User login

Adapting to Changes in Acne Management: Take One Step at a Time

After most dermatology residents graduate from their programs, they go out into practice and will often carry with them what they learned from their teachers, especially clinicians. Everyone else in their dermatology residency programs approaches disease management and the use of different therapies in the same way, right?

It does not take very long before these same dermatology residents realize that things are different in real-world clinical practice in many ways. Most clinicians develop a range of fairly predictable patterns in how they approach and treat common skin disorders such as acne, rosacea, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis/eczema, and seborrheic dermatitis. These patterns often include what testing is performed at baseline and at follow-up.

Recently, I have been giving thought to how clinicians—myself included—change their approaches to management of specific skin diseases over time, especially as new information and therapies emerge. Are we fast adopters, or are we slow adopters? How much evidence do we need to see before we consider adjusting our approach? Is the needle moving too fast or not fast enough?

I would like to use an example that relates to acne treatment, especially as this is one of the most common skin disorders encountered in outpatient dermatologic practice. Despite lack of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use in acne, oral spironolactone commonly is used in females, especially adults, with acne vulgaris and has a long history as an acceptable approach in dermatology.1 Because spironolactone is a potassium-sparing diuretic, one question that commonly arises is: Do we monitor serum potassium levels at baseline and periodically during treatment with spironolactone? There has never been a definitive consensus on which approach to take. However, there has been evidence to suggest that such monitoring is not necessary in young healthy women due to a negligible risk for clinically relevant hyperkalemia.2,3

In fact, the suggestion that there is a very low risk for clinically significant hyperkalemia in healthy young women treated with spironolactone is accurate based on population-based studies. Nevertheless, the clinician is faced with confirming the patient is in fact healthy rather than assuming this is the case due to her “young” age. In addition, it is important to exclude potential drug-drug interactions that can increase the risk for hyperkalemia when coadministered with spironolactone and also to exclude an unknown underlying decrease in renal function.1 At the end of the day, I support the continued research that is being done to evaluate questions that can challenge the recycled dogma on how we manage patients, and I do not fault those who follow what they believe to be new cogent evidence. However, in the case of oral spironolactone use, I also could never fault a clinician for monitoring renal function and electrolytes including serum potassium levels in a female patient treated for acne, especially with a drug that has the known potential to cause hyperkalemia in certain clinical situations and is not FDA approved for the indication of acne (ie, the guidance that accompanies the level of investigation needed for such FDA approval is missing). The clinical judgment of the clinician who is responsible for the individual patient trumps the results from population-based studies completed thus far. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of that clinician to assure the safety of their patient in a manner that they are comfortable with.

It takes time to make changes in our approaches to patient management, and in the majority of cases, that is rightfully so. There are several potential limitations to how certain data are collected, and a reasonable verification of results over time is what tends to change behavior patterns. Ultimately, the common goal is to do what is in the best interest of our patients. No one can argue successfully against that.

- Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:37-50.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Arash Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:941-944.

- Barbieri JS, Margolis DJ, Mostaghimi A. Temporal trends and clinician variability in potassium monitoring of healthy young women treated for acne with spironolactone. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:296-300.

After most dermatology residents graduate from their programs, they go out into practice and will often carry with them what they learned from their teachers, especially clinicians. Everyone else in their dermatology residency programs approaches disease management and the use of different therapies in the same way, right?

It does not take very long before these same dermatology residents realize that things are different in real-world clinical practice in many ways. Most clinicians develop a range of fairly predictable patterns in how they approach and treat common skin disorders such as acne, rosacea, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis/eczema, and seborrheic dermatitis. These patterns often include what testing is performed at baseline and at follow-up.

Recently, I have been giving thought to how clinicians—myself included—change their approaches to management of specific skin diseases over time, especially as new information and therapies emerge. Are we fast adopters, or are we slow adopters? How much evidence do we need to see before we consider adjusting our approach? Is the needle moving too fast or not fast enough?

I would like to use an example that relates to acne treatment, especially as this is one of the most common skin disorders encountered in outpatient dermatologic practice. Despite lack of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use in acne, oral spironolactone commonly is used in females, especially adults, with acne vulgaris and has a long history as an acceptable approach in dermatology.1 Because spironolactone is a potassium-sparing diuretic, one question that commonly arises is: Do we monitor serum potassium levels at baseline and periodically during treatment with spironolactone? There has never been a definitive consensus on which approach to take. However, there has been evidence to suggest that such monitoring is not necessary in young healthy women due to a negligible risk for clinically relevant hyperkalemia.2,3

In fact, the suggestion that there is a very low risk for clinically significant hyperkalemia in healthy young women treated with spironolactone is accurate based on population-based studies. Nevertheless, the clinician is faced with confirming the patient is in fact healthy rather than assuming this is the case due to her “young” age. In addition, it is important to exclude potential drug-drug interactions that can increase the risk for hyperkalemia when coadministered with spironolactone and also to exclude an unknown underlying decrease in renal function.1 At the end of the day, I support the continued research that is being done to evaluate questions that can challenge the recycled dogma on how we manage patients, and I do not fault those who follow what they believe to be new cogent evidence. However, in the case of oral spironolactone use, I also could never fault a clinician for monitoring renal function and electrolytes including serum potassium levels in a female patient treated for acne, especially with a drug that has the known potential to cause hyperkalemia in certain clinical situations and is not FDA approved for the indication of acne (ie, the guidance that accompanies the level of investigation needed for such FDA approval is missing). The clinical judgment of the clinician who is responsible for the individual patient trumps the results from population-based studies completed thus far. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of that clinician to assure the safety of their patient in a manner that they are comfortable with.

It takes time to make changes in our approaches to patient management, and in the majority of cases, that is rightfully so. There are several potential limitations to how certain data are collected, and a reasonable verification of results over time is what tends to change behavior patterns. Ultimately, the common goal is to do what is in the best interest of our patients. No one can argue successfully against that.

After most dermatology residents graduate from their programs, they go out into practice and will often carry with them what they learned from their teachers, especially clinicians. Everyone else in their dermatology residency programs approaches disease management and the use of different therapies in the same way, right?

It does not take very long before these same dermatology residents realize that things are different in real-world clinical practice in many ways. Most clinicians develop a range of fairly predictable patterns in how they approach and treat common skin disorders such as acne, rosacea, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis/eczema, and seborrheic dermatitis. These patterns often include what testing is performed at baseline and at follow-up.

Recently, I have been giving thought to how clinicians—myself included—change their approaches to management of specific skin diseases over time, especially as new information and therapies emerge. Are we fast adopters, or are we slow adopters? How much evidence do we need to see before we consider adjusting our approach? Is the needle moving too fast or not fast enough?

I would like to use an example that relates to acne treatment, especially as this is one of the most common skin disorders encountered in outpatient dermatologic practice. Despite lack of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use in acne, oral spironolactone commonly is used in females, especially adults, with acne vulgaris and has a long history as an acceptable approach in dermatology.1 Because spironolactone is a potassium-sparing diuretic, one question that commonly arises is: Do we monitor serum potassium levels at baseline and periodically during treatment with spironolactone? There has never been a definitive consensus on which approach to take. However, there has been evidence to suggest that such monitoring is not necessary in young healthy women due to a negligible risk for clinically relevant hyperkalemia.2,3

In fact, the suggestion that there is a very low risk for clinically significant hyperkalemia in healthy young women treated with spironolactone is accurate based on population-based studies. Nevertheless, the clinician is faced with confirming the patient is in fact healthy rather than assuming this is the case due to her “young” age. In addition, it is important to exclude potential drug-drug interactions that can increase the risk for hyperkalemia when coadministered with spironolactone and also to exclude an unknown underlying decrease in renal function.1 At the end of the day, I support the continued research that is being done to evaluate questions that can challenge the recycled dogma on how we manage patients, and I do not fault those who follow what they believe to be new cogent evidence. However, in the case of oral spironolactone use, I also could never fault a clinician for monitoring renal function and electrolytes including serum potassium levels in a female patient treated for acne, especially with a drug that has the known potential to cause hyperkalemia in certain clinical situations and is not FDA approved for the indication of acne (ie, the guidance that accompanies the level of investigation needed for such FDA approval is missing). The clinical judgment of the clinician who is responsible for the individual patient trumps the results from population-based studies completed thus far. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of that clinician to assure the safety of their patient in a manner that they are comfortable with.

It takes time to make changes in our approaches to patient management, and in the majority of cases, that is rightfully so. There are several potential limitations to how certain data are collected, and a reasonable verification of results over time is what tends to change behavior patterns. Ultimately, the common goal is to do what is in the best interest of our patients. No one can argue successfully against that.

- Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:37-50.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Arash Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:941-944.

- Barbieri JS, Margolis DJ, Mostaghimi A. Temporal trends and clinician variability in potassium monitoring of healthy young women treated for acne with spironolactone. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:296-300.

- Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:37-50.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Arash Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:941-944.

- Barbieri JS, Margolis DJ, Mostaghimi A. Temporal trends and clinician variability in potassium monitoring of healthy young women treated for acne with spironolactone. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:296-300.

Administrative Burden of iPLEDGE Deters Isotretinoin Prescriptions: Results From a Survey of Dermatologists

Isotretinoin is the most effective treatment of recalcitrant acne, but because of its teratogenicity and potential association with psychiatric adverse effects, it has been heavily regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) through the iPLEDGE program since 2006.1,2 To manage the risk of teratogenicity associated with isotretinoin, various pregnancy prevention programs have been developed, but none of these programs have demonstrated a zero fetal exposure rate. The FDA reported 122 isotretinoin-exposed pregnancies during the first year iPLEDGE was implemented, which was a slight increase from the 120 pregnancies reported the year after the implementation of the System to Manage Accutane-Related Teratogenicity program, iPLEDGE’s predecessor.3 The iPLEDGE program requires registration of all wholesalers distributing isotretinoin, all health care providers prescribing isotretinoin, all pharmacies dispensing isotretinoin, and all female and male patients prescribed isotretinoin to create a verifiable link that only enables patients who have met all criteria to pick up their prescriptions. For patients of reproductive potential, there are additional qualification criteria and monthly requirements; before receiving their prescription every month, patients of reproductive potential must undergo a urine or serum pregnancy test with negative results, and patients must be counseled by prescribers regarding the risks of the drug and verify they are using 2 methods of contraception (or practicing abstinence) each month before completing online questions that test their understanding of the drug’s side effects and their chosen methods of contraception.4 These requirements place burdens on both patients and prescribers. Studies have shown that in the 2 years after the implementation of iPLEDGE, there was a 29% decrease in isotretinoin prescriptions.1-3

We conducted a survey study to see if clinicians chose not to prescribe isotretinoin to appropriate candidates specifically because of the administrative burden of iPLEDGE. Secondarily, we investigated the medications these clinicians would prescribe instead of isotretinoin.

Methods

In March 2020, we administered an anonymous online survey consisting of 12 multiple-choice questions to verified board-certified dermatologists in the United States using a social media group. The University of Rochester’s (Rochester, New York) institutional review board determined that our protocol met criteria for exemption (IRB STUDY00004693).

Statistical Analysis—Primary analyses used Pearson χ2 tests to identify significant differences among respondent groups, practice settings, age of respondents, and time spent registering patients for iPLEDGE.

