User login

On March 21, 2010, the United States Congress passed the most comprehensive healthcare reform bill since the formation of Medicare. The legislation's greatest impact will be to improve access for nearly 50 million Americans who are presently uninsured. Yet the bill does little to tackle the fundamental problems of the payment and delivery systemsproblems that have resulted in major quality gaps, large numbers of medical errors, fragmented care, and backbreaking costs.

While these tough questions were mostly kicked down the road, the debate did bring many of the key questions and potential solutions into high relief. Our political leaders, pundits, and health policy scholars introduced or popularized a number of terms during the healthcare debates of 2009‐2010 (Table 1). I will attempt to place them in context and discuss their implications for future healthcare reform efforts.

|

| Value‐based purchasing |

| Bending the cost curve |

| Comparative effectiveness research (see also NICE) |

| Dartmouth atlas (see also McAllen, Texas) |

| Death panels (see also rationing) |

| Bundled payments |

| Accountable care organizations (see also Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, Geisinger; replaces HMOs) |

Some Context for the Healthcare Reform Debate

In our capitalistic economy, we make most purchases based on considerations of value: quality divided by cost. There are few among us wealthy enough to always buy the best product, or cheap enough to always buy the least expensive. Instead, we try to determine value when we purchase a restaurant meal, a house, or a vacation.

Healthcare has traditionally been the major exception to this rule, both because healthcare insurance has partly insulated consumers (patients or their proxies) from the cost consequences of their decisions, and because it is so difficult to determine the quality of healthcare. But, over the past 10 to 15 years, problems with both the numerator and denominator of this equation have created widespread recognition of the need for change.

In the numerator, we now appreciate that there are nearly 100,000 deaths per year from medical mistakes;1 that we deliver evidence‐based care only about half the time,2 and that our healthcare system is extraordinarily fragmented and chaotic. We also know that there are more than 40 million people without healthcare insurance, a uniquely American problem, since other industrialized countries manage to guarantee coverage.

This is the fundamental conundrum that needs to be addressed by healthcare reform: we have a system that produces surprisingly low‐quality, unreliable care at an exorbitant and ever‐increasing cost, and does so while leaving more than 1 out of 8 citizens without coverage. Although government is a large payer (through Medicare, Medicaid, the Veterans Affairs [VA] programs and others), most Americans receive healthcare coverage as an employee benefit; a smaller number pay for health insurance themselves. The government has a key role even in these nongovernment‐sponsored payment systems, by providing tax breaks for healthcare coverage, creating a regulatory framework, and often defining the market through its actions in its public programs.

The end result is that all the involved partiesgovernments, businesses, providers, and patientsare crying out for change. An observer of this situation feels compelled to invoke the popular version of Stein's Law: if a trend can't continue, it won't.

