User login

Field Cancerization in Dermatology: Updates on Treatment Considerations and Emerging Therapies

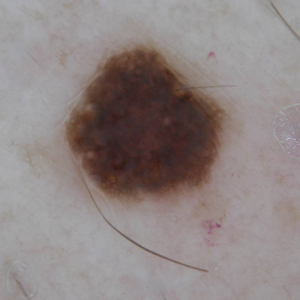

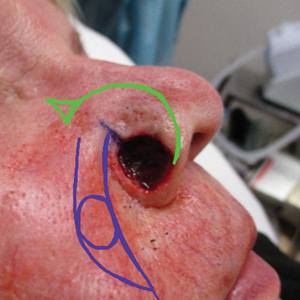

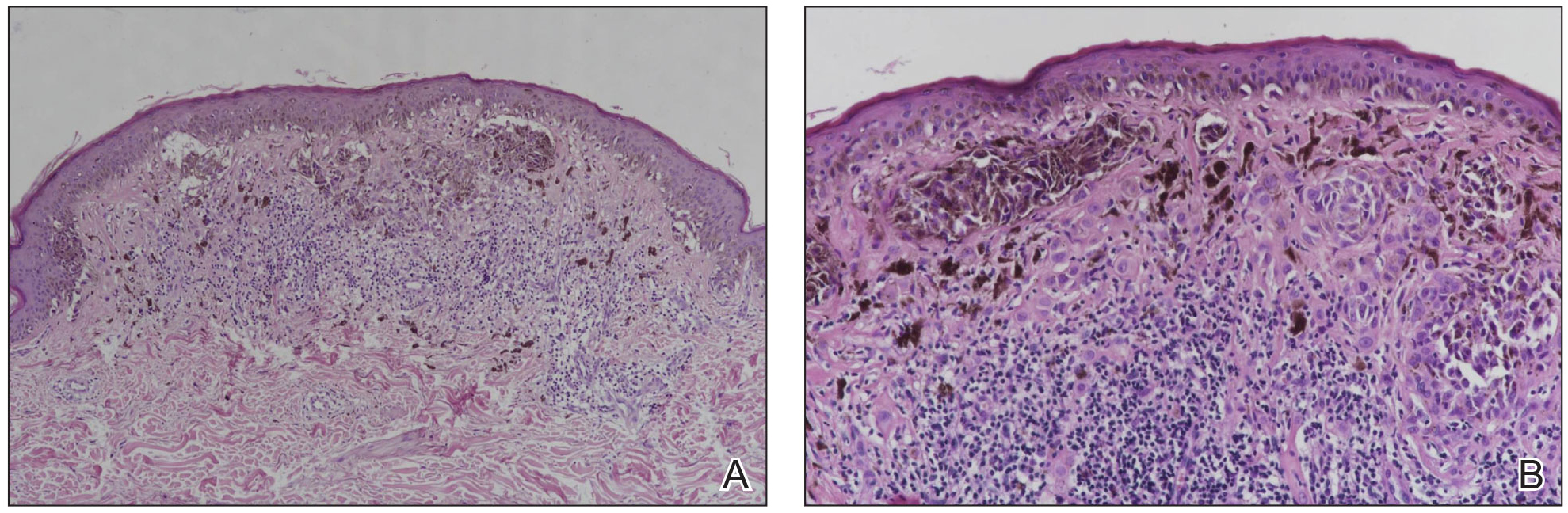

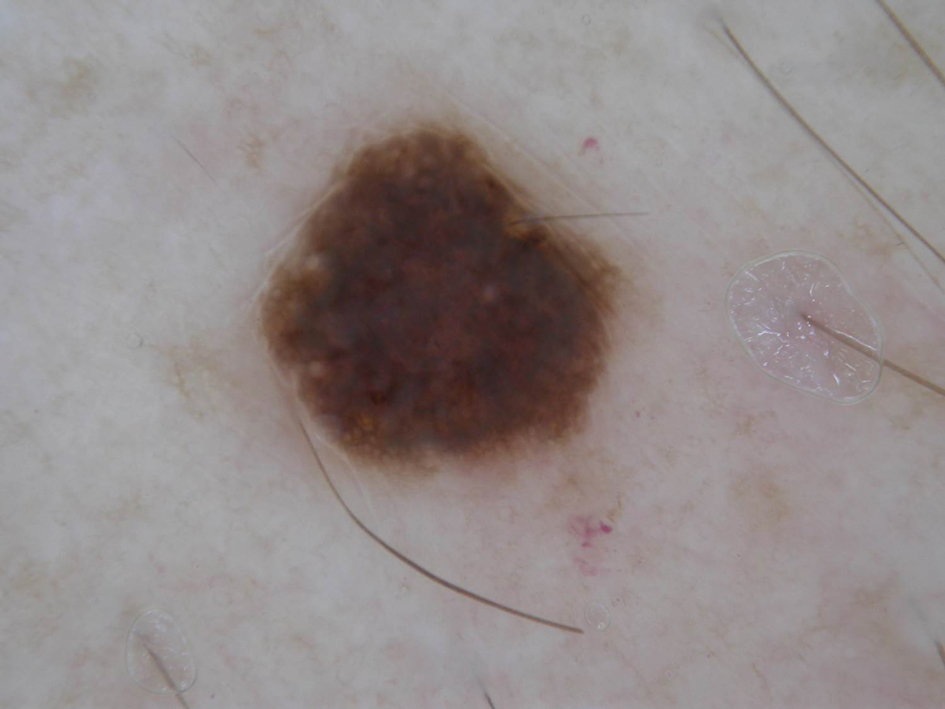

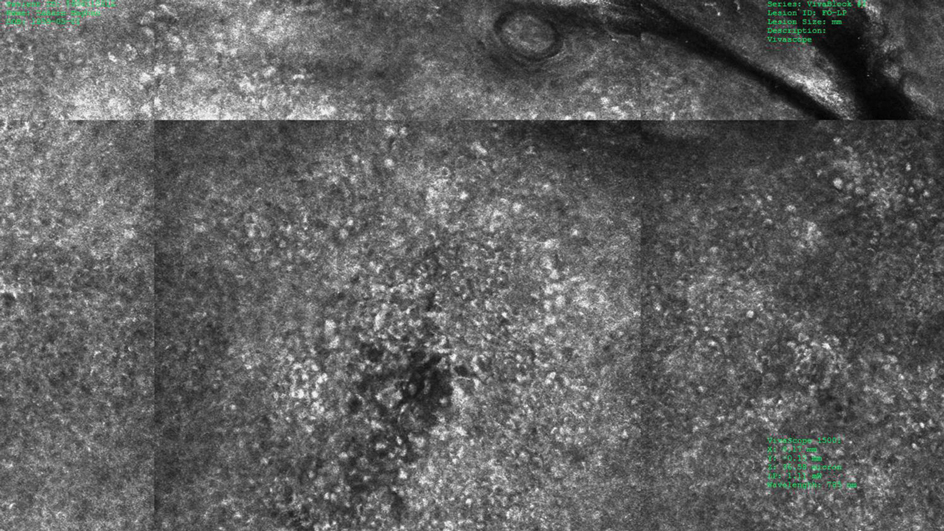

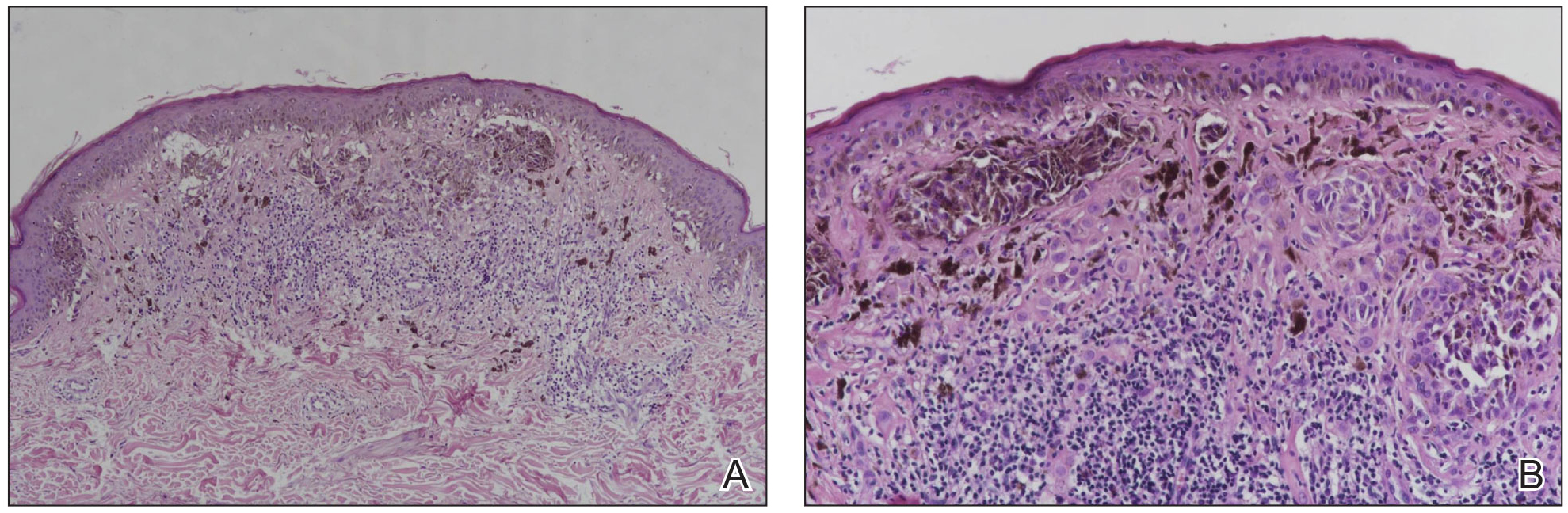

There has been increasing awareness of field cancerization in dermatology and how it relates to actinic damage, actinic keratoses (AKs), and the development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). The concept of field cancerization, which was first described in the context of oropharyngeal SCCs, attempted to explain the repeated observation of local recurrences that were instead multiple primary oropharyngeal SCCs occurring within a specific region of tissue. It was hypothesized that the tissue surrounding a malignancy also harbors irreversible oncogenic damage and therefore predisposes the surrounding tissue to developing further malignancy.1 The development of additional malignant lesions would be considered distinct from a true recurrence of the original malignancy.

