANCED trial, which used an AI decision support algorithm to identify patients with moderate to severe aortic stenosis, which is associated with poor survival if left untreated. She correctly highlighted that while we are discussing the merits of AI-driven assessment of aortic stenosis, we are doing so in an era when many echo interpreters exclude critical information. The vital findings of aortic valve area, Vmax, and ejection fraction are often nowhere to be seen on reports. We should attend to our basic flaws in interpretation and reporting before we shift our focus to AI.

Flawed algorithms

Incorrect AI algorithms that are broadly adopted could negatively affect the health of millions.

Perhaps the most unsettling claim is made by causaLens: “Causal AI is the only technology that can reason and make choices like humans do,” the website states. A tantalizing tag line that is categorically untrue.

Our mysterious and complex neurophysiological function of reasoning still eludes understanding, but one thing is certain: medical reasoning originates with listening, seeing, and touching.

As AI infiltrates mainstream medicine, opportunities for hearing, observing, and palpating will be greatly reduced.

Folkert Asselbergs from University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands, who has cautioned against overhyping AI, was the discussant for an ESC study on the use of causal AI to improve cardiovascular risk estimation.

He flashed a slide of a 2019 Science article on racial bias in an algorithm that U.S. health care systems use. Remedying that bias “would increase the percentage of Black people receiving additional help from 17.7% to 46.5%,” according to the authors.

Successful integration of AI-driven technology will come only if we build human interaction into every patient encounter.

I hope I don’t live to see the rise of the physician cyborg.

Artificial intelligence could be the greatest boon since the invention of the stethoscope, but it will be our downfall if we stop administering a healthy dose of humanity to every patient encounter.

Melissa Walton-Shirley, MD, is a clinical cardiologist in Nashville, Tenn., who has retired from full-time invasive cardiology. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A recent medical meeting I attended included multiple sessions on the use of artificial intelligence (AI), a mere preview, I suspect, of what is to come for both patients and physicians.

I vow not to be a contrarian, but I have concerns. If we’d known how cell phones would permeate nearly every waking moment of our lives, would we have built in more protections from the onset?

Although anyone can see the enormous potential of AI in medicine, harnessing the wonders of it without guarding against the dangers could be paramount to texting and driving.

A palpable disruption in the common work-a-day human interaction is a given. CEOs who mind the bottom line will seek every opportunity to cut personnel whenever machine learning can deliver. As our dependence on algorithms increases, our need to understand electrocardiogram interpretation and echocardiographic calculations will wane. Subtle case information will go undetected. Nuanced subconscious alerts regarding the patient condition will go unnoticed.

These realities are never reflected in the pronouncements of companies who promote and develop AI.

The 2-minute echo

In September 2020, Carolyn Lam, MBBS, PhD, and James Hare, MBA, founders of the AI tech company US2.AI, told Healthcare Transformers that AI advances in echocardiology will turn “a manual process of 30 minutes, 250 clicks, with up to 21% variability among fully trained sonographers analyzing the same exam, into an AI-automated process taking 2 minutes, 1 click, with 0% variability.”

Let’s contrast this 2-minute human-machine interaction with the standard 20- to 30-minute human-to-human echocardiography procedure.

Take Mrs. Smith, for instance. She is referred for echocardiography for shortness of breath. She’s shown to a room and instructed to lie down on a table, where she undergoes a brief AI-directed acquisition of images and then a cheery dismissal from the imaging lab. Medical corporate chief financial officers will salivate at the efficiency, the decrease in cost for personnel, and the sharp increase in put-through for the echo lab schedule.

But what if Mrs. Smith gets a standard 30-minute sonographer-directed exam and the astute echocardiographer notes a left ventricular ejection fraction of 38%. A conversation with the patient reveals that she lost her son a few weeks ago. Upon completion of the study, the patient stands up and then adds, “I hope I can sleep in my bed tonight.” Thinking there may be more to the patient’s insomnia than grief-driven anxiety, the sonographer asks her to explain. “I had to sleep in a chair last night because I couldn’t breathe,” Mrs. Smith replies.

The sonographer reasons correctly that Mrs. Smith is likely a few weeks past an acute coronary syndrome for which she didn’t seek attention and is now in heart failure. The consulting cardiologist is alerted. Mrs. Smith is worked into the office schedule a week earlier than planned, and a costly in-patient stay for acute heart failure or worse is avoided.

