User login

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: Migraine May 2022

Cefaly is a commonly used nonprescription device that uses external trigeminal nerve stimulation (e-TNS) to either abort or prevent migraine attacks. The pivotal Cefaly study was published about 10 years ago, and Cefaly was the first US Food and Drug Administration–cleared neurostimulation device for headache. The initial acute data were gathered primarily in the hospital setting, and the investigators in the study by Kuruvilla and colleagues intended to replicate a more real-world scenario for the acute use of Cefaly.

This was a prospective, multicenter, sham-controlled study. Patients were enrolled if they developed migraine prior to age 50 years and experienced two to eight attacks per month of moderate to severe intensity. Patients were randomized to either Cefaly or a sham device. The Cefaly device itself has two setting: acute and preventive. For this study, the acute setting was used for 2 hours at a time during an acute attack (within the first 4 hours). The supraorbital and supratrochlear branches of trigeminal nerves bilaterally are stimulated with a continuous stimulation via a self-adhesive electrode. This has previously been shown to be safe and effective with the most common side effect noted to be skin irritation at the electrode site.

Patients collected data about their headaches in an e-diary and continued to treat for 2 months. The co-primary outcomes were headache freedom and resolution of most bothersome syndrome at 2 hours. Secondary outcomes were pain relief at 2 hours, resolution of any migraine-associated symptom at 2 hours after beginning e-TNS treatment, sustained pain freedom (defined as pain freedom at 2 hours and pain freedom at 24 hours without the use of antimigraine medication during those 24 hours), and use of a rescue medication between 2 and 24 hours after beginning an e-TNS session.

A total of 538 patients were enrolled. The percentage of patients with both freedom from pain and resolution of the most bothersome symptoms were statistically different in the intervention and sham groups. The secondary outcomes were also statistically improved in the device group, with the exception of use of rescue medications between 2 and 24 hours. The most common adverse events were forehead discomfort and paresthesia.

This study does show the effectiveness of Cefaly, especially when used for longer periods of time than had been previously recommended. The outcomes were all met with the exception of rescue medication use, and there is no contraindication to using any rescue medication while using the Cefaly device. Cefaly can be an excellent add-on for acute treatment, especially in patients that may need to use more than one intervention acutely for their migraine attacks.

Providers often discuss when to start medications but do not as often discuss when to stop medications. This is especially true for preventive medications for migraine. The best-case scenario is that a preventive medication is so effective that it is no longer necessary; but in other circumstances, preventive medications have to be stopped, for instance, during pregnancy planning. One concern especially when starting and stopping a monoclonal antibody (mAb) medication is the development of neutralizing antibodies to negate the effect of restarting the medication. This study was designed to determine whether restarting calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)–mAb medications was still effective after having been previously stopped.

Raffaelli and colleagues managed a small (39 patients) open-label prospective study. Patients either had a diagnosis of episodic or chronic migraine and were initially given CGRP-mAbs for at least 8 months. They then stopped the therapy for at least 3 months and were restarted on the same mAb that they had initially used. They tracked their headache symptoms for 3 months after restarting therapy. If another treatment had been started in between, those patients were excluded.

The primary outcome was change in mean monthly migraine days between the last 4 weeks of treatment discontinuation and weeks 9-12 after restarting therapy. Secondary endpoints were the changes in mean monthly headache days across the other observation points and Headache Impact Test-6 (HIT-6) sum scores. Of the 39 patients enrolled, 16 were given erenumab, 15 galcanezumab, and 8 fremanezumab.

Mean migraine days and mean headache days were shown to have a statistically significant decrease after resumption of therapy. Restarting CGRP medications was not associated with other adverse events associated with these medications. This gives us evidence in favor of restarting the same CGRP medication when a patient's symptoms start to worsen after they have discontinued because of improvement or after pregnancy and breastfeeding.

The use of implanted devices for migraine treatment is considered somewhat controversial. Surgical interventions and implantations for migraine have not been well studied; however small case series have been published, and non-neurologists report anecdotally that these interventions can be helpful for refractory headache disorders. The study by Evans and colleagues reviewed via meta-analysis much of the prior data for nerve stimulation in migraine.

Studies included in this meta-analysis were English-language, peer-reviewed articles of prospective studies with patients over age 18 years for migraine diagnosed according to International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) criteria. The devices were transcutaneous nerve stimulator devices in a single region of the head (occipital, supraorbital/supratrochlear areas) and enrolled a minimum of 10 patients in the treatment groups. A total of 14 studies were identified; 13 of the studies did report significant adverse events related to treatment.

Regarding migraine frequency, only four of the studies were considered comparable, investigating episodic migraine with 2-3 months of transcutaneous stimulation, and two were comparable in investigating chronic migraine. The episodic migraine studies had a pooled reduction by 2.8 days of migraine per month; chronic migraine was noted to be 2.97 days fewer per month. Three comparable studies for episodic migraine showed a pooled reduction in severity by 2.23 points after 3 months.

Occipital and other trigeminal branch stimulation implants are invasive and associated with risk, most prominently leading to migration and worsening headache and neck pain. This meta-analysis did reveal important pooled data, but it becomes less impressive when considering the published data for standard oral or injection therapies. The fact that there can be long-term worsening and adverse events with surgical implantation makes this choice a higher risk. Of note, there are now neurostimulation devices, such as Cefaly, that allow similar transcutaneous stimulation without the risk of surgery.

Cefaly is a commonly used nonprescription device that uses external trigeminal nerve stimulation (e-TNS) to either abort or prevent migraine attacks. The pivotal Cefaly study was published about 10 years ago, and Cefaly was the first US Food and Drug Administration–cleared neurostimulation device for headache. The initial acute data were gathered primarily in the hospital setting, and the investigators in the study by Kuruvilla and colleagues intended to replicate a more real-world scenario for the acute use of Cefaly.

This was a prospective, multicenter, sham-controlled study. Patients were enrolled if they developed migraine prior to age 50 years and experienced two to eight attacks per month of moderate to severe intensity. Patients were randomized to either Cefaly or a sham device. The Cefaly device itself has two setting: acute and preventive. For this study, the acute setting was used for 2 hours at a time during an acute attack (within the first 4 hours). The supraorbital and supratrochlear branches of trigeminal nerves bilaterally are stimulated with a continuous stimulation via a self-adhesive electrode. This has previously been shown to be safe and effective with the most common side effect noted to be skin irritation at the electrode site.

Patients collected data about their headaches in an e-diary and continued to treat for 2 months. The co-primary outcomes were headache freedom and resolution of most bothersome syndrome at 2 hours. Secondary outcomes were pain relief at 2 hours, resolution of any migraine-associated symptom at 2 hours after beginning e-TNS treatment, sustained pain freedom (defined as pain freedom at 2 hours and pain freedom at 24 hours without the use of antimigraine medication during those 24 hours), and use of a rescue medication between 2 and 24 hours after beginning an e-TNS session.

A total of 538 patients were enrolled. The percentage of patients with both freedom from pain and resolution of the most bothersome symptoms were statistically different in the intervention and sham groups. The secondary outcomes were also statistically improved in the device group, with the exception of use of rescue medications between 2 and 24 hours. The most common adverse events were forehead discomfort and paresthesia.

This study does show the effectiveness of Cefaly, especially when used for longer periods of time than had been previously recommended. The outcomes were all met with the exception of rescue medication use, and there is no contraindication to using any rescue medication while using the Cefaly device. Cefaly can be an excellent add-on for acute treatment, especially in patients that may need to use more than one intervention acutely for their migraine attacks.

Providers often discuss when to start medications but do not as often discuss when to stop medications. This is especially true for preventive medications for migraine. The best-case scenario is that a preventive medication is so effective that it is no longer necessary; but in other circumstances, preventive medications have to be stopped, for instance, during pregnancy planning. One concern especially when starting and stopping a monoclonal antibody (mAb) medication is the development of neutralizing antibodies to negate the effect of restarting the medication. This study was designed to determine whether restarting calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)–mAb medications was still effective after having been previously stopped.

Raffaelli and colleagues managed a small (39 patients) open-label prospective study. Patients either had a diagnosis of episodic or chronic migraine and were initially given CGRP-mAbs for at least 8 months. They then stopped the therapy for at least 3 months and were restarted on the same mAb that they had initially used. They tracked their headache symptoms for 3 months after restarting therapy. If another treatment had been started in between, those patients were excluded.

The primary outcome was change in mean monthly migraine days between the last 4 weeks of treatment discontinuation and weeks 9-12 after restarting therapy. Secondary endpoints were the changes in mean monthly headache days across the other observation points and Headache Impact Test-6 (HIT-6) sum scores. Of the 39 patients enrolled, 16 were given erenumab, 15 galcanezumab, and 8 fremanezumab.

Mean migraine days and mean headache days were shown to have a statistically significant decrease after resumption of therapy. Restarting CGRP medications was not associated with other adverse events associated with these medications. This gives us evidence in favor of restarting the same CGRP medication when a patient's symptoms start to worsen after they have discontinued because of improvement or after pregnancy and breastfeeding.

