User login

Commentary: Concomitant Therapies May Affect NSCLC Survival, August 2022

A Danish population-based cohort study by Ehrenstein and colleagues involved 21,282 patients with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), 8758 of whom received a diagnosis at stage I-IIIA. Of those, 4071 (46%) were tested for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations at diagnosis. Median overall survival (OS) was 5.7 years among patients with EGFR mutation–positive status (n = 361) and 4.4 years among patients with EGFR mutation–negative status (n = 3710). EGFR mutation–positive status was associated with lower all-cause mortality in all subgroups. This is not surprising, because EGFR-mutated lung cancers are associated with never or light smoking history and the patients tend to be younger and have fewer medical comorbidities. Nevertheless, the lower risk for all-cause mortality was consistent across all subgroups (stage at diagnosis, age, sex, comorbidity, and surgery receipt), with hazard ratios (HR) ranging from 0.48 to 0.83. In addition, targeted therapies, such as osimertinib, improved OS and progression-free survival (PFS) in the metastatic setting as first-line treatment. Now that the ADAURA study has demonstrated a substantial disease-free survival benefit with osimertinib in the adjuvant setting in early-stage EGFR-mutated NSCLC (with final OS results still to come) it will be interesting to see whether this magnitude of difference in OS grows over time.

Wang and colleagues conducted a large meta-analysis of 10 retrospective studies and one prospective study including a total of 5892 patients with NSCLC who were receiving programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/ programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors with the concomitant use of gastric acid suppressants (GAS). Use of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with vs without GAS worsened PFS by 32% (HR 1.32; P < .001) and OS by 36% (HR 1.36; P < .001). The GAS in these studies were predominantly proton-pump inhibitors (PPI). There is still much to learn about medications that may influence outcomes to immune checkpoint blockade, such as steroids, antibiotics, GAS, and others. We are also learning that the microbiome probably plays an important role in contributing to activity of PD-1/PDL-1 antibodies and PPI may modify the microbiome. More research is needed, but it is reasonable to try and switch patients receiving PD-1/PDL-1 inhibitors from PPI to other GAS, if clinically appropriate.

Nazha and colleagues performed a SEER-Medicare database analysis evaluating 367,750 patients with lung cancer. A total of 11,061 patients had an initial prostate cancer diagnosis and subsequent lung cancer diagnosis, 3017 had an initial lung cancer diagnosis and subsequent prostate cancer diagnosis, and the remaining patients had an isolated lung cancer diagnosis. Patients who received androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for a previously diagnosed prostate cancer showed improved survival after lung cancer diagnosis (adjusted HR for death 0.88; P = .02) and a shorter latency period to the diagnosis of lung cancer (40 vs 47 months; P < .001) compared with those who did not receive ADT. This finding applied mainly to White patients and may not apply to Black patients because there was an underrepresentation of Black patients in the study. The association of ADT for prostate cancer improving clinical outcomes in patients subsequently diagnosed with lung cancer is intriguing. There is known crosstalk between receptor kinase signaling and androgen receptor signaling that may biologically explain the findings in this study. This theoretically could apply more to certain molecular subtypes of lung cancer, such as EGFR-mutated lung cancer. However, further studies are needed to confirm this because confounding factors and immortal time bias (where patients receiving ADT may be more likely to have more frequent interactions in the healthcare system and thus receive an earlier lung cancer diagnosis) may in part explain the findings in this retrospective analysis. More research is needed to determine whether patients with prostate cancer receiving ADT had improved survival compared with those who did not receive ADT.

A Danish population-based cohort study by Ehrenstein and colleagues involved 21,282 patients with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), 8758 of whom received a diagnosis at stage I-IIIA. Of those, 4071 (46%) were tested for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations at diagnosis. Median overall survival (OS) was 5.7 years among patients with EGFR mutation–positive status (n = 361) and 4.4 years among patients with EGFR mutation–negative status (n = 3710). EGFR mutation–positive status was associated with lower all-cause mortality in all subgroups. This is not surprising, because EGFR-mutated lung cancers are associated with never or light smoking history and the patients tend to be younger and have fewer medical comorbidities. Nevertheless, the lower risk for all-cause mortality was consistent across all subgroups (stage at diagnosis, age, sex, comorbidity, and surgery receipt), with hazard ratios (HR) ranging from 0.48 to 0.83. In addition, targeted therapies, such as osimertinib, improved OS and progression-free survival (PFS) in the metastatic setting as first-line treatment. Now that the ADAURA study has demonstrated a substantial disease-free survival benefit with osimertinib in the adjuvant setting in early-stage EGFR-mutated NSCLC (with final OS results still to come) it will be interesting to see whether this magnitude of difference in OS grows over time.

Wang and colleagues conducted a large meta-analysis of 10 retrospective studies and one prospective study including a total of 5892 patients with NSCLC who were receiving programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/ programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors with the concomitant use of gastric acid suppressants (GAS). Use of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with vs without GAS worsened PFS by 32% (HR 1.32; P < .001) and OS by 36% (HR 1.36; P < .001). The GAS in these studies were predominantly proton-pump inhibitors (PPI). There is still much to learn about medications that may influence outcomes to immune checkpoint blockade, such as steroids, antibiotics, GAS, and others. We are also learning that the microbiome probably plays an important role in contributing to activity of PD-1/PDL-1 antibodies and PPI may modify the microbiome. More research is needed, but it is reasonable to try and switch patients receiving PD-1/PDL-1 inhibitors from PPI to other GAS, if clinically appropriate.

Nazha and colleagues performed a SEER-Medicare database analysis evaluating 367,750 patients with lung cancer. A total of 11,061 patients had an initial prostate cancer diagnosis and subsequent lung cancer diagnosis, 3017 had an initial lung cancer diagnosis and subsequent prostate cancer diagnosis, and the remaining patients had an isolated lung cancer diagnosis. Patients who received androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for a previously diagnosed prostate cancer showed improved survival after lung cancer diagnosis (adjusted HR for death 0.88; P = .02) and a shorter latency period to the diagnosis of lung cancer (40 vs 47 months; P < .001) compared with those who did not receive ADT. This finding applied mainly to White patients and may not apply to Black patients because there was an underrepresentation of Black patients in the study. The association of ADT for prostate cancer improving clinical outcomes in patients subsequently diagnosed with lung cancer is intriguing. There is known crosstalk between receptor kinase signaling and androgen receptor signaling that may biologically explain the findings in this study. This theoretically could apply more to certain molecular subtypes of lung cancer, such as EGFR-mutated lung cancer. However, further studies are needed to confirm this because confounding factors and immortal time bias (where patients receiving ADT may be more likely to have more frequent interactions in the healthcare system and thus receive an earlier lung cancer diagnosis) may in part explain the findings in this retrospective analysis. More research is needed to determine whether patients with prostate cancer receiving ADT had improved survival compared with those who did not receive ADT.

A Danish population-based cohort study by Ehrenstein and colleagues involved 21,282 patients with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), 8758 of whom received a diagnosis at stage I-IIIA. Of those, 4071 (46%) were tested for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations at diagnosis. Median overall survival (OS) was 5.7 years among patients with EGFR mutation–positive status (n = 361) and 4.4 years among patients with EGFR mutation–negative status (n = 3710). EGFR mutation–positive status was associated with lower all-cause mortality in all subgroups. This is not surprising, because EGFR-mutated lung cancers are associated with never or light smoking history and the patients tend to be younger and have fewer medical comorbidities. Nevertheless, the lower risk for all-cause mortality was consistent across all subgroups (stage at diagnosis, age, sex, comorbidity, and surgery receipt), with hazard ratios (HR) ranging from 0.48 to 0.83. In addition, targeted therapies, such as osimertinib, improved OS and progression-free survival (PFS) in the metastatic setting as first-line treatment. Now that the ADAURA study has demonstrated a substantial disease-free survival benefit with osimertinib in the adjuvant setting in early-stage EGFR-mutated NSCLC (with final OS results still to come) it will be interesting to see whether this magnitude of difference in OS grows over time.

Wang and colleagues conducted a large meta-analysis of 10 retrospective studies and one prospective study including a total of 5892 patients with NSCLC who were receiving programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/ programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors with the concomitant use of gastric acid suppressants (GAS). Use of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with vs without GAS worsened PFS by 32% (HR 1.32; P < .001) and OS by 36% (HR 1.36; P < .001). The GAS in these studies were predominantly proton-pump inhibitors (PPI). There is still much to learn about medications that may influence outcomes to immune checkpoint blockade, such as steroids, antibiotics, GAS, and others. We are also learning that the microbiome probably plays an important role in contributing to activity of PD-1/PDL-1 antibodies and PPI may modify the microbiome. More research is needed, but it is reasonable to try and switch patients receiving PD-1/PDL-1 inhibitors from PPI to other GAS, if clinically appropriate.

Nazha and colleagues performed a SEER-Medicare database analysis evaluating 367,750 patients with lung cancer. A total of 11,061 patients had an initial prostate cancer diagnosis and subsequent lung cancer diagnosis, 3017 had an initial lung cancer diagnosis and subsequent prostate cancer diagnosis, and the remaining patients had an isolated lung cancer diagnosis. Patients who received androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for a previously diagnosed prostate cancer showed improved survival after lung cancer diagnosis (adjusted HR for death 0.88; P = .02) and a shorter latency period to the diagnosis of lung cancer (40 vs 47 months; P < .001) compared with those who did not receive ADT. This finding applied mainly to White patients and may not apply to Black patients because there was an underrepresentation of Black patients in the study. The association of ADT for prostate cancer improving clinical outcomes in patients subsequently diagnosed with lung cancer is intriguing. There is known crosstalk between receptor kinase signaling and androgen receptor signaling that may biologically explain the findings in this study. This theoretically could apply more to certain molecular subtypes of lung cancer, such as EGFR-mutated lung cancer. However, further studies are needed to confirm this because confounding factors and immortal time bias (where patients receiving ADT may be more likely to have more frequent interactions in the healthcare system and thus receive an earlier lung cancer diagnosis) may in part explain the findings in this retrospective analysis. More research is needed to determine whether patients with prostate cancer receiving ADT had improved survival compared with those who did not receive ADT.

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022: Military Sexual Trauma

- Hard truths and the duty to change: recommendations from the Independent Review Commission on Sexual Assault in the Military. Published July 1, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2022. https://media.defense.gov/2021/Jul/02/2002755437/-1/-1/0/IRC-FULL-REPORT-FINAL-1923-7-1-2.PDF

- Gross GM, Ronzitti S, Combellick JL, et al. Sex differences in military sexual trauma and severe self-directed violence. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58(5):675-682. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.12.006

- Nitcher B, Holliday R, Monteith LL, et al. Military sexual trauma in the United States: results from a population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2022;306:19-27. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.03.016

- Lofgreen AM, Carroll KK, Dugan SA, Karnik NS. An overview of sexual trauma in the US Military. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2017;15(4):411-419. http://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20170024

- Schuyler AC, Klemmer C, Mamey MR, et al. Experiences of sexual harassment, stalking, and sexual assault during military service among LGBT and non-LGBT service members. J Trauma Stress. 2020;33(3):257-266. http://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22506

- Department of Defense annual report on sexual assault in the military: fiscal year 2020. May 15, 2021. Accessed March 24, 2022. https://www.sapr.mil/sites/default/files/DOD_Annual_Report_on_Sexual_Assault_in_the_Military_FY2020.pdf

- Department of Defense annual report on sexual assault in the military: fiscal year 2020. Appendix B: statistical data on sexual assault. May 15, 2021. Accessed March 24, 2022. https://www.sapr.mil/sites/default/files/Appendix_B_Statistical_Data_On_Sexual_Assault_FY2020.pdf

- Department of Defense annual report on sexual assault in the military: fiscal year 2020. Appendix C: metrics and non-metrics on sexual assault. May 15, 2021. Accessed March 24, 2022. https://www.sapr.mil/sites/default/files/Appendix_C_Metrics_and_NonMetrics_on_Sexual_Assault_FY2020.pdf

- Barth SK, Kimerling RE, Pavao J, et al. Military sexual trauma among recent veterans: correlates of sexual assault and sexual harassment. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(1):77-86. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.012

- Military sexual trauma. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated March 11, 2022. Accessed March 24, 2022. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/msthome/index.asp

- Hahn CK, Turchik J, Kimerling R. A latent class analysis of mental health beliefs related to military sexual trauma. J Trauma Stress. 2021;34(2):394-404. http://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22585

- Hard truths and the duty to change: recommendations from the Independent Review Commission on Sexual Assault in the Military. Published July 1, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2022. https://media.defense.gov/2021/Jul/02/2002755437/-1/-1/0/IRC-FULL-REPORT-FINAL-1923-7-1-2.PDF

- Gross GM, Ronzitti S, Combellick JL, et al. Sex differences in military sexual trauma and severe self-directed violence. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58(5):675-682. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.12.006

- Nitcher B, Holliday R, Monteith LL, et al. Military sexual trauma in the United States: results from a population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2022;306:19-27. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.03.016

- Lofgreen AM, Carroll KK, Dugan SA, Karnik NS. An overview of sexual trauma in the US Military. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2017;15(4):411-419. http://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20170024

- Schuyler AC, Klemmer C, Mamey MR, et al. Experiences of sexual harassment, stalking, and sexual assault during military service among LGBT and non-LGBT service members. J Trauma Stress. 2020;33(3):257-266. http://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22506

- Department of Defense annual report on sexual assault in the military: fiscal year 2020. May 15, 2021. Accessed March 24, 2022. https://www.sapr.mil/sites/default/files/DOD_Annual_Report_on_Sexual_Assault_in_the_Military_FY2020.pdf

- Department of Defense annual report on sexual assault in the military: fiscal year 2020. Appendix B: statistical data on sexual assault. May 15, 2021. Accessed March 24, 2022. https://www.sapr.mil/sites/default/files/Appendix_B_Statistical_Data_On_Sexual_Assault_FY2020.pdf

- Department of Defense annual report on sexual assault in the military: fiscal year 2020. Appendix C: metrics and non-metrics on sexual assault. May 15, 2021. Accessed March 24, 2022. https://www.sapr.mil/sites/default/files/Appendix_C_Metrics_and_NonMetrics_on_Sexual_Assault_FY2020.pdf

- Barth SK, Kimerling RE, Pavao J, et al. Military sexual trauma among recent veterans: correlates of sexual assault and sexual harassment. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(1):77-86. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.012

- Military sexual trauma. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated March 11, 2022. Accessed March 24, 2022. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/msthome/index.asp

- Hahn CK, Turchik J, Kimerling R. A latent class analysis of mental health beliefs related to military sexual trauma. J Trauma Stress. 2021;34(2):394-404. http://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22585

- Hard truths and the duty to change: recommendations from the Independent Review Commission on Sexual Assault in the Military. Published July 1, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2022. https://media.defense.gov/2021/Jul/02/2002755437/-1/-1/0/IRC-FULL-REPORT-FINAL-1923-7-1-2.PDF

