User login

Doug Brunk is a San Diego-based award-winning reporter who began covering health care in 1991. Before joining the company, he wrote for the health sciences division of Columbia University and was an associate editor at Contemporary Long Term Care magazine when it won a Jesse H. Neal Award. His work has been syndicated by the Los Angeles Times and he is the author of two books related to the University of Kentucky Wildcats men's basketball program. Doug has a master’s degree in magazine journalism from the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. Follow him on Twitter @dougbrunk.

CDC: Five confirmed 2019-nCoV cases in the U.S.

Five cases of the new infectious coronavirus, 2019-nCoV, have been confirmed in the United States, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during a Jan. 27 press briefing.

A total of 110 individuals are under investigation in 26 states, she said. While five cases have been confirmed positive for the virus, 32 cases were confirmed negative. There have been no new cases overnight.

Last week, CDC scientists developed a real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test that can diagnose the virus in respiratory and serum samples from clinical specimens. On Jan. 24, the protocol for this test was publicly posted. “This is essentially a blueprint to make the test,” Dr. Messonnier explained. “Currently, we are refining the use of the test so that it can provide optimal guidance to states and labs on how to use it. We are working on a plan so that priority states get these test kits as soon as possible. In the coming weeks, we will share these tests with domestic and international partners so they can test for this virus themselves.”

The CDC uploaded the entire genome of the virus from the first two cases in the United States to GenBank. It was similar to the one that China had previously posted. “Right now, based on CDC’s analysis of the available data, it doesn’t look like the virus has mutated,” she said. “And we are growing the virus in cell culture, which is necessary for further studies, including the additional genetic characterization.”

As of today, 16 international locations, including the United States, have identified cases of the virus. CDC officials are continuing to screen passengers from Wuhan, China, at five designated airports. “This serves two purposes: first to detect the illness and rapidly respond to [affected] people entering the country,” Dr. Messonnier said. “The second purpose is to educate travelers about the symptoms of this new virus, and what to do if they develop symptoms. I expect that in the coming days, our travel recommendations will change. Risk depends on exposure. Right now, we have an handful of new patients with this new virus here in the U.S. However, at this time in the U.S., this virus is not spreading in the community. For that reason, we believe that the immediate health risk of the new virus to the general American public is low.”

The CDC is asking its clinical lab partners to send virus samples to the CDC to ensure that results are analyzed as accurately as possible.

Five cases of the new infectious coronavirus, 2019-nCoV, have been confirmed in the United States, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during a Jan. 27 press briefing.

A total of 110 individuals are under investigation in 26 states, she said. While five cases have been confirmed positive for the virus, 32 cases were confirmed negative. There have been no new cases overnight.

Last week, CDC scientists developed a real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test that can diagnose the virus in respiratory and serum samples from clinical specimens. On Jan. 24, the protocol for this test was publicly posted. “This is essentially a blueprint to make the test,” Dr. Messonnier explained. “Currently, we are refining the use of the test so that it can provide optimal guidance to states and labs on how to use it. We are working on a plan so that priority states get these test kits as soon as possible. In the coming weeks, we will share these tests with domestic and international partners so they can test for this virus themselves.”

The CDC uploaded the entire genome of the virus from the first two cases in the United States to GenBank. It was similar to the one that China had previously posted. “Right now, based on CDC’s analysis of the available data, it doesn’t look like the virus has mutated,” she said. “And we are growing the virus in cell culture, which is necessary for further studies, including the additional genetic characterization.”

As of today, 16 international locations, including the United States, have identified cases of the virus. CDC officials are continuing to screen passengers from Wuhan, China, at five designated airports. “This serves two purposes: first to detect the illness and rapidly respond to [affected] people entering the country,” Dr. Messonnier said. “The second purpose is to educate travelers about the symptoms of this new virus, and what to do if they develop symptoms. I expect that in the coming days, our travel recommendations will change. Risk depends on exposure. Right now, we have an handful of new patients with this new virus here in the U.S. However, at this time in the U.S., this virus is not spreading in the community. For that reason, we believe that the immediate health risk of the new virus to the general American public is low.”

The CDC is asking its clinical lab partners to send virus samples to the CDC to ensure that results are analyzed as accurately as possible.

Five cases of the new infectious coronavirus, 2019-nCoV, have been confirmed in the United States, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said during a Jan. 27 press briefing.

A total of 110 individuals are under investigation in 26 states, she said. While five cases have been confirmed positive for the virus, 32 cases were confirmed negative. There have been no new cases overnight.

Last week, CDC scientists developed a real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test that can diagnose the virus in respiratory and serum samples from clinical specimens. On Jan. 24, the protocol for this test was publicly posted. “This is essentially a blueprint to make the test,” Dr. Messonnier explained. “Currently, we are refining the use of the test so that it can provide optimal guidance to states and labs on how to use it. We are working on a plan so that priority states get these test kits as soon as possible. In the coming weeks, we will share these tests with domestic and international partners so they can test for this virus themselves.”

The CDC uploaded the entire genome of the virus from the first two cases in the United States to GenBank. It was similar to the one that China had previously posted. “Right now, based on CDC’s analysis of the available data, it doesn’t look like the virus has mutated,” she said. “And we are growing the virus in cell culture, which is necessary for further studies, including the additional genetic characterization.”

As of today, 16 international locations, including the United States, have identified cases of the virus. CDC officials are continuing to screen passengers from Wuhan, China, at five designated airports. “This serves two purposes: first to detect the illness and rapidly respond to [affected] people entering the country,” Dr. Messonnier said. “The second purpose is to educate travelers about the symptoms of this new virus, and what to do if they develop symptoms. I expect that in the coming days, our travel recommendations will change. Risk depends on exposure. Right now, we have an handful of new patients with this new virus here in the U.S. However, at this time in the U.S., this virus is not spreading in the community. For that reason, we believe that the immediate health risk of the new virus to the general American public is low.”

The CDC is asking its clinical lab partners to send virus samples to the CDC to ensure that results are analyzed as accurately as possible.

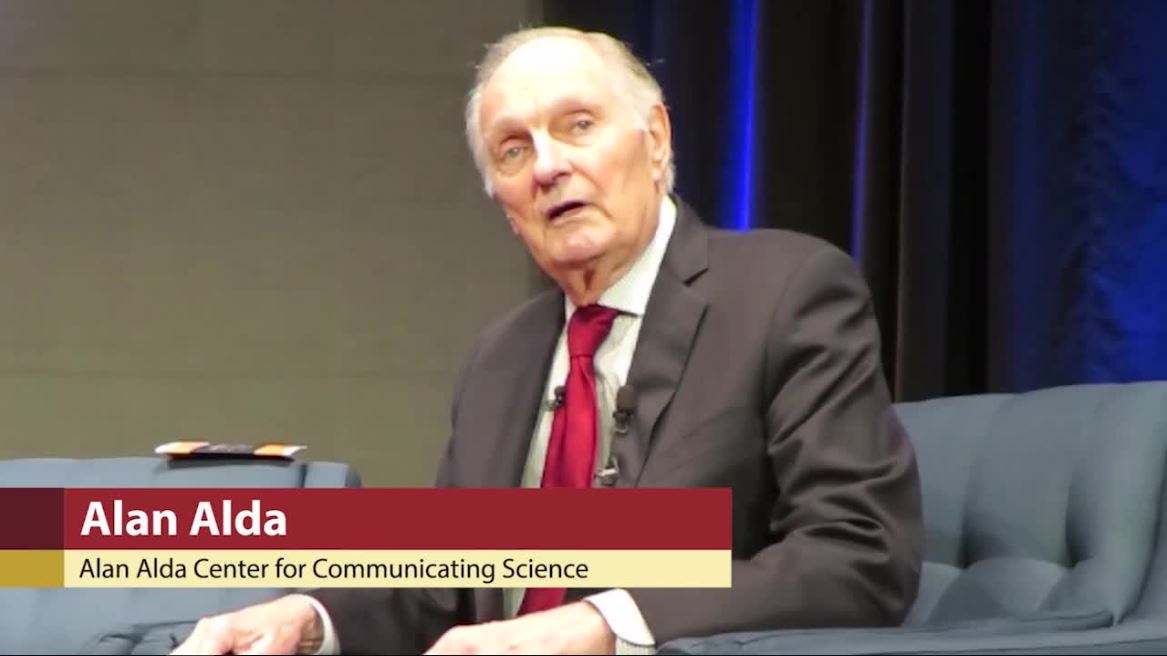

Actor Alan Alda discusses using empathy as an antidote to burnout

LA JOLLA, CALIF. – Physicians and other medical professionals who routinely foster empathic connections with patients may be helping themselves steer clear of burnout.