Here’s a true-life example (some details have been changed to protect the patient’s identity): Mr. Rodriquez was referred for echocardiography because of dizziness. The sonographer notes significant mitral regurgitation and a decline in left ventricular ejection fraction from moderately impaired to severely reduced. When the sonographer inquires about a fresh bruise over Mr. Rodriguez’s left eye, he replies that he “must have fallen, but can’t remember.” The sonographer also notes runs of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia on the echo telemetry, and after a phone call from the echo lab to the ordering physician, Mr. Rodriquez is admitted. Instead of chancing a sudden death at home while awaiting follow-up, he undergoes catheterization and gets an implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

These scenarios illustrate that a 2-minute visit for AI-directed acquisition of echocardiogram images will never garner the protections of a conversation with a human. Any attempts at downplaying the importance of these human interactions are misguided.

Sometimes we embrace the latest advances in medicine while failing to tend to the most rudimentary necessities of data analysis and reporting. Catherine M. Otto, MD, director of the heart valve clinic and a professor of cardiology at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, is a fan of the basics.

At the recent annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, she commented on the AI-ENHANCED trial, which used an AI decision support algorithm to identify patients with moderate to severe aortic stenosis, which is associated with poor survival if left untreated. She correctly highlighted that while we are discussing the merits of AI-driven assessment of aortic stenosis, we are doing so in an era when many echo interpreters exclude critical information. The vital findings of aortic valve area, Vmax, and ejection fraction are often nowhere to be seen on reports. We should attend to our basic flaws in interpretation and reporting before we shift our focus to AI.

Flawed algorithms

Incorrect AI algorithms that are broadly adopted could negatively affect the health of millions.

Perhaps the most unsettling claim is made by causaLens: “Causal AI is the only technology that can reason and make choices like humans do,” the website states. A tantalizing tag line that is categorically untrue.

Our mysterious and complex neurophysiological function of reasoning still eludes understanding, but one thing is certain: medical reasoning originates with listening, seeing, and touching.

As AI infiltrates mainstream medicine, opportunities for hearing, observing, and palpating will be greatly reduced.

Folkert Asselbergs from University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands, who has cautioned against overhyping AI, was the discussant for an ESC study on the use of causal AI to improve cardiovascular risk estimation.

He flashed a slide of a 2019 Science article on racial bias in an algorithm that U.S. health care systems use. Remedying that bias “would increase the percentage of Black people receiving additional help from 17.7% to 46.5%,” according to the authors.

Successful integration of AI-driven technology will come only if we build human interaction into every patient encounter.

I hope I don’t live to see the rise of the physician cyborg.

Artificial intelligence could be the greatest boon since the invention of the stethoscope, but it will be our downfall if we stop administering a healthy dose of humanity to every patient encounter.

Melissa Walton-Shirley, MD, is a clinical cardiologist in Nashville, Tenn., who has retired from full-time invasive cardiology. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A recent medical meeting I attended included multiple sessions on the use of artificial intelligence (AI), a mere preview, I suspect, of what is to come for both patients and physicians.

I vow not to be a contrarian, but I have concerns. If we’d known how cell phones would permeate nearly every waking moment of our lives, would we have built in more protections from the onset?

Although anyone can see the enormous potential of AI in medicine, harnessing the wonders of it without guarding against the dangers could be paramount to texting and driving.

A palpable disruption in the common work-a-day human interaction is a given. CEOs who mind the bottom line will seek every opportunity to cut personnel whenever machine learning can deliver. As our dependence on algorithms increases, our need to understand electrocardiogram interpretation and echocardiographic calculations will wane. Subtle case information will go undetected. Nuanced subconscious alerts regarding the patient condition will go unnoticed.

These realities are never reflected in the pronouncements of companies who promote and develop AI.

The 2-minute echo

In September 2020, Carolyn Lam, MBBS, PhD, and James Hare, MBA, founders of the AI tech company US2.AI, told Healthcare Transformers that AI advances in echocardiology will turn “a manual process of 30 minutes, 250 clicks, with up to 21% variability among fully trained sonographers analyzing the same exam, into an AI-automated process taking 2 minutes, 1 click, with 0% variability.”