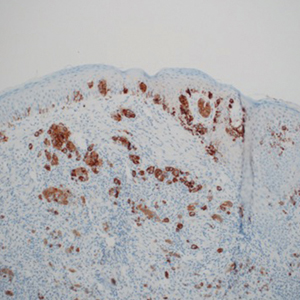

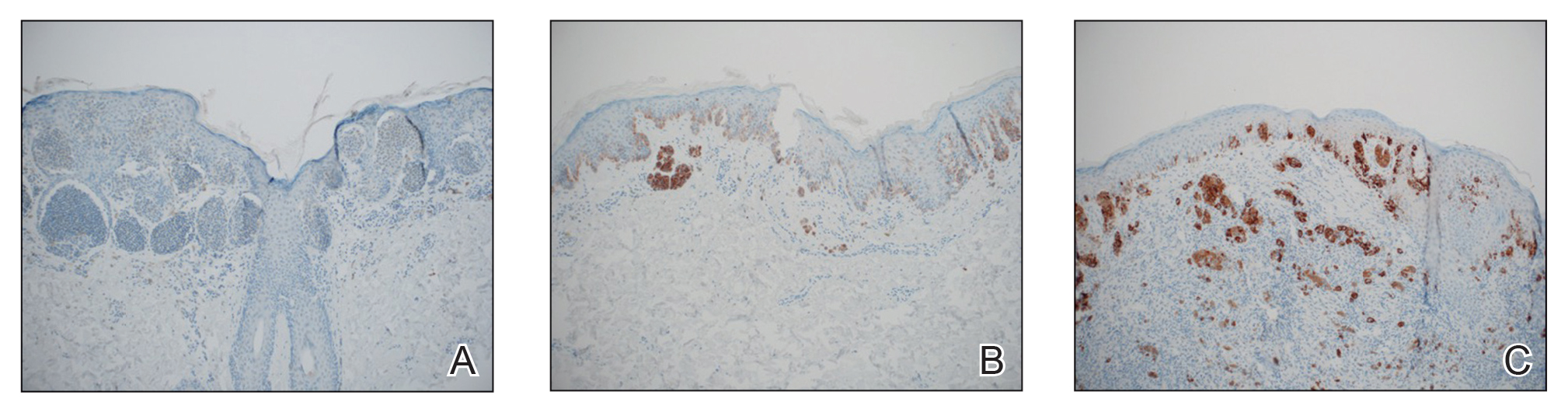

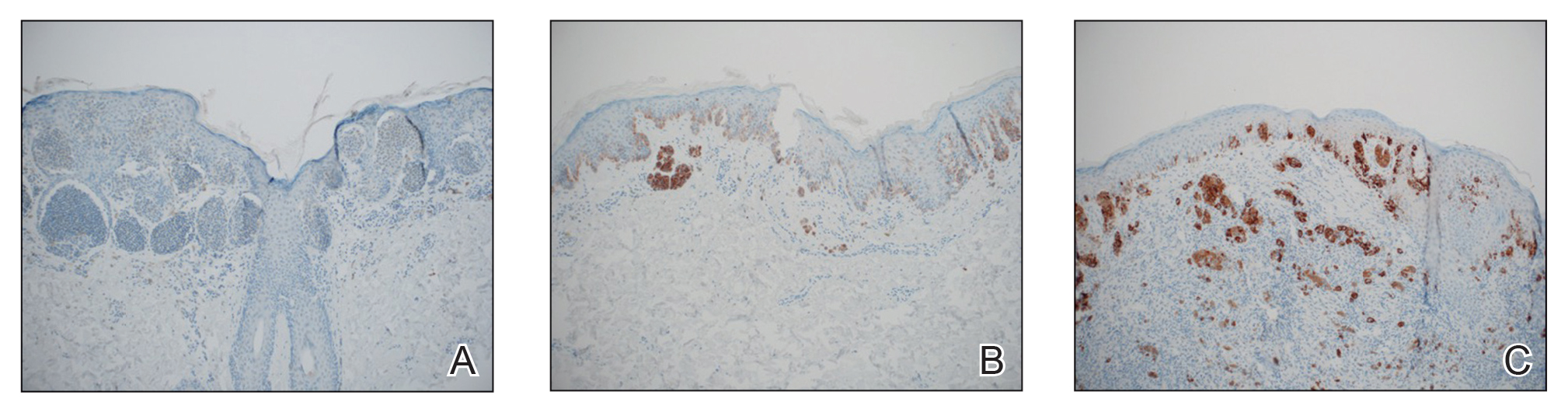

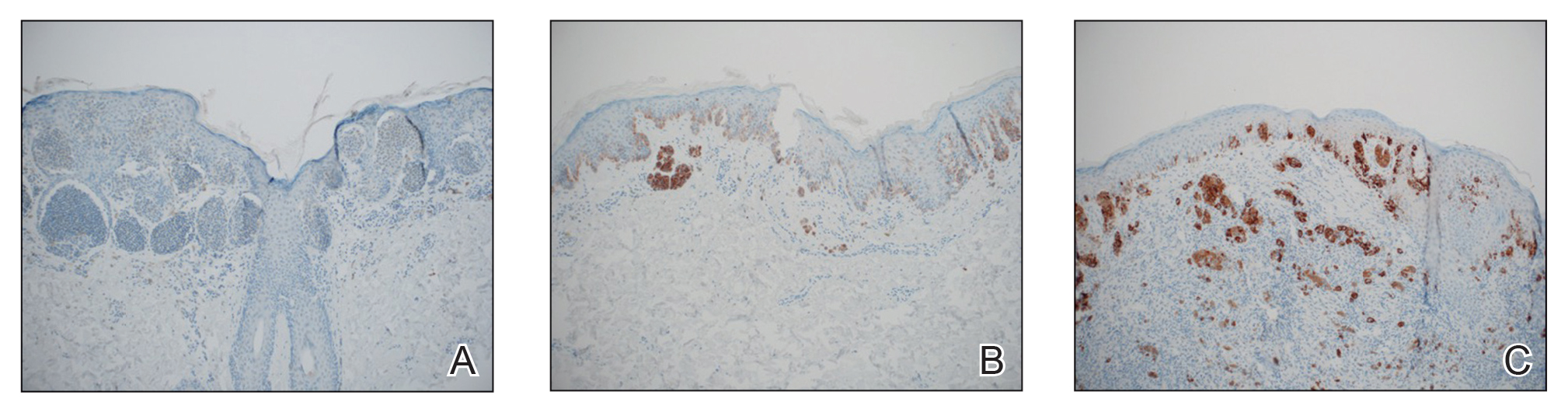

Field cancerization may be partially explained by a genetic basis, as mutations in the tumor suppressor gene, TP53—the most frequently observed mutation in cutaneous SCCs—also is found in sun-exposed but clinically normal skin.2,3 The finding of oncogenic mutations in nonlesional skin supports the theory of field cancerization, in which a region contains multiple genetically altered populations, some of which may progress to cancer. Because there currently is no widely accepted clinical definition or validated clinical measurement of field cancerization in dermatology, it may be difficult for dermatologists to recognize which patients may be at risk for developing further malignancy in a potential area of field cancerization. Willenbrink et al4 updated the definition of field cancerization in dermatology as “multifocal clinical atypia characterized by AKs or SCCs in situ with or without invasive disease occurring in a field exposed to chronic UV radiation.” Managing patients with field cancerization can be challenging. Herein, we discuss updates to nonsurgical field-directed and lesion-directed therapies as well as other emerging therapies.

Field-Directed Therapies

Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and imiquimod cream 5% used as field-directed therapies help reduce the extent of AKs and actinic damage in areas of possible field cancerization.5 The addition of calcipotriol to topical 5-FU, which theoretically augments the skin’s T-cell antitumor response via the cytokine thymic stromal lymphopoietin, recently has been studied using short treatment courses resulting in an 87.8% reduction in AKs compared to a 26.3% reduction with topical 5-FU alone (when used twice daily for 4 days) and conferred a reduced risk of cutaneous SCCs 3 years after treatment (hazard ratio, 0.215 [95% CI, 0.048-0.972]; P=.032).6,7 Chemowraps using topical 5-FU may be considered in more difficult-to-treat areas of field cancerization with multiple AKs or keratinocyte carcinomas of the lower extremities.8 The routine use of chemowraps—weekly application of 5-FU covered with an occlusive dressing—may be limited by the inability to control the extent of epidermal damage and subsequent systemic absorption. Ingenol mebutate, which was approved for treatment of AKs in 2012, was removed from both the European and US markets in 2020 because the medication may paradoxically increase the long-term incidence of skin cancer.9

Meta-analysis has shown that photodynamic therapy (PDT) with aminolevulinic acid demonstrated complete AK clearance in 75.8% of patients (N=156)(95% CI, 55.4%-96.2%).10 A more recent method of PDT using natural sunlight as the activation source demonstrated AK clearance of 95.5%, and it appeared to be a less painful alternative to traditional PDT.11 Tacalcitol, another form of vitamin D, also has been shown to enhance the efficacy of PDT for AKs.12

Field-directed treatment with erbium:YAG and CO2 lasers, which physically remove the actinically damaged epidermis, have been shown to possibly be as efficacious as topical 5-FU and 30% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) but possibly inferior to PDT.13 There has been growing interest in laser-assisted therapy, in which an ablative fractional laser is used to generate microscopic channels to theoretically enhance the absorption of a topical medication. A meta-analysis of the use of laser-assisted therapy for photosensitizing agents in PDT demonstrated a 33% increased chance of AK clearance compared to PDT alone (P<.01).14