The use of implanted devices for migraine treatment is considered somewhat controversial. Surgical interventions and implantations for migraine have not been well studied; however small case series have been published, and non-neurologists report anecdotally that these interventions can be helpful for refractory headache disorders. The study by Evans and colleagues reviewed via meta-analysis much of the prior data for nerve stimulation in migraine.

Studies included in this meta-analysis were English-language, peer-reviewed articles of prospective studies with patients over age 18 years for migraine diagnosed according to International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) criteria. The devices were transcutaneous nerve stimulator devices in a single region of the head (occipital, supraorbital/supratrochlear areas) and enrolled a minimum of 10 patients in the treatment groups. A total of 14 studies were identified; 13 of the studies did report significant adverse events related to treatment.

Regarding migraine frequency, only four of the studies were considered comparable, investigating episodic migraine with 2-3 months of transcutaneous stimulation, and two were comparable in investigating chronic migraine. The episodic migraine studies had a pooled reduction by 2.8 days of migraine per month; chronic migraine was noted to be 2.97 days fewer per month. Three comparable studies for episodic migraine showed a pooled reduction in severity by 2.23 points after 3 months.

Occipital and other trigeminal branch stimulation implants are invasive and associated with risk, most prominently leading to migration and worsening headache and neck pain. This meta-analysis did reveal important pooled data, but it becomes less impressive when considering the published data for standard oral or injection therapies. The fact that there can be long-term worsening and adverse events with surgical implantation makes this choice a higher risk. Of note, there are now neurostimulation devices, such as Cefaly, that allow similar transcutaneous stimulation without the risk of surgery.

Cefaly is a commonly used nonprescription device that uses external trigeminal nerve stimulation (e-TNS) to either abort or prevent migraine attacks. The pivotal Cefaly study was published about 10 years ago, and Cefaly was the first US Food and Drug Administration–cleared neurostimulation device for headache. The initial acute data were gathered primarily in the hospital setting, and the investigators in the study by Kuruvilla and colleagues intended to replicate a more real-world scenario for the acute use of Cefaly.

This was a prospective, multicenter, sham-controlled study. Patients were enrolled if they developed migraine prior to age 50 years and experienced two to eight attacks per month of moderate to severe intensity. Patients were randomized to either Cefaly or a sham device. The Cefaly device itself has two setting: acute and preventive. For this study, the acute setting was used for 2 hours at a time during an acute attack (within the first 4 hours). The supraorbital and supratrochlear branches of trigeminal nerves bilaterally are stimulated with a continuous stimulation via a self-adhesive electrode. This has previously been shown to be safe and effective with the most common side effect noted to be skin irritation at the electrode site.

Patients collected data about their headaches in an e-diary and continued to treat for 2 months. The co-primary outcomes were headache freedom and resolution of most bothersome syndrome at 2 hours. Secondary outcomes were pain relief at 2 hours, resolution of any migraine-associated symptom at 2 hours after beginning e-TNS treatment, sustained pain freedom (defined as pain freedom at 2 hours and pain freedom at 24 hours without the use of antimigraine medication during those 24 hours), and use of a rescue medication between 2 and 24 hours after beginning an e-TNS session.

A total of 538 patients were enrolled. The percentage of patients with both freedom from pain and resolution of the most bothersome symptoms were statistically different in the intervention and sham groups. The secondary outcomes were also statistically improved in the device group, with the exception of use of rescue medications between 2 and 24 hours. The most common adverse events were forehead discomfort and paresthesia.

This study does show the effectiveness of Cefaly, especially when used for longer periods of time than had been previously recommended. The outcomes were all met with the exception of rescue medication use, and there is no contraindication to using any rescue medication while using the Cefaly device. Cefaly can be an excellent add-on for acute treatment, especially in patients that may need to use more than one intervention acutely for their migraine attacks.

Providers often discuss when to start medications but do not as often discuss when to stop medications. This is especially true for preventive medications for migraine. The best-case scenario is that a preventive medication is so effective that it is no longer necessary; but in other circumstances, preventive medications have to be stopped, for instance, during pregnancy planning. One concern especially when starting and stopping a monoclonal antibody (mAb) medication is the development of neutralizing antibodies to negate the effect of restarting the medication. This study was designed to determine whether restarting calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)–mAb medications was still effective after having been previously stopped.

Raffaelli and colleagues managed a small (39 patients) open-label prospective study. Patients either had a diagnosis of episodic or chronic migraine and were initially given CGRP-mAbs for at least 8 months. They then stopped the therapy for at least 3 months and were restarted on the same mAb that they had initially used. They tracked their headache symptoms for 3 months after restarting therapy. If another treatment had been started in between, those patients were excluded.

The primary outcome was change in mean monthly migraine days between the last 4 weeks of treatment discontinuation and weeks 9-12 after restarting therapy. Secondary endpoints were the changes in mean monthly headache days across the other observation points and Headache Impact Test-6 (HIT-6) sum scores. Of the 39 patients enrolled, 16 were given erenumab, 15 galcanezumab, and 8 fremanezumab.

Mean migraine days and mean headache days were shown to have a statistically significant decrease after resumption of therapy. Restarting CGRP medications was not associated with other adverse events associated with these medications. This gives us evidence in favor of restarting the same CGRP medication when a patient's symptoms start to worsen after they have discontinued because of improvement or after pregnancy and breastfeeding.

The use of implanted devices for migraine treatment is considered somewhat controversial. Surgical interventions and implantations for migraine have not been well studied; however small case series have been published, and non-neurologists report anecdotally that these interventions can be helpful for refractory headache disorders. The study by Evans and colleagues reviewed via meta-analysis much of the prior data for nerve stimulation in migraine.

Studies included in this meta-analysis were English-language, peer-reviewed articles of prospective studies with patients over age 18 years for migraine diagnosed according to International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) criteria. The devices were transcutaneous nerve stimulator devices in a single region of the head (occipital, supraorbital/supratrochlear areas) and enrolled a minimum of 10 patients in the treatment groups. A total of 14 studies were identified; 13 of the studies did report significant adverse events related to treatment.

Regarding migraine frequency, only four of the studies were considered comparable, investigating episodic migraine with 2-3 months of transcutaneous stimulation, and two were comparable in investigating chronic migraine. The episodic migraine studies had a pooled reduction by 2.8 days of migraine per month; chronic migraine was noted to be 2.97 days fewer per month. Three comparable studies for episodic migraine showed a pooled reduction in severity by 2.23 points after 3 months.

Occipital and other trigeminal branch stimulation implants are invasive and associated with risk, most prominently leading to migration and worsening headache and neck pain. This meta-analysis did reveal important pooled data, but it becomes less impressive when considering the published data for standard oral or injection therapies. The fact that there can be long-term worsening and adverse events with surgical implantation makes this choice a higher risk. Of note, there are now neurostimulation devices, such as Cefaly, that allow similar transcutaneous stimulation without the risk of surgery.

