User login

Hot in the tropics

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient’s case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant. The bolded text represents the patient’s case. Each paragraph that follows represents the discussant’s thoughts.

A 42-year-old Malaysian construction worker with subjective fevers of 4 days’ duration presented to an emergency department in Singapore. He reported nonproductive cough, chills without rigors, sore throat, and body aches. He denied sick contacts. Past medical history included chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. The patient was not taking any medications.

For this patient presenting acutely with subjective fevers, nonproductive cough, chills, aches, and lethargy, initial considerations include infection with a common virus (influenza virus, adenovirus, Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]), acute human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, emerging infection (severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS], Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus [MERS-CoV] infection, avian influenza), and tropical infection (dengue, chikungunya). Also possible are bacterial infections (eg, with Salmonella typhi or Rickettsia or Mycoplasma species), parasitic infections (eg, malaria), and noninfectious illnesses (eg, autoimmune diseases, thyroiditis, acute leukemia, environmental exposures).

The patient’s temperature was 38.5°C; blood pressure, 133/73 mm Hg; heart rate, 95 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths per minute; and oxygen saturation, 100% on ambient air. On physical examination, he appeared comfortable, and heart, lung, abdomen, skin, and extremities were normal. Laboratory test results included white blood cell (WBC) count, 4400/μL (with normal differential); hemoglobin, 16.1 g/dL; and platelet count, 207,000/μL. Serum chemistries were normal. C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 44.6 mg/L (reference range, 0.2-9.1 mg/L), and procalcitonin level was 0.13 ng/mL (reference range, <0.50 ng/mL). Chest radiograph was normal. Dengue antibodies (immunoglobulin M, immunoglobulin G [IgG]) and dengue NS1 antigen were negative. The patient was discharged with a presumptive diagnosis of viral upper respiratory tract infection.

There is no left shift characteristic of bacterial infection or lymphopenia characteristic of rickettsial disease or acute HIV infection. The serologic testing and the patient’s overall appearance make dengue unlikely. The low procalcitonin supports a nonbacterial cause of illness. CRP elevation may indicate an inflammatory process and is relatively nonspecific.

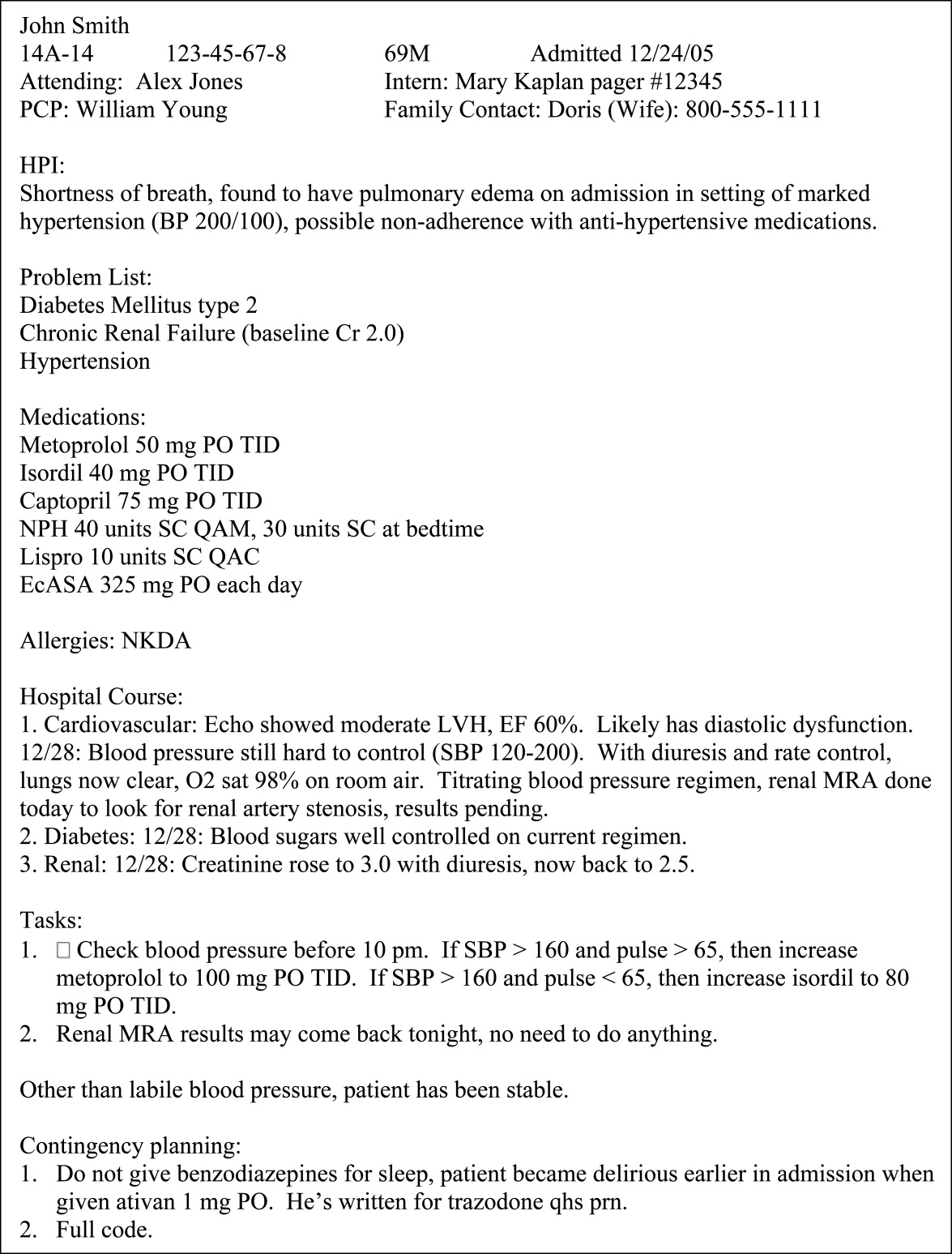

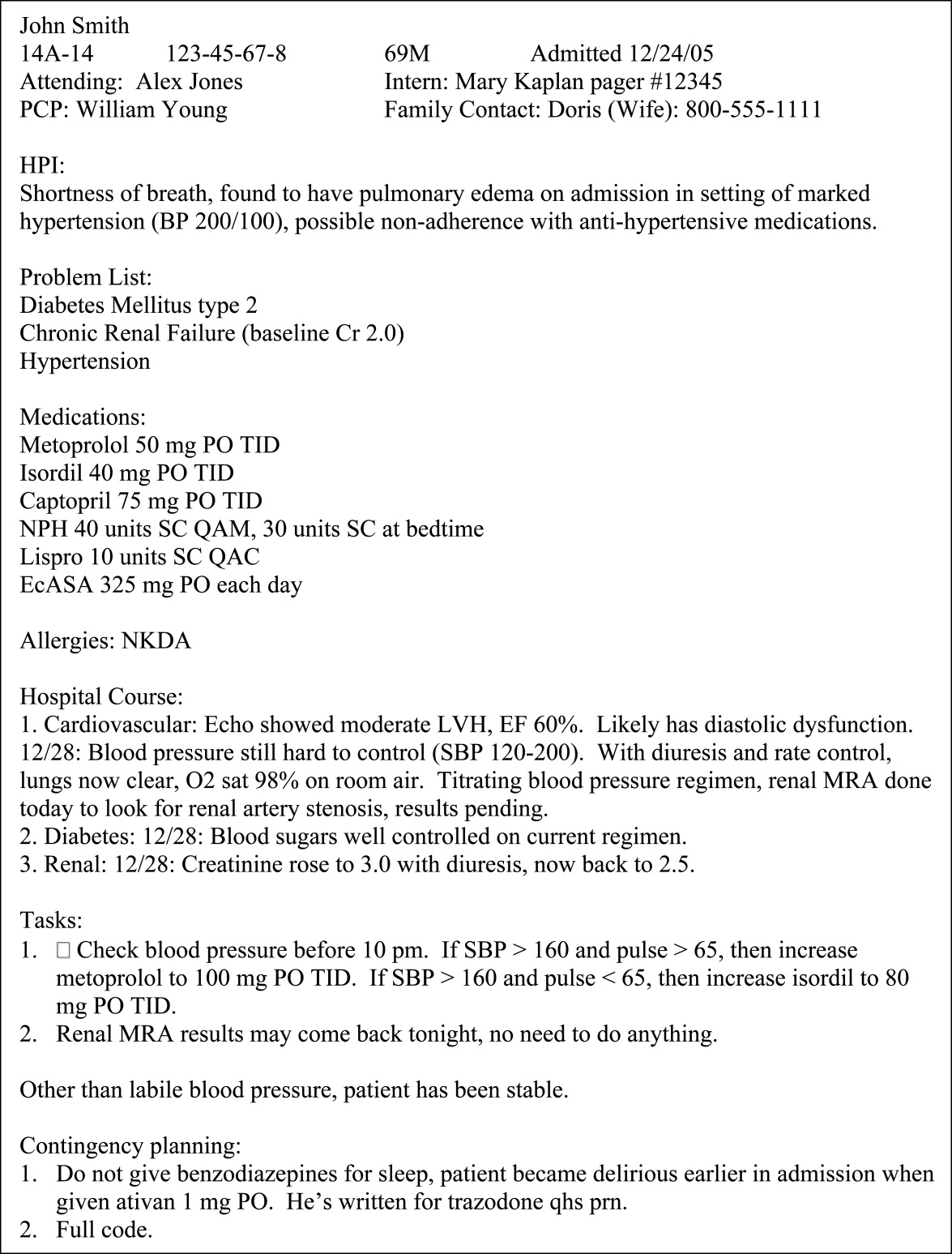

Myalgias, pharyngitis, and cough improved over several days, but fevers persisted, and a rash developed over the lower abdomen. The patient returned to the emergency department and was admitted. He denied weight loss and night sweats. He had multiple female sexual partners, including commercial sex workers, within the previous 6 months. Temperature was 38.5°C. The posterior oropharynx was slightly erythematous. There was no lymphadenopathy. Firm, mildly erythematous macules were present on the anterior abdominal wall (Figure 1). The rest of the physical examination was normal.

Laboratory testing revealed WBC count, 5800/μL (75% neutrophils, 19% lymphocytes, 3% monocytes, 2% atypical mononuclear cells); hemoglobin, 16.3 g/dL; platelet count, 185,000/μL; sodium, 131 mmol/L; potassium, 3.4 mmol/L; creatinine, 0.9 mg/dL; albumin, 3.2 g/dL; alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 99 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 137 U/L; alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 63 U/L; and total bilirubin, 1.9 mg/dL. Prothrombin time was 11.1 seconds; partial thromboplastin time, 36.1 seconds; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 14 mm/h; and CRP, 62.2 mg/L.

EBV, acute HIV, and cytomegalovirus infections often present with adenopathy, which is absent here. Disseminated gonococcal infection can manifest with fever, body aches, and rash, but his rash and the absence of penile discharge, migratory arthritis, and enthesitis are not characteristic. Mycoplasma infection can present with macules, urticaria, or erythema multiforme. Rickettsia illnesses typically cause vasculitis with progression to petechiae or purpura resulting from endothelial damage. Patients with secondary syphilis may have widespread macular lesions, and the accompanying syphilitic hepatitis often manifests with elevations in ALP instead of ALT and AST. The mild elevation in ALT and AST can occur with many systemic viral infections. Sweet syndrome may manifest with febrile illness and rash, but the acuity of this patient’s illness and the rapid evolution favor infection.

The patient’s fevers (35°-40°C) continued without pattern over the next 3 days. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test of the nasal mucosa was negative for respiratory viruses. PCR blood tests for EBV, HIV-1, and cytomegalovirus were also negative. Antistreptolysin O (ASO) titer was 400 IU/mm (reference range, <200 IU/mm). Antinuclear antibodies were negative, and rheumatoid factor was 12.4 U/mL (reference range, <10.3 U/mL). Computed tomography (CT) of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis was normal. Results of a biopsy of an anterior abdominal wall skin lesion showed perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic inflammation. Amoxicillin was started for the treatment of possible group A streptococcal infection.

PCR for HIV would be positive at a high level in acute HIV. The skin biopsy is not characteristic of Sweet syndrome, which typically shows neutrophilic infiltrate without leukocytoclastic vasculitis, or of syphilis, which typically shows a plasma cell infiltrate.

