User login

Skull Base Regeneration During Treatment With Chemoradiation for Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Case Report

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) differs from other head and neck (H&N) cancers in its epidemiology and treatment. Unlike other H&N cancers, NPC has a distinct geographical distribution with a much higher incidence in endemic areas, such as southern China, than in areas where it is relatively uncommon, such as the United States.1 The etiology of NPC varies based on the geographical distribution, with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) thought to be the primary etiologic agent in endemic areas. On the other hand, in North America 2 additional subsets of NPC have been identified: human papillomavirus (HPV)–positive/EBV-negative and HPV-negative/EBV-negative.2,3 NPC arises from the epithelial lining of the nasopharynx, often in the fossa of Rosenmuller, and is the most seen tumor in the nasopharynx.4 NPC is less surgically accessible than other H&N cancers, and surgery to the nasopharynx poses more risks given the proximity of critical surrounding structures. NPC is radiosensitive, and therefore radiotherapy (RT), in combination with chemotherapy for locally advanced tumors, has become the mainstay of treatment for nonmetastatic NPC.4

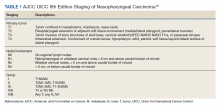

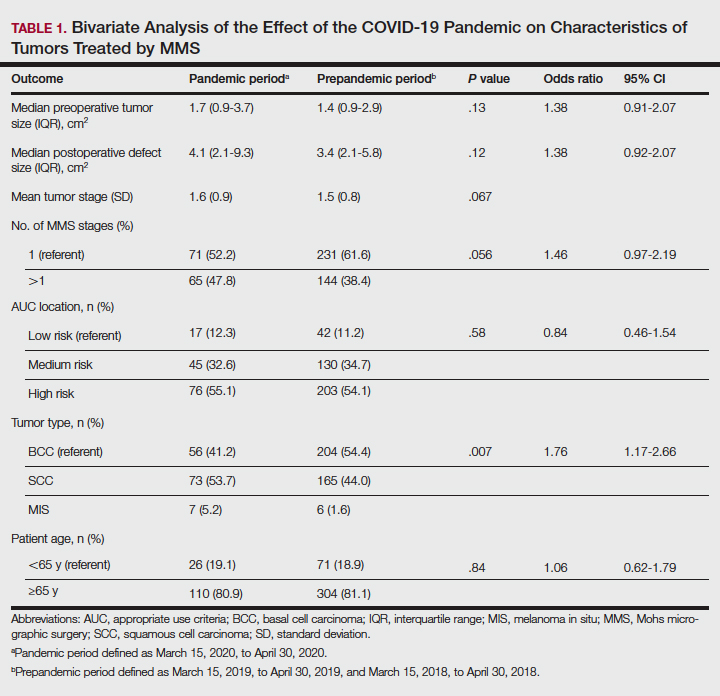

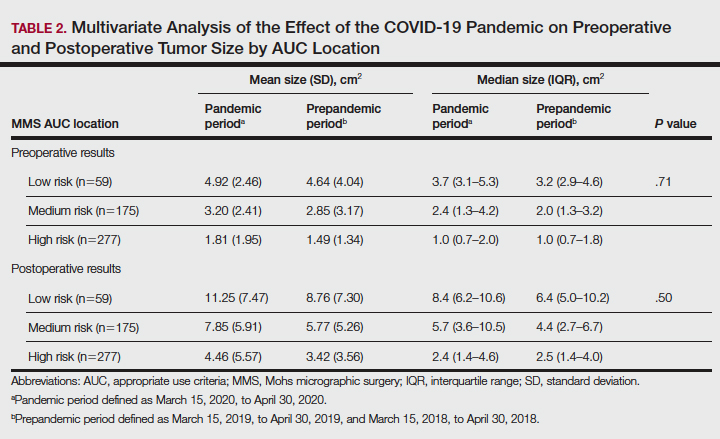

NPC often presents with an asymptomatic neck mass or with symptoms of epistaxis, nasal obstruction, and otitis media.5 Advanced cases of NPC can present with direct extension into the skull base, paranasal sinuses, and orbit, as well as involvement of cranial nerves. Radiation planning for tumors of the nasopharynx is complicated by the need to deliver an adequate dose to the tumor while limiting dose and toxicity to nearby critical structures such as the brainstem, optic chiasm, eyes, spinal cord (SC), temporal lobes, and cochleae. Achieving an adequate dose to nasopharyngeal primary tumors is especially complicated for T4 tumors invading the skull base with intracranial extension, in direct contact with these critical structures (Table 1).

Skull base invasion is a poor prognostic factor, predicting for an increased risk of locoregional recurrence and worse overall survival. Furthermore, the extent of skull base invasion in NPC affects overall prognosis, with cranial nerve involvement and intracranial extension predictive for worse outcomes.5 Depending on the extent of destruction, a bony defect along the skull base could develop with tumor shrinkage during RT, resulting in complications such as cerebrospinal fluid leaks, herniation, and atlantoaxial instability.6

There is a paucity of literature on the ability of bone to regenerate during or after RT for cases of NPC with skull base destruction. To our knowledge, nothing has been published detailing the extent of bony regeneration that can occur during treatment itself, as the tumor regresses and poses a threat of a skull base defect. Here we present a case of T4 HPV-positive/EBV-negative NPC with intracranial extension and describe the RT planning methods leading to prolonged local control, limited toxicities, and bony regeneration of the skull base during treatment.

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old male patient with no previous medical history presented to the emergency department with worsening diplopia, nasal obstruction, facial pain, and neck stiffness. The patient reported a 3 pack-year smoking history with recent smoking cessation. His physical examination was notable for a right abducens nerve palsy and an ulcerated nasopharyngeal mass on endoscopy.

Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 7-cm mass in the nasopharynx, eroding through the skull base with destruction and replacement of the clivus by tumor. Also noted was erosion of the petrous apices, carotid canals, sella turcica, dens, and the bilateral occipital condyles. There was intracranial extension with replacement of portions of the cavernous sinuses as well as mass effect on the prepontine cistern. Additional brain imaging studies, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans, were obtained for completion of the staging workup. The MRI correlated with the findings noted on CT and demonstrated involvement of Meckel cave, foramen ovale, foramen rotundum, Dorello canal, and the hypoglossal canals. No cervical lymphadenopathy or distant metastases were noted on imaging. Pathology from biopsy revealed poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, EBV-negative, strongly p16-positive, HPV-16 positive, and P53-negative.

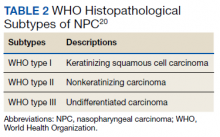

The H&N multidisciplinary tumor board recommended concurrent chemoradiation for this stage IVA (T4N0M0) EBV-negative, HPV-positive, Word Health Organization type I NPC (Table 2). The patient underwent CT simulation for RT planning, and both tumor volumes and critical normal structures were contoured. The goal was to deliver 70 Gy to the gross tumor. However, given the inability to deliver this dose while meeting the SC dose tolerance of < 45 Gy, a 2-Gy fraction was removed. Therefore, 34 fractions of 2 Gy were delivered to the tumor volume for a total dose of 68 Gy. Weekly cisplatin, at a dose of 40 mg/m2, was administered concurrently with RT.

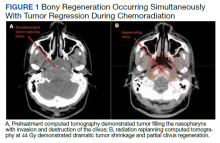

RT planning was complicated by the tumor’s contact with the brainstem and upper cervical SC, as well as proximity of the tumor to the optic apparatus. The patient underwent 2 replanning CT scans at 26 Gy and 44 Gy to evaluate for tumor shrinkage. These CT scans demonstrated shrinkage of the tumor away from critical neural structures, allowing the treatment volume to be reduced away from these structures in order to achieve required dose tolerances (brainstem < 54 Gy, optic nerves and chiasm < 50 Gy, SC < 45 Gy for this case). The replanning CT scan at 44 Gy, 5 weeks after treatment initiation, demonstrated that dramatic tumor shrinkage had occurred early in treatment, with separation of the remaining tumor from the area of the SC and brainstem with which it was initially in contact (Figure 1). This improvement allowed for shrinkage of the high-dose radiation field away from these critical neural structures.