Bending the Cost Curve

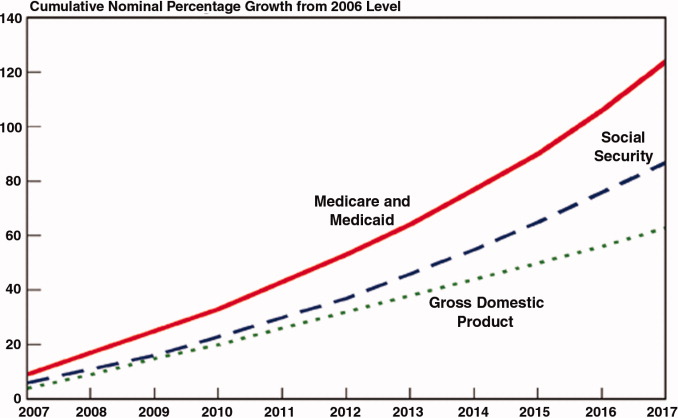

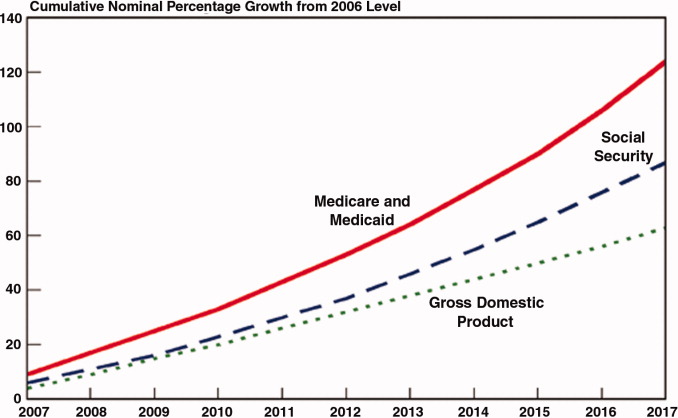

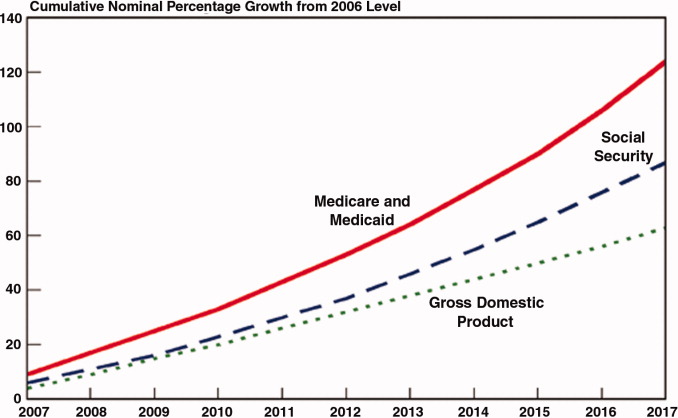

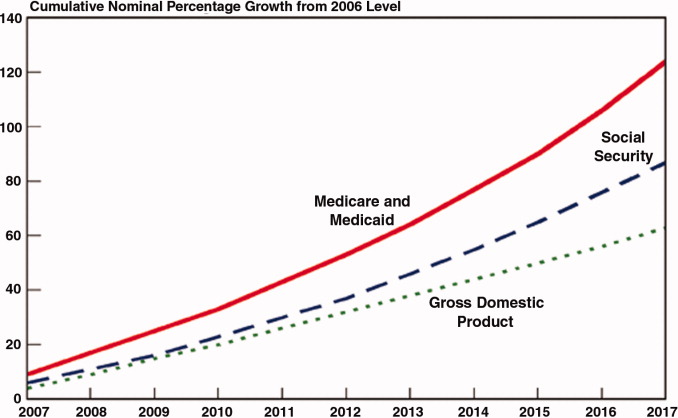

Everyone is now familiar with the scary trends (such as in Figure 1) demonstrating the unsustainable rate of healthcare inflation in the US, trends that are projected to lead to the insolvency of the Medicare Trust Fund within a decade. The term bending the cost curve implies that our solvency depends not on lowering total costs (a political impossibility), but rather on simply decreasing the rate of rise. There are only so many ways to do this.

The most attractive, of course, is to stop providing expensive care that adds no or little value in terms of patient outcomes. The term comparative effectiveness research (CER) emerged over the past few years to describe research that pits one approach against another (or, presumably, against no treatment) on both outcomes and cost.3 Obviously, one would favor the less expensive treatment if the efficacy were equal. However, the more common (and politically fraught) question is whether a more expensive but slightly better approach is worth its additional cost.

This, of course, makes complete sense in a world of limited resources, and some countries, mostly notably the United Kingdom, are using CER to inform healthcare coverage decisions. In the United Kingdom, the research is analyzed, and coverage recommendations made, by an organization called the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).4 While NICE appears to be working well, all signs indicate that the US political system is not ready for such an approach. In fact, although Medicare generally supports CER, most of the healthcare reform proposals considered by Congress explicitly prohibited Medicare from using CER results to influence payment decisions.

If an overall CER approach is too politically difficult for the US, how about focusing on 1 small segment of healthcare: expensive care at the end of life? Over the past 30 years, a group of Dartmouth researchers has examined the costs and quality of care across the entire country, demonstrating a ubiquitous pattern of highly variable costs (varying up to 2‐fold) that is unassociated with quality and outcomes (and sometimes even inversely associated).5 The findings, well known among healthcare researchers but relatively unknown by the public until recently, were brought to public attention by a 2009 New Yorker article that made the border town of McAllen, Texas the poster child for a medical culture that produces high costs without comparable benefits.6 The Dartmouth researchers, who publish their data in a document known as The Dartmouth Atlas, have found striking variations in care at the end of life. For example, even among academic medical centers (which presumably have similarly sick patient populations), the number of hospital days in the last 6 months of life varies strikingly: patients at New York University average 27.1 days, whereas those in my hospital average 11.5 days.7

So promoting better end‐of‐life carebeing sure that patients are aware of their options and that high‐quality palliative care is availableseemed like an obvious solution to part of our cost‐quality conundrum. Some early drafts of reform bills in Congress contained provisions to pay for physicians' time to discuss end‐of‐life options. This, of course, was caricaturized into the now famous Death Panelsproving that American political discourse is not yet mature enough to support realistic discussions about difficult subjects.8

It seems like having payers (government, insurance companies) make formal decisions about which services to cover (ie, rationing) is too hard. Is there another way to force these tough choices but do so without creating a political piata?

