User login

Preventive Effect of Maternal Probiotic Supplementation in Atopic Dermatitis

Key clinical point: Maternal probiotic supplementation was effective in preventing atopic dermatitis (AD) in children regardless of their filaggrin (FLG) gene mutation status.

Major finding: Heterozygous FLG mutations were observed in 7% of children. The risk for AD after maternal probiotic supplementation was similar between children who expressed a FLG mutation (risk ratio [RR] 0.6; 95% CI 0.1-4.1) and those having a wild-type FLG (RR 0.6; 95% CI 0.4-0.9).

Study details: This exploratory study included the data of 228 children from the Probiotic in the Prevention of Allergy among Children in Trondheim (ProPACT) study who did or did not have FLG mutations and whose mothers received probiotic or placebo milk from 36 weeks of gestation until 3 months post delivery while breastfeeding.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Liaison Committee between the Central Norway Regional Health Authority and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, and the Norwegian Research Council. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Zakiudin DP, Thyssen JP, Zachariae C, Videm V, Øien T, Simpson MR. Filaggrin mutation status and prevention of atopic dermatitis with maternal probiotic supplementation. Acta Derm Venereol. 2024;104:adv24360 (Apr 24). doi: 10.2340/actadv.v104.24360 Source

Key clinical point: Maternal probiotic supplementation was effective in preventing atopic dermatitis (AD) in children regardless of their filaggrin (FLG) gene mutation status.

Major finding: Heterozygous FLG mutations were observed in 7% of children. The risk for AD after maternal probiotic supplementation was similar between children who expressed a FLG mutation (risk ratio [RR] 0.6; 95% CI 0.1-4.1) and those having a wild-type FLG (RR 0.6; 95% CI 0.4-0.9).

Study details: This exploratory study included the data of 228 children from the Probiotic in the Prevention of Allergy among Children in Trondheim (ProPACT) study who did or did not have FLG mutations and whose mothers received probiotic or placebo milk from 36 weeks of gestation until 3 months post delivery while breastfeeding.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Liaison Committee between the Central Norway Regional Health Authority and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, and the Norwegian Research Council. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Zakiudin DP, Thyssen JP, Zachariae C, Videm V, Øien T, Simpson MR. Filaggrin mutation status and prevention of atopic dermatitis with maternal probiotic supplementation. Acta Derm Venereol. 2024;104:adv24360 (Apr 24). doi: 10.2340/actadv.v104.24360 Source

Key clinical point: Maternal probiotic supplementation was effective in preventing atopic dermatitis (AD) in children regardless of their filaggrin (FLG) gene mutation status.

Major finding: Heterozygous FLG mutations were observed in 7% of children. The risk for AD after maternal probiotic supplementation was similar between children who expressed a FLG mutation (risk ratio [RR] 0.6; 95% CI 0.1-4.1) and those having a wild-type FLG (RR 0.6; 95% CI 0.4-0.9).

Study details: This exploratory study included the data of 228 children from the Probiotic in the Prevention of Allergy among Children in Trondheim (ProPACT) study who did or did not have FLG mutations and whose mothers received probiotic or placebo milk from 36 weeks of gestation until 3 months post delivery while breastfeeding.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Liaison Committee between the Central Norway Regional Health Authority and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, and the Norwegian Research Council. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Zakiudin DP, Thyssen JP, Zachariae C, Videm V, Øien T, Simpson MR. Filaggrin mutation status and prevention of atopic dermatitis with maternal probiotic supplementation. Acta Derm Venereol. 2024;104:adv24360 (Apr 24). doi: 10.2340/actadv.v104.24360 Source

Pharmacological Interventions in Atopic Dermatitis Reduce Anxiety and Depression

Key clinical point: Pharmacological interventions aimed at reducing disease severity in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) are also effective for improving anxiety and depression.

Major finding: Pharmacologic interventions for AD led to significant improvements in anxiety levels (standardized mean difference [SMD] −0.29; 95% CI −0.49 to −0.09) and depression severity (SMD −0.27; 95% CI −0.45 to −0.08) and an overall significant improvement in Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale scores (SMD −0.50; 95% CI −0.064 to −0.35).

Study details: This meta-analysis of seven phase 2b or 3 randomized controlled trials included 4723 patients with AD who were treated with either abrocitinib, baricitinib, dupilumab, tralokinumab, or placebo.

Disclosures: This study did not disclose any funding source. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Hartono SP, Chatrath S, Aktas ON, et al. Interventions for anxiety and depression in patients with atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:8844 (Apr 17). Source

Key clinical point: Pharmacological interventions aimed at reducing disease severity in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) are also effective for improving anxiety and depression.

Major finding: Pharmacologic interventions for AD led to significant improvements in anxiety levels (standardized mean difference [SMD] −0.29; 95% CI −0.49 to −0.09) and depression severity (SMD −0.27; 95% CI −0.45 to −0.08) and an overall significant improvement in Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale scores (SMD −0.50; 95% CI −0.064 to −0.35).

Study details: This meta-analysis of seven phase 2b or 3 randomized controlled trials included 4723 patients with AD who were treated with either abrocitinib, baricitinib, dupilumab, tralokinumab, or placebo.

Disclosures: This study did not disclose any funding source. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Hartono SP, Chatrath S, Aktas ON, et al. Interventions for anxiety and depression in patients with atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:8844 (Apr 17). Source

Key clinical point: Pharmacological interventions aimed at reducing disease severity in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) are also effective for improving anxiety and depression.

Major finding: Pharmacologic interventions for AD led to significant improvements in anxiety levels (standardized mean difference [SMD] −0.29; 95% CI −0.49 to −0.09) and depression severity (SMD −0.27; 95% CI −0.45 to −0.08) and an overall significant improvement in Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale scores (SMD −0.50; 95% CI −0.064 to −0.35).

Study details: This meta-analysis of seven phase 2b or 3 randomized controlled trials included 4723 patients with AD who were treated with either abrocitinib, baricitinib, dupilumab, tralokinumab, or placebo.

Disclosures: This study did not disclose any funding source. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Hartono SP, Chatrath S, Aktas ON, et al. Interventions for anxiety and depression in patients with atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:8844 (Apr 17). Source

Comparable Efficacy of Tralokinumab and Dupilumab in Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis

Key clinical point: When combined with topical corticosteroids (TCS), tralokinumab and dupilumab demonstrate similar efficacy in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) at 32 weeks of therapy.

Major finding: At week 32, tralokinumab and dupilumab treatment, both in combination with TCS, led to a similar proportion of patients achieving an Investigator's Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 (49.9% vs 39.3%; P = .95) or 75% improvement in the Eczema Area Severity Index scores (71.5% vs 71.9%; P = .95).

Study details: This unanchored matching-adjusted indirect comparison study analyzed the individual patient data of adults with moderate to severe AD (sample size 123.4) treated with tralokinumab plus TCS in ECZTRA 3, which were matched with the aggregate data of 106 patients treated with dupilumab plus TCS in the LIBERTY AD CHRONOS trial.

Disclosures: This study was funded by LEO Pharma. Four authors declared being employees of LEO Pharma. The other authors declared receiving consultancy or speaker honoraria from or having other ties with various sources, including LEO Pharma.

Source: Torres T, Sohrt Petersen A, Ivens U, et al. Matching-adjusted indirect comparison of the efficacy at week 32 of tralokinumab and dupilumab in the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024;14:983-992 (Apr 13). doi: 10.1007/s13555-024-01143-x Source

Key clinical point: When combined with topical corticosteroids (TCS), tralokinumab and dupilumab demonstrate similar efficacy in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) at 32 weeks of therapy.

Major finding: At week 32, tralokinumab and dupilumab treatment, both in combination with TCS, led to a similar proportion of patients achieving an Investigator's Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 (49.9% vs 39.3%; P = .95) or 75% improvement in the Eczema Area Severity Index scores (71.5% vs 71.9%; P = .95).

Study details: This unanchored matching-adjusted indirect comparison study analyzed the individual patient data of adults with moderate to severe AD (sample size 123.4) treated with tralokinumab plus TCS in ECZTRA 3, which were matched with the aggregate data of 106 patients treated with dupilumab plus TCS in the LIBERTY AD CHRONOS trial.

Disclosures: This study was funded by LEO Pharma. Four authors declared being employees of LEO Pharma. The other authors declared receiving consultancy or speaker honoraria from or having other ties with various sources, including LEO Pharma.

Source: Torres T, Sohrt Petersen A, Ivens U, et al. Matching-adjusted indirect comparison of the efficacy at week 32 of tralokinumab and dupilumab in the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024;14:983-992 (Apr 13). doi: 10.1007/s13555-024-01143-x Source

Key clinical point: When combined with topical corticosteroids (TCS), tralokinumab and dupilumab demonstrate similar efficacy in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) at 32 weeks of therapy.

Major finding: At week 32, tralokinumab and dupilumab treatment, both in combination with TCS, led to a similar proportion of patients achieving an Investigator's Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 (49.9% vs 39.3%; P = .95) or 75% improvement in the Eczema Area Severity Index scores (71.5% vs 71.9%; P = .95).

Study details: This unanchored matching-adjusted indirect comparison study analyzed the individual patient data of adults with moderate to severe AD (sample size 123.4) treated with tralokinumab plus TCS in ECZTRA 3, which were matched with the aggregate data of 106 patients treated with dupilumab plus TCS in the LIBERTY AD CHRONOS trial.

Disclosures: This study was funded by LEO Pharma. Four authors declared being employees of LEO Pharma. The other authors declared receiving consultancy or speaker honoraria from or having other ties with various sources, including LEO Pharma.

Source: Torres T, Sohrt Petersen A, Ivens U, et al. Matching-adjusted indirect comparison of the efficacy at week 32 of tralokinumab and dupilumab in the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024;14:983-992 (Apr 13). doi: 10.1007/s13555-024-01143-x Source

Topical Ruxolitinib Provides Long-Term Disease Control in Adolescents With Atopic Dermatitis

Key clinical point: Topical 1.5% ruxolitinib was effective and well-tolerated and offered long-term disease control with as-needed use in adolescents with atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At week 8, a substantially higher number of patients receiving 1.5% ruxolitinib vs vehicle achieved an Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1 with ≥2 grade improvement from baseline (50.6% vs 14.0%) and ≥75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index score (60.9% vs 34.9%), with sustained or increased proportion of patients achieving an IGA score of 0 or 1 during the long-term safety (LTS) period. No serious adverse events were reported.

Study details: This study used pooled data from two phase 3 trials (TRuE-AD1 and TRuE-AD2) and included 137 adolescents (age, 12-17 years) with AD who were randomly assigned to receive 0.75% or 1.5% ruxolitinib cream or vehicle twice daily for 8 weeks, followed by an LTS period lasting up to 52 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Incyte Corporation. Four authors declared being employees or shareholders of Incyte Corporation. Several authors declared ties with various sources, including Incyte Corporation.

