User login

Monotherapy as good as combo for antibiotic-resistant infections in low-risk patients

VIENNA – A single, well-targeted antibiotic may be enough to effectively combat serous bloodstream infections in patients who have a low baseline mortality risk.

Among these patients, overall mortality was similar among those receiving a single antibiotic and those getting multiple antibiotics (35% vs. 41%). Patients with a high baseline mortality risk, however, did experience a significant 44% survival benefit when treated with a combination regimen, Jesus Rodríguez-Baño, MD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

The finding is important when considering the ever-increasing imperative of antibiotic stewardship, Dr. Rodríguez-Baño said in an interview.

“In areas where these pathogens are common, particularly in intensive care units, where they can become epidemic and infect many patients, the overuse of combination therapy will be fueling the problem,” said Dr. Rodríguez-Baño, head of infectious diseases and clinical microbiology at the University Hospital Virgin Macarena, Seville, Spain. “This is a way to avoid the overuse of some broad-spectrum antibiotics. Selecting the patients who should not receive combination therapy may significantly reduce the total consumption” on a unit.

The retrospective study, dubbed INCREMENT, was conducted at 37 hospitals in 10 countries. It enrolled patients with bloodstream infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase- or carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Dr. Rodríguez-Baño reported results for 437 patients whose infections were caused by the carbapenemase-producing strain.

It was simultaneously published in Lancet Infectious Diseases (Lancet Inf Dis 2017; DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30228-1).

These patients were a mean of 66 years old; most (60%) were male. The primary infective agent was Klebsiella pneumonia (86%); most infections were nosocomial. The origin of infections varied, but most (80%) arose from places other than the urinary or biliary tract. Sources were vascular catheters, pneumonia, intraabdominal, and skin and soft tissue. About half of the patients were in severe sepsis or septic shock when treated.

The group was first divided into those who received appropriate or inappropriate therapy (78% vs. 22%). Appropriate therapy was considered to be the early administration of a drug that could effectively target the infective organism. Next, those who got appropriate therapy were parsed by whether they received mono- or combination therapy (61%, 39%). Finally, these patients were stratified by a specially designed mortality risk score, the INCREMENT Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) Mortality Score (Mayo Clinic Proceedings. doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.06.024).

- Severe sepsis or shock at presentation (5 points)

- Pitt score of 6 or more (4 points)

- Charlson comorbidity index of 2 or more (3 points)

- Source of bloodstream infection other than urinary or biliary tract (3 points)

- Inappropriate empirical therapy and inappropriate early targeted therapy (2 points)

Patients were considered low risk if they had a score of 0-7, and high of they had a score of 8 or more.

The risk assessment took is quick, easy to figure, and extremely important, Dr. Rodríguez-Baño noted. “This is a very easy-to-use tool that can help us make many patient management decisions. All of the information is already available in the patient’s chart, so it doesn’t require any additional assessments. It’s a very good way to individualize treatment.”

In the initial analysis, all-cause mortality at 30 days was 22% lower among patients who received appropriate early therapy than those who did not (38.5% vs. 60.6%). This translated to a 55% decrease in the risk of death (HR 0.45 in the fully adjusted model).

The investigators next turned their attention toward the group that received appropriate therapy. All-cause 30-day mortality was 41% in those who got monotherapy and 34.8% among those who got combination therapy..

Finally, this group was stratified according to the INCREMENT-CPE mortality risk score.

In the low-risk category, combination therapy did not confer a survival advantage over monotherapy. Death occurred in 20% of those getting monotherapy and 24% receiving combination treatment – not a significant difference (HR 1.21).

Combination therapy did, however, confer a significant survival benefit in the high-risk group. Death occurred in 62% of those receiving monotherapy and 48% of those receiving combination therapy – a 44% risk reduction (HR 0.56).

As long as they were appropriately targeted against the infective organism, all drugs used in the high-mortality risk group were similarly effective at reducing the risk of death. Compared to colistin monotherapy, a combination that included tigecycline reduced the risk of death by 55% (HR 0.45); combination with aminoglycosides by 58% (HR 0.42); and combination with carbapenems by 44% (HR 0.56).

A secondary analysis of this group determined that time was a critical factor in survival. Each day delay after day 2 significantly increased the risk of death, Dr. Rodríguez-Baño said. This 48-hour period gives clinicians a chance to wait for the culture and antibiogram to return, and then choose and initiate the best treatment. Before the results come back, empiric antibiotic therapy is appropriate, but changes should be made immediately after the results come back.

“We tend to think we must give the very best antibiotic at the very first moment that we see a patient with a serious infection,” he said. “But what we found is that it’s not critical to give the perfect antibiotic on the first day. It is critical, however, to give the correct one once you know which bacteria is causing the infection. Since it takes 48 hours for those results to come back, this is perfect timing.”

INCREMENT was funded in large part by the Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases. Dr. Rodríguez-Baño has been a scientific advisor for Merck, AstraZeneca, and InfectoPharm.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

VIENNA – A single, well-targeted antibiotic may be enough to effectively combat serous bloodstream infections in patients who have a low baseline mortality risk.

Among these patients, overall mortality was similar among those receiving a single antibiotic and those getting multiple antibiotics (35% vs. 41%). Patients with a high baseline mortality risk, however, did experience a significant 44% survival benefit when treated with a combination regimen, Jesus Rodríguez-Baño, MD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

The finding is important when considering the ever-increasing imperative of antibiotic stewardship, Dr. Rodríguez-Baño said in an interview.

“In areas where these pathogens are common, particularly in intensive care units, where they can become epidemic and infect many patients, the overuse of combination therapy will be fueling the problem,” said Dr. Rodríguez-Baño, head of infectious diseases and clinical microbiology at the University Hospital Virgin Macarena, Seville, Spain. “This is a way to avoid the overuse of some broad-spectrum antibiotics. Selecting the patients who should not receive combination therapy may significantly reduce the total consumption” on a unit.

The retrospective study, dubbed INCREMENT, was conducted at 37 hospitals in 10 countries. It enrolled patients with bloodstream infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase- or carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Dr. Rodríguez-Baño reported results for 437 patients whose infections were caused by the carbapenemase-producing strain.

It was simultaneously published in Lancet Infectious Diseases (Lancet Inf Dis 2017; DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30228-1).

These patients were a mean of 66 years old; most (60%) were male. The primary infective agent was Klebsiella pneumonia (86%); most infections were nosocomial. The origin of infections varied, but most (80%) arose from places other than the urinary or biliary tract. Sources were vascular catheters, pneumonia, intraabdominal, and skin and soft tissue. About half of the patients were in severe sepsis or septic shock when treated.

The group was first divided into those who received appropriate or inappropriate therapy (78% vs. 22%). Appropriate therapy was considered to be the early administration of a drug that could effectively target the infective organism. Next, those who got appropriate therapy were parsed by whether they received mono- or combination therapy (61%, 39%). Finally, these patients were stratified by a specially designed mortality risk score, the INCREMENT Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) Mortality Score (Mayo Clinic Proceedings. doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.06.024).

- Severe sepsis or shock at presentation (5 points)

- Pitt score of 6 or more (4 points)

- Charlson comorbidity index of 2 or more (3 points)

- Source of bloodstream infection other than urinary or biliary tract (3 points)

- Inappropriate empirical therapy and inappropriate early targeted therapy (2 points)

Patients were considered low risk if they had a score of 0-7, and high of they had a score of 8 or more.

The risk assessment took is quick, easy to figure, and extremely important, Dr. Rodríguez-Baño noted. “This is a very easy-to-use tool that can help us make many patient management decisions. All of the information is already available in the patient’s chart, so it doesn’t require any additional assessments. It’s a very good way to individualize treatment.”

In the initial analysis, all-cause mortality at 30 days was 22% lower among patients who received appropriate early therapy than those who did not (38.5% vs. 60.6%). This translated to a 55% decrease in the risk of death (HR 0.45 in the fully adjusted model).

The investigators next turned their attention toward the group that received appropriate therapy. All-cause 30-day mortality was 41% in those who got monotherapy and 34.8% among those who got combination therapy..

Finally, this group was stratified according to the INCREMENT-CPE mortality risk score.

In the low-risk category, combination therapy did not confer a survival advantage over monotherapy. Death occurred in 20% of those getting monotherapy and 24% receiving combination treatment – not a significant difference (HR 1.21).

Combination therapy did, however, confer a significant survival benefit in the high-risk group. Death occurred in 62% of those receiving monotherapy and 48% of those receiving combination therapy – a 44% risk reduction (HR 0.56).

As long as they were appropriately targeted against the infective organism, all drugs used in the high-mortality risk group were similarly effective at reducing the risk of death. Compared to colistin monotherapy, a combination that included tigecycline reduced the risk of death by 55% (HR 0.45); combination with aminoglycosides by 58% (HR 0.42); and combination with carbapenems by 44% (HR 0.56).

A secondary analysis of this group determined that time was a critical factor in survival. Each day delay after day 2 significantly increased the risk of death, Dr. Rodríguez-Baño said. This 48-hour period gives clinicians a chance to wait for the culture and antibiogram to return, and then choose and initiate the best treatment. Before the results come back, empiric antibiotic therapy is appropriate, but changes should be made immediately after the results come back.

“We tend to think we must give the very best antibiotic at the very first moment that we see a patient with a serious infection,” he said. “But what we found is that it’s not critical to give the perfect antibiotic on the first day. It is critical, however, to give the correct one once you know which bacteria is causing the infection. Since it takes 48 hours for those results to come back, this is perfect timing.”

