User login

Arginine deficiency implicated in novel hemorrhagic fever fatality

Deficiency of the amino acid arginine is implicated in the low platelet counts of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS), and a measure of global arginine bioavailability had prognostic value for mortality from the causal bunyavirus, according to a metabolomics analysis of serum from SFTS patients.

The new study also reported results from a randomized, controlled trial of intravenous arginine supplementation in SFTS; the 53 patients who received 20 g of arginine once daily had faster viral clearance than the 60 patients who received supportive care only and a placebo infusion (P = .047). Also, SFTS patients who received arginine had quicker resolution of liver transaminase elevations (P = .001).

There was no survival benefit in arginine administration, though the study’s first author, Xiao-Kun Li, MD, and colleagues noted low overall fatality rates in arginine-treated and placebo groups, at 5.7% and 8.3%, respectively.

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome is caused by a bunyavirus first identified in 2009; SFTS is being seen with increasing frequency in mainland China, Korea, Japan, and the United States. Infection with the virus “is associated with a wide clinical spectrum, with most of the patients having mild disease but more than 10% developing a fatal outcome,” wrote Dr. Li and the other researchers in Science Translational Medicine.

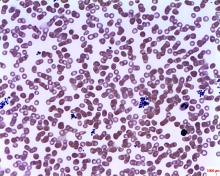

In the case of individuals with SFTS who fare poorly, previous work had implicated a disordered host immune response leading to severe thrombocytopenia with subsequent bleeding and disseminated intravascular coagulation, said Dr. Li and colleagues. The exact pathogenesis of this mechanism had been unknown, however, so the investigators used a metabolomics analysis on serum samples from prospectively observed SFTS patients. “[W]e determined arginine metabolism to be a key pathway that was involved in the interaction between SFTS [virus] and host response,” they wrote.

In a prospective cohort study that used liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry, Dr. Li of the Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology and colleagues examined 166 metabolites from 242 clinical samples to perform the metabolomics analysis. Of the SFTS patients in the study, 46 had both acute and convalescent samples that were matched with 46 healthy controls and 46 patients with fever not caused by SFTS. In a separate analysis, a series of samples were drawn from 10 patients who died of SFTS and matched to 10 who survived the infection and 10 healthy controls.

Statistical analyses allowed the investigators to identify metabolomics signatures that were unique for each sample group. Alteration of the arginine metabolism pathway stood out as the most pronounced differentiator in acute SFTS infection and fatality, wrote Dr. Li and coauthors. “By extracting the relative concentrations of arginine-related metabolites along the pathway, we found that arginine RC was significantly reduced in the acute phase of SFTS compared to healthy controls,” they wrote (P less than .001).

Patients who succumbed to SFTS had even lower arginine concentrations than did those who survived; arginine levels climbed during recovery for survivors, but stayed low in serum samples from SFTS fatalities.

There’s a logical mechanism by which arginine could contribute to platelet dysfunction and thrombocytopenia, noted Dr. Li and collaborators: Arginine is a nitric oxide precursor, and this pathway is known to be a potent inhibitor of platelet activation.

Low arginine levels would have the effect of taking the brakes off platelet activation, and the investigators did find increases in platelet-monocyte complexes and platelet apoptosis in SFTS virus infection (P = .007 and P less than .001, respectively), which further suggests “that platelet hyperactivation might contribute to reduced platelet counts in circulation,” they wrote.

Low arginine levels also have the effect of suppressing T-cell activity, and mediators along this pathway were also altered in patients with SFTS, and even more profoundly altered in patients who died of SFTS.

Dr. Li and colleagues probed the metabolomics data to see whether a global arginine bioavailability ratio (GABR), expressed as arginine/(ornithine + citrulline), could be used to prognosticate clinical outcome in SFTS virus infection. After multivariable analysis, they found that decreased GABR was associated with fatality (P = .039). Further, a low GABR early in infection was prognostic of later fatality, with an area under the receiver operating curve (ROC) of 0.713.

In the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of arginine supplementation during SFTS, Dr. Li and coinvestigators found that arginine supplementation did not significantly alter most other laboratory values besides liver transaminases. However, blood urea nitrogen concentration was elevated in those who received arginine, and arginine supplementation was also associated with slightly more vomiting. Serum sampling also revealed that platelet activation and T-cell activity were both corrected in patients given arginine, which gives clues to the means by which arginine supplementation might boost host immune response and promote viral clearing and return to homeostasis of clotting pathways.

Limitations of the clinical trial included relatively small sample sizes and the fact that individuals with severe bleeding were excluded from participation in the trial. Also, the study didn’t account for dietary arginine intake, acknowledged Dr. Li and coauthors.

However, the metabolomics and clinical work taken together used state-of-the-art analytic methods and rigorous experimental design to show “the causal relationship between arginine deficiency and platelet deprivation or immunosuppression by SFTSV infection,” wrote Dr. Li and colleagues.

Disturbance in the arginine–nitric oxide pathway is likely “to be a key biochemical pathway that also plays [a] part in other viral hemorrhagic fever,” said the investigators. “The potential of arginine in treating such infectious diseases [with] similar clinical features as SFTS warrants exploration.”

The study was partially funded by a Bayer Investigator Award; Dr. Li and coauthors reported no other conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Li X-K et al. Sci Transl Med. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat4162.

Deficiency of the amino acid arginine is implicated in the low platelet counts of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS), and a measure of global arginine bioavailability had prognostic value for mortality from the causal bunyavirus, according to a metabolomics analysis of serum from SFTS patients.

The new study also reported results from a randomized, controlled trial of intravenous arginine supplementation in SFTS; the 53 patients who received 20 g of arginine once daily had faster viral clearance than the 60 patients who received supportive care only and a placebo infusion (P = .047). Also, SFTS patients who received arginine had quicker resolution of liver transaminase elevations (P = .001).

There was no survival benefit in arginine administration, though the study’s first author, Xiao-Kun Li, MD, and colleagues noted low overall fatality rates in arginine-treated and placebo groups, at 5.7% and 8.3%, respectively.

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome is caused by a bunyavirus first identified in 2009; SFTS is being seen with increasing frequency in mainland China, Korea, Japan, and the United States. Infection with the virus “is associated with a wide clinical spectrum, with most of the patients having mild disease but more than 10% developing a fatal outcome,” wrote Dr. Li and the other researchers in Science Translational Medicine.

In the case of individuals with SFTS who fare poorly, previous work had implicated a disordered host immune response leading to severe thrombocytopenia with subsequent bleeding and disseminated intravascular coagulation, said Dr. Li and colleagues. The exact pathogenesis of this mechanism had been unknown, however, so the investigators used a metabolomics analysis on serum samples from prospectively observed SFTS patients. “[W]e determined arginine metabolism to be a key pathway that was involved in the interaction between SFTS [virus] and host response,” they wrote.

In a prospective cohort study that used liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry, Dr. Li of the Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology and colleagues examined 166 metabolites from 242 clinical samples to perform the metabolomics analysis. Of the SFTS patients in the study, 46 had both acute and convalescent samples that were matched with 46 healthy controls and 46 patients with fever not caused by SFTS. In a separate analysis, a series of samples were drawn from 10 patients who died of SFTS and matched to 10 who survived the infection and 10 healthy controls.

Statistical analyses allowed the investigators to identify metabolomics signatures that were unique for each sample group. Alteration of the arginine metabolism pathway stood out as the most pronounced differentiator in acute SFTS infection and fatality, wrote Dr. Li and coauthors. “By extracting the relative concentrations of arginine-related metabolites along the pathway, we found that arginine RC was significantly reduced in the acute phase of SFTS compared to healthy controls,” they wrote (P less than .001).

Patients who succumbed to SFTS had even lower arginine concentrations than did those who survived; arginine levels climbed during recovery for survivors, but stayed low in serum samples from SFTS fatalities.

There’s a logical mechanism by which arginine could contribute to platelet dysfunction and thrombocytopenia, noted Dr. Li and collaborators: Arginine is a nitric oxide precursor, and this pathway is known to be a potent inhibitor of platelet activation.

Low arginine levels would have the effect of taking the brakes off platelet activation, and the investigators did find increases in platelet-monocyte complexes and platelet apoptosis in SFTS virus infection (P = .007 and P less than .001, respectively), which further suggests “that platelet hyperactivation might contribute to reduced platelet counts in circulation,” they wrote.

