User login

Erratum: Investing in the future: Building an academic hospitalist faculty development program

The disclosure statement for the following article, Investing in the Future: Building an Academic Hospitalist Faculty Development Program, by Niraj L. Sehgal, MD, MPH, Bradley A. Sharpe, MD, Andrew A. Auerbach, MD, MPH, Robert M. Wachter, MD, that published in Volume 6, Issue 3 pages 161166 of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, was incorrect. The correct disclosure statement is: All authors report no relevant conflicts of interest. The publisher regrets this error.

The disclosure statement for the following article, Investing in the Future: Building an Academic Hospitalist Faculty Development Program, by Niraj L. Sehgal, MD, MPH, Bradley A. Sharpe, MD, Andrew A. Auerbach, MD, MPH, Robert M. Wachter, MD, that published in Volume 6, Issue 3 pages 161166 of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, was incorrect. The correct disclosure statement is: All authors report no relevant conflicts of interest. The publisher regrets this error.

The disclosure statement for the following article, Investing in the Future: Building an Academic Hospitalist Faculty Development Program, by Niraj L. Sehgal, MD, MPH, Bradley A. Sharpe, MD, Andrew A. Auerbach, MD, MPH, Robert M. Wachter, MD, that published in Volume 6, Issue 3 pages 161166 of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, was incorrect. The correct disclosure statement is: All authors report no relevant conflicts of interest. The publisher regrets this error.

The Hospitalist Field Turns 15

Many people date the start of the hospitalist field to my 1996 New England Journal of Medicine article,1 which first introduced the concept to a broad audience. That makes 2011 the field's 15th year, andif you have kidsyou know this is a tough and exciting age. The cuteness of childhood has faded, and bad decisions can no longer be excused as youthful indiscretions.

That's an apt metaphor for our field as we celebrate our 15th birthday. We are now an established part of the health care landscape, with a clear place in the House of Medicine. All of the measures of a successful specialty are ours: a thriving professional society, high‐quality training programs, increasingly robust research, a flourishing journal, and more. The field has truly arrived.

But these successes are also tempered by several challenges that have become more evident in recent years. In this article, I'll reflect on some of these successes and challenges.

The Hospitalist Field's Successes and Growth

In our 1996 article, Goldman and I1 wrote about the forces promoting the hospitalist model:

It seems unlikelythat high value care can be delivered in the hospital by physicians who spend only a small fraction of their time in this setting. As hospital stays become shorter and inpatient care becomes more intensive, a greater premium will be placed on the skill, experience, and availability of physicians caring for inpatients.

When we cited the search for value as a driving force in 1996, we were a bit ahead of our time, since there was relatively little skin in this game at the time. Remember that when our field launched, none of these value‐promoting forces existed: robust unannounced hospital inspections by the Joint Commission, public reporting of quality data, pay for performance, no pay for errors, state reporting of sentinel events, and more. In other words, until recently, neither a hospital's income stream nor its reputation was threatened by poor performance.

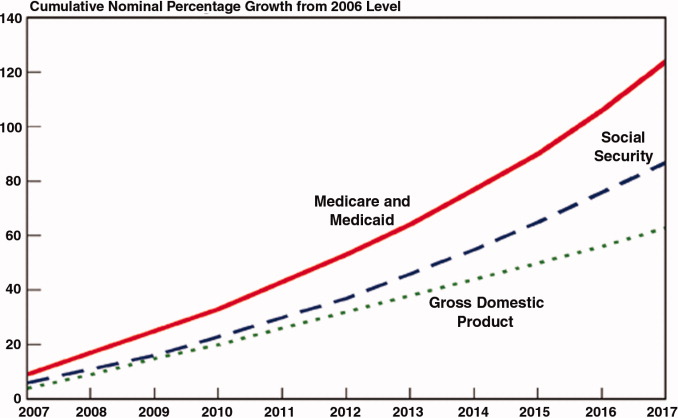

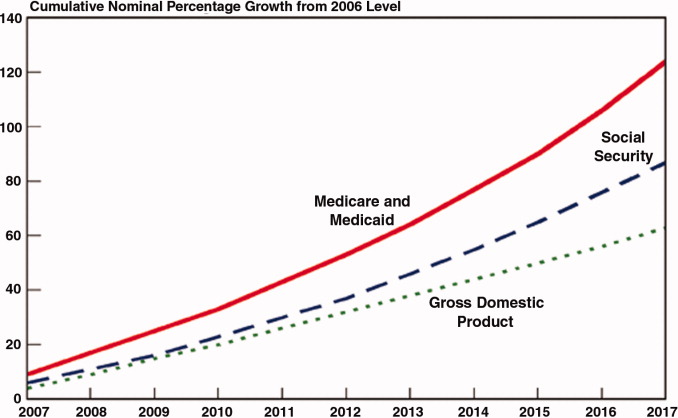

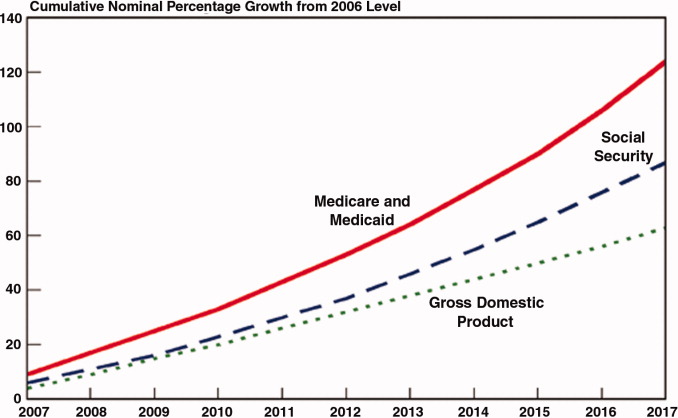

But this landscape is undergoing a sea change. By 2015, fully 9% of a hospital's Medicare reimbursements will be at risk through a variety of initiatives, including value‐based purchasing and meaningful use standards. And private payers are beginning to replicate Medicare's standards, particularly when they perceive that they may lead to both improved quality and lower costs.

Hospitals and health systems increasingly recognize how indispensable hospitalists can be as they demonstrate that their presence improves value. But this is only one of the forces driving the fieldalready the fastest growing specialty in medical historyto even higher levels of growth. These others include: the exodus of primary care physicians from the hospital, the fact that the specialists have left the building, comanagement of nonmedical patients, new opportunities in systems leadership, and dealing with housestaff duty hours reductions. I'll say a word about each.

The Exodus of Primary Care Physicians

In the early days of our field, one of the major sources of pushback was the desire of many primary care doctors to continue managing their own inpatients. Beginning a decade ago, this pressure began to abate, as many primary care physicians began to recognize the potential advantages of working with hospitalists.2

Over the next several years, I predict that the growth in the patient‐centered medical home model3with the physician's new responsibilities to provide comprehensive patient‐centered carewill make it even less likely that primary care doctors will have the time to manage their own inpatients. Luckily, information systems now being installed throughout the country (fueled by federal subsidies) will lead to unprecedented connectivity between the inpatient and outpatient worlds,4 hopefully resulting in improving handoffs.

Moreover, the increasing scrutiny of, and upcoming penalties for, high readmission rates are driving hospitals and clinics into creating more robust systems of care to improve inpatientoutpatient communications. The bottom line is that the main Achilles heel of hospitalist systemsthe handoff at hospital admission and dischargeshould improve over the next few years, making it easier than ever for primary care doctors to forego hospital care without losing track of critical patient information.

The Specialists Have Left the Building

One of the more interesting phenomena in the recent history of the hospitalist field is the growth of what I call hyphenated hospitalists: neurology hospitalists, ob‐gyn hospitalists, surgical hospitalists, and the like. The forces promoting these models are similar to those that catalyzed the hospitalist model: the recognition that bifurcating inpatient and outpatient care sometimes makes sense when several conditions are met (Table 1).

|

| 1) Is the number of inpatients who require the services of that specialty (either for consults or principal care) large enough to justify having at least one doctor in the house during daytime? |

| 2) Is the specialist frequently needed to see an inpatient urgently? |

| 3) Under the usual model of mixed inpatient and outpatient care, is the specialist frequently busy in the office, operating room, or procedural suite at times where they are urgently needed in the hospital (see #2)? |

| 4) Has the field become sub‐sub specialized, such that many covering physicians are now uncomfortable managing common acute inpatient problems (i.e., the headache neurologist asked to handle an acute stroke)? |

The emergence of hyphenated hospitalists raises all sorts of questions for the hospitalist field, many of which I have addressed elsewhere.5 But the bottom line is that the growth of specialty hospitalists may help create a new hospital home teama group of dedicated inpatient physicians spanning virtually every specialty who share best practices, work together on systems improvements, and operate under similar accountabilities. This development may well be the most exciting one in the field's recent history.

