User login

Opioid deaths and suicides – twin tragedies that need a community-wide response

WASHINGTON - Community pressures drive the twin tragedies of suicide and opioid deaths, which destroy community structure and must be addressed by community efforts, experts said during a panel discussion.

These so-called “deaths of despair” are inextricably linked, according to thought leaders in clinical medicine, volunteerism, and advocacy who gathered to share data and brainstorm solutions. A clear picture emerged of a professional community struggling to create a unified plan of attack and a unified voice to bring that plan to fruition.

The event was sponsored by the Education Development Center, a nonprofit that implements and evaluates programs to improve education, health, and economic opportunity worldwide, and the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention.

“We convened key leaders, including health care systems, federal agencies, national nonprofits, and faith-based organizations to strengthen our community response to suicide and opioids misuse and restore hope across the United States,” said Jerry Reed, PhD, EDC senior vice president. “To identify positive and lasting solutions requires collaboration from all sectors to achieve not only a nation free of suicide, but [also] a nation where all individuals are resilient, hopeful, and leading healthier lives.”

While several of the leading causes of death in the United States – including heart disease, stroke, and cancer – are declining, suicides and opioid deaths are surging, Alex Crosby, MD, told the gathering. An epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Crosby cited the most recent national data, gathered in 2015. The numbers present a picture of two terrible problems striking virtually identical communities.

“Suicide rates increased 25% from 2000 to 2015,” said Dr. Crosby, who is also the senior adviser in the division of violence prevention at the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. “In 2000, there were 30,000 suicides, and in 2015, there were 44,000. We are now looking at a suicide every 12 minutes in this country.”

Suicides cluster in several demographics, he said, “This is something that disproportionately affects males, working adults aged 25-64, non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic Native Americans, Alaskan natives, and rural areas.”

Deaths from drug overdoses, 60% of which now involve opioids, are on a parallel increase. “These have quadrupled since 1999, and the at-risk groups significantly overlap, with males, adults aged 24-52, non-Hispanic whites and Native Americans, Alaska natives, and rural communities most impacted. These are the very same groups seeing that increase in suicides.”

Joint tragedies, overlapping causes

The center is taking a public health stance on researching and managing both issues, Dr. Crosby said. “As we start looking at risk factors, we see that chronic health conditions, mental health, and pain management are factors common to both groups. But in addition to individual risks, there are societal risks … things in the family, community, and general society also influence these deaths.”

Former U.S. Rep. Patrick J. Kennedy agreed. Now a mental health policy advocate, Mr. Kennedy is not surprised that overlapping communities suffer these joint problems.

“On a societal level, these issues are directly related to the hollowing out of the manufacturing class, anxiety in a new generation that sees no financial stability,” he said. “Clearly, these are some of the reasons that these deaths track parts of the country that have been hardest hit economically. On top of that, we are lacking the kind of community connectedness we once had.”

Mr. Kennedy also faulted the marginalization of people with mental illnesses and the dearth of early screening that could identify mental disorders before they balloon into related substance abuse disorders. “Those are folks who, if screened and found to have a vulnerability from a mental illness, could be properly treated. These are illnesses that pathologize by neglect.”

The lack of awareness isn’t just a broad societal concept, but a specific weakness in the medical community, said Elinore F. McCance-Katz, MD, assistant secretary for mental health and substance use at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

“There’s not a lot of attention paid to this issue unless you’re in a profession like psychiatry, where we are taught to systematically assess for suicidality,” Dr. McCance-Katz noted. “But unless you’re trained to address it, it’s not something you think about; and if you don’t think about it, you won’t uncover it.

“In primary care, for example, we see many with a pain complaint,” she continued. “That pain will be treated medically, but the psychological component, which might be devastating, won’t be. This can cause depression and suicidal thinking, and if patients are not asked about it, they will not offer it. So, we have the terrible situation where someone can leave the office with the means to harm themselves, but not the help they need to save their life.”

How to reach the vulnerable

When a medical disorder and its attendant comorbidities present a multifactorial etiology, the clinician must address the problem as a unit. This isn’t happening with suicide and drug overdose deaths, said Arthur C. Evans Jr, PhD, chief executive officer of the American Psychological Association.

“These conditions are tied to societal determinants, but our approach to them is still focused at the individual level,” said Dr. Evans. “As long as our primary way is to build treatment programs and expect people to find their way into them on their own, it’s not going to work. We know that 90% of patients with substance abuse problems don’t come to treatment. So, our strategy is missing a whole lot of people.”

A better way, he said, is to proactively provide holistic person-centered care. He has some very specific ideas, honed by his 12 years as commissioner of Philadelphia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability Service, a $1.2 billion health care agency that is the safety net for 1.5 million Philadelphians with behavioral health and intellectual disabilities. Dr. Evans is credited with transforming the agency into a community-integrated, recovery-oriented treatment model.

He would like to see a similar national transformation in how at-risk groups are targeted, educated, screened, and treated. “We can create a culture where these issues are better understood by the public, so they can recognize problems early and connect to better health care.”

“Hope is at the center of our work,” Dr. Evans said. “The whole recovery movement has been about helping people have the hope that they can get better, that their lives can improve. Fundamentally, this must be the basis for treatment. We have focused for too long on the symptoms people bring to us, and missed the fact that these problems of suicide and drug abuse arise because people are hurting, both physically and psychologically. To recover, they need to believe there is a future in which they can feel better.”

If there’s a way, is there a will?

But while thought leaders continue to fine-tune their message, people continue to die, Mr. Kennedy said.

“We have all the experts who know what to do; the thing that is missing is the political will to do it,” he noted. “It’s driven by the stigma, the silence of families suffering from these illnesses. If we can’t talk about it in our families, we can’t talk about it to our legislators, and if they don’t hear from us, they do nothing. We need a political answer, ultimately. We appropriated a billion dollars over 2 years for the opioid crisis, but within 3 days of Hurricane Harvey, we appropriated $15 billion. It may seem we are making progress because we have great forums, but it’s a lot of talk, and people are dying every day.”

He likened the suicide and opioid death crisis to a natural disaster that requires not just money, but a highly coordinated response that targets multiple impacted areas.

“We need a Federal Emergency Management Agency–like response to this,” Mr. Kennedy said. “FEMA is designed to address all the missing pieces necessary for someone to recover from a disaster. In recovery, we have a physical problem, a mental obsession, and a spiritual malady. People need medical help – access to medication to get their lives stabilized. They need the psychological component of cognitive behavioral therapy. And they need the spiritual angle, which is social support, people reaching out to each other.

“Right now, everyone thinks this is a problem to be dealt with ‘over there,’ but it isn’t,” he added. “It involves all of us, and if we want to put these communities back together, we need everyone energized and contributing.”

WASHINGTON - Community pressures drive the twin tragedies of suicide and opioid deaths, which destroy community structure and must be addressed by community efforts, experts said during a panel discussion.

These so-called “deaths of despair” are inextricably linked, according to thought leaders in clinical medicine, volunteerism, and advocacy who gathered to share data and brainstorm solutions. A clear picture emerged of a professional community struggling to create a unified plan of attack and a unified voice to bring that plan to fruition.

The event was sponsored by the Education Development Center, a nonprofit that implements and evaluates programs to improve education, health, and economic opportunity worldwide, and the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention.

“We convened key leaders, including health care systems, federal agencies, national nonprofits, and faith-based organizations to strengthen our community response to suicide and opioids misuse and restore hope across the United States,” said Jerry Reed, PhD, EDC senior vice president. “To identify positive and lasting solutions requires collaboration from all sectors to achieve not only a nation free of suicide, but [also] a nation where all individuals are resilient, hopeful, and leading healthier lives.”

While several of the leading causes of death in the United States – including heart disease, stroke, and cancer – are declining, suicides and opioid deaths are surging, Alex Crosby, MD, told the gathering. An epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Crosby cited the most recent national data, gathered in 2015. The numbers present a picture of two terrible problems striking virtually identical communities.