Low arginine levels also have the effect of suppressing T-cell activity, and mediators along this pathway were also altered in patients with SFTS, and even more profoundly altered in patients who died of SFTS.

Dr. Li and colleagues probed the metabolomics data to see whether a global arginine bioavailability ratio (GABR), expressed as arginine/(ornithine + citrulline), could be used to prognosticate clinical outcome in SFTS virus infection. After multivariable analysis, they found that decreased GABR was associated with fatality (P = .039). Further, a low GABR early in infection was prognostic of later fatality, with an area under the receiver operating curve (ROC) of 0.713.

In the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of arginine supplementation during SFTS, Dr. Li and coinvestigators found that arginine supplementation did not significantly alter most other laboratory values besides liver transaminases. However, blood urea nitrogen concentration was elevated in those who received arginine, and arginine supplementation was also associated with slightly more vomiting. Serum sampling also revealed that platelet activation and T-cell activity were both corrected in patients given arginine, which gives clues to the means by which arginine supplementation might boost host immune response and promote viral clearing and return to homeostasis of clotting pathways.

Limitations of the clinical trial included relatively small sample sizes and the fact that individuals with severe bleeding were excluded from participation in the trial. Also, the study didn’t account for dietary arginine intake, acknowledged Dr. Li and coauthors.

However, the metabolomics and clinical work taken together used state-of-the-art analytic methods and rigorous experimental design to show “the causal relationship between arginine deficiency and platelet deprivation or immunosuppression by SFTSV infection,” wrote Dr. Li and colleagues.

Disturbance in the arginine–nitric oxide pathway is likely “to be a key biochemical pathway that also plays [a] part in other viral hemorrhagic fever,” said the investigators. “The potential of arginine in treating such infectious diseases [with] similar clinical features as SFTS warrants exploration.”

The study was partially funded by a Bayer Investigator Award; Dr. Li and coauthors reported no other conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Li X-K et al. Sci Transl Med. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat4162.

Deficiency of the amino acid arginine is implicated in the low platelet counts of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS), and a measure of global arginine bioavailability had prognostic value for mortality from the causal bunyavirus, according to a metabolomics analysis of serum from SFTS patients.

The new study also reported results from a randomized, controlled trial of intravenous arginine supplementation in SFTS; the 53 patients who received 20 g of arginine once daily had faster viral clearance than the 60 patients who received supportive care only and a placebo infusion (P = .047). Also, SFTS patients who received arginine had quicker resolution of liver transaminase elevations (P = .001).

There was no survival benefit in arginine administration, though the study’s first author, Xiao-Kun Li, MD, and colleagues noted low overall fatality rates in arginine-treated and placebo groups, at 5.7% and 8.3%, respectively.

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome is caused by a bunyavirus first identified in 2009; SFTS is being seen with increasing frequency in mainland China, Korea, Japan, and the United States. Infection with the virus “is associated with a wide clinical spectrum, with most of the patients having mild disease but more than 10% developing a fatal outcome,” wrote Dr. Li and the other researchers in Science Translational Medicine.

In the case of individuals with SFTS who fare poorly, previous work had implicated a disordered host immune response leading to severe thrombocytopenia with subsequent bleeding and disseminated intravascular coagulation, said Dr. Li and colleagues. The exact pathogenesis of this mechanism had been unknown, however, so the investigators used a metabolomics analysis on serum samples from prospectively observed SFTS patients. “[W]e determined arginine metabolism to be a key pathway that was involved in the interaction between SFTS [virus] and host response,” they wrote.

In a prospective cohort study that used liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry, Dr. Li of the Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology and colleagues examined 166 metabolites from 242 clinical samples to perform the metabolomics analysis. Of the SFTS patients in the study, 46 had both acute and convalescent samples that were matched with 46 healthy controls and 46 patients with fever not caused by SFTS. In a separate analysis, a series of samples were drawn from 10 patients who died of SFTS and matched to 10 who survived the infection and 10 healthy controls.

Statistical analyses allowed the investigators to identify metabolomics signatures that were unique for each sample group. Alteration of the arginine metabolism pathway stood out as the most pronounced differentiator in acute SFTS infection and fatality, wrote Dr. Li and coauthors. “By extracting the relative concentrations of arginine-related metabolites along the pathway, we found that arginine RC was significantly reduced in the acute phase of SFTS compared to healthy controls,” they wrote (P less than .001).

Patients who succumbed to SFTS had even lower arginine concentrations than did those who survived; arginine levels climbed during recovery for survivors, but stayed low in serum samples from SFTS fatalities.

There’s a logical mechanism by which arginine could contribute to platelet dysfunction and thrombocytopenia, noted Dr. Li and collaborators: Arginine is a nitric oxide precursor, and this pathway is known to be a potent inhibitor of platelet activation.

Low arginine levels would have the effect of taking the brakes off platelet activation, and the investigators did find increases in platelet-monocyte complexes and platelet apoptosis in SFTS virus infection (P = .007 and P less than .001, respectively), which further suggests “that platelet hyperactivation might contribute to reduced platelet counts in circulation,” they wrote.

Low arginine levels also have the effect of suppressing T-cell activity, and mediators along this pathway were also altered in patients with SFTS, and even more profoundly altered in patients who died of SFTS.

Dr. Li and colleagues probed the metabolomics data to see whether a global arginine bioavailability ratio (GABR), expressed as arginine/(ornithine + citrulline), could be used to prognosticate clinical outcome in SFTS virus infection. After multivariable analysis, they found that decreased GABR was associated with fatality (P = .039). Further, a low GABR early in infection was prognostic of later fatality, with an area under the receiver operating curve (ROC) of 0.713.

In the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of arginine supplementation during SFTS, Dr. Li and coinvestigators found that arginine supplementation did not significantly alter most other laboratory values besides liver transaminases. However, blood urea nitrogen concentration was elevated in those who received arginine, and arginine supplementation was also associated with slightly more vomiting. Serum sampling also revealed that platelet activation and T-cell activity were both corrected in patients given arginine, which gives clues to the means by which arginine supplementation might boost host immune response and promote viral clearing and return to homeostasis of clotting pathways.

Limitations of the clinical trial included relatively small sample sizes and the fact that individuals with severe bleeding were excluded from participation in the trial. Also, the study didn’t account for dietary arginine intake, acknowledged Dr. Li and coauthors.

However, the metabolomics and clinical work taken together used state-of-the-art analytic methods and rigorous experimental design to show “the causal relationship between arginine deficiency and platelet deprivation or immunosuppression by SFTSV infection,” wrote Dr. Li and colleagues.

Disturbance in the arginine–nitric oxide pathway is likely “to be a key biochemical pathway that also plays [a] part in other viral hemorrhagic fever,” said the investigators. “The potential of arginine in treating such infectious diseases [with] similar clinical features as SFTS warrants exploration.”

The study was partially funded by a Bayer Investigator Award; Dr. Li and coauthors reported no other conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Li X-K et al. Sci Transl Med. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat4162.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Low arginine bioavailability was associated with increased risk for severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) fatality.

Major finding: Arginine bioavailability had an area under the receiver operating curve of 0.713 for predicting fatality.

Study details: A prospective cohort metabolomics study of 242 serum samples from patients with and without SFTS and a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of 113 patients given intravenous arginine supplementation or vehicle alone, in conjunction with supportive care.

Disclosures: The study was partially funded by a Bayer Investigator Award; Dr. Li and coauthors reported no other conflicts of interest.

Source: Li X-K et al. Sci Transl Med. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat4162.

Opioids don’t treat pain better than ibuprofen after venous ablation surgery

ST. LOUIS – Compared with ibuprofen, opioid pain medication offered little benefit for pain control after venous ablation surgery, in the experience of one surgical center.

Sharing study results at a poster session at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgery Society, Jana Sacco, MD, and her colleagues found that patients who received opioid prescriptions after venous ablations did not have significantly different postsurgical pain than did those who received ibuprofen alone.