Comanagement of Nonmedical Patients

The same forces that led to the emergence of the hospitalist field are also catalyzing the growth of hospitalist comanagement programs. There is a shortage of general surgeons, and in teaching hospitals, there are fewer surgical residents available to help provide floor‐based pre‐ and post‐operative care. And surgical patients are under the same value pressures as medical patients, with increasing public reporting of quality processes and outcomes and new pay for performance programs coming on line. Although the evidence of benefit is mixed,68 many hospitalists are finding that increasing parts of their work involve comanagement.

Comanagement raises several issues, all of which need to be addressed. How do we define clear boundaries between what the hospitalist does and what the specialist does? Comanagement programs, to be effective, need very clear rules of engagement and open lines of communication to work through inevitable conflicts.6 How does the money flow? Most hospitalist programs receive hospital support, but it is legitimate to wonder whether the specialists, particularly surgeons, should chip in to support the program, particularly if they continue to collect a global case rate that was predicated on their provision of pre‐ and post‐operative care. How do comanagement programs and specialty hospitalist programs interrelate, and what are the relative advantages and disadvantages of each? To my mind, programs that meet the conditions outlined in Table 1 probably would do well to start a specialty hospitalist program, assuming that they can find high‐quality specialists to staff it. But there will be myriad variations on these themes. In my hospital, for example, we have both neurohospitalists and medical hospitalists who co‐manage neurosurgery patients.

New Opportunities in Systems Leadership

The growth of the hospitalist field will partly come from individuals who begin their careers performing clinical work, but who transition over time to managerial and leadership roles. This is a natural transition: Who better than a hospitalist to help organize and deliver educational programs, manage clinical operations, implement information technology systems, or lead quality, safety, or utilization management efforts? Of course, as hospitalists assume these roles, others need to take their places covering their clinical shifts.

This might seem like a relatively unimportant driver of personnel growth, but in more advanced systems, it can become a major one. Table 2 lists the faculty in my Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) who have major institutional (i.e., nondivisional) roles. These roles, spread across eight faculty, account for 3.7 full‐time equivalents (FTEs).

| Role | Works for Whom? | Approximate % FTE |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Associate Chief Medical Officer | Medical Center | 80% |

| Associate Medical Director for Information Technology | Medical Center | 80% |

| Associate Chair for Quality and Safety | Department of Medicine | 50% |

| Director of Quality and Patient Safety | Department of Neurosurgery | 50% |

| Associate Medicine Residency Director (two people) | Department of Medicine | 30% (for each) |

| Director of Medical Student Clerkships | Department of Medicine | 25% |

| Director of Patient Safety/Quality Programs | Office of Graduate Medical Education, School of Medicine | 25% |

| Total FTEs: 3.7 | ||

Dealing with New ACGME Regulations

In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) issued its first housestaff duty hours reductions (limiting housestaff to a maximum of 80 hours per week, with no single shift lasting longer than 30 hours). This reduction led to the development of nonteaching services in most teaching hospitals; the vast majority of such programs have hospitalists at their core.

In July 2011, new ACGME regulations go into effect,10 which will further cut the availability of housestaff to cover clinical services. Although the 80‐hour weekly limit remains, intern shifts are now limited to 16 hours, meaning that the traditional long call system involving interns must be replaced by a shift‐based system. Like the earlier changes, these new regulations are leading to additional hospitalist growth in the nation's teaching hospitals. By the time the changes are fully implemented, many hospitalist programs will have half or more of their hospitalist FTEs devoted to covering patients previously cared for by residents.

Challenges for Hospitalist Programs

These powerful forces promoting the growth in the hospitalist field continue to ensure that hospitalists are in high demand. As a practical matter, this has resulted in increasing salaries and improved job conditions for hospitalists.

But this growth brings many challenges. Many hospitalist programs are poorly managed, often because the leaders lack the training and experience to effectively run such a rapidly growing and complex enterprise. One manifestation of these leadership challenges is that schedules are often created around the convenience and desires of the physicians rather than the needs of the patients. For example, the increasingly prevalent seven‐days‐on, seven‐days‐off schedule often leads to burnout and a feeling by the hospitalists that they are working too hard. Yet many groups are unwilling to consider modifications to the schedule that might decrease the intensity, if the cost is fewer days off.

On the other hand, some groups pay little attention to patient continuity in constructing their schedules. I know of programs that schedule their hospitalists in 24‐hour shifts (followed by a few days off), which means that admitted patients will see a different hospitalist every day. I see this as highly problematic, particularly because the most common complaint I hear from patients about hospitalist programs is that I saw a different doctor every day.

Many of the field's challenges stem from hospitalists' near‐total dependency on hospital funding to create sustainable job descriptions.11 While I continue to believe that this bit of financial happenstance has been good for both hospitalists and hospitalssince it has driven uncommon degrees of interdependency and alignmentit does mean that a difficult budget battle is virtually assured every year. As hospital finances become tighter, one can expect these battles to grow even more heated. Speaking for hospitalists, I am not too worried about the outcomes of these battles, since hospitalists provide a mission‐critical service at a fair price, there are no viable lower‐priced replacements (expect perhaps for nonphysician providers such as nurse practitioners for the less‐complex patients), and hospitalists are extraordinarily mobilethere are virtually no barriers for a hospitalist, or an entire group, to transfer to another institution. Nevertheless, it seems inevitable that these battles will leave scars, scars that may ultimately compromise the crucial collaboration that both hospitalists and hospitals depend on.

The Bottom Line

Even at age 15, an age at which many adolescents are irredeemably cynical, the hospitalist field retains much of its sense of limitless possibility and exuberance. This is not because things are perfectthey are not. Some hospitalist jobs are poorly constructed, some groups have poor leadership, some hospitalists are burning out, there are examples of spotty quality and collaboration, and hospitalists continue to have to work to earn the respect of colleagues and patients that other specialists take for granted.

That said, the field of hospital medicine remains uniquely exciting, in part because it is so tightly linked to the broader changes in the health care policy landscape. Many other specialties see the profound changes underway in health care as an existential threat to their professional values and incomes. Hospitalists, on the other hand, see these changes as raising the pressure on hospitals to deliver the highest quality, most satisfying, and safest care at the lowest cost. Framed this way, forward‐thinking hospitalists quite naturally see these changes as yet another catalyst for the growth and indispensability of their field.

- ,.The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system.N Engl J Med.1996;335:514–517.

- ,,,.How physicians perceive hospitalist services after implementation: Anticipation vs reality.Arch Intern Med.2003;163:2330–2336.

- ,,.Medical homes: Challenges in translating theory into practice.Med Care.2009;47:714–722.

- ,.Improving safety with information technology.N Engl J Med.2003;348:2526–2534.

- The New Home Team: The Remarkable Rise of the Hyphenated Hospitalist. Wachter's World blog, January 16,2011. Available at: http://tinyurl. com/4h2jy7e. Accessed February 12, 2011.

- ,,, et al.Comanagement of surgical patients between neurosurgeons and hospitalists.Arch Intern Med.2010;170:2004–2010.

- ,,, et al.Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: A randomized, controlled trial.Ann Intern Med.2004;141:28–38.

- ,,,,.Comanagement of hospitalized surgical patients by medicine physicians in the United States.Arch Intern Med.2010;170:363–368.

- ,,.Neurohospitalists: An emerging model for inpatient neurological care.Ann Neurol.2008;63:135–140.

- ,,;ACGME Duty Hour Task Force. The new recommendations on duty hours from the ACGME Task Force.N Engl J Med.2010 Jul 8;363(2):e3. Epub 2010 Jun 23. PubMed PMID: 20573917. The website is here: http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsb1005800.

