User login

CABG costs more in patients with diabetes

The rate of diabetic coronary artery bypass graft patients has increased more than fivefold in recent decades, and these patients are more likely to have worse outcomes and higher treatment costs, a study showed.

The percentage of patients who had diabetes among all those undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) increased from 7% in the 1970s to 37% in the 2000s, according to a database study of 55,501 patients operated on at the Cleveland Clinic.

Patients were identified and preoperative, operative, and postoperative variables were identified, resulting in 45,139 nondiabetic patients assessed and 10,362 diabetic patients (defined as those diabetic patients pharmacologically treated with either insulin or an oral agent) evaluated. The endpoints assessed were in-hospital adverse outcomes as determined by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database, in-hospital direct technical costs, and time-related mortality, according to Dr. Sajjad Raza and his colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic in the August issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (150:294-301).

Compared with nondiabetics, diabetic patients undergoing CABG were older and were more likely to be overweight, to be women, and to have a history of heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, carotid disease, hypertension, renal failure, stroke, and advanced coronary artery disease. Over time, the cardiovascular risk profile of the entire population changed, becoming even more pronounced for all patients, but more so for diabetics.

Overall long-term survival at 6 months and at 1, 5 10, 15, and 20 years for diabetic patients was 95%, 94%, 80%, 54%, 31%, and 18%, respectively, compared with 97%, 97%, 90%, 76%, 59%, and 42% for nondiabetic patients, a significant difference at P <.0001.

Propensity matching of similar diabetic and nondiabetic patients showed that deep sternal wound infection and stroke occurred significantly more often in diabetics, although there were no significant differences in cost remaining after matching, even though the length of stay greater than 14 days remained higher for diabetic patients.

Among diabetics, overall survival at 6 months and at 1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 years after CABG was 95%, 94%, 80%, 54%, 31%, and 18%, respectively, compared with overall survival in nondiabetics at 97%, 97%, 90%, 76%, 59%, and 42%, respectively, a significant difference (P <.0001).

“Although long-term survival after CABG is worse in diabetics and high-risk nondiabetics, it is important to note that, in general, high-risk patients reap the greatest survival benefit from CABG. Moreover, using surgical techniques that are associated with better long-term survival after CABG in diabetics could further enhance this survival benefit,” Dr. Raza and his colleagues wrote.

“Diabetes is both a marker for high-risk, resource-intensive, and expensive care after CABG and an independent risk factor for reduced long-term survival,” they added. “Diabetic patients and those with a similar high-risk profile set to undergo CABG should be made aware that their risks of postoperative complications are higher than average, and measures should be taken to reduce their postoperative complications,” Dr. Raza and his colleagues concluded.

The authors reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Patients with diabetes, with or without metabolic syndrome, represent an increasing challenge for cardiac surgery. CABG has been shown to convey a mortality benefit in such patients who also have multivessel disease. This study confirms what most clinicians already know – that the outcomes of patients with diabetes are worse than those in nondiabetic patients, according to Dr. Mani Arsalan and Dr. Michael Mack. “What is particularly important about this study, however, is that it is a single institutional experience with known surgical excellence and a very meticulous and complete outcomes database,” they wrote (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015;150:284-5).

Given their findings and the fact that CABG can be expected to remain the mainstay of treatment of multivessel disease in diabetics because of the results of the FREEDOM (Future Revascularization Evaluation in Patients With Diabetes Mellitus: Optimal Management of Multivessel Disease) trial, surgeons should pay increased attention to the details of the procedure for these patients. There should be an increased use of bilateral internal mammary arteries, which has been distressingly low, and yet can provide a 23% mortality benefit. “Two arteries are better than one.” Despite the increased risk of deep sternal infection, “the use of skeletonized bilateral internal mammary arteries in young, nonobese diabetic patients with a greater than 10-year life expectancy seems a reasonable risk to take,” Dr. Arsalan and Dr. Mack wrote. In addition, where possible, reaching satisfactory glycemic control before surgery can help decrease early complications. “The weight may be increasingly on our patients, but the real weight is on us as surgeons to help improve their early and long-term survival,” they concluded.

Dr. Arsalan and Dr. Mack are cardiovascular surgeons at Baylor Scott & White Health, Dallas. Their remarks were part of an invited commentary published with the paper.

Patients with diabetes, with or without metabolic syndrome, represent an increasing challenge for cardiac surgery. CABG has been shown to convey a mortality benefit in such patients who also have multivessel disease. This study confirms what most clinicians already know – that the outcomes of patients with diabetes are worse than those in nondiabetic patients, according to Dr. Mani Arsalan and Dr. Michael Mack. “What is particularly important about this study, however, is that it is a single institutional experience with known surgical excellence and a very meticulous and complete outcomes database,” they wrote (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015;150:284-5).

Given their findings and the fact that CABG can be expected to remain the mainstay of treatment of multivessel disease in diabetics because of the results of the FREEDOM (Future Revascularization Evaluation in Patients With Diabetes Mellitus: Optimal Management of Multivessel Disease) trial, surgeons should pay increased attention to the details of the procedure for these patients. There should be an increased use of bilateral internal mammary arteries, which has been distressingly low, and yet can provide a 23% mortality benefit. “Two arteries are better than one.” Despite the increased risk of deep sternal infection, “the use of skeletonized bilateral internal mammary arteries in young, nonobese diabetic patients with a greater than 10-year life expectancy seems a reasonable risk to take,” Dr. Arsalan and Dr. Mack wrote. In addition, where possible, reaching satisfactory glycemic control before surgery can help decrease early complications. “The weight may be increasingly on our patients, but the real weight is on us as surgeons to help improve their early and long-term survival,” they concluded.

Dr. Arsalan and Dr. Mack are cardiovascular surgeons at Baylor Scott & White Health, Dallas. Their remarks were part of an invited commentary published with the paper.

Patients with diabetes, with or without metabolic syndrome, represent an increasing challenge for cardiac surgery. CABG has been shown to convey a mortality benefit in such patients who also have multivessel disease. This study confirms what most clinicians already know – that the outcomes of patients with diabetes are worse than those in nondiabetic patients, according to Dr. Mani Arsalan and Dr. Michael Mack. “What is particularly important about this study, however, is that it is a single institutional experience with known surgical excellence and a very meticulous and complete outcomes database,” they wrote (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015;150:284-5).

Given their findings and the fact that CABG can be expected to remain the mainstay of treatment of multivessel disease in diabetics because of the results of the FREEDOM (Future Revascularization Evaluation in Patients With Diabetes Mellitus: Optimal Management of Multivessel Disease) trial, surgeons should pay increased attention to the details of the procedure for these patients. There should be an increased use of bilateral internal mammary arteries, which has been distressingly low, and yet can provide a 23% mortality benefit. “Two arteries are better than one.” Despite the increased risk of deep sternal infection, “the use of skeletonized bilateral internal mammary arteries in young, nonobese diabetic patients with a greater than 10-year life expectancy seems a reasonable risk to take,” Dr. Arsalan and Dr. Mack wrote. In addition, where possible, reaching satisfactory glycemic control before surgery can help decrease early complications. “The weight may be increasingly on our patients, but the real weight is on us as surgeons to help improve their early and long-term survival,” they concluded.

Dr. Arsalan and Dr. Mack are cardiovascular surgeons at Baylor Scott & White Health, Dallas. Their remarks were part of an invited commentary published with the paper.

The rate of diabetic coronary artery bypass graft patients has increased more than fivefold in recent decades, and these patients are more likely to have worse outcomes and higher treatment costs, a study showed.

The percentage of patients who had diabetes among all those undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) increased from 7% in the 1970s to 37% in the 2000s, according to a database study of 55,501 patients operated on at the Cleveland Clinic.

Patients were identified and preoperative, operative, and postoperative variables were identified, resulting in 45,139 nondiabetic patients assessed and 10,362 diabetic patients (defined as those diabetic patients pharmacologically treated with either insulin or an oral agent) evaluated. The endpoints assessed were in-hospital adverse outcomes as determined by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database, in-hospital direct technical costs, and time-related mortality, according to Dr. Sajjad Raza and his colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic in the August issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (150:294-301).