Let’s contrast this 2-minute human-machine interaction with the standard 20- to 30-minute human-to-human echocardiography procedure.

Take Mrs. Smith, for instance. She is referred for echocardiography for shortness of breath. She’s shown to a room and instructed to lie down on a table, where she undergoes a brief AI-directed acquisition of images and then a cheery dismissal from the imaging lab. Medical corporate chief financial officers will salivate at the efficiency, the decrease in cost for personnel, and the sharp increase in put-through for the echo lab schedule.

But what if Mrs. Smith gets a standard 30-minute sonographer-directed exam and the astute echocardiographer notes a left ventricular ejection fraction of 38%. A conversation with the patient reveals that she lost her son a few weeks ago. Upon completion of the study, the patient stands up and then adds, “I hope I can sleep in my bed tonight.” Thinking there may be more to the patient’s insomnia than grief-driven anxiety, the sonographer asks her to explain. “I had to sleep in a chair last night because I couldn’t breathe,” Mrs. Smith replies.

The sonographer reasons correctly that Mrs. Smith is likely a few weeks past an acute coronary syndrome for which she didn’t seek attention and is now in heart failure. The consulting cardiologist is alerted. Mrs. Smith is worked into the office schedule a week earlier than planned, and a costly in-patient stay for acute heart failure or worse is avoided.

Here’s a true-life example (some details have been changed to protect the patient’s identity): Mr. Rodriquez was referred for echocardiography because of dizziness. The sonographer notes significant mitral regurgitation and a decline in left ventricular ejection fraction from moderately impaired to severely reduced. When the sonographer inquires about a fresh bruise over Mr. Rodriguez’s left eye, he replies that he “must have fallen, but can’t remember.” The sonographer also notes runs of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia on the echo telemetry, and after a phone call from the echo lab to the ordering physician, Mr. Rodriquez is admitted. Instead of chancing a sudden death at home while awaiting follow-up, he undergoes catheterization and gets an implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

These scenarios illustrate that a 2-minute visit for AI-directed acquisition of echocardiogram images will never garner the protections of a conversation with a human. Any attempts at downplaying the importance of these human interactions are misguided.

Sometimes we embrace the latest advances in medicine while failing to tend to the most rudimentary necessities of data analysis and reporting. Catherine M. Otto, MD, director of the heart valve clinic and a professor of cardiology at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, is a fan of the basics.

At the recent annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, she commented on the AI-ENHANCED trial, which used an AI decision support algorithm to identify patients with moderate to severe aortic stenosis, which is associated with poor survival if left untreated. She correctly highlighted that while we are discussing the merits of AI-driven assessment of aortic stenosis, we are doing so in an era when many echo interpreters exclude critical information. The vital findings of aortic valve area, Vmax, and ejection fraction are often nowhere to be seen on reports. We should attend to our basic flaws in interpretation and reporting before we shift our focus to AI.

Flawed algorithms

Incorrect AI algorithms that are broadly adopted could negatively affect the health of millions.

Perhaps the most unsettling claim is made by causaLens: “Causal AI is the only technology that can reason and make choices like humans do,” the website states. A tantalizing tag line that is categorically untrue.

Our mysterious and complex neurophysiological function of reasoning still eludes understanding, but one thing is certain: medical reasoning originates with listening, seeing, and touching.

As AI infiltrates mainstream medicine, opportunities for hearing, observing, and palpating will be greatly reduced.

Folkert Asselbergs from University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands, who has cautioned against overhyping AI, was the discussant for an ESC study on the use of causal AI to improve cardiovascular risk estimation.

He flashed a slide of a 2019 Science article on racial bias in an algorithm that U.S. health care systems use. Remedying that bias “would increase the percentage of Black people receiving additional help from 17.7% to 46.5%,” according to the authors.

Successful integration of AI-driven technology will come only if we build human interaction into every patient encounter.

I hope I don’t live to see the rise of the physician cyborg.

Artificial intelligence could be the greatest boon since the invention of the stethoscope, but it will be our downfall if we stop administering a healthy dose of humanity to every patient encounter.

Melissa Walton-Shirley, MD, is a clinical cardiologist in Nashville, Tenn., who has retired from full-time invasive cardiology. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Weighted blankets promote melatonin release, may improve sleep

, compared with a lighter blanket of only about 2.4% of body weight.

