User login

Home BP monitoring is essential

I believe that the most important recommendation from the American Heart Association in recent years is to confirm office blood pressure (BP) readings with repeated home BP measurements, for both diagnosis and management of hypertension. Office BPs are notoriously inaccurate, because it is exceedingly difficult to measure BP properly in a busy office setting. Even when measured correctly, the office BP does not accurately reflect a person’s BP throughout the day, which is the best predictor of cardiovascular damage from hypertension.

Among the problems with relying on office BP readings:We would treat many people for hypertension who are not hypertensive, because 15% to 30% of those with elevated office BP readings have “white-coat” hypertension, which does not require medication.1 White-coat hypertension can only be diagnosed with home BP readings or 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring.

We would miss the diagnosis of hypertension in patients with “masked” hypertension—that is, people who have normal BP in the office but elevated ambulatory BP. It is estimated that 12% of US adults have masked hypertension.2

We would overtreat some patients who have hypertension and undertreat others, since office BP measurements can underestimate BP by an average of 24/14 mm Hg and overestimate BP by an average of 33/23 mm Hg.3

In this issue of JFP, Spaulding and colleagues4 provide an extensive summary of the research that supports the recommendation for home BP measurements. Here are 3 key takeaways:

- Use an automated BP monitor to measure BP in the office. Automated BP monitors that take repeated BPs over the course of about 5 minutes and average the results provide a much better estimate of 24-hour BP. It is worth the extra time and may be the only basis for making decisions about medications if a patient is unwilling or unable to take home BP readings.

- Provide training to patients who are willing to monitor their BP at home. Explain how to take their BP properly and instruct them to record at least 12 readings over the course of 3 days prior to office visits.

- Recommend patients use a validated BP monitor that uses the brachial artery for measurement, not the wrist (visit www.stridebp.org/bp-monitors and choose “Home”).

1. Muntner P, Shimbo D, Carey RM, et al. Measurement of blood pressure in humans: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2019;73:e35-e66. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000087

2. Wang YC, Shimbo D, Muntner P, et al. Prevalence of masked hypertension among US adults with non-elevated clinic blood pressure. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185:194-202. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww237

3. Kallioinen N, Hill A, Horswill MS, et al. Sources of inaccuracy in the measurement of adult patients’ resting blood pressure in clinical settings: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2017; 35:421-441. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001197

4. Spaulding J, Kasper RE, Viera AJ. Hypertension—or not? Looking beyond office BP readings. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:151-158. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0399

I believe that the most important recommendation from the American Heart Association in recent years is to confirm office blood pressure (BP) readings with repeated home BP measurements, for both diagnosis and management of hypertension. Office BPs are notoriously inaccurate, because it is exceedingly difficult to measure BP properly in a busy office setting. Even when measured correctly, the office BP does not accurately reflect a person’s BP throughout the day, which is the best predictor of cardiovascular damage from hypertension.

Among the problems with relying on office BP readings:We would treat many people for hypertension who are not hypertensive, because 15% to 30% of those with elevated office BP readings have “white-coat” hypertension, which does not require medication.1 White-coat hypertension can only be diagnosed with home BP readings or 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring.

We would miss the diagnosis of hypertension in patients with “masked” hypertension—that is, people who have normal BP in the office but elevated ambulatory BP. It is estimated that 12% of US adults have masked hypertension.2

We would overtreat some patients who have hypertension and undertreat others, since office BP measurements can underestimate BP by an average of 24/14 mm Hg and overestimate BP by an average of 33/23 mm Hg.3

In this issue of JFP, Spaulding and colleagues4 provide an extensive summary of the research that supports the recommendation for home BP measurements. Here are 3 key takeaways:

- Use an automated BP monitor to measure BP in the office. Automated BP monitors that take repeated BPs over the course of about 5 minutes and average the results provide a much better estimate of 24-hour BP. It is worth the extra time and may be the only basis for making decisions about medications if a patient is unwilling or unable to take home BP readings.

- Provide training to patients who are willing to monitor their BP at home. Explain how to take their BP properly and instruct them to record at least 12 readings over the course of 3 days prior to office visits.

- Recommend patients use a validated BP monitor that uses the brachial artery for measurement, not the wrist (visit www.stridebp.org/bp-monitors and choose “Home”).

I believe that the most important recommendation from the American Heart Association in recent years is to confirm office blood pressure (BP) readings with repeated home BP measurements, for both diagnosis and management of hypertension. Office BPs are notoriously inaccurate, because it is exceedingly difficult to measure BP properly in a busy office setting. Even when measured correctly, the office BP does not accurately reflect a person’s BP throughout the day, which is the best predictor of cardiovascular damage from hypertension.

Among the problems with relying on office BP readings:We would treat many people for hypertension who are not hypertensive, because 15% to 30% of those with elevated office BP readings have “white-coat” hypertension, which does not require medication.1 White-coat hypertension can only be diagnosed with home BP readings or 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring.

We would miss the diagnosis of hypertension in patients with “masked” hypertension—that is, people who have normal BP in the office but elevated ambulatory BP. It is estimated that 12% of US adults have masked hypertension.2

We would overtreat some patients who have hypertension and undertreat others, since office BP measurements can underestimate BP by an average of 24/14 mm Hg and overestimate BP by an average of 33/23 mm Hg.3

In this issue of JFP, Spaulding and colleagues4 provide an extensive summary of the research that supports the recommendation for home BP measurements. Here are 3 key takeaways:

- Use an automated BP monitor to measure BP in the office. Automated BP monitors that take repeated BPs over the course of about 5 minutes and average the results provide a much better estimate of 24-hour BP. It is worth the extra time and may be the only basis for making decisions about medications if a patient is unwilling or unable to take home BP readings.

- Provide training to patients who are willing to monitor their BP at home. Explain how to take their BP properly and instruct them to record at least 12 readings over the course of 3 days prior to office visits.

- Recommend patients use a validated BP monitor that uses the brachial artery for measurement, not the wrist (visit www.stridebp.org/bp-monitors and choose “Home”).

1. Muntner P, Shimbo D, Carey RM, et al. Measurement of blood pressure in humans: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2019;73:e35-e66. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000087

2. Wang YC, Shimbo D, Muntner P, et al. Prevalence of masked hypertension among US adults with non-elevated clinic blood pressure. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185:194-202. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww237

3. Kallioinen N, Hill A, Horswill MS, et al. Sources of inaccuracy in the measurement of adult patients’ resting blood pressure in clinical settings: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2017; 35:421-441. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001197

4. Spaulding J, Kasper RE, Viera AJ. Hypertension—or not? Looking beyond office BP readings. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:151-158. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0399

1. Muntner P, Shimbo D, Carey RM, et al. Measurement of blood pressure in humans: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2019;73:e35-e66. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000087

2. Wang YC, Shimbo D, Muntner P, et al. Prevalence of masked hypertension among US adults with non-elevated clinic blood pressure. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185:194-202. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww237

3. Kallioinen N, Hill A, Horswill MS, et al. Sources of inaccuracy in the measurement of adult patients’ resting blood pressure in clinical settings: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2017; 35:421-441. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001197

4. Spaulding J, Kasper RE, Viera AJ. Hypertension—or not? Looking beyond office BP readings. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:151-158. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0399

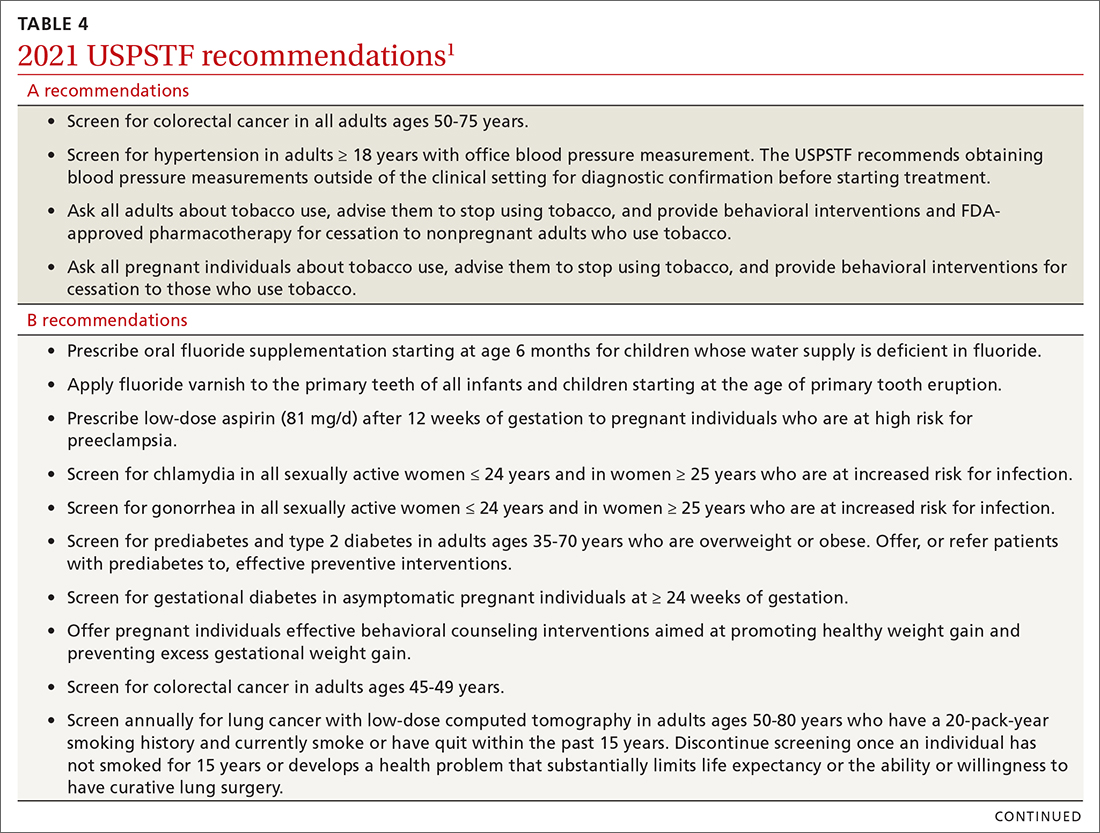

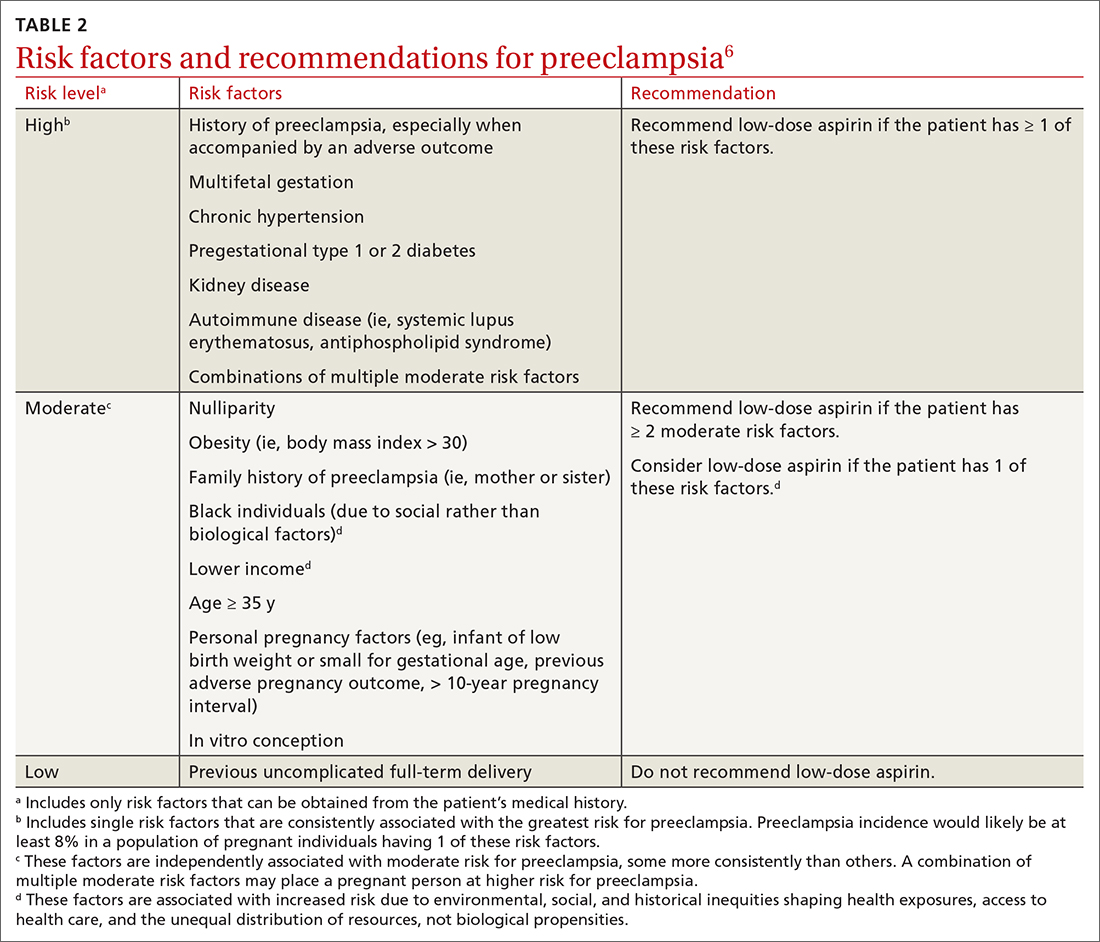

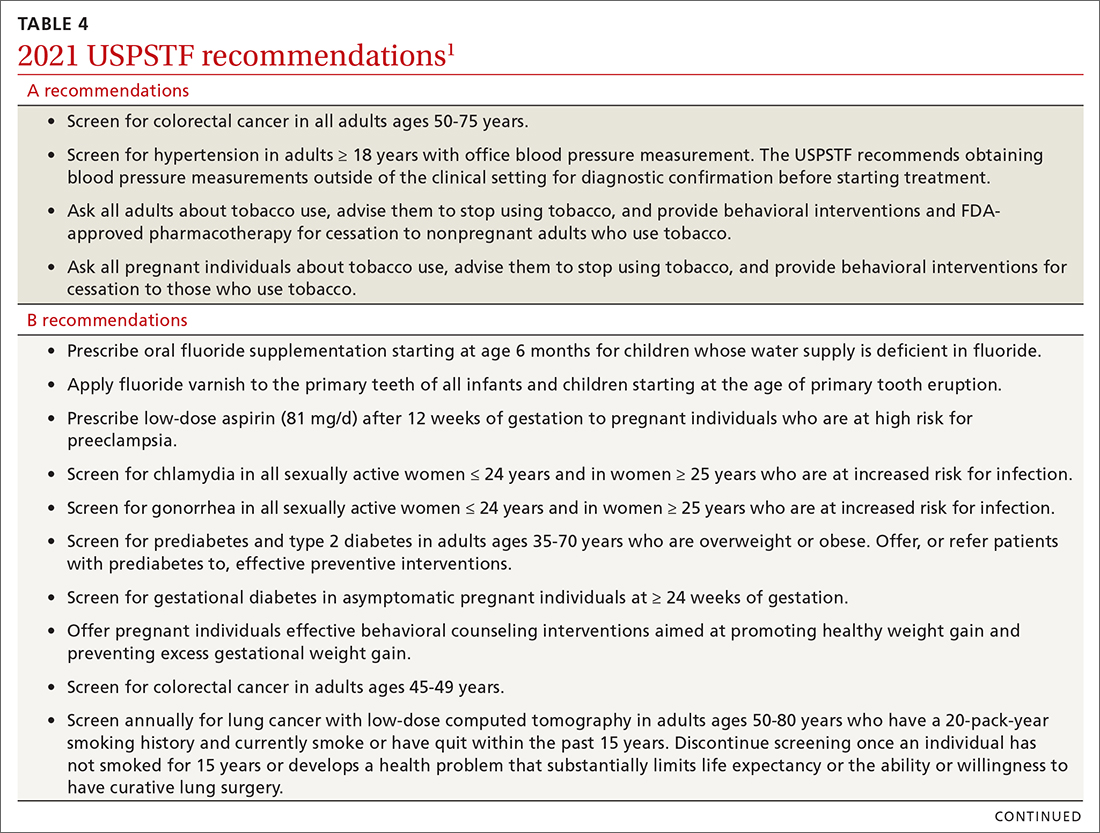

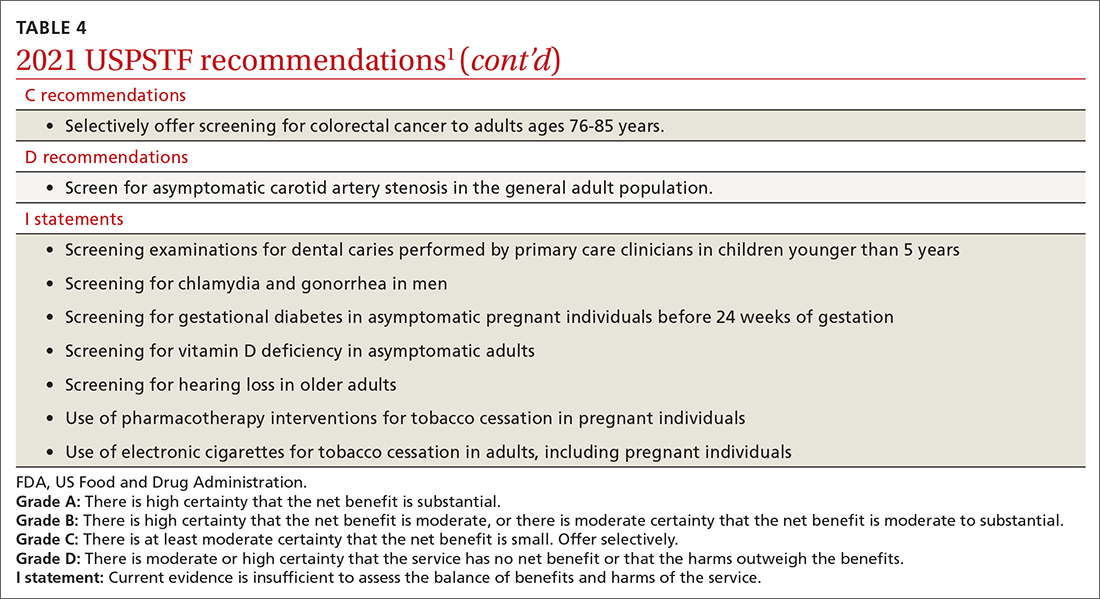

USPSTF recommendation roundup

In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) considered 13 topics and made a total of 23 recommendations. They reviewed only 1 new topic. The other 12 were updates of topics previously addressed; no changes were made in 9 of them. In 3, the recommended age of screening or the criteria for screening were expanded. This Practice Alert will review the recommendations made and highlight new recommendations and any changes to previous ones. All complete recommendation statements, rationales, clinical considerations, and evidence reports can be found on the USPSTF website at https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/home.1