Lesion-Directed Therapies

Multiple KAs or cutaneous SCCs may develop in an area of field cancerization, and surgically treating these multiple lesions in a concentrated area may be challenging. Intralesional agents, including methotrexate, 5-FU, bleomycin, and interferon, are known treatments for KAs.15 Intralesional 5-FU (25 mg once weekly for 3–4 weeks) in particular produced complete resolution in 92% of cutaneous SCCs and may be optimal for multiple or rapidly growing lesions, especially on the extremities.16

Oral Therapies

Oral therapies are considered in high-risk patients with multiple or recurrent cutaneous SCCs or in those who are immunosuppressed. Two trials demonstrated that nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily for 4 and 12 months decreased AKs by 29% to 35% and 13% (average of 3–5 fewer AKs as compared to baseline), respectively.17,18 A meta-analysis found a reduction of cutaneous SCCs (rate ratio, 0.48 [95% CI, 0.26-0.88]; I2=67%; 552 patients, 5 trials), and given the favorable safety profile, nicotinamide can be considered for chemoprevention.19

Acitretin, shown to reduce AKs by 13.4% to 50%, is the primary oral chemoprevention recommended in transplant recipients.20 Interestingly, a recent meta-analysis failed to find significant differences between the efficacy of acitretin and nicotinamide.21 The tolerability of acitretin requires serious consideration, as 52.2% of patients withdrew due to adverse effects in one trial.22

Capecitabine (250–1150 mg twice daily), the oral form of 5-FU, decreased the incidence of AKs and cutaneous SCCs in 53% and 72% of transplant recipients, respectively.23 Although several reports observed paradoxical eruptions of AKs following capecitabine for other malignancies, this actually underscores the efficacy of capecitabine, as the newly emerged AKs resolved thereafter.24 Still, the evidence supporting capecitabine does not include any controlled studies.

Novel Therapies

In 2021, tirbanibulin ointment 1%, a Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor of tubulin polymerization that induces p53 expression and subsequent cell death, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of AKs.25 Two trials reported AK clearance rates of 44% and 54% with application of tirbanibulin once daily for 5 days (vs 5% and 13%, respectively, with placebo, each with P<.001) at 2 months and a sustained clearance rate of 27% at 1 year. The predominant adverse effects were local skin reactions, including application-site pain, pruritus, mild erythema, or scaling. Unlike in other treatments such as 5-FU or cryotherapy, erosions, dyspigmentation, or scarring were not notably observed.

Intralesional talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), an oncolytic, genetically modified herpes simplex virus type 1 that incites antitumor immune responses, received US Food and Drug Administration approval in 2015 for the treatment of cutaneous and lymph node metastases of melanoma that are unable to be surgically resected. More recently, T-VEC has been investigated for oropharyngeal SCC. A phase 1 and phase 2 trial of 17 stage III/IV SCC patients receiving T-VEC and cisplatin demonstrated pathologic remission in 14 of 15 (93%) patients, with 82.4% survival at 29 months.26 A multicenter phase 1b trial of 36 patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck SCCs treated with T-VEC and pembrolizumab exhibited a tolerable safety profile, and 5 cases had a partial response.27 However, phase 3 trials of T-VEC have yet to be pursued. Regarding its potential use for cutaneous SCCs, it has been reportedly used in a liver transplant recipient with metastatic cutaneous SCCs who received 2 doses of T-VEC (1 month apart) and attained remission of disease.28 There currently is a phase 2 trial examining the effectiveness of T-VEC in patients with cutaneous SCCs (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03714828).

Final Thoughts

It is important for dermatologists to bear in mind the possible role of field cancerization in their comprehensive care of patients at risk for multiple skin cancers. Management of areas of field cancerization can be challenging, particularly in patients who develop multiple KAs or cutaneous SCCs in a concentrated area and may need to involve different levels of treatment options, including field-directed therapies and lesion-directed therapies, as well as systemic chemoprevention.

- Braakhuis BJM, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727-1730.

- Ashford BG, Clark J, Gupta R, et al. Reviewing the genetic alterations in high-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a search for prognostic markers and therapeutic targets. Head Neck. 2017;39:1462-1469. doi:10.1002/hed.24765

- Albibas AA, Rose-Zerilli MJJ, Lai C, et al. Subclonal evolution of cancer-related gene mutations in p53 immunopositive patches in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:189-198. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2017.07.844

- Willenbrink TJ, Ruiz ES, Cornejo CM, et al. Field cancerization: definition, epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:709-717. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.126

- Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Randomized trial of four treatment approaches for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-946. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1811850

- Cunningham TJ, Tabacchi M, Eliane JP, et al. Randomized trial of calcipotriol combined with 5-fluorouracil for skin cancer precursor immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:106-116. doi:10.1172/JCI89820

- Rosenberg AR, Tabacchi M, Ngo KH, et al. Skin cancer precursor immunotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma prevention. JCI Insight. 2019;4:125476. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.125476

- Peuvrel L, Saint-Jean M, Quereux G, et al. 5-fluorouracil chemowraps for the treatment of multiple actinic keratoses. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:635-640. doi:10.1684/ejd.2017.3128

- Eisen DB, Asgari MM, Bennett DD, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:E209-E233. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.082

- Vegter S, Tolley K. A network meta-analysis of the relative efficacy of treatments for actinic keratosis of the face or scalp in Europe. PLoS One. 2014;9:E96829. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096829

- Zhu L, Wang P, Zhang G, et al. Conventional versus daylight photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis: a randomized and prospective study in China. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2018;24:366-371. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2018.10.010

- Borgia F, Riso G, Catalano F, et al. Topical tacalcitol as neoadjuvant for photodynamic therapy of acral actinic keratoses: an intra-patient randomized study. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2020;31:101803. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101803

- Tai F, Shah M, Pon K, et al. Laser resurfacing monotherapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:634-642. doi:10.1177/12034754211027515

- Steeb T, Schlager JG, Kohl C, et al. Laser-assisted photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:947-956. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.021

- Intralesional chemotherapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: a practical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:689-702. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.048

- Maxfield L, Shah M, Schwartz C, et al. Intralesional 5-fluorouracil for the treatment of squamous cell carcinomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1696-1697. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.12.049

- Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin-cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506197

- Surjana D, Halliday GM, Martin AJ, et al. Oral nicotinamide reduces actinic keratoses in phase II double-blinded randomized controlled trials. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1497-1500. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.459

- Mainville L, Smilga AS, Fortin PR. Effect of nicotinamide in skin cancer and actinic keratoses chemoprophylaxis, and adverse effects related to nicotinamide: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online February 8, 2022]. J Cutan Med Surg. doi:10.1177/12034754221078201

- Massey PR, Schmults CD, Li SJ, et al. Consensus-based recommendations on the prevention of squamous cell carcinoma in solid organ transplant recipients: a Delphi Consensus Statement. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1219-1226. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3180

- Tee LY, Sultana R, Tam SYC, et al. Chemoprevention of keratinocyte carcinoma and actinic keratosis in solid-organ transplant recipients: systematic review and meta-analyses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:528-530. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.160

- George R, Weightman W, Russ GR, et al. Acitretin for chemoprevention of non-melanoma skin cancers in renal transplant recipients. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:269-273. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0960.2002.00613.x

- Schauder DM, Kim J, Nijhawan RI. Evaluation of the use of capecitabine for the treatment and prevention of actinic keratoses, squamous cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1117-1124. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2327

- Antoniolli LP, Escobar GF, Peruzzo J. Inflammatory actinic keratosis following capecitabine therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14082. doi:10.1111/dth.14082

- Blauvelt A, Kempers S, Lain E, et al. Phase 3 trials of tirbanibulin ointment for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:512-520. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2024040

- Harrington KJ, Hingorani M, Tanay MA, et al. Phase I/II study of oncolytic HSV GM-CSF in combination with radiotherapy and cisplatin in untreated stage III/IV squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4005-4015. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0196

- Harrington KJ, Kong A, Mach N, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec and pembrolizumab in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (MASTERKEY-232): a multicenter, phase 1b study. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:5153-5161. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1170

- Nguyen TA, Offner M, Hamid O, et al. Complete and sustained remission of metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in a liver transplant patient treated with talimogene laherparepvec. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:820-822. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002739

There has been increasing awareness of field cancerization in dermatology and how it relates to actinic damage, actinic keratoses (AKs), and the development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). The concept of field cancerization, which was first described in the context of oropharyngeal SCCs, attempted to explain the repeated observation of local recurrences that were instead multiple primary oropharyngeal SCCs occurring within a specific region of tissue. It was hypothesized that the tissue surrounding a malignancy also harbors irreversible oncogenic damage and therefore predisposes the surrounding tissue to developing further malignancy.1 The development of additional malignant lesions would be considered distinct from a true recurrence of the original malignancy.

Field cancerization may be partially explained by a genetic basis, as mutations in the tumor suppressor gene, TP53—the most frequently observed mutation in cutaneous SCCs—also is found in sun-exposed but clinically normal skin.2,3 The finding of oncogenic mutations in nonlesional skin supports the theory of field cancerization, in which a region contains multiple genetically altered populations, some of which may progress to cancer. Because there currently is no widely accepted clinical definition or validated clinical measurement of field cancerization in dermatology, it may be difficult for dermatologists to recognize which patients may be at risk for developing further malignancy in a potential area of field cancerization. Willenbrink et al4 updated the definition of field cancerization in dermatology as “multifocal clinical atypia characterized by AKs or SCCs in situ with or without invasive disease occurring in a field exposed to chronic UV radiation.” Managing patients with field cancerization can be challenging. Herein, we discuss updates to nonsurgical field-directed and lesion-directed therapies as well as other emerging therapies.