- .Elevated expectations.The Hospitalist. January2011. Available at: http://www.the‐hospitalist.org/details/article/972781/Elevated_Expectations.html. Accessed February 12, 2011.

Many people date the start of the hospitalist field to my 1996 New England Journal of Medicine article,1 which first introduced the concept to a broad audience. That makes 2011 the field's 15th year, andif you have kidsyou know this is a tough and exciting age. The cuteness of childhood has faded, and bad decisions can no longer be excused as youthful indiscretions.

That's an apt metaphor for our field as we celebrate our 15th birthday. We are now an established part of the health care landscape, with a clear place in the House of Medicine. All of the measures of a successful specialty are ours: a thriving professional society, high‐quality training programs, increasingly robust research, a flourishing journal, and more. The field has truly arrived.

But these successes are also tempered by several challenges that have become more evident in recent years. In this article, I'll reflect on some of these successes and challenges.

The Hospitalist Field's Successes and Growth

In our 1996 article, Goldman and I1 wrote about the forces promoting the hospitalist model:

It seems unlikelythat high value care can be delivered in the hospital by physicians who spend only a small fraction of their time in this setting. As hospital stays become shorter and inpatient care becomes more intensive, a greater premium will be placed on the skill, experience, and availability of physicians caring for inpatients.

When we cited the search for value as a driving force in 1996, we were a bit ahead of our time, since there was relatively little skin in this game at the time. Remember that when our field launched, none of these value‐promoting forces existed: robust unannounced hospital inspections by the Joint Commission, public reporting of quality data, pay for performance, no pay for errors, state reporting of sentinel events, and more. In other words, until recently, neither a hospital's income stream nor its reputation was threatened by poor performance.

But this landscape is undergoing a sea change. By 2015, fully 9% of a hospital's Medicare reimbursements will be at risk through a variety of initiatives, including value‐based purchasing and meaningful use standards. And private payers are beginning to replicate Medicare's standards, particularly when they perceive that they may lead to both improved quality and lower costs.

Hospitals and health systems increasingly recognize how indispensable hospitalists can be as they demonstrate that their presence improves value. But this is only one of the forces driving the fieldalready the fastest growing specialty in medical historyto even higher levels of growth. These others include: the exodus of primary care physicians from the hospital, the fact that the specialists have left the building, comanagement of nonmedical patients, new opportunities in systems leadership, and dealing with housestaff duty hours reductions. I'll say a word about each.

The Exodus of Primary Care Physicians

In the early days of our field, one of the major sources of pushback was the desire of many primary care doctors to continue managing their own inpatients. Beginning a decade ago, this pressure began to abate, as many primary care physicians began to recognize the potential advantages of working with hospitalists.2

Over the next several years, I predict that the growth in the patient‐centered medical home model3with the physician's new responsibilities to provide comprehensive patient‐centered carewill make it even less likely that primary care doctors will have the time to manage their own inpatients. Luckily, information systems now being installed throughout the country (fueled by federal subsidies) will lead to unprecedented connectivity between the inpatient and outpatient worlds,4 hopefully resulting in improving handoffs.

Moreover, the increasing scrutiny of, and upcoming penalties for, high readmission rates are driving hospitals and clinics into creating more robust systems of care to improve inpatientoutpatient communications. The bottom line is that the main Achilles heel of hospitalist systemsthe handoff at hospital admission and dischargeshould improve over the next few years, making it easier than ever for primary care doctors to forego hospital care without losing track of critical patient information.

The Specialists Have Left the Building

One of the more interesting phenomena in the recent history of the hospitalist field is the growth of what I call hyphenated hospitalists: neurology hospitalists, ob‐gyn hospitalists, surgical hospitalists, and the like. The forces promoting these models are similar to those that catalyzed the hospitalist model: the recognition that bifurcating inpatient and outpatient care sometimes makes sense when several conditions are met (Table 1).

|

| 1) Is the number of inpatients who require the services of that specialty (either for consults or principal care) large enough to justify having at least one doctor in the house during daytime? |

| 2) Is the specialist frequently needed to see an inpatient urgently? |

| 3) Under the usual model of mixed inpatient and outpatient care, is the specialist frequently busy in the office, operating room, or procedural suite at times where they are urgently needed in the hospital (see #2)? |

| 4) Has the field become sub‐sub specialized, such that many covering physicians are now uncomfortable managing common acute inpatient problems (i.e., the headache neurologist asked to handle an acute stroke)? |

The emergence of hyphenated hospitalists raises all sorts of questions for the hospitalist field, many of which I have addressed elsewhere.5 But the bottom line is that the growth of specialty hospitalists may help create a new hospital home teama group of dedicated inpatient physicians spanning virtually every specialty who share best practices, work together on systems improvements, and operate under similar accountabilities. This development may well be the most exciting one in the field's recent history.

Comanagement of Nonmedical Patients

The same forces that led to the emergence of the hospitalist field are also catalyzing the growth of hospitalist comanagement programs. There is a shortage of general surgeons, and in teaching hospitals, there are fewer surgical residents available to help provide floor‐based pre‐ and post‐operative care. And surgical patients are under the same value pressures as medical patients, with increasing public reporting of quality processes and outcomes and new pay for performance programs coming on line. Although the evidence of benefit is mixed,68 many hospitalists are finding that increasing parts of their work involve comanagement.

Comanagement raises several issues, all of which need to be addressed. How do we define clear boundaries between what the hospitalist does and what the specialist does? Comanagement programs, to be effective, need very clear rules of engagement and open lines of communication to work through inevitable conflicts.6 How does the money flow? Most hospitalist programs receive hospital support, but it is legitimate to wonder whether the specialists, particularly surgeons, should chip in to support the program, particularly if they continue to collect a global case rate that was predicated on their provision of pre‐ and post‐operative care. How do comanagement programs and specialty hospitalist programs interrelate, and what are the relative advantages and disadvantages of each? To my mind, programs that meet the conditions outlined in Table 1 probably would do well to start a specialty hospitalist program, assuming that they can find high‐quality specialists to staff it. But there will be myriad variations on these themes. In my hospital, for example, we have both neurohospitalists and medical hospitalists who co‐manage neurosurgery patients.

New Opportunities in Systems Leadership

The growth of the hospitalist field will partly come from individuals who begin their careers performing clinical work, but who transition over time to managerial and leadership roles. This is a natural transition: Who better than a hospitalist to help organize and deliver educational programs, manage clinical operations, implement information technology systems, or lead quality, safety, or utilization management efforts? Of course, as hospitalists assume these roles, others need to take their places covering their clinical shifts.

This might seem like a relatively unimportant driver of personnel growth, but in more advanced systems, it can become a major one. Table 2 lists the faculty in my Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) who have major institutional (i.e., nondivisional) roles. These roles, spread across eight faculty, account for 3.7 full‐time equivalents (FTEs).

| Role | Works for Whom? | Approximate % FTE |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Associate Chief Medical Officer | Medical Center | 80% |

| Associate Medical Director for Information Technology | Medical Center | 80% |

| Associate Chair for Quality and Safety | Department of Medicine | 50% |

| Director of Quality and Patient Safety | Department of Neurosurgery | 50% |

| Associate Medicine Residency Director (two people) | Department of Medicine | 30% (for each) |

| Director of Medical Student Clerkships | Department of Medicine | 25% |

| Director of Patient Safety/Quality Programs | Office of Graduate Medical Education, School of Medicine | 25% |

| Total FTEs: 3.7 | ||

Dealing with New ACGME Regulations

In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) issued its first housestaff duty hours reductions (limiting housestaff to a maximum of 80 hours per week, with no single shift lasting longer than 30 hours). This reduction led to the development of nonteaching services in most teaching hospitals; the vast majority of such programs have hospitalists at their core.

In July 2011, new ACGME regulations go into effect,10 which will further cut the availability of housestaff to cover clinical services. Although the 80‐hour weekly limit remains, intern shifts are now limited to 16 hours, meaning that the traditional long call system involving interns must be replaced by a shift‐based system. Like the earlier changes, these new regulations are leading to additional hospitalist growth in the nation's teaching hospitals. By the time the changes are fully implemented, many hospitalist programs will have half or more of their hospitalist FTEs devoted to covering patients previously cared for by residents.