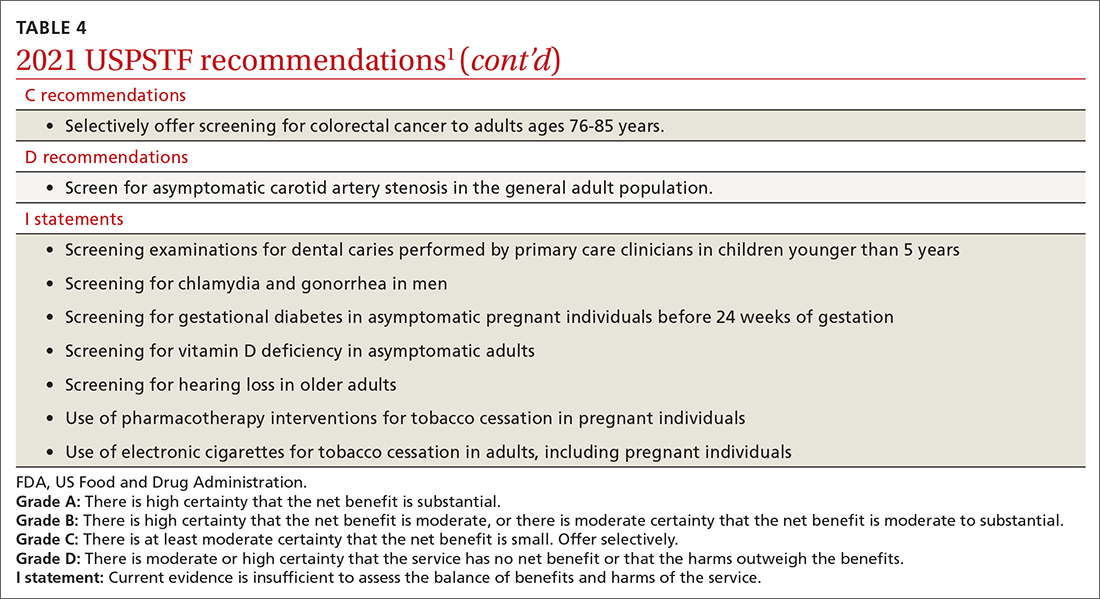

Dental caries in children

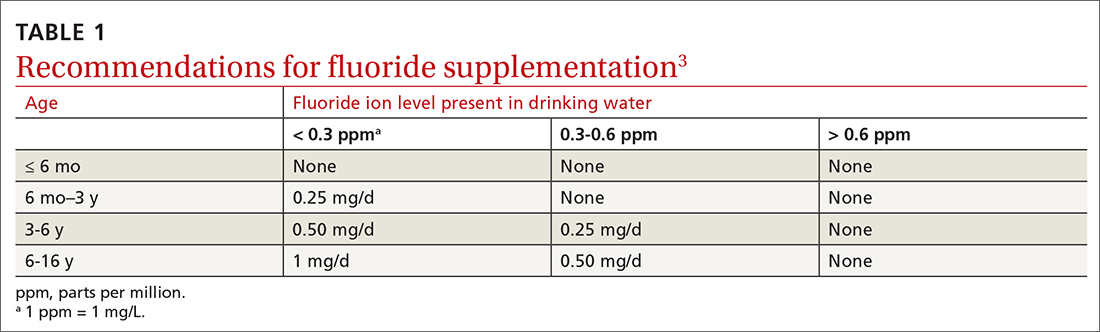

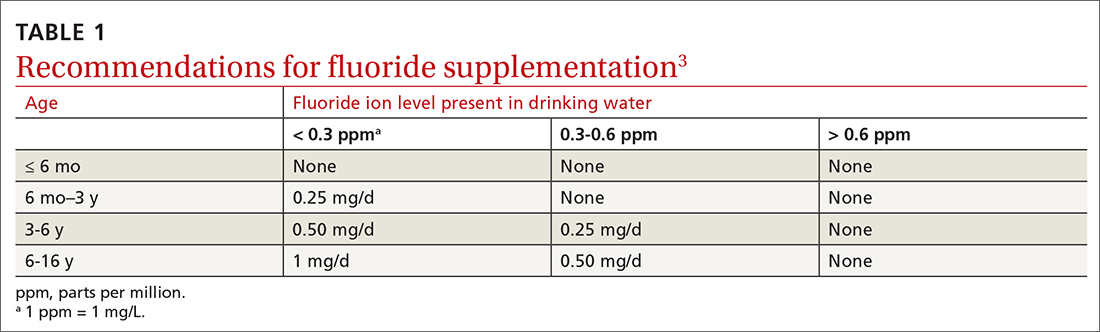

Dental caries affect about 23% of children between the ages of 2 and 5 years and are associated with multiple adverse social outcomes and medical conditions.2 The best way to prevent tooth decay, other than regular brushing with fluoride toothpaste, is to drink water with recommended amounts of fluoride (≥ 0.6 parts fluoride per million parts water).2 The USPSTF reaffirmed its recommendation from 2014 that stated when a local water supply lacks sufficient fluoride, primary care clinicians should prescribe oral supplementation for infants and children in the form of fluoride drops starting at age 6 months. The dosage of fluoride depends on patient age and fluoride concentration in the local water (TABLE 13). The USPSTF also recommends applying topical fluoride as 5% sodium fluoride varnish, every 6 months, starting when the primary teeth erupt.2

In addition to fluoride supplements and topical varnish, should clinicians perform screening examinations looking for dental caries? The USPSTF feels there is not enough evidence to assess this practice and gives it an “I” rating (insufficient evidence).

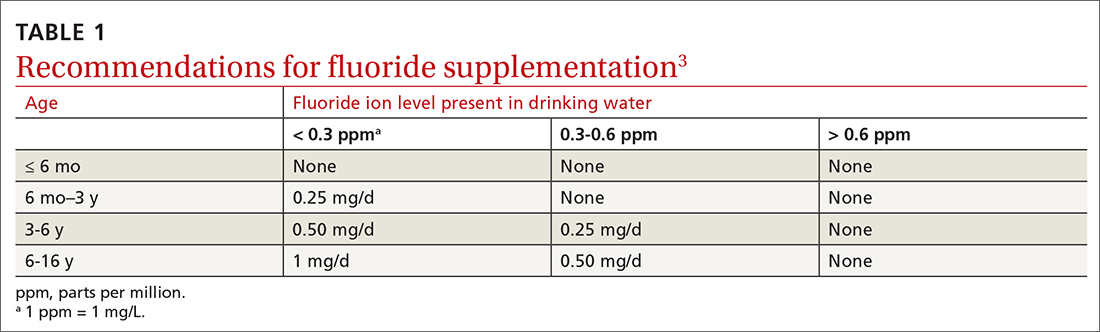

Preventive interventions in pregnancy

In 2021, the USPSTF assessed 3 topics related to pregnancy and prenatal care.

Screening for gestational diabetes. The USPSTF gave a “B” recommendation for screening at 24 weeks of pregnancy or after, but an “I” statement for screening prior to 24 weeks.4 Screening can involve a 1-step or 2-step protocol.

The 2-step protocol is most commonly used in the United States. It involves first measuring serum glucose after a nonfasting 50-g oral glucose challenge; if the resulting level is high, the second step is a 75- or 100-g oral glucose tolerance test lasting 3 hours. The 1-step protocol involves measuring a fasting glucose level, followed by a 75-g oral glucose challenge with glucose levels measured at 1 and 2 hours.

Healthy weight gain in pregnancy. This was the only new topic the USPSTF assessed last year. The resulting recommendation is to offer pregnant women behavioral counseling to promote healthy weight gain and to prevent excessive weight gain in pregnancy. The recommended weight gain depends on the mother’s prepregnancy weight status: 28 to 40 lbs if the mother is underweight; 25 to 35 lbs if she is not under- or overweight; 15 to 25 lbs if she is overweight; and 11 to 20 lbs if she is obese.5 Healthy weight gain contributes to preventing gestational diabetes, emergency cesarean sections, and infant macrosomia.

Continue to: Low-dose aspirin

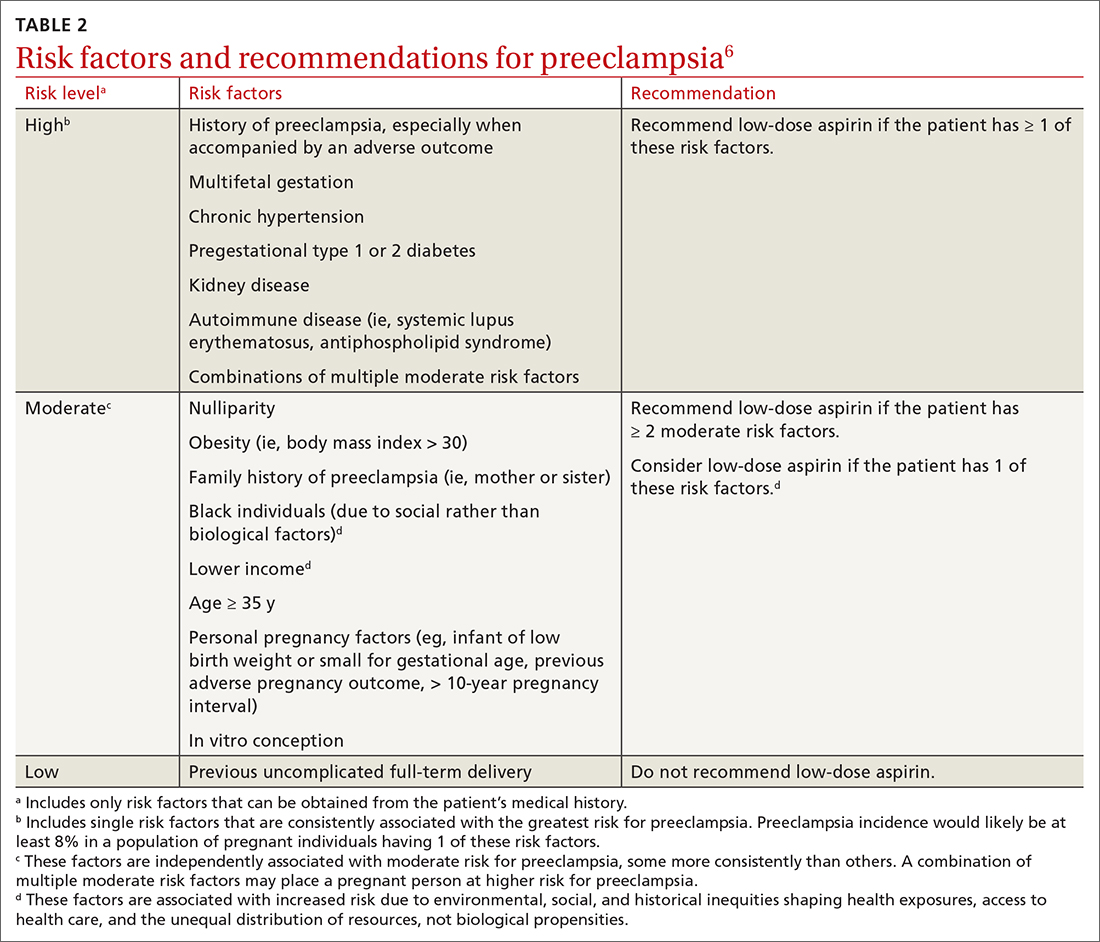

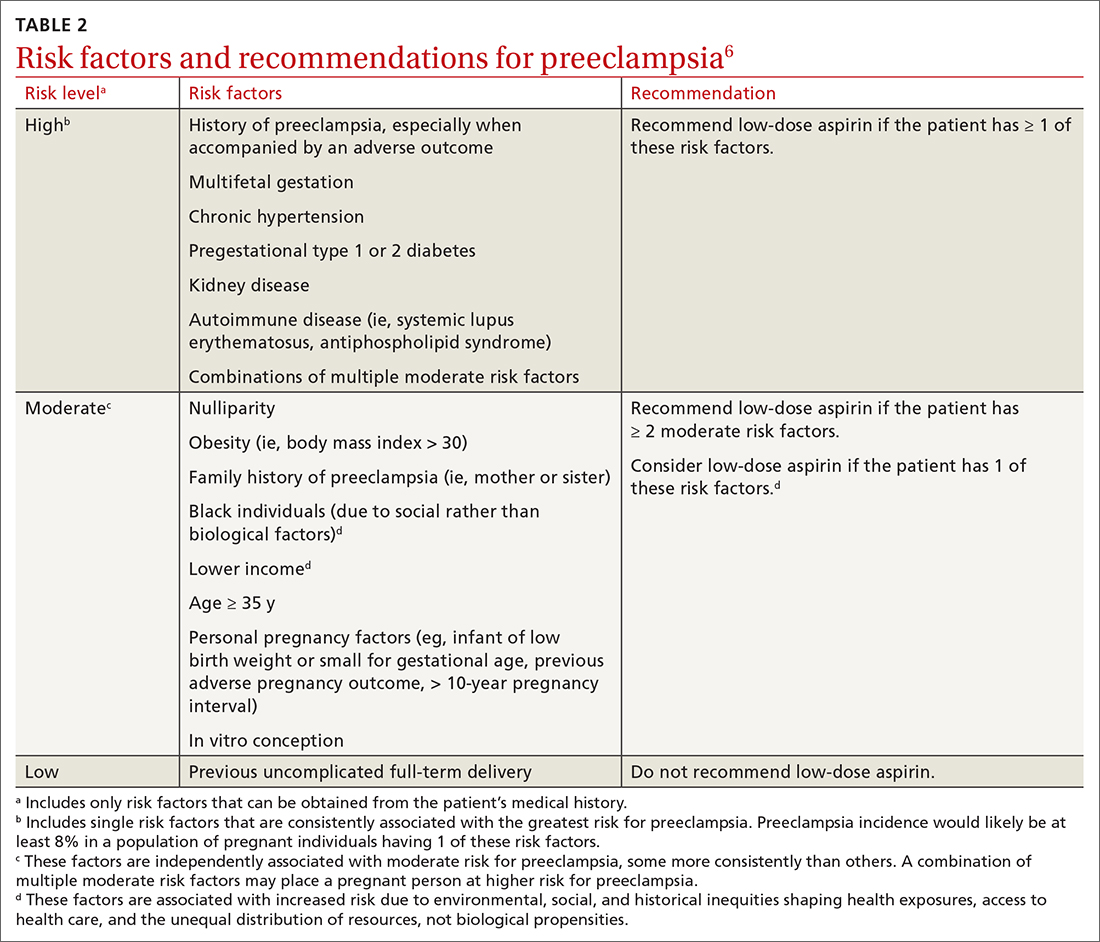

Low-dose aspirin. Reaffirming a recommendation from 2014, the USPSTF advises low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) starting after 12 weeks’ gestation for all pregnant women who are at high risk for preeclampsia. TABLE 26 lists high- and moderate-risk conditions for preeclampsia and the recommendation for the use of low-dose aspirin.