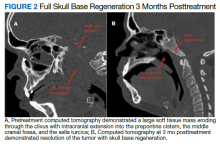

Baseline destruction of the skull base by tumor raised concern for craniospinal instability with tumor response. The patient was evaluated by neurosurgery before the start of RT, and the recommendation was for reimaging during treatment and close follow-up of the patient’s symptoms to determine whether surgical fixation would be indicated during or after treatment. The patient underwent a replanning CT scan at 44 Gy, 5 weeks after treatment initiation, that demonstrated impressive bony regeneration occurring during chemoradiation. New bone formation was noted in the region of the clivus and bilateral occipital condyles, which had been absent on CT prior to treatment initiation. Another CT at 54 Gy demonstrated further ossification of the clivus and bilateral occipital condyles, and bony regeneration occurring rapidly during chemoradiation. The posttreatment CT 3 months after completion of chemoradiation demonstrated complete skull base regeneration, maintaining stability of this area and precluding the need for neurosurgical intervention (Figure 2).

During RT,

The patient had no evidence of disease at 5 years posttreatment. After completing treatment, the patient experienced ongoing intermittent nasal congestion and occasional aural fullness. He experienced an early decay of several teeth starting 1 year after completion of RT, and he continues to visit his dentist for management. He experienced no other treatment-related toxicities. In particular, he has exhibited no signs of neurologic toxicity to date.

Discussion

RT for NPC is complicated by the proximity of these tumors to critical surrounding neural structures. It is challenging to achieve the required dose constraints to surrounding neural tissues while delivering the usual 70-Gy dose to the gross tumor, especially when the tumor comes into direct contact with these structures.

This case provides an example of response-adapted RT using imaging during treatment to shrink the high-dose target as the tumor shrinks away from critical surrounding structures.7 This strategy permits delivery of the maximum dose to the tumor while minimizing radiation dose, and therefore risk of toxicity, to normal surrounding structures. While it is typical to deliver 70 Gy to the full extent of tumor involvement for H&N tumors, this was not possible in this case as the tumor was in contact with the brainstem and upper cervical SC. Delivering the full 70 Gy to these areas of tumor would have placed this patient at substantial risk of brainstem and/or SC toxicity. This report demonstrates that response-adapted RT with shrinking fields can allow for tumor control while avoiding toxicity to critical neural structures for cases of locally advanced NPC in which tumor is abutting these structures.

Bony regeneration of the skull base following RT has been reported in the literature, but in limited reviews. Early reports used plain radiography to follow changes. Unger and colleagues demonstrated the regeneration of bone using skull radiographs 4 to 6 months after completion of RT for NPC.8 More recent literature details the ability of bone to regenerate after RT based on CT findings. Fang and colleagues reported on 90 cases of NPC with skull base destruction, with 63% having bony regeneration on posttreatment CT.9 Most of the patients in Fang’s report had bony regeneration within 1 year of treatment, and in general, bony regeneration became more evident on imaging with longer follow-up. Of note, local control was significantly greater in patients with regeneration vs persistent destruction (77% vs 21%, P < .001). On multivariate analysis, complete tumor response was significantly associated with bony regeneration; other factors such as age, sex, radiation dose, and chemotherapy were not significantly associated with the likelihood of bony regeneration.

Our report details a nasopharyngeal tumor that destroyed the skull base with no intact bony barrier. In such cases, concern arises regarding craniospinal instability with tumor regression if there is not simultaneous bone regeneration. Tumor invasion of the skull base and C1-2 vertebral bodies and complications from treatment of such tumor extent can lead to symptoms of craniospinal instability, including pain, difficulty with neck range of motion, and loss of strength and sensation in the upper and lower extremities.10 A case report of a woman treated with chemoradiation for a plasmacytoma of the skull base detailed her posttreatment presentation with quadriparesis resulting from craniospinal instability after tumor regression.11 Such instability is generally treated surgically, and during this woman’s surgery, there was an injury to the right vertebral artery, although this did not cause any additional neurologic deficits.

RT leads to hypocellularity, hypovascularity, and hypoxia of treated tissues, resulting in a reduced ability for growth and healing. Studies demonstrate that irradiated bone contains fewer osteoblast cells and osteocytes than unirradiated bone, resulting in reduced regenerative capacity.12,13 Furthermore, the reconstruction of bony defects resulting after cancer treatment has been shown to be difficult and associated with a high risk of complications.14 Given the impaired ability of irradiated bone to regenerate, studies have evaluated the use of growth factors and gene therapy to promote bone formation after treatment.15 Bone marrow stem cells have been shown to reverse radiation-induced cellular depletion and to increase osteocyte counts in animal studies.12 Further, overexpression of miR-34a, a tumor suppressor involved in tissue development, has been shown to improve osteoblastic differentiation of irradiated bone marrow stem cells and promote bone regeneration in vitro and in animal studies.13 While several techniques are being studied in vitro and in animal studies to promote bony regeneration after RT, there is a lack of data on use of these techniques in humans with cancer.

With our case, there was great uncertainty related to the ability of bone to regenerate during treatment and concern regarding consequences of formation of a skull base defect during treatment. CT imaging revealed bony regeneration of the central skull base and clivus, as well as occipital condyles, that occurred throughout the RT course. There was clear evidence of bone regeneration on the replanning CT obtained 5 weeks after treatment initiation. To our knowledge, this is the first report to demonstrate rapid bony regeneration during RT, thereby maintaining the integrity of the skull base and precluding the need for neurosurgical intervention. Moving forward, imaging should be considered during treatment for patients with tumor-related destruction of the skull base and upper cervical spine to evaluate the extent of bony regeneration during treatment and estimate the potential risk of craniocervical instability. Further studies with imaging during treatment are needed for more information on the likelihood of bony regeneration and factors that correlate with bony regeneration during treatment. As in other reports, our case demonstrates that bony regeneration may predict complete response to RT.9

Our patient’s tumor was HPV-positive and EBV-negative. In the US, the rate of HPV-positive NPC is 35%.16 However, HPV-positive NPC is much less common in endemic areas. A recent study from China of 1,328 patients with NPC revealed a 6.4% rate of HPV-positive/EBV-negative cases.17 In that study, patients with HPV-positive/EBV-negative tumors had improved survival compared to patients whose tumors were HPV-negative/EBV-positive. Another study suggests that the impact of HPV in NPC varies according to race, with HPV-positivity predicting for improved outcomes in East Asian patients and worse outcomes in White patients.17 A study from the University of Michigan suggests that both HPV-positive/EBV-negative and HPV-negative/EBV-negative NPC are associated with worse overall survival and locoregional control than EBV-positive NPC.2 Overall, the prognostic role of HPV in NPC remains unclear given conflicting information in the literature and the lack of large population studies.18

Conclusions

There is a paucity of literature on bony regeneration in patients with skull base destruction from advanced NPC, and in particular, the ability of skull base regeneration to occur during treatment simultaneous with tumor regression. Our patient had HPV-positive/EBV-negative NPC, but it is unclear how this subtype affected his prognosis. Factors such as tumor histology, radiosensitivity with rapid tumor regression, and young age may have all contributed to the rapidity of bone regeneration in our patient. This case report demonstrates that an impressive tumor response to chemoradiation with simultaneous bony regeneration is possible among patients presenting with tumor destruction of the skull base, precluding the need for neurosurgical intervention.

1. Chang ET, Adami HO. The enigmatic epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(10):1765-1777. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0353

2. Stenmark MH, McHugh JB, Schipper M, et al. Nonendemic HPV-positive nasopharyngeal carcinoma: association with poor prognosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(3):580-588. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.11.246

3. Maxwell JH, Kumar B, Feng FY, et al. HPV-positive/p16-positive/EBV-negative nasopharyngeal carcinoma in white North Americans. Head Neck. 2010;32(5):562-567. doi:10.1002/hed.21216

4. Chen YP, Chan ATC, Le QT, Blanchard P, Sun Y, Ma J. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet. 2019;394(10192):64-80. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30956-0

5. Roh JL, Sung MW, Kim KH, et al.. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma with skull base invasion: a necessity of staging subdivision. Am J Otolaryngol. 2004;25(1):26-32. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2003.09.011

6. Orr RD, Salo PT. Atlantoaxial instability complicating radiation therapy for recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. A case report. Spine. 1998;23(11):1280-1282. doi:10.1097/00007632-199806010-00021

7. Morgan HE, Sher DJ. Adaptive radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Cancers Head Neck. 2020;5:1. doi:10.1186/s41199-019-0046-z

8. Unger JD, Chiang LC, Unger GF. Apparent reformation of the base of the skull following radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiology. 1978;126(3):779-782. doi:10.1148/126.3.779

9. Fang FM, Leung SW, Wang CJ, et al. Computed tomography findings of bony regeneration after radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma with skull base destruction: implications for local control. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44(2):305-309. doi:10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00004-8

10. Tiruchelvarayan R, Lee KA, Ng I. Surgery for atlanto-axial (C1-2) involvement or instability in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Singapore Med J. 2012;53(6):416-421.