INCREMENT was funded in large part by the Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases. Dr. Rodríguez-Baño has been a scientific advisor for Merck, AstraZeneca, and InfectoPharm.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

VIENNA – A single, well-targeted antibiotic may be enough to effectively combat serous bloodstream infections in patients who have a low baseline mortality risk.

Among these patients, overall mortality was similar among those receiving a single antibiotic and those getting multiple antibiotics (35% vs. 41%). Patients with a high baseline mortality risk, however, did experience a significant 44% survival benefit when treated with a combination regimen, Jesus Rodríguez-Baño, MD, said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress.

The finding is important when considering the ever-increasing imperative of antibiotic stewardship, Dr. Rodríguez-Baño said in an interview.

“In areas where these pathogens are common, particularly in intensive care units, where they can become epidemic and infect many patients, the overuse of combination therapy will be fueling the problem,” said Dr. Rodríguez-Baño, head of infectious diseases and clinical microbiology at the University Hospital Virgin Macarena, Seville, Spain. “This is a way to avoid the overuse of some broad-spectrum antibiotics. Selecting the patients who should not receive combination therapy may significantly reduce the total consumption” on a unit.

The retrospective study, dubbed INCREMENT, was conducted at 37 hospitals in 10 countries. It enrolled patients with bloodstream infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase- or carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Dr. Rodríguez-Baño reported results for 437 patients whose infections were caused by the carbapenemase-producing strain.

It was simultaneously published in Lancet Infectious Diseases (Lancet Inf Dis 2017; DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30228-1).

These patients were a mean of 66 years old; most (60%) were male. The primary infective agent was Klebsiella pneumonia (86%); most infections were nosocomial. The origin of infections varied, but most (80%) arose from places other than the urinary or biliary tract. Sources were vascular catheters, pneumonia, intraabdominal, and skin and soft tissue. About half of the patients were in severe sepsis or septic shock when treated.

The group was first divided into those who received appropriate or inappropriate therapy (78% vs. 22%). Appropriate therapy was considered to be the early administration of a drug that could effectively target the infective organism. Next, those who got appropriate therapy were parsed by whether they received mono- or combination therapy (61%, 39%). Finally, these patients were stratified by a specially designed mortality risk score, the INCREMENT Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) Mortality Score (Mayo Clinic Proceedings. doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.06.024).

- Severe sepsis or shock at presentation (5 points)

- Pitt score of 6 or more (4 points)

- Charlson comorbidity index of 2 or more (3 points)

- Source of bloodstream infection other than urinary or biliary tract (3 points)

- Inappropriate empirical therapy and inappropriate early targeted therapy (2 points)

Patients were considered low risk if they had a score of 0-7, and high of they had a score of 8 or more.

The risk assessment took is quick, easy to figure, and extremely important, Dr. Rodríguez-Baño noted. “This is a very easy-to-use tool that can help us make many patient management decisions. All of the information is already available in the patient’s chart, so it doesn’t require any additional assessments. It’s a very good way to individualize treatment.”

In the initial analysis, all-cause mortality at 30 days was 22% lower among patients who received appropriate early therapy than those who did not (38.5% vs. 60.6%). This translated to a 55% decrease in the risk of death (HR 0.45 in the fully adjusted model).

The investigators next turned their attention toward the group that received appropriate therapy. All-cause 30-day mortality was 41% in those who got monotherapy and 34.8% among those who got combination therapy..

Finally, this group was stratified according to the INCREMENT-CPE mortality risk score.

In the low-risk category, combination therapy did not confer a survival advantage over monotherapy. Death occurred in 20% of those getting monotherapy and 24% receiving combination treatment – not a significant difference (HR 1.21).

Combination therapy did, however, confer a significant survival benefit in the high-risk group. Death occurred in 62% of those receiving monotherapy and 48% of those receiving combination therapy – a 44% risk reduction (HR 0.56).

As long as they were appropriately targeted against the infective organism, all drugs used in the high-mortality risk group were similarly effective at reducing the risk of death. Compared to colistin monotherapy, a combination that included tigecycline reduced the risk of death by 55% (HR 0.45); combination with aminoglycosides by 58% (HR 0.42); and combination with carbapenems by 44% (HR 0.56).

A secondary analysis of this group determined that time was a critical factor in survival. Each day delay after day 2 significantly increased the risk of death, Dr. Rodríguez-Baño said. This 48-hour period gives clinicians a chance to wait for the culture and antibiogram to return, and then choose and initiate the best treatment. Before the results come back, empiric antibiotic therapy is appropriate, but changes should be made immediately after the results come back.

“We tend to think we must give the very best antibiotic at the very first moment that we see a patient with a serious infection,” he said. “But what we found is that it’s not critical to give the perfect antibiotic on the first day. It is critical, however, to give the correct one once you know which bacteria is causing the infection. Since it takes 48 hours for those results to come back, this is perfect timing.”

INCREMENT was funded in large part by the Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases. Dr. Rodríguez-Baño has been a scientific advisor for Merck, AstraZeneca, and InfectoPharm.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among these patients, correctly targeted monotherapy decreased the risk of death by 44% – just about the same risk reduction as conferred by combination therapy.

Data source: The INCREMENT retrospective study comprised 437 patients.

Disclosures: INCREMENT was funded in large part by the Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases. Dr. Rodríguez-Baño has been a scientific advisor for Merck, AstraZeneca, and InfectoPharm.

Plazomicin beats gold standard antibiotics in complex, gram-negative bacterial infections

VIENNA – An investigational antibiotic effective against several types of gram-negative antibiotic-resistant bacteria has proved its mettle against serious infections of the urinary tract, respiratory tract, and bloodstream.

Plazomicin (Achaogen, San Francisco) posted good results in two phase III studies, handily besting comparator drugs considered gold standard for treating complicated urinary tract infections and pyelonephritis, as well as bloodstream infections and hospital- and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia.

Both the EPIC (Evaluating Plazomicin In cUTI) and CARE (Combating Antibiotic Resistant Enterobacteriaceae) trials have provided enough positive data for the company to move forward with a new drug application later this year. The company also plans to seek European Medicines Agency approval in 2018.

Plazomicin is an aminoglycoside that has been modified with several side chains that block aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes, Daniel Cloutier, PhD, principal clinical scientist of Achaogen said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Disease annual congress.

“Aminoglycoside enzymes tend to travel along with beta-lactamases and carbapenemases as well, so this drug retains potent bactericidal activity against extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, and aminoglycoside-resistant Enterobacteriaceae,” said Dr. Cloutier, who presented the results of the EPIC trial. The drug is given once-daily as a 30-minute intravenous infusion.

EPIC enrolled 609 adult patients with complicated urinary tract infections or acute pyelonephritis; Dr. Cloutier presented a modified intent-to-treat analysis comprising 388 of these. They were randomized to plazomicin 15 mg/kg every 25 hours or to IV meropenem 1 gram every 24 hours. Treatment proceeded for 4-7 days, after which patients could step down to oral therapy (levofloxacin 500 m/day), for a total of 7-10 days of treatment. About 80% of patients had both IV and oral therapy. At 15-19 days from the first dose, patients had a test of cure; at 24-32 days from first dose, they returned for a safety follow-up.

Patients were a mean of 60 years old. About 60% had a complicated UTI; the rest had acute pyelonephritis. About 35% had a mean creatinine clearance of more than 30-60 mL/min; the rest had a mean clearance of more than 60-90 mL/min.

The primary efficacy endpoint was microbial eradication. Plazomicin performed significantly better than meropenem in this measure (87% vs.72%), a mean difference of about 15%. Patients with pyelonephritis responded marginally better than those with complicated UTI, both groups favoring plazomicin (mean treatment differences of 17.5% and 13.7%, respectively).

The results were similar when the investigators examined groups by whether they needed oral step-down treatment. In the IV-only groups, plazomicin bested meropenem in microbiological eradication by almost 19% (84% vs. 65%). In the IV plus oral therapy group, the mean difference was 14%, also in favor of plazomicin (88% vs. 74%).

Plazomicin was significantly more effective then meropenem in all of the resistant Enterobacteriaceae groups (ESBL-positive, and levofloxacin- and aminoglycoside-resistant). It was also significantly more effective against E. coli (17% treatment difference), Klebsiella pneumonia (9%), and Proteus mirabilis (25%). However, it was 20% less effective than meropenem against E. cloacae.

At late follow-up, 2% of the plazomicin group and 8% of the meropenem group had relapsed – a significant difference.

Plazomicin and meropenem had similar safety profiles. Diarrhea and hypertension were the most common adverse events (about 2% in each group). Headache occurred in 3% of the meropenem patients and 1% of the plazomicin patients. Nausea, vomiting, and anemia occurred in about 1% of each group.

More patients taking plazomicin experienced a serum creatinine clearance increase of at least 0.5 mg/dL during treatment (7% vs. 4%). All but two patients taking plazomicin experienced a full recovery by the last follow-up visit.

The CARE trial was much smaller, comprised of 39 patients who had either bloodstream infections, or hospital-acquired or ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia caused by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Lynn Connolly, MD, senior medical director and head of late development at Achaogen, presented the data. Recruitment for such a narrow diagnosis was difficult, and hampered patient accrual, she noted.

CARE’s primary endpoints were a combination of all-cause mortality and significant disease-related complications, and all-cause mortality only, both at 28 days.

