User login

Orf Virus in Humans: Case Series and Clinical Review

A patient presenting with a hand pustule is a phenomenon encountered worldwide requiring careful history-taking. Some occupations, activities, and various religious practices (eg, Eid al-Adha, Passover, Easter) have been implicated worldwide in orf infection. In the United States, orf virus usually is spread from infected animal hosts to humans. Herein, we review the differential for a single hand pustule, which includes both infectious and noninfectious causes. Recognizing orf virus as the etiology of a cutaneous hand pustule in patients is important, as misdiagnosis can lead to unnecessary invasive testing and/or treatments with suboptimal clinical outcomes.

Case Series

When conducting a search for orf virus cases at our institution (University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa), 5 patient cases were identified.

Patient 1—A 27-year-old otherwise healthy woman presented to clinic with a tender red bump on the right ring finger that had been slowly growing over the course of 2 weeks and had recently started to bleed. A social history revealed that she owned several goats, which she frequently milked; 1 of the goats had a cyst on the mouth, which she popped approximately 1 to 2 weeks prior to the appearance of the lesion on the finger. She also endorsed that she owned several cattle and various other animals with which she had frequent contact. A biopsy was obtained with features consistent with orf virus.

Patient 2—A 33-year-old man presented to clinic with a lesion of concern on the left index finger. Several days prior to presentation, the patient had visited the emergency department for swelling and erythema of the same finger after cutting himself with a knife while preparing sheep meat. Radiographs were normal, and the patient was referred to dermatology. In clinic, there was a 0.5-cm fluctuant mass on the distal interphalangeal joint of the third finger. The patient declined a biopsy, and the lesion healed over 4 to 6 weeks without complication.

Patient 3—A 38-year-old man presented to clinic with 2 painless, large, round nodules on the right proximal index finger, with open friable centers noted on physical examination (Figure 1). The patient reported cutting the finger while preparing sheep meat several days prior. The nodules had been present for a few weeks and continued to grow. A punch biopsy revealed evidence of parapoxvirus infection consistent with a diagnosis of orf.

Patient 4—A 48-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a bleeding lesion on the left middle finger. Physical examination revealed an exophytic, friable, ulcerated nodule on the dorsal aspect of the left middle finger (Figure 2). Upon further questioning, the patient mentioned that he handled raw lamb meat after cutting the finger. A punch biopsy was obtained and was consistent with orf virus infection.

Patient 5—A 43-year-old woman presented to clinic with a chronic wound on the mid lower back that was noted to drain and crust over. She thought the lesion was improving, but it had become painful over the last few weeks. A shave biopsy of the lesion was consistent with orf virus. At follow-up, the patient was unable to identify any recent contact with animals.

Comment

Transmission From Animals to Humans—Orf virus is a member of the Parapoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family.1 This virus is highly contagious among animals and has been described around the globe. The resulting disease also is known as contagious pustular dermatitis,2 soremuzzle,3 ecthyma contagiosum of sheep,4 and scabby mouth.5 This virus most commonly infects young lambs and manifests as raw to crusty papules, pustules, or vesicles around the mouth and nose of the animal.4 Additional signs include excessive salivation and weight loss or starvation from the inability to suckle because of the lesions.5 Although ecthyma contagiosum infection of sheep and goats has been well known for centuries, human infection was first reported in the literature in 1934.6

Transmission of orf to humans can occur when direct contact with an infected animal exhibiting active lesions occurs.7 Orf virus also can be transmitted through fomites (eg, from knives, wool, buildings, equipment) that previously were in contact with infected animals, making it relevant to ask all farmers about any animals with pustules around the mouth, nose, udders, or other commonly affected areas. Although sanitation efforts are important for prevention, orf virus is hardy, and fomites can remain on surfaces for many months.8 Transmission among animals and from animals to humans frequently occurs; however, human-to-human transmission is less common.9 Ecthyma contagiosum is considered an occupational hazard, with the disease being most prevalent in shepherds, veterinarians, and butchers.1,8 Disease prevalence in these occupations has been reported to be as high as 50%.10 Infections also are seen in patients who attend petting zoos or who slaughter goats and sheep for cultural practices.8

Clinical Characteristics in Humans—The clinical diagnosis of orf is dependent on taking a thorough patient history that includes social, occupational, and religious activities. Development of a nodule or papule on a patient’s hand with recent exposure to fomites or direct contact with a goat or sheep up to 1 week prior is extremely suggestive of an orf virus infection.

Clinically, orf most often begins as an individual papule or nodule on the dorsal surface of the patient’s finger or hand and ranges from completely asymptomatic to pruritic or even painful.1,8 Depending on how the infection was inoculated, lesions can vary in size and number. Other sites that have been reported less frequently include the genitals, legs, axillae, and head.11,12 Lesions are roughly 1 cm in diameter but can vary in size. Ecthyma contagiosum is not a static disease but changes in appearance over the course of infection. Typically, lesions will appear 3 to 7 days after inoculation with the orf virus and will self-resolve 6 to 8 weeks later.

Orf lesions have been described to progress through 6 distinct phases before resolving: maculopapular (erythematous macule or papule forms), targetoid (formation of a necrotic center with red outer halo), acute (lesion begins to weep), regenerative (lesion becomes dry), papilloma (dry crust becomes papillomatous), and regression (skin returns to normal appearance).1,8,9 Each phase of ecthyma contagiosum is unique and will last up to 1 week before progressing. Because of this prolonged clinical course, patients can present at any stage.

Reports of systemic symptoms are uncommon but can include lymphadenopathy, fever, and malaise.13 Although the disease course in immunocompetent individuals is quite mild, immunocompromised patients may experience persistent orf lesions that are painful and can be much larger, with reports of several centimeters in diameter.14