Results

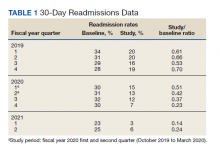

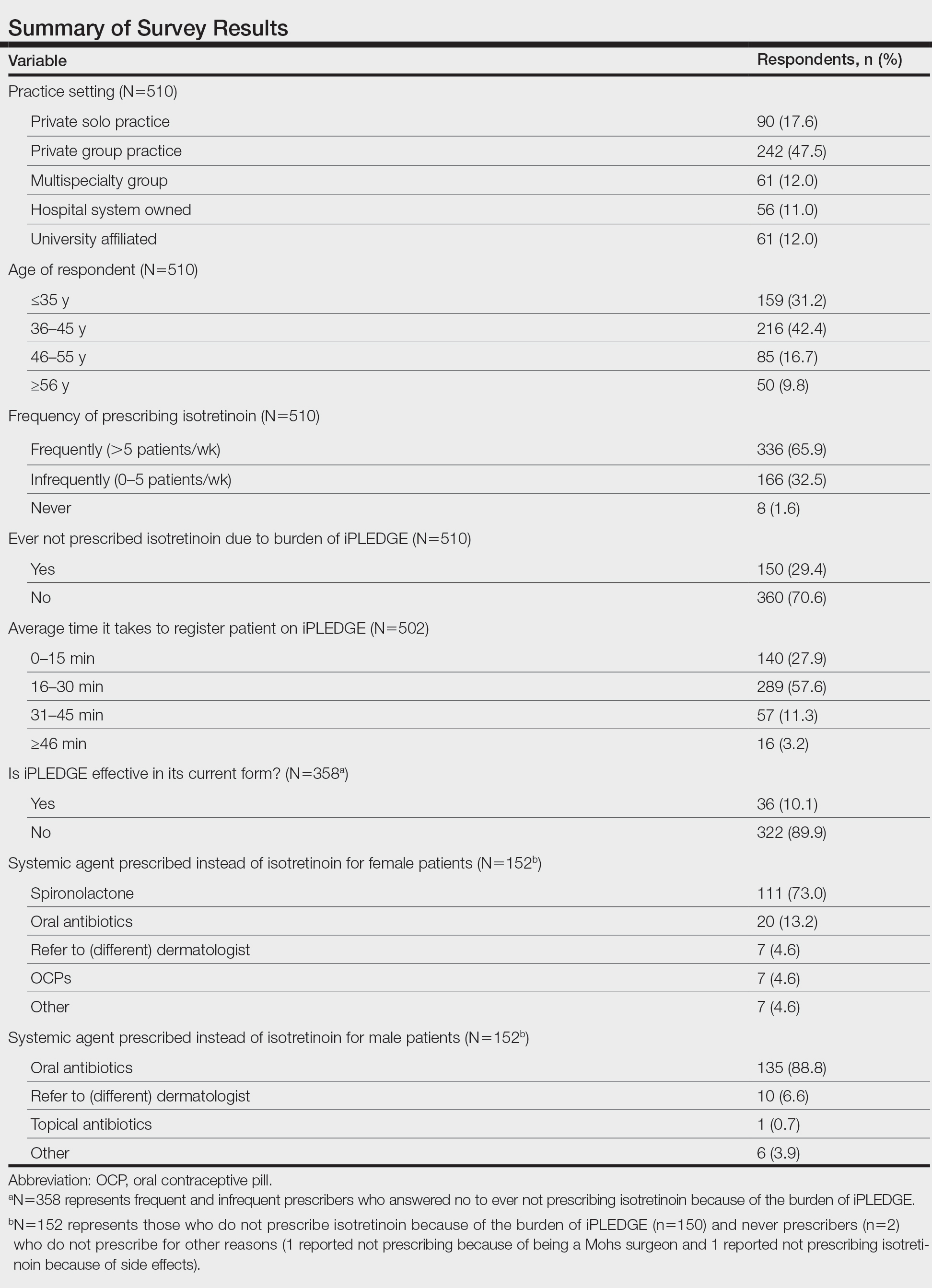

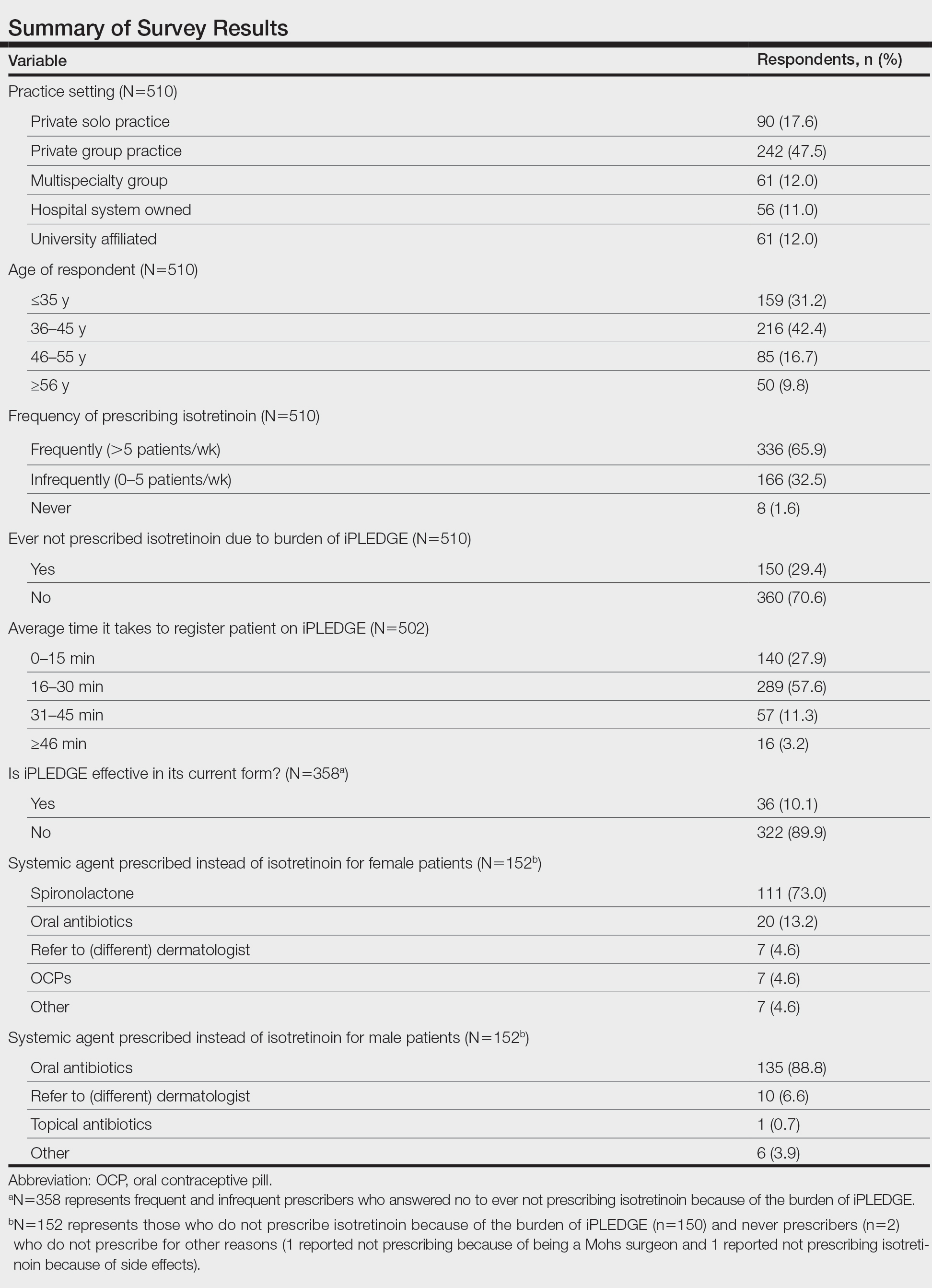

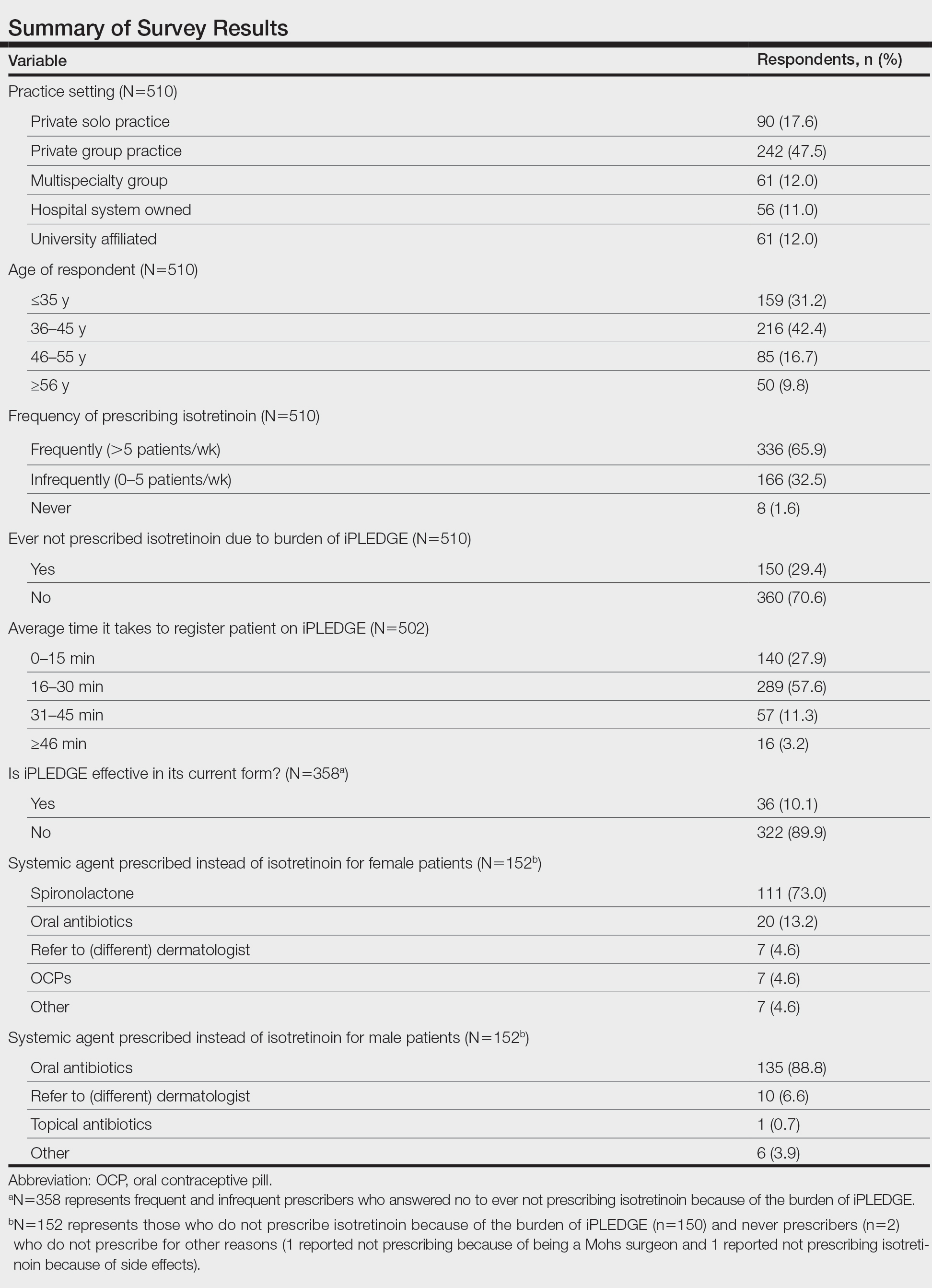

Survey results from 510 respondents are summarized in the Table.

Burden of iPLEDGE—Of the respondents, 336 (65.9%) were frequent prescribers of isotretinoin, 166 (32.5%) were infrequent prescribers, and 8 (1.6%) were never prescribers. Significantly more isotretinoin prescribers estimated that their offices spend 16 to 30 minutes registering a new isotretinoin patient with the iPLEDGE program (289 [57.6%]) compared with 0 to 15 minutes (140 [27.9%]), 31 to 45 minutes (57 [11.3%]), and morethan 45 minutes (16 [3.2%])(χ23=22.09, P<.0001). Furthermore, 150 dermatologists reported sometimes not prescribing, and 2 reported never prescribing isotretinoin because of the burden of iPLEDGE.

Systemic Agents Prescribed Instead of Isotretinoin—Of the respondents, 73.0% (n=111) prescribed spironolactone to female patients and 88.8% (n=135) prescribed oral antibiotics to male patients instead of isotretinoin. Spironolactone typically is not prescribed to male patients with acne because of its feminizing side effects, such as gynecomastia.5 According to the American Academy of Dermatology guidelines on acne, systemic antibiotic usage should be limited to the shortest possible duration (ie, less than 3–4 months) because of potential bacterial resistance and reported associations with inflammatory bowel disease, Clostridium difficile infection, and candidiasis.6,7