Patients were randomized 1:1 to either plazomicin 15 mg/kg every 24 hours, or colistin in a 300-mg loading dose, followed by daily infusions of 5 mg/kg. Everyone, regardless of treatment group, could also receive meropenem or tigecycline if deemed necessary. Treatment lasted 7-14 days. There was a test of cure at 7 days from the last IV dose, a safety assessment at 28 days, and a long-term follow-up at 60 days.

The patients’ mean age was about 65 years. Most (about 80%) had a bloodstream infection; bacterial pneumonias were present in the remainder. Most infections (85%) were monomicrobial, with polymicrobial infections making up the balance. Tigecycline was the favored adjunctive therapy (60%), followed by meropenem.

At day 28, plazomicin was associated with significantly better overall outcomes than colistin. It reduced the combination mortality/significant disease complications endpoint by 26% (23% vs. 50% meropenem). This translated to a 53% relative reduction in the risk of death.

Plazomicin also reduced all-cause mortality only by 28% (12% vs. 40% meropenem). This translated to a relative risk reduction of 70.5%.

The study drug performed well in the subgroup of patients with bloodstream infections, reducing the occurrence of the composite endpoint by 39% (14% vs. 53%), and of the mortality-only endpoint by 33% (7% vs. 40%). This translated to a 63% increased chance of 60-day survival in the plazomicin group.

Almost all patients in each group experienced at least one adverse event; 28% were deemed related to plazomicin and 43% to colistin. Many of these events were related to renal function (33% plazomicin, 52% colistin). Serum creatinine increases of at least 0.5 mg/dL during IV treatment occurred in fewer taking plazomicin (1 vs. 6 taking colistin). Full renal recovery occurred in the patient taking plazomicin, but only in three taking colistin.

“These data suggest that plazomicin could offer an important new treatment option for patients with serious infections due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae,” Dr. Connolly said.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

VIENNA – An investigational antibiotic effective against several types of gram-negative antibiotic-resistant bacteria has proved its mettle against serious infections of the urinary tract, respiratory tract, and bloodstream.

Plazomicin (Achaogen, San Francisco) posted good results in two phase III studies, handily besting comparator drugs considered gold standard for treating complicated urinary tract infections and pyelonephritis, as well as bloodstream infections and hospital- and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia.

Both the EPIC (Evaluating Plazomicin In cUTI) and CARE (Combating Antibiotic Resistant Enterobacteriaceae) trials have provided enough positive data for the company to move forward with a new drug application later this year. The company also plans to seek European Medicines Agency approval in 2018.

Plazomicin is an aminoglycoside that has been modified with several side chains that block aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes, Daniel Cloutier, PhD, principal clinical scientist of Achaogen said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Disease annual congress.

“Aminoglycoside enzymes tend to travel along with beta-lactamases and carbapenemases as well, so this drug retains potent bactericidal activity against extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, and aminoglycoside-resistant Enterobacteriaceae,” said Dr. Cloutier, who presented the results of the EPIC trial. The drug is given once-daily as a 30-minute intravenous infusion.

EPIC enrolled 609 adult patients with complicated urinary tract infections or acute pyelonephritis; Dr. Cloutier presented a modified intent-to-treat analysis comprising 388 of these. They were randomized to plazomicin 15 mg/kg every 25 hours or to IV meropenem 1 gram every 24 hours. Treatment proceeded for 4-7 days, after which patients could step down to oral therapy (levofloxacin 500 m/day), for a total of 7-10 days of treatment. About 80% of patients had both IV and oral therapy. At 15-19 days from the first dose, patients had a test of cure; at 24-32 days from first dose, they returned for a safety follow-up.

Patients were a mean of 60 years old. About 60% had a complicated UTI; the rest had acute pyelonephritis. About 35% had a mean creatinine clearance of more than 30-60 mL/min; the rest had a mean clearance of more than 60-90 mL/min.

The primary efficacy endpoint was microbial eradication. Plazomicin performed significantly better than meropenem in this measure (87% vs.72%), a mean difference of about 15%. Patients with pyelonephritis responded marginally better than those with complicated UTI, both groups favoring plazomicin (mean treatment differences of 17.5% and 13.7%, respectively).

The results were similar when the investigators examined groups by whether they needed oral step-down treatment. In the IV-only groups, plazomicin bested meropenem in microbiological eradication by almost 19% (84% vs. 65%). In the IV plus oral therapy group, the mean difference was 14%, also in favor of plazomicin (88% vs. 74%).

Plazomicin was significantly more effective then meropenem in all of the resistant Enterobacteriaceae groups (ESBL-positive, and levofloxacin- and aminoglycoside-resistant). It was also significantly more effective against E. coli (17% treatment difference), Klebsiella pneumonia (9%), and Proteus mirabilis (25%). However, it was 20% less effective than meropenem against E. cloacae.

At late follow-up, 2% of the plazomicin group and 8% of the meropenem group had relapsed – a significant difference.

Plazomicin and meropenem had similar safety profiles. Diarrhea and hypertension were the most common adverse events (about 2% in each group). Headache occurred in 3% of the meropenem patients and 1% of the plazomicin patients. Nausea, vomiting, and anemia occurred in about 1% of each group.

More patients taking plazomicin experienced a serum creatinine clearance increase of at least 0.5 mg/dL during treatment (7% vs. 4%). All but two patients taking plazomicin experienced a full recovery by the last follow-up visit.

The CARE trial was much smaller, comprised of 39 patients who had either bloodstream infections, or hospital-acquired or ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia caused by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Lynn Connolly, MD, senior medical director and head of late development at Achaogen, presented the data. Recruitment for such a narrow diagnosis was difficult, and hampered patient accrual, she noted.

CARE’s primary endpoints were a combination of all-cause mortality and significant disease-related complications, and all-cause mortality only, both at 28 days.

Patients were randomized 1:1 to either plazomicin 15 mg/kg every 24 hours, or colistin in a 300-mg loading dose, followed by daily infusions of 5 mg/kg. Everyone, regardless of treatment group, could also receive meropenem or tigecycline if deemed necessary. Treatment lasted 7-14 days. There was a test of cure at 7 days from the last IV dose, a safety assessment at 28 days, and a long-term follow-up at 60 days.

The patients’ mean age was about 65 years. Most (about 80%) had a bloodstream infection; bacterial pneumonias were present in the remainder. Most infections (85%) were monomicrobial, with polymicrobial infections making up the balance. Tigecycline was the favored adjunctive therapy (60%), followed by meropenem.

At day 28, plazomicin was associated with significantly better overall outcomes than colistin. It reduced the combination mortality/significant disease complications endpoint by 26% (23% vs. 50% meropenem). This translated to a 53% relative reduction in the risk of death.

Plazomicin also reduced all-cause mortality only by 28% (12% vs. 40% meropenem). This translated to a relative risk reduction of 70.5%.

The study drug performed well in the subgroup of patients with bloodstream infections, reducing the occurrence of the composite endpoint by 39% (14% vs. 53%), and of the mortality-only endpoint by 33% (7% vs. 40%). This translated to a 63% increased chance of 60-day survival in the plazomicin group.

Almost all patients in each group experienced at least one adverse event; 28% were deemed related to plazomicin and 43% to colistin. Many of these events were related to renal function (33% plazomicin, 52% colistin). Serum creatinine increases of at least 0.5 mg/dL during IV treatment occurred in fewer taking plazomicin (1 vs. 6 taking colistin). Full renal recovery occurred in the patient taking plazomicin, but only in three taking colistin.

“These data suggest that plazomicin could offer an important new treatment option for patients with serious infections due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae,” Dr. Connolly said.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

VIENNA – An investigational antibiotic effective against several types of gram-negative antibiotic-resistant bacteria has proved its mettle against serious infections of the urinary tract, respiratory tract, and bloodstream.

Plazomicin (Achaogen, San Francisco) posted good results in two phase III studies, handily besting comparator drugs considered gold standard for treating complicated urinary tract infections and pyelonephritis, as well as bloodstream infections and hospital- and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia.

Both the EPIC (Evaluating Plazomicin In cUTI) and CARE (Combating Antibiotic Resistant Enterobacteriaceae) trials have provided enough positive data for the company to move forward with a new drug application later this year. The company also plans to seek European Medicines Agency approval in 2018.

Plazomicin is an aminoglycoside that has been modified with several side chains that block aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes, Daniel Cloutier, PhD, principal clinical scientist of Achaogen said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Disease annual congress.

“Aminoglycoside enzymes tend to travel along with beta-lactamases and carbapenemases as well, so this drug retains potent bactericidal activity against extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, and aminoglycoside-resistant Enterobacteriaceae,” said Dr. Cloutier, who presented the results of the EPIC trial. The drug is given once-daily as a 30-minute intravenous infusion.

EPIC enrolled 609 adult patients with complicated urinary tract infections or acute pyelonephritis; Dr. Cloutier presented a modified intent-to-treat analysis comprising 388 of these. They were randomized to plazomicin 15 mg/kg every 25 hours or to IV meropenem 1 gram every 24 hours. Treatment proceeded for 4-7 days, after which patients could step down to oral therapy (levofloxacin 500 m/day), for a total of 7-10 days of treatment. About 80% of patients had both IV and oral therapy. At 15-19 days from the first dose, patients had a test of cure; at 24-32 days from first dose, they returned for a safety follow-up.

Patients were a mean of 60 years old. About 60% had a complicated UTI; the rest had acute pyelonephritis. About 35% had a mean creatinine clearance of more than 30-60 mL/min; the rest had a mean clearance of more than 60-90 mL/min.