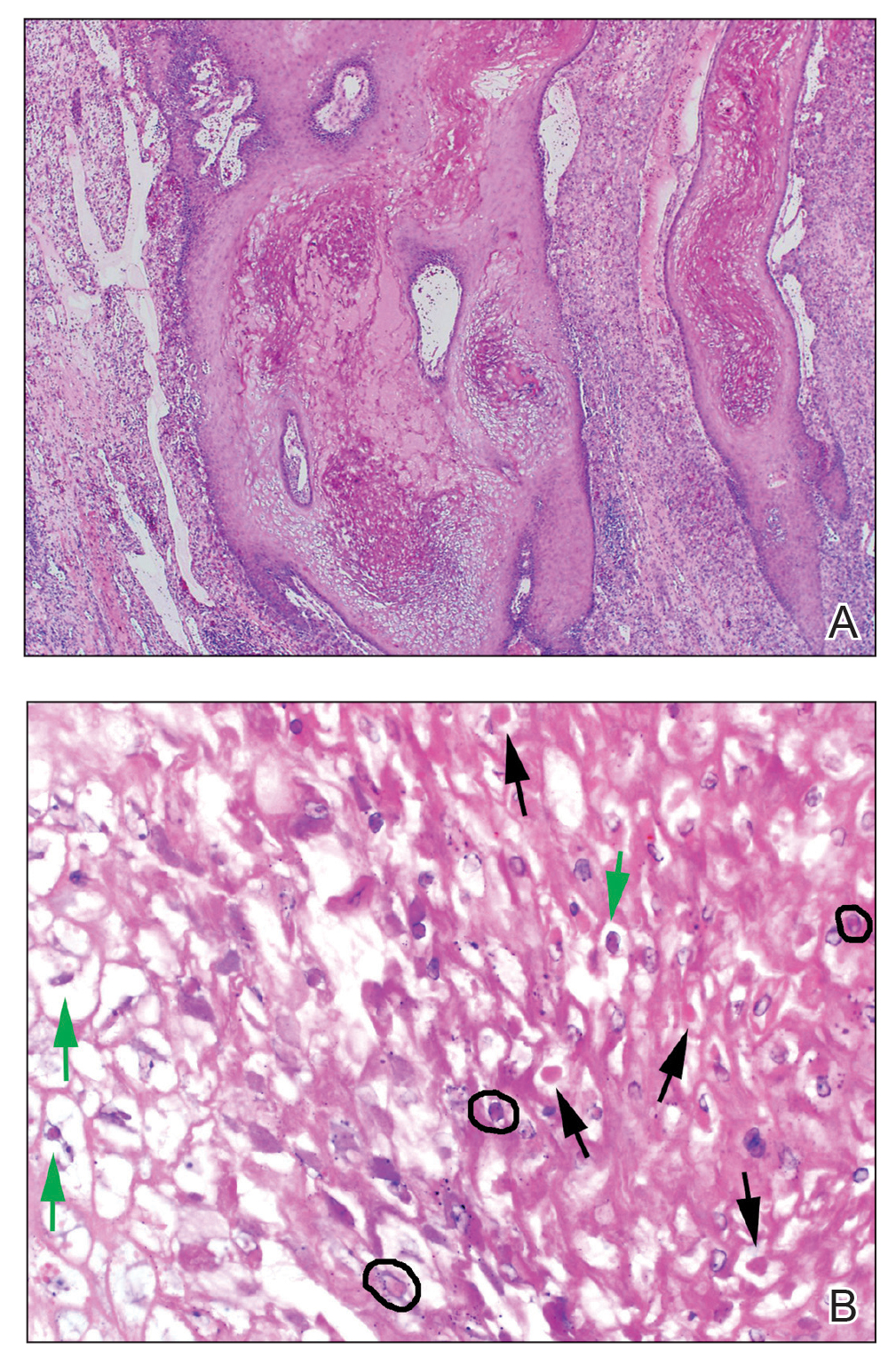

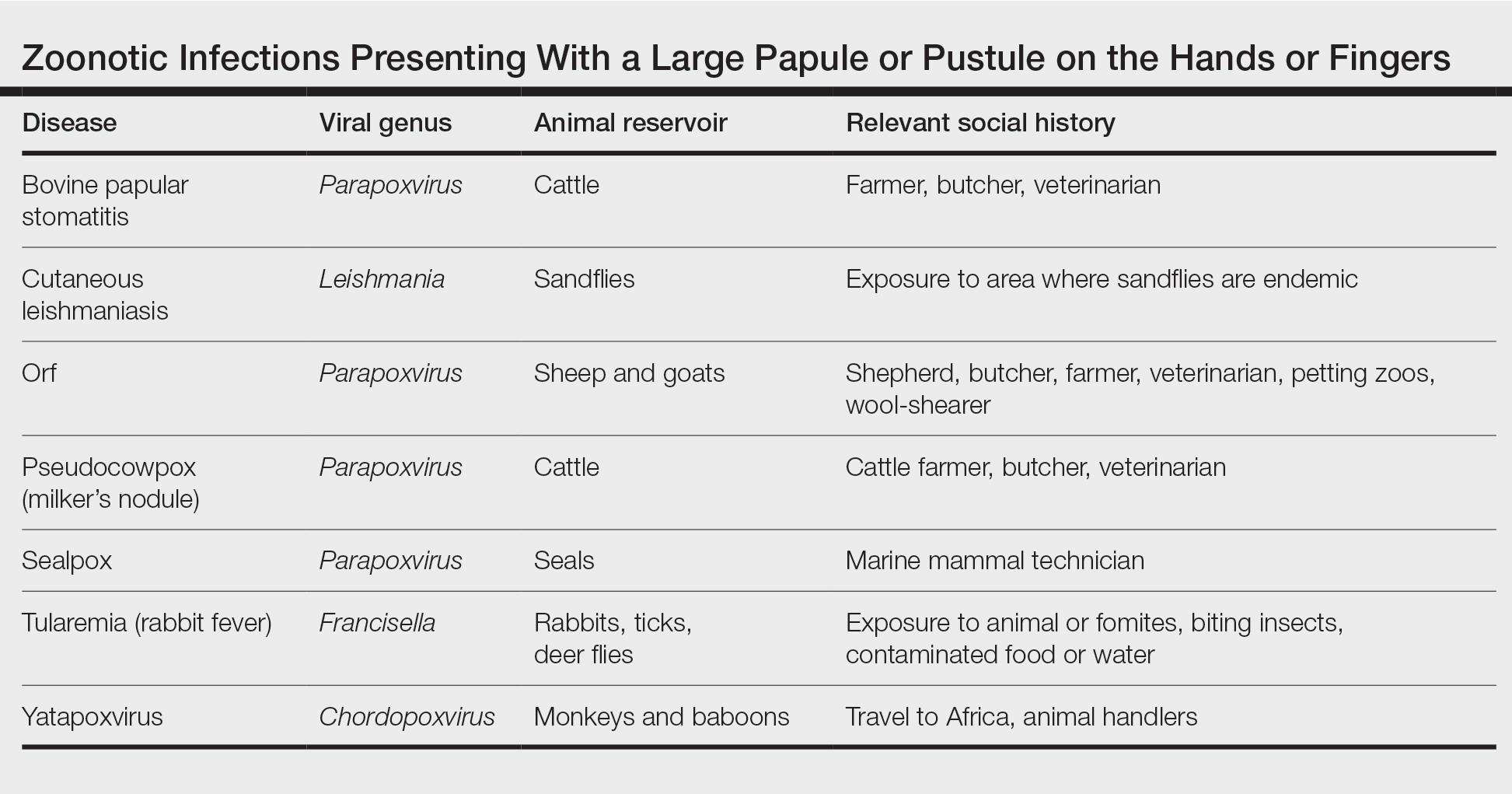

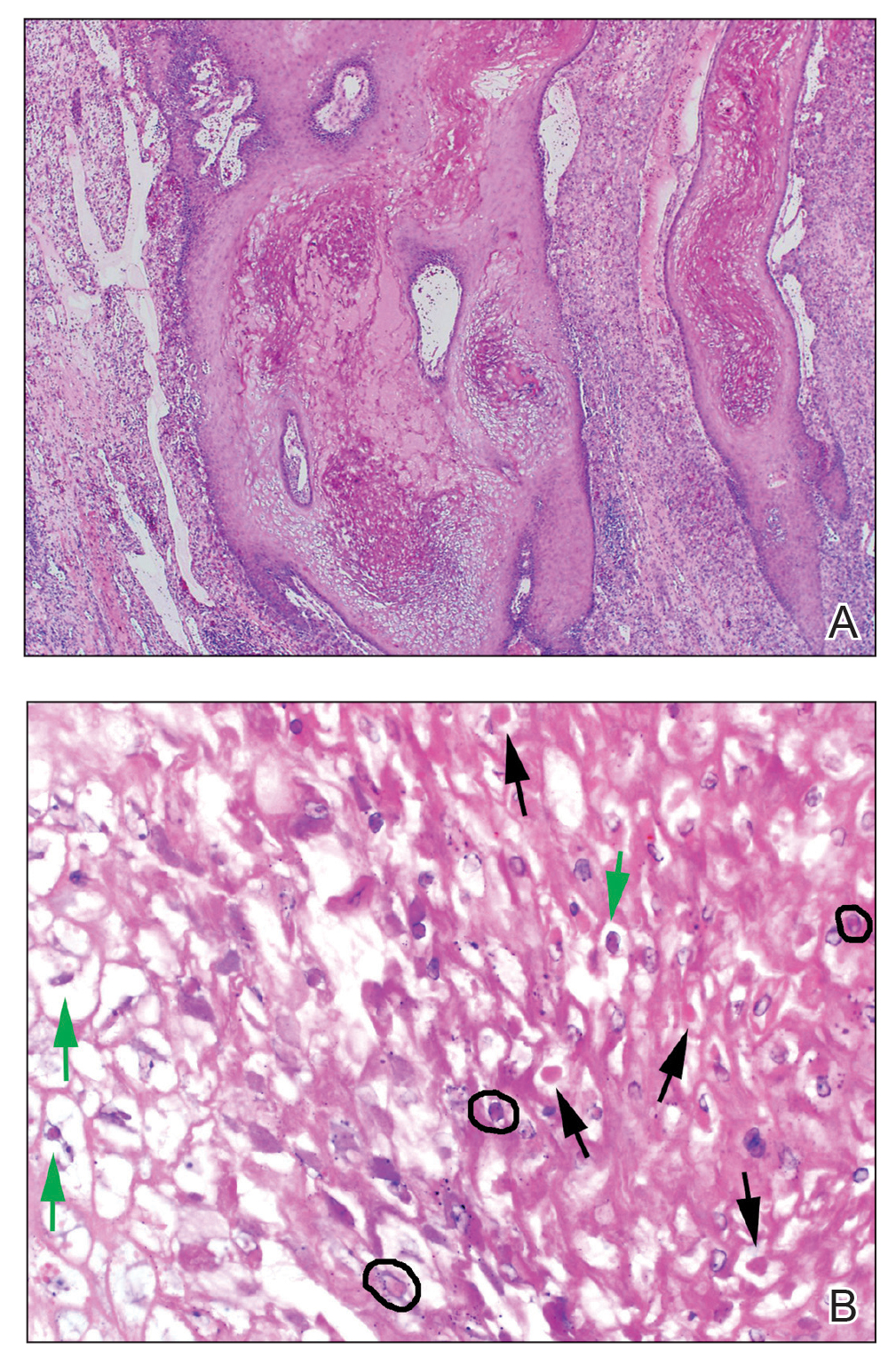

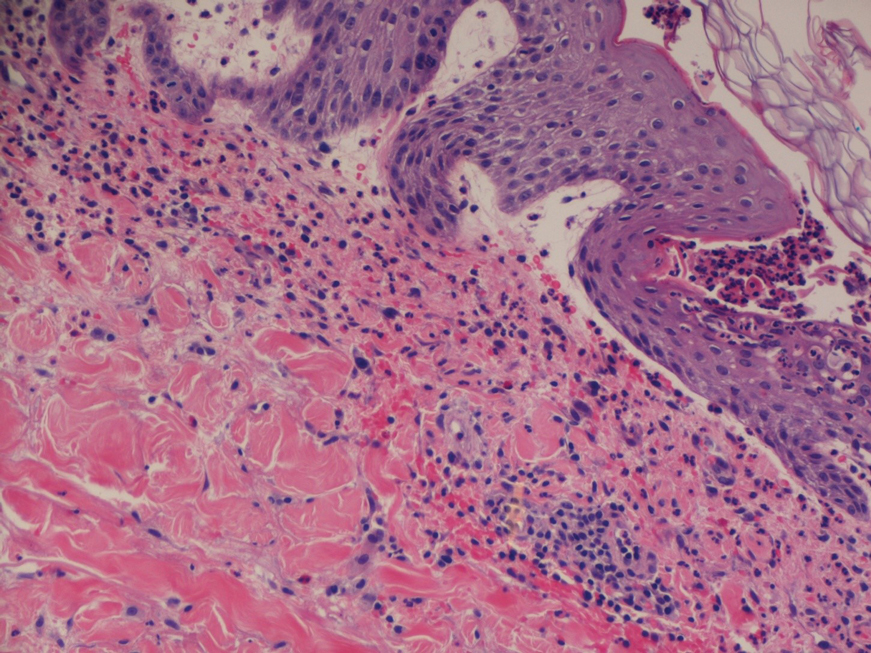

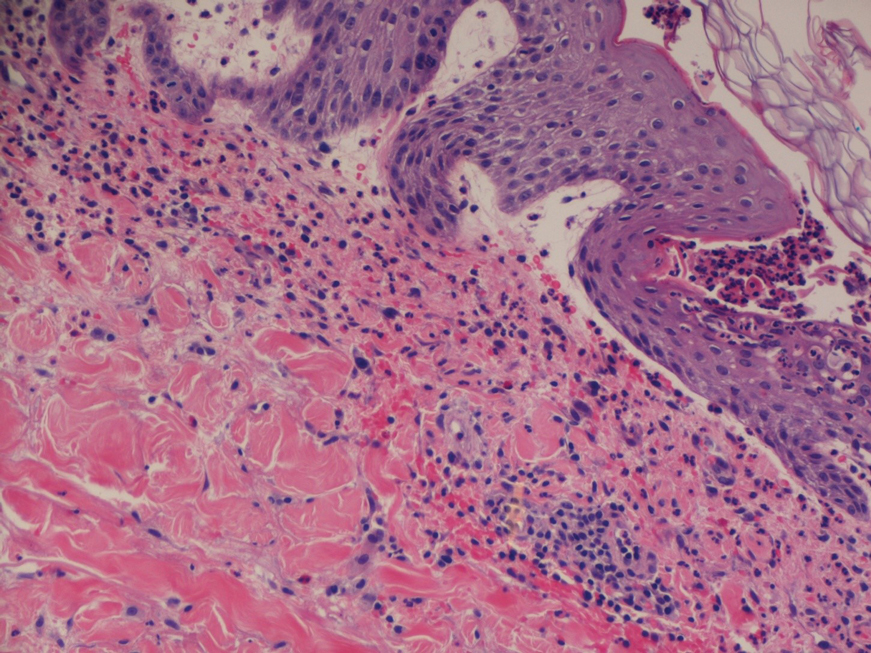

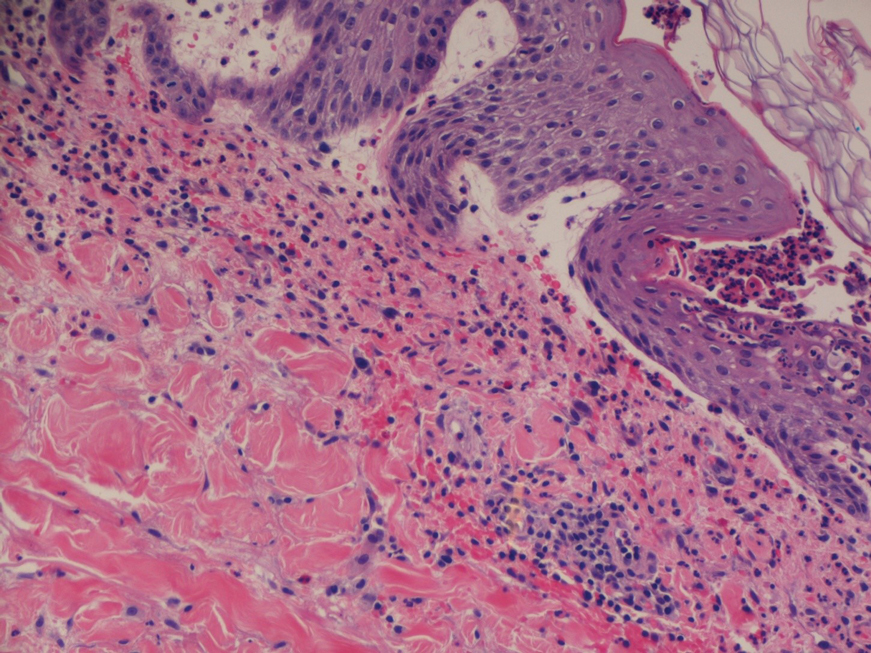

Dermatopathology and Molecular Studies—When a clinical diagnosis is not possible, biopsy or molecular studies can be helpful.8 Histopathology can vary depending on the phase of the lesion. Early stages are characterized by spongiform degeneration of the epidermis with variable vesiculation of the superficial epidermis and eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusion bodies of keratinocytes (Figure 3). Later stages demonstrate full-thickness necrosis with epidermal balloon degeneration and dense inflammation of the dermis with edema and extravasated erythrocytes from dilated blood vessels. Both early- and late-stage disease commonly show characteristic elongated thin rete ridges.8

Molecular studies are another reliable method for diagnosis, though these are not always readily available. Polymerase chain reaction can be used for sensitive and rapid diagnosis.15 Less commonly, electron microscopy, Western blot, or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays are used.16 Laboratory studies, such as complete blood cell count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein, often are unnecessary but may be helpful in ruling out other infectious causes. Tissue culture can be considered if bacterial, fungal, or acid-fast bacilli are in the differential; however, no growth will be seen in the case of orf viral infection.