The study, conducted against the national backdrop of greater scrutiny of postsurgical opioid prescribing, was the first to look at post–venous ablation pain management strategies, said Dr. Sacco, a resident physician at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit. Venous ablation surgery can improve quality of life for patients with varicose veins, but best practices for managing postprocedure discomfort had not been clear; some patients receive opioid pain medications, while others are directed to use ibuprofen as needed for pain control.

The retrospective, single-center study assessed pre- and postoperative pain for patients undergoing venous ablation procedures over a 2-year period, said Dr. Sacco.

Patients who were prescribed opioids were compared with patients who were simply asked to take ibuprofen for pain control.

Comparing preoperative to postoperative pain scores, Dr. Sacco and her colleagues defined a change of 2-3 points on a 0-10 Likert scale as “good” improvement; a change of 1 point was defined as “mild” improvement, and no change or worsening was defined as no improvement.

Of the 268 patients for whom postoperative follow-up data were available, 142 received opioid prescriptions, while 126 did not.

Across the entire group of patients studied, those who had moderate to severe preoperative pain had significant improvement in pain after their procedures.

Whether patients received opioid pain medication after their venous ablation was not correlated with the degree of improvement in postprocedure pain scores. Of those who saw no improvement, 30 patients (45%) received opioids and 36 (55%) did not. Of the 89 patients who saw mild postprocedure improvement in pain, 35 (40%) were not discharged on opioids, and of 65 patients who had good improvement in postprocedure pain, 44% were not discharged on opioids (P = .7 for difference across groups).

When Dr. Sacco and her fellow researchers examined such patient characteristics as sex, race, body mass index, smoking status, and CEAP venous severity classification, they did not see any significant differences in pain scores. Similarly, neither the type of procedure (radiofrequency or laser ablation) nor information on whether compression treatment was used was associated with a difference in pain scores.

Dr. Sacco and her coauthors noted that the study was limited by its retrospective nature and the fact that patients were all drawn from a single institution. Additionally, the investigators were only able to ascertain whether opioids had been prescribed, not whether – or how much – medication was actually taken by patients.

“Most patients report an improvement in symptoms after undergoing vein ablation procedures,” reported Dr. Sacco and her colleagues, and most patients also do well with nonopioid pain control regimens. “Overprescribing opioids exposes patients to the risk of narcotic overdose and chronic opioid use and should be used with caution for patients undergoing vein ablation surgery,” they wrote.

Dr. Sacco reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

ST. LOUIS – Compared with ibuprofen, opioid pain medication offered little benefit for pain control after venous ablation surgery, in the experience of one surgical center.

Sharing study results at a poster session at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgery Society, Jana Sacco, MD, and her colleagues found that patients who received opioid prescriptions after venous ablations did not have significantly different postsurgical pain than did those who received ibuprofen alone.

The study, conducted against the national backdrop of greater scrutiny of postsurgical opioid prescribing, was the first to look at post–venous ablation pain management strategies, said Dr. Sacco, a resident physician at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit. Venous ablation surgery can improve quality of life for patients with varicose veins, but best practices for managing postprocedure discomfort had not been clear; some patients receive opioid pain medications, while others are directed to use ibuprofen as needed for pain control.

The retrospective, single-center study assessed pre- and postoperative pain for patients undergoing venous ablation procedures over a 2-year period, said Dr. Sacco.

Patients who were prescribed opioids were compared with patients who were simply asked to take ibuprofen for pain control.

Comparing preoperative to postoperative pain scores, Dr. Sacco and her colleagues defined a change of 2-3 points on a 0-10 Likert scale as “good” improvement; a change of 1 point was defined as “mild” improvement, and no change or worsening was defined as no improvement.

Of the 268 patients for whom postoperative follow-up data were available, 142 received opioid prescriptions, while 126 did not.

Across the entire group of patients studied, those who had moderate to severe preoperative pain had significant improvement in pain after their procedures.

Whether patients received opioid pain medication after their venous ablation was not correlated with the degree of improvement in postprocedure pain scores. Of those who saw no improvement, 30 patients (45%) received opioids and 36 (55%) did not. Of the 89 patients who saw mild postprocedure improvement in pain, 35 (40%) were not discharged on opioids, and of 65 patients who had good improvement in postprocedure pain, 44% were not discharged on opioids (P = .7 for difference across groups).

When Dr. Sacco and her fellow researchers examined such patient characteristics as sex, race, body mass index, smoking status, and CEAP venous severity classification, they did not see any significant differences in pain scores. Similarly, neither the type of procedure (radiofrequency or laser ablation) nor information on whether compression treatment was used was associated with a difference in pain scores.

Dr. Sacco and her coauthors noted that the study was limited by its retrospective nature and the fact that patients were all drawn from a single institution. Additionally, the investigators were only able to ascertain whether opioids had been prescribed, not whether – or how much – medication was actually taken by patients.

“Most patients report an improvement in symptoms after undergoing vein ablation procedures,” reported Dr. Sacco and her colleagues, and most patients also do well with nonopioid pain control regimens. “Overprescribing opioids exposes patients to the risk of narcotic overdose and chronic opioid use and should be used with caution for patients undergoing vein ablation surgery,” they wrote.

Dr. Sacco reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

ST. LOUIS – Compared with ibuprofen, opioid pain medication offered little benefit for pain control after venous ablation surgery, in the experience of one surgical center.

Sharing study results at a poster session at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgery Society, Jana Sacco, MD, and her colleagues found that patients who received opioid prescriptions after venous ablations did not have significantly different postsurgical pain than did those who received ibuprofen alone.

The study, conducted against the national backdrop of greater scrutiny of postsurgical opioid prescribing, was the first to look at post–venous ablation pain management strategies, said Dr. Sacco, a resident physician at Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit. Venous ablation surgery can improve quality of life for patients with varicose veins, but best practices for managing postprocedure discomfort had not been clear; some patients receive opioid pain medications, while others are directed to use ibuprofen as needed for pain control.

The retrospective, single-center study assessed pre- and postoperative pain for patients undergoing venous ablation procedures over a 2-year period, said Dr. Sacco.

Patients who were prescribed opioids were compared with patients who were simply asked to take ibuprofen for pain control.

Comparing preoperative to postoperative pain scores, Dr. Sacco and her colleagues defined a change of 2-3 points on a 0-10 Likert scale as “good” improvement; a change of 1 point was defined as “mild” improvement, and no change or worsening was defined as no improvement.

Of the 268 patients for whom postoperative follow-up data were available, 142 received opioid prescriptions, while 126 did not.

Across the entire group of patients studied, those who had moderate to severe preoperative pain had significant improvement in pain after their procedures.

Whether patients received opioid pain medication after their venous ablation was not correlated with the degree of improvement in postprocedure pain scores. Of those who saw no improvement, 30 patients (45%) received opioids and 36 (55%) did not. Of the 89 patients who saw mild postprocedure improvement in pain, 35 (40%) were not discharged on opioids, and of 65 patients who had good improvement in postprocedure pain, 44% were not discharged on opioids (P = .7 for difference across groups).

When Dr. Sacco and her fellow researchers examined such patient characteristics as sex, race, body mass index, smoking status, and CEAP venous severity classification, they did not see any significant differences in pain scores. Similarly, neither the type of procedure (radiofrequency or laser ablation) nor information on whether compression treatment was used was associated with a difference in pain scores.

Dr. Sacco and her coauthors noted that the study was limited by its retrospective nature and the fact that patients were all drawn from a single institution. Additionally, the investigators were only able to ascertain whether opioids had been prescribed, not whether – or how much – medication was actually taken by patients.

“Most patients report an improvement in symptoms after undergoing vein ablation procedures,” reported Dr. Sacco and her colleagues, and most patients also do well with nonopioid pain control regimens. “Overprescribing opioids exposes patients to the risk of narcotic overdose and chronic opioid use and should be used with caution for patients undergoing vein ablation surgery,” they wrote.

Dr. Sacco reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM MIDWESTERN VASCULAR 2018

Key clinical point: Prescribing opioids after venous ablation surgery didn’t improve pain control over ibuprofen.

Major finding:

Study details: Retrospective, single-institution study of 268 patients undergoing venous ablation surgery.

Disclosures: Dr. Sacco reported no conflicts of interest and no outside sources of funding.