This suggests that weighted blankets may help promote sleep in patients suffering from insomnia, according to the results from the small, in-laboratory crossover study.

“Melatonin is produced by the pineal gland and plays an essential role in sleep timing,” lead author Elisa Meth, PhD student, Uppsala University, Sweden, and colleagues observe.

“Using a weighted blanket increased melatonin concentration in saliva by about 30%,” Ms. Meth added in a statement.

“Future studies should investigate whether the stimulatory effect on melatonin secretion remains when using a weighted blanket over more extended periods,” the researchers observe, and caution that “it is also unclear whether the observed increase in melatonin is therapeutically relevant.”

The study was published online in the Journal of Sleep Research.

Weighted blankets are commercially available at least in some countries in Scandinavia and Germany, as examples, and in general, they are sold for therapeutic purposes. And at least one study found that weighted blankets were an effective and safe intervention for insomnia in patients with major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and led to improvements in daytime symptoms and levels of activity.

Study done in healthy volunteers

The study involved a total of 26 healthy volunteers, 15 men and 11 women, none of whom had any sleep issues. “The day before the first testing session, the participants visited the laboratory for an adaptation night,” the authors observe. There were two experimental test nights, one in which the weighted blanket was used and the second during which the lighter blanket was used.

On the test nights, lights were dimmed between 9 PM and 11 PM and participants used a weighted blanket covering the extremities, abdomen, and chest 1 hour before and during 8 hours of sleep. As the authors explain, the filling of the weighted blanket consisted of honed glass pearls, combined with polyester wadding, which corresponded to 12.2% of participants’ body weight.

“Saliva was collected every 20 minutes between 22:00 and 23:00,” Ms. Meth and colleagues note. Participants’ subjective sleepiness was also assessed every 20 minutes using the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale both before the hour that lights were turned off and the next morning.

“Sleep duration in each experimental night was recorded with the OURA ring,” investigators explain.

The OURA ring is a commercial multisensor wearable device that measures physiological variables indicative of sleep. Investigators focused on total sleep duration as the primary outcome measure.

On average, salivary melatonin concentrations rose by about 5.8 pg/mL between 10 PM and 11 PM (P < .001), but the average increase in salivary melatonin concentrations was greater under weighted blanket conditions at 6.6 pg/mL, compared with 5.0 pg/mL during the lighter blanket session (P = .011).

Oxytocin in turn rose by about 315 pg/mL initially, but this rise was only transient, and over time, no significant difference in oxytocin levels was observed between the two blanket conditions. There were also no differences in cortisol levels or the activity of the sympathetic nervous system between the weighted and light blanket sessions.

Importantly, as well, no significant differences were seen in the level of sleepiness between participants when either blanket was used nor was there a significant difference in total sleep duration.

“Our study cannot identify the underlying mechanism for the observed stimulatory effects of the weighted blanket on melatonin,” the investigators caution.

However, one explanation could be that the pressure exerted by the weighted blanket activates cutaneous sensory afferent nerves, carrying information to the brain. The region where the sensory information is delivered stimulates oxytocinergic neurons that can promote calm and well-being and decrease fear, stress, and pain. In addition, these neurons also connect to the pineal gland to influence the release of melatonin, the authors explain.

Melatonin often viewed in the wrong context

Senior author Christian Benedict, PhD, associate professor of pharmacology, Uppsala University, Sweden, explained that some people think of melatonin in the wrong context.

In point of fact, “it’s not a sleep-promoting hormone. It prepares your body and brain for the biological night ... [and] sleep coincides with the biological night, but it’s not like you take melatonin and you have a very nice uninterrupted slumber – this is not true,” he told this news organization.

He also noted that certain groups respond to melatonin better than others. For example, children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder may have some benefit from melatonin supplements, as may the elderly who can no longer produce sufficient amounts of melatonin and for whom supplements may help promote the timing of sleep.

However, the bottom line is that, even in those who do respond to melatonin supplements, they likely do so through a placebo effect that meta-analyses have shown plays a powerful role in promoting sleep.

Dr. Benedict also stressed that just because the body makes melatonin, itself, does not mean that melatonin supplements are necessarily “safe.”

“We know melatonin has some impact on puberty – it may delay the onset of puberty – and we know that it can also impair blood glucose, so when people are eating and have a lot of melatonin on board, the melatonin will tell the pancreas to turn off insulin production, which can give rise to hyperglycemia,” he said.