Challenges for Hospitalist Programs

These powerful forces promoting the growth in the hospitalist field continue to ensure that hospitalists are in high demand. As a practical matter, this has resulted in increasing salaries and improved job conditions for hospitalists.

But this growth brings many challenges. Many hospitalist programs are poorly managed, often because the leaders lack the training and experience to effectively run such a rapidly growing and complex enterprise. One manifestation of these leadership challenges is that schedules are often created around the convenience and desires of the physicians rather than the needs of the patients. For example, the increasingly prevalent seven‐days‐on, seven‐days‐off schedule often leads to burnout and a feeling by the hospitalists that they are working too hard. Yet many groups are unwilling to consider modifications to the schedule that might decrease the intensity, if the cost is fewer days off.

On the other hand, some groups pay little attention to patient continuity in constructing their schedules. I know of programs that schedule their hospitalists in 24‐hour shifts (followed by a few days off), which means that admitted patients will see a different hospitalist every day. I see this as highly problematic, particularly because the most common complaint I hear from patients about hospitalist programs is that I saw a different doctor every day.

Many of the field's challenges stem from hospitalists' near‐total dependency on hospital funding to create sustainable job descriptions.11 While I continue to believe that this bit of financial happenstance has been good for both hospitalists and hospitalssince it has driven uncommon degrees of interdependency and alignmentit does mean that a difficult budget battle is virtually assured every year. As hospital finances become tighter, one can expect these battles to grow even more heated. Speaking for hospitalists, I am not too worried about the outcomes of these battles, since hospitalists provide a mission‐critical service at a fair price, there are no viable lower‐priced replacements (expect perhaps for nonphysician providers such as nurse practitioners for the less‐complex patients), and hospitalists are extraordinarily mobilethere are virtually no barriers for a hospitalist, or an entire group, to transfer to another institution. Nevertheless, it seems inevitable that these battles will leave scars, scars that may ultimately compromise the crucial collaboration that both hospitalists and hospitals depend on.

The Bottom Line

Even at age 15, an age at which many adolescents are irredeemably cynical, the hospitalist field retains much of its sense of limitless possibility and exuberance. This is not because things are perfectthey are not. Some hospitalist jobs are poorly constructed, some groups have poor leadership, some hospitalists are burning out, there are examples of spotty quality and collaboration, and hospitalists continue to have to work to earn the respect of colleagues and patients that other specialists take for granted.

That said, the field of hospital medicine remains uniquely exciting, in part because it is so tightly linked to the broader changes in the health care policy landscape. Many other specialties see the profound changes underway in health care as an existential threat to their professional values and incomes. Hospitalists, on the other hand, see these changes as raising the pressure on hospitals to deliver the highest quality, most satisfying, and safest care at the lowest cost. Framed this way, forward‐thinking hospitalists quite naturally see these changes as yet another catalyst for the growth and indispensability of their field.

Many people date the start of the hospitalist field to my 1996 New England Journal of Medicine article,1 which first introduced the concept to a broad audience. That makes 2011 the field's 15th year, andif you have kidsyou know this is a tough and exciting age. The cuteness of childhood has faded, and bad decisions can no longer be excused as youthful indiscretions.

That's an apt metaphor for our field as we celebrate our 15th birthday. We are now an established part of the health care landscape, with a clear place in the House of Medicine. All of the measures of a successful specialty are ours: a thriving professional society, high‐quality training programs, increasingly robust research, a flourishing journal, and more. The field has truly arrived.

But these successes are also tempered by several challenges that have become more evident in recent years. In this article, I'll reflect on some of these successes and challenges.

The Hospitalist Field's Successes and Growth

In our 1996 article, Goldman and I1 wrote about the forces promoting the hospitalist model:

It seems unlikelythat high value care can be delivered in the hospital by physicians who spend only a small fraction of their time in this setting. As hospital stays become shorter and inpatient care becomes more intensive, a greater premium will be placed on the skill, experience, and availability of physicians caring for inpatients.

When we cited the search for value as a driving force in 1996, we were a bit ahead of our time, since there was relatively little skin in this game at the time. Remember that when our field launched, none of these value‐promoting forces existed: robust unannounced hospital inspections by the Joint Commission, public reporting of quality data, pay for performance, no pay for errors, state reporting of sentinel events, and more. In other words, until recently, neither a hospital's income stream nor its reputation was threatened by poor performance.

But this landscape is undergoing a sea change. By 2015, fully 9% of a hospital's Medicare reimbursements will be at risk through a variety of initiatives, including value‐based purchasing and meaningful use standards. And private payers are beginning to replicate Medicare's standards, particularly when they perceive that they may lead to both improved quality and lower costs.

Hospitals and health systems increasingly recognize how indispensable hospitalists can be as they demonstrate that their presence improves value. But this is only one of the forces driving the fieldalready the fastest growing specialty in medical historyto even higher levels of growth. These others include: the exodus of primary care physicians from the hospital, the fact that the specialists have left the building, comanagement of nonmedical patients, new opportunities in systems leadership, and dealing with housestaff duty hours reductions. I'll say a word about each.

The Exodus of Primary Care Physicians

In the early days of our field, one of the major sources of pushback was the desire of many primary care doctors to continue managing their own inpatients. Beginning a decade ago, this pressure began to abate, as many primary care physicians began to recognize the potential advantages of working with hospitalists.2

Over the next several years, I predict that the growth in the patient‐centered medical home model3with the physician's new responsibilities to provide comprehensive patient‐centered carewill make it even less likely that primary care doctors will have the time to manage their own inpatients. Luckily, information systems now being installed throughout the country (fueled by federal subsidies) will lead to unprecedented connectivity between the inpatient and outpatient worlds,4 hopefully resulting in improving handoffs.

Moreover, the increasing scrutiny of, and upcoming penalties for, high readmission rates are driving hospitals and clinics into creating more robust systems of care to improve inpatientoutpatient communications. The bottom line is that the main Achilles heel of hospitalist systemsthe handoff at hospital admission and dischargeshould improve over the next few years, making it easier than ever for primary care doctors to forego hospital care without losing track of critical patient information.

The Specialists Have Left the Building

One of the more interesting phenomena in the recent history of the hospitalist field is the growth of what I call hyphenated hospitalists: neurology hospitalists, ob‐gyn hospitalists, surgical hospitalists, and the like. The forces promoting these models are similar to those that catalyzed the hospitalist model: the recognition that bifurcating inpatient and outpatient care sometimes makes sense when several conditions are met (Table 1).

|

| 1) Is the number of inpatients who require the services of that specialty (either for consults or principal care) large enough to justify having at least one doctor in the house during daytime? |

| 2) Is the specialist frequently needed to see an inpatient urgently? |

| 3) Under the usual model of mixed inpatient and outpatient care, is the specialist frequently busy in the office, operating room, or procedural suite at times where they are urgently needed in the hospital (see #2)? |

| 4) Has the field become sub‐sub specialized, such that many covering physicians are now uncomfortable managing common acute inpatient problems (i.e., the headache neurologist asked to handle an acute stroke)? |

The emergence of hyphenated hospitalists raises all sorts of questions for the hospitalist field, many of which I have addressed elsewhere.5 But the bottom line is that the growth of specialty hospitalists may help create a new hospital home teama group of dedicated inpatient physicians spanning virtually every specialty who share best practices, work together on systems improvements, and operate under similar accountabilities. This development may well be the most exciting one in the field's recent history.

Comanagement of Nonmedical Patients

The same forces that led to the emergence of the hospitalist field are also catalyzing the growth of hospitalist comanagement programs. There is a shortage of general surgeons, and in teaching hospitals, there are fewer surgical residents available to help provide floor‐based pre‐ and post‐operative care. And surgical patients are under the same value pressures as medical patients, with increasing public reporting of quality processes and outcomes and new pay for performance programs coming on line. Although the evidence of benefit is mixed,68 many hospitalists are finding that increasing parts of their work involve comanagement.