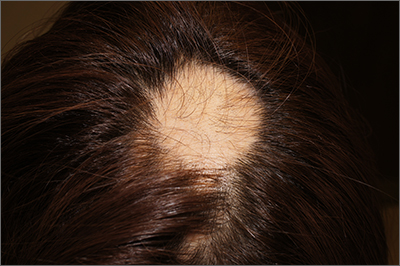

Focal hair loss

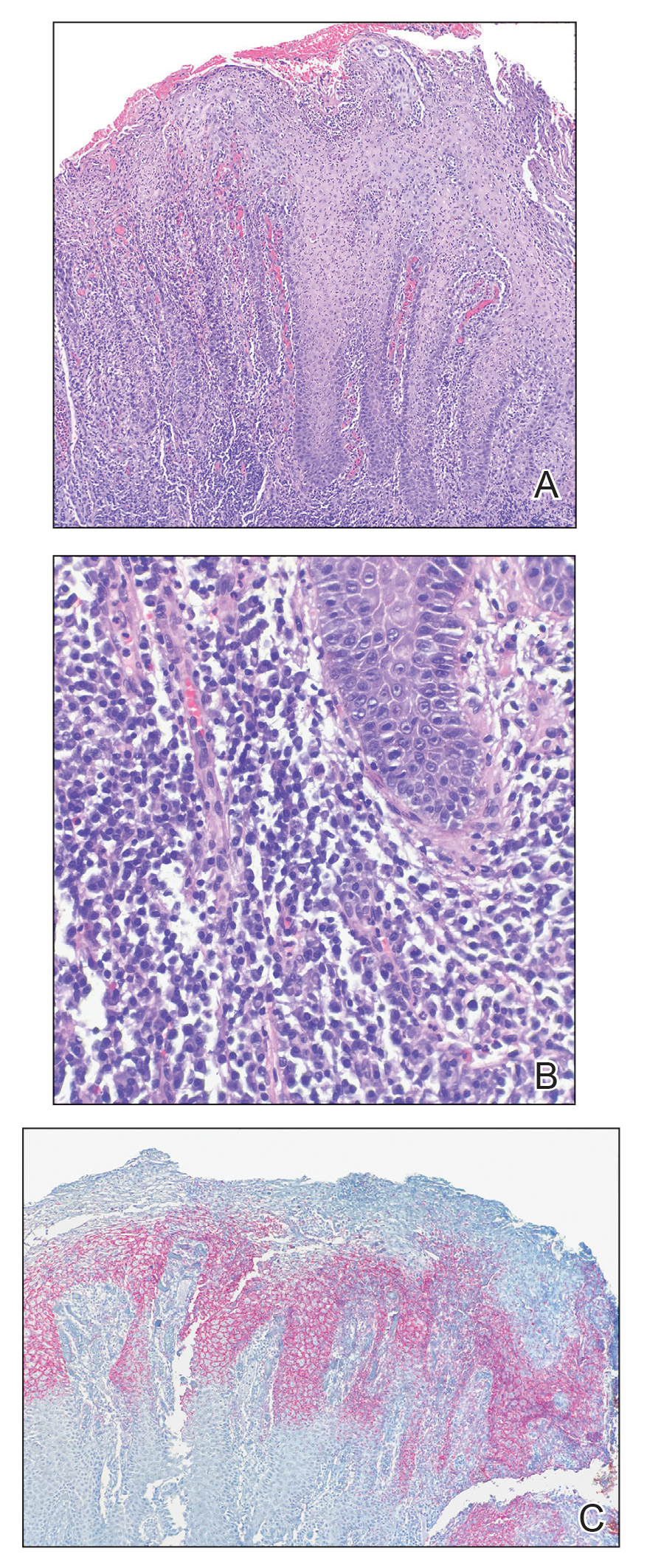

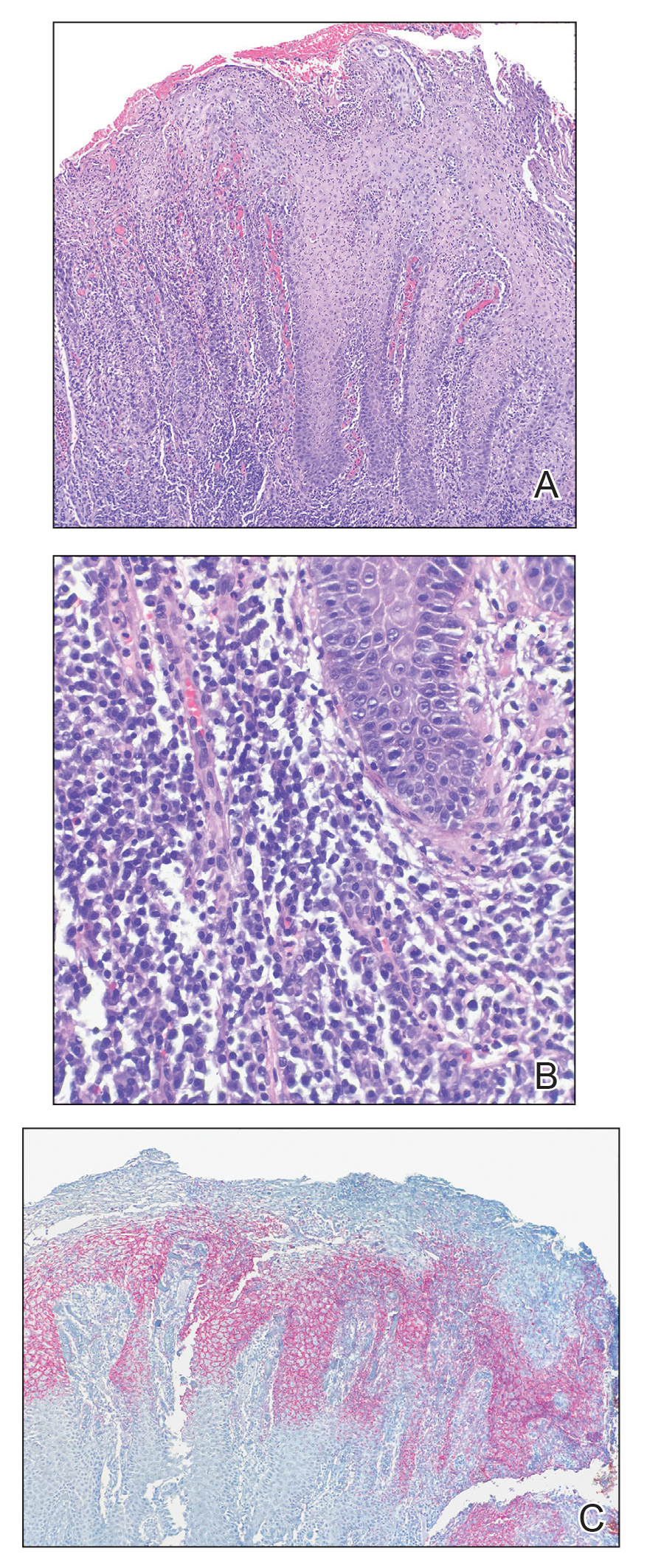

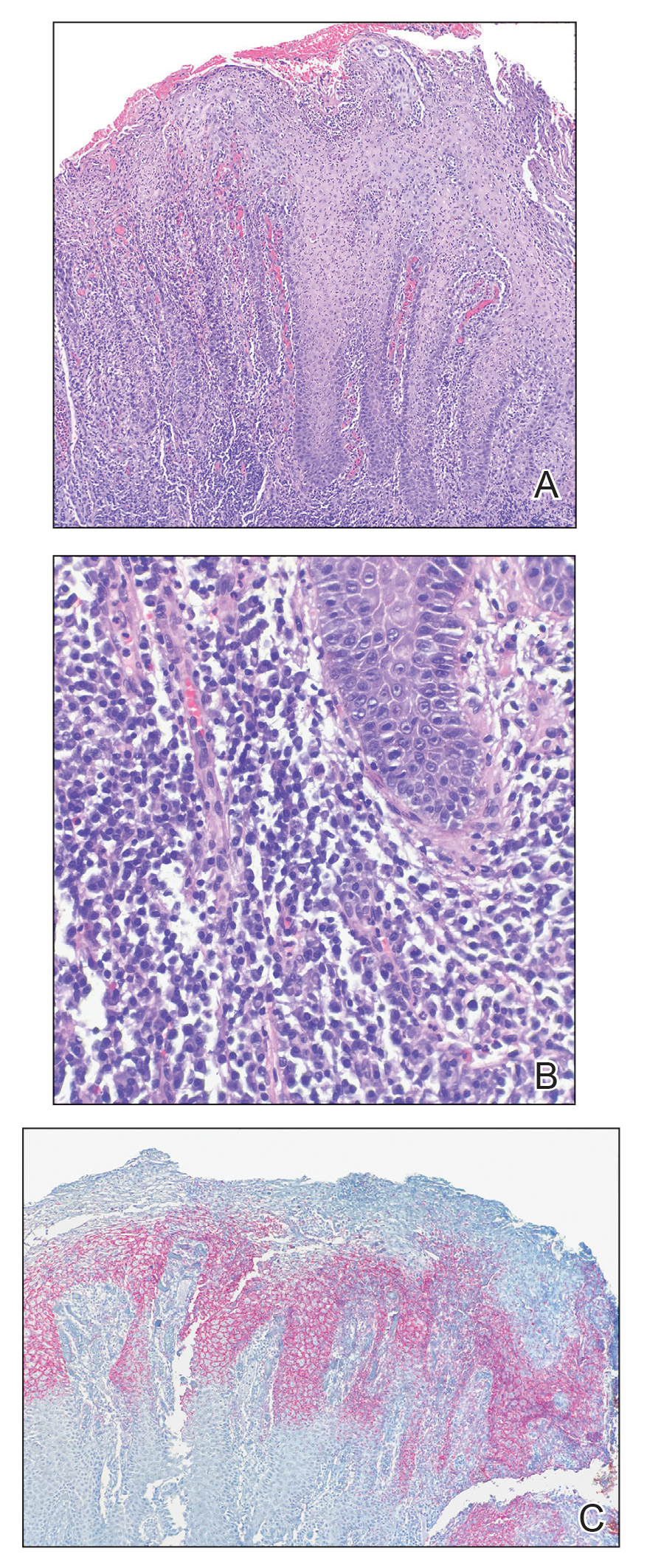

The findings of smooth, round alopecia occurring rapidly without associated scarring, pain, or itching, is consistent with the diagnosis of alopecia areata.