However, Dr. Benedict cautioned that weighted blankets don’t come cheap. A quick Google search brings up examples that cost upwards of $350. “MDs can say try one if you can afford these blankets, but perhaps people can use several less costly blankets,” he said. “But I definitely think if there are cheap options, why not?” he concluded.

Dr. Benedict has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, compared with a lighter blanket of only about 2.4% of body weight.

This suggests that weighted blankets may help promote sleep in patients suffering from insomnia, according to the results from the small, in-laboratory crossover study.

“Melatonin is produced by the pineal gland and plays an essential role in sleep timing,” lead author Elisa Meth, PhD student, Uppsala University, Sweden, and colleagues observe.

“Using a weighted blanket increased melatonin concentration in saliva by about 30%,” Ms. Meth added in a statement.

“Future studies should investigate whether the stimulatory effect on melatonin secretion remains when using a weighted blanket over more extended periods,” the researchers observe, and caution that “it is also unclear whether the observed increase in melatonin is therapeutically relevant.”

The study was published online in the Journal of Sleep Research.

Weighted blankets are commercially available at least in some countries in Scandinavia and Germany, as examples, and in general, they are sold for therapeutic purposes. And at least one study found that weighted blankets were an effective and safe intervention for insomnia in patients with major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and led to improvements in daytime symptoms and levels of activity.

Study done in healthy volunteers

The study involved a total of 26 healthy volunteers, 15 men and 11 women, none of whom had any sleep issues. “The day before the first testing session, the participants visited the laboratory for an adaptation night,” the authors observe. There were two experimental test nights, one in which the weighted blanket was used and the second during which the lighter blanket was used.

On the test nights, lights were dimmed between 9 PM and 11 PM and participants used a weighted blanket covering the extremities, abdomen, and chest 1 hour before and during 8 hours of sleep. As the authors explain, the filling of the weighted blanket consisted of honed glass pearls, combined with polyester wadding, which corresponded to 12.2% of participants’ body weight.

“Saliva was collected every 20 minutes between 22:00 and 23:00,” Ms. Meth and colleagues note. Participants’ subjective sleepiness was also assessed every 20 minutes using the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale both before the hour that lights were turned off and the next morning.

“Sleep duration in each experimental night was recorded with the OURA ring,” investigators explain.

The OURA ring is a commercial multisensor wearable device that measures physiological variables indicative of sleep. Investigators focused on total sleep duration as the primary outcome measure.

On average, salivary melatonin concentrations rose by about 5.8 pg/mL between 10 PM and 11 PM (P < .001), but the average increase in salivary melatonin concentrations was greater under weighted blanket conditions at 6.6 pg/mL, compared with 5.0 pg/mL during the lighter blanket session (P = .011).

Oxytocin in turn rose by about 315 pg/mL initially, but this rise was only transient, and over time, no significant difference in oxytocin levels was observed between the two blanket conditions. There were also no differences in cortisol levels or the activity of the sympathetic nervous system between the weighted and light blanket sessions.

Importantly, as well, no significant differences were seen in the level of sleepiness between participants when either blanket was used nor was there a significant difference in total sleep duration.

“Our study cannot identify the underlying mechanism for the observed stimulatory effects of the weighted blanket on melatonin,” the investigators caution.

However, one explanation could be that the pressure exerted by the weighted blanket activates cutaneous sensory afferent nerves, carrying information to the brain. The region where the sensory information is delivered stimulates oxytocinergic neurons that can promote calm and well-being and decrease fear, stress, and pain. In addition, these neurons also connect to the pineal gland to influence the release of melatonin, the authors explain.

Melatonin often viewed in the wrong context

Senior author Christian Benedict, PhD, associate professor of pharmacology, Uppsala University, Sweden, explained that some people think of melatonin in the wrong context.

In point of fact, “it’s not a sleep-promoting hormone. It prepares your body and brain for the biological night ... [and] sleep coincides with the biological night, but it’s not like you take melatonin and you have a very nice uninterrupted slumber – this is not true,” he told this news organization.

He also noted that certain groups respond to melatonin better than others. For example, children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder may have some benefit from melatonin supplements, as may the elderly who can no longer produce sufficient amounts of melatonin and for whom supplements may help promote the timing of sleep.