Comanagement raises several issues, all of which need to be addressed. How do we define clear boundaries between what the hospitalist does and what the specialist does? Comanagement programs, to be effective, need very clear rules of engagement and open lines of communication to work through inevitable conflicts.6 How does the money flow? Most hospitalist programs receive hospital support, but it is legitimate to wonder whether the specialists, particularly surgeons, should chip in to support the program, particularly if they continue to collect a global case rate that was predicated on their provision of pre‐ and post‐operative care. How do comanagement programs and specialty hospitalist programs interrelate, and what are the relative advantages and disadvantages of each? To my mind, programs that meet the conditions outlined in Table 1 probably would do well to start a specialty hospitalist program, assuming that they can find high‐quality specialists to staff it. But there will be myriad variations on these themes. In my hospital, for example, we have both neurohospitalists and medical hospitalists who co‐manage neurosurgery patients.

New Opportunities in Systems Leadership

The growth of the hospitalist field will partly come from individuals who begin their careers performing clinical work, but who transition over time to managerial and leadership roles. This is a natural transition: Who better than a hospitalist to help organize and deliver educational programs, manage clinical operations, implement information technology systems, or lead quality, safety, or utilization management efforts? Of course, as hospitalists assume these roles, others need to take their places covering their clinical shifts.

This might seem like a relatively unimportant driver of personnel growth, but in more advanced systems, it can become a major one. Table 2 lists the faculty in my Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) who have major institutional (i.e., nondivisional) roles. These roles, spread across eight faculty, account for 3.7 full‐time equivalents (FTEs).

| Role | Works for Whom? | Approximate % FTE |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Associate Chief Medical Officer | Medical Center | 80% |

| Associate Medical Director for Information Technology | Medical Center | 80% |

| Associate Chair for Quality and Safety | Department of Medicine | 50% |

| Director of Quality and Patient Safety | Department of Neurosurgery | 50% |

| Associate Medicine Residency Director (two people) | Department of Medicine | 30% (for each) |

| Director of Medical Student Clerkships | Department of Medicine | 25% |

| Director of Patient Safety/Quality Programs | Office of Graduate Medical Education, School of Medicine | 25% |

| Total FTEs: 3.7 | ||

Dealing with New ACGME Regulations

In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) issued its first housestaff duty hours reductions (limiting housestaff to a maximum of 80 hours per week, with no single shift lasting longer than 30 hours). This reduction led to the development of nonteaching services in most teaching hospitals; the vast majority of such programs have hospitalists at their core.

In July 2011, new ACGME regulations go into effect,10 which will further cut the availability of housestaff to cover clinical services. Although the 80‐hour weekly limit remains, intern shifts are now limited to 16 hours, meaning that the traditional long call system involving interns must be replaced by a shift‐based system. Like the earlier changes, these new regulations are leading to additional hospitalist growth in the nation's teaching hospitals. By the time the changes are fully implemented, many hospitalist programs will have half or more of their hospitalist FTEs devoted to covering patients previously cared for by residents.

Challenges for Hospitalist Programs

These powerful forces promoting the growth in the hospitalist field continue to ensure that hospitalists are in high demand. As a practical matter, this has resulted in increasing salaries and improved job conditions for hospitalists.

But this growth brings many challenges. Many hospitalist programs are poorly managed, often because the leaders lack the training and experience to effectively run such a rapidly growing and complex enterprise. One manifestation of these leadership challenges is that schedules are often created around the convenience and desires of the physicians rather than the needs of the patients. For example, the increasingly prevalent seven‐days‐on, seven‐days‐off schedule often leads to burnout and a feeling by the hospitalists that they are working too hard. Yet many groups are unwilling to consider modifications to the schedule that might decrease the intensity, if the cost is fewer days off.

On the other hand, some groups pay little attention to patient continuity in constructing their schedules. I know of programs that schedule their hospitalists in 24‐hour shifts (followed by a few days off), which means that admitted patients will see a different hospitalist every day. I see this as highly problematic, particularly because the most common complaint I hear from patients about hospitalist programs is that I saw a different doctor every day.

Many of the field's challenges stem from hospitalists' near‐total dependency on hospital funding to create sustainable job descriptions.11 While I continue to believe that this bit of financial happenstance has been good for both hospitalists and hospitalssince it has driven uncommon degrees of interdependency and alignmentit does mean that a difficult budget battle is virtually assured every year. As hospital finances become tighter, one can expect these battles to grow even more heated. Speaking for hospitalists, I am not too worried about the outcomes of these battles, since hospitalists provide a mission‐critical service at a fair price, there are no viable lower‐priced replacements (expect perhaps for nonphysician providers such as nurse practitioners for the less‐complex patients), and hospitalists are extraordinarily mobilethere are virtually no barriers for a hospitalist, or an entire group, to transfer to another institution. Nevertheless, it seems inevitable that these battles will leave scars, scars that may ultimately compromise the crucial collaboration that both hospitalists and hospitals depend on.

The Bottom Line

Even at age 15, an age at which many adolescents are irredeemably cynical, the hospitalist field retains much of its sense of limitless possibility and exuberance. This is not because things are perfectthey are not. Some hospitalist jobs are poorly constructed, some groups have poor leadership, some hospitalists are burning out, there are examples of spotty quality and collaboration, and hospitalists continue to have to work to earn the respect of colleagues and patients that other specialists take for granted.

That said, the field of hospital medicine remains uniquely exciting, in part because it is so tightly linked to the broader changes in the health care policy landscape. Many other specialties see the profound changes underway in health care as an existential threat to their professional values and incomes. Hospitalists, on the other hand, see these changes as raising the pressure on hospitals to deliver the highest quality, most satisfying, and safest care at the lowest cost. Framed this way, forward‐thinking hospitalists quite naturally see these changes as yet another catalyst for the growth and indispensability of their field.

- ,.The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system.N Engl J Med.1996;335:514–517.

- ,,,.How physicians perceive hospitalist services after implementation: Anticipation vs reality.Arch Intern Med.2003;163:2330–2336.

- ,,.Medical homes: Challenges in translating theory into practice.Med Care.2009;47:714–722.

- ,.Improving safety with information technology.N Engl J Med.2003;348:2526–2534.

- The New Home Team: The Remarkable Rise of the Hyphenated Hospitalist. Wachter's World blog, January 16,2011. Available at: http://tinyurl. com/4h2jy7e. Accessed February 12, 2011.

- ,,, et al.Comanagement of surgical patients between neurosurgeons and hospitalists.Arch Intern Med.2010;170:2004–2010.

- ,,, et al.Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: A randomized, controlled trial.Ann Intern Med.2004;141:28–38.

- ,,,,.Comanagement of hospitalized surgical patients by medicine physicians in the United States.Arch Intern Med.2010;170:363–368.

- ,,.Neurohospitalists: An emerging model for inpatient neurological care.Ann Neurol.2008;63:135–140.

- ,,;ACGME Duty Hour Task Force. The new recommendations on duty hours from the ACGME Task Force.N Engl J Med.2010 Jul 8;363(2):e3. Epub 2010 Jun 23. PubMed PMID: 20573917. The website is here: http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsb1005800.

- .Elevated expectations.The Hospitalist. January2011. Available at: http://www.the‐hospitalist.org/details/article/972781/Elevated_Expectations.html. Accessed February 12, 2011.

- ,.The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system.N Engl J Med.1996;335:514–517.

- ,,,.How physicians perceive hospitalist services after implementation: Anticipation vs reality.Arch Intern Med.2003;163:2330–2336.

- ,,.Medical homes: Challenges in translating theory into practice.Med Care.2009;47:714–722.

- ,.Improving safety with information technology.N Engl J Med.2003;348:2526–2534.

- The New Home Team: The Remarkable Rise of the Hyphenated Hospitalist. Wachter's World blog, January 16,2011. Available at: http://tinyurl. com/4h2jy7e. Accessed February 12, 2011.

- ,,, et al.Comanagement of surgical patients between neurosurgeons and hospitalists.Arch Intern Med.2010;170:2004–2010.

- ,,, et al.Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: A randomized, controlled trial.Ann Intern Med.2004;141:28–38.

- ,,,,.Comanagement of hospitalized surgical patients by medicine physicians in the United States.Arch Intern Med.2010;170:363–368.

- ,,.Neurohospitalists: An emerging model for inpatient neurological care.Ann Neurol.2008;63:135–140.

- ,,;ACGME Duty Hour Task Force. The new recommendations on duty hours from the ACGME Task Force.N Engl J Med.2010 Jul 8;363(2):e3. Epub 2010 Jun 23. PubMed PMID: 20573917. The website is here: http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsb1005800.