Compared with nondiabetics, diabetic patients undergoing CABG were older and were more likely to be overweight, to be women, and to have a history of heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, carotid disease, hypertension, renal failure, stroke, and advanced coronary artery disease. Over time, the cardiovascular risk profile of the entire population changed, becoming even more pronounced for all patients, but more so for diabetics.

Overall long-term survival at 6 months and at 1, 5 10, 15, and 20 years for diabetic patients was 95%, 94%, 80%, 54%, 31%, and 18%, respectively, compared with 97%, 97%, 90%, 76%, 59%, and 42% for nondiabetic patients, a significant difference at P <.0001.

Propensity matching of similar diabetic and nondiabetic patients showed that deep sternal wound infection and stroke occurred significantly more often in diabetics, although there were no significant differences in cost remaining after matching, even though the length of stay greater than 14 days remained higher for diabetic patients.

Among diabetics, overall survival at 6 months and at 1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 years after CABG was 95%, 94%, 80%, 54%, 31%, and 18%, respectively, compared with overall survival in nondiabetics at 97%, 97%, 90%, 76%, 59%, and 42%, respectively, a significant difference (P <.0001).

“Although long-term survival after CABG is worse in diabetics and high-risk nondiabetics, it is important to note that, in general, high-risk patients reap the greatest survival benefit from CABG. Moreover, using surgical techniques that are associated with better long-term survival after CABG in diabetics could further enhance this survival benefit,” Dr. Raza and his colleagues wrote.

“Diabetes is both a marker for high-risk, resource-intensive, and expensive care after CABG and an independent risk factor for reduced long-term survival,” they added. “Diabetic patients and those with a similar high-risk profile set to undergo CABG should be made aware that their risks of postoperative complications are higher than average, and measures should be taken to reduce their postoperative complications,” Dr. Raza and his colleagues concluded.

The authors reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

The rate of diabetic coronary artery bypass graft patients has increased more than fivefold in recent decades, and these patients are more likely to have worse outcomes and higher treatment costs, a study showed.

The percentage of patients who had diabetes among all those undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) increased from 7% in the 1970s to 37% in the 2000s, according to a database study of 55,501 patients operated on at the Cleveland Clinic.

Patients were identified and preoperative, operative, and postoperative variables were identified, resulting in 45,139 nondiabetic patients assessed and 10,362 diabetic patients (defined as those diabetic patients pharmacologically treated with either insulin or an oral agent) evaluated. The endpoints assessed were in-hospital adverse outcomes as determined by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database, in-hospital direct technical costs, and time-related mortality, according to Dr. Sajjad Raza and his colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic in the August issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (150:294-301).

Compared with nondiabetics, diabetic patients undergoing CABG were older and were more likely to be overweight, to be women, and to have a history of heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, carotid disease, hypertension, renal failure, stroke, and advanced coronary artery disease. Over time, the cardiovascular risk profile of the entire population changed, becoming even more pronounced for all patients, but more so for diabetics.

Overall long-term survival at 6 months and at 1, 5 10, 15, and 20 years for diabetic patients was 95%, 94%, 80%, 54%, 31%, and 18%, respectively, compared with 97%, 97%, 90%, 76%, 59%, and 42% for nondiabetic patients, a significant difference at P <.0001.

Propensity matching of similar diabetic and nondiabetic patients showed that deep sternal wound infection and stroke occurred significantly more often in diabetics, although there were no significant differences in cost remaining after matching, even though the length of stay greater than 14 days remained higher for diabetic patients.

Among diabetics, overall survival at 6 months and at 1, 5, 10, 15, and 20 years after CABG was 95%, 94%, 80%, 54%, 31%, and 18%, respectively, compared with overall survival in nondiabetics at 97%, 97%, 90%, 76%, 59%, and 42%, respectively, a significant difference (P <.0001).

“Although long-term survival after CABG is worse in diabetics and high-risk nondiabetics, it is important to note that, in general, high-risk patients reap the greatest survival benefit from CABG. Moreover, using surgical techniques that are associated with better long-term survival after CABG in diabetics could further enhance this survival benefit,” Dr. Raza and his colleagues wrote.

“Diabetes is both a marker for high-risk, resource-intensive, and expensive care after CABG and an independent risk factor for reduced long-term survival,” they added. “Diabetic patients and those with a similar high-risk profile set to undergo CABG should be made aware that their risks of postoperative complications are higher than average, and measures should be taken to reduce their postoperative complications,” Dr. Raza and his colleagues concluded.

The authors reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: The percentage of CABG patients with diabetes increased from 7% in the 1970s to 37% in the 2000s. The risk/benefit ratio warrants greater use of bilateral mammary arteries except in obese women with diabetes.

Major finding: Diabetic patients had significantly worse outcomes than nondiabetics with regard to hospital death, deep sternal wound infections, strokes, and renal failure as well as hospital stay and costs.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of a prospective database of patients undergoing first-time CABG at the Cleveland Clinic from 1972 to 2011.

Disclosures: The authors reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Carrots and sticks lead to smoking cessation

Rewarding smokers for quitting was a more popular option for smoking cessation compared to sanctions-based treatment, but about the same number of participants in either group had quit smoking after 1 year.

Reward-based smoking cessation programs were accepted by 90% of those randomized, compared with 13.7% acceptance of deposit-based programs, and at 6 months, significantly more reward-based participants had ceased smoking, compared with deposit-based participants (15.2% vs. 10.2%). However, as with most such studies, at 1 year, nearly 50% of those who had achieved abstinence at 6 months had returned to smoking in all groups, according to a randomized controlled study of 2,538 CVS Caremark employees and their friends and relatives (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01526265).

Participants were assigned to one of five groups: 468 to usual care only as the control, reported Dr. Scott D. Halpern of the University of Pennsylvania and his colleagues (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:2108-17). They and all participants received information about local smoking cessation resources, cessation guides produced by the American Cancer Society, and, the 41% of the participants receiving health benefits through CVS Caremark had free access to a behavioral-modification program and nicotine-replacement therapy.

In addition, 498 were assigned to individual reward (eligible to receive $200 if they had biochemically confirmed abstinence at each of three times: 14 days, 30 days, and 6 months after quitting, with an additional $200 bonus at 6 months, for a total of $800); 519 to collaborative reward (in addition to the $800, patients were grouped into cohorts of six individuals who would receive an additional $100 per time point if one participant quit smoking to $600 per time point per participant if all six quit); 582 to individual deposit (the $800 dollars included a $150 deposit that would be refunded to participants who quit smoking), and 471 to competitive deposit (included the $150 deposit with the addition of a $450 matching reward per member ($3,600 total), which was redistributed among members who quit at each time point).

In intention-to-treat analyses, all four programs yielded greater rates of sustained cessation through 6 months (range, 9.4%-16.0%) than did usual care (6.0%) (P < .05 for all comparisons).

At 6 months, sustained abstinence was greater with reward-based incentives (15.7%) than with deposit-based (10.2%) (P < .001) and was similar between individual-incentive programs and group-incentive ones (12.1% vs. 13.7%, P = 0.29).

In addition, in instrumental-variable analyses that accounted for differential acceptance, the rate of abstinence at 6 months was 13.2% higher in the deposit-based programs than in the reward-based programs among those who would accept participation in either type of program, the authors stated, indicating that the use of such a program might be of great cost-effectiveness to a health care provider.

Dr. Halpern reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. The National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Aging, and CVS Caremark supported the study.

Smoking remains the leading cause of preventable deaths in America. It is estimated that employing a smoker costs nearly $6,000 more per year than employing nonsmokers. The article cited, in the New England Journal of Medicine, describes a randomized controlled trial of CVS Caremark employees, their families, and friends who smoke more than five cigarettes per day. The trial compared usual care to four different interventions designed to assess whether a financial incentive would entice greater quitting and abstinence rates.

The researchers looked at whether group participation with potential peer pressure would improve quitting rates. The group-oriented arms were not more effective than individual incentive arms. The psychology of loss aversion versus cash incentive was addressed by asking participants in one group to deposit money and get it back after 6 months of being smoking free. Requiring deposits resulted in decreased participation overall but in those who committed to this arm higher abstinence rates were seen. Overall, incentive rewards over 6 months of participation nearly tripled the rate of smoking cessation compared to usual care.

|

Dr. Michael Liptay |

The severity of cigarette smoking addiction was highlighted by a maximum success rate of around 15% in the best arm as well as a 50% return to smoking rate in those original quitters at 1 year after trial inception. Future innovations in employee benefit design must address the need for shared participation in health maintenance and some form of lifelong risk/reward system that engages people to be responsible for their own health choices.