“Suicide rates increased 25% from 2000 to 2015,” said Dr. Crosby, who is also the senior adviser in the division of violence prevention at the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. “In 2000, there were 30,000 suicides, and in 2015, there were 44,000. We are now looking at a suicide every 12 minutes in this country.”

Suicides cluster in several demographics, he said, “This is something that disproportionately affects males, working adults aged 25-64, non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic Native Americans, Alaskan natives, and rural areas.”

Deaths from drug overdoses, 60% of which now involve opioids, are on a parallel increase. “These have quadrupled since 1999, and the at-risk groups significantly overlap, with males, adults aged 24-52, non-Hispanic whites and Native Americans, Alaska natives, and rural communities most impacted. These are the very same groups seeing that increase in suicides.”

Joint tragedies, overlapping causes

The center is taking a public health stance on researching and managing both issues, Dr. Crosby said. “As we start looking at risk factors, we see that chronic health conditions, mental health, and pain management are factors common to both groups. But in addition to individual risks, there are societal risks … things in the family, community, and general society also influence these deaths.”

Former U.S. Rep. Patrick J. Kennedy agreed. Now a mental health policy advocate, Mr. Kennedy is not surprised that overlapping communities suffer these joint problems.

“On a societal level, these issues are directly related to the hollowing out of the manufacturing class, anxiety in a new generation that sees no financial stability,” he said. “Clearly, these are some of the reasons that these deaths track parts of the country that have been hardest hit economically. On top of that, we are lacking the kind of community connectedness we once had.”

Mr. Kennedy also faulted the marginalization of people with mental illnesses and the dearth of early screening that could identify mental disorders before they balloon into related substance abuse disorders. “Those are folks who, if screened and found to have a vulnerability from a mental illness, could be properly treated. These are illnesses that pathologize by neglect.”

The lack of awareness isn’t just a broad societal concept, but a specific weakness in the medical community, said Elinore F. McCance-Katz, MD, assistant secretary for mental health and substance use at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

“There’s not a lot of attention paid to this issue unless you’re in a profession like psychiatry, where we are taught to systematically assess for suicidality,” Dr. McCance-Katz noted. “But unless you’re trained to address it, it’s not something you think about; and if you don’t think about it, you won’t uncover it.

“In primary care, for example, we see many with a pain complaint,” she continued. “That pain will be treated medically, but the psychological component, which might be devastating, won’t be. This can cause depression and suicidal thinking, and if patients are not asked about it, they will not offer it. So, we have the terrible situation where someone can leave the office with the means to harm themselves, but not the help they need to save their life.”

How to reach the vulnerable

When a medical disorder and its attendant comorbidities present a multifactorial etiology, the clinician must address the problem as a unit. This isn’t happening with suicide and drug overdose deaths, said Arthur C. Evans Jr, PhD, chief executive officer of the American Psychological Association.

“These conditions are tied to societal determinants, but our approach to them is still focused at the individual level,” said Dr. Evans. “As long as our primary way is to build treatment programs and expect people to find their way into them on their own, it’s not going to work. We know that 90% of patients with substance abuse problems don’t come to treatment. So, our strategy is missing a whole lot of people.”

A better way, he said, is to proactively provide holistic person-centered care. He has some very specific ideas, honed by his 12 years as commissioner of Philadelphia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability Service, a $1.2 billion health care agency that is the safety net for 1.5 million Philadelphians with behavioral health and intellectual disabilities. Dr. Evans is credited with transforming the agency into a community-integrated, recovery-oriented treatment model.

He would like to see a similar national transformation in how at-risk groups are targeted, educated, screened, and treated. “We can create a culture where these issues are better understood by the public, so they can recognize problems early and connect to better health care.”

“Hope is at the center of our work,” Dr. Evans said. “The whole recovery movement has been about helping people have the hope that they can get better, that their lives can improve. Fundamentally, this must be the basis for treatment. We have focused for too long on the symptoms people bring to us, and missed the fact that these problems of suicide and drug abuse arise because people are hurting, both physically and psychologically. To recover, they need to believe there is a future in which they can feel better.”

If there’s a way, is there a will?

But while thought leaders continue to fine-tune their message, people continue to die, Mr. Kennedy said.

“We have all the experts who know what to do; the thing that is missing is the political will to do it,” he noted. “It’s driven by the stigma, the silence of families suffering from these illnesses. If we can’t talk about it in our families, we can’t talk about it to our legislators, and if they don’t hear from us, they do nothing. We need a political answer, ultimately. We appropriated a billion dollars over 2 years for the opioid crisis, but within 3 days of Hurricane Harvey, we appropriated $15 billion. It may seem we are making progress because we have great forums, but it’s a lot of talk, and people are dying every day.”

He likened the suicide and opioid death crisis to a natural disaster that requires not just money, but a highly coordinated response that targets multiple impacted areas.

“We need a Federal Emergency Management Agency–like response to this,” Mr. Kennedy said. “FEMA is designed to address all the missing pieces necessary for someone to recover from a disaster. In recovery, we have a physical problem, a mental obsession, and a spiritual malady. People need medical help – access to medication to get their lives stabilized. They need the psychological component of cognitive behavioral therapy. And they need the spiritual angle, which is social support, people reaching out to each other.

“Right now, everyone thinks this is a problem to be dealt with ‘over there,’ but it isn’t,” he added. “It involves all of us, and if we want to put these communities back together, we need everyone energized and contributing.”

WASHINGTON - Community pressures drive the twin tragedies of suicide and opioid deaths, which destroy community structure and must be addressed by community efforts, experts said during a panel discussion.

These so-called “deaths of despair” are inextricably linked, according to thought leaders in clinical medicine, volunteerism, and advocacy who gathered to share data and brainstorm solutions. A clear picture emerged of a professional community struggling to create a unified plan of attack and a unified voice to bring that plan to fruition.

The event was sponsored by the Education Development Center, a nonprofit that implements and evaluates programs to improve education, health, and economic opportunity worldwide, and the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention.

“We convened key leaders, including health care systems, federal agencies, national nonprofits, and faith-based organizations to strengthen our community response to suicide and opioids misuse and restore hope across the United States,” said Jerry Reed, PhD, EDC senior vice president. “To identify positive and lasting solutions requires collaboration from all sectors to achieve not only a nation free of suicide, but [also] a nation where all individuals are resilient, hopeful, and leading healthier lives.”

While several of the leading causes of death in the United States – including heart disease, stroke, and cancer – are declining, suicides and opioid deaths are surging, Alex Crosby, MD, told the gathering. An epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Crosby cited the most recent national data, gathered in 2015. The numbers present a picture of two terrible problems striking virtually identical communities.

“Suicide rates increased 25% from 2000 to 2015,” said Dr. Crosby, who is also the senior adviser in the division of violence prevention at the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. “In 2000, there were 30,000 suicides, and in 2015, there were 44,000. We are now looking at a suicide every 12 minutes in this country.”

Suicides cluster in several demographics, he said, “This is something that disproportionately affects males, working adults aged 25-64, non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic Native Americans, Alaskan natives, and rural areas.”

Deaths from drug overdoses, 60% of which now involve opioids, are on a parallel increase. “These have quadrupled since 1999, and the at-risk groups significantly overlap, with males, adults aged 24-52, non-Hispanic whites and Native Americans, Alaska natives, and rural communities most impacted. These are the very same groups seeing that increase in suicides.”

Joint tragedies, overlapping causes

The center is taking a public health stance on researching and managing both issues, Dr. Crosby said. “As we start looking at risk factors, we see that chronic health conditions, mental health, and pain management are factors common to both groups. But in addition to individual risks, there are societal risks … things in the family, community, and general society also influence these deaths.”

