User login

Generalized Pustular Psoriasis: A Review of the Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Acute generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a rare severe variant of psoriasis characterized by the sudden widespread eruption of sterile pustules.1,2 The cutaneous manifestations of GPP also may be accompanied by signs of systemic inflammation, including fever, malaise, and leukocytosis.2 Complications are common and may be life-threatening, especially in older patients with comorbid diseases.3 Generalized pustular psoriasis most commonly occurs in patients with a preceding history of psoriasis, but it also may occur de novo.4 Generalized pustular psoriasis is associated with notable morbidity and mortality, and relapses are common.3,4 Many triggers of GPP have been identified, including initiation and withdrawal of various medications, infections, pregnancy, and other conditions.5,6 Although GPP most often occurs in adults, it also may arise in children and infants.3 In pregnancy, GPP is referred to as impetigo herpetiformis, despite having no etiologic ties with either herpes simplex virus or staphylococcal or streptococcal infection. Impetigo herpetiformis is considered one of the most dangerous dermatoses of pregnancy because of high rates of associated maternal and fetal morbidity.6,7

Acute GPP has proven to be a challenging disease to treat due to the rarity and relapsing-remitting nature of the disease; additionally, there are relatively few randomized controlled trials investigating the efficacy and safety of treatments for GPP. This review summarizes the features of GPP, including the pathophysiology of the disease, clinical and histological manifestations, and recommendations for management based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using MeSH terms pertaining to the disease, including generalized pustular psoriasis, impetigo herpetiformis, and von Zumbusch psoriasis.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of GPP is only partially understood, but it is thought to have a distinct pattern of immune activation compared with plaque psoriasis.8 Although there is a considerable amount of overlap and cross-talk among cytokine pathways, GPP generally is driven by innate immunity and unrestrained IL-36 cytokine activity. In contrast, adaptive immune responses—namely the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, IL-23, IL-17, and IL-22 axes—underlie plaque psoriasis.8-10

Proinflammatory IL-36 cytokines α, β, and γ, which are all part of the IL-1 superfamily, bind to the IL-36 receptor (IL-36R) to recruit and activate immune cells via various mediators, including IL-1β; IL-8; and chemokines CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL8.3 The IL-36 receptor antagonist (IL-36ra) acts to inhibit this inflammatory cascade.3,8 Microarray analyses of skin biopsy samples have shown that overexpression of IL-17A, TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-36 are seen in both GPP and plaque psoriasis lesions, but GPP lesions had higher expression of IL-1β, IL-36α, and IL-36γ and elevated neutrophil chemokines—CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL8—compared with plaque psoriasis lesions.8

Gene Mutations Associated With GPP

There are 3 gene mutations that have been associated with pustular variants of psoriasis, though these mutations account for a minority of cases of GPP.4 Genetic screenings are not routinely indicated in patients with GPP, but they may be warranted in severe cases when a familial pattern of inheritance is suspected.4

IL36RN—The gene IL36RN codes the anti-inflammatory IL-36ra. Loss-of-function mutations in IL36RN lead to impairment of IL-36ra and consequently hyperactivity of the proinflammatory responses triggered by IL-36.3 Homozygous and heterozygous mutations in IL36RN have been observed in both familial and sporadic cases of GPP.11-13 Subsequent retrospective analyses have identified the presence of IL36RN mutations in patients with GPP with frequencies ranging from 23% to 37%.14-17IL36RN mutations are thought to be more common in patients without concomitant plaque psoriasis and have been associated with severe disease and early disease onset.15

CARD14—A gain-of-function mutation in CARD14 results in overactivation of the proinflammatory nuclear factor κB pathway and has been implicated in cases of GPP with concurrent psoriasis vulgaris. Interestingly, this may suggest distinct etiologies underlying GPP de novo and GPP in patients with a history of psoriasis.18,19

AP1S3—A loss-of-function mutation in AP1S3 results in abnormal endosomal trafficking and autophagy as well as increased expression of IL-36α.20,21

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis Cutaneous Manifestations of GPP