- Gross GM, Ronzitti S, Combellick JL, et al. Sex differences in military sexual trauma and severe self-directed violence. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58(5):675-682. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.12.006

- Nitcher B, Holliday R, Monteith LL, et al. Military sexual trauma in the United States: results from a population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2022;306:19-27. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.03.016

- Lofgreen AM, Carroll KK, Dugan SA, Karnik NS. An overview of sexual trauma in the US Military. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2017;15(4):411-419. http://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20170024

- Schuyler AC, Klemmer C, Mamey MR, et al. Experiences of sexual harassment, stalking, and sexual assault during military service among LGBT and non-LGBT service members. J Trauma Stress. 2020;33(3):257-266. http://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22506

- Department of Defense annual report on sexual assault in the military: fiscal year 2020. May 15, 2021. Accessed March 24, 2022. https://www.sapr.mil/sites/default/files/DOD_Annual_Report_on_Sexual_Assault_in_the_Military_FY2020.pdf

- Department of Defense annual report on sexual assault in the military: fiscal year 2020. Appendix B: statistical data on sexual assault. May 15, 2021. Accessed March 24, 2022. https://www.sapr.mil/sites/default/files/Appendix_B_Statistical_Data_On_Sexual_Assault_FY2020.pdf

- Department of Defense annual report on sexual assault in the military: fiscal year 2020. Appendix C: metrics and non-metrics on sexual assault. May 15, 2021. Accessed March 24, 2022. https://www.sapr.mil/sites/default/files/Appendix_C_Metrics_and_NonMetrics_on_Sexual_Assault_FY2020.pdf

- Barth SK, Kimerling RE, Pavao J, et al. Military sexual trauma among recent veterans: correlates of sexual assault and sexual harassment. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(1):77-86. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.012

- Military sexual trauma. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated March 11, 2022. Accessed March 24, 2022. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/msthome/index.asp

- Hahn CK, Turchik J, Kimerling R. A latent class analysis of mental health beliefs related to military sexual trauma. J Trauma Stress. 2021;34(2):394-404. http://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22585

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022: LGBTQ+ Veterans

- Ring T. VA eases the path to benefits for LGBTQ+ and HIV-positive vets. The Advocate. September 21, 2021. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://www.advocate.com/news/2021/9/21/va-eases-path-benefits-lgbtq-and-hiv-positive-vets

- Gay veterans top one million. Urban.org. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/59711/900642-gay-veterans-top-one-million.pdf

- 2018 Workplace and Gender Relations Survey of Active Duty Members Overview Report. US Department of Defense. Published October 18, 2018. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.sapr.mil/sites/default/files/Annex_1_2018_WGRA_Overview_Report_0.pdf

- Meadows SO, Engel CC, Collins RL et al. 2018 Health related behaviors survey: sexual orientation and health among the active component. RAND Corporation. 2021. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB10116z7.html

- Gates, GJ and Herman, JL. Transgender military service in the United States. Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. Published May 1, 2014. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://escholarship.org/content/qt1t24j53h/qt1t24j53h.pdf?t=nsm5a0

- Downing J, Conron K, Herman JL, Blosnich JR. Transgender and cisgender US veterans have few health differences. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(7):1160-1168. http://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0027

- Meadows SO, Engel CC, Collins RL, et al. 2015 Health related behaviors survey: sexual orientation, transgender identity, and health among U.S. active-duty service members. RAND Corporation. 2018. Accessed March 15, 2022. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9955z6.html

- Korshak L, Hilgeman MM, Lange-Altman T. Health disparities among LGBT veterans. Published July 2020. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Health_Disparities_Among_LGBT_Veterans.asp

- Ring T. VA eases the path to benefits for LGBTQ+ and HIV-positive vets. The Advocate. September 21, 2021. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://www.advocate.com/news/2021/9/21/va-eases-path-benefits-lgbtq-and-hiv-positive-vets

- Gay veterans top one million. Urban.org. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/59711/900642-gay-veterans-top-one-million.pdf

- 2018 Workplace and Gender Relations Survey of Active Duty Members Overview Report. US Department of Defense. Published October 18, 2018. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.sapr.mil/sites/default/files/Annex_1_2018_WGRA_Overview_Report_0.pdf

- Meadows SO, Engel CC, Collins RL et al. 2018 Health related behaviors survey: sexual orientation and health among the active component. RAND Corporation. 2021. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB10116z7.html

- Gates, GJ and Herman, JL. Transgender military service in the United States. Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. Published May 1, 2014. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://escholarship.org/content/qt1t24j53h/qt1t24j53h.pdf?t=nsm5a0

- Downing J, Conron K, Herman JL, Blosnich JR. Transgender and cisgender US veterans have few health differences. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(7):1160-1168. http://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0027

- Meadows SO, Engel CC, Collins RL, et al. 2015 Health related behaviors survey: sexual orientation, transgender identity, and health among U.S. active-duty service members. RAND Corporation. 2018. Accessed March 15, 2022. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9955z6.html

- Korshak L, Hilgeman MM, Lange-Altman T. Health disparities among LGBT veterans. Published July 2020. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Health_Disparities_Among_LGBT_Veterans.asp

- Ring T. VA eases the path to benefits for LGBTQ+ and HIV-positive vets. The Advocate. September 21, 2021. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://www.advocate.com/news/2021/9/21/va-eases-path-benefits-lgbtq-and-hiv-positive-vets

- Gay veterans top one million. Urban.org. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/59711/900642-gay-veterans-top-one-million.pdf

- 2018 Workplace and Gender Relations Survey of Active Duty Members Overview Report. US Department of Defense. Published October 18, 2018. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.sapr.mil/sites/default/files/Annex_1_2018_WGRA_Overview_Report_0.pdf

- Meadows SO, Engel CC, Collins RL et al. 2018 Health related behaviors survey: sexual orientation and health among the active component. RAND Corporation. 2021. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB10116z7.html

- Gates, GJ and Herman, JL. Transgender military service in the United States. Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. Published May 1, 2014. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://escholarship.org/content/qt1t24j53h/qt1t24j53h.pdf?t=nsm5a0

- Downing J, Conron K, Herman JL, Blosnich JR. Transgender and cisgender US veterans have few health differences. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(7):1160-1168. http://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0027

- Meadows SO, Engel CC, Collins RL, et al. 2015 Health related behaviors survey: sexual orientation, transgender identity, and health among U.S. active-duty service members. RAND Corporation. 2018. Accessed March 15, 2022. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9955z6.html

- Korshak L, Hilgeman MM, Lange-Altman T. Health disparities among LGBT veterans. Published July 2020. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Health_Disparities_Among_LGBT_Veterans.asp

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022: Mental Health and Related Disorders

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee to Evaluate the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. Dimensions of quality in mental health care. In: Evaluation of the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. National Academies Press; January 31, 2018; chap 7. Accessed April 25, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499503

- Panza KE, Kline AC, Na PJ, Potenza MN, Norman SB, Pietrzak RH. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder in U.S. military veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;231:109240. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109240

- Warrener CD, Valentin EM, Gallin C, et al. The role of oxytocin signaling in depression and suicidality in returning war veterans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2021;126:105085. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.105085

- Adams RE, Hu Y, Figley CR, et al. Risk and protective factors associated with mental health among female military veterans: results from the Veterans' Health Study. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):55. http://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01181-z

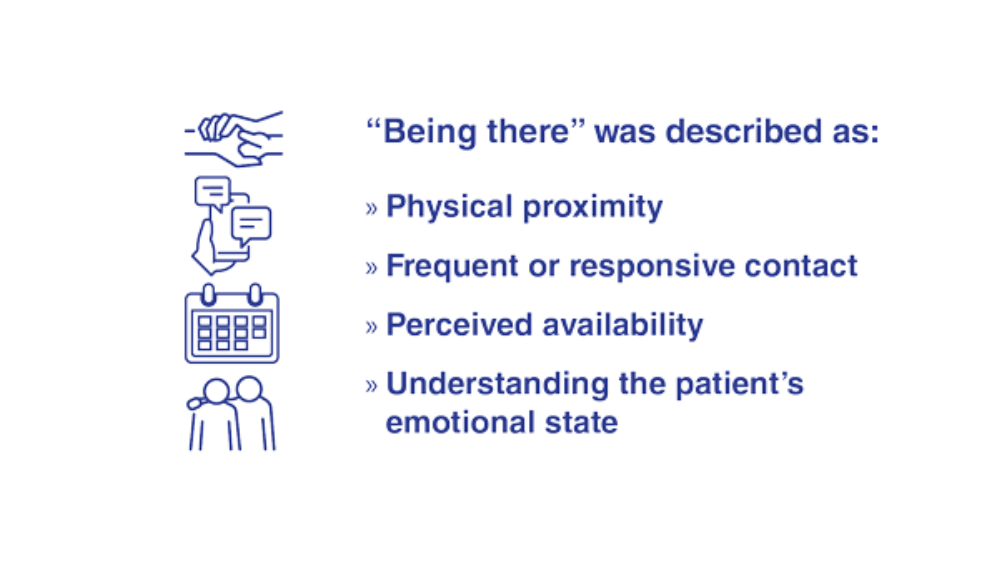

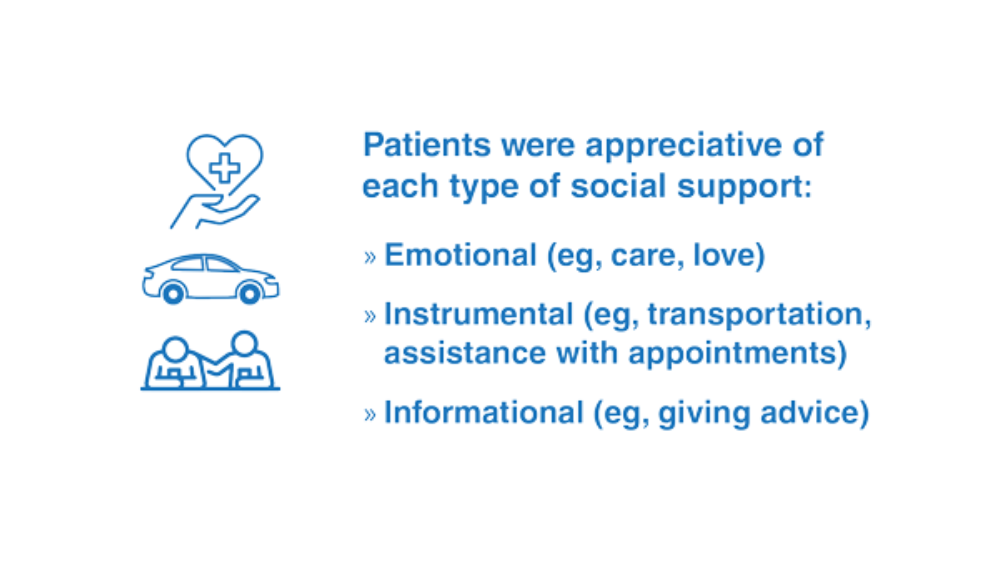

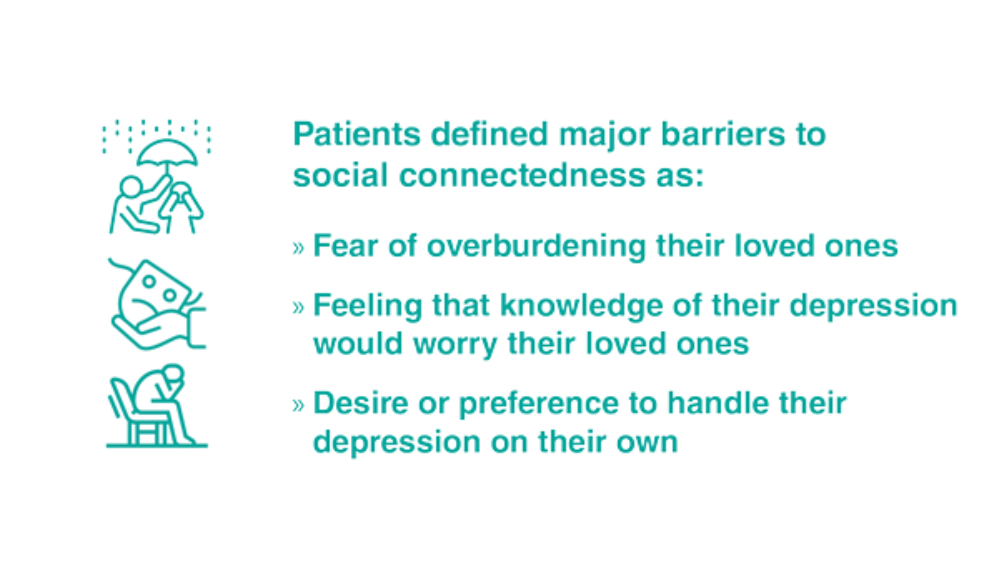

- Teo AR, Marsh HE, Ono SS, Nicolaidis C, Saha S, Dobscha SK. The importance of "being there": a qualitative study of what veterans with depression want in social support. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(7):1954-1962. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05692-7

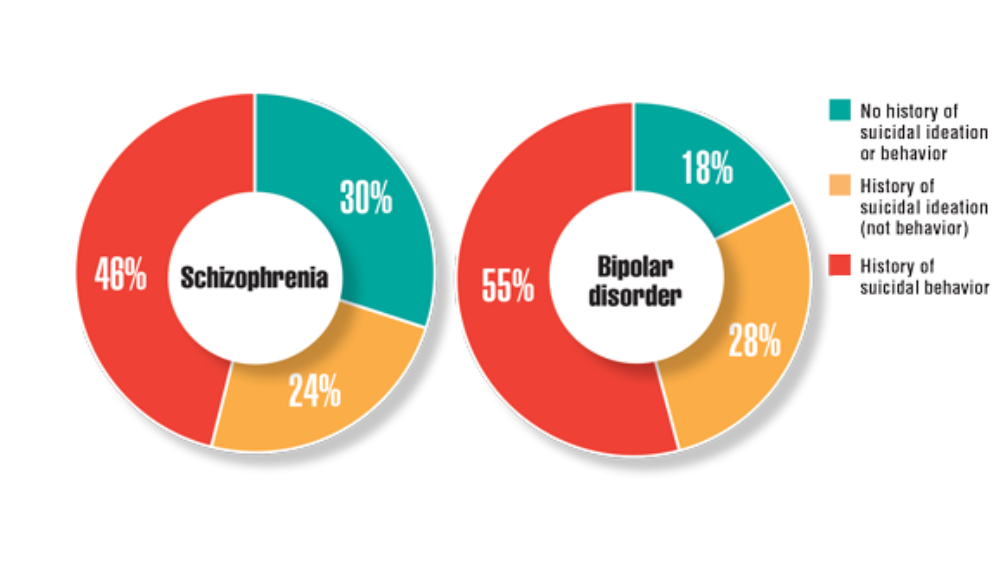

- Harvey PD, Bigdeli TB, Fanous AH, et al. Cooperative Studies Program (CSP) #572: a study of serious mental illness in veterans as a pathway to personalized medicine in schizophrenia and bipolar illness. Pers Med Psychiatry. 2021;27-28. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmip.2021.100078

