User login

Commentary: Meningococcal vaccine shows moderate protective effect against gonorrhea

The data on cross-protection against gonorrhea by outer membrane vesicle (OMV)–based meningococcal B vaccine continue to look encouraging from a recent study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (2022; doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac436). The authors report matched-cohort study data involving over 33,000 teens/young adults followed at Kaiser Permanente Southern California during 2016-2020. Like the studies above, chlamydia-infected patients (n = 26,471) served as negative controls for the 6,641 gonorrhea patients. The researchers compared chances of getting gonorrhea vs. getting chlamydia in light of having previously gotten C4MenB vaccine (OMV-based) or MenACWY vaccine (not OMV-based). The authors reported gonorrhea incidence rates of 2.0/1,000 person-years (95% CI, 1.3–2.8) in 4CMenB vaccinees vs. 5.2 (4.6–5.8) for MenACWY recipients. An adjusted analysis revealed 46% lower gonorrhea rates in 4CMenB vs. MenACWY vaccinees. There was no difference in chlamydia rates.

We await prospective controlled data to validate these observational studies. However, it is intriguing that OMV-based meningococcal vaccine may be a two-fer vaccine with partial cross protection against gonorrhea because of outer membrane protein similarities between the two pathogens. These data seem worth sharing with families who are making decisions about whether to vaccinate their children against B strains of meningococcus whether or not the child has already had conjugate MenACWY.

Christopher J. Harrison, MD, is professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. He has no financial conflicts of interest.

The data on cross-protection against gonorrhea by outer membrane vesicle (OMV)–based meningococcal B vaccine continue to look encouraging from a recent study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (2022; doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac436). The authors report matched-cohort study data involving over 33,000 teens/young adults followed at Kaiser Permanente Southern California during 2016-2020. Like the studies above, chlamydia-infected patients (n = 26,471) served as negative controls for the 6,641 gonorrhea patients. The researchers compared chances of getting gonorrhea vs. getting chlamydia in light of having previously gotten C4MenB vaccine (OMV-based) or MenACWY vaccine (not OMV-based). The authors reported gonorrhea incidence rates of 2.0/1,000 person-years (95% CI, 1.3–2.8) in 4CMenB vaccinees vs. 5.2 (4.6–5.8) for MenACWY recipients. An adjusted analysis revealed 46% lower gonorrhea rates in 4CMenB vs. MenACWY vaccinees. There was no difference in chlamydia rates.

We await prospective controlled data to validate these observational studies. However, it is intriguing that OMV-based meningococcal vaccine may be a two-fer vaccine with partial cross protection against gonorrhea because of outer membrane protein similarities between the two pathogens. These data seem worth sharing with families who are making decisions about whether to vaccinate their children against B strains of meningococcus whether or not the child has already had conjugate MenACWY.

Christopher J. Harrison, MD, is professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. He has no financial conflicts of interest.

The data on cross-protection against gonorrhea by outer membrane vesicle (OMV)–based meningococcal B vaccine continue to look encouraging from a recent study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (2022; doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac436). The authors report matched-cohort study data involving over 33,000 teens/young adults followed at Kaiser Permanente Southern California during 2016-2020. Like the studies above, chlamydia-infected patients (n = 26,471) served as negative controls for the 6,641 gonorrhea patients. The researchers compared chances of getting gonorrhea vs. getting chlamydia in light of having previously gotten C4MenB vaccine (OMV-based) or MenACWY vaccine (not OMV-based). The authors reported gonorrhea incidence rates of 2.0/1,000 person-years (95% CI, 1.3–2.8) in 4CMenB vaccinees vs. 5.2 (4.6–5.8) for MenACWY recipients. An adjusted analysis revealed 46% lower gonorrhea rates in 4CMenB vs. MenACWY vaccinees. There was no difference in chlamydia rates.

We await prospective controlled data to validate these observational studies. However, it is intriguing that OMV-based meningococcal vaccine may be a two-fer vaccine with partial cross protection against gonorrhea because of outer membrane protein similarities between the two pathogens. These data seem worth sharing with families who are making decisions about whether to vaccinate their children against B strains of meningococcus whether or not the child has already had conjugate MenACWY.

Christopher J. Harrison, MD, is professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. He has no financial conflicts of interest.

Has the anti-benzodiazepine backlash gone too far?

When benzodiazepines were first introduced, they were greeted with enthusiasm. Librium came first, in 1960, followed by Valium in 1962, and they were seen as an improvement over barbiturates for the treatment of anxiety, insomnia, and seizures. From 1968 to 1982, Valium (diazepam) was the No. 1–selling U.S. pharmaceutical: 2.3 billion tablets of Valium were sold in 1978 alone. Valium was even the subject of a 1966 Rolling Stones hit, “Mother’s Little Helper.”

By the 1980s, it became apparent that there was a downside to these medications: patients became tolerant, dependent, and some became addicted to the medications. In older patients an association was noted with falls and cognitive impairment. And while safe in overdoses when they are the only agent, combined with alcohol or opioids, benzodiazepines can be lethal and have played a significant role in the current overdose crisis.

Because of the problems that are associated with their use, benzodiazepines and their relatives, the Z-drugs used for sleep, have become stigmatized, as have the patients who use them and perhaps even the doctors who prescribe them. Still, there are circumstances where patients find these medications to be helpful, where other medications don’t work, or don’t work quickly enough. They provide fast relief in conditions where there are not always good alternatives.

In the Facebook group, “Psychiatry for All Physicians,” it’s not uncommon for physicians to ask what to do with older patients who are transferred to them on therapeutic doses of benzodiazepines or zolpidem. These are outpatients coming for routine care, and they find the medications helpful and don’t want to discontinue them. They have tried other medications that were not helpful. I’ve been surprised at how often the respondents insist the patient should be told he must taper off the medication. “Just say no,” is often the advice, and perhaps it’s more about the doctor’s discomfort than it is about the individual patient. For sleep issues, cognitive-behavioral therapy is given as the gold-standard treatment, while in my practice I have found it difficult to motivate patients to engage in it, and of those who do, it is sometimes helpful, but not a panacea. Severe anxiety and sleepless nights, however, are not benign conditions.

This “just say no, hold the line” sentiment has me wondering if our pendulum has swung too far with respect to prescribing benzodiazepines. Is this just one more issue that has become strongly polarized? Certainly the literature would support that idea, with some physicians writing about how benzodiazepines are underused, and others urging avoidance.

I posted a poll on Twitter: Has the anti-benzo movement gone too far? In addition, I started a Twitter thread of my own thoughts about prescribing and deprescribing these medications and will give a synopsis of those ideas here.

Clearly, benzodiazepines are harmful to some patients, they have side effects, can be difficult to stop because of withdrawal symptoms, and they carry the risk of addiction. That’s not in question. Many medications, however, have the potential to do more harm than good, for example ibuprofen can cause bleeding or renal problems, and Fosamax, used to treat osteoporosis, can cause osteonecrosis of the jaw and femur, to name just two.

It would be so much easier if we could know in advance who benzodiazepines will harm, just as it would be good if we could know in advance who will get tardive dyskinesia or dyslipidemia from antipsychotic medications, or who will have life-threatening adverse reactions from cancer chemotherapy with no tumor response. There are risks to both starting and stopping sedatives, and if we insist a patient stop a medication because of potential risk, then we are cutting them off from being a partner in their own care. It also creates an adversarial relationship that can be draining for the doctor and upsetting for the patient.

By definition, if someone needs hospitalization for a psychiatric condition, their outpatient benzodiazepine is not keeping them stable and stopping it may be a good idea. If someone is seen in an ED for a fall, it’s common to blame the benzodiazepine, but older people who are not on these medications also fall and have memory problems. In his book, “Being Mortal: Illness, Medicine, and What Matters Most in the End” (New York: Picador, 2014), Atul Gawande, MD, makes the point that taking more than four prescriptions medications increases the risk for falls in the elderly. Still, no one is suggesting patients be taken off their antidepressants, antihypertensives, or blood thinners.

Finally, the question is not should we be giving benzodiazepines out without careful consideration – the answer is clearly no. Physicians don’t pass out benzodiazepines “like candy” for all the above reasons. They are initiated because the patient is suffering and sometimes desperate. Anxiety, panic, intractable insomnia, and severe agitation are all miserable, and alternative treatments may take weeks to work, or not work at all. Yet these subjective symptoms may be dismissed by physicians.