11. Samprón N, Arrazola M, Urculo E. Skull-base plasmacytoma with craniocervical instability [in Spanish]. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2009;20(5):478-483.

12. Zheutlin AR, Deshpande SS, Nelson NS, et al. Bone marrow stem cells assuage radiation-induced damage in a murine model of distraction osteogenesis: a histomorphometric evaluation. Cytotherapy. 2016;18(5):664-672. doi:10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.01.013

13. Liu H, Dong Y, Feng X, et al. miR-34a promotes bone regeneration in irradiated bone defects by enhancing osteoblast differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells in rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):180. doi:10.1186/s13287-019-1285-y

14. Holzapfel BM, Wagner F, Martine LC, et al. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine in musculoskeletal oncology. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016;35(3):475-487. doi:10.1007/s10555-016-9635-z

15. Hu WW, Ward BB, Wang Z, Krebsbach PH. Bone regeneration in defects compromised by radiotherapy. J Dent Res. 2010;89(1):77-81. doi:10.1177/0022034509352151

16. Wotman M, Oh EJ, Ahn S, Kraus D, Constantino P, Tham T. HPV status in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the United States: a SEER database study. Am J Otolaryngol. 2019;40(5):705-710. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2019.06.00717. Huang WB, Chan JYW, Liu DL. Human papillomavirus and World Health Organization type III nasopharyngeal carcinoma: multicenter study from an endemic area in Southern China. Cancer. 2018;124(3):530-536. doi:10.1002/cncr.31031.

18. Verma V, Simone CB 2nd, Lin C. Human papillomavirus and nasopharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2018;40(4):696-706. doi:10.1002/hed.24978

19. Lee AWM, Lydiatt WM, Colevas AD, et al. Nasopharynx. In: Amin MB, ed. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017:103.

20. Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, eds. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumors. In: World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. IARC Press; 2005.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) differs from other head and neck (H&N) cancers in its epidemiology and treatment. Unlike other H&N cancers, NPC has a distinct geographical distribution with a much higher incidence in endemic areas, such as southern China, than in areas where it is relatively uncommon, such as the United States.1 The etiology of NPC varies based on the geographical distribution, with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) thought to be the primary etiologic agent in endemic areas. On the other hand, in North America 2 additional subsets of NPC have been identified: human papillomavirus (HPV)–positive/EBV-negative and HPV-negative/EBV-negative.2,3 NPC arises from the epithelial lining of the nasopharynx, often in the fossa of Rosenmuller, and is the most seen tumor in the nasopharynx.4 NPC is less surgically accessible than other H&N cancers, and surgery to the nasopharynx poses more risks given the proximity of critical surrounding structures. NPC is radiosensitive, and therefore radiotherapy (RT), in combination with chemotherapy for locally advanced tumors, has become the mainstay of treatment for nonmetastatic NPC.4

NPC often presents with an asymptomatic neck mass or with symptoms of epistaxis, nasal obstruction, and otitis media.5 Advanced cases of NPC can present with direct extension into the skull base, paranasal sinuses, and orbit, as well as involvement of cranial nerves. Radiation planning for tumors of the nasopharynx is complicated by the need to deliver an adequate dose to the tumor while limiting dose and toxicity to nearby critical structures such as the brainstem, optic chiasm, eyes, spinal cord (SC), temporal lobes, and cochleae. Achieving an adequate dose to nasopharyngeal primary tumors is especially complicated for T4 tumors invading the skull base with intracranial extension, in direct contact with these critical structures (Table 1).

Skull base invasion is a poor prognostic factor, predicting for an increased risk of locoregional recurrence and worse overall survival. Furthermore, the extent of skull base invasion in NPC affects overall prognosis, with cranial nerve involvement and intracranial extension predictive for worse outcomes.5 Depending on the extent of destruction, a bony defect along the skull base could develop with tumor shrinkage during RT, resulting in complications such as cerebrospinal fluid leaks, herniation, and atlantoaxial instability.6

There is a paucity of literature on the ability of bone to regenerate during or after RT for cases of NPC with skull base destruction. To our knowledge, nothing has been published detailing the extent of bony regeneration that can occur during treatment itself, as the tumor regresses and poses a threat of a skull base defect. Here we present a case of T4 HPV-positive/EBV-negative NPC with intracranial extension and describe the RT planning methods leading to prolonged local control, limited toxicities, and bony regeneration of the skull base during treatment.

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old male patient with no previous medical history presented to the emergency department with worsening diplopia, nasal obstruction, facial pain, and neck stiffness. The patient reported a 3 pack-year smoking history with recent smoking cessation. His physical examination was notable for a right abducens nerve palsy and an ulcerated nasopharyngeal mass on endoscopy.

Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 7-cm mass in the nasopharynx, eroding through the skull base with destruction and replacement of the clivus by tumor. Also noted was erosion of the petrous apices, carotid canals, sella turcica, dens, and the bilateral occipital condyles. There was intracranial extension with replacement of portions of the cavernous sinuses as well as mass effect on the prepontine cistern. Additional brain imaging studies, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans, were obtained for completion of the staging workup. The MRI correlated with the findings noted on CT and demonstrated involvement of Meckel cave, foramen ovale, foramen rotundum, Dorello canal, and the hypoglossal canals. No cervical lymphadenopathy or distant metastases were noted on imaging. Pathology from biopsy revealed poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, EBV-negative, strongly p16-positive, HPV-16 positive, and P53-negative.

The H&N multidisciplinary tumor board recommended concurrent chemoradiation for this stage IVA (T4N0M0) EBV-negative, HPV-positive, Word Health Organization type I NPC (Table 2). The patient underwent CT simulation for RT planning, and both tumor volumes and critical normal structures were contoured. The goal was to deliver 70 Gy to the gross tumor. However, given the inability to deliver this dose while meeting the SC dose tolerance of < 45 Gy, a 2-Gy fraction was removed. Therefore, 34 fractions of 2 Gy were delivered to the tumor volume for a total dose of 68 Gy. Weekly cisplatin, at a dose of 40 mg/m2, was administered concurrently with RT.

RT planning was complicated by the tumor’s contact with the brainstem and upper cervical SC, as well as proximity of the tumor to the optic apparatus. The patient underwent 2 replanning CT scans at 26 Gy and 44 Gy to evaluate for tumor shrinkage. These CT scans demonstrated shrinkage of the tumor away from critical neural structures, allowing the treatment volume to be reduced away from these structures in order to achieve required dose tolerances (brainstem < 54 Gy, optic nerves and chiasm < 50 Gy, SC < 45 Gy for this case). The replanning CT scan at 44 Gy, 5 weeks after treatment initiation, demonstrated that dramatic tumor shrinkage had occurred early in treatment, with separation of the remaining tumor from the area of the SC and brainstem with which it was initially in contact (Figure 1). This improvement allowed for shrinkage of the high-dose radiation field away from these critical neural structures.

Baseline destruction of the skull base by tumor raised concern for craniospinal instability with tumor response. The patient was evaluated by neurosurgery before the start of RT, and the recommendation was for reimaging during treatment and close follow-up of the patient’s symptoms to determine whether surgical fixation would be indicated during or after treatment. The patient underwent a replanning CT scan at 44 Gy, 5 weeks after treatment initiation, that demonstrated impressive bony regeneration occurring during chemoradiation. New bone formation was noted in the region of the clivus and bilateral occipital condyles, which had been absent on CT prior to treatment initiation. Another CT at 54 Gy demonstrated further ossification of the clivus and bilateral occipital condyles, and bony regeneration occurring rapidly during chemoradiation. The posttreatment CT 3 months after completion of chemoradiation demonstrated complete skull base regeneration, maintaining stability of this area and precluding the need for neurosurgical intervention (Figure 2).

During RT,

The patient had no evidence of disease at 5 years posttreatment. After completing treatment, the patient experienced ongoing intermittent nasal congestion and occasional aural fullness. He experienced an early decay of several teeth starting 1 year after completion of RT, and he continues to visit his dentist for management. He experienced no other treatment-related toxicities. In particular, he has exhibited no signs of neurologic toxicity to date.

Discussion

RT for NPC is complicated by the proximity of these tumors to critical surrounding neural structures. It is challenging to achieve the required dose constraints to surrounding neural tissues while delivering the usual 70-Gy dose to the gross tumor, especially when the tumor comes into direct contact with these structures.