- .Elevated expectations.The Hospitalist. January2011. Available at: http://www.the‐hospitalist.org/details/article/972781/Elevated_Expectations.html. Accessed February 12, 2011.

Nonprocedural “Time Out”

Communication and teamwork failures are the most frequently cited cause of adverse events.1, 2 Strategies to improve communication have focused on implementing formal teamwork training programs and/or teaching specific communication skills.36 For instance, many institutions have adopted SBAR (Situation‐Background‐Assessment‐Recommendation) as a method for providers to deliver critical clinical information in a structured format.7 SBAR focuses on the immediate and urgent event at hand and can occur between any 2 providers. The situation is a brief description of the event (eg, Hi Dr. Smith, this is Paul from 14‐Long, I'm calling about Mrs. Jones in 1427 who is in acute respiratory distress). The background describes details relevant to the situation (eg, She was admitted with a COPD exacerbation yesterday night, and, for the past couple hours, she appears in more distress. Her vital signs are). The assessment (eg, Her breath sounds are diminished and she's moving less air) and recommendation (eg, I'd like to call respiratory therapy and would like you to come assess her now) drive toward having an action defined at the end. Given the professional silos that exist in healthcare, the advent of a shared set of communication tools helps bridge existing gaps in training, experience, and teamwork between different providers.

Regulatory agencies have been heavily invested in attempts to standardize communication in healthcare settings. In 2003, the Joint Commission elevated the concerns for wrong‐site surgery by making its prevention a National Patient Safety Goal, and the following year required compliance with a Universal Protocol (UP).8 In addition to adequate preoperative identification of the patient and marking of their surgical site, the UP called for a time out (TO) just prior to the surgery or procedure. The UP states that a TO requires active communication among all members of the surgical/procedure team, consistently initiated by a designated member of the team, conducted in a fail‐safe mode, so that the planned procedure is not started if a member of the team has concerns.8 Simply, the TO provides an opportunity to clarify plans for care and discuss events anticipated during the procedure among all members of the team (eg, surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses, technicians). This all‐important pause point ensures that each team member is on the same page.

Whereas a TO involves many high‐risk procedural settings, a significant proportion of hospital care occurs outside of procedures. Patients are often evaluated in an emergency department, admitted to a medical/surgical ward, treated without the need for a procedure, and ultimately discharged home or transferred to another healthcare facility (eg, skilled nursing or acute rehabilitation). In this paper, we introduce the concept of Critical Conversations, a form of nonprocedural time out, as a tool, intervention, and policy that promotes communication and teamwork at the most vulnerable junctures in a patient's hospitalization.

Rationale for Critical Conversations: a Case Scenario

An 82‐year‐old man with hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is admitted to the hospital with community‐acquired pneumonia and an exacerbation of his COPD. The admitting physician evaluates the patient in the emergency department and completes admission orders. The patient arrives on the medical/surgical unit and the unit clerk processes the orders, stimulating a cascade of downstream events for different providers.

Nurse

The nurse reviews the medication list, notices antibiotics and bronchodilators, and wonders why aren't we administering steroids for his COPD? Do any of these medications need to be given now? Is there anything the physician is worried about? What specific things should prompt me to call the physician with an update or change in condition? I'm not sure if it's safe to send the patient down for the ordered radiographic study because he still looks pretty short of breath. I hate paging the physician several times to get these questions answered because I know that person is busy as well. I also know the patient will have questions about the care plans, which I won't be able to answer. I wonder if I should finish administering evening medications for my other patients as I'm running behind schedule on my other tasks.

Respiratory therapist

At the same time, the respiratory therapist (RT) is contacted to assist with nebulizer therapy for the patient. In reviewing the order for bronchodilators, the RT silently asks, do we think he is going to need continuous nebulizers? What is our oxygen saturation goaldo we want him at 90% or above 95%? I wonder if this patient has a history of CO2 retention and if I should have a BiPAP machine at the bedside.

Physician

After completing the orders for the patient, the physician remains in the emergency department to admit a different patient with a gastrointestinal bleed. This is the fifth admission in the past few hours. The physician feels the impact of constant paging interruptions. A unit clerk pages asking for clarification about a radiographic study that was ordered. A bedside nurse pages and asks if the physician can come and speak to the family about the diagnosis and treatment plans for an earlier admission (something the nurse is not clear about, either). A second bedside nurse pages, stating a different admission is still tachycardic after 3 liters of intravenous fluids and wants to know whether the fluids should be continued. Finally, the bedside nurse pages about whether the new COPD admission can go off the floor for the ordered chest CT or remain on continuous pulse oximetry because of shortness of breath.

Our case scenario is representative of most non‐surgical admissions to a hospital. The hypothetical questions posed from different provider perspectives are also common and often remain unanswered in a timely fashion. Partly because there is no site to mark and no anesthesia to deliver, the clinical encounter escapes attention as an opportunity for error prevention. In our experience, there are specific times during a hospitalization when communication failures are most likely to compromise patient care: the time of admission, the time of discharge,9 and any time when a patient's clinical condition changes acutely. Whereas handoff communications focus on transitions between providers (eg, shift changes), these circumstances are driven by patient transitions. Indirect communications, such as phone, email, or faxes, are suboptimal forms of communication at such times.10 We believe that there should be an expectation for direct communication at these junctures, and we define these direct communications as Critical Conversations.

Description of a Critical Conversation

In the hours that follow an admission, providers (and often the patients or their family as well) invariably exchange any number of inefficient calls or pages to clarify care plans, discuss a suspected diagnosis, anticipate concerns in the first night, and/or highlight which orders should be prioritized, such as medications or diagnostic studies. A Critical Conversation at time of admission does in this circumstance exactly what a TO attempts to provide before a procedure foster communication and teamwork as a patient is about to be placed at risk for adverse events. The exchange involves discussion of the following:

Admitting diagnosis

Immediate treatment plan

Medications ordered (particularly those new to a patient to anticipate an adverse event)

Priority for completing any admitting orders

Guidelines for physician notification when a change in patient condition occurs.

At the other end of a hospitalization, with the known complications arising from a patient's discharge,11, 12 the same process is needed. Rather than having each discipline focus on an individual role or task in getting a patient safely discharged, Critical Conversations allow the entire team, including the patient,13 to ensure that concerns have been addressed. This might help clarify simple measures around follow‐up appointments, whom to call with questions after discharge, or symptoms to watch for that may warrant a repeat evaluation. Nurses anecdotally lament that they first learn about a planned discharge only when the discharge order is written in the chart or if a patient informs them. Both scenarios reflect poorly on the teamwork required to assure patients we're working together, and that key providers are on the same page with respect to discharge planning. The exchange at discharge involves discussion of these elements:

Discharge diagnosis

Follow‐up plans

Need for education/training prior to discharge

Necessary paperwork completed

Anticipated time of discharge.

Finally, where many patients are admitted to a hospital, improve, and then return home, others develop acute changes during their hospitalization. For example, the patient in our case scenario could develop respiratory failure and require transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU). Or a different patient might have an acute change in mental status, a new fever, a new abnormal vital sign (eg, tachycardia or hypoxia), or an acute change re existing abdominal painall of which may require a battery of diagnostic tests. These circumstances define the third time for a Critical Conversation: a change in clinical condition. Such situations often require a change in the care plan, a change in priorities for delivering care at that time (for the patient in need and for other patients being cared for by the same nurse and physician), a need for additional resources (eg, respiratory therapist, phlebotomist, pharmacist), and, ultimately, a well‐orchestrated team effort to make it all happen. The specific item prompting the Critical Conversation may impact the nature of the exchange, which involves discussion of these components:

Suspected diagnosis

Immediate treatment plan

Medications ordered (particularly those new to a patient to anticipate an adverse event)

Priority for completing any new orders

Guidelines for physician notification when a change in patient condition occurs.

In addition to the above checklist for each Critical Conversation, each exchange should also address two open‐ended questions: 1) what do you anticipate happening in the next 24 hours, and 2) what questions might the patient/family have?