Dr. Michael Liptay is the medical editor for Thoracic Surgery News.

Smoking remains the leading cause of preventable deaths in America. It is estimated that employing a smoker costs nearly $6,000 more per year than employing nonsmokers. The article cited, in the New England Journal of Medicine, describes a randomized controlled trial of CVS Caremark employees, their families, and friends who smoke more than five cigarettes per day. The trial compared usual care to four different interventions designed to assess whether a financial incentive would entice greater quitting and abstinence rates.

The researchers looked at whether group participation with potential peer pressure would improve quitting rates. The group-oriented arms were not more effective than individual incentive arms. The psychology of loss aversion versus cash incentive was addressed by asking participants in one group to deposit money and get it back after 6 months of being smoking free. Requiring deposits resulted in decreased participation overall but in those who committed to this arm higher abstinence rates were seen. Overall, incentive rewards over 6 months of participation nearly tripled the rate of smoking cessation compared to usual care.

|

Dr. Michael Liptay |

The severity of cigarette smoking addiction was highlighted by a maximum success rate of around 15% in the best arm as well as a 50% return to smoking rate in those original quitters at 1 year after trial inception. Future innovations in employee benefit design must address the need for shared participation in health maintenance and some form of lifelong risk/reward system that engages people to be responsible for their own health choices.

Dr. Michael Liptay is the medical editor for Thoracic Surgery News.

Smoking remains the leading cause of preventable deaths in America. It is estimated that employing a smoker costs nearly $6,000 more per year than employing nonsmokers. The article cited, in the New England Journal of Medicine, describes a randomized controlled trial of CVS Caremark employees, their families, and friends who smoke more than five cigarettes per day. The trial compared usual care to four different interventions designed to assess whether a financial incentive would entice greater quitting and abstinence rates.

The researchers looked at whether group participation with potential peer pressure would improve quitting rates. The group-oriented arms were not more effective than individual incentive arms. The psychology of loss aversion versus cash incentive was addressed by asking participants in one group to deposit money and get it back after 6 months of being smoking free. Requiring deposits resulted in decreased participation overall but in those who committed to this arm higher abstinence rates were seen. Overall, incentive rewards over 6 months of participation nearly tripled the rate of smoking cessation compared to usual care.

|

Dr. Michael Liptay |

The severity of cigarette smoking addiction was highlighted by a maximum success rate of around 15% in the best arm as well as a 50% return to smoking rate in those original quitters at 1 year after trial inception. Future innovations in employee benefit design must address the need for shared participation in health maintenance and some form of lifelong risk/reward system that engages people to be responsible for their own health choices.

Dr. Michael Liptay is the medical editor for Thoracic Surgery News.

Rewarding smokers for quitting was a more popular option for smoking cessation compared to sanctions-based treatment, but about the same number of participants in either group had quit smoking after 1 year.

Reward-based smoking cessation programs were accepted by 90% of those randomized, compared with 13.7% acceptance of deposit-based programs, and at 6 months, significantly more reward-based participants had ceased smoking, compared with deposit-based participants (15.2% vs. 10.2%). However, as with most such studies, at 1 year, nearly 50% of those who had achieved abstinence at 6 months had returned to smoking in all groups, according to a randomized controlled study of 2,538 CVS Caremark employees and their friends and relatives (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01526265).

Participants were assigned to one of five groups: 468 to usual care only as the control, reported Dr. Scott D. Halpern of the University of Pennsylvania and his colleagues (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:2108-17). They and all participants received information about local smoking cessation resources, cessation guides produced by the American Cancer Society, and, the 41% of the participants receiving health benefits through CVS Caremark had free access to a behavioral-modification program and nicotine-replacement therapy.

In addition, 498 were assigned to individual reward (eligible to receive $200 if they had biochemically confirmed abstinence at each of three times: 14 days, 30 days, and 6 months after quitting, with an additional $200 bonus at 6 months, for a total of $800); 519 to collaborative reward (in addition to the $800, patients were grouped into cohorts of six individuals who would receive an additional $100 per time point if one participant quit smoking to $600 per time point per participant if all six quit); 582 to individual deposit (the $800 dollars included a $150 deposit that would be refunded to participants who quit smoking), and 471 to competitive deposit (included the $150 deposit with the addition of a $450 matching reward per member ($3,600 total), which was redistributed among members who quit at each time point).

In intention-to-treat analyses, all four programs yielded greater rates of sustained cessation through 6 months (range, 9.4%-16.0%) than did usual care (6.0%) (P < .05 for all comparisons).

At 6 months, sustained abstinence was greater with reward-based incentives (15.7%) than with deposit-based (10.2%) (P < .001) and was similar between individual-incentive programs and group-incentive ones (12.1% vs. 13.7%, P = 0.29).

In addition, in instrumental-variable analyses that accounted for differential acceptance, the rate of abstinence at 6 months was 13.2% higher in the deposit-based programs than in the reward-based programs among those who would accept participation in either type of program, the authors stated, indicating that the use of such a program might be of great cost-effectiveness to a health care provider.

Dr. Halpern reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. The National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Aging, and CVS Caremark supported the study.

Rewarding smokers for quitting was a more popular option for smoking cessation compared to sanctions-based treatment, but about the same number of participants in either group had quit smoking after 1 year.

Reward-based smoking cessation programs were accepted by 90% of those randomized, compared with 13.7% acceptance of deposit-based programs, and at 6 months, significantly more reward-based participants had ceased smoking, compared with deposit-based participants (15.2% vs. 10.2%). However, as with most such studies, at 1 year, nearly 50% of those who had achieved abstinence at 6 months had returned to smoking in all groups, according to a randomized controlled study of 2,538 CVS Caremark employees and their friends and relatives (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01526265).

Participants were assigned to one of five groups: 468 to usual care only as the control, reported Dr. Scott D. Halpern of the University of Pennsylvania and his colleagues (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:2108-17). They and all participants received information about local smoking cessation resources, cessation guides produced by the American Cancer Society, and, the 41% of the participants receiving health benefits through CVS Caremark had free access to a behavioral-modification program and nicotine-replacement therapy.

In addition, 498 were assigned to individual reward (eligible to receive $200 if they had biochemically confirmed abstinence at each of three times: 14 days, 30 days, and 6 months after quitting, with an additional $200 bonus at 6 months, for a total of $800); 519 to collaborative reward (in addition to the $800, patients were grouped into cohorts of six individuals who would receive an additional $100 per time point if one participant quit smoking to $600 per time point per participant if all six quit); 582 to individual deposit (the $800 dollars included a $150 deposit that would be refunded to participants who quit smoking), and 471 to competitive deposit (included the $150 deposit with the addition of a $450 matching reward per member ($3,600 total), which was redistributed among members who quit at each time point).

In intention-to-treat analyses, all four programs yielded greater rates of sustained cessation through 6 months (range, 9.4%-16.0%) than did usual care (6.0%) (P < .05 for all comparisons).

At 6 months, sustained abstinence was greater with reward-based incentives (15.7%) than with deposit-based (10.2%) (P < .001) and was similar between individual-incentive programs and group-incentive ones (12.1% vs. 13.7%, P = 0.29).

In addition, in instrumental-variable analyses that accounted for differential acceptance, the rate of abstinence at 6 months was 13.2% higher in the deposit-based programs than in the reward-based programs among those who would accept participation in either type of program, the authors stated, indicating that the use of such a program might be of great cost-effectiveness to a health care provider.

Dr. Halpern reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. The National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Aging, and CVS Caremark supported the study.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Reward-based smoking cessation incentive programs were more acceptable and effective than were reward plus penalty-based programs.

Major finding: At 6 months, significantly more reward-based participants had ceased smoking compared with deposit-based participants (15.2% vs. 10.2%).

Data source: A five-group randomized, controlled trial of 2,538 CVS-Caremark employees comparing usual care with four incentive programs aimed at sustained abstinence from smoking.