However, the bottom line is that, even in those who do respond to melatonin supplements, they likely do so through a placebo effect that meta-analyses have shown plays a powerful role in promoting sleep.

Dr. Benedict also stressed that just because the body makes melatonin, itself, does not mean that melatonin supplements are necessarily “safe.”

“We know melatonin has some impact on puberty – it may delay the onset of puberty – and we know that it can also impair blood glucose, so when people are eating and have a lot of melatonin on board, the melatonin will tell the pancreas to turn off insulin production, which can give rise to hyperglycemia,” he said.

However, Dr. Benedict cautioned that weighted blankets don’t come cheap. A quick Google search brings up examples that cost upwards of $350. “MDs can say try one if you can afford these blankets, but perhaps people can use several less costly blankets,” he said. “But I definitely think if there are cheap options, why not?” he concluded.

Dr. Benedict has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, compared with a lighter blanket of only about 2.4% of body weight.

This suggests that weighted blankets may help promote sleep in patients suffering from insomnia, according to the results from the small, in-laboratory crossover study.

“Melatonin is produced by the pineal gland and plays an essential role in sleep timing,” lead author Elisa Meth, PhD student, Uppsala University, Sweden, and colleagues observe.

“Using a weighted blanket increased melatonin concentration in saliva by about 30%,” Ms. Meth added in a statement.

“Future studies should investigate whether the stimulatory effect on melatonin secretion remains when using a weighted blanket over more extended periods,” the researchers observe, and caution that “it is also unclear whether the observed increase in melatonin is therapeutically relevant.”

The study was published online in the Journal of Sleep Research.

Weighted blankets are commercially available at least in some countries in Scandinavia and Germany, as examples, and in general, they are sold for therapeutic purposes. And at least one study found that weighted blankets were an effective and safe intervention for insomnia in patients with major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and led to improvements in daytime symptoms and levels of activity.

Study done in healthy volunteers

The study involved a total of 26 healthy volunteers, 15 men and 11 women, none of whom had any sleep issues. “The day before the first testing session, the participants visited the laboratory for an adaptation night,” the authors observe. There were two experimental test nights, one in which the weighted blanket was used and the second during which the lighter blanket was used.

On the test nights, lights were dimmed between 9 PM and 11 PM and participants used a weighted blanket covering the extremities, abdomen, and chest 1 hour before and during 8 hours of sleep. As the authors explain, the filling of the weighted blanket consisted of honed glass pearls, combined with polyester wadding, which corresponded to 12.2% of participants’ body weight.

“Saliva was collected every 20 minutes between 22:00 and 23:00,” Ms. Meth and colleagues note. Participants’ subjective sleepiness was also assessed every 20 minutes using the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale both before the hour that lights were turned off and the next morning.

“Sleep duration in each experimental night was recorded with the OURA ring,” investigators explain.

The OURA ring is a commercial multisensor wearable device that measures physiological variables indicative of sleep. Investigators focused on total sleep duration as the primary outcome measure.

On average, salivary melatonin concentrations rose by about 5.8 pg/mL between 10 PM and 11 PM (P < .001), but the average increase in salivary melatonin concentrations was greater under weighted blanket conditions at 6.6 pg/mL, compared with 5.0 pg/mL during the lighter blanket session (P = .011).

Oxytocin in turn rose by about 315 pg/mL initially, but this rise was only transient, and over time, no significant difference in oxytocin levels was observed between the two blanket conditions. There were also no differences in cortisol levels or the activity of the sympathetic nervous system between the weighted and light blanket sessions.

Importantly, as well, no significant differences were seen in the level of sleepiness between participants when either blanket was used nor was there a significant difference in total sleep duration.

“Our study cannot identify the underlying mechanism for the observed stimulatory effects of the weighted blanket on melatonin,” the investigators caution.

However, one explanation could be that the pressure exerted by the weighted blanket activates cutaneous sensory afferent nerves, carrying information to the brain. The region where the sensory information is delivered stimulates oxytocinergic neurons that can promote calm and well-being and decrease fear, stress, and pain. In addition, these neurons also connect to the pineal gland to influence the release of melatonin, the authors explain.

Melatonin often viewed in the wrong context

Senior author Christian Benedict, PhD, associate professor of pharmacology, Uppsala University, Sweden, explained that some people think of melatonin in the wrong context.