Encircling a Population

Rather than explicitly rationing care (using CER results, for example), another way of constraining costs is to place a population of patients on a fixed budget. There is evidence that provider organizations, working within such a budget (structured in a way that permits the providers to pocket any savings), are able to reorganize and change their practice style in a way that can cut costs.9 In the 1990s, we conducted a national experiment by promoting managed care, working through integrated delivery systems called Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) that received fixed, capitated payments for every patient. And, in fact, these organizations did cut overall costs.

The problem was that patients neither liked HMOs nor trusted that they were acting in their best interests. Ultimately, managed care became a less important delivery mechanism, and even patients who remained in HMOs had fewer constraints on their choices. Of course, the softening of the managed care market resulted in an uptick in healthcare inflation, contributing to our present predicament.

The concept of fixed payments has resurfaced, but with some modern twists. It appears that organizations that perform best on the Dartmouth measures (namely, they provide high quality care at lower costs) are generally large delivery systems with advanced information technology, strong primary care infrastructures, andprobably most importantlytight integration between physicians and the rest of the organization. During the healthcare debate, the organizations that received the most attention were the Mayo and Cleveland Clinics and the Geisinger system in central Pennsylvania. The problem is that the defining characteristic of these organizations (and others like them) is that they have been at this business of integrated care for more than 50 years! Can the model be emulated?

Two main policy changes have been promoted to try to achieve this integration: one is a change in payment structure, the other a change in organization. The first is known as bundlingin which multiple providers are reimbursed a single sum for all the care related to an episode of illness (such as a hospitalization and a 60‐ or 90‐day period afterwards). You will recognize this as a new form of capitation, but, rather than covering all of a patient's care, a more circumscribed version, focusing on a single illness or procedure. There is some evidence that bundling does reduce costs and may improve quality, by forcing hospitals, post‐acute care facilities, and doctors into collaborative arrangements (both to deliver care and, just as complex, to split the single payment without undue acrimony).10 Fisher et al.11 have promoted a new structure to deliver this kind of bundled care more effectively: The Accountable Care Organization (ACO), which is best thought of as a less ambitious, and potentially more virtual, incarnation of the HMO.

Interestingly, while many healthcare organizations have struggled to remake themselves in Mayo's image in preparation for upcoming pressures to form ACOs, some organizations with hospitalist programs need look no further than these programs to chart a course toward more effective physician‐hospital integration.12 Why? The majority of US hospitals now have hospitalists, and virtually all hospitalist programs receive support payments from their hospital (a sizable minority are on salary from the hospital). Hospitalists recognize that part of their value equation (which justifies the hospital support dollars) is that they help the hospital deliver higher quality care more efficiently. Because of this relationship, a well‐functioning hospitalist program can assume many of the attributes of an ACO, even in organizations with otherwise challenging physician‐hospital relations. It may be that hospitals and doctors need not look to Rochester, Minnesota or Danville, Pennsylvania for positive examples of physician‐hospital integration, but simply to their own local hospitalist groups.

The Bottom Line

While proponents of the Obama reform plan celebrate its passage, virtually all experts agree that it left fundamental problems with the healthcare system unaddressed. Although the 20092010 debate did not solve these problems, the new vocabulary introduced during the debateboth reasonable policy ideas like bundling and ACOs and cynical caricatures like death panelsare here to stay. Understanding these terms and the context that shaped them will be critical for hospitalists and other stakeholders interested in the future of the American healthcare system.

- ,,, eds.To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System.Washington DC:Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. National Academy Press,2000.

- ,,, et al.The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States.N Engl J Med.2003;348:2635–2645.

- ,.Health care reform and the need for comparative‐effectiveness research.N Engl J Med.2010;362:e6.

- .Saying no isn't NICE—the travails of Britain's National Institute for health and clinical excellence.N Engl J Med.2008;359:1977–1981.

- .Wrestling with variation: an interview with Jack Wennberg [interviewed by Fitzhugh Mullan].Health Aff (Millwood).2004; Suppl Web Exclsives:VAR73–80.

- .The cost conundrum. What a Texas town can teach us about health care.The New Yorker2009. Available at: http://www.newyorker. com/reporting/2009/06/01/090601fa_fact_gawande. Accessed February 2010.