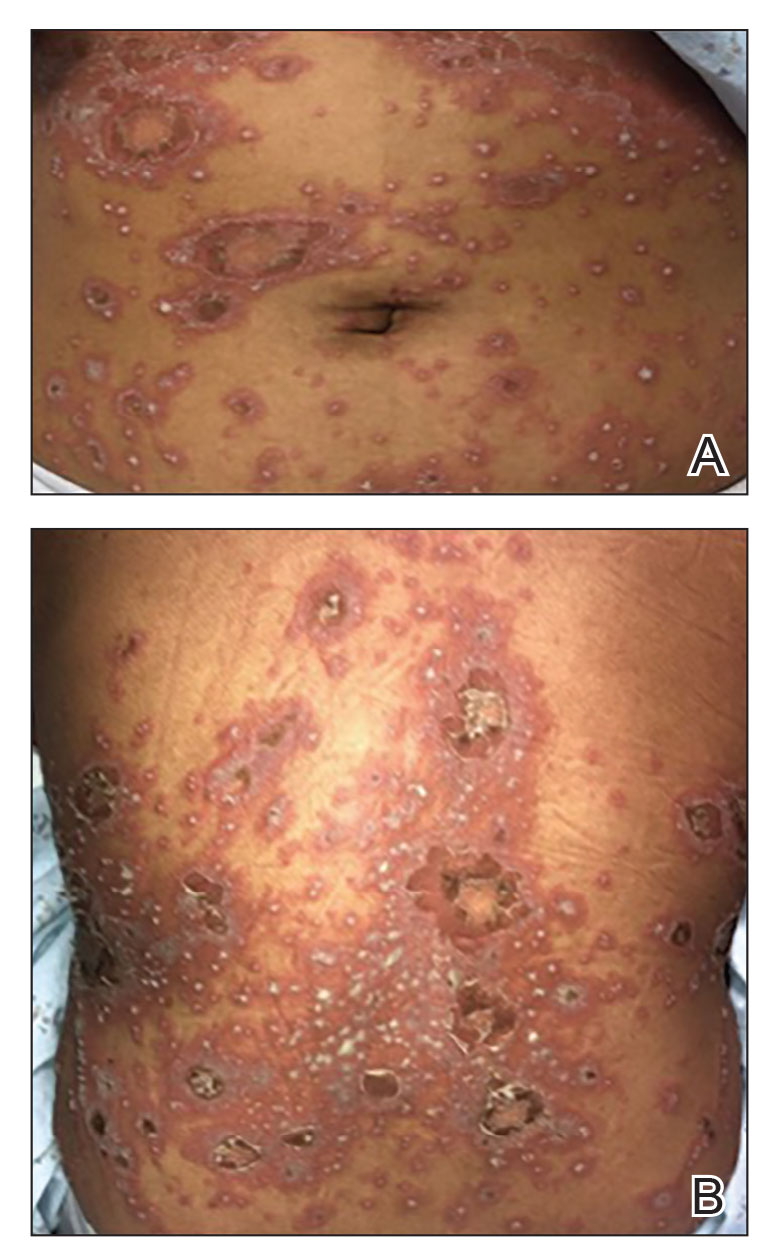

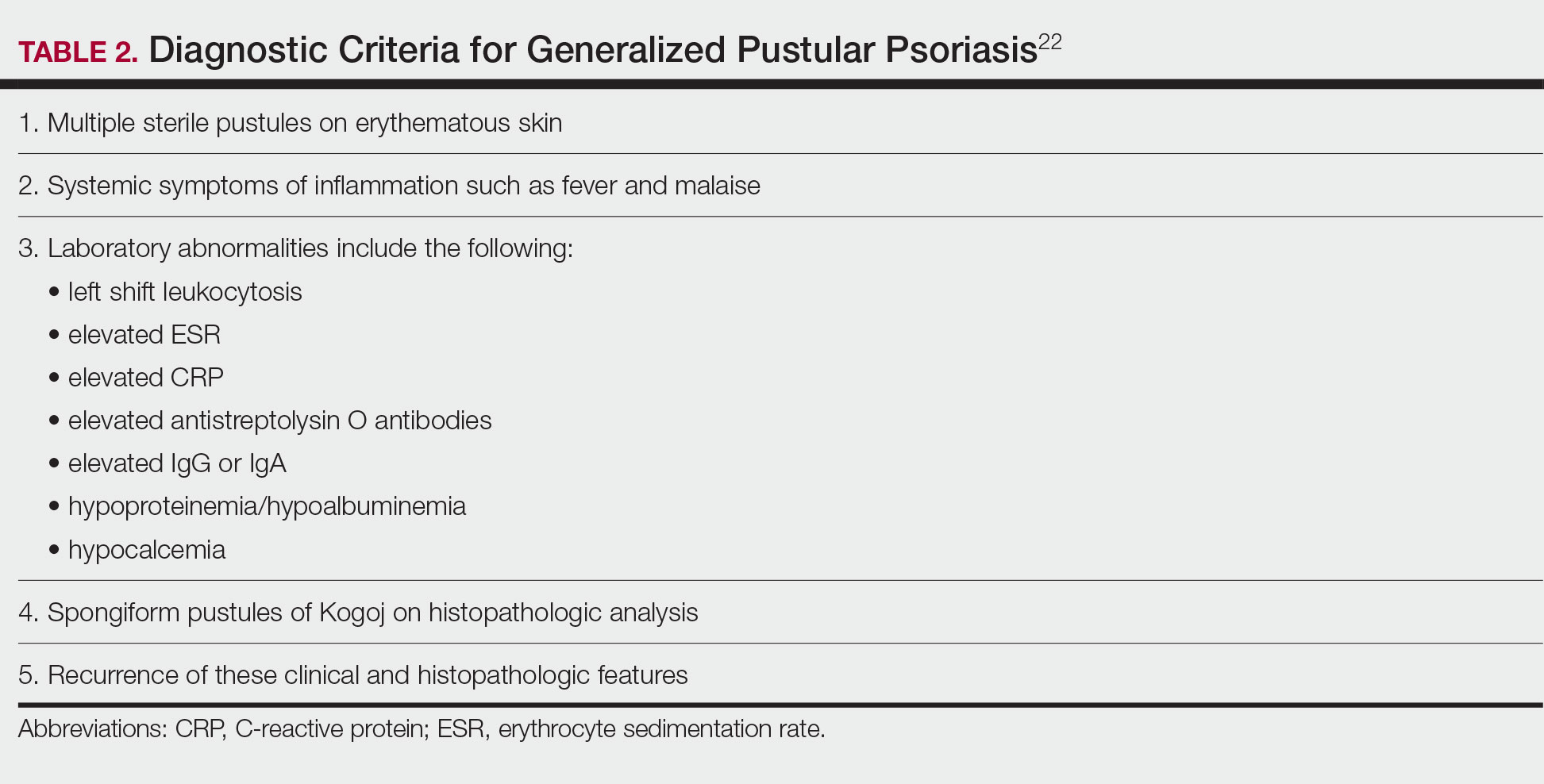

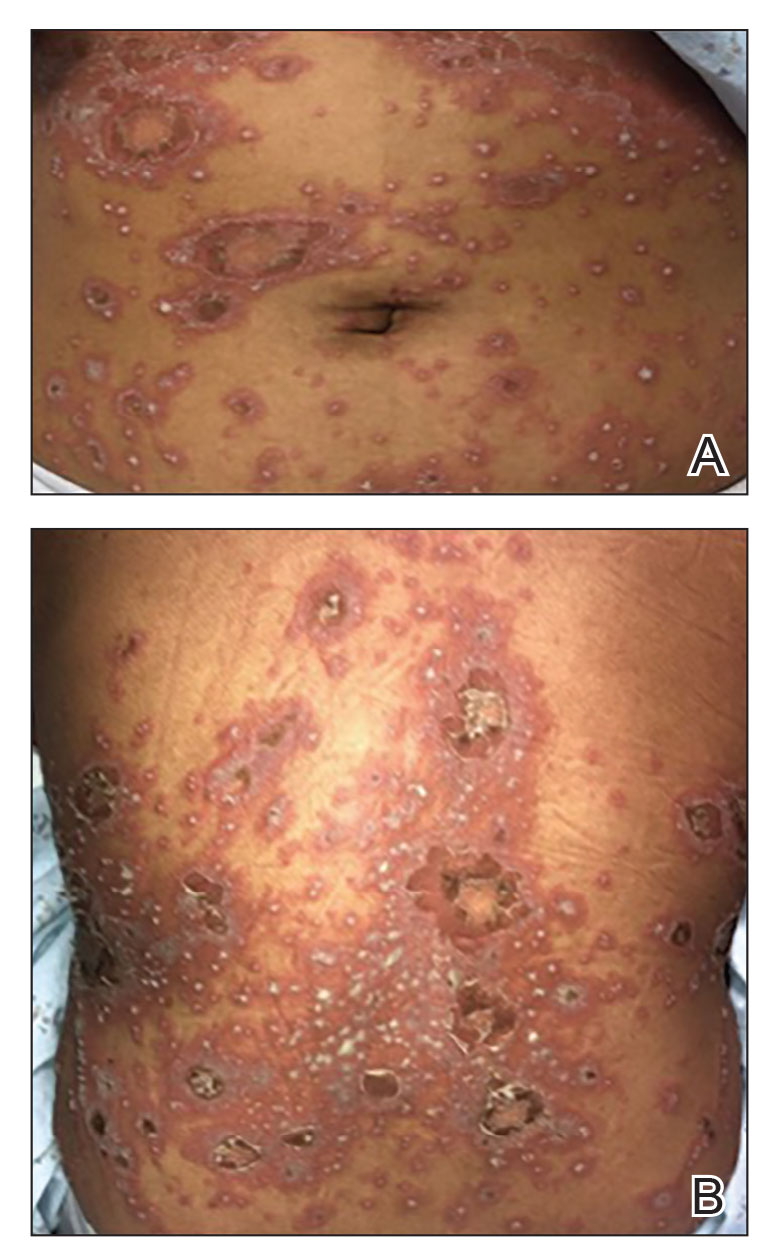

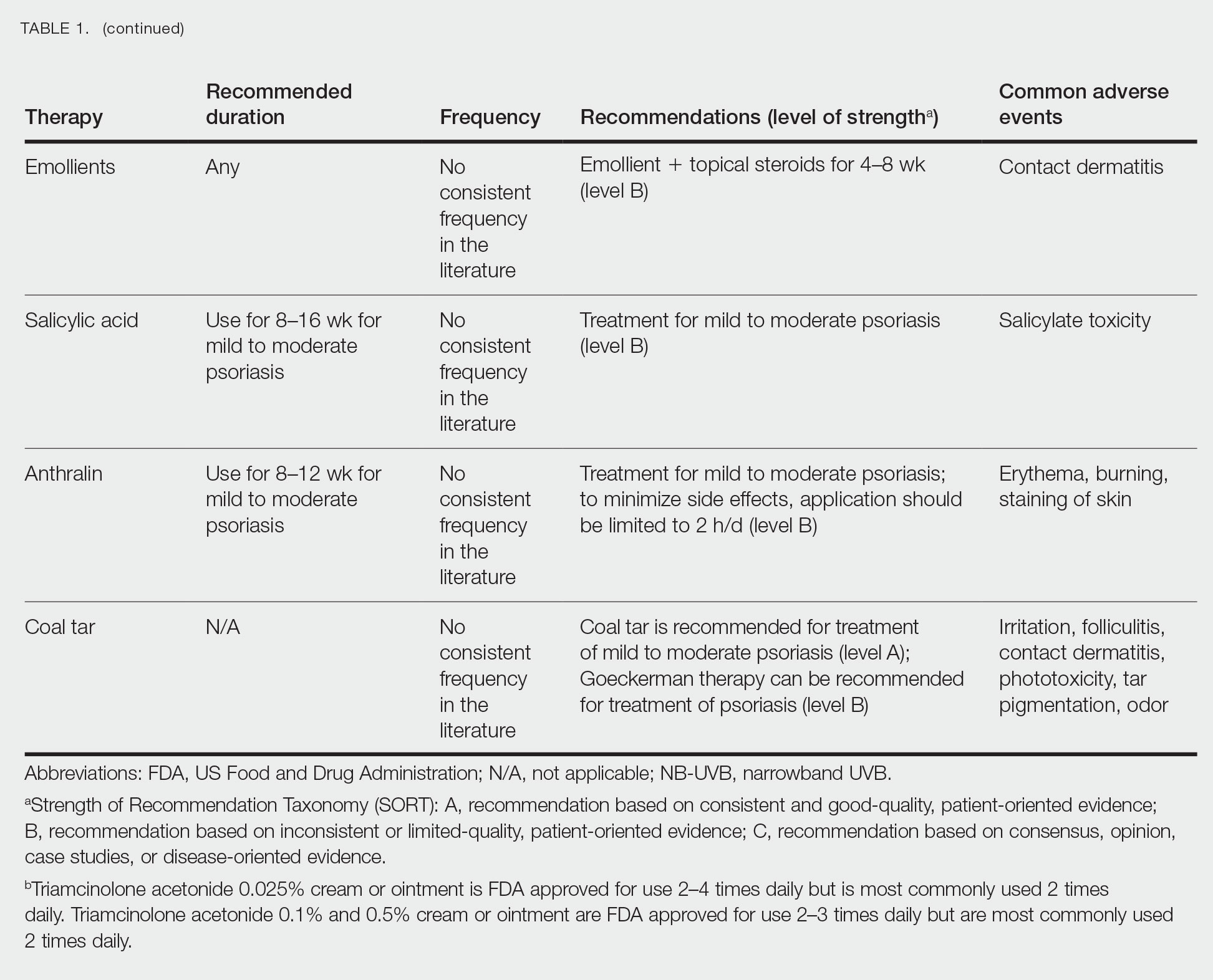

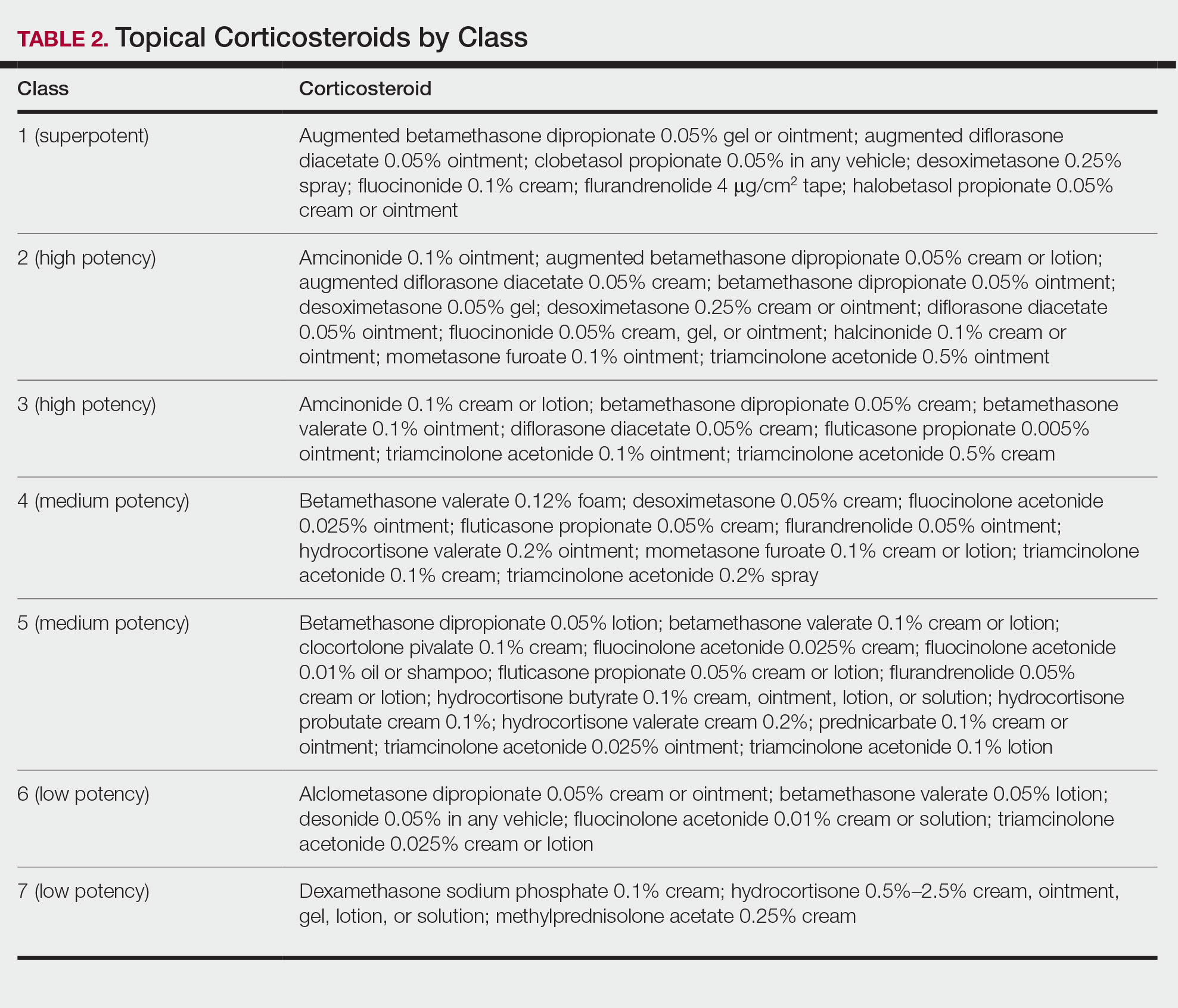

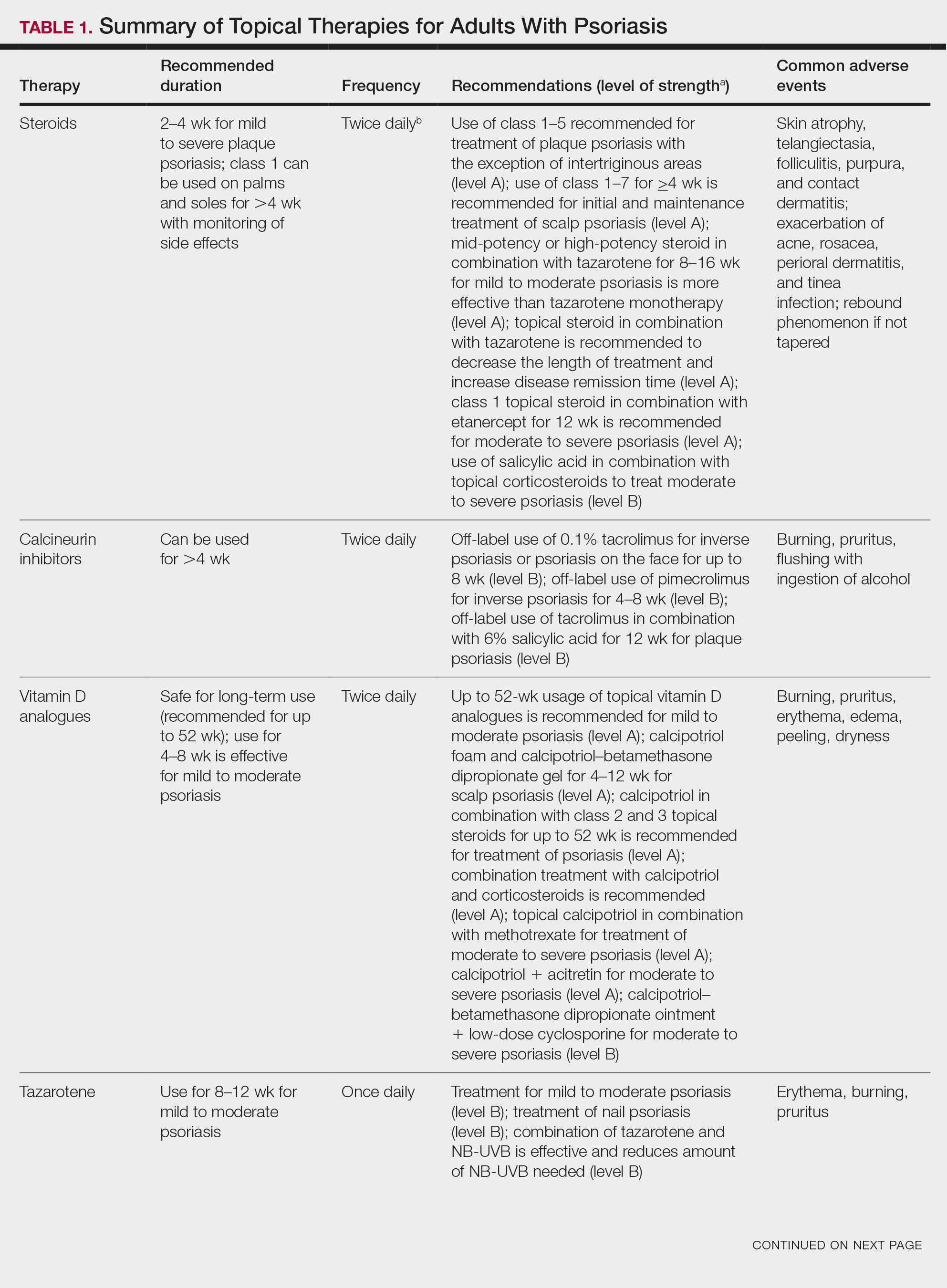

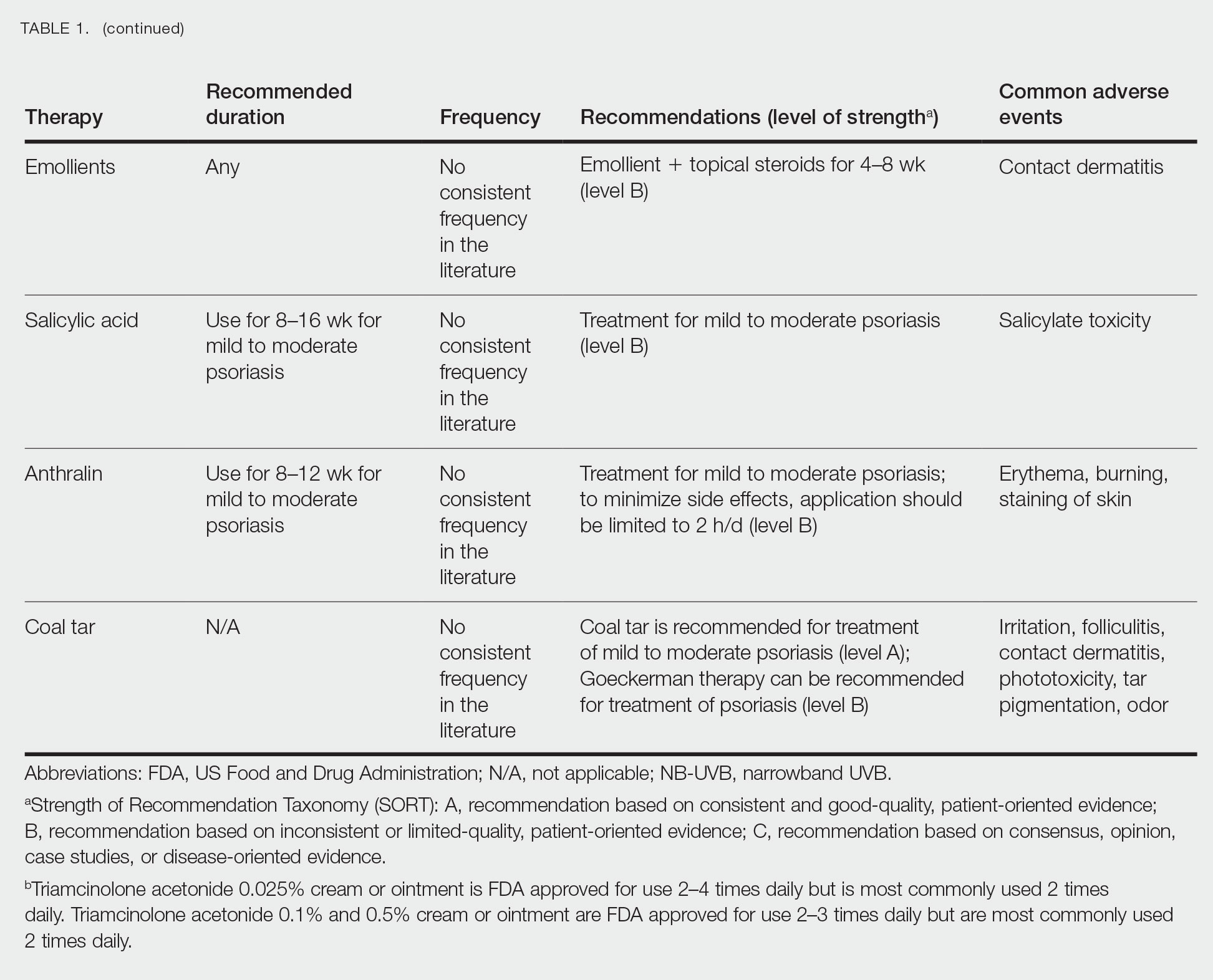

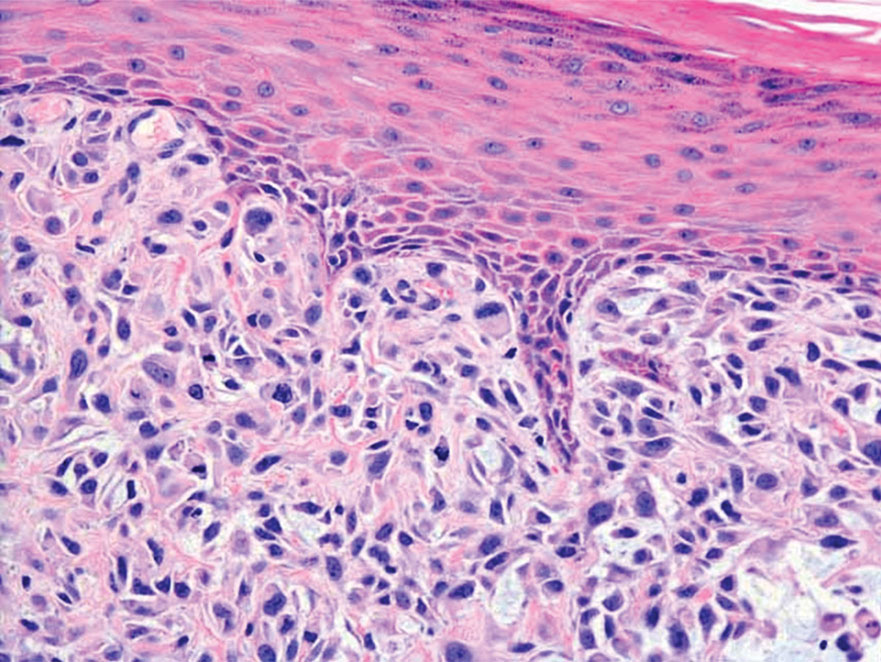

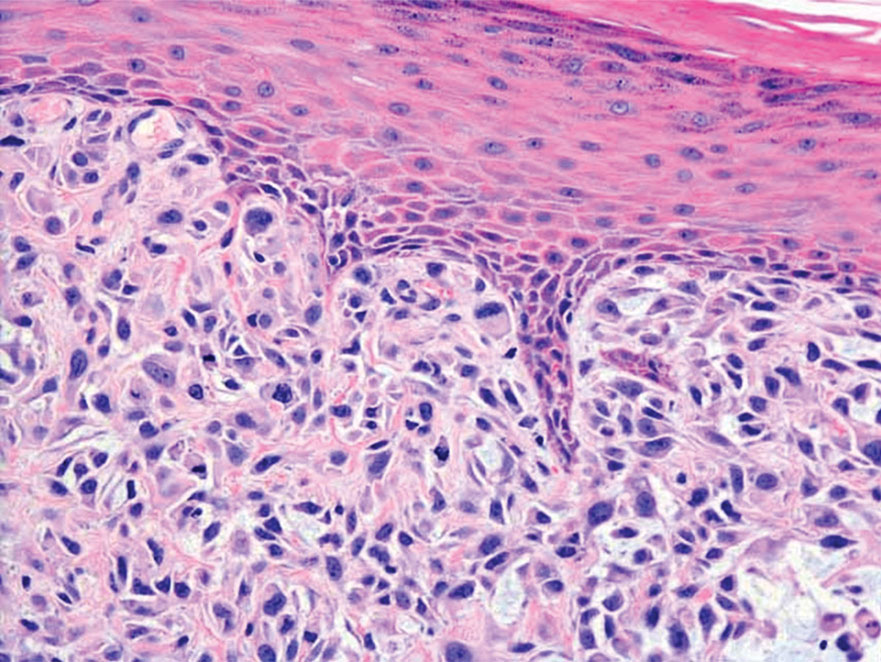

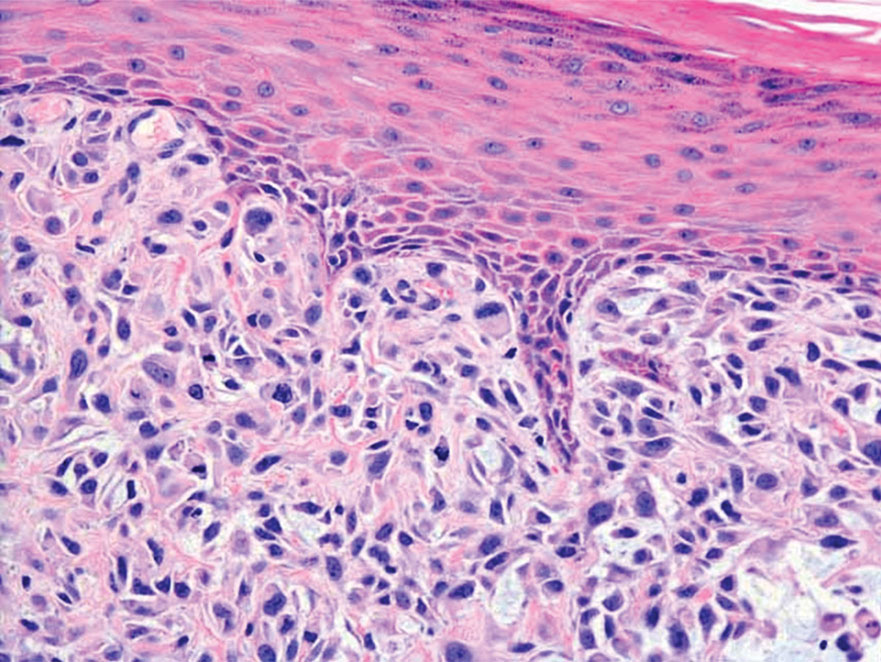

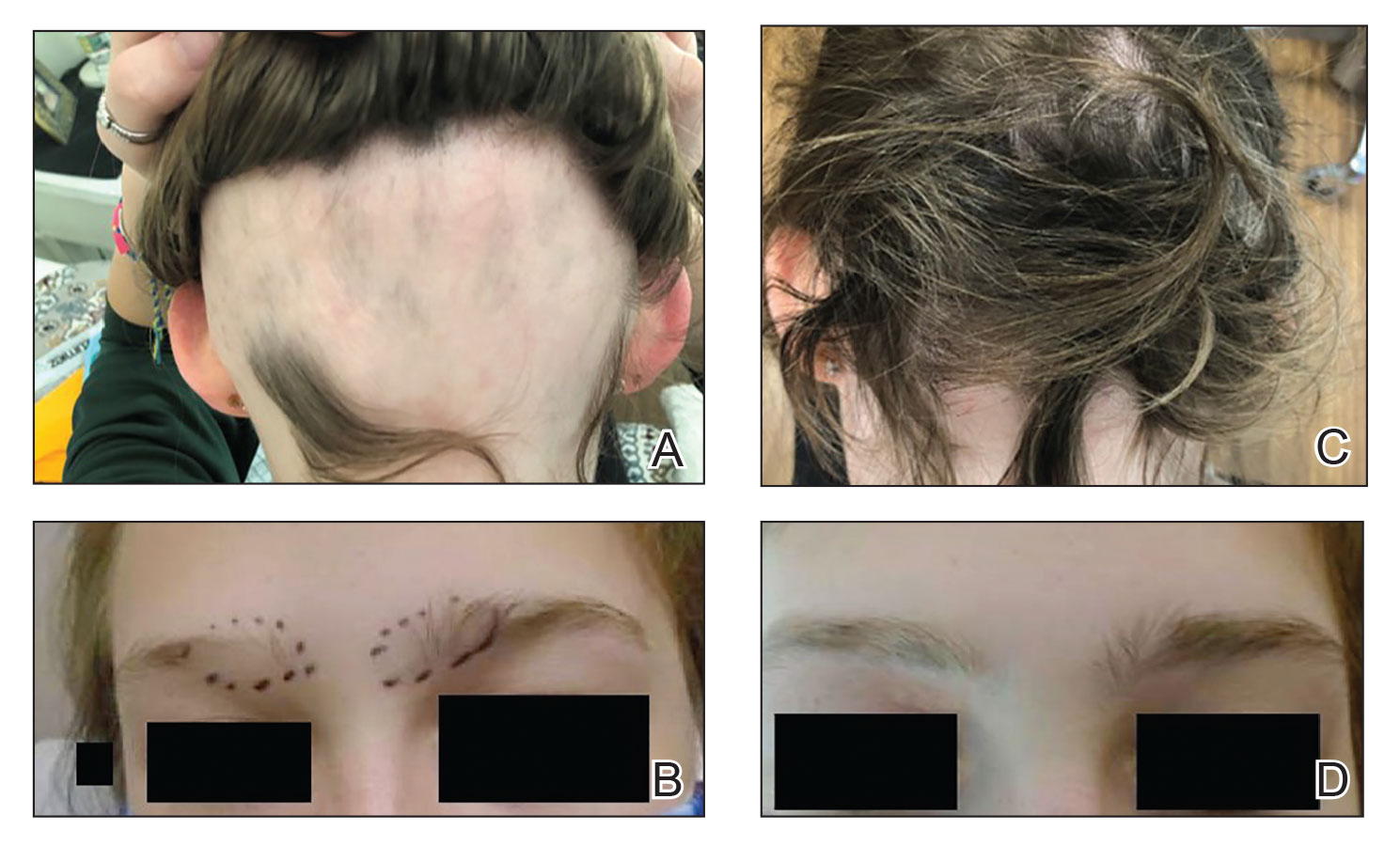

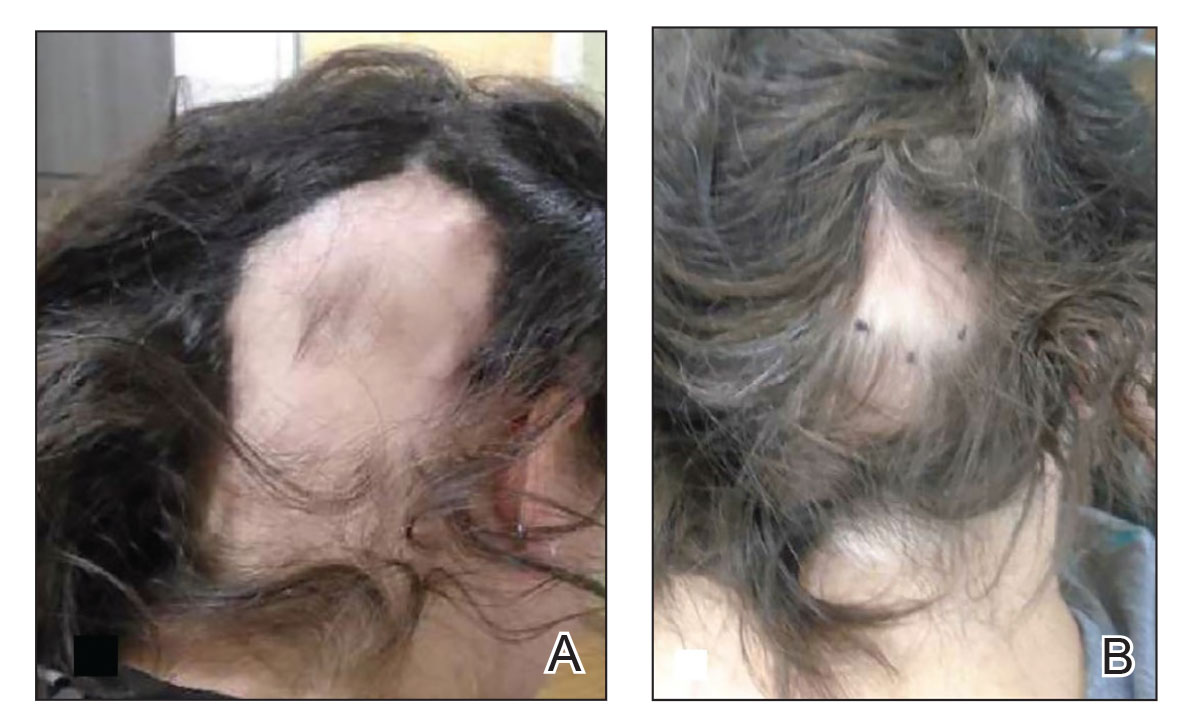

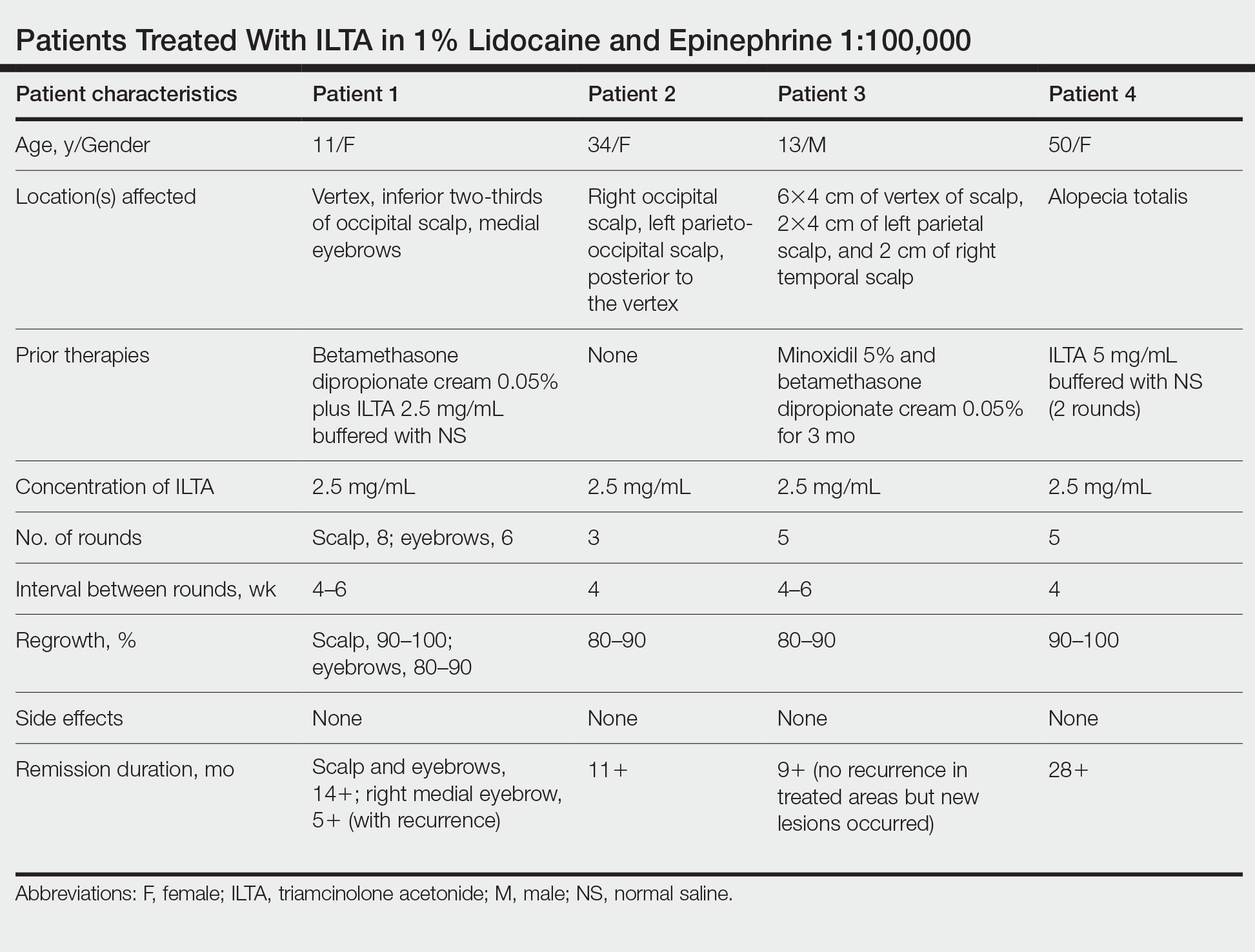

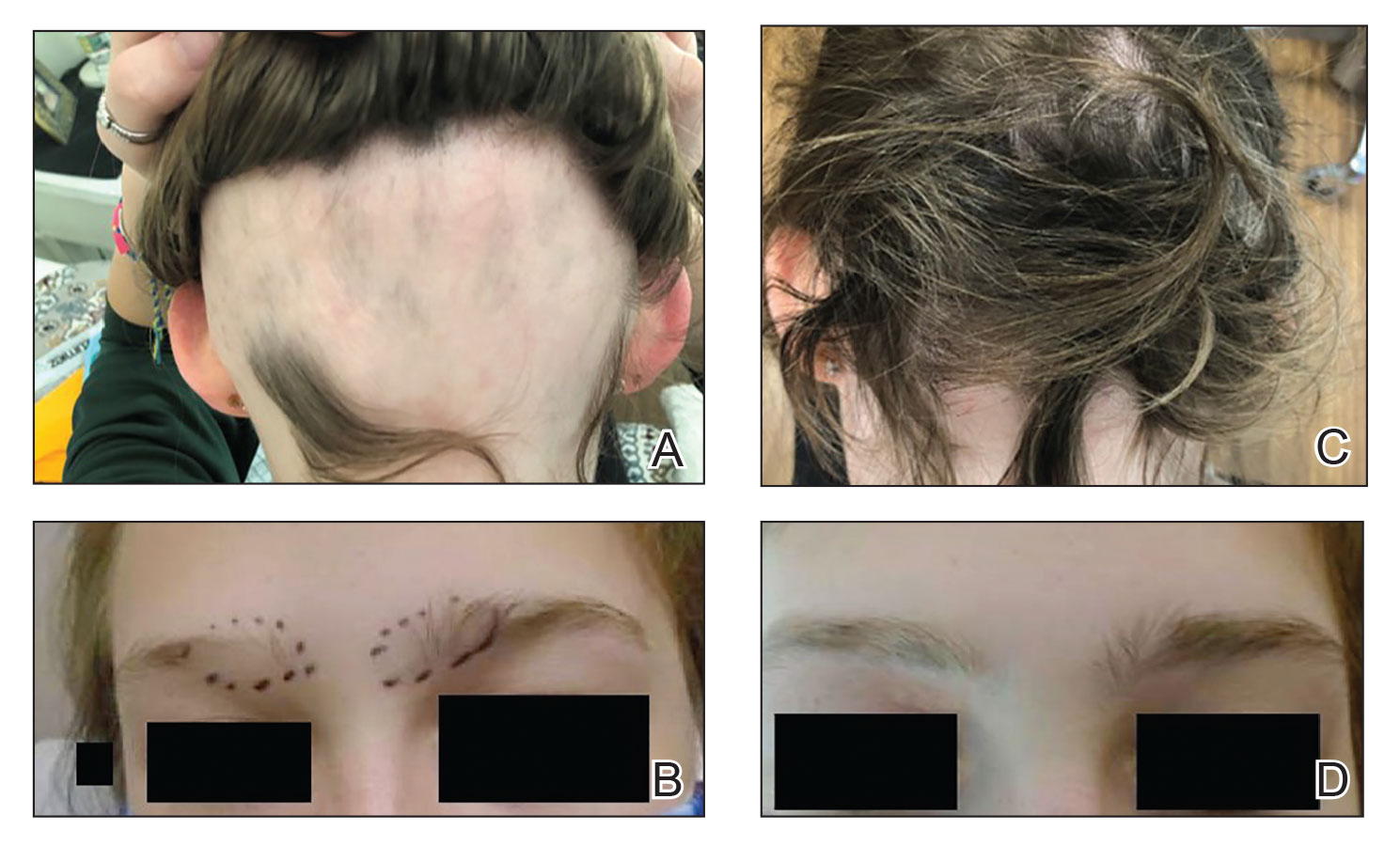

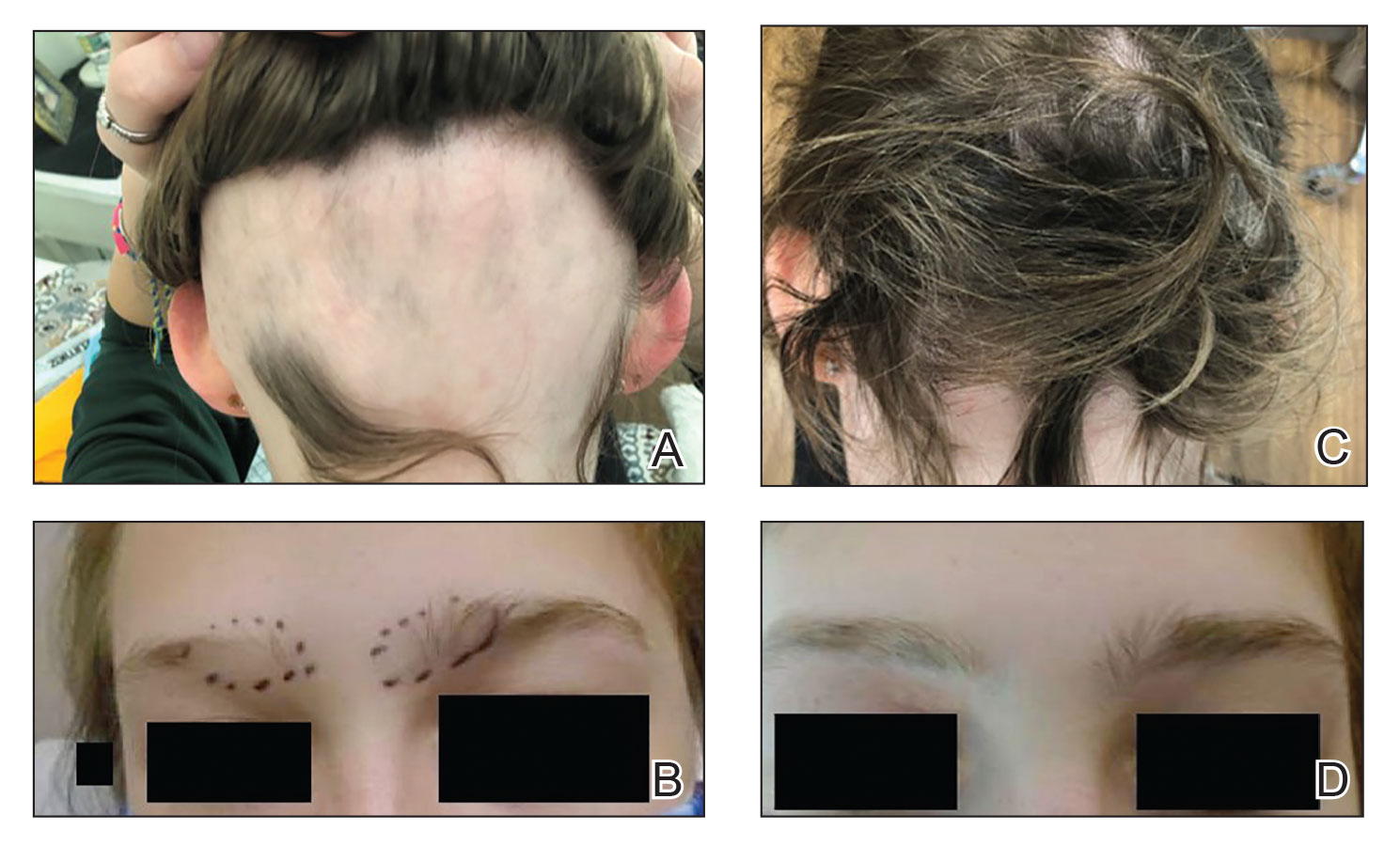

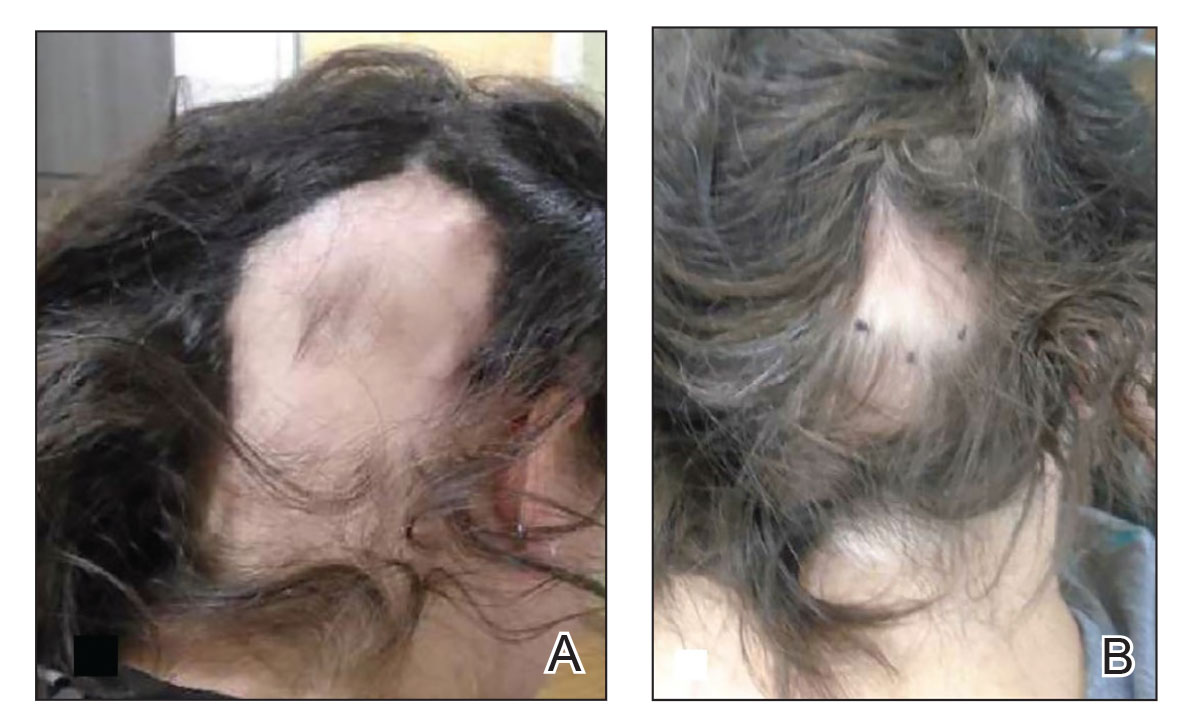

Generalized pustular psoriasis is characterized by the onset of widespread 2- to 3-mm sterile pustules on erythematous skin or within psoriasiform plaques4 (Figure). In patients with skin of color, the erythema may appear less obvious or perhaps slightly violaceous compared to White skin. Pustules may coalesce to form “lakes” of pus.5 Cutaneous symptoms include pain, burning, and pruritus. Associated mucosal findings may include cheilitis, geographic tongue, conjunctivitis, and uveitis.4

The severity of symptoms can vary greatly among patients as well as between flares within the same patient.2,3 Four distinct patterns of GPP have been described. The von Zumbusch pattern is characterized by a rapid, generalized, painful, erythematous and pustular eruption accompanied by fever and asthenia. The pustules usually resolve after several days with extensive scaling. The annular pattern is characterized by annular, erythematous, scaly lesions with pustules present centrifugally. The lesions enlarge by centrifugal expansion over a period of hours to days, while healing occurs centrally. The exanthematic type is an acute eruption of small pustules that abruptly appear and disappear within a few days, usually from infection or medication initiation. Sometimes pustules appear within or at the edge of existing psoriatic plaques in a localized pattern—the fourth pattern—often following the exposure to irritants (eg, tars, anthralin).5