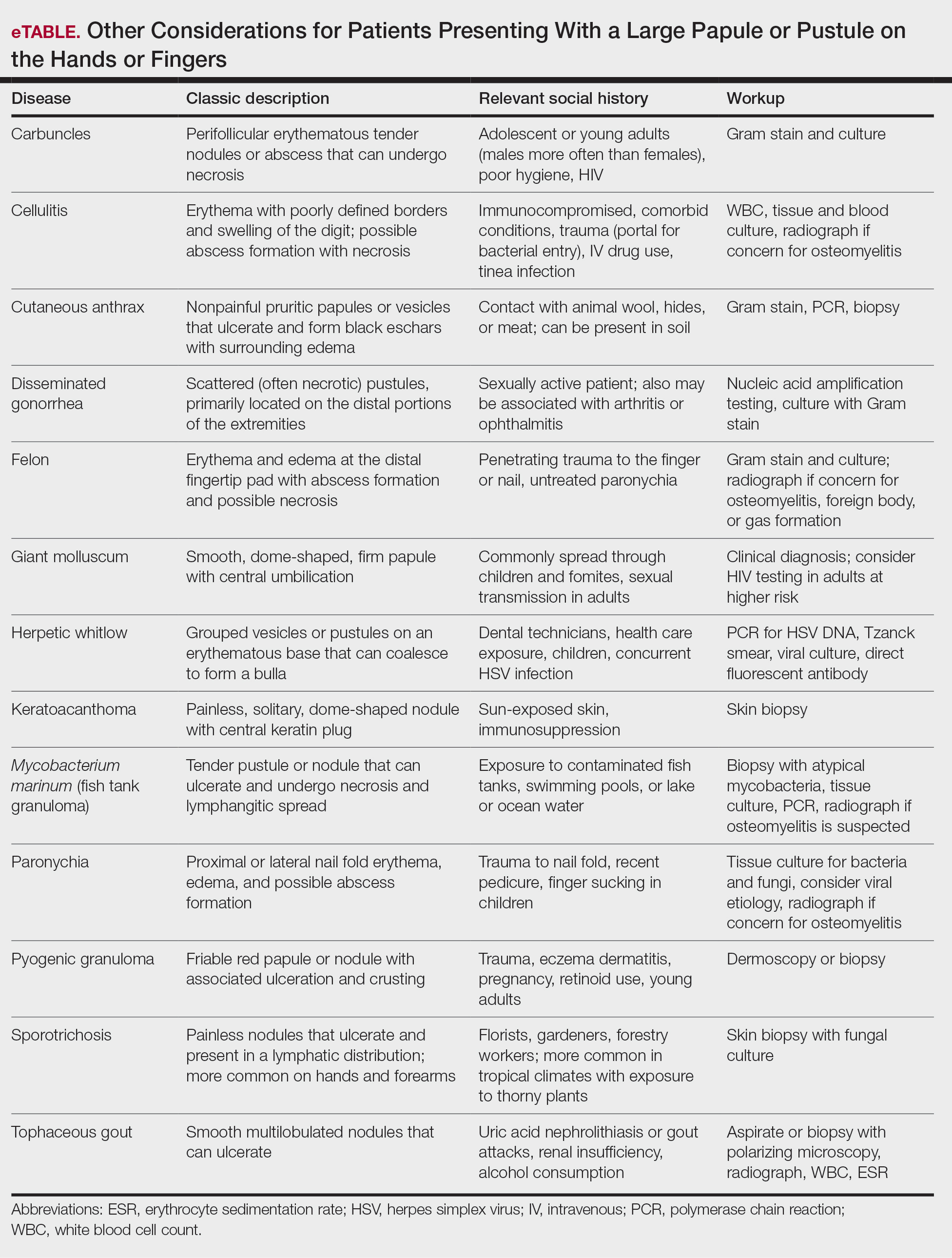

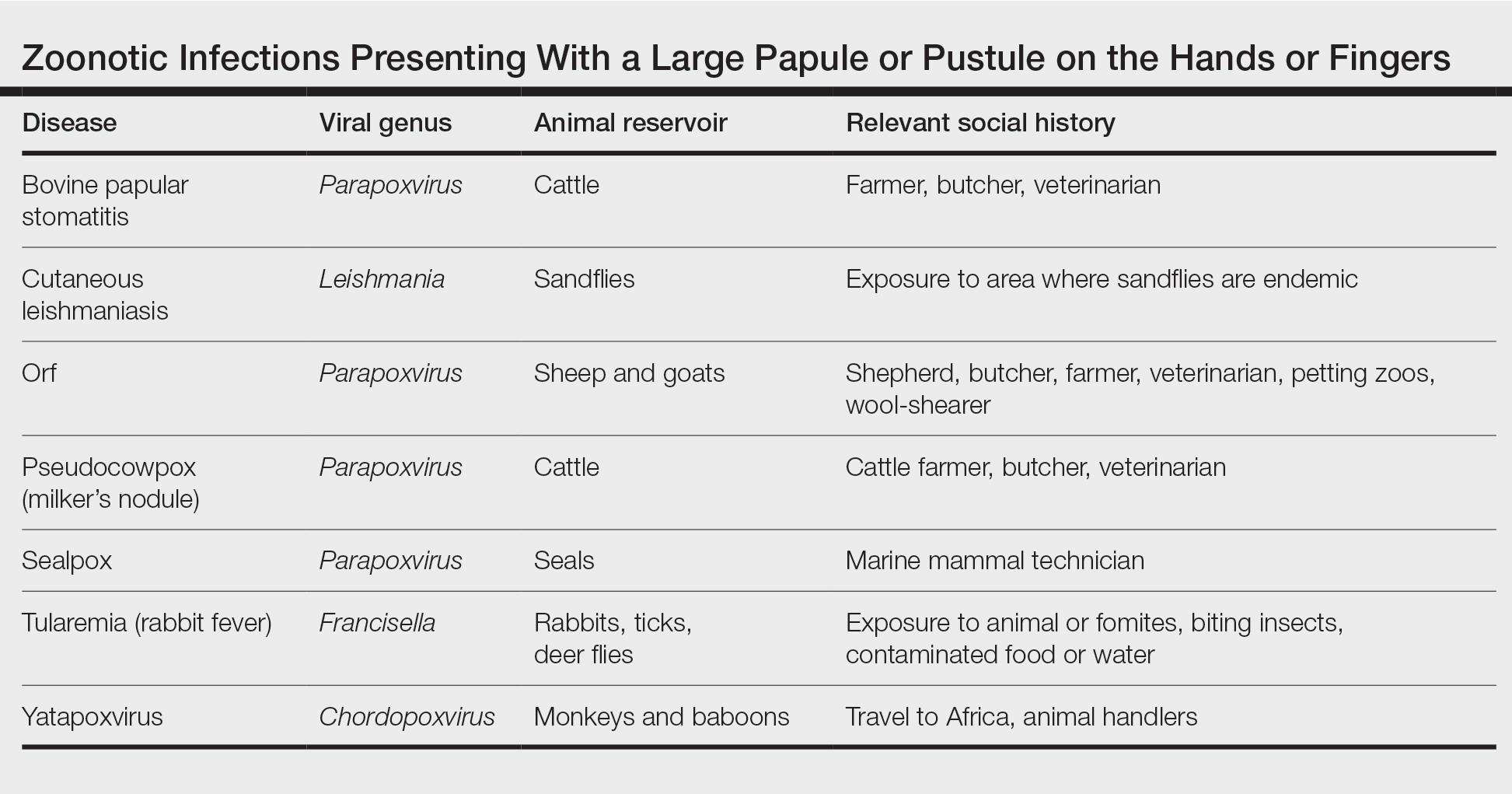

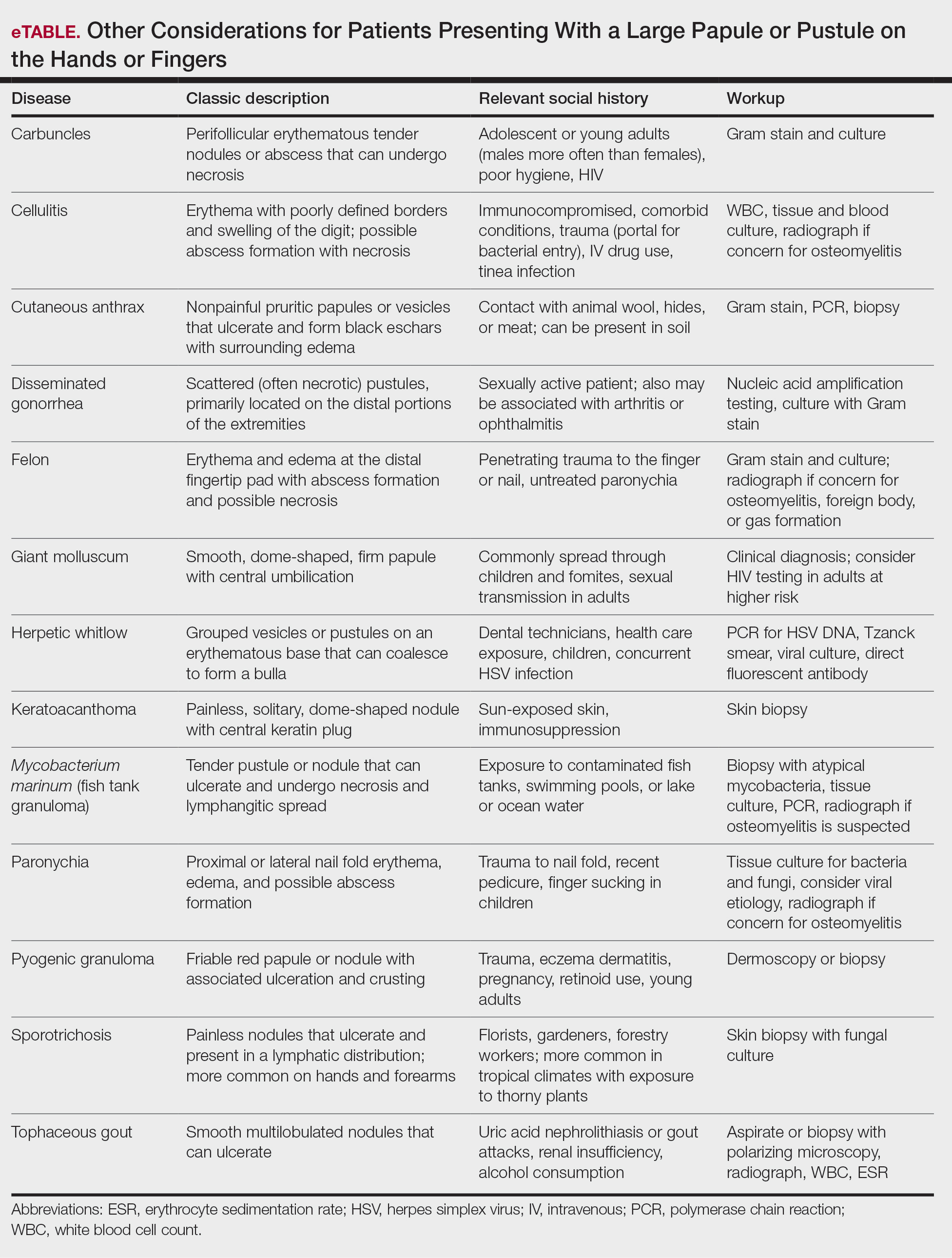

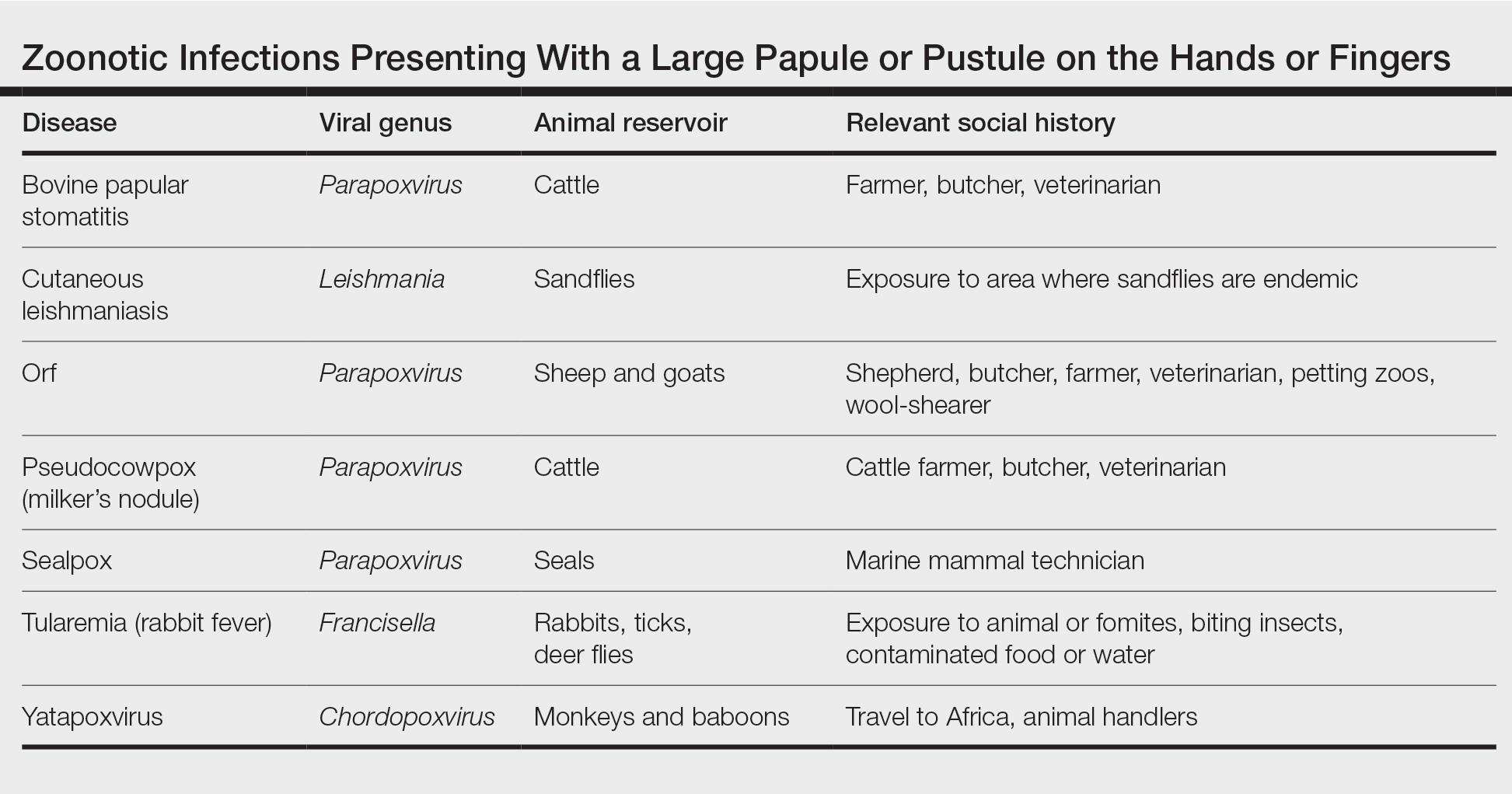

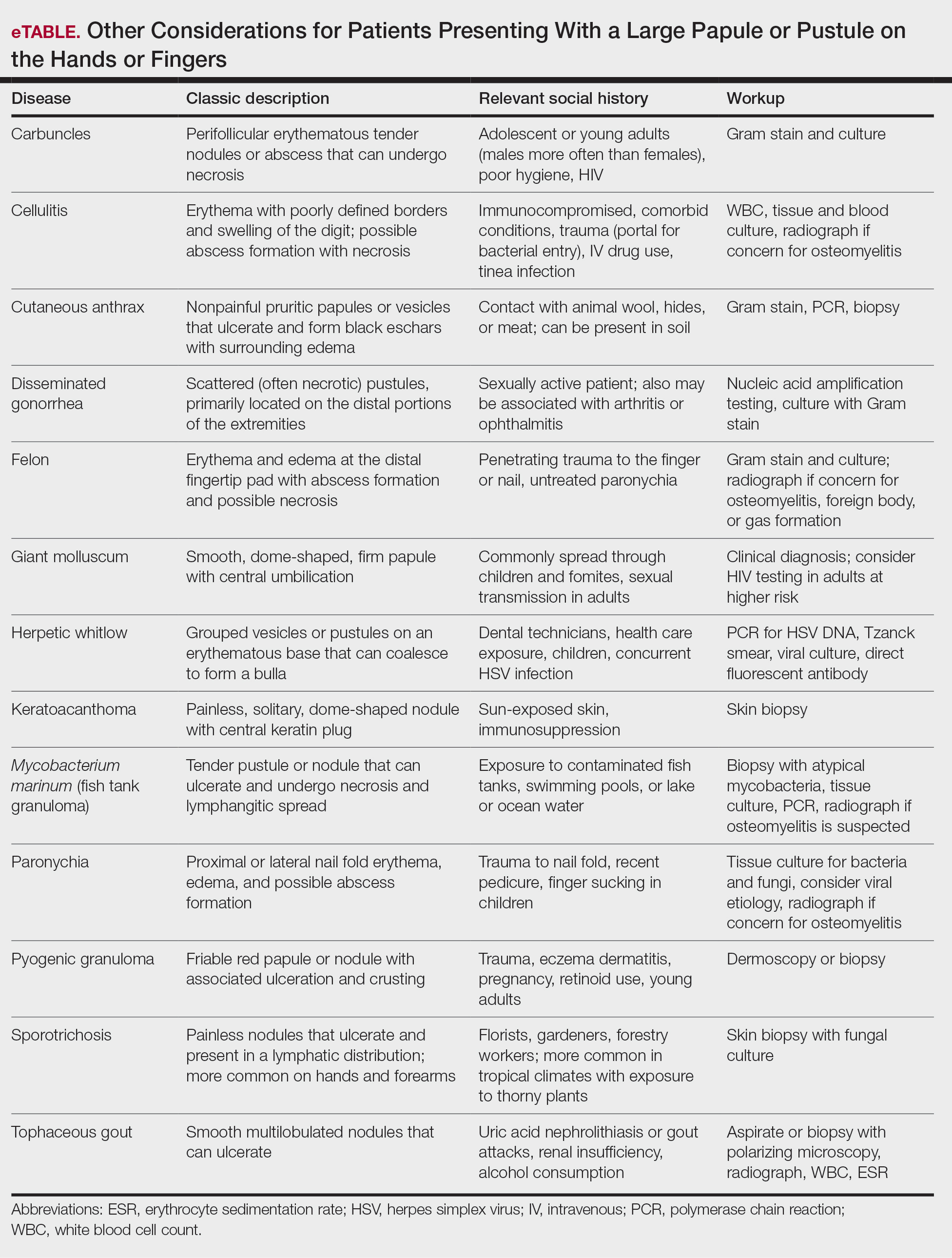

Differential Diagnosis—The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with a large pustule on the hand or fingers can depend on geographic location, as the potential etiology may vary widely around the world. Several zoonotic viral infections other than orf can present with pustular lesions on the hands (Table).17-24