- .Researchers find huge variations in end‐of‐life treatment.New York Times.2008. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/07/health/policy/07care.html?_r=1. Accessed February 2010.

- .Ending end‐of‐life phobia—a prescription for enlightened health care reform.N Engl J Med.2009. Available at: http://healthcarere form.nejm.org/?p=2580. Accessed February 2010.

- ,.The RAND Health Insurance Experiment and HMOs.Med Care.1990;28:191–200.

- ,,.Cost savings and physician responses to global bundled payments for Medicare heart bypass surgery.Health Care Fin Rev.1997;19:41–57.

- ,,,.Creating accountable care organizations: the extended hospital medical staff.Health Aff (Millwood).2007;26(1):w44–w57.

- . Hospitalists: a little slice of Mayo. Available at: http://community.the‐hospitalist.org/blogs/wachters_world/archive/2009/08/30/hospitalists‐a‐little‐slice‐of‐mayo.aspx. Accessed February 2010.

On March 21, 2010, the United States Congress passed the most comprehensive healthcare reform bill since the formation of Medicare. The legislation's greatest impact will be to improve access for nearly 50 million Americans who are presently uninsured. Yet the bill does little to tackle the fundamental problems of the payment and delivery systemsproblems that have resulted in major quality gaps, large numbers of medical errors, fragmented care, and backbreaking costs.

While these tough questions were mostly kicked down the road, the debate did bring many of the key questions and potential solutions into high relief. Our political leaders, pundits, and health policy scholars introduced or popularized a number of terms during the healthcare debates of 2009‐2010 (Table 1). I will attempt to place them in context and discuss their implications for future healthcare reform efforts.

|

| Value‐based purchasing |

| Bending the cost curve |

| Comparative effectiveness research (see also NICE) |

| Dartmouth atlas (see also McAllen, Texas) |

| Death panels (see also rationing) |

| Bundled payments |

| Accountable care organizations (see also Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, Geisinger; replaces HMOs) |

Some Context for the Healthcare Reform Debate

In our capitalistic economy, we make most purchases based on considerations of value: quality divided by cost. There are few among us wealthy enough to always buy the best product, or cheap enough to always buy the least expensive. Instead, we try to determine value when we purchase a restaurant meal, a house, or a vacation.

Healthcare has traditionally been the major exception to this rule, both because healthcare insurance has partly insulated consumers (patients or their proxies) from the cost consequences of their decisions, and because it is so difficult to determine the quality of healthcare. But, over the past 10 to 15 years, problems with both the numerator and denominator of this equation have created widespread recognition of the need for change.

In the numerator, we now appreciate that there are nearly 100,000 deaths per year from medical mistakes;1 that we deliver evidence‐based care only about half the time,2 and that our healthcare system is extraordinarily fragmented and chaotic. We also know that there are more than 40 million people without healthcare insurance, a uniquely American problem, since other industrialized countries manage to guarantee coverage.

This is the fundamental conundrum that needs to be addressed by healthcare reform: we have a system that produces surprisingly low‐quality, unreliable care at an exorbitant and ever‐increasing cost, and does so while leaving more than 1 out of 8 citizens without coverage. Although government is a large payer (through Medicare, Medicaid, the Veterans Affairs [VA] programs and others), most Americans receive healthcare coverage as an employee benefit; a smaller number pay for health insurance themselves. The government has a key role even in these nongovernment‐sponsored payment systems, by providing tax breaks for healthcare coverage, creating a regulatory framework, and often defining the market through its actions in its public programs.

The end result is that all the involved partiesgovernments, businesses, providers, and patientsare crying out for change. An observer of this situation feels compelled to invoke the popular version of Stein's Law: if a trend can't continue, it won't.

Bending the Cost Curve

Everyone is now familiar with the scary trends (such as in Figure 1) demonstrating the unsustainable rate of healthcare inflation in the US, trends that are projected to lead to the insolvency of the Medicare Trust Fund within a decade. The term bending the cost curve implies that our solvency depends not on lowering total costs (a political impossibility), but rather on simply decreasing the rate of rise. There are only so many ways to do this.

The most attractive, of course, is to stop providing expensive care that adds no or little value in terms of patient outcomes. The term comparative effectiveness research (CER) emerged over the past few years to describe research that pits one approach against another (or, presumably, against no treatment) on both outcomes and cost.3 Obviously, one would favor the less expensive treatment if the efficacy were equal. However, the more common (and politically fraught) question is whether a more expensive but slightly better approach is worth its additional cost.