That’s what iconic actor Alan Alda suggested during a media briefing at Scripps Research on Jan. 16, 2020.

“There’s a tremendous pressure on doctors now to have shorter and shorter visits with their patients,” said the 83-year-old Mr. Alda, who received the Public Welfare Medal from the National Academy of Sciences in 2016 for his work as a champion of science. “A lot of that time is taken up with recording on a computer, which can only put pressure on the doctor.”

Practicing empathy, he continued, “kind of opens people up to one another, which inspirits them.”

Mr. Alda appeared on the research campus to announce that Scripps Research will serve as the new West Coast home of Alda Communication Training, which will work in tandem with the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook (N.Y.) University, a nonprofit organization that Mr. Alda helped found in 2009.

“This will be a center where people can come to get training in effective communication,” Mr. Alda, who is the winner of six Emmy Awards and six Golden Globe awards, told an audience of scientists and medical professionals prior to the media briefing.

“It’s an experiential kind of training,” he explained. “We don’t give tips. We don’t give lectures. We put you through exercises that are fun and actually make you laugh, but turn you into a better communicator, so you’re better able to connect to the people you’re talking to.”

During a question-and-answer session, Mr. Alda opened up about his Parkinson’s disease, which he said was diagnosed about 5 years ago. In 2018, he decided to speak publicly about his diagnosis for the first time.

“The reason was that I wanted to communicate to people who had recently been diagnosed not to believe or give into the stereotype that, when you get a diagnosis, your life is over,” said Mr. Alda, who played army surgeon “Hawkeye” Pierce on the TV series “M*A*S*H.”

“Under the burden of that belief, some people won’t tell their family or workplace colleagues,” he said. “There are exercises you can do and medications you can take to prolong the time it takes before Parkinson’s gets much more serious. It’s not to diminish the fact that it can get really bad; but to think that your life is over as soon as you get a diagnosis is wrong.”

The first 2-day training session at Scripps Research will be held in June 2020. Additional sessions are scheduled to take place in October and December. Registration is available at aldacommunicationtraining.com/workshops.

LA JOLLA, CALIF. – Physicians and other medical professionals who routinely foster empathic connections with patients may be helping themselves steer clear of burnout.

That’s what iconic actor Alan Alda suggested during a media briefing at Scripps Research on Jan. 16, 2020.

“There’s a tremendous pressure on doctors now to have shorter and shorter visits with their patients,” said the 83-year-old Mr. Alda, who received the Public Welfare Medal from the National Academy of Sciences in 2016 for his work as a champion of science. “A lot of that time is taken up with recording on a computer, which can only put pressure on the doctor.”

Practicing empathy, he continued, “kind of opens people up to one another, which inspirits them.”

Mr. Alda appeared on the research campus to announce that Scripps Research will serve as the new West Coast home of Alda Communication Training, which will work in tandem with the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook (N.Y.) University, a nonprofit organization that Mr. Alda helped found in 2009.

“This will be a center where people can come to get training in effective communication,” Mr. Alda, who is the winner of six Emmy Awards and six Golden Globe awards, told an audience of scientists and medical professionals prior to the media briefing.

“It’s an experiential kind of training,” he explained. “We don’t give tips. We don’t give lectures. We put you through exercises that are fun and actually make you laugh, but turn you into a better communicator, so you’re better able to connect to the people you’re talking to.”

During a question-and-answer session, Mr. Alda opened up about his Parkinson’s disease, which he said was diagnosed about 5 years ago. In 2018, he decided to speak publicly about his diagnosis for the first time.

“The reason was that I wanted to communicate to people who had recently been diagnosed not to believe or give into the stereotype that, when you get a diagnosis, your life is over,” said Mr. Alda, who played army surgeon “Hawkeye” Pierce on the TV series “M*A*S*H.”

“Under the burden of that belief, some people won’t tell their family or workplace colleagues,” he said. “There are exercises you can do and medications you can take to prolong the time it takes before Parkinson’s gets much more serious. It’s not to diminish the fact that it can get really bad; but to think that your life is over as soon as you get a diagnosis is wrong.”

The first 2-day training session at Scripps Research will be held in June 2020. Additional sessions are scheduled to take place in October and December. Registration is available at aldacommunicationtraining.com/workshops.

LA JOLLA, CALIF. – Physicians and other medical professionals who routinely foster empathic connections with patients may be helping themselves steer clear of burnout.

That’s what iconic actor Alan Alda suggested during a media briefing at Scripps Research on Jan. 16, 2020.

“There’s a tremendous pressure on doctors now to have shorter and shorter visits with their patients,” said the 83-year-old Mr. Alda, who received the Public Welfare Medal from the National Academy of Sciences in 2016 for his work as a champion of science. “A lot of that time is taken up with recording on a computer, which can only put pressure on the doctor.”

Practicing empathy, he continued, “kind of opens people up to one another, which inspirits them.”

Mr. Alda appeared on the research campus to announce that Scripps Research will serve as the new West Coast home of Alda Communication Training, which will work in tandem with the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook (N.Y.) University, a nonprofit organization that Mr. Alda helped found in 2009.

“This will be a center where people can come to get training in effective communication,” Mr. Alda, who is the winner of six Emmy Awards and six Golden Globe awards, told an audience of scientists and medical professionals prior to the media briefing.

“It’s an experiential kind of training,” he explained. “We don’t give tips. We don’t give lectures. We put you through exercises that are fun and actually make you laugh, but turn you into a better communicator, so you’re better able to connect to the people you’re talking to.”

During a question-and-answer session, Mr. Alda opened up about his Parkinson’s disease, which he said was diagnosed about 5 years ago. In 2018, he decided to speak publicly about his diagnosis for the first time.

“The reason was that I wanted to communicate to people who had recently been diagnosed not to believe or give into the stereotype that, when you get a diagnosis, your life is over,” said Mr. Alda, who played army surgeon “Hawkeye” Pierce on the TV series “M*A*S*H.”

“Under the burden of that belief, some people won’t tell their family or workplace colleagues,” he said. “There are exercises you can do and medications you can take to prolong the time it takes before Parkinson’s gets much more serious. It’s not to diminish the fact that it can get really bad; but to think that your life is over as soon as you get a diagnosis is wrong.”

The first 2-day training session at Scripps Research will be held in June 2020. Additional sessions are scheduled to take place in October and December. Registration is available at aldacommunicationtraining.com/workshops.