So what do I do in my own practice? I don’t encourage patients to take potentially addictive medications, but I do sometimes use them. I give ‘as needed’ benzodiazepines to people in distress who don’t have a history of misusing them. I never plan to start them as a permanent standing medication, though once in a while that ends up happening. As with other medications, it is best to use the minimally effective dose.

There is some controversy as to whether it is best to use anxiety medications on an “as-needed” basis or as a standing dosage. Psychiatrists who prescribe benzodiazepines more liberally often feel it’s better to give standing doses and prevent breakthrough anxiety. Patients may appear to be ‘medication seeking’ not because they are addicted, but because the doses used are too low to adequately treat their anxiety.

My hope is that there is less risk of tolerance, dependence, or addiction with less-frequent dosing, and I prescribe as-needed benzodiazepines for panic attacks, agitated major depression while we wait for the antidepressant to “kick in,” insomnia during manic episodes, and to people who get very anxious in specific situations such as flying or for medical procedures. I sometimes prescribe them for people with insomnia that does not respond to other treatments, or for disabling generalized anxiety.

For patients who have taken benzodiazepines for many years, I continue to discuss the risks, but often they are not looking to fix something that isn’t broken, or to live a risk-free life. A few of the patients who have come to me on low standing doses of sedatives are now in their 80’s, yet they remain active, live independently, drive, travel, and have busy social lives. One could argue either that the medications are working, or that the patient has become dependent on them and needs them to prevent withdrawal.

These medications present a quandary: by denying patients treatment with benzodiazepines, we are sparing some people addictions (this is good, we should be careful), but we are leaving some people to suffer. There is no perfect answer.

What I do know is that doctors should think carefully and consider the patient in front of them. “No Benzos Ever For Anyone” or “you must come off because there is risk and people will think I am a bad doctor for prescribing them to you” can be done by a robot.

So, yes, I think the pendulum has swung a bit too far; there is a place for these medications in acute treatment for those at low risk of addiction, and there are people who benefit from them over the long run. At times, they provide immense relief to someone who is really struggling.

So what was the result of my Twitter poll? Of the 219 voters, 34.2% voted: “No, the pendulum has not swung too far, and these medications are harmful”; 65.8% voted: “Yes, these medications are helpful.” There were many comments expressing a wide variety of sentiments. Of those who had taken prescription benzodiazepines, some felt they had been harmed and wished they had never been started on them, and others continue to find them helpful. Psychiatrists, it seems, see them from the vantage point of the populations they treat.

People who are uncomfortable search for answers, and those answers may come in the form of meditation or exercise, medicines, or illicit drugs. It’s interesting that these same patients can now easily obtain “medical” marijuana, and the Rolling Stones’ “Mother’s Little Helper” is often replaced by a gin and tonic.

Dr. Dinah Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. Dr. Miller has no conflicts of interest.

When benzodiazepines were first introduced, they were greeted with enthusiasm. Librium came first, in 1960, followed by Valium in 1962, and they were seen as an improvement over barbiturates for the treatment of anxiety, insomnia, and seizures. From 1968 to 1982, Valium (diazepam) was the No. 1–selling U.S. pharmaceutical: 2.3 billion tablets of Valium were sold in 1978 alone. Valium was even the subject of a 1966 Rolling Stones hit, “Mother’s Little Helper.”

By the 1980s, it became apparent that there was a downside to these medications: patients became tolerant, dependent, and some became addicted to the medications. In older patients an association was noted with falls and cognitive impairment. And while safe in overdoses when they are the only agent, combined with alcohol or opioids, benzodiazepines can be lethal and have played a significant role in the current overdose crisis.

Because of the problems that are associated with their use, benzodiazepines and their relatives, the Z-drugs used for sleep, have become stigmatized, as have the patients who use them and perhaps even the doctors who prescribe them. Still, there are circumstances where patients find these medications to be helpful, where other medications don’t work, or don’t work quickly enough. They provide fast relief in conditions where there are not always good alternatives.

In the Facebook group, “Psychiatry for All Physicians,” it’s not uncommon for physicians to ask what to do with older patients who are transferred to them on therapeutic doses of benzodiazepines or zolpidem. These are outpatients coming for routine care, and they find the medications helpful and don’t want to discontinue them. They have tried other medications that were not helpful. I’ve been surprised at how often the respondents insist the patient should be told he must taper off the medication. “Just say no,” is often the advice, and perhaps it’s more about the doctor’s discomfort than it is about the individual patient. For sleep issues, cognitive-behavioral therapy is given as the gold-standard treatment, while in my practice I have found it difficult to motivate patients to engage in it, and of those who do, it is sometimes helpful, but not a panacea. Severe anxiety and sleepless nights, however, are not benign conditions.

This “just say no, hold the line” sentiment has me wondering if our pendulum has swung too far with respect to prescribing benzodiazepines. Is this just one more issue that has become strongly polarized? Certainly the literature would support that idea, with some physicians writing about how benzodiazepines are underused, and others urging avoidance.

I posted a poll on Twitter: Has the anti-benzo movement gone too far? In addition, I started a Twitter thread of my own thoughts about prescribing and deprescribing these medications and will give a synopsis of those ideas here.

Clearly, benzodiazepines are harmful to some patients, they have side effects, can be difficult to stop because of withdrawal symptoms, and they carry the risk of addiction. That’s not in question. Many medications, however, have the potential to do more harm than good, for example ibuprofen can cause bleeding or renal problems, and Fosamax, used to treat osteoporosis, can cause osteonecrosis of the jaw and femur, to name just two.

It would be so much easier if we could know in advance who benzodiazepines will harm, just as it would be good if we could know in advance who will get tardive dyskinesia or dyslipidemia from antipsychotic medications, or who will have life-threatening adverse reactions from cancer chemotherapy with no tumor response. There are risks to both starting and stopping sedatives, and if we insist a patient stop a medication because of potential risk, then we are cutting them off from being a partner in their own care. It also creates an adversarial relationship that can be draining for the doctor and upsetting for the patient.

By definition, if someone needs hospitalization for a psychiatric condition, their outpatient benzodiazepine is not keeping them stable and stopping it may be a good idea. If someone is seen in an ED for a fall, it’s common to blame the benzodiazepine, but older people who are not on these medications also fall and have memory problems. In his book, “Being Mortal: Illness, Medicine, and What Matters Most in the End” (New York: Picador, 2014), Atul Gawande, MD, makes the point that taking more than four prescriptions medications increases the risk for falls in the elderly. Still, no one is suggesting patients be taken off their antidepressants, antihypertensives, or blood thinners.

Finally, the question is not should we be giving benzodiazepines out without careful consideration – the answer is clearly no. Physicians don’t pass out benzodiazepines “like candy” for all the above reasons. They are initiated because the patient is suffering and sometimes desperate. Anxiety, panic, intractable insomnia, and severe agitation are all miserable, and alternative treatments may take weeks to work, or not work at all. Yet these subjective symptoms may be dismissed by physicians.

So what do I do in my own practice? I don’t encourage patients to take potentially addictive medications, but I do sometimes use them. I give ‘as needed’ benzodiazepines to people in distress who don’t have a history of misusing them. I never plan to start them as a permanent standing medication, though once in a while that ends up happening. As with other medications, it is best to use the minimally effective dose.

There is some controversy as to whether it is best to use anxiety medications on an “as-needed” basis or as a standing dosage. Psychiatrists who prescribe benzodiazepines more liberally often feel it’s better to give standing doses and prevent breakthrough anxiety. Patients may appear to be ‘medication seeking’ not because they are addicted, but because the doses used are too low to adequately treat their anxiety.

My hope is that there is less risk of tolerance, dependence, or addiction with less-frequent dosing, and I prescribe as-needed benzodiazepines for panic attacks, agitated major depression while we wait for the antidepressant to “kick in,” insomnia during manic episodes, and to people who get very anxious in specific situations such as flying or for medical procedures. I sometimes prescribe them for people with insomnia that does not respond to other treatments, or for disabling generalized anxiety.

For patients who have taken benzodiazepines for many years, I continue to discuss the risks, but often they are not looking to fix something that isn’t broken, or to live a risk-free life. A few of the patients who have come to me on low standing doses of sedatives are now in their 80’s, yet they remain active, live independently, drive, travel, and have busy social lives. One could argue either that the medications are working, or that the patient has become dependent on them and needs them to prevent withdrawal.