Impetigo Herpetiformis—Impetigo herpetiformis is a form of GPP associated with pregnancy. It generally presents early in the third trimester with symmetric erythematous plaques in flexural and intertriginous areas with pustules present at lesion margins. Lesions expand centrifugally, with pustulation present at the advancing edge.6,7 Patients often are acutely ill with fever, delirium, vomiting, and tetany. Mucous membranes, including the tongue, mouth, and esophagus, also may be involved. The eruption typically resolves after delivery, though it often recurs with subsequent pregnancies, with the morbidity risk rising with each successive pregnancy.7

Systemic and Extracutaneous Manifestations of GPP

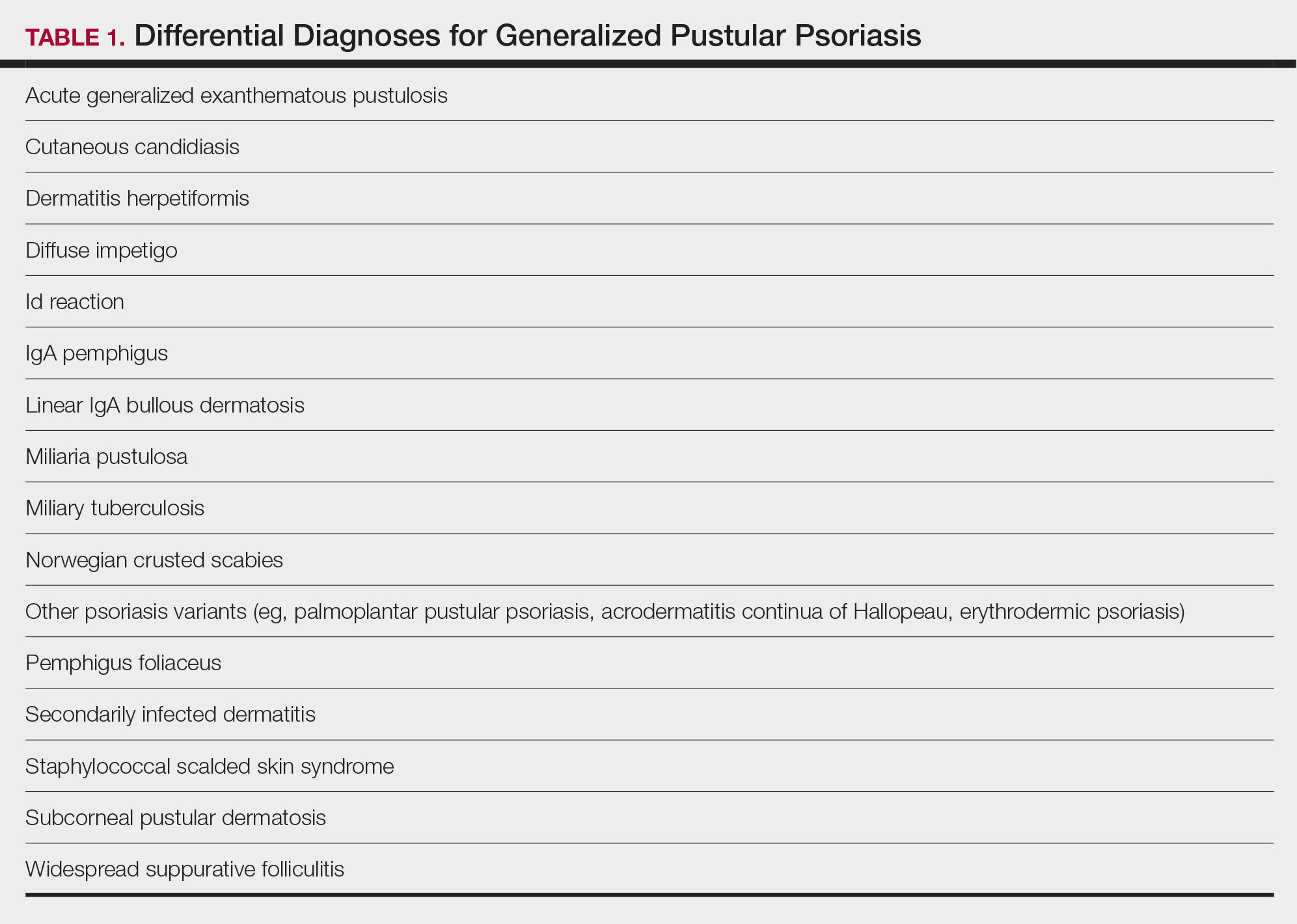

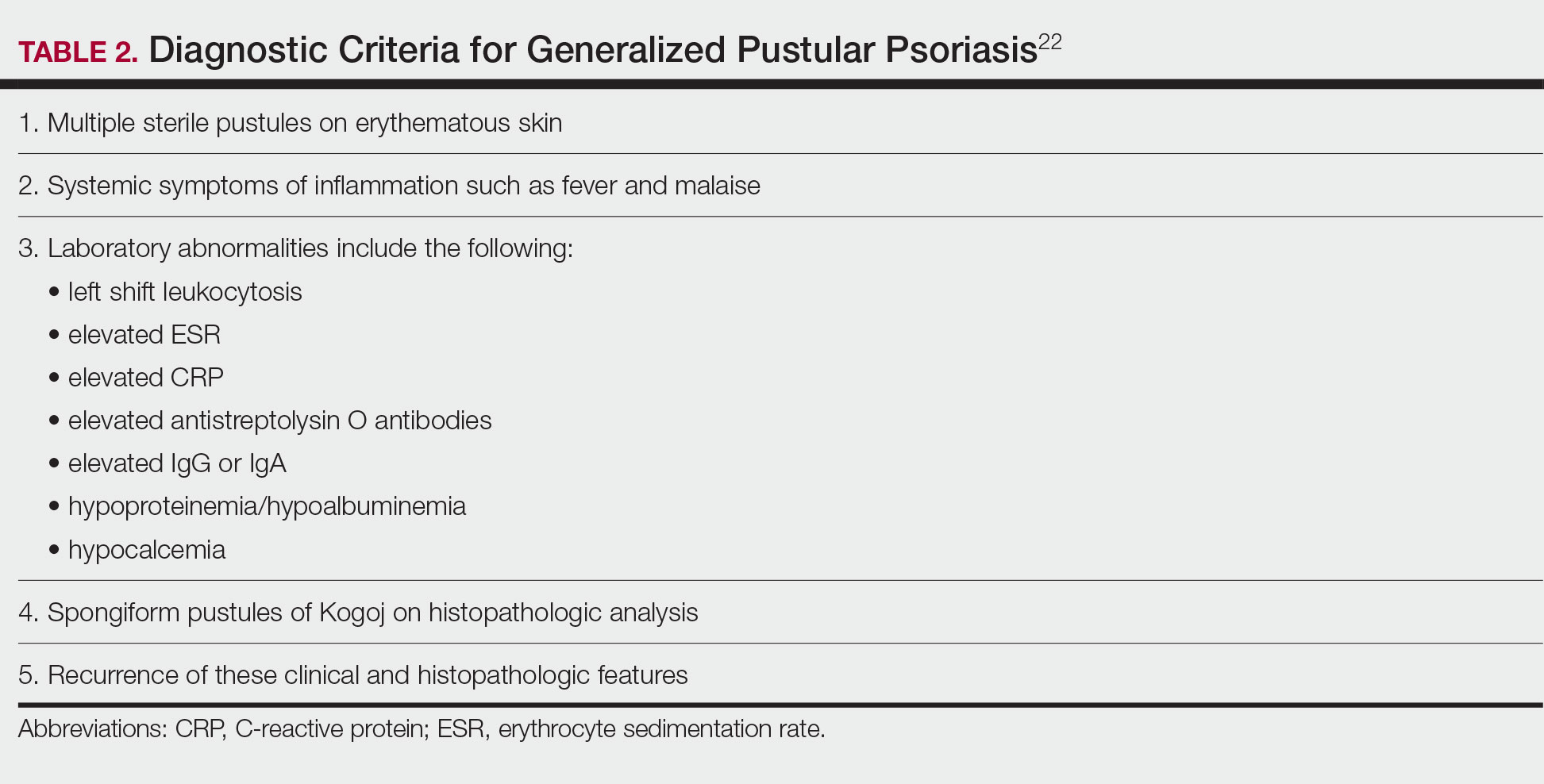

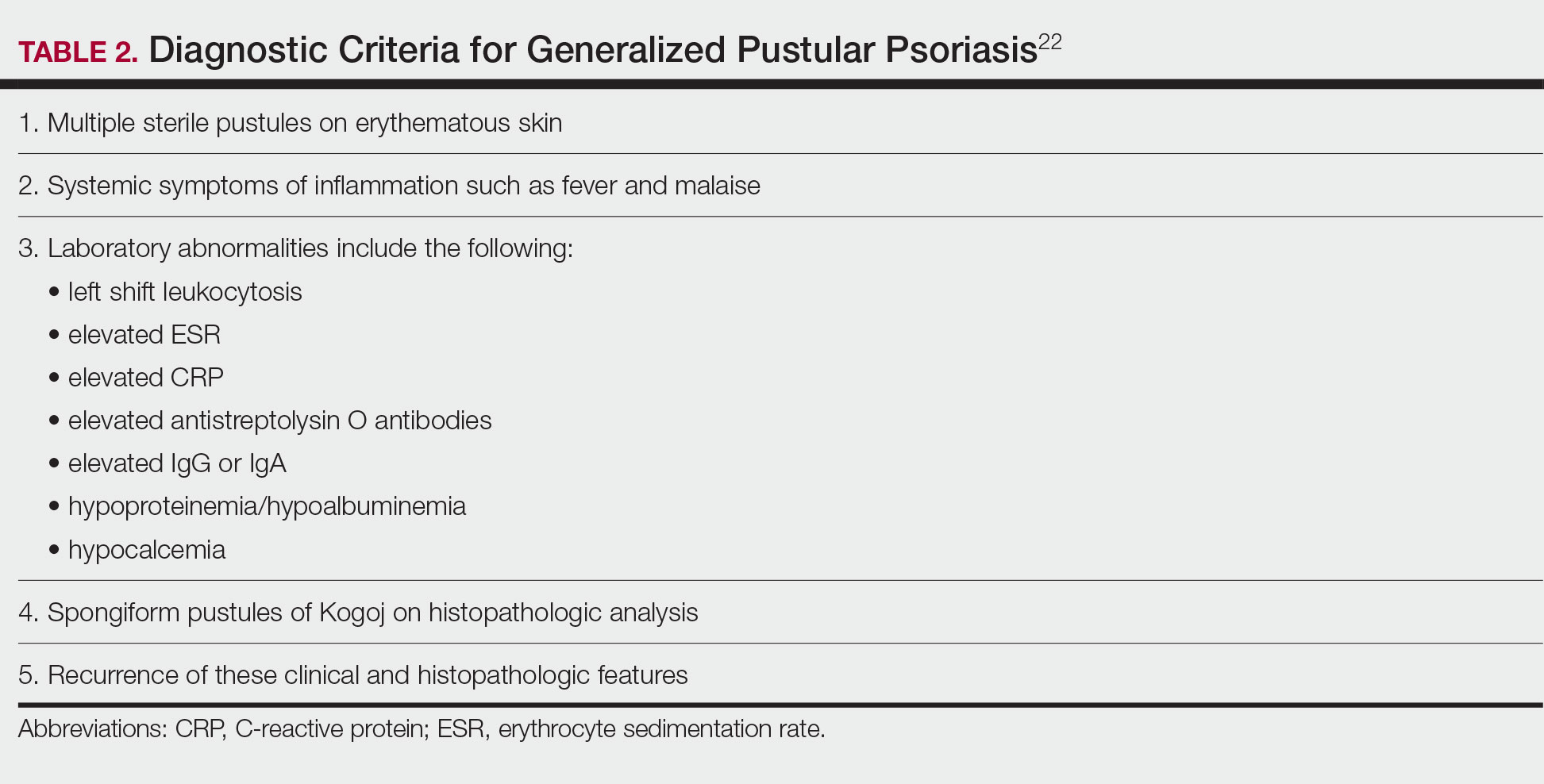

Although the severity of GPP is highly variable, skin manifestations often are accompanied by systemic manifestations of inflammation, including fever and malaise. Common laboratory abnormalities include leukocytosis with peripheral neutrophilia, a high serum C-reactive protein level, hypocalcemia, and hypoalbuminemia.22 Abnormal liver enzymes often are present and result from neutrophilic cholangitis, with alternating strictures and dilations of biliary ducts observed on magnetic resonance imaging.23 Additional laboratory abnormalities are provided in Table 2. Other extracutaneous findings associated with GPP include arthralgia, edema, and characteristic psoriatic nail changes.4 Fatal complications include acute respiratory distress syndrome, renal dysfunction, cardiovascular shock, and sepsis.24,25