In point of fact, “it’s not a sleep-promoting hormone. It prepares your body and brain for the biological night ... [and] sleep coincides with the biological night, but it’s not like you take melatonin and you have a very nice uninterrupted slumber – this is not true,” he told this news organization.

He also noted that certain groups respond to melatonin better than others. For example, children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder may have some benefit from melatonin supplements, as may the elderly who can no longer produce sufficient amounts of melatonin and for whom supplements may help promote the timing of sleep.

However, the bottom line is that, even in those who do respond to melatonin supplements, they likely do so through a placebo effect that meta-analyses have shown plays a powerful role in promoting sleep.

Dr. Benedict also stressed that just because the body makes melatonin, itself, does not mean that melatonin supplements are necessarily “safe.”

“We know melatonin has some impact on puberty – it may delay the onset of puberty – and we know that it can also impair blood glucose, so when people are eating and have a lot of melatonin on board, the melatonin will tell the pancreas to turn off insulin production, which can give rise to hyperglycemia,” he said.

However, Dr. Benedict cautioned that weighted blankets don’t come cheap. A quick Google search brings up examples that cost upwards of $350. “MDs can say try one if you can afford these blankets, but perhaps people can use several less costly blankets,” he said. “But I definitely think if there are cheap options, why not?” he concluded.

Dr. Benedict has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF SLEEP RESEARCH

Emerging invasive fungal infections call for multidisciplinary cooperation

BUENOS AIRES – Emerging invasive fungal infections represent a new diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. To address their growing clinical impact on immunocompromised patients requires better local epidemiologic records, said a specialist at the XXII Congress of the Argentine Society of Infectology.

“To know that these fungal infections exist, I believe that in this respect we are falling short,” said Javier Afeltra, PhD, a mycologist at the Ramos Mejía Hospital in Buenos Aires, professor of microbiology at the School of Medicine of the University of Buenos Aires, and coordinator of the commission of immunocompromised patients of the Argentine Society of Infectious Diseases.

“There is some change in mentality that encourages professionals to report the cases they detect – for example, in scientific meetings,” Dr. Afeltra told this news orgnization. “But the problem is that there is no unified registry.

“That’s what we lack: a place to record all those isolated cases. Records where clinical and microbiological data are together within a click. Perhaps the microbiologists report their findings to the Malbrán Institute, an Argentine reference center for infectious disease research, but we do not know what the patients had. And we doctors may get together to make records of what happens clinically with the patient, but the germ data are elsewhere. We need a common registry,” he stressed.

“The main importance of a registry of this type is that it would allow a diagnostic and therapeutic decision to be made that is appropriate to the epidemiological profile of the country and the region, not looking at what they do in the North. Most likely, the best antifungal treatment for our country differs from what is indicated in the guidelines written elsewhere,” said Dr. Afeltra.

Dr. Afeltra pointed out that in the United States, when an oncohematology patient does not respond to antimicrobial treatment, the first thing that doctors think is that the patient has aspergillosis or mucormycosis, in which the fungal infection is caused by filamentous fungi.

But an analysis of data from the REMINI registry – the only prospective, observational, multicenter surveillance registry for invasive mycoses in immunocompromised patients (excluding HIV infection) in Argentina, which has been in existence since 2010 – tells a different story. The most prevalent fungal infections turned out to be those caused by Aspergillus species, followed by Fusarium species. Together, they account for more than half of cases. Mucoral infections (mucormycosis) account for less than 6%. And the initial treatments for these diseases could be different.

Changes in the local epidemiology can occur because the behavior of phytopathogenic fungi found in the environment can be modified. For example, cases of chronic mucormycosis can be detected in China but are virtually nonexistent on this side of the Greenwich meridian, Dr. Afeltra said.

“Nature is not the same in geographical areas, and the fungi … we breathe are completely different, so patients have different infections and require different diagnostic and treatment approaches,” he stressed.

Dr. Afeltra mentioned different fungi that are emerging locally and globally, including yeasts, septate, dimorphic, and pigmented hyaline fungi, that have a variable response to antifungal drugs and are associated with high mortality, “which has a lot to do with a later diagnosis,” he said, noting that reports have increased worldwide. A barrier to sharing this information more widely with the professional community, in addition to the lack of records, is the difficulty in publishing cases or series of cases in indexed journals.