These medications present a quandary: by denying patients treatment with benzodiazepines, we are sparing some people addictions (this is good, we should be careful), but we are leaving some people to suffer. There is no perfect answer.

What I do know is that doctors should think carefully and consider the patient in front of them. “No Benzos Ever For Anyone” or “you must come off because there is risk and people will think I am a bad doctor for prescribing them to you” can be done by a robot.

So, yes, I think the pendulum has swung a bit too far; there is a place for these medications in acute treatment for those at low risk of addiction, and there are people who benefit from them over the long run. At times, they provide immense relief to someone who is really struggling.

So what was the result of my Twitter poll? Of the 219 voters, 34.2% voted: “No, the pendulum has not swung too far, and these medications are harmful”; 65.8% voted: “Yes, these medications are helpful.” There were many comments expressing a wide variety of sentiments. Of those who had taken prescription benzodiazepines, some felt they had been harmed and wished they had never been started on them, and others continue to find them helpful. Psychiatrists, it seems, see them from the vantage point of the populations they treat.

People who are uncomfortable search for answers, and those answers may come in the form of meditation or exercise, medicines, or illicit drugs. It’s interesting that these same patients can now easily obtain “medical” marijuana, and the Rolling Stones’ “Mother’s Little Helper” is often replaced by a gin and tonic.

Dr. Dinah Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. Dr. Miller has no conflicts of interest.

When benzodiazepines were first introduced, they were greeted with enthusiasm. Librium came first, in 1960, followed by Valium in 1962, and they were seen as an improvement over barbiturates for the treatment of anxiety, insomnia, and seizures. From 1968 to 1982, Valium (diazepam) was the No. 1–selling U.S. pharmaceutical: 2.3 billion tablets of Valium were sold in 1978 alone. Valium was even the subject of a 1966 Rolling Stones hit, “Mother’s Little Helper.”

By the 1980s, it became apparent that there was a downside to these medications: patients became tolerant, dependent, and some became addicted to the medications. In older patients an association was noted with falls and cognitive impairment. And while safe in overdoses when they are the only agent, combined with alcohol or opioids, benzodiazepines can be lethal and have played a significant role in the current overdose crisis.

Because of the problems that are associated with their use, benzodiazepines and their relatives, the Z-drugs used for sleep, have become stigmatized, as have the patients who use them and perhaps even the doctors who prescribe them. Still, there are circumstances where patients find these medications to be helpful, where other medications don’t work, or don’t work quickly enough. They provide fast relief in conditions where there are not always good alternatives.

In the Facebook group, “Psychiatry for All Physicians,” it’s not uncommon for physicians to ask what to do with older patients who are transferred to them on therapeutic doses of benzodiazepines or zolpidem. These are outpatients coming for routine care, and they find the medications helpful and don’t want to discontinue them. They have tried other medications that were not helpful. I’ve been surprised at how often the respondents insist the patient should be told he must taper off the medication. “Just say no,” is often the advice, and perhaps it’s more about the doctor’s discomfort than it is about the individual patient. For sleep issues, cognitive-behavioral therapy is given as the gold-standard treatment, while in my practice I have found it difficult to motivate patients to engage in it, and of those who do, it is sometimes helpful, but not a panacea. Severe anxiety and sleepless nights, however, are not benign conditions.

This “just say no, hold the line” sentiment has me wondering if our pendulum has swung too far with respect to prescribing benzodiazepines. Is this just one more issue that has become strongly polarized? Certainly the literature would support that idea, with some physicians writing about how benzodiazepines are underused, and others urging avoidance.

I posted a poll on Twitter: Has the anti-benzo movement gone too far? In addition, I started a Twitter thread of my own thoughts about prescribing and deprescribing these medications and will give a synopsis of those ideas here.

Clearly, benzodiazepines are harmful to some patients, they have side effects, can be difficult to stop because of withdrawal symptoms, and they carry the risk of addiction. That’s not in question. Many medications, however, have the potential to do more harm than good, for example ibuprofen can cause bleeding or renal problems, and Fosamax, used to treat osteoporosis, can cause osteonecrosis of the jaw and femur, to name just two.

It would be so much easier if we could know in advance who benzodiazepines will harm, just as it would be good if we could know in advance who will get tardive dyskinesia or dyslipidemia from antipsychotic medications, or who will have life-threatening adverse reactions from cancer chemotherapy with no tumor response. There are risks to both starting and stopping sedatives, and if we insist a patient stop a medication because of potential risk, then we are cutting them off from being a partner in their own care. It also creates an adversarial relationship that can be draining for the doctor and upsetting for the patient.

By definition, if someone needs hospitalization for a psychiatric condition, their outpatient benzodiazepine is not keeping them stable and stopping it may be a good idea. If someone is seen in an ED for a fall, it’s common to blame the benzodiazepine, but older people who are not on these medications also fall and have memory problems. In his book, “Being Mortal: Illness, Medicine, and What Matters Most in the End” (New York: Picador, 2014), Atul Gawande, MD, makes the point that taking more than four prescriptions medications increases the risk for falls in the elderly. Still, no one is suggesting patients be taken off their antidepressants, antihypertensives, or blood thinners.

Finally, the question is not should we be giving benzodiazepines out without careful consideration – the answer is clearly no. Physicians don’t pass out benzodiazepines “like candy” for all the above reasons. They are initiated because the patient is suffering and sometimes desperate. Anxiety, panic, intractable insomnia, and severe agitation are all miserable, and alternative treatments may take weeks to work, or not work at all. Yet these subjective symptoms may be dismissed by physicians.

So what do I do in my own practice? I don’t encourage patients to take potentially addictive medications, but I do sometimes use them. I give ‘as needed’ benzodiazepines to people in distress who don’t have a history of misusing them. I never plan to start them as a permanent standing medication, though once in a while that ends up happening. As with other medications, it is best to use the minimally effective dose.

There is some controversy as to whether it is best to use anxiety medications on an “as-needed” basis or as a standing dosage. Psychiatrists who prescribe benzodiazepines more liberally often feel it’s better to give standing doses and prevent breakthrough anxiety. Patients may appear to be ‘medication seeking’ not because they are addicted, but because the doses used are too low to adequately treat their anxiety.

My hope is that there is less risk of tolerance, dependence, or addiction with less-frequent dosing, and I prescribe as-needed benzodiazepines for panic attacks, agitated major depression while we wait for the antidepressant to “kick in,” insomnia during manic episodes, and to people who get very anxious in specific situations such as flying or for medical procedures. I sometimes prescribe them for people with insomnia that does not respond to other treatments, or for disabling generalized anxiety.

For patients who have taken benzodiazepines for many years, I continue to discuss the risks, but often they are not looking to fix something that isn’t broken, or to live a risk-free life. A few of the patients who have come to me on low standing doses of sedatives are now in their 80’s, yet they remain active, live independently, drive, travel, and have busy social lives. One could argue either that the medications are working, or that the patient has become dependent on them and needs them to prevent withdrawal.

These medications present a quandary: by denying patients treatment with benzodiazepines, we are sparing some people addictions (this is good, we should be careful), but we are leaving some people to suffer. There is no perfect answer.

What I do know is that doctors should think carefully and consider the patient in front of them. “No Benzos Ever For Anyone” or “you must come off because there is risk and people will think I am a bad doctor for prescribing them to you” can be done by a robot.

So, yes, I think the pendulum has swung a bit too far; there is a place for these medications in acute treatment for those at low risk of addiction, and there are people who benefit from them over the long run. At times, they provide immense relief to someone who is really struggling.

So what was the result of my Twitter poll? Of the 219 voters, 34.2% voted: “No, the pendulum has not swung too far, and these medications are harmful”; 65.8% voted: “Yes, these medications are helpful.” There were many comments expressing a wide variety of sentiments. Of those who had taken prescription benzodiazepines, some felt they had been harmed and wished they had never been started on them, and others continue to find them helpful. Psychiatrists, it seems, see them from the vantage point of the populations they treat.

People who are uncomfortable search for answers, and those answers may come in the form of meditation or exercise, medicines, or illicit drugs. It’s interesting that these same patients can now easily obtain “medical” marijuana, and the Rolling Stones’ “Mother’s Little Helper” is often replaced by a gin and tonic.