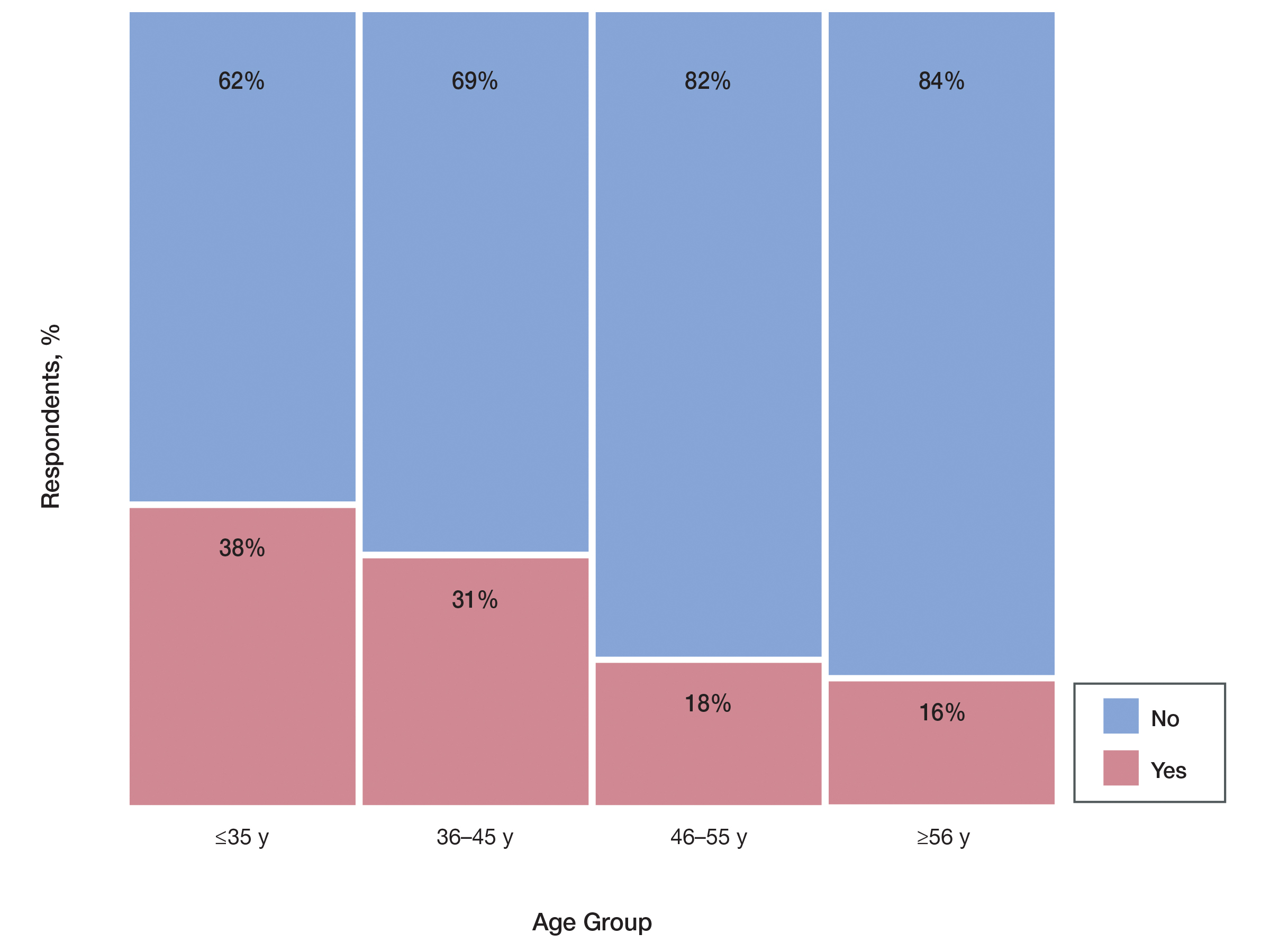

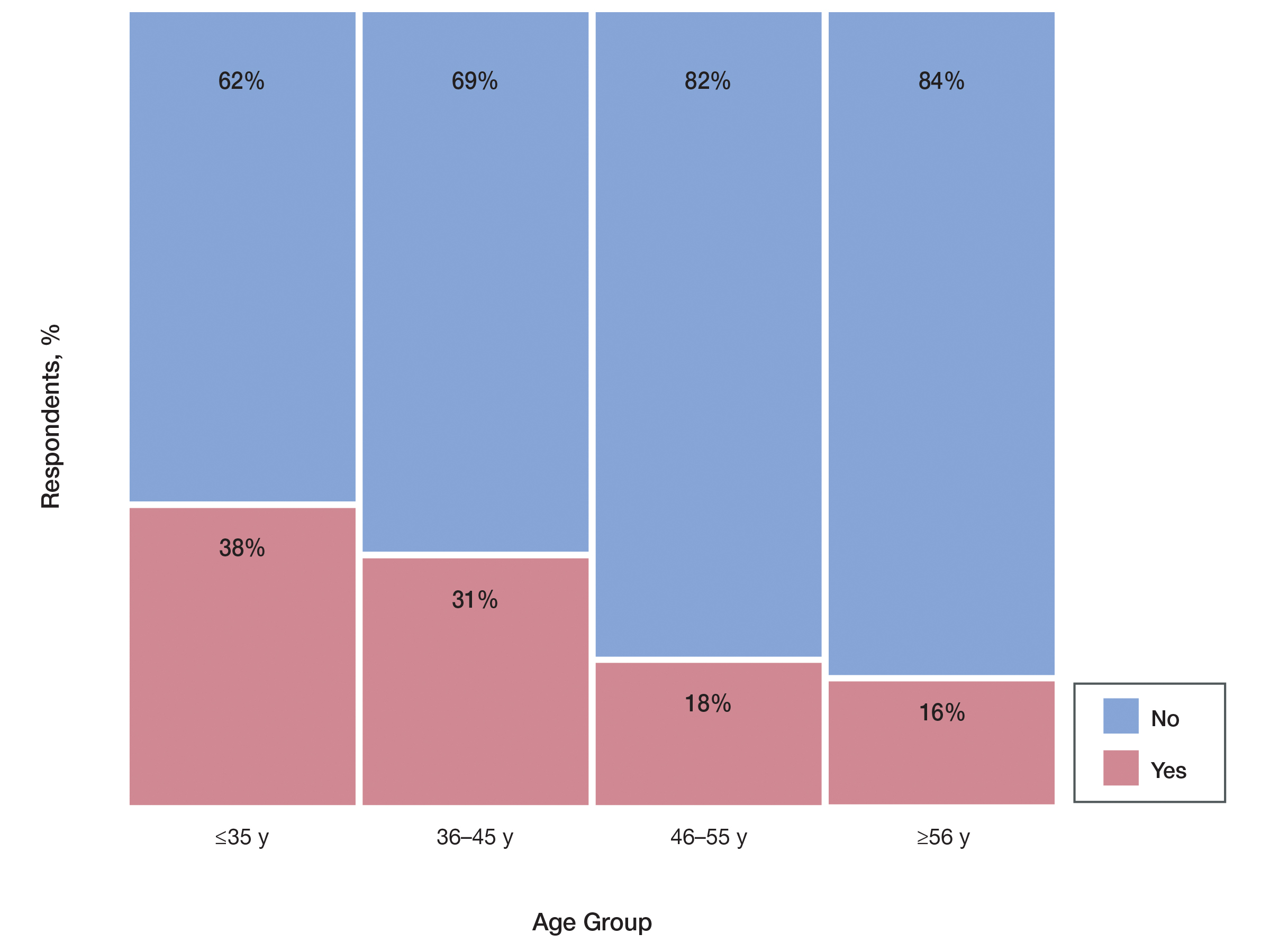

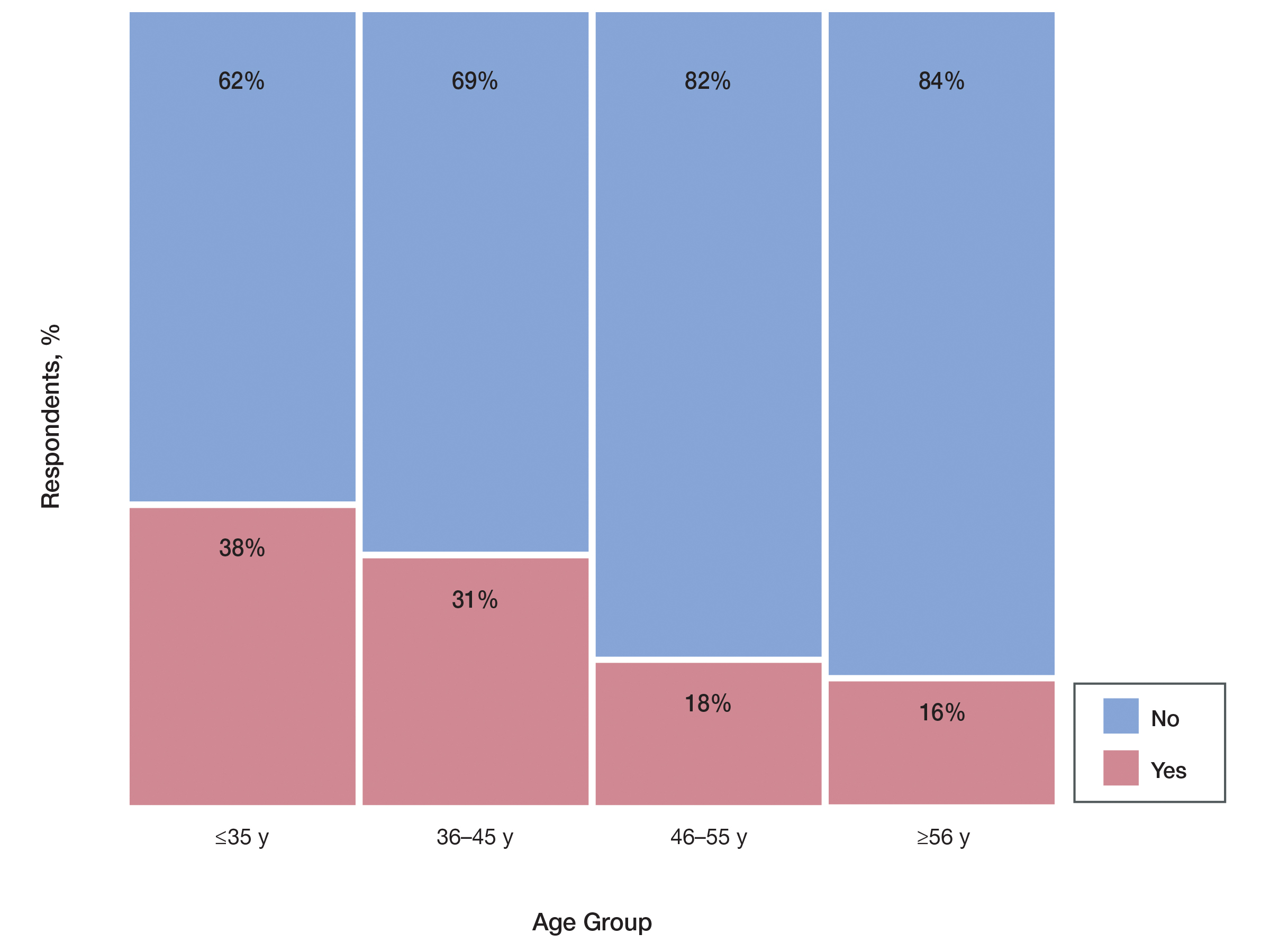

Prescriber Demographics—The frequency of not prescribing isotretinoin did not vary by practice setting (χ 24=6.44, P=.1689) but did vary by age of the dermatologist (χ23=15.57, P=.0014). Dermatologists younger than 46 years were more likely (Figure) to report not prescribing isotretinoin because of the administrative burden of iPLEDGE. We speculate that this is because younger dermatologists are less established in their practices and therefore may have less support to complete registration without interruption of clinic workflow.

Comment

The results of our survey suggest that the administrative burden of iPLEDGE may be compelling prescribers to refrain from prescribing isotretinoin therapy to appropriate candidates when it would otherwise be the drug of choice.

Recent Changes to iPLEDGE—The FDA recently approved a modification to the iPLEDGE Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program based on the advocacy efforts from the American Academy of Dermatology. Starting December 13, 2021, the 3 patient risk categories were consolidated into 2 gender-neutral categories: patients who can get pregnant and patients who cannot get pregnant.8 The iPLEDGE website was transitioned to a new system, and all iPLEDGE REMS users had to update their iPLEDGE accounts. After the implementation of the modified program, user access issues arose, leading to delayed treatment when patients, providers, and pharmacists were all locked out of the online system; users also experienced long hold times with the call center.8 This change highlights the ongoing critical need for a streamlined program that increases patient access to isotretinoin while maintaining safety.

Study Limitations—The main limitation of this study was the inability to calculate a true response rate to our survey. We distributed the survey via social media to maintain anonymity of the respondents. We could not track how many saw the link to compare with the number of respondents. Therefore, the only way we could calculate a response rate was with the total number of members in the group, which fluctuated around 4000 at the time we administered the survey. We calculated that we would need at least 351 responses to have a 5% margin of error at 95% confidence for our results to be generalizable and significant. We ultimately received 510 responses, which gave us a 4.05% margin of error at 95% confidence and an estimated 12.7% response rate. Since some members of the group are not active and did not see the survey link, our true response rate was likely higher. Therefore, we concluded that the survey was successful, and our significant responses were representative of US dermatologists.

Suggestions to Improve iPLEDGE Process—Our survey study should facilitate further discussions on the importance of simplifying iPLEDGE. One suggestion for improving iPLEDGE is to remove the initial registration month so care is not delayed. Currently, a patient who can get pregnant must be on 2 forms of contraception for 30 days after they register as a patient before they are eligible to fill their prescription.4 This process is unnecessarily long and arduous and could be eliminated as long as the patient has already been on an effective form of contraception and has a negative pregnancy test on the day of registration. The need to repeat contraception comprehension questions monthly is redundant and also could be removed. Another suggestion is to remove the category of patients who cannot become pregnant from the system entirely. Isotretinoin does not appear to be associated with adverse psychiatric effects as shown through the systematic review and meta-analysis of numerous studies.9 If anything, the treatment of acne with isotretinoin appears to mitigate depressive symptoms. The iPLEDGE program does not manage this largely debunked idea. Because the program’s sole goal is to manage the risk of isotretinoin’s teratogenicity, the category of those who cannot become pregnant should not be included.

Conclusion

This survey highlights the burdens of iPLEDGE for dermatologists and the need for a more streamlined risk management program. The burden was felt equally among all practice types but especially by younger dermatologists (<46 years). This time-consuming program is deterring some dermatologists from prescribing isotretinoin and ultimately limiting patient access to an effective medication.

Acknowledgment—The authors thank all of the responding clinicians who provided insight into the impact of iPLEDGE on their isotretinoin prescribing patterns.

- Prevost N, English JC. Isotretinoin: update on controversial issues. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:290-293.

- Tkachenko E, Singer S, Sharma P, et al. US Food and Drug Administration reports of pregnancy and pregnancy-related adverse events associated with isotretinoin. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1175-1179.

- Shin J, Cheetham TC, Wong L, et al. The impact of the IPLEDGE program on isotretinoin fetal exposure in an integrated health care system. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1117-1125.

- iPLEDGE Program. About iPLEDGE. Accessed June 13, 2022. https://ipledgeprogram.com/#Main/AboutiPledge

- Marson JW, Baldwin HE. An overview of acne therapy, part 2: hormonal therapy and isotretinoin. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:195-203.

- Margolis DJ, Fanelli M, Hoffstad O, et al. Potential association between the oral tetracycline class of antimicrobials used to treat acne and inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2610-2616.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.e33.

- iPLEDGE Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). Updated January 14, 2022. Accessed June 13, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/ipledge-risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategy-rems

- Huang YC, Cheng YC. Isotretinoin treatment for acne and risk of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1068-1076.e9.

Isotretinoin is the most effective treatment of recalcitrant acne, but because of its teratogenicity and potential association with psychiatric adverse effects, it has been heavily regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) through the iPLEDGE program since 2006.1,2 To manage the risk of teratogenicity associated with isotretinoin, various pregnancy prevention programs have been developed, but none of these programs have demonstrated a zero fetal exposure rate. The FDA reported 122 isotretinoin-exposed pregnancies during the first year iPLEDGE was implemented, which was a slight increase from the 120 pregnancies reported the year after the implementation of the System to Manage Accutane-Related Teratogenicity program, iPLEDGE’s predecessor.3 The iPLEDGE program requires registration of all wholesalers distributing isotretinoin, all health care providers prescribing isotretinoin, all pharmacies dispensing isotretinoin, and all female and male patients prescribed isotretinoin to create a verifiable link that only enables patients who have met all criteria to pick up their prescriptions. For patients of reproductive potential, there are additional qualification criteria and monthly requirements; before receiving their prescription every month, patients of reproductive potential must undergo a urine or serum pregnancy test with negative results, and patients must be counseled by prescribers regarding the risks of the drug and verify they are using 2 methods of contraception (or practicing abstinence) each month before completing online questions that test their understanding of the drug’s side effects and their chosen methods of contraception.4 These requirements place burdens on both patients and prescribers. Studies have shown that in the 2 years after the implementation of iPLEDGE, there was a 29% decrease in isotretinoin prescriptions.1-3

We conducted a survey study to see if clinicians chose not to prescribe isotretinoin to appropriate candidates specifically because of the administrative burden of iPLEDGE. Secondarily, we investigated the medications these clinicians would prescribe instead of isotretinoin.

Methods

In March 2020, we administered an anonymous online survey consisting of 12 multiple-choice questions to verified board-certified dermatologists in the United States using a social media group. The University of Rochester’s (Rochester, New York) institutional review board determined that our protocol met criteria for exemption (IRB STUDY00004693).

Statistical Analysis—Primary analyses used Pearson χ2 tests to identify significant differences among respondent groups, practice settings, age of respondents, and time spent registering patients for iPLEDGE.

Results

Survey results from 510 respondents are summarized in the Table.