Disclosures: Dr. Halpern reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. The National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Aging, and CVS Caremark supported the study.

Perioperative factors influenced open TAAA repair

Open thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA) repair produced respectable early outcomes, although preoperative and intraoperative factors were found to influence risk, according to Dr. Joseph S. Coselli, who presented the results of the study he and his colleagues at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston performed at the annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

They analyzed data from 3,309 open TAAA repairs performed between October 1986 and December 2014.

“I have been very fortunate to have spent my entire career at Baylor College of Medicine, the epicenter of aortic surgery in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, as well as to have been mentored by Dr. E. Stanley Crawford, who was arguably the finest aortic surgeon of his era. Since transitioning from Dr. Crawford’s surgical practice to my own surgical practice, we have kept his pioneering spirit alive by developing a multimodal strategy for thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair that is based on the Crawford extent of repair and our evolving investigation. We sought to describe our series of over 3,000 TAAA repairs and to identify predictors of early death and other adverse postoperative outcomes,” said Dr. Coselli.

The median patient age was around 67 years, and the repairs involved acute or subacute aortic dissection in about 5% of the cases. Nearly 31% of the case involved chronic dissection, with nearly 22% emergent or urgent repairs and around 5% ruptured aneurysms. Connective tissue disorders were present in roughly 10% of patients. “Operatively, we tend to reserve surgical adjuncts for use in the most-extensive repairs, namely extents I and II TAAA repair; intercostal or lumbar artery reattachment was used in just over half of the repairs, left heart bypass (LHB) was used in around 45% of patients, cold renal perfusion was performed in 58%. and cerebrospinal fluid drainage (CSFD) was used in 45%,” said Dr. Coselli.

There was substantial atherosclerotic disease in older patients, and in nearly 41% of repairs, a visceral vessel procedure was performed.

Unlike many aortic centers that routinely use deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (HCA) for extensive TAAA repair, Dr. Coselli reserved this approach for a small number of highly complex repairs (1.4%) in which the aorta could not be safely clamped.

Of the more than a thousand most extensive (i.e., Crawford extent II) repairs, intercostal/lumbar artery reattachment was used in the vast majority (88%), LHB in 82%, and CSFD in 61%. They used multivariable analysis to identify predictors of operative (30-day or in-hospital) mortality and adverse event, a composite outcome comprising operative death and permanent (present at discharge) spinal cord deficit, renal failure, or stroke, according to Dr. Coselli.

Their results showed an operative mortality rate of 7.5%, a 30-day death rate of 4.8%, with the adverse event outcome occurring in about 14% of repairs. A video of his presentation is available at the AATS website.

The statistically significant predictors of operative death were rupture; renal insufficiency, symptoms, procedures targeting visceral vessels, increasing age, and increasing clamp time, while extent IV repair (the least extensive form of TAAA repair) was inversely associated with death. Their analysis showed that the significant predictors of adverse event were use of HCA, renal insufficiency, rupture, extent II repair, visceral vessel procedures, urgent or emergent repair, increasing age, and increasing clamp time. In addition, they used multivariable analysis to identify predictors of renal failure and paraplegia.

In the 3,060 early survivors, roughly 7% had a life-altering complication at discharge: Nearly 3% of patients had renal failure necessitating dialysis, slightly more than 1% had a unresolved stroke, and about 4% had unresolved paraplegia or paraparesis. Repair failure, primarily pseudoaneurysm, or patch aneurysm, occurred after nearly 3% of repairs, said Dr. Coselli.

Outcomes differed by extent of repair, with the risk being greatest in extent II repair. Actuarial survival was 63.6% at 5 years, 36.8% at 10 years, and 18.3% at 15 years. Freedom from repair failure was nearly 98% at 5 years, around 95% at 10 years, and 94% at 15 years.

“Along with respectable early outcomes, after repair, patients have acceptable long-term survival, and late repair failure was uncommon. Notably, there are several subgroups of patients that do exceedingly well. Paraplegia in young patients with connective tissue disorders, even in the most-extensive repair (extent II), is remarkably rare – these patients do extremely well across the board,” he concluded.

Dr. Cosselli reported that he is a principal investigator and consultant for Medtronic and W.L. Gore & Assoc., as well as being a principal investigator, consultant, and having various financial relationships with Vascutek.

Open thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA) repair produced respectable early outcomes, although preoperative and intraoperative factors were found to influence risk, according to Dr. Joseph S. Coselli, who presented the results of the study he and his colleagues at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston performed at the annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

They analyzed data from 3,309 open TAAA repairs performed between October 1986 and December 2014.

“I have been very fortunate to have spent my entire career at Baylor College of Medicine, the epicenter of aortic surgery in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, as well as to have been mentored by Dr. E. Stanley Crawford, who was arguably the finest aortic surgeon of his era. Since transitioning from Dr. Crawford’s surgical practice to my own surgical practice, we have kept his pioneering spirit alive by developing a multimodal strategy for thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair that is based on the Crawford extent of repair and our evolving investigation. We sought to describe our series of over 3,000 TAAA repairs and to identify predictors of early death and other adverse postoperative outcomes,” said Dr. Coselli.

The median patient age was around 67 years, and the repairs involved acute or subacute aortic dissection in about 5% of the cases. Nearly 31% of the case involved chronic dissection, with nearly 22% emergent or urgent repairs and around 5% ruptured aneurysms. Connective tissue disorders were present in roughly 10% of patients. “Operatively, we tend to reserve surgical adjuncts for use in the most-extensive repairs, namely extents I and II TAAA repair; intercostal or lumbar artery reattachment was used in just over half of the repairs, left heart bypass (LHB) was used in around 45% of patients, cold renal perfusion was performed in 58%. and cerebrospinal fluid drainage (CSFD) was used in 45%,” said Dr. Coselli.

There was substantial atherosclerotic disease in older patients, and in nearly 41% of repairs, a visceral vessel procedure was performed.

Unlike many aortic centers that routinely use deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (HCA) for extensive TAAA repair, Dr. Coselli reserved this approach for a small number of highly complex repairs (1.4%) in which the aorta could not be safely clamped.

Of the more than a thousand most extensive (i.e., Crawford extent II) repairs, intercostal/lumbar artery reattachment was used in the vast majority (88%), LHB in 82%, and CSFD in 61%. They used multivariable analysis to identify predictors of operative (30-day or in-hospital) mortality and adverse event, a composite outcome comprising operative death and permanent (present at discharge) spinal cord deficit, renal failure, or stroke, according to Dr. Coselli.

Their results showed an operative mortality rate of 7.5%, a 30-day death rate of 4.8%, with the adverse event outcome occurring in about 14% of repairs. A video of his presentation is available at the AATS website.

The statistically significant predictors of operative death were rupture; renal insufficiency, symptoms, procedures targeting visceral vessels, increasing age, and increasing clamp time, while extent IV repair (the least extensive form of TAAA repair) was inversely associated with death. Their analysis showed that the significant predictors of adverse event were use of HCA, renal insufficiency, rupture, extent II repair, visceral vessel procedures, urgent or emergent repair, increasing age, and increasing clamp time. In addition, they used multivariable analysis to identify predictors of renal failure and paraplegia.

In the 3,060 early survivors, roughly 7% had a life-altering complication at discharge: Nearly 3% of patients had renal failure necessitating dialysis, slightly more than 1% had a unresolved stroke, and about 4% had unresolved paraplegia or paraparesis. Repair failure, primarily pseudoaneurysm, or patch aneurysm, occurred after nearly 3% of repairs, said Dr. Coselli.

Outcomes differed by extent of repair, with the risk being greatest in extent II repair. Actuarial survival was 63.6% at 5 years, 36.8% at 10 years, and 18.3% at 15 years. Freedom from repair failure was nearly 98% at 5 years, around 95% at 10 years, and 94% at 15 years.

“Along with respectable early outcomes, after repair, patients have acceptable long-term survival, and late repair failure was uncommon. Notably, there are several subgroups of patients that do exceedingly well. Paraplegia in young patients with connective tissue disorders, even in the most-extensive repair (extent II), is remarkably rare – these patients do extremely well across the board,” he concluded.