The patient’s erythematous oropharynx may indicate recent streptococcal pharyngitis. The fevers, elevated ASO titer, and CRP level are consistent with acute rheumatic fever, but arthritis, carditis, and neurologic manifestations are lacking. Erythema marginatum manifests on the trunk and limbs as macules or papules with central clearing as the lesions spread outward—and differs from the patient’s rash, which is firm and restricted to the abdominal wall.

Fevers persisted through hospital day 7. The WBC count was 1100/μL (75.7% neutrophils, 22.5% lymphocytes), hemoglobin was 10.3 g/dL, and platelet count was 52,000/μL. Additional laboratory test results included ALP, 234 U/L; ALT, 250 U/L; AST, 459 U/L; lactate dehydrogenase, 2303 U/L (reference range, 222-454 U/L); and ferritin, 14,964 ng/mL (reference range, 47-452 ng/mL).

The duration of illness and negative diagnostic tests for infections increases suspicion for a noninfectious illness. Conditions commonly associated with marked hyperferritinemia include adult-onset Still disease (AOSD) and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). Of the 9 AOSD diagnostic (Yamaguchi) criteria, 5 are met in this case: fever, rash, sore throat, abnormal liver function tests, and negative rheumatologic tests. However, the patient lacks arthritis, leukocytosis, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly. Except for the elevated ferritin, the AOSD criteria overlap substantially with the criteria for acute rheumatic fever, and still require that infections be adequately excluded. HLH, a state of abnormal immune activation with resultant organ dysfunction, can be a primary disorder, but in adults more often is secondary to underlying infectious, autoimmune, or malignant (often lymphoma) conditions. Elevated ferritin, cytopenias, elevated ALT and AST, elevated CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase are consistent with HLH. The HLH diagnosis can be more firmly established with the more specific findings of hypertriglyceridemia, hypofibrinogenemia, and elevated soluble CD25 level. The histopathologic finding of hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow, lymph nodes, or liver may further support the diagnosis of HLH.

Rash and fevers persisted. Hepatitis A, hepatitis C, Rickettsia IgG, Burkholderia pseudomallei (the causative organism of melioidosis), and Leptospira serologies, as well as PCR for herpes simplex virus and parvovirus, were all negative. Hepatitis B viral load was 962 IU/mL (2.98 log), hepatitis B envelope antigen was negative, and hepatitis B envelope antibody was positive. Orientia tsutsugamushi (organism responsible for scrub typhus) IgG titer was elevated at 1:128. Antiliver kidney microsomal antibodies and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative. Fibrinogen level was 0.69 g/L (reference range, 1.8-4.8 g/L), and beta-2 microglobulin level was 5078 ng/mL (reference range, 878-2000 ng/mL). Bone marrow biopsy results showed hypocellular marrow with suppressed myelopoiesis, few atypical lymphoid cells, and few hemophagocytes. Flow cytometry was negative for clonal B lymphocytes and aberrant expression of T lymphocytes. Bone marrow myobacterial PCR and fungal cultures were negative.

The patient’s chronic HBV infection is unlikely to be related to his presentation given his low viral load and absence of signs of hepatic dysfunction. Excluding rickettsial disease requires paired acute and convalescent serologies. O tsutsugamushi, the causative agent of the rickettsial disease scrub typhus, is endemic in Malaysia; thus, his positive O tsutsugamushi IgG may indicate past exposure. His fevers, myalgias, truncal rash, and hepatitis are consistent with scrub typhus, but he lacks the characteristic severe headache and generalized lymphadenopathy. Although eschar formation with evolution of a papular rash is common in scrub typhus, it is often absent in the variant found in Southeast Asia. Although elevated β2 microglobulin level is used as a prognostic marker in multiple myeloma and Waldenström macroglobulinemia, it can be elevated in many immune-active states. The patient likely has HLH, which is supported by the hemophagocytosis seen on bone marrow biopsy, and the hypofibrinogenemia. Potential HLH triggers include O tsutsugamushi infection or recent streptococcal pharyngitis.

A deep-punch skin biopsy of the anterior abdominal wall skin lesion was performed because of the absence of subcutaneous fat in the first biopsy specimen. The latest biopsy results showed irregular interstitial expansion of medium-size lymphocytes in a lobular panniculated pattern. The lymphocytes contained enlarged, irregularly contoured nucleoli and were positive for T-cell markers CD2 and CD3 with reduction in CD5 expression. The lymphomatous cells were of CD8+ with uniform expression of activated cytotoxic granule protein granzyme B and were positive for T-cell hemireceptor β.

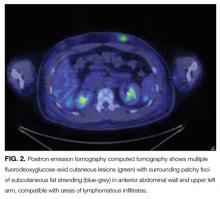

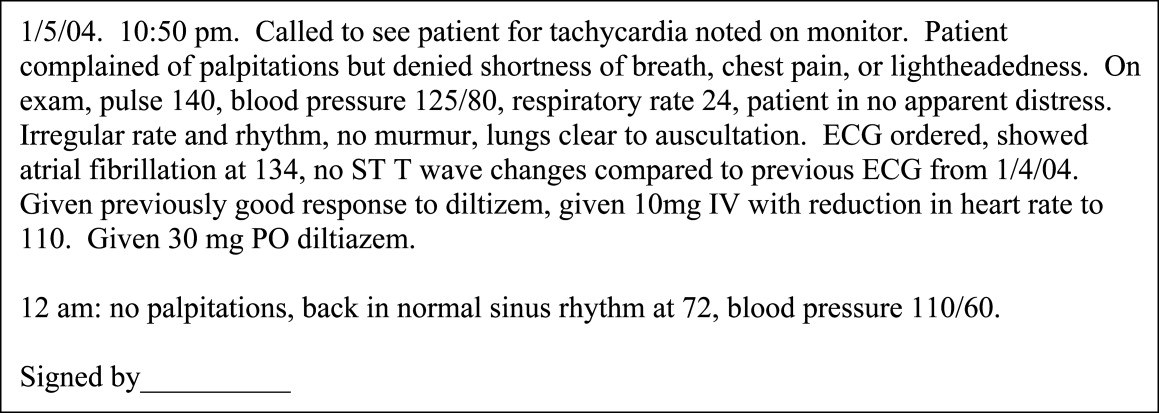

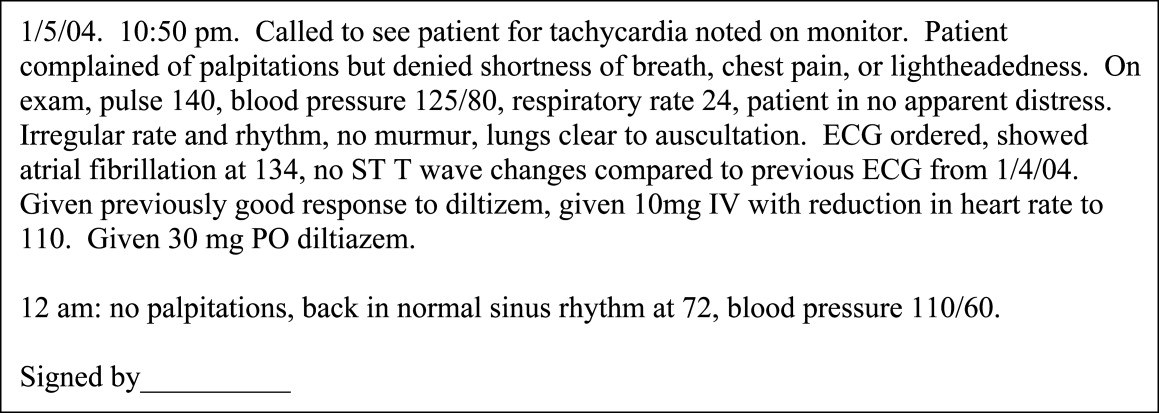

Positron emission tomography (PET) CT, obtained for staging purposes, showed multiple hypermetabolic subcutaneous and cutaneous lesions over the torso and upper and lower limbs—compatible with lymphomatous infiltrates (Figure 2). Examination, pathology, and imaging findings suggested a rare neoplasm: subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL). SPTCL was confirmed by T-cell receptor gene rearrangements studies.

HLH was diagnosed on the basis of the fevers, cytopenias, hypofibrinogenemia, elevated ferritin level, and evidence of hemophagocytosis. SPTCL was suspected as the HLH trigger.

The patient was treated with cyclophosphamide, hydroxydoxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. While on this regimen, he developed new skin lesions, and his ferritin level was persistently elevated. He was switched to romidepsin, a histone deacetylase inhibitor that specifically targets cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, but the lesions continued to progress. The patient then was treated with gemcitabine, dexamethasone, and cisplatin, and the rashes resolved. The most recent PET-CT showed nearly complete resolution of the subcutaneous lesions.

DISCUSSION

When residents or visitors to tropical or sub-tropical regions, those located near or between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, present with fever, physicians usually first think of infectious diseases. This patient’s case is a reminder that these important first considerations should not be the last.

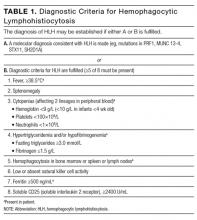

Generating a differential diagnosis for tropical illnesses begins with the patient’s history. Factors to be considered include location (regional disease prevalence), exposures (food/water ingestion, outdoor work/recreation, sexual contact, animal contact), and timing (temporal relationship of symptom development to possible exposure). Common tropical infections are malaria, dengue, typhoid, and emerging infections such as chikungunya, avian influenza, and Zika virus infection.1This case underscores the need to analyze diagnostic tests critically. Interpreting tests as simply positive or negative, irrespective of disease features, epidemiology, and test characteristics, can contribute to diagnostic error. For example, the patient’s positive ASO titer requires an understanding of disease features and a nuanced interpretation based on the clinical presentation. The erythematous posterior oropharynx prompted concern for postinfectious sequelae of streptococcal pharyngitis, but his illness was more severe and more prolonged than is typical of that condition. The isolated elevated O tsutsugamushi IgG titer provides an example of the role of epidemiology in test interpretation. Although a single positive value might indicate a new exposure for a visitor to an endemic region, IgG seropositivity in Singapore, where scrub typhus is endemic, likely reflects prior exposure to the organism. Diagnosing an acute scrub typhus infection in a patient in an endemic region requires PCR testing. The skin biopsy results highlight the importance of understanding test characteristics. A skin biopsy specimen must be adequate in order to draw valid and accurate conclusions. In this case, the initial skin biopsy was superficial, and the specimen inadequate, but the test was not “negative.” In the diagnostic skin biopsy, deeper tissue was sampled, and panniculitis (inflammation of subcutaneous fat), which arises in inflammatory, infectious, traumatic, enzymatic, and malignant conditions, was identified. An adequate biopsy specimen that contains subcutaneous fat is essential in making this diagnosis.2This patient eventually manifested several elements of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), a syndrome of excessive inflammation and resultant organ injury relating to abnormal immune activation and excessive inflammation. HLH results from deficient down-regulation of activated macrophages and lymphocytes.3 It was initially described in pediatric patients but is now recognized in adults, and associated with mortality as high as 50%.3 A high ferritin level (>2000 ng/mL) has 70% sensitivity and 68% specificity for pediatric HLH and should trigger consideration of HLH in any age group.4 The diagnostic criteria for HLH initially proposed in 2004 by the Histiocyte Society to identify patients for recruitment into a clinical trial included molecular testing consistent with HLH and/or 5 of 8 clinical, laboratory, or histopathologic features (Table 1).5 HScore is a more recent validated scoring system that predicts the probability of HLH (Table 2). A score above 169 signifies diagnostic sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 86%.6

The diagnosis of HLH warrants a search for its underlying cause. Common triggers are viral infections (eg, EBV), autoimmune diseases (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus), and hematologic malignancies. These triggers typically stimulate or suppress the immune system. Initial management involves treatment of the underlying trigger and, potentially, immunosuppression with high

In this case, SPTCL triggered HLH. SPTCL is a rare non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by painless subcutaneous nodules or indurated plaques (panniculitis-like) on the trunk or extremities, constitutional symptoms, and, in some cases, HLH.7-10 SPTCL is diagnosed by deep skin biopsy, with immunohistochemistry showing CD8-positive pathologic T cells expressing cytotoxic proteins (eg, granzyme B).9,11 SPTCL can either have an alpha/beta T-cell phenotype (SPTCL-AB) or gamma/delta T-cell phenotype (SPTCL-GD). Seventeen percent of patients with SPTCL-AB and 45% of patients with SPTCL-GD have HLH on diagnosis. Concomitant HLH is associated with decreased 5-year survival.12This patient presented with fevers and was ultimately diagnosed with HLH secondary to SPLTCL. His case is a reminder that not all diseases in the tropics are tropical diseases. In the diagnosis of a febrile illness, a broad evaluative framework and rigorous test results evaluation are essential—no matter where a patient lives or visits.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

- A febrile illness acquired in the tropics is not always attributable to a tropical infection.