Another challenge in characterizing the phenomenon is in regard to taxonomic reclassifications of fungi. Such reclassifications can mean that “perhaps we are speaking of the same pathogen in similar situations, believing that we are referring to different pathogens,” said Dr. Afeltra.

Clinical pearls related to emerging fungal pathogens

Candida auris. This organism has emerged simultaneously on several continents. It has pathogenicity factors typical of the genus, such as biofilm formation and production of phospholipases and proteinases, although it has greater thermal tolerance. In hospitals, it colonizes for weeks and months. In Argentina, it is resistant to multiple antifungal agents. Sensitivity is variable in different geographical regions. Most strains are resistant to fluconazole, and there is variable resistance to the other triazoles [which are not normally used to treat candidemia]. In the United States, in vitro resistance to amphotericin B is up to 30%, and resistance to echinocandins is up to 5%. New drugs such as rezafungin and ibrexafungerp are being studied. Infection control is similar to that used to control Clostridium difficile.

Fusarium. This genus affects immunocompromised patients, including transplant recipients of solid organs and hematopoietic progenitor cells and patients with neutropenia. The genus has various species, included within complexes, such as F. solani SC, F. oxysporum SC, and F. fujikuroi SC, with clinical manifestations similar to those of aspergillosis. In addition to the pulmonary and disseminated forms, there may be skin involvement attributable to dissemination from a respiratory focus or by contiguity from a focus of onychomycosis. In general, mortality is high, and responses to antifungal agents are variable. Some species are more sensitive to voriconazole or posaconazole, and others less so. All show in vitro resistance to itraconazole. In Argentina, voriconazole is usually used as initial treatment, and in special cases, liposomal amphotericin B or combinations. Fosmanogepix is being evaluated for the future.

Azole-resistant aspergillosis. This infection has shown resistance to itraconazole and third-generation azole drugs. In immunocompromised patients, mortlaity is high. Early detection is key. It is sensitive to amphotericin B and echinocandins. It is generally treated with liposomal amphotericin B. Olorofim and fosmanogepix are being studied.

Pulmonary aspergillosis associated with COVID-19. This infection is associated with high mortality among intubated patients. Signs and symptoms include fever, pleural effusion, hemoptysis, and chest pain, with infiltrates or cavitations on imaging. Determining the diagnosis is difficult. “We couldn’t perform lung biopsies, and it was difficult for us to get patients out of intensive care units for CT scans. We treated the proven cases. We treated the probable cases, and those that had a very low certainty of disease were also treated. We came across this emergency and tried to do the best we could,” said Dr. Afeltra. A digital readout lateral flow trial (Sona Aspergillus Galactomannan LFA) for the quantification of galactomannan, a cell wall component of the Aspergillus genus, proved to be a useful tool for screening and diagnosing patients with probable pulmonary aspergillosis associated with COVID-19. The incidence of invasive mycosis was around 10% among 185 seriously ill COVID-19 patients, according to an Argentine multicenter prospective study in which Dr. Afeltra participated.

Scedosporium and Lomentospora. These genera are rarer septate hyaline fungi. Scedosporium is a complex of species. One species, S. apiospermum, can colonize pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis. Lomentospora prolificans is a multiresistant fungus. It produces pulmonary compromise or disseminated infection. The response to antifungal agents is variable, with a high minimum inhibitory concentration for amphotericin B and isavuconazole. Patients are usually treated with voriconazole alone or in combination with terbinafine or micafungin. Olorofim is emerging as a promising treatment.

Dr. Afeltra has received fees from Biotoscana, Gador, Pfizer, Merck, and Sandoz.

This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish edition, a version appeared on Medscape.com.

BUENOS AIRES – Emerging invasive fungal infections represent a new diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. To address their growing clinical impact on immunocompromised patients requires better local epidemiologic records, said a specialist at the XXII Congress of the Argentine Society of Infectology.

“To know that these fungal infections exist, I believe that in this respect we are falling short,” said Javier Afeltra, PhD, a mycologist at the Ramos Mejía Hospital in Buenos Aires, professor of microbiology at the School of Medicine of the University of Buenos Aires, and coordinator of the commission of immunocompromised patients of the Argentine Society of Infectious Diseases.