Burden of iPLEDGE—Of the respondents, 336 (65.9%) were frequent prescribers of isotretinoin, 166 (32.5%) were infrequent prescribers, and 8 (1.6%) were never prescribers. Significantly more isotretinoin prescribers estimated that their offices spend 16 to 30 minutes registering a new isotretinoin patient with the iPLEDGE program (289 [57.6%]) compared with 0 to 15 minutes (140 [27.9%]), 31 to 45 minutes (57 [11.3%]), and morethan 45 minutes (16 [3.2%])(χ23=22.09, P<.0001). Furthermore, 150 dermatologists reported sometimes not prescribing, and 2 reported never prescribing isotretinoin because of the burden of iPLEDGE.

Systemic Agents Prescribed Instead of Isotretinoin—Of the respondents, 73.0% (n=111) prescribed spironolactone to female patients and 88.8% (n=135) prescribed oral antibiotics to male patients instead of isotretinoin. Spironolactone typically is not prescribed to male patients with acne because of its feminizing side effects, such as gynecomastia.5 According to the American Academy of Dermatology guidelines on acne, systemic antibiotic usage should be limited to the shortest possible duration (ie, less than 3–4 months) because of potential bacterial resistance and reported associations with inflammatory bowel disease, Clostridium difficile infection, and candidiasis.6,7

Prescriber Demographics—The frequency of not prescribing isotretinoin did not vary by practice setting (χ 24=6.44, P=.1689) but did vary by age of the dermatologist (χ23=15.57, P=.0014). Dermatologists younger than 46 years were more likely (Figure) to report not prescribing isotretinoin because of the administrative burden of iPLEDGE. We speculate that this is because younger dermatologists are less established in their practices and therefore may have less support to complete registration without interruption of clinic workflow.

Comment

The results of our survey suggest that the administrative burden of iPLEDGE may be compelling prescribers to refrain from prescribing isotretinoin therapy to appropriate candidates when it would otherwise be the drug of choice.

Recent Changes to iPLEDGE—The FDA recently approved a modification to the iPLEDGE Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program based on the advocacy efforts from the American Academy of Dermatology. Starting December 13, 2021, the 3 patient risk categories were consolidated into 2 gender-neutral categories: patients who can get pregnant and patients who cannot get pregnant.8 The iPLEDGE website was transitioned to a new system, and all iPLEDGE REMS users had to update their iPLEDGE accounts. After the implementation of the modified program, user access issues arose, leading to delayed treatment when patients, providers, and pharmacists were all locked out of the online system; users also experienced long hold times with the call center.8 This change highlights the ongoing critical need for a streamlined program that increases patient access to isotretinoin while maintaining safety.

Study Limitations—The main limitation of this study was the inability to calculate a true response rate to our survey. We distributed the survey via social media to maintain anonymity of the respondents. We could not track how many saw the link to compare with the number of respondents. Therefore, the only way we could calculate a response rate was with the total number of members in the group, which fluctuated around 4000 at the time we administered the survey. We calculated that we would need at least 351 responses to have a 5% margin of error at 95% confidence for our results to be generalizable and significant. We ultimately received 510 responses, which gave us a 4.05% margin of error at 95% confidence and an estimated 12.7% response rate. Since some members of the group are not active and did not see the survey link, our true response rate was likely higher. Therefore, we concluded that the survey was successful, and our significant responses were representative of US dermatologists.

Suggestions to Improve iPLEDGE Process—Our survey study should facilitate further discussions on the importance of simplifying iPLEDGE. One suggestion for improving iPLEDGE is to remove the initial registration month so care is not delayed. Currently, a patient who can get pregnant must be on 2 forms of contraception for 30 days after they register as a patient before they are eligible to fill their prescription.4 This process is unnecessarily long and arduous and could be eliminated as long as the patient has already been on an effective form of contraception and has a negative pregnancy test on the day of registration. The need to repeat contraception comprehension questions monthly is redundant and also could be removed. Another suggestion is to remove the category of patients who cannot become pregnant from the system entirely. Isotretinoin does not appear to be associated with adverse psychiatric effects as shown through the systematic review and meta-analysis of numerous studies.9 If anything, the treatment of acne with isotretinoin appears to mitigate depressive symptoms. The iPLEDGE program does not manage this largely debunked idea. Because the program’s sole goal is to manage the risk of isotretinoin’s teratogenicity, the category of those who cannot become pregnant should not be included.

Conclusion

This survey highlights the burdens of iPLEDGE for dermatologists and the need for a more streamlined risk management program. The burden was felt equally among all practice types but especially by younger dermatologists (<46 years). This time-consuming program is deterring some dermatologists from prescribing isotretinoin and ultimately limiting patient access to an effective medication.

Acknowledgment—The authors thank all of the responding clinicians who provided insight into the impact of iPLEDGE on their isotretinoin prescribing patterns.

Isotretinoin is the most effective treatment of recalcitrant acne, but because of its teratogenicity and potential association with psychiatric adverse effects, it has been heavily regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) through the iPLEDGE program since 2006.1,2 To manage the risk of teratogenicity associated with isotretinoin, various pregnancy prevention programs have been developed, but none of these programs have demonstrated a zero fetal exposure rate. The FDA reported 122 isotretinoin-exposed pregnancies during the first year iPLEDGE was implemented, which was a slight increase from the 120 pregnancies reported the year after the implementation of the System to Manage Accutane-Related Teratogenicity program, iPLEDGE’s predecessor.3 The iPLEDGE program requires registration of all wholesalers distributing isotretinoin, all health care providers prescribing isotretinoin, all pharmacies dispensing isotretinoin, and all female and male patients prescribed isotretinoin to create a verifiable link that only enables patients who have met all criteria to pick up their prescriptions. For patients of reproductive potential, there are additional qualification criteria and monthly requirements; before receiving their prescription every month, patients of reproductive potential must undergo a urine or serum pregnancy test with negative results, and patients must be counseled by prescribers regarding the risks of the drug and verify they are using 2 methods of contraception (or practicing abstinence) each month before completing online questions that test their understanding of the drug’s side effects and their chosen methods of contraception.4 These requirements place burdens on both patients and prescribers. Studies have shown that in the 2 years after the implementation of iPLEDGE, there was a 29% decrease in isotretinoin prescriptions.1-3

We conducted a survey study to see if clinicians chose not to prescribe isotretinoin to appropriate candidates specifically because of the administrative burden of iPLEDGE. Secondarily, we investigated the medications these clinicians would prescribe instead of isotretinoin.

Methods

In March 2020, we administered an anonymous online survey consisting of 12 multiple-choice questions to verified board-certified dermatologists in the United States using a social media group. The University of Rochester’s (Rochester, New York) institutional review board determined that our protocol met criteria for exemption (IRB STUDY00004693).

Statistical Analysis—Primary analyses used Pearson χ2 tests to identify significant differences among respondent groups, practice settings, age of respondents, and time spent registering patients for iPLEDGE.

Results

Survey results from 510 respondents are summarized in the Table.

Burden of iPLEDGE—Of the respondents, 336 (65.9%) were frequent prescribers of isotretinoin, 166 (32.5%) were infrequent prescribers, and 8 (1.6%) were never prescribers. Significantly more isotretinoin prescribers estimated that their offices spend 16 to 30 minutes registering a new isotretinoin patient with the iPLEDGE program (289 [57.6%]) compared with 0 to 15 minutes (140 [27.9%]), 31 to 45 minutes (57 [11.3%]), and morethan 45 minutes (16 [3.2%])(χ23=22.09, P<.0001). Furthermore, 150 dermatologists reported sometimes not prescribing, and 2 reported never prescribing isotretinoin because of the burden of iPLEDGE.

Systemic Agents Prescribed Instead of Isotretinoin—Of the respondents, 73.0% (n=111) prescribed spironolactone to female patients and 88.8% (n=135) prescribed oral antibiotics to male patients instead of isotretinoin. Spironolactone typically is not prescribed to male patients with acne because of its feminizing side effects, such as gynecomastia.5 According to the American Academy of Dermatology guidelines on acne, systemic antibiotic usage should be limited to the shortest possible duration (ie, less than 3–4 months) because of potential bacterial resistance and reported associations with inflammatory bowel disease, Clostridium difficile infection, and candidiasis.6,7

Prescriber Demographics—The frequency of not prescribing isotretinoin did not vary by practice setting (χ 24=6.44, P=.1689) but did vary by age of the dermatologist (χ23=15.57, P=.0014). Dermatologists younger than 46 years were more likely (Figure) to report not prescribing isotretinoin because of the administrative burden of iPLEDGE. We speculate that this is because younger dermatologists are less established in their practices and therefore may have less support to complete registration without interruption of clinic workflow.

Comment

The results of our survey suggest that the administrative burden of iPLEDGE may be compelling prescribers to refrain from prescribing isotretinoin therapy to appropriate candidates when it would otherwise be the drug of choice.

Recent Changes to iPLEDGE—The FDA recently approved a modification to the iPLEDGE Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program based on the advocacy efforts from the American Academy of Dermatology. Starting December 13, 2021, the 3 patient risk categories were consolidated into 2 gender-neutral categories: patients who can get pregnant and patients who cannot get pregnant.8 The iPLEDGE website was transitioned to a new system, and all iPLEDGE REMS users had to update their iPLEDGE accounts. After the implementation of the modified program, user access issues arose, leading to delayed treatment when patients, providers, and pharmacists were all locked out of the online system; users also experienced long hold times with the call center.8 This change highlights the ongoing critical need for a streamlined program that increases patient access to isotretinoin while maintaining safety.

Study Limitations—The main limitation of this study was the inability to calculate a true response rate to our survey. We distributed the survey via social media to maintain anonymity of the respondents. We could not track how many saw the link to compare with the number of respondents. Therefore, the only way we could calculate a response rate was with the total number of members in the group, which fluctuated around 4000 at the time we administered the survey. We calculated that we would need at least 351 responses to have a 5% margin of error at 95% confidence for our results to be generalizable and significant. We ultimately received 510 responses, which gave us a 4.05% margin of error at 95% confidence and an estimated 12.7% response rate. Since some members of the group are not active and did not see the survey link, our true response rate was likely higher. Therefore, we concluded that the survey was successful, and our significant responses were representative of US dermatologists.

Suggestions to Improve iPLEDGE Process—Our survey study should facilitate further discussions on the importance of simplifying iPLEDGE. One suggestion for improving iPLEDGE is to remove the initial registration month so care is not delayed. Currently, a patient who can get pregnant must be on 2 forms of contraception for 30 days after they register as a patient before they are eligible to fill their prescription.4 This process is unnecessarily long and arduous and could be eliminated as long as the patient has already been on an effective form of contraception and has a negative pregnancy test on the day of registration. The need to repeat contraception comprehension questions monthly is redundant and also could be removed. Another suggestion is to remove the category of patients who cannot become pregnant from the system entirely. Isotretinoin does not appear to be associated with adverse psychiatric effects as shown through the systematic review and meta-analysis of numerous studies.9 If anything, the treatment of acne with isotretinoin appears to mitigate depressive symptoms. The iPLEDGE program does not manage this largely debunked idea. Because the program’s sole goal is to manage the risk of isotretinoin’s teratogenicity, the category of those who cannot become pregnant should not be included.

Conclusion

This survey highlights the burdens of iPLEDGE for dermatologists and the need for a more streamlined risk management program. The burden was felt equally among all practice types but especially by younger dermatologists (<46 years). This time-consuming program is deterring some dermatologists from prescribing isotretinoin and ultimately limiting patient access to an effective medication.

Acknowledgment—The authors thank all of the responding clinicians who provided insight into the impact of iPLEDGE on their isotretinoin prescribing patterns.

- Prevost N, English JC. Isotretinoin: update on controversial issues. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:290-293.

- Tkachenko E, Singer S, Sharma P, et al. US Food and Drug Administration reports of pregnancy and pregnancy-related adverse events associated with isotretinoin. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1175-1179.

- Shin J, Cheetham TC, Wong L, et al. The impact of the IPLEDGE program on isotretinoin fetal exposure in an integrated health care system. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1117-1125.

- iPLEDGE Program. About iPLEDGE. Accessed June 13, 2022. https://ipledgeprogram.com/#Main/AboutiPledge

- Marson JW, Baldwin HE. An overview of acne therapy, part 2: hormonal therapy and isotretinoin. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:195-203.

- Margolis DJ, Fanelli M, Hoffstad O, et al. Potential association between the oral tetracycline class of antimicrobials used to treat acne and inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2610-2616.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.e33.

- iPLEDGE Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). Updated January 14, 2022. Accessed June 13, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/ipledge-risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategy-rems

- Huang YC, Cheng YC. Isotretinoin treatment for acne and risk of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1068-1076.e9.

- Prevost N, English JC. Isotretinoin: update on controversial issues. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:290-293.

- Tkachenko E, Singer S, Sharma P, et al. US Food and Drug Administration reports of pregnancy and pregnancy-related adverse events associated with isotretinoin. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1175-1179.

- Shin J, Cheetham TC, Wong L, et al. The impact of the IPLEDGE program on isotretinoin fetal exposure in an integrated health care system. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1117-1125.

- iPLEDGE Program. About iPLEDGE. Accessed June 13, 2022. https://ipledgeprogram.com/#Main/AboutiPledge

- Marson JW, Baldwin HE. An overview of acne therapy, part 2: hormonal therapy and isotretinoin. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:195-203.

- Margolis DJ, Fanelli M, Hoffstad O, et al. Potential association between the oral tetracycline class of antimicrobials used to treat acne and inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2610-2616.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.e33.

- iPLEDGE Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). Updated January 14, 2022. Accessed June 13, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/ipledge-risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategy-rems

- Huang YC, Cheng YC. Isotretinoin treatment for acne and risk of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1068-1076.e9.

Practice Points

- Of clinicians who regularly prescribe isotretinoin, approximately 30% have at times chosen not to prescribe isotretinoin to patients with severe acne because of the burden of the iPLEDGE program.

- The US Food and Drug Administration should consider further streamlining the iPLEDGE program, as it is causing physician burden and therefore suboptimal treatment plans for patients.

Simple Intraoperative Technique to Improve Wound Edge Approximation for Residents

Practice Gap

Dermatology residents can struggle with surgical closure early in their training years. Although experienced dermatologic surgeons may intuitively be able to align edges for maximal cosmesis, doing so can prove challenging in the context of learning basic surgical techniques for early residents.