- To avoid diagnostic error, weigh positive or negative test results against disease features, patient epidemiology, and test characteristics.

- HLH is characterized by fevers, cytopenias, hepatosplenomegaly, hyperferritinemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypofibrinogenemia. In tissue specimens, hemophagocytosis may help differentiate HLH from competing conditions.

- After HLH is diagnosed, try to determine its underlying cause, which may be an infection, autoimmunity, or a malignancy (commonly, a lymphoma).

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Destinations [list]. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/list/. Accessed April 22, 2016.

2. Diaz Cascajo C, Borghi S, Weyers W. Panniculitis: definition of terms and diagnostic strategy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22(6):530-549. PubMed

3. Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, Khamashta MA, Bosch X. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet. 2014;383(9927):1503-1516. PubMed

4. Lehmberg K, McClain KL, Janka GE, Allen CE. Determination of an appropriate cut-off value for ferritin in the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(11):2101-2103. PubMed

5. Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(2):124-131. PubMed

6. Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, et al. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(9):2613-2620. PubMed

7. Aronson IK, Worobed CM. Cytophagic histiocytic panniculitis and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: an overview. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23(4):389-402. PubMed

8. Willemze R, Jansen PM, Cerroni L, et al; EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Group. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: definition, classification, and prognostic factors: an EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Group study of 83 cases. Blood. 2008;111(2):838-845. PubMed

9. Kumar S, Krenacs L, Medeiros J, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitic T-cell lymphoma is a tumor of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Hum Pathol. 1998;29(4):397-403. PubMed

10. Salhany KE, Macon WR, Choi JK, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and genotypic analysis of alpha/beta and gamma/delta subtypes. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22(7):881-893. PubMed

11. Jaffe ES, Nicolae A, Pittaluga S. Peripheral T-cell and NK-cell lymphomas in the WHO classification: pearls and pitfalls. Mod Pathol. 2013;26(suppl 1):S71-S87. PubMed

12. Willemze R, Hodak E, Zinzani PL, Specht L, Ladetto M; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Primary cutaneous lymphomas: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(suppl 6):vi149-vi154. PubMed

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient’s case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant. The bolded text represents the patient’s case. Each paragraph that follows represents the discussant’s thoughts.

A 42-year-old Malaysian construction worker with subjective fevers of 4 days’ duration presented to an emergency department in Singapore. He reported nonproductive cough, chills without rigors, sore throat, and body aches. He denied sick contacts. Past medical history included chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. The patient was not taking any medications.

For this patient presenting acutely with subjective fevers, nonproductive cough, chills, aches, and lethargy, initial considerations include infection with a common virus (influenza virus, adenovirus, Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]), acute human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, emerging infection (severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS], Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus [MERS-CoV] infection, avian influenza), and tropical infection (dengue, chikungunya). Also possible are bacterial infections (eg, with Salmonella typhi or Rickettsia or Mycoplasma species), parasitic infections (eg, malaria), and noninfectious illnesses (eg, autoimmune diseases, thyroiditis, acute leukemia, environmental exposures).

The patient’s temperature was 38.5°C; blood pressure, 133/73 mm Hg; heart rate, 95 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths per minute; and oxygen saturation, 100% on ambient air. On physical examination, he appeared comfortable, and heart, lung, abdomen, skin, and extremities were normal. Laboratory test results included white blood cell (WBC) count, 4400/μL (with normal differential); hemoglobin, 16.1 g/dL; and platelet count, 207,000/μL. Serum chemistries were normal. C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 44.6 mg/L (reference range, 0.2-9.1 mg/L), and procalcitonin level was 0.13 ng/mL (reference range, <0.50 ng/mL). Chest radiograph was normal. Dengue antibodies (immunoglobulin M, immunoglobulin G [IgG]) and dengue NS1 antigen were negative. The patient was discharged with a presumptive diagnosis of viral upper respiratory tract infection.

There is no left shift characteristic of bacterial infection or lymphopenia characteristic of rickettsial disease or acute HIV infection. The serologic testing and the patient’s overall appearance make dengue unlikely. The low procalcitonin supports a nonbacterial cause of illness. CRP elevation may indicate an inflammatory process and is relatively nonspecific.

Myalgias, pharyngitis, and cough improved over several days, but fevers persisted, and a rash developed over the lower abdomen. The patient returned to the emergency department and was admitted. He denied weight loss and night sweats. He had multiple female sexual partners, including commercial sex workers, within the previous 6 months. Temperature was 38.5°C. The posterior oropharynx was slightly erythematous. There was no lymphadenopathy. Firm, mildly erythematous macules were present on the anterior abdominal wall (Figure 1). The rest of the physical examination was normal.

Laboratory testing revealed WBC count, 5800/μL (75% neutrophils, 19% lymphocytes, 3% monocytes, 2% atypical mononuclear cells); hemoglobin, 16.3 g/dL; platelet count, 185,000/μL; sodium, 131 mmol/L; potassium, 3.4 mmol/L; creatinine, 0.9 mg/dL; albumin, 3.2 g/dL; alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 99 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 137 U/L; alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 63 U/L; and total bilirubin, 1.9 mg/dL. Prothrombin time was 11.1 seconds; partial thromboplastin time, 36.1 seconds; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 14 mm/h; and CRP, 62.2 mg/L.

EBV, acute HIV, and cytomegalovirus infections often present with adenopathy, which is absent here. Disseminated gonococcal infection can manifest with fever, body aches, and rash, but his rash and the absence of penile discharge, migratory arthritis, and enthesitis are not characteristic. Mycoplasma infection can present with macules, urticaria, or erythema multiforme. Rickettsia illnesses typically cause vasculitis with progression to petechiae or purpura resulting from endothelial damage. Patients with secondary syphilis may have widespread macular lesions, and the accompanying syphilitic hepatitis often manifests with elevations in ALP instead of ALT and AST. The mild elevation in ALT and AST can occur with many systemic viral infections. Sweet syndrome may manifest with febrile illness and rash, but the acuity of this patient’s illness and the rapid evolution favor infection.

The patient’s fevers (35°-40°C) continued without pattern over the next 3 days. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test of the nasal mucosa was negative for respiratory viruses. PCR blood tests for EBV, HIV-1, and cytomegalovirus were also negative. Antistreptolysin O (ASO) titer was 400 IU/mm (reference range, <200 IU/mm). Antinuclear antibodies were negative, and rheumatoid factor was 12.4 U/mL (reference range, <10.3 U/mL). Computed tomography (CT) of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis was normal. Results of a biopsy of an anterior abdominal wall skin lesion showed perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic inflammation. Amoxicillin was started for the treatment of possible group A streptococcal infection.

PCR for HIV would be positive at a high level in acute HIV. The skin biopsy is not characteristic of Sweet syndrome, which typically shows neutrophilic infiltrate without leukocytoclastic vasculitis, or of syphilis, which typically shows a plasma cell infiltrate.

The patient’s erythematous oropharynx may indicate recent streptococcal pharyngitis. The fevers, elevated ASO titer, and CRP level are consistent with acute rheumatic fever, but arthritis, carditis, and neurologic manifestations are lacking. Erythema marginatum manifests on the trunk and limbs as macules or papules with central clearing as the lesions spread outward—and differs from the patient’s rash, which is firm and restricted to the abdominal wall.

Fevers persisted through hospital day 7. The WBC count was 1100/μL (75.7% neutrophils, 22.5% lymphocytes), hemoglobin was 10.3 g/dL, and platelet count was 52,000/μL. Additional laboratory test results included ALP, 234 U/L; ALT, 250 U/L; AST, 459 U/L; lactate dehydrogenase, 2303 U/L (reference range, 222-454 U/L); and ferritin, 14,964 ng/mL (reference range, 47-452 ng/mL).

The duration of illness and negative diagnostic tests for infections increases suspicion for a noninfectious illness. Conditions commonly associated with marked hyperferritinemia include adult-onset Still disease (AOSD) and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). Of the 9 AOSD diagnostic (Yamaguchi) criteria, 5 are met in this case: fever, rash, sore throat, abnormal liver function tests, and negative rheumatologic tests. However, the patient lacks arthritis, leukocytosis, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly. Except for the elevated ferritin, the AOSD criteria overlap substantially with the criteria for acute rheumatic fever, and still require that infections be adequately excluded. HLH, a state of abnormal immune activation with resultant organ dysfunction, can be a primary disorder, but in adults more often is secondary to underlying infectious, autoimmune, or malignant (often lymphoma) conditions. Elevated ferritin, cytopenias, elevated ALT and AST, elevated CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase are consistent with HLH. The HLH diagnosis can be more firmly established with the more specific findings of hypertriglyceridemia, hypofibrinogenemia, and elevated soluble CD25 level. The histopathologic finding of hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow, lymph nodes, or liver may further support the diagnosis of HLH.

Rash and fevers persisted. Hepatitis A, hepatitis C, Rickettsia IgG, Burkholderia pseudomallei (the causative organism of melioidosis), and Leptospira serologies, as well as PCR for herpes simplex virus and parvovirus, were all negative. Hepatitis B viral load was 962 IU/mL (2.98 log), hepatitis B envelope antigen was negative, and hepatitis B envelope antibody was positive. Orientia tsutsugamushi (organism responsible for scrub typhus) IgG titer was elevated at 1:128. Antiliver kidney microsomal antibodies and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative. Fibrinogen level was 0.69 g/L (reference range, 1.8-4.8 g/L), and beta-2 microglobulin level was 5078 ng/mL (reference range, 878-2000 ng/mL). Bone marrow biopsy results showed hypocellular marrow with suppressed myelopoiesis, few atypical lymphoid cells, and few hemophagocytes. Flow cytometry was negative for clonal B lymphocytes and aberrant expression of T lymphocytes. Bone marrow myobacterial PCR and fungal cultures were negative.

The patient’s chronic HBV infection is unlikely to be related to his presentation given his low viral load and absence of signs of hepatic dysfunction. Excluding rickettsial disease requires paired acute and convalescent serologies. O tsutsugamushi, the causative agent of the rickettsial disease scrub typhus, is endemic in Malaysia; thus, his positive O tsutsugamushi IgG may indicate past exposure. His fevers, myalgias, truncal rash, and hepatitis are consistent with scrub typhus, but he lacks the characteristic severe headache and generalized lymphadenopathy. Although eschar formation with evolution of a papular rash is common in scrub typhus, it is often absent in the variant found in Southeast Asia. Although elevated β2 microglobulin level is used as a prognostic marker in multiple myeloma and Waldenström macroglobulinemia, it can be elevated in many immune-active states. The patient likely has HLH, which is supported by the hemophagocytosis seen on bone marrow biopsy, and the hypofibrinogenemia. Potential HLH triggers include O tsutsugamushi infection or recent streptococcal pharyngitis.

A deep-punch skin biopsy of the anterior abdominal wall skin lesion was performed because of the absence of subcutaneous fat in the first biopsy specimen. The latest biopsy results showed irregular interstitial expansion of medium-size lymphocytes in a lobular panniculated pattern. The lymphocytes contained enlarged, irregularly contoured nucleoli and were positive for T-cell markers CD2 and CD3 with reduction in CD5 expression. The lymphomatous cells were of CD8+ with uniform expression of activated cytotoxic granule protein granzyme B and were positive for T-cell hemireceptor β.

Positron emission tomography (PET) CT, obtained for staging purposes, showed multiple hypermetabolic subcutaneous and cutaneous lesions over the torso and upper and lower limbs—compatible with lymphomatous infiltrates (Figure 2). Examination, pathology, and imaging findings suggested a rare neoplasm: subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL). SPTCL was confirmed by T-cell receptor gene rearrangements studies.

HLH was diagnosed on the basis of the fevers, cytopenias, hypofibrinogenemia, elevated ferritin level, and evidence of hemophagocytosis. SPTCL was suspected as the HLH trigger.

The patient was treated with cyclophosphamide, hydroxydoxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. While on this regimen, he developed new skin lesions, and his ferritin level was persistently elevated. He was switched to romidepsin, a histone deacetylase inhibitor that specifically targets cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, but the lesions continued to progress. The patient then was treated with gemcitabine, dexamethasone, and cisplatin, and the rashes resolved. The most recent PET-CT showed nearly complete resolution of the subcutaneous lesions.