Source: Eichenfield LF, Simpson EL, Papp K, et al. Efficacy, safety, and long-term disease control of ruxolitinib cream among adolescents with atopic dermatitis: Pooled results from two randomized phase 3 studies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2024 (May 2). doi: 10.1007/s40257-024-00855-2 Source

Key clinical point: Topical 1.5% ruxolitinib was effective and well-tolerated and offered long-term disease control with as-needed use in adolescents with atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At week 8, a substantially higher number of patients receiving 1.5% ruxolitinib vs vehicle achieved an Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1 with ≥2 grade improvement from baseline (50.6% vs 14.0%) and ≥75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index score (60.9% vs 34.9%), with sustained or increased proportion of patients achieving an IGA score of 0 or 1 during the long-term safety (LTS) period. No serious adverse events were reported.

Study details: This study used pooled data from two phase 3 trials (TRuE-AD1 and TRuE-AD2) and included 137 adolescents (age, 12-17 years) with AD who were randomly assigned to receive 0.75% or 1.5% ruxolitinib cream or vehicle twice daily for 8 weeks, followed by an LTS period lasting up to 52 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Incyte Corporation. Four authors declared being employees or shareholders of Incyte Corporation. Several authors declared ties with various sources, including Incyte Corporation.

Source: Eichenfield LF, Simpson EL, Papp K, et al. Efficacy, safety, and long-term disease control of ruxolitinib cream among adolescents with atopic dermatitis: Pooled results from two randomized phase 3 studies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2024 (May 2). doi: 10.1007/s40257-024-00855-2 Source

Key clinical point: Topical 1.5% ruxolitinib was effective and well-tolerated and offered long-term disease control with as-needed use in adolescents with atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At week 8, a substantially higher number of patients receiving 1.5% ruxolitinib vs vehicle achieved an Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1 with ≥2 grade improvement from baseline (50.6% vs 14.0%) and ≥75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index score (60.9% vs 34.9%), with sustained or increased proportion of patients achieving an IGA score of 0 or 1 during the long-term safety (LTS) period. No serious adverse events were reported.

Study details: This study used pooled data from two phase 3 trials (TRuE-AD1 and TRuE-AD2) and included 137 adolescents (age, 12-17 years) with AD who were randomly assigned to receive 0.75% or 1.5% ruxolitinib cream or vehicle twice daily for 8 weeks, followed by an LTS period lasting up to 52 weeks.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Incyte Corporation. Four authors declared being employees or shareholders of Incyte Corporation. Several authors declared ties with various sources, including Incyte Corporation.

Source: Eichenfield LF, Simpson EL, Papp K, et al. Efficacy, safety, and long-term disease control of ruxolitinib cream among adolescents with atopic dermatitis: Pooled results from two randomized phase 3 studies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2024 (May 2). doi: 10.1007/s40257-024-00855-2 Source

Obesity Associated With Disease Severity in Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis

Key clinical point: Obesity is significantly associated with patient- and physician-assessed measures of atopic dermatitis (AD) disease severity.

Major finding: Increased body mass index (BMI) values were associated with higher disease severity as assessed by objective Scoring AD (adjusted β 1.24; P = .013) and patient-oriented eczema measure (adjusted β 1.09; P = .038) scores.

Study details: This study based on data from the prospective observational TREATgermany registry included 1416 patients with moderate to severe AD who were either underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2; n = 33), normal weight or overweight (nonobese; BMI ≥ 18.5 and < 30 kg/m2; n = 1149), or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2; n = 234).

Disclosures: The TREATgermany registry is supported by AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG, Galderma SA, LEO Pharma GmbH, Lilly Deutschland GmbH, Pfizer Inc., and Sanofi. Eight authors declared serving as consultants or lecturers for or receiving research grants, personal fees, or lecture or consulting honoraria from various sources, including some of the supporters of TREATgermany.

Source: Traidl S, Hollstein MM, Kroeger N, et al, and The TREATgermany Study Group. Obesity is linked to disease severity in moderate to severe atopic dermatitis—Data from the prospective observational TREATgermany registry. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024 (Apr 25). doi: 10.1111/jdv.20042 Source

Key clinical point: Obesity is significantly associated with patient- and physician-assessed measures of atopic dermatitis (AD) disease severity.

Major finding: Increased body mass index (BMI) values were associated with higher disease severity as assessed by objective Scoring AD (adjusted β 1.24; P = .013) and patient-oriented eczema measure (adjusted β 1.09; P = .038) scores.

Study details: This study based on data from the prospective observational TREATgermany registry included 1416 patients with moderate to severe AD who were either underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2; n = 33), normal weight or overweight (nonobese; BMI ≥ 18.5 and < 30 kg/m2; n = 1149), or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2; n = 234).

Disclosures: The TREATgermany registry is supported by AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG, Galderma SA, LEO Pharma GmbH, Lilly Deutschland GmbH, Pfizer Inc., and Sanofi. Eight authors declared serving as consultants or lecturers for or receiving research grants, personal fees, or lecture or consulting honoraria from various sources, including some of the supporters of TREATgermany.

Source: Traidl S, Hollstein MM, Kroeger N, et al, and The TREATgermany Study Group. Obesity is linked to disease severity in moderate to severe atopic dermatitis—Data from the prospective observational TREATgermany registry. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024 (Apr 25). doi: 10.1111/jdv.20042 Source

Key clinical point: Obesity is significantly associated with patient- and physician-assessed measures of atopic dermatitis (AD) disease severity.

Major finding: Increased body mass index (BMI) values were associated with higher disease severity as assessed by objective Scoring AD (adjusted β 1.24; P = .013) and patient-oriented eczema measure (adjusted β 1.09; P = .038) scores.

Study details: This study based on data from the prospective observational TREATgermany registry included 1416 patients with moderate to severe AD who were either underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2; n = 33), normal weight or overweight (nonobese; BMI ≥ 18.5 and < 30 kg/m2; n = 1149), or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2; n = 234).

Disclosures: The TREATgermany registry is supported by AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG, Galderma SA, LEO Pharma GmbH, Lilly Deutschland GmbH, Pfizer Inc., and Sanofi. Eight authors declared serving as consultants or lecturers for or receiving research grants, personal fees, or lecture or consulting honoraria from various sources, including some of the supporters of TREATgermany.

Source: Traidl S, Hollstein MM, Kroeger N, et al, and The TREATgermany Study Group. Obesity is linked to disease severity in moderate to severe atopic dermatitis—Data from the prospective observational TREATgermany registry. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024 (Apr 25). doi: 10.1111/jdv.20042 Source

Antibiotics in Early Infancy Disrupt Gut Microbiome and Increase Risk for Atopic Dermatitis

Key clinical point: Antibiotic use early in life, especially within one year of age, disrupts the gut microbiome and increases the risk for atopic dermatitis (AD) at 5 years of age.

Major finding: Children who received antibiotics during the first year of life vs later were significantly more likely to develop AD at 5 years of age (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.81; P < .001), with an increased number of antibiotic courses leading to a dose-response-like increased risk for AD (1 course: aOR 1.67; P = .0044; ≥ 2 courses: aOR 2.16; P = .0030).

Study details: This study analyzed the clinical data for AD diagnosis at age 5 years of 2484 children from the prospective, general population CHILD birth cohort, which enrolled pregnant women and infants with no congenital abnormalities born at ≥ 34 weeks of gestation.

Disclosures: The CHILD Study is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Allergy, Genes, and Environment Network of Centres of Excellence, Debbie and Don Morrison, and others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Hoskinson C, Medeleanu MV, Reyna ME, et al. Antibiotics within first year are linked to infant gut microbiome disruption and elevated atopic dermatitis risk. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024 (Apr 24). doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2024.03.025 Source

Key clinical point: Antibiotic use early in life, especially within one year of age, disrupts the gut microbiome and increases the risk for atopic dermatitis (AD) at 5 years of age.

Major finding: Children who received antibiotics during the first year of life vs later were significantly more likely to develop AD at 5 years of age (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.81; P < .001), with an increased number of antibiotic courses leading to a dose-response-like increased risk for AD (1 course: aOR 1.67; P = .0044; ≥ 2 courses: aOR 2.16; P = .0030).

Study details: This study analyzed the clinical data for AD diagnosis at age 5 years of 2484 children from the prospective, general population CHILD birth cohort, which enrolled pregnant women and infants with no congenital abnormalities born at ≥ 34 weeks of gestation.

Disclosures: The CHILD Study is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Allergy, Genes, and Environment Network of Centres of Excellence, Debbie and Don Morrison, and others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Hoskinson C, Medeleanu MV, Reyna ME, et al. Antibiotics within first year are linked to infant gut microbiome disruption and elevated atopic dermatitis risk. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024 (Apr 24). doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2024.03.025 Source

Key clinical point: Antibiotic use early in life, especially within one year of age, disrupts the gut microbiome and increases the risk for atopic dermatitis (AD) at 5 years of age.

Major finding: Children who received antibiotics during the first year of life vs later were significantly more likely to develop AD at 5 years of age (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.81; P < .001), with an increased number of antibiotic courses leading to a dose-response-like increased risk for AD (1 course: aOR 1.67; P = .0044; ≥ 2 courses: aOR 2.16; P = .0030).

Study details: This study analyzed the clinical data for AD diagnosis at age 5 years of 2484 children from the prospective, general population CHILD birth cohort, which enrolled pregnant women and infants with no congenital abnormalities born at ≥ 34 weeks of gestation.

Disclosures: The CHILD Study is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Allergy, Genes, and Environment Network of Centres of Excellence, Debbie and Don Morrison, and others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Hoskinson C, Medeleanu MV, Reyna ME, et al. Antibiotics within first year are linked to infant gut microbiome disruption and elevated atopic dermatitis risk. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024 (Apr 24). doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2024.03.025 Source

Reactive Granulomatous Dermatitis: Variability of the Predominant Inflammatory Cell Type

To the Editor:

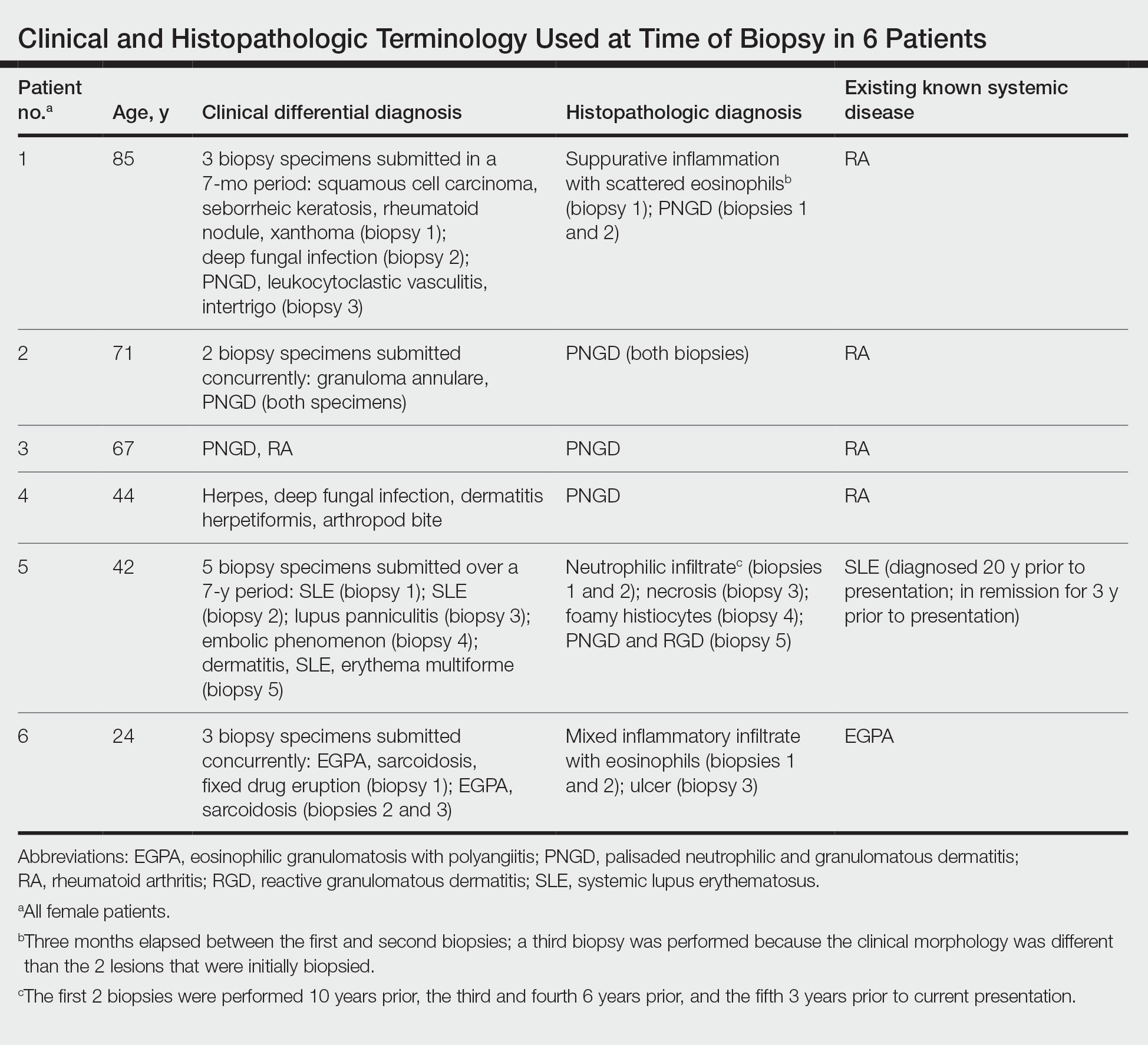

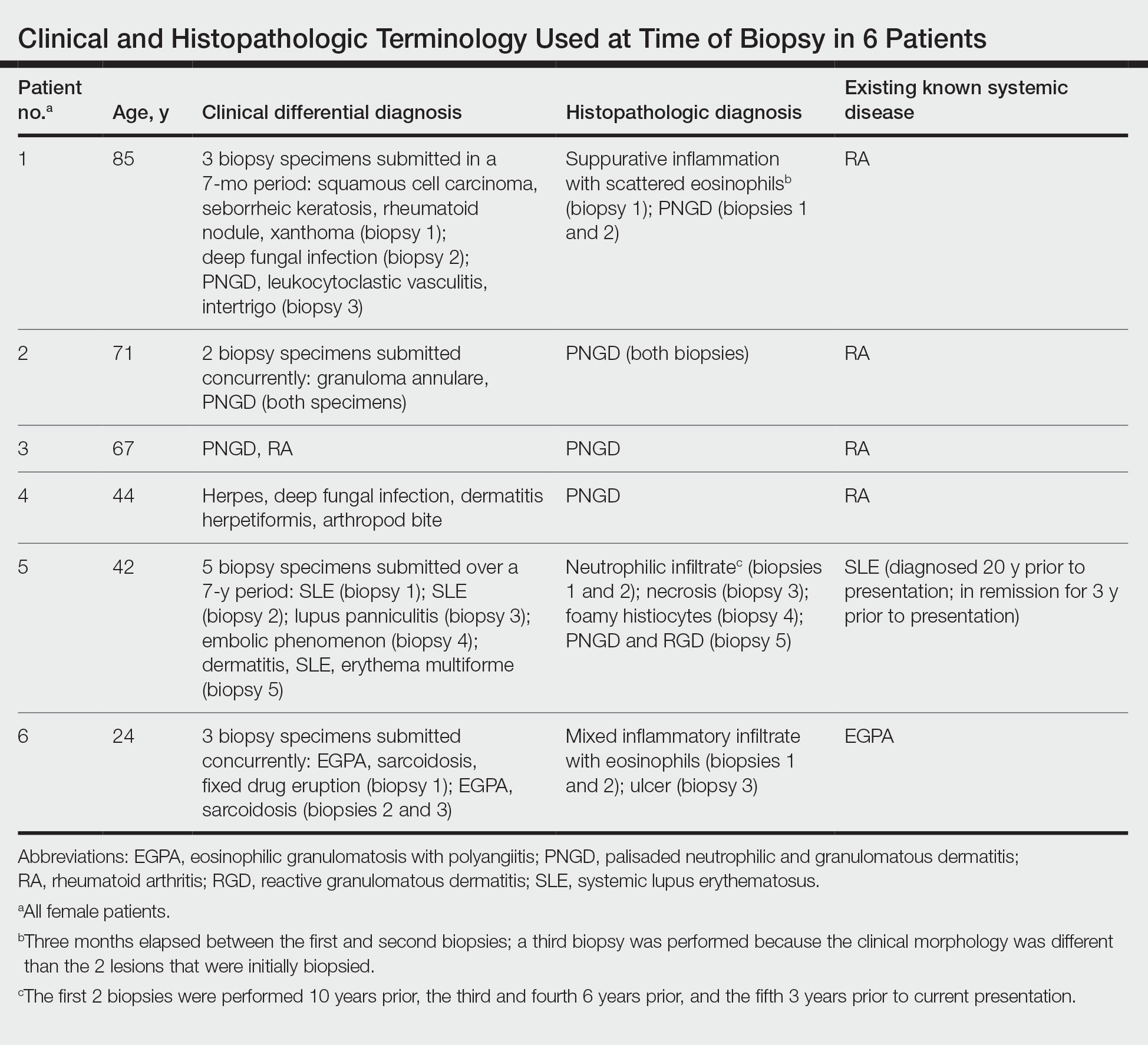

The term palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) has been proposed to encompass various conditions, including Winkelmann granuloma and superficial ulcerating rheumatoid necrobiosis. More recently, PNGD has been classified along with interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and interstitial granulomatous drug reaction under a unifying rubric of reactive granulomatous dermatitis (RGD).1-4 The diagnosis of RGD can be challenging because of a range of clinical and histopathologic features as well as variable nomenclature.1-3,5