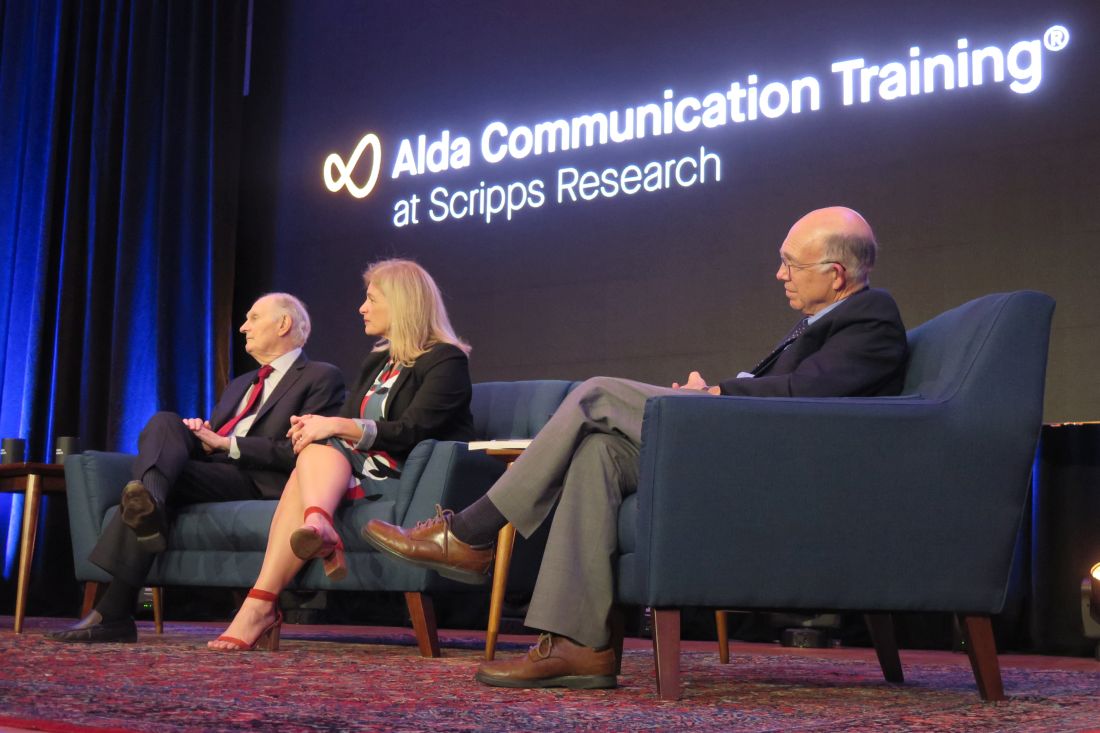

Alan Alda, Scripps Research join forces to improve science communication

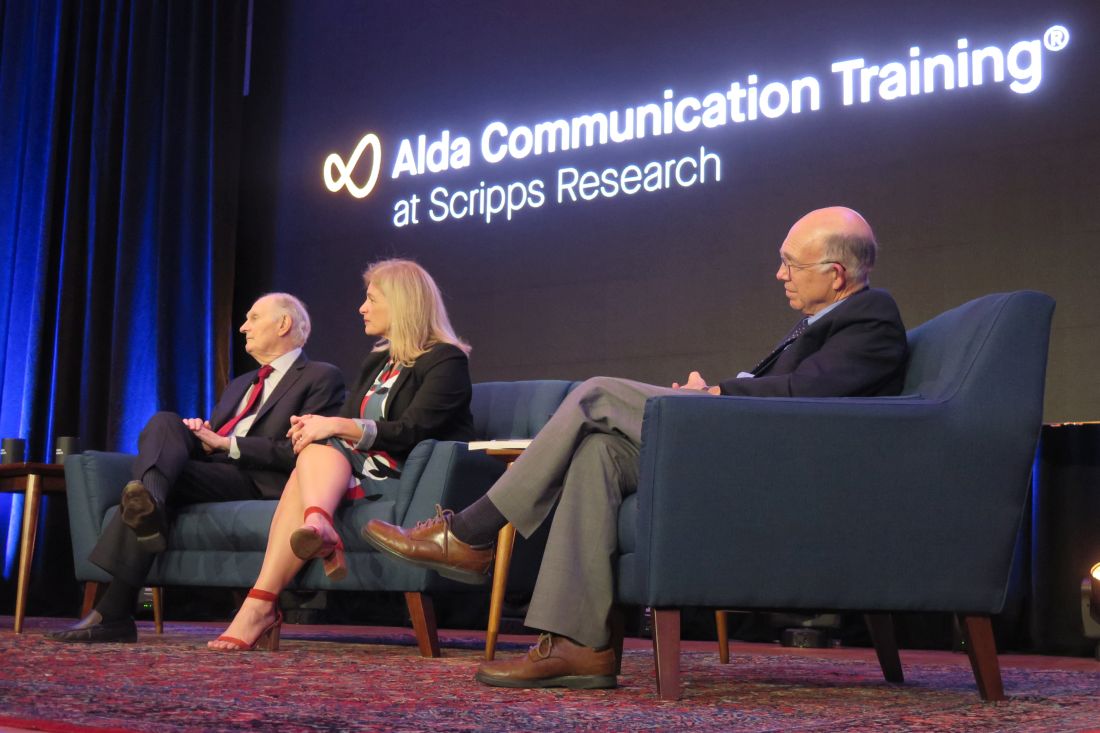

LA JOLLA, CALIF. – The first time that legendary actor Alan Alda conducted an interview for “Scientific American Frontiers” on PBS, an award-winning series that ran for more than a decade, he remembers learning a lesson in humility.

“I wasn’t as smart as I thought I was,” he told a crowd of largely scientists and medical professionals who gathered in a small auditorium on the campus of Scripps Research on Jan. 16, 2020. “I didn’t realize the value of ignorance. I have a natural supply of it. I began to use it and say [to interviewees]: ‘I don’t understand what that means.’ Sometimes it would be basic physics and they’d look at me like I was a school child. I am a very curious person. What I discovered was, I was bringing out their humanity by my own curiosity, by the way I related to them, which I developed through studying improvisation as an actor, and relating as an actor to other actors.”

Mr. Alda, 83, appeared on the research campus to announce that Scripps Research is the new West Coast home of Alda Communication Training, which will work in tandem with the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, a nonprofit organization that Mr. Alda helped found in 2009.

Immersive training experience

“This will be a center where people can come to get training in effective communication,” said Mr. Alda, who is the winner of six Emmy Awards and six Golden Globe awards. “It’s an experiential kind of training. We don’t give tips. We don’t give lectures. We put you through exercises that are fun and actually make you laugh, but turn you into a better communicator, so you’re better able to connect to the people you’re talking to.”

To date, the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science has trained more than 15,000 scientific leaders in the United States and other countries. The location at Scripps Research makes it more convenient for West Coast–based researchers and industry leaders to participate. “One of the things we wished, for years, we had was a place where we could train scientists and researchers and medical professionals all up and down the West Coast,” he said.

Recently, more than 30 of Scripps Research scientists participated in Mr. Alda’s training program, an immersive and engaging experience that helps participants learn to empathize with an audience and present their work in a way that connects with different stakeholders. The skills and strategies can help participants relate to prospective investors and philanthropists, government officials, members of the media, peers across scientific disciplines, and the general public.

Earlier in the day that he spoke on the Scripps campus, Mr. Alda encountered some of the Scripps researchers who had participated in that training. “One group of scientists came in and we shook hands,” he said. “They introduced themselves and said: ‘We’re working on infectious diseases.’ I said: ‘Oh my God; I just shook hands with you!’ No matter what I asked them, they had a clear way to express what they did. Then I realized they had studied with Alda Communications.”

Why communication matters

During the early stages of forming what became the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science, one Nobel Prize winner at a major university dismissed the importance of improving the communication skills of young scientists. “He said to me: ‘We don’t have time for that; we have too much science to teach,’ ” said Mr. Alda, who played Army surgeon “Hawkeye” Pierce on the TV series “M*A*S*H”. “But communication is the essence of science. How can you do science unless you communicate with other scientists? There’s a stereotype that scientists are not as good at communicating as other people are. It’s true that they often speak a language that a lot of us don’t understand, but we all speak a language that is hard for other people to understand if we know something in great depth. We want to tell all the details; we want to speak in our special language because it makes us feel good.”

He underscored the importance of scientists being able to effectively communicate with the general public, “because the public needs to understand how important science is to their lives. It matters because at a place like [Scripps Research], understanding how nature works is put to work to keep our health secure.” Members of the public, he continued, “are busy living their lives; they’re busy working and bringing up their children. They haven’t spent 20, 30, 40 years devoted to a single aspect of nature the way scientists have. We can’t expect them to know as much as professional scientists, so we have to help them understand it. I hope we find ways to increase curiosity. I don’t know how to do that. I wish somebody would do a study on it, how you can take someone with a modicum of curiosity and help them enlarge it so it gives them the pleasure of discovering things about nature or understanding things about nature that other people don’t discover. Curiosity is the key to staying alive. That would bring us to a point of more people understanding science.”

Cultivating a sense of responsibility is another key to effective communication. “It’s the job of the person leading the discussion to make clear to the person listening,” Mr. Alda said. “You get the impression that ‘this person is my responsibility. I have to take care of them, so they understand what’s going on.’ ”

Parkinson’s disease diagnosis

During a question-and-answer session, Mr. Alda opened up about his Parkinson’s disease, which he said was diagnosed about 5 years ago. In 2018, he decided to speak publicly about his diagnosis for the first time.

“The reason was that I wanted to communicate to people who had recently been diagnosed not to believe or give into the stereotype that when you get a diagnosis, your life is over,” said Mr. Alda, who received the Public Welfare Medal from the National Academy of Sciences in 2016. “Under the burden of that belief, some people won’t tell their family or workplace colleagues. There are exercises you can do and medications you can take to prolong the time it takes before Parkinson’s gets much more serious. It’s not to diminish the fact that it can get really bad; but to think that your life is over as soon as you get a diagnosis is wrong.”

He added: “I’ve gone 5 years and I’m almost busier than I’ve ever been. I’m getting a lot accomplished and I look forward to I don’t know how many years. As long as I have them, I’m going to be grateful. It’s amazing how great it feels not to keep the diagnosis a secret.”

The first 2-day training session at Scripps Research will be held in June 2020. Additional sessions are scheduled to take place in October and December. Registration is available at aldacommunicationtraining.com/workshops.

LA JOLLA, CALIF. – The first time that legendary actor Alan Alda conducted an interview for “Scientific American Frontiers” on PBS, an award-winning series that ran for more than a decade, he remembers learning a lesson in humility.