Vascular programs without NIVL curriculum leave trainees feeling unprepared

ST. LOUIS – Many vascular surgery trainees felt unprepared to take the Registered Physician in Vascular Interpretation (RPVI) exam, according to a recent survey. However, trainees in a program without a structured noninvasive vascular laboratory (NIVL) curriculum felt particularly unprepared, said Daisy Chou, MD.

“There is wide variation in NIVL experience amongst vascular surgery training programs,” noted Dr. Chou, a vascular surgery fellow at the Ohio State University, Columbus. She presented survey results at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgical Society. The survey constructed by Dr. Chou and her colleagues went out to trainees in both 0+5 and 5+2 vascular surgery training programs in September, 2017, in 114 unique programs.

Eventually, trainees from just over half of the programs responded (N = 61 programs, 53.5%), said Dr. Chou. Using responses from individual trainees, the authors grouped programs into one of two categories: those whose trainees felt well prepared for the RPVI, and those whose trainees felt unprepared for the RPVI.

In addition to a yes/no question about preparedness, the survey also asked whether training programs had a structured curriculum; respondents were asked to identify specific NIVL-related training activities. The survey asked about individual didactic components, as well as whether the trainee spent individual time with an attending physician and hands-on time with vascular technologists. Respondents were asked about the amount of time, measured in half days per week, spent in the vascular laboratory.

Finally, the survey asked whether trainees took a pre-RPVI exam review course, and whether they passed the RPVI exam on their first attempt.

Overall, 34 of the programs with respondents (55.7%) had structured curricula; the same number included lectures. Twenty programs (32.8%) provided video content, and 29 (47.5%) used textbooks. Just 18 programs (29.5%) assigned articles.

One-on-one time spent with an attending physician and focused on NIVL techniques was reported for 32 programs (52.5%). More programs (n = 37; 60.7%) provided trainees hands-on experience with vascular technologists.

Most programs (n = 32; 52.5%) had trainees spending less than one half day per week in the vascular laboratory, according to survey respondents.

In terms of preparedness, respondents for over half of the programs did not respond to the question asking whether they felt prepared for the RPVI, presumably because they had not yet taken the exam. This, acknowledged Dr. Chou, was a significant limitation of the survey. There was a timing problem: Trainees were surveyed at the start of the 2017-2018 academic year, but the RPVI exam isn’t usually taken until the end of the final year of training, with review courses taken not long before that.

Of the 32 programs with trainees who reported taking the RPVI exam, 18 had trainees who felt unprepared, and 14 program had trainees who felt well prepared. About a quarter of programs (N = 15; 24.6%) had trainees who took a review course prior to taking the exam.

Dr. Chou and her colleagues then examined the survey responses another way, seeing what differentiated the programs whose trainees felt well prepared from those with trainees who felt unprepared.

Statistically, the clear standout was whether the program had a structured curriculum: The 14 programs with a structured curriculum all had students who reported feeling well prepared. Just one-third of the 18 programs with unprepared students had a structured curriculum, which was a significant difference (P = .0001).

Also, programs that assigned articles and those that gave formal lectures were more likely to have students who felt prepared to sit for the RPVI exam (P = .002 and .004, respectively). A higher number of programs that gave trainees hands-on time with vascular technologists had trainees who felt prepared, but the difference wasn’t quite statistically significant (P = .05).

Having taken a review course prior to the exam was associated with feeling well prepared (P = .03).

Dr. Chou and her colleagues performed a logistic regression analysis to arrive at the educational components associated with the highest odds for trainees feeling well prepared. Lectures and articles came out on top in this analysis (odds ratios for feeling well prepared, 15.88 and 15.97, respectively). Hands-on time with vascular technologists had an odds ratio of 5.12 for feeling prepared.

Taking a review course boosted preparedness as well, with an odds ratio of 11.85 for feeling well prepared for the RPVI exam. This created a bit of a conundrum for the investigators, said Dr. Chou: “All well prepared programs had a structured NIVL curriculum, but most of their trainees still took an RPVI review course, so it’s unclear if the structured curriculum or the review course is responsible for trainees feeling well prepared for the RPVI exam,” she said.

An important caveat to the analysis of survey results, said Dr. Chou, is that “It’s unknown how these results will translate into pass rates.

“Vascular surgery leadership should not leave NIVL education to review courses,” said Dr. Chou. The ultimate goal, she said, should be to achieve expertise in the service of providing better patient care. To this end, Dr. Chou and her coauthors recommend that a structured NIVL curriculum be incorporated into vascular surgery training, and that the program include time spent with vascular technologists, a formal lecture-based component, and structured reading, as is provided by a journal club.

Dr. Chou reported no conflicts of interest, and no external sources of funding.

ST. LOUIS – Many vascular surgery trainees felt unprepared to take the Registered Physician in Vascular Interpretation (RPVI) exam, according to a recent survey. However, trainees in a program without a structured noninvasive vascular laboratory (NIVL) curriculum felt particularly unprepared, said Daisy Chou, MD.

“There is wide variation in NIVL experience amongst vascular surgery training programs,” noted Dr. Chou, a vascular surgery fellow at the Ohio State University, Columbus. She presented survey results at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgical Society. The survey constructed by Dr. Chou and her colleagues went out to trainees in both 0+5 and 5+2 vascular surgery training programs in September, 2017, in 114 unique programs.

Eventually, trainees from just over half of the programs responded (N = 61 programs, 53.5%), said Dr. Chou. Using responses from individual trainees, the authors grouped programs into one of two categories: those whose trainees felt well prepared for the RPVI, and those whose trainees felt unprepared for the RPVI.

In addition to a yes/no question about preparedness, the survey also asked whether training programs had a structured curriculum; respondents were asked to identify specific NIVL-related training activities. The survey asked about individual didactic components, as well as whether the trainee spent individual time with an attending physician and hands-on time with vascular technologists. Respondents were asked about the amount of time, measured in half days per week, spent in the vascular laboratory.

Finally, the survey asked whether trainees took a pre-RPVI exam review course, and whether they passed the RPVI exam on their first attempt.

Overall, 34 of the programs with respondents (55.7%) had structured curricula; the same number included lectures. Twenty programs (32.8%) provided video content, and 29 (47.5%) used textbooks. Just 18 programs (29.5%) assigned articles.

One-on-one time spent with an attending physician and focused on NIVL techniques was reported for 32 programs (52.5%). More programs (n = 37; 60.7%) provided trainees hands-on experience with vascular technologists.

Most programs (n = 32; 52.5%) had trainees spending less than one half day per week in the vascular laboratory, according to survey respondents.

In terms of preparedness, respondents for over half of the programs did not respond to the question asking whether they felt prepared for the RPVI, presumably because they had not yet taken the exam. This, acknowledged Dr. Chou, was a significant limitation of the survey. There was a timing problem: Trainees were surveyed at the start of the 2017-2018 academic year, but the RPVI exam isn’t usually taken until the end of the final year of training, with review courses taken not long before that.

Of the 32 programs with trainees who reported taking the RPVI exam, 18 had trainees who felt unprepared, and 14 program had trainees who felt well prepared. About a quarter of programs (N = 15; 24.6%) had trainees who took a review course prior to taking the exam.

Dr. Chou and her colleagues then examined the survey responses another way, seeing what differentiated the programs whose trainees felt well prepared from those with trainees who felt unprepared.

Statistically, the clear standout was whether the program had a structured curriculum: The 14 programs with a structured curriculum all had students who reported feeling well prepared. Just one-third of the 18 programs with unprepared students had a structured curriculum, which was a significant difference (P = .0001).

Also, programs that assigned articles and those that gave formal lectures were more likely to have students who felt prepared to sit for the RPVI exam (P = .002 and .004, respectively). A higher number of programs that gave trainees hands-on time with vascular technologists had trainees who felt prepared, but the difference wasn’t quite statistically significant (P = .05).

Having taken a review course prior to the exam was associated with feeling well prepared (P = .03).

Dr. Chou and her colleagues performed a logistic regression analysis to arrive at the educational components associated with the highest odds for trainees feeling well prepared. Lectures and articles came out on top in this analysis (odds ratios for feeling well prepared, 15.88 and 15.97, respectively). Hands-on time with vascular technologists had an odds ratio of 5.12 for feeling prepared.