Field-Directed Therapies

Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and imiquimod cream 5% used as field-directed therapies help reduce the extent of AKs and actinic damage in areas of possible field cancerization.5 The addition of calcipotriol to topical 5-FU, which theoretically augments the skin’s T-cell antitumor response via the cytokine thymic stromal lymphopoietin, recently has been studied using short treatment courses resulting in an 87.8% reduction in AKs compared to a 26.3% reduction with topical 5-FU alone (when used twice daily for 4 days) and conferred a reduced risk of cutaneous SCCs 3 years after treatment (hazard ratio, 0.215 [95% CI, 0.048-0.972]; P=.032).6,7 Chemowraps using topical 5-FU may be considered in more difficult-to-treat areas of field cancerization with multiple AKs or keratinocyte carcinomas of the lower extremities.8 The routine use of chemowraps—weekly application of 5-FU covered with an occlusive dressing—may be limited by the inability to control the extent of epidermal damage and subsequent systemic absorption. Ingenol mebutate, which was approved for treatment of AKs in 2012, was removed from both the European and US markets in 2020 because the medication may paradoxically increase the long-term incidence of skin cancer.9

Meta-analysis has shown that photodynamic therapy (PDT) with aminolevulinic acid demonstrated complete AK clearance in 75.8% of patients (N=156)(95% CI, 55.4%-96.2%).10 A more recent method of PDT using natural sunlight as the activation source demonstrated AK clearance of 95.5%, and it appeared to be a less painful alternative to traditional PDT.11 Tacalcitol, another form of vitamin D, also has been shown to enhance the efficacy of PDT for AKs.12

Field-directed treatment with erbium:YAG and CO2 lasers, which physically remove the actinically damaged epidermis, have been shown to possibly be as efficacious as topical 5-FU and 30% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) but possibly inferior to PDT.13 There has been growing interest in laser-assisted therapy, in which an ablative fractional laser is used to generate microscopic channels to theoretically enhance the absorption of a topical medication. A meta-analysis of the use of laser-assisted therapy for photosensitizing agents in PDT demonstrated a 33% increased chance of AK clearance compared to PDT alone (P<.01).14

Lesion-Directed Therapies

Multiple KAs or cutaneous SCCs may develop in an area of field cancerization, and surgically treating these multiple lesions in a concentrated area may be challenging. Intralesional agents, including methotrexate, 5-FU, bleomycin, and interferon, are known treatments for KAs.15 Intralesional 5-FU (25 mg once weekly for 3–4 weeks) in particular produced complete resolution in 92% of cutaneous SCCs and may be optimal for multiple or rapidly growing lesions, especially on the extremities.16

Oral Therapies

Oral therapies are considered in high-risk patients with multiple or recurrent cutaneous SCCs or in those who are immunosuppressed. Two trials demonstrated that nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily for 4 and 12 months decreased AKs by 29% to 35% and 13% (average of 3–5 fewer AKs as compared to baseline), respectively.17,18 A meta-analysis found a reduction of cutaneous SCCs (rate ratio, 0.48 [95% CI, 0.26-0.88]; I2=67%; 552 patients, 5 trials), and given the favorable safety profile, nicotinamide can be considered for chemoprevention.19

Acitretin, shown to reduce AKs by 13.4% to 50%, is the primary oral chemoprevention recommended in transplant recipients.20 Interestingly, a recent meta-analysis failed to find significant differences between the efficacy of acitretin and nicotinamide.21 The tolerability of acitretin requires serious consideration, as 52.2% of patients withdrew due to adverse effects in one trial.22

Capecitabine (250–1150 mg twice daily), the oral form of 5-FU, decreased the incidence of AKs and cutaneous SCCs in 53% and 72% of transplant recipients, respectively.23 Although several reports observed paradoxical eruptions of AKs following capecitabine for other malignancies, this actually underscores the efficacy of capecitabine, as the newly emerged AKs resolved thereafter.24 Still, the evidence supporting capecitabine does not include any controlled studies.

Novel Therapies

In 2021, tirbanibulin ointment 1%, a Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor of tubulin polymerization that induces p53 expression and subsequent cell death, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of AKs.25 Two trials reported AK clearance rates of 44% and 54% with application of tirbanibulin once daily for 5 days (vs 5% and 13%, respectively, with placebo, each with P<.001) at 2 months and a sustained clearance rate of 27% at 1 year. The predominant adverse effects were local skin reactions, including application-site pain, pruritus, mild erythema, or scaling. Unlike in other treatments such as 5-FU or cryotherapy, erosions, dyspigmentation, or scarring were not notably observed.

Intralesional talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), an oncolytic, genetically modified herpes simplex virus type 1 that incites antitumor immune responses, received US Food and Drug Administration approval in 2015 for the treatment of cutaneous and lymph node metastases of melanoma that are unable to be surgically resected. More recently, T-VEC has been investigated for oropharyngeal SCC. A phase 1 and phase 2 trial of 17 stage III/IV SCC patients receiving T-VEC and cisplatin demonstrated pathologic remission in 14 of 15 (93%) patients, with 82.4% survival at 29 months.26 A multicenter phase 1b trial of 36 patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck SCCs treated with T-VEC and pembrolizumab exhibited a tolerable safety profile, and 5 cases had a partial response.27 However, phase 3 trials of T-VEC have yet to be pursued. Regarding its potential use for cutaneous SCCs, it has been reportedly used in a liver transplant recipient with metastatic cutaneous SCCs who received 2 doses of T-VEC (1 month apart) and attained remission of disease.28 There currently is a phase 2 trial examining the effectiveness of T-VEC in patients with cutaneous SCCs (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03714828).

Final Thoughts

It is important for dermatologists to bear in mind the possible role of field cancerization in their comprehensive care of patients at risk for multiple skin cancers. Management of areas of field cancerization can be challenging, particularly in patients who develop multiple KAs or cutaneous SCCs in a concentrated area and may need to involve different levels of treatment options, including field-directed therapies and lesion-directed therapies, as well as systemic chemoprevention.

There has been increasing awareness of field cancerization in dermatology and how it relates to actinic damage, actinic keratoses (AKs), and the development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). The concept of field cancerization, which was first described in the context of oropharyngeal SCCs, attempted to explain the repeated observation of local recurrences that were instead multiple primary oropharyngeal SCCs occurring within a specific region of tissue. It was hypothesized that the tissue surrounding a malignancy also harbors irreversible oncogenic damage and therefore predisposes the surrounding tissue to developing further malignancy.1 The development of additional malignant lesions would be considered distinct from a true recurrence of the original malignancy.

Field cancerization may be partially explained by a genetic basis, as mutations in the tumor suppressor gene, TP53—the most frequently observed mutation in cutaneous SCCs—also is found in sun-exposed but clinically normal skin.2,3 The finding of oncogenic mutations in nonlesional skin supports the theory of field cancerization, in which a region contains multiple genetically altered populations, some of which may progress to cancer. Because there currently is no widely accepted clinical definition or validated clinical measurement of field cancerization in dermatology, it may be difficult for dermatologists to recognize which patients may be at risk for developing further malignancy in a potential area of field cancerization. Willenbrink et al4 updated the definition of field cancerization in dermatology as “multifocal clinical atypia characterized by AKs or SCCs in situ with or without invasive disease occurring in a field exposed to chronic UV radiation.” Managing patients with field cancerization can be challenging. Herein, we discuss updates to nonsurgical field-directed and lesion-directed therapies as well as other emerging therapies.

Field-Directed Therapies

Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and imiquimod cream 5% used as field-directed therapies help reduce the extent of AKs and actinic damage in areas of possible field cancerization.5 The addition of calcipotriol to topical 5-FU, which theoretically augments the skin’s T-cell antitumor response via the cytokine thymic stromal lymphopoietin, recently has been studied using short treatment courses resulting in an 87.8% reduction in AKs compared to a 26.3% reduction with topical 5-FU alone (when used twice daily for 4 days) and conferred a reduced risk of cutaneous SCCs 3 years after treatment (hazard ratio, 0.215 [95% CI, 0.048-0.972]; P=.032).6,7 Chemowraps using topical 5-FU may be considered in more difficult-to-treat areas of field cancerization with multiple AKs or keratinocyte carcinomas of the lower extremities.8 The routine use of chemowraps—weekly application of 5-FU covered with an occlusive dressing—may be limited by the inability to control the extent of epidermal damage and subsequent systemic absorption. Ingenol mebutate, which was approved for treatment of AKs in 2012, was removed from both the European and US markets in 2020 because the medication may paradoxically increase the long-term incidence of skin cancer.9

Meta-analysis has shown that photodynamic therapy (PDT) with aminolevulinic acid demonstrated complete AK clearance in 75.8% of patients (N=156)(95% CI, 55.4%-96.2%).10 A more recent method of PDT using natural sunlight as the activation source demonstrated AK clearance of 95.5%, and it appeared to be a less painful alternative to traditional PDT.11 Tacalcitol, another form of vitamin D, also has been shown to enhance the efficacy of PDT for AKs.12

Field-directed treatment with erbium:YAG and CO2 lasers, which physically remove the actinically damaged epidermis, have been shown to possibly be as efficacious as topical 5-FU and 30% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) but possibly inferior to PDT.13 There has been growing interest in laser-assisted therapy, in which an ablative fractional laser is used to generate microscopic channels to theoretically enhance the absorption of a topical medication. A meta-analysis of the use of laser-assisted therapy for photosensitizing agents in PDT demonstrated a 33% increased chance of AK clearance compared to PDT alone (P<.01).14

Lesion-Directed Therapies

Multiple KAs or cutaneous SCCs may develop in an area of field cancerization, and surgically treating these multiple lesions in a concentrated area may be challenging. Intralesional agents, including methotrexate, 5-FU, bleomycin, and interferon, are known treatments for KAs.15 Intralesional 5-FU (25 mg once weekly for 3–4 weeks) in particular produced complete resolution in 92% of cutaneous SCCs and may be optimal for multiple or rapidly growing lesions, especially on the extremities.16

Oral Therapies

Oral therapies are considered in high-risk patients with multiple or recurrent cutaneous SCCs or in those who are immunosuppressed. Two trials demonstrated that nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily for 4 and 12 months decreased AKs by 29% to 35% and 13% (average of 3–5 fewer AKs as compared to baseline), respectively.17,18 A meta-analysis found a reduction of cutaneous SCCs (rate ratio, 0.48 [95% CI, 0.26-0.88]; I2=67%; 552 patients, 5 trials), and given the favorable safety profile, nicotinamide can be considered for chemoprevention.19

Acitretin, shown to reduce AKs by 13.4% to 50%, is the primary oral chemoprevention recommended in transplant recipients.20 Interestingly, a recent meta-analysis failed to find significant differences between the efficacy of acitretin and nicotinamide.21 The tolerability of acitretin requires serious consideration, as 52.2% of patients withdrew due to adverse effects in one trial.22

Capecitabine (250–1150 mg twice daily), the oral form of 5-FU, decreased the incidence of AKs and cutaneous SCCs in 53% and 72% of transplant recipients, respectively.23 Although several reports observed paradoxical eruptions of AKs following capecitabine for other malignancies, this actually underscores the efficacy of capecitabine, as the newly emerged AKs resolved thereafter.24 Still, the evidence supporting capecitabine does not include any controlled studies.

