User login

Color‐coded wristbands: Promoting safety or confusion?

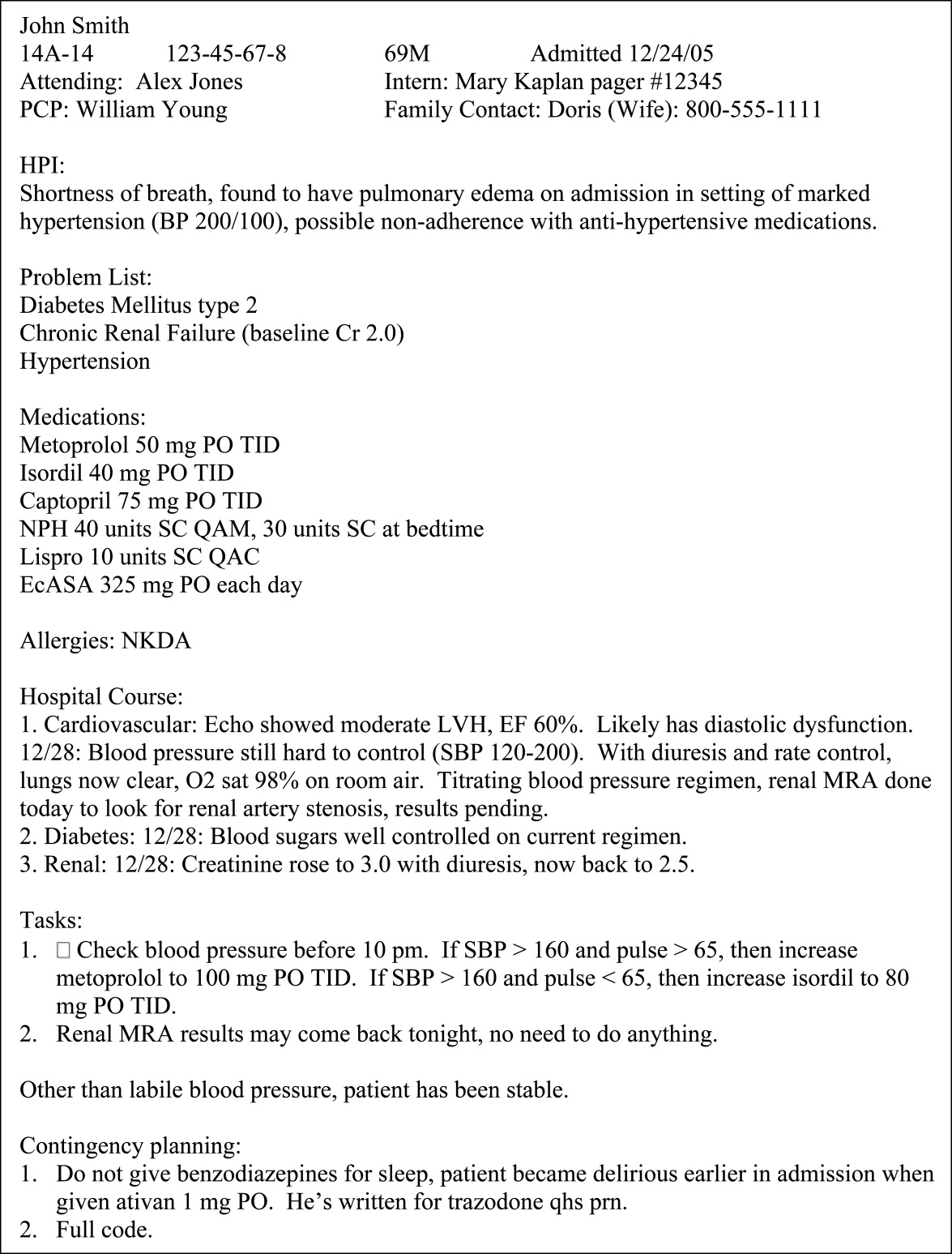

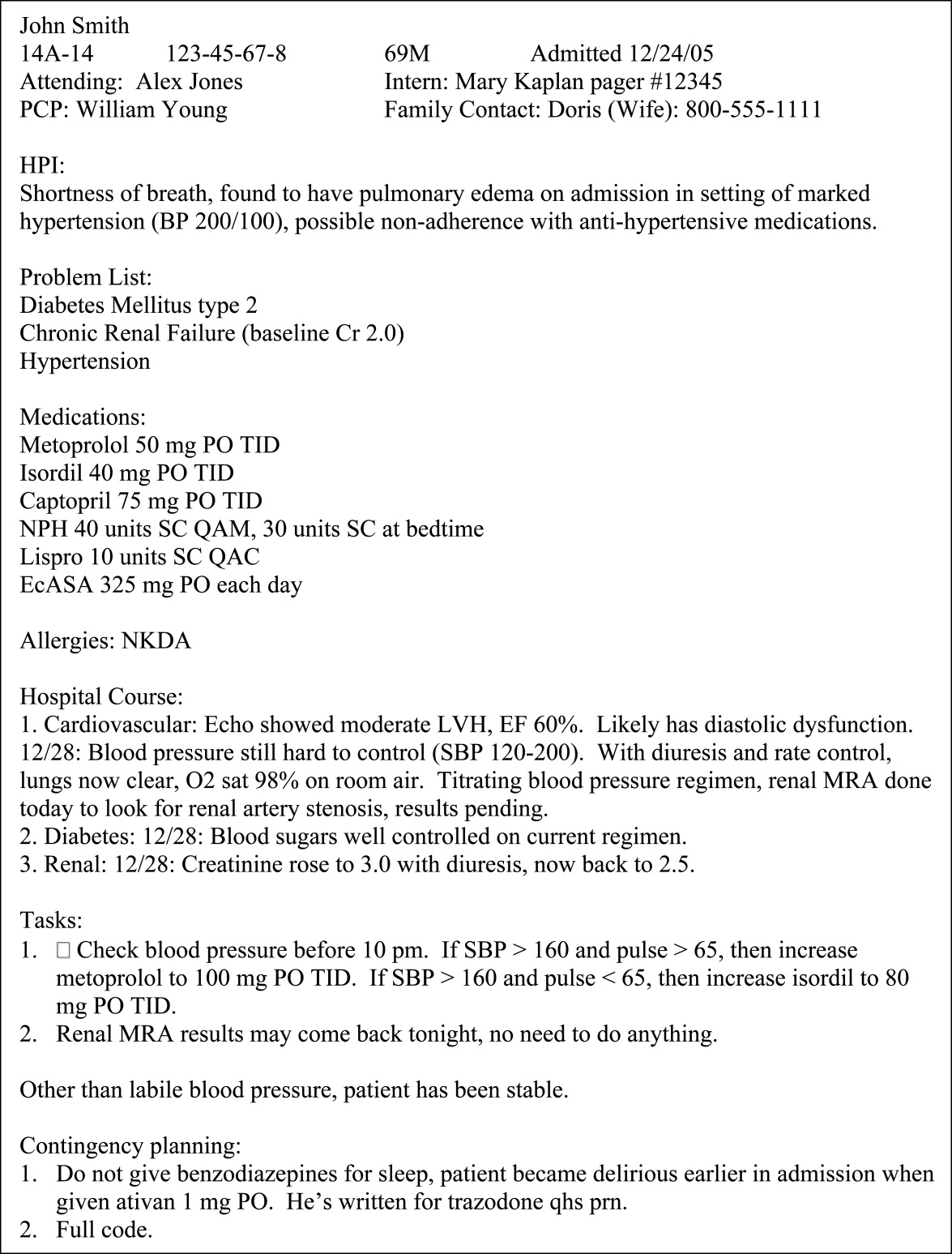

A 62‐year‐old man was transferred from an outside hospital for evaluation of a complicated spinal infection. Like many patients, he had color‐coded wristbands to help identify potential safety hazards (see Fig. 1). The patient, an educated and alert individual, could describe the indications for only 3 of the 5 wristbands, and the transferring hospital supplied no legend. As it turned out, the green band represented a fall risk, the red one a drug allergy alert, and the purple one a tape allergy, whereas the white one was for patient identification. We're still not certain what the yellow one represented, but it was not a Lance Armstrong Livestrong bracelet; such wristbands have been reported to cause confusion in hospitals that have adopted yellow for their do not resuscitate wristbands.1 Although attempts at ensuring patient safety by using color‐coded wristbands are a common practice, the lack of standardization may pose an unknown hazard. Elsewhere in this journal, we present findings from a survey reinforcing the need for standardization around this issue.

- .Wristbands called patient safety risk.St. Petersburg Times 10 Dec2004. p1A.

A 62‐year‐old man was transferred from an outside hospital for evaluation of a complicated spinal infection. Like many patients, he had color‐coded wristbands to help identify potential safety hazards (see Fig. 1). The patient, an educated and alert individual, could describe the indications for only 3 of the 5 wristbands, and the transferring hospital supplied no legend. As it turned out, the green band represented a fall risk, the red one a drug allergy alert, and the purple one a tape allergy, whereas the white one was for patient identification. We're still not certain what the yellow one represented, but it was not a Lance Armstrong Livestrong bracelet; such wristbands have been reported to cause confusion in hospitals that have adopted yellow for their do not resuscitate wristbands.1 Although attempts at ensuring patient safety by using color‐coded wristbands are a common practice, the lack of standardization may pose an unknown hazard. Elsewhere in this journal, we present findings from a survey reinforcing the need for standardization around this issue.

A 62‐year‐old man was transferred from an outside hospital for evaluation of a complicated spinal infection. Like many patients, he had color‐coded wristbands to help identify potential safety hazards (see Fig. 1). The patient, an educated and alert individual, could describe the indications for only 3 of the 5 wristbands, and the transferring hospital supplied no legend. As it turned out, the green band represented a fall risk, the red one a drug allergy alert, and the purple one a tape allergy, whereas the white one was for patient identification. We're still not certain what the yellow one represented, but it was not a Lance Armstrong Livestrong bracelet; such wristbands have been reported to cause confusion in hospitals that have adopted yellow for their do not resuscitate wristbands.1 Although attempts at ensuring patient safety by using color‐coded wristbands are a common practice, the lack of standardization may pose an unknown hazard. Elsewhere in this journal, we present findings from a survey reinforcing the need for standardization around this issue.

- .Wristbands called patient safety risk.St. Petersburg Times 10 Dec2004. p1A.

- .Wristbands called patient safety risk.St. Petersburg Times 10 Dec2004. p1A.