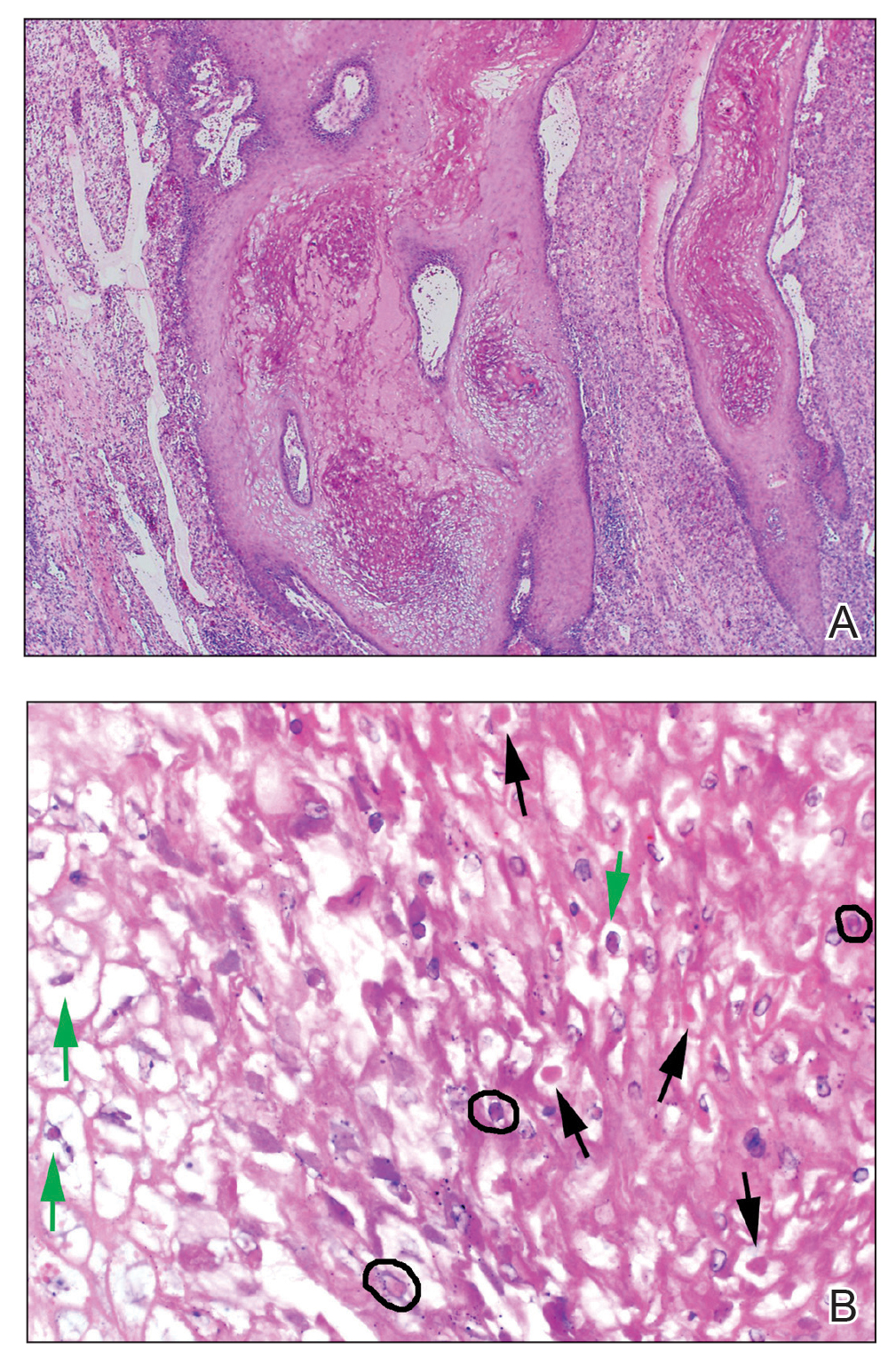

Clinically, infection with these named viruses can be hard to distinguish; however, appropriate social history or polymerase chain reaction can be obtained to differentiate them. Other infectious entities include herpetic whitlow, giant molluscum, and anthrax (eTable).24-26 Biopsy of the lesion with bacterial tissue culture may lead to definitive diagnosis.26

Treatment—Because of the self-resolving nature of orf, treatment usually is not needed in immunocompetent patients with a solitary lesion. However, wound care is essential to prevent secondary infections of the lesion. If secondarily infected, topical or oral antibiotics may be prescribed. Immunocompromised individuals are at increased risk for developing large persistent lesions and sometimes require intervention for successful treatment. Several successful treatment methods have been described and include intralesional interferon injections, electrocautery, topical imiquimod, topical cidofovir, and cryotherapy.8,14,27-30 Infections that continue to be refractory to less-invasive treatment can be considered for wide local excision; however, recurrence is possible.8 Vaccinations are available for animals to prevent the spread of infection in the flock, but there are no formulations of vaccines for human use. Prevention of spread to humans can be done through animal vaccination, careful handling of animal products while wearing nonporous gloves, and proper sanitation techniques.

Complications—Orf has an excellent long-term prognosis in immunocompetent patients, as the virus is epitheliotropic, and inoculation does not lead to viremia.2 Although lesions typically are asymptomatic in most patients, complications can occur, especially in immunosuppressed individuals. These complications include systemic symptoms, giant persistent lesions prone to infection or scarring, erysipelas, lymphadenitis, and erythema multiforme.8,31 Common systemic symptoms of ecthyma contagiosum include fever, fatigue, and myalgia. Lymphadenitis can occur along with local swelling and lymphatic streaking. Although erythema multiforme is a rare complication occurring after initial ecthyma contagiosum infection, this hypersensitivity reaction is postulated to be in response to the immunologic clearing of the orf virus.32,33 Patients receiving systemic immunosuppressive medications are at an increased risk of developing complications from infection and may even be required to pause systemic treatment for complete resolution of orf lesions.34 Other cutaneous diseases that decrease the skin’s barrier protection, such as bullous pemphigoid or eczema, also can place patients at an increased risk for complications.35 Although human-to-human orf virus transmission is exceptionally rare, there is a case report of this phenomenon in immunosuppressed patients residing in a burn unit.36 Transplant recipients on immunosuppressive medications also can experience orf lesions with exaggerated presentations that continue to grow up to several centimeters in diameter.31 Long-term prognosis is still good in these patients with appropriate disease recognition and treatment. Reinfection is not uncommon with repeated exposure to the source, but lesions are less severe and resolve faster than with initial infection.1,8

Conclusion

The contagious hand pustule caused by orf virus is a distinct clinical entity that is prevalent worldwide and requires thorough evaluation of the clinical course of the lesion and the patient’s social history. Several zoonotic viral infections have been implicated in this presentation. Although biopsy and molecular studies can be helpful, the expert diagnostician can make a clinical diagnosis with careful attention to social history, geographic location, and cultural practices.

- Haig DM, Mercer AA. Ovine diseases. orf. Vet Res. 1998;29:311-326.

- Glover RE. Contagious pustular dermatitis of the sheep. J Comp Pathol Ther. 1928;41:318-340.

- Hardy WT, Price DA. Soremuzzle of sheep.

J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1952;120:23-25. - Boughton IB, Hardy WT. Contagious ecthyma (sore mouth) of sheep and goats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1934;85:150-178.

- Gardiner MR, Craig VMD, Nairn ME. An unusual outbreak of contagious ecthyma (scabby mouth) in sheep. Aust Vet J. 1967;43:163-165.

- Newsome IE, Cross F. Sore mouth in sheep transmissible to man. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1934;84:790-802.

- Demiraslan H, Dinc G, Doganay M. An overview of orf virus infection in humans and animals. Recent Pat Anti Infect Drug Discov. 2017;12:21-30.

- Bergqvist C, Kurban M, Abbas O. Orf virus infection. Rev Med Virol. 2017;27:E1932.

- Duchateau NC, Aerts O, Lambert J. Autoinoculation with orf virus (ecthyma contagiosum). Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E60-E62.

- Paiba GA, Thomas DR, Morgan KL, et al. Orf (contagious pustular dermatitis) in farmworkers: prevalence and risk factors in three areas of England. Vet Rec. 1999;145:7-11

- Kandemir H, Ciftcioglu MA, Yilmaz E. Genital orf. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:460-461.

- Weide B, Metzler G, Eigentler TK, et al. Inflammatory nodules around the axilla: an uncommon localization of orf virus infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:240-242.

- Wilkinson JD. Orf: a family with unusual complications. Br J Dermatol. 1977;97:447-450.

- Zaharia D, Kanitakis J, Pouteil-Noble C, et al. Rapidly growing orf in a renal transplant recipient: favourable outcome with reduction of immunosuppression and imiquimod. Transpl Int. 2010;23:E62-E64.

- Bora DP, Venkatesan G, Bhanuprakash V, et al. TaqMan real-time PCR assay based on DNA polymerase gene for rapid detection of orf infection. J Virol Methods. 2011;178:249-252.

- Töndury B, Kühne A, Kutzner H, et al. Molecular diagnostics of parapox virus infections. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:681-684.

- Handler NS, Handler MZ, Rubins A, et al. Milker’s nodule: an occupational infection and threat to the immunocompromised. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:537-541.

- Groves RW, Wilson-Jones E, MacDonald DM. Human orf and milkers’ nodule: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:706-711.

- Bowman KF, Barbery RT, Swango LJ, et al. Cutaneous form of bovine papular stomatitis in man. JAMA. 1981;246;1813-1818.

- Nagington J, Lauder IM, Smith JS. Bovine papular stomatitis, pseudocowpox and milker’s nodules. Vet Rec. 1967;79:306-313.

- Clark C, McIntyre PG, Evans A, et al. Human sealpox resulting from a seal bite: confirmation that sealpox virus is zoonotic. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:791-793.

- Downie AW, Espana C. A comparative study of tanapox and yaba viruses. J Gen Virol. 1973;19:37-49.

- Zimmermann P, Thordsen I, Frangoulidis D, et al. Real-time PCR assay for the detection of tanapox virus and yaba-like disease virus. J Virol Methods. 2005;130:149-153.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2018.

- Wenner KA, Kenner JR. Anthrax. Dermatol Clin. 2004;22:247-256.

- Brachman P, Kaufmann A. Anthrax. In: Evans A, Brachman P, eds. Bacterial Infections of Humans: Epidemiology and Control. 3rd ed. Plenum Publishing; 1998:95.

- Ran M, Lee M, Gong J, et al. Oral acyclovir and intralesional interferon injections for treatment of giant pyogenic granuloma-like lesions in an immunocompromised patient with human orf. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1032-1034.

- Degraeve C, De Coninck A, Senneseael J, et al. Recurrent contagious ecthyma (orf) in an immunocompromised host successfully treated with cryotherapy. Dermatology. 1999;198:162-163.

- Geerinck K, Lukito G, Snoeck R, et al. A case of human orf in an immunocompromised patient treated successfully with cidofovir cream. J Med Virol. 2001;64:543-549.

- Ertekin S, Gurel M, Erdemir A, et al. Systemic interferon alfa injections for the treatment of a giant orf. Cutis. 2017;99:E19-E21.

- Hunskaar S. Giant orf in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:631-634.

- Ozturk P, Sayar H, Karakas T, et al. Erythema multiforme as a result of orf disease. Acta Dermatovenereol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2012;21:45-46.

- Shahmoradi Z, Abtahi-Naeini B, Pourazizi M, et al. Orf disease following ‘eid ul-adha’: a rare cause of erythema multiforme. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:912-914.

- Kostopoulos M, Gerodimos C, Batsila E, et al. Orf disease in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2018;29:89-91.

- Murphy JK, Ralphs IG. Bullous pemphigoid complicating human orf. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:929-930.

- Midilli K, Erkiliç A, Kus¸kucu M, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of disseminated orf infection in a burn unit, Gaziantep, Turkey, October to December 2012. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20425.

A patient presenting with a hand pustule is a phenomenon encountered worldwide requiring careful history-taking. Some occupations, activities, and various religious practices (eg, Eid al-Adha, Passover, Easter) have been implicated worldwide in orf infection. In the United States, orf virus usually is spread from infected animal hosts to humans. Herein, we review the differential for a single hand pustule, which includes both infectious and noninfectious causes. Recognizing orf virus as the etiology of a cutaneous hand pustule in patients is important, as misdiagnosis can lead to unnecessary invasive testing and/or treatments with suboptimal clinical outcomes.

Case Series

When conducting a search for orf virus cases at our institution (University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa), 5 patient cases were identified.

Patient 1—A 27-year-old otherwise healthy woman presented to clinic with a tender red bump on the right ring finger that had been slowly growing over the course of 2 weeks and had recently started to bleed. A social history revealed that she owned several goats, which she frequently milked; 1 of the goats had a cyst on the mouth, which she popped approximately 1 to 2 weeks prior to the appearance of the lesion on the finger. She also endorsed that she owned several cattle and various other animals with which she had frequent contact. A biopsy was obtained with features consistent with orf virus.

Patient 2—A 33-year-old man presented to clinic with a lesion of concern on the left index finger. Several days prior to presentation, the patient had visited the emergency department for swelling and erythema of the same finger after cutting himself with a knife while preparing sheep meat. Radiographs were normal, and the patient was referred to dermatology. In clinic, there was a 0.5-cm fluctuant mass on the distal interphalangeal joint of the third finger. The patient declined a biopsy, and the lesion healed over 4 to 6 weeks without complication.

Patient 3—A 38-year-old man presented to clinic with 2 painless, large, round nodules on the right proximal index finger, with open friable centers noted on physical examination (Figure 1). The patient reported cutting the finger while preparing sheep meat several days prior. The nodules had been present for a few weeks and continued to grow. A punch biopsy revealed evidence of parapoxvirus infection consistent with a diagnosis of orf.

Patient 4—A 48-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a bleeding lesion on the left middle finger. Physical examination revealed an exophytic, friable, ulcerated nodule on the dorsal aspect of the left middle finger (Figure 2). Upon further questioning, the patient mentioned that he handled raw lamb meat after cutting the finger. A punch biopsy was obtained and was consistent with orf virus infection.

Patient 5—A 43-year-old woman presented to clinic with a chronic wound on the mid lower back that was noted to drain and crust over. She thought the lesion was improving, but it had become painful over the last few weeks. A shave biopsy of the lesion was consistent with orf virus. At follow-up, the patient was unable to identify any recent contact with animals.

Comment

Transmission From Animals to Humans—Orf virus is a member of the Parapoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family.1 This virus is highly contagious among animals and has been described around the globe. The resulting disease also is known as contagious pustular dermatitis,2 soremuzzle,3 ecthyma contagiosum of sheep,4 and scabby mouth.5 This virus most commonly infects young lambs and manifests as raw to crusty papules, pustules, or vesicles around the mouth and nose of the animal.4 Additional signs include excessive salivation and weight loss or starvation from the inability to suckle because of the lesions.5 Although ecthyma contagiosum infection of sheep and goats has been well known for centuries, human infection was first reported in the literature in 1934.6

Transmission of orf to humans can occur when direct contact with an infected animal exhibiting active lesions occurs.7 Orf virus also can be transmitted through fomites (eg, from knives, wool, buildings, equipment) that previously were in contact with infected animals, making it relevant to ask all farmers about any animals with pustules around the mouth, nose, udders, or other commonly affected areas. Although sanitation efforts are important for prevention, orf virus is hardy, and fomites can remain on surfaces for many months.8 Transmission among animals and from animals to humans frequently occurs; however, human-to-human transmission is less common.9 Ecthyma contagiosum is considered an occupational hazard, with the disease being most prevalent in shepherds, veterinarians, and butchers.1,8 Disease prevalence in these occupations has been reported to be as high as 50%.10 Infections also are seen in patients who attend petting zoos or who slaughter goats and sheep for cultural practices.8

Clinical Characteristics in Humans—The clinical diagnosis of orf is dependent on taking a thorough patient history that includes social, occupational, and religious activities. Development of a nodule or papule on a patient’s hand with recent exposure to fomites or direct contact with a goat or sheep up to 1 week prior is extremely suggestive of an orf virus infection.