Former U.S. Rep. Patrick J. Kennedy agreed. Now a mental health policy advocate, Mr. Kennedy is not surprised that overlapping communities suffer these joint problems.

“On a societal level, these issues are directly related to the hollowing out of the manufacturing class, anxiety in a new generation that sees no financial stability,” he said. “Clearly, these are some of the reasons that these deaths track parts of the country that have been hardest hit economically. On top of that, we are lacking the kind of community connectedness we once had.”

Mr. Kennedy also faulted the marginalization of people with mental illnesses and the dearth of early screening that could identify mental disorders before they balloon into related substance abuse disorders. “Those are folks who, if screened and found to have a vulnerability from a mental illness, could be properly treated. These are illnesses that pathologize by neglect.”

The lack of awareness isn’t just a broad societal concept, but a specific weakness in the medical community, said Elinore F. McCance-Katz, MD, assistant secretary for mental health and substance use at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

“There’s not a lot of attention paid to this issue unless you’re in a profession like psychiatry, where we are taught to systematically assess for suicidality,” Dr. McCance-Katz noted. “But unless you’re trained to address it, it’s not something you think about; and if you don’t think about it, you won’t uncover it.

“In primary care, for example, we see many with a pain complaint,” she continued. “That pain will be treated medically, but the psychological component, which might be devastating, won’t be. This can cause depression and suicidal thinking, and if patients are not asked about it, they will not offer it. So, we have the terrible situation where someone can leave the office with the means to harm themselves, but not the help they need to save their life.”

How to reach the vulnerable

When a medical disorder and its attendant comorbidities present a multifactorial etiology, the clinician must address the problem as a unit. This isn’t happening with suicide and drug overdose deaths, said Arthur C. Evans Jr, PhD, chief executive officer of the American Psychological Association.

“These conditions are tied to societal determinants, but our approach to them is still focused at the individual level,” said Dr. Evans. “As long as our primary way is to build treatment programs and expect people to find their way into them on their own, it’s not going to work. We know that 90% of patients with substance abuse problems don’t come to treatment. So, our strategy is missing a whole lot of people.”

A better way, he said, is to proactively provide holistic person-centered care. He has some very specific ideas, honed by his 12 years as commissioner of Philadelphia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability Service, a $1.2 billion health care agency that is the safety net for 1.5 million Philadelphians with behavioral health and intellectual disabilities. Dr. Evans is credited with transforming the agency into a community-integrated, recovery-oriented treatment model.

He would like to see a similar national transformation in how at-risk groups are targeted, educated, screened, and treated. “We can create a culture where these issues are better understood by the public, so they can recognize problems early and connect to better health care.”

“Hope is at the center of our work,” Dr. Evans said. “The whole recovery movement has been about helping people have the hope that they can get better, that their lives can improve. Fundamentally, this must be the basis for treatment. We have focused for too long on the symptoms people bring to us, and missed the fact that these problems of suicide and drug abuse arise because people are hurting, both physically and psychologically. To recover, they need to believe there is a future in which they can feel better.”

If there’s a way, is there a will?

But while thought leaders continue to fine-tune their message, people continue to die, Mr. Kennedy said.

“We have all the experts who know what to do; the thing that is missing is the political will to do it,” he noted. “It’s driven by the stigma, the silence of families suffering from these illnesses. If we can’t talk about it in our families, we can’t talk about it to our legislators, and if they don’t hear from us, they do nothing. We need a political answer, ultimately. We appropriated a billion dollars over 2 years for the opioid crisis, but within 3 days of Hurricane Harvey, we appropriated $15 billion. It may seem we are making progress because we have great forums, but it’s a lot of talk, and people are dying every day.”

He likened the suicide and opioid death crisis to a natural disaster that requires not just money, but a highly coordinated response that targets multiple impacted areas.

“We need a Federal Emergency Management Agency–like response to this,” Mr. Kennedy said. “FEMA is designed to address all the missing pieces necessary for someone to recover from a disaster. In recovery, we have a physical problem, a mental obsession, and a spiritual malady. People need medical help – access to medication to get their lives stabilized. They need the psychological component of cognitive behavioral therapy. And they need the spiritual angle, which is social support, people reaching out to each other.

“Right now, everyone thinks this is a problem to be dealt with ‘over there,’ but it isn’t,” he added. “It involves all of us, and if we want to put these communities back together, we need everyone energized and contributing.”

AT AN EXPERT PANEL ON SUICIDE AND OPIOID DEATHS

Personality changes may not occur before Alzheimer’s onset

Personality changes do not presage dementia, at least when examined through the lens of self-report, a large retrospective study has determined.

Dementia patients do show personality characteristics that are different from those of their cognitively normal peers, wrote Antonio Terracciano, PhD (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Sep 20. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2816). Notably, they tend to be more neurotic and less conscientious, he noted. But among more than 2,000 older adults with up to 36 years of data, no temporal associations were found between these traits and the onset of cognitive difficulty, even within a few years of the onset of dementia symptoms.

“From a clinical perspective, these findings suggest that tracking change in self-rated personality as an early indicator of dementia is unlikely to be fruitful, while a single assessment provides reliable information on the personality traits that increase resilience [e.g., conscientiousness] or vulnerability [e.g., neuroticism] to clinical dementia,” wrote Dr. Terracciano of Florida State University, Tallahassee, and his coauthors.

However, the authors noted, it’s possible that self-reported personality may not be as good a marker of dementia-related personality change as informant report.

“Self-rated personality provides participants’ perspectives of themselves. … Individuals with AD could be anosognosic to change in their psychological trains and functioning. Self-reported personality might remain stable and reflect premorbid functioning more than current traits,” the researchers wrote.

The study tracked 2,046 community-living older adults who were part of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, which began in 1958. Healthy individuals of different ages are continuously enrolled in the study and assessed with regular follow-up visits. These visits include cognitive and neuropsychiatric assessments, from which data for this study were extracted. The mean follow-up time was about 12 years, but some subjects had up to 36 years. From 1980 to 2016, the group completed more than 8,000 assessments and accumulated 24,569 person/years of follow-up.

Dr. Terracciano examined the cohort’s Revised NEO Personality Inventory results, a 240-item questionnaire that assesses 30 facets of personality in the dimensions of neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Cognitive decline was assessed by results on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale and the older Dementia Questionnaire.

At the end of the follow-up period, 104 subjects (5%) had developed mild cognitive impairment, and 255 (12.5%) all-cause dementia; of those, 194 (9.5%) were later diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. In an unadjusted analysis, the authors found that the group that eventually developed AD scored higher on neuroticism, and lower on extraversion, openness, and conscientiousness than did the nonaffected subjects.

Over time, the authors found some changes in the reference group, including small declines in neuroticism and extraversion, and small increases in agreeableness and conscientiousness. However, when they looked at the trajectory of change, they found no significant differences in the rate of any change, compared with the AD group – although that group continued to display changes in its baseline difference of neuroticism and conscientiousness.

“Although the trajectories were similar, there were significant ... differences on the intercept,” they wrote. “The AD cohort scored higher on neuroticism and lower on conscientiousness and extraversion than the nonimpaired group.”

The team ran several temporal analyses on the data, and none found any significant temporal association with accelerated personality change in the AD group, the MCI group, or the all-cause dementia groups compared with the reference group, with one exception: Subjects with MCI showed a steeper decline in openness than did nonaffected subjects.

Those results were consistent even when they examined the two assessments performed just before the onset of cognitive symptoms (a mean of 6 and 3 years). “Consistent with the results and the broader literature, the AD group scored higher on neuroticism and lower on conscientiousness. Contrary to expectations, the AD group did not increase in neuroticism and decline in conscientiousness.”

The findings may shed some light on the chicken-or-egg question of personality change and dementia, they suggested.