Alopecia areata is a common autoimmune disease caused by T lymphocytes targeting hair follicles and resulting in rapid and nonscarring hair loss. It is usually self-resolving and about 2% of all individuals are affected at some point during their lifetime, with an average age of onset of 33 years.1 Some patients may progress to loss of all scalp hair (alopecia totalis) or all hair on the scalp and body (alopecia universalis).1

It is important to inspect a patient’s scalp, face, and body for more subtle areas of loss that could signal other disorders, such as lichen planopilaris, discoid lupus, or telogen effluvium. It is worth noting that alopecia areata is not associated with scalp lesions, crusting, or scars without follicles. Such findings should be further investigated with a 4-mm punch biopsy of affected and adjacent follicular units. Carefully labeling biopsy specimens as scalp specimens for hair loss will aid in a correct histopathologic diagnosis.

Systematic data comparing treatments for alopecia areata are lacking. For localized disease, topical or intradermal triamcinolone injections at a concentration of 5 to 10 mg/mL, with about 0.1 mL to 0.05 mL injected every square centimeter of affected area (up to 40 mg per visit), can provide rapid regrowth.1 Within 4 months of the monthly injections, 63% of patients experience complete regrowth.1 Despite this favorable outcome, there is also a high rate of recurrence.

For more widespread disease, contact immunotherapy with squaric acid dibutyl ester or diphencyprone can provoke a low-grade contact allergy and induce antigenic completion. This therapy is painless but can be itchy; medications must be compounded and titrated to activity.

The patient in this case opted to receive monthly triamcinolone injections in an undiluted concentration of 10 mg/mL for 3 months, at which point she experienced excellent hair regrowth. A small patch of recurrence was noted a year later and treated twice with monthly triamcinolone injections.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Darwin E, Hirt PA, Fertig R, et al. Alopecia areata: review of epidemiology, clinical features, pathogenesis, and new treatment options. Int J Trichology. 2018;10:51-60. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_99_17

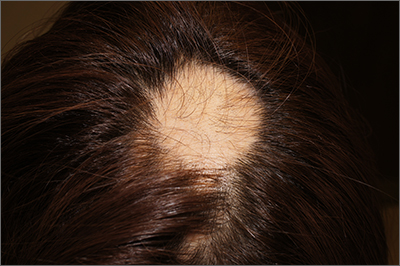

The findings of smooth, round alopecia occurring rapidly without associated scarring, pain, or itching, is consistent with the diagnosis of alopecia areata.

Alopecia areata is a common autoimmune disease caused by T lymphocytes targeting hair follicles and resulting in rapid and nonscarring hair loss. It is usually self-resolving and about 2% of all individuals are affected at some point during their lifetime, with an average age of onset of 33 years.1 Some patients may progress to loss of all scalp hair (alopecia totalis) or all hair on the scalp and body (alopecia universalis).1

It is important to inspect a patient’s scalp, face, and body for more subtle areas of loss that could signal other disorders, such as lichen planopilaris, discoid lupus, or telogen effluvium. It is worth noting that alopecia areata is not associated with scalp lesions, crusting, or scars without follicles. Such findings should be further investigated with a 4-mm punch biopsy of affected and adjacent follicular units. Carefully labeling biopsy specimens as scalp specimens for hair loss will aid in a correct histopathologic diagnosis.

Systematic data comparing treatments for alopecia areata are lacking. For localized disease, topical or intradermal triamcinolone injections at a concentration of 5 to 10 mg/mL, with about 0.1 mL to 0.05 mL injected every square centimeter of affected area (up to 40 mg per visit), can provide rapid regrowth.1 Within 4 months of the monthly injections, 63% of patients experience complete regrowth.1 Despite this favorable outcome, there is also a high rate of recurrence.

For more widespread disease, contact immunotherapy with squaric acid dibutyl ester or diphencyprone can provoke a low-grade contact allergy and induce antigenic completion. This therapy is painless but can be itchy; medications must be compounded and titrated to activity.

The patient in this case opted to receive monthly triamcinolone injections in an undiluted concentration of 10 mg/mL for 3 months, at which point she experienced excellent hair regrowth. A small patch of recurrence was noted a year later and treated twice with monthly triamcinolone injections.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

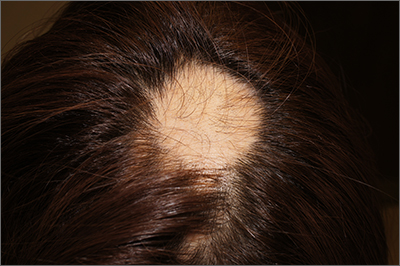

The findings of smooth, round alopecia occurring rapidly without associated scarring, pain, or itching, is consistent with the diagnosis of alopecia areata.

Alopecia areata is a common autoimmune disease caused by T lymphocytes targeting hair follicles and resulting in rapid and nonscarring hair loss. It is usually self-resolving and about 2% of all individuals are affected at some point during their lifetime, with an average age of onset of 33 years.1 Some patients may progress to loss of all scalp hair (alopecia totalis) or all hair on the scalp and body (alopecia universalis).1

It is important to inspect a patient’s scalp, face, and body for more subtle areas of loss that could signal other disorders, such as lichen planopilaris, discoid lupus, or telogen effluvium. It is worth noting that alopecia areata is not associated with scalp lesions, crusting, or scars without follicles. Such findings should be further investigated with a 4-mm punch biopsy of affected and adjacent follicular units. Carefully labeling biopsy specimens as scalp specimens for hair loss will aid in a correct histopathologic diagnosis.

Systematic data comparing treatments for alopecia areata are lacking. For localized disease, topical or intradermal triamcinolone injections at a concentration of 5 to 10 mg/mL, with about 0.1 mL to 0.05 mL injected every square centimeter of affected area (up to 40 mg per visit), can provide rapid regrowth.1 Within 4 months of the monthly injections, 63% of patients experience complete regrowth.1 Despite this favorable outcome, there is also a high rate of recurrence.

For more widespread disease, contact immunotherapy with squaric acid dibutyl ester or diphencyprone can provoke a low-grade contact allergy and induce antigenic completion. This therapy is painless but can be itchy; medications must be compounded and titrated to activity.

The patient in this case opted to receive monthly triamcinolone injections in an undiluted concentration of 10 mg/mL for 3 months, at which point she experienced excellent hair regrowth. A small patch of recurrence was noted a year later and treated twice with monthly triamcinolone injections.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Darwin E, Hirt PA, Fertig R, et al. Alopecia areata: review of epidemiology, clinical features, pathogenesis, and new treatment options. Int J Trichology. 2018;10:51-60. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_99_17

1. Darwin E, Hirt PA, Fertig R, et al. Alopecia areata: review of epidemiology, clinical features, pathogenesis, and new treatment options. Int J Trichology. 2018;10:51-60. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_99_17

Reading Chekhov on the Cancer Ward

Burnout and other forms of psychosocial distress are common among health care professionals necessitating measures to promote well-being and reduce burnout.1 Studies have shown that nonmedical reading is associated with low burnout and that small group study sections can promote wellness.2,3 Narrative medicine, which proposes a model for humane and effective medical practice, advocates for the necessity of narrative competence.

Short Story Club

Narrative competence is the ability to acknowledge, interpret, and act on the stories of others. The narrative skill of close reading also encourages reflective practice, equipping practitioners to better weather the tides of illness.4 In our case, we formed a short story club intervention to closely read, or read and reflect, on literary fiction. We explored how reading and reflecting would result in profound changes in thinking and feeling and noted different ways by which they can cause such well-being. We describe here the 7 ways in which stories led us to increase bonding, improve empathy, and promote meaning in medicine.

Slowing Down

The short story club helped to bond us together and increase our sense of meaning in medicine by slowing us down. One member of the group likened the experience to increasing the pixels in a painting, thereby improving the resolution and seeing more clearly. Another member mentioned the experience as a form of meditation in slowing down the brain, breathing in the story, and breathing out impressions. One story by Anatole Broyard emphasized the importance of slowing down and “brooding” over a patient.5 The author describes his experience as a prostate cancer patient, in which his body was treated but his story was ignored. He begged his doctors to pay more attention to his story to listen and to brood over him. This story was enlightening to us; we saw how desperate our patients are to tell their stories, and for us to hear their stories.

Mirrors and Windows

Another way reading and reflecting on short stories helped was by reflecting our practices to ourselves, as though looking into a mirror to see ourselves and out of a window to see others. We found that stories mirrored our own world and allowed us to discuss issues close to us without the embarrassment or stigma of owning the story. In one session we read “The Doctor’s Visit” by Anton Chekhov.6 Some of the members resonated with the doctor of this story who awkwardly attended to his lady patient whose son was dying of a brain tumor. The doctor was nervous, insecure, and unable to express any empathy. He was also the father of the child who was dying and refused to admit any responsibility. One member of the group stated that he could relate to the doctor’s insecurities and mentioned that he too felt insecure and even sometimes felt like an imposter. This led to a discussion of insecurities, ways to bolster self-confidence, and ways to accept and respect limitations. This was a conversation that may not have taken place without the story as anchor to discuss insecurities that we individually may not have been willing to admit to the group.