Sexually transmitted infections

Screening for both chlamydia and gonorrhea in sexually active females through age 24 years was given a “B” recommendation, reaffirming the 2014 recommendation.7 Screening for these 2 sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is also recommended for women 25 years and older who are at increased risk of STIs. Risk is defined as having a new sex partner, more than 1 sex partner, a sex partner who has other sex partners, or a sex partner who has an STI; not using condoms consistently; having a previous STI; exchanging sex for money or drugs; or having a history of incarceration.

Screen for both infections simultaneously using a nucleic acid amplification test, testing all sites of sexual exposure. Urine testing can replace cervical, vaginal, and urethral testing. Those found to be positive for either STI should be treated according to the most recent treatment guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). And sexual partners should be advised to undergo testing.8,9

The USPSTF could not find evidence for the benefits and harms of screening for STIs in men. Remember that screening applies to those who are asymptomatic. Male sex partners of those found to be infected should be tested, as should those who show any signs or symptoms of an STI. A recent Practice Alert described the most current CDC guidance for diagnosing and treating STIs.9

Type 2 diabetes and prediabetes

Screening for type 2 diabetes (T2D) and prediabetes is now recommended for adults ages 35 to 70 years who are overweight or obese.10 The age to start screening has been lowered to 35 years from the previous recommendation in 2015, which recommended starting at age 40. In addition, the recommendation states that patients with prediabetes should be referred for preventive interventions. It is important that referral is included in the statement because the Affordable Care Act mandates that USPSTF “A” and “B” recommendations must be covered by commercial health insurance with no copay or deductible.

Continue to: Screening can be conducted...

Screening can be conducted using a fasting plasma glucose or A1C level, or with an oral glucose tolerance test. Interventions that can prevent or delay the onset of T2D in those with prediabetes include lifestyle interventions that focus on diet and physical activity, and the use of metformin (although metformin has not been approved for this by the US Food and Drug Administration).

Changes to cancer screening recommendations

In 2021, the USPSTF reviewed and modified its recommendations on screening for 2 types of cancer: colorectal and lung.

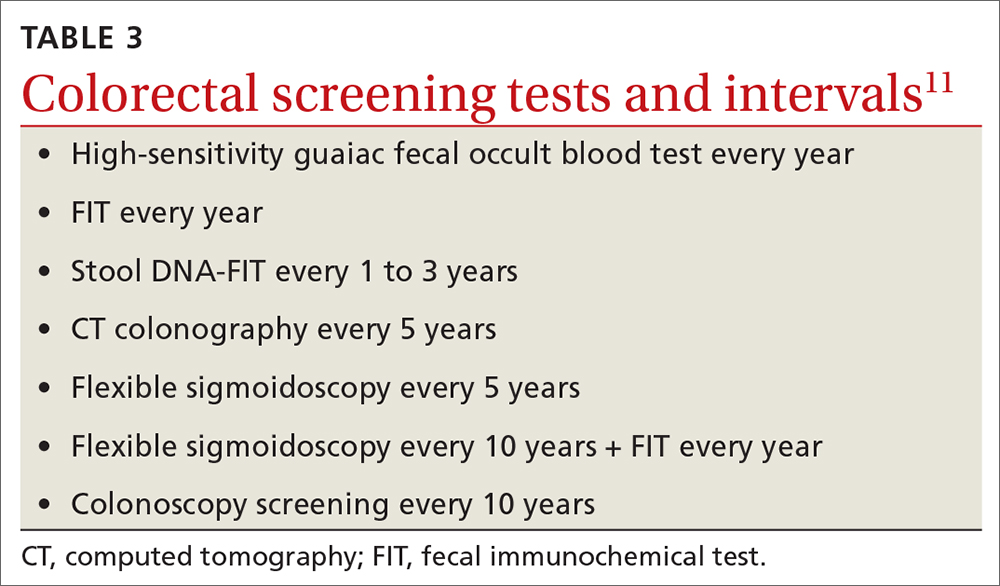

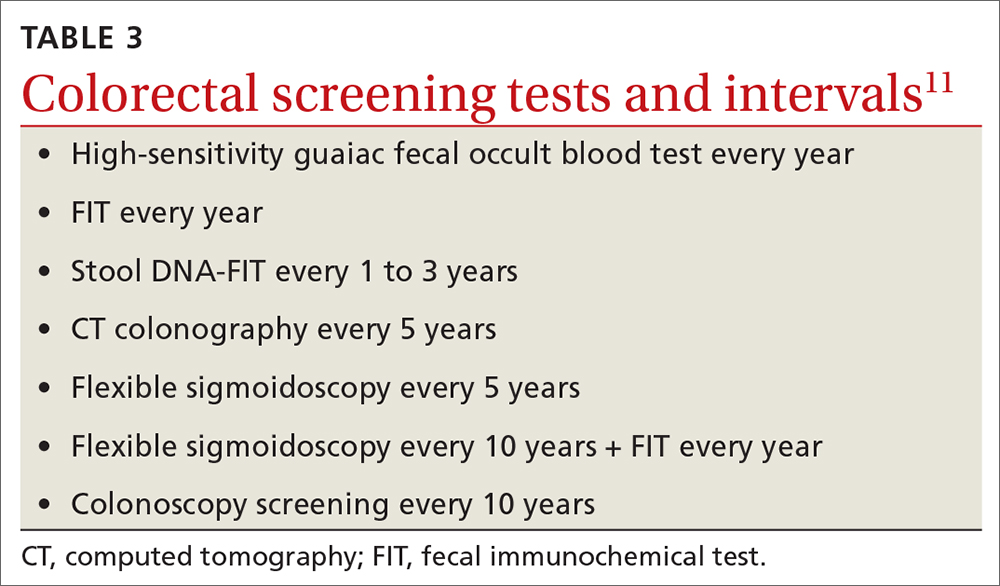

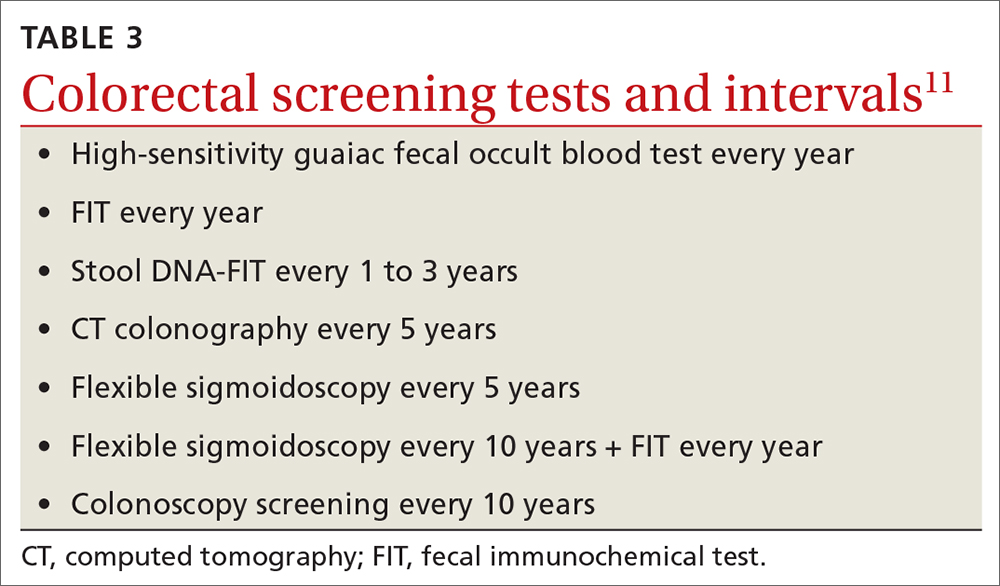

For colorectal cancer, the age at which to start screening was lowered from 50 years to 45 years.11 Screening at this earlier age is a “B” recommendation, because, while there is benefit from screening, it is less than for older age groups. Screening individuals ages 50 to 75 years remains an “A” recommendation, and for those ages 76 to 85 years it remains a “C” recommendation. A “C” recommendation means that the overall benefits are small but some individuals might benefit based on their overall health and prior screening results. In its clinical considerations, the USPSTF recommends against screening in those ages 85 and older but, curiously, does not list it as a “D” recommendation. The screening methods and recommended screening intervals for each appear in TABLE 3.11

For lung cancer, annual screening using low-dose computed tomography (CT) was first recommended by the USPSTF in 2013 for adults ages 55 to 80 years with a 30-pack-year smoking history. Screening could stop once 15 years had passed since smoking cessation. In 2021, the USPSTF lowered the age to initiate screening to 50 years, and the smoking history threshold to 20 pack-years.12 If these recommendations are followed, a current smoker who does not quit smoking could possibly receive 30 annual CT scans. The recommendation does state that screening should stop once a person develops a health condition that significantly affects life expectancy or ability to have lung surgery.

For primary prevention of lung cancer and other chronic diseases through smoking cessation, the USPSTF also reassessed its 2015 recommendations. It reaffirmed the “A” recommendation to ask adults about tobacco use and, for tobacco users, to recommend cessation and provide behavioral therapy and approved pharmacotherapy.13 The recommendation differed for pregnant adults in that the USPSTF is unsure about the potential harms of pharmacotherapy in pregnancy and gives that an “I” statement.13 An additional “I” statement was made about the use of electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation; the USPSTF recommends using behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions with proven effectiveness and safety instead.

Continue to: 4 additional recommendation updates with no changes

4 additional recommendation updates with no changes

Screening for high blood pressure in adults ages 18 years and older continues to receive an “A” recommendation.14 Importantly, the recommendation states that confirmation of high blood pressure should be made in an out-of-office setting before initiating treatment. Screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults and hearing loss in older adults both continue with “I” statements,15,16 and screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis continues to receive a “D” recommendation.17 The implications of the vitamin D “I” statement were discussed in a previous Practice Alert.18

Continuing value of the USPSTF

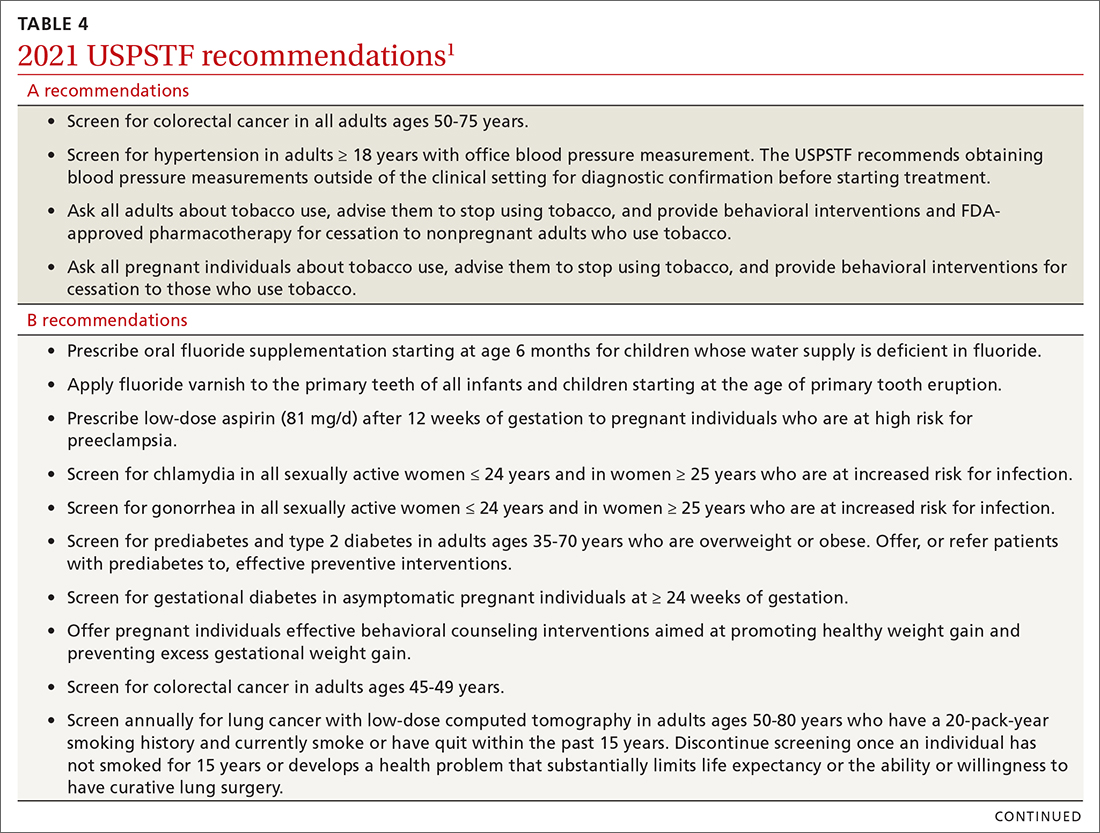

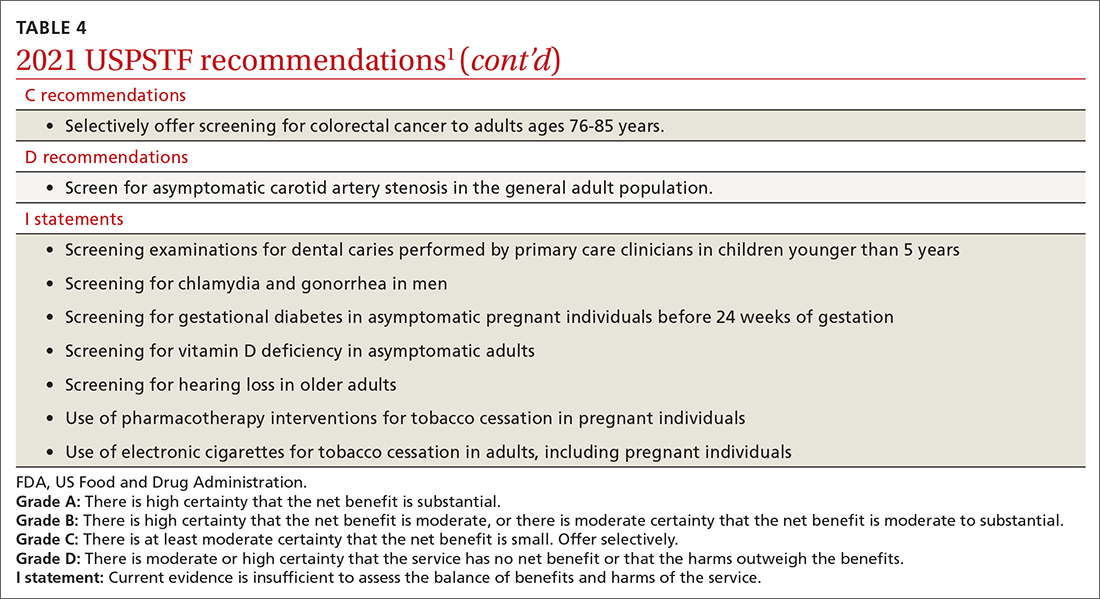

The USPSTF continues to set the gold standard for assessment of preventive interventions, and its decisions affect first-dollar coverage by commercial health insurance. The reaffirmation of past recommendations demonstrates the value of adhering to rigorous evidence-based methods (if they are done correctly, they rarely must be markedly changed). And the updating of screening criteria shows the need to constantly review the evolving evidence for current recommendations. Once again, however, funding and staffing limitations allowed the USPSTF to assess only 1 new topic. A listing of all the 2021 recommendations is in TABLE 4.1

1. USPSTF. Recommendation topics. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation-topics

2. USPSTF. Prevention of dental caries in children younger than 5 years: screening and interventions. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-dental-caries-in-children-younger-than-age-5-years-screening-and-interventions1#bootstrap-panel—4

3. ADA. Dietary fluoride supplements: evidence-based clinical recommendations. Accessed April 14, 2022. www.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/research/ada_evidence-based_fluoride_supplement_chairside_guide.pdf?rev=60850dca0dcc41038efda83d42b1c2e0&hash=FEC2BBEA0C892FB12C098E33344E48B4

4. USPSTF. Gestational diabetes: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/gestational-diabetes-screening

5. USPSTF. Healthy weight and weight gain in pregnancy: behavioral counseling interventions. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/healthy-weight-and-weight-gain-during-pregnancy-behavioral-counseling-interventions

6. USPSTF. Aspirin use to prevent preeclampsia and related morbidity and mortality: preventive medication. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-from-preeclampsia-preventive-medication

7. USPSTF. Chlamydia and gonorrhea: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/chlamydia-and-gonorrhea-screening

8. Workowski KA, Bauchman LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1-187.

9. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC guidelines on sexually transmitted infections. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:506-509.