Novel Therapies

In 2021, tirbanibulin ointment 1%, a Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor of tubulin polymerization that induces p53 expression and subsequent cell death, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of AKs.25 Two trials reported AK clearance rates of 44% and 54% with application of tirbanibulin once daily for 5 days (vs 5% and 13%, respectively, with placebo, each with P<.001) at 2 months and a sustained clearance rate of 27% at 1 year. The predominant adverse effects were local skin reactions, including application-site pain, pruritus, mild erythema, or scaling. Unlike in other treatments such as 5-FU or cryotherapy, erosions, dyspigmentation, or scarring were not notably observed.

Intralesional talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), an oncolytic, genetically modified herpes simplex virus type 1 that incites antitumor immune responses, received US Food and Drug Administration approval in 2015 for the treatment of cutaneous and lymph node metastases of melanoma that are unable to be surgically resected. More recently, T-VEC has been investigated for oropharyngeal SCC. A phase 1 and phase 2 trial of 17 stage III/IV SCC patients receiving T-VEC and cisplatin demonstrated pathologic remission in 14 of 15 (93%) patients, with 82.4% survival at 29 months.26 A multicenter phase 1b trial of 36 patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck SCCs treated with T-VEC and pembrolizumab exhibited a tolerable safety profile, and 5 cases had a partial response.27 However, phase 3 trials of T-VEC have yet to be pursued. Regarding its potential use for cutaneous SCCs, it has been reportedly used in a liver transplant recipient with metastatic cutaneous SCCs who received 2 doses of T-VEC (1 month apart) and attained remission of disease.28 There currently is a phase 2 trial examining the effectiveness of T-VEC in patients with cutaneous SCCs (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03714828).

Final Thoughts

It is important for dermatologists to bear in mind the possible role of field cancerization in their comprehensive care of patients at risk for multiple skin cancers. Management of areas of field cancerization can be challenging, particularly in patients who develop multiple KAs or cutaneous SCCs in a concentrated area and may need to involve different levels of treatment options, including field-directed therapies and lesion-directed therapies, as well as systemic chemoprevention.

- Braakhuis BJM, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727-1730.

- Ashford BG, Clark J, Gupta R, et al. Reviewing the genetic alterations in high-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a search for prognostic markers and therapeutic targets. Head Neck. 2017;39:1462-1469. doi:10.1002/hed.24765

- Albibas AA, Rose-Zerilli MJJ, Lai C, et al. Subclonal evolution of cancer-related gene mutations in p53 immunopositive patches in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:189-198. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2017.07.844

- Willenbrink TJ, Ruiz ES, Cornejo CM, et al. Field cancerization: definition, epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:709-717. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.126

- Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Randomized trial of four treatment approaches for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-946. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1811850

- Cunningham TJ, Tabacchi M, Eliane JP, et al. Randomized trial of calcipotriol combined with 5-fluorouracil for skin cancer precursor immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:106-116. doi:10.1172/JCI89820

- Rosenberg AR, Tabacchi M, Ngo KH, et al. Skin cancer precursor immunotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma prevention. JCI Insight. 2019;4:125476. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.125476

- Peuvrel L, Saint-Jean M, Quereux G, et al. 5-fluorouracil chemowraps for the treatment of multiple actinic keratoses. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:635-640. doi:10.1684/ejd.2017.3128

- Eisen DB, Asgari MM, Bennett DD, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:E209-E233. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.082

- Vegter S, Tolley K. A network meta-analysis of the relative efficacy of treatments for actinic keratosis of the face or scalp in Europe. PLoS One. 2014;9:E96829. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096829

- Zhu L, Wang P, Zhang G, et al. Conventional versus daylight photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis: a randomized and prospective study in China. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2018;24:366-371. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2018.10.010

- Borgia F, Riso G, Catalano F, et al. Topical tacalcitol as neoadjuvant for photodynamic therapy of acral actinic keratoses: an intra-patient randomized study. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2020;31:101803. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101803

- Tai F, Shah M, Pon K, et al. Laser resurfacing monotherapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:634-642. doi:10.1177/12034754211027515

- Steeb T, Schlager JG, Kohl C, et al. Laser-assisted photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:947-956. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.021

- Intralesional chemotherapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: a practical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:689-702. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.048

- Maxfield L, Shah M, Schwartz C, et al. Intralesional 5-fluorouracil for the treatment of squamous cell carcinomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1696-1697. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.12.049

- Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin-cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506197

- Surjana D, Halliday GM, Martin AJ, et al. Oral nicotinamide reduces actinic keratoses in phase II double-blinded randomized controlled trials. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1497-1500. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.459

- Mainville L, Smilga AS, Fortin PR. Effect of nicotinamide in skin cancer and actinic keratoses chemoprophylaxis, and adverse effects related to nicotinamide: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online February 8, 2022]. J Cutan Med Surg. doi:10.1177/12034754221078201

- Massey PR, Schmults CD, Li SJ, et al. Consensus-based recommendations on the prevention of squamous cell carcinoma in solid organ transplant recipients: a Delphi Consensus Statement. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1219-1226. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3180

- Tee LY, Sultana R, Tam SYC, et al. Chemoprevention of keratinocyte carcinoma and actinic keratosis in solid-organ transplant recipients: systematic review and meta-analyses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:528-530. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.160

- George R, Weightman W, Russ GR, et al. Acitretin for chemoprevention of non-melanoma skin cancers in renal transplant recipients. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:269-273. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0960.2002.00613.x

- Schauder DM, Kim J, Nijhawan RI. Evaluation of the use of capecitabine for the treatment and prevention of actinic keratoses, squamous cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1117-1124. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2327

- Antoniolli LP, Escobar GF, Peruzzo J. Inflammatory actinic keratosis following capecitabine therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14082. doi:10.1111/dth.14082

- Blauvelt A, Kempers S, Lain E, et al. Phase 3 trials of tirbanibulin ointment for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:512-520. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2024040

- Harrington KJ, Hingorani M, Tanay MA, et al. Phase I/II study of oncolytic HSV GM-CSF in combination with radiotherapy and cisplatin in untreated stage III/IV squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4005-4015. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0196

- Harrington KJ, Kong A, Mach N, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec and pembrolizumab in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (MASTERKEY-232): a multicenter, phase 1b study. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:5153-5161. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1170

- Nguyen TA, Offner M, Hamid O, et al. Complete and sustained remission of metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in a liver transplant patient treated with talimogene laherparepvec. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:820-822. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002739

- Braakhuis BJM, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727-1730.

- Ashford BG, Clark J, Gupta R, et al. Reviewing the genetic alterations in high-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a search for prognostic markers and therapeutic targets. Head Neck. 2017;39:1462-1469. doi:10.1002/hed.24765

- Albibas AA, Rose-Zerilli MJJ, Lai C, et al. Subclonal evolution of cancer-related gene mutations in p53 immunopositive patches in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:189-198. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2017.07.844

- Willenbrink TJ, Ruiz ES, Cornejo CM, et al. Field cancerization: definition, epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:709-717. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.126

- Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Randomized trial of four treatment approaches for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-946. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1811850

- Cunningham TJ, Tabacchi M, Eliane JP, et al. Randomized trial of calcipotriol combined with 5-fluorouracil for skin cancer precursor immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:106-116. doi:10.1172/JCI89820

- Rosenberg AR, Tabacchi M, Ngo KH, et al. Skin cancer precursor immunotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma prevention. JCI Insight. 2019;4:125476. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.125476

- Peuvrel L, Saint-Jean M, Quereux G, et al. 5-fluorouracil chemowraps for the treatment of multiple actinic keratoses. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:635-640. doi:10.1684/ejd.2017.3128

- Eisen DB, Asgari MM, Bennett DD, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:E209-E233. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.082

- Vegter S, Tolley K. A network meta-analysis of the relative efficacy of treatments for actinic keratosis of the face or scalp in Europe. PLoS One. 2014;9:E96829. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096829

- Zhu L, Wang P, Zhang G, et al. Conventional versus daylight photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis: a randomized and prospective study in China. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2018;24:366-371. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2018.10.010

- Borgia F, Riso G, Catalano F, et al. Topical tacalcitol as neoadjuvant for photodynamic therapy of acral actinic keratoses: an intra-patient randomized study. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2020;31:101803. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101803

- Tai F, Shah M, Pon K, et al. Laser resurfacing monotherapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:634-642. doi:10.1177/12034754211027515

- Steeb T, Schlager JG, Kohl C, et al. Laser-assisted photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:947-956. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.021

- Intralesional chemotherapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: a practical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:689-702. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.048

- Maxfield L, Shah M, Schwartz C, et al. Intralesional 5-fluorouracil for the treatment of squamous cell carcinomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1696-1697. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.12.049

- Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin-cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506197

- Surjana D, Halliday GM, Martin AJ, et al. Oral nicotinamide reduces actinic keratoses in phase II double-blinded randomized controlled trials. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1497-1500. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.459