DISCUSSION

When residents or visitors to tropical or sub-tropical regions, those located near or between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, present with fever, physicians usually first think of infectious diseases. This patient’s case is a reminder that these important first considerations should not be the last.

Generating a differential diagnosis for tropical illnesses begins with the patient’s history. Factors to be considered include location (regional disease prevalence), exposures (food/water ingestion, outdoor work/recreation, sexual contact, animal contact), and timing (temporal relationship of symptom development to possible exposure). Common tropical infections are malaria, dengue, typhoid, and emerging infections such as chikungunya, avian influenza, and Zika virus infection.1This case underscores the need to analyze diagnostic tests critically. Interpreting tests as simply positive or negative, irrespective of disease features, epidemiology, and test characteristics, can contribute to diagnostic error. For example, the patient’s positive ASO titer requires an understanding of disease features and a nuanced interpretation based on the clinical presentation. The erythematous posterior oropharynx prompted concern for postinfectious sequelae of streptococcal pharyngitis, but his illness was more severe and more prolonged than is typical of that condition. The isolated elevated O tsutsugamushi IgG titer provides an example of the role of epidemiology in test interpretation. Although a single positive value might indicate a new exposure for a visitor to an endemic region, IgG seropositivity in Singapore, where scrub typhus is endemic, likely reflects prior exposure to the organism. Diagnosing an acute scrub typhus infection in a patient in an endemic region requires PCR testing. The skin biopsy results highlight the importance of understanding test characteristics. A skin biopsy specimen must be adequate in order to draw valid and accurate conclusions. In this case, the initial skin biopsy was superficial, and the specimen inadequate, but the test was not “negative.” In the diagnostic skin biopsy, deeper tissue was sampled, and panniculitis (inflammation of subcutaneous fat), which arises in inflammatory, infectious, traumatic, enzymatic, and malignant conditions, was identified. An adequate biopsy specimen that contains subcutaneous fat is essential in making this diagnosis.2This patient eventually manifested several elements of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), a syndrome of excessive inflammation and resultant organ injury relating to abnormal immune activation and excessive inflammation. HLH results from deficient down-regulation of activated macrophages and lymphocytes.3 It was initially described in pediatric patients but is now recognized in adults, and associated with mortality as high as 50%.3 A high ferritin level (>2000 ng/mL) has 70% sensitivity and 68% specificity for pediatric HLH and should trigger consideration of HLH in any age group.4 The diagnostic criteria for HLH initially proposed in 2004 by the Histiocyte Society to identify patients for recruitment into a clinical trial included molecular testing consistent with HLH and/or 5 of 8 clinical, laboratory, or histopathologic features (Table 1).5 HScore is a more recent validated scoring system that predicts the probability of HLH (Table 2). A score above 169 signifies diagnostic sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 86%.6

The diagnosis of HLH warrants a search for its underlying cause. Common triggers are viral infections (eg, EBV), autoimmune diseases (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus), and hematologic malignancies. These triggers typically stimulate or suppress the immune system. Initial management involves treatment of the underlying trigger and, potentially, immunosuppression with high

In this case, SPTCL triggered HLH. SPTCL is a rare non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by painless subcutaneous nodules or indurated plaques (panniculitis-like) on the trunk or extremities, constitutional symptoms, and, in some cases, HLH.7-10 SPTCL is diagnosed by deep skin biopsy, with immunohistochemistry showing CD8-positive pathologic T cells expressing cytotoxic proteins (eg, granzyme B).9,11 SPTCL can either have an alpha/beta T-cell phenotype (SPTCL-AB) or gamma/delta T-cell phenotype (SPTCL-GD). Seventeen percent of patients with SPTCL-AB and 45% of patients with SPTCL-GD have HLH on diagnosis. Concomitant HLH is associated with decreased 5-year survival.12This patient presented with fevers and was ultimately diagnosed with HLH secondary to SPLTCL. His case is a reminder that not all diseases in the tropics are tropical diseases. In the diagnosis of a febrile illness, a broad evaluative framework and rigorous test results evaluation are essential—no matter where a patient lives or visits.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

- A febrile illness acquired in the tropics is not always attributable to a tropical infection.

- To avoid diagnostic error, weigh positive or negative test results against disease features, patient epidemiology, and test characteristics.

- HLH is characterized by fevers, cytopenias, hepatosplenomegaly, hyperferritinemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypofibrinogenemia. In tissue specimens, hemophagocytosis may help differentiate HLH from competing conditions.

- After HLH is diagnosed, try to determine its underlying cause, which may be an infection, autoimmunity, or a malignancy (commonly, a lymphoma).

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient’s case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant. The bolded text represents the patient’s case. Each paragraph that follows represents the discussant’s thoughts.

A 42-year-old Malaysian construction worker with subjective fevers of 4 days’ duration presented to an emergency department in Singapore. He reported nonproductive cough, chills without rigors, sore throat, and body aches. He denied sick contacts. Past medical history included chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. The patient was not taking any medications.

For this patient presenting acutely with subjective fevers, nonproductive cough, chills, aches, and lethargy, initial considerations include infection with a common virus (influenza virus, adenovirus, Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]), acute human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, emerging infection (severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS], Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus [MERS-CoV] infection, avian influenza), and tropical infection (dengue, chikungunya). Also possible are bacterial infections (eg, with Salmonella typhi or Rickettsia or Mycoplasma species), parasitic infections (eg, malaria), and noninfectious illnesses (eg, autoimmune diseases, thyroiditis, acute leukemia, environmental exposures).

The patient’s temperature was 38.5°C; blood pressure, 133/73 mm Hg; heart rate, 95 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths per minute; and oxygen saturation, 100% on ambient air. On physical examination, he appeared comfortable, and heart, lung, abdomen, skin, and extremities were normal. Laboratory test results included white blood cell (WBC) count, 4400/μL (with normal differential); hemoglobin, 16.1 g/dL; and platelet count, 207,000/μL. Serum chemistries were normal. C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 44.6 mg/L (reference range, 0.2-9.1 mg/L), and procalcitonin level was 0.13 ng/mL (reference range, <0.50 ng/mL). Chest radiograph was normal. Dengue antibodies (immunoglobulin M, immunoglobulin G [IgG]) and dengue NS1 antigen were negative. The patient was discharged with a presumptive diagnosis of viral upper respiratory tract infection.

There is no left shift characteristic of bacterial infection or lymphopenia characteristic of rickettsial disease or acute HIV infection. The serologic testing and the patient’s overall appearance make dengue unlikely. The low procalcitonin supports a nonbacterial cause of illness. CRP elevation may indicate an inflammatory process and is relatively nonspecific.

Myalgias, pharyngitis, and cough improved over several days, but fevers persisted, and a rash developed over the lower abdomen. The patient returned to the emergency department and was admitted. He denied weight loss and night sweats. He had multiple female sexual partners, including commercial sex workers, within the previous 6 months. Temperature was 38.5°C. The posterior oropharynx was slightly erythematous. There was no lymphadenopathy. Firm, mildly erythematous macules were present on the anterior abdominal wall (Figure 1). The rest of the physical examination was normal.

Laboratory testing revealed WBC count, 5800/μL (75% neutrophils, 19% lymphocytes, 3% monocytes, 2% atypical mononuclear cells); hemoglobin, 16.3 g/dL; platelet count, 185,000/μL; sodium, 131 mmol/L; potassium, 3.4 mmol/L; creatinine, 0.9 mg/dL; albumin, 3.2 g/dL; alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 99 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 137 U/L; alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 63 U/L; and total bilirubin, 1.9 mg/dL. Prothrombin time was 11.1 seconds; partial thromboplastin time, 36.1 seconds; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 14 mm/h; and CRP, 62.2 mg/L.

EBV, acute HIV, and cytomegalovirus infections often present with adenopathy, which is absent here. Disseminated gonococcal infection can manifest with fever, body aches, and rash, but his rash and the absence of penile discharge, migratory arthritis, and enthesitis are not characteristic. Mycoplasma infection can present with macules, urticaria, or erythema multiforme. Rickettsia illnesses typically cause vasculitis with progression to petechiae or purpura resulting from endothelial damage. Patients with secondary syphilis may have widespread macular lesions, and the accompanying syphilitic hepatitis often manifests with elevations in ALP instead of ALT and AST. The mild elevation in ALT and AST can occur with many systemic viral infections. Sweet syndrome may manifest with febrile illness and rash, but the acuity of this patient’s illness and the rapid evolution favor infection.

The patient’s fevers (35°-40°C) continued without pattern over the next 3 days. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test of the nasal mucosa was negative for respiratory viruses. PCR blood tests for EBV, HIV-1, and cytomegalovirus were also negative. Antistreptolysin O (ASO) titer was 400 IU/mm (reference range, <200 IU/mm). Antinuclear antibodies were negative, and rheumatoid factor was 12.4 U/mL (reference range, <10.3 U/mL). Computed tomography (CT) of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis was normal. Results of a biopsy of an anterior abdominal wall skin lesion showed perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic inflammation. Amoxicillin was started for the treatment of possible group A streptococcal infection.

PCR for HIV would be positive at a high level in acute HIV. The skin biopsy is not characteristic of Sweet syndrome, which typically shows neutrophilic infiltrate without leukocytoclastic vasculitis, or of syphilis, which typically shows a plasma cell infiltrate.

The patient’s erythematous oropharynx may indicate recent streptococcal pharyngitis. The fevers, elevated ASO titer, and CRP level are consistent with acute rheumatic fever, but arthritis, carditis, and neurologic manifestations are lacking. Erythema marginatum manifests on the trunk and limbs as macules or papules with central clearing as the lesions spread outward—and differs from the patient’s rash, which is firm and restricted to the abdominal wall.

Fevers persisted through hospital day 7. The WBC count was 1100/μL (75.7% neutrophils, 22.5% lymphocytes), hemoglobin was 10.3 g/dL, and platelet count was 52,000/μL. Additional laboratory test results included ALP, 234 U/L; ALT, 250 U/L; AST, 459 U/L; lactate dehydrogenase, 2303 U/L (reference range, 222-454 U/L); and ferritin, 14,964 ng/mL (reference range, 47-452 ng/mL).

The duration of illness and negative diagnostic tests for infections increases suspicion for a noninfectious illness. Conditions commonly associated with marked hyperferritinemia include adult-onset Still disease (AOSD) and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). Of the 9 AOSD diagnostic (Yamaguchi) criteria, 5 are met in this case: fever, rash, sore throat, abnormal liver function tests, and negative rheumatologic tests. However, the patient lacks arthritis, leukocytosis, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly. Except for the elevated ferritin, the AOSD criteria overlap substantially with the criteria for acute rheumatic fever, and still require that infections be adequately excluded. HLH, a state of abnormal immune activation with resultant organ dysfunction, can be a primary disorder, but in adults more often is secondary to underlying infectious, autoimmune, or malignant (often lymphoma) conditions. Elevated ferritin, cytopenias, elevated ALT and AST, elevated CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase are consistent with HLH. The HLH diagnosis can be more firmly established with the more specific findings of hypertriglyceridemia, hypofibrinogenemia, and elevated soluble CD25 level. The histopathologic finding of hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow, lymph nodes, or liver may further support the diagnosis of HLH.

Rash and fevers persisted. Hepatitis A, hepatitis C, Rickettsia IgG, Burkholderia pseudomallei (the causative organism of melioidosis), and Leptospira serologies, as well as PCR for herpes simplex virus and parvovirus, were all negative. Hepatitis B viral load was 962 IU/mL (2.98 log), hepatitis B envelope antigen was negative, and hepatitis B envelope antibody was positive. Orientia tsutsugamushi (organism responsible for scrub typhus) IgG titer was elevated at 1:128. Antiliver kidney microsomal antibodies and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative. Fibrinogen level was 0.69 g/L (reference range, 1.8-4.8 g/L), and beta-2 microglobulin level was 5078 ng/mL (reference range, 878-2000 ng/mL). Bone marrow biopsy results showed hypocellular marrow with suppressed myelopoiesis, few atypical lymphoid cells, and few hemophagocytes. Flow cytometry was negative for clonal B lymphocytes and aberrant expression of T lymphocytes. Bone marrow myobacterial PCR and fungal cultures were negative.