The primary efficacy endpoint was microbial eradication. Plazomicin performed significantly better than meropenem in this measure (87% vs.72%), a mean difference of about 15%. Patients with pyelonephritis responded marginally better than those with complicated UTI, both groups favoring plazomicin (mean treatment differences of 17.5% and 13.7%, respectively).

The results were similar when the investigators examined groups by whether they needed oral step-down treatment. In the IV-only groups, plazomicin bested meropenem in microbiological eradication by almost 19% (84% vs. 65%). In the IV plus oral therapy group, the mean difference was 14%, also in favor of plazomicin (88% vs. 74%).

Plazomicin was significantly more effective then meropenem in all of the resistant Enterobacteriaceae groups (ESBL-positive, and levofloxacin- and aminoglycoside-resistant). It was also significantly more effective against E. coli (17% treatment difference), Klebsiella pneumonia (9%), and Proteus mirabilis (25%). However, it was 20% less effective than meropenem against E. cloacae.

At late follow-up, 2% of the plazomicin group and 8% of the meropenem group had relapsed – a significant difference.

Plazomicin and meropenem had similar safety profiles. Diarrhea and hypertension were the most common adverse events (about 2% in each group). Headache occurred in 3% of the meropenem patients and 1% of the plazomicin patients. Nausea, vomiting, and anemia occurred in about 1% of each group.

More patients taking plazomicin experienced a serum creatinine clearance increase of at least 0.5 mg/dL during treatment (7% vs. 4%). All but two patients taking plazomicin experienced a full recovery by the last follow-up visit.

The CARE trial was much smaller, comprised of 39 patients who had either bloodstream infections, or hospital-acquired or ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia caused by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Lynn Connolly, MD, senior medical director and head of late development at Achaogen, presented the data. Recruitment for such a narrow diagnosis was difficult, and hampered patient accrual, she noted.

CARE’s primary endpoints were a combination of all-cause mortality and significant disease-related complications, and all-cause mortality only, both at 28 days.

Patients were randomized 1:1 to either plazomicin 15 mg/kg every 24 hours, or colistin in a 300-mg loading dose, followed by daily infusions of 5 mg/kg. Everyone, regardless of treatment group, could also receive meropenem or tigecycline if deemed necessary. Treatment lasted 7-14 days. There was a test of cure at 7 days from the last IV dose, a safety assessment at 28 days, and a long-term follow-up at 60 days.

The patients’ mean age was about 65 years. Most (about 80%) had a bloodstream infection; bacterial pneumonias were present in the remainder. Most infections (85%) were monomicrobial, with polymicrobial infections making up the balance. Tigecycline was the favored adjunctive therapy (60%), followed by meropenem.

At day 28, plazomicin was associated with significantly better overall outcomes than colistin. It reduced the combination mortality/significant disease complications endpoint by 26% (23% vs. 50% meropenem). This translated to a 53% relative reduction in the risk of death.

Plazomicin also reduced all-cause mortality only by 28% (12% vs. 40% meropenem). This translated to a relative risk reduction of 70.5%.

The study drug performed well in the subgroup of patients with bloodstream infections, reducing the occurrence of the composite endpoint by 39% (14% vs. 53%), and of the mortality-only endpoint by 33% (7% vs. 40%). This translated to a 63% increased chance of 60-day survival in the plazomicin group.

Almost all patients in each group experienced at least one adverse event; 28% were deemed related to plazomicin and 43% to colistin. Many of these events were related to renal function (33% plazomicin, 52% colistin). Serum creatinine increases of at least 0.5 mg/dL during IV treatment occurred in fewer taking plazomicin (1 vs. 6 taking colistin). Full renal recovery occurred in the patient taking plazomicin, but only in three taking colistin.

“These data suggest that plazomicin could offer an important new treatment option for patients with serious infections due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae,” Dr. Connolly said.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

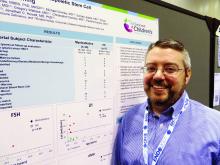

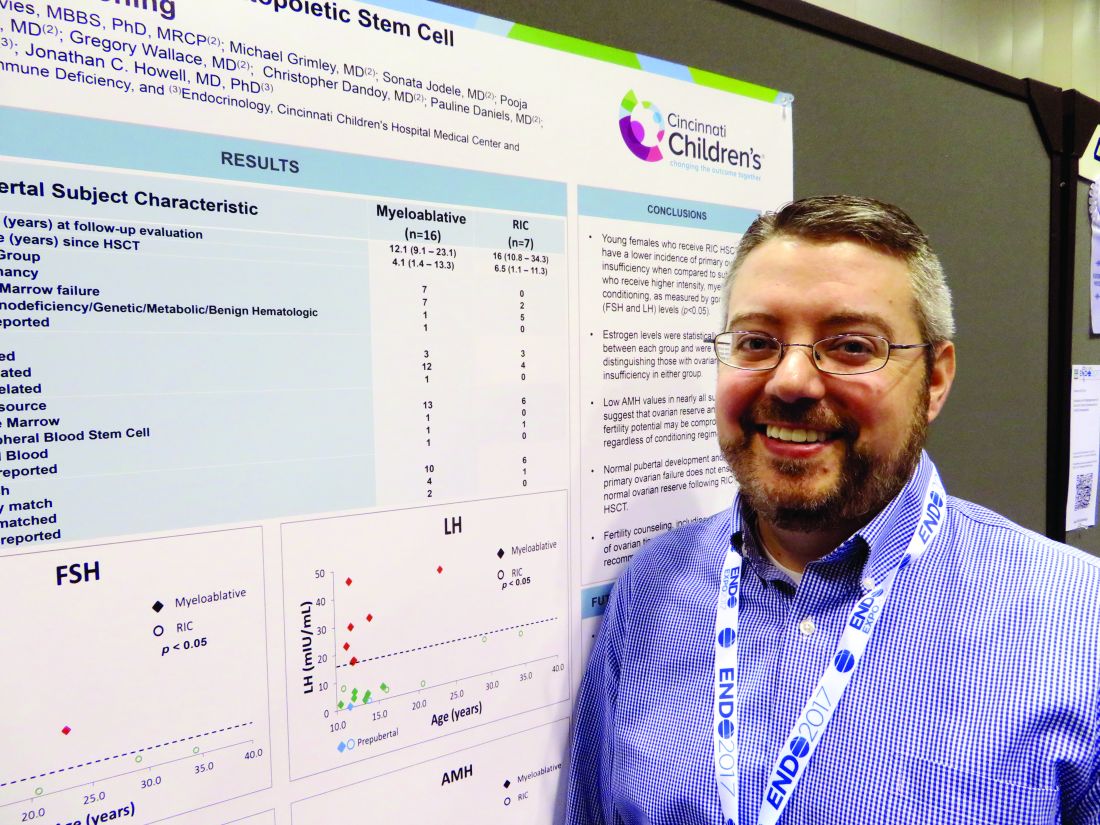

Reduced-intensity conditioning may not preserve fertility in young girls after bone marrow transplant

ORLANDO – Girls who undergo reduced-intensity conditioning for a bone marrow transplant may face fertility problems in the future, even if they experience an outwardly normal puberty.

In the first-ever study to compare high- and low-intensity chemotherapeutic conditioning regimens among young girls, significantly more who underwent the reduced-intensity regimen had normal estradiol, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone compared with those who had high-intensity conditioning. But anti-Müllerian hormone was low or absent in almost all the girls, no matter which conditioning regimen they had, Jonathan C. Howell, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

While not a perfect predictor of future fertility, anti-Müllerian hormone is a good indicator of ovarian follicular reserve, said Dr. Howell, a pediatric endocrinologist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Howell and his colleagues, Holly R. Hoefgen, MD, Kasiani C. Myers, MD, and Helen Oquendo-Del Toro, MD, all of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, are following 49 females aged 1-40 years who had preconditioning chemotherapy in advance of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

At the meeting, Dr. Howell reported data on 23 girls who were in puberty during their treatment (mean age 12 years). The mean follow-up was 4 years, but this varied widely, from 1 to 13 years. Most (16) had high-intensity myeloablation; the remainder had reduced-intensity conditioning. Diagnoses varied between the groups. Among those with high-intensity conditioning, malignancy and bone marrow failure were the most common indications (seven patients each); one patient had an immunodeficiency, and the cause was unknown for another.

Among those who had the reduced-intensity regimen, five had an immunodeficiency and two had bone marrow failure.

The discrepancy in diagnoses between the groups isn’t surprising, Dr. Howell said. “Diagnosis can dictate which treatment patients receive. People with malignancies or a prior history of leukemia or lymphoma often receive the high-intensity conditioning. You want to wipe out every single malignant cell.”

Reduced-intensity conditioning may be an option for patients with other problems such as bone marrow failure, immunodeficiencies, or genetic or metabolic problems. The less-intense regimen does confer some benefits, Dr. Howell noted. “The short-term need for intensive medical therapy while getting the stem cells is less. The medical benefit of these less-intense regimens is certainly there, but the long-term endocrine impact has yet to be defined.”

Most of the girls in the high-intensity regimen group (64%) had high follicle stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone, suggesting primary ovarian failure; 71% of them also had low estradiol levels. However, all of these hormones were normal in the reduced-intensity group. But regardless of conditioning treatment, anti-Müllerian hormone was abnormally low in nearly all of the patients (87%). Only one girl with myeloablative conditioning and two girls with reduced intensity condition had normal anti-Müllerian levels. “This tells us that fertility potential may not be preserved, despite [their] getting the reduced-intensity conditioning,” Dr. Howell said.