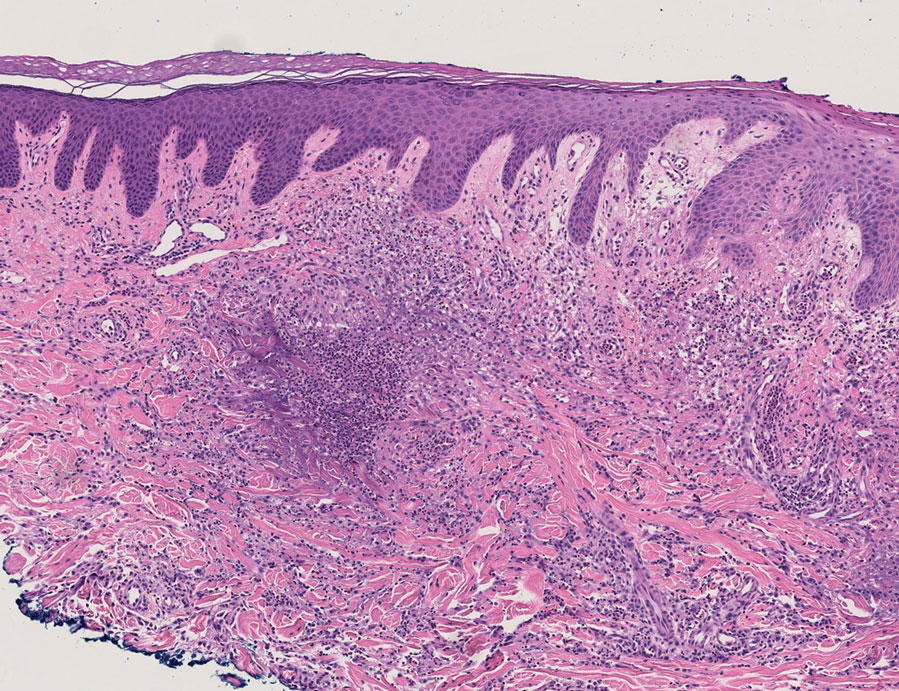

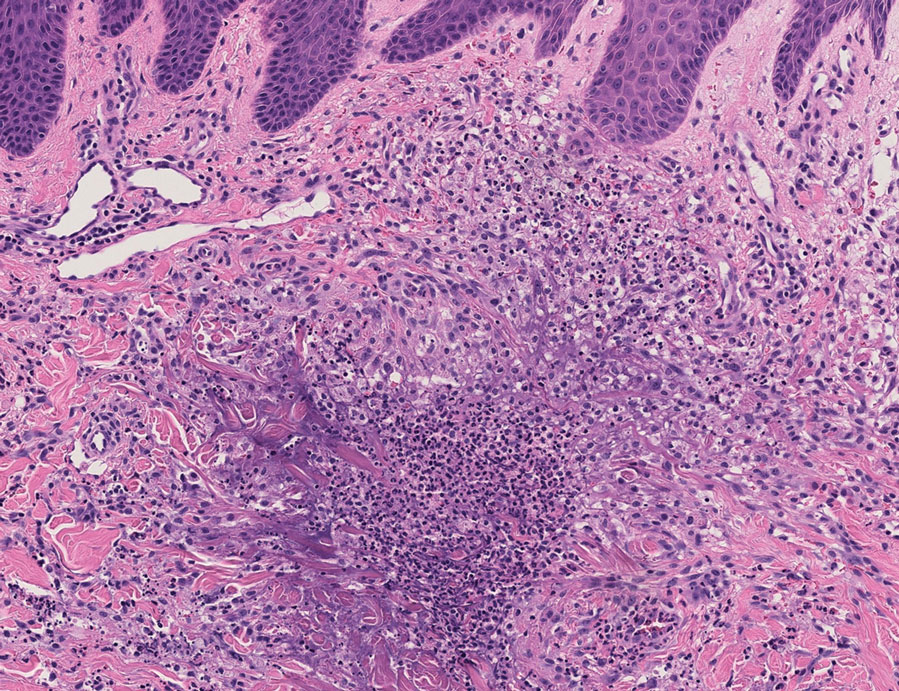

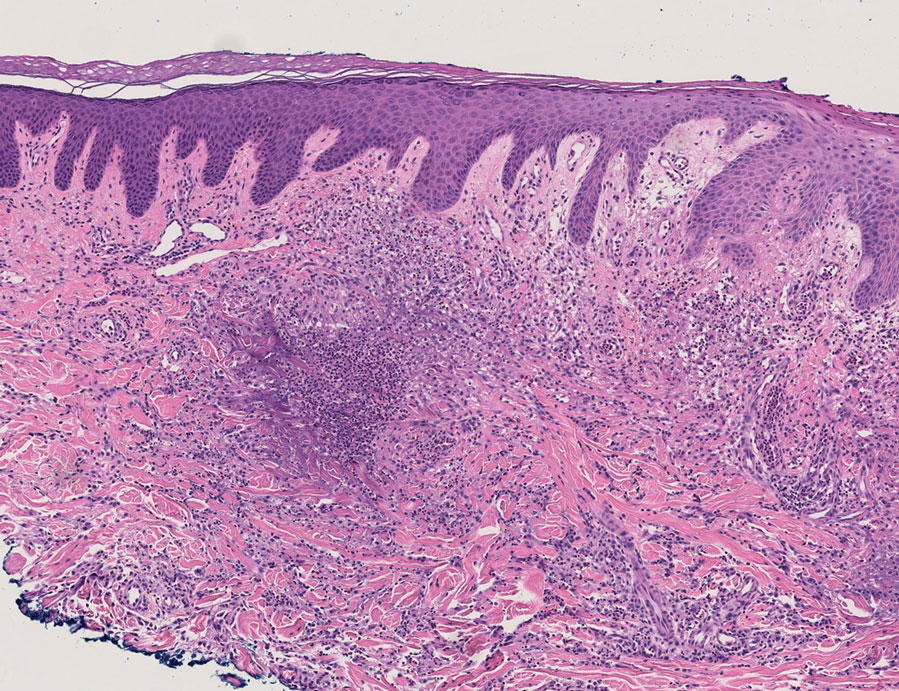

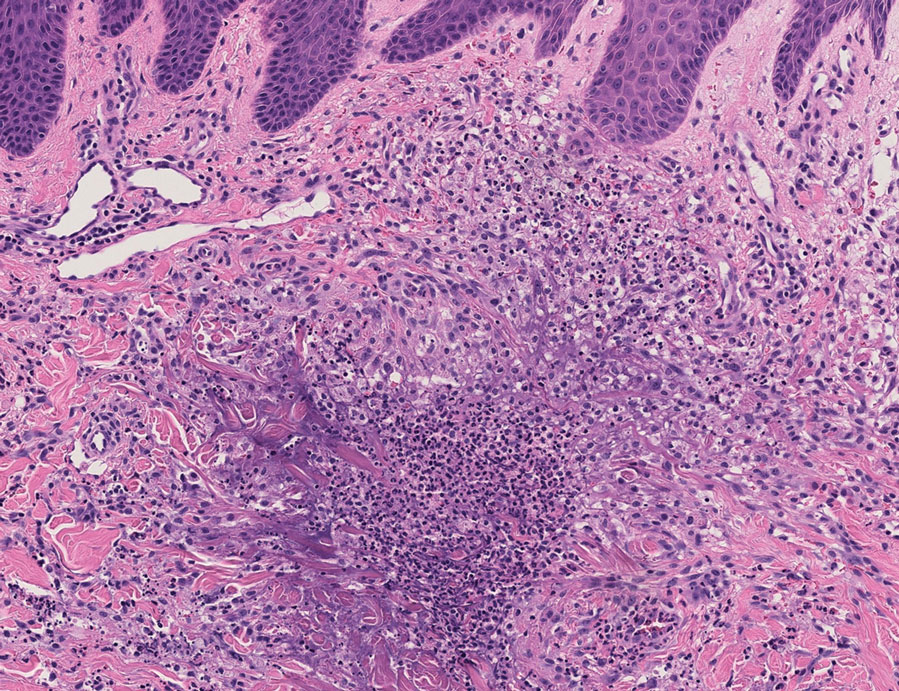

Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis classically manifests with papules and small plaques on the extensor extremities, with histopathology showing characteristic necrobiosis with both neutrophils and histiocytes.1,2,6 We report 6 cases of RGD, including an index case in which a predominance of neutrophils in the infiltrate impeded the diagnosis.

An 85-year-old woman (the index patient) presented with a several-week history of asymmetric crusted papules on the right upper extremity—3 lesions on the elbow and forearm and 1 lesion on a finger. She was an avid gardener with severe rheumatoid arthritis treated with Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor therapy. An initial biopsy of the elbow revealed a dense infiltrate of neutrophils and sparse eosinophils within the dermis. Special stains for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast organisms were negative.

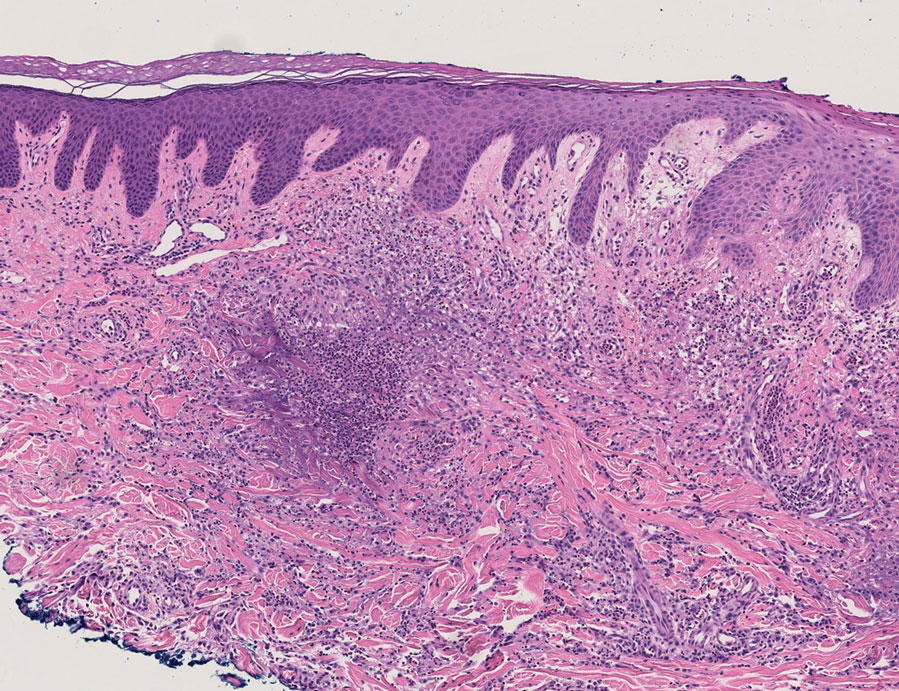

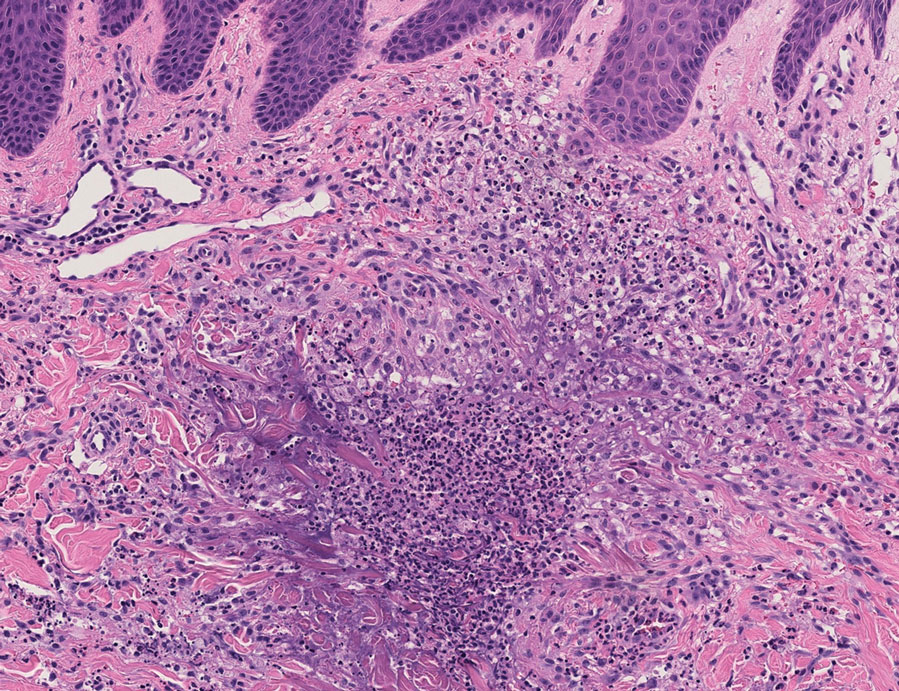

Because infection with sporotrichoid spread remained high in the differential diagnosis, the JAK inhibitor was discontinued and an antifungal agent was initiated. Given the persistence of the lesions, a subsequent biopsy of the right finger revealed scarce neutrophils and predominant histiocytes with rare foci of degenerated collagen. Sporotrichosis remained the leading diagnosis for these unilateral lesions. The patient subsequently developed additional crusted papules on the left arm (Figure 1). A biopsy of a left elbow lesion revealed palisades of histiocytes around degenerated collagen and collections of neutrophils compatible with RGD (Figures 2 and 3). Incidentally, the patient also presented with bilateral lower extremity palpable purpura, with a biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Antifungal therapy was discontinued and JAK inhibitor therapy resumed, with partial resolution of both the arm and right finger lesions and complete resolution of the lower extremity palpable purpura over several months.