10. USPSTF. Prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-for-prediabetes-and-type-2-diabetes

11. USPSTF. Colorectal cancer: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening

12. USPSTF. Lung cancer: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/lung-cancer-screening

13. USPSTF. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons: interventions. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions

14. USPSTF. Hypertension in adults: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hypertension-in-adults-screening

15. USPSTF. Vitamin D deficiency in adults: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/vitamin-d-deficiency-screening

16. USPSTF. Hearing loss in older adults: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hearing-loss-in-older-adults-screening

17. USPSTF. Asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis: screening. Access April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/carotid-artery-stenosis-screening

18. Campos-Outcalt D. How to proceed when it comes to vitamin D. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:289-292.

In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) considered 13 topics and made a total of 23 recommendations. They reviewed only 1 new topic. The other 12 were updates of topics previously addressed; no changes were made in 9 of them. In 3, the recommended age of screening or the criteria for screening were expanded. This Practice Alert will review the recommendations made and highlight new recommendations and any changes to previous ones. All complete recommendation statements, rationales, clinical considerations, and evidence reports can be found on the USPSTF website at https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/home.1

Dental caries in children

Dental caries affect about 23% of children between the ages of 2 and 5 years and are associated with multiple adverse social outcomes and medical conditions.2 The best way to prevent tooth decay, other than regular brushing with fluoride toothpaste, is to drink water with recommended amounts of fluoride (≥ 0.6 parts fluoride per million parts water).2 The USPSTF reaffirmed its recommendation from 2014 that stated when a local water supply lacks sufficient fluoride, primary care clinicians should prescribe oral supplementation for infants and children in the form of fluoride drops starting at age 6 months. The dosage of fluoride depends on patient age and fluoride concentration in the local water (TABLE 13). The USPSTF also recommends applying topical fluoride as 5% sodium fluoride varnish, every 6 months, starting when the primary teeth erupt.2

In addition to fluoride supplements and topical varnish, should clinicians perform screening examinations looking for dental caries? The USPSTF feels there is not enough evidence to assess this practice and gives it an “I” rating (insufficient evidence).

Preventive interventions in pregnancy

In 2021, the USPSTF assessed 3 topics related to pregnancy and prenatal care.

Screening for gestational diabetes. The USPSTF gave a “B” recommendation for screening at 24 weeks of pregnancy or after, but an “I” statement for screening prior to 24 weeks.4 Screening can involve a 1-step or 2-step protocol.

The 2-step protocol is most commonly used in the United States. It involves first measuring serum glucose after a nonfasting 50-g oral glucose challenge; if the resulting level is high, the second step is a 75- or 100-g oral glucose tolerance test lasting 3 hours. The 1-step protocol involves measuring a fasting glucose level, followed by a 75-g oral glucose challenge with glucose levels measured at 1 and 2 hours.

Healthy weight gain in pregnancy. This was the only new topic the USPSTF assessed last year. The resulting recommendation is to offer pregnant women behavioral counseling to promote healthy weight gain and to prevent excessive weight gain in pregnancy. The recommended weight gain depends on the mother’s prepregnancy weight status: 28 to 40 lbs if the mother is underweight; 25 to 35 lbs if she is not under- or overweight; 15 to 25 lbs if she is overweight; and 11 to 20 lbs if she is obese.5 Healthy weight gain contributes to preventing gestational diabetes, emergency cesarean sections, and infant macrosomia.

Continue to: Low-dose aspirin

Low-dose aspirin. Reaffirming a recommendation from 2014, the USPSTF advises low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) starting after 12 weeks’ gestation for all pregnant women who are at high risk for preeclampsia. TABLE 26 lists high- and moderate-risk conditions for preeclampsia and the recommendation for the use of low-dose aspirin.

Sexually transmitted infections

Screening for both chlamydia and gonorrhea in sexually active females through age 24 years was given a “B” recommendation, reaffirming the 2014 recommendation.7 Screening for these 2 sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is also recommended for women 25 years and older who are at increased risk of STIs. Risk is defined as having a new sex partner, more than 1 sex partner, a sex partner who has other sex partners, or a sex partner who has an STI; not using condoms consistently; having a previous STI; exchanging sex for money or drugs; or having a history of incarceration.

Screen for both infections simultaneously using a nucleic acid amplification test, testing all sites of sexual exposure. Urine testing can replace cervical, vaginal, and urethral testing. Those found to be positive for either STI should be treated according to the most recent treatment guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). And sexual partners should be advised to undergo testing.8,9

The USPSTF could not find evidence for the benefits and harms of screening for STIs in men. Remember that screening applies to those who are asymptomatic. Male sex partners of those found to be infected should be tested, as should those who show any signs or symptoms of an STI. A recent Practice Alert described the most current CDC guidance for diagnosing and treating STIs.9

Type 2 diabetes and prediabetes

Screening for type 2 diabetes (T2D) and prediabetes is now recommended for adults ages 35 to 70 years who are overweight or obese.10 The age to start screening has been lowered to 35 years from the previous recommendation in 2015, which recommended starting at age 40. In addition, the recommendation states that patients with prediabetes should be referred for preventive interventions. It is important that referral is included in the statement because the Affordable Care Act mandates that USPSTF “A” and “B” recommendations must be covered by commercial health insurance with no copay or deductible.

Continue to: Screening can be conducted...

Screening can be conducted using a fasting plasma glucose or A1C level, or with an oral glucose tolerance test. Interventions that can prevent or delay the onset of T2D in those with prediabetes include lifestyle interventions that focus on diet and physical activity, and the use of metformin (although metformin has not been approved for this by the US Food and Drug Administration).

Changes to cancer screening recommendations

In 2021, the USPSTF reviewed and modified its recommendations on screening for 2 types of cancer: colorectal and lung.

For colorectal cancer, the age at which to start screening was lowered from 50 years to 45 years.11 Screening at this earlier age is a “B” recommendation, because, while there is benefit from screening, it is less than for older age groups. Screening individuals ages 50 to 75 years remains an “A” recommendation, and for those ages 76 to 85 years it remains a “C” recommendation. A “C” recommendation means that the overall benefits are small but some individuals might benefit based on their overall health and prior screening results. In its clinical considerations, the USPSTF recommends against screening in those ages 85 and older but, curiously, does not list it as a “D” recommendation. The screening methods and recommended screening intervals for each appear in TABLE 3.11

For lung cancer, annual screening using low-dose computed tomography (CT) was first recommended by the USPSTF in 2013 for adults ages 55 to 80 years with a 30-pack-year smoking history. Screening could stop once 15 years had passed since smoking cessation. In 2021, the USPSTF lowered the age to initiate screening to 50 years, and the smoking history threshold to 20 pack-years.12 If these recommendations are followed, a current smoker who does not quit smoking could possibly receive 30 annual CT scans. The recommendation does state that screening should stop once a person develops a health condition that significantly affects life expectancy or ability to have lung surgery.

For primary prevention of lung cancer and other chronic diseases through smoking cessation, the USPSTF also reassessed its 2015 recommendations. It reaffirmed the “A” recommendation to ask adults about tobacco use and, for tobacco users, to recommend cessation and provide behavioral therapy and approved pharmacotherapy.13 The recommendation differed for pregnant adults in that the USPSTF is unsure about the potential harms of pharmacotherapy in pregnancy and gives that an “I” statement.13 An additional “I” statement was made about the use of electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation; the USPSTF recommends using behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions with proven effectiveness and safety instead.

Continue to: 4 additional recommendation updates with no changes

4 additional recommendation updates with no changes

Screening for high blood pressure in adults ages 18 years and older continues to receive an “A” recommendation.14 Importantly, the recommendation states that confirmation of high blood pressure should be made in an out-of-office setting before initiating treatment. Screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults and hearing loss in older adults both continue with “I” statements,15,16 and screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis continues to receive a “D” recommendation.17 The implications of the vitamin D “I” statement were discussed in a previous Practice Alert.18

Continuing value of the USPSTF

The USPSTF continues to set the gold standard for assessment of preventive interventions, and its decisions affect first-dollar coverage by commercial health insurance. The reaffirmation of past recommendations demonstrates the value of adhering to rigorous evidence-based methods (if they are done correctly, they rarely must be markedly changed). And the updating of screening criteria shows the need to constantly review the evolving evidence for current recommendations. Once again, however, funding and staffing limitations allowed the USPSTF to assess only 1 new topic. A listing of all the 2021 recommendations is in TABLE 4.1

In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) considered 13 topics and made a total of 23 recommendations. They reviewed only 1 new topic. The other 12 were updates of topics previously addressed; no changes were made in 9 of them. In 3, the recommended age of screening or the criteria for screening were expanded. This Practice Alert will review the recommendations made and highlight new recommendations and any changes to previous ones. All complete recommendation statements, rationales, clinical considerations, and evidence reports can be found on the USPSTF website at https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/home.1

Dental caries in children

Dental caries affect about 23% of children between the ages of 2 and 5 years and are associated with multiple adverse social outcomes and medical conditions.2 The best way to prevent tooth decay, other than regular brushing with fluoride toothpaste, is to drink water with recommended amounts of fluoride (≥ 0.6 parts fluoride per million parts water).2 The USPSTF reaffirmed its recommendation from 2014 that stated when a local water supply lacks sufficient fluoride, primary care clinicians should prescribe oral supplementation for infants and children in the form of fluoride drops starting at age 6 months. The dosage of fluoride depends on patient age and fluoride concentration in the local water (TABLE 13). The USPSTF also recommends applying topical fluoride as 5% sodium fluoride varnish, every 6 months, starting when the primary teeth erupt.2

In addition to fluoride supplements and topical varnish, should clinicians perform screening examinations looking for dental caries? The USPSTF feels there is not enough evidence to assess this practice and gives it an “I” rating (insufficient evidence).

Preventive interventions in pregnancy

In 2021, the USPSTF assessed 3 topics related to pregnancy and prenatal care.

Screening for gestational diabetes. The USPSTF gave a “B” recommendation for screening at 24 weeks of pregnancy or after, but an “I” statement for screening prior to 24 weeks.4 Screening can involve a 1-step or 2-step protocol.

The 2-step protocol is most commonly used in the United States. It involves first measuring serum glucose after a nonfasting 50-g oral glucose challenge; if the resulting level is high, the second step is a 75- or 100-g oral glucose tolerance test lasting 3 hours. The 1-step protocol involves measuring a fasting glucose level, followed by a 75-g oral glucose challenge with glucose levels measured at 1 and 2 hours.

Healthy weight gain in pregnancy. This was the only new topic the USPSTF assessed last year. The resulting recommendation is to offer pregnant women behavioral counseling to promote healthy weight gain and to prevent excessive weight gain in pregnancy. The recommended weight gain depends on the mother’s prepregnancy weight status: 28 to 40 lbs if the mother is underweight; 25 to 35 lbs if she is not under- or overweight; 15 to 25 lbs if she is overweight; and 11 to 20 lbs if she is obese.5 Healthy weight gain contributes to preventing gestational diabetes, emergency cesarean sections, and infant macrosomia.

Continue to: Low-dose aspirin

Low-dose aspirin. Reaffirming a recommendation from 2014, the USPSTF advises low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d) starting after 12 weeks’ gestation for all pregnant women who are at high risk for preeclampsia. TABLE 26 lists high- and moderate-risk conditions for preeclampsia and the recommendation for the use of low-dose aspirin.

Sexually transmitted infections

Screening for both chlamydia and gonorrhea in sexually active females through age 24 years was given a “B” recommendation, reaffirming the 2014 recommendation.7 Screening for these 2 sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is also recommended for women 25 years and older who are at increased risk of STIs. Risk is defined as having a new sex partner, more than 1 sex partner, a sex partner who has other sex partners, or a sex partner who has an STI; not using condoms consistently; having a previous STI; exchanging sex for money or drugs; or having a history of incarceration.

Screen for both infections simultaneously using a nucleic acid amplification test, testing all sites of sexual exposure. Urine testing can replace cervical, vaginal, and urethral testing. Those found to be positive for either STI should be treated according to the most recent treatment guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). And sexual partners should be advised to undergo testing.8,9

The USPSTF could not find evidence for the benefits and harms of screening for STIs in men. Remember that screening applies to those who are asymptomatic. Male sex partners of those found to be infected should be tested, as should those who show any signs or symptoms of an STI. A recent Practice Alert described the most current CDC guidance for diagnosing and treating STIs.9

Type 2 diabetes and prediabetes

Screening for type 2 diabetes (T2D) and prediabetes is now recommended for adults ages 35 to 70 years who are overweight or obese.10 The age to start screening has been lowered to 35 years from the previous recommendation in 2015, which recommended starting at age 40. In addition, the recommendation states that patients with prediabetes should be referred for preventive interventions. It is important that referral is included in the statement because the Affordable Care Act mandates that USPSTF “A” and “B” recommendations must be covered by commercial health insurance with no copay or deductible.

Continue to: Screening can be conducted...

Screening can be conducted using a fasting plasma glucose or A1C level, or with an oral glucose tolerance test. Interventions that can prevent or delay the onset of T2D in those with prediabetes include lifestyle interventions that focus on diet and physical activity, and the use of metformin (although metformin has not been approved for this by the US Food and Drug Administration).

Changes to cancer screening recommendations

In 2021, the USPSTF reviewed and modified its recommendations on screening for 2 types of cancer: colorectal and lung.

For colorectal cancer, the age at which to start screening was lowered from 50 years to 45 years.11 Screening at this earlier age is a “B” recommendation, because, while there is benefit from screening, it is less than for older age groups. Screening individuals ages 50 to 75 years remains an “A” recommendation, and for those ages 76 to 85 years it remains a “C” recommendation. A “C” recommendation means that the overall benefits are small but some individuals might benefit based on their overall health and prior screening results. In its clinical considerations, the USPSTF recommends against screening in those ages 85 and older but, curiously, does not list it as a “D” recommendation. The screening methods and recommended screening intervals for each appear in TABLE 3.11

For lung cancer, annual screening using low-dose computed tomography (CT) was first recommended by the USPSTF in 2013 for adults ages 55 to 80 years with a 30-pack-year smoking history. Screening could stop once 15 years had passed since smoking cessation. In 2021, the USPSTF lowered the age to initiate screening to 50 years, and the smoking history threshold to 20 pack-years.12 If these recommendations are followed, a current smoker who does not quit smoking could possibly receive 30 annual CT scans. The recommendation does state that screening should stop once a person develops a health condition that significantly affects life expectancy or ability to have lung surgery.

For primary prevention of lung cancer and other chronic diseases through smoking cessation, the USPSTF also reassessed its 2015 recommendations. It reaffirmed the “A” recommendation to ask adults about tobacco use and, for tobacco users, to recommend cessation and provide behavioral therapy and approved pharmacotherapy.13 The recommendation differed for pregnant adults in that the USPSTF is unsure about the potential harms of pharmacotherapy in pregnancy and gives that an “I” statement.13 An additional “I” statement was made about the use of electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation; the USPSTF recommends using behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions with proven effectiveness and safety instead.

Continue to: 4 additional recommendation updates with no changes

4 additional recommendation updates with no changes

Screening for high blood pressure in adults ages 18 years and older continues to receive an “A” recommendation.14 Importantly, the recommendation states that confirmation of high blood pressure should be made in an out-of-office setting before initiating treatment. Screening for vitamin D deficiency in adults and hearing loss in older adults both continue with “I” statements,15,16 and screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis continues to receive a “D” recommendation.17 The implications of the vitamin D “I” statement were discussed in a previous Practice Alert.18

Continuing value of the USPSTF

The USPSTF continues to set the gold standard for assessment of preventive interventions, and its decisions affect first-dollar coverage by commercial health insurance. The reaffirmation of past recommendations demonstrates the value of adhering to rigorous evidence-based methods (if they are done correctly, they rarely must be markedly changed). And the updating of screening criteria shows the need to constantly review the evolving evidence for current recommendations. Once again, however, funding and staffing limitations allowed the USPSTF to assess only 1 new topic. A listing of all the 2021 recommendations is in TABLE 4.1

1. USPSTF. Recommendation topics. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation-topics

2. USPSTF. Prevention of dental caries in children younger than 5 years: screening and interventions. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-dental-caries-in-children-younger-than-age-5-years-screening-and-interventions1#bootstrap-panel—4

3. ADA. Dietary fluoride supplements: evidence-based clinical recommendations. Accessed April 14, 2022. www.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/research/ada_evidence-based_fluoride_supplement_chairside_guide.pdf?rev=60850dca0dcc41038efda83d42b1c2e0&hash=FEC2BBEA0C892FB12C098E33344E48B4

4. USPSTF. Gestational diabetes: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/gestational-diabetes-screening

5. USPSTF. Healthy weight and weight gain in pregnancy: behavioral counseling interventions. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/healthy-weight-and-weight-gain-during-pregnancy-behavioral-counseling-interventions

6. USPSTF. Aspirin use to prevent preeclampsia and related morbidity and mortality: preventive medication. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-from-preeclampsia-preventive-medication

7. USPSTF. Chlamydia and gonorrhea: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/chlamydia-and-gonorrhea-screening

8. Workowski KA, Bauchman LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1-187.

9. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC guidelines on sexually transmitted infections. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:506-509.