Taking a review course boosted preparedness as well, with an odds ratio of 11.85 for feeling well prepared for the RPVI exam. This created a bit of a conundrum for the investigators, said Dr. Chou: “All well prepared programs had a structured NIVL curriculum, but most of their trainees still took an RPVI review course, so it’s unclear if the structured curriculum or the review course is responsible for trainees feeling well prepared for the RPVI exam,” she said.

An important caveat to the analysis of survey results, said Dr. Chou, is that “It’s unknown how these results will translate into pass rates.

“Vascular surgery leadership should not leave NIVL education to review courses,” said Dr. Chou. The ultimate goal, she said, should be to achieve expertise in the service of providing better patient care. To this end, Dr. Chou and her coauthors recommend that a structured NIVL curriculum be incorporated into vascular surgery training, and that the program include time spent with vascular technologists, a formal lecture-based component, and structured reading, as is provided by a journal club.

Dr. Chou reported no conflicts of interest, and no external sources of funding.

ST. LOUIS – Many vascular surgery trainees felt unprepared to take the Registered Physician in Vascular Interpretation (RPVI) exam, according to a recent survey. However, trainees in a program without a structured noninvasive vascular laboratory (NIVL) curriculum felt particularly unprepared, said Daisy Chou, MD.

“There is wide variation in NIVL experience amongst vascular surgery training programs,” noted Dr. Chou, a vascular surgery fellow at the Ohio State University, Columbus. She presented survey results at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgical Society. The survey constructed by Dr. Chou and her colleagues went out to trainees in both 0+5 and 5+2 vascular surgery training programs in September, 2017, in 114 unique programs.

Eventually, trainees from just over half of the programs responded (N = 61 programs, 53.5%), said Dr. Chou. Using responses from individual trainees, the authors grouped programs into one of two categories: those whose trainees felt well prepared for the RPVI, and those whose trainees felt unprepared for the RPVI.

In addition to a yes/no question about preparedness, the survey also asked whether training programs had a structured curriculum; respondents were asked to identify specific NIVL-related training activities. The survey asked about individual didactic components, as well as whether the trainee spent individual time with an attending physician and hands-on time with vascular technologists. Respondents were asked about the amount of time, measured in half days per week, spent in the vascular laboratory.

Finally, the survey asked whether trainees took a pre-RPVI exam review course, and whether they passed the RPVI exam on their first attempt.

Overall, 34 of the programs with respondents (55.7%) had structured curricula; the same number included lectures. Twenty programs (32.8%) provided video content, and 29 (47.5%) used textbooks. Just 18 programs (29.5%) assigned articles.

One-on-one time spent with an attending physician and focused on NIVL techniques was reported for 32 programs (52.5%). More programs (n = 37; 60.7%) provided trainees hands-on experience with vascular technologists.

Most programs (n = 32; 52.5%) had trainees spending less than one half day per week in the vascular laboratory, according to survey respondents.

In terms of preparedness, respondents for over half of the programs did not respond to the question asking whether they felt prepared for the RPVI, presumably because they had not yet taken the exam. This, acknowledged Dr. Chou, was a significant limitation of the survey. There was a timing problem: Trainees were surveyed at the start of the 2017-2018 academic year, but the RPVI exam isn’t usually taken until the end of the final year of training, with review courses taken not long before that.

Of the 32 programs with trainees who reported taking the RPVI exam, 18 had trainees who felt unprepared, and 14 program had trainees who felt well prepared. About a quarter of programs (N = 15; 24.6%) had trainees who took a review course prior to taking the exam.

Dr. Chou and her colleagues then examined the survey responses another way, seeing what differentiated the programs whose trainees felt well prepared from those with trainees who felt unprepared.

Statistically, the clear standout was whether the program had a structured curriculum: The 14 programs with a structured curriculum all had students who reported feeling well prepared. Just one-third of the 18 programs with unprepared students had a structured curriculum, which was a significant difference (P = .0001).

Also, programs that assigned articles and those that gave formal lectures were more likely to have students who felt prepared to sit for the RPVI exam (P = .002 and .004, respectively). A higher number of programs that gave trainees hands-on time with vascular technologists had trainees who felt prepared, but the difference wasn’t quite statistically significant (P = .05).

Having taken a review course prior to the exam was associated with feeling well prepared (P = .03).

Dr. Chou and her colleagues performed a logistic regression analysis to arrive at the educational components associated with the highest odds for trainees feeling well prepared. Lectures and articles came out on top in this analysis (odds ratios for feeling well prepared, 15.88 and 15.97, respectively). Hands-on time with vascular technologists had an odds ratio of 5.12 for feeling prepared.

Taking a review course boosted preparedness as well, with an odds ratio of 11.85 for feeling well prepared for the RPVI exam. This created a bit of a conundrum for the investigators, said Dr. Chou: “All well prepared programs had a structured NIVL curriculum, but most of their trainees still took an RPVI review course, so it’s unclear if the structured curriculum or the review course is responsible for trainees feeling well prepared for the RPVI exam,” she said.

An important caveat to the analysis of survey results, said Dr. Chou, is that “It’s unknown how these results will translate into pass rates.

“Vascular surgery leadership should not leave NIVL education to review courses,” said Dr. Chou. The ultimate goal, she said, should be to achieve expertise in the service of providing better patient care. To this end, Dr. Chou and her coauthors recommend that a structured NIVL curriculum be incorporated into vascular surgery training, and that the program include time spent with vascular technologists, a formal lecture-based component, and structured reading, as is provided by a journal club.

Dr. Chou reported no conflicts of interest, and no external sources of funding.

REPORTING FROM MIDWESTERN VASCULAR 2018

Key clinical point: Many vascular surgery trainees do not feel prepared to take the RPVI exam.

Major finding: Lectures and textbook reading were highly associated with feeling prepared (P = .002 and .004, respectively).

Study details: Survey of trainees in 114 vascular surgery training programs.

Disclosures: The author reported no outside sources of funding, and no conflicts of interest.

NHLBI commits to a sickle cell cure

“We have new exigency and intensity of effort to enable curative strategies for sickle cell disease to move forward,” said W. Keith Hoots, MD, the director of the division of blood diseases at NHLBI.

The key word in the cure effort is partnership – whether it’s among federal agencies, with public and private organizations, or with patients and families.

“Developmental strategies are built on partnerships to enhance care and accelerate cure for sickle cell disease in the U.S. and worldwide,” Dr. Hoots said at the 12th annual symposium of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research in Washington.

The reach also extends internationally. Supporting research in sub-Saharan Africa has promised to accelerate the clinical trial process by bringing advanced research capabilities to a region with a very high per capita rate of SCD. While in the United States, infrastructure is being built for a future research network, with the goal of developing a secure database of shared elements that harmonize and unite existing data.

Future cohort studies, enhanced newborn screening, and higher uptake of hydroxyurea will all be supported as part of this effort, Dr. Hoots said.

In the United States, patients can participate in a meaningful way as citizen-scientists, as new technology makes it possible to crowdsource high-quality data collection securely.

And including both community organizations and primary care providers in the “circle of partners” means not only that advances are brought out to patients expeditiously but also that the voices of patients and families have a clear channel back to researchers and policy makers through formal patient engagement and lay participation at all levels, Dr. Hoots said.

“The number of presently interested partners may surprise you,” Dr. Hoots said.

This multifaceted approach allows for “multiple shots on goal, with the acceptance that there could potentially be some failures,” Dr. Hoots said. Keeping all players better connected, though, should allow efforts to be redirected when needed, with a particular focus on accelerating work toward genetic therapies for SCD.

Perhaps the flagship effort is the Cure Sickle Cell Disease Initiative, a new partnership focused on accelerating cure-focused SCD research by filling in gaps left in the network of other funding strategies.

NHLBI named Edward J. Benz Jr., MD, the president and CEO emeritus of Boston’s Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, as the executive director and the Emmes Corporation, a contract research organization with expertise in clinical trials, as the coordinating center.

Traveling the last mile

New strategies also need to focus on how to boost uptake of such currently available best practices in SCD treatment as hydroxyurea use. To that end, Dr. Hoots said, NHLBI is drawing on implementation science, a discipline that, in a medical setting, can help solve such “last-mile” problems as bringing best practices in SCD treatment to patients.