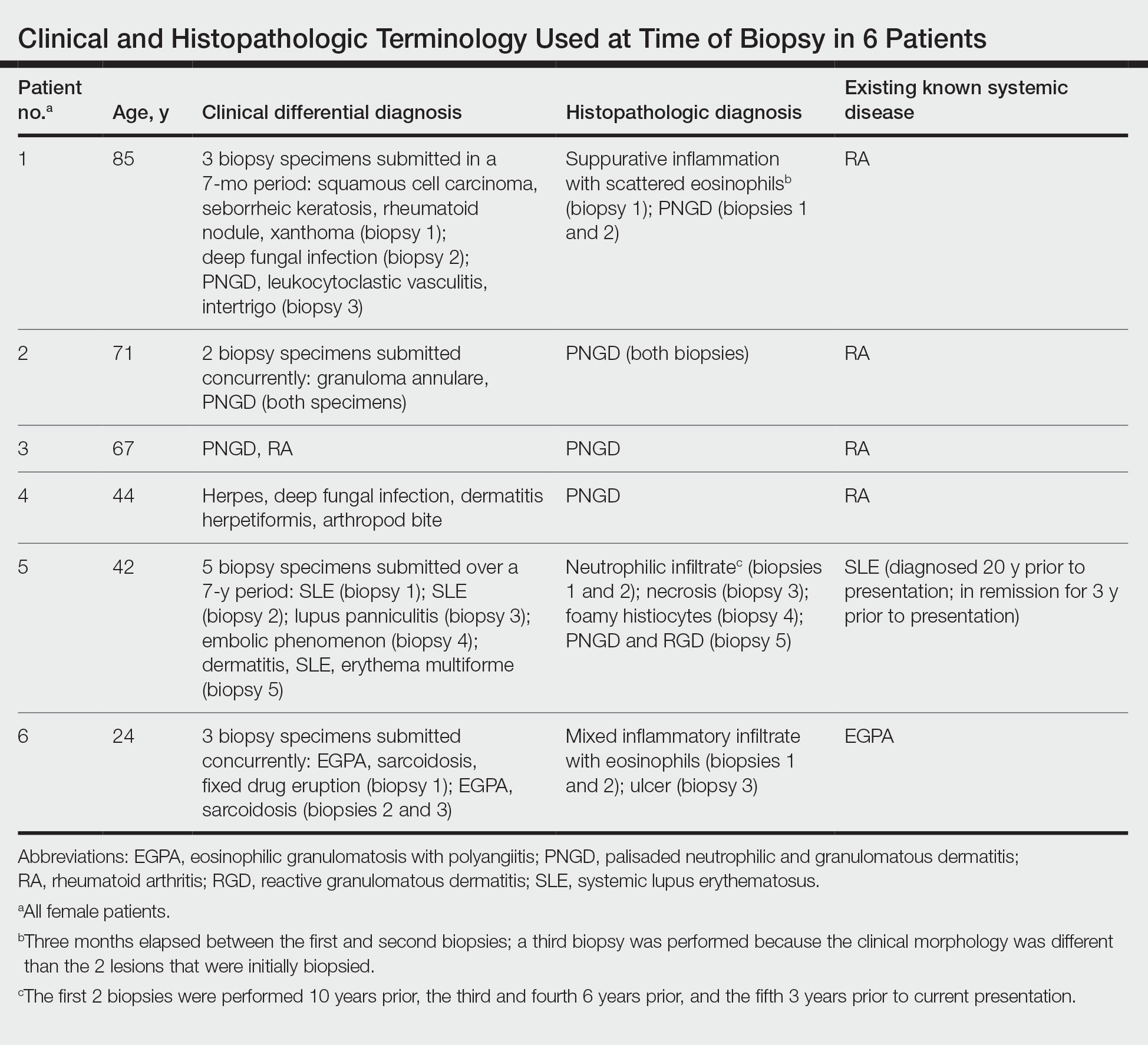

The dense neutrophilic infiltrate and asymmetric presentation seen in our index patient’s initial biopsy hindered categorization of the cutaneous findings as RGD in association with her rheumatoid arthritis rather than as an infectious process. To ascertain whether diagnosis also was difficult in other cases of RGD, we conducted a search of the Yale Dermatopathology database for the diagnosis palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, a term consistently used at our institution over the past decade. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut), and informed consent was waived. The search covered a 10-year period; 13 patients were found. Eight patients were eliminated because further clinical information or follow-up could not be obtained, leaving 5 additional cases (Table). The 8 eliminated cases were consultations submitted to the laboratory by outside pathologists from other institutions.

In one case (patient 5), the diagnosis of RGD was delayed for 7 years from first documentation of an RGD-compatible neutrophil-predominant infiltrate (Table). In 3 other cases, PNGD was in the clinical differential diagnosis. In patient 6 with known eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, biopsy findings included a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils, and the clinical and histopathologic findings were deemed compatible with RGD by group consensus at Grand Rounds.

In practice, a consistent unifying nomenclature has not been achieved for RGD and the diseases it encompasses—PNGD, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, and interstitial granulomatous drug reaction. In this small series, a diagnosis of PNGD was given in the dermatopathology report only when biopsy specimens were characterized by histiocytes, neutrophils, and necrobiosis. Histopathology reports for neutrophil-predominant, histiocyte-predominant, and eosinophil-predominant cases did not mention PNGD or RGD, though potential association with systemic disease generally was noted.

Given the variability in the predominant inflammatory cell type in these patients, adding a qualifier to the histopathologic diagnosis—“RGD, eosinophil rich,” “RGD, histiocyte rich,” or “RGD, neutrophil rich”1—would underscore the range of inflammatory cells in this entity. Employing this terminology rather than stating a solely descriptive diagnosis such as neutrophilic infiltrate, which may bias clinicians toward an infectious process, would aid in the association of a given rash with systemic disease and may prevent unnecessary tissue sampling. Indeed, 3 patients in this small series underwent more than 2 biopsies; multiple procedures might have been avoided had there been better communication about the spectrum of inflammatory cells compatible with RGD.

The inflammatory infiltrate in biopsy specimens of RGD can be solely neutrophil or histiocyte predominant or even have prominent eosinophils depending on the stage of disease. Awareness of variability in the predominant inflammatory cell in RGD may facilitate an accurate diagnosis as well as an association with any underlying autoimmune process, thereby allowing better management and treatment.1

- Rosenbach M, English JC. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a review of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, and a proposed reclassification. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.005

- Wanat KA, Caplan A, Messenger E, et al. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a useful and encompassing term. JAAD Intl. 2022;7:126-128. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.03.004

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283. doi:10.1001/archderm.1994.01690100062010

- Dykman CJ, Galens GJ, Good AE. Linear subcutaneous bands in rheumatoid arthritis: an unusual form of rheumatoid granuloma. Ann Intern Med. 1965;63:134-140. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-63-1-134

- Rodríguez-Garijo N, Bielsa I, Mascaró JM Jr, et al. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis as a histological pattern including manifestations of interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic and granulomtous dermatitis: a study of 52 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:988-994. doi:10.1111/jdv.17010

- Kalen JE, Shokeen D, Ramos-Caro F, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis: spectrum of histologic findings in a single patient. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:425. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.06.010

To the Editor:

The term palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) has been proposed to encompass various conditions, including Winkelmann granuloma and superficial ulcerating rheumatoid necrobiosis. More recently, PNGD has been classified along with interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and interstitial granulomatous drug reaction under a unifying rubric of reactive granulomatous dermatitis (RGD).1-4 The diagnosis of RGD can be challenging because of a range of clinical and histopathologic features as well as variable nomenclature.1-3,5

Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis classically manifests with papules and small plaques on the extensor extremities, with histopathology showing characteristic necrobiosis with both neutrophils and histiocytes.1,2,6 We report 6 cases of RGD, including an index case in which a predominance of neutrophils in the infiltrate impeded the diagnosis.

An 85-year-old woman (the index patient) presented with a several-week history of asymmetric crusted papules on the right upper extremity—3 lesions on the elbow and forearm and 1 lesion on a finger. She was an avid gardener with severe rheumatoid arthritis treated with Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor therapy. An initial biopsy of the elbow revealed a dense infiltrate of neutrophils and sparse eosinophils within the dermis. Special stains for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast organisms were negative.

Because infection with sporotrichoid spread remained high in the differential diagnosis, the JAK inhibitor was discontinued and an antifungal agent was initiated. Given the persistence of the lesions, a subsequent biopsy of the right finger revealed scarce neutrophils and predominant histiocytes with rare foci of degenerated collagen. Sporotrichosis remained the leading diagnosis for these unilateral lesions. The patient subsequently developed additional crusted papules on the left arm (Figure 1). A biopsy of a left elbow lesion revealed palisades of histiocytes around degenerated collagen and collections of neutrophils compatible with RGD (Figures 2 and 3). Incidentally, the patient also presented with bilateral lower extremity palpable purpura, with a biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Antifungal therapy was discontinued and JAK inhibitor therapy resumed, with partial resolution of both the arm and right finger lesions and complete resolution of the lower extremity palpable purpura over several months.

The dense neutrophilic infiltrate and asymmetric presentation seen in our index patient’s initial biopsy hindered categorization of the cutaneous findings as RGD in association with her rheumatoid arthritis rather than as an infectious process. To ascertain whether diagnosis also was difficult in other cases of RGD, we conducted a search of the Yale Dermatopathology database for the diagnosis palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, a term consistently used at our institution over the past decade. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut), and informed consent was waived. The search covered a 10-year period; 13 patients were found. Eight patients were eliminated because further clinical information or follow-up could not be obtained, leaving 5 additional cases (Table). The 8 eliminated cases were consultations submitted to the laboratory by outside pathologists from other institutions.

In one case (patient 5), the diagnosis of RGD was delayed for 7 years from first documentation of an RGD-compatible neutrophil-predominant infiltrate (Table). In 3 other cases, PNGD was in the clinical differential diagnosis. In patient 6 with known eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, biopsy findings included a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils, and the clinical and histopathologic findings were deemed compatible with RGD by group consensus at Grand Rounds.

In practice, a consistent unifying nomenclature has not been achieved for RGD and the diseases it encompasses—PNGD, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, and interstitial granulomatous drug reaction. In this small series, a diagnosis of PNGD was given in the dermatopathology report only when biopsy specimens were characterized by histiocytes, neutrophils, and necrobiosis. Histopathology reports for neutrophil-predominant, histiocyte-predominant, and eosinophil-predominant cases did not mention PNGD or RGD, though potential association with systemic disease generally was noted.

Given the variability in the predominant inflammatory cell type in these patients, adding a qualifier to the histopathologic diagnosis—“RGD, eosinophil rich,” “RGD, histiocyte rich,” or “RGD, neutrophil rich”1—would underscore the range of inflammatory cells in this entity. Employing this terminology rather than stating a solely descriptive diagnosis such as neutrophilic infiltrate, which may bias clinicians toward an infectious process, would aid in the association of a given rash with systemic disease and may prevent unnecessary tissue sampling. Indeed, 3 patients in this small series underwent more than 2 biopsies; multiple procedures might have been avoided had there been better communication about the spectrum of inflammatory cells compatible with RGD.

The inflammatory infiltrate in biopsy specimens of RGD can be solely neutrophil or histiocyte predominant or even have prominent eosinophils depending on the stage of disease. Awareness of variability in the predominant inflammatory cell in RGD may facilitate an accurate diagnosis as well as an association with any underlying autoimmune process, thereby allowing better management and treatment.1

To the Editor:

The term palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) has been proposed to encompass various conditions, including Winkelmann granuloma and superficial ulcerating rheumatoid necrobiosis. More recently, PNGD has been classified along with interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and interstitial granulomatous drug reaction under a unifying rubric of reactive granulomatous dermatitis (RGD).1-4 The diagnosis of RGD can be challenging because of a range of clinical and histopathologic features as well as variable nomenclature.1-3,5

Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis classically manifests with papules and small plaques on the extensor extremities, with histopathology showing characteristic necrobiosis with both neutrophils and histiocytes.1,2,6 We report 6 cases of RGD, including an index case in which a predominance of neutrophils in the infiltrate impeded the diagnosis.

An 85-year-old woman (the index patient) presented with a several-week history of asymmetric crusted papules on the right upper extremity—3 lesions on the elbow and forearm and 1 lesion on a finger. She was an avid gardener with severe rheumatoid arthritis treated with Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor therapy. An initial biopsy of the elbow revealed a dense infiltrate of neutrophils and sparse eosinophils within the dermis. Special stains for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast organisms were negative.