The story here is only beginning to unfold, he said. “Fertility is defined as the ability to conceive a child, and that’s not something we have looked at yet. We would like to know the long-term outcomes of fertility in these patients, and whether they can conceive when they’re ready to start a family. Our goal is to follow these young women into their 20s and 30s, and to see if that’s an opportunity they are able to experience.”

The study is a cooperative project involving the hospital’s divisions of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, Bone Marrow Transplantation and Immunology, and Endocrinology.

Neither Dr. Howell nor any of his colleagues had any financial disclosures.

Fertility preservation talks: The earlier, the better

A talk about fertility preservation can be the first step into a new future for families of children with a cancer diagnosis.

“Talking about your baby having a baby can be the farthest thing from your mind,” when you’re the parent of a child about to undergo cancer treatment, said Dr. Hoefgen. “But we know from survivors that this can be a very important issue in the future. We simply start by telling parents, ‘This will be important to your child at some point, and we want to talk about it now, while there is still something we may be able to do about it.’ ”

Dr. Hoefgen, a staff member at the hospital’s Comprehensive Fertility Care and Preservation Program, said parents “sometimes find it weird” to be talking about unborn grandchildren when they’re consumed with making critical decisions for their own child. But by asking them to consider that child’s long-term future, the discussion offers its own message of hope.

The talks always begin with a basic discussion of how cancer treatments can affect the reproductive organs. The hospital has a series of short animated videos that are very helpful in relaying the information. Another video in that series describes the different methods of fertility preservation: mature oocyte or sperm harvesting, or, for younger patients, removing and freezing ovarian and testicular tissue. Parents and children can watch them together, get grounding in the basics, and be prepared for a productive conversation.

Talks always include the team oncologist, who creates a specialized risk assessment for each patient. The group discusses each preservation method, the risks and benefits, and the cost. But the talks are exploratory, too, helping both clinicians and families understand what’s most important to them, she said.

“Common things that we typically talk about are genetics, religion, and ethics – which may mean different things to different families.”

Dr. Hoefgen and her team reach out to more than 95% of families that face a pediatric cancer diagnosis. After the in-depth discussions, she said, about 20% decide to investigate some form of fertility preservation.

“The most important thing is having the conversation early, while we still have options,” she said.

Dr. Hoefgen had no financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – Girls who undergo reduced-intensity conditioning for a bone marrow transplant may face fertility problems in the future, even if they experience an outwardly normal puberty.

In the first-ever study to compare high- and low-intensity chemotherapeutic conditioning regimens among young girls, significantly more who underwent the reduced-intensity regimen had normal estradiol, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone compared with those who had high-intensity conditioning. But anti-Müllerian hormone was low or absent in almost all the girls, no matter which conditioning regimen they had, Jonathan C. Howell, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

While not a perfect predictor of future fertility, anti-Müllerian hormone is a good indicator of ovarian follicular reserve, said Dr. Howell, a pediatric endocrinologist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Howell and his colleagues, Holly R. Hoefgen, MD, Kasiani C. Myers, MD, and Helen Oquendo-Del Toro, MD, all of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, are following 49 females aged 1-40 years who had preconditioning chemotherapy in advance of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

At the meeting, Dr. Howell reported data on 23 girls who were in puberty during their treatment (mean age 12 years). The mean follow-up was 4 years, but this varied widely, from 1 to 13 years. Most (16) had high-intensity myeloablation; the remainder had reduced-intensity conditioning. Diagnoses varied between the groups. Among those with high-intensity conditioning, malignancy and bone marrow failure were the most common indications (seven patients each); one patient had an immunodeficiency, and the cause was unknown for another.

Among those who had the reduced-intensity regimen, five had an immunodeficiency and two had bone marrow failure.

The discrepancy in diagnoses between the groups isn’t surprising, Dr. Howell said. “Diagnosis can dictate which treatment patients receive. People with malignancies or a prior history of leukemia or lymphoma often receive the high-intensity conditioning. You want to wipe out every single malignant cell.”

Reduced-intensity conditioning may be an option for patients with other problems such as bone marrow failure, immunodeficiencies, or genetic or metabolic problems. The less-intense regimen does confer some benefits, Dr. Howell noted. “The short-term need for intensive medical therapy while getting the stem cells is less. The medical benefit of these less-intense regimens is certainly there, but the long-term endocrine impact has yet to be defined.”

Most of the girls in the high-intensity regimen group (64%) had high follicle stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone, suggesting primary ovarian failure; 71% of them also had low estradiol levels. However, all of these hormones were normal in the reduced-intensity group. But regardless of conditioning treatment, anti-Müllerian hormone was abnormally low in nearly all of the patients (87%). Only one girl with myeloablative conditioning and two girls with reduced intensity condition had normal anti-Müllerian levels. “This tells us that fertility potential may not be preserved, despite [their] getting the reduced-intensity conditioning,” Dr. Howell said.

The story here is only beginning to unfold, he said. “Fertility is defined as the ability to conceive a child, and that’s not something we have looked at yet. We would like to know the long-term outcomes of fertility in these patients, and whether they can conceive when they’re ready to start a family. Our goal is to follow these young women into their 20s and 30s, and to see if that’s an opportunity they are able to experience.”

The study is a cooperative project involving the hospital’s divisions of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, Bone Marrow Transplantation and Immunology, and Endocrinology.

Neither Dr. Howell nor any of his colleagues had any financial disclosures.

Fertility preservation talks: The earlier, the better

A talk about fertility preservation can be the first step into a new future for families of children with a cancer diagnosis.

“Talking about your baby having a baby can be the farthest thing from your mind,” when you’re the parent of a child about to undergo cancer treatment, said Dr. Hoefgen. “But we know from survivors that this can be a very important issue in the future. We simply start by telling parents, ‘This will be important to your child at some point, and we want to talk about it now, while there is still something we may be able to do about it.’ ”

Dr. Hoefgen, a staff member at the hospital’s Comprehensive Fertility Care and Preservation Program, said parents “sometimes find it weird” to be talking about unborn grandchildren when they’re consumed with making critical decisions for their own child. But by asking them to consider that child’s long-term future, the discussion offers its own message of hope.

The talks always begin with a basic discussion of how cancer treatments can affect the reproductive organs. The hospital has a series of short animated videos that are very helpful in relaying the information. Another video in that series describes the different methods of fertility preservation: mature oocyte or sperm harvesting, or, for younger patients, removing and freezing ovarian and testicular tissue. Parents and children can watch them together, get grounding in the basics, and be prepared for a productive conversation.

Talks always include the team oncologist, who creates a specialized risk assessment for each patient. The group discusses each preservation method, the risks and benefits, and the cost. But the talks are exploratory, too, helping both clinicians and families understand what’s most important to them, she said.

“Common things that we typically talk about are genetics, religion, and ethics – which may mean different things to different families.”

Dr. Hoefgen and her team reach out to more than 95% of families that face a pediatric cancer diagnosis. After the in-depth discussions, she said, about 20% decide to investigate some form of fertility preservation.

“The most important thing is having the conversation early, while we still have options,” she said.

Dr. Hoefgen had no financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – Girls who undergo reduced-intensity conditioning for a bone marrow transplant may face fertility problems in the future, even if they experience an outwardly normal puberty.

In the first-ever study to compare high- and low-intensity chemotherapeutic conditioning regimens among young girls, significantly more who underwent the reduced-intensity regimen had normal estradiol, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone compared with those who had high-intensity conditioning. But anti-Müllerian hormone was low or absent in almost all the girls, no matter which conditioning regimen they had, Jonathan C. Howell, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

While not a perfect predictor of future fertility, anti-Müllerian hormone is a good indicator of ovarian follicular reserve, said Dr. Howell, a pediatric endocrinologist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Howell and his colleagues, Holly R. Hoefgen, MD, Kasiani C. Myers, MD, and Helen Oquendo-Del Toro, MD, all of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, are following 49 females aged 1-40 years who had preconditioning chemotherapy in advance of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

At the meeting, Dr. Howell reported data on 23 girls who were in puberty during their treatment (mean age 12 years). The mean follow-up was 4 years, but this varied widely, from 1 to 13 years. Most (16) had high-intensity myeloablation; the remainder had reduced-intensity conditioning. Diagnoses varied between the groups. Among those with high-intensity conditioning, malignancy and bone marrow failure were the most common indications (seven patients each); one patient had an immunodeficiency, and the cause was unknown for another.

Among those who had the reduced-intensity regimen, five had an immunodeficiency and two had bone marrow failure.

The discrepancy in diagnoses between the groups isn’t surprising, Dr. Howell said. “Diagnosis can dictate which treatment patients receive. People with malignancies or a prior history of leukemia or lymphoma often receive the high-intensity conditioning. You want to wipe out every single malignant cell.”

Reduced-intensity conditioning may be an option for patients with other problems such as bone marrow failure, immunodeficiencies, or genetic or metabolic problems. The less-intense regimen does confer some benefits, Dr. Howell noted. “The short-term need for intensive medical therapy while getting the stem cells is less. The medical benefit of these less-intense regimens is certainly there, but the long-term endocrine impact has yet to be defined.”

Most of the girls in the high-intensity regimen group (64%) had high follicle stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone, suggesting primary ovarian failure; 71% of them also had low estradiol levels. However, all of these hormones were normal in the reduced-intensity group. But regardless of conditioning treatment, anti-Müllerian hormone was abnormally low in nearly all of the patients (87%). Only one girl with myeloablative conditioning and two girls with reduced intensity condition had normal anti-Müllerian levels. “This tells us that fertility potential may not be preserved, despite [their] getting the reduced-intensity conditioning,” Dr. Howell said.

