User login

Prolonged Drug-Induced Hypersensitivity Syndrome/DRESS With Alopecia Areata and Autoimmune Thyroiditis

Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS), also called drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, is a potentially fatal drug-induced hypersensitivity reaction that is characterized by a cutaneous eruption, multiorgan involvement, viral reactivation, and hematologic abnormalities. As the nomenclature of this disease advances, consensus groups have adopted DIHS/DRESS to underscore that both names refer to the same clinical phenomenon.1 Autoimmune sequelae have been reported after DIHS/DRESS that include vitiligo, thyroid disease, and type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). We present a case of lamotrigine-associated DIHS/DRESS complicated by an unusually prolonged course requiring oral corticosteroids and narrow-band ultraviolet B (UVB) treatment and with development of extensive alopecia areata and autoimmune thyroiditis.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old female Filipino patient was prescribed lamotrigine 25 mg daily for bipolar II disorder and titrated to 100 mg twice daily after 1 month. One week after the increase, the patient developed a diffuse morbilliform rash covering their entire body along with facial swelling and generalized pruritus. Lamotrigine was discontinued after lamotrigine allergy was diagnosed. The patient improved following a 9-day oral prednisone taper and was placed on oxcarbazepine 300 mg twice daily to manage their bipolar disorder. One day after completing the taper, the patient presented again with worsening rash, swelling, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Oxcarbazepine was discontinued, and oral prednisone 60 mg was reinstituted for an additional 11 days.

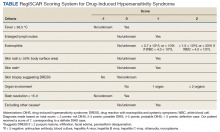

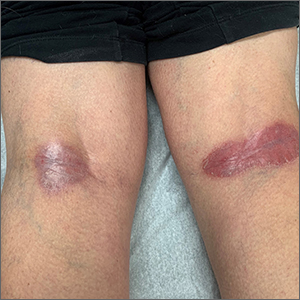

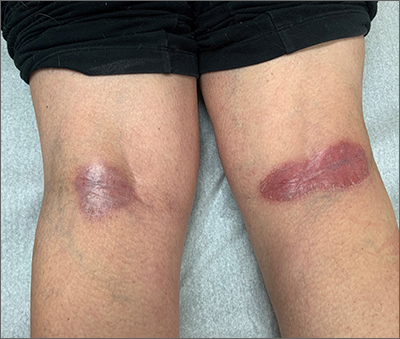

Dermatology evaluated the patient 10 days after completion of the second oral steroid taper (1 month after cessation of lamotrigine). The patient had erythroderma along with malaise, fevers, chills, and fatigue and a diffuse burning sensation (Figure 1). The patient was hypotensive and tachycardic with significant eosinophilia (42%; reference range, 0%-8%), transaminitis, and renal insufficiency. The patient was diagnosed with DIHS/DRESS based on their clinical presentation and calculated RegiSCAR score of 7 (score > 5 corresponds with definite DIHS/DRESS and points were given for fever, enlarged lymph nodes, eosinophilia ≥ 20%, skin rash extending > 50% of their body, edema and scaling, and 2 organs involved).2 A punch biopsy was confirmatory (Figure 2A).3 The patient was started on prednisone 80 mg once daily along with topical fluocinonide 0.05% ointment. However, the patient’s clinical status deteriorated, requiring hospital admission for heart failure evaluation. The echocardiogram revealed hyperdynamic circulation but was otherwise unremarkable.

The patient was maintained on prednisone 70 to 80 mg daily for 2 months before improvement of the rash and pruritus. The prednisone was slowly tapered over a 6-week period and then discontinued. Shortly after discontinuation, the patient redeveloped erythroderma. Skin biopsy and complete blood count (17.3% eosinophilia) confirmed the suspected DIHS/DRESS relapse (Figure 2B). In addition, the patient reported upper respiratory tract symptoms and concurrently tested positive for human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6). The patient was restarted on prednisone and low-dose narrow-band UVB (nbUVB) therapy was added. Over the following 2 months, they responded well to low-dose nbUVB therapy. By the end of nbUVB treatment, about 5 months after initial presentation, the patient’s erythroderma improved, eosinophilia resolved, and they were able to tolerate prednisone taper. Ten months after cessation of lamotrigine, prednisone was finally discontinued. Two weeks later, the patient was screened for adrenal insufficiency (AI) given the prolonged steroid course. Their serum morning cortisol level was within normal limits.

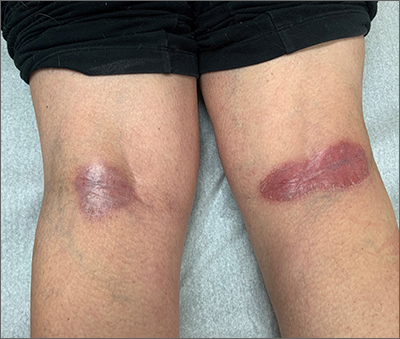

Four months after DIHS/DRESS resolution and cessation of steroids, the patient noted significant patches of smooth alopecia on their posterior scalp and was diagnosed with alopecia areata. Treatment with intralesional triamcinolone over 2 months resulted in regrowth of hair (Figure 3). A month later, the patient reported increasing fatigue and anorexia. The patient was evaluated once more for AI, this time with low morning cortisol and low adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) levels—consistent with AI secondary to prolonged glucocorticoid therapy. The patient also was concomitantly evaluated for hypothyroidism with significantly elevated thyroperoxidase antibodies—confirming the diagnosis of Hashimoto thyroiditis.

Discussion

DIHS/DRESS syndrome is a rare, but potentially life-threatening hypersensitivity to a medication, often beginning 2 to 6 weeks after exposure to the causative agent. The incidence of DIHS/DRESS in the general population is about 2 per 100,000.3 Our patient presented with DIHS/DRESS 33 days after starting lamotrigine, which corresponds with the published mean onset of anticonvulsant-induced DIHS/DRESS (29.7-33.3 days).4 Recent evidence shows that time from drug exposure to DIHS/DRESS symptoms may vary by drug class, with antibiotics implicated as precipitating DIHS/DRESS in < 15 days.3 The diagnosis of DIHS/DRESS may be complicated for many reasons. The accompanying rash may be morbilliform, erythroderma, or exfoliative dermatitis with multiple anatomic regions affected.5 Systemic involvement with various internal organs occurs in > 90% of cases, with the liver and kidney involved most frequently.5 Overall mortality rate may be as high as 10% most commonly due to acute liver failure.5 Biopsy may be helpful in the diagnosis but is not always specific.5 Diagnostic criteria include RegiSCAR and J-SCAR scores; our patient met criteria for both (Table).5

The pathogenesis of DIHS/DRESS remains unclear. Proposed mechanisms include genetic predisposition with human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplotypes, autoimmune with a delayed cell-mediated immune response associated with herpesviruses, and abnormal enzymatic pathways that metabolize medications.2 Although no HLA has been identified between lamotrigine and DIHS, HLA-A*02:07 and HLA-B*15:02 have been associated with lamotrigine-induced cutaneous drug reactions in patients of Thai ancestry.6 Immunosuppression also is a risk factor, especially when accompanied by a primary or reactivated HHV-6 infection, as seen in our patient.2 Additionally, HHV-6 infection may be a common link between DIHS/DRESS and autoimmune thyroiditis but is believed to involve elevated levels of interferon-γ-induced protein-10 (IP-10) that may lead to excessive recruitment of cytotoxic T cells into target tissues.7 Elevated levels of IP-10 are seen in many autoimmune conditions, such as autoimmune thyroiditis, Sjögren syndrome, and Graves disease.8

DIHS/DRESS syndrome has been associated with development of autoimmune diseases as long-term sequelae. The most commonly affected organs are the thyroid and pancreas; approximately 4.8% of patients develop autoimmune thyroiditis and 3.5% develop fulminant T1DM.9 The time from onset of DIHS/DRESS to development of autoimmune thyroiditis can range from 2 months to 2 years, whereas the range from DIHS/DRESS onset to fulminant T1DM is about 40 days.9 Alopecia had been reported in 1, occurring 4 months after DIHS/DRESS onset. Our patient’s alopecia areata and Hashimoto thyroiditis occurred 14 and 15 months after DIHS/DRESS presentation, respectively.

Treatment

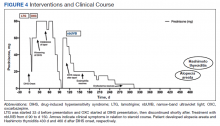

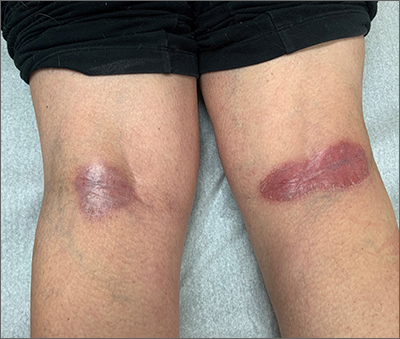

For management, early recognition and discontinuation of the offending agent is paramount. Systemic corticosteroids are the accepted treatment standard. Symptoms of DIHS/DRESS usually resolve between 3 and 18 weeks, with the mean resolution time at 7 weeks.10 Our patient developed a prolonged course with persistent eosinophilia for 20 weeks and cutaneous symptoms for 32 weeks—requiring 40 weeks of oral prednisone. The most significant clinical improvement occurred during the 8-week period low-dose nbUVB was used (Figure 4). There also are reports outlining the successful use of intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, or plasma exchange in cases refractory to oral corticosteroids.11

A recent retrospective case control study showed that treatment of DIHS/DRESS with cyclosporine in patients who had a contraindication to steroids resulted in faster resolution of symptoms, shorter treatment durations, and shorter hospitalizations than did those treated with corticosteroids.12 However, the data are limited by a significantly smaller number of patients treated with cyclosporine than steroids and the cyclosporine treatment group having milder cases of DIHS/DRESS.12

The risk of AI is increased for patients who have taken > 20 mg of prednisone daily ≥ 3 weeks, an evening dose ≥ 5 mg for a few weeks, or have a Cushingoid appearance.13 Patients may not regain full adrenal function for 12 to 18 months.14 Our patient had a normal basal serum cortisol level 2 weeks after prednisone cessation and then presented 5 months later with AI. While the reason for this period of normality is unclear, it may partly be due to the variable length of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis recovery time. Thus, ACTH stimulation tests in addition to serum cortisol may be done in patients with suspected AI for higher diagnostic certainty.10

Conclusions

DIHS/DRESS is a severe cutaneous adverse reaction that may require a prolonged treatment course until symptom resolution (40 weeks of oral prednisone in our patient). Oral corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment, but long-term use is associated with significant adverse effects, such as AI in our patient. Alternative therapies, such as cyclosporine, look promising, but further studies are needed to determine safety profile and efficacy.12 Additionally, patients with DIHS/DRESS should be educated and followed for potential autoimmune sequelae; in our patient alopecia areata and autoimmune thyroiditis were late sequelae, occurring 14 and 15 months, respectively, after onset of DIHS/DRESS.

1. RegiSCAR. Accessed June 3, 2022. http://www.regiscar.org

2. Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DiHS)/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an update in 2019. Allergol Int. 2019;68(3):301-308. doi:10.1016/j.alit.2019.03.006

3. Wolfson AR, Zhou L, Li Y, Phadke NA, Chow OA, Blumenthal KG. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome identified in the electronic health record allergy module. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(2):633-640. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2018.08.013

4. Sasidharanpillai S, Govindan A, Riyaz N, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): a histopathology based analysis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82(1):28. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.168934

5. Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie‐Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. Results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(5):1071-1080. doi:10.1111/bjd.12501

6. Koomdee N, Pratoomwun J, Jantararoungtong T, et al. Association of HLA-A and HLA-B alleles with lamotrigine-induced cutaneous adverse drug reactions in the Thai population. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00879

7. Yang C-W, Cho Y-T, Hsieh Y-C, Hsu S-H, Chen K-L, Chu C-Y. The interferon-γ-induced protein 10/CXCR3 axis is associated with human herpesvirus-6 reactivation and the development of sequelae in drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(5):909-919. doi:10.1111/bjd.18942

8. Ruffilli I, Ferrari SM, Colaci M, Ferri C, Fallahi P, Antonelli A. IP-10 in autoimmune thyroiditis. Horm Metab Res. 2014;46(9):597-602. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1382053

9. Kano Y, Tohyama M, Aihara M, et al. Sequelae in 145 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: survey conducted by the Asian Research Committee on Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (ASCAR). J Dermatol. 2015;42(3):276-282. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12770

10. Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med. 2011;124(7):588-597. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.01.017

11. Bommersbach TJ, Lapid MI, Leung JG, Cunningham JL, Rummans TA, Kung S. Management of psychotropic drug-induced dress syndrome: a systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(6):787-801. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.03.006

12. Nguyen E, Yanes D, Imadojemu S, Kroshinsky D. Evaluation of cyclosporine for the treatment of DRESS syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(6):704-706. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0048

13. Joseph RM, Hunter AL, Ray DW, Dixon WG. Systemic glucocorticoid therapy and adrenal insufficiency in adults: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46(1):133-141. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.03.001

14. Jamilloux Y, Liozon E, Pugnet G, et al. Recovery of adrenal function after long-term glucocorticoid therapy for giant cell arteritis: a cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):e68713. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068713

Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS), also called drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, is a potentially fatal drug-induced hypersensitivity reaction that is characterized by a cutaneous eruption, multiorgan involvement, viral reactivation, and hematologic abnormalities. As the nomenclature of this disease advances, consensus groups have adopted DIHS/DRESS to underscore that both names refer to the same clinical phenomenon.1 Autoimmune sequelae have been reported after DIHS/DRESS that include vitiligo, thyroid disease, and type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). We present a case of lamotrigine-associated DIHS/DRESS complicated by an unusually prolonged course requiring oral corticosteroids and narrow-band ultraviolet B (UVB) treatment and with development of extensive alopecia areata and autoimmune thyroiditis.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old female Filipino patient was prescribed lamotrigine 25 mg daily for bipolar II disorder and titrated to 100 mg twice daily after 1 month. One week after the increase, the patient developed a diffuse morbilliform rash covering their entire body along with facial swelling and generalized pruritus. Lamotrigine was discontinued after lamotrigine allergy was diagnosed. The patient improved following a 9-day oral prednisone taper and was placed on oxcarbazepine 300 mg twice daily to manage their bipolar disorder. One day after completing the taper, the patient presented again with worsening rash, swelling, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Oxcarbazepine was discontinued, and oral prednisone 60 mg was reinstituted for an additional 11 days.

Dermatology evaluated the patient 10 days after completion of the second oral steroid taper (1 month after cessation of lamotrigine). The patient had erythroderma along with malaise, fevers, chills, and fatigue and a diffuse burning sensation (Figure 1). The patient was hypotensive and tachycardic with significant eosinophilia (42%; reference range, 0%-8%), transaminitis, and renal insufficiency. The patient was diagnosed with DIHS/DRESS based on their clinical presentation and calculated RegiSCAR score of 7 (score > 5 corresponds with definite DIHS/DRESS and points were given for fever, enlarged lymph nodes, eosinophilia ≥ 20%, skin rash extending > 50% of their body, edema and scaling, and 2 organs involved).2 A punch biopsy was confirmatory (Figure 2A).3 The patient was started on prednisone 80 mg once daily along with topical fluocinonide 0.05% ointment. However, the patient’s clinical status deteriorated, requiring hospital admission for heart failure evaluation. The echocardiogram revealed hyperdynamic circulation but was otherwise unremarkable.

The patient was maintained on prednisone 70 to 80 mg daily for 2 months before improvement of the rash and pruritus. The prednisone was slowly tapered over a 6-week period and then discontinued. Shortly after discontinuation, the patient redeveloped erythroderma. Skin biopsy and complete blood count (17.3% eosinophilia) confirmed the suspected DIHS/DRESS relapse (Figure 2B). In addition, the patient reported upper respiratory tract symptoms and concurrently tested positive for human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6). The patient was restarted on prednisone and low-dose narrow-band UVB (nbUVB) therapy was added. Over the following 2 months, they responded well to low-dose nbUVB therapy. By the end of nbUVB treatment, about 5 months after initial presentation, the patient’s erythroderma improved, eosinophilia resolved, and they were able to tolerate prednisone taper. Ten months after cessation of lamotrigine, prednisone was finally discontinued. Two weeks later, the patient was screened for adrenal insufficiency (AI) given the prolonged steroid course. Their serum morning cortisol level was within normal limits.

Four months after DIHS/DRESS resolution and cessation of steroids, the patient noted significant patches of smooth alopecia on their posterior scalp and was diagnosed with alopecia areata. Treatment with intralesional triamcinolone over 2 months resulted in regrowth of hair (Figure 3). A month later, the patient reported increasing fatigue and anorexia. The patient was evaluated once more for AI, this time with low morning cortisol and low adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) levels—consistent with AI secondary to prolonged glucocorticoid therapy. The patient also was concomitantly evaluated for hypothyroidism with significantly elevated thyroperoxidase antibodies—confirming the diagnosis of Hashimoto thyroiditis.

Discussion

DIHS/DRESS syndrome is a rare, but potentially life-threatening hypersensitivity to a medication, often beginning 2 to 6 weeks after exposure to the causative agent. The incidence of DIHS/DRESS in the general population is about 2 per 100,000.3 Our patient presented with DIHS/DRESS 33 days after starting lamotrigine, which corresponds with the published mean onset of anticonvulsant-induced DIHS/DRESS (29.7-33.3 days).4 Recent evidence shows that time from drug exposure to DIHS/DRESS symptoms may vary by drug class, with antibiotics implicated as precipitating DIHS/DRESS in < 15 days.3 The diagnosis of DIHS/DRESS may be complicated for many reasons. The accompanying rash may be morbilliform, erythroderma, or exfoliative dermatitis with multiple anatomic regions affected.5 Systemic involvement with various internal organs occurs in > 90% of cases, with the liver and kidney involved most frequently.5 Overall mortality rate may be as high as 10% most commonly due to acute liver failure.5 Biopsy may be helpful in the diagnosis but is not always specific.5 Diagnostic criteria include RegiSCAR and J-SCAR scores; our patient met criteria for both (Table).5

The pathogenesis of DIHS/DRESS remains unclear. Proposed mechanisms include genetic predisposition with human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplotypes, autoimmune with a delayed cell-mediated immune response associated with herpesviruses, and abnormal enzymatic pathways that metabolize medications.2 Although no HLA has been identified between lamotrigine and DIHS, HLA-A*02:07 and HLA-B*15:02 have been associated with lamotrigine-induced cutaneous drug reactions in patients of Thai ancestry.6 Immunosuppression also is a risk factor, especially when accompanied by a primary or reactivated HHV-6 infection, as seen in our patient.2 Additionally, HHV-6 infection may be a common link between DIHS/DRESS and autoimmune thyroiditis but is believed to involve elevated levels of interferon-γ-induced protein-10 (IP-10) that may lead to excessive recruitment of cytotoxic T cells into target tissues.7 Elevated levels of IP-10 are seen in many autoimmune conditions, such as autoimmune thyroiditis, Sjögren syndrome, and Graves disease.8

DIHS/DRESS syndrome has been associated with development of autoimmune diseases as long-term sequelae. The most commonly affected organs are the thyroid and pancreas; approximately 4.8% of patients develop autoimmune thyroiditis and 3.5% develop fulminant T1DM.9 The time from onset of DIHS/DRESS to development of autoimmune thyroiditis can range from 2 months to 2 years, whereas the range from DIHS/DRESS onset to fulminant T1DM is about 40 days.9 Alopecia had been reported in 1, occurring 4 months after DIHS/DRESS onset. Our patient’s alopecia areata and Hashimoto thyroiditis occurred 14 and 15 months after DIHS/DRESS presentation, respectively.

Treatment

For management, early recognition and discontinuation of the offending agent is paramount. Systemic corticosteroids are the accepted treatment standard. Symptoms of DIHS/DRESS usually resolve between 3 and 18 weeks, with the mean resolution time at 7 weeks.10 Our patient developed a prolonged course with persistent eosinophilia for 20 weeks and cutaneous symptoms for 32 weeks—requiring 40 weeks of oral prednisone. The most significant clinical improvement occurred during the 8-week period low-dose nbUVB was used (Figure 4). There also are reports outlining the successful use of intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, or plasma exchange in cases refractory to oral corticosteroids.11

A recent retrospective case control study showed that treatment of DIHS/DRESS with cyclosporine in patients who had a contraindication to steroids resulted in faster resolution of symptoms, shorter treatment durations, and shorter hospitalizations than did those treated with corticosteroids.12 However, the data are limited by a significantly smaller number of patients treated with cyclosporine than steroids and the cyclosporine treatment group having milder cases of DIHS/DRESS.12

The risk of AI is increased for patients who have taken > 20 mg of prednisone daily ≥ 3 weeks, an evening dose ≥ 5 mg for a few weeks, or have a Cushingoid appearance.13 Patients may not regain full adrenal function for 12 to 18 months.14 Our patient had a normal basal serum cortisol level 2 weeks after prednisone cessation and then presented 5 months later with AI. While the reason for this period of normality is unclear, it may partly be due to the variable length of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis recovery time. Thus, ACTH stimulation tests in addition to serum cortisol may be done in patients with suspected AI for higher diagnostic certainty.10

Conclusions

DIHS/DRESS is a severe cutaneous adverse reaction that may require a prolonged treatment course until symptom resolution (40 weeks of oral prednisone in our patient). Oral corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment, but long-term use is associated with significant adverse effects, such as AI in our patient. Alternative therapies, such as cyclosporine, look promising, but further studies are needed to determine safety profile and efficacy.12 Additionally, patients with DIHS/DRESS should be educated and followed for potential autoimmune sequelae; in our patient alopecia areata and autoimmune thyroiditis were late sequelae, occurring 14 and 15 months, respectively, after onset of DIHS/DRESS.

Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS), also called drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, is a potentially fatal drug-induced hypersensitivity reaction that is characterized by a cutaneous eruption, multiorgan involvement, viral reactivation, and hematologic abnormalities. As the nomenclature of this disease advances, consensus groups have adopted DIHS/DRESS to underscore that both names refer to the same clinical phenomenon.1 Autoimmune sequelae have been reported after DIHS/DRESS that include vitiligo, thyroid disease, and type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). We present a case of lamotrigine-associated DIHS/DRESS complicated by an unusually prolonged course requiring oral corticosteroids and narrow-band ultraviolet B (UVB) treatment and with development of extensive alopecia areata and autoimmune thyroiditis.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old female Filipino patient was prescribed lamotrigine 25 mg daily for bipolar II disorder and titrated to 100 mg twice daily after 1 month. One week after the increase, the patient developed a diffuse morbilliform rash covering their entire body along with facial swelling and generalized pruritus. Lamotrigine was discontinued after lamotrigine allergy was diagnosed. The patient improved following a 9-day oral prednisone taper and was placed on oxcarbazepine 300 mg twice daily to manage their bipolar disorder. One day after completing the taper, the patient presented again with worsening rash, swelling, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Oxcarbazepine was discontinued, and oral prednisone 60 mg was reinstituted for an additional 11 days.

Dermatology evaluated the patient 10 days after completion of the second oral steroid taper (1 month after cessation of lamotrigine). The patient had erythroderma along with malaise, fevers, chills, and fatigue and a diffuse burning sensation (Figure 1). The patient was hypotensive and tachycardic with significant eosinophilia (42%; reference range, 0%-8%), transaminitis, and renal insufficiency. The patient was diagnosed with DIHS/DRESS based on their clinical presentation and calculated RegiSCAR score of 7 (score > 5 corresponds with definite DIHS/DRESS and points were given for fever, enlarged lymph nodes, eosinophilia ≥ 20%, skin rash extending > 50% of their body, edema and scaling, and 2 organs involved).2 A punch biopsy was confirmatory (Figure 2A).3 The patient was started on prednisone 80 mg once daily along with topical fluocinonide 0.05% ointment. However, the patient’s clinical status deteriorated, requiring hospital admission for heart failure evaluation. The echocardiogram revealed hyperdynamic circulation but was otherwise unremarkable.

The patient was maintained on prednisone 70 to 80 mg daily for 2 months before improvement of the rash and pruritus. The prednisone was slowly tapered over a 6-week period and then discontinued. Shortly after discontinuation, the patient redeveloped erythroderma. Skin biopsy and complete blood count (17.3% eosinophilia) confirmed the suspected DIHS/DRESS relapse (Figure 2B). In addition, the patient reported upper respiratory tract symptoms and concurrently tested positive for human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6). The patient was restarted on prednisone and low-dose narrow-band UVB (nbUVB) therapy was added. Over the following 2 months, they responded well to low-dose nbUVB therapy. By the end of nbUVB treatment, about 5 months after initial presentation, the patient’s erythroderma improved, eosinophilia resolved, and they were able to tolerate prednisone taper. Ten months after cessation of lamotrigine, prednisone was finally discontinued. Two weeks later, the patient was screened for adrenal insufficiency (AI) given the prolonged steroid course. Their serum morning cortisol level was within normal limits.

Four months after DIHS/DRESS resolution and cessation of steroids, the patient noted significant patches of smooth alopecia on their posterior scalp and was diagnosed with alopecia areata. Treatment with intralesional triamcinolone over 2 months resulted in regrowth of hair (Figure 3). A month later, the patient reported increasing fatigue and anorexia. The patient was evaluated once more for AI, this time with low morning cortisol and low adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) levels—consistent with AI secondary to prolonged glucocorticoid therapy. The patient also was concomitantly evaluated for hypothyroidism with significantly elevated thyroperoxidase antibodies—confirming the diagnosis of Hashimoto thyroiditis.

Discussion

DIHS/DRESS syndrome is a rare, but potentially life-threatening hypersensitivity to a medication, often beginning 2 to 6 weeks after exposure to the causative agent. The incidence of DIHS/DRESS in the general population is about 2 per 100,000.3 Our patient presented with DIHS/DRESS 33 days after starting lamotrigine, which corresponds with the published mean onset of anticonvulsant-induced DIHS/DRESS (29.7-33.3 days).4 Recent evidence shows that time from drug exposure to DIHS/DRESS symptoms may vary by drug class, with antibiotics implicated as precipitating DIHS/DRESS in < 15 days.3 The diagnosis of DIHS/DRESS may be complicated for many reasons. The accompanying rash may be morbilliform, erythroderma, or exfoliative dermatitis with multiple anatomic regions affected.5 Systemic involvement with various internal organs occurs in > 90% of cases, with the liver and kidney involved most frequently.5 Overall mortality rate may be as high as 10% most commonly due to acute liver failure.5 Biopsy may be helpful in the diagnosis but is not always specific.5 Diagnostic criteria include RegiSCAR and J-SCAR scores; our patient met criteria for both (Table).5

The pathogenesis of DIHS/DRESS remains unclear. Proposed mechanisms include genetic predisposition with human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplotypes, autoimmune with a delayed cell-mediated immune response associated with herpesviruses, and abnormal enzymatic pathways that metabolize medications.2 Although no HLA has been identified between lamotrigine and DIHS, HLA-A*02:07 and HLA-B*15:02 have been associated with lamotrigine-induced cutaneous drug reactions in patients of Thai ancestry.6 Immunosuppression also is a risk factor, especially when accompanied by a primary or reactivated HHV-6 infection, as seen in our patient.2 Additionally, HHV-6 infection may be a common link between DIHS/DRESS and autoimmune thyroiditis but is believed to involve elevated levels of interferon-γ-induced protein-10 (IP-10) that may lead to excessive recruitment of cytotoxic T cells into target tissues.7 Elevated levels of IP-10 are seen in many autoimmune conditions, such as autoimmune thyroiditis, Sjögren syndrome, and Graves disease.8

DIHS/DRESS syndrome has been associated with development of autoimmune diseases as long-term sequelae. The most commonly affected organs are the thyroid and pancreas; approximately 4.8% of patients develop autoimmune thyroiditis and 3.5% develop fulminant T1DM.9 The time from onset of DIHS/DRESS to development of autoimmune thyroiditis can range from 2 months to 2 years, whereas the range from DIHS/DRESS onset to fulminant T1DM is about 40 days.9 Alopecia had been reported in 1, occurring 4 months after DIHS/DRESS onset. Our patient’s alopecia areata and Hashimoto thyroiditis occurred 14 and 15 months after DIHS/DRESS presentation, respectively.

Treatment

For management, early recognition and discontinuation of the offending agent is paramount. Systemic corticosteroids are the accepted treatment standard. Symptoms of DIHS/DRESS usually resolve between 3 and 18 weeks, with the mean resolution time at 7 weeks.10 Our patient developed a prolonged course with persistent eosinophilia for 20 weeks and cutaneous symptoms for 32 weeks—requiring 40 weeks of oral prednisone. The most significant clinical improvement occurred during the 8-week period low-dose nbUVB was used (Figure 4). There also are reports outlining the successful use of intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, or plasma exchange in cases refractory to oral corticosteroids.11

A recent retrospective case control study showed that treatment of DIHS/DRESS with cyclosporine in patients who had a contraindication to steroids resulted in faster resolution of symptoms, shorter treatment durations, and shorter hospitalizations than did those treated with corticosteroids.12 However, the data are limited by a significantly smaller number of patients treated with cyclosporine than steroids and the cyclosporine treatment group having milder cases of DIHS/DRESS.12

The risk of AI is increased for patients who have taken > 20 mg of prednisone daily ≥ 3 weeks, an evening dose ≥ 5 mg for a few weeks, or have a Cushingoid appearance.13 Patients may not regain full adrenal function for 12 to 18 months.14 Our patient had a normal basal serum cortisol level 2 weeks after prednisone cessation and then presented 5 months later with AI. While the reason for this period of normality is unclear, it may partly be due to the variable length of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis recovery time. Thus, ACTH stimulation tests in addition to serum cortisol may be done in patients with suspected AI for higher diagnostic certainty.10

Conclusions

DIHS/DRESS is a severe cutaneous adverse reaction that may require a prolonged treatment course until symptom resolution (40 weeks of oral prednisone in our patient). Oral corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment, but long-term use is associated with significant adverse effects, such as AI in our patient. Alternative therapies, such as cyclosporine, look promising, but further studies are needed to determine safety profile and efficacy.12 Additionally, patients with DIHS/DRESS should be educated and followed for potential autoimmune sequelae; in our patient alopecia areata and autoimmune thyroiditis were late sequelae, occurring 14 and 15 months, respectively, after onset of DIHS/DRESS.

1. RegiSCAR. Accessed June 3, 2022. http://www.regiscar.org

2. Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DiHS)/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an update in 2019. Allergol Int. 2019;68(3):301-308. doi:10.1016/j.alit.2019.03.006

3. Wolfson AR, Zhou L, Li Y, Phadke NA, Chow OA, Blumenthal KG. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome identified in the electronic health record allergy module. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(2):633-640. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2018.08.013

4. Sasidharanpillai S, Govindan A, Riyaz N, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): a histopathology based analysis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82(1):28. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.168934

5. Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie‐Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. Results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(5):1071-1080. doi:10.1111/bjd.12501

6. Koomdee N, Pratoomwun J, Jantararoungtong T, et al. Association of HLA-A and HLA-B alleles with lamotrigine-induced cutaneous adverse drug reactions in the Thai population. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00879

7. Yang C-W, Cho Y-T, Hsieh Y-C, Hsu S-H, Chen K-L, Chu C-Y. The interferon-γ-induced protein 10/CXCR3 axis is associated with human herpesvirus-6 reactivation and the development of sequelae in drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(5):909-919. doi:10.1111/bjd.18942

8. Ruffilli I, Ferrari SM, Colaci M, Ferri C, Fallahi P, Antonelli A. IP-10 in autoimmune thyroiditis. Horm Metab Res. 2014;46(9):597-602. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1382053

9. Kano Y, Tohyama M, Aihara M, et al. Sequelae in 145 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: survey conducted by the Asian Research Committee on Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (ASCAR). J Dermatol. 2015;42(3):276-282. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12770

10. Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med. 2011;124(7):588-597. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.01.017

11. Bommersbach TJ, Lapid MI, Leung JG, Cunningham JL, Rummans TA, Kung S. Management of psychotropic drug-induced dress syndrome: a systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(6):787-801. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.03.006

12. Nguyen E, Yanes D, Imadojemu S, Kroshinsky D. Evaluation of cyclosporine for the treatment of DRESS syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(6):704-706. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0048

13. Joseph RM, Hunter AL, Ray DW, Dixon WG. Systemic glucocorticoid therapy and adrenal insufficiency in adults: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46(1):133-141. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.03.001

14. Jamilloux Y, Liozon E, Pugnet G, et al. Recovery of adrenal function after long-term glucocorticoid therapy for giant cell arteritis: a cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):e68713. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068713

1. RegiSCAR. Accessed June 3, 2022. http://www.regiscar.org

2. Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DiHS)/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an update in 2019. Allergol Int. 2019;68(3):301-308. doi:10.1016/j.alit.2019.03.006

3. Wolfson AR, Zhou L, Li Y, Phadke NA, Chow OA, Blumenthal KG. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome identified in the electronic health record allergy module. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(2):633-640. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2018.08.013

4. Sasidharanpillai S, Govindan A, Riyaz N, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): a histopathology based analysis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82(1):28. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.168934

5. Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie‐Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. Results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(5):1071-1080. doi:10.1111/bjd.12501

6. Koomdee N, Pratoomwun J, Jantararoungtong T, et al. Association of HLA-A and HLA-B alleles with lamotrigine-induced cutaneous adverse drug reactions in the Thai population. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00879

7. Yang C-W, Cho Y-T, Hsieh Y-C, Hsu S-H, Chen K-L, Chu C-Y. The interferon-γ-induced protein 10/CXCR3 axis is associated with human herpesvirus-6 reactivation and the development of sequelae in drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(5):909-919. doi:10.1111/bjd.18942

8. Ruffilli I, Ferrari SM, Colaci M, Ferri C, Fallahi P, Antonelli A. IP-10 in autoimmune thyroiditis. Horm Metab Res. 2014;46(9):597-602. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1382053

9. Kano Y, Tohyama M, Aihara M, et al. Sequelae in 145 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: survey conducted by the Asian Research Committee on Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (ASCAR). J Dermatol. 2015;42(3):276-282. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12770

10. Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med. 2011;124(7):588-597. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.01.017

11. Bommersbach TJ, Lapid MI, Leung JG, Cunningham JL, Rummans TA, Kung S. Management of psychotropic drug-induced dress syndrome: a systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(6):787-801. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.03.006

12. Nguyen E, Yanes D, Imadojemu S, Kroshinsky D. Evaluation of cyclosporine for the treatment of DRESS syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(6):704-706. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0048

13. Joseph RM, Hunter AL, Ray DW, Dixon WG. Systemic glucocorticoid therapy and adrenal insufficiency in adults: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46(1):133-141. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.03.001

14. Jamilloux Y, Liozon E, Pugnet G, et al. Recovery of adrenal function after long-term glucocorticoid therapy for giant cell arteritis: a cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):e68713. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068713

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022: HIV Care in the VA

- Backus L, Czarnogorski M, Yip G, et al. HIV care continuum applied to the US Department of Veterans Affairs: HIV virologic outcomes in an integrated health care system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(4):474-480. http://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000615

- VA HIV Testing Information for Health Care Providers. US Department of Veterans Affairs. January 2021. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.hiv.va.gov/pdf/GetChecked-FactSheet-Providers-2021-508.pdf

- Associated Press. Judge rules US Military can’t discharge HIV-positive troops. ABC News. Published April 10, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2022. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/wireStory/judge-rules-us-military-discharge-hiv-positive-troops-84000771

- Bokhour BG, Bolton RE, Asch SM, et al. How should we organize care for patients with human immunodeficiency virus and comorbidities? A multisite qualitative study of human immunodeficiency virus care in the United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 2021;59(8):727-735. http://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001563

- Goulet JL, Fultz SL, Rimland D, et al. Aging and infectious diseases: do patterns of comorbidity vary by HIV status, age, and HIV severity? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(12):1593-1601. http://doi.org/10.1086/523577

- Backus L, Czarnogorski M, Yip G, et al. HIV care continuum applied to the US Department of Veterans Affairs: HIV virologic outcomes in an integrated health care system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(4):474-480. http://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000615

- VA HIV Testing Information for Health Care Providers. US Department of Veterans Affairs. January 2021. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.hiv.va.gov/pdf/GetChecked-FactSheet-Providers-2021-508.pdf

- Associated Press. Judge rules US Military can’t discharge HIV-positive troops. ABC News. Published April 10, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2022. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/wireStory/judge-rules-us-military-discharge-hiv-positive-troops-84000771

- Bokhour BG, Bolton RE, Asch SM, et al. How should we organize care for patients with human immunodeficiency virus and comorbidities? A multisite qualitative study of human immunodeficiency virus care in the United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 2021;59(8):727-735. http://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001563

- Goulet JL, Fultz SL, Rimland D, et al. Aging and infectious diseases: do patterns of comorbidity vary by HIV status, age, and HIV severity? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(12):1593-1601. http://doi.org/10.1086/523577

- Backus L, Czarnogorski M, Yip G, et al. HIV care continuum applied to the US Department of Veterans Affairs: HIV virologic outcomes in an integrated health care system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(4):474-480. http://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000615

- VA HIV Testing Information for Health Care Providers. US Department of Veterans Affairs. January 2021. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.hiv.va.gov/pdf/GetChecked-FactSheet-Providers-2021-508.pdf

- Associated Press. Judge rules US Military can’t discharge HIV-positive troops. ABC News. Published April 10, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2022. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/wireStory/judge-rules-us-military-discharge-hiv-positive-troops-84000771

- Bokhour BG, Bolton RE, Asch SM, et al. How should we organize care for patients with human immunodeficiency virus and comorbidities? A multisite qualitative study of human immunodeficiency virus care in the United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 2021;59(8):727-735. http://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001563

- Goulet JL, Fultz SL, Rimland D, et al. Aging and infectious diseases: do patterns of comorbidity vary by HIV status, age, and HIV severity? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(12):1593-1601. http://doi.org/10.1086/523577

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022: Respiratory Illnesses

- Federal Register. Presumptive service connection for respiratory conditions due to exposure to particulate matter. Published August 5, 2021. Accessed April 6, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-08-05/pdf/2021-16693.pdf

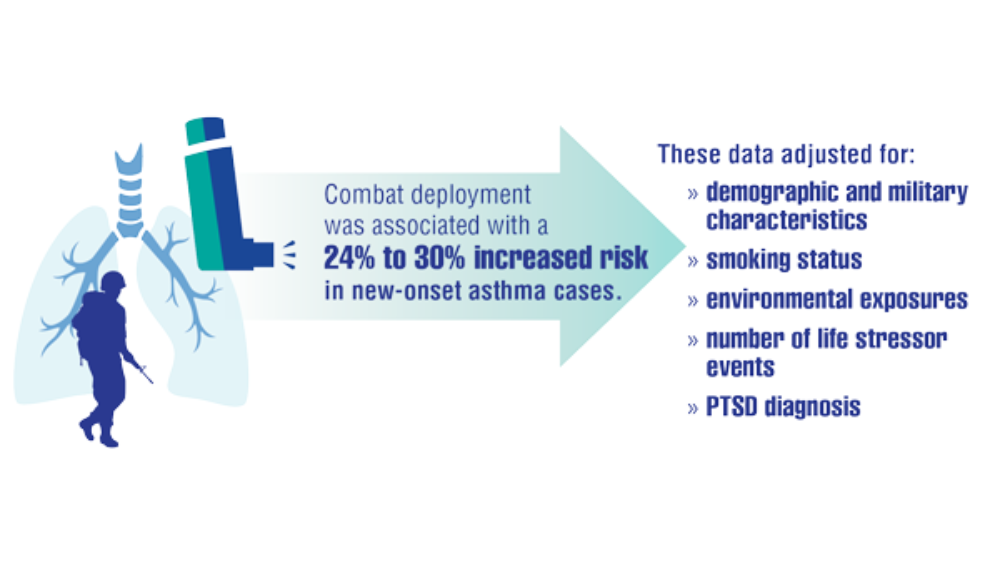

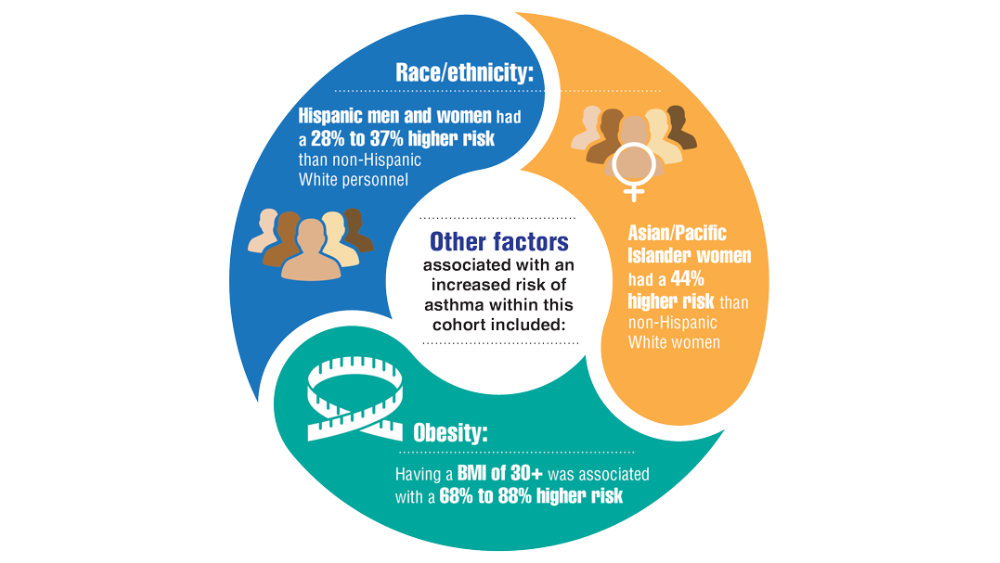

- Rivera AC, Powell TM, Boyko EJ, et al. New-onset asthma and combat deployment: findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(10):2136-2144.

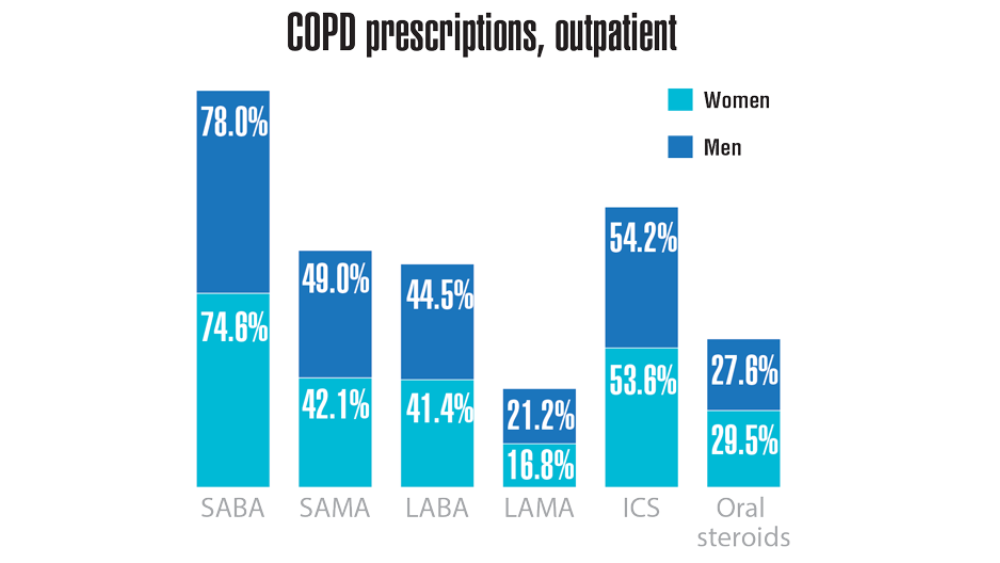

- Rinne ST, Elwy AR, Liu CF et al. Implementation of guideline-based therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: differences between men and women veterans. Chron Respir Dis. 2017;14(4):385-391. http://doi.org/10.1177/1479972317702141

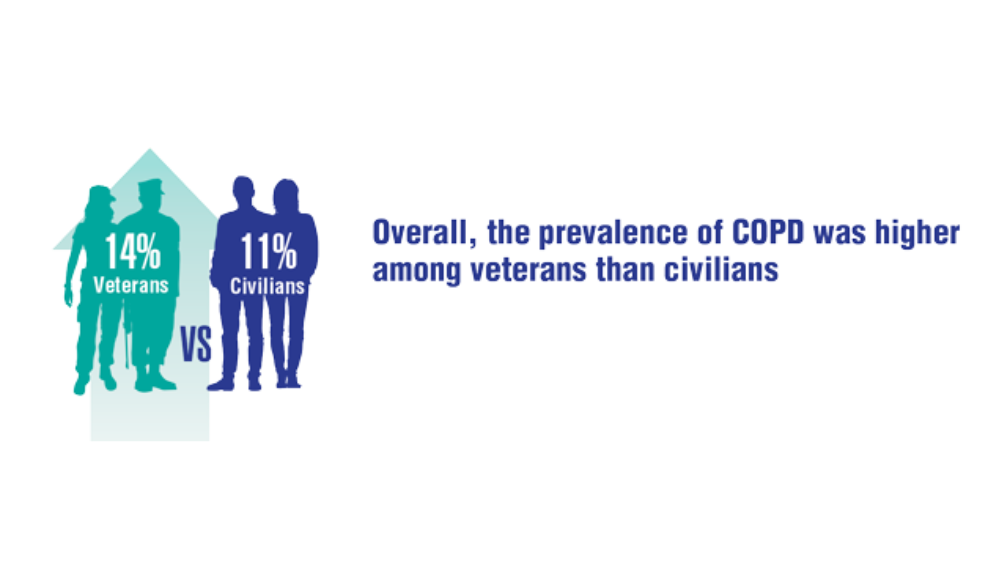

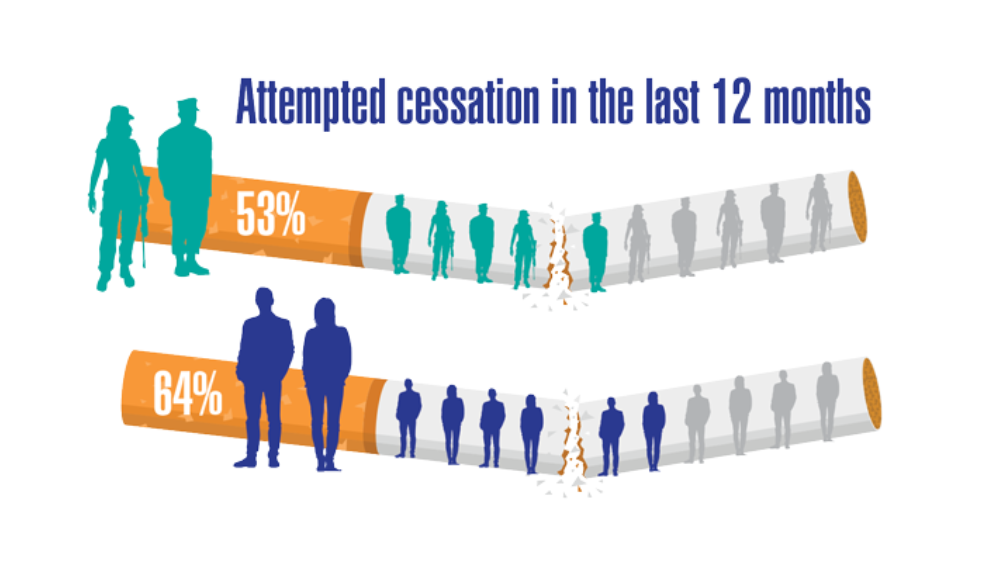

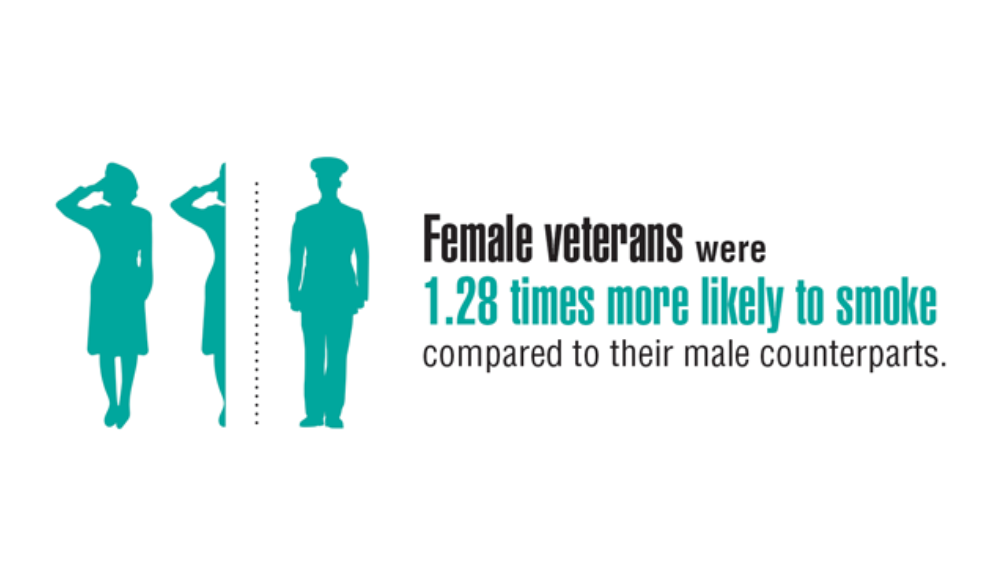

- Greiner B, Ottwell R, Corcoran A, Hartwell M. Smoking and physical activity patterns of US Military veterans with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an analysis of 2017 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Mil Med. 2021;186:e1-5. http://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usaa330

- Federal Register. Presumptive service connection for respiratory conditions due to exposure to particulate matter. Published August 5, 2021. Accessed April 6, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-08-05/pdf/2021-16693.pdf

- Rivera AC, Powell TM, Boyko EJ, et al. New-onset asthma and combat deployment: findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(10):2136-2144.

- Rinne ST, Elwy AR, Liu CF et al. Implementation of guideline-based therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: differences between men and women veterans. Chron Respir Dis. 2017;14(4):385-391. http://doi.org/10.1177/1479972317702141

- Greiner B, Ottwell R, Corcoran A, Hartwell M. Smoking and physical activity patterns of US Military veterans with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an analysis of 2017 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Mil Med. 2021;186:e1-5. http://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usaa330

- Federal Register. Presumptive service connection for respiratory conditions due to exposure to particulate matter. Published August 5, 2021. Accessed April 6, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2021-08-05/pdf/2021-16693.pdf

- Rivera AC, Powell TM, Boyko EJ, et al. New-onset asthma and combat deployment: findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(10):2136-2144.

- Rinne ST, Elwy AR, Liu CF et al. Implementation of guideline-based therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: differences between men and women veterans. Chron Respir Dis. 2017;14(4):385-391. http://doi.org/10.1177/1479972317702141

- Greiner B, Ottwell R, Corcoran A, Hartwell M. Smoking and physical activity patterns of US Military veterans with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an analysis of 2017 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Mil Med. 2021;186:e1-5. http://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usaa330

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022

Federal Health Care Data Trends (click to view the digital edition) is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner highlighting the latest research and study outcomes related to the health of veteran and active-duty populations.

In this issue:

- Vaccinations

- Mental Health and Related Disorders

- LGBTQ+ Veterans

- Military Sexual Trauma

- Sleep Disorders

- Respiratory Illnesses

- HIV Care in the VA

- Rheumatologic Diseases

- The Cancer-Obesity Connection

- Skin Health for Active-Duty Personnel

- Contraception

- Chronic Kidney Disease

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- Neurologic Disorders

- Hearing, Vision, and Balance

Federal Practitioner would like to thank the following experts for their review of content and helpful guidance in developing this issue:

Kelvin N.V. Bush, MD, FACC, CCDS; Sonya Borrero, MD, MS; Kenneth L. Cameron, PhD, MPH, ATC, FNATA; Jason DeViva, PhD; Ellen Lockard Edens, MD; Leonard E. Egede, MD, MS; Amy Justice, MD, PhD; Stephanie Knudson, MD; Willis H. Lyford, MD; Sarah O. Meadows, PhD; Tamara Schult, PhD, MPH; Eric L. Singman, MD, PhD; Art Wallace, MD, PhD; Elizabeth Waterhouse, MD, FAAN

Federal Health Care Data Trends (click to view the digital edition) is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner highlighting the latest research and study outcomes related to the health of veteran and active-duty populations.

In this issue:

- Vaccinations

- Mental Health and Related Disorders

- LGBTQ+ Veterans

- Military Sexual Trauma

- Sleep Disorders

- Respiratory Illnesses

- HIV Care in the VA

- Rheumatologic Diseases

- The Cancer-Obesity Connection

- Skin Health for Active-Duty Personnel

- Contraception

- Chronic Kidney Disease

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- Neurologic Disorders

- Hearing, Vision, and Balance

Federal Practitioner would like to thank the following experts for their review of content and helpful guidance in developing this issue:

Kelvin N.V. Bush, MD, FACC, CCDS; Sonya Borrero, MD, MS; Kenneth L. Cameron, PhD, MPH, ATC, FNATA; Jason DeViva, PhD; Ellen Lockard Edens, MD; Leonard E. Egede, MD, MS; Amy Justice, MD, PhD; Stephanie Knudson, MD; Willis H. Lyford, MD; Sarah O. Meadows, PhD; Tamara Schult, PhD, MPH; Eric L. Singman, MD, PhD; Art Wallace, MD, PhD; Elizabeth Waterhouse, MD, FAAN

Federal Health Care Data Trends (click to view the digital edition) is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner highlighting the latest research and study outcomes related to the health of veteran and active-duty populations.

In this issue:

- Vaccinations

- Mental Health and Related Disorders

- LGBTQ+ Veterans

- Military Sexual Trauma

- Sleep Disorders

- Respiratory Illnesses

- HIV Care in the VA

- Rheumatologic Diseases

- The Cancer-Obesity Connection

- Skin Health for Active-Duty Personnel

- Contraception

- Chronic Kidney Disease

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- Neurologic Disorders

- Hearing, Vision, and Balance

Federal Practitioner would like to thank the following experts for their review of content and helpful guidance in developing this issue:

Kelvin N.V. Bush, MD, FACC, CCDS; Sonya Borrero, MD, MS; Kenneth L. Cameron, PhD, MPH, ATC, FNATA; Jason DeViva, PhD; Ellen Lockard Edens, MD; Leonard E. Egede, MD, MS; Amy Justice, MD, PhD; Stephanie Knudson, MD; Willis H. Lyford, MD; Sarah O. Meadows, PhD; Tamara Schult, PhD, MPH; Eric L. Singman, MD, PhD; Art Wallace, MD, PhD; Elizabeth Waterhouse, MD, FAAN

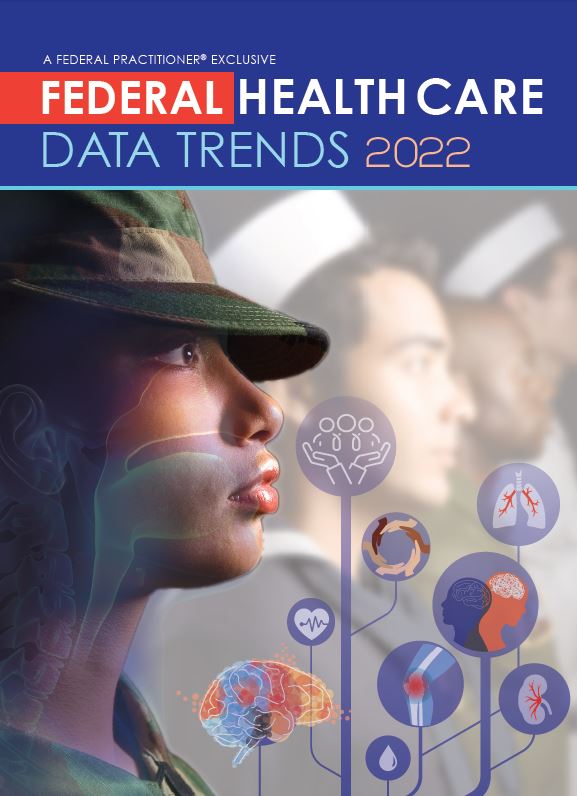

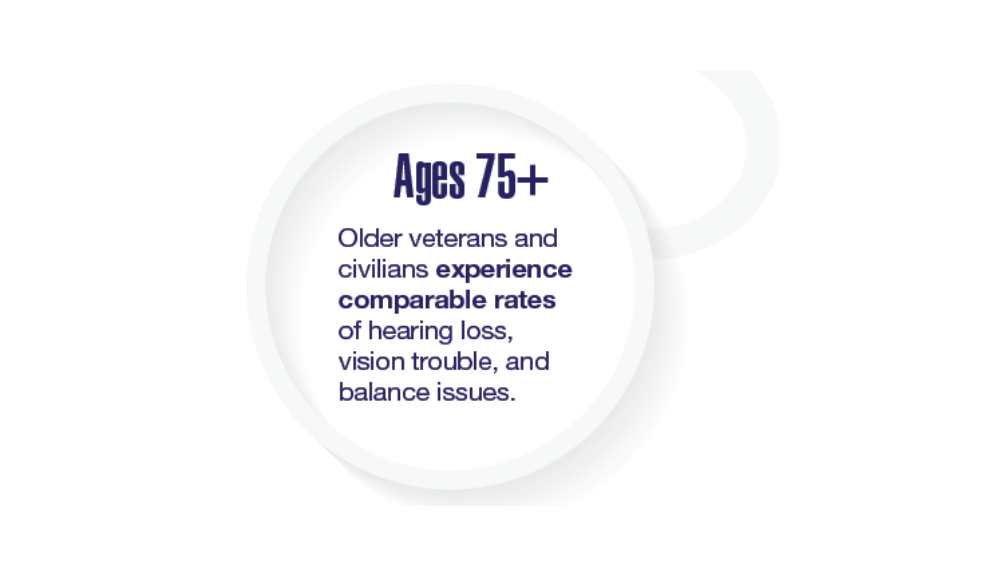

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022: Hearing, Vision, and Balance

- Lucas JW, Zelaya CE. Hearing difficulty, vision trouble, and balance problems among male veterans and nonveterans. Natl Health Stat Report. 2020;(142):1-8. Accessed March 30, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr142-508.pdf

- Shrauner W, Lord EM, Nguyen XMT, et al. Frailty and cardiovascular mortality in more than 3 million US veterans. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(8):818-826. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab850

- Defense Health Agency, Vision Center of Excellence (email, March 23, 2022).

- Frick KD, Singman EL. Cost of military eye injury and vision impairment related to traumatic brain injury: 2001–2017. Mil Med. 2019;184(5-6):e338. http://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy420

- Hussain SF, Raza Z, Cash ATG, et al. Traumatic brain injury and sight loss in military and veteran populations – a review. Mil Med Res. 2021;8(1):42. http://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-021-00334-3

- Lucas JW, Zelaya CE. Hearing difficulty, vision trouble, and balance problems among male veterans and nonveterans. Natl Health Stat Report. 2020;(142):1-8. Accessed March 30, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr142-508.pdf

- Shrauner W, Lord EM, Nguyen XMT, et al. Frailty and cardiovascular mortality in more than 3 million US veterans. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(8):818-826. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab850

- Defense Health Agency, Vision Center of Excellence (email, March 23, 2022).

- Frick KD, Singman EL. Cost of military eye injury and vision impairment related to traumatic brain injury: 2001–2017. Mil Med. 2019;184(5-6):e338. http://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy420

- Hussain SF, Raza Z, Cash ATG, et al. Traumatic brain injury and sight loss in military and veteran populations – a review. Mil Med Res. 2021;8(1):42. http://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-021-00334-3

- Lucas JW, Zelaya CE. Hearing difficulty, vision trouble, and balance problems among male veterans and nonveterans. Natl Health Stat Report. 2020;(142):1-8. Accessed March 30, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr142-508.pdf

- Shrauner W, Lord EM, Nguyen XMT, et al. Frailty and cardiovascular mortality in more than 3 million US veterans. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(8):818-826. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab850

- Defense Health Agency, Vision Center of Excellence (email, March 23, 2022).

- Frick KD, Singman EL. Cost of military eye injury and vision impairment related to traumatic brain injury: 2001–2017. Mil Med. 2019;184(5-6):e338. http://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy420

- Hussain SF, Raza Z, Cash ATG, et al. Traumatic brain injury and sight loss in military and veteran populations – a review. Mil Med Res. 2021;8(1):42. http://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-021-00334-3

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022: Sleep Disorders

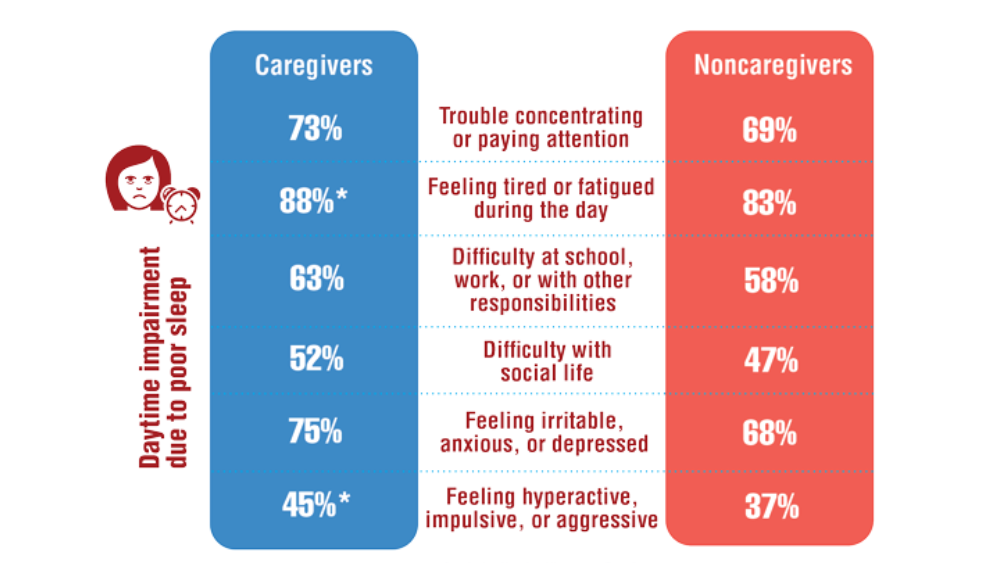

- Song Y, Carlson GC, McGowan SK, et al. Sleep disruption due to stress in women veterans: a comparison between caregivers and noncaregivers. Behav Sleep Med. 2021;19(2):243-254. http://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2020.1732981

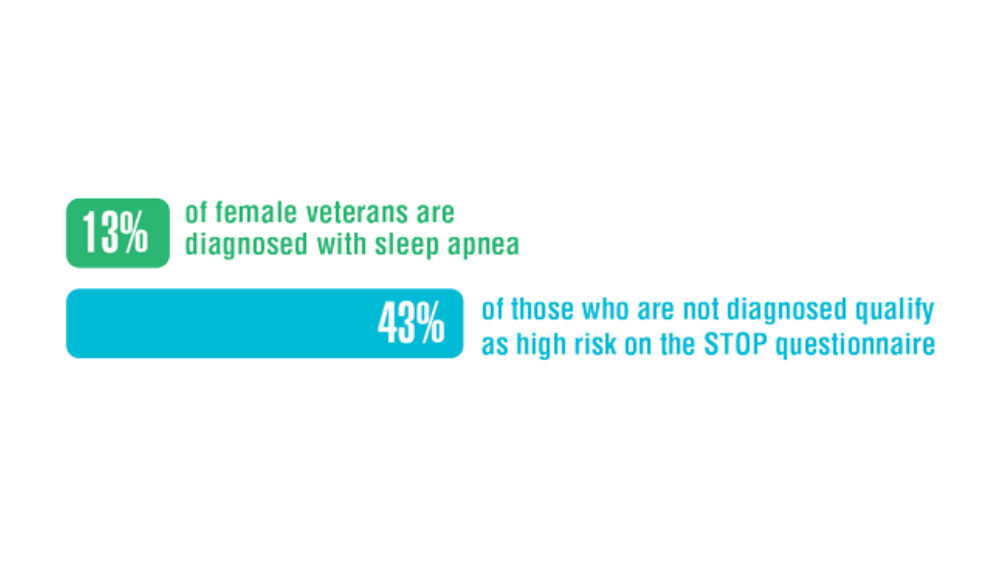

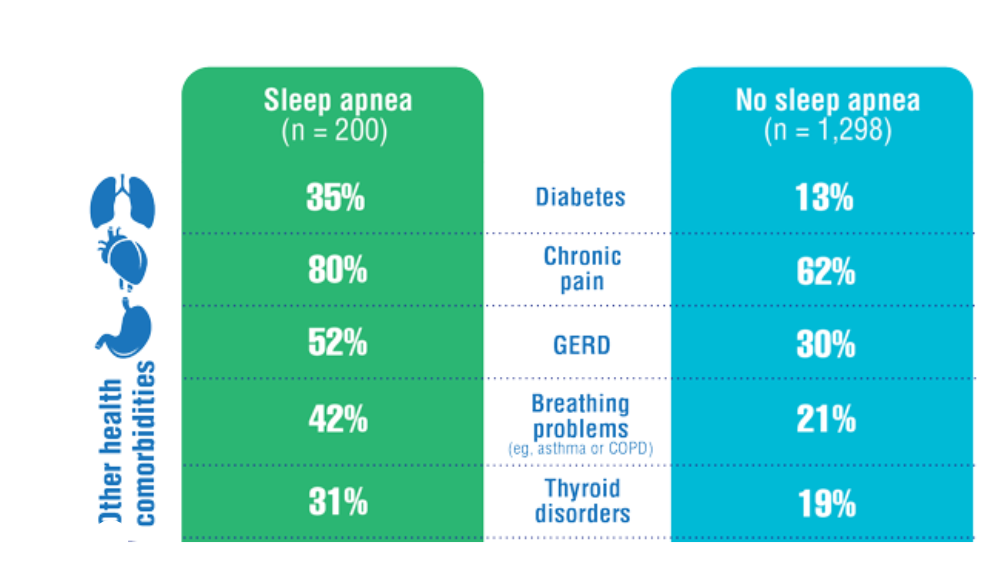

- Martin JL, Carlson G, Kelly M, et al. Sleep apnea in women veterans: results of a national survey of VA health care users. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(3):555-565. http://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8956

- Song Y, Carlson GC, McGowan SK, et al. Sleep disruption due to stress in women veterans: a comparison between caregivers and noncaregivers. Behav Sleep Med. 2021;19(2):243-254. http://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2020.1732981

- Martin JL, Carlson G, Kelly M, et al. Sleep apnea in women veterans: results of a national survey of VA health care users. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(3):555-565. http://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8956

- Song Y, Carlson GC, McGowan SK, et al. Sleep disruption due to stress in women veterans: a comparison between caregivers and noncaregivers. Behav Sleep Med. 2021;19(2):243-254. http://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2020.1732981

- Martin JL, Carlson G, Kelly M, et al. Sleep apnea in women veterans: results of a national survey of VA health care users. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(3):555-565. http://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8956

Impact of Race on Outcomes of High-Risk Patients With Prostate Cancer Treated With Moderately Hypofractionated Radiotherapy in an Equal Access Setting

Although moderately hypofractionated radiotherapy (MHRT) is an accepted treatment for localized prostate cancer, its adaptation remains limited in the United States.1,2 MHRT theoretically exploits α/β ratio differences between the prostate (1.5 Gy), bladder (5-10 Gy), and rectum (3 Gy), thereby reducing late treatment-related adverse effects compared with those of conventional fractionation at biologically equivalent doses.3-8 Multiple randomized noninferiority trials have demonstrated equivalent outcomes between MHRT and conventional fraction with no appreciable increase in patient-reported toxicity.9-14 Although these studies have led to the acceptance of MHRT as a standard treatment, the majority of these trials involve individuals with low- and intermediate-risk disease.

There are less phase 3 data addressing MHRT for high-risk prostate cancer (HRPC).10,12,14-17 Only 2 studies examined predominately high-risk populations, accounting for 83 and 292 patients, respectively.15,16 Additional phase 3 trials with small proportions of high-risk patients (n = 126, 12%; n = 53, 35%) offer limited additional information regarding clinical outcomes and toxicity rates specific to high-risk disease.10-12 Numerous phase 1 and 2 studies report various field designs and fractionation plans for MHRT in the context of high-risk disease, although the applicability of these data to off-trial populations remains limited.18-20

Furthermore, African American individuals are underrepresented in the trials establishing the role of MHRT despite higher rates of prostate cancer incidence, more advanced disease stage at diagnosis, and higher rates of prostate cancer–specific survival (PCSS) when compared with White patients.21 Racial disparities across patients with prostate cancer and their management are multifactorial across health care literacy, education level, access to care (including transportation issues), and issues of adherence and distrust.22-25 Correlation of patient race to prostate cancer outcomes varies greatly across health care systems, with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) equal access system providing robust mental health services and transportation services for some patients, while demonstrating similar rates of stage-adjusted PCSS between African American and White patients across a broad range of treatment modalities.26-28 Given the paucity of data exploring outcomes following MHRT for African American patients with HRPC, the present analysis provides long-term clinical outcomes and toxicity profiles for an off-trial majority African American population with HRPC treated with MHRT within the VA.

Methods

Records were retrospectively reviewed under an institutional review board–approved protocol for all patients with HRPC treated with definitive MHRT at the Durham Veterans Affairs Healthcare System in North Carolina between November 2008 and August 2018. Exclusion criteria included < 12 months of follow-up or elective nodal irradiation. Demographic variables obtained included age at diagnosis, race, clinical T stage, pre-MHRT prostate-specific antigen (PSA), Gleason grade group at diagnosis, favorable vs unfavorable high-risk disease, pre-MHRT international prostate symptom score (IPSS), and pre-MHRT urinary medication usage (yes/no).29

Concurrent androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) was initiated 6 to 8 weeks before MHRT unless medically contraindicated per the discretion of the treating radiation oncologist. Patients generally received 18 to 24 months of ADT, with those with favorable HRPC (ie, T1c disease with either Gleason 4+4 and PSA < 10 mg/mL or Gleason 3+3 and PSA > 20 ng/mL) receiving 6 months after 2015.29 Patients were simulated supine in either standard or custom immobilization with a full bladder and empty rectum. MHRT fractionation plans included 70 Gy at 2.5 Gy per fraction and 60 Gy at 3 Gy per fraction. Radiotherapy targets included the prostate and seminal vesicles without elective nodal coverage per institutional practice. Treatments were delivered following image guidance, either prostate matching with cone beam computed tomography or fiducial matching with kilo voltage imaging. All patients received intensity-modulated radiotherapy. For plans delivering 70 Gy at 2.5 Gy per fraction, constraints included bladder V (volume receiving) 70 < 10 cc, V65 ≤ 15%, V40 ≤ 35%, rectum V70 < 10 cc, V65 ≤ 10%, V40 ≤ 35%, femoral heads maximum point dose ≤ 40 Gy, penile bulb mean dose ≤ 50 Gy, and small bowel V40 ≤ 1%. For plans delivering 60 Gy at 3 Gy per fraction, constraints included rectum V57 ≤ 15%, V46 ≤ 30%, V37 ≤ 50%, bladder V60 ≤ 5%, V46 ≤ 30%, V37 ≤ 50%, and femoral heads V43 ≤ 5%.

Gastrointestinal (GI) and genitourinary (GU) toxicities were graded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 5.0, with acute toxicity defined as on-treatment < 3 months following completion of MHRT. Late toxicity was defined as ≥ 3 months following completion of MHRT. Individuals were seen in follow-up at 6 weeks and 3 months with PSA and testosterone after MHRT completion, then every 6 to 12 months for 5 years and annually thereafter. Each follow-up visit included history, physical examination, IPSS, and CTCAE grading for GI and GU toxicity.

The Wilcoxon rank sum test and χ2 test were used to compare differences in demographic data, dosimetric parameters, and frequency of toxicity events with respect to patient race. Clinical endpoints including biochemical recurrence-free survival (BRFS; defined by Phoenix criteria as 2.0 above PSA nadir), distant metastases-free survival (DMFS), PCSS, and overall survival (OS) were estimated from time of radiotherapy completion by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared between African American and White race by log-rank testing.30 Late GI and GU toxicity-free survival were estimated by Kaplan-Meier plots and compared between African American and White patients by the log-rank test. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4.

Results

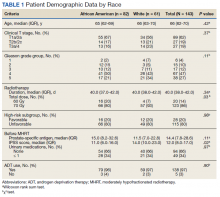

We identified 143 patients with HRPC treated with definitive MHRT between November 2008 and August 2018 (Table 1). Mean age was 65 years (range, 36-80 years); 57% were African American men. Eighty percent of individuals had unfavorable high-risk disease. Median (IQR) PSA was 14.4 (7.8-28.6). Twenty-six percent had grade group 1-3 disease, 47% had grade group 4 disease, and 27% had grade group 5 disease. African American patients had significantly lower pre-MHRT IPSS scores than White patients (mean IPSS, 11 vs 14, respectively; P = .02) despite similar rates of preradiotherapy urinary medication usage (66% and 66%, respectively).

Eighty-six percent received 70 Gy over 28 fractions, with institutional protocol shifting to 60 Gy over 20 fractions (14%) in June 2017. The median (IQR) duration of radiotherapy was 39 (38-42) days, with 97% of individuals undergoing ADT for a median (IQR) duration of 24 (24-36) months. The median follow-up time was 38 months, with 57 (40%) patients followed for at least 60 months.

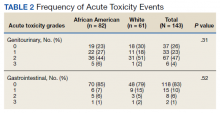

Grade 3 GI and GU acute toxicity events were observed in 1% and 4% of all individuals, respectively (Table 2). No acute GI or GU grade 4+ events were observed. No significant differences in acute GU or GI toxicity were observed between African American and White patients.

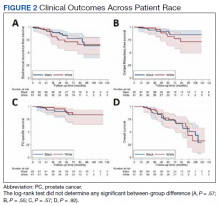

No significant differences between African American and White patients were observed for late grade 2+ GI (P = .19) or GU (P = .55) toxicity. Late grade 2+ GI toxicity was observed in 17 (12%) patients overall (Figure 1A). One grade 3 and 1 grade 4 late GI event were observed following MHRT completion: The latter involved hospitalization for bleeding secondary to radiation proctitis in the context of cirrhosis predating MHRT. Late grade 2+ GU toxicity was observed in 80 (56%) patients, with late grade 2 events steadily increasing over time (Figure 1B). Nine late grade 3 GU toxicity events were observed at a median of 13 months following completion of MHRT, 2 of which occurred more than 24 months after MHRT completion. No late grade 4 or 5 GU events were observed. IPSS values both before MHRT and at time of last follow-up were available for 65 (40%) patients, with a median (IQR) IPSS of 10 (6-16) before MHRT and 12 (8-16) at last follow-up at a median (IQR) interval of 36 months (26-76) from radiation completion.

No significant differences were observed between African American and White patients with respect to BRFS, DMFS, PCSS, or OS (Figure 2). Overall, 21 of 143 (15%) patients experienced biochemical recurrence: 5-year BRFS was 77% (95% CI, 67%-85%) for all patients, 83% (95% CI, 70%-91%) for African American patients, and 71% (95% CI, 53%-82%) for White patients. Five-year DMFS was 87% (95% CI, 77%-92%) for all individuals, 91% (95% CI, 80%-96%) for African American patients, and 81% (95% CI, 62%-91%) for White patients. Five-year PCSS was 89% (95% CI, 80%-94%) for all patients, with 5-year PCSS rates of 90% (95% CI, 79%-95%) for African American patients and 87% (95% CI, 70%-95%) for White patients. Five-year OS was 75% overall (95% CI, 64%-82%), with 5-year OS rates of 73% (95% CI, 58%-83%) for African American patients and 77% (95% CI, 60%-87%) for White patients.

Discussion

In this study, we reported acute and late GI and GU toxicity rates as well as clinical outcomes for a majority African American population with predominately unfavorable HRPC treated with MHRT in an equal access health care environment. We found that MHRT was well tolerated with high rates of biochemical control, PCSS, and OS. Additionally, outcomes were not significantly different across patient race. To our knowledge, this is the first report of MHRT for HRPC in a majority African American population.

We found that MHRT was an effective treatment for patients with HRPC, in particular those with unfavorable high-risk disease. While prior prospective and randomized studies have investigated the use of MHRT, our series was larger than most and had a predominately unfavorable high-risk population.12,15-17 Our biochemical and PCSS rates compare favorably with those of HRPC trial populations, particularly given the high proportion of unfavorable high-risk disease.12,15,16 Despite similar rates of biochemical control, OS was lower in the present cohort than in HRPC trial populations, even with a younger median age at diagnosis. The similarly high rates of non–HRPC-related death across race may reflect differences in baseline comorbidities compared with trial populations as well as reported differences between individuals in the VA and the private sector.31 This suggests that MHRT can be an effective treatment for patients with unfavorable HRPC.

We did not find any differences in outcomes between African American and White individuals with HRPC treated with MHRT. Furthermore, our study demonstrates long-term rates of BRFS and PCSS in a majority African American population with predominately unfavorable HRPC that are comparable with those of prior randomized MHRT studies in high-risk, predominately White populations.12,15,16 Prior reports have found that African American men with HRPC may be at increased risk for inferior clinical outcomes due to a number of socioeconomic, biologic, and cultural mediators.26,27,32 Such individuals may disproportionally benefit from shorter treatment courses that improve access to radiotherapy, a well-documented disparity for African American men with localized prostate cancer.33-36 The VA is an ideal system for studying racial disparities within prostate cancer, as accessibility of mental health and transportation services, income, and insurance status are not barriers to preventative or acute care.37 Our results are concordant with those previously seen for African American patients with prostate cancer seen in the VA, which similarly demonstrate equal outcomes with those of other races.28,36 Incorporation of the earlier mentioned VA services into oncologic care across other health care systems could better characterize determinants of racial disparities in prostate cancer, including the prognostic significance of shortening treatment duration and number of patient visits via MHRT.

Despite widespread acceptance in prostate cancer radiotherapy guidelines, routine use of MHRT seems limited across all stages of localized prostate cancer.1,2 Late toxicity is a frequently noted concern regarding MHRT use. Higher rates of late grade 2+ GI toxicity were observed in the hypofractionation arm of the HYPRO trial.17 While RTOG 0415 did not include patients with HRPC, significantly higher rates of physician-reported (but not patient-reported) late grade 2+ GI and GU toxicity were observed using the same MHRT fractionation regimen used for the majority of individuals in our cohort.9 In our study, the steady increase in late grade 2 GU toxicity is consistent with what is seen following conventionally fractionated radiotherapy and is likely multifactorial.38 The mean IPSS difference of 2/35 from pre-MHRT baseline to the time of last follow-up suggests minimal quality of life decline. The relatively stable IPSSs over time alongside the > 50% prevalence of late grade 2 GU toxicity per CTCAE grading seems consistent with the discrepancy noted in RTOG 0415 between increased physician-reported late toxicity and favorable patient-reported quality of life scores.9 Moreover, significant variance exists in toxicity grading across scoring systems, revised editions of CTCAE, and physician-specific toxicity classification, particularly with regard to the use of adrenergic receptor blocker medications. In light of these factors, the high rate of late grade 2 GU toxicity in our study should be interpreted in the context of largely stable post-MHRT IPSSs and favorable rates of late GI grade 2+ and late GU grade 3+ toxicity.

Limitations

This study has several inherent limitations. While the size of the current HRPC cohort is notably larger than similar populations within the majority of phase 3 MHRT trials, these data derive from a single VA hospital. It is unclear whether these outcomes would be representative in a similar high-risk population receiving care outside of the VA equal access system. Follow-up data beyond 5 years was available for less than half of patients, partially due to nonprostate cancer–related mortality at a higher rate than observed in HRPC trial populations.12,15,16 Furthermore, all GI toxicity events were exclusively physician reported, and GU toxicity reporting was limited in the off-trial setting with not all patients routinely completing IPSS questionnaires following MHRT completion. However, all patients were treated similarly, and radiation quality was verified over the treatment period with mandated accreditation, frequent standardized output checks, and systematic treatment review.39

Conclusions

Patients with HRPC treated with MHRT in an equal access, off-trial setting demonstrated favorable rates of biochemical control with acceptable rates of acute and late GI and GU toxicities. Clinical outcomes, including biochemical control, were not significantly different between African American and White patients, which may reflect equal access to care within the VA irrespective of income and insurance status. Incorporating VA services, such as access to primary care, mental health services, and transportation across other health care systems may aid in characterizing and mitigating racial and gender disparities in oncologic care.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this work were presented at the November 2020 ASTRO conference. 40

1. Stokes WA, Kavanagh BD, Raben D, Pugh TJ. Implementation of hypofractionated prostate radiation therapy in the United States: a National Cancer Database analysis. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2017;7:270-278. doi:10.1016/j.prro.2017.03.011

2. Jaworski L, Dominello MM, Heimburger DK, et al. Contemporary practice patterns for intact and post-operative prostate cancer: results from a statewide collaborative. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;105(1):E282. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.06.1915

3. Miralbell R, Roberts SA, Zubizarreta E, Hendry JH. Dose-fractionation sensitivity of prostate cancer deduced from radiotherapy outcomes of 5,969 patients in seven international institutional datasets: α/β = 1.4 (0.9-2.2) Gy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(1):e17-e24. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.075

4. Tree AC, Khoo VS, van As NJ, Partridge M. Is biochemical relapse-free survival after profoundly hypofractionated radiotherapy consistent with current radiobiological models? Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2014;26(4):216-229. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2014.01.008

5. Brenner DJ. Fractionation and late rectal toxicity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60(4):1013-1015. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.04.014

6. Tucker SL, Thames HD, Michalski JM, et al. Estimation of α/β for late rectal toxicity based on RTOG 94-06. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(2):600-605. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.11.080

7. Dasu A, Toma-Dasu I. Prostate alpha/beta revisited—an analysis of clinical results from 14 168 patients. Acta Oncol. 2012;51(8):963-974. doi:10.3109/0284186X.2012.719635 start

8. Proust-Lima C, Taylor JMG, Sécher S, et al. Confirmation of a Low α/β ratio for prostate cancer treated by external beam radiation therapy alone using a post-treatment repeated-measures model for PSA dynamics. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79(1):195-201. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.008

9. Lee WR, Dignam JJ, Amin MB, et al. Randomized phase III noninferiority study comparing two radiotherapy fractionation schedules in patients with low-risk prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(20): 2325-2332. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.67.0448

10. Dearnaley D, Syndikus I, Mossop H, et al. Conventional versus hypofractionated high-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: 5-year outcomes of the randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):1047-1060. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30102-4

11. Catton CN, Lukka H, Gu C-S, et al. Randomized trial of a hypofractionated radiation regimen for the treatment of localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(17):1884-1890. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.71.7397

12. Pollack A, Walker G, Horwitz EM, et al. Randomized trial of hypofractionated external-beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(31):3860-3868. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1972

13. Hoffman KE, Voong KR, Levy LB, et al. Randomized trial of hypofractionated, dose-escalated, intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) versus conventionally fractionated IMRT for localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(29):2943-2949. doi:10.1200/JCO.2018.77.9868

14. Wilkins A, Mossop H, Syndikus I, et al. Hypofractionated radiotherapy versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for patients with intermediate-risk localised prostate cancer: 2-year patient-reported outcomes of the randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(16):1605-1616. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00280-6

15. Incrocci L, Wortel RC, Alemayehu WG, et al. Hypofractionated versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for patients with localised prostate cancer (HYPRO): final efficacy results from a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):1061-1069. doi.10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30070-5

16. Arcangeli G, Saracino B, Arcangeli S, et al. Moderate hypofractionation in high-risk, organ-confined prostate cancer: final results of a phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(17):1891-1897. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.70.4189

17. Aluwini S, Pos F, Schimmel E, et al. Hypofractionated versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for patients with prostate cancer (HYPRO): late toxicity results from a randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(4):464-474. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00567-7

18. Pervez N, Small C, MacKenzie M, et al. Acute toxicity in high-risk prostate cancer patients treated with androgen suppression and hypofractionated intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(1):57-64. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.01.048

19. Magli A, Moretti E, Tullio A, Giannarini G. Hypofractionated simultaneous integrated boost (IMRT- cancer: results of a prospective phase II trial SIB) with pelvic nodal irradiation and concurrent androgen deprivation therapy for high-risk prostate cancer: results of a prospective phase II trial. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2018;21(2):269-276. doi:10.1038/s41391-018-0034-0

20. Di Muzio NG, Fodor A, Noris Chiorda B, et al. Moderate hypofractionation with simultaneous integrated boost in prostate cancer: long-term results of a phase I–II study. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2016;28(8):490-500. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2016.02.005

21. DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(3):21-233. doi:10.3322/caac.21555

22. Wolf MS, Knight SJ, Lyons EA, et al. Literacy, race, and PSA level among low-income men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer. Urology. 2006(1);68:89-93. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2006.01.064

23. Rebbeck TR. Prostate cancer disparities by race and ethnicity: from nucleotide to neighborhood. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8(9):a030387. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a030387

24. Guidry JJ, Aday LA, Zhang D, Winn RJ. Transportation as a barrier to cancer treatment. Cancer Pract. 1997;5(6):361-366.

25. Friedman DB, Corwin SJ, Dominick GM, Rose ID. African American men’s understanding and perceptions about prostate cancer: why multiple dimensions of health literacy are important in cancer communication. J Community Health. 2009;34(5):449-460. doi:10.1007/s10900-009-9167-3

26. Connell PP, Ignacio L, Haraf D, et al. Equivalent racial outcome after conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer: a single departmental experience. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(1):54-61. doi:10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.54

27. Dess RT, Hartman HE, Mahal BA, et al. Association of black race with prostate cancer-specific and other-cause mortality. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(1):975-983. doi:10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.54

28. McKay RR, Sarkar RR, Kumar A, et al. Outcomes of Black men with prostate cancer treated with radiation therapy in the Veterans Health Administration. Cancer. 2021;127(3):403-411. doi:10.1002/cncr.33224

29. Muralidhar V, Chen M-H, Reznor G, et al. Definition and validation of “favorable high-risk prostate cancer”: implications for personalizing treatment of radiation-managed patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;93(4):828-835. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.07.2281

30. Roach M 3rd, Hanks G, Thames H Jr, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(4):965-974. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.029

31. Freeman VL, Durazo-Arvizu R, Arozullah AM, Keys LC. Determinants of mortality following a diagnosis of prostate cancer in Veterans Affairs and private sector health care systems. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(100):1706-1712. doi:10.2105/ajph.93.10.1706

32. Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54(2):78-93. doi:10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78

33. Zemplenyi AT, Kaló Z, Kovacs G, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of intensity-modulated radiation therapy with normal and hypofractionated schemes for the treatment of localised prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2018;27(1):e12430. doi:10.1111/ecc.12430

34. Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Harlan LC, Kramer BS. Trends and black/white differences in treatment for nonmetastatic prostate cancer. Med Care. 1998;36(9):1337-1348. doi:10.1097/00005650-199809000-00006

35. Harlan L, Brawley O, Pommerenke F, Wali P, Kramer B. Geographic, age, and racial variation in the treatment of local/regional carcinoma of the prostate. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(1):93-100. doi:10.1200/JCO.1995.13.1.93

36. Riviere P, Luterstein E, Kumar A, et al. Racial equity among African-American and non-Hispanic white men diagnosed with prostate cancer in the veterans affairs healthcare system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;105:E305.

37. Peterson K, Anderson J, Boundy E, Ferguson L, McCleery E, Waldrip K. Mortality disparities in racial/ethnic minority groups in the Veterans Health Administration: an evidence review and map. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(3):e1-e11. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.304246

38. Zietman AL, DeSilvio ML, Slater JD, et al. Comparison of conventional-dose vs high-dose conformal radiation therapy in clinically localized adenocarcinoma of the prostate: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294(10):1233-1239. doi:10.1001/jama.294.10.1233

39. Hagan M, Kapoor R, Michalski J, et al. VA-Radiation Oncology Quality Surveillance program. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;106(3):639-647. doi.10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.08.064