Identification of Inpatient DNR Status / Sehgal and Wachter

As modern medicine developed the technological capacity to deliver aggressive life‐sustaining interventionsthrough methods such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), intensive care units, and mechanical ventilationthe concept of do‐not‐resuscitate (DNR) orders emerged to allow individual patients to choose to forego selected treatments. To encourage patients to articulate these preferences, Congress passed the Patient Self‐Determination Act in 1991, a measure that required health care facilities to discuss advance directives with patients as they enter their system.1 Although the act has had less of an impact on the quality of DNR discussions than originally hoped for,25 its passage was evidence of the importance our society places on patientclinician discussions regarding goals of care. In addition to this legislative push, many organizations and advocacy groups use a variety of marketing campaigns, accreditation standards,6 and standard instruments and tools79 to promote the use of advance directives

Despite all these efforts, fewer than 30% of Americans (54% older than age 65) have completed advance directives.10 Nevertheless, many patientsparticularly those at highest risk for requiring end‐of‐life caredo express preferences regarding resuscitation at the time of hospital admission. In an ideal world, these preferences would be available for all providers to view, respect, and act on.

Unfortunately, research on patient safety and quality has demonstrated wide gaps between ideal and actual practice.1112 In the context of DNR wishes, despite strong efforts to collect patients' preferences, no current regulation provides or mandates a best practice on making these preferences operational. There are also few data that indicate whether patients' preferences are in fact transmitted to providers at the point of care and in an accurate and reliable manner.

Past research on proper identification of DNR orders is limited, with much of the focus on prehospital protocols.1315 Anecdotally, hospitals seem to employ varying strategies to highlight DNR orders using a combination of paper or electronic documentation and color‐coded patient wristbands. There have been several reports of errors involving this issue, including patients receiving CPR despite stated DNR preferences and a patient having CPR withheld because the wrong chart (of another patient with a DNR order) was mistakenly pulled.1617

The patient safety field emphasizes standardization as a key strategy to prevent errors. Because of problems articulating DNR orders (and other important patient‐related information), several hospitals promote the use of color‐coded wristbands to denote preferences for resuscitation. However, without national regulations or standards, the possibility remains that one safety hazard (advance directives on a paper chart distant from a patient's room) may be traded for another hazard (front‐line providers interpreting a color‐coded wristband incorrectly). In addition to the ethical problems inherent in failing to adhere to patients' resuscitation preferences, errors in following advance directives may also create legal liability.18 With all this in mind, we conducted a national survey to determine practice variations in the identification of DNR orders and the use of color‐coded patient wristbands. We hypothesized that there is considerable variation both in identification practices and in the use of color‐coded wristbands across academic medical centers.

METHODS

The project was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research. We anonymously surveyed nursing executives who are members of the University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC), an alliance of 97 academic medical centers and their affiliated hospitals representing 90% of the nation's nonprofit academic medical centers.19 The nursing executives are senior nursing leaders at participating UHC institutions and members of a dedicated UHC Chief Nursing Officer Council E‐mail listserv. We designed a brief survey and distributed it via their E‐mail listserv using an online commercial survey administration tool.20 Respondents were asked to complete the survey or have one of their colleagues familiar with local DNR identification practices complete it on their behalf. The online tool also provided summary reports and descriptive findings to meet the study objectives. We provided a 1‐month window (during summer 2006) with 1 interval E‐mail reminder to complete the surveys.