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee to Evaluate the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. Dimensions of quality in mental health care. In: Evaluation of the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. National Academies Press; January 31, 2018; chap 7. Accessed April 25, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499503

- Panza KE, Kline AC, Na PJ, Potenza MN, Norman SB, Pietrzak RH. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder in U.S. military veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;231:109240. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109240

- Warrener CD, Valentin EM, Gallin C, et al. The role of oxytocin signaling in depression and suicidality in returning war veterans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2021;126:105085. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.105085

- Adams RE, Hu Y, Figley CR, et al. Risk and protective factors associated with mental health among female military veterans: results from the Veterans' Health Study. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):55. http://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01181-z

- Teo AR, Marsh HE, Ono SS, Nicolaidis C, Saha S, Dobscha SK. The importance of "being there": a qualitative study of what veterans with depression want in social support. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(7):1954-1962. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05692-7

- Harvey PD, Bigdeli TB, Fanous AH, et al. Cooperative Studies Program (CSP) #572: a study of serious mental illness in veterans as a pathway to personalized medicine in schizophrenia and bipolar illness. Pers Med Psychiatry. 2021;27-28. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmip.2021.100078

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee to Evaluate the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. Dimensions of quality in mental health care. In: Evaluation of the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. National Academies Press; January 31, 2018; chap 7. Accessed April 25, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499503

- Panza KE, Kline AC, Na PJ, Potenza MN, Norman SB, Pietrzak RH. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder in U.S. military veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;231:109240. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109240

- Warrener CD, Valentin EM, Gallin C, et al. The role of oxytocin signaling in depression and suicidality in returning war veterans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2021;126:105085. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.105085

- Adams RE, Hu Y, Figley CR, et al. Risk and protective factors associated with mental health among female military veterans: results from the Veterans' Health Study. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):55. http://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01181-z

- Teo AR, Marsh HE, Ono SS, Nicolaidis C, Saha S, Dobscha SK. The importance of "being there": a qualitative study of what veterans with depression want in social support. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(7):1954-1962. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05692-7

- Harvey PD, Bigdeli TB, Fanous AH, et al. Cooperative Studies Program (CSP) #572: a study of serious mental illness in veterans as a pathway to personalized medicine in schizophrenia and bipolar illness. Pers Med Psychiatry. 2021;27-28. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmip.2021.100078

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022: Neurologic Disorders

- Williams KA. Headache management in a veteran population: First considerations. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2020;32(11):758-763. https://doi.org/10.1097/JXX.0000000000000539

- Yin JH, Lin YK, Yang CP, et al. Prevalence and association of lifestyle and medical-, psychiatric-, and pain-related comorbidities in patients with migraine: a cross-sectional study. Headache. 2021;61(5):715-726. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14106

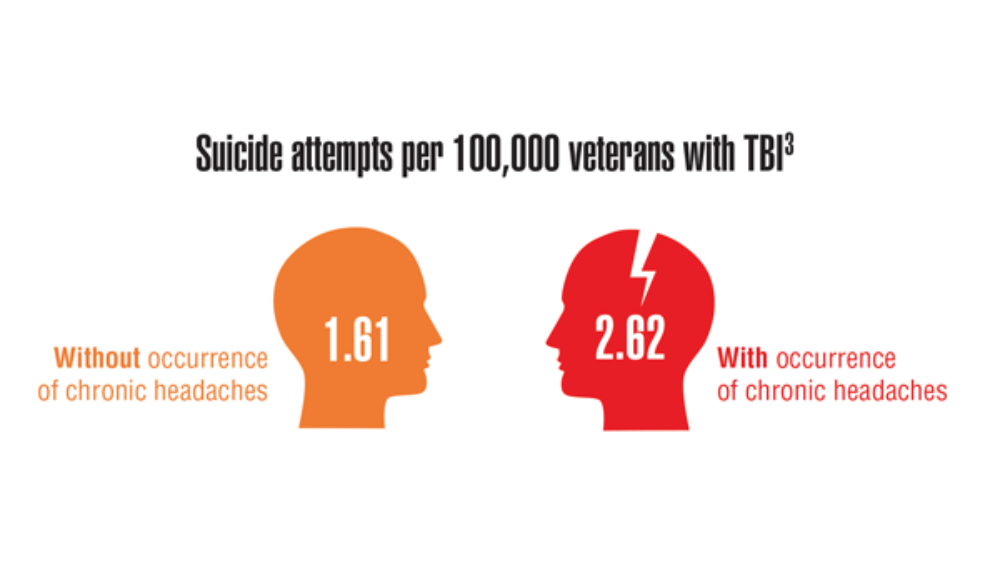

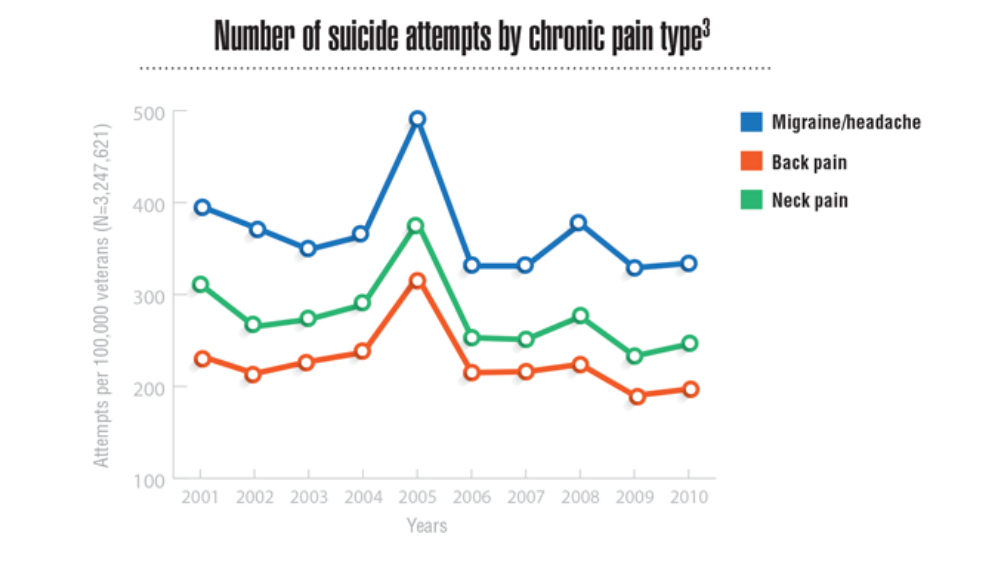

- Androulakis XM, Guo S, Zhang J, et al. Suicide attempts in US veterans with chronic headache disorders: a 10-year retrospective cohort study. J Pain Res. 2021;14:2629-2639. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S322432

- Chen XY, Chen ZY, Dong Z, Liu MQ, Yu SY. Regional volume changes of the brain in migraine chronification. Neural Regen Res. 2020;15(9):1701-1708. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.276360

- Wallin MT, Whitham R, Maloni H, et al. The Multiple Sclerosis Surveillance Registry: a novel interactive database within the Veterans Health Administration. Fed Pract. 2020;37(suppl 1):S18-S23.

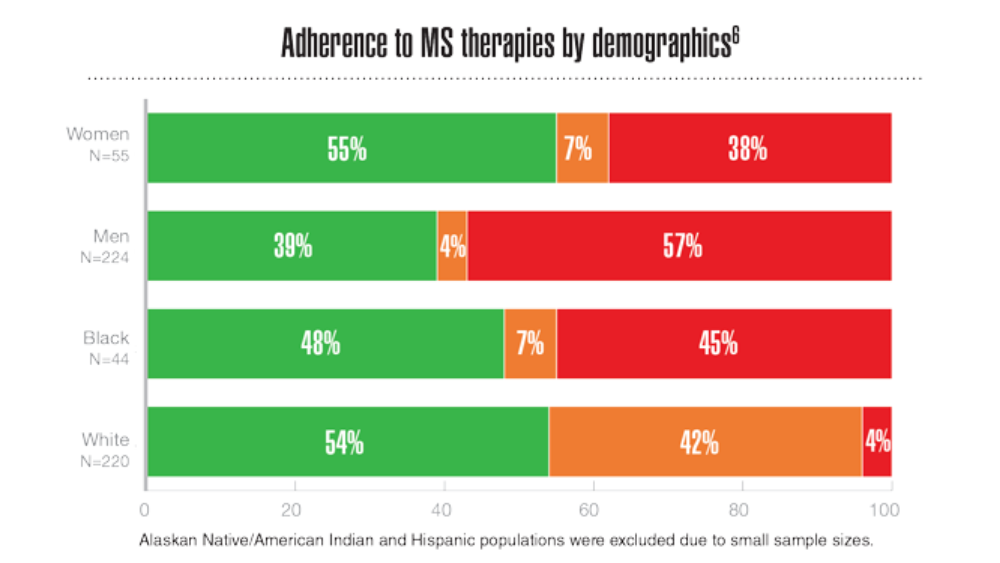

- Rabadi MH, Just K, Xu C. The impact of adherence to disease-modifying therapies on functional outcomes in veterans with multiple sclerosis. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 2021;13:11795735211028769. http://doi.org/10.1177/11795735211028769

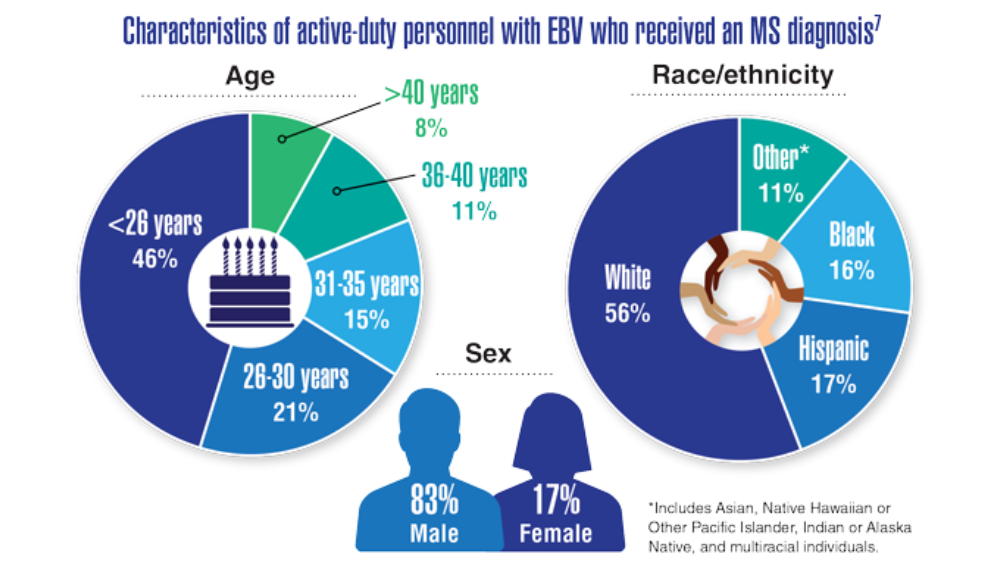

- Bjornevik K, Cortese M, Healy BC, et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science. 2022;375(6578):296-301. http://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj8222

- Nelson RE, Xie Y, DuVall SL, et al. Multiple sclerosis and risk of infection-related hospitalization and death in US veterans. Int J MS Care. 2015;17(5):221-230. http://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2014-035

- Williams KA. Headache management in a veteran population: First considerations. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2020;32(11):758-763. https://doi.org/10.1097/JXX.0000000000000539

- Yin JH, Lin YK, Yang CP, et al. Prevalence and association of lifestyle and medical-, psychiatric-, and pain-related comorbidities in patients with migraine: a cross-sectional study. Headache. 2021;61(5):715-726. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14106

- Androulakis XM, Guo S, Zhang J, et al. Suicide attempts in US veterans with chronic headache disorders: a 10-year retrospective cohort study. J Pain Res. 2021;14:2629-2639. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S322432

- Chen XY, Chen ZY, Dong Z, Liu MQ, Yu SY. Regional volume changes of the brain in migraine chronification. Neural Regen Res. 2020;15(9):1701-1708. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.276360

- Wallin MT, Whitham R, Maloni H, et al. The Multiple Sclerosis Surveillance Registry: a novel interactive database within the Veterans Health Administration. Fed Pract. 2020;37(suppl 1):S18-S23.

- Rabadi MH, Just K, Xu C. The impact of adherence to disease-modifying therapies on functional outcomes in veterans with multiple sclerosis. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 2021;13:11795735211028769. http://doi.org/10.1177/11795735211028769

- Bjornevik K, Cortese M, Healy BC, et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science. 2022;375(6578):296-301. http://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj8222

- Nelson RE, Xie Y, DuVall SL, et al. Multiple sclerosis and risk of infection-related hospitalization and death in US veterans. Int J MS Care. 2015;17(5):221-230. http://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2014-035

- Williams KA. Headache management in a veteran population: First considerations. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2020;32(11):758-763. https://doi.org/10.1097/JXX.0000000000000539

- Yin JH, Lin YK, Yang CP, et al. Prevalence and association of lifestyle and medical-, psychiatric-, and pain-related comorbidities in patients with migraine: a cross-sectional study. Headache. 2021;61(5):715-726. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14106

- Androulakis XM, Guo S, Zhang J, et al. Suicide attempts in US veterans with chronic headache disorders: a 10-year retrospective cohort study. J Pain Res. 2021;14:2629-2639. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S322432

- Chen XY, Chen ZY, Dong Z, Liu MQ, Yu SY. Regional volume changes of the brain in migraine chronification. Neural Regen Res. 2020;15(9):1701-1708. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.276360

- Wallin MT, Whitham R, Maloni H, et al. The Multiple Sclerosis Surveillance Registry: a novel interactive database within the Veterans Health Administration. Fed Pract. 2020;37(suppl 1):S18-S23.