The story here is only beginning to unfold, he said. “Fertility is defined as the ability to conceive a child, and that’s not something we have looked at yet. We would like to know the long-term outcomes of fertility in these patients, and whether they can conceive when they’re ready to start a family. Our goal is to follow these young women into their 20s and 30s, and to see if that’s an opportunity they are able to experience.”

The study is a cooperative project involving the hospital’s divisions of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, Bone Marrow Transplantation and Immunology, and Endocrinology.

Neither Dr. Howell nor any of his colleagues had any financial disclosures.

Fertility preservation talks: The earlier, the better

A talk about fertility preservation can be the first step into a new future for families of children with a cancer diagnosis.

“Talking about your baby having a baby can be the farthest thing from your mind,” when you’re the parent of a child about to undergo cancer treatment, said Dr. Hoefgen. “But we know from survivors that this can be a very important issue in the future. We simply start by telling parents, ‘This will be important to your child at some point, and we want to talk about it now, while there is still something we may be able to do about it.’ ”

Dr. Hoefgen, a staff member at the hospital’s Comprehensive Fertility Care and Preservation Program, said parents “sometimes find it weird” to be talking about unborn grandchildren when they’re consumed with making critical decisions for their own child. But by asking them to consider that child’s long-term future, the discussion offers its own message of hope.

The talks always begin with a basic discussion of how cancer treatments can affect the reproductive organs. The hospital has a series of short animated videos that are very helpful in relaying the information. Another video in that series describes the different methods of fertility preservation: mature oocyte or sperm harvesting, or, for younger patients, removing and freezing ovarian and testicular tissue. Parents and children can watch them together, get grounding in the basics, and be prepared for a productive conversation.

Talks always include the team oncologist, who creates a specialized risk assessment for each patient. The group discusses each preservation method, the risks and benefits, and the cost. But the talks are exploratory, too, helping both clinicians and families understand what’s most important to them, she said.

“Common things that we typically talk about are genetics, religion, and ethics – which may mean different things to different families.”

Dr. Hoefgen and her team reach out to more than 95% of families that face a pediatric cancer diagnosis. After the in-depth discussions, she said, about 20% decide to investigate some form of fertility preservation.

“The most important thing is having the conversation early, while we still have options,” she said.

Dr. Hoefgen had no financial disclosures.

AT ENDO 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Anti-Müllerian hormone was abnormally low or absent in all treated girls, whether they had reduced-intensity or high-intensity conditioning.

Data source: The prospective study is following 49 females aged 1-40 years.

Disclosures: Neither Dr. Howell nor any of his colleagues had any financial disclosures.

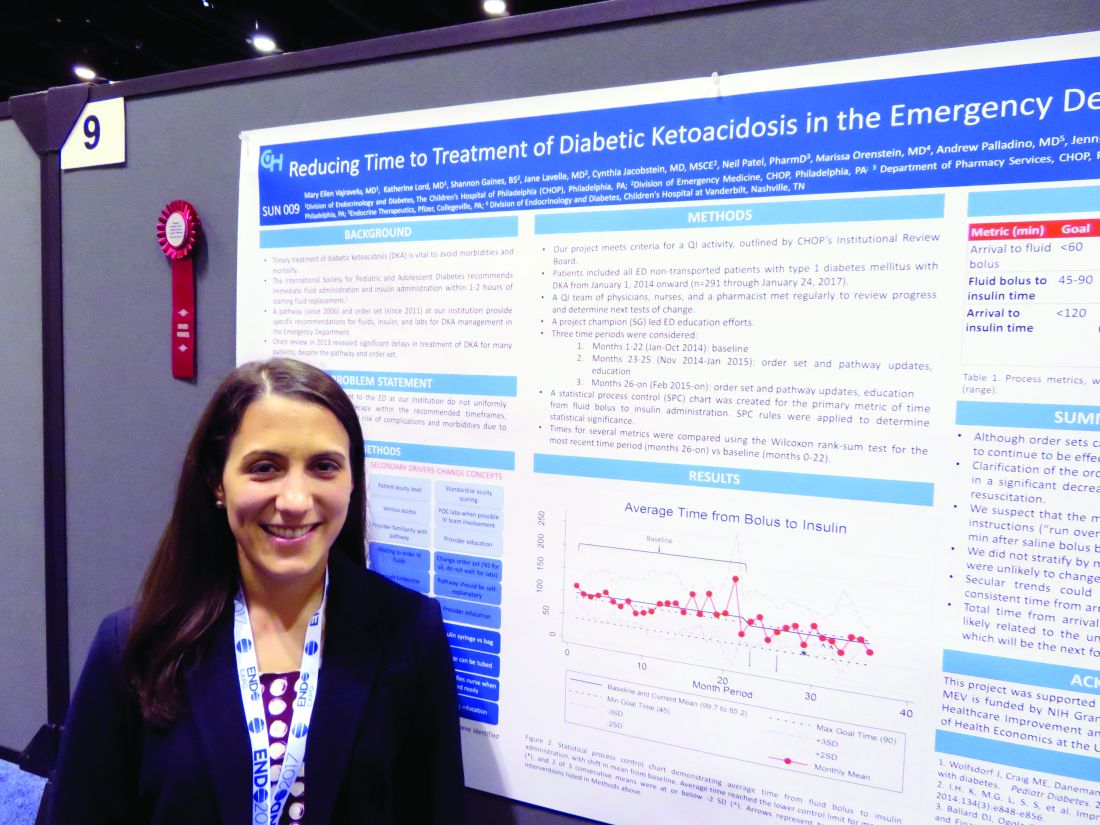

Simple changes shorten door-to-insulin time for diabetic ketoacidosis

ORLANDO – A few simple adjustments in standing orders shaved 20 minutes off the time one emergency department took to deliver insulin to pediatric patients with diabetic ketoacidosis, according to Mary Ellen Vajravelu, MD.

Door-to-insulin time decreased from a mean of 168 minutes to 146 minutes after the changes went into effect. Most of the time was saved in the period between starting the initial fluid bolus and starting the insulin, she said during an interview at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

A single patient’s experience inspired the quality improvement project.

“A couple of years ago, we saw a patient in the emergency department with diabetic ketoacidosis who had to wait more than 6 hours before insulin was started,” she explained. “Fortunately, there were no adverse clinical outcomes from that,” but the case signaled that the treatment process needed some streamlining.

The International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes recommends immediate fluid administration and insulin within 1-2 hours of starting fluid replacement.

The hospital had been following in-house recommendations for fluids, insulin, and labs for patients with diabetic ketoacidosis that were established in 2006 and 2011. When they examined a baseline cohort of patients treated from January to October 2014, they immediately saw that those order sets were not achieving the recommended times.

“We went back and looked at our cases and saw that overall, it was taking more than 2 hours from the time of arrival for these patients to get their insulin,” Dr. Vajravelu said.

She and her colleagues formed a quality improvement team consisting of physicians, nurses, and a pharmacist. They broke down the wait time into three components: arrival to fluid bolus, fluid bolus start to insulin start, and the overall arrival-to-insulin time. They then set specific time goals for each of those periods: giving fluids within 60 minutes of arrival, starting insulin 45-90 minutes from the bolus, and an overall door-to-insulin time of less than 120 minutes.

The team tried to determine key clinical drivers that were affecting these times. One of the first findings was a delay in diagnosing diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). This was driven by lack of consistency in scoring patient acuity and problems with venous access.

“To address this, we standardized acuity scoring, got an IV team involved, and used point-of-care labs when possible, and educated our providers,” Dr. Vajravelu said.

The team also found that there were delays in ordering the insulin. These were driven by long wait times for intravenous fluids, by waiting for endocrinology consults, and by providers not being familiar with the DKA order sets.

To address these issues, the team changed the order set to use normal saline for all suspected DKA patients without waiting for lab results. The old orders called for delivering the fluid over a 1-hour period; that was changed to running it over 30 minutes, Dr. Vajravelu said. “That shaved off half an hour right there.”

The team examined reasons that insulin infusion was delayed. Pharmacy orders were a big part of this problem, one of which was the way the insulin was sent up from the pharmacy in a bag. “We changed that to being delivered in a syringe and tube system,” she explained.

They also changed the standing order for when insulin was started, from 60 minutes after fluid to 45 minutes.

These changes were instituted in November 2014, and the team trained clinicians on them through January 2015. Since then, the team has reassessed the situation several times, tracking 291 patients in all. They saw improvement in all three time periods, which was significant in two of them.

Arrival to fluid bolus time dropped significantly, from 55 minutes to 53 minutes – an improvement, even though the baseline time was still within the goal. Fluid bolus-to-insulin time fell significantly as well, from 96 minutes to 74 minutes – well within the new goal.

Overall arrival-to-insulin time thus decreased, from 168 minutes to 146 minutes. However, Dr. Vajravelu said, this is still longer than their goal of less than 120 minutes from door to treatment.

“We are now going back to try and see just where the delay still is,” she said. “It may be getting IV access; it may be labs. We need to tease that out.”

Fortunately, the consistent delays in treatment haven’t resulted in any adverse clinical outcomes.

“I think the biggest benefit we will see will be saving time and money in the emergency department,” Dr. Vajravelu predicted. “We hope to get patients out of there faster, getting them admitted into the hospital and treated in the appropriate department. Speeding up care and reducing waste go together in that sense.”

Dr. Vajravelu had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

ORLANDO – A few simple adjustments in standing orders shaved 20 minutes off the time one emergency department took to deliver insulin to pediatric patients with diabetic ketoacidosis, according to Mary Ellen Vajravelu, MD.