The patient’s chronic HBV infection is unlikely to be related to his presentation given his low viral load and absence of signs of hepatic dysfunction. Excluding rickettsial disease requires paired acute and convalescent serologies. O tsutsugamushi, the causative agent of the rickettsial disease scrub typhus, is endemic in Malaysia; thus, his positive O tsutsugamushi IgG may indicate past exposure. His fevers, myalgias, truncal rash, and hepatitis are consistent with scrub typhus, but he lacks the characteristic severe headache and generalized lymphadenopathy. Although eschar formation with evolution of a papular rash is common in scrub typhus, it is often absent in the variant found in Southeast Asia. Although elevated β2 microglobulin level is used as a prognostic marker in multiple myeloma and Waldenström macroglobulinemia, it can be elevated in many immune-active states. The patient likely has HLH, which is supported by the hemophagocytosis seen on bone marrow biopsy, and the hypofibrinogenemia. Potential HLH triggers include O tsutsugamushi infection or recent streptococcal pharyngitis.

A deep-punch skin biopsy of the anterior abdominal wall skin lesion was performed because of the absence of subcutaneous fat in the first biopsy specimen. The latest biopsy results showed irregular interstitial expansion of medium-size lymphocytes in a lobular panniculated pattern. The lymphocytes contained enlarged, irregularly contoured nucleoli and were positive for T-cell markers CD2 and CD3 with reduction in CD5 expression. The lymphomatous cells were of CD8+ with uniform expression of activated cytotoxic granule protein granzyme B and were positive for T-cell hemireceptor β.

Positron emission tomography (PET) CT, obtained for staging purposes, showed multiple hypermetabolic subcutaneous and cutaneous lesions over the torso and upper and lower limbs—compatible with lymphomatous infiltrates (Figure 2). Examination, pathology, and imaging findings suggested a rare neoplasm: subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL). SPTCL was confirmed by T-cell receptor gene rearrangements studies.

HLH was diagnosed on the basis of the fevers, cytopenias, hypofibrinogenemia, elevated ferritin level, and evidence of hemophagocytosis. SPTCL was suspected as the HLH trigger.

The patient was treated with cyclophosphamide, hydroxydoxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. While on this regimen, he developed new skin lesions, and his ferritin level was persistently elevated. He was switched to romidepsin, a histone deacetylase inhibitor that specifically targets cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, but the lesions continued to progress. The patient then was treated with gemcitabine, dexamethasone, and cisplatin, and the rashes resolved. The most recent PET-CT showed nearly complete resolution of the subcutaneous lesions.

DISCUSSION

When residents or visitors to tropical or sub-tropical regions, those located near or between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, present with fever, physicians usually first think of infectious diseases. This patient’s case is a reminder that these important first considerations should not be the last.

Generating a differential diagnosis for tropical illnesses begins with the patient’s history. Factors to be considered include location (regional disease prevalence), exposures (food/water ingestion, outdoor work/recreation, sexual contact, animal contact), and timing (temporal relationship of symptom development to possible exposure). Common tropical infections are malaria, dengue, typhoid, and emerging infections such as chikungunya, avian influenza, and Zika virus infection.1This case underscores the need to analyze diagnostic tests critically. Interpreting tests as simply positive or negative, irrespective of disease features, epidemiology, and test characteristics, can contribute to diagnostic error. For example, the patient’s positive ASO titer requires an understanding of disease features and a nuanced interpretation based on the clinical presentation. The erythematous posterior oropharynx prompted concern for postinfectious sequelae of streptococcal pharyngitis, but his illness was more severe and more prolonged than is typical of that condition. The isolated elevated O tsutsugamushi IgG titer provides an example of the role of epidemiology in test interpretation. Although a single positive value might indicate a new exposure for a visitor to an endemic region, IgG seropositivity in Singapore, where scrub typhus is endemic, likely reflects prior exposure to the organism. Diagnosing an acute scrub typhus infection in a patient in an endemic region requires PCR testing. The skin biopsy results highlight the importance of understanding test characteristics. A skin biopsy specimen must be adequate in order to draw valid and accurate conclusions. In this case, the initial skin biopsy was superficial, and the specimen inadequate, but the test was not “negative.” In the diagnostic skin biopsy, deeper tissue was sampled, and panniculitis (inflammation of subcutaneous fat), which arises in inflammatory, infectious, traumatic, enzymatic, and malignant conditions, was identified. An adequate biopsy specimen that contains subcutaneous fat is essential in making this diagnosis.2This patient eventually manifested several elements of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), a syndrome of excessive inflammation and resultant organ injury relating to abnormal immune activation and excessive inflammation. HLH results from deficient down-regulation of activated macrophages and lymphocytes.3 It was initially described in pediatric patients but is now recognized in adults, and associated with mortality as high as 50%.3 A high ferritin level (>2000 ng/mL) has 70% sensitivity and 68% specificity for pediatric HLH and should trigger consideration of HLH in any age group.4 The diagnostic criteria for HLH initially proposed in 2004 by the Histiocyte Society to identify patients for recruitment into a clinical trial included molecular testing consistent with HLH and/or 5 of 8 clinical, laboratory, or histopathologic features (Table 1).5 HScore is a more recent validated scoring system that predicts the probability of HLH (Table 2). A score above 169 signifies diagnostic sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 86%.6

The diagnosis of HLH warrants a search for its underlying cause. Common triggers are viral infections (eg, EBV), autoimmune diseases (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus), and hematologic malignancies. These triggers typically stimulate or suppress the immune system. Initial management involves treatment of the underlying trigger and, potentially, immunosuppression with high

In this case, SPTCL triggered HLH. SPTCL is a rare non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by painless subcutaneous nodules or indurated plaques (panniculitis-like) on the trunk or extremities, constitutional symptoms, and, in some cases, HLH.7-10 SPTCL is diagnosed by deep skin biopsy, with immunohistochemistry showing CD8-positive pathologic T cells expressing cytotoxic proteins (eg, granzyme B).9,11 SPTCL can either have an alpha/beta T-cell phenotype (SPTCL-AB) or gamma/delta T-cell phenotype (SPTCL-GD). Seventeen percent of patients with SPTCL-AB and 45% of patients with SPTCL-GD have HLH on diagnosis. Concomitant HLH is associated with decreased 5-year survival.12This patient presented with fevers and was ultimately diagnosed with HLH secondary to SPLTCL. His case is a reminder that not all diseases in the tropics are tropical diseases. In the diagnosis of a febrile illness, a broad evaluative framework and rigorous test results evaluation are essential—no matter where a patient lives or visits.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

- A febrile illness acquired in the tropics is not always attributable to a tropical infection.

- To avoid diagnostic error, weigh positive or negative test results against disease features, patient epidemiology, and test characteristics.

- HLH is characterized by fevers, cytopenias, hepatosplenomegaly, hyperferritinemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypofibrinogenemia. In tissue specimens, hemophagocytosis may help differentiate HLH from competing conditions.

- After HLH is diagnosed, try to determine its underlying cause, which may be an infection, autoimmunity, or a malignancy (commonly, a lymphoma).

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Destinations [list]. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/list/. Accessed April 22, 2016.

2. Diaz Cascajo C, Borghi S, Weyers W. Panniculitis: definition of terms and diagnostic strategy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22(6):530-549. PubMed

3. Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, Khamashta MA, Bosch X. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet. 2014;383(9927):1503-1516. PubMed

4. Lehmberg K, McClain KL, Janka GE, Allen CE. Determination of an appropriate cut-off value for ferritin in the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(11):2101-2103. PubMed

5. Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(2):124-131. PubMed

6. Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, et al. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(9):2613-2620. PubMed

7. Aronson IK, Worobed CM. Cytophagic histiocytic panniculitis and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: an overview. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23(4):389-402. PubMed

8. Willemze R, Jansen PM, Cerroni L, et al; EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Group. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: definition, classification, and prognostic factors: an EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Group study of 83 cases. Blood. 2008;111(2):838-845. PubMed

9. Kumar S, Krenacs L, Medeiros J, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitic T-cell lymphoma is a tumor of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Hum Pathol. 1998;29(4):397-403. PubMed

10. Salhany KE, Macon WR, Choi JK, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and genotypic analysis of alpha/beta and gamma/delta subtypes. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22(7):881-893. PubMed

11. Jaffe ES, Nicolae A, Pittaluga S. Peripheral T-cell and NK-cell lymphomas in the WHO classification: pearls and pitfalls. Mod Pathol. 2013;26(suppl 1):S71-S87. PubMed

12. Willemze R, Hodak E, Zinzani PL, Specht L, Ladetto M; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Primary cutaneous lymphomas: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(suppl 6):vi149-vi154. PubMed

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Destinations [list]. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/list/. Accessed April 22, 2016.

2. Diaz Cascajo C, Borghi S, Weyers W. Panniculitis: definition of terms and diagnostic strategy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22(6):530-549. PubMed

3. Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, Khamashta MA, Bosch X. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet. 2014;383(9927):1503-1516. PubMed

4. Lehmberg K, McClain KL, Janka GE, Allen CE. Determination of an appropriate cut-off value for ferritin in the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(11):2101-2103. PubMed

5. Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(2):124-131. PubMed

6. Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, et al. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(9):2613-2620. PubMed

7. Aronson IK, Worobed CM. Cytophagic histiocytic panniculitis and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: an overview. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23(4):389-402. PubMed

8. Willemze R, Jansen PM, Cerroni L, et al; EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Group. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: definition, classification, and prognostic factors: an EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Group study of 83 cases. Blood. 2008;111(2):838-845. PubMed

9. Kumar S, Krenacs L, Medeiros J, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitic T-cell lymphoma is a tumor of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Hum Pathol. 1998;29(4):397-403. PubMed

10. Salhany KE, Macon WR, Choi JK, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and genotypic analysis of alpha/beta and gamma/delta subtypes. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22(7):881-893. PubMed

11. Jaffe ES, Nicolae A, Pittaluga S. Peripheral T-cell and NK-cell lymphomas in the WHO classification: pearls and pitfalls. Mod Pathol. 2013;26(suppl 1):S71-S87. PubMed

12. Willemze R, Hodak E, Zinzani PL, Specht L, Ladetto M; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Primary cutaneous lymphomas: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(suppl 6):vi149-vi154. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

UCSF Hospitalist Mini‐College

I hear and I forget, I see and I remember, I do and I understand.

Confucius

Hospital medicine, first described in 1996,[1] is the fastest growing specialty in United States medical history, now with approximately 40,000 practitioners.[2] Although hospitalists undoubtedly learned many of their key clinical skills during residency training, there is no hospitalist‐specific residency training pathway and a limited number of largely research‐oriented fellowships.[3] Furthermore, hospitalists are often asked to care for surgical patients, those with acute neurologic disorders, and patients in intensive care units, while also contributing to quality improvement and patient safety initiatives.[4] This suggests that the vast majority of hospitalists have not had specific training in many key competencies for the field.[5]

Continuing medical education (CME) has traditionally been the mechanism to maintain, develop, or increase the knowledge, skills, and professional performance of physicians.[6] Most CME activities, including those for hospitalists, are staged as live events in hotel conference rooms or as local events in a similarly passive learning environment (eg, grand rounds and medical staff meetings). Online programs, audiotapes, and expanding electronic media provide increasing and alternate methods for hospitalists to obtain their required CME. All of these activities passively deliver content to a group of diverse and experienced learners. They fail to take advantage of adult learning principles and may have little direct impact on professional practice.[7, 8] Traditional CME is often derided as a barrier to innovative educational methods for these reasons, as adults learn best through active participation, when the information is relevant and practically applied.[9, 10]

To provide practicing hospitalists with necessary continuing education, we designed the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Hospitalist Mini‐College (UHMC). This 3‐day course brings adult learners to the bedside for small‐group and active learning focused on content areas relevant to today's hospitalists. We describe the development, content, outcomes, and lessons learned from UHMC's first 5 years.

METHODS

Program Development

We aimed to develop a program that focused on curricular topics that would be highly valued by practicing hospitalists delivered in an active learning small‐group environment. We first conducted an informal needs assessment of community‐based hospitalists to better understand their roles and determine their perceptions of gaps in hospitalist training compared to current requirements for practice. We then reviewed available CME events targeting hospitalists and compared these curricula to the gaps discovered from the needs assessment. We also reviewed the Society of Hospital Medicine's core competencies to further identify gaps in scope of practice.[4] Finally, we reviewed the literature to identify CME curricular innovations in the clinical setting and found no published reports.