- Rabadi MH, Just K, Xu C. The impact of adherence to disease-modifying therapies on functional outcomes in veterans with multiple sclerosis. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 2021;13:11795735211028769. http://doi.org/10.1177/11795735211028769

- Bjornevik K, Cortese M, Healy BC, et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science. 2022;375(6578):296-301. http://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj8222

- Nelson RE, Xie Y, DuVall SL, et al. Multiple sclerosis and risk of infection-related hospitalization and death in US veterans. Int J MS Care. 2015;17(5):221-230. http://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2014-035

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022: Cardiovascular Diseases

- Howard JT, Stewart IJ, Kolaja CA, et al. Hypertension in military veterans is associated with combat exposure and combat injury. J Hypertens. 2020;38(7):1293-1301. http://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000002364

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A closer look at African American men and high blood pressure control. Reviewed November 2, 2020. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/aa_sourcebook.htm

- CDC. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. What to expect and information collected. Reviewed November 16, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/participant/information-collected.htm

- Keaton JM, Hellwege JN, Giri A, et al. Associations of biogeographic ancestry with hypertension traits. J Hypertens. 2021;39(4):633-642. http://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000002701

- Groeneveld PW, Medvedeva EL, Walker L, Segal AG, Richardson DM, Epstein AJ. Outcomes of care for ischemic heart disease and chronic heart failure in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(7):563-571. http://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2018.1115

- Cho ME, Hansen JL, Sauer BC, Cheung AK, Agarwal A, Greene T. Heart failure hospitalization risk associated with iron status in veterans with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16(4):522-531. http://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.15360920

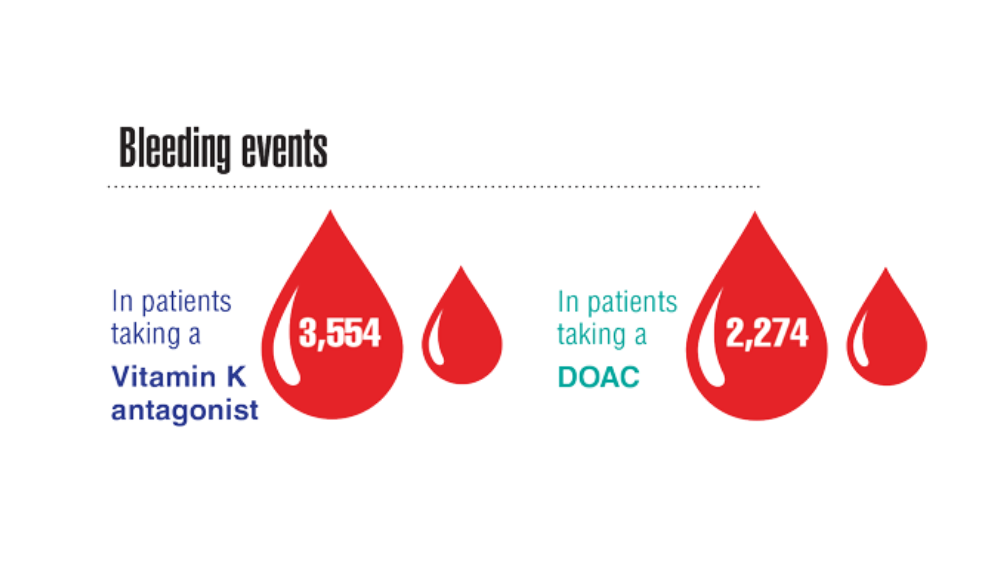

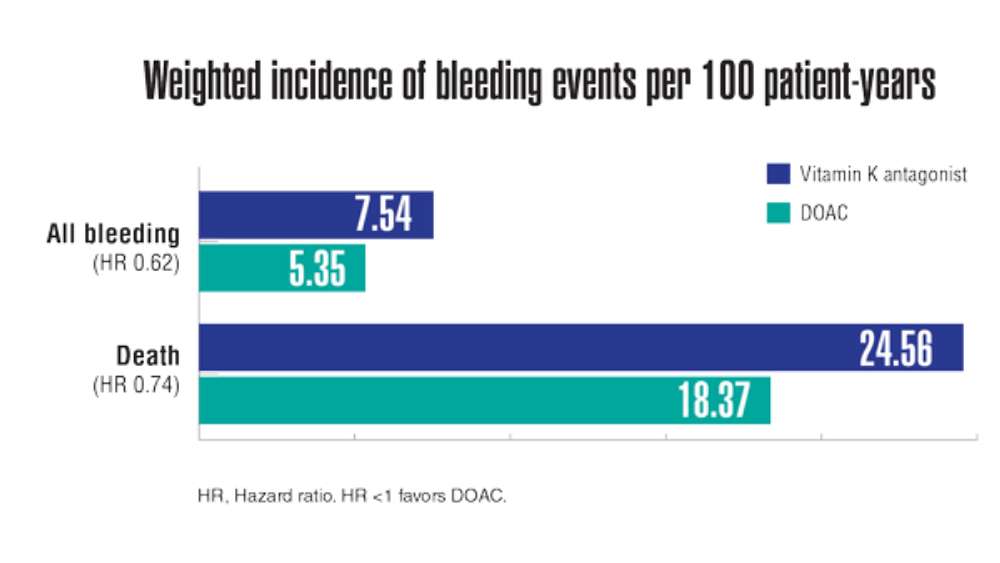

- Jackevicius CA, Lu L, Ghaznavi Z, Warner AL. Bleeding risk of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2021;14(2):e007230. http://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.007230

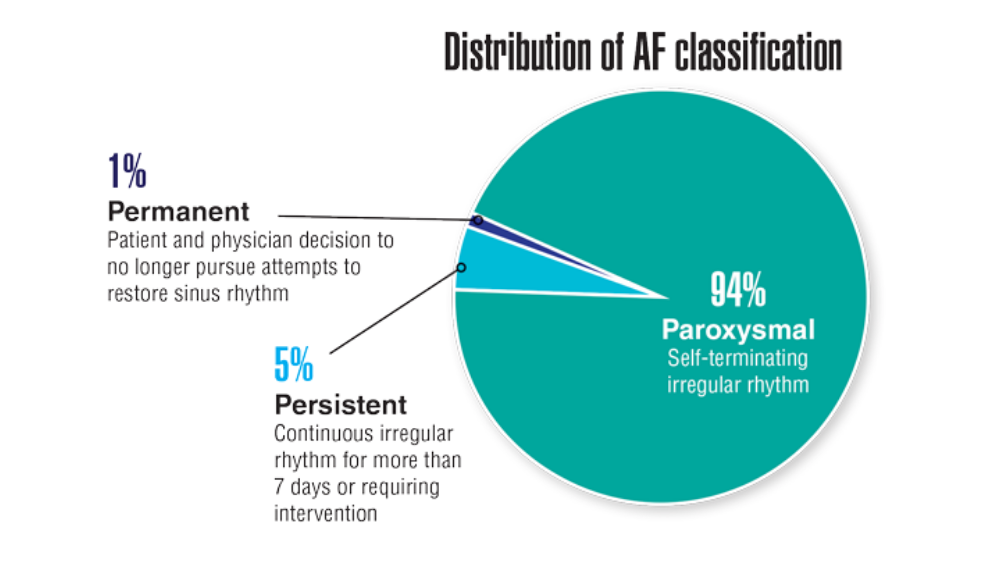

- Keithler AN, Wilson AS, Yuan A, Sosa JM, Bush KNV. Characteristics of United States military pilots with atrial fibrillation and deployment and retention rates. BMJ Mil Health. 2021;0:1-5. http://doi.org/10.1136/bmjmilitary-2020-001665

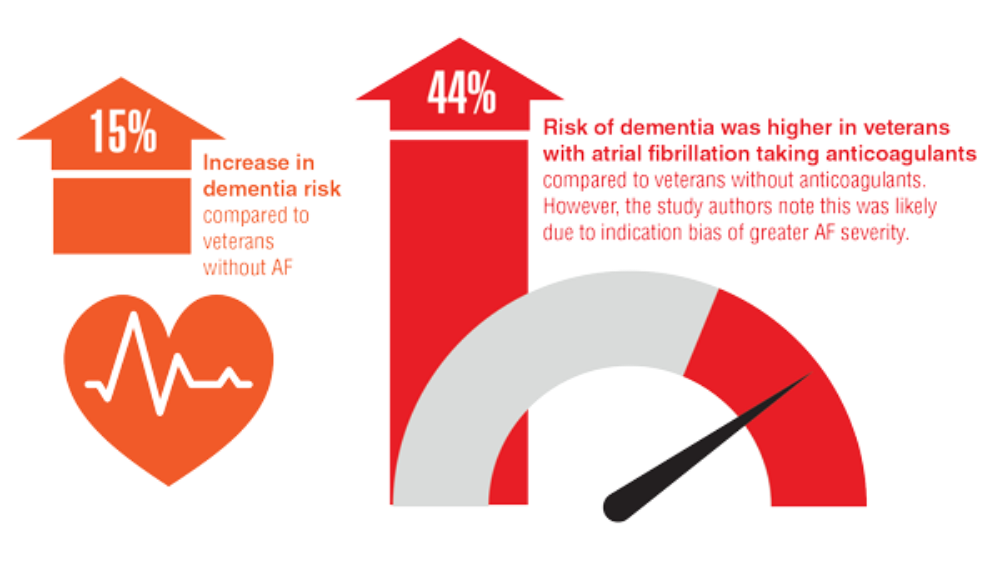

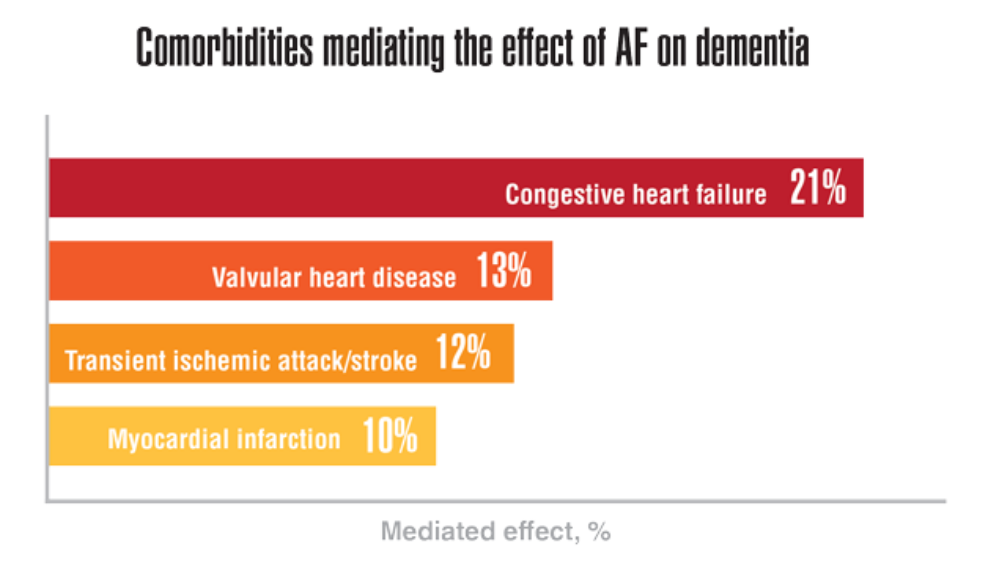

- Rouch L, Xia F, Bahorik A, Olgin J, Yaffe K. Atrial fibrillation is associated with greater risk of dementia in older veterans. J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;29(11):1092-1098. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2021.02.038

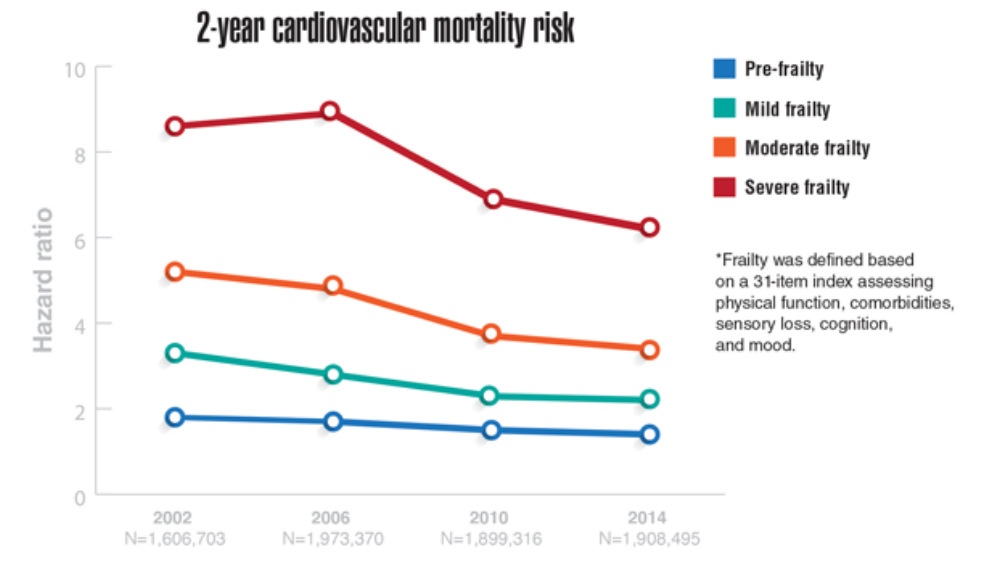

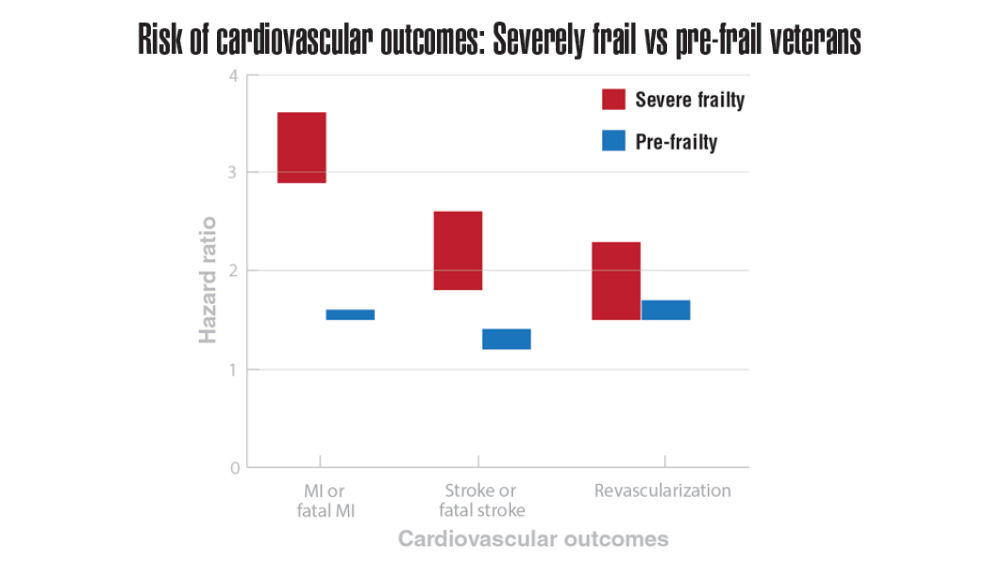

- Shrauner W, Lord EM, Nguyen XMT, et al. Frailty and cardiovascular mortality in more than 3 million US veterans. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(8):818-826. http://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab850

- Howard JT, Stewart IJ, Kolaja CA, et al. Hypertension in military veterans is associated with combat exposure and combat injury. J Hypertens. 2020;38(7):1293-1301. http://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000002364

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A closer look at African American men and high blood pressure control. Reviewed November 2, 2020. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/aa_sourcebook.htm

- CDC. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. What to expect and information collected. Reviewed November 16, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/participant/information-collected.htm

- Keaton JM, Hellwege JN, Giri A, et al. Associations of biogeographic ancestry with hypertension traits. J Hypertens. 2021;39(4):633-642. http://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000002701