Because infection with sporotrichoid spread remained high in the differential diagnosis, the JAK inhibitor was discontinued and an antifungal agent was initiated. Given the persistence of the lesions, a subsequent biopsy of the right finger revealed scarce neutrophils and predominant histiocytes with rare foci of degenerated collagen. Sporotrichosis remained the leading diagnosis for these unilateral lesions. The patient subsequently developed additional crusted papules on the left arm (Figure 1). A biopsy of a left elbow lesion revealed palisades of histiocytes around degenerated collagen and collections of neutrophils compatible with RGD (Figures 2 and 3). Incidentally, the patient also presented with bilateral lower extremity palpable purpura, with a biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Antifungal therapy was discontinued and JAK inhibitor therapy resumed, with partial resolution of both the arm and right finger lesions and complete resolution of the lower extremity palpable purpura over several months.

The dense neutrophilic infiltrate and asymmetric presentation seen in our index patient’s initial biopsy hindered categorization of the cutaneous findings as RGD in association with her rheumatoid arthritis rather than as an infectious process. To ascertain whether diagnosis also was difficult in other cases of RGD, we conducted a search of the Yale Dermatopathology database for the diagnosis palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, a term consistently used at our institution over the past decade. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut), and informed consent was waived. The search covered a 10-year period; 13 patients were found. Eight patients were eliminated because further clinical information or follow-up could not be obtained, leaving 5 additional cases (Table). The 8 eliminated cases were consultations submitted to the laboratory by outside pathologists from other institutions.

In one case (patient 5), the diagnosis of RGD was delayed for 7 years from first documentation of an RGD-compatible neutrophil-predominant infiltrate (Table). In 3 other cases, PNGD was in the clinical differential diagnosis. In patient 6 with known eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, biopsy findings included a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils, and the clinical and histopathologic findings were deemed compatible with RGD by group consensus at Grand Rounds.

In practice, a consistent unifying nomenclature has not been achieved for RGD and the diseases it encompasses—PNGD, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, and interstitial granulomatous drug reaction. In this small series, a diagnosis of PNGD was given in the dermatopathology report only when biopsy specimens were characterized by histiocytes, neutrophils, and necrobiosis. Histopathology reports for neutrophil-predominant, histiocyte-predominant, and eosinophil-predominant cases did not mention PNGD or RGD, though potential association with systemic disease generally was noted.

Given the variability in the predominant inflammatory cell type in these patients, adding a qualifier to the histopathologic diagnosis—“RGD, eosinophil rich,” “RGD, histiocyte rich,” or “RGD, neutrophil rich”1—would underscore the range of inflammatory cells in this entity. Employing this terminology rather than stating a solely descriptive diagnosis such as neutrophilic infiltrate, which may bias clinicians toward an infectious process, would aid in the association of a given rash with systemic disease and may prevent unnecessary tissue sampling. Indeed, 3 patients in this small series underwent more than 2 biopsies; multiple procedures might have been avoided had there been better communication about the spectrum of inflammatory cells compatible with RGD.

The inflammatory infiltrate in biopsy specimens of RGD can be solely neutrophil or histiocyte predominant or even have prominent eosinophils depending on the stage of disease. Awareness of variability in the predominant inflammatory cell in RGD may facilitate an accurate diagnosis as well as an association with any underlying autoimmune process, thereby allowing better management and treatment.1

- Rosenbach M, English JC. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a review of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, and a proposed reclassification. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.005

- Wanat KA, Caplan A, Messenger E, et al. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a useful and encompassing term. JAAD Intl. 2022;7:126-128. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.03.004

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283. doi:10.1001/archderm.1994.01690100062010

- Dykman CJ, Galens GJ, Good AE. Linear subcutaneous bands in rheumatoid arthritis: an unusual form of rheumatoid granuloma. Ann Intern Med. 1965;63:134-140. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-63-1-134

- Rodríguez-Garijo N, Bielsa I, Mascaró JM Jr, et al. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis as a histological pattern including manifestations of interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic and granulomtous dermatitis: a study of 52 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:988-994. doi:10.1111/jdv.17010

- Kalen JE, Shokeen D, Ramos-Caro F, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis: spectrum of histologic findings in a single patient. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:425. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.06.010

- Rosenbach M, English JC. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a review of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, and a proposed reclassification. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.005

- Wanat KA, Caplan A, Messenger E, et al. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a useful and encompassing term. JAAD Intl. 2022;7:126-128. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.03.004

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283. doi:10.1001/archderm.1994.01690100062010

- Dykman CJ, Galens GJ, Good AE. Linear subcutaneous bands in rheumatoid arthritis: an unusual form of rheumatoid granuloma. Ann Intern Med. 1965;63:134-140. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-63-1-134

- Rodríguez-Garijo N, Bielsa I, Mascaró JM Jr, et al. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis as a histological pattern including manifestations of interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic and granulomtous dermatitis: a study of 52 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:988-994. doi:10.1111/jdv.17010

- Kalen JE, Shokeen D, Ramos-Caro F, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis: spectrum of histologic findings in a single patient. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:425. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.06.010

Practice Points

- The term reactive granulomatous dermatitis (RGD) provides a unifying rubric for palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, and interstitial granulomatous drug reaction.

- Reactive granulomatous dermatitis can have a variable infiltrate that includes neutrophils, histiocytes, and/or eosinophils.

- Awareness of the variability in inflammatory cell type is important for the diagnosis of RGD.

New and Emerging Treatments for Major Depressive Disorder

Outside of treating major depressive disorder (MDD) through the monoamine system with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, exploration of other treatment pathways has opened the possibility of faster onset of action and fewer side effects.

In this ReCAP, Dr Joseph Goldberg, from Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, NY, outlines how a better understanding of the glutamate system has led to the emergence of ketamine and esketamine as important treatment options, as well as the combination therapy of dextromethorphan with bupropion.

Dr Goldberg also discusses new results from serotonin system modulation through the 5HT1A receptor with gepirone, or the 5HT2A receptor with psilocybin. He also reports on a new compound esmethadone, known as REL-1017. Finally, he discusses the first approval of a digital therapeutic app designed to augment pharmacotherapy, and the dopamine partial agonist cariprazine as an adjunctive therapy.

--

Joseph F. Goldberg, MD, Clinical Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai; Teaching Attending, Department of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY

Joseph F. Goldberg, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: AbbVie; Genomind; Luye Pharma; Neuroma; Neurelis; Otsuka; Sunovion

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: AbbVie; Alkermes; Axsome; Intracellular Therapies

Receive(d) royalties from: American Psychiatric Publishing; Cambridge University Press

Outside of treating major depressive disorder (MDD) through the monoamine system with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, exploration of other treatment pathways has opened the possibility of faster onset of action and fewer side effects.

In this ReCAP, Dr Joseph Goldberg, from Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, NY, outlines how a better understanding of the glutamate system has led to the emergence of ketamine and esketamine as important treatment options, as well as the combination therapy of dextromethorphan with bupropion.

Dr Goldberg also discusses new results from serotonin system modulation through the 5HT1A receptor with gepirone, or the 5HT2A receptor with psilocybin. He also reports on a new compound esmethadone, known as REL-1017. Finally, he discusses the first approval of a digital therapeutic app designed to augment pharmacotherapy, and the dopamine partial agonist cariprazine as an adjunctive therapy.

--

Joseph F. Goldberg, MD, Clinical Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai; Teaching Attending, Department of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY

Joseph F. Goldberg, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: AbbVie; Genomind; Luye Pharma; Neuroma; Neurelis; Otsuka; Sunovion

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: AbbVie; Alkermes; Axsome; Intracellular Therapies

Receive(d) royalties from: American Psychiatric Publishing; Cambridge University Press

Outside of treating major depressive disorder (MDD) through the monoamine system with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, exploration of other treatment pathways has opened the possibility of faster onset of action and fewer side effects.

In this ReCAP, Dr Joseph Goldberg, from Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, NY, outlines how a better understanding of the glutamate system has led to the emergence of ketamine and esketamine as important treatment options, as well as the combination therapy of dextromethorphan with bupropion.

Dr Goldberg also discusses new results from serotonin system modulation through the 5HT1A receptor with gepirone, or the 5HT2A receptor with psilocybin. He also reports on a new compound esmethadone, known as REL-1017. Finally, he discusses the first approval of a digital therapeutic app designed to augment pharmacotherapy, and the dopamine partial agonist cariprazine as an adjunctive therapy.

--

Joseph F. Goldberg, MD, Clinical Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai; Teaching Attending, Department of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY

Joseph F. Goldberg, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: AbbVie; Genomind; Luye Pharma; Neuroma; Neurelis; Otsuka; Sunovion

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: AbbVie; Alkermes; Axsome; Intracellular Therapies

Receive(d) royalties from: American Psychiatric Publishing; Cambridge University Press