Program Setting, Participants, and Faculty

The UHMC course was developed and offered first in 2008 as a precourse to the UCSF Management of the Hospitalized Medicine course, a traditional CME offering that occurs annually in a hotel setting.[11] The UHMC takes place on the campus of UCSF Medical Center, a 600‐bed academic medical center in San Francisco. Registered participants were required to complete limited credentialing paperwork, which allowed them to directly observe clinical care and interact with hospitalized patients. Participants were not involved in any clinical decision making for the patients they met or examined. The course was limited to a maximum of 33 participants annually to optimize active participation, small‐group bedside activities, and a personalized learning experience. UCSF faculty selected to teach in the UHMC were chosen based on exemplary clinical and teaching skills. They collaborated with course directors in the development of their session‐specific goals and curriculum.

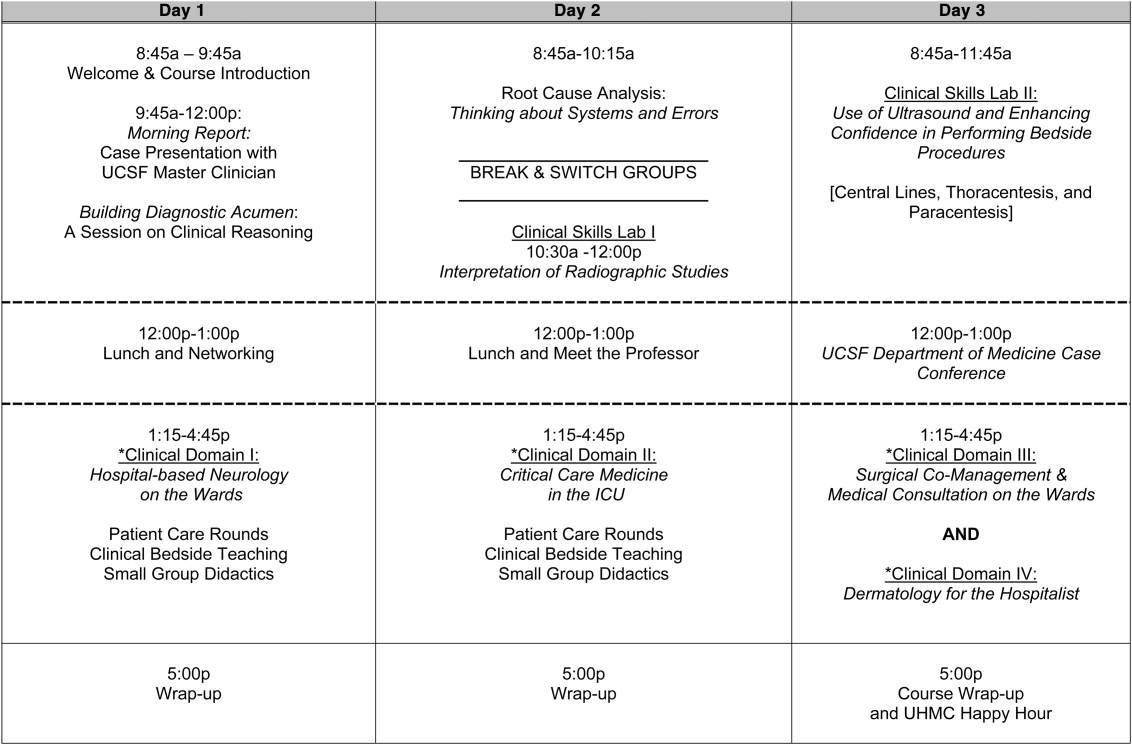

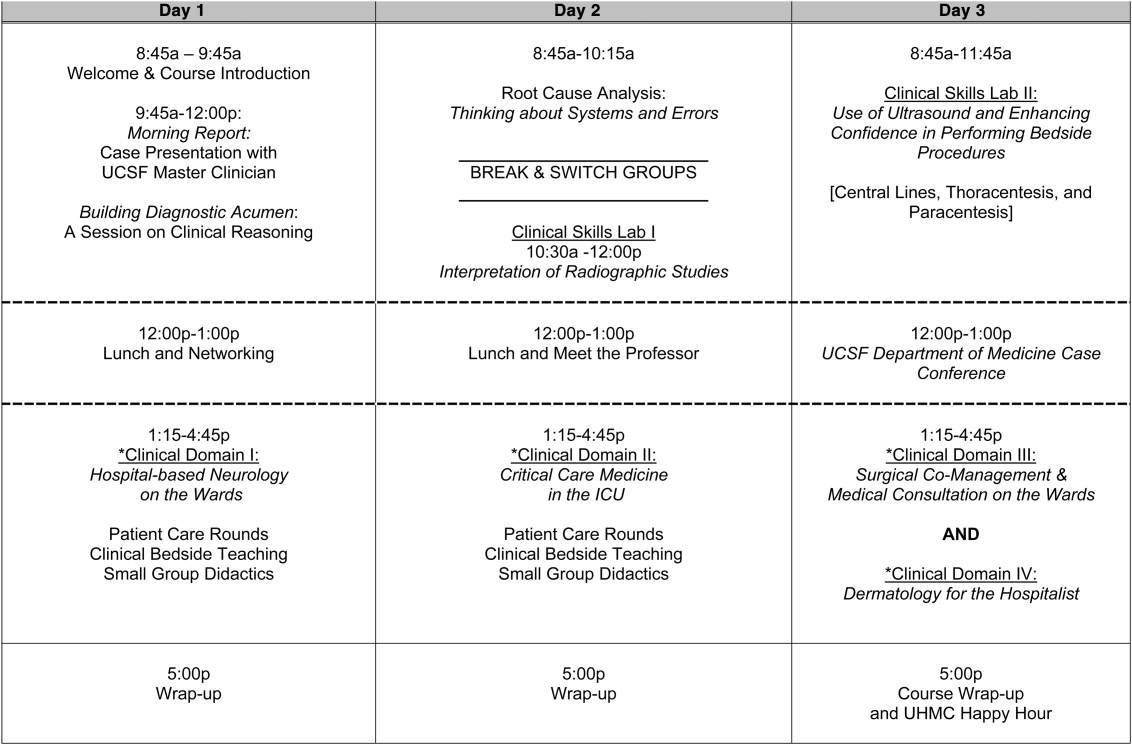

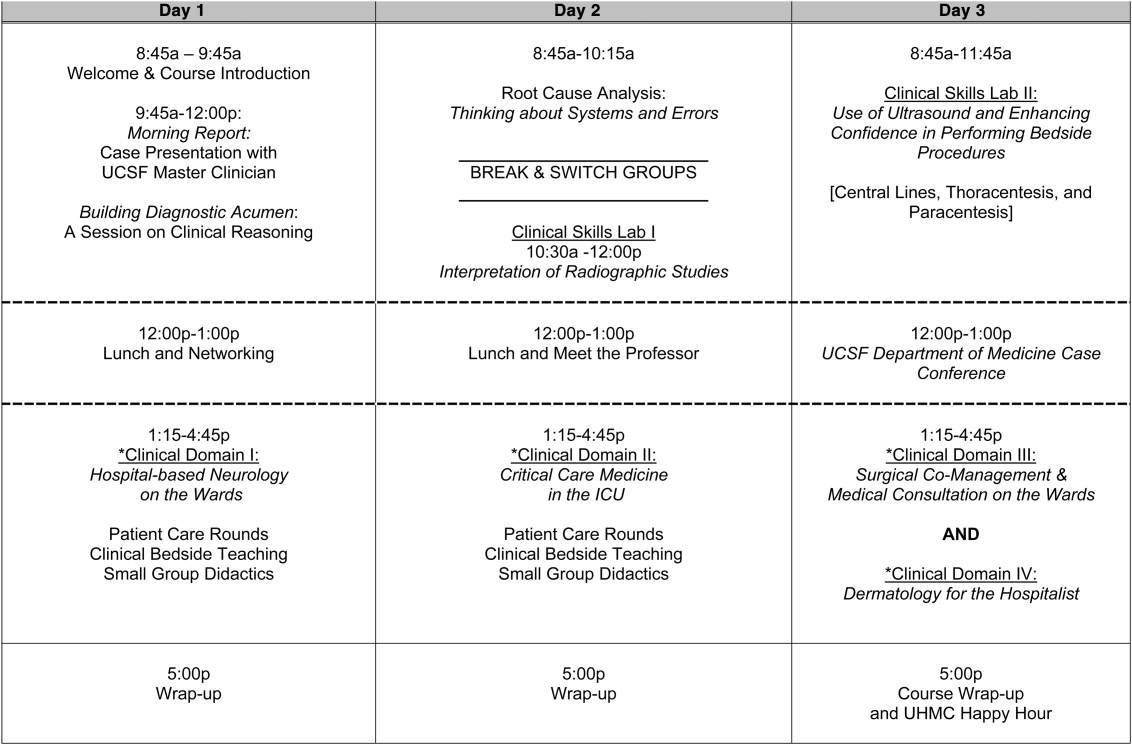

Program Description

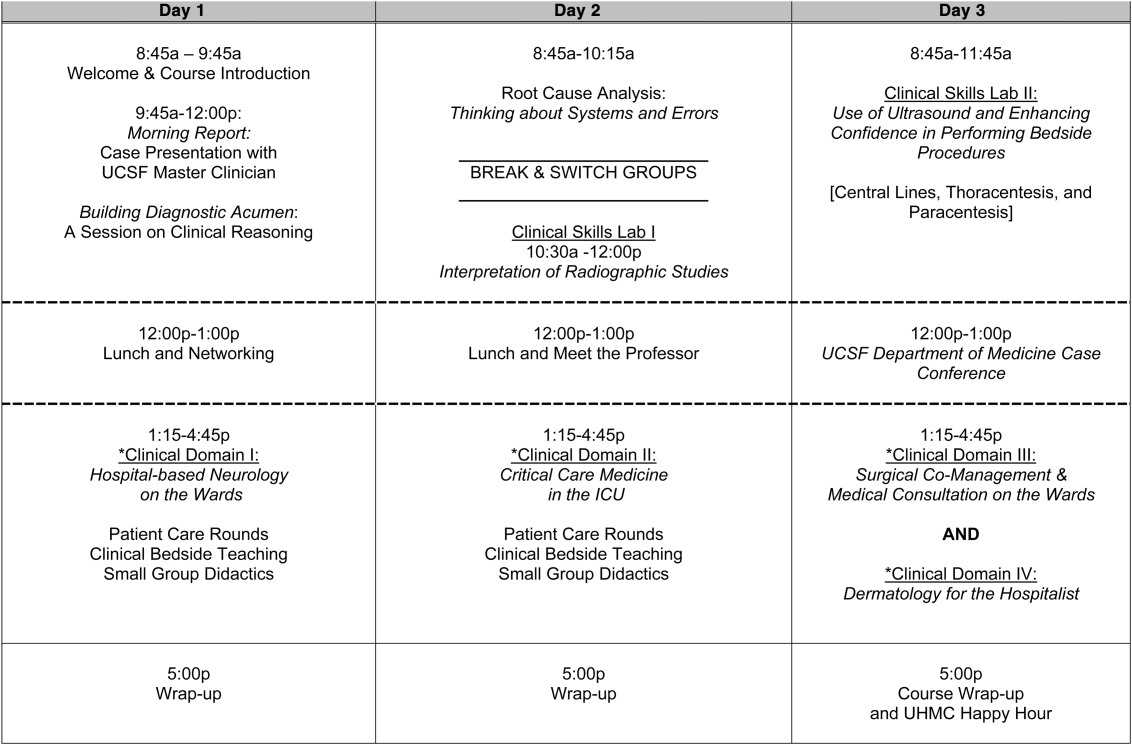

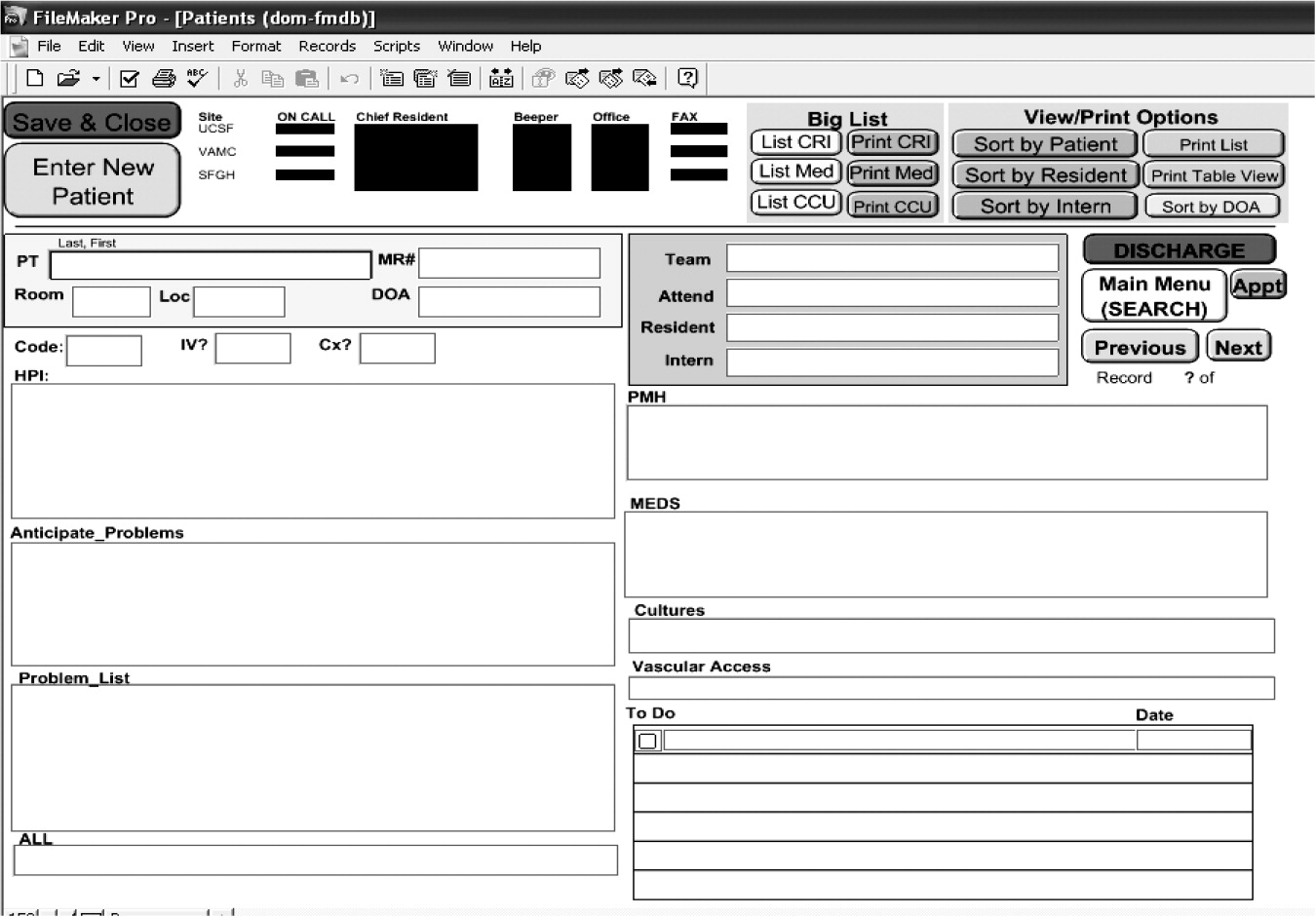

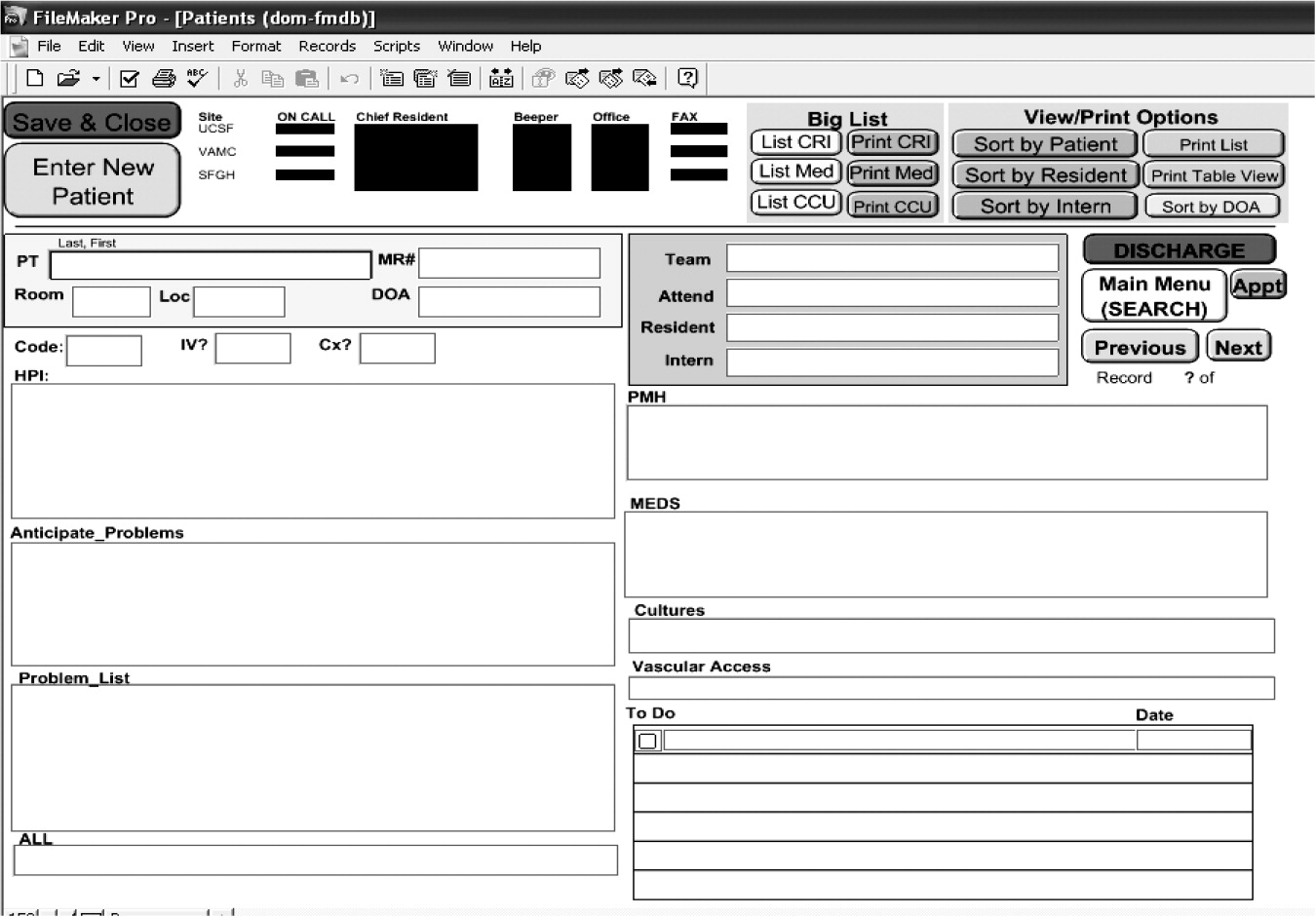

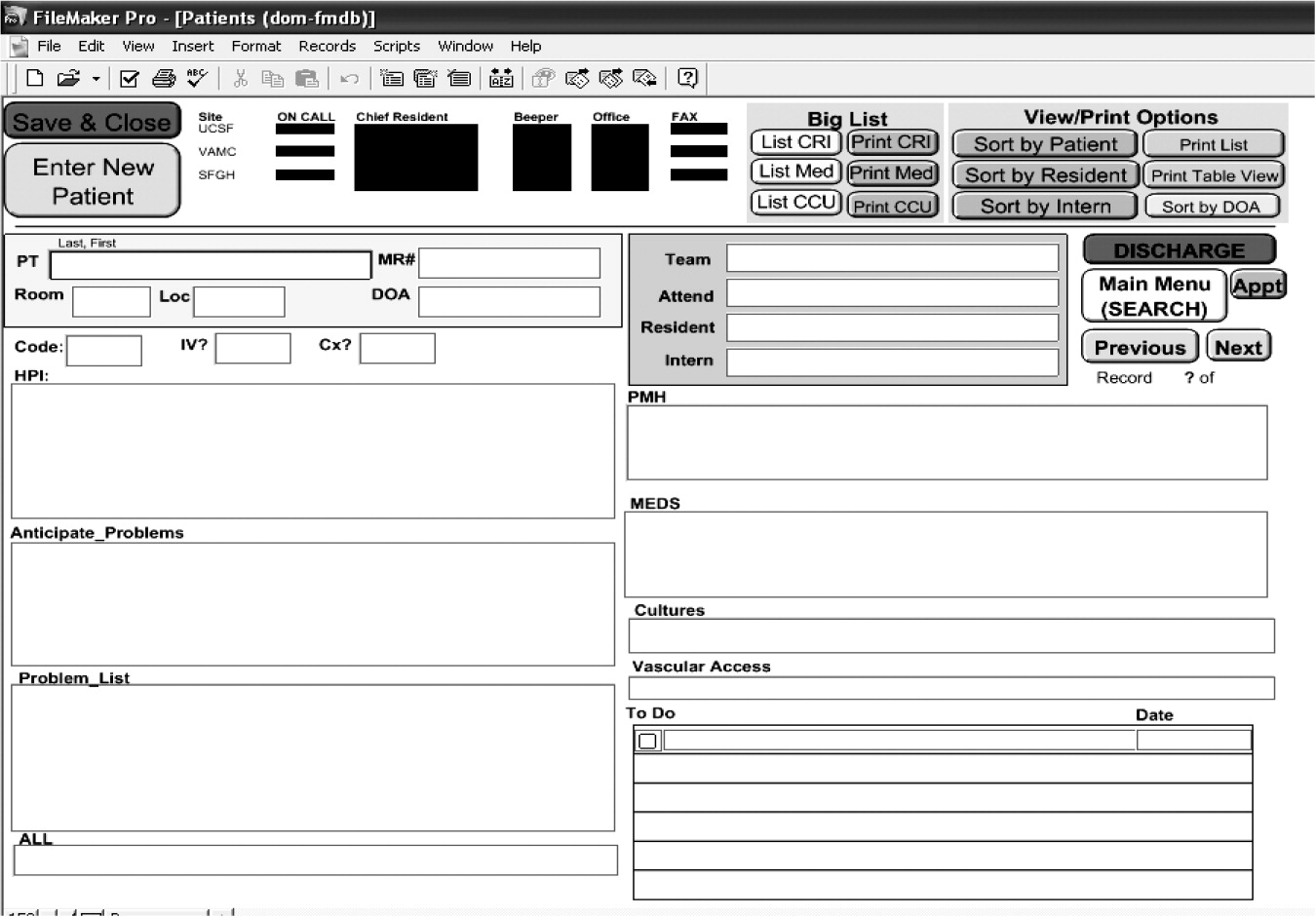

Figure 1 is a representative calendar view of the 3‐day UHMC course. The curricular topics were selected based on the findings from our needs assessment, our ability to deliver that curriculum using our small‐group active learning framework, and to minimize overlap with content of the larger course. Course curriculum was refined annually based on participant feedback and course director observations.