Dr. Cosselli reported that he is a principal investigator and consultant for Medtronic and W.L. Gore & Assoc., as well as being a principal investigator, consultant, and having various financial relationships with Vascutek.

Open thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA) repair produced respectable early outcomes, although preoperative and intraoperative factors were found to influence risk, according to Dr. Joseph S. Coselli, who presented the results of the study he and his colleagues at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston performed at the annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

They analyzed data from 3,309 open TAAA repairs performed between October 1986 and December 2014.

“I have been very fortunate to have spent my entire career at Baylor College of Medicine, the epicenter of aortic surgery in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, as well as to have been mentored by Dr. E. Stanley Crawford, who was arguably the finest aortic surgeon of his era. Since transitioning from Dr. Crawford’s surgical practice to my own surgical practice, we have kept his pioneering spirit alive by developing a multimodal strategy for thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair that is based on the Crawford extent of repair and our evolving investigation. We sought to describe our series of over 3,000 TAAA repairs and to identify predictors of early death and other adverse postoperative outcomes,” said Dr. Coselli.

The median patient age was around 67 years, and the repairs involved acute or subacute aortic dissection in about 5% of the cases. Nearly 31% of the case involved chronic dissection, with nearly 22% emergent or urgent repairs and around 5% ruptured aneurysms. Connective tissue disorders were present in roughly 10% of patients. “Operatively, we tend to reserve surgical adjuncts for use in the most-extensive repairs, namely extents I and II TAAA repair; intercostal or lumbar artery reattachment was used in just over half of the repairs, left heart bypass (LHB) was used in around 45% of patients, cold renal perfusion was performed in 58%. and cerebrospinal fluid drainage (CSFD) was used in 45%,” said Dr. Coselli.

There was substantial atherosclerotic disease in older patients, and in nearly 41% of repairs, a visceral vessel procedure was performed.

Unlike many aortic centers that routinely use deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (HCA) for extensive TAAA repair, Dr. Coselli reserved this approach for a small number of highly complex repairs (1.4%) in which the aorta could not be safely clamped.

Of the more than a thousand most extensive (i.e., Crawford extent II) repairs, intercostal/lumbar artery reattachment was used in the vast majority (88%), LHB in 82%, and CSFD in 61%. They used multivariable analysis to identify predictors of operative (30-day or in-hospital) mortality and adverse event, a composite outcome comprising operative death and permanent (present at discharge) spinal cord deficit, renal failure, or stroke, according to Dr. Coselli.

Their results showed an operative mortality rate of 7.5%, a 30-day death rate of 4.8%, with the adverse event outcome occurring in about 14% of repairs. A video of his presentation is available at the AATS website.

The statistically significant predictors of operative death were rupture; renal insufficiency, symptoms, procedures targeting visceral vessels, increasing age, and increasing clamp time, while extent IV repair (the least extensive form of TAAA repair) was inversely associated with death. Their analysis showed that the significant predictors of adverse event were use of HCA, renal insufficiency, rupture, extent II repair, visceral vessel procedures, urgent or emergent repair, increasing age, and increasing clamp time. In addition, they used multivariable analysis to identify predictors of renal failure and paraplegia.

In the 3,060 early survivors, roughly 7% had a life-altering complication at discharge: Nearly 3% of patients had renal failure necessitating dialysis, slightly more than 1% had a unresolved stroke, and about 4% had unresolved paraplegia or paraparesis. Repair failure, primarily pseudoaneurysm, or patch aneurysm, occurred after nearly 3% of repairs, said Dr. Coselli.

Outcomes differed by extent of repair, with the risk being greatest in extent II repair. Actuarial survival was 63.6% at 5 years, 36.8% at 10 years, and 18.3% at 15 years. Freedom from repair failure was nearly 98% at 5 years, around 95% at 10 years, and 94% at 15 years.

“Along with respectable early outcomes, after repair, patients have acceptable long-term survival, and late repair failure was uncommon. Notably, there are several subgroups of patients that do exceedingly well. Paraplegia in young patients with connective tissue disorders, even in the most-extensive repair (extent II), is remarkably rare – these patients do extremely well across the board,” he concluded.

Dr. Cosselli reported that he is a principal investigator and consultant for Medtronic and W.L. Gore & Assoc., as well as being a principal investigator, consultant, and having various financial relationships with Vascutek.

AT THE AATS ANNUAL MEETING

Disruptive medicine: 3-D printing revolution

The emergence of 3-D printing is beginning to look like a case of ‘disruptive medicine.’ Exploratory research in this area is ongoing in cardiology and orthopaedic and plastic surgery, and the experimental applications multiply daily.

Currently, 3-D printed models are being used for simulation training, preprocedural planning, development of personalized surgical equipment, and in a few cases, temporary structures for insertion in patients. As 3-D printers become cheaper, costs for their use in medicine are expected to decline

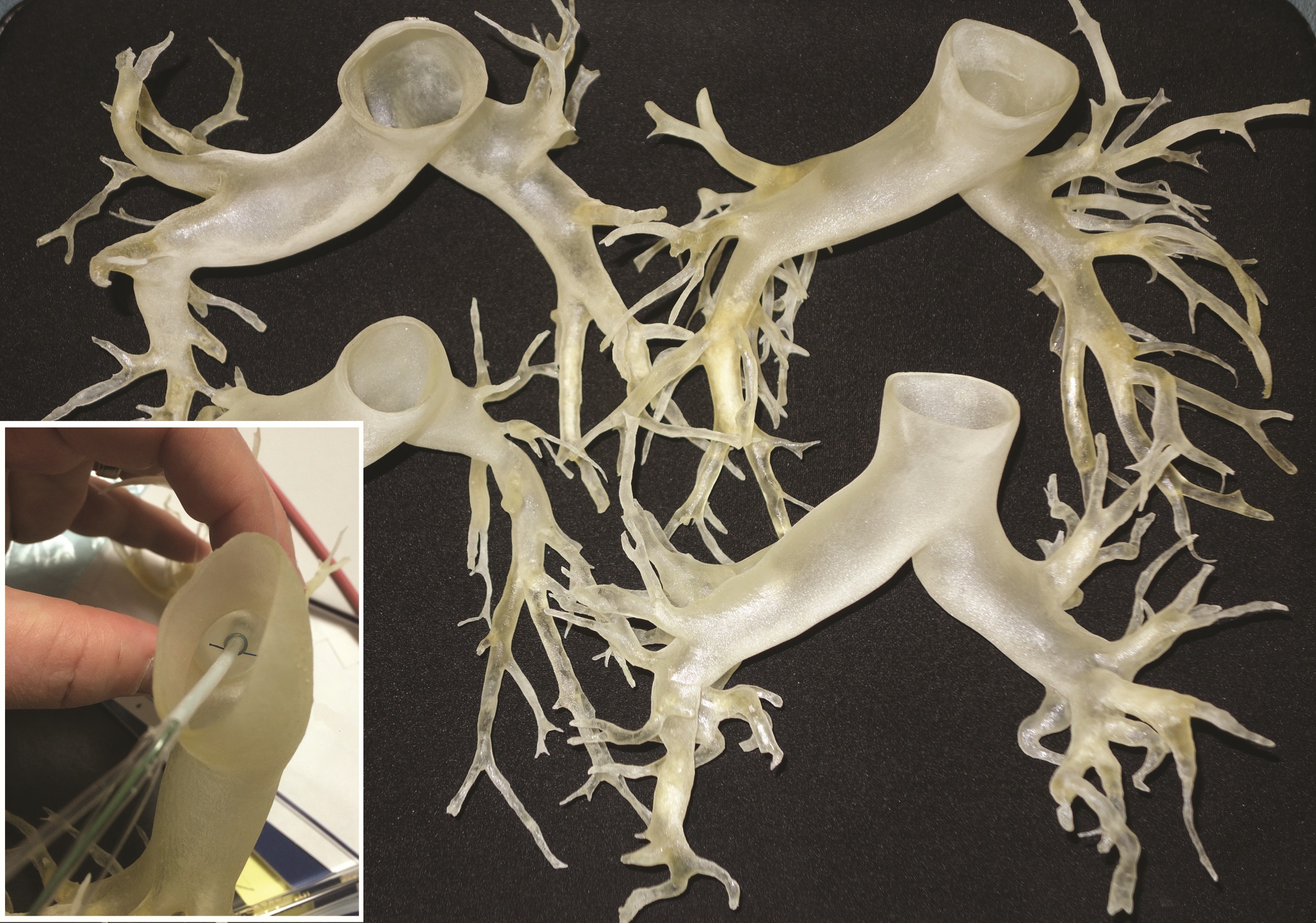

This rapidly developing technology is being applied in cardiothoracic surgery. The 3-D printing technology was used to construct flexible 3-D models of 10 human patient pulmonary arteries as part of a project to develop a new delivery catheter for regional lung chemotherapy.