Dr. Dinah Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. Dr. Miller has no conflicts of interest.

Contraception for women taking enzyme-inducing antiepileptics

Topiramate, introduced as an antiepileptic drug (AED), is currently most widely used for prevention of migraine headaches.

Because reproductive-aged women represent a population in which migraines are prevalent, clinicians need guidance to help women taking topiramate make sound contraceptive choices.

Several issues are relevant here. First, women who have migraines with aura should avoid estrogen-containing contraceptive pills, patches, and rings. Instead, progestin-only methods, including the contraceptive implant, may be recommended to patients with migraines.

Second, because topiramate, as with a number of other AEDs, is a teratogen, women using this medication need highly effective contraception. This consideration may also lead clinicians to recommend use of the implant in women with migraines.

Finally, topiramate, along with other AEDs (phenytoin, carbamazepine, barbiturates, primidone, and oxcarbazepine) induces hepatic enzymes, which results in reduced serum contraceptive steroid levels.

Because there is uncertainty regarding the degree to which the use of topiramate reduces serum levels of etonogestrel (the progestin released by the implant), investigators performed a prospective study to assess the pharmacokinetic impact of topiramate in women with the implant.

Ongoing users of contraceptive implants who agreed to use additional nonhormonal contraception were recruited to a 6-week study, during which they took topiramate and periodically had blood drawn.

Overall, use of topiramate was found to lower serum etonogestrel levels from baseline on a dose-related basis. At study completion, almost one-third of study participants were found to have serum progestin levels lower than the threshold associated with predictable ovulation suppression.

The results of this carefully conducted study support guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that women seeking contraception and using topiramate or other enzyme-inducing AEDs should be encouraged to use intrauterine devices or injectable contraception. The contraceptive efficacy of these latter methods is not diminished by concomitant use of enzyme inducers.

I am Andrew Kaunitz. Please take care of yourself and each other.

Any views expressed above are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Andrew M. Kaunitz is a professor and Associate Chairman, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Florida, Jacksonville.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Topiramate, introduced as an antiepileptic drug (AED), is currently most widely used for prevention of migraine headaches.

Because reproductive-aged women represent a population in which migraines are prevalent, clinicians need guidance to help women taking topiramate make sound contraceptive choices.

Several issues are relevant here. First, women who have migraines with aura should avoid estrogen-containing contraceptive pills, patches, and rings. Instead, progestin-only methods, including the contraceptive implant, may be recommended to patients with migraines.

Second, because topiramate, as with a number of other AEDs, is a teratogen, women using this medication need highly effective contraception. This consideration may also lead clinicians to recommend use of the implant in women with migraines.

Finally, topiramate, along with other AEDs (phenytoin, carbamazepine, barbiturates, primidone, and oxcarbazepine) induces hepatic enzymes, which results in reduced serum contraceptive steroid levels.

Because there is uncertainty regarding the degree to which the use of topiramate reduces serum levels of etonogestrel (the progestin released by the implant), investigators performed a prospective study to assess the pharmacokinetic impact of topiramate in women with the implant.

Ongoing users of contraceptive implants who agreed to use additional nonhormonal contraception were recruited to a 6-week study, during which they took topiramate and periodically had blood drawn.

Overall, use of topiramate was found to lower serum etonogestrel levels from baseline on a dose-related basis. At study completion, almost one-third of study participants were found to have serum progestin levels lower than the threshold associated with predictable ovulation suppression.

The results of this carefully conducted study support guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that women seeking contraception and using topiramate or other enzyme-inducing AEDs should be encouraged to use intrauterine devices or injectable contraception. The contraceptive efficacy of these latter methods is not diminished by concomitant use of enzyme inducers.

I am Andrew Kaunitz. Please take care of yourself and each other.

Any views expressed above are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Andrew M. Kaunitz is a professor and Associate Chairman, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Florida, Jacksonville.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Topiramate, introduced as an antiepileptic drug (AED), is currently most widely used for prevention of migraine headaches.

Because reproductive-aged women represent a population in which migraines are prevalent, clinicians need guidance to help women taking topiramate make sound contraceptive choices.

Several issues are relevant here. First, women who have migraines with aura should avoid estrogen-containing contraceptive pills, patches, and rings. Instead, progestin-only methods, including the contraceptive implant, may be recommended to patients with migraines.

Second, because topiramate, as with a number of other AEDs, is a teratogen, women using this medication need highly effective contraception. This consideration may also lead clinicians to recommend use of the implant in women with migraines.

Finally, topiramate, along with other AEDs (phenytoin, carbamazepine, barbiturates, primidone, and oxcarbazepine) induces hepatic enzymes, which results in reduced serum contraceptive steroid levels.

Because there is uncertainty regarding the degree to which the use of topiramate reduces serum levels of etonogestrel (the progestin released by the implant), investigators performed a prospective study to assess the pharmacokinetic impact of topiramate in women with the implant.

Ongoing users of contraceptive implants who agreed to use additional nonhormonal contraception were recruited to a 6-week study, during which they took topiramate and periodically had blood drawn.

Overall, use of topiramate was found to lower serum etonogestrel levels from baseline on a dose-related basis. At study completion, almost one-third of study participants were found to have serum progestin levels lower than the threshold associated with predictable ovulation suppression.

The results of this carefully conducted study support guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that women seeking contraception and using topiramate or other enzyme-inducing AEDs should be encouraged to use intrauterine devices or injectable contraception. The contraceptive efficacy of these latter methods is not diminished by concomitant use of enzyme inducers.

I am Andrew Kaunitz. Please take care of yourself and each other.

Any views expressed above are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Andrew M. Kaunitz is a professor and Associate Chairman, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Florida, Jacksonville.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What COVID-19 taught us: The challenge of maintaining contingency level care to proactively forestall crisis care

In 2014, the Task Force for Mass Critical Care (TFMCC) published a CHEST consensus statement on disaster preparedness principles in caring for the critically ill during disasters and pandemics (Christian et al. CHEST. 2014;146[4_suppl]:8s-34s). This publication attempted to guide preparedness for both single-event disasters and more prolonged events, including a feared influenza pandemic.

Despite the foundation of planning and support this guidance provided, the COVID-19 pandemic response revealed substantial gaps in our understanding and preparedness for these more prolonged and widespread events.

In New York City, as the first COVID-19 wave began in March and April of 2020, area hospitals responded with surge plans that prioritized what was felt to be most important (Griffin et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Jun 1;201[11]:1337-44). Tiered, creative staffing structures were rapidly created with intensivists supervising non-ICU physicians and APPs. Procedure teams were created for intubation, proning, and central line placement. ICU space was created with adaptations to ORs and PACUs, and rooms on med-surg floors and step-down units underwent emergency renovations to allow creation of new “pop-up” ICUs. Triage protocols were altered: patients on high levels of supplemental oxygen, who would under normal circumstances have been admitted to an ICU, were triaged to floors and stepdown units. Equipment was reused, modified, and substituted creatively to optimize care for the maximum number of patients.

In the face of all of these struggles, many around the country and the world felt the efforts, though heroic, resulted in less than standard of care. Two subsequent publications validated this concern (Kadri et al. Ann Int Med. 2021,174;9:1240-51; Bravata DM et al. JAMA Open Network. 2021;4[1]:e2034266), demonstrating during severe surge, COVID-19 patients’ mortality increased significantly beyond that seen in non-surging or less-severe surging times, demonstrating a mortality effect of surge itself. Though these studies observed COVID-19 patients only, there is every reason to believe the findings applied to all critically ill patients cared for during these surges.