“I wasn’t as smart as I thought I was,” he told a crowd of largely scientists and medical professionals who gathered in a small auditorium on the campus of Scripps Research on Jan. 16, 2020. “I didn’t realize the value of ignorance. I have a natural supply of it. I began to use it and say [to interviewees]: ‘I don’t understand what that means.’ Sometimes it would be basic physics and they’d look at me like I was a school child. I am a very curious person. What I discovered was, I was bringing out their humanity by my own curiosity, by the way I related to them, which I developed through studying improvisation as an actor, and relating as an actor to other actors.”

Mr. Alda, 83, appeared on the research campus to announce that Scripps Research is the new West Coast home of Alda Communication Training, which will work in tandem with the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, a nonprofit organization that Mr. Alda helped found in 2009.

Immersive training experience

“This will be a center where people can come to get training in effective communication,” said Mr. Alda, who is the winner of six Emmy Awards and six Golden Globe awards. “It’s an experiential kind of training. We don’t give tips. We don’t give lectures. We put you through exercises that are fun and actually make you laugh, but turn you into a better communicator, so you’re better able to connect to the people you’re talking to.”

To date, the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science has trained more than 15,000 scientific leaders in the United States and other countries. The location at Scripps Research makes it more convenient for West Coast–based researchers and industry leaders to participate. “One of the things we wished, for years, we had was a place where we could train scientists and researchers and medical professionals all up and down the West Coast,” he said.

Recently, more than 30 of Scripps Research scientists participated in Mr. Alda’s training program, an immersive and engaging experience that helps participants learn to empathize with an audience and present their work in a way that connects with different stakeholders. The skills and strategies can help participants relate to prospective investors and philanthropists, government officials, members of the media, peers across scientific disciplines, and the general public.

Earlier in the day that he spoke on the Scripps campus, Mr. Alda encountered some of the Scripps researchers who had participated in that training. “One group of scientists came in and we shook hands,” he said. “They introduced themselves and said: ‘We’re working on infectious diseases.’ I said: ‘Oh my God; I just shook hands with you!’ No matter what I asked them, they had a clear way to express what they did. Then I realized they had studied with Alda Communications.”

Why communication matters

During the early stages of forming what became the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science, one Nobel Prize winner at a major university dismissed the importance of improving the communication skills of young scientists. “He said to me: ‘We don’t have time for that; we have too much science to teach,’ ” said Mr. Alda, who played Army surgeon “Hawkeye” Pierce on the TV series “M*A*S*H”. “But communication is the essence of science. How can you do science unless you communicate with other scientists? There’s a stereotype that scientists are not as good at communicating as other people are. It’s true that they often speak a language that a lot of us don’t understand, but we all speak a language that is hard for other people to understand if we know something in great depth. We want to tell all the details; we want to speak in our special language because it makes us feel good.”

He underscored the importance of scientists being able to effectively communicate with the general public, “because the public needs to understand how important science is to their lives. It matters because at a place like [Scripps Research], understanding how nature works is put to work to keep our health secure.” Members of the public, he continued, “are busy living their lives; they’re busy working and bringing up their children. They haven’t spent 20, 30, 40 years devoted to a single aspect of nature the way scientists have. We can’t expect them to know as much as professional scientists, so we have to help them understand it. I hope we find ways to increase curiosity. I don’t know how to do that. I wish somebody would do a study on it, how you can take someone with a modicum of curiosity and help them enlarge it so it gives them the pleasure of discovering things about nature or understanding things about nature that other people don’t discover. Curiosity is the key to staying alive. That would bring us to a point of more people understanding science.”

Cultivating a sense of responsibility is another key to effective communication. “It’s the job of the person leading the discussion to make clear to the person listening,” Mr. Alda said. “You get the impression that ‘this person is my responsibility. I have to take care of them, so they understand what’s going on.’ ”

Parkinson’s disease diagnosis

During a question-and-answer session, Mr. Alda opened up about his Parkinson’s disease, which he said was diagnosed about 5 years ago. In 2018, he decided to speak publicly about his diagnosis for the first time.

“The reason was that I wanted to communicate to people who had recently been diagnosed not to believe or give into the stereotype that when you get a diagnosis, your life is over,” said Mr. Alda, who received the Public Welfare Medal from the National Academy of Sciences in 2016. “Under the burden of that belief, some people won’t tell their family or workplace colleagues. There are exercises you can do and medications you can take to prolong the time it takes before Parkinson’s gets much more serious. It’s not to diminish the fact that it can get really bad; but to think that your life is over as soon as you get a diagnosis is wrong.”

He added: “I’ve gone 5 years and I’m almost busier than I’ve ever been. I’m getting a lot accomplished and I look forward to I don’t know how many years. As long as I have them, I’m going to be grateful. It’s amazing how great it feels not to keep the diagnosis a secret.”

The first 2-day training session at Scripps Research will be held in June 2020. Additional sessions are scheduled to take place in October and December. Registration is available at aldacommunicationtraining.com/workshops.

LA JOLLA, CALIF. – The first time that legendary actor Alan Alda conducted an interview for “Scientific American Frontiers” on PBS, an award-winning series that ran for more than a decade, he remembers learning a lesson in humility.

“I wasn’t as smart as I thought I was,” he told a crowd of largely scientists and medical professionals who gathered in a small auditorium on the campus of Scripps Research on Jan. 16, 2020. “I didn’t realize the value of ignorance. I have a natural supply of it. I began to use it and say [to interviewees]: ‘I don’t understand what that means.’ Sometimes it would be basic physics and they’d look at me like I was a school child. I am a very curious person. What I discovered was, I was bringing out their humanity by my own curiosity, by the way I related to them, which I developed through studying improvisation as an actor, and relating as an actor to other actors.”

Mr. Alda, 83, appeared on the research campus to announce that Scripps Research is the new West Coast home of Alda Communication Training, which will work in tandem with the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, a nonprofit organization that Mr. Alda helped found in 2009.

Immersive training experience

“This will be a center where people can come to get training in effective communication,” said Mr. Alda, who is the winner of six Emmy Awards and six Golden Globe awards. “It’s an experiential kind of training. We don’t give tips. We don’t give lectures. We put you through exercises that are fun and actually make you laugh, but turn you into a better communicator, so you’re better able to connect to the people you’re talking to.”

To date, the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science has trained more than 15,000 scientific leaders in the United States and other countries. The location at Scripps Research makes it more convenient for West Coast–based researchers and industry leaders to participate. “One of the things we wished, for years, we had was a place where we could train scientists and researchers and medical professionals all up and down the West Coast,” he said.

Recently, more than 30 of Scripps Research scientists participated in Mr. Alda’s training program, an immersive and engaging experience that helps participants learn to empathize with an audience and present their work in a way that connects with different stakeholders. The skills and strategies can help participants relate to prospective investors and philanthropists, government officials, members of the media, peers across scientific disciplines, and the general public.

Earlier in the day that he spoke on the Scripps campus, Mr. Alda encountered some of the Scripps researchers who had participated in that training. “One group of scientists came in and we shook hands,” he said. “They introduced themselves and said: ‘We’re working on infectious diseases.’ I said: ‘Oh my God; I just shook hands with you!’ No matter what I asked them, they had a clear way to express what they did. Then I realized they had studied with Alda Communications.”

Why communication matters

During the early stages of forming what became the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science, one Nobel Prize winner at a major university dismissed the importance of improving the communication skills of young scientists. “He said to me: ‘We don’t have time for that; we have too much science to teach,’ ” said Mr. Alda, who played Army surgeon “Hawkeye” Pierce on the TV series “M*A*S*H”. “But communication is the essence of science. How can you do science unless you communicate with other scientists? There’s a stereotype that scientists are not as good at communicating as other people are. It’s true that they often speak a language that a lot of us don’t understand, but we all speak a language that is hard for other people to understand if we know something in great depth. We want to tell all the details; we want to speak in our special language because it makes us feel good.”

He underscored the importance of scientists being able to effectively communicate with the general public, “because the public needs to understand how important science is to their lives. It matters because at a place like [Scripps Research], understanding how nature works is put to work to keep our health secure.” Members of the public, he continued, “are busy living their lives; they’re busy working and bringing up their children. They haven’t spent 20, 30, 40 years devoted to a single aspect of nature the way scientists have. We can’t expect them to know as much as professional scientists, so we have to help them understand it. I hope we find ways to increase curiosity. I don’t know how to do that. I wish somebody would do a study on it, how you can take someone with a modicum of curiosity and help them enlarge it so it gives them the pleasure of discovering things about nature or understanding things about nature that other people don’t discover. Curiosity is the key to staying alive. That would bring us to a point of more people understanding science.”

Cultivating a sense of responsibility is another key to effective communication. “It’s the job of the person leading the discussion to make clear to the person listening,” Mr. Alda said. “You get the impression that ‘this person is my responsibility. I have to take care of them, so they understand what’s going on.’ ”

Parkinson’s disease diagnosis

During a question-and-answer session, Mr. Alda opened up about his Parkinson’s disease, which he said was diagnosed about 5 years ago. In 2018, he decided to speak publicly about his diagnosis for the first time.