Clinically, orf most often begins as an individual papule or nodule on the dorsal surface of the patient’s finger or hand and ranges from completely asymptomatic to pruritic or even painful.1,8 Depending on how the infection was inoculated, lesions can vary in size and number. Other sites that have been reported less frequently include the genitals, legs, axillae, and head.11,12 Lesions are roughly 1 cm in diameter but can vary in size. Ecthyma contagiosum is not a static disease but changes in appearance over the course of infection. Typically, lesions will appear 3 to 7 days after inoculation with the orf virus and will self-resolve 6 to 8 weeks later.

Orf lesions have been described to progress through 6 distinct phases before resolving: maculopapular (erythematous macule or papule forms), targetoid (formation of a necrotic center with red outer halo), acute (lesion begins to weep), regenerative (lesion becomes dry), papilloma (dry crust becomes papillomatous), and regression (skin returns to normal appearance).1,8,9 Each phase of ecthyma contagiosum is unique and will last up to 1 week before progressing. Because of this prolonged clinical course, patients can present at any stage.

Reports of systemic symptoms are uncommon but can include lymphadenopathy, fever, and malaise.13 Although the disease course in immunocompetent individuals is quite mild, immunocompromised patients may experience persistent orf lesions that are painful and can be much larger, with reports of several centimeters in diameter.14

Dermatopathology and Molecular Studies—When a clinical diagnosis is not possible, biopsy or molecular studies can be helpful.8 Histopathology can vary depending on the phase of the lesion. Early stages are characterized by spongiform degeneration of the epidermis with variable vesiculation of the superficial epidermis and eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusion bodies of keratinocytes (Figure 3). Later stages demonstrate full-thickness necrosis with epidermal balloon degeneration and dense inflammation of the dermis with edema and extravasated erythrocytes from dilated blood vessels. Both early- and late-stage disease commonly show characteristic elongated thin rete ridges.8

Molecular studies are another reliable method for diagnosis, though these are not always readily available. Polymerase chain reaction can be used for sensitive and rapid diagnosis.15 Less commonly, electron microscopy, Western blot, or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays are used.16 Laboratory studies, such as complete blood cell count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein, often are unnecessary but may be helpful in ruling out other infectious causes. Tissue culture can be considered if bacterial, fungal, or acid-fast bacilli are in the differential; however, no growth will be seen in the case of orf viral infection.

Differential Diagnosis—The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with a large pustule on the hand or fingers can depend on geographic location, as the potential etiology may vary widely around the world. Several zoonotic viral infections other than orf can present with pustular lesions on the hands (Table).17-24

Clinically, infection with these named viruses can be hard to distinguish; however, appropriate social history or polymerase chain reaction can be obtained to differentiate them. Other infectious entities include herpetic whitlow, giant molluscum, and anthrax (eTable).24-26 Biopsy of the lesion with bacterial tissue culture may lead to definitive diagnosis.26

Treatment—Because of the self-resolving nature of orf, treatment usually is not needed in immunocompetent patients with a solitary lesion. However, wound care is essential to prevent secondary infections of the lesion. If secondarily infected, topical or oral antibiotics may be prescribed. Immunocompromised individuals are at increased risk for developing large persistent lesions and sometimes require intervention for successful treatment. Several successful treatment methods have been described and include intralesional interferon injections, electrocautery, topical imiquimod, topical cidofovir, and cryotherapy.8,14,27-30 Infections that continue to be refractory to less-invasive treatment can be considered for wide local excision; however, recurrence is possible.8 Vaccinations are available for animals to prevent the spread of infection in the flock, but there are no formulations of vaccines for human use. Prevention of spread to humans can be done through animal vaccination, careful handling of animal products while wearing nonporous gloves, and proper sanitation techniques.

Complications—Orf has an excellent long-term prognosis in immunocompetent patients, as the virus is epitheliotropic, and inoculation does not lead to viremia.2 Although lesions typically are asymptomatic in most patients, complications can occur, especially in immunosuppressed individuals. These complications include systemic symptoms, giant persistent lesions prone to infection or scarring, erysipelas, lymphadenitis, and erythema multiforme.8,31 Common systemic symptoms of ecthyma contagiosum include fever, fatigue, and myalgia. Lymphadenitis can occur along with local swelling and lymphatic streaking. Although erythema multiforme is a rare complication occurring after initial ecthyma contagiosum infection, this hypersensitivity reaction is postulated to be in response to the immunologic clearing of the orf virus.32,33 Patients receiving systemic immunosuppressive medications are at an increased risk of developing complications from infection and may even be required to pause systemic treatment for complete resolution of orf lesions.34 Other cutaneous diseases that decrease the skin’s barrier protection, such as bullous pemphigoid or eczema, also can place patients at an increased risk for complications.35 Although human-to-human orf virus transmission is exceptionally rare, there is a case report of this phenomenon in immunosuppressed patients residing in a burn unit.36 Transplant recipients on immunosuppressive medications also can experience orf lesions with exaggerated presentations that continue to grow up to several centimeters in diameter.31 Long-term prognosis is still good in these patients with appropriate disease recognition and treatment. Reinfection is not uncommon with repeated exposure to the source, but lesions are less severe and resolve faster than with initial infection.1,8

Conclusion

The contagious hand pustule caused by orf virus is a distinct clinical entity that is prevalent worldwide and requires thorough evaluation of the clinical course of the lesion and the patient’s social history. Several zoonotic viral infections have been implicated in this presentation. Although biopsy and molecular studies can be helpful, the expert diagnostician can make a clinical diagnosis with careful attention to social history, geographic location, and cultural practices.

A patient presenting with a hand pustule is a phenomenon encountered worldwide requiring careful history-taking. Some occupations, activities, and various religious practices (eg, Eid al-Adha, Passover, Easter) have been implicated worldwide in orf infection. In the United States, orf virus usually is spread from infected animal hosts to humans. Herein, we review the differential for a single hand pustule, which includes both infectious and noninfectious causes. Recognizing orf virus as the etiology of a cutaneous hand pustule in patients is important, as misdiagnosis can lead to unnecessary invasive testing and/or treatments with suboptimal clinical outcomes.

Case Series

When conducting a search for orf virus cases at our institution (University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa), 5 patient cases were identified.

Patient 1—A 27-year-old otherwise healthy woman presented to clinic with a tender red bump on the right ring finger that had been slowly growing over the course of 2 weeks and had recently started to bleed. A social history revealed that she owned several goats, which she frequently milked; 1 of the goats had a cyst on the mouth, which she popped approximately 1 to 2 weeks prior to the appearance of the lesion on the finger. She also endorsed that she owned several cattle and various other animals with which she had frequent contact. A biopsy was obtained with features consistent with orf virus.

Patient 2—A 33-year-old man presented to clinic with a lesion of concern on the left index finger. Several days prior to presentation, the patient had visited the emergency department for swelling and erythema of the same finger after cutting himself with a knife while preparing sheep meat. Radiographs were normal, and the patient was referred to dermatology. In clinic, there was a 0.5-cm fluctuant mass on the distal interphalangeal joint of the third finger. The patient declined a biopsy, and the lesion healed over 4 to 6 weeks without complication.

Patient 3—A 38-year-old man presented to clinic with 2 painless, large, round nodules on the right proximal index finger, with open friable centers noted on physical examination (Figure 1). The patient reported cutting the finger while preparing sheep meat several days prior. The nodules had been present for a few weeks and continued to grow. A punch biopsy revealed evidence of parapoxvirus infection consistent with a diagnosis of orf.

Patient 4—A 48-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a bleeding lesion on the left middle finger. Physical examination revealed an exophytic, friable, ulcerated nodule on the dorsal aspect of the left middle finger (Figure 2). Upon further questioning, the patient mentioned that he handled raw lamb meat after cutting the finger. A punch biopsy was obtained and was consistent with orf virus infection.

Patient 5—A 43-year-old woman presented to clinic with a chronic wound on the mid lower back that was noted to drain and crust over. She thought the lesion was improving, but it had become painful over the last few weeks. A shave biopsy of the lesion was consistent with orf virus. At follow-up, the patient was unable to identify any recent contact with animals.

Comment

Transmission From Animals to Humans—Orf virus is a member of the Parapoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family.1 This virus is highly contagious among animals and has been described around the globe. The resulting disease also is known as contagious pustular dermatitis,2 soremuzzle,3 ecthyma contagiosum of sheep,4 and scabby mouth.5 This virus most commonly infects young lambs and manifests as raw to crusty papules, pustules, or vesicles around the mouth and nose of the animal.4 Additional signs include excessive salivation and weight loss or starvation from the inability to suckle because of the lesions.5 Although ecthyma contagiosum infection of sheep and goats has been well known for centuries, human infection was first reported in the literature in 1934.6

Transmission of orf to humans can occur when direct contact with an infected animal exhibiting active lesions occurs.7 Orf virus also can be transmitted through fomites (eg, from knives, wool, buildings, equipment) that previously were in contact with infected animals, making it relevant to ask all farmers about any animals with pustules around the mouth, nose, udders, or other commonly affected areas. Although sanitation efforts are important for prevention, orf virus is hardy, and fomites can remain on surfaces for many months.8 Transmission among animals and from animals to humans frequently occurs; however, human-to-human transmission is less common.9 Ecthyma contagiosum is considered an occupational hazard, with the disease being most prevalent in shepherds, veterinarians, and butchers.1,8 Disease prevalence in these occupations has been reported to be as high as 50%.10 Infections also are seen in patients who attend petting zoos or who slaughter goats and sheep for cultural practices.8

Clinical Characteristics in Humans—The clinical diagnosis of orf is dependent on taking a thorough patient history that includes social, occupational, and religious activities. Development of a nodule or papule on a patient’s hand with recent exposure to fomites or direct contact with a goat or sheep up to 1 week prior is extremely suggestive of an orf virus infection.

Clinically, orf most often begins as an individual papule or nodule on the dorsal surface of the patient’s finger or hand and ranges from completely asymptomatic to pruritic or even painful.1,8 Depending on how the infection was inoculated, lesions can vary in size and number. Other sites that have been reported less frequently include the genitals, legs, axillae, and head.11,12 Lesions are roughly 1 cm in diameter but can vary in size. Ecthyma contagiosum is not a static disease but changes in appearance over the course of infection. Typically, lesions will appear 3 to 7 days after inoculation with the orf virus and will self-resolve 6 to 8 weeks later.

Orf lesions have been described to progress through 6 distinct phases before resolving: maculopapular (erythematous macule or papule forms), targetoid (formation of a necrotic center with red outer halo), acute (lesion begins to weep), regenerative (lesion becomes dry), papilloma (dry crust becomes papillomatous), and regression (skin returns to normal appearance).1,8,9 Each phase of ecthyma contagiosum is unique and will last up to 1 week before progressing. Because of this prolonged clinical course, patients can present at any stage.

Reports of systemic symptoms are uncommon but can include lymphadenopathy, fever, and malaise.13 Although the disease course in immunocompetent individuals is quite mild, immunocompromised patients may experience persistent orf lesions that are painful and can be much larger, with reports of several centimeters in diameter.14

Dermatopathology and Molecular Studies—When a clinical diagnosis is not possible, biopsy or molecular studies can be helpful.8 Histopathology can vary depending on the phase of the lesion. Early stages are characterized by spongiform degeneration of the epidermis with variable vesiculation of the superficial epidermis and eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusion bodies of keratinocytes (Figure 3). Later stages demonstrate full-thickness necrosis with epidermal balloon degeneration and dense inflammation of the dermis with edema and extravasated erythrocytes from dilated blood vessels. Both early- and late-stage disease commonly show characteristic elongated thin rete ridges.8

Molecular studies are another reliable method for diagnosis, though these are not always readily available. Polymerase chain reaction can be used for sensitive and rapid diagnosis.15 Less commonly, electron microscopy, Western blot, or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays are used.16 Laboratory studies, such as complete blood cell count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein, often are unnecessary but may be helpful in ruling out other infectious causes. Tissue culture can be considered if bacterial, fungal, or acid-fast bacilli are in the differential; however, no growth will be seen in the case of orf viral infection.

Differential Diagnosis—The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with a large pustule on the hand or fingers can depend on geographic location, as the potential etiology may vary widely around the world. Several zoonotic viral infections other than orf can present with pustular lesions on the hands (Table).17-24

Clinically, infection with these named viruses can be hard to distinguish; however, appropriate social history or polymerase chain reaction can be obtained to differentiate them. Other infectious entities include herpetic whitlow, giant molluscum, and anthrax (eTable).24-26 Biopsy of the lesion with bacterial tissue culture may lead to definitive diagnosis.26

Treatment—Because of the self-resolving nature of orf, treatment usually is not needed in immunocompetent patients with a solitary lesion. However, wound care is essential to prevent secondary infections of the lesion. If secondarily infected, topical or oral antibiotics may be prescribed. Immunocompromised individuals are at increased risk for developing large persistent lesions and sometimes require intervention for successful treatment. Several successful treatment methods have been described and include intralesional interferon injections, electrocautery, topical imiquimod, topical cidofovir, and cryotherapy.8,14,27-30 Infections that continue to be refractory to less-invasive treatment can be considered for wide local excision; however, recurrence is possible.8 Vaccinations are available for animals to prevent the spread of infection in the flock, but there are no formulations of vaccines for human use. Prevention of spread to humans can be done through animal vaccination, careful handling of animal products while wearing nonporous gloves, and proper sanitation techniques.