“This research has relevance to the question of reverse causality for the association between personality and risk of incident AD. That is, if personality changed in response to increasing neuropathology in the brain in the preclinical phase, the association between personality and AD could have been due to the disease process rather than personality as an independent risk factor. We did not, however, find any evidence that neuroticism and conscientiousness changed significantly as the onset of disease approached. Thus, rather than an effect of AD neuropathology, these traits appear to confer risk for the development of the disease.”

The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging is supported by the National Institutes of Health. Neither Dr. Terracciano nor his colleagues had financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

Personality changes do not presage dementia, at least when examined through the lens of self-report, a large retrospective study has determined.

Dementia patients do show personality characteristics that are different from those of their cognitively normal peers, wrote Antonio Terracciano, PhD (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Sep 20. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2816). Notably, they tend to be more neurotic and less conscientious, he noted. But among more than 2,000 older adults with up to 36 years of data, no temporal associations were found between these traits and the onset of cognitive difficulty, even within a few years of the onset of dementia symptoms.

“From a clinical perspective, these findings suggest that tracking change in self-rated personality as an early indicator of dementia is unlikely to be fruitful, while a single assessment provides reliable information on the personality traits that increase resilience [e.g., conscientiousness] or vulnerability [e.g., neuroticism] to clinical dementia,” wrote Dr. Terracciano of Florida State University, Tallahassee, and his coauthors.

However, the authors noted, it’s possible that self-reported personality may not be as good a marker of dementia-related personality change as informant report.

“Self-rated personality provides participants’ perspectives of themselves. … Individuals with AD could be anosognosic to change in their psychological trains and functioning. Self-reported personality might remain stable and reflect premorbid functioning more than current traits,” the researchers wrote.

The study tracked 2,046 community-living older adults who were part of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, which began in 1958. Healthy individuals of different ages are continuously enrolled in the study and assessed with regular follow-up visits. These visits include cognitive and neuropsychiatric assessments, from which data for this study were extracted. The mean follow-up time was about 12 years, but some subjects had up to 36 years. From 1980 to 2016, the group completed more than 8,000 assessments and accumulated 24,569 person/years of follow-up.

Dr. Terracciano examined the cohort’s Revised NEO Personality Inventory results, a 240-item questionnaire that assesses 30 facets of personality in the dimensions of neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Cognitive decline was assessed by results on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale and the older Dementia Questionnaire.

At the end of the follow-up period, 104 subjects (5%) had developed mild cognitive impairment, and 255 (12.5%) all-cause dementia; of those, 194 (9.5%) were later diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. In an unadjusted analysis, the authors found that the group that eventually developed AD scored higher on neuroticism, and lower on extraversion, openness, and conscientiousness than did the nonaffected subjects.

Over time, the authors found some changes in the reference group, including small declines in neuroticism and extraversion, and small increases in agreeableness and conscientiousness. However, when they looked at the trajectory of change, they found no significant differences in the rate of any change, compared with the AD group – although that group continued to display changes in its baseline difference of neuroticism and conscientiousness.

“Although the trajectories were similar, there were significant ... differences on the intercept,” they wrote. “The AD cohort scored higher on neuroticism and lower on conscientiousness and extraversion than the nonimpaired group.”

The team ran several temporal analyses on the data, and none found any significant temporal association with accelerated personality change in the AD group, the MCI group, or the all-cause dementia groups compared with the reference group, with one exception: Subjects with MCI showed a steeper decline in openness than did nonaffected subjects.

Those results were consistent even when they examined the two assessments performed just before the onset of cognitive symptoms (a mean of 6 and 3 years). “Consistent with the results and the broader literature, the AD group scored higher on neuroticism and lower on conscientiousness. Contrary to expectations, the AD group did not increase in neuroticism and decline in conscientiousness.”

The findings may shed some light on the chicken-or-egg question of personality change and dementia, they suggested.

“This research has relevance to the question of reverse causality for the association between personality and risk of incident AD. That is, if personality changed in response to increasing neuropathology in the brain in the preclinical phase, the association between personality and AD could have been due to the disease process rather than personality as an independent risk factor. We did not, however, find any evidence that neuroticism and conscientiousness changed significantly as the onset of disease approached. Thus, rather than an effect of AD neuropathology, these traits appear to confer risk for the development of the disease.”

The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging is supported by the National Institutes of Health. Neither Dr. Terracciano nor his colleagues had financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

Personality changes do not presage dementia, at least when examined through the lens of self-report, a large retrospective study has determined.

Dementia patients do show personality characteristics that are different from those of their cognitively normal peers, wrote Antonio Terracciano, PhD (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Sep 20. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2816). Notably, they tend to be more neurotic and less conscientious, he noted. But among more than 2,000 older adults with up to 36 years of data, no temporal associations were found between these traits and the onset of cognitive difficulty, even within a few years of the onset of dementia symptoms.

“From a clinical perspective, these findings suggest that tracking change in self-rated personality as an early indicator of dementia is unlikely to be fruitful, while a single assessment provides reliable information on the personality traits that increase resilience [e.g., conscientiousness] or vulnerability [e.g., neuroticism] to clinical dementia,” wrote Dr. Terracciano of Florida State University, Tallahassee, and his coauthors.

However, the authors noted, it’s possible that self-reported personality may not be as good a marker of dementia-related personality change as informant report.

“Self-rated personality provides participants’ perspectives of themselves. … Individuals with AD could be anosognosic to change in their psychological trains and functioning. Self-reported personality might remain stable and reflect premorbid functioning more than current traits,” the researchers wrote.

The study tracked 2,046 community-living older adults who were part of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, which began in 1958. Healthy individuals of different ages are continuously enrolled in the study and assessed with regular follow-up visits. These visits include cognitive and neuropsychiatric assessments, from which data for this study were extracted. The mean follow-up time was about 12 years, but some subjects had up to 36 years. From 1980 to 2016, the group completed more than 8,000 assessments and accumulated 24,569 person/years of follow-up.

Dr. Terracciano examined the cohort’s Revised NEO Personality Inventory results, a 240-item questionnaire that assesses 30 facets of personality in the dimensions of neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Cognitive decline was assessed by results on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale and the older Dementia Questionnaire.

At the end of the follow-up period, 104 subjects (5%) had developed mild cognitive impairment, and 255 (12.5%) all-cause dementia; of those, 194 (9.5%) were later diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. In an unadjusted analysis, the authors found that the group that eventually developed AD scored higher on neuroticism, and lower on extraversion, openness, and conscientiousness than did the nonaffected subjects.

Over time, the authors found some changes in the reference group, including small declines in neuroticism and extraversion, and small increases in agreeableness and conscientiousness. However, when they looked at the trajectory of change, they found no significant differences in the rate of any change, compared with the AD group – although that group continued to display changes in its baseline difference of neuroticism and conscientiousness.

“Although the trajectories were similar, there were significant ... differences on the intercept,” they wrote. “The AD cohort scored higher on neuroticism and lower on conscientiousness and extraversion than the nonimpaired group.”

The team ran several temporal analyses on the data, and none found any significant temporal association with accelerated personality change in the AD group, the MCI group, or the all-cause dementia groups compared with the reference group, with one exception: Subjects with MCI showed a steeper decline in openness than did nonaffected subjects.

Those results were consistent even when they examined the two assessments performed just before the onset of cognitive symptoms (a mean of 6 and 3 years). “Consistent with the results and the broader literature, the AD group scored higher on neuroticism and lower on conscientiousness. Contrary to expectations, the AD group did not increase in neuroticism and decline in conscientiousness.”

The findings may shed some light on the chicken-or-egg question of personality change and dementia, they suggested.

“This research has relevance to the question of reverse causality for the association between personality and risk of incident AD. That is, if personality changed in response to increasing neuropathology in the brain in the preclinical phase, the association between personality and AD could have been due to the disease process rather than personality as an independent risk factor. We did not, however, find any evidence that neuroticism and conscientiousness changed significantly as the onset of disease approached. Thus, rather than an effect of AD neuropathology, these traits appear to confer risk for the development of the disease.”