Door-to-insulin time decreased from a mean of 168 minutes to 146 minutes after the changes went into effect. Most of the time was saved in the period between starting the initial fluid bolus and starting the insulin, she said during an interview at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

A single patient’s experience inspired the quality improvement project.

“A couple of years ago, we saw a patient in the emergency department with diabetic ketoacidosis who had to wait more than 6 hours before insulin was started,” she explained. “Fortunately, there were no adverse clinical outcomes from that,” but the case signaled that the treatment process needed some streamlining.

The International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes recommends immediate fluid administration and insulin within 1-2 hours of starting fluid replacement.

The hospital had been following in-house recommendations for fluids, insulin, and labs for patients with diabetic ketoacidosis that were established in 2006 and 2011. When they examined a baseline cohort of patients treated from January to October 2014, they immediately saw that those order sets were not achieving the recommended times.

“We went back and looked at our cases and saw that overall, it was taking more than 2 hours from the time of arrival for these patients to get their insulin,” Dr. Vajravelu said.

She and her colleagues formed a quality improvement team consisting of physicians, nurses, and a pharmacist. They broke down the wait time into three components: arrival to fluid bolus, fluid bolus start to insulin start, and the overall arrival-to-insulin time. They then set specific time goals for each of those periods: giving fluids within 60 minutes of arrival, starting insulin 45-90 minutes from the bolus, and an overall door-to-insulin time of less than 120 minutes.

The team tried to determine key clinical drivers that were affecting these times. One of the first findings was a delay in diagnosing diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). This was driven by lack of consistency in scoring patient acuity and problems with venous access.

“To address this, we standardized acuity scoring, got an IV team involved, and used point-of-care labs when possible, and educated our providers,” Dr. Vajravelu said.

The team also found that there were delays in ordering the insulin. These were driven by long wait times for intravenous fluids, by waiting for endocrinology consults, and by providers not being familiar with the DKA order sets.

To address these issues, the team changed the order set to use normal saline for all suspected DKA patients without waiting for lab results. The old orders called for delivering the fluid over a 1-hour period; that was changed to running it over 30 minutes, Dr. Vajravelu said. “That shaved off half an hour right there.”

The team examined reasons that insulin infusion was delayed. Pharmacy orders were a big part of this problem, one of which was the way the insulin was sent up from the pharmacy in a bag. “We changed that to being delivered in a syringe and tube system,” she explained.

They also changed the standing order for when insulin was started, from 60 minutes after fluid to 45 minutes.

These changes were instituted in November 2014, and the team trained clinicians on them through January 2015. Since then, the team has reassessed the situation several times, tracking 291 patients in all. They saw improvement in all three time periods, which was significant in two of them.

Arrival to fluid bolus time dropped significantly, from 55 minutes to 53 minutes – an improvement, even though the baseline time was still within the goal. Fluid bolus-to-insulin time fell significantly as well, from 96 minutes to 74 minutes – well within the new goal.

Overall arrival-to-insulin time thus decreased, from 168 minutes to 146 minutes. However, Dr. Vajravelu said, this is still longer than their goal of less than 120 minutes from door to treatment.

“We are now going back to try and see just where the delay still is,” she said. “It may be getting IV access; it may be labs. We need to tease that out.”

Fortunately, the consistent delays in treatment haven’t resulted in any adverse clinical outcomes.

“I think the biggest benefit we will see will be saving time and money in the emergency department,” Dr. Vajravelu predicted. “We hope to get patients out of there faster, getting them admitted into the hospital and treated in the appropriate department. Speeding up care and reducing waste go together in that sense.”

Dr. Vajravelu had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

ORLANDO – A few simple adjustments in standing orders shaved 20 minutes off the time one emergency department took to deliver insulin to pediatric patients with diabetic ketoacidosis, according to Mary Ellen Vajravelu, MD.

Door-to-insulin time decreased from a mean of 168 minutes to 146 minutes after the changes went into effect. Most of the time was saved in the period between starting the initial fluid bolus and starting the insulin, she said during an interview at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

A single patient’s experience inspired the quality improvement project.

“A couple of years ago, we saw a patient in the emergency department with diabetic ketoacidosis who had to wait more than 6 hours before insulin was started,” she explained. “Fortunately, there were no adverse clinical outcomes from that,” but the case signaled that the treatment process needed some streamlining.

The International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes recommends immediate fluid administration and insulin within 1-2 hours of starting fluid replacement.

The hospital had been following in-house recommendations for fluids, insulin, and labs for patients with diabetic ketoacidosis that were established in 2006 and 2011. When they examined a baseline cohort of patients treated from January to October 2014, they immediately saw that those order sets were not achieving the recommended times.

“We went back and looked at our cases and saw that overall, it was taking more than 2 hours from the time of arrival for these patients to get their insulin,” Dr. Vajravelu said.

She and her colleagues formed a quality improvement team consisting of physicians, nurses, and a pharmacist. They broke down the wait time into three components: arrival to fluid bolus, fluid bolus start to insulin start, and the overall arrival-to-insulin time. They then set specific time goals for each of those periods: giving fluids within 60 minutes of arrival, starting insulin 45-90 minutes from the bolus, and an overall door-to-insulin time of less than 120 minutes.

The team tried to determine key clinical drivers that were affecting these times. One of the first findings was a delay in diagnosing diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). This was driven by lack of consistency in scoring patient acuity and problems with venous access.

“To address this, we standardized acuity scoring, got an IV team involved, and used point-of-care labs when possible, and educated our providers,” Dr. Vajravelu said.

The team also found that there were delays in ordering the insulin. These were driven by long wait times for intravenous fluids, by waiting for endocrinology consults, and by providers not being familiar with the DKA order sets.

To address these issues, the team changed the order set to use normal saline for all suspected DKA patients without waiting for lab results. The old orders called for delivering the fluid over a 1-hour period; that was changed to running it over 30 minutes, Dr. Vajravelu said. “That shaved off half an hour right there.”

The team examined reasons that insulin infusion was delayed. Pharmacy orders were a big part of this problem, one of which was the way the insulin was sent up from the pharmacy in a bag. “We changed that to being delivered in a syringe and tube system,” she explained.

They also changed the standing order for when insulin was started, from 60 minutes after fluid to 45 minutes.

These changes were instituted in November 2014, and the team trained clinicians on them through January 2015. Since then, the team has reassessed the situation several times, tracking 291 patients in all. They saw improvement in all three time periods, which was significant in two of them.

Arrival to fluid bolus time dropped significantly, from 55 minutes to 53 minutes – an improvement, even though the baseline time was still within the goal. Fluid bolus-to-insulin time fell significantly as well, from 96 minutes to 74 minutes – well within the new goal.

Overall arrival-to-insulin time thus decreased, from 168 minutes to 146 minutes. However, Dr. Vajravelu said, this is still longer than their goal of less than 120 minutes from door to treatment.

“We are now going back to try and see just where the delay still is,” she said. “It may be getting IV access; it may be labs. We need to tease that out.”

Fortunately, the consistent delays in treatment haven’t resulted in any adverse clinical outcomes.

“I think the biggest benefit we will see will be saving time and money in the emergency department,” Dr. Vajravelu predicted. “We hope to get patients out of there faster, getting them admitted into the hospital and treated in the appropriate department. Speeding up care and reducing waste go together in that sense.”

Dr. Vajravelu had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_gal

AT ENDO 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Overall door-to-insulin time decreased from 168 minutes to 146 minutes.

Data source: A 2-year quality improvement project involving 291 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Vajravelu had no relevant financial disclosures.

Dulera inhaler linked to adrenocorticotropic suppression in small case series

ORLANDO – A combination corticosteroid asthma inhaler has, for the first time, been associated with growth delay and adrenocorticotropic suppression in children.

The single-center case series is small, but the results highlight the need to regularly monitor growth and adrenal function in children using inhaled mometasone furoate/formoterol fumarate (Dulera; Merck), investigators said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

“We are hoping to raise awareness of this risk in our pediatric endocrinology colleagues, as well as among allergists, pulmonologists, and pediatricians who treat these children,” said Fadi Al Muhaisen, MD. “These kids should be regularly screened for growth delay and adrenal insufficiency and have their growth plotted at every visit as well.”

Dulera was approved in the United States in 2010 as a maintenance therapy for chronic asthma in adults and children aged 12 years and older. Mometasone furoate is a potent corticosteroid, and formoterol fumarate is a long-acting beta2-adrenergic agonist. The prescribing information says that mometasone furoate exerts less effect on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis than other inhaled corticosteroids, and that adrenal suppression is unlikely to occur when used at recommended dosages. These range from a low of 100 mcg/5 mcg, two puffs daily to a maximum dose of 800 mcg/20 mcg daily.

The review involved 18 children, all of whom were seen in the endocrinology clinic for growth failure or short stature and were receiving Dulera for management of their asthma. Of these, eight (44%) had a full adrenal evaluation. Six had biochemical evidence of adrenal suppression and two had normal adrenal function. The remaining 10 patients had not undergone an adrenal evaluation. None of them were on any other inhaled corticosteroid. The six children diagnosed with adrenal insufficiency had a mean age of 9.7 years, but ranged in age from 7 to 12 years. They had been using the medication for a mean of 1.3 years, although that varied widely, from just a few months to about 2 years. Only one had been on oral steroids in the preceding 6 months before coming to the endocrinology clinic. Five were using the 200 mcg/5 mcg dose, two puffs daily; one child was taking one puff daily of 100 mcg/5 mcg at the time of diagnosis but had been using the higher dose for the preceding 18 months. Three were using concomitant nasal steroids.