In a different session, we discussed the story “Interpreter of Maladies” by Jhumpa Lahiri in which a settled Indian American family returns to India to tour and learn about their heritage from a guide (the interpreter of maladies) who interpreted the culture for them.7 The family professed to be interested in knowing about the culture but could not concentrate: the wife stayed busy flirting with the guide and revealing outrageous secrets to him, the children were engrossed in their squabbles, and the father was essentially absent taking photographs as souvenirs instead of seeing the sites firsthand. Some of the members of the group were Indian American and could relate to the alienation from their home and nostalgia for their country, while others could relate to the same alienation, albeit from other cultures and countries. This allowed us to talk about deeply personal topics, without having to own the topic or reveal personal issues. The discussion led to a deep understanding and empathy for us and our colleagues knowing the pain of alienation that some of them felt but could not discuss.

The stories also served as windows into the world of others which enabled us to see and become the other. For example, in one session we reflected on “Babylon Revisited” by F. Scott Fitzgerald.8 In this story, an American man returns to Paris after the Great Depression and recalls his life as a young artist in the American artist expatriate community of Paris in the 1920s and 1930s. During that time, he partied, drank in excess, lost his wife to pneumonia (for which he was at least partially responsible), lost custody of his daughter, and lost his fortune. As he returned to Paris to try to reclaim his daughter, we feel his pain as he tries but fails to overcome chronic alcoholism, sexual indiscretions, and losses. This gave rise to discussion of losses in general as we became one with the main character. This increased our empathy for others in a way that could not have been possible without this short story as anchor.

In another session we reflected on “Hills Like White Elephants” by Ernest Hemingway, in which a man is waiting for a train while proposing his girlfriend get an abortion.9 She agonizes over her choices and makes no decision in this story. Yet, we the reader could “become” the woman in the story faced with hard choices of having a baby but losing the man she loves, or having an abortion and maybe losing him anyway. In becoming this woman, we could experience the complex emotions and feel an experience of the other.

Exploring the Taboo

A third aspect of the club was enabling discussion of controversial topics. There were topics that arose in the group which never would have arisen in clinical practice discussions. These had to do with the taboo topics such as romantic attachments to patients. We read “The Caves of Lascaux” and reflected on the story of a young doctor who becomes enamored and obsessed with his beautiful but dying patient.10 He becomes so obsessed with her that he almost abandons his wife, family, and stable livelihood to descend with her into the caves. This story gave rise to discussions about romantic attachment to patients and how to handle and extricate one from the situation. The senior doctors explained some of their relevant experiences and how they either transferred care or sought counseling to extricate themselves from a potentially dangerous situation, especially when they too fell under the spell of forbidden romance.

Moral Grounding

These sessions also served to define the moral basis of our own practice. Much of health care psychosocial distress is related to moral injury in which health care professionals do the wrong thing or fail to do the right thing at the right time, due to external pressures related to financial or other gains. Reading and reflecting put us face-to-face with moral dilemmas and let us find our moral grounding. In reading “The Haircut” by Ring Lardner, we explored the disruptive town scoundrel who harassed and tortured his friends and neighbors but in such outrageous ways that he was considered a comedian rather than an abuser.11 Despite his hurtful acts, the townspeople (including the narrator) considered him a clown and laughed at his racist and sexist statements as well as his tricks.He faced no consequences such as confrontation, until the end when fate caught up. This story gave rise to a discussion of how we handle unkind, racist, sexist, or other comments which are disguised as humor, and to what extent we tolerate such controversial behavior. Do we go along with the scoundrel and laugh, or do we confront such people and insist that they respect and honor other people? The story sensitized the group to the ways in which prejudice and racism or sexism can be masked as humor, and to consider our moral responsibilities in society.

In another session we read and reflected on “Three Questions” by Leo Tolstoy.12 In this story, a king travels to another territory but gets distracted by helping a neighbor in need, and thereby inadvertently and fortunately avoids the trap that had been devised to kill him. The author gives us his moral basis by asking and answering 3 questions: Who is the most important person? What is the most important thing to do? What is the most important thing to do now? His answers provided his moral grounding. We discussed our answers and the basis of our moral grounding, whether it be the injunction do no harm, the more complex religious backgrounds of our childhood, or otherwise.

Symbols and Metaphors

The practice of reading and reflecting also taught us symbols and metaphors. Symbols and metaphors are the essence of storytelling, and they provide keys to understanding people. We sought out and studied the metaphors and symbols in each of the stories we read. In “I Stood There Ironing”, a woman is ironing as she is being questioned by a social worker on the upbringing of her first daughter, and its impact on her psychosocial distress.13 The woman remembers the hardships in raising her daughter and her neglect and abuse of the child due to circumstances beyond her control. She keeps ironing back and forth as she recounts the ways in which she neglected her child. The ironing provides a metaphor for attempting to straighten out her life and for recognizing finally at the end of the story that the daughter should not be the dress, under which her iron is pressing. This gave rise to a discussion of metaphors in our lives and the meanings they carry.

Problem-solving Guide

A sixth way the reflections helped was by serving as a guide to solving our problems. Some of the stories we read resonated deeply with members of the group and provided guides to solving problems. In one meeting we discussed “Those Are as Brothers” by Nancy Hale, a story in which a Nazi concentration camp survivor finds refuge in a country home and develops a friendship with a survivor of an abusive marriage.14 Reading and reflecting on this story enabled us to see the impact of trauma on ourselves, our life choices, professions, ways of being, philosophies, and even on our next generation. The story was personal for several members of the group, some of whom were second-generation Holocaust survivors, and for one who admitted to severe trauma as a child. Discussing our backgrounds together, we empathized with each other and helped each other heal. The story also provided a guide to healing from trauma, as its title indicates: sharing stories together can be a way to heal. The solidarity of standing together, as brothers, heals. The concentration camp survivor was mistreated in his job, but the abuse trauma victim rushes to his defense and vows her friendship and support. This soothed his soul and healed his mind. The guidance is clear: we can do the same, find friends, treat them like brothers, support each other and heal.

Bonding Through Shared Experience

The final and possibly most important way in which the club helped was by serving as an adventure to bond group members together through shared experience. We believe that literature can capture imagination in extraordinary ways and provide an opportunity to undertake remarkable journeys. As such, together we traveled to the ends of the earth from the beginning to the end of time and beyond. We traveled through the hills of Africa, meandered in the streets of Russia and Poland, watched the racetracks in Italy, toured the Taj Mahal in India, and descended into the caves of Lascaux, all while working in Little Rock, Arkansas. We shared a wide array of experiences together, which allowed us to know ourselves and others better, to share stories, and to develop a common vision, common ground, and common culture.

Conclusions

Through reading and reflecting on stories, we bonded as a group, increased our empathy for each other and others, and found meaning in medicine. Other studies have shown that participation in small study groups promote physician well-being, improve job satisfaction, and decrease burnout.3 We synergized this effort by reading nonmedical stories on a consistent basis, hoping to gain resilience to psychosocial distress.3 We chose short stories rather than novels to minimize any stress from excess reading. Combining these interventions, small group studies and nonmedical reading, into a single intervention as is typical in the practice of narrative medicine may provide a way to improve team functioning.

This pilot study showed that it is possible to form short story clubs even in a busy oncology program and that such programs benefit participants in a variety of ways with no apparent adverse effects. Further research is needed to study the impact of reading and reflecting on medical work in small study groups in larger numbers of subjects and to evaluate their impact on burnout. Further study is also needed to develop narrative medicine curricula that best address the needs of particular subspecialties and to determine the optimal conditions for implementation.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Erick Messias for inspiring and encouraging this project at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences where he was Associate Dean for Faculty Affairs. He is presently Chair of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience at the St. Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri.

1. Messias E, Gathright MM, Freeman ES, et al. Differences in burnout prevalence between clinical professionals and biomedical scientists in an academic medical centre: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e023506. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023506

2. Marchalik D, Rodriguez A, Namath A, et al. The impact of non-medical reading on clinical burnout: a national survey of palliative care providers. Ann Palliat Med. 2019;8(4):428-435. doi:10.21037/apm.2019.05.02

3. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-533. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14387

4. Charon R. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and tust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897–1902. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

5. Broyard A. Doctor Talk to Me. August 26, 1990. Accessed September 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/1990/08/26/magazine/doctor-talk-to-me.html

6. Chekhov A. A Doctor’s Visit,. In: Reynolds R, Stone J, eds. On Doctoring. Simon and Shuster;1995:50-59.

7. Lahiri J. Interpreter of Maladies. In: Lahiri J. Interpreter of Maladies. Mariner Books;2019.

8. Fitzgerald FS. Babylon Revisited. In: Moore L, Pitlor H, eds. 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt;2015:62-81.

9. Hemingway E. Hills like White Elephants. In: Reynolds R, Stone J, eds. On Doctoring. Simon and Shuster;1995:108-111.

10. Karmel M. Caves of Lascaux. In: Ofri D, Staff of the Bellavue Literary Review, eds. The Best of the Bellevue Literary Review. Bellevue Literary Press;2008:168-174.