The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging is supported by the National Institutes of Health. Neither Dr. Terracciano nor his colleagues had financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Although patients with AD scored higher on neuroticism and lower on conscientiousness, those traits did not change any faster than personality traits in the nonaffected subjects.

Data source: The study comprised 2,046 subjects with up to 36 years’ follow-up.

Disclosures: The Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging is funded by the National Institutes of Health. Neither Dr. Terracciano nor his coauthors had financial disclosures.

Postsurgical antibiotics cut infection in obese women after C-section

A 48-hour course of postoperative cephalexin and metronidazole, plus typical preoperative antibiotics, cut surgical site infections by 59% in obese women who had a cesarean delivery.

The benefit of the additional postoperative treatment was driven by a significant, 69% risk reduction among women who had ruptured membranes, Amy M. Valent, DO, and her colleagues reported (JAMA. 2017;318[11]:1026-34). However, the authors noted, “tests for interaction between the intact membranes and [ruptured] subgroups and postpartum cephalexin-metronidazole were not statistically different and should not be interpreted as showing a difference in significance or effect size among the subgroups with and without [rupture].”

The trial comprised 403 obese women who had a cesarean delivery. They were a mean of 28 years old. The mean body mass index was 40 kg/m2, and the mean subcutaneous adipose tissue thickness was about 3.4 cm. About a third of each treatment group was positive for Group B streptococcus; 31% had ruptured membranes at the onset of labor. More than 60% of women in both groups had a scheduled cesarean delivery.

All women had standard preoperative care, including skin prep with a chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine cleansing and an intravenous infusion of 2 g cefazolin. After delivery, they were randomized to placebo or to oral cephalexin 500 mg plus metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours for 48 hours. The primary outcome was surgical site infection incidence within 30 days.

The overall rate of surgical site infection was 10.9% (44 women). Infections developed in 13 women in the active group and 31 in the placebo group (6.4% vs. 15.4%) – a significant difference, translating to a 59% risk reduction (relative risk, 0.41). Cellulitis was the only secondary outcome that was significantly reduced by prophylactic antibiotics, with infections occurring in 5.9% of the metronidazole-cephalexin group vs. 13.4% of the placebo group (RR, 0.44). The antibiotic regimen didn’t affect the other secondary endpoints, which included rates of incisional morbidity, endometritis, fever of unknown etiology, and wound separation.

The authors conducted a post-hoc analysis to examine the antibiotics’ effects on women who had ruptured and intact membranes at the time of delivery. The benefit was greatest among those with ruptured membranes. There were six infections among the active group and 19 among the placebo group (9.5% vs. 30.2%). This difference translated to a relative risk of 0.31 – a 69% risk reduction.

Among women with intact membranes, there were seven infections in the active group and 12 in the placebo group (5% vs. 8.7%). This translated to a 0.58 relative risk, which was not statistically significant.

“Interaction testing was performed between study groups (cephalexin-metronidazole vs. placebo) and by membrane status (intact vs. ruptured),” the authors noted. “The rate of surgical site infection was highest in those with [ruptured membranes] who received placebo (30.2%) and lowest in those with intact membranes who received antibiotics (5.0%), but the test for interaction did not show statistical significance at P = .30.”

There were no serious adverse events or allergic reactions reported for cephalexin or metronidazole. The authors noted that both drugs are excreted into breast milk in small amounts, but that no study has ever linked them with neonatal harm through breast milk exposure. However, they added, “Long-term childhood or adverse neonatal outcomes specific to cephalexin-metronidazole exposure cannot be determined, as outcome measures were not evaluated for this study protocol. Recognizing the maternal and neonatal benefit of breastfeeding, the lack of known neonatal adverse effects, and maternal reduction in [surgical site infection], the benefit of this antibiotic regimen likely outweighs the theoretical risks of breast milk exposure in the obese population.”

The University of Cincinnati Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology sponsored the trial. None of the authors reported any financial conflicts.

Despite the positive outcomes of this trial, it’s not yet time to tack on yet more antibiotics for every obese woman who undergoes a cesarean delivery, David P. Calfee, MD, and Amos Grünebaum, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2017;318[11]:1012-3).

“When determining if and how the results of this study should alter current clinical practice, it is important to recognize that the results of this study are quite different from those of several previous studies conducted in other surgical patient populations in which no benefit from postoperative antimicrobial prophylaxis was found and on which current clinical guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis are based,” they wrote. “The explanation for this difference may be as simple as the identification in the current study of a very specific, high-risk group of patients for which the intervention is effective. However, several questions are worthy of additional consideration and study.”

For instance, the study was conducted over 5 years and may not reflect current practices for managing these patients, such as glycemic control and maintaining normothermia. Additionally, there may be additional risks to women that were not identified in the study, such as infection from antimicrobial-resistant pathogens.

Dr. Calfee and Dr. Grünebaum are at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. Dr. Calfee reported receiving grants from Merck, Sharp, and Dohme.

Despite the positive outcomes of this trial, it’s not yet time to tack on yet more antibiotics for every obese woman who undergoes a cesarean delivery, David P. Calfee, MD, and Amos Grünebaum, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2017;318[11]:1012-3).

“When determining if and how the results of this study should alter current clinical practice, it is important to recognize that the results of this study are quite different from those of several previous studies conducted in other surgical patient populations in which no benefit from postoperative antimicrobial prophylaxis was found and on which current clinical guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis are based,” they wrote. “The explanation for this difference may be as simple as the identification in the current study of a very specific, high-risk group of patients for which the intervention is effective. However, several questions are worthy of additional consideration and study.”

For instance, the study was conducted over 5 years and may not reflect current practices for managing these patients, such as glycemic control and maintaining normothermia. Additionally, there may be additional risks to women that were not identified in the study, such as infection from antimicrobial-resistant pathogens.

Dr. Calfee and Dr. Grünebaum are at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. Dr. Calfee reported receiving grants from Merck, Sharp, and Dohme.

Despite the positive outcomes of this trial, it’s not yet time to tack on yet more antibiotics for every obese woman who undergoes a cesarean delivery, David P. Calfee, MD, and Amos Grünebaum, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2017;318[11]:1012-3).

“When determining if and how the results of this study should alter current clinical practice, it is important to recognize that the results of this study are quite different from those of several previous studies conducted in other surgical patient populations in which no benefit from postoperative antimicrobial prophylaxis was found and on which current clinical guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis are based,” they wrote. “The explanation for this difference may be as simple as the identification in the current study of a very specific, high-risk group of patients for which the intervention is effective. However, several questions are worthy of additional consideration and study.”

For instance, the study was conducted over 5 years and may not reflect current practices for managing these patients, such as glycemic control and maintaining normothermia. Additionally, there may be additional risks to women that were not identified in the study, such as infection from antimicrobial-resistant pathogens.

Dr. Calfee and Dr. Grünebaum are at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. Dr. Calfee reported receiving grants from Merck, Sharp, and Dohme.

A 48-hour course of postoperative cephalexin and metronidazole, plus typical preoperative antibiotics, cut surgical site infections by 59% in obese women who had a cesarean delivery.

The benefit of the additional postoperative treatment was driven by a significant, 69% risk reduction among women who had ruptured membranes, Amy M. Valent, DO, and her colleagues reported (JAMA. 2017;318[11]:1026-34). However, the authors noted, “tests for interaction between the intact membranes and [ruptured] subgroups and postpartum cephalexin-metronidazole were not statistically different and should not be interpreted as showing a difference in significance or effect size among the subgroups with and without [rupture].”