- Mainville L, Smilga AS, Fortin PR. Effect of nicotinamide in skin cancer and actinic keratoses chemoprophylaxis, and adverse effects related to nicotinamide: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online February 8, 2022]. J Cutan Med Surg. doi:10.1177/12034754221078201

- Massey PR, Schmults CD, Li SJ, et al. Consensus-based recommendations on the prevention of squamous cell carcinoma in solid organ transplant recipients: a Delphi Consensus Statement. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1219-1226. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3180

- Tee LY, Sultana R, Tam SYC, et al. Chemoprevention of keratinocyte carcinoma and actinic keratosis in solid-organ transplant recipients: systematic review and meta-analyses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:528-530. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.160

- George R, Weightman W, Russ GR, et al. Acitretin for chemoprevention of non-melanoma skin cancers in renal transplant recipients. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43:269-273. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0960.2002.00613.x

- Schauder DM, Kim J, Nijhawan RI. Evaluation of the use of capecitabine for the treatment and prevention of actinic keratoses, squamous cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1117-1124. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2327

- Antoniolli LP, Escobar GF, Peruzzo J. Inflammatory actinic keratosis following capecitabine therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14082. doi:10.1111/dth.14082

- Blauvelt A, Kempers S, Lain E, et al. Phase 3 trials of tirbanibulin ointment for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:512-520. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2024040

- Harrington KJ, Hingorani M, Tanay MA, et al. Phase I/II study of oncolytic HSV GM-CSF in combination with radiotherapy and cisplatin in untreated stage III/IV squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4005-4015. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0196

- Harrington KJ, Kong A, Mach N, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec and pembrolizumab in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (MASTERKEY-232): a multicenter, phase 1b study. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:5153-5161. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1170

- Nguyen TA, Offner M, Hamid O, et al. Complete and sustained remission of metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in a liver transplant patient treated with talimogene laherparepvec. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:820-822. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002739

Safety Concerns with CGRP Monoclonal Antibodies

Editors’ note: For the April edition of Expert Perspectives, we asked 2 leading neurologists to present differing views on the use of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for the treatment of migraine. Here, Lawrence Robbins, MD, of the Robbins Headache Clinic in Riverwoods, IL, discusses potential safety concerns associated with this drug class. To read a counterargument in which Jack D. Schim, MD, of the Neurology Center of Southern California, discusses the observed benefits of CGRP mAbs, click here.

Lawrence Robbins, MD is an associate professor of neurology at Chicago Medical School and is in private practice in Riverwoods, IL.

Dr. Robbins discloses speaker’s bureau remuneration from AbbVie, Amgen, Biohaven, Impel NeuroPharma, Lundbeck, and Teva.

The calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were introduced in 2018 as efficacious with few adverse effects. Unfortunately, the phase 3 trials failed to indicate the considerable number of adverse effects that have since been identified. This is a common occurrence with new drugs and mAbs.

There are few adverse events identified in the package insert (PI) for any of the 4 CGRP mAbs, but again that is not restricted to this class. Post-approval, it frequently takes time to piece together the true adverse effect profile. Reasons that phase 3 studies may miss adverse effects include 1) The studies are powered for efficacy but are not powered for adverse effects in terms of both the number of patients and the length of the study; 2) Studies do not use a checklist of likely adverse effects; and 3) Adverse effects become “disaggregated” (for example, 1 person states they have malaise, another tiredness, and another fatigue).

In the ensuing years since the launch of the CGRP mAbs, various lines of evidence pointed to the adverse effects attributed to these mAbs. These include the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)/FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) website, published studies, the collective experience of high prescribers, and filtered comments from patient chat boards. In addition, I have received hundreds of letters from providers and patients regarding serious adverse effects, which are detailed further in this article.

As of March 2022, the FDA/FAERS website has listed approximately 50,000 adverse events in connection with the CGRP mAbs. The number of serious events (hospitalization or life-threatening issues) was about 7000. These large numbers, just 3.75 years after launch, are like those listed for onabotulinumtoxin A after 30 years! Most of the reports involve erenumab. This is because erenumab was approved first and is the most prescribed drug in this class. I do not believe it is more dangerous than the others. Considering that the vast majority of adverse events go unreported, these are staggering numbers. Regarding serious adverse events, only 1% to 10% are actually reported to the FDA. Nobody knows the true percentage of milder adverse events that are actually reported, but in my experience, it is extremely low.

Unfortunately, the FDA/FAERS website lists on only adverse events, not adverse effects, which are just as important to discuss. In my small practice I have observed 4 serious adverse effects in women I believe are attributable to CGRP mAbs. These include a cerebrovascular accident in a 21-year-old patient, a case of reversible cerebral vasoconstrictive syndrome in a 61-year-old patient, severe joint pain in a 66-year-old patient, and a constellation of symptoms that resembled multiple sclerosis in a 30-year-old patient. I have administered onabotulinumtoxinA to thousands of patients for 25 years, with no serious adverse effects.

There have been a number of post-approval articles, studies, and case reports published since the launch of the CGRP mAbs. Many “review” or “meta-analysis” articles tend to repeat the results of the pharma-sponsored studies. They typically characterize the CGRP mAbs as safe, with few adverse events. Long-term safety extension studies almost always conclude that the drug is safe. In my opinion, the results from these studies are not reliable because of their possible ties to phrama.

Other studies tell a different tale. One observational study of erenumab concluded that adverse effects contributed to 33% of the discontinuations. Another study reported that 63.3% of patients taking mAbs described at least 1 adverse effect. A study of patients who had been prescribed erenumab indicated that 48% reported a non-serious adverse event after 3 months.

Neurologists are generally unaware of the dangers posed by CGRP mAbs. In September 2021, I engaged in a debate on this topic during the International 15th World Congress on Controversies in Neurology (CONy). Prior to the debate, the audience members were polled. 94% believed the CGRP mAbs to be safe. After our debate, only 40% felt that these mAbs were safe. I think that the audience, primarily consisting of neurologists, was not informed as to the potential dangers of the CGRP mAbs.

In our practice

For refractory patients, I do prescribe these CGRP mAbs. However, I feel they should only be prescribed after several other, safer options have failed. These include the natural approaches (butterbur, magnesium, riboflavin), several of the standard medications (amitriptyline, beta blockers, topiramate, valproate, angiotensin II receptor blockers), and onabotulinumtoxinA. Additionally, the newer gepants for prevention (rimegepant and atogepant) appear to be safer options than the CGRP mAbs, although we cannot say this definitively at this time.

In 2018, our clinic began a retrospective study that lasted until January 2020. We assessed 119 patients with chronic migraine who had been prescribed one of the CGRP mAbs. This study incorporated the use of a checklist of possible adverse effects. Each of these adverse effects had created a “signal.” We initially asked the patients, “Have you experienced any issues, problems, or side effects due to the CGRP monoclonal antibody?” The patients subsequently were interviewed and asked about each possible adverse effect included on the checklist. The patient and physician determined whether any adverse effect mentioned by the patient was due to the CGRP mAb. After discussing the checklist, 66% of the patients concluded they had experienced 1 additional adverse effect that they attributed to the CGRP mAb and had not originally disclosed in response to the initial question. Most of these patients identified more than 1 additional adverse effect through use of the checklist.

Gathering data

To determine the true adverse event profile post-approval, we rely upon the input of high prescribers, who often can provide this necessary feedback. I have assessed input from headache provider chat boards, private correspondence with many providers, and discussions with colleagues at conferences. The opinions do vary, with some headache providers arguing that there are not that many adverse effects arising from the CGRP mAbs. Many others believe, as I do, that there are a large number of adverse events. In my observations, there is not a consensus among headache providers.

The CGRP patient chat boards are another valuable line of evidence. I have screened 2800 comments from patients regarding adverse events. I filtered these down into 490 “highly believable” comments. Among those, the adverse events described align very well with our other lines of evidence.

If we put all the post-approval lines of evidence together, we come up with the following list of “adverse effect signals” attribututed to the CGRP mAbs. These include constipation (it may be severe; hence the warning in the erenumab PI), injection site reactions, joint pain, anxiety, muscle pain or cramps, hypertension or worsening hypertension (there is a warning in the erenumab PI), nausea (it may be severe; “area postrema syndrome” has occurred), rash, increased headache, fatigue, depression, insomnia, hair loss, tachycardia (and other cardiac arrhythmias), stroke, angina and myocardial infarction, weight gain or loss, irritability, and sexual dysfunction. There are also other adverse events. In his review of the CGRP mAbs, Thomas Moore, a leading expert in adverse events, cited the “sheer number of case reports, and it is likely that AEs of this migraine preventive were underestimated in the clinical trials.”

This discussion has focused on short-term adverse events. We have no idea regarding long-term effects, but I suspect that we will encounter serious ones. Evolution has deemed CGRP to be vital for 450 million years. We ignore evolution at our peril.

CGRP is a powerful vasodilator and protects our cardiovascular and cerebrovascular systems. CGRP resists the onset of hypertension. Wound and burn healing, as well as tissue repair, require CGRP. Bony metabolism and bone healing are partly dependent upon CGRP. CGRP protects from gastrointestinal (GI) ulcers and aids GI motility. CGRP mitigates the effects of sepsis.

CGRP is also involved with flushing, thermoregulation, cold hypersensitivity, protecting the kidneys when under stress, helping regulate insulin release, and mediating the adrenal glucocorticoid response to acute stress (particularly in the mature fetus). Effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis are worrisome but unknown. CGRP is important as a vasodilator during stress, and the CGRP mAbs have not yet been tested under stress.

The CGRP mAbs have been terrific for many patients, and their efficacy is on par with onabotulinumtoxinA. However, in a short period of time we have witnessed a plethora of serious (and non-serious) adverse effects from short-term use. CGRP plays an important role in many physiologic processes. We have no idea as to the long-term consequences of blocking CGRP and we should proceed with caution.