11. Lardner R. The Haircut. In Moore L, Pitlor H, eds. 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt;2015:48-61.

12. Tolstoy L. The Three Questions. Accessed September 2021. https://www.plough.com/en/topics/culture/short-stories/the-three-questions

13. Olsen T. I Stand Here Ironing. In Moore L, Pitlor H, eds. 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt;2015:173-180.

14. Hale N. Those Are as Brothers. In: Moore L, Pitlor H, eds. 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt;2015:132-141.

Burnout and other forms of psychosocial distress are common among health care professionals necessitating measures to promote well-being and reduce burnout.1 Studies have shown that nonmedical reading is associated with low burnout and that small group study sections can promote wellness.2,3 Narrative medicine, which proposes a model for humane and effective medical practice, advocates for the necessity of narrative competence.

Short Story Club

Narrative competence is the ability to acknowledge, interpret, and act on the stories of others. The narrative skill of close reading also encourages reflective practice, equipping practitioners to better weather the tides of illness.4 In our case, we formed a short story club intervention to closely read, or read and reflect, on literary fiction. We explored how reading and reflecting would result in profound changes in thinking and feeling and noted different ways by which they can cause such well-being. We describe here the 7 ways in which stories led us to increase bonding, improve empathy, and promote meaning in medicine.

Slowing Down

The short story club helped to bond us together and increase our sense of meaning in medicine by slowing us down. One member of the group likened the experience to increasing the pixels in a painting, thereby improving the resolution and seeing more clearly. Another member mentioned the experience as a form of meditation in slowing down the brain, breathing in the story, and breathing out impressions. One story by Anatole Broyard emphasized the importance of slowing down and “brooding” over a patient.5 The author describes his experience as a prostate cancer patient, in which his body was treated but his story was ignored. He begged his doctors to pay more attention to his story to listen and to brood over him. This story was enlightening to us; we saw how desperate our patients are to tell their stories, and for us to hear their stories.

Mirrors and Windows

Another way reading and reflecting on short stories helped was by reflecting our practices to ourselves, as though looking into a mirror to see ourselves and out of a window to see others. We found that stories mirrored our own world and allowed us to discuss issues close to us without the embarrassment or stigma of owning the story. In one session we read “The Doctor’s Visit” by Anton Chekhov.6 Some of the members resonated with the doctor of this story who awkwardly attended to his lady patient whose son was dying of a brain tumor. The doctor was nervous, insecure, and unable to express any empathy. He was also the father of the child who was dying and refused to admit any responsibility. One member of the group stated that he could relate to the doctor’s insecurities and mentioned that he too felt insecure and even sometimes felt like an imposter. This led to a discussion of insecurities, ways to bolster self-confidence, and ways to accept and respect limitations. This was a conversation that may not have taken place without the story as anchor to discuss insecurities that we individually may not have been willing to admit to the group.

In a different session, we discussed the story “Interpreter of Maladies” by Jhumpa Lahiri in which a settled Indian American family returns to India to tour and learn about their heritage from a guide (the interpreter of maladies) who interpreted the culture for them.7 The family professed to be interested in knowing about the culture but could not concentrate: the wife stayed busy flirting with the guide and revealing outrageous secrets to him, the children were engrossed in their squabbles, and the father was essentially absent taking photographs as souvenirs instead of seeing the sites firsthand. Some of the members of the group were Indian American and could relate to the alienation from their home and nostalgia for their country, while others could relate to the same alienation, albeit from other cultures and countries. This allowed us to talk about deeply personal topics, without having to own the topic or reveal personal issues. The discussion led to a deep understanding and empathy for us and our colleagues knowing the pain of alienation that some of them felt but could not discuss.

The stories also served as windows into the world of others which enabled us to see and become the other. For example, in one session we reflected on “Babylon Revisited” by F. Scott Fitzgerald.8 In this story, an American man returns to Paris after the Great Depression and recalls his life as a young artist in the American artist expatriate community of Paris in the 1920s and 1930s. During that time, he partied, drank in excess, lost his wife to pneumonia (for which he was at least partially responsible), lost custody of his daughter, and lost his fortune. As he returned to Paris to try to reclaim his daughter, we feel his pain as he tries but fails to overcome chronic alcoholism, sexual indiscretions, and losses. This gave rise to discussion of losses in general as we became one with the main character. This increased our empathy for others in a way that could not have been possible without this short story as anchor.

In another session we reflected on “Hills Like White Elephants” by Ernest Hemingway, in which a man is waiting for a train while proposing his girlfriend get an abortion.9 She agonizes over her choices and makes no decision in this story. Yet, we the reader could “become” the woman in the story faced with hard choices of having a baby but losing the man she loves, or having an abortion and maybe losing him anyway. In becoming this woman, we could experience the complex emotions and feel an experience of the other.

Exploring the Taboo

A third aspect of the club was enabling discussion of controversial topics. There were topics that arose in the group which never would have arisen in clinical practice discussions. These had to do with the taboo topics such as romantic attachments to patients. We read “The Caves of Lascaux” and reflected on the story of a young doctor who becomes enamored and obsessed with his beautiful but dying patient.10 He becomes so obsessed with her that he almost abandons his wife, family, and stable livelihood to descend with her into the caves. This story gave rise to discussions about romantic attachment to patients and how to handle and extricate one from the situation. The senior doctors explained some of their relevant experiences and how they either transferred care or sought counseling to extricate themselves from a potentially dangerous situation, especially when they too fell under the spell of forbidden romance.

Moral Grounding

These sessions also served to define the moral basis of our own practice. Much of health care psychosocial distress is related to moral injury in which health care professionals do the wrong thing or fail to do the right thing at the right time, due to external pressures related to financial or other gains. Reading and reflecting put us face-to-face with moral dilemmas and let us find our moral grounding. In reading “The Haircut” by Ring Lardner, we explored the disruptive town scoundrel who harassed and tortured his friends and neighbors but in such outrageous ways that he was considered a comedian rather than an abuser.11 Despite his hurtful acts, the townspeople (including the narrator) considered him a clown and laughed at his racist and sexist statements as well as his tricks.He faced no consequences such as confrontation, until the end when fate caught up. This story gave rise to a discussion of how we handle unkind, racist, sexist, or other comments which are disguised as humor, and to what extent we tolerate such controversial behavior. Do we go along with the scoundrel and laugh, or do we confront such people and insist that they respect and honor other people? The story sensitized the group to the ways in which prejudice and racism or sexism can be masked as humor, and to consider our moral responsibilities in society.

In another session we read and reflected on “Three Questions” by Leo Tolstoy.12 In this story, a king travels to another territory but gets distracted by helping a neighbor in need, and thereby inadvertently and fortunately avoids the trap that had been devised to kill him. The author gives us his moral basis by asking and answering 3 questions: Who is the most important person? What is the most important thing to do? What is the most important thing to do now? His answers provided his moral grounding. We discussed our answers and the basis of our moral grounding, whether it be the injunction do no harm, the more complex religious backgrounds of our childhood, or otherwise.

Symbols and Metaphors

The practice of reading and reflecting also taught us symbols and metaphors. Symbols and metaphors are the essence of storytelling, and they provide keys to understanding people. We sought out and studied the metaphors and symbols in each of the stories we read. In “I Stood There Ironing”, a woman is ironing as she is being questioned by a social worker on the upbringing of her first daughter, and its impact on her psychosocial distress.13 The woman remembers the hardships in raising her daughter and her neglect and abuse of the child due to circumstances beyond her control. She keeps ironing back and forth as she recounts the ways in which she neglected her child. The ironing provides a metaphor for attempting to straighten out her life and for recognizing finally at the end of the story that the daughter should not be the dress, under which her iron is pressing. This gave rise to a discussion of metaphors in our lives and the meanings they carry.

Problem-solving Guide

A sixth way the reflections helped was by serving as a guide to solving our problems. Some of the stories we read resonated deeply with members of the group and provided guides to solving problems. In one meeting we discussed “Those Are as Brothers” by Nancy Hale, a story in which a Nazi concentration camp survivor finds refuge in a country home and develops a friendship with a survivor of an abusive marriage.14 Reading and reflecting on this story enabled us to see the impact of trauma on ourselves, our life choices, professions, ways of being, philosophies, and even on our next generation. The story was personal for several members of the group, some of whom were second-generation Holocaust survivors, and for one who admitted to severe trauma as a child. Discussing our backgrounds together, we empathized with each other and helped each other heal. The story also provided a guide to healing from trauma, as its title indicates: sharing stories together can be a way to heal. The solidarity of standing together, as brothers, heals. The concentration camp survivor was mistreated in his job, but the abuse trauma victim rushes to his defense and vows her friendship and support. This soothed his soul and healed his mind. The guidance is clear: we can do the same, find friends, treat them like brothers, support each other and heal.