The trial comprised 403 obese women who had a cesarean delivery. They were a mean of 28 years old. The mean body mass index was 40 kg/m2, and the mean subcutaneous adipose tissue thickness was about 3.4 cm. About a third of each treatment group was positive for Group B streptococcus; 31% had ruptured membranes at the onset of labor. More than 60% of women in both groups had a scheduled cesarean delivery.

All women had standard preoperative care, including skin prep with a chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine cleansing and an intravenous infusion of 2 g cefazolin. After delivery, they were randomized to placebo or to oral cephalexin 500 mg plus metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours for 48 hours. The primary outcome was surgical site infection incidence within 30 days.

The overall rate of surgical site infection was 10.9% (44 women). Infections developed in 13 women in the active group and 31 in the placebo group (6.4% vs. 15.4%) – a significant difference, translating to a 59% risk reduction (relative risk, 0.41). Cellulitis was the only secondary outcome that was significantly reduced by prophylactic antibiotics, with infections occurring in 5.9% of the metronidazole-cephalexin group vs. 13.4% of the placebo group (RR, 0.44). The antibiotic regimen didn’t affect the other secondary endpoints, which included rates of incisional morbidity, endometritis, fever of unknown etiology, and wound separation.

The authors conducted a post-hoc analysis to examine the antibiotics’ effects on women who had ruptured and intact membranes at the time of delivery. The benefit was greatest among those with ruptured membranes. There were six infections among the active group and 19 among the placebo group (9.5% vs. 30.2%). This difference translated to a relative risk of 0.31 – a 69% risk reduction.

Among women with intact membranes, there were seven infections in the active group and 12 in the placebo group (5% vs. 8.7%). This translated to a 0.58 relative risk, which was not statistically significant.

“Interaction testing was performed between study groups (cephalexin-metronidazole vs. placebo) and by membrane status (intact vs. ruptured),” the authors noted. “The rate of surgical site infection was highest in those with [ruptured membranes] who received placebo (30.2%) and lowest in those with intact membranes who received antibiotics (5.0%), but the test for interaction did not show statistical significance at P = .30.”

There were no serious adverse events or allergic reactions reported for cephalexin or metronidazole. The authors noted that both drugs are excreted into breast milk in small amounts, but that no study has ever linked them with neonatal harm through breast milk exposure. However, they added, “Long-term childhood or adverse neonatal outcomes specific to cephalexin-metronidazole exposure cannot be determined, as outcome measures were not evaluated for this study protocol. Recognizing the maternal and neonatal benefit of breastfeeding, the lack of known neonatal adverse effects, and maternal reduction in [surgical site infection], the benefit of this antibiotic regimen likely outweighs the theoretical risks of breast milk exposure in the obese population.”

The University of Cincinnati Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology sponsored the trial. None of the authors reported any financial conflicts.

A 48-hour course of postoperative cephalexin and metronidazole, plus typical preoperative antibiotics, cut surgical site infections by 59% in obese women who had a cesarean delivery.

The benefit of the additional postoperative treatment was driven by a significant, 69% risk reduction among women who had ruptured membranes, Amy M. Valent, DO, and her colleagues reported (JAMA. 2017;318[11]:1026-34). However, the authors noted, “tests for interaction between the intact membranes and [ruptured] subgroups and postpartum cephalexin-metronidazole were not statistically different and should not be interpreted as showing a difference in significance or effect size among the subgroups with and without [rupture].”

The trial comprised 403 obese women who had a cesarean delivery. They were a mean of 28 years old. The mean body mass index was 40 kg/m2, and the mean subcutaneous adipose tissue thickness was about 3.4 cm. About a third of each treatment group was positive for Group B streptococcus; 31% had ruptured membranes at the onset of labor. More than 60% of women in both groups had a scheduled cesarean delivery.

All women had standard preoperative care, including skin prep with a chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine cleansing and an intravenous infusion of 2 g cefazolin. After delivery, they were randomized to placebo or to oral cephalexin 500 mg plus metronidazole 500 mg every 8 hours for 48 hours. The primary outcome was surgical site infection incidence within 30 days.

The overall rate of surgical site infection was 10.9% (44 women). Infections developed in 13 women in the active group and 31 in the placebo group (6.4% vs. 15.4%) – a significant difference, translating to a 59% risk reduction (relative risk, 0.41). Cellulitis was the only secondary outcome that was significantly reduced by prophylactic antibiotics, with infections occurring in 5.9% of the metronidazole-cephalexin group vs. 13.4% of the placebo group (RR, 0.44). The antibiotic regimen didn’t affect the other secondary endpoints, which included rates of incisional morbidity, endometritis, fever of unknown etiology, and wound separation.

The authors conducted a post-hoc analysis to examine the antibiotics’ effects on women who had ruptured and intact membranes at the time of delivery. The benefit was greatest among those with ruptured membranes. There were six infections among the active group and 19 among the placebo group (9.5% vs. 30.2%). This difference translated to a relative risk of 0.31 – a 69% risk reduction.

Among women with intact membranes, there were seven infections in the active group and 12 in the placebo group (5% vs. 8.7%). This translated to a 0.58 relative risk, which was not statistically significant.

“Interaction testing was performed between study groups (cephalexin-metronidazole vs. placebo) and by membrane status (intact vs. ruptured),” the authors noted. “The rate of surgical site infection was highest in those with [ruptured membranes] who received placebo (30.2%) and lowest in those with intact membranes who received antibiotics (5.0%), but the test for interaction did not show statistical significance at P = .30.”

There were no serious adverse events or allergic reactions reported for cephalexin or metronidazole. The authors noted that both drugs are excreted into breast milk in small amounts, but that no study has ever linked them with neonatal harm through breast milk exposure. However, they added, “Long-term childhood or adverse neonatal outcomes specific to cephalexin-metronidazole exposure cannot be determined, as outcome measures were not evaluated for this study protocol. Recognizing the maternal and neonatal benefit of breastfeeding, the lack of known neonatal adverse effects, and maternal reduction in [surgical site infection], the benefit of this antibiotic regimen likely outweighs the theoretical risks of breast milk exposure in the obese population.”

The University of Cincinnati Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology sponsored the trial. None of the authors reported any financial conflicts.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Infections developed in 13 women in the active group and 31 in the placebo group (6.4% vs. 15.4%) – a significant difference, translating to a 59% risk reduction (relative risk, 0.41).

Data source: The randomized, placebo-controlled study comprised 403 women.

Disclosures: The University of Cincinnati Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology sponsored the study. None of the authors reported any financial conflicts.

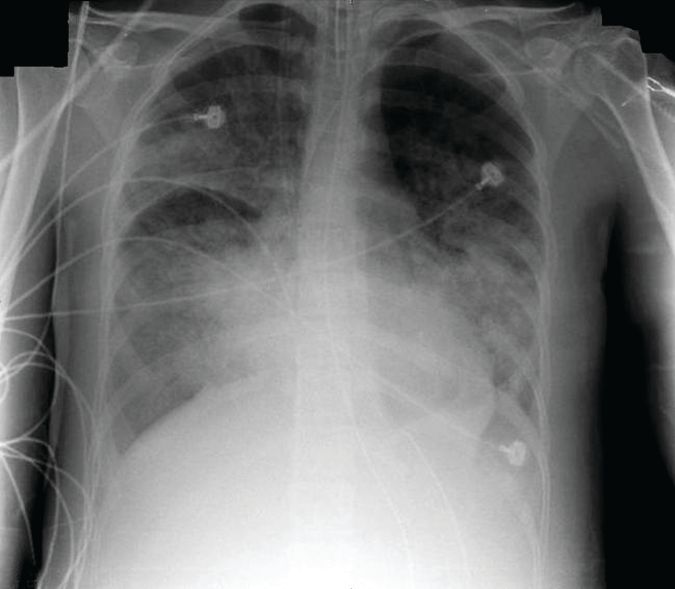

Bedside imaging allowed for individualized PEEP adjustments

A noninvasive bedside imaging technique can individually calibrate positive end-expiratory pressure settings in patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), a study showed.