Furthermore, local anesthesia can distort cutaneous anatomy and surgical landmarks, requiring the surgeon to reexamine their closure technique. Patients may require position changes or may make involuntary movements, both of which require dynamic thinking and planning on the part of the dermatologic surgeon to achieve optimal outcomes.

The Technique

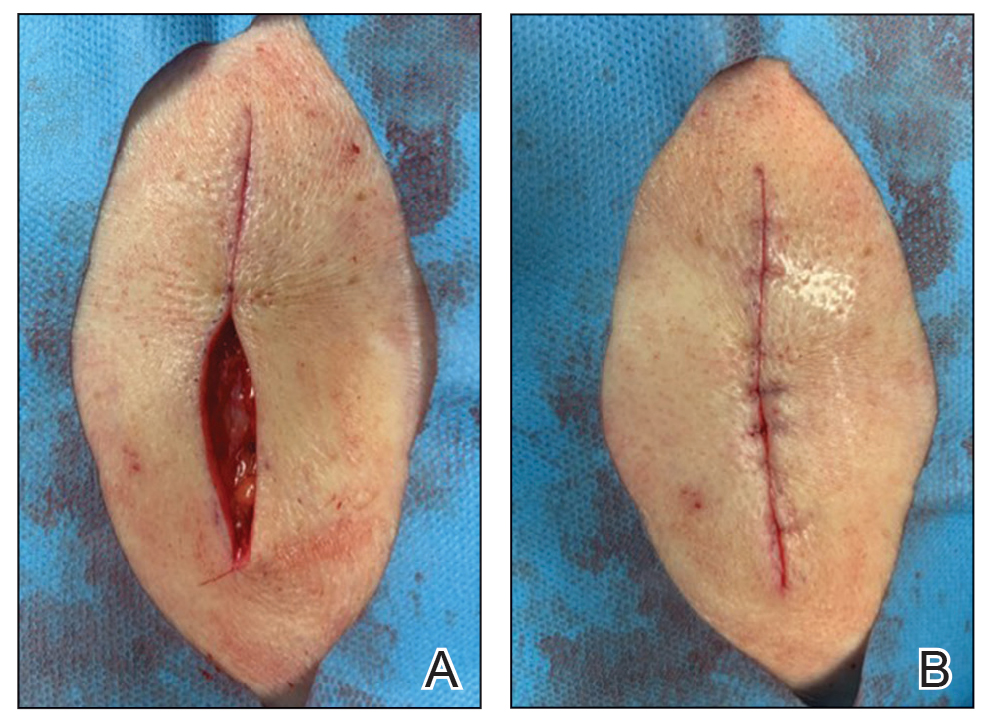

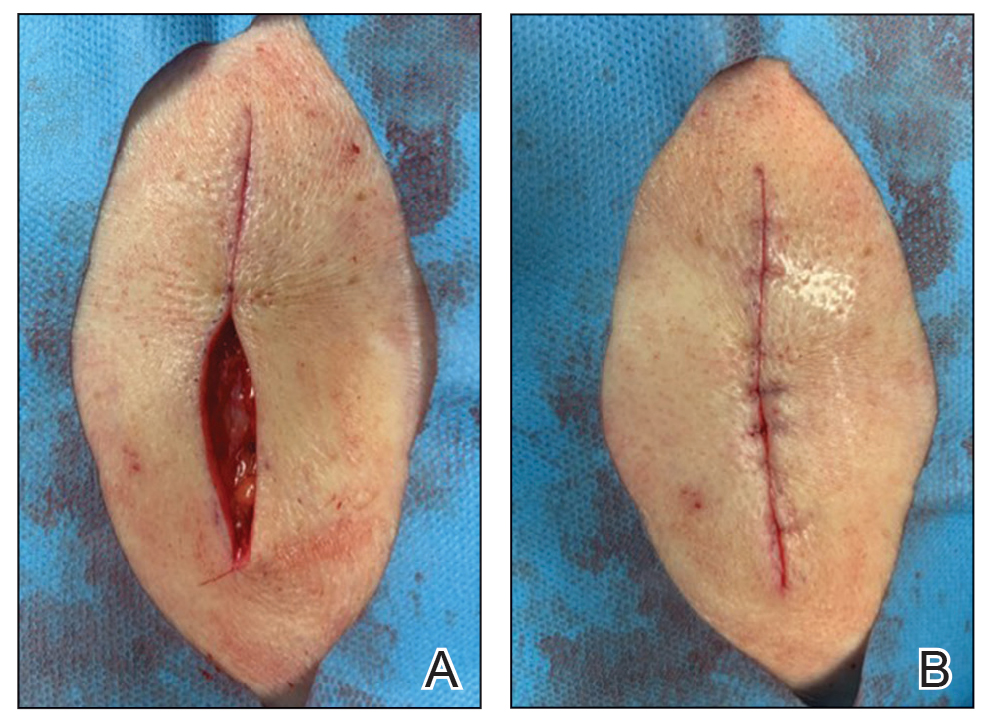

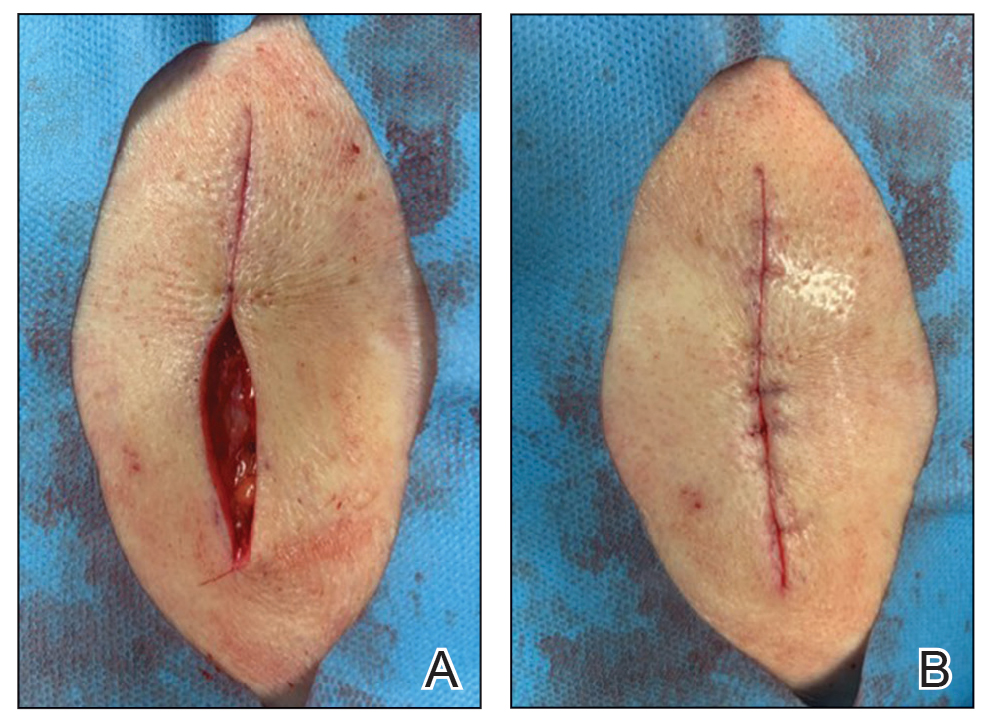

We propose the use of sutures to intraoperatively guide placement of the dermal needle. This technique can be used for various closure types; here, we demonstrate its use in a standard elliptical excision.

To begin, a standard length to width ellipse ratio of 3:1 is drawn with appropriate margins around a neoplasm.1 After excision and appropriate undermining of the ellipse, we typically use deep sutures to close the deep space. The first pass of the needle through tissue can be performed in a place of the surgeon’s preference but typically abides by the rule of halves or the zipper method (Figure 1A). To determine optimal placement of the second needle pass through tissue, we recommend applying gentle opposing traction forces to the wound apices to approximate the linear outcome of the wound edges. The surgeon can use a skin hook to guide placement of the needle to the contralateral wound edge in an unassisted method of this technique (Figure 1B). The surgeon’s assistant also can aid in applying cutaneous traction along the length of the excision if the surgeon wishes to free their hands (Figure 1C). Because the risk of needlestick injury at this step is small, it is prudent for the surgeon to advise the assistant to avoid needlestick injury by keeping their hands away from the needle path in the surgical site.

Although traction is being applied to the wound apices, the deep suture should extend across the wound with just enough pressure to leave a serosanguineous notched mark in the contralateral tissue edge (Figure 1D). After releasing traction on the wound edges, the surgeon can effortlessly visualize the target for needle placement and make a throw through the tissue accordingly.

This process can be continued until wound closure is complete (Figure 2). Top sutures or adhesive strips can be placed afterward for completing approximation of the wound edges superficially.

Practice Implications

By using this technique to align wound edges intraoperatively, the surgeon can have a functional guide for needle placement. The technique allows improvement of function and cosmesis of surgical wounds, while also accounting for topographical variations in the patient’s surgical site. Approximation of the wound edges is particularly important at the beginning of closure, as the wound edges align and approximate more with each subsequent stitch, with decreasing tension.2

In addition, when operating on a curvilinear or challenging topographical surface of the body, this technique can provide a clear template for guiding suture placement for approximating wound edges. Furthermore, local biodynamic anatomy might become distorted after excision of the tissue specimen due to release of centripetal tangential forces that were present in the pre-excised skin.1 Local change in biodynamic forces may be difficult to plan for preoperatively using other techniques.3

Although this technique can be utilized for all suture placements in closure, it is of greatest value when placing the first few sutures and when operating on nonplanar surfaces that might become distorted after excision. To ensure the best outcome, it is important to be certain that the area has been properly cleaned prior to surgery and a sterile technique is used.

- Paul SP. Biodynamic excisional skin tension lines for excisional surgery of the lower limb and the technique of using parallel relaxing incisions to further reduce wound tension. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5:E1614. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000001614

- Miller CJ, Antunes MB, Sobanko JF. Surgical technique for optimal outcomes: part II. repairing tissue: suturing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:389-402. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.006

- Parikh SA, Sloan B. Clinical pearl: a simple and effective technique for improving surgical closures for the early-learning resident. Cutis. 2017;100:338-339.

Practice Gap

Dermatology residents can struggle with surgical closure early in their training years. Although experienced dermatologic surgeons may intuitively be able to align edges for maximal cosmesis, doing so can prove challenging in the context of learning basic surgical techniques for early residents.

Furthermore, local anesthesia can distort cutaneous anatomy and surgical landmarks, requiring the surgeon to reexamine their closure technique. Patients may require position changes or may make involuntary movements, both of which require dynamic thinking and planning on the part of the dermatologic surgeon to achieve optimal outcomes.

The Technique

We propose the use of sutures to intraoperatively guide placement of the dermal needle. This technique can be used for various closure types; here, we demonstrate its use in a standard elliptical excision.

To begin, a standard length to width ellipse ratio of 3:1 is drawn with appropriate margins around a neoplasm.1 After excision and appropriate undermining of the ellipse, we typically use deep sutures to close the deep space. The first pass of the needle through tissue can be performed in a place of the surgeon’s preference but typically abides by the rule of halves or the zipper method (Figure 1A). To determine optimal placement of the second needle pass through tissue, we recommend applying gentle opposing traction forces to the wound apices to approximate the linear outcome of the wound edges. The surgeon can use a skin hook to guide placement of the needle to the contralateral wound edge in an unassisted method of this technique (Figure 1B). The surgeon’s assistant also can aid in applying cutaneous traction along the length of the excision if the surgeon wishes to free their hands (Figure 1C). Because the risk of needlestick injury at this step is small, it is prudent for the surgeon to advise the assistant to avoid needlestick injury by keeping their hands away from the needle path in the surgical site.

Although traction is being applied to the wound apices, the deep suture should extend across the wound with just enough pressure to leave a serosanguineous notched mark in the contralateral tissue edge (Figure 1D). After releasing traction on the wound edges, the surgeon can effortlessly visualize the target for needle placement and make a throw through the tissue accordingly.

This process can be continued until wound closure is complete (Figure 2). Top sutures or adhesive strips can be placed afterward for completing approximation of the wound edges superficially.

Practice Implications

By using this technique to align wound edges intraoperatively, the surgeon can have a functional guide for needle placement. The technique allows improvement of function and cosmesis of surgical wounds, while also accounting for topographical variations in the patient’s surgical site. Approximation of the wound edges is particularly important at the beginning of closure, as the wound edges align and approximate more with each subsequent stitch, with decreasing tension.2

In addition, when operating on a curvilinear or challenging topographical surface of the body, this technique can provide a clear template for guiding suture placement for approximating wound edges. Furthermore, local biodynamic anatomy might become distorted after excision of the tissue specimen due to release of centripetal tangential forces that were present in the pre-excised skin.1 Local change in biodynamic forces may be difficult to plan for preoperatively using other techniques.3

Although this technique can be utilized for all suture placements in closure, it is of greatest value when placing the first few sutures and when operating on nonplanar surfaces that might become distorted after excision. To ensure the best outcome, it is important to be certain that the area has been properly cleaned prior to surgery and a sterile technique is used.

Practice Gap

Dermatology residents can struggle with surgical closure early in their training years. Although experienced dermatologic surgeons may intuitively be able to align edges for maximal cosmesis, doing so can prove challenging in the context of learning basic surgical techniques for early residents.

Furthermore, local anesthesia can distort cutaneous anatomy and surgical landmarks, requiring the surgeon to reexamine their closure technique. Patients may require position changes or may make involuntary movements, both of which require dynamic thinking and planning on the part of the dermatologic surgeon to achieve optimal outcomes.

The Technique

We propose the use of sutures to intraoperatively guide placement of the dermal needle. This technique can be used for various closure types; here, we demonstrate its use in a standard elliptical excision.