Complications—Orf has an excellent long-term prognosis in immunocompetent patients, as the virus is epitheliotropic, and inoculation does not lead to viremia.2 Although lesions typically are asymptomatic in most patients, complications can occur, especially in immunosuppressed individuals. These complications include systemic symptoms, giant persistent lesions prone to infection or scarring, erysipelas, lymphadenitis, and erythema multiforme.8,31 Common systemic symptoms of ecthyma contagiosum include fever, fatigue, and myalgia. Lymphadenitis can occur along with local swelling and lymphatic streaking. Although erythema multiforme is a rare complication occurring after initial ecthyma contagiosum infection, this hypersensitivity reaction is postulated to be in response to the immunologic clearing of the orf virus.32,33 Patients receiving systemic immunosuppressive medications are at an increased risk of developing complications from infection and may even be required to pause systemic treatment for complete resolution of orf lesions.34 Other cutaneous diseases that decrease the skin’s barrier protection, such as bullous pemphigoid or eczema, also can place patients at an increased risk for complications.35 Although human-to-human orf virus transmission is exceptionally rare, there is a case report of this phenomenon in immunosuppressed patients residing in a burn unit.36 Transplant recipients on immunosuppressive medications also can experience orf lesions with exaggerated presentations that continue to grow up to several centimeters in diameter.31 Long-term prognosis is still good in these patients with appropriate disease recognition and treatment. Reinfection is not uncommon with repeated exposure to the source, but lesions are less severe and resolve faster than with initial infection.1,8

Conclusion

The contagious hand pustule caused by orf virus is a distinct clinical entity that is prevalent worldwide and requires thorough evaluation of the clinical course of the lesion and the patient’s social history. Several zoonotic viral infections have been implicated in this presentation. Although biopsy and molecular studies can be helpful, the expert diagnostician can make a clinical diagnosis with careful attention to social history, geographic location, and cultural practices.

- Haig DM, Mercer AA. Ovine diseases. orf. Vet Res. 1998;29:311-326.

- Glover RE. Contagious pustular dermatitis of the sheep. J Comp Pathol Ther. 1928;41:318-340.

- Hardy WT, Price DA. Soremuzzle of sheep.

J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1952;120:23-25. - Boughton IB, Hardy WT. Contagious ecthyma (sore mouth) of sheep and goats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1934;85:150-178.

- Gardiner MR, Craig VMD, Nairn ME. An unusual outbreak of contagious ecthyma (scabby mouth) in sheep. Aust Vet J. 1967;43:163-165.

- Newsome IE, Cross F. Sore mouth in sheep transmissible to man. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1934;84:790-802.

- Demiraslan H, Dinc G, Doganay M. An overview of orf virus infection in humans and animals. Recent Pat Anti Infect Drug Discov. 2017;12:21-30.

- Bergqvist C, Kurban M, Abbas O. Orf virus infection. Rev Med Virol. 2017;27:E1932.

- Duchateau NC, Aerts O, Lambert J. Autoinoculation with orf virus (ecthyma contagiosum). Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E60-E62.

- Paiba GA, Thomas DR, Morgan KL, et al. Orf (contagious pustular dermatitis) in farmworkers: prevalence and risk factors in three areas of England. Vet Rec. 1999;145:7-11

- Kandemir H, Ciftcioglu MA, Yilmaz E. Genital orf. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:460-461.

- Weide B, Metzler G, Eigentler TK, et al. Inflammatory nodules around the axilla: an uncommon localization of orf virus infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:240-242.

- Wilkinson JD. Orf: a family with unusual complications. Br J Dermatol. 1977;97:447-450.

- Zaharia D, Kanitakis J, Pouteil-Noble C, et al. Rapidly growing orf in a renal transplant recipient: favourable outcome with reduction of immunosuppression and imiquimod. Transpl Int. 2010;23:E62-E64.

- Bora DP, Venkatesan G, Bhanuprakash V, et al. TaqMan real-time PCR assay based on DNA polymerase gene for rapid detection of orf infection. J Virol Methods. 2011;178:249-252.

- Töndury B, Kühne A, Kutzner H, et al. Molecular diagnostics of parapox virus infections. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:681-684.

- Handler NS, Handler MZ, Rubins A, et al. Milker’s nodule: an occupational infection and threat to the immunocompromised. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:537-541.

- Groves RW, Wilson-Jones E, MacDonald DM. Human orf and milkers’ nodule: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:706-711.

- Bowman KF, Barbery RT, Swango LJ, et al. Cutaneous form of bovine papular stomatitis in man. JAMA. 1981;246;1813-1818.

- Nagington J, Lauder IM, Smith JS. Bovine papular stomatitis, pseudocowpox and milker’s nodules. Vet Rec. 1967;79:306-313.

- Clark C, McIntyre PG, Evans A, et al. Human sealpox resulting from a seal bite: confirmation that sealpox virus is zoonotic. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:791-793.

- Downie AW, Espana C. A comparative study of tanapox and yaba viruses. J Gen Virol. 1973;19:37-49.

- Zimmermann P, Thordsen I, Frangoulidis D, et al. Real-time PCR assay for the detection of tanapox virus and yaba-like disease virus. J Virol Methods. 2005;130:149-153.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2018.

- Wenner KA, Kenner JR. Anthrax. Dermatol Clin. 2004;22:247-256.

- Brachman P, Kaufmann A. Anthrax. In: Evans A, Brachman P, eds. Bacterial Infections of Humans: Epidemiology and Control. 3rd ed. Plenum Publishing; 1998:95.

- Ran M, Lee M, Gong J, et al. Oral acyclovir and intralesional interferon injections for treatment of giant pyogenic granuloma-like lesions in an immunocompromised patient with human orf. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1032-1034.

- Degraeve C, De Coninck A, Senneseael J, et al. Recurrent contagious ecthyma (orf) in an immunocompromised host successfully treated with cryotherapy. Dermatology. 1999;198:162-163.

- Geerinck K, Lukito G, Snoeck R, et al. A case of human orf in an immunocompromised patient treated successfully with cidofovir cream. J Med Virol. 2001;64:543-549.

- Ertekin S, Gurel M, Erdemir A, et al. Systemic interferon alfa injections for the treatment of a giant orf. Cutis. 2017;99:E19-E21.

- Hunskaar S. Giant orf in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:631-634.

- Ozturk P, Sayar H, Karakas T, et al. Erythema multiforme as a result of orf disease. Acta Dermatovenereol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2012;21:45-46.

- Shahmoradi Z, Abtahi-Naeini B, Pourazizi M, et al. Orf disease following ‘eid ul-adha’: a rare cause of erythema multiforme. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:912-914.

- Kostopoulos M, Gerodimos C, Batsila E, et al. Orf disease in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2018;29:89-91.

- Murphy JK, Ralphs IG. Bullous pemphigoid complicating human orf. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:929-930.

- Midilli K, Erkiliç A, Kus¸kucu M, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of disseminated orf infection in a burn unit, Gaziantep, Turkey, October to December 2012. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20425.

- Haig DM, Mercer AA. Ovine diseases. orf. Vet Res. 1998;29:311-326.

- Glover RE. Contagious pustular dermatitis of the sheep. J Comp Pathol Ther. 1928;41:318-340.

- Hardy WT, Price DA. Soremuzzle of sheep.

J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1952;120:23-25. - Boughton IB, Hardy WT. Contagious ecthyma (sore mouth) of sheep and goats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1934;85:150-178.

- Gardiner MR, Craig VMD, Nairn ME. An unusual outbreak of contagious ecthyma (scabby mouth) in sheep. Aust Vet J. 1967;43:163-165.

- Newsome IE, Cross F. Sore mouth in sheep transmissible to man. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1934;84:790-802.

- Demiraslan H, Dinc G, Doganay M. An overview of orf virus infection in humans and animals. Recent Pat Anti Infect Drug Discov. 2017;12:21-30.

- Bergqvist C, Kurban M, Abbas O. Orf virus infection. Rev Med Virol. 2017;27:E1932.

- Duchateau NC, Aerts O, Lambert J. Autoinoculation with orf virus (ecthyma contagiosum). Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E60-E62.

- Paiba GA, Thomas DR, Morgan KL, et al. Orf (contagious pustular dermatitis) in farmworkers: prevalence and risk factors in three areas of England. Vet Rec. 1999;145:7-11

- Kandemir H, Ciftcioglu MA, Yilmaz E. Genital orf. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:460-461.

- Weide B, Metzler G, Eigentler TK, et al. Inflammatory nodules around the axilla: an uncommon localization of orf virus infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:240-242.

- Wilkinson JD. Orf: a family with unusual complications. Br J Dermatol. 1977;97:447-450.

- Zaharia D, Kanitakis J, Pouteil-Noble C, et al. Rapidly growing orf in a renal transplant recipient: favourable outcome with reduction of immunosuppression and imiquimod. Transpl Int. 2010;23:E62-E64.

- Bora DP, Venkatesan G, Bhanuprakash V, et al. TaqMan real-time PCR assay based on DNA polymerase gene for rapid detection of orf infection. J Virol Methods. 2011;178:249-252.

- Töndury B, Kühne A, Kutzner H, et al. Molecular diagnostics of parapox virus infections. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:681-684.

- Handler NS, Handler MZ, Rubins A, et al. Milker’s nodule: an occupational infection and threat to the immunocompromised. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:537-541.

- Groves RW, Wilson-Jones E, MacDonald DM. Human orf and milkers’ nodule: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:706-711.

- Bowman KF, Barbery RT, Swango LJ, et al. Cutaneous form of bovine papular stomatitis in man. JAMA. 1981;246;1813-1818.

- Nagington J, Lauder IM, Smith JS. Bovine papular stomatitis, pseudocowpox and milker’s nodules. Vet Rec. 1967;79:306-313.

- Clark C, McIntyre PG, Evans A, et al. Human sealpox resulting from a seal bite: confirmation that sealpox virus is zoonotic. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:791-793.

- Downie AW, Espana C. A comparative study of tanapox and yaba viruses. J Gen Virol. 1973;19:37-49.

- Zimmermann P, Thordsen I, Frangoulidis D, et al. Real-time PCR assay for the detection of tanapox virus and yaba-like disease virus. J Virol Methods. 2005;130:149-153.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2018.

- Wenner KA, Kenner JR. Anthrax. Dermatol Clin. 2004;22:247-256.

- Brachman P, Kaufmann A. Anthrax. In: Evans A, Brachman P, eds. Bacterial Infections of Humans: Epidemiology and Control. 3rd ed. Plenum Publishing; 1998:95.

- Ran M, Lee M, Gong J, et al. Oral acyclovir and intralesional interferon injections for treatment of giant pyogenic granuloma-like lesions in an immunocompromised patient with human orf. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1032-1034.

- Degraeve C, De Coninck A, Senneseael J, et al. Recurrent contagious ecthyma (orf) in an immunocompromised host successfully treated with cryotherapy. Dermatology. 1999;198:162-163.

- Geerinck K, Lukito G, Snoeck R, et al. A case of human orf in an immunocompromised patient treated successfully with cidofovir cream. J Med Virol. 2001;64:543-549.

- Ertekin S, Gurel M, Erdemir A, et al. Systemic interferon alfa injections for the treatment of a giant orf. Cutis. 2017;99:E19-E21.

- Hunskaar S. Giant orf in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:631-634.

- Ozturk P, Sayar H, Karakas T, et al. Erythema multiforme as a result of orf disease. Acta Dermatovenereol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2012;21:45-46.

- Shahmoradi Z, Abtahi-Naeini B, Pourazizi M, et al. Orf disease following ‘eid ul-adha’: a rare cause of erythema multiforme. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:912-914.

- Kostopoulos M, Gerodimos C, Batsila E, et al. Orf disease in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2018;29:89-91.

- Murphy JK, Ralphs IG. Bullous pemphigoid complicating human orf. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:929-930.

- Midilli K, Erkiliç A, Kus¸kucu M, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of disseminated orf infection in a burn unit, Gaziantep, Turkey, October to December 2012. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20425.

Practice Points

- Ecthyma contagiosum is a discrete clinical entity that occurs worldwide and demands careful attention to clinical course and social history.

- Ecthyma contagiosum is caused by orf virus, an epitheliotropic zoonotic infection that spreads from ruminants to humans.

- Early and rapid diagnosis of this classic condition is critical to prevent unnecessary biopsies or extensive testing, and determination of etiology can be important in preventing reinfection or spread to other humans by the same infected animal.

Surgical Specimens and Margins

We have attended grand rounds presentations at which students announce that Mohs micrographic surgery evaluates 100% of the surgical margin, whereas standard excision samples 1% to 2% of the margin; we have even fielded questions from neighbors who have come across this information on the internet.1-5 This statement describes a best-case scenario for Mohs surgery and a worst-case scenario for standard excision. We believe that it is important for clinicians to have a more nuanced understanding of how simple excisions are processed so that they can have pertinent discussions with patients, especially now that there is increasing access to personal health information along with increased agency in patient decision-making.