The program was built on a structure of 4 clinical domains and 2 clinical skills labs. The clinical domains included: (1) Hospital‐Based Neurology, (2) Critical Care Medicine in the Intensive Care Unit, (3) Surgical Comanagement and Medical Consultation, and (4) Hospital‐Based Dermatology. Participants were divided into 3 groups of 10 participants each and rotated through each domain in the afternoons. The clinical skills labs included: (1) Interpretation of Radiographic Studies and (2) Use of Ultrasound and Enhancing Confidence in Performing Bedside Procedures. We also developed specific sessions to teach about patient safety and to allow course attendees to participate in traditional academic learning vehicles (eg, a Morning Report and Morbidity and Mortality case conference). Below, we describe each session's format and content.

Clinical Domains

Hospital‐Based Neurology

Attendees participated in both bedside evaluation and case‐based discussions of common neurologic conditions seen in the hospital. In small groups of 5, participants were assigned patients to examine on the neurology ward. After their evaluations, they reported their findings to fellow participants and the faculty, setting the foundation for discussion of clinical management, review of neuroimaging, and exploration of current evidence to inform the patient's diagnosis and management. Participants and faculty then returned to the bedside to hone neurologic examination skills and complete the learning process. Given the unpredictability of what conditions would be represented on the ward in a given day, review of commonly seen conditions was always a focus, such as stroke, seizures, delirium, and neurologic examination pearls.

Critical Care

Attendees participated in case‐based discussions of common clinical conditions with similar review of current evidence, relevant imaging, and bedside exam pearls for the intubated patient. For this domain, attendees also participated in an advanced simulation tutorial in ventilator management, which was then applied at the bedside of intubated patients. Specific topics covered include sepsis, decompensated chronic obstructive lung disease, vasopressor selection, novel therapies in critically ill patients, and use of clinical pathways and protocols for improved quality of care.