“The reason was that I wanted to communicate to people who had recently been diagnosed not to believe or give into the stereotype that when you get a diagnosis, your life is over,” said Mr. Alda, who received the Public Welfare Medal from the National Academy of Sciences in 2016. “Under the burden of that belief, some people won’t tell their family or workplace colleagues. There are exercises you can do and medications you can take to prolong the time it takes before Parkinson’s gets much more serious. It’s not to diminish the fact that it can get really bad; but to think that your life is over as soon as you get a diagnosis is wrong.”

He added: “I’ve gone 5 years and I’m almost busier than I’ve ever been. I’m getting a lot accomplished and I look forward to I don’t know how many years. As long as I have them, I’m going to be grateful. It’s amazing how great it feels not to keep the diagnosis a secret.”

The first 2-day training session at Scripps Research will be held in June 2020. Additional sessions are scheduled to take place in October and December. Registration is available at aldacommunicationtraining.com/workshops.

Sarcopenia associated with increased cardiometabolic risk

LOS ANGELES –

“Loss of lean body mass and function with aging decreases the amount of metabolically active tissue, which can lead to insulin resistance,” Elena Volpi, MD, said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. “Insulin resistance reduces muscle protein anabolism and accelerates sarcopenia, perpetuating a vicious cycle.”

Sarcopenia, the involuntary loss of muscle mass and function that occurs with aging, is an ICD-10 codable condition that can be diagnosed by measuring muscle strength and quality, said Dr. Volpi, director of the Sealy Center on Aging at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. In the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study (Health ABC), researchers followed 2,292 relatively healthy adults aged 70-79 years for an average of 4.9 years (J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med. 2006;61[1]:72-7). The researchers used isokinetic dynamometry to measure knee extension strength, isometric dynamometry to measure grip strength, CT scan to measure thigh muscle area, and dual X-ray absorptiometry to determine leg and arm lean soft-tissue mass. “Those individuals who started with the highest levels of muscle strength had the greatest survival, while those who had the lowest levels of muscle strength died earlier,” said Dr. Volpi, who was not affiliated with the study. “That was true for both men and women.”

More recently, researchers conducted a pooled analysis of nine cohort studies involving 34,485 community-dwelling older individuals who were tested with gait speed and followed for 6-21 years (JAMA. 2011;305[1]:50-8). They found that a higher gait speed was associated with higher survival at 5 and 10 years (P less than .001). “Muscle mass also appears to be associated in part with mortality and survival, although the association is not as strong as measures of strength and gait speed,” Dr. Volpi said.

Data from the 2009 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey of 1,537 participants, aged 65 years and older, found that sarcopenia is independently associated with cardiovascular disease (PLoS One. 2013 Mar 22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060119). Most of the risk factors for cardiovascular disease – such as age, waist circumference, body mass index, fasting plasma glucose, and total cholesterol – showed significant negative correlations with the ratio between appendicular skeletal muscle mass and body weight. Multiple logistic regression analysis demonstrated that sarcopenia was associated with cardiovascular disease, independent of other well-documented risk factors, renal function, and medications (odds ratio, 1.77; P = .025).

In addition, data from the British Regional Heart Study, which followed 4,252 older men for a mean of 11.3 years, found an association of sarcopenia and adiposity with cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality (J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62[2]:253-60). Specifically, all-cause mortality risk was significantly greater in men in the sarcopenic and obese groups (HRs, 1.41 and 1.21, respectively), compared with those in the optimal reference group, with the highest risk in sarcopenic obese individuals (HR, 1.72) after adjustment for lifestyle characteristics.

“Diabetes also accelerates loss of lean body mass in older adults,” added Dr. Volpi. “Data from the Health ABC study showed that individuals who did not have diabetes at the beginning of the 6-year observation period ... lost the least amount of muscle, compared with those who had undiagnosed or already diagnosed diabetes.”

The precise way in which sarcopenia is linked to metabolic disease remains elusive, she continued, but current evidence suggests that sarcopenia is characterized by a reduction in the protein synthetic response to metabolic stimulation by amino acids, exercise, and insulin in skeletal muscle. “This reduction in the anabolic response to protein synthesis is called anabolic resistance of aging, and it is mediated by reduced acute activation of mTORC1 [mTOR complex 1] signaling,” Dr. Volpi said. “There’s another step upstream of the mTORC1, in which the amino acids and insulin have to cross the blood-muscle barrier. Amino acids need to be transported into the muscle actively, like glucose. That is an important unexplored area that may contribute to sarcopenia.”

Dr. Volpi went on to note that endothelial dysfunction underlies muscle anabolic resistance and cardiovascular risk and is likely to be a fundamental cause of both problems. Recent studies have shown that increased levels of physical activity improve endothelial function, enhance insulin sensitivity and anabolic sensitivity to nutrients, and reduce cardiovascular risk.

For example, in a cohort of 45 nonfrail older adults with a mean age of 72 years, Dr. Volpi and colleagues carried out a phase 1, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial to determine if chronic essential amino acid supplementation, aerobic exercise training, or a combination of the two interventions could improve muscle mass and function by stimulating muscle protein synthesis over the course of 24 weeks (J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74[10]:1598-604). “We found that exercise supervised three times per week on a treadmill for 6 months improved physical function in both groups randomized to exercise,” Dr. Volpi said. “Disappointingly, there was no change in total lean mass with any of the interventions. There was a decrease in fat mass with exercise alone, and no change with exercise and amino acids. [Of note is that] the individuals who were randomized to the amino acids plus exercise group had a significant increase in leg strength, whereas the others did not.”

Preliminary findings from ongoing work by Dr. Volpi and colleagues suggest that, in diabetes, muscle protein synthesis and blood flow really “are not different in response to insulin in healthy older adults and diabetic older adults because they don’t change at all. However, we did find alterations in amino acid trafficking in diabetes. We found that older individuals with type 2 diabetes had a reduction of amino acid transport and a higher intracellular amino acid concentration, compared with age-matched, healthier individuals. The intracellular amino acid clearance improved in the healthy, nondiabetic older adults with hyperinsulinemia, whereas it did not change in diabetic older adults. As a result, the net muscle protein balance improved a little in the nondiabetic patients, but did not change in the diabetic patients.”

The researchers are evaluating older patients with type 2 diabetes to see whether there are alterations in vascular reactivity and protein synthesis and whether those can be overcome by resistance-exercise training. “Preliminary results show that flow-mediated dilation can actually increase in an older diabetic patient with resistance exercise training three times a week for 3 months,” she said. “Exercise can improve both endothelial dysfunction and sarcopenia and therefore improve physical function and reduce cardiovascular risk.”

Dr. Volpi reported having no relevant disclosures.

LOS ANGELES –

“Loss of lean body mass and function with aging decreases the amount of metabolically active tissue, which can lead to insulin resistance,” Elena Volpi, MD, said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. “Insulin resistance reduces muscle protein anabolism and accelerates sarcopenia, perpetuating a vicious cycle.”

Sarcopenia, the involuntary loss of muscle mass and function that occurs with aging, is an ICD-10 codable condition that can be diagnosed by measuring muscle strength and quality, said Dr. Volpi, director of the Sealy Center on Aging at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. In the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study (Health ABC), researchers followed 2,292 relatively healthy adults aged 70-79 years for an average of 4.9 years (J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med. 2006;61[1]:72-7). The researchers used isokinetic dynamometry to measure knee extension strength, isometric dynamometry to measure grip strength, CT scan to measure thigh muscle area, and dual X-ray absorptiometry to determine leg and arm lean soft-tissue mass. “Those individuals who started with the highest levels of muscle strength had the greatest survival, while those who had the lowest levels of muscle strength died earlier,” said Dr. Volpi, who was not affiliated with the study. “That was true for both men and women.”

More recently, researchers conducted a pooled analysis of nine cohort studies involving 34,485 community-dwelling older individuals who were tested with gait speed and followed for 6-21 years (JAMA. 2011;305[1]:50-8). They found that a higher gait speed was associated with higher survival at 5 and 10 years (P less than .001). “Muscle mass also appears to be associated in part with mortality and survival, although the association is not as strong as measures of strength and gait speed,” Dr. Volpi said.

Data from the 2009 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey of 1,537 participants, aged 65 years and older, found that sarcopenia is independently associated with cardiovascular disease (PLoS One. 2013 Mar 22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060119). Most of the risk factors for cardiovascular disease – such as age, waist circumference, body mass index, fasting plasma glucose, and total cholesterol – showed significant negative correlations with the ratio between appendicular skeletal muscle mass and body weight. Multiple logistic regression analysis demonstrated that sarcopenia was associated with cardiovascular disease, independent of other well-documented risk factors, renal function, and medications (odds ratio, 1.77; P = .025).