- Groeneveld PW, Medvedeva EL, Walker L, Segal AG, Richardson DM, Epstein AJ. Outcomes of care for ischemic heart disease and chronic heart failure in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(7):563-571. http://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2018.1115

- Cho ME, Hansen JL, Sauer BC, Cheung AK, Agarwal A, Greene T. Heart failure hospitalization risk associated with iron status in veterans with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16(4):522-531. http://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.15360920

- Jackevicius CA, Lu L, Ghaznavi Z, Warner AL. Bleeding risk of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2021;14(2):e007230. http://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.007230

- Keithler AN, Wilson AS, Yuan A, Sosa JM, Bush KNV. Characteristics of United States military pilots with atrial fibrillation and deployment and retention rates. BMJ Mil Health. 2021;0:1-5. http://doi.org/10.1136/bmjmilitary-2020-001665

- Rouch L, Xia F, Bahorik A, Olgin J, Yaffe K. Atrial fibrillation is associated with greater risk of dementia in older veterans. J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;29(11):1092-1098. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2021.02.038

- Shrauner W, Lord EM, Nguyen XMT, et al. Frailty and cardiovascular mortality in more than 3 million US veterans. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(8):818-826. http://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab850

- Howard JT, Stewart IJ, Kolaja CA, et al. Hypertension in military veterans is associated with combat exposure and combat injury. J Hypertens. 2020;38(7):1293-1301. http://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000002364

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A closer look at African American men and high blood pressure control. Reviewed November 2, 2020. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/aa_sourcebook.htm

- CDC. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. What to expect and information collected. Reviewed November 16, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/participant/information-collected.htm

- Keaton JM, Hellwege JN, Giri A, et al. Associations of biogeographic ancestry with hypertension traits. J Hypertens. 2021;39(4):633-642. http://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000002701

- Groeneveld PW, Medvedeva EL, Walker L, Segal AG, Richardson DM, Epstein AJ. Outcomes of care for ischemic heart disease and chronic heart failure in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(7):563-571. http://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2018.1115

- Cho ME, Hansen JL, Sauer BC, Cheung AK, Agarwal A, Greene T. Heart failure hospitalization risk associated with iron status in veterans with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16(4):522-531. http://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.15360920

- Jackevicius CA, Lu L, Ghaznavi Z, Warner AL. Bleeding risk of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2021;14(2):e007230. http://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.007230

- Keithler AN, Wilson AS, Yuan A, Sosa JM, Bush KNV. Characteristics of United States military pilots with atrial fibrillation and deployment and retention rates. BMJ Mil Health. 2021;0:1-5. http://doi.org/10.1136/bmjmilitary-2020-001665

- Rouch L, Xia F, Bahorik A, Olgin J, Yaffe K. Atrial fibrillation is associated with greater risk of dementia in older veterans. J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;29(11):1092-1098. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2021.02.038

- Shrauner W, Lord EM, Nguyen XMT, et al. Frailty and cardiovascular mortality in more than 3 million US veterans. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(8):818-826. http://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab850

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022: Chronic Kidney Disease

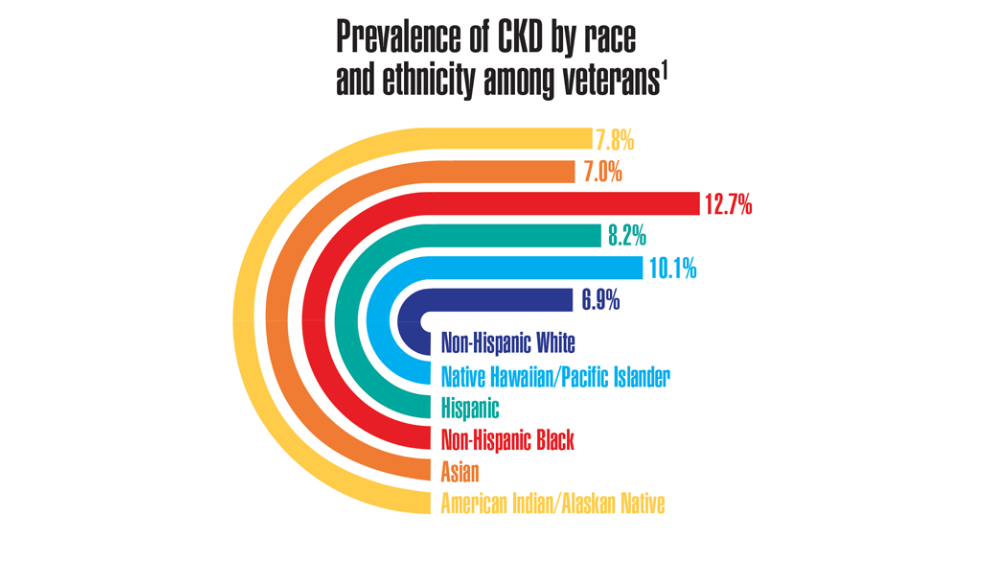

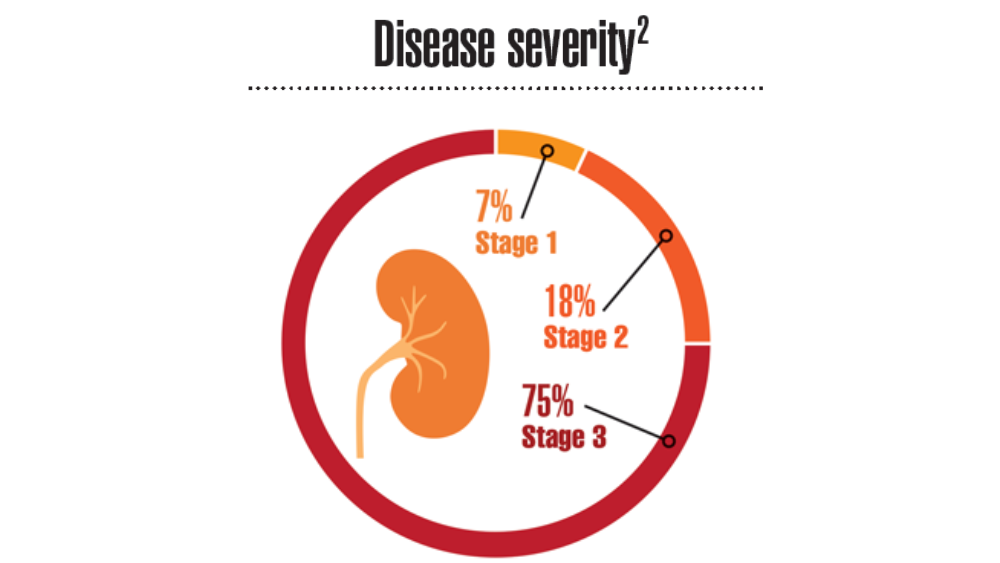

- Kidney disease in veterans. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated May 13, 2020. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Kidney_Disease_In_Veterans.asp

- Ozieh MN, Gebregziabher M, Ward RC, Taber DJ, Egede LE. Creating a 13-year National Longitudinal Cohort of veterans with chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:241. http://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-019-1430-y

- Patel N, Golzy M, Nainani N, et al. Prevalence of various comorbidities among veterans with chronic kidney disease and its comparison with other datasets. Ren Fail. 2016;38(2):204-208. http://doi.org/10.3109/0886022X.2015.1117924

- Kidney disease in veterans. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated May 13, 2020. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Kidney_Disease_In_Veterans.asp

- Ozieh MN, Gebregziabher M, Ward RC, Taber DJ, Egede LE. Creating a 13-year National Longitudinal Cohort of veterans with chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:241. http://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-019-1430-y

- Patel N, Golzy M, Nainani N, et al. Prevalence of various comorbidities among veterans with chronic kidney disease and its comparison with other datasets. Ren Fail. 2016;38(2):204-208. http://doi.org/10.3109/0886022X.2015.1117924

- Kidney disease in veterans. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated May 13, 2020. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Kidney_Disease_In_Veterans.asp

- Ozieh MN, Gebregziabher M, Ward RC, Taber DJ, Egede LE. Creating a 13-year National Longitudinal Cohort of veterans with chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:241. http://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-019-1430-y

- Patel N, Golzy M, Nainani N, et al. Prevalence of various comorbidities among veterans with chronic kidney disease and its comparison with other datasets. Ren Fail. 2016;38(2):204-208. http://doi.org/10.3109/0886022X.2015.1117924

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022: The Cancer-Obesity Connection

- VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of adult overweight and obesity. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. Version 3.0. 2020. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/obesity/VADoDObesityCPGFinal5087242020.pdf

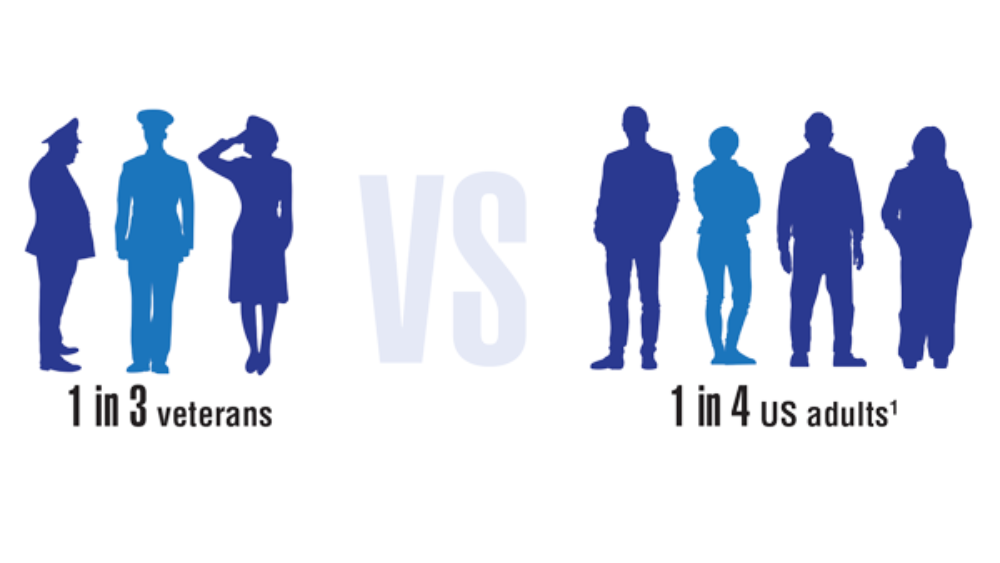

- Obesity and overweight. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated September 10, 2021. Accessed March 18, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm

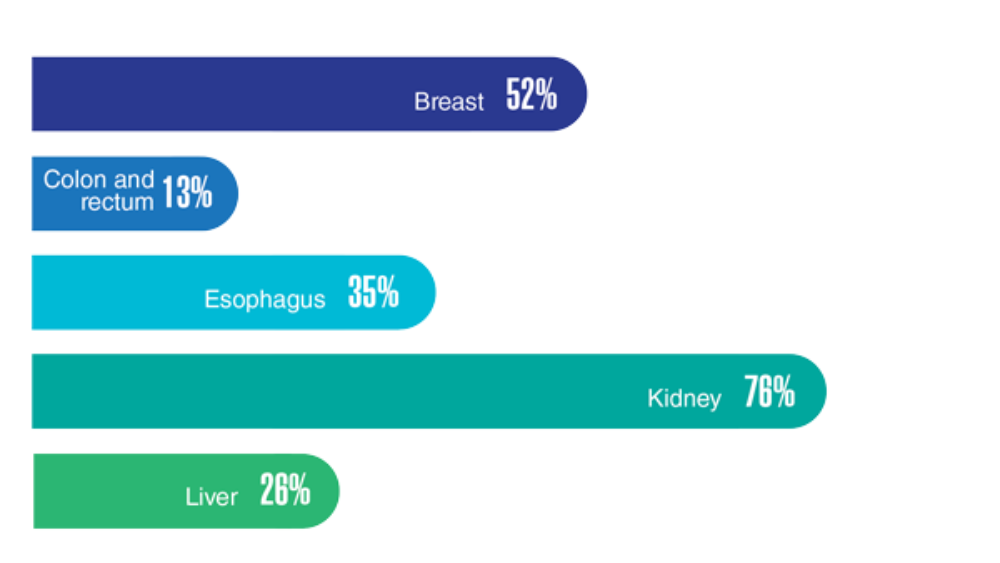

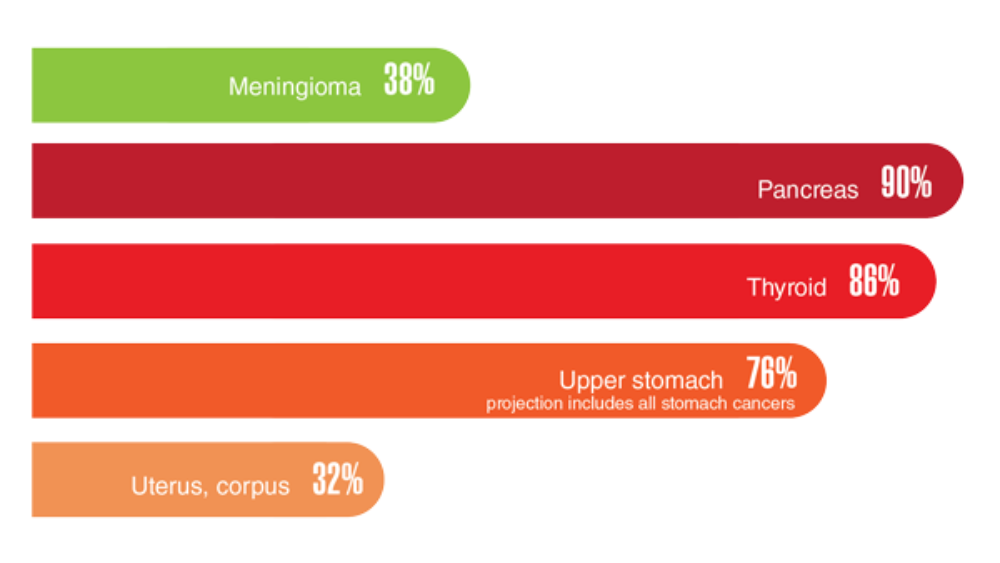

- Obesity and cancer. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated February 18, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/obesity/index.htm

- Nelson KM. The burden of obesity among a national probability sample of veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(9):915-919. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00526.x

- Schult TM, Schmunk SK, Marzolf JR, Mohr DC. The health status of veteran employees compared to civilian employees in Veterans Health Administration. Mil Med. 2019;184(7-8):e218-e224. http://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy410

- Weir HK, Thompson TD, Stewart SL, White MC. Cancer incidence projections in the United States between 2015 and 2050. Prev Chronic Dis. 2021;18:E59. http://doi.org/10.5888/pcd18.210006