This case provides an example of response-adapted RT using imaging during treatment to shrink the high-dose target as the tumor shrinks away from critical surrounding structures.7 This strategy permits delivery of the maximum dose to the tumor while minimizing radiation dose, and therefore risk of toxicity, to normal surrounding structures. While it is typical to deliver 70 Gy to the full extent of tumor involvement for H&N tumors, this was not possible in this case as the tumor was in contact with the brainstem and upper cervical SC. Delivering the full 70 Gy to these areas of tumor would have placed this patient at substantial risk of brainstem and/or SC toxicity. This report demonstrates that response-adapted RT with shrinking fields can allow for tumor control while avoiding toxicity to critical neural structures for cases of locally advanced NPC in which tumor is abutting these structures.

Bony regeneration of the skull base following RT has been reported in the literature, but in limited reviews. Early reports used plain radiography to follow changes. Unger and colleagues demonstrated the regeneration of bone using skull radiographs 4 to 6 months after completion of RT for NPC.8 More recent literature details the ability of bone to regenerate after RT based on CT findings. Fang and colleagues reported on 90 cases of NPC with skull base destruction, with 63% having bony regeneration on posttreatment CT.9 Most of the patients in Fang’s report had bony regeneration within 1 year of treatment, and in general, bony regeneration became more evident on imaging with longer follow-up. Of note, local control was significantly greater in patients with regeneration vs persistent destruction (77% vs 21%, P < .001). On multivariate analysis, complete tumor response was significantly associated with bony regeneration; other factors such as age, sex, radiation dose, and chemotherapy were not significantly associated with the likelihood of bony regeneration.

Our report details a nasopharyngeal tumor that destroyed the skull base with no intact bony barrier. In such cases, concern arises regarding craniospinal instability with tumor regression if there is not simultaneous bone regeneration. Tumor invasion of the skull base and C1-2 vertebral bodies and complications from treatment of such tumor extent can lead to symptoms of craniospinal instability, including pain, difficulty with neck range of motion, and loss of strength and sensation in the upper and lower extremities.10 A case report of a woman treated with chemoradiation for a plasmacytoma of the skull base detailed her posttreatment presentation with quadriparesis resulting from craniospinal instability after tumor regression.11 Such instability is generally treated surgically, and during this woman’s surgery, there was an injury to the right vertebral artery, although this did not cause any additional neurologic deficits.

RT leads to hypocellularity, hypovascularity, and hypoxia of treated tissues, resulting in a reduced ability for growth and healing. Studies demonstrate that irradiated bone contains fewer osteoblast cells and osteocytes than unirradiated bone, resulting in reduced regenerative capacity.12,13 Furthermore, the reconstruction of bony defects resulting after cancer treatment has been shown to be difficult and associated with a high risk of complications.14 Given the impaired ability of irradiated bone to regenerate, studies have evaluated the use of growth factors and gene therapy to promote bone formation after treatment.15 Bone marrow stem cells have been shown to reverse radiation-induced cellular depletion and to increase osteocyte counts in animal studies.12 Further, overexpression of miR-34a, a tumor suppressor involved in tissue development, has been shown to improve osteoblastic differentiation of irradiated bone marrow stem cells and promote bone regeneration in vitro and in animal studies.13 While several techniques are being studied in vitro and in animal studies to promote bony regeneration after RT, there is a lack of data on use of these techniques in humans with cancer.

With our case, there was great uncertainty related to the ability of bone to regenerate during treatment and concern regarding consequences of formation of a skull base defect during treatment. CT imaging revealed bony regeneration of the central skull base and clivus, as well as occipital condyles, that occurred throughout the RT course. There was clear evidence of bone regeneration on the replanning CT obtained 5 weeks after treatment initiation. To our knowledge, this is the first report to demonstrate rapid bony regeneration during RT, thereby maintaining the integrity of the skull base and precluding the need for neurosurgical intervention. Moving forward, imaging should be considered during treatment for patients with tumor-related destruction of the skull base and upper cervical spine to evaluate the extent of bony regeneration during treatment and estimate the potential risk of craniocervical instability. Further studies with imaging during treatment are needed for more information on the likelihood of bony regeneration and factors that correlate with bony regeneration during treatment. As in other reports, our case demonstrates that bony regeneration may predict complete response to RT.9

Our patient’s tumor was HPV-positive and EBV-negative. In the US, the rate of HPV-positive NPC is 35%.16 However, HPV-positive NPC is much less common in endemic areas. A recent study from China of 1,328 patients with NPC revealed a 6.4% rate of HPV-positive/EBV-negative cases.17 In that study, patients with HPV-positive/EBV-negative tumors had improved survival compared to patients whose tumors were HPV-negative/EBV-positive. Another study suggests that the impact of HPV in NPC varies according to race, with HPV-positivity predicting for improved outcomes in East Asian patients and worse outcomes in White patients.17 A study from the University of Michigan suggests that both HPV-positive/EBV-negative and HPV-negative/EBV-negative NPC are associated with worse overall survival and locoregional control than EBV-positive NPC.2 Overall, the prognostic role of HPV in NPC remains unclear given conflicting information in the literature and the lack of large population studies.18

Conclusions

There is a paucity of literature on bony regeneration in patients with skull base destruction from advanced NPC, and in particular, the ability of skull base regeneration to occur during treatment simultaneous with tumor regression. Our patient had HPV-positive/EBV-negative NPC, but it is unclear how this subtype affected his prognosis. Factors such as tumor histology, radiosensitivity with rapid tumor regression, and young age may have all contributed to the rapidity of bone regeneration in our patient. This case report demonstrates that an impressive tumor response to chemoradiation with simultaneous bony regeneration is possible among patients presenting with tumor destruction of the skull base, precluding the need for neurosurgical intervention.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) differs from other head and neck (H&N) cancers in its epidemiology and treatment. Unlike other H&N cancers, NPC has a distinct geographical distribution with a much higher incidence in endemic areas, such as southern China, than in areas where it is relatively uncommon, such as the United States.1 The etiology of NPC varies based on the geographical distribution, with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) thought to be the primary etiologic agent in endemic areas. On the other hand, in North America 2 additional subsets of NPC have been identified: human papillomavirus (HPV)–positive/EBV-negative and HPV-negative/EBV-negative.2,3 NPC arises from the epithelial lining of the nasopharynx, often in the fossa of Rosenmuller, and is the most seen tumor in the nasopharynx.4 NPC is less surgically accessible than other H&N cancers, and surgery to the nasopharynx poses more risks given the proximity of critical surrounding structures. NPC is radiosensitive, and therefore radiotherapy (RT), in combination with chemotherapy for locally advanced tumors, has become the mainstay of treatment for nonmetastatic NPC.4

NPC often presents with an asymptomatic neck mass or with symptoms of epistaxis, nasal obstruction, and otitis media.5 Advanced cases of NPC can present with direct extension into the skull base, paranasal sinuses, and orbit, as well as involvement of cranial nerves. Radiation planning for tumors of the nasopharynx is complicated by the need to deliver an adequate dose to the tumor while limiting dose and toxicity to nearby critical structures such as the brainstem, optic chiasm, eyes, spinal cord (SC), temporal lobes, and cochleae. Achieving an adequate dose to nasopharyngeal primary tumors is especially complicated for T4 tumors invading the skull base with intracranial extension, in direct contact with these critical structures (Table 1).

Skull base invasion is a poor prognostic factor, predicting for an increased risk of locoregional recurrence and worse overall survival. Furthermore, the extent of skull base invasion in NPC affects overall prognosis, with cranial nerve involvement and intracranial extension predictive for worse outcomes.5 Depending on the extent of destruction, a bony defect along the skull base could develop with tumor shrinkage during RT, resulting in complications such as cerebrospinal fluid leaks, herniation, and atlantoaxial instability.6

There is a paucity of literature on the ability of bone to regenerate during or after RT for cases of NPC with skull base destruction. To our knowledge, nothing has been published detailing the extent of bony regeneration that can occur during treatment itself, as the tumor regresses and poses a threat of a skull base defect. Here we present a case of T4 HPV-positive/EBV-negative NPC with intracranial extension and describe the RT planning methods leading to prolonged local control, limited toxicities, and bony regeneration of the skull base during treatment.

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old male patient with no previous medical history presented to the emergency department with worsening diplopia, nasal obstruction, facial pain, and neck stiffness. The patient reported a 3 pack-year smoking history with recent smoking cessation. His physical examination was notable for a right abducens nerve palsy and an ulcerated nasopharyngeal mass on endoscopy.

Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 7-cm mass in the nasopharynx, eroding through the skull base with destruction and replacement of the clivus by tumor. Also noted was erosion of the petrous apices, carotid canals, sella turcica, dens, and the bilateral occipital condyles. There was intracranial extension with replacement of portions of the cavernous sinuses as well as mass effect on the prepontine cistern. Additional brain imaging studies, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans, were obtained for completion of the staging workup. The MRI correlated with the findings noted on CT and demonstrated involvement of Meckel cave, foramen ovale, foramen rotundum, Dorello canal, and the hypoglossal canals. No cervical lymphadenopathy or distant metastases were noted on imaging. Pathology from biopsy revealed poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, EBV-negative, strongly p16-positive, HPV-16 positive, and P53-negative.

The H&N multidisciplinary tumor board recommended concurrent chemoradiation for this stage IVA (T4N0M0) EBV-negative, HPV-positive, Word Health Organization type I NPC (Table 2). The patient underwent CT simulation for RT planning, and both tumor volumes and critical normal structures were contoured. The goal was to deliver 70 Gy to the gross tumor. However, given the inability to deliver this dose while meeting the SC dose tolerance of < 45 Gy, a 2-Gy fraction was removed. Therefore, 34 fractions of 2 Gy were delivered to the tumor volume for a total dose of 68 Gy. Weekly cisplatin, at a dose of 40 mg/m2, was administered concurrently with RT.

RT planning was complicated by the tumor’s contact with the brainstem and upper cervical SC, as well as proximity of the tumor to the optic apparatus. The patient underwent 2 replanning CT scans at 26 Gy and 44 Gy to evaluate for tumor shrinkage. These CT scans demonstrated shrinkage of the tumor away from critical neural structures, allowing the treatment volume to be reduced away from these structures in order to achieve required dose tolerances (brainstem < 54 Gy, optic nerves and chiasm < 50 Gy, SC < 45 Gy for this case). The replanning CT scan at 44 Gy, 5 weeks after treatment initiation, demonstrated that dramatic tumor shrinkage had occurred early in treatment, with separation of the remaining tumor from the area of the SC and brainstem with which it was initially in contact (Figure 1). This improvement allowed for shrinkage of the high-dose radiation field away from these critical neural structures.

Baseline destruction of the skull base by tumor raised concern for craniospinal instability with tumor response. The patient was evaluated by neurosurgery before the start of RT, and the recommendation was for reimaging during treatment and close follow-up of the patient’s symptoms to determine whether surgical fixation would be indicated during or after treatment. The patient underwent a replanning CT scan at 44 Gy, 5 weeks after treatment initiation, that demonstrated impressive bony regeneration occurring during chemoradiation. New bone formation was noted in the region of the clivus and bilateral occipital condyles, which had been absent on CT prior to treatment initiation. Another CT at 54 Gy demonstrated further ossification of the clivus and bilateral occipital condyles, and bony regeneration occurring rapidly during chemoradiation. The posttreatment CT 3 months after completion of chemoradiation demonstrated complete skull base regeneration, maintaining stability of this area and precluding the need for neurosurgical intervention (Figure 2).

During RT,

The patient had no evidence of disease at 5 years posttreatment. After completing treatment, the patient experienced ongoing intermittent nasal congestion and occasional aural fullness. He experienced an early decay of several teeth starting 1 year after completion of RT, and he continues to visit his dentist for management. He experienced no other treatment-related toxicities. In particular, he has exhibited no signs of neurologic toxicity to date.

Discussion

RT for NPC is complicated by the proximity of these tumors to critical surrounding neural structures. It is challenging to achieve the required dose constraints to surrounding neural tissues while delivering the usual 70-Gy dose to the gross tumor, especially when the tumor comes into direct contact with these structures.

This case provides an example of response-adapted RT using imaging during treatment to shrink the high-dose target as the tumor shrinks away from critical surrounding structures.7 This strategy permits delivery of the maximum dose to the tumor while minimizing radiation dose, and therefore risk of toxicity, to normal surrounding structures. While it is typical to deliver 70 Gy to the full extent of tumor involvement for H&N tumors, this was not possible in this case as the tumor was in contact with the brainstem and upper cervical SC. Delivering the full 70 Gy to these areas of tumor would have placed this patient at substantial risk of brainstem and/or SC toxicity. This report demonstrates that response-adapted RT with shrinking fields can allow for tumor control while avoiding toxicity to critical neural structures for cases of locally advanced NPC in which tumor is abutting these structures.

Bony regeneration of the skull base following RT has been reported in the literature, but in limited reviews. Early reports used plain radiography to follow changes. Unger and colleagues demonstrated the regeneration of bone using skull radiographs 4 to 6 months after completion of RT for NPC.8 More recent literature details the ability of bone to regenerate after RT based on CT findings. Fang and colleagues reported on 90 cases of NPC with skull base destruction, with 63% having bony regeneration on posttreatment CT.9 Most of the patients in Fang’s report had bony regeneration within 1 year of treatment, and in general, bony regeneration became more evident on imaging with longer follow-up. Of note, local control was significantly greater in patients with regeneration vs persistent destruction (77% vs 21%, P < .001). On multivariate analysis, complete tumor response was significantly associated with bony regeneration; other factors such as age, sex, radiation dose, and chemotherapy were not significantly associated with the likelihood of bony regeneration.

Our report details a nasopharyngeal tumor that destroyed the skull base with no intact bony barrier. In such cases, concern arises regarding craniospinal instability with tumor regression if there is not simultaneous bone regeneration. Tumor invasion of the skull base and C1-2 vertebral bodies and complications from treatment of such tumor extent can lead to symptoms of craniospinal instability, including pain, difficulty with neck range of motion, and loss of strength and sensation in the upper and lower extremities.10 A case report of a woman treated with chemoradiation for a plasmacytoma of the skull base detailed her posttreatment presentation with quadriparesis resulting from craniospinal instability after tumor regression.11 Such instability is generally treated surgically, and during this woman’s surgery, there was an injury to the right vertebral artery, although this did not cause any additional neurologic deficits.

RT leads to hypocellularity, hypovascularity, and hypoxia of treated tissues, resulting in a reduced ability for growth and healing. Studies demonstrate that irradiated bone contains fewer osteoblast cells and osteocytes than unirradiated bone, resulting in reduced regenerative capacity.12,13 Furthermore, the reconstruction of bony defects resulting after cancer treatment has been shown to be difficult and associated with a high risk of complications.14 Given the impaired ability of irradiated bone to regenerate, studies have evaluated the use of growth factors and gene therapy to promote bone formation after treatment.15 Bone marrow stem cells have been shown to reverse radiation-induced cellular depletion and to increase osteocyte counts in animal studies.12 Further, overexpression of miR-34a, a tumor suppressor involved in tissue development, has been shown to improve osteoblastic differentiation of irradiated bone marrow stem cells and promote bone regeneration in vitro and in animal studies.13 While several techniques are being studied in vitro and in animal studies to promote bony regeneration after RT, there is a lack of data on use of these techniques in humans with cancer.

With our case, there was great uncertainty related to the ability of bone to regenerate during treatment and concern regarding consequences of formation of a skull base defect during treatment. CT imaging revealed bony regeneration of the central skull base and clivus, as well as occipital condyles, that occurred throughout the RT course. There was clear evidence of bone regeneration on the replanning CT obtained 5 weeks after treatment initiation. To our knowledge, this is the first report to demonstrate rapid bony regeneration during RT, thereby maintaining the integrity of the skull base and precluding the need for neurosurgical intervention. Moving forward, imaging should be considered during treatment for patients with tumor-related destruction of the skull base and upper cervical spine to evaluate the extent of bony regeneration during treatment and estimate the potential risk of craniocervical instability. Further studies with imaging during treatment are needed for more information on the likelihood of bony regeneration and factors that correlate with bony regeneration during treatment. As in other reports, our case demonstrates that bony regeneration may predict complete response to RT.9

Our patient’s tumor was HPV-positive and EBV-negative. In the US, the rate of HPV-positive NPC is 35%.16 However, HPV-positive NPC is much less common in endemic areas. A recent study from China of 1,328 patients with NPC revealed a 6.4% rate of HPV-positive/EBV-negative cases.17 In that study, patients with HPV-positive/EBV-negative tumors had improved survival compared to patients whose tumors were HPV-negative/EBV-positive. Another study suggests that the impact of HPV in NPC varies according to race, with HPV-positivity predicting for improved outcomes in East Asian patients and worse outcomes in White patients.17 A study from the University of Michigan suggests that both HPV-positive/EBV-negative and HPV-negative/EBV-negative NPC are associated with worse overall survival and locoregional control than EBV-positive NPC.2 Overall, the prognostic role of HPV in NPC remains unclear given conflicting information in the literature and the lack of large population studies.18

Conclusions

There is a paucity of literature on bony regeneration in patients with skull base destruction from advanced NPC, and in particular, the ability of skull base regeneration to occur during treatment simultaneous with tumor regression. Our patient had HPV-positive/EBV-negative NPC, but it is unclear how this subtype affected his prognosis. Factors such as tumor histology, radiosensitivity with rapid tumor regression, and young age may have all contributed to the rapidity of bone regeneration in our patient. This case report demonstrates that an impressive tumor response to chemoradiation with simultaneous bony regeneration is possible among patients presenting with tumor destruction of the skull base, precluding the need for neurosurgical intervention.