Margins for Mohs Surgery

Theoretically, Mohs surgery should sample all true surgical margins by complete circumferential, peripheral, and deep-margin assessment. Unfortunately, some sections are not cut full face—sections may not always sample a complete surface—when technicians make an error or lack expertise. Some sections may have small tissue folds or small gaps that prevent complete visualization. We estimate that the Mohs sections we review in consultation that are prepared by private practice Mohs surgeons in our communities visualize approximately 98% of surgical margins on average. Incomplete sections contribute to the rare tumor recurrences after Mohs surgery of approximately 2% to 3%.6

Standard Excision Margins

When we obtained the references cited in articles asserting that

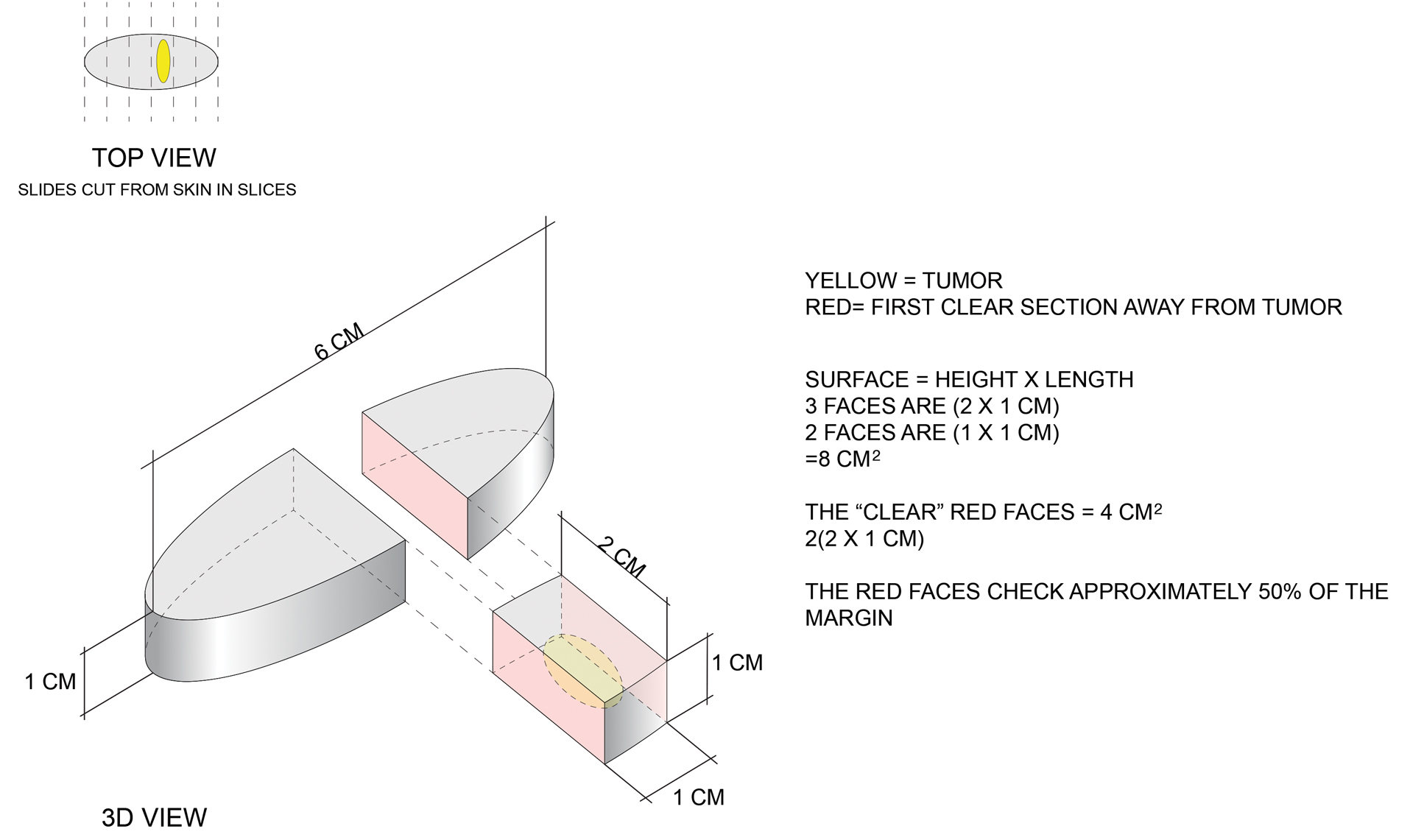

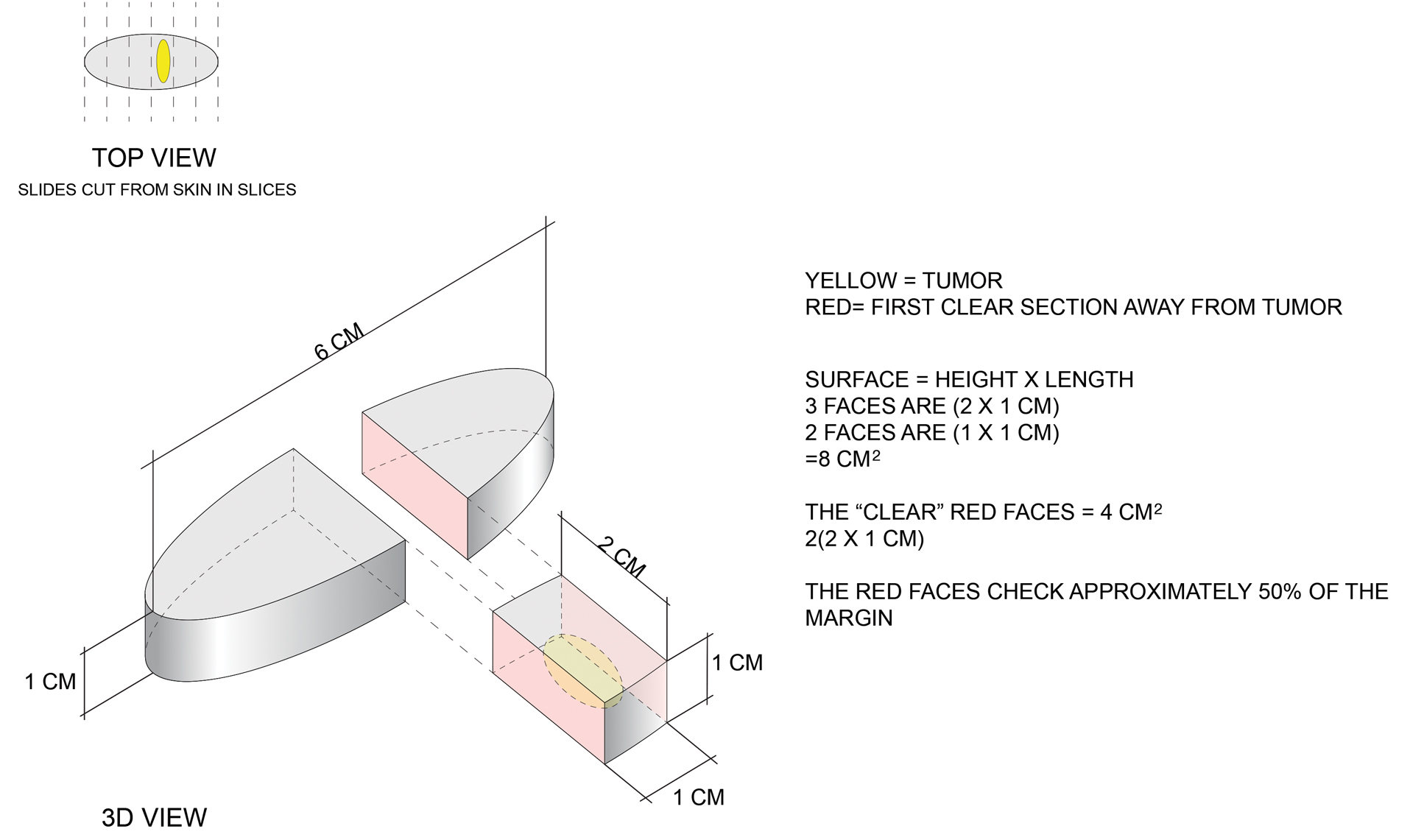

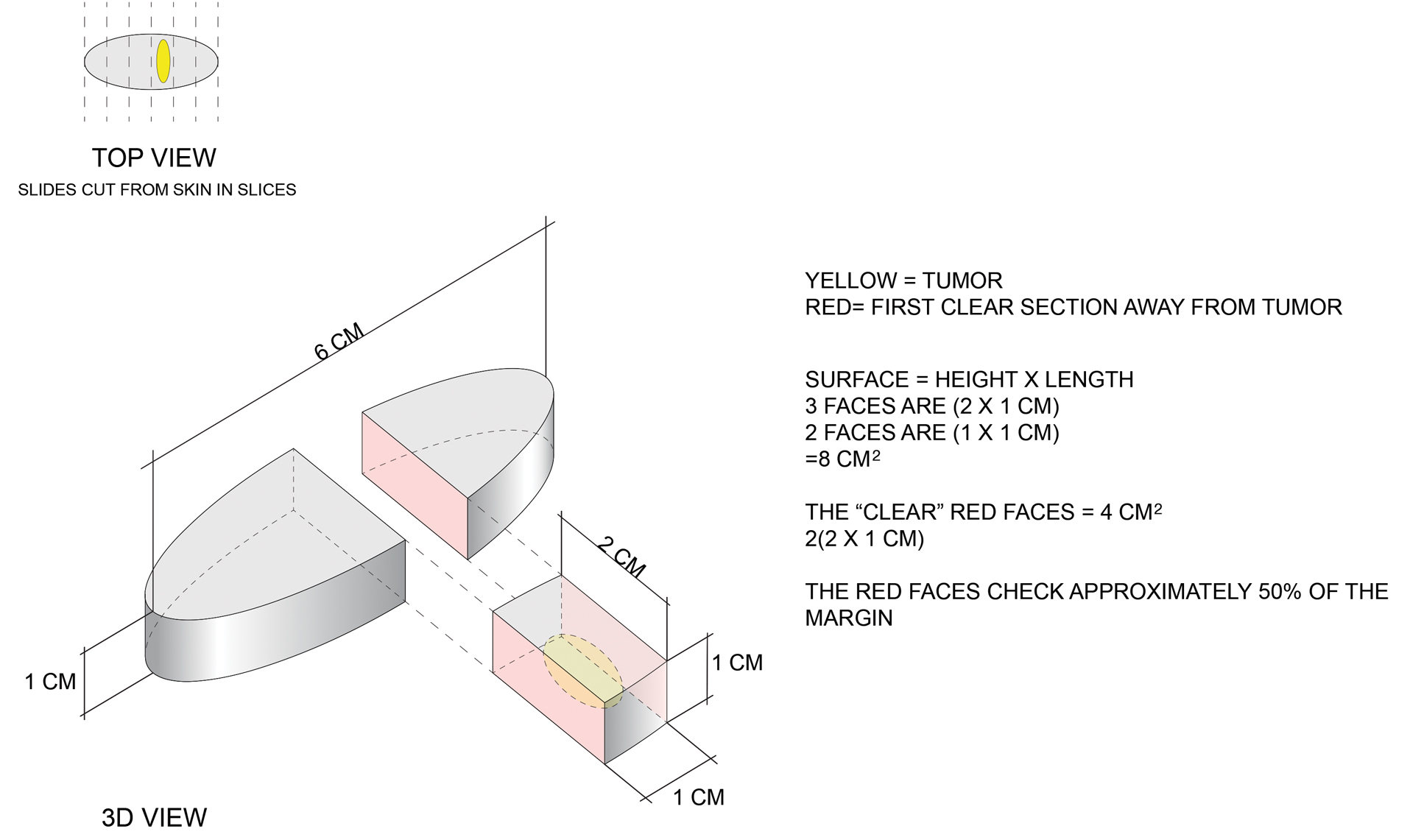

Here is a simple example to show that more margin is accessed in some cases. Consider this hypothetical situation: If a tumor can be readily visualized grossly and housed entirely within an imaginary cuboid (rectangular) prism that is removed in an elliptical specimen with a length of 6 cm, a width of 2 cm, and a height of 1 cm (Figure), then standard sectioning assesses a greater margin.

Bread-loaf sectioning would be expected to examine the complete surface of 2 sides (faces) of the cuboid. Assessing 2 of the 5 clinically relevant sides provides information for approximately 50% of the margins, as sections in the next parallel plane can be expected to be clear after the first clear section is identified. The clinically useful information is not limited to the sum of the widths of sections. Encountering a clear plane typically indicates that there will be no tumor in more distal parallel planes. Warne et al6 developed a formula that can accurately predict the percentage of the margin evaluated by proxy that considers the curvature of the ellipse.

Comparing Standard Excision and Mohs Surgery

Mohs surgery consistently results in the best outcomes, but standard excision is effective, too. Standard excision is relatively simple, requires less equipment, is less time consuming, and can provide good value when resources are finite. Data on recurrence of basal cell carcinoma after simple excision are limited, but the recurrence rate is reported to be approximately 3%.7,8 A meta-analysis found that the recurrence rate of basal cell carcinoma treated with standard excision was 0.4%, 1.6%, 2.6%, and 4% with 5-mm, 4-mm, 3-mm, and 2-mm surgical margins, respectively.9

Mohs surgery is the best, most effective, and most tissue-sparing technique for certain nonmelanoma skin cancers. This observation is reflected in guidelines worldwide.10 The adequacy of standard approaches to margin evaluation depends on the capabilities and focus of the laboratory team. Dermatopathologists often are called to the laboratory to decide which technique will be best for a particular case.11 Technicians are trained to take more sections in areas where abnormalities are seen, and some laboratories take photographs of specimens or provide sketches for correlation. Dermatopathologists also routinely request additional sections in areas where visible tumor extends close to surgical margins on microscopic examination.

It is not simply a matter of knowing how much of the margin is sampled but if the most pertinent areas are adequately sampled. Simple sectioning can work well and be cost effective. Many clinicians are unaware of how tissue processing can vary from laboratory to laboratory. There are no uniformly accepted standards for how tissue should be processed. Assiduous and thoughtful evaluation of specimens can affect results. As with any service, some laboratories provide more detailed and conscientious care while others focus more on immediate costs. Clinicians should understand how their specimens are processed by discussing margin evaluation with their dermatopathologist.

Final Thoughts

Used appropriately, Mohs surgery is an excellent technique that can provide outstanding results. Standard excision also has an important place in the dermatologist’s armamentarium and typically provides information about more than 1% to 2% of the margin. Understanding the techniques used to process specimens is critical to delivering the best possible care.

- Tolkachjov SN, Brodland DG, Coldiron BM, et al. Understanding Mohs micrographic surgery: a review and practical guide for the nondermatologist. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1261-1271. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.04.009

- Thomas RM, Amonette RA. Mohs micrographic surgery. Am Fam Physician. 1988;37:135-142.

- Buker JL, Amonette RA. Micrographic surgery. Clin Dermatol. 1992:10:309-315. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(92)90074-9

- Kauvar ANB. Mohs: the gold standard. The Skin Cancer Foundation website. Updated March 9, 2021. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.skincancer.org/treatment-resources/mohs-surgery/mohs-the-gold-standard/

- van Delft LCJ, Nelemans PJ, van Loo E, et al. The illusion of conventional histological resection margin control. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1240-1241. doi:10.1111/bjd.17510

- Warne MM, Klawonn MM, Brodell RT. Bread loaf sections provide useful information on more than 0.5% of surgical margins [published July 5, 2022]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.21740

- Mehrany K, Weenig RH, Pittelkow MR, et al. High recurrence rates of basal cell carcinoma after Mohs surgery in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:985-988. doi:10.1001/archderm.140.8.985

- Smeets NWJ, Krekels GAM, Ostertag JU, et al. Surgical excision vs Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal-cell carcinoma of the face: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1766-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17399-6

- Gulleth Y, Goldberg N, Silverman RP, et al. What is the best surgical margin for a basal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of theliterature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1222-1231. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ea450d

- Nahhas AF, Scarbrough CA, Trotter S. A review of the global guidelines on surgical margins for nonmelanoma skin cancers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:37-46.

- Rapini RP. Comparison of methods for checking surgical margins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990; 23:288-294. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70212-z

We have attended grand rounds presentations at which students announce that Mohs micrographic surgery evaluates 100% of the surgical margin, whereas standard excision samples 1% to 2% of the margin; we have even fielded questions from neighbors who have come across this information on the internet.1-5 This statement describes a best-case scenario for Mohs surgery and a worst-case scenario for standard excision. We believe that it is important for clinicians to have a more nuanced understanding of how simple excisions are processed so that they can have pertinent discussions with patients, especially now that there is increasing access to personal health information along with increased agency in patient decision-making.