This, of course, makes complete sense in a world of limited resources, and some countries, mostly notably the United Kingdom, are using CER to inform healthcare coverage decisions. In the United Kingdom, the research is analyzed, and coverage recommendations made, by an organization called the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).4 While NICE appears to be working well, all signs indicate that the US political system is not ready for such an approach. In fact, although Medicare generally supports CER, most of the healthcare reform proposals considered by Congress explicitly prohibited Medicare from using CER results to influence payment decisions.

If an overall CER approach is too politically difficult for the US, how about focusing on 1 small segment of healthcare: expensive care at the end of life? Over the past 30 years, a group of Dartmouth researchers has examined the costs and quality of care across the entire country, demonstrating a ubiquitous pattern of highly variable costs (varying up to 2‐fold) that is unassociated with quality and outcomes (and sometimes even inversely associated).5 The findings, well known among healthcare researchers but relatively unknown by the public until recently, were brought to public attention by a 2009 New Yorker article that made the border town of McAllen, Texas the poster child for a medical culture that produces high costs without comparable benefits.6 The Dartmouth researchers, who publish their data in a document known as The Dartmouth Atlas, have found striking variations in care at the end of life. For example, even among academic medical centers (which presumably have similarly sick patient populations), the number of hospital days in the last 6 months of life varies strikingly: patients at New York University average 27.1 days, whereas those in my hospital average 11.5 days.7

So promoting better end‐of‐life carebeing sure that patients are aware of their options and that high‐quality palliative care is availableseemed like an obvious solution to part of our cost‐quality conundrum. Some early drafts of reform bills in Congress contained provisions to pay for physicians' time to discuss end‐of‐life options. This, of course, was caricaturized into the now famous Death Panelsproving that American political discourse is not yet mature enough to support realistic discussions about difficult subjects.8

It seems like having payers (government, insurance companies) make formal decisions about which services to cover (ie, rationing) is too hard. Is there another way to force these tough choices but do so without creating a political piata?

Encircling a Population

Rather than explicitly rationing care (using CER results, for example), another way of constraining costs is to place a population of patients on a fixed budget. There is evidence that provider organizations, working within such a budget (structured in a way that permits the providers to pocket any savings), are able to reorganize and change their practice style in a way that can cut costs.9 In the 1990s, we conducted a national experiment by promoting managed care, working through integrated delivery systems called Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) that received fixed, capitated payments for every patient. And, in fact, these organizations did cut overall costs.

The problem was that patients neither liked HMOs nor trusted that they were acting in their best interests. Ultimately, managed care became a less important delivery mechanism, and even patients who remained in HMOs had fewer constraints on their choices. Of course, the softening of the managed care market resulted in an uptick in healthcare inflation, contributing to our present predicament.

The concept of fixed payments has resurfaced, but with some modern twists. It appears that organizations that perform best on the Dartmouth measures (namely, they provide high quality care at lower costs) are generally large delivery systems with advanced information technology, strong primary care infrastructures, andprobably most importantlytight integration between physicians and the rest of the organization. During the healthcare debate, the organizations that received the most attention were the Mayo and Cleveland Clinics and the Geisinger system in central Pennsylvania. The problem is that the defining characteristic of these organizations (and others like them) is that they have been at this business of integrated care for more than 50 years! Can the model be emulated?

Two main policy changes have been promoted to try to achieve this integration: one is a change in payment structure, the other a change in organization. The first is known as bundlingin which multiple providers are reimbursed a single sum for all the care related to an episode of illness (such as a hospitalization and a 60‐ or 90‐day period afterwards). You will recognize this as a new form of capitation, but, rather than covering all of a patient's care, a more circumscribed version, focusing on a single illness or procedure. There is some evidence that bundling does reduce costs and may improve quality, by forcing hospitals, post‐acute care facilities, and doctors into collaborative arrangements (both to deliver care and, just as complex, to split the single payment without undue acrimony).10 Fisher et al.11 have promoted a new structure to deliver this kind of bundled care more effectively: The Accountable Care Organization (ACO), which is best thought of as a less ambitious, and potentially more virtual, incarnation of the HMO.