One may ask, and we did, why not have a direct communication daily between a physician and a bedside nurse on each patient? Most physicians and nurses know the importance of direct communication, but there are also times when each is prioritizing work in competing fashions. Adopting Critical Conversations isn't meant to deter from communications that are vital to patient care; rather, it is intended to codify distinct times when a direct communication is required for patient safety.

Lessons Learned

Table 1 provides an example of a Critical Conversation using the sample case scenario. Table 2 lists the most frequent outcomes that resulted from providers engaging in Critical Conversations. These were captured from discussions with bedside nurses and internal medicine residents on our primary medical unit. Both tables highlight how these deliberate and direct communications can create a shared understanding of the patient's medical problems, can help prioritize what tasks should take place (eg, radiology study, medication administration, calling another provider), can improve communication between providers and patients, and potentially accomplish all of these goals in a more efficient manner.

| Physician: Hi Nurse X, I'm Dr. Y, and I just wrote admission orders for Mr. Z whom, I understand, you'll be admitting. He's 82 with a history of COPD and is having an exacerbation related to a community‐acquired pneumonia. He looks comfortable right now as he's received his first dose of antibiotics, a liter of IVF, and 2 nebulizer treatments with some relief of his dyspnea. The main thing he needs up on the floor right now is to have respiratory therapy evaluate him. He's apparently been intubated before for his COPD, so I'd like to have them on board early and consider placing a BiPAP machine at the bedside for the next few hours. I don't anticipate an acute worsening of his condition given his initial improvements in the ED, but you should call me with any change in his condition. I haven't met the family yet because they were not at the bedside, but please convey the plans to them as well. I'll be up later to talk to them directly. Do you have any questions for me right now? |

| Nurse: I'll call the respiratory therapist right now and we'll make sure to contact you with any changes in his respiratory status. It looks like a chest CT was ordered, but not completed yet. Would you like him to go down for it off monitor? |

| Physician: Actually, let's watch him for a few hours to make sure he's continuing to improve. I initially ordered the chest CT to exclude a pulmonary embolus, but his history, exam, and chest x‐ray seem consistent with pneumonia. Let's reassess in a few hours. |

| Nurse: Sounds good. I'll text‐message you a set of his vital signs in 3‐4 hours to give you an update on his respiratory status. |

| General Themes | Specific Examples |

|---|---|

| Clarity on plan of care | Clear understanding of action steps at critical junctures of hospitalization |

| Goals of admission discussed rather than gleaned from chart or less direct modes of communication | |

| Discharge planning more proactive with better anticipation of timing among patients and providers | |

| Expectation for shared understanding of care plans | |

| Assistance with prioritization of tasks (as well as for competing tasks) | Allows RNs to prioritize tasks for new admissions or planned discharges, to determine whether these tasks outweigh tasks for other patients, and to provide early planning when additional resources will be required |

| Allows MDs to prioritize communications to ensure critical orders receive attention, to obtain support for care plans that require multiple disciplines, and to confirm that intended care plans are implemented with shared sense of priority | |

| Ability to communicate plans to patient and family members | Improved consistency in information provided to patients at critical hospital junctures |

| Increased engagement of patients in understanding their care plans | |

| Better model for teamwork curative for patients when providers on the same page with communication | |

| More efficient and effective use of resources | Fewer pages between admitting RN and MD with time saved from paging and waiting for responses |

| Less time trying to interpret plans of care from chart and other less direct modes of communication | |

| Improved sharing and knowledge of information with less duplication of gathering from patients and among providers | |

| Improved teamwork | Fosters a culture for direct communication and opens lines for questioning and speaking up when care plans are not clear |

Making Critical Conversations Happen

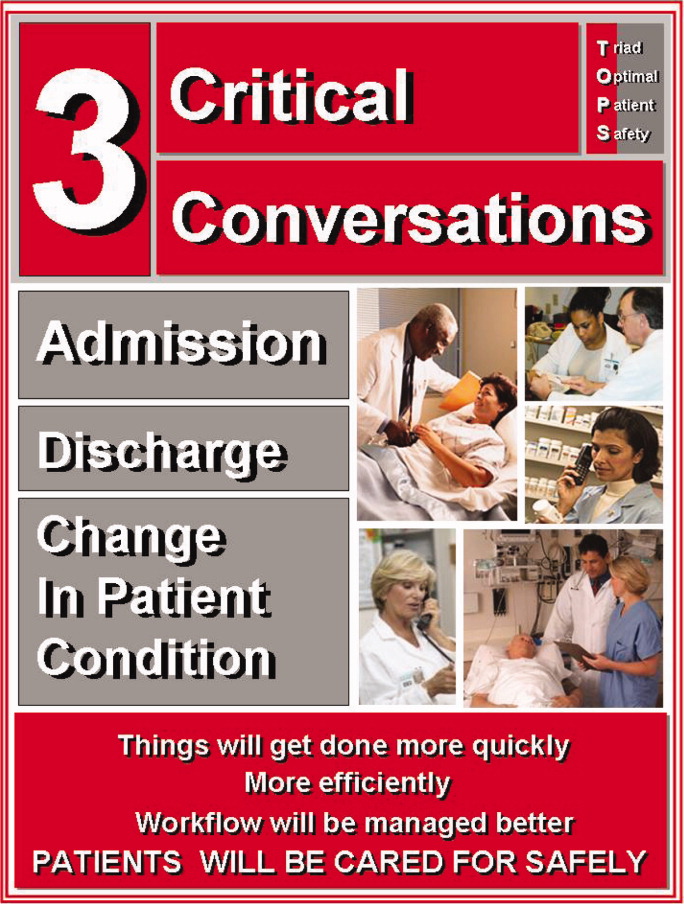

Integrating Critical Conversations into practice requires both buy‐in among providers and a plan for monitoring the interactions. We recommend beginning with educational efforts (eg, at a physician or nurse staff meeting) and reinforcing them with visual cues, such as posters on the unit (Figure 1). These actions promote awareness and generate expectations that this new clinical policy is being supported by clinical and hospital leadership. Our experiences have demonstrated tremendous learning, including numerous anecdotes about the value of Critical Conversations (Table 3). Our implementation efforts also raised a number of questions that ultimately led to improved clarity in later iterations.

| Nothing is worse than meeting a patient for the first time at admission and not being able to answer the basic question of why they were admitted or what the plan is. It gives the impression that we don't talk to each other in caring for patients. [Critical Conversations] can really minimize that interaction and reassure patients, rather than make them worried about the apparent mixed messages or lack of communication and teamwork.Bedside Nurse |

| [Critical Conversations] seemed like an additional timely responsibility, and not always a part of my workflow, when sitting in the emergency department admitting patients. But, I found that the often 60 second conversations decreased the number of pages I would get for the same patientactually saving me time.Physician |

| I don't need to have direct communications for every order written. In fact, it would be inefficient for me and the doctors. On the other hand, being engaged in a Critical Conversation provides an opportunity for me to prioritize not only my tasks for the patient in need, but also in context of the other patients I'm caring for.Bedside Nurse |

| Late in the afternoon, there will often be several admissions coming to our unit simultaneously. Prioritizing what orders need to be processed or faxed is a typically blind task based on the way charts get organizedrather than someone telling me this is a priority.Unit Clerk |

| There are so many times when I'm trying to determine what the care plans are for a new admission, and simply having a quick conversation allows me to feel part of the team, and, more importantly, allows me to reinforce education and support for the patients and their family members.Bedside Nurse |

| Discharge always seems chaotic with everyone racing to fill out forms and meet their own tasks and requirements. Invariably, you get called to fix, change, or add new information to the discharge process that would have been easily averted by actually having a brief conversation with the bedside nurse or case manager. Every time I have [a Critical Conversation], I realize its importance for patient care.Physician |

Who should be involved in a Critical Conversation?

Identifying which healthcare team members should be involved in Critical Conversations is best determined by the conversation owner. That is, we found communication was most effective when the individual initiating the Critical Conversation directed others who needed to be involved. At admission, the physician writing the admission orders is best suited to make this determination; at a minimum, he or she should engage the bedside nurse but, as in the case example presented, the physician may also need to engage other services in particularly complex situations (eg, respiratory therapy, pharmacy). At time of discharge, there should be a physiciannurse Critical Conversation; however, the owner of the discharge process may determine that other conversations should occur, and this may be inclusive of or driven by a case manager or social worker. Because local culture and practices may drive specific ownership, it's key to outline a protocol for how this should occur. For instance, at admission, we asked the admitting physicians to take responsibility in contacting the bedside nurse. In other venues, this may work more effectively if the bedside nurse pages the physician once the orders are received and reviewed.