1. Chang ET, Adami HO. The enigmatic epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(10):1765-1777. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0353

2. Stenmark MH, McHugh JB, Schipper M, et al. Nonendemic HPV-positive nasopharyngeal carcinoma: association with poor prognosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(3):580-588. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.11.246

3. Maxwell JH, Kumar B, Feng FY, et al. HPV-positive/p16-positive/EBV-negative nasopharyngeal carcinoma in white North Americans. Head Neck. 2010;32(5):562-567. doi:10.1002/hed.21216

4. Chen YP, Chan ATC, Le QT, Blanchard P, Sun Y, Ma J. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet. 2019;394(10192):64-80. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30956-0

5. Roh JL, Sung MW, Kim KH, et al.. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma with skull base invasion: a necessity of staging subdivision. Am J Otolaryngol. 2004;25(1):26-32. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2003.09.011

6. Orr RD, Salo PT. Atlantoaxial instability complicating radiation therapy for recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. A case report. Spine. 1998;23(11):1280-1282. doi:10.1097/00007632-199806010-00021

7. Morgan HE, Sher DJ. Adaptive radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Cancers Head Neck. 2020;5:1. doi:10.1186/s41199-019-0046-z

8. Unger JD, Chiang LC, Unger GF. Apparent reformation of the base of the skull following radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiology. 1978;126(3):779-782. doi:10.1148/126.3.779

9. Fang FM, Leung SW, Wang CJ, et al. Computed tomography findings of bony regeneration after radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma with skull base destruction: implications for local control. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44(2):305-309. doi:10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00004-8

10. Tiruchelvarayan R, Lee KA, Ng I. Surgery for atlanto-axial (C1-2) involvement or instability in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Singapore Med J. 2012;53(6):416-421.

11. Samprón N, Arrazola M, Urculo E. Skull-base plasmacytoma with craniocervical instability [in Spanish]. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2009;20(5):478-483.

12. Zheutlin AR, Deshpande SS, Nelson NS, et al. Bone marrow stem cells assuage radiation-induced damage in a murine model of distraction osteogenesis: a histomorphometric evaluation. Cytotherapy. 2016;18(5):664-672. doi:10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.01.013

13. Liu H, Dong Y, Feng X, et al. miR-34a promotes bone regeneration in irradiated bone defects by enhancing osteoblast differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells in rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):180. doi:10.1186/s13287-019-1285-y

14. Holzapfel BM, Wagner F, Martine LC, et al. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine in musculoskeletal oncology. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016;35(3):475-487. doi:10.1007/s10555-016-9635-z

15. Hu WW, Ward BB, Wang Z, Krebsbach PH. Bone regeneration in defects compromised by radiotherapy. J Dent Res. 2010;89(1):77-81. doi:10.1177/0022034509352151

16. Wotman M, Oh EJ, Ahn S, Kraus D, Constantino P, Tham T. HPV status in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the United States: a SEER database study. Am J Otolaryngol. 2019;40(5):705-710. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2019.06.00717. Huang WB, Chan JYW, Liu DL. Human papillomavirus and World Health Organization type III nasopharyngeal carcinoma: multicenter study from an endemic area in Southern China. Cancer. 2018;124(3):530-536. doi:10.1002/cncr.31031.

18. Verma V, Simone CB 2nd, Lin C. Human papillomavirus and nasopharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2018;40(4):696-706. doi:10.1002/hed.24978

19. Lee AWM, Lydiatt WM, Colevas AD, et al. Nasopharynx. In: Amin MB, ed. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017:103.

20. Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, eds. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumors. In: World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. IARC Press; 2005.

1. Chang ET, Adami HO. The enigmatic epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(10):1765-1777. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0353

2. Stenmark MH, McHugh JB, Schipper M, et al. Nonendemic HPV-positive nasopharyngeal carcinoma: association with poor prognosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(3):580-588. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.11.246

3. Maxwell JH, Kumar B, Feng FY, et al. HPV-positive/p16-positive/EBV-negative nasopharyngeal carcinoma in white North Americans. Head Neck. 2010;32(5):562-567. doi:10.1002/hed.21216

4. Chen YP, Chan ATC, Le QT, Blanchard P, Sun Y, Ma J. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet. 2019;394(10192):64-80. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30956-0

5. Roh JL, Sung MW, Kim KH, et al.. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma with skull base invasion: a necessity of staging subdivision. Am J Otolaryngol. 2004;25(1):26-32. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2003.09.011

6. Orr RD, Salo PT. Atlantoaxial instability complicating radiation therapy for recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. A case report. Spine. 1998;23(11):1280-1282. doi:10.1097/00007632-199806010-00021

7. Morgan HE, Sher DJ. Adaptive radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Cancers Head Neck. 2020;5:1. doi:10.1186/s41199-019-0046-z

8. Unger JD, Chiang LC, Unger GF. Apparent reformation of the base of the skull following radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiology. 1978;126(3):779-782. doi:10.1148/126.3.779

9. Fang FM, Leung SW, Wang CJ, et al. Computed tomography findings of bony regeneration after radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma with skull base destruction: implications for local control. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44(2):305-309. doi:10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00004-8

10. Tiruchelvarayan R, Lee KA, Ng I. Surgery for atlanto-axial (C1-2) involvement or instability in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Singapore Med J. 2012;53(6):416-421.

11. Samprón N, Arrazola M, Urculo E. Skull-base plasmacytoma with craniocervical instability [in Spanish]. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2009;20(5):478-483.

12. Zheutlin AR, Deshpande SS, Nelson NS, et al. Bone marrow stem cells assuage radiation-induced damage in a murine model of distraction osteogenesis: a histomorphometric evaluation. Cytotherapy. 2016;18(5):664-672. doi:10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.01.013

13. Liu H, Dong Y, Feng X, et al. miR-34a promotes bone regeneration in irradiated bone defects by enhancing osteoblast differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells in rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):180. doi:10.1186/s13287-019-1285-y

14. Holzapfel BM, Wagner F, Martine LC, et al. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine in musculoskeletal oncology. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016;35(3):475-487. doi:10.1007/s10555-016-9635-z

15. Hu WW, Ward BB, Wang Z, Krebsbach PH. Bone regeneration in defects compromised by radiotherapy. J Dent Res. 2010;89(1):77-81. doi:10.1177/0022034509352151

16. Wotman M, Oh EJ, Ahn S, Kraus D, Constantino P, Tham T. HPV status in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the United States: a SEER database study. Am J Otolaryngol. 2019;40(5):705-710. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2019.06.00717. Huang WB, Chan JYW, Liu DL. Human papillomavirus and World Health Organization type III nasopharyngeal carcinoma: multicenter study from an endemic area in Southern China. Cancer. 2018;124(3):530-536. doi:10.1002/cncr.31031.

18. Verma V, Simone CB 2nd, Lin C. Human papillomavirus and nasopharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2018;40(4):696-706. doi:10.1002/hed.24978

19. Lee AWM, Lydiatt WM, Colevas AD, et al. Nasopharynx. In: Amin MB, ed. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017:103.

20. Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, eds. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumors. In: World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. IARC Press; 2005.

Screening for diabetes at normal BMIs could cut racial disparities

Use of race-based diabetes screening thresholds could reduce the disparity that arises from current screening guidelines in the United States, new research suggests.

In August 2021, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) lowered the recommended age for type 2 diabetes screening from 40 to 35 years among people with a body mass index of 25 kg/m2 or greater.

However, the diabetes rate among ethnic minorities aged 35-70 years in the United States is not just higher overall but, in certain populations, also occurs more frequently at a younger age and at lower BMIs, the new study indicates.

Among people with a BMI below 25 kg/m2, the diabetes prevalence is two to four times higher among Asian, Black, and Hispanic Americans than among the U.S. White population.

And the authors of the new study, led by Rahul Aggarwal, MD, predict that if screening begins at age 35 years, the BMI cut-off equivalent to 25 kg/m2 for White Americans would be 18.5 kg/m2 for Hispanic and Black Americans and 20 kg/m2 for Asian Americans.

“While diabetes has often been thought of as a disease that primarily affects adults with overweight or [obesity], our findings suggest that normal-weight adults in minority groups have surprisingly high rates of diabetes,” Dr. Aggarwal, senior resident physician in internal medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, told this news organization.

“Assessing diabetes risks in certain racial/ethnic groups will be necessary, even if these adults do not have overweight or [obesity],” he added.

Not screening in this way “is a missed opportunity for early intervention,” he noted.

And both the authors and an editorialist stress that the issue isn’t just theoretical.

“USPSTF recommendations influence what payers choose to cover, which in turn determines access to preventative services ... Addressing the staggering inequities in diabetes outcomes will require substantial investments in diabetes prevention and treatment, but making screening more equitable is a good place to start,” said senior author Dhruv S. Kazi, MD, of the Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology and director of the Cardiac Critical Care Unit at Beth Israel, Boston.

Screen minorities at a younger age if current BMI threshold kept

In their study, based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for 2011-2018, Dr. Aggarwal and colleagues also calculated that, if the BMI threshold is kept at 25 kg/m2, then the equivalent age cut-offs for Asian, Black, and Hispanic Americans would be 23, 21, and 25 years, respectively, compared with 35 years for White Americans.

The findings were published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The prevalence of diabetes in those aged 35-70 years in the NHANES population was 17.3% for Asian Americans and 12.5% for those who were White (odds ratio, 1.51 vs. Whites). Among Black Americans and Mexican Americans, the prevalence was 20.7% and 20.6%, respectively, almost twice the prevalence in Whites (OR, 1.85 and 1.80). For other Hispanic Americans, the prevalence was 16.4% (OR, 1.37 vs. Whites). All of those differences were significant, compared with White Americans.

Undiagnosed diabetes was also significantly more common among minority populations, at 27.6%, 22.8%, 21.2%, and 23.5% for Asian, Black, Mexican, and other Hispanic Americans, respectively, versus 12.5% for White Americans.

‘The time has come for USPSTF to offer more concrete guidance’

“While there is more work to be done on carefully examining the long-term risk–benefit trade-off of various diabetes screening, I believe the time has come for USPSTF to offer more concrete guidance on the use of lower thresholds for screening higher-risk individuals,” Dr. Kazi told this news organization.

The author of an accompanying editorial agrees, noting that in a recent commentary the USPSTF, itself, “acknowledged the persistent inequalities across the screening-to-treatment continuum that result in racial/ethnic health disparities in the United States.”

And the USPSTF “emphasized the need to improve systems of care to ensure equitable and consistent delivery of high-quality preventive and treatment services, with special attention to racial/ethnic groups who may experience worse health outcomes,” continues Quyen Ngo-Metzger, MD, Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, Pasadena, California.

For other conditions, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and infectious disease, the USPSTF already recommends risk-based preventive services.

“To address the current inequity in diabetes screening, the USPSTF should apply the same consideration to its diabetes screening recommendation,” she notes.

‘Implementation will require an eye for pragmatism’

Asked about how this recommendation might be carried out in the real world, Dr. Aggarwal said in an interview that, because all three minority groups with normal weight had similar diabetes risk profiles to White adults with overweight, “one way for clinicians to easily implement these findings is by screening all Asian, Black, and Hispanic adults ages 35-70 years with normal weight for diabetes, similarly to how all White adults ages 35-70 years with overweight are currently recommended for screening.”

Dr. Kazi said: “I believe that implementation will require an eye for pragmatism,” noting that another option would be to have screening algorithms embedded in the electronic health record to flag individuals who qualify.

In any case, “the simplicity of the current one-size-fits-all approach is alluring, but it is profoundly inequitable. The more I look at the empiric evidence on diabetes burden in our communities, the more the status quo becomes untenable.”

However, Dr. Kazi also noted, “the benefit of any screening program relates to what we do with the information. The key is to ensure that folks identified as having diabetes – or better still prediabetes – receive timely lifestyle and pharmacological interventions to avert its long-term complications.”

This study was supported by institutional funds from the Richard A. and Susan F. Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology. Dr. Aggarwal, Dr. Kazi, and Dr. Ngo-Metzger have reported no relevant relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Use of race-based diabetes screening thresholds could reduce the disparity that arises from current screening guidelines in the United States, new research suggests.

In August 2021, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) lowered the recommended age for type 2 diabetes screening from 40 to 35 years among people with a body mass index of 25 kg/m2 or greater.

However, the diabetes rate among ethnic minorities aged 35-70 years in the United States is not just higher overall but, in certain populations, also occurs more frequently at a younger age and at lower BMIs, the new study indicates.

Among people with a BMI below 25 kg/m2, the diabetes prevalence is two to four times higher among Asian, Black, and Hispanic Americans than among the U.S. White population.

And the authors of the new study, led by Rahul Aggarwal, MD, predict that if screening begins at age 35 years, the BMI cut-off equivalent to 25 kg/m2 for White Americans would be 18.5 kg/m2 for Hispanic and Black Americans and 20 kg/m2 for Asian Americans.

“While diabetes has often been thought of as a disease that primarily affects adults with overweight or [obesity], our findings suggest that normal-weight adults in minority groups have surprisingly high rates of diabetes,” Dr. Aggarwal, senior resident physician in internal medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, told this news organization.

“Assessing diabetes risks in certain racial/ethnic groups will be necessary, even if these adults do not have overweight or [obesity],” he added.

Not screening in this way “is a missed opportunity for early intervention,” he noted.

And both the authors and an editorialist stress that the issue isn’t just theoretical.

“USPSTF recommendations influence what payers choose to cover, which in turn determines access to preventative services ... Addressing the staggering inequities in diabetes outcomes will require substantial investments in diabetes prevention and treatment, but making screening more equitable is a good place to start,” said senior author Dhruv S. Kazi, MD, of the Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology and director of the Cardiac Critical Care Unit at Beth Israel, Boston.

Screen minorities at a younger age if current BMI threshold kept

In their study, based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for 2011-2018, Dr. Aggarwal and colleagues also calculated that, if the BMI threshold is kept at 25 kg/m2, then the equivalent age cut-offs for Asian, Black, and Hispanic Americans would be 23, 21, and 25 years, respectively, compared with 35 years for White Americans.

The findings were published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The prevalence of diabetes in those aged 35-70 years in the NHANES population was 17.3% for Asian Americans and 12.5% for those who were White (odds ratio, 1.51 vs. Whites). Among Black Americans and Mexican Americans, the prevalence was 20.7% and 20.6%, respectively, almost twice the prevalence in Whites (OR, 1.85 and 1.80). For other Hispanic Americans, the prevalence was 16.4% (OR, 1.37 vs. Whites). All of those differences were significant, compared with White Americans.

Undiagnosed diabetes was also significantly more common among minority populations, at 27.6%, 22.8%, 21.2%, and 23.5% for Asian, Black, Mexican, and other Hispanic Americans, respectively, versus 12.5% for White Americans.

‘The time has come for USPSTF to offer more concrete guidance’

“While there is more work to be done on carefully examining the long-term risk–benefit trade-off of various diabetes screening, I believe the time has come for USPSTF to offer more concrete guidance on the use of lower thresholds for screening higher-risk individuals,” Dr. Kazi told this news organization.

The author of an accompanying editorial agrees, noting that in a recent commentary the USPSTF, itself, “acknowledged the persistent inequalities across the screening-to-treatment continuum that result in racial/ethnic health disparities in the United States.”

And the USPSTF “emphasized the need to improve systems of care to ensure equitable and consistent delivery of high-quality preventive and treatment services, with special attention to racial/ethnic groups who may experience worse health outcomes,” continues Quyen Ngo-Metzger, MD, Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, Pasadena, California.

For other conditions, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and infectious disease, the USPSTF already recommends risk-based preventive services.

“To address the current inequity in diabetes screening, the USPSTF should apply the same consideration to its diabetes screening recommendation,” she notes.

‘Implementation will require an eye for pragmatism’

Asked about how this recommendation might be carried out in the real world, Dr. Aggarwal said in an interview that, because all three minority groups with normal weight had similar diabetes risk profiles to White adults with overweight, “one way for clinicians to easily implement these findings is by screening all Asian, Black, and Hispanic adults ages 35-70 years with normal weight for diabetes, similarly to how all White adults ages 35-70 years with overweight are currently recommended for screening.”

Dr. Kazi said: “I believe that implementation will require an eye for pragmatism,” noting that another option would be to have screening algorithms embedded in the electronic health record to flag individuals who qualify.

In any case, “the simplicity of the current one-size-fits-all approach is alluring, but it is profoundly inequitable. The more I look at the empiric evidence on diabetes burden in our communities, the more the status quo becomes untenable.”

However, Dr. Kazi also noted, “the benefit of any screening program relates to what we do with the information. The key is to ensure that folks identified as having diabetes – or better still prediabetes – receive timely lifestyle and pharmacological interventions to avert its long-term complications.”

This study was supported by institutional funds from the Richard A. and Susan F. Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology. Dr. Aggarwal, Dr. Kazi, and Dr. Ngo-Metzger have reported no relevant relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Use of race-based diabetes screening thresholds could reduce the disparity that arises from current screening guidelines in the United States, new research suggests.

In August 2021, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) lowered the recommended age for type 2 diabetes screening from 40 to 35 years among people with a body mass index of 25 kg/m2 or greater.

However, the diabetes rate among ethnic minorities aged 35-70 years in the United States is not just higher overall but, in certain populations, also occurs more frequently at a younger age and at lower BMIs, the new study indicates.

Among people with a BMI below 25 kg/m2, the diabetes prevalence is two to four times higher among Asian, Black, and Hispanic Americans than among the U.S. White population.

And the authors of the new study, led by Rahul Aggarwal, MD, predict that if screening begins at age 35 years, the BMI cut-off equivalent to 25 kg/m2 for White Americans would be 18.5 kg/m2 for Hispanic and Black Americans and 20 kg/m2 for Asian Americans.

“While diabetes has often been thought of as a disease that primarily affects adults with overweight or [obesity], our findings suggest that normal-weight adults in minority groups have surprisingly high rates of diabetes,” Dr. Aggarwal, senior resident physician in internal medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, told this news organization.

“Assessing diabetes risks in certain racial/ethnic groups will be necessary, even if these adults do not have overweight or [obesity],” he added.

Not screening in this way “is a missed opportunity for early intervention,” he noted.

And both the authors and an editorialist stress that the issue isn’t just theoretical.

“USPSTF recommendations influence what payers choose to cover, which in turn determines access to preventative services ... Addressing the staggering inequities in diabetes outcomes will require substantial investments in diabetes prevention and treatment, but making screening more equitable is a good place to start,” said senior author Dhruv S. Kazi, MD, of the Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology and director of the Cardiac Critical Care Unit at Beth Israel, Boston.

Screen minorities at a younger age if current BMI threshold kept

In their study, based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for 2011-2018, Dr. Aggarwal and colleagues also calculated that, if the BMI threshold is kept at 25 kg/m2, then the equivalent age cut-offs for Asian, Black, and Hispanic Americans would be 23, 21, and 25 years, respectively, compared with 35 years for White Americans.

The findings were published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The prevalence of diabetes in those aged 35-70 years in the NHANES population was 17.3% for Asian Americans and 12.5% for those who were White (odds ratio, 1.51 vs. Whites). Among Black Americans and Mexican Americans, the prevalence was 20.7% and 20.6%, respectively, almost twice the prevalence in Whites (OR, 1.85 and 1.80). For other Hispanic Americans, the prevalence was 16.4% (OR, 1.37 vs. Whites). All of those differences were significant, compared with White Americans.

Undiagnosed diabetes was also significantly more common among minority populations, at 27.6%, 22.8%, 21.2%, and 23.5% for Asian, Black, Mexican, and other Hispanic Americans, respectively, versus 12.5% for White Americans.

‘The time has come for USPSTF to offer more concrete guidance’

“While there is more work to be done on carefully examining the long-term risk–benefit trade-off of various diabetes screening, I believe the time has come for USPSTF to offer more concrete guidance on the use of lower thresholds for screening higher-risk individuals,” Dr. Kazi told this news organization.

The author of an accompanying editorial agrees, noting that in a recent commentary the USPSTF, itself, “acknowledged the persistent inequalities across the screening-to-treatment continuum that result in racial/ethnic health disparities in the United States.”

And the USPSTF “emphasized the need to improve systems of care to ensure equitable and consistent delivery of high-quality preventive and treatment services, with special attention to racial/ethnic groups who may experience worse health outcomes,” continues Quyen Ngo-Metzger, MD, Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, Pasadena, California.

For other conditions, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and infectious disease, the USPSTF already recommends risk-based preventive services.

“To address the current inequity in diabetes screening, the USPSTF should apply the same consideration to its diabetes screening recommendation,” she notes.

‘Implementation will require an eye for pragmatism’

Asked about how this recommendation might be carried out in the real world, Dr. Aggarwal said in an interview that, because all three minority groups with normal weight had similar diabetes risk profiles to White adults with overweight, “one way for clinicians to easily implement these findings is by screening all Asian, Black, and Hispanic adults ages 35-70 years with normal weight for diabetes, similarly to how all White adults ages 35-70 years with overweight are currently recommended for screening.”

Dr. Kazi said: “I believe that implementation will require an eye for pragmatism,” noting that another option would be to have screening algorithms embedded in the electronic health record to flag individuals who qualify.

In any case, “the simplicity of the current one-size-fits-all approach is alluring, but it is profoundly inequitable. The more I look at the empiric evidence on diabetes burden in our communities, the more the status quo becomes untenable.”

However, Dr. Kazi also noted, “the benefit of any screening program relates to what we do with the information. The key is to ensure that folks identified as having diabetes – or better still prediabetes – receive timely lifestyle and pharmacological interventions to avert its long-term complications.”

This study was supported by institutional funds from the Richard A. and Susan F. Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology. Dr. Aggarwal, Dr. Kazi, and Dr. Ngo-Metzger have reported no relevant relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Agony of choice’ for clinicians treating leukemia

“Targeted therapies have outnumbered chemoimmunotherapy-based treatment approaches, demonstrating superior efficacy and tolerability profiles across nearly all CLL patient subgroups in the frontline and relapsed disease treatment setting,” author Jan-Paul Bohn, MD, PhD, of the department of internal medicine V, hematology and oncology, at Medical University of Innsbruck (Austria), reported in the review published in Memo, the Magazine of European Medical Oncology.

The options leave clinicians “spoilt for choice when selecting optimal therapy,” he said.

The three major drug classes to emerge – inhibitors of Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK), antiapoptotic protein B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) and phosphoinositide 3’-kinase (PI3K) – all appear similar in efficacy and tolerability.

Particularly in high-risk patients, the drugs have been so effective that the less desirable previous standard of “chemoimmunotherapy has widely faded into the background in the Western hemisphere,” Dr. Bohn wrote.

However, with caveats of the newer drugs including acquired resistances and potential toxicities, challenges have shifted to determining how to best juggle and/or combine the agents.

Frontline therapy

In terms of frontline options for CLL therapy, the BTK inhibitors, along with the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax have been key in negating the need for chemotherapy, with some of the latest data showing superiority of venetoclax in combination with obinutuzumab (GVe) over chemotherapy even in the higher-risk subset of patients with mutated IGHV status and without TP53 disruption.

Hence, “chemoimmunotherapy may now even be questioned in the remaining subset of CLL patients with mutated IGHV status and without TP53 disruption,” Dr. Bohn reported.

That being said, the criteria for treatment choices in the frontline setting among the newer drug classes can often come down to the key issues of patients’ comorbidities and treatment preferences.

For example, in terms of patients who have higher risk because of tumor lysis syndrome (TLS), or issues including declining renal function, continuous BTK inhibitor treatment may be the preferred choice over the combination of venetoclax plus obinutuzumab (GVe), Dr. Bohn noted.

Conversely, for patients with cardiac comorbidities or a higher risk of bleeding, the GVe combination may be preferred over ibrutinib, with recent findings showing ibrutinib to be associated with as much as an 18-times higher risk of sudden unexplained death or cardiac death in young and fit patients who had preexisting arterial hypertension and/or a history of cardiac disorders requiring therapy.

For those with cardiac comorbidities, the more selective second-generation BTK inhibitor acalabrutinib is a potentially favorable alternative, as the drug is “at least similarly effective and more favorable in terms of tolerability, compared with ibrutinib, particularly as far as cardiac and bleeding side effects are considered,” Dr. Bohn said.

And in higher-risk cases involving TP53 dysfunction, a BTK inhibitor may be superior to GVe for frontline treatment, Dr. Bohn noted, with data showing progression-free survival in patients with and without deletion 17p to be significantly reduced with GVe versus the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib.

Relapsed and refractory disease

With similarly high efficacy observed with the new drug classes among relapsed and/or refractory patients, chemoimmunotherapy has likewise “become obsolete in nearly all patients naive to novel agents at relapse who typically present with genetically high-risk disease,” Dr. Bohn noted.