10. USPSTF. Prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-for-prediabetes-and-type-2-diabetes

11. USPSTF. Colorectal cancer: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening

12. USPSTF. Lung cancer: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/lung-cancer-screening

13. USPSTF. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons: interventions. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions

14. USPSTF. Hypertension in adults: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hypertension-in-adults-screening

15. USPSTF. Vitamin D deficiency in adults: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/vitamin-d-deficiency-screening

16. USPSTF. Hearing loss in older adults: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hearing-loss-in-older-adults-screening

17. USPSTF. Asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis: screening. Access April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/carotid-artery-stenosis-screening

18. Campos-Outcalt D. How to proceed when it comes to vitamin D. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:289-292.

1. USPSTF. Recommendation topics. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation-topics

2. USPSTF. Prevention of dental caries in children younger than 5 years: screening and interventions. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-dental-caries-in-children-younger-than-age-5-years-screening-and-interventions1#bootstrap-panel—4

3. ADA. Dietary fluoride supplements: evidence-based clinical recommendations. Accessed April 14, 2022. www.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/research/ada_evidence-based_fluoride_supplement_chairside_guide.pdf?rev=60850dca0dcc41038efda83d42b1c2e0&hash=FEC2BBEA0C892FB12C098E33344E48B4

4. USPSTF. Gestational diabetes: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/gestational-diabetes-screening

5. USPSTF. Healthy weight and weight gain in pregnancy: behavioral counseling interventions. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/healthy-weight-and-weight-gain-during-pregnancy-behavioral-counseling-interventions

6. USPSTF. Aspirin use to prevent preeclampsia and related morbidity and mortality: preventive medication. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-from-preeclampsia-preventive-medication

7. USPSTF. Chlamydia and gonorrhea: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/chlamydia-and-gonorrhea-screening

8. Workowski KA, Bauchman LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1-187.

9. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC guidelines on sexually transmitted infections. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:506-509.

10. USPSTF. Prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-for-prediabetes-and-type-2-diabetes

11. USPSTF. Colorectal cancer: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening

12. USPSTF. Lung cancer: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/lung-cancer-screening

13. USPSTF. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons: interventions. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions

14. USPSTF. Hypertension in adults: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hypertension-in-adults-screening

15. USPSTF. Vitamin D deficiency in adults: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/vitamin-d-deficiency-screening

16. USPSTF. Hearing loss in older adults: screening. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hearing-loss-in-older-adults-screening

17. USPSTF. Asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis: screening. Access April 14, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/carotid-artery-stenosis-screening

18. Campos-Outcalt D. How to proceed when it comes to vitamin D. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:289-292.

Hypertension—or not? Looking beyond office BP readings

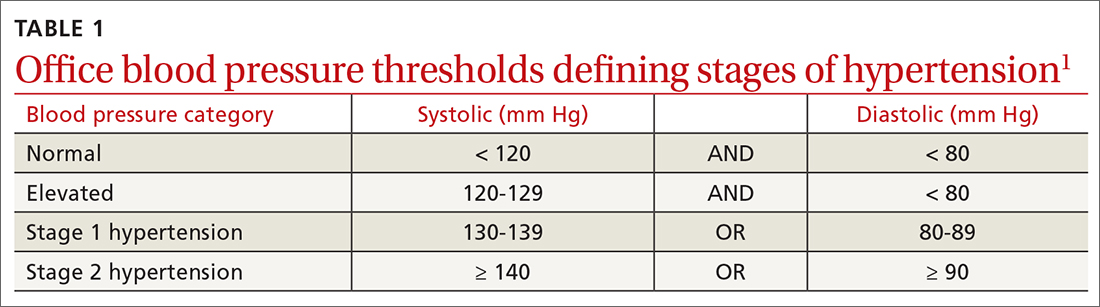

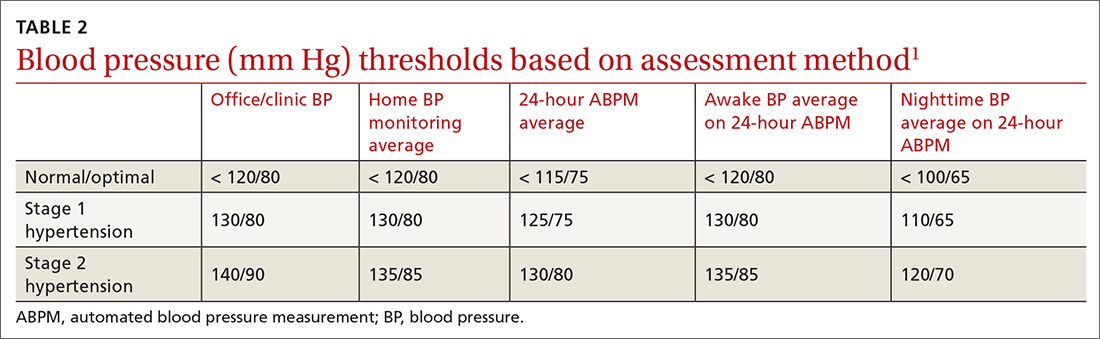

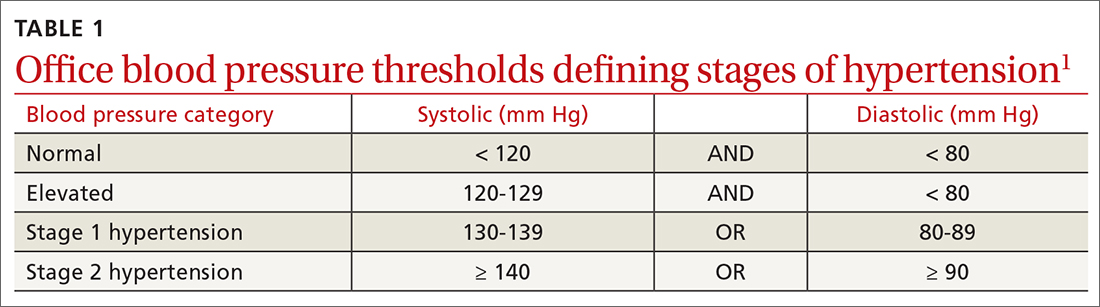

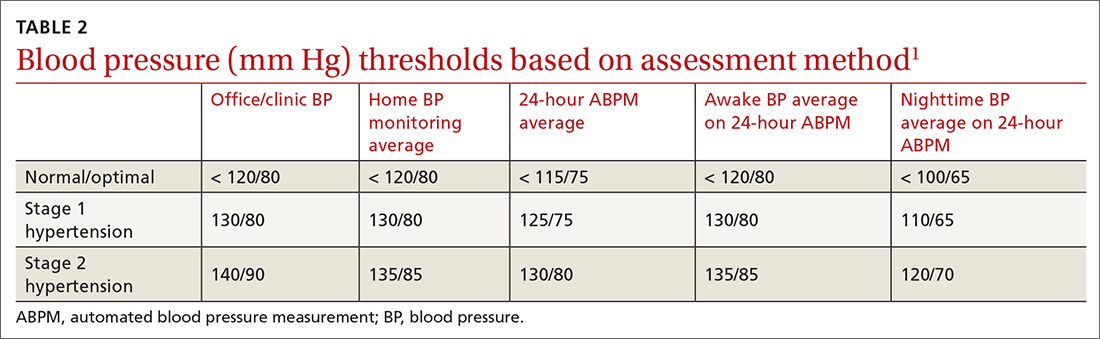

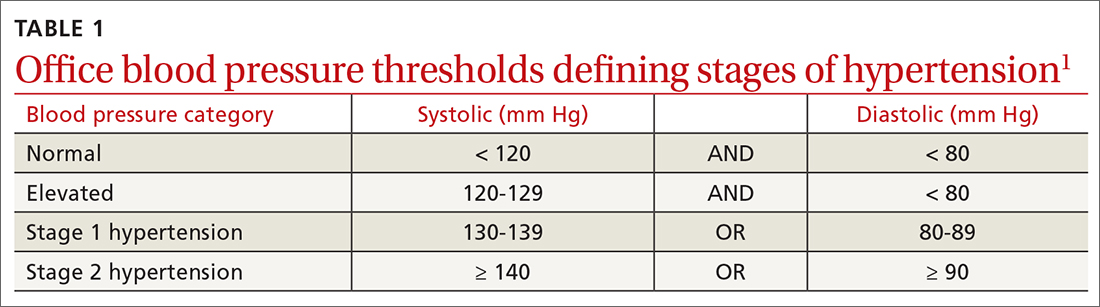

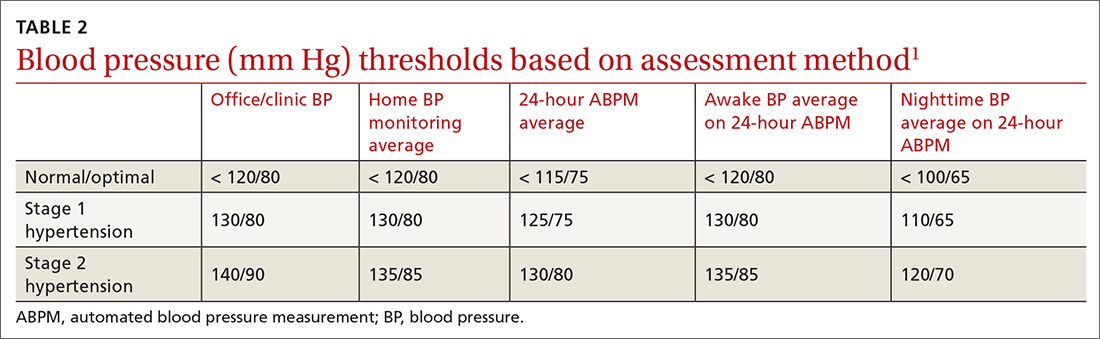

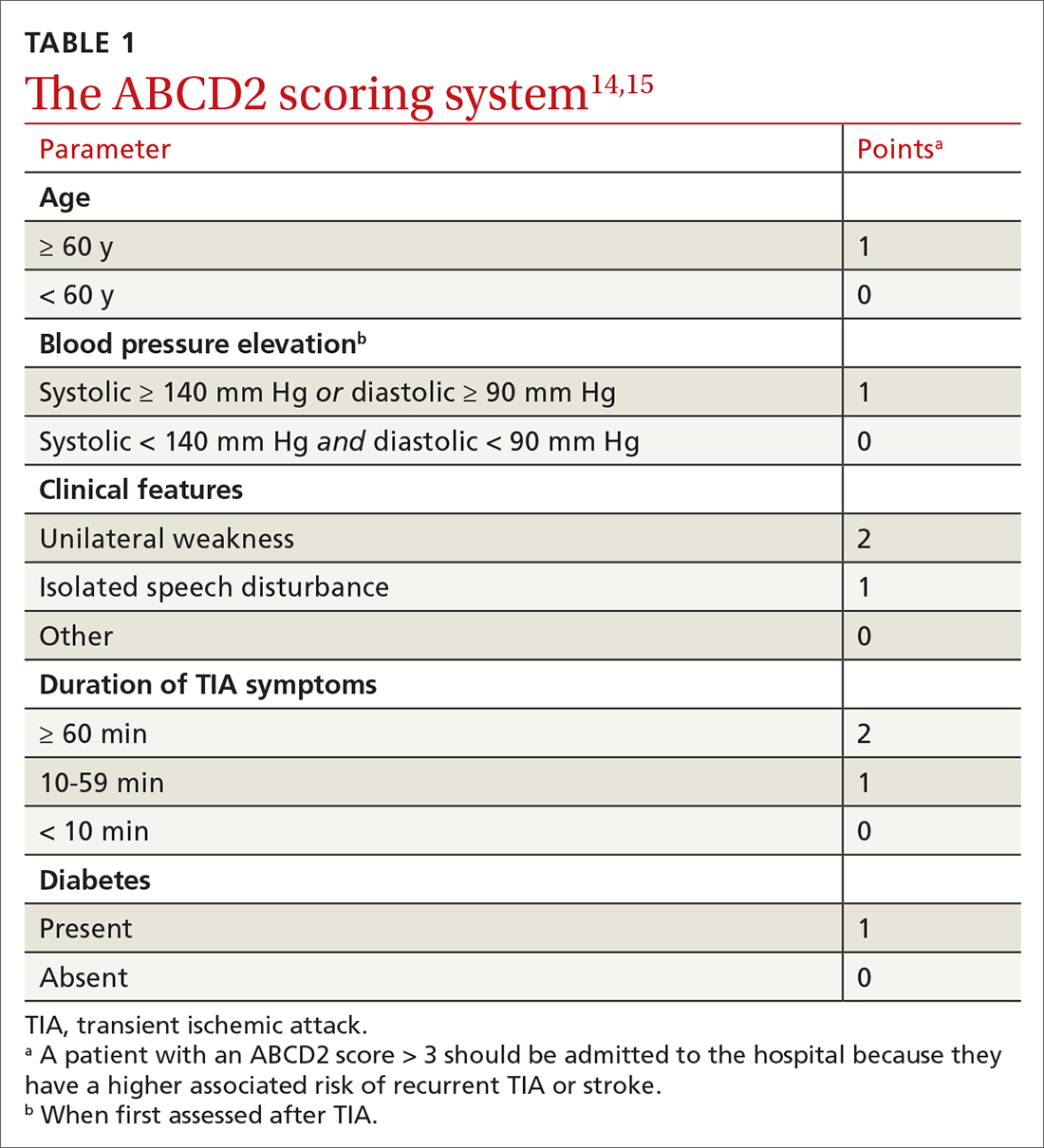

Normal blood pressure (BP) is defined as systolic BP (SBP) < 120 mm Hg and diastolic BP (DBP) < 80 mm Hg.1 The thresholds for hypertension (HTN) are shown in TABLE 1.1 These thresholds must be met on at least 2 separate occasions to merit a diagnosis of HTN.1

Given the high prevalence of HTN and its associated comorbidities, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently reaffirmed its recommendation that every adult be screened for HTN, regardless of risk factors.2 Patients 40 years of age and older and those with risk factors (obesity, family history of HTN, diabetes) should have their BP checked at least annually. Individuals ages 18 to 39 years without risk factors who are initially normotensive should be rescreened within 3 to 5 years.2

Patients are most commonly screened for HTN in the outpatient setting. However, office BP measurements may be inaccurate and are of limited diagnostic utility when taken as a single reading.1,3,4 As will be described later, office BP measurements are subject to multiple sources of error that can result in a mean underestimation of 24 mm Hg to a mean overestimation of 33 mm Hg for SBP, and a mean underestimation of 14 mm Hg to a mean overestimation of 23 mm Hg for DBP.4

Differences to this degree between true BP and measured BP can have important implications for the diagnosis, surveillance, and management of HTN. To diminish this potential for error, the American Heart Association HTN guideline and USPSTF recommendation advise clinicians to obtain out-of-office BP measurements to confirm a diagnosis of HTN before initiating treatment.1,2 The preferred methods for out-of-office BP assessment are home BP monitoring (HBPM) and 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM).