Margins for Mohs Surgery

Theoretically, Mohs surgery should sample all true surgical margins by complete circumferential, peripheral, and deep-margin assessment. Unfortunately, some sections are not cut full face—sections may not always sample a complete surface—when technicians make an error or lack expertise. Some sections may have small tissue folds or small gaps that prevent complete visualization. We estimate that the Mohs sections we review in consultation that are prepared by private practice Mohs surgeons in our communities visualize approximately 98% of surgical margins on average. Incomplete sections contribute to the rare tumor recurrences after Mohs surgery of approximately 2% to 3%.6

Standard Excision Margins

When we obtained the references cited in articles asserting that

Here is a simple example to show that more margin is accessed in some cases. Consider this hypothetical situation: If a tumor can be readily visualized grossly and housed entirely within an imaginary cuboid (rectangular) prism that is removed in an elliptical specimen with a length of 6 cm, a width of 2 cm, and a height of 1 cm (Figure), then standard sectioning assesses a greater margin.

Bread-loaf sectioning would be expected to examine the complete surface of 2 sides (faces) of the cuboid. Assessing 2 of the 5 clinically relevant sides provides information for approximately 50% of the margins, as sections in the next parallel plane can be expected to be clear after the first clear section is identified. The clinically useful information is not limited to the sum of the widths of sections. Encountering a clear plane typically indicates that there will be no tumor in more distal parallel planes. Warne et al6 developed a formula that can accurately predict the percentage of the margin evaluated by proxy that considers the curvature of the ellipse.

Comparing Standard Excision and Mohs Surgery

Mohs surgery consistently results in the best outcomes, but standard excision is effective, too. Standard excision is relatively simple, requires less equipment, is less time consuming, and can provide good value when resources are finite. Data on recurrence of basal cell carcinoma after simple excision are limited, but the recurrence rate is reported to be approximately 3%.7,8 A meta-analysis found that the recurrence rate of basal cell carcinoma treated with standard excision was 0.4%, 1.6%, 2.6%, and 4% with 5-mm, 4-mm, 3-mm, and 2-mm surgical margins, respectively.9

Mohs surgery is the best, most effective, and most tissue-sparing technique for certain nonmelanoma skin cancers. This observation is reflected in guidelines worldwide.10 The adequacy of standard approaches to margin evaluation depends on the capabilities and focus of the laboratory team. Dermatopathologists often are called to the laboratory to decide which technique will be best for a particular case.11 Technicians are trained to take more sections in areas where abnormalities are seen, and some laboratories take photographs of specimens or provide sketches for correlation. Dermatopathologists also routinely request additional sections in areas where visible tumor extends close to surgical margins on microscopic examination.

It is not simply a matter of knowing how much of the margin is sampled but if the most pertinent areas are adequately sampled. Simple sectioning can work well and be cost effective. Many clinicians are unaware of how tissue processing can vary from laboratory to laboratory. There are no uniformly accepted standards for how tissue should be processed. Assiduous and thoughtful evaluation of specimens can affect results. As with any service, some laboratories provide more detailed and conscientious care while others focus more on immediate costs. Clinicians should understand how their specimens are processed by discussing margin evaluation with their dermatopathologist.

Final Thoughts

Used appropriately, Mohs surgery is an excellent technique that can provide outstanding results. Standard excision also has an important place in the dermatologist’s armamentarium and typically provides information about more than 1% to 2% of the margin. Understanding the techniques used to process specimens is critical to delivering the best possible care.

We have attended grand rounds presentations at which students announce that Mohs micrographic surgery evaluates 100% of the surgical margin, whereas standard excision samples 1% to 2% of the margin; we have even fielded questions from neighbors who have come across this information on the internet.1-5 This statement describes a best-case scenario for Mohs surgery and a worst-case scenario for standard excision. We believe that it is important for clinicians to have a more nuanced understanding of how simple excisions are processed so that they can have pertinent discussions with patients, especially now that there is increasing access to personal health information along with increased agency in patient decision-making.

Margins for Mohs Surgery

Theoretically, Mohs surgery should sample all true surgical margins by complete circumferential, peripheral, and deep-margin assessment. Unfortunately, some sections are not cut full face—sections may not always sample a complete surface—when technicians make an error or lack expertise. Some sections may have small tissue folds or small gaps that prevent complete visualization. We estimate that the Mohs sections we review in consultation that are prepared by private practice Mohs surgeons in our communities visualize approximately 98% of surgical margins on average. Incomplete sections contribute to the rare tumor recurrences after Mohs surgery of approximately 2% to 3%.6

Standard Excision Margins

When we obtained the references cited in articles asserting that

Here is a simple example to show that more margin is accessed in some cases. Consider this hypothetical situation: If a tumor can be readily visualized grossly and housed entirely within an imaginary cuboid (rectangular) prism that is removed in an elliptical specimen with a length of 6 cm, a width of 2 cm, and a height of 1 cm (Figure), then standard sectioning assesses a greater margin.

Bread-loaf sectioning would be expected to examine the complete surface of 2 sides (faces) of the cuboid. Assessing 2 of the 5 clinically relevant sides provides information for approximately 50% of the margins, as sections in the next parallel plane can be expected to be clear after the first clear section is identified. The clinically useful information is not limited to the sum of the widths of sections. Encountering a clear plane typically indicates that there will be no tumor in more distal parallel planes. Warne et al6 developed a formula that can accurately predict the percentage of the margin evaluated by proxy that considers the curvature of the ellipse.

Comparing Standard Excision and Mohs Surgery

Mohs surgery consistently results in the best outcomes, but standard excision is effective, too. Standard excision is relatively simple, requires less equipment, is less time consuming, and can provide good value when resources are finite. Data on recurrence of basal cell carcinoma after simple excision are limited, but the recurrence rate is reported to be approximately 3%.7,8 A meta-analysis found that the recurrence rate of basal cell carcinoma treated with standard excision was 0.4%, 1.6%, 2.6%, and 4% with 5-mm, 4-mm, 3-mm, and 2-mm surgical margins, respectively.9

Mohs surgery is the best, most effective, and most tissue-sparing technique for certain nonmelanoma skin cancers. This observation is reflected in guidelines worldwide.10 The adequacy of standard approaches to margin evaluation depends on the capabilities and focus of the laboratory team. Dermatopathologists often are called to the laboratory to decide which technique will be best for a particular case.11 Technicians are trained to take more sections in areas where abnormalities are seen, and some laboratories take photographs of specimens or provide sketches for correlation. Dermatopathologists also routinely request additional sections in areas where visible tumor extends close to surgical margins on microscopic examination.

It is not simply a matter of knowing how much of the margin is sampled but if the most pertinent areas are adequately sampled. Simple sectioning can work well and be cost effective. Many clinicians are unaware of how tissue processing can vary from laboratory to laboratory. There are no uniformly accepted standards for how tissue should be processed. Assiduous and thoughtful evaluation of specimens can affect results. As with any service, some laboratories provide more detailed and conscientious care while others focus more on immediate costs. Clinicians should understand how their specimens are processed by discussing margin evaluation with their dermatopathologist.

Final Thoughts

Used appropriately, Mohs surgery is an excellent technique that can provide outstanding results. Standard excision also has an important place in the dermatologist’s armamentarium and typically provides information about more than 1% to 2% of the margin. Understanding the techniques used to process specimens is critical to delivering the best possible care.

- Tolkachjov SN, Brodland DG, Coldiron BM, et al. Understanding Mohs micrographic surgery: a review and practical guide for the nondermatologist. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1261-1271. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.04.009

- Thomas RM, Amonette RA. Mohs micrographic surgery. Am Fam Physician. 1988;37:135-142.

- Buker JL, Amonette RA. Micrographic surgery. Clin Dermatol. 1992:10:309-315. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(92)90074-9

- Kauvar ANB. Mohs: the gold standard. The Skin Cancer Foundation website. Updated March 9, 2021. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.skincancer.org/treatment-resources/mohs-surgery/mohs-the-gold-standard/

- van Delft LCJ, Nelemans PJ, van Loo E, et al. The illusion of conventional histological resection margin control. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1240-1241. doi:10.1111/bjd.17510

- Warne MM, Klawonn MM, Brodell RT. Bread loaf sections provide useful information on more than 0.5% of surgical margins [published July 5, 2022]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.21740

- Mehrany K, Weenig RH, Pittelkow MR, et al. High recurrence rates of basal cell carcinoma after Mohs surgery in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:985-988. doi:10.1001/archderm.140.8.985

- Smeets NWJ, Krekels GAM, Ostertag JU, et al. Surgical excision vs Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal-cell carcinoma of the face: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1766-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17399-6

- Gulleth Y, Goldberg N, Silverman RP, et al. What is the best surgical margin for a basal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of theliterature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1222-1231. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ea450d

- Nahhas AF, Scarbrough CA, Trotter S. A review of the global guidelines on surgical margins for nonmelanoma skin cancers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:37-46.

- Rapini RP. Comparison of methods for checking surgical margins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990; 23:288-294. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70212-z

- Tolkachjov SN, Brodland DG, Coldiron BM, et al. Understanding Mohs micrographic surgery: a review and practical guide for the nondermatologist. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1261-1271. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.04.009

- Thomas RM, Amonette RA. Mohs micrographic surgery. Am Fam Physician. 1988;37:135-142.

- Buker JL, Amonette RA. Micrographic surgery. Clin Dermatol. 1992:10:309-315. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(92)90074-9

- Kauvar ANB. Mohs: the gold standard. The Skin Cancer Foundation website. Updated March 9, 2021. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.skincancer.org/treatment-resources/mohs-surgery/mohs-the-gold-standard/

- van Delft LCJ, Nelemans PJ, van Loo E, et al. The illusion of conventional histological resection margin control. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1240-1241. doi:10.1111/bjd.17510

- Warne MM, Klawonn MM, Brodell RT. Bread loaf sections provide useful information on more than 0.5% of surgical margins [published July 5, 2022]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.21740

- Mehrany K, Weenig RH, Pittelkow MR, et al. High recurrence rates of basal cell carcinoma after Mohs surgery in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:985-988. doi:10.1001/archderm.140.8.985

- Smeets NWJ, Krekels GAM, Ostertag JU, et al. Surgical excision vs Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal-cell carcinoma of the face: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1766-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17399-6

- Gulleth Y, Goldberg N, Silverman RP, et al. What is the best surgical margin for a basal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of theliterature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1222-1231. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ea450d

- Nahhas AF, Scarbrough CA, Trotter S. A review of the global guidelines on surgical margins for nonmelanoma skin cancers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:37-46.

- Rapini RP. Comparison of methods for checking surgical margins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990; 23:288-294. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70212-z

Practice Points

- Margin analysis in simple excisions can provide useful information by proxy about more than the 1% of the margin often quoted in the literature.

- Simple excisions of uncomplicated keratinocytic carcinomas are associated with high cure rates.

Nail dystrophy and foot pain

These findings are consistent with a type of heritable keratoderma called pachyonychia congenita (also called twenty-nails dystrophy). It is easy to mistake this unusual cause of thickening nails with a more common cause: onychomycosis.

Pachyonychia congenita describes a set of disorders driven by heritable defects in 1 of 5 keratin genes. The disorder is often transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion, although a third of patients are thought to have a spontaneous mutation.1 These gene changes can cause 1 or multiple dystrophic nails, thickened nail beds, natal teeth, thick plantar or palmar nodules or plaques, and hearing difficulties. Some patients may have symptoms at birth, while other patients do not develop symptoms until later in life.1

There is currently no cure for pachyonychia congenita. Patients with suspected heritable keratoderma benefit from referral to Medical Genetics and a dermatologist who is comfortable treating keratodermas. Patients can obtain free genetic testing, educational material, and additional resources through pachyonychia.org.

This patient was prescribed topical urea 40% cream that was to be applied to the feet nightly, until the nodules became less painful. He was also evaluated for pressure-offloading orthotics. Nails may be treated with topical urea lacquer nightly until patients are satisfied with the appearance, although this patient chose to forgo the lacquer.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Smith FJD, Hansen CD, Hull PR, et al. Pachyonychia congenita. In: Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, et al., eds. GeneReviews. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 2006. Updated November 30, 2017. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1280/

These findings are consistent with a type of heritable keratoderma called pachyonychia congenita (also called twenty-nails dystrophy). It is easy to mistake this unusual cause of thickening nails with a more common cause: onychomycosis.

Pachyonychia congenita describes a set of disorders driven by heritable defects in 1 of 5 keratin genes. The disorder is often transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion, although a third of patients are thought to have a spontaneous mutation.1 These gene changes can cause 1 or multiple dystrophic nails, thickened nail beds, natal teeth, thick plantar or palmar nodules or plaques, and hearing difficulties. Some patients may have symptoms at birth, while other patients do not develop symptoms until later in life.1

There is currently no cure for pachyonychia congenita. Patients with suspected heritable keratoderma benefit from referral to Medical Genetics and a dermatologist who is comfortable treating keratodermas. Patients can obtain free genetic testing, educational material, and additional resources through pachyonychia.org.

This patient was prescribed topical urea 40% cream that was to be applied to the feet nightly, until the nodules became less painful. He was also evaluated for pressure-offloading orthotics. Nails may be treated with topical urea lacquer nightly until patients are satisfied with the appearance, although this patient chose to forgo the lacquer.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

These findings are consistent with a type of heritable keratoderma called pachyonychia congenita (also called twenty-nails dystrophy). It is easy to mistake this unusual cause of thickening nails with a more common cause: onychomycosis.

Pachyonychia congenita describes a set of disorders driven by heritable defects in 1 of 5 keratin genes. The disorder is often transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion, although a third of patients are thought to have a spontaneous mutation.1 These gene changes can cause 1 or multiple dystrophic nails, thickened nail beds, natal teeth, thick plantar or palmar nodules or plaques, and hearing difficulties. Some patients may have symptoms at birth, while other patients do not develop symptoms until later in life.1

There is currently no cure for pachyonychia congenita. Patients with suspected heritable keratoderma benefit from referral to Medical Genetics and a dermatologist who is comfortable treating keratodermas. Patients can obtain free genetic testing, educational material, and additional resources through pachyonychia.org.

This patient was prescribed topical urea 40% cream that was to be applied to the feet nightly, until the nodules became less painful. He was also evaluated for pressure-offloading orthotics. Nails may be treated with topical urea lacquer nightly until patients are satisfied with the appearance, although this patient chose to forgo the lacquer.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).