The step-down PEEP (positive end-expiratory pressure) trial could not identify a single PEEP setting that optimally balanced lung overdistension and lung collapse for all 15 patients. But, electrical impedance tomography (EIT) allowed investigators to individually titrate PEEP settings for each patient, Guillaume Franchineau, MD, wrote (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196[4]:447-57 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201605-1055OC).

The 4-month study involved 15 patients (aged, 18-79 years) who were in acute respiratory distress syndrome for a variety of reasons, including influenza (7 patients), pneumonia (3), leukemia (2), and 1 case each of Pneumocystis, antisynthetase syndrome, and trauma. All patients were receiving ECMO with a constant driving pressure of 14 cm H2O. After verifying that the inspiratory flow was 0 at the end of inspiration, PEEP was increased to 20 cm H2O (PEEP 20) with a peak inspiratory pressure of 34 cm H2O. PEEP 20 was held for 20 minutes and then lowered by 5 cm H2O decrements with the potential of reaching PEEP 0.

The EIT device, consisting of a silicone belt with 16 surface electrodes, was placed around the thorax aligning with the sixth intercostal parasternal space and connected to a monitor. By measuring conductivity and impeditivity in the underlying tissues, the device generates a low-resolution, two-dimensional image. The image was sufficient to show lung distension and collapse as the PEEP settings changed. Investigators looked for the best compromise between overdistension and collapsed zones, which they defined as the lowest pressure able to limit EIT-assessed collapse to no more than 15% with the least overdistension.

There was no one-size-fits-all PEEP setting, the authors found. The setting that minimized both overdistension and collapse was PEEP 15 in seven patients, PEEP 10 in six patients, and PEEP 5 in two patients.

At each patient’s optimal PEEP setting, the median tidal volume was similar: 3.8 mL/kg ideal body weight for PEEP 15, 3.9 mL/kg ideal body weight for PEEP 10, and 4.3 mL/kg ideal body weight for PEEP 5.

Respiratory system compliance was also similar among the groups, at 20 mL/cm H2O, 18 mL/cm H2O, and 21 mL/cm H2O, respectively. However, arterial partial pressure of oxygen decreased as the PEEP setting decreased, dropping from 148 mm Hg to 128 mm Hg to 100 mm Hg, respectively. Conversely, arterial partial pressure of CO2 increased (32-41 mm Hg).

EIT also allowed clinicians to pinpoint areas of distension or collapse. As PEEP decreased, there was steady ventilation loss in the medial-dorsal and dorsal regions, which shifted to the medial-ventral and ventral regions.

“Most end-expiratory lung impedances were located in medial-dorsal and medial-ventral regions, whereas the dorsal region constantly contributed less than 10% of total end-expiratory lung impedance,” the authors noted.

“The broad variability of EIT-based best compromise PEEPs in these patients with severe ARDS reinforces the need to provide ventilation settings individually tailored to the regional ARDS-lesion distribution,” they concluded. “To achieve that goal, EIT seems to be an interesting bedside noninvasive tool to provide real-time monitoring of the PEEP effect and ventilation distribution on ECMO.”

Dr. Franchineau reported receiving speakers fees from Mapquet.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

This first study to examine electrical impedance tomography (EIT) in patients under extracorporeal membrane oxygenation shows important clinical potential, but also raises important questions, Claude Guerin, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial. (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0167ed).

The ability to titrate PEEP settings to a patient’s individual needs could substantially reduce the risk of lung derecruitment or damage by overdistension.

The current study, however, has limitations that must be addressed in the next phase of research, before this technique can be adopted into clinical practice, Dr. Guerin said: The 5-cm H20 PEEP steps may be too large to detect relevant changes.

In several other studies, PEEP was reduced more gradually in 2- to 3-cm H2O increments. “Surprisingly, PEEP was reduced to 0 cm H2O in this study, with this step maintained for 20 minutes, raising the risk of derecruitment and further stretching once higher PEEP levels were resumed.”

The investigators did not perform any recruitment maneuvers before proceeding with PEEP adjustment. This is contrary to what has been done in prior animal and human studies.

The computation of driving pressure was done without taking total PEEP into account. “As total PEEP is frequently greater than PEEP in patients with [acute respiratory distress syndrome], driving pressure can be overestimated with the common computation.”

The optimal PEEP that the investigators aimed for was determined retrospectively from an offline analysis of the data; this technique would not be suitable for bedside management. “When ‘optimal’ PEEP was defined from [EIT criteria], from a higher PaO2 [arterial partial pressure of oxygen] or from a higher compliance of the respiratory system during the decremental PEEP trial, these three criteria were observed together in only four patients with [acute respiratory distress syndrome].”

The study was done only once and cannot comply with the need for regular PEEP-level assessments over time, as could be done with some other strategies.

“Further studies should also consider taking into account the role of chest wall mechanics,” Dr. Guerin said.

Nevertheless, he concluded, EIT-based PEEP titration for each individual patient represents a prospective tool for assisting with the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome, and should be fully investigated in a large, prospective trial.

Dr. Guerin is a pulmonologist at the Hospital de la Croix Rousse, Lyon, France. He had no relevant financial disclosures.

This first study to examine electrical impedance tomography (EIT) in patients under extracorporeal membrane oxygenation shows important clinical potential, but also raises important questions, Claude Guerin, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial. (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0167ed).

The ability to titrate PEEP settings to a patient’s individual needs could substantially reduce the risk of lung derecruitment or damage by overdistension.

The current study, however, has limitations that must be addressed in the next phase of research, before this technique can be adopted into clinical practice, Dr. Guerin said: The 5-cm H20 PEEP steps may be too large to detect relevant changes.

In several other studies, PEEP was reduced more gradually in 2- to 3-cm H2O increments. “Surprisingly, PEEP was reduced to 0 cm H2O in this study, with this step maintained for 20 minutes, raising the risk of derecruitment and further stretching once higher PEEP levels were resumed.”

The investigators did not perform any recruitment maneuvers before proceeding with PEEP adjustment. This is contrary to what has been done in prior animal and human studies.

The computation of driving pressure was done without taking total PEEP into account. “As total PEEP is frequently greater than PEEP in patients with [acute respiratory distress syndrome], driving pressure can be overestimated with the common computation.”

The optimal PEEP that the investigators aimed for was determined retrospectively from an offline analysis of the data; this technique would not be suitable for bedside management. “When ‘optimal’ PEEP was defined from [EIT criteria], from a higher PaO2 [arterial partial pressure of oxygen] or from a higher compliance of the respiratory system during the decremental PEEP trial, these three criteria were observed together in only four patients with [acute respiratory distress syndrome].”

The study was done only once and cannot comply with the need for regular PEEP-level assessments over time, as could be done with some other strategies.

“Further studies should also consider taking into account the role of chest wall mechanics,” Dr. Guerin said.

Nevertheless, he concluded, EIT-based PEEP titration for each individual patient represents a prospective tool for assisting with the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome, and should be fully investigated in a large, prospective trial.

Dr. Guerin is a pulmonologist at the Hospital de la Croix Rousse, Lyon, France. He had no relevant financial disclosures.

This first study to examine electrical impedance tomography (EIT) in patients under extracorporeal membrane oxygenation shows important clinical potential, but also raises important questions, Claude Guerin, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial. (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0167ed).

The ability to titrate PEEP settings to a patient’s individual needs could substantially reduce the risk of lung derecruitment or damage by overdistension.

The current study, however, has limitations that must be addressed in the next phase of research, before this technique can be adopted into clinical practice, Dr. Guerin said: The 5-cm H20 PEEP steps may be too large to detect relevant changes.

In several other studies, PEEP was reduced more gradually in 2- to 3-cm H2O increments. “Surprisingly, PEEP was reduced to 0 cm H2O in this study, with this step maintained for 20 minutes, raising the risk of derecruitment and further stretching once higher PEEP levels were resumed.”