Throbbing headache and nausea

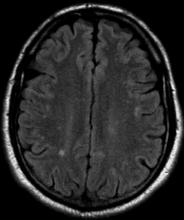

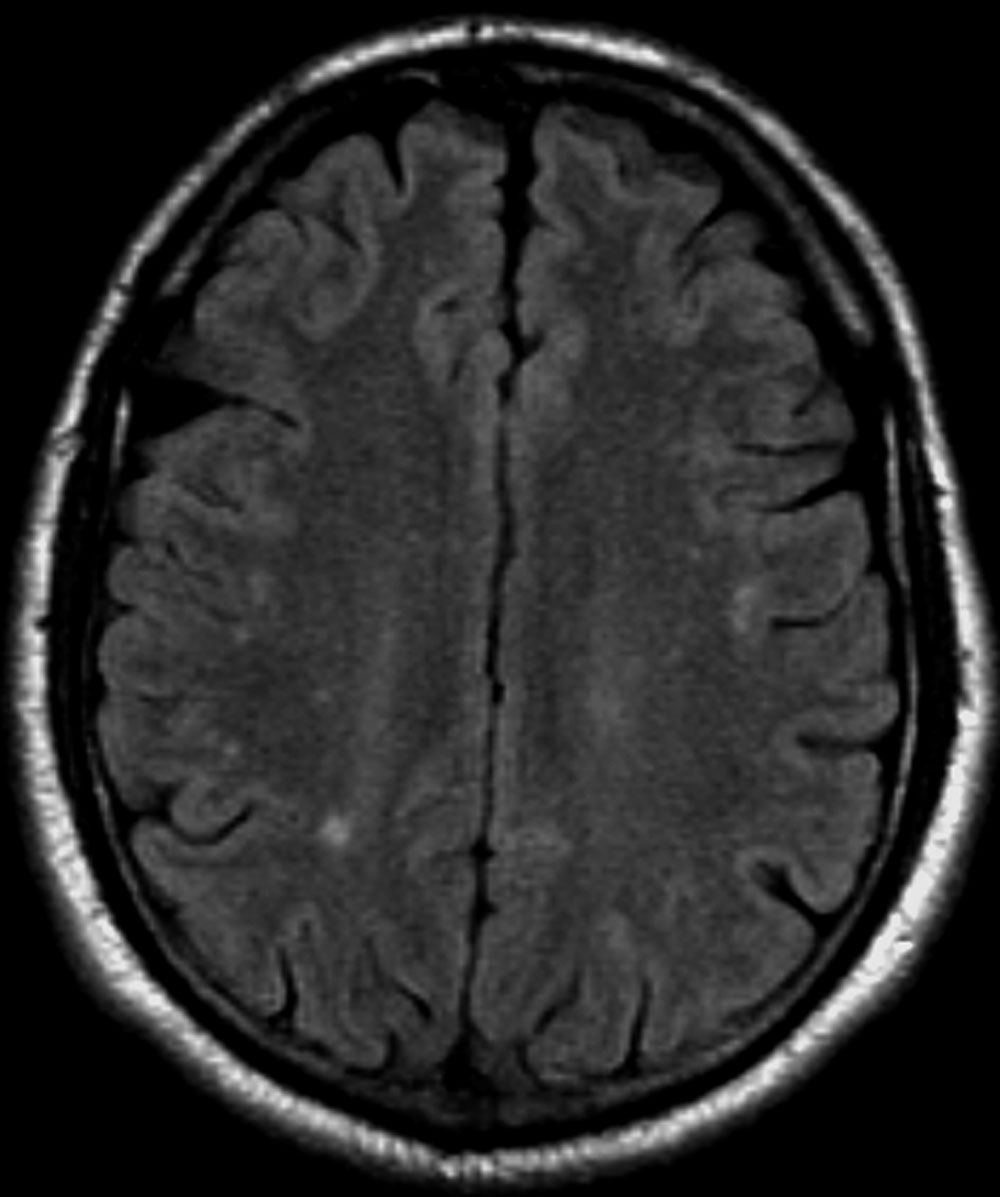

Migraine is a form of recurrent headache that can present as migraine with aura or migraine without aura, with the latter being the most common form. As in this patient, migraine without aura is a chronic form of headache of moderate to severe intensity that usually lasts for several hours but rarely may persist for up to 3 days. Headache pain is unilateral and often aggravated by triggers such as routine physical activity. The American Headache Society diagnostic criteria for migraine without aura include having symptoms of nausea and/or hypersensitivity to light or sound. This patient also described symptoms typical of the prodromal phase of migraine, which include yawning, temperature control, excessive thirst, and mood swings.

Patients who have migraine with aura also have unilateral headache pain of several hours' duration but experience visual (eg, dots or flashes) or sensory (prickly sensation on skin) symptoms, or may have brief difficulty with speech or motor function. These aura symptoms generally last 5 to 60 minutes before abating.

The worldwide impact of migraine potentially reaches a billion individuals. Its prevalence is second only to tension-type headaches. Migraine occurs in patients of all ages and affects women at a rate two to three times higher than in men. Prevalence appears to peak in the third and fourth decades of life and tends to be lower among older adults. Migraine also has a negative effect on patients' work, school, or social lives, and is associated with increased rates of depression and anxiety in adults. For patients who are prone to migraines, potential triggers include some foods and beverages (including those that contain caffeine and alcohol), menstrual cycles in women, exposure to strobing or bright lights or loud sounds, stressful situations, extra physical activity, and too much or too little sleep.

Migraine is a clinical diagnosis based on number of headaches (five or more episodes) plus two or more of the characteristic signs (unilateral, throbbing pain, pain intensity of ≥ 5 on a 10-point scale, and pain aggravated by routine physical motion, such as climbing stairs or bending over) plus nausea and/or photosensitivity or phonosensitivity. Prodrome symptoms are reported by about 70% of adult patients. Diagnosis rarely requires neuroimaging; however, before prescribing medication, a complete lab and metabolic workup should be done.

Management of migraine without aura includes acute and preventive interventions. Acute interventions cited by the American Headache Society include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen for mild pain, and migraine-specific therapies such as the triptans, ergotamine derivatives, gepants (rimegepant, ubrogepant), and lasmiditan. Because response to any of these therapies will differ among patients with migraine, shared decision-making with patients about benefits and potential side effects is necessary and should include flexibility to change therapy if needed.

Preventive therapy should be offered to patients experiencing six or more migraines a month (regardless of impairment) and those, like this patient, with three or more migraines a month that significantly impair daily activities. Preventive therapy can be considered for those with fewer monthly episodes, depending on the degree of impairment. Oral preventive therapies with established efficacy include candesartan, certain beta-blockers, topiramate, and valproate. Parenteral monoclonal antibodies that inhibit calcitonin gene-related peptide activity (eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab) and onabotulinumtoxinA may be considered if oral therapies provide inadequate prevention.

Tension-type headache is the most common form of primary headache. These headaches are bilateral and characterized by a pressing or dull sensation that is often mild in intensity. They are different from migraine in that they occur infrequently, lack sensory symptoms, and generally are of shorter duration (30 minutes to 24 hours). Fasting-related headache is characterized by diffuse, nonpulsating pain and is relieved with food.

Heidi Moawad, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Heidi Moawad, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Migraine is a form of recurrent headache that can present as migraine with aura or migraine without aura, with the latter being the most common form. As in this patient, migraine without aura is a chronic form of headache of moderate to severe intensity that usually lasts for several hours but rarely may persist for up to 3 days. Headache pain is unilateral and often aggravated by triggers such as routine physical activity. The American Headache Society diagnostic criteria for migraine without aura include having symptoms of nausea and/or hypersensitivity to light or sound. This patient also described symptoms typical of the prodromal phase of migraine, which include yawning, temperature control, excessive thirst, and mood swings.

Patients who have migraine with aura also have unilateral headache pain of several hours' duration but experience visual (eg, dots or flashes) or sensory (prickly sensation on skin) symptoms, or may have brief difficulty with speech or motor function. These aura symptoms generally last 5 to 60 minutes before abating.

The worldwide impact of migraine potentially reaches a billion individuals. Its prevalence is second only to tension-type headaches. Migraine occurs in patients of all ages and affects women at a rate two to three times higher than in men. Prevalence appears to peak in the third and fourth decades of life and tends to be lower among older adults. Migraine also has a negative effect on patients' work, school, or social lives, and is associated with increased rates of depression and anxiety in adults. For patients who are prone to migraines, potential triggers include some foods and beverages (including those that contain caffeine and alcohol), menstrual cycles in women, exposure to strobing or bright lights or loud sounds, stressful situations, extra physical activity, and too much or too little sleep.

Migraine is a clinical diagnosis based on number of headaches (five or more episodes) plus two or more of the characteristic signs (unilateral, throbbing pain, pain intensity of ≥ 5 on a 10-point scale, and pain aggravated by routine physical motion, such as climbing stairs or bending over) plus nausea and/or photosensitivity or phonosensitivity. Prodrome symptoms are reported by about 70% of adult patients. Diagnosis rarely requires neuroimaging; however, before prescribing medication, a complete lab and metabolic workup should be done.

Management of migraine without aura includes acute and preventive interventions. Acute interventions cited by the American Headache Society include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen for mild pain, and migraine-specific therapies such as the triptans, ergotamine derivatives, gepants (rimegepant, ubrogepant), and lasmiditan. Because response to any of these therapies will differ among patients with migraine, shared decision-making with patients about benefits and potential side effects is necessary and should include flexibility to change therapy if needed.

Preventive therapy should be offered to patients experiencing six or more migraines a month (regardless of impairment) and those, like this patient, with three or more migraines a month that significantly impair daily activities. Preventive therapy can be considered for those with fewer monthly episodes, depending on the degree of impairment. Oral preventive therapies with established efficacy include candesartan, certain beta-blockers, topiramate, and valproate. Parenteral monoclonal antibodies that inhibit calcitonin gene-related peptide activity (eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab) and onabotulinumtoxinA may be considered if oral therapies provide inadequate prevention.

Tension-type headache is the most common form of primary headache. These headaches are bilateral and characterized by a pressing or dull sensation that is often mild in intensity. They are different from migraine in that they occur infrequently, lack sensory symptoms, and generally are of shorter duration (30 minutes to 24 hours). Fasting-related headache is characterized by diffuse, nonpulsating pain and is relieved with food.

Heidi Moawad, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Heidi Moawad, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Migraine is a form of recurrent headache that can present as migraine with aura or migraine without aura, with the latter being the most common form. As in this patient, migraine without aura is a chronic form of headache of moderate to severe intensity that usually lasts for several hours but rarely may persist for up to 3 days. Headache pain is unilateral and often aggravated by triggers such as routine physical activity. The American Headache Society diagnostic criteria for migraine without aura include having symptoms of nausea and/or hypersensitivity to light or sound. This patient also described symptoms typical of the prodromal phase of migraine, which include yawning, temperature control, excessive thirst, and mood swings.

Patients who have migraine with aura also have unilateral headache pain of several hours' duration but experience visual (eg, dots or flashes) or sensory (prickly sensation on skin) symptoms, or may have brief difficulty with speech or motor function. These aura symptoms generally last 5 to 60 minutes before abating.

The worldwide impact of migraine potentially reaches a billion individuals. Its prevalence is second only to tension-type headaches. Migraine occurs in patients of all ages and affects women at a rate two to three times higher than in men. Prevalence appears to peak in the third and fourth decades of life and tends to be lower among older adults. Migraine also has a negative effect on patients' work, school, or social lives, and is associated with increased rates of depression and anxiety in adults. For patients who are prone to migraines, potential triggers include some foods and beverages (including those that contain caffeine and alcohol), menstrual cycles in women, exposure to strobing or bright lights or loud sounds, stressful situations, extra physical activity, and too much or too little sleep.

Migraine is a clinical diagnosis based on number of headaches (five or more episodes) plus two or more of the characteristic signs (unilateral, throbbing pain, pain intensity of ≥ 5 on a 10-point scale, and pain aggravated by routine physical motion, such as climbing stairs or bending over) plus nausea and/or photosensitivity or phonosensitivity. Prodrome symptoms are reported by about 70% of adult patients. Diagnosis rarely requires neuroimaging; however, before prescribing medication, a complete lab and metabolic workup should be done.

Management of migraine without aura includes acute and preventive interventions. Acute interventions cited by the American Headache Society include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen for mild pain, and migraine-specific therapies such as the triptans, ergotamine derivatives, gepants (rimegepant, ubrogepant), and lasmiditan. Because response to any of these therapies will differ among patients with migraine, shared decision-making with patients about benefits and potential side effects is necessary and should include flexibility to change therapy if needed.

Preventive therapy should be offered to patients experiencing six or more migraines a month (regardless of impairment) and those, like this patient, with three or more migraines a month that significantly impair daily activities. Preventive therapy can be considered for those with fewer monthly episodes, depending on the degree of impairment. Oral preventive therapies with established efficacy include candesartan, certain beta-blockers, topiramate, and valproate. Parenteral monoclonal antibodies that inhibit calcitonin gene-related peptide activity (eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab) and onabotulinumtoxinA may be considered if oral therapies provide inadequate prevention.

Tension-type headache is the most common form of primary headache. These headaches are bilateral and characterized by a pressing or dull sensation that is often mild in intensity. They are different from migraine in that they occur infrequently, lack sensory symptoms, and generally are of shorter duration (30 minutes to 24 hours). Fasting-related headache is characterized by diffuse, nonpulsating pain and is relieved with food.