Limitations of office BP measurement

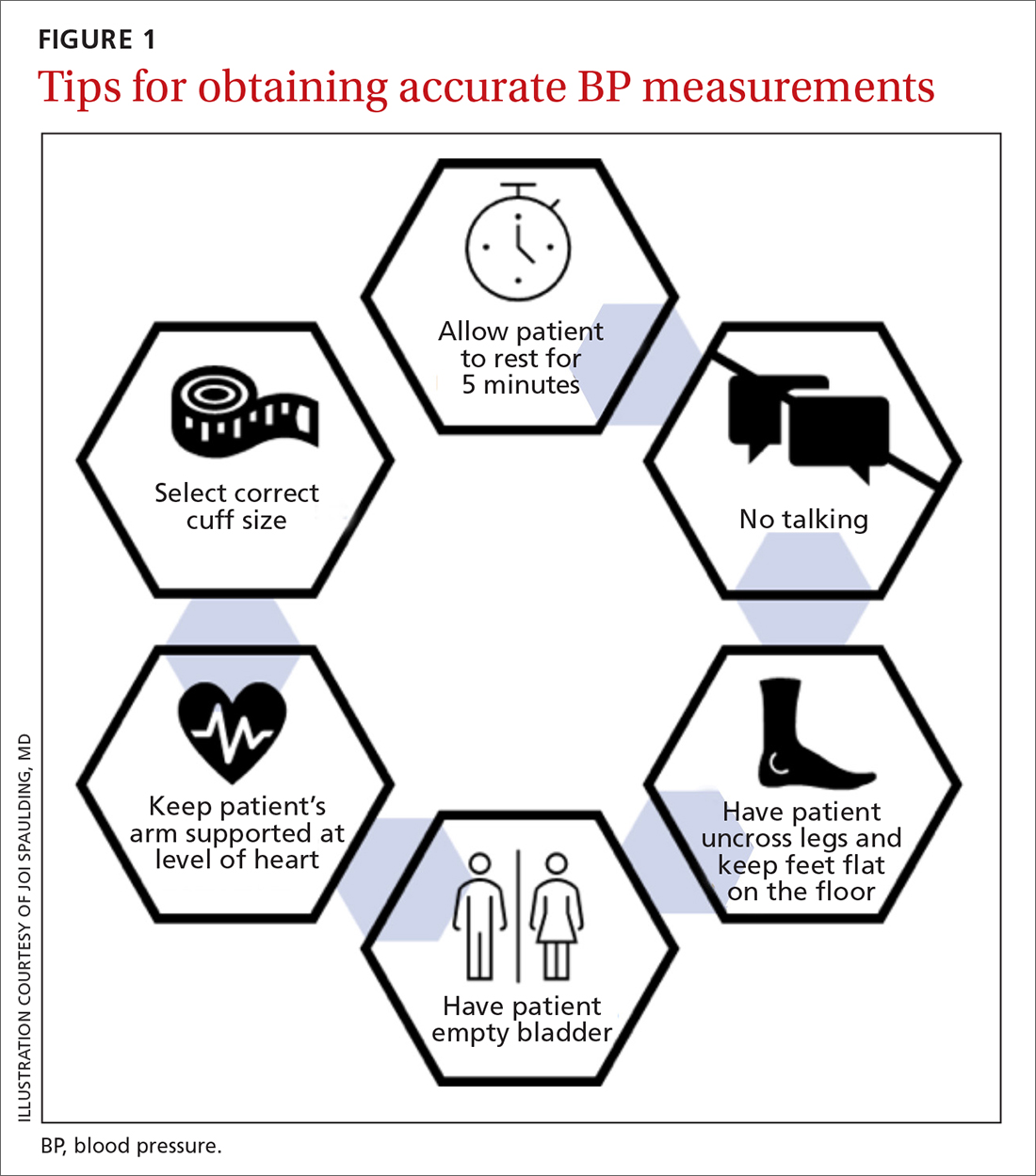

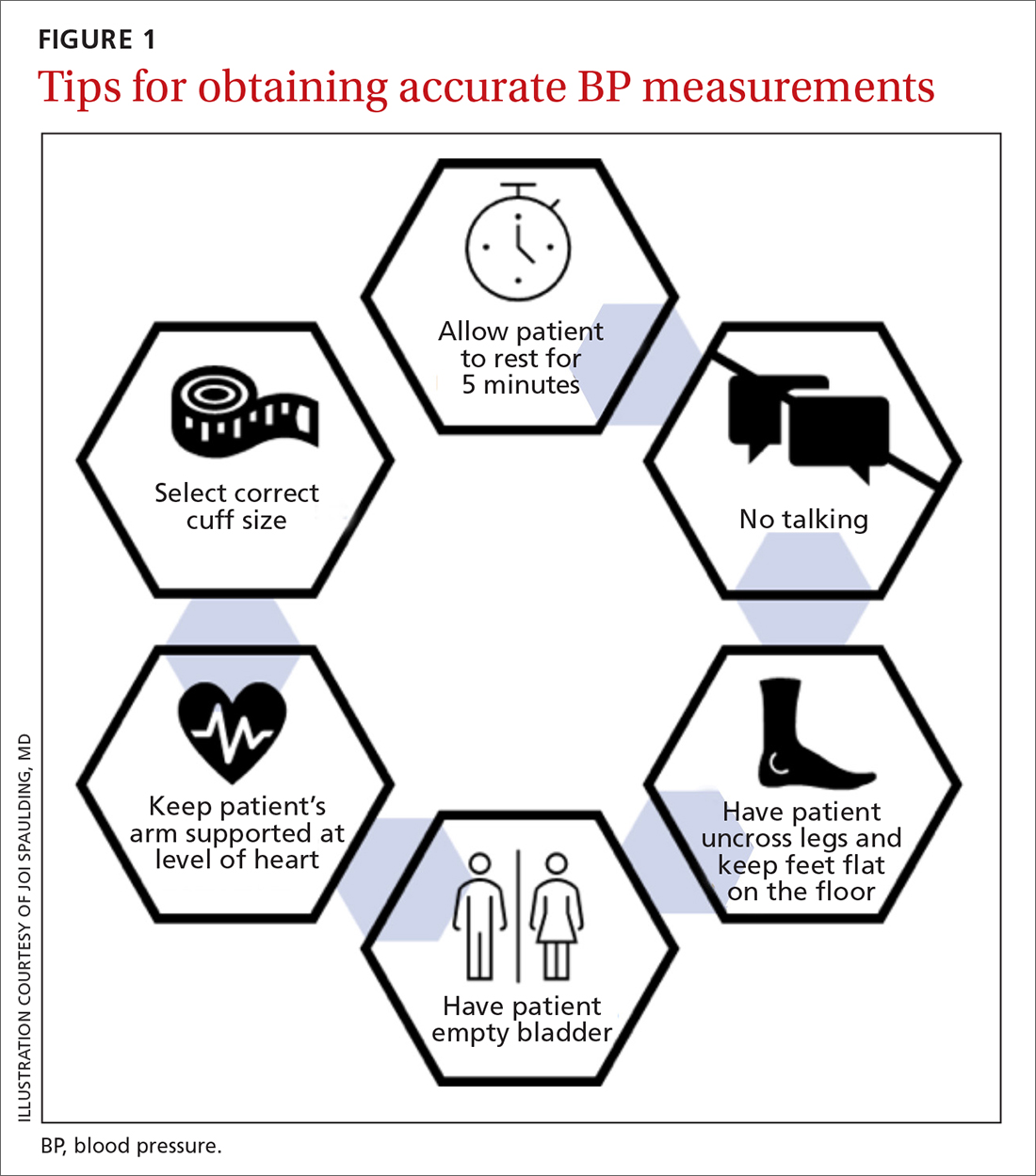

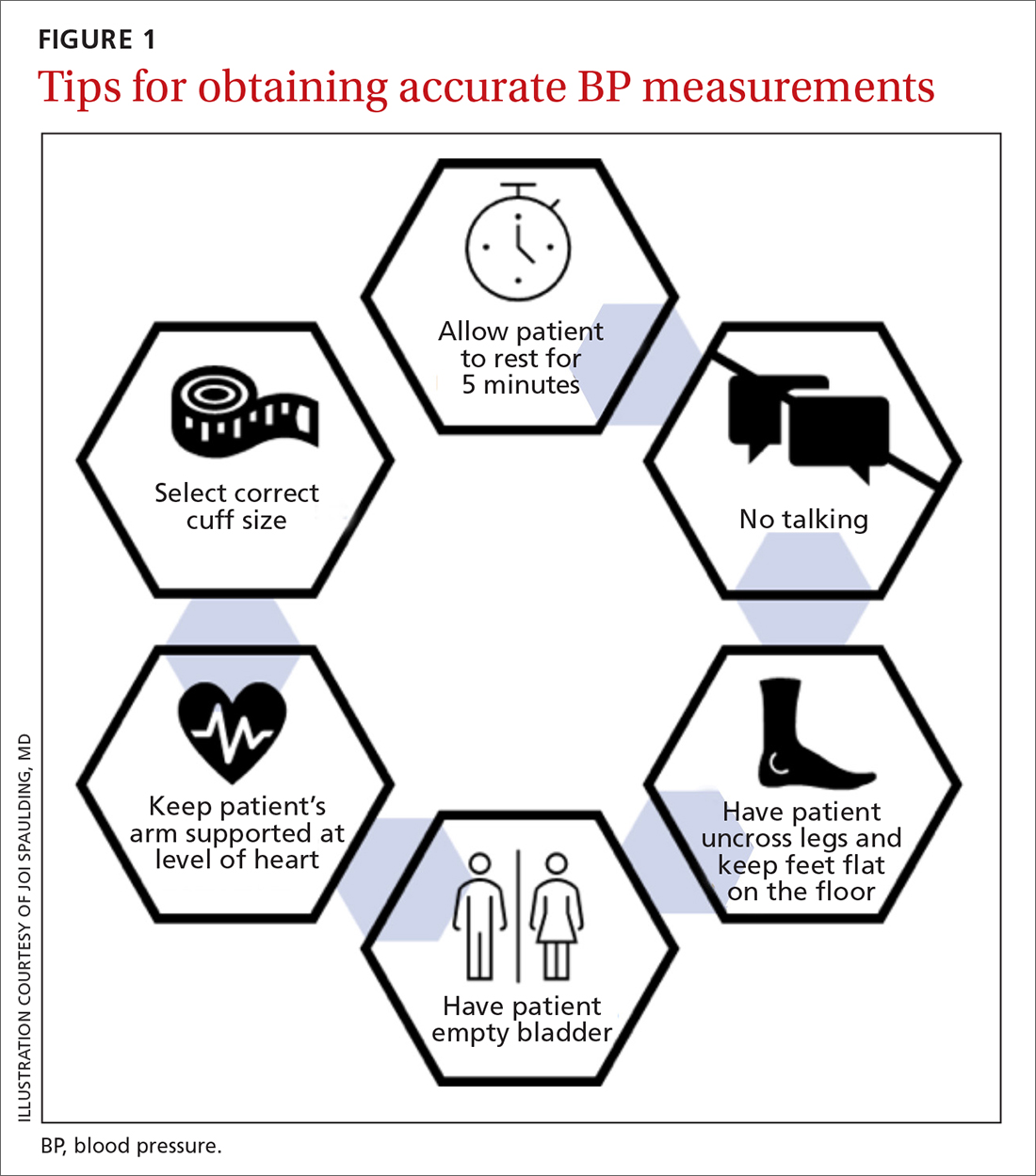

Multiple sources of error can lead to wide variability in the measurement of office BP, whether taken via the traditional sphygmomanometer auscultatory approach or with an oscillometric monitor.1,4 Measurement error can be patient related (eg, talking during the reading, or eating or using tobacco prior to measurement), device related (eg, device has not been calibrated or validated), or procedure related (eg, miscuffing, improper patient positioning).

Although use of validated oscillometric monitors eliminates some sources of error such as terminal digit bias, rapid cuff deflation, and missed Korotkoff sounds, their use does not eliminate other sources of error. For example, a patient’s use of tobacco 30 to 60 minutes prior to measurement can raise SBP by 2.8 to 25 mm Hg and DBP 2 to 18 mm Hg.4 Having a full bladder can elevate SBP by 4.2 to 33 mm Hg and DBP by 2.8 to 18.5 mm Hg.4 If the patient is talking during measurement, is crossing one leg over the opposite knee, or has an unsupported arm below the level of the heart, SBP and DBP can rise, respectively, by an estimated mean 2 to 23 mm Hg and 2 to 14 mm Hg.4

Although many sources of BP measurement error can be reduced or eliminated through standardization of technique across office staff, some sources of inaccuracy will persist. Even if all variables are optimized, relying solely on office BP monitoring will still misclassify BP phenotypes, which require out-of-office BP assessments.1,3FIGURE 1 reviews key tips for maximizing the accuracy of BP measurement, regardless of where the measurement is done.

Continue to: Automated office BP

Automated office BP (AOBP) lessens some of the limitations inherent with the traditional sphygmomanometer auscultatory and single-measurement oscillometric devices. AOBP combines oscillometric technology with the capacity to record multiple BP readings within a single activation, thereby providing an average of these readings.1 The total time required for AOBP is 4 to 6 minutes, including a brief rest period before the measurement starts. Studies have reported comparable readings between staff-attended and unattended AOBP, which is an encouraging way to eliminate some measurement error (eg, talking with the patient) and to improve efficiency.5,6

Waiting several minutes per patient to record BP may not be practical in a busy office setting and may require an alteration of workflow. There is a paucity of literature evaluating practice realities, which makes it difficult to know how many patients are getting their BP checked in this manner. Several studies have shown that BP measured with AOBP is closer to awake out-of-office BP as measured with ABPM (discussed in a bit),5-8 largely through mitigation of white-coat effect. Canada now recommends AOBP as the preferred method for diagnosing HTN and monitoring BP.9

Home blood pressure monitoring

HBPM refers to individuals measuring their own BP at home. It is important to remember this definition,