To begin, a standard length to width ellipse ratio of 3:1 is drawn with appropriate margins around a neoplasm.1 After excision and appropriate undermining of the ellipse, we typically use deep sutures to close the deep space. The first pass of the needle through tissue can be performed in a place of the surgeon’s preference but typically abides by the rule of halves or the zipper method (Figure 1A). To determine optimal placement of the second needle pass through tissue, we recommend applying gentle opposing traction forces to the wound apices to approximate the linear outcome of the wound edges. The surgeon can use a skin hook to guide placement of the needle to the contralateral wound edge in an unassisted method of this technique (Figure 1B). The surgeon’s assistant also can aid in applying cutaneous traction along the length of the excision if the surgeon wishes to free their hands (Figure 1C). Because the risk of needlestick injury at this step is small, it is prudent for the surgeon to advise the assistant to avoid needlestick injury by keeping their hands away from the needle path in the surgical site.

Although traction is being applied to the wound apices, the deep suture should extend across the wound with just enough pressure to leave a serosanguineous notched mark in the contralateral tissue edge (Figure 1D). After releasing traction on the wound edges, the surgeon can effortlessly visualize the target for needle placement and make a throw through the tissue accordingly.

This process can be continued until wound closure is complete (Figure 2). Top sutures or adhesive strips can be placed afterward for completing approximation of the wound edges superficially.

Practice Implications

By using this technique to align wound edges intraoperatively, the surgeon can have a functional guide for needle placement. The technique allows improvement of function and cosmesis of surgical wounds, while also accounting for topographical variations in the patient’s surgical site. Approximation of the wound edges is particularly important at the beginning of closure, as the wound edges align and approximate more with each subsequent stitch, with decreasing tension.2

In addition, when operating on a curvilinear or challenging topographical surface of the body, this technique can provide a clear template for guiding suture placement for approximating wound edges. Furthermore, local biodynamic anatomy might become distorted after excision of the tissue specimen due to release of centripetal tangential forces that were present in the pre-excised skin.1 Local change in biodynamic forces may be difficult to plan for preoperatively using other techniques.3

Although this technique can be utilized for all suture placements in closure, it is of greatest value when placing the first few sutures and when operating on nonplanar surfaces that might become distorted after excision. To ensure the best outcome, it is important to be certain that the area has been properly cleaned prior to surgery and a sterile technique is used.

- Paul SP. Biodynamic excisional skin tension lines for excisional surgery of the lower limb and the technique of using parallel relaxing incisions to further reduce wound tension. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5:E1614. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000001614

- Miller CJ, Antunes MB, Sobanko JF. Surgical technique for optimal outcomes: part II. repairing tissue: suturing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:389-402. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.006

- Parikh SA, Sloan B. Clinical pearl: a simple and effective technique for improving surgical closures for the early-learning resident. Cutis. 2017;100:338-339.

- Paul SP. Biodynamic excisional skin tension lines for excisional surgery of the lower limb and the technique of using parallel relaxing incisions to further reduce wound tension. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5:E1614. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000001614

- Miller CJ, Antunes MB, Sobanko JF. Surgical technique for optimal outcomes: part II. repairing tissue: suturing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:389-402. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.006

- Parikh SA, Sloan B. Clinical pearl: a simple and effective technique for improving surgical closures for the early-learning resident. Cutis. 2017;100:338-339.