Interestingly, while many healthcare organizations have struggled to remake themselves in Mayo's image in preparation for upcoming pressures to form ACOs, some organizations with hospitalist programs need look no further than these programs to chart a course toward more effective physician‐hospital integration.12 Why? The majority of US hospitals now have hospitalists, and virtually all hospitalist programs receive support payments from their hospital (a sizable minority are on salary from the hospital). Hospitalists recognize that part of their value equation (which justifies the hospital support dollars) is that they help the hospital deliver higher quality care more efficiently. Because of this relationship, a well‐functioning hospitalist program can assume many of the attributes of an ACO, even in organizations with otherwise challenging physician‐hospital relations. It may be that hospitals and doctors need not look to Rochester, Minnesota or Danville, Pennsylvania for positive examples of physician‐hospital integration, but simply to their own local hospitalist groups.

The Bottom Line

While proponents of the Obama reform plan celebrate its passage, virtually all experts agree that it left fundamental problems with the healthcare system unaddressed. Although the 20092010 debate did not solve these problems, the new vocabulary introduced during the debateboth reasonable policy ideas like bundling and ACOs and cynical caricatures like death panelsare here to stay. Understanding these terms and the context that shaped them will be critical for hospitalists and other stakeholders interested in the future of the American healthcare system.

On March 21, 2010, the United States Congress passed the most comprehensive healthcare reform bill since the formation of Medicare. The legislation's greatest impact will be to improve access for nearly 50 million Americans who are presently uninsured. Yet the bill does little to tackle the fundamental problems of the payment and delivery systemsproblems that have resulted in major quality gaps, large numbers of medical errors, fragmented care, and backbreaking costs.

While these tough questions were mostly kicked down the road, the debate did bring many of the key questions and potential solutions into high relief. Our political leaders, pundits, and health policy scholars introduced or popularized a number of terms during the healthcare debates of 2009‐2010 (Table 1). I will attempt to place them in context and discuss their implications for future healthcare reform efforts.

|

| Value‐based purchasing |

| Bending the cost curve |

| Comparative effectiveness research (see also NICE) |

| Dartmouth atlas (see also McAllen, Texas) |

| Death panels (see also rationing) |

| Bundled payments |

| Accountable care organizations (see also Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, Geisinger; replaces HMOs) |

Some Context for the Healthcare Reform Debate

In our capitalistic economy, we make most purchases based on considerations of value: quality divided by cost. There are few among us wealthy enough to always buy the best product, or cheap enough to always buy the least expensive. Instead, we try to determine value when we purchase a restaurant meal, a house, or a vacation.

Healthcare has traditionally been the major exception to this rule, both because healthcare insurance has partly insulated consumers (patients or their proxies) from the cost consequences of their decisions, and because it is so difficult to determine the quality of healthcare. But, over the past 10 to 15 years, problems with both the numerator and denominator of this equation have created widespread recognition of the need for change.

In the numerator, we now appreciate that there are nearly 100,000 deaths per year from medical mistakes;1 that we deliver evidence‐based care only about half the time,2 and that our healthcare system is extraordinarily fragmented and chaotic. We also know that there are more than 40 million people without healthcare insurance, a uniquely American problem, since other industrialized countries manage to guarantee coverage.

This is the fundamental conundrum that needs to be addressed by healthcare reform: we have a system that produces surprisingly low‐quality, unreliable care at an exorbitant and ever‐increasing cost, and does so while leaving more than 1 out of 8 citizens without coverage. Although government is a large payer (through Medicare, Medicaid, the Veterans Affairs [VA] programs and others), most Americans receive healthcare coverage as an employee benefit; a smaller number pay for health insurance themselves. The government has a key role even in these nongovernment‐sponsored payment systems, by providing tax breaks for healthcare coverage, creating a regulatory framework, and often defining the market through its actions in its public programs.

The end result is that all the involved partiesgovernments, businesses, providers, and patientsare crying out for change. An observer of this situation feels compelled to invoke the popular version of Stein's Law: if a trend can't continue, it won't.

Bending the Cost Curve

Everyone is now familiar with the scary trends (such as in Figure 1) demonstrating the unsustainable rate of healthcare inflation in the US, trends that are projected to lead to the insolvency of the Medicare Trust Fund within a decade. The term bending the cost curve implies that our solvency depends not on lowering total costs (a political impossibility), but rather on simply decreasing the rate of rise. There are only so many ways to do this.

The most attractive, of course, is to stop providing expensive care that adds no or little value in terms of patient outcomes. The term comparative effectiveness research (CER) emerged over the past few years to describe research that pits one approach against another (or, presumably, against no treatment) on both outcomes and cost.3 Obviously, one would favor the less expensive treatment if the efficacy were equal. However, the more common (and politically fraught) question is whether a more expensive but slightly better approach is worth its additional cost.