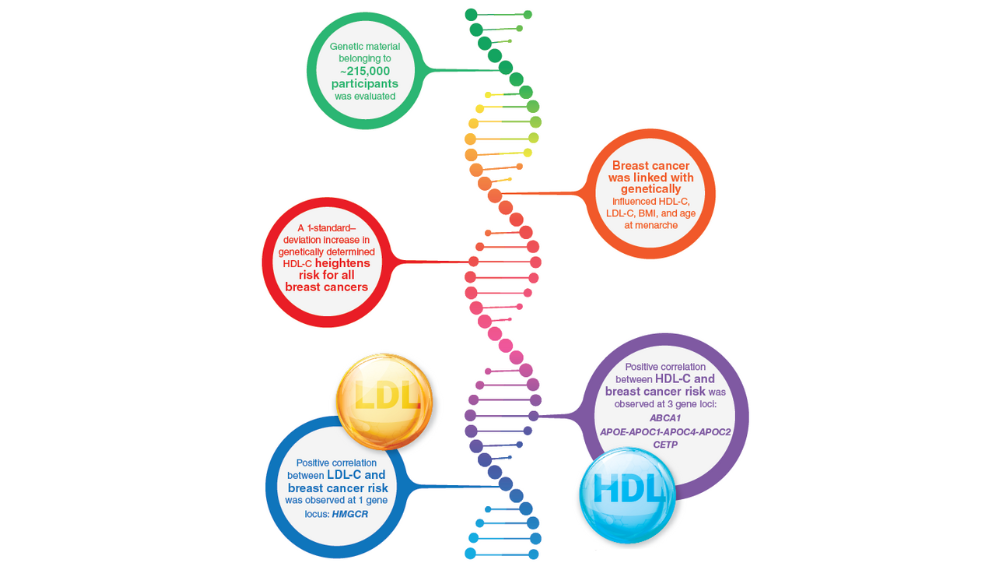

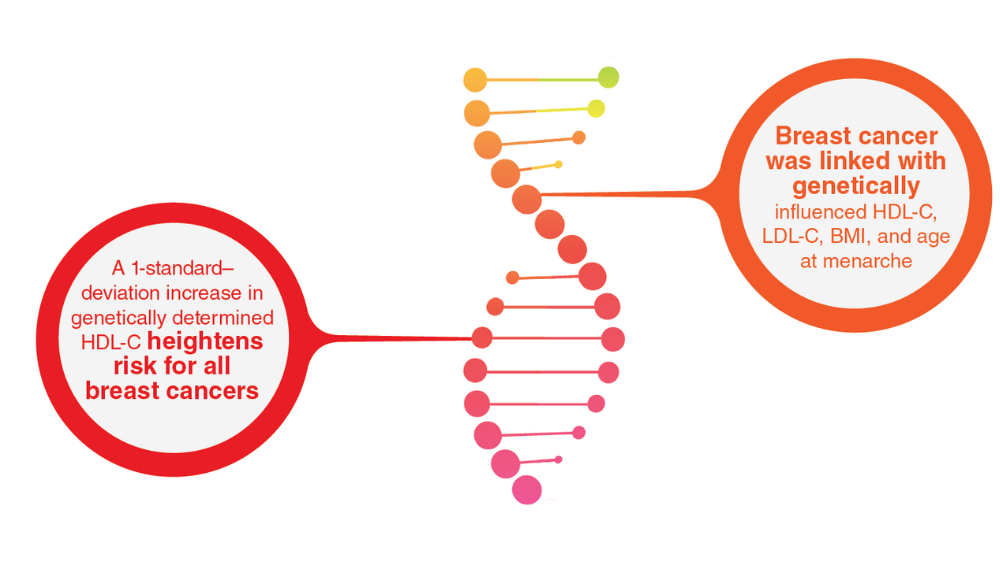

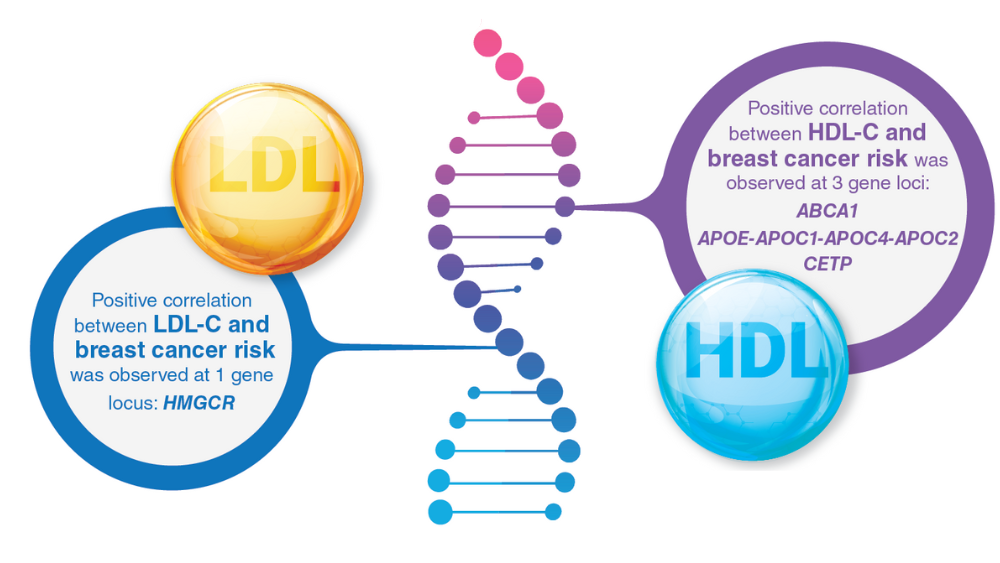

- Johnson KE, Siewert KM, Klarin D, et al. The relationship between circulating lipids and breast cancer risk: a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(9):e1003302. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.100330

- MOVE! weight management program. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated May 2, 2022. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://www.move.va.gov/

- Gray KE, Hoerster KD, Spohr SA, Breland JY, Raffa SD. National Veterans Health Administration MOVE! weight management program participation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Chronic Dis. 2022;19:E11. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd19.210303

- VA Office of Patient Centered Care & Cultural Transformation (email, May 27, 2022).

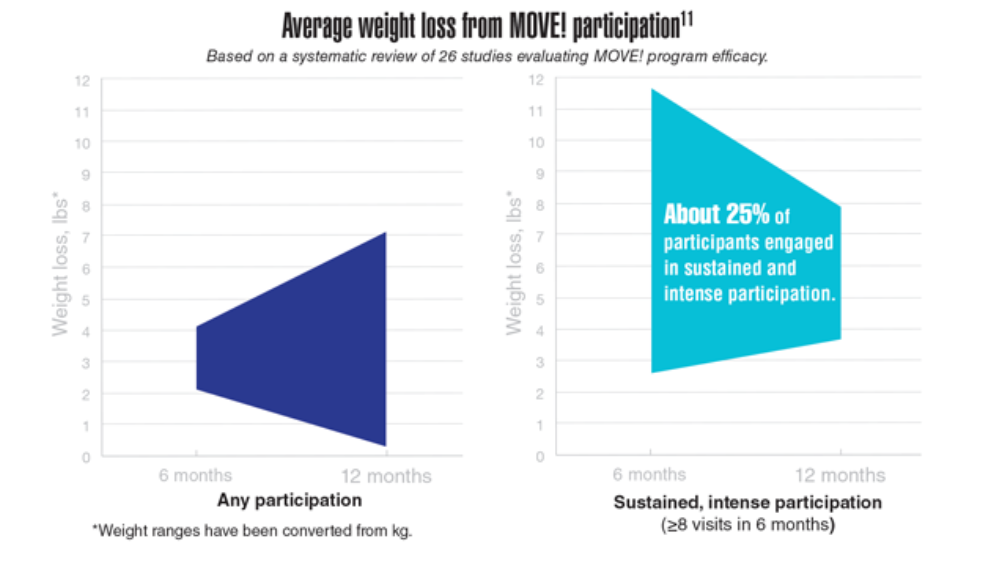

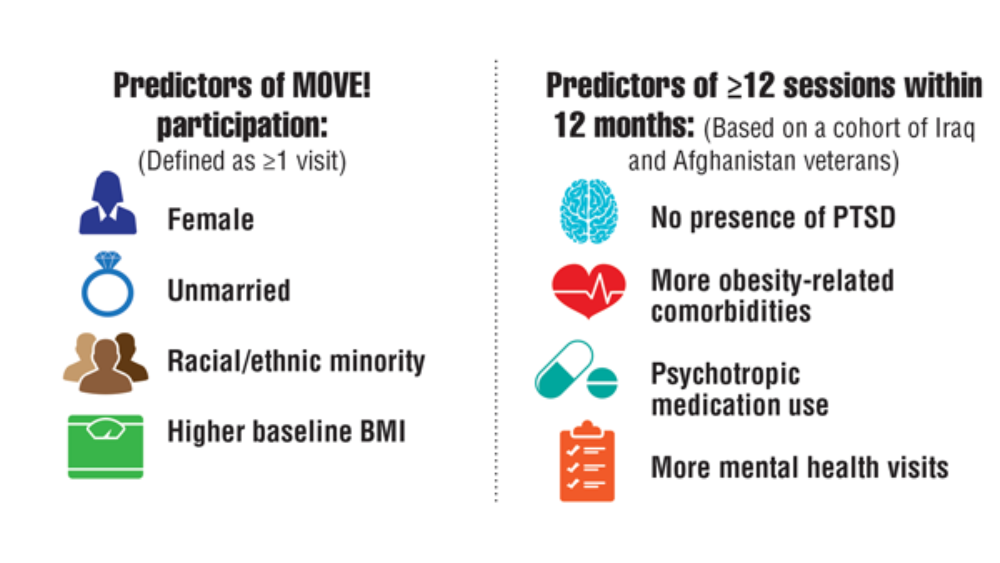

- Maciejewski ML, Shepherd-Banigan M, Raffa SD, Weidenbacher HJ. Systematic review of behavioral weight management program MOVE! for veterans. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(5):704-714. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.029

- VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of adult overweight and obesity. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. Version 3.0. 2020. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/obesity/VADoDObesityCPGFinal5087242020.pdf

- Obesity and overweight. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated September 10, 2021. Accessed March 18, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm

- Obesity and cancer. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated February 18, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/obesity/index.htm

- Nelson KM. The burden of obesity among a national probability sample of veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(9):915-919. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00526.x

- Schult TM, Schmunk SK, Marzolf JR, Mohr DC. The health status of veteran employees compared to civilian employees in Veterans Health Administration. Mil Med. 2019;184(7-8):e218-e224. http://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy410

- Weir HK, Thompson TD, Stewart SL, White MC. Cancer incidence projections in the United States between 2015 and 2050. Prev Chronic Dis. 2021;18:E59. http://doi.org/10.5888/pcd18.210006

- Johnson KE, Siewert KM, Klarin D, et al. The relationship between circulating lipids and breast cancer risk: a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(9):e1003302. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.100330

- MOVE! weight management program. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated May 2, 2022. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://www.move.va.gov/

- Gray KE, Hoerster KD, Spohr SA, Breland JY, Raffa SD. National Veterans Health Administration MOVE! weight management program participation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Chronic Dis. 2022;19:E11. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd19.210303

- VA Office of Patient Centered Care & Cultural Transformation (email, May 27, 2022).

- Maciejewski ML, Shepherd-Banigan M, Raffa SD, Weidenbacher HJ. Systematic review of behavioral weight management program MOVE! for veterans. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(5):704-714. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.029

- VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of adult overweight and obesity. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. Version 3.0. 2020. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/obesity/VADoDObesityCPGFinal5087242020.pdf

- Obesity and overweight. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated September 10, 2021. Accessed March 18, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm

- Obesity and cancer. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated February 18, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/obesity/index.htm

- Nelson KM. The burden of obesity among a national probability sample of veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(9):915-919. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00526.x

- Schult TM, Schmunk SK, Marzolf JR, Mohr DC. The health status of veteran employees compared to civilian employees in Veterans Health Administration. Mil Med. 2019;184(7-8):e218-e224. http://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy410

- Weir HK, Thompson TD, Stewart SL, White MC. Cancer incidence projections in the United States between 2015 and 2050. Prev Chronic Dis. 2021;18:E59. http://doi.org/10.5888/pcd18.210006

- Johnson KE, Siewert KM, Klarin D, et al. The relationship between circulating lipids and breast cancer risk: a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(9):e1003302. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.100330

- MOVE! weight management program. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated May 2, 2022. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://www.move.va.gov/

- Gray KE, Hoerster KD, Spohr SA, Breland JY, Raffa SD. National Veterans Health Administration MOVE! weight management program participation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Chronic Dis. 2022;19:E11. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd19.210303

- VA Office of Patient Centered Care & Cultural Transformation (email, May 27, 2022).

- Maciejewski ML, Shepherd-Banigan M, Raffa SD, Weidenbacher HJ. Systematic review of behavioral weight management program MOVE! for veterans. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(5):704-714. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.029