In addition, data from the British Regional Heart Study, which followed 4,252 older men for a mean of 11.3 years, found an association of sarcopenia and adiposity with cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality (J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62[2]:253-60). Specifically, all-cause mortality risk was significantly greater in men in the sarcopenic and obese groups (HRs, 1.41 and 1.21, respectively), compared with those in the optimal reference group, with the highest risk in sarcopenic obese individuals (HR, 1.72) after adjustment for lifestyle characteristics.

“Diabetes also accelerates loss of lean body mass in older adults,” added Dr. Volpi. “Data from the Health ABC study showed that individuals who did not have diabetes at the beginning of the 6-year observation period ... lost the least amount of muscle, compared with those who had undiagnosed or already diagnosed diabetes.”

The precise way in which sarcopenia is linked to metabolic disease remains elusive, she continued, but current evidence suggests that sarcopenia is characterized by a reduction in the protein synthetic response to metabolic stimulation by amino acids, exercise, and insulin in skeletal muscle. “This reduction in the anabolic response to protein synthesis is called anabolic resistance of aging, and it is mediated by reduced acute activation of mTORC1 [mTOR complex 1] signaling,” Dr. Volpi said. “There’s another step upstream of the mTORC1, in which the amino acids and insulin have to cross the blood-muscle barrier. Amino acids need to be transported into the muscle actively, like glucose. That is an important unexplored area that may contribute to sarcopenia.”

Dr. Volpi went on to note that endothelial dysfunction underlies muscle anabolic resistance and cardiovascular risk and is likely to be a fundamental cause of both problems. Recent studies have shown that increased levels of physical activity improve endothelial function, enhance insulin sensitivity and anabolic sensitivity to nutrients, and reduce cardiovascular risk.

For example, in a cohort of 45 nonfrail older adults with a mean age of 72 years, Dr. Volpi and colleagues carried out a phase 1, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial to determine if chronic essential amino acid supplementation, aerobic exercise training, or a combination of the two interventions could improve muscle mass and function by stimulating muscle protein synthesis over the course of 24 weeks (J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74[10]:1598-604). “We found that exercise supervised three times per week on a treadmill for 6 months improved physical function in both groups randomized to exercise,” Dr. Volpi said. “Disappointingly, there was no change in total lean mass with any of the interventions. There was a decrease in fat mass with exercise alone, and no change with exercise and amino acids. [Of note is that] the individuals who were randomized to the amino acids plus exercise group had a significant increase in leg strength, whereas the others did not.”

Preliminary findings from ongoing work by Dr. Volpi and colleagues suggest that, in diabetes, muscle protein synthesis and blood flow really “are not different in response to insulin in healthy older adults and diabetic older adults because they don’t change at all. However, we did find alterations in amino acid trafficking in diabetes. We found that older individuals with type 2 diabetes had a reduction of amino acid transport and a higher intracellular amino acid concentration, compared with age-matched, healthier individuals. The intracellular amino acid clearance improved in the healthy, nondiabetic older adults with hyperinsulinemia, whereas it did not change in diabetic older adults. As a result, the net muscle protein balance improved a little in the nondiabetic patients, but did not change in the diabetic patients.”

The researchers are evaluating older patients with type 2 diabetes to see whether there are alterations in vascular reactivity and protein synthesis and whether those can be overcome by resistance-exercise training. “Preliminary results show that flow-mediated dilation can actually increase in an older diabetic patient with resistance exercise training three times a week for 3 months,” she said. “Exercise can improve both endothelial dysfunction and sarcopenia and therefore improve physical function and reduce cardiovascular risk.”

Dr. Volpi reported having no relevant disclosures.

LOS ANGELES –

“Loss of lean body mass and function with aging decreases the amount of metabolically active tissue, which can lead to insulin resistance,” Elena Volpi, MD, said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. “Insulin resistance reduces muscle protein anabolism and accelerates sarcopenia, perpetuating a vicious cycle.”

Sarcopenia, the involuntary loss of muscle mass and function that occurs with aging, is an ICD-10 codable condition that can be diagnosed by measuring muscle strength and quality, said Dr. Volpi, director of the Sealy Center on Aging at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. In the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study (Health ABC), researchers followed 2,292 relatively healthy adults aged 70-79 years for an average of 4.9 years (J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med. 2006;61[1]:72-7). The researchers used isokinetic dynamometry to measure knee extension strength, isometric dynamometry to measure grip strength, CT scan to measure thigh muscle area, and dual X-ray absorptiometry to determine leg and arm lean soft-tissue mass. “Those individuals who started with the highest levels of muscle strength had the greatest survival, while those who had the lowest levels of muscle strength died earlier,” said Dr. Volpi, who was not affiliated with the study. “That was true for both men and women.”

More recently, researchers conducted a pooled analysis of nine cohort studies involving 34,485 community-dwelling older individuals who were tested with gait speed and followed for 6-21 years (JAMA. 2011;305[1]:50-8). They found that a higher gait speed was associated with higher survival at 5 and 10 years (P less than .001). “Muscle mass also appears to be associated in part with mortality and survival, although the association is not as strong as measures of strength and gait speed,” Dr. Volpi said.

Data from the 2009 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey of 1,537 participants, aged 65 years and older, found that sarcopenia is independently associated with cardiovascular disease (PLoS One. 2013 Mar 22. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060119). Most of the risk factors for cardiovascular disease – such as age, waist circumference, body mass index, fasting plasma glucose, and total cholesterol – showed significant negative correlations with the ratio between appendicular skeletal muscle mass and body weight. Multiple logistic regression analysis demonstrated that sarcopenia was associated with cardiovascular disease, independent of other well-documented risk factors, renal function, and medications (odds ratio, 1.77; P = .025).

In addition, data from the British Regional Heart Study, which followed 4,252 older men for a mean of 11.3 years, found an association of sarcopenia and adiposity with cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality (J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62[2]:253-60). Specifically, all-cause mortality risk was significantly greater in men in the sarcopenic and obese groups (HRs, 1.41 and 1.21, respectively), compared with those in the optimal reference group, with the highest risk in sarcopenic obese individuals (HR, 1.72) after adjustment for lifestyle characteristics.

“Diabetes also accelerates loss of lean body mass in older adults,” added Dr. Volpi. “Data from the Health ABC study showed that individuals who did not have diabetes at the beginning of the 6-year observation period ... lost the least amount of muscle, compared with those who had undiagnosed or already diagnosed diabetes.”

The precise way in which sarcopenia is linked to metabolic disease remains elusive, she continued, but current evidence suggests that sarcopenia is characterized by a reduction in the protein synthetic response to metabolic stimulation by amino acids, exercise, and insulin in skeletal muscle. “This reduction in the anabolic response to protein synthesis is called anabolic resistance of aging, and it is mediated by reduced acute activation of mTORC1 [mTOR complex 1] signaling,” Dr. Volpi said. “There’s another step upstream of the mTORC1, in which the amino acids and insulin have to cross the blood-muscle barrier. Amino acids need to be transported into the muscle actively, like glucose. That is an important unexplored area that may contribute to sarcopenia.”

Dr. Volpi went on to note that endothelial dysfunction underlies muscle anabolic resistance and cardiovascular risk and is likely to be a fundamental cause of both problems. Recent studies have shown that increased levels of physical activity improve endothelial function, enhance insulin sensitivity and anabolic sensitivity to nutrients, and reduce cardiovascular risk.

For example, in a cohort of 45 nonfrail older adults with a mean age of 72 years, Dr. Volpi and colleagues carried out a phase 1, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial to determine if chronic essential amino acid supplementation, aerobic exercise training, or a combination of the two interventions could improve muscle mass and function by stimulating muscle protein synthesis over the course of 24 weeks (J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74[10]:1598-604). “We found that exercise supervised three times per week on a treadmill for 6 months improved physical function in both groups randomized to exercise,” Dr. Volpi said. “Disappointingly, there was no change in total lean mass with any of the interventions. There was a decrease in fat mass with exercise alone, and no change with exercise and amino acids. [Of note is that] the individuals who were randomized to the amino acids plus exercise group had a significant increase in leg strength, whereas the others did not.”