RESULTS

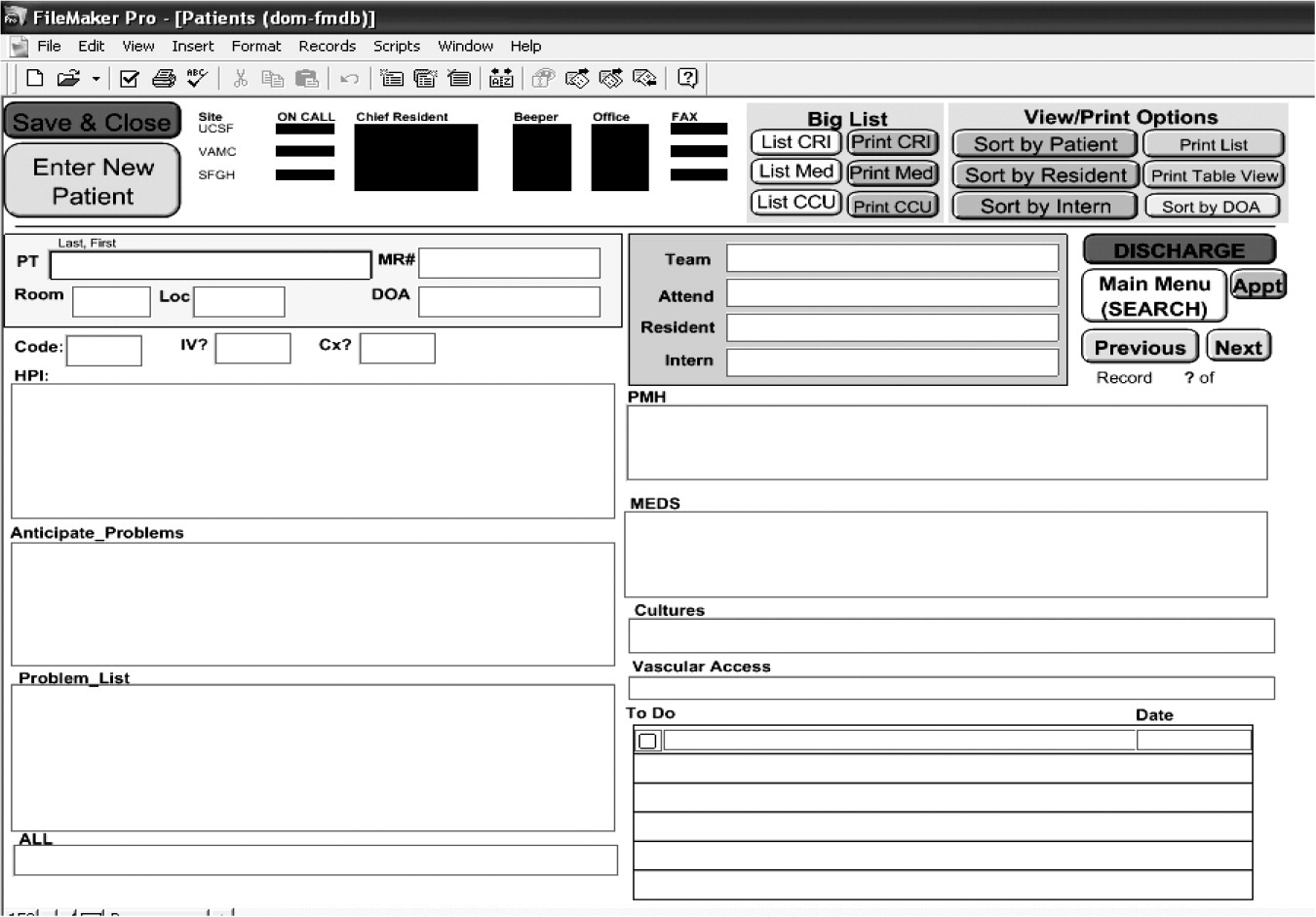

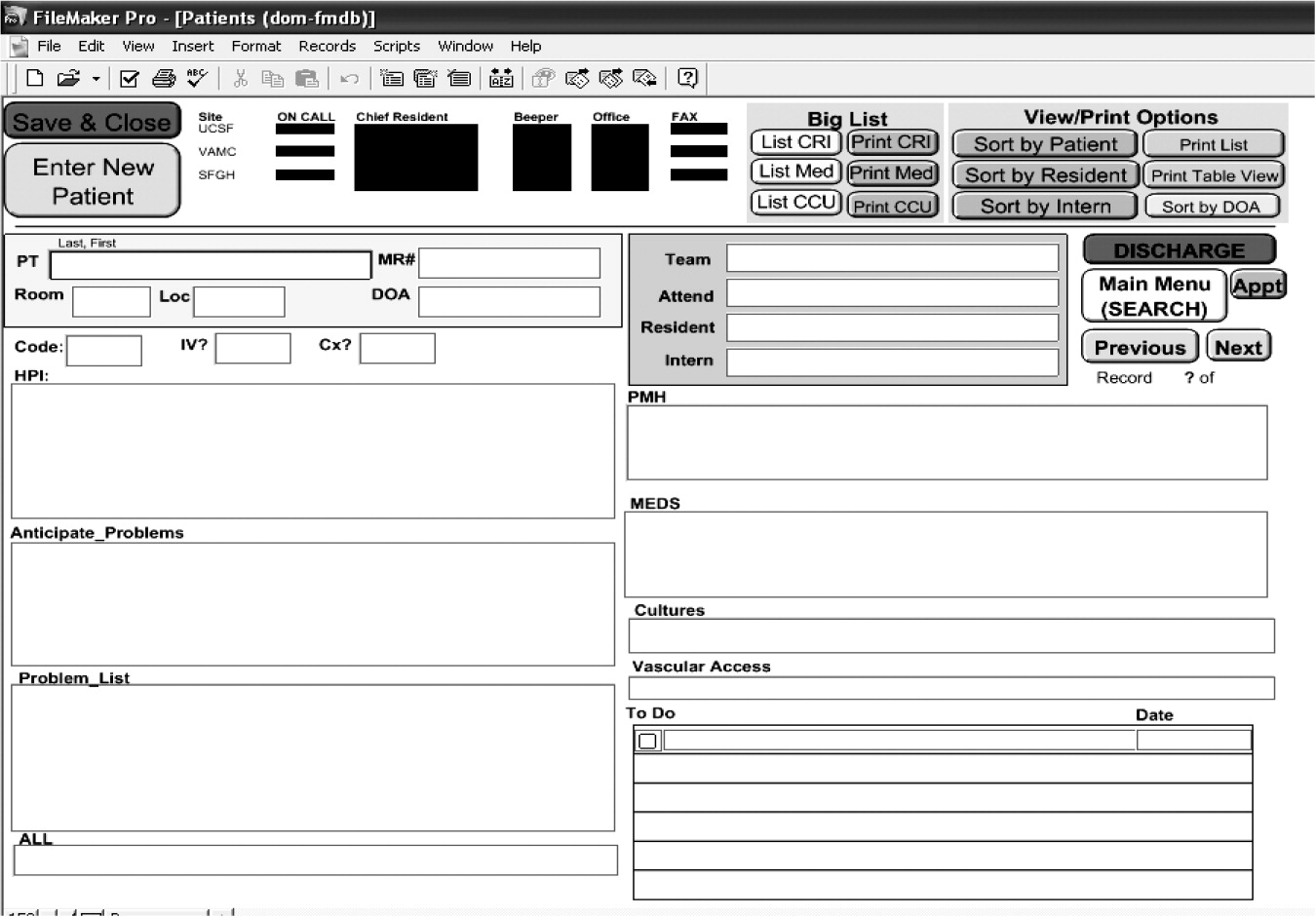

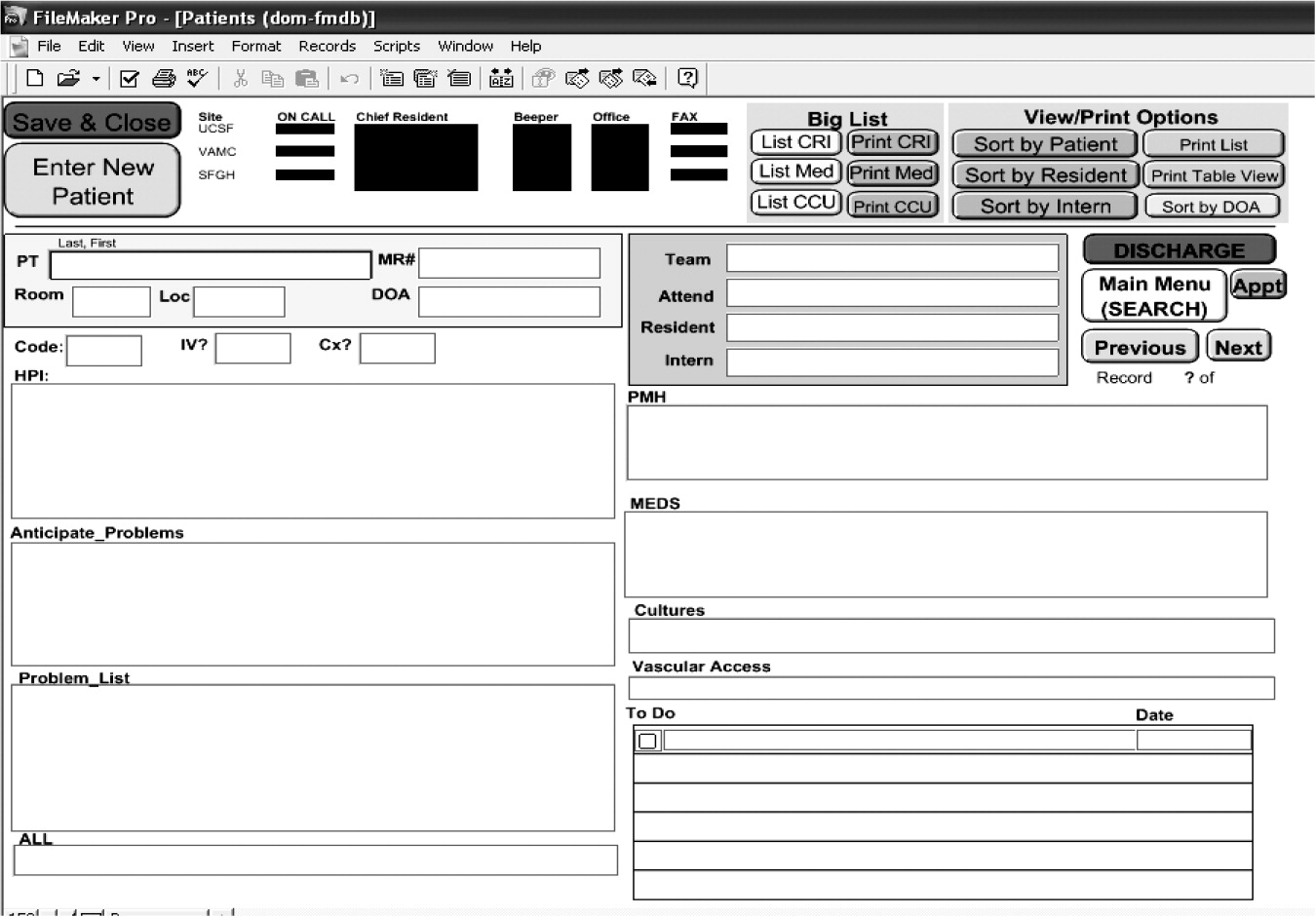

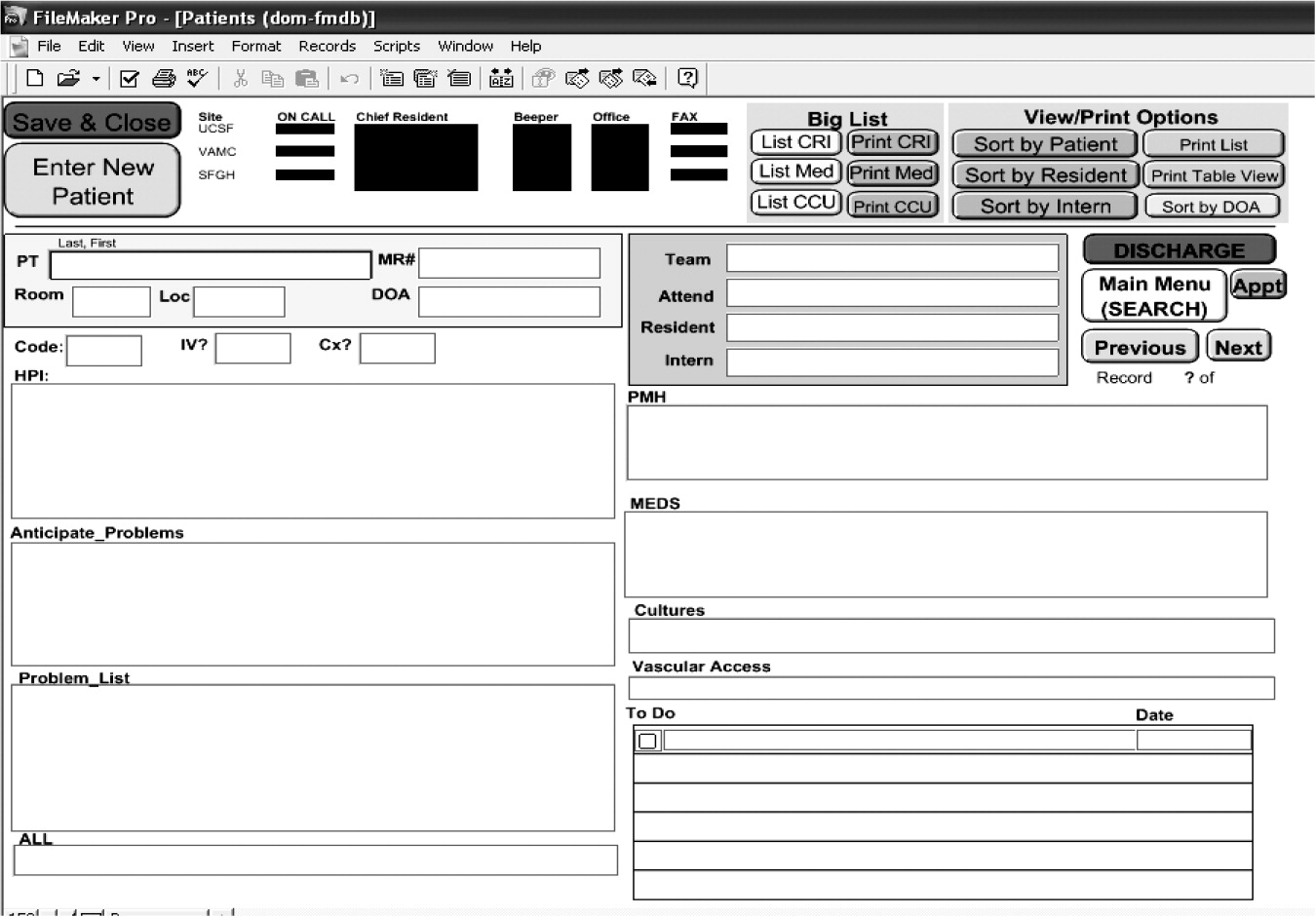

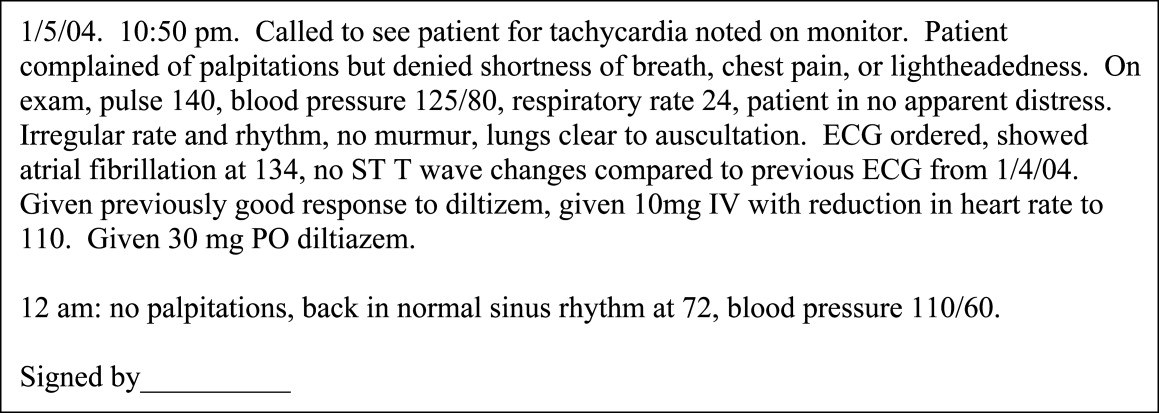

Survey announcements were E‐mailed to 127 nursing executives, 69 of whom completed it (response rate 54%). The respondents represented mostly academic medical centers (87%; another 13% represented affiliated community teaching hospitals), public institutions (89%), and large facilities (60% with more than 400 beds; 40% with 201‐400 beds). More than half the respondents (56%) reported their hospitals use paper chart documentation as the only method of identifying patients with a DNR order, whereas 16% reported their hospitals use only electronic health record (EHR) documentation (Fig. 1). Twenty‐five percent of hospitals (n = 17) use a color‐coded patient wristband in addition to either paper or electronic documentation. Of these 17 hospitals, a total of 8 colors or color schemes were employed to designate DNR status (Table 1).

| Green5 |

| Yellow3 |

| Blue3 |

| White with blue stars versus green stars (full DNR versus limited DNR)1 |

| Red1 |

| Red and white1 |

| Purple1 |

| Gold1 |

| Other (not listed)1 |

The use of color‐coded wristbands was not limited to identification of DNR status. Fifty‐five percent of hospitals (n = 31) use color‐coded wristbands to indicate another piece of patient‐related data such as an allergy, fall risk, or same last name alert (Table 2). In fact, 12 indications were depicted by various colors, with variations in both the color choice for a given indication (eg, allergy wristbands red at one hospital and yellow at another) and across indications (eg, red for allergy at one hospital and red for bleeding risk at another). Nearly 3 of 4 respondents (n = 48) reported being aware of a case at your institution in which confusion about a DNR order led to problems or confusion in patient care. A few respondents shared a brief anecdote of the event, illustrating the spectrum of clinical scenarios that lead to potential confusion (Table 3). Respondents reporting a case of confusion were not more likely to be from an institution that used color‐coded wristbands.