Computed tomography and CT angiography in combination with software-driven segmentation techniques were used for generation and adjustment of 3-D polygon mesh to form reconstructed models of the pulmonary arteries. The reconstructed models were exported as stereolithographic data sets and further processed, according to Sergei N. Kurenov of the department of thoracic surgery, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, N.Y., and his colleagues.

How the process works

In this process, producing the anatomical pulmonary artery models required a series of steps: data acquisition from the patient CT digital data, 3-D visualization and segmentation, surface rendering and creating a 3-D polygon mesh, geometrical surface preparation – simplification, refinement, and geometry fixing, and the hollowing of an existing volume to “thicken” the walls.

Three contrast CT data sets with a 0.625-mm, 1-mm, and 2-mm slice thickness were gathered for each patient.

The scans were processed using commercial software packages. Because of the high variability of curvature and embedding in complex anatomical scenes with other vessels interference, the pulmary artery segmentation using the software tools required a clear understanding of the patient’s anatomy, which took 4-8 hours for the experienced operator, according to the researchers.

After further computer processing of the virtual reconstructed pulmonary model, it was sent to the 3-D printer, which used a rubberlike material that is elastic and semitransparent, behaving similarly to polyurethane.

The 10 unique models were successfully created with no print failures, although the original plan of using a 1-mm mural thickness proved too fragile, so the entire group was printed with a 1.5-mm wall. The design process took 8 hours from CT image to stereolithographic model, and printing required an overall total of 97 hours, according to the report published online in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.12.059].

Accurate models of individual patients’ anatomy

The physical measurements of the model were accurate for clinical purposes, with the 95% confidence levels for the 10 models demonstrating equivalence. Anatomic measurements using this process could be useful for general pulmonary artery catheter design, according to the authors. These measurements showed sufficient similarity for a design to be created that would be effective for most patients, although this finding would have to be validated with a larger sample of patients.

“While many of the measurements could have been made with software analysis of the 3-D files, some measurements were greatly facilitated by bending the model and aligning the physical catheter. These measurements represent distance beyond which a catheter might cause damage,” they added.

Biological 3-D printing of organs

Gut is a perfect beginning project for 3-D printing, Dr. John Geibel said at the 2015 American Gastroenterological Association Tech Summit, which was sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. It has a very simple shape – just a long hollow tube. Epithelial cells grow and turn over very quickly, suggesting that a length of artificial intestine could be grown relatively quickly. And although intestine is composed of a number of distinct layers, a 3-D bioprinter would have no trouble laying down concentric circles of each one to recreate their natural morphology.

“It will take time. It will take planning. But this is going to happen,” said Dr. Geibel of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

To create a length of intestine, the print heads of a bioprinter would be loaded with cells from all of the gut layers – the serosa, the different muscle strata, the mucosa. Each would be laid down in its respective anatomic ring, supported all around by a hydrogel. The print sequence would be repeated over and over until the required length of intestine was created. From then, Dr. Geibel said, it would be only a matter of days before the cells knit themselves together so well that the gel could be dissolved and the new tissue ready for transplant.

Liver would likely be the next organ up for printing, with the ultimate goal of creating fully transplantable organs. The need is enormous, and can’t be overstated. Patients who need a new liver wait an average of 4 years before they receive one.

The liver is much more complicated than a length of gut. It is cellularly complex and highly vascularized. But liver-printing is already a reality. Bioprinted “3-D liver-in-a-dish,” created by San Diego–based Organovo, has function, if not form. The cells work together; they grow, divide, and secrete bile acids. However, they exist as a formless, nonvascular blob.

As it stands (or rather, lies) now, bioprinted liver is a perfect preclinical model – perfectly replicating how the liver would respond to drugs without any of the messy adverse events that hurt patients. But it needs some backbone, or more accurately, some matrix, in order to morph again and grow into a complete organ. A liver-shaped collagen matrix could provide the necessary frame for cells to grow in and around; tunnels through it would form pathways for a similarly engineered vasculature.

The project to create 3-D models of pulmonary arteries is one of many ongoing efforts in this field. “Going forward, this technology competes with virtual educational media for health care professionals, trainees, and patients. Complex anatomy can be visualized easily on a scale model at the operating table (rather than by manipulating a nonsterile pointing device on a computer). The [pulmonary arteries] we printed could be used in a relatively low-cost lifelike [video-assisted thoracoscopic] lobectomy trainer,” the authors stated, while acknowledging the current issue of cost and time.

Printing services were funded by an unrestricted grant from Incodema3D, which employs Dan Sammons, one of the authors of the study. The other authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

“Disruptive medicine: 3-D printing revolution” reports on an important new technology well worth surgeons’ attention. The basic process reported is a simple, but in many ways, revolutionary approach to manufacturing or assembly. 3-D printing is an additive manufacturing process, exactly the opposite from the usual subtractive process. As an example, a block of steel might be milled, drilled and machined into an engine block in a series of processes to remove material from the original piece of steel, a subtractive process.

3-D printing is an additive manufacturing process whereby materials (metal, plastic, other) are layered together to make a complex three-dimensional solid object. Working from a CAD file, material is laid down in successive layers until the entire object is created. Each layer deposited can be imagined as a thinly sliced horizontal cross-section of the eventual object. As such, 3-D printing is really a stack of 2-D prints. The technique was invented by Charles Hull in 1986 and is revolutionizing prototyping and, in some cases, manufacturing. Applications have included prototyping, metal casting, architectural design and building, and in 3-D design and visualization: this application is well-demonstrated in the medical application of pulmonary artery reconstruction outlined in this article. In this case, complex anatomy can be easily visualized on a solid full-scale model of the pulmonary vasculature, and treatment plans more easily formulated and even modeled.

An extensive, thoughtful discussion of medical 3-D printing can be found in the November 24, 2014 The New Yorker article entitled “Print Thyself: How 3-D printing is revolutionizing medicine.” Other medical applications described include 3-D reconstruction in complex craniofacial repairs, modeling of abnormalities in the tracheobronchial tree to design surgical strategies to manage airway stenosis, and in reconstructive modeling for complex traumatic injuries in bone and soft tissue.

Beyond such applications, concepts have evolved to areas of 3-D printing using mixtures of cells and matrix as an approach to the engineering and additive assembly of complex tissues, and even organs. Thus, functional organs might someday be produced; a massive step beyond simple prototyping.

As in many areas of science and technology, the field moves quickly. The March 20, 2015 issue of Science published a report on “Continuous liquid interface production (CLIP) of 3D objects.” This true 3-D printing process is up to 100 times faster than current technologies and is compatible with producing objects from soft elastic materials, ceramics and biologics! More to come…

Thomas M. Krummel, MD, FACS, is the Emile Holman Professor and Chair, Department of Surgery at Stanford University and the Co-Director, Biodesign Innovation Program at Stanford. He is also a member of the Board of Directors of the Fogarty Institute for Innovation.

“Disruptive medicine: 3-D printing revolution” reports on an important new technology well worth surgeons’ attention. The basic process reported is a simple, but in many ways, revolutionary approach to manufacturing or assembly. 3-D printing is an additive manufacturing process, exactly the opposite from the usual subtractive process. As an example, a block of steel might be milled, drilled and machined into an engine block in a series of processes to remove material from the original piece of steel, a subtractive process.

3-D printing is an additive manufacturing process whereby materials (metal, plastic, other) are layered together to make a complex three-dimensional solid object. Working from a CAD file, material is laid down in successive layers until the entire object is created. Each layer deposited can be imagined as a thinly sliced horizontal cross-section of the eventual object. As such, 3-D printing is really a stack of 2-D prints. The technique was invented by Charles Hull in 1986 and is revolutionizing prototyping and, in some cases, manufacturing. Applications have included prototyping, metal casting, architectural design and building, and in 3-D design and visualization: this application is well-demonstrated in the medical application of pulmonary artery reconstruction outlined in this article. In this case, complex anatomy can be easily visualized on a solid full-scale model of the pulmonary vasculature, and treatment plans more easily formulated and even modeled.

An extensive, thoughtful discussion of medical 3-D printing can be found in the November 24, 2014 The New Yorker article entitled “Print Thyself: How 3-D printing is revolutionizing medicine.” Other medical applications described include 3-D reconstruction in complex craniofacial repairs, modeling of abnormalities in the tracheobronchial tree to design surgical strategies to manage airway stenosis, and in reconstructive modeling for complex traumatic injuries in bone and soft tissue.

Beyond such applications, concepts have evolved to areas of 3-D printing using mixtures of cells and matrix as an approach to the engineering and additive assembly of complex tissues, and even organs. Thus, functional organs might someday be produced; a massive step beyond simple prototyping.

As in many areas of science and technology, the field moves quickly. The March 20, 2015 issue of Science published a report on “Continuous liquid interface production (CLIP) of 3D objects.” This true 3-D printing process is up to 100 times faster than current technologies and is compatible with producing objects from soft elastic materials, ceramics and biologics! More to come…

Thomas M. Krummel, MD, FACS, is the Emile Holman Professor and Chair, Department of Surgery at Stanford University and the Co-Director, Biodesign Innovation Program at Stanford. He is also a member of the Board of Directors of the Fogarty Institute for Innovation.

“Disruptive medicine: 3-D printing revolution” reports on an important new technology well worth surgeons’ attention. The basic process reported is a simple, but in many ways, revolutionary approach to manufacturing or assembly. 3-D printing is an additive manufacturing process, exactly the opposite from the usual subtractive process. As an example, a block of steel might be milled, drilled and machined into an engine block in a series of processes to remove material from the original piece of steel, a subtractive process.

3-D printing is an additive manufacturing process whereby materials (metal, plastic, other) are layered together to make a complex three-dimensional solid object. Working from a CAD file, material is laid down in successive layers until the entire object is created. Each layer deposited can be imagined as a thinly sliced horizontal cross-section of the eventual object. As such, 3-D printing is really a stack of 2-D prints. The technique was invented by Charles Hull in 1986 and is revolutionizing prototyping and, in some cases, manufacturing. Applications have included prototyping, metal casting, architectural design and building, and in 3-D design and visualization: this application is well-demonstrated in the medical application of pulmonary artery reconstruction outlined in this article. In this case, complex anatomy can be easily visualized on a solid full-scale model of the pulmonary vasculature, and treatment plans more easily formulated and even modeled.

An extensive, thoughtful discussion of medical 3-D printing can be found in the November 24, 2014 The New Yorker article entitled “Print Thyself: How 3-D printing is revolutionizing medicine.” Other medical applications described include 3-D reconstruction in complex craniofacial repairs, modeling of abnormalities in the tracheobronchial tree to design surgical strategies to manage airway stenosis, and in reconstructive modeling for complex traumatic injuries in bone and soft tissue.

Beyond such applications, concepts have evolved to areas of 3-D printing using mixtures of cells and matrix as an approach to the engineering and additive assembly of complex tissues, and even organs. Thus, functional organs might someday be produced; a massive step beyond simple prototyping.

As in many areas of science and technology, the field moves quickly. The March 20, 2015 issue of Science published a report on “Continuous liquid interface production (CLIP) of 3D objects.” This true 3-D printing process is up to 100 times faster than current technologies and is compatible with producing objects from soft elastic materials, ceramics and biologics! More to come…

Thomas M. Krummel, MD, FACS, is the Emile Holman Professor and Chair, Department of Surgery at Stanford University and the Co-Director, Biodesign Innovation Program at Stanford. He is also a member of the Board of Directors of the Fogarty Institute for Innovation.

The emergence of 3-D printing is beginning to look like a case of ‘disruptive medicine.’ Exploratory research in this area is ongoing in cardiology and orthopaedic and plastic surgery, and the experimental applications multiply daily.

Currently, 3-D printed models are being used for simulation training, preprocedural planning, development of personalized surgical equipment, and in a few cases, temporary structures for insertion in patients. As 3-D printers become cheaper, costs for their use in medicine are expected to decline

This rapidly developing technology is being applied in cardiothoracic surgery. The 3-D printing technology was used to construct flexible 3-D models of 10 human patient pulmonary arteries as part of a project to develop a new delivery catheter for regional lung chemotherapy.

Computed tomography and CT angiography in combination with software-driven segmentation techniques were used for generation and adjustment of 3-D polygon mesh to form reconstructed models of the pulmonary arteries. The reconstructed models were exported as stereolithographic data sets and further processed, according to Sergei N. Kurenov of the department of thoracic surgery, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, N.Y., and his colleagues.

How the process works

In this process, producing the anatomical pulmonary artery models required a series of steps: data acquisition from the patient CT digital data, 3-D visualization and segmentation, surface rendering and creating a 3-D polygon mesh, geometrical surface preparation – simplification, refinement, and geometry fixing, and the hollowing of an existing volume to “thicken” the walls.

Three contrast CT data sets with a 0.625-mm, 1-mm, and 2-mm slice thickness were gathered for each patient.

The scans were processed using commercial software packages. Because of the high variability of curvature and embedding in complex anatomical scenes with other vessels interference, the pulmary artery segmentation using the software tools required a clear understanding of the patient’s anatomy, which took 4-8 hours for the experienced operator, according to the researchers.

After further computer processing of the virtual reconstructed pulmonary model, it was sent to the 3-D printer, which used a rubberlike material that is elastic and semitransparent, behaving similarly to polyurethane.

The 10 unique models were successfully created with no print failures, although the original plan of using a 1-mm mural thickness proved too fragile, so the entire group was printed with a 1.5-mm wall. The design process took 8 hours from CT image to stereolithographic model, and printing required an overall total of 97 hours, according to the report published online in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.12.059].

Accurate models of individual patients’ anatomy

The physical measurements of the model were accurate for clinical purposes, with the 95% confidence levels for the 10 models demonstrating equivalence. Anatomic measurements using this process could be useful for general pulmonary artery catheter design, according to the authors. These measurements showed sufficient similarity for a design to be created that would be effective for most patients, although this finding would have to be validated with a larger sample of patients.

“While many of the measurements could have been made with software analysis of the 3-D files, some measurements were greatly facilitated by bending the model and aligning the physical catheter. These measurements represent distance beyond which a catheter might cause damage,” they added.

Biological 3-D printing of organs

Gut is a perfect beginning project for 3-D printing, Dr. John Geibel said at the 2015 American Gastroenterological Association Tech Summit, which was sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. It has a very simple shape – just a long hollow tube. Epithelial cells grow and turn over very quickly, suggesting that a length of artificial intestine could be grown relatively quickly. And although intestine is composed of a number of distinct layers, a 3-D bioprinter would have no trouble laying down concentric circles of each one to recreate their natural morphology.

“It will take time. It will take planning. But this is going to happen,” said Dr. Geibel of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

To create a length of intestine, the print heads of a bioprinter would be loaded with cells from all of the gut layers – the serosa, the different muscle strata, the mucosa. Each would be laid down in its respective anatomic ring, supported all around by a hydrogel. The print sequence would be repeated over and over until the required length of intestine was created. From then, Dr. Geibel said, it would be only a matter of days before the cells knit themselves together so well that the gel could be dissolved and the new tissue ready for transplant.

Liver would likely be the next organ up for printing, with the ultimate goal of creating fully transplantable organs. The need is enormous, and can’t be overstated. Patients who need a new liver wait an average of 4 years before they receive one.

The liver is much more complicated than a length of gut. It is cellularly complex and highly vascularized. But liver-printing is already a reality. Bioprinted “3-D liver-in-a-dish,” created by San Diego–based Organovo, has function, if not form. The cells work together; they grow, divide, and secrete bile acids. However, they exist as a formless, nonvascular blob.