Editors’ note: For the April edition of Expert Perspectives, we asked 2 leading neurologists to present differing views on the use of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for the treatment of migraine. Here, Lawrence Robbins, MD, of the Robbins Headache Clinic in Riverwoods, IL, discusses potential safety concerns associated with this drug class. To read a counterargument in which Jack D. Schim, MD, of the Neurology Center of Southern California, discusses the observed benefits of CGRP mAbs, click here.

Lawrence Robbins, MD is an associate professor of neurology at Chicago Medical School and is in private practice in Riverwoods, IL.

Dr. Robbins discloses speaker’s bureau remuneration from AbbVie, Amgen, Biohaven, Impel NeuroPharma, Lundbeck, and Teva.

The calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were introduced in 2018 as efficacious with few adverse effects. Unfortunately, the phase 3 trials failed to indicate the considerable number of adverse effects that have since been identified. This is a common occurrence with new drugs and mAbs.

There are few adverse events identified in the package insert (PI) for any of the 4 CGRP mAbs, but again that is not restricted to this class. Post-approval, it frequently takes time to piece together the true adverse effect profile. Reasons that phase 3 studies may miss adverse effects include 1) The studies are powered for efficacy but are not powered for adverse effects in terms of both the number of patients and the length of the study; 2) Studies do not use a checklist of likely adverse effects; and 3) Adverse effects become “disaggregated” (for example, 1 person states they have malaise, another tiredness, and another fatigue).

In the ensuing years since the launch of the CGRP mAbs, various lines of evidence pointed to the adverse effects attributed to these mAbs. These include the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)/FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) website, published studies, the collective experience of high prescribers, and filtered comments from patient chat boards. In addition, I have received hundreds of letters from providers and patients regarding serious adverse effects, which are detailed further in this article.

As of March 2022, the FDA/FAERS website has listed approximately 50,000 adverse events in connection with the CGRP mAbs. The number of serious events (hospitalization or life-threatening issues) was about 7000. These large numbers, just 3.75 years after launch, are like those listed for onabotulinumtoxin A after 30 years! Most of the reports involve erenumab. This is because erenumab was approved first and is the most prescribed drug in this class. I do not believe it is more dangerous than the others. Considering that the vast majority of adverse events go unreported, these are staggering numbers. Regarding serious adverse events, only 1% to 10% are actually reported to the FDA. Nobody knows the true percentage of milder adverse events that are actually reported, but in my experience, it is extremely low.

Unfortunately, the FDA/FAERS website lists on only adverse events, not adverse effects, which are just as important to discuss. In my small practice I have observed 4 serious adverse effects in women I believe are attributable to CGRP mAbs. These include a cerebrovascular accident in a 21-year-old patient, a case of reversible cerebral vasoconstrictive syndrome in a 61-year-old patient, severe joint pain in a 66-year-old patient, and a constellation of symptoms that resembled multiple sclerosis in a 30-year-old patient. I have administered onabotulinumtoxinA to thousands of patients for 25 years, with no serious adverse effects.

There have been a number of post-approval articles, studies, and case reports published since the launch of the CGRP mAbs. Many “review” or “meta-analysis” articles tend to repeat the results of the pharma-sponsored studies. They typically characterize the CGRP mAbs as safe, with few adverse events. Long-term safety extension studies almost always conclude that the drug is safe. In my opinion, the results from these studies are not reliable because of their possible ties to phrama.

Other studies tell a different tale. One observational study of erenumab concluded that adverse effects contributed to 33% of the discontinuations. Another study reported that 63.3% of patients taking mAbs described at least 1 adverse effect. A study of patients who had been prescribed erenumab indicated that 48% reported a non-serious adverse event after 3 months.

Neurologists are generally unaware of the dangers posed by CGRP mAbs. In September 2021, I engaged in a debate on this topic during the International 15th World Congress on Controversies in Neurology (CONy). Prior to the debate, the audience members were polled. 94% believed the CGRP mAbs to be safe. After our debate, only 40% felt that these mAbs were safe. I think that the audience, primarily consisting of neurologists, was not informed as to the potential dangers of the CGRP mAbs.

In our practice

For refractory patients, I do prescribe these CGRP mAbs. However, I feel they should only be prescribed after several other, safer options have failed. These include the natural approaches (butterbur, magnesium, riboflavin), several of the standard medications (amitriptyline, beta blockers, topiramate, valproate, angiotensin II receptor blockers), and onabotulinumtoxinA. Additionally, the newer gepants for prevention (rimegepant and atogepant) appear to be safer options than the CGRP mAbs, although we cannot say this definitively at this time.

In 2018, our clinic began a retrospective study that lasted until January 2020. We assessed 119 patients with chronic migraine who had been prescribed one of the CGRP mAbs. This study incorporated the use of a checklist of possible adverse effects. Each of these adverse effects had created a “signal.” We initially asked the patients, “Have you experienced any issues, problems, or side effects due to the CGRP monoclonal antibody?” The patients subsequently were interviewed and asked about each possible adverse effect included on the checklist. The patient and physician determined whether any adverse effect mentioned by the patient was due to the CGRP mAb. After discussing the checklist, 66% of the patients concluded they had experienced 1 additional adverse effect that they attributed to the CGRP mAb and had not originally disclosed in response to the initial question. Most of these patients identified more than 1 additional adverse effect through use of the checklist.

Gathering data

To determine the true adverse event profile post-approval, we rely upon the input of high prescribers, who often can provide this necessary feedback. I have assessed input from headache provider chat boards, private correspondence with many providers, and discussions with colleagues at conferences. The opinions do vary, with some headache providers arguing that there are not that many adverse effects arising from the CGRP mAbs. Many others believe, as I do, that there are a large number of adverse events. In my observations, there is not a consensus among headache providers.

The CGRP patient chat boards are another valuable line of evidence. I have screened 2800 comments from patients regarding adverse events. I filtered these down into 490 “highly believable” comments. Among those, the adverse events described align very well with our other lines of evidence.

If we put all the post-approval lines of evidence together, we come up with the following list of “adverse effect signals” attribututed to the CGRP mAbs. These include constipation (it may be severe; hence the warning in the erenumab PI), injection site reactions, joint pain, anxiety, muscle pain or cramps, hypertension or worsening hypertension (there is a warning in the erenumab PI), nausea (it may be severe; “area postrema syndrome” has occurred), rash, increased headache, fatigue, depression, insomnia, hair loss, tachycardia (and other cardiac arrhythmias), stroke, angina and myocardial infarction, weight gain or loss, irritability, and sexual dysfunction. There are also other adverse events. In his review of the CGRP mAbs, Thomas Moore, a leading expert in adverse events, cited the “sheer number of case reports, and it is likely that AEs of this migraine preventive were underestimated in the clinical trials.”

This discussion has focused on short-term adverse events. We have no idea regarding long-term effects, but I suspect that we will encounter serious ones. Evolution has deemed CGRP to be vital for 450 million years. We ignore evolution at our peril.

CGRP is a powerful vasodilator and protects our cardiovascular and cerebrovascular systems. CGRP resists the onset of hypertension. Wound and burn healing, as well as tissue repair, require CGRP. Bony metabolism and bone healing are partly dependent upon CGRP. CGRP protects from gastrointestinal (GI) ulcers and aids GI motility. CGRP mitigates the effects of sepsis.

CGRP is also involved with flushing, thermoregulation, cold hypersensitivity, protecting the kidneys when under stress, helping regulate insulin release, and mediating the adrenal glucocorticoid response to acute stress (particularly in the mature fetus). Effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis are worrisome but unknown. CGRP is important as a vasodilator during stress, and the CGRP mAbs have not yet been tested under stress.

The CGRP mAbs have been terrific for many patients, and their efficacy is on par with onabotulinumtoxinA. However, in a short period of time we have witnessed a plethora of serious (and non-serious) adverse effects from short-term use. CGRP plays an important role in many physiologic processes. We have no idea as to the long-term consequences of blocking CGRP and we should proceed with caution.

Editors’ note: For the April edition of Expert Perspectives, we asked 2 leading neurologists to present differing views on the use of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for the treatment of migraine. Here, Lawrence Robbins, MD, of the Robbins Headache Clinic in Riverwoods, IL, discusses potential safety concerns associated with this drug class. To read a counterargument in which Jack D. Schim, MD, of the Neurology Center of Southern California, discusses the observed benefits of CGRP mAbs, click here.

Lawrence Robbins, MD is an associate professor of neurology at Chicago Medical School and is in private practice in Riverwoods, IL.

Dr. Robbins discloses speaker’s bureau remuneration from AbbVie, Amgen, Biohaven, Impel NeuroPharma, Lundbeck, and Teva.

The calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were introduced in 2018 as efficacious with few adverse effects. Unfortunately, the phase 3 trials failed to indicate the considerable number of adverse effects that have since been identified. This is a common occurrence with new drugs and mAbs.

There are few adverse events identified in the package insert (PI) for any of the 4 CGRP mAbs, but again that is not restricted to this class. Post-approval, it frequently takes time to piece together the true adverse effect profile. Reasons that phase 3 studies may miss adverse effects include 1) The studies are powered for efficacy but are not powered for adverse effects in terms of both the number of patients and the length of the study; 2) Studies do not use a checklist of likely adverse effects; and 3) Adverse effects become “disaggregated” (for example, 1 person states they have malaise, another tiredness, and another fatigue).

In the ensuing years since the launch of the CGRP mAbs, various lines of evidence pointed to the adverse effects attributed to these mAbs. These include the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)/FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) website, published studies, the collective experience of high prescribers, and filtered comments from patient chat boards. In addition, I have received hundreds of letters from providers and patients regarding serious adverse effects, which are detailed further in this article.

As of March 2022, the FDA/FAERS website has listed approximately 50,000 adverse events in connection with the CGRP mAbs. The number of serious events (hospitalization or life-threatening issues) was about 7000. These large numbers, just 3.75 years after launch, are like those listed for onabotulinumtoxin A after 30 years! Most of the reports involve erenumab. This is because erenumab was approved first and is the most prescribed drug in this class. I do not believe it is more dangerous than the others. Considering that the vast majority of adverse events go unreported, these are staggering numbers. Regarding serious adverse events, only 1% to 10% are actually reported to the FDA. Nobody knows the true percentage of milder adverse events that are actually reported, but in my experience, it is extremely low.