The six children evaluated had been using the medication for a mean of 1.3 years, although that varied widely, from just a few months to about 2 years. Only one had been on oral steroids during the 2 years before coming to the endocrinology clinic. Five were using the 200 mcg/5 mcg dose, two puffs daily; one child was taking one puff daily of 100 mcg/5 mcg at time of diagnosis, but had been using the higher dose for 18 months before that. Three were using concomitant nasal steroids.

All presented with growth failure, with bone age 1-3 years behind chronological age. One child was referred to the clinic after an emergency department visit for headache, nausea, diarrhea, and fatigue – symptoms of adrenal failure. That child had an adrenocroticotropin (ACTH) level of 10 pg/mL. Both his random peak cortisol measures after ACTH stimulation were less than 1 mcg/mL.

ACTH levels in four of the children were less than 5-6 pg/ml, with random and peak stimulated cortisols of around 1 mcg/mL. One patient had an ACTH level of 68 pg/mL, a random cortisol of less than 1 mcg/mL, and a peak stimulated cortisol of 8.7 mcg/mL.

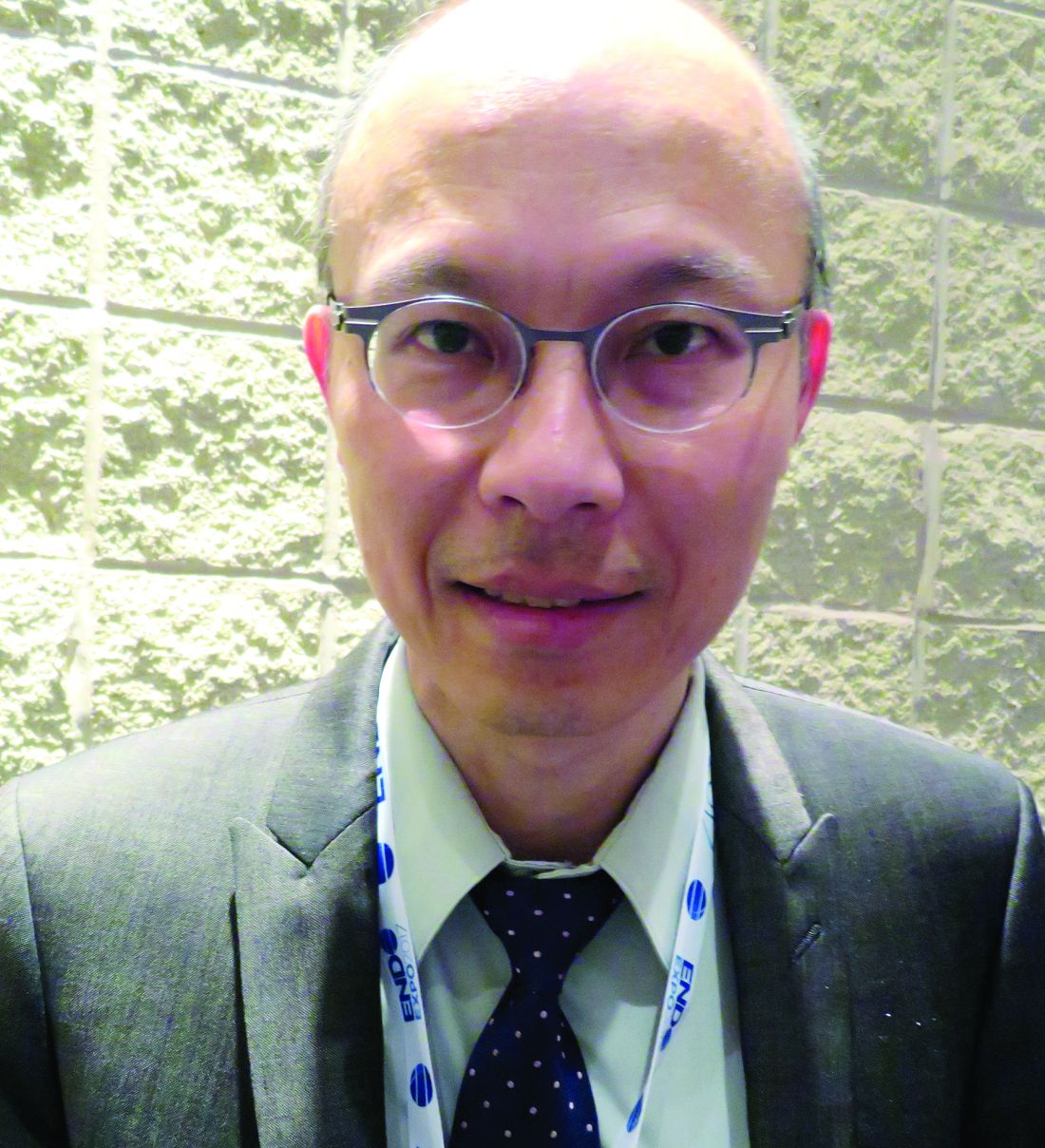

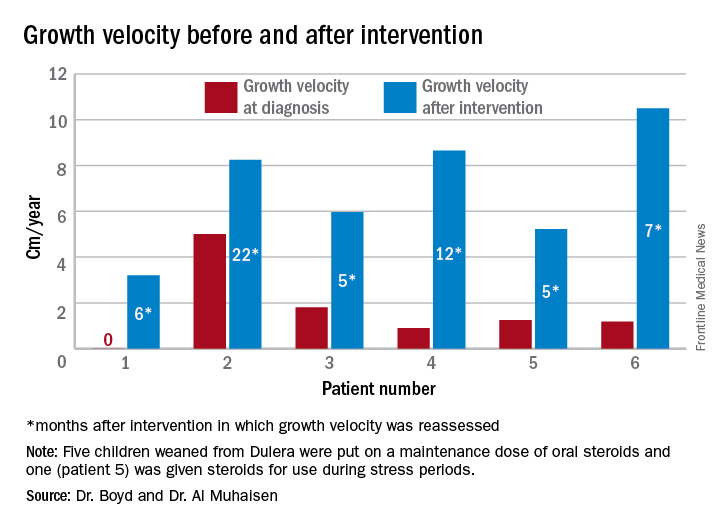

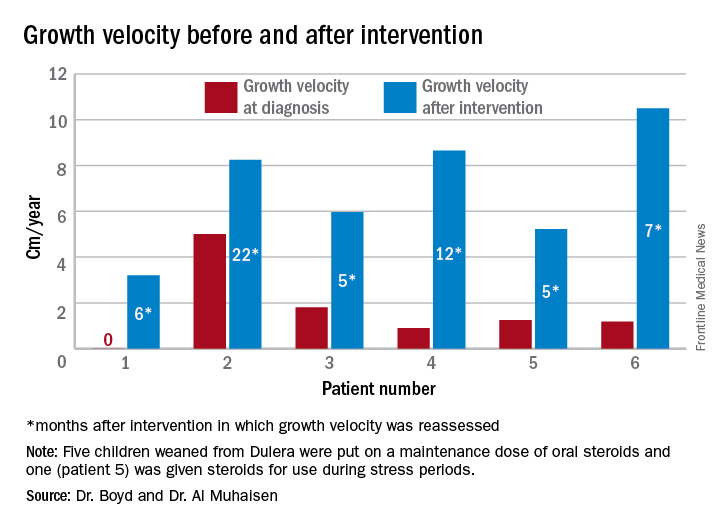

The results were all normal in the four subjects who had repeat adrenal function evaluation after intervention. Adrenal recovery took a mean of 20 months (5-30 months).

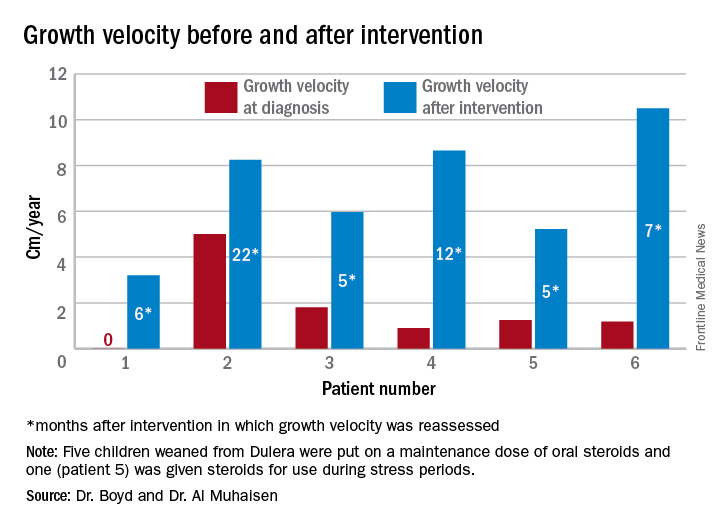

Growth accelerated rapidly after intervention, which was either initiation of maintenance oral steroids and discontinuation of Dulera or, in one patient, after Dulera was weaned. At time of adrenal insufficiency diagnosis, four patients had grown 1-2 cm in the prior year; one had not grown at all, and one had grown about 4.5 cm. After discontinuing or weaning the medication, all experienced growth spurts: 3 cm/year in 6 months; 8 cm/year in 22 months; 6 cm/year in 5 months; 8 cm/year in 12 months; 5 cm/year in 5 months; and 10 cm/year in 7 months.

There were no exacerbations in asthma, despite discontinuing the inhaled medication, Dr. Al Muhaisen said. Changing the asthma treatment required some open discussion between the investigators and the treating pulmonologists, he noted.