Bonding Through Shared Experience

The final and possibly most important way in which the club helped was by serving as an adventure to bond group members together through shared experience. We believe that literature can capture imagination in extraordinary ways and provide an opportunity to undertake remarkable journeys. As such, together we traveled to the ends of the earth from the beginning to the end of time and beyond. We traveled through the hills of Africa, meandered in the streets of Russia and Poland, watched the racetracks in Italy, toured the Taj Mahal in India, and descended into the caves of Lascaux, all while working in Little Rock, Arkansas. We shared a wide array of experiences together, which allowed us to know ourselves and others better, to share stories, and to develop a common vision, common ground, and common culture.

Conclusions

Through reading and reflecting on stories, we bonded as a group, increased our empathy for each other and others, and found meaning in medicine. Other studies have shown that participation in small study groups promote physician well-being, improve job satisfaction, and decrease burnout.3 We synergized this effort by reading nonmedical stories on a consistent basis, hoping to gain resilience to psychosocial distress.3 We chose short stories rather than novels to minimize any stress from excess reading. Combining these interventions, small group studies and nonmedical reading, into a single intervention as is typical in the practice of narrative medicine may provide a way to improve team functioning.

This pilot study showed that it is possible to form short story clubs even in a busy oncology program and that such programs benefit participants in a variety of ways with no apparent adverse effects. Further research is needed to study the impact of reading and reflecting on medical work in small study groups in larger numbers of subjects and to evaluate their impact on burnout. Further study is also needed to develop narrative medicine curricula that best address the needs of particular subspecialties and to determine the optimal conditions for implementation.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Erick Messias for inspiring and encouraging this project at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences where he was Associate Dean for Faculty Affairs. He is presently Chair of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience at the St. Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri.

Burnout and other forms of psychosocial distress are common among health care professionals necessitating measures to promote well-being and reduce burnout.1 Studies have shown that nonmedical reading is associated with low burnout and that small group study sections can promote wellness.2,3 Narrative medicine, which proposes a model for humane and effective medical practice, advocates for the necessity of narrative competence.

Short Story Club

Narrative competence is the ability to acknowledge, interpret, and act on the stories of others. The narrative skill of close reading also encourages reflective practice, equipping practitioners to better weather the tides of illness.4 In our case, we formed a short story club intervention to closely read, or read and reflect, on literary fiction. We explored how reading and reflecting would result in profound changes in thinking and feeling and noted different ways by which they can cause such well-being. We describe here the 7 ways in which stories led us to increase bonding, improve empathy, and promote meaning in medicine.

Slowing Down

The short story club helped to bond us together and increase our sense of meaning in medicine by slowing us down. One member of the group likened the experience to increasing the pixels in a painting, thereby improving the resolution and seeing more clearly. Another member mentioned the experience as a form of meditation in slowing down the brain, breathing in the story, and breathing out impressions. One story by Anatole Broyard emphasized the importance of slowing down and “brooding” over a patient.5 The author describes his experience as a prostate cancer patient, in which his body was treated but his story was ignored. He begged his doctors to pay more attention to his story to listen and to brood over him. This story was enlightening to us; we saw how desperate our patients are to tell their stories, and for us to hear their stories.

Mirrors and Windows

Another way reading and reflecting on short stories helped was by reflecting our practices to ourselves, as though looking into a mirror to see ourselves and out of a window to see others. We found that stories mirrored our own world and allowed us to discuss issues close to us without the embarrassment or stigma of owning the story. In one session we read “The Doctor’s Visit” by Anton Chekhov.6 Some of the members resonated with the doctor of this story who awkwardly attended to his lady patient whose son was dying of a brain tumor. The doctor was nervous, insecure, and unable to express any empathy. He was also the father of the child who was dying and refused to admit any responsibility. One member of the group stated that he could relate to the doctor’s insecurities and mentioned that he too felt insecure and even sometimes felt like an imposter. This led to a discussion of insecurities, ways to bolster self-confidence, and ways to accept and respect limitations. This was a conversation that may not have taken place without the story as anchor to discuss insecurities that we individually may not have been willing to admit to the group.

In a different session, we discussed the story “Interpreter of Maladies” by Jhumpa Lahiri in which a settled Indian American family returns to India to tour and learn about their heritage from a guide (the interpreter of maladies) who interpreted the culture for them.7 The family professed to be interested in knowing about the culture but could not concentrate: the wife stayed busy flirting with the guide and revealing outrageous secrets to him, the children were engrossed in their squabbles, and the father was essentially absent taking photographs as souvenirs instead of seeing the sites firsthand. Some of the members of the group were Indian American and could relate to the alienation from their home and nostalgia for their country, while others could relate to the same alienation, albeit from other cultures and countries. This allowed us to talk about deeply personal topics, without having to own the topic or reveal personal issues. The discussion led to a deep understanding and empathy for us and our colleagues knowing the pain of alienation that some of them felt but could not discuss.

The stories also served as windows into the world of others which enabled us to see and become the other. For example, in one session we reflected on “Babylon Revisited” by F. Scott Fitzgerald.8 In this story, an American man returns to Paris after the Great Depression and recalls his life as a young artist in the American artist expatriate community of Paris in the 1920s and 1930s. During that time, he partied, drank in excess, lost his wife to pneumonia (for which he was at least partially responsible), lost custody of his daughter, and lost his fortune. As he returned to Paris to try to reclaim his daughter, we feel his pain as he tries but fails to overcome chronic alcoholism, sexual indiscretions, and losses. This gave rise to discussion of losses in general as we became one with the main character. This increased our empathy for others in a way that could not have been possible without this short story as anchor.

In another session we reflected on “Hills Like White Elephants” by Ernest Hemingway, in which a man is waiting for a train while proposing his girlfriend get an abortion.9 She agonizes over her choices and makes no decision in this story. Yet, we the reader could “become” the woman in the story faced with hard choices of having a baby but losing the man she loves, or having an abortion and maybe losing him anyway. In becoming this woman, we could experience the complex emotions and feel an experience of the other.

Exploring the Taboo

A third aspect of the club was enabling discussion of controversial topics. There were topics that arose in the group which never would have arisen in clinical practice discussions. These had to do with the taboo topics such as romantic attachments to patients. We read “The Caves of Lascaux” and reflected on the story of a young doctor who becomes enamored and obsessed with his beautiful but dying patient.10 He becomes so obsessed with her that he almost abandons his wife, family, and stable livelihood to descend with her into the caves. This story gave rise to discussions about romantic attachment to patients and how to handle and extricate one from the situation. The senior doctors explained some of their relevant experiences and how they either transferred care or sought counseling to extricate themselves from a potentially dangerous situation, especially when they too fell under the spell of forbidden romance.

Moral Grounding

These sessions also served to define the moral basis of our own practice. Much of health care psychosocial distress is related to moral injury in which health care professionals do the wrong thing or fail to do the right thing at the right time, due to external pressures related to financial or other gains. Reading and reflecting put us face-to-face with moral dilemmas and let us find our moral grounding. In reading “The Haircut” by Ring Lardner, we explored the disruptive town scoundrel who harassed and tortured his friends and neighbors but in such outrageous ways that he was considered a comedian rather than an abuser.11 Despite his hurtful acts, the townspeople (including the narrator) considered him a clown and laughed at his racist and sexist statements as well as his tricks.He faced no consequences such as confrontation, until the end when fate caught up. This story gave rise to a discussion of how we handle unkind, racist, sexist, or other comments which are disguised as humor, and to what extent we tolerate such controversial behavior. Do we go along with the scoundrel and laugh, or do we confront such people and insist that they respect and honor other people? The story sensitized the group to the ways in which prejudice and racism or sexism can be masked as humor, and to consider our moral responsibilities in society.

In another session we read and reflected on “Three Questions” by Leo Tolstoy.12 In this story, a king travels to another territory but gets distracted by helping a neighbor in need, and thereby inadvertently and fortunately avoids the trap that had been devised to kill him. The author gives us his moral basis by asking and answering 3 questions: Who is the most important person? What is the most important thing to do? What is the most important thing to do now? His answers provided his moral grounding. We discussed our answers and the basis of our moral grounding, whether it be the injunction do no harm, the more complex religious backgrounds of our childhood, or otherwise.

Symbols and Metaphors

The practice of reading and reflecting also taught us symbols and metaphors. Symbols and metaphors are the essence of storytelling, and they provide keys to understanding people. We sought out and studied the metaphors and symbols in each of the stories we read. In “I Stood There Ironing”, a woman is ironing as she is being questioned by a social worker on the upbringing of her first daughter, and its impact on her psychosocial distress.13 The woman remembers the hardships in raising her daughter and her neglect and abuse of the child due to circumstances beyond her control. She keeps ironing back and forth as she recounts the ways in which she neglected her child. The ironing provides a metaphor for attempting to straighten out her life and for recognizing finally at the end of the story that the daughter should not be the dress, under which her iron is pressing. This gave rise to a discussion of metaphors in our lives and the meanings they carry.