Itchy Vesicular Rash

The Diagnosis: Tinea Corporis Bullosa

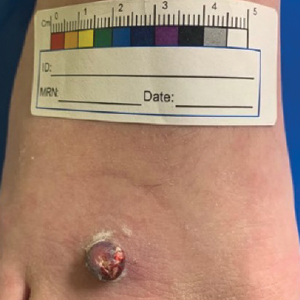

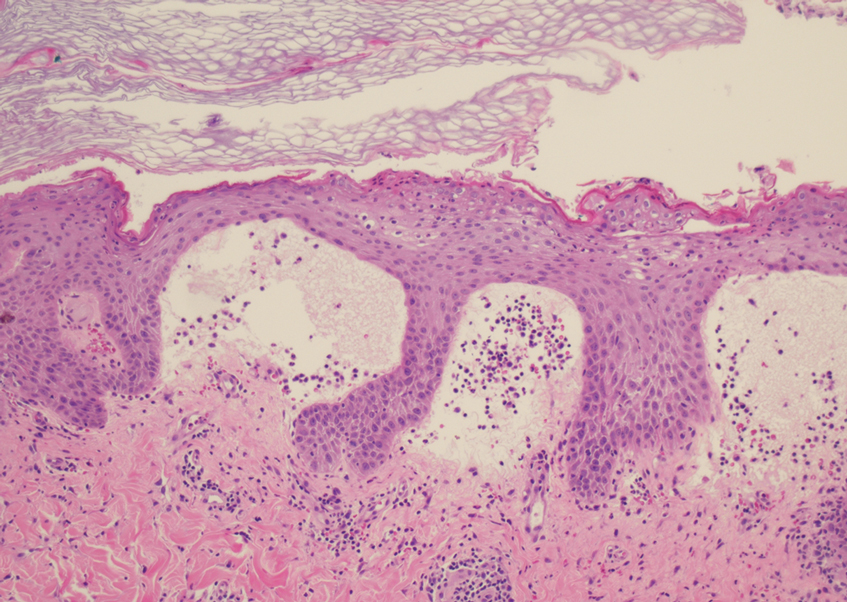

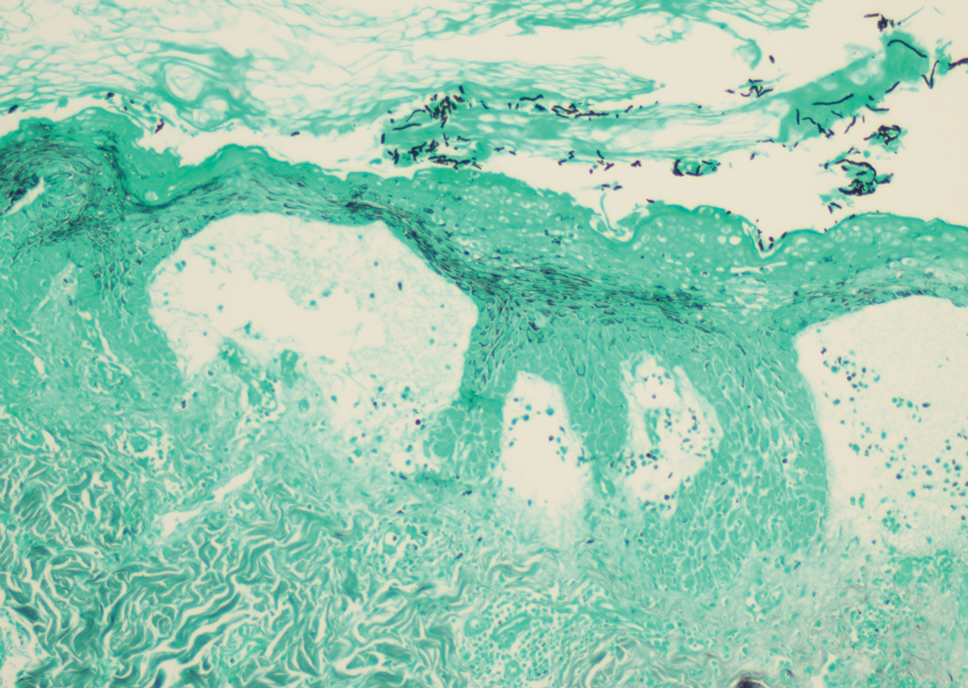

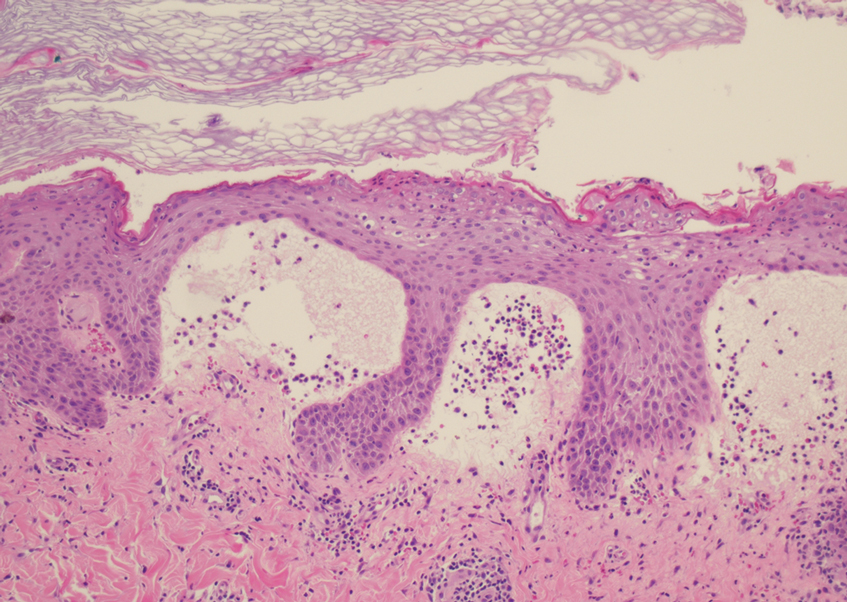

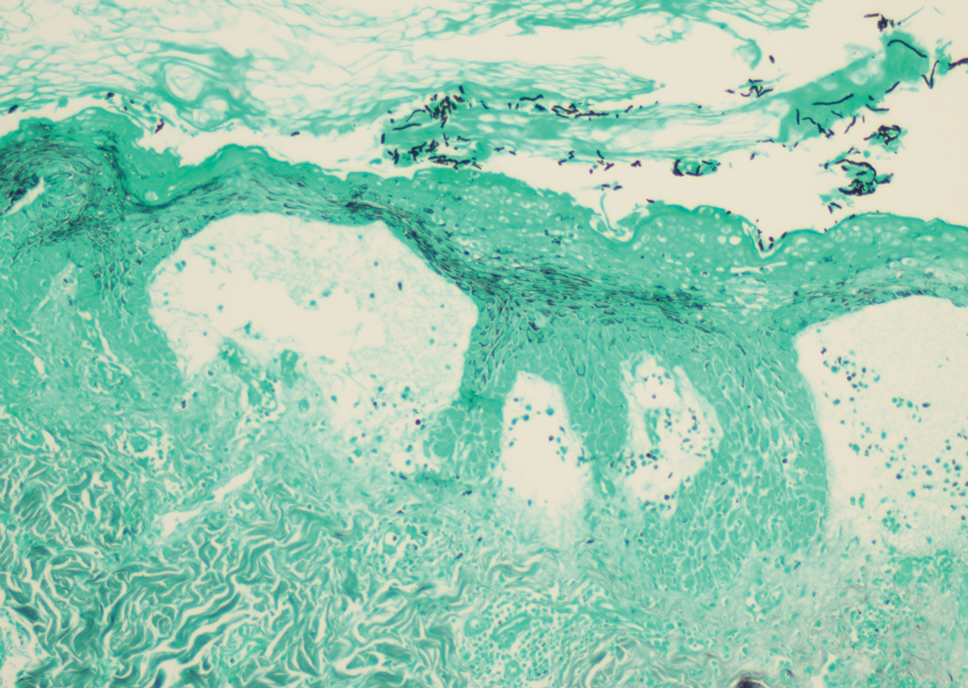

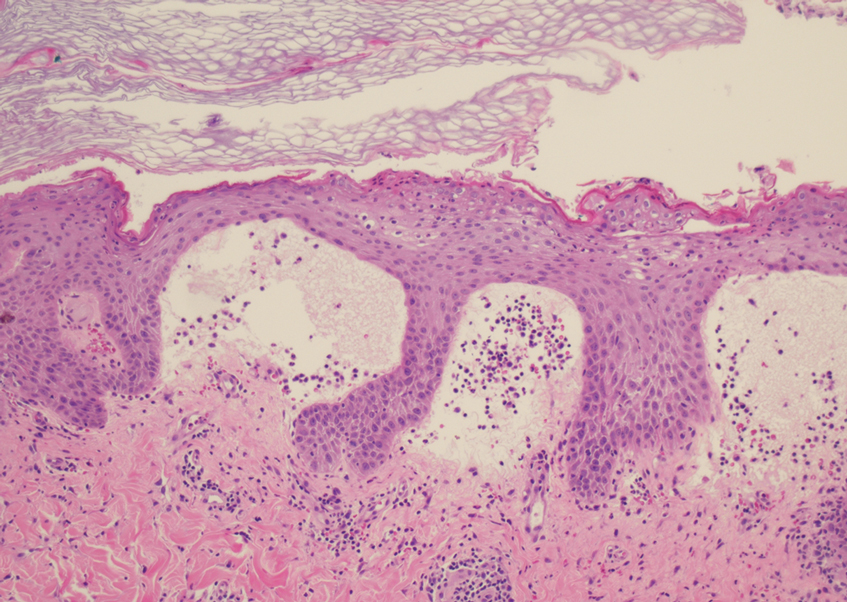

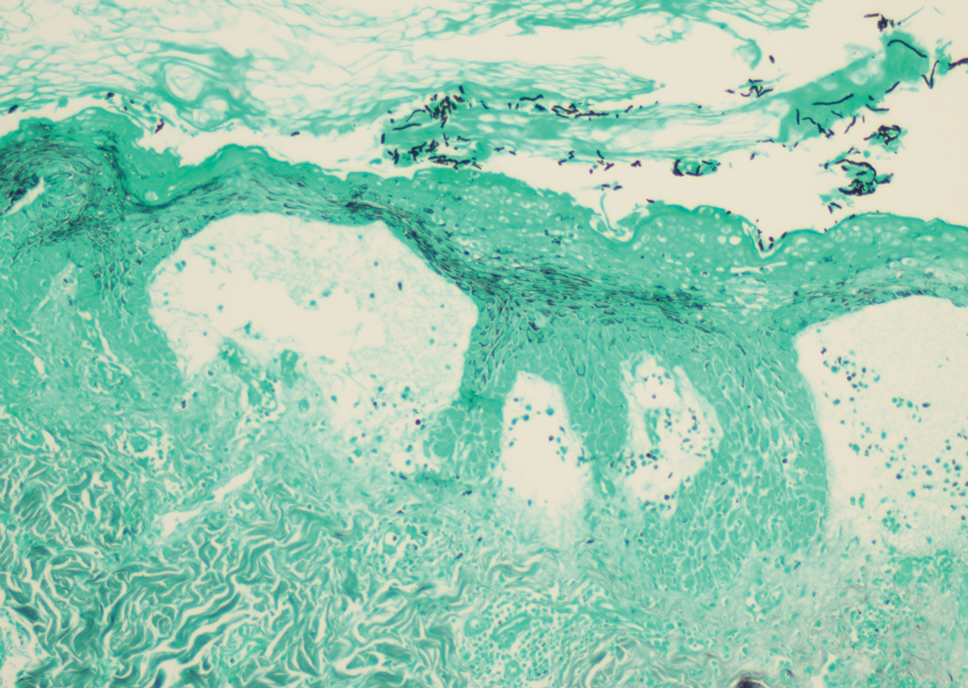

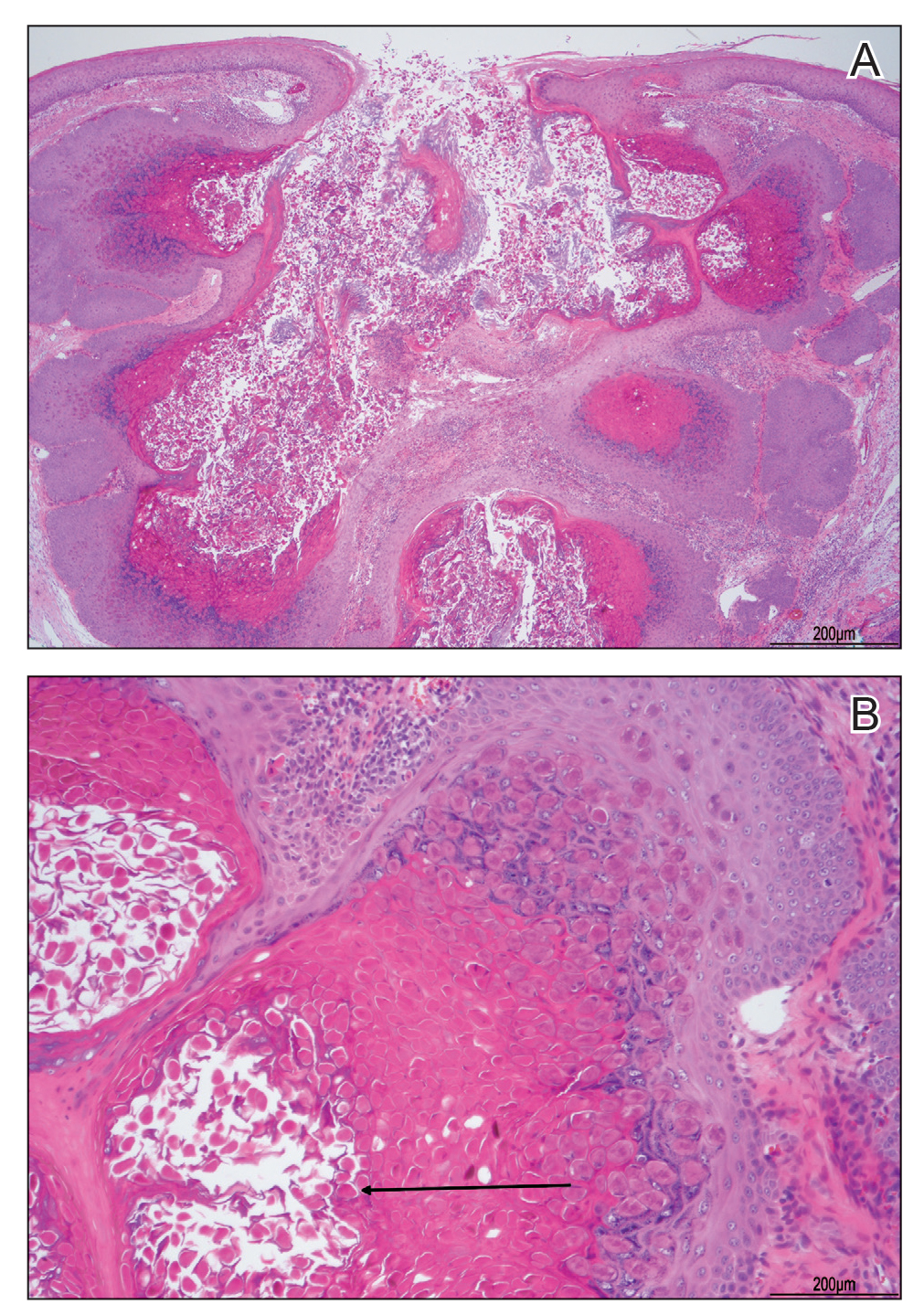

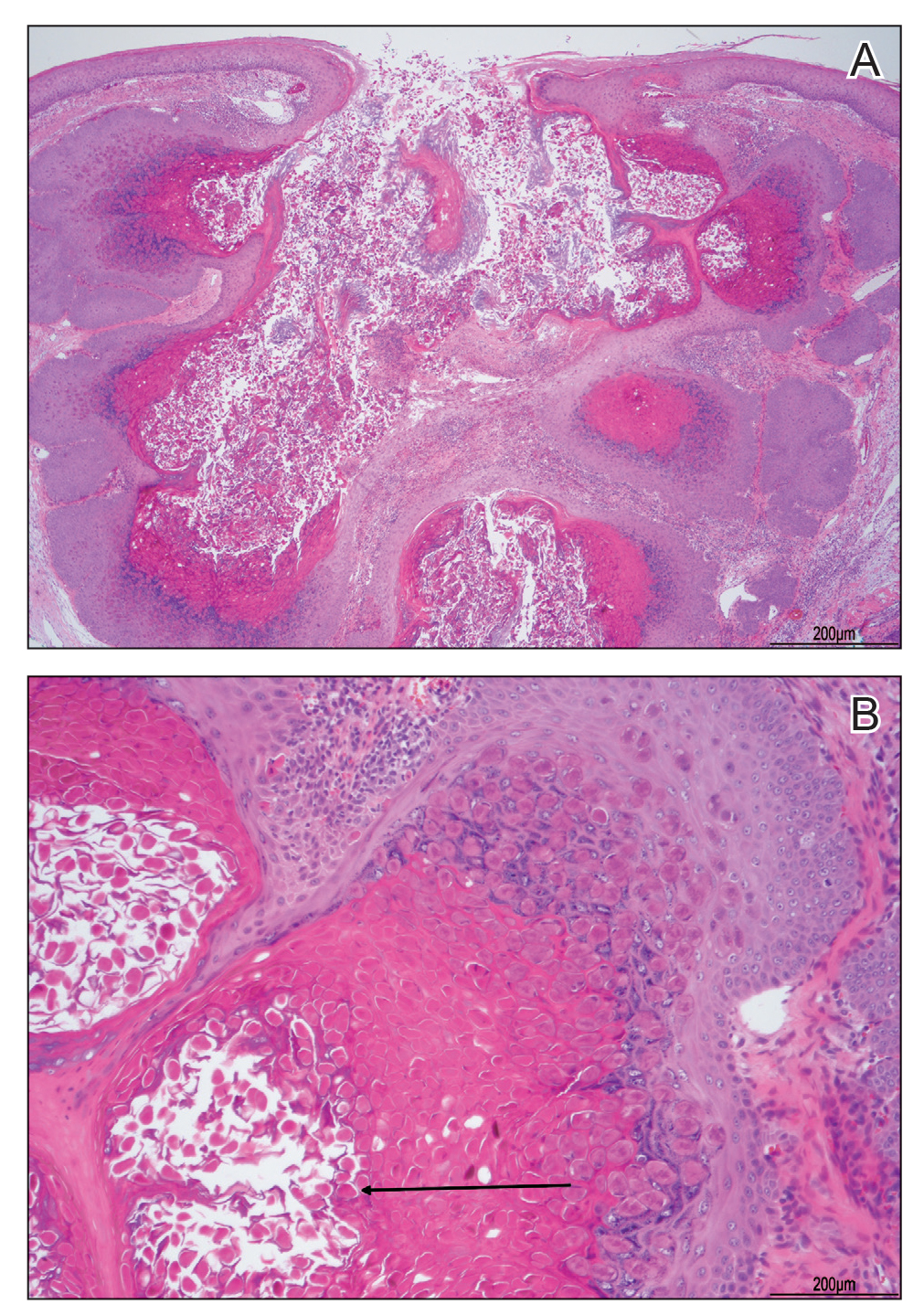

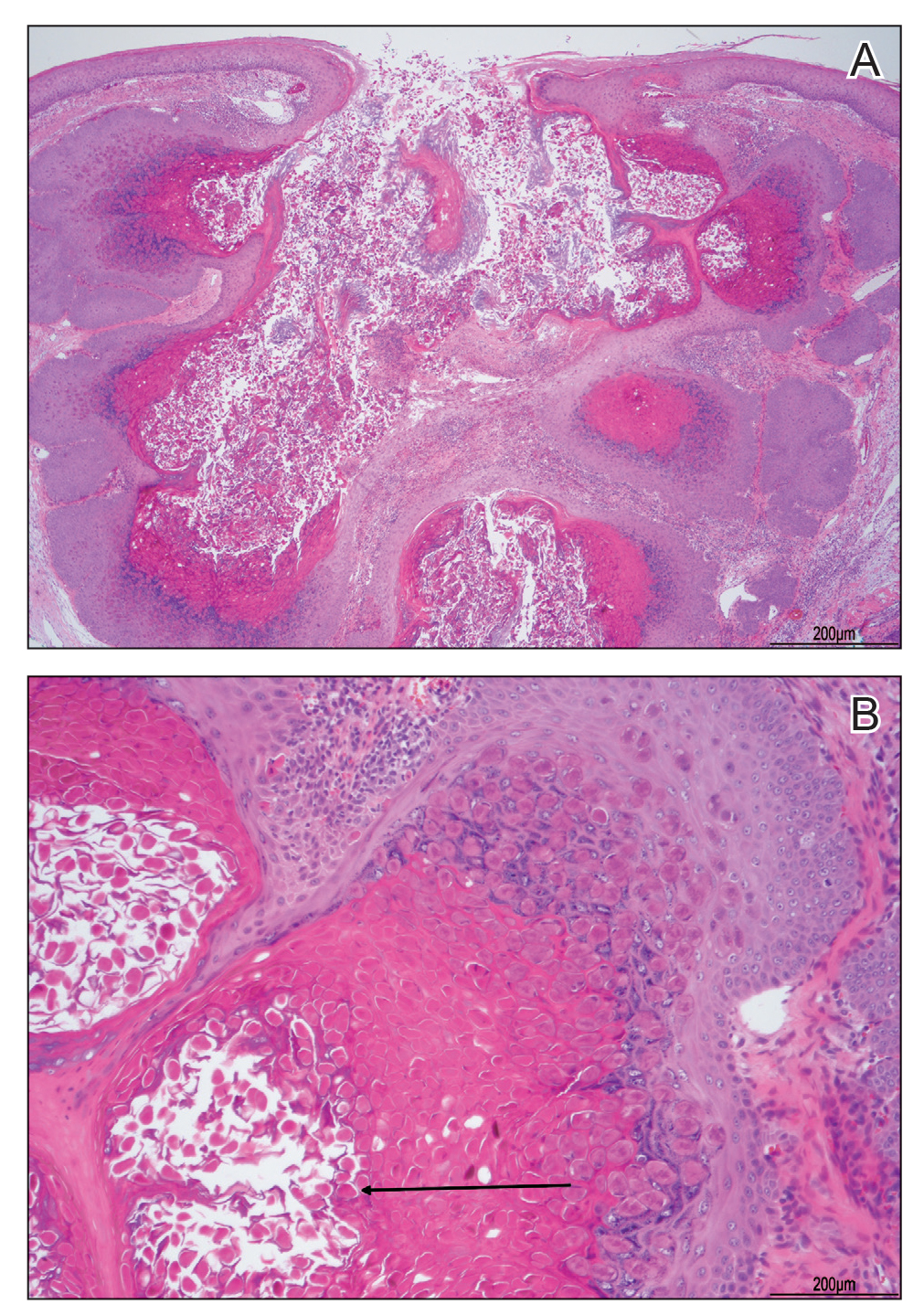

At the time of presentation, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, fungal culture, and punch biopsy of the right ventral wrist was performed. The KOH preparation was positive for fungal hyphae characteristic of dermatophyte infections. Histologically, the biopsy showed intraepidermal and subepidermal blisters with neutrophil- and lymphocyte-rich contents (Figure 1). Fungal hyphae and spores were present within the stratum corneum and superficial epidermis (Figure 2), and fungal cultures grew Microsporum canis. The extent of the rash (upper and lower extremities, chest, and back), positive fungal culture, and KOH preparation all supported the diagnosis of tinea corporis bullosa, which was confirmed with biopsy. Oral prednisone use was discouraged and triamcinolone ointment was discontinued given that inappropriate treatment with steroids in the setting of fungal infection suppresses an inflammatory response and alters clinical appearance, obviating the persistent underlying infection.

Tinea corporis bullosa is a rare superficial dermatophyte fungal infection that often is acquired by close personto- person contact or contact with domestic animals. The infection begins as a circular pruritic plaque, generally with raised borders, which may be erythematous or hyperpigmented. By definition, tinea corporis occurs in sites other than the face, feet, hands, or groin area. Bullae formation is thought to be secondary to a delayed hypersensitivity reaction provoked by the presence of a dermatophyte antigen.1

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an immunemediated disease characterized by IgA deposition at the dermoepidermal junction. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis classically presents as widespread tense vesicles in an arciform or annular pattern. Mucosal involvement is common and typically presents with erosions, ulcerations, and scarring.2 Given the absence of mucosal involvement in our patient and a positive KOH preparation, linear IgA bullous dermatosis was an unlikely diagnosis.

Benign inoculation lymphoreticulosis, more commonly known as cat scratch disease (CSD), is a Bartonella henselae infection that results from a cat scratch or bite. Cat scratch disease can present as localized cutaneous and nodal involvement (lymphadenopathy) near the site of inoculation, or it may present as disseminated disease. Cutaneous lesions generally progress through vesicular, erythematous, and papular phases. Regional lymphadenopathy proximal to the inoculation site is the hallmark of CSD.3 Given the absence of lymphadenopathy in our patient as well as the sporadic distribution of lesions, CSD was an unlikely diagnosis.