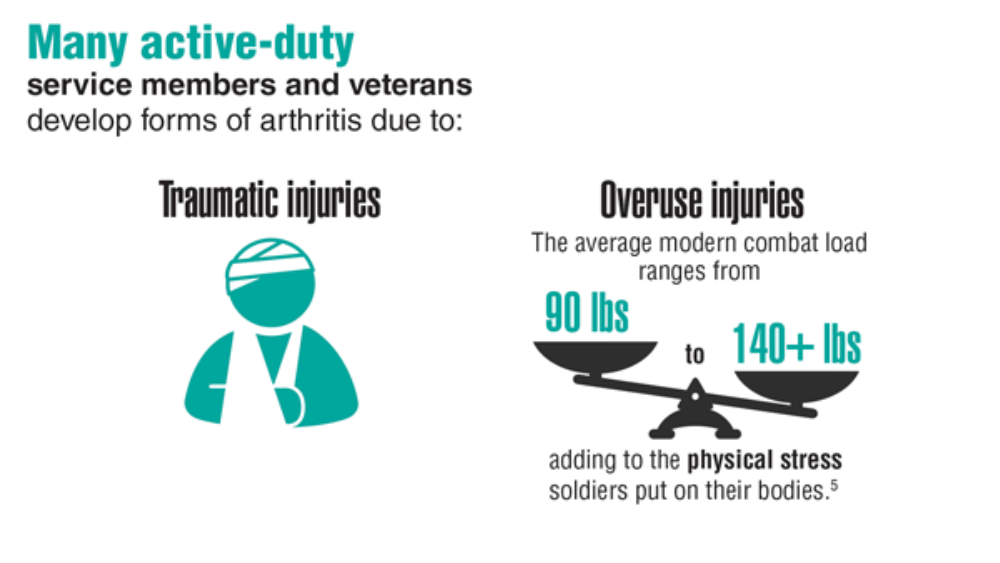

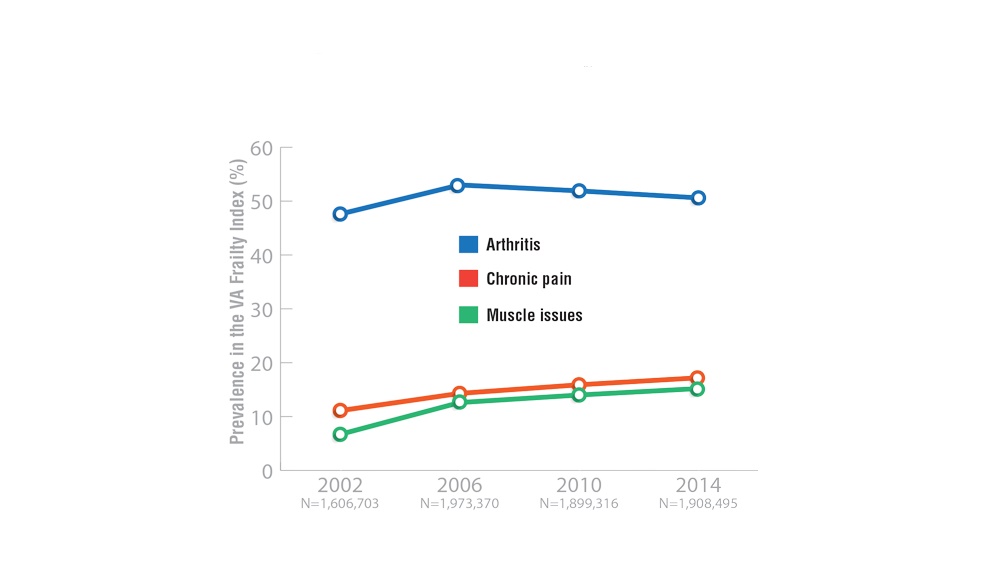

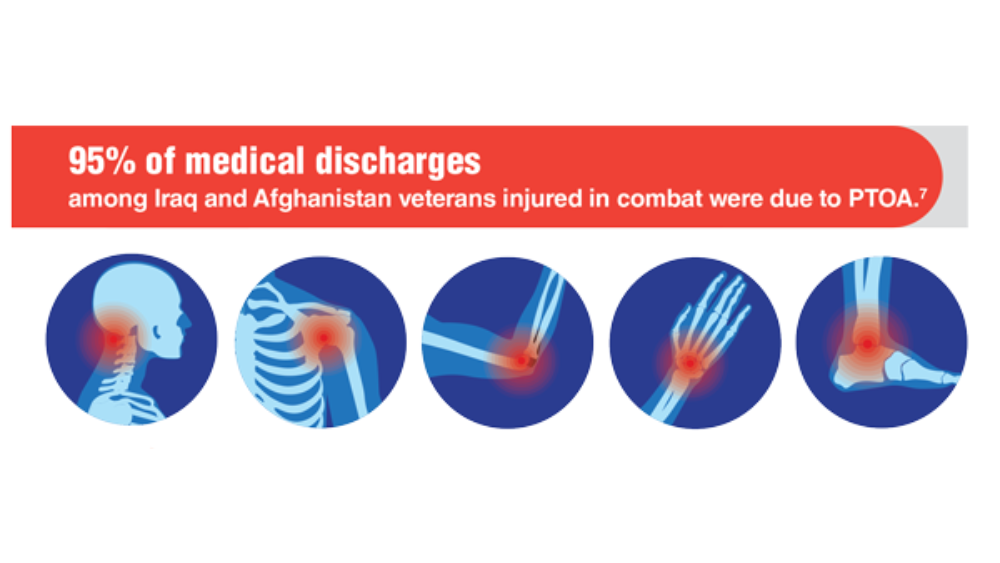

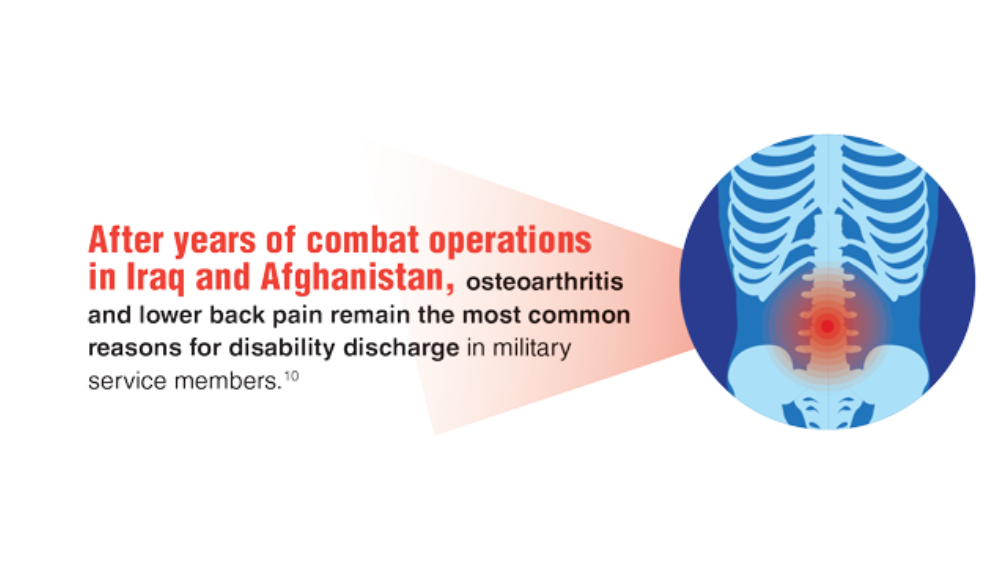

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022: Rheumatologic Diseases

- Arthritis help for veterans. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 10, 2020. Accessed March 20, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/communications/features/arthritis-among-veterans.html

- Cameron KL, Hsiao MS, Owens BD, Burks R, Svoboda SJ. Incidence of physician-diagnosed osteoarthritis among active duty United States military service members. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(10):2974-2982. http://doi.org/10.1002/art.30498

- Ebel AV, Lutt G, Poole JA, et al. Association of agricultural, occupational, and military inhalants with autoantibodies and disease features in US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(3):392-400. http://doi.org/10.1002/art.41559

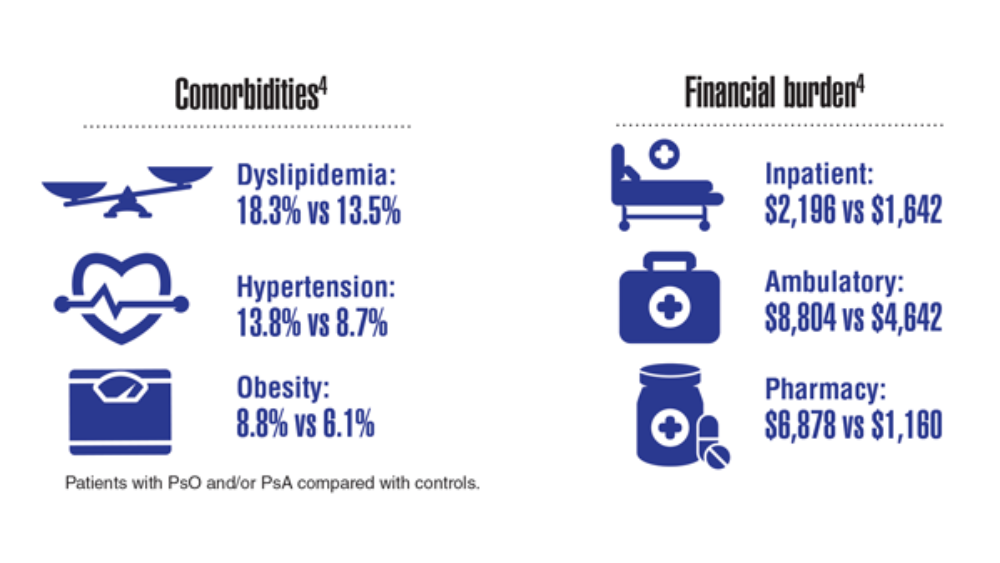

- Lee S, Xie L, Wang Y, Vaidya N, Baser O. Comorbidity and economic burden among moderate-to-severe psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis patients in the US Department of Defense population. J Med Econ. 2018;21(6):564-570. http://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2018.1431921

- Fish L, Scharre P. The soldier’s heavy load. Center for a New American Security. Published September 26, 2018. Accessed April 27, 2022. https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/the-soldiers-heavy-load-1

- Shrauner W, Lord EM, Nguyen XMT, et al. Frailty and cardiovascular mortality in more than 3 million US veterans. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(8):818-826. http://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab850

- Tyrer J. Military service leads to post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Published April 2021. Accessed March 25, 2022. https://www.arthritis.org/diseases/more-about/military-service-leads-to-post-traumatic-osteoarth

- Cameron KL, Shing TL, Kardouni JR. The incidence of post-traumatic osteoarthritis in the knee in active duty military personnel compared to estimates in the general population. Presented at the Osteoarthritis Research Society International World Congress on Osteoarthritis, April 27-30, 2017, Las Vegas, NV.

- Rivera JD, Wenke JC, Buckwalter JA, Ficke JR, Johnson AE. Posttraumatic osteoarthritis caused by battlefield injuries: The primary source of disability in warriors. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(01):S64-S69. http://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-20-08-S64

- Patzkowski JC, Rivera JC, FIcke JR, Wenke JC. The changing face of disability in the US Army: The Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom Effect. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012; 20(S1): S23-S30. http://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-20-08-S23

- Related conditions of psoriasis. National Psoriasis Foundation. Updated October 8, 2020. Accessed March 25, 2022. https://www.psoriasis.org/related-conditions/

- Arthritis help for veterans. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 10, 2020. Accessed March 20, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/communications/features/arthritis-among-veterans.html

- Cameron KL, Hsiao MS, Owens BD, Burks R, Svoboda SJ. Incidence of physician-diagnosed osteoarthritis among active duty United States military service members. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(10):2974-2982. http://doi.org/10.1002/art.30498

- Ebel AV, Lutt G, Poole JA, et al. Association of agricultural, occupational, and military inhalants with autoantibodies and disease features in US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(3):392-400. http://doi.org/10.1002/art.41559

- Lee S, Xie L, Wang Y, Vaidya N, Baser O. Comorbidity and economic burden among moderate-to-severe psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis patients in the US Department of Defense population. J Med Econ. 2018;21(6):564-570. http://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2018.1431921

- Fish L, Scharre P. The soldier’s heavy load. Center for a New American Security. Published September 26, 2018. Accessed April 27, 2022. https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/the-soldiers-heavy-load-1

- Shrauner W, Lord EM, Nguyen XMT, et al. Frailty and cardiovascular mortality in more than 3 million US veterans. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(8):818-826. http://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab850

- Tyrer J. Military service leads to post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Published April 2021. Accessed March 25, 2022. https://www.arthritis.org/diseases/more-about/military-service-leads-to-post-traumatic-osteoarth

- Cameron KL, Shing TL, Kardouni JR. The incidence of post-traumatic osteoarthritis in the knee in active duty military personnel compared to estimates in the general population. Presented at the Osteoarthritis Research Society International World Congress on Osteoarthritis, April 27-30, 2017, Las Vegas, NV.

- Rivera JD, Wenke JC, Buckwalter JA, Ficke JR, Johnson AE. Posttraumatic osteoarthritis caused by battlefield injuries: The primary source of disability in warriors. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(01):S64-S69. http://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-20-08-S64

- Patzkowski JC, Rivera JC, FIcke JR, Wenke JC. The changing face of disability in the US Army: The Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom Effect. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012; 20(S1): S23-S30. http://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-20-08-S23

- Related conditions of psoriasis. National Psoriasis Foundation. Updated October 8, 2020. Accessed March 25, 2022. https://www.psoriasis.org/related-conditions/

- Arthritis help for veterans. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 10, 2020. Accessed March 20, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/communications/features/arthritis-among-veterans.html

- Cameron KL, Hsiao MS, Owens BD, Burks R, Svoboda SJ. Incidence of physician-diagnosed osteoarthritis among active duty United States military service members. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(10):2974-2982. http://doi.org/10.1002/art.30498

- Ebel AV, Lutt G, Poole JA, et al. Association of agricultural, occupational, and military inhalants with autoantibodies and disease features in US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(3):392-400. http://doi.org/10.1002/art.41559

- Lee S, Xie L, Wang Y, Vaidya N, Baser O. Comorbidity and economic burden among moderate-to-severe psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis patients in the US Department of Defense population. J Med Econ. 2018;21(6):564-570. http://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2018.1431921

- Fish L, Scharre P. The soldier’s heavy load. Center for a New American Security. Published September 26, 2018. Accessed April 27, 2022. https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/the-soldiers-heavy-load-1

- Shrauner W, Lord EM, Nguyen XMT, et al. Frailty and cardiovascular mortality in more than 3 million US veterans. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(8):818-826. http://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab850

- Tyrer J. Military service leads to post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Published April 2021. Accessed March 25, 2022. https://www.arthritis.org/diseases/more-about/military-service-leads-to-post-traumatic-osteoarth

- Cameron KL, Shing TL, Kardouni JR. The incidence of post-traumatic osteoarthritis in the knee in active duty military personnel compared to estimates in the general population. Presented at the Osteoarthritis Research Society International World Congress on Osteoarthritis, April 27-30, 2017, Las Vegas, NV.

- Rivera JD, Wenke JC, Buckwalter JA, Ficke JR, Johnson AE. Posttraumatic osteoarthritis caused by battlefield injuries: The primary source of disability in warriors. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(01):S64-S69. http://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-20-08-S64

- Patzkowski JC, Rivera JC, FIcke JR, Wenke JC. The changing face of disability in the US Army: The Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom Effect. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012; 20(S1): S23-S30. http://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-20-08-S23

- Related conditions of psoriasis. National Psoriasis Foundation. Updated October 8, 2020. Accessed March 25, 2022. https://www.psoriasis.org/related-conditions/

Value of a Pharmacy-Adjudicated Community Care Prior Authorization Drug Request Service

Veterans’ access to medical care was expanded outside of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities with the inception of the 2014 Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act (Choice Act).1 This legislation aimed to remove barriers some veterans were experiencing, specifically access to health care. In subsequent years, approximately 17% of veterans receiving care from the VA did so under the Choice Act.2 The Choice Act positively impacted medical care access for veterans but presented new challenges for VA pharmacies processing community care (CC) prescriptions, including limited access to outside health records, lack of interface between CC prescribers and the VA order entry system, and limited awareness of the VA national formulary.3,4 These factors made it difficult for VA pharmacies to assess prescriptions for clinical appropriateness, evaluate patient safety parameters, and manage expenditures.

In 2019, the Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act, which expanded CC support and better defined which veterans are able to receive care outside the VA, updated the Choice Act.4,5 However, VA pharmacies faced challenges in managing pharmacy drug costs and ensuring clinical appropriateness of prescription drug therapy. As a result, VA pharmacy departments have adjusted how they allocate workload, time, and funds.5

Pharmacists improve clinical outcomes and reduce health care costs by decreasing medication errors, unnecessary prescribing, and adverse drug events.6-12 Pharmacist-driven formulary management through evaluation of prior authorization drug requests (PADRs) has shown economic value.13,14 VA pharmacy review of community care PADRs is important because outside health care professionals (HCPs) might not be familiar with the VA formulary. This could lead to high volume of PADRs that do not meet criteria and could result in increased potential for medication misuse, adverse drug events, medication errors, and cost to the health system. It is imperative that CC orders are evaluated as critically as traditional orders.