| Indication (n) | Colors used (n) |

|---|---|

| Drug/allergy (22) | Red (16) Yellow (4) White (1) Orange (1) |

| Fall risk (18) | Orange (5) Green (3) (and lime green [1]) Blue (3) Purple (3) Yellow (2) (and fluorescent yellow [1]) |

| Same name alert (7) | Blue (3) Orange (2) Yellow2) |

| Bleeding risk (3) | Red |

| Patient identification (3) | Green Red White |

| Wandering risk (3) | Pink (2) (and hot pink [1]) |

| Contact isolation (2) | Green |

| Latex allergy (2) | Purple |

| No blood draws on this arm (1) | Orange |

| MRSA infection (1) | Green |

| No blood products (1) | Red |

| Sleep apnea (1) | Purple |

| The patient had a DNR order written in the chart but no other identifiers at bedside, so a consult service started CPR while trying to determine code status. |

| Nurse called a code on a patient who was DNR because she failed to see order in chart. |

| Resuscitation efforts took place on a patient with a DNR order because the entire chart did not accompany the patient to a diagnostic testing area. |

| Patient was off the unit for a procedure, and staff in the other department did not know patients code status (DNR) and called a code. |

| Patient transported off nursing unit to radiology and coded. Patient was a DNR, but the order was buried in thinned chart materials. |

| Prior to implementing the wristbands, there were delays in care. Once wristbands were implemented with stars only, there was confusion as to what a blue star meant and what a green star meant (limited versus no resuscitation efforts). |

| We used to place a sticker on the chart. A sticker was left on the chart of a discharged patient when a new patient was admitted. The mistake was caught before an incident occurred. |

When asked whether most (greater than 75%) physicians and nurses could properly identify the color associated with a DNR patient wristband, responses differed by discipline. Eight‐five percent of respondents believed that most nurses at their institutions could correctly report the color for DNR, whereas only 15% believed physicians could do the same. Only 22% of respondents anticipated a change in the current system within the next 2 years; all these changes were a transition from paper to electronic documentation systems.

DISCUSSION

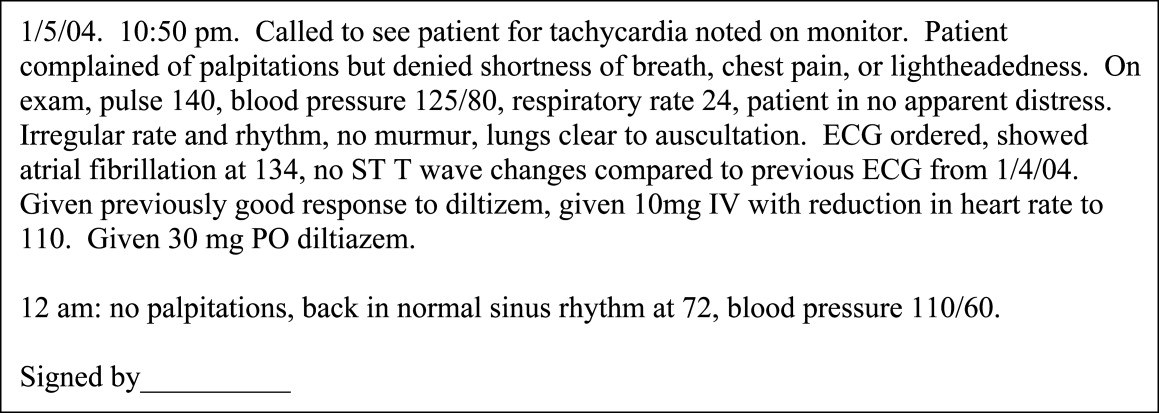

Regardless of whether the DNR documentation occurs in paper or electronic form (and our study demonstrates significant practice variation in the documentation method), the risk that a hospitalized patient may suddenly stop breathing or become pulseless is ever present. When such a patient is discovered, providers race to the bedside and initiate care, but immediately ask, Is the patient a full code? In these often‐chaotic moments, accurate and timely information about DNR status is critical to respecting a patient's preferences and avoiding a potentially devastating error. A number of the anecdotes shared by survey respondents and highlighted in Table 3 reinforce this concern. Many of these scenarios occur in the middle of the night or off a patient's primary unit (ie, at a test or procedure area), increasing the need for quick and easy identification of DNR status.

Our study demonstrates that a logical point‐of‐care solutiona color‐coded DNR patient wristbandmay create its own safety hazards, particularly if the color designations are not known by all providers (including floating and traveling nurses or trainees who rotate at different hospitals) and if the colors being employed represent different indications at a given hospital (see accompanying Images Dx, page 445). We found that approximately 1 in 4 surveyed hospitals depict DNR status by a color‐coded wristband. We also discovered remarkable variation in the colors chosen and the degree to which institutions use color‐coded wristbands to signal a panoply of other patient‐related issues. Human factors research demonstrates that even well‐meaning patient safety solutions may cause harm in new ways if they are poorly implemented or if the interface between the technology and human work patterns is not well appreciated. For example, recent studies illustrate unintended consequences from safety‐driven solutions, such as the implementation of computerized order entry,2122 quality measurement,23 adoption of EHRs,24 and bar code medication administration systems.25 Because standardization is a key mechanism for decreasing the opportunities for error, our findings raise serious concerns about current wristband use.

Interestingly, the lack of standardization and its related risk of failing to recall the conditions associated with color‐coded wristbands are complicated by societal trends. In December 2004 the issue of patient wristbands made headlines in Florida, when hospitals using yellow DNR wristbands (as was the case in 3 hospitals in our sample) reported several near‐misses among patients wearing yellow Lance Armstrong Livestrong bracelets.2627 Given recent estimates that nearly 1 in 5 Americans wears these bracelets to support people living with cancer,28 even safety‐minded journals and national newspapers have highlighted the issue.2930 Most hospitals that continue to use yellow DNR wristbands now either remove or cover Livestrong bracelets at the time of hospital admission. Furthermore, many other self‐help organizations now issue wristbands in a variety of colors as well, creating a potential hazard for any person wearing one in the hospital. Although patients do not mind wearing color‐coded wristbands,31 they might feel differently if they knew the potential for confusion.

After these anecdotal reports of identification mistakes surfaced, several states, most notably Arizona and Pennsylvania, launched initiatives to address the problem.3233 Arizona, after discovering 8 colors being used in the state, developed plans for a purple DNR color‐coded wristband. The choice of purple, and the careful decision to avoid blue, occurred because many hospitals call their resuscitative efforts a code blue, creating yet another potential source of confusion if a blue wristband is associated with a DNR order. The Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority also found tremendous color variations in patient wristbands used in a statewide survey. Both states ultimately promoted standardized colors and indications and provided tool kits and implementation manuals.3233

Although statewide initiatives represent a step forward, we believe that a national standard for color‐coded wristbands would improve patient safety. Precedents for this call to action exist. For many years, anecdotal information circulated about the errors caused by ambiguous use of abbreviations, such as qd instead of daily or U instead of units. Individual hospitals often banned or limited the use of such abbreviations, but no standard list of high‐risk abbreviations guided practice or required adherence, and cross‐hospital variation undoubtedly led to confusion. In 2004 the Joint Commission created a uniform list of high‐risk abbreviations as part of their National Patient Safety Goals, which instantly ended the debate about which abbreviations to ban and mandated compliance with the safety practice.34 A national group of stakeholders should similarly be convened to develop a list of colors and associated conditions that should be widely disseminated and enforced by the Joint Commission or a similar body. The statewide efforts by Arizona and Pennsylvania are instructive in this regard. Despite being guided by the goal of standardization, these 2 states chose different colors for DNR identification (interestingly, Pennsylvania chose blue for DNR, perhaps for the same reason that Arizona avoided itcode blue), further supporting the need for national guidelines (Table 4).

| Indication | Color (PA) | Color (AZ) |

|---|---|---|

| DNR | Blue | Purple |

| Allergy | Red | Red |

| Fall risk | Yellow | Yellow |

| Latex allergy | Green | |

| Restricted extremity | Pink | |

| Preregistration in emergency room | Yellow | |

| Admission and identification | Clear |

Our study represents the first national sample of DNR identification practices. Although it targeted academic health centers and affiliated institutions, we believe that these practice variations likely exist in all health care settings. Our study limitations included reliance on self‐reported institutional practices rather than direct review of existing policies and limited information about the surveyed population, making it impossible to compare respondents and nonrespondents. However, we have no reason to believe that these groups differed sufficiently to influence the study's main findings.

In the future, better technology may ultimately replace color‐coded wristbands. For instance, the time may come when wireless technologies seamlessly linked to the electronic health record will alert providers to a patient's DNR status when entering the patient's room. However, for today, point‐of‐care solutions using color‐coded wristbands remain a reasonable solution. Creating a nationally enforced standardized methodology, understandable and memorable to providers and free of stigma to patients (eg, a black wristband for DNR or writing DNR on a wristband) should be a patient safety priority. Because simplification is another key characteristic of safe systems, it seems prudent to aim for a national system that involves a maximum of 3‐4 colors.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients and families dedicate tremendous energy to making decisions about their advance directives, and discussions of these issues often create considerable angst and sadness. Health care providers are trained to elicit and advocate for such directives so they can act with patients' wishes in mind. Despite the high stakes, all these efforts can be undermined when the system for making providers aware of a patient's DNR status is flawed. Our data confirm the tremendous variability in the systems used to indicate DNR status (and other types of indications), variability that may place patients at risk from catastrophic errors. Following the lead of a few states, we call for a national mandate to standardize the identification of DNR orders and to make the colors of wristbands for a small set of indications uniform in every hospital across the country.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mark Keroack, MD, MPH, and Cathy Krsek, RN, MSN, MBA, from the University HealthSystem Consortium for their contributions to the survey and assistance with administration. We also thank members of the UHC Chief Nursing Council for participating in the survey study.

As modern medicine developed the technological capacity to deliver aggressive life‐sustaining interventionsthrough methods such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), intensive care units, and mechanical ventilationthe concept of do‐not‐resuscitate (DNR) orders emerged to allow individual patients to choose to forego selected treatments. To encourage patients to articulate these preferences, Congress passed the Patient Self‐Determination Act in 1991, a measure that required health care facilities to discuss advance directives with patients as they enter their system.1 Although the act has had less of an impact on the quality of DNR discussions than originally hoped for,25 its passage was evidence of the importance our society places on patientclinician discussions regarding goals of care. In addition to this legislative push, many organizations and advocacy groups use a variety of marketing campaigns, accreditation standards,6 and standard instruments and tools79 to promote the use of advance directives

Despite all these efforts, fewer than 30% of Americans (54% older than age 65) have completed advance directives.10 Nevertheless, many patientsparticularly those at highest risk for requiring end‐of‐life caredo express preferences regarding resuscitation at the time of hospital admission. In an ideal world, these preferences would be available for all providers to view, respect, and act on.