Preliminary findings from ongoing work by Dr. Volpi and colleagues suggest that, in diabetes, muscle protein synthesis and blood flow really “are not different in response to insulin in healthy older adults and diabetic older adults because they don’t change at all. However, we did find alterations in amino acid trafficking in diabetes. We found that older individuals with type 2 diabetes had a reduction of amino acid transport and a higher intracellular amino acid concentration, compared with age-matched, healthier individuals. The intracellular amino acid clearance improved in the healthy, nondiabetic older adults with hyperinsulinemia, whereas it did not change in diabetic older adults. As a result, the net muscle protein balance improved a little in the nondiabetic patients, but did not change in the diabetic patients.”

The researchers are evaluating older patients with type 2 diabetes to see whether there are alterations in vascular reactivity and protein synthesis and whether those can be overcome by resistance-exercise training. “Preliminary results show that flow-mediated dilation can actually increase in an older diabetic patient with resistance exercise training three times a week for 3 months,” she said. “Exercise can improve both endothelial dysfunction and sarcopenia and therefore improve physical function and reduce cardiovascular risk.”

Dr. Volpi reported having no relevant disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCIRDC 2019

Bariatric surgery is most effective early in the diabetes trajectory

LOS ANGELES – In the clinical experience of Kurt GMM Alberti, DPhil, FRCP, FRCPath, The problem is, far fewer people with diabetes are being referred for the surgery than would benefit from it.

At the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease, Dr. Alberti said that only about 1% of eligible patients in the United States undergo bariatric surgery, compared with just 0.22% of eligible patients in the United Kingdom.

“Obesity is an increasing problem,” said Dr. Alberti, a senior research investigator in the section of diabetes, endocrinology, and metabolism at Imperial College, London. “The United States is leading the field [in obesity], and it doesn’t seem to be going away. This is in parallel with diabetes. According to the 2019 International Diabetes Federation’s Diabetes Atlas, the diabetes prevalence worldwide is now 463 million. It’s projected to reach 578 million by 2030 and 700 million by 2045. We have a major problem.”

Lifestyle modification with diet and exercise have been the cornerstone of diabetes therapy for more than 100 years, with only modest success. “A range of oral agents have been added [and they] certainly improve glycemic control, but few achieve lasting success, and few achieve remission,” Dr. Alberti said. Findings from DiRECT (Lancet. 2018;391:541-51) and the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study (N Engl J Med. 2013;369:145-54) have shown dramatic improvements in glycemia, but only in the minority of patients who achieved weight loss of 10 kg or more. “In this group, 80% achieved remission after 2 years in DiRECT,” he said. “It is uncertain whether this can be sustained long term in real life, and how many people will respond. Major community prevention programs are under way in the U.S. and [United Kingdom], but many target individuals with prediabetes. Currently, it is unknown how successful these programs will be.”

The 2018 American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes clinical guidelines state that bariatric surgery is a recommended treatment option for adults with type 2 diabetes and a body mass index of either 40.0 kg/m2 or higher (or 37.5 kg/m2 or higher in people of Asian ancestry) or 35.0-39.9 kg/m2 (32.5-37.4 kg/m2 in people of Asian ancestry) and who do not achieve durable weight loss and improvement in comorbidities with reasonable nonsurgical methods. According to Dr. Alberti, surgery should be an accepted option in people who have type 2 diabetes and a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or higher, and priority should be given to adolescents, young adults, and those with a shorter duration of diabetes.

The main suggestive evidence in favor of bariatric surgery having an impact on diabetes comes from the Swedish Obese Subjects Study, which had a median follow-up of 10 years (J Intern Med. 2013;273[3]:219-34). In patients with diabetes at baseline, 30% were still in remission at 15 years after surgery. After 18 years, cumulative microvascular disease had fallen from 42 to 21 per 1,000 person-years, and macrovascular complications had fallen by 25%. “This was not a randomized, controlled trial, however,” Dr. Alberti said. Several of these studies have now been performed, including the STAMPEDE trial (N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-51) and recent studies led by Geltrude Mingrone, MD, PhD, which show major glycemic benefit (Lancet. 2015;386[9997]:P964-73) with bariatric surgery.

According to Dr. Alberti, laparoscopic adjustable gastric lap band is the easiest bariatric surgery to perform but it has fallen out of favor because of lower diabetes remission rates, compared with the other procedures. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and biliary pancreatic diversion are all in use. Slightly higher remission rates have been shown with biliary pancreatic diversion. “There have also been consistent improvements in quality of life and cardiovascular risk factors,” he said. “Long-term follow-up is still [needed], but, in general, it seems that diabetic complications are lower than in medically treated control groups, and mortality may also be lower. The real question is, what is the impact on complications? There we have a problem, because we do not have any good randomized, controlled trials covering a 10- to 20-year period, which would give us clear evidence. There is reasonable evidence from cohort studies, though.”

Added benefits of bariatric surgery include improved quality of life, decreased blood pressure, less sleep apnea, improved cardiovascular risk factors, and better musculoskeletal function. For now, though, an unmet need persists. “The problem is that far fewer people are referred for bariatric surgery than would benefit,” Dr. Alberti said. “There are several barriers to greater use of bariatric surgery in those with diabetes. These include physician attitudes, inadequate referrals, patient perceptions, lack of awareness among patients, inadequate insurance coverage, and particularly health system capacity. There is also a lack of sympathy for overweight people in some places.”

Dr. Alberti reported having no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – In the clinical experience of Kurt GMM Alberti, DPhil, FRCP, FRCPath, The problem is, far fewer people with diabetes are being referred for the surgery than would benefit from it.

At the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease, Dr. Alberti said that only about 1% of eligible patients in the United States undergo bariatric surgery, compared with just 0.22% of eligible patients in the United Kingdom.

“Obesity is an increasing problem,” said Dr. Alberti, a senior research investigator in the section of diabetes, endocrinology, and metabolism at Imperial College, London. “The United States is leading the field [in obesity], and it doesn’t seem to be going away. This is in parallel with diabetes. According to the 2019 International Diabetes Federation’s Diabetes Atlas, the diabetes prevalence worldwide is now 463 million. It’s projected to reach 578 million by 2030 and 700 million by 2045. We have a major problem.”

Lifestyle modification with diet and exercise have been the cornerstone of diabetes therapy for more than 100 years, with only modest success. “A range of oral agents have been added [and they] certainly improve glycemic control, but few achieve lasting success, and few achieve remission,” Dr. Alberti said. Findings from DiRECT (Lancet. 2018;391:541-51) and the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study (N Engl J Med. 2013;369:145-54) have shown dramatic improvements in glycemia, but only in the minority of patients who achieved weight loss of 10 kg or more. “In this group, 80% achieved remission after 2 years in DiRECT,” he said. “It is uncertain whether this can be sustained long term in real life, and how many people will respond. Major community prevention programs are under way in the U.S. and [United Kingdom], but many target individuals with prediabetes. Currently, it is unknown how successful these programs will be.”

The 2018 American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes clinical guidelines state that bariatric surgery is a recommended treatment option for adults with type 2 diabetes and a body mass index of either 40.0 kg/m2 or higher (or 37.5 kg/m2 or higher in people of Asian ancestry) or 35.0-39.9 kg/m2 (32.5-37.4 kg/m2 in people of Asian ancestry) and who do not achieve durable weight loss and improvement in comorbidities with reasonable nonsurgical methods. According to Dr. Alberti, surgery should be an accepted option in people who have type 2 diabetes and a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or higher, and priority should be given to adolescents, young adults, and those with a shorter duration of diabetes.

The main suggestive evidence in favor of bariatric surgery having an impact on diabetes comes from the Swedish Obese Subjects Study, which had a median follow-up of 10 years (J Intern Med. 2013;273[3]:219-34). In patients with diabetes at baseline, 30% were still in remission at 15 years after surgery. After 18 years, cumulative microvascular disease had fallen from 42 to 21 per 1,000 person-years, and macrovascular complications had fallen by 25%. “This was not a randomized, controlled trial, however,” Dr. Alberti said. Several of these studies have now been performed, including the STAMPEDE trial (N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-51) and recent studies led by Geltrude Mingrone, MD, PhD, which show major glycemic benefit (Lancet. 2015;386[9997]:P964-73) with bariatric surgery.

According to Dr. Alberti, laparoscopic adjustable gastric lap band is the easiest bariatric surgery to perform but it has fallen out of favor because of lower diabetes remission rates, compared with the other procedures. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and biliary pancreatic diversion are all in use. Slightly higher remission rates have been shown with biliary pancreatic diversion. “There have also been consistent improvements in quality of life and cardiovascular risk factors,” he said. “Long-term follow-up is still [needed], but, in general, it seems that diabetic complications are lower than in medically treated control groups, and mortality may also be lower. The real question is, what is the impact on complications? There we have a problem, because we do not have any good randomized, controlled trials covering a 10- to 20-year period, which would give us clear evidence. There is reasonable evidence from cohort studies, though.”