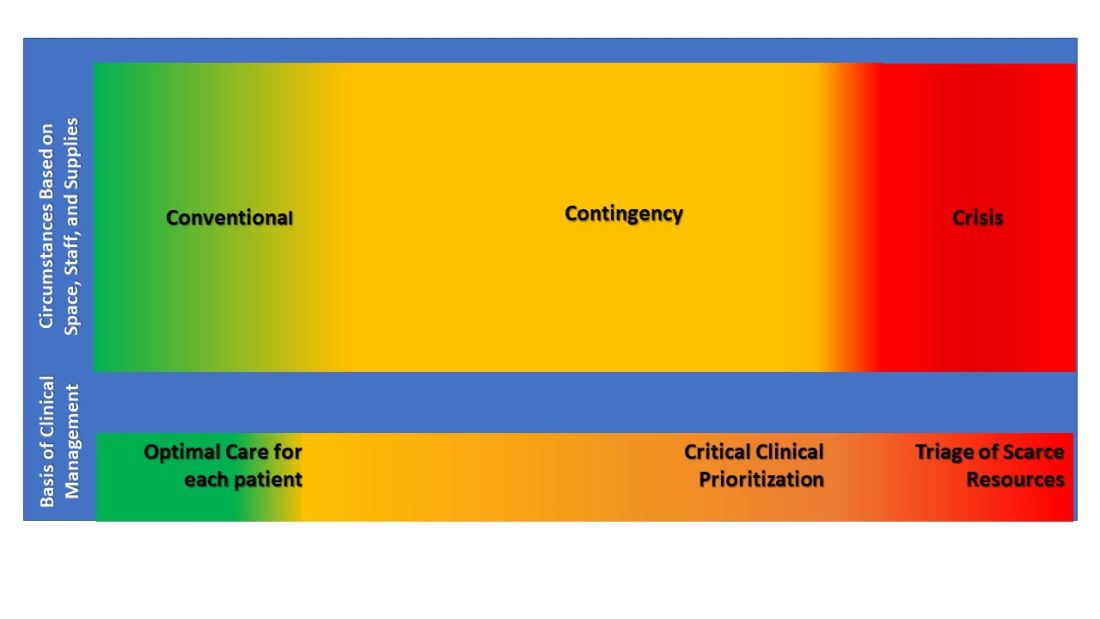

These experiences led the TFMCC to report updated strategies for remaining in contingency care levels and avoiding crisis care (Dichter JR et al. CHEST. 2022;161[2]:429-47). Contingency is equivalent to routine care though may require adaptations and employment of otherwise non-traditional resources. The ultimate goal of mass critical care in a public health emergency is to avoid crisis-operating conditions, crisis standards of care, and their associated challenging triage decisions regarding allocation of scarce resources.

The 10 suggestions included in the most recent TFMCC publication include staffing strategies and suggestions based on COVID-19 experiences for graded staff-to-patient ratios, and support processes to preserve the existing health care work force. Strategies also include reduction of redundant documentation, limiting overtime, and most importantly, approaches for improving teamwork and supporting psychological well-being and resilience. Examples include daily unit huddles to update care and share experiences, genuine intra-team recognition and appreciation, and embedding emotional health experts within teams to provide ongoing support.

Consistent communication between incident command and frontline clinicians was also a suggested priority, perhaps with a newly proposed position of physician clinical support supervisor. This would be a formal role within hospital incident command, a liaison between the two groups.

Surge strategies should include empowerment of bedside clinicians and leaders with both planning and real-time assessment of the clinical situation, as being at the front line of care enables the situational awareness to assess ICU strain most effectively. Further, ICU clinicians must recognize when progression deeper into contingency operations occurs and they become perilously close to crisis mode. At this point, decisions are made and scarce resources are modified beyond routine standards of care to preserve life. TFMCC designates this gray area between contingency and crisis as the Critical Clinical Prioritization level (Figure).

At this point, more resources must be provided, or patients must be transferred to other resourced hospitals.

Critical Clinical Prioritization is an illustration of necessity being the mother of invention, as these are adaptations clinicians devised under duress. Some particularly poignant examples are the spreading of 24 hours of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) resource between two and sometimes three patients to provide life sustainment to all; and when ventilators were in short supply, determining which patients required full ICU ventilator support vs those who could manage with lower functioning ventilators, and trading them between patients when demands changed.

These adaptations can only be done by experienced clinicians proactively managing bedside critical care under duress, further underscoring the importance of our suggestion that Critical Clinical Prioritization and ICU strain be managed by bedside clinicians and leaders.

The response of early transfer of patients – load-balancing - should be considered as soon as any hospital enters contingency conditions. This strategy is commonly implemented within larger health systems, ideally before reaching Critical Clinical Prioritization. Formal, organized state or regional load-balancing coordination, now referred to as medical operations command centers (MOCCs), were highly effective and proved lifesaving for those states that implemented them (including Arizona, Washington, California, Minnesota, and others). Support for establishment of MOCC’s is crucial in prolonging contingency operations and further helps support and protect disadvantaged populations (White et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;385[24]:2211-4).

Establishment of MOCCs has met resistance due to challenges that include interhospital/intersystem competition, logistics of moving critically ill patients sometimes across significant physical distance, and the costs of assuming care of uninsured or underinsured patients. Nevertheless, the benefits to the population as a whole necessitate working through these obstacles as successful MOCCs have done, usually with government and hospital association support.

In their final suggestion of the 2022 updated strategies, TFMCC suggests that hospitals use telemedicine technology both to expand specialists’ ability to provide care and facilitate families virtually visiting their critically ill loved one when safety precludes in-person visits.

These suggestions are pivotal in planning for future public health emergencies that include mass critical care, even during events that are limited in scope and duration.

Lastly, intensivists struggled with legal and ethical concerns when mired in crisis care circumstances and decisions of allocation, and potential reallocation, of scarce resources. These issues were not well addressed during the COVID-19 pandemic, further emphasizing the importance of maintaining contingency level care and requiring further involvement from legal and medical ethics professionals for future planning.

The guiding principle of disaster preparedness is that we must do all the planning we can to ensure that we never need crisis standards of care (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020 Mar 28. Rapid Expert Consultation on Crisis Standards of Care for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.).

We must be prepared. Guidelines and suggestions laid out through decades of experience gained a real-world test in the COVID-19 pandemic. Now we must all reorganize and create new plans or augment old ones with the information we have gained. The time is now. The work must continue.

Dr. Griffin is Assistant Professor of Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital – Weill Cornell Medicine. Dr. Dichter is Associate Professor of Medicine, University of Minnesota.

In 2014, the Task Force for Mass Critical Care (TFMCC) published a CHEST consensus statement on disaster preparedness principles in caring for the critically ill during disasters and pandemics (Christian et al. CHEST. 2014;146[4_suppl]:8s-34s). This publication attempted to guide preparedness for both single-event disasters and more prolonged events, including a feared influenza pandemic.

Despite the foundation of planning and support this guidance provided, the COVID-19 pandemic response revealed substantial gaps in our understanding and preparedness for these more prolonged and widespread events.

In New York City, as the first COVID-19 wave began in March and April of 2020, area hospitals responded with surge plans that prioritized what was felt to be most important (Griffin et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Jun 1;201[11]:1337-44). Tiered, creative staffing structures were rapidly created with intensivists supervising non-ICU physicians and APPs. Procedure teams were created for intubation, proning, and central line placement. ICU space was created with adaptations to ORs and PACUs, and rooms on med-surg floors and step-down units underwent emergency renovations to allow creation of new “pop-up” ICUs. Triage protocols were altered: patients on high levels of supplemental oxygen, who would under normal circumstances have been admitted to an ICU, were triaged to floors and stepdown units. Equipment was reused, modified, and substituted creatively to optimize care for the maximum number of patients.

In the face of all of these struggles, many around the country and the world felt the efforts, though heroic, resulted in less than standard of care. Two subsequent publications validated this concern (Kadri et al. Ann Int Med. 2021,174;9:1240-51; Bravata DM et al. JAMA Open Network. 2021;4[1]:e2034266), demonstrating during severe surge, COVID-19 patients’ mortality increased significantly beyond that seen in non-surging or less-severe surging times, demonstrating a mortality effect of surge itself. Though these studies observed COVID-19 patients only, there is every reason to believe the findings applied to all critically ill patients cared for during these surges.