Histologic Features

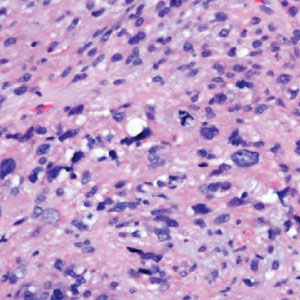

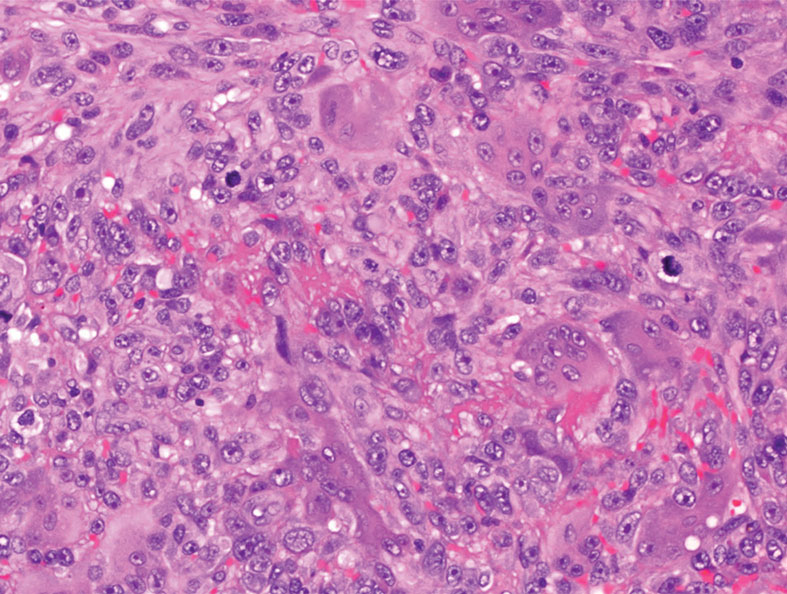

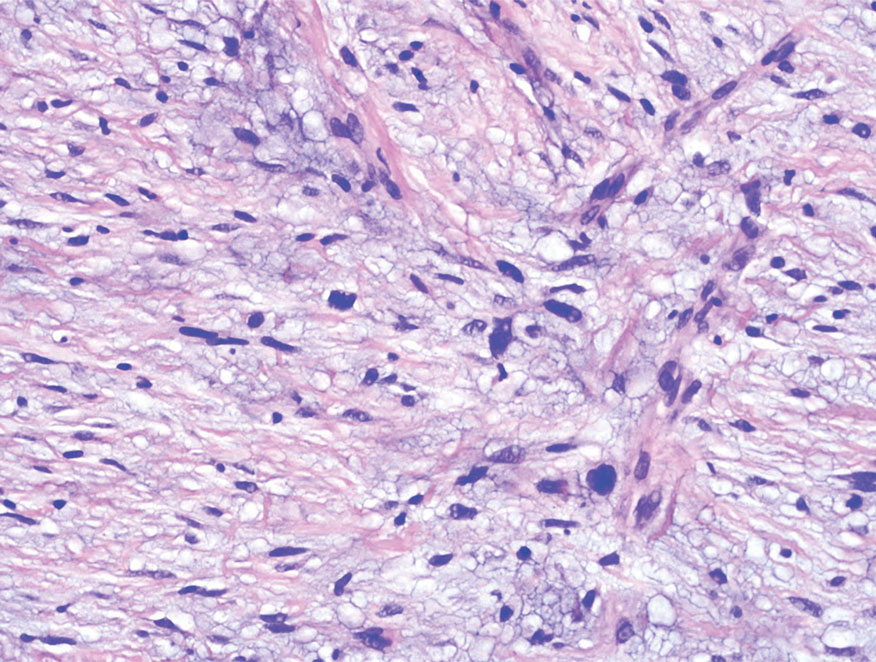

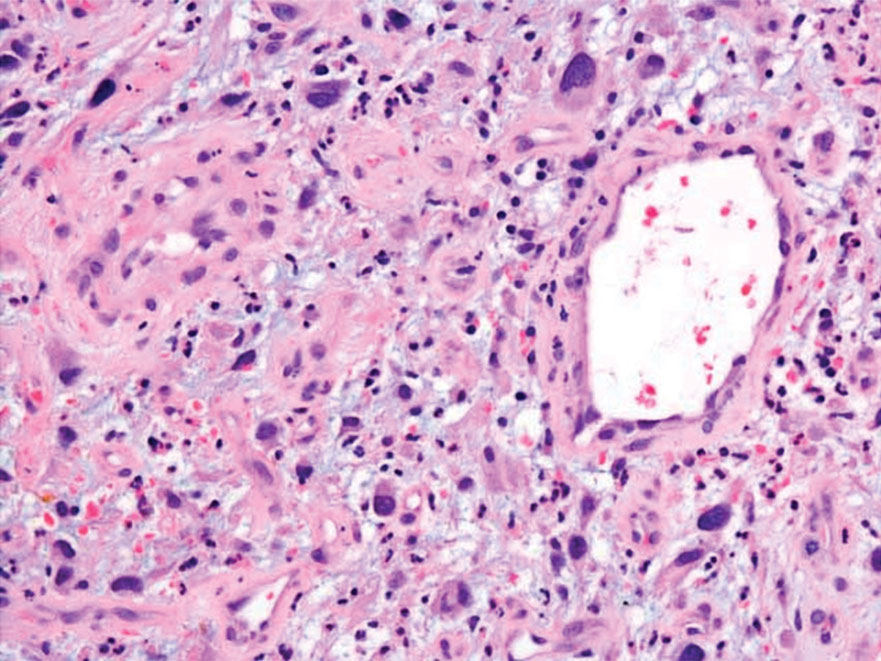

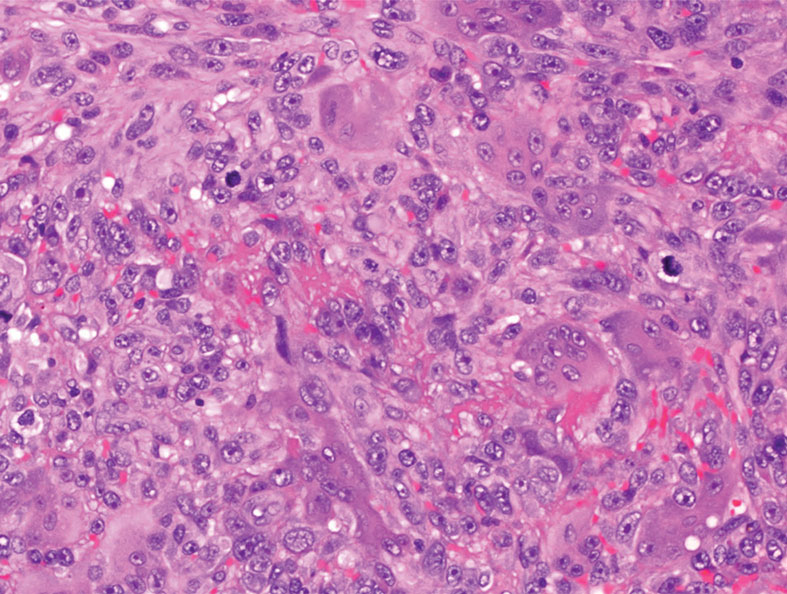

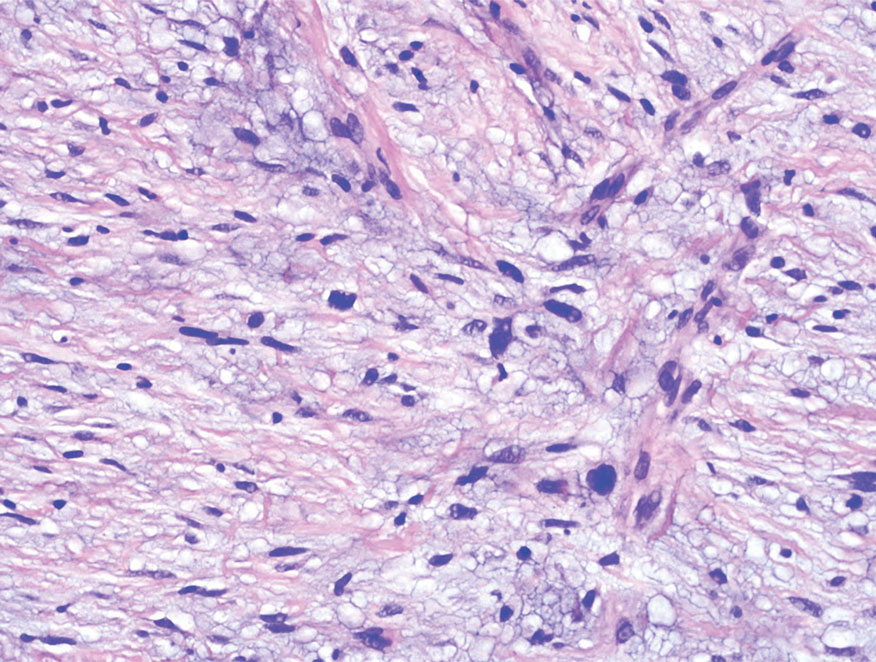

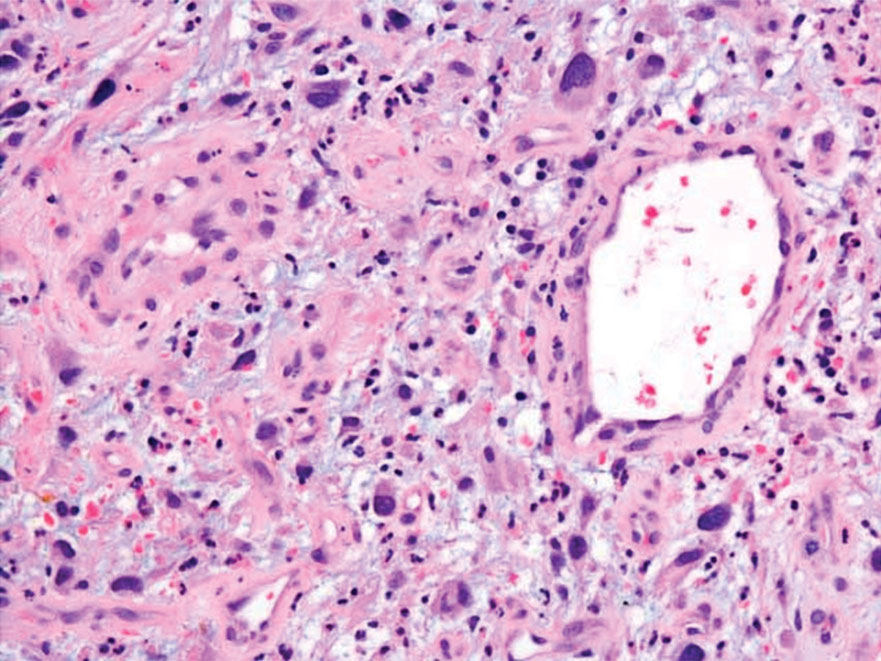

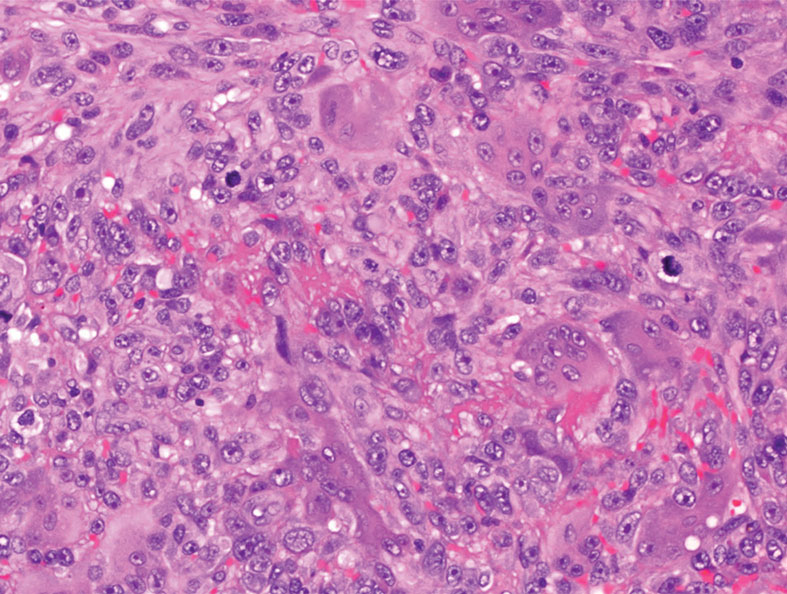

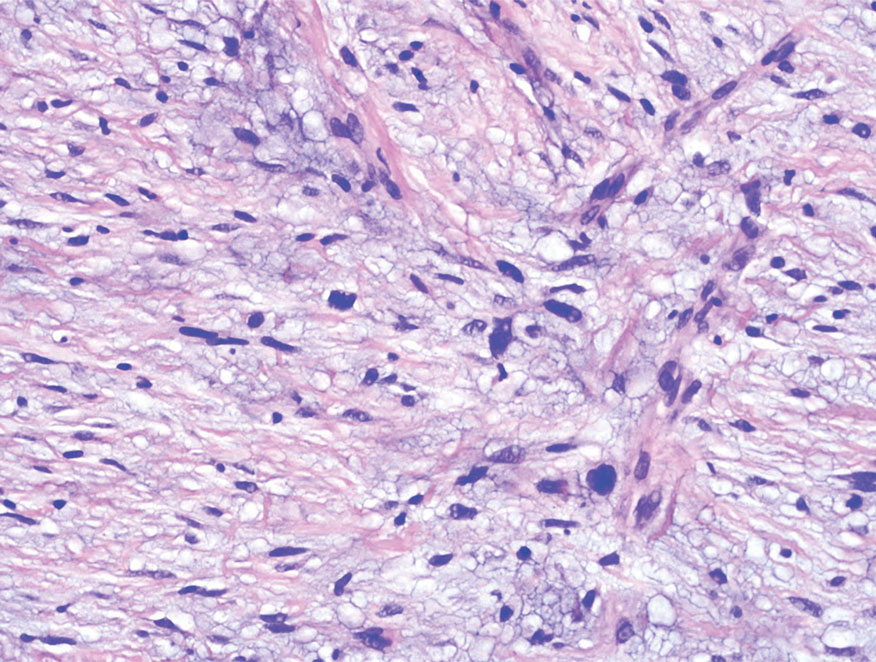

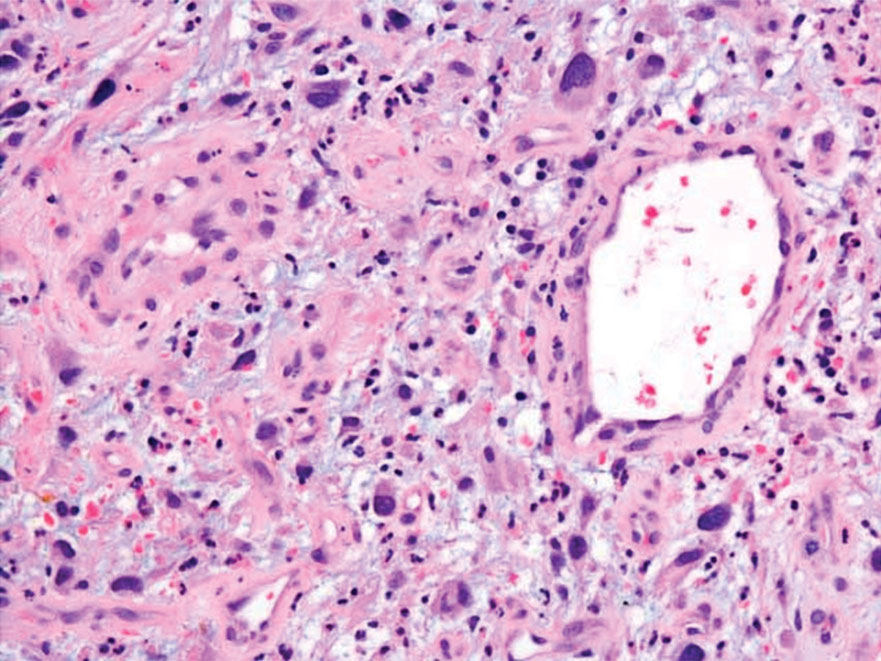

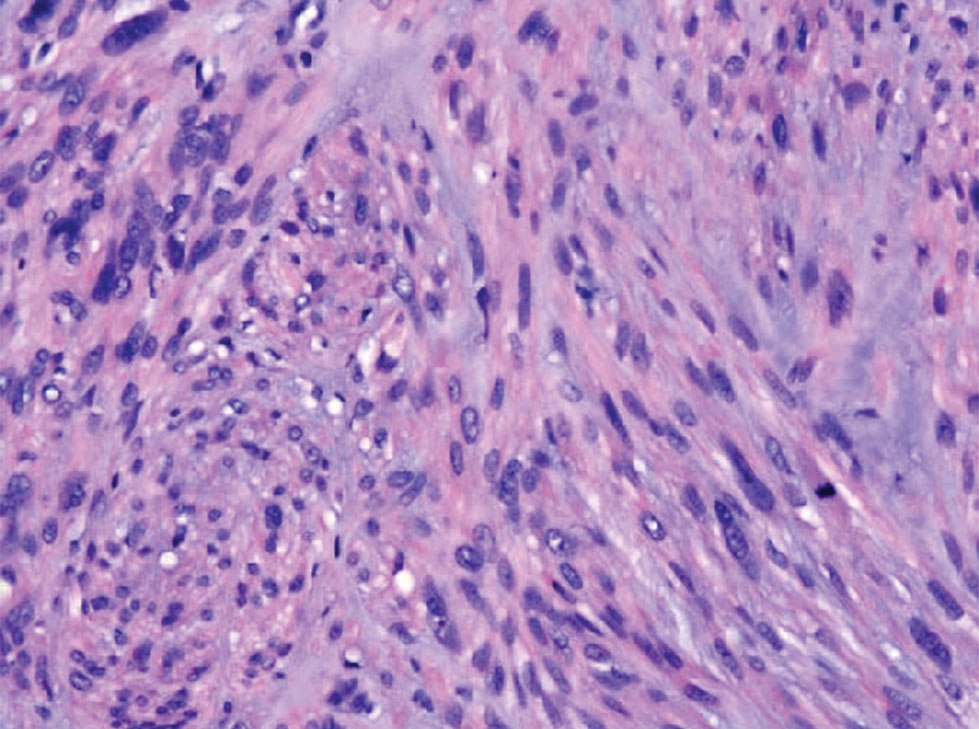

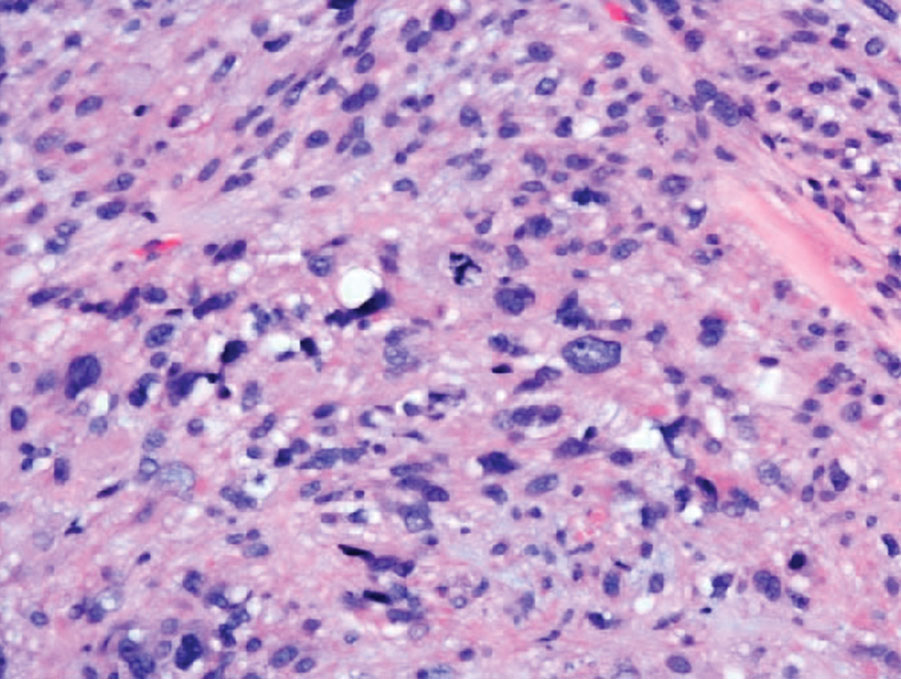

Given the potential for the skin manifestations of GPP to mimic other disorders, a skin biopsy is warranted to confirm the diagnosis. Generalized pustular psoriasis is histologically characterized by the presence of subcorneal macropustules (ie, spongiform pustules of Kogoj) formed by neutrophil infiltration into the spongelike network of the epidermis.6 Otherwise, the architecture of the epithelium in GPP is similar to that seen with plaque psoriasis, with parakeratosis, acanthosis, rete-ridge elongation, diminished stratum granulosum, and thinning of the suprapapillary epidermis, though the inflammatory cell infiltrate and edema are markedly more severe in GPP than plaque psoriasis.3,4

Differential Diagnosis

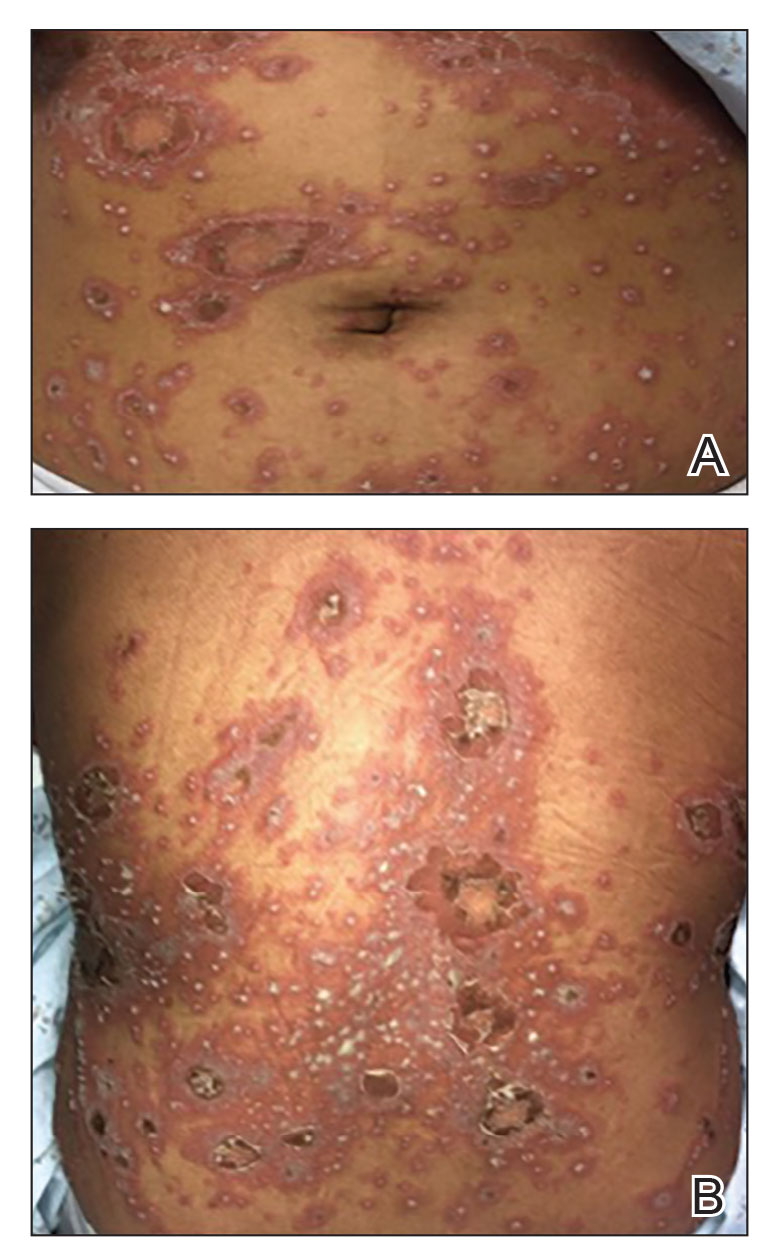

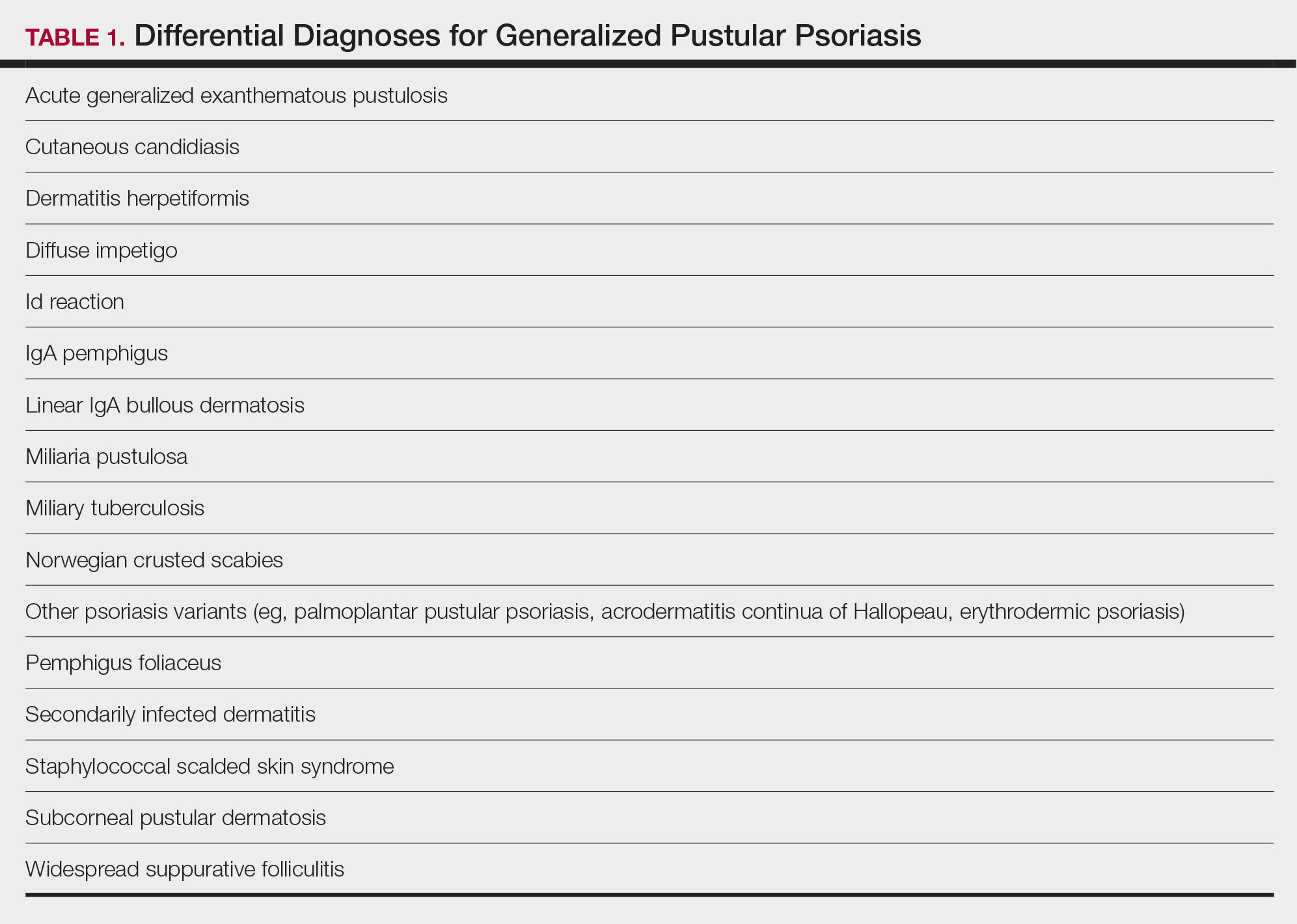

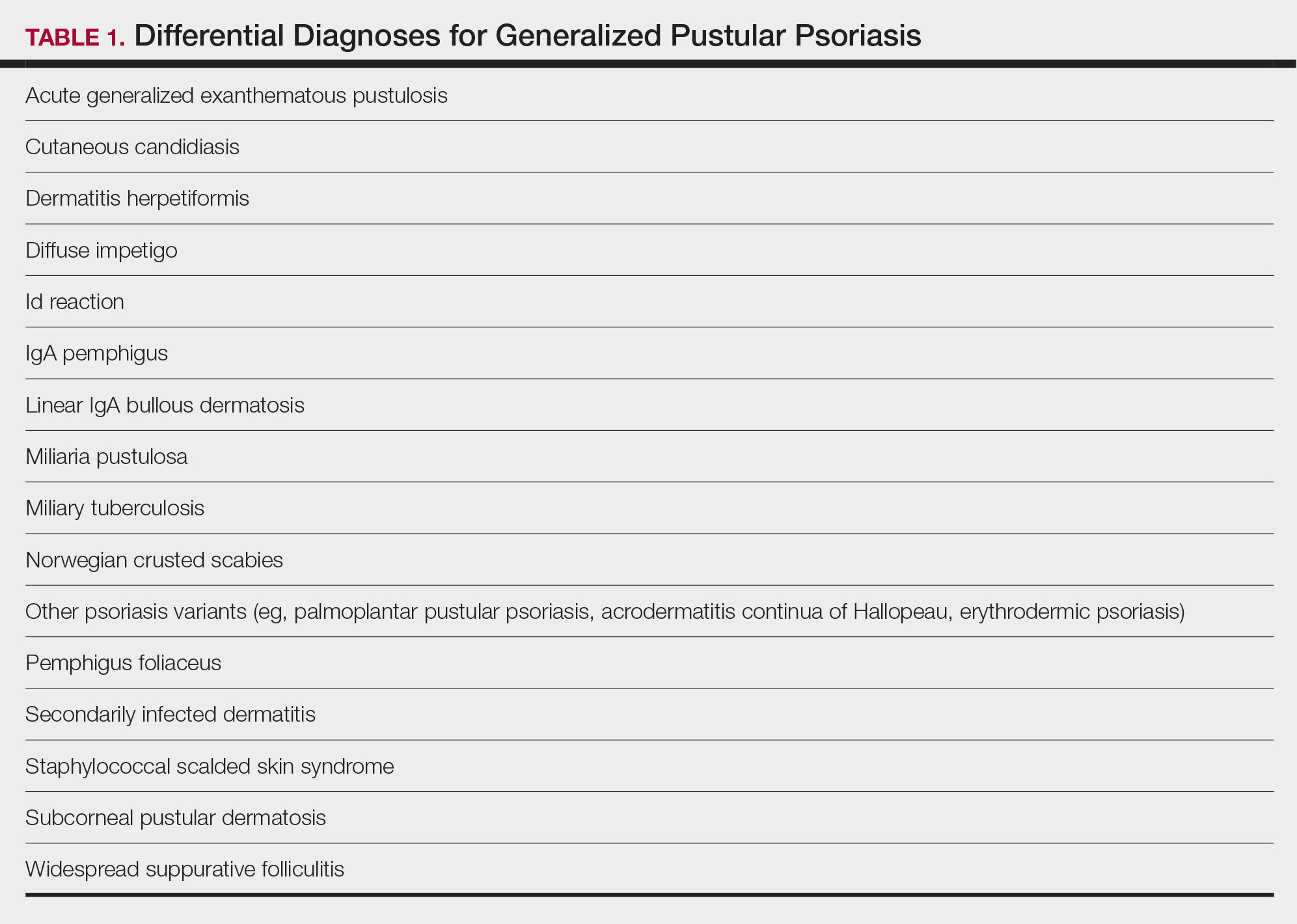

There are many other cutaneous pustular diagnoses that must be ruled out when evaluating a patient with GPP (Table 1).26 Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a common mimicker of GPP that is differentiated histologically by the presence of eosinophils and necrotic keratinocytes.4 In addition to its distinct histopathologic findings, AGEP is classically associated with recent initiation of certain medications, most commonly penicillins, macrolides, quinolones, sulfonamides, terbinafine, and diltiazem.27 In contrast, GPP more commonly is related to withdrawal of corticosteroids as well as initiation of some biologic medications, including anti-TNF agents.3 Generalized pustular psoriasis should be suspected over AGEP in patients with a personal or family history of psoriasis, though GPP may arise in patients with or without a history of psoriasis. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis usually is more abrupt in both onset and resolution compared with GPP, with clearance of pustules within a few days to weeks following cessation of the triggering factor.4

Other pustular variants of psoriasis (eg, palmoplantar pustular psoriasis, acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau) are differentiated from GPP by their chronicity and localization to palmoplantar and/or ungual surfaces.5 Other differential diagnoses are listed in Table 1.

Diagnostic Criteria for GPP

Diagnostic criteria have been proposed for GPP (Table 2), including (1) the presence of sterile pustules, (2) systemic signs of inflammation, (3) laboratory abnormalities, (4) histopathologic confirmation of spongiform pustules of Kogoj, and (5) recurrence of symptoms.22 To definitively diagnose GPP, all 5 criteria must be met. To rule out mimickers, it may be worthwhile to perform Gram staining, potassium hydroxide preparation, in vitro cultures, and/or immunofluorescence testing.6

Treatment

Given the high potential for mortality associated with GPP, the most essential component of management is to ensure adequate supportive care. Any temperature, fluid, or electrolyte imbalances should be corrected as they arise. Secondary infections also must be identified and treated, if present, to reduce the risk for fatal complications, including systemic infection and sepsis. Precautions must be taken to ensure that serious end-organ damage, including hepatic, renal, and respiratory dysfunction, is avoided.

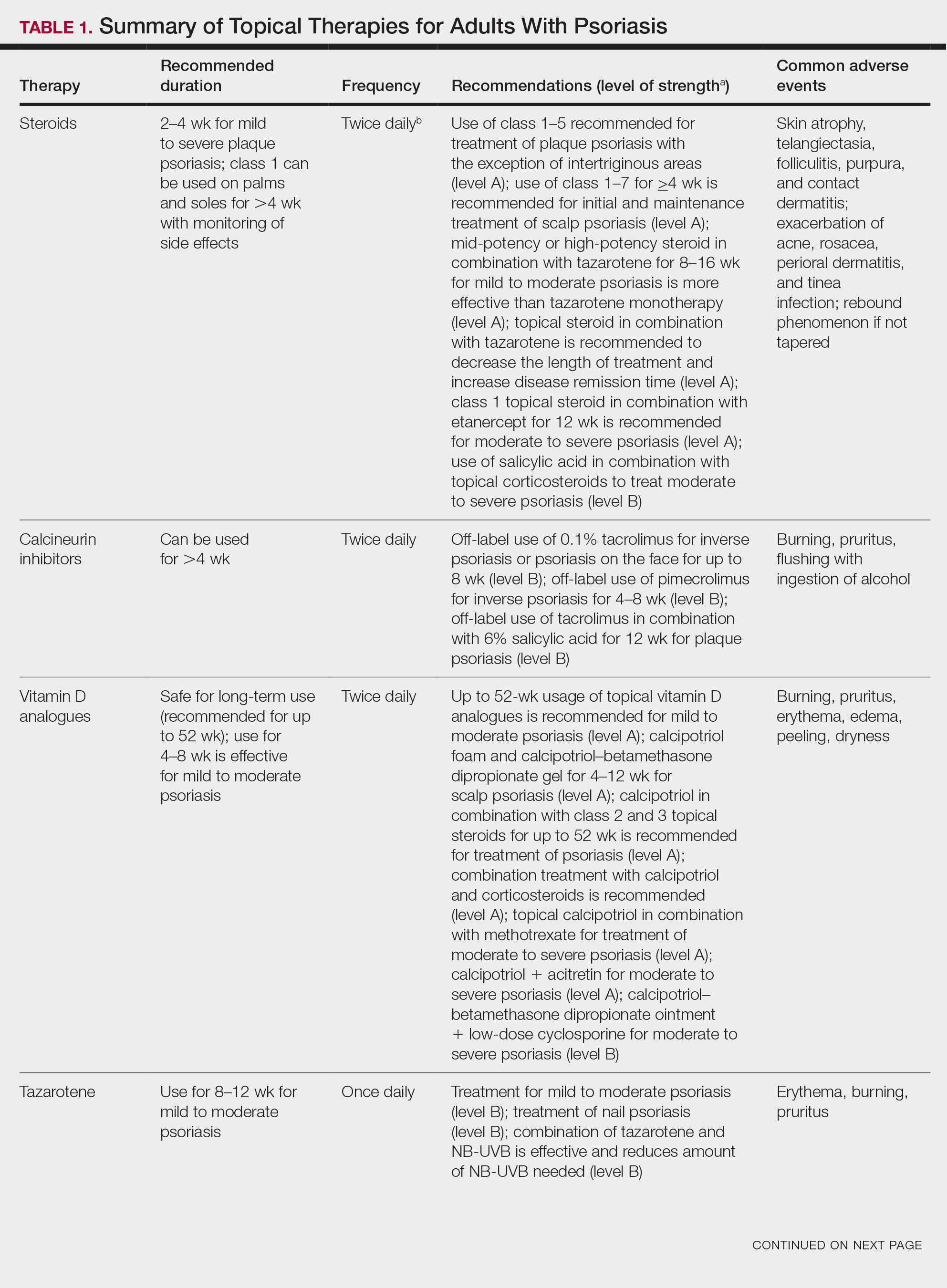

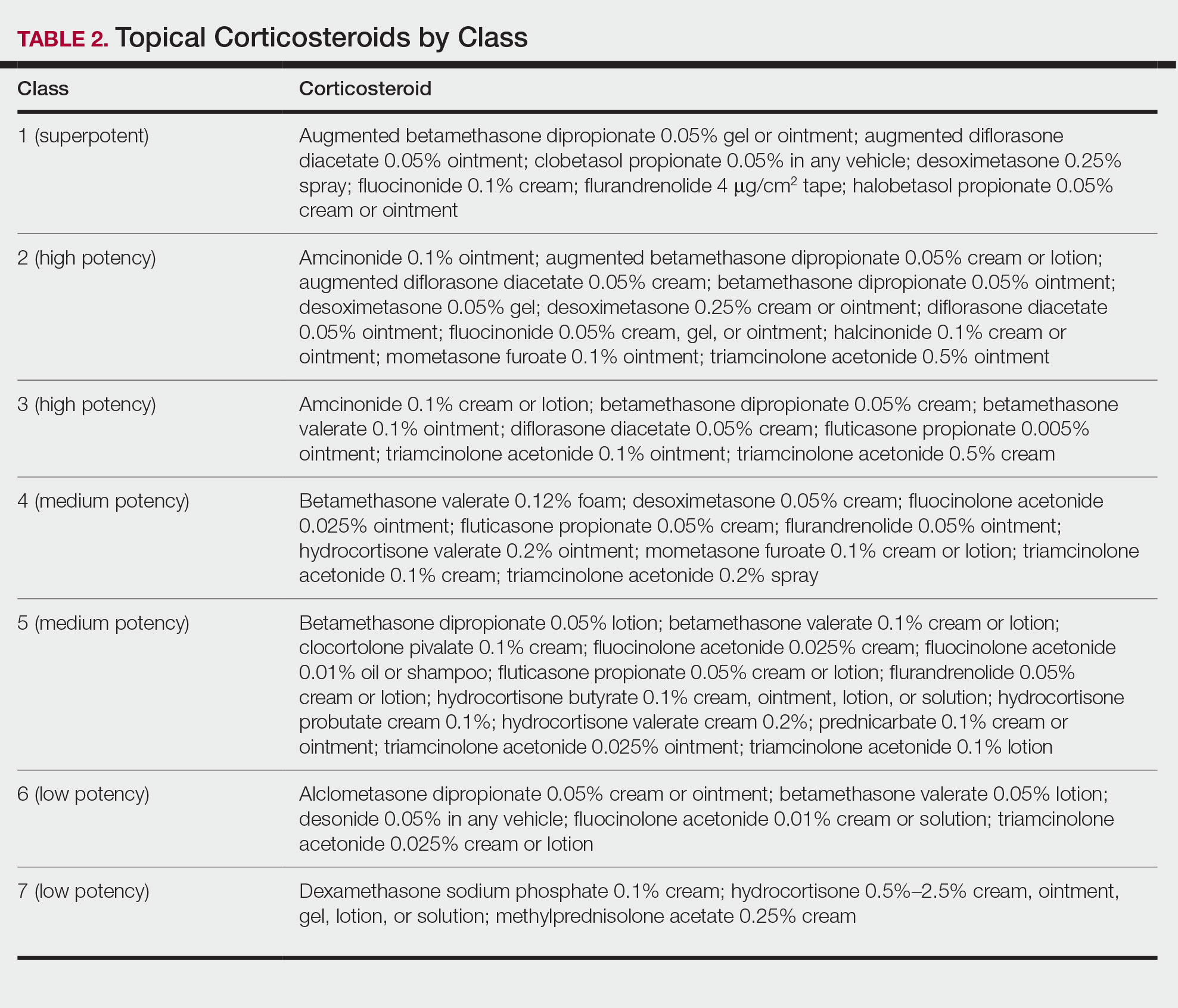

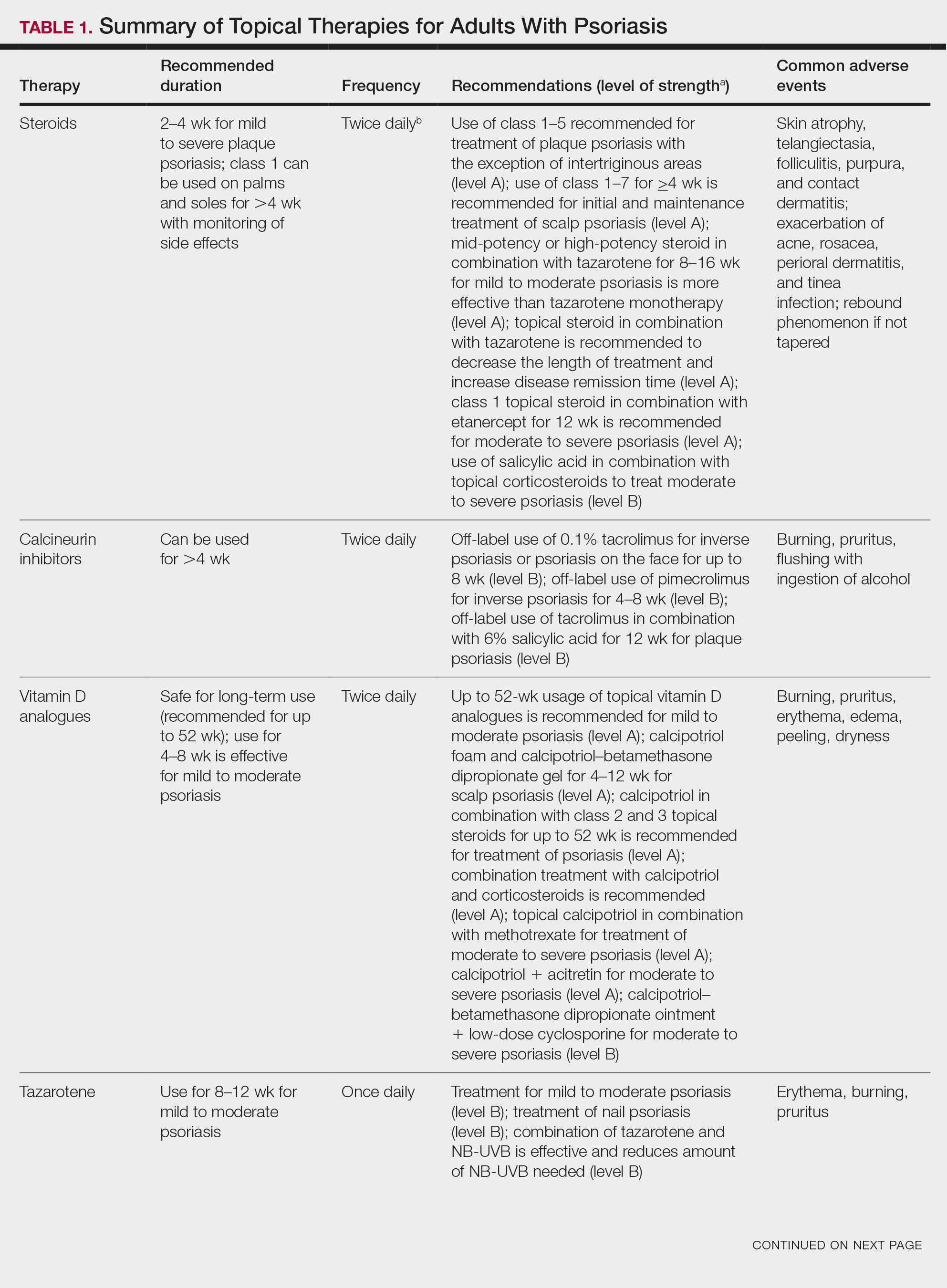

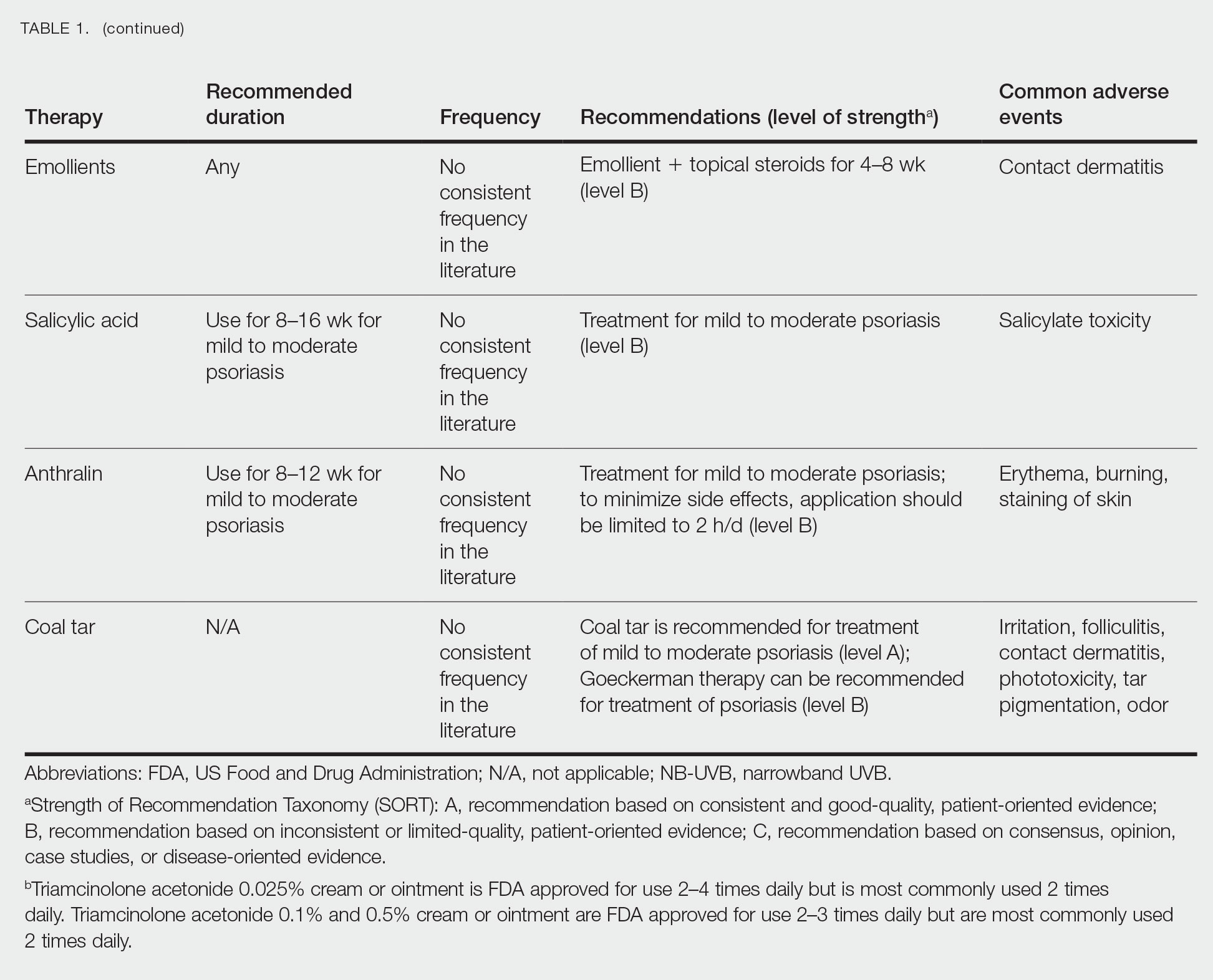

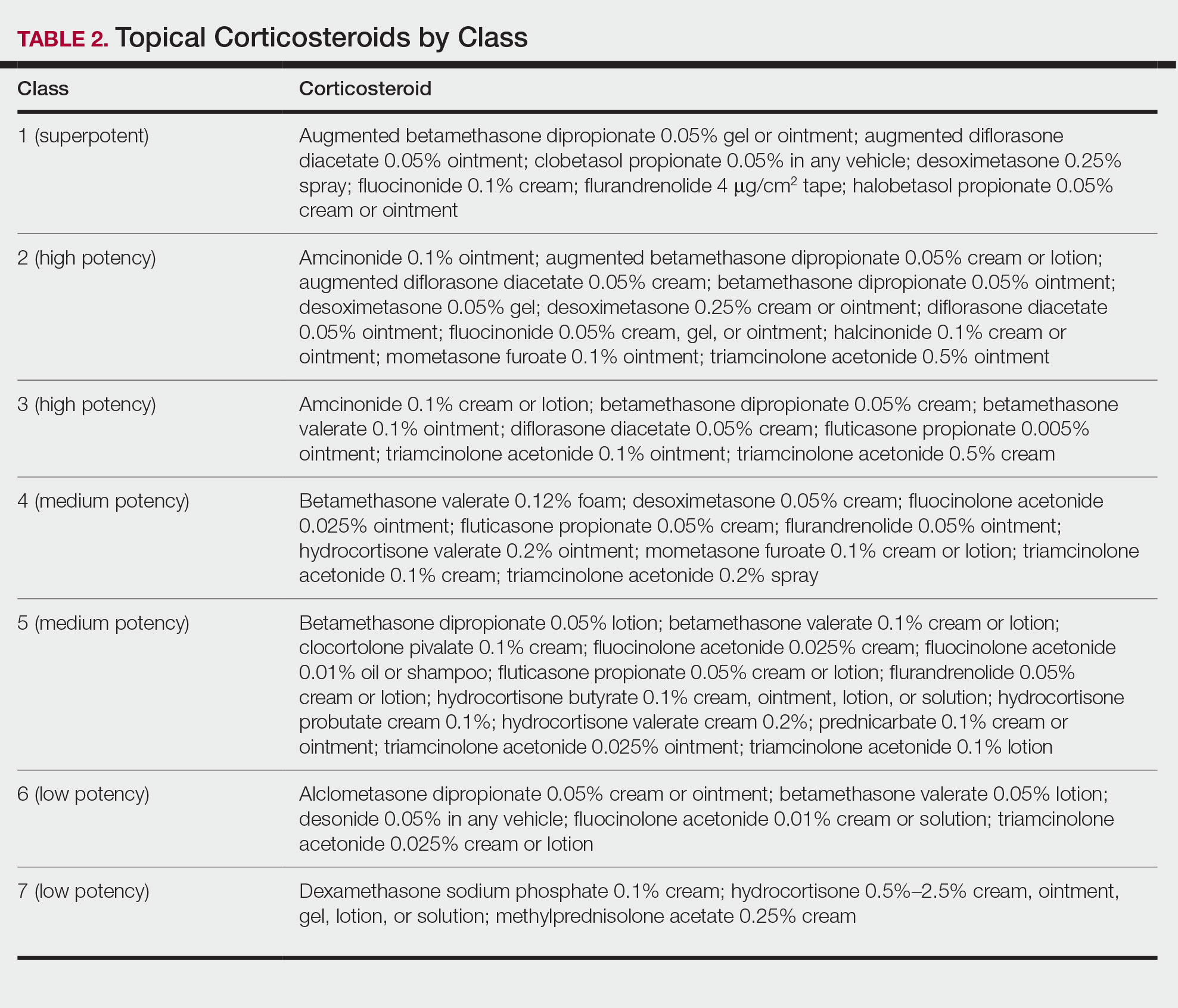

Adjunctive topical intervention often is initiated with bland emollients, corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and/or vitamin D derivatives to help soothe skin symptoms, but treatment with systemic therapies usually is warranted to achieve symptom control.2,25 Importantly, there are no systemic or topical agents that have specifically been approved for the treatment of GPP in Europe or the United States.3 Given the absence of universally accepted treatment guidelines, therapeutic agents for GPP usually are selected based on clinical experience while also taking the extent of involvement and disease severity into consideration.3

Treatment Recommendations for Adults

Oral Systemic Agents—Treatment guidelines set forth by the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) in 2012 proposed that first-line therapies for GPP should be acitretin, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and infliximab.28 However, since those guidelines were established, many new biologic therapies have been approved for the treatment of psoriasis and often are considered in the treatment of psoriasis subtypes, including GPP.29 Although retinoids previously were considered to be a preferred first-line therapy, they are associated with a high incidence of adverse effects and must be used with caution in women of childbearing age.6 Oral acitretin at a dosage of 0.75 to 1.0 mg/kg/d has been shown to result in clinical improvement within 1 to 2 weeks, and a maintenance dosage of 0.125 to 0.25 mg/kg/d is required for several months to prevent recurrence.30 Methotrexate—5.0 to 15.0 mg/wk, or perhaps higher in patients with refractory disease, increased by 2.5-mg intervals until symptoms improve—is recommended by the NPF in patients who are unresponsive or cannot tolerate retinoids, though close monitoring for hematologic abnormalities is required. Cyclosporine 2.5 to 5.0 mg/kg/d is considered an alternative to methotrexate and retinoids; it has a faster onset of action, with improvement reported as early as 2 weeks after initiation of therapy.1,28 Although cyclosporine may be effective in the acute phase, especially in severe cases of GPP, long-term use of cyclosporine is not recommended because of the potential for renal dysfunction and hypertension.31

Biologic Agents—More recent evidence has accumulated supporting the efficacy of anti-TNF agents in the treatment of GPP, suggesting the positioning of these agents as first line. A number of case series have shown dramatic and rapid improvement of GPP with intravenous infliximab 3 to 5 mg/kg, with results observed hours to days after the first infusion.32-37 Thus, infliximab is recommended as first-line treatment in severe acute cases, though its efficacy as a maintenance therapy has not been sufficiently investigated.6 Case reports and case series document the safety and efficacy of adalimumab 40 to 80 mg every 1 to 2 weeks38,39 and etanercept 25 to 50 mg twice weekly40-42 in patients with recalcitrantGPP. Therefore, these anti-TNF agents may be considered in patients who are nonresponsive to treatment with infliximab.

Rarely, there have been reports of paradoxical induction of GPP with the use of some anti-TNF agents,43-45 which may be due to a cytokine imbalance characterized by unopposed IFN-α activation.6 In patients with a history of GPP after initiation of a biologic, treatment with agents from within the offending class should be avoided.

The IL-17A monoclonal antibodies secukinumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab have been shown in open-label phase 3 studies to result in disease remission at 12 weeks.46-48 Treatment with guselkumab, an IL-23 monoclonal antibody, also has demonstrated efficacy in patients with GPP.49 Ustekinumab, an IL-12/23 inhibitor, in combination with acitretin also has been shown to be successful in achieving disease remission after a few weeks of treatment.50

More recent case reports have shown the efficacy of IL-1 inhibitors including gevokizumab, canakinumab, and anakinra in achieving GPP clearance, though more prospective studies are needed to evaluate their efficacy.51-53 Given the etiologic association between IL-1 disinhibition and GPP, future investigations of these therapies as well as those that target the IL-36 pathway may prove to be particularly interesting.

Phototherapy and Combination Therapies—Phototherapy may be considered as maintenance therapy after disease control is achieved, though it is not considered appropriate for acute cases.28 Combination therapies with a biologic plus a nonbiologic systemic agent or alternating among various biologics may allow physicians to maximize benefits and minimize adverse effects in the long term, though there is insufficient evidence to suggest any specific combination treatment algorithm for GPP.28

Treatment Recommendations for Pediatric Patients

Based on a small number of case series and case reports, the first-line treatment strategy for children with GPP is similar to adults. Given the notable adverse events of most oral systemic agents, biologic therapies may emerge as first-line therapy in the pediatric population as more evidence accumulates.28

Treatment Recommendations for Pregnant Patients

Systemic corticosteroids are widely considered to be the first-line treatments for the management of impetigo herpetiformis.7 Low-dose prednisone (15–30 mg/d) usually is effective, but severe cases may require increasing the dosage to 60 mg/d.6 Given the potential for rebound flares upon withdrawal of systemic corticosteroids, these agents must be gradually tapered after the resolution of symptoms.

Certolizumab pegol also is an attractive option in pregnant patients with impetigo herpetiformis because of its favorable safety profile and negligible mother-to-infant transfer through the placenta or breast milk. It has been shown to be effective in treating GPP and impetigo herpetiformis during pregnancy in recently published case reports.54,55 In refractory cases, other TNF-α inhibitors (eg, adalimumab, infliximab, etanercept) or cyclosporine may be considered. However, cautious medical monitoring is warranted, as little is known about the potential adverse effects of these agents to the mother and fetus.28,56 Data from transplant recipients along with several case reports indicate that cyclosporine is not associated with an increased risk for adverse effects during pregnancy at a dose of 2 to 3 mg/kg.57-59 Both methotrexate and retinoids are known teratogens and are therefore contraindicated in pregnant patients.56

If pustules do not resolve in the postpartum period, patients should be treated with standard GPP therapies. However, long-term and population studies are lacking regarding the potential for infant exposure to systemic agents in breast milk. Therefore, the NPF recommends avoiding breastfeeding while taking systemic medications, if possible.56

Limitations of Treatment Recommendations

The ability to generate an evidence-based treatment strategy for GPP is limited by a lack of high-quality studies investigating the efficacy and safety of treatments in patients with GPP due to the rarity and relapsing-remitting nature of the disease, which makes randomized controlled trials difficult to conduct. The quality of the available research is further limited by the lack of validated outcome measures to specifically assess improvements in patients with GPP, such that results are difficult to synthesize and compare among studies.31

Conclusion

Although limited, the available research suggests that treatment with various biologics, especially infliximab, is effective in achieving rapid clearance in patients with GPP. In general, biologics may be the most appropriate treatment option in patients with GPP given their relatively favorable safety profiles. Other oral systemic agents, including acitretin, cyclosporine, and methotrexate, have limited evidence to support their use in the acute phase, but their safety profiles often limit their utility in the long-term. Emerging evidence regarding the association of GPP with IL36RN mutations suggests a unique role for agents targeting the IL-36 or IL-1 pathways, though this has yet to be thoroughly investigated.

- Benjegerdes KE, Hyde K, Kivelevitch D, et al. Pustular psoriasis: pathophysiology and current treatment perspectives. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2016;6:131‐144.

- Bachelez H. Pustular psoriasis and related pustular skin diseases. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:614‐618.

- Gooderham MJ, Van Voorhees AS, Lebwohl MG. An update on generalized pustular psoriasis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019;15:907‐919.

- Ly K, Beck KM, Smith MP, et al. Diagnosis and screening of patients with generalized pustular psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2019;9:37‐42.

- van de Kerkhof PCM, Nestle FO. Psoriasis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012:138-160.

- Hoegler KM, John AM, Handler MZ, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a review and update on treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1645‐1651.

- Oumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:101‐104.

- Johnston A, Xing X, Wolterink L, et al. IL-1 and IL-36 are dominant cytokines in generalized pustular psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:109-120.

- Furue K, Yamamura K, Tsuji G, et al. Highlighting interleukin-36 signalling in plaque psoriasis and pustular psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:5-13.

- Ogawa E, Sato Y, Minagawa A, et al. Pathogenesis of psoriasis and development of treatment. J Dermatol. 2018;45:264-272.

- Marrakchi S, Guigue P, Renshaw BR, et al. Interleukin-36-receptor antagonist deficiency and generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:620-628.

- Onoufriadis A, Simpson MA, Pink AE, et al. Mutations in IL36RN/IL1F5 are associated with the severe episodic inflammatory skin disease known as generalized pustular psoriasis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:432-437.

- Setta-Kaffetzi N, Navarini AA, Patel VM, et al. Rare pathogenic variants in IL36RN underlie a spectrum of psoriasis-associated pustular phenotypes. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1366-1369.

- Sugiura K, Takemoto A, Yamaguchi M, et al. The majority of generalized pustular psoriasis without psoriasis vulgaris is caused by deficiency of interleukin-36 receptor antagonist. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:2514-2521.

- Hussain S, Berki DM, Choon SE, et al. IL36RN mutations define a severe autoinflammatory phenotype of generalized pustular psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:1067-1070.e9.

- Körber A, Mossner R, Renner R, et al. Mutations in IL36RN in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:2634-2637.

- Twelves S, Mostafa A, Dand N, et al. Clinical and genetic differences between pustular psoriasis subtypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:1021-1026.

- Sugiura K. The genetic background of generalized pustular psoriasis: IL36RN mutations and CARD14 gain-of-function variants. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;74:187-192

- Wang Y, Cheng R, Lu Z, et al. Clinical profiles of pediatric patients with GPP alone and with different IL36RN genotypes. J Dermatol Sci. 2017;85:235-240.

- Setta-Kaffetzi N, Simpson MA, Navarini AA, et al. AP1S3 mutations are associated with pustular psoriasis and impaired Toll-like receptor 3 trafficking. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:790-797.

- Mahil SK, Twelves S, Farkas K, et al. AP1S3 mutations cause skin autoinflammation by disrupting keratinocyte autophagy and upregulating IL-36 production. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:2251-2259.

- Umezawa Y, Ozawa A, Kawasima T, et al. Therapeutic guidelines for the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) based on a proposed classification of disease severity. Arch Dermatol Res. 2003;295(suppl 1):S43-S54.

- Viguier M, Allez M, Zagdanski AM, et al. High frequency of cholestasis in generalized pustular psoriasis: evidence for neutrophilic involvement of the biliary tract. Hepatology. 2004;40:452-458.

- Ryan TJ, Baker H. The prognosis of generalized pustular psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1971;85:407-411.

- Kalb RE. Pustular psoriasis: management. In: Ofori AO, Duffin KC, eds. UpToDate. UpToDate; 2014. Accessed July 20, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pustular-psoriasis-management/print

- Naik HB, Cowen EW. Autoinflammatory pustular neutrophilic diseases. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31:405-425.

- Sidoroff A, Dunant A, Viboud C, et al. Risk factors for acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—results of a multinational case-control study (EuroSCAR). Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:989-996.

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279‐288.

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072.

- Mengesha YM, Bennett ML. Pustular skin disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol 2002;3:389-400.

- Zhou LL, Georgakopoulos JR, Ighani A, et al. Systemic monotherapy treatments for generalized pustular psoriasis: a systematic review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22:591‐601.

- Elewski BE. Infliximab for the treatment of severe pustular psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:796-797.

- Kim HS, You HS, Cho HH, et al. Two cases of generalized pustular psoriasis: successful treatment with infliximab. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:787-788.

- Trent JT, Kerdel FA. Successful treatment of Von Zumbusch pustular psoriasis with infliximab. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:224-228.

- Poulalhon N, Begon E, Lebbé C, et al. A follow-up study in 28 patients treated with infliximab for severe recalcitrant psoriasis: evidence for efficacy and high incidence of biological autoimmunity. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:329-336.

- Routhouska S, Sheth PB, Korman NJ. Long-term management of generalized pustular psoriasis with infliximab: case series. J Cutan Med Surg. 2008;12:184-188.

- Lisby S, Gniadecki R. Infliximab (Remicade) for acute, severe pustular and erythrodermic psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84:247-248.

- Zangrilli A, Papoutsaki M, Talamonti M, et al. Long-term efficacy of adalimumab in generalized pustular psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat. 2008;19:185-187.

- Matsumoto A, Komine M, Karakawa M, et al. Adalimumab administration after infliximab therapy is a successful treatment strategy for generalized pustular psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2017;44:202-204.

- Kamarashev J, Lor P, Forster A, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis induced by cyclosporin in a withdrawal responding to the tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitor etanercept. Dermatology. 2002;205:213-216.

- Esposito M, Mazzotta A, Casciello C, et al. Etanercept at different dosages in the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis: a case series. Dermatology. 2008;216:355-360.

- Lo Schiavo A, Brancaccio G, Puca RV, et al. Etanercept in the treatment of generalized annular pustular psoriasis. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:233-234.

- Goiriz R, Daudén E, Pérez-Gala S, et al. Flare and change of psoriasis morphology during the course of treatment with tumor necrosis factor blockers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;32:176-179.

- Collamer AN, Battafarano DF. Psoriatic skin lesions induced by tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy: clinical features and possible immunopathogenesis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;40:233-240.

- Almutairi D, Sheasgreen C, Weizman A, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis induced by infliximab in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;1:507-510.

- Imafuku S, Honma M, Okubo Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: a 52-week analysis from phase III open-label multicenter Japanese study. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1011-1017

- Saeki H, Nakagawa H, Ishii T, et al. Efficacy and safety of open-label ixekizumab treatment in Japanese patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, erythrodermic psoriasis, and generalized pustular psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1148-1155.

- Yamasaki K, Nakagawa H, Kubo Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of brodalumab in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis and psoriatic erythroderma: results from a 52-week, open-label study. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:741-751.

- Sano S, Kubo H, Morishima H, et al. Guselkumab, a human interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody in Japanese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis and erythrodermic psoriasis: efficacy and safety analyses of a 52-week, phase 3, multicenter, open-label study. J Dermatol. 2018;45:529‐539.

- Arakawa A, Ruzicka T, Prinz JC. Therapeutic efficacy of interleukin 12/interleukin 23 blockade in generalized pustular psoriasis regardless of IL36RN mutation status. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:825-828.

- Mansouri B, Richards L, Menter A. Treatment of two patients with generalized pustular psoriasis with the interleukin-1beta inhibitor gevokizumab. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:239-241.

- Skendros P, Papagoras C, Lefaki I, et al. Successful response in a case of severe pustular psoriasis after interleukin-1 beta inhibition. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:212-215.

- Viguier M, Guigue P, Pagès C, et al. Successful treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis with the interleukin-1-receptor antagonist Anakinra: lack of correlation with IL1RN mutations. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:66-67.

- Fukushima H, Iwata Y, Arima M, et al. Efficacy and safety of treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor‐α drugs for severe impetigo herpetiformis. J Dermatol. 2021;48:207-210.

- Mizutani Y, Mizutani YH, Matsuyama K, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis in pregnancy, successfully treated with certolizumab pegol. J Dermatol. 2021;47:e262-e263.

- Bae YS, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Review of treatment options for psoriasis in pregnant or lactating women: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:459‐477.

- Finch TM, Tan CY. Pustular psoriasis exacerbated by pregnancy and controlled by cyclosporin A. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:582-584.

- Gaughan WJ, Moritz MJ, Radomski JS, et al. National Transplantation Pregnancy Registry: report on outcomes of cyclosporine-treated female kidney transplant recipients with an interval from transplantation to pregnancy of greater than five years. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;28:266-269.

- Kura MM, Surjushe AU. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy treated with oral cyclosporin. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:458-459.

Acute generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a rare severe variant of psoriasis characterized by the sudden widespread eruption of sterile pustules.1,2 The cutaneous manifestations of GPP also may be accompanied by signs of systemic inflammation, including fever, malaise, and leukocytosis.2 Complications are common and may be life-threatening, especially in older patients with comorbid diseases.3 Generalized pustular psoriasis most commonly occurs in patients with a preceding history of psoriasis, but it also may occur de novo.4 Generalized pustular psoriasis is associated with notable morbidity and mortality, and relapses are common.3,4 Many triggers of GPP have been identified, including initiation and withdrawal of various medications, infections, pregnancy, and other conditions.5,6 Although GPP most often occurs in adults, it also may arise in children and infants.3 In pregnancy, GPP is referred to as impetigo herpetiformis, despite having no etiologic ties with either herpes simplex virus or staphylococcal or streptococcal infection. Impetigo herpetiformis is considered one of the most dangerous dermatoses of pregnancy because of high rates of associated maternal and fetal morbidity.6,7

Acute GPP has proven to be a challenging disease to treat due to the rarity and relapsing-remitting nature of the disease; additionally, there are relatively few randomized controlled trials investigating the efficacy and safety of treatments for GPP. This review summarizes the features of GPP, including the pathophysiology of the disease, clinical and histological manifestations, and recommendations for management based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using MeSH terms pertaining to the disease, including generalized pustular psoriasis, impetigo herpetiformis, and von Zumbusch psoriasis.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of GPP is only partially understood, but it is thought to have a distinct pattern of immune activation compared with plaque psoriasis.8 Although there is a considerable amount of overlap and cross-talk among cytokine pathways, GPP generally is driven by innate immunity and unrestrained IL-36 cytokine activity. In contrast, adaptive immune responses—namely the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, IL-23, IL-17, and IL-22 axes—underlie plaque psoriasis.8-10

Proinflammatory IL-36 cytokines α, β, and γ, which are all part of the IL-1 superfamily, bind to the IL-36 receptor (IL-36R) to recruit and activate immune cells via various mediators, including IL-1β; IL-8; and chemokines CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL8.3 The IL-36 receptor antagonist (IL-36ra) acts to inhibit this inflammatory cascade.3,8 Microarray analyses of skin biopsy samples have shown that overexpression of IL-17A, TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-36 are seen in both GPP and plaque psoriasis lesions, but GPP lesions had higher expression of IL-1β, IL-36α, and IL-36γ and elevated neutrophil chemokines—CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL8—compared with plaque psoriasis lesions.8

Gene Mutations Associated With GPP

There are 3 gene mutations that have been associated with pustular variants of psoriasis, though these mutations account for a minority of cases of GPP.4 Genetic screenings are not routinely indicated in patients with GPP, but they may be warranted in severe cases when a familial pattern of inheritance is suspected.4

IL36RN—The gene IL36RN codes the anti-inflammatory IL-36ra. Loss-of-function mutations in IL36RN lead to impairment of IL-36ra and consequently hyperactivity of the proinflammatory responses triggered by IL-36.3 Homozygous and heterozygous mutations in IL36RN have been observed in both familial and sporadic cases of GPP.11-13 Subsequent retrospective analyses have identified the presence of IL36RN mutations in patients with GPP with frequencies ranging from 23% to 37%.14-17IL36RN mutations are thought to be more common in patients without concomitant plaque psoriasis and have been associated with severe disease and early disease onset.15

CARD14—A gain-of-function mutation in CARD14 results in overactivation of the proinflammatory nuclear factor κB pathway and has been implicated in cases of GPP with concurrent psoriasis vulgaris. Interestingly, this may suggest distinct etiologies underlying GPP de novo and GPP in patients with a history of psoriasis.18,19

AP1S3—A loss-of-function mutation in AP1S3 results in abnormal endosomal trafficking and autophagy as well as increased expression of IL-36α.20,21

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis Cutaneous Manifestations of GPP

Generalized pustular psoriasis is characterized by the onset of widespread 2- to 3-mm sterile pustules on erythematous skin or within psoriasiform plaques4 (Figure). In patients with skin of color, the erythema may appear less obvious or perhaps slightly violaceous compared to White skin. Pustules may coalesce to form “lakes” of pus.5 Cutaneous symptoms include pain, burning, and pruritus. Associated mucosal findings may include cheilitis, geographic tongue, conjunctivitis, and uveitis.4

The severity of symptoms can vary greatly among patients as well as between flares within the same patient.2,3 Four distinct patterns of GPP have been described. The von Zumbusch pattern is characterized by a rapid, generalized, painful, erythematous and pustular eruption accompanied by fever and asthenia. The pustules usually resolve after several days with extensive scaling. The annular pattern is characterized by annular, erythematous, scaly lesions with pustules present centrifugally. The lesions enlarge by centrifugal expansion over a period of hours to days, while healing occurs centrally. The exanthematic type is an acute eruption of small pustules that abruptly appear and disappear within a few days, usually from infection or medication initiation. Sometimes pustules appear within or at the edge of existing psoriatic plaques in a localized pattern—the fourth pattern—often following the exposure to irritants (eg, tars, anthralin).5

Impetigo Herpetiformis—Impetigo herpetiformis is a form of GPP associated with pregnancy. It generally presents early in the third trimester with symmetric erythematous plaques in flexural and intertriginous areas with pustules present at lesion margins. Lesions expand centrifugally, with pustulation present at the advancing edge.6,7 Patients often are acutely ill with fever, delirium, vomiting, and tetany. Mucous membranes, including the tongue, mouth, and esophagus, also may be involved. The eruption typically resolves after delivery, though it often recurs with subsequent pregnancies, with the morbidity risk rising with each successive pregnancy.7

Systemic and Extracutaneous Manifestations of GPP

Although the severity of GPP is highly variable, skin manifestations often are accompanied by systemic manifestations of inflammation, including fever and malaise. Common laboratory abnormalities include leukocytosis with peripheral neutrophilia, a high serum C-reactive protein level, hypocalcemia, and hypoalbuminemia.22 Abnormal liver enzymes often are present and result from neutrophilic cholangitis, with alternating strictures and dilations of biliary ducts observed on magnetic resonance imaging.23 Additional laboratory abnormalities are provided in Table 2. Other extracutaneous findings associated with GPP include arthralgia, edema, and characteristic psoriatic nail changes.4 Fatal complications include acute respiratory distress syndrome, renal dysfunction, cardiovascular shock, and sepsis.24,25

Histologic Features

Given the potential for the skin manifestations of GPP to mimic other disorders, a skin biopsy is warranted to confirm the diagnosis. Generalized pustular psoriasis is histologically characterized by the presence of subcorneal macropustules (ie, spongiform pustules of Kogoj) formed by neutrophil infiltration into the spongelike network of the epidermis.6 Otherwise, the architecture of the epithelium in GPP is similar to that seen with plaque psoriasis, with parakeratosis, acanthosis, rete-ridge elongation, diminished stratum granulosum, and thinning of the suprapapillary epidermis, though the inflammatory cell infiltrate and edema are markedly more severe in GPP than plaque psoriasis.3,4

Differential Diagnosis

There are many other cutaneous pustular diagnoses that must be ruled out when evaluating a patient with GPP (Table 1).26 Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a common mimicker of GPP that is differentiated histologically by the presence of eosinophils and necrotic keratinocytes.4 In addition to its distinct histopathologic findings, AGEP is classically associated with recent initiation of certain medications, most commonly penicillins, macrolides, quinolones, sulfonamides, terbinafine, and diltiazem.27 In contrast, GPP more commonly is related to withdrawal of corticosteroids as well as initiation of some biologic medications, including anti-TNF agents.3 Generalized pustular psoriasis should be suspected over AGEP in patients with a personal or family history of psoriasis, though GPP may arise in patients with or without a history of psoriasis. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis usually is more abrupt in both onset and resolution compared with GPP, with clearance of pustules within a few days to weeks following cessation of the triggering factor.4

Other pustular variants of psoriasis (eg, palmoplantar pustular psoriasis, acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau) are differentiated from GPP by their chronicity and localization to palmoplantar and/or ungual surfaces.5 Other differential diagnoses are listed in Table 1.

Diagnostic Criteria for GPP

Diagnostic criteria have been proposed for GPP (Table 2), including (1) the presence of sterile pustules, (2) systemic signs of inflammation, (3) laboratory abnormalities, (4) histopathologic confirmation of spongiform pustules of Kogoj, and (5) recurrence of symptoms.22 To definitively diagnose GPP, all 5 criteria must be met. To rule out mimickers, it may be worthwhile to perform Gram staining, potassium hydroxide preparation, in vitro cultures, and/or immunofluorescence testing.6

Treatment

Given the high potential for mortality associated with GPP, the most essential component of management is to ensure adequate supportive care. Any temperature, fluid, or electrolyte imbalances should be corrected as they arise. Secondary infections also must be identified and treated, if present, to reduce the risk for fatal complications, including systemic infection and sepsis. Precautions must be taken to ensure that serious end-organ damage, including hepatic, renal, and respiratory dysfunction, is avoided.

Adjunctive topical intervention often is initiated with bland emollients, corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and/or vitamin D derivatives to help soothe skin symptoms, but treatment with systemic therapies usually is warranted to achieve symptom control.2,25 Importantly, there are no systemic or topical agents that have specifically been approved for the treatment of GPP in Europe or the United States.3 Given the absence of universally accepted treatment guidelines, therapeutic agents for GPP usually are selected based on clinical experience while also taking the extent of involvement and disease severity into consideration.3

Treatment Recommendations for Adults

Oral Systemic Agents—Treatment guidelines set forth by the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) in 2012 proposed that first-line therapies for GPP should be acitretin, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and infliximab.28 However, since those guidelines were established, many new biologic therapies have been approved for the treatment of psoriasis and often are considered in the treatment of psoriasis subtypes, including GPP.29 Although retinoids previously were considered to be a preferred first-line therapy, they are associated with a high incidence of adverse effects and must be used with caution in women of childbearing age.6 Oral acitretin at a dosage of 0.75 to 1.0 mg/kg/d has been shown to result in clinical improvement within 1 to 2 weeks, and a maintenance dosage of 0.125 to 0.25 mg/kg/d is required for several months to prevent recurrence.30 Methotrexate—5.0 to 15.0 mg/wk, or perhaps higher in patients with refractory disease, increased by 2.5-mg intervals until symptoms improve—is recommended by the NPF in patients who are unresponsive or cannot tolerate retinoids, though close monitoring for hematologic abnormalities is required. Cyclosporine 2.5 to 5.0 mg/kg/d is considered an alternative to methotrexate and retinoids; it has a faster onset of action, with improvement reported as early as 2 weeks after initiation of therapy.1,28 Although cyclosporine may be effective in the acute phase, especially in severe cases of GPP, long-term use of cyclosporine is not recommended because of the potential for renal dysfunction and hypertension.31

Biologic Agents—More recent evidence has accumulated supporting the efficacy of anti-TNF agents in the treatment of GPP, suggesting the positioning of these agents as first line. A number of case series have shown dramatic and rapid improvement of GPP with intravenous infliximab 3 to 5 mg/kg, with results observed hours to days after the first infusion.32-37 Thus, infliximab is recommended as first-line treatment in severe acute cases, though its efficacy as a maintenance therapy has not been sufficiently investigated.6 Case reports and case series document the safety and efficacy of adalimumab 40 to 80 mg every 1 to 2 weeks38,39 and etanercept 25 to 50 mg twice weekly40-42 in patients with recalcitrantGPP. Therefore, these anti-TNF agents may be considered in patients who are nonresponsive to treatment with infliximab.

Rarely, there have been reports of paradoxical induction of GPP with the use of some anti-TNF agents,43-45 which may be due to a cytokine imbalance characterized by unopposed IFN-α activation.6 In patients with a history of GPP after initiation of a biologic, treatment with agents from within the offending class should be avoided.

The IL-17A monoclonal antibodies secukinumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab have been shown in open-label phase 3 studies to result in disease remission at 12 weeks.46-48 Treatment with guselkumab, an IL-23 monoclonal antibody, also has demonstrated efficacy in patients with GPP.49 Ustekinumab, an IL-12/23 inhibitor, in combination with acitretin also has been shown to be successful in achieving disease remission after a few weeks of treatment.50

More recent case reports have shown the efficacy of IL-1 inhibitors including gevokizumab, canakinumab, and anakinra in achieving GPP clearance, though more prospective studies are needed to evaluate their efficacy.51-53 Given the etiologic association between IL-1 disinhibition and GPP, future investigations of these therapies as well as those that target the IL-36 pathway may prove to be particularly interesting.

Phototherapy and Combination Therapies—Phototherapy may be considered as maintenance therapy after disease control is achieved, though it is not considered appropriate for acute cases.28 Combination therapies with a biologic plus a nonbiologic systemic agent or alternating among various biologics may allow physicians to maximize benefits and minimize adverse effects in the long term, though there is insufficient evidence to suggest any specific combination treatment algorithm for GPP.28

Treatment Recommendations for Pediatric Patients

Based on a small number of case series and case reports, the first-line treatment strategy for children with GPP is similar to adults. Given the notable adverse events of most oral systemic agents, biologic therapies may emerge as first-line therapy in the pediatric population as more evidence accumulates.28

Treatment Recommendations for Pregnant Patients

Systemic corticosteroids are widely considered to be the first-line treatments for the management of impetigo herpetiformis.7 Low-dose prednisone (15–30 mg/d) usually is effective, but severe cases may require increasing the dosage to 60 mg/d.6 Given the potential for rebound flares upon withdrawal of systemic corticosteroids, these agents must be gradually tapered after the resolution of symptoms.

Certolizumab pegol also is an attractive option in pregnant patients with impetigo herpetiformis because of its favorable safety profile and negligible mother-to-infant transfer through the placenta or breast milk. It has been shown to be effective in treating GPP and impetigo herpetiformis during pregnancy in recently published case reports.54,55 In refractory cases, other TNF-α inhibitors (eg, adalimumab, infliximab, etanercept) or cyclosporine may be considered. However, cautious medical monitoring is warranted, as little is known about the potential adverse effects of these agents to the mother and fetus.28,56 Data from transplant recipients along with several case reports indicate that cyclosporine is not associated with an increased risk for adverse effects during pregnancy at a dose of 2 to 3 mg/kg.57-59 Both methotrexate and retinoids are known teratogens and are therefore contraindicated in pregnant patients.56

If pustules do not resolve in the postpartum period, patients should be treated with standard GPP therapies. However, long-term and population studies are lacking regarding the potential for infant exposure to systemic agents in breast milk. Therefore, the NPF recommends avoiding breastfeeding while taking systemic medications, if possible.56

Limitations of Treatment Recommendations

The ability to generate an evidence-based treatment strategy for GPP is limited by a lack of high-quality studies investigating the efficacy and safety of treatments in patients with GPP due to the rarity and relapsing-remitting nature of the disease, which makes randomized controlled trials difficult to conduct. The quality of the available research is further limited by the lack of validated outcome measures to specifically assess improvements in patients with GPP, such that results are difficult to synthesize and compare among studies.31

Conclusion

Although limited, the available research suggests that treatment with various biologics, especially infliximab, is effective in achieving rapid clearance in patients with GPP. In general, biologics may be the most appropriate treatment option in patients with GPP given their relatively favorable safety profiles. Other oral systemic agents, including acitretin, cyclosporine, and methotrexate, have limited evidence to support their use in the acute phase, but their safety profiles often limit their utility in the long-term. Emerging evidence regarding the association of GPP with IL36RN mutations suggests a unique role for agents targeting the IL-36 or IL-1 pathways, though this has yet to be thoroughly investigated.