Unfortunately, the FDA/FAERS website lists on only adverse events, not adverse effects, which are just as important to discuss. In my small practice I have observed 4 serious adverse effects in women I believe are attributable to CGRP mAbs. These include a cerebrovascular accident in a 21-year-old patient, a case of reversible cerebral vasoconstrictive syndrome in a 61-year-old patient, severe joint pain in a 66-year-old patient, and a constellation of symptoms that resembled multiple sclerosis in a 30-year-old patient. I have administered onabotulinumtoxinA to thousands of patients for 25 years, with no serious adverse effects.

There have been a number of post-approval articles, studies, and case reports published since the launch of the CGRP mAbs. Many “review” or “meta-analysis” articles tend to repeat the results of the pharma-sponsored studies. They typically characterize the CGRP mAbs as safe, with few adverse events. Long-term safety extension studies almost always conclude that the drug is safe. In my opinion, the results from these studies are not reliable because of their possible ties to phrama.

Other studies tell a different tale. One observational study of erenumab concluded that adverse effects contributed to 33% of the discontinuations. Another study reported that 63.3% of patients taking mAbs described at least 1 adverse effect. A study of patients who had been prescribed erenumab indicated that 48% reported a non-serious adverse event after 3 months.

Neurologists are generally unaware of the dangers posed by CGRP mAbs. In September 2021, I engaged in a debate on this topic during the International 15th World Congress on Controversies in Neurology (CONy). Prior to the debate, the audience members were polled. 94% believed the CGRP mAbs to be safe. After our debate, only 40% felt that these mAbs were safe. I think that the audience, primarily consisting of neurologists, was not informed as to the potential dangers of the CGRP mAbs.

In our practice

For refractory patients, I do prescribe these CGRP mAbs. However, I feel they should only be prescribed after several other, safer options have failed. These include the natural approaches (butterbur, magnesium, riboflavin), several of the standard medications (amitriptyline, beta blockers, topiramate, valproate, angiotensin II receptor blockers), and onabotulinumtoxinA. Additionally, the newer gepants for prevention (rimegepant and atogepant) appear to be safer options than the CGRP mAbs, although we cannot say this definitively at this time.

In 2018, our clinic began a retrospective study that lasted until January 2020. We assessed 119 patients with chronic migraine who had been prescribed one of the CGRP mAbs. This study incorporated the use of a checklist of possible adverse effects. Each of these adverse effects had created a “signal.” We initially asked the patients, “Have you experienced any issues, problems, or side effects due to the CGRP monoclonal antibody?” The patients subsequently were interviewed and asked about each possible adverse effect included on the checklist. The patient and physician determined whether any adverse effect mentioned by the patient was due to the CGRP mAb. After discussing the checklist, 66% of the patients concluded they had experienced 1 additional adverse effect that they attributed to the CGRP mAb and had not originally disclosed in response to the initial question. Most of these patients identified more than 1 additional adverse effect through use of the checklist.

Gathering data

To determine the true adverse event profile post-approval, we rely upon the input of high prescribers, who often can provide this necessary feedback. I have assessed input from headache provider chat boards, private correspondence with many providers, and discussions with colleagues at conferences. The opinions do vary, with some headache providers arguing that there are not that many adverse effects arising from the CGRP mAbs. Many others believe, as I do, that there are a large number of adverse events. In my observations, there is not a consensus among headache providers.

The CGRP patient chat boards are another valuable line of evidence. I have screened 2800 comments from patients regarding adverse events. I filtered these down into 490 “highly believable” comments. Among those, the adverse events described align very well with our other lines of evidence.

If we put all the post-approval lines of evidence together, we come up with the following list of “adverse effect signals” attribututed to the CGRP mAbs. These include constipation (it may be severe; hence the warning in the erenumab PI), injection site reactions, joint pain, anxiety, muscle pain or cramps, hypertension or worsening hypertension (there is a warning in the erenumab PI), nausea (it may be severe; “area postrema syndrome” has occurred), rash, increased headache, fatigue, depression, insomnia, hair loss, tachycardia (and other cardiac arrhythmias), stroke, angina and myocardial infarction, weight gain or loss, irritability, and sexual dysfunction. There are also other adverse events. In his review of the CGRP mAbs, Thomas Moore, a leading expert in adverse events, cited the “sheer number of case reports, and it is likely that AEs of this migraine preventive were underestimated in the clinical trials.”

This discussion has focused on short-term adverse events. We have no idea regarding long-term effects, but I suspect that we will encounter serious ones. Evolution has deemed CGRP to be vital for 450 million years. We ignore evolution at our peril.

CGRP is a powerful vasodilator and protects our cardiovascular and cerebrovascular systems. CGRP resists the onset of hypertension. Wound and burn healing, as well as tissue repair, require CGRP. Bony metabolism and bone healing are partly dependent upon CGRP. CGRP protects from gastrointestinal (GI) ulcers and aids GI motility. CGRP mitigates the effects of sepsis.

CGRP is also involved with flushing, thermoregulation, cold hypersensitivity, protecting the kidneys when under stress, helping regulate insulin release, and mediating the adrenal glucocorticoid response to acute stress (particularly in the mature fetus). Effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis are worrisome but unknown. CGRP is important as a vasodilator during stress, and the CGRP mAbs have not yet been tested under stress.

The CGRP mAbs have been terrific for many patients, and their efficacy is on par with onabotulinumtoxinA. However, in a short period of time we have witnessed a plethora of serious (and non-serious) adverse effects from short-term use. CGRP plays an important role in many physiologic processes. We have no idea as to the long-term consequences of blocking CGRP and we should proceed with caution.

CGRPs: They’ve Been a Long Time Coming

Editors’ note: For the April edition of Expert Perspectives, we asked two leading neurologists to present differing views on the use of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRPs) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for the treatment of migraine. Here, Jack D. Schim, MD, of the Neurology Center of Southern California, discusses the observed benefits of the CGRP mAbs. To read a counter-argument in which Lawrence Robbins, MD, of the Robbins Headache Clinic in Riverwoods, IL, discusses potential safety concerns associated with this drug class, click here.

Dr. Schim is Co-Director of The Headache Center of Southern California, The Neurology Center. He is Board Member and past President of the Headache Consortium of the Pacific, Board Member and past President, American Heart Association San Diego, a Past President of the California Neurologic Society, and an active member of the American Academy of Neurology, American Stroke Association, and American Headache Society.

The identification of CGRP as a crucial pain signaling molecule in the trigeminal pathway, thereby establishing its link to migraine pain, has transformed care for patients with episodic and chronic migraine. Since 2018, the FDA has approved 4 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that either block the CGRP receptor or bind its ligand to prevent attachment to the receptor.

These medications are helping patients with medication overuse headache (MOH) and chronic migraine; one study involving 139 patients showed that half the patients saw their headache days per month cut by half, and migraine days per month cut by 62%. In another small study, 23 patients (47%) with medication overuse headache reported having no MOH issues after 3 months. Most of these patients had a history of medication overuse, but no specific diagnosis of MOH.

In a survey, 277 physicians said that nearly half of their patients had resistant migraine, and 29% had refractory migraine. For these patients, the mAbs have helped restore some normalcy in their lives.

But are these medications safe? Some clinicians posed this question even before the 2018 approval.

It is a valid question. The CGRP neuropeptide is a powerful dilator, establishing vascular homeostasis, organ development in utero, wound healing, and more. It is expressed in the peripheral and central nervous system and found abundantly in neurons and the unmyelinated A-fibers of the peripheral trigeminovascular system and trigeminal ganglion.

So, would blocking CGRP function in one area affect its function in another? So far, I have to say the answer is no. Neither the literature nor my observations say otherwise.

Trials vs the real world

Finding an answer to this question takes more than reading clinical trials data. Participants in these trials do not necessarily represent the real world – no complicated morbidities, no pregnant or lactating women. And trial lengths are generally short.

Thus, it is important to assess the safety of these medications in the real world.

In the trials of the subcutaneous mAbs, local injection site reactions were the most common adverse event. More specifically, erenumab showed increased incidence of constipation, and post-marketing surveillance has revealed some risk of hypertension; pooled analysis from 4 trial phases showed that across treatment groups, 20 people out of 2443 began treatment for hypertension. Some patients enrolled in trials for atogepant, an oral small molecule CGRP receptor agonist, also reported constipation and nausea, suggesting that receptor blockade may result in a higher incidence of GI disturbance. In addition, these medicines on occasion have caused alopecia, fatigue, or achiness.

Eptinezumab is administered intravenously, every 3 months, and thus does not have injection site reactions as a safety concern. In clinical trials, the most common adverse event was nasopharyngitis and hypersensitivity; Datta et al have provided a summary of safety and efficacy.

Raynaud’s and cluster headaches

A retrospective chart review study from the Mayo Clinic looking at individuals with Raynaud’s disease who were treated with CGRP antagonists showed that 5.3% of 169 patients had microvascular complications such as gangrene or autoimmune necrosis. There was no significant difference in demographic characteristics or rheumatologic history among those with Raynaud's who did or did not experience complications. In addition, microvascular complications of migraine therapies have preceded the use of CGRP modulators, as this has been documented in the past with other vasoactive substances such as ergots, triptans, and beta blockers.

In a tolerability and safety study of galcanezumab in patients with chronic cluster headache, with up to 15 months of treatment, the most common treatment emergent adverse events were nasopharyngitis and injection site pain. In this population with 11% to 12% of individuals having baseline hypertension and nearly 63% currently using tobacco, less than 2.5% had any abnormalities on ECG.

Vascular complications including pulmonary embolism, TIA, myocardial infarction, and atrial fibrillation have been reported but with no apparent relation between galcanezumab dosing and onset, with onset following the second to up to the eleventh monthly dose.