This, of course, makes complete sense in a world of limited resources, and some countries, mostly notably the United Kingdom, are using CER to inform healthcare coverage decisions. In the United Kingdom, the research is analyzed, and coverage recommendations made, by an organization called the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).4 While NICE appears to be working well, all signs indicate that the US political system is not ready for such an approach. In fact, although Medicare generally supports CER, most of the healthcare reform proposals considered by Congress explicitly prohibited Medicare from using CER results to influence payment decisions.

If an overall CER approach is too politically difficult for the US, how about focusing on 1 small segment of healthcare: expensive care at the end of life? Over the past 30 years, a group of Dartmouth researchers has examined the costs and quality of care across the entire country, demonstrating a ubiquitous pattern of highly variable costs (varying up to 2‐fold) that is unassociated with quality and outcomes (and sometimes even inversely associated).5 The findings, well known among healthcare researchers but relatively unknown by the public until recently, were brought to public attention by a 2009 New Yorker article that made the border town of McAllen, Texas the poster child for a medical culture that produces high costs without comparable benefits.6 The Dartmouth researchers, who publish their data in a document known as The Dartmouth Atlas, have found striking variations in care at the end of life. For example, even among academic medical centers (which presumably have similarly sick patient populations), the number of hospital days in the last 6 months of life varies strikingly: patients at New York University average 27.1 days, whereas those in my hospital average 11.5 days.7

So promoting better end‐of‐life carebeing sure that patients are aware of their options and that high‐quality palliative care is availableseemed like an obvious solution to part of our cost‐quality conundrum. Some early drafts of reform bills in Congress contained provisions to pay for physicians' time to discuss end‐of‐life options. This, of course, was caricaturized into the now famous Death Panelsproving that American political discourse is not yet mature enough to support realistic discussions about difficult subjects.8

It seems like having payers (government, insurance companies) make formal decisions about which services to cover (ie, rationing) is too hard. Is there another way to force these tough choices but do so without creating a political piata?

Encircling a Population

Rather than explicitly rationing care (using CER results, for example), another way of constraining costs is to place a population of patients on a fixed budget. There is evidence that provider organizations, working within such a budget (structured in a way that permits the providers to pocket any savings), are able to reorganize and change their practice style in a way that can cut costs.9 In the 1990s, we conducted a national experiment by promoting managed care, working through integrated delivery systems called Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) that received fixed, capitated payments for every patient. And, in fact, these organizations did cut overall costs.

The problem was that patients neither liked HMOs nor trusted that they were acting in their best interests. Ultimately, managed care became a less important delivery mechanism, and even patients who remained in HMOs had fewer constraints on their choices. Of course, the softening of the managed care market resulted in an uptick in healthcare inflation, contributing to our present predicament.

The concept of fixed payments has resurfaced, but with some modern twists. It appears that organizations that perform best on the Dartmouth measures (namely, they provide high quality care at lower costs) are generally large delivery systems with advanced information technology, strong primary care infrastructures, andprobably most importantlytight integration between physicians and the rest of the organization. During the healthcare debate, the organizations that received the most attention were the Mayo and Cleveland Clinics and the Geisinger system in central Pennsylvania. The problem is that the defining characteristic of these organizations (and others like them) is that they have been at this business of integrated care for more than 50 years! Can the model be emulated?

Two main policy changes have been promoted to try to achieve this integration: one is a change in payment structure, the other a change in organization. The first is known as bundlingin which multiple providers are reimbursed a single sum for all the care related to an episode of illness (such as a hospitalization and a 60‐ or 90‐day period afterwards). You will recognize this as a new form of capitation, but, rather than covering all of a patient's care, a more circumscribed version, focusing on a single illness or procedure. There is some evidence that bundling does reduce costs and may improve quality, by forcing hospitals, post‐acute care facilities, and doctors into collaborative arrangements (both to deliver care and, just as complex, to split the single payment without undue acrimony).10 Fisher et al.11 have promoted a new structure to deliver this kind of bundled care more effectively: The Accountable Care Organization (ACO), which is best thought of as a less ambitious, and potentially more virtual, incarnation of the HMO.