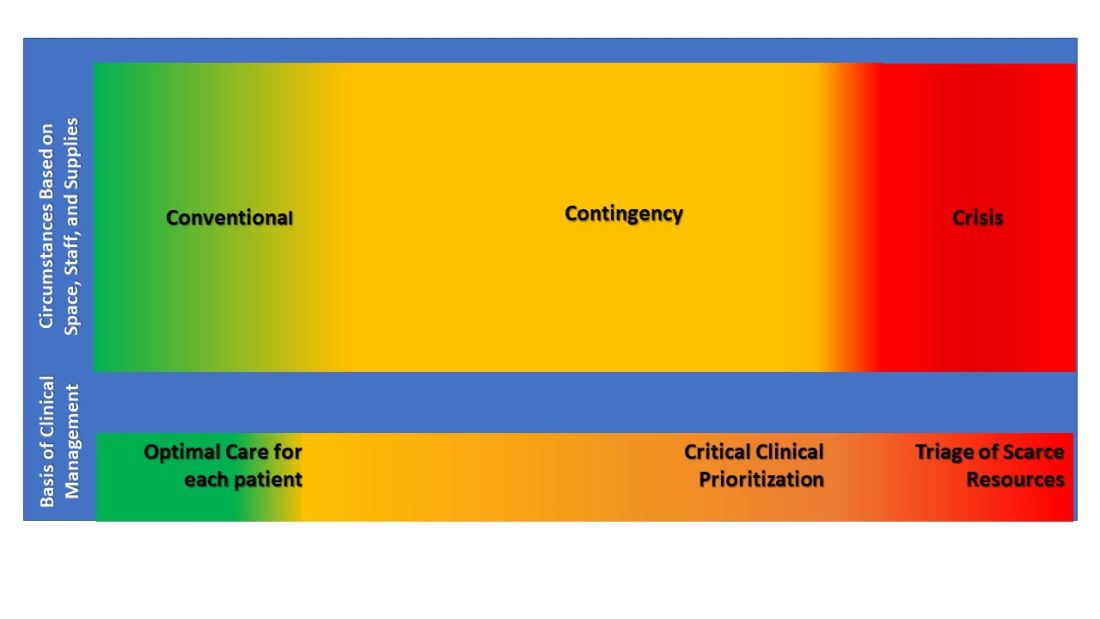

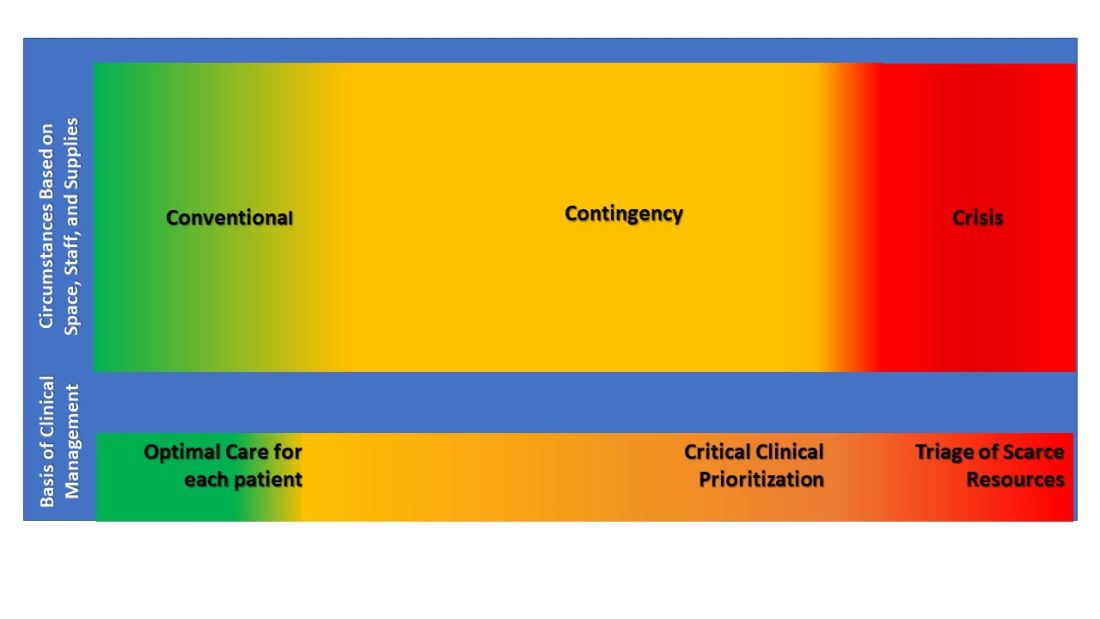

These experiences led the TFMCC to report updated strategies for remaining in contingency care levels and avoiding crisis care (Dichter JR et al. CHEST. 2022;161[2]:429-47). Contingency is equivalent to routine care though may require adaptations and employment of otherwise non-traditional resources. The ultimate goal of mass critical care in a public health emergency is to avoid crisis-operating conditions, crisis standards of care, and their associated challenging triage decisions regarding allocation of scarce resources.

The 10 suggestions included in the most recent TFMCC publication include staffing strategies and suggestions based on COVID-19 experiences for graded staff-to-patient ratios, and support processes to preserve the existing health care work force. Strategies also include reduction of redundant documentation, limiting overtime, and most importantly, approaches for improving teamwork and supporting psychological well-being and resilience. Examples include daily unit huddles to update care and share experiences, genuine intra-team recognition and appreciation, and embedding emotional health experts within teams to provide ongoing support.

Consistent communication between incident command and frontline clinicians was also a suggested priority, perhaps with a newly proposed position of physician clinical support supervisor. This would be a formal role within hospital incident command, a liaison between the two groups.

Surge strategies should include empowerment of bedside clinicians and leaders with both planning and real-time assessment of the clinical situation, as being at the front line of care enables the situational awareness to assess ICU strain most effectively. Further, ICU clinicians must recognize when progression deeper into contingency operations occurs and they become perilously close to crisis mode. At this point, decisions are made and scarce resources are modified beyond routine standards of care to preserve life. TFMCC designates this gray area between contingency and crisis as the Critical Clinical Prioritization level (Figure).

At this point, more resources must be provided, or patients must be transferred to other resourced hospitals.

Critical Clinical Prioritization is an illustration of necessity being the mother of invention, as these are adaptations clinicians devised under duress. Some particularly poignant examples are the spreading of 24 hours of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) resource between two and sometimes three patients to provide life sustainment to all; and when ventilators were in short supply, determining which patients required full ICU ventilator support vs those who could manage with lower functioning ventilators, and trading them between patients when demands changed.

These adaptations can only be done by experienced clinicians proactively managing bedside critical care under duress, further underscoring the importance of our suggestion that Critical Clinical Prioritization and ICU strain be managed by bedside clinicians and leaders.

The response of early transfer of patients – load-balancing - should be considered as soon as any hospital enters contingency conditions. This strategy is commonly implemented within larger health systems, ideally before reaching Critical Clinical Prioritization. Formal, organized state or regional load-balancing coordination, now referred to as medical operations command centers (MOCCs), were highly effective and proved lifesaving for those states that implemented them (including Arizona, Washington, California, Minnesota, and others). Support for establishment of MOCC’s is crucial in prolonging contingency operations and further helps support and protect disadvantaged populations (White et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;385[24]:2211-4).

Establishment of MOCCs has met resistance due to challenges that include interhospital/intersystem competition, logistics of moving critically ill patients sometimes across significant physical distance, and the costs of assuming care of uninsured or underinsured patients. Nevertheless, the benefits to the population as a whole necessitate working through these obstacles as successful MOCCs have done, usually with government and hospital association support.

In their final suggestion of the 2022 updated strategies, TFMCC suggests that hospitals use telemedicine technology both to expand specialists’ ability to provide care and facilitate families virtually visiting their critically ill loved one when safety precludes in-person visits.

These suggestions are pivotal in planning for future public health emergencies that include mass critical care, even during events that are limited in scope and duration.

Lastly, intensivists struggled with legal and ethical concerns when mired in crisis care circumstances and decisions of allocation, and potential reallocation, of scarce resources. These issues were not well addressed during the COVID-19 pandemic, further emphasizing the importance of maintaining contingency level care and requiring further involvement from legal and medical ethics professionals for future planning.

The guiding principle of disaster preparedness is that we must do all the planning we can to ensure that we never need crisis standards of care (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020 Mar 28. Rapid Expert Consultation on Crisis Standards of Care for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.).

We must be prepared. Guidelines and suggestions laid out through decades of experience gained a real-world test in the COVID-19 pandemic. Now we must all reorganize and create new plans or augment old ones with the information we have gained. The time is now. The work must continue.

Dr. Griffin is Assistant Professor of Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital – Weill Cornell Medicine. Dr. Dichter is Associate Professor of Medicine, University of Minnesota.

In 2014, the Task Force for Mass Critical Care (TFMCC) published a CHEST consensus statement on disaster preparedness principles in caring for the critically ill during disasters and pandemics (Christian et al. CHEST. 2014;146[4_suppl]:8s-34s). This publication attempted to guide preparedness for both single-event disasters and more prolonged events, including a feared influenza pandemic.