In clinical practice, this might look like solving transportation issues for family members so that appointments aren’t missed and hydroxyurea prescriptions are filled. For researchers, implementation science can help with thorny details of participant recruitment and retention.

Established in 2016, the Sickle Cell Disease Implementation Consortium comprises nine U.S. research centers and NHLBI, which are each seeking to recruit at least 300 participants with SCD, aged 15-45 years, to study effective identification of barriers to care, and the best means to overcome them.

However, Dr. Hoots said, NHLBI also will continue funding SCD research through the traditional investigator-initiated application process, in conjunction with “a suite of specialized programs that can support translational and clinical research in SCD.”

Some of the features rolling out within the Cure SCD Initiative are included in direct response to stakeholder feedback about pressing needs and top priorities. For example, an economic case needed to be made in order for insurance companies, public and private alike, to reimburse for genetic SCD treatments. This requires an understanding of the lifetime cost burden of SCD, as well as determining what the long-term follow-up of costs of gene therapy will be.

Patients, family members and those providing primary care for SCD patients all agreed that clinical trials should have endpoints that reflect meaningful outcomes for patients and should be designed with the input of both patients and providers.

When queried, sickle cell disease researchers expressed a need to identify common data elements in SCD research, and wished for a secure yet accessible national data warehouse for data from gene and cell therapy trials.

At present, there are three clinical trials of curative stem cell approaches for SCD registered with the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network and several more early phase clinical trials underway, Dr. Hoots said. A primary focus is the use of autologous cells for genomic editing, gene therapy, and erythroid-specific vectors.

Genetic research

As an example of the new collaboration, research centers and biotechnology companies sent their cell and genetic therapy experts to an NIH-sponsored gathering in March 2017. By pooling expertise in this way, the group was able to “identify some unprecedented opportunities, as well as some necessary barriers to overcome,” he said. These players continue to collaborate in the ongoing clinical trials of novel – and potentially curative – SCD therapies.

The TOPMed (Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine) program is a key mechanism to support SCD-related genetic research. For example, Dr. Hoots said, TOPMed is being used in support of whole-genome sequencing in a longitudinal cohort of patients with SCD who receive transfusion care at four large centers in Brazil.

These renewed efforts, set against the backdrop of paradigm-shifting genetic therapies, represent new promise for a generation of individuals with SCD, Dr. Hoots said. “It takes all of us to address the SCD challenge.”

ASH initiatives

NHLBI isn’t alone in making SCD a priority. The American Society of Hematology also is putting a spotlight on the condition.

The ASH multifaceted sickle cell disease (SCD) initiative addresses the disease burden both within the United States and globally, said LaTasha Lee, PhD, senior manager of sickle cell disease policy and programs for ASH.

Speaking at the 12th annual symposium of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research, Dr. Lee said that four prongs make up the initiative: disease research, attention to global issues, a renewed focus on access to care in the United States, and work to develop ASH’s new SCD guidelines.

New guidelines on the management of acute and chronic complications of SCD are in the works, with an anticipated 2019 date for publication of five separate guidelines. Topics covered in the guidelines will include pain, cerebrovascular disease, cardiopulmonary and kidney disease, transfusion support, and stem cell transplantation.

“We have new exigency and intensity of effort to enable curative strategies for sickle cell disease to move forward,” said W. Keith Hoots, MD, the director of the division of blood diseases at NHLBI.

The key word in the cure effort is partnership – whether it’s among federal agencies, with public and private organizations, or with patients and families.

“Developmental strategies are built on partnerships to enhance care and accelerate cure for sickle cell disease in the U.S. and worldwide,” Dr. Hoots said at the 12th annual symposium of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research in Washington.

The reach also extends internationally. Supporting research in sub-Saharan Africa has promised to accelerate the clinical trial process by bringing advanced research capabilities to a region with a very high per capita rate of SCD. While in the United States, infrastructure is being built for a future research network, with the goal of developing a secure database of shared elements that harmonize and unite existing data.

Future cohort studies, enhanced newborn screening, and higher uptake of hydroxyurea will all be supported as part of this effort, Dr. Hoots said.

In the United States, patients can participate in a meaningful way as citizen-scientists, as new technology makes it possible to crowdsource high-quality data collection securely.

And including both community organizations and primary care providers in the “circle of partners” means not only that advances are brought out to patients expeditiously but also that the voices of patients and families have a clear channel back to researchers and policy makers through formal patient engagement and lay participation at all levels, Dr. Hoots said.

“The number of presently interested partners may surprise you,” Dr. Hoots said.

This multifaceted approach allows for “multiple shots on goal, with the acceptance that there could potentially be some failures,” Dr. Hoots said. Keeping all players better connected, though, should allow efforts to be redirected when needed, with a particular focus on accelerating work toward genetic therapies for SCD.

Perhaps the flagship effort is the Cure Sickle Cell Disease Initiative, a new partnership focused on accelerating cure-focused SCD research by filling in gaps left in the network of other funding strategies.

NHLBI named Edward J. Benz Jr., MD, the president and CEO emeritus of Boston’s Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, as the executive director and the Emmes Corporation, a contract research organization with expertise in clinical trials, as the coordinating center.

Traveling the last mile

New strategies also need to focus on how to boost uptake of such currently available best practices in SCD treatment as hydroxyurea use. To that end, Dr. Hoots said, NHLBI is drawing on implementation science, a discipline that, in a medical setting, can help solve such “last-mile” problems as bringing best practices in SCD treatment to patients.

In clinical practice, this might look like solving transportation issues for family members so that appointments aren’t missed and hydroxyurea prescriptions are filled. For researchers, implementation science can help with thorny details of participant recruitment and retention.

Established in 2016, the Sickle Cell Disease Implementation Consortium comprises nine U.S. research centers and NHLBI, which are each seeking to recruit at least 300 participants with SCD, aged 15-45 years, to study effective identification of barriers to care, and the best means to overcome them.

However, Dr. Hoots said, NHLBI also will continue funding SCD research through the traditional investigator-initiated application process, in conjunction with “a suite of specialized programs that can support translational and clinical research in SCD.”

Some of the features rolling out within the Cure SCD Initiative are included in direct response to stakeholder feedback about pressing needs and top priorities. For example, an economic case needed to be made in order for insurance companies, public and private alike, to reimburse for genetic SCD treatments. This requires an understanding of the lifetime cost burden of SCD, as well as determining what the long-term follow-up of costs of gene therapy will be.

Patients, family members and those providing primary care for SCD patients all agreed that clinical trials should have endpoints that reflect meaningful outcomes for patients and should be designed with the input of both patients and providers.

When queried, sickle cell disease researchers expressed a need to identify common data elements in SCD research, and wished for a secure yet accessible national data warehouse for data from gene and cell therapy trials.

At present, there are three clinical trials of curative stem cell approaches for SCD registered with the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network and several more early phase clinical trials underway, Dr. Hoots said. A primary focus is the use of autologous cells for genomic editing, gene therapy, and erythroid-specific vectors.

Genetic research

As an example of the new collaboration, research centers and biotechnology companies sent their cell and genetic therapy experts to an NIH-sponsored gathering in March 2017. By pooling expertise in this way, the group was able to “identify some unprecedented opportunities, as well as some necessary barriers to overcome,” he said. These players continue to collaborate in the ongoing clinical trials of novel – and potentially curative – SCD therapies.

The TOPMed (Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine) program is a key mechanism to support SCD-related genetic research. For example, Dr. Hoots said, TOPMed is being used in support of whole-genome sequencing in a longitudinal cohort of patients with SCD who receive transfusion care at four large centers in Brazil.

These renewed efforts, set against the backdrop of paradigm-shifting genetic therapies, represent new promise for a generation of individuals with SCD, Dr. Hoots said. “It takes all of us to address the SCD challenge.”

ASH initiatives

NHLBI isn’t alone in making SCD a priority. The American Society of Hematology also is putting a spotlight on the condition.

The ASH multifaceted sickle cell disease (SCD) initiative addresses the disease burden both within the United States and globally, said LaTasha Lee, PhD, senior manager of sickle cell disease policy and programs for ASH.

Speaking at the 12th annual symposium of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research, Dr. Lee said that four prongs make up the initiative: disease research, attention to global issues, a renewed focus on access to care in the United States, and work to develop ASH’s new SCD guidelines.