Interestingly, while many healthcare organizations have struggled to remake themselves in Mayo's image in preparation for upcoming pressures to form ACOs, some organizations with hospitalist programs need look no further than these programs to chart a course toward more effective physician‐hospital integration.12 Why? The majority of US hospitals now have hospitalists, and virtually all hospitalist programs receive support payments from their hospital (a sizable minority are on salary from the hospital). Hospitalists recognize that part of their value equation (which justifies the hospital support dollars) is that they help the hospital deliver higher quality care more efficiently. Because of this relationship, a well‐functioning hospitalist program can assume many of the attributes of an ACO, even in organizations with otherwise challenging physician‐hospital relations. It may be that hospitals and doctors need not look to Rochester, Minnesota or Danville, Pennsylvania for positive examples of physician‐hospital integration, but simply to their own local hospitalist groups.

The Bottom Line

While proponents of the Obama reform plan celebrate its passage, virtually all experts agree that it left fundamental problems with the healthcare system unaddressed. Although the 20092010 debate did not solve these problems, the new vocabulary introduced during the debateboth reasonable policy ideas like bundling and ACOs and cynical caricatures like death panelsare here to stay. Understanding these terms and the context that shaped them will be critical for hospitalists and other stakeholders interested in the future of the American healthcare system.

- ,,, eds.To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System.Washington DC:Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. National Academy Press,2000.

- ,,, et al.The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States.N Engl J Med.2003;348:2635–2645.

- ,.Health care reform and the need for comparative‐effectiveness research.N Engl J Med.2010;362:e6.

- .Saying no isn't NICE—the travails of Britain's National Institute for health and clinical excellence.N Engl J Med.2008;359:1977–1981.

- .Wrestling with variation: an interview with Jack Wennberg [interviewed by Fitzhugh Mullan].Health Aff (Millwood).2004; Suppl Web Exclsives:VAR73–80.

- .The cost conundrum. What a Texas town can teach us about health care.The New Yorker2009. Available at: http://www.newyorker. com/reporting/2009/06/01/090601fa_fact_gawande. Accessed February 2010.

- .Researchers find huge variations in end‐of‐life treatment.New York Times.2008. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/07/health/policy/07care.html?_r=1. Accessed February 2010.

- .Ending end‐of‐life phobia—a prescription for enlightened health care reform.N Engl J Med.2009. Available at: http://healthcarere form.nejm.org/?p=2580. Accessed February 2010.

- ,.The RAND Health Insurance Experiment and HMOs.Med Care.1990;28:191–200.

- ,,.Cost savings and physician responses to global bundled payments for Medicare heart bypass surgery.Health Care Fin Rev.1997;19:41–57.

- ,,,.Creating accountable care organizations: the extended hospital medical staff.Health Aff (Millwood).2007;26(1):w44–w57.

- . Hospitalists: a little slice of Mayo. Available at: http://community.the‐hospitalist.org/blogs/wachters_world/archive/2009/08/30/hospitalists‐a‐little‐slice‐of‐mayo.aspx. Accessed February 2010.

- ,,, eds.To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System.Washington DC:Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. National Academy Press,2000.

- ,,, et al.The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States.N Engl J Med.2003;348:2635–2645.

- ,.Health care reform and the need for comparative‐effectiveness research.N Engl J Med.2010;362:e6.

- .Saying no isn't NICE—the travails of Britain's National Institute for health and clinical excellence.N Engl J Med.2008;359:1977–1981.

- .Wrestling with variation: an interview with Jack Wennberg [interviewed by Fitzhugh Mullan].Health Aff (Millwood).2004; Suppl Web Exclsives:VAR73–80.

- .The cost conundrum. What a Texas town can teach us about health care.The New Yorker2009. Available at: http://www.newyorker. com/reporting/2009/06/01/090601fa_fact_gawande. Accessed February 2010.

- .Researchers find huge variations in end‐of‐life treatment.New York Times.2008. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/07/health/policy/07care.html?_r=1. Accessed February 2010.

- .Ending end‐of‐life phobia—a prescription for enlightened health care reform.N Engl J Med.2009. Available at: http://healthcarere form.nejm.org/?p=2580. Accessed February 2010.

- ,.The RAND Health Insurance Experiment and HMOs.Med Care.1990;28:191–200.

- ,,.Cost savings and physician responses to global bundled payments for Medicare heart bypass surgery.Health Care Fin Rev.1997;19:41–57.

- ,,,.Creating accountable care organizations: the extended hospital medical staff.Health Aff (Millwood).2007;26(1):w44–w57.

- . Hospitalists: a little slice of Mayo. Available at: http://community.the‐hospitalist.org/blogs/wachters_world/archive/2009/08/30/hospitalists‐a‐little‐slice‐of‐mayo.aspx. Accessed February 2010.