Despite the foundation of planning and support this guidance provided, the COVID-19 pandemic response revealed substantial gaps in our understanding and preparedness for these more prolonged and widespread events.

In New York City, as the first COVID-19 wave began in March and April of 2020, area hospitals responded with surge plans that prioritized what was felt to be most important (Griffin et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Jun 1;201[11]:1337-44). Tiered, creative staffing structures were rapidly created with intensivists supervising non-ICU physicians and APPs. Procedure teams were created for intubation, proning, and central line placement. ICU space was created with adaptations to ORs and PACUs, and rooms on med-surg floors and step-down units underwent emergency renovations to allow creation of new “pop-up” ICUs. Triage protocols were altered: patients on high levels of supplemental oxygen, who would under normal circumstances have been admitted to an ICU, were triaged to floors and stepdown units. Equipment was reused, modified, and substituted creatively to optimize care for the maximum number of patients.

In the face of all of these struggles, many around the country and the world felt the efforts, though heroic, resulted in less than standard of care. Two subsequent publications validated this concern (Kadri et al. Ann Int Med. 2021,174;9:1240-51; Bravata DM et al. JAMA Open Network. 2021;4[1]:e2034266), demonstrating during severe surge, COVID-19 patients’ mortality increased significantly beyond that seen in non-surging or less-severe surging times, demonstrating a mortality effect of surge itself. Though these studies observed COVID-19 patients only, there is every reason to believe the findings applied to all critically ill patients cared for during these surges.

These experiences led the TFMCC to report updated strategies for remaining in contingency care levels and avoiding crisis care (Dichter JR et al. CHEST. 2022;161[2]:429-47). Contingency is equivalent to routine care though may require adaptations and employment of otherwise non-traditional resources. The ultimate goal of mass critical care in a public health emergency is to avoid crisis-operating conditions, crisis standards of care, and their associated challenging triage decisions regarding allocation of scarce resources.

The 10 suggestions included in the most recent TFMCC publication include staffing strategies and suggestions based on COVID-19 experiences for graded staff-to-patient ratios, and support processes to preserve the existing health care work force. Strategies also include reduction of redundant documentation, limiting overtime, and most importantly, approaches for improving teamwork and supporting psychological well-being and resilience. Examples include daily unit huddles to update care and share experiences, genuine intra-team recognition and appreciation, and embedding emotional health experts within teams to provide ongoing support.

Consistent communication between incident command and frontline clinicians was also a suggested priority, perhaps with a newly proposed position of physician clinical support supervisor. This would be a formal role within hospital incident command, a liaison between the two groups.

Surge strategies should include empowerment of bedside clinicians and leaders with both planning and real-time assessment of the clinical situation, as being at the front line of care enables the situational awareness to assess ICU strain most effectively. Further, ICU clinicians must recognize when progression deeper into contingency operations occurs and they become perilously close to crisis mode. At this point, decisions are made and scarce resources are modified beyond routine standards of care to preserve life. TFMCC designates this gray area between contingency and crisis as the Critical Clinical Prioritization level (Figure).

At this point, more resources must be provided, or patients must be transferred to other resourced hospitals.

Critical Clinical Prioritization is an illustration of necessity being the mother of invention, as these are adaptations clinicians devised under duress. Some particularly poignant examples are the spreading of 24 hours of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) resource between two and sometimes three patients to provide life sustainment to all; and when ventilators were in short supply, determining which patients required full ICU ventilator support vs those who could manage with lower functioning ventilators, and trading them between patients when demands changed.

These adaptations can only be done by experienced clinicians proactively managing bedside critical care under duress, further underscoring the importance of our suggestion that Critical Clinical Prioritization and ICU strain be managed by bedside clinicians and leaders.

The response of early transfer of patients – load-balancing - should be considered as soon as any hospital enters contingency conditions. This strategy is commonly implemented within larger health systems, ideally before reaching Critical Clinical Prioritization. Formal, organized state or regional load-balancing coordination, now referred to as medical operations command centers (MOCCs), were highly effective and proved lifesaving for those states that implemented them (including Arizona, Washington, California, Minnesota, and others). Support for establishment of MOCC’s is crucial in prolonging contingency operations and further helps support and protect disadvantaged populations (White et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;385[24]:2211-4).

Establishment of MOCCs has met resistance due to challenges that include interhospital/intersystem competition, logistics of moving critically ill patients sometimes across significant physical distance, and the costs of assuming care of uninsured or underinsured patients. Nevertheless, the benefits to the population as a whole necessitate working through these obstacles as successful MOCCs have done, usually with government and hospital association support.

In their final suggestion of the 2022 updated strategies, TFMCC suggests that hospitals use telemedicine technology both to expand specialists’ ability to provide care and facilitate families virtually visiting their critically ill loved one when safety precludes in-person visits.

These suggestions are pivotal in planning for future public health emergencies that include mass critical care, even during events that are limited in scope and duration.

Lastly, intensivists struggled with legal and ethical concerns when mired in crisis care circumstances and decisions of allocation, and potential reallocation, of scarce resources. These issues were not well addressed during the COVID-19 pandemic, further emphasizing the importance of maintaining contingency level care and requiring further involvement from legal and medical ethics professionals for future planning.

The guiding principle of disaster preparedness is that we must do all the planning we can to ensure that we never need crisis standards of care (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020 Mar 28. Rapid Expert Consultation on Crisis Standards of Care for the COVID-19 Pandemic. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.).

We must be prepared. Guidelines and suggestions laid out through decades of experience gained a real-world test in the COVID-19 pandemic. Now we must all reorganize and create new plans or augment old ones with the information we have gained. The time is now. The work must continue.

Dr. Griffin is Assistant Professor of Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital – Weill Cornell Medicine. Dr. Dichter is Associate Professor of Medicine, University of Minnesota.

Patients need Sep-1: Why don’t some doctors like it?

Since its inception, the CMS Sep-1 Core Quality Measure has been unpopular in some circles. It is now under official attack by the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), along with a handful of smaller professional societies. These societies appealed the National Quality Forum’s (NQF) 2021 recommendation that the measure be renewed. The NQF is the multidisciplinary and broadly representative group of evaluators who evaluate proposals for CMS-sponsored quality improvement on behalf of the American people and of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Readers of CHEST Physician are likely familiar with core measures, in general, and with Sep-1, in particular. CMS requires hospitals to publicly report their compliance with several Core Quality Measures, and the failure to do so results in across the board reductions in Medicare payments. As of now, no penalties are levied for the degree of compliance but only for failure to report the degree of compliance.

The measure asks, in the main, for hospitals to perform what most physicians can agree should be standard care for patients with sepsis. Depending on whether shock is present, the measure requires:

1. Blood cultures before antibiotics

2. Antibiotics within 3 hours of recognition of sepsis

3. Serum lactate measurement in the first 3 hours and, if increased, a repeat measurement by 6 hours

4. If the patient is hypotensive, 30 mL/kg IV crystalloid within 3 hours, or documentation of why that is not appropriate for the patient

5. If hypotension persists, vasopressors within 6 hours

6. Repeat cardiovascular assessment within 6 hours for patients with shock

If I evaluate these criteria as a patient who has been hospitalized for a serious infection, which I am, they do not seem particularly stringent. In fact, as a patient, I would want my doctors and nurses to act substantially faster than this if I had sepsis or septic shock. If my doctor did not come back in less than 6 hours to check on my shock status, I would be disappointed, to say the least. Nevertheless, some physicians and professional societies see no reason why these should be standards and state that the data underlying them are of low quality. Meanwhile, according to CMS’ own careful evaluation, national compliance with the measures is less than 50%, while being compliant with the measures reduces absolute overall mortality by approximately 4%, from 26.3% to 22.2% (Townsend SR et al. Chest. 2022;161[2]:392-406). This would translate to between 14,000 and 15,000 fewer patients dying from sepsis per year, if all patients received bundled, measure-compliant care. These are patients I don’t care to ignore.