Conclusions

We introduced Critical Conversations as an innovative tool and policy that promotes communication and teamwork in a structured format and at a consistent time. Developing formal systems that decrease communication failures in high‐risk circumstances remains a focus in patient safety, evidenced by guidelines for TOs in procedural settings, handoffs in patient care (eg, sign‐out between providers),14, 15 and transitions into and from the hospital setting.16 Furthermore, there is growing evidence that such structured times for communication and teamwork, such as with briefings, can improve efficiency and reduce delays in care.17, 18 However, handoffs, which address provider transitions, and daily multidisciplinary rounds, which bring providers together regularly, are provider‐centered rather than patient‐centered. Critical Conversations focus on times when patients require direct communication about their care plans to ensure safe and high quality outcomes.

Implementation of Critical Conversations provides an opportunity to codify a professional standard for patient‐centered communication at times when it should be expected. Critical Conversations also help build a system that supports a positive safety culture and encourages teamwork and direct communication. This is particularly true at a time when rapid adoption of information technology may have the unintended and opposite effect. For instance, as our hospital moved toward an entirely electronic health record, providers were increasingly relocating from patient care units into remote offices, corner hideaways, or designated computer rooms to complete orders and documentation. Although this may reduce many related errors in these processes and potentially improve communication via shared access to an electronic record, it does allow for less direct communicationa circumstance that traditionally occurs (even informally) when providers share the same clinical work areas. This situation is aggravated where the nurses are unit‐based and other providers (eg, physicians, therapists, case managers) are service‐based.

Integrating Critical Conversations into practice comes with expected challenges, most notably around workflow (eg, adds a step, although may save steps down the line) and the expectations concomitant with any change in standard of care (possible enforcement or auditing of their occurrence). Certain cultural barriers may also play a significant role, such as the presence of hierarchies that can hinder open communication and the related ability to speak up with concerns, as related in the TO literature. Where these cultural barriers highlight historical descriptions of the doctornurse relationship and its effect on patient care,1921 Critical Conversations provide an opportunity to improve such interdisciplinary relationships by providing a shared tool for direct communication.

In summary, we described an innovative communication tool that promotes direct communication at critical junctures during a hospitalization. With the growing complexity of hospital care and greater interdependence between teams that deliver this care, Critical Conversations provide an opportunity to further address the known communication failures that contribute to medical errors.

Acknowledgements

Critical Conversations was developed during the Triad for Optimal Patient Safety (TOPS) project, an effort focused on improving unit‐based safety culture through improved teamwork and communication. We thank the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation for their active support and funding of the TOPS project, which was a collaboration between the Schools of Medicine, Nursing, and Pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco.

- ,,,,.Communication failures in patient sign‐out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis.Qual Saf Health Care.2005;14(6):401–407.

- ,,.Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps.Acad Med.2004;79(2):186–194.

- ,.TeamSTEPPS: assuring optimal teamwork in clinical settings.Am J Med Qual.2007;22(3):214–217.

- ,,,,,.Medical team training: applying crew resource management in the Veterans Health Administration.Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2007;33(6):317–325.

- ,,,,,,,,,.A multidisciplinary teamwork training program: the Triad for Optimal Patient Safety (TOPS) Experience.J Gen Intern Med.2008;23(12):2053–2057.

- ,,.The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care.Qual Saf Health Care.2004;13Suppl‐1:i85–90.

- ,,.SBAR: a shared mental model for improving communication between clinicians.Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2006;32(3):167–175.

- The Joint Commission Universal Protocol for Preventing Wrong Site, Wrong Procedure, Wrong Person Surgery. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/E3C600EB‐043B‐4E86‐B04E‐CA4A89AD5433/0/universal_protocol.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2010.

- ,,.The hospital discharge: a review of a high risk care transition with highlights of a reengineered discharge process.J Patient Saf.2007;3:97–106.

- How do we communicate? Communication on Agile Software Projects. Available at: www.agilemodeling.com/essays/communication.htm. Accessed January 24, 2010.

- ,,,.Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists.J Hosp Med.2007;2(5):314–323.

- ,,,,,.Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care.JAMA.2007;297(8):831–841.

- .Engaging patients at hospital discharge.J Hosp Med.2008;3(6):498–500.

- ,,,,.Managing discontinuity in academic medical centers: strategies for a safe and effective resident sign‐out.J Hosp Med.2006;1(4):257–266.

- ,.Lost in transition: challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of transitional care.Ann Intern Med.2004;141(7):533–536.

- ,,, et al.Transition of care for hospitalized elderly patients—development of a discharge checklist for hospitalists.J Hosp Med.2006;1(6):354–360.

- ,,, et al.Impact of preoperative briefings on operating room delays.Arch Surg.2008;143(11):1068–1072.

- ,,, et al.Operating room briefings: working on the same page.Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2006;32(6):351–355.

- .Doctors and nurses: a troubled partnership.Ann Surg.1999;230(3):279–288.

- ,,, et al.Association between nurse‐physician collaboration and patient outcomes in three intensive care units.Crit Care Med.1999;27(9):1991–1998.

- ,,, et al.Evaluation of a preoperative checklist and team briefing among surgeons, nurses, and anesthesiologists to reduce failures in communication.Arch Surg.2008;143(1):12–17.

Communication and teamwork failures are the most frequently cited cause of adverse events.1, 2 Strategies to improve communication have focused on implementing formal teamwork training programs and/or teaching specific communication skills.36 For instance, many institutions have adopted SBAR (Situation‐Background‐Assessment‐Recommendation) as a method for providers to deliver critical clinical information in a structured format.7 SBAR focuses on the immediate and urgent event at hand and can occur between any 2 providers. The situation is a brief description of the event (eg, Hi Dr. Smith, this is Paul from 14‐Long, I'm calling about Mrs. Jones in 1427 who is in acute respiratory distress). The background describes details relevant to the situation (eg, She was admitted with a COPD exacerbation yesterday night, and, for the past couple hours, she appears in more distress. Her vital signs are). The assessment (eg, Her breath sounds are diminished and she's moving less air) and recommendation (eg, I'd like to call respiratory therapy and would like you to come assess her now) drive toward having an action defined at the end. Given the professional silos that exist in healthcare, the advent of a shared set of communication tools helps bridge existing gaps in training, experience, and teamwork between different providers.

Regulatory agencies have been heavily invested in attempts to standardize communication in healthcare settings. In 2003, the Joint Commission elevated the concerns for wrong‐site surgery by making its prevention a National Patient Safety Goal, and the following year required compliance with a Universal Protocol (UP).8 In addition to adequate preoperative identification of the patient and marking of their surgical site, the UP called for a time out (TO) just prior to the surgery or procedure. The UP states that a TO requires active communication among all members of the surgical/procedure team, consistently initiated by a designated member of the team, conducted in a fail‐safe mode, so that the planned procedure is not started if a member of the team has concerns.8 Simply, the TO provides an opportunity to clarify plans for care and discuss events anticipated during the procedure among all members of the team (eg, surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses, technicians). This all‐important pause point ensures that each team member is on the same page.

Whereas a TO involves many high‐risk procedural settings, a significant proportion of hospital care occurs outside of procedures. Patients are often evaluated in an emergency department, admitted to a medical/surgical ward, treated without the need for a procedure, and ultimately discharged home or transferred to another healthcare facility (eg, skilled nursing or acute rehabilitation). In this paper, we introduce the concept of Critical Conversations, a form of nonprocedural time out, as a tool, intervention, and policy that promotes communication and teamwork at the most vulnerable junctures in a patient's hospitalization.

Rationale for Critical Conversations: a Case Scenario

An 82‐year‐old man with hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is admitted to the hospital with community‐acquired pneumonia and an exacerbation of his COPD. The admitting physician evaluates the patient in the emergency department and completes admission orders. The patient arrives on the medical/surgical unit and the unit clerk processes the orders, stimulating a cascade of downstream events for different providers.

Nurse