Acute generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a rare severe variant of psoriasis characterized by the sudden widespread eruption of sterile pustules.1,2 The cutaneous manifestations of GPP also may be accompanied by signs of systemic inflammation, including fever, malaise, and leukocytosis.2 Complications are common and may be life-threatening, especially in older patients with comorbid diseases.3 Generalized pustular psoriasis most commonly occurs in patients with a preceding history of psoriasis, but it also may occur de novo.4 Generalized pustular psoriasis is associated with notable morbidity and mortality, and relapses are common.3,4 Many triggers of GPP have been identified, including initiation and withdrawal of various medications, infections, pregnancy, and other conditions.5,6 Although GPP most often occurs in adults, it also may arise in children and infants.3 In pregnancy, GPP is referred to as impetigo herpetiformis, despite having no etiologic ties with either herpes simplex virus or staphylococcal or streptococcal infection. Impetigo herpetiformis is considered one of the most dangerous dermatoses of pregnancy because of high rates of associated maternal and fetal morbidity.6,7

Acute GPP has proven to be a challenging disease to treat due to the rarity and relapsing-remitting nature of the disease; additionally, there are relatively few randomized controlled trials investigating the efficacy and safety of treatments for GPP. This review summarizes the features of GPP, including the pathophysiology of the disease, clinical and histological manifestations, and recommendations for management based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using MeSH terms pertaining to the disease, including generalized pustular psoriasis, impetigo herpetiformis, and von Zumbusch psoriasis.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of GPP is only partially understood, but it is thought to have a distinct pattern of immune activation compared with plaque psoriasis.8 Although there is a considerable amount of overlap and cross-talk among cytokine pathways, GPP generally is driven by innate immunity and unrestrained IL-36 cytokine activity. In contrast, adaptive immune responses—namely the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, IL-23, IL-17, and IL-22 axes—underlie plaque psoriasis.8-10

Proinflammatory IL-36 cytokines α, β, and γ, which are all part of the IL-1 superfamily, bind to the IL-36 receptor (IL-36R) to recruit and activate immune cells via various mediators, including IL-1β; IL-8; and chemokines CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL8.3 The IL-36 receptor antagonist (IL-36ra) acts to inhibit this inflammatory cascade.3,8 Microarray analyses of skin biopsy samples have shown that overexpression of IL-17A, TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-36 are seen in both GPP and plaque psoriasis lesions, but GPP lesions had higher expression of IL-1β, IL-36α, and IL-36γ and elevated neutrophil chemokines—CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL8—compared with plaque psoriasis lesions.8

Gene Mutations Associated With GPP

There are 3 gene mutations that have been associated with pustular variants of psoriasis, though these mutations account for a minority of cases of GPP.4 Genetic screenings are not routinely indicated in patients with GPP, but they may be warranted in severe cases when a familial pattern of inheritance is suspected.4

IL36RN—The gene IL36RN codes the anti-inflammatory IL-36ra. Loss-of-function mutations in IL36RN lead to impairment of IL-36ra and consequently hyperactivity of the proinflammatory responses triggered by IL-36.3 Homozygous and heterozygous mutations in IL36RN have been observed in both familial and sporadic cases of GPP.11-13 Subsequent retrospective analyses have identified the presence of IL36RN mutations in patients with GPP with frequencies ranging from 23% to 37%.14-17IL36RN mutations are thought to be more common in patients without concomitant plaque psoriasis and have been associated with severe disease and early disease onset.15

CARD14—A gain-of-function mutation in CARD14 results in overactivation of the proinflammatory nuclear factor κB pathway and has been implicated in cases of GPP with concurrent psoriasis vulgaris. Interestingly, this may suggest distinct etiologies underlying GPP de novo and GPP in patients with a history of psoriasis.18,19

AP1S3—A loss-of-function mutation in AP1S3 results in abnormal endosomal trafficking and autophagy as well as increased expression of IL-36α.20,21

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis Cutaneous Manifestations of GPP

Generalized pustular psoriasis is characterized by the onset of widespread 2- to 3-mm sterile pustules on erythematous skin or within psoriasiform plaques4 (Figure). In patients with skin of color, the erythema may appear less obvious or perhaps slightly violaceous compared to White skin. Pustules may coalesce to form “lakes” of pus.5 Cutaneous symptoms include pain, burning, and pruritus. Associated mucosal findings may include cheilitis, geographic tongue, conjunctivitis, and uveitis.4

The severity of symptoms can vary greatly among patients as well as between flares within the same patient.2,3 Four distinct patterns of GPP have been described. The von Zumbusch pattern is characterized by a rapid, generalized, painful, erythematous and pustular eruption accompanied by fever and asthenia. The pustules usually resolve after several days with extensive scaling. The annular pattern is characterized by annular, erythematous, scaly lesions with pustules present centrifugally. The lesions enlarge by centrifugal expansion over a period of hours to days, while healing occurs centrally. The exanthematic type is an acute eruption of small pustules that abruptly appear and disappear within a few days, usually from infection or medication initiation. Sometimes pustules appear within or at the edge of existing psoriatic plaques in a localized pattern—the fourth pattern—often following the exposure to irritants (eg, tars, anthralin).5

Impetigo Herpetiformis—Impetigo herpetiformis is a form of GPP associated with pregnancy. It generally presents early in the third trimester with symmetric erythematous plaques in flexural and intertriginous areas with pustules present at lesion margins. Lesions expand centrifugally, with pustulation present at the advancing edge.6,7 Patients often are acutely ill with fever, delirium, vomiting, and tetany. Mucous membranes, including the tongue, mouth, and esophagus, also may be involved. The eruption typically resolves after delivery, though it often recurs with subsequent pregnancies, with the morbidity risk rising with each successive pregnancy.7

Systemic and Extracutaneous Manifestations of GPP

Although the severity of GPP is highly variable, skin manifestations often are accompanied by systemic manifestations of inflammation, including fever and malaise. Common laboratory abnormalities include leukocytosis with peripheral neutrophilia, a high serum C-reactive protein level, hypocalcemia, and hypoalbuminemia.22 Abnormal liver enzymes often are present and result from neutrophilic cholangitis, with alternating strictures and dilations of biliary ducts observed on magnetic resonance imaging.23 Additional laboratory abnormalities are provided in Table 2. Other extracutaneous findings associated with GPP include arthralgia, edema, and characteristic psoriatic nail changes.4 Fatal complications include acute respiratory distress syndrome, renal dysfunction, cardiovascular shock, and sepsis.24,25

Histologic Features

Given the potential for the skin manifestations of GPP to mimic other disorders, a skin biopsy is warranted to confirm the diagnosis. Generalized pustular psoriasis is histologically characterized by the presence of subcorneal macropustules (ie, spongiform pustules of Kogoj) formed by neutrophil infiltration into the spongelike network of the epidermis.6 Otherwise, the architecture of the epithelium in GPP is similar to that seen with plaque psoriasis, with parakeratosis, acanthosis, rete-ridge elongation, diminished stratum granulosum, and thinning of the suprapapillary epidermis, though the inflammatory cell infiltrate and edema are markedly more severe in GPP than plaque psoriasis.3,4

Differential Diagnosis

There are many other cutaneous pustular diagnoses that must be ruled out when evaluating a patient with GPP (Table 1).26 Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a common mimicker of GPP that is differentiated histologically by the presence of eosinophils and necrotic keratinocytes.4 In addition to its distinct histopathologic findings, AGEP is classically associated with recent initiation of certain medications, most commonly penicillins, macrolides, quinolones, sulfonamides, terbinafine, and diltiazem.27 In contrast, GPP more commonly is related to withdrawal of corticosteroids as well as initiation of some biologic medications, including anti-TNF agents.3 Generalized pustular psoriasis should be suspected over AGEP in patients with a personal or family history of psoriasis, though GPP may arise in patients with or without a history of psoriasis. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis usually is more abrupt in both onset and resolution compared with GPP, with clearance of pustules within a few days to weeks following cessation of the triggering factor.4

Other pustular variants of psoriasis (eg, palmoplantar pustular psoriasis, acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau) are differentiated from GPP by their chronicity and localization to palmoplantar and/or ungual surfaces.5 Other differential diagnoses are listed in Table 1.

Diagnostic Criteria for GPP

Diagnostic criteria have been proposed for GPP (Table 2), including (1) the presence of sterile pustules, (2) systemic signs of inflammation, (3) laboratory abnormalities, (4) histopathologic confirmation of spongiform pustules of Kogoj, and (5) recurrence of symptoms.22 To definitively diagnose GPP, all 5 criteria must be met. To rule out mimickers, it may be worthwhile to perform Gram staining, potassium hydroxide preparation, in vitro cultures, and/or immunofluorescence testing.6

Treatment

Given the high potential for mortality associated with GPP, the most essential component of management is to ensure adequate supportive care. Any temperature, fluid, or electrolyte imbalances should be corrected as they arise. Secondary infections also must be identified and treated, if present, to reduce the risk for fatal complications, including systemic infection and sepsis. Precautions must be taken to ensure that serious end-organ damage, including hepatic, renal, and respiratory dysfunction, is avoided.

Adjunctive topical intervention often is initiated with bland emollients, corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and/or vitamin D derivatives to help soothe skin symptoms, but treatment with systemic therapies usually is warranted to achieve symptom control.2,25 Importantly, there are no systemic or topical agents that have specifically been approved for the treatment of GPP in Europe or the United States.3 Given the absence of universally accepted treatment guidelines, therapeutic agents for GPP usually are selected based on clinical experience while also taking the extent of involvement and disease severity into consideration.3

Treatment Recommendations for Adults

Oral Systemic Agents—Treatment guidelines set forth by the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) in 2012 proposed that first-line therapies for GPP should be acitretin, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and infliximab.28 However, since those guidelines were established, many new biologic therapies have been approved for the treatment of psoriasis and often are considered in the treatment of psoriasis subtypes, including GPP.29 Although retinoids previously were considered to be a preferred first-line therapy, they are associated with a high incidence of adverse effects and must be used with caution in women of childbearing age.6 Oral acitretin at a dosage of 0.75 to 1.0 mg/kg/d has been shown to result in clinical improvement within 1 to 2 weeks, and a maintenance dosage of 0.125 to 0.25 mg/kg/d is required for several months to prevent recurrence.30 Methotrexate—5.0 to 15.0 mg/wk, or perhaps higher in patients with refractory disease, increased by 2.5-mg intervals until symptoms improve—is recommended by the NPF in patients who are unresponsive or cannot tolerate retinoids, though close monitoring for hematologic abnormalities is required. Cyclosporine 2.5 to 5.0 mg/kg/d is considered an alternative to methotrexate and retinoids; it has a faster onset of action, with improvement reported as early as 2 weeks after initiation of therapy.1,28 Although cyclosporine may be effective in the acute phase, especially in severe cases of GPP, long-term use of cyclosporine is not recommended because of the potential for renal dysfunction and hypertension.31

Biologic Agents—More recent evidence has accumulated supporting the efficacy of anti-TNF agents in the treatment of GPP, suggesting the positioning of these agents as first line. A number of case series have shown dramatic and rapid improvement of GPP with intravenous infliximab 3 to 5 mg/kg, with results observed hours to days after the first infusion.32-37 Thus, infliximab is recommended as first-line treatment in severe acute cases, though its efficacy as a maintenance therapy has not been sufficiently investigated.6 Case reports and case series document the safety and efficacy of adalimumab 40 to 80 mg every 1 to 2 weeks38,39 and etanercept 25 to 50 mg twice weekly40-42 in patients with recalcitrantGPP. Therefore, these anti-TNF agents may be considered in patients who are nonresponsive to treatment with infliximab.

Rarely, there have been reports of paradoxical induction of GPP with the use of some anti-TNF agents,43-45 which may be due to a cytokine imbalance characterized by unopposed IFN-α activation.6 In patients with a history of GPP after initiation of a biologic, treatment with agents from within the offending class should be avoided.

The IL-17A monoclonal antibodies secukinumab, ixekizumab, and brodalumab have been shown in open-label phase 3 studies to result in disease remission at 12 weeks.46-48 Treatment with guselkumab, an IL-23 monoclonal antibody, also has demonstrated efficacy in patients with GPP.49 Ustekinumab, an IL-12/23 inhibitor, in combination with acitretin also has been shown to be successful in achieving disease remission after a few weeks of treatment.50

More recent case reports have shown the efficacy of IL-1 inhibitors including gevokizumab, canakinumab, and anakinra in achieving GPP clearance, though more prospective studies are needed to evaluate their efficacy.51-53 Given the etiologic association between IL-1 disinhibition and GPP, future investigations of these therapies as well as those that target the IL-36 pathway may prove to be particularly interesting.

Phototherapy and Combination Therapies—Phototherapy may be considered as maintenance therapy after disease control is achieved, though it is not considered appropriate for acute cases.28 Combination therapies with a biologic plus a nonbiologic systemic agent or alternating among various biologics may allow physicians to maximize benefits and minimize adverse effects in the long term, though there is insufficient evidence to suggest any specific combination treatment algorithm for GPP.28

Treatment Recommendations for Pediatric Patients

Based on a small number of case series and case reports, the first-line treatment strategy for children with GPP is similar to adults. Given the notable adverse events of most oral systemic agents, biologic therapies may emerge as first-line therapy in the pediatric population as more evidence accumulates.28

Treatment Recommendations for Pregnant Patients

Systemic corticosteroids are widely considered to be the first-line treatments for the management of impetigo herpetiformis.7 Low-dose prednisone (15–30 mg/d) usually is effective, but severe cases may require increasing the dosage to 60 mg/d.6 Given the potential for rebound flares upon withdrawal of systemic corticosteroids, these agents must be gradually tapered after the resolution of symptoms.

Certolizumab pegol also is an attractive option in pregnant patients with impetigo herpetiformis because of its favorable safety profile and negligible mother-to-infant transfer through the placenta or breast milk. It has been shown to be effective in treating GPP and impetigo herpetiformis during pregnancy in recently published case reports.54,55 In refractory cases, other TNF-α inhibitors (eg, adalimumab, infliximab, etanercept) or cyclosporine may be considered. However, cautious medical monitoring is warranted, as little is known about the potential adverse effects of these agents to the mother and fetus.28,56 Data from transplant recipients along with several case reports indicate that cyclosporine is not associated with an increased risk for adverse effects during pregnancy at a dose of 2 to 3 mg/kg.57-59 Both methotrexate and retinoids are known teratogens and are therefore contraindicated in pregnant patients.56

If pustules do not resolve in the postpartum period, patients should be treated with standard GPP therapies. However, long-term and population studies are lacking regarding the potential for infant exposure to systemic agents in breast milk. Therefore, the NPF recommends avoiding breastfeeding while taking systemic medications, if possible.56

Limitations of Treatment Recommendations

The ability to generate an evidence-based treatment strategy for GPP is limited by a lack of high-quality studies investigating the efficacy and safety of treatments in patients with GPP due to the rarity and relapsing-remitting nature of the disease, which makes randomized controlled trials difficult to conduct. The quality of the available research is further limited by the lack of validated outcome measures to specifically assess improvements in patients with GPP, such that results are difficult to synthesize and compare among studies.31

Conclusion

Although limited, the available research suggests that treatment with various biologics, especially infliximab, is effective in achieving rapid clearance in patients with GPP. In general, biologics may be the most appropriate treatment option in patients with GPP given their relatively favorable safety profiles. Other oral systemic agents, including acitretin, cyclosporine, and methotrexate, have limited evidence to support their use in the acute phase, but their safety profiles often limit their utility in the long-term. Emerging evidence regarding the association of GPP with IL36RN mutations suggests a unique role for agents targeting the IL-36 or IL-1 pathways, though this has yet to be thoroughly investigated.

- Benjegerdes KE, Hyde K, Kivelevitch D, et al. Pustular psoriasis: pathophysiology and current treatment perspectives. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2016;6:131‐144.

- Bachelez H. Pustular psoriasis and related pustular skin diseases. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:614‐618.

- Gooderham MJ, Van Voorhees AS, Lebwohl MG. An update on generalized pustular psoriasis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019;15:907‐919.

- Ly K, Beck KM, Smith MP, et al. Diagnosis and screening of patients with generalized pustular psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2019;9:37‐42.

- van de Kerkhof PCM, Nestle FO. Psoriasis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012:138-160.

- Hoegler KM, John AM, Handler MZ, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a review and update on treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1645‐1651.

- Oumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:101‐104.

- Johnston A, Xing X, Wolterink L, et al. IL-1 and IL-36 are dominant cytokines in generalized pustular psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:109-120.

- Furue K, Yamamura K, Tsuji G, et al. Highlighting interleukin-36 signalling in plaque psoriasis and pustular psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:5-13.

- Ogawa E, Sato Y, Minagawa A, et al. Pathogenesis of psoriasis and development of treatment. J Dermatol. 2018;45:264-272.

- Marrakchi S, Guigue P, Renshaw BR, et al. Interleukin-36-receptor antagonist deficiency and generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:620-628.

- Onoufriadis A, Simpson MA, Pink AE, et al. Mutations in IL36RN/IL1F5 are associated with the severe episodic inflammatory skin disease known as generalized pustular psoriasis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:432-437.

- Setta-Kaffetzi N, Navarini AA, Patel VM, et al. Rare pathogenic variants in IL36RN underlie a spectrum of psoriasis-associated pustular phenotypes. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1366-1369.

- Sugiura K, Takemoto A, Yamaguchi M, et al. The majority of generalized pustular psoriasis without psoriasis vulgaris is caused by deficiency of interleukin-36 receptor antagonist. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:2514-2521.

- Hussain S, Berki DM, Choon SE, et al. IL36RN mutations define a severe autoinflammatory phenotype of generalized pustular psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:1067-1070.e9.

- Körber A, Mossner R, Renner R, et al. Mutations in IL36RN in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:2634-2637.

- Twelves S, Mostafa A, Dand N, et al. Clinical and genetic differences between pustular psoriasis subtypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:1021-1026.

- Sugiura K. The genetic background of generalized pustular psoriasis: IL36RN mutations and CARD14 gain-of-function variants. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;74:187-192

- Wang Y, Cheng R, Lu Z, et al. Clinical profiles of pediatric patients with GPP alone and with different IL36RN genotypes. J Dermatol Sci. 2017;85:235-240.

- Setta-Kaffetzi N, Simpson MA, Navarini AA, et al. AP1S3 mutations are associated with pustular psoriasis and impaired Toll-like receptor 3 trafficking. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:790-797.

- Mahil SK, Twelves S, Farkas K, et al. AP1S3 mutations cause skin autoinflammation by disrupting keratinocyte autophagy and upregulating IL-36 production. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:2251-2259.

- Umezawa Y, Ozawa A, Kawasima T, et al. Therapeutic guidelines for the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) based on a proposed classification of disease severity. Arch Dermatol Res. 2003;295(suppl 1):S43-S54.

- Viguier M, Allez M, Zagdanski AM, et al. High frequency of cholestasis in generalized pustular psoriasis: evidence for neutrophilic involvement of the biliary tract. Hepatology. 2004;40:452-458.

- Ryan TJ, Baker H. The prognosis of generalized pustular psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1971;85:407-411.

- Kalb RE. Pustular psoriasis: management. In: Ofori AO, Duffin KC, eds. UpToDate. UpToDate; 2014. Accessed July 20, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pustular-psoriasis-management/print

- Naik HB, Cowen EW. Autoinflammatory pustular neutrophilic diseases. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31:405-425.

- Sidoroff A, Dunant A, Viboud C, et al. Risk factors for acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—results of a multinational case-control study (EuroSCAR). Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:989-996.

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279‐288.

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072.

- Mengesha YM, Bennett ML. Pustular skin disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol 2002;3:389-400.

- Zhou LL, Georgakopoulos JR, Ighani A, et al. Systemic monotherapy treatments for generalized pustular psoriasis: a systematic review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22:591‐601.

- Elewski BE. Infliximab for the treatment of severe pustular psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:796-797.

- Kim HS, You HS, Cho HH, et al. Two cases of generalized pustular psoriasis: successful treatment with infliximab. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:787-788.

- Trent JT, Kerdel FA. Successful treatment of Von Zumbusch pustular psoriasis with infliximab. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:224-228.

- Poulalhon N, Begon E, Lebbé C, et al. A follow-up study in 28 patients treated with infliximab for severe recalcitrant psoriasis: evidence for efficacy and high incidence of biological autoimmunity. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:329-336.

- Routhouska S, Sheth PB, Korman NJ. Long-term management of generalized pustular psoriasis with infliximab: case series. J Cutan Med Surg. 2008;12:184-188.

- Lisby S, Gniadecki R. Infliximab (Remicade) for acute, severe pustular and erythrodermic psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84:247-248.

- Zangrilli A, Papoutsaki M, Talamonti M, et al. Long-term efficacy of adalimumab in generalized pustular psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat. 2008;19:185-187.

- Matsumoto A, Komine M, Karakawa M, et al. Adalimumab administration after infliximab therapy is a successful treatment strategy for generalized pustular psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2017;44:202-204.

- Kamarashev J, Lor P, Forster A, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis induced by cyclosporin in a withdrawal responding to the tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitor etanercept. Dermatology. 2002;205:213-216.

- Esposito M, Mazzotta A, Casciello C, et al. Etanercept at different dosages in the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis: a case series. Dermatology. 2008;216:355-360.

- Lo Schiavo A, Brancaccio G, Puca RV, et al. Etanercept in the treatment of generalized annular pustular psoriasis. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:233-234.

- Goiriz R, Daudén E, Pérez-Gala S, et al. Flare and change of psoriasis morphology during the course of treatment with tumor necrosis factor blockers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;32:176-179.

- Collamer AN, Battafarano DF. Psoriatic skin lesions induced by tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy: clinical features and possible immunopathogenesis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;40:233-240.

- Almutairi D, Sheasgreen C, Weizman A, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis induced by infliximab in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;1:507-510.

- Imafuku S, Honma M, Okubo Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: a 52-week analysis from phase III open-label multicenter Japanese study. J Dermatol. 2016;43:1011-1017

- Saeki H, Nakagawa H, Ishii T, et al. Efficacy and safety of open-label ixekizumab treatment in Japanese patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, erythrodermic psoriasis, and generalized pustular psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1148-1155.

- Yamasaki K, Nakagawa H, Kubo Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of brodalumab in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis and psoriatic erythroderma: results from a 52-week, open-label study. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:741-751.

- Sano S, Kubo H, Morishima H, et al. Guselkumab, a human interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody in Japanese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis and erythrodermic psoriasis: efficacy and safety analyses of a 52-week, phase 3, multicenter, open-label study. J Dermatol. 2018;45:529‐539.

- Arakawa A, Ruzicka T, Prinz JC. Therapeutic efficacy of interleukin 12/interleukin 23 blockade in generalized pustular psoriasis regardless of IL36RN mutation status. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:825-828.

- Mansouri B, Richards L, Menter A. Treatment of two patients with generalized pustular psoriasis with the interleukin-1beta inhibitor gevokizumab. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:239-241.

- Skendros P, Papagoras C, Lefaki I, et al. Successful response in a case of severe pustular psoriasis after interleukin-1 beta inhibition. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:212-215.

- Viguier M, Guigue P, Pagès C, et al. Successful treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis with the interleukin-1-receptor antagonist Anakinra: lack of correlation with IL1RN mutations. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:66-67.

- Fukushima H, Iwata Y, Arima M, et al. Efficacy and safety of treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor‐α drugs for severe impetigo herpetiformis. J Dermatol. 2021;48:207-210.

- Mizutani Y, Mizutani YH, Matsuyama K, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis in pregnancy, successfully treated with certolizumab pegol. J Dermatol. 2021;47:e262-e263.

- Bae YS, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Review of treatment options for psoriasis in pregnant or lactating women: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:459‐477.

- Finch TM, Tan CY. Pustular psoriasis exacerbated by pregnancy and controlled by cyclosporin A. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:582-584.

- Gaughan WJ, Moritz MJ, Radomski JS, et al. National Transplantation Pregnancy Registry: report on outcomes of cyclosporine-treated female kidney transplant recipients with an interval from transplantation to pregnancy of greater than five years. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;28:266-269.

- Kura MM, Surjushe AU. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy treated with oral cyclosporin. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:458-459.

- Benjegerdes KE, Hyde K, Kivelevitch D, et al. Pustular psoriasis: pathophysiology and current treatment perspectives. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2016;6:131‐144.

- Bachelez H. Pustular psoriasis and related pustular skin diseases. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:614‐618.

- Gooderham MJ, Van Voorhees AS, Lebwohl MG. An update on generalized pustular psoriasis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019;15:907‐919.

- Ly K, Beck KM, Smith MP, et al. Diagnosis and screening of patients with generalized pustular psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2019;9:37‐42.

- van de Kerkhof PCM, Nestle FO. Psoriasis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012:138-160.

- Hoegler KM, John AM, Handler MZ, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a review and update on treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1645‐1651.

- Oumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:101‐104.

- Johnston A, Xing X, Wolterink L, et al. IL-1 and IL-36 are dominant cytokines in generalized pustular psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:109-120.

- Furue K, Yamamura K, Tsuji G, et al. Highlighting interleukin-36 signalling in plaque psoriasis and pustular psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:5-13.

- Ogawa E, Sato Y, Minagawa A, et al. Pathogenesis of psoriasis and development of treatment. J Dermatol. 2018;45:264-272.

- Marrakchi S, Guigue P, Renshaw BR, et al. Interleukin-36-receptor antagonist deficiency and generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:620-628.