Added benefits of bariatric surgery include improved quality of life, decreased blood pressure, less sleep apnea, improved cardiovascular risk factors, and better musculoskeletal function. For now, though, an unmet need persists. “The problem is that far fewer people are referred for bariatric surgery than would benefit,” Dr. Alberti said. “There are several barriers to greater use of bariatric surgery in those with diabetes. These include physician attitudes, inadequate referrals, patient perceptions, lack of awareness among patients, inadequate insurance coverage, and particularly health system capacity. There is also a lack of sympathy for overweight people in some places.”

Dr. Alberti reported having no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – In the clinical experience of Kurt GMM Alberti, DPhil, FRCP, FRCPath, The problem is, far fewer people with diabetes are being referred for the surgery than would benefit from it.

At the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease, Dr. Alberti said that only about 1% of eligible patients in the United States undergo bariatric surgery, compared with just 0.22% of eligible patients in the United Kingdom.

“Obesity is an increasing problem,” said Dr. Alberti, a senior research investigator in the section of diabetes, endocrinology, and metabolism at Imperial College, London. “The United States is leading the field [in obesity], and it doesn’t seem to be going away. This is in parallel with diabetes. According to the 2019 International Diabetes Federation’s Diabetes Atlas, the diabetes prevalence worldwide is now 463 million. It’s projected to reach 578 million by 2030 and 700 million by 2045. We have a major problem.”

Lifestyle modification with diet and exercise have been the cornerstone of diabetes therapy for more than 100 years, with only modest success. “A range of oral agents have been added [and they] certainly improve glycemic control, but few achieve lasting success, and few achieve remission,” Dr. Alberti said. Findings from DiRECT (Lancet. 2018;391:541-51) and the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study (N Engl J Med. 2013;369:145-54) have shown dramatic improvements in glycemia, but only in the minority of patients who achieved weight loss of 10 kg or more. “In this group, 80% achieved remission after 2 years in DiRECT,” he said. “It is uncertain whether this can be sustained long term in real life, and how many people will respond. Major community prevention programs are under way in the U.S. and [United Kingdom], but many target individuals with prediabetes. Currently, it is unknown how successful these programs will be.”

The 2018 American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes clinical guidelines state that bariatric surgery is a recommended treatment option for adults with type 2 diabetes and a body mass index of either 40.0 kg/m2 or higher (or 37.5 kg/m2 or higher in people of Asian ancestry) or 35.0-39.9 kg/m2 (32.5-37.4 kg/m2 in people of Asian ancestry) and who do not achieve durable weight loss and improvement in comorbidities with reasonable nonsurgical methods. According to Dr. Alberti, surgery should be an accepted option in people who have type 2 diabetes and a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or higher, and priority should be given to adolescents, young adults, and those with a shorter duration of diabetes.

The main suggestive evidence in favor of bariatric surgery having an impact on diabetes comes from the Swedish Obese Subjects Study, which had a median follow-up of 10 years (J Intern Med. 2013;273[3]:219-34). In patients with diabetes at baseline, 30% were still in remission at 15 years after surgery. After 18 years, cumulative microvascular disease had fallen from 42 to 21 per 1,000 person-years, and macrovascular complications had fallen by 25%. “This was not a randomized, controlled trial, however,” Dr. Alberti said. Several of these studies have now been performed, including the STAMPEDE trial (N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-51) and recent studies led by Geltrude Mingrone, MD, PhD, which show major glycemic benefit (Lancet. 2015;386[9997]:P964-73) with bariatric surgery.

According to Dr. Alberti, laparoscopic adjustable gastric lap band is the easiest bariatric surgery to perform but it has fallen out of favor because of lower diabetes remission rates, compared with the other procedures. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and biliary pancreatic diversion are all in use. Slightly higher remission rates have been shown with biliary pancreatic diversion. “There have also been consistent improvements in quality of life and cardiovascular risk factors,” he said. “Long-term follow-up is still [needed], but, in general, it seems that diabetic complications are lower than in medically treated control groups, and mortality may also be lower. The real question is, what is the impact on complications? There we have a problem, because we do not have any good randomized, controlled trials covering a 10- to 20-year period, which would give us clear evidence. There is reasonable evidence from cohort studies, though.”

Added benefits of bariatric surgery include improved quality of life, decreased blood pressure, less sleep apnea, improved cardiovascular risk factors, and better musculoskeletal function. For now, though, an unmet need persists. “The problem is that far fewer people are referred for bariatric surgery than would benefit,” Dr. Alberti said. “There are several barriers to greater use of bariatric surgery in those with diabetes. These include physician attitudes, inadequate referrals, patient perceptions, lack of awareness among patients, inadequate insurance coverage, and particularly health system capacity. There is also a lack of sympathy for overweight people in some places.”

Dr. Alberti reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCIRDC 2019

Treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is a work in progress

LOS ANGELES – When it comes to the optimal treatment of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and diabetes, cardiologists like Mark T. Kearney, MB ChB, MD, remain stumped.

“Over the years, the diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction has been notoriously difficult [to treat], controversial, and ultimately involves aggressive catheterization of the heart to assess diastolic dysfunction, complex echocardiography, and invasive tests,” Dr. Kearney said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease. “These patients have an ejection fraction of over 50% and classic signs and symptoms of heart failure. Studies of beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin II receptor blockers have been unsuccessful in this group of patients. We’re at the beginning of a journey in understanding this disorder, and it’s important, because more and more patients present to us with signs and symptoms of heart failure with an ejection fraction greater than 50%.”

In a recent analysis of 1,797 patients with chronic heart failure, Dr. Kearney, British Heart Foundation Professor of Cardiovascular and Diabetes Research at the Leeds (England) Institute of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Medicine, and colleagues examined whether beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors were associated with differential effects on mortality in patients with and without diabetes (Diabetes Care. 2018;41:136-42). Mean follow-up was 4 years.

For the ACE inhibitor component of the trial, the researchers correlated the dose of ramipril to outcomes and found that each milligram increase of ramipril reduced the risk of death by about 3%. “In the nondiabetic patients who did not receive an ACE inhibitor, mortality was about 60% – worse than most cancers,” Dr. Kearney said. “In patients with diabetes, there was a similar pattern. If you didn’t get an ACE inhibitor, mortality was 70%. So, if you get patients on an optimal dose of an ACE inhibitor, you improve their mortality substantially, whether they have diabetes or not.”

The beta-blocker component of the trial yielded similar results. “Among patients who did not receive a beta-blocker, the mortality was about 70% at 5 years – really terrible,” he said. “Every milligram of bisoprolol was associated with a reduction in mortality of about 9%. So, if a patient gets on an optimal dose of a beta-blocker and they have diabetes, it’s associated with prolongation of life over a year.”

Dr. Kearney said that patients often do not want to take an increased dose of a beta-blocker because of concerns about side effects, such as tiredness. “They ask me what the side effects of an increased dose would be. My answer is: ‘It will make you live longer.’ Usually, they’ll respond by agreeing to have a little bit more of the beta-blocker. The message here is, if you have a patient with ejection fraction heart failure and diabetes, get them on the optimal dose of a beta-blocker, even at the expense of an ACE inhibitor.”

In 2016, the European Society of Cardiology introduced guidelines for physicians to make a diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. The guidelines mandate that a diagnosis requires signs and symptoms of heart failure, elevated levels of natriuretic peptide, and echocardiographic abnormalities of cardiac structure and/or function in the presence of a left ventricular ejection fraction of 50% or more (Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18[8]:891-975).

“Signs and symptoms of heart failure, elevated BNP [brain natriuretic peptide], and echocardiography allow us to make a diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction,” Dr. Kearney, who is also dean of the Leeds University School of Medicine. “But we don’t know the outcome of these patients, we don’t know how to treat them, and we don’t know the impact on hospitalizations.”

In a large, unpublished cohort study conducted at Leeds, Dr. Kearney and colleagues evaluated how many patients met criteria for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction after undergoing a BNP measurement. Ultimately, 959 patients met criteria. After assessment, 23% had no heart failure, 44% had heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, and 33% had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. They found that patients with preserved ejection fraction were older (mean age, 84 years); were more likely to be female; and had less ischemia, less diabetes, and more hypertension. In addition, patients with preserved ejection fraction had significantly better survival than patients with reduced ejection fraction over 5 years follow-up.

“What was really interesting were the findings related to hospitalization,” he said. “All 959 patients accounted for 20,517 days in the hospital over 5 years, which is the equivalent of 1 patient occupying a hospital bed for 56 years. This disorder [heart failure with preserved ejection fraction], despite having a lower mortality than heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, leads to a significant burden on health care systems.”