Unfortunately, research on patient safety and quality has demonstrated wide gaps between ideal and actual practice.1112 In the context of DNR wishes, despite strong efforts to collect patients' preferences, no current regulation provides or mandates a best practice on making these preferences operational. There are also few data that indicate whether patients' preferences are in fact transmitted to providers at the point of care and in an accurate and reliable manner.

Past research on proper identification of DNR orders is limited, with much of the focus on prehospital protocols.1315 Anecdotally, hospitals seem to employ varying strategies to highlight DNR orders using a combination of paper or electronic documentation and color‐coded patient wristbands. There have been several reports of errors involving this issue, including patients receiving CPR despite stated DNR preferences and a patient having CPR withheld because the wrong chart (of another patient with a DNR order) was mistakenly pulled.1617

The patient safety field emphasizes standardization as a key strategy to prevent errors. Because of problems articulating DNR orders (and other important patient‐related information), several hospitals promote the use of color‐coded wristbands to denote preferences for resuscitation. However, without national regulations or standards, the possibility remains that one safety hazard (advance directives on a paper chart distant from a patient's room) may be traded for another hazard (front‐line providers interpreting a color‐coded wristband incorrectly). In addition to the ethical problems inherent in failing to adhere to patients' resuscitation preferences, errors in following advance directives may also create legal liability.18 With all this in mind, we conducted a national survey to determine practice variations in the identification of DNR orders and the use of color‐coded patient wristbands. We hypothesized that there is considerable variation both in identification practices and in the use of color‐coded wristbands across academic medical centers.

METHODS

The project was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research. We anonymously surveyed nursing executives who are members of the University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC), an alliance of 97 academic medical centers and their affiliated hospitals representing 90% of the nation's nonprofit academic medical centers.19 The nursing executives are senior nursing leaders at participating UHC institutions and members of a dedicated UHC Chief Nursing Officer Council E‐mail listserv. We designed a brief survey and distributed it via their E‐mail listserv using an online commercial survey administration tool.20 Respondents were asked to complete the survey or have one of their colleagues familiar with local DNR identification practices complete it on their behalf. The online tool also provided summary reports and descriptive findings to meet the study objectives. We provided a 1‐month window (during summer 2006) with 1 interval E‐mail reminder to complete the surveys.

RESULTS

Survey announcements were E‐mailed to 127 nursing executives, 69 of whom completed it (response rate 54%). The respondents represented mostly academic medical centers (87%; another 13% represented affiliated community teaching hospitals), public institutions (89%), and large facilities (60% with more than 400 beds; 40% with 201‐400 beds). More than half the respondents (56%) reported their hospitals use paper chart documentation as the only method of identifying patients with a DNR order, whereas 16% reported their hospitals use only electronic health record (EHR) documentation (Fig. 1). Twenty‐five percent of hospitals (n = 17) use a color‐coded patient wristband in addition to either paper or electronic documentation. Of these 17 hospitals, a total of 8 colors or color schemes were employed to designate DNR status (Table 1).

| Green5 |

| Yellow3 |

| Blue3 |

| White with blue stars versus green stars (full DNR versus limited DNR)1 |

| Red1 |

| Red and white1 |

| Purple1 |

| Gold1 |

| Other (not listed)1 |

The use of color‐coded wristbands was not limited to identification of DNR status. Fifty‐five percent of hospitals (n = 31) use color‐coded wristbands to indicate another piece of patient‐related data such as an allergy, fall risk, or same last name alert (Table 2). In fact, 12 indications were depicted by various colors, with variations in both the color choice for a given indication (eg, allergy wristbands red at one hospital and yellow at another) and across indications (eg, red for allergy at one hospital and red for bleeding risk at another). Nearly 3 of 4 respondents (n = 48) reported being aware of a case at your institution in which confusion about a DNR order led to problems or confusion in patient care. A few respondents shared a brief anecdote of the event, illustrating the spectrum of clinical scenarios that lead to potential confusion (Table 3). Respondents reporting a case of confusion were not more likely to be from an institution that used color‐coded wristbands.

| Indication (n) | Colors used (n) |

|---|---|

| Drug/allergy (22) | Red (16) Yellow (4) White (1) Orange (1) |

| Fall risk (18) | Orange (5) Green (3) (and lime green [1]) Blue (3) Purple (3) Yellow (2) (and fluorescent yellow [1]) |

| Same name alert (7) | Blue (3) Orange (2) Yellow2) |

| Bleeding risk (3) | Red |

| Patient identification (3) | Green Red White |

| Wandering risk (3) | Pink (2) (and hot pink [1]) |

| Contact isolation (2) | Green |

| Latex allergy (2) | Purple |

| No blood draws on this arm (1) | Orange |

| MRSA infection (1) | Green |

| No blood products (1) | Red |

| Sleep apnea (1) | Purple |

| The patient had a DNR order written in the chart but no other identifiers at bedside, so a consult service started CPR while trying to determine code status. |

| Nurse called a code on a patient who was DNR because she failed to see order in chart. |

| Resuscitation efforts took place on a patient with a DNR order because the entire chart did not accompany the patient to a diagnostic testing area. |

| Patient was off the unit for a procedure, and staff in the other department did not know patients code status (DNR) and called a code. |

| Patient transported off nursing unit to radiology and coded. Patient was a DNR, but the order was buried in thinned chart materials. |

| Prior to implementing the wristbands, there were delays in care. Once wristbands were implemented with stars only, there was confusion as to what a blue star meant and what a green star meant (limited versus no resuscitation efforts). |

| We used to place a sticker on the chart. A sticker was left on the chart of a discharged patient when a new patient was admitted. The mistake was caught before an incident occurred. |

When asked whether most (greater than 75%) physicians and nurses could properly identify the color associated with a DNR patient wristband, responses differed by discipline. Eight‐five percent of respondents believed that most nurses at their institutions could correctly report the color for DNR, whereas only 15% believed physicians could do the same. Only 22% of respondents anticipated a change in the current system within the next 2 years; all these changes were a transition from paper to electronic documentation systems.

DISCUSSION

Regardless of whether the DNR documentation occurs in paper or electronic form (and our study demonstrates significant practice variation in the documentation method), the risk that a hospitalized patient may suddenly stop breathing or become pulseless is ever present. When such a patient is discovered, providers race to the bedside and initiate care, but immediately ask, Is the patient a full code? In these often‐chaotic moments, accurate and timely information about DNR status is critical to respecting a patient's preferences and avoiding a potentially devastating error. A number of the anecdotes shared by survey respondents and highlighted in Table 3 reinforce this concern. Many of these scenarios occur in the middle of the night or off a patient's primary unit (ie, at a test or procedure area), increasing the need for quick and easy identification of DNR status.

Our study demonstrates that a logical point‐of‐care solutiona color‐coded DNR patient wristbandmay create its own safety hazards, particularly if the color designations are not known by all providers (including floating and traveling nurses or trainees who rotate at different hospitals) and if the colors being employed represent different indications at a given hospital (see accompanying Images Dx, page 445). We found that approximately 1 in 4 surveyed hospitals depict DNR status by a color‐coded wristband. We also discovered remarkable variation in the colors chosen and the degree to which institutions use color‐coded wristbands to signal a panoply of other patient‐related issues. Human factors research demonstrates that even well‐meaning patient safety solutions may cause harm in new ways if they are poorly implemented or if the interface between the technology and human work patterns is not well appreciated. For example, recent studies illustrate unintended consequences from safety‐driven solutions, such as the implementation of computerized order entry,2122 quality measurement,23 adoption of EHRs,24 and bar code medication administration systems.25 Because standardization is a key mechanism for decreasing the opportunities for error, our findings raise serious concerns about current wristband use.

Interestingly, the lack of standardization and its related risk of failing to recall the conditions associated with color‐coded wristbands are complicated by societal trends. In December 2004 the issue of patient wristbands made headlines in Florida, when hospitals using yellow DNR wristbands (as was the case in 3 hospitals in our sample) reported several near‐misses among patients wearing yellow Lance Armstrong Livestrong bracelets.2627 Given recent estimates that nearly 1 in 5 Americans wears these bracelets to support people living with cancer,28 even safety‐minded journals and national newspapers have highlighted the issue.2930 Most hospitals that continue to use yellow DNR wristbands now either remove or cover Livestrong bracelets at the time of hospital admission. Furthermore, many other self‐help organizations now issue wristbands in a variety of colors as well, creating a potential hazard for any person wearing one in the hospital. Although patients do not mind wearing color‐coded wristbands,31 they might feel differently if they knew the potential for confusion.

After these anecdotal reports of identification mistakes surfaced, several states, most notably Arizona and Pennsylvania, launched initiatives to address the problem.3233 Arizona, after discovering 8 colors being used in the state, developed plans for a purple DNR color‐coded wristband. The choice of purple, and the careful decision to avoid blue, occurred because many hospitals call their resuscitative efforts a code blue, creating yet another potential source of confusion if a blue wristband is associated with a DNR order. The Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority also found tremendous color variations in patient wristbands used in a statewide survey. Both states ultimately promoted standardized colors and indications and provided tool kits and implementation manuals.3233

Although statewide initiatives represent a step forward, we believe that a national standard for color‐coded wristbands would improve patient safety. Precedents for this call to action exist. For many years, anecdotal information circulated about the errors caused by ambiguous use of abbreviations, such as qd instead of daily or U instead of units. Individual hospitals often banned or limited the use of such abbreviations, but no standard list of high‐risk abbreviations guided practice or required adherence, and cross‐hospital variation undoubtedly led to confusion. In 2004 the Joint Commission created a uniform list of high‐risk abbreviations as part of their National Patient Safety Goals, which instantly ended the debate about which abbreviations to ban and mandated compliance with the safety practice.34 A national group of stakeholders should similarly be convened to develop a list of colors and associated conditions that should be widely disseminated and enforced by the Joint Commission or a similar body. The statewide efforts by Arizona and Pennsylvania are instructive in this regard. Despite being guided by the goal of standardization, these 2 states chose different colors for DNR identification (interestingly, Pennsylvania chose blue for DNR, perhaps for the same reason that Arizona avoided itcode blue), further supporting the need for national guidelines (Table 4).

| Indication | Color (PA) | Color (AZ) |

|---|---|---|

| DNR | Blue | Purple |

| Allergy | Red | Red |

| Fall risk | Yellow | Yellow |

| Latex allergy | Green | |

| Restricted extremity | Pink | |

| Preregistration in emergency room | Yellow | |

| Admission and identification | Clear |

Our study represents the first national sample of DNR identification practices. Although it targeted academic health centers and affiliated institutions, we believe that these practice variations likely exist in all health care settings. Our study limitations included reliance on self‐reported institutional practices rather than direct review of existing policies and limited information about the surveyed population, making it impossible to compare respondents and nonrespondents. However, we have no reason to believe that these groups differed sufficiently to influence the study's main findings.