Surgical Comanagement and Medical Consultation

Attendees participated in case‐based discussions applying current evidence to perioperative controversies and the care of the surgical patient. They also discussed the expanding role of the hospitalist in nonmedical patients.

Hospital‐Based Dermatology

Attendees participated in bedside evaluation of acute skin eruptions based on available patients admitted to the hospital. They discussed the approach to skin eruptions, key diagnoses, and when dermatologists should be consulted for their expertise. Specific topics included drug reactions, the red leg, life‐threating conditions (eg, Stevens‐Johnson syndrome), and dermatologic examination pearls. This domain was added in 2010.

Clinical Skills Labs

Radiology

In groups of 15, attendees reviewed common radiographs that hospitalists frequently order or evaluate (eg, chest x‐rays; kidney, ureter, and bladder; placement of endotracheal or feeding tube). They also reviewed the most relevant and not‐to‐miss findings on other commonly ordered studies such as abdominal or brain computerized tomography scans.

Hospital Procedures With Bedside Ultrasound

Attendees participated in a half‐day session to gain experience with the following procedures: paracentesis, lumbar puncture, thoracentesis, and central lines. They participated in an initial overview of procedural safety followed by hands‐on application sessions, in which they rotated through clinical workstations in groups of 5. At each work station, they were provided an opportunity to practice techniques, including the safe use of ultrasound on both live (standardized patients) and simulation models.

Other Sessions

Building Diagnostic Acumen and Clinical Reasoning

The opening session of the UHMC reintroduces attendees to the traditional academic morning report format, in which a case is presented and participants are asked to assess the information, develop differential diagnoses, discuss management options, and consider their own clinical reasoning skills. This provides frameworks for diagnostic reasoning, highlights common cognitive errors, and teaches attendees how to develop expertise in their own diagnostic thinking. The session also sets the stage and expectation for active learning and participation in the UHMC.

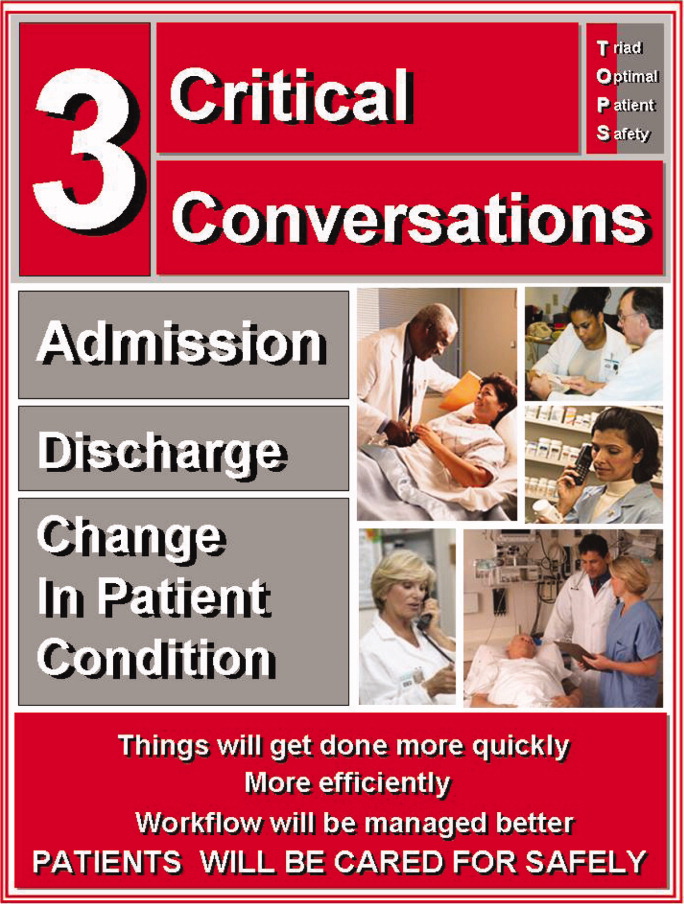

Root Cause Analysis and Systems Thinking

As the only nonclinical session in the UHMC, this session introduces participants to systems thinking and patient safety. Attendees participate in a root cause analysis role play surrounding a serious medical error and discuss the implications, their reflections, and then propose solutions through interactive table discussions. The session also emphasizes the key role hospitalists should play in improving patient safety.

Clinical Case Conference

Attendees participated in the weekly UCSF Department of Medicine Morbidity and Mortality conference. This is a traditional case conference that brings together learners, expert discussants, and an interesting or challenging case. This allows attendees to synthesize much of the course learning through active participation in the case discussion. Rather than creating a new conference for the participants, we brought the participants to the existing conference as part of their UHMC immersion experience.

Meet the Professor

Attendees participated in an informal discussion with a national leader (R.M.W.) in hospital medicine. This allowed for an interactive exchange of ideas and an understanding of the field overall.

Online Search Strategies

This interactive computer lab session allowed participants to explore the ever‐expanding number of online resources to answer clinical queries. This session was replaced in 2010 with the dermatology clinical domain based on participant feedback.

Program Evaluation

Participants completed a pre‐UHMC survey that provided demographic information and attributes about themselves, their clinical practice, and experience. Participants also completed course evaluations consistent with Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education standards following the program. The questions asked for each activity were rated on a 1‐to‐5 scale (1=poor, 5=excellent) and also included open‐ended questions to assess overall experiences.

RESULTS

Participant Demographics

During the first 5 years of the UHMC, 152 participants enrolled and completed the program; 91% completed the pre‐UHMC survey and 89% completed the postcourse evaluation. Table 1 describes the self‐reported participant demographics, including years in practice, number of hospitalist jobs, overall job satisfaction, and time spent doing clinical work. Overall, 68% of all participants had been self‐described hospitalists for <4 years, with 62% holding only 1 hospitalist job during that time; 77% reported being pretty or very satisfied with their jobs, and 72% reported clinical care as the attribute they love most in their job. Table 2 highlights the type of work attendees participate in within their clinical practice. More than half manage patients with neurologic disorders and care for critically ill patients, whereas virtually all perform preoperative medical evaluations and medical consultation

| Question | Response Options | 2008 (n=4) | 2009 (n=26) | 2010 (n=29) | 2011 (n=31) | 2012 (n=28) | Average (n=138) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| How long have you been a hospitalist? | <2 years | 52% | 35% | 37% | 30% | 25% | 36% |

| 24 years | 26% | 39% | 30% | 30% | 38% | 32% | |

| 510 years | 11% | 17% | 15% | 26% | 29% | 20% | |

| >10 years | 11% | 9% | 18% | 14% | 8% | 12% | |

| How many hospitalist jobs have you had? | 1 | 63% | 61% | 62% | 62% | 58% | 62% |

| 2 to 3 | 37% | 35% | 23% | 35% | 29% | 32% | |

| >3 | 0% | 4% | 15% | 1% | 13% | 5% | |

| How satisfied are you with your current position? | Not satisfied | 1% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 0% | 4% |

| Somewhat satisfied | 11% | 13% | 39% | 17% | 17% | 19% | |

| Pretty satisfied | 59% | 52% | 35% | 57% | 38% | 48% | |

| Very satisfied | 26% | 30% | 23% | 22% | 46% | 29% | |

| What do you love most about your job? | Clinical care | 85% | 61% | 65% | 84% | 67% | 72% |

| Teaching | 1% | 17% | 12% | 1% | 4% | 7% | |

| QI or safety work | 0% | 4% | 0% | 1% | 8% | 3% | |

| Other (not specified) | 14% | 18% | 23% | 14% | 21% | 18% | |

| What percent of your time is spent doing clinical care? | 100% | 39% | 36% | 52% | 46% | 58% | 46% |

| 75%100% | 58% | 50% | 37% | 42% | 33% | 44% | |

| 5075% | 0% | 9% | 11% | 12% | 4% | 7% | |

| 25%50% | 4% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 3% | |

| <25% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| Question | Response Options | 2008 (n=24) | 2009 (n=26) | 2010 (n=29) | 2011 (n=31) | 2012 (n=28) | Average(n=138) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Do you primarily manage patients with neurologic disorders in your hospital? | Yes | 62% | 50% | 62% | 62% | 63% | 60% |

| Do you primarily manage critically ill ICU patients in your hospital? | Yes and without an intensivist | 19% | 23% | 19% | 27% | 21% | 22% |

| Yes but with an intensivist | 54% | 50% | 44% | 42% | 67% | 51% | |

| No | 27% | 27% | 37% | 31% | 13% | 27% | |

| Do you perform preoperative medical evaluations and medical consultation? | Yes | 96% | 91% | 96% | 96% | 92% | 94% |

| Which of the following describes your role in the care of surgical patients? | Traditional medical consultant | 33% | 28% | 28% | 30% | 24% | 29% |

| Comanagement (shared responsibility with surgeon) | 33% | 34% | 42% | 39% | 35% | 37% | |

| Attending of record with surgeon acting as consultant | 26% | 24% | 26% | 30% | 35% | 28% | |

| Do you have bedside ultrasound available in your daily practice? | Yes | 38% | 32% | 52% | 34% | 38% | 39% |

Participant Experience

Overall, participants rated the quality of the UHMC course highly (4.65; 15 scale). The neurology clinical domain (4.83) and clinical reasoning session (4.72) were the highest‐rated sessions. Compared to all UCSF CME course offerings between January 2010 and September 2012, the UHMC rated higher than the cumulative overall rating from those 227 courses (4.65 vs 4.44). For UCSF CME courses offered in 2011 and 2012, 78% of participants (n=11,447) reported a high or definite likelihood to change practice. For UHMC participants during the same time period (n=57), 98% reported a similar likelihood to change practice. Table 3 provides selected participant comments from their postcourse evaluations.

|

| Great pearls, broad ranging discussion of many controversial and common topics, and I loved the teaching format. |

| I thought the conception of the teaching model was really effectivehands‐on exams in small groups, each demonstrating a different part of the neurologic exam, followed by presentation and discussion, and ending in bedside rounds with the teaching faculty. |

| Excellent review of key topicswide variety of useful and practical points. Very high application value. |

| Great course. I'd take it again and again. It was a superb opportunity to review technique, equipment, and clinical decision making. |

| Overall outstanding course! Very informative and fun. Format was great. |

| Forward and clinically relevant. Like the bedside teaching and how they did it.The small size of the course and the close attention paid by the faculty teaching the course combined with the opportunity to see and examine patients in the hospital was outstanding. |

DISCUSSION

We developed an innovative CME program that brought participants to an academic health center for a participatory, hands‐on, and small‐group experience. They learned about topics relevant to today's hospitalists, rated the experience very highly, and reported a nearly unanimous likelihood to change their practice. Reflecting on our program's first 5 years, there were several lessons learned that may guide others committed to providing a similar CME experience.

First, hospital medicine is a dynamic field. Conducting a needs assessment to match clinical topics to what attendees required in their own practice was critical. Iterative changes from year to year reflected formal participant feedback as well as informal conversations with the teaching faculty. For instance, attendees were not only interested in the clinical topics but often wanted to see examples of clinical pathways, order sets, and other systems in place to improve care for patients with common conditions. Our participant presurvey also helped identify and reinforce the curricular topics that teaching faculty focused on each year. Being responsive to the changing needs of hospitalists and the environment is a crucial part of providing a relevant CME experience.

We also used an innovative approach to teaching, founded in adult and effective CME learning principles. CME activities are geared toward adult physicians, and studies of their effectiveness recommend that sessions should be interactive and utilize multiple modalities of learning.[12] When attendees actively participate and are provided an opportunity to practice skills, it may have a positive effect on patient outcomes.[13] All UHMC faculty were required to couple presentations of the latest evidence for clinical topics with small‐group and hands‐on learning modalities. This also required that we utilize a teaching faculty known for both their clinical expertise and teaching recognition. Together, the learning modalities and the teaching faculty likely accounted for the highly rated course experience and likelihood to change practice.

Finally, our course brought participants to an academic medical center and into the mix of clinical care as opposed to the more traditional hotel venue. This was necessary to deliver the curriculum as described, but also had the unexpected benefit of energizing the participants. Many had not been in a teaching setting since their residency training, and bringing them back into this milieu motivated them to learn and share their inspiration. As there are no published studies of CME experiences in the clinical environment, this observation is noteworthy and deserves to be explored and evaluated further.