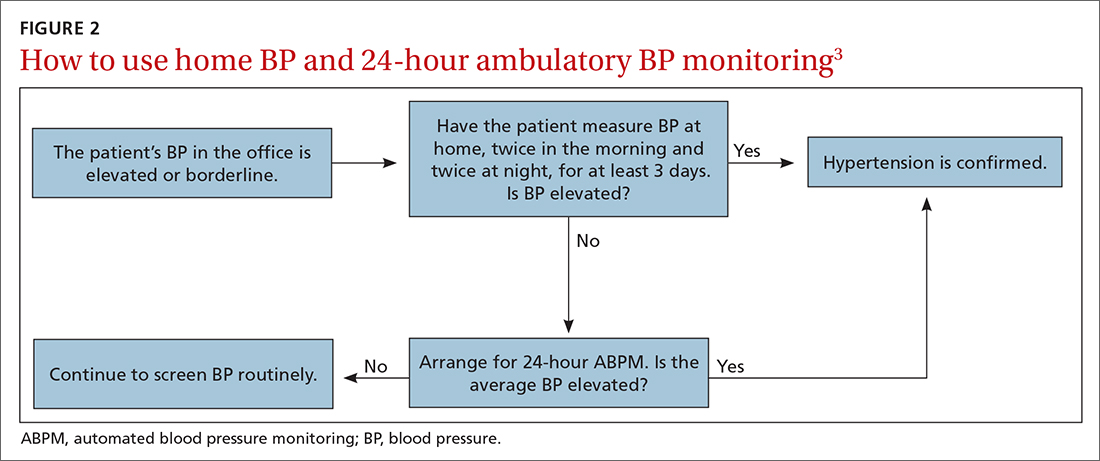

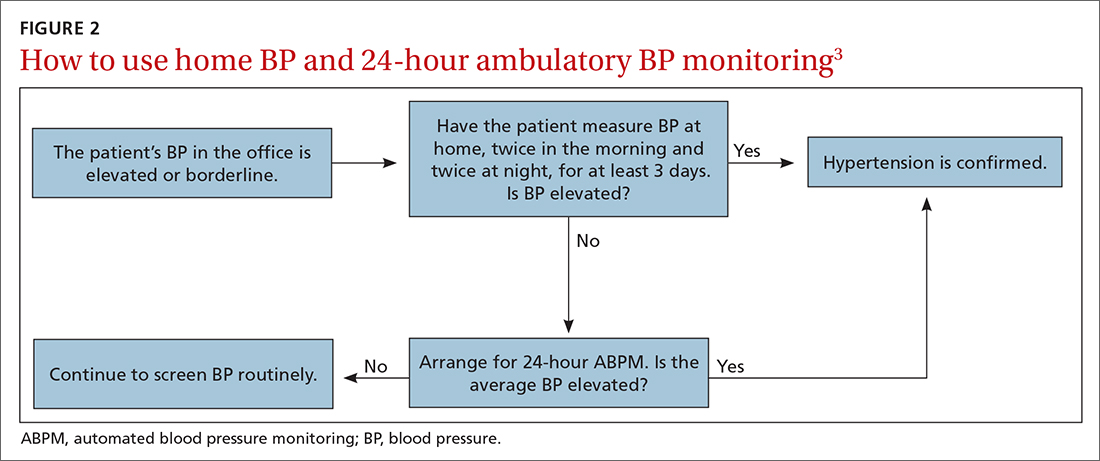

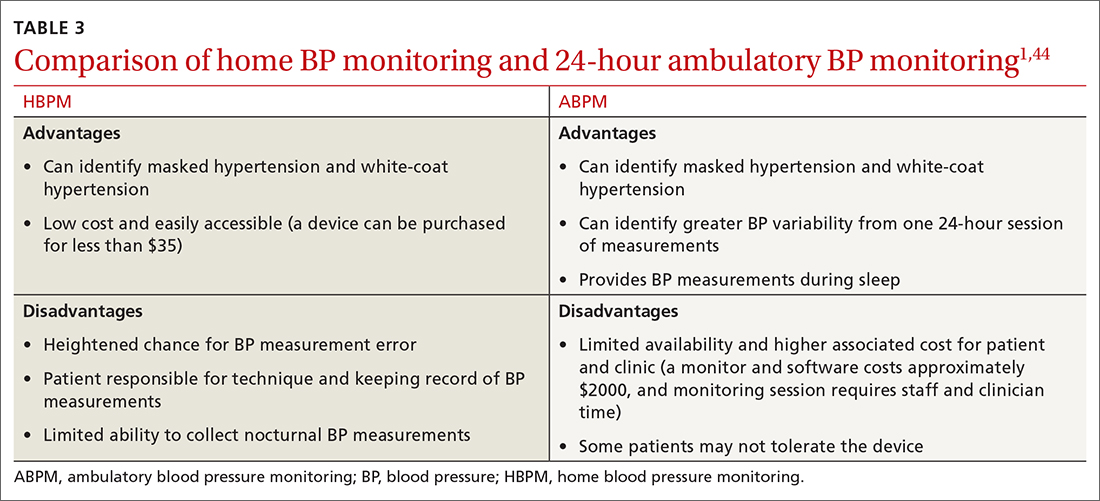

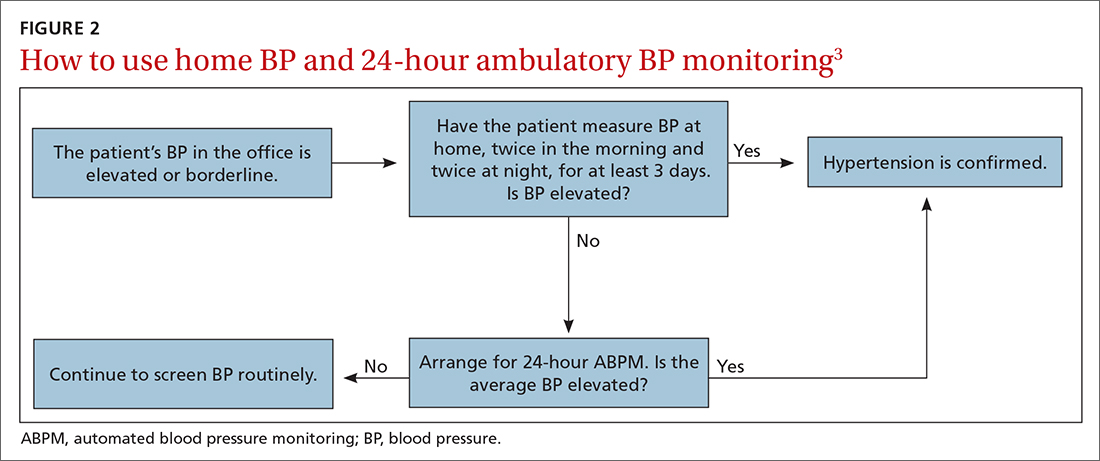

There is strong evidence that HBPM adds value over and above office measurements in predicting end-organ damage and cardiovascular disease (CVD) outcomes, and it has a stronger relationship with CVD risk than office BP.1 Compared with office BP measurement, HBPM is a better predictor of echocardiographic left ventricular mass index, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio, proteinuria, silent cerebrovascular disease, nonfatal cardiovascular outcomes, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality.15,16 There is no strong evidence demonstrating the superiority of HBPM over ABPM, or vice versa, for predicting CVD events or mortality.17 Both ABPM and HBPM have important roles in out-of-office monitoring (FIGURE 23).

Clinical indications for HBPM

HBPM can facilitate diagnosis of white-coat HTN or effect (if already on BP-lowering medication) as well as masked uncontrolled HTN and masked HTN. Importantly, masked HTN is associated with nearly the same risk of target organ damage and cardiovascular events as sustained HTN. In one meta-analysis the overall adjusted hazard ratio for CVD events was 2.00 (95% CI, 1.58-2.52) for masked HTN and 2.28 (95% CI, 1.87-2.78) for sustained HTN, compared with normotensive individuals.18 Other studies support these results, demonstrating that masked HTN confers risk similar to sustained HTN.19,20

Even treated subjects with masked uncontrolled HTN (normal office and high home BP) have higher CVD risk, likely due to undertreatment given lower BP in the office setting. Among 1451 treated patients in a large cohort study who were followed for a median of 8.3 years, CVD was higher in those with masked uncontrolled HTN (adjusted hazard ratio = 1.76; 95% CI, 1.23-2.53) compared to treated controlled patients (normal office and home BP).21

HBPM also can be used to monitor BP levels over time, to increase patient involvement in chronic disease management, and to improve adherence with medications. Since 2008, several meta-analyses have been published showing improved BP control when HBPM is combined with other interventions and patient education.22-25 Particularly relevant in the age of increased telehealth, several meta-analyses demonstrate improvement in BP control when HBPM is combined with web- or phone-based support, systematic medication titration, patient education, and provider counseling.22-25 A comprehensive systematic review found HBPM with this kind of ongoing support (compared with usual care) led to clinic SBP reductions of 3.2 mm Hg (95% CI, 1.6-4.9) at 12 months.22

Continue to: HBPM nuts and bolts

HBPM nuts and bolts

When using HBPM to obtain a BP average either for confirming a diagnosis or assessing HTN control, patients should be instructed to record their BP measurements twice in the morning and twice at night for a minimum of 3 days (ie, 12 readings).26,27 For each monitoring period, both SBP and DBP readings should be recorded, although protocols differ as to whether to discard the initial reading of each day, or the entire first day of readings.26-29 Consecutive days of monitoring are preferred, although nonconsecutive days also are likely to provide valid data. Once BP stabilizes, monitoring 1 to 3 days a week is likely sufficient.

Most guidelines cite a mean BP of ≥ 135/85 mm Hg as the indication of high BP on HBPM.1,28,29 This value corresponds to an office BP average of 140/90 mm Hg. TABLE 21 shows the comparison of home, ambulatory, and office BP thresholds.

Device selection and validation

As with any BP device, validation and proper technique are important. Recommend only upper-arm cuff devices that have passed validation protocols.30 To eliminate the burden on patients to accurately record and store their BP readings, and to eliminate this step as a source of bias, additionally recommend devices with built-in memory. Although easy-to-use wrist and finger monitors have become popular, there are important limitations in terms of accurate positioning and a lack of validated protocols.31,32

The brachial artery is still the recommended measurement location, unless otherwise precluded due to arm size (the largest size for most validated upper-arm cuffs is 42 cm), patient discomfort, medical contraindication (eg, lymphedema), or immobility (eg, due to injury). Arm size limitation is particularly important as obesity rates continue to rise. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey indicate that 52% of men and 38% of women with HTN need a different cuff size than the US standard.33 If the brachial artery is not an option, there are no definitive data to recommend finger over wrist devices, as both are limited by lack of validated protocols.

The website www.stridebp.org maintains a current list of validated and preferred BP devices, and is supported by the European Society of Hypertension, the International Society of Hypertension, and the World Hypertension League. There are more than 4000 devices on the global market, but only 8% have been validated according to StrideBP.

Advances in HBPM that offset previous limitations

The usefulness of HBPM depends on patient factors such as a commitment to monitoring, applying standardized technique, and accurately recording measurements. Discuss these matters with patients before recommending HBPM. Until recently, HBPM devices could not measure BP during sleep. However, a device that assesses BP during sleep has now come on the US market, with preliminary data suggesting the BP measurements are similar to those obtained with ABPM.34 Advances in device memory and data storage and increased availability of electronic health record connection continue to improve the standardization and reliability of HBPM. In fact, there is a growing list of electronic health portals that can be synced with apps for direct transfer of HBPM data.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring

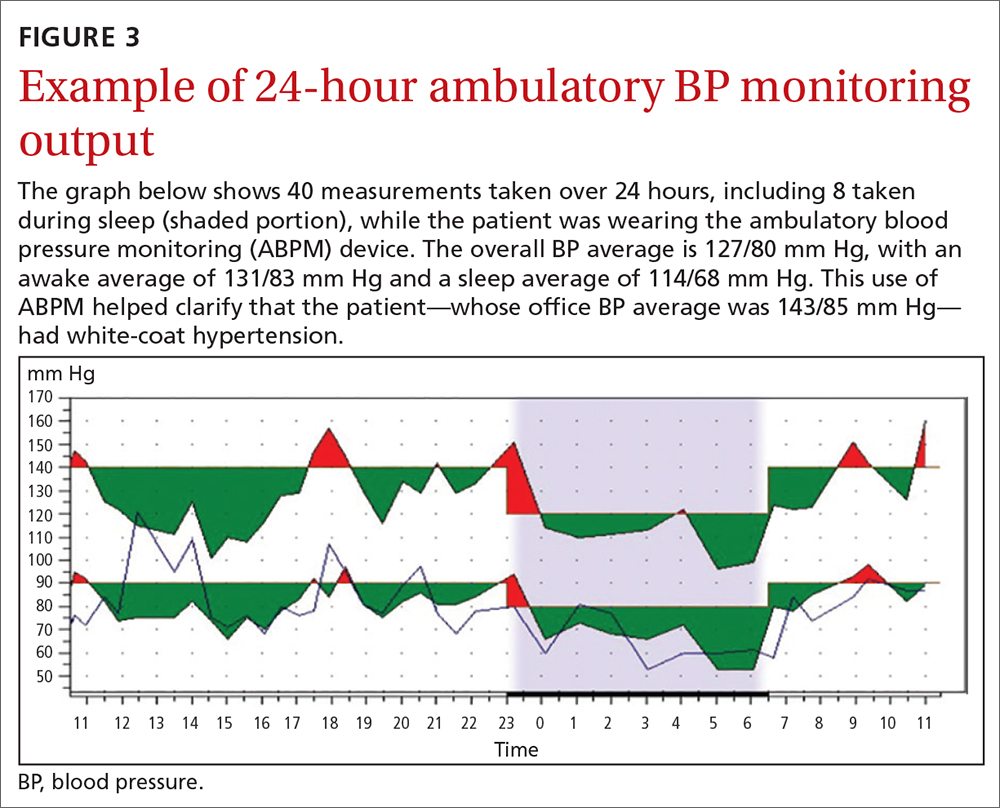

ABPM involves wearing a small device connected to an arm BP cuff that measures BP at pre-programmed intervals over a 24-hour period, during sleep and wakefulness. ABPM is the standard against which HBPM and office BP are compared.1-3

Continue to: Clinical indications for ABPM

Clinical indications for ABPM

Compared with office-based BP measurements, ABPM has a stronger positive correlation with clinical CVD outcomes and HTN-related organ damage.1 ABPM has the advantage of being able to provide a large number of measurements over the course of a patient’s daily activities, including sleep. It is useful to evaluate for a wide spectrum of hypertensive or hypotensive patterns, including nocturnal, postprandial, and drug-related patterns. ABPM also is used to assess for white-coat HTN and masked HTN.1

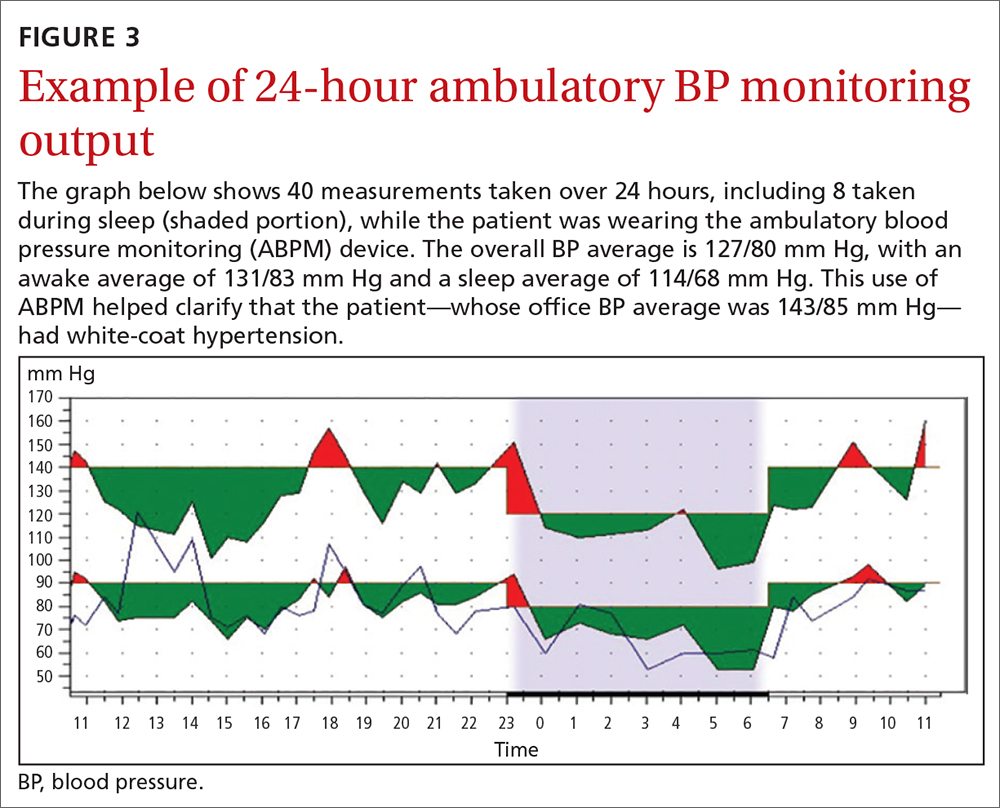

Among these BP phenotypes, an estimated 15% to 30% of adults in the United States exhibit white-coat HTN.1 Most evidence suggests that white-coat HTN confers similar cardiovascular risk as normotension, and it therefore does not require treatment.35 Confirming this diagnosis saves the individual and the health care system the cost of unnecessary diagnosis and treatment.

One cost-effectiveness study using ABPM for annual screening with subsequent treatment for those confirmed to be hypertensive found that ABPM reduced treatment-years by correctly identifying white-coat HTN, and also delayed treatment for those who would eventually develop HTN with advancing age.36 The estimates in savings were 3% to 14% for total cost of care for hypertension and 10% to 23% reduction in treatment days.36 An Australian study showed similar cost reductions.37 A more recent analysis demonstrated that compared with clinic BP measurement alone, incorporation of ABPM is associated with lifetime cost-savings ranging from $77 to $5013, depending on the age and sex of the patients modeled.38

ABPM can also be used to rule out white-coat effect in patients being evaluated for resistant HTN. Several studies demonstrate that among patients with apparent resistant HTN, approximately one-third have controlled BP when assessed by ABPM.39-41 Thus, it is recommended to conduct an out-of-office BP assessment in patients with apparent resistant HTN prior to adding another medication.41Twelve percent of US adults have masked HTN.42 As described earlier, these patients, unrecognized without out-of-office BP assessment, are twice as likely to experience a CVD event compared with normotensive patients.1,42,43