New guidelines on the management of acute and chronic complications of SCD are in the works, with an anticipated 2019 date for publication of five separate guidelines. Topics covered in the guidelines will include pain, cerebrovascular disease, cardiopulmonary and kidney disease, transfusion support, and stem cell transplantation.

“We have new exigency and intensity of effort to enable curative strategies for sickle cell disease to move forward,” said W. Keith Hoots, MD, the director of the division of blood diseases at NHLBI.

The key word in the cure effort is partnership – whether it’s among federal agencies, with public and private organizations, or with patients and families.

“Developmental strategies are built on partnerships to enhance care and accelerate cure for sickle cell disease in the U.S. and worldwide,” Dr. Hoots said at the 12th annual symposium of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research in Washington.

The reach also extends internationally. Supporting research in sub-Saharan Africa has promised to accelerate the clinical trial process by bringing advanced research capabilities to a region with a very high per capita rate of SCD. While in the United States, infrastructure is being built for a future research network, with the goal of developing a secure database of shared elements that harmonize and unite existing data.

Future cohort studies, enhanced newborn screening, and higher uptake of hydroxyurea will all be supported as part of this effort, Dr. Hoots said.

In the United States, patients can participate in a meaningful way as citizen-scientists, as new technology makes it possible to crowdsource high-quality data collection securely.

And including both community organizations and primary care providers in the “circle of partners” means not only that advances are brought out to patients expeditiously but also that the voices of patients and families have a clear channel back to researchers and policy makers through formal patient engagement and lay participation at all levels, Dr. Hoots said.

“The number of presently interested partners may surprise you,” Dr. Hoots said.

This multifaceted approach allows for “multiple shots on goal, with the acceptance that there could potentially be some failures,” Dr. Hoots said. Keeping all players better connected, though, should allow efforts to be redirected when needed, with a particular focus on accelerating work toward genetic therapies for SCD.

Perhaps the flagship effort is the Cure Sickle Cell Disease Initiative, a new partnership focused on accelerating cure-focused SCD research by filling in gaps left in the network of other funding strategies.

NHLBI named Edward J. Benz Jr., MD, the president and CEO emeritus of Boston’s Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, as the executive director and the Emmes Corporation, a contract research organization with expertise in clinical trials, as the coordinating center.

Traveling the last mile

New strategies also need to focus on how to boost uptake of such currently available best practices in SCD treatment as hydroxyurea use. To that end, Dr. Hoots said, NHLBI is drawing on implementation science, a discipline that, in a medical setting, can help solve such “last-mile” problems as bringing best practices in SCD treatment to patients.

In clinical practice, this might look like solving transportation issues for family members so that appointments aren’t missed and hydroxyurea prescriptions are filled. For researchers, implementation science can help with thorny details of participant recruitment and retention.

Established in 2016, the Sickle Cell Disease Implementation Consortium comprises nine U.S. research centers and NHLBI, which are each seeking to recruit at least 300 participants with SCD, aged 15-45 years, to study effective identification of barriers to care, and the best means to overcome them.

However, Dr. Hoots said, NHLBI also will continue funding SCD research through the traditional investigator-initiated application process, in conjunction with “a suite of specialized programs that can support translational and clinical research in SCD.”

Some of the features rolling out within the Cure SCD Initiative are included in direct response to stakeholder feedback about pressing needs and top priorities. For example, an economic case needed to be made in order for insurance companies, public and private alike, to reimburse for genetic SCD treatments. This requires an understanding of the lifetime cost burden of SCD, as well as determining what the long-term follow-up of costs of gene therapy will be.

Patients, family members and those providing primary care for SCD patients all agreed that clinical trials should have endpoints that reflect meaningful outcomes for patients and should be designed with the input of both patients and providers.

When queried, sickle cell disease researchers expressed a need to identify common data elements in SCD research, and wished for a secure yet accessible national data warehouse for data from gene and cell therapy trials.

At present, there are three clinical trials of curative stem cell approaches for SCD registered with the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network and several more early phase clinical trials underway, Dr. Hoots said. A primary focus is the use of autologous cells for genomic editing, gene therapy, and erythroid-specific vectors.

Genetic research

As an example of the new collaboration, research centers and biotechnology companies sent their cell and genetic therapy experts to an NIH-sponsored gathering in March 2017. By pooling expertise in this way, the group was able to “identify some unprecedented opportunities, as well as some necessary barriers to overcome,” he said. These players continue to collaborate in the ongoing clinical trials of novel – and potentially curative – SCD therapies.

The TOPMed (Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine) program is a key mechanism to support SCD-related genetic research. For example, Dr. Hoots said, TOPMed is being used in support of whole-genome sequencing in a longitudinal cohort of patients with SCD who receive transfusion care at four large centers in Brazil.

These renewed efforts, set against the backdrop of paradigm-shifting genetic therapies, represent new promise for a generation of individuals with SCD, Dr. Hoots said. “It takes all of us to address the SCD challenge.”

ASH initiatives

NHLBI isn’t alone in making SCD a priority. The American Society of Hematology also is putting a spotlight on the condition.

The ASH multifaceted sickle cell disease (SCD) initiative addresses the disease burden both within the United States and globally, said LaTasha Lee, PhD, senior manager of sickle cell disease policy and programs for ASH.

Speaking at the 12th annual symposium of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research, Dr. Lee said that four prongs make up the initiative: disease research, attention to global issues, a renewed focus on access to care in the United States, and work to develop ASH’s new SCD guidelines.

New guidelines on the management of acute and chronic complications of SCD are in the works, with an anticipated 2019 date for publication of five separate guidelines. Topics covered in the guidelines will include pain, cerebrovascular disease, cardiopulmonary and kidney disease, transfusion support, and stem cell transplantation.