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) is an autoimmune disorder with cutaneous manifestations of gluten sensitivity. Dermatitis herpetiformis presents as extremely pruritic papules and vesicles arranged in groups on areas such as the elbows, dorsal aspects of the forearms, knees, scalp, back, and buttocks. Most patients with DH have celiac disease or small bowel disease related to gluten sensitivity.4 Given our patient’s acute presentation in adulthood and lack of gluten sensitivity, DH was an unlikely diagnosis.

Bullous fixed drug reaction is a cutaneous eruption that typically presents in the setting of exposure to an offending drug/agent. Drug reactions can have various cutaneous presentations, with the most common being pigmented macules that progress into plaques.5 Given the isolated nature of our patient’s episode and apparent lack of association with medication, bullous fixed drug reaction was an unlikely diagnosis.

Tinea corporis bullosa is a rare clinical variant of tinea corporis that has only been reported in patients with a history of contact with different animals. There are many causative organisms related to tinea corporis; Trichophyton rubrum is the most common etiology of tinea corporis, while tinea corporis due to close contact with domesticated animals often is caused by M canis.6 The immunoinhibitory properties of the mannans in the fungal cell wall allow the organisms to adhere to the skin prior to invasion. Cutaneous invasion into dead cornified layers of the skin is credited to the proteases, subtilisinlike proteases (subtilases), and keratinases produced by the fungus.1 There are many different clinical presentations of tinea corporis due to the variability of causative organisms. An annular (ring-shaped) lesion with a central plaque and advancing border is the most typical presentation. Tinea corporis bullosa is characterized by the presence of bullae or vesicles in the borders of the scaly plaque. Rupture of the bullae subsequently leads to erosions and crusts over the plaque.

The diagnosis of tinea corporis bullosa often is clinical if the lesion is typical and can be confirmed using KOH preparation and fungal culture. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, topical antifungals are the standard treatment approach for localized superficial tinea corporis. Systemic antifungal treatment can be initiated if the lesion is extensive, recurrent, chronic, or unresponsive to topical treatment.1 Given our patient’s characteristic presentation, she was managed with an over-the-counter topical antifungal (terbinafine). The patient’s lesions dramatically improved, rendering oral therapy unnecessary. At 1-month follow-up, the rash had nearly resolved.

- Leung AK, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Tinea corporis: an updated review [published online July 20, 2020]. Drugs Context. doi:10.7573/dic.2020-5-6

- Guide SV, Marinkovich MP. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:719-727.

- Lamps LW, Scott MA. Cat-scratch disease: historic, clinical, and pathologic perspectives. Pathology Patterns Reviews. 2004;121(suppl):S71-S80.

- Caproni M, Antiga E, Melani L, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:633-638.

- Patel S, John AM, Handler MZ, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: an update, emphasizing the potentially lethal generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:393-399.

- Ziemer M, Seyfarth F, Elsner P, et al. Atypical manifestations of tinea corporis. Mycoses. 2007;50:31-35.

The Diagnosis: Tinea Corporis Bullosa

At the time of presentation, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, fungal culture, and punch biopsy of the right ventral wrist was performed. The KOH preparation was positive for fungal hyphae characteristic of dermatophyte infections. Histologically, the biopsy showed intraepidermal and subepidermal blisters with neutrophil- and lymphocyte-rich contents (Figure 1). Fungal hyphae and spores were present within the stratum corneum and superficial epidermis (Figure 2), and fungal cultures grew Microsporum canis. The extent of the rash (upper and lower extremities, chest, and back), positive fungal culture, and KOH preparation all supported the diagnosis of tinea corporis bullosa, which was confirmed with biopsy. Oral prednisone use was discouraged and triamcinolone ointment was discontinued given that inappropriate treatment with steroids in the setting of fungal infection suppresses an inflammatory response and alters clinical appearance, obviating the persistent underlying infection.

Tinea corporis bullosa is a rare superficial dermatophyte fungal infection that often is acquired by close personto- person contact or contact with domestic animals. The infection begins as a circular pruritic plaque, generally with raised borders, which may be erythematous or hyperpigmented. By definition, tinea corporis occurs in sites other than the face, feet, hands, or groin area. Bullae formation is thought to be secondary to a delayed hypersensitivity reaction provoked by the presence of a dermatophyte antigen.1

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an immunemediated disease characterized by IgA deposition at the dermoepidermal junction. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis classically presents as widespread tense vesicles in an arciform or annular pattern. Mucosal involvement is common and typically presents with erosions, ulcerations, and scarring.2 Given the absence of mucosal involvement in our patient and a positive KOH preparation, linear IgA bullous dermatosis was an unlikely diagnosis.

Benign inoculation lymphoreticulosis, more commonly known as cat scratch disease (CSD), is a Bartonella henselae infection that results from a cat scratch or bite. Cat scratch disease can present as localized cutaneous and nodal involvement (lymphadenopathy) near the site of inoculation, or it may present as disseminated disease. Cutaneous lesions generally progress through vesicular, erythematous, and papular phases. Regional lymphadenopathy proximal to the inoculation site is the hallmark of CSD.3 Given the absence of lymphadenopathy in our patient as well as the sporadic distribution of lesions, CSD was an unlikely diagnosis.

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) is an autoimmune disorder with cutaneous manifestations of gluten sensitivity. Dermatitis herpetiformis presents as extremely pruritic papules and vesicles arranged in groups on areas such as the elbows, dorsal aspects of the forearms, knees, scalp, back, and buttocks. Most patients with DH have celiac disease or small bowel disease related to gluten sensitivity.4 Given our patient’s acute presentation in adulthood and lack of gluten sensitivity, DH was an unlikely diagnosis.

Bullous fixed drug reaction is a cutaneous eruption that typically presents in the setting of exposure to an offending drug/agent. Drug reactions can have various cutaneous presentations, with the most common being pigmented macules that progress into plaques.5 Given the isolated nature of our patient’s episode and apparent lack of association with medication, bullous fixed drug reaction was an unlikely diagnosis.

Tinea corporis bullosa is a rare clinical variant of tinea corporis that has only been reported in patients with a history of contact with different animals. There are many causative organisms related to tinea corporis; Trichophyton rubrum is the most common etiology of tinea corporis, while tinea corporis due to close contact with domesticated animals often is caused by M canis.6 The immunoinhibitory properties of the mannans in the fungal cell wall allow the organisms to adhere to the skin prior to invasion. Cutaneous invasion into dead cornified layers of the skin is credited to the proteases, subtilisinlike proteases (subtilases), and keratinases produced by the fungus.1 There are many different clinical presentations of tinea corporis due to the variability of causative organisms. An annular (ring-shaped) lesion with a central plaque and advancing border is the most typical presentation. Tinea corporis bullosa is characterized by the presence of bullae or vesicles in the borders of the scaly plaque. Rupture of the bullae subsequently leads to erosions and crusts over the plaque.

The diagnosis of tinea corporis bullosa often is clinical if the lesion is typical and can be confirmed using KOH preparation and fungal culture. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, topical antifungals are the standard treatment approach for localized superficial tinea corporis. Systemic antifungal treatment can be initiated if the lesion is extensive, recurrent, chronic, or unresponsive to topical treatment.1 Given our patient’s characteristic presentation, she was managed with an over-the-counter topical antifungal (terbinafine). The patient’s lesions dramatically improved, rendering oral therapy unnecessary. At 1-month follow-up, the rash had nearly resolved.

The Diagnosis: Tinea Corporis Bullosa

At the time of presentation, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, fungal culture, and punch biopsy of the right ventral wrist was performed. The KOH preparation was positive for fungal hyphae characteristic of dermatophyte infections. Histologically, the biopsy showed intraepidermal and subepidermal blisters with neutrophil- and lymphocyte-rich contents (Figure 1). Fungal hyphae and spores were present within the stratum corneum and superficial epidermis (Figure 2), and fungal cultures grew Microsporum canis. The extent of the rash (upper and lower extremities, chest, and back), positive fungal culture, and KOH preparation all supported the diagnosis of tinea corporis bullosa, which was confirmed with biopsy. Oral prednisone use was discouraged and triamcinolone ointment was discontinued given that inappropriate treatment with steroids in the setting of fungal infection suppresses an inflammatory response and alters clinical appearance, obviating the persistent underlying infection.

Tinea corporis bullosa is a rare superficial dermatophyte fungal infection that often is acquired by close personto- person contact or contact with domestic animals. The infection begins as a circular pruritic plaque, generally with raised borders, which may be erythematous or hyperpigmented. By definition, tinea corporis occurs in sites other than the face, feet, hands, or groin area. Bullae formation is thought to be secondary to a delayed hypersensitivity reaction provoked by the presence of a dermatophyte antigen.1

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an immunemediated disease characterized by IgA deposition at the dermoepidermal junction. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis classically presents as widespread tense vesicles in an arciform or annular pattern. Mucosal involvement is common and typically presents with erosions, ulcerations, and scarring.2 Given the absence of mucosal involvement in our patient and a positive KOH preparation, linear IgA bullous dermatosis was an unlikely diagnosis.

Benign inoculation lymphoreticulosis, more commonly known as cat scratch disease (CSD), is a Bartonella henselae infection that results from a cat scratch or bite. Cat scratch disease can present as localized cutaneous and nodal involvement (lymphadenopathy) near the site of inoculation, or it may present as disseminated disease. Cutaneous lesions generally progress through vesicular, erythematous, and papular phases. Regional lymphadenopathy proximal to the inoculation site is the hallmark of CSD.3 Given the absence of lymphadenopathy in our patient as well as the sporadic distribution of lesions, CSD was an unlikely diagnosis.

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) is an autoimmune disorder with cutaneous manifestations of gluten sensitivity. Dermatitis herpetiformis presents as extremely pruritic papules and vesicles arranged in groups on areas such as the elbows, dorsal aspects of the forearms, knees, scalp, back, and buttocks. Most patients with DH have celiac disease or small bowel disease related to gluten sensitivity.4 Given our patient’s acute presentation in adulthood and lack of gluten sensitivity, DH was an unlikely diagnosis.

Bullous fixed drug reaction is a cutaneous eruption that typically presents in the setting of exposure to an offending drug/agent. Drug reactions can have various cutaneous presentations, with the most common being pigmented macules that progress into plaques.5 Given the isolated nature of our patient’s episode and apparent lack of association with medication, bullous fixed drug reaction was an unlikely diagnosis.

Tinea corporis bullosa is a rare clinical variant of tinea corporis that has only been reported in patients with a history of contact with different animals. There are many causative organisms related to tinea corporis; Trichophyton rubrum is the most common etiology of tinea corporis, while tinea corporis due to close contact with domesticated animals often is caused by M canis.6 The immunoinhibitory properties of the mannans in the fungal cell wall allow the organisms to adhere to the skin prior to invasion. Cutaneous invasion into dead cornified layers of the skin is credited to the proteases, subtilisinlike proteases (subtilases), and keratinases produced by the fungus.1 There are many different clinical presentations of tinea corporis due to the variability of causative organisms. An annular (ring-shaped) lesion with a central plaque and advancing border is the most typical presentation. Tinea corporis bullosa is characterized by the presence of bullae or vesicles in the borders of the scaly plaque. Rupture of the bullae subsequently leads to erosions and crusts over the plaque.

The diagnosis of tinea corporis bullosa often is clinical if the lesion is typical and can be confirmed using KOH preparation and fungal culture. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, topical antifungals are the standard treatment approach for localized superficial tinea corporis. Systemic antifungal treatment can be initiated if the lesion is extensive, recurrent, chronic, or unresponsive to topical treatment.1 Given our patient’s characteristic presentation, she was managed with an over-the-counter topical antifungal (terbinafine). The patient’s lesions dramatically improved, rendering oral therapy unnecessary. At 1-month follow-up, the rash had nearly resolved.

- Leung AK, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Tinea corporis: an updated review [published online July 20, 2020]. Drugs Context. doi:10.7573/dic.2020-5-6

- Guide SV, Marinkovich MP. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:719-727.

- Lamps LW, Scott MA. Cat-scratch disease: historic, clinical, and pathologic perspectives. Pathology Patterns Reviews. 2004;121(suppl):S71-S80.

- Caproni M, Antiga E, Melani L, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:633-638.

- Patel S, John AM, Handler MZ, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: an update, emphasizing the potentially lethal generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:393-399.

- Ziemer M, Seyfarth F, Elsner P, et al. Atypical manifestations of tinea corporis. Mycoses. 2007;50:31-35.

- Leung AK, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Tinea corporis: an updated review [published online July 20, 2020]. Drugs Context. doi:10.7573/dic.2020-5-6

- Guide SV, Marinkovich MP. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:719-727.

- Lamps LW, Scott MA. Cat-scratch disease: historic, clinical, and pathologic perspectives. Pathology Patterns Reviews. 2004;121(suppl):S71-S80.

- Caproni M, Antiga E, Melani L, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:633-638.

- Patel S, John AM, Handler MZ, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: an update, emphasizing the potentially lethal generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:393-399.

- Ziemer M, Seyfarth F, Elsner P, et al. Atypical manifestations of tinea corporis. Mycoses. 2007;50:31-35.

A 38-year-old woman presented with a rash of 5 days’ duration that initially appeared on the wrists after playing with her kitten, with subsequent involvement of the chest, back, abdomen, and upper and lower extremities. Physical examination revealed multiple annular plaques with raised erythematous borders, rare peripheral vesicles, and superficial central scaling. Extreme pruritus accompanied the plaques, both of which developed after playing with her kitten. The patient noted that all lesions on the upper extremities evolved in areas subject to deep puncture while more superficially excoriated areas were unaffected. She denied any other prior skin conditions and had received a 5-day course of azithromycin without improvement prior to presentation; triamcinolone ointment 0.1% had provided only temporary relief. Primary care providers prescribed a short course of oral prednisone; however, she did not start it prior to presentation.

Monkeypox: What FPs need to know, now

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization are investigating an outbreak of monkeypox cases that have occurred around the world in countries that do not have endemic monkeypox virus.1,2 As of July 5, there have been 6924 cases documented in 52 countries, including 560 cases that have occurred in the United States.2 In the United States, as well as globally, a large proportion of cases have been in men who have sex with men.