Heidi Moawad, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Heidi Moawad, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 30-year-old female patient (140 lb and 5 ft 7 in; BMI 21.9) presents at the emergency department with a throbbing headache that began after dinner and was accompanied by queasy nausea. She reports immediately going to bed and sleeping through the night, but pain and other symptoms were still present in the morning. At this point, headache duration is approaching 15 hours. The patient describes the headache pain as throbbing and intense on the left side of her head.

The patient has a demanding job in advertising and often works very long hours on little sleep; this latest headache developed after working through the night before. When asked, she admits to feeling lethargic, yawning (to the point where coworkers commented), and experiencing intervals of excessive sweating earlier in the day before the headache emerged. The patient attributed these to being tired and hungry because of skipped meals since the previous night's dinner.

She has no history of cardiovascular or other chronic illness, and her blood pressure is within normal range. She describes having had about seven similar headaches of shorter duration, over the past 2 months; in each case, the headache led to a missed workday or having to leave work early and/or cancel social plans.

Migraine Treatment Outcomes

Outcomes of Acute and Preventive Migraine Therapy Based on Patient Sex

I previously have addressed myths about migraine as they pertain to men and women. When I found an interesting study recently published in Cephalalgia investigating the effectiveness of calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor (CGRP-R) antagonists (gepants) for acute care and prevention of episodic migraine and CGRP monoclonal antibodies for preventive treatment of episodic and chronic migraine in men and women, I thought I would discuss it here.

The study’s aim was to discern if patient sex contributed to outcomes in each specific treatment arm. Female sex hormones have been recognized as factors in promoting migraine, and women show increased severity, persistence, and comorbidity in migraine profiles, and increased prevalence of migraine relative to men.

Gepants used for acute therapy (ubrogepant, rimegepant, zavegepant) and preventive therapy (atogepant, rimegepant) were studied in this trial. Erenumab, fremanezumab, galcanezumab, and eptinezumab are monoclonal antibodies that either sit on the CGRP receptor (erenumab) or inactivate the CGRP ligand (fremanezumab, galcanezumab, and eptinezumab) and are used for migraine prevention. CGRP-based therapies are not effective in all patients and understanding which patient groups respond preferentially could reduce trial and error in treatment selection. The effectiveness of treatments targeting CGRP or the CGRP receptor may not be uniform in men and women, highlighting the need for further research and understanding of CGRP neurobiology in both sexes.

Key findings:

- In the trial by Porreca et al: In women, the 3 gepants approved by the FDA for the acute care of migraine (ubrogepant, rimegepant, zavegepant) produced a statistically significant drug effect for the 2-hour pain freedom (2h-PF) endpoint, with an average drug effect of 9.5% (CI: 7.4 to 11.6) and an average number needed to treat (NNT) of 11.

- Men did not show statistically significant effects with the acute use of gepants. The average drug effect was 2.8%, and the average NNT was 36.

- For both men and women, CGRP-targeting therapies for prevention of migraine (the 4 monoclonal antibodies) were equally effective; however, possible sex differences remain uncertain and need further study.

- In patients with chronic migraine, CGRP/CGRP-R antibodies were similarly effective in both men and women.

- For the 2-hour freedom from most bothersome symptom (2h-MBS) endpoint when gepants were given acutely, the effects were much better in women than men, with an average drug effect of 10.2% and an average NNT of 10.

- In men, these medications produced observed treatment effects on 2h-MBS with an average drug effect of 3.2% and an average NNT of 32.

- In men, 5 out of 12 estimates favored placebo over the active treatment, suggesting a treatment with little to no effect.

- The pooled treatment effects for women were 3 times as large, at 9.2% and 10.2%, respectively.

- The placebo response rates for 2 of the 3 ubrogepant studies and one of 2 zavegepant studies were higher in men than in women.

The study concludes that, while small molecule CGRP-R antagonists are dramatically effective for acute therapy of migraine in women, available data do not demonstrate effectiveness in men. The treatment effect was found to always favor active treatment numerically for both men and women for prevention of episodic and chronic migraine. The data highlight possible differential effects of CGRP-targeted therapies in different patient populations and the need for increased understanding of CGRP neurobiology in men and women. The study also emphasizes the need to understand which patient groups preferentially respond to CGRP-based therapies to reduce trial and error in treatment. Note that rimegepant data on prevention were not available for analysis at the time of the writing.

It would be interesting to perform a meta-analysis of multiple well-done, large, real-world studies to see if the same differences and similarities are found in men versus women for acute care of migraine and prevention of episodic and chronic migraine. I suspect that we would find that acute care results favor women but that some men do well.

The Effectiveness of Prednisolone for Treating Medication Overuse Headache

I often discuss medication overuse headache (MOH), as it is difficult to diagnose and treat, so I wanted to comment on another pertinent study. It is a post hoc analysis of the Registry for Load and Management of Medication Overuse Headache (RELEASE). The RELEASE trial is an ongoing, multicenter, observational, cohort study of MOH that has been conducted in Korea since April 2020. Findings were recently published in Headache by Lee et al.

MOH is a secondary headache disorder that develops in patients with a preexisting primary headache when they overuse acute care headache medications of any type except gepants. This includes prescription medications such as triptans, ergots, butalbital-containing medications; opioids; aspirin; acetaminophen; any type of combination medication often containing caffeine; or a combination of medications. This condition significantly impacts patients’ quality of life and productivity, usually increasing the frequency of headaches per month and leading to higher healthcare-related costs.

Treating MOH is challenging due to the lack of high-quality drug trials specifically designed for MOH and doctor inexperience. Current evidence is based largely on subgroup analyses of drug trials for the treatment of chronic migraine that contain these patient types.

Withdrawal of acute care headache medications that are being overused has traditionally been considered an important aspect of MOH treatment, although this may be changing. Withdrawal symptoms, such as increased intensity of headache pain, frequency of headaches, and other symptoms like agitation and sleep disturbance, can prevent patients from discontinuing overused medications. Systemic corticosteroids are widely used to reduce these withdrawal headaches, but clinical trials are sparse and have failed to meet proper endpoints. Despite this, corticosteroids have shown potential benefits, such as decreasing withdrawal headaches, reducing the use of rescue medications, and lowering headache intensity at certain time points after treatment.

Given these findings, this published study hypothesized that prednisolone may play a role in converting MOH to non-MOH at 3 months after treatment. The objective was to evaluate the outcome of prednisolone therapy in reversing medication overuse at 3 months posttreatment in patients with MOH using prospective multicenter registry data. Prednisolone was prescribed to 59 out of 309 patients (19.1%) enrolled during this observational study period, with doses ranging from 10 to 40 mg/day for 5-14 days. Of these patients, 228 (73.8%) completed the 3-month follow-up period.

Key findings:

- The MOH reversal rates at 3 months postbaseline were 76% (31/41) in the prednisolone group and 57.8% (108/187) in the no prednisolone group (p = 0.034).

- The steroid effect remained significant (adjusted odds ratio, 2.78; 95% confidence interval 1.27-6.1, p = 0.010) after adjusting for the number of monthly headache days at baseline, mode of discontinuation of overused medication, use of early preventive medications, and the number of combined preventive medications.

The study had several strengths, including the multicenter collection of data, prospective follow-ups, and comprehensiveness of data acquisition. However, it also had significant limitations, such as the noninterventional, observational nature of the study, potential bias in steroid prescription (every doctor prescribed what they wanted), and heterogeneity in the patient population. Also, there were a variety of treatments, and they were not standardized. Further external validation may be necessary before generalizing the study results.

Despite these limitations, the results do suggest that prednisolone may be one part of a valid treatment option for patients with MOH. I suspect, if the proper studies are done, we will see that using a good preventive medication, with few adverse events, and with careful education of the patient, formal detoxification will not be necessary when treating many patients with MOH. This has been my experience with MOH treatment utilizing the newer anti-CGRP preventive medications, including the older monoclonal antibodies and the newer gepants.

Outcomes of Acute and Preventive Migraine Therapy Based on Patient Sex

I previously have addressed myths about migraine as they pertain to men and women. When I found an interesting study recently published in Cephalalgia investigating the effectiveness of calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor (CGRP-R) antagonists (gepants) for acute care and prevention of episodic migraine and CGRP monoclonal antibodies for preventive treatment of episodic and chronic migraine in men and women, I thought I would discuss it here.

The study’s aim was to discern if patient sex contributed to outcomes in each specific treatment arm. Female sex hormones have been recognized as factors in promoting migraine, and women show increased severity, persistence, and comorbidity in migraine profiles, and increased prevalence of migraine relative to men.

Gepants used for acute therapy (ubrogepant, rimegepant, zavegepant) and preventive therapy (atogepant, rimegepant) were studied in this trial. Erenumab, fremanezumab, galcanezumab, and eptinezumab are monoclonal antibodies that either sit on the CGRP receptor (erenumab) or inactivate the CGRP ligand (fremanezumab, galcanezumab, and eptinezumab) and are used for migraine prevention. CGRP-based therapies are not effective in all patients and understanding which patient groups respond preferentially could reduce trial and error in treatment selection. The effectiveness of treatments targeting CGRP or the CGRP receptor may not be uniform in men and women, highlighting the need for further research and understanding of CGRP neurobiology in both sexes.

Key findings:

- In the trial by Porreca et al: In women, the 3 gepants approved by the FDA for the acute care of migraine (ubrogepant, rimegepant, zavegepant) produced a statistically significant drug effect for the 2-hour pain freedom (2h-PF) endpoint, with an average drug effect of 9.5% (CI: 7.4 to 11.6) and an average number needed to treat (NNT) of 11.

- Men did not show statistically significant effects with the acute use of gepants. The average drug effect was 2.8%, and the average NNT was 36.

- For both men and women, CGRP-targeting therapies for prevention of migraine (the 4 monoclonal antibodies) were equally effective; however, possible sex differences remain uncertain and need further study.

- In patients with chronic migraine, CGRP/CGRP-R antibodies were similarly effective in both men and women.

- For the 2-hour freedom from most bothersome symptom (2h-MBS) endpoint when gepants were given acutely, the effects were much better in women than men, with an average drug effect of 10.2% and an average NNT of 10.

- In men, these medications produced observed treatment effects on 2h-MBS with an average drug effect of 3.2% and an average NNT of 32.

- In men, 5 out of 12 estimates favored placebo over the active treatment, suggesting a treatment with little to no effect.

- The pooled treatment effects for women were 3 times as large, at 9.2% and 10.2%, respectively.

- The placebo response rates for 2 of the 3 ubrogepant studies and one of 2 zavegepant studies were higher in men than in women.

The study concludes that, while small molecule CGRP-R antagonists are dramatically effective for acute therapy of migraine in women, available data do not demonstrate effectiveness in men. The treatment effect was found to always favor active treatment numerically for both men and women for prevention of episodic and chronic migraine. The data highlight possible differential effects of CGRP-targeted therapies in different patient populations and the need for increased understanding of CGRP neurobiology in men and women. The study also emphasizes the need to understand which patient groups preferentially respond to CGRP-based therapies to reduce trial and error in treatment. Note that rimegepant data on prevention were not available for analysis at the time of the writing.