The investigators did not perform any recruitment maneuvers before proceeding with PEEP adjustment. This is contrary to what has been done in prior animal and human studies.

The computation of driving pressure was done without taking total PEEP into account. “As total PEEP is frequently greater than PEEP in patients with [acute respiratory distress syndrome], driving pressure can be overestimated with the common computation.”

The optimal PEEP that the investigators aimed for was determined retrospectively from an offline analysis of the data; this technique would not be suitable for bedside management. “When ‘optimal’ PEEP was defined from [EIT criteria], from a higher PaO2 [arterial partial pressure of oxygen] or from a higher compliance of the respiratory system during the decremental PEEP trial, these three criteria were observed together in only four patients with [acute respiratory distress syndrome].”

The study was done only once and cannot comply with the need for regular PEEP-level assessments over time, as could be done with some other strategies.

“Further studies should also consider taking into account the role of chest wall mechanics,” Dr. Guerin said.

Nevertheless, he concluded, EIT-based PEEP titration for each individual patient represents a prospective tool for assisting with the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome, and should be fully investigated in a large, prospective trial.

Dr. Guerin is a pulmonologist at the Hospital de la Croix Rousse, Lyon, France. He had no relevant financial disclosures.

A noninvasive bedside imaging technique can individually calibrate positive end-expiratory pressure settings in patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), a study showed.

The step-down PEEP (positive end-expiratory pressure) trial could not identify a single PEEP setting that optimally balanced lung overdistension and lung collapse for all 15 patients. But, electrical impedance tomography (EIT) allowed investigators to individually titrate PEEP settings for each patient, Guillaume Franchineau, MD, wrote (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196[4]:447-57 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201605-1055OC).

The 4-month study involved 15 patients (aged, 18-79 years) who were in acute respiratory distress syndrome for a variety of reasons, including influenza (7 patients), pneumonia (3), leukemia (2), and 1 case each of Pneumocystis, antisynthetase syndrome, and trauma. All patients were receiving ECMO with a constant driving pressure of 14 cm H2O. After verifying that the inspiratory flow was 0 at the end of inspiration, PEEP was increased to 20 cm H2O (PEEP 20) with a peak inspiratory pressure of 34 cm H2O. PEEP 20 was held for 20 minutes and then lowered by 5 cm H2O decrements with the potential of reaching PEEP 0.

The EIT device, consisting of a silicone belt with 16 surface electrodes, was placed around the thorax aligning with the sixth intercostal parasternal space and connected to a monitor. By measuring conductivity and impeditivity in the underlying tissues, the device generates a low-resolution, two-dimensional image. The image was sufficient to show lung distension and collapse as the PEEP settings changed. Investigators looked for the best compromise between overdistension and collapsed zones, which they defined as the lowest pressure able to limit EIT-assessed collapse to no more than 15% with the least overdistension.

There was no one-size-fits-all PEEP setting, the authors found. The setting that minimized both overdistension and collapse was PEEP 15 in seven patients, PEEP 10 in six patients, and PEEP 5 in two patients.

At each patient’s optimal PEEP setting, the median tidal volume was similar: 3.8 mL/kg ideal body weight for PEEP 15, 3.9 mL/kg ideal body weight for PEEP 10, and 4.3 mL/kg ideal body weight for PEEP 5.

Respiratory system compliance was also similar among the groups, at 20 mL/cm H2O, 18 mL/cm H2O, and 21 mL/cm H2O, respectively. However, arterial partial pressure of oxygen decreased as the PEEP setting decreased, dropping from 148 mm Hg to 128 mm Hg to 100 mm Hg, respectively. Conversely, arterial partial pressure of CO2 increased (32-41 mm Hg).

EIT also allowed clinicians to pinpoint areas of distension or collapse. As PEEP decreased, there was steady ventilation loss in the medial-dorsal and dorsal regions, which shifted to the medial-ventral and ventral regions.

“Most end-expiratory lung impedances were located in medial-dorsal and medial-ventral regions, whereas the dorsal region constantly contributed less than 10% of total end-expiratory lung impedance,” the authors noted.

“The broad variability of EIT-based best compromise PEEPs in these patients with severe ARDS reinforces the need to provide ventilation settings individually tailored to the regional ARDS-lesion distribution,” they concluded. “To achieve that goal, EIT seems to be an interesting bedside noninvasive tool to provide real-time monitoring of the PEEP effect and ventilation distribution on ECMO.”

Dr. Franchineau reported receiving speakers fees from Mapquet.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

A noninvasive bedside imaging technique can individually calibrate positive end-expiratory pressure settings in patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), a study showed.

The step-down PEEP (positive end-expiratory pressure) trial could not identify a single PEEP setting that optimally balanced lung overdistension and lung collapse for all 15 patients. But, electrical impedance tomography (EIT) allowed investigators to individually titrate PEEP settings for each patient, Guillaume Franchineau, MD, wrote (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196[4]:447-57 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201605-1055OC).

The 4-month study involved 15 patients (aged, 18-79 years) who were in acute respiratory distress syndrome for a variety of reasons, including influenza (7 patients), pneumonia (3), leukemia (2), and 1 case each of Pneumocystis, antisynthetase syndrome, and trauma. All patients were receiving ECMO with a constant driving pressure of 14 cm H2O. After verifying that the inspiratory flow was 0 at the end of inspiration, PEEP was increased to 20 cm H2O (PEEP 20) with a peak inspiratory pressure of 34 cm H2O. PEEP 20 was held for 20 minutes and then lowered by 5 cm H2O decrements with the potential of reaching PEEP 0.

The EIT device, consisting of a silicone belt with 16 surface electrodes, was placed around the thorax aligning with the sixth intercostal parasternal space and connected to a monitor. By measuring conductivity and impeditivity in the underlying tissues, the device generates a low-resolution, two-dimensional image. The image was sufficient to show lung distension and collapse as the PEEP settings changed. Investigators looked for the best compromise between overdistension and collapsed zones, which they defined as the lowest pressure able to limit EIT-assessed collapse to no more than 15% with the least overdistension.

There was no one-size-fits-all PEEP setting, the authors found. The setting that minimized both overdistension and collapse was PEEP 15 in seven patients, PEEP 10 in six patients, and PEEP 5 in two patients.

At each patient’s optimal PEEP setting, the median tidal volume was similar: 3.8 mL/kg ideal body weight for PEEP 15, 3.9 mL/kg ideal body weight for PEEP 10, and 4.3 mL/kg ideal body weight for PEEP 5.

Respiratory system compliance was also similar among the groups, at 20 mL/cm H2O, 18 mL/cm H2O, and 21 mL/cm H2O, respectively. However, arterial partial pressure of oxygen decreased as the PEEP setting decreased, dropping from 148 mm Hg to 128 mm Hg to 100 mm Hg, respectively. Conversely, arterial partial pressure of CO2 increased (32-41 mm Hg).

EIT also allowed clinicians to pinpoint areas of distension or collapse. As PEEP decreased, there was steady ventilation loss in the medial-dorsal and dorsal regions, which shifted to the medial-ventral and ventral regions.

“Most end-expiratory lung impedances were located in medial-dorsal and medial-ventral regions, whereas the dorsal region constantly contributed less than 10% of total end-expiratory lung impedance,” the authors noted.

“The broad variability of EIT-based best compromise PEEPs in these patients with severe ARDS reinforces the need to provide ventilation settings individually tailored to the regional ARDS-lesion distribution,” they concluded. “To achieve that goal, EIT seems to be an interesting bedside noninvasive tool to provide real-time monitoring of the PEEP effect and ventilation distribution on ECMO.”

Dr. Franchineau reported receiving speakers fees from Mapquet.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF RESPIRATORY AND CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE

Key clinical point: