User login

Anatomy of VSD in outflow tract defects indicates a continuum and has surgical relevance

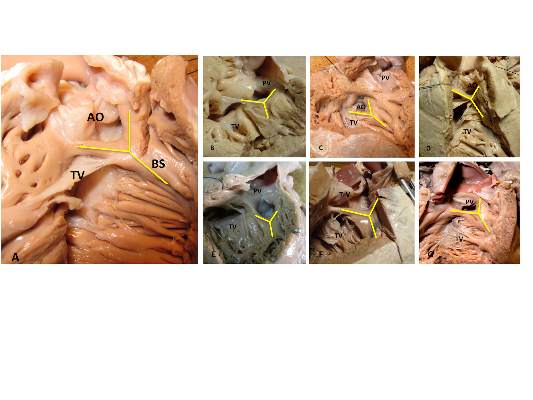

The outlet ventricular septal defect is a cornerstone of the outflow tract defects and exists on a continuum that is anatomically different from the isolated central perimembranous VSD, according to the results of an observational study of 277 preserved heart specimens with isolated outlet ventricular septal defect without subpulmonary stenosis.

“In all of the specimens studied, the VSD always opened in the outlet of the right ventricle, cradled between the two limbs of the septal band, irrespective of the presence or absence of a fibrous continuity between the aortic and tricuspid valves, and the presence of an outlet septum,” according to the report published in the March issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery by Dr. Meriem Mostefa-Kara of the Paris Descartes University and her colleagues.

The 277 specimens comprised 19 with isolated ventricular septal defect; 71 with tetralogy of Fallot (TOF); 51 with TOF with pulmonary atresia (PA); 54 with common arterial trunk (CAT); 65 with double-outlet right ventricle (DORV), with subaortic, doubly committed, or subpulmonary ventricular septal defect; and 17 with interrupted aortic arch (IAA) type B (doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.11.087).

Previous studies have shown that all malalignment defects include a VSD because of the malalignment and the absence of fusion between the outlet septum and the rest of the ventricular septum, and all authors agree that this VSD is cradled between the two limbs of the septal band, according to the researchers.

They found such an outlet VSD in all of the heart specimens studied, Dr. Mostefa-Kara and her colleagues added. In addition, they found that its anatomic variants were distributed differently according to the defect involved. This was especially true when focusing of the posteroinferior rim and particularly on the aortic-tricuspid fibrous continuity. In addition, this continuity occurred with different frequency among the various outflow tract defects studied.

They found the highest rate of continuity in isolated outlet VSD, then decreasing progressively from TOF to TOF-PA, then DORV, becoming “exceedingly rare” in CAT and absent in IAA type B.

The researchers also analyzed 26 hearts with isolated central perimembranous VSD from their anatomic collection and compared these with the outlet VSD hearts. All 26 of these VSDs were located behind the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve, under the posteroinferior limb of the septal band, and NOT between the two limbs of the septal band as was the case with the outlet VSDs.

This led them to state that there was a “blatant anatomical difference between the these two types of VSDs,” and pointed out the risk of confusion. “The presence of a fibrous continuity at the posteroinferior rim of the VSD is important for the surgeon, because it makes the conduction axis vulnerable during surgery and therefore must be described specifically in the preoperative assessment of the defect,” they warned.

“This anatomic approach places the outlet VSD as a cornerstone of the outflow tract defects, anatomically different from the isolated central perimembranous VSD. This may help us to better understand the anatomy of the VSDs and to clarify their classification and terminology,” Dr. Mostefa-Kara and her colleagues concluded.

The study was sponsored by the French Society of Cardiology. The authors reported having no relevant disclosures.

The Paris researchers’ study is important for several reasons, according to the invited editorial commentary by Dr. Robert H. Anderson (doi:10.1016/j,jtcvs.2014.12.003). “First, it shows that careful examination of archives of autopsied hearts can still provide new information. Second, to provide all the information required to achieve safe and secure surgical closures of channels between the ventricles, they emphasize that knowledge is required how the defect opens toward the right ventricle and regarding the boundaries around which the surgeon will place a patch to restore septal integrity. The location of the defect relative to the right ventricle is geography. The details of the margins of the channel requiring closure represent its geometry. In earlier years, investigators tended to use either the geography or the geometry to provide their definitions, or else they accorded priority to one of these features. Both features are surgically important.” In addition, “as the Parisian investigators stress, it is not sufficient simply to state that a defect is perimembranous. We should now be distinguishing between perimembranous defects opening centrally, those that open to the outlet of the right ventricle between the limbs of the septal band, and those that can open to the right ventricular inlet. Another important feature of their research is the presence or absence of septal malalignment.”

Dr. Anderson is a professorial fellow at the Institute of Genetic Medicine, Newcastle University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England.

The Paris researchers’ study is important for several reasons, according to the invited editorial commentary by Dr. Robert H. Anderson (doi:10.1016/j,jtcvs.2014.12.003). “First, it shows that careful examination of archives of autopsied hearts can still provide new information. Second, to provide all the information required to achieve safe and secure surgical closures of channels between the ventricles, they emphasize that knowledge is required how the defect opens toward the right ventricle and regarding the boundaries around which the surgeon will place a patch to restore septal integrity. The location of the defect relative to the right ventricle is geography. The details of the margins of the channel requiring closure represent its geometry. In earlier years, investigators tended to use either the geography or the geometry to provide their definitions, or else they accorded priority to one of these features. Both features are surgically important.” In addition, “as the Parisian investigators stress, it is not sufficient simply to state that a defect is perimembranous. We should now be distinguishing between perimembranous defects opening centrally, those that open to the outlet of the right ventricle between the limbs of the septal band, and those that can open to the right ventricular inlet. Another important feature of their research is the presence or absence of septal malalignment.”

Dr. Anderson is a professorial fellow at the Institute of Genetic Medicine, Newcastle University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England.

The Paris researchers’ study is important for several reasons, according to the invited editorial commentary by Dr. Robert H. Anderson (doi:10.1016/j,jtcvs.2014.12.003). “First, it shows that careful examination of archives of autopsied hearts can still provide new information. Second, to provide all the information required to achieve safe and secure surgical closures of channels between the ventricles, they emphasize that knowledge is required how the defect opens toward the right ventricle and regarding the boundaries around which the surgeon will place a patch to restore septal integrity. The location of the defect relative to the right ventricle is geography. The details of the margins of the channel requiring closure represent its geometry. In earlier years, investigators tended to use either the geography or the geometry to provide their definitions, or else they accorded priority to one of these features. Both features are surgically important.” In addition, “as the Parisian investigators stress, it is not sufficient simply to state that a defect is perimembranous. We should now be distinguishing between perimembranous defects opening centrally, those that open to the outlet of the right ventricle between the limbs of the septal band, and those that can open to the right ventricular inlet. Another important feature of their research is the presence or absence of septal malalignment.”

Dr. Anderson is a professorial fellow at the Institute of Genetic Medicine, Newcastle University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England.

The outlet ventricular septal defect is a cornerstone of the outflow tract defects and exists on a continuum that is anatomically different from the isolated central perimembranous VSD, according to the results of an observational study of 277 preserved heart specimens with isolated outlet ventricular septal defect without subpulmonary stenosis.

“In all of the specimens studied, the VSD always opened in the outlet of the right ventricle, cradled between the two limbs of the septal band, irrespective of the presence or absence of a fibrous continuity between the aortic and tricuspid valves, and the presence of an outlet septum,” according to the report published in the March issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery by Dr. Meriem Mostefa-Kara of the Paris Descartes University and her colleagues.

The 277 specimens comprised 19 with isolated ventricular septal defect; 71 with tetralogy of Fallot (TOF); 51 with TOF with pulmonary atresia (PA); 54 with common arterial trunk (CAT); 65 with double-outlet right ventricle (DORV), with subaortic, doubly committed, or subpulmonary ventricular septal defect; and 17 with interrupted aortic arch (IAA) type B (doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.11.087).

Previous studies have shown that all malalignment defects include a VSD because of the malalignment and the absence of fusion between the outlet septum and the rest of the ventricular septum, and all authors agree that this VSD is cradled between the two limbs of the septal band, according to the researchers.

They found such an outlet VSD in all of the heart specimens studied, Dr. Mostefa-Kara and her colleagues added. In addition, they found that its anatomic variants were distributed differently according to the defect involved. This was especially true when focusing of the posteroinferior rim and particularly on the aortic-tricuspid fibrous continuity. In addition, this continuity occurred with different frequency among the various outflow tract defects studied.

They found the highest rate of continuity in isolated outlet VSD, then decreasing progressively from TOF to TOF-PA, then DORV, becoming “exceedingly rare” in CAT and absent in IAA type B.

The researchers also analyzed 26 hearts with isolated central perimembranous VSD from their anatomic collection and compared these with the outlet VSD hearts. All 26 of these VSDs were located behind the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve, under the posteroinferior limb of the septal band, and NOT between the two limbs of the septal band as was the case with the outlet VSDs.

This led them to state that there was a “blatant anatomical difference between the these two types of VSDs,” and pointed out the risk of confusion. “The presence of a fibrous continuity at the posteroinferior rim of the VSD is important for the surgeon, because it makes the conduction axis vulnerable during surgery and therefore must be described specifically in the preoperative assessment of the defect,” they warned.

“This anatomic approach places the outlet VSD as a cornerstone of the outflow tract defects, anatomically different from the isolated central perimembranous VSD. This may help us to better understand the anatomy of the VSDs and to clarify their classification and terminology,” Dr. Mostefa-Kara and her colleagues concluded.

The study was sponsored by the French Society of Cardiology. The authors reported having no relevant disclosures.

The outlet ventricular septal defect is a cornerstone of the outflow tract defects and exists on a continuum that is anatomically different from the isolated central perimembranous VSD, according to the results of an observational study of 277 preserved heart specimens with isolated outlet ventricular septal defect without subpulmonary stenosis.

“In all of the specimens studied, the VSD always opened in the outlet of the right ventricle, cradled between the two limbs of the septal band, irrespective of the presence or absence of a fibrous continuity between the aortic and tricuspid valves, and the presence of an outlet septum,” according to the report published in the March issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery by Dr. Meriem Mostefa-Kara of the Paris Descartes University and her colleagues.

The 277 specimens comprised 19 with isolated ventricular septal defect; 71 with tetralogy of Fallot (TOF); 51 with TOF with pulmonary atresia (PA); 54 with common arterial trunk (CAT); 65 with double-outlet right ventricle (DORV), with subaortic, doubly committed, or subpulmonary ventricular septal defect; and 17 with interrupted aortic arch (IAA) type B (doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.11.087).

Previous studies have shown that all malalignment defects include a VSD because of the malalignment and the absence of fusion between the outlet septum and the rest of the ventricular septum, and all authors agree that this VSD is cradled between the two limbs of the septal band, according to the researchers.

They found such an outlet VSD in all of the heart specimens studied, Dr. Mostefa-Kara and her colleagues added. In addition, they found that its anatomic variants were distributed differently according to the defect involved. This was especially true when focusing of the posteroinferior rim and particularly on the aortic-tricuspid fibrous continuity. In addition, this continuity occurred with different frequency among the various outflow tract defects studied.

They found the highest rate of continuity in isolated outlet VSD, then decreasing progressively from TOF to TOF-PA, then DORV, becoming “exceedingly rare” in CAT and absent in IAA type B.

The researchers also analyzed 26 hearts with isolated central perimembranous VSD from their anatomic collection and compared these with the outlet VSD hearts. All 26 of these VSDs were located behind the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve, under the posteroinferior limb of the septal band, and NOT between the two limbs of the septal band as was the case with the outlet VSDs.

This led them to state that there was a “blatant anatomical difference between the these two types of VSDs,” and pointed out the risk of confusion. “The presence of a fibrous continuity at the posteroinferior rim of the VSD is important for the surgeon, because it makes the conduction axis vulnerable during surgery and therefore must be described specifically in the preoperative assessment of the defect,” they warned.

“This anatomic approach places the outlet VSD as a cornerstone of the outflow tract defects, anatomically different from the isolated central perimembranous VSD. This may help us to better understand the anatomy of the VSDs and to clarify their classification and terminology,” Dr. Mostefa-Kara and her colleagues concluded.

The study was sponsored by the French Society of Cardiology. The authors reported having no relevant disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: The presence of a fibrous continuity at the postinferior rim of the VSD is important for the surgeon because it makes the conduction axis vulnerable during surgery and therefore must be described specifically in the preoperative assessment.

Major finding: The outlet VSD is a cornerstone of the outflow tract defects and exists on a continuum that is anatomically different from the isolated central perimembranous VSD.

Data source: The researchers examined 277 preserved heart specimens with isolated outlet ventricular septal defect.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the French Society of Cardiology. The authors reported having no relevant disclosures.

Predicting recurrence after mitral valve repair for severe regurgitation

A predictive model identifying patients who will survive 2 years without recurrent mitral regurgitation after mitral valve repair has been developed by Dr. Irving L. Kron and his colleagues in the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network.

The model, published in the March issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, showed good discrimination (C-statistic = 0.82) and was developed using a subgroup analysis of a recent randomized trial of 251 patients by the CTSN (clinicaltrials.gov NCT00807040). The study also found that basal aneurysms and dyskinesis, which occurred commonly in the patient population, were strongly associated with recurrent moderate or severe MR.

The original trial compared complete chordal-sparing mitral valve (MV) replacement with MV repair with a complete downsized ring in patients with severe ischemic mitral regurgitation (MR). Ring size averaged 28.3 mm in men and 27.3 mm in women.

The subgroup analyzed the characteristics and outcomes of the 116 patients who were randomized to and received mitral valve repair, including 70 men (60%) with an overall mean age of around 69 years (6 of the patients were scheduled for repair, but received replacement instead when repair failed to correct MR in the operating room). Concomitant procedures occurred in 85% of the patients, including coronary bypass grafting (CABG), tricuspid valve repair (11%), atrial ablation (12%), and other (25%) (doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs,2014.10.120).

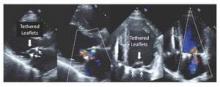

All of the 110 patients receiving successful repair had mild or less MR on intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography after repair. Subsequent transthoracic echocardiography follow-up showed the following MR recurrence for surviving patients: at 30 days: 24.8% moderate, 3.0% severe; at 6 months: 25.5% and 4.3%; at 12 months: 29.7% and 4.4%; and at 24 months: 39.0% and 1.3%. Mitral valve leaflet tethering was found to be the mechanism largely responsible for recurrent mitral regurgitation (Figure 1).

The mortality rate was 14.7% at 1 year, increasing to 19.8% at 2 years.

Overall, during the 2-year follow-up, among the 76 patients who developed moderate/severe MR recurrences or died, there were 53 MR recurrences, 13 MR recurrences plus death, and 10 deaths without recurrence.

The model originally assessed 30 variable candidates. Of these, the final model comprised 10 variables: age, body mass index, sex, race, effective regurgitant orifice area (EROA), basal aneurysm/dyskinesis, New York Heart Association class (NYHA), and prior CABG, percutaneous coronary intervention, or ventricular arrhythmias. None of the baseline echocardiographic measures of MV geometric tethering by themselves were associated with moderate/severe MR, but the presence of basal aneurysm/dyskinesis (52/116 or 45%) was strongly associated with this outcome.

The probabilities of recurrent MR or death estimated from the multivariable model yielded an area under the curve of 0.82; for recurrent MR, the receiver operating characteristic curve had an AUC of 0.83.

“We have developed a model that holds promise for predicting which patients will develop recurrent ischemic MR so that they can be better treated with MV replacement or more complex repair techniques that directly address leaflet tethering,” Dr. Kron and his colleagues concluded.

The study was funded by a cooperative agreement of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; and the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke. Dr. Kron reported having no financial disclosures.

|

Dr. Paul Kurlansky |

Dr. Kron and his colleagues attempted to decipher the clinical characteristics that might help to identify those patients most likely to experience the return of severe mitral regurgitation (MR) after repair. They were able to generate a model predictive of the combined endpoint of MR recurrence and death with an admirable C-statistic of 0.82. However, the elements act somewhat as a unified entity – the numbers did not permit a model sufficiently robust to evaluate the relative contributions of each element, according to Dr. Paul Kurlansky in his invited editorial commentary (doi:10.1016/j/jtcvs.2014.11.023).

“The clinician confronted with a patient who has both similarities and dissimilarities to the patient described in the model will be somewhat at a loss as to determine whether the patient is an appropriate candidate for repair,” he wrote. In addition, “there is no ability to distinguish whether or not the failure of repair was a result of patient selection or repair technique.” Dr. Kurlansky also pointed out that the answers to these questions, even after analysis of the PRCT study, remain largely unanswered and only careful integration of the Cardiothroacic Surgical Trials Network trial data with insightful analysis of retrospective trials will allow clinical relevance to emerge.

Dr. Kurlansky is a cardiothoracic surgeon at the department of surgery, Columbia University, New York. He had nothing to disclose with regard to commercial support.

|

Dr. Paul Kurlansky |

Dr. Kron and his colleagues attempted to decipher the clinical characteristics that might help to identify those patients most likely to experience the return of severe mitral regurgitation (MR) after repair. They were able to generate a model predictive of the combined endpoint of MR recurrence and death with an admirable C-statistic of 0.82. However, the elements act somewhat as a unified entity – the numbers did not permit a model sufficiently robust to evaluate the relative contributions of each element, according to Dr. Paul Kurlansky in his invited editorial commentary (doi:10.1016/j/jtcvs.2014.11.023).

“The clinician confronted with a patient who has both similarities and dissimilarities to the patient described in the model will be somewhat at a loss as to determine whether the patient is an appropriate candidate for repair,” he wrote. In addition, “there is no ability to distinguish whether or not the failure of repair was a result of patient selection or repair technique.” Dr. Kurlansky also pointed out that the answers to these questions, even after analysis of the PRCT study, remain largely unanswered and only careful integration of the Cardiothroacic Surgical Trials Network trial data with insightful analysis of retrospective trials will allow clinical relevance to emerge.

Dr. Kurlansky is a cardiothoracic surgeon at the department of surgery, Columbia University, New York. He had nothing to disclose with regard to commercial support.

|

Dr. Paul Kurlansky |

Dr. Kron and his colleagues attempted to decipher the clinical characteristics that might help to identify those patients most likely to experience the return of severe mitral regurgitation (MR) after repair. They were able to generate a model predictive of the combined endpoint of MR recurrence and death with an admirable C-statistic of 0.82. However, the elements act somewhat as a unified entity – the numbers did not permit a model sufficiently robust to evaluate the relative contributions of each element, according to Dr. Paul Kurlansky in his invited editorial commentary (doi:10.1016/j/jtcvs.2014.11.023).

“The clinician confronted with a patient who has both similarities and dissimilarities to the patient described in the model will be somewhat at a loss as to determine whether the patient is an appropriate candidate for repair,” he wrote. In addition, “there is no ability to distinguish whether or not the failure of repair was a result of patient selection or repair technique.” Dr. Kurlansky also pointed out that the answers to these questions, even after analysis of the PRCT study, remain largely unanswered and only careful integration of the Cardiothroacic Surgical Trials Network trial data with insightful analysis of retrospective trials will allow clinical relevance to emerge.

Dr. Kurlansky is a cardiothoracic surgeon at the department of surgery, Columbia University, New York. He had nothing to disclose with regard to commercial support.

A predictive model identifying patients who will survive 2 years without recurrent mitral regurgitation after mitral valve repair has been developed by Dr. Irving L. Kron and his colleagues in the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network.

The model, published in the March issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, showed good discrimination (C-statistic = 0.82) and was developed using a subgroup analysis of a recent randomized trial of 251 patients by the CTSN (clinicaltrials.gov NCT00807040). The study also found that basal aneurysms and dyskinesis, which occurred commonly in the patient population, were strongly associated with recurrent moderate or severe MR.

The original trial compared complete chordal-sparing mitral valve (MV) replacement with MV repair with a complete downsized ring in patients with severe ischemic mitral regurgitation (MR). Ring size averaged 28.3 mm in men and 27.3 mm in women.

The subgroup analyzed the characteristics and outcomes of the 116 patients who were randomized to and received mitral valve repair, including 70 men (60%) with an overall mean age of around 69 years (6 of the patients were scheduled for repair, but received replacement instead when repair failed to correct MR in the operating room). Concomitant procedures occurred in 85% of the patients, including coronary bypass grafting (CABG), tricuspid valve repair (11%), atrial ablation (12%), and other (25%) (doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs,2014.10.120).

All of the 110 patients receiving successful repair had mild or less MR on intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography after repair. Subsequent transthoracic echocardiography follow-up showed the following MR recurrence for surviving patients: at 30 days: 24.8% moderate, 3.0% severe; at 6 months: 25.5% and 4.3%; at 12 months: 29.7% and 4.4%; and at 24 months: 39.0% and 1.3%. Mitral valve leaflet tethering was found to be the mechanism largely responsible for recurrent mitral regurgitation (Figure 1).

The mortality rate was 14.7% at 1 year, increasing to 19.8% at 2 years.

Overall, during the 2-year follow-up, among the 76 patients who developed moderate/severe MR recurrences or died, there were 53 MR recurrences, 13 MR recurrences plus death, and 10 deaths without recurrence.

The model originally assessed 30 variable candidates. Of these, the final model comprised 10 variables: age, body mass index, sex, race, effective regurgitant orifice area (EROA), basal aneurysm/dyskinesis, New York Heart Association class (NYHA), and prior CABG, percutaneous coronary intervention, or ventricular arrhythmias. None of the baseline echocardiographic measures of MV geometric tethering by themselves were associated with moderate/severe MR, but the presence of basal aneurysm/dyskinesis (52/116 or 45%) was strongly associated with this outcome.

The probabilities of recurrent MR or death estimated from the multivariable model yielded an area under the curve of 0.82; for recurrent MR, the receiver operating characteristic curve had an AUC of 0.83.

“We have developed a model that holds promise for predicting which patients will develop recurrent ischemic MR so that they can be better treated with MV replacement or more complex repair techniques that directly address leaflet tethering,” Dr. Kron and his colleagues concluded.

The study was funded by a cooperative agreement of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; and the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke. Dr. Kron reported having no financial disclosures.

A predictive model identifying patients who will survive 2 years without recurrent mitral regurgitation after mitral valve repair has been developed by Dr. Irving L. Kron and his colleagues in the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network.

The model, published in the March issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, showed good discrimination (C-statistic = 0.82) and was developed using a subgroup analysis of a recent randomized trial of 251 patients by the CTSN (clinicaltrials.gov NCT00807040). The study also found that basal aneurysms and dyskinesis, which occurred commonly in the patient population, were strongly associated with recurrent moderate or severe MR.

The original trial compared complete chordal-sparing mitral valve (MV) replacement with MV repair with a complete downsized ring in patients with severe ischemic mitral regurgitation (MR). Ring size averaged 28.3 mm in men and 27.3 mm in women.

The subgroup analyzed the characteristics and outcomes of the 116 patients who were randomized to and received mitral valve repair, including 70 men (60%) with an overall mean age of around 69 years (6 of the patients were scheduled for repair, but received replacement instead when repair failed to correct MR in the operating room). Concomitant procedures occurred in 85% of the patients, including coronary bypass grafting (CABG), tricuspid valve repair (11%), atrial ablation (12%), and other (25%) (doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs,2014.10.120).

All of the 110 patients receiving successful repair had mild or less MR on intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography after repair. Subsequent transthoracic echocardiography follow-up showed the following MR recurrence for surviving patients: at 30 days: 24.8% moderate, 3.0% severe; at 6 months: 25.5% and 4.3%; at 12 months: 29.7% and 4.4%; and at 24 months: 39.0% and 1.3%. Mitral valve leaflet tethering was found to be the mechanism largely responsible for recurrent mitral regurgitation (Figure 1).

The mortality rate was 14.7% at 1 year, increasing to 19.8% at 2 years.

Overall, during the 2-year follow-up, among the 76 patients who developed moderate/severe MR recurrences or died, there were 53 MR recurrences, 13 MR recurrences plus death, and 10 deaths without recurrence.

The model originally assessed 30 variable candidates. Of these, the final model comprised 10 variables: age, body mass index, sex, race, effective regurgitant orifice area (EROA), basal aneurysm/dyskinesis, New York Heart Association class (NYHA), and prior CABG, percutaneous coronary intervention, or ventricular arrhythmias. None of the baseline echocardiographic measures of MV geometric tethering by themselves were associated with moderate/severe MR, but the presence of basal aneurysm/dyskinesis (52/116 or 45%) was strongly associated with this outcome.

The probabilities of recurrent MR or death estimated from the multivariable model yielded an area under the curve of 0.82; for recurrent MR, the receiver operating characteristic curve had an AUC of 0.83.

“We have developed a model that holds promise for predicting which patients will develop recurrent ischemic MR so that they can be better treated with MV replacement or more complex repair techniques that directly address leaflet tethering,” Dr. Kron and his colleagues concluded.

The study was funded by a cooperative agreement of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; and the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke. Dr. Kron reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: A model (C-statistic = 0.82), which included multiple patient characteristics has been developed for predicting MR recurrence after repair.

Major finding: Basal aneurysms and dyskinesis, which occurred commonly in the patient population, were strongly associated with recurrent moderate or severe MR.

Data source: The study analyzed a subgroup of 116 patients from a recent Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network trial who were randomized to and received mitral valve repair.

Disclosures: The study was funded by a cooperative agreement of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research; and the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke. Dr. Kron reported having no financial disclosures.

Real-world CAS results in Medicare patients not up to trial standards

The presence of competing risks and overall lower levels of provider proficiency appeared to limit the benefits of carotid artery stenting in Medicare beneficiaries, according to the results of a large retrospective cohort study of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CAS database (2005-2009).

Periprocedural mortality was more than twice the rate in this patient population than in those earlier patients those involved in the pivotal CREST and SAPPHIRE clinical trials, according to a report published online Jan. 12 in JAMA Neurology [doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3638].

“The higher risk of periprocedural complications and the burden of competing risks owing to age and comorbidity burden must be carefully considered when deciding between carotid stenosis treatments for Medicare beneficiaries,” according to Jessica J. Jalbert, Ph.D., of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her colleagues.

Over 22,000 patients were assessed in the study. The mean patient age was just over 76 years, 60.5% were men, and 94% were white. Approximately half were symptomatic, 91.2% were at high surgical risk, and 97.4% had carotid stenosis of at least 70%.

Almost 80% of the patients undergoing carotid artery stenting (CAS) met the SAPPHIRE trial indications and about half met at least one of the SAPPHIRE criteria for high surgical risk.

In the mean follow-up of approximately 2 years, mortality risks exceeded one-third for patients who were 80 years of age or older (41.5% mortality risk), symptomatic (37.3% risk), at high surgical risk with symptomatic carotid stenosis of at least 50% (37.3% risk), or admitted nonelectively (36.2% risk). In addition, among asymptomatic patients, mortality after the periprocedural period exceeded one-third for patients at least 80 years old.

Of particular concern, few of these Medicare beneficiaries undergoing CAS as per the National Coverage Determinations were treated by providers with proficiency levels similar to those required in the clinical trials. This is a potential problem because lower annual volume and early operator experience are associated with increased periprocedural mortality, the authors wrote.

CAS was performed primarily by male physicians (98.4%), specializing in cardiology (52.9%), practicing within a group (79.4%), and residing in the South (42.5%). The mean number of past-year CAS procedures performed was only 13.9 for physicians and 29.8 for hospitals. This translated to more than 80% of the physicians not meeting the minimum CAS volume requirements and/or minimum complication rates of the SAPPHIRE trial, and more than 90% not meeting the requirements of the CREST trial.

“Our results may support concerns about the limited generalizability of [randomized clinical trial] findings,” the researchers stated.

“Real-world observational studies comparing CAS, carotid endarterectomy, and medical management are needed to determine the performance of carotid stenosis treatment options for Medicare beneficiaries,” Dr. Jalbert and her colleagues concluded.

The authors reported no relevant disclosures. The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

The presence of competing risks and overall lower levels of provider proficiency appeared to limit the benefits of carotid artery stenting in Medicare beneficiaries, according to the results of a large retrospective cohort study of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CAS database (2005-2009).

Periprocedural mortality was more than twice the rate in this patient population than in those earlier patients those involved in the pivotal CREST and SAPPHIRE clinical trials, according to a report published online Jan. 12 in JAMA Neurology [doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3638].

“The higher risk of periprocedural complications and the burden of competing risks owing to age and comorbidity burden must be carefully considered when deciding between carotid stenosis treatments for Medicare beneficiaries,” according to Jessica J. Jalbert, Ph.D., of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her colleagues.

Over 22,000 patients were assessed in the study. The mean patient age was just over 76 years, 60.5% were men, and 94% were white. Approximately half were symptomatic, 91.2% were at high surgical risk, and 97.4% had carotid stenosis of at least 70%.

Almost 80% of the patients undergoing carotid artery stenting (CAS) met the SAPPHIRE trial indications and about half met at least one of the SAPPHIRE criteria for high surgical risk.

In the mean follow-up of approximately 2 years, mortality risks exceeded one-third for patients who were 80 years of age or older (41.5% mortality risk), symptomatic (37.3% risk), at high surgical risk with symptomatic carotid stenosis of at least 50% (37.3% risk), or admitted nonelectively (36.2% risk). In addition, among asymptomatic patients, mortality after the periprocedural period exceeded one-third for patients at least 80 years old.

Of particular concern, few of these Medicare beneficiaries undergoing CAS as per the National Coverage Determinations were treated by providers with proficiency levels similar to those required in the clinical trials. This is a potential problem because lower annual volume and early operator experience are associated with increased periprocedural mortality, the authors wrote.

CAS was performed primarily by male physicians (98.4%), specializing in cardiology (52.9%), practicing within a group (79.4%), and residing in the South (42.5%). The mean number of past-year CAS procedures performed was only 13.9 for physicians and 29.8 for hospitals. This translated to more than 80% of the physicians not meeting the minimum CAS volume requirements and/or minimum complication rates of the SAPPHIRE trial, and more than 90% not meeting the requirements of the CREST trial.

“Our results may support concerns about the limited generalizability of [randomized clinical trial] findings,” the researchers stated.

“Real-world observational studies comparing CAS, carotid endarterectomy, and medical management are needed to determine the performance of carotid stenosis treatment options for Medicare beneficiaries,” Dr. Jalbert and her colleagues concluded.

The authors reported no relevant disclosures. The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

The presence of competing risks and overall lower levels of provider proficiency appeared to limit the benefits of carotid artery stenting in Medicare beneficiaries, according to the results of a large retrospective cohort study of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CAS database (2005-2009).

Periprocedural mortality was more than twice the rate in this patient population than in those earlier patients those involved in the pivotal CREST and SAPPHIRE clinical trials, according to a report published online Jan. 12 in JAMA Neurology [doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3638].

“The higher risk of periprocedural complications and the burden of competing risks owing to age and comorbidity burden must be carefully considered when deciding between carotid stenosis treatments for Medicare beneficiaries,” according to Jessica J. Jalbert, Ph.D., of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her colleagues.

Over 22,000 patients were assessed in the study. The mean patient age was just over 76 years, 60.5% were men, and 94% were white. Approximately half were symptomatic, 91.2% were at high surgical risk, and 97.4% had carotid stenosis of at least 70%.

Almost 80% of the patients undergoing carotid artery stenting (CAS) met the SAPPHIRE trial indications and about half met at least one of the SAPPHIRE criteria for high surgical risk.

In the mean follow-up of approximately 2 years, mortality risks exceeded one-third for patients who were 80 years of age or older (41.5% mortality risk), symptomatic (37.3% risk), at high surgical risk with symptomatic carotid stenosis of at least 50% (37.3% risk), or admitted nonelectively (36.2% risk). In addition, among asymptomatic patients, mortality after the periprocedural period exceeded one-third for patients at least 80 years old.

Of particular concern, few of these Medicare beneficiaries undergoing CAS as per the National Coverage Determinations were treated by providers with proficiency levels similar to those required in the clinical trials. This is a potential problem because lower annual volume and early operator experience are associated with increased periprocedural mortality, the authors wrote.

CAS was performed primarily by male physicians (98.4%), specializing in cardiology (52.9%), practicing within a group (79.4%), and residing in the South (42.5%). The mean number of past-year CAS procedures performed was only 13.9 for physicians and 29.8 for hospitals. This translated to more than 80% of the physicians not meeting the minimum CAS volume requirements and/or minimum complication rates of the SAPPHIRE trial, and more than 90% not meeting the requirements of the CREST trial.

“Our results may support concerns about the limited generalizability of [randomized clinical trial] findings,” the researchers stated.

“Real-world observational studies comparing CAS, carotid endarterectomy, and medical management are needed to determine the performance of carotid stenosis treatment options for Medicare beneficiaries,” Dr. Jalbert and her colleagues concluded.

The authors reported no relevant disclosures. The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Mortality risks exceeded one-third for patients who were 80 years of age or older, symptomatic, at high surgical risk with symptomatic carotid stenosis of at least 50%, or admitted nonelectively.

Major finding: More than 80% of the physicians performing CAS in the real world did not meet the minimum CAS volume requirements and/or minimum complication rates of the SAPPPHIRE trial.

Data source: Data were obtained from a large retrospective cohort study of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services CAS database (2005-2009).

Disclosures: The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

Bioprosthetic aortic valves may be a reasonable choice in younger patients

No differences were seen in the 15-year stroke or survival rates in more than 4,000 propensity-matched patients in the age range of 50-69 years who received either a mechanical or a bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement, according to the results of a retrospective cohort analysis.

However, valves differed in two other major complications, according to a report published in the Oct. 1 issue of JAMA. Mechanical valve patients had a significantly higher 15-year cumulative incidence of bleeding compared with the bioprosthetic valve group, but had a significantly lower 15-year cumulative incidence of reoperation, according to Yuting P. Chiang and colleagues at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York.

This study calls into question current practice guidelines, which recommend either a bioprosthetic or mechanical prosthetic aortic valve in patients aged 60-70 years, and a mechanical valve in patients younger than 60 years in the absence of a contraindication to warfarin (Coumadin), according to the researchers.

From an original population of more than 10,000 patients aged 50-69 with valve replacement, 4,253 remained after researchers applied exclusionary criteria such as prior valve repair and coronary artery bypass grafting. Of these, 1,466 (34.5%) received a bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement, and 2,787 received a mechanical valve.

Median follow-up was 10.6 and 10.9 years, respectively. Propensity scoring matching produced 1,001 patient pairs. After propensity matching, age and all baseline comorbidities were balanced between the two groups.

Overall, there were no differences in 30-day mortality in the matched groups (3% in both), nor in any other short-term outcome (JAMA 2014;312:1323-29).

In terms of long-term survival, there were no differences seen in the matched cohort, with an actuarial 15-year survival of 60.6% for the prosthetic valve group, and 62.1% for the mechanical valve group (P = .74).

Similarly, there was no significant difference in the cumulative 15-year stroke rate (7.7% for the bioprosthetic group, 8.6% for the mechanical group, P = .84). The 30-day mortality rate after stroke was 18.7%.

There was a significantly higher rate of aortic valve reoperation in the bioprosthetic group (cumulative 15-year incidence of 12.1%) compared with the mechanical group (cumulative incidence of 6.9%, P = .001). The 30-day mortality rate after aortic valve reoperation was 9.0%.

In contrast, cumulative major bleeding over 15 years was significantly higher in the mechanical group (13.0%), than in the bioprosthetic group (6.6%, P = .001). Thirty-day mortality after a major bleeding event was 13.2%.

In discussing the differences between this study and the randomized clinical trials that contributed to the class IIa recommendations on age-based valve choice, the researchers pointed out that two of the studies “enrolled patients nearly 4 decades ago and evaluated prostheses since superseded by more durable and less thrombogenic models.”

The analysis “supports the view that either prosthesis is a reasonable choice in patients aged 60 to 69 years and suggests that this recommendation could reasonably be extended to patients aged 50 to 59 years,” they concluded.

Potential problems inherent in a database analysis and the tendency for deaths at a younger age to be missing from the Social Security Death Master File were limitations of the study. Younger patients were more likely to receive a mechanical valve.

Mr. Chiang reported a research stipend from the Icahn School of Medicine, which receives royalty payments from Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic related to two mitral valve and 1 tricuspid valve ring that Dr. David H. Adams, a coauthor, helped develop. Dr. Adams is coprincipal investigator for the CoreValve United States pivotal trial, supported by Medtronic.

No differences were seen in the 15-year stroke or survival rates in more than 4,000 propensity-matched patients in the age range of 50-69 years who received either a mechanical or a bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement, according to the results of a retrospective cohort analysis.

However, valves differed in two other major complications, according to a report published in the Oct. 1 issue of JAMA. Mechanical valve patients had a significantly higher 15-year cumulative incidence of bleeding compared with the bioprosthetic valve group, but had a significantly lower 15-year cumulative incidence of reoperation, according to Yuting P. Chiang and colleagues at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York.

This study calls into question current practice guidelines, which recommend either a bioprosthetic or mechanical prosthetic aortic valve in patients aged 60-70 years, and a mechanical valve in patients younger than 60 years in the absence of a contraindication to warfarin (Coumadin), according to the researchers.

From an original population of more than 10,000 patients aged 50-69 with valve replacement, 4,253 remained after researchers applied exclusionary criteria such as prior valve repair and coronary artery bypass grafting. Of these, 1,466 (34.5%) received a bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement, and 2,787 received a mechanical valve.

Median follow-up was 10.6 and 10.9 years, respectively. Propensity scoring matching produced 1,001 patient pairs. After propensity matching, age and all baseline comorbidities were balanced between the two groups.

Overall, there were no differences in 30-day mortality in the matched groups (3% in both), nor in any other short-term outcome (JAMA 2014;312:1323-29).

In terms of long-term survival, there were no differences seen in the matched cohort, with an actuarial 15-year survival of 60.6% for the prosthetic valve group, and 62.1% for the mechanical valve group (P = .74).

Similarly, there was no significant difference in the cumulative 15-year stroke rate (7.7% for the bioprosthetic group, 8.6% for the mechanical group, P = .84). The 30-day mortality rate after stroke was 18.7%.

There was a significantly higher rate of aortic valve reoperation in the bioprosthetic group (cumulative 15-year incidence of 12.1%) compared with the mechanical group (cumulative incidence of 6.9%, P = .001). The 30-day mortality rate after aortic valve reoperation was 9.0%.

In contrast, cumulative major bleeding over 15 years was significantly higher in the mechanical group (13.0%), than in the bioprosthetic group (6.6%, P = .001). Thirty-day mortality after a major bleeding event was 13.2%.

In discussing the differences between this study and the randomized clinical trials that contributed to the class IIa recommendations on age-based valve choice, the researchers pointed out that two of the studies “enrolled patients nearly 4 decades ago and evaluated prostheses since superseded by more durable and less thrombogenic models.”

The analysis “supports the view that either prosthesis is a reasonable choice in patients aged 60 to 69 years and suggests that this recommendation could reasonably be extended to patients aged 50 to 59 years,” they concluded.

Potential problems inherent in a database analysis and the tendency for deaths at a younger age to be missing from the Social Security Death Master File were limitations of the study. Younger patients were more likely to receive a mechanical valve.

Mr. Chiang reported a research stipend from the Icahn School of Medicine, which receives royalty payments from Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic related to two mitral valve and 1 tricuspid valve ring that Dr. David H. Adams, a coauthor, helped develop. Dr. Adams is coprincipal investigator for the CoreValve United States pivotal trial, supported by Medtronic.

No differences were seen in the 15-year stroke or survival rates in more than 4,000 propensity-matched patients in the age range of 50-69 years who received either a mechanical or a bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement, according to the results of a retrospective cohort analysis.

However, valves differed in two other major complications, according to a report published in the Oct. 1 issue of JAMA. Mechanical valve patients had a significantly higher 15-year cumulative incidence of bleeding compared with the bioprosthetic valve group, but had a significantly lower 15-year cumulative incidence of reoperation, according to Yuting P. Chiang and colleagues at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York.

This study calls into question current practice guidelines, which recommend either a bioprosthetic or mechanical prosthetic aortic valve in patients aged 60-70 years, and a mechanical valve in patients younger than 60 years in the absence of a contraindication to warfarin (Coumadin), according to the researchers.

From an original population of more than 10,000 patients aged 50-69 with valve replacement, 4,253 remained after researchers applied exclusionary criteria such as prior valve repair and coronary artery bypass grafting. Of these, 1,466 (34.5%) received a bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement, and 2,787 received a mechanical valve.

Median follow-up was 10.6 and 10.9 years, respectively. Propensity scoring matching produced 1,001 patient pairs. After propensity matching, age and all baseline comorbidities were balanced between the two groups.

Overall, there were no differences in 30-day mortality in the matched groups (3% in both), nor in any other short-term outcome (JAMA 2014;312:1323-29).

In terms of long-term survival, there were no differences seen in the matched cohort, with an actuarial 15-year survival of 60.6% for the prosthetic valve group, and 62.1% for the mechanical valve group (P = .74).

Similarly, there was no significant difference in the cumulative 15-year stroke rate (7.7% for the bioprosthetic group, 8.6% for the mechanical group, P = .84). The 30-day mortality rate after stroke was 18.7%.

There was a significantly higher rate of aortic valve reoperation in the bioprosthetic group (cumulative 15-year incidence of 12.1%) compared with the mechanical group (cumulative incidence of 6.9%, P = .001). The 30-day mortality rate after aortic valve reoperation was 9.0%.

In contrast, cumulative major bleeding over 15 years was significantly higher in the mechanical group (13.0%), than in the bioprosthetic group (6.6%, P = .001). Thirty-day mortality after a major bleeding event was 13.2%.

In discussing the differences between this study and the randomized clinical trials that contributed to the class IIa recommendations on age-based valve choice, the researchers pointed out that two of the studies “enrolled patients nearly 4 decades ago and evaluated prostheses since superseded by more durable and less thrombogenic models.”

The analysis “supports the view that either prosthesis is a reasonable choice in patients aged 60 to 69 years and suggests that this recommendation could reasonably be extended to patients aged 50 to 59 years,” they concluded.

Potential problems inherent in a database analysis and the tendency for deaths at a younger age to be missing from the Social Security Death Master File were limitations of the study. Younger patients were more likely to receive a mechanical valve.

Mr. Chiang reported a research stipend from the Icahn School of Medicine, which receives royalty payments from Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic related to two mitral valve and 1 tricuspid valve ring that Dr. David H. Adams, a coauthor, helped develop. Dr. Adams is coprincipal investigator for the CoreValve United States pivotal trial, supported by Medtronic.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Bioprosthetic and mechanical aortic valves were equivalent in stroke and survival rates across propensity-matched patients aged 50-69 years.

Major finding: Actuarial 15-year survival was 60.6% for bioprosthetic valves and 62.1% for mechanical valves.

Data source: A retrospective cohort analysis of 1,001 propensity-matched patient pairs who had a mechanical or bioprosthetic aortic valve replacement in New York State from 1997 through 2004.

Disclosures: Mr. Chiang reported a research stipend from the Icahn School of Medicine, which receives royalty payments from Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic related to two mitral valve and 1 tricuspid valve ring that Dr. David H. Adams, a coauthor, helped develop. Dr. Adams is coprincipal investigator for the CoreValve United States pivotal trial, supported by Medtronic.

Statins do not worsen diabetes microvascular complications, may be protective

Contrary to expectations, statin use before the development of type II diabetes did not worsen microvascular complications such as retinopathy, neuropathy, and gangrene of the foot.

In fact, despite concerns that statins have been seen to increase glucose levels and the risk of diabetes development, they may provide a protective effect from these conditions in newly developed diabetic patients, according to an analysis of data from more than 60,000 individuals in the Danish Patient Registry.

“The cumulative incidences of diabetic retinopathy, diabetic neuropathy, and gangrene were reduced in statin users compared with non–statin users, but [the] risk of diabetic nephropathy was similar for all patients with diabetes,” stated Dr. Sune F. Nielsen, Ph.D., and Dr. Børge G. Nordestgaard of the Herlev Hospital, Copenhagen University Hospital. However, they did find that statin use, as previously seen, did significantly increase the risk of developing diabetes in the first place. Their study was publishedin the Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology (2014 Sept. 10 [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70173-1]).

The researchers performed a nested matched study of all men and women living in Denmark who were diagnosed with incident diabetes during 1996-2009 at age 40 years or older, and assessed their outcomes through use of the Danish Civil Registration System, the Danish Patient Registry, and the Danish Registry of Medicinal Product Statistics. After exclusions, 62,716 patients with diabetes were randomly selected for the study: 15,679 statin users and 47,037 non–statin users. The primary outcome was the incidence of diabetic retinopathy, diabetic neuropathy, diabetic nephropathy, and gangrene of the foot. The design “captured 100% of individuals in Denmark who had ever used a statin within the time frame of the study.”

Follow-up was censored at date of death for 9,560 individuals. During 215,725 person-years of follow-up, diabetic retinopathy was recorded in 2,866 patients, diabetic neuropathy in 1,406, diabetic nephropathy in 1,248, and gangrene of the foot in 2,392. Over a median follow-up of 2.7 years, statin users were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with diabetic neuropathy (hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.57-0.75: P less than .0001) and diabetic retinopathy (HR, 0.60; 95% CI 0.54-0.66: P less than<i/>.0001) than were those who had not received statins. However, no difference was noted in the incidence of diabetic nephropathy (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.85-1.10; P = .62).

In contrast, the researchers found that statin use significantly increased the risk of developing diabetes in people who did not have the disease when the study began. When they compared a random selection of 272,994 non–statin users with 90,998 statin users, the multivariable adjusted hazard ratio for the risk of developing diabetes was 1.17 (95% CI, 1.14-1.21). These results are similar to those seen in previous randomized studies of statin use.

“In conclusion, we found no evidence that statin use is associated with an increased risk of microvascular disease; this result is important and clinically reassuring on its own. Whether or not statins are protective against some forms of microvascular disease, a possibility raised by these data, and by which mechanism, will need to be addressed in studies similar to ours, or in Mendelian randomization studies,” said Dr. Nielsen and Dr. Nordestgaard. “Ideally, however, this question should be addressed in the setting of a randomized controlled trial,” they added.

Dr. Nordestgaard has received consultancy fees or lecture honoraria from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Merck, and Dr. Nielsen declared no competing interests. The work was supported by Herlev Hospital, Copenhagen University Hospital.

View on The News

|

Dr. Russell H. Samson |

I am constantly questioned by my patients about the risks of statins. It seems every patient has a “friend” or someone that they know or have heard of that had some terrible complication from taking statins. Usually the event they describe is something that could never be related to those drugs. For example, their friend’s nose turned green or within 2 weeks of taking the drug their dog died! I mean it’s getting ridiculous. On the other hand, new-onset diabetes is something that we must acknowledge. However, we have been reassured that the increased risk of developing diabetes is still small and is outweighed by the cardiovascular benefits of the statins. This latest article adds even more reassurance by informing us that even if diabetes does occur more frequently its disastrous side effects are not increased and may even be decreased by statins.

Dr. Russell Samson is a clinical professor of surgery (vascular) at Florida State University Medical School, and the medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

View on The News

|

Dr. Russell H. Samson |

I am constantly questioned by my patients about the risks of statins. It seems every patient has a “friend” or someone that they know or have heard of that had some terrible complication from taking statins. Usually the event they describe is something that could never be related to those drugs. For example, their friend’s nose turned green or within 2 weeks of taking the drug their dog died! I mean it’s getting ridiculous. On the other hand, new-onset diabetes is something that we must acknowledge. However, we have been reassured that the increased risk of developing diabetes is still small and is outweighed by the cardiovascular benefits of the statins. This latest article adds even more reassurance by informing us that even if diabetes does occur more frequently its disastrous side effects are not increased and may even be decreased by statins.

Dr. Russell Samson is a clinical professor of surgery (vascular) at Florida State University Medical School, and the medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

View on The News

|

Dr. Russell H. Samson |

I am constantly questioned by my patients about the risks of statins. It seems every patient has a “friend” or someone that they know or have heard of that had some terrible complication from taking statins. Usually the event they describe is something that could never be related to those drugs. For example, their friend’s nose turned green or within 2 weeks of taking the drug their dog died! I mean it’s getting ridiculous. On the other hand, new-onset diabetes is something that we must acknowledge. However, we have been reassured that the increased risk of developing diabetes is still small and is outweighed by the cardiovascular benefits of the statins. This latest article adds even more reassurance by informing us that even if diabetes does occur more frequently its disastrous side effects are not increased and may even be decreased by statins.

Dr. Russell Samson is a clinical professor of surgery (vascular) at Florida State University Medical School, and the medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

Contrary to expectations, statin use before the development of type II diabetes did not worsen microvascular complications such as retinopathy, neuropathy, and gangrene of the foot.

In fact, despite concerns that statins have been seen to increase glucose levels and the risk of diabetes development, they may provide a protective effect from these conditions in newly developed diabetic patients, according to an analysis of data from more than 60,000 individuals in the Danish Patient Registry.

“The cumulative incidences of diabetic retinopathy, diabetic neuropathy, and gangrene were reduced in statin users compared with non–statin users, but [the] risk of diabetic nephropathy was similar for all patients with diabetes,” stated Dr. Sune F. Nielsen, Ph.D., and Dr. Børge G. Nordestgaard of the Herlev Hospital, Copenhagen University Hospital. However, they did find that statin use, as previously seen, did significantly increase the risk of developing diabetes in the first place. Their study was publishedin the Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology (2014 Sept. 10 [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70173-1]).

The researchers performed a nested matched study of all men and women living in Denmark who were diagnosed with incident diabetes during 1996-2009 at age 40 years or older, and assessed their outcomes through use of the Danish Civil Registration System, the Danish Patient Registry, and the Danish Registry of Medicinal Product Statistics. After exclusions, 62,716 patients with diabetes were randomly selected for the study: 15,679 statin users and 47,037 non–statin users. The primary outcome was the incidence of diabetic retinopathy, diabetic neuropathy, diabetic nephropathy, and gangrene of the foot. The design “captured 100% of individuals in Denmark who had ever used a statin within the time frame of the study.”

Follow-up was censored at date of death for 9,560 individuals. During 215,725 person-years of follow-up, diabetic retinopathy was recorded in 2,866 patients, diabetic neuropathy in 1,406, diabetic nephropathy in 1,248, and gangrene of the foot in 2,392. Over a median follow-up of 2.7 years, statin users were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with diabetic neuropathy (hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.57-0.75: P less than .0001) and diabetic retinopathy (HR, 0.60; 95% CI 0.54-0.66: P less than<i/>.0001) than were those who had not received statins. However, no difference was noted in the incidence of diabetic nephropathy (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.85-1.10; P = .62).

In contrast, the researchers found that statin use significantly increased the risk of developing diabetes in people who did not have the disease when the study began. When they compared a random selection of 272,994 non–statin users with 90,998 statin users, the multivariable adjusted hazard ratio for the risk of developing diabetes was 1.17 (95% CI, 1.14-1.21). These results are similar to those seen in previous randomized studies of statin use.

“In conclusion, we found no evidence that statin use is associated with an increased risk of microvascular disease; this result is important and clinically reassuring on its own. Whether or not statins are protective against some forms of microvascular disease, a possibility raised by these data, and by which mechanism, will need to be addressed in studies similar to ours, or in Mendelian randomization studies,” said Dr. Nielsen and Dr. Nordestgaard. “Ideally, however, this question should be addressed in the setting of a randomized controlled trial,” they added.

Dr. Nordestgaard has received consultancy fees or lecture honoraria from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Merck, and Dr. Nielsen declared no competing interests. The work was supported by Herlev Hospital, Copenhagen University Hospital.

Contrary to expectations, statin use before the development of type II diabetes did not worsen microvascular complications such as retinopathy, neuropathy, and gangrene of the foot.

In fact, despite concerns that statins have been seen to increase glucose levels and the risk of diabetes development, they may provide a protective effect from these conditions in newly developed diabetic patients, according to an analysis of data from more than 60,000 individuals in the Danish Patient Registry.

“The cumulative incidences of diabetic retinopathy, diabetic neuropathy, and gangrene were reduced in statin users compared with non–statin users, but [the] risk of diabetic nephropathy was similar for all patients with diabetes,” stated Dr. Sune F. Nielsen, Ph.D., and Dr. Børge G. Nordestgaard of the Herlev Hospital, Copenhagen University Hospital. However, they did find that statin use, as previously seen, did significantly increase the risk of developing diabetes in the first place. Their study was publishedin the Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology (2014 Sept. 10 [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70173-1]).

The researchers performed a nested matched study of all men and women living in Denmark who were diagnosed with incident diabetes during 1996-2009 at age 40 years or older, and assessed their outcomes through use of the Danish Civil Registration System, the Danish Patient Registry, and the Danish Registry of Medicinal Product Statistics. After exclusions, 62,716 patients with diabetes were randomly selected for the study: 15,679 statin users and 47,037 non–statin users. The primary outcome was the incidence of diabetic retinopathy, diabetic neuropathy, diabetic nephropathy, and gangrene of the foot. The design “captured 100% of individuals in Denmark who had ever used a statin within the time frame of the study.”

Follow-up was censored at date of death for 9,560 individuals. During 215,725 person-years of follow-up, diabetic retinopathy was recorded in 2,866 patients, diabetic neuropathy in 1,406, diabetic nephropathy in 1,248, and gangrene of the foot in 2,392. Over a median follow-up of 2.7 years, statin users were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with diabetic neuropathy (hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.57-0.75: P less than .0001) and diabetic retinopathy (HR, 0.60; 95% CI 0.54-0.66: P less than<i/>.0001) than were those who had not received statins. However, no difference was noted in the incidence of diabetic nephropathy (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.85-1.10; P = .62).

In contrast, the researchers found that statin use significantly increased the risk of developing diabetes in people who did not have the disease when the study began. When they compared a random selection of 272,994 non–statin users with 90,998 statin users, the multivariable adjusted hazard ratio for the risk of developing diabetes was 1.17 (95% CI, 1.14-1.21). These results are similar to those seen in previous randomized studies of statin use.

“In conclusion, we found no evidence that statin use is associated with an increased risk of microvascular disease; this result is important and clinically reassuring on its own. Whether or not statins are protective against some forms of microvascular disease, a possibility raised by these data, and by which mechanism, will need to be addressed in studies similar to ours, or in Mendelian randomization studies,” said Dr. Nielsen and Dr. Nordestgaard. “Ideally, however, this question should be addressed in the setting of a randomized controlled trial,” they added.

Dr. Nordestgaard has received consultancy fees or lecture honoraria from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Merck, and Dr. Nielsen declared no competing interests. The work was supported by Herlev Hospital, Copenhagen University Hospital.

Key clinical point: Statins may protect against microvascular complications in diabetes patients.

Major finding: Statin users were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with diabetic neuropathy (HR, 0.66) and diabetic retinopathy (HR, 0.60) than non–statin users.

Data source: A registry study compared 62,716 patients with diabetes: 15,679 statin users and 47,037 non–statin users.

Disclosures: Dr. Nordestgaard has received consultancy fees or lecture honoraria from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Merck, and Dr. Nielsen declared no competing interests. The work was supported by Herlev Hospital, Copenhagen University Hospital.

Helping history come alive online in Vascular Specialist

Medical history is more than just the praise of great heroes and heroines and the nearly mythical stories of serendipitous discovery and invention. It is the means by which we learn to understand and appreciate the qualities and conditions that lead to innovation and it illuminates the present by honoring the past.

Since its inception in 2005, Vascular Specialist has highlighted some of the most important persons and events in the history of vascular surgery and medicine in our column, Vascular Surgery Chronicles.

Most of these articles are out of print and have not been available online. But that has changed.

As part of our new and improved wesbite, we are now placing these articles on the Vascular Specialist web site, where they can be visited here, and we are renewing our committment to making the Vascular Surgery Chronicles column a more frequent feature of the print edition and also our special online-only newsletters.

Currently available articles on the web site highlight such notable figures as:

Look for these and other articles and stay tuned for more windows on the vascular past online and in the pages of Vascular Specialist.

Medical history is more than just the praise of great heroes and heroines and the nearly mythical stories of serendipitous discovery and invention. It is the means by which we learn to understand and appreciate the qualities and conditions that lead to innovation and it illuminates the present by honoring the past.

Since its inception in 2005, Vascular Specialist has highlighted some of the most important persons and events in the history of vascular surgery and medicine in our column, Vascular Surgery Chronicles.

Most of these articles are out of print and have not been available online. But that has changed.

As part of our new and improved wesbite, we are now placing these articles on the Vascular Specialist web site, where they can be visited here, and we are renewing our committment to making the Vascular Surgery Chronicles column a more frequent feature of the print edition and also our special online-only newsletters.

Currently available articles on the web site highlight such notable figures as:

Look for these and other articles and stay tuned for more windows on the vascular past online and in the pages of Vascular Specialist.

Medical history is more than just the praise of great heroes and heroines and the nearly mythical stories of serendipitous discovery and invention. It is the means by which we learn to understand and appreciate the qualities and conditions that lead to innovation and it illuminates the present by honoring the past.

Since its inception in 2005, Vascular Specialist has highlighted some of the most important persons and events in the history of vascular surgery and medicine in our column, Vascular Surgery Chronicles.

Most of these articles are out of print and have not been available online. But that has changed.

As part of our new and improved wesbite, we are now placing these articles on the Vascular Specialist web site, where they can be visited here, and we are renewing our committment to making the Vascular Surgery Chronicles column a more frequent feature of the print edition and also our special online-only newsletters.

Currently available articles on the web site highlight such notable figures as:

Look for these and other articles and stay tuned for more windows on the vascular past online and in the pages of Vascular Specialist.

Pioneer Heart Surgeon, Dr. Michael DeBakey

Dr. Michael Ellis DeBakey, pioneer heart surgeon and medical device innovator, died July 11, 2008 in Houston, about 2 months shy of his 100th birthday on Sept. 7.

In his lifetime, Dr. DeBakey was renowned for his immense contributions to the progress of medical science, such that he was declared a "living legend" by the Library of Congress and was this year awarded a Congressional Gold Medal for his lifetime achievements, in particular his pioneering work as a heart surgeon.

Even before Dr. DeBakey received his medical degree from Tulane University in 1932, he began his contributions to modern medicine by developing a small continuous flow–roller pump designed to improve blood transfusion—a device that would later be used by Dr. John Gibbon as a crucial component of his heart-lung machine. And in 1939, with his mentor, Dr. Alton Ochsner, Dr. DeBakey suggested a strong link between smoking and lung cancer.

After internships in New Orleans and surgical training in Europe, Dr. DeBakey volunteered for service during World War II and was assigned to the U.S. Army Surgeon General’s office. From his observations in the field, he became convinced of the need for a mobile surgical unit that would give soldiers access to high-level medical treatment on the combat field and convinced the surgeon general to form what would become the mobile army surgical hospitals (MASH units)—an innovation that gained him the U.S. Army Legion of Merit in 1945.

His government service continued throughout his civilian career, as he helped to establish the Veterans Administration medical center research system. He also initiated the movement that in 1956 took the Army’s poorly housed medical library and used it to create the National Library of Medicine, of which he was first board member and then chairman. He served three terms on the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Advisory Council as well. He was responsible for helping establish health care systems in a host of countries, including Belgium, China, Egypt, England, Germany, Saudi Arabia, Australia, and numerous other Middle Eastern and Central and South American nations.

According to the Web site of Baylor College of Medicine’s department of surgery, where he spent almost his entire postwar career, Dr. DeBakey operated on more than 60,000 patients in the Houston area alone. But these were not all just standard operations. In 1953, he performed the first successful carotid endarterectomy, as well as the first successful removal and graft replacement of a fusiform thoracic aortic aneurysm, and in 1954, the first successful resection and graft replacement of an aneurysm of the distal aortic arch and upper descending thoracic aorta.

In 1955 he performed the first successful resection of a thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm using the DeBakey Dacron graft—the first artificial arterial graft of its kind.

"If we now tried to develop the Dacron graft the way we developed it, I am not sure we would have it today with the way they regulate things. ...When I went down to the department store . . . they said ‘We are fresh out of nylon, but we do have a new material called Dacron.’ I felt it, and it looked good to me. So I bought a yard of it. . . . I took this yard of Dacron cloth, I cut two sheets the width I wanted, sewed the edges on each side, and made a tube out of it . . . .We put the graft on a stent, wrapped nylon thread around it, pushed it together, and baked it.. . . After about two or three years of laboratory work on my own [including experiments in dogs], I decided that it was time to put the graft in a human being. I did not have a committee to approve it. . . . In 1954, I put the first one in during an abdominal aortic aneurysm. That first patient lived, I think, for 13 years and never had any trouble," Dr. DeBakey related in an interview published in 1996 in the Journal of Vascular Surgery.

And among his other pioneering surgical developments, in 1964, Dr. DeBakey was the first to perform a successful coronary artery bypass, using a portion of leg vein as the graft, in what is now one of the most commonly performed heart operations—coronary artery bypass grafting.

As if surgically repairing failing hearts was not enough, Dr. DeBakey became a pioneer of artificial heart research and of cardiac assist devices. On July 18, 1963, after years of animal research, he performed the first successful human implantation of a left ventricular assist device (LVAD), one which he devised; the patient died after 4 days from causes unrelated to the technology. In 1966, Dr. DeBakey’s redesigned, extracorporeal pneumatic pump was used in a 37-year old woman who could not be weaned from the heart-lung machine after dual valve replacement. After 10 days of LVAD support, she recovered sufficiently for the pump to be removed and she survived. This pump served as the basis of Dr. DeBakey’s first total artificial heart model, created in 1968.