ABPM nuts and bolts

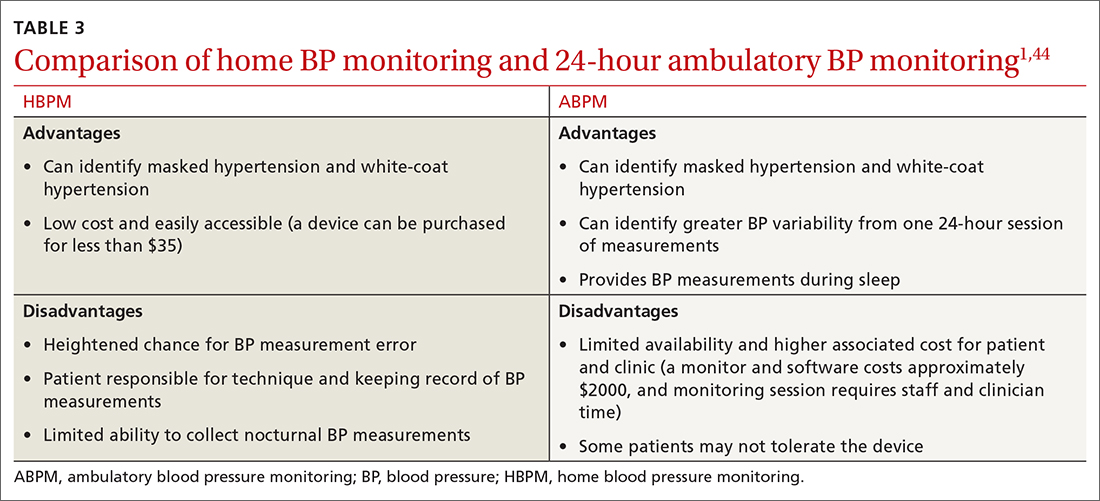

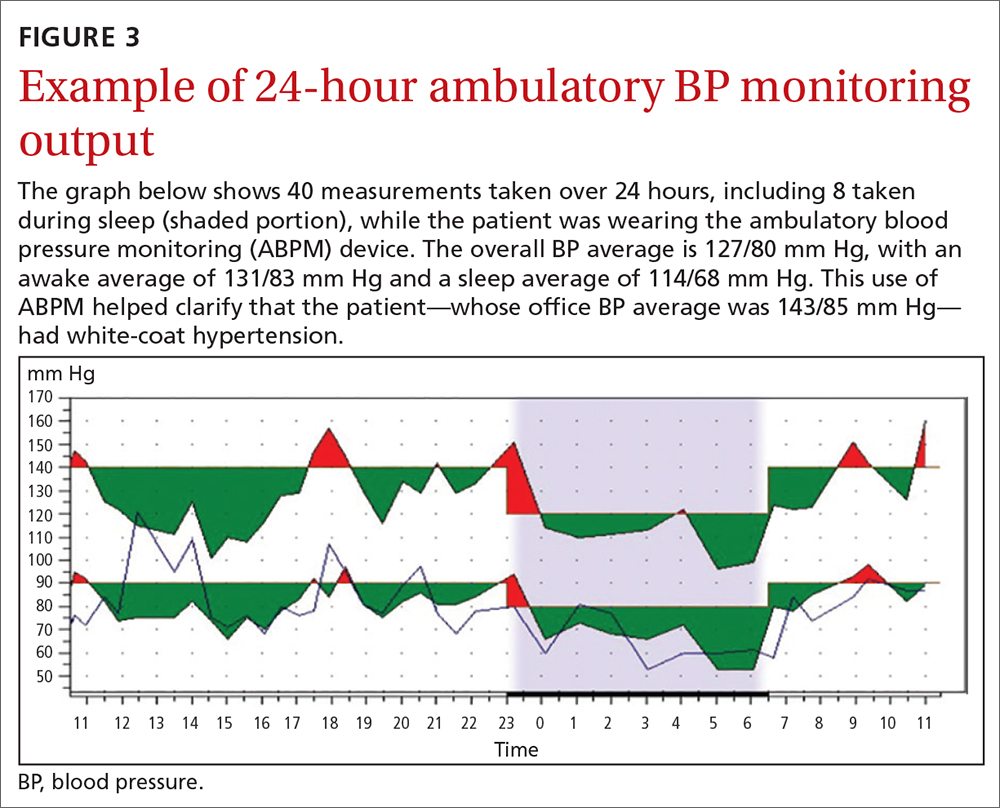

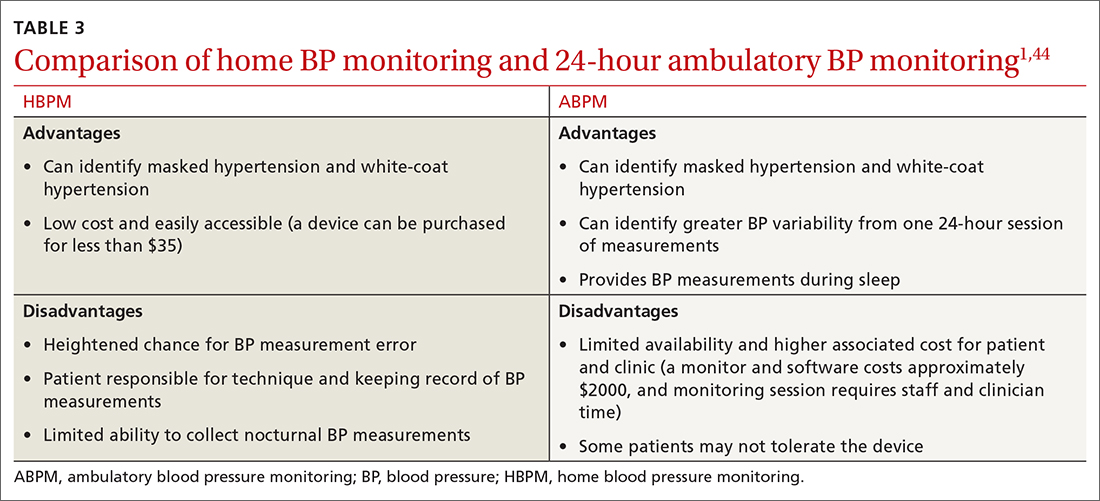

ABPM devices are typically worn for 24 hours and with little interruption to daily routines. Prior to BP capture, the device will alert the patient to ensure the patient’s arm can be held still while the BP measurement is being captured.44 At the completion of 24 hours, specific software uses the stored data to calculate the BP and heart rate averages, as well as minimums and maximums throughout the monitoring period. Clinical decision-making should be driven by the average BP measurements during times of sleep and wakefulness.1,14,44FIGURE 3 is an example of output from an ABPM session. TABLE 31,44 offers a comparison of HBPM and ABPM.

Limitations of ABPM

While ABPM has been designed to be almost effortless to use, some may find it inconvenient to wear. The repeated cuff inflations can cause discomfort or bruising, and the device can interfere with sleep.45 Inconsistent or incorrect wear of ABPM can diminish the quality of BP measurements, which can potentially affect interpretation and subsequent clinical decision-making. Therefore, consider the likelihood of correct and complete usage before ordering ABPM for your patient. Such deliberation is particularly relevant when there is concern for BP phenotypes such as nocturnal nondipping (failure of BP to fall appropriately during sleep) and postprandial HTN and hypotension.

Trained personnel are needed to oversee coordination of the ABPM service within the clinic and to educate patients about proper wear. Additionally, ABPM has not been widely used in US clinical practices to date, in part because this diagnostic strategy is not favorably reimbursed. Based on geographic region, Medicare currently pays between $56 and $122 per 24-hour ABPM session, and only for suspected white-coat HTN.38 Discrepancies remain between commercial and Medicaid/Medicare coverage.44

Continue to: Other modes of monitoring BP

Other modes of monitoring BP

The COVID pandemic has changed health care in many ways, including the frequency of in-person visits. As clinics come to rely more on virtual visits and telehealth, accurate monitoring of out-of-office BP has become more important. Kiosks and smart technology offer the opportunity to supplement traditional in-office BP readings. Kiosks are commonly found in pharmacies and grocery stores. These stations facilitate BP monitoring, as long as the device is appropriately validated and calibrated. Unfortunately, most kiosks have only one cuff size that is too small for many US adults, and some do not have a back support.46,47 Additionally, despite US Food and Drug Administration clearance, many kiosks do not have validated protocols, and the reproducibility of kiosk-measured BP is questionable.46,47

Mobile health technology is increasingly being examined as an effective means of providing health information, support, and management in chronic disease. Smartphone technology, wearable sensors, and cuffless BP monitors offer promise for providing BP data in more convenient ways. However, as with kiosk devices, very few of these have been validated, and several have been shown to have poor accuracy compared with oscillometric devices.48-50 For these reasons, kiosk and smart technology for BP monitoring are not recommended at this time, unless no alternatives are available to the patient.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anthony J. Viera, MD, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, Duke University School of Medicine, 2200 West Main Street, Suite 400, Durham, NC 27705; [email protected]

1. Muntner P, Shimbo D, Carey RM, et al. Measurement of blood pressure in humans: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2019;73:e35-e66. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000087

2. Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, et al; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hypertension in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325:1650-1656. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.4987

3. Viera AJ, Yano Y, Lin FC, et al. Does this adult patient have hypertension?: the Rational Clinical Examination systematic review. JAMA. 2021;326:339-347. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.4533

4. Kallioinen N, Hill A, Horswill MS, et al. Sources of inaccuracy in the measurement of adult patients’ resting blood pressure in clinical settings: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2017; 35:421-441. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001197

5. Armstrong D, Matangi M, Brouillard D, et al. Automated office blood pressure: being alone and not location is what matters most. Blood Press Monit. 2015;20:204-208. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0000000000000133

6. Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Consistent relationship between automated office blood pressure recorded in different settings. Blood Press Monit. 2009;14:108-111. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e32832c5167

7. Myers MG, Godwin M, Dawes M, et al. Conventional versus automated measurement of blood pressure in primary care patients with systolic hypertension: randomized parallel design controlled trial. BMJ. 2011;342:d286. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d286

8. Ringrose JS, Cena J, Ip S, et al. Comparability of automated office blood pressure to daytime 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34:61-65. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.09.022

9. Leung AA, Daskalopoulou SS, Dasgupta K, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2017 guidelines for diagnosis, risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of hypertension in adults. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33:557-576. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.03.005

10. Sakuma M, Imai Y, Nagai K, et al. Reproducibility of home blood pressure measurements over a 1-year period. Am J Hypertens. 1997;10:798-803. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(97)00117-9

11. Brody S, Veit R, Rau H. Four-year test-retest reliability of self-measured blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1007-1008. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.9.1007

12. Calvo-Vargas C, Padilla Rios V, Troyo-Sanromán R, et al. Reproducibility and cost of blood pressure self-measurement using the ‘Loaned Self-measurement Equipment Model.’ Blood Press Monit. 2001;6:225-232. doi: 10.1097/00126097-200110000-00001

13. Scisney-Matlock M, Grand A, Steigerwalt SP, et al. Reliability and reproducibility of clinic and home blood pressure measurements in hypertensive women according to age and ethnicity. Blood Press Monit. 2009;14:49-57. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e3283263064

14. Shimbo D, Abdalla M, Falzon L, et al. Role of ambulatory and home blood pressure monitoring in clinical practice: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:691-700. doi: 10.7326/M15-1270

15. Bliziotis IA, Destounis A, Stergiou GS. Home versus ambulatory and office blood pressure in predicting target organ damage in hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1289-1299. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283531eaf

16. Fuchs SC, Mello RG, Fuchs FC. Home blood pressure monitoring is better predictor of cardiovascular disease and target organ damage than office blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Cardiol Rep.2013;15:413. doi: 10.1007/s11886-013-0413-z

17. Shimbo D, Abdalla M, Falzon L, et al. Studies comparing ambulatory blood pressure and home blood pressure on cardiovascular disease and mortality outcomes: a systematic review. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2016;10:224-234. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2015.12.013

18. Fagard RH, Cornelessen VA. Incidence of cardiovascular events in white-coat, masked and sustained hypertension versus true normotension: a meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2007;25:2193-2198. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282ef6185

19. Pierdomenico SD, Cuccurullo F. Prognostic value of white-coat and masked hypertension diagnosed by ambulatory monitoring in initially untreated subjects: an updated meta-analysis. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:52-58. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.203

20. Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Metoki H, et al. Prognosis of “masked” hypertension and “white-coat” hypertension detected by 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring 10-year follow-up from the Ohasama study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:508-515. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.070

21. Stergiou GS, Asayama K, Thijs L, et al; on behalf of the International Database on Home blood pressure in relation to Cardiovascular Outcome (IDHOCO) Investigators. Prognosis of white-coat and masked hypertension: International Database of HOme blood pressure in relation to Cardiovascular Outcome. Hypertension. 2014;63:675-682. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02741

22. Tucker KL, Sheppard JP, Stevens R, et al. Self-monitoring of blood pressure in hypertension: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002389

23. Bray EP, Holder R, Mant J, et al. Does self-monitoring reduce blood pressure? Meta-analysis with meta-regression of randomized controlled trials. Ann Med. 2010;42:371-386. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2010.489567

24. Glynn LG, Murphy AW, Smith SM, et al. Self-monitoring and other non-pharmacological interventions to improve the management of hypertension in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60:e476-e488. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X544113

25. Agarwal R, Bills JE, Hecht TJ, et al. Role of home blood pressure monitoring in overcoming therapeutic inertia and improving hypertension control: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2011;57:29-38. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.160911

26. Stergiou GS, Skeva II, Zourbaki AS, et al. Self-monitoring of blood pressure at home: how many measurements are needed? J Hypertens. 1998;16:725-773. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816060-00002

27. Stergiou GS, Nasothimiou EG, Kalogeropoulos PG, et al. The optimal home blood pressure monitoring schedule based on the Didima outcome study. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:158-164. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2009.54

28. Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, et al; ESH Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring. European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for home blood pressure monitoring. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:779-785. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2010.54

29. Imai Y, Kario K, Shimada K, et al; Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee for Guidelines for Self-monitoring of Blood Pressure at Home. The Japanese Society of Hypertension guidelines for self-monitoring of blood pressure at home (second edition). Hypertens Res.2012;35:777-795. doi: 10.1038/hr.2012.56

30. O’Brien E, Atkins N, Stergiou G, et al; Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring of the European Society of Hypertension. European Society of Hypertension international protocol revision 2010 for the validation of blood pressure measuring devices in adults. Blood Press Monit. 2010; 15:23-38. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e3283360e98

31. Casiglia E, Tikhonoff V, Albertini F, et al. Poor reliability of wrist blood pressure self-measurement at home: a population-based study. Hypertension. 2016;68:896-903. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07961

32. Harju J, Vehkaoja A, Kumpulainen P, et al. Comparison of non-invasive blood pressure monitoring using modified arterial applanation tonometry with intra-arterial measurement. J Clin Monit Comput. 2018;32:13-22. doi: 10.1007/s10877-017-9984-3

33. Ostchega Y, Hughes JP, Zhang G, et al. Mean mid-arm circumference and blood pressure cuff sizes for U.S. adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2010. Blood Press Monit. 2013;18:138-143. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e3283617606

34. White WB, Barber V. Ambulatory monitoring of blood pressure: an overview of devices, analyses, and clinical utility. In: White WB, ed. Blood Pressure Monitoring in Cardiovascular Medicine and Therapeutics. Springer International Publishing; 2016:55-76.

35. Franklin SS, Thijs L, Asayama K, et al; IDACO Investigators. The cardiovascular risk of white-coat hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2033-2043. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.035

36. Krakoff LR. Cost-effectiveness of ambulatory blood pressure: a reanalysis. Hypertension. 2006;47:29-34. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000197195.84725.66

37. Ewald B, Pekarsky B. Cost analysis of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in initiating antihypertensive drug treatment in Australian general practice. Med J Aust. 2002;176:580-583. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04588.x

38. Beyhaghi H, Viera AJ. Comparative cost-effectiveness of clinic, home, or ambulatory blood pressure measurement for hypertension diagnosis in US adults. Hypertension. 2019;73:121-131. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11715

39. De la Sierra A, Segura J, Banegas JR, et al. Clinical features of 8295 patients with resistant hypertension classified on the basis of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Hypertension. 2011;57:898-902. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.168948

40. Brown MA, Buddle ML, Martin A. Is resistant hypertension really resistant? Am J Hypertens. 2001;14:1263-1269. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02193-8

41. Carey RM, Calhoun DA, Bakris GL, et al. Resistant hypertension: detection, evaluation, and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2018;72:e53-e90. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000084

42. Wang YC, Shimbo D, Muntner P, et al. Prevalence of masked hypertension among US adults with non-elevated clinic blood pressure. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185:194-202. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww237

43. Thakkar HV, Pope A, Anpalahan M. Masked hypertension: a systematic review. Heart Lung Circ. 2020;29:102-111. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2019.08.006

44. Kronish IM, Hughes C, Quispe K, et al. Implementing ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in primary care practice. Fam Pract Manag. 2020;27:19-25.

45. Viera AJ, Lingley K, Hinderliter AL. Tolerability of the Oscar 2 ambulatory blood pressure monitor among research participants: a cross-sectional repeated measures study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-59

46. Alpert BS, Dart RA, Sica DA. Public-use blood pressure measurement: the kiosk quandary. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014;8:739-742. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2014.07.034

47. Al Hamarneh YN, Houle SK, Chatterley P, et al. The validity of blood pressure kiosk validation studies: a systematic review. Blood Press Monit. 2013;18:167-172. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e328360fb85

48. Kumar N, Khunger M, Gupta A, et al. A content analysis of smartphone-based applications for hypertension management. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2015;9:130-136. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2014.12.001

49. Bruining N, Caiani E, Chronaki C, et al. Acquisition and analysis of cardiovascular signals on smartphones: potential, pitfalls and perspectives: by the Task Force of the e-Cardiology Working Group of European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21(suppl 2):4-13. doi: 10.1177/2047487314552604

50. Chandrasekaran V, Dantu R, Jonnada S, et al. Cuffless differential blood pressure estimation using smart phones. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2013;60:1080-1089. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2012.2211078

Normal blood pressure (BP) is defined as systolic BP (SBP) < 120 mm Hg and diastolic BP (DBP) < 80 mm Hg.1 The thresholds for hypertension (HTN) are shown in TABLE 1.1 These thresholds must be met on at least 2 separate occasions to merit a diagnosis of HTN.1

Given the high prevalence of HTN and its associated comorbidities, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently reaffirmed its recommendation that every adult be screened for HTN, regardless of risk factors.2 Patients 40 years of age and older and those with risk factors (obesity, family history of HTN, diabetes) should have their BP checked at least annually. Individuals ages 18 to 39 years without risk factors who are initially normotensive should be rescreened within 3 to 5 years.2

Patients are most commonly screened for HTN in the outpatient setting. However, office BP measurements may be inaccurate and are of limited diagnostic utility when taken as a single reading.1,3,4 As will be described later, office BP measurements are subject to multiple sources of error that can result in a mean underestimation of 24 mm Hg to a mean overestimation of 33 mm Hg for SBP, and a mean underestimation of 14 mm Hg to a mean overestimation of 23 mm Hg for DBP.4

Differences to this degree between true BP and measured BP can have important implications for the diagnosis, surveillance, and management of HTN. To diminish this potential for error, the American Heart Association HTN guideline and USPSTF recommendation advise clinicians to obtain out-of-office BP measurements to confirm a diagnosis of HTN before initiating treatment.1,2 The preferred methods for out-of-office BP assessment are home BP monitoring (HBPM) and 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM).

Limitations of office BP measurement