The value of a centralized CC pharmacy team has not been assessed in the literature. The primary objective of this study was to assess the direct cost savings achieved through a centralized CC PADR process. Secondary objectives were to characterize the CC PADRs submitted to the site, including approval rate, reason for nonapproval, which medications were requested and by whom, and to compare CC prescriptions with other high-complexity (1a) VA facilities.

Community Care Pharmacy

VA health systems are stratified according to complexity, which reflects size, patient population, and services offered. This study was conducted at the Durham Veterans Affairs Health Care System (DVAHCS), North Carolina, a high-complexity, 251-bed, tertiary care referral, teaching, and research system. DVAHCS provides general and specialty medical, surgical, inpatient psychiatric, and ambulatory services, and serves as a major referral center.

DVAHCS created a centralized pharmacy team for processing CC prescriptions and managing customer service. This team’s goal is to increase CC prescription processing efficiency and transparency, ensure accountability of the health care team, and promote veteran-centric customer service. The pharmacy team includes a pharmacist program manager and a dedicated CC pharmacist with administrative support from a health benefits assistant and 4 pharmacy technicians. The CC pharmacy team assesses every new prescription to ensure the veteran is authorized to receive care in the community. Once eligibility is verified, a pharmacy technician or pharmacist evaluates the prescription to ensure it contains all required information, then contacts the prescriber for any missing data. If clinically appropriate, the pharmacist processes the prescription.

In 2020, the CC pharmacy team implemented a new process for reviewing and documenting CC prescriptions that require a PADR. The closed national VA formulary is set up so that all nonformulary medications and some formulary medications, including those that are restricted because of safety and/or cost, require a PADR.15 After a CC pharmacy technician confirms a veteran’s eligibility, the technician assesses whether the requested medication requires submitting a PADR to the VA internal electronic health record. The PADR is then adjudicated by a formulary management pharmacist, CC program manager, or CC pharmacist who reviews health records to determine whether the CC prescription meets VA medication use policy requirements.

If additional information is needed or an alternate medication is suggested, the pharmacist comments back on the PADR and a CC pharmacy technician contacts the prescriber. The PADR is canceled administratively then resubmitted once all information is obtained. While waiting for a response from the prescriber, the CC pharmacy technician contacts that veteran to give an update on the prescription status, as appropriate. Once there is sufficient information to adjudicate the PADR, the outcome is documented, and if approved, the order is processed.

Methods

The DVAHCS Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective review of CC PADRs submitted from June 1, 2020, through November 30, 2020. CC PADRs were excluded if they were duplicates or were reactivated administratively but had an initial submission date before the study period. Local data were collected for nonapproved CC PADRs including drug requested, dosage and directions, medication specialty, alternative drug recommended, drug acquisition cost, PADR submission date, PADR completion date, PADR nonapproval rationale, and documented time spent per PADR. Additional data was obtained for CC prescriptions at all 42 high-complexity VA facilities from the VA national CC prescription database for the study time interval and included total PADRs, PADR approval status, total CC prescription cost, and total CC fills.

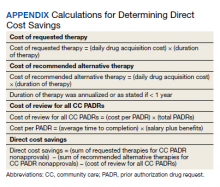

Direct cost savings were calculated by assessing the cost of requested therapy that was not approved minus the cost of recommended therapy and cost to review all PADRs, as described by Britt and colleagues.13 The cost of the requested and recommended therapy was calculated based on VA drug acquisition cost at time of data collection and multiplied by the expected duration of therapy up to 1 year. For each CC prescription, duration of therapy was based on the duration limit in the prescription or annualized if no duration limit was documented. Cost of PADR review was calculated based on the total time pharmacists and pharmacy technicians documented for each step of the review process for a representative sample of 100 nonapproved PADRs and then multiplied by the salary plus benefits of an entry-level pharmacist and pharmacy technician.16 The eAppendix describes specific equations used for determining direct cost savings. Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate study results.

Results

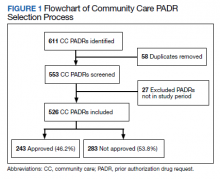

During the 6-month study period, 611 CC PADRs were submitted to the pharmacy and 526 met inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Of those, 243 (46.2%) were approved and 283 (53.8%) were not approved. The cost of requested therapies for nonapproved CC PADRs totaled $584,565.48 and the cost of all recommended therapies was $57,473.59. The mean time per CC PADR was 24 minutes; 16 minutes for pharmacists and 8 minutes for pharmacy technicians. Given an hourly wage (plus benefits) of $67.25 for a pharmacist and $25.53 for a pharmacy technician, the total cost of review per CC PADR was $21.33. After subtracting the costs of all recommended therapies and review of all included CC PADRs, the process generated $515,872.31 in direct cost savings. After factoring in administrative lag time, such as HCP communication, an average of 8 calendar days was needed to complete a nonapproved PADR.

The most common rationale for PADR nonapproval was that the formulary alternative was not exhausted. Ondansetron orally disintegrating tablets was the most commonly nonapproved medication and azelastine was the most commonly approved medication. Dulaglutide was the most expensive nonapproved and tafamidis was the most expensive approved PADR (Table 1). Gastroenterology, endocrinology, and neurology were the top specialties for nonapproved PADRs while neurology, pulmonology, and endocrinology were the top specialties for approved PADRs (Table 2).

Several high-complexity VA facilities had no reported data; we used the median for the analysis to account for these outliers (Figure 2). The median (IQR) adjudicated CC PADRs for all facilities was 97 (20-175), median (IQR) CC PADR approval rate was 80.9% (63.7%-96.8%), median (IQR) total CC prescriptions was 8440 (2464-14,466), and median (IQR) cost per fill was $136.05 ($76.27-$221.28).

Discussion

This study demonstrated direct cost savings of $515,872.31 over 6 months with theadjudication of CC PADRs by a centralized CC pharmacy team. This could result in > $1,000,000 of cost savings per fiscal year.

The CC PADRs observed at DVAHCS had a 46.2% approval rate; almost one-half the approval rate of 84.1% of all PADRs submitted to the study site by VA HCPs captured by Britt and colleagues.13 Results from this study showed that coordination of care for nonapproved CC PADRs between the VA pharmacy and non-VA prescriber took an average of 8 calendar days. The noted CC PADR approval rate and administrative burden might be because of lack of familiarity of non-VA providers regarding the VA national formulary. The National VA Pharmacy Benefits Management determines the formulary using cost-effectiveness criteria that considers the medical literature and VA-specific contract pricing and prepares extensive guidance for restricted medications via relevant criteria for use.15 HCPs outside the VA might not know this information is available online. Because gastroenterology, endocrinology, and neurology specialty medications were among the most frequently nonapproved PADRs, VA formulary education could begin with CC HCPs in these practice areas.

This study showed that the CC PADR process was not solely driven by cost, but also included patient safety. Nonapproval rationale for some requests included submission without an indication, submission by a prescriber that did not have the authority to prescribe a type of medication, or contraindication based on patient-specific factors.

Compared with other VA high-complexity facilities, DVAHCS was among the top health care systems for total volume of CC prescriptions (n = 16,096) and among the lowest for cost/fill ($75.74). Similarly, DVAHCS was among the top sites for total adjudicated CC PADRs within the 6-month study period (n = 611) and the lowest approval rate (44.2%). This study shows that despite high volumes of overall CC prescriptions and CC PADRs, it is possible to maintain a low overall CC prescription cost/fill compared with other similarly complex sites across the country. Wide variance in reported results exists across high-complexity VA facilities because some sites had low to no CC fills and/or CC PADRs. This is likely a result of administrative differences when handling CC prescriptions and presents an opportunity to standardize this process nationally.

Limitations

CC PADRs were assessed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which might have resulted in lower-than-normal CC prescription and PADR volumes, therefore underestimating the potential for direct cost savings. Entry-level salary was used to demonstrate cost savings potential from the perspective of a newly hired CC team; however, the cost savings might have been less if the actual salaries of site personnel were higher. National contract pricing data were gathered at the time of data collection and might have been different than at the time of PADR submission. Chronic medication prescriptions were annualized, which could overestimate cost savings if the medication was discontinued or changed to an alternative therapy within that time period.

The study’s exclusion criteria could only be applied locally and did not include data received from the VA CC prescription database. This can be seen by the discrepancy in CC PADR approval rates from the local and national data (46.2% vs 44.2%, respectively) and CC PADR volume. High-complexity VA facility data were captured without assessing the CC prescription process at each site. As a result, definitive conclusions cannot be made regarding the impact of a centralized CC pharmacy team compared with other facilities.

Conclusions

Adjudication of CC PADRs by a centralized CC pharmacy team over a 6-month period provided > $500,000 in direct cost savings to a VA health care system. Considering the CC PADR approval rate seen in this study, the VA could allocate resources to educate CC providers about the VA formulary to increase the PADR approval rate and reduce administrative burden for VA pharmacies and prescribers. Future research should evaluate CC prescription handling practices at other VA facilities to compare the effectiveness among varying approaches and develop recommendations for a nationally standardized process.

Acknowledgments

Concept and design (AJJ, JNB, RBB, LAM, MD, MGH); acquisition of data (AJJ, MGH); analysis and interpretation of data (AJJ, JNB, RBB, LAM, MD, MGH); drafting of the manuscript (AJJ); critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (AJJ, JNB, RBB, LAM, MD, MGH); statistical analysis (AJJ); administrative, technical, or logistic support (LAM, MGH); and supervision (MGH).

1. Gellad WF, Cunningham FE, Good CB, et al. Pharmacy use in the first year of the Veterans Choice Program: a mixed-methods evaluation. Med Care. 2017(7 suppl 1);55:S26. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000661

2. Mattocks KM, Yehia B. Evaluating the veterans choice program: lessons for developing a high-performing integrated network. Med Care. 2017(7 suppl 1);55:S1-S3. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000743.

3. Mattocks KM, Mengeling M, Sadler A, Baldor R, Bastian L. The Veterans Choice Act: a qualitative examination of rapid policy implementation in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 2017;55(7 suppl 1):S71-S75. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000667

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1108.08: VHA formulary management process. November 2, 2016. Accessed June 9, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=3291

5. Massarweh NN, Itani KMF, Morris MS. The VA MISSION act and the future of veterans’ access to quality health care. JAMA. 2020;324:343-344. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4505

6. Jourdan JP, Muzard A, Goyer I, et al. Impact of pharmacist interventions on clinical outcome and cost avoidance in a university teaching hospital. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(6):1474-1481. doi:10.1007/s11096-018-0733-6

7. Lee AJ, Boro MS, Knapp KK, Meier JL, Korman NE. Clinical and economic outcomes of pharmacist recommendations in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59(21):2070-2077. doi:10.1093/ajhp/59.21.2070

8. Dalton K, Byrne S. Role of the pharmacist in reducing healthcare costs: current insights. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2017;6:37-46. doi:10.2147/IPRP.S108047

9. De Rijdt T, Willems L, Simoens S. Economic effects of clinical pharmacy interventions: a literature review. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(12):1161-1172. doi:10.2146/ajhp070506

10. Perez A, Doloresco F, Hoffman J, et al. Economic evaluation of clinical pharmacy services: 2001-2005. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(1):128. doi:10.1592/phco.29.1.128

11. Nesbit TW, Shermock KM, Bobek MB, et al. Implementation and pharmacoeconomic analysis of a clinical staff pharmacist practice model. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58(9):784-790. doi:10.1093/ajhp/58.9.784

12. Yang S, Britt RB, Hashem MG, Brown JN. Outcomes of pharmacy-led hepatitis C direct-acting antiviral utilization management at a Veterans Affairs medical center. J Manag Care Pharm. 2017;23(3):364-369. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.3.364

13. Britt RB, Hashem MG, Bryan WE III, Kothapalli R, Brown JN. Economic outcomes associated with a pharmacist-adjudicated formulary consult service in a Veterans Affairs medical center. J Manag Care Pharm. 2016;22(9):1051-1061. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.9.1051

14. Jacob S, Britt RB, Bryan WE, Hashem MG, Hale JC, Brown JN. Economic outcomes associated with safety interventions by a pharmacist-adjudicated prior authorization consult service. J Manag Care Pharm. 2019;25(3):411-416. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2019.25.3.411

15. Aspinall SL, Sales MM, Good CB, et al. Pharmacy benefits management in the Veterans Health Administration revisited: a decade of advancements, 2004-2014. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(9):1058-1063. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.9.1058

16. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer. Title 38 Pay Schedules. Updated January 26, 2022. Accessed June 9, 2022. https://www.va.gov/ohrm/pay

Veterans’ access to medical care was expanded outside of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities with the inception of the 2014 Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act (Choice Act).1 This legislation aimed to remove barriers some veterans were experiencing, specifically access to health care. In subsequent years, approximately 17% of veterans receiving care from the VA did so under the Choice Act.2 The Choice Act positively impacted medical care access for veterans but presented new challenges for VA pharmacies processing community care (CC) prescriptions, including limited access to outside health records, lack of interface between CC prescribers and the VA order entry system, and limited awareness of the VA national formulary.3,4 These factors made it difficult for VA pharmacies to assess prescriptions for clinical appropriateness, evaluate patient safety parameters, and manage expenditures.

In 2019, the Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act, which expanded CC support and better defined which veterans are able to receive care outside the VA, updated the Choice Act.4,5 However, VA pharmacies faced challenges in managing pharmacy drug costs and ensuring clinical appropriateness of prescription drug therapy. As a result, VA pharmacy departments have adjusted how they allocate workload, time, and funds.5

Pharmacists improve clinical outcomes and reduce health care costs by decreasing medication errors, unnecessary prescribing, and adverse drug events.6-12 Pharmacist-driven formulary management through evaluation of prior authorization drug requests (PADRs) has shown economic value.13,14 VA pharmacy review of community care PADRs is important because outside health care professionals (HCPs) might not be familiar with the VA formulary. This could lead to high volume of PADRs that do not meet criteria and could result in increased potential for medication misuse, adverse drug events, medication errors, and cost to the health system. It is imperative that CC orders are evaluated as critically as traditional orders.

The value of a centralized CC pharmacy team has not been assessed in the literature. The primary objective of this study was to assess the direct cost savings achieved through a centralized CC PADR process. Secondary objectives were to characterize the CC PADRs submitted to the site, including approval rate, reason for nonapproval, which medications were requested and by whom, and to compare CC prescriptions with other high-complexity (1a) VA facilities.

Community Care Pharmacy

VA health systems are stratified according to complexity, which reflects size, patient population, and services offered. This study was conducted at the Durham Veterans Affairs Health Care System (DVAHCS), North Carolina, a high-complexity, 251-bed, tertiary care referral, teaching, and research system. DVAHCS provides general and specialty medical, surgical, inpatient psychiatric, and ambulatory services, and serves as a major referral center.