As it stands (or rather, lies) now, bioprinted liver is a perfect preclinical model – perfectly replicating how the liver would respond to drugs without any of the messy adverse events that hurt patients. But it needs some backbone, or more accurately, some matrix, in order to morph again and grow into a complete organ. A liver-shaped collagen matrix could provide the necessary frame for cells to grow in and around; tunnels through it would form pathways for a similarly engineered vasculature.

The project to create 3-D models of pulmonary arteries is one of many ongoing efforts in this field. “Going forward, this technology competes with virtual educational media for health care professionals, trainees, and patients. Complex anatomy can be visualized easily on a scale model at the operating table (rather than by manipulating a nonsterile pointing device on a computer). The [pulmonary arteries] we printed could be used in a relatively low-cost lifelike [video-assisted thoracoscopic] lobectomy trainer,” the authors stated, while acknowledging the current issue of cost and time.

Printing services were funded by an unrestricted grant from Incodema3D, which employs Dan Sammons, one of the authors of the study. The other authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

The emergence of 3-D printing is beginning to look like a case of ‘disruptive medicine.’ Exploratory research in this area is ongoing in cardiology and orthopaedic and plastic surgery, and the experimental applications multiply daily.

Currently, 3-D printed models are being used for simulation training, preprocedural planning, development of personalized surgical equipment, and in a few cases, temporary structures for insertion in patients. As 3-D printers become cheaper, costs for their use in medicine are expected to decline

This rapidly developing technology is being applied in cardiothoracic surgery. The 3-D printing technology was used to construct flexible 3-D models of 10 human patient pulmonary arteries as part of a project to develop a new delivery catheter for regional lung chemotherapy.

Computed tomography and CT angiography in combination with software-driven segmentation techniques were used for generation and adjustment of 3-D polygon mesh to form reconstructed models of the pulmonary arteries. The reconstructed models were exported as stereolithographic data sets and further processed, according to Sergei N. Kurenov of the department of thoracic surgery, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, N.Y., and his colleagues.

How the process works

In this process, producing the anatomical pulmonary artery models required a series of steps: data acquisition from the patient CT digital data, 3-D visualization and segmentation, surface rendering and creating a 3-D polygon mesh, geometrical surface preparation – simplification, refinement, and geometry fixing, and the hollowing of an existing volume to “thicken” the walls.

Three contrast CT data sets with a 0.625-mm, 1-mm, and 2-mm slice thickness were gathered for each patient.

The scans were processed using commercial software packages. Because of the high variability of curvature and embedding in complex anatomical scenes with other vessels interference, the pulmary artery segmentation using the software tools required a clear understanding of the patient’s anatomy, which took 4-8 hours for the experienced operator, according to the researchers.

After further computer processing of the virtual reconstructed pulmonary model, it was sent to the 3-D printer, which used a rubberlike material that is elastic and semitransparent, behaving similarly to polyurethane.

The 10 unique models were successfully created with no print failures, although the original plan of using a 1-mm mural thickness proved too fragile, so the entire group was printed with a 1.5-mm wall. The design process took 8 hours from CT image to stereolithographic model, and printing required an overall total of 97 hours, according to the report published online in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.12.059].

Accurate models of individual patients’ anatomy

The physical measurements of the model were accurate for clinical purposes, with the 95% confidence levels for the 10 models demonstrating equivalence. Anatomic measurements using this process could be useful for general pulmonary artery catheter design, according to the authors. These measurements showed sufficient similarity for a design to be created that would be effective for most patients, although this finding would have to be validated with a larger sample of patients.

“While many of the measurements could have been made with software analysis of the 3-D files, some measurements were greatly facilitated by bending the model and aligning the physical catheter. These measurements represent distance beyond which a catheter might cause damage,” they added.

Biological 3-D printing of organs

Gut is a perfect beginning project for 3-D printing, Dr. John Geibel said at the 2015 American Gastroenterological Association Tech Summit, which was sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. It has a very simple shape – just a long hollow tube. Epithelial cells grow and turn over very quickly, suggesting that a length of artificial intestine could be grown relatively quickly. And although intestine is composed of a number of distinct layers, a 3-D bioprinter would have no trouble laying down concentric circles of each one to recreate their natural morphology.

“It will take time. It will take planning. But this is going to happen,” said Dr. Geibel of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

To create a length of intestine, the print heads of a bioprinter would be loaded with cells from all of the gut layers – the serosa, the different muscle strata, the mucosa. Each would be laid down in its respective anatomic ring, supported all around by a hydrogel. The print sequence would be repeated over and over until the required length of intestine was created. From then, Dr. Geibel said, it would be only a matter of days before the cells knit themselves together so well that the gel could be dissolved and the new tissue ready for transplant.

Liver would likely be the next organ up for printing, with the ultimate goal of creating fully transplantable organs. The need is enormous, and can’t be overstated. Patients who need a new liver wait an average of 4 years before they receive one.

The liver is much more complicated than a length of gut. It is cellularly complex and highly vascularized. But liver-printing is already a reality. Bioprinted “3-D liver-in-a-dish,” created by San Diego–based Organovo, has function, if not form. The cells work together; they grow, divide, and secrete bile acids. However, they exist as a formless, nonvascular blob.

As it stands (or rather, lies) now, bioprinted liver is a perfect preclinical model – perfectly replicating how the liver would respond to drugs without any of the messy adverse events that hurt patients. But it needs some backbone, or more accurately, some matrix, in order to morph again and grow into a complete organ. A liver-shaped collagen matrix could provide the necessary frame for cells to grow in and around; tunnels through it would form pathways for a similarly engineered vasculature.

The project to create 3-D models of pulmonary arteries is one of many ongoing efforts in this field. “Going forward, this technology competes with virtual educational media for health care professionals, trainees, and patients. Complex anatomy can be visualized easily on a scale model at the operating table (rather than by manipulating a nonsterile pointing device on a computer). The [pulmonary arteries] we printed could be used in a relatively low-cost lifelike [video-assisted thoracoscopic] lobectomy trainer,” the authors stated, while acknowledging the current issue of cost and time.

Printing services were funded by an unrestricted grant from Incodema3D, which employs Dan Sammons, one of the authors of the study. The other authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Cost comparison favors minimally invasive over conventional AVR

Outcomes were similar, but hospital costs improved with use of mini-aortic valve replacement, compared with conventional AVR, according to the results of a Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database study of 1,341 patients who underwent primary AVR at 17 hospitals.

A propensity match cohort analysis was done to compare patients who had conventional (67%) vs. mini-AVR (33%) performed using either partial sternotomy or right thoracotomy.

Mortality, stroke, renal failure, atrial fibrillation, reoperation for bleeding, and respiratory insufficiency were not statistically significantly different between the two groups. There was also no significant difference in ICU or hospital length of stay between the two groups. However, mini-AVR was associated with both significantly decreased ventilator time (5 vs. 6 hours) and blood product transfusion (25% vs. 32%), according to the report, which was published online and scheduled for the April issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (doi:10.1016/j/jtcvs.2015.01.014).

Total hospital cost was significantly lower in the mini-AVR group ($36,348) vs. the conventional repair group ($38,239, P = .02), wrote Dr. Ravi Kiran Ghanta of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, and his colleagues.

The authors discussed the previously raised issue of longer cross-clamp and bypass times seen in earlier studies of mini-AVR. In their current study, such was not the case, with mini-AVR appearing equivalent with conventional operations. The authors suggested that surgeons have now adopted techniques to reduce bypass and cross-clamp times with mini-AVR.

Data were limited to in-hospital costs. Other costs, such as those of rehabilitation and lost productivity, were not included in the analysis. “Including these health-care costs may have increased overall savings with mini-AVR compared to conventional AVR,” the authors noted.

“Mini-AVR is associated with decreased ventilator time, blood product utilization, early discharge, and reduced total hospital cost. In contemporary clinical practice, mini-AVR is safe and cost-effective,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts.

“Measurement of cost and outcome, the determinant of ‘value’ in health care, is assuming increasing importance in the evaluation of all medial interventions, especially those surgical procedures done frequently and at higher cost,” wrote Dr. Verdi J. DiSesa in his invited commentary (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015 [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.01.049]).