In the future, better technology may ultimately replace color‐coded wristbands. For instance, the time may come when wireless technologies seamlessly linked to the electronic health record will alert providers to a patient's DNR status when entering the patient's room. However, for today, point‐of‐care solutions using color‐coded wristbands remain a reasonable solution. Creating a nationally enforced standardized methodology, understandable and memorable to providers and free of stigma to patients (eg, a black wristband for DNR or writing DNR on a wristband) should be a patient safety priority. Because simplification is another key characteristic of safe systems, it seems prudent to aim for a national system that involves a maximum of 3‐4 colors.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients and families dedicate tremendous energy to making decisions about their advance directives, and discussions of these issues often create considerable angst and sadness. Health care providers are trained to elicit and advocate for such directives so they can act with patients' wishes in mind. Despite the high stakes, all these efforts can be undermined when the system for making providers aware of a patient's DNR status is flawed. Our data confirm the tremendous variability in the systems used to indicate DNR status (and other types of indications), variability that may place patients at risk from catastrophic errors. Following the lead of a few states, we call for a national mandate to standardize the identification of DNR orders and to make the colors of wristbands for a small set of indications uniform in every hospital across the country.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mark Keroack, MD, MPH, and Cathy Krsek, RN, MSN, MBA, from the University HealthSystem Consortium for their contributions to the survey and assistance with administration. We also thank members of the UHC Chief Nursing Council for participating in the survey study.

As modern medicine developed the technological capacity to deliver aggressive life‐sustaining interventionsthrough methods such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), intensive care units, and mechanical ventilationthe concept of do‐not‐resuscitate (DNR) orders emerged to allow individual patients to choose to forego selected treatments. To encourage patients to articulate these preferences, Congress passed the Patient Self‐Determination Act in 1991, a measure that required health care facilities to discuss advance directives with patients as they enter their system.1 Although the act has had less of an impact on the quality of DNR discussions than originally hoped for,25 its passage was evidence of the importance our society places on patientclinician discussions regarding goals of care. In addition to this legislative push, many organizations and advocacy groups use a variety of marketing campaigns, accreditation standards,6 and standard instruments and tools79 to promote the use of advance directives

Despite all these efforts, fewer than 30% of Americans (54% older than age 65) have completed advance directives.10 Nevertheless, many patientsparticularly those at highest risk for requiring end‐of‐life caredo express preferences regarding resuscitation at the time of hospital admission. In an ideal world, these preferences would be available for all providers to view, respect, and act on.

Unfortunately, research on patient safety and quality has demonstrated wide gaps between ideal and actual practice.1112 In the context of DNR wishes, despite strong efforts to collect patients' preferences, no current regulation provides or mandates a best practice on making these preferences operational. There are also few data that indicate whether patients' preferences are in fact transmitted to providers at the point of care and in an accurate and reliable manner.

Past research on proper identification of DNR orders is limited, with much of the focus on prehospital protocols.1315 Anecdotally, hospitals seem to employ varying strategies to highlight DNR orders using a combination of paper or electronic documentation and color‐coded patient wristbands. There have been several reports of errors involving this issue, including patients receiving CPR despite stated DNR preferences and a patient having CPR withheld because the wrong chart (of another patient with a DNR order) was mistakenly pulled.1617

The patient safety field emphasizes standardization as a key strategy to prevent errors. Because of problems articulating DNR orders (and other important patient‐related information), several hospitals promote the use of color‐coded wristbands to denote preferences for resuscitation. However, without national regulations or standards, the possibility remains that one safety hazard (advance directives on a paper chart distant from a patient's room) may be traded for another hazard (front‐line providers interpreting a color‐coded wristband incorrectly). In addition to the ethical problems inherent in failing to adhere to patients' resuscitation preferences, errors in following advance directives may also create legal liability.18 With all this in mind, we conducted a national survey to determine practice variations in the identification of DNR orders and the use of color‐coded patient wristbands. We hypothesized that there is considerable variation both in identification practices and in the use of color‐coded wristbands across academic medical centers.

METHODS

The project was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research. We anonymously surveyed nursing executives who are members of the University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC), an alliance of 97 academic medical centers and their affiliated hospitals representing 90% of the nation's nonprofit academic medical centers.19 The nursing executives are senior nursing leaders at participating UHC institutions and members of a dedicated UHC Chief Nursing Officer Council E‐mail listserv. We designed a brief survey and distributed it via their E‐mail listserv using an online commercial survey administration tool.20 Respondents were asked to complete the survey or have one of their colleagues familiar with local DNR identification practices complete it on their behalf. The online tool also provided summary reports and descriptive findings to meet the study objectives. We provided a 1‐month window (during summer 2006) with 1 interval E‐mail reminder to complete the surveys.

RESULTS

Survey announcements were E‐mailed to 127 nursing executives, 69 of whom completed it (response rate 54%). The respondents represented mostly academic medical centers (87%; another 13% represented affiliated community teaching hospitals), public institutions (89%), and large facilities (60% with more than 400 beds; 40% with 201‐400 beds). More than half the respondents (56%) reported their hospitals use paper chart documentation as the only method of identifying patients with a DNR order, whereas 16% reported their hospitals use only electronic health record (EHR) documentation (Fig. 1). Twenty‐five percent of hospitals (n = 17) use a color‐coded patient wristband in addition to either paper or electronic documentation. Of these 17 hospitals, a total of 8 colors or color schemes were employed to designate DNR status (Table 1).

| Green5 |

| Yellow3 |

| Blue3 |

| White with blue stars versus green stars (full DNR versus limited DNR)1 |

| Red1 |

| Red and white1 |

| Purple1 |

| Gold1 |

| Other (not listed)1 |

The use of color‐coded wristbands was not limited to identification of DNR status. Fifty‐five percent of hospitals (n = 31) use color‐coded wristbands to indicate another piece of patient‐related data such as an allergy, fall risk, or same last name alert (Table 2). In fact, 12 indications were depicted by various colors, with variations in both the color choice for a given indication (eg, allergy wristbands red at one hospital and yellow at another) and across indications (eg, red for allergy at one hospital and red for bleeding risk at another). Nearly 3 of 4 respondents (n = 48) reported being aware of a case at your institution in which confusion about a DNR order led to problems or confusion in patient care. A few respondents shared a brief anecdote of the event, illustrating the spectrum of clinical scenarios that lead to potential confusion (Table 3). Respondents reporting a case of confusion were not more likely to be from an institution that used color‐coded wristbands.

| Indication (n) | Colors used (n) |

|---|---|

| Drug/allergy (22) | Red (16) Yellow (4) White (1) Orange (1) |

| Fall risk (18) | Orange (5) Green (3) (and lime green [1]) Blue (3) Purple (3) Yellow (2) (and fluorescent yellow [1]) |

| Same name alert (7) | Blue (3) Orange (2) Yellow2) |

| Bleeding risk (3) | Red |

| Patient identification (3) | Green Red White |

| Wandering risk (3) | Pink (2) (and hot pink [1]) |

| Contact isolation (2) | Green |

| Latex allergy (2) | Purple |

| No blood draws on this arm (1) | Orange |

| MRSA infection (1) | Green |

| No blood products (1) | Red |

| Sleep apnea (1) | Purple |

| The patient had a DNR order written in the chart but no other identifiers at bedside, so a consult service started CPR while trying to determine code status. |

| Nurse called a code on a patient who was DNR because she failed to see order in chart. |

| Resuscitation efforts took place on a patient with a DNR order because the entire chart did not accompany the patient to a diagnostic testing area. |

| Patient was off the unit for a procedure, and staff in the other department did not know patients code status (DNR) and called a code. |

| Patient transported off nursing unit to radiology and coded. Patient was a DNR, but the order was buried in thinned chart materials. |

| Prior to implementing the wristbands, there were delays in care. Once wristbands were implemented with stars only, there was confusion as to what a blue star meant and what a green star meant (limited versus no resuscitation efforts). |

| We used to place a sticker on the chart. A sticker was left on the chart of a discharged patient when a new patient was admitted. The mistake was caught before an incident occurred. |

When asked whether most (greater than 75%) physicians and nurses could properly identify the color associated with a DNR patient wristband, responses differed by discipline. Eight‐five percent of respondents believed that most nurses at their institutions could correctly report the color for DNR, whereas only 15% believed physicians could do the same. Only 22% of respondents anticipated a change in the current system within the next 2 years; all these changes were a transition from paper to electronic documentation systems.

DISCUSSION

Regardless of whether the DNR documentation occurs in paper or electronic form (and our study demonstrates significant practice variation in the documentation method), the risk that a hospitalized patient may suddenly stop breathing or become pulseless is ever present. When such a patient is discovered, providers race to the bedside and initiate care, but immediately ask, Is the patient a full code? In these often‐chaotic moments, accurate and timely information about DNR status is critical to respecting a patient's preferences and avoiding a potentially devastating error. A number of the anecdotes shared by survey respondents and highlighted in Table 3 reinforce this concern. Many of these scenarios occur in the middle of the night or off a patient's primary unit (ie, at a test or procedure area), increasing the need for quick and easy identification of DNR status.

Our study demonstrates that a logical point‐of‐care solutiona color‐coded DNR patient wristbandmay create its own safety hazards, particularly if the color designations are not known by all providers (including floating and traveling nurses or trainees who rotate at different hospitals) and if the colors being employed represent different indications at a given hospital (see accompanying Images Dx, page 445). We found that approximately 1 in 4 surveyed hospitals depict DNR status by a color‐coded wristband. We also discovered remarkable variation in the colors chosen and the degree to which institutions use color‐coded wristbands to signal a panoply of other patient‐related issues. Human factors research demonstrates that even well‐meaning patient safety solutions may cause harm in new ways if they are poorly implemented or if the interface between the technology and human work patterns is not well appreciated. For example, recent studies illustrate unintended consequences from safety‐driven solutions, such as the implementation of computerized order entry,2122 quality measurement,23 adoption of EHRs,24 and bar code medication administration systems.25 Because standardization is a key mechanism for decreasing the opportunities for error, our findings raise serious concerns about current wristband use.

Interestingly, the lack of standardization and its related risk of failing to recall the conditions associated with color‐coded wristbands are complicated by societal trends. In December 2004 the issue of patient wristbands made headlines in Florida, when hospitals using yellow DNR wristbands (as was the case in 3 hospitals in our sample) reported several near‐misses among patients wearing yellow Lance Armstrong Livestrong bracelets.2627 Given recent estimates that nearly 1 in 5 Americans wears these bracelets to support people living with cancer,28 even safety‐minded journals and national newspapers have highlighted the issue.2930 Most hospitals that continue to use yellow DNR wristbands now either remove or cover Livestrong bracelets at the time of hospital admission. Furthermore, many other self‐help organizations now issue wristbands in a variety of colors as well, creating a potential hazard for any person wearing one in the hospital. Although patients do not mind wearing color‐coded wristbands,31 they might feel differently if they knew the potential for confusion.

After these anecdotal reports of identification mistakes surfaced, several states, most notably Arizona and Pennsylvania, launched initiatives to address the problem.3233 Arizona, after discovering 8 colors being used in the state, developed plans for a purple DNR color‐coded wristband. The choice of purple, and the careful decision to avoid blue, occurred because many hospitals call their resuscitative efforts a code blue, creating yet another potential source of confusion if a blue wristband is associated with a DNR order. The Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority also found tremendous color variations in patient wristbands used in a statewide survey. Both states ultimately promoted standardized colors and indications and provided tool kits and implementation manuals.3233

Although statewide initiatives represent a step forward, we believe that a national standard for color‐coded wristbands would improve patient safety. Precedents for this call to action exist. For many years, anecdotal information circulated about the errors caused by ambiguous use of abbreviations, such as qd instead of daily or U instead of units. Individual hospitals often banned or limited the use of such abbreviations, but no standard list of high‐risk abbreviations guided practice or required adherence, and cross‐hospital variation undoubtedly led to confusion. In 2004 the Joint Commission created a uniform list of high‐risk abbreviations as part of their National Patient Safety Goals, which instantly ended the debate about which abbreviations to ban and mandated compliance with the safety practice.34 A national group of stakeholders should similarly be convened to develop a list of colors and associated conditions that should be widely disseminated and enforced by the Joint Commission or a similar body. The statewide efforts by Arizona and Pennsylvania are instructive in this regard. Despite being guided by the goal of standardization, these 2 states chose different colors for DNR identification (interestingly, Pennsylvania chose blue for DNR, perhaps for the same reason that Arizona avoided itcode blue), further supporting the need for national guidelines (Table 4).

| Indication | Color (PA) | Color (AZ) |

|---|---|---|

| DNR | Blue | Purple |

| Allergy | Red | Red |

| Fall risk | Yellow | Yellow |

| Latex allergy | Green | |

| Restricted extremity | Pink | |

| Preregistration in emergency room | Yellow | |

| Admission and identification | Clear |

Our study represents the first national sample of DNR identification practices. Although it targeted academic health centers and affiliated institutions, we believe that these practice variations likely exist in all health care settings. Our study limitations included reliance on self‐reported institutional practices rather than direct review of existing policies and limited information about the surveyed population, making it impossible to compare respondents and nonrespondents. However, we have no reason to believe that these groups differed sufficiently to influence the study's main findings.

In the future, better technology may ultimately replace color‐coded wristbands. For instance, the time may come when wireless technologies seamlessly linked to the electronic health record will alert providers to a patient's DNR status when entering the patient's room. However, for today, point‐of‐care solutions using color‐coded wristbands remain a reasonable solution. Creating a nationally enforced standardized methodology, understandable and memorable to providers and free of stigma to patients (eg, a black wristband for DNR or writing DNR on a wristband) should be a patient safety priority. Because simplification is another key characteristic of safe systems, it seems prudent to aim for a national system that involves a maximum of 3‐4 colors.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients and families dedicate tremendous energy to making decisions about their advance directives, and discussions of these issues often create considerable angst and sadness. Health care providers are trained to elicit and advocate for such directives so they can act with patients' wishes in mind. Despite the high stakes, all these efforts can be undermined when the system for making providers aware of a patient's DNR status is flawed. Our data confirm the tremendous variability in the systems used to indicate DNR status (and other types of indications), variability that may place patients at risk from catastrophic errors. Following the lead of a few states, we call for a national mandate to standardize the identification of DNR orders and to make the colors of wristbands for a small set of indications uniform in every hospital across the country.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mark Keroack, MD, MPH, and Cathy Krsek, RN, MSN, MBA, from the University HealthSystem Consortium for their contributions to the survey and assistance with administration. We also thank members of the UHC Chief Nursing Council for participating in the survey study.

Copyright © 2007 Society of Hospital Medicine

Penetrating Point

Soon after they form, most new medical fields begin agitating for a special certification, something that says, We're here, and we're different. As I've noted previously in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the field of hospital medicine resisted this impulse in its early years, fearing that any special designation or certification would actually harm the field's growth and status.1 The concern was that managed‐care organizationsconvinced by the evidence that hospitalists improve efficiency and might improve quality2would react to any new hospitalist sheepskin by mandating that anyone providing hospital care to its covered patients have one. The backlash from primary care physicians locked out of the hospital by such a mandate would have been swift and ultimately damaging to hospitalists. In addition to these political considerations, the early field of hospital medicine lacked the academic credibility and scientific underpinning needed for specialty designation.3

Times have changed. There are now more than 15,000 hospitalists in the United States, and nearly half of American hospitals have hospitalists on their medical staffs. In many markets, including my own, hospitalists care for most internal medicine inpatients, as well as significant numbers of pediatric and surgical patients. The field has achieved academic legitimacy, with this journal, several textbooks, large and flourishing groups in every academic medical center, and several residency tracks and fellowship programs.4, 5 The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) has grown to more than 6000 members, become a widely respected and dynamic member of the community of professional societies, and published its core competencies.6

With this as a background, in 2004 SHM asked the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) to consider a program of certification for hospitalists. As a past SHM president and now a member of the ABIM Board of Directors, I am privileged to have a bird's‐eye view of the process. In this article, I reflect on some of the key issues it raises.

THE NUTS AND BOLTS OF BOARD CERTIFICATION

Since the first board (ophthalmology) was formed in 1917, 24 specialty boards have emerged, all under the umbrella of the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS).7 Because no one type of physician can do it all, certifying boards have had to struggle not only with how to assess competency in existing disciplines, but with the dynamic and often controversial questions raised when new fields emerge. In the past few decades, certifying boards have grappled with specialties formed around new procedures (such as cardiac electrophysiology), discrete populations (geriatrics, palliative care), complex diseases (HIV medicine), and sites of care (intensive care medicine, emergency medicine). It is this latter category that now includes hospital medicine.

In the past, it was relatively simple for a physician to obtain board certification. Residency or fellowship training was believed to confer on its graduates the presumption of competence and professionalismthe program director's attestation served as the graduate's Good Housekeeping seal of approval. Passing the board exam was the final step, ensuring that newly minted graduates had the requisite knowledge and judgment to practice in their fields.

Remarkably, for the first half century of the specialty boards, all certifications lasted for a physician's professional lifetime. Beginning with the 1969 decision of the American Board of Family Practice to limit the validity of its certificates to 7 years, all ABMS member boards now time limit their certifications, usually to 7‐10 years.7 Of course, in an environment of rapidly changing medical knowledge and new procedures, periodiceven continuousdemonstration of competence is increasingly expected by the public.

For ABIM, the mechanism to promote lifelong learning and demonstrate ongoing competence in the face of a rapidly changing environment is known as maintenance of certification (MOC).8 Through MOC, board‐certified internists demonstrate their ongoing clinical expertise and judgment, their involvement in lifelong learning and quality improvement activities, and their professionalism. Because MOC involves no new training requirements and includes an assessment of a physician's actual practice, it provides a potential mechanism, heretofore untapped, of demonstrating a unique professional focus that emerges after the completion of formal training.

HOSPITALIST CERTIFICATION AND THE MOC PROCESS

As ABIM considered a separate certification pathway for hospital medicine, it faced a conundrum. The vast majority of hospitalists are general internists (most of the rest are generalists in family medicine or pediatrics) who entered hospital medicine at the completion of their internal medicine training or after a period of primary care practice. Job opportunities for hospitalists are plentiful, andexcept for additional training in quality improvement, systems leadership, care transitions, palliative care, and communication9there is little clinical rationale to prolong internal medicine training for hospitalists (some individuals may opt for fellowships to enhance their leadership skills or to launch a research career,5 but few would argue for mandatory additional clinical training in hospital medicine at this time).

So, in the absence of formal training, how could the ABIM (or other boards) recognize the focused practice of hospitalists? This question must be framed within a broader challenge: Is it possible and appropriate for certifying boards to recognize expertise and focus that is accrued not through formal training, but through actual practice experience and accompanying self‐directed learning?

In 2006, the ABIM took up this question, producing a report (New and Emerging Disciplines in Internal Medicine II [NEDIM II]) that delineated several criteria to guide whether a new field merited focused recognition through MOC (Table 1). Judging by these criteria, hospital medicine appears to be a suitable first candidate for recognition of focused practice through MOC.

|

PRELIMINARY THOUGHTS ON FOCUSED RECOGNITION IN HOSPITAL MEDICINE

The ABIM has endorsed the concept of recognition of focused practice in hospital medicine and charged a subcommittee (that I chair) with working out the details. It would be premature to describe the committee's deliberations in detail (particularly because the final plan needs to be approved by both the ABIM and the ABMS), but the following are some key issues being discussed.

First, demonstration of focused practice requires some minimum volume of hospitalized patients. In the absence of hard data defining a threshold number of cases for hospitalists, we are likely to endorse a number that has face validity and that reliably separates self‐identified hospitalists from nonhospitalist generalists. As with all volume requirements, we will struggle over how to handle academic physicians, physician‐administrators, and physician‐researchers who limit their overall clinical practice but who spend most of their clinical time in hospital medicine and the bulk of their nonclinical time trying to improve hospital care.

The requirements to demonstrate performance in practice and lifelong learning may be more straightforward. As with all such MOC requirements, the ABIM is increasingly looking to use real practice data, trying to harmonize its data requirements with those of other organizations such as insurers, Medicare, the Joint Commission, or for pay‐for‐performance initiatives. Despite the operational challenges, this effort is vital: for MOC (including focused recognition) to be highly valued by patients, purchasers, and diplomates, it will increasingly need to measure not only what physicians know, but also what they do.

Finally, there is the test. It is likely that a secure exam for MOC with Recognition of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine will involve core content in internal medicine (information that every internist should know), augmented by substantial and challenging content in hospital medicine. Because it will be vital that a competent hospitalist understand key elements of outpatient practice, the exam will not be stripped of ambulatory content but will likely have fewer questions on topics that hospitalists are unlikely to confront (osteoporosis, cancer screening).

ONGOING ISSUES

As hospital medicine continues its explosive growth, it is important to develop ways to make board certification relevant to hospitalists. The ABIM believes that modifying the MOC process to recognize physicians who have focused their practice and achieved special expertise in hospital medicine is a good way to launch this effort. Ultimately, this process is likely to evolve, particularly if separate training pathways for hospital medicine emerge. For now, the development of Recognition of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine will further legitimize the new field, provide ABIM with insights into how to recognize physicians who have advanced through practice‐based learning rather than through training, and help to guide other certifying boards (particularly family medicine and pediatrics) considering hospitalist certification. In the end, the process will need to be user‐friendly for and satisfying to diplomates, flexible enough to allow for career transitions (both toward and away from hospital medicine), and sufficiently rigorous to be credible to all stakeholders, particularly patients.

- .Reflections: the hospitalist movement a decade later.J Hosp Med.2006;1:248–252.

- ,.The hospitalist movement 5 years later.JAMA2002;287:487–94.

- .The hospitalist: a new medical specialty?Ann Intern Med.1999;130:373–375.

- ,.Implications of the hospitalist movement for academic departments of medicine: lessons from the UCSF experience.Am J Med.1999;106:127–133.

- ,,,.Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress.Am J Med.2006;119:72.e1–e7.

- ,,,,.Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology.J Hosp Med.2006;1:48–56.

- .Recertification in the United States.BMJ.1999;319:1183–1185.

- ,.Professional standards in the USA: overview and new developments.Clin Med.2006;6:363–367.

- ,,,.Hospitalists' perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey.Am J Med.2001;111:247–254.

Soon after they form, most new medical fields begin agitating for a special certification, something that says, We're here, and we're different. As I've noted previously in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the field of hospital medicine resisted this impulse in its early years, fearing that any special designation or certification would actually harm the field's growth and status.1 The concern was that managed‐care organizationsconvinced by the evidence that hospitalists improve efficiency and might improve quality2would react to any new hospitalist sheepskin by mandating that anyone providing hospital care to its covered patients have one. The backlash from primary care physicians locked out of the hospital by such a mandate would have been swift and ultimately damaging to hospitalists. In addition to these political considerations, the early field of hospital medicine lacked the academic credibility and scientific underpinning needed for specialty designation.3

Times have changed. There are now more than 15,000 hospitalists in the United States, and nearly half of American hospitals have hospitalists on their medical staffs. In many markets, including my own, hospitalists care for most internal medicine inpatients, as well as significant numbers of pediatric and surgical patients. The field has achieved academic legitimacy, with this journal, several textbooks, large and flourishing groups in every academic medical center, and several residency tracks and fellowship programs.4, 5 The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) has grown to more than 6000 members, become a widely respected and dynamic member of the community of professional societies, and published its core competencies.6

With this as a background, in 2004 SHM asked the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) to consider a program of certification for hospitalists. As a past SHM president and now a member of the ABIM Board of Directors, I am privileged to have a bird's‐eye view of the process. In this article, I reflect on some of the key issues it raises.

THE NUTS AND BOLTS OF BOARD CERTIFICATION

Since the first board (ophthalmology) was formed in 1917, 24 specialty boards have emerged, all under the umbrella of the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS).7 Because no one type of physician can do it all, certifying boards have had to struggle not only with how to assess competency in existing disciplines, but with the dynamic and often controversial questions raised when new fields emerge. In the past few decades, certifying boards have grappled with specialties formed around new procedures (such as cardiac electrophysiology), discrete populations (geriatrics, palliative care), complex diseases (HIV medicine), and sites of care (intensive care medicine, emergency medicine). It is this latter category that now includes hospital medicine.

In the past, it was relatively simple for a physician to obtain board certification. Residency or fellowship training was believed to confer on its graduates the presumption of competence and professionalismthe program director's attestation served as the graduate's Good Housekeeping seal of approval. Passing the board exam was the final step, ensuring that newly minted graduates had the requisite knowledge and judgment to practice in their fields.

Remarkably, for the first half century of the specialty boards, all certifications lasted for a physician's professional lifetime. Beginning with the 1969 decision of the American Board of Family Practice to limit the validity of its certificates to 7 years, all ABMS member boards now time limit their certifications, usually to 7‐10 years.7 Of course, in an environment of rapidly changing medical knowledge and new procedures, periodiceven continuousdemonstration of competence is increasingly expected by the public.

For ABIM, the mechanism to promote lifelong learning and demonstrate ongoing competence in the face of a rapidly changing environment is known as maintenance of certification (MOC).8 Through MOC, board‐certified internists demonstrate their ongoing clinical expertise and judgment, their involvement in lifelong learning and quality improvement activities, and their professionalism. Because MOC involves no new training requirements and includes an assessment of a physician's actual practice, it provides a potential mechanism, heretofore untapped, of demonstrating a unique professional focus that emerges after the completion of formal training.

HOSPITALIST CERTIFICATION AND THE MOC PROCESS

As ABIM considered a separate certification pathway for hospital medicine, it faced a conundrum. The vast majority of hospitalists are general internists (most of the rest are generalists in family medicine or pediatrics) who entered hospital medicine at the completion of their internal medicine training or after a period of primary care practice. Job opportunities for hospitalists are plentiful, andexcept for additional training in quality improvement, systems leadership, care transitions, palliative care, and communication9there is little clinical rationale to prolong internal medicine training for hospitalists (some individuals may opt for fellowships to enhance their leadership skills or to launch a research career,5 but few would argue for mandatory additional clinical training in hospital medicine at this time).

So, in the absence of formal training, how could the ABIM (or other boards) recognize the focused practice of hospitalists? This question must be framed within a broader challenge: Is it possible and appropriate for certifying boards to recognize expertise and focus that is accrued not through formal training, but through actual practice experience and accompanying self‐directed learning?

In 2006, the ABIM took up this question, producing a report (New and Emerging Disciplines in Internal Medicine II [NEDIM II]) that delineated several criteria to guide whether a new field merited focused recognition through MOC (Table 1). Judging by these criteria, hospital medicine appears to be a suitable first candidate for recognition of focused practice through MOC.

|

PRELIMINARY THOUGHTS ON FOCUSED RECOGNITION IN HOSPITAL MEDICINE

The ABIM has endorsed the concept of recognition of focused practice in hospital medicine and charged a subcommittee (that I chair) with working out the details. It would be premature to describe the committee's deliberations in detail (particularly because the final plan needs to be approved by both the ABIM and the ABMS), but the following are some key issues being discussed.

First, demonstration of focused practice requires some minimum volume of hospitalized patients. In the absence of hard data defining a threshold number of cases for hospitalists, we are likely to endorse a number that has face validity and that reliably separates self‐identified hospitalists from nonhospitalist generalists. As with all volume requirements, we will struggle over how to handle academic physicians, physician‐administrators, and physician‐researchers who limit their overall clinical practice but who spend most of their clinical time in hospital medicine and the bulk of their nonclinical time trying to improve hospital care.

The requirements to demonstrate performance in practice and lifelong learning may be more straightforward. As with all such MOC requirements, the ABIM is increasingly looking to use real practice data, trying to harmonize its data requirements with those of other organizations such as insurers, Medicare, the Joint Commission, or for pay‐for‐performance initiatives. Despite the operational challenges, this effort is vital: for MOC (including focused recognition) to be highly valued by patients, purchasers, and diplomates, it will increasingly need to measure not only what physicians know, but also what they do.

Finally, there is the test. It is likely that a secure exam for MOC with Recognition of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine will involve core content in internal medicine (information that every internist should know), augmented by substantial and challenging content in hospital medicine. Because it will be vital that a competent hospitalist understand key elements of outpatient practice, the exam will not be stripped of ambulatory content but will likely have fewer questions on topics that hospitalists are unlikely to confront (osteoporosis, cancer screening).

ONGOING ISSUES

As hospital medicine continues its explosive growth, it is important to develop ways to make board certification relevant to hospitalists. The ABIM believes that modifying the MOC process to recognize physicians who have focused their practice and achieved special expertise in hospital medicine is a good way to launch this effort. Ultimately, this process is likely to evolve, particularly if separate training pathways for hospital medicine emerge. For now, the development of Recognition of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine will further legitimize the new field, provide ABIM with insights into how to recognize physicians who have advanced through practice‐based learning rather than through training, and help to guide other certifying boards (particularly family medicine and pediatrics) considering hospitalist certification. In the end, the process will need to be user‐friendly for and satisfying to diplomates, flexible enough to allow for career transitions (both toward and away from hospital medicine), and sufficiently rigorous to be credible to all stakeholders, particularly patients.

Soon after they form, most new medical fields begin agitating for a special certification, something that says, We're here, and we're different. As I've noted previously in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the field of hospital medicine resisted this impulse in its early years, fearing that any special designation or certification would actually harm the field's growth and status.1 The concern was that managed‐care organizationsconvinced by the evidence that hospitalists improve efficiency and might improve quality2would react to any new hospitalist sheepskin by mandating that anyone providing hospital care to its covered patients have one. The backlash from primary care physicians locked out of the hospital by such a mandate would have been swift and ultimately damaging to hospitalists. In addition to these political considerations, the early field of hospital medicine lacked the academic credibility and scientific underpinning needed for specialty designation.3

Times have changed. There are now more than 15,000 hospitalists in the United States, and nearly half of American hospitals have hospitalists on their medical staffs. In many markets, including my own, hospitalists care for most internal medicine inpatients, as well as significant numbers of pediatric and surgical patients. The field has achieved academic legitimacy, with this journal, several textbooks, large and flourishing groups in every academic medical center, and several residency tracks and fellowship programs.4, 5 The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) has grown to more than 6000 members, become a widely respected and dynamic member of the community of professional societies, and published its core competencies.6

With this as a background, in 2004 SHM asked the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) to consider a program of certification for hospitalists. As a past SHM president and now a member of the ABIM Board of Directors, I am privileged to have a bird's‐eye view of the process. In this article, I reflect on some of the key issues it raises.

THE NUTS AND BOLTS OF BOARD CERTIFICATION

Since the first board (ophthalmology) was formed in 1917, 24 specialty boards have emerged, all under the umbrella of the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS).7 Because no one type of physician can do it all, certifying boards have had to struggle not only with how to assess competency in existing disciplines, but with the dynamic and often controversial questions raised when new fields emerge. In the past few decades, certifying boards have grappled with specialties formed around new procedures (such as cardiac electrophysiology), discrete populations (geriatrics, palliative care), complex diseases (HIV medicine), and sites of care (intensive care medicine, emergency medicine). It is this latter category that now includes hospital medicine.

In the past, it was relatively simple for a physician to obtain board certification. Residency or fellowship training was believed to confer on its graduates the presumption of competence and professionalismthe program director's attestation served as the graduate's Good Housekeeping seal of approval. Passing the board exam was the final step, ensuring that newly minted graduates had the requisite knowledge and judgment to practice in their fields.