ACEP and IDSA point specifically to the new Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines (SSC) recommendations as evidence that the antibiotic measure is based on low quality evidence (Evans L et al. Crit Care Med. 2021;49[11]:1974-82). In this regard, they are technically correct; the system of evidence review that the SSC panel uses, Grading of Assessment, Recommendations, and Evaluation (GRADE), considers that retrospective analyses, which nearly all of these studies are, can be graded no higher than low quality. Clearly, retrospective studies will never achieve the level of certainty that we achieve with randomized controlled trials, but the NQF, itself, typically views that when a number of well-performed retrospective studies point in the same direction, the level of evidence is at least moderate. After all, just as it would be inappropriate to randomize participants to decades of smoking vs nonsmoking in order prove that smoking causes lung cancer, it is not appropriate to randomize patients with sepsis to receive delayed antibiotics before we accept that such delays are harmful to them.

ACEP and IDSA also assert that the association of early antibiotics with survival is “stronger” for septic shock than for sepsis. In fact, the association is quite strong for both severities of illness. Until it progresses to septic shock, the expected mortality of sepsis is lower, and the percent reduction in mortality is less than for septic shock. However, the opportunity for lives preserved is quite large, because the number of patients with sepsis at presentation is approximately 10 times higher than the number with septic shock at presentation. Antibiotic delays are also associated with progression from infection or sepsis to septic shock (Whiles BB et al. Crit Care Med. 2017;45[4]:623-29; Bisarya R et al. Chest. 2022;161[1]:112-20). Importantly, SSC gave a strong recommendation for all patients with suspected sepsis to receive antibiotics within 3 hours of suspecting sepsis and within 1 hour of suspecting septic shock, a recommendation even stronger than that of Sep-1.

Critics opine that CMS should stop looking at the process measures and focus only on the outcomes of sepsis care. There is a certain attractiveness to this proposition. One could say that it does not matter so much how a hospital achieves lower mortality as long as they do achieve it. However, the question would then become – how low should the mortality rate be? I have a notion that whatever the number, the Sep-1 critics would find it unbearable.

There is a core principle embedded in the Sep-1 process measures, in SSC guidelines, and in the concept of early goal-directed therapy that preceded them: success is not dependent only on what we do but on when we do it. All of you have experienced this. Each of you has attended a professional school, whether medical, nursing, respiratory therapy, etc. None of you showed up unannounced on opening day of the semester and was admitted to that school. All of you garnered the grades, solicited the letters of recommendation, took the entrance exams, and submitted an application. Some of you went to an interview. All of these things were done in a timely fashion; professional schools do not accept incomplete applications or late applications. Doing the right things at the wrong time would have left us all pursuing different careers.

Very early in my career as an attending physician in the ICU, I found myself exasperated by the circumstances of many patients who we received in the ICU with sepsis. I would peruse their medical records and find that they had been septic, ie, had met criteria for severe sepsis, 1 to 2 days before their deterioration to septic shock, yet they had not been diagnosed with sepsis until shock developed. In the ICU, we began resuscitative fluids, ensured appropriate antibiotics, and started vasopressors, but it was often to no avail. The treatments we gave made no difference for many patients, because they were given too late. For me, this was career altering; much of my career since that time has focused on teaching medical personnel how to recognize sepsis, how to give timely and appropriate treatments, and how to keep the data to show when they have done that and when they have not.

Before Sep-1 many, if not most, of the hospitals in the United States had no particular strategy in place to recognize and treat patients with sepsis, even though it was and is the most common cause of death and the costliest condition in American hospitals. Now, most hospitals do have such strategies. Assertions by professional societies that it is difficult to collect the data for Sep-1 reporting are likely true. However, keeping patients safe and alive is a hospital’s primary reason for existing. As long as hospitals are tracking each antibiotic and every liter of fluid so that they can bill for them, my own ears are deaf to hearing that it is too difficult to make sure that we are doing our job. Modifying or eliminating Sep-1 for any reason except data that show we can clearly further improve the outcome for all patients with sepsis is the wrong move to make. So far, other professional societies want to remove elements of Sep-1 without evidence that it would improve our care for patients with sepsis or their outcomes. Thankfully, from the time we proposed the first criteria for diagnosing sepsis, CHEST has promoted what is best for patients, whether it is difficult or not.

Dr. Simpson is a pulmonologist and intensivist with an extensive background in sepsis and in critical care quality improvement, including by serving as a senior adviser to the Solving Sepsis initiative of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and an author of the 2016 and 2020 updates of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines. Dr. Simpson is the senior medical adviser for Sepsis Alliance, a nationwide patient information and advocacy organization. He is the immediate past president of CHEST.

Since its inception, the CMS Sep-1 Core Quality Measure has been unpopular in some circles. It is now under official attack by the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), along with a handful of smaller professional societies. These societies appealed the National Quality Forum’s (NQF) 2021 recommendation that the measure be renewed. The NQF is the multidisciplinary and broadly representative group of evaluators who evaluate proposals for CMS-sponsored quality improvement on behalf of the American people and of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Readers of CHEST Physician are likely familiar with core measures, in general, and with Sep-1, in particular. CMS requires hospitals to publicly report their compliance with several Core Quality Measures, and the failure to do so results in across the board reductions in Medicare payments. As of now, no penalties are levied for the degree of compliance but only for failure to report the degree of compliance.

The measure asks, in the main, for hospitals to perform what most physicians can agree should be standard care for patients with sepsis. Depending on whether shock is present, the measure requires:

1. Blood cultures before antibiotics

2. Antibiotics within 3 hours of recognition of sepsis

3. Serum lactate measurement in the first 3 hours and, if increased, a repeat measurement by 6 hours

4. If the patient is hypotensive, 30 mL/kg IV crystalloid within 3 hours, or documentation of why that is not appropriate for the patient

5. If hypotension persists, vasopressors within 6 hours

6. Repeat cardiovascular assessment within 6 hours for patients with shock

If I evaluate these criteria as a patient who has been hospitalized for a serious infection, which I am, they do not seem particularly stringent. In fact, as a patient, I would want my doctors and nurses to act substantially faster than this if I had sepsis or septic shock. If my doctor did not come back in less than 6 hours to check on my shock status, I would be disappointed, to say the least. Nevertheless, some physicians and professional societies see no reason why these should be standards and state that the data underlying them are of low quality. Meanwhile, according to CMS’ own careful evaluation, national compliance with the measures is less than 50%, while being compliant with the measures reduces absolute overall mortality by approximately 4%, from 26.3% to 22.2% (Townsend SR et al. Chest. 2022;161[2]:392-406). This would translate to between 14,000 and 15,000 fewer patients dying from sepsis per year, if all patients received bundled, measure-compliant care. These are patients I don’t care to ignore.

ACEP and IDSA point specifically to the new Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines (SSC) recommendations as evidence that the antibiotic measure is based on low quality evidence (Evans L et al. Crit Care Med. 2021;49[11]:1974-82). In this regard, they are technically correct; the system of evidence review that the SSC panel uses, Grading of Assessment, Recommendations, and Evaluation (GRADE), considers that retrospective analyses, which nearly all of these studies are, can be graded no higher than low quality. Clearly, retrospective studies will never achieve the level of certainty that we achieve with randomized controlled trials, but the NQF, itself, typically views that when a number of well-performed retrospective studies point in the same direction, the level of evidence is at least moderate. After all, just as it would be inappropriate to randomize participants to decades of smoking vs nonsmoking in order prove that smoking causes lung cancer, it is not appropriate to randomize patients with sepsis to receive delayed antibiotics before we accept that such delays are harmful to them.

ACEP and IDSA also assert that the association of early antibiotics with survival is “stronger” for septic shock than for sepsis. In fact, the association is quite strong for both severities of illness. Until it progresses to septic shock, the expected mortality of sepsis is lower, and the percent reduction in mortality is less than for septic shock. However, the opportunity for lives preserved is quite large, because the number of patients with sepsis at presentation is approximately 10 times higher than the number with septic shock at presentation. Antibiotic delays are also associated with progression from infection or sepsis to septic shock (Whiles BB et al. Crit Care Med. 2017;45[4]:623-29; Bisarya R et al. Chest. 2022;161[1]:112-20). Importantly, SSC gave a strong recommendation for all patients with suspected sepsis to receive antibiotics within 3 hours of suspecting sepsis and within 1 hour of suspecting septic shock, a recommendation even stronger than that of Sep-1.

Critics opine that CMS should stop looking at the process measures and focus only on the outcomes of sepsis care. There is a certain attractiveness to this proposition. One could say that it does not matter so much how a hospital achieves lower mortality as long as they do achieve it. However, the question would then become – how low should the mortality rate be? I have a notion that whatever the number, the Sep-1 critics would find it unbearable.