Problem-solving Guide

A sixth way the reflections helped was by serving as a guide to solving our problems. Some of the stories we read resonated deeply with members of the group and provided guides to solving problems. In one meeting we discussed “Those Are as Brothers” by Nancy Hale, a story in which a Nazi concentration camp survivor finds refuge in a country home and develops a friendship with a survivor of an abusive marriage.14 Reading and reflecting on this story enabled us to see the impact of trauma on ourselves, our life choices, professions, ways of being, philosophies, and even on our next generation. The story was personal for several members of the group, some of whom were second-generation Holocaust survivors, and for one who admitted to severe trauma as a child. Discussing our backgrounds together, we empathized with each other and helped each other heal. The story also provided a guide to healing from trauma, as its title indicates: sharing stories together can be a way to heal. The solidarity of standing together, as brothers, heals. The concentration camp survivor was mistreated in his job, but the abuse trauma victim rushes to his defense and vows her friendship and support. This soothed his soul and healed his mind. The guidance is clear: we can do the same, find friends, treat them like brothers, support each other and heal.

Bonding Through Shared Experience

The final and possibly most important way in which the club helped was by serving as an adventure to bond group members together through shared experience. We believe that literature can capture imagination in extraordinary ways and provide an opportunity to undertake remarkable journeys. As such, together we traveled to the ends of the earth from the beginning to the end of time and beyond. We traveled through the hills of Africa, meandered in the streets of Russia and Poland, watched the racetracks in Italy, toured the Taj Mahal in India, and descended into the caves of Lascaux, all while working in Little Rock, Arkansas. We shared a wide array of experiences together, which allowed us to know ourselves and others better, to share stories, and to develop a common vision, common ground, and common culture.

Conclusions

Through reading and reflecting on stories, we bonded as a group, increased our empathy for each other and others, and found meaning in medicine. Other studies have shown that participation in small study groups promote physician well-being, improve job satisfaction, and decrease burnout.3 We synergized this effort by reading nonmedical stories on a consistent basis, hoping to gain resilience to psychosocial distress.3 We chose short stories rather than novels to minimize any stress from excess reading. Combining these interventions, small group studies and nonmedical reading, into a single intervention as is typical in the practice of narrative medicine may provide a way to improve team functioning.

This pilot study showed that it is possible to form short story clubs even in a busy oncology program and that such programs benefit participants in a variety of ways with no apparent adverse effects. Further research is needed to study the impact of reading and reflecting on medical work in small study groups in larger numbers of subjects and to evaluate their impact on burnout. Further study is also needed to develop narrative medicine curricula that best address the needs of particular subspecialties and to determine the optimal conditions for implementation.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Erick Messias for inspiring and encouraging this project at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences where he was Associate Dean for Faculty Affairs. He is presently Chair of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience at the St. Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri.

1. Messias E, Gathright MM, Freeman ES, et al. Differences in burnout prevalence between clinical professionals and biomedical scientists in an academic medical centre: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e023506. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023506

2. Marchalik D, Rodriguez A, Namath A, et al. The impact of non-medical reading on clinical burnout: a national survey of palliative care providers. Ann Palliat Med. 2019;8(4):428-435. doi:10.21037/apm.2019.05.02

3. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-533. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14387

4. Charon R. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and tust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897–1902. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

5. Broyard A. Doctor Talk to Me. August 26, 1990. Accessed September 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/1990/08/26/magazine/doctor-talk-to-me.html

6. Chekhov A. A Doctor’s Visit,. In: Reynolds R, Stone J, eds. On Doctoring. Simon and Shuster;1995:50-59.

7. Lahiri J. Interpreter of Maladies. In: Lahiri J. Interpreter of Maladies. Mariner Books;2019.

8. Fitzgerald FS. Babylon Revisited. In: Moore L, Pitlor H, eds. 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt;2015:62-81.

9. Hemingway E. Hills like White Elephants. In: Reynolds R, Stone J, eds. On Doctoring. Simon and Shuster;1995:108-111.

10. Karmel M. Caves of Lascaux. In: Ofri D, Staff of the Bellavue Literary Review, eds. The Best of the Bellevue Literary Review. Bellevue Literary Press;2008:168-174.

11. Lardner R. The Haircut. In Moore L, Pitlor H, eds. 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt;2015:48-61.

12. Tolstoy L. The Three Questions. Accessed September 2021. https://www.plough.com/en/topics/culture/short-stories/the-three-questions

13. Olsen T. I Stand Here Ironing. In Moore L, Pitlor H, eds. 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt;2015:173-180.

14. Hale N. Those Are as Brothers. In: Moore L, Pitlor H, eds. 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt;2015:132-141.

1. Messias E, Gathright MM, Freeman ES, et al. Differences in burnout prevalence between clinical professionals and biomedical scientists in an academic medical centre: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e023506. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023506

2. Marchalik D, Rodriguez A, Namath A, et al. The impact of non-medical reading on clinical burnout: a national survey of palliative care providers. Ann Palliat Med. 2019;8(4):428-435. doi:10.21037/apm.2019.05.02

3. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-533. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.14387

4. Charon R. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and tust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897–1902. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

5. Broyard A. Doctor Talk to Me. August 26, 1990. Accessed September 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/1990/08/26/magazine/doctor-talk-to-me.html

6. Chekhov A. A Doctor’s Visit,. In: Reynolds R, Stone J, eds. On Doctoring. Simon and Shuster;1995:50-59.

7. Lahiri J. Interpreter of Maladies. In: Lahiri J. Interpreter of Maladies. Mariner Books;2019.

8. Fitzgerald FS. Babylon Revisited. In: Moore L, Pitlor H, eds. 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt;2015:62-81.

9. Hemingway E. Hills like White Elephants. In: Reynolds R, Stone J, eds. On Doctoring. Simon and Shuster;1995:108-111.

10. Karmel M. Caves of Lascaux. In: Ofri D, Staff of the Bellavue Literary Review, eds. The Best of the Bellevue Literary Review. Bellevue Literary Press;2008:168-174.

11. Lardner R. The Haircut. In Moore L, Pitlor H, eds. 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt;2015:48-61.

12. Tolstoy L. The Three Questions. Accessed September 2021. https://www.plough.com/en/topics/culture/short-stories/the-three-questions

13. Olsen T. I Stand Here Ironing. In Moore L, Pitlor H, eds. 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt;2015:173-180.

14. Hale N. Those Are as Brothers. In: Moore L, Pitlor H, eds. 100 Years of the Best American Short Stories. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt;2015:132-141.

Should you be screening for eating disorders?

The US Preventive Services Task Force recently released its findings on screening for eating disorders—including binge eating, bulimia nervosa, and anorexia nervosa—in adolescents and adults.1 This is the first time the Task Force has addressed this topic.

For those who have no signs or symptoms of an eating disorder, the Task Force found insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and harms of screening. Signs and symptoms of an eating disorder include rapid changes in weight (gain or loss), delayed puberty, bradycardia, oligomenorrhea, or amenorrhea.1

Screening vs diagnostic work-up. The term screening means looking for the presence of a condition in an asymptomatic person. Those who have signs or symptoms that could be due to an eating disorder should be assessed for these conditions, but this would be classified as diagnostic testing rather than preventive screening.

Relatively uncommon but serious. The estimated lifetime prevalence of anorexia is 1.42% in women and 0.12% in men; for bulimia, 0.46% in women and 0.08% in men; and for binge eating, 1.25% in women and 0.42% in men.1 Those suspected of having an eating disorder need psychological, behavioral, medical, and nutritional care provided by those with expertise in diagnosing and treating these disorders. (A systematic review of treatment options was recently published in American Family Physician.2)

If you suspect an eating disorder … Several tools for the assessment of eating disorders have been described in the literature, including the Eating Disorder Screen for Primary Care (EDS-PC) tool, but the Task Force identified enough evidence to comment on the accuracy of only one: the SCOFF questionnaire. There is adequate evidence on its accuracy for use in adult women but not in adolescents or males.1

The SCOFF tool, which originated in the United Kingdom, consists of 5 questions3:

- Do you make yourself Sick because you feel uncomfortably full?

- Do you worry that you have lost Control over how much you eat?

- Have you recently lost more than One stone (14 lb) in a 3-month period?

- Do you believe yourself to be Fat when others say you are too thin?

- Would you say that Food dominates your life?

A threshold of 2 or more “Yes” answers on the SCOFF questionnaire has a pooled sensitivity of 84% for all 3 disorders combined and a pooled specificity of 80%.4

What should you do routinely? For adolescents and adults who have no indication of an eating disorder, there is no proven value to screening. Measuring height and weight, calculating body mass index, and continuing to track these measurements for all patients over time is considered standard practice. For those patients who have signs or symptoms that could be due to an eating disorder, administer the SCOFF tool; further assess those with 2 or more positive responses, and refer for diagnosis and treatment those suspected of having an eating disorder.

1. USPSTF. Screening for eating disorders in adolescents and adults. JAMA. 2022;327:1061-1066. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.1806

2. Klein DA, Sylvester JE, Schvey NA. Eating disorders in primary care: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2021;103:22-32.