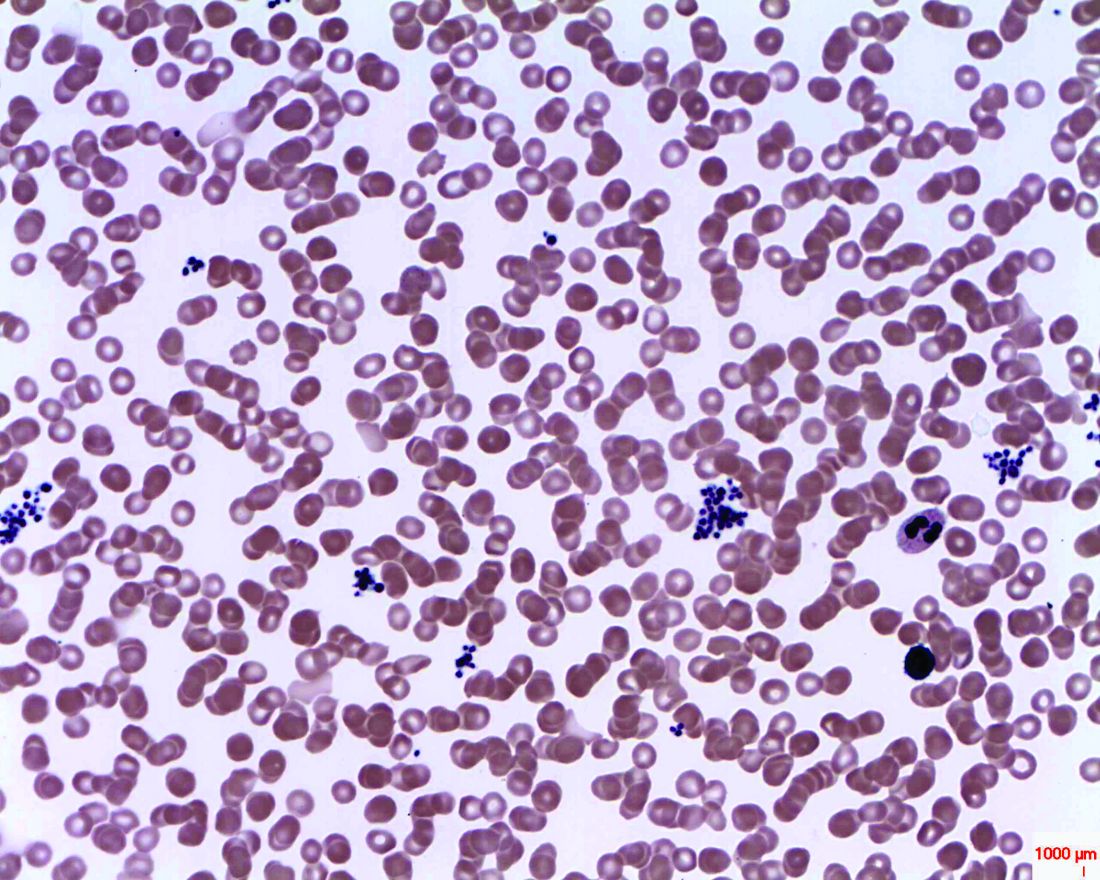

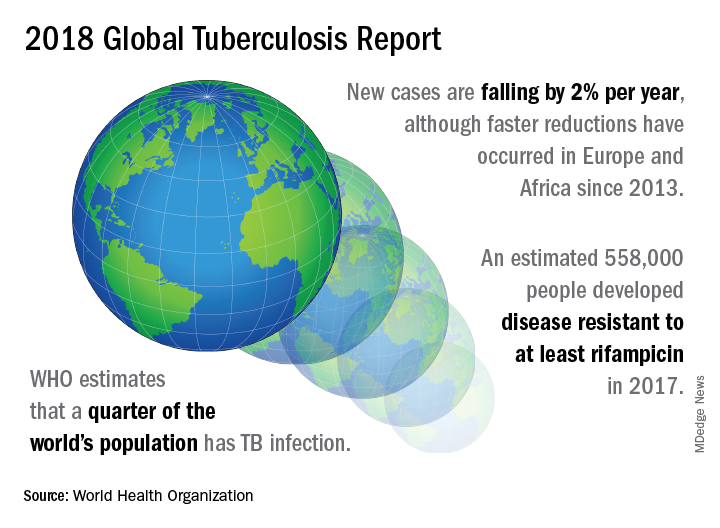

UN aims to eradicate TB by 2030

A concerted a lethal disease affecting one-quarter of the world’s population by the year 2030.

On September 26 the United Nations General Assembly will convene a high-level meeting of global stakeholders to solidify the eradication plan, addressing the global crisis of tuberculosis (TB), the world’s most deadly infectious disease.

“We must seize the moment,” said Tereza Kasaeva, MD, director of the World Health Organization’s global TB program, speaking at a telebriefing and press conference accompanying the release of the World Health Organization’s annual global tuberculosis report. “It’s unacceptable in the 21st century that millions lose their lives to this preventable and curable disease.”

TB caused 1.6 million deaths globally in 2017, and the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that of the 10 million new cases of TB last year, 558,000 are multi-drug resistant (MDR) infections.

Though death rates and new cases are falling globally each year, significantly more resources are needed to boost access to preventive treatment for latent TB infection; “Most people needing it are not yet accessing care,” according to the press briefing accompanying the report.

A review and commentary on TB incubation and latency published in BMJ (2018;362:k2738 doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2738; e-pub 23 Aug 2018) has called into question the focus preventive treatment of latent cases at the expense of reaching those most likely to die from TB (e.g., HIV patients, children of individuals living with active TB). The authors state that “latent” TB is identified by indirect evidence of present or past infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis as inferred by a detectable adaptive immune response to M tuberculosis antigens. Active TB infection is overwhelmingly the result of a primary infection and almost always occurs within two years.

In order to meet the ambitious goal of TB eradication by the year 2030, treatment coverage must rise to 90% globally from the current 64%, according to the report.

Progress in southern Africa and in the Russian Federation, where efforts have led to a 30% reduction in TB mortality and a decrease in incidence of 5% per year, show that steep reductions in TB are possible when resources are brought to bear on the problem, said Dr. Kasaeva. “We should acknowledge that actions in some countries and regions show that progress can accelerate,” she said. Still, she noted, “Four thousand lives per day are lost to TB. Tuberculosis is the leading killer of people living with HIV, and the major cause of deaths related to antimicrobial resistance” at a global level.

Two thirds of all TB cases occur in eight countries, with India, China, and Indonesia leading this group. About half of the cases of MDR TB occur in India, China, and Russia, said Dr. Kasaeva, and globally only one in four individuals with MDR TB who need access to treatment have received it. “We need to urgently tackle the multidrug resistant TB public health crisis,” she said.

Major impediments to successful public health efforts against TB are underdiagnosis and underreporting: It is estimated that 3.6 million of 2017’s 10 million new cases were not officially recorded or reported. Countries where these problems are most serious include India, Indonesia, and Nigeria. Fewer than half of the children with TB are reported globally, according to the report.

People living with HIV/AIDS who are also infected with TB number nearly 1,000,000, but only about half of these were officially reported in 2017.

In terms of prevention priorities, WHO has recommended targeting treatment of latent TB in two groups: People living with HIV/AIDS, and children under the age of 5 years who live in households with TB-infected individuals.

“To enable these actions,” said Dr. Kasaeva, “we need strengthened commitments not just for TB care, but for overall health services. So the aim for universal coverage is real.” Underreporting is particularly prevalent in lower income countries with large unregulated private sectors, she said, though India and Indonesia have taken corrective steps to increase reporting.

A meaningful global initiative will not come cheap: The current annual shortfall in funding for TB prevention, diagnosis, and treatment is about $3.5 billion. By the year 2022, the gap between funding and what’s needed to stay on track for the 2030 target will be over $6 billion, said Dr. Kasaeva.

The best use of increased resources for TB eradication will be in locally focused efforts, said Irene Koek, MD, the United States Agency for International Development’s deputy administrator for global health. “It is likely that each region requires a tailored response.” Further, “to improve quality of care we need to ensure that services are patient centered,” she said at the press conference.

To that end, Dr. Koek expects that at the upcoming high-level meeting, the United Nations member states will be called on to develop an open framework, with clear accountability for monitoring and reviewing progress. The road forward should “celebrate accomplishments and acknowledge shortcomings,” she said. Some recent studies have shown that treatment success rates above 80% for patients with MDR TB can be achieved.

“Lessons learned from these experiences should be documented and shared in order to replicate success globally,” said Dr. Koek.

The United States, said Dr. Koek, is the leading global investor in TB research and treatment. “We welcome increased partnerships, especially with countries with the highest burden, to end global suffering from this disease.”

Eric Goosby, MD, the United Nations special envoy on TB, used his speaking time to lend some perspective to the social framework around TB’s longtime lethality.

There are aspects of TB infection that differentiate it from HIV/AIDS, said Dr. Goosby, who has spent most of his clinical and public health career on HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention. In contrast to an infection that at present requires a lifetime of treatment, TB can ordinarily be treated in 6 months, making it an unpleasant episode that an individual may be eager to move past. Additionally, the fact that TB has had a “hold on the world since the time of the ancient Egyptians” may paradoxically have served to lessen urgency in research and treatment efforts, he noted.

Dr. Goosby also spoke of the stigma surrounding TB, whose sufferers are likely to be facing dire poverty, malnutrition, and other infectious disease burdens. Civil society concerned with TB, he said, has spoken up “for those without a voice, for those who have difficulty advocating for themselves.”

Dr. Kasaeva agreed, noting that TB “affects the poorest of the poor, which makes it extraordinarily difficult for activism to come from that population.”

However, others have spoken for those affected, said Dr. Goosby. “The TB civil society has put its heart and soul this last year into gathering political will from leaders around the world…. It’s not a passive effort; it involves a lot of work.” During the past year of concerted effort, he said, “All of us have known the difficulty of pushing a political leader up that learning curve.”

As the upcoming high-level meeting approaches, those who have been working on the effort can feel the momentum, said Dr. Goosby. Still, he noted, “While there’s a significant step forward, this is not the time for a victory dance. This is really the time for a reflection...Do we understand the burden in our respective countries, and has the response been adequate?”

The goal for the meeting is to have leaders “step up to commit, not for one day, or for one meeting, but for the duration of the effort,” said Dr. Goosby. “We must make sure that the words that we hear next week from our leaders translate into action...Next week the world will say, ‘No more. No longer. No one is immune to TB. Tuberculosis is preventable; tuberculosis is treatable; tuberculosis is curable.’”